Tiberias - Southern Gate

Ferrario et al (2020) report that the Southern Gate, located ca. 200 m S of the Theatre, was originally built during the

Early Roman period as a free-standing structure

, in Byzantine times, the gate was incorporated in

the newly-built city wall, and in Umayyad-to-Fatimid periods other buildings and retaining walls were constructed at the site

(Hartal et al., 2010)

.

- from Hartal et al. (2010)

- from Tiberias - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 4 Map of ancient Tiberias

from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Map of ancient Tiberias (modified after Hirschfeld & Gutfeld, 2008) with indication of the inferred lineament and trench position.

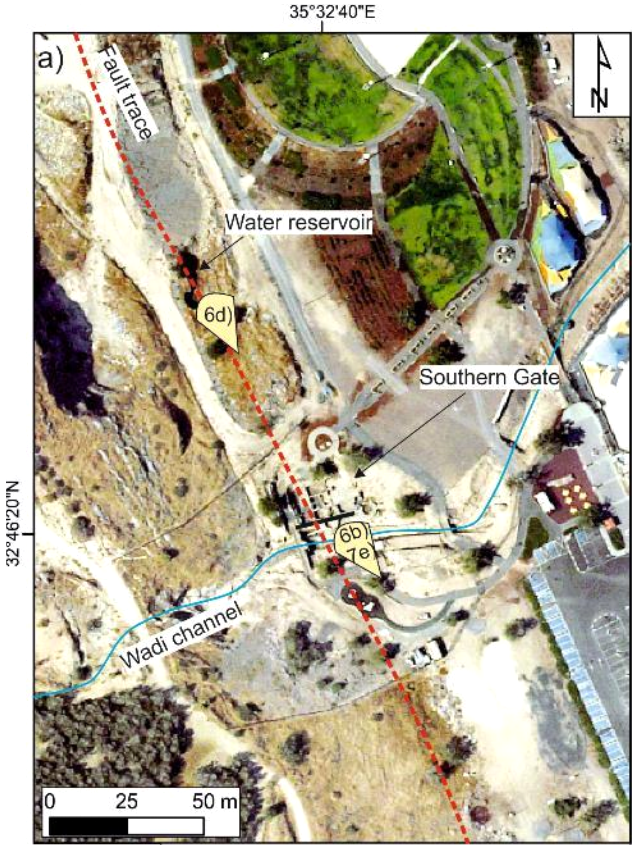

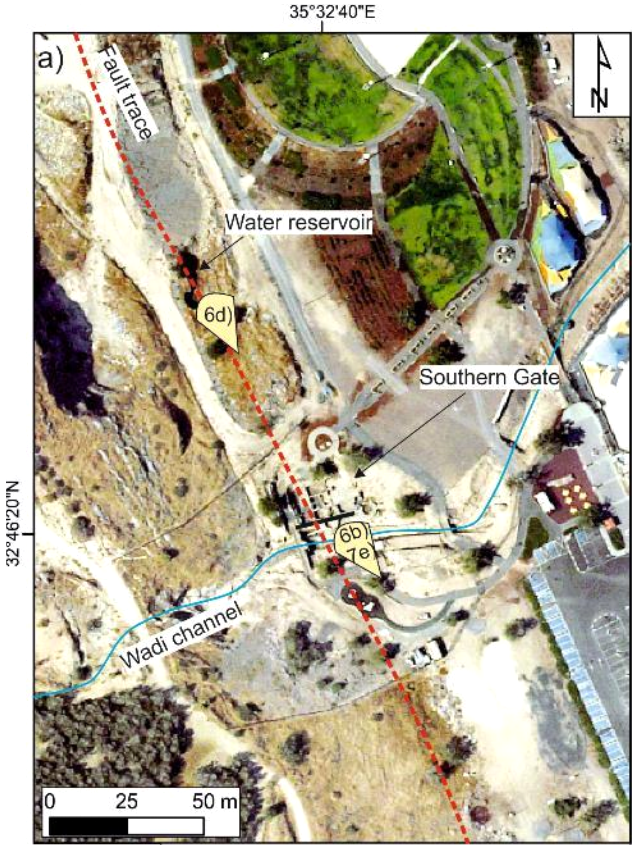

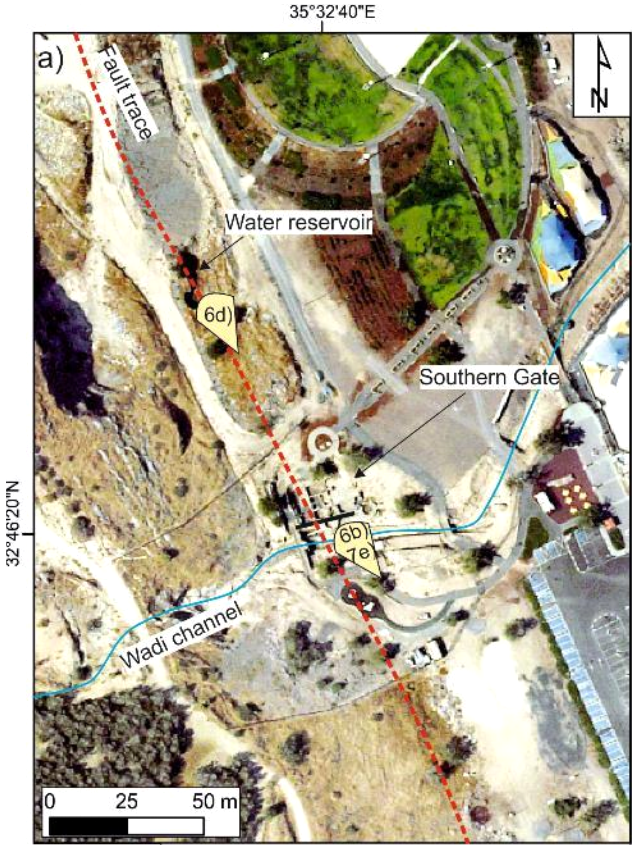

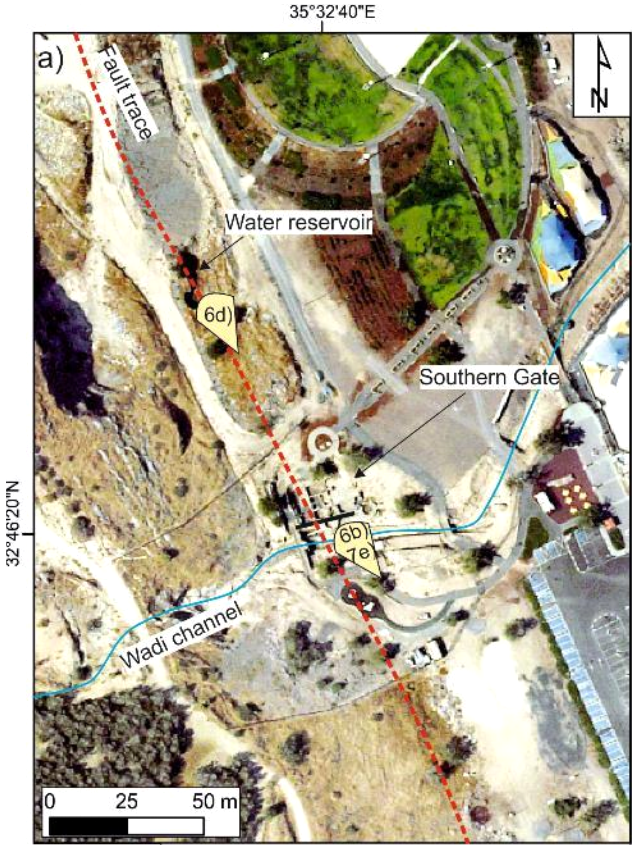

Ferrario et al (2015) - Fig. 6a Map of Southern

Gate and water reservoir from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 6a

Figure 6a

Map of the Southern Gate and water reservoir sites, ca. 200 m S of the Theatre, along the Jordan Valley Western Boundary (JVWB) Fault strike, with indication of picture view angles and trace of total station profile. Fault trace is marked by red dashed line

Ferrario et al (2020)

- Fig. 1 Aerial view of the

southern gate and surroundings from Hartal (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the excavation area

Hartal (2010) - Fig. B Roman Gate and

courtyard-house of the Fatimid period from Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Figure B

Figure B

Roman Gate and courtyard-house of the Fatimid period abutting the west tower at Berko Park

Photo by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project.

Cytryn-Silverman (2015) - The Southern Gate in Tiberias in Google Earth

- The Southern Gate in Tiberias on govmap.gov.il

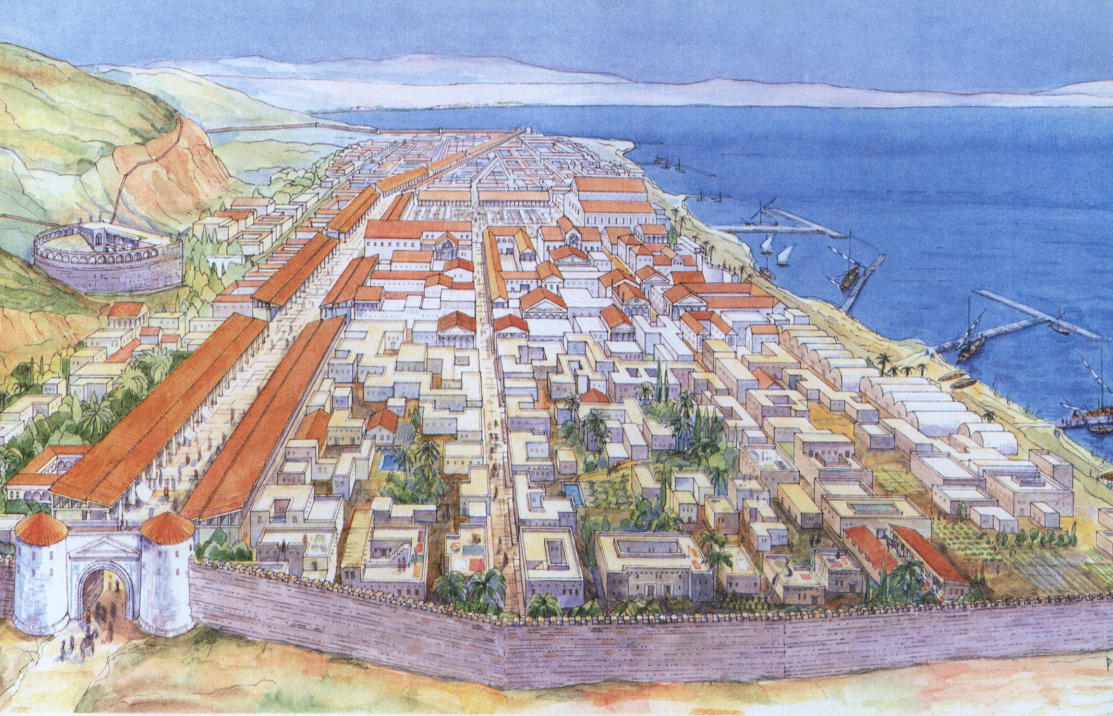

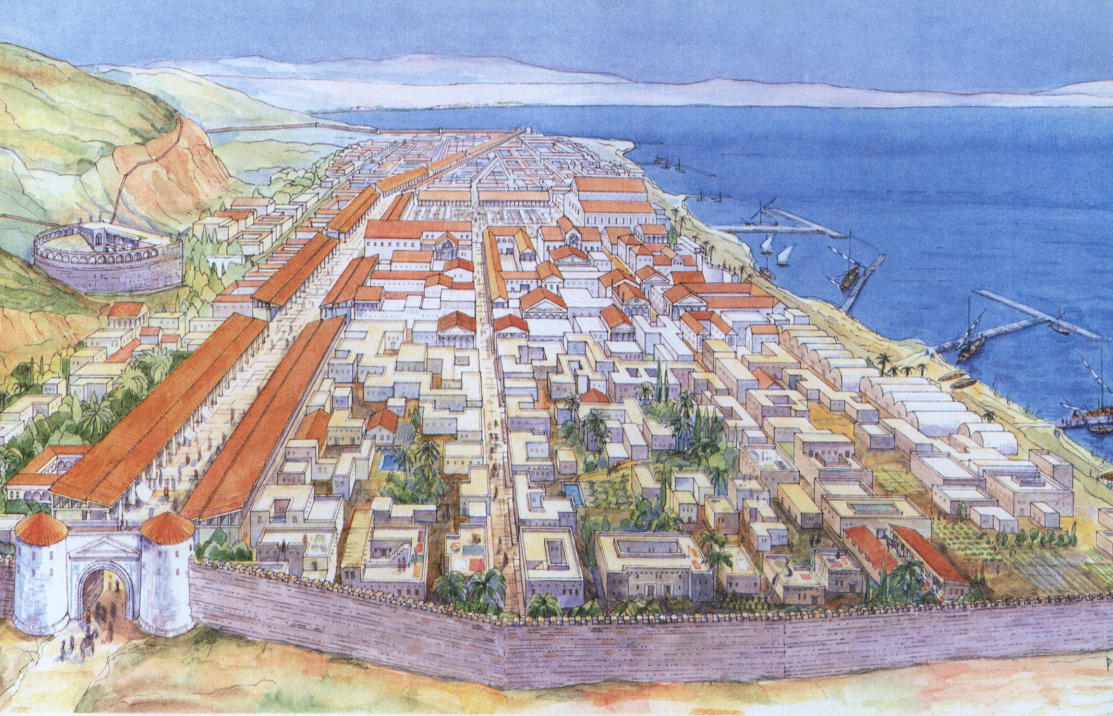

- Fig. 14 Proposed reconstruction

of the ancient city of Tiberias from Hirschfeld and Galor (2007) and Atrash (2012)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Proposed reconstruction of the ancient city of Tiberias, looking north

(drawn by Dov Porotzky)

Caption from Hirschfeld and Galor (2007) and image from Atrash (2012)

- from Hartal et al. (2010)

| Period | Date Range (CE) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Roman |

Description

The excavation clarified that the gate was constructed on a stone base, at the top of a deep channel’s bank (Fig. 2).

The southern wall of the base was built to a great height (in excess of 2.8 m), owing to the depth of the channel.

This wall consisted of six courses of roughly hewn stones bonded with gray mortar, which were set on a two-level

stepped foundation. The eastern wall of the base was built in a similar manner; however, it was not as high toward

the north, in accordance with the depth of the channel. The western wall of the base curved in keeping with the

wall of the western tower. Only a small portion of the western wall was exposed because of later construction above it. |

|

| Byzantine |

Description

The area south of the gate also laid outside the city precincts in this period. The gate continued to be used

with minor changes and it seems that the vault to its south was used as well. The most important change in this

period was the construction of the city wall, in which the gate was incorporated. The section of the city wall

exposed in the excavation was part of a long wall that began at the shore of the Kinneret in the northeast,

continued beneath the Jordan River Hotel toward the ridge west of Tiberias, encircled Mount Berenice, descended

to the region of the gate and returned to the Kinneret. It appears that this city wall was founded during the

reign of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century CE (Procopius, On Buildings V, 9, 21). The wall encompassed an

extensive area in the Byzantine period; however, it is known from excavations conducted in different parts of

Tiberias that many sections of this area were uninhabited and the city itself was significantly smaller than the walled-in area. |

|

| Umayyad |

Description

Construction outside the gate had begun in this period. West of the gate and c. 1.9 m south of the city wall,

three columns were discovered, 2.7 m apart (see Fig. 5). They were preserved one–two column drums high and

were set on plain bases. A layer of soil, which contained a large amount of ash and potsherds from the Umayyad

period, abutted the columns. A wall built next to the columns in the Abbasid period disturbed the remains

dating to the Umayyad period. Nevertheless, it seems that the columns were not part of a building; rather

they were placed parallel to the city wall, as part of a promenade that ran along the wadi channel. |

|

| Abbasid |

Description

The city of Tiberias expanded greatly during this period and the gate no longer served its original function,

although the structure continued to be used. Buildings whose walls were founded on vaults and retaining walls

were constructed on either side of the wadi channel. A new vault, used as a bridge, was built on the middle

part of the vault remains from the Roman period, which had been destroyed in the earthquake (Figs. 4, 10).

The vault was apparently built of the rubble taken from the ruinous vault of the Roman period, but the

quality of its construction was poor. The sides of the vault from the Abbasid period sloped more steeply

than those of the vault from the Roman period because a thick layer of sediment had accumulated in the

wadi channel and it was therefore necessary to raise the vault, which caused the bridge to be c. 1 m

higher than the gate. The bridge was paved with basalt flagstones (Fig. 11). The road on either side

of the bridge was unpaved. East of the bridge, in the area where the Roman-period vault had stood, three arches

of ashlars were built (Fig. 12). One of the arches was built on a pillar consisting of a column drum topped

with an inverted base of a column. The columns probably supported a floor that was laid on wooden beams and

was used as a plaza east of the bridge. A vault (length 12 m; Fig. 13), built of ashlars and roughly hewn fieldstones,

was just to the west of the bridge. The walls discovered north of the wadi channel indicate that a building was probably

constructed above the vault, which facilitated the flow of water in the channel. Alluvium that contained potsherds from

the Abbasid period had built up inside the vault. West of the vault and on the northern bank of the channel, a structure

that was supported on the city wall and its southern wall extended down, as far as the bottom of the channel (Fig. 6), was

built. Remains of other buildings were discovered on the southern bank of the channel. |

|

| Fatimid |

Description

The complex from the Fatimid period was a direct continuation of the Abbasid-period construction.

Tiberias continued to prosper and remains from this period were discovered almost everywhere in the

city. The principal change in the excavation area was the destruction of the vault from the Abbasid period. |

| Stratum | Period | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Late Fatimid | 11th century CE | construction above the collapse caused by an earthquake (in 1033 CE?) |

| II | Early Fatimid | 9th - 10th centuries CE | continued use of the street with shops. |

| III | Abbasid | 8th - 9th centuries CE | a row of shops, the basilica building was renovated. |

| IV | Byzantine–Umayyad | 5th - 7th centuries CE | the eastern wing was added to the basilica building; the paved street; destruction was caused by the earthquake in 749 CE. |

| V | Late Roman | 4th century CE | construction of the basilica complex, as well as the city’s institutions, i. e., the bathhouse and the covered market place. |

| VI | Roman | 2nd - 3rd centuries CE | establishment of the Hadrianeum in the second century CE (temple dedicated to Hadrian that was never completed) and industrial installations; the paving of the cardo and the city’s infrastructure. |

| VII | Early Roman | 1st century CE | founding of Tiberias, construction of the palace with the marble floor on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, opus sectile, fresco. |

| VIII | Hellenistic | 1st - 2nd centuries BCE | fragments of typical pottery vessels (fish plates, Megarian bowls). |

Ferrario et al (2020) measured 46 cm. of vertical throw across a warped Byzantine wall a bit west

of the Southern Gate. They inferred an approximately N-S fault from this warping. Just east of the warped Byzantine wall and slightly west of the southern gate,

Hartal et al. (2010) uncovered 3 stranded columns which were identified as Umayyad

based on a large amount of ash and potsherds from the Umayyad period

in a soil layer which abutted the columns. The columns were presumed to be part of a vault

which ran west of the gate. Hartal et al. (2010) suggested that the vault collapsed

during the 749 CE earthquake (one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes).

With Hartal et al. (2010) reporting that the Byzantine wall was constructed the 6th century CE1

and Hartal et al. (2010) dating the stranded columns from the presumed vault collapse to the

Umayyad period, a terminus post quem of 661 CE can be established. Abbasid constructions uncovered by

Hartal et al. (2010) on top of the vault provides a terminus ante quem

of sometime in the 10th century CE - probably significantly earlier.

1 Ferrario et al (2020) reports that the Byzantine wall was

archaeologically dated at ca. 530 CE

however, absent extremely fortuitous coin evidence (which isn't reported), such a precise date seems implausible and it was likely historically dated

by archaeologists. Hartal et al. (2010) reports that it appears that this city wall was

founded during the reign of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century CE (Procopius, On Buildings V, 9, 21)

.

Justinian I ruled from 527-565 CE.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warped and Folded Wall | Byzantine Wall - under the wood bridge

Roman Gate with warped Byzantine wall area highlighted in red

Roman Gate with warped Byzantine wall area highlighted in redPhoto by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project. Modified by JW from Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Figure 6 b

Figure 6 bview of the Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate site Ferrario et al (2020) |

Figure 6 c

Figure 6 cdetail of the warped Byzantine wall. The wooded frame, holding the pedestrian bridge, is situated above the fault line. The dashed black line marks a down throw of an originally horizontal datum Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7a

Figure 7aJW: Topographic Profile across the southern Gate. View from the N. Plotted on a vertical scale with vertical exaggeration of ~4x. Only the Southern gate profile is shown in this extraction. Modified by JW from Ferrario et al (2020) |

|

| Vault Collapse | west of south gate, south of the city wall, and north of the wadi

Roman Gate Area with area of vault collapse highlighted in pink

Roman Gate Area with area of vault collapse highlighted in pinkPhoto by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project. Modified by JW from Cytryn-Silverman (2015) |

Figure 5

Figure 5The inside of the city wall from the Byzantine period, looking north (in front of the wall, columns from the Umayyad period). Hartal et al. (2010) |

|

- Fig. 6a Map of Southern

Gate and water reservoir from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 6a

Figure 6a

Map of the Southern Gate and water reservoir sites, ca. 200 m S of the Theatre, along the Jordan Valley Western Boundary (JVWB) Fault strike, with indication of picture view angles and trace of total station profile. Fault trace is marked by red dashed line

Ferrario et al (2020) - Fig. B Roman Gate and

courtyard-house of the Fatimid period from Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Figure B

Figure B

Roman Gate and courtyard-house of the Fatimid period abutting the west tower at Berko Park

Photo by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project.

Cytryn-Silverman (2015) - Fig. 6b Annotated Photo of

Southern Gate from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 6 b

Figure 6 b

view of the Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate site

Ferrario et al (2020) - Fig. 6c Warping of Byzantine

wall from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 6 c

Figure 6 c

detail of the warped Byzantine wall. The wooded frame, holding the pedestrian bridge, is situated above the fault line. The dashed black line marks a down throw of an originally horizontal datum

Ferrario et al (2020) - Fig. 7 a-e Total Station

profiles of sites in Ancient Tiberias from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7

Figure 7

a) Topographic profiles obtained with a total station showing the vertical displacement across the studied fault at Tiberias Theatre and the Southern Gate. Each profile is plotted on a relative vertical scale with a vertical exaggeration of ca. 4x

b-e) photos of the measured points at Theatre (b-d) and Southern Gate (e), colored dots represent shooting points.

Ferrario et al (2020) - Fig. 7 e Total Station

profile of the Southern Gate from Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7e) photo of the measured points at the Southern Gate, colored dots represent shooting points

Figure 7e) photo of the measured points at the Southern Gate, colored dots represent shooting points

Ferrario et al (2020)

The Southern Gate is built on a bedrock (Cretaceous limestone), which outcrops at the base of the wadi channel which runs in a general E-W direction within the site. Displacement at the Southern Gate is represented by warping of a Byzantine E-W wall, archaeologically dated at ca. 530 CE1 (Fig. 6 b

Figure 6 b) view of the Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate site

Figure 6 b) view of the Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate site

Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 6 c) detail of the warped Byzantine wall. The wooded frame, holding the

pedestrian bridge, is situated above the fault line. The dashed black line marks a down throw of

an originally horizontal datum

Figure 6 c) detail of the warped Byzantine wall. The wooded frame, holding the

pedestrian bridge, is situated above the fault line. The dashed black line marks a down throw of

an originally horizontal datum

Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7

Figure 7a) Topographic profiles obtained with a total station showing the vertical displacement across the studied fault at Tiberias Theatre and the Southern Gate. Each profile is plotted on a relative vertical scale with a vertical exaggeration of ca. 4x

b-e) photos of the measured points at Theatre (b-d) and Southern Gate (e), colored dots represent shooting points.

Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7e) photo of the measured points at the Southern Gate, colored dots represent shooting points

Figure 7e) photo of the measured points at the Southern Gate, colored dots represent shooting points

Ferrario et al (2020)

1 Ferrario et al (2020) reports that the Byzantine wall was

archaeologically dated at ca. 530 CE

however, absent extremely fortuitous coin evidence (which isn't reported), such a precise date seems implausible and it was likely historically dated

by archaeologists. Hartal et al. (2010) reports that it appears that this city wall was

founded during the reign of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century CE (Procopius, On Buildings V, 9, 21)

.

Justinian I ruled from 527-565 CE.

- Modified by JW from Fig. B of Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. B of Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warped and Folded Wall | Byzantine Wall - under the wood bridge

Roman Gate with warped Byzantine wall area highlighted in red

Roman Gate with warped Byzantine wall area highlighted in redPhoto by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project. Modified by JW from Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Figure 6 b

Figure 6 bview of the Byzantine wall at the Southern Gate site Ferrario et al (2020) |

Figure 6 c

Figure 6 cdetail of the warped Byzantine wall. The wooded frame, holding the pedestrian bridge, is situated above the fault line. The dashed black line marks a down throw of an originally horizontal datum Ferrario et al (2020)

Figure 7a

Figure 7aJW: Topographic Profile across the southern Gate. View from the N. Plotted on a vertical scale with vertical exaggeration of ~4x. Only the Southern gate profile is shown in this extraction. Modified by JW from Ferrario et al (2020) |

|

VII+ |

| Vault Collapse | west of south gate, south of the city wall, and north of the wadi

Roman Gate Area with area of vault collapse highlighted in pink

Roman Gate Area with area of vault collapse highlighted in pinkPhoto by David Silverman, The New Tiberias Excavation Project. Modified by JW from Cytryn-Silverman (2015) |

Figure 5

Figure 5The inside of the city wall from the Byzantine period, looking north (in front of the wall, columns from the Umayyad period). Hartal et al. (2010) |

|

VIII+ |

Cytryn-Silverman, K, 2015, “Tiberias, from its foundation to the early Islamic period,”

in Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods Volume 2: The Archaeological Record from Galilean Cities,

Towns, and Villages, edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange, Minneapolis, 2015, pp.186-210.

Ferrario, M. F., et al. (2020). "The mid-8th century CE surface faulting along the

Dead Sea Fault at Tiberias (Sea of Galilee, Israel)." Tectonics 39(9).

Hartal, M., Dalali-Amos, E., and Hilman, A., 2010, Preliminary report on the excavations at Tiberias.

Hadashot Arkheologiyot v. 128

Procopius Of the Buildings of Justinian trans. Aubrey Stewart - open access at project gutenberg

Procopius Of the Buildings of Justinian trans. Henry Bronson Dewing - open access at project ToposText

Procopius reports in Book V Chapter IX of On the Buildings of Justinian

(trans. Aubrey Stewart - Project Gutenberg) that

Justinian I built the wall of Tiberias

. In the

version of this text translated by Henry Bronson Dewing (available at Topos Text), a margin note dates this "event" to 550 CE.

Justinian I ruled from 527-565 CE.