Amman Citadel - Umayyad Structures

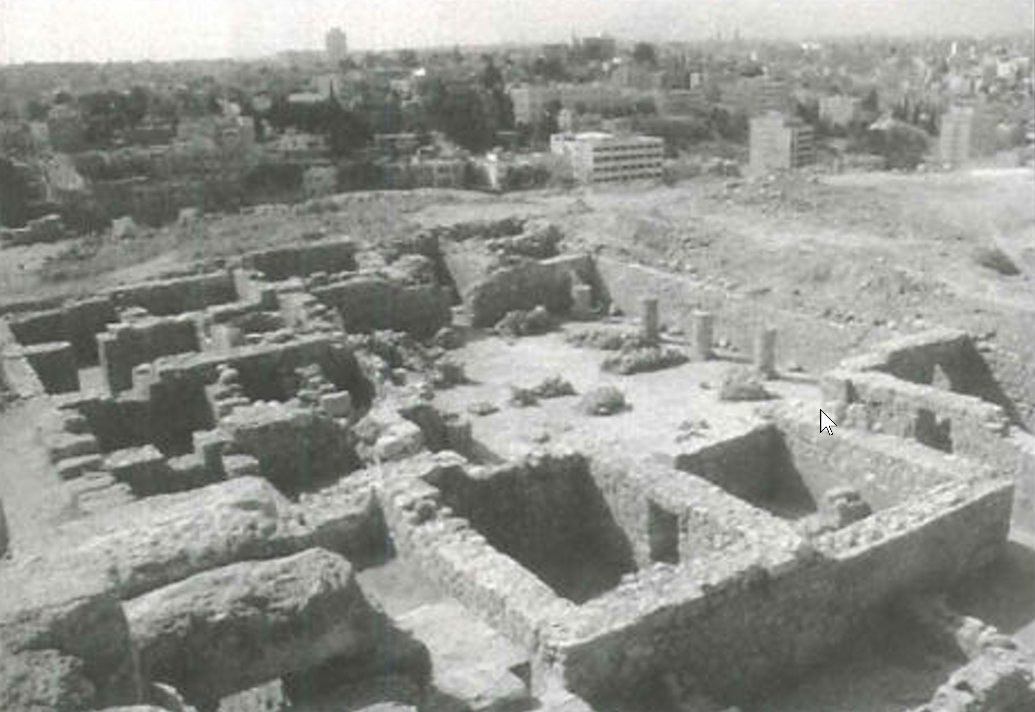

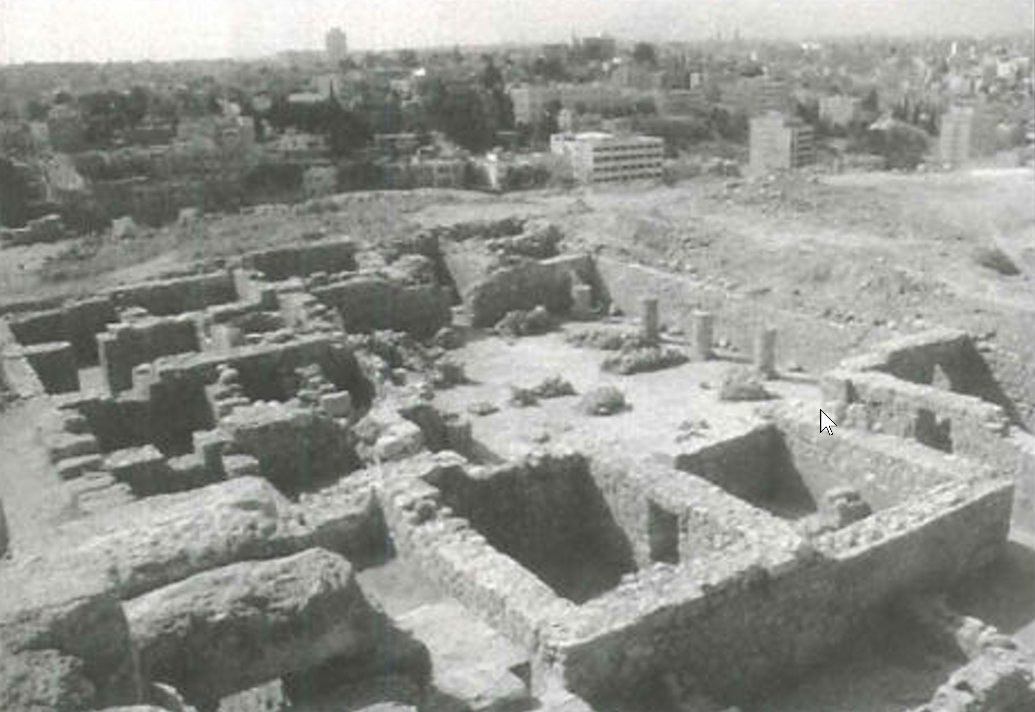

Aerial Photograph of the Northern part of Citadel in Amman with the Umayyad Palace and Umayyad Structures

Aerial Photograph of the Northern part of Citadel in Amman with the Umayyad Palace and Umayyad StructuresAPAAME CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Umayyad Palace | English | |

| al-Qasr | Arabic | القصر |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 19 June 2025

The layout reflects early Islamic adaptations of Byzantine and Sassanian palace models, with finely cut limestone blocks, column bases reused from earlier Roman-period structures, and a combination of open courtyard and vaulted reception areas. The complex was severely damaged in the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes but retained enough of its original form to allow substantial reconstruction of its plan. Today, the Umayyad complex is one of the key features that dominates the northern side of the Citadel and serves as a visual and historical anchor for the site's Islamic-period occupation.

Wikipedia (2024), Amman Citadel

Williams, Jefferson (2024), 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, Dead Sea Earthquake Catalog

- from Amman - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Site Plan of the entire

Citadel in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

- Area Plan of the entire

Citadel in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

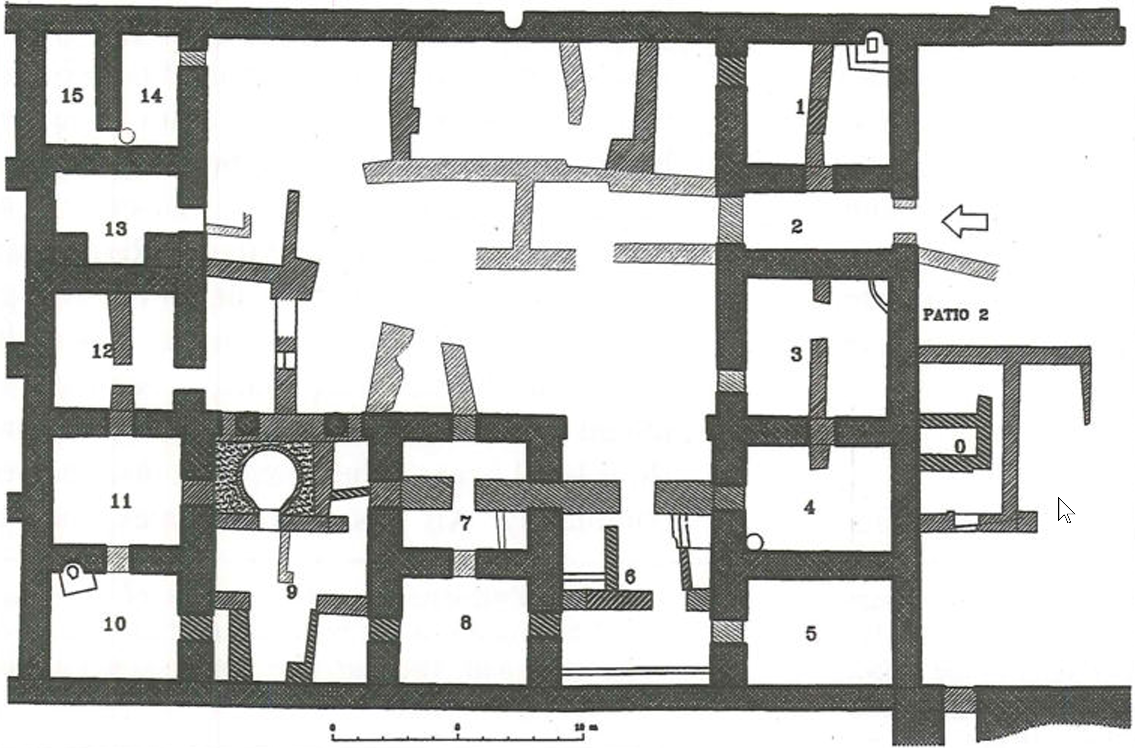

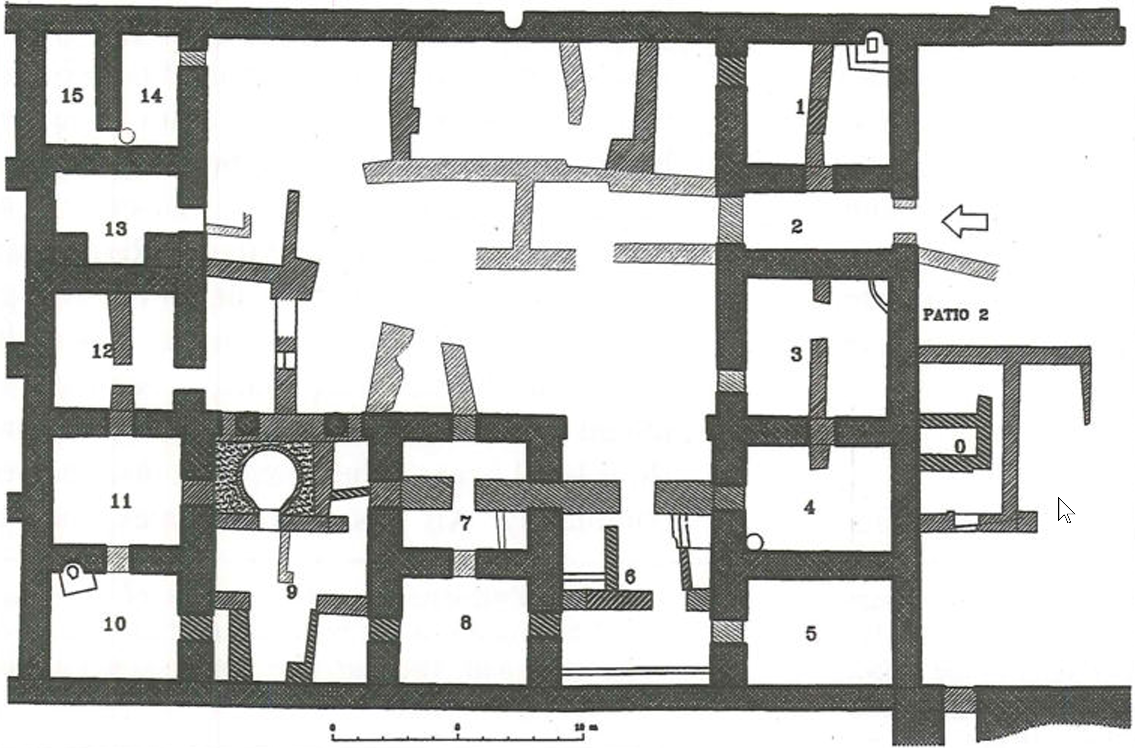

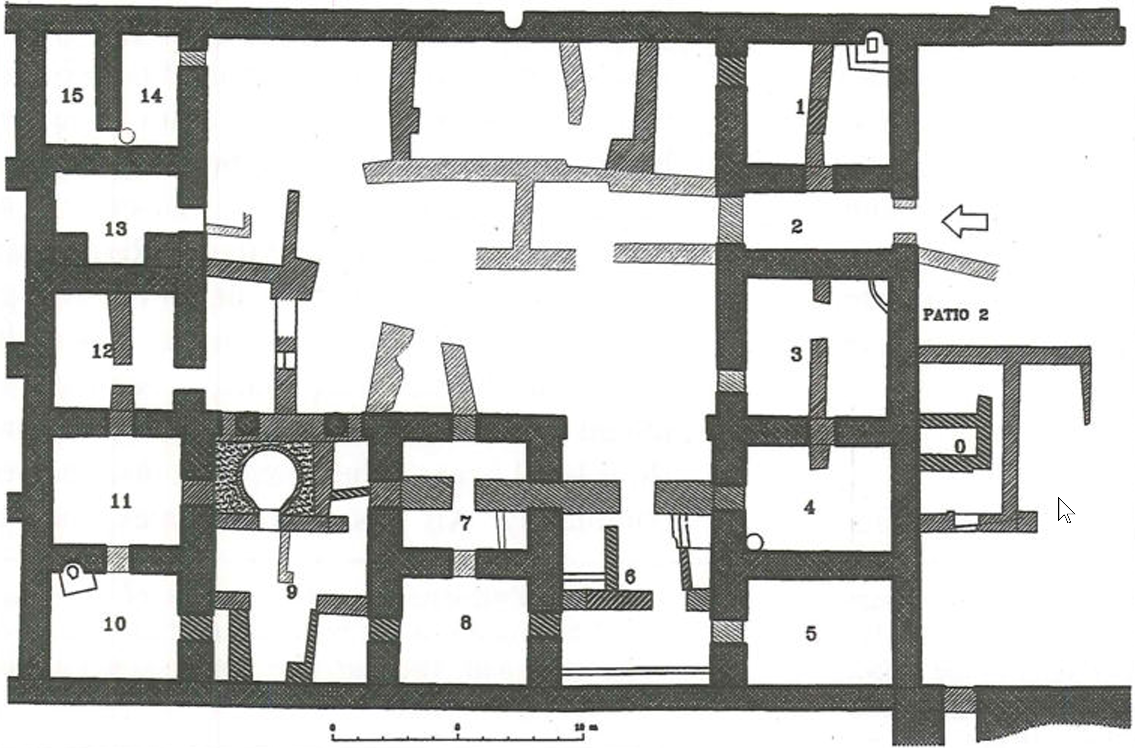

- Fig. 1 - General plan of

the north part of the Amman citadel from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel.

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 1 - Congregational

Mosque and Souq Square on the Citadel in Amman from Arce (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Congregational Mosque and Souq Square at Amman Citadel:

- General plan

- Elevation of the souq east portico.

- View to north of the souq east portico

- View of the blind arch on the western façade of the vestibule

Arce (2000)

- Fig. 1 - General plan of

the north part of the Amman citadel from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel.

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 1 - Congregational

Mosque and Souq Square on the Citadel in Amman from Arce (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Congregational Mosque and Souq Square at Amman Citadel:

- General plan

- Elevation of the souq east portico.

- View to north of the souq east portico

- View of the blind arch on the western façade of the vestibule

Arce (2000)

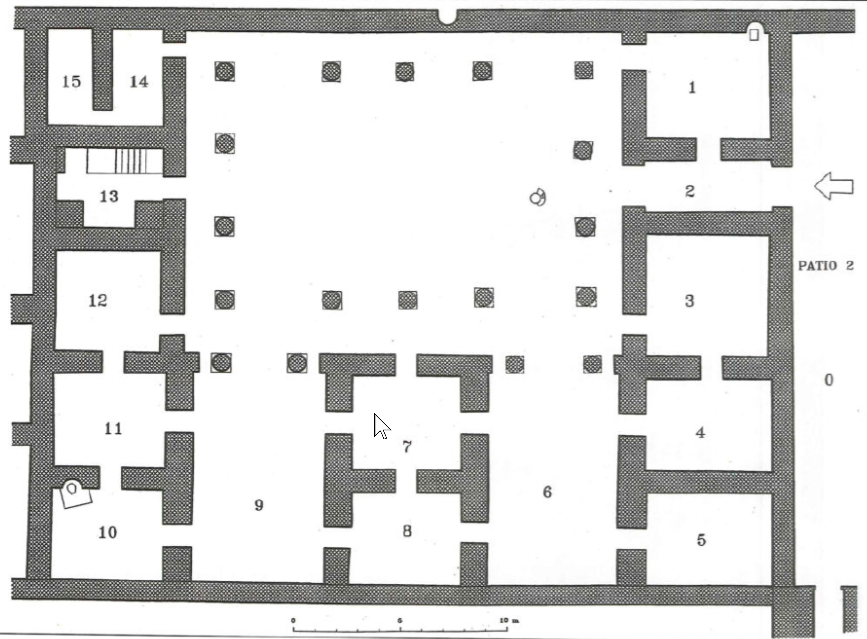

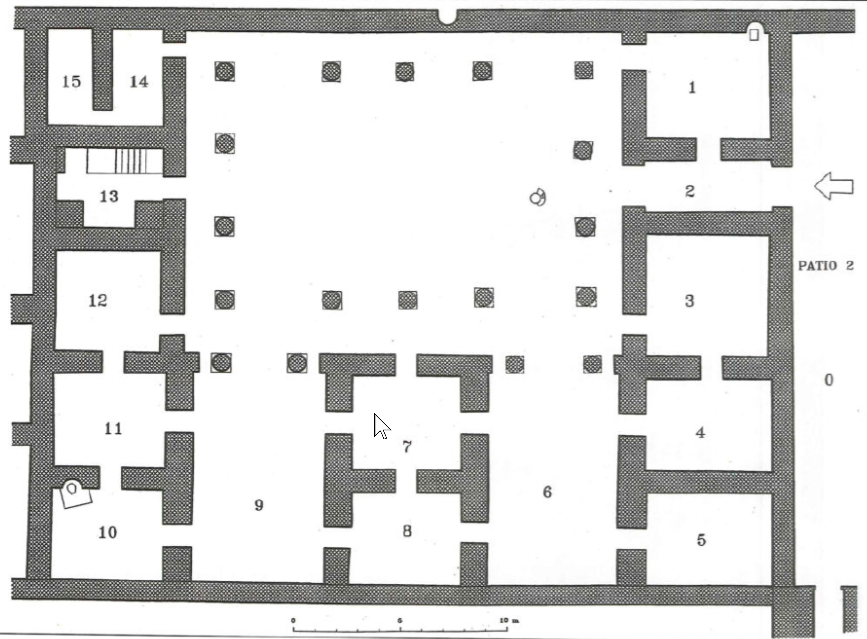

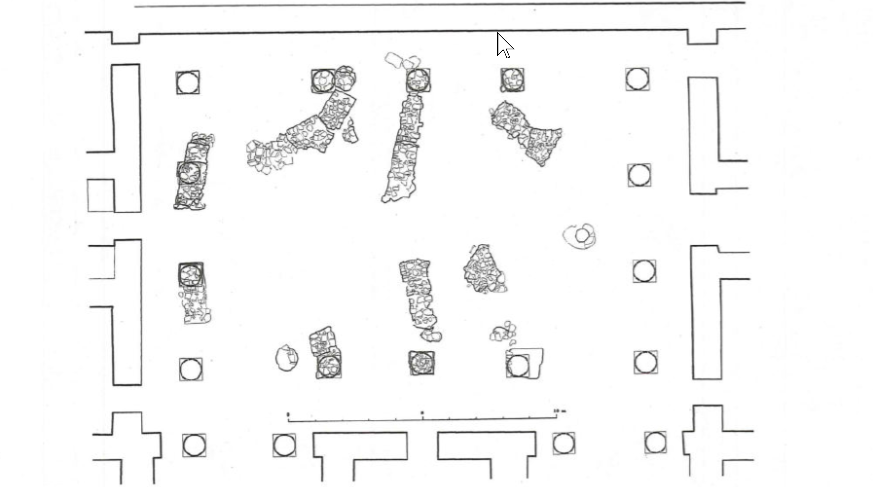

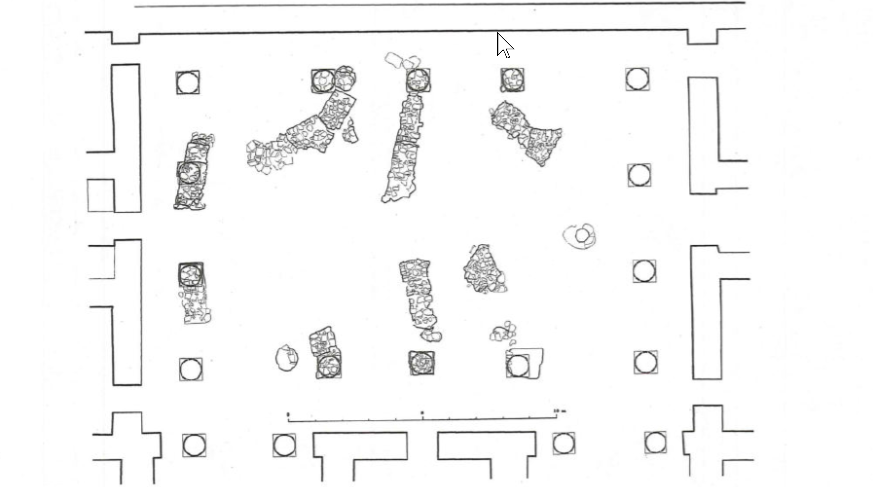

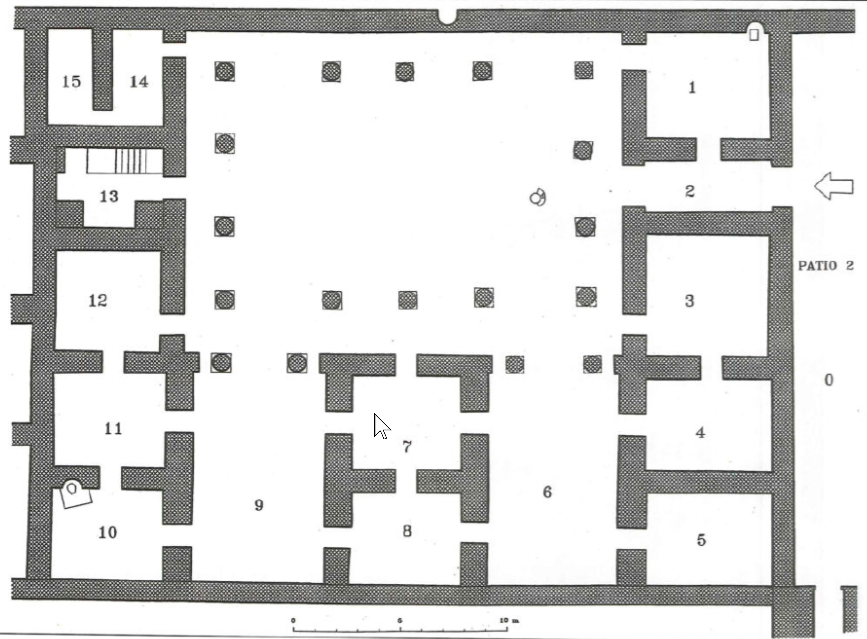

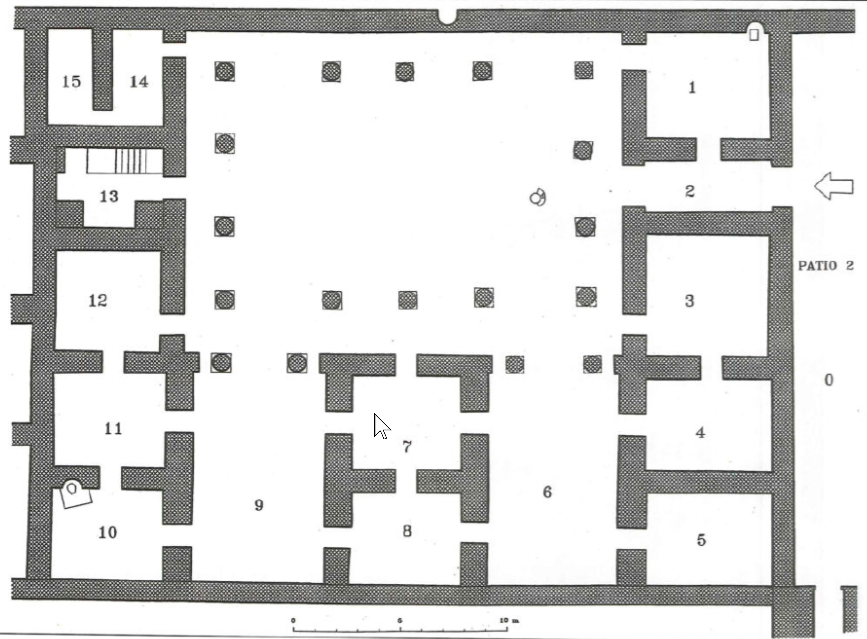

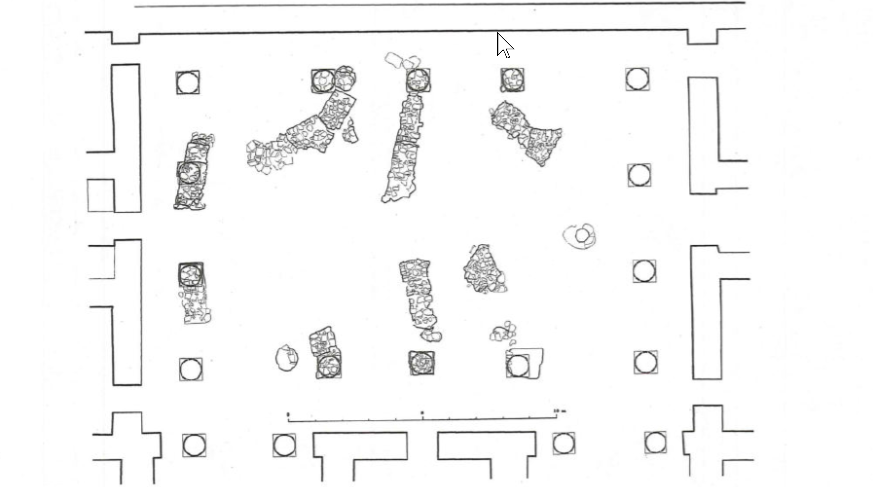

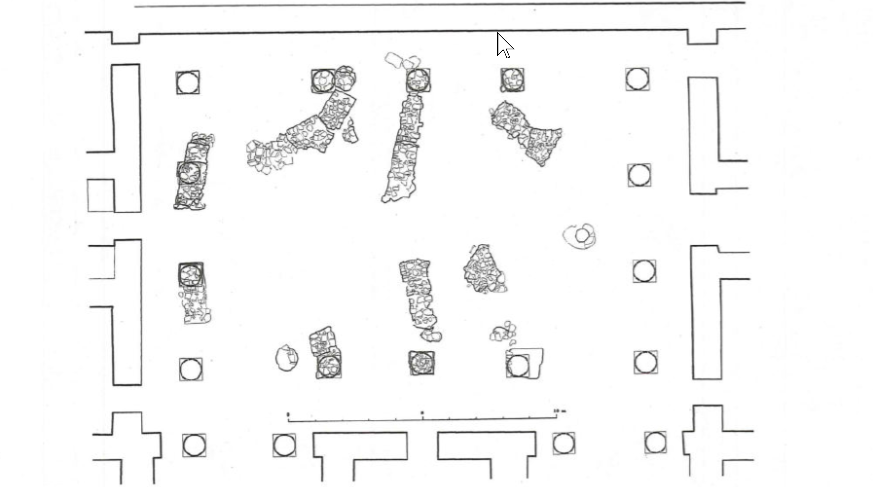

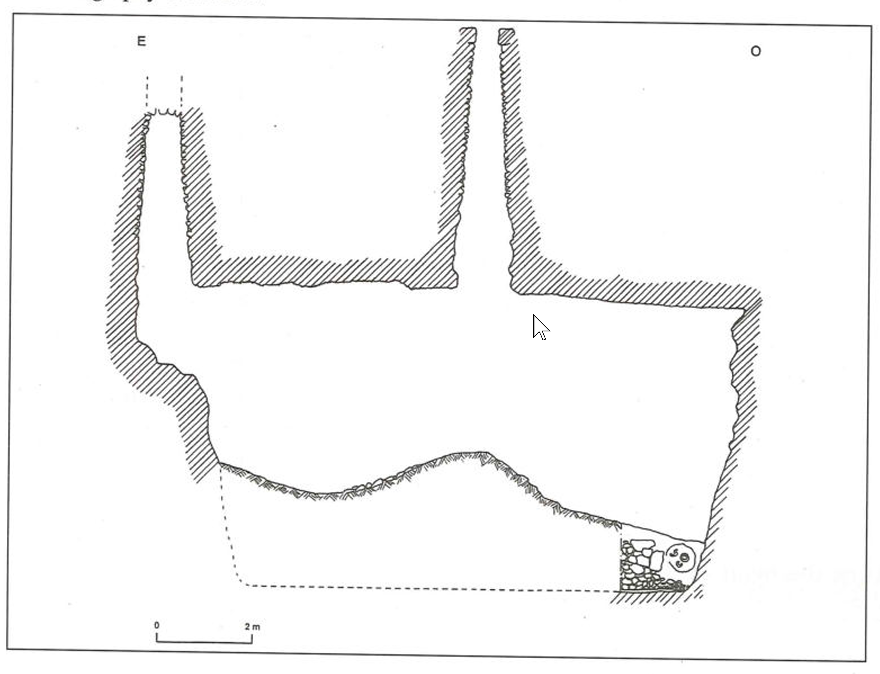

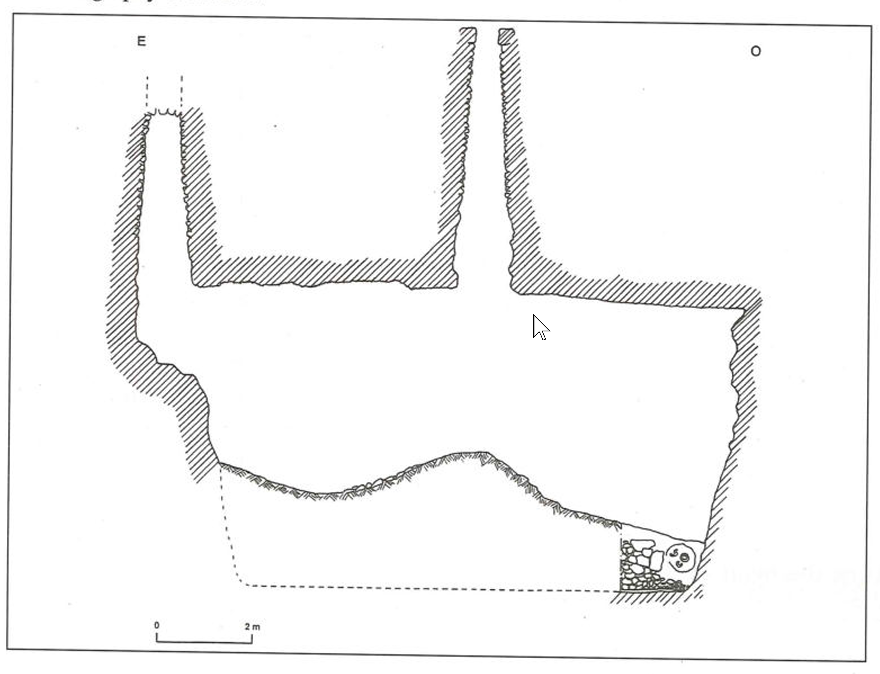

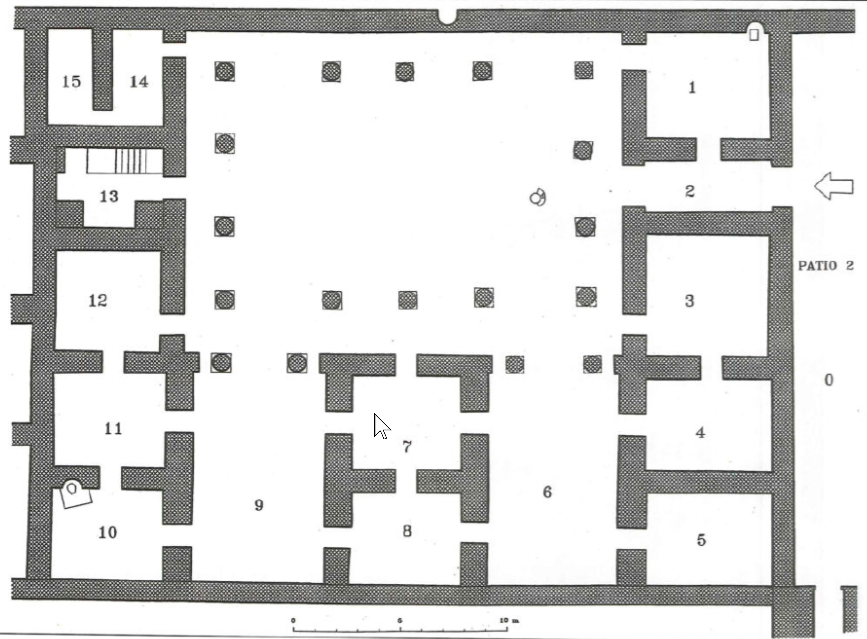

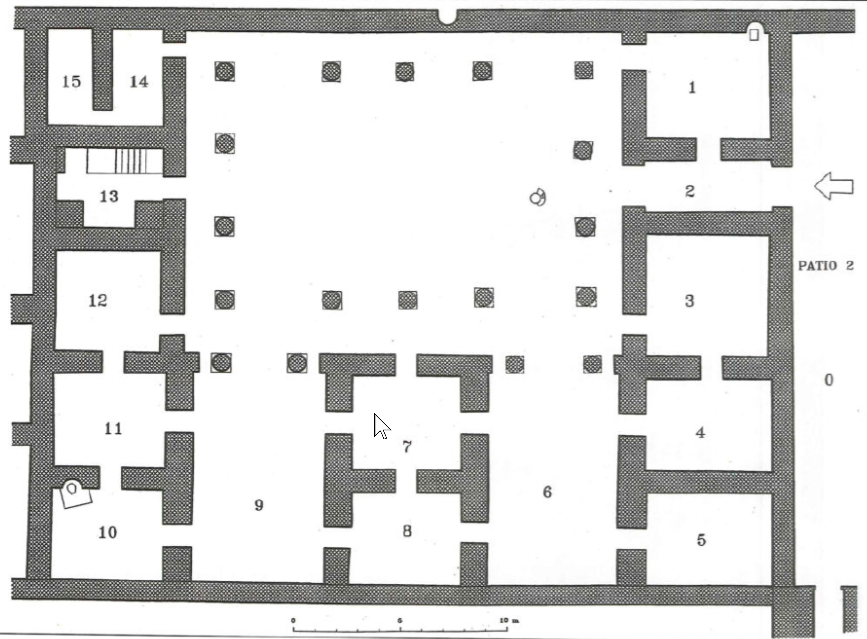

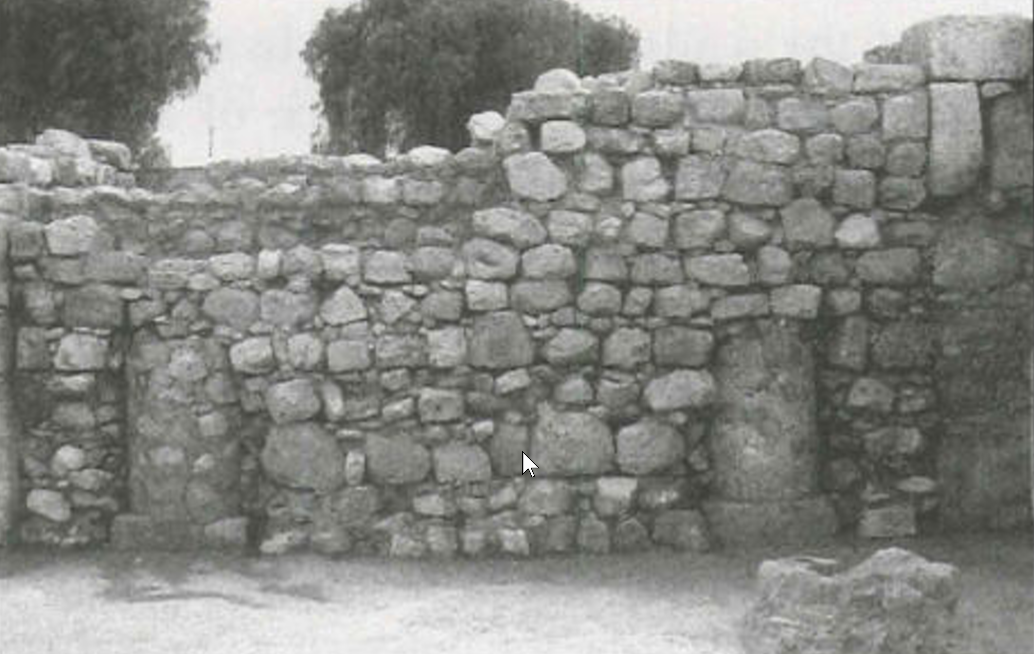

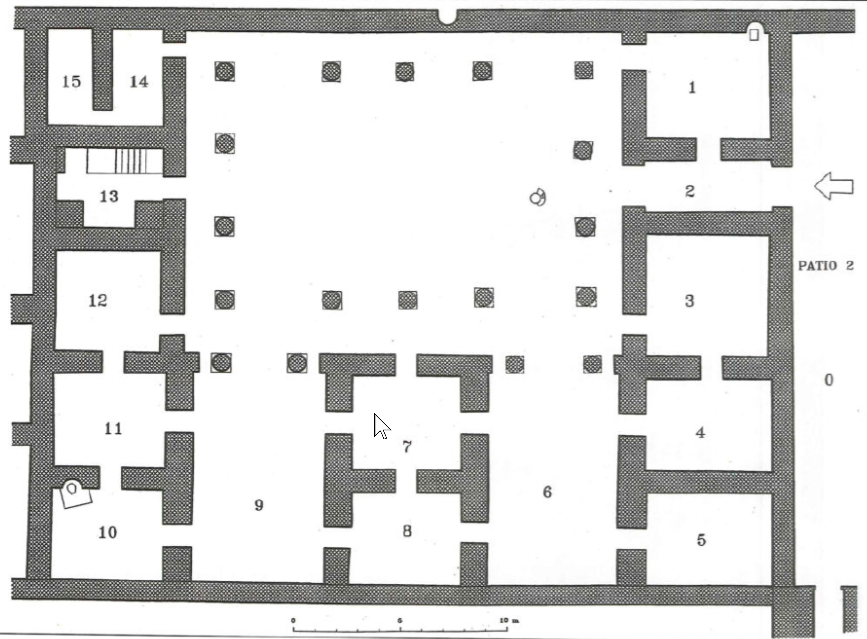

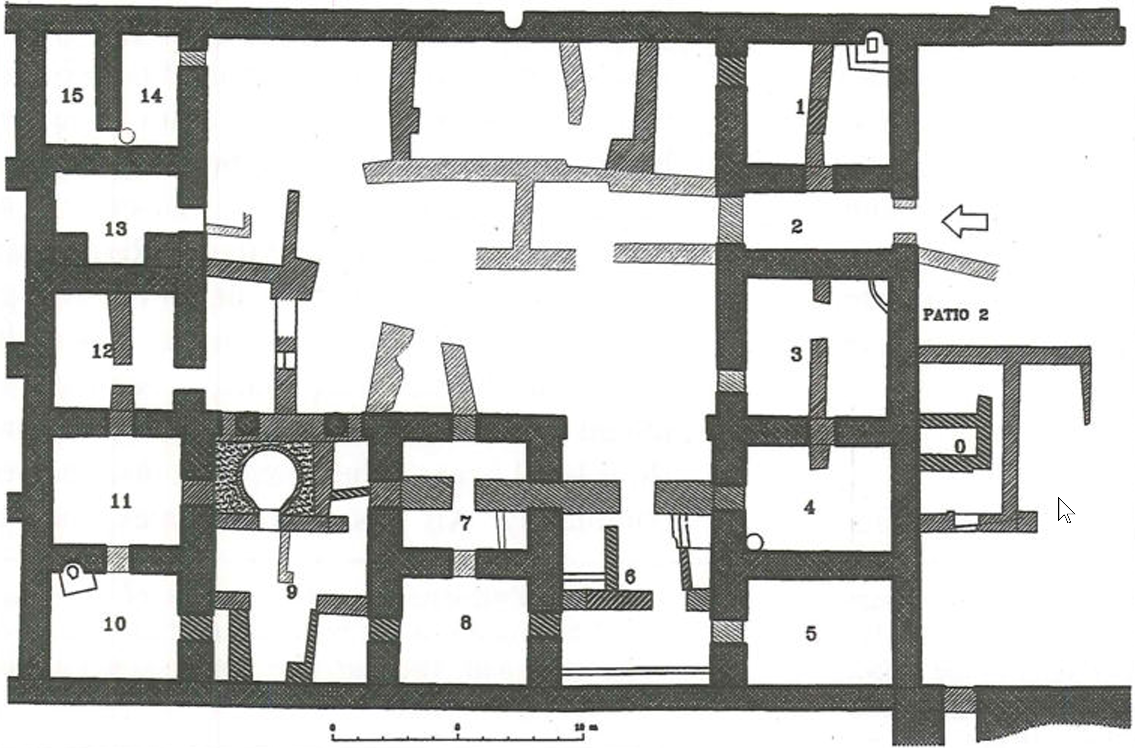

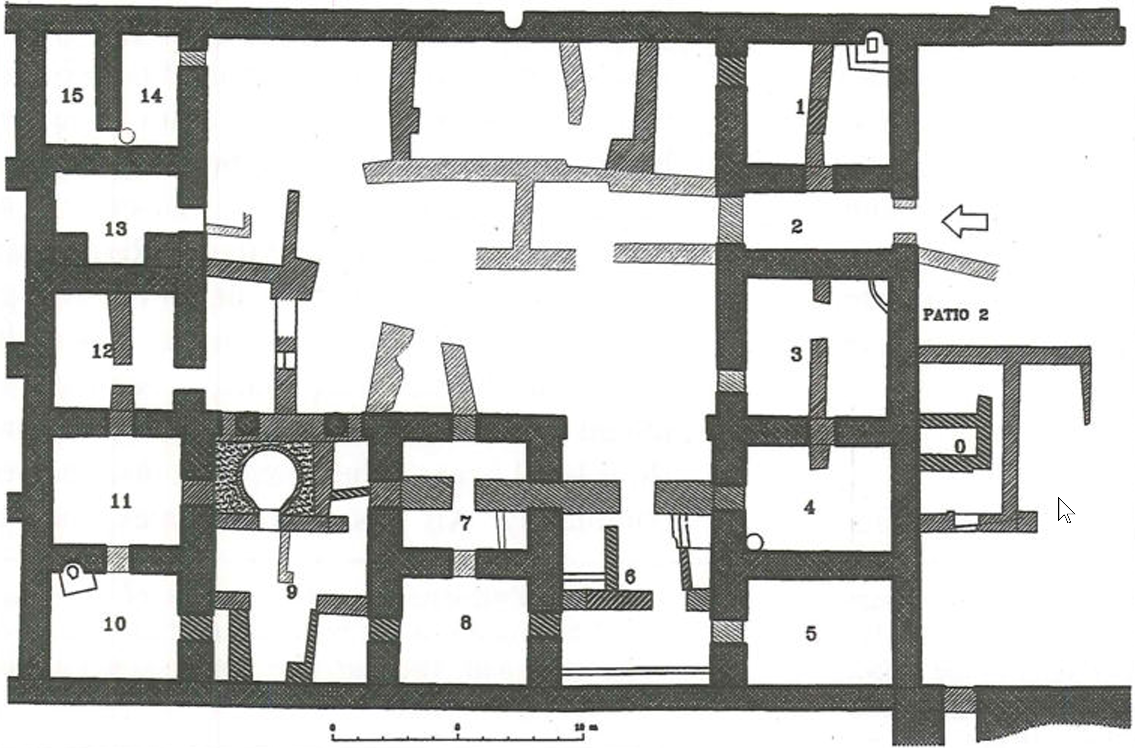

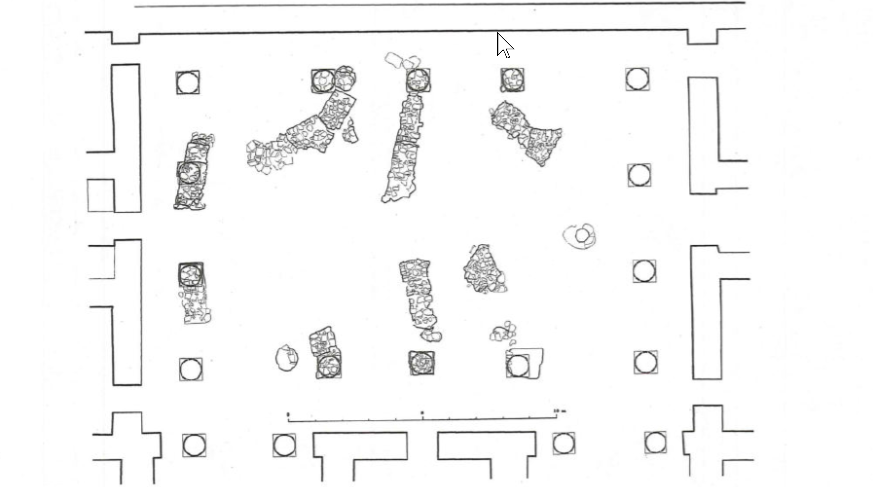

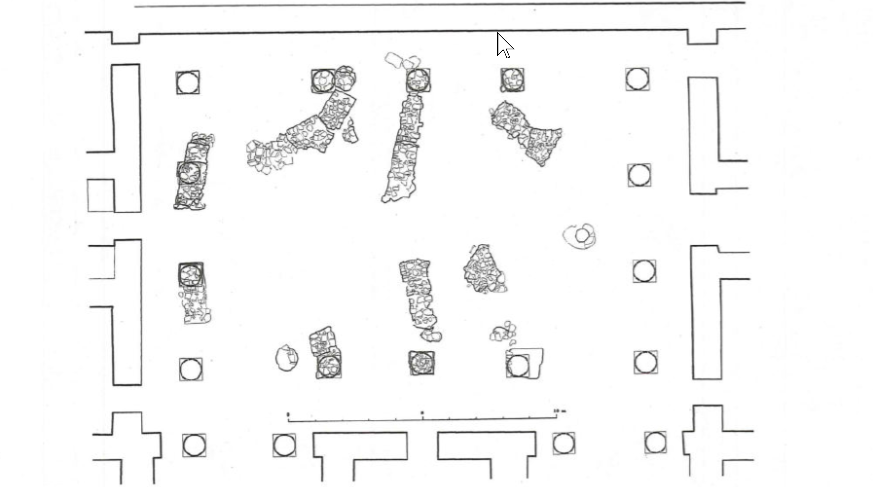

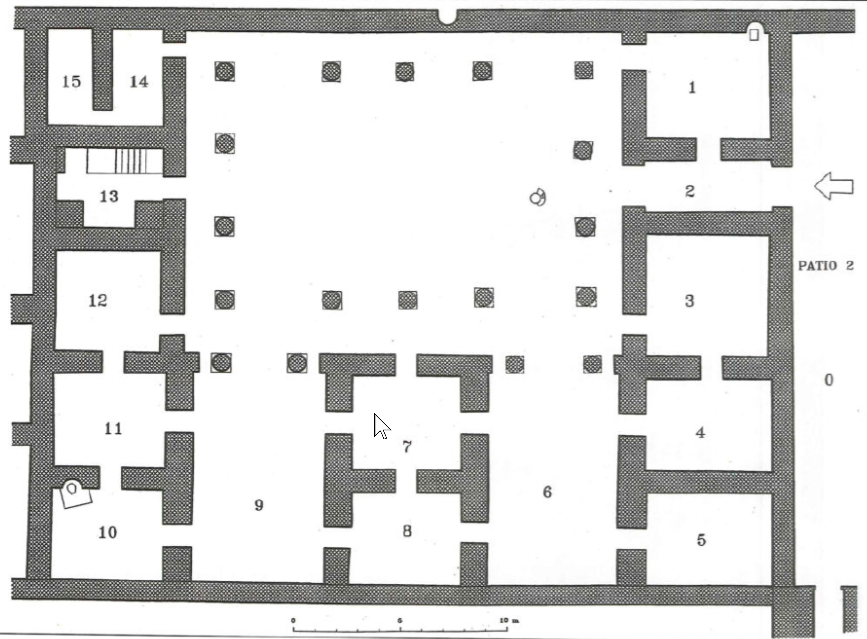

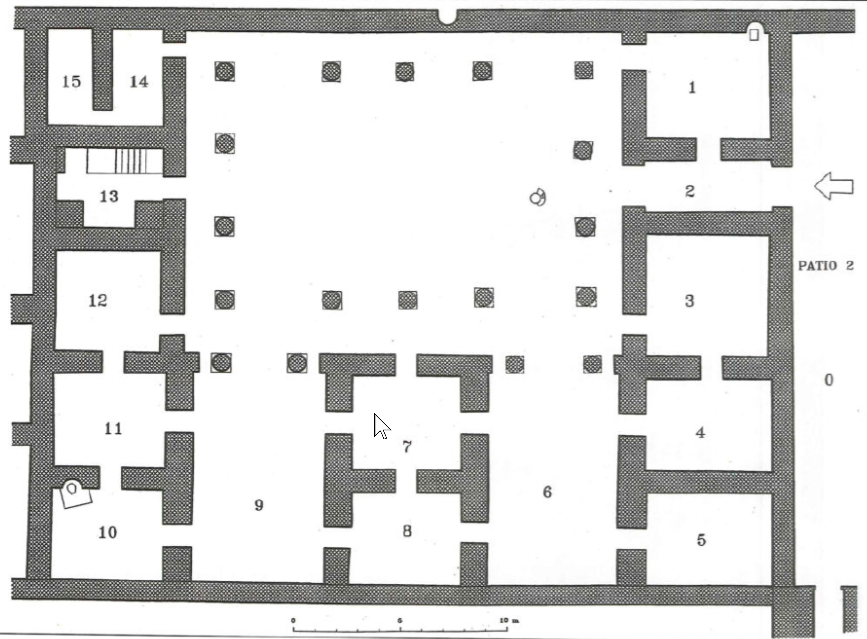

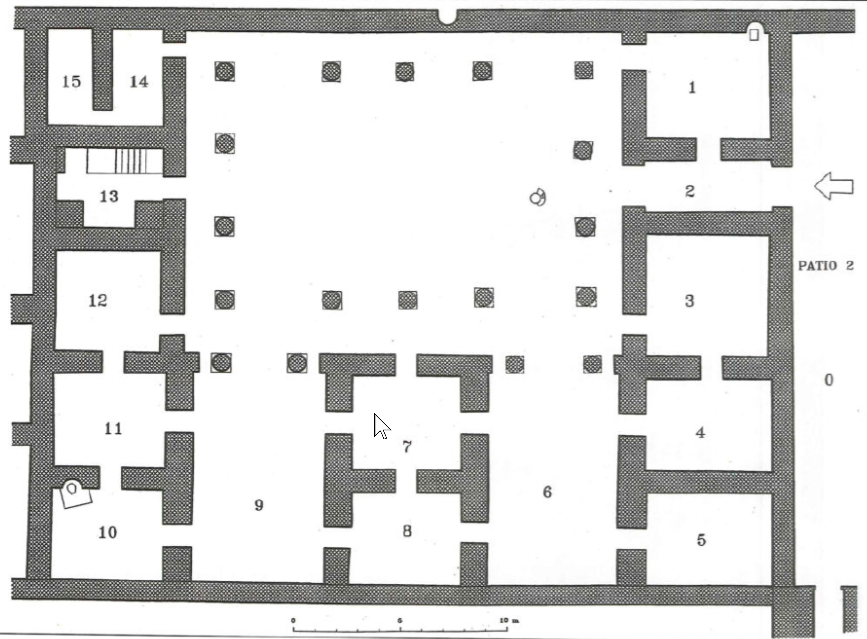

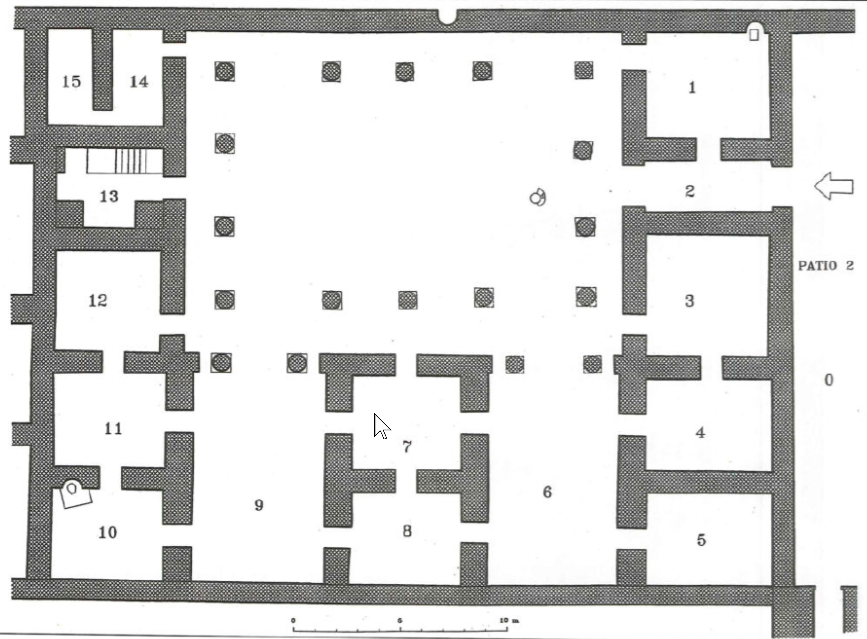

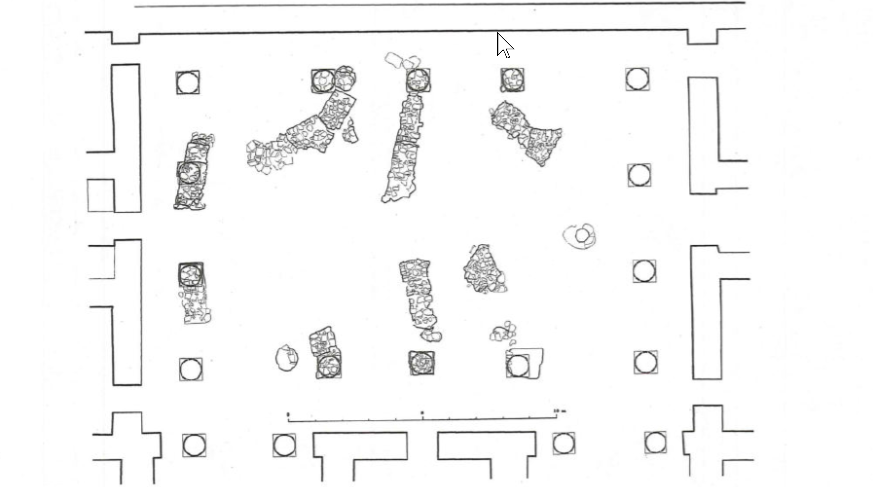

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Building F

from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of Building F

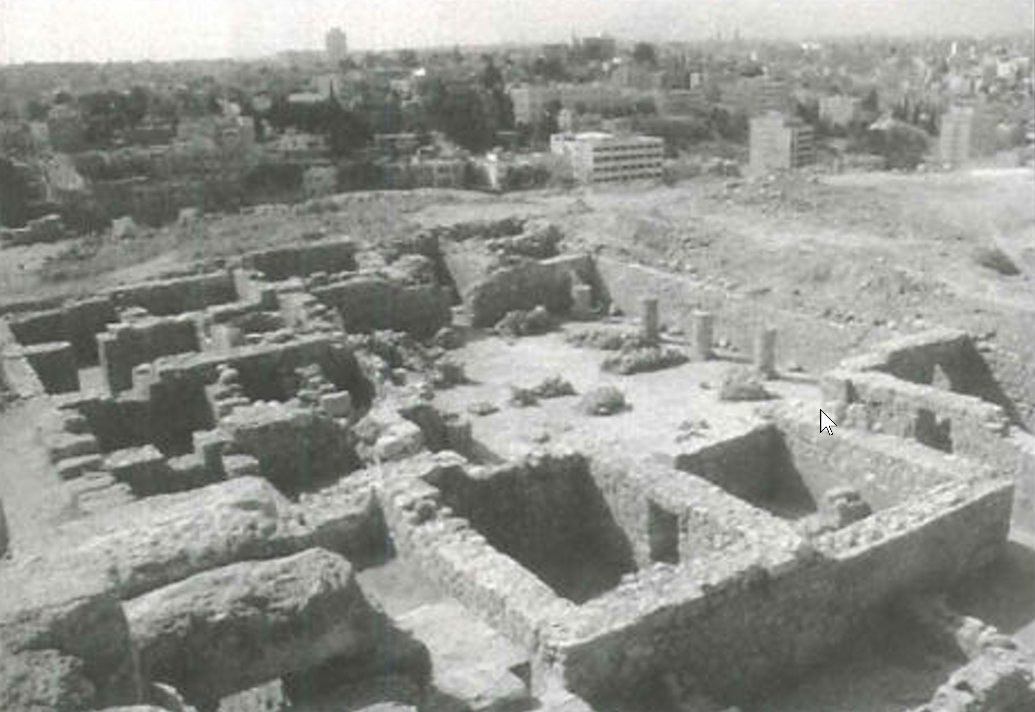

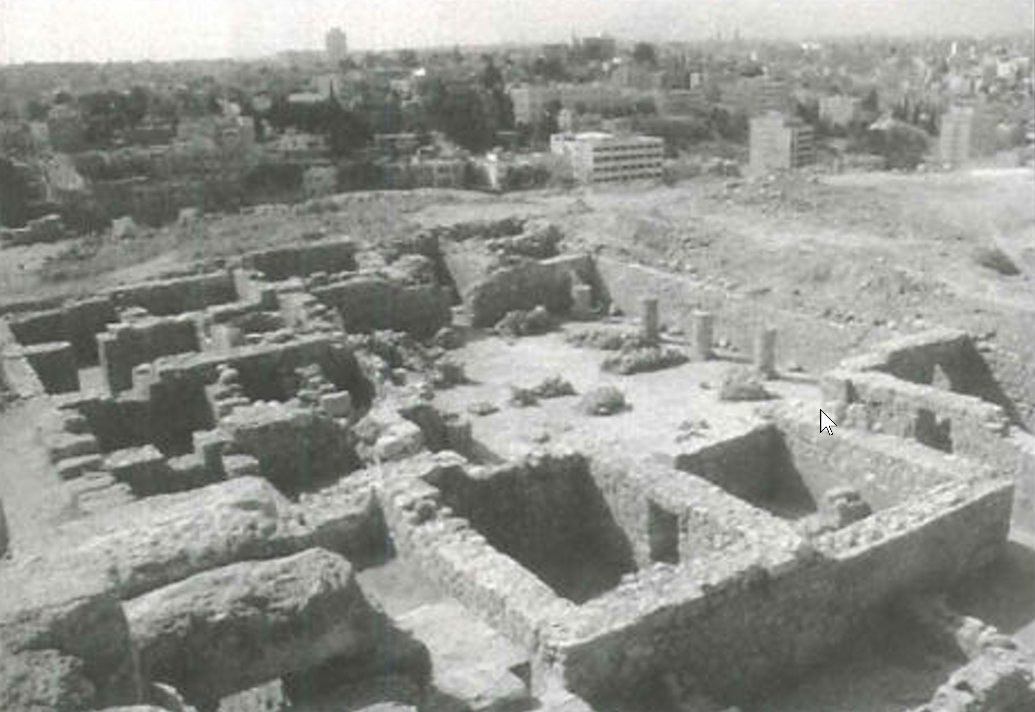

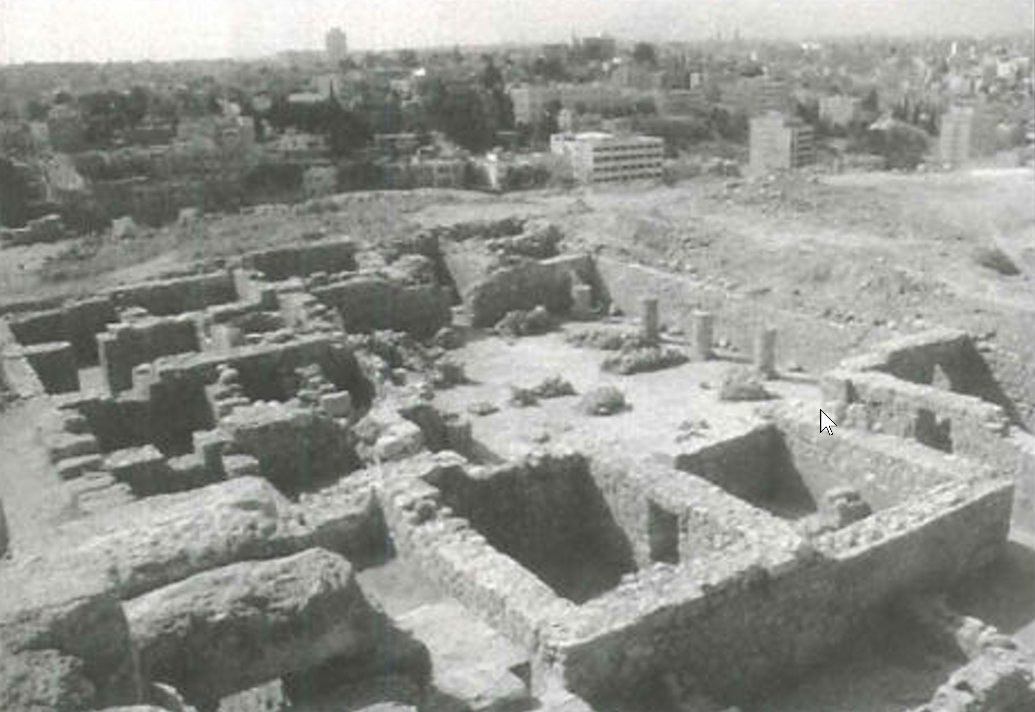

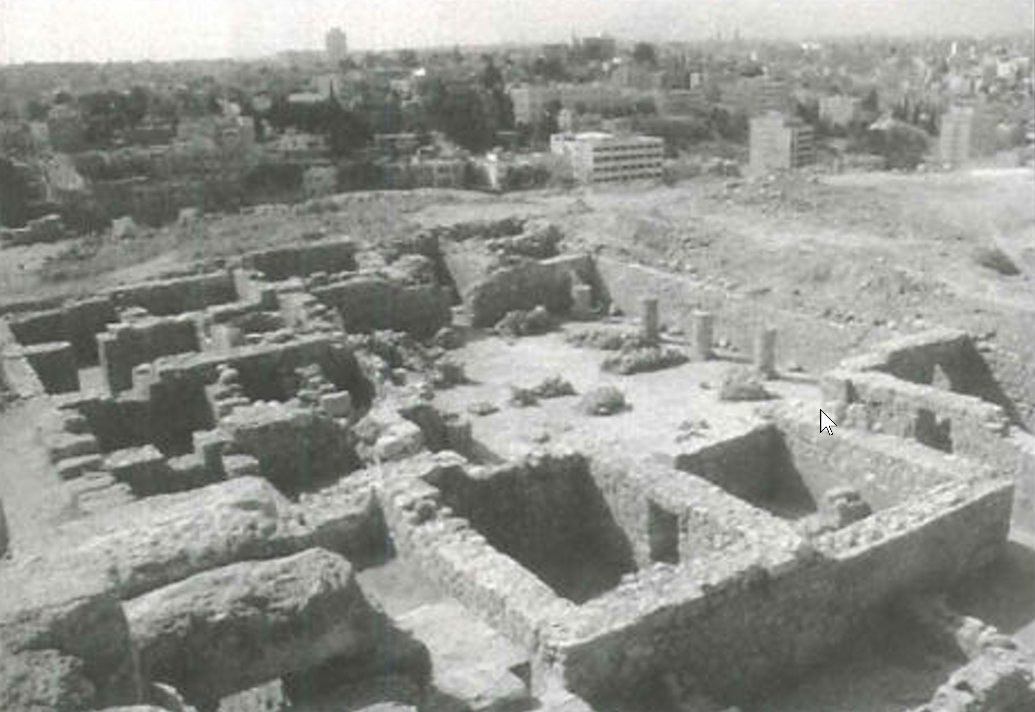

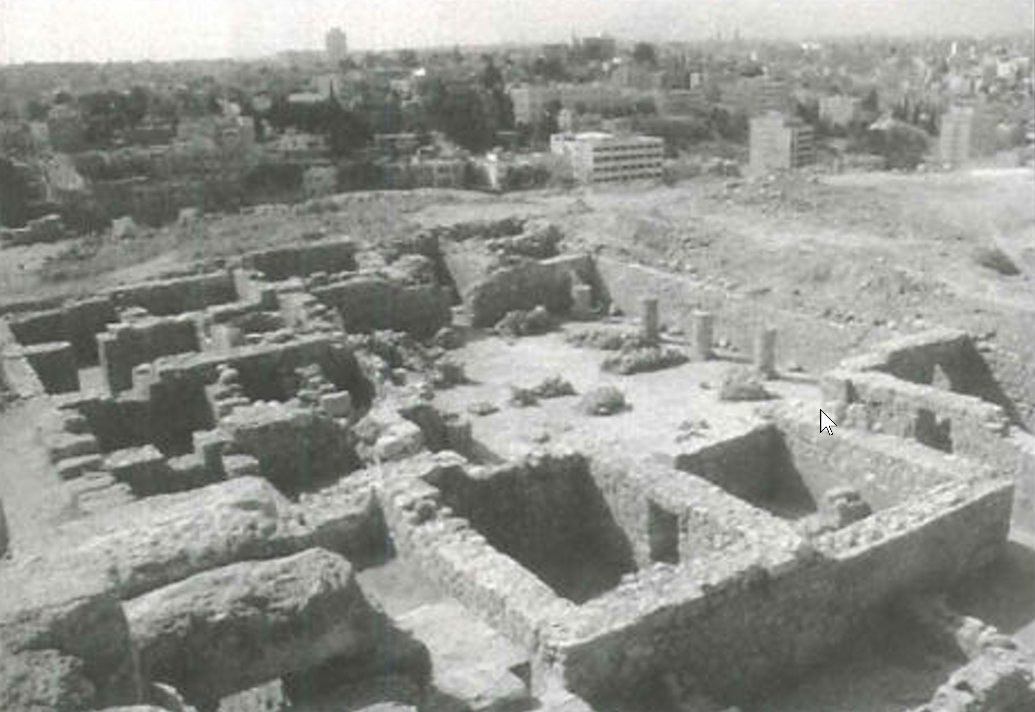

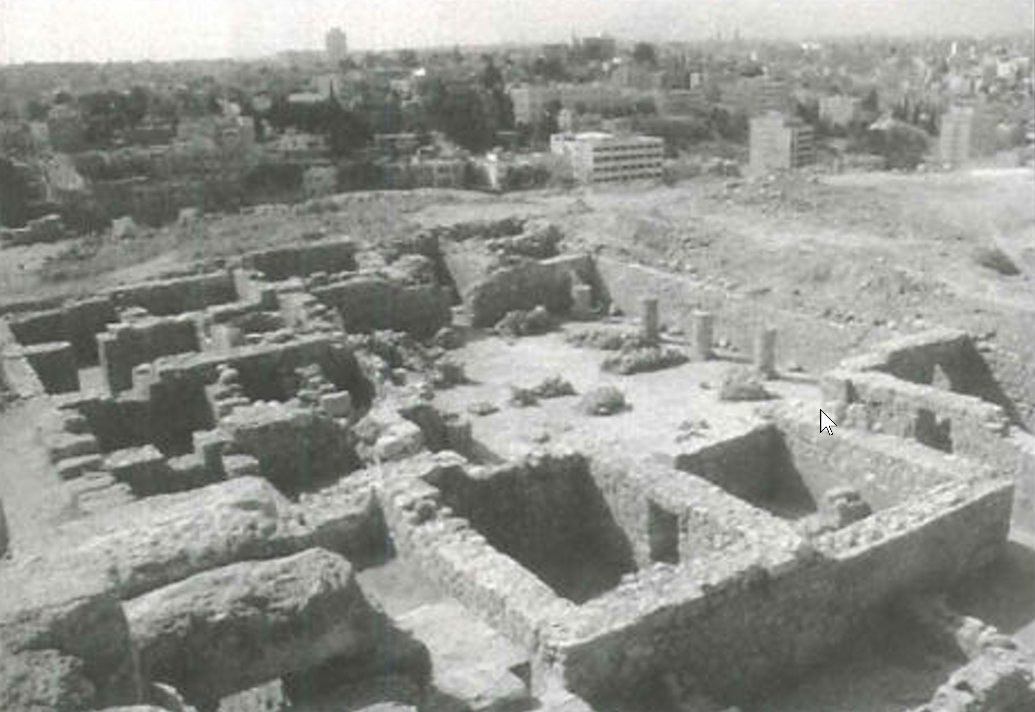

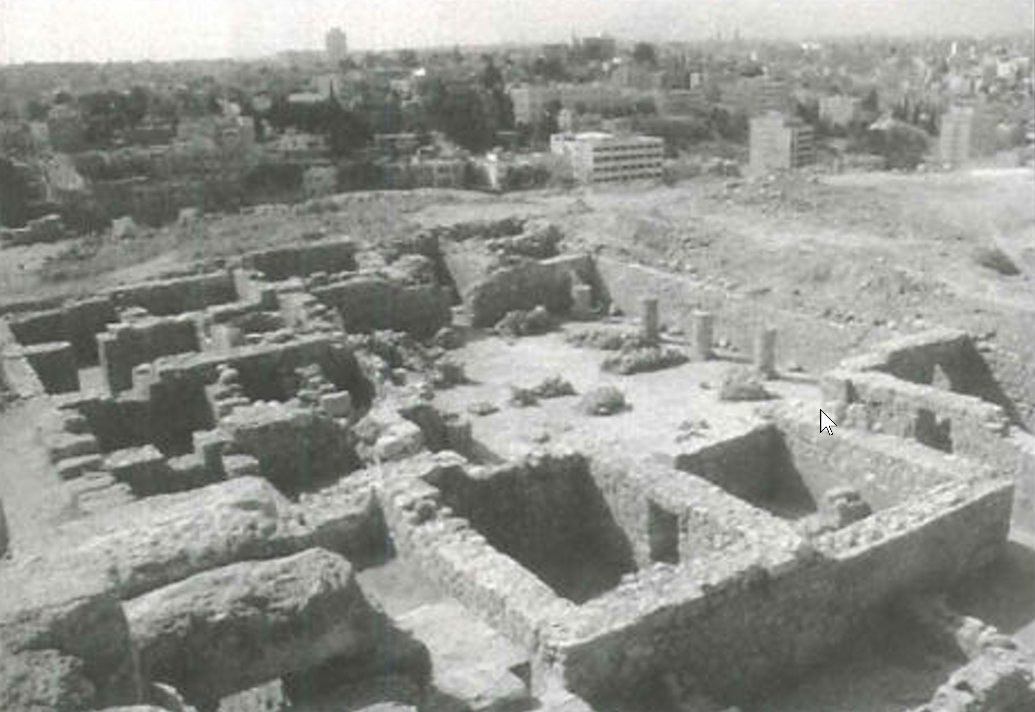

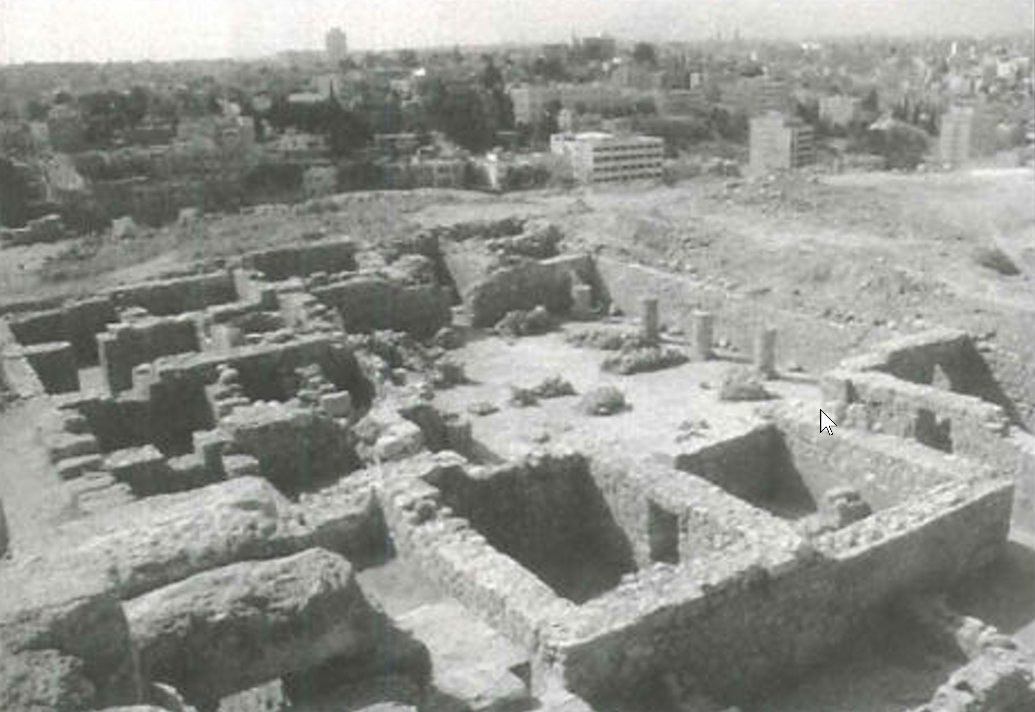

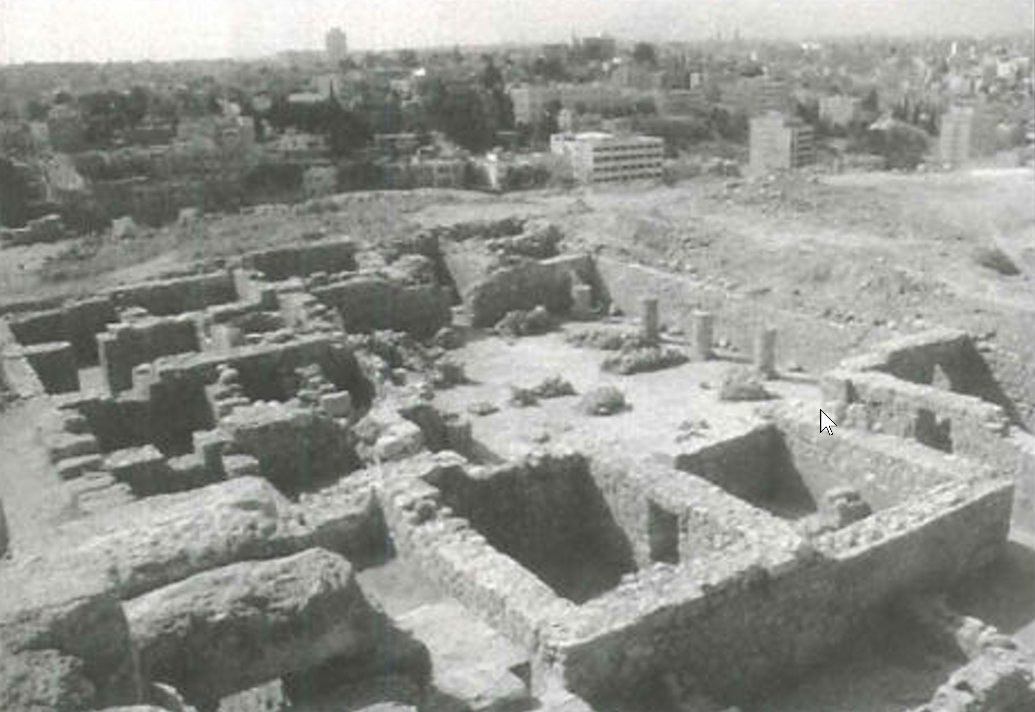

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View of

Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome

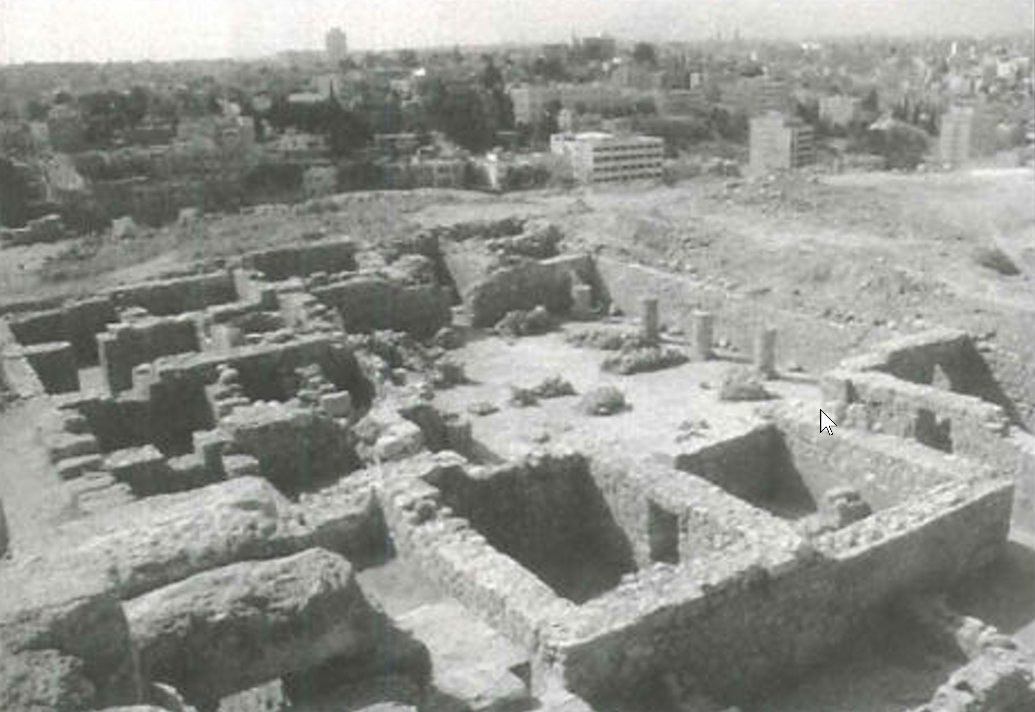

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 5 - Aerial View of

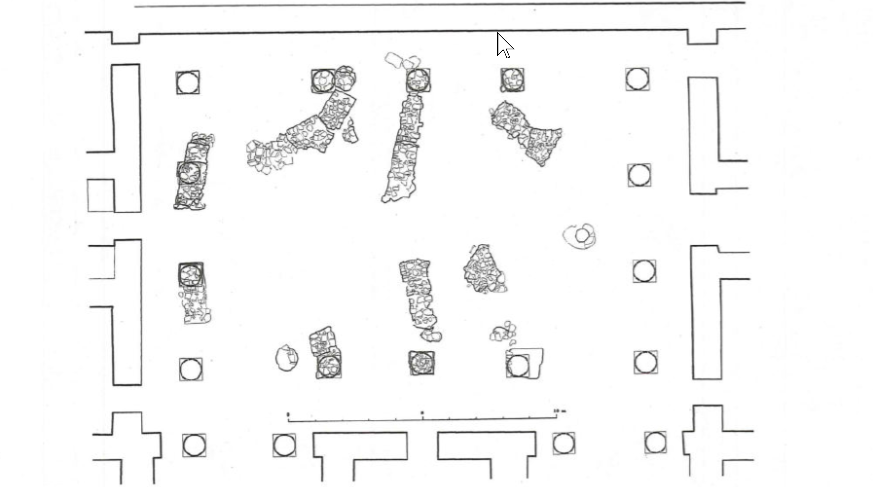

Building F and the courtyard with remains of columns and arches from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches

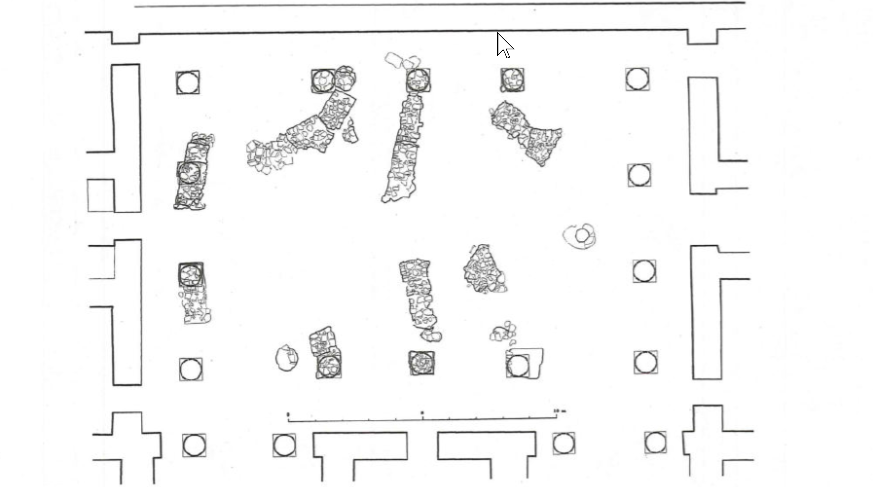

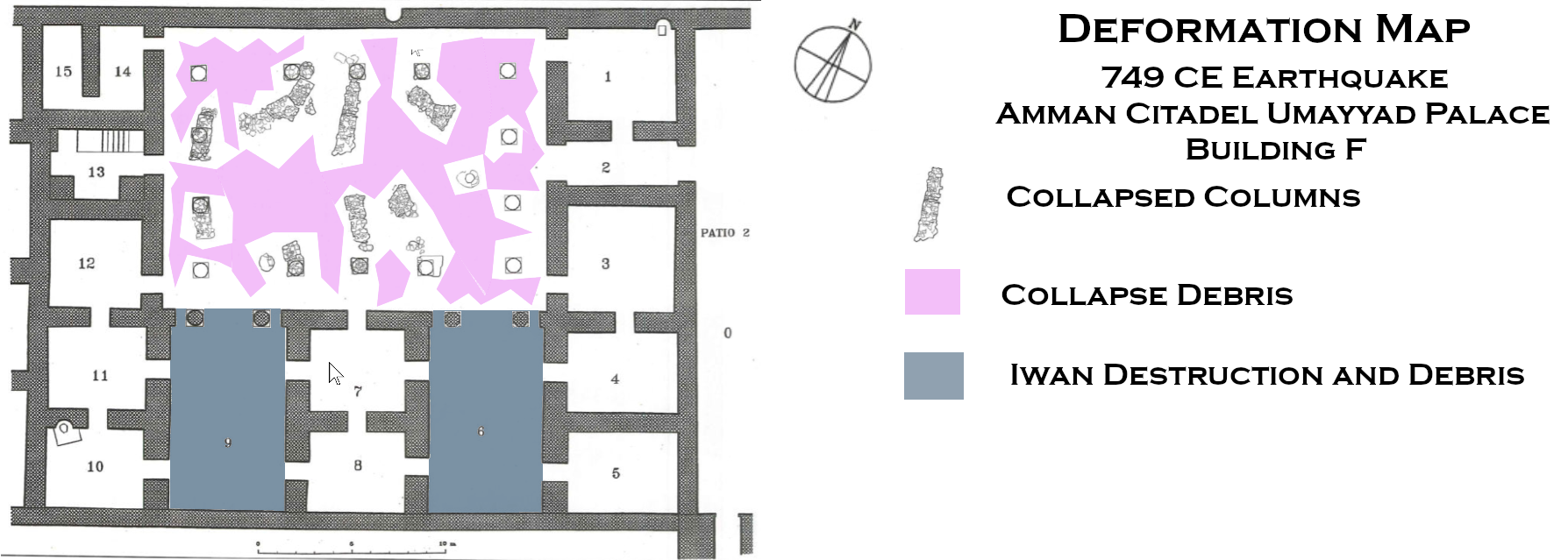

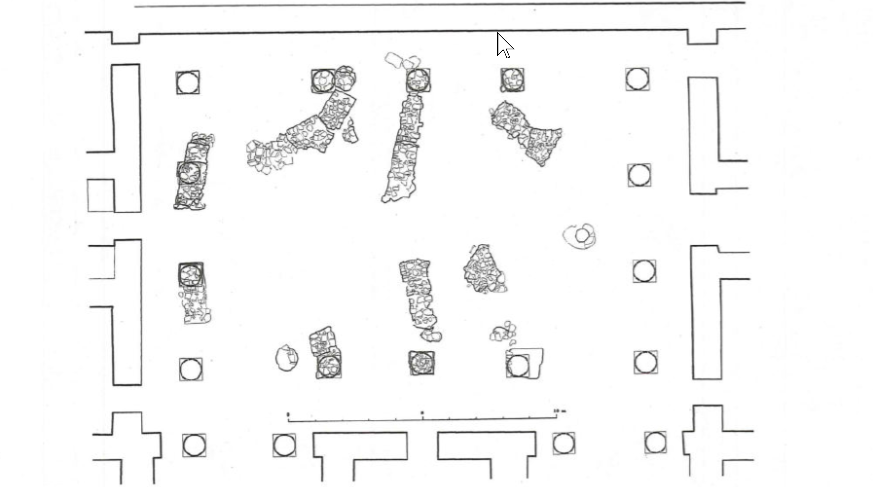

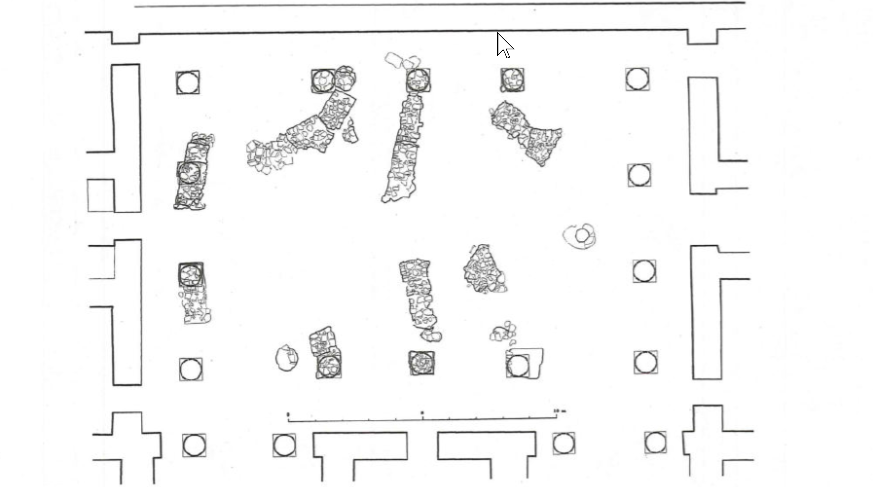

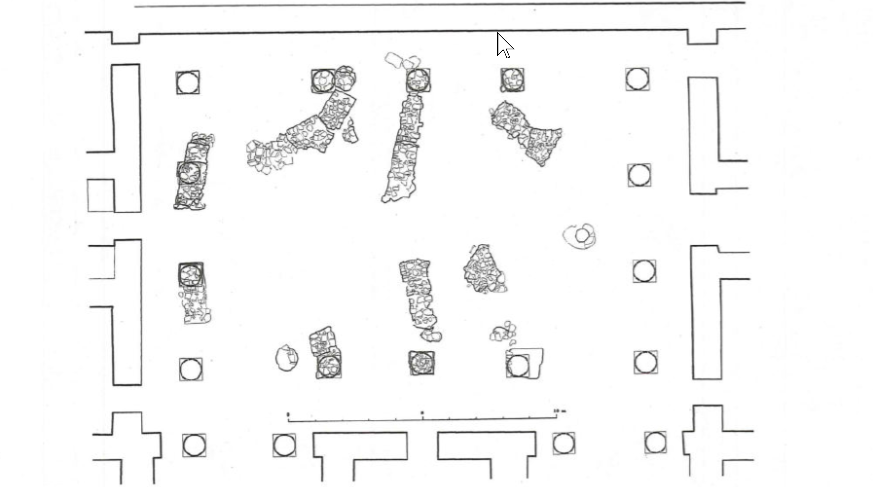

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 6 - Plan of remains

of columns and arches in the courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F

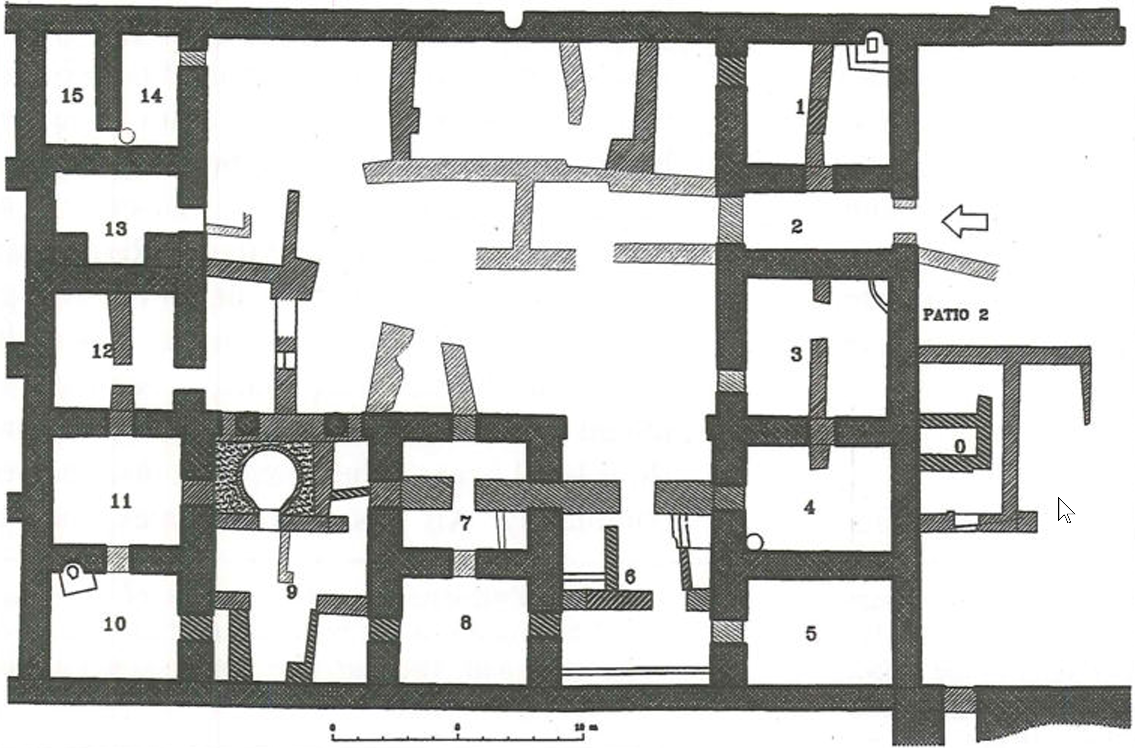

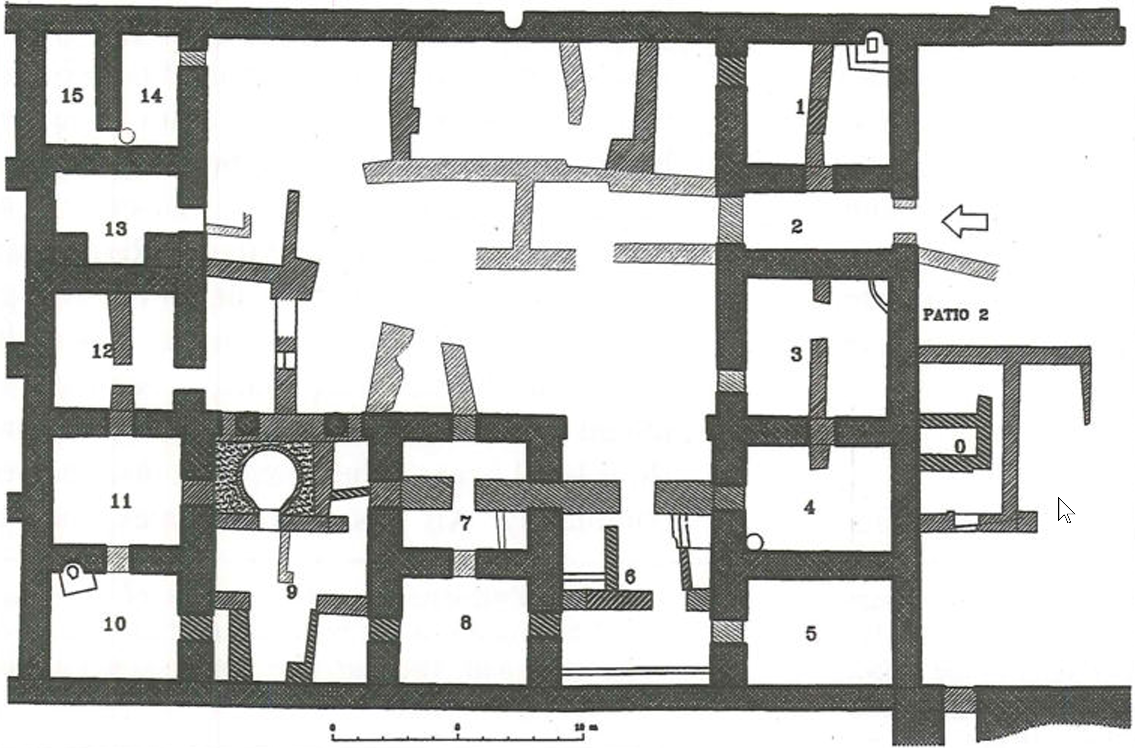

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 12 - Late structures

in building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Late structures in building F

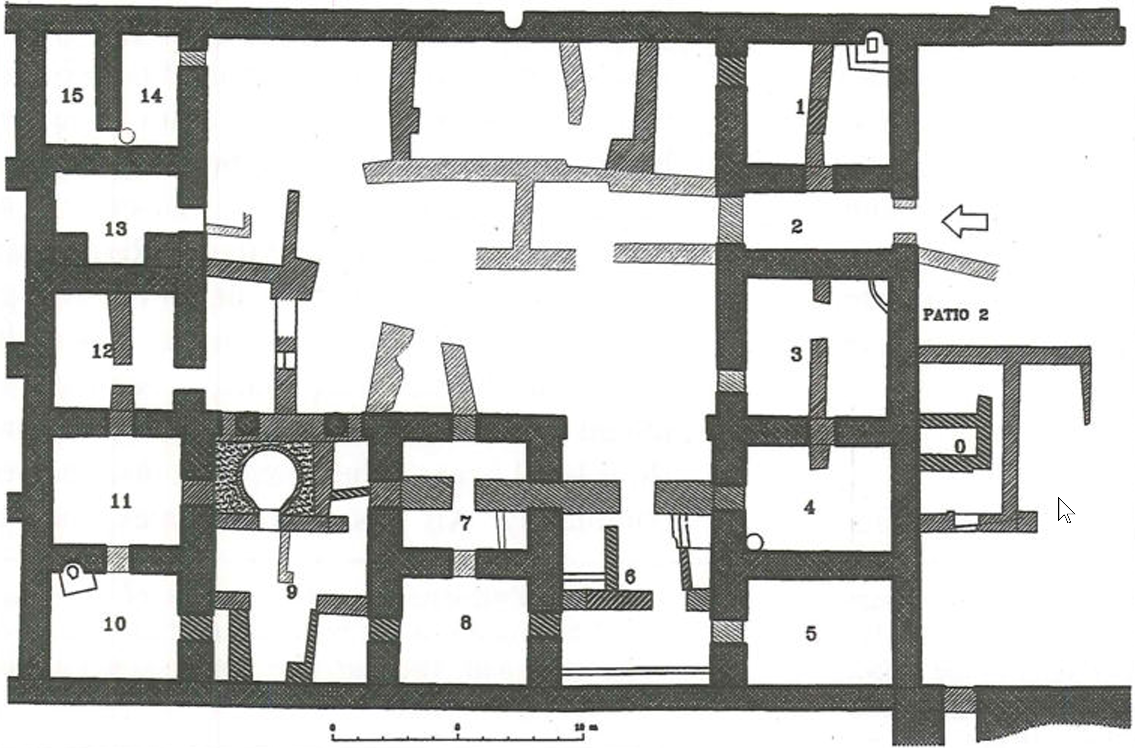

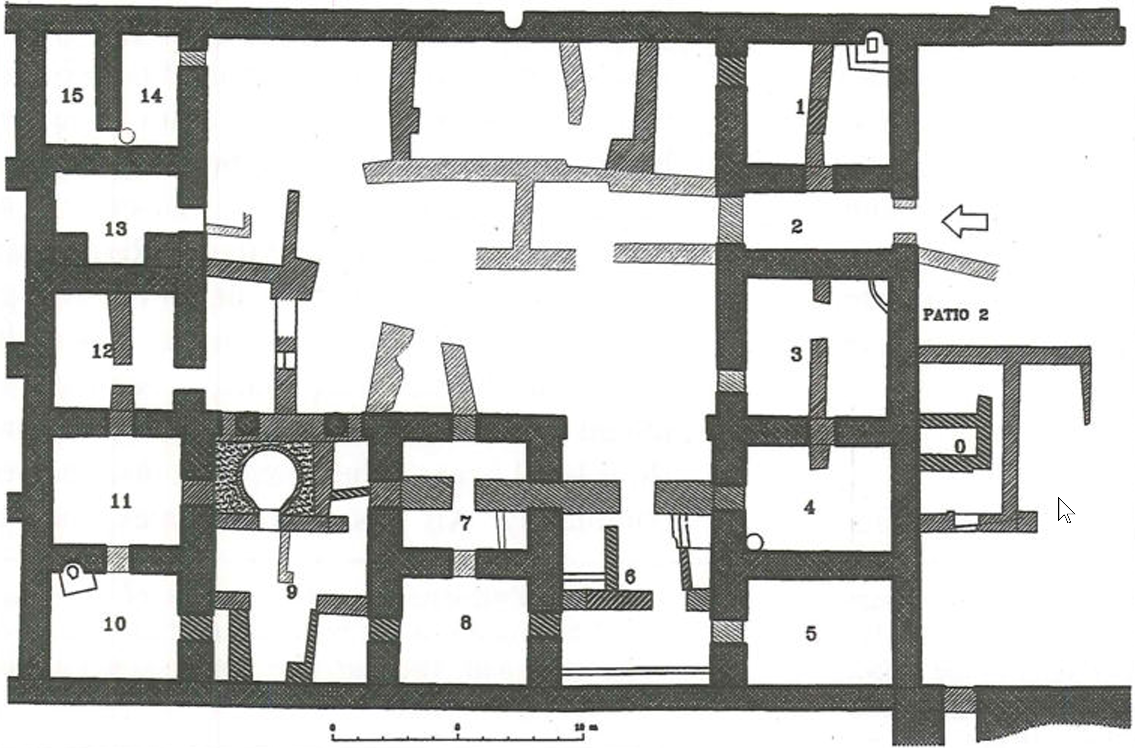

Alamgro et al (2000) - Early and Late structures

in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Sign at Amman Citadel

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Building F

from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of Building F

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View of

Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 5 - Aerial View of

Building F and the courtyard with remains of columns and arches from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 6 - Plan of remains

of columns and arches in the courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 12 - Late structures

in building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Late structures in building F

Alamgro et al (2000) - Early and Late structures

in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Sign at Amman Citadel

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

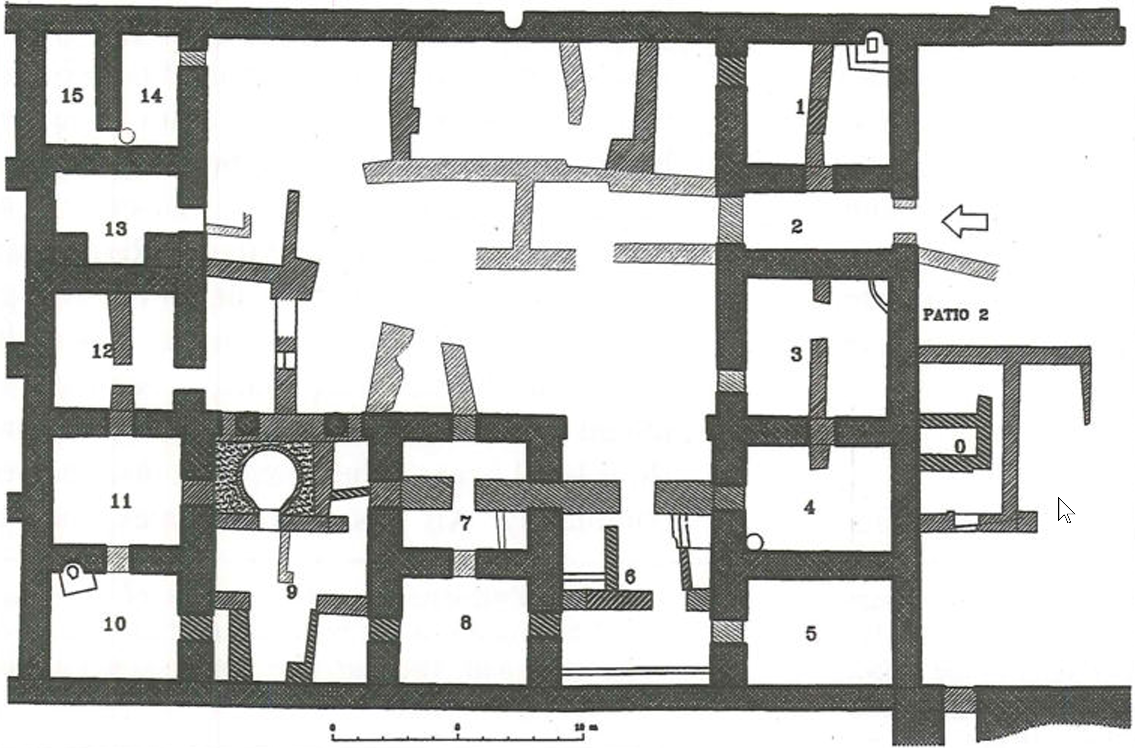

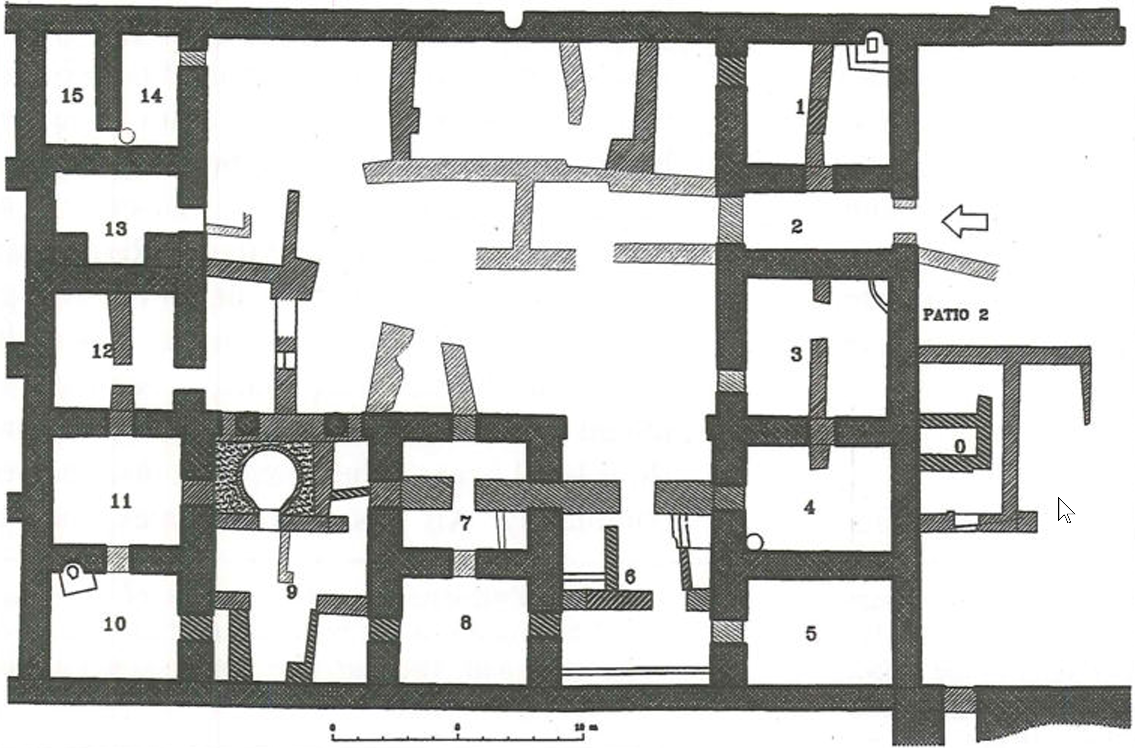

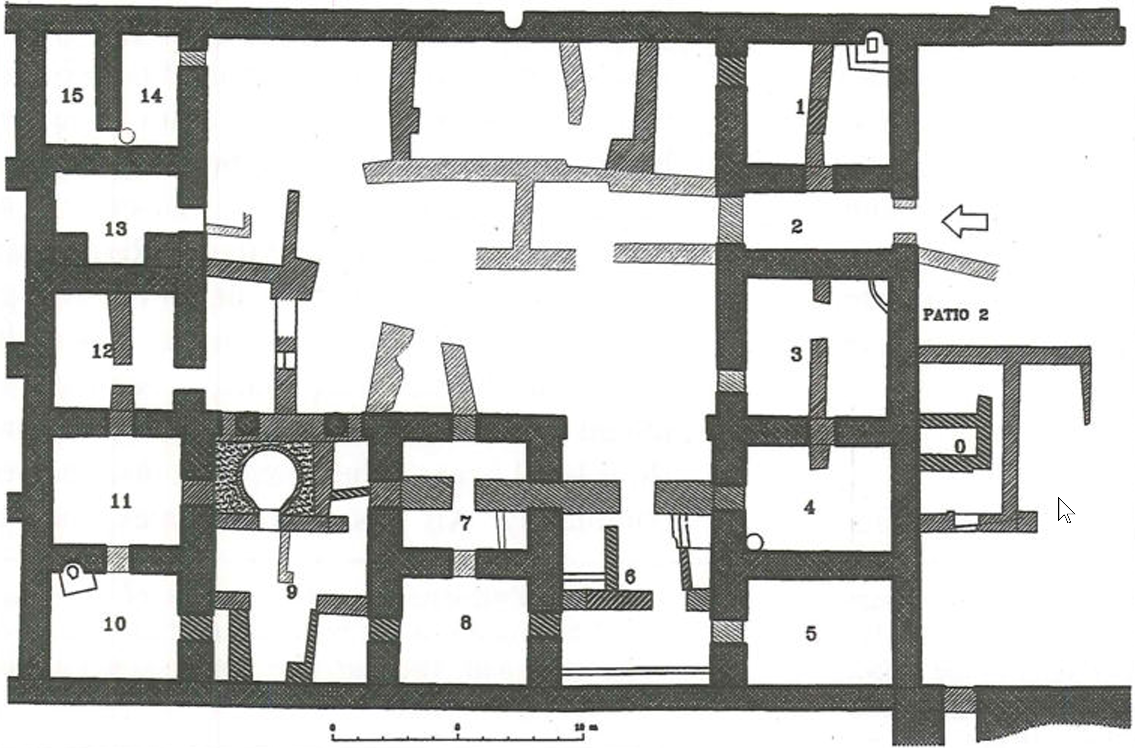

- Fig. 1 - Plan from

Harding (1951)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Harding (1951)

- Fig. 1 - Plan from

Harding (1951)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Harding (1951)

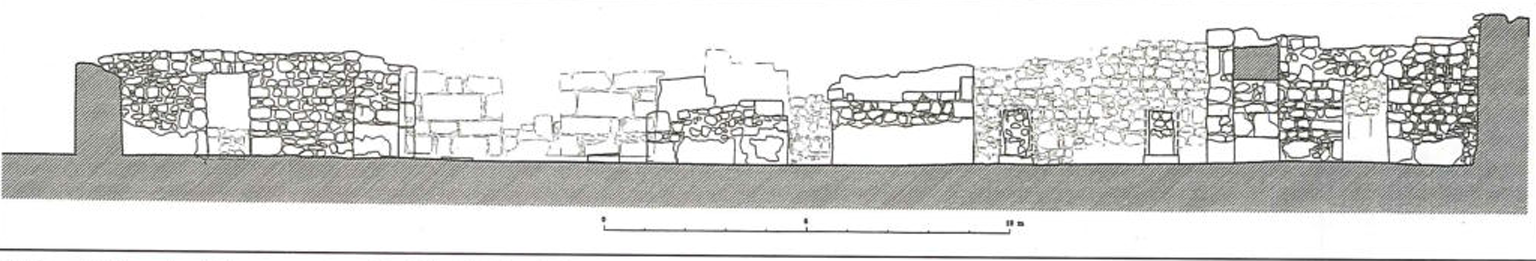

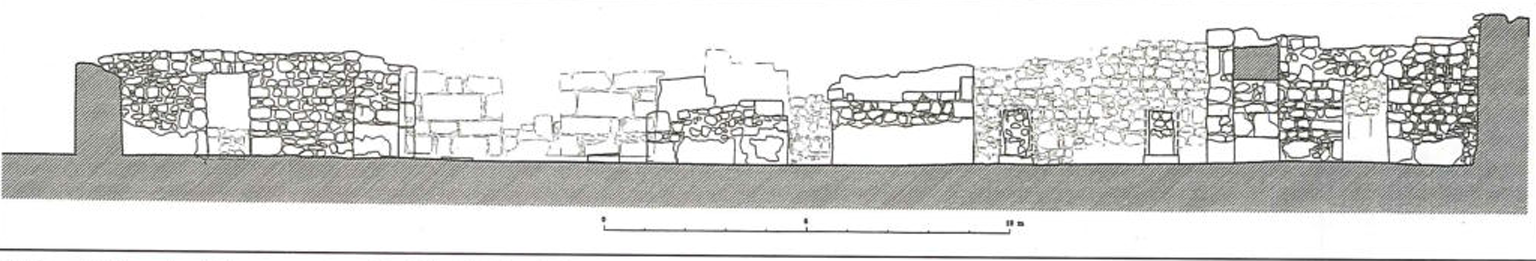

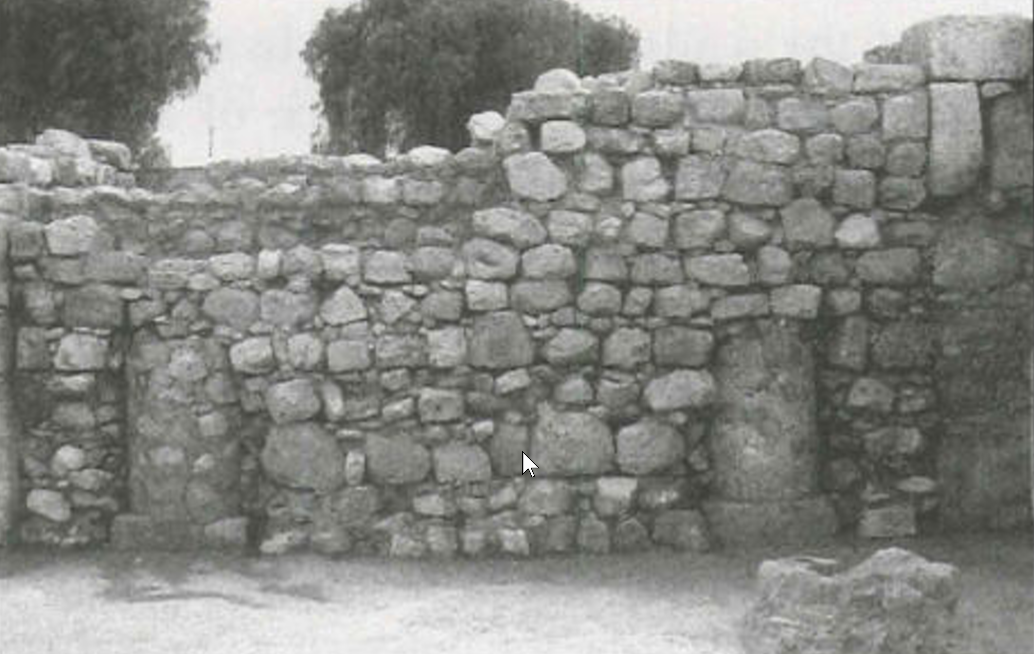

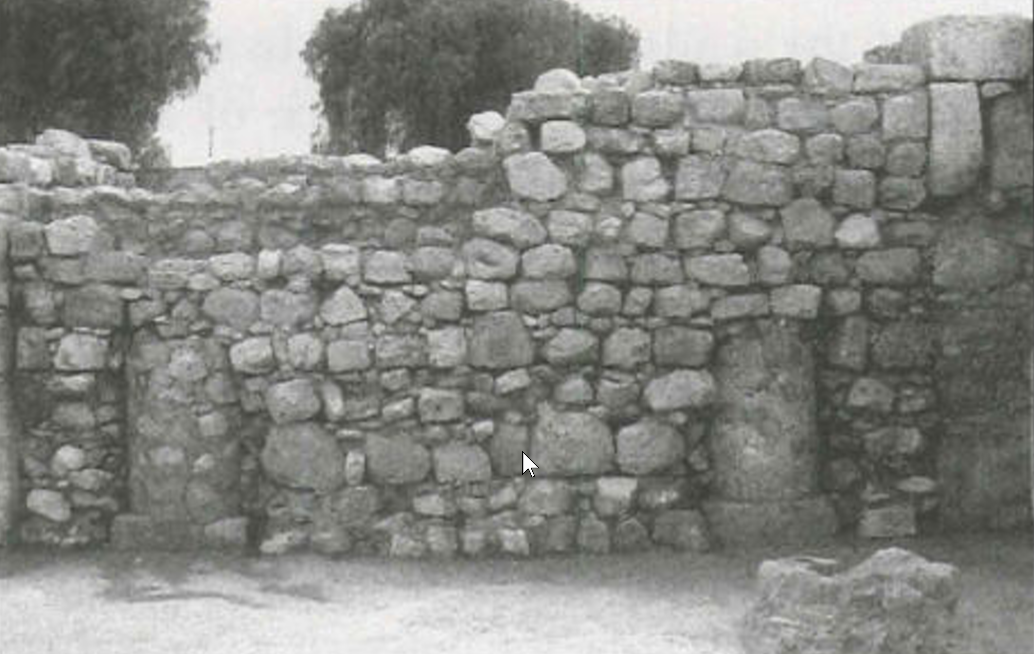

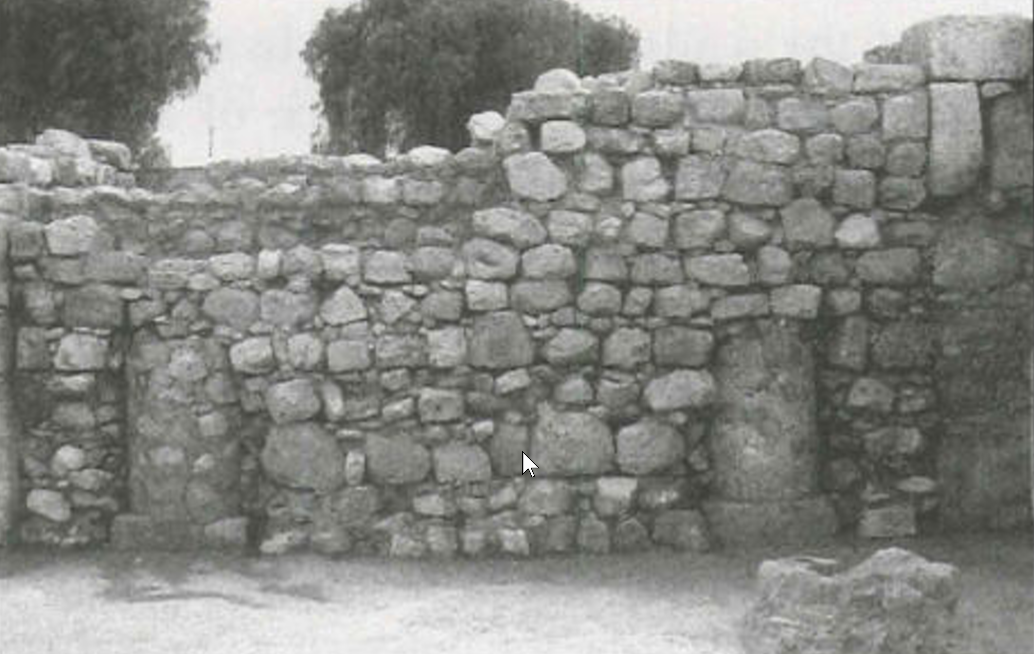

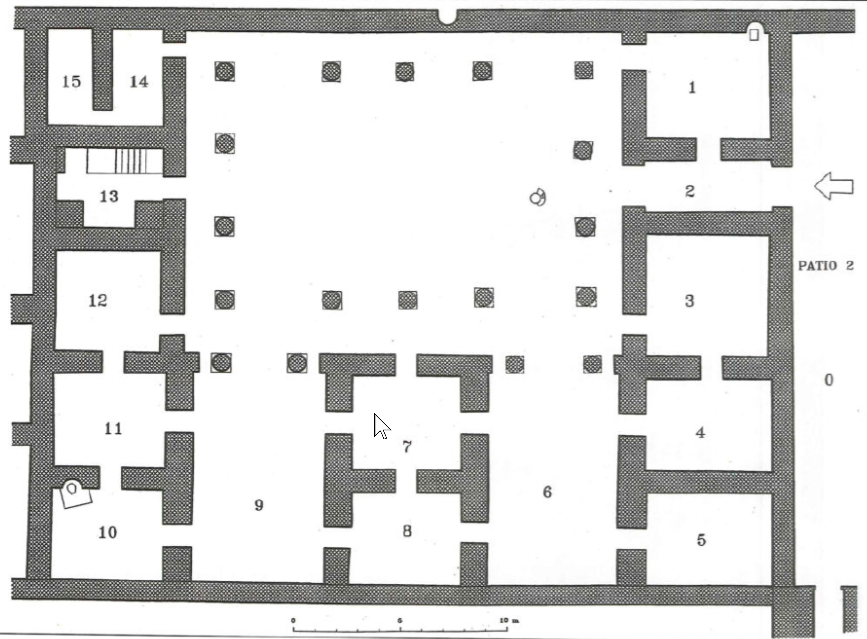

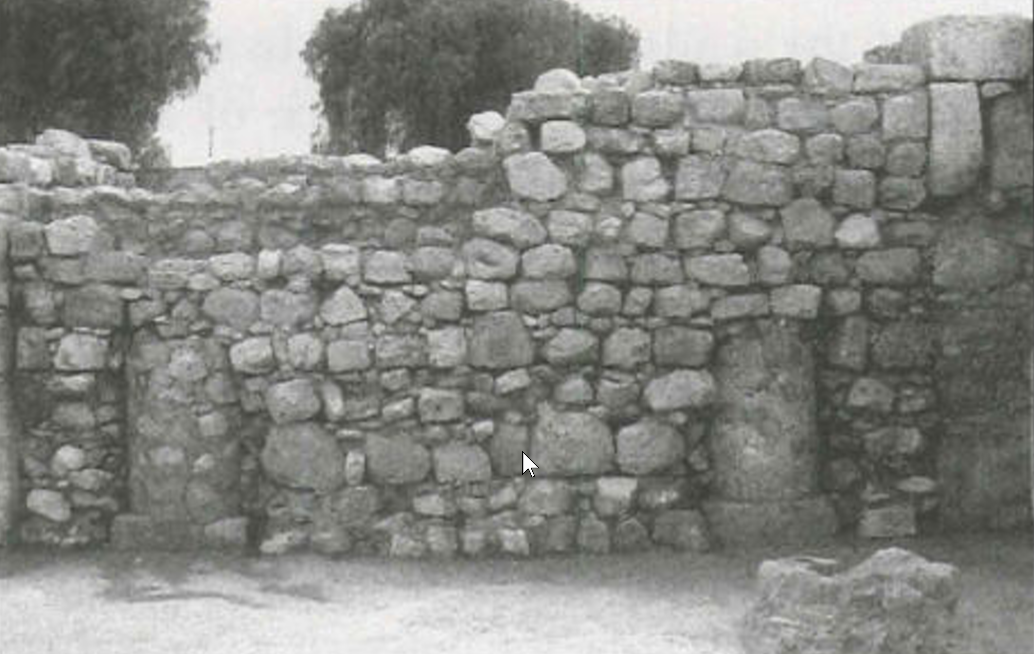

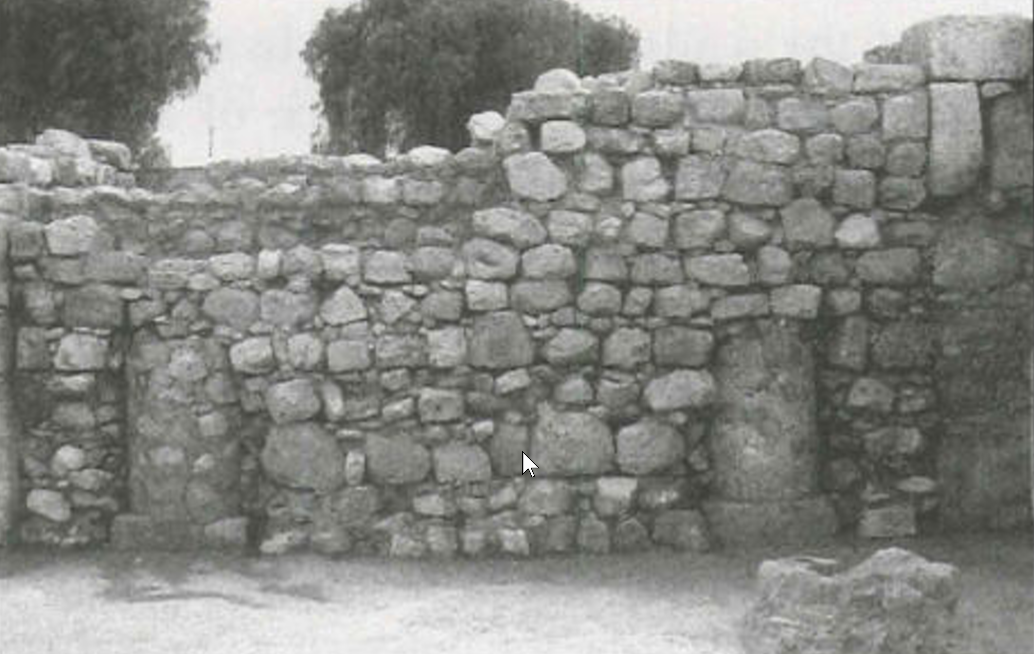

- Fig. 7 - South Front of

Courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 7

Figure 7

South Front of Courtyard of Building F

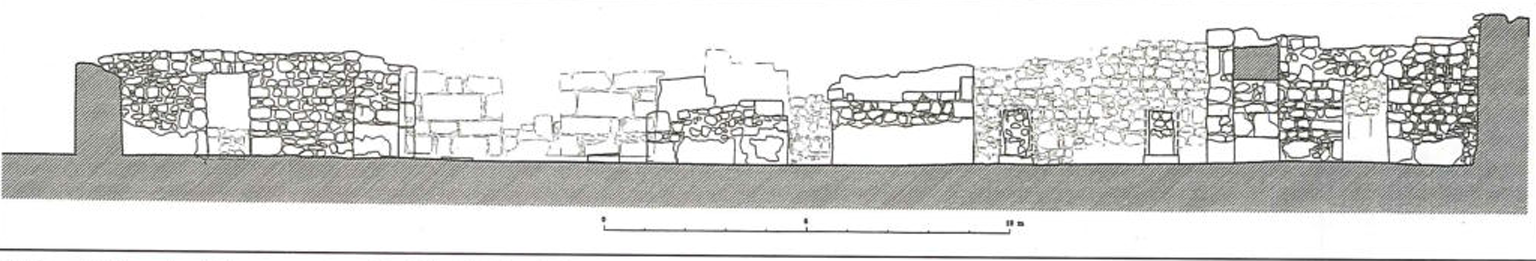

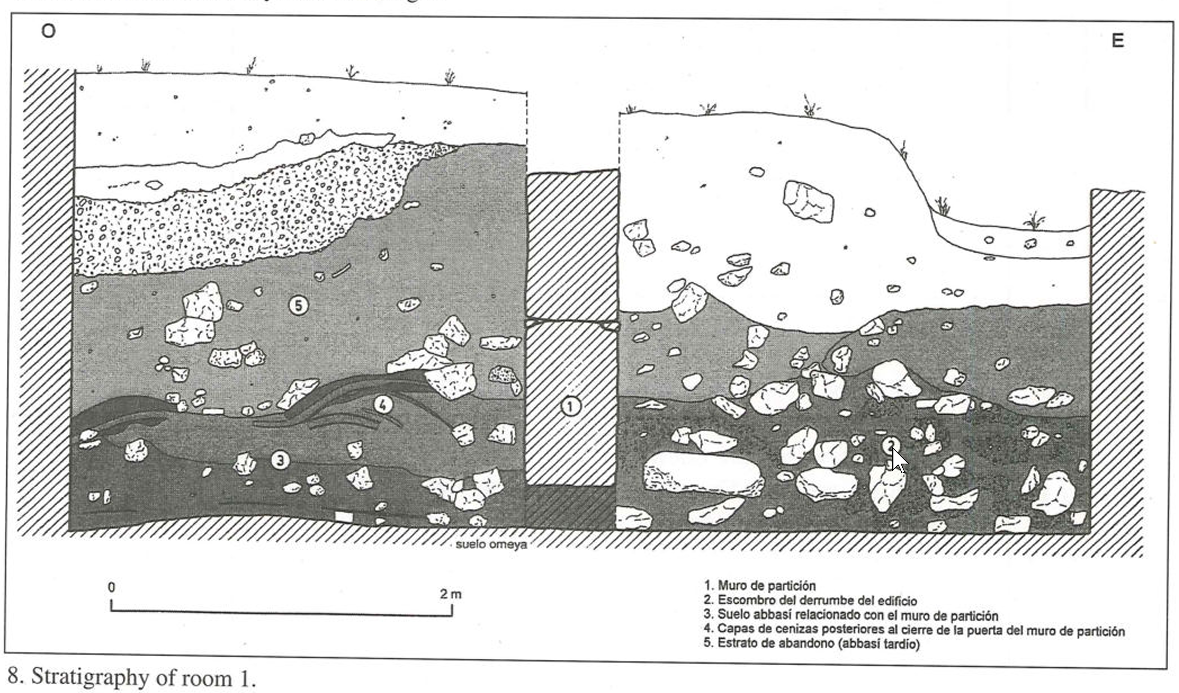

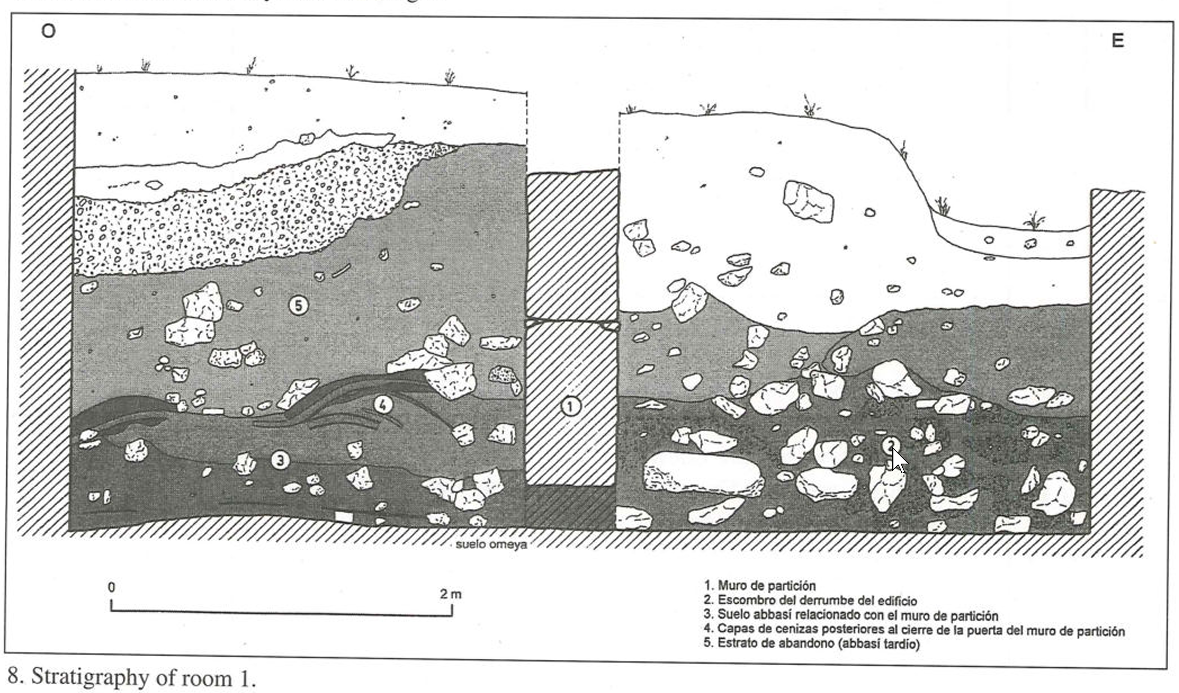

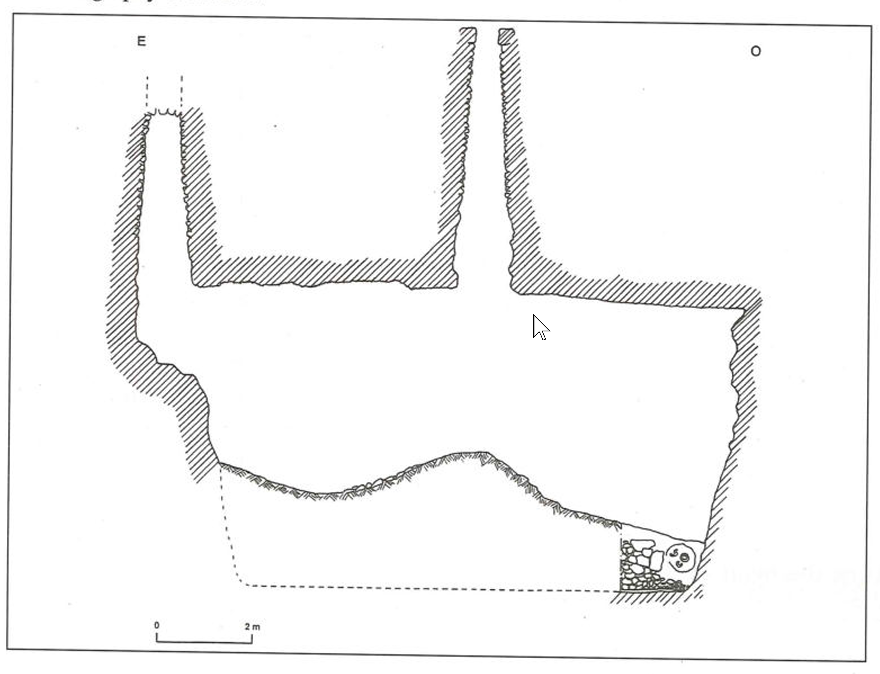

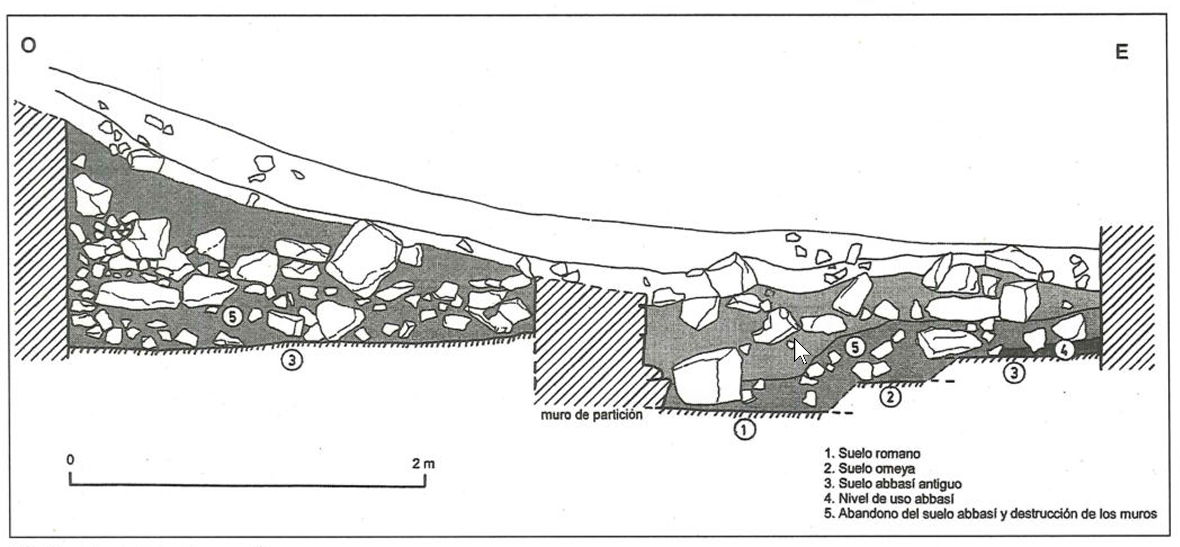

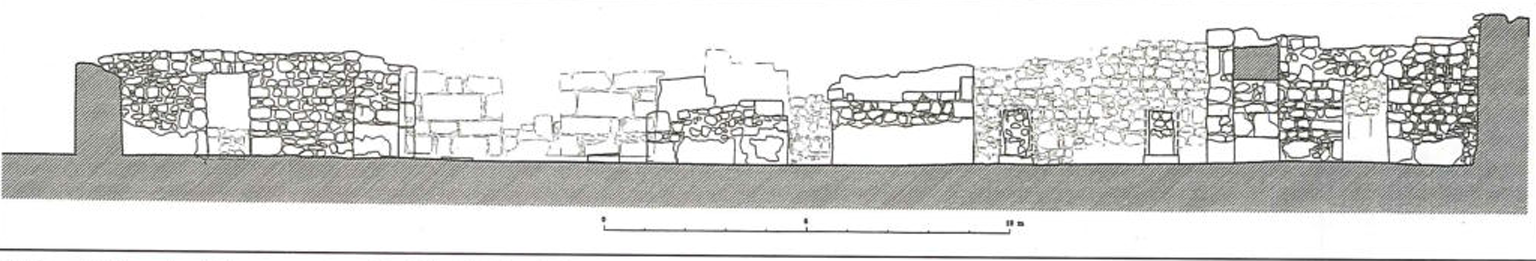

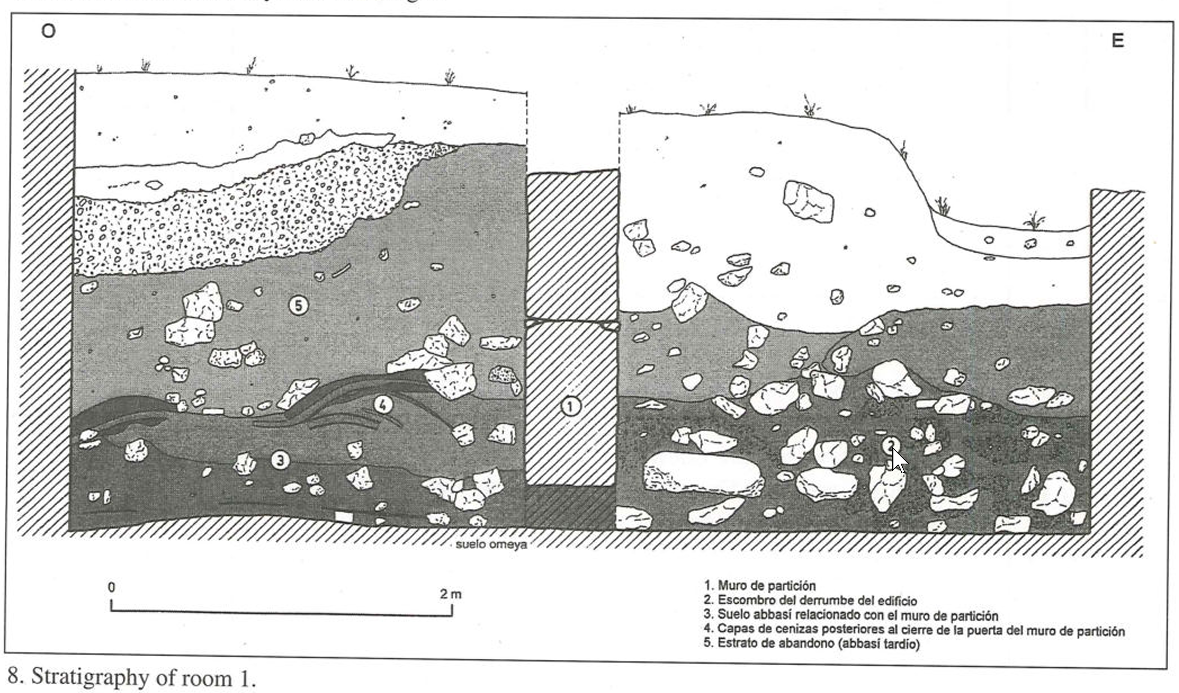

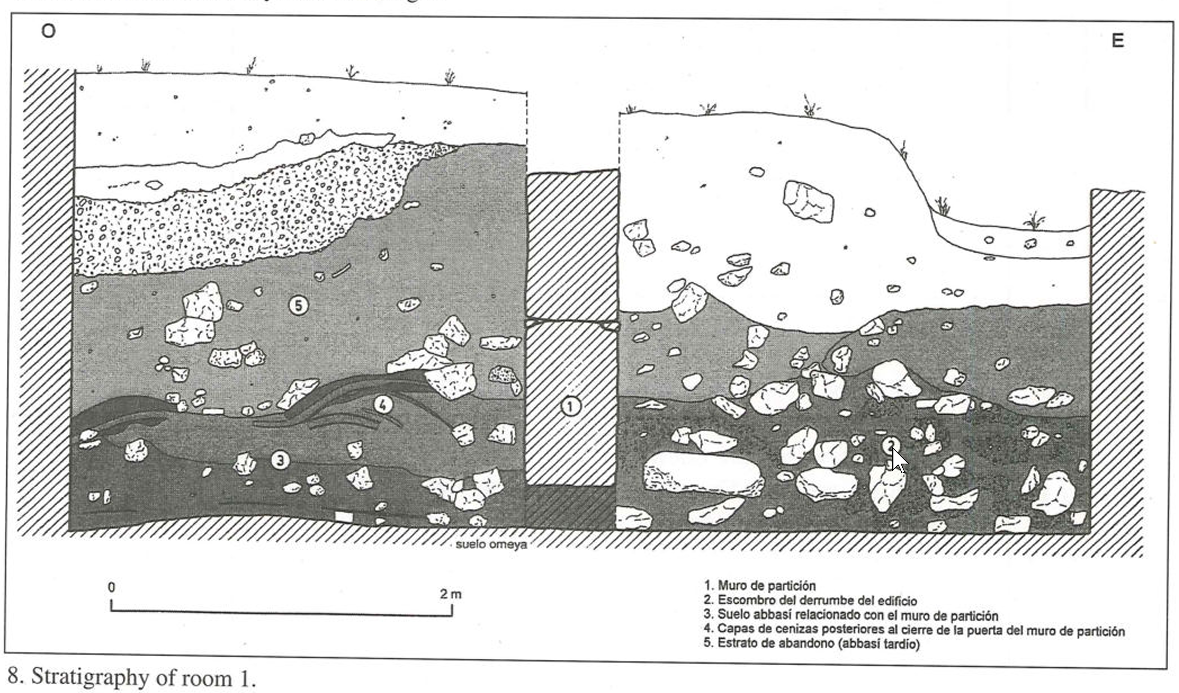

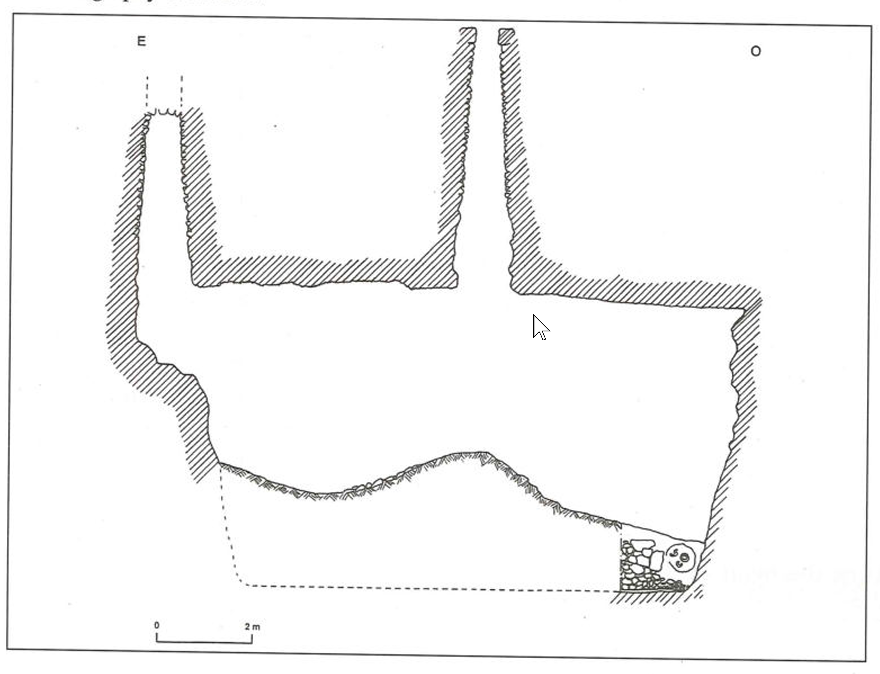

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 8 - Stratigraphy of

Room 1 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Stratigraphy of Room 1

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 9 - Cross-section

of cistern in Room 1 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Cross-section of cistern in Room 1

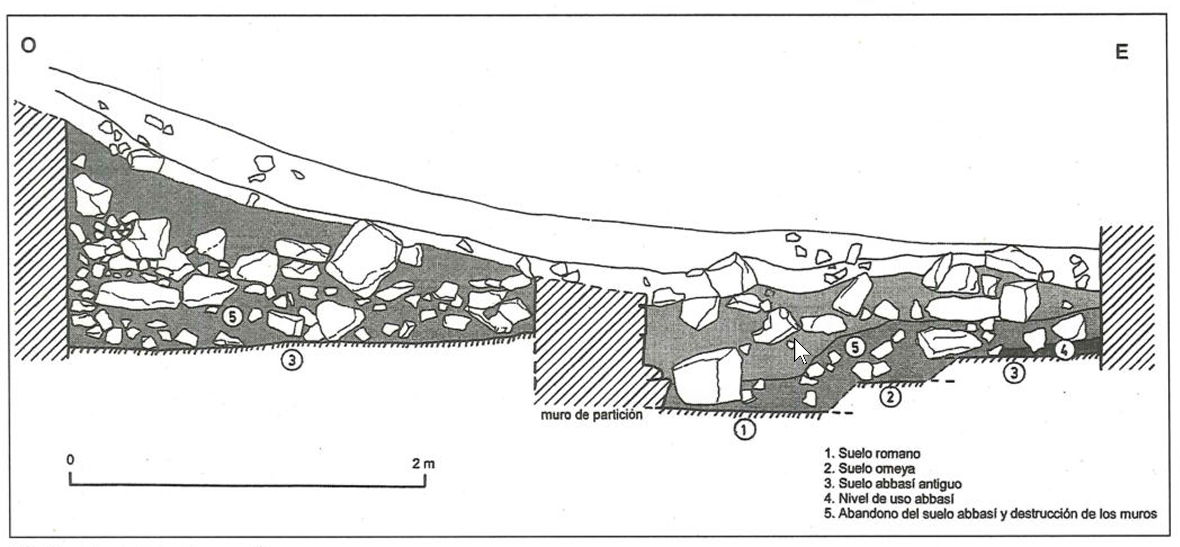

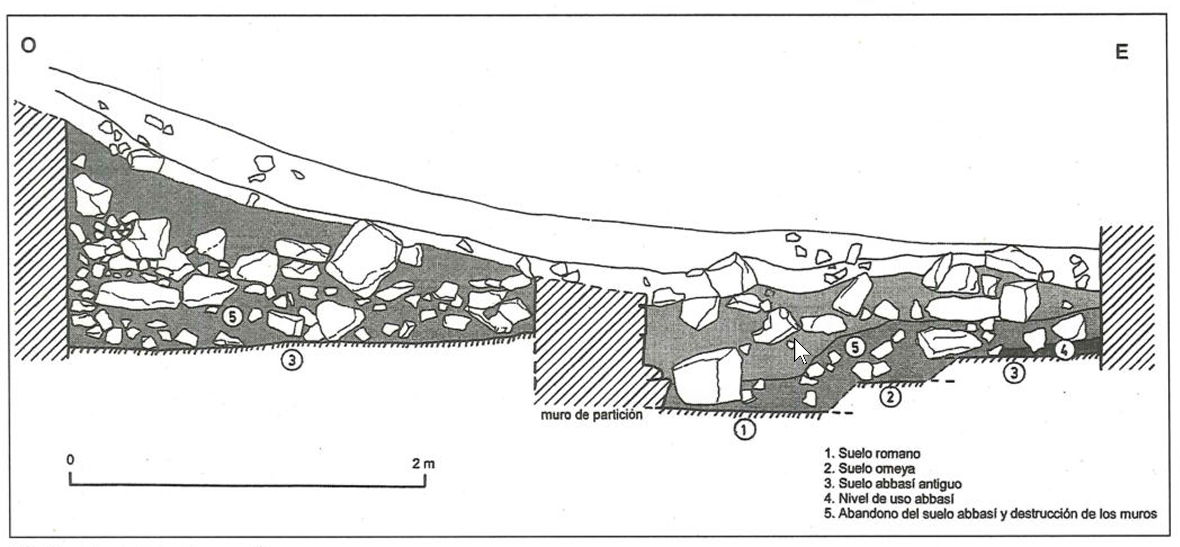

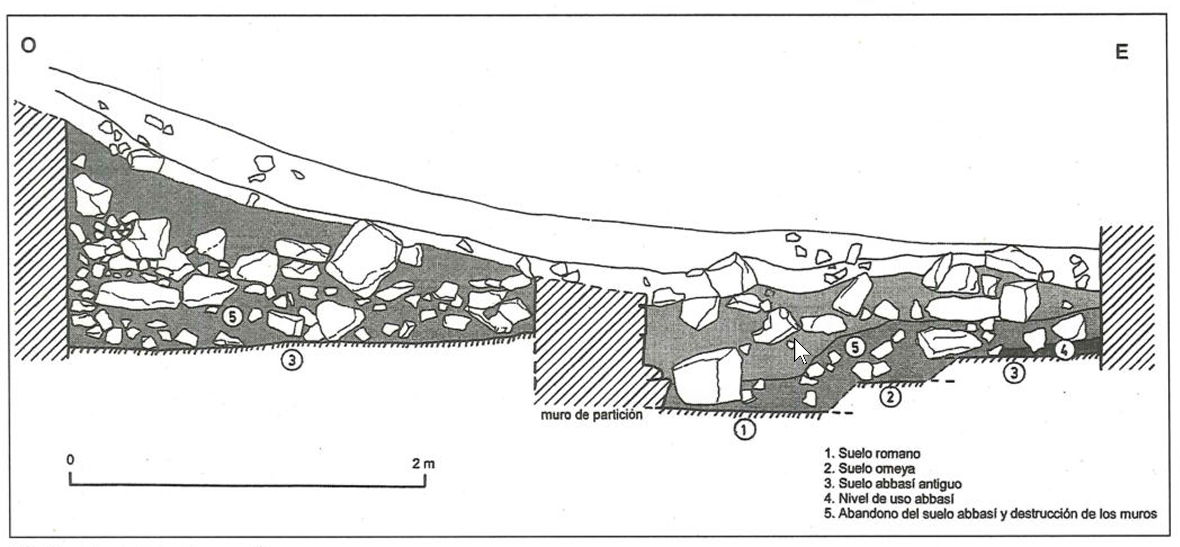

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 10 - Stratigraphy of

Room 3 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Stratigraphy of Room 3

Alamgro et al (2000)

- Fig. 7 - South Front of

Courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 7

Figure 7

South Front of Courtyard of Building F

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 8 - Stratigraphy of

Room 1 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Stratigraphy of Room 1

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 9 - Cross-section

of cistern in Room 1 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Cross-section of cistern in Room 1

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 10 - Stratigraphy of

Room 3 of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Stratigraphy of Room 3

Alamgro et al (2000)

- Fig. 11 - Column and Capital

made with rubble masonry and gypsum mortar in Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Column and Capital made with rubble masonry and gypsum mortar

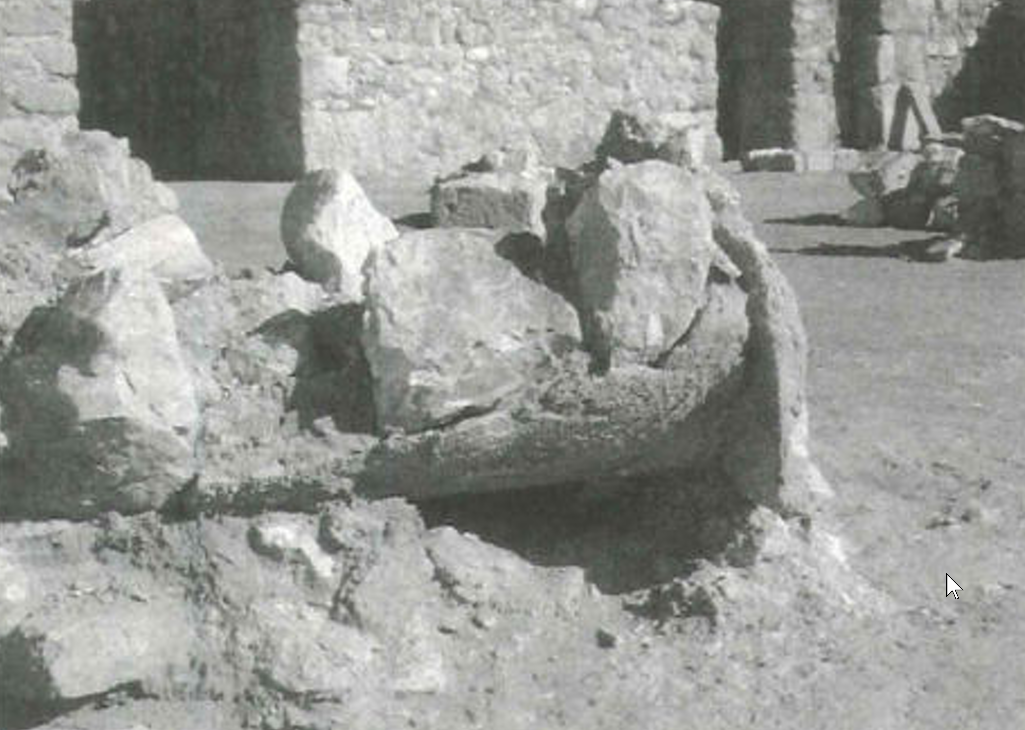

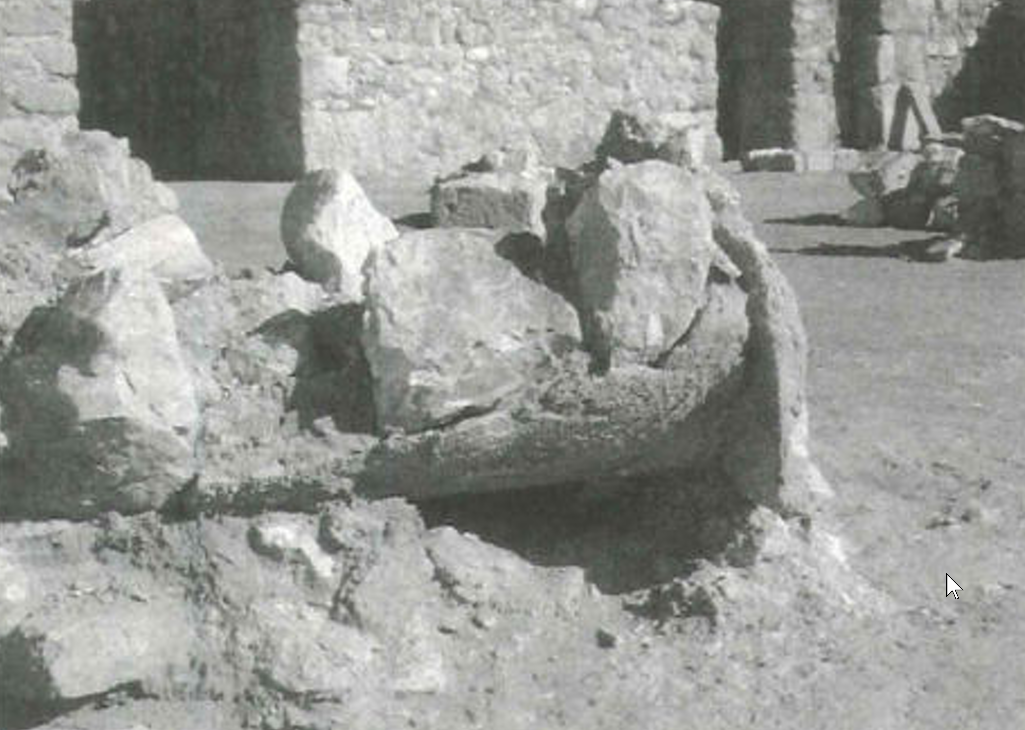

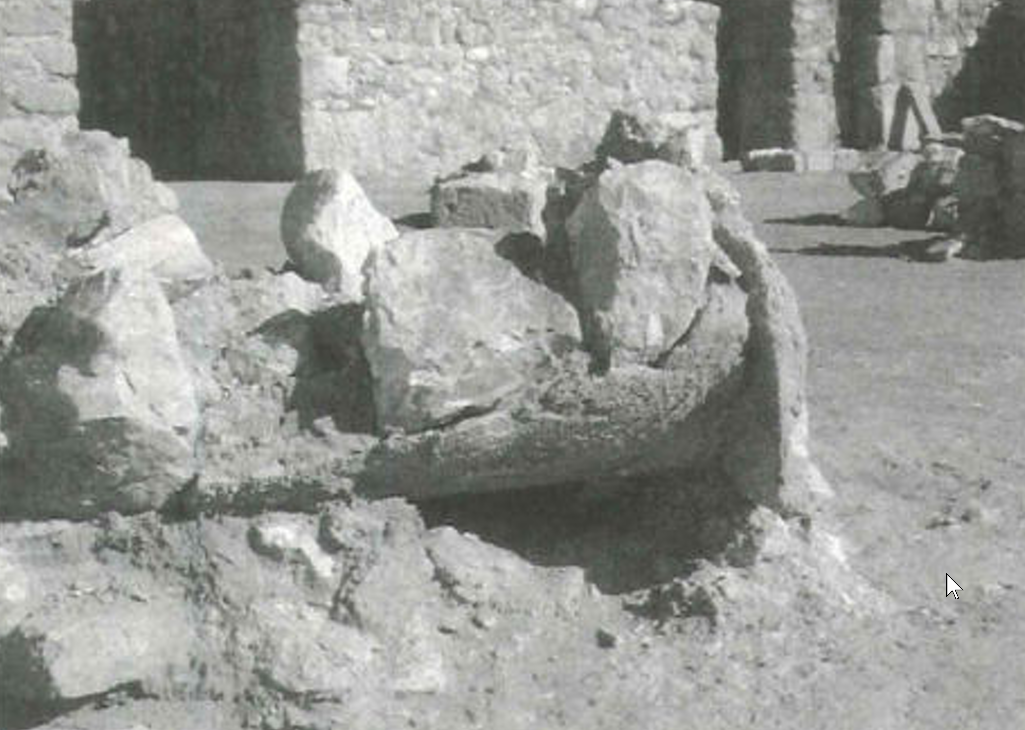

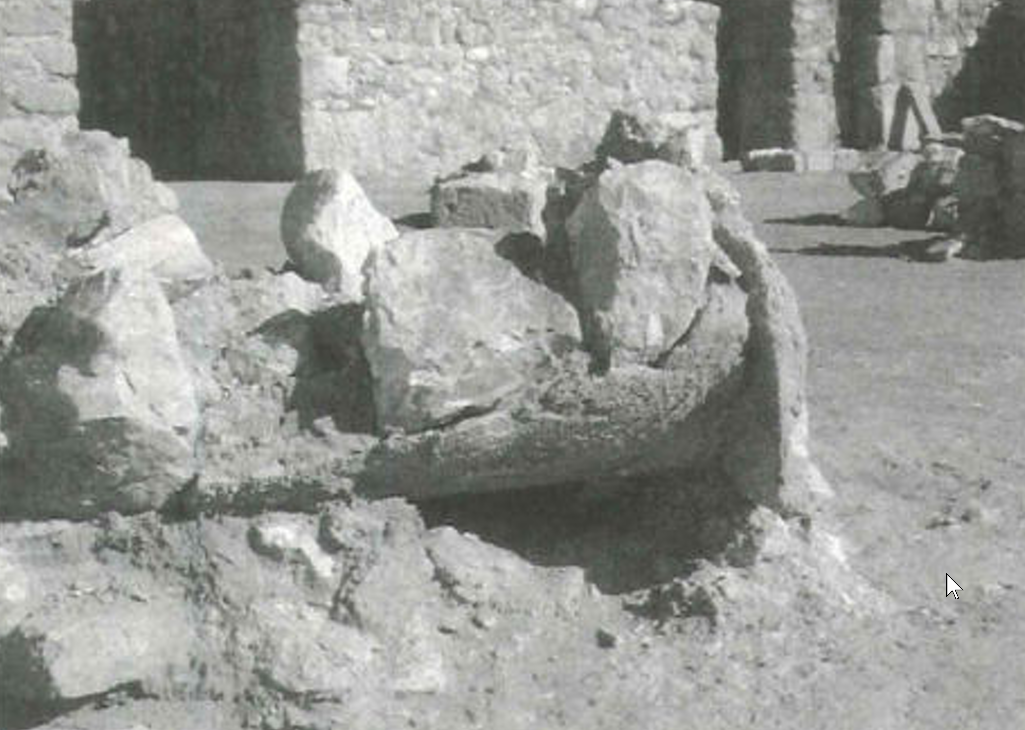

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 13 - Base Column and

Arch collapsed in the courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard

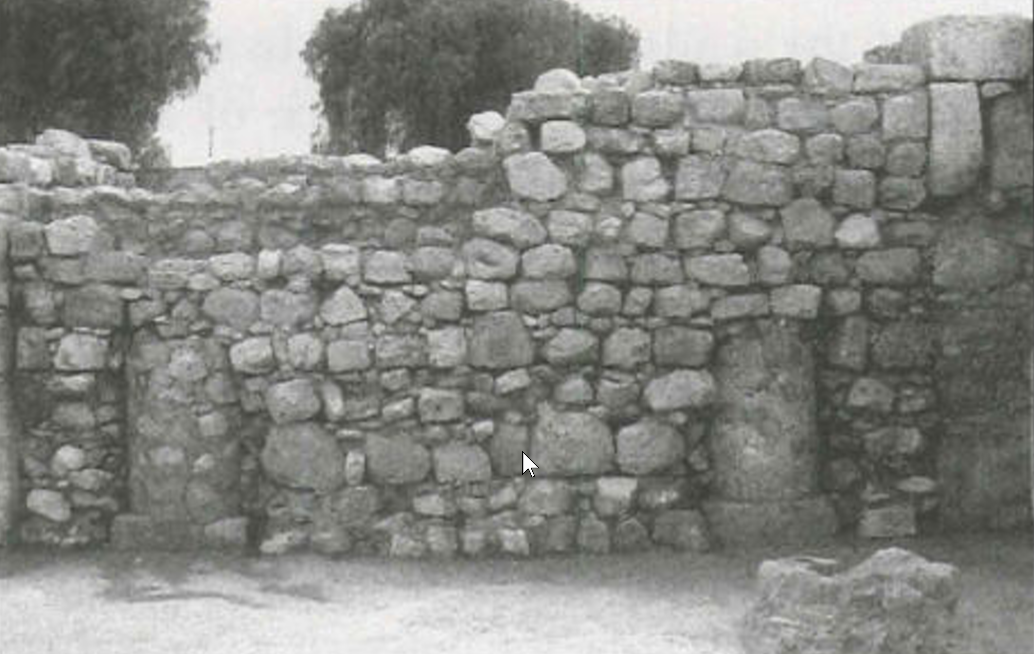

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 14 - The west iwan

blocked by late structures of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 14

Figure 14

The west iwan blocked by late structures

Alamgro et al (2000) - Plaster Level in Building

F - photo by JW

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building F

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Plaster Level in Building

F - another photo by JW

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building F

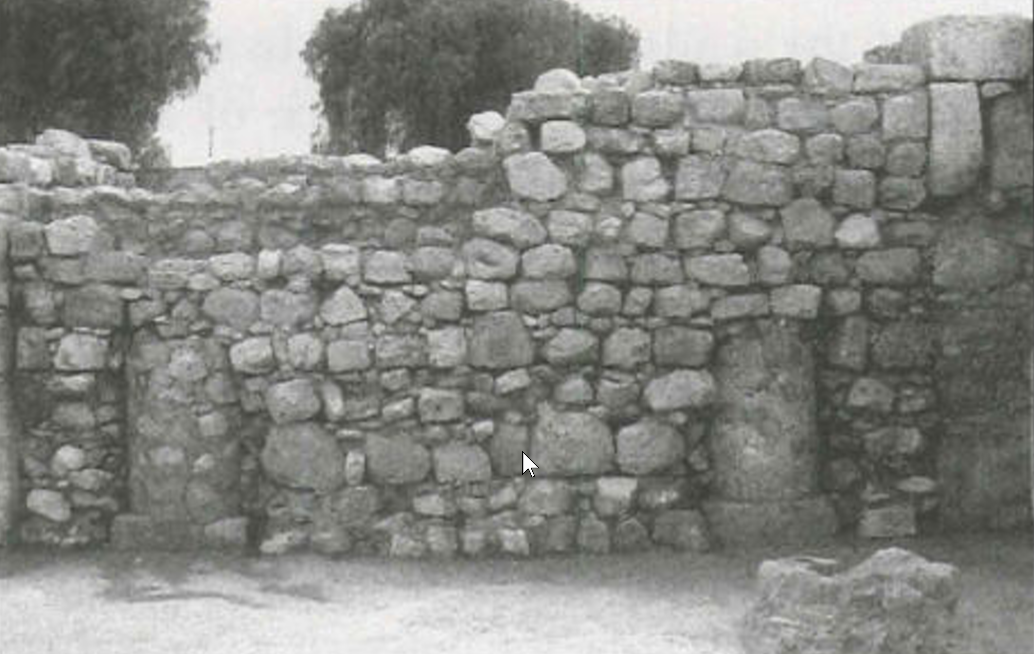

Another Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - ~E-W Walls in Building F

- original Ummayad construction ? - photo by JW

~E-W Walls in Building F - original Ummayad construction ?

~E-W Walls in Building F - original Ummayad construction ?

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

- Fig. 11 - Column and Capital

made with rubble masonry and gypsum mortar in Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Column and Capital made with rubble masonry and gypsum mortar

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 13 - Base Column and

Arch collapsed in the courtyard of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 14 - The west iwan

blocked by late structures of Building F from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 14

Figure 14

The west iwan blocked by late structures

Alamgro et al (2000) - Plaster Level in Building

F - photo by JW

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building F

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Plaster Level in Building

F - another photo by JW

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building F

Another Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - ~E-W Walls in Building F

- original Ummayad construction ? - photo by JW

~E-W Walls in Building F - original Ummayad construction ?

~E-W Walls in Building F - original Ummayad construction ?

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

| Period | Phase | Dates (CE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umayyad | Phase UA 1 | c. 705–730 | Original construction: palace, gateway, audience hall, colonnade. |

| Umayyad | Phase UA 2 | c. 731–749 | Minor additions; completion of decorative elements, water cisterns. |

| Post‑Umayyad | Phase UM‑PD 1 | c. 750–900 | Limited reuse, partial collapse after earthquake; sporadic occupation. |

| Abbasid–Ayyubid | Phase AA 1 | c. 900–1200 | Granary and administrative reuse of rooms; informal refurbishments. |

| Ottoman | Phase OT 1 | c. 1516–1900 | Fort–watchtower on palace ruins; stone‐roofed adaptations as shelter. |

Wikipedia (2024), Amman Citadel

Williams, Jefferson (2024), 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, Dead Sea Earthquake Catalog

- from Almagro et al. (2000:448, 452-453)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

- summarized by ChatGPT version 4o

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Late Umayyad | Early–mid 8th century CE | Final occupation phase before destruction. Associated with residential rooms and courtyard reconfigurations built with reused ashlars, set approximately 30 cm above the Umayyad floor level. Pottery includes bowls with red-on-white slip, cooking pots, pyriform jugs, and glazed items. Glazed ware suggests cultural influence from Mesopotamia and a terminus ante quem of 749 CE. Destroyed by the 749 CE earthquake. |

| III | Umayyad | Late 7th to early 8th century CE | Primary structural construction of Building F, including masonry and ashlar walls set in grey mortar. Represents elite urban architecture, possibly palace associated. Pottery of this phase includes classic Umayyad forms, such as red-slipped ataifores and semicircular cooking pots. This level was buried by collapse debris >1 m thick. |

| II | Byzantine | 5th–7th century CE | Earlier occupation beneath Umayyad floors. Pottery types include short-necked jars with spherical bodies. Some reused in Umayyad phase. Possible early usage of some courtyard spaces prior to Umayyad construction. |

| I | Roman | 1st–4th century CE | Lowest visible floor level in excavation, a paved Roman surface beneath Building F’s foundations. No direct architectural use in later phases, but formed the base upon which later phases were built. Ash deposits ~38 cm above this pavement mark the later Umayyad room level. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

| Earthquake | Notes |

|---|---|

| 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes | Severe damage recorded in Umayyad structures; collapsed walls and domes; reconstruction phases evident in later architectural strata. |

| 11th Century CE Palestine Quakes | Regional seismic event causing cracking in surviving Umayyad and later reused structures; not primary collapse agent at the site. |

| 1202 CE Quake | Minor fissures and structural stress evident in remaining arches and columns; later Ottoman adaptations suggest post-event stabilization work. |

Williams, Jefferson (2024), 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, Dead Sea Earthquake Catalog

Williams, Jefferson (2024), 11th Century CE Palestine Quakes, Dead Sea Earthquake Catalog

Williams, Jefferson (2024), 1202 CE Quake, Dead Sea Earthquake Catalog

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

- summarized by ChatGPT version 4o

In the courtyard, the columns and arches fell inward, and large quantities of square bricks, likely from a parapet above the arches, were found scattered on the floor. Vault voussoirs and intrados plaster fragments were also recovered. Plaster on walls survived only where buried under collapse debris. Rooms varied in damage: some, like the hallway, remained intact; others, like iwans 6 and 9, were severely damaged and filled with rubble up to the height of surviving plaster (about 1.5 m).

Following the earthquake, Building F was partially reoccupied. Surviving spaces were reused as modest domestic units. New walls, built from reused stone and joined with clay, subdivided rooms and supported new flat ceilings. In iwan 6, a new rear wall and pilasters were added for ceiling beams. Iwan 9 was converted into an oven room, but the oven was never used. The courtyard was partially cleared but never restored. Some zones were walled off as open-air enclosures; floor levels varied by up to 1 meter due to uneven debris removal.

Pottery recovered from destruction layers includes classic late Umayyad forms: painted bowls (red on white slip), cooking pots, jugs, lids, and a few glazed fragments. These vessels were similar to material from contemporaneous sites in the region. The ceramic assemblage suggests a date in the later Umayyad period, before the Abbasid transition.

The archaeological context indicates that the building was never fully finished nor heavily inhabited at the time of destruction. Its partial and impoverished reuse lasted only briefly and represents a decline from its original palatial function. The magnitude of structural damage, the suddenness of collapse, and the stratigraphic sealing of material all support attribution to a major seismic event during the mid-8th century.

Alamgro et al (2000) excavated Building F

in the Umayyad Palace on the Amman Citadel between 1989 and 1995. There they concluded that

the appearance of the remains leads us to believe that the ruin of the building, and specifically of the

arches of the courtyard happened in a sudden and catastrophic way, in all probability as a result of an earthquake.

The instantaneous nature of the event is discussed below:

In the sector of the courtyard and those rooms that were not cleared of rubble - 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11 and 14-15, there is evidence of the characteristic stratum produced by the violent destruction of the building. It is a layer which may be even greater than 1 m in depth, and which is characterised by ample building material: masonry, ashlars and even bricks in the courtyard, and particularly by the dark grey mortar and ash used in the Umayyad construction. The characteristics of the stratum in question prove that the collapse undoubtedly occurred instantaneously; we are not in any way dealing with the slow decay of an abandoned building, but rather with the devastating effects of a natural disaster.The dating of the destruction layer is discussed below:

Unfortunately, there has been no discovery of any coins or anything else which might offer an exact dating. Generally speaking, the archaeological records are very scarce with regard to objects, and only the pottery findings are of relative significance (Fig. 15-17), even though they are scarce, but they are clearly from the Umayyad period, as has been shown from a detailed study. In fact, the pottery found seems to be from the later part of the Umayyad period, which has characteristic forms such as bowls painted in red over white slip, round cooking pots, and even the undoubtedly exceptional discovery of some glazed items. This refers to a set of items closely related to others dated as mid-eighth century, for example, the oldest level of Khirbat al-Mafjar, or the destruction of the Umayyad houses excavated by Bennet and Northedge in the same citadel of Amman.Alamgro et al (2000) did not explicitly discuss dating evidence for the layer above the destruction layer but they did describe it.

... The materials found, especially the pottery, make it possible to confirm that the event in question took place at about the middle of the eighth century.

After the catastrophe, in Building F there were a series of proceedings of minor importance from a constructive point of view, and which represent a rather regressive process, but which provide evidence of the reuse of the space in question at a time which we believe to be immediately after the earthquake, since there are no signs that point to an intermediate period when it was abandoned. Strictly speaking, the partial reuse of the building can hardly be considered as a new constructive phase, but what is clear is that they made good use of the existing walls and spaces. At any rate, after its destruction, the building was never again used for its original purpose, as a palatial residence.Alamgro et al (2000)'s conclusions were as follows:

- The building was never completely finished: construction of the walls, vaults and columns was completed, but not the plastering of the walls, only the basic plaster. The same can be applied to the buildings of the eastern sector excavated by the Italian delegation, judging by the photographs we have seen. In any case, we are dealing with circumstances which did not affect the possibility of inhabiting the building.

- At the time of its destruction by the earthquake, the building hardly seems to have been inhabited, since in none of the sectors where rubble from the disaster has been excavated, have there been any signs of domestic utensils, organic remains, or even the bodies of people or animals which would normally accompany such levels in other sites and even in other parts of the citadel of Amman.

- Immediately after the earthquake, the building was partially and marginally re-exploited; this consisted basically of clearing up certain rooms and reusing them as simple dwellings. One of the iwans was even transformed into the workshop of the oven which was never put into use. This phase seems to have lasted only a short time, probably no more than some decades, and certainly it cannot date from long before the Abbasid period.

... All the surfaces of the series of arches must have been plastered, or at least this must have been envisaged, although there are no remains with this finish. The front of the series of arches must have been completed with a brickwork parapet. This hypothesis is based on the appearance of a large number of bricks just under the arches, fragments of which we found in the inside of the courtyard. The appearance of the remains leads us to believe that the ruin of the building, and specifically of the arches of the courtyard happened in a sudden and catastrophic way, in all probability as a result of an earthquake. The corridors of the porticoes in the courtyard were covered with stone vaults formed by rough ashlars cut in the shape of voussoirs, some of which have appeared in the excavation. ...

... The stonework used in the construction of the walls is from local origin, the same as the plastering. In both cases a low quality lime mortar is used—with plenty of organic ashes—in the stone settlement of the walls, and of higher quality and consistency in the plastering.

In our opinion, the construction techniques of Persian and Mesopotamian origin are of greater interest. Among these, the most outstanding is the use of gypsum, used in a specific form in certain constructive elements of the palace. Gypsum appears to have been used in elements requiring an immediate loading, as in the lintels of the doors, formed by irregular stones laid as rough voussoirs. The columns and arches of the courtyards were also constructed with irregular masonry.

Among the remains of the series of arches in building F, undoubtedly fallen in an earthquake, we have been able to make a clear distinction of the use of prefabricated gypsum elements. In the first place, we are dealing with 80 cm² plaques, 4 or 5 cm thick, used as capitals over the cylindrical columns, and which served as the transition of the circular section of the column to the square section of the impost of the arches.

Other prefabricated items are some flat pieces with curved guidelines used to define the groins of the intrados of the arches, which carried out various functions. In the first place they defined the form of the arches while the work was being carried out, and at the same time acted as centering for the masonry that formed the arches; as this was joined with gypsum, these pieces easily adhered to the surface, and in this way the whole structure could be built with the minimum of auxiliary means.

The majority of the most fragile structures of Building F, particularly the series of arches in the courtyard, the entrance arches to the iwans and part of the roofing, were destroyed at some time near to their actual construction, because there is no previous evidence of the characteristic repairs to walls and, in particular, to paving, which is usually evidence of prolonged use of a building. The characteristics of the deep stratum of destruction affecting arches and columns give us some clues to understanding the ruin of this building. The level is composed exclusively of rubble among which it can easily be seen that the elements of construction have fallen in situ, and therefore they have not been brought from elsewhere. On the other hand, the fact that there is a lack of wind-deposited earth (soil erosion) and that there is an overwhelming presence of broken-up gypsum mortar between bricks and masonry shows that the collapse happened suddenly and so, consequently, we are not dealing with the effects of a slow process of destruction. There is no evidence of any charred remains to show that the cause might have been a fire or action of war. If we take into account the date of the materials in the ruins, which is late Umayyad, as we shall see in the corresponding section, and the fact that in other sites in the country and in the citadel of Amman itself very similar levels of destruction to what we have found have been recorded archaeologically, and that they have been identified as the effects of an earthquake, we are inclined to believe that this was the cause of the destruction of Building F.

After the catastrophe, in Building F there were a series of proceedings of minor importance from a constructive point of view, and which represent a rather regressive process, but which provide evidence of the reuse of the space in question at a time which we believe to be immediately after the earthquake, since there are no signs that point to an intermediate period when it was abandoned. Strictly speaking, the partial reuse of the building can hardly be considered as a new constructive phase, but what is clear is that they made good use of the existing walls and spaces. At any rate, after its destruction, the building was never again used for its original purpose, as a palatial residence.

The depth of the stratum of destruction varies according to the different spaces, since some were abandoned, others cleared up wholly or partially, and it seems that in some rooms they did not even suffer the collapse of the covering. At any rate, it always coincides with the height at which the plastering materials covering the walls is conserved. In fact, this layer seems to have fallen off all those walls that were left uncovered after the earthquake, and it has only been conserved in the parts of the walls that were buried under the rubble. In practically all the excavated areas, the height at which the layer is conserved coincides with the accumulation of rubble on the Umayyad floor.

This is the space which provides the clearest evidence of the effects of the earthquake. On the paving we can find an important amount of rubble reaching a height of more than 1 m in some areas, acting as a support for the columns and arches of the portico, broken and shattered on the floor of the palace.

Among the building material, especially in the centre of the courtyard, a large number of square bricks were found, with remains of the characteristic lime mortar with ashes, identical to that of the walls they had been taken from. We are uncertain which part of the building these bricks were used in, although from their position among the collapsed rubble, and since there is no trace of them among the standing remains, we are inclined to think that they formed part of the construction over the series of arches of the courtyard, maybe a parapet. Bricks were hardly found in the perimeter corridor, between the series of arches and the walls, as they tended to fall towards the centre of the courtyard; however, a considerable number of yellowish limestone ashlars, cut in the shape of voussoirs were found, probably ones which formed part of the vaulting covering the portico. Remains of the plaster which covered the intrados were found on several of them.

The effect of the earthquake on the different rooms does not appear to have been the same; some of them suffered such severe deterioration that they were considered irreparable, while others appear to have withstood the disaster.

From the former category we should point out rooms 9 and 10, in which the stratum of rubble reaches a height of 1.5 m, the same as the height of the plastering which has been conserved. In both cases it seems that we can confirm that the deposit could only be due to the collapse of the roofing and even to the upper part of the walls. The roofs of the two iwans had also fallen in, which is logical enough if we bear in mind that we are dealing with the largest rooms, and therefore their roofs would be the most fragile.

In some cases, the roofs appear to have withstood the earthquake, as is the case in the hallway. On excavating this room a deep stratum was found, of approximately 1.20 m, which constituted the Umayyad floor and which was sealed by a paving of hardened earth. This deposit contained rubble which was, undoubtedly, from the ruins of the Umayyad building, judging from the presence of the lime mortar with ash characteristically used in building; however, the greater part of the stratum was formed by grey and brown earth deposited by the wind and gravel from outside. All of this indicates that we are dealing with a stratum generated by the gradual ruin of the building and not by any sudden destruction caused by an earthquake. The height up to which the plaster is conserved is also an unequivocal sign which confirms this hypothesis, since the layers of mortar have hardly been maintained a few centimetres above the Umayyad floor level here, if they have not disappeared completely. All this data indicates that the roofs of the hallway did not collapse with the earthquake, or that the rubble was carefully cleared away. Although we do not have unmistakable proof in one way or the other, we are inclined to believe in the first possibility, given the fact that this room was covered by the vault tectonically the most resistant of those which existed in Building F, since it had the smallest span.

The earthquake also seems to have been withstood by some rooms which, after the disaster, were partitioned by means of walls which were probably meant to support the roofs: this is the case of rooms 1 and 12. In others, however, the construction of such interior walls must have been accompanied by the reconstruction of roofs. This must have happened, for example, in room 3, because the partition wall was founded on top of a stratum of rubble from the Umayyad building.

After its violent destruction, Building F was partially reoccupied (Fig. 12). Some rooms that had withstood the earthquake were partitioned and converted into domestic units, to which the adjacent part of the courtyard was added, partially cleared of rubble and walled off. Others were cleared of rubble and completely remade, like iwan no. 6, after its covering had collapsed. Finally, iwan no. 9 was not cleared, and an oven and the corresponding workshop were situated on top of the rubble.

The large quantity of debris covering the ground, which included the fallen archways, shows that the courtyard of Building F never regained its former splendour as a porticoed courtyard. None of the columns, including those of the iwans, withstood the earthquake, and those who reoccupied the building did not rebuild them; they did not even clear the rubble from the area (Fig. 13). In fact, in spite of partially clearing some parts of the courtyard—the parts opposite certain rooms—in other parts they left more than a metre of rubble, which meant that the level of the ground varied between 40 and 50 cm from some parts to others. Part of the surface of the courtyard was partitioned by means of thick walls, creating some small, modest dwellings, maybe open to the sky.

The clearing up of the courtyard was incomplete and decreasing, so that the eastern area—near the hallway (which seems to have continued to be used as such) and near iwan no. 6—was cleared to a height of 30 cm above the level of the Umayyad paving. For this reason there are no remains of any column or arch from the east flank, and only the first line of stones survives from the bases. On the contrary, the height above ground level of the fallen structures on the western area of the courtyard, which reached as high as 1 m in some cases, shows that the new level of rooms must have been situated at this height.

The difference in level between the western and the eastern areas of the courtyard was solved by means of a slight slope that can be observed both in the stratigraphy and in the height at which the mortar for the plastering of the lower part of the walls is conserved. In fact, if we observe the height in the space of the previously mentioned plastering, it seems to bear witness to the fact that the clearing-up of rubble was carried out in a very irregular manner, since the height of conservation of the plaster on the perimeter walls in the western part of the courtyard reaches 1.20 m; however, this height decreases progressively towards the eastern side, which confirms the existence of a very slight slope in that direction.

What had originally been a grand residential nucleus, articulated but unique, became converted into a set of cells of independent rooms, juxtaposed and of little significance. For this reason, certain sectors of the courtyard were closed in by badly fabricated walls and became part of new domestic units that also comprised one or two of the old dwellings of the buildings.

The opening which communicated Room 1 with the hallway was blocked up and this room was partitioned with the construction of a north–south wall, built of treated masonry joined with clay and abundant sneck in the joints, and in which a doorway was opened up in order to communicate between the two resulting units. Access to these rooms was, of course, from the old courtyard, where a rectangular space was marked out opposite the door.

Room no. 3 was subjected to important alterations after the earthquake: the door communicating with room 4 was blocked up and it was divided in two by means of a partition wall in which a door was opened up. In the room at the back, a structure was built of a rounded arch shape, against the northwest corner, roughly fabricated using stones and clay, and which seems to correspond to a manger. The transformation carried out in the room in question appears to be roughly parallel to that executed in room 1. In both cases the space was subdivided by a wall in a north–south direction, resting against the blocking-off wall that had been built in the opening that communicated with the other room, therefore leaving only one possible entrance from the courtyard. In this way, internal circulation between the rooms was eliminated once and for all, leaving the courtyard as the true articulating nucleus of the building.

Opposite the entrance to room 12, in the southwest angle of the courtyard, another rectangular space was closed off; it had similar characteristics to the one mentioned relating to room 1. This unit, which we believe could have been without any covering, communicated with the courtyard through an existing door in the east wall. The height of the floor of this room was about 40 cm above the Umayyad one—i.e., about 50 cm lower than the level of the rubble in this section; for this reason, the walls surrounding it served at the same time as retaining walls.

The difference in level must have been levelled out at the entrance by means of a step constituted by the threshold of the door. The stratigraphy of the interior of the room reveals the existence of as many as five successive room levels, the oldest of which was built directly on the fallen rubble. Room 12, in the same way as rooms 1 and 3, was divided up by a wall of masonry joined with clay in which there was a door communicating with the two rooms. The wall does not rest directly on the Umayyad floor, but rather it starts at 30 cm above the original paving.

In several of the residential buildings composing the palace, the iwans have been observed to be the parts which were most seriously damaged in the earthquake, due to the fragile character of the vaults and columnar fronts. In iwan no. 6 there was no trace, as there was in other rooms, of the deep layer of rubble that showed theviolent collapse of the covering; however, the important alterations to which it was subjected seem to prove that it was one of the parts that was most seriously affected in the disaster.

The original three-way access must have collapsed and the remains were removed, because the new façade, which was considerably different, was set back with respect to the original one. The arches giving access were substituted by a strong wall made from large reused ashlars with one entrance only. This wall began from the opening, which had been previously blocked up, that communicated the original iwan with room 4. At the other side, it blocks also the entrance into room 7. In the southernmost third part of the room we are dealing with, there were two pilasters face to face, made from reused ashlars which must have been the support for the base of a transversal arch designed to support the beams of the new flat ceiling that substituted the previous vaulting.

At some moment prior to the construction of the wall forming the façade of the iwan, which we imagine was after the earthquake, and probably for a short period of time, the original iwan communicated with room 4 when it had already been divided by a partition wall and isolated from room 3.

Iwan 9 underwent radical alterations in order to install an oven and the corresponding workroom in the previous state room. In the first place, communication with the courtyard was completely cut off with the construction of a wall that started from the two jambs and closed up the three existing openings (Fig. 14). This wall was based on an open foundation on the deep layer of rubble (approximately 1.20 m) proceeding from the devastation of the building. The purpose of this wall was to provide an inner space in which to place an oven, while at the same time it would constitute the retaining wall for the installation.

The oven was confined to the south by a wall in an east–west direction, where its opening was set. This was placed at a height of 1 m above the floor level of the room situated to the south, with the idea of making work easier for the workmen, setting the work surface at waist level of a person of normal height. These walls, together with those that separated the unit from room 11, enclosed the chamber, which had a round ground plan, culminating in a dome and constructed with bricks.

So, we are dealing with an oven with one single dome-shaped compartment. To the east of the last of the walls described, there is a narrow rectangular space with access from the south by means of an opening similar to the opening of the oven.

Anyway, the absence of layers of ashes inside the oven and surrounding floors, as well as the lack of a blackened surface on the inside of the bricks or other evidence of exposure to flames, leads us to believe that the oven was never used. As there were no remains of any production, it is even more difficult to know what use this particular oven was intended for.

Technically speaking, it does not look like the clay or glass kilns, whether of one or two compartments, so we think we can rule out these two possible uses. It may have been intended for baking bread, although it is undoubtedly of a much larger size than would have been required for just one family.

The workshop, to the south of the oven, was also partitioned by divisions which must have supported a transversal arch, which was of a similar arrangement to that adopted in iwan no. 6.

Points of access to the old iwan were very limited. There was no longer any possibility of communication with the courtyard or with rooms 7 and 11, so access could only be through rooms 8 and 10. As the latter only communicated with the workroom and with room 11, which at the same time could only connect with room 9, we believe that access from the outside to the oven and workroom must have been by passing successively through rooms 6 and 8.

The courtyard, referred to as n° 2, situated on the east of Building F, had already been partially cleared of rubble at the time of the Italian campaign, as shown in a photo graph taken in 1939, in which we can see how the two thirds of the eastern part of the area are completely cleared. However, we do not have any information on the stratigraphy or of the later structures that there may have been in this courtyard. Only the western third has been unaltered since the 1970s, when the SW corner was lowered to allow access to the heavy machines passing over room 5 of Building F, and the NW corner was completely dug out to Umayyad ground level. Therefore, when we began the excavation of Building F only the deposit adjacent to rooms 3, 4 and 5 remained unaltered, and we decided to excavate the southernmost area of it, leaving the corner opposite room 5, since this is at present still the only practicable entry for vehicles.

The excavation revealed a rectangular room of 6.10 by 3.40 m, limited on the west by the wall of the façade of Building F and on the north, south and east by walls of masonry set in clay, of 60 cm thick. The room in question opened onto a space situated to the south through an opening of 85 cm which had mouchettes set on the south end of the jambs. We are unaware of the nature of the space from which there was entry through this door into the room we have described, since, as we have said, that sector is still to be excavated. The arrangement of the mouchettes would seem to indicate that we are dealing with an open-topped space, either courtyard or street, although the difference in level with respect to the room we excavated contradicts such a theory, since we would have to admit that in the case of rain, the water would accumulate in the covered room. The wall enclosing the room on the north, is prolonged in an eastern direction, which goes to prove that the occupation reached up to the centre of Courtyard 2.

The E-W sector of the room shows how the later wall was built, in the same way as the wall of the façade of Building F, on the Roman floor of the square. The level of the floor related with the room would be indicated by a layer of ash at about 38 cm above the Roman paving. On the occupied area there is a stratum of destruction composed of abundant masonry and lime mortar from the ruins of the wall of Building F. It is obvious that this ruin took place after the construction of the later wall, and not before, since there is no evidence of any foundation ditch in the layer of rubble. On top of this stratum there were another two layers, and the higher of the two is associated with a wall of reused ashlars which runs in an E-W direction and divides up the room.

From a technical point of view, the walls built in Courtyard 2 have an identical construction technique to the dividing walls of rooms 1, 3, 4 and 12 in Building F. They are also situated at a similar height, about 30 cm above the Umayyad floor, which leads us to believe that they must be constructed in relation with this same building period. The ceramic materials associated with the level of occupation and with the level of destruction can therefore be classified generically as being of eighth century AD, so we consider that we are dealing with buildings that are probably of a residential nature, constructed after the violent destruction that we have recorded in the inside of Building F.

In the sector of the courtyard and those rooms that were not cleared of rubble – 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11 and 14–15, there is evidence of the characteristic stratum produced by the violent destruction of the building. It is a layer which may be even greater than 1 m in depth, and which is characterised by ample building material: masonry, ashlars and even bricks in the courtyard, and particularly by the dark grey mortar and ash used in the Umayyad construction. The characteristics of the stratum in question prove that the collapse undoubtedly occurred instantaneously; we are not in any way dealing with the slow decay of an abandoned building, but rather with the devastating effects of a natural disaster. As we shall see in the next section, there is sufficient archaeological evidence to prove that these are the results of an earthquake which has ample written documentation, as it devastated Southern Syria, Palestine and the Valley of Jordan in 749 AD. However, a thorough study of the materials found in the pertinent stratigraphical remains is fundamental in order to confirm this hypothesis.

Unfortunately, there has been no discovery of any coins or anything else which might offer an exact dating. Generally speaking, the archaeological records are very scarce with regard to objects, and only the pottery findings are of relative significance (Fig. 15–17), even though they are scarce, but they are clearly from the Umayyad period, as has been shown from a detailed study. In fact, the pottery found seems to be from the later part of the Umayyad period, which has characteristic forms such as bowls painted in red over white slip, round cooking pots, and even the undoubtedly exceptional discovery of some glazed items. This refers to a set of items closely related to others dated as mid-eighth century, for example, the oldest level of Khirbat al-Mafjar, or the destruction of the Umayyad houses excavated by Bennet and Northedge in the same citadel of Amman.

Among the kitchen items, there is a predominant amount of cooking pots rather than casseroles, although as we are dealing with fairly open objects, probably they were used indistinctively for making meals which required continuous boiling or cooking with little liquid. Almost all the cooking pots are semicircular, some deeper and some of them shallower. They have horizontal handles and a concave base. There is good documentary evidence in other sites in the area, as in Pella, Dhiban, Umm ar-Ra4, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Mount Nebo and Amman itself.8 This type of cooking pot, which began to appear at the end of the Byzantine period, seems to have gradually taken over from the pot with a short neck and spherical body, and by the end of the Umayyad period it was the most commonly used pot.9

Some examples of the typical lids for these semicircular cooking pots have been found, of a conical type and a knob-type handle. This is a very usual shape, good examples of which have been found among the Umayyad remains in the sites at Pella, Dhiban, Umm ar-Rasas, Amman, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Mount Nebo and Jarash.10

The jugs, jars, canteens and pilgrim flasks are made from very refined clay and the cracks are clean and straight. They are often covered with a thin layer of white slip, which offered itself to painting motifs in red; in other cases, there is white painted directly on a grey background. One of the most frequent pots is the pyriform jug, with a conical-type neck and very slightly marked shoulder where the very pronounced semicircular handles are fixed. They stem from Byzantine types, although the neck of those from Umayyad times is more developed than the former ones. They frequently appear with decorations based on simple geo metrical motifs drawn with white paint on the grey background of the paste11.

We were able to recover a whole jug which had the handles similarly arranged to the previously mentioned type; unlike them, the diameter at the level of the shoulder is greater than the lower third of the jug, the neck is shorter and has a retouched lip.12

On some occasions, the jugs may appear profusely decorated with a variety of techniques, such as red ochre painting or incisions using a needle. Among the former there is one decorated with simple geometrical motifs: horizontal and wavy lines, spirals, semi-circular bands covered with a line of dots, etc. The pitcher in question has an inverted conical neck, where the handles are joined to the body, and a globular, slightly inclined body. Both in its shape and decoration, this piece is identical to another one found in the Umayyad levels in Jarash.13

The "ataifores" (dishes) which were recovered are specimens usually with a straight edge and lip which is rounded or thicker at the end. They are decorated on the inner surface with simple geometrical motifs painted in red ochre over white slip. Generally they have a ring base, although there are also flat bases.

Bowls with straight sides and flat base are one of the most characteristic shapes of the repertoire of pottery of the Umayyad period and the best represented shape as regards those which have been studied. We refer to vessels which are usually decorated on the outer surface, using red ochre on white slip. Generally speaking, the decoration is quite simple, and is characterised by thick strokes, wavy bands, concentric circles, etc. However, it is not unusual to find pieces decorated with more complex designs and finer strokes: friezes with stylised, spiky acanthus and bands of complicated motifs and very varied geometrical designs.14

Among the levels we are concerned with, we have found some fragments of an open shape covered with glaze (with a vitreous glaze), which are worth commenting on in detail, since the time when this technique extended through the Syrian-Jordanian territory is at the moment the subject of dispute. Although glazing was to be found in Iraq and Iran before the Islamic conquest,15 the appearance of this technique in Greater Syria is associated with the rise to the Caliphate of the Abbasid dynasty and the consequent spread of Persian and Iraqi cultural elements. Nevertheless, some authors have considered the possibility that glazed pottery began to be used in the last years of the Umayyad dynasty.16 If we take into account the early existence of glazing in Mesopotamia and the enormous amount of influence from that region on the palace which is being studied – both on the design of the ground plan and on the repertoire of decoration and even construction techniques – it does not seem surprising that some items finished in this way should have arrived prior to 749 at the citadel of Amman.

In short, the pottery items recovered show that the levels of destruction excavated can without too much difficulty be assigned to the late Umayyad period. The kitchenware, typical painted bowls, jugs both with and without decoration, etc., have close similarity to analogous levels in other sites in the area, as has been shown. However, there are some archaic shapes to be found, particularly in some plates and cooking pots, which seem to be remains and probably were already of very restricted use. These relatively rare archaic pieces seem to indicate that we are not dealing with a very advanced date in the eighth century. On the contrary, the four glazed fragments that were recovered are proof that the date is relatively recent. All this evidence fits in perfectly with the chronology of the earthquake of 749 AD, which in all probability, from a historiographical point of view was the cause of destruction of the building concerned.

8. For the variant of Fig. 15.1, see the parallels of Pella:

McNicoll, Smith and Hennessy, 1982: 167, no. 2; Mount

Nebo: Schneider 1950: Fig. 4, no. 1; and Amman:

Olavarri 1985: Fig. 17, no. 4.

9. Olavarri, 1985: 27.

10. See Sauer 1986: Figs. 6 and 14; Alliata 1991: Fig. 19,

no. 3; Northedge 1992: Fig. 133, nos. 3 and 4; Olavarri

1985: Fig. 17, nos. 7 and 8; Baramki 1942: Fig. 13,

no. 21; Schneider 1950: Fig. 14, no. 1; Uscatescu 1996:

Fig. 17, Group XVIII, nos. 1 and 2.

11. A. Uscatescu claims this, based on the diachronic

series from Gerasa (Uscatescu 1996: Fig. 23). He

calls them amphorae and associates them with

maritime commerce (p. 164), which we disagree with.

We believe they are domestic containers, for the same

reasons Uscatescu attributes to similar Byzantine

recipients (pp. 157–158). Numerous parallels exist

from the Umayyad period.

12. This item appeared during the exploration inside the

cistern in Room 1 of Building F.

13. Walmsley 1995: 663.

14. Amr 1986.

15. Rousset 1994: 38 and following.

16. Sauer (1986: 308) considers glazed pottery

exceptional in the Umayyad period: "If there is any

glazed pottery at all in the Umayyad period (one

possible sherd from Hammam es-Sarakh, several

possible sherds from Tell Hesban), it is very rare

indeed." Olavarri (1985: 39), based on excavations

in the citadel of Amman, dates the introduction of

glazing between 750–775 AD. He notes that between

740–750: "...this same type of polychrome glazed

bowls appeared together with fragments of painted

Umayyad pottery in the levels of the first Abbasid

occupation. It therefore seems convenient to state

that they were already made in the initial stages of

the Abbasid rule (750–775), that is, if they were not

already introduced during the last years of the

Umayyad period (740–750), which is not impossible."

- from Almagro et al. (2000:448, 452-453)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

- summarized by ChatGPT version 4o

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Late Umayyad | Early–mid 8th century CE | Final occupation phase before destruction. Associated with residential rooms and courtyard reconfigurations built with reused ashlars, set approximately 30 cm above the Umayyad floor level. Pottery includes bowls with red-on-white slip, cooking pots, pyriform jugs, and glazed items. Glazed ware suggests cultural influence from Mesopotamia and a terminus ante quem of 749 CE. Destroyed by the 749 CE earthquake. |

| III | Umayyad | Late 7th to early 8th century CE | Primary structural construction of Building F, including masonry and ashlar walls set in grey mortar. Represents elite urban architecture, possibly palace associated. Pottery of this phase includes classic Umayyad forms, such as red-slipped ataifores and semicircular cooking pots. This level was buried by collapse debris >1 m thick. |

| II | Byzantine | 5th–7th century CE | Earlier occupation beneath Umayyad floors. Pottery types include short-necked jars with spherical bodies. Some reused in Umayyad phase. Possible early usage of some courtyard spaces prior to Umayyad construction. |

| I | Roman | 1st–4th century CE | Lowest visible floor level in excavation, a paved Roman surface beneath Building F’s foundations. No direct architectural use in later phases, but formed the base upon which later phases were built. Ash deposits ~38 cm above this pavement mark the later Umayyad room level. |

The archaeological study of Building F has enabled us to reach the following conclusions:

1. The building was never completely finished: construction of the walls, vaults and columns was completed, but not the plastering. The same can be applied to the buildings of the eastern sector excavated by the Italian delegation, judging by the photographs we have seen. In any case, we are dealing with circumstances which did not affect the possibility of inhabiting the building.

2. At the time of its destruction by the earthquake, the building hardly seems to have been inhabited, since in none of the sectors where rubble from the disaster has been excavated, have there been any signs of domestic utensils, organic remains, or even the bodies of people or animals which would normally accompany such levels in other sites and even in other parts of the citadel of Amman.

3. Immediately after the earthquake, the building was partially and marginally re-exploited; this consisted basically of clearing up certain rooms and reusing them as simple dwellings. One of the iwans was even transformed into the workshop of the oven which was never put into use. This phase seems to have lasted only a short time, probably no more than some decades, and certainly it cannot date from long before the Abbasid period.

The archaeological evidence we have been putting forward shows that the building suffered the devastating effects of a natural disaster of enormous proportions. A large part of the roofing, series of arches, and even the façades of the iwans collapsed, leaving huge quantities of rubble which in some parts reached a depth of more than one metre. The materials found, especially the pottery, make it possible to confirm that the event in question took place at about the middle of the eighth century, and therefore we can suppose that we are dealing with the earthquake of 749 AD. The seismic effects were felt with great violence, not only in the palace, but also in the whole citadel of Amman, as ample archaeological evidence has borne out. The columns of the portico and the architrave of the magnificent temple of Hercules ... were demolished by the earthquake. In the sector that Northedge denominated "C", the remains of two houses from the Umayyad period were discovered, together with the street which separated them. The westernmost one was so seriously affected by the seismic movement that it could only be partially reused in later periods. The easternmost dwelling showed similar signs of destruction to the previous one, and of a partial reoccupation after the disaster; the human skeleton of one of the victims was discovered here.18

Written sources have left detailed evidence of the magnitude of the disaster which affected the South of Syria, Palestine and the Valley of Jordan in 749 AD19, and whose effects were felt from Persia to Egypt. The event was frequently mentioned in Byzantine, Arab and Jewish written sources. The first to describe it is Theophanes, who dates it in the sixth year of the government of Constantine V and the third year of the Caliph Marwan I.20 According to the chronicler, the earthquake, which happened at about 10:00 in the morning, killed tens of thousands of people and destroyed churches and monasteries, particularly in the regions near Jerusalem. In fact, the quake affected the Holy City seriously, where it partially destroyed the al-Aqsa mosque, which had to be reconstructed some years later by the Caliph al-Manar.21 According to the chronicle by Miguel the Syrian (twelfth century AD), the earthquake devastated Tiberias, which was confirmed by the Hebrew text lamenting the death of many Jews in that region.22

The archaeological evidence has been as eloquent as the texts with regard to the catastrophic effects of the earthquake in question. In fact, excavations have revealed considerable layers of destruction, generated by a sudden disaster which surprised people and animals, causing death and destroying innumerable buildings. As an example of this there are the sites of Jarash,23 Pella,24 Cafarnaum,25 Hippos,26 Scythopolis,27 the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar in Jericho,28 and Jerusalem itself.29

The possibility of continuity after a catastrophe of such magnitude was even more traumatic due to the geopolitical circumstances that coincided with this event. One year after the earthquake, the last Umayyad caliph and his whole family were exterminated, giving way to a new dynasty, the Abbasids. Such an event was of enormous significance for the region, which had recently been devastated, since the change in the centre of power from Syria to Iraq meant as a consequence a social crisis which had a serious effect on the once splendid cities and finally ruined many of them.

The excavation has provided evidence that after the earthquake Building F was reoccupied and, therefore, slightly reconditioned. The seismic movement meant the collapse of some of the vaults covering the rooms of the building, as shown by the deep layers of rubble excavated in the rooms. There is a stratum of variable depth, sometimes reaching more than one metre, resting directly on the original floor. Roughly-hewn, medium-sized stones are plentiful, and there are remains of the characteristic lime mortar with ash used in the construction of the walls and which supported the masonry of the vaults, as shown by the roofing which is conserved in one of the rooms of Building H. Evidence of such violent destruction is particularly visible in the courtyard, since a considerable part of the series of arches of the portico was found just as it had collapsed during the earthquake. Not in all the rooms can we see so clearly the ruins of the vaults covering them, either because they withstood the seism or, as was more frequently the case, the rubble was wholly or partially cleared away following the catastrophe. Similarly, large areas of the courtyard were cleaned up, to a certain extent, by those who took over the ruined building. Efforts to rehabilitate the building were not only limited to clearing up the rubble, but also, as a matter of priority, to reconstructing the covering. In order to do this, partition walls were built in many rooms, using treated masonry, similar to that used in the original construction, but joined with clay instead of lime mortar. These are walls which subdivide the original rooms, normally with an opening which allows communication between the two rooms; they are approximately 60–70 cm wide. As these walls halved the room space, it was possible to use beams that were not excessively long to support a flat ceiling. This type of construction is much simpler, from a technical point of view, than the use of vaults which do, however, permit the covering of much wider spaces like the original ones. From an architectural perspective, the new construction is a considerable impoverishment in keeping with the precarious nature indicated by, for example, the partial clearing of rubble from the courtyard.

However, the most important transformations are brought about by a new concept of space: what was originally an articulated but unitary building, went on to become a juxtaposition of independent, in all probability domestic, units. This conversion can be observed in the majority of the openings allowing outer communication between the different rooms without the necessity of passing through the courtyard, the surface of which was occupied by some of the new radial domestic units. In its original concept, the courtyard was the inner area of a private domestic nucleus, but the following transformations converted it into an outer area consisting of several dwellings. That is to say, the reoccupation of the building converted the original courtyard, from a functional point of view, into a semi-public square more similar to a back lane of a classical Islamic town than to a domestic courtyard. The occupation of Courtyard 2, undoubtedly important from a point of view of protocol in the Umayyad palace, is another obvious proof that this palatial building underwent a complete transformation and was indeed disfigured under the Abbasids: no doubt it was still occupied and inhabited, maybe even to a greater extent than during the previous period, although it was no longer an organised palace, but rather had become a second-rate residential area.

17. Almagro 1983: Ill. 51.a. and 51.b.

18. Northedge 1992: 143.

19. Until the present day there has been no unanimity as to the

date when the event took place, and different hypotheses from

747 to 749 have been considered. Nevertheless, recent

archaeological discoveries carried out on the site of Bet Shean

seem to show unequivocally that the correct date is 749: see

Tsafrir and Foerster 1992: 231–235.

20. Theophanes 1883: 442.

21. Tsafrir and Foerster 1992: 232.

22. Tsafrir and Foerster 1992: 232.

23. Ostratz 1989: 74–77.

24. McNicoll et al. 1982: 123–141.

25. Tzaferis 1988: 145–179.

26. Karcz and Kafri 1978: 237–253.

27. Tsafrir and Foerster 1992.

28. Hamilton 1959.

29. Mazar 1969: 20.

- Area Plan of the Citadel

in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map - Fig. 1 - General plan of

the north part of the Amman citadel from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel.

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 1 - Congregational

Mosque and Souq Square on the Citadel in Amman from Arce (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Congregational Mosque and Souq Square at Amman Citadel:

- General plan

- Elevation of the souq east portico.

- View to north of the souq east portico

- View of the blind arch on the western façade of the vestibule

Arce (2000) - Fig. 1 - Plan from

Harding (1951)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Harding (1951)

- Area Plan of the Citadel

in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map - Fig. 1 - General plan of

the north part of the Amman citadel from Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel.

Alamgro et al (2000) - Fig. 1 - Congregational

Mosque and Souq Square on the Citadel in Amman from Arce (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Congregational Mosque and Souq Square at Amman Citadel:

- General plan

- Elevation of the souq east portico.

- View to north of the souq east portico

- View of the blind arch on the western façade of the vestibule

Arce (2000) - Fig. 1 - Plan from

Harding (1951)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Harding (1951)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 20 June 2025

- summarized by ChatGPT version 4o

- from Harding (1951)

- some ChatGPT hallucinations appear to be present in this summary

The most telling evidence of possible earthquake-related destruction comes from Rooms L and M. These rooms originally featured a basement and a ground floor, both supported by arches. The basement arches remained intact, while those of the ground floor had collapsed entirely into the basement. The selective failure of upper-level architecture, while lower supports remained stable, strongly suggests a sudden downward structural failure, consistent with seismic damage.

The presence of a dome-capped sandstone fire altar, scattered over a vertical fill range, and the collapsed cistern entry by Room F also align with seismic disturbance. The absence of late Abbasid or Byzantine reoccupation levels, and the Umayyad character of coins and pottery, supports a terminus ante quem of mid-8th century CE, matching the known 749 CE earthquake that affected Amman.

Harding notes that these were some of the few examples of domestic Umayyad buildings uncovered in Jordan, as most others had been long built over. The quantity and preservation of household artifacts, combined with structural collapse, make the case for archaeoseismic evidence particularly strong at this site.

Harding (1951:10-11) described wall collapse in Room H

of one of the Umayyad structures on the Citadel in Amman. Harding (1951:7)

describes the area excavated as being located on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadel

.

Harding (1951:10-11) associated this wall collapse with fragments of a

sandstone fire altar

which he presumed was on a shelf before the wall collapsed.

Russell (1985) cites

Harding (1951) when reporting on collapsed

Umayyad structures uncovered during excavation of the Citadel in 1949.

- from Harding (1951:7-8)

The area is situated on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadel, and it appears that during the Roman (or less probably the Hellenistic) period all early remains were swept away to make room for a new town planning scheme. This is confirmed by deep excavations by builders on the slopes of the citadel which reveal jumbled but inverted stratification. It is only on the lower, eastern section that there are any early remains, and these appear to be mostly of the Iron Age. It is certain, however, from a tomb group in the vicinity, that it was also occupied during the Hyksos period, and one would expect so strongly defended a position, with such a fine water supply close by, to have been occupied during all the historic periods.

The material is important inasmuch as it is one of the rare occasions when we have Umayyad buildings and objects of the ordinary man. Most work in the period has been done on palaces, and indeed there are not many sites where it is possible to find the common houses, most of them having been long since built over.1

The Buildings (see plan, Fig. 1). The main house consisted of a courtyard, the entrance to which must be outside the area of excavation to the west, with rooms opening off it on the west, north and east sides. One room on the north side had a door considerably wider than any of the others: it was probably the open liwan or guest-room. Walls are fairly thick and built of reused Roman blocks and rough flint rubble held together by mud plaster. Only rooms C, D and F had traces of lime plaster on the walls. Floors were of beaten earth, and door sills, except for the stone sill to room F (Pl. I, 6), were flush with the floors.

In the courtyard was a kind of raised platform of very rough construction, and from the north-east and north-west corners channels conducted water from the roof to the cistern in room J. This cistern is cut in the rock (see section) and is probably earlier than the building in which it was incorporated. There was an entrance to another cistern against the north wall of F, but it had collapsed, and it was not possible to clear it. The door between rooms D and E had been blocked up and used as a cupboard (Pl. I, 1), in which was found a selection of glass, pottery and lamps. A rectangular limestone trough was in the south-east corner of room N, and a circular one in the same corner of J. A clay oven stood against the west wall of F, close by which were a number of soapstone cooking pots (Pl. I, 7), and a water jar, No. 48.

The house on the east, of which only one complete room and parts of three others were seen, was more ambitious architecturally. A great quantity of plain large white tesserae in room K suggested that the upper storey at that point had a mosaic floor: in this room was another large rectangular limestone trough (Pl. I, 4). Rooms L and M had what was probably a basement and a ground floor level both supported on arches (see section, Fig. 1 and Pl. I, 5). The arches of the basement were intact, but those of the ground floor had collapsed and fallen through into the basement. These rooms were only cleared up to the limit required by the building.

There is little to say about the houses on the north and south, except that that on the north was at a much higher level, and they were both of inferior workmanship to the main house. The walls of rooms A and D are built on the remains of earlier walls.

The Objects. The only objects other than sherds from the houses on the north, west and south were the bone inlay from rooms A and B (Pl. II), the glass and glass mosaics from room M (Pl. V, 24) and a few amorphous pieces of iron and iron nails from various rooms.

From the main house, however, we recovered a good selection of objects of all kinds, including a few coins. Only one of the latter, definitely Umayyad, was found in the floor of room J: the rest were in the filling, and consist of two more early Umayyad, one Byzantine-Arab transition and one of Claudius Gothicus. They have been identified by Sir Tatéz-Kirkbride, K.C.M.G.

1. In Syria XX (1939), pp. 239 ff., Sauvaget describes the Umayyad remains at Jebel Seis, but there was no excavation, and only plans and photographs of buildings are given. These are remarkably well squared up for Umayyad buildings.

- from Harding (1951:10-11)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Building F

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of Building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12Late structures in building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building FSign at Amman Citadel Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Figure 5

Figure 5Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 14

Figure 14The west iwan blocked by late structures Alamgro et al (2000)

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building FPhoto by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building FAnother Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Description

|

|

Courtyard of Building F

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of Building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12Late structures in building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building FSign at Amman Citadel Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Figure 5

Figure 5Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard Alamgro et al (2000) |

Description

|

| Broken Columns | Colonnaded Street between Buildings C and B to the east and D and E to the west

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000) |

Broken Columns at Colonnaded Street in Umayyad Palace Amman, Jordan

Broken Columns at Colonnaded Street in Umayyad Palace Amman, JordanPhoto by Jefferson Williams |

JW: These breaks, albeit undated, may have occurred as a result of the Mid 8th century CE earthquake |

|

Room H of Harding (1951).

Harding (1951:7)

describes the area excavated as being located on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadelbeneath what is now the Jordan Museum.

Amman Citadel

Amman CitadelJW: Umayyad Palace at top of map from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

Figure 1

Figure 1Harding (1951) |

Harding (1951:10-11) described wall collapse in Room H

associated with a fragments of a sandstone fire altarwhich he presumed was on a shelf before the wall collapsed. |

|

|

Rooms L and M of Harding (1951).

Harding (1951:7)

describes the area excavated as being located on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadelbeneath what is now the Jordan Museum.

Amman Citadel

Amman CitadelJW: Umayyad Palace at top of map from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

Figure 1

Figure 1Harding (1951) |

Rooms L and M had what was probably a basement and a ground floor level both supported on arches. The arches of the basement were intact, but those of the ground floor had collapsed and fallen through into the basement.- Harding (1951:7-8) |

|

|

the portico and the architrave of the magnificent temple of Hercules

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadelfrom maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map |

Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

Fallen Column at Temple of HerculusJW: I do not know the reason for or date of the column collapse Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

The columns of the portico and the architrave of the magnificent temple of Hercules, which is a building from the middle of the second century A.D., which was already being used as a quarry, were demolished by the earthquake.- Alamgro et al (2000) |

|

Two Umayyad houses in the sector that Northedge denominated "C"

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadelfrom maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map |

In the sector that Northedge denominated "C", the remains of two houses from the Umayyad period were discovered, together with the street which separated them. The westernmost one was so seriously affected by the seismic movement that it could only be partially reused in later periods. The easternmost dwelling showed similar signs of destruction to the previous one, and of a partial reoccupation after the disaster; the human skeleton of one of the victims was discovered here- Alamgro et al (2000) |

- Modified by JW from Figs. 2 and 6 of Almagro et al. (2000)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Figs. 2 and 6 of of Almagro et al. (2000)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Building F

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of Building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12Late structures in building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building FSign at Amman Citadel Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Figure 5

Figure 5Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 14

Figure 14The west iwan blocked by late structures Alamgro et al (2000)

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building FPhoto by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

Plaster Level in Building F

Plaster Level in Building FAnother Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Description

|

|

|

Courtyard of Building F

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of Building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 3

Figure 3Building F from the top of the entrance hall dome Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 12

Figure 12Late structures in building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Plan of Early and Late structures in building F

Plan of Early and Late structures in building FSign at Amman Citadel Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 |

Figure 5

Figure 5Building F and the courtyard with remains of the columns and arches Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 6

Figure 6Remains of columns and arches in the courtyard of building F Alamgro et al (2000)

Figure 13

Figure 13Base Column and Arch collapsed in the courtyard Alamgro et al (2000) |

Description

|

|

| Broken Columns | Colonnaded Street between Buildings C and B to the east and D and E to the west

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the north part of the Amman citadel. Alamgro et al (2000) |

Broken Columns at Colonnaded Street in Umayyad Palace Amman, Jordan

Broken Columns at Colonnaded Street in Umayyad Palace Amman, JordanPhoto by Jefferson Williams |

JW: These breaks, albeit undated, may have occurred as a result of the Mid 8th century CE earthquake | VIII+ |

|

Room H of Harding (1951).

Harding (1951:7)

describes the area excavated as being located on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadelbeneath what is now the Jordan Museum.

Amman Citadel

Amman CitadelJW: Umayyad Palace at top of map from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

Figure 1

Figure 1Harding (1951) |

Harding (1951:10-11) described wall collapse in Room H

associated with a fragments of a sandstone fire altarwhich he presumed was on a shelf before the wall collapsed. |

|

|

|

Rooms L and M of Harding (1951).

Harding (1951:7)

describes the area excavated as being located on the south side of the western, highest part of the citadelbeneath what is now the Jordan Museum.

Amman Citadel

Amman CitadelJW: Umayyad Palace at top of map from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

Figure 1

Figure 1Harding (1951) |