Amman - Introduction

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Amman | Arabic | عَمَّان |

| Philadelphia | Ancient Greek | Φιλαδέλφεια |

| Rabbat Amman | Ammonite | |

| Rabbat Bnei ʿAmmon" | Biblical Hebrew | רבת בני עמון |

| Rabbaṯ Bəne ʿAmmôn | Tiberian Hebrew | |

| Rabbat Ammon | Modern Hebrew | |

| Bit Ammanu | Assyrian | |

| KURBīt Ammān | Akkadian |

In the earliest references, it is designated as 'Amman of the Bene 'Ammon or as Rabbat Bene 'Ammon and is referred to as Bit Ammanu in Assyrian texts. It was renamed Philadelphia at the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283-246 BCE); its earliest name was revived as 'Amman in the Islamic period. The Amman district is a fertile area that drops down through rough terrain and occasionally forested hillsides to the Jordan Valley to the west and merges gradually into the steppe like desert to the east.

The city has a long history dating back to the sixth millennium; remains found in its vicinity date back even earlier, to the Paleolithic period. Jebel Qal'a, Amman's citadel, was the focus of settlement for thousands of years; numerous sites occupied in many different periods are scattered around the city. Some — Sahab, Tell el-'Umeiri, 'Ain Ghazal, and Safut — were significant settlements in size, strategic location, and preserved artifacts. Amman was still flourishing in the tenth century CE according to the Arab historian al-Muqaddasi, but by the fifteenth century it was described as a field of ruins.

Amman was a spectacular Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad ruin for many centuries until late in the Ottoman period, with impressive stretches of fortification walls, colonnaded streets, and many substantially preserved buildings. Although adventurers made the trip to ancient ruins east of the Jordan River late in that period, serious surveys of sites such as Amman were not initiated until the nineteenth century. Claude R. Conder visited Amman in 1880 and Howard Crosby Buder published the results of the Princeton Archaeological Survey there in 1921. The survey included the careful mapping and examination of ruins in Amman and elsewhere in Transjordan. The gradual resettlement of Amman began in 1878, as a small village among the ruins, with a group of Circassians relocated by Ottoman Turkish authorities. The village expanded after Prince Abdullah chose Amman as the seat of government in 1921 and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan was established in 1946. Another expansion of the city took place in the 1970s and 1980s. It now covers more than 900 sq km (558 sq. mi.), with a population approaching two million.

Throughout history, the communication essential to the prosperity of Amman and the surrounding area traversed the desert highway and the Kings Highway. Nelson Glueck's extensive Trans Jordanian survey (1932-1949) has recentiy been augmented by surveys connected with the Cultural Resource Management program in Jordan and by the Madaba Plains Project. This has led to a better understanding of land-use patterns and the interrelationships between remains in the countryside (farmsteads, storage towers, and forts) and occupation on the region's tells.

The earliest major settlement around Amman is the Neolithic village of 'Ain Ghazal. Its occupation extended from the Natufian and Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) periods through an early pottery phase of the Yarmukian culture. The site's most remarkable remains are rectilinear structures with plastered walls from the PPNB that are associated with burials of plastered skulls and caches of the earliest known reed-and-plaster human statuary.

Occupation on the citadel, Jebel Qal'a, can be traced to the Neolithic as well, but, except for Chalcolithic pottery found in a cave on its second plateau, remains are extremely scanty for any period before the Middle Bronze Age. Early Bronze Age tombs have been found on Jebel Qal'a, Jebel et-Taj, Jebel Abdali, and other nearby sites like Umm el-Bighal. The traditions recorded in the biblical accounts of Lot and Abraham indicate an early political Ammonite entity (Gn. 19:28).

Walls of substantial MB buildings and stretches of the fortifications have been excavated on the citadel, but the remains are scattered and do not provide information about how the site was organized then. The importance of the MB settlement is demonstrated by the many rich tomb groups excavated on Jebel Qal'a and in the nearby hills, The assemblage includes distinctive, well-made vessels; scarabs; cylinder seals; metal pins and implements; ivory inlays; beads; and alabaster jars. The chocolate-on-white wares and the white burnished wares from the end of the period and the beginning of the Late Bronze Age are exceptionally finely made. Bronze Age remains have been found on the highest and second plateau of Jebel Qal'a, indicating that the city (at least 20 ha [49 acres] in extent) was probably as large and important as the Iron Age city (see below). Little is known about the periods of occupation on the lowest, or third, plateau in any period because it is covered with modern houses.

The richest remains from Late Bronze Age in the Amman district come at present from the temple at the old airport, northeast of the city. [See Amman Airport Temple] Excavation of this substantial, isolated building yielded significant quantities of foreign, Cypriot and Mycenaean and luxury wares, and important small finds such as cylinder seals, jewelry, Egyptian scarabs, amulets, and alabaster vessels. Similar artifacts have been found in lesser quantities in Amman area tombs. An architecturally similar structure was discovered nearby at el-Mabrak (Yassine, 1988, pp . 61-64)

Remains of the Iron Age occupation on Jebel Qal'a have been excavated in more areas and in larger exposures than for earlier periods, but still not enough to reveal a coherent plan. Several centuries of Iron II occupation are represented, but they only give limited insight into the nature of the settlement. Portions of fortification walls and a possible gateway were excavated from the tenth and ninth centuries BCE (Dornemann, 1983, pp. 90-92) and sections of defense walls have been found in several other areas (Humbert and Zayadine, 1992). A large building of late Iron II date has been excavated on the second plateau (Humbert and Zayadine, 1992). The first excavators, an Italian expedition in 1934 (Bartoccini, 1933-1934), suggested that temple remains existed in what was later the precinct of the Roman Temple of Hercules. However, the "temple " was badly destroyed by the Roman construction, making the designation questionable. A large number of rich Iron Age tombs have been excavated in Amman and its vicinity. A tomb near the royal palace provided evidence that spanned the end of the Bronze Age and Iron I and II. This supplements the meager evidence from Jebel Qal'a for the beginning of the Iron Age. The early pottery traditions of the Iron Age show limited examples of the decorated pottery with an Aegean influence that is so characteristic in coastal assemblages from the period. Although a variety of painted pottery is present, the assemblage is dominated by plain wares that show a transition in form and technique from the Bronze Age to Iron II materials. A long list of neighboring sites has now been investigated to help develop a picture of the area's material culture in the Iron Age. Excavation has now been carried out or tombs excavated at Tell el-'Umeiri, Tell Jawa, Tell Safut, Tell Siran, Khilda, Khirbet el-Hajjar, Meqabelein, Rujm el-Malfuf, and Tell Sahab. [See 'Umeiri, Tell el-; Safut, Tell; and Sahab.]

Many of the excavated tomb groups and much of the pottery encountered on the site date to the seventh and sixth centuries BCE. The pottery tradition is impressive for its sophistication. Red-burnished ware is the most distinctive Iron II feature, with some very sophisticated, finely made examples of bowls and jars. These traditions can be established in a broader regional context with examples that rival the best production in neighboring lands, particularly the Phoenician coast, if they are not examples of imports. A characteristic corpus of simple painted pottery also exists. The tombs demonstrate a burial tradition that includes anthropoid coffins. One of the Ammonite kings, 'Ammi-Nadab, is mentioned on the seal of one of his officers that was found in one of these tombs, in a rich assemblage that also contained gold and silver jewelry and decorated seals. Handmade and mold-made figurines illustrate the period's artistic conventions, with horse and rider figurines predominating that apparently enjoyed special significance locally, at least in the Amman District.

Rabbat Ammon was the capital of an Iron Age state that at times stretched from the modern Wadi Mujib (biblical Arnon River) to the Wadi Zerqa (biblical Jabbok River), from the Jordan River to the desert, and at times beyond. Its relationships with the neighboring states of Moab and Israel, as well as the mighty Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and Persian empires shifted constantly and dramatically from peaceful and cooperative to hostile. Amman is first mentioned as a state in the Jephthah stories in Judges 3 and 11 and played an important role in the time of David and Solomon. It fought as a member of a coalition of Syrian and neighboring states against Assyrian advances in the ninth century BCE but eventually was incorporated into the Assyrian provincial administration under Tiglath-Pileser III. Two Ammonite rulers of the seventh century BCE are mentioned in an inscription on a Bronze bottle from Tell Siran, adding to the still incomplete series of royal names that extends from the late eleventh through the sixth centuries BCE. Amman came successively under Neo-Babylonian and then Persian rule (under the Persian governorship of Arabia). The Tobiad family, powerful Jewish landowners in the Ammonite area connected with the Jerusalemite priesthood, was influential in Amman in the Persian and Hellenistic periods.

A small corpus of Ammonite inscriptions and an extensive collection of inscribed seals exist. The Amman citadel inscription and the inscribed bottle from Tell Siran are the longest texts. They illustrate an Ammonite language, but it is difficult to translate because the corpus is so limited. Ammonite script is related to Hebrew, Phoenician, Aramaic, and Moabite. [See Ammonite Inscriptions.]

A rich collection of sculpture and other small finds indicates many elements incorporated from a variety of sources, particularly Egyptian, Phoenician, Syrian, Assyrian, and Cypriot. The corpus of Ammonite limestone and basalt sculpture continues to grow and is quite distinctive: small freestanding sculptures in the round with unusual and unrealistic proportions, frequently with oversized heads, feet, and other body parts. Some pieces are very polished in their rendering and others heavily stylized (see figure 2).

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Amman was included in the sphere of control of the Ptolemies. Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-247 BCE) rebuilt the city and renamed it Philadelphia. Amman later came under the control of the Seleucid dynasty of Syria. Only scattered building remains of this period have bee n encountered so far on the two upper plateaus of the citadel, but the ceramic remains, coins, and other small finds again indicate a rich and prosperous city.

Amman became part of the Roman Empire in the first century BCE, a result of Pompey's victories. Marcus Antonius [Mark Anthony] took the Ammonite area from Nabatean control and gave it to Egypt. With his defeat at Actium (31 BCE), the city regained its independence in the Roman world. A new height in the city's prosperity was reached in the second century BCE, when Trajan's annexation of the Nabatean kingdom reduced competition for trade. Amman was associated with the Decapolis league of cities and was an important stop on a newly established road system, the Via Nova Trajana. [See Decapolis.]

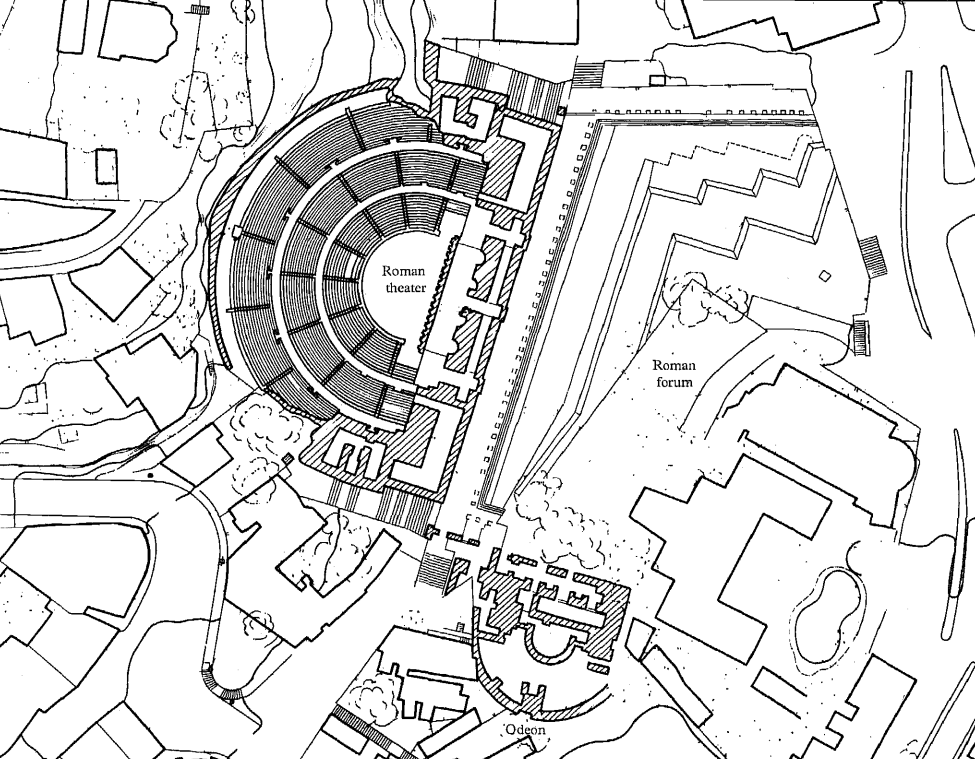

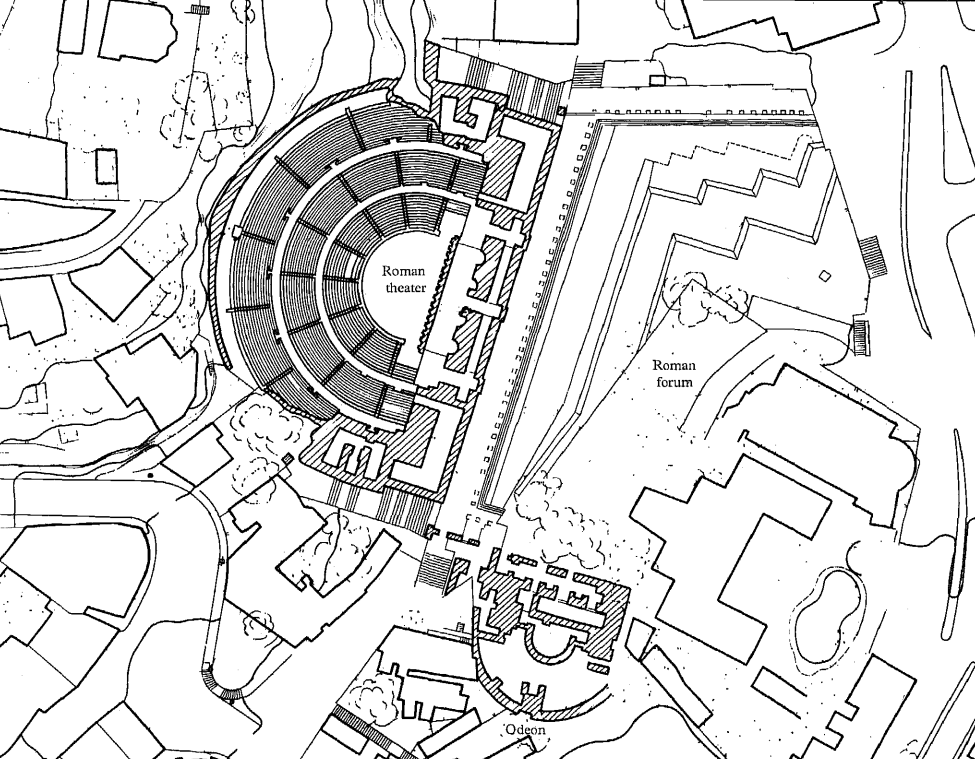

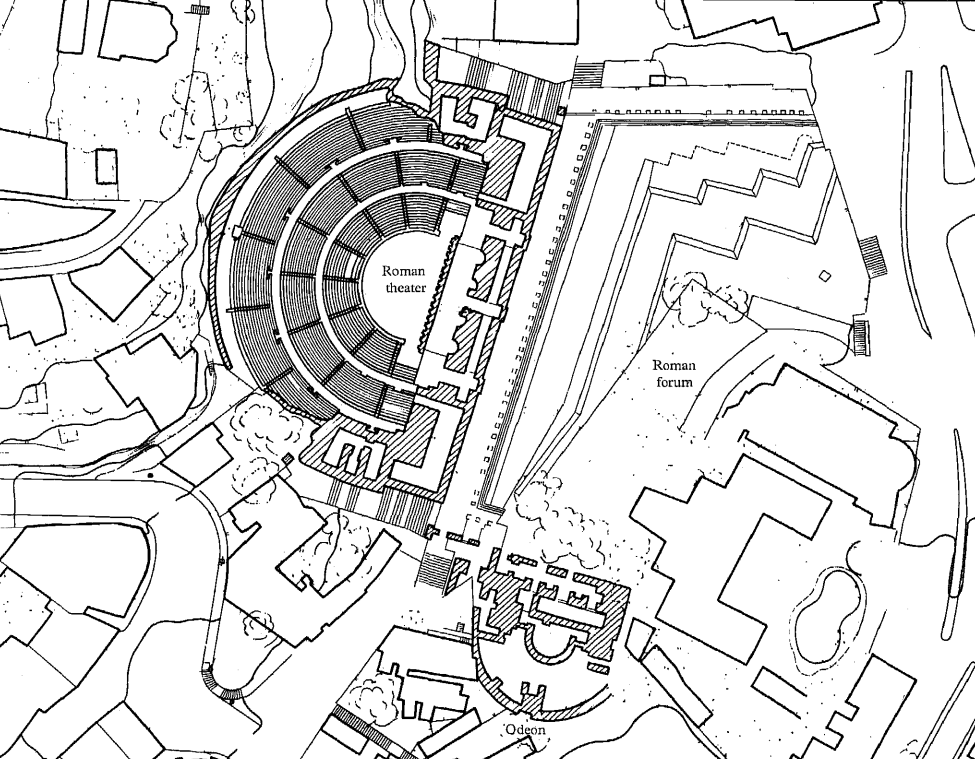

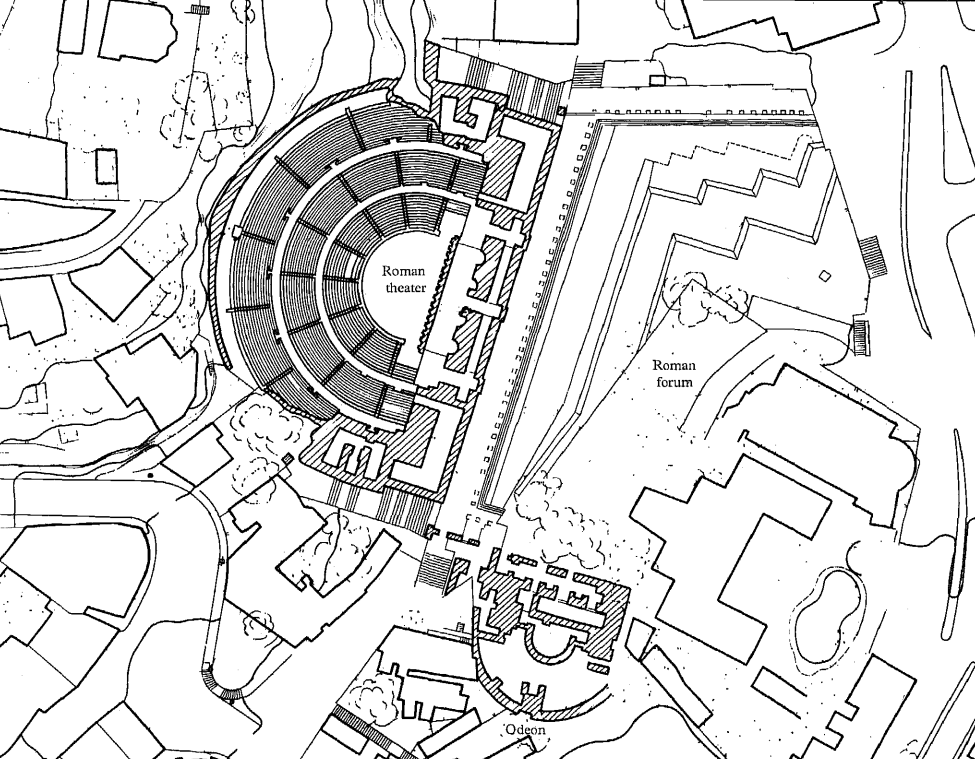

Amman's expansion and prosperity in the Roman period (second century CE) entitled it to all of the trappings of a major city in the empire: temples adorned its acropolis and a theater/odeum complex and other impressive structures, such as the nymphaeum on the banks of the stream, the Seil Ammon, adorned the downtown area (see figure 3). A system of colonnaded streets organized the city's areas: its cardo ran down the main wadi along the Seil Ammon , which was vaulted, its decumanus intersected the cardo near the present-day Husseni mosque in the downtown area; and another street extended up the slopes of the citadel through a monumental gateway. The partiy restored temple on the citadel is now securely attributed to Hercules by two fragments of an inscription on the architrave of the portico that dedicates the building to the emperors Marcus Aurelius Antonius and Lucius Aurelius Verus (161-169 CE), during the governorship of P. Julius Geminius Mercianus.

Philadelphia was the seat of a bishopric in the Byzantine period. Remains of several churches were recorded on early twentieth century maps of the downtown' area and a church dedicated to St. Elianos (a third-century Christian martyr from Amman) stands excavated on the citadel. The traditional location of the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, on the outskirts of Amman, at Rajib, near Sahab, still venerated, traces its origins to Byzantine legends. The Roman city was rebuilt in both the Byzantine and Islamic periods. The ancient name Amman was again given to a burgeoning city substantially renewed by walls, streets, and an impressive palace complex on the citadel in the Islamic period. Amman prospered under the Umayyad dynasty and was the granary of the 'Abbasid province. Following the Islamic period, the city waned in importance, its decline hastened by the shift of major administrative functions to other cities — to Kerak, Hesban, and Salt, in turn. By the fourteenth century, Abul Fida, an Arab writer, described the city as a ruin.

- Area Plan of the Citadel

in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

- Area Plan of the Citadel

in Amman from maps-amman.com

Amman Citadel

Amman Citadel

JW: Umayyad Palace at top of map

from maps-amman.com/amman-citadel-map

- Fig. 3 - Plan of the

Roman Theater and Forum Area from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan of the Roman Theater and Forum Area

Courtesy of R. Dornemann

Meyers et. al. (1997)

- Fig. 3 - Plan of the

Roman Theater and Forum Area from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan of the Roman Theater and Forum Area

Courtesy of R. Dornemann

Meyers et. al. (1997)

- Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

on the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

JW: I do not know the reason for or date of the column collapse

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Displaced voissor in arch

in Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

Displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

JW: LOcation was in the Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel. Cause and date of displacement unknown

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Closeup of Displaced voissor

in arch in Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Closeup of displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

Closeup of displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

JW: LOcation was in the Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel. Cause and date of displacement unknown

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

- Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

on the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

Fallen Column at Temple of Herculus

JW: I do not know the reason for or date of the column collapse

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Displaced voissor in arch

in Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

Displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

JW: LOcation was in the Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel. Cause and date of displacement unknown

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025 - Closeup of Displaced voissor

in arch in Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel - photo by JW

Closeup of displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

Closeup of displaced voissor in arch on Amman Citadel

JW: LOcation was in the Ummayad part of the Amman Citadel. Cause and date of displacement unknown

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 19 June 2025

Northedge, A., et al.:

1992 Studies on Roman and Islamic Amman. The Excavations of Mrs C.-M.

Bennett and Other investigations, British Academy Monographs in

Archaeology, 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the British Institute

at Amman for Archaeology and History).

Northedge, A., et al.:

1992 Studies on Roman and Islamic Amman. The Excavations of Mrs C.-M.

Bennett and Other investigations, British Academy Monographs in

Archaeology, 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press for the British Institute

at Amman for Archaeology and History).

Northedge, A. and C. M. Bennett (1992). "Studies on Roman and Islamic `Amman : the excavations of Mrs. C-M Bennett and other investigations."

Almagro Gorbea, A. (1983). El palacio Omeya de Amman. Institution Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, Dir. General de Ralaciones Culturales.

Olávarri-Goicoechea, E. (1985). El Palacio omeya de Amman II: la Arquologia, Instituto Espanol Biblico y Arquelogico.

Almagro Gorbea, A. et al (2000). El Palacio Omeya de 'Ammān, III. Investigación arqueológica y restauración, 1989-1997 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (España)

Almagro, Gorbea Antonio. "The Photogrammetric Survey of the Citadel of Amman and Other Archaeological Sites in Jordan. " Annual

of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 24 (1980); 111-119 .

Bartoccini, Renato. "Scavi ad Amman della missione archeologica

italiana." Bolleltino dell' Associazione interna degli studi mediterranei 4

(1933-1934): fasc. 4-5 , PP. 10-15 .

Butler, Howard Crosby. Ancient Architecture in Syria. Publications of

the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria,

1904-1905 and 1909, Division 2, Section A. Leiden, 1907. Includes

a survey of Amman when major ruins were still visible (see pp .

34-62)-

Dornemann, Rudolph H. The Archaeology of the Transjordan in the

Bronze and Iron Ages. Milwaukee, 1983. Major synthesis of archaeological remains in the Transjordan concentrating on remains from

Amman.

Geraty, Lawrence T., et al. "Madeba Plains Project: A Preliminary

Report of the 1987 Season at Tell 'Umeiri and Vicinity." Bulletin of

the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 26 (1990): 59-88. Re

port of an ongoing project that is doing major work in the area and

integrating remains from stratigraphic excavation with systematic

survey of the surroundings.

Glueck, Nelson. Explorations in Eastern Palestine. Vol. 3. Annual of the

American Schools of Oriental Research, 18/19 . New Haven, 1939.

One of four volumes in a landmark survey covering all of the Transjordan, including materials from the Amman area.

Harding, G. Lankester. The Antiquities of Jordan. London, 1959. Excellent overview of the cultural remains of Jordan.

Homes-Fredericq, Denyse, and J. Basil Hennessy, eds. Archaeology of

Jordan, vol. I, Bibliography and Gazetteer of Surveys and Sites. Louvain, 1986. Very useful summary of sites and excavations in Jordan.

Humbert, Jean-Baptiste, and Fawzi Zayadine. "Trois campagnes de

fouilles a Amma n (1988-1991). Trosieme Terrasse de la citadelle

(Mission Franco-Jordanienne)." Revue Biblique 99 (1992): 214-260 .

LaBianca, Oystein S. Hesban, vol. 1, Sedentarization and Nomadization:

Food System Cycles at Hesban and Vicinity in Transjordan. Berrien

Springs, Mich., 1990. Innovative work interpreting tire remains encountered in surveys of the Hesban and Amman areas.

Landes, George M. "The Material Civilization of the Ammonites. "

Biblical Archaeologist 24 (1961): 65-86. Important synthesis of Ammonite culture and history.

Northedge, Alastair. Studies on Roman and Islamic Amman: The Excavations of Mrs. C.-M. Bennett, and Other Investigations. Oxford, 1992.

Major study of the architecture and other remains of the Roman and

Islamic periods in Amman .

Yassine, Khair. Archaeology of Jordan: Essays and Reports. Amman ,

1988.