Jerash - Southwest Hill

- from Blanke et al. (2015) describing the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAJP)

- Fig. 2 - Areas A-E of

the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAJP) from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E

© Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project)

Blanke et al (2015) - Fig. 5 - Detail of hilltop

in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4 from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Detail of hilltop in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4. © LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

- Fig. 2 - Areas A-E of

the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAJP) from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E

© Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project)

Blanke et al (2015) - Fig. 5 - Detail of hilltop

in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4 from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Detail of hilltop in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4. © LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

The southwest part of Jarash is characterised by a gradually rising landscape that slopes upwards west of the South Decumanus and the Umayyad congregational mosque towards the town wall. From the south, a series of terraces overlook the South Theatre. The hilltop is defined by a relatively flat area that measures some 100 by 80 metres at the summit of the main slope. The location of the hilltop at some distance from the major thoroughfares means that modern activity has largely been restricted to grazing goats and a partial conversion of the area to a football field. Tourists seldom make their way to the hill-top, partly owing to the steep climb and partly to the limited archaeological work conducted in this part of the town.

The occupational history of the hilltop and its immediate surroundings has been traced from the Hellenistic Period — where natural caves were modified to accommodate tombs — to the eighth century AD. The latter date was produced in the excavations of the Mortuary Church and the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul (built in the early 7th century (Gatier 1987: 135)) where it was defined through secondary architectural use and the discovery of two coins. When we began our survey, little was known of the periods between these two dates.

Our survey contained two main components. The first component entailed a comprehensive recording of the area between the mosque, the South Decumanus and the town wall where all visible wall lines, cisterns, previous excavated areas, bedrock cuts, terracing and dumps of excavated soil were recorded and mapped with a total station. These data were combined with excavation plans from the IJP [Islamic Jerash Project] using GIS (Geographical Information System) software and superimposed on a recent Google Earth image of the site. An aerial photo of Jarash from 1928 from the Yale University archive was used to trace land use and its impact on the archaeological landscape during the past 80 years.

The second component comprised a focused study of five adjoining areas, all located on the hilltop or immediately adjacent to its main features. These areas were first cleared of vegetation and, thereafter, recorded in detail, using written description combined with a full drawn and photographic record.

The five areas on the hilltop are (Fig. 2: A-E):

- A building on two levels and a cistern

- A plateau with a series of bedrock cuts

- A rectangular space, defined to the south and west by long, straight cuts into the bedrock

- A building complex with a cistern, located on the northern edge of the hilltop

- A street that runs from the South Decumanus to the hilltop

- from Jerash - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 4.1 - Map of the

territories around Baysān/Scythopolis, Fiḥl/Pella and Jarash/Gerasa showing late Roman and early Islamic provincial structures from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.1

Map of the territories around Baysān/Scythopolis, Fiḥl/Pella and Jarash/Gerasa, showing late Roman and early Islamic provincial structures

(Alan Walmsley).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

- Fig. 4.1 - Map of the

territories around Baysān/Scythopolis, Fiḥl/Pella and Jarash/Gerasa showing late Roman and early Islamic provincial structures from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.1

Map of the territories around Baysān/Scythopolis, Fiḥl/Pella and Jarash/Gerasa, showing late Roman and early Islamic provincial structures

(Alan Walmsley).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

- Fig. 1 - Aerial photo

showing southwest hill and surroundings from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 1

Figure 1

1928 aerial photo from Yale University archive showing general survey area and hilltop.

Blanke et al (2015) - Jerash Southwest Hill in Google Earth

- Fig. 1 - Aerial photo

showing southwest hill and surroundings from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 1

Figure 1

1928 aerial photo from Yale University archive showing general survey area and hilltop.

Blanke et al (2015) - Jerash Southwest Hill in Google Earth

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

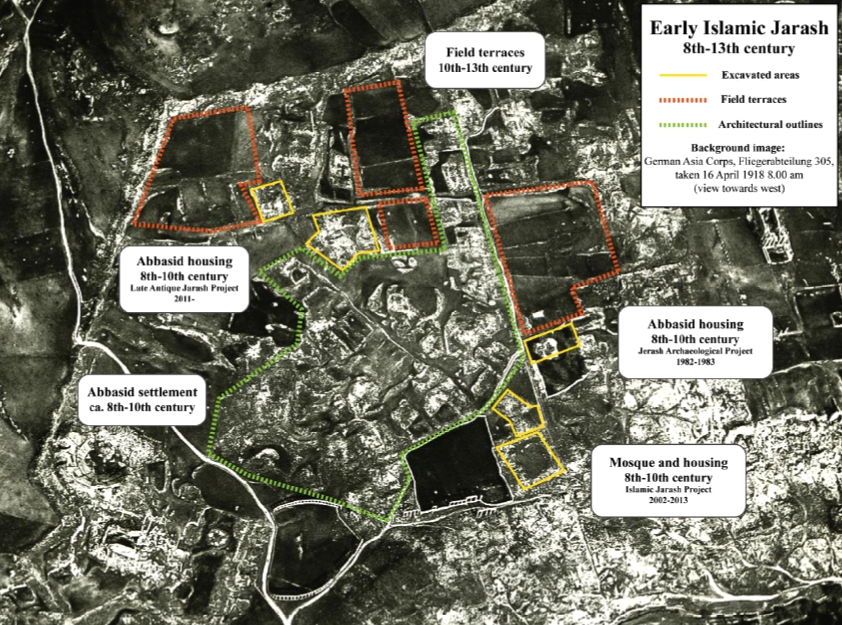

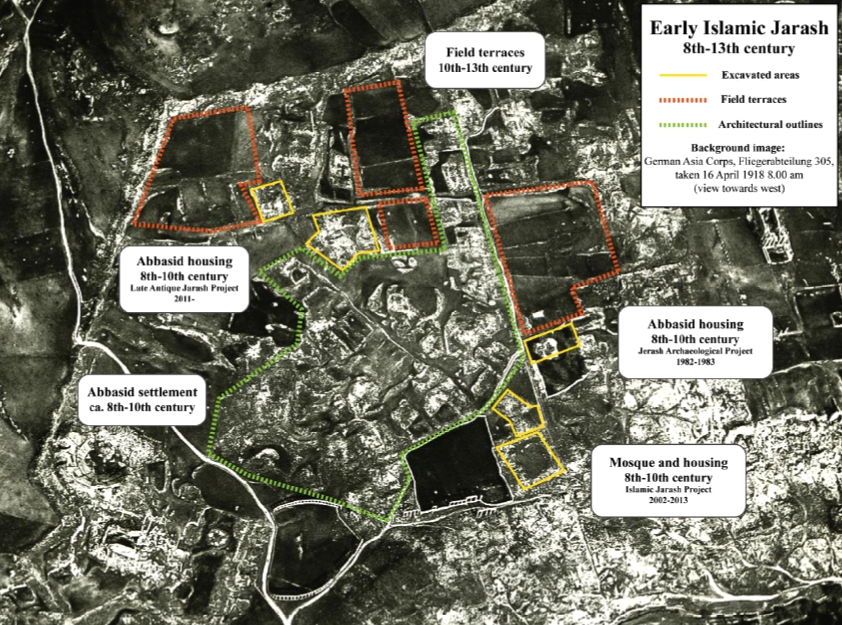

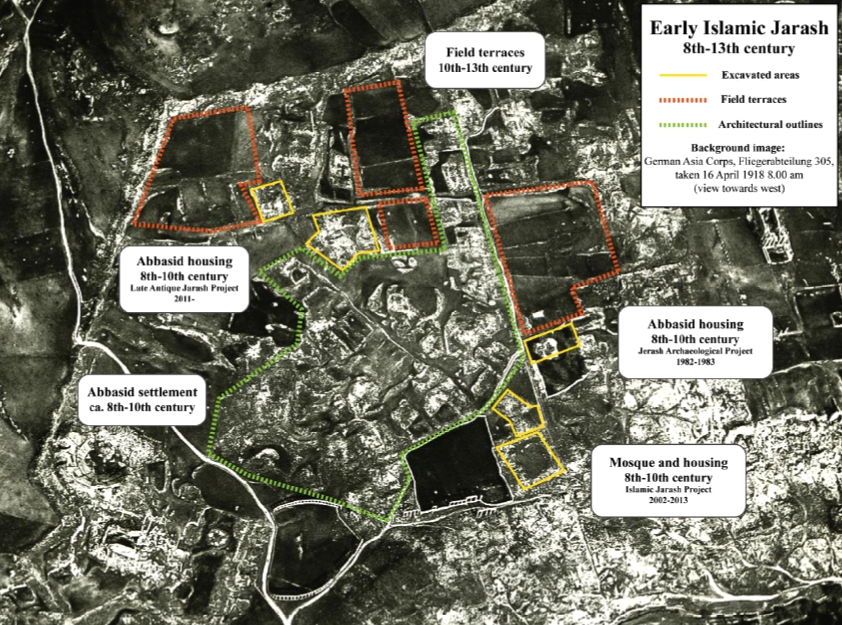

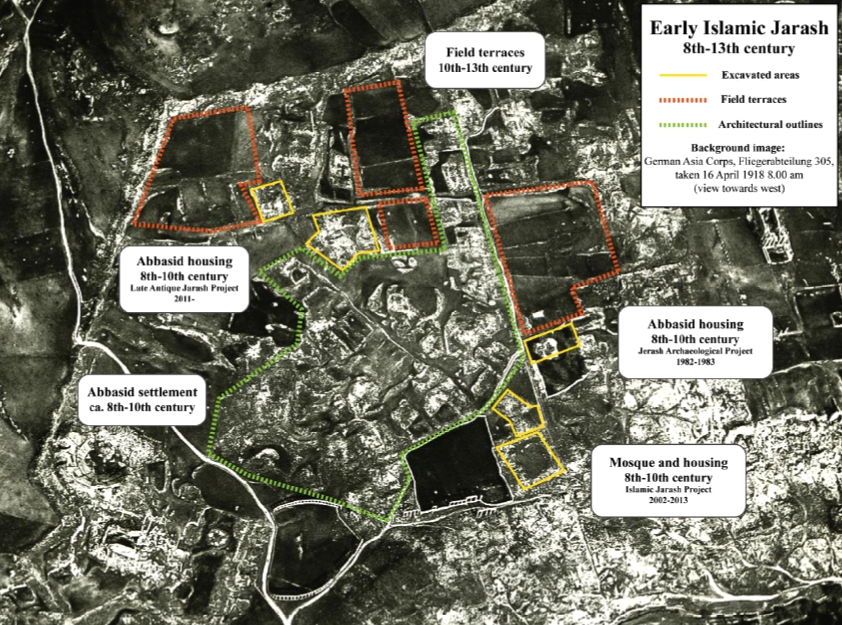

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

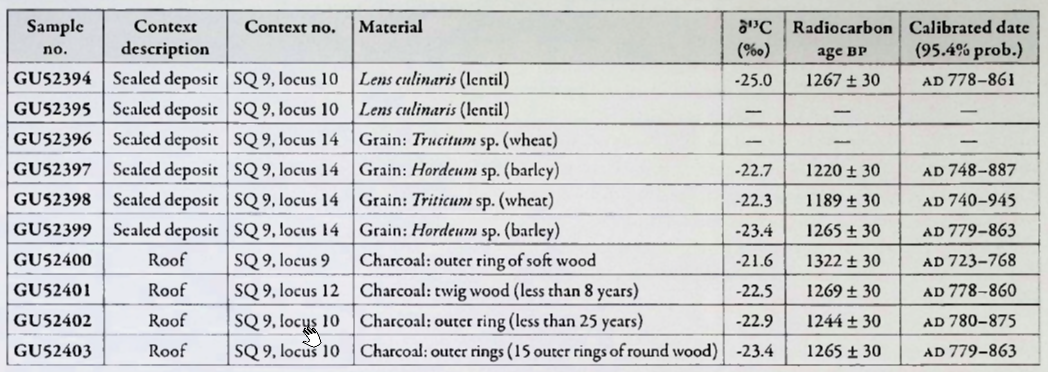

- Fig. 1 - Map of Jarash’s

southwest district from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Jarash’s southwest district with emphasis on survey area and the hilltop, which has so far been the focus of the excavations carried out by LAJP.

© LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

- Fig. 1 - Map of Jarash’s

southwest district from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Jarash’s southwest district with emphasis on survey area and the hilltop, which has so far been the focus of the excavations carried out by LAJP.

© LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

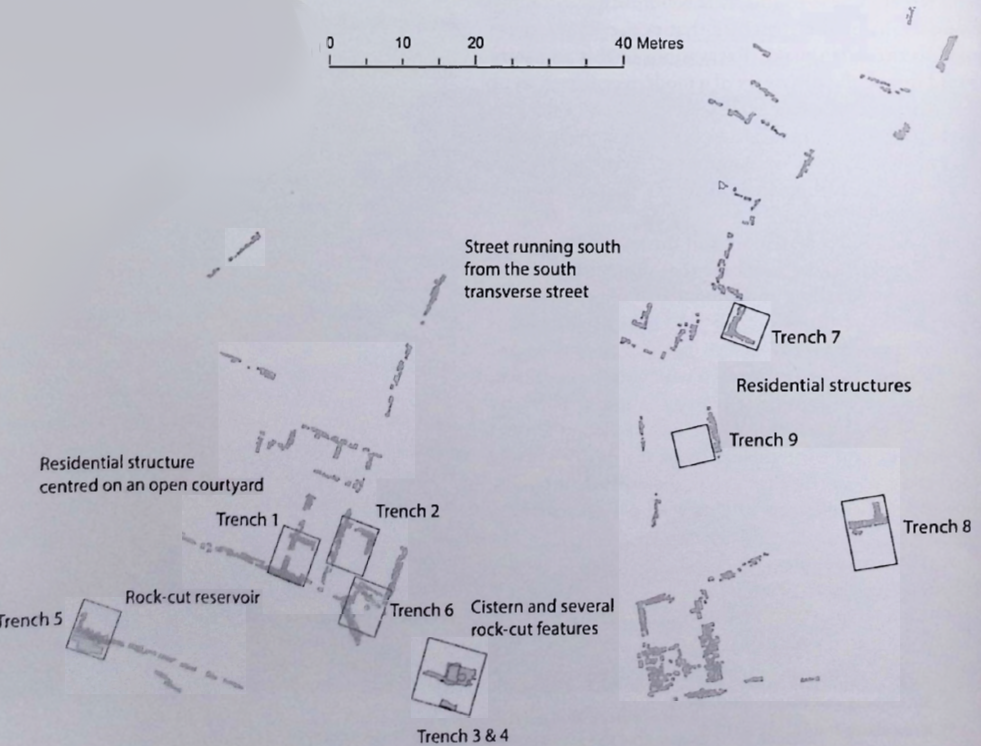

- Fig. 3.4 Location of

Trenches in Jerash's south-west neighborhood from Blanke in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 4.1 Maps of excavation

areas in the LAJP in 2025 and 2017 from Blanke in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2 - Areas A-E of

the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAJP) from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E

© Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project)

Blanke et al (2015) - Fig. 5 - Detail of hilltop

in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4 from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Detail of hilltop in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4. © LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 2 - Survey map

showing location of Trench 5-9 on the southwest hilltop from Blanke et al. (2024)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Survey map showing location of Trench 5-9 on the southwest hilltop

© LAJP.

Blanke et al. (2024)

- Fig. 3.4 Location of

Trenches in Jerash's south-west neighborhood from Blanke in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 4.1 Maps of excavation

areas in the LAJP in 2025 and 2017 from Blanke in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2 - Areas A-E of

the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAJP) from Blanke et al. (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E

© Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project)

Blanke et al (2015) - Fig. 5 - Detail of hilltop

in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4 from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Detail of hilltop in southwest district showing location of Trenches 1-4. © LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 2 - Survey map

showing location of Trench 5-9 on the southwest hilltop from Blanke et al. (2024)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Survey map showing location of Trench 5-9 on the southwest hilltop

© LAJP.

Blanke et al. (2024)

- Fig. 7 - Pottery crushed

by late 9th/early 10th century CE earthquake (in Trench 1) from Blanke et al. (2021)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Remains of two ceramic pithoi embedded into the construction of the floor.

© LAJP

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 8 - Blocked Doorway

in Wall1 of Trench 2 from Blanke et al. (2021)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Trench 2 showing Wall 1 with blocked doorway. View towards the west

© LAJP

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 3.6 Trench 9 after

excavation showing prayer platform and possible stone fractures from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6

Trench 9 after excavation showing prayer platform in the room's south-west corner. Note vertical bedrock cut in the right side of the photo and remains of moulded plaster on south wall

JW: Some stones show possible fractures from impact of falling objects

(photo by the Late Antique Jerash Project)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 7 - Pottery crushed

by late 9th/early 10th century CE earthquake (in Trench 1) from Blanke et al. (2021)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Remains of two ceramic pithoi embedded into the construction of the floor.

© LAJP

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 8 - Blocked Doorway

in Wall1 of Trench 2 from Blanke et al. (2021)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Trench 2 showing Wall 1 with blocked doorway. View towards the west

© LAJP

Blanke et al (2021) - Fig. 3.6 Trench 9 after

excavation showing prayer platform and possible stone fractures from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6

Trench 9 after excavation showing prayer platform in the room's south-west corner. Note vertical bedrock cut in the right side of the photo and remains of moulded plaster on south wall

JW: Some stones show possible fractures from impact of falling objects

(photo by the Late Antique Jerash Project)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 4 - Interpretation

of magnetic data (shows roads) from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Interpretation of magnetic data from prospection of Jarash’s southwest district.

© LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

- Fig. 4 - Interpretation

of magnetic data (shows roads) from Blanke et al (2021)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Interpretation of magnetic data from prospection of Jarash’s southwest district.

© LAJP.

Blanke et al (2021)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- sources: Blanke (2018:31)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hellenistic | Hellenistic period | Construction of a staircase leading to a natural spring cave. Water was retrieved manually. No reservoir yet built. |

| 2 | Early Roman | Early Roman period | Staircase was blocked and backfilled. A Roman- period reservoir was constructed above the cave. Southwest corner and part of the system exposed. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- sources: Blanke (2018:32)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Late Antique | Late Antique period | Residential buildings encroached on the Roman street, reducing its width from 8 m to 4 m. Street still in use but modified. |

| 2 | Abbasid | 8th–9th century CE | Street was stripped down to its Roman surface. Two walls constructed across its southern extent, putting it out of use. Area used for dumping household refuse. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- sources: Blanke et al. (2024:101–102)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roman | undated Roman period | Earliest use includes a stone bench possibly serving as a foundation, associated with a collapse layer and white lime mortar. The area was not excavated to bedrock. Destruction dated to the Roman period by ceramics. A thick sealing deposit above the collapse contained tesserae, marble, bones, and other materials. |

| 2 | Umayyad / Transitional | 7th–8th century CE | New wall construction reused Phase 1 features; associated ceramics include Umayyad buffware and a white painted Jarash bowl. A walking surface was found above the walls. Structural collapse layer included lime mortar, terra rossa, and organic rooftop residue. JW: Although excavators state that collapse may relate to the mid‑8th century earthquake (i.e. the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes), the presence of Abassid ceramics in a sealed destruction layer suggests otherwise, since the Abbasid Caliphate only came to power in 750 CE. |

| 3 | Abbasid | Abbasid period | Rebuilding of Phase 2 walls with a packed soil surface. A make-up layer rich in Abbasid ceramics, including egg shell ware and cut ware, leveled the floor. Later deposit included jewelry, glass, wall tiles, marble, basalt, and reused architectural materials. |

| 4 | Unspecified | undated (post-Abbasid) | New construction after destruction of Phase 3. Stones used were uncut, bonded with fist-sized stones and thick earthen mortar. Final collapse deposit contained building debris and domestic waste. Area was abandoned after this phase. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- sources: Blanke (2018:32)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abbasid | 8th century CE | Use of a room with a stamped clay floor, stone walls, and a flat roof made of wooden beams and clay. Roof collapsed during a fire, sealing carbonized lentils, wheat, barley, figs, and dates. A crushed ceramic bowl and oil lamp confirm Abbasid dating. |

South-west Jerash is characterized by a gradually rising landscape from the mosque area in the east towards the town wall in the west and by a series of artificial terraces that overlook the South Theatre. Past archaeological research includes excavations of the Church of Sts Peter and Paul and the adjacent Mortuary Church in the late 1920s and early 1930s by the Yale-British School Joint Mission. In the 1980s, Asem Barghouti excavated sections of the south transverse street and one of its tributaries — a street that runs c. 400 m from the triple church complex of Sts Cosmas and Damianus, St George, and St John the Baptist in the north, to a plateau (c. 80 by 100 m) in the south. LAJP was initiated in 2015 and has so far carried out geophysical survey and recording of architectural surface remains throughout south-west Jerash and has excavated nine trenches on the plateau and in its immediate vicinity (Fig. 3.1). These examinations have documented a residential neighbourhood, which after the earthquake of 749 saw significant refurbishment to ensure the continuation of urban life.44

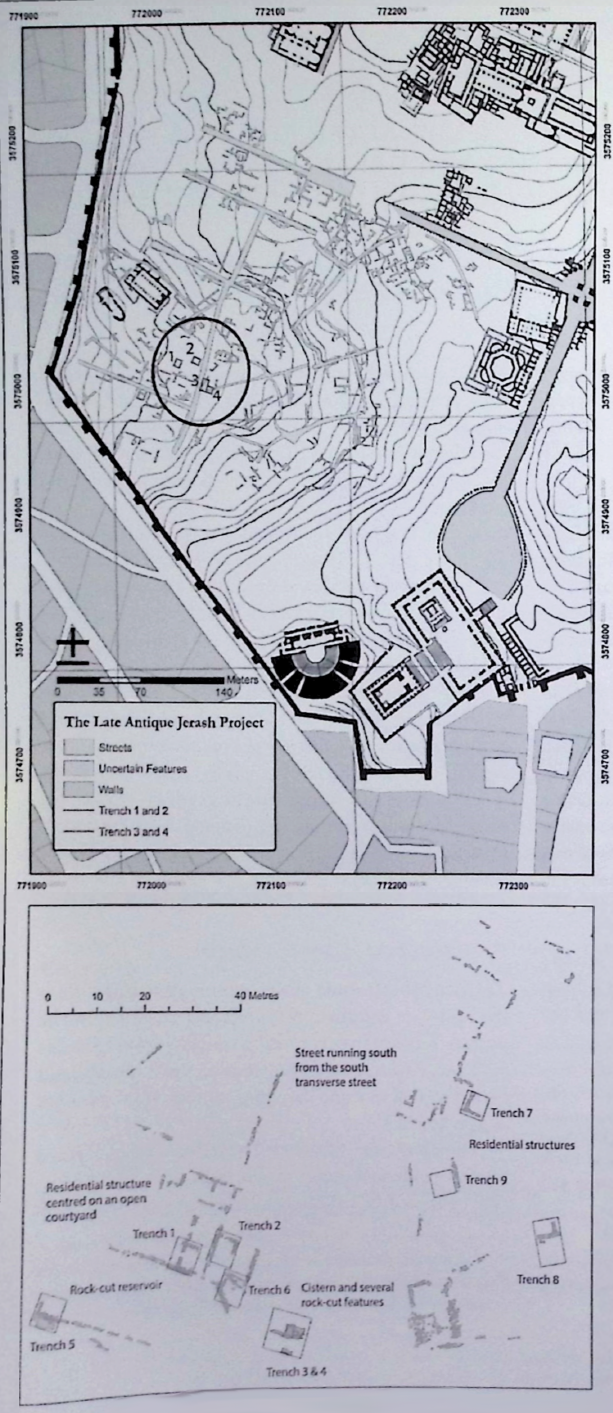

Seven of LAJP's nine trenches contained data supporting post-earthquake occupation. This data is summarized in Table 3.1 and discussed in detail below under the headings of ‘Residential Structures’ (trenches 1, 7, and 9) and ‘Thoroughfares’ (trenches 2, 6, and 8). Other data pertaining to the overall development of Jerash's south-west neighbourhood has been discussed elsewhere and will not be repeated here (this includes the Abbasid-period ceramics obtained from rubbish deposits in trench 5).45

44. The main results from LAJP are published in

Blanke 2018; 2022; Blanke and Walmsley 2022;

Blanke and others 2015; 2022; Blanke and others

2024b; Pappalardo 2019.

45. Blanke 2018; Blanke and others 2022; 2024b.

Trench 1 is situated in the southernmost part of a residential structure (c. 20 by 25 m), which comprises at least five rooms organized around a courtyard.18 The structure borders the street running north–south to the east (part of which has been excavated in trenches 2 and 6) and an alley running east–west to the north. Trench 1 was laid out to excavate a section of a room that opens onto the southern half of the courtyard (Fig. 3.5). The room consists of stone-built walls that sit directly on the bedrock and are preserved to a height of 1.7 m. The interior surface consists of hard stamped yellow clay. The remains of piers along the north and south walls as well as arch stones found in the wall collapse suggest that the roof was supported by a series of arches, which were covered by wood or reed and topped by stamped clay of the same type that was used on the floor. This type of roof construction was also observed in trenches 7 and 9 (see below) and in the post-earthquake residential structure to the west of the congregational mosque. The pattern of wall collapse shows that the room collapsed in a single event (rather than piecemeal over a longer period, which would have resulted in accumulated debris between the layers of wall tumble). The assemblage of finds retrieved from below the rubble shows that the room was in use at the time of collapse. The context of the room has been described in detail elsewhere and will be briefly summarized here47.

The assemblage of mainly ceramic finds suggests that the room was used for household storage and most likely to store foodstuffs. The sealed deposit comprised c. 960 sherds that amount to twenty-two nearly intact vessels with only a few sherds from other pots. These vessels comprised several large storage jars (including nine pithoi), cooking pots, and a few examples of fine wares. Among these vessels were ceramic forms that date to the Abbasid period. Of particular importance were several examples of cutware/Kerbschnitt and also a black polished beaker that is comparable in shape and fabric to vessels found in ninth-century layers at Pella, Aylah, Jerusalem, Capernaum, and Nabratein.48 Other finds from the sealed deposit include loom weights, grinding stones, and the blade of a knife, all of which confirms the residential usage.49

47. Blanke 2018; Blanke and others 2022; Pappalardo

2019.

48. Blanke and others 2022, 593–95, 598–601;

Pappalardo 2019, 218–24. See also Magness

1994, 200–01.

49. Blanke and others 2022, 593–95. For comparative

residential contexts in Jerash, see, for example,

Gawlikowski 1986; Lichtenberger and others

2016; Rattenborg and Blanke 2017.

Another room in what appears to be a residential structure was excavated in trench 7. The excavation revealed a complex architectural stratigraphy with four main phases spanning the Roman period to the Early Abbasid period. Unlike most other trenches excavated by LAJP, it was possible to establish the transition from pre- to post-earthquake occupation (phases three and four). Phase three (the pre-earthquake occupation) was disrupted by a collapse and phase four (the post-earthquake occupation) was characterized by rebuilding. In phase three, the ceramic assemblage included typical transitional period ceramics, such as Umayyad buff ware and a white painted Jerash bowl, which suggests that this phase should be dated to the seventh or early eighth century.50 A thin but compacted red clay layer has been interpreted as the remains of a walking surface. Directly on top of this surface, a structural collapse was identified across the entire trench. The collapse layer consists of a mix of lime mortar, terra rossa, and lenses of yellow clay and is rich in organic residue, which is typical for the type of flat rooftops also seen in trenches 1 and 9. The organic soil deposits — probably from disintegrated wooden beams — appear as horizontal lines, suggesting that the rooftop did not experience long-term decay but rather a sudden collapse. It is likely that the collapse was associated with the earthquake of 749.

The post-earthquake phase saw the rebuilding of two of the walls and also a make-up layer which served to cover the collapse and to level the room in order to support a surface of packed earth. The make-up layer was rich in ceramic sherds, many of which can be dated to the Abbasid period: included in the assemblage was a complete cutware/Kerbschnitt lid and an eggshell ware jug.51 So far, we have not been able to date the final abandonment of the structure in trench 7, but the last use of the area entailed using the now-abandoned structure to dispose of discarded building material including stones, brick, tegula, tesserae, and plaster, as well as rubbish from one or more nearby residential structures.

50. See ceramic report in Blanke and others 2024b and also Pappalardo, this volume.

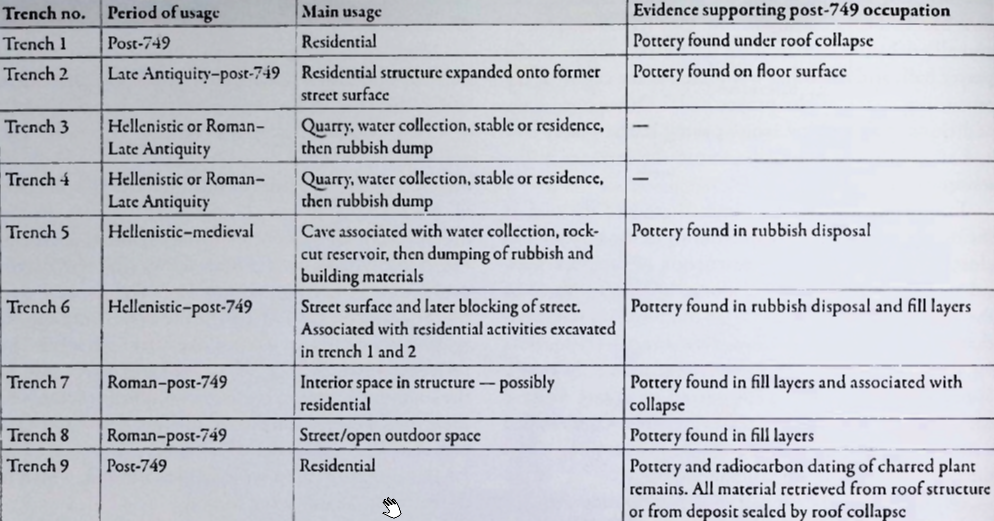

The excavation of trench 9 proved to be most serendipitous in terms of elucidating the hill-top's post-earthquake settlement. Trench 9 is located at the southern extent of the cluster of structures to which the room that was partially excavated in trench 7 also belonged. The southern extent of the trench is defined by a wall running east–west, which was visible on the surface prior to excavation. The excavation revealed a section of a room which was used for a variety of purposes, one being food storage.

The east–west wall delineates the southern extent of the room, while the western edge was defined by bedrock, which had been cut to form a vertical face (Fig. 3.6). The northern and eastern walls of the room were not present within the excavated trench and the room's full size is yet to be determined. The floor comprised stamped clay and the roof was made from wooden beams and smaller branches, which had been packed with the same type of clay that was used on the floor. Our excavations showed that the roof collapsed in a fire, which carbonized the wood and hardened the clay, thus sealing the room and its contents. Amongst the finds retrieved from the room were an abundance of charred plant remains including hundreds of barley and wheat grains, hundreds of cultivated pulses, as well as two intact dates. Four wood samples and six grain samples were submitted for radiocarbon dating (Table 3.2). The radiocarbon dating of two of the samples failed, but the remaining eight samples show that the calibrated dates lean towards the late eighth or first half of the ninth century.

Other objects obtained from the sealed deposit in trench 9 included eight nearly intact vessels dated to the Abbasid period including an oil lamp, which was heavily damaged by the fire, and a small column base with a smooth surface, which may have been used to spread dough in preparation for baking flat bread52.

In addition to the rich finds of charred plant remains, the room contained a rare architectural feature known as a prayer platform, which was built for private Muslim worship and is known from a handful of ninth-century sites. The platform measures 1.5 by 1 m and consists of a raised area built from five reused marble slabs that were set against the cut bedrock and lined with limestone blocks on the east side. The platform faces the room's south wall, which bears traces of moulded plaster in the shape of two raised columns. A comparative example from the post-earthquake settlement in Baysan shows a similar arrangement in which the moulded plaster formed an arch supported by two columns, which is a commonly used iconography for sacred space — in this case the mihrab, which is found in mosques and marks the direction of prayer towards Makkah.53 Other examples are known from an Abbasid-period domestic context in Madinat al-Far and from a private house in ninth-century Ramla.54 At Ramla, a mosaic floor with mihrab iconography contains the words in kufic script 'al-qibla' followed by a quote from the Qur'an (7.205) saying 'and be not negligent.

The orientation of the room in trench 9 containing the prayer platform is significant. Unlike adjacent structures it follows a slightly different alignment, which is comparable to that of the mosque, suggesting that a deliberate attempt was made to orientate the room towards Makkah. The discovery of a prayer platform gives us a rare insight into the practice of private religion in post-earthquake Jerash and in the world of early Islam more broadly.

52 Pers. coin. Apollinc Vernet 2017.

53 Fitzgerald 1931, pl. XXIII-2; reviewed in Vernet 2016.

54 Madinat Haase 2007, 458; Itarnla: Rosen-Ayalon

1976, 116-19.

In addition to the data retrieved from the three residential units, LAJP's excavations of the thoroughfares in the south-west neighbourhood has yielded further evidence for Jerash's post-earthquake settlement. The plateau was accessed via two main thoroughfares, one described above, leading due south from the south transverse street, and one leading south-west from the congregational mosque. The former followed the Roman-period grid system, while the latter followed an earlier system, which appears to have been in use from the Hellenistic period and served as the main thoroughfare from the residential neighbourhood to the mosque in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods.55

Trenches 2 and 6 were excavated on the north–south thoroughfare in order to examine encroachment from the residential unit onto the street, which at first reduced the width of this street from c. 8 m to c. 4 m and in the Abbasid period blocked the street altogether. Trench 8 was excavated on the thoroughfare running south-west from the congregational mosque to the residential neighbourhood with the aim of studying its stratigraphy and its development through time. Unfortunately, the remains of the thoroughfare in trench 8 were thoroughly disturbed by later activities, including agriculture, dumping, and levelling, which means that very little evidence for the layout of the post-earthquake street was obtained. Trench 8 was, however, rich in ceramic material providing a full ceramic sequence from the Roman period and well into the Abbasid period with an extraordinary selection of e.g. eighth- or ninth-century cutware/Kerbschnitt from the trench's upper levels.

55. The street grids are discussed in detail in Blanke 2018, 47–49.

The excavation of trench 2 uncovered a section of a room that protruded onto the street from the residential building to which the room in trench 1 belonged. Trench 2 exposed three walls (east, west, and north) that were built directly on bedrock with no remains of a surface other than the bedrock (Fig. 3.7). A doorway providing access from the residential structure was found blocked and the surface of the room in trench 2 gave the impression of having been swept before abandonment: the trench yielded fewer than five hundred sherds of sixth- to ninth-century date of which only sixty-seven were diagnostic. The limited material meant that while it was possible to establish that the room was in use into the post-earthquake period, its usage remains obscure as does the date of the encroachment.

Trench 6 was opened almost adjacent to trench 2 to further our understanding of the usage of the north–south thoroughfare (Fig. 3.8). Our excavations revealed that at some point after the earthquake of 749, the southern section of the street had gone out of use altogether as it was now spanned by two walls protruding from the encroachment partially excavated in trench 2. This observation is interesting in the light of the blocking of the doorway in the north wall of the mosque, which suggests a lessening of the importance of the south transverse street at some point after 749. Although speculative, the discontinuation of the north–south tributary in the south-west district may suggest an urban focus on the southern sector of the town.

The excavations carried out in the urban centre by IJP and in the south-west neighbourhood by LAJP have enabled us to form a picture of the strategies employed in the refurbishment of Jerash after the earthquake of 749 (Figs. 3.7–3.8). Structures that were integral to governance, religious practice, and commerce were prioritized for rebuilding as were the residential neighbourhoods in their vicinity. Here, urban life continued for centuries while other sectors of the town remained abandoned.

The evidence obtained so far suggests a thriving community engaged in both private and communal worship, with active commerce, and a water supply system that operated on both a private and communal level. We have been able to establish that post-earthquake Jerash was concentrated around the urban core and south-west neighbourhood, but it is likely that the rebuilding also involved areas further south towards the Oval Piazza and perhaps also east into the modern sector of the town.

The evidence for Muslim religious practice is important, but it raises the question of what happened to the town's Christian population. The late ninth-century geography by Al-Ya‘qubi states that Jerash was inhabited by a mix of Arabs and Greeks, however, we have yet to secure evidence for the continuation of communal Christian worship after 74956. Instead, our data suggests that Jerash was rebuilt as a Muslim town, perhaps because the financial means to refurbish the town were obtained from the Muslim authorities or from a local Muslim elite. Inscriptions from Baysan and Askhelon confirm the involvement of the Muslim administration in the funding of mosques, but such evidence does not exist from Jerash.57

Regarding the urban water supply system, two contemporaneous systems appear to have been in place. The residential units excavated adjacent to the mosque and in the south-west neighbourhood were equipped with their own bottle-shaped cisterns. It is likely that the cisterns were reused from structures that predated the earthquake — a similar arrangement is observed in the Umayyad-period houses that have been excavated in the North-West Quarter58. Their presence informs us that the residents were responsible for the collection and storage of water for household consumption.59

Evidence for a communal water supply is found within and adjacent to the mosque. The ablution feature, which was built by the interior side of the entrance in the western wall, received water through a pipe in the mosque’s wall. This water source may also have supplied the basin that was found on the northern side of the residential unit just west of the mosque. As such, the mosque and its adjacent structures may have played a pivotal role in providing water to the public — a role that to some extent was managed by the churches in Late Antiquity.60

While the earthquake of 749 did not cause the abandonment of Jerash urban centre and its adjacent residential neighbourhoods, other, later, earthquakes appear to have been at least partially responsible for the urban retraction towards the centre. At least two of the buildings in the residential neighbourhood were abandoned because of a catastrophic event, which took place at some point in the later ninth century. The roof and walls of the room in trench 1 collapsed in an earthquake and the conflagration that ended the occupation of the room in trench 9 may have been caused by the same event. LAJP’s examinations suggest that the area was gradually given over to agricultural purposes, which eventually transformed Jerash into an agricultural village.

The residential area immediately west of the mosque also saw an end to its residential phase at some point in the ninth century while the second phase of the mosque may have continued into the tenth century until it was destroyed in another catastrophic event. It was, however, partially rebuilt in a reduced form with the enclosed room in the prayer hall serving as the main mosque. A new entrance was built in the west wall, and a staircase was built to give access to the roof space for the call to prayer. The final phase of the mosque ended in the Ayyubid–Mamluk period with the collapse of the roof, which was followed by widespread evidence for stone removal, pit digging, and agricultural usage.61

56 Le Strange 1890, 462 after Lichtenberger and Raja

2016, 68.

57 In AH 155/AD 771–772 Caliph Mansur (entitled

al-Mahdi in the inscription) ordered the building of a

mosque and minaret in Ashkelon (Sharon 1997, 144). An

inscription from Baysan dating to AH 135/AD 753

commemorates commissions by ʿAbdallah as-Saffah

(AD 749–754), the first caliph of the Abbasids.

Unfortunately, the inscription is incomplete, and it is

unclear what was commissioned. Sharon (1999, 214)

states that this inscription shows “that particular

interest was paid to the building of the city by people

of the highest class — members, in one way or the

other, of the royal [family].”

58 Lichtenberger and Raja 2020; Lichtenberger and others

2013, 13; Kalaitzoglou and others 2013, 68–75.

59 See Vernet 2014; 2016 for an overview of water usage

in early Islamic houses.

60 Pickett 2015, 33–78.

61 Walmsley 2018, 250.

For nearly a hundred years (since the first investigations by Western archaeologists and historians), Jerash was believed to have been destroyed by the earthquake of 749 and subsequently abandoned. We can now state with certainty that this was not the case: instead, its inhabitants proved resilient and resourceful in organizing a strategic rebuilding of the structures most central to the maintenance of governance, commerce, religion, and habitation. This marks a new chapter for the history of Jerash and for its archaeological exploration. Over the coming seasons of work, LAJP's main aim will be to further our understanding of the extent and nature of the post-earthquake occupation and the town's centuries-long transition into an agricultural community.

The excavation of Trench 1 in 2015 uncovered a section of a room within a housing complex that collapsed in a sudden catastrophic event - possibly an earthquake - which sealed the room below 1.5m of wall tumble (the room forms a part of Area D, see Blanke et al. 2015: 232; 2021). The ceramic assemblage uncovered from the room was mainly Late Antique (including Umayyad) and Abbasid in date (Pappalardo 2019). Importantly, the architectural stratigraphy of the building revealed that it was constructed directly on bedrock, with only few architectural modifications identified. Our current interpretation of the room is that it was either built from new or massively restored after the earthquake in the middle of the 8th century AD.

A major objective in 2017 was to further investigate the residential structures on the hilltop in order to expand our understanding of the layout, size and fabric of the city in the Abbasid period, while also addressing questions of the organization of the residential structures themselves. Two trenches (Trench 7 and 9) in two different housing units were excavated and within a large (80×50m) area, known as Area F, all standing surface remains of walls were drawn (Fig. 2)

Trench 7 is located within the cluster of residential structures defined as Area F (see below). Following the results of the excavation of Trench 1 (Blanke 2016; Blanke et al. 2021) the aim was to further examine the extent of southwest district as well as investigate the area’s development over the longue durée. The trench was laid out according to two walls that were visible on the surface and constituted the western and southern limits of a 4×4m trench. The excavation revealed several occupational sequences and displays the different construction techniques applied in this area through different periods.

The earliest use of the area (defined here as Phase 1) saw remains of a Roman period occupation (Fig. 8). Given the small space available, the excavation was stopped in Trench 7 before reaching the bedrock. At present, a stone bench is the earliest occupation identified within the excavation, but it was probably not the first construction in the area. The top of the bench was uncovered ca. 2m below the current surface level. Partly obscured by the construction of later walls, the eastern face was made from stone blocks showing no regular layout, bonded with medium stones and fixed with white lime mortar. At first glance, it could be interpreted as a foundation but unfortunately, comparanda with other Roman period underground construction techniques are scarce within Jarash (but see Gawlikowski 1986, plate IIIB; Blanke 2015). The layout of the bench suggests that it served as foundation for a building of substantial size. It is associated with a collapse layer of large ashlar blocks and the same white lime mortar that is found within the bench. It is not possible to speculate on the use of the building, but a careful ceramic analysis dates its destruction to the Roman period (see ceramic analysis, this report). It is also associated with a thick sealing deposit (0.30m) on top of the collapse, which consist of light brown soil with inclusions of glass, bones, metal, tesserae and chunks of marble. The remains of the structure add to the list of several Roman period discoveries made by the LAJP in 2015 and 2017 (see Trench 5, 6 and 8, this report, and Blanke et al. 2021).

The Roman abandonment deposit was cut along the western end of Trench 7 in order to use the above‑mentioned bench as a foundation for a new north‑south running wall. The associated ceramic material suggests that this second phase of use should be dated to the 7th or 8th century (Fig. 9). Importantly, the area appears to have been untouched for centuries since the filling of the cut (i.e. the foundation trench) contains typical transitional period ceramics, such as Umayyad buffware and a white painted Jarash bowl. The new north-south running wall is associated with an east-west running wall in the northern part of the square; both are made of roughly cut medium-sized stones on top of which squared limestone blocks were laid. A thin but compacted red clay layer has been interpreted as the remains of a walking surface, but nothing remains on the floor to suggest the purpose of the new room. Directly on top of this surface, a structural collapse was identified across the entire trench. The collapse layer consists of a mix of lime mortar, terra rossa and lenses of yellow clay. The deposit is rich in organic residue (a soil sample has been collected for further analysis), which is typical for flat rooftops in the Eastern Mediterranean, which would commonly comprise wooded beams It is important to note that in the section, the organic soil deposits appear as horizontal lines suggesting that the rooftop did not experience a long‑term decay but rather a sudden collapse. Considering the period under study, it is possible that the collapse was associated with the earthquake that took place in the mid‑8th century AD and is well attested throughout Jarash and nearby cities (for a detailed list on earthquakes in the region, see Ambraseys 2009).

The third phase was initiated with a cut through the western end of the Phase 2 destruction in order to use the remains of the north‑south running wall as a foundation for the rebuilding of this wall. Phase 3 also saw new courses added to the east‑west running wall (Fig. 10). The rebuilding of the wall was accompanied by a make-up layer (5cm along the cut to 40cm in the western section) to level the room and serve as a foundation for a packed soil surface. The make-up layer was rich in ceramics dating to the Abbasid period comprising an abundance of e.g. cut ware and egg shell ware (see ceramic report).

Finally, the room was discovered filled with a packed earth deposit that was rich in finds such as jewellery, glass, disused construction material (wall tiles, tesserae, marble, basalt and wall plaster). As no proper abandonment layer or clear pattern of sudden destruction has been identified, one can hypothesize that the deposit was obtained from a nearby destroyed household.

The final use of the area (Phase 4), comprise construction activity after a sudden destruction that brought an end to Phase 3 (Fig. 11). First, new courses of rough stones were laid along the east‑west running wall in the northern end of the trench, which delineated an area to the north which remained untouched and filled with collapsed building material. Second, the southern part of the trench saw the construction of a new east‑west running wall that was bonded with the rebuilt north‑south wall. The medium‑sized stones used for this rebuilding bear no proper cut marks, and the stones are bonded with fist‑sized stones set within a thick earthen mortar. It has not been possible to date Phase 4, but in the newly constructed room, a deposit associated with the destruction of Phase 4 contains a large quantity of discarded building material (medium‑sized stones, brick, tegulae, marble, tesserae, glass tesserae and plaster) as well as domestic waste (ceramics, metal fragments, bones and a soapstone fragment). Following the destruction of phase 4, the area was abandoned.

Four phases ranging from the Roman to the Abbasid period were identified in the excavation of Trench 7. As described above, the interpretation of Phase 1 is meagre, but added to the numerous discoveries made by LAJP (Blanke 2018a and this article) one can begin to assert the extent and general use of the area in the Roman period. During Late Antiquity, this area seems to have been disused as demonstrated by the hiatus in occupation until the construction of the foundation trench prior to the reuse of the Roman building remains in the Umayyad period. Even if it is not currently possible to understand how the building was used, the continuous use of the north-south wall suggests that the Roman-period structure remained an maintained the memory of the antique building, which was probably already in ruins.

The excavation shows how the area underwent major breaks during the early Islamic period. Following the Umayyad occupation, Trench 7 was used twice as a dumping area during the Abbasid period offering a large quantity of artefacts and construction material. The Abbasid-period dumps probably originated from a nearby residential area. Importantly, the material retrieved from the sealed context in Trench 9 (see below) contains the same ceramic horizon as that found in Trench 7 suggesting a wider use of the area at this time and perhaps also suggesting that nearby buildings were in use while others (such as that found in Trench 7) had been transformed to be used for the disposal of rubbish.

Blanke (2018) reports rebuilding evidence for the 749 earthquake in Southwest Hill (Late Antique Jerash Project)

The partial excavation of two residential structures (Trenches 7 and 9) confirmed that Jarash’s southwest district saw a major refurbishment after the earthquake in A.D. 749. Large quantities of ceramics dating to the Abbasid period were retrieved from Trench 7. The excavation of Trench 9 exposed a section of a room that went out of use after a devastating conflagration. The room comprised a stamped clay floor, stone walls, and a flat roof made from wooden beams that supported a thick layer of packed clay. The fire caused the beams to burn and the roof to collapse, thus sealing all material relating to the final use of the room. This material included thousands of carbonized lentils, wheat, barley, and a few figs and dates. The lentils were found in a large pile on top of a stone platform, which implies that they were kept in a sack that disintegrated in the fire. The grain and fruit were found in and around a ceramic vessel that was crushed by the weight of the collapsed roof. This bowl, along with a severely damaged oil lamp, is clearly Abbasid in date. Further analysis and dating of the carbonized material are currently underway.

South-west Jerash is characterized by a gradually rising landscape from the mosque area in the east towards the town wall in the west and by a series of artificial terraces that overlook the South Theatre. Past archaeological research includes excavations of the Church of Sts Peter and Paul and the adjacent Mortuary Church in the late 1920s and early 1930s by the Yale-British School Joint Mission. In the 1980s, Asem Barghouti excavated sections of the south transverse street and one of its tributaries — a street that runs c. 400 m from the triple church complex of Sts Cosmas and Damianus, St George, and St John the Baptist in the north, to a plateau (c. 80 by 100 m) in the south. LAJP was initiated in 2015 and has so far carried out geophysical survey and recording of architectural surface remains throughout south-west Jerash and has excavated nine trenches on the plateau and in its immediate vicinity (Fig. 3.1). These examinations have documented a residential neighbourhood, which after the earthquake of 749 saw significant refurbishment to ensure the continuation of urban life.44

Seven of LAJP's nine trenches contained data supporting post-earthquake occupation. This data is summarized in Table 3.1 and discussed in detail below under the headings of ‘Residential Structures’ (trenches 1, 7, and 9) and ‘Thoroughfares’ (trenches 2, 6, and 8). Other data pertaining to the overall development of Jerash's south-west neighbourhood has been discussed elsewhere and will not be repeated here (this includes the Abbasid-period ceramics obtained from rubbish deposits in trench 5).45

44. The main results from LAJP are published in

Blanke 2018; 2022; Blanke and Walmsley 2022;

Blanke and others 2015; 2022; Blanke and others

2024b; Pappalardo 2019.

45. Blanke 2018; Blanke and others 2022; 2024b.

Trench 1 is situated in the southernmost part of a residential structure (c. 20 by 25 m), which comprises at least five rooms organized around a courtyard.18 The structure borders the street running north–south to the east (part of which has been excavated in trenches 2 and 6) and an alley running east–west to the north. Trench 1 was laid out to excavate a section of a room that opens onto the southern half of the courtyard (Fig. 3.5). The room consists of stone-built walls that sit directly on the bedrock and are preserved to a height of 1.7 m. The interior surface consists of hard stamped yellow clay. The remains of piers along the north and south walls as well as arch stones found in the wall collapse suggest that the roof was supported by a series of arches, which were covered by wood or reed and topped by stamped clay of the same type that was used on the floor. This type of roof construction was also observed in trenches 7 and 9 (see below) and in the post-earthquake residential structure to the west of the congregational mosque. The pattern of wall collapse shows that the room collapsed in a single event (rather than piecemeal over a longer period, which would have resulted in accumulated debris between the layers of wall tumble). The assemblage of finds retrieved from below the rubble shows that the room was in use at the time of collapse. The context of the room has been described in detail elsewhere and will be briefly summarized here47.

The assemblage of mainly ceramic finds suggests that the room was used for household storage and most likely to store foodstuffs. The sealed deposit comprised c. 960 sherds that amount to twenty-two nearly intact vessels with only a few sherds from other pots. These vessels comprised several large storage jars (including nine pithoi), cooking pots, and a few examples of fine wares. Among these vessels were ceramic forms that date to the Abbasid period. Of particular importance were several examples of cutware/Kerbschnitt and also a black polished beaker that is comparable in shape and fabric to vessels found in ninth-century layers at Pella, Aylah, Jerusalem, Capernaum, and Nabratein.48 Other finds from the sealed deposit include loom weights, grinding stones, and the blade of a knife, all of which confirms the residential usage.49

47. Blanke 2018; Blanke and others 2022; Pappalardo

2019.

48. Blanke and others 2022, 593–95, 598–601;

Pappalardo 2019, 218–24. See also Magness

1994, 200–01.

49. Blanke and others 2022, 593–95. For comparative

residential contexts in Jerash, see, for example,

Gawlikowski 1986; Lichtenberger and others

2016; Rattenborg and Blanke 2017.

Another room in what appears to be a residential structure was excavated in trench 7. The excavation revealed a complex architectural stratigraphy with four main phases spanning the Roman period to the Early Abbasid period. Unlike most other trenches excavated by LAJP, it was possible to establish the transition from pre- to post-earthquake occupation (phases three and four). Phase three (the pre-earthquake occupation) was disrupted by a collapse and phase four (the post-earthquake occupation) was characterized by rebuilding. In phase three, the ceramic assemblage included typical transitional period ceramics, such as Umayyad buff ware and a white painted Jerash bowl, which suggests that this phase should be dated to the seventh or early eighth century.50 A thin but compacted red clay layer has been interpreted as the remains of a walking surface. Directly on top of this surface, a structural collapse was identified across the entire trench. The collapse layer consists of a mix of lime mortar, terra rossa, and lenses of yellow clay and is rich in organic residue, which is typical for the type of flat rooftops also seen in trenches 1 and 9. The organic soil deposits — probably from disintegrated wooden beams — appear as horizontal lines, suggesting that the rooftop did not experience long-term decay but rather a sudden collapse. It is likely that the collapse was associated with the earthquake of 749.

The post-earthquake phase saw the rebuilding of two of the walls and also a make-up layer which served to cover the collapse and to level the room in order to support a surface of packed earth. The make-up layer was rich in ceramic sherds, many of which can be dated to the Abbasid period: included in the assemblage was a complete cutware/Kerbschnitt lid and an eggshell ware jug.51 So far, we have not been able to date the final abandonment of the structure in trench 7, but the last use of the area entailed using the now-abandoned structure to dispose of discarded building material including stones, brick, tegula, tesserae, and plaster, as well as rubbish from one or more nearby residential structures.

50. See ceramic report in Blanke and others 2024b and also Pappalardo, this volume.

The excavation of trench 9 proved to be most serendipitous in terms of elucidating the hill-top's post-earthquake settlement. Trench 9 is located at the southern extent of the cluster of structures to which the room that was partially excavated in trench 7 also belonged. The southern extent of the trench is defined by a wall running east–west, which was visible on the surface prior to excavation. The excavation revealed a section of a room which was used for a variety of purposes, one being food storage.

The east–west wall delineates the southern extent of the room, while the western edge was defined by bedrock, which had been cut to form a vertical face (Fig. 3.6). The northern and eastern walls of the room were not present within the excavated trench and the room's full size is yet to be determined. The floor comprised stamped clay and the roof was made from wooden beams and smaller branches, which had been packed with the same type of clay that was used on the floor. Our excavations showed that the roof collapsed in a fire, which carbonized the wood and hardened the clay, thus sealing the room and its contents. Amongst the finds retrieved from the room were an abundance of charred plant remains including hundreds of barley and wheat grains, hundreds of cultivated pulses, as well as two intact dates. Four wood samples and six grain samples were submitted for radiocarbon dating (Table 3.2). The radiocarbon dating of two of the samples failed, but the remaining eight samples show that the calibrated dates lean towards the late eighth or first half of the ninth century.

Other objects obtained from the sealed deposit in trench 9 included eight nearly intact vessels dated to the Abbasid period including an oil lamp, which was heavily damaged by the fire, and a small column base with a smooth surface, which may have been used to spread dough in preparation for baking flat bread52.

In addition to the rich finds of charred plant remains, the room contained a rare architectural feature known as a prayer platform, which was built for private Muslim worship and is known from a handful of ninth-century sites. The platform measures 1.5 by 1 m and consists of a raised area built from five reused marble slabs that were set against the cut bedrock and lined with limestone blocks on the east side. The platform faces the room's south wall, which bears traces of moulded plaster in the shape of two raised columns. A comparative example from the post-earthquake settlement in Baysan shows a similar arrangement in which the moulded plaster formed an arch supported by two columns, which is a commonly used iconography for sacred space — in this case the mihrab, which is found in mosques and marks the direction of prayer towards Makkah.53 Other examples are known from an Abbasid-period domestic context in Madinat al-Far and from a private house in ninth-century Ramla.54 At Ramla, a mosaic floor with mihrab iconography contains the words in kufic script 'al-qibla' followed by a quote from the Qur'an (7.205) saying 'and be not negligent.

The orientation of the room in trench 9 containing the prayer platform is significant. Unlike adjacent structures it follows a slightly different alignment, which is comparable to that of the mosque, suggesting that a deliberate attempt was made to orientate the room towards Makkah. The discovery of a prayer platform gives us a rare insight into the practice of private religion in post-earthquake Jerash and in the world of early Islam more broadly.

52 Pers. coin. Apollinc Vernet 2017.

53 Fitzgerald 1931, pl. XXIII-2; reviewed in Vernet 2016.

54 Madinat Haase 2007, 458; Itarnla: Rosen-Ayalon

1976, 116-19.

In addition to the data retrieved from the three residential units, LAJP's excavations of the thoroughfares in the south-west neighbourhood has yielded further evidence for Jerash's post-earthquake settlement. The plateau was accessed via two main thoroughfares, one described above, leading due south from the south transverse street, and one leading south-west from the congregational mosque. The former followed the Roman-period grid system, while the latter followed an earlier system, which appears to have been in use from the Hellenistic period and served as the main thoroughfare from the residential neighbourhood to the mosque in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods.55

Trenches 2 and 6 were excavated on the north–south thoroughfare in order to examine encroachment from the residential unit onto the street, which at first reduced the width of this street from c. 8 m to c. 4 m and in the Abbasid period blocked the street altogether. Trench 8 was excavated on the thoroughfare running south-west from the congregational mosque to the residential neighbourhood with the aim of studying its stratigraphy and its development through time. Unfortunately, the remains of the thoroughfare in trench 8 were thoroughly disturbed by later activities, including agriculture, dumping, and levelling, which means that very little evidence for the layout of the post-earthquake street was obtained. Trench 8 was, however, rich in ceramic material providing a full ceramic sequence from the Roman period and well into the Abbasid period with an extraordinary selection of e.g. eighth- or ninth-century cutware/Kerbschnitt from the trench's upper levels.

55. The street grids are discussed in detail in Blanke 2018, 47–49.

The excavation of trench 2 uncovered a section of a room that protruded onto the street from the residential building to which the room in trench 1 belonged. Trench 2 exposed three walls (east, west, and north) that were built directly on bedrock with no remains of a surface other than the bedrock (Fig. 3.7). A doorway providing access from the residential structure was found blocked and the surface of the room in trench 2 gave the impression of having been swept before abandonment: the trench yielded fewer than five hundred sherds of sixth- to ninth-century date of which only sixty-seven were diagnostic. The limited material meant that while it was possible to establish that the room was in use into the post-earthquake period, its usage remains obscure as does the date of the encroachment.

Trench 6 was opened almost adjacent to trench 2 to further our understanding of the usage of the north–south thoroughfare (Fig. 3.8). Our excavations revealed that at some point after the earthquake of 749, the southern section of the street had gone out of use altogether as it was now spanned by two walls protruding from the encroachment partially excavated in trench 2. This observation is interesting in the light of the blocking of the doorway in the north wall of the mosque, which suggests a lessening of the importance of the south transverse street at some point after 749. Although speculative, the discontinuation of the north–south tributary in the south-west district may suggest an urban focus on the southern sector of the town.

The excavations carried out in the urban centre by IJP and in the south-west neighbourhood by LAJP have enabled us to form a picture of the strategies employed in the refurbishment of Jerash after the earthquake of 749 (Figs. 3.7–3.8). Structures that were integral to governance, religious practice, and commerce were prioritized for rebuilding as were the residential neighbourhoods in their vicinity. Here, urban life continued for centuries while other sectors of the town remained abandoned.

The evidence obtained so far suggests a thriving community engaged in both private and communal worship, with active commerce, and a water supply system that operated on both a private and communal level. We have been able to establish that post-earthquake Jerash was concentrated around the urban core and south-west neighbourhood, but it is likely that the rebuilding also involved areas further south towards the Oval Piazza and perhaps also east into the modern sector of the town.

The evidence for Muslim religious practice is important, but it raises the question of what happened to the town's Christian population. The late ninth-century geography by Al-Ya‘qubi states that Jerash was inhabited by a mix of Arabs and Greeks, however, we have yet to secure evidence for the continuation of communal Christian worship after 74956. Instead, our data suggests that Jerash was rebuilt as a Muslim town, perhaps because the financial means to refurbish the town were obtained from the Muslim authorities or from a local Muslim elite. Inscriptions from Baysan and Askhelon confirm the involvement of the Muslim administration in the funding of mosques, but such evidence does not exist from Jerash.57

Regarding the urban water supply system, two contemporaneous systems appear to have been in place. The residential units excavated adjacent to the mosque and in the south-west neighbourhood were equipped with their own bottle-shaped cisterns. It is likely that the cisterns were reused from structures that predated the earthquake — a similar arrangement is observed in the Umayyad-period houses that have been excavated in the North-West Quarter58. Their presence informs us that the residents were responsible for the collection and storage of water for household consumption.59

Evidence for a communal water supply is found within and adjacent to the mosque. The ablution feature, which was built by the interior side of the entrance in the western wall, received water through a pipe in the mosque’s wall. This water source may also have supplied the basin that was found on the northern side of the residential unit just west of the mosque. As such, the mosque and its adjacent structures may have played a pivotal role in providing water to the public — a role that to some extent was managed by the churches in Late Antiquity.60

While the earthquake of 749 did not cause the abandonment of Jerash urban centre and its adjacent residential neighbourhoods, other, later, earthquakes appear to have been at least partially responsible for the urban retraction towards the centre. At least two of the buildings in the residential neighbourhood were abandoned because of a catastrophic event, which took place at some point in the later ninth century. The roof and walls of the room in trench 1 collapsed in an earthquake and the conflagration that ended the occupation of the room in trench 9 may have been caused by the same event. LAJP’s examinations suggest that the area was gradually given over to agricultural purposes, which eventually transformed Jerash into an agricultural village.

The residential area immediately west of the mosque also saw an end to its residential phase at some point in the ninth century while the second phase of the mosque may have continued into the tenth century until it was destroyed in another catastrophic event. It was, however, partially rebuilt in a reduced form with the enclosed room in the prayer hall serving as the main mosque. A new entrance was built in the west wall, and a staircase was built to give access to the roof space for the call to prayer. The final phase of the mosque ended in the Ayyubid–Mamluk period with the collapse of the roof, which was followed by widespread evidence for stone removal, pit digging, and agricultural usage.61

56 Le Strange 1890, 462 after Lichtenberger and Raja

2016, 68.

57 In AH 155/AD 771–772 Caliph Mansur (entitled

al-Mahdi in the inscription) ordered the building of a

mosque and minaret in Ashkelon (Sharon 1997, 144). An

inscription from Baysan dating to AH 135/AD 753

commemorates commissions by ʿAbdallah as-Saffah

(AD 749–754), the first caliph of the Abbasids.

Unfortunately, the inscription is incomplete, and it is

unclear what was commissioned. Sharon (1999, 214)

states that this inscription shows “that particular

interest was paid to the building of the city by people

of the highest class — members, in one way or the

other, of the royal [family].”

58 Lichtenberger and Raja 2020; Lichtenberger and others

2013, 13; Kalaitzoglou and others 2013, 68–75.

59 See Vernet 2014; 2016 for an overview of water usage

in early Islamic houses.

60 Pickett 2015, 33–78.

61 Walmsley 2018, 250.

For nearly a hundred years (since the first investigations by Western archaeologists and historians), Jerash was believed to have been destroyed by the earthquake of 749 and subsequently abandoned. We can now state with certainty that this was not the case: instead, its inhabitants proved resilient and resourceful in organizing a strategic rebuilding of the structures most central to the maintenance of governance, commerce, religion, and habitation. This marks a new chapter for the history of Jerash and for its archaeological exploration. Over the coming seasons of work, LAJP's main aim will be to further our understanding of the extent and nature of the post-earthquake occupation and the town's centuries-long transition into an agricultural community.

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:19-21) report arcaheoseismic evidence as follows:

On the southwest hill, excavations conducted by the Late Antique Jarash Project (LAW) exposed a storeroom located in the southern part of a residential building and opening onto a courtyard. The stone-built walls were placed directly on bedrock with a floor comprised by hard-packed yellow clay. The installation of piers along the north and south walls as well as the recovery of arch-stones shows that the roof was vaulted and covered in the same yellow clay that was also used for the walls. The building collapsed in a single violent event — an earthquake — causing the structure to be abandoned.Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:29) noted that

A deposit associated with the final use of the building and sealed by collapse, contained ceramic vessels associated with cooking and the storage of food. The ceramic assemblage comprised roughly 1,000 sherds amounting to 22 nearly intact vessels with only a few sherds from other pots. Of the 22 vessels, nine were larger pithoi-style storage containers, while the remaining 13 comprised smaller storage jars, cooking pots and a few examples of fine wares (Pappalardo forthcoming). Several vessels can confidently be dated to the Abbasid period. Most striking are sherds from three vessels that were produced in a hard black fabric with a polished surface, which are comparable to sherds found in Abbasid layers near the congregational mosque in the centre of town. A black beaker is distinctively Abbasid in its form and is comparable in shape to vessels found in e.g. Pella and Jerusalem and dating to the late 8th or 9th centuries. The fabric matches a rare ceramic specimen from Nabratein of the same early Abbasid date (Magness 1994).

the available archaeological record of the 9th-11th centuries is notoriously meagre and marred by a dissatisfying degree of chronological control.

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th | 9th | Medium | 854 | South-West Quarter | 11 | Rattenborg and Blanke 2017, 324; Blanke 2018, 44. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Trench 7 |

|

|

|

Trench 9 |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Storeroom located in the southern part of Area D residential building opening onto a courtyard - Trench 1

Figure 2

Figure 2Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E © Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project) Blanke et al (2015) |

Figure 7

Figure 7Remains of two ceramic pithoi embedded into the construction of the floor. © LAJP Blanke et al (2021) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trench 7 |

|

|

|

|

Trench 9 |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Storeroom located in the southern part of Area D residential building opening onto a courtyard - Trench 1

Figure 2

Figure 2Architectural remains on hilltop showing Areas A-E © Louise Blanke and IJP (Islamic Jerash Project) Blanke et al (2015) |

Figure 7

Figure 7Remains of two ceramic pithoi embedded into the construction of the floor. © LAJP Blanke et al (2021) |

|

|

Blanke, L et al. (2015) The 2011 season of The Late antique Jarash Project: results from the survey southwest of the Umayyad congregationaL mosque

ADAJ 57

Blanke, L. (2018). The Late Antique Jarash Project. In (eds.) h, 31-32. Archaeology in Jordan Newsletter: 2016 and 2017 seasons. B. A. P. a. C. B. S. John D.M. Green, The American Center of Oriental Researc: 31-32.

Blanke, L. (2018) Abbasid Jerash reconsidered: suburban life in southwest Jerash over the longue durée.

In Achim Lichtenberger and Rubina Raja (eds.) 110 years of excavation in Jerash, Jordan. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers

Blanke, L., et al. (2021). "Excavation and magnetic prospection in Jarash’s southwest district: The 2015 and 2016 seasons of the Late Antique Jarash Project." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 60.

Blanke, L. and A. Walmsley (2022). Resilient cities: Renewal after disaster in three late antique towns of the East Mediterranean. Remembering and Forgetting the Ancient City, Oxbow Books: 69-109.

Blanke, L., et al. (2024). A Millenium of Unbroken Habitation in Jarash's Southwest District: The 2017 season of the Late Antique Jarash Project.

ADAJ 61: 95-135.

Blanke, L. (2025) Chapter 3 Urban Renewal After the Earthquake of AD 749: New Archaeological Evidence from Jerashs' SouthWest District

in Lichtenberger and Raja eds. Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749, Brepolis

Pappalardo, R. (2019) Life after the earthquake: an early Abbasid domestic assemblage from Jerash ICHAJ Florence, Italy 20 Jan. 2019

Rattenborg, R. and L. Blanke (2017). "Jarash in the Islamic Ages (c. 700–1200 CE): a critical review." Levant 49(3): 312-332.