Aerial view of the Nabataean mansion in EZ IV under excavation

Aerial view of the Nabataean mansion in EZ IV under excavationKolb (2002)

Aerial view of the Nabataean mansion in EZ IV under excavation

Aerial view of the Nabataean mansion in EZ IV under excavation| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| az Zantur | Arabic | از زانتور |

Figure 2

Figure 2

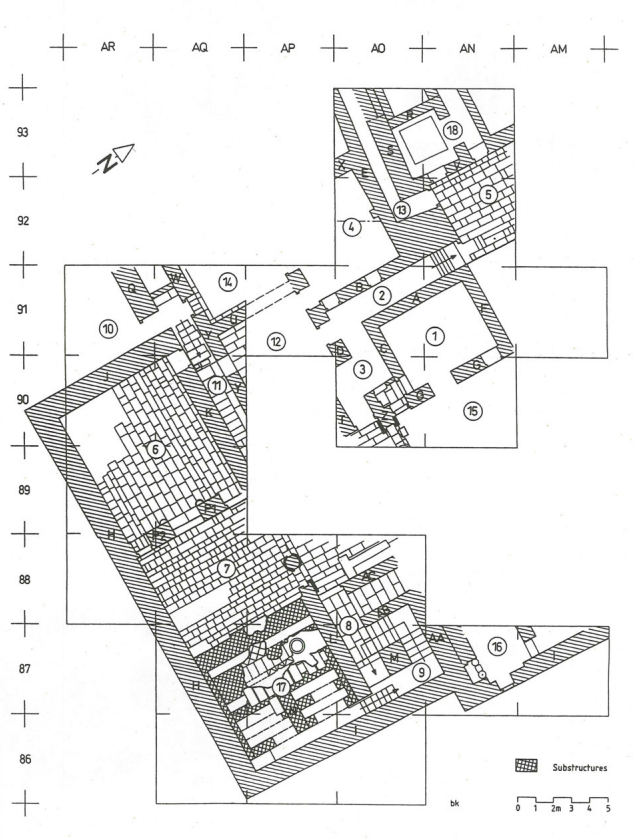

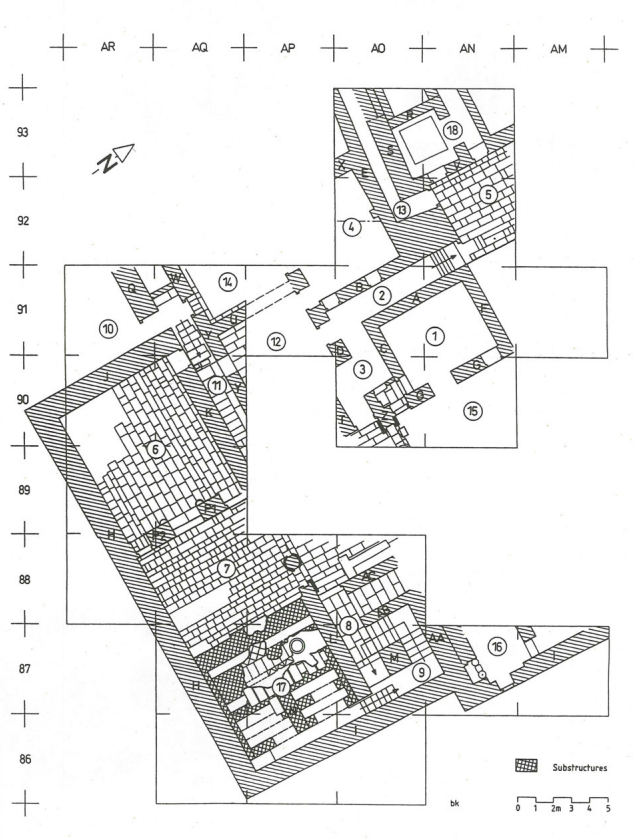

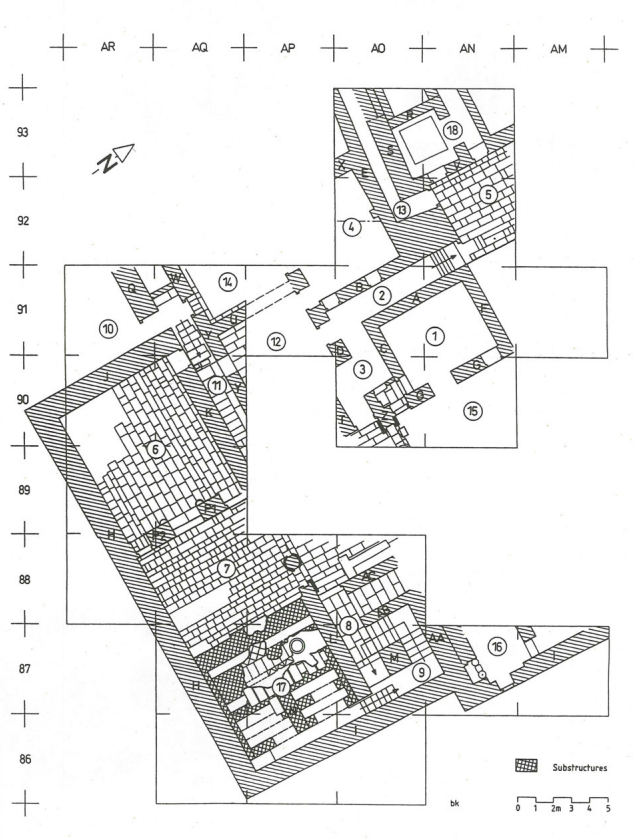

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

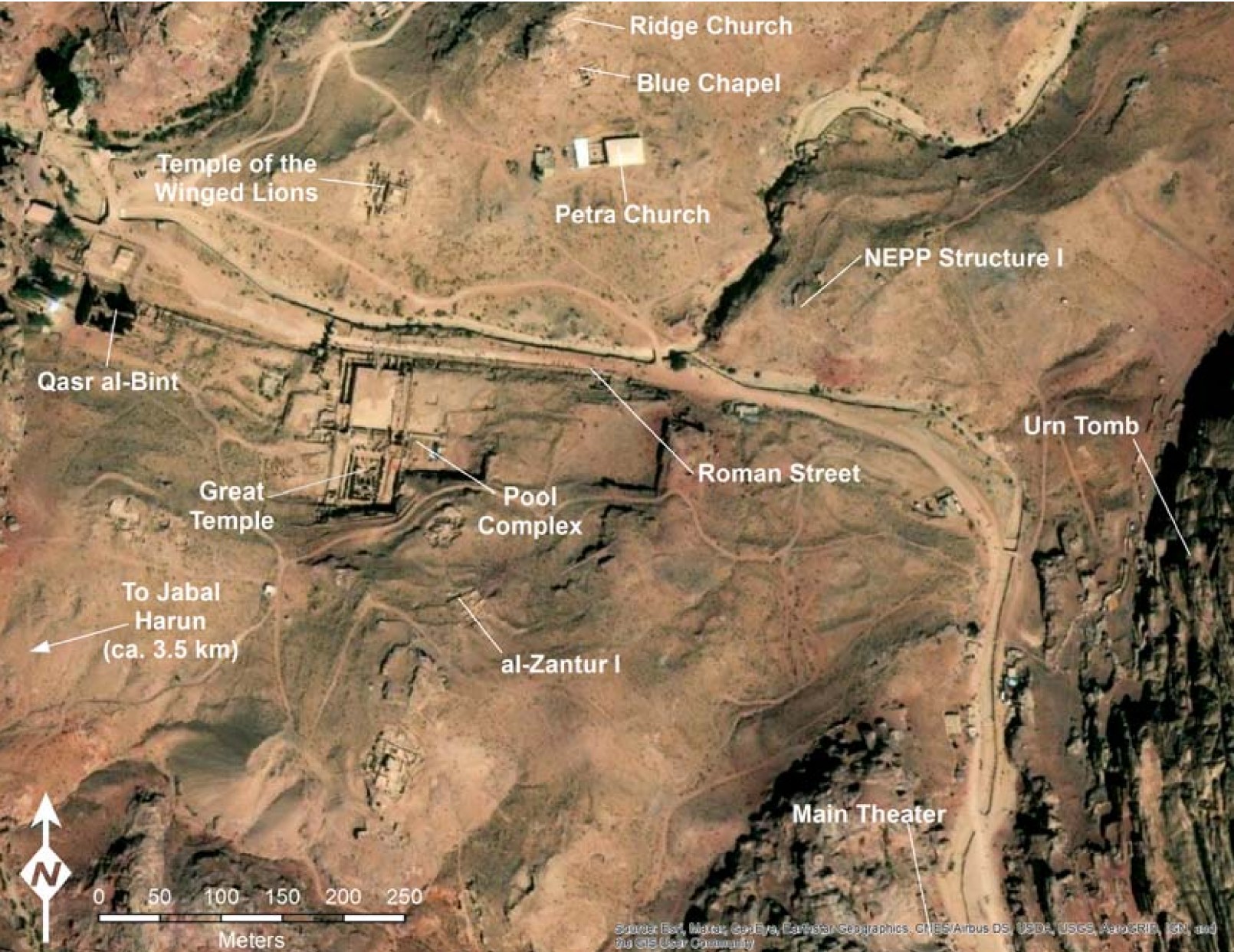

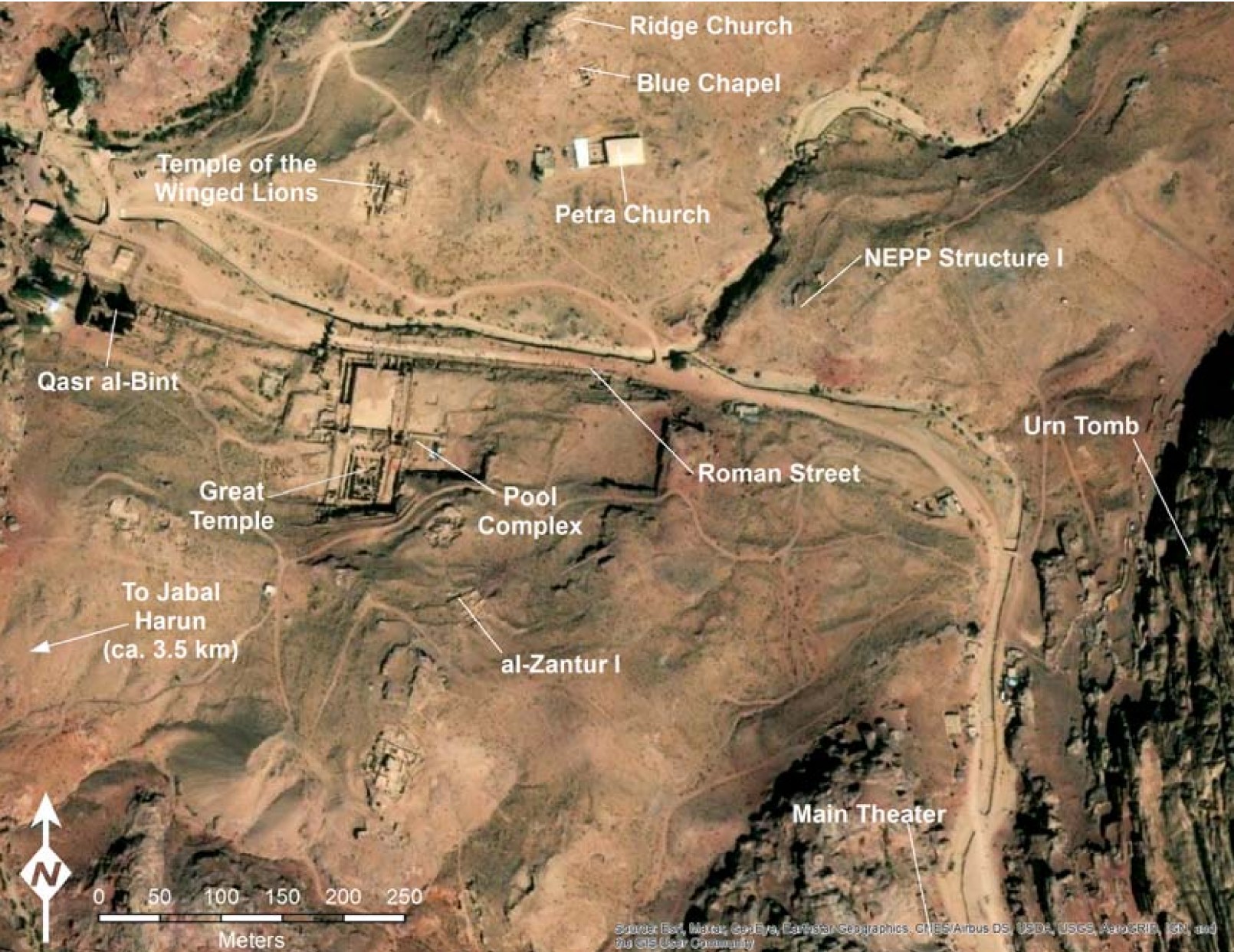

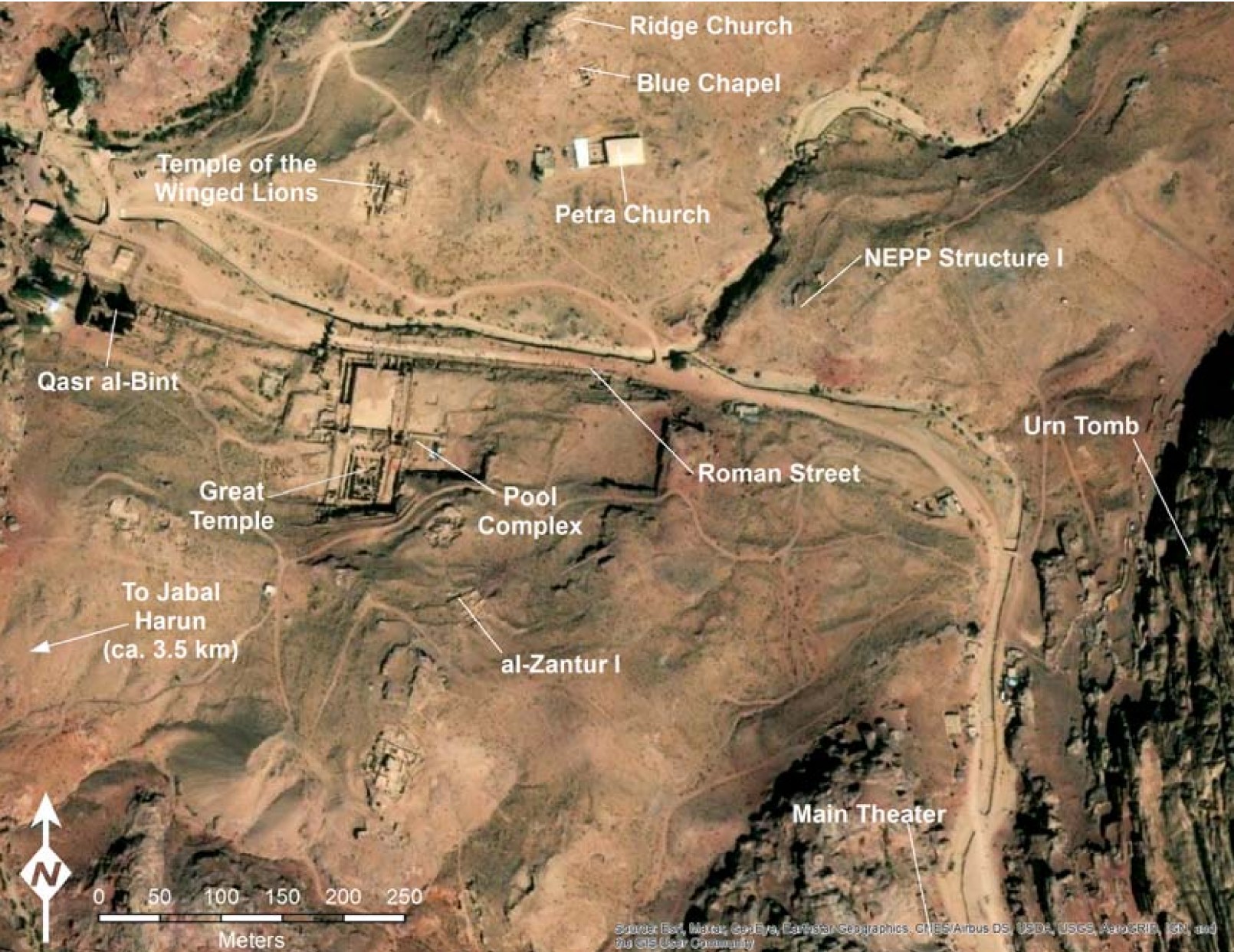

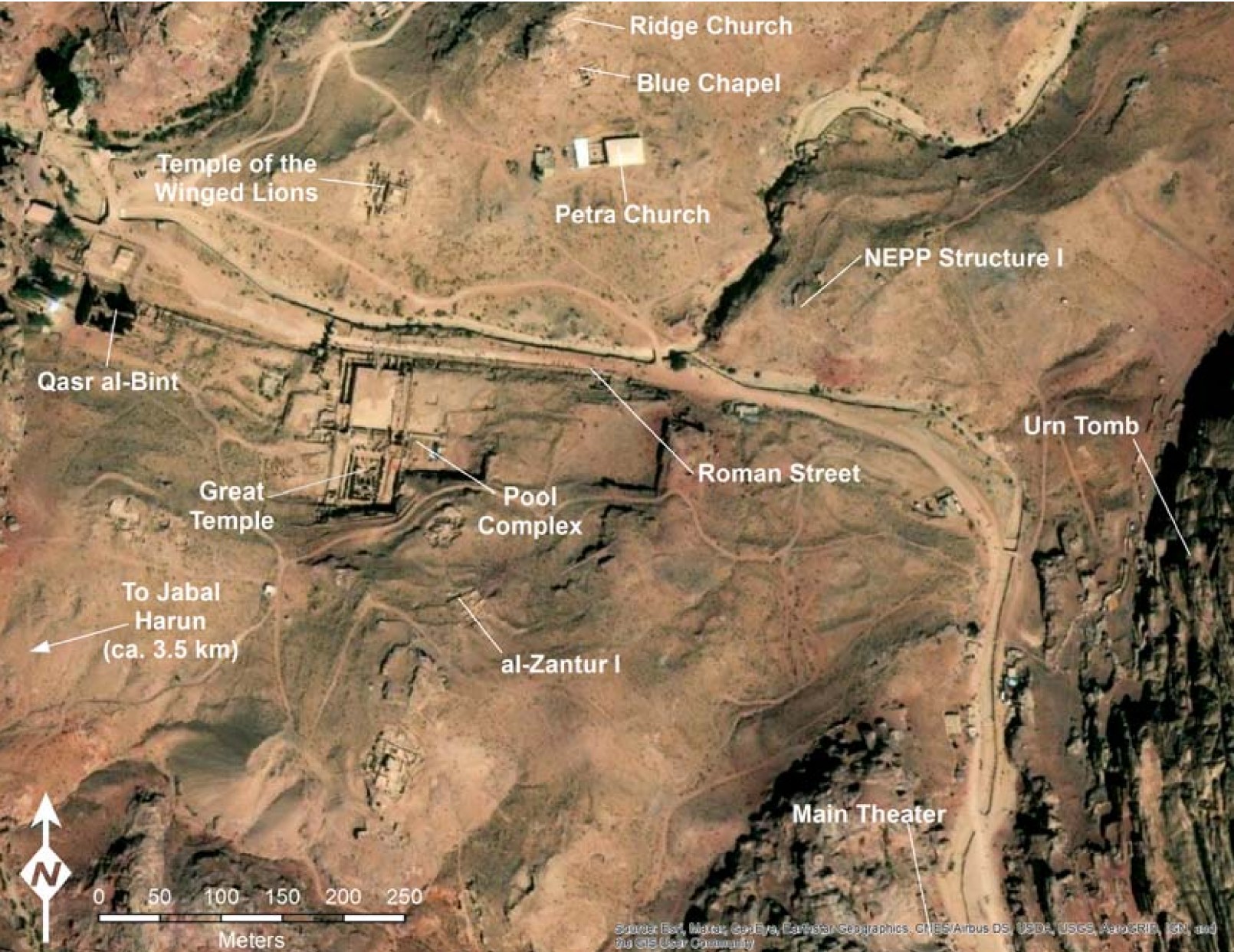

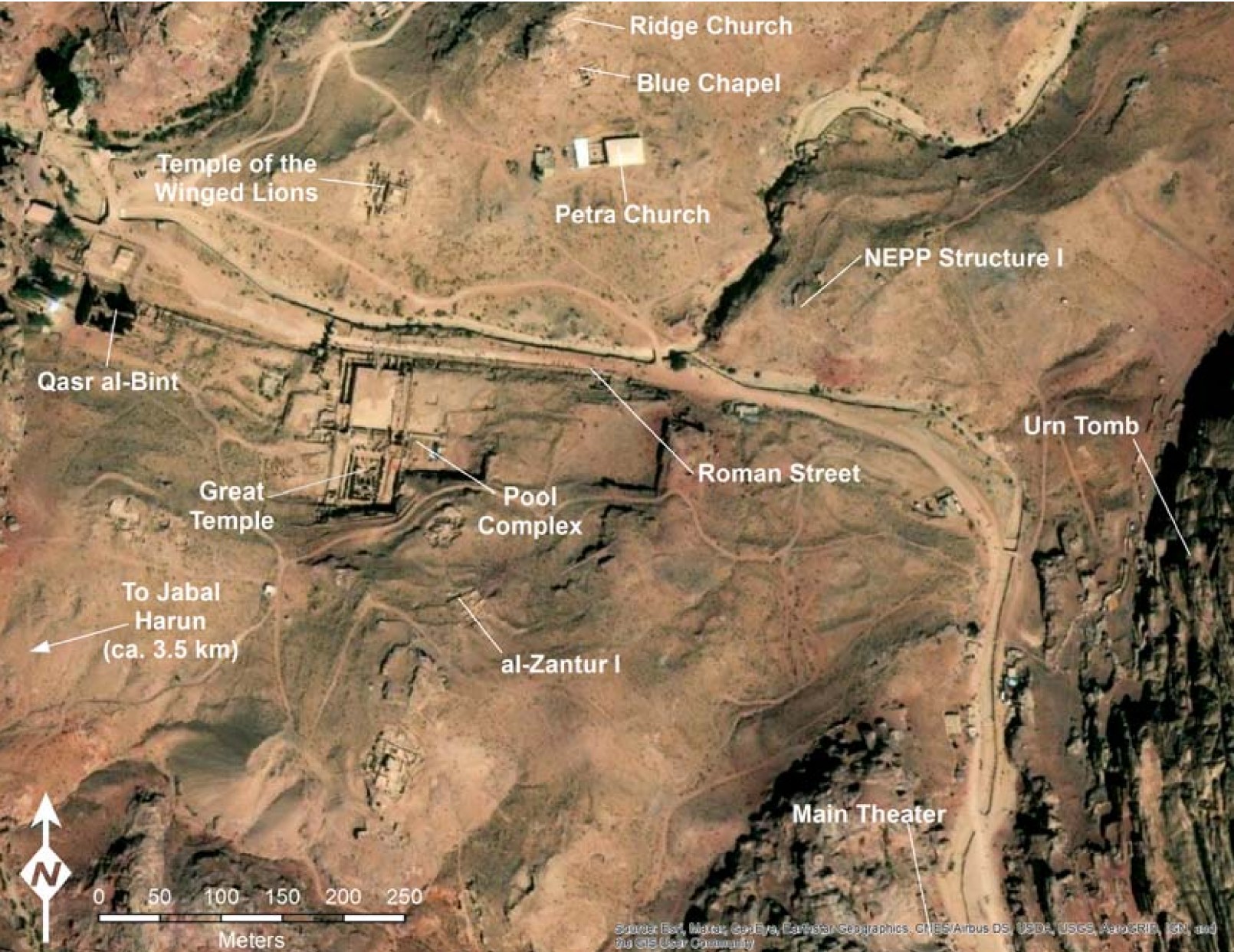

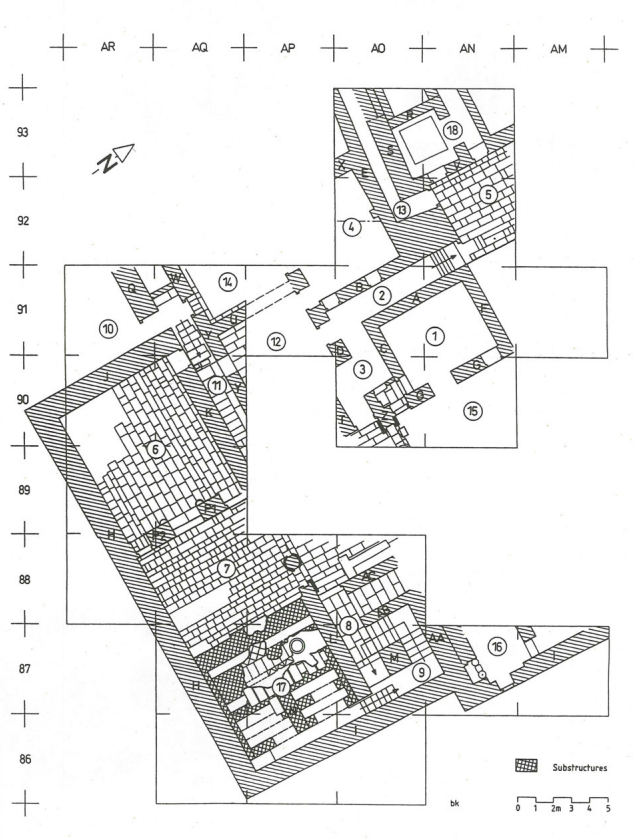

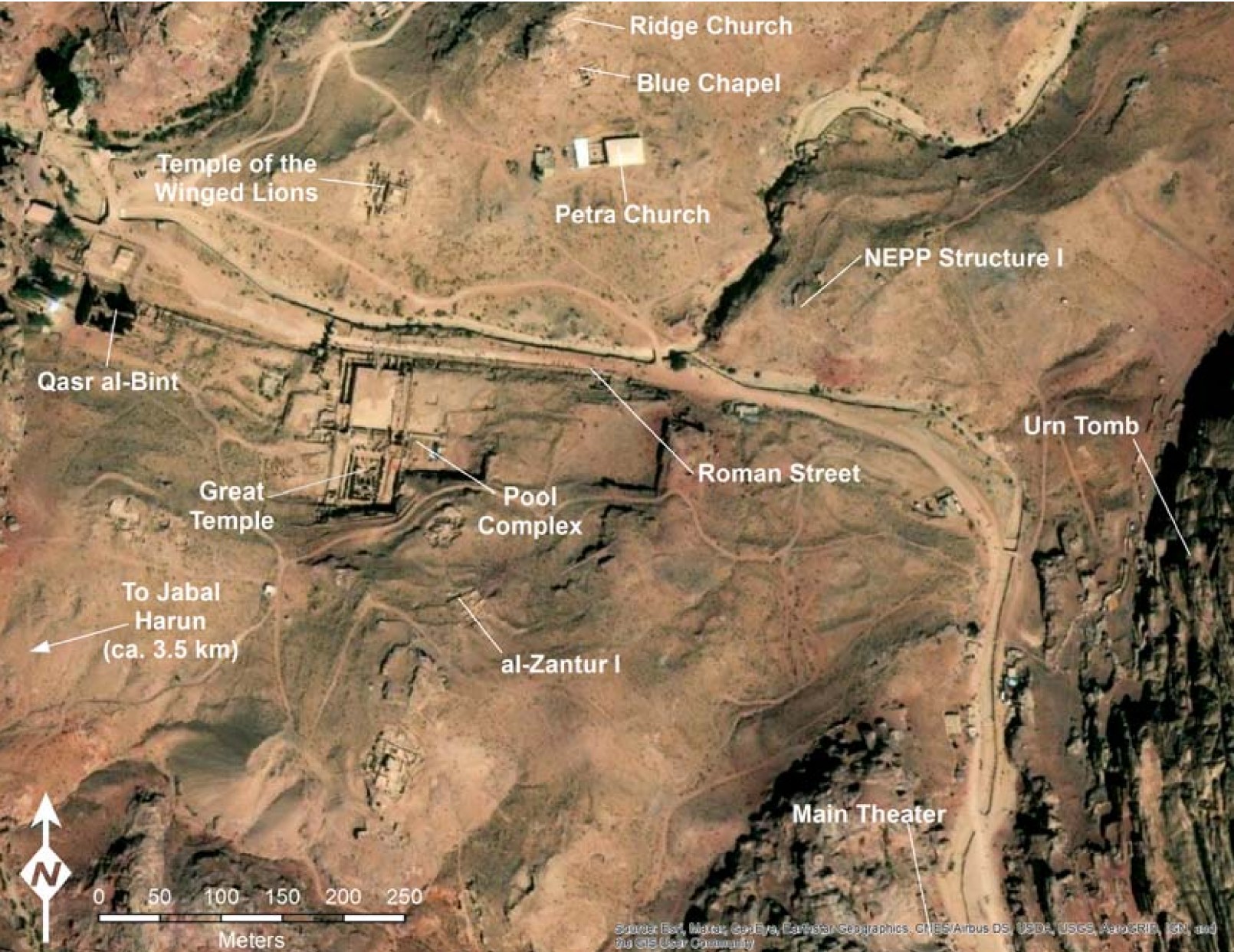

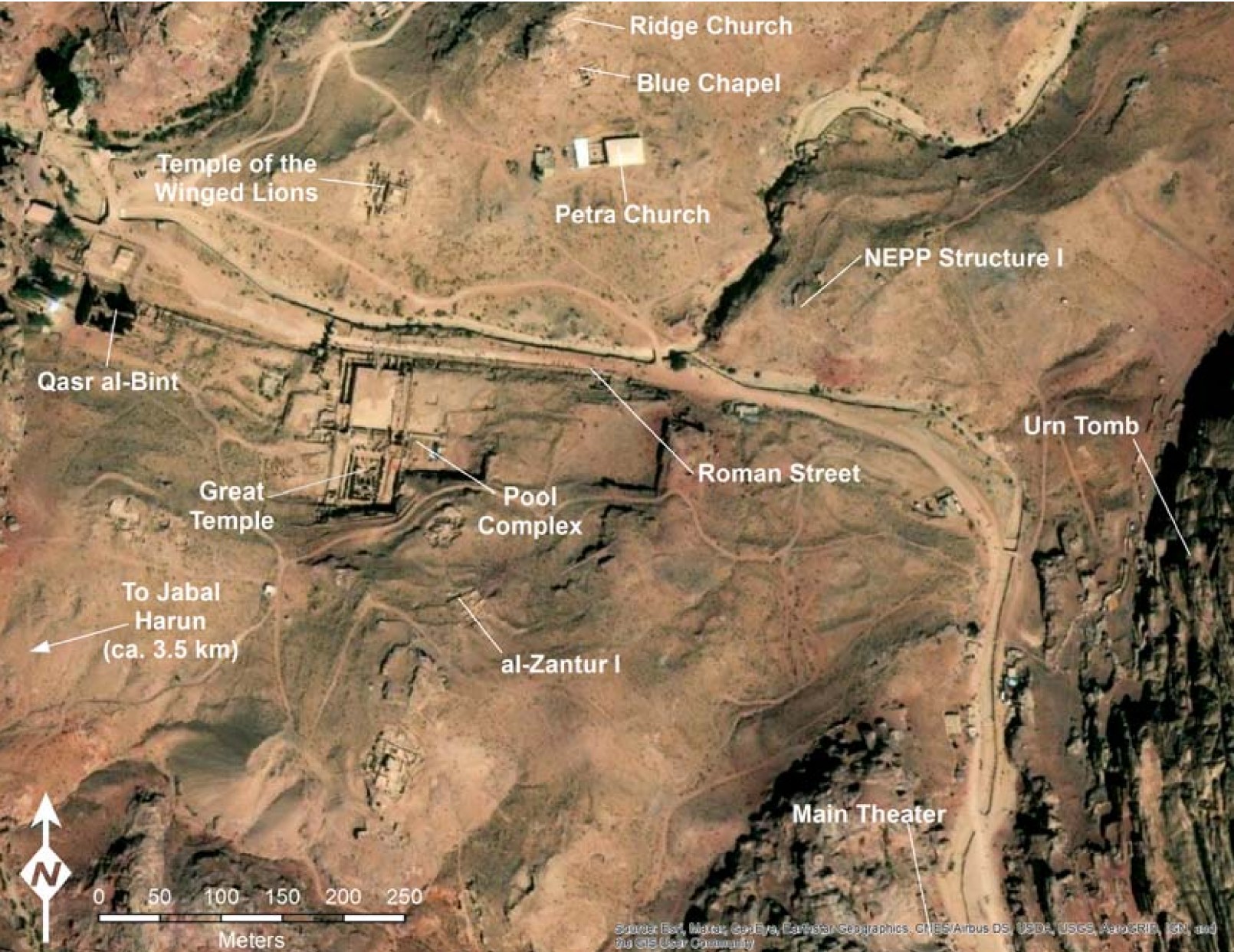

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

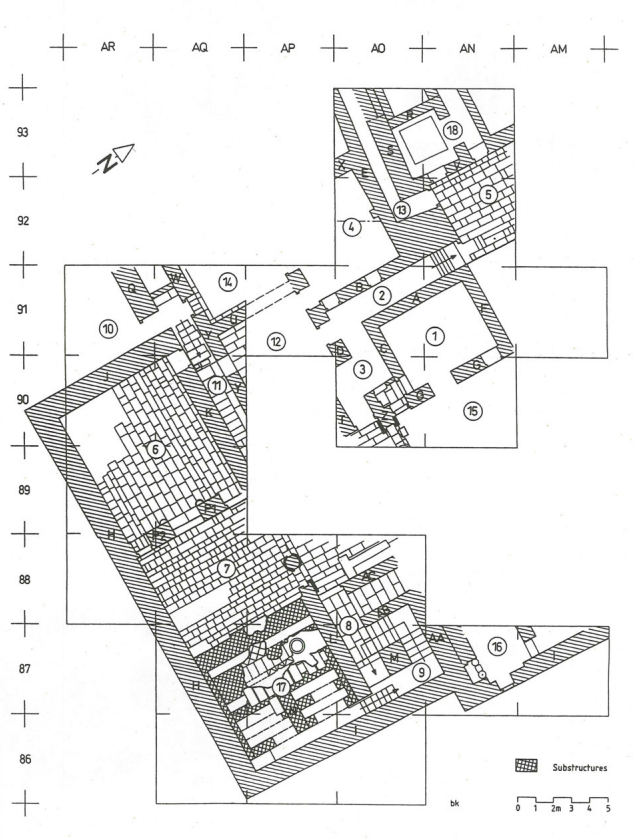

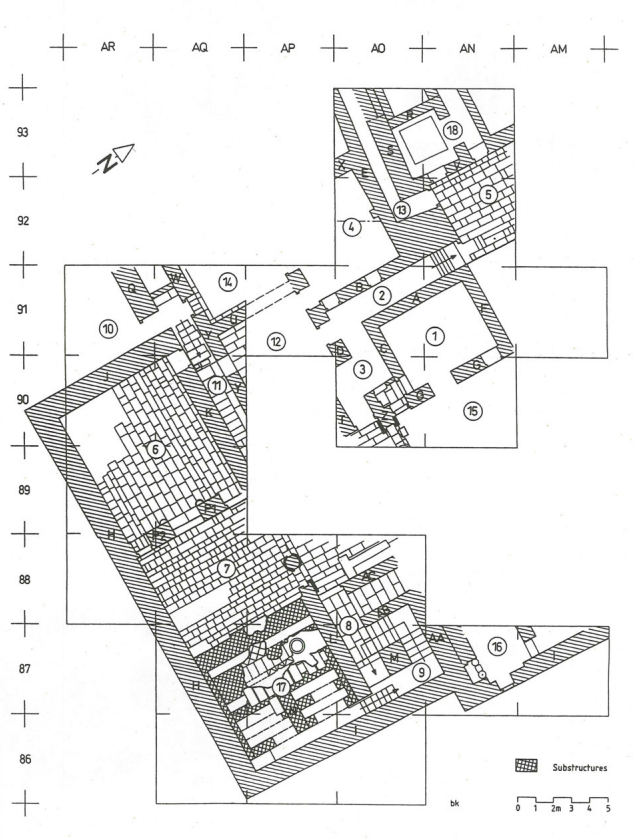

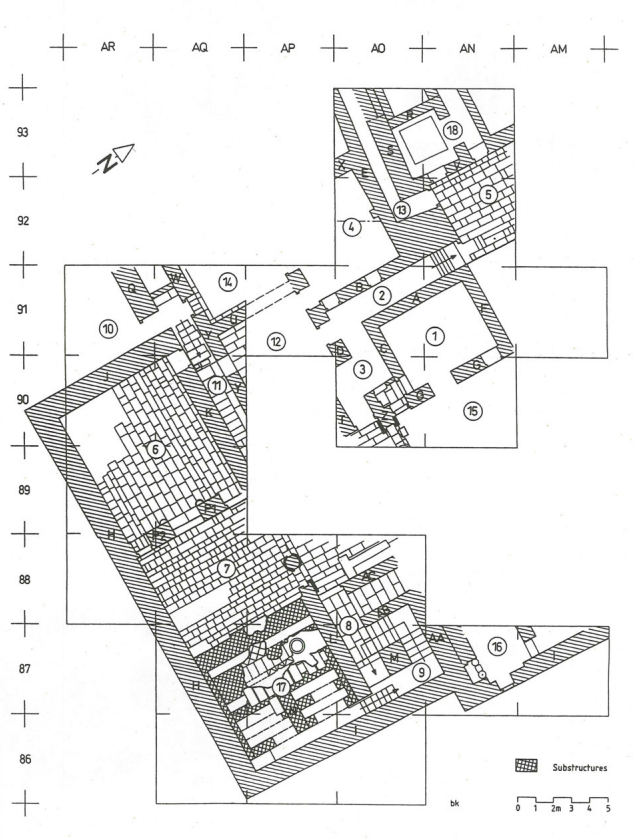

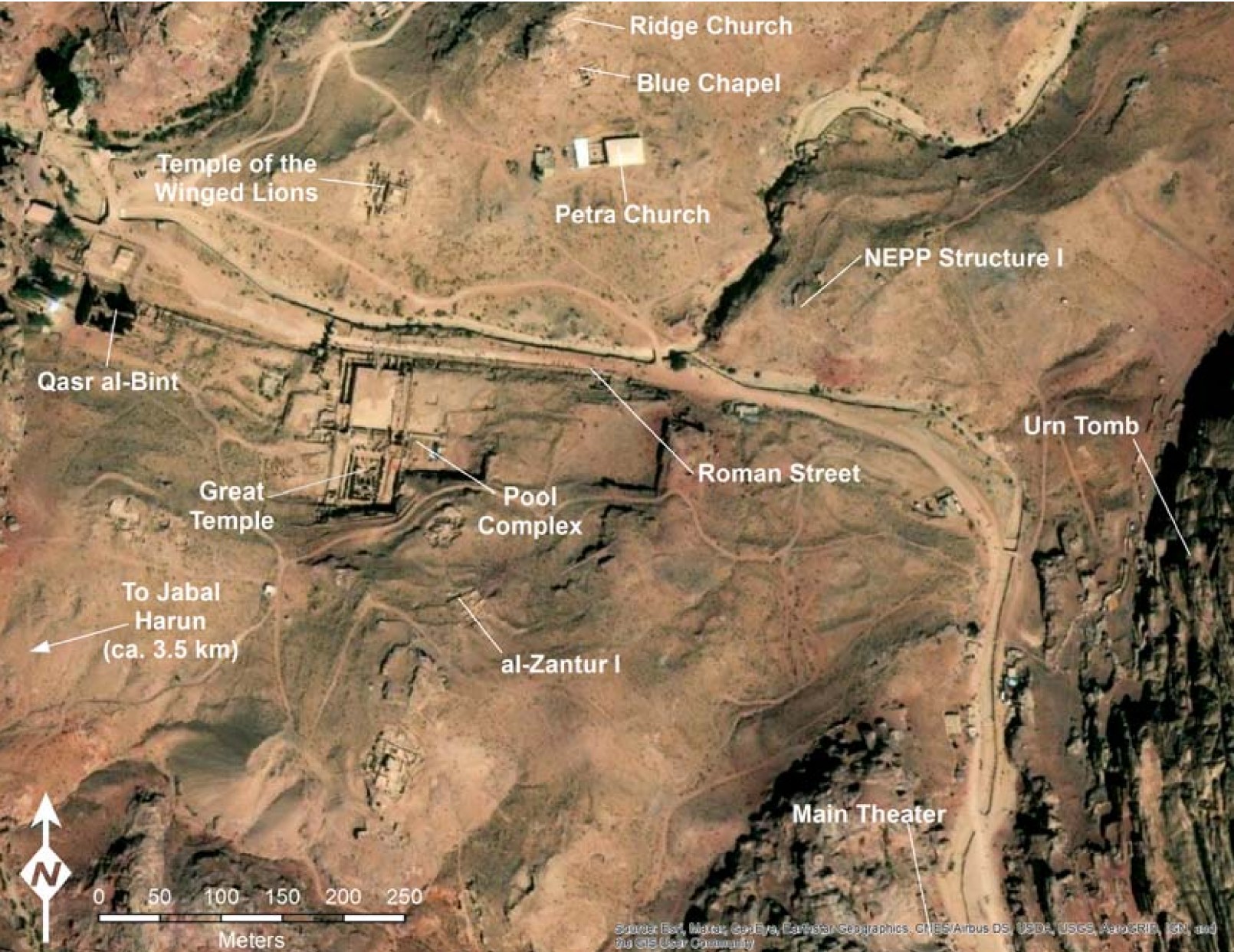

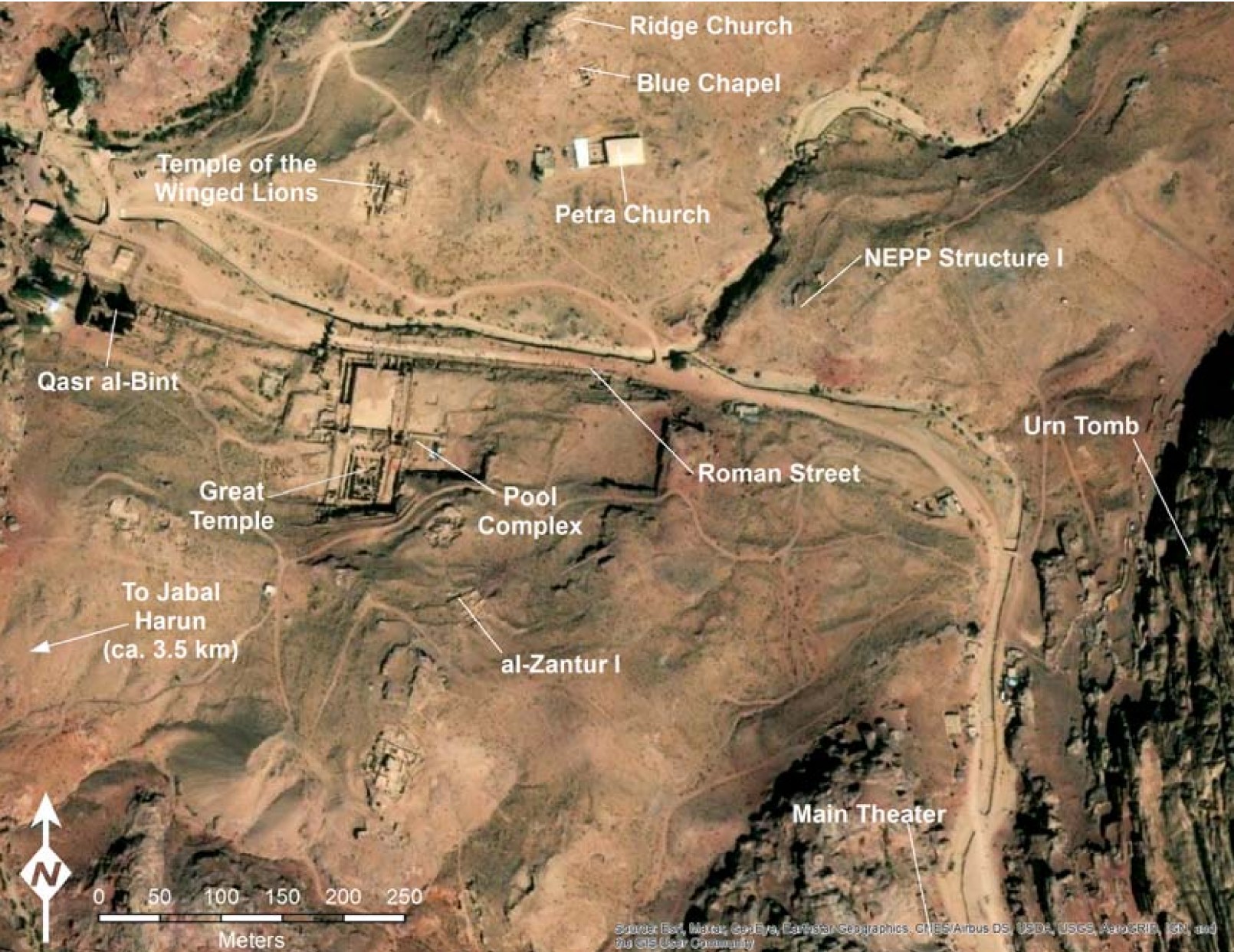

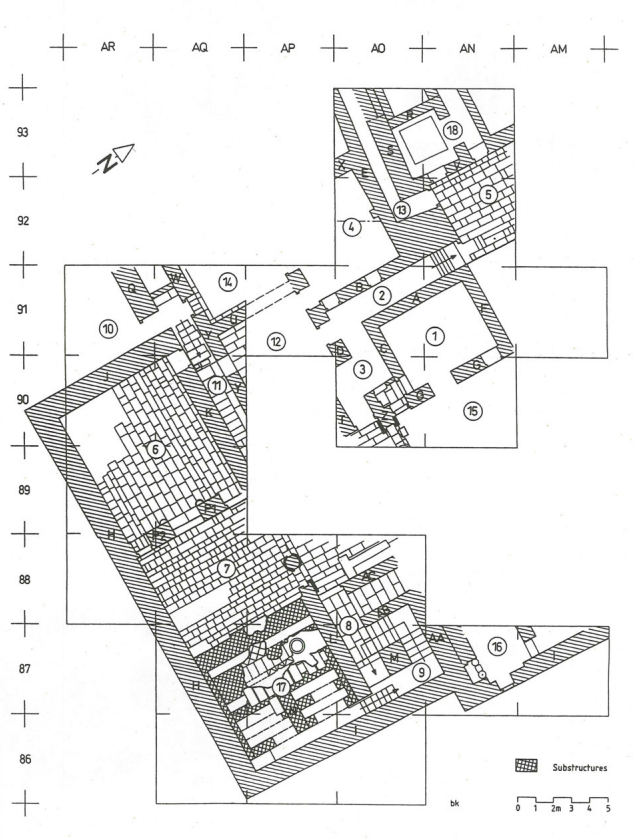

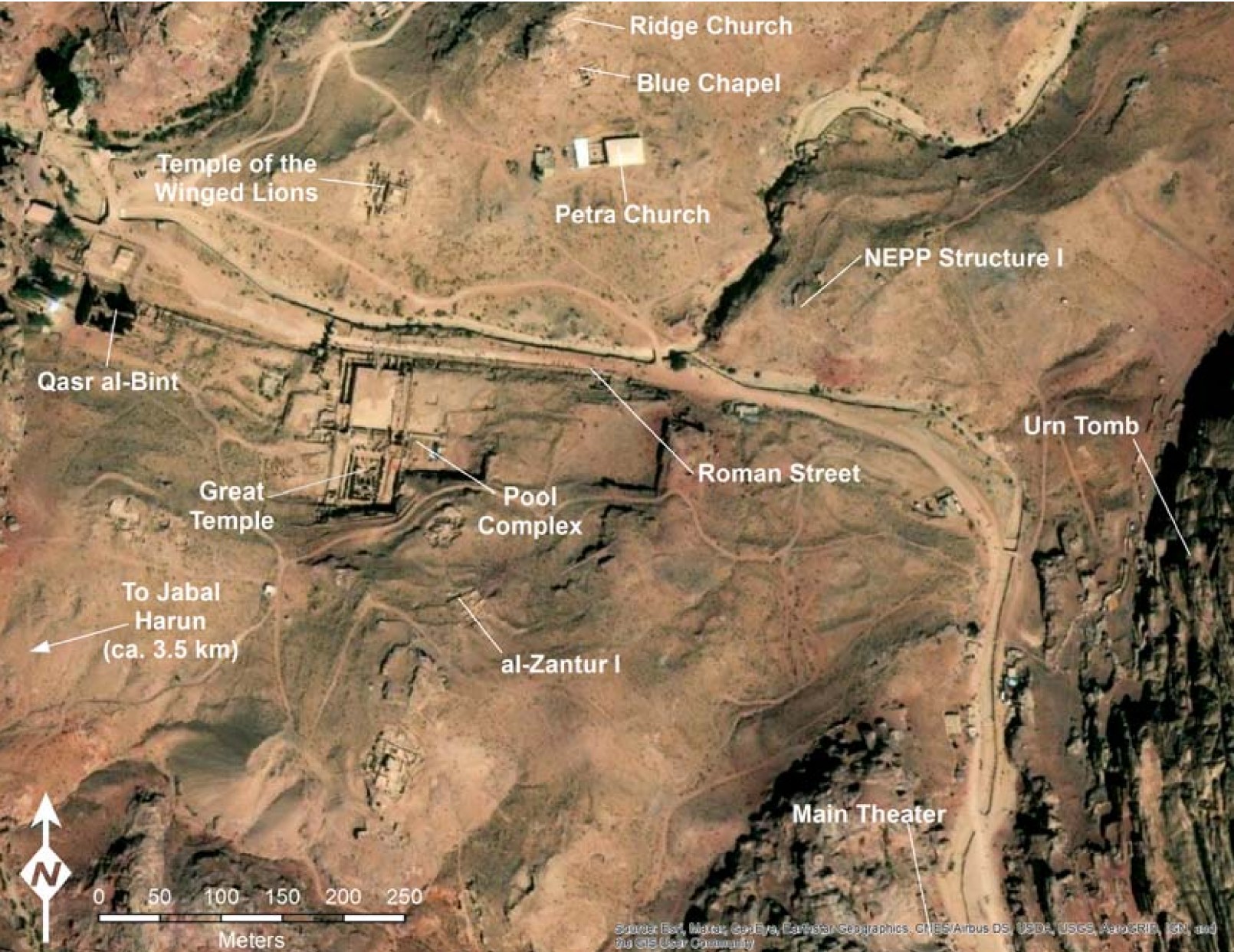

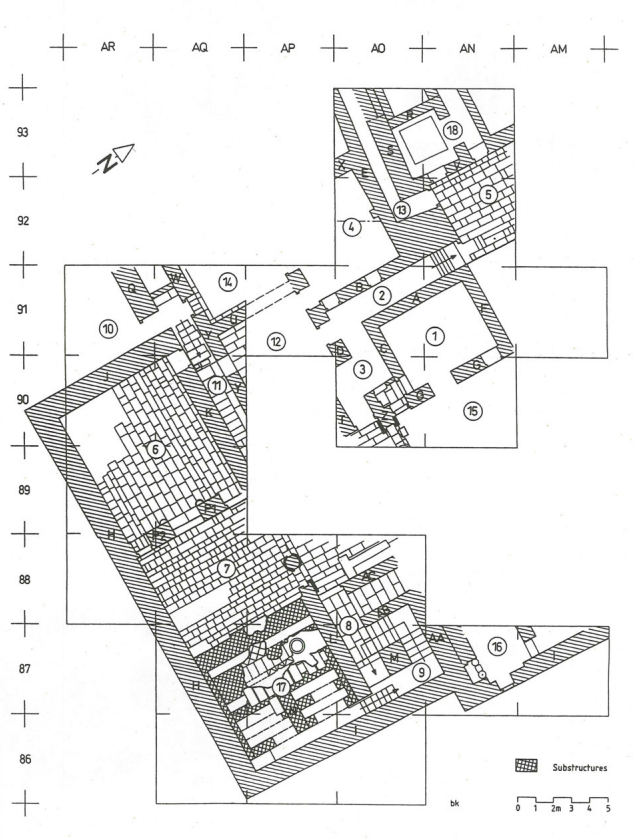

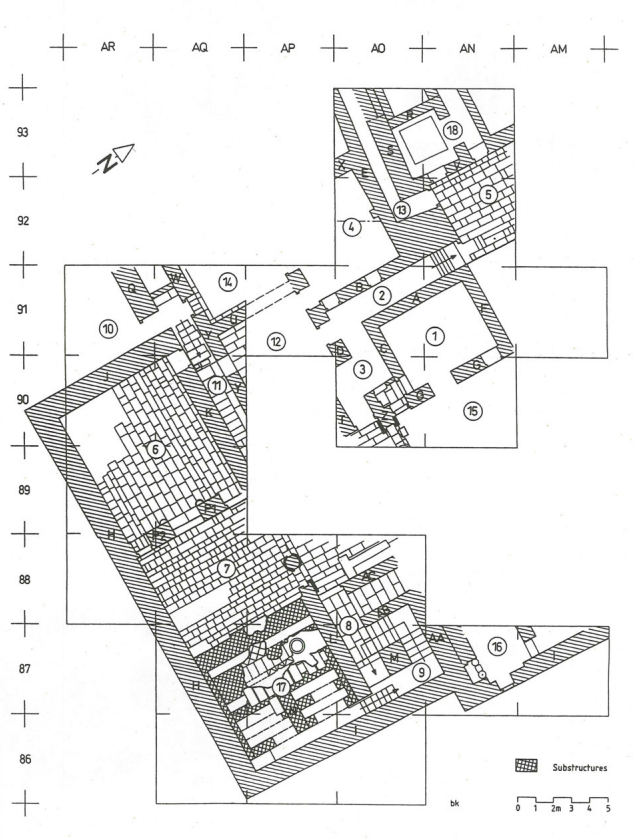

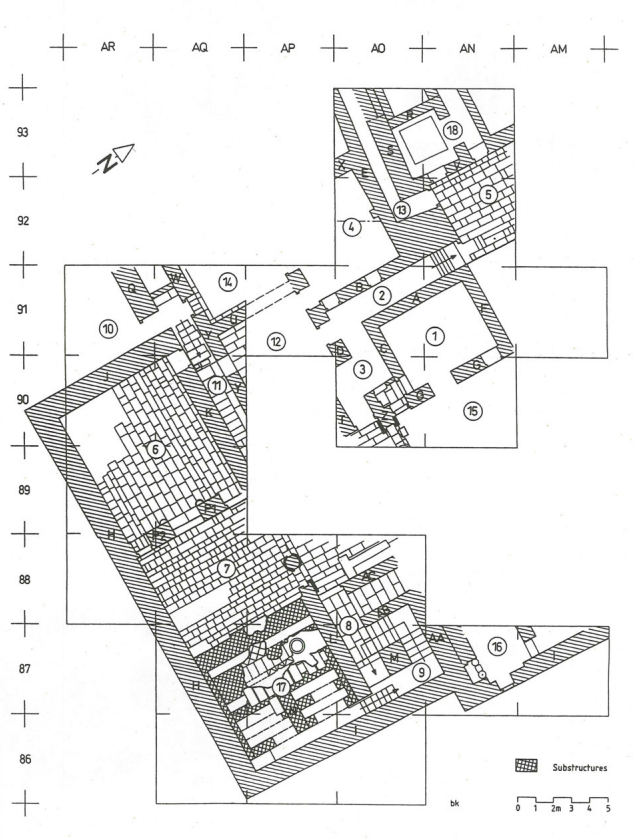

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

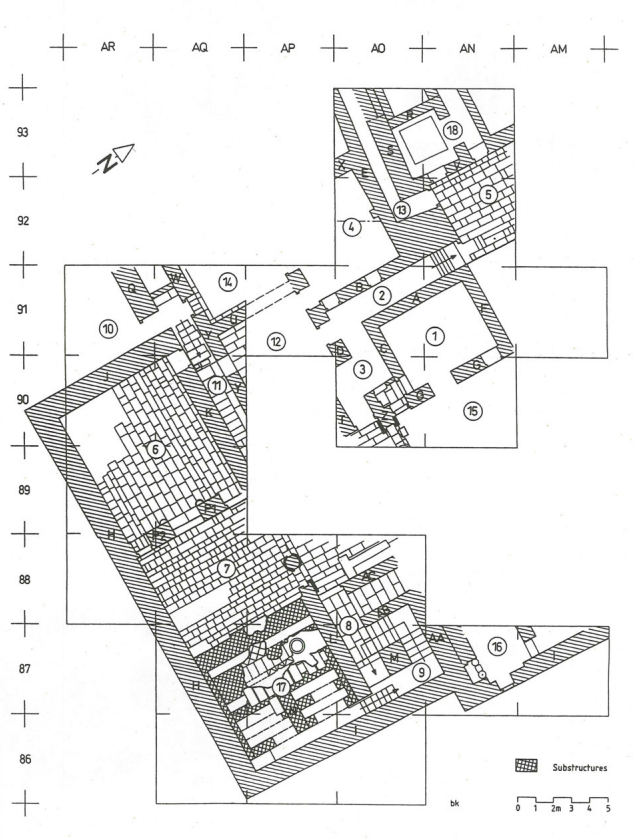

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 6.35a

Fig. 6.35a

Fig. 6.35b

Fig. 6.35b

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 6.35a

Fig. 6.35a

Fig. 6.35b

Fig. 6.35b

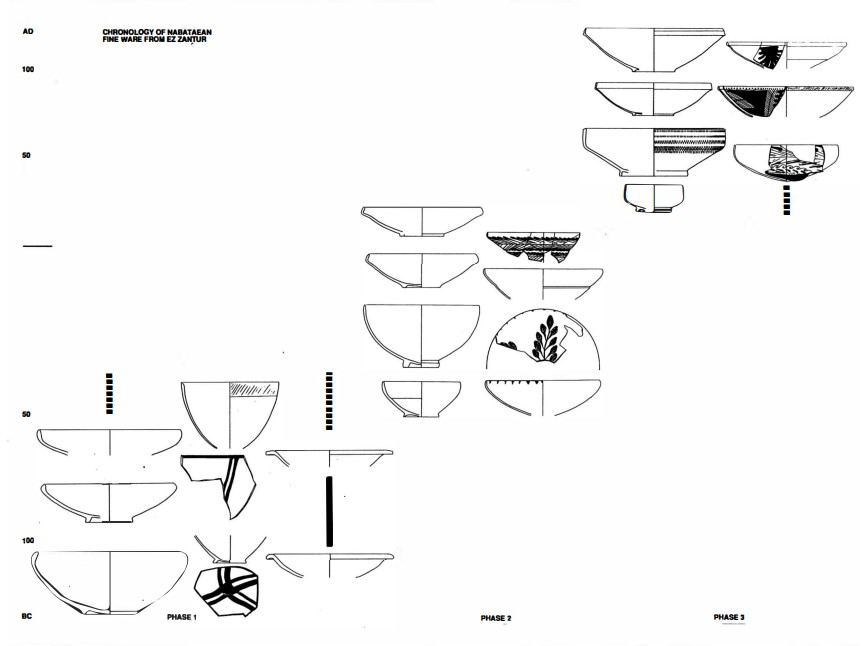

| Phase | Dates - Ez-Zantur Excavations | Dates - Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 20-70/90 CE | 20-80 CE |

|

| 3b | 80-100 CE | later 2nd and early 3rd centuries |

|

| 3c | 100-150 CE | later 2nd and early 3rd centuries |

|

| Phase | Dates - Ez-Zantur Excavations | Dates - Jones (2021) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauphase Spatromisch II ('Construction Phase Late Roman II') |

363-419 CE | 5th? -6th century CE |

|

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

Fig. 1as well as in the plaster bedding of the painted wall decorations in room 1. Earthquake induced structural damage led to a remodeling phase which was dated to

the early decades of the 2nd century CE(Kolb, 2002:260-261). A terminus post quem of 103-106 CE for the remodel was provided by a coin struck under King Rabbel II found in some rough plaster (rendering coat) in Room 212 of site EZ III (Kolb, 1998:263).

Room 33 is the work-shop proper. This is indicated by the finds that were encountered in a thick and seemingly undisturbed destruction layer, sealed by the debris of the rooms arched roof. While any indication for the cause of this destruction evades us, the dating of the event is clear. Through the evidence of the coins an the floor we arrive at a terminus post quem of 98 AD. As there is plenty of fine ware in the destruction level, belonging to Schmid's phase 3b, but none of phase 3c, which according to him starts ±100 AD, the destruction must have taken place at the end of the first or early in the second century AD.Kolb B. and Keller D. (2002:286) also discussed archeoseismic evidence at ez-Zantur

Stratigraphic excavation in square 86/AN unexpectedly brought useful data on the history of the mansion' s construction phases and destruction. The ash deposit in Abs. 2 with FK 3524 and 3533 provided clear indications as to the final destruction in 363. A further chronological "bar line" — a some-what vaguely defined construction phase 2 in various parts of the terrace in the late first or second century AD — received clear confirmation in the form of a thin layer of ash. The lamp and glass finds from the associated FK 3546 date homogeneously from the second century AD, and confirm the assumption of a moderately severe (not historically documented) earthquake that led to the structural repairs observed in various places and the renewal of a number of interior decorations.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

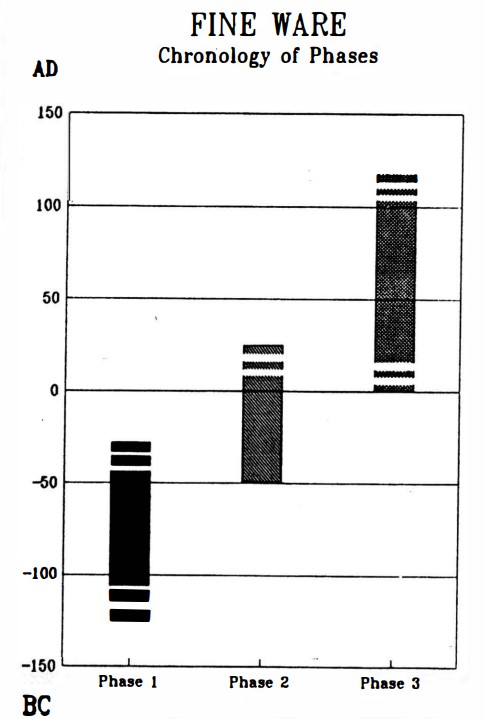

Fig. 1A re-examination of the Zantur fineware chronology by the writer has revealed that it contains a number of serious difficulties.25 The main difficulties in the Zantur chronology center on Phase 3, which covers most of the 1st through 3rd c. CE. Zantur Phase 3 is divided into three sub-phases: 3a (20-80 CE), 3b (80-100 CE) and 3c (100-150 CE). The dating of Phase 3 is based on a very small amount of datable material, for example, the main table showing the datable material (Schmid 2000: Abb. 420) shows that no coins were available to date either Phase 3a or Phase 3c. Moreover, the earliest sub-phase, 3a, was vastly underrepresented.26 At Zantur, there appears to be little justification for the beginning dates for either Phase 3b (80 CE) or 3c (100 CE) or their terminal dates (100 CE and 150 CE respectively). No `clean' loci, i.e., sealed contexts, were offered to prove the dating of Phases 3b and 3c and the contexts are mixed with both earlier (3b) and later (3c) material (ibid., 184). This raises the question as to why a terminal date of 100 CE was fixed for Sub-phase 3b. The coin evidence for Sub-phase 3b is scanty and some of the coins could date as late as 106 CE while there is a discrepancy between the dates of the coins and the imported wares, many of which date later than 100 or 106 CE. In order to date Phase 3 in Zantur, there was a heavy dependence an a very small quantity of imported fineware sherds, mainly ESA. Of the forms used, Hayes 56 is listed in both Phase 3b and 3c (ibid.) and since this particular form dates later than 150 CE (Hayes 1985: 39) the majority of the forms and motifs of both sub-phases 3b and 3c should be assigned to the later 2nd and early 3rd centuries. with its purported range of 60 years.Footnotes25 "Problems and Solutions in the Dating of Nabataean Pottery of the Roman Period," presented on February 20, 2014 in the 2nd Roundtable "Roman Pottery in the Near East" in Amman, Jordan on the premises of the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR).

26 In the words of the report: "Unfortunately, so far only a few homogeneous FKs (find spots/loci) have been registered with fineware exclusively from Phase 3a. After all, if the Western Terra Sigillata form, Conspectus 20, 4 from FK 1122 (Abb. 420, 421 Nr. 43) accurately reflects the duration of Phase 3a, we can thus estimate [the period] as from 20 to 70/80 CE" (Schmid 2000: 38).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Coin hoard in situ

Coin hoard in situ

Fig. 10

Fig. 10EZ IV: The Nabataean "Villa"Seismic effects from Room 6 at ez-Zantur IV (EZ IV) included broken columns, debris, and a cracked flagstone floor under 6 carbonized wood beams which Kolb et al (1998) described as

The Last Phase of Occupation

Household objects such as a basalt hand mill, two bone spoons, an alabaster pyxis and a number of unidentifiable iron objects, as well as large quantities of ceramics and glass vessels of the fourth century AD lay buried on the pavement, along walls H and K, beneath innumerable fragments of stucco from the wall and ceiling decoration (see below for the contributions of D. Keller and Y. Gerber). The datable objects confirm last year's findings from room 2, where the coins indicated that the end of the final phase of occupation came with the earthquake of 363 AD (Kolb 1997: 234).

The thick layer of mural and moulded stucco fragments on top of the household utensils of the fourth century proves beyond any doubt that the Nabataean decor remained on the walls up till the aforementioned natural catastrophe.3Footnotes3 In Palmyra M. Gawlikowski demonstrated stratigraphically that a dwelling of the second century AD was still decorated with its original stuccoed and painted wall decoration in the Abassid period, i.e. about 600 years later! Cf. M. Gawlikowski, Fouilles recentes a Palmyre, in: Academie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Comptes rendus des seances de l'annee 1991: 399-410.3"

a witness to the violence with which the wood hit the floor. Also found in ez-Zantur IV were cracked steps (see Fig. 10 in Figures and Photos above) which may have been seismically damaged. There were no indications from the article what lay below the steps and whether geotechnical factors could have played a role in cracking the steps. Kolb et al (1998) report that some structures at EZ IV were built directly on bedrock.

Stratigraphic excavation in square 86/AN unexpectedly brought useful data on the history of the mansion' s construction phases and destruction. The ash deposit in Abs. 2 with FK 3524 and 3533 provided clear indications as to the final destruction in 363. A further chronological "bar line" — a some-what vaguely defined construction phase 2 in various parts of the terrace in the late first or second century AD — received clear confirmation in the form of a thin layer of ash. The lamp and glass finds from the associated FK 3546 date homogeneously from the second century AD, and confirm the assumption of a moderately severe (not historically documented) earthquake that led to the structural repairs observed in various places and the renewal of a number of interior decorations.Kolb and Keller (2000:366-368) discovered some glass lamps normally dated to a later time period associated with 363 CE debris (see "Glass finds of Kolb and Keller (2000) which cast doubt on a 363 CE date" collapsible panel).

6 Kolb, Keller and Fellmann Brogli 1997:234

Kolb, Keller, and Gerber 1998:261-262, 264, 267-275

Kolb, Gorgerat and Grawehr 1999:262, 266, 268

7. Neither in the late Roman houses on EZ I, destroyed in the early fifth century AD, nor in the shops on the

southern side of the Colonnaded Street, which were in use until the 5th and 6th century AD, nor in the Byzantine

monastery on Jabal Härün has this type of glass lamp been recorded.

8. One was found in a church at Como (Italy), an-other one at Luni (Uboldi 1995: 108; Figs. 2,6-7).

9. von Salden 1980: 47-49; No. 246-248; 250 Pl.11;246-247; 23; 246; 250.

10. Among the late Roman and Byzantine glass finds from the excavations of the Hippodrome at Gerasa

the were no fragments of such glass lamps (this glass will be studied by the author under the supervision of Kehrberg).

11. Bagatti-Milik 1958: 148 ,No. 11, Fig. 35,11, I 40,125,15. For the date of this tomb: Kuhnen 198 Beilage 3, No. 98.

12. For the date: Fiema 1998: 415; 420.

13. For the use of the rooms XXVI-XXVIII until the later 5th to the 6th century: Fiema 1998: 420-421.

14. The glass finds from the Finnish Jabal Härün Project will be studied by J. Lindblom (University of Helsinki) and the author.

15. Davidson Weinberg 1988: 85,No. 386-387, Fig. 4-44,386-387, Pl. 4-16,386.

15. Rehovot: Patrich 1988: 134-136, P1. 12

Nessana: Harden 1962: 84 Nos. 47-50, Pl. 20,47

el-Lejjun: Jones 1987: 627-628, Fig. 135.71, 136.72-73, 76

Gerasa: Baur 1938: 524, 526, 531 No. 17, 29, 49, Fig. 20,376. 21,382. 22,380; Meyer 1986: 263 Fig. 23h; Kehrberg 1986: 379, 381, Nos. 29, 35-38 Fig. 9,29. 35-38; Kehrberg 1998: 431; Shavei Zion: Barag 1967: 68-69, Nos. 21-22, Fig. 16,21-22.

17. en-Boqeq: Gichon 1993: 435 P1. 51,7-8, 60,28

Mezad Tamar: Erdmann 1977: 100, 112-114 Nos. 3-12 Pl. 1,3-7.

19. pers. comm. M. Grawehr.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

The area to the north and south of ez-Zantur with Swiss excavation sites EZ I, EZ III, and EZ IV. This area seems to have been residential.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Figure 3

Figure 3 Fig. 1

Fig. 1Kolb (1996: 51, 89; 2000: 238, 244; 2007: 157) attributes the destruction of the final occupation phase of al-Zantur I, Spatromisch II, to the 418/419 earthquake. As with many of the sites discussed above, this attribution is based primarily on numismatic finds, which decline sharply after the 4th century. Like most other regions of the Eastern Mediterranean, however, a lack of 5th century coinage is typical for sites in southern Jordan. For example, in their discussion of coins collected (and purchased) in Faynan, Kind et al. (2005: 188) note a decline in coin frequencies after about 420 AD. While this does not rule out an earthquake, many sites that seem to lack 5th century coinage were, on close inspection, occupied during the 5th century.A much more extensive discussion of dating evidence and interpretation can be found in Jones (2021). Some of his conclusions follow:

The discussion of the coin finds at al-Zantur I also gives cause for pause. The author states,An end of the settlement of ez Zantur after the earthquake of 419 AD could be harmonized well with the coin series, if not for the discovery of a small bronze coin of Marcianus, which was minted in the years 450-457 AD, discovered in the ash layer of Room 28, in the immediate vicinity of the remains of a kitchen inventory destroyed in an earthquake. ( Peter 1996: 92, translation I. Jones)Peter goes on to point out that, as the only mid-5th century coin at the site, it may be intrusive, which would allow for an earthquake destruction of Spatromisch II in 418/419. It is worth noting, however, the presence of 25 unidentifiable small bronze coins, 15 of which could be dated to the 4th-5th century ( Peter 1996: 98-100, nos 89-113). At least some of these are likely to be issues of the 5th century.

The discussion of the ceramic assemblage follows a similar pattern. The latest imports present at Spatromisch II are African Red Slip Ware (ARS) Forms 91C and 93B, both dated by Hayes (1972: 144, 148) to the 6th century (Schneider 1996: 40). Schneider (1996: 41) argues that Hayes's (1972) dating for the southern Levant is not entirely secure, and the presence of these forms in Spatromisch II is evidence for an early 5th century appearance. At production sites in Tunisia, however, neither form appears before the mid-5th century (Mackensen and Schneider 2002: 127-30). Likewise, Form 93 does not appear in Carthage until the 5th century, and first appears at Karanis, in the Fayyum, in the '420s CE or later' (Pollard 1998: 150). It is very unlikely that these forms appeared at al-Zantur earlier than they did in North Africa.

The `local' ceramic assemblage from Spatromisch II also contains several forms that postdate 419. Of note are several `Aqaba amphorae (Fellman Brogli 1996: 255, abb. 766-67), which date no earlier than the early 5th century (Parker 2013: 741); Magness's (1993: 206) Arched-Rim Basin Form 2, dating to the 6th-7th century (Fellman Brogli 1996: 260, abb. 790); and local interpretations of late 5th-6th century ARS, e.g. Forms 84 and 99 (Fellman Brogli 1996: 263, abb. 809-10). Gerber (2001: 361-62) also notes the similarity of the Spatromisch II ceramics to those apparently from 6th century phases at the Petra Church, although these contexts are not secure enough to make this comparison definitive.

Overall, the argument that Spatromisch II was destroyed in the 418/419 earthquake is rather circular. A lack of 5th century coinage is presented as evidence of this destruction, and this in turn is used to dismiss a mid-5th century coin as intrusive. If this is accepted, an earlier date must also be accepted for the otherwise mid-5th-6th century ceramics. When considering the evidence together, however, the more parsimonious explanation is that al-Zantur I was occupied, perhaps on a small scale or even intermittently, into the 6th century, which would bring al-Zantur I into line with other sites in Petra and the broader region with 363 and (late) 6th century destruction layers (see Table 1 - below).If an earthquake did cause the destruction of Spatromisch II, the best candidate would seem to be the Areopolis earthquake of c. 597 AD. This event is known primarily from an inscription that describes repairs performed in the year 492, of the calender of the province of Arabia (597/8 AD), following an earthquake, found by Zayadine (1971) at al-Rabba (ancient Areopolis), on the Karak Plateau (see also Ambraseys 2009: 216-17). Rucker and Niemi (2010: 101-03) have argued, primarily on the basis of the continued use of the Petra Church into the last decade of the 6th century, as evidenced by the Petra Papyri, that this earthquake is a better fit for the 6th century destructions in Petra previously attributed to the earthquake of 551. Accepting c. 597 as the date of the destruction of Spatromisch II is not critical to this paper's argument, but it follows from accepting the excavators' identification of an earthquake destruction and considering the events postdating 418/419 that could plausibly have affected southern Jordan. The possible events listed in the most recent Ambraseys (2009: 179, 199-203, 216-17) catalogue are the 502 Acre earthquake, which seems to have caused little damage inland; the 551 Beirut earthquake, an attribution Ambraseys explicitly rejects due to the lack of major destruction in Jerusalem; and the c. 597 Areopolis earthquake, which is the most likely possibility if the first two are ruled out. Of course, it is not possible to rule out destruction during a later earthquake, an otherwise unknown earthquake, or due to another cause entirely. Likewise, the destruction of the building does not necessarily coincide with the end of the occupation; it is entirely possible for an earthquake to destroy a previously abandoned building. Regardless of the exact date of the destruction, the evidence discussed above indicates that occupation continued into the 6th century.Table 1 - Summary of Archeoseismic Evidence from the 4th-6th centuries CE in Petra

- from Jones (2021)

Table 1

List of sites in and near Petra (other than al-Zantur) with destructions attributable to earthquakes in 363 AD and the 6th century

Jones (2021)

The ceramics from al-Zantur are an important chronological anchor in the Petra region, and it has generally been accepted that those from Spatromisch II date to the narrow period between 363 and 419. Expanding the dating of this phase to the late 4th-6th century, therefore, has implications for the dating of other sites in Petra, notably the Petra Church.

A critical review of the dating evidence from al-Zantur I Spatromisch II indicates that this destruction has been misdated by at least a century. Spatromisch II was occupied at least into the 6th century, and if an earthquake was responsible for its destruction, the Areopolis earthquake of c. 597 is a more likely candidate. This returns the emergence of the Negev wheel-made lamp to the 6th century, in line with essentially every other site where it occurs. This revision also has implications for the dating of the Petra Church, which relied heavily on comparison to the material from al-Zantur, and other sites in Petra. Taken on its own, the evidence indicates that the Petra Church was built in the early 6th century, rather than the mid-5th.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Walls | wall sections P1 and P2 between rooms 6 and 7 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

consolidation had to be undertaken to support wall sections P1 and P2 between rooms 6 and 7in EZ IV among other structural modifications. - Kolb (2002) |

|

| Broken Pottery | Room 15 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Fig. 14

Fig. 14EZ IV, room 15. Nabatean fine ware-ensemble in situ photo: D. Keller Kolb et al (1998) |

JW: Pottery may have fallen due to seismic activity. Kolb et al (1998) did not speculate that this pottery find was due to seismic activity |

|

Room 33 at the bronze workshop in EZ I

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Northern edge of the terrace EZ I and the slope north of it with the bronze workshop. Schematic plan with building phases and room numbers indicated. Isometric reconstructions of the building in its two phases drawings M. Grawehr Grawehr (2007) |

a thick and seemingly undisturbed destruction layer, sealed by the debris of the room's [Room 33] arched roofat the bronze workshop in EZ I - Grawehr (2007:399) |

|

|

various places | a moderately severe (not historically documented) earthquake that led to the structural repairs observed in various places and the renewal of a number of interior decorations- Kolb and Keller (2002:286) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Roof and Walls | Room 1 of EZ I

Figure 3

Figure 3General plan of the area excavation. Nabataean Masonry ridges rasterized. Stucky (1990) |

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Stucky (1990) |

Stucky (1990:270-271) reports a collapsed roof and masonry atop two skeletons in Room 1 of EZ I |

| Cracked Steps | Corridor 2 and steps leading up to room 5 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Fig. 10

Fig. 10EZ IV. Corridor 2 and steps leading up to room 5 (photo: D. Keller). Kolb et al (1998) |

JW: Steps appear to have cracked due to seismic activity or differential subsidence. Kolb et al (1998) did not speculate that the cracked steps may be due to seismic activity. |

| Broken Columns | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports broken columns in Room 6 of EZ IV | |

| Debris | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports debris in Room 6 of EZ IV | |

| Cracked Floor | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports a cracked flagstone floor under 6 carbonized wood beams in Room 6 of EZ IV | |

| Warped Walls | Room 14 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

The findings on the pavement indicate that the tubuli were broken out of wall AF by the tremors during the earthquake of 363 and thrown together on the floor with fragmented wall-decorationin Room 14 at EZ IV - Kolb and Keller (2000:362) |

|

|

northern and southern cellars (86-87/AP-AQ) of Room 17 as well as cracked stones in Room 7 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Kolb and Keller (2001:317-318) reported the presence of rubble due to what they purport to be the 363 CE earthquake in the northern and southern cellars (86-87/AP-AQ) of Room 17 as well as cracked stones in Room 7 in EZ IV. | |

|

Room 19 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

collapsing architectural members damaged the sandstone flagging mainly in the central and north-western sections of the pavementin Room 19 at EZ IV. ... A considerable deposit of earthquake debris covers a ca. 20-30 cm thick layer consisting of fragmented stucco decoration from the walls and columns. The latter context simultaneously seals the stratum of the last phase of occupation- Kolb and Keller (2000:358) |

|

| Destroyed Wall | Wall B in Room 37 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

extensive destruction of Wall B [in Room 37 of EZ IV] in the earthquake of 363- Kolb and Keller (2002:284) |

|

| Collapsed Walls - courses intact | Northern outer wall (PQ 90-91/AK) of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Figure 3

Figure 3EZ IV Main entrance, Courtyard 28 and collapsed facade seen from the northwest (photo D. Keller) Kolb and Keller (2001) |

Kolb and Keller (2001:312) reports that

the northern outer wall (PQ 90-91/AK), unlike the western and southern outer walls H and I, was largely destroyed during the earthquake of AD 363 |

| Structural Damage | Squares 88/AL-AM of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

it is impossible to reconstruct the original layout of the rooms in the eastern wing for the structures [Squares 88/AL-AM at EZ IV] had obviously been badly affected by the tremors of the earthquake of 363- Kolb and Keller (2000:364) |

|

| Debris | EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Due to the sudden destruction of the house on EZ IV during the earthquake of AD 363, excellent archaeological contexts are preserved as the debris of the collapsed walls sealed the finds underneath them.- Kolb and Keller (2002:290) |

|

| Destruction layer | Pool Complex | Bedal et al. (2007) reports a destruction layer composed of architectural elements of the pool complex of Ez-Zantur | |

| Debris | ? | The thick layer of mural and moulded stucco fragments on top of the household utensils of the fourth century proves beyond any doubt that the Nabataean decor remained on the walls up till the aforementioned natural catastrophe [363 CE]- Kolb et al (1998) |

Deformation Map

Deformation Map

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Walls (suggesting that original walls were displaced) | wall sections P1 and P2 between rooms 6 and 7 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

consolidation had to be undertaken to support wall sections P1 and P2 between rooms 6 and 7in EZ IV among other structural modifications. - Kolb (2002) |

VII+ | |

| Broken Pottery | Room 15 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Fig. 14

Fig. 14EZ IV, room 15. Nabatean fine ware-ensemble in situ photo: D. Keller Kolb et al (1998) |

JW: Pottery may have fallen due to seismic activity. Kolb et al (1998) did not speculate that this pottery find was due to seismic activity | VII+ |

|

Room 33 at the bronze workshop in EZ I

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Northern edge of the terrace EZ I and the slope north of it with the bronze workshop. Schematic plan with building phases and room numbers indicated. Isometric reconstructions of the building in its two phases drawings M. Grawehr Grawehr (2007) |

|

|

|

|

various places | a moderately severe (not historically documented) earthquake that led to the structural repairs observed in various places and the renewal of a number of interior decorations- Kolb and Keller, 2002:286 |

|

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Roof and Walls | Room 1 of EZ I

Figure 3

Figure 3General plan of the area excavation. Nabataean Masonry ridges rasterized. Stucky (1990) |

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Room 1 with Skeletons - a woman and child

Stucky (1990) |

Stucky (1990:270-271) reports a collapsed roof and masonry atop two skeletons in Room 1 of EZ I | VIII+ |

| Cracked Steps | Corridor 2 and steps leading up to room 5 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Fig. 10

Fig. 10EZ IV. Corridor 2 and steps leading up to room 5 (photo: D. Keller). Kolb et al (1998) |

JW: Steps appear to have cracked due to seismic activity or differential subsidence. Kolb et al (1998) did not speculate that the cracked steps may be due to seismic activity. | ? |

| Broken Columns | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports broken columns in Room 6 of EZ IV | VIII+ | |

| Debris | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports debris in Room 6 of EZ IV | ? | |

| Cracked Floor | Room 6 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) EZ IV Plan closeup

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.JW: closeup on rooms 6 and 7 - P sections in middle of the two rooms Kolb (2002) |

Kolb et al (1998) reports a cracked flagstone floor under 6 carbonized wood beams in Room 6 of EZ IV | ? | |

| Warped Walls | Room 14 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

The findings on the pavement indicate that the tubuli were broken out of wall AF by the tremors during the earthquake of 363 and thrown together on the floor with fragmented wall-decorationin Room 14 at EZ IV - Kolb and Keller (2000:362) |

VII+ | |

|

northern and southern cellars (86-87/AP-AQ) of Room 17 as well as cracked stones in Room 7 in EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Kolb and Keller (2001:317-318) reported the presence of rubble due to what they purport to be the 363 CE earthquake in the northern and southern cellars (86-87/AP-AQ) of Room 17 as well as cracked stones in Room 7 in EZ IV. |

|

|

|

Room 19 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

collapsing architectural members damaged the sandstone flagging mainly in the central and north-western sections of the pavementin Room 19 at EZ IV. ... A considerable deposit of earthquake debris covers a ca. 20-30 cm thick layer consisting of fragmented stucco decoration from the walls and columns. The latter context simultaneously seals the stratum of the last phase of occupation- Kolb and Keller (2000:358) |

|

|

| Destroyed Wall (collapsed wall) | Wall B in Room 37 of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

extensive destruction of Wall B [in Room 37 of EZ IV] in the earthquake of 363- Kolb and Keller (2002:284) |

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed Walls - courses intact | Northern outer wall (PQ 90-91/AK) of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Figure 3

Figure 3EZ IV Main entrance, Courtyard 28 and collapsed facade seen from the northwest (photo D. Keller) Kolb and Keller (2001) |

Kolb and Keller (2001:312) reports that

the northern outer wall (PQ 90-91/AK), unlike the western and southern outer walls H and I, was largely destroyed during the earthquake of AD 363 |

VIII+ |

| Structural Damage (displaced walls ?) | Squares 88/AL-AM of EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

it is impossible to reconstruct the original layout of the rooms in the eastern wing for the structures [Squares 88/AL-AM at EZ IV] had obviously been badly affected by the tremors of the earthquake of 363- Kolb and Keller (2000:364) |

VII+ | |

| Debris from collapsed walls | EZ IV EZ IV Plan

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

EZ IV. Schematic plan of the Nabataean mansion showing the structure's three main functional areas: the servants quarters, the public area and the private residence.

Kolb (2002) |

Due to the sudden destruction of the house on EZ IV during the earthquake of AD 363, excellent archaeological contexts are preserved as the debris of the collapsed walls sealed the finds underneath them.- Kolb and Keller (2002:290) |

VIII+ | |

| Destruction layer (collapsed walls) | Pool Complex | Bedal et al. (2007) reports a destruction layer composed of architectural elements of the pool complex of Ez-Zantur | VIII+ | |

| Debris (from collapsed walls) | ? | The thick layer of mural and moulded stucco fragments on top of the household utensils of the fourth century proves beyond any doubt that the Nabataean decor remained on the walls up till the aforementioned natural catastrophe [363 CE]- Kolb et al (1998) |

VIII+ |

Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017) AN ASSESSMENT AND RE-EXAMINATION OF THE AMERICAN EXPEDITION IN PETRA EXCAVATION IN THE RESIDENTIAL AREA (AREA I), 1974-1977: THE EARLY HOUSE AND RELATED CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGES

in The Socio-economic History and Material Culture of the Roman and Byzantine Near East. Essays in Honor of S. Thomas Parker. Edited by Walter D. Ward.

Grawehr M. (2007). Production of Bronze Works in the Nabataean Kingdom. SHAJ 9, 397-403.

Jones, I. W. N. (2021). "The southern Levantine earthquake of 418/419 AD and the archaeology of Byzantine Petra." Levant: 1-15.

Kolb, B. 1996 Die spätrömischen Bauten. Pp. 47-89 in A. Bignasca et al., Petra. Ez Zantur I. Er-gebnisse der Schwiezerisch-Liechtensteinischen Ausgrabungen 1988-1992.

Terra Archaeologica Bd. II. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

B. Kolb – D. Keller – Y. Gerber, 1998,

Swiss-Liechtenstein Excavations at az-Zantur in Petra 1997. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 42, 1998, 259–277.

B. Kolb – L. Gorgerat – M. Grawehr, 1999,

Swiss-Liechtenstein Excavations on az-Zantur in Petra 1998, ADAJ 43, 1999, 261–277.

Kolb B. and Keller D., 2000, Swiss-Liechtenstein Excavation at az-Zantur – Petra.

The Tenth Season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 44, 2000, 355–372.

Kolb, B., 2001, A Nabataean mansion at Petra: Some Reflections on its Architecture and Interior

Design. in: Bisheh, G. (ed), Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan VII, 2001, 437–445.

Kolb B. and Keller D., 2001, Swiss-Liechtenstein Excavation at az-Zantur – Petra.

The Eleventh Season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 45, 2001, 311–324.

Kolb B. and Keller D. (2002:286). Swiss-Liechtenstein Excavation at Az-Zantur / Petra: The Twelfth Season. ADAJ, 46, 279-294.

Kolb, B. 2007. Nabataean private architecture. In, Politis, K. D. (ed.),

The World of the Nabataeans

Schmid, S. (1995) Nabataean Fine Ware from Petra SHAJ V

Schmid, S.G. 2000. Petra ez Zantur II. Ergebnisse der Schweizerisch-Liechtensteinischen Ausgrabungen.

Teil I: Die Feinkeramik der Nabatäer. Typologie, Chronologie und kulturhistorische Hintergründe.

Terra Archaeologica vol. IV. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Schmid, S. G. (2000). Die Feinkeramik der Nabatäer. Typologie, Chronologie und kulturhistorische Hintergründe, Petra - Ez Zantur II 1 (Mainz 2000) -

from Ph.D. Dissertation - examines chronology of Nabatean Fineware