Jerusalem - Haram esh-Sharif and adjacent Umayyad structures

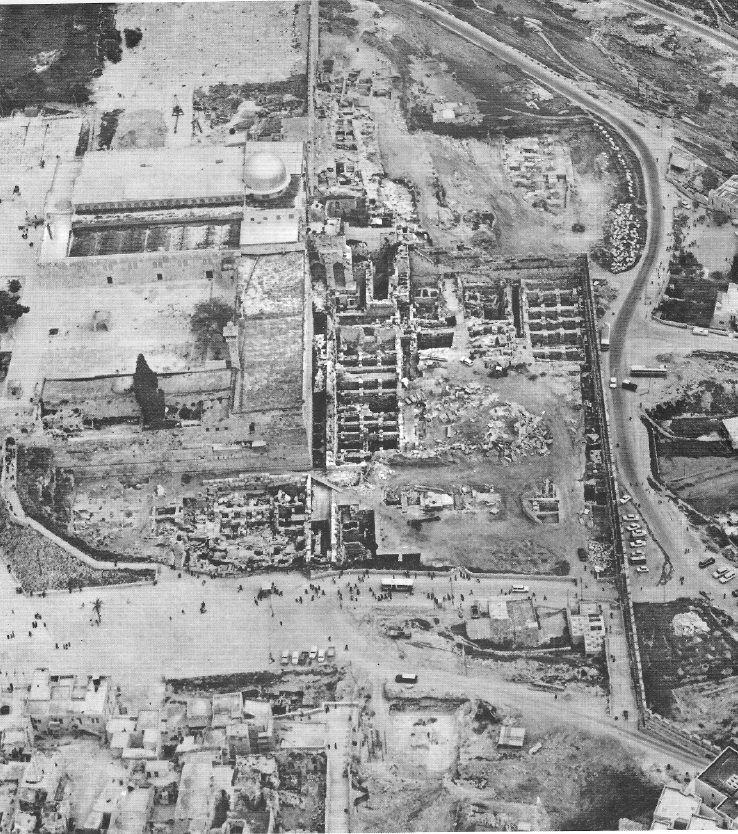

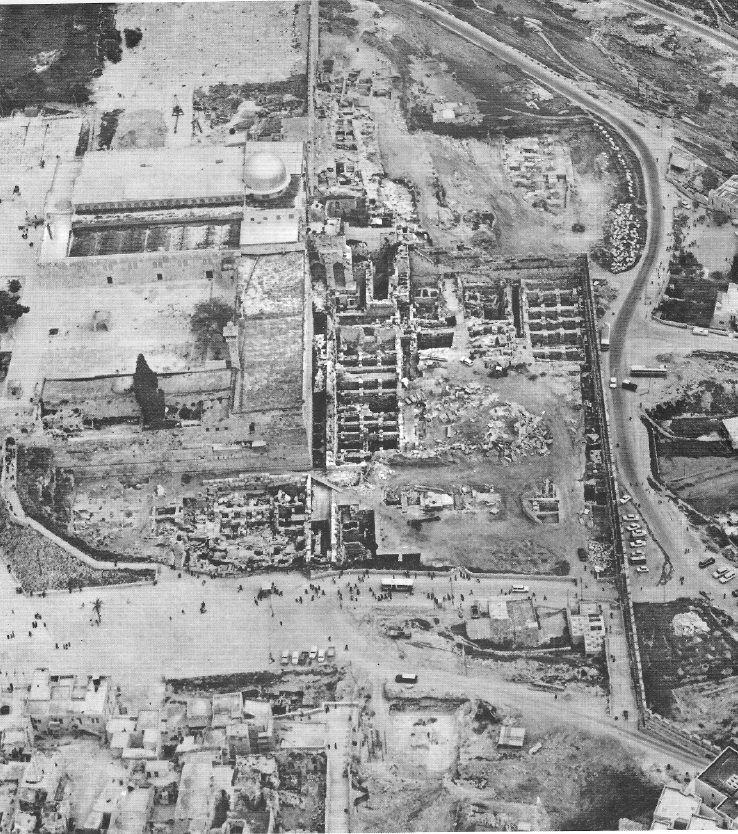

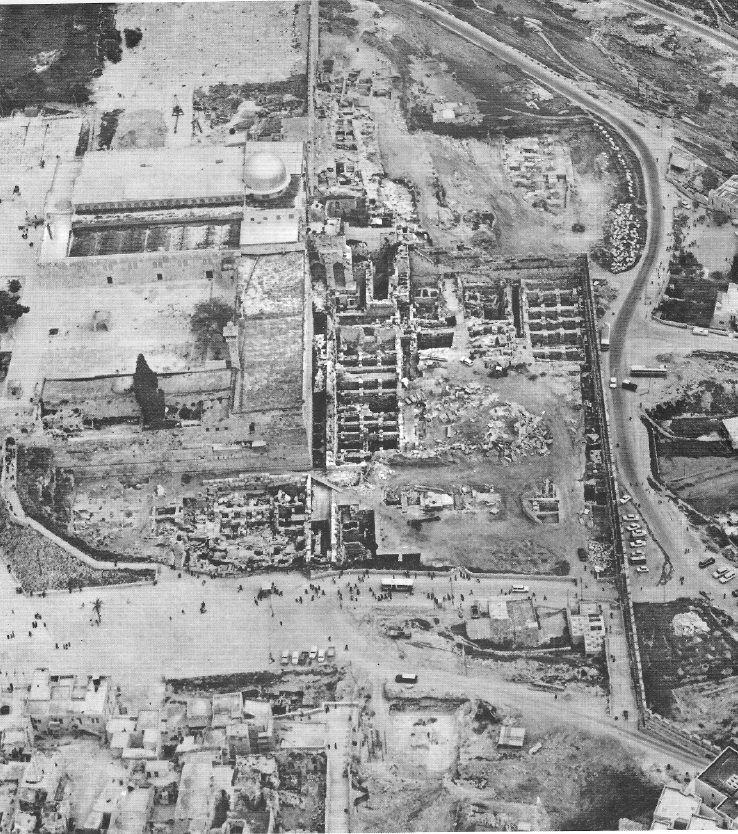

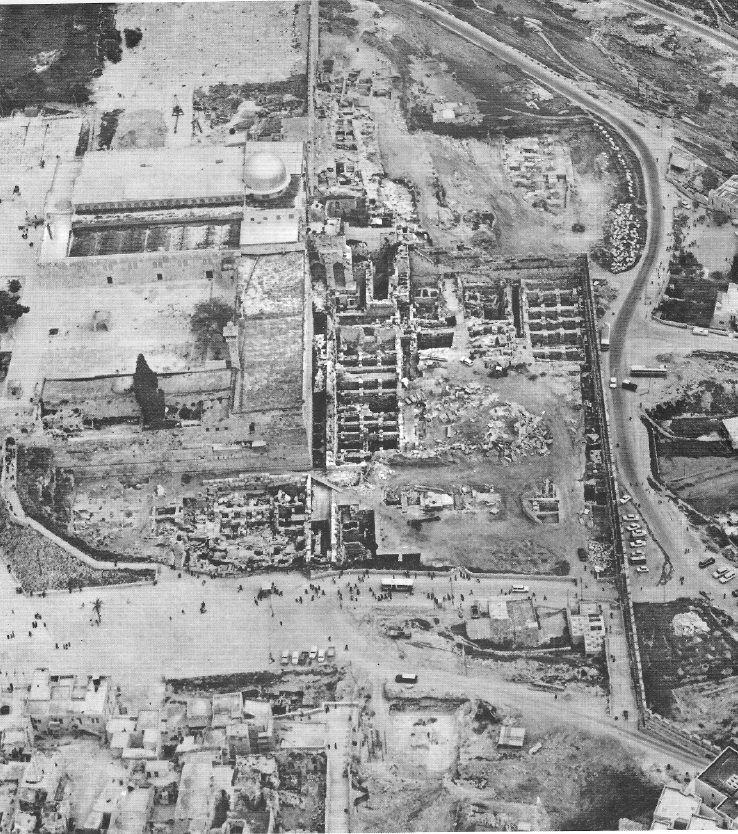

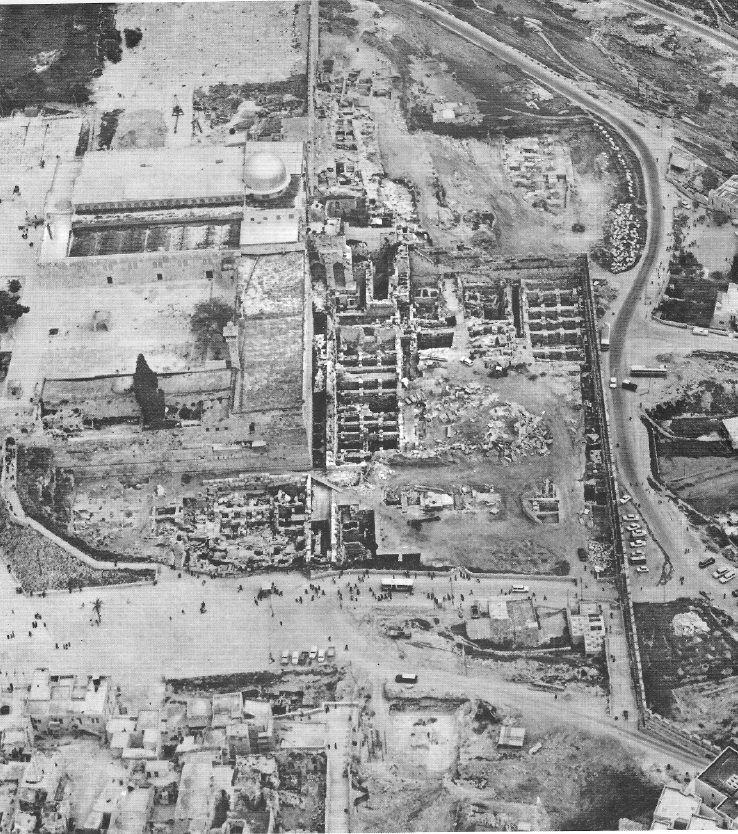

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavations

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavationsYadin et al (1976)

Transliterated Name

Language

Name

Haram esh-Sharif

Arabic

الحرم الشريف

Temple Mount

Jerusalem's holy esplanade

Har haBayīt

Hebrew

הַר הַבַּיִת

Transliterated Name

Language

Name

Al-Aqsa Mosque

Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā

Arabic

جامع الأقصى

al-Muṣallā al-Qiblī

Arabic

المصلى القبلي

al-Masjid al-'Aqṣa

Arabic

لمسجد الاقصى ا

Transliterated Name

Language

Name

Dome of the Rock

Qubbat aṣ-Ṣaḵra

Arabic

قبة الصخرة

- from Rutenberg and Levy

- some earthquake date assignments are incorrect

The al Aqsa, the third most sacred mosque in the Muslim religion (after Mecca and Medina), was constructed at the southern side of Temple Mount at the end of the 7th and early 8th century. It is a traditional stone masonry building. Damaged in the 710 and 713/14(?) EQs, and destroyed in the 749 (746 -748?) EQ, it was rebuilt in 758. It was again damaged due to poor construction and/or EQs in 771 and 774, and then rebuilt on a new plan in 780. It was again damaged in 859, 1033, following which extensive rebuilding took place in 1035, including the cupola that still stand to this day. In 1060 the roof of al Aqsa collapsed. The Crusaders who occupied Jerusalem in 1099 turned it into a royal palace, and part of it was given to the Templars. During that period some internal changes took place and several wings were added. No EQ damage to the al Aqsa was reported until 1927. However, the British, who occupied Palestine in 1917, found the mosque, and also other building in Temple Mount, in a state of total neglect and on the verge of collapse. Restoration work started in 1924 most probably saved the building from total collapse in the 1927 EQ. The damage from the 1927 event was extensive (Fig. 7), and necessitated the continuation of the restoration. Following a minor EQ in 1937 extensive restoration took place during 1938-1942, involving demolition of the eastern longitudinal walls and arcades. Old columns were replaced by new marble ones imported from Italy. Following arson in 1969, the mosque was severely damaged, and restoration work was completed only in the mid 1990's. Stabilization of the mosque's foundations by massive concreting in the underground voids adjacent to the Ancient al Aqsa (or the Double Gate) - located under the mosque - was carried out in the 1970's, and its extensive excavations and restoration of took place in the 1990's. A detailed description of the mosque can be found in Hamilton's monograph (1949).

- from Rutenberg and Levy

- some earthquake date assignments are incorrect

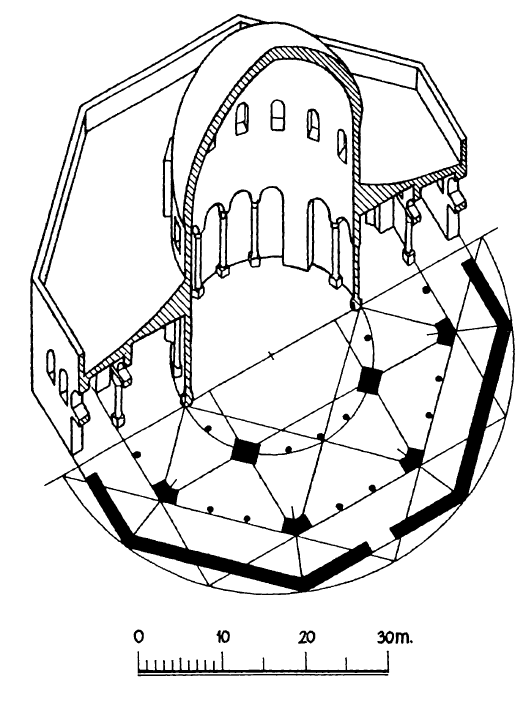

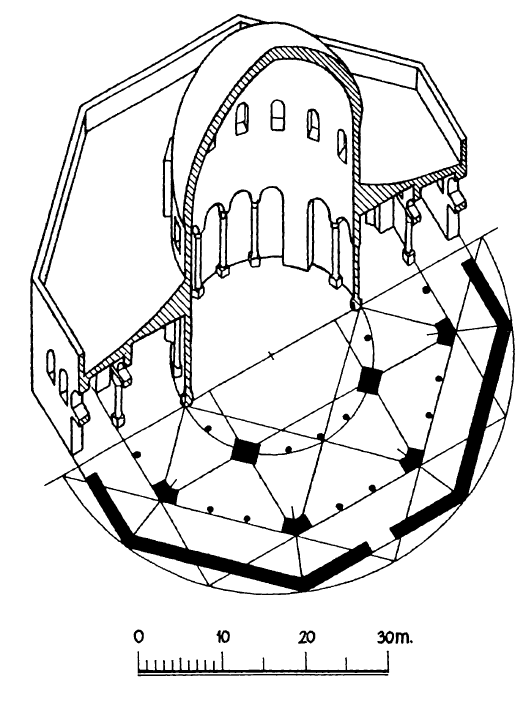

After the conquest of Jerusalem in 638 the Muslims embraced the sanctity of Temple Mount, and built the original al Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock, both at the late 7th and early 8th century. The octagonal building dates from the early 9th century. It is covered by two practically independent wooden domes: an external one of an elliptical shape recently covered by gilded copper sheets, and internal one of circular shape, with circa one metre space between the two to allow inspection and maintenance. Whereas the present ornamented internal dome dates from the early 11th century, the external one, built to protect the former, is recent. After the reoccupation of Jerusalem by the Arabs in 1187 the dome was refurbished. The building is considered to be an architectural gem by most experts.

The structure was severely damaged by the 749 (746-748?) EQ. Renovation started in the 780's and apparently completed by Mamoun in 813. Some damage to the dome, or just the fall

of its candelabra, was reported following the 1060 EQ. The dome was damaged again in 1068. The 1546 ML = 7 EQ caused the collapse of the dome. As already noted, the British found the

Dome of the Rock in a state of neglect, and restoration work started in 1924. It is difficult to estimate the effect of the 1927 EQ on the building. One press report stated that the Dome

of the Rock was badly shaken and many repairs of recent years were made useless

.

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

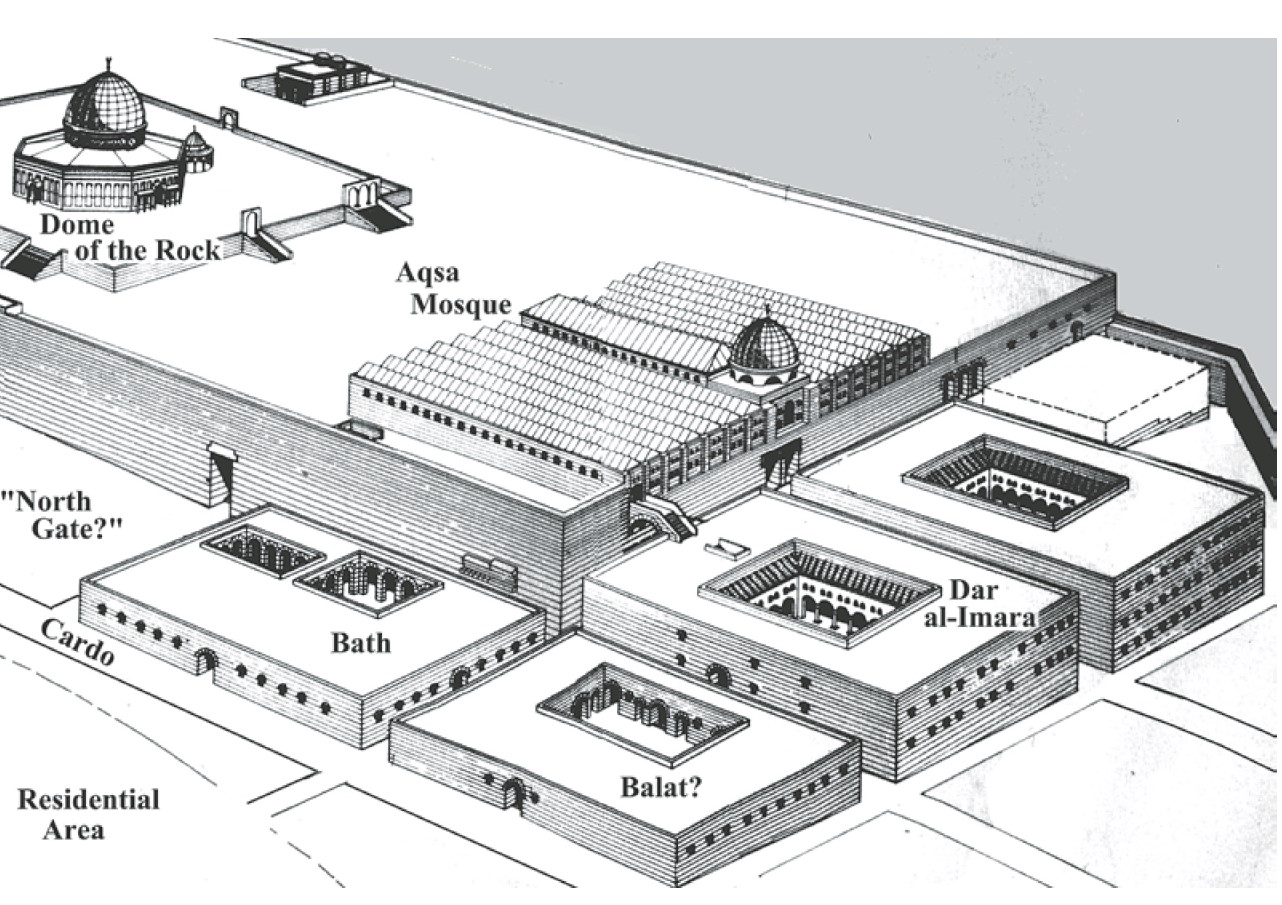

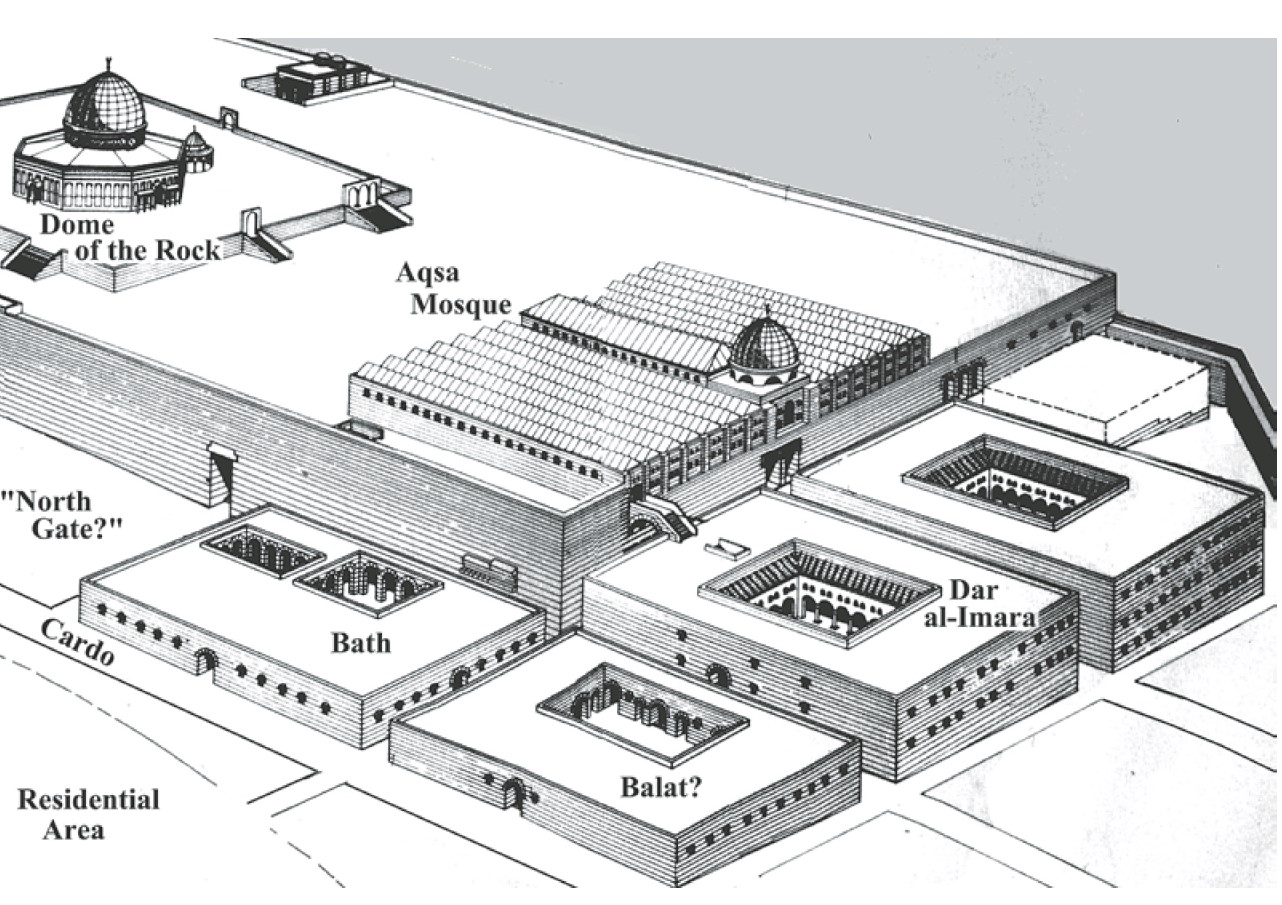

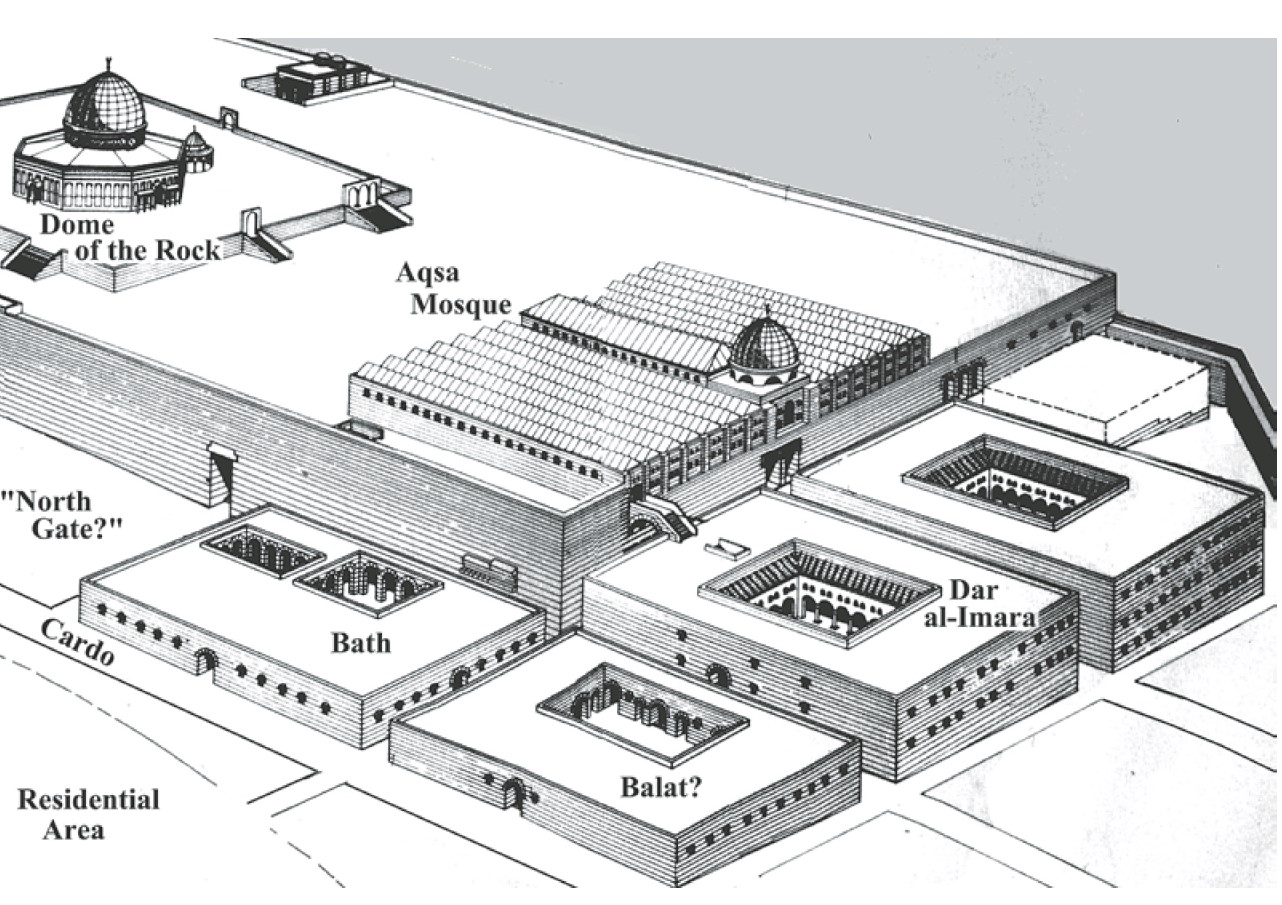

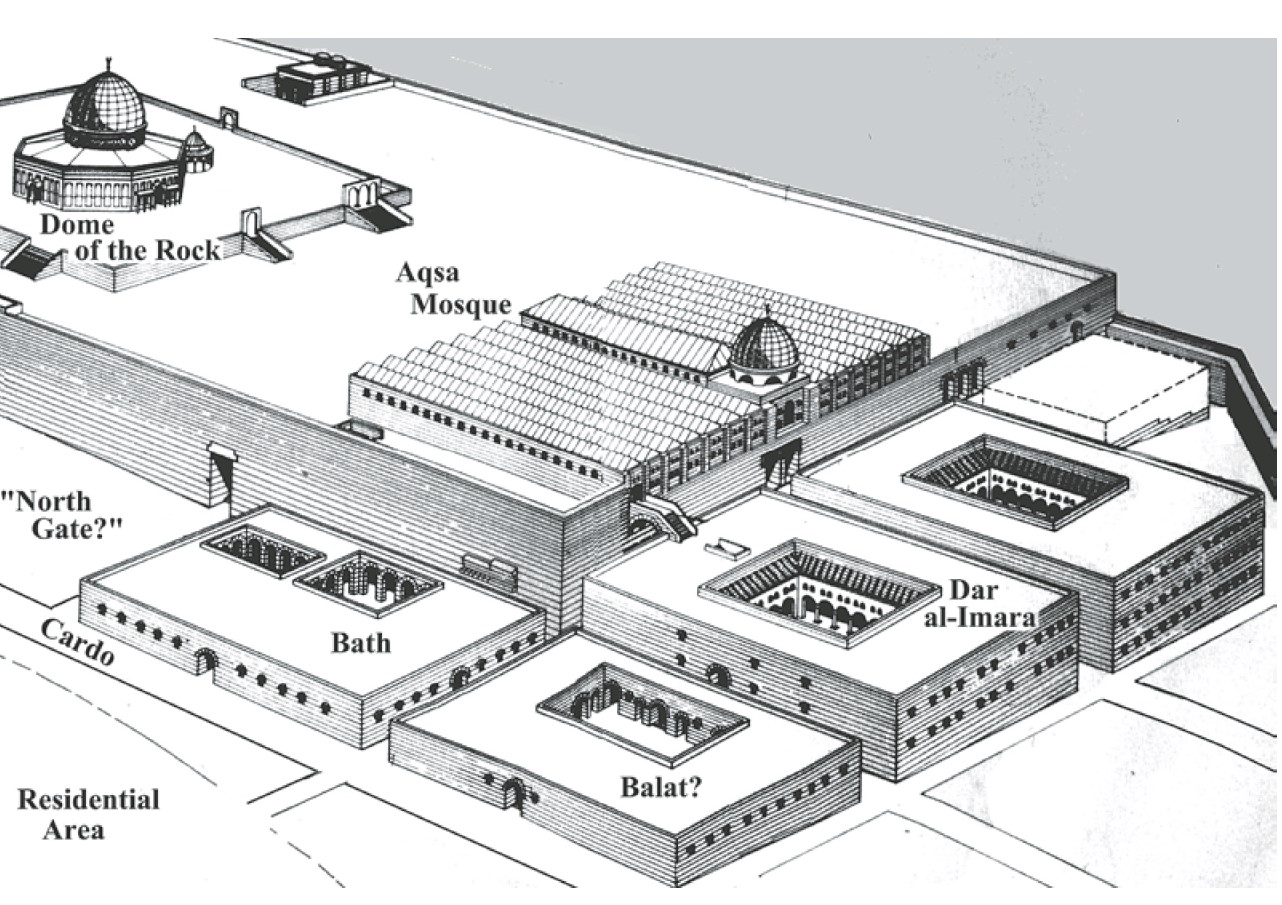

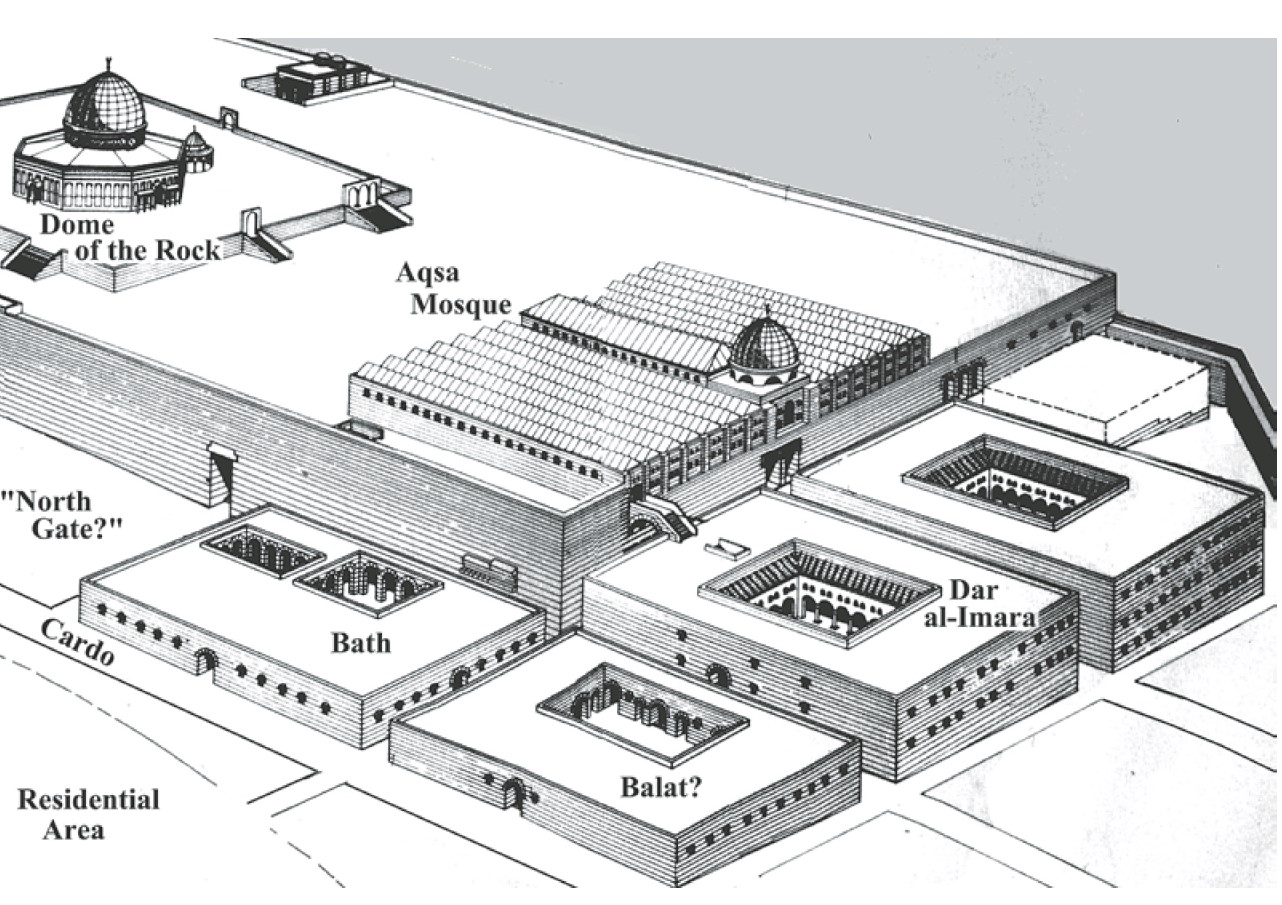

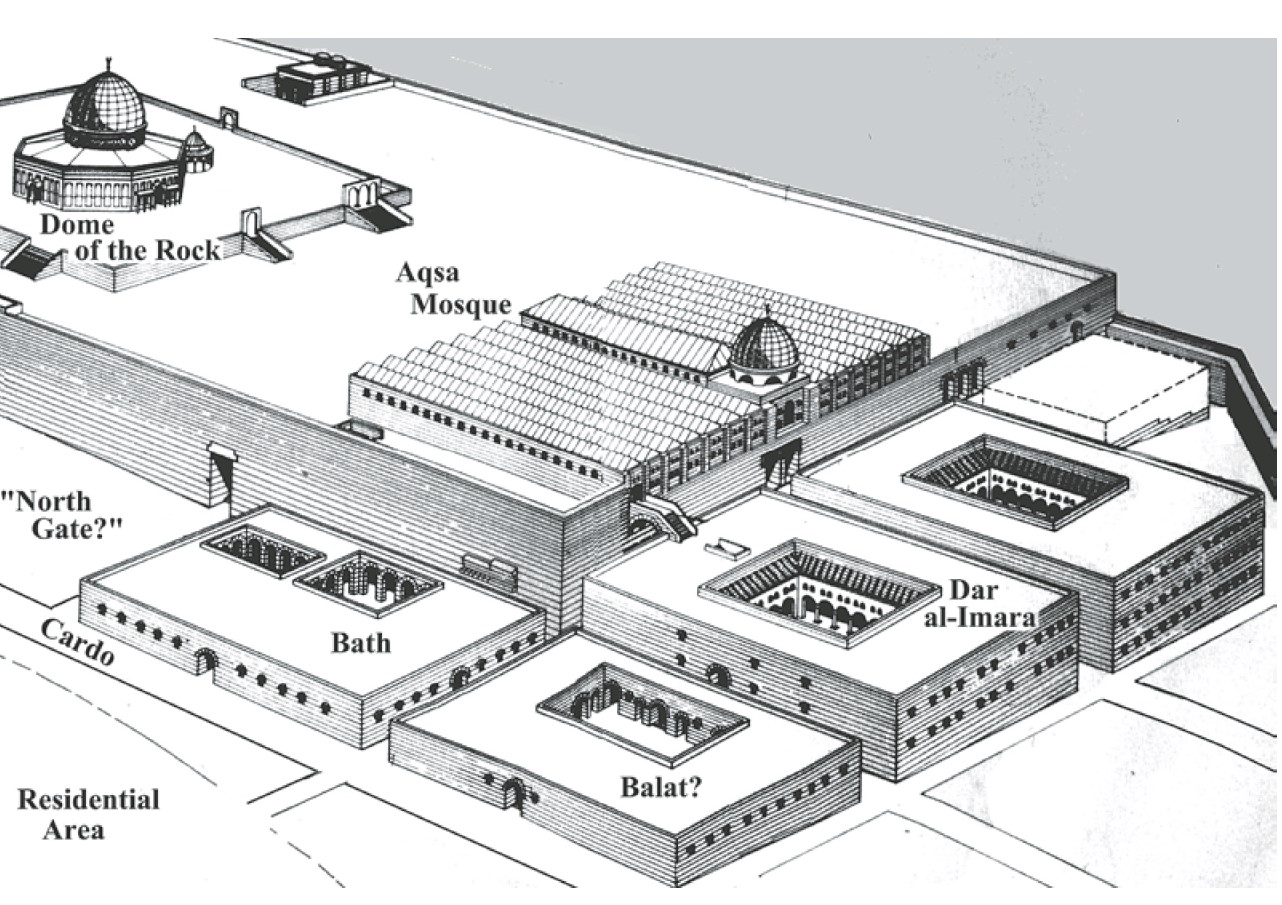

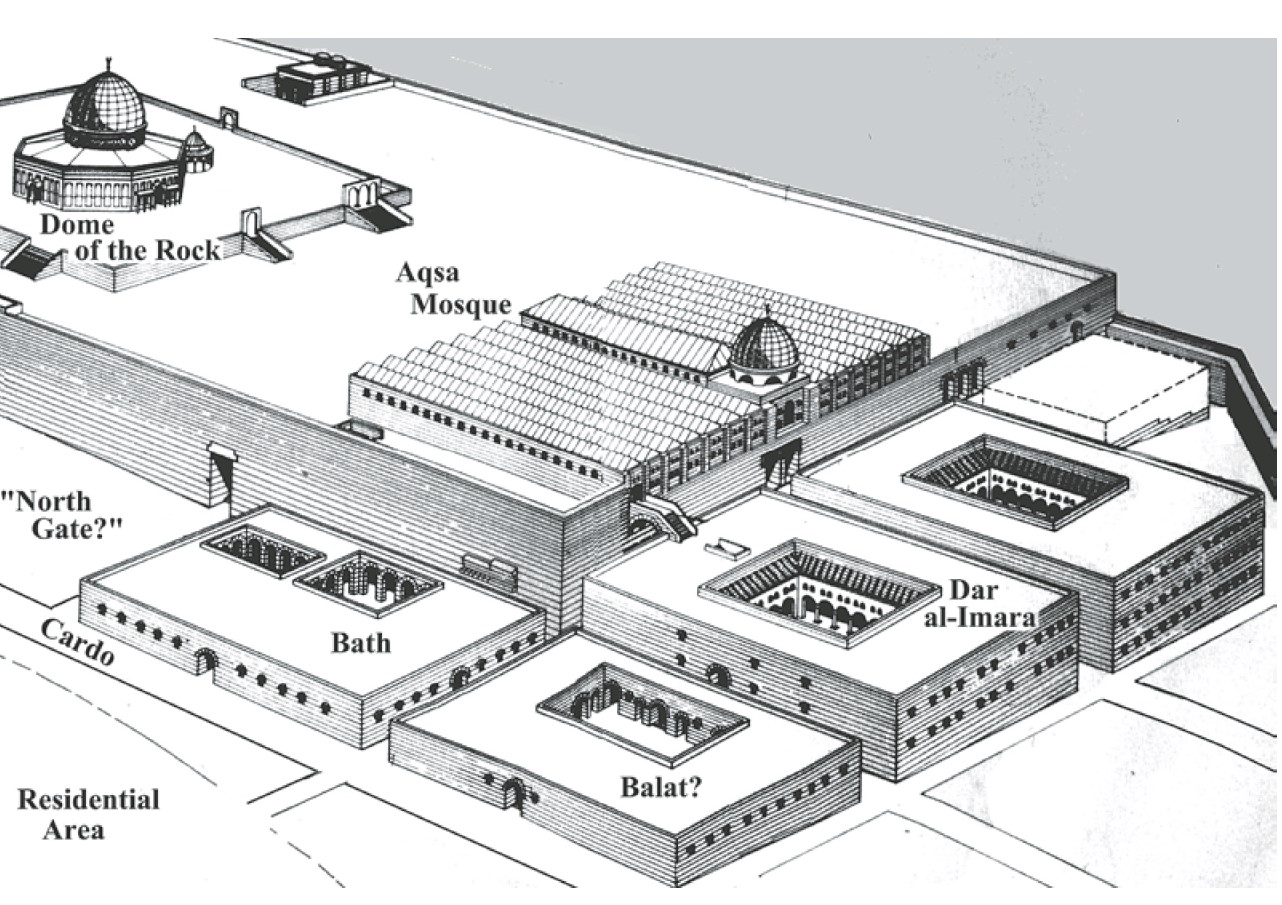

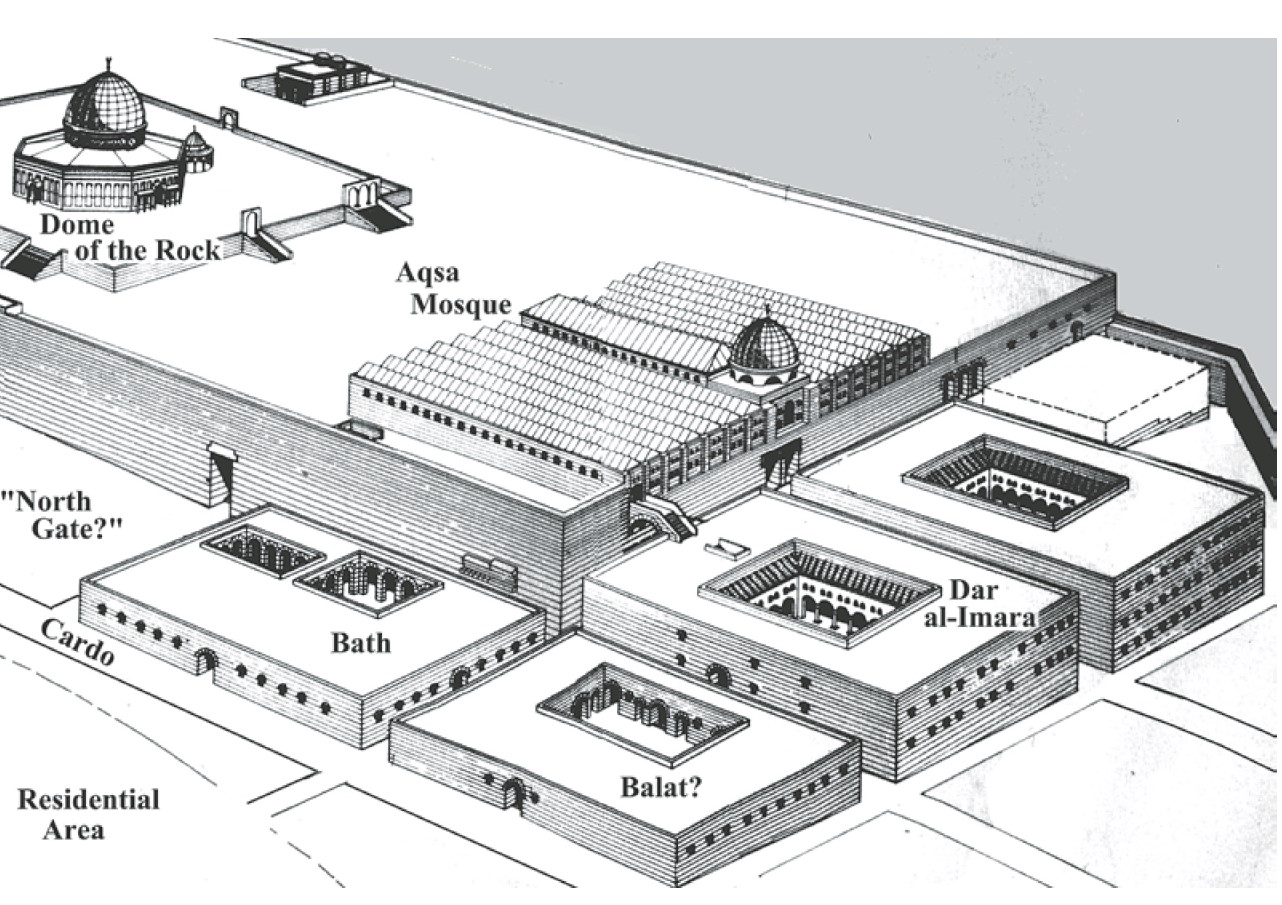

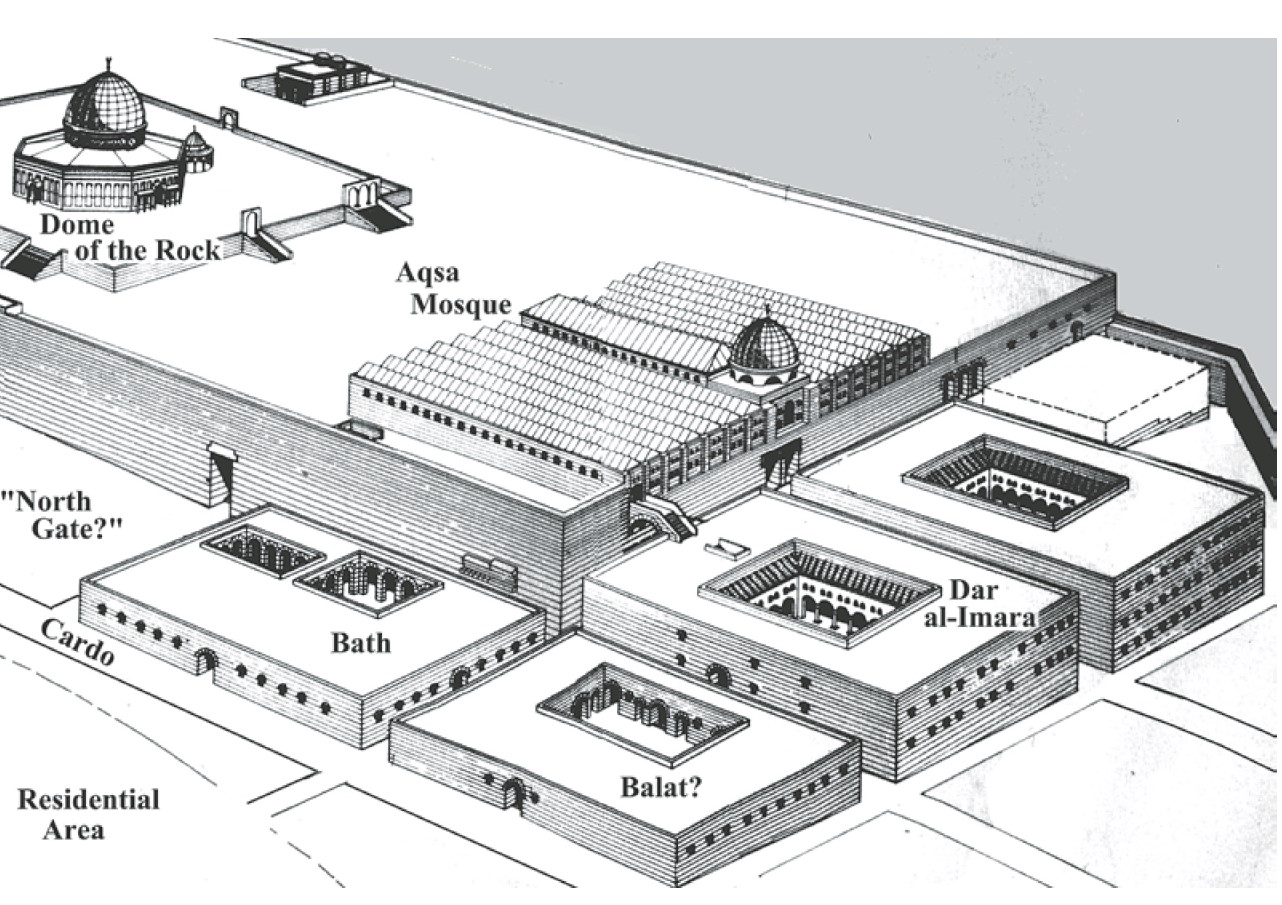

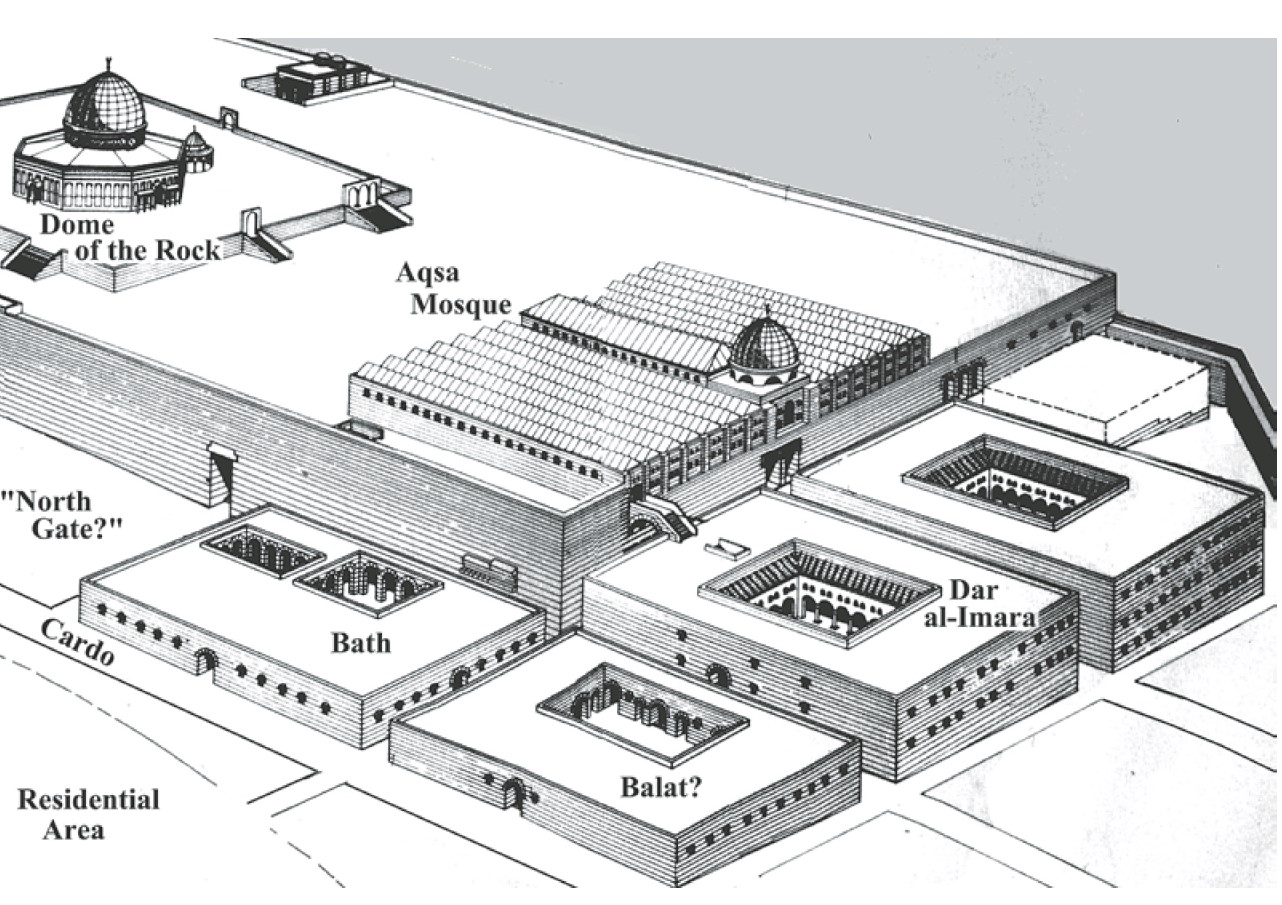

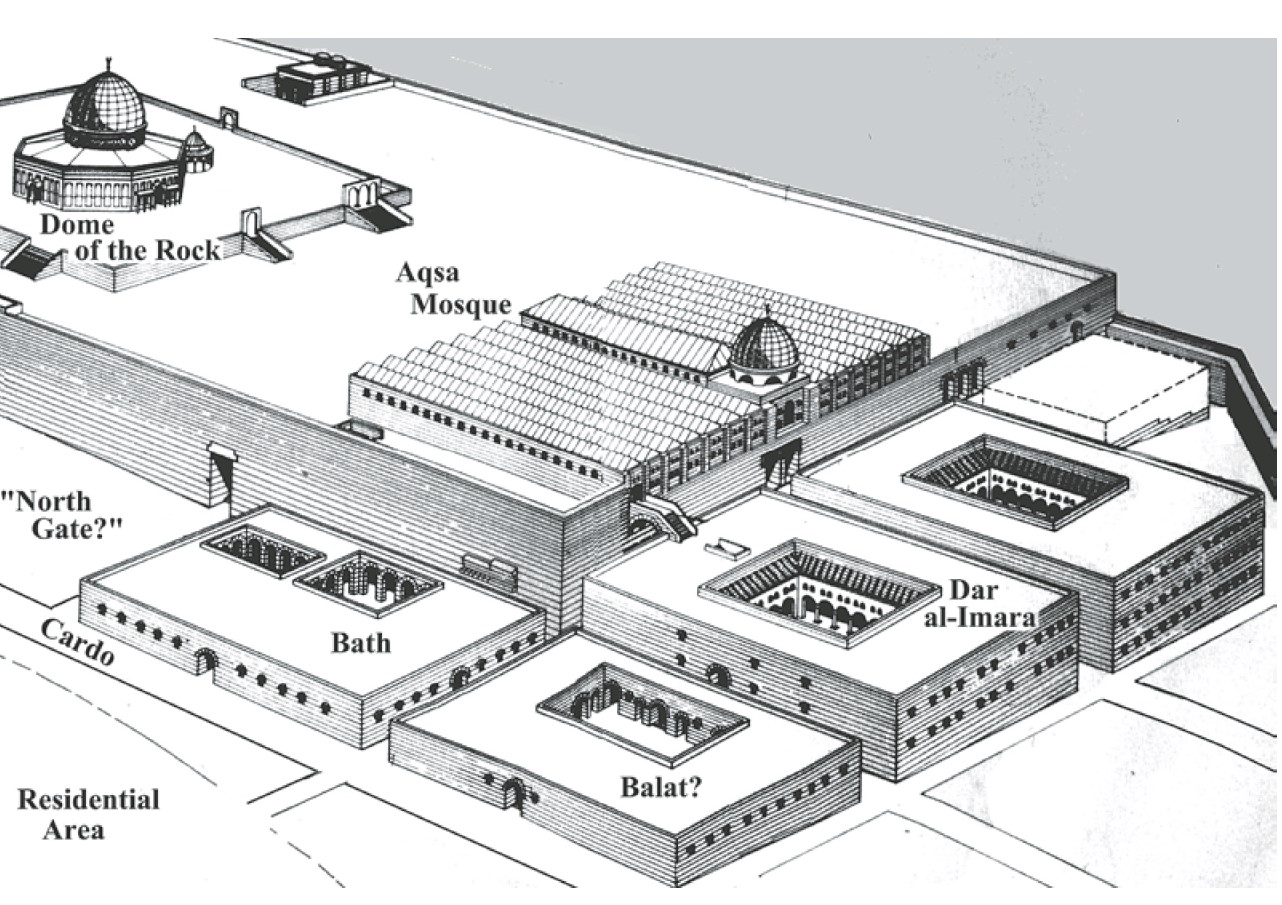

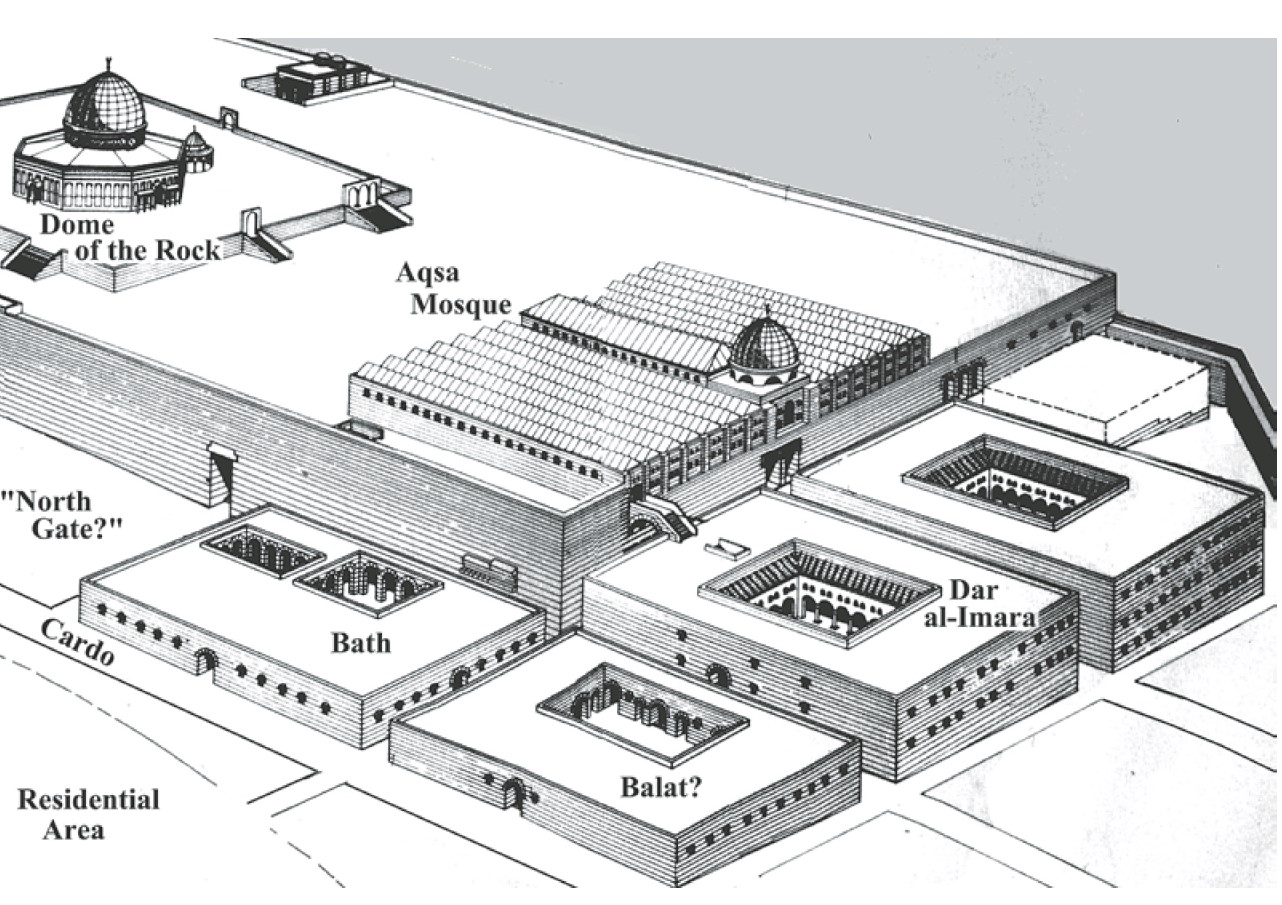

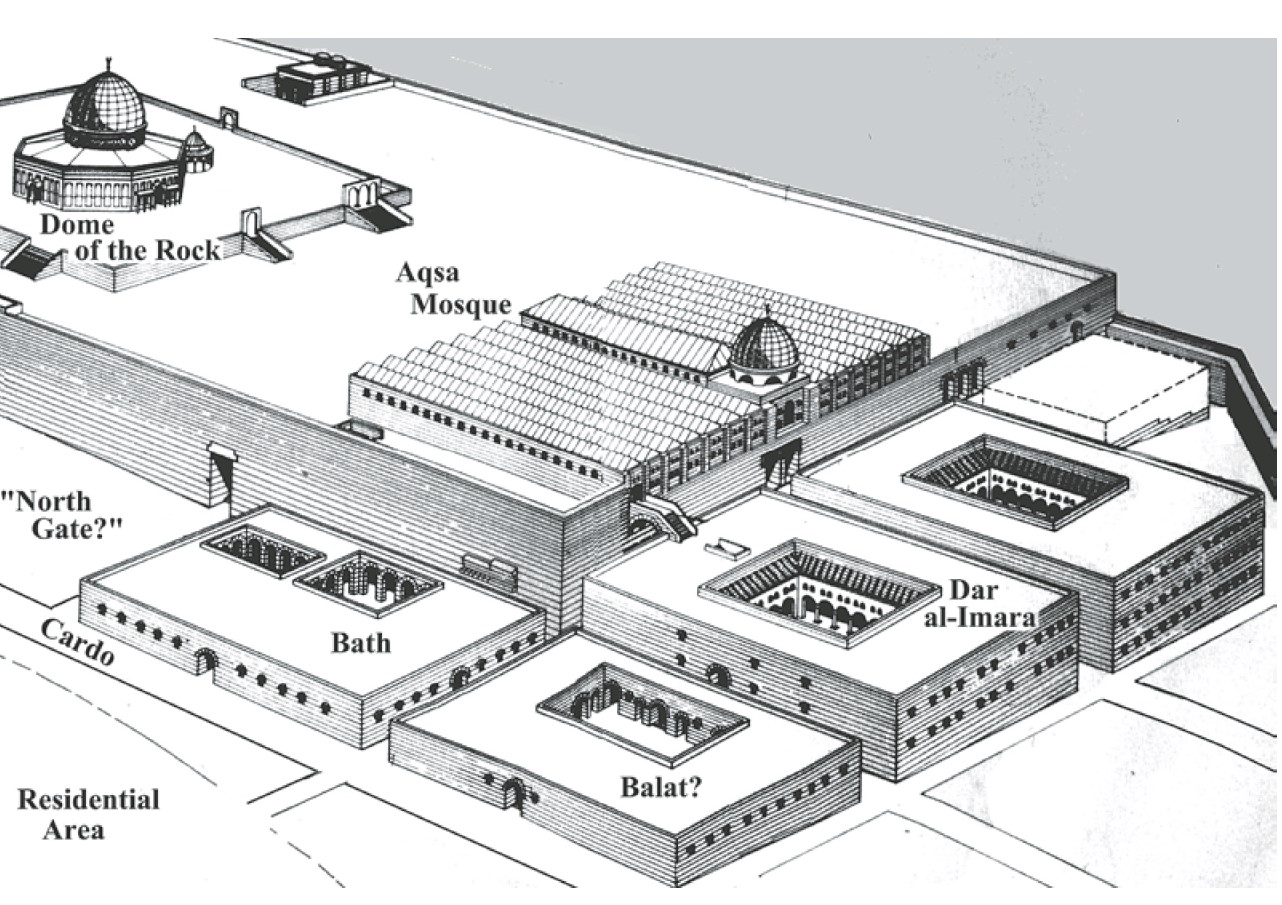

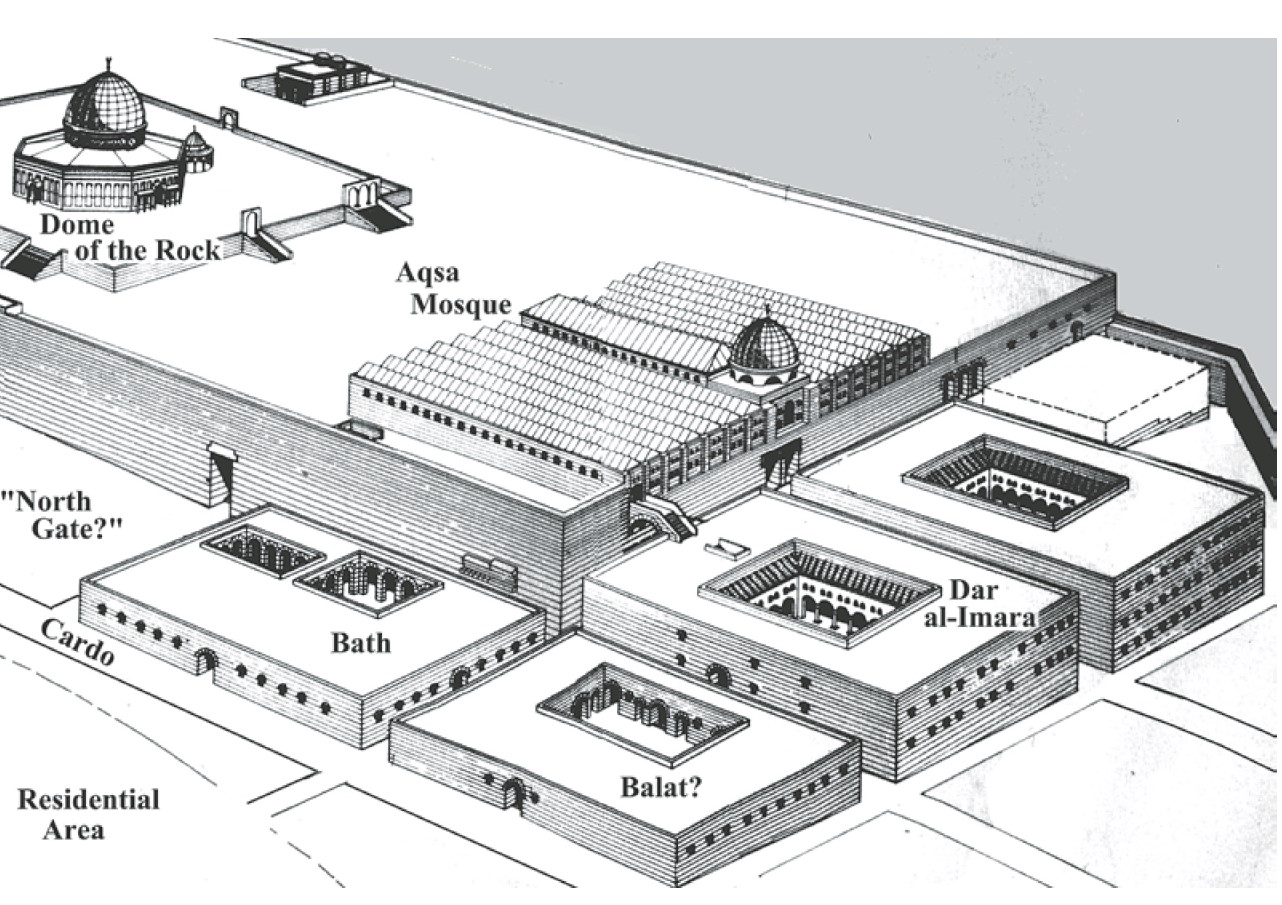

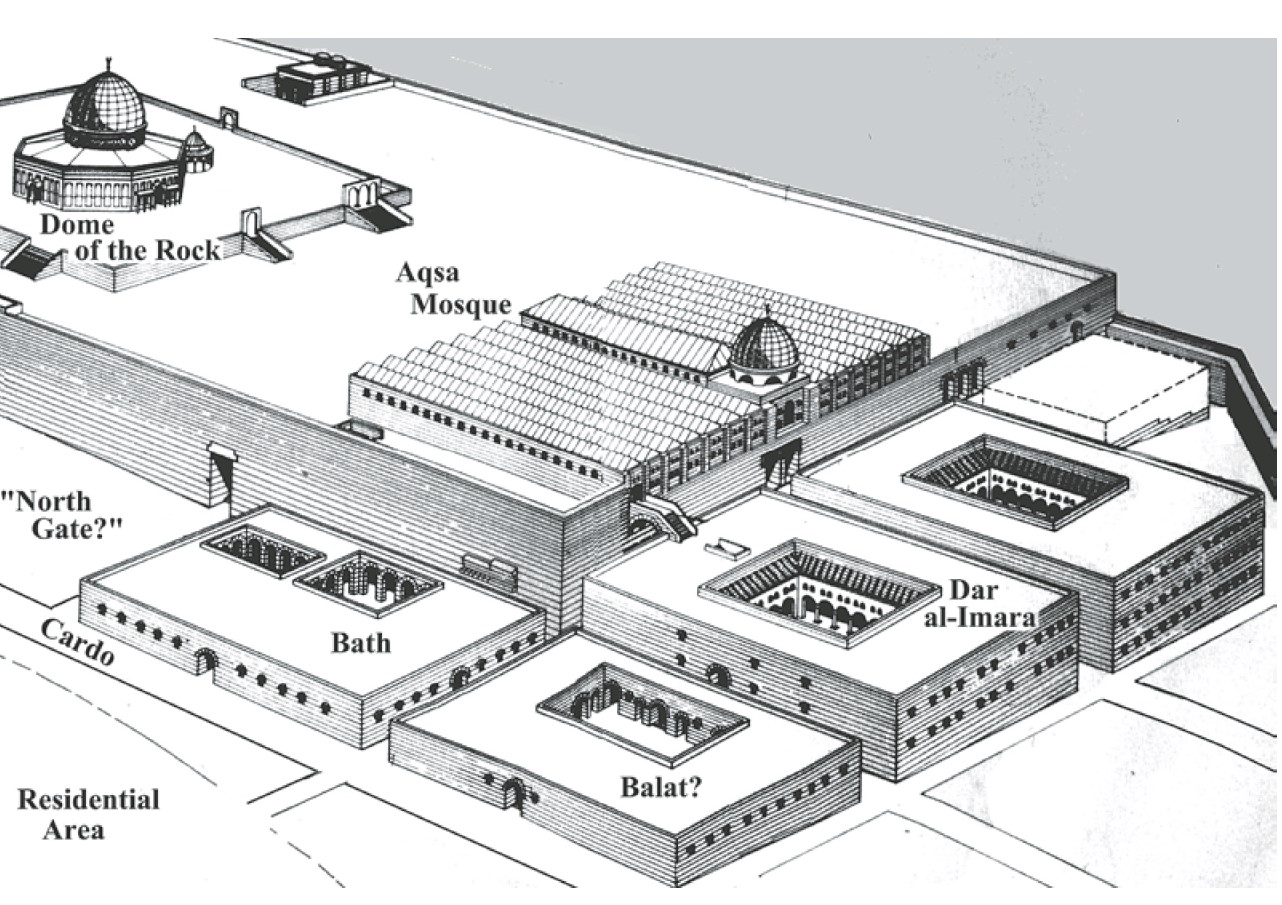

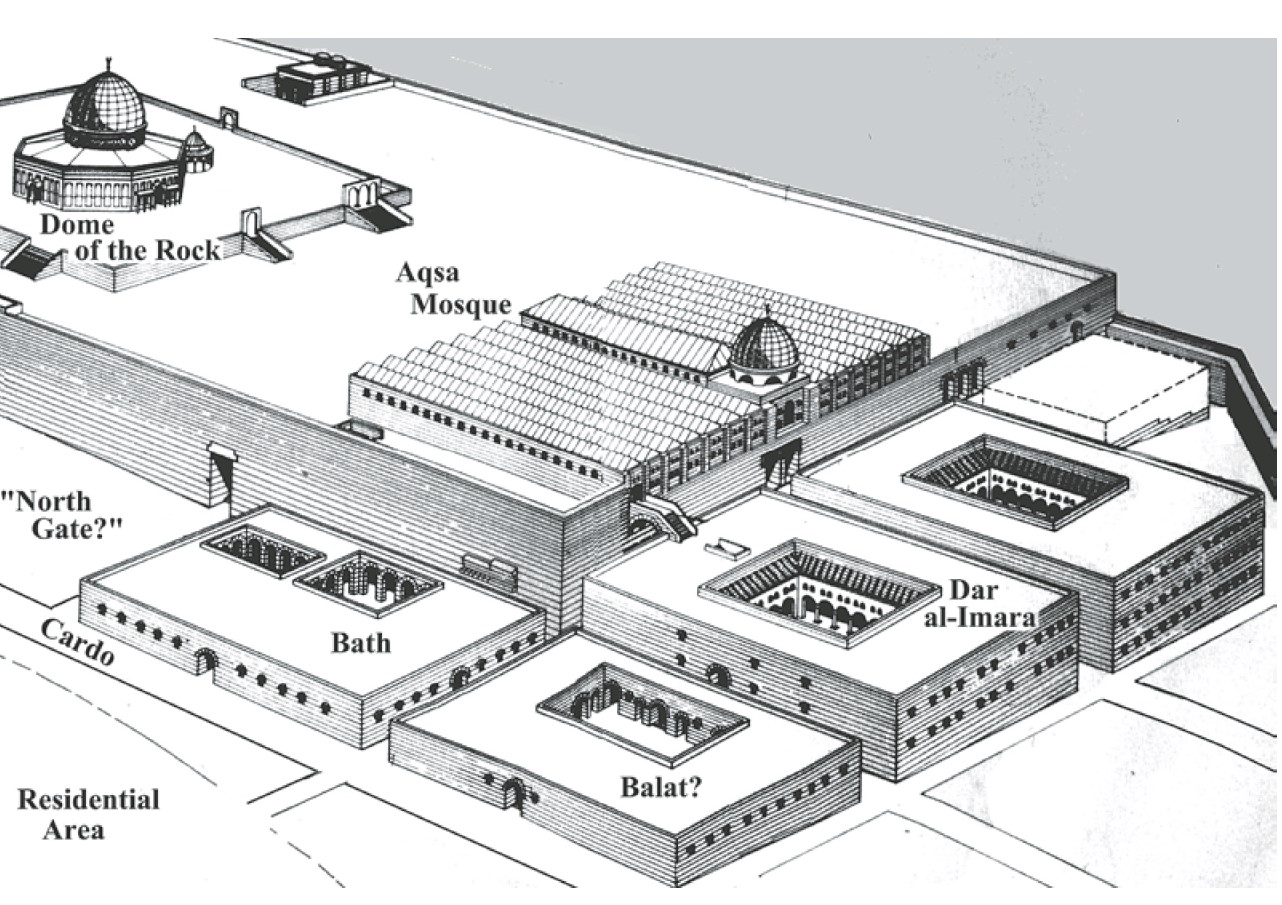

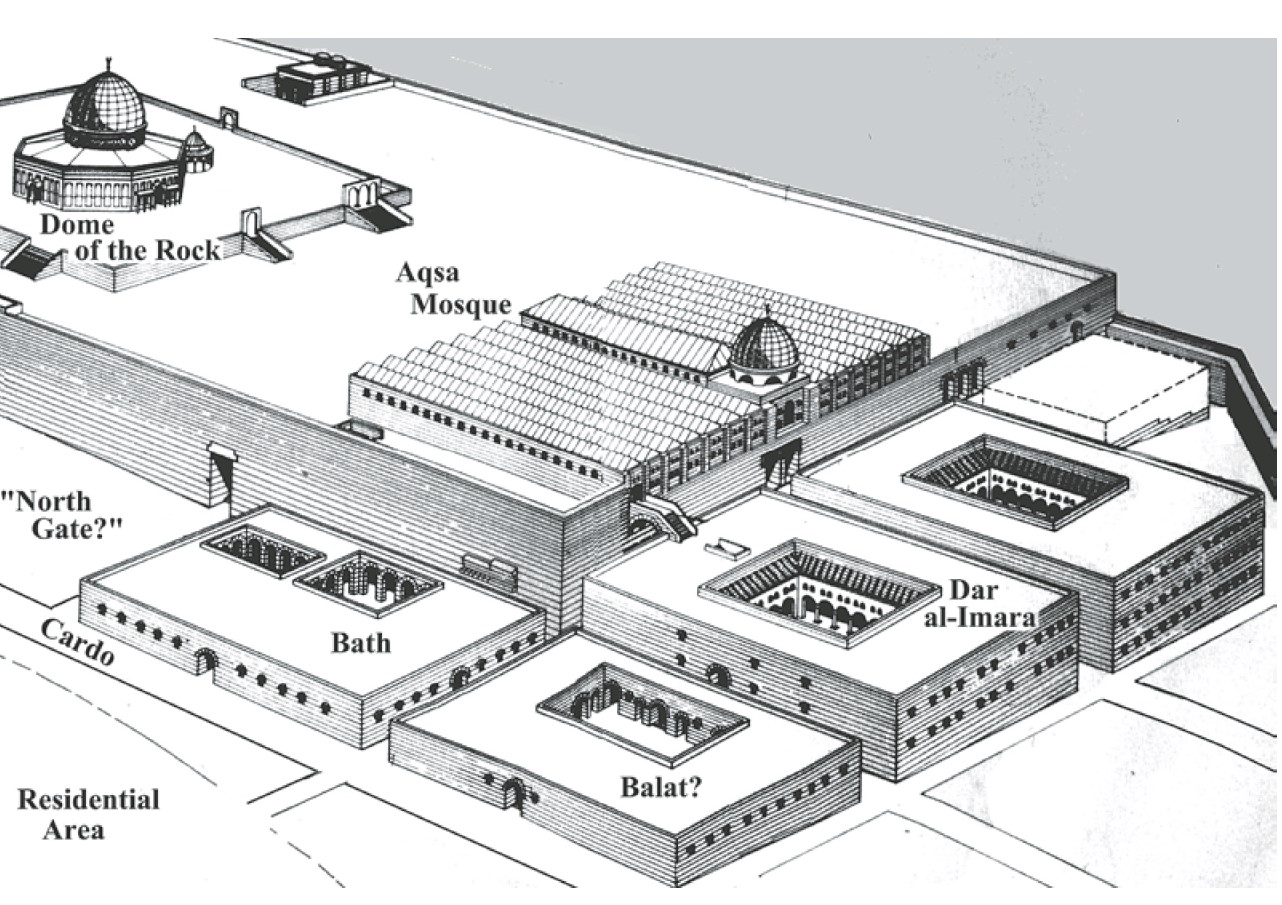

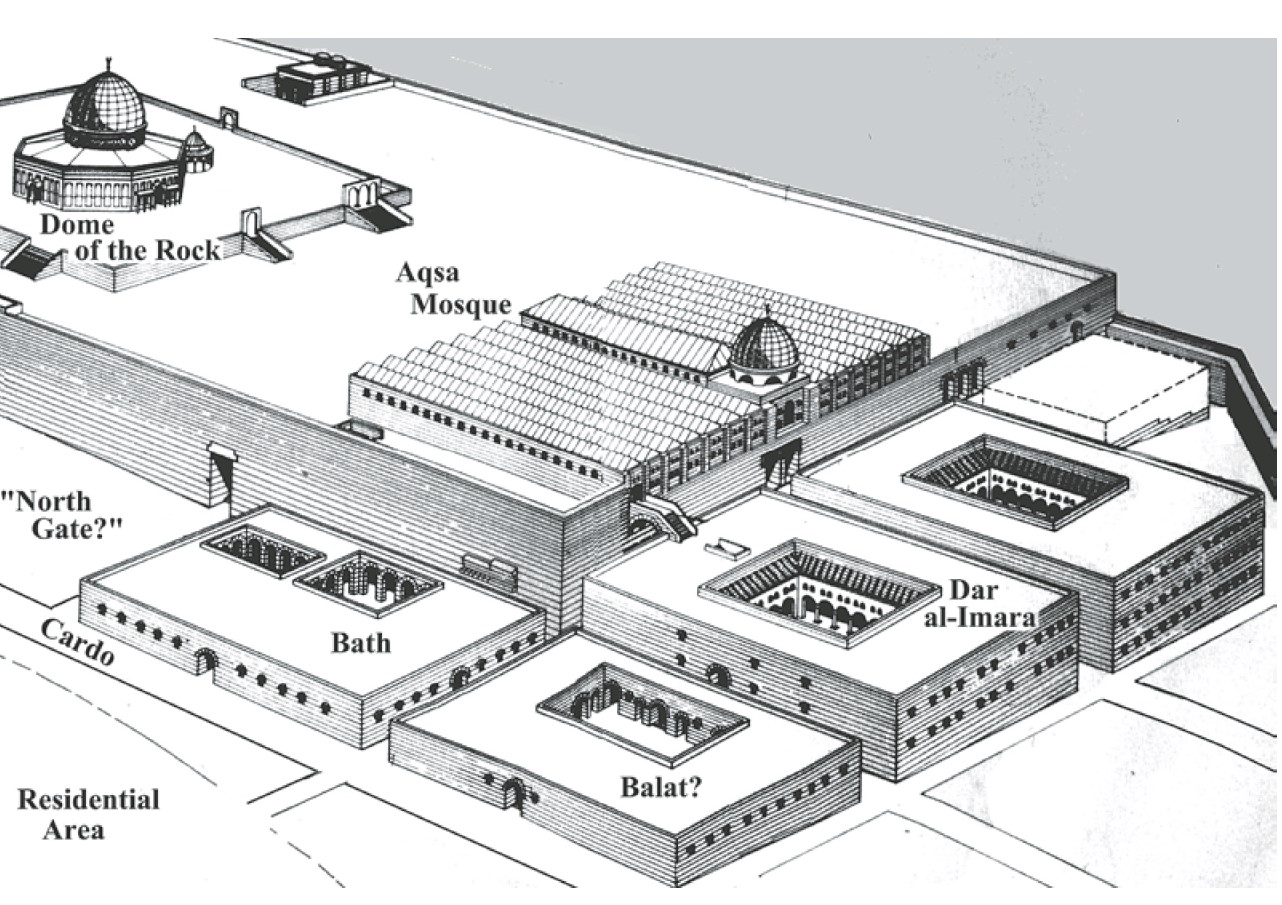

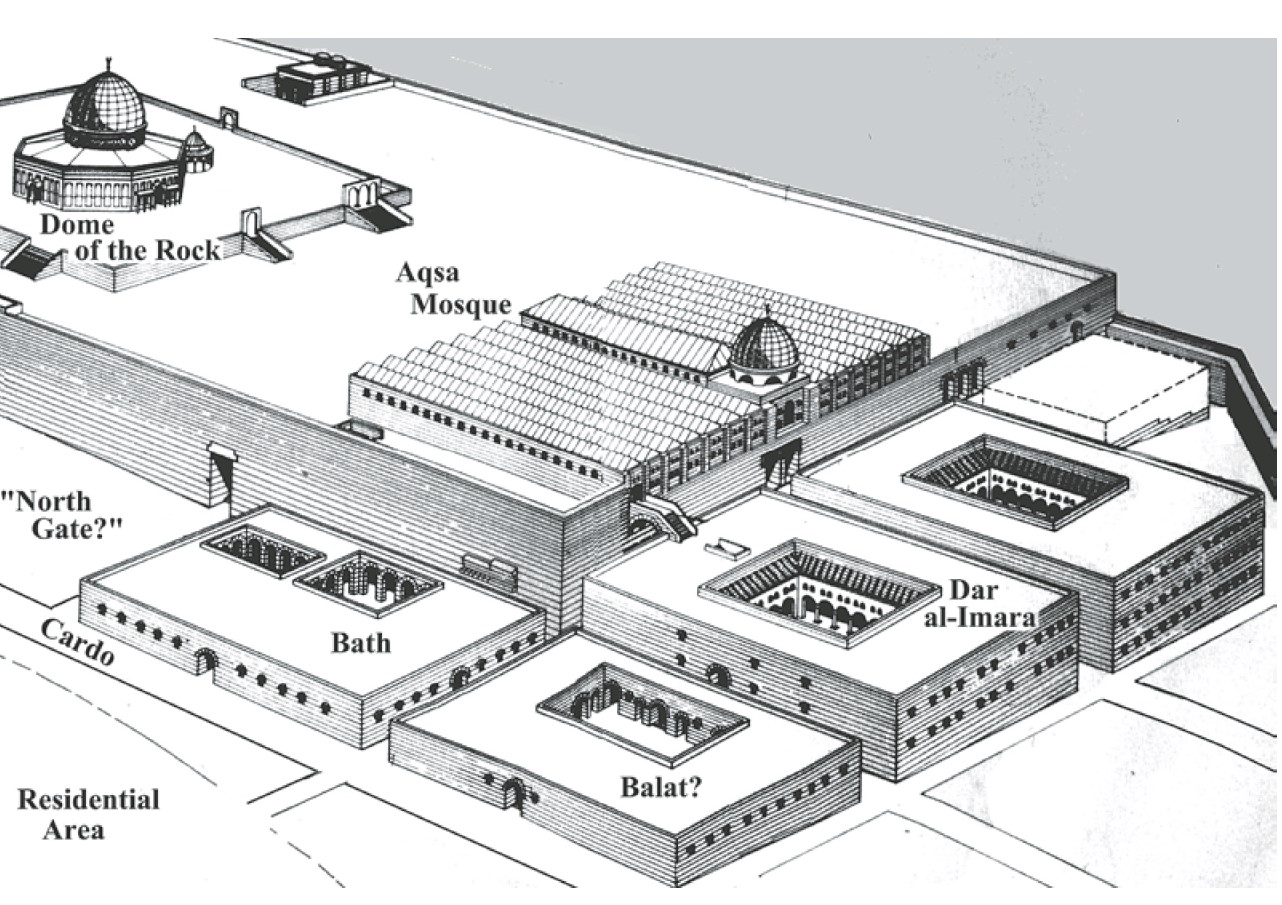

- Fig. 1.11 Plan of early

Islamic Jerusalem from Whitcomb (2016)

Figure 1.11

Figure 1.11

Plan of early Islamic Jerusalem

(after Whitcomb, “Jerusalem and the Beginnings of the Islamic City”)

Whitcomb (2016)

- Aerial photo of Umayyad structures

adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) during excavations from Yadin et al (1976)

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavations

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavations

Yadin et al (1976) - Umayyad structures adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif in Google Earth

- Umayyad structures adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif on govmap.gov.il

- Aerial photo of Umayyad

structures adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) during excavations from Yadin et al (1976)

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavations

Air view of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount, during excavations

Yadin et al (1976)

- Plan of Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount)

from Yadin et al (1976)

Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount)

Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount)

Yadin et al (1976)

- Plan of Haram esh-Sharif

(aka Temple Mount) from Yadin et al (1976)

Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount)

Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount)

Yadin et al (1976)

- Plan of Umayyad structures

adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) from Yadin et al (1976)

Plan of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Plan of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Yadin et al (1976) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Building 2

from Prag (2000)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of Building 2 in Jerusalem (after Mazar and Ben-Dov 1971), with the areas excavated in 1962–63 by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and the Joint Expedition superimposed.

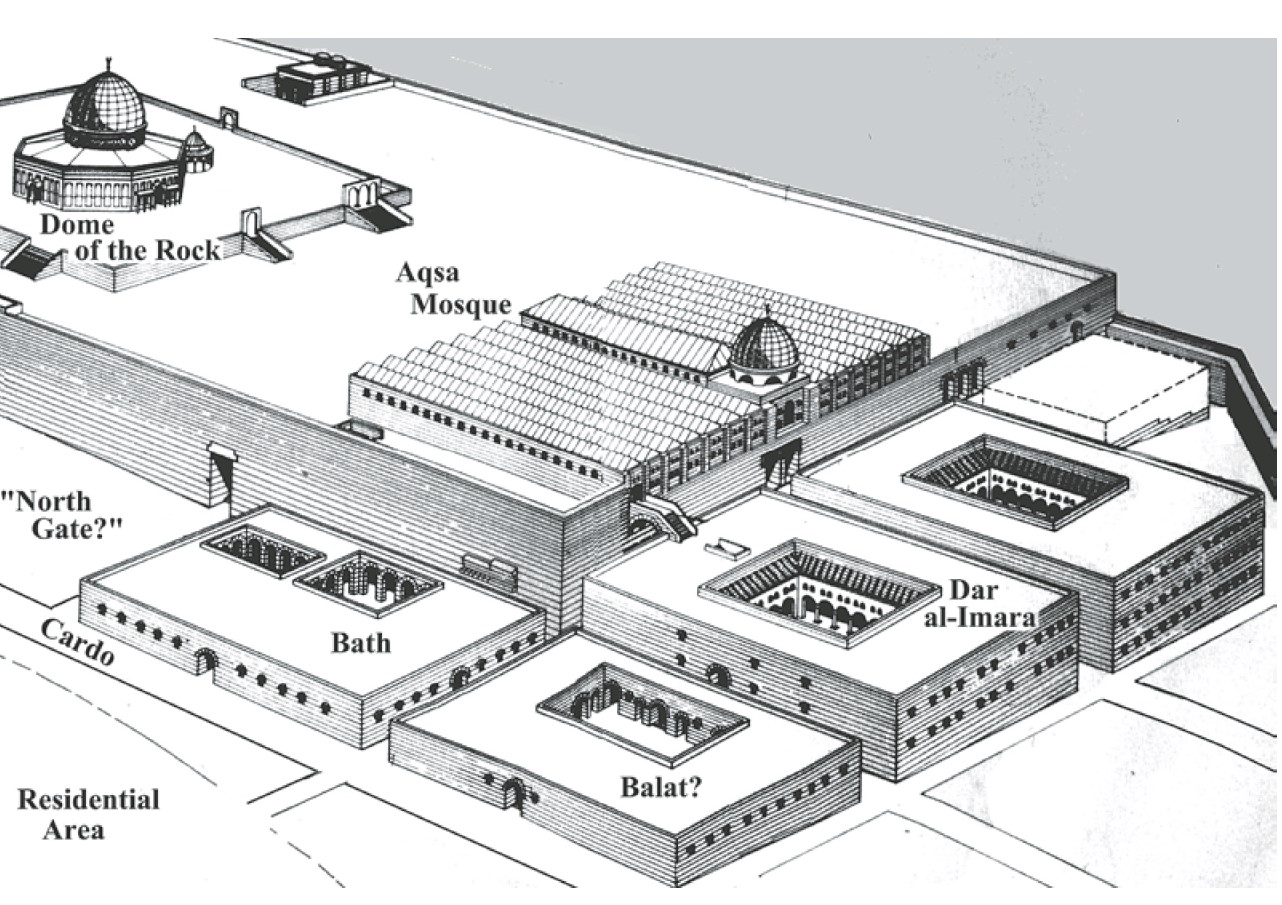

Prag (2000) - Fig. 9 - Reconstruction of

area south of Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) in the Umayyad period from Whitcomb in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Reconstruction of Haram and surrounding buildings (after Bahat 1989: 82-83).

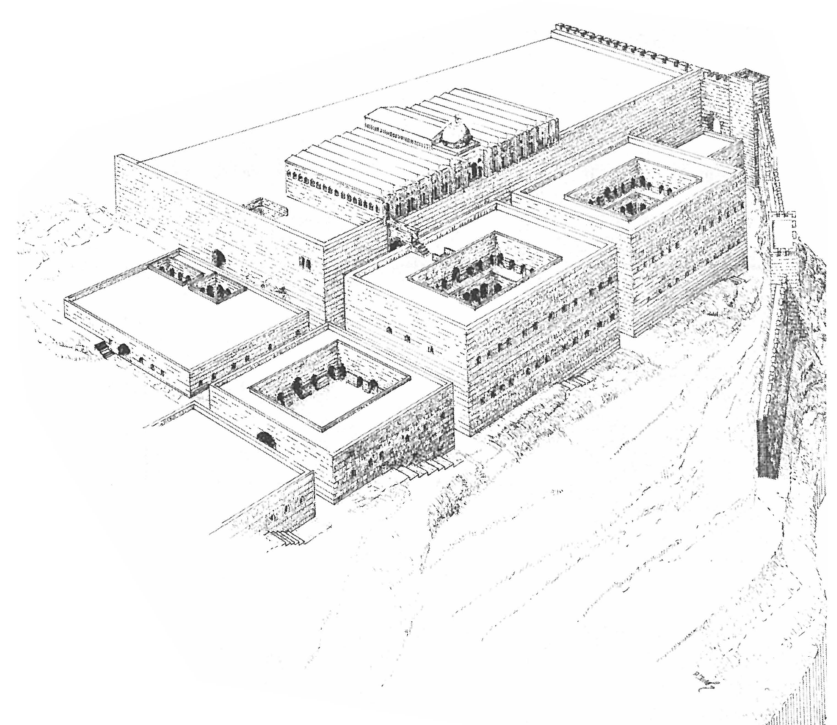

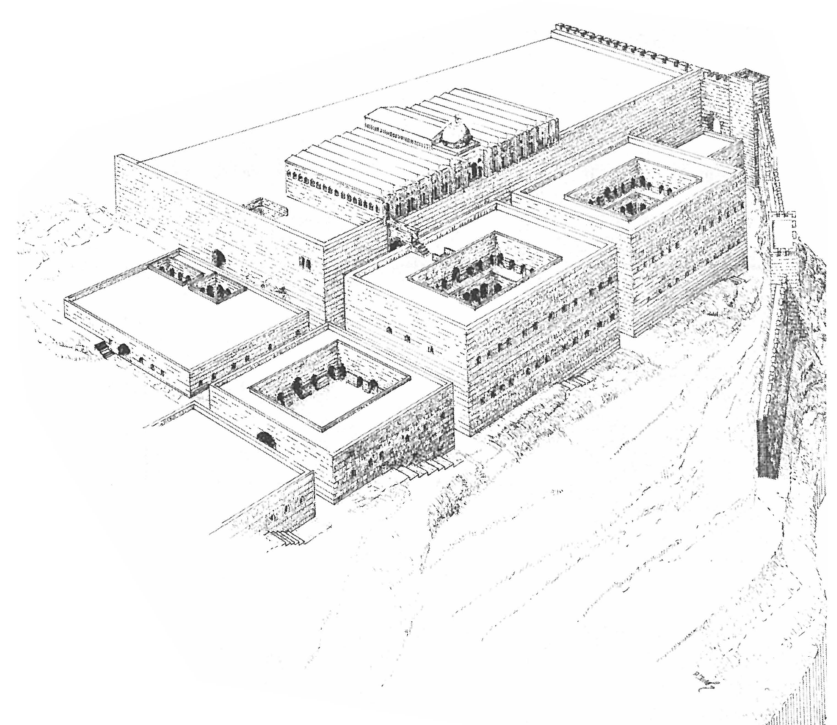

Whitcomb in Galor and Avni (2011) - Isometric reconstruction of

Umayyad structures adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) from Yadin et al (1976)

Isometric reconstruction of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Isometric reconstruction of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Yadin et al (1976) - Fig. 2 Reconstruction of

Umayyad Structures from Lassner (2017)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Reconstruction of the Administrative Center

(M. Ben-Dov)

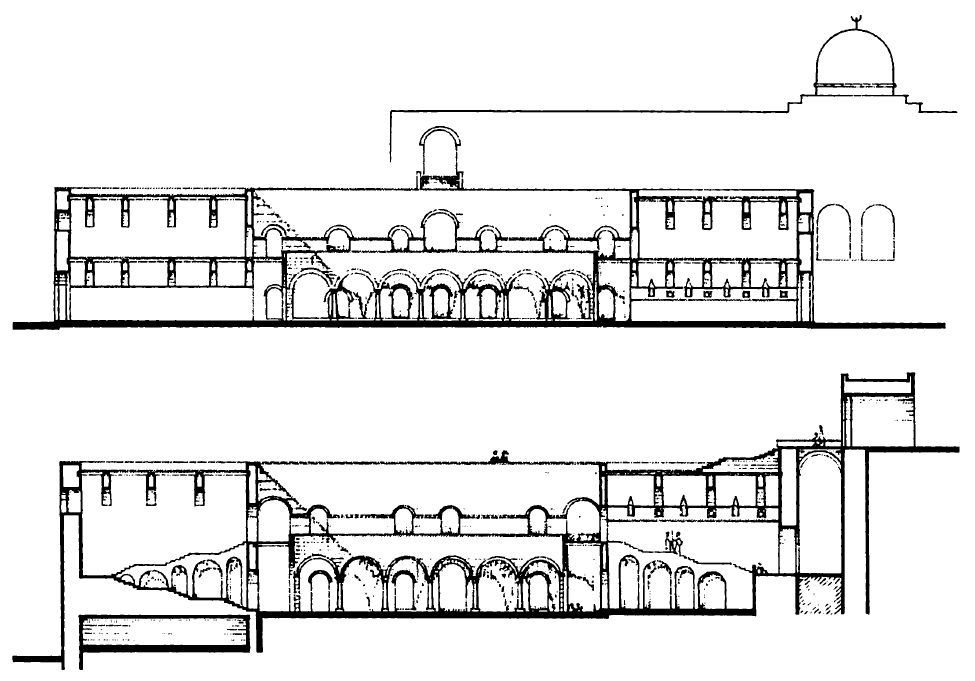

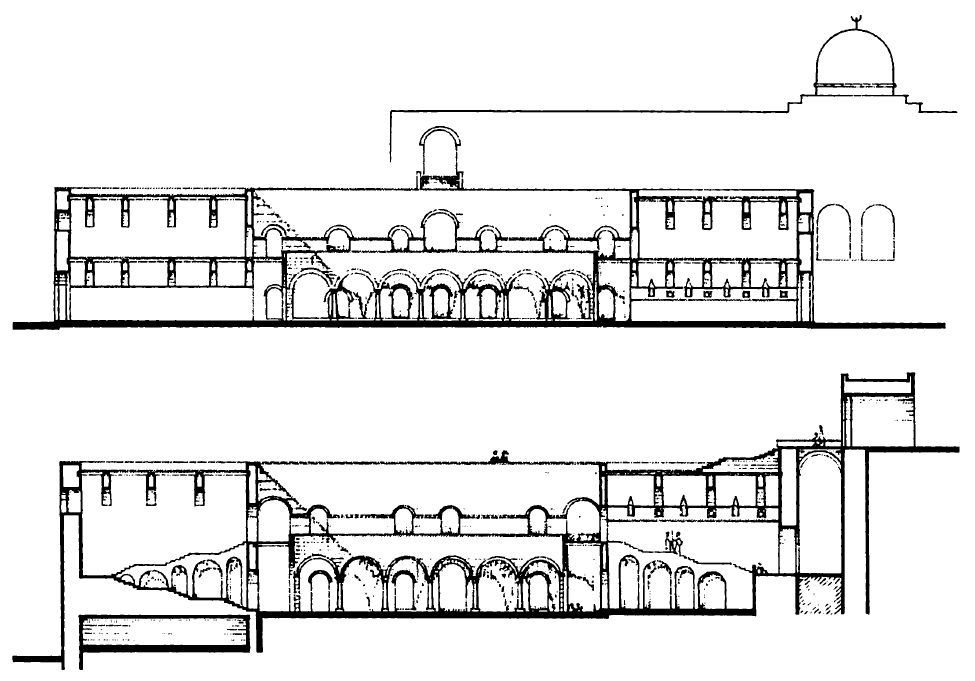

Lassner (2017) - Fig. 3 Cross-section of the

Umayyad Palace from Lassner (2017)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Cross-section of the Umayyad Palace

(M. Ben-Dov)

Lassner (2017)

- Plan of Umayyad structures

adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) from Yadin et al (1976)

Plan of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Plan of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Yadin et al (1976) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Building 2

from Prag (2000)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of Building 2 in Jerusalem (after Mazar and Ben-Dov 1971), with the areas excavated in 1962–63 by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and the Joint Expedition superimposed.

Prag (2000) - Fig. 9 - Reconstruction of

area south of Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) in the Umayyad period from Whitcomb in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Reconstruction of Haram and surrounding buildings (after Bahat 1989: 82-83).

Whitcomb in Galor and Avni (2011) - Isometric reconstruction of

Umayyad structures adjacent to Haram esh-Sharif (Temple Mount) from Yadin et al (1976)

Isometric reconstruction of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Isometric reconstruction of Omayyad structures adjacent to Temple Mount

Yadin et al (1976)

- Reconstruction of Al Aqsa Mosque

in the 8th century CE from Yadin et al (1976)

Reconstruction of original el-Aqsa mosque, 8th century C.E.

Reconstruction of original el-Aqsa mosque, 8th century C.E.

Yadin et al (1976)

- Reconstruction of Al Aqsa

Mosque in the 8th century CE from Yadin et al (1976)

Reconstruction of original el-Aqsa mosque, 8th century C.E.

Reconstruction of original el-Aqsa mosque, 8th century C.E.

Yadin et al (1976)

- Fig. 7 Reconstruction of the

Dome of the Rock from Lassner (2017)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

The Dome of the Rock

(K. A. C. Creswell)

Lassner (2017)

- from Mazar (1969)

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Section E 6, cutting through the street some 5 m east of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount (lowest height 715 m above sea-level).

JW: 5 m west of the SW corner of Temple Mount and not the same as Warren's shaft in the City of David next to the Gihon spring

Mazar (1969)

- Plate II/5 Stratum A1 of

the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount - paved street and Umayyad Building - from Mazar (1969)

Plate II/5

Plate II/5

The paved street and the all of the Omayyad building (stratum A 1)

Mazar (1969) - Plate II/6 Stratum A1 of

the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount - foundation of the pavement to the left of the gate of the Umayyad Building - from Mazar (1969)

Plate II/6

Plate II/6

The foundation of the pavement to the left of the gate of the Omayyad building (stratum A 1)

Mazar (1969) - Plate II/7 Stratum A1 of

the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount - pavement and the plastered water channel - from Mazar (1969)

Plate II/7

Plate II/7

The pavement and the plastered water channel (stratum A 1)

Mazar (1969)

The AD 749 earthquake that shook the entire southern Levant region also struck Jerusalem, as various historical sources describe.1 The seismological data suggests the damage suffered in Jerusalem was disastrous and resulted in grave architectural damage.2 The written, mainly Muslim,3 accounts however focus their description regarding the earthquake and its impact on the area around the al-Haram al-Sharif, mentioning mostly architectural damage to the religious buildings.4 Several narratives developed around the effects of the earthquake in Jerusalem, which were then carried over into later chronicles—for instance, the report of injuries to the descendants of Shadad al Aws, one of the Prophet's companions, and the destruction of their house.5

However, apart from the al-Haram al-Sharif area, little is known about the fate of other parts of Jerusalem since the historical sources seem to omit descriptions of domestic quarters damaged by the earthquake.

The recent DEI6 excavations on the southern slope of Mount Zion brought new archaeological evidence to light, which will be presented here. It shows that other parts of Jerusalem, especially the south-western hill, were also strongly affected by the earthquake. There, it becomes evident that urban life in this part of the city after the so-called "Muslim conquest" in AD 638 continued without any archaeologically noticeable changes for the following century7—until a catastrophic event hit the quarter. This destruction can be connected to the earthquake in AD 749. Following that, the urban character on the south-western hill changed drastically8.

Moreover, in light of this new archaeological evidence of the DEI excavations, this study aims to investigate and reassess further sites regarding potential impacts that the disastrous seismic tremor has left in Jerusalem. Several examples are assessed in the following: the area around the al-Haram al-Sharif, the new excavations of the DEI, the Armenian Garden, as well as the excavations in the modern-day Jewish Quarter and the case of the city walls (Fig. 10.1).

1. Theophanes (AD 758–817), as the main source on the earthquake, does

not report any damages specifically in Jerusalem in either of the

earthquakes he mentioned. However, he described that some cities were

completely or partially destroyed (Theophanes, Chronicle 423, p. 112;

426, p. 115). A similar report was written by Severus Ibn al-Muqaffa

(died in AD 987), who stated that between the years 744–768 a great

earthquake shook the entire East “from the city of Gaza to the furthest

extremity of Persia,” destroying many cities (Ibn al-Muqaffa, pp.

139–40). Further, Ibn Taghribirdi (c. AD 1409/1410–1470) and

al-Dhahabi (1274–1348) also reported heavy damage in Jerusalem as a

result of that earthquake (Ibn Taghribirdi, an-Nujūm az-zāhira fī

mulūk Miṣr wa-l-Qāhira, p. 311; al-Dhahabi, Tārīkh al-Islām

wa-ṭabaqāt al-mashāhīr, 121–40, pp. 29–30).

2. Marco et al. 2003, 667; table 2.

3. No damage is mentioned in Jerusalem by Samaritan sources (Karcz 2004,

784). The Cairo Geniza text, as a Jewish source, mentions a

commemoration list thought to commemorate the earthquake that struck

Jerusalem (Karcz 2004, 785). For a more detailed discussion of the

historical sources regarding the earthquake see Karcz 2004, 78–87;

Tsafrir and Foerster 1992.

4. See below. It has to be considered that these sources are based on

compilations from the eleventh century CE and therefore should not be

regarded as contemporary reports (Karcz 2004, 783).

5. Al-Dhahabi 121–40, pp. 29–30; Ibn Taghribirdi repeats the narrative

about the death of the descendants of Shadad al-Aws (an-Nujūm

az-zāhira, p. 311).

6. German: Deutsches Evangelisches Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des

Heiligen Landes (English: German Protestant Institute of Archaeology

of the Holy Land).

7. See Namdar et al. 2024.

8. Zimni 2023, 388–90.

The earthquake damage in and around the area of the al-Haram al-Sharif is well documented by historical sources and by archaeological evidence. The area (Fig. 10.1 no. 1) experienced massive remodelling at the beginning of the Umayyad period, when the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock, as well as Umayyad buildings (Fig. 10.1 no. 2) located south of the religious edifices were built.9

Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence that can be gathered from the Holy Sanctuaries — the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock — is limited.9 Therefore, the study of the written accounts is an essential source for investigating the extent of the architectural damage in this area. For instance, it is described by al-Wasiti that the al-Aqsa Mosque suffered severe damage from an earthquake in the middle of the eighth century AD.10 He tells that in the days of the reign of Caliph al-Mansur (AD 754–775), the eastern and western portions of the mosque fell due to an earthquake in the year AH 130.11 As a consequence, Caliph al-Mansur ordered the mosque’s restoration. Since no money was available for this, it is also known from the description of al-Wasiti, that the gold and silver plates decorating the mosque’s gates were to be stripped off, and dinars and dirham were to be coined from them.12 Moreover, he also stated that shortly afterwards another earthquake hit the mosque, which was then restored by the caliph’s successor, Caliph al-Mahdi.13

Furthermore, in the tenth century AD the writer al-Muqadassi wrote about the earthquake damage in the mosque: he described that the earthquake destroyed most of the building, except for the corner around the mihrab.14

South of the Mosque complex, several buildings were constructed during the Umayyad period. Those are interpreted as administrative centres,15 whereas one of these buildings (‘Building ii’) stands out as a possible ‘Umayyad palace’.16 According to the excavators, this complex shows clear archaeological evidence of damage by the 749 earthquake. The damage is described as “cracked walls and warped foundations, fallen columns and sunken floors.”17 The archaeological material also provides evidence for the dating of this destruction: a sewage channel within one of the buildings was blocked shortly before the building went out of use. The material found there was interpreted as Khirbet Mafjar Ware, dating to the first half of the eighth century AD.18

9. Only reports of earlier investigations are available

(Hamilton 1949; Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1999).

10. It needs to be kept in mind that the dating of the

described earthquake damage cannot be clarified with

certainty.

11. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92;

referring to AD 747/748 according to Karcz 2004, 780.

12. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92.

Here, it is debatable whether al-Wasiti refers only to the

Mosque itself or the entire Haram al-Sharif area (Elad

1995, n. 77).

13. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 256, p. 92.

For a suggestion of the archaeological layout of these

rebuilding measures see Küchler 2007, 226–34. G. Le

Strange assumes the year AD 770–771 for the visit of

Caliph al-Mansur, whereas others suggest that this visit

already took place in AD 758 (Elad 1995, 40; Küchler

2007, 228).

14. al-Muqadassi, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the

Regions, trans. by B. Collins, p. 276.

15. Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8.

16. Ben-Dov 1985; Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8–11.

17. Ben-Dov 1985, 321.

18. Ben-Dov 1985, 2–20; however, this chronology by the

early excavators was doubted by J. Magness who

redates the construction date of these buildings as well

as doubting their damage from the 749 earthquake due

to ceramic evidence supporting the buildings’ existence

throughout the Abbasid period (Magness 2010, 153).

However, in the author’s opinion, the damage described

by the excavators does suggest that a destructive event,

such as an earthquake, occurred in these buildings,

resulting in the described architectural remains.

The ‘Givʿati parking lot’ excavation site is located further south of the previously discussed Umayyad administrative buildings in the Ophel area (Fig. 10.1 no. 3). This is, except for the Haram al-Sharif area, the only place in Jerusalem which was drastically reconstructed at the beginning of the Umayyad period.19 This area was turned from what had been a prosperous Byzantine domestic quarter into an industrial quarter — mainly through the construction of a lime-kiln.20 This layout changed again “at some time during the eighth century CE” when, with the beginning of the Abbasid period, the lime-kiln was partly dismantled and covered, but only a few installations, wall stubs as well as pits were scattered throughout the area.21

In conclusion, one can say that at the site of the ‘Givʿati parking lot’ excavations noticeable changes occurred during the eighth century AD, but the causes cannot be determined with certainty. However, no archaeological traces of earthquake damage were observed at the site.22

19 Tchekhanovets 2018.

20 Ben-Ami 2020, 2–4.

21 Ben-Ami 2020, 283, 287 – pers. comm. Tchekhanovets.

22 Ben-Ami 2020, 283 – pers. comm. Tchekhanovets.

The excavation areas of the DEI project23 (Fig. 10.1 no. 4) are located on the southern slope of Mount Zion. The site to be discussed in the following — area 1 (Fig. 10.2) — is located within the boundaries of the Anglican-Prussian cemetery. There, parts of the fortification walls as well as inner-city buildings from the Late Hellenistic period until the Middle Ages were uncovered.24 The original urban layout of the domestic quarter can be dated back to the Early Roman period, but underwent significant remodelling and reuse during the Byzantine and Umayyad periods. These include the Byzantine city wall with an inserted city gate and eleven rooms. Two of these — rooms A and B — are crucial for the investigation of the damage done by the AD 749 earthquake and will be discussed in more detail in the following. The other rooms were partly destroyed by later building activities, such as the construction of medieval terracing walls, extending across the entire site.

The Byzantine domestic quarter was built around the fifth/sixth century AD and was inhabited throughout the Umayyad period. The site's proximity to the large Hagia Sion church on the plateau of Mount Zion — which continued to be in use until the Crusader period — the discovery of a mould for a cross-shaped pendant, as well as the archaeozoological evidence, suggest Christian inhabitation even throughout the Umayyad period.25 Its occupation continued until a destructive event caused the end of the quarter's inhabitation, evidenced primarily by a destruction layer mainly recorded archaeologically in room B.

Following the violent end of the domestic quarter, a lime-kiln was built in the midst of the former rooms, even destroying a few of them. Thus ending the previous period of a prosperous domestic quarter and turning it into an industrial one. Since the lime-kiln was built in the middle of the former living rooms, it provides a terminus post quem for the inhabited rooms.

23 Directed by D. Vieweger, K. Soennecken and the author. The project

started in 2015 and is still being continued.

24 Zimni 2023; Vieweger and others 2020.

25 Namdar and others 2024; Zimni 2023, 388–93.

The earthquake's impact was mainly recorded in room B (Figs 10.3, 10.4). The rectangular room measures 5 × 6 m. A cistern below supplied its inhabitants with fresh water. It was likely fed by water collected from the roof, which was led by a pipe on the room's western side into a settling basin — from there into the cistern.

A destruction layer was found which filled the entire room (Fig. 10.5). It contained many larger stones which were previously used as building material. Remains of the former vaulting arch can be observed as well. Other building material, such as numerous roof tiles, remnants of wall plaster, a large number of tesserae, and several pieces of ceramic pipes, was also found in this destruction layer. Most of the archaeological material was found burnt — in addition, large chunks of charcoal were also excavated.

This destruction was found in situ and was not removed for later building activity as is the case in all the other rooms, but overbuilt by an early Islamic channel. It provided a unique opportunity to investigate the transitional period from a domestic quarter to an industrial one in the eighth century AD.

Various events may be considered to be responsible for this destruction: the Persian conquest in AD 614, the “Muslim conquest” in AD 638, and the AD 749 earthquake. A closer analysis of the finds from the destruction layer allows us to state that this destruction of the room had occurred not earlier than the Umayyad period. The pottery material, mainly fine ware, found within the contexts in question dates into the Umayyad period, but not later than that, indicating that the room was in use during that time.

Moreover, a C14 sample collected at the entrance to the cistern situated below the room also suggests continuous habitation during the early eighth century AD (Fig. 10.6).

Consequently, one can conclude that the destruction layer was caused by the AD 749 earthquake since the other possible options such as the Persian as well as the “Muslim conquest” for this destruction are dated in the seventh century AD only and therefore can be excluded. After that, the room's destruction layer was sealed by the building of a water channel on top of it. This might be connected to the lime-kiln mentioned above, which was built after the rooms were no longer inhabited.

Wall 10070, forming the western boundary of rooms A and B, provides further evidence of seismic activity. It does not run (anymore) in a straight line, but seems to be slightly warped and crooked (Fig. 10.7). Such a tilt is considered a characteristic sign of earthquake damage by S. Marco.26 Perhaps the vault attached to the inner side of the wall made the wall unstable and more prone to possible damage. Unfortunately, the southern continuation of the wall could not be excavated further without endangering the wall's stability. Therefore, an earthen corner was left in the south-west (Fig. 10.7). Consequently, one cannot see if the stone blocks of the warped part of wall 10070 are perhaps shifted somehow.

26 Marco 2008, 151, fig. 2L.

Room A (Figs 10.2, 10.8, 10.9) also underwent remodelling during the same period. The room, similar to room B, was built on top of a cistern whose entrance is situated within the room's north-western corner A (Fig. 10.7). The cistern probably belonged to the room's original Early Roman layout but was used throughout the Byzantine period. During the Early Islamic period, the cistern's entrance was raised approximately 0.50 m higher than its original floor level. A stone slab integrated into the room's outer wall suggests that the early Islamic floor level was also raised to the same height. Finds taken from the contexts to which the cistern's entrance was raised can be dated at the latest to the Umayyad period.

It can be concluded that the damage caused by the earthquake of AD 749 initiated architectural changes in the domestic neighbourhood on the southern slope of Mount Zion, marking the end of its residential use. After this severe destruction, which can be traced archaeologically in room B, the inhabitants decided not to rebuild the former domestic quarter but rather to build a lime-kiln in the same place. Thus, turning the previous residential quarter into an industrial quarter, partially built on top of the remains of the destroyed rooms, partially destroying the former rooms.

It can be assumed that already earlier, during the seventh century AD, archaeologically not tangible structural changes must have taken place within the society, resulting in the final decision not to rebuild that quarter. The destruction caused by the earthquake only seems to have been the final triggering factor for those urban changes on Mount Zion.

With its detailed publication, the excavations in the Armenian Garden under the direction of A. D. Tushingham27 from 1961 to 1967 provide lots of material for studying the Byzantine–Early Islamic period. This site might also show archaeological evidence for the AD 749 earthquake which was not interpreted as such by the excavator.

Three phases of buildings of the Byzantine–Early Islamic period were distinguished: the phase entitled ‘Byzantine I’, which clearly served a religious (Christian) purpose, likely a chapel or even a small church.28 Attributed to this phase are an apse, the ‘Hare Mosaic’, an additional mosaic, some cisterns, and a few walls.29 The excavators attribute this phase to the end of the reign of Justinian. A. D. Tushingham assumes this phase was short,30 suggesting an “abrupt end by a washout.”31

After that, a completely different constructed building sounded the bell for a new architectural phase in this area. The so-called ‘Byzantine II’ phase consists of a building erected with a completely different orientation. It had a central courtyard and three adjoining smaller rooms. A. D. Tushingham describes this building as a possible khan or a caravanserai.32

Additionally, an area enclosed with walls containing structures which are called ‘bins’, is attributed to this period.33 Their function is not entirely clear. The bins seem to have contained several pieces of burned plaster and burned stones as well as a large number of tiles.34 However, possible use as a kiln was excluded by the excavator.35 This phase was brought to an end by a ‘great washout’, similar to the previous one. It is described by A. D. Tushingham as follows: “It is difficult to believe that rains alone could have been responsible for such a flood, but there is no doubt that the water was the agent of the destruction.”36

The last phase, ‘Byzantine III’, was a reconstruction of the previous one but with a reduction of the large central courtyard, which was cut in half by an inserted wall.38 The excavator interpreted both of the latter buildings as a possible caravanserai or a pension for pilgrims.39

In the light of the interpretation of the DEI area I results, the transition between the different phases should be reassessed. A. D. Tushingham claims that the last of the phases, ‘Byzantine III’, was destroyed during the seventh century AD, either by the Persian conquest in AD 614 or by the ‘Muslim conquest’ in AD 638 and only resettled in the medieval period.40 Such an occupation gap does not seem very likely, considering that during the Umayyad period, the south-western hill was still a flourishing place, especially for Christian pilgrims, as is known from various sources.

However, A. D. Tushingham still reports excavated material, such as pottery and coins, from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, mainly in various fillings.41 This does indicate that the area was occupied during this period, but no architectural features were attributed to this period.

J. Magness reassessed the pottery assemblages found in the excavations of the Armenian Garden. She discovered that the pottery of the Byzantine levels includes a mixture of types that can be dated from the sixth to the eighth centuries AD. Therefore, she concludes that it might be possible that the settlement phase in the Armenian Garden cannot be dated exclusively to the Byzantine period but can also have continued throughout the Umayyad period.42 Considering again the archaeological evidence of continuous occupation from DEI area I,43 a similar inhabitation pattern throughout the Umayyad period in the nearby Armenian Garden seems very likely.

Therefore, the author suggests in the following a reassessment of the Byzantine occupational phases — at least the later ones — into the Early Islamic period. Instead of ‘washouts’ (or the ‘Muslim conquest’) which were described by the excavator, these events might be connected to the earthquake. Following each ‘washout’ the area was rebuilt differently. Similarities can be drawn with the excavation results of the nearby DEI area I — after the destructive earthquake, the urban layout was altered drastically, thus changing the nature of the site.

The transition between the excavator’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ in particular may be looked at here: from a chapel to an architecturally completely different, possible caravanserai.

Two possible solutions can be considered for the reconstruction of the Armenian Garden’s history:

Either the earthquake occurred between Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ and as a consequence, the former chapel with an apse was overbuilt by the suggested caravanserai (instead of rebuilding the chapel). In any case, these measures changed the nature of the site altogether. The other option is the modification of the caravanserai in Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine II’ and ‘Byzantine III’ might be a possible result of rebuilding measures following the earthquake.44

J. Magness has also reassessed the dating of the repairing of the city wall to the Early Islamic period (see below); as is analysed by A. D. Tushingham, this repair work corresponds with his ‘Byzantine II’ period.45 This dating would confirm that Tushingham’s ‘Byzantine II’ phase can be dated post-earthquake.

Consequently, the ‘Byzantine III’ phase was a time in which the Armenian Garden was extensively repaired and rebuilt. Perhaps this was necessary after a destructive event, such as an earthquake, similar to DEI area I.

Furthermore, the so-called ‘bins’ mentioned above, which can also be attributed to the possible early Islamic layers, contain a lot of burnt material and former building material, such as burnt plaster and tiles, as described by A. D. Tushingham.47 It can be suggested that this material could be the remains of the destroyed former buildings, the ‘Byzantine I’ structures. Those ‘bins’ were sealed, as described by A. D. Tushingham, by the latest ‘Byzantine III’ floor, which supports that argument.48 For this, a detailed find analysis of the content of these ‘bins’ would be necessary.

Certainly, this chapter cannot provide a complete detailed reassessment of all the stratigraphical contexts and corresponding finds of the excavation in the Armenian Garden; still, it can provide cause to reconsider the archaeological history of the site during the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period.

27 From 1962 onwards; the first year (1961) was under the

direction of R. de Vaux and J. A. Callaway (Tushingham 1985, 3).

28 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

29 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

30 Without providing a further time frame for “short.”

31 Tushingham 1985, 101. It remains uncertain what exactly

is meant by “washout.”

32 Tushingham 1985, 104.

33 Tushingham 1985, 101–02, pl. 6.

34 Tushingham 1985, 79.

35 Tushingham 1985, 79.

36 Tushingham 1985, 69.

37 Which is actually subdivided into IIIA

(redressing the damage caused by the previous 'washout') and IIIB

(actual rebuilding measures; Tushingham 1985, 103).

38 Tushingham 1985, 103–04.

38 Tushingham 1985. 103-04.

39 Tushingham 1985. 104.

40 Tushingham 1985, 104-05. Many earlier scholars,

especially from the 1960s and 1970s, attributed any

urban changes during this period to the `Muslim

conquest, neglecting the possibility of the AD 749

earthquake. But this view is no longer reflected in

modern research (Avni 2014, 14).

41 Tushingham 1985, 105-06. He wrote that the majority of

the Umayyad and Abbasid coins stems from 'deposits

that on stratigraphic grounds can be assigned to the

fills chat precede the first medieval, that is Ayyubid,

occupation of the site' (Tushingham 1985, 106).

42 Magness 1991, 212.

43 Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024.

44 We must also consider the possibility that several earthquakes

or aftershocks occurred in a short time, causing two different

“washouts” in the Armenian Garden.

45 Keeping in mind, that these repairs are either a result of the

earthquake or might also be the result of the reconstruction of the

city walls by Caliph Hisham.

46 Tushingham 1985, 65.

47 Tushingham 1985, 79.

48 Tushingham 1985, 79.

The excavations directed by N. Avigad from 1969 to 1982 in the modern-day Jewish Quarter within the Old City are usually a rich source for reconstructing Jerusalem's history and archaeology. However, no explicit hints suggest an impact of the AD 749 earthquake on the Jewish Quarter. In many areas, the remains from the eighth century AD onwards, even until the Ottoman period are combined into one stratum.49 This is likely the result of modern building activity there, which may have destroyed many of the remains that date later than the Byzantine period.50

Nevertheless, the modern Jewish Quarter excavations also revealed the Roman-Byzantine Cardo as the main thoroughfare during that time. The areas including the western Cardo (area X), do not seem to record any structures between the sixth to the thirteenth centuries AD.51 The same can be said about the pottery deriving from the fills above the Cardo — only a few examples of the pottery shards can be dated to the Early Islamic period, whereas most of the pottery can be dated to later periods.52 In contrast, a few coins from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods nevertheless suggest a use throughout these periods.53 Moreover, the excavations carried out in Jerusalem's eastern Cardo did not reveal any earthquake damage. It is described that the eastern Cardo was partially overbuilt by a new building which also dismantled parts of the Cardo.54

It can be assumed that any possible damage caused by the earthquake in those areas was simply rebuilt in the same way as before, and therefore no destroyed architecture was found. But according to the reports, no repair layers were observed in the architectural remains that could support such a rebuilding.

49 See for area A: Geva and Reich 2000, 43; area W: Geva and

Avigad 2000, 135; area E: no strata later than the Byzantine

period are recorded at all (Geva 2006, 11, 70); area B: the

last stratum combines remains from the Byzantine period

to the Mamluk period (Geva 2010, 10); area Q also does not

distinguish between any different strata during the Early

Islamic period — it ranges from the eighth to thirteenth

centuries AD (Geva 2017a, 8, 33); in area H the majority of

the archaeological remains later than the Early Roman period

were destroyed by building activity of the modern Jewish

Quarter buildings (Geva 2017b, 156). Severe damage from

the building activity seems to have occurred in areas F-2, P,

and P-2, since the last stratum covers all the remains from

the Late Roman until the Ottoman period (Geva 2021, 12).

50 See for instance Geva 2010, 10; 2017a, 8, 33.

51 Gutfeld 2012a, 27, 29, 41, 84.

52 Avissar 2012, 312.

53 Bijovsky and Berman 2012, 346–49.

54 Weksler-Bdolah and Onn 2019, 55. It seems very likely that

this phenomenon can be seen in the light of the “usual”

urban change in that period which includes encroachment

of colonnaded streets.

The excavations in the Jewish Quarter also revealed remains of the 'New Church of the Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary,' commonly known as the 'Nea Church.55 The church, depicted on the Madaba Map, was one of the most significant building ventures undertaken by Emperor Justinian I and therefore played a central role in Christian Jerusalem.56 The final days of the Nea Church have not yet been fully studied. The pottery from the areas within the church clearly shows continuation of the church throughout the Umayyad period,57 but found its end sometime during the Abbasid period.58 Different dates are suggested for the church's discontinuation: N. Avigad indicated that it was destroyed by an earthquake in the eighth century AD.59 D. Bahat, on the other hand, suggested an earthquake in AD 846, although he also suggested the possibility that the church was destroyed during the earthquake of AD 749.60 These assumptions about the church being damaged in the earthquake are based on account of the Commemoratorium de casis Dei — written in the ninth century: “The Church of St Mary which was thrown down by the earthquake and engulfed by the earth has side walls 39 dexteri long.”61 The Nea Church is the only church mentioned in this source as having suffered damage from the earthquake — no other churches were mentioned.

But in contrast to the textual evidence, no actual archaeological evidence was recorded indicating any impact of the earthquake. Following the types of possible seismic damage by S. Marco,62 it can be assumed that there is archaeological evidence for the earthquake in the Nea Church: a published photograph of the site63 shows the height difference which can be seen in different parts of the church's marble pavement — some parts that were not supported by a wall running below it are located 0.10 m lower than other parts.64 Additionally, it must be noted that most of the marble slabs were broken, which may perhaps hint at seismic damage.65 But the suggestions remain merely assumptions, as no other evidence for this can be retrieved.

55 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

56 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

57 Areas D and D-1; Avissar 2012, 311-12; Although the

stratigraphy published in the excavation report does not

subdivide the Early Islamic phases further (Gutfeld 2012b,

149, 215).

58 Gutfeld 2012a, 10.

59 Avigad 1977, 145.

60 Bahat 1996, 59.

61 Commemoratorium de casis Dei, p.138.

62 Marco 2008.

63 Gutfeld 2012b, 174, ph. 5.26 (L.2191 is located higher than

L.2199; Gutfeld 2012b, 176).

64 Gutfeld 2012b, 174.

65 Gutfeld 2012b, 224; Marco 2008, 151–52.

It seems likely that when Jerusalem's buildings suffered several destructions during the earthquake, that its city wall was also damaged.66 Indeed, several excavations around the city walls show signs of repair works during the period in question.

Precisely when the wall circuit used during the Byzantine period — the so-called 'Eudocia Wall' — was built and how long it remained functional is debated amongst scholars.67 However, one can be quite certain that during the eighth century AD, under discussion here, the same city wall was still in use.

J. Magness reassessed some of these repair phases in the Byzantine–Early Islamic city wall circuit based on a re-evaluation of the pottery — especially the precise distinction of Byzantine and Umayyad ceramic material — to clarify the chronology of the wall repairs. She concluded that, for instance, excavations by R. Hamilton along the northern part of the city wall during the 1930s revealed “clear evidence for a reconstruction of the city wall in the vicinity of the Damascus Gate no earlier than the first half of the eighth century C.E.”68

In the city's south-west, an additional stretch of the city wall with “clear evidence for a major rebuild” from the same time period was found in the Armenian Garden by A. D. Tushingham.69 This part of the wall was also reassessed based on the pottery evidence by J. Magness. She re-attributes some of the excavated pottery forms found in the city wall’s foundation trenches to the (Late) Umayyad period70. Consequently, J. Magness suggests an Early Islamic, Umayyad date for the repair of the city wall rather than the sixth century, as stated by A. D. Tushingham.71

Therefore, it can be said that Jerusalem’s city walls were reconstructed or renovated in the middle of the eighth century AD based on the two re-evaluated archaeological examples, which show that renovation works were carried out in this time period.72 However, it cannot be stated with certainty that these repair phases of the city wall are a result of the AD 749 earthquake rather than later measures to reconstruct buildings. It is also possible that these rebuilding measures were part of other construction projects in the eighth century AD — for instance, the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s city walls ordered by Caliph Hisham between AD 728 and 744 — because the walls were previously torn down by his predecessor Caliph Marwan II, as described by Theophanes.73

The archaeological material does provide a terminus post quem —the first half of the eighth century AD—for the partial reconstruction of the city walls, but due to the proximity of both events in question, an exact attribution to one of them, at least in the case of the city walls, cannot be given.

66 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421.

67 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421-24; Zimni 2023, 286-90.

68 Magness 1991, 212.

69 Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

70 Magness 1991, 212-13.

71 Magness 1991, 215; Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

72 Excavations in the area of the citadel suggest further

alterations of the early Islamic city wall (Magness 1991,

214; Wightmann 1993, 233).

73 Theophanes, Chronicle 422, p.114; Wightmann 1993, 235;

Magness 1991, 215.

It has become evident — both from historical records as well as from archaeological evidence — that Jerusalem's buildings suffered severe damage from the AD 749 earthquake. The al-Aqsa Mosque in particular faced partial destruction as described in various historical sources. Additionally, the area located south of it — the “Umayyad palaces” — also shows archaeological evidence of similar architectural damage.

While the primary written Muslim sources for that time only describe the damage that occurred in the al-Aqsa Mosque in more detail, other religious edifices were also affected by that earthquake damage — such as the Nea Church, for instance, as can also be learned from historical sources. But with this being the only larger Christian building mentioned, it certainly raises the question of the fate of other significant churches, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or the Hagia Sion.74 Not much is known about any earthquake damage to the latter buildings during the eighth century AD. Pilgrim itineraries do not mention the remains of any destruction during that time75.

New archaeological research from the south-western hill in DEI area I provides compelling evidence that Jerusalem's domestic quarters also suffered damage from the earthquake. A clear destruction layer in room B suggests that these buildings were severely destroyed, leading to extensive remodelling that altered the character of the area.

Reassessment of the archaeological data from the Armenian Garden indicates similar transformations.

It can be said that the devastating seismic catastrophe functioned — certainly at least on Jerusalem’s south-western hill — as an agent of change for the cityscape, triggering drastic urban alterations, thus changing the nature of the respective quarters.

These alterations were very likely the result of structural changes within society that preceded the earthquake and created the need to change the nature of a few parts of the city.

Unfortunately, not as much is known about other parts of the city, since the Jewish Quarter excavations, for instance, cannot contribute as much to that question as most of the archaeological remains from the period in question have fallen victim to modern construction works.

However, the study also shows that the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period cannot be looked at in the city as a whole. Instead, it needs to be looked at independently in different parts of Jerusalem on a smaller scale to understand the larger-scale image of the city.76

This contribution shows the importance of the earthquake of AD 749 (and its impacts) for investigating the development of Jerusalem during the transitional period, especially from the Umayyad to the Abbasid period. In many cases, the archaeological contexts do not show evident damage which can be connected to the earthquake or are not interpreted as such.

In general, the lack of archaeological material, such as apparent destruction layers, cannot be taken as evidence that Jerusalem was not affected by the earthquake, since, as shown in this study, extensive remodelling and reuse would not leave many destruction layers visible in situ in the archaeological record.

Therefore, future excavations in Jerusalem might shed more light on the transitional phases as well as on the impact of the earthquake in AD 749 and its consequences for Jerusalem's urban layout.

74 The sparsity of the archaeological remains of this

church might also affect that state of knowledge.

75 The only known destruction of the Hagia Sion is during

the Persian Conquest in AD 614.

76 This is already obvious in previous transitional periods,

such as the beginning of the Umayyad period. Whereas the south-eastern part

of the city is massively reconstructed (see also Whitcomb 2011) the

south-western hill shows urban continuity until the middle of the

eighth century AD - which likely only ended with the earthquake

(see Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024).

- from Mazar (1969)

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Section E 6, cutting through the street some 5 m east of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount (lowest height 715 m above sea-level).

JW: 5 m west of the SW corner of Temple Mount and not the same as Warren's shaft in the City of David next to the Gihon spring

Mazar (1969)

- from Mazar (1969)

| Strata | Period | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A8 | ||

| A7 | After the Seljuk conquest of Jerusalem in 1071 CE ? | |

| A6 | Arab | Fatimid |

| A5 | Arab | Fatimid |

| A4 | Arab | Fatimid |

| A3 | Arab | |

| A2 | Arab | Post Umayyad |

| A1 | Early Arab | Umayyad |

| B1 - B4 | Byzantine | |

| R1 - R2 | Roman | |

| H | Herodian | the period from Herod the Great to the destruction of the Second Temple |

- from Mazar (1969)

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Section E 6, cutting through the street some 5 m east of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount (lowest height 715 m above sea-level).

JW: 5 m west of the SW corner of Temple Mount and not the same as Warren's shaft in the City of David next to the Gihon spring

Mazar (1969)

Mazar (1969)

concluded that stratum A1 ended with an earthquake which destroyed a large Umayyad Building south of Temple Mount

about a generation or two after its construction

. The earthquake was said to have

collapsed its walls and columns

and produced a considerable pile of rubble. They correlated the earthquake with one

of the Sabbatical Year Quakes.

They further noted that there were partial repairs during the Abbasid period

(second half of the 8th century A.D.)

and that the paved street and the gateway of the building continued

to be used in stratum A2, and the water system was modified drastically

.

Ben Dov (1985:275-276) examined artifacts from a sewage canal that collected refuse from before the building was destroyed. In the canal,

he found pottery (Khirbet Mafjar ware) dating to the first half of the 8th century CE.

Ben Dov (1985:321) reports archaeoseismic

evidence from the earthquake including cracked walls, warped foundations, fallen columns, and sunken floors. All this evidence would have come from Building 2 immediately S of Haram esh-Sharif - according to

Prag (2000:245).

Ben-Dov in Yadin et al (1976:97-101) reported the following:

So far, six enormous buildings have been found, comprising a single complex. The plan of the largest of them, building II, closely resembles those of the palaces of the Omayyad period in this country, in Transjordan and in Syria.Prag (2000:245) reports that

... The stratigraphic picture and the finds confirm this dating. Beneath the floors of the building and beneath the associated streets - houses, installations and channels came to light together with an abundance of finds including much pottery and thousands of coins, and stamped roof-tiles of the Byzantine period — all from late in that period. In the stratum above the building-complex, which was destroyed in a natural catastrophe and not rebuilt (see below), remains of a very meagre settlement of the 9th century C.E. were found amongst the ruins. The complex had been equipped with a broad, well-planned sewer network, which remained unknown to the people of the meagre settlement. Various finds came to light in this sewer network, which relate to the latest phase of its use, including complete pottery vessels of "Khirbet Mefjer ware", and coins of the 8th century C.E. This was a most important archaeological discovery, for it is the first time large structures of the Omayyad period (660-750 C.E.) were found outside the Haram esh-Sherif.

... At the end of the Byzantine period, a residential quarter lay adjacent to the walls of the Temple Mount, which appear to have towered to their full height at that time. This quarter included public buildings, and private houses of one and two storeys, with open areas between utilized for gardening. The Parthian conquest of Jerusalem in 614 C.E. also left its imprint here. The Southern Wall was especially damaged, a large breach having been forced. During the Byzantine reconquest, and early in the period of the Arab conquest, no significant changes seem to have taken place in this area, occurring only under the Omayyad caliphs, who established an extensive religious centre in Jerusalem. Of this project we had known only of the structures within the Haram: the Dome of the Rock, el-Aqsa mosque and other smaller monuments. We now know that the large breach in the Southern Wall was repaired by the planners of the entire Omayyad complex, and that the "Double Gate" in its present form was also built by them.

The six structures uncovered were planned as a complex in conjunction with the Temple Mount. As noted, the outstanding structure is building II, which we have defined as a palace. This definition is based largely on the evidence of a bridge which had connected the roof of building II with el-Aqsa mosque, spanning the street running along the Southern Wall and enabling direct access from the roof of the building into the mosque. It is assumed that the place was erected by the Caliph el-Walid I (705-715 C.E.).

... The existence of a second storey in building II is indicated by the level of the abovementioned bridge, as well as by a system of drain-pipes lying within the walls, leading to the central sewers beneath the groundfloor-level. There seem to have been various installations in this upper storey, such as kitchens and toilets.

... The five other buildings around building II have only incompletely been excavated, and thus their full study remains for the future.

... From among the plethora of finds from these buildings, we may note the large number of architectural fragments — capitals, friezes, architraves and balustres, as well as fresco fragments and some stucco-work. Among the many pottery types of this period, most notable are the zoomorphic and glazed vessels, which already began making their appearance in this country at this time. Many gold, silver and bronze coins have come to light, mostly struck at Ramla and Jerusalem ("Aelia", on the coins), and some from Damascus. Glassware, metal objects and bone implements also were found.

The building-complex was destroyed by a heavy earthquake, traces of which can still be observed. This was the disastrous quake of 747/748 C.E. which hit Jerusalem especially hard; Talmudic literature denotes this catastrophe as the "quake in the sabbatical year".

The area was not renewed in its former plan after the disaster, and the rise of the Abbasids put an end to Omayyad aspirations for Jerusalem. Not only were no renovations or construction carried out here, but the ruins became a huge quarry, a source for building stone for anyone needing such material. In the 11th century it served as a cemetery, indicating that the immense complex which had stood here was entirely forgotten. The history of the site in Abbasid through Ottoman times reflects its wretched state. From time to time, ripples of activity were felt here, but the few structures which rose over the ruins were of a private nature, and the area never recovered its former splendour.

according to Ben-Dov (1976: 101; 1985: 276), on the evidence from the contents of the drains, the palace was destroyed in the great earthquake of A.D. 749.

The earthquake damage in and around the area of the al-Haram al-Sharif is well documented by historical sources and by archaeological evidence. The area (Fig. 10.1 no. 1) experienced massive remodelling at the beginning of the Umayyad period, when the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock, as well as Umayyad buildings (Fig. 10.1 no. 2) located south of the religious edifices were built.9

Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence that can be gathered from the Holy Sanctuaries — the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock — is limited.9 Therefore, the study of the written accounts is an essential source for investigating the extent of the architectural damage in this area. For instance, it is described by al-Wasiti that the al-Aqsa Mosque suffered severe damage from an earthquake in the middle of the eighth century AD.10 He tells that in the days of the reign of Caliph al-Mansur (AD 754–775), the eastern and western portions of the mosque fell due to an earthquake in the year AH 130.11 As a consequence, Caliph al-Mansur ordered the mosque’s restoration. Since no money was available for this, it is also known from the description of al-Wasiti, that the gold and silver plates decorating the mosque’s gates were to be stripped off, and dinars and dirham were to be coined from them.12 Moreover, he also stated that shortly afterwards another earthquake hit the mosque, which was then restored by the caliph’s successor, Caliph al-Mahdi.13

Furthermore, in the tenth century AD the writer al-Muqadassi wrote about the earthquake damage in the mosque: he described that the earthquake destroyed most of the building, except for the corner around the mihrab.14

South of the Mosque complex, several buildings were constructed during the Umayyad period. Those are interpreted as administrative centres,15 whereas one of these buildings (‘Building ii’) stands out as a possible ‘Umayyad palace’.16 According to the excavators, this complex shows clear archaeological evidence of damage by the 749 earthquake. The damage is described as “cracked walls and warped foundations, fallen columns and sunken floors.”17 The archaeological material also provides evidence for the dating of this destruction: a sewage channel within one of the buildings was blocked shortly before the building went out of use. The material found there was interpreted as Khirbet Mafjar Ware, dating to the first half of the eighth century AD.18

9. Only reports of earlier investigations are available

(Hamilton 1949; Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1999).

10. It needs to be kept in mind that the dating of the

described earthquake damage cannot be clarified with

certainty.

11. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92;

referring to AD 747/748 according to Karcz 2004, 780.

12. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92.

Here, it is debatable whether al-Wasiti refers only to the

Mosque itself or the entire Haram al-Sharif area (Elad

1995, n. 77).

13. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 256, p. 92.

For a suggestion of the archaeological layout of these

rebuilding measures see Küchler 2007, 226–34. G. Le

Strange assumes the year AD 770–771 for the visit of

Caliph al-Mansur, whereas others suggest that this visit

already took place in AD 758 (Elad 1995, 40; Küchler

2007, 228).

14. al-Muqadassi, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the

Regions, trans. by B. Collins, p. 276.

15. Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8.

16. Ben-Dov 1985; Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8–11.

17. Ben-Dov 1985, 321.

18. Ben-Dov 1985, 2–20; however, this chronology by the

early excavators was doubted by J. Magness who

redates the construction date of these buildings as well

as doubting their damage from the 749 earthquake due

to ceramic evidence supporting the buildings’ existence

throughout the Abbasid period (Magness 2010, 153).

However, in the author’s opinion, the damage described

by the excavators does suggest that a destructive event,

such as an earthquake, occurred in these buildings,

resulting in the described architectural remains.

- from Magness (2010:147)

Excavations directed by the late Benjamin Mazar and by Meir Ben-Dov after 1967 brought to light a series of monumental early Islamic buildings around the southern and western sides of Jerusalem’s Haram (see Figure 7.1).1 The largest (Building II), located south of the Haram, measures approximately 96 x 84 m and has outer walls that are 2.75–3.10 m thick.2 It consists of a central open courtyard encircled by a peristyle and surrounded by rows of elongated rooms on all four sides. The rooms measure between 17–20 m long by 4–8 m wide. Square piers at regular intervals along the long walls supported a system of vaults.3 The excavators suggested that staircases on four sides of the complex (in narrow passages between the rooms on the north and south sides on the one hand, and the east and west sides on the other) provided access to a second-story level. Each story was at least 6.5 m high. The main gate was located in the middle of the east side of the building, and others were located in the middle of the west and north sides. A bridge on the north side at the second-story level provided access directly to the al-Aqsa mosque. The building was served by a sophisticated system of gutters and drainage channels for rainwater and waste.4

A second building (III) located immediately to the west of Building II has a similar plan consisting of elongated rooms around a central peristyle courtyard. A row of six elongated rooms is located in the southeast corner of the building, while large square piers in the southwest corner supported a system of arches and vaults. The main gate was in the middle of the east side (directly opposite the west gate of Building II), and other gates were located in the middle of the north and west sides, as in Building II. Like Building II, Building III was equipped with a sophisticated drainage system.5

Renewed excavations conducted since 1995 by Ronny Reich and Yaakov Billig, and by Yuval Baruch, have revealed that Building III is larger than Mazar and Ben-Dov thought, measuring ca. 75 x 75 m. It extends as far as the line of the Cardo along the bottom of the Tyropoeon Valley, which Baruch and Reich suggest separated the administrative or government quarter from the civilian part of town.6 Baruch and Reich excavated four elongated rooms in the southeast corner of Building III (C–F) that have square piers at regular intervals as in Building II. They note that these rooms contained deliberately dumped fills. In some cases the fills were dumped in conjunction with the raising of the walls, and in other cases they were dumped after the walls were finished. In other words, the elongated rooms represent foundations that were filled with dumped material in order to level the area.7

In Buildings II and III, the lower parts of the walls of the elongated rooms were constructed of a concrete mixture consisting of stone and grey lime mortar. This mixture was poured into a wood form or scaffolding. The upper parts of the walls were constructed of large roughly cut stones, with small stones between them, held together by grey mortar containing much charcoal. The walls were not plastered.8

Mazar and Ben-Dov uncovered part of a third building (IV) to the north of Building III, west of the Haram and opposite Robinson’s Arch. It differs in plan from the other two buildings, having two large courtyards surrounded by rows of square piers but no elongated rooms.9 In my opinion elongated rooms were used to create the foundations in areas where the bedrock is very deep and steeply sloping, whereas square piers were employed in areas where the bedrock was close to the contemporary ground level.10 Ben-Dov describes this technique as follows: “Sometimes the terrain was exceptionally low, making it necessary to build foundation walls and cover them with fill.”11 Building IV incorporates the remains of a Roman legionary bath house, which seems to have remained in use as a bath house.12

Mazar and Ben-Dov noted that all three buildings had been robbed out, leaving only small sections of the walls and a few patches of floors surviving at or above ground level.13 Baruch and Reich also found little evidence of floors in Building III.14 Much of the robbing seems to have occurred in the Fatimid period (eleventh century).15 Most of the floors on the ground story of the buildings were of stone. Because the flagstones were laid on a layer of terra rosa, Ben-Dov suggests they represent temporary floors that were meant to be replaced with mosaics.16 In some places patches of mosaics were preserved, mostly of large white tesserae with no design or simple designs.17 In Building IV a pavement of large square polished flagstones was preserved.18 Small colored tesserae (some of glass) found in the fills in the buildings probably come from wall or ceiling mosaics.19 Fragments of wall paintings were also found in the fills.20

Mazar and Ben-Dov dated the buildings to the Umayyad period based on the following considerations: (1) the buildings directly overlie houses from the end of the Byzantine period; (2) the plans of the buildings resemble Umayyad palaces and fortified enclosures such as those at Khirbet al-Mafjar and Khirbet al-Minya; (3) they dated the finds from the drainage channels in the buildings to the Umayyad period.21 Specifically, Mazar and Ben-Dov attributed the construction of these buildings to al-Walid (705–15), the son of ‘Abd al-Malik (685–705). They suggested that the Bab al-Walid, a gate in the Haram mentioned by al-Muqaddasi, should be identified with the gate leading from Building II to the south end of the Haram.22 If they are correct, this gate was still functioning in the tenth century.

According to Mazar and Ben-Dov the buildings were destroyed in the earthquake of 747/48.23 Because there were no signs of collapse (that is, no piles of stones associated with the collapse of the walls) and few surviving floors, the excavators concluded that construction halted before completion of the project: “The ambitious building program inaugurated in the days of ‘Abd al-Malik was never fully consummated, so that several details of the Omayyad buildings — including the final flooring — were never completed.”24

In all of the buildings the excavators found evidence of later reoccupation, which they associated with squatters, including later walls that incorporated spolia and abutted the original walls, creating rooms that had no relationship to the original building plan. The floors associated with this reoccupation lay at a higher level than the original floor level.25 In Building III Baruch and Reich found mosaic floors, some with simple designs, at a higher level, which they associated with this later reoccupation.26 Elsewhere Baruch and Reich describe lime or chalk floors with ovens, thin walls, channels, and pits.27 Mazar and Ben-Dov, and Baruch and Reich, dated the reoccupation of these buildings to the Abbasid period (late eighth to ninth century) based on the associated finds.28 Specifically, Baruch and Reich describe the associated finds as including “glazed pottery and large quantities of animal bones, especially sheep.”29 After this brief reoccupation the buildings were abandoned and robbed out.30

According to Mazar and Ben-Dov, this grandiose Umayyad building project was abandoned before the earthquake of 747/48 due to economic decline.31 The unfinished buildings were brought down by the earthquake, which Ben-Dov says caused cracked or warped foundations and walls, fallen columns, and sunken floors.32 With the fall of the Umayyads and rise of the Abbasid dynasty the following year the center of power shifted to the east, leaving Syria and Palestine a backwater. As Ben-Dov puts it, “the rabid prejudice of the ‘Abbasid caliphs and the historians under their patronage ... went far out of their way to obliterate all reference to anything Omayyad.”33 “Hence the role played by the ‘Abbasids in the area around the Temple Mount ranged from abstaining from building activity to outright, deliberate destruction, and the stratum dating from their reign is essentially a negative one from an archaeological viewpoint. Actually, it is not a stratum in the strict sense of the word, but rather evidence of the destruction caused to the Omayyad buildings.”34 Even Paul Wheatley repeats the standard trope describing ‘Abbasid neglect of Jerusalem.35

It is difficult to evaluate the excavators’ proposed chronology as no final excavation reports have been published. Nevertheless, in my opinion the available archaeological evidence points to a different sequence of events. First, Baruch and Reich mention finding Umayyad coins in the foundation level fills in Building III. These include a group of coins discovered inside the foundations of the courtyard’s peristyle wall, the latest of which dates to ca. 730.36 This indicates that construction of these buildings was still underway during the reign of Hisham (assuming the project was initiated by al-Walid I), not surprising given the scale of the undertaking. Second, the signs of damage described by Ben-Dov (cracked walls and warped foundations, fallen columns, and sunken floors) could have been caused by a later earthquake, perhaps that of 1033, which apparently damaged the al-Aqsa mosque as well (as a result the number of gates into the mosque was reduced).37 It was apparently after this earthquake (of 1033) that the city walls were rebuilt, along the lines preserved today, with the south wall of the Old City overlying the early Islamic buildings.38 The robbing activity apparently occurred after this.39

I also question the excavators’ conclusion that the buildings were unfinished (Ben-Dov describes them as “shells”) when construction stopped.40 If this were the case, we would not expect the plumbing system to have been functioning. However, according to Ben-Dov, the sewage system, which included drainage pipes from the second-story level, was blocked with occupational debris and refuse.41 This material, which “dated to the final years of the building’s [II] existence,” included buff ware vessels described by Ben-Dov as “light-colored and decorated with molded designs characteristic of ‘Khirbet Mafjar ware’.”42 Other pottery found in the drainage channels and in association with the main occupation of the palaces included zoomorphic vessels and “chamber pots” glazed on the inside in dark green or dark brown. The presence of mold-made buff ware and glazed pottery indicates that the main phase of occupation continued at least into the ninth century.

The evidence reviewed here suggests the following chronology and sequence. The buildings were constructed in the latter part of the Umayyad period. Even if the project was initiated by al-Walid I, work continued at least through the reign of Hisham. Elsewhere I have suggested that the fortification walls of Jerusalem were repaired by Hisham.43 Contrary to the excavators’ conclusion, construction of the buildings around the Haram seems to have been completed, at least to the point where the plumbing system was fully functioning, including at the second-story level. It is not clear whether the earthquake of 749 caused significant damage. However, the ceramic evidence indicates that occupation continued well into the Abbasid period. This scenario is supported by Mazar and Ben-Dov’s identification of the Bab al-Walid as the gate leading from Building II to the south end of the Haram, which, if they are correct, was still functioning in al-Muqaddasi’s time.44 However, around this time or soon afterward the buildings were abandoned and began to collapse, and some of the original floors and parts of the walls were robbed out.45 This was followed by a brief phase of reoccupation by a different population. Although this occupation is poorer than the original phase, the presence of mosaic floors indicates that the inhabitants were not squatters. I propose dating this occupation phase to the tenth to early eleventh century. The earthquake of 1033 may have caused the damage noted by Ben-Dov, after which time the buildings were abandoned permanently and the remaining walls and floors were robbed out.

1 I am not concerned here with the function of these

buildings, which are usually referred to as “palaces.”

The excavators designated the buildings with Roman numerals

(II–IV). All dates refer to the Common Era unless otherwise

indicated.

2 Ben-Dov 1971a: 36 (the same report was published in

Ben-Dov 1971b); Ben-Dov 1985: 297 (where the dimensions are

given as 94 x 84 m).

3 Ben-Dov 1971a: 36.

4 Ben-Dov 1971a: 37; Ben-Dov 1985: 294, 307–8.

5 Ben-Dov 1971a: 38; Ben-Dov 1985: 312.

6 Baruch and Reich 1999: 131, 140.

7 Baruch and Reich 1999: 131, 136 and Fig. 1b;

Ben-Dov 1973: 85.

8 Baruch and Reich 1999: 132 and Figs. 5, 9;

Ben-Dov 1973: 83–4; Ben-Dov 1985: 309.

9 Ben-Dov 1971a: 38–9.

10 Ben-Dov 19716: 37 and 1985: 309 notes that the foundations of Building II were up to nine meters deep.

11 Ben-Dov 1985: 309 (describing Building II).

12 Ben-Dov 1985: 316–17; on 288 he notes that the

buildings of Aelia Capitolina must have remained standing

until the end of the Byzantine period.

13 Ben-Dov 1971a: 35; Ben-Dov 1971b: 35.

14 Baruch and Reich 1999: 132.

15 Ben-Dov 1971b: 35; but on p. 38 he says that the

pottery and coins from the robbers’ trenches of the walls of

Building II indicate that the robbing activity occurred in

the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, apparently at the time

the Crusader city wall was built.

16 Ben-Dov 1985: 311.

17 Ben-Dov 1971a: 38–9; Baruch and Reich 1999: 132.

18 Ben-Dov 1971a: 39.

19 Ben-Dov 1971a: 39.

20 Ben-Dov 1971a: 36–7; Ben-Dov 1985: 294–5, 304.

21 Ben-Dov 1971a: 36.

22 Ben-Dov 1971a: 39; Le Strange 1965: 94.

23 Ben-Dov 1971a: 38; earthquake now redated to 749:

Tsafrir and Foerster 1997: 136 n. 227.

24 Ben-Dov 1985: 312.

25 Ben-Dov 1971a: 35.

26 Baruch and Reich 1999: 132.

27 Baruch and Reich 1999: 139.

28 Ben-Dov 1971a: 35, 39; Baruch and Reich 1999: 139.

29 Baruch and Reich 1999: 139 (my translation from the Hebrew).

30 Ben-Dov 1971a: 35, 37–8.

31 Ben-Dov 1985: 312.

32 Bcn-Dov 1985: 321. Baruch and Reich 1999: 135, also claim to have found evidence that

the construction of Building III was never completed.

33 Ben-Dov 1985: 293.

34 Ben-Dov 1985: 323.

35 Wheatley 2001: 297.

36 Baruch and Reich 1999: 139.

37 For this earthquake see Stacey 2004: 8; Le Strange 1965: 23; Bahat 1990: 82 attributes the

destruction of the palaces to this earthquake.

38 Bahat 1993: 786, who describes the earthquake of 1033 as the worst to hit Jerusalem. In contrast see Wheatley 2001: 297.

39 See Ben-Dov 1985: 321.

40 Ben-Dov 1971b: 35, 37; Ben-Dov 1985: 307–8.

41 Ben-Dov 1985: 276.

42 Ben-Dov 1985: 319–20.

43 Magness 1992.

44 In fact, Bcn-Dov 19716: 40, suggests that the northern wing of Building II

was inhabited until the 10th century, in order CO account for al-Muqadasi's reference to the Bab al-Walid.

45 Ben-Dov 1971b: 35, describes "a dump of walls and ceilings" in the 1.5 meter thick layer separating

the original floors from the later floors above. However, Reich and Baruch 1999: 135, note an absence

of evidence of building collapse on top of the original floor level.

- from Magness (2010:147)

Excavations directed by the late Benjamin Mazar and by Meir Ben-Dov after 1967 brought to light a series of monumental early Islamic buildings around the southern and western sides of Jerusalem’s Haram (see Figure 7.1).1 The largest (Building II), located south of the Haram, measures approximately 96 x 84 m and has outer walls that are 2.75–3.10 m thick.2 It consists of a central open courtyard encircled by a peristyle and surrounded by rows of elongated rooms on all four sides. The rooms measure between 17–20 m long by 4–8 m wide. Square piers at regular intervals along the long walls supported a system of vaults.3 The excavators suggested that staircases on four sides of the complex (in narrow passages between the rooms on the north and south sides on the one hand, and the east and west sides on the other) provided access to a second-story level. Each story was at least 6.5 m high. The main gate was located in the middle of the east side of the building, and others were located in the middle of the west and north sides. A bridge on the north side at the second-story level provided access directly to the al-Aqsa mosque. The building was served by a sophisticated system of gutters and drainage channels for rainwater and waste.4

A second building (III) located immediately to the west of Building II has a similar plan consisting of elongated rooms around a central peristyle courtyard. A row of six elongated rooms is located in the southeast corner of the building, while large square piers in the southwest corner supported a system of arches and vaults. The main gate was in the middle of the east side (directly opposite the west gate of Building II), and other gates were located in the middle of the north and west sides, as in Building II. Like Building II, Building III was equipped with a sophisticated drainage system.5

Renewed excavations conducted since 1995 by Ronny Reich and Yaakov Billig, and by Yuval Baruch, have revealed that Building III is larger than Mazar and Ben-Dov thought, measuring ca. 75 x 75 m. It extends as far as the line of the Cardo along the bottom of the Tyropoeon Valley, which Baruch and Reich suggest separated the administrative or government quarter from the civilian part of town.6 Baruch and Reich excavated four elongated rooms in the southeast corner of Building III (C–F) that have square piers at regular intervals as in Building II. They note that these rooms contained deliberately dumped fills. In some cases the fills were dumped in conjunction with the raising of the walls, and in other cases they were dumped after the walls were finished. In other words, the elongated rooms represent foundations that were filled with dumped material in order to level the area.7

In Buildings II and III, the lower parts of the walls of the elongated rooms were constructed of a concrete mixture consisting of stone and grey lime mortar. This mixture was poured into a wood form or scaffolding. The upper parts of the walls were constructed of large roughly cut stones, with small stones between them, held together by grey mortar containing much charcoal. The walls were not plastered.8

Mazar and Ben-Dov uncovered part of a third building (IV) to the north of Building III, west of the Haram and opposite Robinson’s Arch. It differs in plan from the other two buildings, having two large courtyards surrounded by rows of square piers but no elongated rooms.9 In my opinion elongated rooms were used to create the foundations in areas where the bedrock is very deep and steeply sloping, whereas square piers were employed in areas where the bedrock was close to the contemporary ground level.10 Ben-Dov describes this technique as follows: “Sometimes the terrain was exceptionally low, making it necessary to build foundation walls and cover them with fill.”11 Building IV incorporates the remains of a Roman legionary bath house, which seems to have remained in use as a bath house.12