el-Lejjun (aka Betthorus)

APAAME

- Reference: APAAME_20070419_DLK-0009

- Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

Click photo for high res magnifiable image

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| el-Lejjun | Arabic | يل ليججون |

| Legio | Latin | |

| Betthorus | Greek ? | Bετθορuσ |

| Baetarus |

The Lejjun Legionary Fortress which was probably Betthorus, the base of Legio IV Martia as specified in the Notita Dignitatum however no proof of this has been found on the site (Parker, 2006).

The site of el-Lejjun is in Jordan, about 60 km (37 mi.) east of the Dead Sea and 17 km (11.5 mi.) northeast of Kerak in biblical Moab, at an elevation of some 700 m above sea level (map reference 233.072). A perennial spring, 'Ain Lejjun, feeds Wadi Lejjun, a tributary of the upper Wadi Mujib. The site lies in a shallow valley surrounded by low hills on all sides but the east. Although situated near the edge of the desert, rainfall is sufficient for dry farming wheat in winter; the present outflow of the spring is adequate to irrigate cultivation of the valley in summer.

The earliest settlement now attested at Lejjun is a substantial fortified city from the Early Bronze Age, as yet unexcavated. Excavations have demonstrated that the Roman fort (castellum) of Khirbet el-Fityan, 1.5 km (1 mi.) northwest of the spring, was built on top of an Iron Age structure. In the Early Roman period, a Nabatean watchpost (Rujm Beni Yasser) was constructed on top of a hill about one kilometer (less than a mile) east of the spring. The so-called altar, a masonry edifice about 21 m sq, noticed by nineteenth-century investigators (but since completely robbed), may have been a Nabatean cultic structure. Occupation of el-Lejjun resumed in about 300 CE, with the construction of a Roman legionary fortress for the Legio IV Martia, the smaller castellum of Fityan, and the reoccupation and reconstruction of Yasser. The site was then known as Betthorus, if the commonly held identification is accepted (Notitia Dignitatum, Or. 37 .22), a key element in the Roman fortified frontier, the Limes Arabicus. The limes was intended to control the incursions of neighboring nomadic Arab desert tribes. The modern Arabic name, Lejjun, seems to be a corruption of the Latin legio. The fortress was abandoned after an earthquake that affected Palestine and Arabia in 551 [JW: unlikley - Late 6th century Inscription at Areopolis Quake more likely]. Just before World War I, a Turkish military garrison was briefly established here; rows of Turkish barracks on a ridge southwest of the fortress were built with stones robbed from the fortress, and water mills were built below the spring.

R. Brunnow and A. von Domaszewski conducted the first thorough survey of the Lejjun fortress in 1897 and published plans and photographs of the site. N. Glueck identified the Early Bronze site and published the first aerial photograph of the Roman fortress in 1934. S. T. Parker conducted survey work between 1975 and 1979.

Five seasons of excavations at Lejjun and four other Roman military sites were conducted between 1980 and 1989 as part of the Limes Arabicus Project by Parker for the North Carolina State University and the American Center of Oriental Research. Excavations examined the several structures within the legionary fortress, amansio (staging post and inn) and Roman temple outside the fortress; the fortlet of Rujm Beni Yasser; and the Roman castella of Khirbet el-Fityan, Qasr Bshir (c. 15 km, or 9 mi. northeast of Lejjun), and Da'janiya (c. 75 km, or 47 mi. south of Lejjun). Some 537 other sites in the region were surveyed by the project

- Map of Limes Arabicus

Fortresses in Jordan from Wikipedia

Limes arabicus, central part in Jordan - Azraq basin and Wadi el-Mujib basin. Red squares are

Roman fortresses and forts from the end of the 3rd/beginning of the 4th century.

Limes arabicus, central part in Jordan - Azraq basin and Wadi el-Mujib basin. Red squares are

Roman fortresses and forts from the end of the 3rd/beginning of the 4th century.

(modified from S. T. Parker, An Empire's New Holy Land: The Byzantine Perio, Near Eastern Archaeology , Sep., 1999, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Sep., 1999), p. 138)

Ursus - Wikipedia - CC-BY-SA 4.0 - Location Map from

Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

El-Lejjun: map of the site and its surroundings

El-Lejjun: map of the site and its surroundings

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Aerial view of El-Lejjun

from APAAME

Aerial view of El-Lejjun

Aerial view of El-Lejjun

APAAME

- Reference: APAAME_20070419_DLK-0009

- Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

- El-Lejjun in Google Earth

- Aerial Photo El-Lejjun

and environs from Parker et al (2006)

Pl 3.1

Pl 3.1

Aerial photo (1982) of el-Lejjun:

- Roman fortress

- Early Bronze (EB) Age site

- 'Ain Lejjun (spring)

- Khirbet el-Fityan

- Ottoman barracks

(Royal Geographic Centre of Jordan

Parker et al (2006)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified (?) from Parker et al (2006) - oriented to match with the APAAME photo

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress

Mike Bishop flickr modified (?) from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997) - Illustrated reconstruction of

El-Lejjun from Campbell (2006)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Reconstruction of El-Lejjun

Campbell (2006:59)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the principia

(headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Fig. 4.1 Plan of the principia

(headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Plan of the principia in the Early Byzantine period (Strata VA-IV) with excavation squares

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.2 Plan of the

three rooms of the northern range of the principia from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.2

Fig. 4.2

Plan of the three rooms of the northern range of the principia, with excavation squares (A.12-14)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.5A Axonometric view

of the southwest corner of the principia from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.5A

Fig. 4.5A

Axonometric view of the southwest corner of the principia, showing the cross hall, southern entrance, southern tribunal, aedes, southern passageway, and southern room of the official block

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.5B Perspective view

of the arcaded portico, southern entrance, and southern tribunal of principia from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.5B

Fig. 4.5B

Perspective view of the arcaded portico, southern entrance, and southern tribunal of principia

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.6A Axonometric view

of the southern half of the aedes from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.6A

Fig. 4.6A

Axonometric view of the southern half of the aedes, showing the steps up to the elevated platform and to the base for the legionary stnadrad in the apsidal niche against the rear wall

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.6C Section view

of the barrel vaults along the south wall of the aedes from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.6C

Fig. 4.6C

Elevation of the barrel vaults along the south wall of the aedes, looking south

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 4.1 Plan of the principia

(headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Plan of the principia in the Early Byzantine period (Strata VA-IV) with excavation squares

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.2 Plan of the

three rooms of the northern range of the principia from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.2

Fig. 4.2

Plan of the three rooms of the northern range of the principia, with excavation squares (A.12-14)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.6C Section view

of the barrel vaults along the south wall of the aedes from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.6C

Fig. 4.6C

Elevation of the barrel vaults along the south wall of the aedes, looking south

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 4.3 Plan of the

western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3

Plan of the western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.4 Section through

the south doorways of the groma from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4

Section through the south doorways of the groma, looking south

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 4.3 Plan of the

western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3

Plan of the western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 4.4 Section through

the south doorways of the groma from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4

Section through the south doorways of the groma, looking south

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 5.1 Plan of the

early Byzantine barracks (Area B) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Plan of Area B: the Early Byzantine Barracks (Strata VA-IV)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 5.2 Plan of the

early Late Roman Barracks (Area B) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

Plan of Area B: the Late Roman Barracks (Stratum VI)

Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the barracks

from ACOR website

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of Byzantine barracks

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of Byzantine barracks

ACOR website

- Fig. 5.1 Plan of the

early Byzantine barracks (Area B) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Plan of Area B: the Early Byzantine Barracks (Strata VA-IV)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 5.2 Plan of the

early Late Roman Barracks (Area B) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

Plan of Area B: the Late Roman Barracks (Stratum VI)

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 6.8 Plan of the north gate

from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.8

Fig. 6.8

Plan of the north gate (porta principalis sinistra) of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the north gate

from Wikipedia (Mediatus)

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus project

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus project

Betthorus legionary camp - excavation plan of the Porta principalis sinistra , Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan.

Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0 - Fig. 6.9 Partially

reconstructed north facade of the north gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.9

Fig. 6.9

Partially reconstructed north facade of the north gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.10 The rampart

stairway of the northern gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.10

Fig. 6.10

The rampart stairway of the northern gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.11 Perspective

of the north gate at eye level of an approaching rider from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.11

Fig. 6.11

Perspective of the north gate at eye level of an approaching rider

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.12 Plan of

Late Byzantine domestic complex near the north gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.12

Fig. 6.12

Plan of Late Byzantine domestic complex near the north gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.2 Reconstruction

of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Reconstruction of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 6.8 Plan of the north gate

from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.8

Fig. 6.8

Plan of the north gate (porta principalis sinistra) of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the north gate

from Wikipedia (Mediatus)

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus project

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus project

Betthorus legionary camp - excavation plan of the Porta principalis sinistra , Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan.

Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0 - Fig. 6.9 Partially

reconstructed north facade of the north gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.9

Fig. 6.9

Partially reconstructed north facade of the north gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.10 The rampart

stairway of the northern gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.10

Fig. 6.10

The rampart stairway of the northern gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.11 Perspective

of the north gate at eye level of an approaching rider from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.11

Fig. 6.11

Perspective of the north gate at eye level of an approaching rider

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.12 Plan of

Late Byzantine domestic complex near the north gate from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.12

Fig. 6.12

Plan of Late Byzantine domestic complex near the north gate

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.2 Reconstruction

of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Reconstruction of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall

Parker et al (2006)

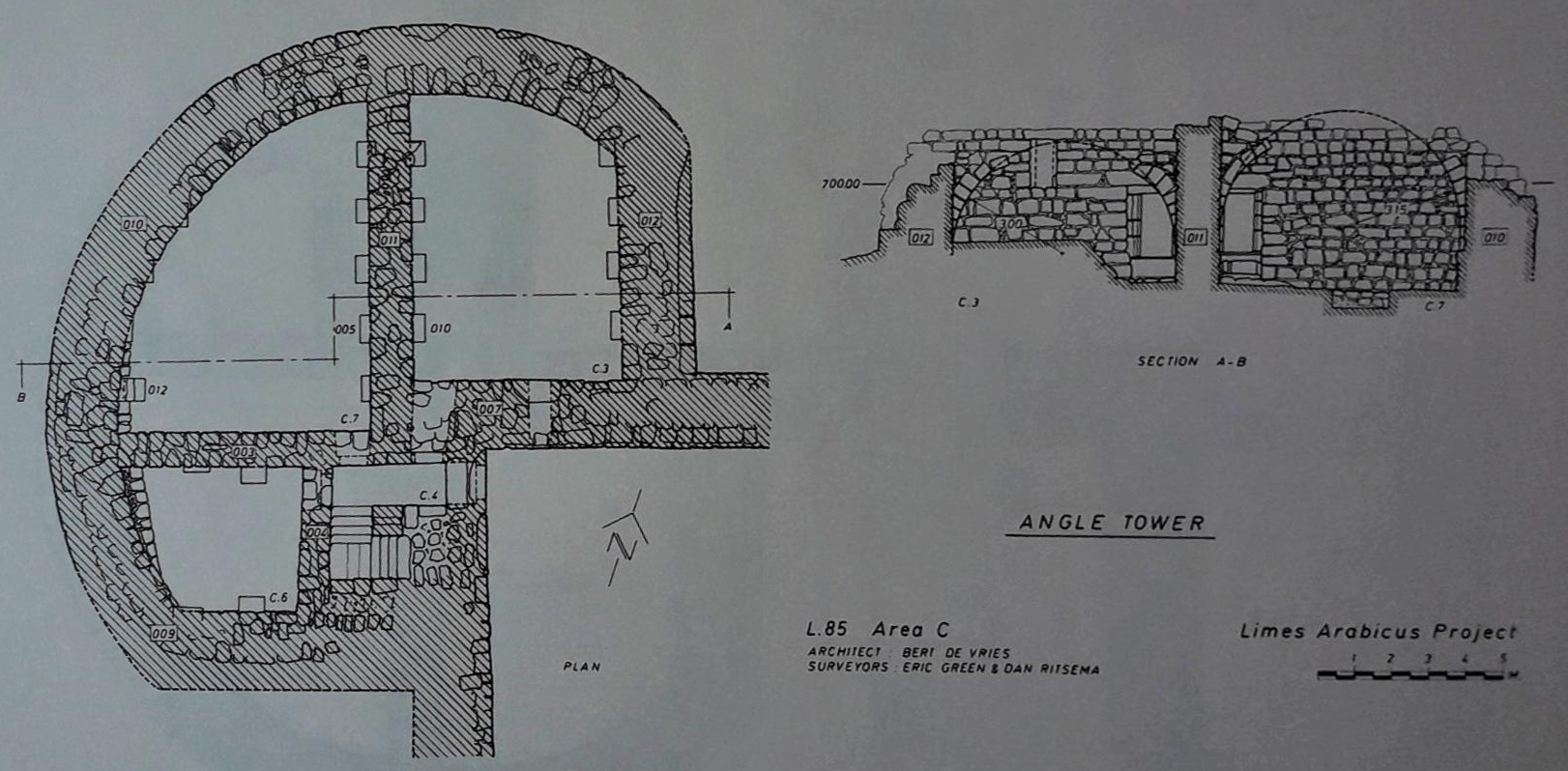

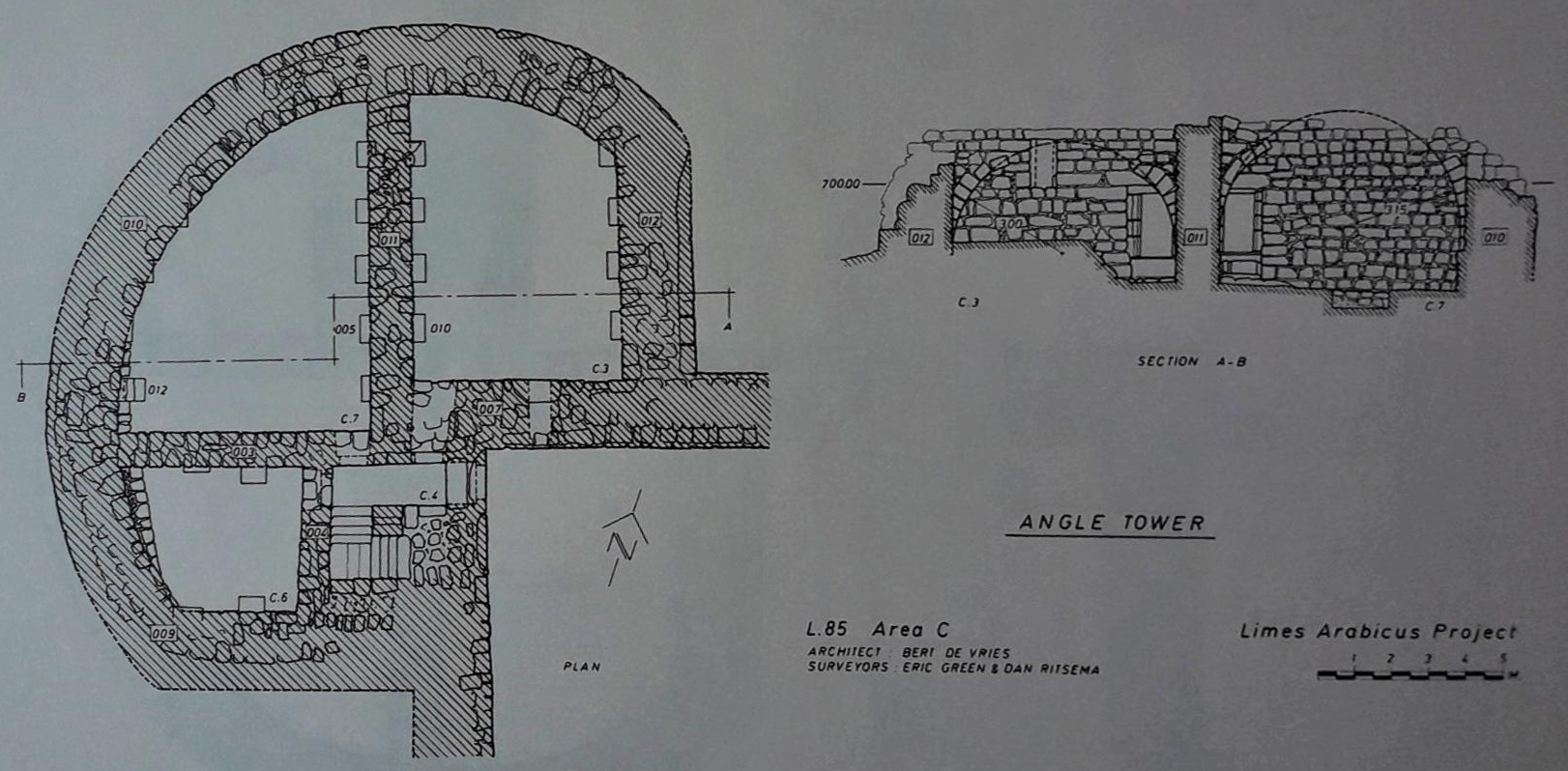

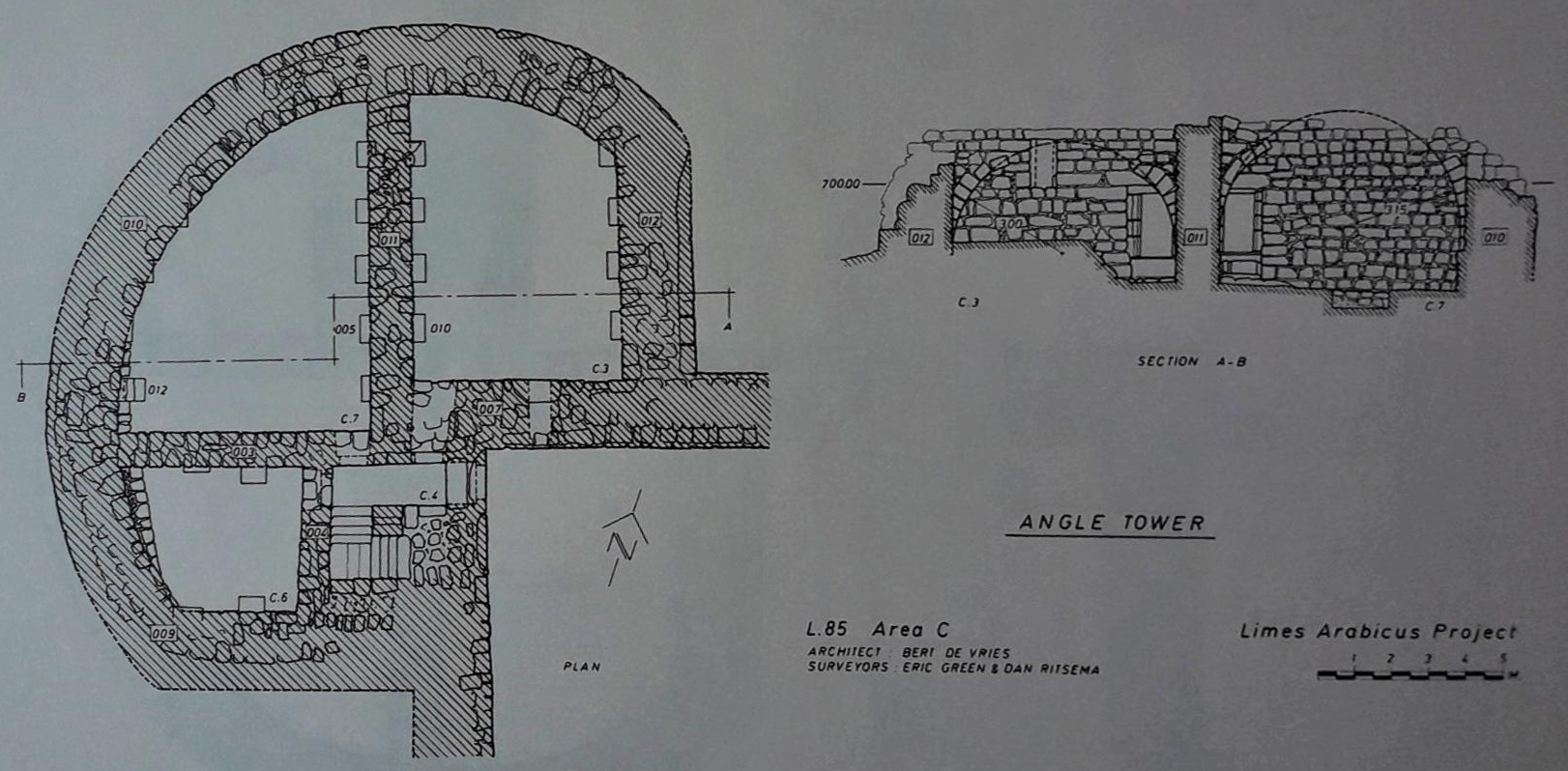

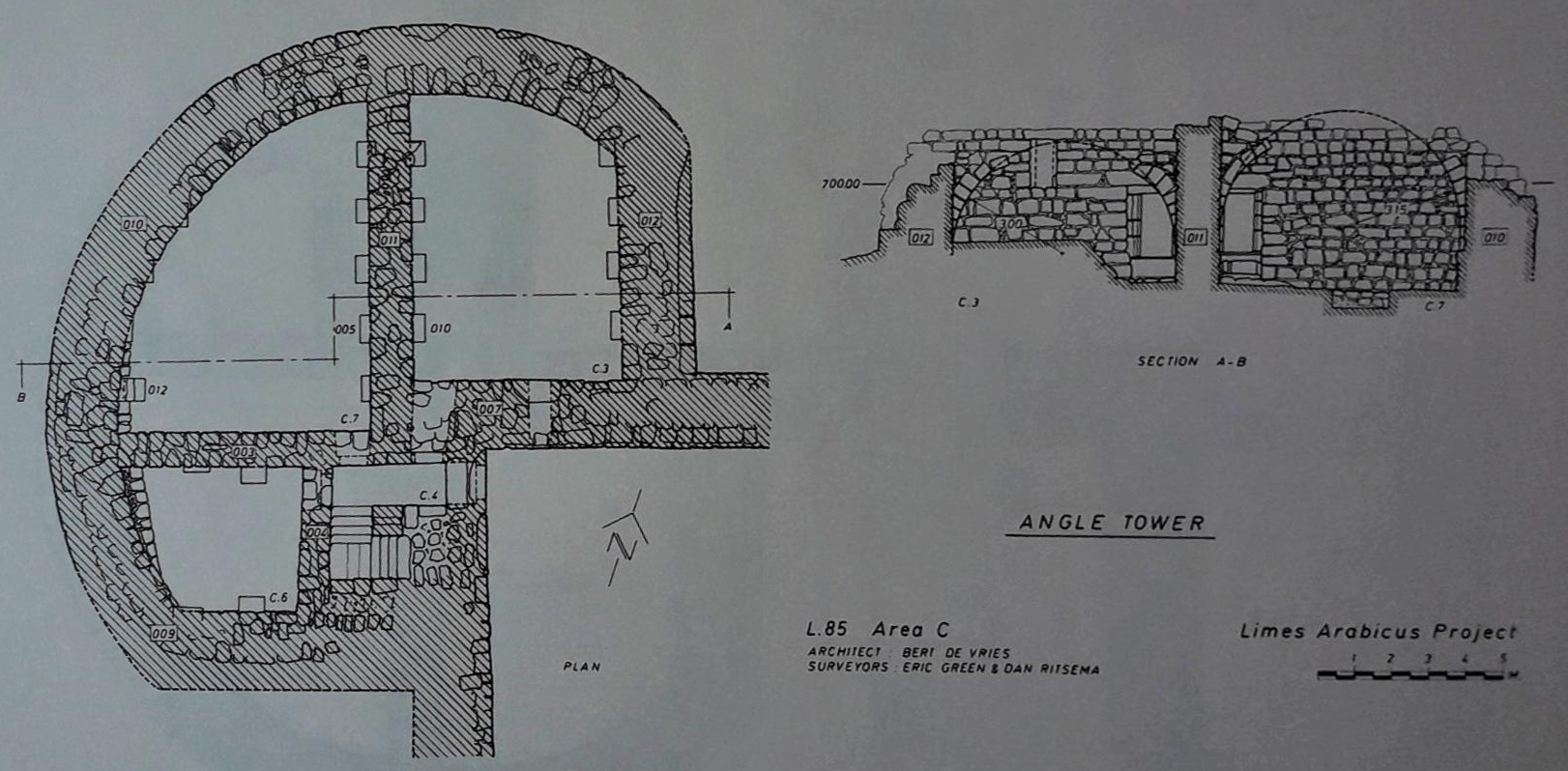

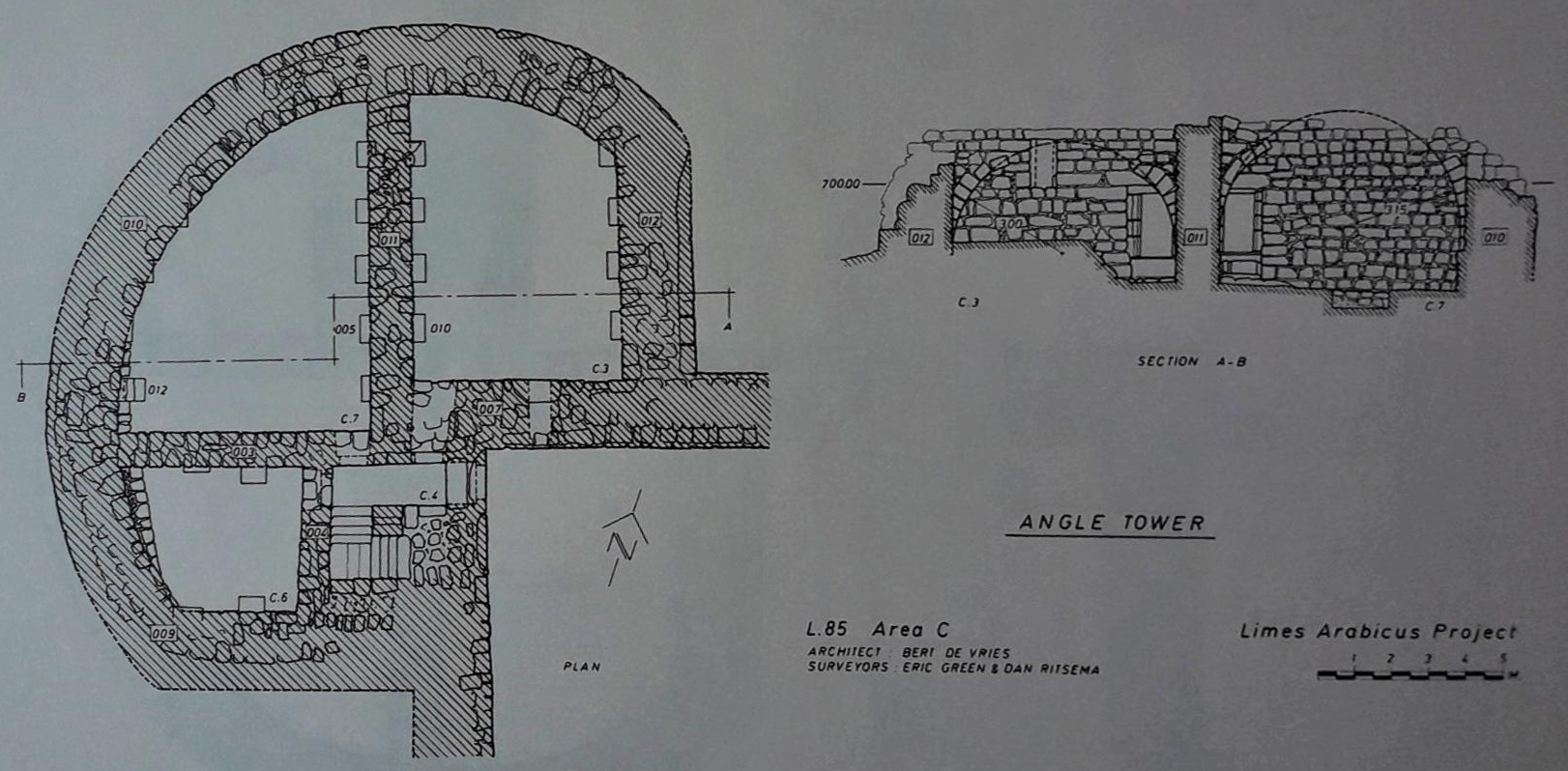

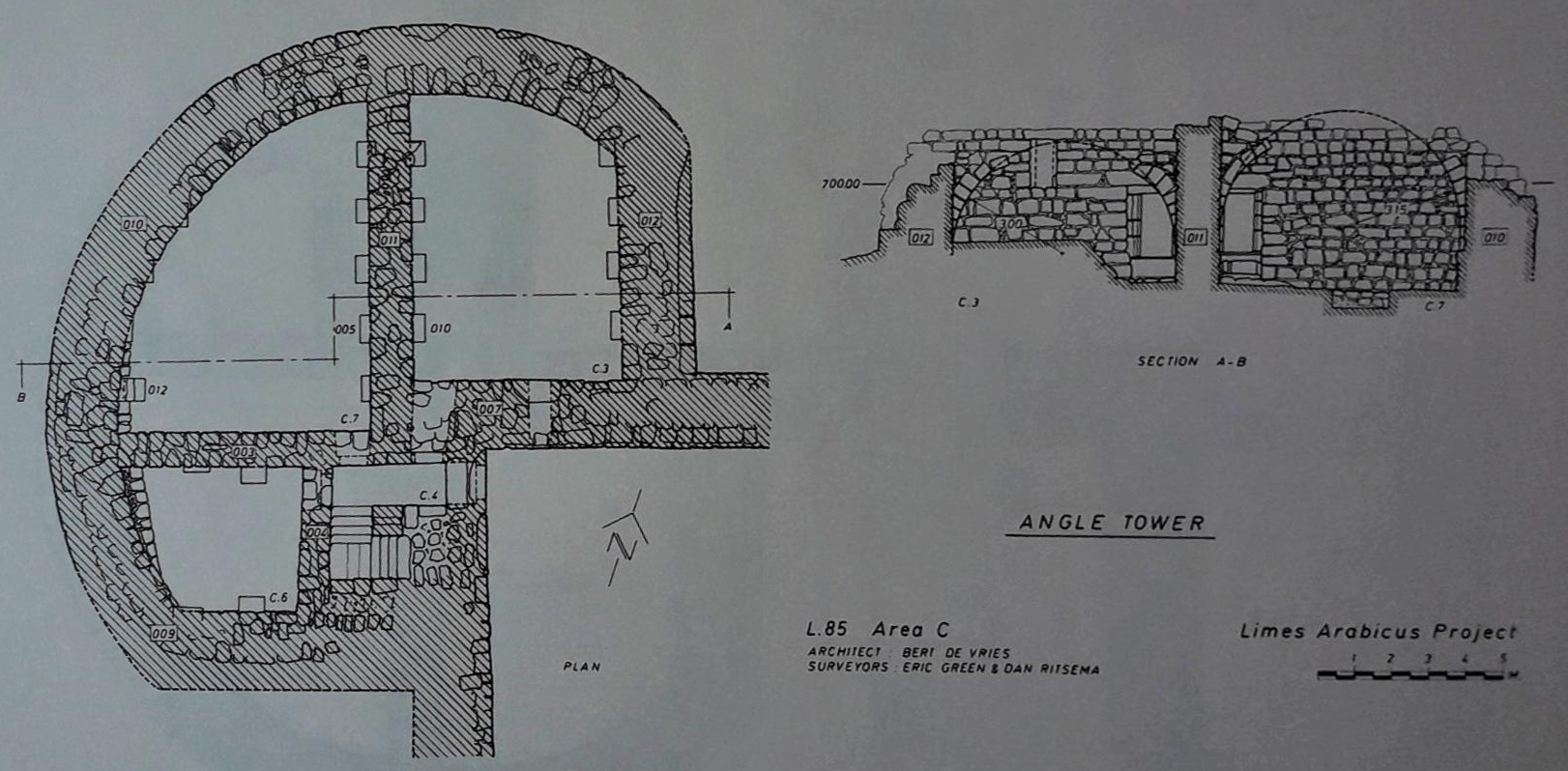

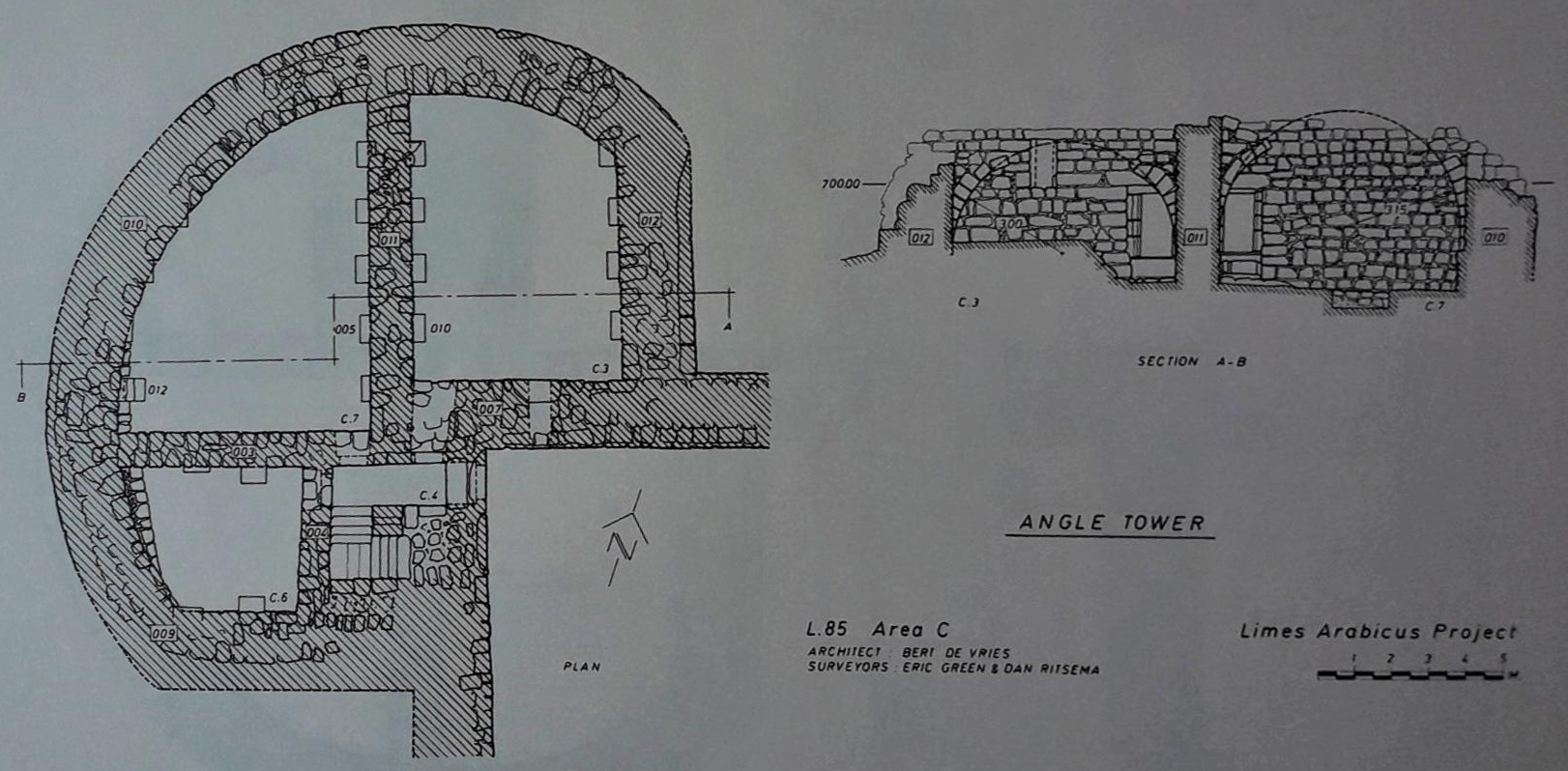

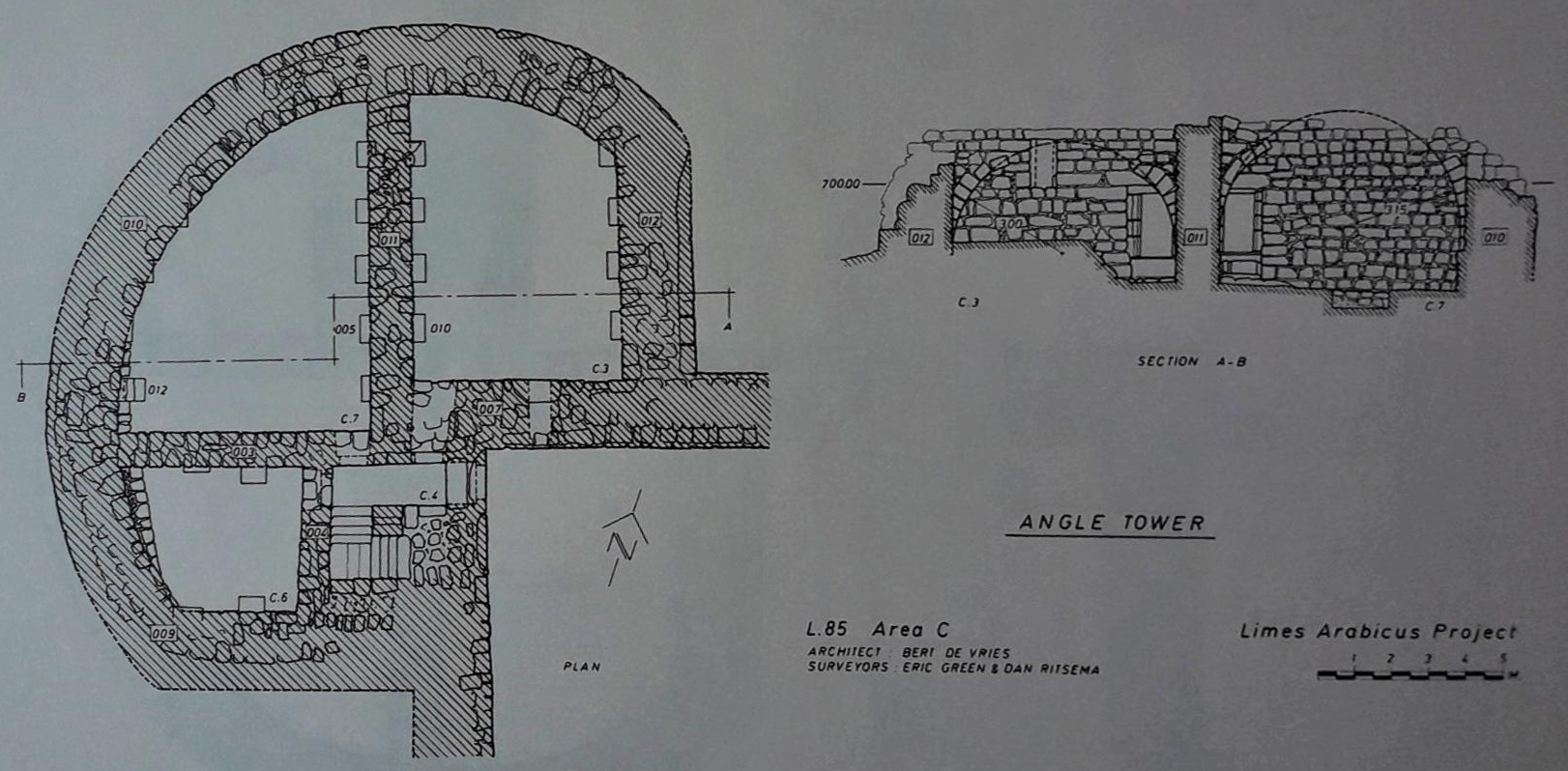

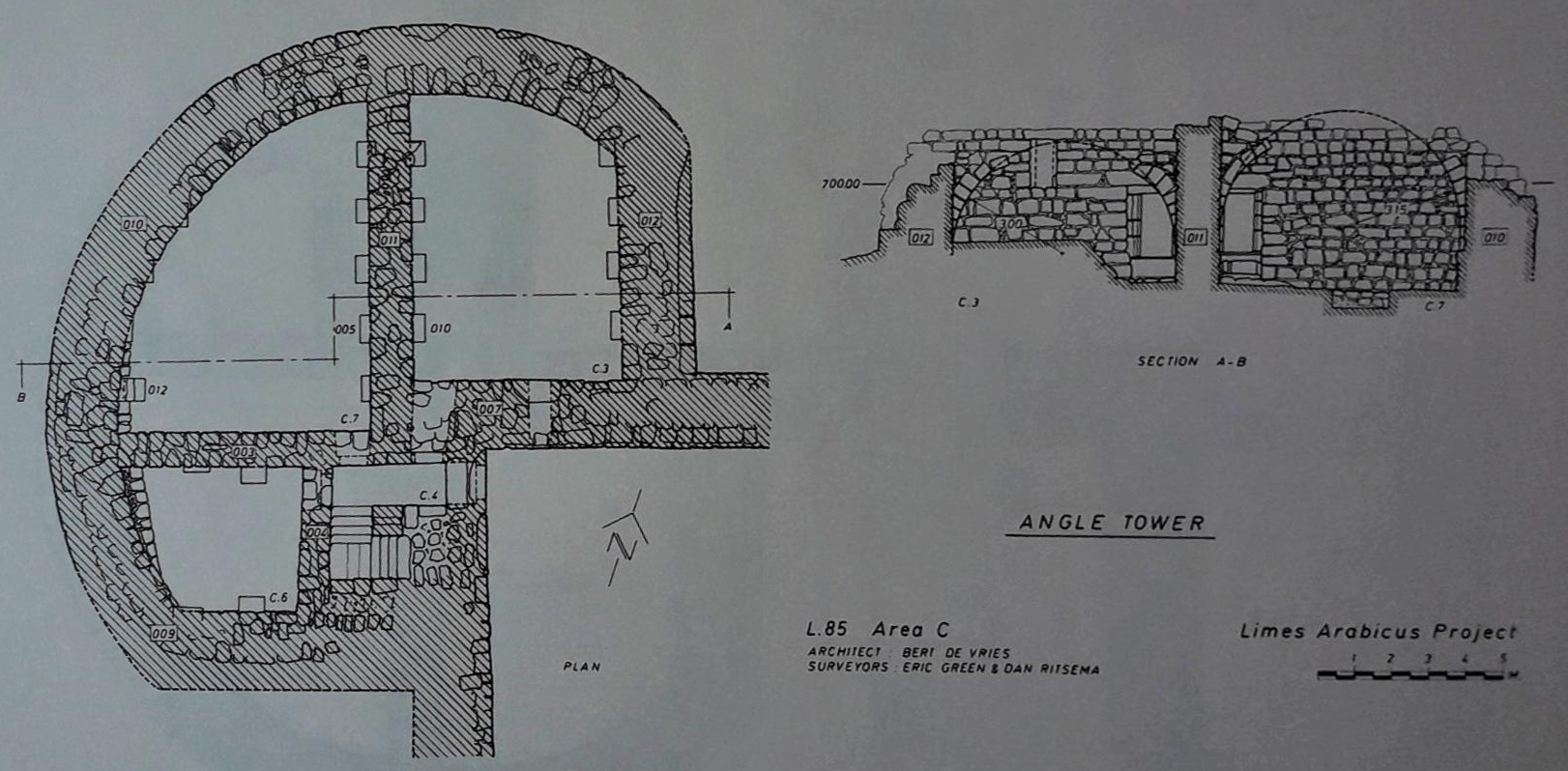

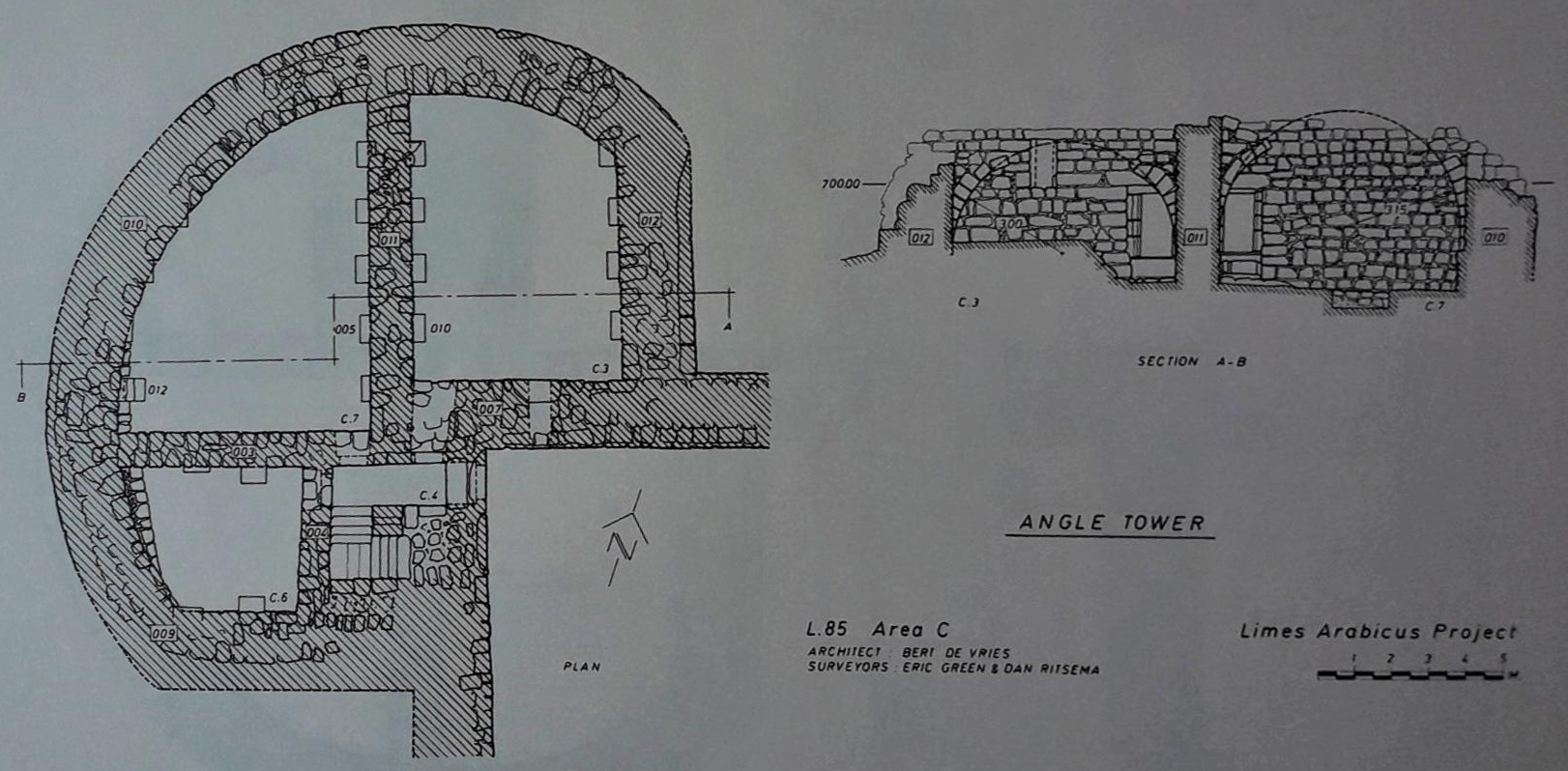

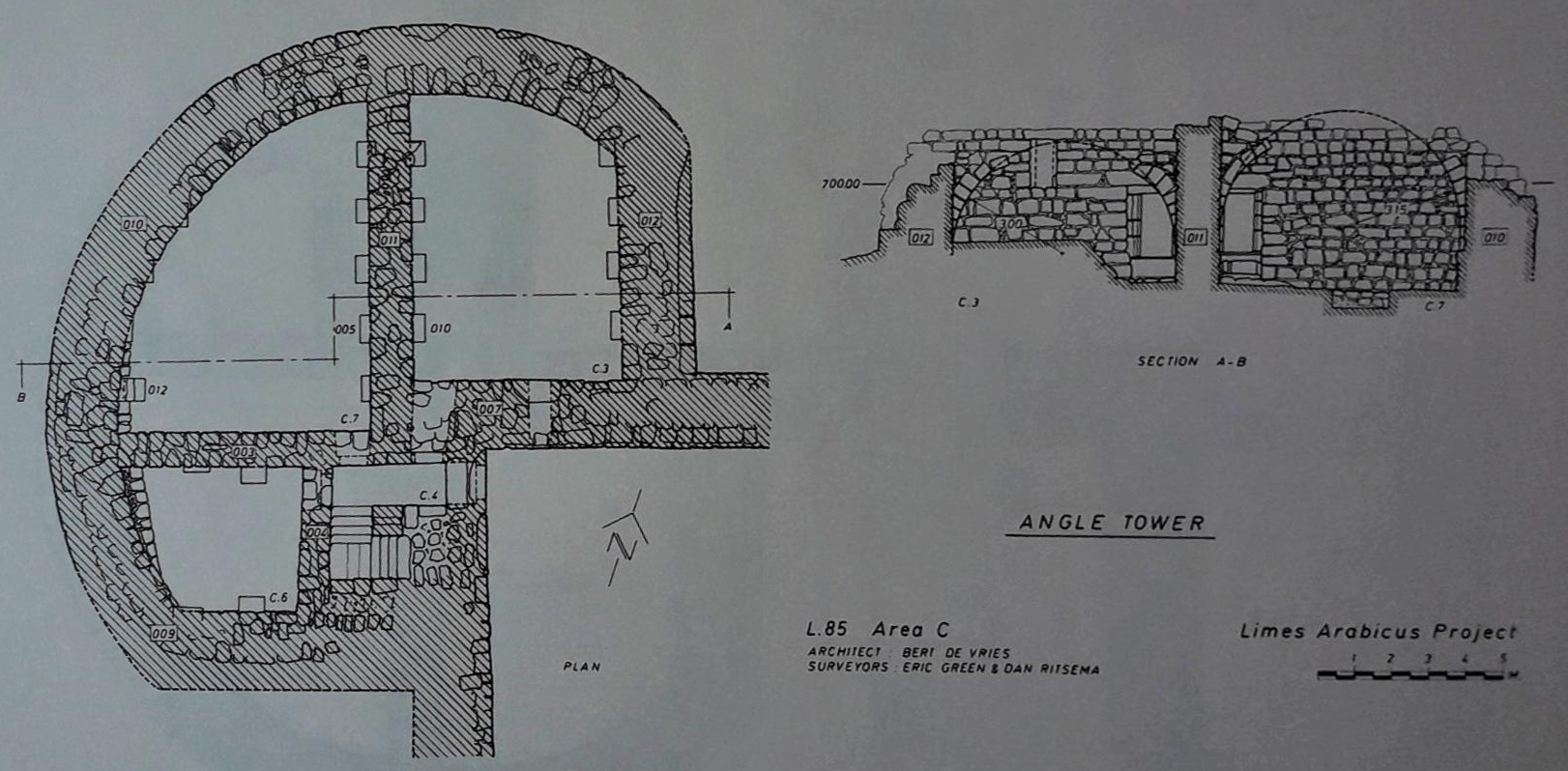

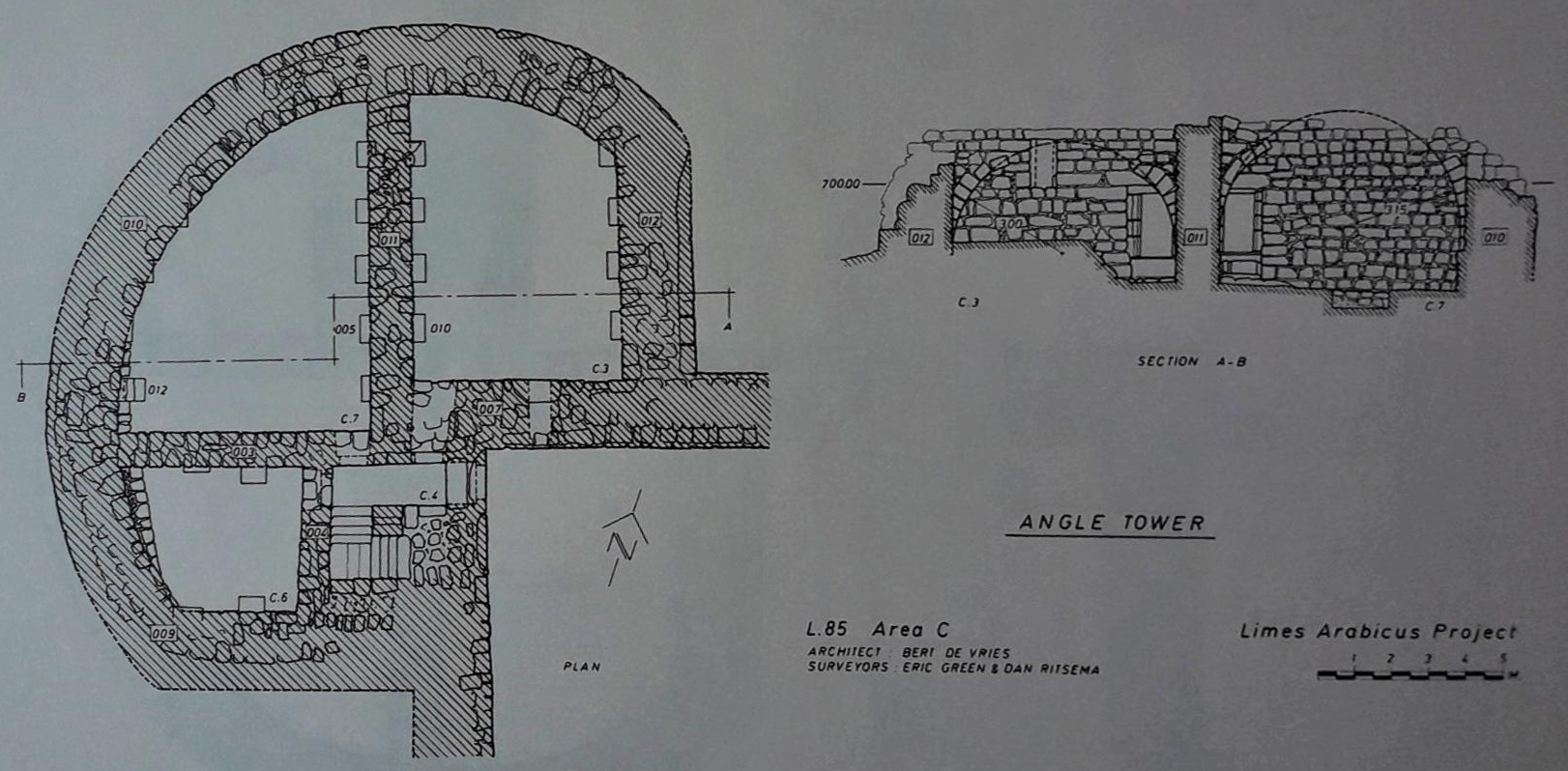

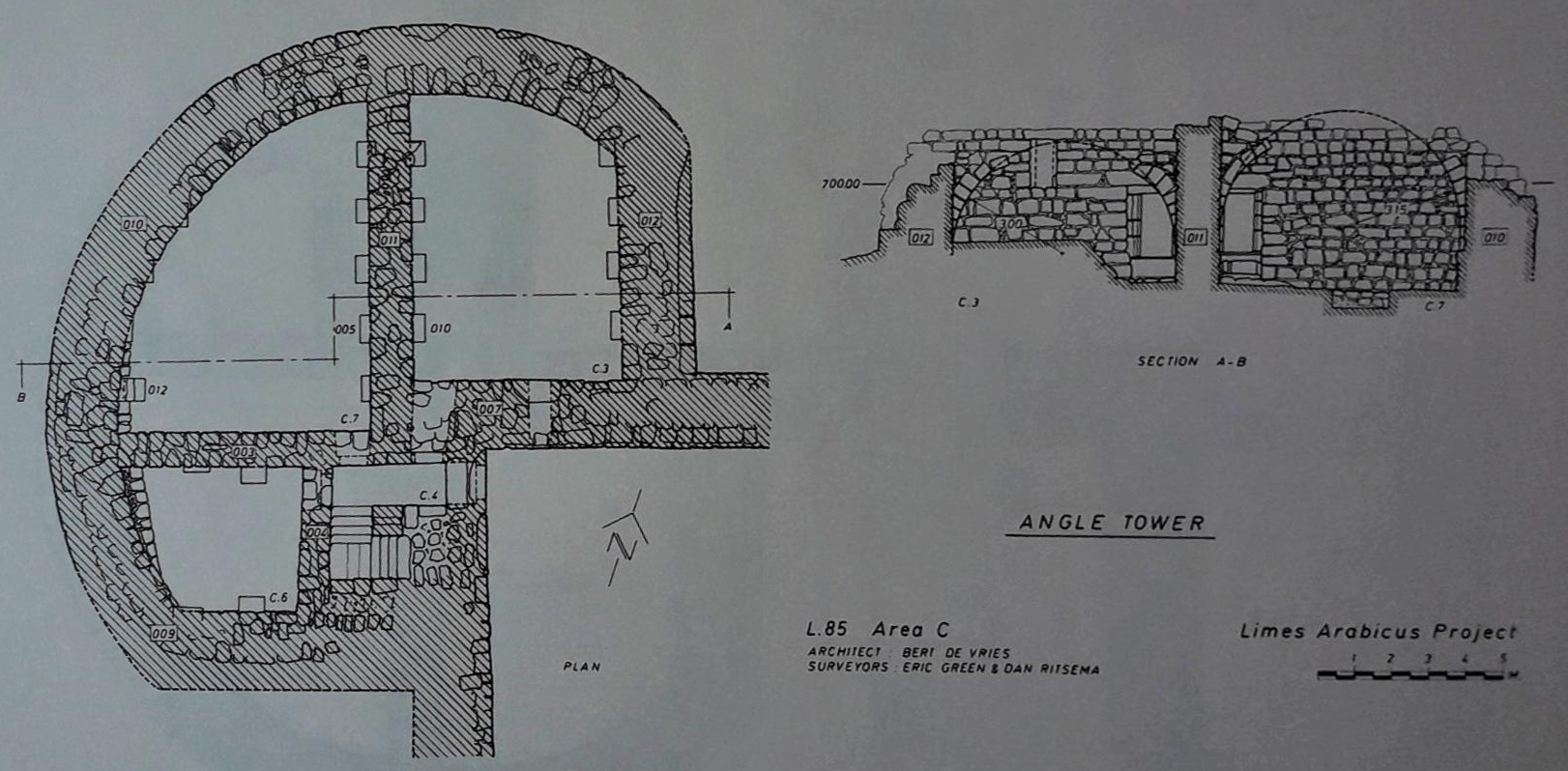

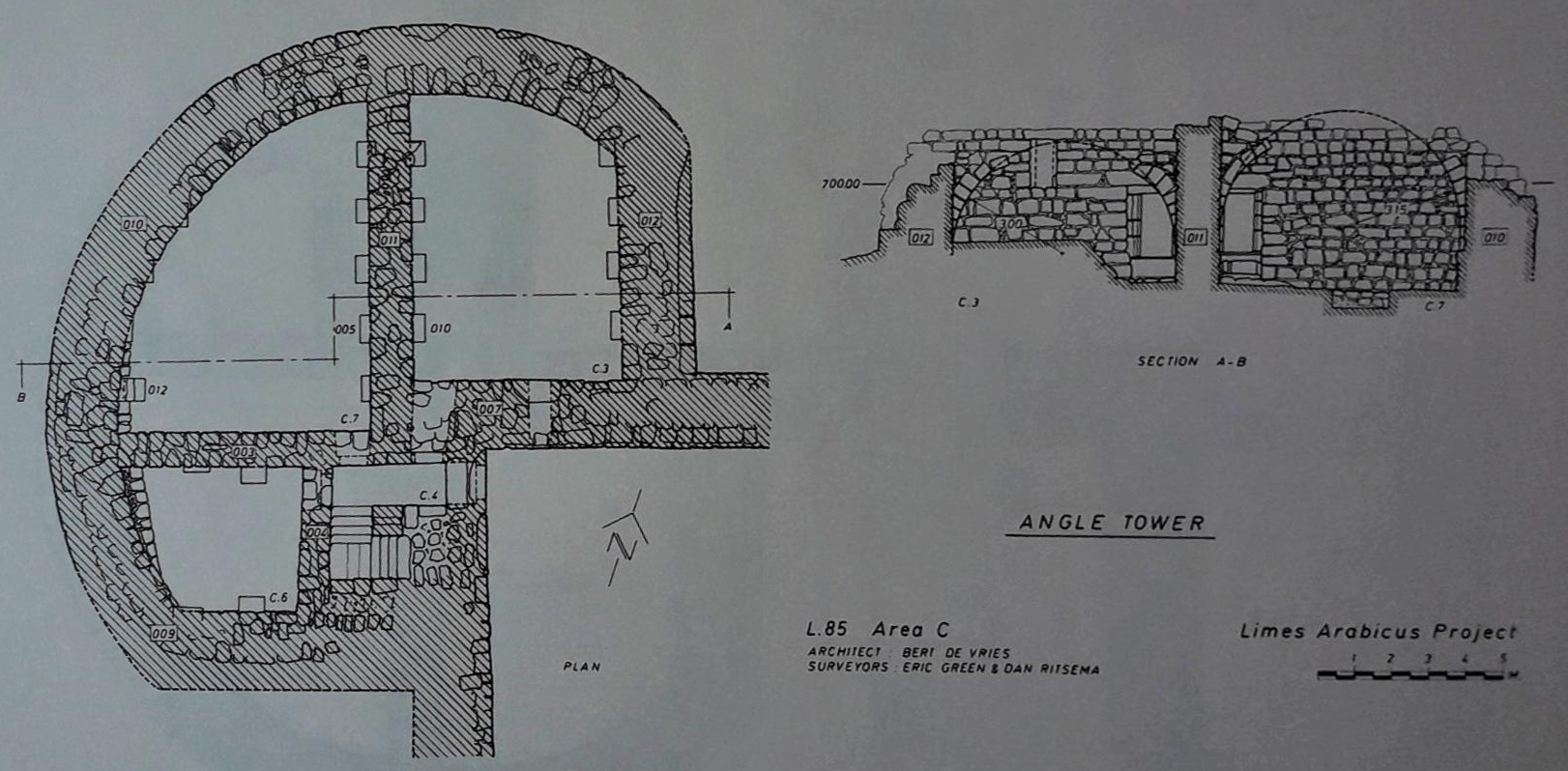

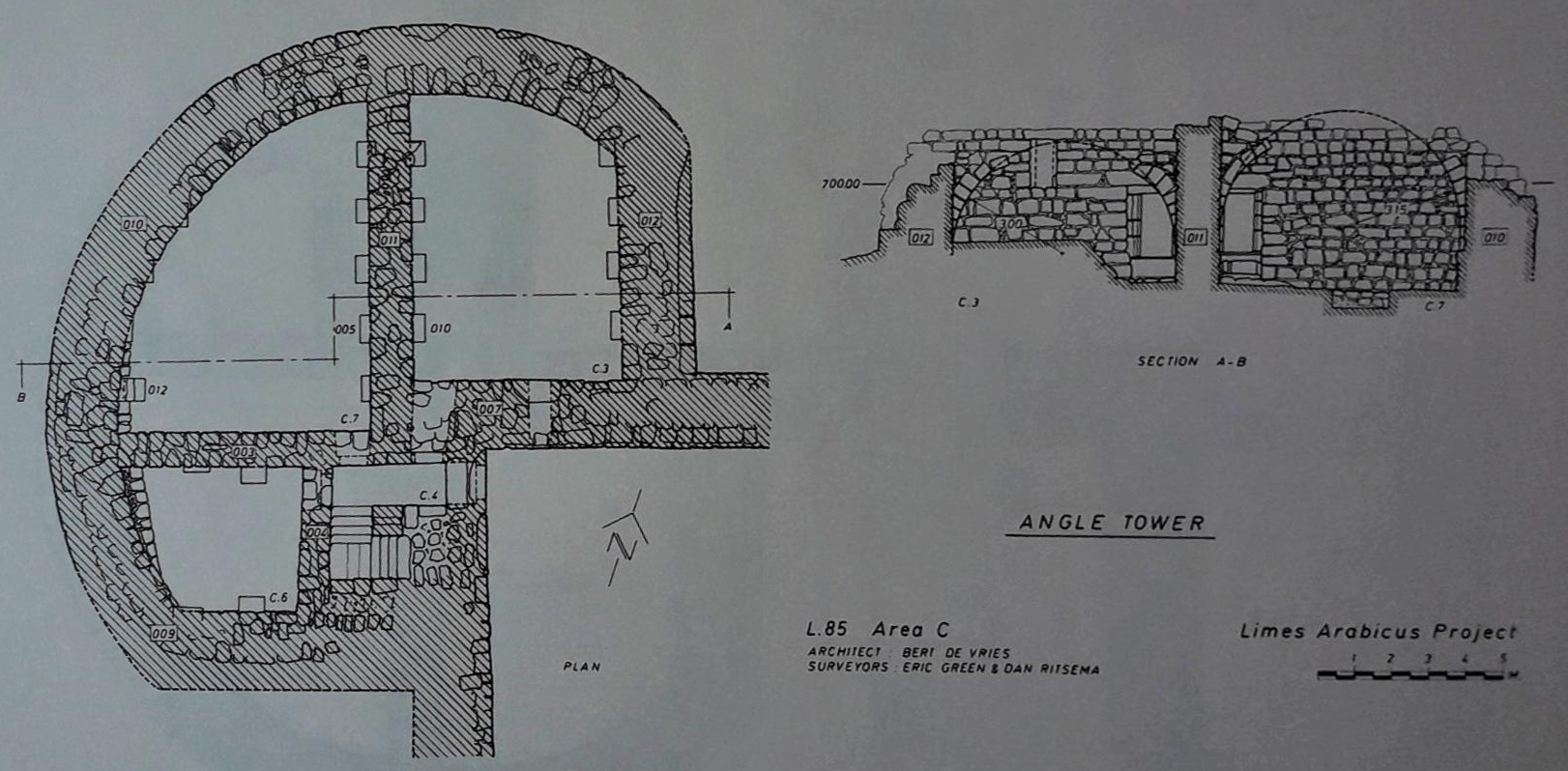

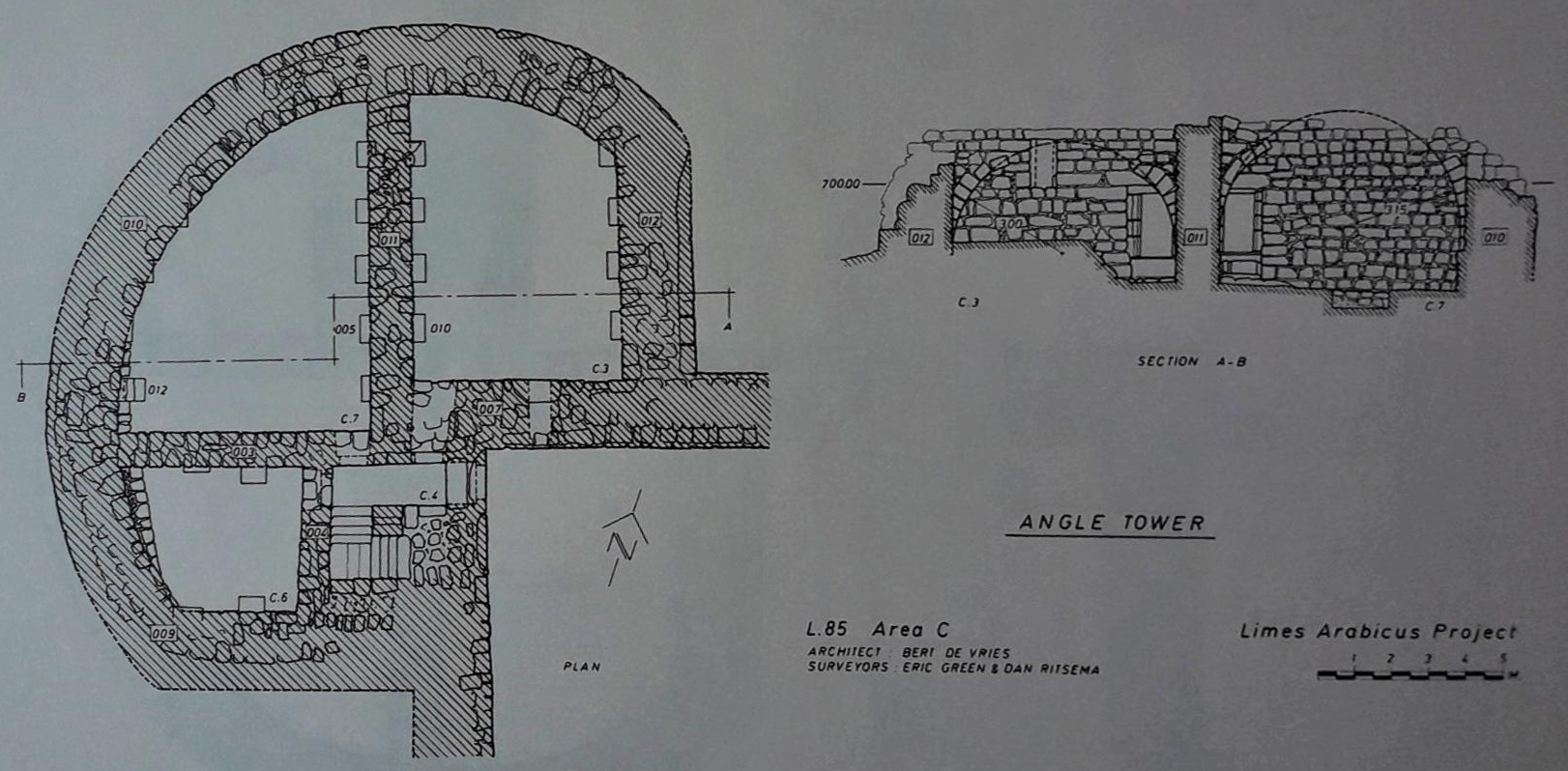

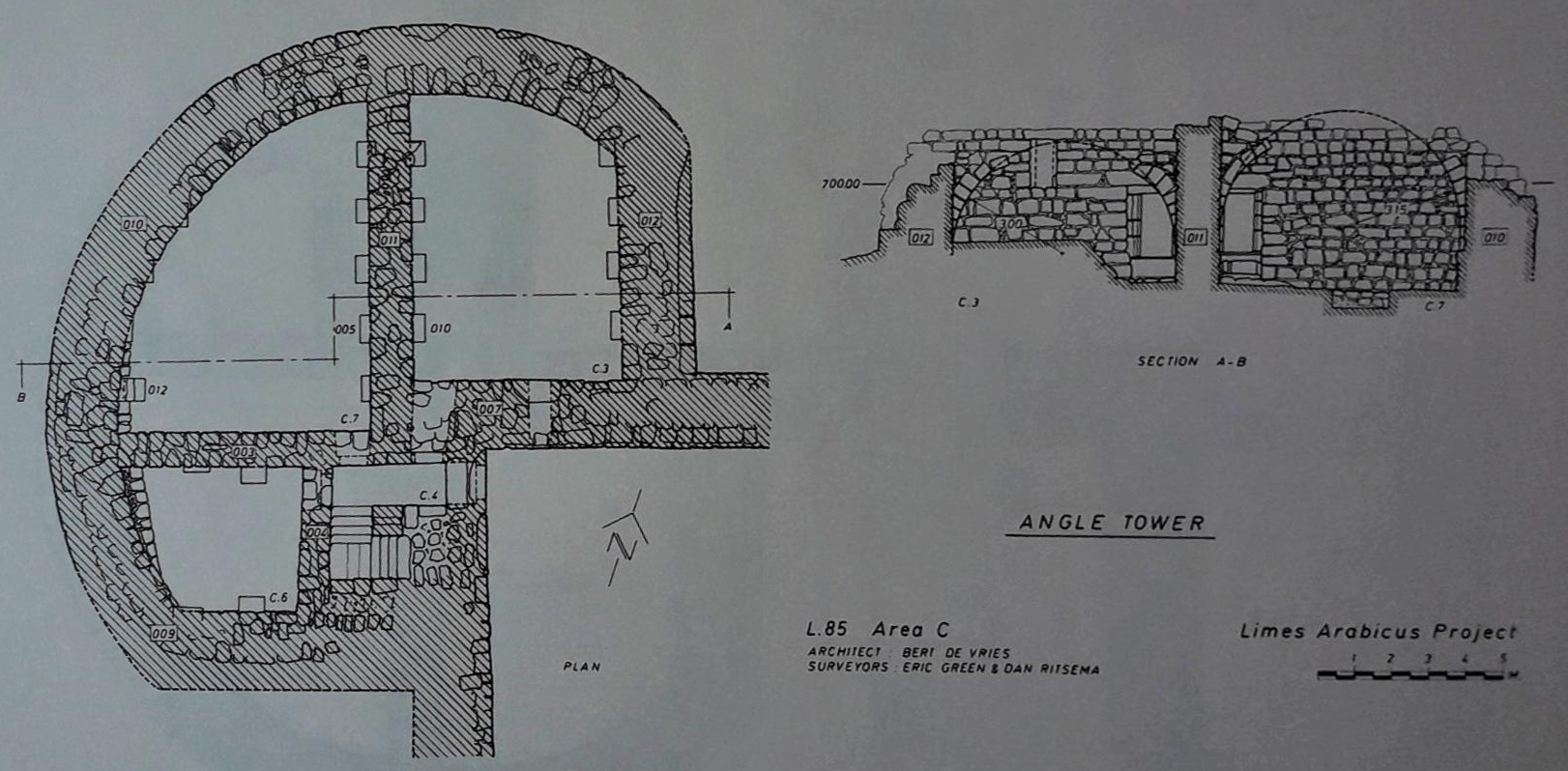

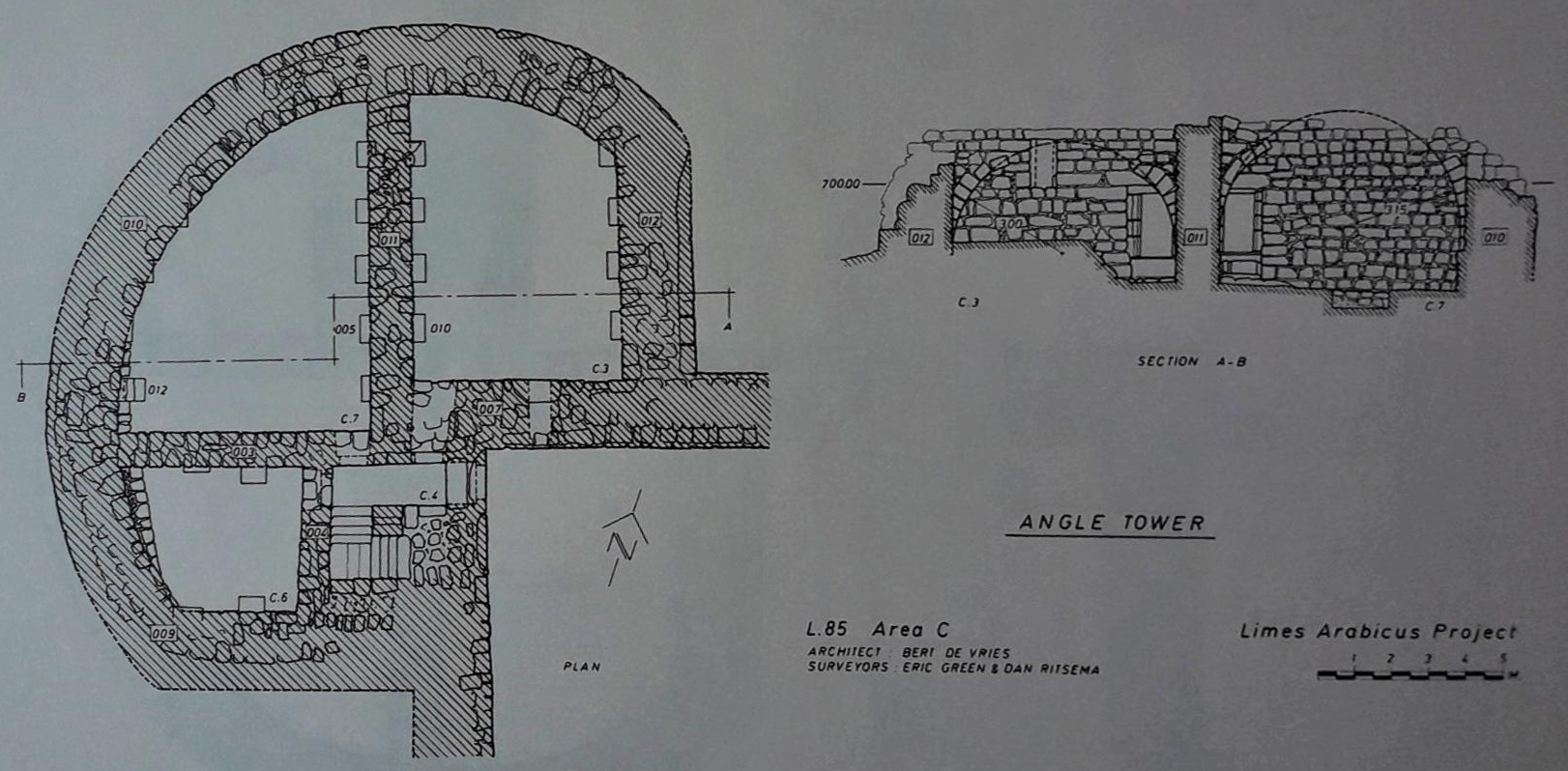

- Fig. 6.3 Plan and section

of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3

Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.4 Plan and section

of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4

Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.5 Schematic section

of loci in C.6, southwest room of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.5

Fig. 6.5

Schematic section of loci in C.6, southwest room of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.6 Plans

and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6

Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.7 Restored section C-D

showing the angle tower from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7

Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors

Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the NW tower

from ACOR website

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of north west tower

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of north west tower

ACOR website

- Fig. 6.3 Plan and section

of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3

Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.4 Plan and section

of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4

Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.5 Schematic section

of loci in C.6, southwest room of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.5

Fig. 6.5

Schematic section of loci in C.6, southwest room of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.6 Plans

and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6

Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 6.7 Restored section C-D

showing the angle tower from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7

Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors

Parker et al (2006) - Plan of the NW tower

from ACOR website

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of north west tower

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of north west tower

ACOR website

- Plan of north part of the fort

from Wikipedia (Mediatus)

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figure

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figure

Legion camp Betthorus - Plan of the excavations, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan. Only the late Roman expansion phase is taken into account.

Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0 - Fig. 6.2 Reconstruction

of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Reconstruction of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall

Parker et al (2006)

- Plan of north part of the fort

from Wikipedia (Mediatus)

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figure

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figure

Legion camp Betthorus - Plan of the excavations, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan. Only the late Roman expansion phase is taken into account.

Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0 - Fig. 6.2 Reconstruction

of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Reconstruction of the juncture of the interval tower and curtain wall

Parker et al (2006)

- Plan of a structure

in the vicus from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

El-Lejjun: plan of a structure in the vicus (civilian settlement)

El-Lejjun: plan of a structure in the vicus (civilian settlement)

Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

- Plan of the bath

from ACOR website

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of bath

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of bath

ACOR website - Plan of the bath

from wikipedia

Betthorus Legion Camp - Plan of the military baths, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan

Betthorus Legion Camp - Plan of the military baths, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan

click on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab

(source: Samuel Thomas Parker: The Roman Frontier in central Jordan. Final Report on the Limes Arabicus Project 1980-1989. Volume 1, (= Dumbarton Oaks studies 40), Fig. 7.1.)

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC-BY-SA-3.0 & GFDL

- Plan of the bath

from ACOR website

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of bath

Jordan. El-Lejjun, plan of bath

ACOR website - Plan of the bath

from wikipedia

Betthorus Legion Camp - Plan of the military baths, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan

Betthorus Legion Camp - Plan of the military baths, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan

click on image to open a high res magnifiable version in a new tab

(source: Samuel Thomas Parker: The Roman Frontier in central Jordan. Final Report on the Limes Arabicus Project 1980-1989. Volume 1, (= Dumbarton Oaks studies 40), Fig. 7.1.)

Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC-BY-SA-3.0 & GFDL

- Fig. 8.1 Plan of

Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.1

Fig. 8.1

Plan of Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 8.2 Balk

sections in room N.2 from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.2

Fig. 8.2

Balk sections in room N.2

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 8.3 West

section of southwest corner balk of room N.3 from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.3

Fig. 8.3

West section of southwest corner balk of room N.3

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 8.1 Plan of

Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3) from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.1

Fig. 8.1

Plan of Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3)

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 8.2 Balk

sections in room N.2 from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.2

Fig. 8.2

Balk sections in room N.2

Parker et al (2006) - Fig. 8.3 West

section of southwest corner balk of room N.3 from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.3

Fig. 8.3

West section of southwest corner balk of room N.3

Parker et al (2006)

- Fig. 4.13 Fallen arch

from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.13

Fig. 4.13

Entrance blocked by fallen arch into room A.12 in the northern range of the principia. The vertical meter stick rests in the southwest corner of the room. View to the south

Parker et al (2006) - Plate 6.1 northeast room

(C.3) within the angle tower with lower layer of tumble from Parker et al (2006)

Plate 6.1

Plate 6.1

The northeast room (C.3) within the angle tower. The two meter sticks rest in the window. Note the arch springers in the walls to the left and right. In the foreground is the lower layer of tumble within the room. View to south.

Parker et al (2006) - Plate 12.3 Collapsed arch

and roof corbels (in situ) in southeast room (Q7) of the Vicus Temple from Parker et al (2006)

Plate 12.3

Plate 12.3

Collapsed arch and roof corbels in situ in southeast room (Q7) of arcade [of the Vicus Temple]. View to the east

Parker et al (2006) - Collapsed Wall in Principia - photo by JW

- Tilted Wall in Principia - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Tilted Wall in Principia - Tilt Measurement of ~4.5 degrees - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Fig. 4.13 Fallen arch

from Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.13

Fig. 4.13

Entrance blocked by fallen arch into room A.12 in the northern range of the principia. The vertical meter stick rests in the southwest corner of the room. View to the south

Parker et al (2006) - Plate 6.1 northeast room

(C.3) within the angle tower with lower layer of tumble from Parker et al (2006)

Plate 6.1

Plate 6.1

The northeast room (C.3) within the angle tower. The two meter sticks rest in the window. Note the arch springers in the walls to the left and right. In the foreground is the lower layer of tumble within the room. View to south.

Parker et al (2006) - Plate 12.3 Collapsed arch

and roof corbels (in situ) in southeast room (Q7) of the Vicus Temple from Parker et al (2006)

Plate 12.3

Plate 12.3

Collapsed arch and roof corbels in situ in southeast room (Q7) of arcade [of the Vicus Temple]. View to the east

Parker et al (2006) - Collapsed Wall in Principia - photo by JW

- Tilted Wall in Principia - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Tilted Wall in Principia - Tilt Measurement of ~4.5 degrees - digital theodolite photo by JW

Ceramic evidence suggests that the fort was first built around 300 CE and occupied until the early 6th century CE with later limited occupation in the Ummayad and Late Islamic

periods (Parker, 2006). Three "identifiable earthquakes"

(Southern Cyril Quake - 363 CE,

Fire in the Sky Quake - 502 CE, and the

551 CE Beirut Quake) were interpreted as providing

breaks in the stratigraphic sequence. The earthquake assignments of 502 and 551 CE are probably incorrect as the epicenters for these quakes were distant. The

502 CE Fire in the Sky Quake should be replaced with

the more local ~500 CE Negev Quake and

the 551 CE Beirut Quake should be

replaced with the late 6th century

Inscription at Areopolis Quake. There is additional evidence on the site for one or two more earthquakes.

The stratigraphic framework was based on numismatic and ceramic evidence. The details of the stratigraphy are fairly complex.

There are a number of apparent dating contradictions in their report that

were explained as intrusive and, while this appears to have been necessary to make sense of the phasing and deal with incidences of stone robbing, etc., it does add some additional uncertainty to

the dating. Since the dates for the 2nd and 3rd earthquakes provided by Parker et al (2006) (502 and 551) are

probably incorrect and may have been relied on to sort through the difficult chronology, dates and date ranges provided on this page are based on information in their report

rather than their earthquake date assignments.

- from Parker, 2006)

| Stratum | Period | Approximate Dates (CE) |

|---|---|---|

| VI | Late Roman IV | 284-324 |

| VB | Early Byzantine I | 324-363 |

| VA | Early Byzantine II | 363-400 |

| IV | Early Byzantine III-IV | 400-502 |

| III | Late Byzantine I-II | 502-551 |

| Post Stratum III Gap | intermittent use of site for camping and as a cemetery | 551-1900 |

| II | Ottoman | 1900-1918 |

| I | Modern | 1918- |

Building History

As Parker was able to state and as the prehistorian Johanna Ritter-Burkert put it, Betthorus was "established on virgin soil". [8] This finding was so important for science because at the beginning of the investigations from 1980, this was one of the few cases in which a late antique legionary camp had been built as a new building. So it was neither an older camp that was rebuilt, as is generally found, nor was it disfigured by post-fort construction. With the legionary camp of Betthorus, the archaeologists at that time had the undisturbed construction plan of a late antique garrison before them. For these reasons, complex stratigraphy was not to be expected. [28]Based on these central selection criteria, Betthorus became the best-studied legionary camp on the eastern border of the empire after Palmyra . [8th]

Parker derived the founding of the fort during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284-305) not only from the construction plan of the complex, but in particular from the numismatic findings and the late Roman ceramics from the area of the enclosing wall and other finds from the foundation areas of the buildings inside of the castle. Apart from a single Nabataean piece, the series of coins begins in the last quarter of the third century with two issues of Emperor Probus (276–282) and one issue of Numerianus (283–284). During the investigations of the Limes Arabic project, about a dozen coins of Diocletian and the First Tetrarchy were discovered(284–305) picked up. The earliest accurately datable coin from this era dates from AD 284-286. Of particular interest is an issue from Diocletian's co-emperor Maximianus (286-305), discovered in the foundation of a late Roman barrack and dating to around 304-304 305 dated. This suggests that the legionary camp was constructed relatively late in the reign of Diocletian - perhaps shortly after AD 300 according to Parker [1]

The occupancy of the camp by the Legio IV Martia, which according to the Notitia Dignitatum was stationed in the Arabic Betthorus, cannot yet be proven on site. [8] The only inscription found in the staff building (Principia) was the rest of a dipino painted in red on white wall plaster. This remains of plaster was still attached to a block of limestone that had been torn from its original context by the earthquake of 551 AD. The Dipinto is written in Latin. Its relatively careful letterforms are typical of the third or fourth century. [29] Overall, however, only a few letters remained [8]of the 0.02 meter high inscription. The ancient historian Michael P. Speidel, who was responsible for the epigraphy during the Limes Arabic project, determined the following reading: [30]

[…] why

[…] t […]

The second inscription found in the military bath consisted of a single Latin letter, an "A" on a fallen block of stone. [31]

The development of fortifications for military use can be roughly divided into two construction phases between the period around 300 AD and 530 AD.

For citations, see Wikipedia page for Betthorus (in German)

- from Wikipedia page for Betthorus (in German)

- Warning - links in table don't work - go to Wikipedia page for Betthorus (in German) for links

| Dates | Events |

|---|---|

| around AD 300 to May 19, AD 363 | Parker's excavations revealed that most of the fort's internal structures date back to a reconstruction [32] that took place after a major earthquake on May 19, 363 AD. [31] The only buildings and components that are known to date back to the original construction around 300 AD are the fence, the wall sections of the subsequently massively rebuilt Principia, which are still partly made of limestone, and the older limestone barracks that were later built over , the remains of limestone walls on the structures that can probably be identified as granaries ( horreum ) and the military baths (balnea) also made of limestone . [32]The founding date could be specified by numismatic and ceramic sources. [1] |

| May 19 AD 363 to AD 530 |

After extensive reconstruction of the interior of the fort and structural changes, chert was used instead of limestone. Troop strength may have been reduced by as much as 50 percent. [3] The fort was probably abandoned by the troops in 530. |

| AD 530 to July 9, AD 551 |

After the military gave up the fort, there was a short period of civilian use. Already in the early 6th century, however, fortifications were neglected. Large amounts of rubbish accumulated on the camp streets and the deceased were left to rot where they died. This last phase apparently culminated in the devastating earthquake of July 9, 551 AD. The numismatic final coins date to the reign of Emperor Justinian I (527–565). [33] |

| 661 AD to 750 AD |

After the Islamic conquest of the Levant, the Roman ruins were only partially used to a very limited extent. For the most part, the Lejjun spring remained the main attraction for short-term nomad deposits. Only two surviving rooms of the north-west corner tower, which collapsed in AD 551, were temporarily reused in the Umayyad period . [2] |

| 1174 AD to 1517 AD |

Also during the Ayyubid - Mamluk period, a room in the north-west corner tower was used for a limited time. At the same time, a temporary use of the Roman building remains of the northern gate could be observed. In the northwest quadrant, late antique structures have been remodeled for a thirteenth-century lime kiln . In the area of the camp village ( vicus ) there were no signs of Islamic structural use. |

| Middle Ages to modern times | Over the centuries, local nomadic tribes and probably also traveling Islamic pilgrims invasively encroached on the entire ruin area, since their dead were buried there. [2] |

- from Wikipedia page for Betthorus (in German)

- Warning - links in table don't work - go to Wikipedia page for Betthorus (in German) for links

| Name/Location | Description/Condition | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirbet Thamayil/Khirbat ath-Thamayil | Within two nested, walled enclosures forming a closed square, a rectangular tower-like ruin borders on the southwestern inside of the inner enclosing wall. The outer wall was 36.70 × 27 meters, the inner 26 × 16.50 meters. The tower-like central building was 7.70 × 10 meters in size [61] and still about five meters high. [62]The enclosing walls of both outer structures are mainly of large unhewn limestone and basalt stones, with some additional megalithic ashlar blocks, and are laid in two rows about a meter wide. Inside the complex there are several depressions that apparently come from cisterns. In the southeast, a large terraced area borders the outside of the enclosing wall. The complex is situated on a hill approximately 750 meters high and overlooks a wadi system to the west, south and east. Immediately in front of the south-west wall of the outer enclosing wall, the terrain drops about 20 meters steeply into Wadi ar-Ramla.

In addition to Parker's Limes Arabic Project, the historian and biblical scholar James Maxwell Miller also investigated the Kirbet Thamayil with his Archaeological Survey of the Kerak Plateau , which took place from 1978 to 1982. Miller reported that during his field visit, mostly Iron Age II pottery fragments surfaced as surface finds. He was also able to identify two Nabataean sherds and one late Roman sherd. [63] Between July and August 1992, the most thorough investigation to date was carried out. They took place as part of the Moab Marginal Agriculture Project , which Canadian archaeologist Bruce Routledgedirected. Routledge, who identified Kirbet Thamayil as the most significant Iron Age II site in his area of study, made two sonde cuts in addition to a thorough planum survey. The archaeologist and his team were able to collect 1180 ceramic fragments, of which only 16 did not belong to the Iron Age, but were dated "Byzantine" as surface finds. [64] The site was probably an Iron Age fortification and was reused to a limited extent in the Nabatean and late Roman-early Byzantine periods. Parker collected 120 sherds of pottery and eight stone tools during his investigation, but these have not yet been identified. The following is an analysis of Parker's pottery finds. [65]The chronological periods and dates follow Parker's 2006 account. [66]

The watchtower Rujm el-Merih, which Parker regarded as a late Roman foundation, [67] which was built about 1.60 kilometers east of Kirbet Thamayil, may have succeeded it. [68] | |||||||||||||||

| Watchtower, Limes Arabic project, field find no. 198 | At this site there is a square, 7.70 × 7.70 meter tower-like structure within a brick enclosure. [69] The building was built of large, roughly hewn blocks of limestone and is located at the highest point of the Jebel-esh-Sharif mountain range, which adjoins the Jebel Abu Rukba with the late Roman watchtower Qasr Abu Rukba to the north- west . [70]From its exposed summit location on Jebel-esh-Sharif, the small fort dominated the country to the north and east - so many other sites, including el-Lejjun, were visible. Parker assumed that this structure was an Iron Age watchtower later used by the Nabataeans. After a long period of vacancy, limited use seems to have taken place again during the late Roman-early Byzantine era. Along with Parker, Miller also visited this site. A total of 86 sherds of pottery were picked up by the employees of the Limes Arabicus Project . In addition, three previously undated stone tools were found. [71] [72]

A little less than four kilometers west of this site was the large settlement of El-Mureigha, an Iron Age foundation that flourished during the Nabatean, Roman and Byzantine periods. [73] |

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

Parker (2006:121) describes the last phase of significant occupation as follows:

The later phase (ca. 530-51) of Stratum III began with the demobilization of the legion ca. 530, as suggested by a passage in Procopius (Anecdota 24.12-14). It is notable that the latest closely dateable Byzantine coins from el-Lejjun are issues of Justinian I, dated 534-65, exactly what one would expect if Procopius' assertion were true. Some structures like the principia, were completely abandoned. Others, like the church, were extensively robbed. Large amounts of trash were dumped in barrack alleyways and even in major thoroughfares, such as the via praetoria. In Area N the rooms rebuilt rebuilt after 502 afterward witnessed little actual occupation. It is especially telling that a human corpse was interred in one room (N.2) that opened directly onto the via principalis a clear sign of the absence of military discipline.The numismatic finds and demobilization evidence described above provide a terminus post quem of ~530 CE for seismic destruction and final abandonment of the fortress at el-Lejjun. A terminus ante quem is not so well defined because after the 3rd earthquake, there is a Post Stratum Gap that lasted until 1900 CE. Parker (2006:121) notes that

Some inhabitants, perhaps discharged soldiers and their families or civilians from the surrounding countryside, continued to live within the fortress, however. The discovery of a human infant within the northwest angle tower in the debris of the earthquake of July 9, 551, implies that families were now living in the fortifications. The earthquake of 551 was a major catastrophe.

there is some evidence of camping and limited reoccupation of the domestic complex near the north gate in the Umayyad period (661-750 CE).

Sherds and coins of Ayyubid/Mamluk (1174-1516) and Ottoman periods [also] attest [to] occasional later use of the fortress. Because Groot et al (2006:183) report discovery of a nearly complete Umayyad Lamp in Square 4 of Area B (Barracks) in the Post Stratum Gap, the Umayyad period (661 - 750 CE) is the terminus ante quem for this earthquake and the date for this earthquake is constrained to ~530 - 750 CE. deVries et al (2006:196) also found Umayyad sherds in the Post Stratum Gap in Rooms C.3, C.4, C.6, and C.7 of the northwest Angle Tower along with an Umayyad coin dated to 700-750 CE in locus C.4.018.

Although Parker et al (2006) attributed the 3rd earthquake to the 551 CE Beirut Quake, this is unlikely as the epicenter was far away - near Beirut. One of the sources for the 551 CE Beirut Quake (The Life of Symeon of the Wondrous Mountain) states that damage was limited south of Tyre and there are no reports of earthquake destruction in Jerusalem which is 121 km. closer to the epicenter than el-Lejjun. The most likely candidate for this earthquake is the Inscription at Areopolis Quake which struck Aeropolis - a mere ~12 km. from el-Lejjun - in the late 6th century - before 597 CE.

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

- Plan of the Fort at El-Lejjun

modified from Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

1980-89

modified by JW from Parker et al (2006) - Fig. I Plan of the Fort at

El-Lejjun from Meyers et al (1997)

Figure I

Figure I

Plan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia

(Courtesy S. T. Parker)

Meyers et al (1997)

Groot et al (2006:183) report discovery of a nearly complete Umayyad Lamp in Square 4 of Area B (Barracks - B.6.038) in the Post Stratum Gap -

above and later than the 3rd earthquake layer. Above the Ummayyad lamp was a 0.7 m thick layer of tumble containing some roof beams and many wall blocks

(Groot et al, 2006:183). They note that the basalt roof beams found embedded in the lowest tumble level (B.6.032) suggests initial massive

destruction rather than gradual decay over time

. The wall blocks, found in the upper layer of tumble, contained one late Islamic (1174-1918 CE) and one Ayyubid/Mamluk (1174-1516 CE) sherd

indicating a significant amount of time may have passed between the possibly seismically induced roof collapse and the wall collapse which was not characterized as necessarily having a seismic origin. This opens up the possibility

that one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes or a later earthquake may have also caused damage at el-Lejjun. deVries et al (2006:196) suggests that

Umayyad abandonment of the northwest tower was probably triggered by further major collapse

. In the North Gate, deVries et al (2006:207) found evidence

of full scale destruction in layers above 3rd earthquake debris and post-earthquake occupation layers

which contained Late Byzantine/Umayyad and Umayyad sherds. Subsoil/tumble was found in C.9.008 (north room),

C.9.009 (south room) and C.9.005 (stairwell) bear ample witness to the destruction of the rooms, perhaps in the Umayyad period

. Although Late Byzantine sherds were found in Post Stratum layers in the North Gate,

if one assumes that the 3rd earthquake was the Inscription at Aeropolis Quake which struck before 597 CE - probably within a decade of

597 CE, one can establish an approximate and fairly conservative terminus post quem for this earthquake of ~600 CE. While the terminus ante quem is the end of the post stratum III gap (1918 CE), it is probable that that the earthquake struck much earlier.

While there are many photos in the Final Report which suggest seismic effects (e.g. cracked lintels, tilted walls, secondary use of building elements, cracked staircases, displaced walls, etc.), only seismic effects described by the authors that appear to be reasonably well dated are listed in the sections below.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roof collapse | Room A.13

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Lain and Parker (2006:144) report that a beaten earth floor and ash layer in Room A.13 which ante-dated the

1st earthquake (Stratum VI-VB) was chock-full of tile fragmentssuggesting an apparent roof collapse due to an unknown cause. Such "collapse" debris was not found in any other excavation areas. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls |

praetentura

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1Plan of Area B: the Early Byzantine Barracks (Strata VA-IV) Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The original limestone barracks in praetentura and possibly elsewhere in the fortress were leveled to their foundations. New chert barracks, only about half their former number, were erected along a slightly different alignment in both the praetentura and in the latera praetoria south of the principia. Rows of barrack-like rooms were erected on either side of the northern via principalis.- Parker (2006:120) |

|

| Collapsed walls | principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The principia also seems to have suffered extensive damage, requiring some portions to be completely rebuilt, such as the interior of the aedes, the rooms in the official block north of the aedes, and the rooms north of the central courtyard [of the principia].- Parker (2006:120) |

|

| Collapsed walls | The mansio in the western

vicus

El-Lejjun: plan of a structure in the vicus (civilian settlement)

El-Lejjun: plan of a structure in the vicus (civilian settlement)Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The mansio in the western vicus was destroyed in 363 and never rebuilt.- Parker (2006:120) |

|

| Roof collapse | principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The earthquake brought down tile roofs throughout the principia- Lain and Parker (2006:131) |

|

| Arch collapse | principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The west arcade between the central courtyard and the cross hall of the principia fell while the major walls were left standing.- Lain and Parker (2006:131) |

|

| Fallen columns | A.7

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Three engaged half and quarter columns with Nabatean style capitals were found in the earthquake debris.- Lain and Parker (2006:133) |

|

| Fractured wall | Wall A.8.003 in principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The wall contains a substantial crack running through the center of its eastern end- Lain and Parker (2006:151) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls and arches | Area B Barracks

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1Plan of Area B: the Early Byzantine Barracks (Strata VA-IV) Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Figure 8

Figure 8Two fallen roof arches caused by earthquake in the barracks, from the north. Parker (1982) |

|

| Collapsed walls | principia and other buildings in the fortress

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The earthquake damaged the principia and many other buildings within the fortress.- Parker (2006:121) |

|

| Collapsed walls and roofs | Area N

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997)

Fig. 8.1

Fig. 8.1Plan of Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3) Parker et al (2006) |

Fig. 8.3

Fig. 8.3West section of southwest corner balk of room N.3 Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.2

Fig. 8.2Balk sections in room N.2 Parker et al (2006) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls | various locations

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

At el-Lejjun, the seismic shock severely affected most parts of the fortress, including the principia, the barracks, the northwest angle tower, the church, and the rooms along the via principalis. Those structures attached to the deep foundations of the curtain wall, such as the horreum and the bath, seem to have better weathered the shock of 551 [JW: Late 6th century CE Inscription at Areopolis Quake a more likely candidate], but even these structures partially collapsed. The fortress was apparently then almost completely abandoned.- Parker (2006:121) |

|

| Collapsed walls | principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Lain and Parker (2006:132) report that the 3rd earthquake toppled original architecture which had survived the

previous two earthquakes and created heavy architectural tumble from walls and installations. |

|

| Northward collapse of walls | principia

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Lain and Parker (2006:132) report that the

direction of architectural collapse was from south to north and that much of the material fell in aligned patterns |

|

| Northward collapsed wall preserving courses | Square A.2 - officium

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Pl 4.11

Pl 4.11Collapsed south wall of the A2, officium within the aedes. The wall fell in the earthquake of 551. View to the west. Parker et al (2006) |

The entire south wall of the room had toppled northward to fill the officium with 18 rows of aligned wall blocks, representing collapsed courses of the wall. The fallen wall overlay roof tile debris that yielded Late Byzantine pottery.- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

| Fallen and broken columns | groma - square A.7

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3Plan of the western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4Section through the south doorways of the groma, looking south Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

drums and capitals dislodged from half and quarter columns lay in aligned rows.- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Collapsed walls | groma - square A.7

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3Plan of the western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4Section through the south doorways of the groma, looking south Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

ashlar limestone and chert blocks from adjacent walls tumbled into the groma's southwest corner- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Roof collapse | groma - square A.7

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3Plan of the western end of the via praetoria at its intersection with the groma Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4Section through the south doorways of the groma, looking south Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The guardroom that adjoined the gate hall was filled with upended basalt roof beams- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Collapsed arches | Square A.1

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

arches of the south portico collapsed in aligned rows between piers of the colonnade- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Roof collapse | aedes

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

first the roof tile caved in.- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Fallen column | aedes

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Next, the three sided podium collapsed, with blocks from its flagstone surface and barrel-vaulted substructures rolling down into the center of the shrine- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Collapsed walls | aedes

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Finally the aedes walls toppled, creating a sloping stratum of jumbled limestone wall blocks.- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Collapsed walls and fallen column | aedes

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

The debris from both the tumbled podium and the collapsed walls of the aedes yielded Late Byzantine pottery.- Lain and Parker (2006:132) |

|

| Collapsed roof and walls | A.15

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

[A subsoil tumble layer in A.15.003] covered the entire square and exhibited marked declivity from south to north, contained ashlar limestone blocks, chert blocks, and basalt roof beams arrayed in patterns indicative of seismic collapse. The basalt beams were concentrated in the south end of the square above the sidewalk. The beams measured 1.75 m in length, and all lay with their short ends oriented north-south. The limestone and chert blocks lay in two fairly regular rows and extended east-west across the square, along the same line as the A.15.008 curb- Lain and Parker (2006:134) |

|

| Collapsed walls | A.13.007

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Lain and Parker (2006:154) report collapsed Walls in tumble layer | |

| Collapsed walls | Areas B and L

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

collapse of most of the remaining barrack rooms still standing in Areas B and L- Groot et al (2006:185) |

|

| Collapsed walls and ceilings | Northwest Angle Tower - C.3 and C.7

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Pl 6.1

Pl 6.1The northeast room (C.3) within the Angle Tower. The two meter sticks rest in the window. Note the arch springers to the left and right. In the foreground is the lower layer of tumble within the room. View to the south. Parker et al (2006) |

deVries et al (2006:196) reports the collapse of upper floors and ceilings |

| Collapsed arches | Northwest Angle Tower - C.3 and C.7

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

destruction of all arches except the southern ones in Room C.3- deVries et al (2006:196) |

|

| Collapsed arches and ceiling | Northwest Angle Tower - C.7

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

deVries et al (2006:192) reports a collapsed ceiling caused by arch collapse and

notes that the earthquake which collapsed the ceiling must have been quite a force to destroy something so sturdy |

|

| Human remains | Angle Tower - C.7

Fig. 6.3

Fig. 6.3Plan and section of the northwest angle tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.4Plan and section of the interval tower of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.6

Fig. 6.6Plans and sections of the northwest angle tower stairway Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 6.7

Fig. 6.7Restored section C-D (see Fig. 6.6) showing the angle tower with either two or three floors Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Pl 6.6

Pl 6.6Skeleton of a human infant found in the northwest room (C.7) of the angle tower. The infant apparently was a casualty of the 551 earthquake. Parker et al (2006) |

deVries et al (2006:193) found the skeleton of an infant in Angle Tower who apparently fell to his/her death from an upper story |

| Collapsed arches and roof | Room N.2

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997)

Fig. 8.1

Fig. 8.1Plan of Area N showing three excavated rooms (N.1-3) Parker et al (2006) |

Pl 8.7

Pl 8.7View of Room N.2, with collapsed arches and roofing slabs, probably from the 551 earthquake. View to the south. Parker et al (2006)

Fig. 8.2

Fig. 8.2Balk sections in room N.2 Parker et al (2006) |

Parker et al (2006) reports collapsed Arches and Roofing slabs in room N.2 which probablyfell during this earthquake |

| Collapsed walls | Horreum

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

Stratum III occupation ended in all three rooms with massive wall collapse, perhaps resulting from the 551 earthquake [JW: more likely the late 6th century Inscription at Areopolis Quake]- Crawford (2006:238) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls and arches | Barracks - Room B.6

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1Plan of Area B: the Early Byzantine Barracks (Strata VA-IV) Parker et al (2006)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

|

|

| Collapsed walls | North Gate - C.9.008 (north room), C.9.009 (south room) and C.9.005 (stairwell)

Fig. 6.8

Fig. 6.8Plan of the north gate (porta principalis sinistra) of the el-Lejjun fortress Parker et al (2006)

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus project

Plan of the Porta Principalis sinistra after partial excavation by the Limes Arabicus projectBetthorus legionary camp - excavation plan of the Porta principalis sinistra , Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan. Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

Fig. 6.12

Fig. 6.12Plan of Late Byzantine domestic complex near the north gate Parker et al (2006)

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figure

The north-western area of the legionary camp with the porta principalis sinistra ,

the military baths, the cistern and accommodation buildings. Only the older, late Roman

expansion phase is taken into account in the figureLegion camp Betthorus - Plan of the excavations, Limes Arabicus Project, Jordan. Only the late Roman expansion phase is taken into account. Click on photo to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab Mediatus - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I

Figure IPlan of el-Lejjun (ancient Betthorus). A later Roman legionary fortress east of the Dead Sea. Built around 300 CE for legio IV Martia (Courtesy S. T. Parker) Meyers et al (1997) |

deVries et al (2006:207) reports full scale destruction in layers above 3rd earthquake debris and post-earthquake occupation layerswhich contained Late Byzantine/Umayyad and Umayyad sherds. Subsoil/tumble was found in C.9.008 (north room), C.9.009 (south room) and C.9.005 (stairwell) which bear ample witness to the destruction of the rooms, perhaps in the Umayyad period |

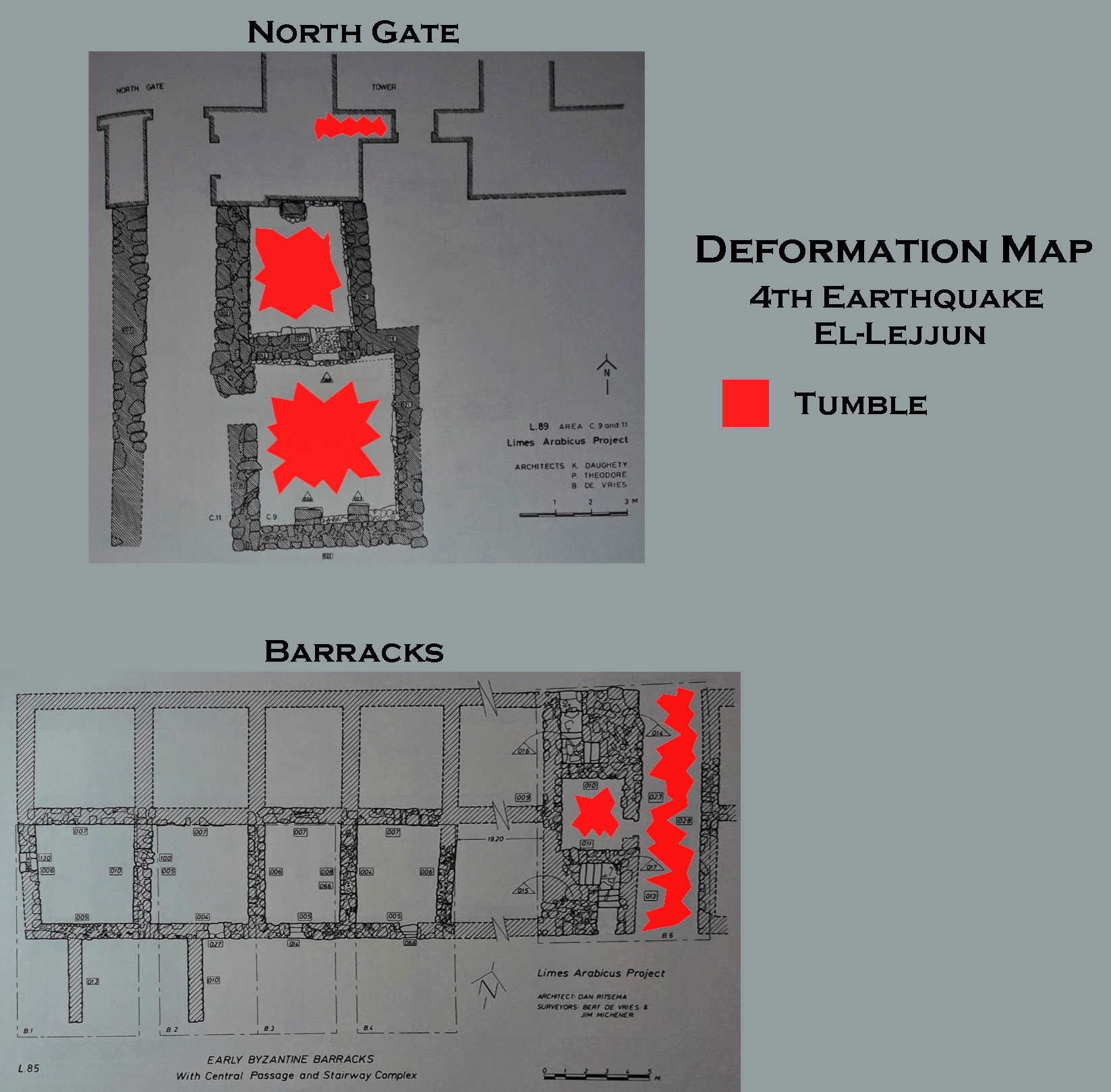

- Modified by JW from a plan in Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from a plan in Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

- Modified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

- Appears to only capture some of the damages

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

- Modified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

- Appears to only capture some of the damages

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

- Modified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. I from Meyers et al (1997)

- Modified by JW from Fig.s 5.1 and 6.12 from Parker et al (2006)

- Appears to only capture some of the damages

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig.s 5.1 and 6.12 from Parker et al (2006)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roof collapse suggests displaced walls | Room A.13

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine period

Plan of the principia (headquarters building) in the Early Byzantine periodStern et al (1993 v. 3)

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas

Plan of el-Lejjun fortress with excavation areas1980-89 modified by JW from Parker et al (2006)

Figure I