Jerash (aka Gerasa) - Introduction

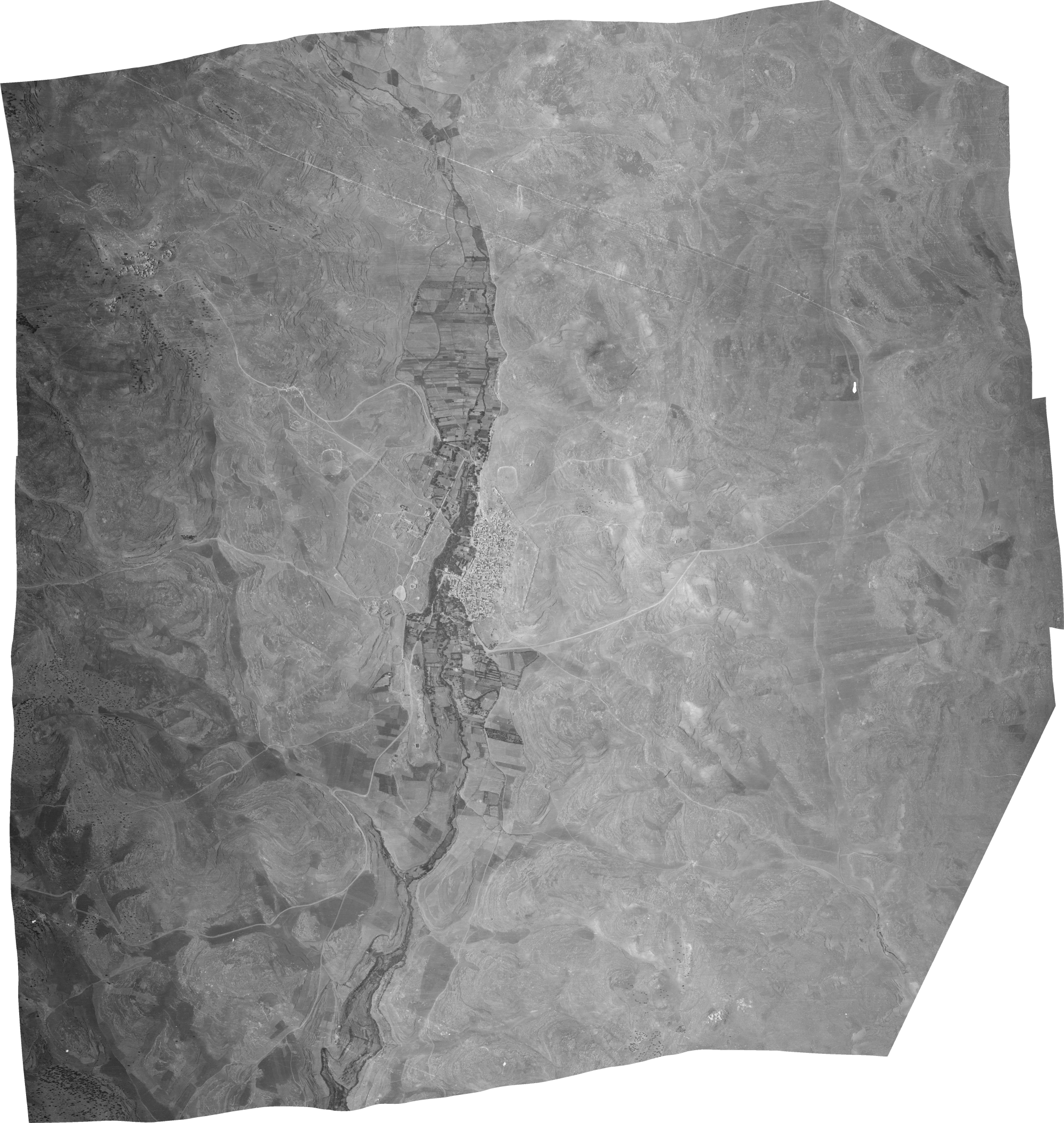

APAAME

- Reference: APAAME_20191030_PF-0241

- Photographer: Pascal Flohr

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Jerash | English | |

| Ǧaraš | Arabic | جرش |

| Gérasa | Greek | Γέρασα |

| Antioch on the Chrysorroas | | |

| Garshu | Semitic/Nabatean |

Gerasa (Greek Γερασα) was a Greek city in Gilead, now modern Jerash, 34 km (21 mi.) north of 'Amman, Jordan. Its identification is based on the similarity of the modern Arabic name to the ancient one and on several inscriptions found here mentioning its inhabitants as των προτεπων Γερασηνων. According to inscriptions and coins from the Roman period, the city's full name was "the city of the Antiochenes on the River Chrysorhoas, formerly [of] the people of Gerasa, holy and sacrosanct." Gerasa is located on a branch of the Via Traiana Nova that was built in 112 CE and links the city to Pella and lies on the banks of the River Chrysorhoas (Wadi Jerash). The river crosses the city north to south, at a height of 570 m above sea level. To the east is a large spring, 'Ein Qeruan. The city was founded at the place where the wadi widens. It is surrounded by broad stretches of arable and pasture land and woodland. The land rises gradually to the west of the valley. The southern hill, on which the temple of Zeus stood, was apparently the original nucleus of the Hellenistic settlement. The fortified enclosure visible today belongs to the Roman-Byzantine city, which extended on both sides of the Chrysorhoas River. The city wall (3,456 m long), encloses an elliptical area of about 210 a. It dates to the end of the first century CE.

Stone Age sites near Gerasa were discovered by G. L. Harding; their details were published by D. Kirkbride. Stone tools of the Acheulo-Levalloisian type were found on the hill to the east of Hadrian's triumphal arch, along with remains from the Neolithic period (animal bones, arrowheads, points, chisels, scrapers, denticulated blades, and awls). In his excavations at the site, Glueck (see below) found evidence of settlement in the area: a walled enclosure on a hill 200 m from the northeast corner of Gerasa contained pottery from the Early Bronze Age I to the Middle Bronze Age I. He also found an Iron Age settlement on the hill north of the city overlooking the Valley of Birketein.

A Greek tradition held that Alexander the Great founded the Hellenistic city for his veterans (γεροντες). According to another tradition, when Alexander captured the city, all the younger men were killed and only the elderly survived, hence the city's name. More trustworthy is the information recorded in an inscription from the Roman period at the site (published by C. B. Welles in Kraeling's excavation report, no. 137), according to which a statue of Perdiccas, Alexander's general, was set up at Gerasa. It may be concluded from this that Perdiccas was regarded as the founder of the Hellenistic settlement. A Roman inscription (Welles, no. 78) reveals that a group of Macedonians were among its first inhabitants. At that time the city was known as Antiochia ad Chrysorhoam (Antioch on the Chrysorhoas River), as in 200 BCE Transjordan had passed to the Seleucid dynasty, and the new name was bestowed in honor of Antiochus III (223~187 BCE) or IV (175 BCE).

Gerasa was an important link in the chain of fortified cities erected by Hellenistic kings to defend their territory against desert tribes. Archaeological evidence of the Hellenistic city is very scanty. On the southern hill, where the temple of Zeus was built, Rhodian stamped jar handles from 210 to 180 BCE have been found. It may be that the cult of Zeus long preceded the Roman period, as the city received the titles of ιερα και απυγος ("holy and sacrosanct"), and therefore enjoyed certain privileges. In Alexander Jannaeus' reign, Zeno and Theodorus, the tyrants of Philadelphia ('Amman), deposited part of their treasure in Gerasa (Josephus, War I, 104; Antiq. XIII, 393). Hence, in their time, the city was no longer within the bounds of the Seleucid Syrian kingdom. Alexander Jannaeus (103~ 76 BCE) captured Gerasa in the last years of his reign and died while besieging Ragaba, in Gerasene territory (Antiq. XIII, 398). The city remained under Hasmonean rule until Pompey's campaign in that region. It may be assumed that Pompey took Gerasa from the Jews, for in the Roman period the city counted its years according to the Pompeian era, starting with 62 BCE. It was listed among the cities of the Decapolis (the League of Ten Cities), as is attested by Stephanus of Byzantium (Ethnika, s.v. Γερασα).

This association and the signs of Nabatean influence (see below) attest to its connection with the trade routes between southern Arabia, Damascus, Phoenicia, and Judea. As long as the Ptolemies ruled in Palestine, this trade went via Gaza and the Red Sea; when the Seleucids took control of the land, the merchants once again made use of the Syrian route. After Alexander Jannaeus severed this route, it was reestablished by the Romans, and the cities of Transjordan, including Gerasa, enjoyed a period of rising prosperity.

During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66-70 CE), the rebels attacked Gerasa, even though friendly relations prevailed between the city and the local Jews (Josephus, War II, 458; II, 480). The city, however, was never in the hands of the rebels. Most scholars, therefore, consider that the Gerasa captured by the Romans before the siege of Jerusalem (War IV, 487-488) was not the Transjordanian town. Additional evidence of this is provided by two inscriptions dated 69/70 CE (Welles, nos. 5-6), attesting to the presence of non-Jewish refugees in Gerasa at that time. Architectural fragments attributed to a synagogue and found in the fill of Hadrian's arch to the south of the city may be evidence that the Jewish community was destroyed during the revolt. However, it may equally indicate that the synagogue was destroyed in Trajan,'s time (cf. Welles, nos. 56 and 57 dedicated to Trajan, in 115 CE). Inscription no. 50, dated 75/76 CE, as well as a Trajanic inscription from Pergamum, dated between 102 and 104 CE, attest that Gerasa belonged at the time to the province of Syria (IG Rom. IV, no. 374), and even the geographer Ptolemy, who wrote under Antoninus Pius (l38-161 CE), reckoned Gerasa as being part of the province of Syria, like the rest of the Decapolis (Geog. V, 15, 23; V, 14, 18). For this, however, he must have followed an earlier, undocumented source, for inscriptions on milestones prove that already under Trajan,, at least from 111 CE, Gerasa belonged to the Provincia Arabia, and probably did so from the moment of its establishment in 106 CE (Welles, nos. 252-257). Signs of Nabatean influence in the city are coins (mostly of Aretas IV, 9 BCE to 40 CE), a Nabatean inscription (Welles, no. 1), and cults of the "Arab god" as well as of Pacidas and Dionysius (Dushara; Welles, nos. 17- 22, 192). The Nabatean influence disappeared with the establishment of the Provincia Arabia in 106 CE.

The city's territory extended as far west as Ragaba (Rajb). On the north it included Enganna ('Ein Jann), Eglon (Khirbet 'Ajlen), Erga, and Samta. Rihab to the northwest was not in its territory. To the east, the border passed near the highway from Philadelphia to Bostra, and in the south close to, but south of, the Jabbok River.

Gerasa was first discovered by U. J. Seetzen in 1806. It was subsequently visited by J. L. Burkhardt (1812) and J. Buckingham (1816). Conditions for visiting improved with the settlement of a Circassian community in 1878. Between 1891 and 1902, Gerasa was explored by G. Schumacher, R. Briinnow, andJ. Germer-Durand. In 1902, a German expedition under 0. Puchstein investigated the ruins. Excavation and conservation work were begun by G. Horsfield under the auspices of the British Mandatory Government, in 1925. The first finds uncovered were the southern theater, the court of the temple of Zeus, the nymphaeum, the propylaea of the temple of Artemis, and the main street, or cardo. Work continued until 1931 under P. A. Richie, A. G. Buchanan, and G. Horsfield. Meanwhile, systematic excavation directed by J. W. Crowfoot had begun in 1928 under the auspices of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and Yale University. In 1930, the American School of Oriental Research replaced the British School, and direction was assumed by C. S. Fisher. N. Glueck continued the work in 1933-1934.

In the 1940s and 1950s preservation and restoration were carried out, mainly in the southern part of the city, in the southern theater (the work was completed in the late 1960s). At that time, the lower terrace of the precinct of Zeus was cleared of its debris and partially restored. The excavation of the temple was only begun in 1987. The elliptical plaza (called the forum by the site's excavators) had already been cleared and partially restored in the 1940s. There were no excavations in Gerasa in the 1960s. The activities of the Jordan Department of Antiquities were limited to clearing debris from both sides of the cardo, mainly in the area of the cathedral precinct, and partially restoring the gates in the precinct of Artemis. Since 1975, an Italian expedition from the University of Turin has been excavating at Gerasa.

- from Stern et. al. (2008)

In 1994, new excavations began on the trapezoidal square in the Temple of Artemis, under the direction of an Italian team headed by R. Parapetti. The excavation revealed an imposing Roman foundation platform, the date of which is suggested by inscriptions to have been during the magistracy of Attidius Cornelianus, who was governor in Arabia between 148 and 151 CE. The Roman square was transformed into a Christian religious complex apparently in the third and fourth quarters of the sixth century. A research project on the Cathedral, initiated in 1993 by B. Brenk of the University of Basel, demonstrated that the structure could not be earlier than 378 CE, and may well date to the fifth century. The excavations also confirmed the existence of a pagan temple at the site, built on a podium with an eastern staircase flanked by antae. It was probably typologically similar to the nearby Temple of Artemis, but considerably smaller and probably some decades earlier.

In 2000, a British expedition headed by I. Kehrberg and J. Manley began work along the city wall of Gerasa. It is well-preserved and extends for about 3.5 km, with five known gates and over 101 square towers. C. H. Kraeling had suggested a late first-century CE date for the wall, while J. Seigne had argued in favor of a late third or early fourth century date. The new excavations securely dated the wall to the early second century CE. The Roman foundation trench clearly cuts into layers containing a pottery kiln waste dump dating from the beginning of the second century CE and a tomb from the late second or early first century BCE with a large quantity of ritual pottery vessels and a gold pectoral. The excavation also showed that the wall collapsed during the late Byzantine period, probably the result of an earthquake.

In 2000, The Gerasa Antique Water-Supply Program began working at the site. One of their most interesting finds was a sixth-century, water-powered sawmill in the courtyard of the Temple of Artemis. In the fifth century CE, the temple had ceased to serve as a place of worship and was converted into a stone quarry for the construction of Byzantine monuments.

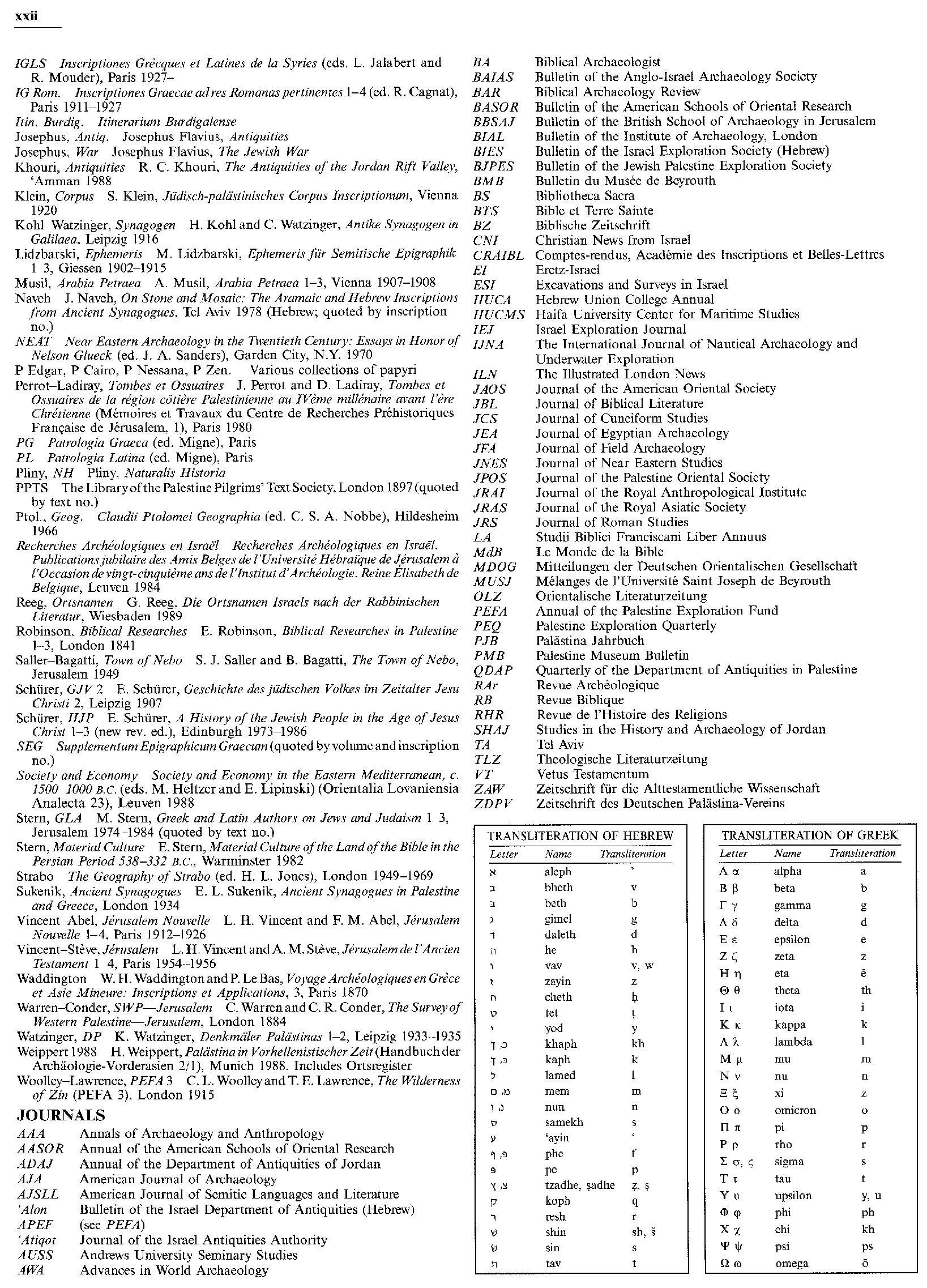

- Site Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 4 - Urbanization of

Jerash from Hellenistic to Late Roman times - from Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2011)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Schematic overview of Gerasa’s urbanisation from Hellenistic to Late Roman

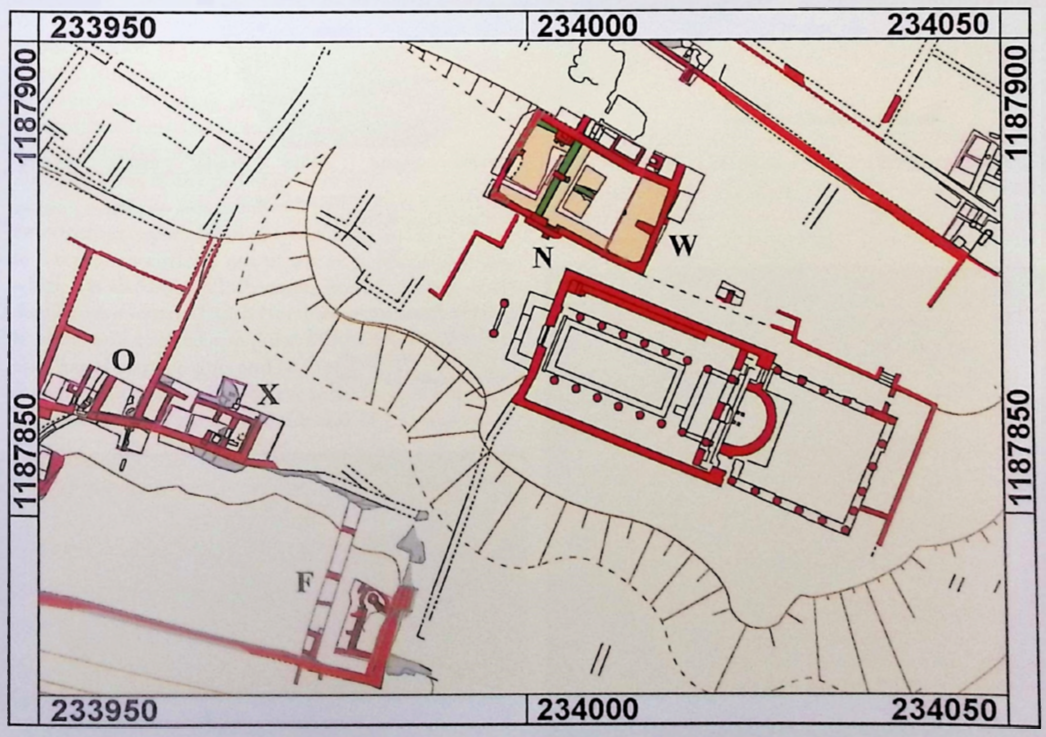

Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2011) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad Jerash

from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

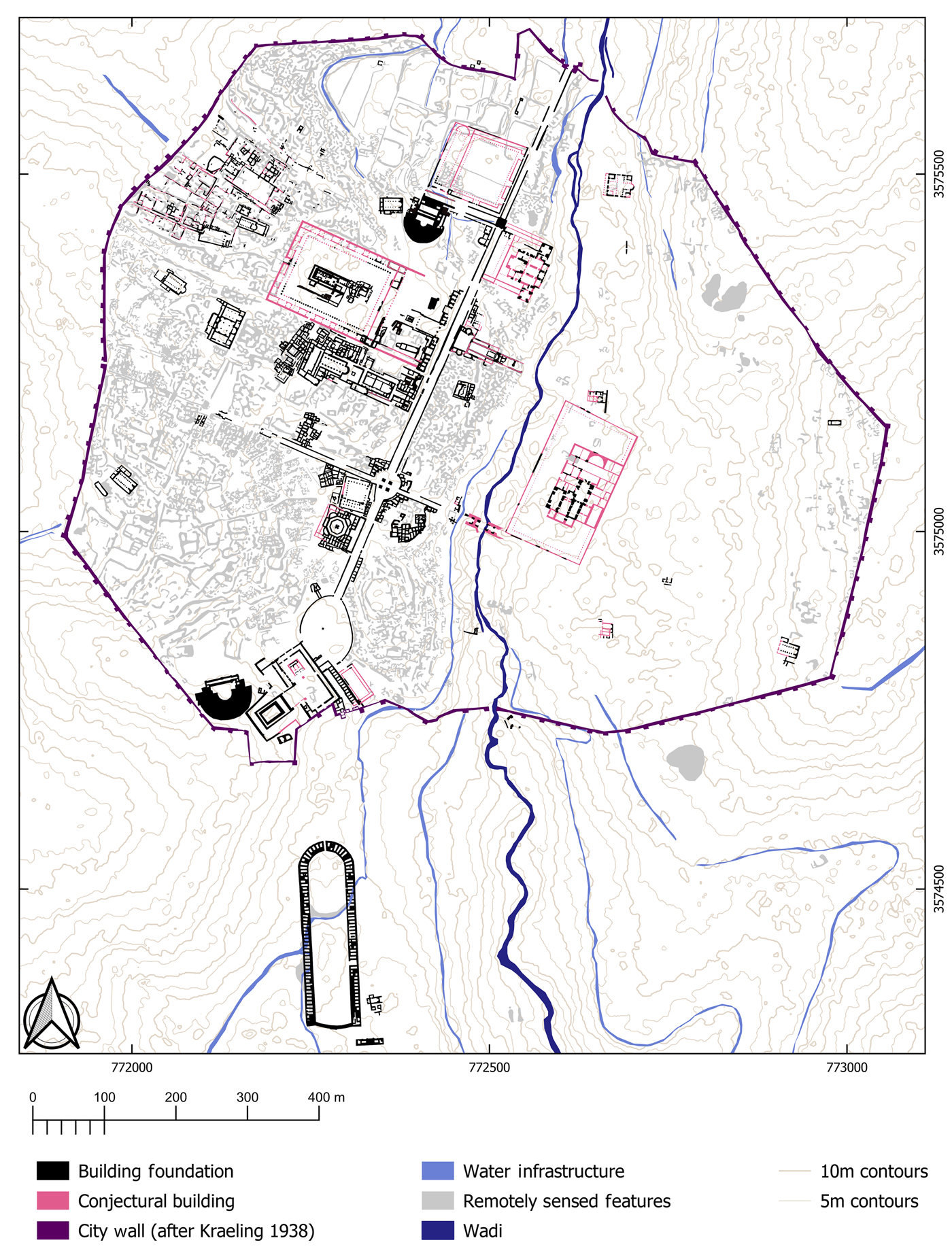

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Jerash

showing location of the town's bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Jerash archaeological site, showing location of the town's bathhouses

(Modified from map by Thomas Lepaon.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Site Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 4 - Urbanization of

Jerash from Hellenistic to Late Roman times - from Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2011)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Schematic overview of Gerasa’s urbanisation from Hellenistic to Late Roman

Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2011) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad Jerash

from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Jerash

showing location of the town's bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Jerash archaeological site, showing location of the town's bathhouses

(Modified from map by Thomas Lepaon.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Central Bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Central Bathhouses highlighting location of latrine and bathhouse sewers

(Plan by Louise Blanke)

Blanke et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View

of latrine in Central Bathhouse from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Overview of latrine in Central Bathhouse looking west.

(© Islamic Jarash Project.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Central Bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Central Bathhouses highlighting location of latrine and bathhouse sewers

(Plan by Louise Blanke)

Blanke et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View

of latrine in Central Bathhouse from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Overview of latrine in Central Bathhouse looking west.

(© Islamic Jarash Project.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

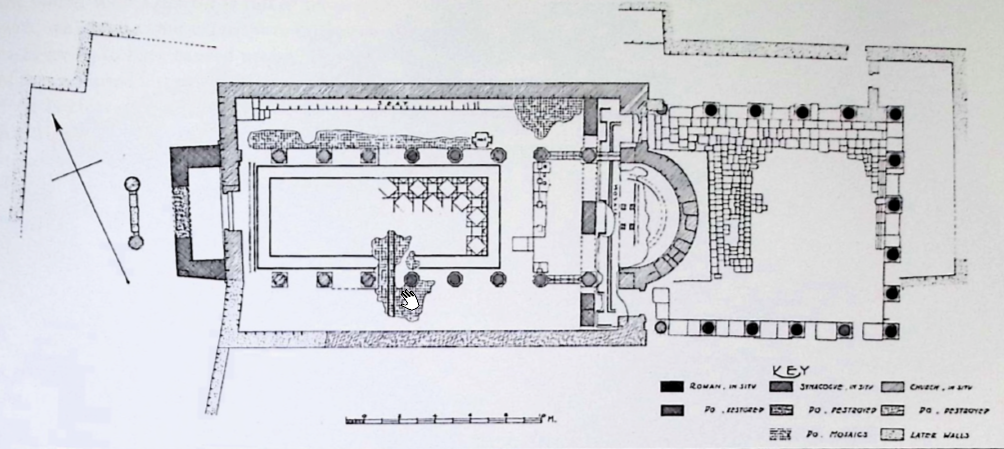

- Fig. 5.10 Plan of the

Synagogue Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 5.11 Plan of the

Synagogue Church and the Mosaic Hall north of it from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 5.10 Plan of the

Synagogue Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 5.11 Plan of the

Synagogue Church and the Mosaic Hall north of it from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Map of potential archaeological features derived from airborne lidar and archival photography. A large number of previously recorded and new features were recorded in the better-preserved part of the city to the west of the wadi

Legend

- Extramural arch (‘Hadrian’s Arch’)

- Church of Bishop Marianos

- Hippodrome

- Sanctuary of Zeus Olympios

- South Gate

- Water Gate

- City walls

- Shops and structures along the South Gate street

- South Theatre

- South-East Gate (blocked)

- Procopius Church

- ‘Oval Piazza’

- Roman house or church (after Schumacher 1902)

- ‘Camp Hill’ (location of modern museum)

- Byzantine villa (after Seigne & Zubi 1997)

- Agora (‘Macellum’)

- Area of the House of the Blues

- South Bridge

- Possible South-West Aqueduct

- East Baths

- Mortuary Church

- Late Antique and Early Islamic structures

- South Tetrapylon

- Church of Sts Peter and Paul

- Side street (‘South Decumanus’)

- Mosque

- Main Street (‘cardo’)

- Early Islamic domestic quarter

- Cathedral complex

- ‘Temple C’ (after Fisher 1938: pl. I

- Church of St Theodore and Fountain Court

- Nymphaion

- Buildings west of the Wadi

- Small Eastern Baths

- Chapel of Elia, Mary and Soreg

- South-West Gate

- Churches of Sts George, John, Cosmas and Damian

- Approximate location of ‘House of the Poets and Muses’

- Ecclesiastic complexes and Baths of Placcus

- Propylaea Church

- Church of Bishop Genesius

- Ottoman House

- West Baths

- Large rock-cut cistern

- Sanctuary of Artemis

- North Theatre

- Spring (Ain Karawan)

- Synagogue/Church of the Electi Iustiniani

- Church of Bishop Isaiah

- Side street (‘North Decumanus’)

- North Tetrapylon

- Hall of the Electi Iustiniani

- Umayyad houses

- Middle Islamic hamlet (and large courtyard)55 Church of the Prophets, Apostles and Martyrs56 Large open area (‘forum’) and basilica

- Roman edifice and cistern

- Middle Islamic structures

- Circassian house

- North-West Aqueduct

- Early modern water channel

- North Gate

- Chrysorrhoas/Wadi Jerash

Lichtenberger et. al. (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2Synthesis of remotely sensed features and existing mapping from previous studies. Hypothetical building elements (after Lepaon Reference Lepaon, 2011; Lichtenberger & Raja, 2017) are highlighted in pink. Most of the buildings on the eastern side of the valley are no longer extant

map © Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter

Lichtenberger et. al. (2019)

Figure 3

Figure 3As Figure 2, with points of interest highlighted (see Table 1)

Legend

- Extramural arch (‘Hadrian’s Arch’)

- Church of Bishop Marianos

- Hippodrome

- Sanctuary of Zeus Olympios

- South Gate

- Water Gate

- City walls

- Shops and structures along the South Gate street

- South Theatre

- South-East Gate (blocked)

- Procopius Church

- ‘Oval Piazza’

- Roman house or church (after Schumacher 1902)

- ‘Camp Hill’ (location of modern museum)

- Byzantine villa (after Seigne & Zubi 1997)

- Agora (‘Macellum’)

- Area of the House of the Blues

- South Bridge

- Possible South-West Aqueduct

- East Baths

- Mortuary Church

- Late Antique and Early Islamic structures

- South Tetrapylon

- Church of Sts Peter and Paul

- Side street (‘South Decumanus’)

- Mosque

- Main Street (‘cardo’)

- Early Islamic domestic quarter

- Cathedral complex

- ‘Temple C’ (after Fisher 1938: pl. I

- Church of St Theodore and Fountain Court

- Nymphaion

- Buildings west of the Wadi

- Small Eastern Baths

- Chapel of Elia, Mary and Soreg

- South-West Gate

- Churches of Sts George, John, Cosmas and Damian

- Approximate location of ‘House of the Poets and Muses’

- Ecclesiastic complexes and Baths of Placcus

- Propylaea Church

- Church of Bishop Genesius

- Ottoman House

- West Baths

- Large rock-cut cistern

- Sanctuary of Artemis

- North Theatre

- Spring (Ain Karawan)

- Synagogue/Church of the Electi Iustiniani

- Church of Bishop Isaiah

- Side street (‘North Decumanus’)

- North Tetrapylon

- Hall of the Electi Iustiniani

- Umayyad houses

- Middle Islamic hamlet (and large courtyard)55 Church of the Prophets, Apostles and Martyrs56 Large open area (‘forum’) and basilica

- Roman edifice and cistern

- Middle Islamic structures

- Circassian house

- North-West Aqueduct

- Early modern water channel

- North Gate

- Chrysorrhoas/Wadi Jerash

Lichtenberger et. al. (2019)

- from figshare

- sourced from Lichtenberger et. al. (2019)

- ~6-8 Mb .tiff and .svg files

- from Stott, Raja, and Lichtenberger (2019)

- from Jerash Aerial Photos at figshare

- Magnifiable image is downsampled - for full resolution image go to download links

2015 Orthophoto of Jerash City

2015 Orthophoto of Jerash CityClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Dataset on figshare authored by David Stott, Rubina Raja, and Achim Lichtenberger in 2019

- from Stott, Raja, and Lichtenberger (2019)

- from Jerash Aerial Photos at figshare

- Magnifiable image is not downsampled

1953 Orthophoto of Wadi Jerash

1953 Orthophoto of Wadi JerashClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Dataset on figshare authored by David Stott, Rubina Raja, and Achim Lichtenberger in 2019

- from figshare

- Datasets provided by Stott, Raja, and Lichtenberger (2019)

- 2015 Orthophoto - 1.5 Gb zipped file containing .tif, .xml, and .ovr files

- 1953 Orthophoto - ~88 Mb zipped file containing a .tif file

- Panorama of West Baths West Baths - photo by JW

- Dropped Archstones and Spalled corner in West Baths - photo by JW

- Dropped Keystones - photo by JW

- Dropped Keystones Closeup - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks and Dropped Keystones - photo by JW

- Shifted Column Segments Shifted Column Segments - photo by JW

- Shifted Keystones and Spalled Corners - photo by JW

- Panorama of West Baths West Baths - photo by JW

- Dropped Archstones and Spalled corner in West Baths - photo by JW

- Dropped Keystones - photo by JW

- Dropped Keystones Closeup - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks - photo by JW

- Shifted Blocks and Dropped Keystones - photo by JW

- Shifted Column Segments Shifted Column Segments - photo by JW

- Shifted Keystones and Spalled Corners - photo by JW

- Shifted Stones, Spalled Corners, Fractures, and Displaced Archstones at Hadrian's Arch - photo by JW

- Shifted Stones, Spalled Corners, Fractures, and Displaced Archstones at Hadrian's Arch - photo by JW

- Through-going Fractures at South Gate - photo by JW

- Spalled Corners and through-going fractures at South Gate - photo by JW

- Through-going Fractures at South Gate - photo by JW

- Spalled Corners and through-going fractures at South Gate - photo by JW

- Fractures at South Theater - photo by JW

- Fractures at South Theater - photo by JW

- Fractures at South Theater - photo by JW

- Fractures at South Theater - photo by JW

- Fig. 5.9 The excavated

Synagogue Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 3.38b Synagogue Church (?)

during excavation showing the orientation of fallen columns from Boyer (2022)

Figure 3.38b

Figure 3.38b

Photographs of the basilica of St Theodore's Church during excavation showing the orientation of fallen columns

JW: This may in fact be from the Synagogue Church as seems to be indicated in the narraive text by Boryer (2022)

London, UCL, StTheodore_23_1441 3273846_98ed97777f o.jpg. UCL, Institute of Archaeology

Click on image to open in a new tab

Boyer (2022)

- Fig. 5.9 The excavated

Synagogue Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 3.38b Synagogue Church (?)

during excavation showing the orientation of fallen columns from Boyer (2022)

Figure 3.38b

Figure 3.38b

Photographs of the basilica of St Theodore's Church during excavation showing the orientation of fallen columns

JW: This may in fact be from the Synagogue Church as seems to be indicated in the narraive text by Boryer (2022)

London, UCL, StTheodore_23_1441 3273846_98ed97777f o.jpg. UCL, Institute of Archaeology

Click on image to open in a new tab

Boyer (2022)

- Fig. 5.7 Photo of the

western side of Gerasa in 1930 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 5.7 Photo of the

western side of Gerasa in 1930 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Opposite to the propylon, another cross-street runs down towards the river, bordered by columns, erect only on the south side; traces are discernible of the ancient pavement, which was raised in the middle of the street, with a trottoir on a low level. It ends in a semicircular platform, built up over the river.

Beyond the propylon, following the course of the main street, and to the left of it, stands another theatre (for wild beasts’ combats) with a colonnade in front of it, from which a third cross-street runs down to the river, meeting the High Street at a rotunda (which has suffered much from the recent earthquake), and ending in an immense accumulation of vaults and arches overhanging the stream—probably baths. The High Street runs on in a north-easterly direction, till it ends at the gate of the town. The ancient pavement is in singular preservation beyond the baths. ...

Jerash has suffered much from the late earthquake; we saw many recent ruins; Mr. Moore was here at the time, and he described the columns as chattering on their bases. But many a previous earth-throb has aided the scythe of Time in the work of destruction ; the pillars consist, for the most part, of several courses of stone, and in repeated instances every course has been shaken out of its place, — and that many a year ago.

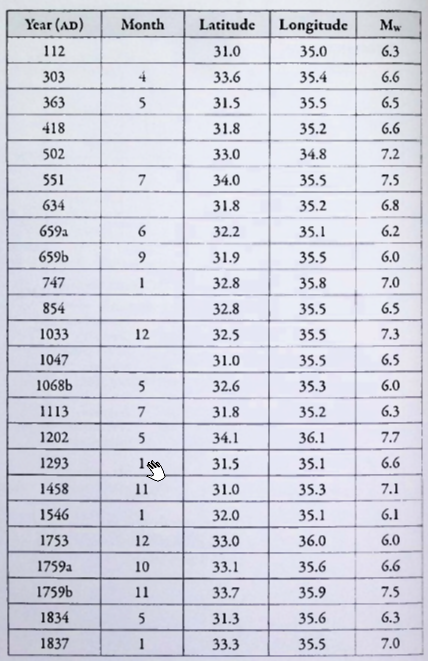

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19th | 1837 | Medium | 1837 | City area (Earthquake witnessed) | Lindsay 1838, 107. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rotunda at Jerash (possibly the North Tetrapylon)

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

|

|

|

Jerash |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects

from Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

- Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

- Synoptic Table of ESI 2007 Intensity Degrees

from Michetti et al. (2007)

- Environmental Effects vs. Intensity

from Michetti et al. (2007)

- Simple MMI Intensity Scale

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rotunda at Jerash (possibly the North Tetrapylon)

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Plan of Jerash. North is to the right.

Click on image to open in a new tab Holger Behr - Wikipedia - Public Domain |

|

|

|

|

Jerash |

|

|

Agusta-Boularot, J. et al. (2011),

Un «nouveau» gouverneur d'Arabie sur un milliaire inédit de la voie Gerasa/Adraa, Mélanges de l'école française de Rome Year 1998 110-1 pp. 243-260

Blanke, L., et al. (2024b). "Down the drain: reconstructing social practice from the content of two sewers in a Late Antique bathhouse in Jerash, Jordan."

Journal of Roman Archaeology: 1-23. - open access

Boyer, D. D. (2018a). Landscape archaeology in the Jarash Valley in northern

Jordan: A preliminary analysis of human interaction in the prehistoric and

historic periods. In B. Salisbury, F. Hoflmayer, & T. Burge (Eds.), Proceedings

of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near

East, 25–29 April 2016, Vienna (Vol. 2, pp. 223–238). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Boyer, D. D. (2018b). The role of landscape in the occupational

history of Gerasa and its hinterland. In A. Lichtenberger & R. Raja

(Eds.), The Archaeology and History of Jerash: 110 Years of

Excavations, Jerash Papers, 1 (pp. 59–86). Turnhout: Brepols.

Boyer, D. D. (2020). The aqueduct systems servicing Gerasa of the

Decapolis. In G. Wiplinger (Ed.), De aquaeductu urbis Romae:

Sextus Julius Frontinus and the Water of Rome, Rome November 10–18,

2018, Babesch Annual Papers on Mediterranean Archaeology, Supplement,

40 (pp. 175–186). Leuven: Peeters.

Boyer, D. D. (2022). Water Management in Gerasa and its Hinterland: From the Romans to AD 750. Jerash Papers, 10. Turnhout: Brepols.

Boyer, D. D. (2024). Horizontal watermill chronologies based on 14C

dating of organics in mortars: A case study from Jarash, Jordan.

Radiocarbon, 66(1), 205–248.

Cressman, P.P. et. al. (ed.s) (2020) Archeology in Jordan II

Crowfoot, J. (1929). "The Church of S. Theodore at Jerash." Palestine exploration quarterly 61(1): 17-36.

Gawlikowski, M. and Musa, A. (1986). The Church of Bishop Marianos.

Jørgensen, C. S. L. (2018). Archaeoseismology in Jerash: Understanding urban dynamics through catastrophic events

. In R. Raja & S. M. Sindbæk

(Eds.), Urban Network Evolutions: Towards a High-Definition

Archaeology (pp. 125–130). Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- open acess at academia.edu

Kehrberg, I. and Manley, J. (2002),

The Jerash City Walls Project (JCWP) 2001-2003 : report of preliminary findings

of the second season 21st September - 14th October 2002, Annual of the Department

of Antiquities of Jordan 47

Kehrberg, I. (2011). ROMAN GERASA SEEN FROM BELOW. An Alternative Study of Urban Landscape. ASCS 32 PROCEEDINGS.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2016). "Ğeraš in the Middle Islamic Period. Connecting Texts and Archaeology through New Evidence from the Northwest Quarter." Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 132: 63-81.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2018). Middle Islamic Jerash (9th Century-15th Century). Archaeology and History of an Ayyubid-Mamluk settlement.

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2018) The Archaeology and History of Jerash: 110 Years of Excavations. Belgium: Brepols.

Lichtenberger, A., Raja, R., & Stott, D. (2019). Mapping Gerasa: A new and open data map of the site. Antiquity, 93(367), E7. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.9

Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (ed.s) (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749 The Fallout of a Disaster

Belgium: Brepols.

Lindsay, A. C. (1838). Letters on Egypt, Edom & the Holy Land v. 2.

London: Colburn.

Moralee, J. (2006). "The Stones of St. Theodore: Disfiguring the Pagan Past in Christian Gerasa." Journal of Early Christian Studies 14: 183-215.

Parapetti R., Jerash (1986). The sanctuary of Artemis, in Homès-Fredericq and J.B. Henessy (eds), Archaeology of Jordan 188 II.1 Field Reports. II.1 Surveys and

Sites A-K

Rasson, A.-M.

and Seigne, J. (1989), ‘Une citerne byzanto-omeyyade sur le

sanctuaire de Zeus.’Jerash Archaeological Project vol.II, 1984-1988, , SYRIA 66: 117-151.

Rasson, A.M. and Seigne, J. et al. (1989),

Une citerne byzantino-omeyyade sur le sanctuaire de Zeus Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire Year 1989 66-1-4 pp. 117-151

Rattenborg, R. and L. Blanke (2017). "Jarash in the Islamic Ages (c. 700–1200 CE): a critical review." Levant 49(3): 312-332.

Russell, K. W. (1981). The earthquake chronology of ancient Palestine and Arabia from the

2nd to the 8th century A.D. Anthropology. Salt Lake City, UT, University of Utah. MS.

Savage, S., K. Zamora, and D. Keller (2003).

"Archaeology in Jordan, 2002 Season." Am. J. Archaeol. 107: 449–475.

Seigne, J. (1985) Sanctuaire de Zeus à Jerash (le) : éléments de chronologie Syria.

Archéologie, Art et histoire Year 1985 62-3-4 pp. 287-295

Seigne, J. et al. (1986). `Recherche sur le sanctuaire de Zeus à Jerash Octobre 1982-

Décembre 1983,' in JAP I: 29-106.

Seigne J., (1989), Jérash. Sanctuaire de Zeus, in Homès-Fredericq and J.B. Henessy (eds), Archaeology of Jordan II.1 Field Reports. II.1 Surveys and

Sites A-K.

Seigne, J. (1992). `Jerash romaine et byzantine: développement urbain d'une ville

provinciale orientale,' SHAJ 4: 331-43.

Seigne, J. (1993). `Découvertes récentes sur le sanctuaire de Zeus à Jerash,' ADAJ 37: 341-58.

Seigne, J and Morin, T. (1993). Preliminary Report on a Mausoleum at the turn of the

BC/AD Century at Jerash,' ADAJ39: 175-92.

Seigne, J. (1997)

De la grotte au périptère. Le sanctuaire de Zeus à Jerash Topoi. Orient-Occident Year 1997 7-2 pp. 993-1004

Seigne, J. et al. (2011) Limites des espaces sacrés antiques : permanences et évolutions, quelques exemples orientaux

Walmsley, A. (2007). Early Islamic Syria: An Archaeological Assessment. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Kraeling, C. (1938) Gerasa: City of the Decapolis, American Schools of Oriental Research. - can be borrowed with a free account at archive.org

Kraeling, C. (1938) Gerasa: City of the Decapolis, American Schools of Oriental Research. - open access at Hathi Trust

Gullini, G. (1983) Gerasa 1 : Report of the Italian Archaeological Expedition at Jerash, Campaigns 1977-1981. 2 vols. Mesopotamia, 18/19 . Florence, 1983—1984.

Zayadine, F. (ed.) (1986) Jerash Archaeological Project, 1981-1983. 1. Department of Antiquities: Amman. page 19

Zayadine, F. (ed.) (1989) Jerash Archaeological Project, vol. 2, Fouilles de Jerash, 1984-1988. Paris, 1989.

Bitti M. C., (1986), The area of the Temple (Artemis/ stairway, Jerash Archaeological Project 1981-1983, I, Amman, pp. 191-192

Parapetti R., (1989a), (AJH 188). Jerash, The sanctuary of Artemis, in Homès-Fredericq and J.B. Henessy (eds), Archaeology of Jordan II.1 Field Reports. II.1 Surveys and

Sites.

Parapetti R., (1989b), Scavi e restauri italiani nel Santuario di Artemide 1984-1987, in ’Jerash Archaeological Project vol.II,.

3D Virtual Reality Images of Jerash from vrjordan.com

GERASA (Jerash) Jordan at the The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites

Damgaard, K. anf Blanke, L. (2004) The Islamic Jarash Project: A Preliminary Report on the First Two Seasons of Fieldwork

Jerash Photo Gallery at ACOR

Jerash Photo Gallery at Manar al-Athar (Oxford University)

Jerash Photo Gallery at PBAse

Jerash at the Madain project

Jerash at the Madain project

Jerash - Revealing a ‘peripheral’ part of an ancient city in northern Jordan

in World Archaeology May 20, 2021

Jerash at ancientworld.hansotten.com

Achim Lichtenberger page on figshare

Downloadable Jerash Data Maps from Lichtenberg et al (2019) at figshare.com

Downloadable Jerash orthophotos at figshare.com

Downloadable interpreted Jerash vector data (e.g. shapefiles for GIS) at figshare.com

Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project - Bibliography at figshare.com

Borkowski, Zbigniew. "Inscriptions on Altars from the Hippodrome of

Gerasa." Syria 66 (1989): 79-83.

Browning, Iain. Jerash and the Decapolis. London, 1982. Broad and very

readable account of early exploration at Jerash and excavations prior

to the Jerash Archaeological Project, with a useful introduction to

other Decapolis cities.

Gerasa 1 : Report of the Italian Archaeological Expedition at Jerash, Campaigns 1977-1981. 2 vols. Mesopotamia, 18/19 . Florence, 1983—1984.

Harding, G. Lankester. "Recent Work on the Jerash Forum." Palestine

Exploration Quarterly 81 (1949): 12-20 .

Harding, G. Lankester. The Antiquities of Jordan. London, 1959.

Kalayan, Haroutine. "Restoration in Jerash (with Observations about

Related Monuments)." Annual of the Department ofAntiquities of Jordan 22 (1977-1978): 163-171 .

Kalayan, Haroutine. "The Symmetry and Harmonic Proportions of the

Temples of Artemis and Zeus at Jerash, and the Origins of Numerals

as Used in the Enlargement of thee South Theater in Jerash." In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, vol. 1, edited by Adnan

Hadidi, pp. 243-254. Amman, 1982.

Kehrberg, Ina. "Selected Lamps and Pottery for the Hippodrome at

Jerash." Syria 66 (1988): 85-97.

Khouri, Rami G. Jerash, a City of the Decapolis. London, 1984.

Khouri, Rami G. Jerash: A Frontier City of the Roman East. London,

1986. Highly useful guide for touring the site, with introductions to

exploration, history, and culture at Jerash from the Hellenistic to

Islamic eras.

Kraeling, Carl H., ed. Gerasa, City of the Decapolis. New Haven, 1938.

Standard reference, includes meticulous measurements and plans for

all structures within and outside the city walls and Welles's (1938)

compilation of inscriptions.

McCown, Chester C. "A New Deity in a Jerash Inscription." Journal

of the American Oriental Society 54 (1934): 178-185 .

Meshorer, Ya'acov. City-Coins of Eretz-Israel and the Decapolis in the

Roman Period. Jerusalem, 1985.

Olavarri, Emilio. Excavaciones en el Agora de Gerasa en 1983. Madrid,

1986.

Parapetti, Roberto. "The Architectural Significance of the Sanctuary

of Artemis at Gerasa." In Studies in the History and Archaeology of

Jordan, vol. 1, edited by Adnan Hadidi, pp. 255-260. Amman, 1982.

Uses archaeological evidence of the Artemion to demonstrate the

importance of symmetry to the aesthetic of sanctuary architecture.

Pouilloux, Jean. "Deux inscriptions au tirefitre sud de Gerasa." Studium

Biblicum Franciscanuml Liber Annuus 27 (1977): 246-254.

Seigne, Jacques. "Le sanctuaire de Zeus a Jerash: Elements de chronologie." Syria 66 (1988): 287-295.

Spijkerman, Augusto. "A List of the Coins of Gerasa Decapoleos."

Studium Biblicum Franciscanuml Liber Annuus 25 (1975): 73-84.

Spijkerman, Augusto. The Coins of the Decapolis and Provincia Arabia.

Jerusalem, 1978.

Thompson, Henry O. Archaeology in Jordan. New York, 1989.

Zayadine, Fawzi, ed. Jerash Archaeological Project, vol. 2, Fouilles de

Jerash, 1984-1988. Paris, 1989. Compilation of essays reporting the

results of the Jerash Archaeological Project; essential companion to

Kraeling (above)

C. H. Kraeling, ed., Gerasa: City of the De capo/is, New Haven 1938

I. Browning, Jerash

and the Decapolis, London 1982

Gerasa 1: Report of the Italian Archaeological Expedition at Jerash,

Campaigns 1977-1981 (Mesopotamia 18-19, 7-134), Florence 1983-1984

R. G. Khouri, Jerash, a City of

the Decapolis, London 1984; id., Jerash: A Frontier City of the Roman East, London 1986

E. Olavarri

Goicoechea, Excavaciones en el Agora de Gerasa en 1983, Madrid 1986

Jerash Archaeological Project l,

1981-1983 (ed. F. Zayadine), Amman 1986; ibid. 2, 1984-1988 (Syria 66), Paris 1989.

C. H. Kraeling (Review), Berytus 7 (1942), 83-86; id., BASOR 83 (1941), 7-14

N. Glueck,

BASOR 75 (1939), 22-30

L. H. Vincent, RB49 (1940), 98-129

A. H. Detweiler, BASOR 87 (1942), 10-

17

G. L. Harding, Official Guide to Jerash, Jerusalem 1944; id., PEQ 81 (1949), 12-20; id., The Antiquities

of Jordan, London 1967, 79-105

J. H. Iliffe, QDAP 11 (1944), 1-26

D. Kirkbride, BIAL I (1958), 9-20;

id., ADAJ 4-5 (1960), 123-127

E. L. Sukenik, Rabinowitz Bulletin I (1949), II

F. S. Ma'ayeh, ADAJ 4-5

(1960), 115-116; id., RB 67 (1960), 228-229; Jordan Department of Antiquities, Jerash, Amman 1962;

H. Bietenhard, ZDPV 79 (1963), 24-58

S. Mittmann, ibid. 80 (1964), 113-136; id., ADAJ II (1966),

65-87

H. Seyrig, Syria 42 (1965), 25-34

M. B. Steinberg, Revista de Historia 39(79 (1969), 197-201

G. W. Bowersock, JRS 61 (1971), 219-242

M. Lyttelton, Baroque Architecture in Classical Antiquity,

London 1974, 241-247

A. Spijkerman, LA 25 (1975), 73-84; id., The Coins of the Decapolis and

Provincia Arabia, Jerusalem 1978, 158-167

M. Sartre, ADAJ 2! (1976), 105-108

J. Pouilloux, LA 27

(1977), 246-254; 29 (1979), 276-278

H. Kalayan, ADAJ22 (1977-1978), 163-171; 25 (1981), 331-334;

id., SHAJ 1 (1982), 243-254

J. A. Sauer, BA 42 (1979), 134

H. Joyce, AJA 84 (1980), 215-216

R. Parapetti, ADAJ 24 (1980), 145-150; id., SHAJ I (1982), 255-260; 2 (1985), 243-247; id.,

Mesopotamia 18-19 (1983-1984), 37-84

E. M. Knauf, ZDPV97 (1981), 188-192

A. Segal, Journal of

the Society of Architectural Historians 40 (1981), 108-121; id., Town Planning and Architecture in

Provincia Arabia (BAR/IS 419), Oxford 1988, 19-48

F. Brossier, MdB 22 (1982), 28-29; I. Browning

(Reviews), Berytus 31 (1983), 161-163. -Mesopotamia 18-19 (1983-1984), 251-253.- PEQ 116

(1984), 149-150

P. L. Gatier, ADAJ 26 (1982), 269-275; 32 (1988), 151-155; id., Syria 62 (1985), 297-

312; E. Will, ibid. (1983), 133-145

J. W. Hanbury Tenison, LA 34 (1984), 437; id., RB 92 (1985), 393;

id., ADAJ 31 (1987), 129-157

R. G. Khouri, Archaeology 38 (1985), 18-25; id., Jerash: A Frontier City

(Review), ZDPV lOS (1989), 197-198; id., Jerash: A Brief Guide to the Antiquities (Al-Kutba Jordan

Guides), Amman 1988

M. Piccirillo, MdB 35 (1984), 16-21

F. Braemer, RB 92 (1985), 419-420, id.,

Syria 62 (1985), 159-164; id., ADAJ 31 (1987), 525-530

J. Seigne, ibid., 287-295; id., RB 93 (1986),

238-247

M. C. Bitti, ADAJ 30 (1986), 207-210; Jerash Archaeological Project (Reviews), LA 36 (1986),

372-374.- ZDPV 104 (1988), 182-183

E. de Montlivault, Berytus 34 (1986), 139-144

H. Stierlin,

Stiidte in der Wiiste (Antike Kunst im Vorderen Orient), Stuttgart 1987

R. Wenning, Der Konigsweg:

9000 Jahre Kunst und Kultur in Jordanien (eds. S. Mittmann et al.), Mainz 1987, 256-266

A. J. 'Amr,

ZDPV 104 (1988), 146-149; id., ADAJ 33 (1989), 353-356

C. Meyers, BASOR Supplement 25 (1988),

175-222; id., ADAJ 33 (1989), 235-244

J. Skurdenis, Archaeology 41/4 (1988), 64-66

M. Weippert

and E. A. Knauf, ZDPV 104 (1988), 150-151

Akkadica Supplementum 7-8 (1989), 316-337

V. A.

Clark, ZDPV 106 (1990), 175-176; MdB 62 (1990)

A. A. Ostrasz, ADAJ 35 (1991), 237-250.

J. W. Crowfoot and R. W. Hamilton, PEQ 61 (1929), 211-219

E. L. Sukenik, ibid. 62

(1930), 48-49

C. H. Kraeling, ed., Gerasa: City of the Decapolis, New Haven 1938,234-241, 318-324

Goodenough, Jewish Symbols l, 259-260.

M. M. Aulama, Jerash: A Unique Example of a Roman City, Amman 1994

M. Alanen,

Architectural Reuse at Jerash: A Case Study in Transformations of the Urban Fabric, 100 BC–750 AD

(Ph.D. diss.), Los Angeles, CA 1995

A. J. Wharton, Refiguring the Post Classical City: Dura Europos,

Jerash, Jerusalem and Ravenna, Cambridge 1995; ibid. (Review) AJA 102 (1998), 817–819

A. U. Barron,

La ceramica del macellum de Gerasa (Yaras, Jordania) (Informes arqueologicos/Jordania), Madrid 1996

T.

Marot, Las monedas del macellum de Gerasa (Yaras, Jordania): aproximacion a la circulacion monetaria

en la Provincia de ‘Arabia, Madrid 1998

S. Belloni & C. Donovan, Jerash: The Heritage of Past Cultures,

Narni 1996

E. Borgia, Jordan, Past & Present: Petra, Jerash, Amman, Rome 2001

Gadara-Gerasa und die

Dekapolis (Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie

Antike Welt Sonderbände; eds. A. Hoffmann & S. Kerner),

Mainz am Rhein 2002; ibid. (Review) Parthica 4 (2002), 179–180

F. Braemer, SHAJ 4 (1992), 191–198

T. Scholl, Archeologia (Poland) 42 (1992), 65–84

M. Gawlikowski, ibid., 357–362; 5 (1995), 669–672; id., Topoi. Orient-Occident 8 (1998), 31–52

I. Kehrberg, Syria

69 (1992), 451–464; id., AJA 98 (1994), 546–547; 99 (1995), 525–528; 106 (2002), 443–445; id. (& A.

A. Ostrasz), SHAJ 6 (1997), 167–174; 7 (2001), 601–605; id. & J. Manley, ADAJ 45 (2001), 437–446; 46

(2002), 197–203; id., La céramique byzantine et proto-islamique en Syrie-Jordanie (IVe–VIIIe siècles apr.

J. C.): Actes du colloque, Amman, 3–5.12.1994 (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 159

eds. E. Villeneuve & P. M. Watson), Beyrouth 2001, 231–239

M. Martin-Bueno, SHAJ 4 (1992), 315–320

J. Sapin,

ibid., 169–174; id., Syria 75 (1998), 107–136

J. Seigne (& C. Wagner), ADAJ 36 (1992), 241–259; 37

(1993), 341–358; 46 (2002), 205–213, 631–637; id., Aram 4 (1992), 183–195; id., SHAJ 4 (1992), 331–342;

id., Les maisons dans la Syrie antique du IIIe millenaire aux debuts de l’Islam: pratiques et representations

de l’espace domestique (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 150; eds. C. Castel et al.), Paris 1997,

73–82; id., Syria 74 (1997), 121–138; id., Topoi. Orient-Occident 7 (1997), 993–1004; 9 (1999), 833–848;

id., ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Boulder, CO 2001, 29, 40

M. Smadeh, ADAJ 36 (1992), 261–279;

41 (1997), 5–12 (with I. Melhem)

A. Uscatescu-Barron, Caesaraugusta 69 (1992), 115–182, 183–218; id.

(& M. Martin-Bueno), BASOR 307 (1997), 67–88; id., La céramique byzantine et proto-islamique en SyrieJordanie (op. cit.),

Beyrouth 2001, 59–76; id., SHAJ 7 (2001), 607–615

J. D. Wineland, Aram 4 (1992),

329–342

R. Abu Dalu, ADAJ 37 (1993), 23–34; 39 (1995), 169–173

P. -L. Gatier, Arabia Antiqua: Hellenistic Centres around Arabia (Serie Orientale Roma 70/2; eds. A. Invernizzi & J. -F. Salles), Roma 1993, 15–37;

id., Presence Arabe dans le Croissant Fertile avant l’Hegire (ed. H. Lozachmeur), Paris 1995, 109–118;

id., Syria 73 (1996), 47–56; 79 (2002), 271–283; id., MdB 158 (2004), 24–25

G. Palumbo et al., ADAJ 37

(1993), 89–117

F. B. Sear, AJA 97 (1993), 687–701; id., ADAJ 40 (1996), 217–230; id., Mediterranean

Archaeology 9–10 (1996–1997), 249–252; id., Ancient Near Eastern Studies 37 (2000), 3–27; id., SHAJ

8 (2004), 389–397

M. Alanen, ASOR Newsletter 44/2 (1994), n.p.

J. M. C. Bowsher, Levant 26 (1994),

237; 29 (1997), 227–246

S. Loffreda, LA 44 (1994), 595–607

B. Brenk et al., ADAJ 38 (1994), 351–357;

39 (1995), 211–220; id., AJA 98 (1994), 546; 101 (1997), 523–524; id., ZDPV 112 (1996), 139–155

N.

Duval, Churches Built in Ancient Times: Recent Studies in Early Christian Archaeology

(Society of Antiquaries Occasional Papers 16; ed. K. S. Painter), London 1994, 150–212

I. Kehrberg & A. Ostrasz, AJA 98

(1994), 546–547; A. Oddy, Aram 6 (1994), 405–418

P. Watson, ibid., 311–332

I. Z’ubi et al., LA 44 (1994),

539–546

N. Amitai-Preiss, INJ 13 (1994–1999), 133–151

K. B. Hendrix, ADAJ 39 (1995), 560–562; 42

(1998), 639–640

A. A. Ostrasz, SHAJ 5 (1995), 183–192

R. Parapetti, ibid., 177–181; 6 (1997), 109–114;

id., ADAJ 42 (1998), 361–368; id., Mesopotamia 33 (1998), 309–319

D. Von Böselager, 5th International

Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, Bath, 5–12.9.1987 (JRA Suppl. Series 9), Ann Arbor, MI 1995, 57–63

P. M. Watson, Hellenistic and Roman Pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean: Advance in Scientific Studies

(eds. H. Meyza & J. Mlynarczyk), Warszawa 1995, 453–462

M. L. Bates & F. L. Kovacs, The Numismatic

Chronicle 156 (1996), 165–173

C. Jaeggi et al., AJA 100 (1996), 530–531; id., ADAJ 41 (1997), 311–320;

42 (1998), 425–432; id., Occident and Orient 2/2 (1997), 31

I. Kader, Propylon und Bogentor (Damaszener

Forschungen 7), Mainz am Rhein 1996

Z. Safrai, Jerusalem Perspective 51 (1996), 16–19

A. G. Walmsley,

Towns in Transition: Urban Evolution in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (eds. N. Christie & S.

T. Loseby), Aldershot 1996, 126–158; id., Antiquity 79/304 (2005), 362–378

M. M. Aubin, OEANE, 3,

New York 1997, 215–219

O. Beverini, Elemente di raccordo e di chiusura nelle vie colonnade dell’oriente

romano: tipologie e funzione (Ph.D. diss.), Pisa 1997, 31–38

J. -P. Braun, Occident and Orient 2/2 (1997),

22–24; id., AJA 102 (1998), 597–598; 105 (2001), 446–447; id. (et al.), ADAJ 45 (2001), 433–446

C. Clamer

et al., MdB 104 (1997), 38–56

R. G. Khouri, Jordan Antiquity Annual, Amman 1997–1998, nos. 1–2

L.

Tholbecq, Aram 9–10 (1997–1998), 153–179

C. Auge, MdB 115 (1998), 74

D. L. Kennedy, Mediterranean

Archaeology 11 (1998), 39–69; id. (& R. Bewley), Antike Welt 34 (2003), 253–263; id., SHAJ 8 (2004),

197–216

S. T. Parker, NEA 62 (1999), 134–180

J. -B. Yon, Die Levante: Geschichte und Archäologie

im Nahen Osten (ed. O. Binst), Köln 1999, 80–138

R. M. Foote, Mediterranean Archaeology 13 (2000),

24–38

H. Kennedy, Bulletin d’Etudes Orientales 52 (2000), 199–204

M. Brizzi et al., ADAJ 45 (2001),

447–459

E. A. Friedland, ibid., 461–477; id., ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Boulder, CO 2001, 34;

id., ASOR Newsletter 51/4 (2001), 9; id., AJA 107 (2003), 413–448

E. C. Lapp, La ceramique byzantine et

proto-islamique en Syrie-Jordanie (op. cit.), Beirut, 2001, 129–137

K. Salameh, SHAJ 7 (2001), 721–724

T. M. Weber, ibid., 531–537; id., Gadara-Umm Qes I: Decapolitana Untersuchungen zur Topographie,

Geschichte, Architektur und der Bildenden Kunst einer “Polis Hellenis” im Ostjordanland

(Abhandlungen des Deutschen-Palästina-Vereins 30), Wiesbaden 2002, 485–504

H. Eristov, Archéologia 385 (2002),

26–38

A. al-Rahim Hazim, LA 52 (2002), 482–483; 53 (2003), 437–439

P. Richardson, City and Sanctuary:

Religion and Architecture in the Roman Near East, London 2002, 77–102

E. Villeneuve, MdB 144 (2002),

54; 158 (2004), 26–27; id., Les églises de Jordanie et leurs mosaïques: Actes de la Journee d’Etudes..., Lyon

4.1989 (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 168; ed. N. Duval), Beirut 2003, 147–150

I. Kerberg,

ADAJ 47 (2003), 83–86; id., SHAJ 8 (2004), 189–196

A. Lichtenberger, Kulte und Kultur der Dekapolis:

Untersuchungen zu numismatischen, archäologischen und epigraphischen Zeugnissen (Abhandlungen des

Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 29), Wiesbaden 2003

J. Mühlenbrock, Tetrapylon: Zur Geschichte des Viertorigen Bogenmonumentes in der römischen Architektur, Paderborn 2003, 231–232

M. Piccirillo, Les églises

de Jordanie et leurs mosaiques (op. cit.), Beirut 2003, 3–16

A. Retzleff & A. Majeed Mjely, ADAJ 47

(2003), 75–82; id., BASOR 336 (2004), 37–47

S. H. Savage et al., AJA 107 (2003), 449–475

J. M. Blázquez

Martiínez et al., Sacralidad y arqueología (T. Ulbert Fest.; Antiqüedad y cristianismo: monografías históricas

sobre la antiqüedad tardía 21), Murcia 2004, 332–334

S. Agusta-Boularot & J. Seigne, Mélanges de l’Ecole

Française de Rome, Antiquite 116 (2004), 481–569

C. Finlayson, ASOR Annual Meeting 2004, www.asor.

org/AM/am.htm

E. Dvorjetski, ZDPV 121 (2005), 140–167

G. Mazor, Free Standing City Gates in the

Eastern Provinces during the Roman Imperial Period (Ph.D. diss.), Ramat-Gan 2004 (Eng. abstract)

H.

Gitler & D. Weisburd, Les villages dans l’empire byzantin (IVe–XVe siècle) (Réalités Byzantines 11; eds. J.

Lefort et al.), Paris 2005, 539–552

P. Gruson, MdB Hors Série 2005, 36–37.

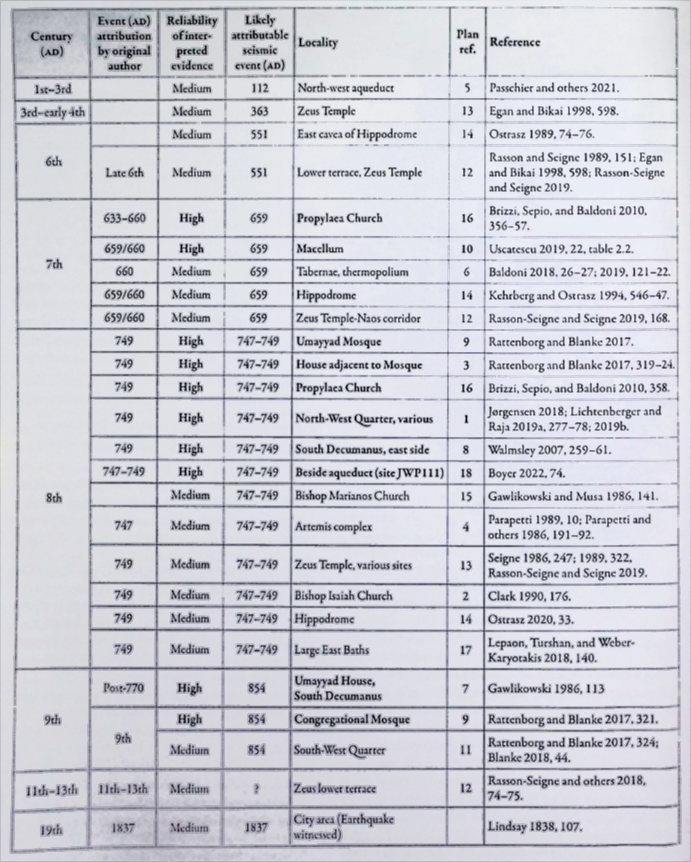

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Table 2.2 List of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Plan of ancient Gerasa showing the location of earthquake-damaged sites referred to in Table 2.2

(after Lichtenberger, Raja, and Stott 2019.fig.2)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st–3rd | Medium | 112 | North-west aqueduct | 5 | Passchier and others 2021. | |

| 3rd–early 4th | Medium | 363 | Zeus Temple | 13 | Egan and Bikai 1998, 598. | |

| 3rd–early 4th | Medium | 551 | East cavea of Hippodrome | 14 | Ostrasz 1989, 74–76. | |

| 6th | Late 6th | Medium | 551 | Lower terrace, Zeus Temple | 12 | Rasson and Seigne 1989, 151; Egan and Bikai 1998, 598; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 7th | 633–660 | High | 659 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 356–57. |

| 7th | 659/660 | High | 659 | Macellum | 10 | Uscatescu 2019, 22, table 2.2. |

| 7th | 660 | Medium | 659 | Taberna, thermopolium | 6 | Baldoni 2018, 26–27; 2019, 121–22. |

| 7th | 659/660 | Medium | 659 | Hippodrome | 14 | Kehrberg and Ostrasz 1994, 546–47. |

| 7th | 659/660 | Medium | 659 | Zeus Temple–Naos corridor | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019, 168. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | Umayyad Mosque | 9 | Rattenborg and Blanke 2017. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | House adjacent to Mosque | 3 | Rattenborg and Blanke 2017, 319–24. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | Propylaea Church | 16 | Brizzi, Seipo, and Baldoni 2010, 358. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | North-West Quarter, various | 1 | Jørgensen 2018; Lichtenberger and Raja 2019a, 277–78; 2019b. |

| 8th | 749 | High | 747–749 | South Decumanus, east side | 8 | Walmsley 2007, 259–61. |

| 8th | 747–749 | High | 747–749 | Beside aqueduct (site JWP111) | 18 | Boyce 2022, 74. |

| 8th | Medium | 747–749 | Bishop Marianos Church | 15 | Gawlikowski and Musa 1986, 141. | |

| 8th | 747 | Medium | 747–749 | Artemis complex | 4 | Parapetti 1989, 10; Parapetti and others 1986, 191–92. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Zeus Temple, various sites | 13 | Seigne 1986, 247; 1989, 322; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Bishop Isaiah Church | 2 | Clark 1990, 176. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Hippodrome | 14 | Ostrasz 2020, 33. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Large East Baths | 17 | Lepaon, Turshan, and Weber-Karyotakis 2018. |

| 9th | Post-770 | High | 854 | Umayyad House, South Decumanus | 7 | Gawlikowski 1986, 113. |

| 9th | 9th | High | 854 | Congregational Mosque | 9 | Rattenborg and Blanke 2017, 321. |

| 9th | 9th | Medium | 854 | South-West Quarter | 11 | Rattenborg and Blanke 2017, 324; Blanke 2018, 44. |

| 11th–13th | 11th–13th | Medium | ? | Zeus lower terrace | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and others 2018, 74–75. |

| 19th | 1837 | Medium | 1837 | City area (Earthquake witnessed) | Lindsay 1838, 107. |

- from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.6 Map of seismic damage

in Jerash between the 1st and 19th centuries CE from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2List of seismically induced damage recorded in Gerasa where the relaibility of the evidence is considered to be medium or high

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

Russell (1985) reports that

Crowfoot (1938: 233) suggested that at Jerash the mid-6th century construction of the Propylae Church occurred after the 551 earthquake had caused the collapse and abandonment of the bridge whose approach had been blocked by this church.

- Ecclesiastical complex at Jerash including the Church of St. Theodore

from Moralee (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Ecclesiastical complex at Gerasa, adapted from Beat Brenk et al., "Neue Forschungen zur Kathedrale von Gerasa: Probleme der Chronologie und der Vorgângerbauten," ZDPV 112 (1996): 139-55, fig. 1.

Moralee (2006)

The transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, the growing insecurity of the country, and a series of disastrous earthquakes led ultimately to the desertion of the place. In the nature of the case we cannot say precisely when this happened. Fractured stones, tumbled columns and many signs of hastily interrupted activities are evidence of the earthquake shocks. Coins and other datable objects show that there was life here until the middle of the eighth century at least and probably longer. In 1122 A.D. William of Tyre mentions the city as having been long deserted, and though it was then reoccupied for a short time, Yaqut describes it as again deserted in the next century.Kraeling, C. (1938:260)

Church of St. Theodore - AtriumKraeling, C. (1938:282)

The west wall of the atrium was built of very massive stones, many of them dangerously dislocated by earthquake shocks. It ran alongside a small street which formed the western limit of the complex. A triple entrance only approximately in the center of this wall led into an entrance hall which was paved with mosaics, and from this three long steps descended into the open court. The court had porticoes on three sides only, the north, east and south: the columns in the porticoes had Ionic capitals. Some of the columns may have been moved here from the Fountain Court when it was reconstructed.

Churches of St. John the Baptist, St. George and SS Cosmas and DamianusRussell (1985)

2. The atrium. The atrium was rhomboidal in plan, much longer from north to south than from east to west. On the east side there was a colonnade of 14 Corinthian columns on a low stylobate. The columns, many of which were obviously displaced, vary in diameter, and the capitals found in this area are very miscellaneous in character (Plate XLVI, b). The colonnade apparently never reached beyond the central doors in the parecclesia, but the walk was continued as shown in the plan (Plan XX XVII). The walk was paved with red and white mosaics of which little remains; enough is preserved, however, to show that there were different patterns in front of each church. Before the final desertion of Gerasa the atrium and colonnade, like those in St. Theodore’s and St. Peter’s, were occupied by squatters who built walls in front of and between the columns; the pottery, glass and bronze articles found in their rooms suggest that the place was finally abandoned in haste, possibly after the earthquake in 746 A. D. This occupation explains the disappearance of the steps leading into the churches and the condition of the atrium mosaics

At Jerash, this earthquake apparently brought an end to the impoverished "squatter" occupation in the Church of St. Theodore (Crowfoot 1929: 25. 1938: 221) and parts of the churches of St. John the Baptist. St. George, and SS. Cosmas and Damianus (Crowfoot 1938: 242, 244).Walmsley(2013:86-87) described seismic destruction in Jerash in the mid 8th century CE.

Its many churches continued in use right through the Umayyad period, only to be suddenly destroyed in the mid-eighth century by a violent act of nature — an earthquake — as graphically revealed during the excavation of the Church of St Theodore by the Yale Joint Mission in the 1930s (Crowfoot 1938: 223-4). The severity of this seismic event was recently confirmed by the discovery of a human victim entombed in a collapsed building along with his mule, some possessions and a hoard of 143 silver dirhams of mostly eastern origin, the last of which was minted in the year of the earthquake.As Walmsley(2013:86-87) did not cite a source for the human victim and mule found inside a collapsed building, it is not known if this occurred in the Church of Saint Theodore.

Barnes et al (2006:306) noted the presence of 749 CE archaeoseismic evidence in Jerash in the Church of Bishop Isaiah

The excavation of the at Jarash, west of North Theatre, has revealed similar roof tiles, both the tegulae and imbrices, in the destruction layer of the church dated to the earthquake of 749 AD (Clark et al. 1986: 313).Clark, V. A., Bowsher, J. M. C. and Stewart, J. D. 1986 The Jerash North Theatre. Architecture and Archaeology 1982-1983. Pp. 205-302 in F. Zayadine (ed.), Jerash Archaeological Project 1, 1981-1983. Amman: Department of Antiquities.

Walmsley (2007) reports the following archeoseismic evidence at Jerash (Gerasa)

At Gerasa the evidence is less categorical but suggests at least sections of the town - but not perhaps all of it - were damaged in A.D. 749. Thick levels of building wreckage were encountered above the cathedral steps, in the church of St Theodore and the group of three churches dedicated to SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John the Baptist, which the Yale Mission attributed to earthquake activity in the 8th c.29 In 2004, further graphic evidence for the impact of the earthquake at Gerasa was recovered from a room on the eastern part of the south decumanus, in which was found the crushed skeletal remains of a human victim and a mule accompanied by a hoard of 148 silver dirhams, of which three were minted in 130 A.H. (A.D. 747/48).

Footnotes

29 Kraeling (1938) 208, 223, 247–49.

El-Isa (1985) reported on archeoseismic evidence

at Jerash including cracking and falling pillars, beams and walls, tilting of walls, and deformation of paved streets. He further

reported that excavations in March 1983 revealed buried buildings which may indicate major subsidence of some ground blocks in

the region brought about by earth faulting - at this stage, however, such phenomena cannot be confirmed and need more investigation.

El-Isa (1985) noted that due to

construction repair and continuous work at the site, it is difficult to extract quantitative archeoseismic information

particularly regarding sense of motion.

He added further that most of the fallen pillars were removed and many cracks and joints were cemented however

standing pillars are sheared and slightly tilted. He stated that indications of motion along surface-shears seem to have a

preferred direction of northwest and a secondary direction of south—west

which may suggest

that damaging earthquakes originated either from the southwest or north-west respectively.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |