Petra - Temple of the Winged Lions

Temple of the Winged Lions

Temple of the Winged LionsBernard Gagnon - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Temple of the Winged Lions | English | |

| Temple of Site II | English |

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 14 January 2026

- from Wikipedia, Temple of the Winged Lions

The building derives its modern name from the distinctive capitals that crowned the columns surrounding the main podium. Instead of standard Corinthian capitals, these columns featured unique Winged Lion capitals, combining Hellenistic architectural forms with Nabataean symbolic imagery. The lions, rendered in high relief, likely held apotropaic and cultic significance and emphasised the sanctuary’s visual and ideological prominence within the urban landscape.

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- from Petra - Near the Temple of the Winged Lions Webpage - click link to open new tab

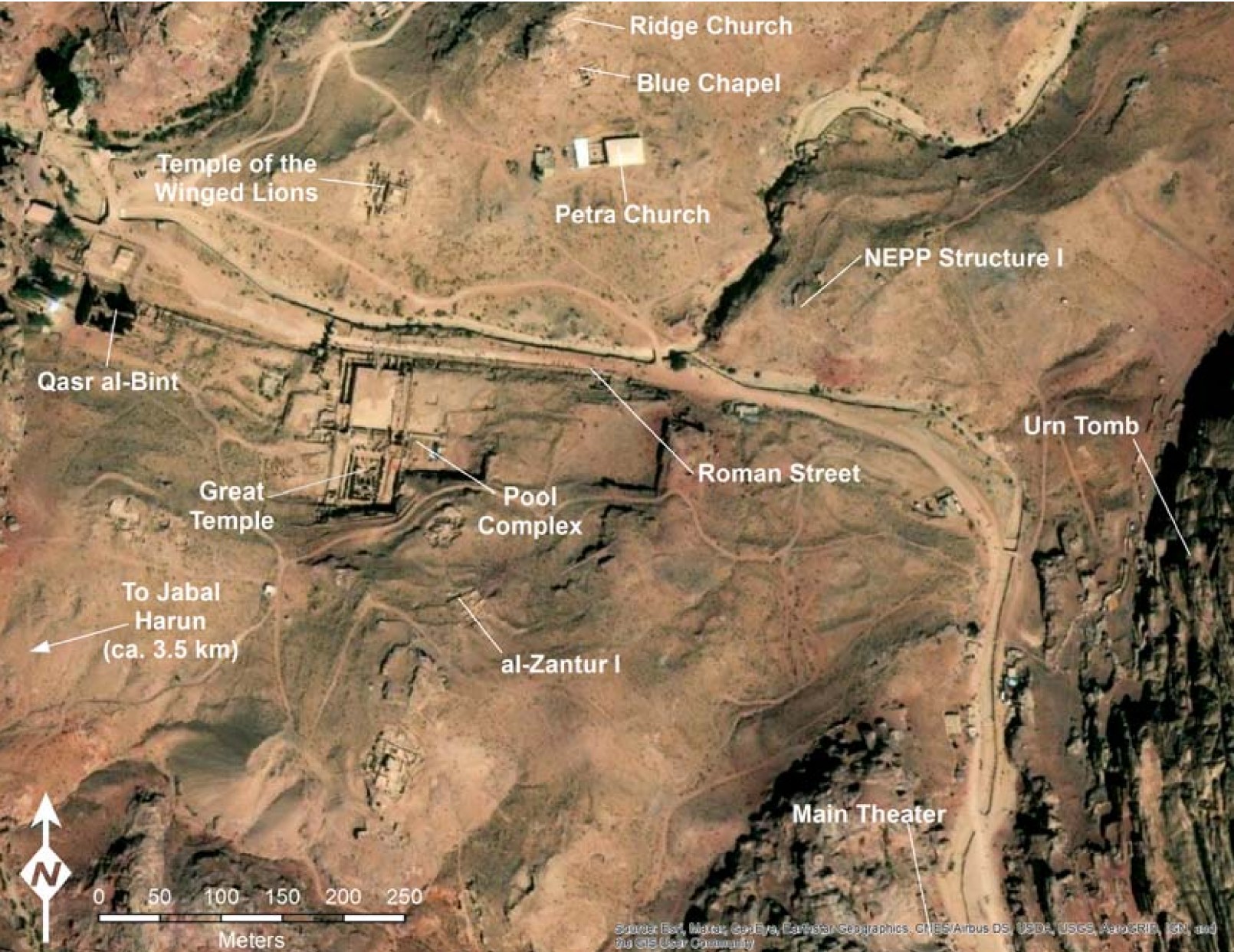

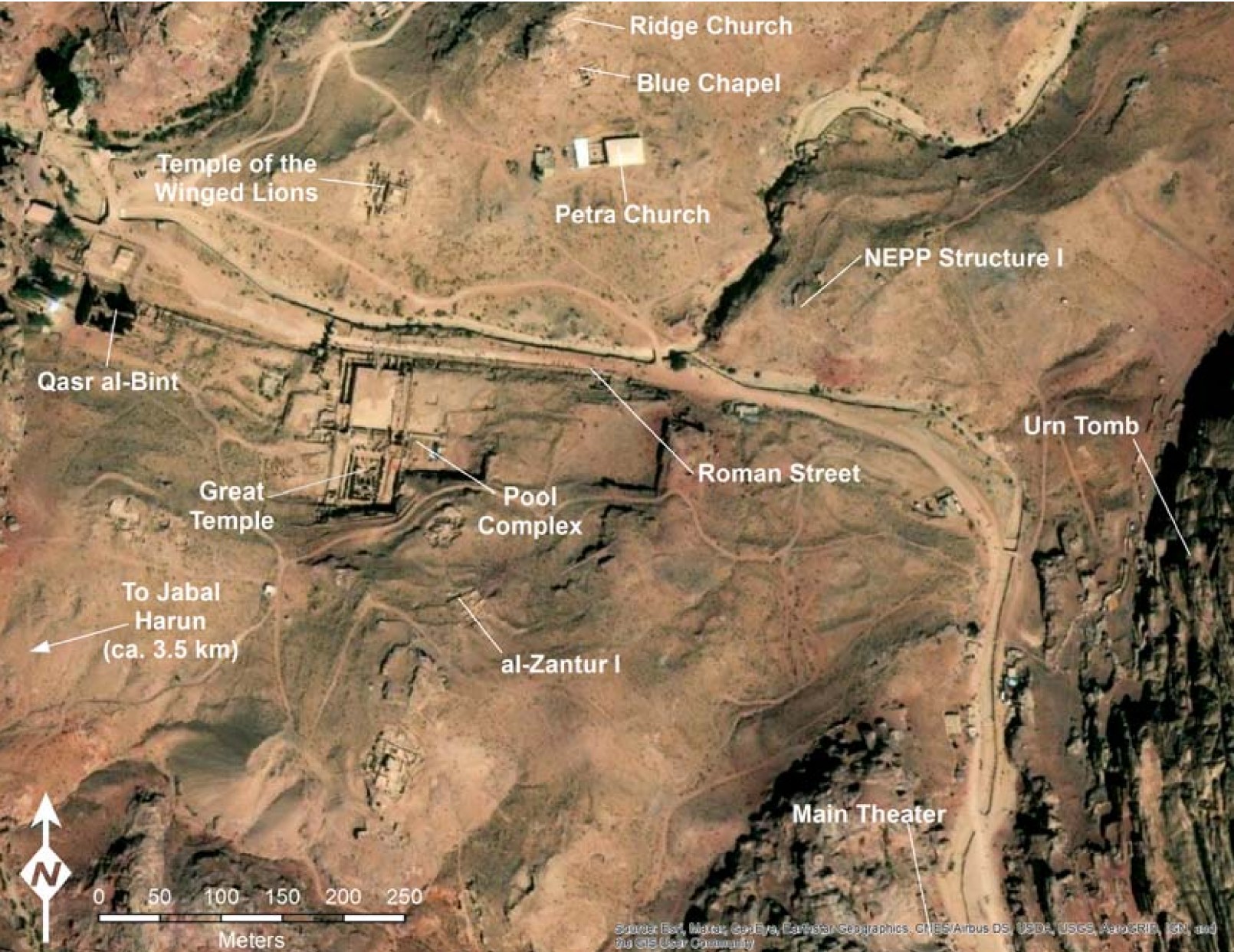

- Temple of the Winged Lions vicinity in Google Earth

- Location Map from Jones (2021)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of Petra with the locations of major excavations marked

Jones (2021)

Basemap: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, USDA FSA, USGS, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, and the GIS User Community

- Fig. 5 - Plan of the Temple

of the Winged Lions from Ward (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions

(Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative).

Ward (2016)

- Fig. 5 - Plan of the Temple

of the Winged Lions from Ward (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions

(Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative).

Ward (2016)

In 1973 and 1974, Hammond (1975) excavated the Temple of the Winged Lions which he labeled as the Temple of Site II. The phasing of the Temple of the Winged Lions and the domestic complex in Area I ~50 meters east of the Temple of the Winged Lions were similar and apparently reconciled in Hammond (1978). Hammond (1978) described the preliminary phasing below as follows:

Although analysis has not been completed3, preliminary field phasing4, strongly suggests some 20 phases, with correlations to the earthquake chronology established at the Main Theater in 1961-1962 and the adjacent temple site (Areas II-III) during the course of the present excavations. Ceramic and numismatic markers within this framework currently tend to strengthen the chronological conclusions offered below.Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017) re-evaluated the excavated materials from Area I and presented a revised chronology but not a table. This revised chronology affects the dating of supposed early 2nd century CE earthquake evidence and should likely apply to both the Temple of the Winged Lions and Area I near to the Temple of the Winged Lions.Footnotes3 Forthcoming as a Ph. D. dissertation, K. Russell, University of Utah

4 Dr. P. C. Hammond/K. Russell, 1978

Russell (1985) noted that during the 1976 excavations at Petra, a brass coin (sestertius) commemorating Trajan's

alimenta italiae endowment was uncovered on a floor-slab

next to several crushed unguentaria in a storage room of a collapsed house

[in Area I according to

Erickson-Gini, T. and C. Tuttle (2017)] of the early 2nd century.

Russell (1985) relates that Sestertii of this type were minted between 103 and 117

(

Robertson 1971: 57-59, and pl. 13, nos. 344, 350, 354). Unfortunately, the consulship was illegible in the

obverse inscription which would have allowed for more precise dating.

Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017)'s analysis suggests that, although early 2nd century CE earthquake evidence is present in Petra and other sites of the Nabateans,

some of Russell (1985)'s

phasing for Area I near the Temple of the Winged Lions was off by up to a couple of centuries. In particular, they suggest that

the abandonment of the Early House in Area I and abandoned hoards in rooms of the Temple of the Winged Lions complex were probably the result of an

epidemic that occurred sometime in the 3rd c. rather than the early 2nd c. earthquake as claimed by Russell

. They explained this as follows:

The primary issue concerning the Early House is the date and manner of its abandonment. An outstanding difficulty in Russell's phasing in Area I is the two hundred year period between the renovations that supposedly took place in the Early House in the early 2nd c. CE (Phase XVI) and the construction of the Middle House in the early 4th c. CE (Phase XII). This gap in the archaeological record is largely artificial and can be attributed to the fact that a single coin was used to date the critical ceramic assemblage found in Room 2 (antechamber) of the Early House (SU 176, 800, 803) to the very beginning of the 2nd c. Rather than its destruction by earthquake in the early 2nd c., the body of evidence points to its abandonment sometime in the early 3rd c. similar to sites along the Petra—Gaza road.Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017), however, do report that

an examination of the records and photographs of the western side of the Temple of the Winged Lions complexreveals

evidence of earthquake damage that precedes that of the 363 CE earthquake- evidence such as

blockage of doorways with architectural fragments that appear to have been derived from the temple, for instance in Area III.8 (SU 113; W2; Aug. 2, 1977), that were also used in the construction of the pavement in WII.1W.

Revetments adding support to walls ... photographed in Area III.7 (AEP 83900)

a hoard of vessels of the late 1st c. BCE and first half of the 1st c. CE ... discovered in the AEP 2000 season in a spot next to the eastern corridor in Area III.10 (SU 19)

- an assemblage whichincluded several plain fineware, carinated bowls that correspond to later forms of Schmid's Gruppe 5 dated to the second half of the 1st c. BCE (2000 AEP RI. 41), (2000: Abb. 41) together with early forms of his Gruppe 6 dated to the 1st c. CE (2000 AEP RI. 11), (2000: Abb. 50) and two early painted ware bowls (2000 AEP RI. 42) corresponding to Schmid's Dekorgruppe 2a (2000: Abbs. 80=81) dated to the end of the 1st c. BCE and early 1st c. CE

.

- Excerpts from Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017)

... The use of a revised ceramic chronology in dating these assemblages will undoubtedly prove to be controversial, however we believe that such a revision is long overdue and is in itself an important tool for the re-examination of the phasing of structures and occupational layers in Petra and other sites in the Provincia Arabia, the vast majority of which have been erroneously dated to the later 1st to early 2nd c. CE.

... In 1977, Russell prepared a tentative phasing of the stratigraphy in Area I. The final phasing prepared by him in 1978 indicates the presence of twenty archaeological phases (Phases XX—I) and the remains of successive domestic structures of the Early Roman (pre-annexation, i.e., the Roman annexation of Nabataea in 106 CE), Middle Roman (post-annexation) and Byzantine periods. He designated these structures the "Early House", the "Middle House", and the "Late House".

... The earliest archaeological material discovered in Area I, uncovered below the earliest architectural remains and in ancient falls, dates to the Hellenistic period. The latest material belongs to an overlying cemetery that Russell dated to the Late Byzantine or Early Islamic periods.

... As we shall see below, the abandonment of the Early House in Area I and abandoned hoards in rooms of the Temple of the Winged Lions complex were probably the result of an epidemic that occurred sometime in the 3rd c. rather than the early 2nd c. earthquake as claimed by Russell.

... EVIDENCE OF AN EARTHQUAKE EVENT IN THE EARLY SECOND CENTURY CE

Russell's misreading of the archaeological evidence led him to attribute the end of the occupation of the Early House in Phase XV to earthquake destruction that he dated to 113/114 CE based on the discovery of the single coin found in the antechamber, a brass sestertius commemorating Trajan's alimenta italiae endowment dated to the period between 103 and 117 CE, together with the hoard of unguentaria and other ceramic vessels (Russell, 1985:40-41). Although the Early House was not destroyed and abandoned by an earthquake in the early 2nd c., evidence of earthquake damage is discernible with the renovations that took place in its final occupation in Phase XVI.

... Subsequent research carried out in several sites64, including Petra itself, indicate that an early 2nd c. earthquake did indeed take place (Erickson-Gini 2010:47) 65. An examination of the records and photographs of the western side of the Temple of the Winged Lions complex also reveals evidence of earthquake damage that precedes that of the 363 CE earthquake. This evidence includes the blockage of doorways with architectural fragments that appear to have been derived from the temple, for instance in Area III.8 (SU 113; W2; Aug. 2, 1977), that were also used in the construction of the pavement in WII.1W. Revetments adding support to walls were photographed in Area III.7 (AEP 83900). In addition, a hoard of vessels of the late 1st c. BCE and first half of the 1st c. CE was discovered in the AEP 2000 season in a spot next to the eastern corridor in Area III.10 (SU 19). This assemblage of restorable vessels included several plain fineware, carinated bowls that correspond to later forms of Schmid's Gruppe 5 dated to the second half of the 1st c. BCE (2000 AEP RI. 41), (2000: Abb. 41) together with early forms of his Gruppe 6 dated to the 1st c. CE (2000 AEP RI. 11), (2000: Abb. 50) and two early painted ware bowls (2000 AEP RI. 42) corresponding to Schmid's Dekorgruppe 2a (2000: Abbs. 80=81) dated to the end of the 1st c. BCE and early 1st c. CE.66 In spite of the presence of these early vessels, the AEP 2000 season finds registries records nearly all of them as dating to 363 CE.

... Russell was correct in dating the early form of the Early House (Phase XVII) to the 1st c. ceramic vessels of that period

... The Early House was obviously renovated, prior to its final form in Phase XVI, similar to other buildings discovered in Petra. Some Nabataean communities, such as Mampsis and Oboda, underwent a wave of new construction in the newly-organized Roman Province of Arabia while sites such as 'En Rahel and 'En Yotvata were destroyed and never re-built. Renovations in wake of structural damage evident in structures in many sites in the years following the annexation, as well as the construction of new buildings, point to a widespread earthquake event in southern Transjordan and the Negev in the early 2nd c. CE. The event may have influenced or even prompted the Roman annexation that occurred soon afterwards. At Petra, the Early House was not destroyed at that time but rather it was renovated and occupied until the early 3rd c. when it was abandoned, possibly in the wake of an epidemic.

... Conclusions

The primary issue concerning the Early House is the date and manner of its abandonment. An outstanding difficulty in Russell's phasing in Area I is the two hundred year period between the renovations that supposedly took place in the Early House in the early 2nd c. CE (Phase XVI) and the construction of the Middle House in the early 4th c. CE (Phase XII). This gap in the archaeological record is largely artificial and can be attributed to the fact that a single coin was used to date the critical ceramic assemblage found in Room 2 (antechamber) of the Early House (SU 176, 800, 803) to the very beginning of the 2nd c. Rather than its destruction by earthquake in the early 2nd c., the body of evidence points to its abandonment sometime in the early 3rd c. similar to sites along the Petra—Gaza road.

64 Evidence of an earthquake at Petra in the late first or early 2nd c. CE has been uncovered by

- Kirkbride and Parr at Petra (Kirkbride 1960: 118-19; Parr 1960: 129

- Joukowsky and Basile 2001: 50) and more recently in the ez-Zantur excavations Kolb and Keller 2002: 286; Grawehr 2007: 399)

- Aqaba (Dolinka 2003: 30-32, Fig. 14)

- 'En Yotvata (Erickson-Gini 2012a)

- Moyat 'Awad and Shdar Ramon (Cohen 1982: 243-44; Erickson-Gini and Israel 2013: 45)

- 'En Rahel (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003)

- Mezad Mahmal (Erickson-Gini 2011)

- Mampsis (Negev 1971: 166; Erickson-Gini 2010: 47)

- Oboda (Erickson-Gini, in press)

- Horvat Hazaza (Erickson-Gini, in press).

65 The occurrence of an early 2nd c. earthquake has been disputed by S.G. Schmid who proposed that destruction contexts indicated in Nabataean sites were the result of Roman military actions in wake of the annexation of Nabataea in 106 CE (1997: 418-420).

66 A lamp in found in close proximity in SU 18 (2000 AEP RI.23) corresponds to Grawhr's Typ 3.D (75-125 CE), (2006: 293). A complete unguentarium of a type with a flat base like that found in the Nabataean fort at 'En Rahel was also present in SU 19 (2000 AEP RI.44).

Russell (1985) noted that during the 1976 excavations at Petra, a brass coin (sestertius) commemorating Trajan's

alimenta italiae endowment was uncovered on a floor-slab

next to several crushed unguentaria in a storage room of a collapsed house

[in Area I according to

Erickson-Gini, T. and C. Tuttle (2017)] of the early 2nd century.

Russell (1985) relates that Sestertii of this type were minted between 103 and 117

(

Robertson 1971: 57-59, and pl. 13, nos. 344, 350, 354). Unfortunately, the consulship was illegible in the

obverse inscription which would have allowed for more precise dating.

Coins of the last Nabataean king, Rabbel II (71- 106), have been noted in association with this destruction evidence

at Petra

(Kirkbride, 1960:118-119; Parr 1960: 129).

- from Russell (1985)

Both ancient textual documentation and archaeological evidence have been previously noted for an early 2nd century earthquake destruction in the study area. Unfortunately, the temporal and spatial dimensions of these separate bodies of data do not seem mutually supportive.

Textual Evidence. The principle ancient account used to document an early 2nd century earthquake in the study region is found within the Chronicon of Eusebius Pamphili (ca. 260-340). Unfortunately, the original form and contents of this work were not preserved, and it survived only through an Armenian translation and partly through a Latin adaptation by St. Jerome (Vasiliev 1958: 119). The relevant passage is rather terse. and may be translated as follows: "Nicopolis and Caesarea collapsed from an earthquake."* Migne's edition of the Chronicon (1844-64: 618) contains a marginal date of 130 for this event, although the narrative was placed at the end of the 226th Olympiad, which encompassed the years 125 through 128 (using a 776 B.C. base date; Bickerman 1974: 75-76).

Further documentation of this earthquake exists in the Chronographia of Elias of Nisibis, composed in Syriac ca. 1019: "There was an earthquake. and Nicopolis and Caesarea were overthrown" (1954: 42). This account forms part of the entry forA.G. 438, thus dating the event to 126/7.4 These narratives would seem to document an earthquake during the reign of Hadrian that affected the Palestinian littoral. However. N. Ambraseys (1985, personal communication) has alternatively suggested that these narratives document an earthquake in northeastern Anatolia in the province of Pontus. As such, the sites affected would have been [Neo]Caesarea (= Niksar) and Nikopolis (= Susehri), both important frontier centers in the early 2nd century. If correct, the use of these narratives to document an early 2nd century earthquake in the study area would be unwarranted.4

Indeed, some support for Ambraseys' suggestion exists in the archaeological evidence of early 2nd century structural damage or rebuilding in the study area, for this evidence would seem to indicate both a greater spatial extent of damage. and an earlier date of occurrence.

Archaeological Data. Early 2nd centuryC\ldence of structural damage or rebuilding has been noted at Caesarea (Fritsch and Ben-Dor 1961: 55). Karcz and Kafri 1978: 45; Toombs 1978: 228. 230). Jerash (Kraeling 1938: 47-48; Illife 1944: 1-3l. Heshbon Hesban (Mitchel 1980: 95-100). the Roman Garrison at Masada ( Yadin 1965 30. 118; 1967 45), Khirbet Tannur (Glueck 1965: 1381 ) Avdat (Negev 1961: 123, 125), Mampsis(Negev 1971: 166), Moje Awad and Mezad Sha 'ar Ramon on the Petra-Gaza road (Cohen 1982: 243-44), and Petra (Kirkbride 1960: 118-19; Parr 1960: 128-29; Hammond 1965: 33-35; 1977-78: 81-84). Coins of the last Nabataean king, Rabbel II (71- 106), have been noted in association with this destruction evidence at Petra (Kirkbride 1960: 118- 19; Parr 1960: 129), Moje Awad (Cohen 1982: 243), and Mezad Sha ar Ramon (Cohen 1982: 244). At Masada, a coin ostensibly struck at Tiberias in 99/100 was recovered from beneath the collapse debris of the bath house, while the latest coin in a horde found beneath the collapse debris of building VII ostensibly dated to 110/111 (Yadin 1965: 118-19; 1967: 45). At Avdat, an imperial coin struck at Alexandria and tentatively identified as Trajanic was apparently found in association with the collapse of the potter's workshop (Negev 1974: 24).

Further, during the 1976 excavations at Petra, a brass sestertius commemorating Trajan's alimenta italiae endowment was uncovered on a floor-slab next to several crushed unguentaria in a storage room of a collapsed house of the early 2nd century. The description of this sestertius is as follows:

OBV.: - TRAIANO AVG GER DAC-. Laureated bust, facing right, slight drapery on left shoulder.

REV.: S P Q R OPTIMO PRINCIPI. S C (left and right in field). ALIM ITAL in exergue. Annona (or Alimentatio?), draped, standing front, head left, holding two corn-ears downwards, and cornucopiae outwards. On left, below cornears, small male figure, togate, standing front, head right, holding roll.

SIZE: 31 mm

Sestertii of this type were minted between 103 and 117 (Robertson 1971: 57-59, and pl. 13, nos. 344, 350, 354). Unfortunately, the consulship was illegible in the obverse inscription; this would have allowed for a more precise dating.

Thus, while the early 2nd century destruction evidence archaeologically attested at Caesarea would seem to match the textual documentation contained in the Chronicon of Eusebius, the cumulative evidence of apparently contemporaneous structural damage or rebuilding in the study area stretches from Caesarea through Hesban and from Jerash through Petra. Further. no coins of Hadrian have yet been reported in association with these destructions.

Analysis and Synthesis. If, as proposed here, this archaeological evidence of early 2nd century structural damage and rebuilding indeed relates to a single catastrophic event, the most parsimonious explanation is that it reflects extensive earthquake damage. The evidence is simply too widespread to support an alternative explanation on the basis of civil turmoil or invasion (e.g., Negev 1966: 95, 1976a: 62, 1976b: 229-30). There is also sufficient evidence to suspect that Trajan himself may have provided funds for tne reconstruction of at least some of the cities damaged at this time.

At Petra, a monumental commemorative arch was dedicated to Trajan by the city late in 114 (Kirkbride 1960: 120), but the sections of the inscription that would have documented the reason for this dedication were not recovered. However, at Jerash, a similar civic dedication to Trajan was installed when a new north gate was constructed early in 115 (Kraeling 1938: 47-48; Welles 1938: 40I); here Trajan is termed the "savior and founder" of the city 5 (This and subsequent translations are the author's,except as noted). These civic dedications to Trajan may well reflect the imperial aid he supplied for reconstruction after a disastrous earthquake in 113 or 114.

The current lack of historical documentation for this proposed event may be primarily credited to Cassius Dio Cocceianus (ca. 155-post-229). Dio (1925: 392-465) failed to record either the earthquake ca. 106 in the province of Asia which damaged Elaea, Myrina, Cyme, and Pytanae (Eusebius Chronicon 1844-64: 606), or the earthquake ca. 122 in the province of Bithynia that damaged Nicomedia, Nicaea, and several other cities (Eusebius Chronicon 1844-64: 613). In fact, the only earthquake Dio did record during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian was that of 115 in Antioch (1925: 404-9), apparently because Trajan himself was nearly killed in it.

Eusebius, writing his Chronicon in the early 4th century, was probably well aware that his native Caesarea had been severely damaged by an earthquake some 200 years earlier, but had to base his account of this event on the only texts available to him which seemingly documented an earthquake in Palestine at approximately the right time.6

Although the Phase X destruction layer was initially misdated to the Crete earthquake of 365 CE, Hammond (1980) later acknowledged this as a mistake. The corrected correlation of the Phase X destruction layer would then be to the southern Cyril Quake of 363 CE. Jones (2021) noted that

Ward (2016: 144) has pointed out that the evidence for dating the major destruction to 363 is quite limited, although this is still the most reasonable date for this destruction.

Jones (2021) noted the following:

Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017: 144-45) note the lack of 6th century material at both the Temple of the Winged Lions and the residential complex in nearby Area I, although this may simply indicate that the area was abandoned prior to its destruction in the late 6th century.

- from Hammond (1975:11-12)

The destruction material isolated here is significant both for the reconstruction of the original structure and for estimating the force of the obvious earthquake which caused its fall.

The former aspect will be considered in detail when Phase XV is discussed below. However, it may be noted here, since it has relevance to the latter question, that much of the building was intact at the point of this destruction—with columns still standing, some capitals and cornices still in place, considerable plaster decoration still in situ, intercolumnar or gate (?) arches (?) still standing, and possibly even sections of the roof (?) still in place. With this earthquake all of the superstructure was tumbled that had survived the earlier earth tremor which had already partially—but only partially— demolished the structure. Hence a relative degree of severity between the two earthquakes may be postulated— precisely as was the case with the Main Theater excavated in 1961–1962 (Hammond, The Excavation of the Main Theater…, 1965:55–65).

As a consequence, it is suggested that the same chronology be postulated for this structure, in terms of destruction, as was established for the Theater: namely that this phase be dated to A.D. 746/748, the second and most severe of the two earthquakes involved.

The overlying recovered materials of the higher phases do not conflict at all with this dating and it can plausibly fit the peculiarities of ceramic materials recovered—i.e. early in the Early Islamic period wherein local potters (“Byzantine”) continued to produce familiar wares and types without yet evidencing “Islamic” influences.

This fall phase was the richest in recovered architectural materials per se, and the specifics of content greatly assist in suggesting possible reconstructions. This quantity of material also attests to the force of the earth tremors which finally brought down the super-structure of the building, as was also the case at the Main Theater.

Hammond (1975) discussed this archaeoseismic evidence as follows:

There can be no question that the architectural debris covered by the silting of the previous phase and resting on the surface of the next phase below represents anything but the final destruction of the building of Phase XV. The direction of this fall ran from the Northwest to the Southeast consistently throughout the excavated areas of the previous phase and resting on the surface of the next phase below represents anything but the final destruction of the building of Phase XV. The direction of this fall ran from the Northwest to the Southeast consistently throughout the excavated areas.

... much of the building was intact at the point of this destruction --with columns still standing, some capitals and cornices still in place, considerable plaster decoration still in situ, intercolumnar or gate (?) arches (?) still standing, and possibly even sections of the roof (?) still in place. With this earthquake all of the superstructure was tumbled that had survived the earlier earth tremor which had already partially - but only partially - demolished the structure.

... it is suggested that the same chronology be postulated for this structure, in terms of destruction, as was established for the Theater: namely that this phase be dated to A. D. 746/748, the second and most severe of the two earthquakes involved. The overlying recovered materials of the higher phases do not conflict at all with this dating and it can plausibly fit the peculiarities of ceramic materials recovered -- i. e. early in the Early Islamic period wherein local potters ("Byzantine") continued to produce familiar wares and types without yet evidencing "Islamic" influences.

... This fall phase was the richest in recovered architectural materials per se, and the specifics of content greatly assist in suggesting possible reconstructions. This quantity of material also attests to the force of the earth tremors which finally brought down the super-structure of the building, as was also the case at the Main Theater.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debris | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

architectural fall debris- Hammond (1975) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

some capitals dislodged, along with cornice-carrying blocks, wall members, and other structural members- Hammond (1975) |

|

| Rotated and Displaced Masonry Blocks in walls and drums in columns | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

|

|

| Displaced Walls | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

a great deal of internal plastered decoration, including undercoatings, was also dislodged- Hammond (1975) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

much of the building was intact at the point of this destruction --with columns still standing, some capitals and cornices still in place, considerable plaster decoration still in situ, intercolumnar or gate (?) arches (?) still standing, and possibly even sections of the roof (?) still in place. With this earthquake all of the superstructure was tumbled that had survived the earlier earth tremor which had already partially - but only partially - demolished the structure.- Hammond (1975) |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

some capitals dislodged, along with cornice-carrying blocks, wall members, and other structural members- Hammond (1975) |

VIII+ | |

| Rotated and Displaced Masonry Blocks in walls and drums in columns | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

|

VIII+ | |

| Displaced Walls | Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

a great deal of internal plastered decoration, including undercoatings, was also dislodged- Hammond (1975) |

VII+ |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Temple of the Winged Lions

Figure 5

Figure 5Plan of the Temple of the Winged Lions (Plan: Qutaiba Dasouqi; courtesy of Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Initiative). Ward (2016) |

much of the building was intact at the point of this destruction --with columns still standing, some capitals and cornices still in place, considerable plaster decoration still in situ, intercolumnar or gate (?) arches (?) still standing, and possibly even sections of the roof (?) still in place. With this earthquake all of the superstructure was tumbled that had survived the earlier earth tremor which had already partially - but only partially - demolished the structure.- Hammond (1975) |

|

Erickson-Gini, T. and C. Tuttle (2017). An Assessment and Re-examination of the American Expedition in Petra Excavation in the Residential Area (Area I), 1974–1977: The Early House and Related Ceramic Assemblages: 91-150.

Hammond, P. C. (1975). "Survey and Excavation at Petra, 1973-1974." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 20 20.

Hammond, P. C. (1978). "Excavations at Petra: 1975-1977

" Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 22.

Hammond, P. C. (1996). The Temple of the Winged Lions, Petra, Jordan, 1973-1990, Petra Pub.

Jones, I. W. N. (2021).

"The southern Levantine earthquake of 418/419 AD and the archaeology of Byzantine Petra." Levant: 1-15.

Kirkbride, D. (1960:118-119). "A Short Account of the Excavations at Petra in 1955-56." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan: 4-5.

Parr, Peter 1959 Rock Engravings from Petra. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 91, pp. 106-108.

Ward, W.D. (2016). The 363 Earthquake and the End of Public Paganism in the Southern Transjordan. Journal of Late Antiquity 9(1), 132-170.

Temple of the Winged Lions Publication Project

Temple of the Winged Lions - ACOR

Photos of the Temple of Winged Lions at Manar al-Athar (Oxford University

Facebook page for Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Project

Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Project at ACOR

About the Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Resource Management Project Initiative at ACOR