Petra - Jabal Harun

Click on Image for higher resolution magnifiable image

- Reference: APAAME_20171001_RHB-0358

- Photographer: Robert Howard Bewley

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Jabal Harun | Arabic | جابال هارون |

| Jabal al-Nabī Hārūn |

Jabal Harun (Mount Harun) rises prominently above southern

Jordan, located roughly 5 km southwest of the main urban

core of Petra. The mountain has long held religious

significance across traditions: Muslims, Christians, and

Jews have traditionally identified it as the burial place

of Aaron, the brother of Moses. This shared sacred

association gave Jabal Harun a significance that extended

well beyond Petra’s Nabataean and Roman

floruit, anchoring

it within a broader biblical and Qurʾanic sacred landscape

(Frosen et al. 2002).

Because of this enduring sanctity, Jabal Harun appears to

have retained an ecclesiastical and pilgrimage role even

after Petra’s political and economic decline in the 7th

century CE. Approximately 150 m below the summit lie the

archaeological remains of what is generally interpreted as

a Byzantine monastery or pilgrimage complex dedicated to

Aaron. These remains suggest continued ritual use of the

mountain in Late Antiquity. Due to its long period of occupation,

it retains the longest archaeoseismic record in Petra.

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Kouki and Lavento (2013)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The Jabal Harun area

Kouki and Lavento (2013)

- Jabal Harun in Google Earth

- Fig. 1 - Aerial View after excavations

from Fiema (2012)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The FJHP site following the end of excavations in 2007

(Photograph by Z. T. Fiema).

Fiema (2012)

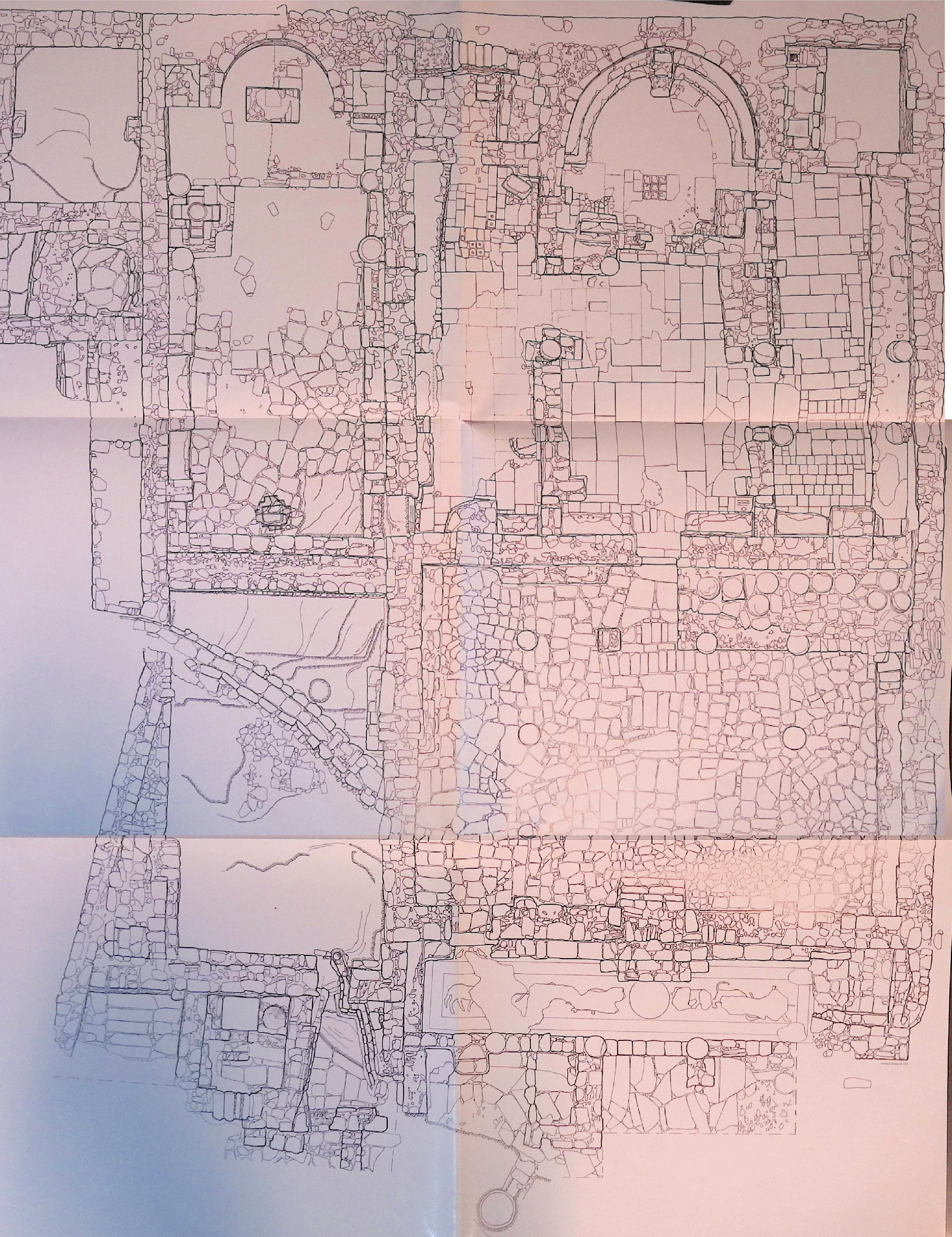

- Fig. 2 - Plan of entire site

from Fiema (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the FJHP site

(by K. Koistenan and V. Putkonen)

Fiema (2013) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the monastery

with walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 2 Chapter 5

Fig. 2 Chapter 5

The plan of the monastery following the 2005 field season.

Fiema (2008)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of

entire site from Fiema (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the FJHP site

(by K. Koistenan and V. Putkonen)

Fiema (2013) - Fig. 2 - Plan of

the monastery with walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 2 Chapter 5

Fig. 2 Chapter 5

The plan of the monastery following the 2005 field season.

Fiema (2008)

- Fig. 8 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 2.

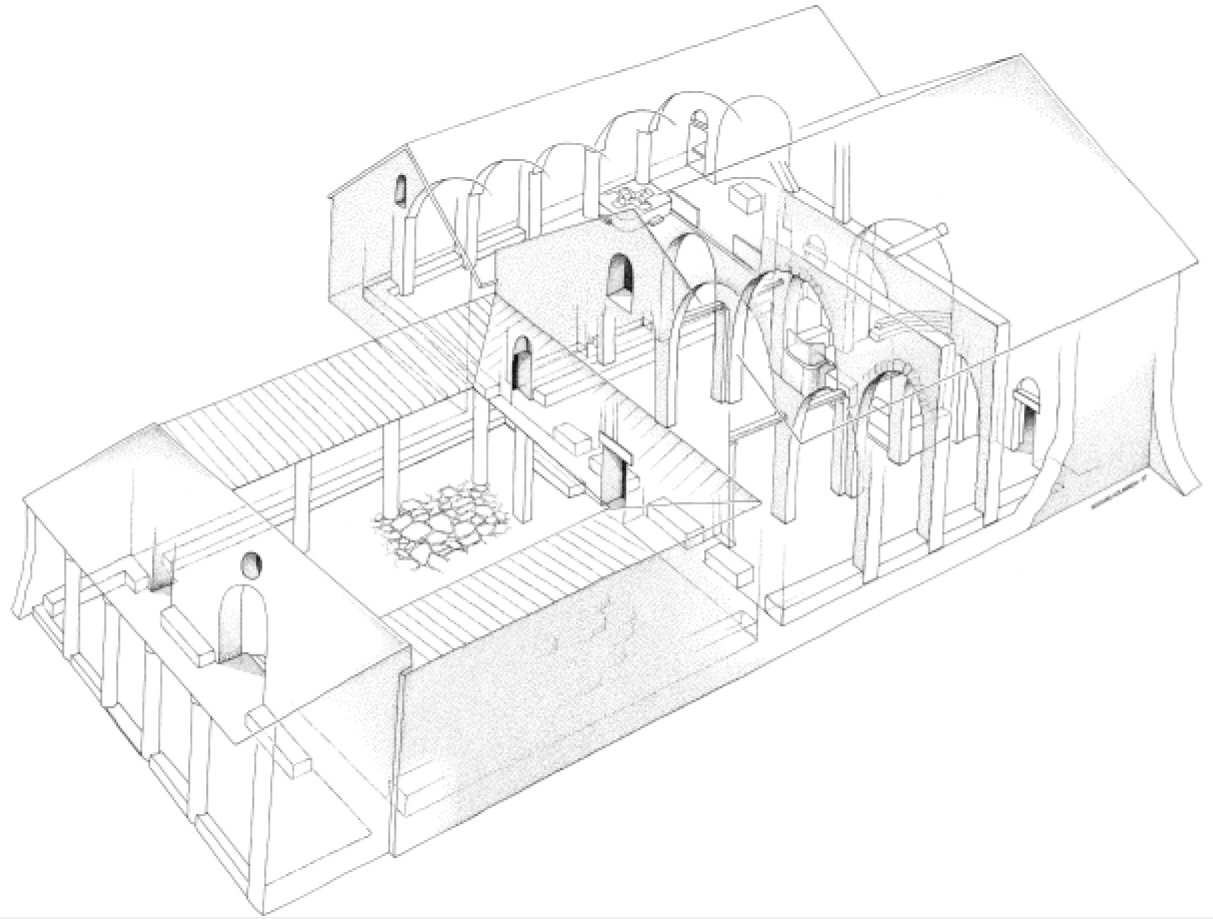

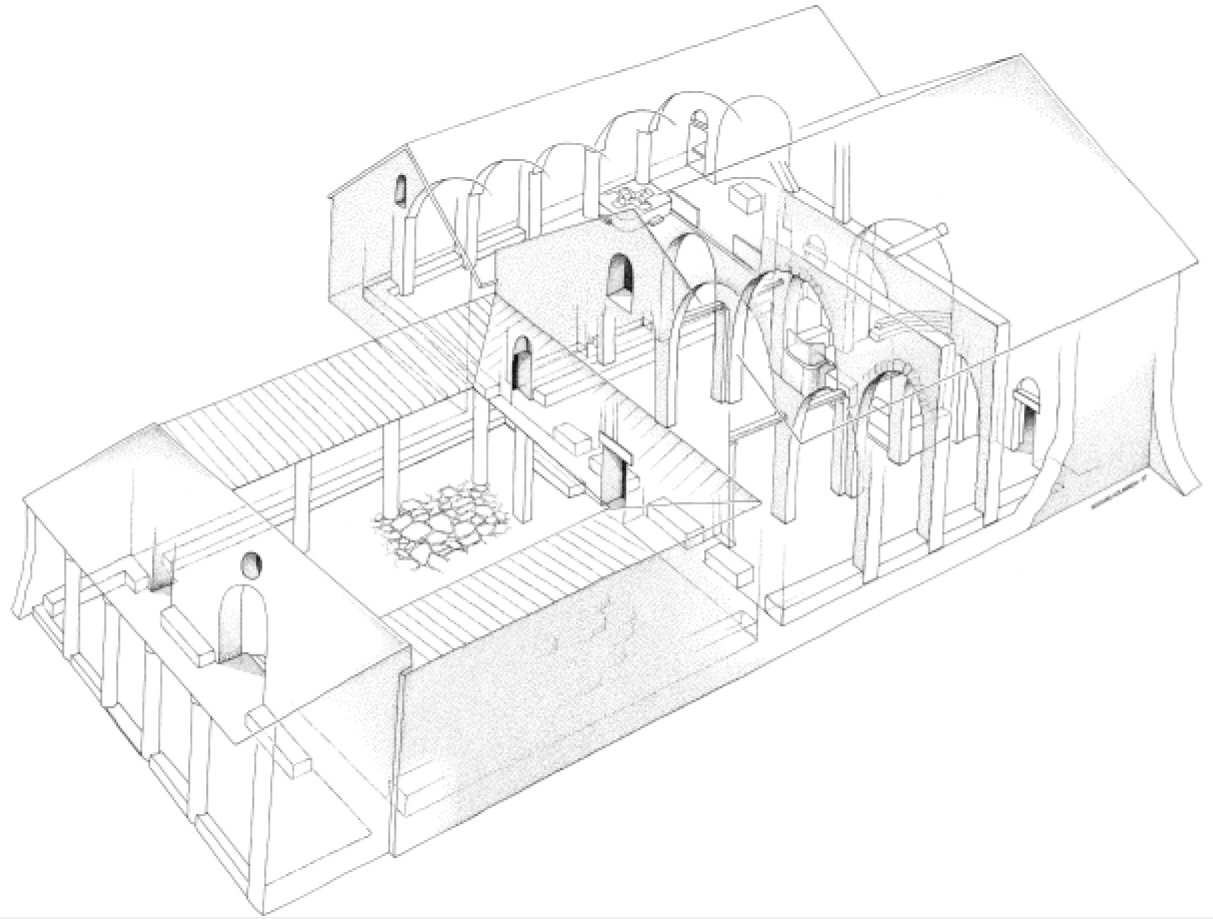

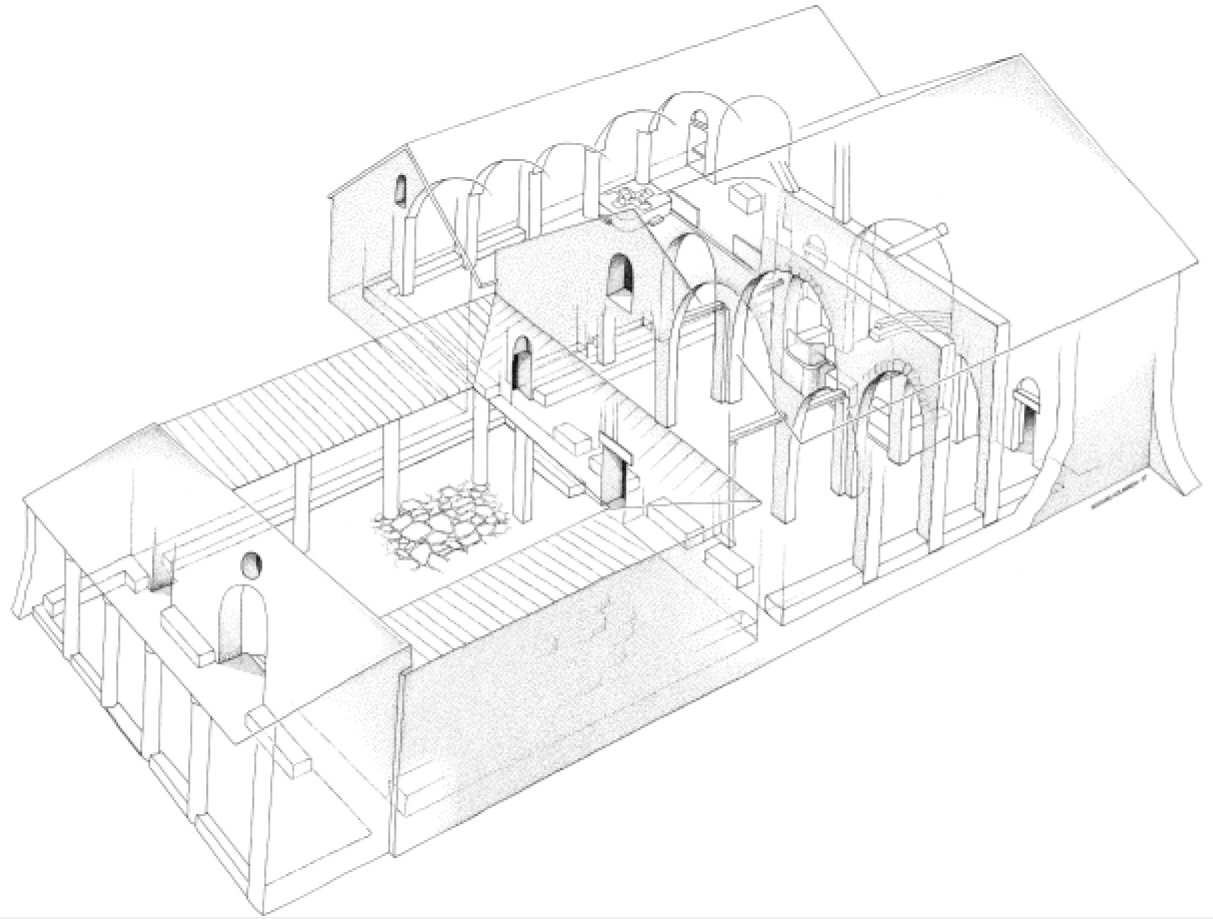

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 10 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phase 2.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 56 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 5.

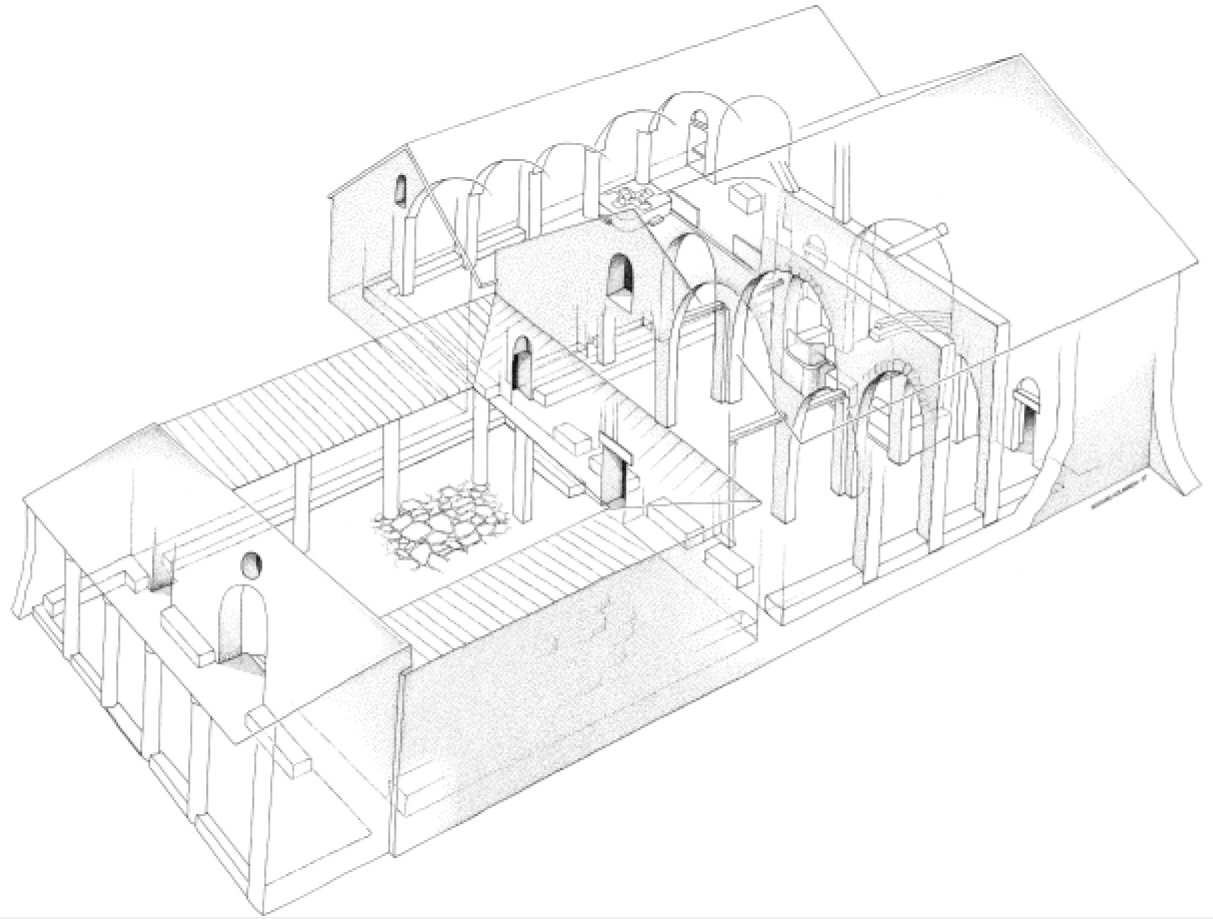

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 37 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 37

Fig. 37

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 59 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 7 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 59 Chapter 6

Fig. 59 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 7.

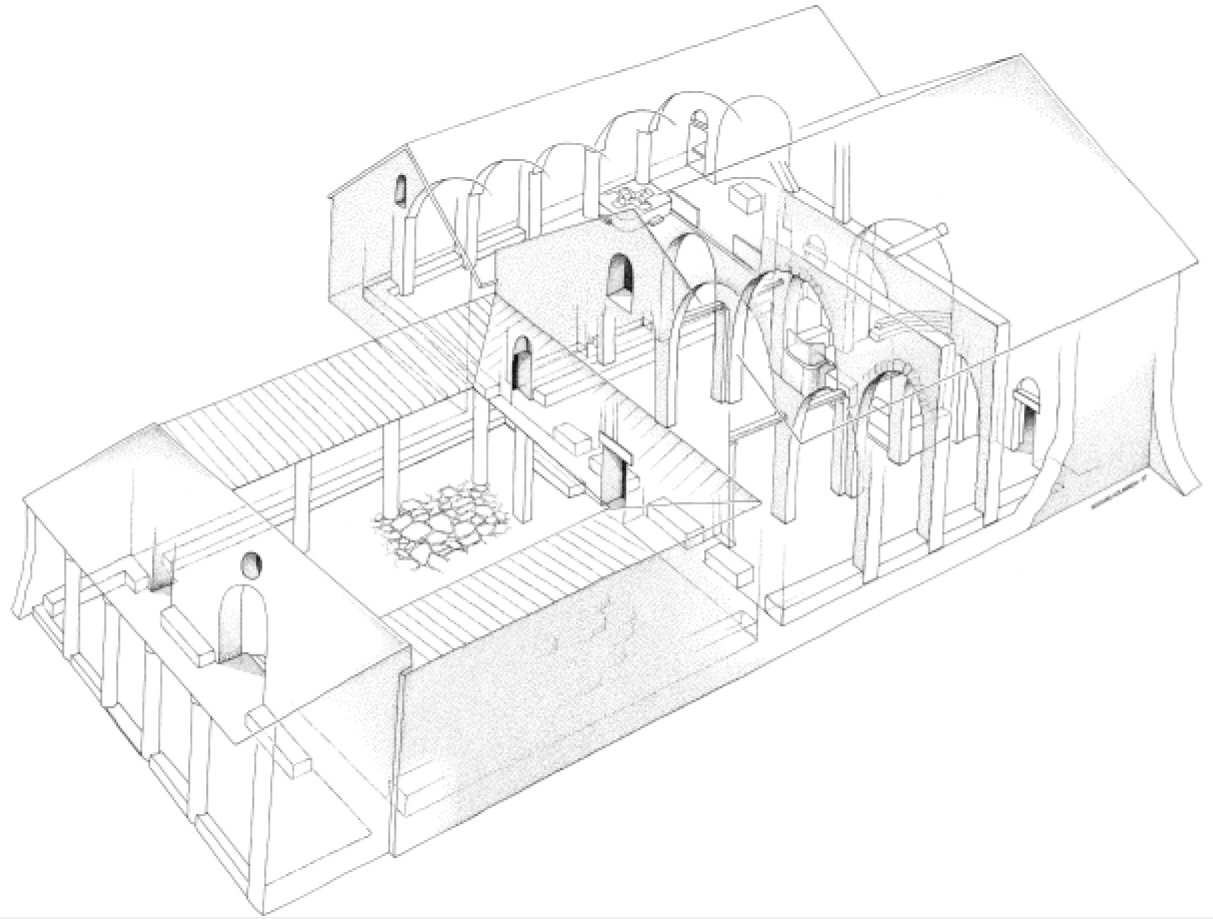

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 67 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phase 7 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 67

Fig. 67

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phase 7.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 81 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 9 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 81 Chapter 6

Fig. 81 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 9.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 88 - Reconstruction of the

appearance of the church and the chapel in Phase 9 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 88

Fig. 88

Tentative reconstruction of the appearance of the church and the chapel in Phase 9.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 107 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 11 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 107 Chapter 6

Fig. 107 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 11.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of

Church and Chapel with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Labeled Plan of

Church and Chapel - modified from Fiema (2008)

Plan of the church and the chapel with parts of the structure labeled in red

Plan of the church and the chapel with parts of the structure labeled in red

modified by JW from Fig. 1 of Fiema (2008)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of

Church and Chapel with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Labeled Plan of

Church and Chapel - modified from Fiema (2008)

Plan of the church and the chapel with parts of the structure labeled in red

Plan of the church and the chapel with parts of the structure labeled in red

modified by JW from Fig. 1 of Fiema (2008)

- Stone by stone plan of

church and chapel from Fiema and Frosen (2008)

- Fig. 17 - Stone by stone

plan of the eastern half of the church from Mikkola et. al. (2008)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

The plan of the eastern half of the church

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 33 - Stone by stone

plan of the northwestern part of the church from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 33

Fig. 33

The plan of the northwestern part of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 36 - Stone by stone

plan of the southwestern part of the church from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 36

Fig. 36

The plan of the southwestern part of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 50 - Stone by stone

plan of the narthex from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Plan of the narthrex

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 25 - Stone by stone

plan of the eastern part of the chapel from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

The plan of the eastern part of the chapel.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 29 - Stone by stone

plan of the western part of the chapel from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 29

Fig. 29

The plan of the western part of the chapel.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Stone by stone plan of

church and chapel from Fiema and Frosen (2008)

- Fig. 33 - Stone by stone

plan of the northwestern part of the church from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 33

Fig. 33

The plan of the northwestern part of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 36 - Stone by stone

plan of the southwestern part of the church from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 36

Fig. 36

The plan of the southwestern part of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 50 - Stone by stone

plan of the narthex from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Plan of the narthrex

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 25 - Stone by stone

plan of the eastern part of the chapel from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

The plan of the eastern part of the chapel.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 29 - Stone by stone

plan of the western part of the chapel from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 29

Fig. 29

The plan of the western part of the chapel.

Mikkola et al (2008)

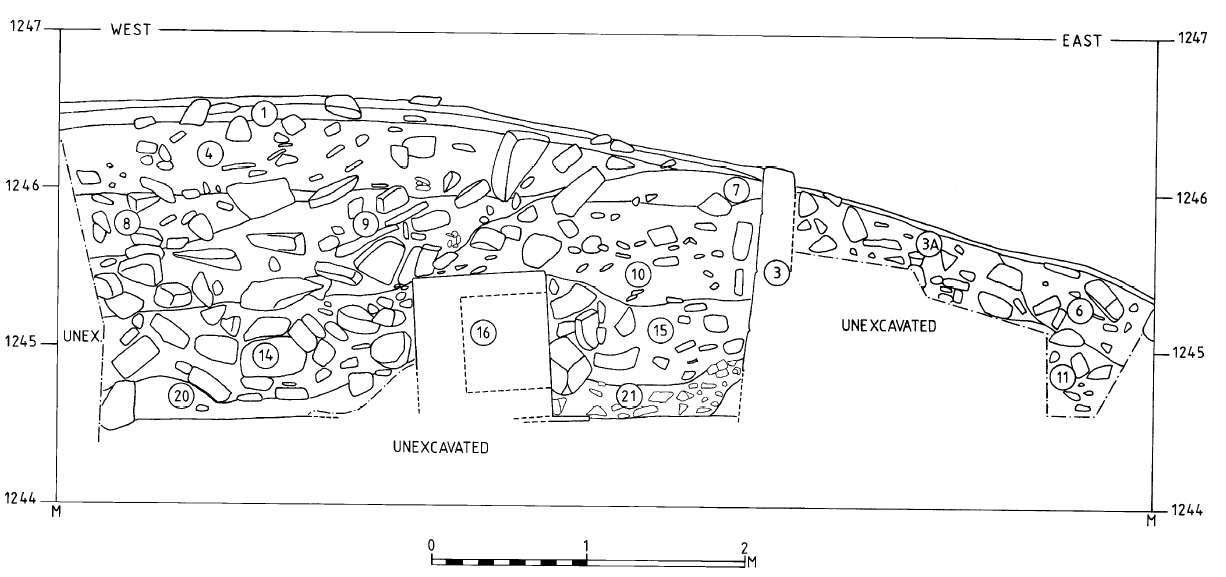

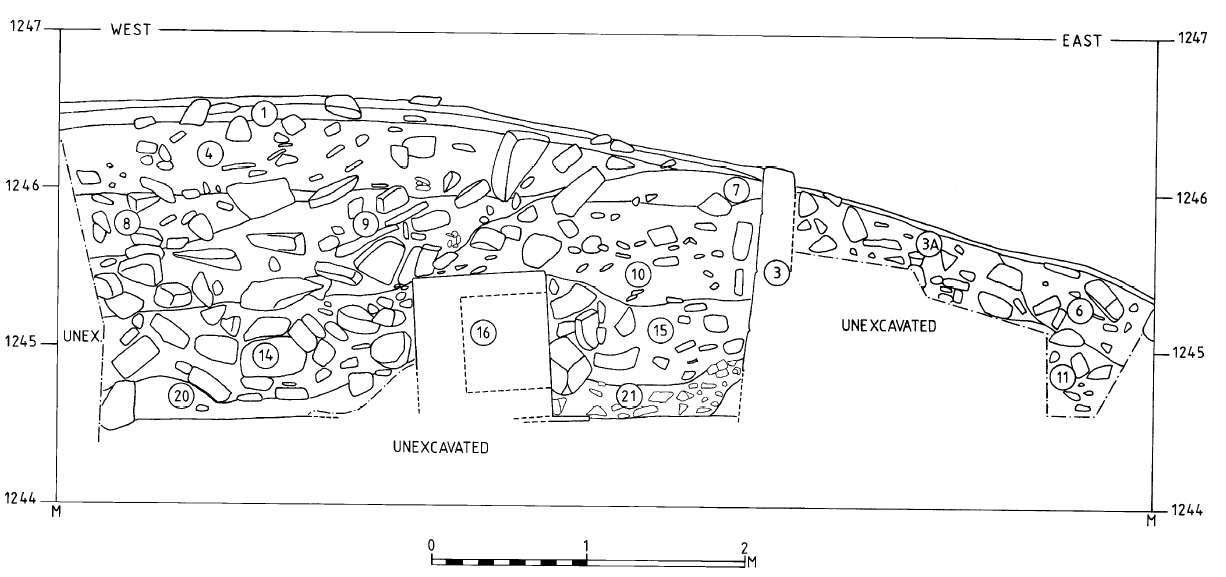

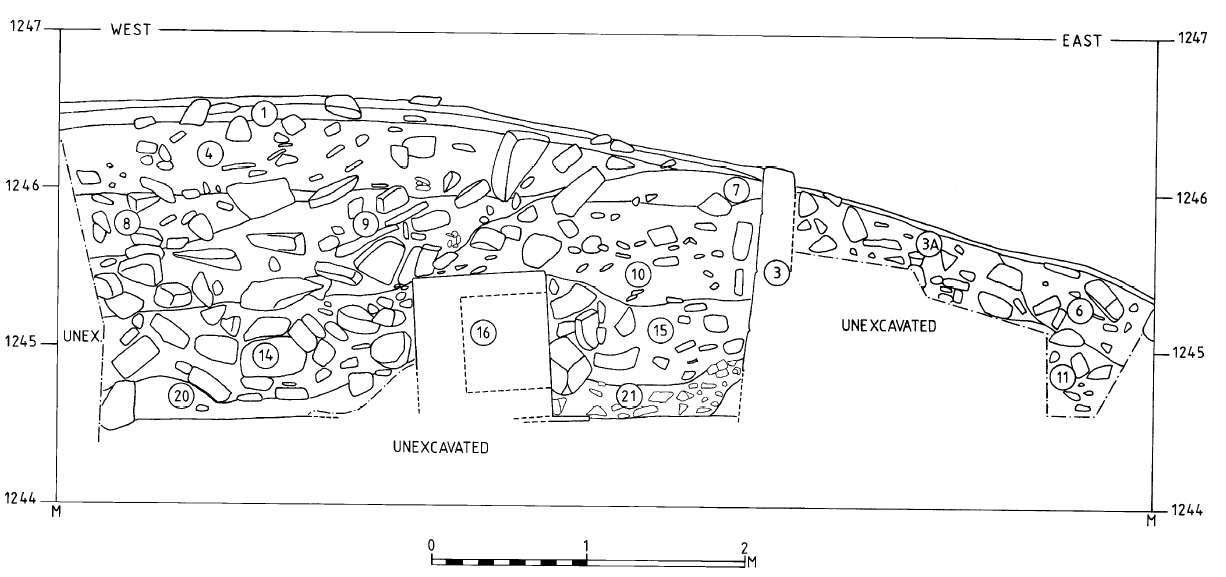

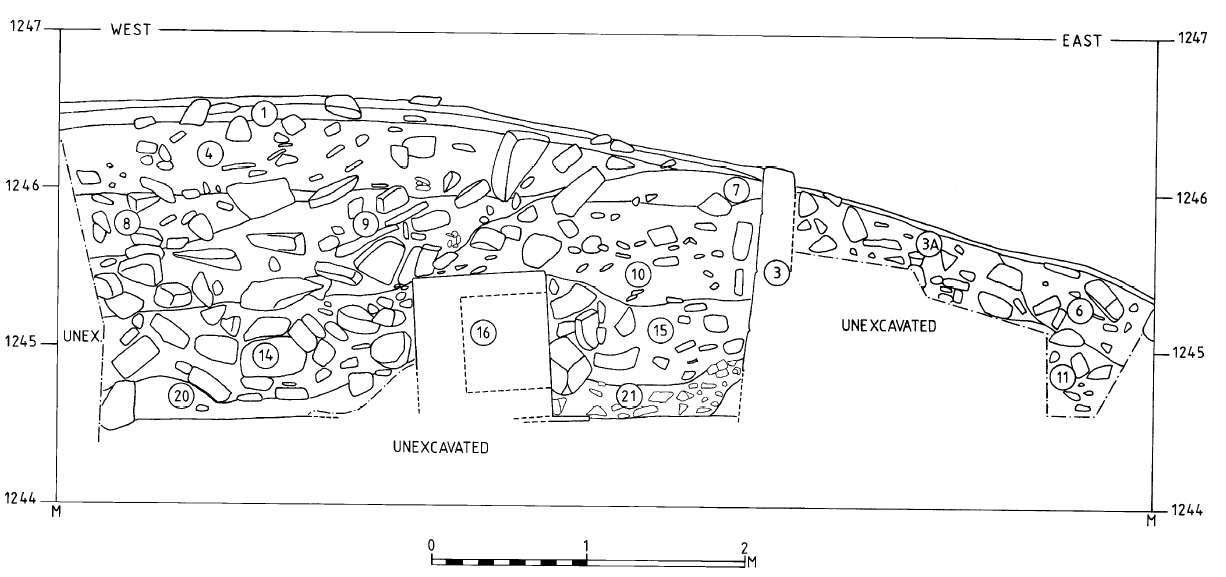

- Fig. 4 - Trench E, western baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Trench E, western baulk

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 13 - Trench F, eastern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

Trench F, eastern baulk. Also showing the façade wall (W. AA, loci F.30 and 31) of the southern pastophorion, the pilaster F.32 of the southern colonnade, and the stone tumbles/soil layers inside the apse.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 19 - Trench E, southern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

Trench E, southern baulk. Showing the profile of the synthronon, the layers of collapse inside the apse and the deposit of mosaic fragments in Phase 13.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 46 - Trench L, northern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Trench L, northern baulk. The stratigraphy of the atrium showing the pavement, location of columns, and subsequent stone collapses.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 58 - Trench B, northern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 58

Fig. 58

Trench B, northern baulk. Featuring the stratigraphy in the atrium showing the pavement, the water channel. locus B.12, the buttress, locus B.02 from Phase 9, and the stone tumbles.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 76 - Trench C, northern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 76

Fig. 76

Trench C, northern baulk. The stratigraphy inside the apse and the bema of the chapel, featuring the masonry altar pedestal, locus C.16, and the layers of stone tumble.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 94 - Trench F, western baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 94

Fig. 94

Trench F, western baulk, featuring the bench, locus F.15, and the stone and soil deposits inside the southern aisle and the nave.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 114 - Trench F, northern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 114

Fig. 114

Trench F, northern baulk, featuring stone tumbles and soil deposits mentioned in the text.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 117 - Trench G, eastern baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 117

Fig. 117

Trench G, eastern baulk, featuring the stone tumbles mentioned in the text.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 3 - The Western Building

[thought to be the core of Nabatean sacral complex] with the bedrock fissure from Fiema (2012)

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - tilt measures ~7 degrees - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Tilted And Collapsed Arches photo by JW

- Tilted And Collapsed Arches digital theodolite photo by JW

- Collapsed Arches photo by JW

- Damaged And Filled In Arch photo by JW

- Blocked Doorway photo by JW

- Cracked Flagstone Floor photo by JW

- Stone Cupboard photo by JW

- Fig. 3 - The Western Building

[thought to be the core of Nabatean sacral complex] with the bedrock fissure from Fiema (2012)

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Wall J tilted southward in Phase 8 Earthquake - tilt measures ~7 degrees - digital theodolite photo by JW

- Tilted And Collapsed Arches photo by JW

- Tilted And Collapsed Arches digital theodolite photo by JW

- Collapsed Arches photo by JW

- Damaged And Filled In Arch photo by JW

- Blocked Doorway photo by JW

- Cracked Flagstone Floor photo by JW

- Stone Cupboard photo by JW

- from Mikkola et al (2008) in Chapter 6 of Petra - the mountain of Aaron : the Finnish archaeological project in Jordan.

1 For the criteria in recognition of a phase, see Chapter 3. The site formation process and the impact of natural phenomena, such as earthquakes, are discussed in Chapter 5

Concordance between the phasing of the Church and Chapel of the site

Concordance between the phasing of the Church and Chapel of the siteFiema and Frosen (2008 Appendix C)

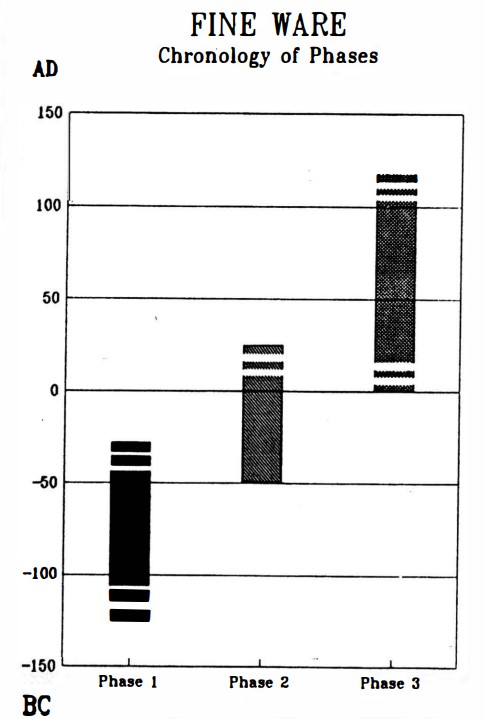

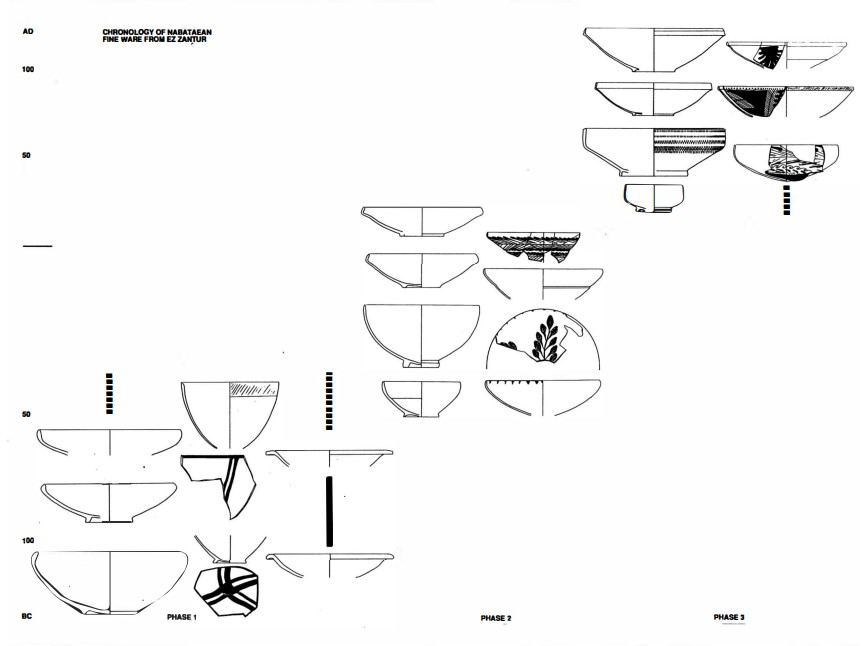

- from Schmid (1995)

- Ez-Zantur Excavations utilized Nabatean fineware chronology of Schmid (2000) - which I don't currently have access to

- reference was made to Schmid's Nabatean fineware chronology in section(s) of the excavation reports dealing with pre-monastic phasing at Jabal Harun

Left

Chronology of Nabatean finewares

Right

Typology and chronology of the Nabataean fine ware

Both from Schmid (1995)

The structures and soundings made in Room 25 provided evidence of an early destruction and the following period of decay that apparently preceded the building of the monastery. A dramatic piece of evidence the shattered second story floor (O.41), some remains of which are still protruding from Wall G (e.g. Fig. 8). The core of Western Building must have partially collapsed and the second story was entirely destroyed, as remains of its floor were incorporated in the Byzantine structures. The superstructure and arches of the southern cistern (Room 36) may also have collapsed. All of this may well be related to the famous earthquake of May 19, 363 CE46 [JW: The southern Cyril Quake struck on the night of May 18, 363 CE] which is archaeologically well-evidenced by excavations in central Petra at sites such the Temple of Winged lions, the Colonnaded Street, the so-called Great Temple, and the residential complex at es-Zantur47. According to a contemporary literary source (Bishop, Cyril of Jerusalem), the earthquake destroyed

more than half of Petra48. Given the fact that the earthquake severely damaged a host of other cities as well, it stems very unlikely that Jabal Harun, located less than five kilometers from downtown Petra, was left unharmed.

JW: I don't have access yet to the full appendix so I could not record the footnotes. What follows are links to pages in this catalog

discussing the specific subjects footnoted.

46 363 CE Cyril Quakes

47 Petra - Ez-Zantur

48 ?

- Fig. 2 - Cistern interior

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The interior of the cistern at the foot of the summit of Jabal Harun.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 3 - Re-used building element

from pre-monastic times in Wall Y from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

An architectural element in Wall Y

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 4 - Trench E, western baulk

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Trench E, western baulk

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 5 - Grey tesserae found

in Trench J from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Large quantities of grey tesserae found in Trench J.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 6 - Water channels

around the cistern from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Four water channels in the area of the cistern. The settling tank is visible in the center.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 7 - Interior of the settling tank

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Interior of the settling tank featuring the hydraulic mortar in the center.

Mikkola et al (2008)

This phase includes all evidence and elements that pre-date the construction of the church and the chapel in the central space of the monastic complex. Generally, the pre-ecclesiastical occupation of the high plateau is well attested. Within the perimeter of the later monastery, the presence of the so-called Western Building is particularly important. It is a building complex featuring very different construction materials and techniques from all the other buildings at the site, including a different kind of mortar and well-dressed ashlars that are two or three times larger than the average size of building stones on the site. That the Western Building is not contemporary with the church is also suggested by fact that its orientation differs markedly from the east-west -orientation of the rest of the complex. Apparently, the Western Building was built as a part of a Nabataean architectural complex at the site,4 but was incorporated into the monastery once it was established.

That the Western Building and the associated, pre-ecclesiastical structures are of a Nabataean date, is also indicated by the stratified finds of Nabataean pottery there and everywhere at the site as well as on the surrounding plateau. Additional evidence of sedentary human presence on plateau is provided by the existence of a large cistern (size ca. 18.0 x 5.0 m), still in use, at the foot of the summit of Jabal Harun, ca. 200 m ENE of the monastery (Fig. 2). The cistern is partially hewn into the bedrock, but has masonry-built walls and is spanned by fifteen arches built in typical Nabataean fashion.5 Similarly, the evidence for a substantial water management system built around the mountain suggests a Nabataean presence. As Jabal Harun is the highest mountain in the vicinity of the city of Petra, with a commanding view over the Wadi ‘Araba rift valley, it seems only natural for the Nabataeans to have established a presence on the mountain.

Only a few features in the area of the church can be securely associated with this early phase. These mainly consist of reused stone blocks that seem to derive from buildings other than those extant at the site. No structures in the area of the church or the chapel can be assigned to a pre-monastic phase with certainty. This is partly due to the fact that archaeological exposure was limited to a relatively small area, because the sandstone bedrock was encountered close to the floor levels in many of the trenches excavated so far. Therefore, it seems possible that if the buildings predating the church and the chapel had masonry-built foundations, these had been removed in the course of the subsequent building activities. The only surviving elements are those that have been carved into the bedrock.

4 The second volume of the FJHP series will fully describe the

Nabataean constructions at the site. Significant discoveries related to the Nabataean phases at the site were made only during

the 2007 fieldwork season.

5 For descriptions, see Wiegand 1920: 141; Lindner 2003: 187,

Abb. 22. Compare also with Dar al-Birka (Site Wadi Musa 18A)

– an arched Nabataean chamber built at a spring in the Wadi

Musa area (‘Amr et al. 1998: 522).

The evidence for the Phase 1 occupation in the area of the church mostly consists of a few building blocks in reused positions, as well as early pottery and glass finds from the strata in soundings made under the floor of the church. The building blocks that do not appear to belong to the church may originate from a building that predates the construction of the Byzantine basilica. These include a decorated architectural stone (fragment of a cornice?) used as an ashlar in Wall Y (Fig. 3) and a limestone fragment of a cornice (0.63 x 0.45 x 0.25 m). The latter has been reused as a building stone in a pilaster (locus U.28) located between the nave and the northern aisle. A similar fragment, ca. 0.60 m wide and 0.34 m long, was used in the southern section of the masonry-built chancel screen (locus F.05h) of Phase 7. This pre-Byzantine, apparently monumental, building appears to have included columns, for some fragments of column drums have been incorporated in the Phase 2 bench (locus B.10) along Wall J, still visible in the area of the later Atrium. Furthermore, a column base (part of locus V.24) carved into the bedrock and probably also of this phase, was found west of the chapel.

Soundings made under the floor of the church yielded some material that predates the construction of the church, including fragments of pottery, bone and glass. Glass fragments found in a sounding (loci E.26a-c) made in the Apse of the church can be dated to the first half of the 5th century at the latest (Fig. 4, also Fig. 19).6 Similarly, a few soundings (including locus B.25e) made under the floor of the church yielded pottery dated exclusively to the Nabataean and Roman periods. This pottery is no doubt related to the pre-monastic presence on the mountain, and was deposited in the area of the church when foundations for the building were laid with soil gathered from the plateau.

6 All dates in A.D. unless otherwise indicated.

The evidence for pre-Byzantine activity in the area of the chapel is similarly sketchy, consisting of reused building blocks and Nabataean pottery found in soundings. The lowermost layer (locus C.24e, a buildup for the original chapel floor; elevation 44.12 m7) in a sounding made in the sanctuary of the chapel contained Nabataean fine ware and common ware, datable to the 2nd-4th centuries. A reused fragment of a limestone cornice (0.55 x 0.30 x 0.15 m) in front of the southern cupboard (locus C.30) is evidently of pre-Byzantine date and it originates from some unknown, yet monumental, structure. A small but interesting element, possibly also relating to such a building, is the piece of opus sectile floor, reused in the Phase 2 step (locus Y.32) in the doorway between the church and the chapel. The outer wall (Wall V) of the building complex also features rather unusual blocks with regard to their size, being much larger than the average blocks used in construction of the church.8 Similar, massive ashlars have been used in the Western Building, and thus appear to relate to some pre-Byzantine building activity on the plateau.

7 Whenever the height of an object or feature is provided in absolute terms, the first two digits are omitted. Thus an object located at 1244.12 m above sea level will be described here as

being at 44.12 m asl, as all tacheometer measurements at the

site are within the range of 1200-1300 m asl.

8 An example is a block in locus Y.12 measuring 1.65 x 0.35 x

0.20 m

Some indications of possible pre-Byzantine activity were also discovered in the area west of the chapel. In particular, the sandstone bedrock there preserves traces of what may well have been a monumental building predating the structures visible now. A column base (part of locus V.24, diameter 0.58 m, height 0.04 m) hewn out of bedrock was encountered west of Wall OO. In theory, it might also have been a feature of the Phase 2 chapel, and if so, associated with a hypothetical doorway in the original western wall of the chapel (infra). There is little evidence for such a doorway, however, and the location of the Phase 2 baptismal font seems incompatible with a doorway. Therefore, it seems more likely that the column base precedes the church and the chapel altogether. Perhaps associated with the column base, the bedrock in the surrounding area had been levelled (loci V.22, V.23).

A number of finds probably deriving from Phase 1 buildings were found in the excavated soil layers. These consist mainly of building blocks reused in the construction of the upper courses of the walls, and of fragments of Nabataean pottery from the soil used as fill for the walls. A few fragments of Nabataean-type stucco decoration were also found in the soil. These may originate from the Western Building, where traces of similar stucco have been found.

Large tesserae (size ca. 0.03 x 0.03 x 0.03 m), made of light grey or bluish limestone (Fig. 5), form an intriguing and problematic group of finds, possibly associated with this phase. The tesserae were found either single or still forming small mosaic chunks. However, even though tens of thousands of such tesserae have been found practically everywhere at the site, the location of a mosaic floor(s) from which they might originate remains unknown. One possibility is that a Phase 1 building had a floor made of such tesserae. However, large limestone tesserae have been used in later phases as well, as is evidenced, e.g., by the repairs made in the Narthex mosaic.9

9 For the description of repairs to the mosaic, see Chapter 9

The use of the large cistern (size ca. 6.00 x 1.00 m) in the central courtyard evidently predates the construction of the church and the chapel. The cistern remains unexcavated, but is apparently partially formed by a natural cavity in the bedrock that had been modified and possibly expanded. Its northwestern edges are eroded and rounded, but the southeastern edge is quite well preserved. Inside the cistern, there appears to be a small subterranean tunnel-like trough entering the cistern from its northeastern end. The clear evidence for the use of the cistern is, however, the presence of four rock-cut water channels on its eastern side (Fig. 6). The channels emerge from under the northern part of the entrance porch to the church complex, and all but the southernmost channel probably predate the construction of the church.10 The two northernmost channels – locus H.34 (0.28 m wide, 0.18 deep), and locus H.35 (0.25 wide, 0.10 m deep) – resemble each other in both shape and size. They run to the northeastern end of the cistern, nearly joining each other close to the edge of the cistern, and both of them end in a flat spout. The third channel from the north, locus H.33 (0.25 m wide, 0.20 m deep), however, differs from the others in that it ends in the finely constructed settling tank (locus H.33b), carved into the bedrock close to the eastern edge of the cistern. The tank is a round (diameter 1.00 m), barrel-shaped space with a flat bottom. The interior of the structure is plastered with typical Nabataean hydraulic mortar (Fig. 7).11 A good parallel for this installation is the settling tank in the Atrium of the Petra church (Phase V), although that was built in the Byzantine period.12

As all the channels approach the cistern from the direction of the church, and as they emerge from under the mosaic floor, it is not possible to know for certain where they come from or with what structure or specific phase they are associated. It is clear, however, that rainwater was collected in the area east of the cistern over a long period of time, and the number of channels running from that direction suggests that the water management system has been modified and/or expanded several times.

10 The southernmost channel is associated with the raised floor of

the Atrium and it belongs to Phase 5.

11 Ueli Bellwald, 2000, personal communication

12 Fiema 2001: 72-73, with references to examples of parallel installations found elsewhere.

The absolute dating of the only certain pre-Byzantine structure at the site, i.e., the Western Building, has yet to be established with precision, but the method of construction strongly suggests a Nabataean date. Combined with the presence of a characteristically Nabataean cistern at the foot of the summit of Jabal Harun, these structures provide evidence for a significant Nabataean presence there. This presence may be as early as the 3rd century B.C., as suggested by a 14C date acquired from a ceramic lamp.13 But this date must be treated with extreme caution since such an early date is so far not confirmed by any other datable elements of material culture found at Jabal Harun.

Specifically in the area of the church and the chapel, further evidence of the early sedentary occupation is offered by the abundant finds of Nabataean fine ware pottery and reused pre-Byzantine architectural elements. The latter can be generally dated to the 1st century B.C./A.D. As for the painted Nabataean fine ware, the finds from the excavation seasons 1998-2001 have been fully analyzed and thus a representative sample achieved.14 The clear majority of altogether 685 painted sherds can be assigned to Phase 3 in Schmid’s typology (20 - early 2nd century).15 Particularly prominently represented were subphases 3b (70/80 - 100) comprising 63% of the sherds, and 3a (20-70/80), to which 24% of the sherds could be assigned. Individual sherds representing phases 2c (1-20) and 4 (later 2nd-3rd centuries) were also found.

As for common ware pottery found in some loci in the area of the chapel that might be associated with the pre-monastic occupation, these include types characteristic of the 4th and early 5th centuries and no later material. More specific information is provided by the glass finds. Glass lamps fragments found in the foundation layers of the Apse (loci E.26a-c) belong to the common glass types of the first half of the 5th century in Petra. This indicates that the church was preceded by an unknown building that was lit with glass lamps and was still occupied in the 5th century. A corroded Byzantine coin (Reg. no. 155), probably from the first half of the 5th century, found in locus E.26b, seems to confirm the dating suggested by the glass finds.16 All these finds offer a good terminus post quem for the construction of the basilica in Phase 2.

Finally, a fragment of an unidentified mammalian bone found in the foundation layers (locus E.26c) of the Apse of the church was dated to 80-220 cal. A.D. (1865 ± 35 BP, Hela-1061). This result indicates that mammalian bones were already scattered around the plateau centuries before the construction of the church. When the church was constructed, these bones, contained in the soil from the plateau, were redeposited as a part of the foundation layer of the Apse.

All these finds suggest that the initial phase of active Nabataean use of the plateau began relatively early and it may mirror parallel development at the site of Petra. Whether or not the occupation of the plateau in the area of the later church and the chapel continued without a break until the construction of the monastic site is unknown. The 363 earthquake which is both historically and archaeologically evidenced at Petra may have caused a destruction and thus a temporary disruption of occupation at Jabal Harun as well.17 However, the ceramic and glass finds indicate that occupation would presumably have resumed in the 5th century.

Based on finds of pottery, glass and coins, Phase 1 can thus be dated approximately between the 1st (3rd ?) century B.C. and the mid-to later 5th century A.D., with the most active period of use beginning sometime in the early 1st century A.D. The mid-to later 5th century date for the end of Phase 1 also coincides well with the postulated construction date of the church and the chapel in Phase 2.

13 An AMS-dating (Hela-968) was acquired from soot in the nozzle of a ceramic lamp found in the lowest stratum (locus O.40)

in the northern room of the Western Building. The date of 390-

200 cal. B.C. (2225 ± 75 BP) is surprisingly early for Jabal

Harun, and it does not provide a dating (apart from a terminus

post quem) for the building itself. The lamp may have been deposited as a part of soil gathered from the plateau in order to lay

the foundations for the building. All radiocarbon datings in

this text have been calibrated using the OxCal v. 3.10 program,

which employs atmospheric data published by Reimer et al.

2004. The calibrated dates are reported in “one sigma” or 68.2%

probablility.

14 Silvonen 2003.

15 Schmid 2000: 147-152, and Fig. 98.

16 We are grateful to Daniel Keller for the initial assessment of the

coin finds from the church and the chapel. The full presentation of the numismatic material will be included in Volume II.

Notably, a Nabataean coin (Reg. no.255) found inside the

“tomb” (locus M.33b) in the southern pastophorion of the

church can be dated to the 1st century. This find must be similarly related to the pre-monastic activities on the plateau, but

has been redeposited during the construction of the basilica.

17 For the impact of that earthquake on Petra, see Russell 1980,

Hammond 1980, and Fiema 2001: 18 (in the area of the Petra

church) and 2002.

Volume II of the Mountain of Aaron series completes the final excavation reports of the Finnish Jabal Harun Project after 11 seasons of fieldwork on Jabal Harun (the Mountain of Aaron) in southern Jordan between 1997 and 2013. Volume II, which includes documentation on the Nabataean sanctuary and the Byzantine monastery, following upon vol. I on the Byzantine church and chapel, published in 2008, and vol. III, the archaeological survey of the environs published in 2013, culminates one of the best researched and published sites in the region of Petra. The Finnish team worked on this isolated desert mountaintop in conditions reminiscent of archaeological expeditions of the early 20th century. Their determination not only to carry out the difficult work but to publish three comprehensive volumes in such a short space of time is extraordinary.

The site is located c. 5 km southwest of the Nabataean and Roman city of Petra. It lies on a plateau 1245 m above sea level next to the upper peak of Jabal Harun which, at 1327 m asl, towers above the Wadi Arabah and Petra, making it one of the most prominent features in the region. An Islamic shrine (weli) housing a sarcophagus traditionally claimed by Muslims, Christians and Jews to be that of the Biblical personage of Aaron (Harun) stands on the upper peak. The mountain has been a site of pilgrimage for all three faiths since Roman times. In the Byzantine period (5th–7th c.), a monastery was established on the plateau, 100 m beneath the upper peak, to facilitate Christian pilgrimage and worship on the mountain. The initial goal of the team was the excavation and documentation of the Byzantine monastery complex (46.7 × 62.9 m), but the volume under review also presents evidence for the presence of a Nabataean shrine (the western building), some of the architecture of which was incorporated into the later monastery. This volume presents a chronology of the site that spans nearly 1000 years, between the 1st and the 9th/10th c. A.D. or later (p. 8).

Volume II contains six sections and no fewer than twenty-three chapters, as well as six appendices and a DVD offering a virtual tour and model of the site, all prepared and written by no fewer than three primary authors (Fiema, Frösén and Holappa) and thirty contributors. Section 1 includes chapter 1 (Fiema), a summary of the project, its goals and methodology, and a revised, updated description of the excavated areas. Section 2 contains three chapters covering the excavation of the three principal areas of the complex: the western building area (chapter 2, A. Lahelma, J. Sipilä and Fiema), the northern court area (chapter 3, K. Juntunen), and the southern court area (chapter 4, M. Holappa and Fiema). Each chapter provides detailed textual and photographic documentation together with well-executed plans and section drawings. Section 3 contains six chapters on the pottery evidence of the Roman and Byzantine periods, including deposits in the monastic complex (Y. Gerber), and of the Islamic period (M. Sinibaldi), a technological study of the pottery and vessel sources and pottery exchange (E. Holmqvist), the pottery lamps with their chemical composition (Holmqvist), glass vessels (D. Keller and J. Lindblom, with an appendix on the chemical glass types by S. Grieff), and mortars and plaster (C. Danielli, with appendices on mortar samples, binding mixtures, and the dating and characterization of two samples). Section 3 continues with a finds catalogue (M. Whiting), stone furnishings and architectural decoration (A. Lehtinen), stone vessels, jewellery and small objects (Whiting), basalt millstones (Fiema), Greek inscriptions (Frösén and Fiema), the numismatic evidence (J. M. C. Bowsher), the types of crosses found at the site (B. Pitarakis), metal spatulas (A. Fröhlich), and the archaeozoology (J. Studer), with a chapter on macrofossil analysis and the evidence for dietary and environmental conditions (T. Tenhunen) and one on the identification of wood samples (Tenhunen and P. Harju). Section 4 focuses on the virtual and 3D modelling (A. Annila, J. Alander, C. Kanellopoulos), with a proposal for shelter for the site (V. Putkonen), which has been covered in the meantime for its protection. In Section 5, thematic studies include a critical review of the evidence for worship of the Great Goddess at Petra (R. Wenning) and an overview of a millennium of history at the site (Fiema). The last section (6) collects appendices that provide valuable documentation of the site’s walls, architecture and phases, and lists of authors and participants. The volume concludes with forty-two color photographs and a DVD with a virtual tour of the site (Kanellopoulos and P. Konstantopoulos) and a virtual model of the site (Annila and Alander).

The final publication of the excavations reveals a phase (I) that the authors suggest was a Nabataean shrine founded in the 1st century A.D. By their own admission (25), the dating is based on circumstantial evidence, due to a lack of datable sealed contexts. The largest amount of Nabataean painted pottery discovered in mixed contexts dates to the second half of the 1st century A.D. If one considers the isolation of the site, the proposed date for this phase is perfectly acceptable. For unexplained reasons, the Nabataean pottery (or indeed any of the pottery of the pre-monastic phases) is not presented in the ceramic report in chapter 5; the reader is expected to be familiar with the ceramic forms and chronology proposed by the Swiss-Liechtenstein excavations in Zantur. A related issue is the interesting, yet underreported, note (25) of activity on the mountain in the 5th century B.C., with Iron Age pottery sherds. The presence of sherds of the Late Iron Age in the immediate region, and particularly on high plateaux difficult of access, is a widespread phenomenon, and it would be surprising if such sherds were not detected on Jabal Harun. According to the excavators, the Phase I shrine was developed into a cultic complex in the late 1st century A.D. and following after the Roman annexation of 106 (Phases II and III). The earliest phase of the western building complex has a “core” area of two freestanding rooms with arches (25–26) and a large staircase along its south side, as well as a typical Nabataean rock-cut cistern (Room 36) (21–25). This “core” area was constructed in front of a natural fissure in the bedrock transformed into a cistern that was apparently the focal point of the cultic structure (24, fig. 12; Appendix 1). The sandstone ashlars used in the construction of the core building are noted for their nearly “megalithic” proportions (21, fig. 5). In Phase II, a room with benches, apparently a Nabataean triclinium (Room 27), was added to the core structure (28–29). In addition to the documentation of the western building, S. G. Schmid offers a detailed appendix dealing with the sacral architecture discovered there and bringing a wealth of experience and first-hand knowledge of Nabataean architecture from his years of work at Petra; his remarks on the connection between water and cultic activities throughout the Near East are of particular interest.

Fiema provides an important summary and interpretation of the Nabataean cultic center and its transition into a Christian site in chapt. 23. The eventual destruction of this area in the earthquake of 363, coupled with its re-use in the later Byzantine period, precludes the possibility of positively identifying the deity that may have been worshipped at the site. However, in a separate publication, Lahelma and Fiema suggested that the Isis shrine in Wadi Abu Olleqah that faces Jabal Harun, together with the ethnographic evidence of blood sacrifices at the foot of the mountain and outside the weli on the summit, in addition to the “Mother of Rain” pilgrimage to the mountain, all point to worship of a female deity, possibly that of al-Uzza/Isis. On this subject, R. Wenning offers a thoroughly interesting and valuable study of the great goddesses worshipped at Petra (chapt. 22).

In the later 5th c., a church and chapel were constructed east of the western building; shortly thereafter, the northern court area, described as a pilgrim hostel, was built north of those structures (85). The pilgrim hostel was made up of at least 17 rooms built around a central courtyard, making up nearly a quarter of the entire monastery complex (74–76; fig. 1). The imported finewares discovered in this area are attributed (557) to the presence of pilgrims staying in the hostel. The excavators posit (556–57) that the monastic community slept in dormitory rooms in the upper floors of the building and stored water in the pre-existing cisterns. The hostel was reportedly destroyed by earthquake and fire in Phase VIII (the mid- to later 6th c.), requiring its “massive” rebuilding, followed by continued use (90). The rebuilding resulted in the reduction of the size of the church (558). The hostel underwent further destructions and rebuilding, and its final occupation dates to the early to mid-8th c. (Phase XIII), based on the presence of early Abbasid pottery (105). The same pattern of destruction, rebuilding and re-occupation as late as the Abbasid period was observed in the excavation of the southern court area located south of the church (chapt. 4). Intriguingly, a Greek inscription found on a stone in the south wall of Room 18 (388) bears the names Obodianos and Panaolbios, names that appear in the carbonized papyri from the Petra Church in the period running from 537 to 593. At Jabal Harun, the inscription is dated (389) to either Phase VI or VII (mid-/late 5th to mid-/late 6th c.). An inscription discovered on a limestone slab in Room 28 bears the name of Nikephoros (390), another name found in the Petra papyri.

In its later phases, the continued function of the northern court area as a hostel is open to debate (110–11). M. Whiting provides a welcome study of monastery hostels in the Near East in her appendix to chapt. 3. This is an important aspect of Byzantine history and archaeology in the region in view of the importance of Christian pilgrimage and the substantial number of monastic facilities that continue to be discovered. She notes (111) that the pilgrim hostel at Jabal Harun is the most thoroughly excavated and published of the kind.

Much of the volume is devoted to study of the finds. The ceramics presented in chapt. 5 and its associated appendix mainly cover only the later periods. While the drawings of vessels are clear and well-executed, the organization is not easily navigated, forcing the reader continually to go back and check the dates of the many phases and the location of particular areas or trenches. This is somewhat alleviated by the discussions of ubiquitous ceramic types found at the site, although most comparisons are provided only in the appendix (176–201), a catalogue of the 380 vessels presented in this particular volume. Here it is apparent that a substantial number of comparisons refer to the pottery chapter in vol. I, while many other comparisons are noted from sites west of Transjordan, especially in the Negev (for the latter, it is preferable to refer to the general region as Cisjordan). A welcome inclusion is the ceramics of the later Islamic periods (M. Sinibaldi, chapt. 6). This is a topic that is quickly becoming prominent in research around Petra; it is important especially in view of the two-century-long Frankish occupation of Oultrejourdain (1099–1291) and the Middle and Late Islamic occupation of sites (including pockets of Christians) such as those in the Bayda area north of Petra or the garden triclinium in Wadi Farasa East (564). The pottery studies of chapts. 5 and 6 are complemented by scientific analyses of wares in chapts. 7 and 8. The study of the chemical composition of the lamps (chapt. 8) is a solid contribution to our understanding of these pieces which are frequently utilized for dating assemblages.

Chapter 9 deals with the evidence of glass vessels and particularly glass lamps discovered in the excavations; there is a thorough catalogue (Appendix 1) and a study of the chemical composition of the glass. The phasing in a well-excavated site such as this provides valuable data for the study of glass recipes, not generally available from many sites (320). An interesting note by D. Keller concerns the limited use of glass in the Nabataean and mid-Roman periods as compared to the mid-5th c. A.D. onwards (295). He notes that glass of the Umayyad period at the site is a more heterogeneous assemblage than in the Byzantine, with most comparisons made with Ramla. The glass of the Abbasid period has comparisons with sites as far away as Egypt, Mesopotamia and Iran (296). The absence of glass vessels from contexts later than the 9th c. is a good indication that the complex had gone out of use by that date.

The numismatic evidence mirrors much of that turning up on sites west of Transjordan. This includes the continued circulation of 4th- and early 5th-c. coins in the 5th and 6th c. as has been investigated by G. Bijovsky, noted here at Jabal Harun (398). One also notes the paucity of coins from the 7th c. and the absence of coins from the later periods (397). Bowsher suggests that this may be an indication of a general socio-economic decline at Petra and the increased isolation of the site following the Islamic conquest.

The archaeozoological and archaeobotanical chapters are both excellent studies, providing many important details regarding the assemblages. The data-sets are comprehensive, providing information, for example, on fish exploitation, with abundant remains of parrotfish from the Red Sea. Pig bones appeared mainly in the Late Byzantine period (Phases VI–VII), prior to the initial destruction of the monastery in Phase VIII (557). Cultivated plants include dates, figs, olives, grapes and almonds, and particularly legumes, wheat and barley (460–64), the last being present in all phases. The volume also contains detailed research on rarely studied topics such as the mortars and plasters at the site.

The continued occupation of Jabal Harun represents an interesting contrast to the city-centre of Petra, as noted by Fiema (561). He suggests that by the Umayyad period Petra was no longer an urban centre and that it had undergone a period of “ruralization” by the later 7th c. Although the material finds indicate that the monastery went out of use before the 10th c., Fiema points out (564) that historical sources of the Crusader and Ayyubid/Mamluk periods indicate that the site continued to attract pilgrims.

...

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Church and Chapel

with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Fig. 8 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 2.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 10 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phase 2.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 30 - Charcoal and molten glass

from the Phase 3 fire from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 30.

Fig. 30.

Locus V. 15 – the deposit of charcoal and molten glass.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 34 - Collapsed Column

found among Phase 13 stone tumble from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 34.

Fig. 34.

Locus T.14 — the collapsed column

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 44 - Repaired marble floor

in the nave of the church - from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 44.

Fig. 44.

The appearance of the marble floor in the nave of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Church and Chapel

with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Fig. 8 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

Fig. 8 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 2.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 10 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phase 2 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phase 2.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 30 - Charcoal and molten glass

from the Phase 3 fire from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 30.

Fig. 30.

Locus V. 15 – the desposit of charcoal and molten glass.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 34 - Collapsed Column

from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 34.

Fig. 34.

Locus T.14 — the collapsed column

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 44 - Repaired marble floor

in the nave of the church - from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 44.

Fig. 44.

The appearance of the marble floor in the nave of the church.

Mikkola et al (2008)

No clear trace of any of the roof supports related to this phase was found. However, it is postulated that in light of the width of the interior of the chapel – almost 6 m – one should envision the existence of transverse arches, rather than horizontal wooden cross-beams. Such arches probably sprung directly from Walls GG and H by means of arch-springers similar to those found in the pastophoria of the church. Alternatively, the arches might have been supported by pilasters, but no trace of such pilasters has been preserved. On top of the arches, a system of roof beams and trusses would have supported the actual roof. As in the church, glass lamps provided lighting, as is evidenced by lamp fragments found in a sounding made in the Bema (locus C.35a). Some of the lamp fragments found in a deposit (locus V.15) outside the western wall of the chapel, and resulting from the clearance after the destruction in Phase 3, may also derive from the chapel.

In spite of the fact that few roof tiles were found during the course of excavation, it is reasonable to assume that – like the early church – the roof of the early chapel was tiled. It is more difficult, however, to ascertain the form of the roof. As the church and the chapel shared the same E-W wall (Wall H), one could imagine that the chapel’s roof was slanted towards the north, basically following the incline of the roof over the northern aisle of the church. This proposition, however, faces several difficulties. First, such an arrangement would have deprived the northern aisle of the church of any window openings, thus the only means providing light to that space would have been through the hanging lamps. Secondly, the slanting roof of the chapel could have been much lower than the end of the slanting roof over the northern aisle, thus providing space for the windows in the upper part of Wall H. However, in such a case, the slanting incline of the chapel’s roof would end at an extremely low position at the point of junction with Wall GG, the northern wall of the chapel. Another possibility is the existence of a flat roof over the chapel in Phase 2. Although such a flat roof is postulated to have covered the church area in Phase 9, this solution for the chapel in Phase 2 does not seem likely.

The preferable solution to this issue is to envisage a pitched roof for the chapel in Phase 2 (and later). Such a roof would allow for the existence of windows in Wall H,86 and it would facilitate the draining of rainwater from the area of the chapel. As such, there would be two buildings – the church and the chapel – standing side by side and connected to each other, each with a pitched roof, the roof of the chapel being lower than that of the church. The evidence for such an arrangement is scant but perhaps it can be reinforced by some iconographic representations. Although the details are unclear and difficult to interpret, the mosaic in the church in Tayyibat al-Imam (northern Syria) portrays a large basilican church, which seems to have a small building with a pitched roof attached to its long side. In another example, two churches, one large and one small (a chapel?), but both with pitched roofs are represented on the mosaic in the Church of Bishop Sergius (6th century) in Umm ar-Rasas. However, the interpretation of the perspective convention used there is difficult; these edifices might or might not have been meant to be viewed as standing side by side.87

The pitched roof over the chapel, allowing for the collection of rainwater, would also find support in the existence of a late channel (locus V.04a) running west of the chapel. It seems to have collected water from the northern side of the chapel roof, suggesting that at least in Phase 9, the roof could not have been flat. Although highly hypothetical, it nonetheless offers a clue that a similar system of a water channel and a pitched roof may have already existed in Phase 2.

86 These either provided the light for the interior of the chapel or

the interior of the northern aisle of the church. The isometric

view presented here (Fig. 10) favors the former option. However, as the height of the church increased in Phase 4 (Fig. 37 ),

the windows in Wall H could provide light for the northern

aisle. At any rate, due to the lack of convincing evidence, the

issue remains unresolved.

87 Both examples are discussed by Duval 2003b: 243-245, fig. 17c

(two separate buildings or a five aisled basilica?) and 2003b:

272-274, fig. 27d.

This phase represents a catastrophic event that caused the first major destruction of the site. Judging by the totality of the damage, a major seismic event seems to be the most likely explanation for the destruction102. It appears that the seismic shock caused the collapse of the upper parts of walls, and the burning oil lamps, falling on the floor, caused the conflagration. The destruction was severe. In many parts of the church, the arches, clerestory walls, columns and upper parts of the walls collapsed. That the roof support system was severely damaged is indicated, among other ways, by the fact that it was completely rearranged in the following phase. The falling stones shattered the marble floor and the furnishings of the church and the chapel, and while the floor was haphazardly repaired in the following phase, much of the furnishings were apparently damaged beyond repair. This is evidenced by the numerous fragments of marble colonnettes, chancel screens, etc., found in reused positions in the structures of Phase 4.

The intensity of the event is also indicated by the evidence of repairs to the upper portions of the walls of the church and the chapel. The repaired walls of Phase 4 feature numerous fragments of marble slabs from the floor of Phase 2, now used as chinking stones. Various kinds of debris ended up in the fills of the walls, especially in Wall I which was constructed in Phase 4. In fact, a large portion of the finds of broken marble furnishing, pottery, glass, nails and roof tiles, found in the late layers of stone tumble, derive from the interior of the repaired walls and therefore predate Phase 3.

The totality of the destruction was ensured by a fire that raged in the buildings.103 The fire was hot enough to melt the glass lamps of the polycandela and leave marks of burning on much of the marble decoration of the church. A deposit (locus V.15) of charcoal and broken, partly melted, lamp fragments, probably associated with Phase 3, was found west of the chapel (Fig. 30). This locus seems to represent burned material cleared from the church and the chapel immediately after the fire and the earthquake. Several of the large iron nails – probably originally used in the structures of the roof – found during the excavations, similarly exhibit signs of exposure to intense heat.

The chapel was also heavily affected. This is indicated by the extent of the repairs made in Phase 4, particularly by the complete rearrangement of the roof supports. The system of pilasters now visible in the chapel is not original, as is evidenced by the presence of wall plaster behind the pilasters, the use of marble slab fragments as chinking stones (in loci Y17 and Y20), and the different construction techniques used. The Phase 4 columns of the chapel, moreover, seem to derive from the collapsed columns of Phase 2 structures, as some of the drums used in them are broken. The original western wall of the chapel also seems to have collapsed to the extent that it was deemed easier to build a new wall (Wall OO). Finally, parts of Wall H also appear to have been badly damaged, as its upper courses were rebuilt in the following phase, using large quantities of recycled material.

102 For the impact of earthquakes on the area of Petra, see Chapter 5

103 For the fire that destroyed the Petra church in Phase VIII, see

Fiema 2001: 91-94.

The destruction in Phase 3 was a momentous event. Therefore, its dating postulated here would equal the date for the end of Phase 2 and, simultaneously, the beginning of Phase 4. As stated in relation to the dating of Phase 2, glass finds, especially from the deposit of burned material west of the chapel (locus V.15), span the 5th to mid-6th centuries, providing an excellent terminus post quem for Phase 3. The lamps are notably the only relics from the excavations, in addition to broken marble pieces from the walls’ interiors that feature the impact of fire. As such, the only destruction episode in the history of the site, which features both structural collapse and fire, must represent the destruction of the Phase 2 occupation. Similarly, the datable ceramics described above as related to Phase 2 indicate the mid- to later 6th century for the end of Phase 2.

Fragments of charcoal scraped from inside some melted glass lamps were radiocarbon-dated (Hela-998). The result of 1440 ±35 B.P. or ca. 594-650 cal. A.D. is problematic, as it apparently contradicts the dating of Phase 3 suggested above. Datings of wood charcoal are generally considered notoriously unreliable because of the possibility of the “old wood” effect104 – making dates appear older than they should – but here, on the contrary, the result seems too late in date. This could be taken to indicate that the deposit of V.15 is, in fact, related to some later event (Phase 6?) rather than Phase 3, which would contradict the well-established glass chronology. However, the possibility of contamination is high – the charcoal in locus V.15 may have been mixed with the later material, either during excavation or already in antiquity.105 Given the fact that the glass lamps have been exposed to intense heat, and that Phase 3 appears to be the only phase with evidence for a fire that could have caused the melting, it seems probable that the lamps (and the charcoal inside them) should be associated with Phase 3.

At any rate, it is safe to postulate that the Phase 3 destruction took place around the mid- to-later 6th century. Again, no historically known human-induced destruction can be proposed here and the seismic event, as postulated above, appears a much more plausible explanation. The only historically documented seismic events of consequence, which affected the Near East in the mid-6th century, are the earthquakes of 551 and 559. The famous earthquake of July 9, 551 struck the areas of coastal Lebanon and Egypt, as well as Arabia, Syria and Palestine.106 It was often associated with the destruction of Petra, but no reliable archaeological evidence in the city can be marshalled to prove its impact.107 The earthquake on Good Friday, 559, affected the areas of Galilee, Palestine and Arabia,108 but again its possible impact on Petra is virtually unknown. Therefore, it must be assumed that the monastery fell victim to one of the less known, more localized but sufficiently destructive, seismic events, which might have had an epicenter in the Wadi ‘Araba area perhaps resulting from the aftershocks of the 551 or 559 earthquakes,.

104 E.g., Renfrew and Bahn 1991: 127.

105 A second attempt (Hela-1062) to obtain a radiocarbon-date for

locus V.15 – this time from bone finds associated with the layer

– proved to be equally problematic. The result – ca. 220-340

cal. A.D. (1765 ± 35 B.P.) – seems much too early for the deposit. Both results illustrate the problems associated with radiocarbon dates made from a material that is not well understood.

The unexpectedly early dating of the bones from V.15 may relate to the fact that bones associated with a pre-monastic occupation at Jabal Harun appear to have been scattered throughout the plateau, and may thus have been redeposited in various

later contexts. This is also indicated by the bones found in the

foundation deposits of Phase 2 (loci E.26a-c), described in relation to Phase 1.

106 Guidoboni et al. 1994: 332-336. See Chapter 5 for details

107 Russell 1985: 45, and Fiema 1991: 214-217. For the recent

reconsideration, see Fiema 2002: 234-235. There is also no indication of that destruction or its potential aftermath in the 6th

century Petra Papyri (Frösén 2001: 490).

108 Di Segni 1999: 154-155, note 32.

- Excerpted from from Mikkola et al (2008:103-117)

...The height of the columns [of the Church] can be estimated to have been at minimum 3.85 m, since both columns were found collapsed among the stone tumble of Phase 3 (Fig. 34).

...The apse of the church appears to have survived the events of Phase 3 comparatively well.

... It is impossible to assess the extent of the damage inflicted on the original marble furnishing of the bema [of the Church] in Phase 3. It must have been considerable, judging from the quantities of broken marble included as fill in both new walls (e.g., Wall I) and the old, reconstructed walls (e.g., Wall H). However, some elements must have survived either intact or in pieces, which could have been reused after necessary modifications.

... The destruction of the fine marble pavement [of the Church] was amongst the more permanent damage caused by the event of Phase 3. The rebuilding in Phase 4 took great effort, using all resources available, and evidently the community of Jabal Harun could not afford to fully replace the broken marble floor with a new pavement. Instead, the broken pavers were painstakingly pieced together, like a huge jigsaw puzzle. The area of the nave (e.g., in locus E24) presents good examples of this (Fig. 44).

... extensive damage suffered by the original western wall of the chapel. ...

Area West of the Chapel

Large quantities of debris, including charcoal, burnt tiles, glass and ceramic sherds broken and fire-damaged, pieces of marble and other stones, were found in the midden located outside the monastery enclosure, excavated in Trench R. Due to the uniformity of these deposits and the clear indication that they originated from a fire-related destruction, it is probable that these represent Phase 3 debris cleared out from the area of the church and the chapel at the beginning of Phase 4.

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Church and Chapel

with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Fig. 56 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 5.

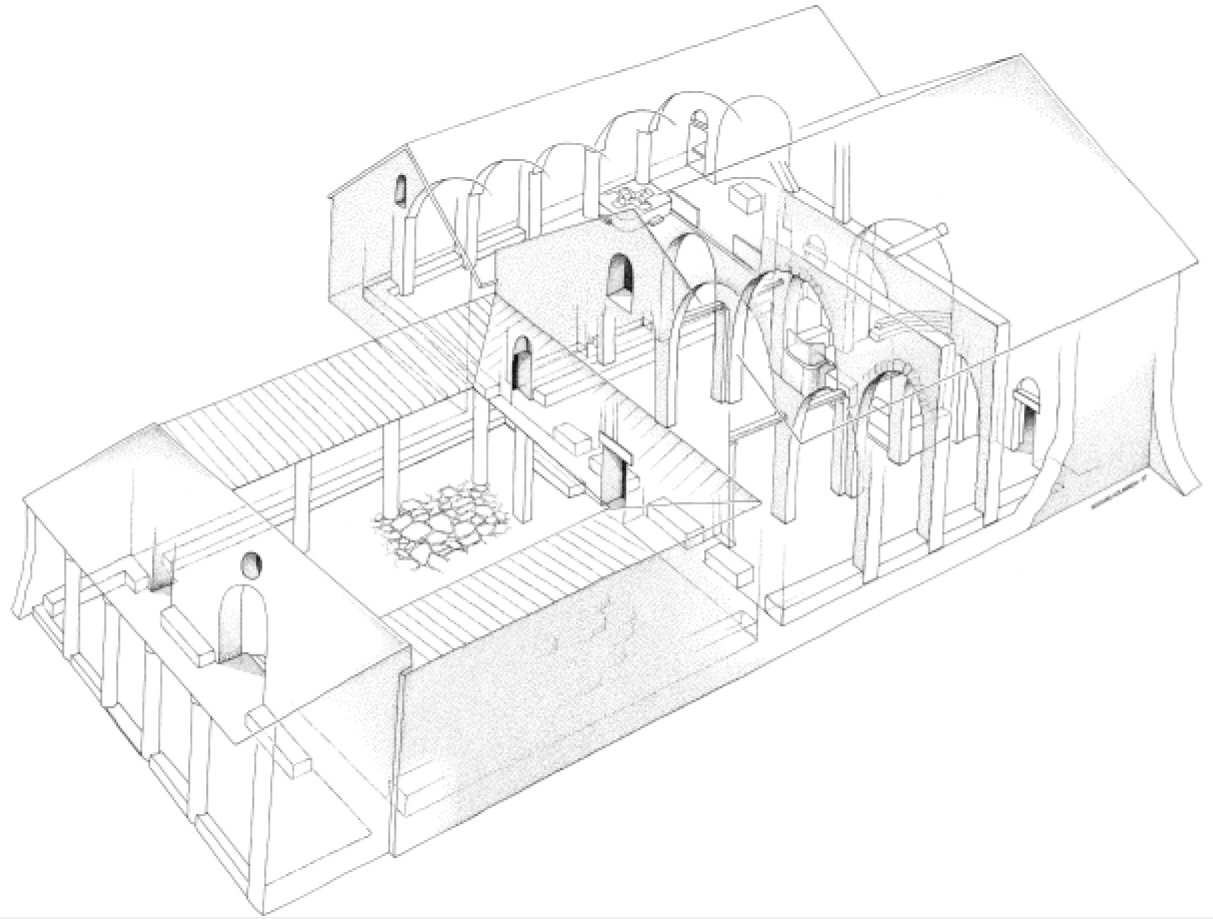

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 37 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 37

Fig. 37

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 5 - Iconoclastic damage

from Fiema (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Iconoclastic damage to the narthex mosaic

(by J. Vihonen)

Fiema (2013)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Church and Chapel

with all walls and trench locations marked from Fiema (2008)

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

Fig. 1 Chapter 5

The plan of the church and the chapel marking all walls and trench locations.

Fiema (2008) - Fig. 56 - Plan of Church and Chapel

in Phase 5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

Fig. 56 Chapter 6

The church and the chapel marking in Phase 5.

Mikkola et al (2008) - Fig. 37 - Isometric reconstruction

of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5 from Mikkola et al (2008)

Fig. 37

Fig. 37

Isometric reconstruction of the church and the chapel in Phases 4-5.

Mikkola et al (2008)

- Fig. 5 - Iconoclastic damage

from Fiema (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Iconoclastic damage to the narthex mosaic

(by J. Vihonen)

Fiema (2013)

The complete rearrangement of the roof support system is one of the major new features of Phase 4. The colonnades of Phase 2 were replaced with a single pair of columns in the middle of the shortened church, supporting two pairs of arches (length 3.80 m) running E-W.115 The arches would have consisted of approximately 20 voussoirs.116 The two columns (loci T.14 and U.25) were erected closer to the central axis of the church than those of Phase 2, making the nave of Phase 4 narrower (ca. 5.70 m) and the aisles wider (ca. 3.75 m) than in Phase 2. The columns were made of reused drums (diameter 0.55 m, height varying between ca. 0.25 and 0.50 m) of Phase 2 and were topped with Nabataean-style capitals. The height of the columns can be estimated to have been at minimum 3.85 m, since both columns were found collapsed among the stone tumble of Phase 13 (Fig. 34).

Supporting the long E-W -running arches at their extremities, two pairs of pilasters were built against the ends of Wall T (the Apse wall) and against Wall I. The pilasters were carefully constructed of well-shaped limestone ashlars and mortar, using the header-stretcher method. In the Apse, the southern pilaster (locus F.06), 0.58 m wide and 0.63 m deep, survives to a height of 1.71 metres and the northern one (locus U.08), 0.52 m wide and 0.73 m deep, remains 1.90 m high. The new pilasters created a narrow 0.05 to 0.10 m space between them and the arch buttresses of Phase 2, and these spaces were filled with small stones and mud mortar – loci F.06a and U.08a on the southern and northern sides, respectively (Fig. 35, see also Fig. 13). The corresponding pilasters, which abut Wall I, were equally well built, using good quality building material. The southern pilaster (locus T.12), 0.58 m wide and 0.74 m deep, surviving to a height of 1.73 m (Fig. 36), and the northern pilaster (locus G.05), 0.52 m wide, 0.75 m deep and 1.71 m high (Fig. 33), show a quality workmanship such as is only rarely found at the site, clearly built with an eye for the unusual stress caused by the long arches. Incidentally, the northern pilaster was built on top of a marble slab, which bears an inscription. Unfortunately, further investigation was not possible and only a few letters could be identified.117

This apparent professional and expert reconstruction of the elements of the roof support in Phase 4 was fully justified. If the height of the two columns in the nave was more or less equal (or even only slightly different) than that of the columns in Phase 2, and the roof support in the aisles remained the same (i.e., beams and trusses), that posed a clear problem for the builders in selecting the proper form of the roof over the church. If the maximum height (ca. 1.90 m) of a semicircular, 3.80 m long arch is added to the known height of the columns (at least 3.85 m), the roof of the church can be estimated to have stood at a height of nearly six meters at least, not counting the height of the clerestory walls. As there is no evidence for N-S arches in the aisles in Phase 4, the horizontal supports for roofing in the aisles would have to be anchored in the space above the E-W arches in the nave, i.e., in the clerestory walls. Although the two arches in the nave appear exceedingly long, there is no reason to doubt that, if well-built, they could support the clerestory walls above them. As such, there are two possibilities for the overall roofing that could have existed in Phase 4. The reconstructed church of Phases 4-5 (Fig. 37) shows the church retaining a classic basilica form, i.e., with the clerestory walls, the pitched roof over the nave and the slanting roofs over the aisles. An alternative is a single pitched roof extending over the nave and the aisles. This would, however, still require the existence of some sort of clerestory, perhaps lower than in Phase 2. Otherwise, with the height of columns being around 4 m, the pitched roof would have, in fact, been close to a flat roof, and the roof supports (horizontal beams) for the aisles would not have had adequate structures for anchorage. Thus, with a composite basilica-type roof, or with a single pitched roof, the presence of the clerestory walls was necessary. Regardless of which option was selected by the Phase 4 builders, it is apparent that the church in this phase was an edifice of unusual proportions: its ground plan nearly square, the nave with a roof at least as high, or higher, than in Phase 2 and the roofs over the aisles definitely higher than in Phase 2.

116 Compare the arches in the vaulted cistern by the summit of

Jabal Harun, which span a similar width (note 5).

117 For further details, see Chapter 10, inscription 11

As noted above, the roof support system of Phase 2 in the chapel is unknown. Regardless of its design, it was now entirely reconstructed or replaced by a system of pilasters and columns serving as pilasters, and transverse arches (Fig. 52). This system is reminiscent of that found in some churches in Arabia Provincia – relatively narrow, monoapsidal edifices, with pilasters or piers against the long walls and the single nave spanned by the transverse arches – such as appear in some churches in Umm alJimal, Sabha, Khirbet es-Samra, and Nitl.143

Two pairs of columns, made of reused drums (diameter 0.55 m) probably originating from the Phase 2 church, were erected in the eastern part of the chapel (Fig. 53, see also Fig. 25) directly against the walls to serve as pilasters. Of the eastern pair of columns, the northern column (locus Y.04) has six drums still standing, with a total height of 2.25 m (elevation 46.75 m). The uppermost drum is badly weathered, but appears to have been decorated with crosses. The southern column (locus C.13), with six drums remaining, is 2.20 m high (elevation 46.63 m). In the western pair of columns (loci Y.14, Y.15), the northern column has seven drums (height 2.05 m), while the southern column with its six drums is 2.07 m high. Both of these columns were topped by an undecorated, conical pilaster cap. Further to the west of the columns, the arches were supported by three pairs of pilasters. In their present appearance, only the westernmost pair (locus I.06, 0.70 m x 0.55, and locus I.11, 0.56 m x 0.55 m), built using the header-stretcher technique, appear to derive from Phase 4 (Fig. 54). The two remaining pairs of pilasters – the eastern pair (loci Y.17, Y.18) and the middle pair (loci I.07, I.09, Y.19, Y.20) – probably stood in the same positions as the current pilasters, but have been substantially repaired or completely rebuilt in Phase 7.

The E-W distances between the individual pilasters and columns are relatively uniform, ranging from 1.35 m to 1.45 m. The only exception to this is the distance between the western pair of columns and the easternmost pair of pilasters, which is some 0.30 m wider (1.75 m). This discrepancy has an obvious explanation in that the Phase 2 doorway is located between these roof supports. At any rate, the distance between all arches is sufficient to allow the installation of a superstructure typical of the region. Presumably wooden, but possibly also stone, horizontal E-W beams would have been placed over the arches’ walls, forming the ceiling of the chapel.144 A series of wooden trusses above the ceiling would then support the pitched roof overlaid with tiles.

The roof support structures are preserved well enough to allow a rough estimate of the height of the roof inside the chapel. The span of the arches between columns Y.14 and Y.15 (which seem to have survived almost completely) was ca. 4.35 m. If the arches formed a perfect semicircle, the height of the room appears to have been ca. 4.20 m (2.05 m plus 2.18 m, or the height of the columns Y.14/Y.15 plus the radius of the arch). Assuming that the average thickness of a voussoir was 0.30 m, it can be estimated that the arches would have consisted of ca. 20 to 25 voussoirs.145

143 E.g., at Umm al-Jimal, the Church of Masechos, the East Church

(Butler 1929: 20-22, discussion p. 187) and the Chapel outside

the East Wall (Michel 2001: 169-173); the “small” church at

Sabha (Michel 2001: 184); the South Church at Umm alQuttayn (Michel 2001: 189), Churches nos. 20, 81, and 90 at

Khirbet es-Samra (Desreumaux and Humbert 2003: 27, 29-

31; Michel 2001: 194-195) and both the North and South

Churches at Nitl (Piccirillo 2001: 272, 276; Michel 2001: 365-

367). For the general characteristics of churches in the Hawran,

see Shereshevski 1991: 114-119, 124-126, 129-133.

144 As in Phase 2,

a pitched roof for the chapel is a preferable solution over a flat roof. For examples featuring flat roofs but also

supported by transverse arches supported by pilasters, see the

vernacular architecture of the region (Hirschfeld 1995: 125-

127, 241-243; Al-Azzawi et al. 1995: 325) but also Room I

(Phase III) adjacent to the Petra church (Fiema 2001: 20-21;

Kanellopoulos 2001: 153-157).

145 This estimate can be calculated using the formula p =pr/0.3m,

where x is the number of voussoirs, r the radius of the semicircle (in this case, 2.175 m) and 0.3 m the average thickness of a

voussoir.

Whereas the event of Phase 3 was almost certainly a massive earthquake coupled with a raging fire, it is much more difficult to interpret precisely what happened in Phase 6. The reason for distinguishing this phase at all is that something must have prompted the extensive rebuilding activities of Phase 7. However, whether it was an earthquake, a spontaneous collapse of the inside structures, or some less dramatic reason, is not immediately clear. The long arches and central columns of Phase 4 were a somewhat unusual feature in Byzantine church architecture, and may have turned out to be structurally too weak to support the building. A partial collapse or the immediate danger of such might have occurred or been anticipated. It is then possible that the old roof supports were dismantled and new ones built in a planned way. Exploiting such an opportunity, a thorough remodelling of the building for aesthetic or functional reasons might then have been executed.

However, there are some problems with this explanation. First of all, the changes made in Phase 7 were not limited to the roof supports, but several new installations were built in the altar areas of both the church and the chapel, and the entire church interior was plastered anew. These changes may or may not have been related to the prevailing liturgical requirements. It also seems curious that the sturdy pilasters of the Phase 4 church were abandoned and replaced by less well-built pillars in Phase 7. That all of this was done for aesthetic or functional reasons seems unlikely. Perhaps the most important clue to the nature of the event is offered by the finds of glass and marble elements. The church of Phase 7 no longer featured a marble chancel screen or ambo, and it was lit with new types of glass lamps. It is not easy to see why the marble decorations and old glass lamps would have been discarded if the building was simply remodelled in an orderly manner. Therefore, one must assume that the roof supports and lamps fell as a result of some event, either an earthquake or a spontaneous collapse due to the structural instability of the building. Such an event might have wrecked most of the church furnishings beyond repair. It should also be mentioned that the Byzantine shrine under the weli, which was studied by Wiegand, may well have been abandoned as a result of an earthquake, and the most convenient phase for this would be Phase 6.156 However, the extent of the damage is uneven throughout the structures and, while some elements must have collapsed, others, such as the columns in the church, seem to have somehow survived. Therefore, it is possible that Phase 6 represents only a relatively minor seismic event, but still one that provided a convenient reason for the extensive remodelling of the church and the chapel in the following phase. The extent of building activities in Phase 7, therefore, need not directly reflect the intensity of the earthquake.

At least some of the arches of the Phase 4 church seem to have fallen, probably causing heavy damage to the floor and furnishings of the church, but, curiously, the two columns of Phase 4 were left standing. Judging by the methods and materials used, the marble floor has been damaged and repaired on several occasions, but it is difficult to attribute a particular series of repairs to the damage inflicted in Phase 6. The same is true of the walls, which have been damaged and repaired on several occasions, but there are few chronological indications to help to date a particular series of repairs. One may only conclude that some of the damage to which the floor and walls bear witness might have been caused by the Phase 6 event.

The Narthex mosaic also appears to have suffered damage, as it was repaired using large limestone tesserae in the following phase. In its northern quarter, an area of repairs (Repair I) running from east to west suggests that something heavy (a column?) fell on it. The extent of the damage may also be related to the relative instability of the Narthex floor, as the early water channels (the two northernmost and the central one) run under the mosaic. Some smaller repairs made with small tesserae may also relate to damage resulting in Phase 6.