Tiberias - Umayyad Mosque

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Aerial view of Ravani’s excavations, looking east. In the foreground are the cardo and shops; in the middle is the pillared building. The bathhouse (partly covered) is to the right. (Photo: courtesy of Sonia Haliday Photographs)

Note by JW: Cytryn-Silverman (2009) interprets the pillared building as the Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Cytryn-Silverman (2009) examined previous excavations made in city center of Tiberias and argued that what was previously interpreted as a covered Byzantine market was in fact part of an Umayyad Mosque something Tiberias (Tabariyya in Arabic) would have had as it was the capital of Jund al-Urdunn (the military district of the Jordan) in the early Islamic period. Cytryn-Silverman (2009)'s argument was based on textual accounts by al-Maqdisi in 985 CE and Nasir i-Khusraw in 1047 CE along with architectural similarities with other Umayyad mosques such as the Great Mosque of Damascus, the Mosque of Khirbet al-Minya, and the mosque of Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi. Cytryn-Silverman (2009) mentions earthquakes in 749, 1033 and possibly 1068 CE but does not present any archaeoseismic evidence as the focus of the article was in identifying the pillared building as an Umayyad mosque.

The foundation date of Tiberias is not certain. Named after Tiberius (reigned 14–37 CE), it is believed to have been founded by Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great, as his capital some-time between 18 and 20. In 39 Antipas’s nephew, Agrippa I, gained control over the city and ruled it up to his death in 44 CE. Until 61 CE it was ruled by the procurators, when its political status changed when it was annexed to the kingdom of Agrippa II, whose capital was at Banias. In about 100 CE it came under direct Roman rule. During Hadrian’s reign (117–138 CE) there commenced the erection of a temple in his honor in the middle of the city, which, however, was never finished.

In the third century, Tiberias flourished: not only was it granted the status of a Roman colony (under Elagabalus [reigned 218–222 CE]), but also it became the capital of the Jewish people, after the Sanhedrin, the Patriarchate, and the leader of the community all had moved there from Sepphoris. Rabbi Yohanan, head of the Sanhedrin, established the bet ha-midrash ha-gadol, where the Palestinian Talmud was mostly written. From the sixth century on, Yeshivat Eretz Israel, the supreme religious institution for the Jews in Palestine and the Diaspora, was active in Tiberias, at least until the tenth century (of note is the fact that the Aleppo Codex was compiled in Tiberias at this time), when it finally moved to Jerusalem. Even then, Tiberias continued to serve as a center for the Masoretes, who dealt with the correct vocalization of the Holy Scriptures, for Hebrew grammarians, as well as for poets and preachers.

The prominent Jewish character of Tiberias might have been the main reason the Christian community did not take off, at least until the fifth century.2 Yet, despite the slow penetration of Christianity into Tiberias, we know that by the mid-fifth century it is already a seat of a bishopric, as its bishop (John) is mentioned in the lists of the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE).3

Tabariyya, as it is named in Arabic, was conquered by Arab armies in 635 CE. According to al-Baladhuri (d. c. 892)4, the terms of surrender guaranteed a smooth and peaceful change of government. Eventually Tabariyya was chosen to be the capital of Jund al-Urdunn, ultimately to the detriment of Baysān/Scythopolis, capital of Palaestina Secunda. It is not clear,nevertheless, when exactly this shift of capitals took place.

Three major earthquakes affected Tiberias during the Early Islamic period: 749 CE, 1033 CE, and 1068 CE. The first certainly caused much destruction, as we learn from the excavations at Galei Kinneret,5 but the earthquake was followed by renovation, building, and expansion. The earthquake of 1033, until recently thought to have brought Tiberias to an end, was not as dramatic for Tiberias. The account of the Persian traveler Nasir-i Khusraw of 1047 CE makes no reference to a devastated city, quite the opposite:6

The city has a strong wall that, beginning at the borders of the lake, goes all round the town; but on the water side there is no wall. There are numerous buildings erected in the very water, for the bed of the lake in this part is rock; and they have built pleasure-houses that are supported on columns of marble, rising up out of the water. The lake is full of fish.Nasir-i Khusraw goes on, describing the Friday Mosque in the middle of the town, as well as another one called Jasmine Mosque, on the western side of the city.

In addition to natural disasters, Islamic Tiberias was hit by invasions and sacking. In 906 CE the Ismaili Qarmatis, fighting against the Tulunids for the leadership of Syria, captured Tiberias, a major army base at the time. The sources tell that, following the resistance of its people, the city was plundered, women taken captive, and many people killed7. The eleventh century was even harder for Tiberians, as in general for the people of Palestine. Even before the earthquake of 1033 CE8, drought and unrest had struck the region. The Banu Jarrah Bedouin caused much instability. In August 1024 CE, their leader al-Hassan b. al-Mufarrij sacked Tiberias and killed its people mercilessly.9

Not withstanding the unrest, southern Syria under the Fatimids — and especially its two capitals, Ramla and Tiberias — witnessed a golden age. Much building and commercial, cultural, and religious activities took place. But toward the 1050s–1060s, the situation changed again, this time creating a political vacuum from which it was dfficult to recover. Jewish letters found in the Geniza are testimony to the stress under which the population of Syria lived.10 This situation, among others, made room for the Seljuq invasion of the 1070s, when Tiberias was made the Seljuq base against the Fatimids.11

In August 1098, the Fatimids managed to regain Jerusalem from the Seljuq Turks, putting an end to their rule over Palestine. Yet the Fatimids’ hold was short, and in July 1099 Palestine fell into the hands of the Crusaders. The old city center of Tiberias became a quarry for building material to the newly established Crusader fortfication to the north of the city.12

2 The Panarion of Epiphanius (fourth century) includes a passage that seems representative of the Jewish sovereignty in Tiberias,

despite being under Christian rule. The passage refers to Count (Comes) Joseph from Tiberias, a Jew converted to Christianity and protégée of

Constantine (reigned 306–337 CE). He planned to build a church at the site of the unfinished Hadrianeum, but the local Jews often

disrupted his works. So he eventually built a small church at the site of the temple, left the city, and settled in Beth She’an. See

The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis (trans. F. Williams; Nag Hammadi Studies 35; Leiden: Brill, 1987), book 1, sections 1–46, §30.12,1–12,9.

3. R. Price and M. Gaddis, trans., The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon (Translated Texts for Historians 45;Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), 1:360.

4. Ahmad ibn Yahyā ibn Jābir al-Balādhurī, Futūh al-buldān (Leiden: Brill, 1866), 115–16

5. License no. A-3607. Moshe Hartal, “Tiberias, Galei Kinneret,” HA-ESI 120 (2008)

6. Nāsir-i Khusraw, Safarnāma, ed., Yahyā al-Khashshāb (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-Jadīd, 1983), 52.

7. Moshe Gil, A History of Palestine, 634–1099 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), §468.

8. A further earthquake, which took place in September 1015, is recorded by the sources, but apparently it was of little consequence,

the main result being the collapse of the dome at the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. See ibid., §581. For the earthquake of 1033 and 1068, see ibid.,

§§595 and 602.

9. Ibid., §585.

10. Ibid., §596.

11. Ibid. §603.

12. On this fortfication, see Yosef Stepansky, “The Crusader Castle of Tiberias,” Crusades 3 (2004): 179–81.

- from Tiberias - Introduction - click link to open new tab

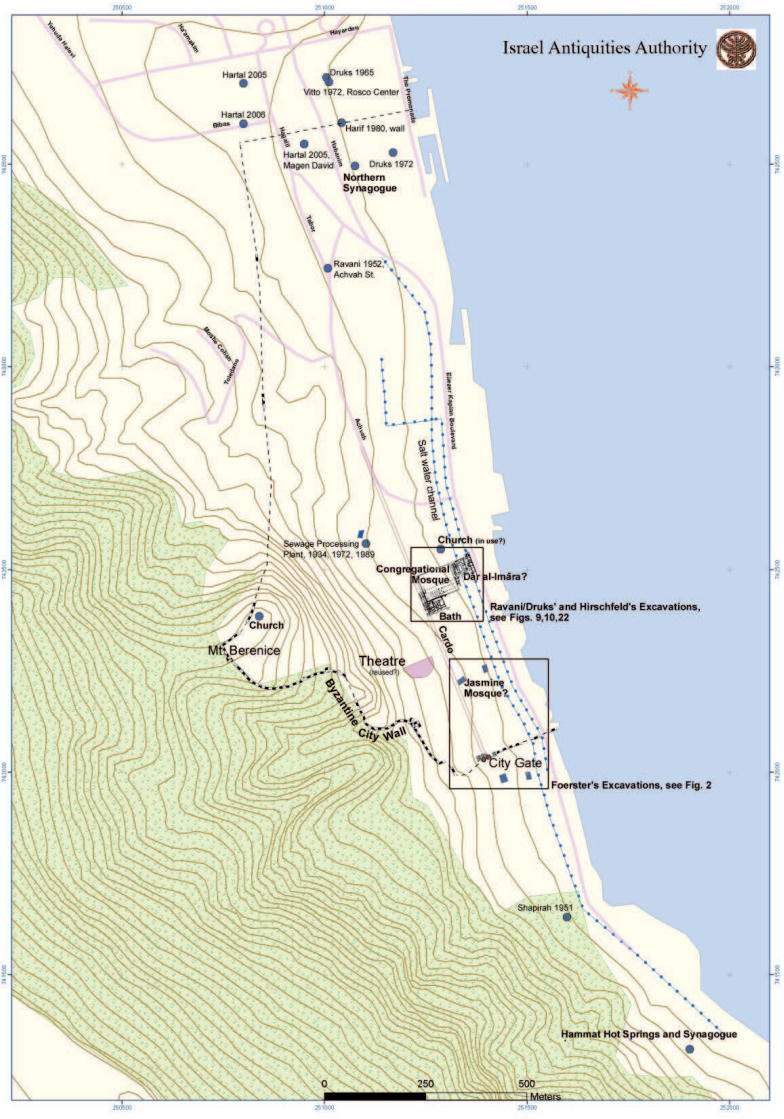

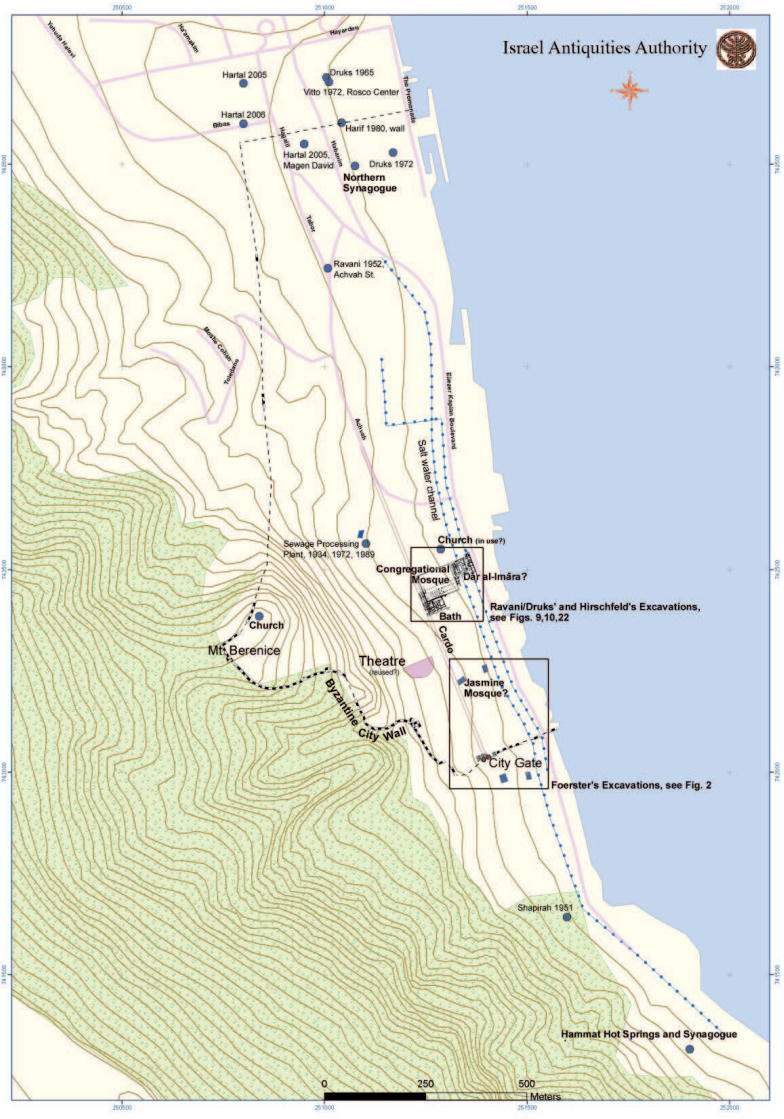

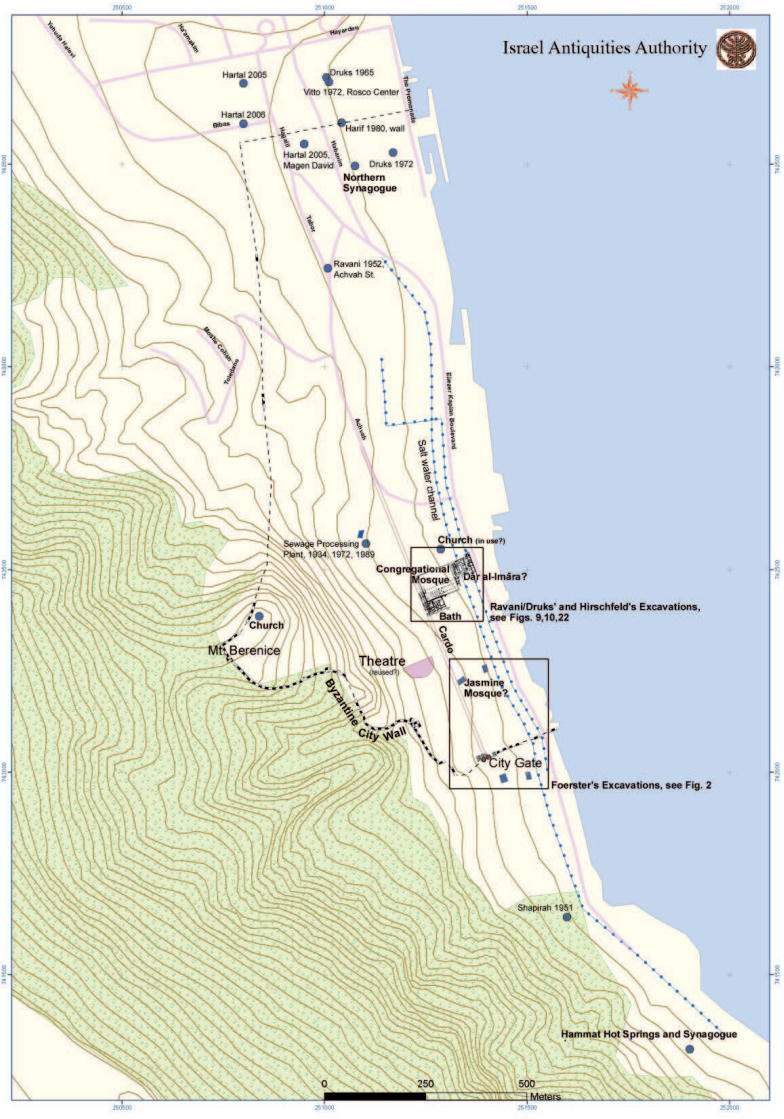

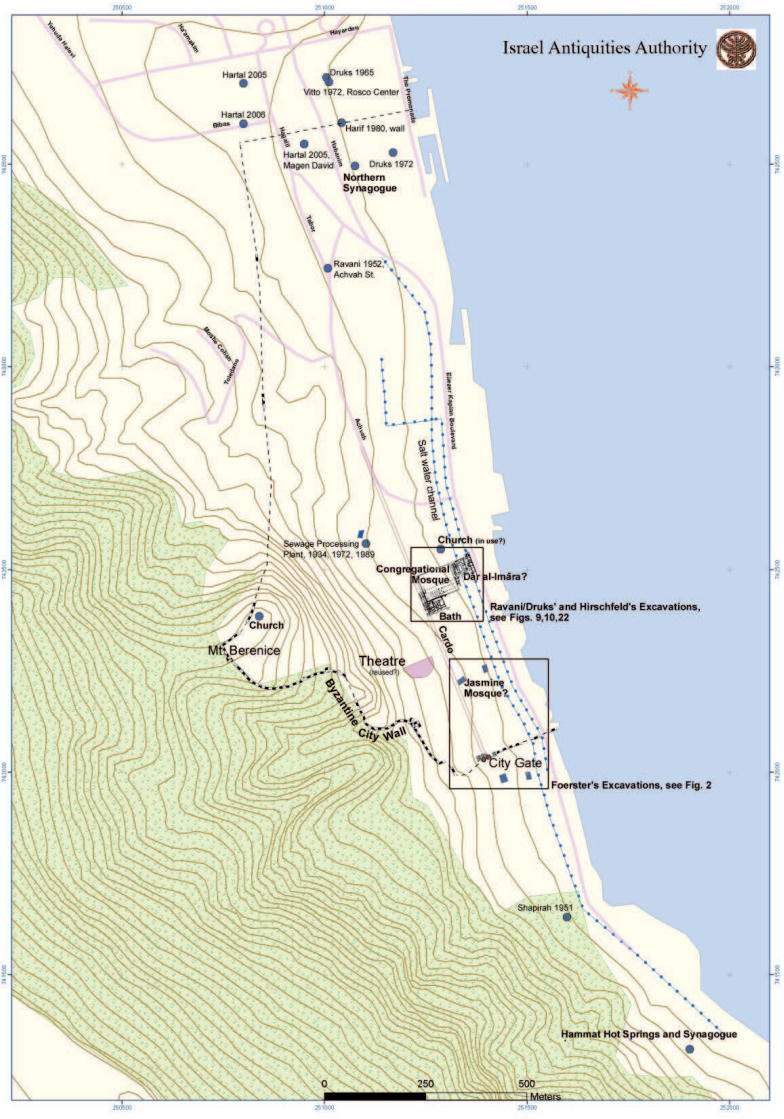

- Fig. 1 Map of Tiberias from

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Tiberias, with sites mentioned in this article. (Map: Leticia Barda, Israel Antiquities Authority [IAA])

Cytryn-Silverman (2009) - Fig. 2 Foerster’s excavation

areas (A–D), 1973–74 from Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Gideon Foerster’s excavation areas (A–D), 1973–74. (After David Stacey, Excavations at Tiberias, 1973–1974: The Early Islamic Periods, IAA Reports 21 [Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2004], plan 4.1)

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

- Fig. 1 Map of Tiberias from

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Tiberias, with sites mentioned in this article. (Map: Leticia Barda, Israel Antiquities Authority [IAA])

Cytryn-Silverman (2009) - Fig. 2 Foerster’s excavation

areas (A–D), 1973–74 from Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Gideon Foerster’s excavation areas (A–D), 1973–74. (After David Stacey, Excavations at Tiberias, 1973–1974: The Early Islamic Periods, IAA Reports 21 [Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2004], plan 4.1)

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

- Fig. L - Remains of Tiberias’

Early Islamic congregational mosque from Cytryn-Silverman (2015)

Figure L

Figure L

Remains of Tiberias’s Early Islamic congregational mosque looking southeast, adjacent to Byzantine bathhouse (under modern roof). Shops of north–south street on the right. On the foreground, remains of massive Roman wall, over which the mosque was erected.

The New Tiberias Excavation Project, photo by David Silverman

Cytryn-Silverman (2015) - Fig. 8 - Remains of Tiberias’

Early Islamic congregational mosque (the pillared building) from Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Aerial view of Ravani’s excavations, looking east. In the foreground are the cardo and shops; in the middle is the pillared building. The bathhouse (partly covered) is to the right.

(Photo: courtesy of Sonia Haliday Photographs)

Note by JW: Cytryn-Silverman (2009) interprets the pillared building as the Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias

Cytryn-Silverman (2009)

Cytryn-Silverman (2015:208) discussed rebuilding evidence

The covered hall of the Umayyad mosque was refurbished at some stage by the introduction of a row of columns in the middle of the aisles (see the area marked in dark blue on Mosque Plan in the Photo Gallery, G-2). This probably took place following the earthquake of 749, and aimed at giving extra support to the roof. The final stage of the mosque, apparently a renovation during the early eleventh century (perhaps following the earthquake of 1033?), canceled the extra row and returned the building to the monumentality of the Umayyad period.

Cytryn-Silverman (2015:208) discussed rebuilding evidence

The covered hall of the Umayyad mosque was refurbished at some stage by the introduction of a row of columns in the middle of the aisles (see the area marked in dark blue on Mosque Plan in the Photo Gallery, G-2). This probably took place following the earthquake of 749, and aimed at giving extra support to the roof. The final stage of the mosque, apparently a renovation during the early eleventh century (perhaps following the earthquake of 1033?), canceled the extra row and returned the building to the monumentality of the Umayyad period.

Cytryn-Silverman (2015:209) discussed abandonment of the mosque

After the mosque was abandoned, most likely following partial destruction by the earthquake in 1068 CE, what remained of its northern section was reoccupied during the Crusader– Ayyubid period (twelfth–early thirteenth century). The debris was not removed, thus creating spaces in different levels, connected by steps when necessary.

Cytryn-Silverman, K. (2009). "The Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias." Muqarnas Online 26: 37-61.

Cytryn-Silverman, K, 2015, “Tiberias, from its foundation to the early Islamic period,”

in Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods Volume 2: The Archaeological Record from Galilean Cities,

Towns, and Villages, edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange, Minneapolis, 2015, pp.186-210.

Hirschfeld, Y. and Galor, K. (2007) New Excavations in Roman, Byzantine,and Early Islamic Tiberias in Zangenberg, J., Attridge,

H. W. and Martin, D. B. (eds), Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition: 207-229. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck.