749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes

~16-18 January 749 CE

by Jefferson Williams

in a coin hoard beneath a collapse layer in Bet She'an - Tsafrir and Foerster (1992b)

Introduction & Summary

Intensity Estimates

Textual Evidence

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damage and Chronology Reports from Textual Sources | |||||

| Byzantine and Syriac Writers - Introduction and Discussion | |||||

| Byzantine Writers - Paul the Deacon | Latin | Christian | End of the 8th c. CE | Lake Como, Italy |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Anastasius Bibliothecarius | Latin | Orthodox (Byzantium) | 871-874 CE | Rome |

|

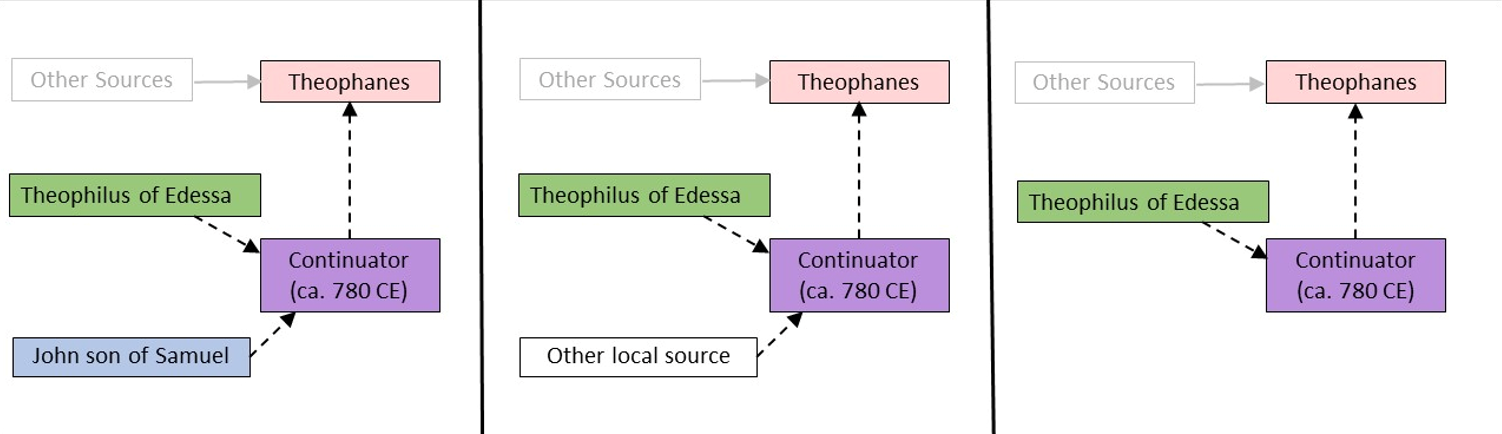

| Byzantine Writers - Theophanes | Greek | Orthodox (Byzantium) | 810-815 CE | Vicinity of Constantinople |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Nicephorus | Greek | Orthodox (Byzantium) | Early 9th c. CE | Constantinople |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Georgius Monachus | Greek | Christian | Last half of 9th c. CE | Constantinople |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Megas Chronographos | Greek | Christian | mid-9th c. CE | ? |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Cedrenus | Greek | Orthodox (Byzantium) | late 11th or early 12th century CE | Anatolia |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Minor Chronicles | Greek | Christian | ? | ? |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Joannes Zonaras | Greek | Christian | 1st half of 12th c. CE | vicinity of Constantinople |

|

| Byzantine Writers - Michael Glycas | Greek | Christian | 2nd half of the 12th century CE | vicinity of Constantinople |

|

| Syriac Writers - Introduction | |||||

| Syriac Writers - Dionysius of Tell-Mahre | Syriac | Syriac Orthodox Church | first half of the 9th century CE | Antioch, Syria |

|

| Syriac Writers - Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre vs. Dionysius of Tell-Mahre |

|

||||

| Syriac Writers - Theophilus of Edessa | Syriac | Chalcedonian Christian | Last Half of the 8th century CE | Edessa ?, Baghdad ? | see the accounts of Michael the Syrian and Chronicon Ad Annum 1234. |

| Syriac Writers - Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre | Syriac | Eastern Christian | 750-775 CE | Zuqnin Monastery |

|

| Syriac Writers - Earthquake Sound Travel and Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre | |||||

| Syriac Writers - Elias of Nisibis | Syriac and Arabic | Church of the East | Early 11th c. | Nusaybin, Turkey |

|

| Syriac Writers - Michael the Syrian | Syriac | Syriac Orthodox Church | late 12th century CE | probably at the Mor Bar Sauma Monastery near Tegenkar, Turkey |

|

| Syriac Writers - Chronicon Ad Annum 1234 | Syriac | beginning of the 13th c. CE | possibly in Edessa or the Monastery of Mar Bar Sauma near Tegenkar, Turkey |

|

|

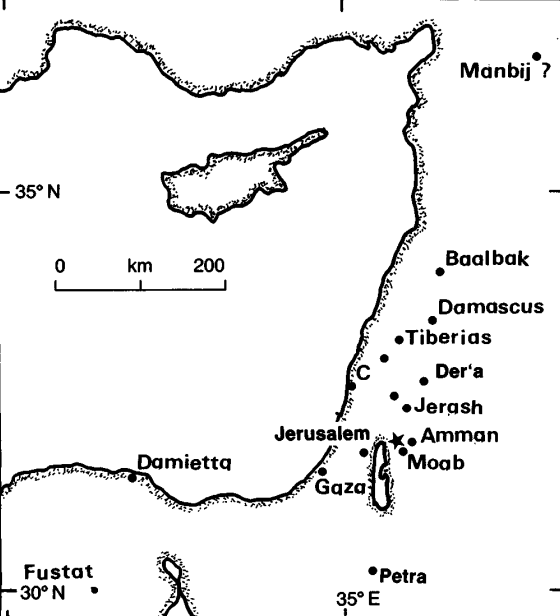

| Christian Writers in Arabic - Agapius of Menbij | Arabic | Melkite | 10th century CE | Manbij, Northern Syria |

|

| Christian Writers in Arabic - al-Muqaffa | Arabic | Coptic Christian | 10th century CE | Egypt |

|

| Christian Writers in Arabic - al-Makin | Arabic | Coptic Christian | 1262-1268 CE | Damascus (parts may have also been written in Cairo) |

|

| Christian Writers in Arabic - Chronicon Orientale | Arabic | Coptic Christian | 13th century CE |

|

|

| Greek Writers - Patriarch Nektarios | Greek | Greek Orthodox Christian | 1677 CE | Sinai peninsula or Jerusalem |

|

| Greek Writers - Tropologion Sin.Gr. ΜΓ 56+5 | Greek | Greek Orthodox Christian | 9th century CE | Jerusalem |

|

| Judaic Texts - Ra'ash shvi'it (רעש שביעית) | Hebrew | Judaism | Difficult to date |

|

|

| Judaic Texts - 10th-11th century book of prayers found in the Cairo Geniza | Hebrew | Judaism | 10th-11th c. |

|

|

| Samaritan Sources - Abu l’Fath | Arabic | Samaritan | 1355 CE |

|

|

| Samaritan Sources - Chronicle Adler | Arabic ? | Samaritan |

|

||

| Armenian Sources - Mekhitar d’Airavanq chronicle | Armenian | Before 1300 CE | Medieval monastery of Geghard |

|

|

| Muslim Writers - Introduction | |||||

| Muslim Writers - al-Masudi | Arabic | Muslim - Shi’ite | mid-10th century CE | Egypt ? |

|

| Muslim Writers - Description of Syria including Palestine by al-Maqdisi | Arabic | Muslim | ca. 985 CE | Jerusalem ? |

|

| Muslim Writers - The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions by al-Maqdisi | Arabic | Muslim | ca. 985 - 990 CE | Jerusalem ? |

|

| Muslim Writers - Ibn Nazif al-Hamawi | Arabic | Muslim | early 1230's CE | Homs, Syria |

|

| Muslim Writers - Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi | Arabic | Hanbali Sunni Muslim - may have had Shi'a tendencies (Keany, 2013:83) | 13th c. CE | Damascus |

|

| Muslim Writers - al-Dhahabi | Arabic | Muslim | Early 14th century CE | Damascus |

|

| Muslim Writers - Jamal ad Din Ahmad | Arabic | Muslim | 1351 CE | Jerusalem ? |

|

| Muslim Writers - Ibn Tagri Birdi | Arabic | Muslim | 15th c. CE | Cairo |

|

| Muslim Writers - as-Suyuti | Arabic | Sufi Muslim | 15th c. CE | Cairo |

|

| Muslim Writers - Mujir al-Din | Arabic | Hanbali Sunni Muslim | ca. 1495 CE | Jerusalem |

|

| Muslim Writers - Other Muslim Writers | Arabic | Muslim | |||

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

Archaeoseismic Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bet She'an | definitive | ≥ 8 | Tsafrir and Foerster (1992b) report that a coin hoard was found underneath a debris and collapse layer. The latest coin was in near mint condition and dated to A.H. 131 (31 Aug. 748 - 19 Aug. 749 CE). This coin provides a terminus post quem for the earthquake and, due to its near mint condition, likely a terminus ante quem as well. Because it is part of a hoard, it is unlikely to be intrusive. Widespread and extensive destruction indicates that Bet She'an experienced high levels of Intensity. |

| Bosra | possible | ≥ 8 | Sabbatical Year Earthquakes - January 749 CE - Michael the Syrian wrote that during one of the

Sabbatical Year Earthquakes in January 749 CE, Bosrah was swallowed up completely. Similarly, Chronicon Ad Annum 1234 reports that Bosrah was entirely swallowed up. Although neither source distinguishes between the Holy Desert Quake and the Talking Mule Quake within the Sabbatical Year sequence, Bosrah’s location near the Sea of Galilee suggests the destruction more likely occurred during the earlier Holy Desert Quake. |

| Jerash - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Jerash - Church of Saint Theodore | probable | ≥ 8 | Mid 8th century CE Earthquake -

Excavations at the Church of Saint Theodore in Jerash revealed compelling

evidence of destruction attributed to the

749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes.

Crowfoot (1929:19) noted that the collapse coincided with the latest material culture

found on the floor levels, consistent with a mid-8th century date. The destruction of the church is dated to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes based on stratigraphic context, 8th-century floor-level finds (Crowfoot, 1929:19), and structural collapse patterns consistent with earthquake damage reported throughout Jerash in this period (Walmsley, 2007). In both his 1929 and 1938 reports, Crowfoot described the collapsed state of the basilica’s columns: all fourteen Corinthian columns were found fallen, none in place, and none removed—indicative of a sudden and violent collapse. The orientation of the fallen columns (inwards in the west half and northwards in the east half) suggests wall failure, while displaced upper blocks at the atrium entrance "turned a somersault in the air," attesting to the force of the shock (Crowfoot, 1929:19 and Crowfoot in Kraeling, 1938:223–224). Crowfoot also observed salvaging activity in adjacent side chambers, with stacked tiles and stones, probably placed there for refurbishing the church right before the earthquake struck, ultimately abandoned when the area was reoccupied by squatters (Crowfoot in Kraeling, 1938:224). The west wall of the atrium , built from massive stone blocks, was dangerously dislocated (Crowfoot in Kraeling, 1938:260). Walmsley (2007) includes the Church of St Theodore among several Gerasa churches where thick deposits of destruction debris were recorded and tentatively linked to the 749 CE quake. He notes that while the destruction was not universal across the city, evidence points to earthquake damage at multiple religious structures, including St George, St John the Baptist, and the cathedral terrace. He also refers to 8th-century coin evidence and a skeleton crushed under collapsed architecture near the South Decumanus. |

| Jerash - Northwest Quarter | possible to probable | ≥ 8 | Evidence for 8th century CE earthquake destruction was found at several sites in the northwest quarter. Collapse evidence suggests that destruction was both extensive and sudden.

An 8th century CE terminus post quem was established at multiple locations from coins, pottery, and radiocarbon while a terminus ante quem was less well established -

due to abandonment of many of the structures. In trenches P and V, a multi-storey Umayyad courtyard house on the so-called East Terrace collapsed leaving crushed pottery, architectural debris, and a skeleton with "completely fractured" bones due to falling "heavy stones" ( Kalaitzoglou et al, 2022:161-162). In Trench T, located in the north-western corner of the so-called Ionic Building, Kalaitzoglou et al (2022:144) uncovered damaged walls bulging in a southeast direction and a thick debris layer of soil and tumbled stones overlying a disturbed layer containing Umayyad fragments of tableware, cooking and common ware, and transport vessels. A residential building exposed in Trench U suffered from sudden roof and wall collapse leaving fallen and crushed pottery in the debris layer ( Kalaitzoglou et al, 2022:152). In the so-called Mosaic Hall exposed in Trench W, Kalaitzoglou et al (2022:169) uncovered a sunken mosaic floor along with wall collapse, roof collapse, and debris. In Trench K in the so-called "House of Scroll", Lichtenberger et al. (2021:28-29) report on the discovery of a collapsed upper storey and 1st floor ceiling where a coin hoard was found under the rubble. |

| Jerash - Umayyad Congregational Mosque | possible | mid 8th century CE Earthquake - The Umayyad Congregational Mosque of Jerash was uncovered

in the 2000s and is located in the southern half of the city,

just north of the Oval Plaza.

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) and

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) both date

its construction to around 725 CE. Barnes et al. (2006:295) identified an apparent single-event collapse layer in the Qiblat Hall of the Mosque but did not provide a chronological attribution. The collapse layer appears to relate to a 9th–10th century collapse layer excavated on the Southwest Hill. Thus it appears that there is only rebuilding evidence for a mid 8th century CE earthquake in the Umayyad Congregational Mosque and environs. Blanke et al. (2010:320) noted, regarding Phase 4 in excavation area GO (GO/4–5), that “we have yet to properly verify the termination of the phase 4 structures as contemporary with the earthquake of 749, even though this seems a tempting link to draw from present evidence.” Blanke and Walmsley (2022:95–97) wrote that “in 749, after only a few decades of use, the mosque along with most of Jarash’s urban fabric was devastated by one or more massive seismic events. The damage caused by the earthquake and the following discontinuation of structures is well documented throughout Jarash and has led scholars to assume a total abandonment of the town—a sentiment that still lingers today.” They continued, “The excavations within north-west Jarash have generally identified a discontinuation after the mid-eighth century. This is evident, for example, in and around the North Theatre, the Artemis precinct and the Propylaeum Church, and further west on the plateau behind the Temple of Artemis and along sections of the south transverse street.” Nonetheless, “sporadic evidence of post-earthquake activities has been found throughout the town. Among these are a coin hoard found within the North Theatre which included a Ṭūlūnid dinar dated to 894 as well as ninth-to-eleventh-century housing found south-east of the theatre’s exterior wall. Some traces of Abbāsid-period occupation of the Macellum adds to the evidence as does pottery finds that suggest some continuous activity in the Temple of Zeus.” According to Blanke and Walmsley, “the evidence for continuous occupation after 749 is by far the strongest in Jarash’s commercial and religious centre at the intersection of the two main thoroughfares and in the south-west district. Recent archaeological investigations in Jarash’s south-west district suggest that this area was crucial to maintaining the central functions of urban life and therefore, the financial investment in the restoration of the town and the efforts put towards reconstruction were concentrated here.” They describe how “after the earthquake of 749, the mosque was rebuilt to its former dimensions, but its main entrance was blocked as was its central miḥrāb. Instead, a new entrance was constructed on the axial street on the east side of the mosque, while a smaller doorway was set into the mosque’s western wall giving access to the porticoed courtyard with an ablution feature set immediately inside the doorway. The prayer hall was subdivided into two with a smaller section set apart in the western end. A new miḥrāb was constructed centrally in the shortened prayer hall, while another was added to the western enclosure. At some point a minaret was added to the north-east interior corner of the courtyard. Following the rebuilding of the mosque, shops were added to its east façade, just south of the new entrance and also across the axial street on its east side. Here, a large building that may have served an administrative purpose was rebuilt using the walls of an earlier building as foundations. The reconfiguration of the mosque marks not only a substantial investment in the built environment after 749, but also allows us to identify a reduction in the importance of the western section of the south transverse street. Instead, the mosque was now accessed from the markets (to the east) and the habitation (to the west).” El-Isa (1985) noted that the Umayyad mosque of Jerash “appears to have been demolished and removed and with a relic of its mihrab the only indications left of its existence.” However, this appears not to refer to the Umayyad Mosque near the Oval Plaza, but rather to a structure in northeastern Jerash discovered and identified as a mosque in 1981 (Naghawi, 1982) whose identification is now considered “somewhat doubtful” (Walmsley and Daamgaard, 2005:364). |

|

| Jerash - Umayyad House | possible | Gawlikowski (1992) dates destruction to after 770 CE which, if correct, suggests an earthquake later than mid 8th century CE | |

| Jerash - Macellum | possible | ≥ 8 |

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:298-299) identified a destruction level composed of ashlar blocks and voussoirs from the fallen walls and vaultswhich was disturbed and thus difficult to date. The destruction layer was not specifically attributed to an earthquake and was approximately dated to second half of the eighth or early ninth centuries CE. |

| Jerash - Southwest Hill (Late Antique Jarash Project) | possible to unlikely | Mid 8th century CE Earthquake (?) - Blanke (2018) reported that partial excavation

of two residential structures in Southwest Hill (Trenches 7 and 9)

confirmed that the area underwent “a major refurbishment after the

earthquake in A.D. 749.” In Trench 7, “large quantities of ceramics

dating to the Abbasid period were retrieved.” In Trench 9,

excavators uncovered “a section of a room that went out of use

after a devastating conflagration.” This room featured “a

stamped clay floor,

stone walls, and a flat roof made from wooden beams that supported

a thick layer of packed clay.” The fire “caused the beams to burn

and the roof to collapse,” sealing the room’s final use phase.

Sealed inside were “thousands of

carbonized lentils, wheat, barley, and a few figs and dates.”

The lentils were “found in a large pile on top of a

stone platform,”

likely once stored in “a sack that disintegrated in the fire.” Additionally, the grains and fruit were “found in and around a ceramic vessel that was crushed by the weight of the collapsed roof.” This vessel, along with “a severely damaged oil lamp,” was identified as “clearly Abbasid in date.” Blanke notes that “further analysis and dating of the carbonized material are currently underway.” Blanke et al. (2024:100) add that "excavation of Trench 1 in 2015 uncovered a section of a room within a housing complex that collapsed in a sudden catastrophic event—possibly an earthquake - which sealed the room below 1.5m of wall tumble.” The associated ceramic assemblage was “mainly Late Antique (including Umayyad) and Abbasid in date (Pappalardo 2019).” The authors interpreted this room as “either built from new or massively restored after the earthquake in the middle of the 8th century AD.” However, the sealed presence of Abbasid pottery in both Trenches 1 and 9 suggests that the destruction event took place after the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes, since the Abbasid Caliphate only came to power in 750 CE. |

|

| Jerash - Temple of Zeus | probable | ≥ 8 | 2nd Cistern Earthquake - 8th century CE - Rasson and Seigne (1989) reported on

excavations of a

cistern beneath the

Temple of Zeus at Jerash. Two episodes of

seismic destruction were identified—

one in the 7th century CE, and a more violent one in the 8th.

The second collapse event left a destruction layer filled with

architectural fragments, animal bones,

and a human skeleton. Following this event, the cistern was

hermetically sealed and abandoned.

A rich set of objectswas uncovered beneath the collapse layer, including ceramics dating up to the first half of the 8th century CE and an Umayyad coin minted in Jerash between 694 and 710 CE. The destruction layer also included fragments of Ionic capitals, window railings, frieze blocks, etc., from the facades of the sanctuary. |

| Jerash - Hippodrome | probable | ≥ 8 | mid-8th century CE Earthquake - Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27–28)

provided detailed observations of structural collapse at the

eastern

carceres (stalls 1E–5E). Stone blocks fell

in a curved, northward arc onto the

arena, with higher blocks found further

from the source, indicating a violent, forward-leaning failure.

The height of detachment—about 2 m above ground—marks a

structural "hinge" where the shock caused rotation before collapse. The masonry construction of the carceres—faced stone around rubble fill— was inherently weak and heavily eroded prior to collapse. Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27–28) conclude that both the construction technique and preexisting erosion amplified the seismic vulnerability of the structure. Western carceres (stalls 1W–5W) also show a northward collapse direction, albeit with less diagnostic evidence. This directional pattern supports a south-to-north fall orientation which may suggest an epicenter to the north (Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz 2020:31–32). Ostrasz (1989:132–136) confirms archaeoseismic signatures in the cavea. Collapse debris—consisting of seat blocks, voussoirs , and outer wall masonry—filled chambers and lay undisturbed atop floor surfaces. Stratigraphy reveals a single tumble layer overlying pre-earthquake fill. In many chambers, the distribution of stones shows clear seismic collapse, followed by extensive but incomplete post-event quarrying. Dating is provided by finds sealed beneath the tumble. A stratified deposit under the eastern arena included ceramics from the 1st to 8th centuries CE, with the latest securely Umayyad. A coin provided a terminus post quem in the first half of the 8th century (Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz 2020:29–30). Further evidence from Ostrasz (1989:137–138) corroborates this chronology. Coins and ceramics from the carceres and cavea fall within the Umayyad period, and no material postdates the mid-8th century. The best-dated coin in the tumble below the carceres dates to the first half of the 8th century; material from chambers E40–E43 dates no later than the 7th century. The absence of later material supports destruction and abandonment after the 749 quake. Ostrasz notes that the neighboring church of Bishop Marianos also collapsed at this time, with sealed coins dated to the early 8th century, and concludes that the hippodrome is a well-attested example of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes in Jerash (Ostrasz 1989:139). |

| Jerash - Wadi Suf | possible to probable | n/a |

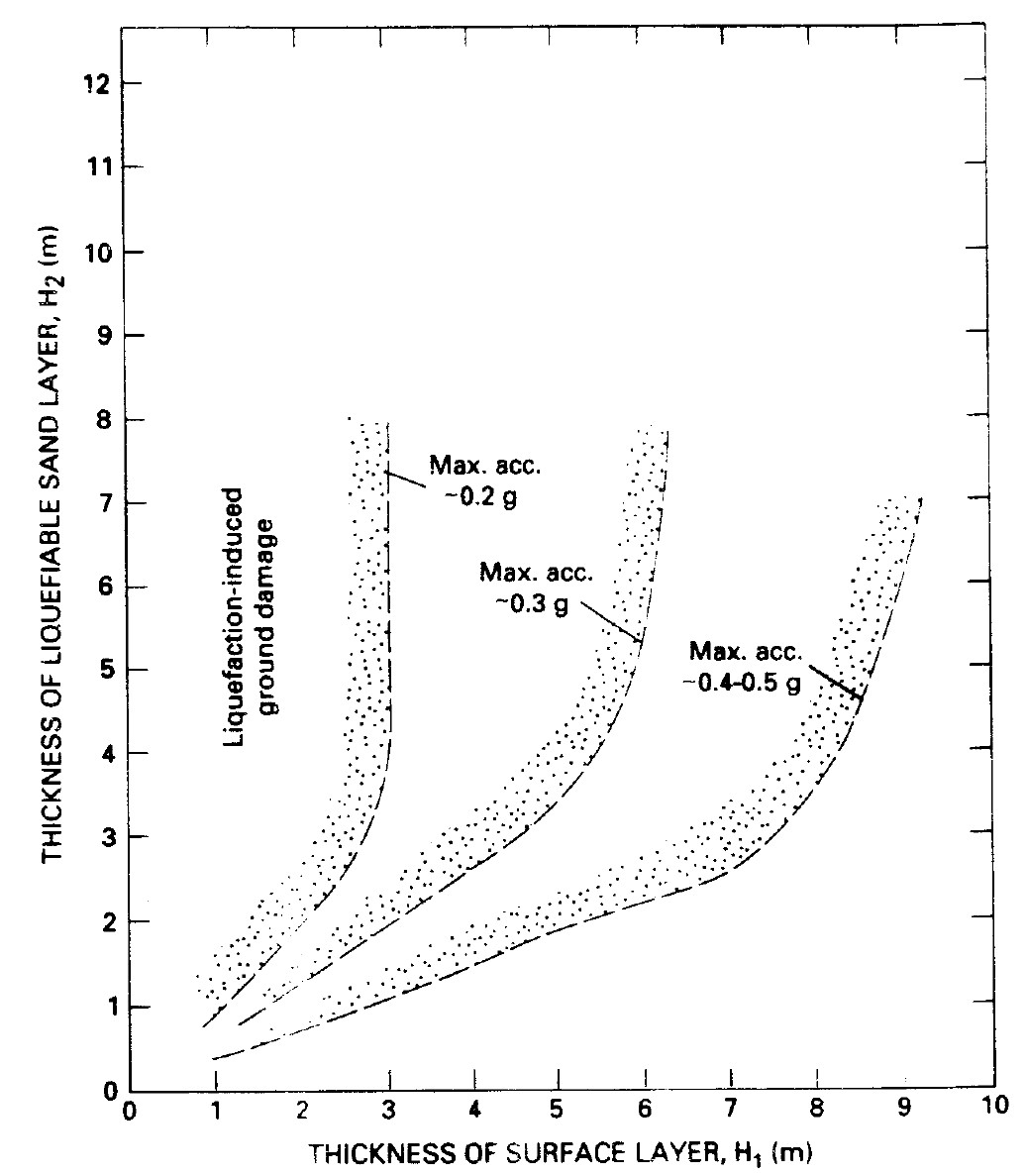

Lichtenberger et. al. (2019) examined three soil profiles in Wadi Suf (surrounding Jerash) using OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence).

They interpreted the profiles to indicate that a change from fluvial to colluvial deposition in A.D. 760 ± 40 was due to a combination of climatic and social (wars and plagues) factors along with

failure of the slope-terrace system and associated irrigation due to shake and liquefactionfrom the 749 A.D. earthquake together with loss of hinterland land management as agricultural demand from the city declined(due to the same earthquake). |

| Amman - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Amman Citadel - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Amman - Ummayad Palace | probable | ≥ 8 | mid 8th century CE Earthquake - Excavations reported by

Almagro et al. (2000) in Building F of the Umayyad Palace at the Amman Citadel

revealed that the structure suffered the devastating effects of a mid-8th century CE

earthquake. Roofs, arches, and façades collapsed, leaving rubble deposits more than a

meter deep in some areas. Pottery recovered from the destruction layers supports this

dating: the ceramic assemblage includes material from the second half of the Umayyad

period, along with a few rare glazed pieces. These glazed wares, exceptionally uncommon

in Umayyad contexts, are characteristic of the final decade of the dynasty and mark the

transitional phase into Abbasid ceramic traditions. The destruction was interpreted as having occurred instantaneously. Structurally vulnerable areas—such as the courtyard and the two iwans—collapsed inward, generating deep rubble layers composed of ashlar, mortar, and vault debris. Not all rooms were equally affected; some areas showed little or no damage. Almagro et al. (2000) also report that the porticoes and architraves of the Temple of Hercules were destroyed in the same event. Citing Northedge (1992), they note that in Sector C of the citadel, two Umayyad houses were also severely damaged—one of which contained a human skeleton. Following the earthquake, Building F was reoccupied and restructured. Vaulted ceilings were replaced by flat roofs supported by short beams. Partition walls were built using reused masonry bonded with clay rather than lime mortar. The original courtyard was transformed into a semi-public space, surrounded by subdivided domestic units that reflect a shift from palatial to residential use. Excavations conducted by Harding (1951) beneath the future site of the Jordan Archaeological Museum on the Amman Citadel revealed multiple Early Umayyad structures that preserved signs of structural failure. The excavated area included a courtyard and multiple rooms of a large domestic building, with standing walls reaching up to 2.1 m in height. In Rooms L and M, ground floor arches had collapsed into the basement level, while the basement arches remained intact. This pattern of selective failure suggests damage consistent with seismic ground shaking. In Room H, wall collapse was inferred from fragments of a sandstone fire altar found scattered from floor level up to 40 cm above it, likely displaced when a shelf and adjacent wall failed. Harding associated this collapse with a structural event that caused the altar to fall. Russell (1985) cites these observations by Harding (1951) as evidence of Umayyad-period structural collapse, likely resulting from the mid-8th century CE earthquake known to have devastated Amman and other Levantine cities. |

| Umayyad Congregational Mosque on the Citadel in Amman | possible | ≥ 8 | mid 8th century CE Earthquake - Arce (2000:130) reports that the Umayyad

Congregational Mosque at the

Amman Citadel collapsed in the

749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes. Structural

damage included displaced column bases and dislocated

foundations, which broke an adjacent water channel.

Arce (2000) notes

that the collapse resulted not only from the seismic shock but

also from poor construction techniques, particularly inadequate

fill compaction and unstable foundation design. Arce (2000) dates the mosque to the Umayyad period based on construction techniques (lime-with-ash mortar, chip jointing), layout parallels with early Islamic hypostyle mosques, and its integration into the broader palatine complex. No direct inscriptions or coins were used to date the mosque itself, but associated architectural style and stratigraphy firmly place it in the early 8th century. The mosque was never rebuilt and was converted into residential use in the Abbasid period, providing an Abassid terminus ante quem for its destruction. Arce (2000:135–140) also reports that multiple architectural elements were found in the 749 CE earthquake debris, including decorative cornices, fragments of façade decoration, niches, and colonnette panels. Four niche fragments displayed trefoil, vegetal, and composite tree motifs, with several pieces identified in undisturbed collapse layers along the west street/ziyada. These smaller-scale niches differ from standard Umayyad assemblies by lacking structural interlocking elements and being designed for close viewing. Arce (2000) concludes they likely came from the lateral façades or interior of the mosque. Their form lacked the mechanically integrated joints found in more robust ashlar masonry, which may have contributed to their vulnerability during the collapse. Additional evidence of interior damage includes fragments of carved stucco retrieved from the mosque’s courtyard and cisterns, indicating that while exterior façades used carved stone, the interior decoration relied on more fragile materials. A marble slab with a carved Kufic inscription—painted in red and blue—was also found in the collapsed debris at the mosque’s west wall. The reverse side bore a rougher reused inscription. Other graffiti found on steps include fragmentary invocations of the divine name "Allah" and phrases such as "Allah ’umma" and "Illa[..]". |

| Khirbet Yajuz | probable | ≥ 8 | An Early Abbasid terminus ante quem from Khalil and Kareem (2002) combined with an Umayyad terminus post quem from Khalil (1998) produces tightly dated archaeoseismic evidence. Extensive seismic damage uncovered at the site. |

| Khirbat Faris | possible | ≥ 8 | McQuitty et al. (2020) uncovered a variety of archaeoseismic evidence in Phase 3 in areas Far V and Far II. Evidence included collapsed walls, doorways, roofs, and arches along with collapse debris and a dump where earthquake debris was deposited post destruction. The collapse was described as sudden and catastrophic. The date of destruction was derived from ceramics and was constrained to between the 7th and 9th centuries CE. |

| Al-Muwaqqar | possible | ≥ 8 | Two seismic destruction events were identified by Najjar (1989). Wall damage or collapse was presumed in the earliest of the two destructions based on rebuilding evidence. A terminus ante quem between 730 and 840 CE was established for this event based on Abbasid pottery above the "destruction" leading to a conclusion that the site was damaged during one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes. |

| Dharih | possible | Second half of the 8th century CE Earthquake -

Al-Muheisen and Villeneuve (2000) assert that

Dharih was abandoned by another earthquake, probably in the second half of the 8th century. |

|

| Jerusalem - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Jerusalem - Umayyad Structures South and Southwest of Temple Mount | probable | ≥ 8 | Mazar (1969) excavated a shaft at the SW corner of Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) and concluded that Umayyad stratum A1 ended with an earthquake. The overlying stratum was classified as Post Umayyad. The earthquake is reported to have collapsed columns and walls and produced a rubble layer in Umayyad structures S and SW of Haram esh-Sharif that were destroyed a generation or two after initial construction. Ben Dov (1985:275-276) examined artifacts from a sewage canal that collected refuse from before Building 2 (S of Haram esh-Sharif) was destroyed. In the canal, he found pottery (Khirbet Mafjar ware) dating to the first half of the 8th century CE. Ben-Dov in Yadin et al (1976:97-101) reports that coins from the 8th century CE were also found in the sewer. Ben Dov (1985:321) reports archaeoseismic evidence in Building 2 that includes cracked walls, warped foundations, fallen columns, and sunken floors. Partial repairs are also reported from the second half of the 8th century CE in the Abbasid Period. |

| Jerusalem's City Walls | possible | ≥ 7 | Magness (1991) examined a report from a previous excavation of the Roman-Byzantine walls near the Damascus Gate and established a

terminus post quem of the 1st half of the 8th century CE for wall repairs. Magness (1991)

characterized the level used to establish the terminus post quem as one of the most securely dated assemblages of published Byzantine and Umayyad pottery from an excavation in Jerusalem. Magness (1991) re-examined another previous report and provided a date of the 7th-8th century CE for wall rebuilding of the Roman-Byzantine walls near the Armenian Garden. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421) dated partial damage, probably by an earthquake, of the Roman-Byzantine walls to the mid 8th century CE. Evidence of renovations was also reported. |

| Baalbek | No archaeoseismic evidence has been reported that we know of. | ||

| Damascus | No archaeoseismic evidence has been reported that we know of. | ||

| Tiberias - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Tiberias - Galei Kinneret | probable | ≥ 8 | Marco et al (2003) observed 0.35-1.0 m of what appears to be coseismic dip slip displacement accompanied by Type I (normal stress) masonry fractures - all on land. Seismic effects observed by Marco et al (2003) are constrained between Umayyad walls which were faulted and Abassid structures which are unfaulted. |

| Tiberias - Beriniki Theatre | probable | ≥ 9 | 7th-10th century CE Earthquake - probably 749 CE -

Ferrario et al (2020) provided what they characterize as a tight

terminus ante quem of not later than the 8th - 11th century CEfor the damaging event at the Theatre based on overlying structures in the Fatimid-Abassid quarter. These structures, built on top of the Theatre and debris flow deposits which covered the Theater, followed a plan similar to the underlying Theatre (see Fig. 5 from Atrash, 2010). The Fatimid-Abassid structures, which were removed in order to access the Theatre, showed no faulting, damage, or deformation in photographs taken prior to removal. Damage, according to Ferrario et al (2020), was limited to the Roman-age flooring and to the debris flow sediments above it. Ferrario et al (2020) noted this was particularly evident in the photos in Figures 5 b-d. A terminus post quem is provided from the Southern Gate area where a deformed Byzantine wall was observed along with presumed vault collapse. According to Procopius, the Byzantine wall was constructed in the 6th century CE. The collapsed vault was dated to the Umayyad period by Hartal et al. (2010). Hartal et al. (2010) also dated structures built above the presumably collapsed vault to the Abbasid period. Taken together, this constrains the date of the archaeoseismic evidence in the Berniki Theater and the South Gate area to the 7th-10th century. |

| Tiberias - Southern Gate | probable | ≥ 8 | Ferrario et al (2020) measured 46 cm. of vertical throw across a warped Byzantine wall a bit west

of the Southern Gate. They inferred an approximately N-S fault from this warping. Just east of the warped Byzantine wall and slightly west of the southern gate,

Hartal et al. (2010) uncovered 3 stranded columns which were identified as Umayyad

based on a large amount of ash and potsherds from the Umayyad periodin a soil layer which abutted the columns. The columns were presumed to be part of a vault which ran west of the gate. Hartal et al. (2010) suggested that the vault collapsed during the 749 CE earthquake (one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes). With Hartal et al. (2010) reporting that the Byzantine wall was constructed in the 6th century CE and Hartal et al. (2010) dating the stranded columns from the presumed vault collapse to the Umayyad period, a terminus post quem of 661 CE can be established. Abbasid constructions uncovered by Hartal et al. (2010) on top of the vault provides a terminus ante quem of sometime in the 10th century CE - probably significantly earlier. |

| Tiberias - Umayyad Water Reservoir | probable | Umayyad (?) Earthquake - Ferrario et al (2020) reports that

during the last excavation phase in 2017 an Umayyad Water Reservoir was uncovered. One of the faces of the reservoir

exhibits a series of steeply inclined fractures between masonry blocks, located in a ca. 1 m wide zone. This fracture zone is situated along the line connecting the graben in the Theatre and the warped Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate, i.e. on the fault line. |

|

| Tiberias - Seismo-Tectonics | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Tiberias - The Umayyad Mosque | possible |

Cytryn-Silverman (2015:208) notes that the covered hall of the Umayyad mosque was refurbished at some stage by the introduction of a row of columns in the middle of the aislesprobably following the earthquake of 749, and aimed at giving extra support to the roof. |

|

| Tiberias - Mount Berineke | possible | ≥ 8 | Cytryn-Silverman (2015:199), citing Hirschfeld (2004b), lists damage and modifications made to the church on Mount Berineke presumably during and after an earthquake in 749 CE. Ferrario et al (2014) performed a preliminary archeoseismic examination of the Church on Mount Berineke. The apparent archaeoseismic evidence is undated. |

| Tiberias - Basilica | possible | ≥ 8 | Hirschfeld and Meir (2004) report that the eastern wing was probably destroyed in the earthquake of 749 CE. |

| Tiberias - House of the Bronzes | no evidence reported | ||

| Tiberias - Site 7354 | possible | ≥ 8 | Stratum III Earthquake ? - 749 CE ? - Dalali-Amos (2016) wrote that

the Stratum III building may have been damaged in the Earthquake of 749 CE [one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes]while noting that remains from this period were found in Stratum III in Hirschfeld’s excavation, which he dated to the end of the fifth century until the Earthquake of 749 CE (Hirschfeld 2004:5). The tops of stratum III walls (e.g. W115 and W116) were removed and leveled before construction began in overlying Stratum II. This left Stratum III walls that were just one course high and that were used as a foundation for the Stratum II construction. Thus, although potential archaeoseismic evidence was removed in Stratum II, the missing tops of these walls may indicate that they collapsed or were severely damaged in an earthquake. |

| Tiberias - Hammath Tiberias | possible | Stratum IA Earthquake (?) - 8th-10th centuries CE - Moshe Dothan in Stern et al (1993 v.2) reports that

all the structures [of Level IA] were destroyed at the beginning of the Abbasid period, in approximately the middle of the eighth century, and never rebuilt. Magness (2005) reports that in his excavation reports, Moshe Dothan interprets the evidence to indicate that the synagogue of Stratum IA was destroyed in one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes however Magness (2005) dates Stratum IA to the 9th-10th centuries CE. |

|

| Sepphoris | possible | mid-8th century CE Earthquake (?) -

Hoglund and Meyers in Nagy et al. (1996:42) note that there are indications of some disruption by burningof the residential quarter on the western summit, perhaps the result of another documented earthquake in the mid-eighth century. |

|

| Hippos Sussita | probable | ≥ 8 | mid 8th century CE earthquake - Archaeoseismic evidence for a mid 8th century CE earthquake was found at multiple locations in Hippos Sussita.

The Northwest Church provided the most secure dating evidence for this event. In this church,

Mlynarczyk (2008:256-257) reports that excavations yielded a number of invaluable archaeological deposits securely sealed by the debris of an earthquakewhich was assigned to one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes. Scores of typical Umayyad-period ceramic vesselsand coins were found in the sealed debris. The latest coin, sealed on the floor of the northern aisle, was minted in Tiberias between A.D. 737 and 746 thus providing a secure terminus post quem. In addition to debris, remains of three victims were discovered in the church. It has been presumed that columns lying on the floor of the cathedral found in sub-parallel directions was also a result of this event. Yagoda-Biran and Hatzor (2010) analyzed the fallen columns which leads to an estimated lower limit of paleo-PGA during the earthquake of 0.2-0.4 g. The potential for a topographic or ridge effect appears to be present at this location. |

| Kedesh | possible | ≥ 8 | The Roman Temple at Kedesh exhibits archaeoseismic effects and appears to have been abandoned in the 4th century CE; possibly due to the northern Cyril Quake of 363 CE. Archaeoseismic evidence at the site could be due to 363 CE and/or other earthquakes in the ensuing ~1600 years including the possibility that one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes damaged the Temple. See Fischer et al (1984) and Schweppe et al (2017) |

| Omrit | Overman in Stern et al (2008) reports that an earthquake in the middle of the eighth century CE appears to have brought about the final destruction of the site and its abandonment. | ||

| Minya | possible | ≥ 8 | Kuhnen et al (2018) reports that excavations indicate that the palace was not completely finished before it was damaged by an earthquake which they presume to have struck in the mid 8th century CE. Collapse evidence was found in a foundation trench. |

| Beit Alpha | possible | ≥ 8 | Based on numismatic evidence, Sukenik (1932) dated seismic destruction and a collapse layer to sometime after the 1st quarter of the 6th century CE |

| Jericho - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Jericho - Hisham's Palace | possible | Although Whitcomb (1988) dates major damage due to a later earthquake, Whitcomb (1988:63) suggests that there was an initial destruction around the mid 8th century CE. | |

| Arbel | possible | ≥ 8 | Ilan and Izdarechet in (Stern et al, 1993) suggested that the synagogue appears to have been destroyed in the mid-eighth century CEbased on coins found at the surface. The site hasn't been systematically excavated |

| Gadara | possible | ≥ 8 |

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015:15) noted the presence of ancient wall destruction (fallen stone layers)in many squares underneath the Abbasid layers, especially in Squares F5 and F6.They also noted the reuse of architectural elements in Abbasid constructions as well as prior destruction of a mosaic floor (El-Khouri and Omoush, 2015:16-17). Dating was based on pottery. |

| Tall Zira'a | possible | Kenkel and Hoss (2020:116, 271, 273) report that the earthquake of 749 CE caused destruction in Tall Zira'a and destroyed parts of nearby Gadara. | |

| Hammat Gader | possible to probable | ≥ 9 | Phase III Earthquake -

Hirschfeld et al. (1997:479) concluded that the bathing complex's existence ended with the great earthquake of 749 C.E.They characterized the destruction as almost totaland noted that the finds dating this destruction are unequivocal - beneath the huge piles of debris consisting of the upper parts of the walls and the ceilings were late finds from the first half of the eighth century C.E.Although Amiran et al (1994:305 note 144) wrote that the date of seismic destruction of the thermal baths at Hammat Gader during the Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year Sequence of 749 CE was proven definitely, as none of the approximately 4,000 coins found postdates 748 (personal communication by Y. Hirschfeld), this assertion is slightly overstated. In the Excavation Report for the Bath Complex, Hirschfeld et al. (1997:297), report that 2875 Roman and Byzantine coins were found in Areas A-J and Hirschfeld et al. (1997:301) report that some 1200 Muslimcoins were also found in the Bath Complex of which only 165 of the latter could be identified. The identifiable coins included so-called Arab-Byzantine coins from the transitional period (ca. 611-697), coins from the Umayyad period, two Abbasid coins, three from the Ayyubid period, and one Mamluk coin, which is the latest. All the Muslim coins were made of Bronze except for one gold Abbasid coin found in Locus 702 of Area G (the Hot Spring Hall). All but 5 of the 165 identified Muslim coins were minted during the Umayyad period ( Hirschfeld et al., 1997:316 Table 1). Yitzar Hirschfeld in Stern et. al. (1993 v.2:566) noted that the fallen debris was eventually covered with earth, and the building was abandoned. Although a mid-8th century terminus post quem is well established, the terminus ante quem is less well defined. Late 10th century Muslim geographer el-Muqaddasi wrote about the baths in the past tense (Yitzar Hirschfeld in Stern et. al., 1993 v.2:566) and Hirschfeld et al. (1997:158) found and identified 33 potsherds from the Abbasid-Fatimid period in a part of the complex that was levelled after the Phase III seismic destruction. This site may be subject to a liquefaction site effect as it is located on an oxbow of the Yarmuk River in a location that sits atop a thermal spring. At the same time, one must consider that the building’s state of preservation and the fact that the walls stand vertically without cracksled Hirschfeld et al. (1997:16) to conclude that the builders of the foundations did an excellent job, taking advantage of the best knowledge, skills, and certainly the well-known Roman cement. Hirschfeld et al. (1997:124) concluded that the general direction of movement during the earthquake of 749 which caused the collapse of the entire structure, including the columned portal, was from the north to the southwhile citing that the upper half of the columns, the capitals and parts of the arcuate lintelof the columned portal in Area C were found lying on the late floor to the south of the columns. |

| Lod/Ramla | probable | 7 | Seismic damage was precisely dated by Gorzalczany (2009b) using ceramics. Seismic effects reported by Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) indicates that the site experienced liquefaction. Thus, the Intensity estimate derived from the EAE chart is downgraded from 8 to 7 - i.e. a lower bedrock intensity is required to explain the observed seismic effects. Rosen-Ayalon (2006) dated a rebuilding phase (2) of the White Mosque in Ramla to ~788/789 CE based on a comparison of unique architectural features found in a nearby cistern whose construction was by dated by inscription to 788/789 CE. Rosen-Ayalon (2006) suggested that the rebuilding phase was a response to seismic damage. |

| Horvat Bira | possible |

Taxel (2013:169) states that a building that was formerly a Byzantine Church in Horvat Bira was destroyed and abandoned, perhaps due to the 747–749 c.e. earthquake(s)- according to the excavators. However, some parts of the chronology of this site is debated (e.g., see Taxel, 2013:169-170). |

|

| Horvat Hermeshit | possible |

Taxel (2013:173) reports that Greenhut (1998) claimed that a wine press found on the site

went out of use at the beginning of the Early Islamic periodand was damaged during the 747–749 c.e. earthquake(s), after it had already been abandoned. |

|

| Kafr Jinnis | possible |

Taxel (2013:173) reports that Messika (2006)

attributed destruction of the Church and the entire Umayyad settlement to the 747–749 c.e. earthquake(s) or toTaxel (2013:173) noted that this suggestion could not be confirmedviolent actions related to religious or political struggles based on the fragmentary evidence available. |

|

| Ṣarafand al-ʿAmar | possible to probable | ≥ 8 | Stratum X Collapse - 8th century CE -

Kohn-Tavor (2008) identified a collapse layer from the end of Stratum X (dated as Umayyad - mid 7th - mid 8th centuries CE).

Part of a building in Area F continued in use during the Abbasid period and another part, which was destroyed at the end of the Umayyad period, was filled with crushed pottery vessels and sealed with stone collapse. |

| Mazliah | probable | 7 |

Taxel (2013:176) suggested that Mazliah most likely ceased to exist due to the 747–749 C.E. earthquake(s)noting that this interpretation is supported by clear and apparently well dated evidence of a severe earthquake that struck the site around the mid-eighth century. Taxel (2013:176) also reports that the settlement was abandoned after its destruction and a vast industrial area was founded above and within the earlier remains. This refers to the same well dated archaeoseismic evidence which is discussed in the page for Lod/Ramla. Gorzalczany (2008b:31) dated a seismic event to the mid 8th century CE in areas K1, J2, and possibly K2 which included collapsed, contorted, and cracked walls, sagging floors, broken pottery found in fallen position, and rebuilding after the event. Intensity estimate is downgraded from ≥ 8 to 7 due to the likely site effect of liquefaction (sandy soil + shallow water table) |

| Mishmar David | possible | ≥ 8 | 8th century CE earthquake - Yannai (2014) noted that in Area B

Stratum VI was destroyed in an earthquake (possibly in 749 CE), after which a number of new walls were built in the area (Stratum V).Yannai (2014) noted that in sub-Area C1 the buildings and tower of Stratum VI were destroyed by an earthquake, perhaps in 749 CEafter which a new quarter of private houses (Stratum V) was built above the previous dwellings.Yannai (2014) noted that in sub-Area C3 Stratum VI structures were destroyed in an earthquakewhich would date to ~749 CE based on the Stratum (VI). |

| Capernaum | possible | ≥ 8 | Vasilios Tzaferis in Stern et al (1993) states that in Area A of the excavations around the Greek Orthodox Church,

Stratum IV was apparently destroyed in the earthquake that struck the region in 746 CE [as] evidenced by the great quantity of huge stones in the piles of debris and by the ash covering the stratum throughout the area [Area A].Magness (1997), however, redated Stratum IV, placing its end date in 2nd half of the 9th century CE rather than the middle of the 8th century. The redating was apparently largely based on comparison with ceramic assemblages at Pella. In Magness (1997)'s redated stratigraphy, Stratum V ended around 750 CE. She noted that it is difficult to ascertain what brought this stratum [V] to an end, though the publication [excavation report of Tzaferis] does not provide explicit evidence for earthquake destruction. |

| Qasrin | probable | ≥ 8 | Stratum III Earthquake - 8th century CE - Ceramics from undisturbed loci beneath a destruction layer in Synagogue B date to late 7th/early 8th century CE (Ma'oz and Killebrew, 1988). Ceramics in a stone tumble layer in House B date to the mid 8th century CE. |

| Kursi | possible | >≥ 8 |

Vassilios Tzaferis in Stern et al. (1993 v. 3:896), without citing specific evidence, reports that at

Kursi, the Monastery, Church (also known as the Basilica), and a small tower and chapel located approximately

200 meters southeast of the Basilica were destroyed by an earthquake and subsequently abandoned in the mid-8th century CE.

At Kursi Beach,

Cohen and Artzy (2017) document that the western section of a building—possibly a synagogue—in Square B2

exhibited a sloping down and westward tilt, probably due to an earthquake. |

| Ramat Rahel | possible | ≥ 8 | Phase 8 Earthquake - Lipschitz et al (2011) found evidence of collapse and conflagration which they dated to 8th century CE/Umayyad noting that it was possibly caused by one of the Sabbatical Year Quakes. |

| Kathisma | no evidence | Much of the remains are missing - pilfered long after its demise and it is this pilfering which may have removed any obvious archeoseismic evidence from earthquakes which struck in the mid 8th century CE. | |

| Pella | probable | ≥ 8 | mid 8th century CE earthquake -

Archaeoseismic evidence for a mid-8th-century CE earthquake

at Tabaqat Fahl (Pella) was documented in the form of

collapsed structures, human and animal skeletons, and

valuable items found within the rubble—including pottery,

coins, and personal belongings. The most compelling evidence

came from an early Islamic domestic level in Area IV, where

Rooms 13, 14, 15, and 16 of House G showed tragic results of

what appears to have been a sudden collapse. In Room 15, five

fallen columns and a pier "originally arranged in two rows on

an east-west axis, with three columns to the south and a

combination of two columns and a pier in the northern row"

were found in the debris. Human and animal skeletons were

present throughout. The destruction layer was dated to the

mid-8th century CE based on pottery and other finds, while

coins gave a terminus post quem of

A.H. 126

(25 October 743 – 12 October 744 CE).

Mid-8th-century CE earthquake evidence was also recorded in other areas of Pella. Walmsley (2007) reports that "the church complex in the central valley (Area IX)" and "the West and East churches (Areas I and V)" were affected. Smith et al. (1989:94) noted that the Area IX church complex had been deconsecrated and partially abandoned before the 749 CE earthquake, though domestic use and animal sheltering continued. Walmsley (2007) reported the discovery of two human skeletons and "several animals, including 7 camels (one in advanced pregnancy), a horse and foal, an ass, and 4 cows" buried beneath the collapsed architectural debris. Smith et al. (1989:94) added that "Umayyad coins of the first half of the 8th century found on the floor of the Chamber of the Camels and coins in the possession of one of the victims confirm the date of the final destruction." In the Western Church Complex (Area I), Smith (1973:166) described how "virtually all of the courses of the walls" not supported by earlier debris "collapsed, generally falling westward," burying "a few vessels in domestic use." He characterized Phase 4 of the complex as a single Umayyad stratum, based on debris (e.g. pottery) and coins—five of latest of which were "post-reform Umayyad coins dating from ca. 700–750." This phase lay immediately below the presumed 749 CE collapse. Walmsley (2013) suggested the earthquake occurred during winter. He observed that "the animals on the ground floor were chiefly cows (Rooms 8 and 9, totaling three) and small equids (mules or donkeys; inner courtyard and Rooms 6 and 7) – more costly animals than sheep and goats, hence their owners’ wish to shelter them properly during winter, the season in which the earthquake struck." The presence of sleeping humans and animals in collapsed structures indicates that the earthquake struck at night. Walmsley in McNicoll et al. (1982:127) noted that one human skeleton in Area IX was found "lying, as if sleeping." Another in Area IV was reportedly wrapped in a cloak or blanket (Walmsley in McNicoll et al., 1982:138). Walmsley in McNicoll et al. (1982:185) described two human skeletons (male and female) that had apparently fallen from an upper story and were buried in textiles identified as fine silk—likely bed clothes. He wrote that "apart from room 16, the main living area of the household was located upstairs. Although doubt surrounds the precise layout of the rooms of the upper storey, some at least were well fitted out with plain mosaic floors, plastered and painted walls, as well as reused marble features (PJI: 140–1). Most likely the owners, including the couple found in room 15 and the individual in 13, occupied the upper floor, while the apparently well-to-do ‘below stairs’ stable-hand occupied the ground floor room 16." |

| Beit-Ras/Capitolias | possible | ≥ 8 | Mlynarczyk (2017) dated archaeoseismic evidence from Area 1-S to the mid 8th century CE based on ceramics. |

| al-Sinnabra/Beth Yerah | possible | ≥ 9 | Greenberg, Tal, and Da'adli (2017:217) noted that the site was dismantled down to the foundations after abandonment thus obscuring potential archaeoseismic evidence. It is possible that foundation cracks reported by Greenberg and Paz (2010) were caused by a mid 8th century CE earthquake which would indicate high levels of local intensity. |

| Karak | no evidence | We are not aware of any published or unpublished pre-Crusader excavations in Karak. | |

| Mount Nebo | possible | ≥ 7 | 4th architectural phase earthquake - Mid-8th Century CE -

Bianchi (2019:210) reports that during the last

architectonical phase of the Memorial to Moses basilica

on Mount Nebo, "the two upper rows of

synthronon and the masonry of the

apse in the

presbytery were restored". Bianchi (2019:210) suggests that "the large amount of pottery and marbles with sharp fractures recovered in the excavation, as well as the disorderly arrangement of stones in the external apse buttress suggest that a brutal destruction occurred in the site" which they indicate is "related probably to the earthquake of 749 AD". Conversely, Bianchi (2019:210) notes that "the morphology of this structure may have been affected by the geological instability of the northern slope". In any case, Bianchi (2019:210) states that "the second half of the eighth century well agrees with the chronology of the pottery recovered beneath the upper rows of synthronon" where "most of the sherds date indeed to the late Umayyad period" and a "few to the Abbasid era". |

| Abila | possible | ≥ 8 | Phase 2 Earthquake - 8th century CE - Mare (1984) dated destruction of a triapsidal basilica in area A to approximately the 8th century CE based on Umayyad pottery sherds found in the vicinity of the Apse. |

| Umm al-Jimal | possible | ≥ 8 | de Vries (1993) noted that Umm al-Jimal was nearly totally abandoned after 750 CE and speculated that an earthquake could have been the cause. While specific archeoseismic evidence was not mentioned in his report, collapsed masonry and debris are mentioned frequently in the various reports and articles about the site and de Vries (1993:448) found Umayyad pottery in the collapse debris in the apse of the Numerianos Church. In a later report, de Vries (2000) characterized the town as having undergone collapse in the 8th century and abandonment in the 9th century CE. Al-Tawalbeh et al (2019) examined the Roman barracks and, while not providing an explicit date, estimated a SW-NE strong motion direction and intensities of VII-VIII (7-8) using the Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224). |

| Iraq el-Amir | no evidence | El-Isa (1985) observed clear and intensiveearthquake deformations at the site however this archaeoseismic evidence is undated. El-Isa (1985) suggested the 31 BCE Josephus Quake as a possible candidate. |

|

| Petra - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Petra - Main Theater | possible | Jones (2021:3 Table 1) states that the Phase VII destruction of the Main Theatre is difficult to date, as the structure had gone out of use long before. Destruction tentatively dated to 6th-8th centuries CE but may have occurred later. See also Hammond (1964). |

|

| Petra - Temple of the Winged Lions | possible | ≥ 7 | Dating presented in Hammond (1975) was based on analogy to Petra Theater. Philip Hammond excavated both the Petra Theater and Temple of the Winged Lions |

| Petra - Jabal Harun | possible | ≥ 8 | Mikkola et al (2008) characterized seismic destruction as major leading to collapse of the church's semidome and columns of the atrium as well as tilting of a wall towards the south. Dating appears to be based on iconoclastic defacing found inside the church which the excavators date, based on historical considerations, to the early 8th century. The excavators presume that the seismic destruction followed soon after the iconoclastic activity. |

| Petra - Petra Church | possible | ≥ 8 | Fiema et al (2001) characterized structural destruction of the church in Phase X as likely caused by an

earthquake with a date that is not easy to determine. A very general terminus post quemof the early 7th century CE was provided. Destruction due to a second earthquake was identified in Phase XIIA which was dated from late Umayyad to early Ottoman. Taken together this suggests that the first earthquake struck in the 7th or 8th century CE and the second struck between the 8th and 16th or 17th century CE. |

| Petra - Blue Chapel and the Ridge Church | probable | ≥ 8 | Phase V-3 earthquake - mid 8th century CE -

Archaeoseismic evidence at the Blue Chapel complex for a mid-8th century CE earthquake

at Petra comes primarily from Building 2 in the Lower Sector.

Perry in Bikai et al (2020:69–70)

reports that "occupation of at least part of

the Blue Chapel likely ceased due to earthquake-related structural instability and

collapse likely caused by seismic activity." A radiocarbon

date from an animal bone found beneath a fallen column

(drum no. 2) in the Blue Chapel yielded a calibrated

range of 658–782 CE (95.4%, 2σ). "The column presumably

fell shortly after this animal's death and consumption by

the building’s occupants." Perry identifies two possible earthquakes in this period:

the 672 CE Gaza–Ashkelon–Ramle event, and the well-documented

749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes. The 672 CE event, as cited in

Russell (1985), is considered dubious. This suggests that the collapse

occurred in the mid-8th century. Ceramic evidence also supports this date. Perry in Bikai et al (2020:470) states that "collapse occurred concurrent with or immediately before abandonment" and that "the pattern of collapse, particularly the dramatic tumble of the columns in the Blue Chapel, would point to a seismic event as the cause." Perry in Bikai et al (2020:470) also noted that "no evidence for an earlier phase of destruction dating to the late 7th c. was discovered in the Blue Chapel complex." Perry in Bikai et al (2020:70–71) identified archaeoseismic evidence from "one apparent destructive earthquake", apparently a mid 8th century CE earthquake, in Phase V subphase 3 deposits in Building 2 of the Lower Sector (i.e. the Blue Chapel), noting the presence of substantial 1–1.5 m thick tumble deposits. She listed loci with archaeoseismic evidence for Phase V Sub-phase 3 in Building 2 (Lower Sector) as follows:

|

| Aqaba - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aqaba - Ayla | probable | ≥ 8 | Damgaard (2008) and Damgaard (2011, Appendices:12) identified collapse and rebuilding evidence due to an 8th century CE earthquake. Whitcomb (1994) suggested an earthquake struck the site in the mid 8th century CE in his phasing for the site. al-Tarazi and Khorjenkov (2007) identified two seismic destructions at the site and provided a terminus ante quem of ~750 CE for the first earthquake. al-Tarazi and Khorjenkov (2007) estimated an intensity of IX or more for the first earthquake and surmised that the epicenter was close - a few tens of kilometers away - and to the NE. The site appears to be susceptible to liquefaction. Ayla was built on a sandy beach close to the Gulf of Aqaba. Modern excavators encountered a shallow water table. |

| Aqaba - Aila | possible | ≥ 8 | Evidence presented in Thomas et al (2007) suggests that Earthquake III is fairly well dated and struck in the 8th century CE. |

| Haluza | possible | ≥ 8 |

Korjenkov and Mazor (2005) identified numerous seismic effects from two earthquakes at the Haluza. The 2ndpost-Byzantine earthquake has an apparently reliable terminus post quem of the 7th century CE but is missing a terminus ante quem due to abandonment. Korjenkov and Mazor (2005) estimated an Intensity of 8-9 with epicenter a few tens of kilometers away to the NE or SW - most likely to the NE. |

| Rehovot ba Negev | possible | ≥ 8 | "Post Abandonment Quake" - 7th - 8th century CE - Seismic Effects uncovered by Tsafrir et al (1988) and Korzhenkov and Mazor (2014) suggests an earthquake struck in the 7th or 8th century CE. Korzhenkov and Mazor (2014) estimate Intensity at 8-9 and appear to locate the epicenter to the ESE. There is a probable site effect present as much but not all of Rehovot Ba Negev was built on weak ground (confirmed by A. Korzhenkov, personal communication, 2021) |

| Shivta | possible | ≥ 8 | Post Abandonment Earthquake(s) - 8th - 15th centuries CE - On the western perimeter of Shivta in Building 121,

Erickson-Gini (2013) found evidence of earthquake induced collapse of the ceilings and parts of the wallswhich she dated to possibly in the Middle Islamic periodafter the site was abandoned at the end of the Early Islamic period.Collapsed arches were also found. The arches appear to be in a crescent pattern. Erickson-Gini (2013) discussed dating of the structure is as follows: The excavation revealed that the structure was built and occupied in the Late Byzantine period (fifth–seventh centuries CE) and continued to be occupied as late as the Early Islamic period (eighth century CE). The structure appears to have collapsed sometime after its abandonment, possibly in the Middle Islamic period.Dateable artifacts in Room 2 came from the Late Byzantine period and the Early Islamic period (eighth century CE). The terminus ante quem for this earthquake is not well established. Korjenkov and Mazor (1999a) report that a site effect is not likely at this location. |

| Hama | Needs investigation. Walmsley (2013:89) reports possible earthquake evidence in Hamah in the 8th century CE:

The mound at Hamah apparently was walled (or re-walled) in the eighth century (Ploug 1985: 109-11), and although Ploug opts for a Byzantine date an Umayyad one fits better. |

||

| Aleppo | no evidence | Gonnella (2006:168-169) reports that textual sources report wall repairs after the muslim conquest (~636-638 CE) were necessary due to prior earthquake damage, Very few pre-Ayyubid remains have been found at this site (the Citadel). No evidence has been uncovered thus far for an 8th century CE earthquake at Aleppo. | |

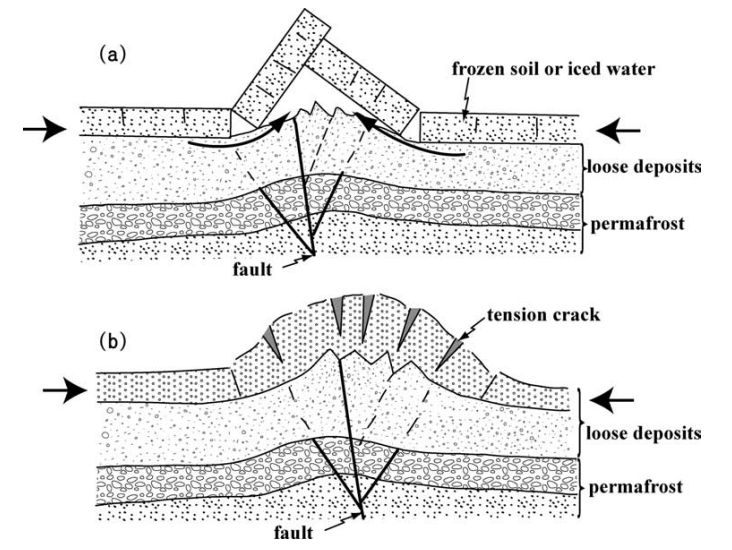

| Reṣafa | possible | Sack et al (2010) reports seismic destruction that led to abandonment of Basilica B

which probably took place before the middle of the seventh century and certainly before the building of the Great Mosque was begun in the second quarter of the eighth century.Al Khabour (2016) notes that the Basilica of St. Sergius (Basilica A) suffered earthquake destructions but did not supply dates. The apse displays fractures that appear to be a result of earthquakes or differential subsidence

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Rusafa: the huge church containing the remains of St. Sergio. Al Khabour (2016) from the building of the church [Basilica A first built in the 5th century CE] up to the abandonment of the city in the 13th century, earthquakes and the building ground weakened by underground dolines [aka sinkholes] have caused considerable damage. |

|

| Palmyra | possible | ≥ 8 | Intagliata (2018:27) reports that water pipes

are believed to have been laid in Umayyad times, but were destroyed after a disastrous earthquake and then replaced in the ʿAbbāsid era (al-Asʿad and Stępniowski 1989, 209–10; Juchniewicz and Żuchowska 2012, 70).Juchniewicz and Żuchowska (2012:70) report the following: Excavation in the Camp of Diocletian, in the area of Water Gate revealed pipeline which is dated by Barański to the Abbasid Period ( Baranski, 1997, 9-10). This pipeline, as well as the earlier one dated to Omayyad Period, is clearly visible in the Great Colonnade, running along the Omayyad suq (al-Asʿad and Stępniowski 1989, 209–10). The Omayyad pipeline was replaced by the later one probably after earthquake. Some of the monumental architraves from the Great Colonnade fell down and destroyed the Omayyad conduits.Gawlikowski (1994:141) suggests that an earthquake struck the then abandoned Basilica around 800 CE leading to wall collapse. |

| Tel Taninnim | possible | Stratum IV Destruction - mid-8th century CE - da Costa (2008:96-97) in her review of Stieglitz et al (2006) suggests that the Stratum IV destruction layer may have been due to one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes (the Holy Desert Quake). | |

| Caesarea | probable | 7 | Ad et al (2018) excavated site LL just north of

Caesarea's inner harbour where several ceilings collapsed inward, and there was evidence of a fire in the eastern warehouse.In the collapse in the corridor, the original order of the courses of the wall or vault could be clearly identifiedadding confidence to a seismic interpretation. Dating was based on ceramics and fairly tightly bound to the middle of the 8th century CE. Everhardt et. al. (2023) analyzed two radiocarbon samples of charcoal and various organic matterin the destruction layer which dated from 605 to 779 CE. Everhardt et. al. (2023) further examined two cores and a baulk in the collapse corridor and concluded that a tsunami stuck the structure soon after the earthquake thus extinguishing the fire and bringing in a deposit of marine sand. Based on Raban and Yankelevitz (2008:81) and Arnon (2008:85), Dey et al (2014) reports evidence for mid 8th century CE seismic destruction adjacent to the Temple Platform and, based on Holum et al (2008:30-31), probably adjacent to the Octagonal Church as well. Dey et al (2014) also interpreted landward marine layers that included a complete human skeleton as tsunamogenic and likely caused by one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes. The marine layer lies in a coastal strip between the Temple Platform and the Theater and is dated to between ~500 and 870 CE. |

| Baydha | no evidence | No evidence has been uncovered as of yet but Sinibaldi (2020:96-97) reports a Byzantine phase underneath Mosque 1 (aka the Eastern Mosque) | |

| Tel Jezreel | possible | Moorhead (1997:147-148) speculated that a fissure in the bedrock in the apse of a Church in Area E may have been a result of an earthquake. However, there is debate as to the date of the fissure and whether an earlier structure was from the Byzantine or Crusader period. Grey (2014) reports that this debate was never resolved. | |

| el-Lejjun | possible | ≥ 8 | Evidence reported by Groot et al (2006:183) for the 4th earthquake at el-Lejjun was found in Area B in the

Barracks but dating can only be constrained to between ~600 and 1918 CE (assuming that the 3rd earthquake was the late 6th century

Inscription at Areopolis Quake).

deVries et al (2006:196) suggests that Umayyad abandonment of the Northwest Tower was likely triggered by a collapse and

deVries et al (2006:207) found evidence of full scale destruction above layers of the 3rd earthquake in the northwest tower

which perhaps occurred in the Umayyad period. |

| Castellum of Qasr Bshir | possible | ≥ 8 | Post Stratum II Gap Earthquake - Clark (1987:489-490) attributed collapse evidence to

an earthquake which likelystruck at the end of the Umayyad period. |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

Landslide Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Minimum PGA (g) | Likely PGA (g) | Likely Intensity1 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umm el-Qanatir | probable | 0.36 | 0.5 | 8.2 | Archeoseismic evidence suggests Intensity ≥ 8 |

| Fishing Dock Landslide | possible | 0.15 - 0.5 | 0.5 | 8.2 | undated landslide |

| Ein Gev Landslide | possible | 0.37 | ? | ≥7.7 | dated to younger than 5 ka BP |

| Gulf Of Aqaba | possible | Event C in R/V Mediterranean Explorer core P27 - ~883 CE 7 cm. thick Mass Transport Deposit Event C was identified in R/V Mediterranean Explorer Canyon Core P27 by Kanari et al (2015) and Ash-Mor et al. (2017). Ash-Mor et al. (2017) provided an unmodeled 14C date of ~883 CE (1067 ± 42 cal years BP) for the mass transport deposit which Kanari et al (2015) associated with the 1068 CE Earthquake although an 8th, 9th, or 10th century CE event seems a better fit - e.g. it may related to Events E4 or E5 which were both dated to between 671 and 845 CE (modeled ages) by Klinger et al. (2015) in the Qatar Trench ~37 km. to the NNE along the Araba Fault. Kanari et al (2015) based association with the 1068 CE Earthquake at least partly on their work in the nearby Elat Sabhka Trenches where Kanari et al. (2020) dated Event E1 in Trench T3 to between 897 and 992 CE and listed the 1068 CE Earthquake as a plausible candidate. Kanari et al. (2020) also identified a dewatering structure (aka liquefaction fluid escape structure) in Elat Sabhka Trench T1 which they dated to before 1269-1389 CE and associated with the 1068 CE or 1212 CE earthquakes. |

|||

| Jordan River Delta | possible | Niemi and Ben-Avraham (1994) estimated that Event 2 was younger than 3-5 ka and older than 1927 CE. | |||

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Minimum PGA (g) | Likely PGA (g) | Likely Intensity1 | Comments |

Tsunamogenic Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caesarea and Jisr al-Zakra | probable | Goodman-Tchernov et al (2009)

identified tsunamites

in cores taken immediately offshore of the harbor of Caesarea which

Goodman-Tchenov and Austin (2015) dated to the 5th - 8th century CE.

Tyuleneva et. al. (2017) identified what appears to be the same tsunamite in a core (Jisr al-Zarka 6) taken offshore of

nearby Jisr al-Zakra. This core was located ~1.5-4.5 km. north of the Caesarea cores. The tsunamite deposit from Jisr al-Zarka

was more tightly dated to 658-781 CE (1292-1169 Cal BP) – within the time window for the Holy Desert Quake of the

Sabbatical Year Earthquake sequence. Ad et al (2018) excavated site LL just north of Caesarea's inner harbour where several ceilings collapsed inward, and there was evidence of a fire in the eastern warehouse.In the collapse in the corridor, the original order of the courses of the wall or vault could be clearly identifiedadding confidence to a seismic interpretation. Dating was based on ceramics and fairly tightly bound to the middle of the 8th century CE. Everhardt et. al. (2023) analyzed two radiocarbon samples of charcoal and various organic matterin the destruction layer which dated from 605 to 779 CE. Everhardt et. al. (2023) further examined two cores and a baulk in the collapse corridor and concluded that a tsunami stuck the structure soon after the earthquake thus extinguishing the fire and bringing in a deposit of marine sand. |

|

| Dead Sea | possible | No physical tsunamogenic evidence from the Sabbatical Year Quakes has been conclusively identified in the Dead Sea. However, Michael the Syrian and Chronicon Ad Annum 1234 both refer to a fortress in Moab inhabited by Yemenite Arabs which was moved 3 miles by a seismic sea wave. There is some ambiguity about location (the location could have been located in the Sea of Galilee) but the most probable interpretation of the text is that this took place on the eastern shores of the Dead Sea. The source for the accounts by Michael the Syrian and Chronicon Ad Annum 1234 may have been the Lost Chronicle of Theophilus of Edessa. | |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

Paleoseismic Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hacipasa Trenches | possible | ≥ 7 | The oldest event identified in the Ziyaret Trench dated to before 983 CE. A lower bound on age was not available due to insufficient radiocarbon dates. |

| Kazzab Trench | possible | ≥ 7 | Ambiguous paleoseismic event ?S2 expressed as displacements along faults F2 and F3. Although Daeron et al (2007) favored an interpretation where this displacement was created during event S1 (dated 926-1381 CE) as a 'mole-track' like feature, they considered another interpretation that ?S2 was caused by a separate seismic event. Their age model date for ?S2 as a separate event spanned from 405 to 945 CE (2σ). |

| Jarmaq Trench | possible | ≥ 7 | Nemer and Meghraoui (2006) date Event Z to after 84-239 CE. They suggested the Safed Earthquake of 1837 CE as the most likely candidate. |

| al-Harif Aqueduct | possible | ≥ 7 | Sbeinati et al (2010)

state that Event Y, characterized from paleoseismology, appears to be older than A.D. 650–810 (unit d, trench A) and younger than A.D. 540–650 (unit d3 in trench C). The results of archaeoseismic investigations indicate that ages of CS-1 (A.D. 650–780) and tufa accumulation CS-3-3 (A.D. 639–883) postdate event Y.Combined together, this constrains Event Y to 540-780 CE. |

| Qiryat-Shemona Rockfalls | no evidence | ||

| Bet Zayda | probable | ≥ 7 | Event CH2-E1 (675-801 CE) from Wechsler et al (2018) - Estimated Magnitude 6.9-7.1. |

| Jordan Valley - Tel Rehov Trench | possible | moderate | Event III of Zilberman et al (2004) could correspond to one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes as it is dated to the 8th century CE. Zilberman et al (2004) indicate that the event produced no vertical displacement and was identified as fractures which crossed Units 1-3. They speculated that the epicenter might have been distant which is also to say that local Intensity may have been moderate. |

| Jordan Valley - Tell Saidiyeh and Ghor Kabed Trenches | possible | ≥ 7 | Ferry et al (2011) detected 12 surface rupturing seismic events in 4 trenches (T1-T4) in Tell Saidiyeh and Ghor Kabed; 10 of which were prehistoric. One of the two historical events (Y and Z) could correlate to one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes however these events are not precisely dated. The tightest chronology came from the Ghor Kabed trenches (T1 and T2) where Events Y and Z were constrained to between 560 and 1800 CE. |

| Jordan Valley - Dir Hagla Trench | possible | ≥ 7 | Event B dated to 700-900 CE |

| Dead Sea - Seismite Types | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Dead Sea - ICDP Core 5017-1 | possible | 7 | 16.5 cm. thick turbidite - age 702 CE ± 44 (658-746 CE) indicating that this turbidite could alternatively have been triggered during the Jordan Valley Quake of 659/660 CE. |

| Dead Sea - En Feshka | probable | 8 - 9 (both seismites) | two seismites are closely spaced to each other

|

| Dead Sea - En Gedi | possible | 5.6 - 7 | 0.2 cm. thick linear wave (Type 1) seismite |

| Dead Sea - Nahal Ze 'elim | probable | 8 - 9 | Site ZA-2, 2 cm. thick brecciated (Type 4) seismite - Modeled Age (1σ) of 774 AD ± 75 |

| Araba - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Araba - Qasr Tilah | possible | ≥ 7 | Event III dated to 7th - 10th centuries CE |

| Araba - Taybeh Trench | possible | ≥ 7 | Event E3 - modeled age 551 CE ± 264 |

| Araba - Qatar Trench | probable | ≥ 7 | Klinger et. al. (2015) reports two earthquakes [E4 and E5] which had to happen very close in time as cracks associated with each event end within a very short distance in our trench. Klinger et. al. (2015) adds: The existence of the distinct unit D [] prevents any ambiguity about the fact that two distinct events are recorded here. Based on our age distribution, the time bracket that includes the two earthquakes is 671 C.E.–845 C.E.. Event E4, the latter of the two earthquakes, produced more ground disruption than Event E5. |

| Araba - Taba Sabhka Trench | possible but unlikely | ≥ 7 | Although Allison (2013)

suggests that EQ IV, the oldest and most strongly expressedseismic event in the trench, was likely caused by a mid 8th century CE earthquake, when two discarded radiocarbon samples are included in developing an age-depth relationship, EQ IV appears to have struck earlier - e.g. between 400 and 100 BCE |

| Araba - Shehoret, Roded, and Avrona Alluvial Fan Trenches | possible | ≥ 7 | Events 7, 8, and 9 in Trench T-18 have a wide spread of ages however, taken together, the evidence suggests the 1212 CE, 1068 CE, and one earlier earthquake, perhaps between ~500 CE and 1000 CE, struck the area. |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |