Resafa

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Resafa: aerial photograph from the northeast (M. Stephani, 1999).

Sack and Gussone (2016)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Ar-Rasafeh | Arabic | |

| Resafa | Arabic | الرصافة |

| Reṣafa | Arabic | الرصافة |

| Rusafat Hisham | Arabic | |

| Sergiopolis | Greek | Σεργιούπολις |

| Sergiopolis | Greek | Σεργιόπολις |

| Anastasiopolis | Greek | Αναστασιόπολις, |

| Raṣappa | Akkadian | |

| Rezeph | Biblical Hebrew | |

| Rezeph | Septuagint | Ράφες |

| Rasaappa | cuneiform sources | |

| Rasappa | cuneiform sources | |

| Rasapi | cuneiform sources | |

| Rhesapha | Koine Greek - Ptolemy | Ρεσαφα |

| Risapa | Latin in Tabula Peutingeriana | |

| Rosafa | Latin in Notitia dignitatum |

Ar-Rasafeh had a long history of occupation until its abandonment in the 13th century in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions (Sack and Gussone, 2016). At various times, it was a fortification of the Limes Arabicus, a Christian pilgrimage site for the veneration of Saint Sergius, and a residence for Umayyad Caliph Hisham bin Abd al-Malik.

- Fig. 7 - Location Map from

Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Roman limes between the Euphrates and Palmyra

(M. Konrad, 2008)

Al Khabour (2016)

- Fig. 7 - Location Map from

Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Roman limes between the Euphrates and Palmyra

(M. Konrad, 2008)

Al Khabour (2016)

- Fig. 6 - Resafa site plan from

Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Resafa: site plan of the city and its surroundings with selected find-sites

(D. Sack and M. Gussone, 2007; based on previous plans by M. Mackensen/H. Tremel and J. Giese/D. Spiegel).

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016)

- Fig. 6 - Resafa site plan from

Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Resafa: site plan of the city and its surroundings with selected find-sites

(D. Sack and M. Gussone, 2007; based on previous plans by M. Mackensen/H. Tremel and J. Giese/D. Spiegel).

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016)

- Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Basilica B from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 2

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings

(redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008.

Key - Phases- The Roman Castrum

- Expansion at the time of Bishop Alexander from Hierapolis

- Expansion under Emperor Zeno (474-491)

- Expansion after peace with the Persians under Anastasius (491-518) and Justin I. (518-527)

- Repairs and expansion under Justinian (527-569) and the Ghassanid phylarch al-Mundhir (569-581/582)

- From the Muslim conquest to the residence of Hisham

- Expansion under the Umayyad Hisham b. Abd al-Malik (724-743)

- Repair and changes in the Abbasid period (8.-10. century)

- From Atabegs to the Ayyubids and the abandonment of the city (11.-13. century)

- use by Bedouins (13.-20. century)

- Changes and restoration since the begin of archaeological excavations till the present

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Basilica B from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 2

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings

(redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008.

Key - Phases- The Roman Castrum

- Expansion at the time of Bishop Alexander from Hierapolis

- Expansion under Emperor Zeno (474-491)

- Expansion after peace with the Persians under Anastasius (491-518) and Justin I. (518-527)

- Repairs and expansion under Justinian (527-569) and the Ghassanid phylarch al-Mundhir (569-581/582)

- From the Muslim conquest to the residence of Hisham

- Expansion under the Umayyad Hisham b. Abd al-Malik (724-743)

- Repair and changes in the Abbasid period (8.-10. century)

- From Atabegs to the Ayyubids and the abandonment of the city (11.-13. century)

- use by Bedouins (13.-20. century)

- Changes and restoration since the begin of archaeological excavations till the present

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Cisterns from

Hof (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Situation plan

(C. Hof)

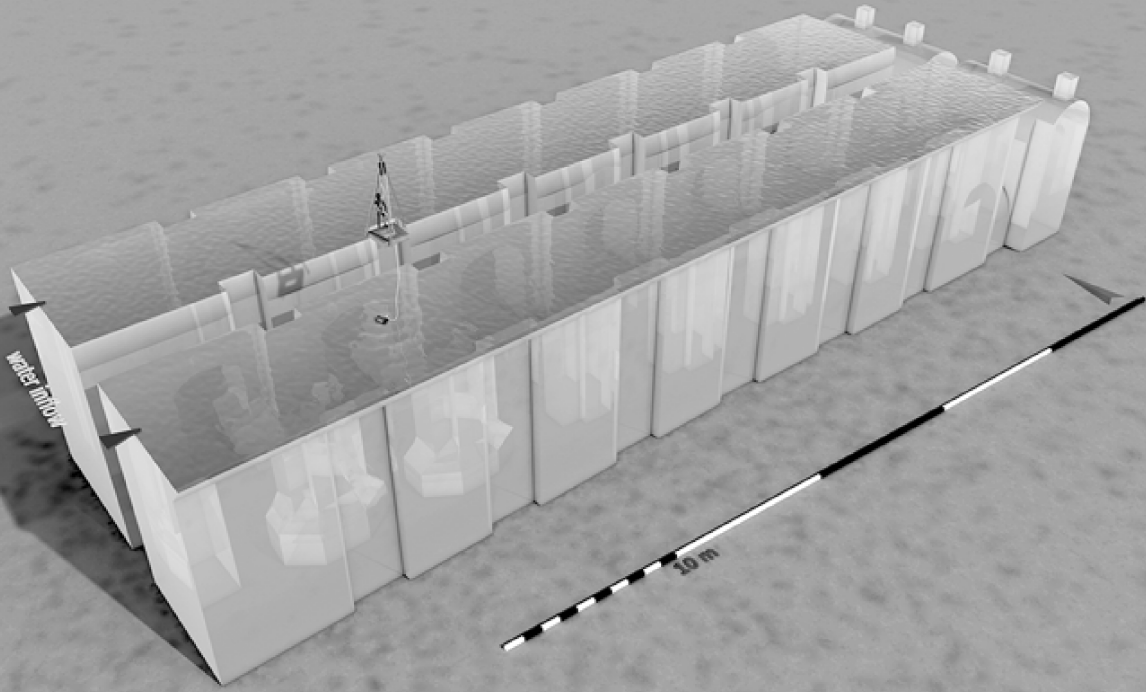

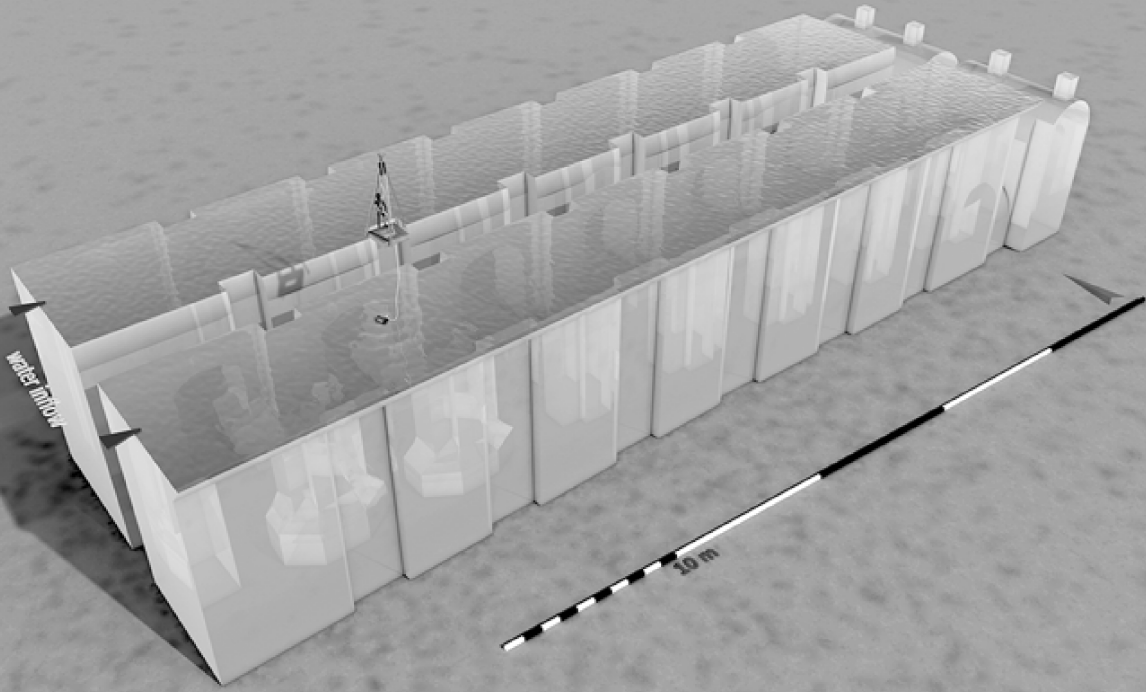

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 5 - 3D model of the

Great Cistern from Hof (2019)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Resafa, Great Cistern, 3D model of maximum water capacity

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 2 - Photo of SW area

with the great cistern from Hof (2019)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Resafa, southwestern city area

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Cisterns from

Hof (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Situation plan

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 1 - Resafa City Wall

reconstruction model from Hof (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction model. Basilica A (solid filled area) was already in existence. Basilica A Annexes, Cisterns, Basilica B and tetraconch Church (outlined areas) were probably under construction as the city wall was just about finished

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 4 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 1 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 1. prototype stretch of the wall (t 10–t 16) and autonomous piece (t 33–t 34) at the hydraulic installations (dam, canal, water culverts, cistern)

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 7 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 2 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 2. Changes at the water culverts after the fall of Amida 503 AD. the building site expands. new wall partitions rise according to the model section with sophisticated tower shapes (round, U-shaped and polygonal)

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 8 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 3 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 3. Further sections are being closed, new towers rise only in rectangular form. towers rise slower than curtain wall. three partitions stay open as operational gaps for traffic

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 9 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 3 (finishing off) from Hof (2016)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 3, finishing off. Closing the last gaps without a wall walk behind the arcades at t6–t10, at t27–t29 and at t47–t49; finishing towers

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016)

- Fig. 1 - Resafa City Wall

reconstruction model from Hof (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction model. Basilica A (solid filled area) was already in existence. Basilica A Annexes, Cisterns, Basilica B and tetraconch Church (outlined areas) were probably under construction as the city wall was just about finished

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 4 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 1 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 1. prototype stretch of the wall (t 10–t 16) and autonomous piece (t 33–t 34) at the hydraulic installations (dam, canal, water culverts, cistern)

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 7 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 2 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 2. Changes at the water culverts after the fall of Amida 503 AD. the building site expands. new wall partitions rise according to the model section with sophisticated tower shapes (round, U-shaped and polygonal)

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 8 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 3 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 3. Further sections are being closed, new towers rise only in rectangular form. towers rise slower than curtain wall. three partitions stay open as operational gaps for traffic

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016) - Fig. 9 - Resafa City Wall

Building stage 3 (finishing off) from Hof (2016)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Resafa, city wall, reconstruction of building stage 3, finishing off. Closing the last gaps without a wall walk behind the arcades at t6–t10, at t27–t29 and at t47–t49; finishing towers

(n. Erbe & C. hof)

Hof (2016)

- Fig. 4 - Great Cistern,

ground plan and sections Hof (2019)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Resafa, Great Cistern, ground plan and sections

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 4 - Great Cistern,

ground plan and sections Hof (2019)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Resafa, Great Cistern, ground plan and sections

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Vertical fractures

in the Apse of "the huge church" from Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Rusafa: the huge church containing the remains of St. Sergio.

JW: Note vertical fracturing in the Apse

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 3 - Basilica A with

butresses from Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Resafa: Basilica A, view from the southwest

(M. Gussone, 2008)

JW: note large buttresses which may have been constructed to shore up the building after an earthquake

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 10 - Fractures and damage

to the vault of North Gate Tower 19 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, north gate tower 19, secondary vault with cross symbols

JW: Note fracture in upper left corner

(C. Hof)

Hof (2016) - Figure 3.6 Throughgoing Gaps,

arch reconstruction, and displaced ashlars in the St. Sergius basilica (aka Basilica A) from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6

Resafa, St. Sergius basilica [aka Basilica A]. Note the two, throughgoing gaps in the apsis on the left, due to lateral extension caused by repeated loading parallel with the wall. The large arch had to be underpinned and subdivided by two smaller arches, supported by three columns. Note the out-of plane displaced ashlar next to the capital of the left column: it is clearly indicated as lateral loading by the earthquake. Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.7 Dropped Keystones

in a gallery within the city wall from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

Resafa, gallery within the city wall. Dropped keystones in each supporting arch of the corridor record vibration loads acting perpendicular to the main wall (also illustrated by Karnapp, 1976).

Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009

Kázmér et al. (2024)

- Fig. 2 - Vertical fractures

in the Apse of "the huge church" from Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Rusafa: the huge church containing the remains of St. Sergio.

JW: Note vertical fracturing in the Apse

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 3 - Basilica A with

butresses from Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Resafa: Basilica A, view from the southwest

(M. Gussone, 2008)

JW: note large buttresses which may have been constructed to shore up the building after an earthquake

Al Khabour (2016) - Fig. 10 - Fractures and damage

to the vault of North Gate Tower 19 from Hof (2016)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, north gate tower 19, secondary vault with cross symbols

JW: Note fracture in upper left corner

(C. Hof)

Hof (2016) - Figure 3.6 Throughgoing Gaps,

arch reconstruction, and displaced ashlars in the St. Sergius basilica (aka Basilica A) from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6

Resafa, St. Sergius basilica [aka Basilica A]. Note the two, throughgoing gaps in the apsis on the left, due to lateral extension caused by repeated loading parallel with the wall. The large arch had to be underpinned and subdivided by two smaller arches, supported by three columns. Note the out-of plane displaced ashlar next to the capital of the left column: it is clearly indicated as lateral loading by the earthquake. Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.7 Dropped Keystones

in a gallery within the city wall from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

Resafa, gallery within the city wall. Dropped keystones in each supporting arch of the corridor record vibration loads acting perpendicular to the main wall (also illustrated by Karnapp, 1976).

Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009

Kázmér et al. (2024)

- Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Basilica B from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 2

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings

(redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008.

Key - Phases- The Roman Castrum

- Expansion at the time of Bishop Alexander from Hierapolis

- Expansion under Emperor Zeno (474-491)

- Expansion after peace with the Persians under Anastasius (491-518) and Justin I. (518-527)

- Repairs and expansion under Justinian (527-569) and the Ghassanid phylarch al-Mundhir (569-581/582)

- From the Muslim conquest to the residence of Hisham

- Expansion under the Umayyad Hisham b. Abd al-Malik (724-743)

- Repair and changes in the Abbasid period (8.-10. century)

- From Atabegs to the Ayyubids and the abandonment of the city (11.-13. century)

- use by Bedouins (13.-20. century)

- Changes and restoration since the begin of archaeological excavations till the present

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Basilica B from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 2

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings

(redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008.

Key - Phases- The Roman Castrum

- Expansion at the time of Bishop Alexander from Hierapolis

- Expansion under Emperor Zeno (474-491)

- Expansion after peace with the Persians under Anastasius (491-518) and Justin I. (518-527)

- Repairs and expansion under Justinian (527-569) and the Ghassanid phylarch al-Mundhir (569-581/582)

- From the Muslim conquest to the residence of Hisham

- Expansion under the Umayyad Hisham b. Abd al-Malik (724-743)

- Repair and changes in the Abbasid period (8.-10. century)

- From Atabegs to the Ayyubids and the abandonment of the city (11.-13. century)

- use by Bedouins (13.-20. century)

- Changes and restoration since the begin of archaeological excavations till the present

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010)

Sack et al (2010) wrote the following about the constructions and destruction of Basilica B

The begin of the building of Basilica B is known to have taken place in spring 518 and thus the last months of the reign of Kaiser Anastasius (491-518)(10). The date of its completion is not certain, but was probable in the reign of Justin I (518-527). It can be assumed that Basilica B was soon so severely damaged by an earthquake that it was not rebuilt and thus abandoned. From the chronological relations to other buildings in Resafa, in which spolia from Basilica B were used, it can be deduced that the destruction probably took place before the middle of the seventh century and certainly before the building of the Great Mosque was begun in the second quarter of the eighth century. Several parts of Basilica B were further used for some time. After the abandoned parts of the basilica were removed, some houses were erected in their place. The ceramic finds and the typological comparison with other ground plans suggest that some of these buildings were inhabited up to the abandonment of the city in the 13th century.Intagliata (2018:112) also reports on seismic damage in Resafa

Al-Rusafa was greatly refurbished after Hisham b. `Abd al-Malik took the caliphate in 724. A transept-type mosque, 56 x 40m in size, was constructed occupying part of the courtyard of Basilica A, therefore linking the new Muslim place of worship to the existing Christian sacred topography. The building makes extensive use of spolia from the ruined Basilica A, which had experienced destructions by an earthquake not long after its construction. Material from the same building was also reused for the construction of a nearby suq, likely contemporary with the mosque, in the western courtyard of Basilica A (Sack 1996; Ulbert 1986; 1992).Kázmér et al. (2024:35-36) constrained the date of this earthquake more tightly - to between 559 and ~579 CE. They noted that the sweeping arches of Basilica A (aka St. Sergius or Holy Cross Basilica)

had to be underpinned and subdivided by a second set of arches within about 20 years of [initial] construction. Initial construction ended when the church was consecrated in 559 CE. The second set of arches thus appear to be reconstruction after lateral shaking

deformed the original arches. Kázmér et al. (2024:36) also noted that

the nave was surrounded by huge buttresses, similar to those of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. This shoring up of the nave may have been due to the same event (between 559 and ~579 CE according to Kázmér et al., 2024:36) that led to the

second set of arches. Kázmér et al. (2024:36) suggest that another earthquake may have struck after the 1st earthquake but before the sack of the city by the Persians (Sasanians) in 616 CE during the Byzantine–Sasanian War. Although they noted that

dropped keystones and voussoirs, in-plane extension, and out-of-plane extrusion of individual ashlars and whole walls (Karnapp 1976; Ulbert 2016)indicate an intensity of IX (9), it is not entirely clear that all of these effects were due to the first earthquake(s) and not also due to the

severeearthquake which they state struck

at the end of the eighth centuryand

left lasting evidence of destruction.. It should be noted that some of the mentioned

seismic effectsmay be due to differential subsidence.

Resafa (Byzantine Sergiopolis, Syria) is already mentioned in Assyrian texts and the Bible. Diocletian, the Roman Emperor (ruled 284–305) established here a frontier fortress to counter the Sasanian threat. Emperor Anastasius I (ruled 491–518) considerably expanded the city, built its ramparts and the construction of the new basilica of St. Sergius proceeded during his reign. Emperor Justinian (ruled 527 565) replaced the mud-brick city walls with stone and added galleries to the walls. Following Persian incursions and the Muslim conquest, it was restored and a Friday mosque was addded to the basilica of St. Sergius. A severe earthquake at the end of the eighth century left lasting evidence of destruction. Inhabitants stayed until the thirteenth century, when they were resettled to Hama. The Mongol invasions of the thirteenth–fourteenth century did not find much to be sacked (Burns 1999).

Most of the standing walls are in the ramparts, 550 × 400 m in dimension. Gate ways, churches, and a palace are worth mentioning. Each bears various features of earthquake damage (Figs. 3.6 and 3.7). The date of this earthquake is possible to constrain between the date of consecration of the so-called Basilica A (St. Sergius or Holy Cross Basilica) in 559 with sweeping arches. These bold structures had to be underpinned and subdivided by a second set of arches within about 20 years of construction, clearly after lateral shaking deformed the original arches. Further more, the nave was surrounded by huge buttresses, similar to those of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Dropped keystones and voussoirs, in-plane extension, and out-of-plane extrusion of individual ashlars and whole walls (Karnapp 1976; Ulbert 2016) indicate intensity I =IX. The earthquake(s) occurred

- after the construction of St. Sergius basilica in 559 and before 580

- before being sacked by the Persians in 616

- Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016) - Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Cisterns from

Hof (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Situation plan

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Resafa city plan from

Sack and Gussone (2016)

Fig. 2

Resafa: city plan

(M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

- al-Mundhir building

- Basilica A

- northern courtyard

- Great Mosque

- Basilica A, western courtyard/shops

- Tetraconch Church

- shops

- Basilica B

- street monument II

- pillar monument

- Basilica D

- street monument III − north gate

- building with two apses

- Basilica C

- vaulted building

- khan

- house

- Arab house

- large cistern

- small cistern

- water distributor

- domed cistern

- northwestern cistern

Sack and Gussone (2016) - Fig. 10 - Plan of Basilica A from

Sack et al (2010)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2.

Sack et al (2010) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Cisterns from

Hof (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Situation plan

(C. Hof)

Sack et al (2010)

- Fig. 2 - Vertical fractures

in the Apse of "the huge church" from Al Khabour (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Rusafa: the huge church containing the remains of St. Sergio.

JW: Note vertical fracturing in the Apse

Al Khabour (2016)

Al Khabour (2016) notes that

the Basilica of St. Sergius (Basilica A) suffered earthquake destructions but did not supply dates. The apse displays fractures that appear to be a result

of earthquakes or differential subsidence (see Fig. 2 in Photos). Sack et al (2010:307) reported that

from the building of the church [Basilica A first built in the 5th century CE] up to the abandonment of the city in the 13th century,

earthquakes and the building ground weakened by underground dolines [aka sinkholes] have caused considerable damage

.

Hof (2019) reports that the Great Cistern and water system at Resafa was maintained in the second quarter of the 8th century [CE] and from then on appears

to have fallen into disrepair.

Catharine Hof (personal communication, 2022) provided the following observations regarding archaeoseismicity at Resafa.

Resafa lies too far away from major earthquake ‘centres’ like the Jordan-fault or even the somewhat endangered Palmyrides. Nevertheless, the damages on the buildings seem to indicate shaking as a cause of damage. But all archaeological evidence has shown, that the different buildings suffered their specific damages at different times. The theory now is, that very slight intensities of remote earthquakes (e. g. maybe the legendary large event from 749?) do reach Resafa, more as slight shiverers rather than actual shakes and far too weak to destroy the entire city in one event. To a certain degree we can assume that intensities at Resafa would not exceed IV MMI. But the sum of those minor events sooner or later would show a locally destructive effect. These shakes must have occurred more or less constantly through history.Although Hof's scenario is possible, local intensities due to later seismic events may have exceeded IV. Kázmér et al. (2024:35-36) suggest that a

a severe earthquake at the end of the eighth centurystruck Resafa, leaving

lasting evidence of destruction. Such evidence may include

dropped keystones and voussoirs, in-plane extension, and out-of-plane extrusion of individual ashlars and whole walls (Karnapp 1976; Ulbert 2016)which, according to Kázmér et al. (2024:36), indicates an intensity of IX (9). It should be noted that these

seismic effectsmay be due to more than one earthquake and some of the

seismic effectsmay be due to differential subsidence.

It is also possible that there is no evidence for an 8th century CE earthquake. Catharine Hof (personal communication, 2022) suggests that the 8th century CE earthquake narrative is a false one.

In the older literature one can read of a large earthquake in the (mid or late) eighth century. This can be traced back to an early statement by the first excavation director Johannes Kollwitz (1959). This alleged earthquake has led to a typical case of circular reasoning, because it had made its way into more recent catalogues (Sbeinati – Darawcheh – Mouty 2005, 387: [053]). Sbeinati's source (Klengel 1985) is a ‘photobook’ of Syria, which gives no evidence. So, there is neither written source nor archaeological evidence for an (extraordinary or large) earthquake at Resafa in the 8th century.

Resafa (Byzantine Sergiopolis, Syria) is already mentioned in Assyrian texts and the Bible. Diocletian, the Roman Emperor (ruled 284–305) established here a frontier fortress to counter the Sasanian threat. Emperor Anastasius I (ruled 491–518) considerably expanded the city, built its ramparts and the construction of the new basilica of St. Sergius proceeded during his reign. Emperor Justinian (ruled 527 565) replaced the mud-brick city walls with stone and added galleries to the walls. Following Persian incursions and the Muslim conquest, it was restored and a Friday mosque was addded to the basilica of St. Sergius. A severe earthquake at the end of the eighth century left lasting evidence of destruction. Inhabitants stayed until the thirteenth century, when they were resettled to Hama. The Mongol invasions of the thirteenth–fourteenth century did not find much to be sacked (Burns 1999).

Most of the standing walls are in the ramparts, 550 × 400 m in dimension. Gate ways, churches, and a palace are worth mentioning. Each bears various features of earthquake damage (Figs. 3.6 and 3.7). The date of this earthquake is possible to constrain between the date of consecration of the so-called Basilica A (St. Sergius or Holy Cross Basilica) in 559 with sweeping arches. These bold structures had to be underpinned and subdivided by a second set of arches within about 20 years of construction, clearly after lateral shaking deformed the original arches. Further more, the nave was surrounded by huge buttresses, similar to those of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Dropped keystones and voussoirs, in-plane extension, and out-of-plane extrusion of individual ashlars and whole walls (Karnapp 1976; Ulbert 2016) indicate intensity I =IX. The earthquake(s) occurred

- after the construction of St. Sergius basilica in 559 and before 580

- before being sacked by the Persians in 616

Although Redwan et. al. (2002) report the following:

8th Century ADthis appears to be an error. Redwan et. al. (2002)'s reference appears to be an earlier version of an earthquake catalog later published by Sbeinati et al (2005). Sbeinati et al (2005)'s final catalog does not contain a reference to Ar-Rasafeh.

A strong earthquake occurred in Ar-Rasafeh transferring its houses to ruins.

Catharine Hof (personal communication, 2022) provided the following information on the probable source of the error

In the older literature one can read of a large earthquake in the (mid or late) eighth century. This can be traced back to an early statement by the first excavation director Johannes Kollwitz (1959). This alleged earthquake has led to a typical case of circular reasoning, because it had made its way into more recent catalogues (Sbeinati – Darawcheh – Mouty 2005, 387: [053]). Sbeinati's source (Klengel 1985) is a ‘photobook’ of Syria, which gives no evidence. So, there is neither written source nor archaeological evidence for an (extraordinary or large) earthquake at Resafa in the 8th century.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Basilica A Site Plan

Resafa: city plan (M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

Sack and Gussone (2016) Basilica A

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2. Sack et al (2010) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Resafa: Basilica A, view from the southwest (M. Gussone, 2008) JW: note large buttresses which may have been constructed to shore up the building after an earthquake Al Khabour (2016)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6Resafa, St. Sergius basilica [aka Basilica A]. Note the two, throughgoing gaps in the apsis on the left, due to lateral extension caused by repeated loading parallel with the wall. The large arch had to be underpinned and subdivided by two smaller arches, supported by three columns. Note the out-of plane displaced ashlar next to the capital of the left column: it is clearly indicated as lateral loading by the earthquake. Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009 Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7Resafa, gallery within the city wall. Dropped keystones in each supporting arch of the corridor record vibration loads acting perpendicular to the main wall (also illustrated by Karnapp, 1976). Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009 Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

Basilica B Site Plan

Resafa: city plan (M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

Sack and Gussone (2016) Basilica B

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings (redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008. Key - Phases

Sack et al (2010) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Basilica A Site Plan

Resafa: city plan (M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

Sack and Gussone (2016) Basilica A

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Resafa, Basilica A, Endangered areas on which temporary consolidation work was carried out in autumn 2008, based on Thilo Ulbert, Resafa II, 1986, plate 80.2. Sack et al (2010) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Resafa: Basilica A, view from the southwest (M. Gussone, 2008) JW: note large buttresses which may have been constructed to shore up the building after an earthquake Al Khabour (2016)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6Resafa, St. Sergius basilica [aka Basilica A]. Note the two, throughgoing gaps in the apsis on the left, due to lateral extension caused by repeated loading parallel with the wall. The large arch had to be underpinned and subdivided by two smaller arches, supported by three columns. Note the out-of plane displaced ashlar next to the capital of the left column: it is clearly indicated as lateral loading by the earthquake. Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009 Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7Resafa, gallery within the city wall. Dropped keystones in each supporting arch of the corridor record vibration loads acting perpendicular to the main wall (also illustrated by Karnapp, 1976). Photo by B. Major, taken in 2009 Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

Basilica B Site Plan

Resafa: city plan (M. Gussone and G. Hell with N. Erbe and I. Salman, 2010).

Sack and Gussone (2016) Basilica B

Basilica B, provisional chronological plan with previous and subsequent buildings (redrawn and revised plans from the published and unpublished original plans from Wolfgang Müller-Wiener and the excavation plan from Michaela Konrad 1992, Fig. 1b). Mapping of the building phases according to relevant city building phases, Dietmar Kurapkat 2008. Key - Phases

Sack et al (2010) |

|

|

Hof (2018) characterized Resafa as a poor building ground with fissures in the bedrock and sink holes

.

Al Khabour, A. (2016). Resafa/Sergiopolis (Raqqa). In A History of Syria in One Hundred Sites.

Al Saeed, M. A. (2009). Resafa-Sergiupolis / Syrien: Dokumentation der Erhaltungsmaßnahmen an der Stadtmauer. Germany: Diplom.de.

Beckers, B. (2012). Ancient food and water supply in drylands: Geoarchaeological perspectives on the water-harvesting systems of the two ancient cities Resafa, Syria and Petra, Jordan (PhD dissertation).

Brinker, W. (1991). Zur Wasserversorgung von Resafa-Sergiupolis. Damaszener Mitteilungen 5: 119–146.

Brinker, W. and Garbrecht, G. (2007). Die Zisternen-Wasserversorgung von Resafa-Sergiupolis. In C. Ohlig (ed.), Antike Zisternen, Schriften der Deutschen Wasserhistorischen Gesellschaft 9, pp. 117–144. Siegburg.

Chaniotis, A., Pleket, H. W., Stroud, R. S. and Strubbe, J. H. M. (1998). SEG 48-1867-1868. Sergioupolis-Resafa: Two inscriptions after 518/528 A.D. Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum.

Garbrecht, G. (1991). Der Staudamm von Resafa-Sergiupolis. In Deutscher Verband für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturbau (ed.), Historische Talsperren 2, pp. 237–248. Stuttgart: Wittwer.

Gatier, P.-L. (1998). Inscriptions grecques de Résafa. Damaszener Mitteilungen 10: 237–241.

Hof, C. (2016). The Late Roman city wall of Resafa/Sergiupolis (Syria): Its evolution and functional transition from representative over protective to concealing. In R. Frederiksen et al. (eds.), Focus on Fortification, pp. 397–412. Oxford: Oxbow.

Hof, C. (2017). Baulos, Werkgruppe und Pensum: Zur Baustellenorganisation an der Stadtmauer von Resafa. In K. Rheidt and W. Lorenz (eds.), Groß Bauen – Großbaustellen als kulturgeschichtliches Phänomen, pp. 63–75, 294–295. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Hof, C. (2018). Late antique vaults in the cisterns of Resafa with “bricks set in squares.” In I. Wouters et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress on Construction History, vol. 2, pp. 755–763. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Hof, C. (2019). The monumental Late Antique cisterns of Resafa, Syria as a refined capacity and water-quality regulation system.

Hof, C. (2020). The revivification of earthen outworks in the eastern and southern empire: The example of Resafa/Syria. In S. Barker et al. (eds.), Constructing City Walls in Late Antiquity.

Karnapp, W. (1976). Die Stadtmauer von Resafa in Syrien. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kázmér, M., Major, B., Al-Tawalbeh, M. and Gaidzik, K. (2024). Destructive intraplate earthquakes in Arabia: The archaeoseismological evidence. In A. Abd el-aal et al. (eds.), Environmental Hazards in the Arabian Gulf Region. Springer.

Kellner-Heinkele, B. (1996). Rusafa in den arabischen Quellen. In D. Sack, Die große Moschee von Resafa – Rusāfat Hišām, Resafa 4, pp. 133–154. Mainz: von Zabern.

Kollwitz, J., Wirth, W. and Karnapp, W. (1958/1959). Die Grabungen in Resafa Herbst 1954 und 1956. Les Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes 8–9: 21–54.

Redwan, et al. (2002). Geology, hydrology, seismology, and geotechnique of Al-Jafra site. AECS Report G/RSS 440.

Sack, D., Sarhan, M. and Gussone, M. (2008). Excavation report 2007. Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 3: 251–267.

Sack, D., Sarhan, M. and Gussone, M. (2010). Excavation report 2008. Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 4: 297–313.

Sack, D., Sarhan, M. and Gussone, M. (2011). Excavation report 2009. Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 5: 199–206.

Sack, D., Sarhan, M. and Gussone, M. (2012). Excavation report 2010. Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 6: 285–292.

Sack, D., Sarhan, M. and Gussone, M. (2015). Excavation report 2012–2013. Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 7: 139–155.

Sack, D., Gussone, M. and Mollenhauer, A. (eds.) (2013). Resafa-Sergiupolis/Rusafat Hisham: Forschungen 1975–2007. Berlin.

Sack, D., Gussone, M. and Kurapkat, D. (2014). A vivid city in the Syrian desert: The case of Resafa-Sergiupolis. In D. Morandi Bonacossi (ed.), Settlement Dynamics and Human-Landscape Interaction in the Steppes and Deserts of Syria, pp. 257–274. Wiesbaden.

Sack, D. et al. (forthcoming). Resafa–Sergiupolis/Rusafat Hisham: Stadt und Umland, Resafa 8.

Sbeinati, M. R., Darawcheh, R. and Mouty, M. (2005). The historical earthquakes of Syria: An analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Annali di Geofisica 48(3): 347–435.

Ulbert, T. (1986). Die Basilika des Heiligen Kreuzes in Resafa-Sergiupolis. Mainz: von Zabern.

Ulbert, T. (1992). Beobachtungen im Westhofbereich der großen Basilika von Resafa. Damaszener Mitteilungen 6: 403–416.

Ulbert, T. and Konrad, M. (2016). Al-Mundir-Bau and Nekropole vor dem Nordtor. In T. Ulbert (ed.), Forschungen in Resafa-Sergiupolis. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

Mackensen, M. (1984). Eine befestigte spätantike Anlage vor den Stadtmauern von Resafa: Ausgrabungen und spätantike Kleinfunde eines Surveys im Umland von Resafa-Sergiupolis. Resafa I. Mainz.

Ulbert, T. (1986). Resafa II: Die Basilika des Heiligen Kreuzes in Resafa-Sergiupolis. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

Ulbert, T. and Rainer, D. (1990). Resafa III: Der kreuzfahrerzeitliche Silberschatz aus Resafa-Sergiupolis. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

Sack, D. (1996). Resafa IV: Die große Moschee von Resafa-Rusafat Hisham. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Konrad, M. (2001). Der spätrömische Limes in Syrien: Archäologische Untersuchungen an den Grenzkastellen von Sura, Tetrapyrgium, Cholle und in Resafa. Resafa V. Mainz.

Brands, G. (2002). Die Bauornamentik von Resafa-Sergiupolis: Studien zur spätantiken Architektur und Bauausstattung in Syrien und Nordmesopotamien. Resafa VI. Mainz.

Ulbert, T. (ed.) (2016). Forschungen in Resafa-Sergiupolis. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

Although Redwan et. al. (2002) report the following:

8th Century ADthis appears to be an error. Redwan et. al. (2002)'s reference appears to be an earlier version of an earthquake catalog later published by Sbeinati et al (2005). Sbeinati et al (2005)'s final catalog does not contain a reference to Ar-Rasafeh.

A strong earthquake occurred in Ar-Rasafeh transferring its houses to ruins.

Catharine Hof (personal communication, 2022) provided the following information on the probable source of the error

In the older literature one can read of a large earthquake in the (mid or late) eighth century. This can be traced back to an early statement by the first excavation director Johannes Kollwitz (1959). This alleged earthquake has led to a typical case of circular reasoning, because it had made its way into more recent catalogues (Sbeinati – Darawcheh – Mouty 2005, 387: [053]). Sbeinati's source (Klengel 1985) is a ‘photobook’ of Syria, which gives no evidence. So, there is neither written source nor archaeological evidence for an (extraordinary or large) earthquake at Resafa in the 8th century.