Jerash - Umayyad Mosque

Figure 5

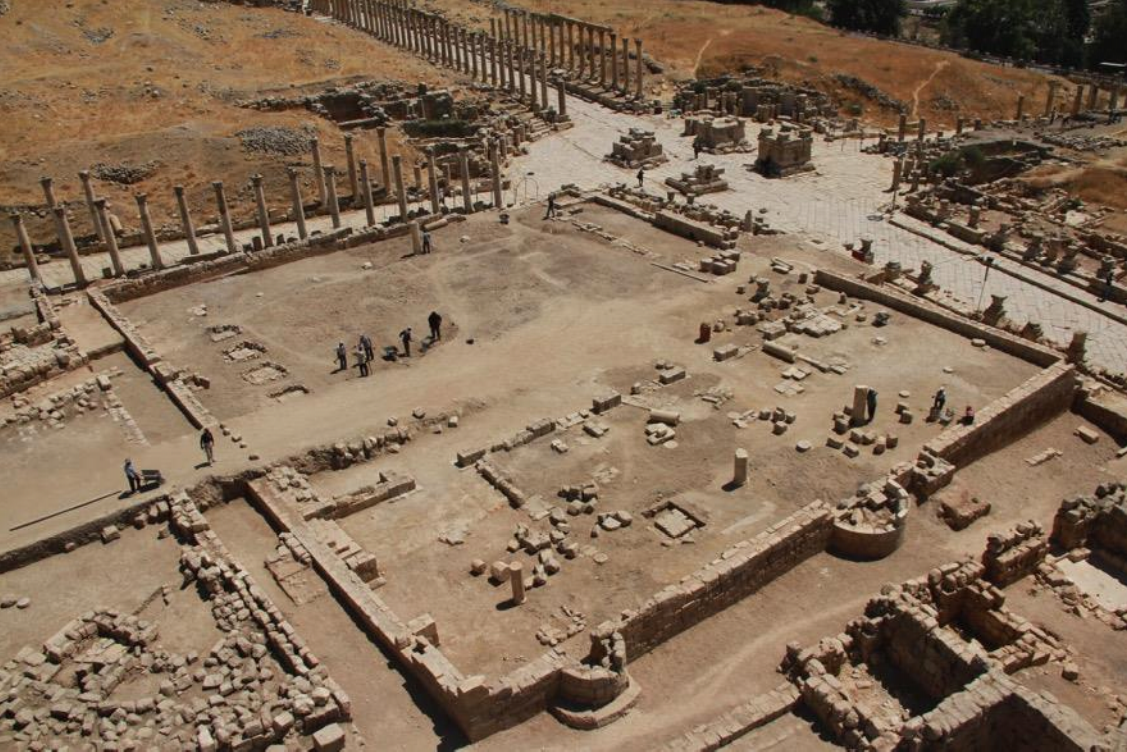

Figure 5Excavated Congregational Mosque at Jerash

JW: View from the south. The Qiblat wall and its three mihrabs are in the foreground

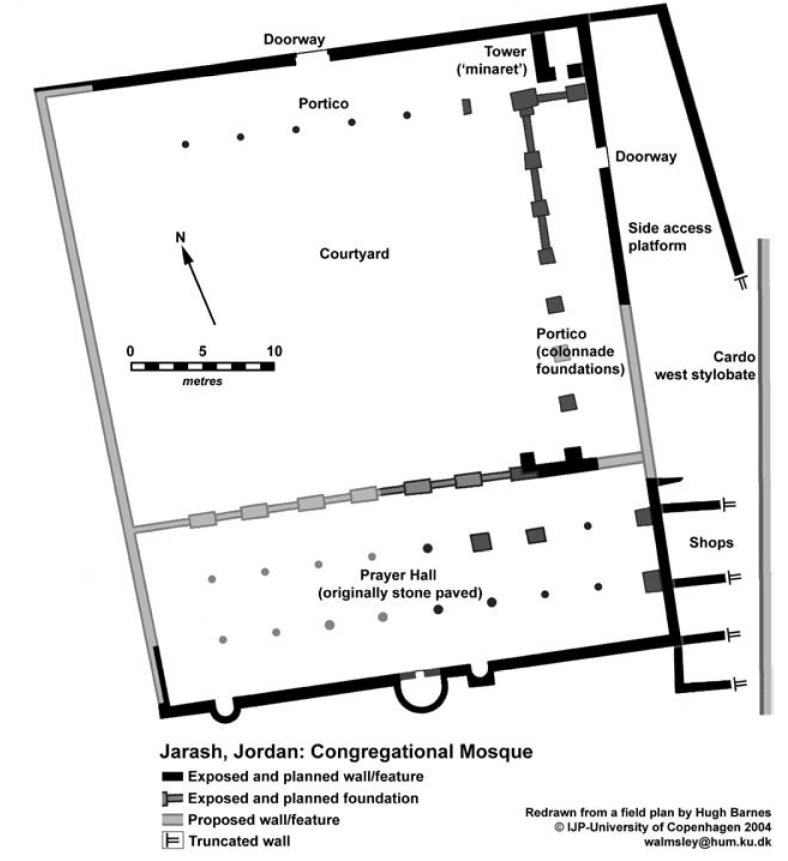

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

- Fig. 16.5 - Two

Mihrabs

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.5

Figure 16.5

The 2002 photo graph of the main (umayyad) miḥrāb of the congregational mosque of Jerash in Phase 1 (c. AD 725–40), with the partially preserved smaller and later Phase 2 (c. mid-eighth to early eleventh centuries) miḥrāb to its left (east). In the foreground are reused column bases that served as foundations for the first colonnade that ran parallel to the qiblat wall of the prayer hall

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

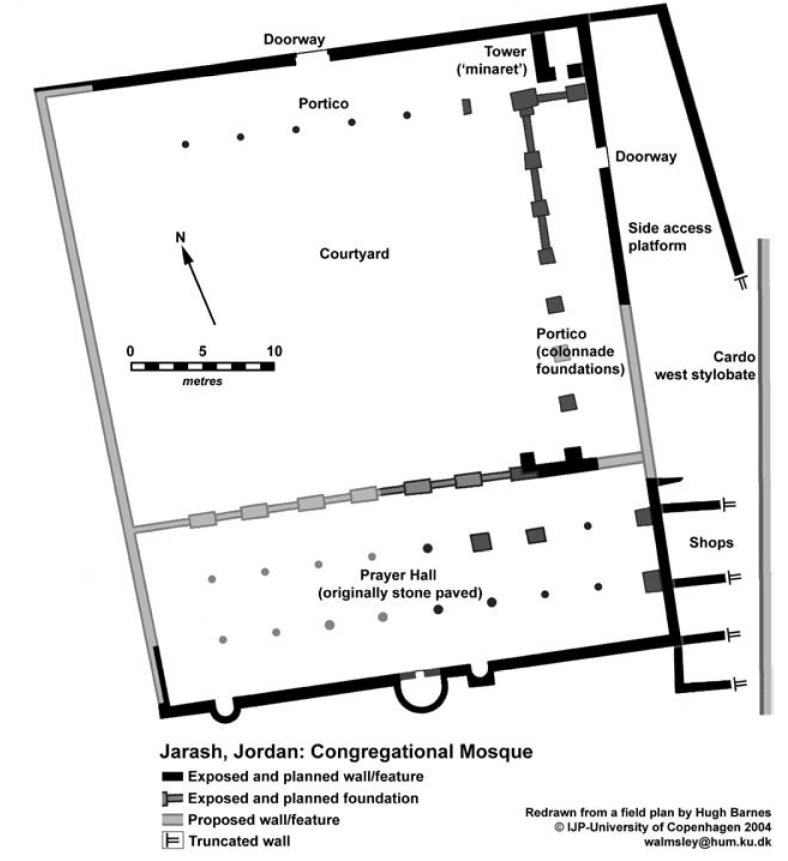

Walmsley (2018) - Fig. 16.6 - The smaller

Mihrab

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6

The southern (external) face of the umayyad miḥrāb following stratigraphic excavations, showing the foundations and skilled stone working by the masons. to the right, a long series of street surfaces are preserved that date to the use of the mosque; the later date of the smaller Phase-2 miḥrāb can be seen in the way it sits on top of surfaces contemporary with the original Phase-1 mosque and its miḥrāb

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

Walmsley (2018)

Walmsley (2018:248-250) dates initial construction of the Umayyad Congregational Mosque to between ca. 725 and ca. 735 CE indicating that it was built during the reign of Hisham b. ‘Abd al-Malik who ruled from 724-743 CE. The presence of 3 Mihrabs indicates that the mosque had a long life with at least three major stages ( Walmsley and Damgaard, 2005). The larger Mihrab in the center of the Qiblat Wall was used first followed by a smaller one ~1-2 meters to the east (see Fig. 16.5). The smaller second Mihrabs (Fig. 16.6) appears to post date seismic destruction in 749 CE. Blanke et al (2010) noted that the third Mihrab is located well to the west where it was

segregated by a perdition wall. The Mosque was built on top of an earlier structure - a bathhouse.

- from Jerash - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

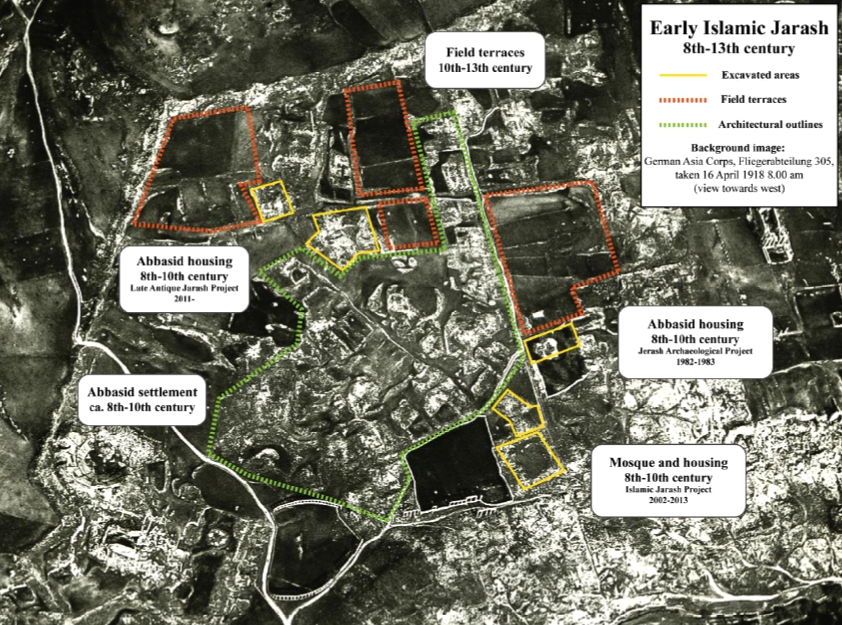

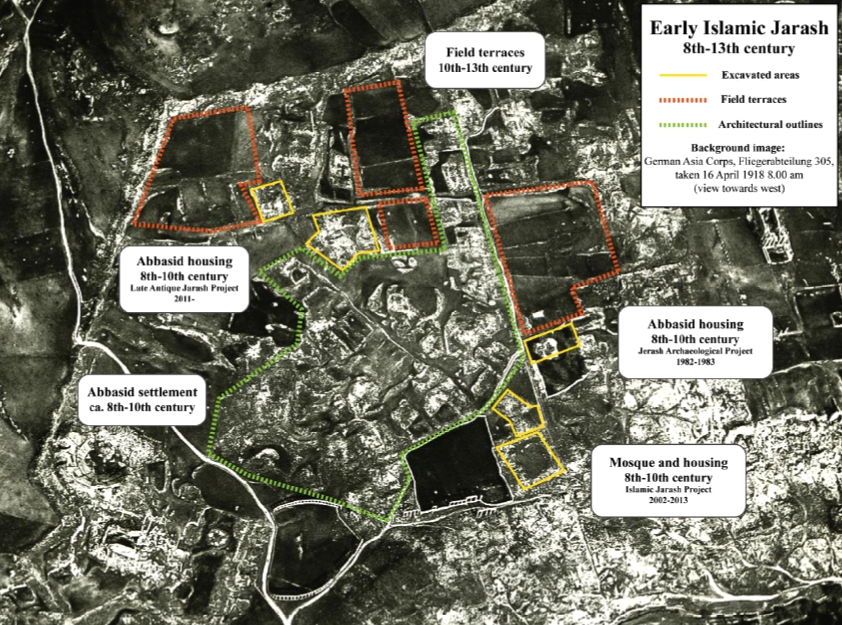

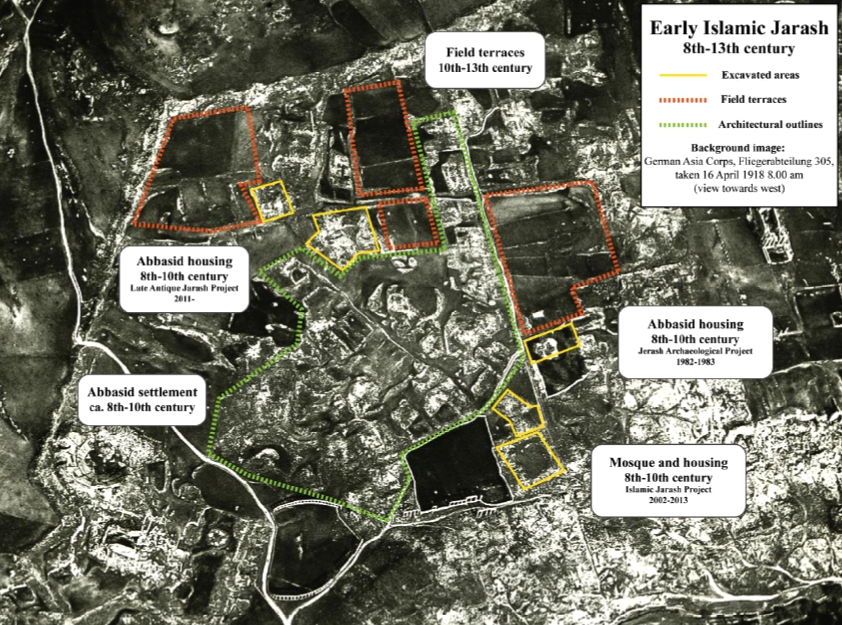

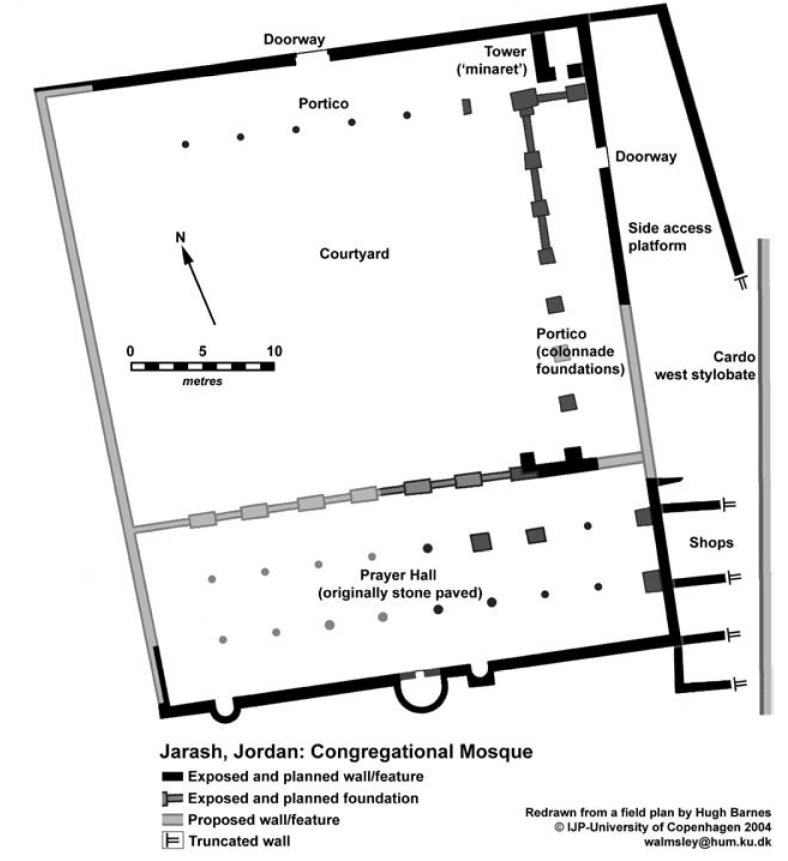

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Jerash

showing location of the town's bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Jerash archaeological site, showing location of the town's bathhouses

(Modified from map by Thomas Lepaon.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad

Jerash from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 13 - Early Islamic

Jerash - 8th to 13th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Early Islamic Jerash

8th to 13th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Jerash

showing location of the town's bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Jerash archaeological site, showing location of the town's bathhouses

(Modified from map by Thomas Lepaon.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

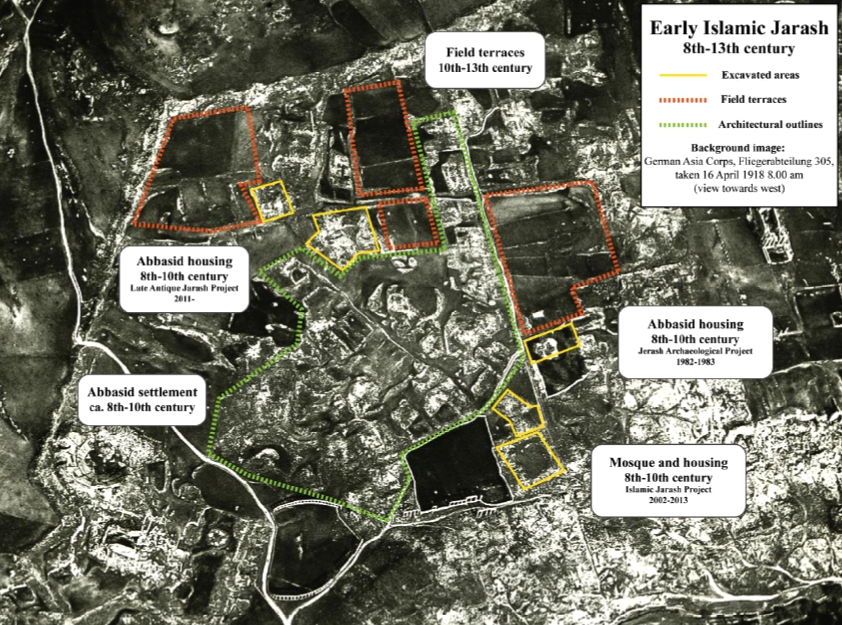

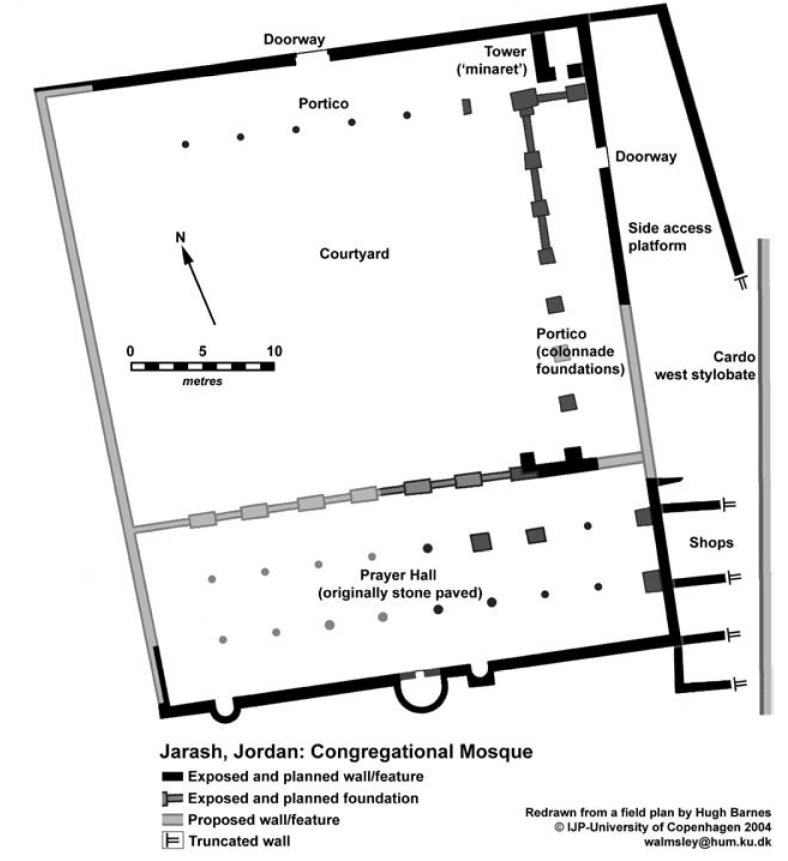

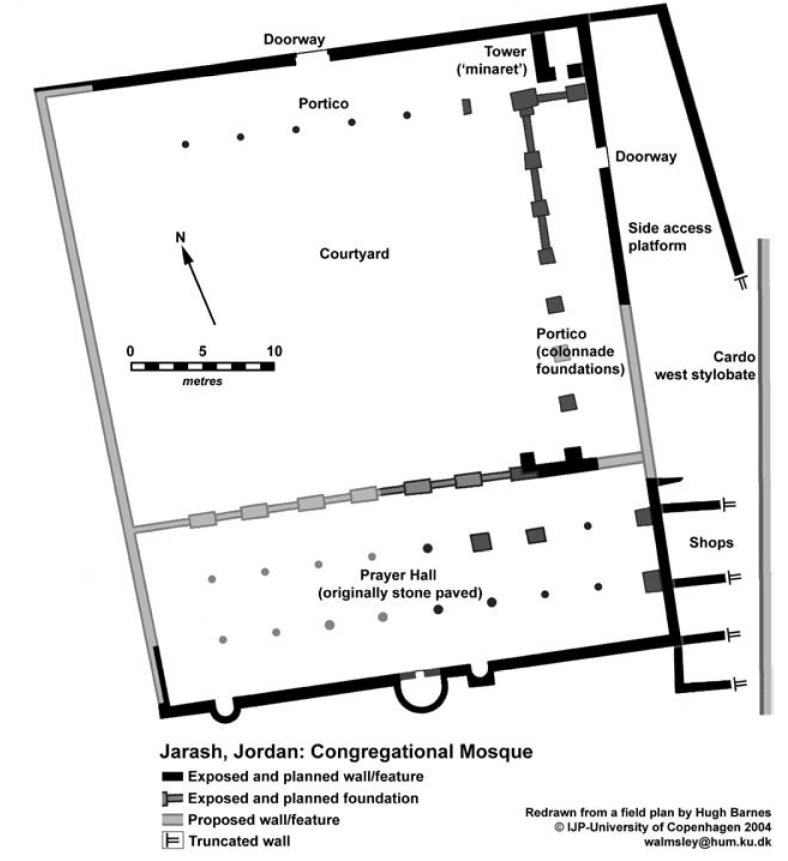

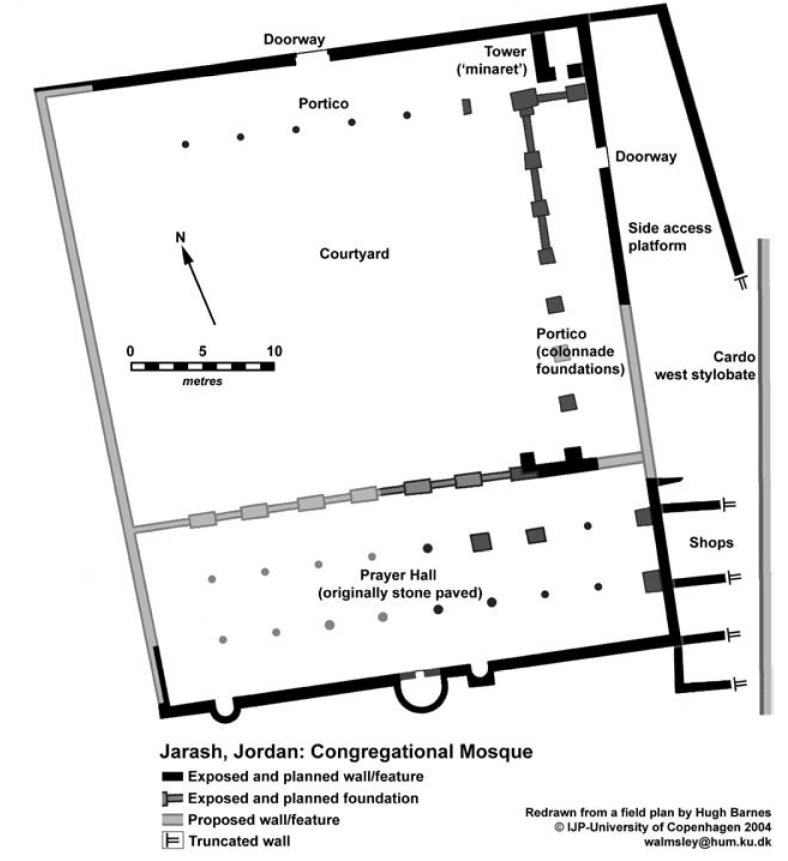

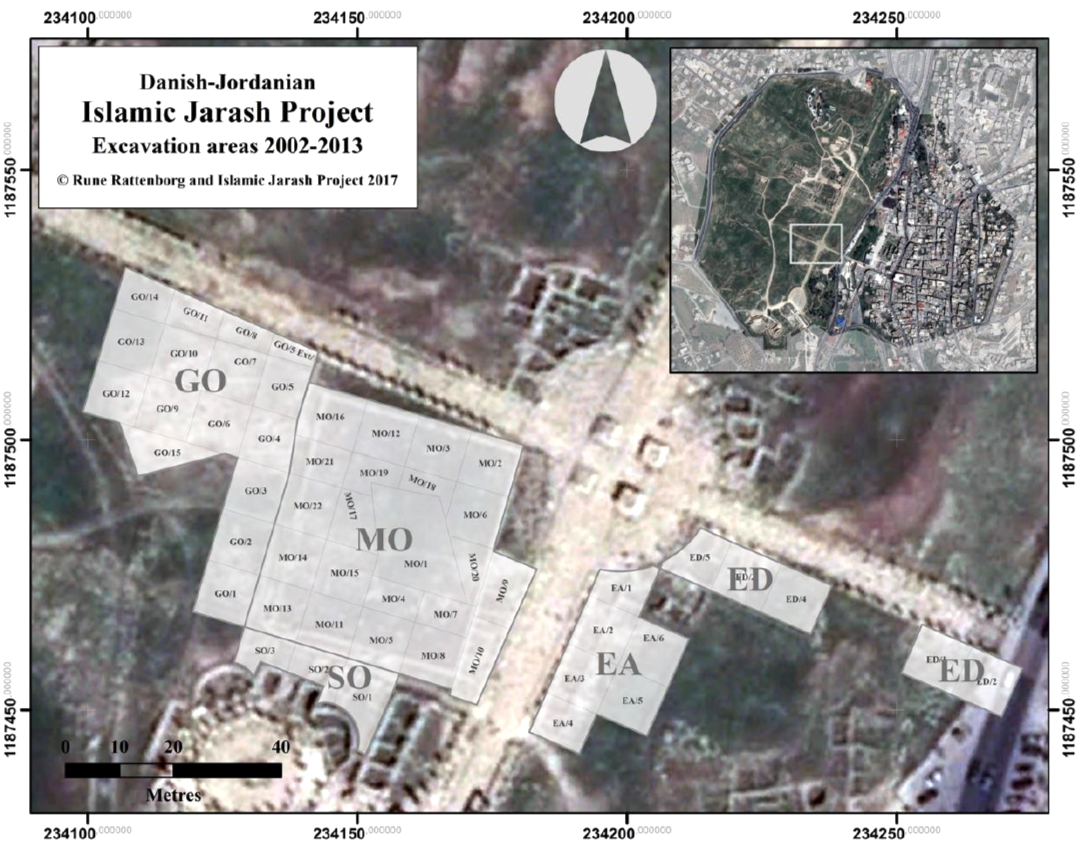

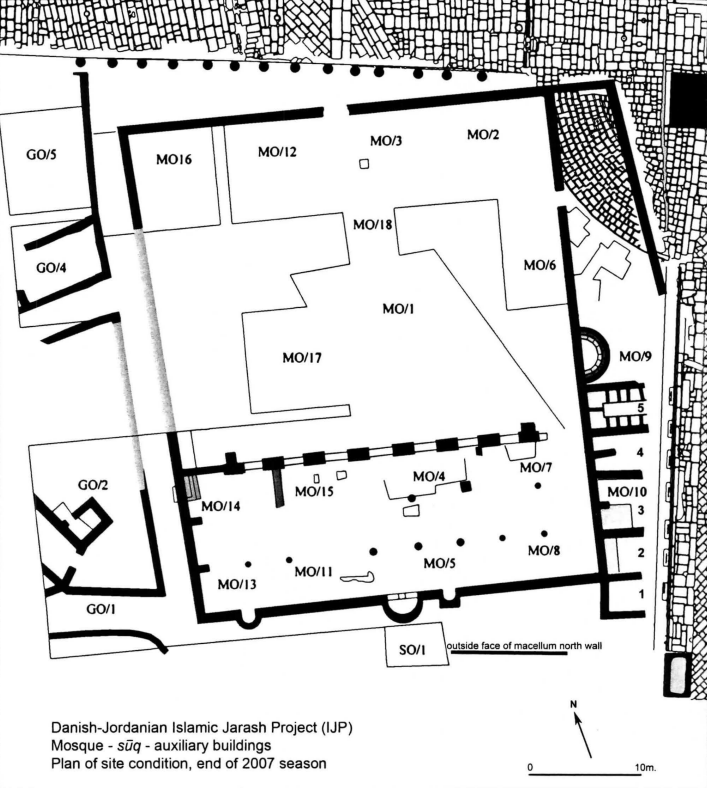

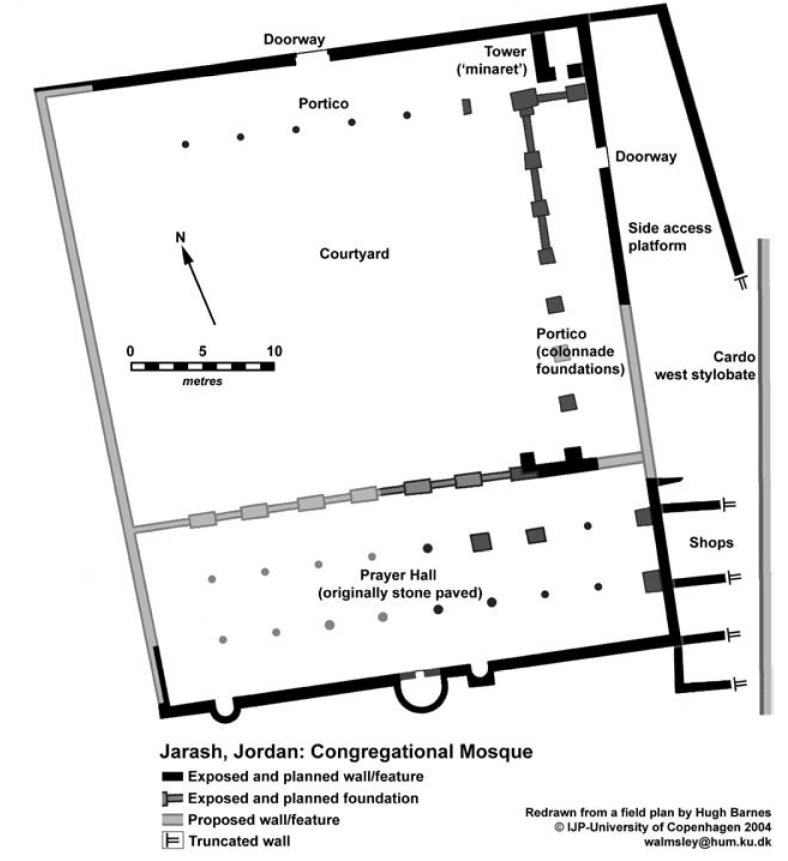

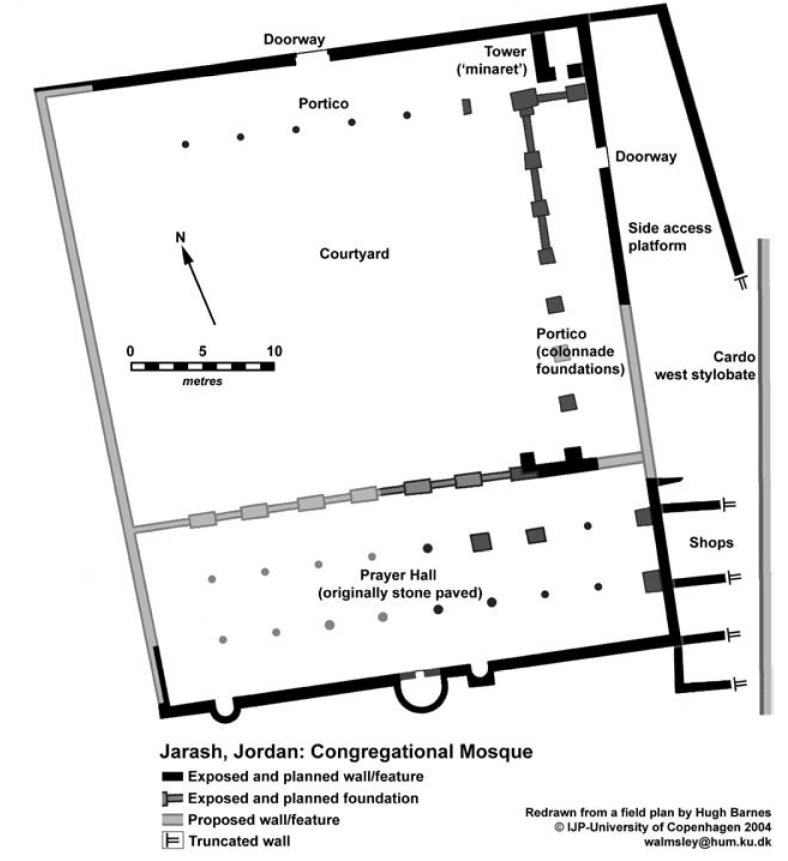

- Fig. 3 - Plan of Congregational

Mosque from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Preliminary outline plan of the Umayyad mosque of Jarash (as after 2004 season).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 4 - Plan of Congregational

Mosque with excavation areas from Barnes et al (2006)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan of the mosque, showing excavated areas to 2004

Barnes et al (2006)

- Fig. 3 - Plan of Congregational

Mosque from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Preliminary outline plan of the Umayyad mosque of Jarash (as after 2004 season).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) - Fig. 4 - Plan of Congregational

Mosque with excavation areas from Barnes et al (2006)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan of the mosque, showing excavated areas to 2004

Barnes et al (2006)

- Fig. 6 - Early Islamic

Jerash - Early 8th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Early Islamic Jerash

Early 8th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 7 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 750-850 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 750-850 CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 10 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 850-950 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 850-950 CE

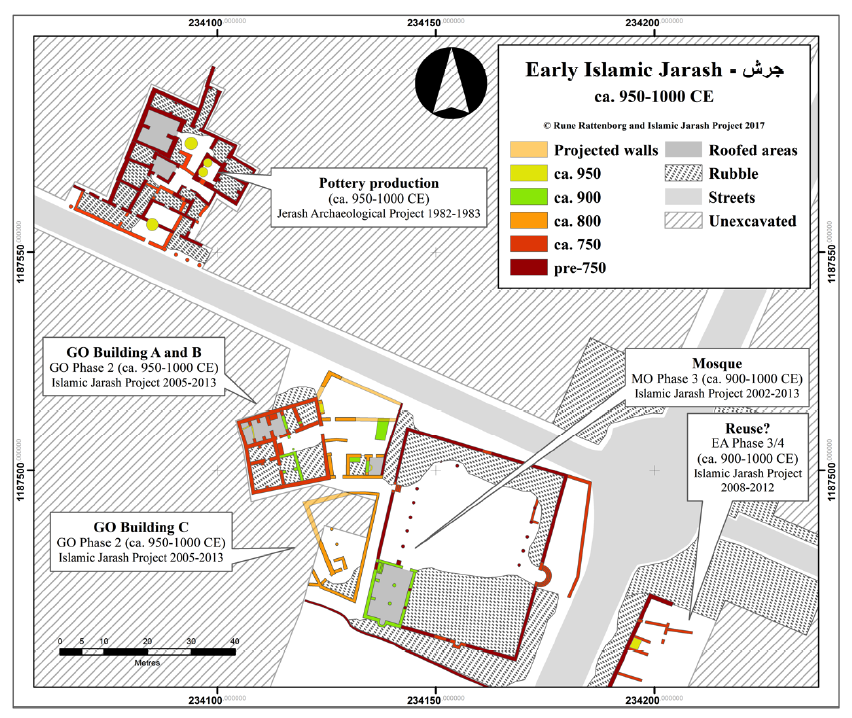

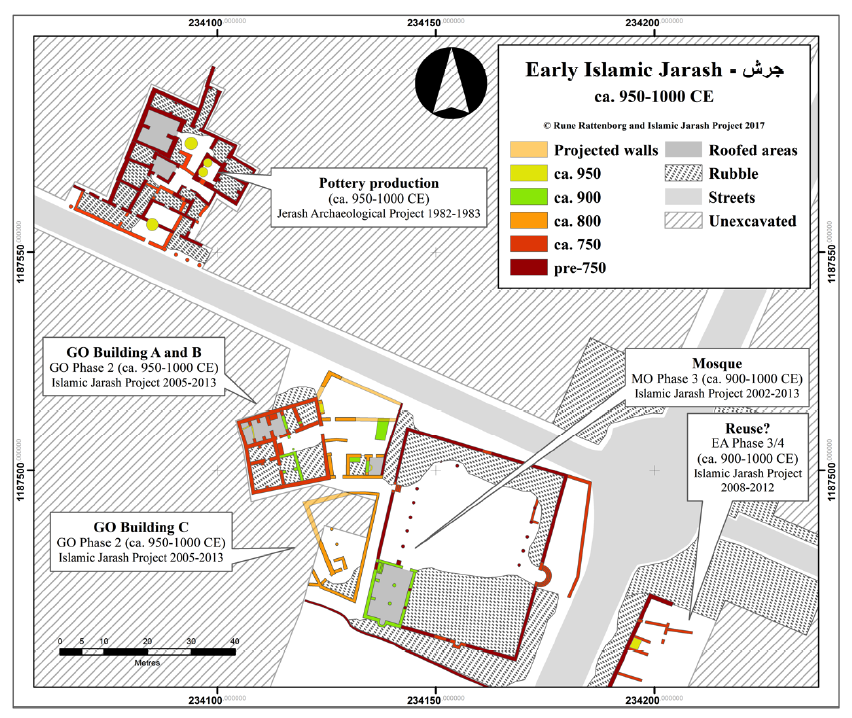

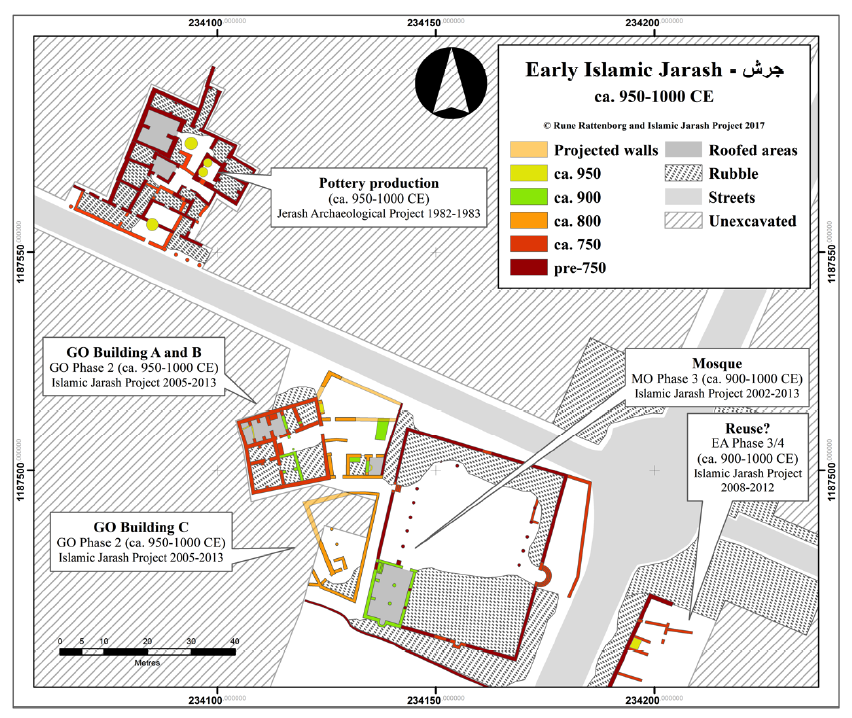

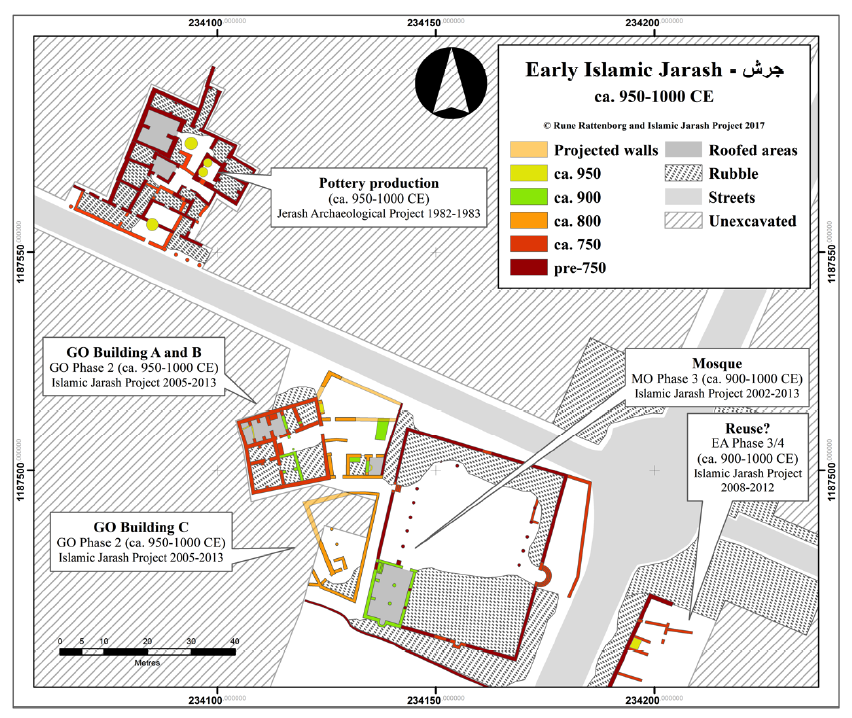

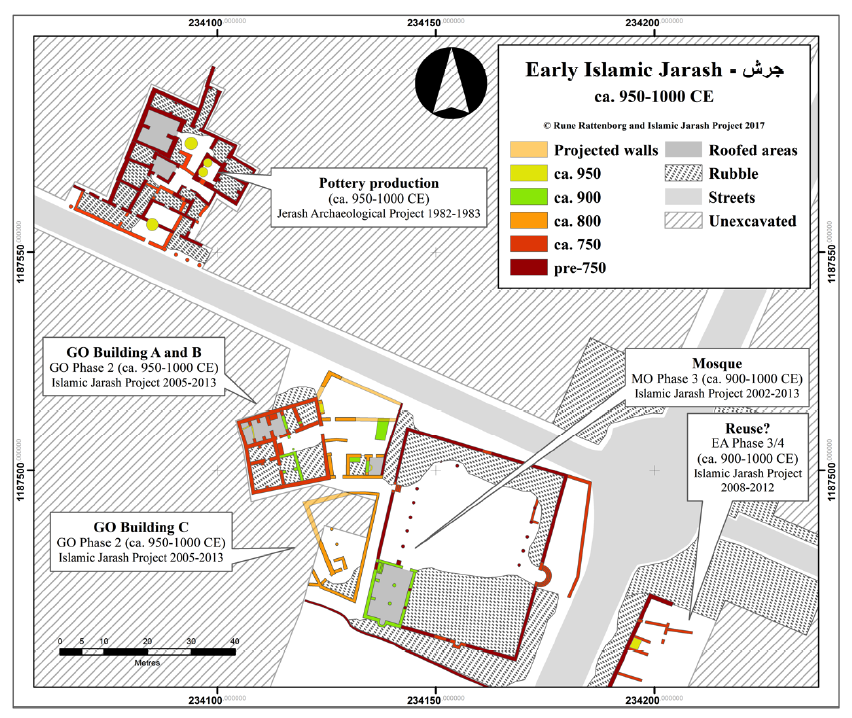

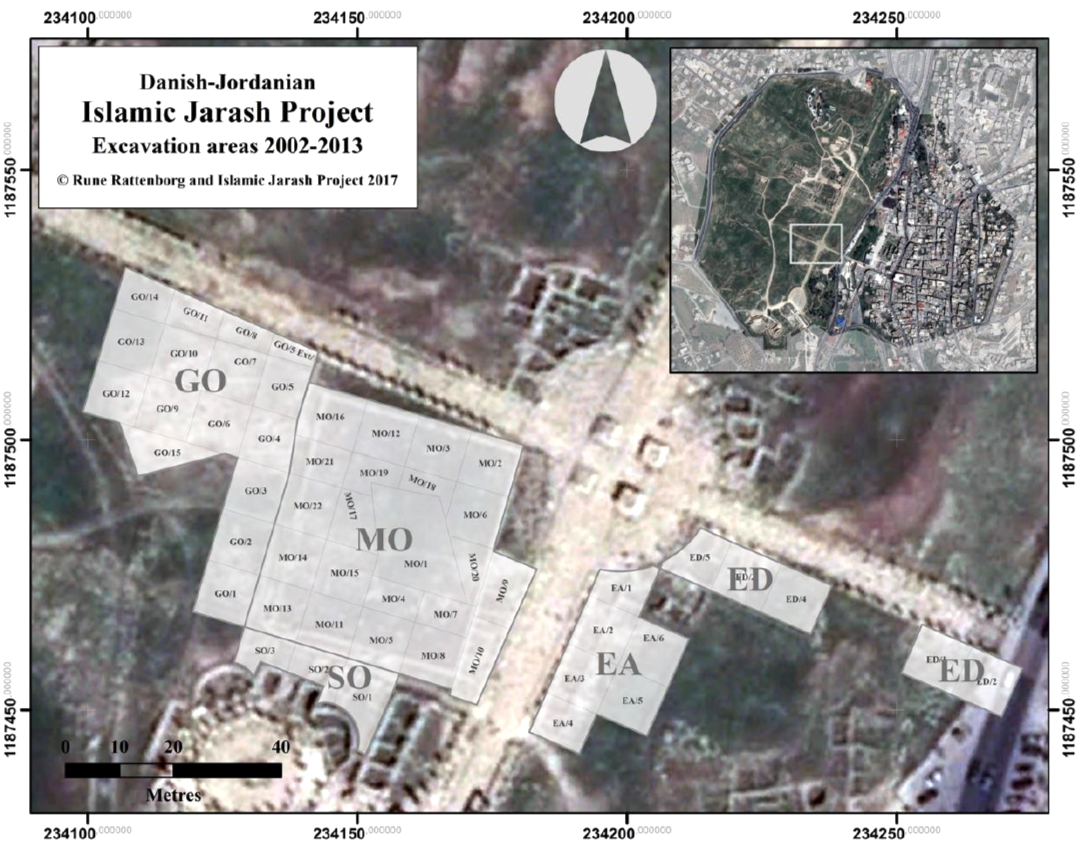

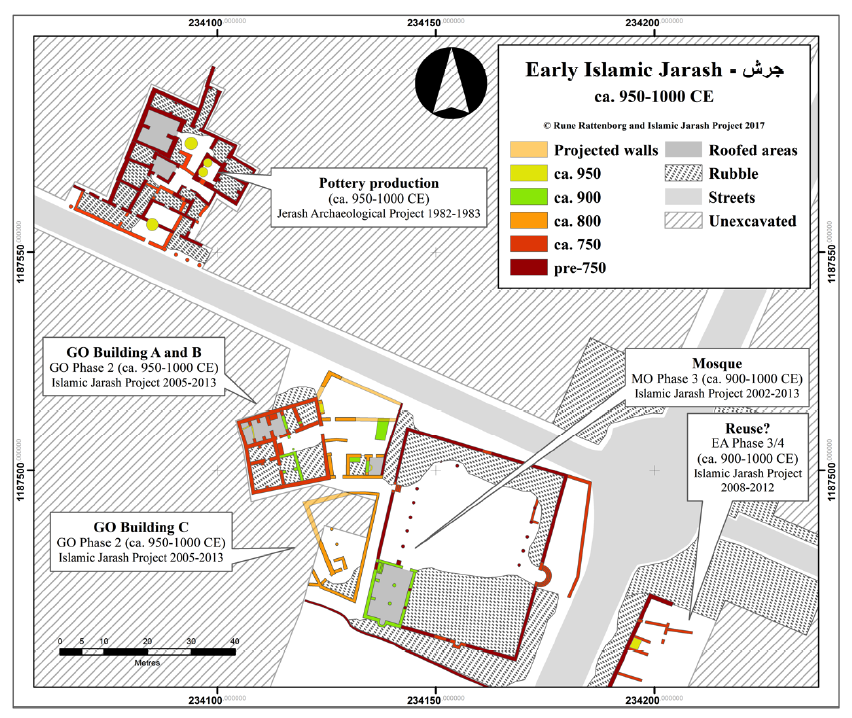

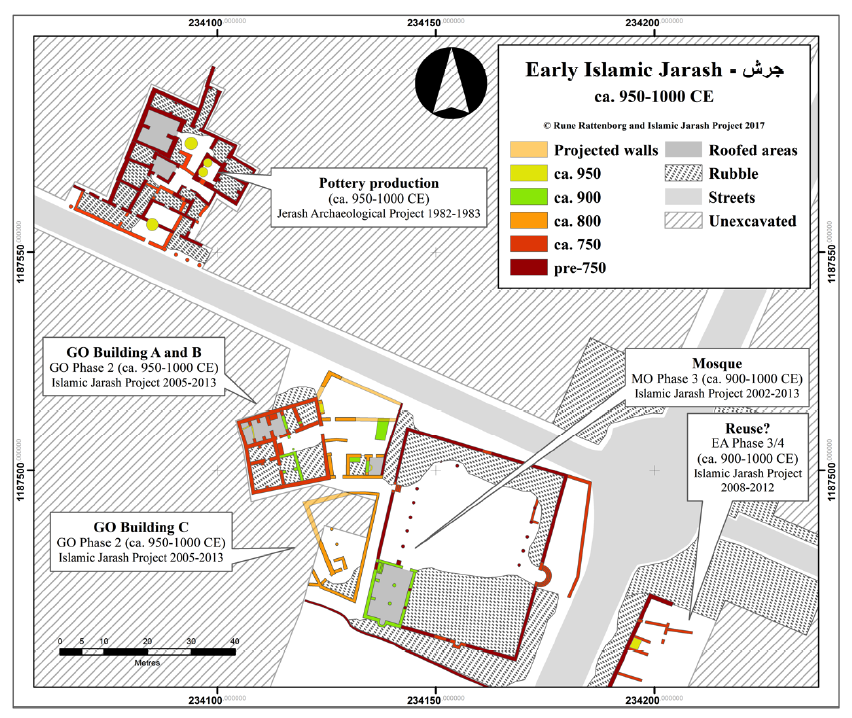

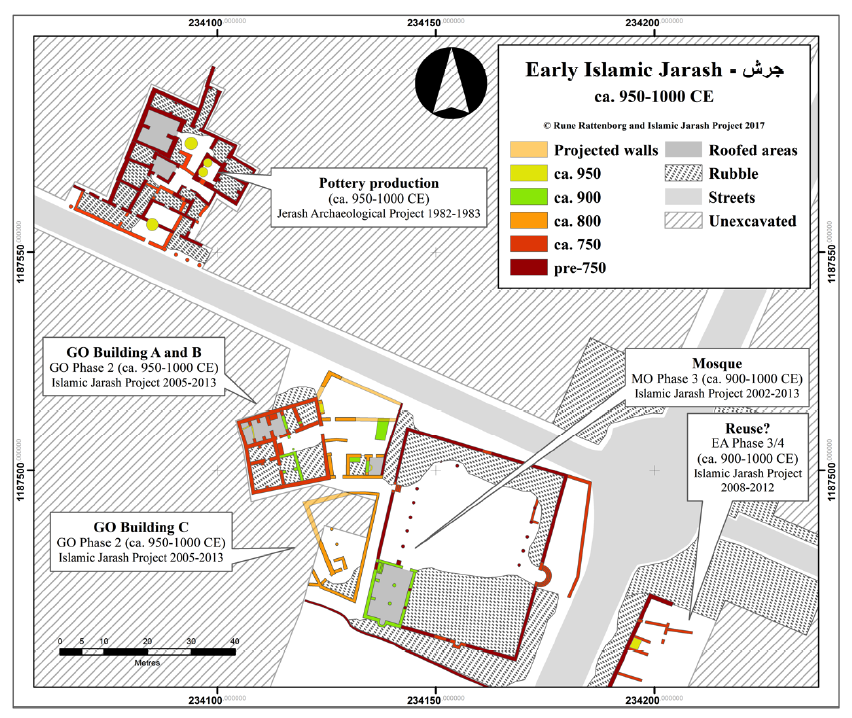

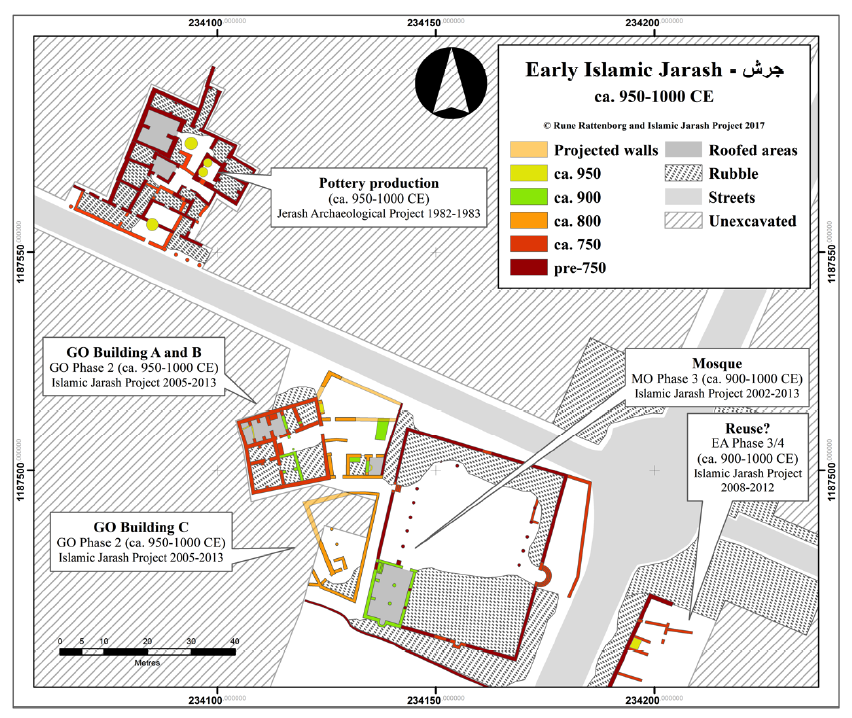

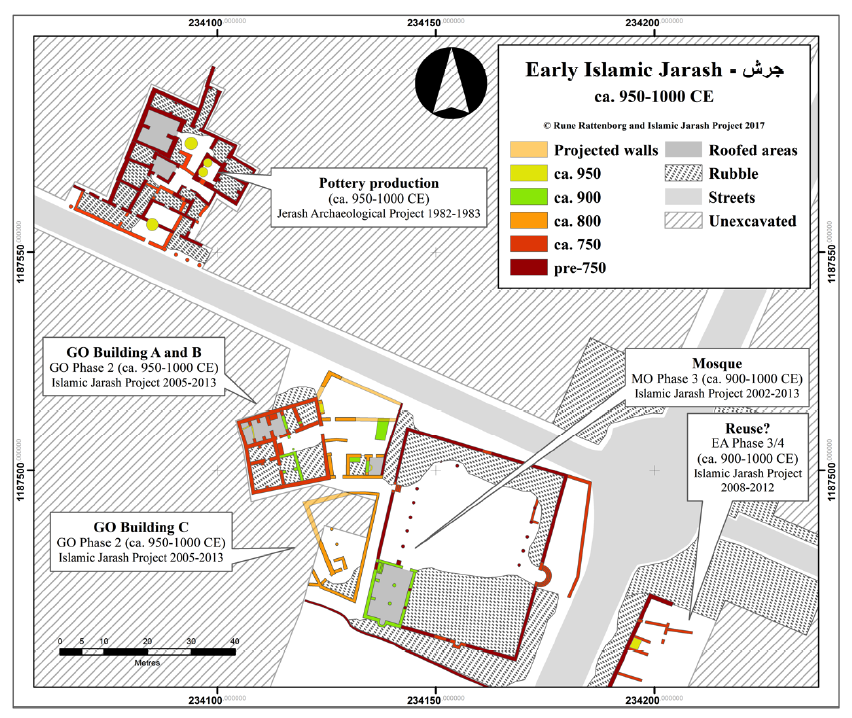

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 11 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 950-1000 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 950-1000 CE

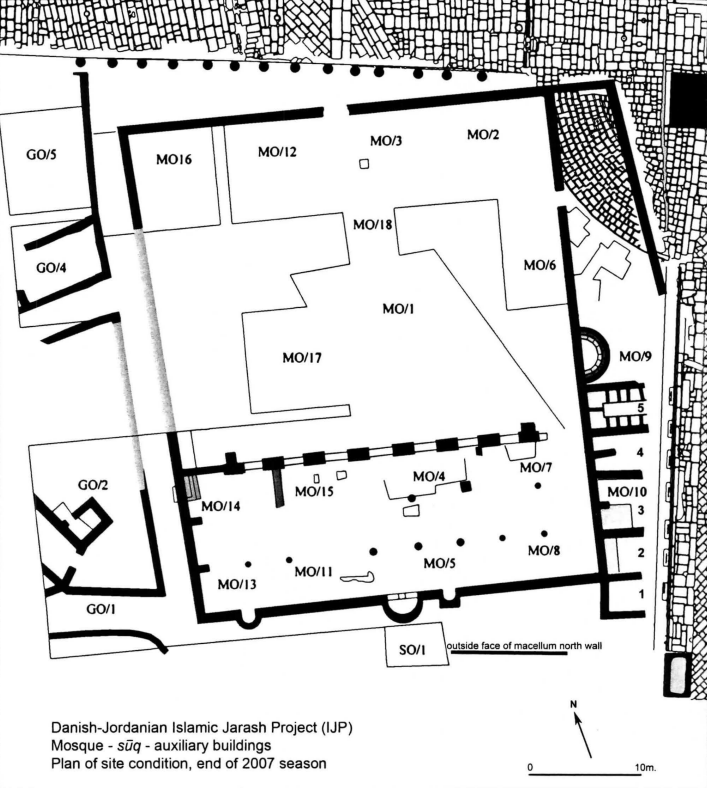

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 16.8 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 800-1000 CE - from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.8

Figure 16.8

Jerash congregational mosque, Phase 2, with surrounding structures of contemporary date (areas GO and EA Phase 3 = mosque Phase 2), dated mid-eighth to mid-tenth centuries AD, with some evidence of use into the early eleventh century AD

(plan by Rune Rattenborg, incorporating material previously published in Gawlikowski 1986; Kraeling 1938a; Simpson 2008a).

Walmsley (2018)

- Fig. 6 - Early Islamic

Jerash - Early 8th century CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Early Islamic Jerash

Early 8th century CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 7 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 750-850 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 750-850 CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 10 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 850-950 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 850-950 CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 11 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 950-1000 CE - from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Early Islamic Jerash

ca. 950-1000 CE

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 16.8 - Early Islamic

Jerash - ca. 800-1000 CE - from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.8

Figure 16.8

Jerash congregational mosque, Phase 2, with surrounding structures of contemporary date (areas GO and EA Phase 3 = mosque Phase 2), dated mid-eighth to mid-tenth centuries AD, with some evidence of use into the early eleventh century AD

(plan by Rune Rattenborg, incorporating material previously published in Gawlikowski 1986; Kraeling 1938a; Simpson 2008a).

Walmsley (2018)

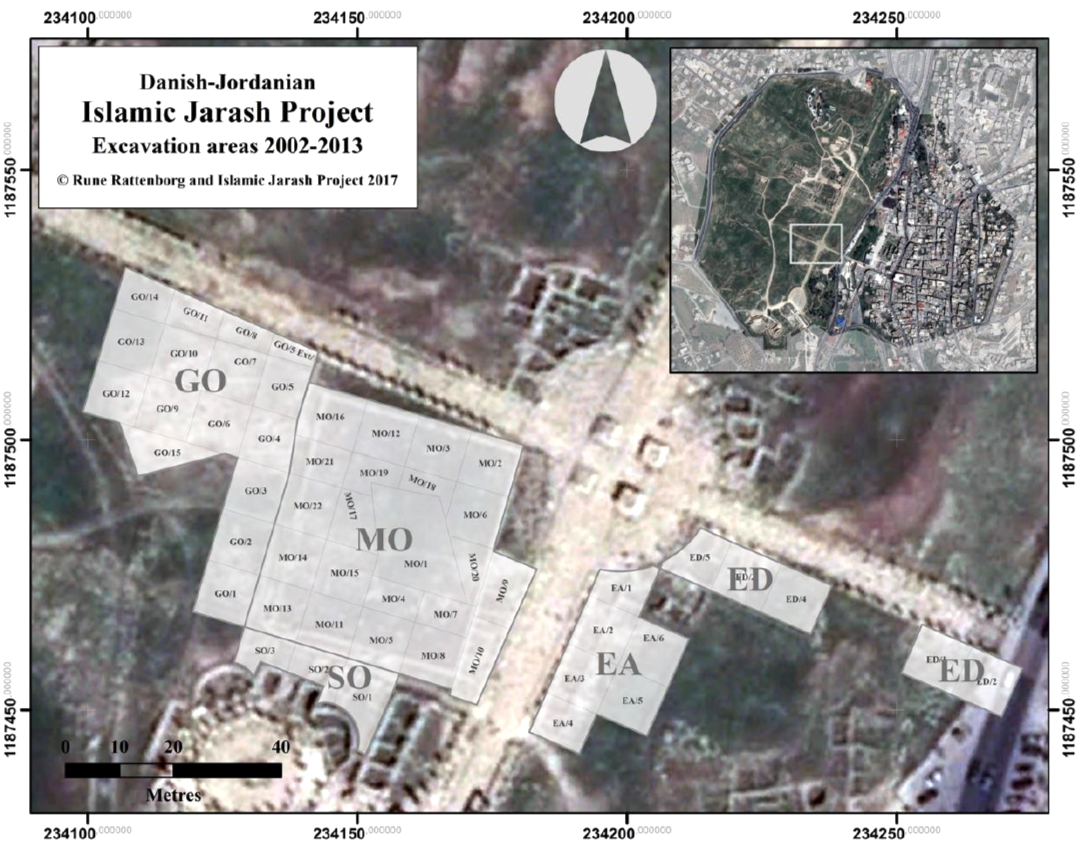

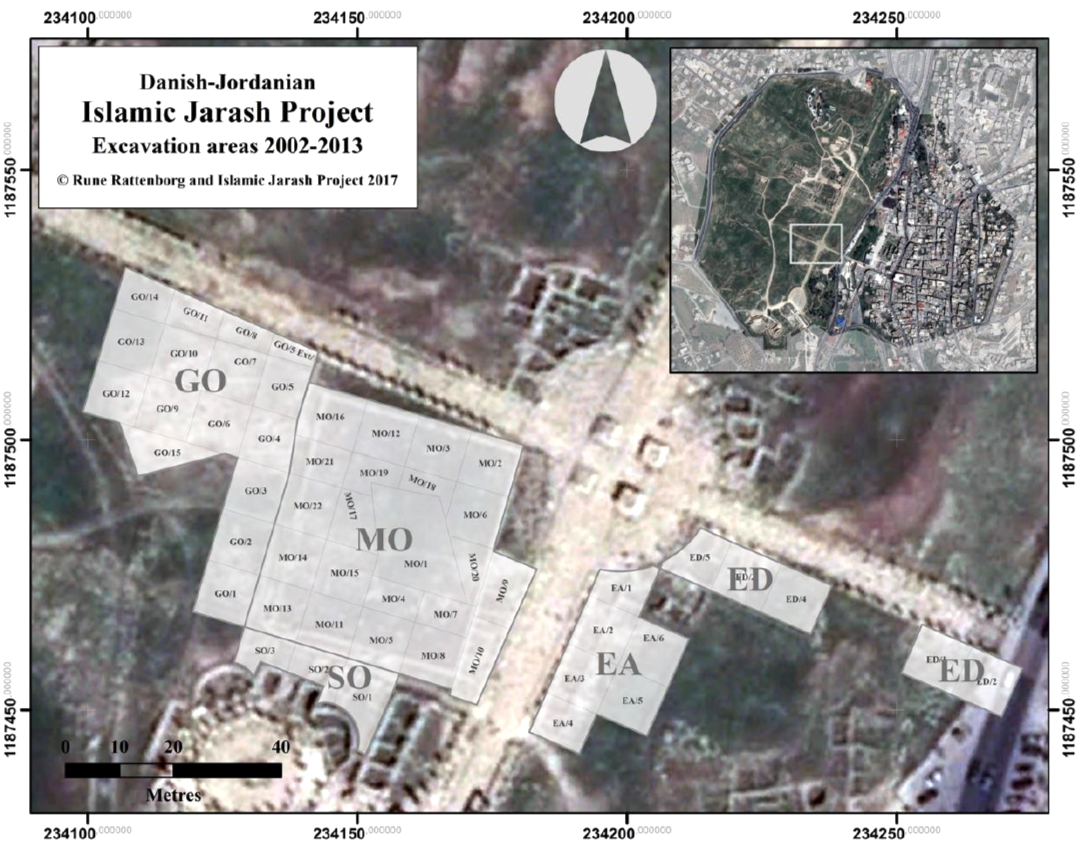

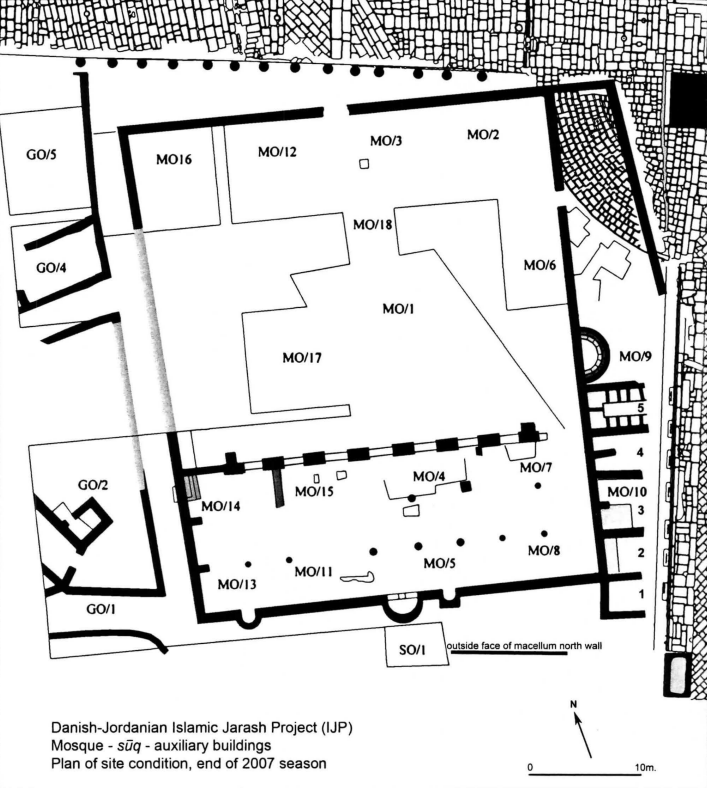

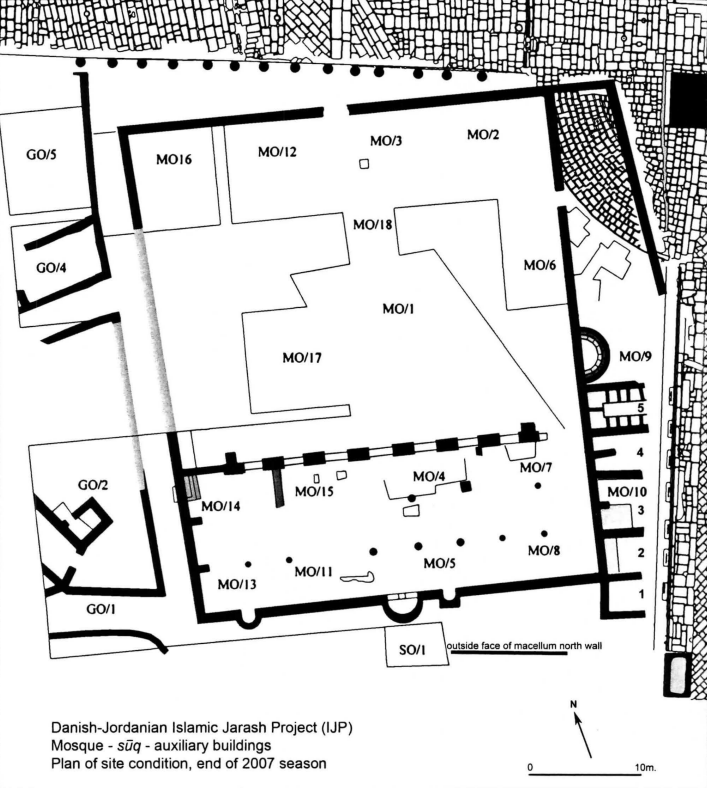

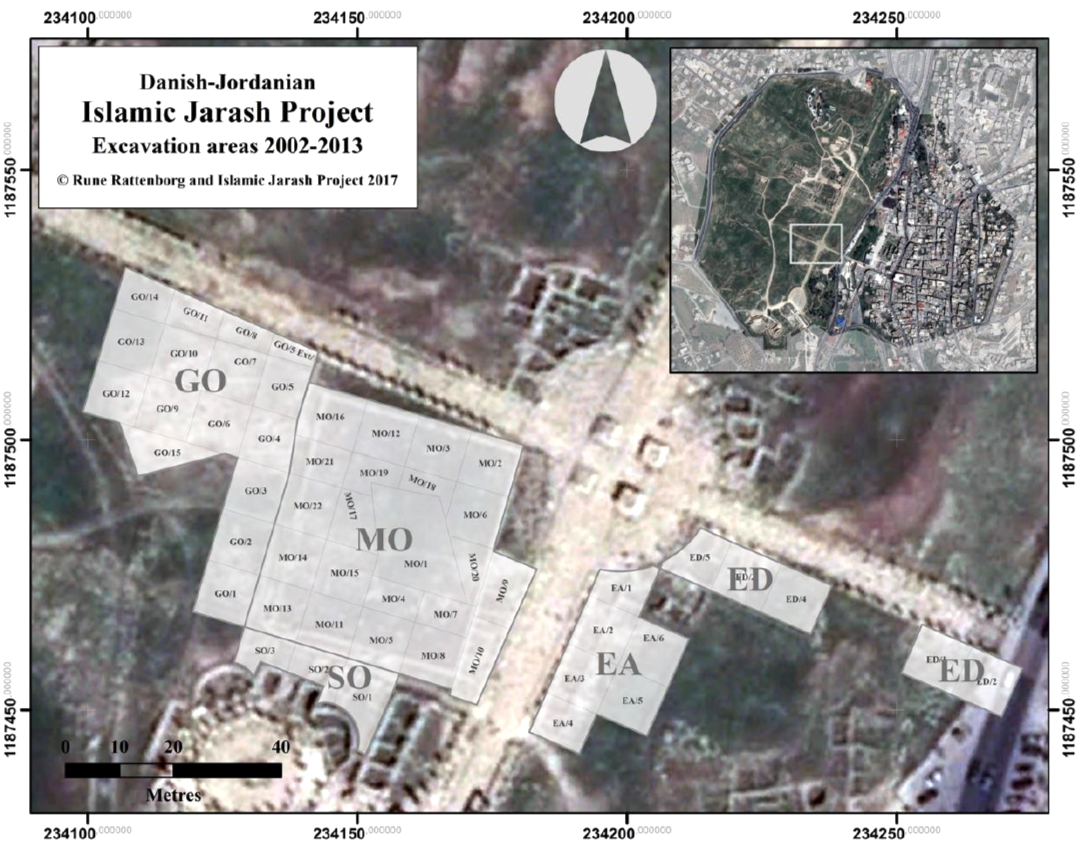

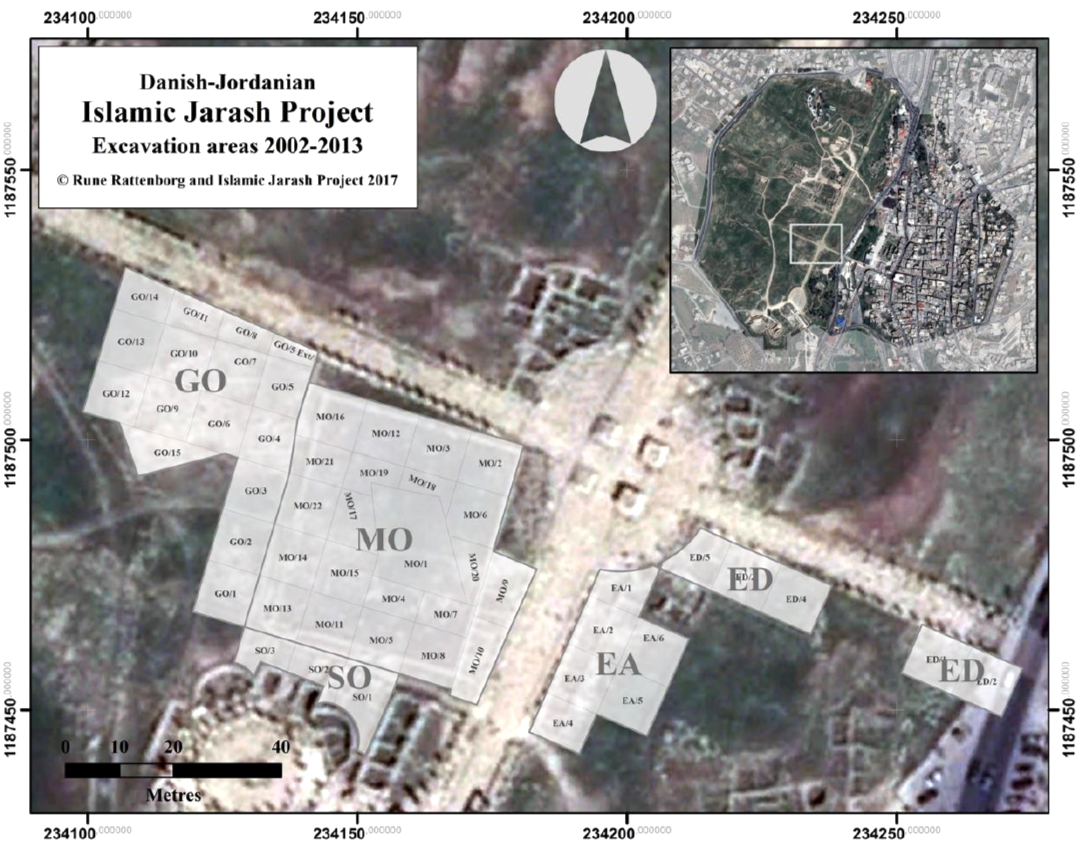

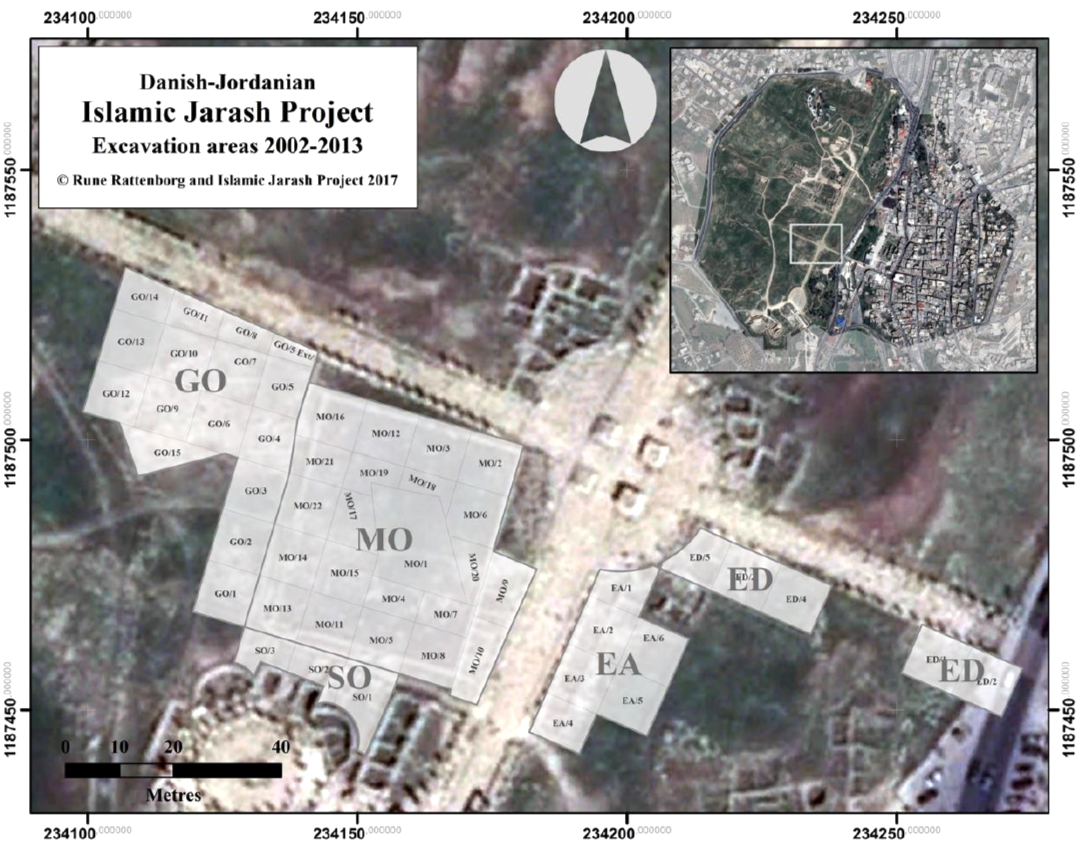

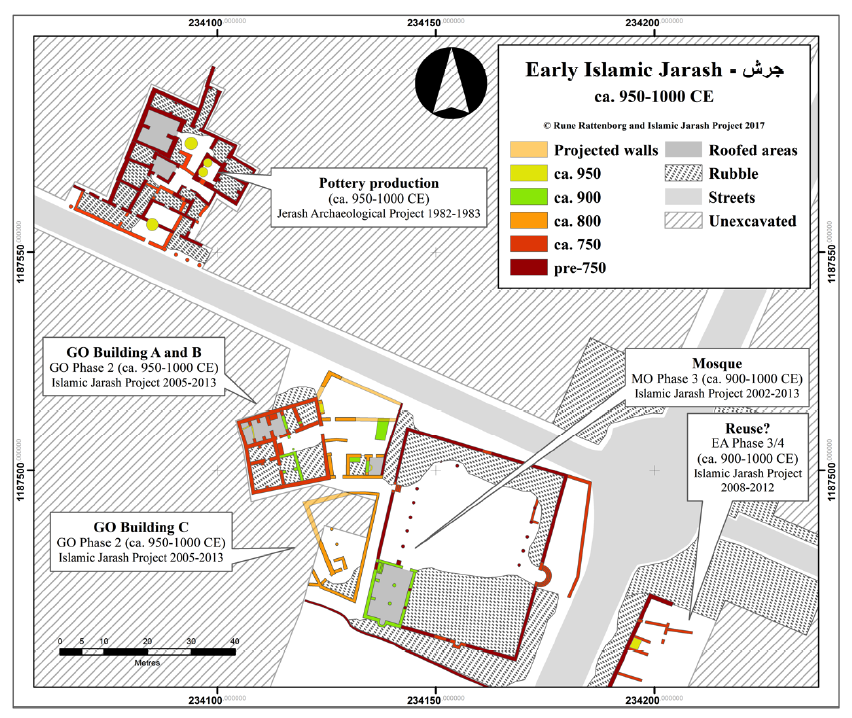

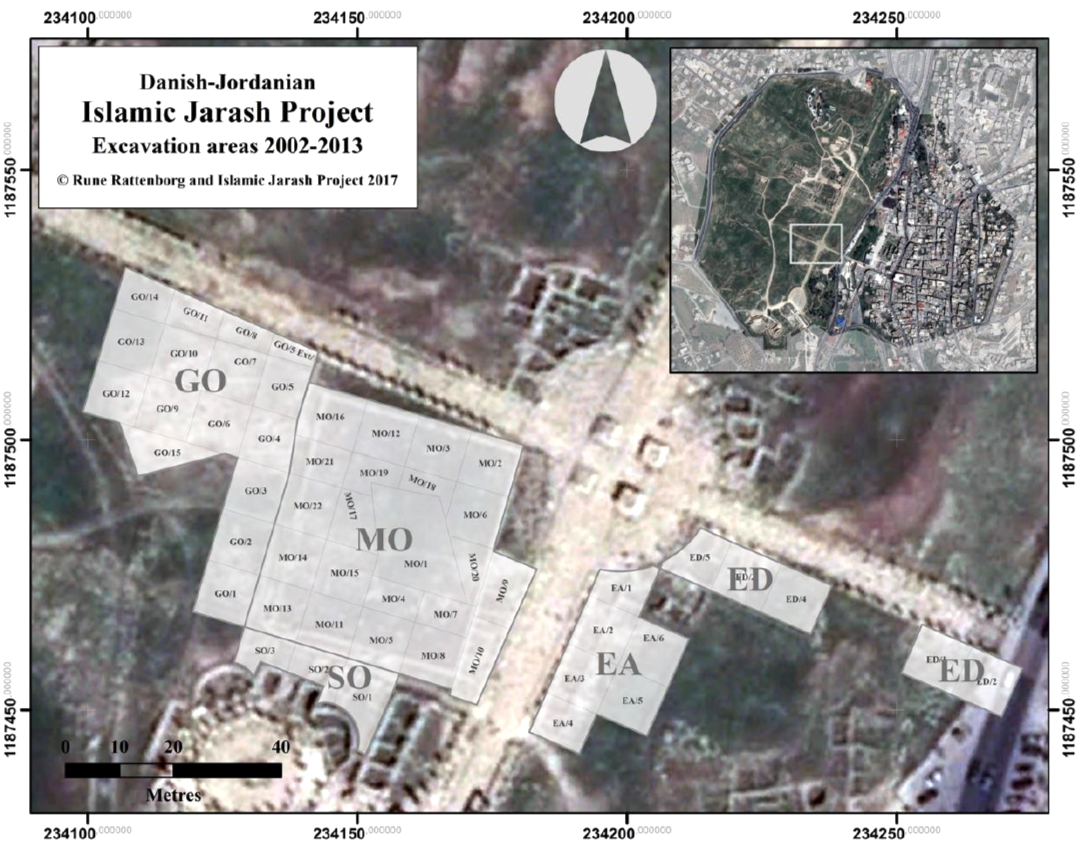

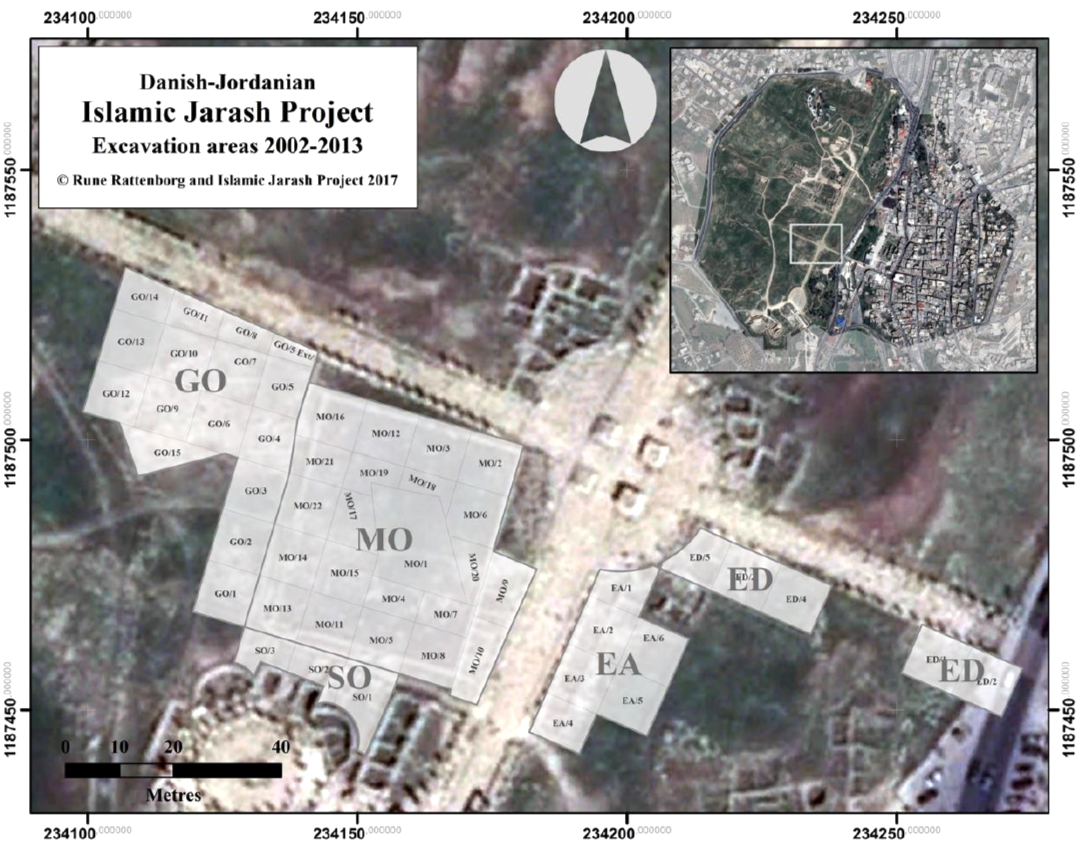

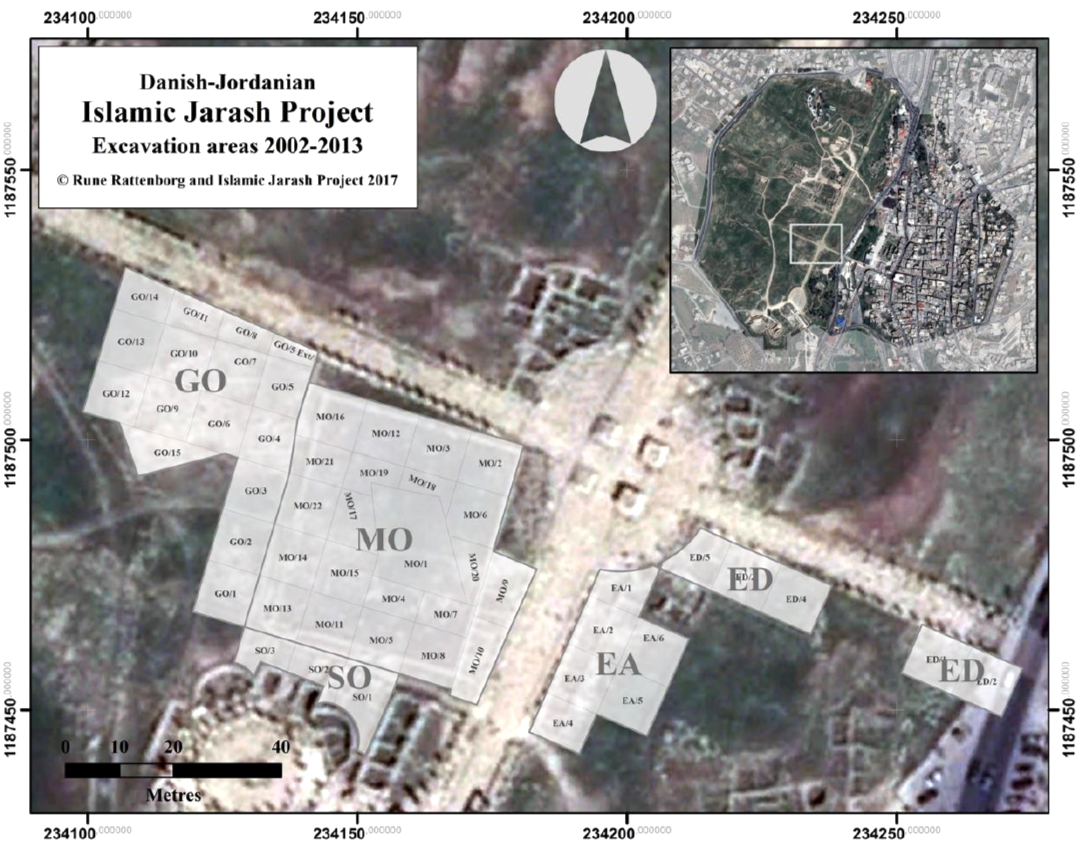

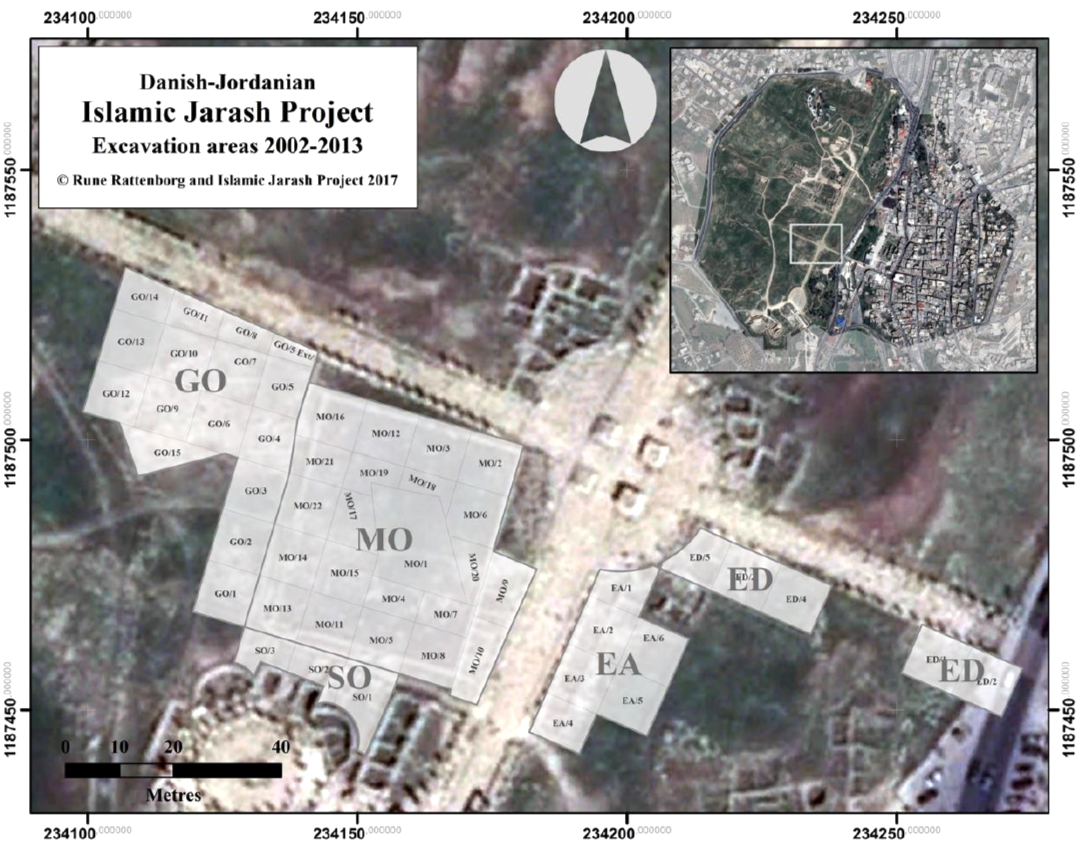

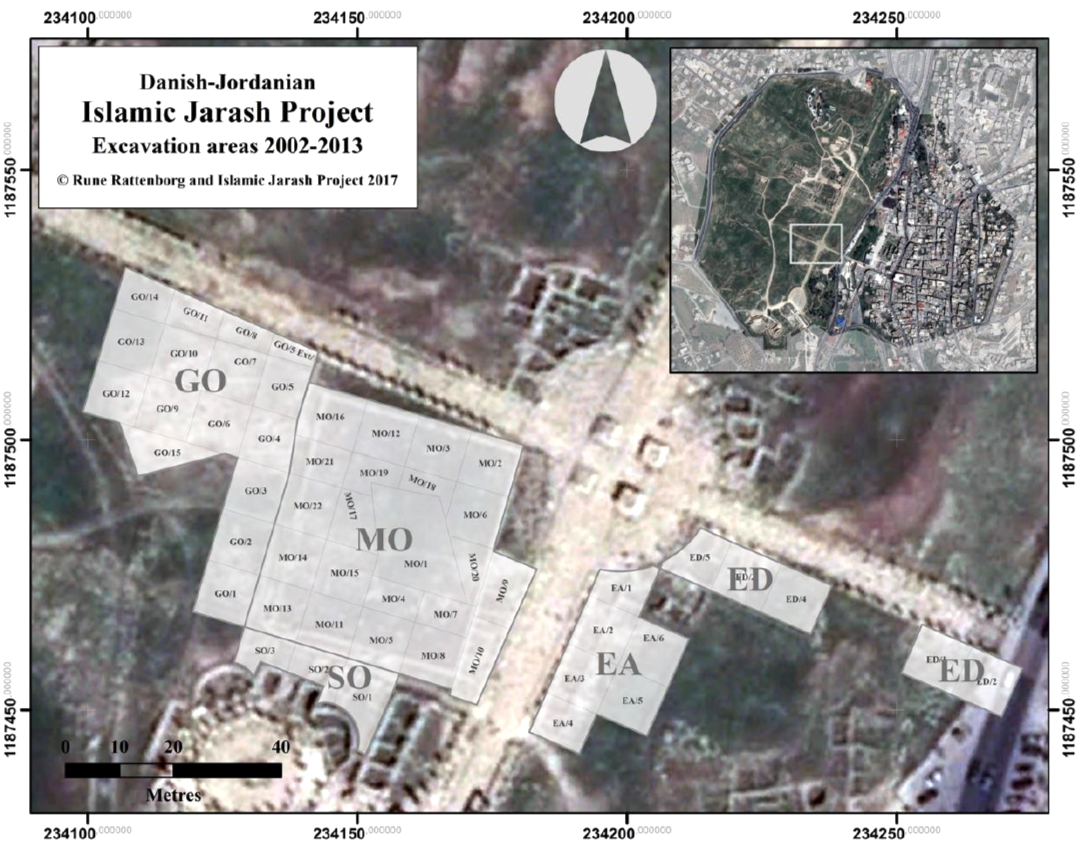

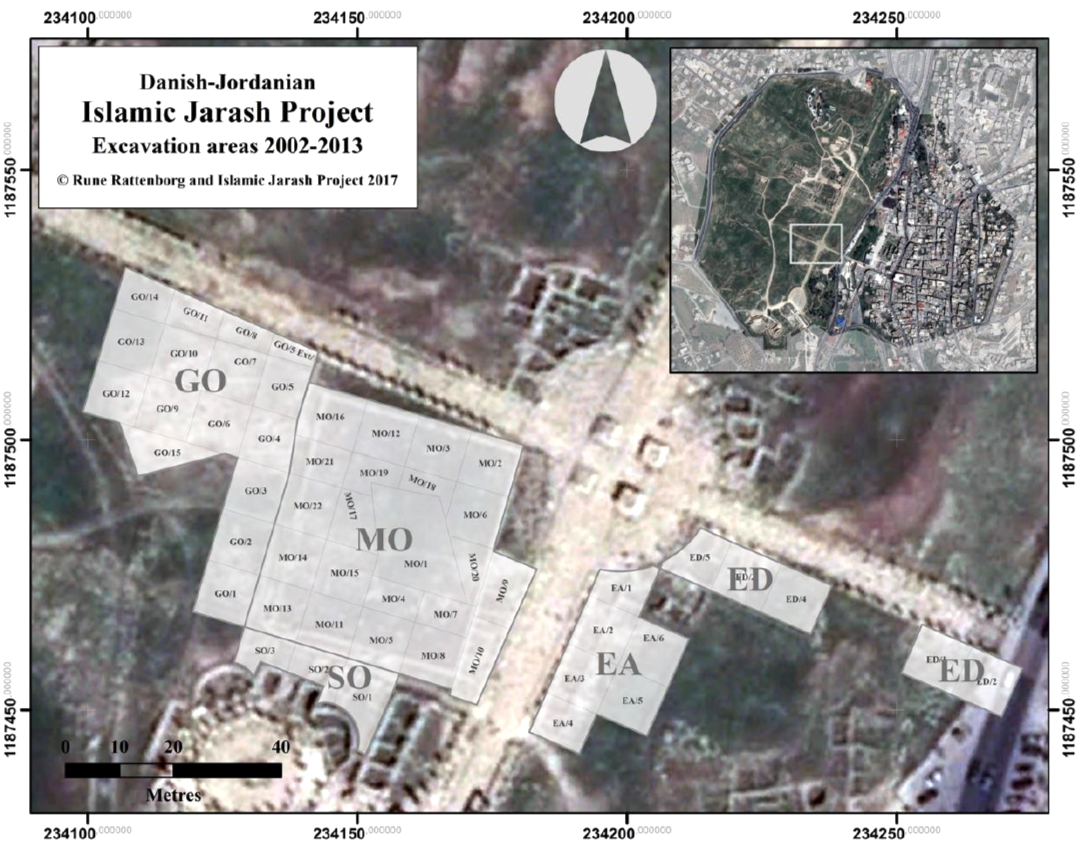

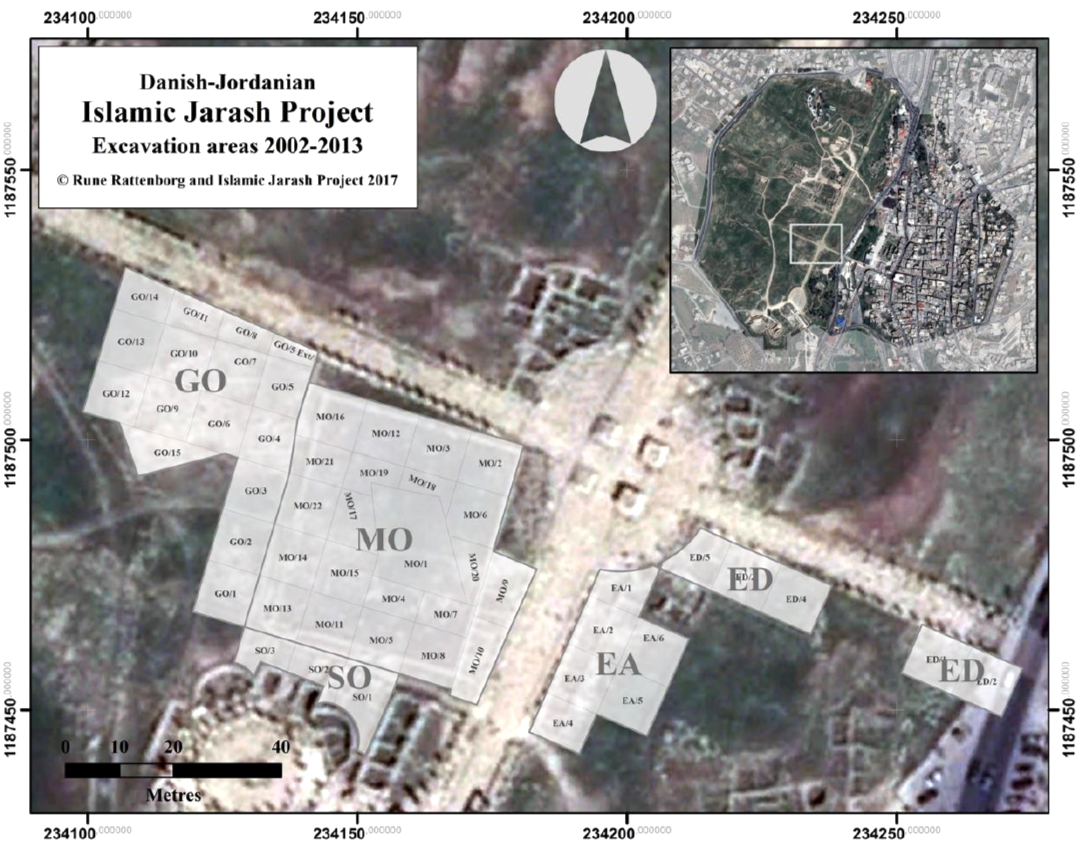

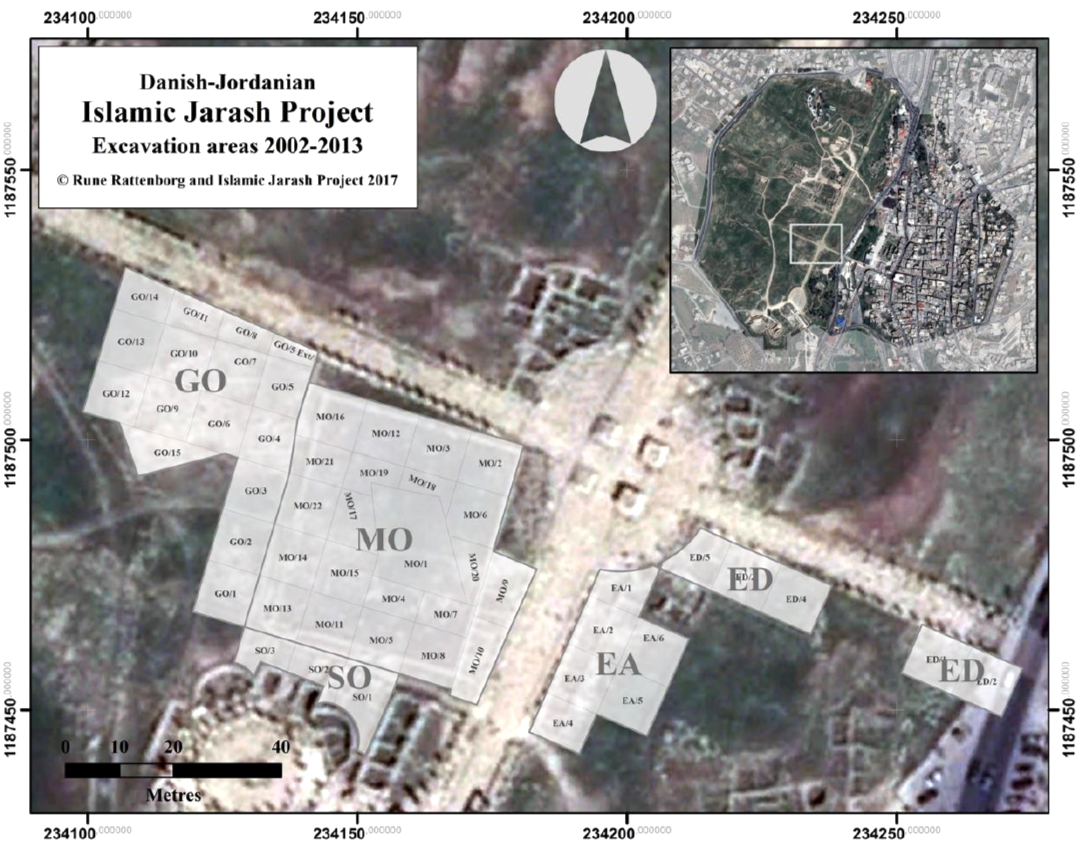

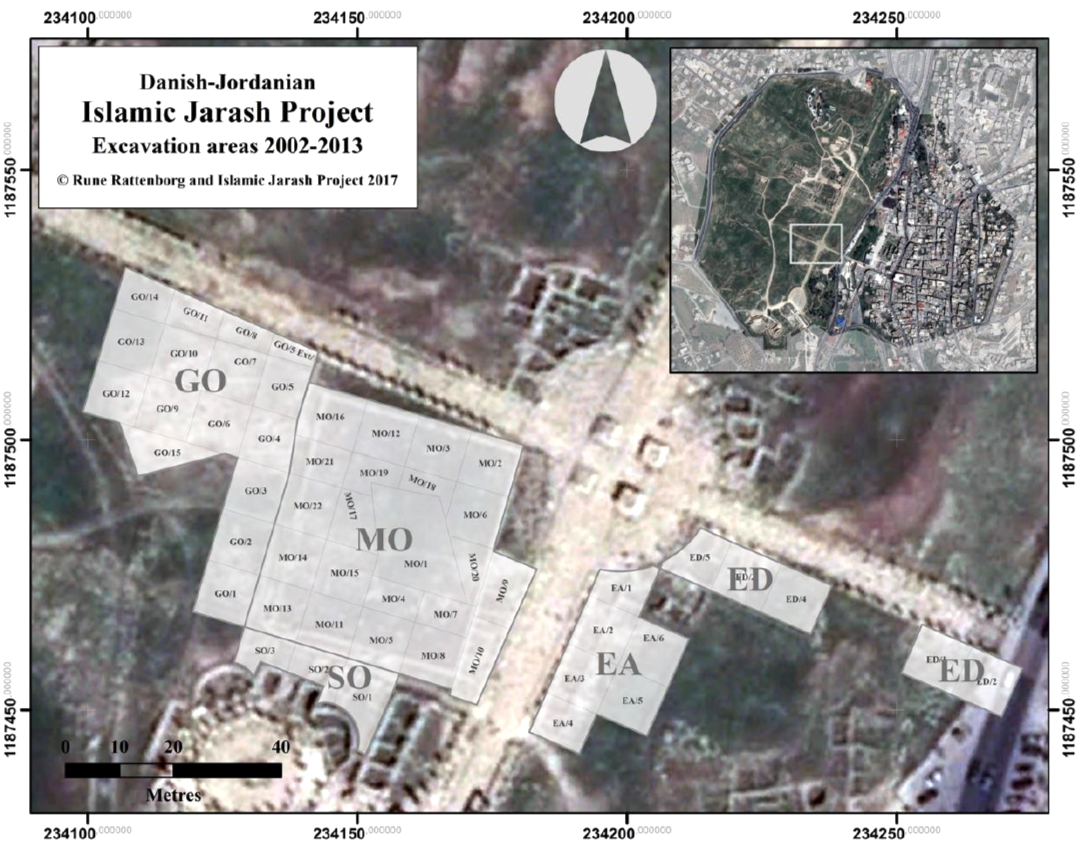

- Fig. 3 - Islamic Jerash Project

Excavation Areas 2002-2013 from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 1 - Square numbers for

2009 Islamic Jerash Project Excavations from Blanke et al (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes).

Blanke et al (2010) - Fig. 1 - Square numbers for

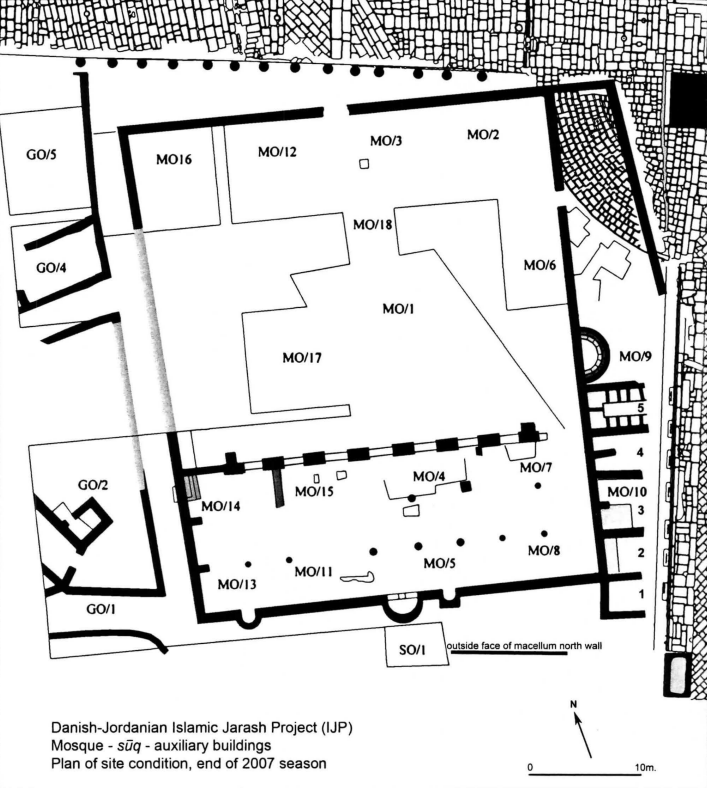

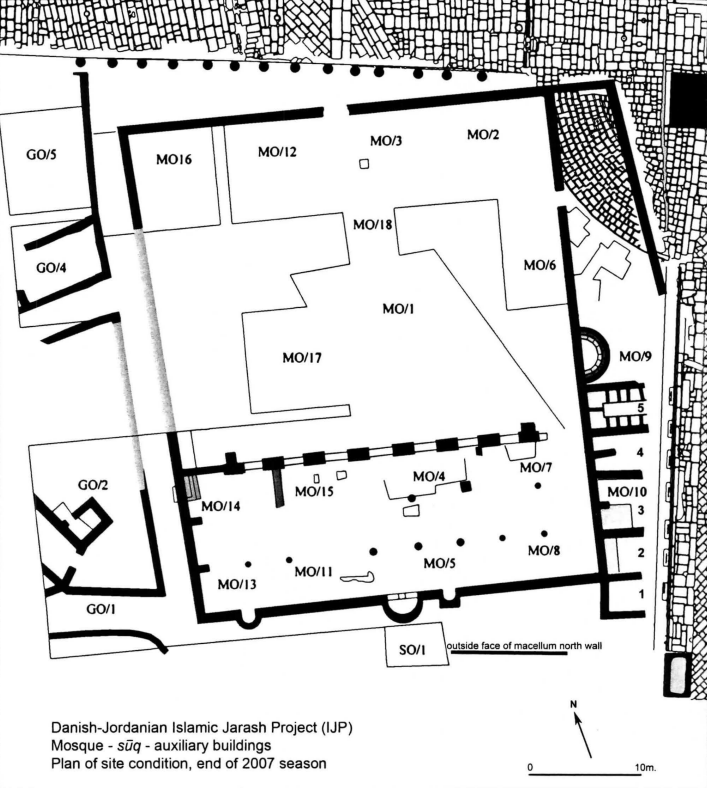

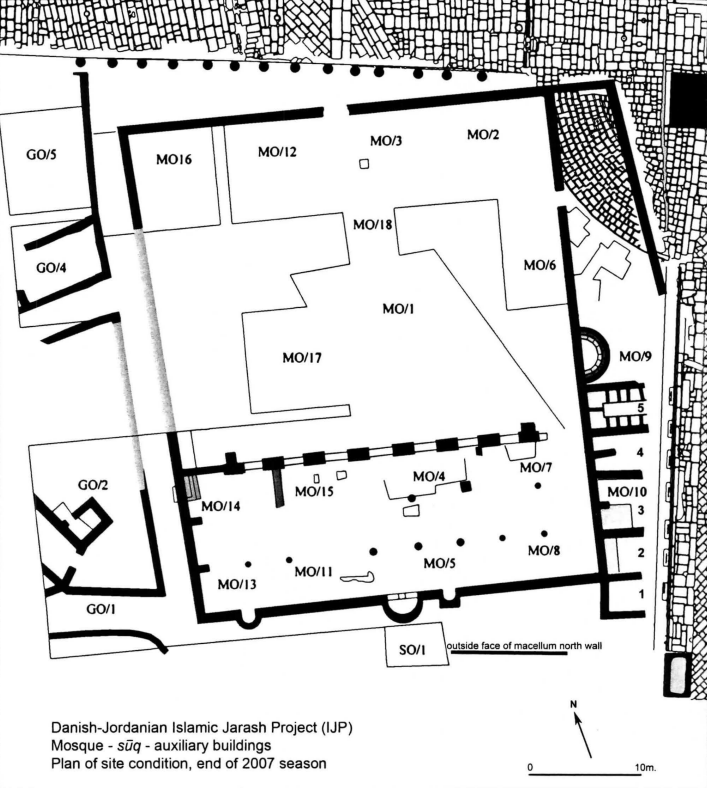

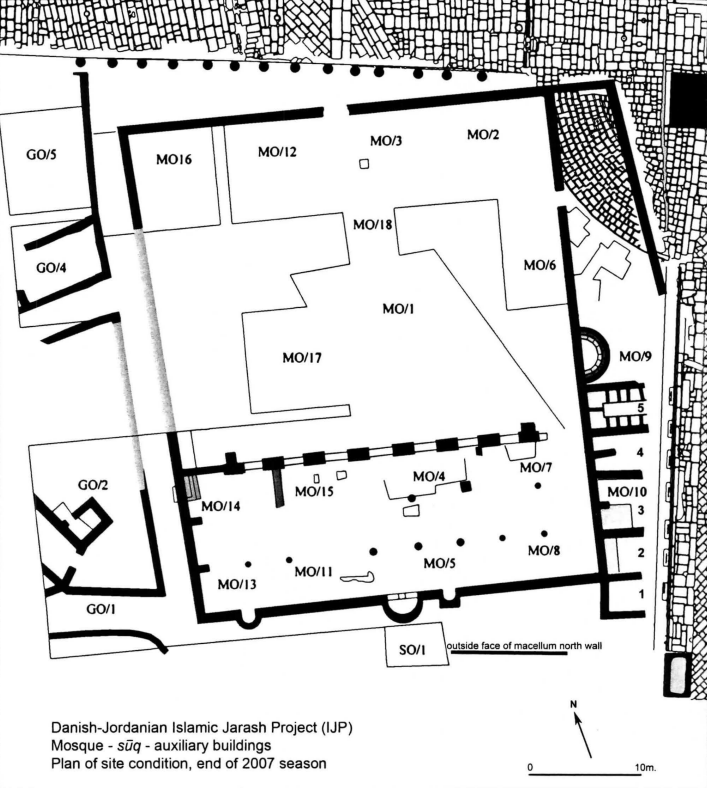

2007 Islamic Jerash Project Excavations from Walmsley et al (2008)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the excavations in central Jarash, to end of 2007 season

(Barnes mod. Walmsley)

Walmsley et al (2008)

- Fig. 3 - Islamic Jerash Project

Excavation Areas 2002-2013 from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Fig. 1 - Square numbers for

2009 Islamic Jerash Project Excavations from Blanke et al (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes).

Blanke et al (2010) - Fig. 1 - Square numbers for

2007 Islamic Jerash Project Excavations from Walmsley et al (2008)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General plan of the excavations in central Jarash, to end of 2007 season

(Barnes mod. Walmsley)

Walmsley et al (2008)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Central Bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Central Bathhouses highlighting location of latrine and bathhouse sewers

(Plan by Louise Blanke)

Blanke et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View

of latrine in Central Bathhouse from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Overview of latrine in Central Bathhouse looking west.

(© Islamic Jarash Project.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Central Bathhouses from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Central Bathhouses highlighting location of latrine and bathhouse sewers

(Plan by Louise Blanke)

Blanke et al. (2024b) - Fig. 3 - Aerial View

of latrine in Central Bathhouse from Blanke et al. (2024b)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Overview of latrine in Central Bathhouse looking west.

(© Islamic Jarash Project.)

Blanke et al. (2024b)

- Fig. 3 - Fallen Column atop

crushed roof tile fragments from Walmsley et al (2008)

Figure 3

Figure 3

A fallen column shaft resting on stone paving of the floor in the mosque hall, with roof tile fragments crushed between the column and paving

JW: The excavators interpreted this on page 111 to be the result of what was left after salvaging activities.

Walmsley et al (2008) - Fig. 16.5 - Two

Mihrabs

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.5

Figure 16.5

The 2002 photo graph of the main (umayyad) miḥrāb of the congregational mosque of Jerash in Phase 1 (c. AD 725–40), with the partially preserved smaller and later Phase 2 (c. mid-eighth to early eleventh centuries) miḥrāb to its left (east). In the foreground are reused column bases that served as foundations for the first colonnade that ran parallel to the qiblat wall of the prayer hall

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

Walmsley (2018) - Fig. 16.6 - The smaller

Mihrab

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6

The southern (external) face of the umayyad miḥrāb following stratigraphic excavations, showing the foundations and skilled stone working by the masons. to the right, a long series of street surfaces are preserved that date to the use of the mosque; the later date of the smaller Phase-2 miḥrāb can be seen in the way it sits on top of surfaces contemporary with the original Phase-1 mosque and its miḥrāb

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

Walmsley (2018) - Fig. 8 - North wall of GO

building B from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Raised bench with mosaic floor paving and adjoining basin along north wall of GO Building B during excavations in 2013, view facing east (IJP_D_15356)

(© Islamic Jarash Project 2017)

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Qibla wall and three mihrabs - photo by JW

- First two mihrabs - photo by JW

- Third mihrab - photo by JW

- Fig. 3 - Fallen Column atop

crushed roof tile fragments from Walmsley et al (2008)

Figure 3

Figure 3

A fallen column shaft resting on stone paving of the floor in the mosque hall, with roof tile fragments crushed between the column and paving

JW: The excavators interpreted this on page 111 to be the result of what was left after salvaging activities.

Walmsley et al (2008) - Fig. 16.5 - Two

Mihrabs

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.5

Figure 16.5

The 2002 photo graph of the main (umayyad) miḥrāb of the congregational mosque of Jerash in Phase 1 (c. AD 725–40), with the partially preserved smaller and later Phase 2 (c. mid-eighth to early eleventh centuries) miḥrāb to its left (east). In the foreground are reused column bases that served as foundations for the first colonnade that ran parallel to the qiblat wall of the prayer hall

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

Walmsley (2018) - Fig. 16.6 - The smaller

Mihrab

from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6

The southern (external) face of the umayyad miḥrāb following stratigraphic excavations, showing the foundations and skilled stone working by the masons. to the right, a long series of street surfaces are preserved that date to the use of the mosque; the later date of the smaller Phase-2 miḥrāb can be seen in the way it sits on top of surfaces contemporary with the original Phase-1 mosque and its miḥrāb

(Islamic Jarash Project/ Department of antiquities of Jordan, IJP_B&W-360).

Walmsley (2018) - Fig. 8 - North wall of GO

building B from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Raised bench with mosaic floor paving and adjoining basin along north wall of GO Building B during excavations in 2013, view facing east (IJP_D_15356)

(© Islamic Jarash Project 2017)

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) - Qibla wall and three mihrabs - photo by JW

- First two mihrabs - photo by JW

- Third mihrab - photo by JW

- from Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

-

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) noted that

in chronological terms, occupational phases are well documented for the 7th-10th centuries, with scarcer bodies of evidence dating to the 11th-13th centuries available from the general excavation area, but with limited stratigraphic grounding

.

| Area | Description |

|---|---|

| MO | congregational mosque on the southwest corner of the Roman tetrakionion |

| GO | adjoined domestic quarters to the west of MO |

| SO | south of the mosque qibla wall in an alleyway bordering the ruins of the Roman macellum |

| EA | eastern side of the main north-south thoroughfare |

| ED | close to the eastern edge of the current antiquities area |

| Phase | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ca. 725-735 CE | an event dated by post-reform Umayyad coinage and ceramics recovered from under-floor fills, and through a comparative study of other mosques datable from the seventh to tenth centuries AD. The building of a mosque could not commence until a three-hundred-year-plus bathhouse had been cleared from the site — which, above all, indicates that the social and commercial centrality of the position, rather than any previous sanctity, determined the choice of the location. |

| 2 | mid-eighth to mid-tenth/early-eleventh centuries AD | This phase, the longest and most complex of the three, sees numerous adaptations in the arrangement of space in and around the mosque and the probable function of these areas resulting from their redesign. The chronology of these changes is not as clear-cut as Phase 1, and there is no evidence to suggest that the different structural rearrangements happened as one event; rather, the changes would seem to represent a progressive and longterm alteration to the role and function of the mosque in central Jerash over several centuries. Sadly, the very disturbed condition of the archaeological deposits within the mosque enclosure was not conducive to providing a distinct stratigraphic framework for dating the Phase 2 (and Phase 3) changes; by and large, the chronology has been developed primarily from Hugh Barnes’s observed architectural sequence. The long history of Phase 2 ended with the catastrophic collapse of the prayer hall and the subsequent salvaging of building materials. During excavation, many pieces of ceramic roof tile were recovered from the prayer-hall area; only a few were discovered unbroken, suggesting the area was picked over to recover usable tile. finds associated with the collapse deposits, including a distinctive coarse-wear lamp found intact, suggests Phase 2 ended sometime in the late tenth to early/mid-eleventh centuries AD. |

| 3 | into the thirteenth century AD or later | A smaller occupation into the thirteenth century AD or later, based on finds recovered from the terminal phase of the mosque floor. Most of the evidence for this phase was recovered from the smaller western room of the prayer hall. The condition and function of the rest of the mosque enclosure area in Phase 3 is unclear due to the complete loss of archaeological deposits through erosion and later interventions. Phase 3 ended with the collapse of the roofing, followed by widespread evidence for subsequent stone removal, pit digging, and agricultural terracing, all of which entailed significant effort. It is about this time that the mamlūk-period mosque was built at the nearby village of suf, using spolia sourced from Jerash. In general terms, while stone removal and farming are activities usually associated with the setting up of a Circassian settlement in Jerash at the end of the nineteenth century, these activities should not be discounted as being practised earlier during Mamlūk and early Ottoman times (c. fourteenth/fifteenth centuries AD and later). |

| Label | Period | Dates | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material resilience and political novelties | ca. 650-749 CE |

Discussion

The surrender of north Jordan to the armies of `Umar in the 630ies left most of the urban principalities in the Jordan highlands and around the

Dead Sea largely untouched by the political upheavals of the day. At an archaeological level, a tangible divide between the old and the new

certainly escapes us (Avni 2014: 101-106; Walmsley 2007a: 46-47). |

|

| The earthquake of 749 - and its aftermath | ca. 750-900 |

Discussion

available archaeological evidence from Jarash demonstrates that whereas the earthquake of 749 may have brought about destruction at an unprecedented scale,

local communities and civic institutions alike proved able to withstand and overcome the disaster that had befallen them. The congregational mosque was

rebuilt to match its former grandeur, in a form that remained in use for perhaps two centuries. As will be shown in more detail below, residential quarters

in Area GO underwent significant remodelling, seeing new and extensive housing structures erected that remained occupied until the end of the 9th century

at the very least. Commercial areas around the tetrakionion remained in use for a comparable span of time (Simpson 2008: 116), and while only partially

excavated, a large compound with spacious, paved rooms east of the crossing in Area EA also seems to have been reused (Blanke et al. 2010: 317-320).

Most recently, survey and excavation further afield from the mosque suggest that not only the centre, but also the city's entire southwest district

saw continuous occupation into at least the 9th century (Blanke et al. 2015: 236; Blanke forthcoming). |

|

| Urban change, contraction, and dissolution | ca. 900-1000 CE |

Discussion

Following another round of structural collapse in the late 9th or early 10th century, the mosque was rebuilt to house a much more modest congregation, utilising only the westernmost third of the prayer hall, and leaving the spacious courtyard in a dilapidated state. Wall collapse clogged the laneway along the northwest perimeter wall of the mosque courtyard, blocking access from the main westward street, and was, apparently, never removed. Curiously enough, this collapse layer was not found in the passageway between the mosque's western entrance and its southwest corner, suggesting that access to the prayer hall from the residential units was maintained for a longer span of time. |

|

| Dissolving urban fabrics | ca. 1000-1200 CE |

Discussion

Moving into the late 10th century and beyond, structural remains in the IJP excavation area in general come to a halt. The exact lifespan of the third

and final phase of the mosque still poses a series of questions, which will be addressed more thoroughly in a forthcoming article by Hugh Barnes and Alan Walmsley.

The cache of 12th-14th century Ayyubid and Mamluk wares retrieved from the mosque prayer hall derives from later intrusions (Walmsley et al. 2008: 134)

and bears no clear relation to the structure itself, which was, apparently, an abandoned ruin at this time. |

|

| Subtle continuities: Jarash in the Early and Middle Islamic Ages |

Discussion

While a proper understanding of Jarash in succeeding centuries, namely during the Crusades and the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods, is still a work in progress, recent findings by the Northwest Quarter Project indicates the presence of agglomerated housing units, perhaps farmsteads, o n the plateau to the northwest (Lichtenberger and Raja 2016; Peterson 2017). Considered together with traces of Mamluk occupation in the southern part of the city near the Temple of Zeus (Tholbecq 1997-1998), there are certainly indications of continued activity throughout Jarash even in the Middle Islamic Period. |

- from Blanke et al (2010:320)

- Blanke et al (2010:320) noted the following:

Currently, excavation within GO numbers six 10 by 10 metres excavation units (GO/1-6) of which all but GO/3 have seen regular excavation over the years. As such, excavations within the GO constitute two separate areas, being GO/1-2 in the southeastern and GO/4-6 in the northeastern quadrant. The former has been excavated from 2005-2007, while investigations in the latter area started in 2007. So far, excavations within GO/4-6 have established a preliminary sequence of four consecutive building phases spanning the Late Umayyad-Early Abbasid periods

| Phase | Period | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | unknown | unknown | |

| 2 | Early Abbasid | 800 - 850 CE | GO/4-5: The Later Phases (1-2) - Preliminary dating of phase 2 suggests mid/late 9th century AD, based on a number of Abbasid Kerbschnitt Ware sherds found whilst excavating the contents of the pit located in the northern courtyard, mentioned above. |

| 3/II | Abbasid | 750 - 800 CE | GO/6: Abbasid Foundations and Cistern - No architectural features within the rectangular GO/6 structure were identified, and excavation only encountered a thick and fairly uniform layer of building stones, stemming either from collapse or used as fill. |

| 3/I | Early Abbasid | 750 - 800 CE | GO/4-5-6: The Early Abbasid Levels (Phase 3/I-II) |

| 4 | Late Umayyad | 700- 750 CE | GO/4-5: The Late Umayyad House (Phase 4) - It should be noted that we have yet to properly verify the termination of the phase 4 structures as contemporary with the earthquake of 749, even though this seems a tempting link to draw from present evidence. |

- from Blanke et al (2010:317)

- Blanke et al (2010:317) noted the following:

Excavations in EA have confirmed the existence of shops along with a large building located east of the cardo, behind the shops. As such, the excavation area was quickly separated into two distinct areas. One area consists of the shops, the other, of the large building, which in the present article will be referred to as Building A.

| Phase | Period | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | unknown | Construction of Building A - The building appears to have been emptied and partly reconstructed, making it difficult to determine the date of its original construction. Its origin may will be in the Umayyad period, although the possibility of an earlier date is not dismissed. The high proportion of tumble uncovered throughout the excavation of EA suggests to a potential second storey. | |

| 2 | Umayyad - Abbasid | Shops - Ceramic evidence from this shop suggests an occupation period ranging from the Umayyad to the Abbasid period. | |

| 3 | Abbasid | about the tenth century | Reconstruction of Building A - The dating of the reconstruction of Building A is, for now, set to the Abbasid period (about the tenth century), based on a characteristic piece of blue glazed ceramic that was found associated with wall 5's foundation trench, thus providing a terminus post quem. |

| 4 | Medieval | Reuse of Building A | |

| 5 | Modern | The top layers |

- Blanke et al (2010) noted that there were 6 phases but did not provide a phasing table.

Sealed numismatic and ceramic finds have dated the construction of the bathhouse to the late third to early fourth century and its demise to the early eight century (Blanke et al. 2007: 196). The Central Baths went out of use when the area was redeveloped for the construction of a mosque.

... Excavations were carried out in an area covering 30 by 17 metres within five excavation units (MO/12, MO/16, MO/18, MO/19 and MO/21)North of the Bathing Suite - Central Baths (LB) Phase Period Dates Notes 1 2 3 4 5 6 - Blanke et al (2024b:4) noted that

numismatic and ceramic finds date the construction of the [central] bathhouse to the late 3rd or early 4th c. and suggest that it was dismantled in theearly 8th c. during the reorganization of the area for the construction of a congregational mosque.13

Footnotes13 A coin of Elagabalus (r. 218–22 CE) in the bathhouse’s foundation along with a 3rd-c. ceramics assemblage provides the terminus post quem for the building’s construction (Blanke et al. 2007, 182). Umayyad-period pre-reform coins (ca. 660–80 CE) were retrieved from the last phases of use, and both pre- and post-reform coins were found in the infill of the hypocaust and the levelling done in preparation for the construction of the mosque (Blanke et al. 2007, 190–96). See also Walmsley 2018.

-

Walmsley (2018:251) discussed the bathhouse that preceded the Umayyad Congregational Mosque

Built around AD 300, the Central Bathhouse took up a space almost equal to that of the mosque and comprised bathing rooms, a service area, a sizable public latrine, and street-side shops. The excavation of the bathhouse (2002–10) revealed how it developed through five main phases until demolished, leaving only the foundations that were filled in to create a strong platform for the mosque builders. The final phase of the bathhouse saw a building much reduced in size, with only few heated rooms in use and bathing reduced to individual bathtubs; however, the evidence recovered reveals that social practices in the bathhouse remained the same. Large numbers of ceramic sherds, bones, jewellery, coins, and gaming pieces reveal a lively bathing culture that continued without a break into the early Islamic period. The excavation of the Central Bathhouse and the careful study of its associated finds offer a rare opportunity to access the daily lives of the people who inhabited Jerash from Roman to early Islamic times, foreshadowing and providing vital information on the rise of the Islamic ḥammām.

- Fig. 16.8 - Early Islamic Jerash

- ca. 800-1000 CE - from Walmsley (2018)

Figure 16.8

Figure 16.8

Jerash congregational mosque, Phase 2, with surrounding structures of contemporary date (areas GO and EA Phase 3 = mosque Phase 2), dated mid-eighth to mid-tenth centuries AD, with some evidence of use into the early eleventh century AD

(plan by Rune Rattenborg, incorporating material previously published in Gawlikowski 1986; Kraeling 1938a; Simpson 2008a).

Walmsley (2018)

Walmsley (2018:251) discussed the Sūq

The discovery of a row of shops along the eastern wall of the Phase-2 mosque (above), and in them a number of marble tablets with shopkeepers’ accounts in proficient Arabic, revealed the central role played by the mosque in the daily operation of the marketplace.Walmsley (2018:251) discussed the Residential Complex

To the west of the mosque, separated from it by a narrow street (fig. 16.8), a large residential complex has been exposed that existed well before the construction of the mosque and continued as residences, with successive modifications, contemporaneously with the mosque. The three courtyard buildings uncovered were constructed around a network of streets and directly connected to the mosque by way of doorways in the west enclosure wall, thereby revealing that this residential quarter was fully integrated in the life of the mosque, most notably in Phase 2

The congregational Mosque of Jerash was uncovered in the 2000s and is located in the south half of Jerash just north of the Oval Plaza. Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) and Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) both date construction to ~725 CE. Barnes et al (2006:295) identified an apparent single event collapse layer in the Qiblat Hall of the Mosque but did not supply a date. The collapse layer appears to be related to a 9th-10th century collapse layer found in nearby excavations of the Southwest Hill. Thus it appears that there is only rebuilding evidence for a mid 8th century CE earthquake in the Umayyad Congregational Mosque and environs. Blanke et al (2010:320) wrote the following about the termination of Phase 4 in excavation area GO (GO/4-5) which uncovered shops and housing east of the congregational mosque.

GO/4-5: The Late Umayyad House (Phase 4) - It should be noted that we have yet to properly verify the termination of the phase 4 structures as contemporary with the earthquake of 749, even though this seems a tempting link to draw from present evidence.Blanke and Walmsley (2022:95-97) described the effects of the earthquake at the Umayyad Congregational Mosque and elsewhere in Jerash

In 749, after only a few decades of use, the mosque along with most of Jarash’s urban fabric was devastated by one or more massive seismic events.108 The damage caused by the earthquake and the following discontinuation of structures is well documented throughout Jarash and has led scholars to assume a total abandonment of the town – a sentiment that still lingers today.109 The excavations within north-west Jarash have generally identified a discontinuation after the mid-eighth century. This is evident, for example, in and around the North Theatre, the Artemis precinct and the Propylaeum Church, and further west on the plateau behind the Temple of Artemis and along sections of the south transverse street.110El-Isa (1985) noted that the Umayyad mosque [of Jerash] appears to have been demolished and removed and with a relic of its Mihrab the only indications left of its existence. This does not appear to refer to the Umayyad Mosque but to a a structure in northeastern Jerash that was discovered and identified as a mosque in 1981 (Naghawi, 1982) but whose identification is now considered

It is worth noting, however, that sporadic evidence of post-earthquake activities has been found throughout the town. Among these are a coin hoard found within the North Theatre which included a Ṭūlūnid dinar dated to 894 as well as ninth-to eleventh-century housing found south-east of the theatre’s exterior wall.111 Some traces of Abbāsid-period occupation of the Macellum adds to the evidence as does pottery finds that suggest some continuous activity in the Temple of Zeus.112

Yet the evidence for continuous occupation after 749 is by far the strongest in Jarash’s commercial and religious centre at the intersection of the two main thoroughfares and in the south-west district. Recent archaeological investigations in Jarash’s south-west district suggests that this area was crucial to maintaining the central functions of urban life and therefore, the financial investment in the restoration of the town and the efforts put towards reconstruction were concentrated here.113

After the earthquake of 749, the mosque was rebuilt to its former dimensions, but its main entrance was blocked as was its central miḥrāb.114 Instead, a new entrance was constructed on the axial street on the east side of the mosque, while a smaller doorway was set into the mosque’s western wall giving access to the porticoed courtyard with an ablution feature set immediately inside the doorway. The prayer hall was subdivided into two with a smaller section set apart in the western end. A new miḥrāb was constructed centrally in the shortened prayer hall, while another was added to the western enclosure. At some point a minaret was added to the north-east interior corner of the courtyard. Following the rebuilding of the mosque, shops were added to its east façade, just south of the new entrance and also across the axial street on its east side. Here, a large building that may have served an administrative purpose was rebuilt using the walls of an earlier building as foundations.115 The reconfiguation of the mosque marks not only a substantial investment in the built environment after 749, but also allows us to identify a reduction in the importance of the western section of the south transverse street. Instead, the mosque was now accessed from the markets (to the east) and the habitation (to the west).116Footnotes108 See summary of textual sources pertinent to this earthquake in Ambraseys, Earthquakes, 230–238.

109 Most recently in 2019, Lichtenberger and Raja have questioned the accuracy of the Islamic Jarash Project's interpretation of an extensive Abbasid-period rebuilding of the mosque. They have also questioned the results of the excavation of the Umayyad House on the north side of the south transverse street, which documented continuous usage into the ninth century Lichtenberger and Raja states that `for now, we need to return to the view that the earthquake of 749 indeed had a catastrophic impact on Jerash, and if anything survived, it was only a shadow of the city's former grandeur: Lichtenberger and Raja, `Defining borders', 282.

110 North theatre: Ball et al., `The North Decumanus', 365; Clark and Bowsher, `The Jerash north theatre'; the Artemis precinct and the Propylaeum Church: Brizzi et al., `Italian excavations at Jarash', 357-358; Plateau behind the Temple of Artemis: see, for example, Lichtenberger and Raja, `Defining borders'; the south transverse street: Barghouti, `Urbanization of Palestine and Jordan', 219-221.

111 Clark and Bowsher, `The Jerash north theatre', 237-238,241-243.

112 Macellum: Uscatescu and Martin Bueno, `The Macellum of Gerasa', 82-84; Uscatescu and Marot, `The Ancient Macellum of Gerasa', 297-299; Temple of Zeus: Bessard, `The urban economy', 411 and fig. 14.

113 Some of this ground is also covered in Blanke, 1Re)constructing Jarash' and in Rattenborg and Blanke, lard in the Islamic Ages'. See also Blanke, Abbasid Jerash Reconsidered'; Blanke et al., `The 2011 season of the Late Antique Jarash Project'; Blanke et al., `Excavation and magnetic prospection'; Blanke et al., A millennium of unbroken habitation'; Pappalardo, `The Late Antique Jerash Project'.

114 This paragraph is summarised from Walmsley, `Urbanism at Islamic Jarash', 248-250.

115 Blanke et al., ‘Changing cityscapes in central Jarash’; Rattenborg and Blanke, ‘Jaraš in the Islamic Ages’.

116 For the markets, see Simpson, ‘Market Buildings at Jarash’. For the habitation, see Rattenborg and Blanke, ‘Jaraš in the Islamic Ages’ and also work by Blanke reporting the usage of the southwest hilltop.

somewhat doubtful( Walmsley and Daamgaard, 2005:364) - i.e. the '1981' mosque is now thought not to have been a mosque.

The Umayyad Congregational Mosque of Jerash was uncovered

in the 2000s and is located in the southern half of the city,

just north of the Oval Plaza.

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) and

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005) both date

its construction to around 725 CE.

Barnes et al. (2006:295) identified an

apparent single-event collapse layer in the

Qiblat Hall of the Mosque but did not provide a

chronological attribution. The collapse layer appears to

relate to a 9th–10th century collapse layer excavated on the

Southwest Hill. Thus it appears that there is

only rebuilding evidence for a mid 8th century CE earthquake

in the Umayyad Congregational Mosque and environs.

Blanke et al. (2010:320) noted, regarding

Phase 4 in excavation area GO (GO/4–5), that “we have yet to

properly verify the termination of the phase 4 structures as

contemporary with the earthquake of 749, even though this

seems a tempting link to draw from present evidence.”

Blanke and Walmsley (2022:95–97) wrote

that “in 749, after only a few decades of use, the mosque

along with most of Jarash’s urban fabric was devastated by

one or more massive seismic events. The damage caused by

the earthquake and the following discontinuation of

structures is well documented throughout Jarash and has led

scholars to assume a total abandonment of the town—a

sentiment that still lingers today.” They continued, “The

excavations within north-west Jarash have generally

identified a discontinuation after the mid-eighth century.

This is evident, for example, in and around the North

Theatre, the Artemis precinct and the Propylaeum Church,

and further west on the plateau behind the

Temple of Artemis and along sections of the

south transverse street.”

Nonetheless, “sporadic evidence of post-earthquake

activities has been found throughout the town. Among these

are a coin hoard found within the North Theatre which

included a Ṭūlūnid dinar dated to 894 as well as

ninth-to-eleventh-century housing found south-east of the

theatre’s exterior wall. Some traces of Abbāsid-period

occupation of the Macellum adds to the evidence as does

pottery finds that suggest some continuous activity in the

Temple of Zeus.”

According to Blanke and Walmsley, “the evidence for

continuous occupation after 749 is by far the strongest in

Jarash’s commercial and religious centre at the intersection

of the two main thoroughfares and in the south-west

district. Recent archaeological investigations in Jarash’s

south-west district suggest that this area was crucial to

maintaining the central functions of urban life and

therefore, the financial investment in the restoration of the

town and the efforts put towards reconstruction were

concentrated here.”

They describe how “after the earthquake of 749, the mosque

was rebuilt to its former dimensions, but its main entrance

was blocked as was its central miḥrāb. Instead, a new

entrance was constructed on the axial street on the east

side of the mosque, while a smaller doorway was set into the

mosque’s western wall giving access to the porticoed

courtyard with an ablution feature set immediately inside

the doorway. The prayer hall was subdivided into two with a

smaller section set apart in the western end. A new miḥrāb

was constructed centrally in the shortened prayer hall, while

another was added to the western enclosure. At some point a

minaret was added to the north-east interior corner of the

courtyard. Following the rebuilding of the mosque, shops

were added to its east façade, just south of the new entrance

and also across the axial street on its east side. Here, a

large building that may have served an administrative

purpose was rebuilt using the walls of an earlier building as

foundations. The reconfiguration of the mosque marks not

only a substantial investment in the built environment after

749, but also allows us to identify a reduction in the

importance of the western section of the south transverse

street. Instead, the mosque was now accessed from the

markets (to the east) and the habitation (to the west).”

El-Isa (1985) noted that the Umayyad mosque

of Jerash “appears to have been demolished and removed and

with a relic of its

mihrab

the only indications left of its existence.” However, this

appears not to refer to the Umayyad Mosque near the Oval

Plaza, but rather to a structure in northeastern Jerash

discovered and identified as a mosque in 1981

(Naghawi, 1982) whose identification is now

considered “somewhat doubtful”

(Walmsley and Daamgaard, 2005:364).

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:11) report the following:

The later phase of occupation in the domestic complexes, bracketed between 800-900, saw the addition of steps in several outer doorways to prevent refuse and accumulated soil on exterior surfaces from slipping into living quarters. This corroborates the long period of usage inferable from architectural alterations. Occupation was punctuated by another round of structural collapse, which is associated with the abandonment of two rooms in the northern wing of Building B and with the collapse and subsequent infilling of the subsurface compartment around the cistern shaft in the courtyard of the same structure. Finds of discarded fragments of reduction-fired roof tiles in subsurface packing of the latest phase of domestic occupation in Area GO can be associated with identical material retrieved from underneath a substantial wall collapse in the laneway between the mosque west wall and Building A, and suggest that the dwellings in Area GO may have had tiled roofs. These strata likely relate to the same event that marked the termination of the penultimate phase of the congregational mosque.Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:13) add:

Given the prolonged usage of the Area GO housing units and the nature of the subsequent collapse, this event should be dated to the latter half of the 9th century at the earliest, perhaps corresponding with the collapse of the residential units on the [Southwest] hilltop (Blanke forthcoming). Associated structural collapse, outside the mosque qiblat wall and within and around the domestic complexes to the east, is less imposing than the mid-8th century collapse layers, but a number of potentially significant earthquakes in the area are known from the late 9th and 10th centuries (see Ghawanmeh 1992: p. 56 Table I; Sbeinati et al. 2005: pp. 365-367 and Table II; also el-Isa 1985: pp. 232-233 and Table 1 JW: I suggest cross-checking catalogues of Ambraseys, 2009, Guidoboni et. al., 1994, and this one instead). Pottery finds from paved floors of GO Phase 3/II in Building A provides a good range of material characteristic of a late 8th — 9th century date with painted red terracotta and cream and pale orange wares well represented, accentuating the changing horizons of Early Islamic material culture (Walmsley 1995: 668; 2001b: 310). A nearly complete decorated Cream Ware jug was retrieved from below wall collapse overlying a paved floor in the eastern part of Building A. Comparable material is available from the Abbasid housings further north (Gawlikowski 1986: Plates XII-XIII; also Gawlikowski 1995), and finds further parallels e.g. in the assemblage from Area Z at Umm Qais (Gadara) (el-Khouri and Omoush 2015: 17-20).

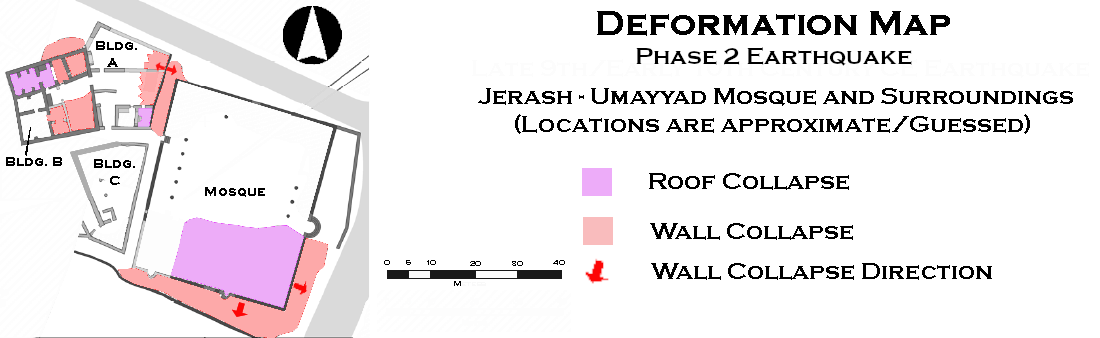

Following another round of structural collapse in the late 9th or early 10th century, the mosque was rebuilt to house a much more modest congregation, utilising only the westernmost third of the prayer hall, and leaving the spacious courtyard in a dilapidated state. Wall collapse clogged the laneway along the northwest perimeter wall of the mosque courtyard, blocking access from the main westward street, and was, apparently, never removed. Curiously enough, this collapse layer was not found in the passageway between the mosque's western entrance and its southwest corner, suggesting that access to the prayer hall from the residential units was maintained for a longer span of time.Based on the above, it appears that the collapse layer described (below) but not dated by Barnes et al (2006:295) fell during the 9th or 10th centuries CE.

The Qiblat Hall (IRS)Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:15) noted that

... So far over five tonnes of roof tile pieces have been found within the Qiblat hall. The oblong plan of the hall, with its qiblat wall, the double colonnade and the row of entrance piers, suggests a long triple-gabled roof covered the qiblat hall. The tile fragments have mostly been recovered from a thick dark layer that is largely uniform throughout the qiblat hall. No complete roofing tiles have been found, probably because any roof tiles that had not smashed were taken for reuse elsewhere after the initial collapse of the roof. Other salvageable building materials were also taken and only a few small areas of the paved floor remain. Post-collapse salvaging activity would explain the disturbance of the collapse layer.

There is a great deal of stone tumble lying outside the mosque walls from the collapse of the qiblat hall. Much less stone is found inside the hall, which shows that the walls fell outwards, pushed by the force of the heavy roof. The pattern of the fallen outer walls, the uniformity of the collapse layer and abundance of roof tile fragments indicate that the roof and some of the mosque walls collapsed in one event.

the extant archaeological record of the 9th-11th centuries is notoriously meagre and marred by an unstaisfactory degree of chronological control.

Abbasid-period housing in Area GO of Jerash shows evidence of

long-term use and architectural modification throughout the

9th century CE. Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:11) report that by

800–900 CE, residents had added steps to outer doorways to

block refuse and soil from entering, indicating prolonged

occupation. This phase ended in structural collapse,

abandoning two rooms in the northern wing of Building B and

collapsing the subsurface compartment around the courtyard

cistern shaft. The reuse of

reduction-fired roof tiles—found

in subsurface packing in Area GO and beneath wall collapse

in the laneway west of the mosque—suggests that tiled roofs

were used in this phase. These layers likely correlate with

the same event that ended the penultimate construction

phase of the congregational mosque.

The nature and distribution of the collapse layers,

including wall fall outside the mosque’s

qiblat wall and in

the adjacent domestic complexes, were less severe than

those from the 749 CE earthquake. Rattenborg and Blanke

argue that this later collapse should be dated no earlier

than the second half of the 9th century CE and may

correspond to damage in residential units on the Southwest

Hill.

Pottery from Building A’s paved floors (Phase 3/II) supports a

late 8th–9th century date. The assemblage includes

painted red terracotta,

cream, and

pale orange wares. A nearly complete

Cream Ware jug was recovered beneath wall collapse

over a paved floor. Similar wares appear in Abbasid housing

further north (Gawlikowski 1986, 1995) and in Area Z at Umm Qais

(el-Khouri and Omoush, 2015:17–20).

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:13) also describe

how collapse in the late 9th or early 10th century

led to the mosque’s partial reconstruction. Only the western

third of the prayer hall was reused; the courtyard remained

in disrepair. Collapse debris blocked the laneway along the

northwest mosque perimeter, severing access from the

main street. However, no collapse was recorded in the

passage from the mosque’s west entrance to its southwest

corner, suggesting that access from the adjacent residences

persisted longer.

This later collapse likely corresponds to the destruction

layer in the

qiblat Hall described

but not dated by Barnes et al. (2006:295). Over five tonnes of

roof tile fragments were recovered from a thick uniform collapse

layer inside the hall. The layout and architectural

features suggest a

triple-gabled roof once spanned the hall.

Post-collapse looting explains the absence of whole tiles

and much of the paving. Outside the mosque walls, large

volumes of stone tumble contrast with the interior,

indicating that the roof’s weight forced the walls to

collapse outward. The combination of roof tile fragments,

uniform collapse debris, and outward-fallen masonry suggests

the roof and walls failed in a single event.

Rattenborg and Blanke (2017:15) caution that

archaeological evidence for the 9th–11th centuries is limited

and often lacks precise chronological resolution.

It appears that archaeoseismic evidence for the mid 8th century CE earthquake at the Congregational Ummayad Mosque and surroundings is based on rebuilding evidence rather than observed and dated seismic destruction layers. The second Mihrab, supposedly built after this earthquake, suggests that an extensive rebuild was required and that the Mosque was heavily damaged during the earthquake.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

GO area - two rooms in the northern wing of Building B and subsurface compartment around the cistern shaft in the courtyard of the same structure

(note that Building B is to the west of building A)

Figure 7

Figure 7Early Islamic Jerash ca. 750-850 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11Early Islamic Jerash ca. 950-1000 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010) |

Fig. 8

Figure 8

Figure 8Raised bench with mosaic floor paving and adjoining basin along north wall of GO Building B during excavations in 2013, view facing east (IJP_D_15356) (© Islamic Jarash Project 2017) Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) |

|

|

GO area - laneway between the mosque west wall and Building A, eastern interior of Building A, and possibly square GO/6 (note that Building B is to the west of building A)

Figure 7

Figure 7Early Islamic Jerash ca. 750-850 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11Early Islamic Jerash ca. 950-1000 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010) |

Fig. 15

Figure 15

Figure 15GO/6 at the end of the 2009 season, seen from the west. Note the cistern drain in the bottom of the picture (by IJP). Blanke et al (2010) |

|

|

Congregational Mosque - qiblat Hall

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan of the mosque, showing excavated areas to 2004 Barnes et al (2006)

Figure 3

Figure 3Preliminary outline plan of the Umayyad mosque of Jarash (as after 2004 season). Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the excavations in central Jarash, to end of 2007 season (Barnes mod. Walmsley) Walmsley et al (2008) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 12 of Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GO area - two rooms in the northern wing of Building B and subsurface compartment around the cistern shaft in the courtyard of the same structure

(note that Building B is to the west of building A)

Figure 7

Figure 7Early Islamic Jerash ca. 750-850 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11Early Islamic Jerash ca. 950-1000 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010) |

Fig. 8

Figure 8

Figure 8Raised bench with mosaic floor paving and adjoining basin along north wall of GO Building B during excavations in 2013, view facing east (IJP_D_15356) (© Islamic Jarash Project 2017) Rattenborg and Blanke (2017) |

|

VIII+ (collapsed walls) |

|

GO area - laneway between the mosque west wall and Building A, eastern interior of Building A, and possibly square GO/6 (note that Building B is to the west of building A)

Figure 7

Figure 7Early Islamic Jerash ca. 750-850 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 11

Figure 11Early Islamic Jerash ca. 950-1000 CE Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010) |

Fig. 15

Figure 15

Figure 15GO/6 at the end of the 2009 season, seen from the west. Note the cistern drain in the bottom of the picture (by IJP). Blanke et al (2010) |

|

VIII+ (collapsed walls) |

|

Congregational Mosque - qiblat Hall

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan of the mosque, showing excavated areas to 2004 Barnes et al (2006)

Figure 3

Figure 3Preliminary outline plan of the Umayyad mosque of Jarash (as after 2004 season). Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 3

Figure 3Islamic Jerash Project Excavation Areas 2002-2013 Rattenborg and Blanke (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1Overview of Islamic Jarash Project following excavations in 2009 (by Hugh Barnes). Blanke et al (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1General plan of the excavations in central Jarash, to end of 2007 season (Barnes mod. Walmsley) Walmsley et al (2008) |

|

VIII+ (collapsed walls) |

Barnes, H. et al. (2006) From ‘Guard House’ to Congregational Mosque. Recent Discoveries on the Urban History of Islamic Jarash, in: Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 50,

285 – 314.

Blanke, L. / P. D. Lorien / R. Rattenborg (2010) Changing Cityscapes in Central Jarash –

between Late Antiquity and the Abbasid Period, in: Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 54, 311– 327.

Blanke, L. and Walmsley, A. (2010) Islamic Jarash Project

In Archaeology in Jordan, 2008 and 2009 seasons, edited by D. Keller and C. Tuttle. American Journal of Archaeology 114 505-545.

Blanke, L., et al. (2021). "Excavation and magnetic prospection in Jarash’s southwest district: The 2015 and 2016 seasons of the Late Antique Jarash Project." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 60.

Blanke, L. and A. Walmsley (2022). Resilient cities: Renewal after disaster in three late antique towns of the East Mediterranean. Remembering and Forgetting the Ancient City, Oxbow Books: 69-109.

Blanke, L., et al. (2024b). "Down the drain: reconstructing social practice from the content of two sewers in a Late Antique bathhouse in Jerash, Jordan."

Journal of Roman Archaeology: 1-23. - open access

Naghaweh, A. (1982) An Umayyad Mosque at Jerash, in: Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan

26, 20 – 22 [Arabic].

Rattenborg, R. and L. Blanke (2017). "Jarash in the Islamic Ages (c. 700–1200 CE): a critical review." Levant 49(3): 312-332. - early manuscript - open access - page numbers differ from final publication

Rattenborg, R. and L. Blanke (2017). "Jarash in the Islamic Ages (c. 700–1200 CE): a critical review." Levant 49(3): 312-332. - final publication - behind a paywall - this is the document referred to on this webpage

Walmsley, A., Damgaard K., (2005) The Umayyad Congregational Mosque of Jarash in Jordan and Its Relationship to Early

Mosques, in: Antiquity 79, 362 – 378.

Walmsley, A. and F. Bessard, L. Blanke, K. Damgaard, A. Mellah, L. Roenje, I. Simpson. (2008) A Mosque, Shops and Bath in Central Jarash: The 2007 Season of the Islamic Jarash Project. ADAJ 52

Walmsley, A. (2018). Urbanism at Islamic Jerash: New Readings from Archaeology and History. in

The archaeology and history of Jerash : 110 years of excavations. A. R. R. Lichtenberger.