Abila

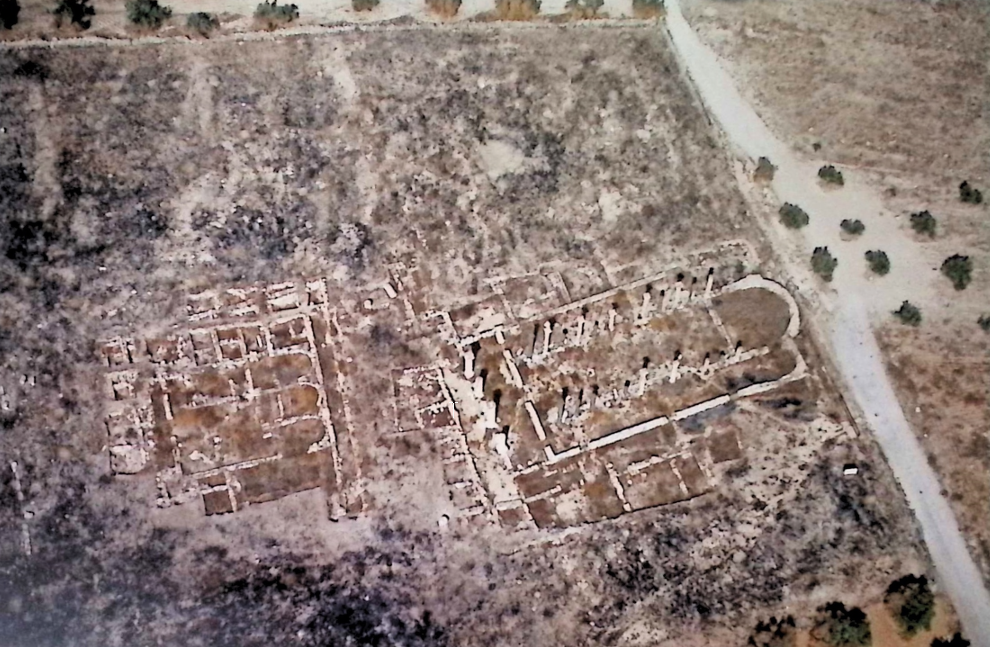

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

- A–Byzantine Church

- AA–Deep Probe

- B–Byzantine Monastic Complex/“Theater Cavea”

- C–Bath Complex

- D– Byzantine Church

- DD–Byzantine Church

- E–Byzantine Church

John Brown University

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Abila | Greek | Ἄβιλα |

| Abila in the Decapolis | Greek | Ἄβιλα Δεκαπόλεως |

| Seleúkeia | Greek | Σελεύκεια |

| Raphana | Greek | Ραφάνα |

| Qweilbeh | Arabic | قويلبة |

| Qwwāīlībāh | Arabic | قووايليباه |

| Qwālībāh | Arabic | قواليباه |

Abila, ~15 km. NNE of Irbid, has a long history of habitation starting between 4000 and 1500 BCE. In Hellenistic times, it became one of the cities of the Decapolis. Habitation continued until Umayyad and other Islamic periods (W. Harold Mare in Stern et al, 1993). At a triapsidal basilica in Area A, a destruction layer was observed in excavations.

Abila, one of the cities of the Decapolis, is known in Arabic as Quailibah. It is located about 15 km (c. 9.5 mi.) north-northeast of the modern city of lrbid in northern Jordan and about 4~5 km (3 mi.) south of Wadi Yarmuk. In relation to other nearby Decapolis cities, it is 18 to 20 km (11-12 mi.) east of Gadara (Umm Qeis), 9.5 km (6 mi.) north of Capitolias (Beit Ras), and abou t40 km (25 mi.) northeast of Pella. These Decapolis cities, together with ancient Hippos (Sussita), Dium, Scythopolis (Beth-Shean), Gerasa (Jerash), and Philadelphia('Amman), seem to have formed a solid block. That this city is Abila of the Decapolis is supported by ancient writers (Eusebius and Jerome) who place Abila 12 Roman miles east of Gadara, by the persistence of the name Tell Abila for one of the mounds at the site into modern times (see below), and by a stone inscription found on the site in 1984 that included the Greek name ΑΒΙΛΑ. Ptolemy (Geog. V, 14), in the second century CE, listed northern Jordan's Abila separately from the Lysanias Abila (west of Damascus). Surface sherding in 1980 showed that the site of Abila had a long archaeological history (from about 4000 BCE to 1500 CE), and excavation from 1980 to 1990 has confirmed this. Abila probably became part of the Decapolis at some time between Alexander's conquest and the zenith of Seleucid power (that is, c. 198 BCE). Polybius (Hist. V, 69~70) states that Antiochus III conquered Abila, Pella, and Gadara in 218 BCE. The New Testament Gospels mention the Decapolis (Mt. 4:25; Mk. 5:20, 7:31 ), but no Decapolis city is named specifically.

The name of the site from the fourth millennium to the first half of the first millennium BCE is not clear; however, it may have been a combination of the Semitic word abel (in Hebrew אנל, "meadow" and in Arabic, "grow green") and an accompanying noun. It is to be noted that several ancient cities with lush meadows and productive agricultural lands connected with the Jordan River and the Jordan Valley water system had the noun abel in their names-Abel-Beth-Maacah (2 Sam. 20:14~15; 1 Kg. 15:20; 2 Kg. 15:29) north of the Sea of Galilee, just west of the Jordan River; Abel Meholah (Jg. 7:22; 1 Kg. 4: 12) in the Jordan Valley south ofBeth-Shean; Abel Shittim (Num. 33:49) in the Jordan Valley east of the Jordan River and north of the Dead Sea; and Abel Keramim (Jg. 11:33) near modern Na'ur and in a wadi system leading down into the Jordan Valley and the Jordan River. Abila, with its perennial spring water and surrounding fertile agricultural land, is also connected with the Jordan River system: its water flows into the Yarmuk River and then into the Jordan River, just below the Sea of Galilee.

Abila of the Decapolis consists of two mounds: Tell Abila in the north and Khirbet Umm el-'Amad (the Ruins of the Mother of the Columns) in the south, with a large saddle depression between them. The area of the site is roughly 1.5 km (c. 1 mi.) long from north to south and 0.5 km (0.3 mi.) wide from east to west. Extensive surface ruins can be seen on Tell Abila, including an acropolis wall along the southern rim of the mound, to the north of which are the remains of a large Byzantine basilica. On the northern slope of Tell Abila are the ruins of a 5-m-high city wall.

Down the slope of the northern rim of Khirbet Ummel-'Amad is the cavea of an ancient theater, with the ruins of a basilica on a ledge directly to the east. On the crest ofUmm el-'Amad are the remains of a large rectangular building, once thought to be a temple but now shown to be another Byzantine basilica.

In the saddle area, just to the north and northeast of the theater cavea, are the massive ruins of a structure( s ). Farther east an ancient road runs east over an ancient bridge in Wadi Quailibah (on the east side of the site), through which a stream runs north to Wadi Yarmuk. The stream issues from the spring 'Ain Quailibah, which is located in the wadi at the bottom of the southern slope of Umm el-'Amad. Wadi Abila is north of the site. The necropolis cemetery areas are located along the wadis, mainly to the east, as well as to the south and north.

There is evidence of three underground aqueducts: the Khureibah aqueduct, which courses through the hill just to the south of 'Ain Quailibah (at the base of Umm el-'Amad's southern slope), and two Umm el-'Amad aqueducts, which run north from' Ain Quailibah under the eastern ledge of Umm el-'Amad (the upper aqueduct runs 1-3m higher up the ledge than the lower aqueduct) toward the central saddle depression

The site of Abila of the Decapolis was unknown for several hundred years until U. J. Seetzen visited it in 1806; later, in 1888, G. Schumacher spent a few days here, describing and drawing what he saw. In 1978, major inquiry began at Abila when W. H. Mare of Covenant Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, visited Abila while preparing an overview of several Decapolis cities in northern Jordan and southern Syria. In 1978, the site was uninhabited, except for groups of wandering Bedouin; parts of the site were being farmed.

In 1980, in cooperation with the Jordan Department of Antiquities and A. Hadidi, its director general, W. H. Mare surveyed the site to determine its periods of occupation. The investigating team used a time-controlled transect surface-sherd-collection technique in spaced north-south transects across the site.

Abila was inhabited at various times from the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods to the Early Bronze Age; on through the Middle Bronze and Late Bronze ages; the Iron Age; the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods; and into the Umayyad and other Islamic periods. The heaviest concentration of finds was from the Byzantine and Umayyad periods, with lesser concentrations from the Roman period, Iron Age II, and Early Bronze Age. Evidence from the excavations, which were conducted every second year from 1982 to 1990, under Mare's direction, generally confirmed the findings of the 1980 survey

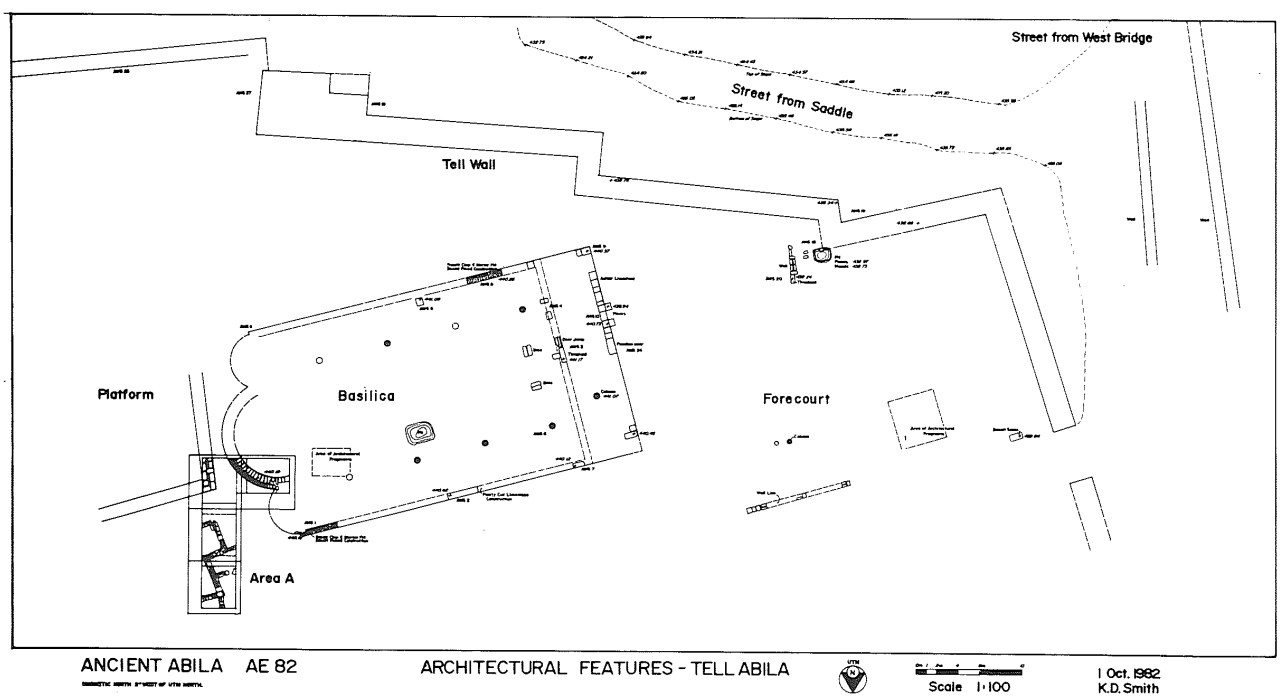

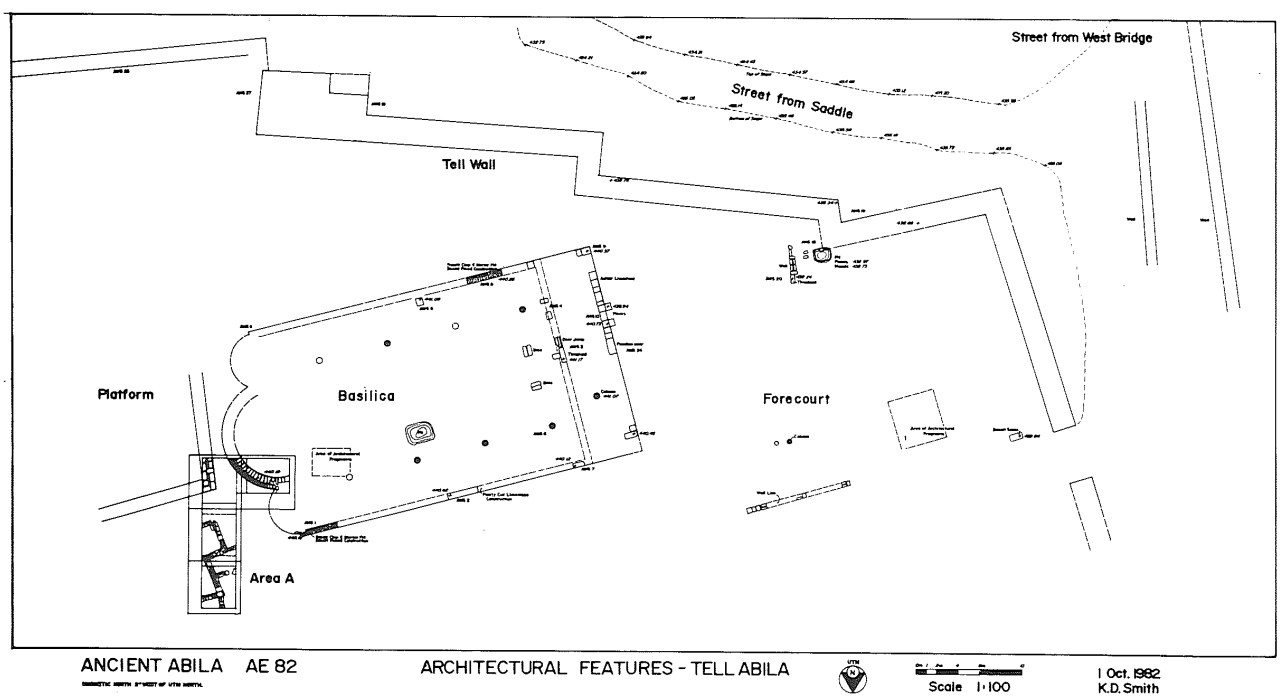

The 1982-1990 excavations at Tell Abila concentrated on what in 1980 was called the public building (area A), located just to the north of the acropolis wall; excavation was also carried out in the areas to the immediate east and west of the building, as well as on the exposed section of the city wall on the northern slope of the mound. Extensive excavation of the "public building" exposed sizable portions of a triapsidal sixth-century CE basilica (the apses were on the east), about 32 by 18m, built on and in connection with an earlier building (a temple or an earlier church). The basilica's foundations were extensive; below them a probe reached Early Bronze Age loci. Rows of twelve columns each flanked the nave, which, along with its side aisles, was paved with opus sectile lozenges of red and white limestone and white marble. To the west, beyond the entrance, an extensive mosaic floor in a geometric pattern was found. Just adjoining the basilica to the east and northeast, a trench 7 to 8 m deep (area AA) was excavated; earlier Roman and Hellenistic walls and soil loci (as evidenced by the pottery) were uncovered. In the deeper parts of the trench Iron and Bronze Age walls and pottery were found, with a predominence of Middle and Early Bronze loci and pottery sherds. Additional evidence from periods prior to the Byzantine were found in an expansion of this deep probe to the east. At the northern city wall on the northern slope of Tell Abila, a probe (area F) was put in perpendicular to and inside the 5-m-high wall, to test its construction and date: the evidence showed that the wall had been added to in the Byzantine and Umayyad periods. However, based on associated pottery found in the earlier courses, down to its foundation course, the lower part of the wall dated to the Hellenistic and Iron ages.

On Umm el-'Amad, the southern mound, at the location of a number of surface architectural fragments (a structure Schumacher suggested was a temple), excavation from 1984 to 1990 revealed a seventh-century CE triapsidal basilica (41 m long and 20m wide) with two rows each of twelve columns flanking the nave. Both the nave and the two side aisles were paved with opus sectile lozenges; some sections had a special design executed in red and black limestone and white marble. Evidence at the entrance to the basilica pointed to one large central door and two flanking doors. Here the area was decorated with a large red Euboean marble column; a porch with four massive columns extended farther west. Extensive sections of mosaic in geometric designs and some with floral heart motifs were found in the porch area and in the side rooms on the south of the basilica. This basilica also seems to have been built on the foundation of an earlier structure.

- Abila in Google Earth

- Aerial Photo showing

excavation areas from The Abila Archaeological Project at John Brown University

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of Abila

Areas

- A–Byzantine Church

- AA–Deep Probe

- B–Byzantine Monastic Complex/“Theater Cavea”

- C–Bath Complex

- D– Byzantine Church

- DD–Byzantine Church

- E–Byzantine Church

John Brown University - Basilica at Abila as seen in a satellite view from google maps

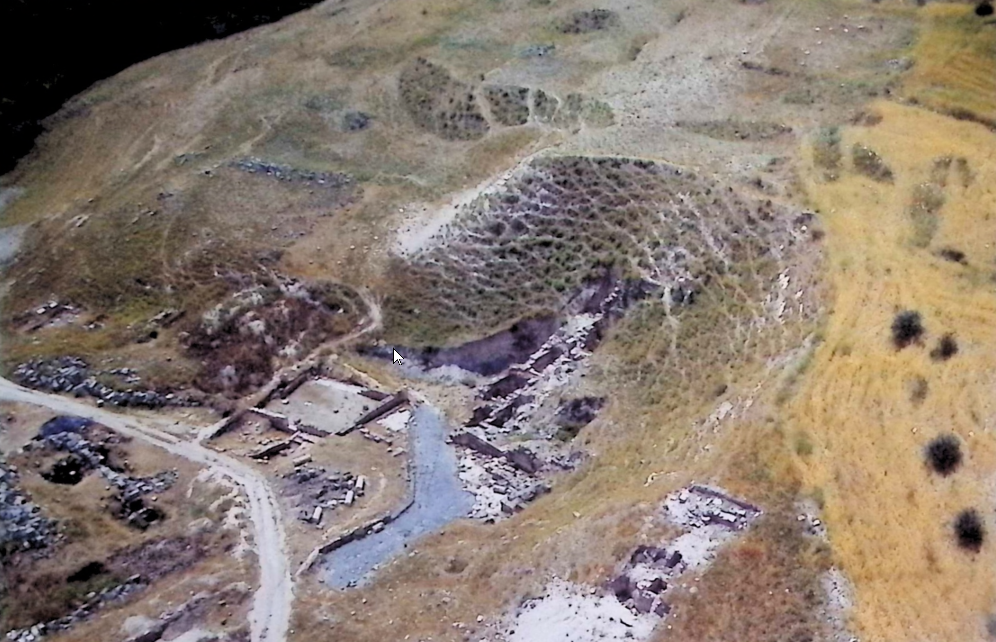

- Fig. 6.1 View of the

north tall from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 6.2 View of the

north tall (foreground) and south tall (background) from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 6.3 View of the

two churches on the south tall from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 6.4 View of the

'theatre cavea' in area B from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 6.6 View of the

restored columns in the area E five-aisled basilica from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

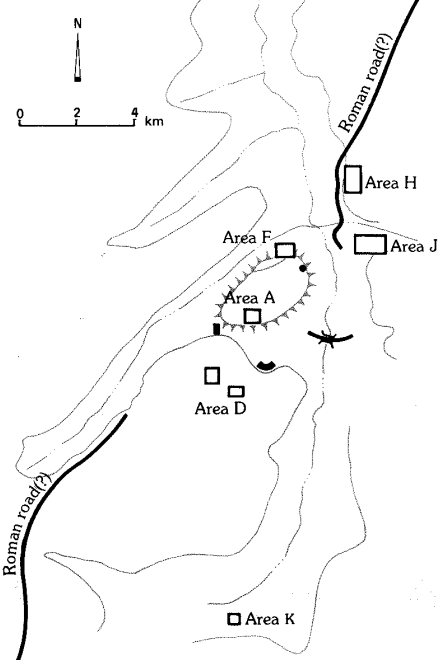

- Excavation Areas from

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

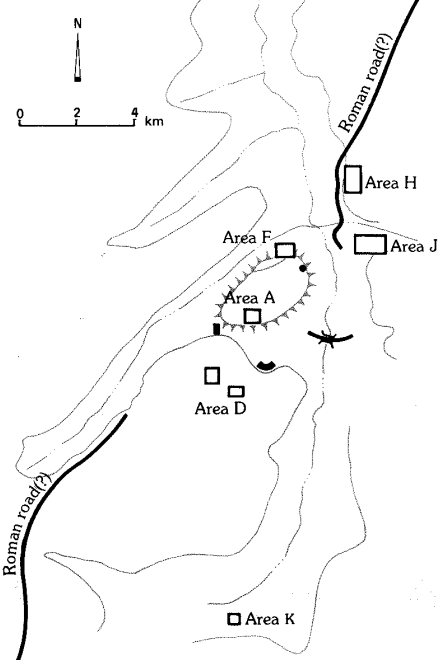

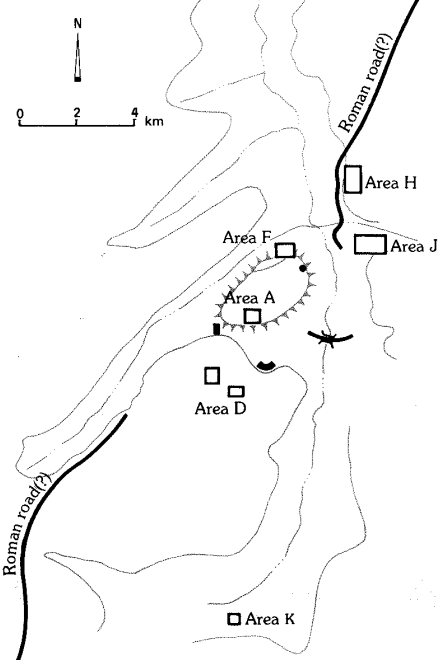

Abila: map of the excavation areas and cemeteries.

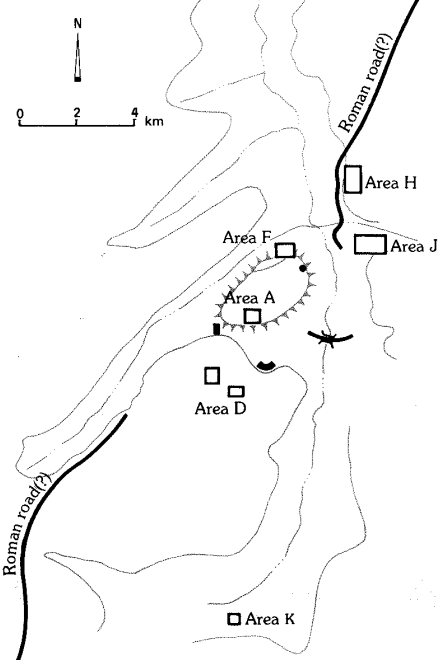

Abila: map of the excavation areas and cemeteries.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - Abila Site plan from

Stern et al (2008)

Abila: plan of the site

Abila: plan of the site

Stern et al (2008)

- Excavation Areas from

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

Abila: map of the excavation areas and cemeteries.

Abila: map of the excavation areas and cemeteries.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - Abila Site plan from

Stern et al (2008)

Abila: plan of the site

Abila: plan of the site

Stern et al (2008)

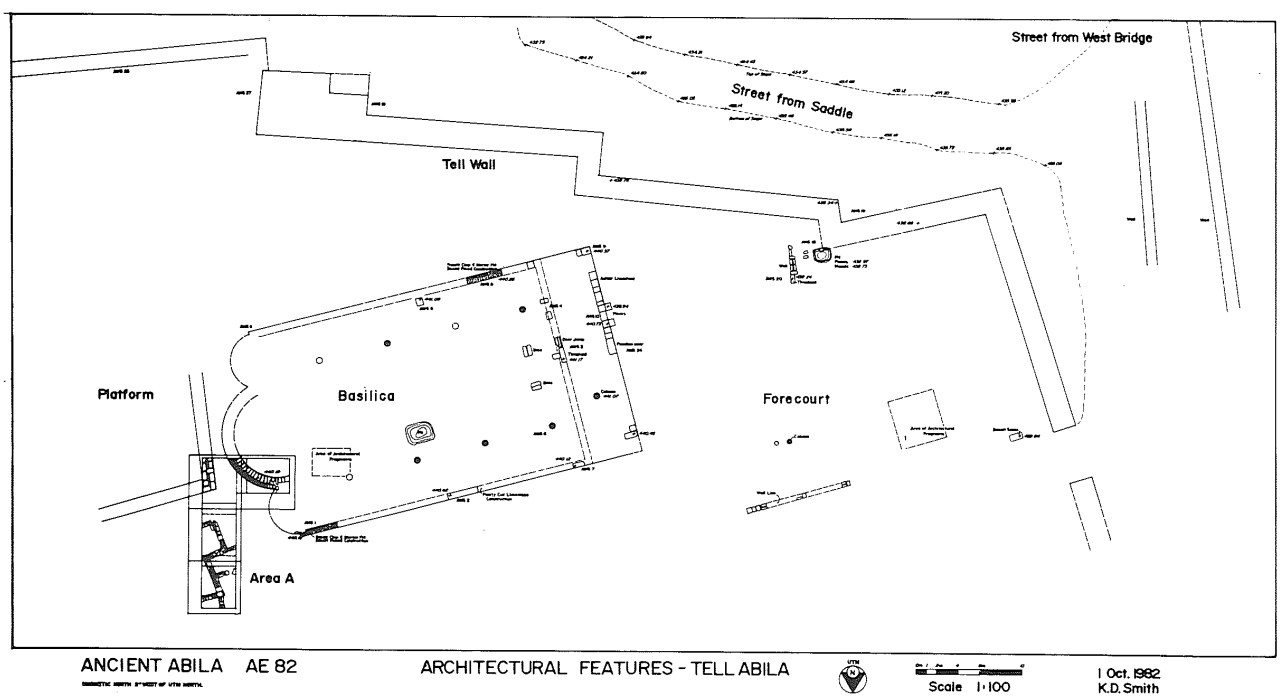

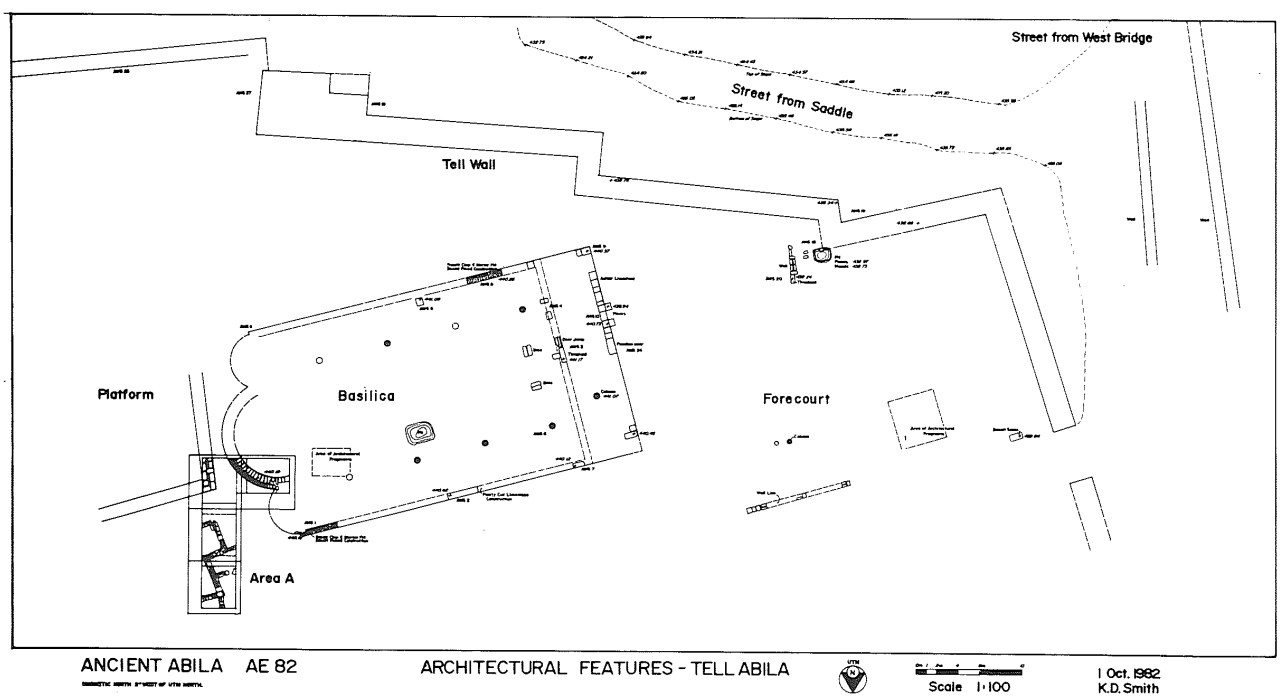

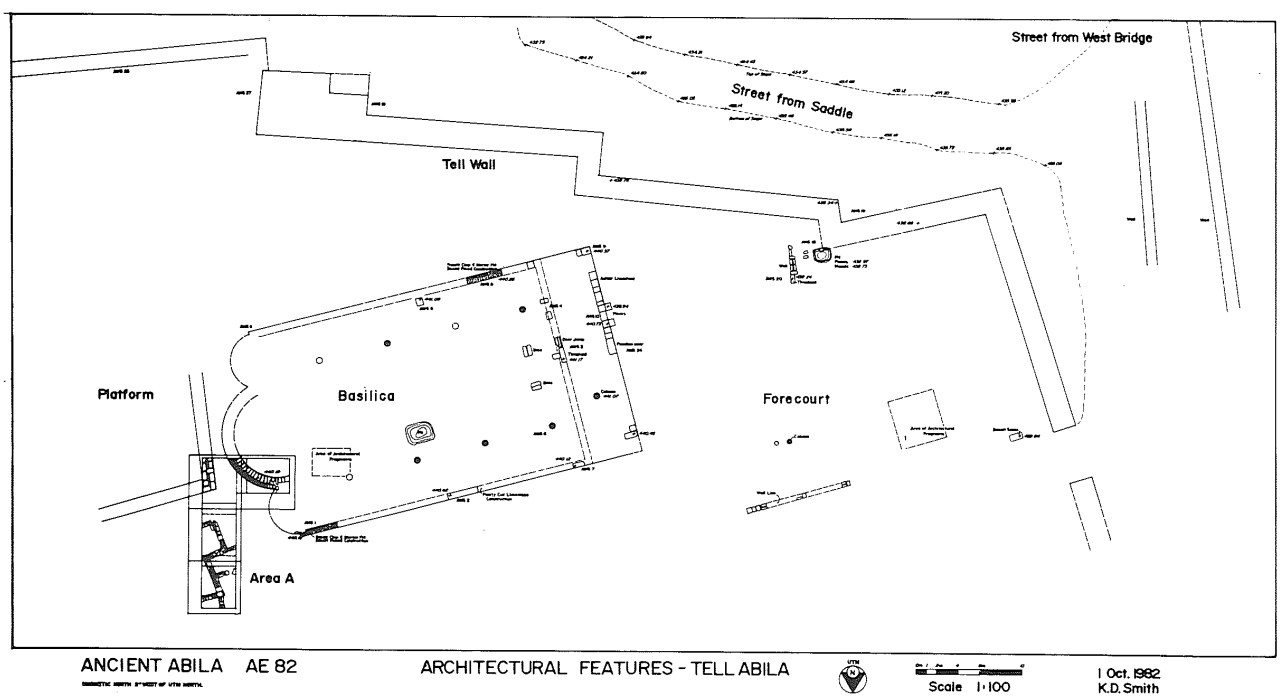

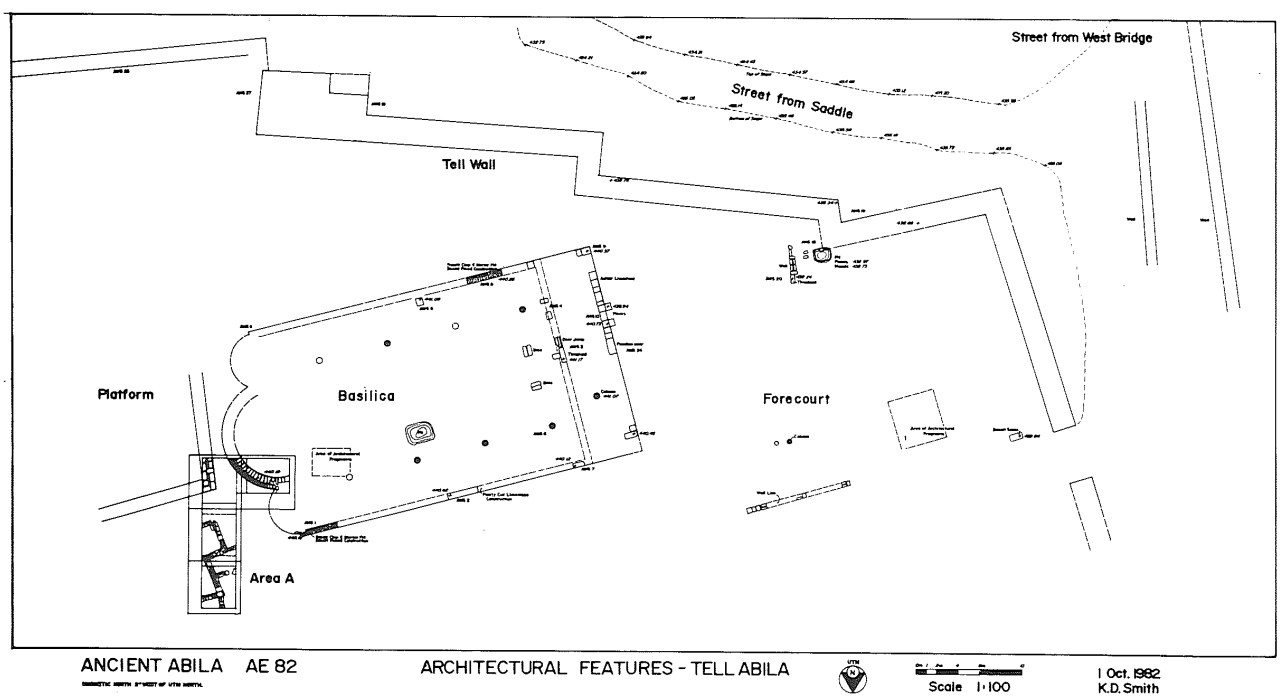

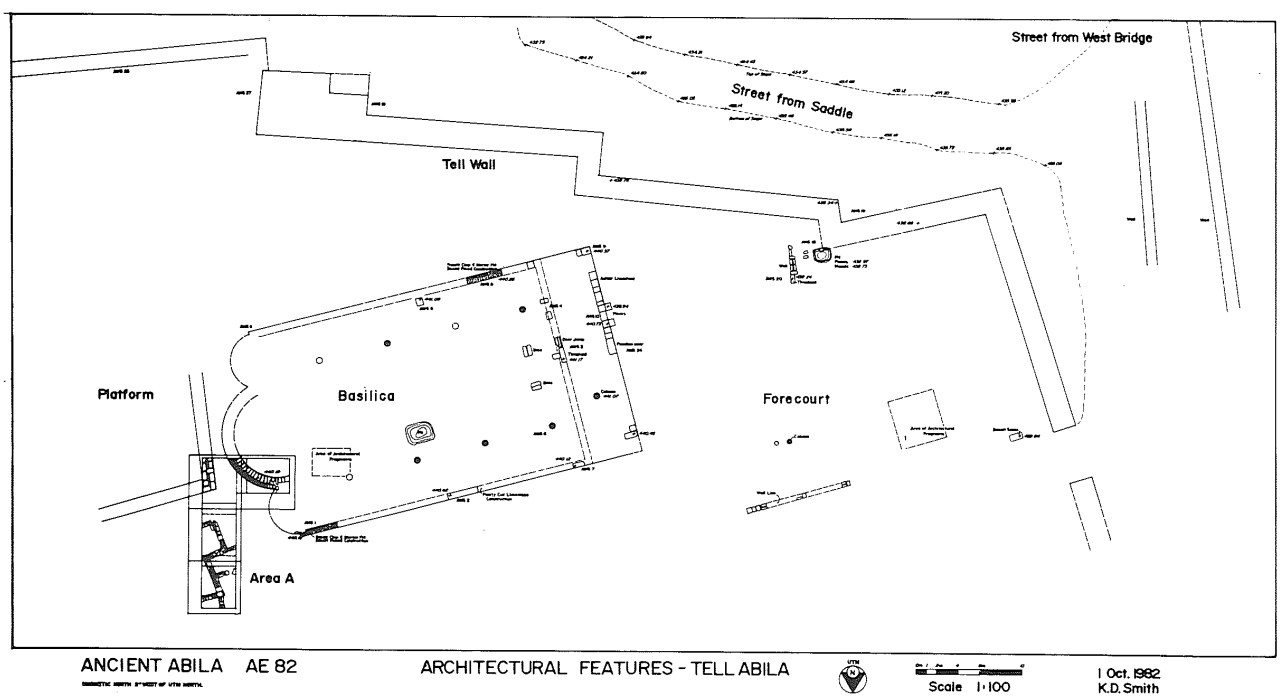

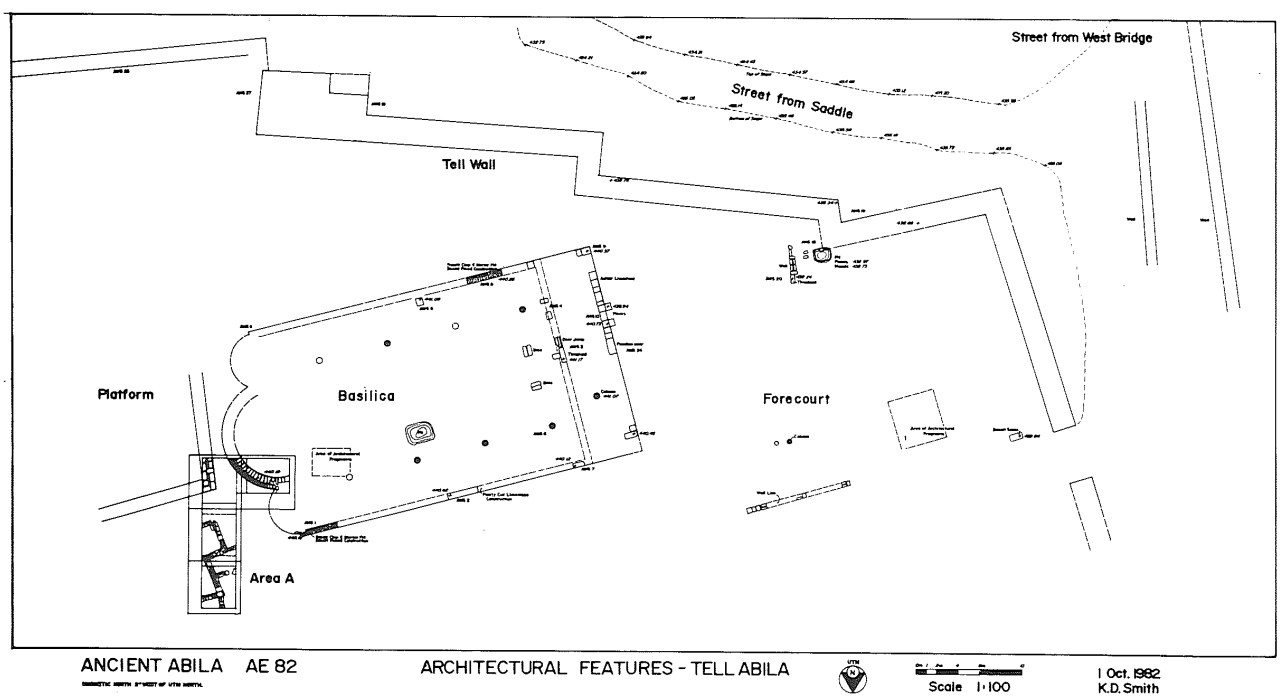

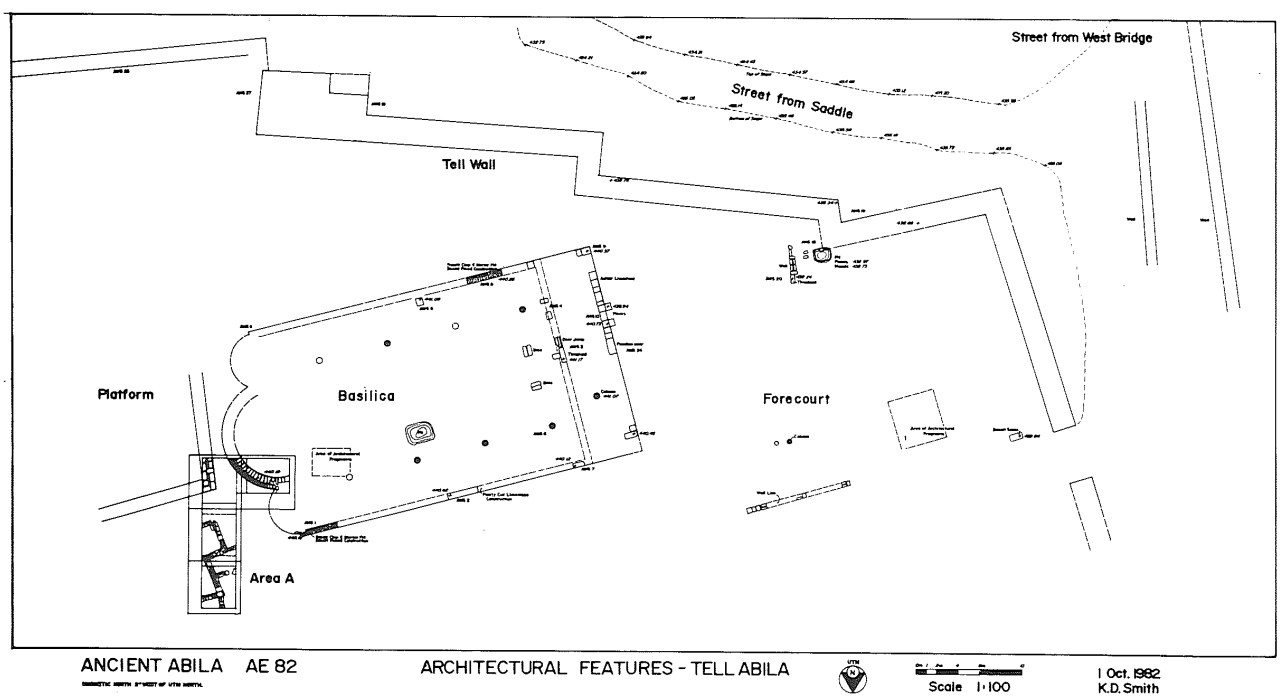

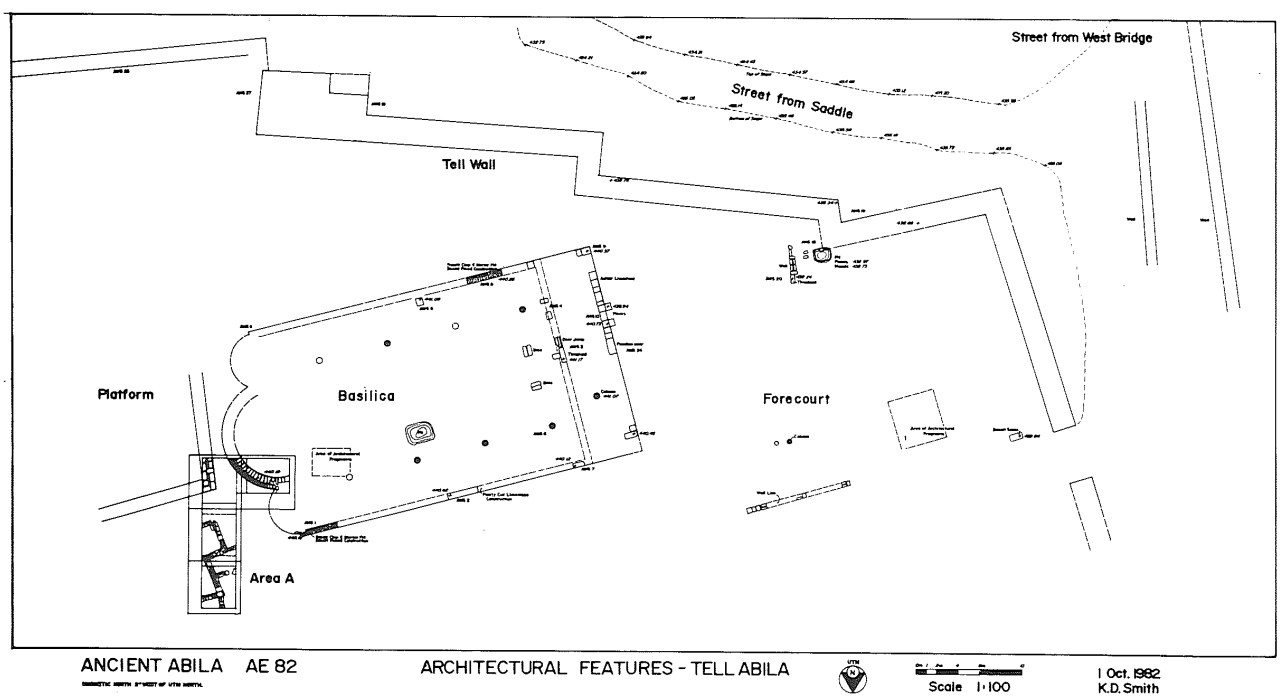

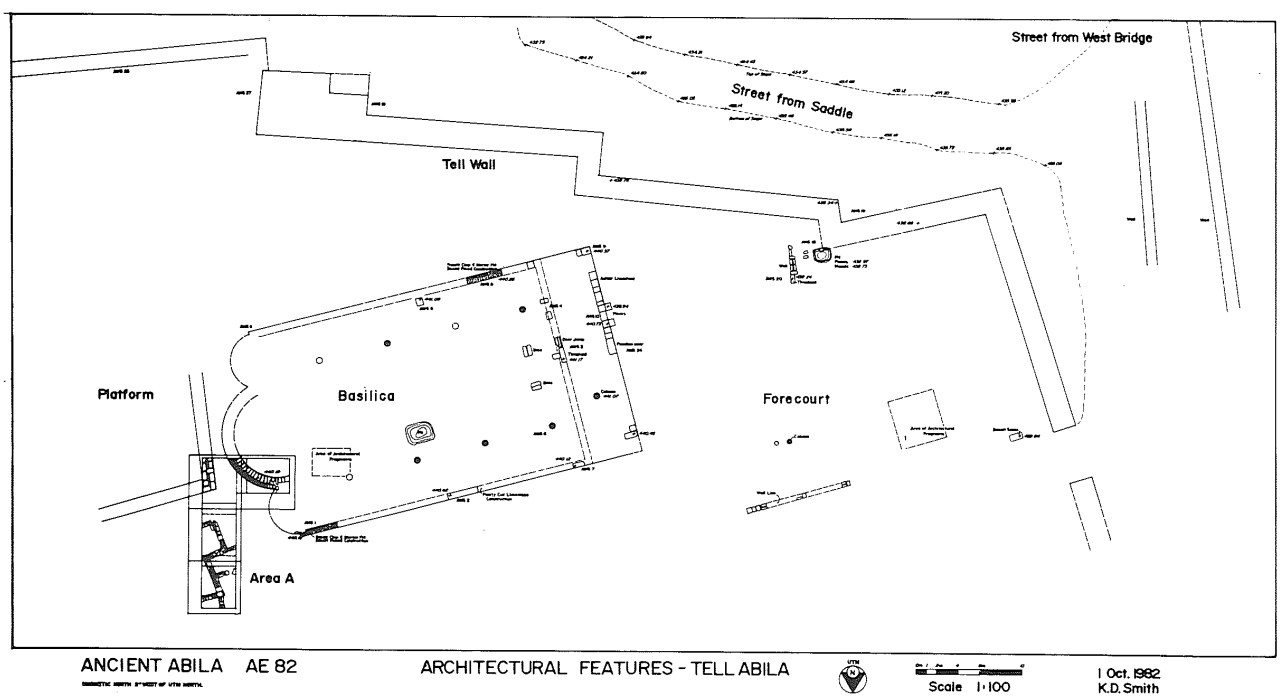

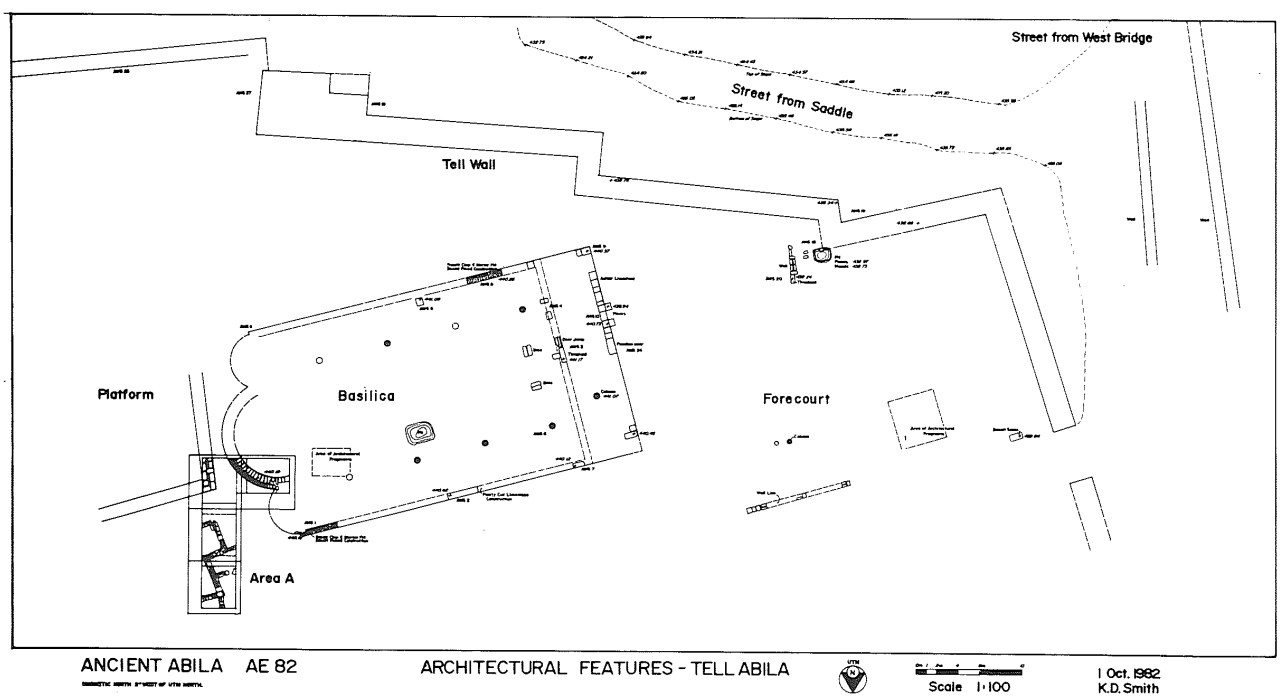

- Fig. 8 Plan of Basilica and

Area A from Mare (1984)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data

Mare (1984) - Plan of Basilica at Abila

from Stern et al (2008)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 8 Plan of Basilica and

Area A from Mare (1984)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data

Mare (1984) - Plan of Basilica at Abila

from Stern et al (2008)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 6.8 Fractured

altar screen and post in the south-west chapel of the area E Basilica from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 6.8 Fractured

altar screen and post in the south-west chapel of the area E Basilica from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- from Mare (1984)

- based on ceramics

| Phase | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Modern and Post Umayyad | |

| 2 | Umayyad | |

| 3 | Byzantine | |

| .4a | Pre-Byzantine - Roman | |

| .4b | Pre-Byzantine - Hellenistic | |

| .4c | Pre-Byzantine - Iron IIC |

... The present essay will survey three of the monumental structures at Abila that show clear evidence of being impacted by the earthquake of 749, the church on the summit of the north tall labelled area A, the church on the summit of the south tall labelled area D, and the church located near the eastern base of the north tall, along the western edge of the Wadi Qweilbah and the Roman Bridge that joins the two sides of the wadi. Then, I will survey some of the indicators that give evidence of continued occupation after the collapse of these structures in 749.

Excavation on the summit of the north tall began in 1982 under the direction of Duane Roller of Wilfrid Laurier University, and quickly uncovered what was believed to be part of an apse of a Byzantine basilica5. In 1994 a life-sized statue of Diana/Artemis was found in the area, and so excavators have assumed that in a previous life the area was home to a Roman temple. In addition, coins minted at Abila, all of which date between the middle of the second and the first quarter of the third centuries AD, commonly depict a large temple at the site6. Most of the excavation of the structure in area A was done during the 1990s, but one final season was needed in 2006 to answer a few lingering questions — namely, our quest for some clear indication of Roman occupation. That season we excavated a few sealed loci beneath a limestone paved plaza just south of the basilica and encountered clean late Roman pottery calls dating that plaza, at least, to the period in which we hypothesized there was a Roman temple, which was confirmed through the statue of Diana/Artemis that was uncovered in the area and the coins depicting such7.

Although several of the early seasons were directed by various archaeologists, most of the area was excavated by John Wineland up through a final season in the field during the summer of 2006. The structure is a tri-apsidal basilica, with all three apses facing east, and measures 35 m from the outer edge of the central threshold to the outside edge of the central, salient apse and 20 m from the outside edges of the north–south walls. Excavation in 1992 focused on the western edge of the basilica and an atrium measuring 16 m by 20 m was uncovered, paved with the larger 3 cm square tesserae commonly found in the atriums of the churches at Abila. Wineland proposes that the church continued in use until the massive earthquake that struck the region in the middle of the eighth century, after which it was used for domestic and light industrial occupation into the Early Abbasid period.

The discussion of this material in the early excavation reports unfortunately seems somewhat confused. Horace Hummel of Concordia Seminary in St. Louis who excavated the area in 1984 notes that the area had four distinct periods of occupation — modern, Umayyad, Byzantine, and pre-Byzantine8. Hummel suggests that a stash of sixteen Corinthian-style capitals and six column drums that were hoarded in squares 8 and 10 were used to divide the 'former church' into smaller domestic or industrial units in the Umayyad period. The destruction of the church structure, according to Wineland (following, it appears, Horace Hummel) came about during the attack of the Sassanid invasion after which the church was reused in a rather haphazard and informal way into the Umayyad period9. The excavators are not to be faulted for this sort of assumption, I don't think. Knowledge of early Islamic archaeology — both the typology of the pottery and sequencing of strata — was still in its infancy in the 1980s. Indeed, David Chapman and Robert Smith, in their re-evaluation of this material correctly conclude that the destruction of this structure came about from the 749 earthquake10. What this means, of course, is that the domestic and light industrial occupation found in the aftermath of the destruction of 749 is not 'Umayyad' but rather 'Abbasid', or more properly, late eighth-century and beyond. One coin that was identifiably Islamic was found in the excavation of these remains, but regrettably was catalogued with the Department of Antiquities before it was studied, and so no more precise identification is possible at this time11.

What is more important for my present purposes, though, is that during the 1984 season of excavation, Duane Roller opened a square on the north-eastern edge of the basilical structure in area A. In that square the very finely constructed corner of a large edifice was uncovered (Fig. 6.2).

From the excavation of that square, it was determined that the building was constructed using basalt ashlars from the destroyed basilica in area A. The dating sequence according to Roller, and followed by Wineland as outlined above, was that the basilica was destroyed during the Sassanid invasion, and that the structure of which the corner was located in the new square was built thus during the Umayyad period. The structure was assumed to be an Umayyad public building since it is a very large, rectangular structure12. As I have discussed elsewhere, though, the structure is likely a large, late eighth-century mosque13. The structure is situated 1.5 m due east of the main Byzantine basilica on the north tall and measures 34.5 m in width east–west by 19 m in length north–south enclosing a total area of approximately 650 m². The orientation of the building is 164 degrees south-east, where the qibla at Abila is at roughly 160 degrees, and the one entrance that was located in this initial probe enters from the north14. The location of this entrance along the western edge of this north wall would seem to indicate that there should be at least one, or possibly two more entrances along this northern wall. In addition, Mattia Guidetti, in his discussion of "The Contiguity of Churches and Mosques" argues: "When it came time to build a congregational mosque, the site selected was often an urban area adjoining an extant main church."15 And with numbers of the examples that Guidetti mentions, it is common for the mosque structures to be built on the east side of the churches when the limitations of space and geography permit. The summation of this material is that, though the earthquake of 749 devastated the church structure built in area A, it also provided the means for continuing domestic and light industrial occupation in that same structure to continue, and more significantly, for the construction of a large mosque to accommodate the growing Muslim population of Abila in the post-earthquake life of the city16. While the precise identification of the large Abbasid structure on the north tall cannot at this time be identified as a mosque — which would indicate a large and somewhat vigorous Muslim population at Abila in the aftermath of the 749 earthquake — at the very least, the continued occupation of Abila is demonstrated by the presence of this large structure.

The excavated remains on the top of the south tall also give strong evidence of both significant damage from a catastrophic event, but also of the continued use of the area after said event. Work in this area, labelled area D, began in 1984 with the excavation of two 15 x 1 m trenches, one on the summit of the tall and the other in what appeared to be an open field just to the south where it was hypothesized that a Roman forum might be found17. The latter probe uncovered what appeared to the excavators to be Byzantine domestic occupation. The former trench was placed in an area that Gottlieb Schumacher referred to as a Roman temple, on account of the various column drums visible from the surface18. In the trench opened by the Abila excavators, they soon discovered a Corinthian capital with a cross inscribed on it, and a black and red checkerboard limestone floor surface. In addition, as more of this area was excavated, the lay of the columns indicated to the excavators that it had fallen in a seismic event, likely our earthquake in 749. Wineland notes from a personal conversation with Reuben Bullard, the Staff Geologist with the Abila Excavation that the evidence seemed to him to point to a catastrophic seismic event19. There was also evidence in the nave of the church of depressions from ashlars that had fallen, breaking through the floor surface. Excavation in area D continued through the summer of 2006 and revealed a tri-apsidal basilica with a baptistry along the outer north-west wall (Fig. 6.3).

On the south of the structure numbers of rooms were uncovered that were likely pastophoria, but showed continued domestic occupation into the late eighth and probably into the tenth century. Thus, due to the significant damage done to the church structure it almost certainly ceased being used as a church, but domestic occupation continued for at least two more centuries, primarily in the rooms adjacent to the church on the south side.21

During the 1992 season, while excavating along the western edge of the atrium of the area D church, what appeared to be the top of a monumental staircase was visible from the surface. Upon further exploration excavators landed upon what appeared to be part of an apse, and no evidence of a staircase was found. So, work there was halted until the 1994 season when excavation resumed under the label of area DD.

Work in DD uncovered a basilical structure measuring 19.5 m from the threshold to the edge of the central apse and 15 m from the edges of the north and south aisles. This is the smallest of the churches at Abila. The north and south aisles were covered in mosaic flooring, while the nave was paved with sheets of marble 1 m by 60 cm and 1 cm thick, large portions of which remained in situ. The structure is tri-apsidal but curiously, unlike all the other tri-apsidal churches at Abila where the nave apse is somewhat larger than the other two, in this church all three apses are of identical size. Several stylobates were uncovered in situ, but there were no capitals, columns, or bases. Excavators have assumed that this church likely fell into disuse and was robbed out to build the church in area D, described previously. Excavators also found an empty sarcophagus that was placed across the eastern end of the north aisle that had been used for mixing plaster, again, probably for use in the construction of the area D church. As with the two previously described churches, this structure also had significant domestic occupation during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. Excavators located both an upper and nether grindstone, numbers of ash pits, several storage containers, as well as significant pottery dating to the Umayyad period, and even more dating to the Abbasid period, including some whole objects. Structural modifications to the north aisle and nave, especially, with walls bisecting both gave evidence of the domestic use of the structure after it had ceased being used as a church.22 Significant also was the finding of numbers of whole glass lamps and a bronze ewer with a handle in the shape of a panther/leopard.23 These were sitting on 15 cm of soil, above the church floor, and so the excavator’s assumption is that they were from the area D Church where, after falling in the earthquake of 749, significant artefacts were stashed in the area called area DD for safekeeping. Work in the area DD church was completed in 2006, and along with the occupation area D on the summit of the south tall and that of area A on the north tall, provides evidence of continued occupation at Abila, into the early medieval period.24

Excavation in area B began in 1986, under the direction of Bastiaan Van Elderen and continued until shortly before his passing in 2004. In his survey of Abila in the late nineteenth century, Gottlieb Schumacher described the remains of a Roman theatre, complete with seats visible from the surface in the area currently designated area B.25 Nelson Glueck, in his visit to Abila in 1942 likewise saw what he believed to be a Roman theatre, but noted that there were no seats visible, and described the remains in much less detail than Schumacher (Fig. 6.4).26

In time, excavation uncovered little evidence of a theatre, despite the unnatural curvature of the hillside, but did uncover what appears to be a monastic complex that functioned into the early medieval period. Although the structure has only been partially excavated, due to fear of collapse from material high on the hillside, excavations did uncover a single apse facing east, in what is believed to be a chapel. A layer of ash and pottery dated to the ‘Ayyubid/Mamluk’ periods led the excavators to conclude that this structure was used for domestic occupation into the twelfth century and beyond.27 Just north-west of the ‘monastic complex’ in area B, and along the edge of a basalt road that runs north–south curving in front of area B, recent excavations have uncovered what is believed to be an early medieval marketplace. The ‘stalls’ in this marketplace lie on the western edge of the basalt road, and were laid in what was an open-air plaza — evidence of the encroachment of these structures into public space in the early medieval period. Finds in this area have uncovered several of the shops, with structures for grain storage, as well as several associated whole objects, including an eighth-century juglet and a glass stamp, similar to ones discovered at Beit Shean (Fig. 6.5).28

Excavation in area B is still in its early stages, and so not much more can be said at present beyond that there was at least some continued occupation after the 749 earthquake. The extent of that occupation will only be known as more of this area is excavated.

A final area of the site that will be discussed is the basilica found in area E. Excavation in area E began in 1990, and has continued down to the present.29 The church in area E is tri-apsidal, though unlike the other churches at Abila, this one has the north and south apses facing north and south respectively — in a clover-leaf, or cruciform shape (Fig. 6.6).

The structure measures 25.4 m from the threshold to the outer edge of the central apse and 26.6 m from the edges of the north and south walls of the sanctuary, being wider than it is long with four aisles and then the nave. To the west, a narthex measuring 5.5 m extends to the back retaining wall that runs up against the side of the northern tall. Two cisterns were located in the narthex, one on the north and the other on the south sides. And on the west wall excavators uncovered what appears to be a bench and a seat built right into the retaining wall. Along the south of the structure pastophoria were excavated. Numbers of crosses were carved into walls and columns. And interestingly, along the south wall three niches were located. Two of them had been filled with plaster in Antiquity leaving only one open, thus looking suspiciously like a mihrab (Fig. 6.7).

In 1991, the late Suliman Basheer published a study of the literary references to the early use of church structures for Muslim prayer.30 And more recently, in an essay on the relationships between church and mosque structures in the Levant, Mattia Guidetti discusses a few examples where it seems that similar things are happening, though he tends to downplay the existence of churches functioning with the faithful of both traditions. I’m fairly convinced that we do have here pastophoria that were converted into a musalla at some point during the Umayyad period, the remaining niche functioning as a mihrab.31 What complicates matters somewhat is that carbon dating of an olive pit extracted from the central niche dates it between the second to third quarters of the seventh century, which may be too early to have a mihrab, much less one in a church. More work will need to be done to confirm whether this is or is not a very primitive musalla in the area E church.

In the south-west corner of this structure a chapel was located. The floor was paved with black and white checkerboard squares and there was an altar screen set up in the middle of the room adjacent to a small column. Across the lower part of both the column and the altar screen there is a break, which seems to us to be consistent with a catastrophic seismic event (Fig. 6.8).

As will be discussed below, pottery associated with what appears to be earthquake damage in this area all date to the middle of the eighth century. Throughout the church, most of the floor surfaces were paved in sheets of marble, and on many of the standing walls there were hooks for hanging marble facing also. A few, but not many ashlars were uncovered with the remains of painted plaster on them. During the 2010 season of excavation, irregularities observed on the outside of the east wall of the structure on the south side of the apse led excavators to hypothesize about the phasing of the structure, and so a probe was taken 3 m on the opposite side of that wall, in the interior of the church. That probe landed on a paved mosaic surface and so squares were opened in the north and south aisles that revealed what we are fairly certain is an earlier church located 1 m below the one being excavated. Crosses in the middle of the aisles as well as an altar screen with a cross in front of it in the north aisle seem to confirm such a view. No more work was done on this lower church because of a desire not to disturb the upper church. Various things have led us to conclude that the upper church was destroyed in the mid-eighth-century earthquake. The lay of columns as they were being excavated, indentations in the floor surfaces from ashlars that fell from a significant height, as well as numbers of whole objects, such as a green glazed pot and other pottery and metal objects which clearly belong to the eighth century which were crushed under falling debris, seem to confirm that the church was destroyed in the mid-eighth century (Fig. 6.9).32

In probes under the floor surface of the upper church, four burials were located. All of the burial pits were oriented east/west, with the deceased facing south, that is, toward the qibla. Recent radiocarbon of a tooth from one of these burials dated it with 82 per cent certainty to a range of AD 870–992, consistent with other evidence about the continued occupation of the area into the tenth century and beyond.33

Another element related to the use of the structure in area E in a post-earthquake environment is the presence of numbers of Arabic inscriptions throughout the area — on columns, around the opening of a cistern, as well as on a plaster wall in what appears to be a baptistry on the north side of the structure. The inscriptions were being deciphered by Andrea Zerbini and Firas Biqain, until the untimely and tragic passing of the former. We hope that within a short time we will be able to publish the findings of this important evidence of the continued use of the structure in a post-ecclesial setting.

In light of the evidence presented above, it is clear that, although the mid-eighth-century earthquake had a significant impact on the monumental architecture at Abila of the Decapolis, there was continued occupation at the site, at least into the tenth or eleventh century. Regrettably, over the past forty years of excavation most of the excavation work has been focused on the monumental structures at the site, and so we arc less able to tell what the occupation and continuity of the city was in a broader sense. Abila is a large site, and future excavation work moving into the areas of domestic occupation will be able to provide more precise data for the lingering occupation at the site, which I am confident will show that although the earthquake had a devastating impact on the city, occupation continued for several centuries and possibly beyond.

5 Roller 1983, especially 16-22.

6 Wineland 2001, see chapter 6 for a discussion of this. See also de Saulcy 1874, pl. 16.

7 Mare 1999a.

8 Hummel 1985. 16-33.

9 Wincland 2001. 112.

10 Chapman and Smith 2009.

11 Wineland 2001, 27.

12 Roller 1984. In later excavations, Horace Hummel suggests that the structure

might be either an administrative building or a mosque, but still dates it to

the 'Umayyad' period. Sec Mare and others 1984; 1985; 1986.

13 Vila 2016; 2018.

14 Thlough, of course, orientation of the earliest mosques was less

a matter of precise scientific orientation than of general direction.

See King 1982; and King and Hawkins 1982, 102-09.

15 Guidetti 2017, 52 as well as Guidetti 2015, especially 11-27.

16 Vila (forthcoming).

17 Grothe 1985, 35-63; and Wincland 2001, 30-32.

18 Schumacher 1889, 25-27.

19 Wineland 2001, 31 n. 75.

20 Wineland 2001, 33.

21 The post-ecclesial use of the structure and adjacent rooms is discussed in Chapman and Smith 2009, 525-33.

22 Vila 2016, 162-63 and references there.

23 Mare and others 1994; 1995; 1996.

24 Vila 2016, 157-66 and Avni 2014, 221-22.

25 Schumacher 1889, 30 -32.

26 Glueck 1951. 125.

27 Van Elderen 1989, 10-20.

28 Hadad 2002. 35-48. The inscription on the stamp from area B at Abila is awaiting further study.

29 Although excavations are ongoing. this is the most published structure at Abila. See discussions in Vineland 2001, 38-03 as

well as Mare 1994; 1995; 1996. 2-5, 12-13; 1997, 25-44: 1999b. 11-12; 2000; Menninga 2004, 40-49; and Smith 2018,649-61.

30 Bashcar 1991, 267-82.

31 I've discussed this in several places, including Vila 2018 and Vila (forthcoming).

32 Vila 2016, 157-66.

33 Radiocarbon dating was performed by Beta Analytic Testing Laboratory on 13 April 2022.

For parallel studies of other early Islamic period burials in the region see Srigyan 2020.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Basilica on the north Tall in Area A

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data Mare (1984)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at AbilaStern et al (2008) |

|

|

| Displaced masonry blocks | Basilica on the north Tall in Area A

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data Mare (1984)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at AbilaStern et al (2008) |

|

|

|

Church on the south Tall in Area D

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University Fig. 6.3 |

|

|

|

Basilica in Area E

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Basilica on the north Tall in Area A

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data Mare (1984)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at AbilaStern et al (2008) |

|

VIII + | |

| Displaced masonry blocks | Basilica on the north Tall in Area A

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Synthesis of Wall structures on the south portion of Tell Abila and the Area A Excavation Data Mare (1984)

Plan of Basilica at Abila

Plan of Basilica at AbilaStern et al (2008) |

|

VIII + | |

|

Church on the south Tall in Area D

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University Fig. 6.3 |

|

|

|

|

Basilica in Area E

Aerial View of Abila

Aerial View of AbilaAreas

John Brown University |

|

|

Fuller, M. J. (1987). Abila of the Decapolis: A Roman-Byzantine City in Transjordan, Washington University.

Mare (1984)

The 1982 Season at Abila of the Decapolis Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 28

Mare et al (1987)

The 1986 Season at Abila of the Decapolis Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 31

Mare, H. (2004) Excavations at Abila of the Decapolis, Northern Jordan

Vila, D. (2025) Chapter 6. The Eighth Century Earthquake at Abila: Destruction and Continued occupation

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis

G. Schumacher, Abila of the Decapolis, London 1889

Briinnow-Domaszewski, Die Provincia Arabia;

H. Bietenhard, ZDPV79 (1963), 24-58

G. W. Bowersock,JRS61 (1971), 219-242

A. Spijkerman, The

Coins of the DecapolisandProvinciaArabia,Jerusalem 1978

W. H. Mare(etal.), BA 44(1981), 179-180;

45 (1982), 57-58

id., LA 31 (1981), 343-345

34 (1984), 440-441

37 (1987), 397-400

38 (1988), 454-457;

40 (1990), 468-475

id., Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin n.s. 17 (1981), 5-25

18 (1981), 5-30

21

(1983), 5-68

22 (1983), 5-64

24 (1985), 7-1 09

25 (1985), 35-90

26 (1986), 5-70

27 (1986), 25-60

28

(1987), 35-75

29 (1987), 31-88

30 (1988), 29-106

31 (1988), 19-66

32-33 (1989), 2-64

34 (1990), 2-

41

35 (1990), 2-56

36 (1991)

id., ADAJ26 (1982), 37-83

28 (1984), 39-54

29 (1985), 221-238

31 (1987),

205-219

35 (1991), 203-221

id., AJA 88 (1984), 252

91 (1987), 304-305

93 (1989), 260

95 (1991), 314-

315

id., Archiv fur Orientforschung 33 (1986), 206-209

id., Akkadica Supplementum 3 (1986), 114, 232

8

(1989), 472 -486

id., RB 96 (1989), 251-258

M. J. Fuller, Abila Reports, Florrisant Valley, Mo. 1986

id.,

Abila oft he Decapolis: A Roman-Byzantine City in Transjordan 1-2 (Ph.D. diss., Washington Univ. 1987;

Ann Arbor 1991)

R. H. Smith, Pella of the Decapolis 1-2, Wooster, Ohio 1973-1989

A. McNichol eta!.,

Pella in Jordan 1, Canberra 1982

A. Barbetand C. Vibert-Guigue, Les Peintures des necropoles Romaines

d'Abila et du nord de Ia Jordanie (Bibliotheque Archeologique et Historique 130), Paris 1988.

M. J. Fuller, Abila of the Decapolis: A Roman-Byzantine City in Transjordan (Ph.D.

diss., Washington University 1987), Ann Arbor, MI 1993

A. Barbet & C. Vibert-Guigue, Les peintures des

necropoles romaines d’Abila et du nord de la Jordanie (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 130), Texte,

Paris 1994

J. D. Wineland, Ancient Abila: An Archaeological History (BAR/IS 989), Oxford 2001

ibid.

(Reviews) NEAS Bulletin 48 (2003), 61–63. — AJA 108 (2004), 138–139.

W. H. Mare, ABD, 1, New York 1992, 19–20

id., Aram 4 (1992), 57–77

6 (1994), 359–379

7

(1995), 189–215

id., LA 42 (1992), 361–366

44 (1994), 630–634

id. (et al.), NEAS Bulletin N.S. 37 (1992),

2–38

38 (1993), 1–59

39–40 (1995), 66–104

41 (1996), 2–36

42 (1997), 25–44

44 (1999), 11–12

id.,

SHAJ 4 (1992), 309–314

5 (1995), 727–736

7 (2001), 499–508

id., AJA 97 (1993), 312

98 (1994), 301;

99 (1995), 307

100 (1996), 371

101 (1997), 339

102 (1998), 406

103 (1999), 276–277

104 (2000), 340;

105 (2001), 445–446

id., ADAJ 38 (1994), 359–378

40 (1996), 259–269

41 (1997), 277–281

303–310

43

(1999), 451–458

id., ASOR Newsletter 44/2 (1994), n.p.

45/2 (1995), 30

46/2 (1996), 20

47/2 (1997), 40;

id., Occident and Orient 3/2 (1997), 28–29

id., OEANE, 1, New York 1997, 5–7

id., Artifax 14/2 (1999),

5

M. J. & N. Fuller, Aram 4 (1992), 157–171

B. de Vries, AJA 96 (1992), 537–538

J. D. Wineland, Aram

4 (1992), 329–342

W. Winter, ibid., 357–369

id., NEAS Bulletin 37 (1992), 26–36

R. Wenning, ZDPV 110

(1994), 1–35

A. Barbet, 5th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics (Bath, England, 5–12.9.1987),

Ann Arbor, MI 1995, 43–56

R. W. Smith, JRA 10 (1997), 307–314

G. M. Cohen, American Journal of

Numismatics 10 (1998), 95–102

T. M. Weber, Gadara-Umm Qes I: Decapolitana Untersuchungen zur

Topographie, Geschichte, Architektur und der Bildenden Kunst einer “Polis Hellenis” im Ostjordanland

(Abhandlungen des Deutschen-Palästina-Vereins 30), Wiesbaden 2002, 465–481

Gadara-Gerasa und

die Dekapolis (Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie

Antike Welt Sonderbände

eds. A. Hoffmann & S.

Kerner), Mainz am Rhein 2002

BAR 29/1 (2003), 50

U. Hübner, Saxa Loquentur, Münster 2003, 97–100;

A. Lichtenberger, Kulte und Kultur der Dekapolis: Untersuchungen zu numismatischen, archäologischen

und epigraphischen Zeugnissen (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 29), Wiesbaden 2003

B.

Lucke, Occident and Orient 8/1 (2003), 14–16

Y. Elitzur, Ancient Place Names in the Holy Land: Preservation and History, Jerusalem 2004, 173–174

J. Häser, SHAJ 8 (2004), 155–159

S. Kerner, Men of Dikes and

Canals: The Archaeology of Water in the Middle East. International Symposium, Petra, 15–20.6.1999 (Orient Archäologie 13

eds. H. -D. Bienert & J. Häser), Rahden 2004, 187–202

C. Menninga, NEA 67 (2004),

40–49

M. S. Shannaq, SHAJ 8 (2004), 405–407

www.abila.org (dead link)

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |