Pella

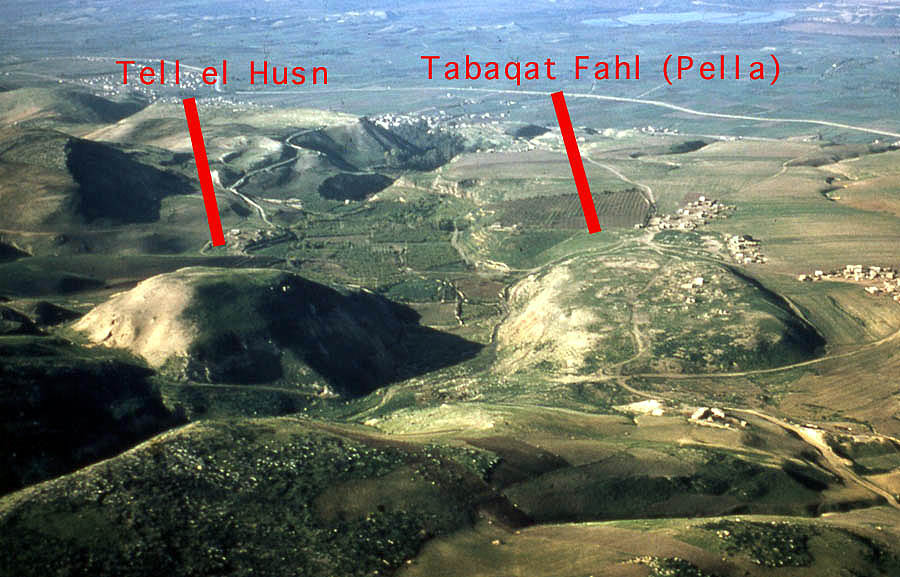

Oblique aerial photograph looking west towards the Jordan River Valley.

This image is scanned from a 1970 era slide taken by Professor Jim Sauer (University of Pennsylvania)

showing the relationship of the two settlement areas at Pella in Jordan.

Oblique aerial photograph looking west towards the Jordan River Valley.

This image is scanned from a 1970 era slide taken by Professor Jim Sauer (University of Pennsylvania)

showing the relationship of the two settlement areas at Pella in Jordan.Dr. Michael J. Fuller

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Pella | Greek | Πέλλα |

| Fahl | Hebrew | פחל |

| Fāhl or Fihl | Arabic | فاهل or فيهل |

| Khīrbīt Fāhl | Arabic | كهيربيت فاهل |

| Tabaqat Fāhl | Arabic | تاباقات فاهل |

| Pihil(um) | Ancient Semitic | |

| Berenike | ||

| Philippeia |

Pella, aka Fahl, is located in the foothills east of the Jordan Valley ~30 km. south of the Sea of Galilee.

It has been accepted as ancient Pella of the Decapolis

(Smith in Stern et al, 1993). Occupation of the site

started in the Neolithic and continued until modern times with relatively few gaps - most notably the late Iron IIB/C

(c. 730-540 BC) and Persian (539-332 BC) periods

(

Tidmarsh, 2024:7-8). In addition to the main mound (known as Khirbet Fahl), occupation has been discovered on Tell Husn to the south

and in several of the valleys in the area.

Since its identification in 1852 by E. Robinson, Khirbet (or Tabaqat) Fahl has been accepted as ancient Pella of the Decapolis. The site lies approximately at sea level amid the foothills of the eastern side of the Jordan Valley, fewer than 30 km (19 mi.) south of the Sea of Galilee (map reference 2075.2065). The word Fahl (or Fihl, as it appears in early Arabic texts) is the linguistic equivalent of the ancient Semitic place name Pihil(um), which occurs as early as 1800 BCE in Egyptian texts. The hellenized name Pella came into use after the conquests of Alexander the Great, who was born in Pella in Macedonia, as a phonetic approximation of the Semitic name.

Abundant water and mild winters made Pella one of the most desirable sites in the valley for habitation in antiquity. Although hot during the summer months, Pella is still cooler than most sites in the Jordan Valley. During the winter it is free from frost, unlike some places in the northern part of the valley. Annual precipitation today, which may not differ greatly from that at times in the past, is 345 mm and, occurring mainly in the months from December to February, is sufficient to permit spring crops. The site also has the important advantage of a powerful perennial spring that flows out of the gravel hill on which the city was built, as it has done for at least eight thousand years and probably much longer.

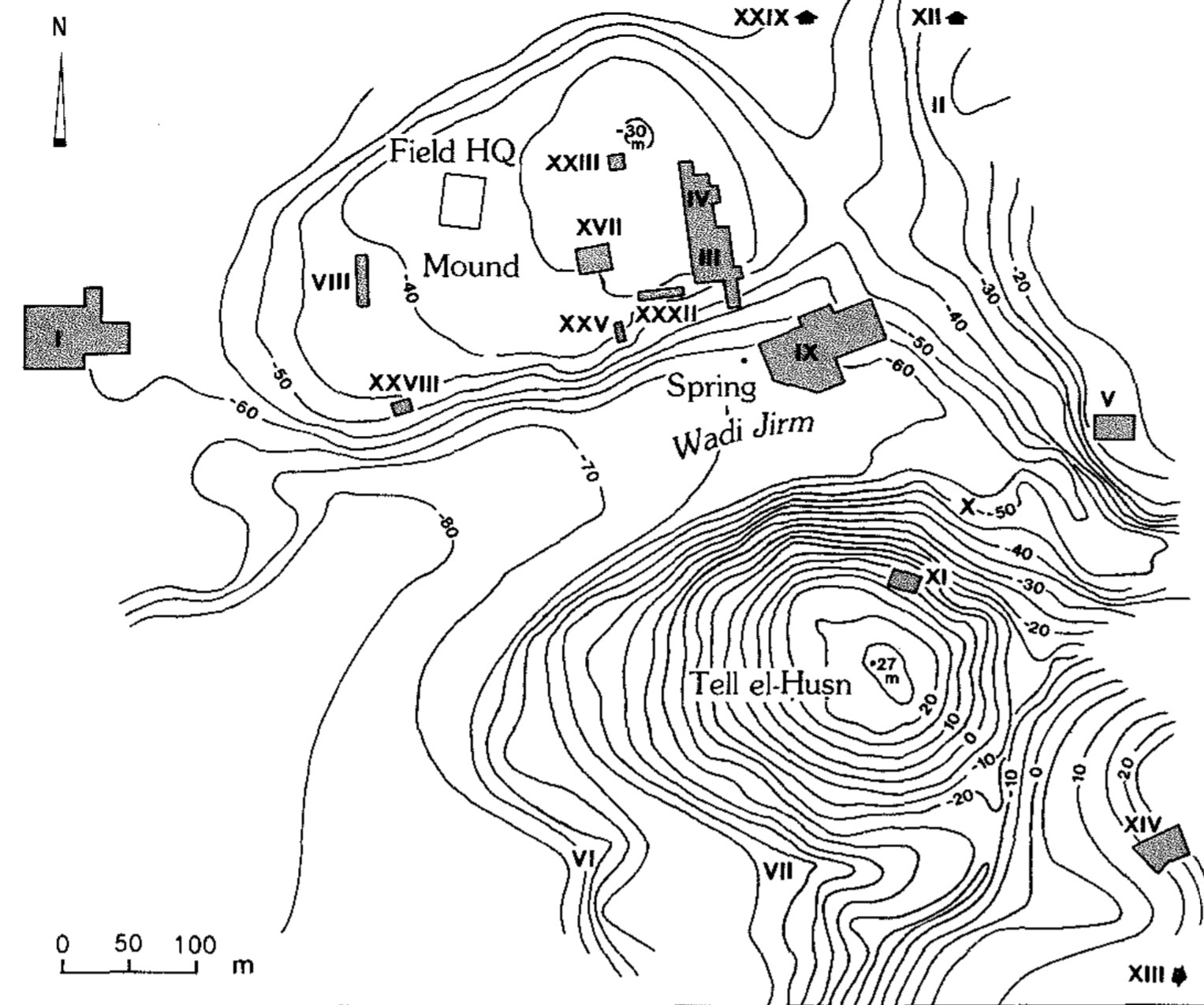

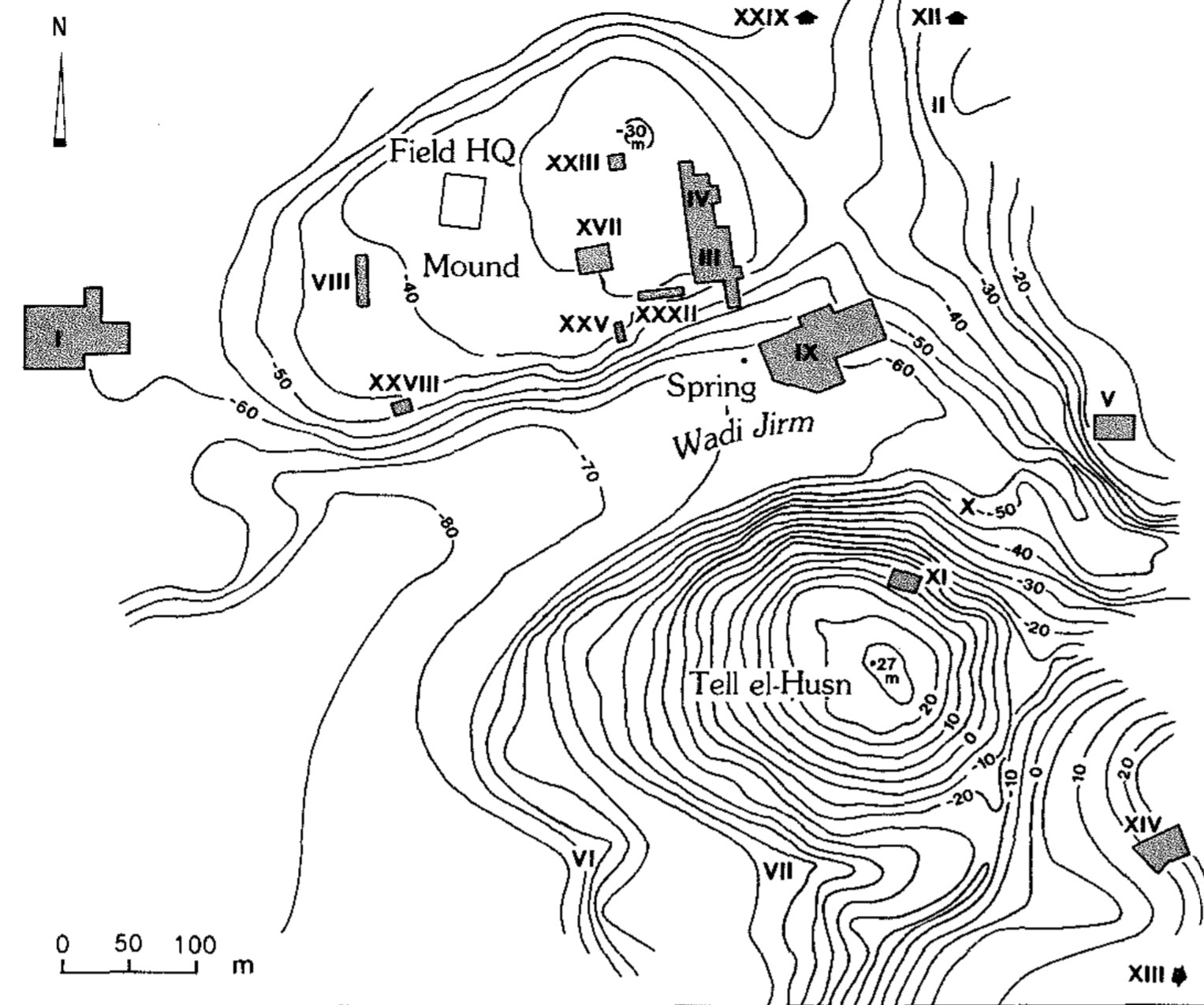

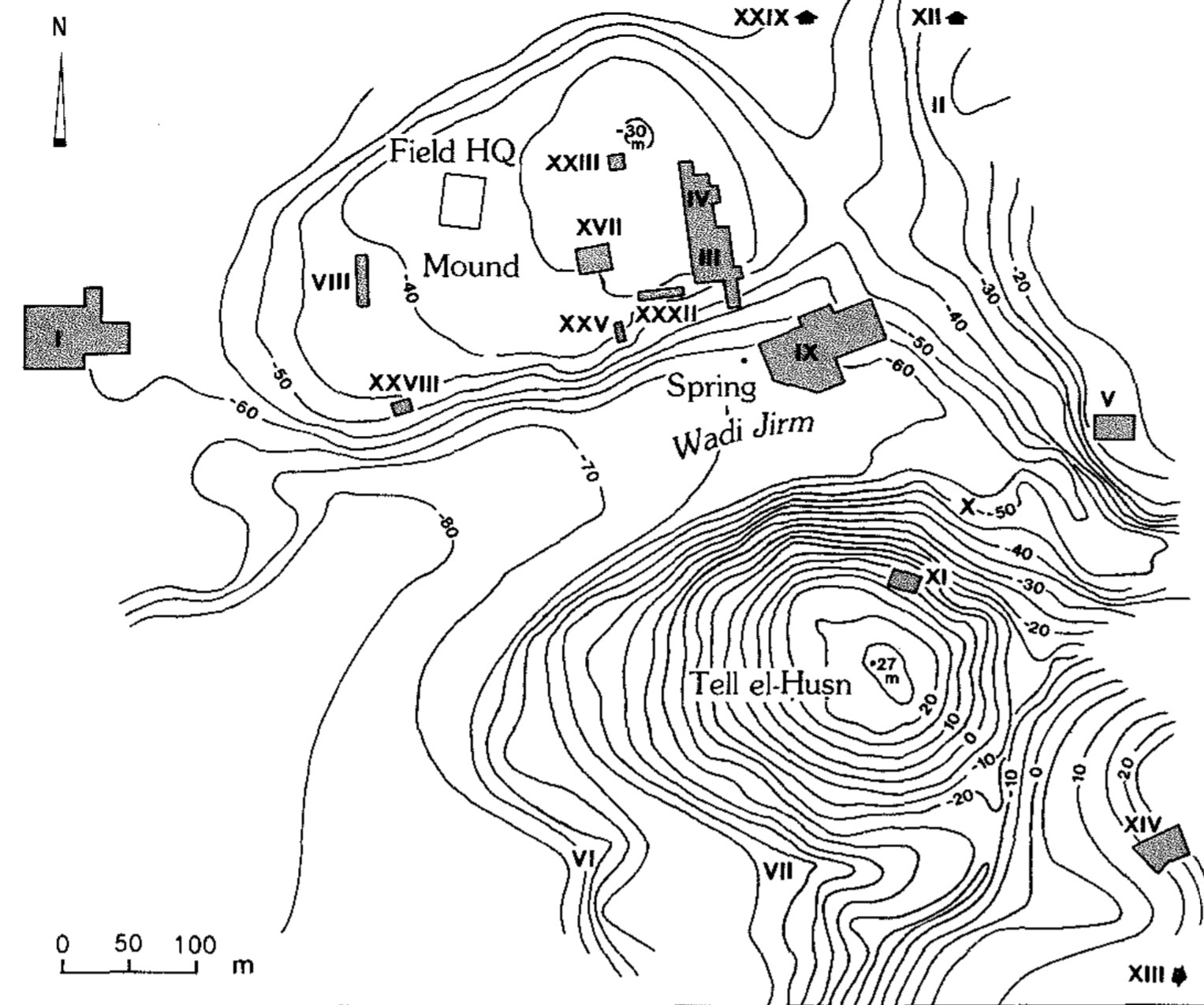

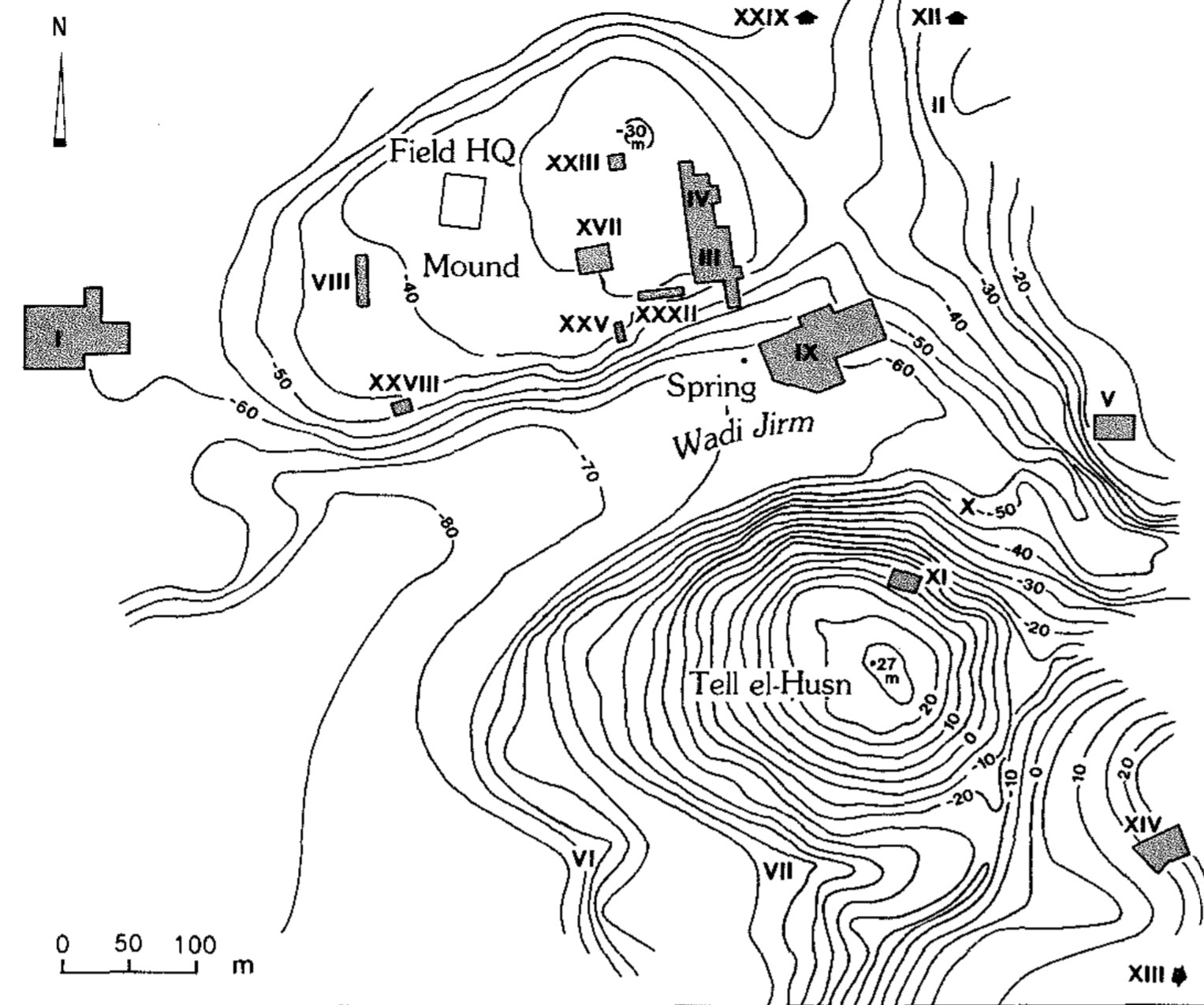

The central feature at the site is a 400-m-long ovoid mound, where the major amount of habitation has taken place through the centuries. Immediately west of the mound is a small tableland (in Arabic tabaqah, an element in the name Tabaqat Fahl) stretching westward I km (0.6 mi.) to the scarp overlooking the Jordan Valley. Low hills that flank the mound on the north and east contain tombs that range in date from the Early Bronze Age through the Byzantine period. South of the central mound, across Wadi Jirm, rises a large natural hill called Tell el-I:Iu~n, much of which was utilized as a cemetery from the Bronze Age onward. Both the crest and the lower slopes of the hill also display occupational remains from late periods, particularly the Byzantine, when the city reached its greatest size and population.

Although it does not appear in the biblical record, Pella is mentioned in about a hundred early historical documents, ranging from Egyptian execration texts through late medieval references. An Egyptian papyrus from the thirteenth century BCE indicates that in the Late Bronze Age Pella supplied chariot parts to Egypt. Josephus relates that Pella was destroyed by Alexander Jannaeus in 83-82 BCE and in 63 BCE was brought under Roman control by Pompey, who is generally credited with having forged Pella and other hellenized cities in southern Syria and northern Transjordan into the federation known as the Decapolis (Josephus, Antiq. XII, 397; XIV, 75; War I, 104, !56; Pliny, NHV, 74). Eusebius, doubtless relying on an early tradition, states that early Christians, seeking to escape the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, fled to Pella (HE 5, 2-3). How long these refugees stayed at Pella is not recorded, but a late first or early second century sarcophagus found beneath the paving of the north apse of the west church may be a relic of their sojourn. By the mid second century, Christianity was firmly enough established at Pella that the city was home to the early Christian apologist Aristo (Eus., HE IV, 6, 3). Epiphanius, a Church father writing not long after Eusebius, reports that these Christians subsequently returned to Jerusalem, but that a heretical form of Christianity subsequently flourished in the vicinity of Pella (Haer. 29, 7). The city's warm baths are mentioned in a third to fourth century rabbinic text (J.T., Shevi'it 6, I, 36c). The city fell under Arab domination in 635 CE, following a major battle with Byzantine forces that is reported in Islamic histories as the "battle of Pella." In 747 CE [JW: Actually 749], Pella was destroyed by a massive earthquake that was recorded by Arab chronographers [JW: not just Arab chronographers]. Although the city is mentioned in some accounts in the Middle Ages, maps of the period show that the location of the city was forgotten with the passing of centuries.

Pella was described and mapped by G. Schumacher in 1887; the report was published in the following year by the Palestine Exploration Fund. In 1933, J. Richmond, of the Mandatory Department of Antiquities, surveyed the site and subsequently published a description and a map of the central ruins. In 1958, R. W. Funk and H. N. Richardson, under the auspices of the American Schools of Oriental Research, conducted two weeks of excavation in two places on the mound. In 1964, a representative of the Jordan Department of Antiquities excavated at least eleven tombs at the site, chiefly on and around Tell el-Husn.

In 1967, The College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio, mounted a major expedition under the direction of R. H. Smith. Excavations had been carried out in only two areas (I and II) when work was interrupted by the Six-Day War. Field operations were not resumed until 1979, when the college was joined by The University of Sydney (Australia), with J. B. Hennessy and A. W. McNicoll as co-directors of the Sydney contingent. Excavations conducted in subsequent years produced a large amount of new information about the site's history and material culture. Between 1979 and 1991, excavations and related investigations were conducted in thirty-four areas at Pella and in the vicinity. The College of Wooster completed its field activities in 1985.

- from Stern et al (2008)

The Cathedral, also known as the Civil Complex Church, was partially excavated in 1979–1985 by a team from Wooster College in Ohio, under the direction of R. H. Smith. In 1994, the University of Sydney team renewed excavations within it, in order to completely expose the structure and partially reconstruct it. The Cathedral cella was covered by extensive earthquake destruction debris in 748/749 CE. Below the debris, a red and white tiled pavement was exposed along the entire northern aisle, while an elaborate mosaic pavement was encountered in the southern. All dated material is consistent with a sixth-century CE construction date for the church, and a final destruction at the very end of the Umayyad period. North of the Cathedral, remains of Umayyad stables, probably for camels, were exposed. This suits the understanding that in the Umayyad period the area was used as a caravanserai.

Excavations below the eastern slopes of the main mound exposed a large rectangular room, perhaps a warehouse or a shop, dating to the fourth century CE. After the destruction of this room, a new structure with a cobbled reinforced doorway was built over it. Several hundred small bronze coins have been found in and around the structure. Late Byzantine houses were exposed nearby.

- from Tidmarsh (2024:7-8)

The first major archaeological excavations at the site were commenced in the spring of 1967 by the College of Wooster under the direction of Robert Smith, who published his results in Pella of the Decapolis 1 (1973). Unfortunately the excavation program was curtailed in its first season by the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli war in June, and work was not resumed until 1979 as a joint project between Wooster and the University of Sydney under the direction of Smith, the late J. Basil Hennessy and the late Anthony McNico11.3 In 1985 the College of Wooster ceased its involvement with the site, the excavations continuing under the auspices of the University of Sydney, at first under the overall direction of Basil Hennessy and, subsequently, of Stephen Bourke.

Besides the excavation reports in the Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research and numerous more specialised articles, the results so far have appeared in detail in Archaeology of Jordan 11.2 (Homes-Fredericq and Hennessy 1989), the College of Wooster publications Pella of the Decapolis 1 (Smith 1973), Pella of the Decapolis 2 (Smith and L.P. Day 1989), the University of Sydney's Pella in Jordan I (McNicoll et al. 1982) and Pella in Jordan 2 (McNicoll et al. 1992). More recently, the coins from the excavations of 1979-90 have been published (Sheedy et al. 2001), as have the results of excavations at the Natufian site of of Wadi al-Hammeh, a westward-flowing tributary of the Jordan River located some 2 kilometres to the north of the tell (Edwards 1992, 2007, 2013; McNicoll et al. 1982:17-27). Numerous Palaeolithic, Kebaran and Natufian artefacts have also been unearthed from scattered sites on the interfluvial ridge and terrace sections adjacent to the wall and close to the shores of the ancestral Like Lisan (Misnumber 1992).

Excavations at Pella Itself have demonstrated that the main mound (Khirbet Fahl) was settled by at least Pre-Pottery Neolithic times (Bourke 1997: 96-7, 2008 2015/16) with relatively few gaps - most notably the late Iron IIB/C (c. 730-540 BC) and Persian (539-332 BC) periods - in its occupation sequence until modern times when, in 1967, the small village of Tabaqat Fahl was moved from the tell to a more westerly position. Work on Tell Husn - the largely natural hill immediately to the south of the Wadi Jirm al-Moz separating it from the main mound - has indicated intermittent occupation since the Chalcolithic period (Bourke 2014; Bourke et al. 1999; Watson and Tidmarsh 1996).

Hellenistic (332-63 BC) architectural remains and artefacts have now been unearthed from many of the plots on the main mound (Figure 1.1) in Areas III, IV, VIII, XXIII, XXVIII, XXXII; in the Wall Jirm al-Moz (Area IX) and on Tell Husn (Areas XI, XXXIV). Furthermore, two fortresses from this period have been located on nearby Jebel Sartaba (Area XIII) and Jebel Hammeh (Area XXX). The fort on Sartaba has been planned and investigated by limited soundings by the College of Wooster inside the structure (McNicoll et al. 1982: 65-7) while the defensive wall on Jebel Hammeh has been partially traced by a University of Sydney team but no excavations undertaken (McNicoll et al. 1992:103-5).

Whereas Hellenistic artefacts have been wowed from numerous plots on the main mound and elsewhere. Early Roman (63 BC -135 AD) material, represented chiefly by 'Roman tonnes of Eastern Sigillata A (ESA), is found only In small quantities and in disturbed deposits on the main mound in plots IIIP, IIIQ and IVL (Table 1.1). The structure(s) associated with this latter material were, however, completely obliterated by later Byzantine and early Islamic (mainly Ummayad) overbuilding. Thus, architectural evidence for the Early Roman period is essentially restricted to the Civic Complex in the Wadi Jirm al-Moz (Area IX), Tell Husn (Areas XI and XXXIV) and the tombs of Areas VI and VII. From Area VI to the south-west of Husn, an unplundered tomb (Tomb 54) dating to the late first or early second century AD was cleared In 1983 (McNicoll et al. 1992:124-333). Much of the organic material from this tomb - including cedar beams, pine planking, and a pair of leather soles - was well preserved with many intact glass vessels also recovered. The tomb contained little in the way of pottery although worth noting was the presence of a wheelmade knife-pared ("Herodian") lamp (McNicoll et al. 1992:pl. 87.4) and three fragments of a 'Galilean" bowl of Kfar Hananya Form IB (Adan-Bayewitz 1993: 91-7).4 A further tomb (Tomb 40) from the same area of late first century at or early first century AD was also explored (McNicoll et al. 1982: 87-8). Five other tombs of Early Roman date (first to second centuries AD), of which at least four had been robbed, were unearthed by the Wooster team in the South Cemetery (Area VII) in 1979 (McNicoll et al., 1980:75-6).4

2 For a full discussion of the early exploration of Pella by Western travellers and archaeologists, see Smith 1973: 10-14.

3 See Smith 1973: 20-2, for a vivid account of the problems faced by the expedition, which was in the field at the outbreak of the 1967 war.

4 With the exception of Areas VIII. IX and XIII (College of Wooster), the other areas from which Hellenistic and Early Roman material

has been recovered were excavated by University of Sydney teams. The results of the College of Wooster excavations in these three areas are

dealt with briefly In this volume for the sake of completion but for a fuller description (although much remains unpublished) see the relevant

sections in Smith (1973), Smith and Day (1989) and McNicoll et al. (1982, 1992) as the excavation reports in Annual of the Department of Antiquities

of Jordan, and Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

5 I am grateful to Sandra Gordon (pers. com.) for further information regarding the Early Roman tombs from Areas VI and VII.

For the later reuse of an Early Roman sarcophagus in the West Church complex (Area I), see Smith 1973:143-9.

- Fig. 0.1 Main sites

in the southern Levant from Tidmarsh (2024)

Figure 0.1

Figure 0.1

The southern Levant, showing main sites mentioned in the text.

Tidmarsh (2024) - Fig. 4.7 Pre and Post 749 features

of Islamic Pella (Fihl) from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.7

Features of pre- and post-749 Islamic Fiḥl. Note all height measurements are minus (below sea level).- Early Islamic commercial centre [khan] composed of two compounds, eight to tenth centuries (partially excavated), -44 m

- courtyard house, damaged in the 659 earthquake, -43 m

- central church and Odeon, -54 m, west (left) of which lies the heavily silted Wādī al-Jirm’, -60 m

- East church, damaged in the 659 tremor and perhaps destroyed by the 749 earthquake, -20 m

- eastern tall residential quarter of the early sixth century, damaged in 659 tremor, destroyed in 749, with evidence for a ninth century rebuilding in the southern part, -42 m

- extremely abraded occupation area of surfaces, floors,stone wall stubs and deep refuse pits dating to the eighth/ninth to eleventh centuries, -38 m

- buildings with late tenth to eleventh century lustre-decorated glass and, north of the number, a later mosque of probable twelfth century date, -43 m

- west residential quarter (excavation back-filled),destroyed in 749, -51 m

- West church, evidence for earlier earthquake(s), probably 659, then great damage in 749, -60 m

- policing and administrative garrison on the summit of Tall al-Ḥuṣn, destroyed in 659 and not rebuilt

-2 m (Base image: Google Earth, 20 August 2021).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022) - Map of Pella and

environs from Schumacher (1888)

- Fig. 24 Topographic

Map of the Jordan Valley surrounding Pella from Smith (1973)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Topographical Map of a part of the Jordan Valley, showing Pella, Beth-shan, and Gadara

Smith (1973) - Fig. 25 Geologic

Map of the Jordan Valley surrounding Pella from Smith (1973)

Figure 25

Figure 25

Geological Map of the northern Jordan Valley at contour intervals of 300 m

Smith (1973)

- Fig. 0.1 Main sites

in the southern Levant from Tidmarsh (2024)

Figure 0.1

Figure 0.1

The southern Levant, showing main sites mentioned in the text.

Tidmarsh (2024) - Fig. 4.7 Pre and Post 749

features of Islamic Pella (Fihl) from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.7

Features of pre- and post-749 Islamic Fiḥl. Note all height measurements are minus (below sea level).- Early Islamic commercial centre [khan] composed of two compounds, eight to tenth centuries (partially excavated), -44 m

- courtyard house, damaged in the 659 earthquake, -43 m

- central church and Odeon, -54 m, west (left) of which lies the heavily silted Wādī al-Jirm’, -60 m

- East church, damaged in the 659 tremor and perhaps destroyed by the 749 earthquake, -20 m

- eastern tall residential quarter of the early sixth century, damaged in 659 tremor, destroyed in 749, with evidence for a ninth century rebuilding in the southern part, -42 m

- extremely abraded occupation area of surfaces, floors,stone wall stubs and deep refuse pits dating to the eighth/ninth to eleventh centuries, -38 m

- buildings with late tenth to eleventh century lustre-decorated glass and, north of the number, a later mosque of probable twelfth century date, -43 m

- west residential quarter (excavation back-filled),destroyed in 749, -51 m

- West church, evidence for earlier earthquake(s), probably 659, then great damage in 749, -60 m

- policing and administrative garrison on the summit of Tall al-Ḥuṣn, destroyed in 659 and not rebuilt

-2 m (Base image: Google Earth, 20 August 2021).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022) - Map of Pella and

environs from Schumacher (1888)

- Fig. 24 Topographic

Map of the Jordan Valley surrounding Pella from Smith (1973)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Topographical Map of a part of the Jordan Valley, showing Pella, Beth-shan, and Gadara

Smith (1973) - Fig. 25 Geologic

Map of the Jordan Valley surrounding Pella from Smith (1973)

Figure 25

Figure 25

Geological Map of the northern Jordan Valley at contour intervals of 300 m

Smith (1973)

- Pella and Tell el-Husn in Google Earth

- Oblique Aerial View of

Areas III, IV, and IX from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

- Oblique Aerial View of

Areas III and IV from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

- Fig. 2 - View of Area XXXII temple precinct

from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

View of Area XXXII temple precinct.

Bourke (2004) - Plate 1B The Civic Complex

in the spring of 1983, near the end of four seasons of excavation from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 1B

Plate 1B

The Civic Complex in the spring of 1983, near the end of four seasons of excavation.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 13B Aerial View of the

Area IX Civic Complex Church during excavation from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 13B

Plate 13B

The western approach to the [Area IX Civic Complex] Church during excavation (aerial view). The paving at the foot of the staircase has not yet been exposed. In the upper part of the photograph is the atrium. The arch stones lying on the paving of the atrium have been reassembled; most of them were found in the same part of the atrium, but in greater disorder (see Fig. 10)

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 4 - Photo of the Pella Houses

A–B in Area IV from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of the Pella Houses A–B in Area IV, after excavation. Part of the section shown in figure 5 remains on the left; note the fallen column (Walmsley).

Walmsley (2008) - Fig. 2 - Photo of Mamluk Mosque

and other structures on main mound at Pella from Walmsley (1997)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

General view to the north-west of the main archaeological mound at Fahl (Pella), showing the Mamlûk mosque (centre-left), the location of the village (upper centre-right) and cemetery (upper far right, where the earlier Byzantine–early Islamic housing is exposed)

Photo: S.J. Bourke.

Walmsley (1997

- Map of Pella and environs

from Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

Pella and its environs: map of the region and excavation areas. Area IV is at middle top.

Pella and its environs: map of the region and excavation areas. Area IV is at middle top.

Smith in Stern et al (1993) - Fig. 1 - Map of archaeological

areas at Pella from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of archaeological areas at Pella

Pella Project, modified Walmsley

Walmsley (2008) - Pella contour plan showing

excavation Areas, 2019 from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

- Map of Pella and environs

from Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

Pella and its environs: map of the region and excavation areas. Area IV is at middle top.

Pella and its environs: map of the region and excavation areas. Area IV is at middle top.

Smith in Stern et al (1993) - Fig. 1 - Map of archaeological

areas at Pella from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of archaeological areas at Pella

Pella Project, modified Walmsley

Walmsley (2008) - Pella contour plan showing

excavation Areas, 2019 from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

- Fig. 3 - General plan of

the Umayyad housing in Area IV from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General plan of the Umayyad housing in Area IV (Walmsley)

Walmsley (2008) - Seismic destruction in

Rooms 13, 14, and 15 of House G in Area IV from Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

Endplate - Area IV - Plan of House - House G

Endplate - Area IV - Plan of House - House G

Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

- Fig. 3 - General plan of

the Umayyad housing in Area IV from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

General plan of the Umayyad housing in Area IV (Walmsley)

Walmsley (2008) - Seismic destruction in

Rooms 13, 14, and 15 of House G in Area IV from Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

Endplate - Area IV - Plan of House - House G

Endplate - Area IV - Plan of House - House G

Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

- Sequential phases of six

superimposed Temples at Pella (MBI-Iron II) from Bourke (2013)

Sequential phases of six superimposed temples showing approximate

position of one above the other from Middle Bronze I to Iron Age II

Sequential phases of six superimposed temples showing approximate

position of one above the other from Middle Bronze I to Iron Age II

Bourke (2013) - Artist’s impression of Pella

"Migdol" Temple in the Middle Bronze Age (1600 BC) from Ben Churcher at Astarte Resources

An artist’s impression of how the Pella Migdol Temple would have looked during the Middle Bronze Age (1600 BC).

An artist’s impression of how the Pella Migdol Temple would have looked during the Middle Bronze Age (1600 BC).

JW: Bourke (2013) identified the 4th phase of the Temples as having theso-called ‘Migdol’ or Fortress Temple form

Ben Churcher at Astarte Resources - Fig. 3 - Schematic plans of

three main phases of temple construction from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Schematic plans of three main phases of temple construction.

Bourke (2004)

- Sequential phases of six

superimposed Temples at Pella (MBI-Iron II) from Bourke (2013)

Sequential phases of six superimposed temples showing approximate

position of one above the other from Middle Bronze I to Iron Age II

Sequential phases of six superimposed temples showing approximate

position of one above the other from Middle Bronze I to Iron Age II

Bourke (2013)

- Fig. 23 - double caravanserai

complex at Pella, 2nd half of the 8th century from Walmsley (2007)

Fig. 23

Fig. 23

Plan of the excavated section of the double caravansery complex at Pella, second half of the eighth century

Walmsley (2007)

- Fig. 23 - double caravanserai

complex at Pella, 2nd half of the 8th century from Walmsley (2007)

Fig. 23

Fig. 23

Plan of the excavated section of the double caravansery complex at Pella, second half of the eighth century

Walmsley (2007)

- Plan of West Church

Complex in Area I from Smith (1973)

Plan of West Church Complex in Area I

Plan of West Church Complex in Area I

Smith (1973) - Fig. 50 Reconstruction

drawing of the West Church Sanctuary and atrium from Smith (1973)

Figure 50

Figure 50

Reconstruction of the West Church Sanctuary and atrium. The placement of windows is conjectural.

Smith (1973)

- Plan of West Church

Complex in Area I from Smith (1973)

Plan of West Church Complex in Area I

Plan of West Church Complex in Area I

Smith (1973)

- Fig. 2 Simplified Plan

of Area IX from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Simplified plan of Area IX, showing the major features

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 18 Detailed Plan

of the "Chamber of Camels" in Area IX with earthquake crushed human and animal skeletons from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Detailed plan of part of the north dependency and Parvis. Locus 50, the "Chamber of the Camels," contains the skeletons of seven camels, a camel foetus, an ass, and Human 2. The small chamber, Locus 43, in the northeast corner of Locus 50, held the skeleton of Human 1. Locus 66, also a chamber, held the skeletons of two cows; the outline of stones beneath the skeletons is somewhat uncertain. Locus 67, a part of the Parvis, had the skeleton of two cows, and Locus 22, an extension of the north dependency, had fragile remains of a horse and a foal. In Locus 23 is the stile across the entrance to the north portal of the atrium, which prevented animals from wandering into the atrium and Church. Excavated portions of drainage channels, declining in a generally westward direction beneath the paving, are indicated by bold straight lines; hypothetical continuations, based on paving patterns, are indicated by rows of dots.

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 26 Reconstructed

plan of the Area IX church in Phase 3 from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 26

Fig. 26

Reconstructed plan of the church in Phase 3, around A.D. 614 until 658-660. The bema has been extended further west. The reconstruction of the west portico of the atrium is purely conjectural, particularly the walls shown at the top of the small staircase. The precise positions of the columns in the west collonade is not known, and the wall at the north end of the monumental staircase is inferred.

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 27 Reconstructed

perspective drawing of the Area IX church in Phase 3 from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 27

Fig. 27

Reconstructed perspective drawing of the church in Phase 3. Details of the way in which the arch was installed in the west wall of the atrium are conjectural. The bases and shafts of the collonade at the top of the monumental staircase are shown as being more uniform than they probably were.

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 28 Reconstructed

plan of the Area IX church in Phase 4 from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Reconstructed plan of the church in Phase 4, from A.D. 658-660 until 717. The plan remained essentially the same, but with continued deterioration, in Phase 5 (A.D. 717-747). The position of columns in the west collonade of the atrium is somewhat uncertain. The drainage channel in the small chamber in the north dependency continued northwest into the Parvis.

Smith et al. (1989)

- Fig. 2 Simplified Plan

of Area IX from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Simplified plan of Area IX, showing the major features

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 18 Detailed Plan

of the "Chamber of Camels" in Area IX with earthquake crushed human and animal skeletons from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Detailed plan of part of the north dependency and Parvis. Locus 50, the "Chamber of the Camels," contains the skeletons of seven camels, a camel foetus, an ass, and Human 2. The small chamber, Locus 43, in the northeast corner of Locus 50, held the skeleton of Human 1. Locus 66, also a chamber, held the skeletons of two cows; the outline of stones beneath the skeletons is somewhat uncertain. Locus 67, a part of the Parvis, had the skeleton of two cows, and Locus 22, an extension of the north dependency, had fragile remains of a horse and a foal. In Locus 23 is the stile across the entrance to the north portal of the atrium, which prevented animals from wandering into the atrium and Church. Excavated portions of drainage channels, declining in a generally westward direction beneath the paving, are indicated by bold straight lines; hypothetical continuations, based on paving patterns, are indicated by rows of dots.

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 26 Reconstructed

plan of the Area IX church in Phase 3 from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 26

Fig. 26

Reconstructed plan of the church in Phase 3, around A.D. 614 until 658-660. The bema has been extended further west. The reconstruction of the west portico of the atrium is purely conjectural, particularly the walls shown at the top of the small staircase. The precise positions of the columns in the west collonade is not known, and the wall at the north end of the monumental staircase is inferred.

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 28 Reconstructed

plan of the Area IX church in Phase 4 from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Reconstructed plan of the church in Phase 4, from A.D. 658-660 until 717. The plan remained essentially the same, but with continued deterioration, in Phase 5 (A.D. 717-747). The position of columns in the west collonade of the atrium is somewhat uncertain. The drainage channel in the small chamber in the north dependency continued northwest into the Parvis.

Smith et al. (1989)

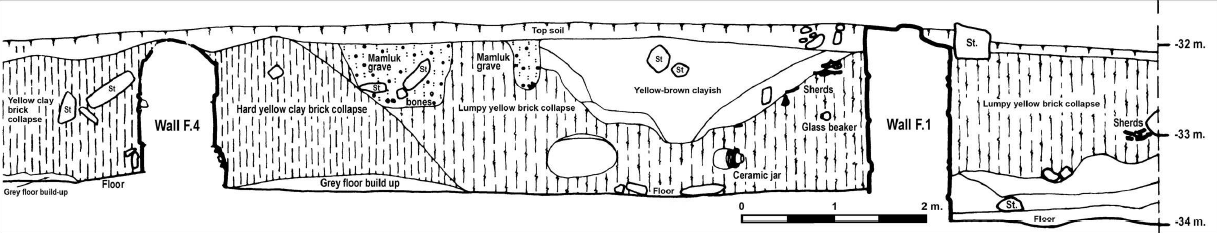

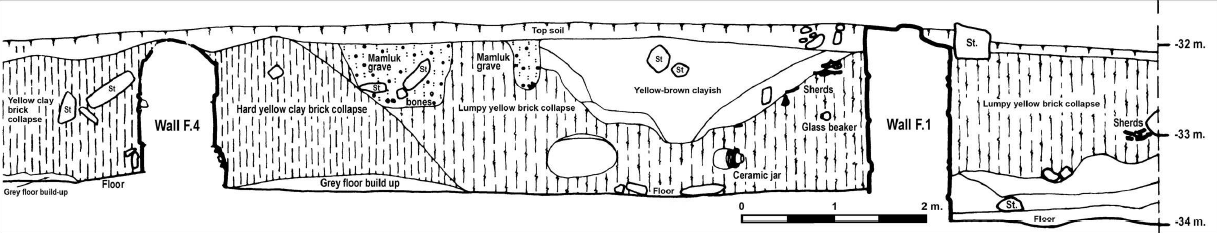

- Fig. 5 - Representative

section through Houses A–B from Walmsley (2008)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Representative section through Houses A–B, showing collapse lines and location of objects.

Walmsley (2008) - Fig. 49 Section thru

the east-west elevation line of the West Church and atrium from Smith (1973)

Figure 49

Figure 49

Section of II S-R along the east-west elevation line through the center of the church and atrium.

Smith (1973) - Fig. 13 Stratigraphic

sections through Area IX Church and Parvis from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 13

Stratigraphic sections through A-A' in the sanctuary of the Church, and B-B' in the Parvis (for locations, see plan in Fig. to). Five levels are identified. Note that Level 2 is not present in section B-B'.

- Level 1: Gray topsoil containing small stones and pockets of Marnluk and post-Mamluk sherds.

- Level 2: Hard-packed brown soil, with some gravel; largely sterile but containing some sherds of various periods washed from upslope. (This level is not present in section B-B'.)

- Level 3: Dense, yellowish-brown loess, largely sterile but containing a few Abbasid-Fatimid sherds. At the beginning of this level a robber-pit was cut into level 4.

- Level 4: Debris from the earthquake of A.D. 747, loose, grayish-brown soil with rubble and architectural stones.

- Level 5: Brown, clayey soil containing trash accumulation from the earthquake of A.D. 717, including rubble, roof tile fragments, bits of mosaic, chunks of cement and artifacts (see Pls. 56—57).

Smith et al. (1989) - Fig. 19 Reconstruction

of Phase 3 gallery in the north dependency of the Area IX church from Smith et al. (1989)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

Reconstruction of the gallery that was constructed in the north dependency during Phase 3 (excavated as Loci 43 and 50), viewed schematically from the north. On the right, behind the upper and lower Ionic colonnade, is the large, reused column of Ajlun limestone that formed the porch of the north portal of the atrium.

(See also the perspective drawing in Fig. 27.)

Smith et al. (1989)

- Destruction layer in Trench XXXIVF 200

showing pottery smash and ashy layer from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

XXXIV F 200, Destruction layer 224.2 pottery smash on surface also showing ashy layer 224.1 to south

XXXIV F 200, Destruction layer 224.2 pottery smash on surface also showing ashy layer 224.1 to south

Pella Project - University of Sydney - Umayyad Collapse in Area IV

from the Pella Project - University of Sydney

- Marble paving slabs shattered

in the January 749 CE Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year Sequence from Smith in ADAJ Plates 1983

Plate LXXVIII.1

Plate LXXVIII.1

Marble paving slabs in the sanctuary of the Civic Complex Church shattered in the earthquake of A.D. 746/47. The fragments were preserved by a column which collapsed on the slabs.

JW: Actually that earthquake struck in 749

Smith in ADAJ Plates 1983 - Skeletons of camels killed

in the January 749 CE Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year Sequence from Smith in ADAJ Plates 1983

Plate LXXXI.2

Plate LXXXI.2

Skeletons found in the courtyard of the "hall of camels" just north of the Civic Complex Church. The animals are lying as they were killed in the earthquake of A.D. 746/7

JW: Actually that earthquake struck in 749

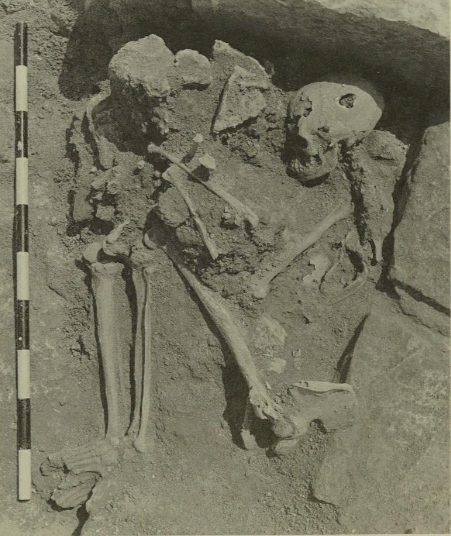

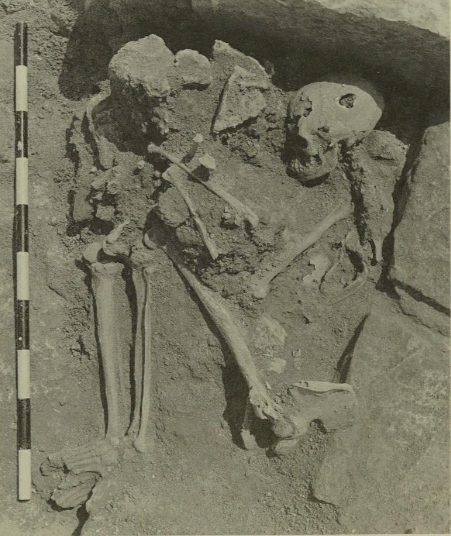

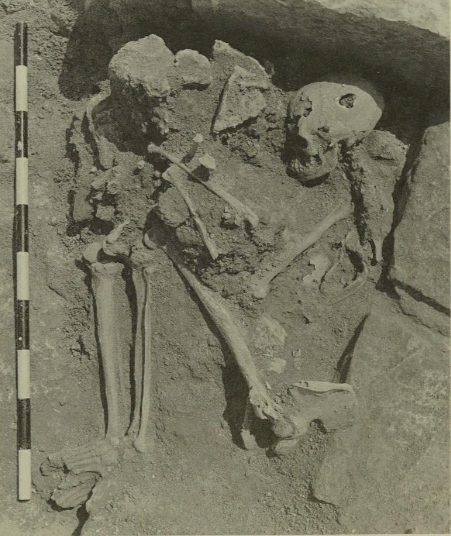

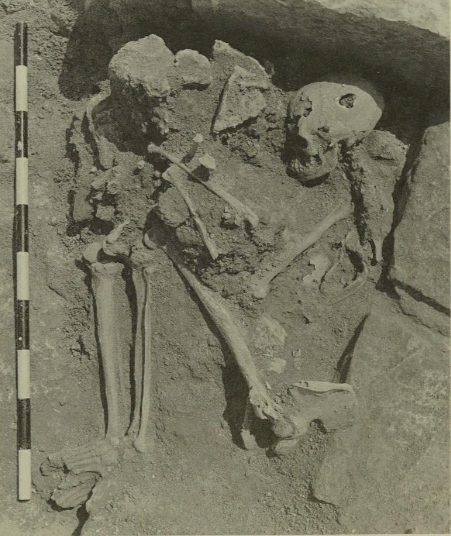

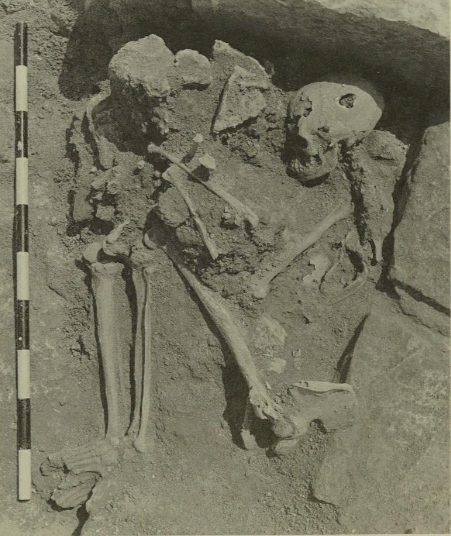

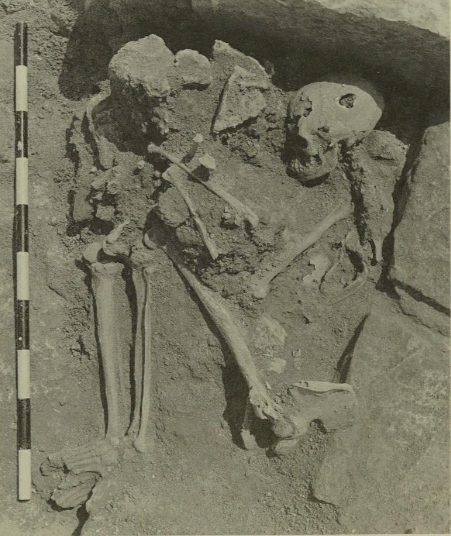

Smith in ADAJ Plates 1983 - Skeletons of humans killed

in the January 749 CE Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year Sequence from Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992)

Plate LXXXI.2

Plate LXXXI.2

Area IV Plot P (extension). Skeletons of two charred adult human beings with covering textiles, found in the AD 746/7 destruction deposit.

JW: Actually that earthquake struck in 749

Walmsley and Smith in McNicoll et al (1992) - Plate 10A Collapse

in the Western Church Complex (Area I) from Smith (1973)

Plate 10A

Plate 10A

I N: view toward the south. One the left is a surviving course of stones of the west front wall of the sanctuary, with the threshold and drain visible. On the right is paving of the atrium colonnade: fallen on the paving is a column drum, and on top of the drum four courses of the collapsed west wall.

Smith (1973) - Plate 12 Phase 4 Collapse

in the Western Church Complex (Area I) from Smith (1973)

Plate 12

Plate 12

I U: view toward the east. The massive block of fallen masonry on the left and the toppled column drum at the rear are the results of the earthquake which ended phase 4 of the [Western] church's history. The capital in the foreground may belong to the same column.

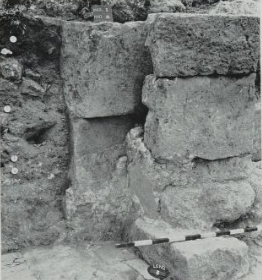

Smith (1973) - Plate 13B Buttress against

east wall of the sanctuary in the Western Church Complex (Area I) from Smith (1973)

Plate 13B

Plate 13B

I G: view toward the east. Buttress against east wall of the sanctuary, with phase 3 plaster visible.

Smith (1973) - Plate 16A Wall 30 (tilted ?)

from Smith (1973)

Plate 16A

Plate 16A

I E: view toward the east. Wall 30 is on the left. Several original pavers are in situ: above them, in shadow, is a tabun.

Smith (1973) - Plate 18B Dented opus sectile

paving in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 18B

Plate 18B

Extant portion of mosaic I surviving beneath later raised paving in the apse [of the Area IX Civic Complex Church]. East is at the top of the photograph. The cylindrical depression in the opus sectile paving was made by a falling column drum.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 19B Spalled column base

from the atrium porch in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 19B

Plate 19B

Base of one of the large columns of the atrium porch [in the Area IX Civic Complex Church].

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 19C Remains of the

lunate bema in the sanctuary of the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 19C

Plate 19C

Remains of the lunate bema in the sanctuary of the [Area IX Civic Complex] Church, with evidence of subsequent modification. Assorted architectural stones were incorporated in the fill around the bema as the floor was raised and enlarged.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 26A Segment of

collapsed wall of the central apse of the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 26A

Plate 26A

Segment of the collapsed wall of the central apse of the [Area IX Civic Complex] Church between the central and southern windows, resting against the soil of the hillside that rises steeply behind it. on each side, lying on the wide lower portion of the semi-circular apse wall, are small rectangular stones that were part of the windows sills.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 37A Skeleton of

a victim of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 37A

Plate 37A

Three of the five skeletons excavated in the [Area IX] Civic Complex. A. Remains found in the southwest corner of the sanctuary

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 37B Skeleton of

a victim of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 37B

Plate 37B

Three of the five skeletons excavated in the [Area IX] Civic Complex. B. Skeleton found in the drainage channel in the triangular chamber.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 37C Skeleton of

a victim of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 in the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 37C

Plate 37C

Three of the five skeletons excavated in the [Area IX] Civic Complex. C. Skeleton found inside the entrance to Locus 50, the Chamber of the Camels.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 37D Nose or ear

ring if a a victim of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 of the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 37D

Plate 37D

Gold ear or nose ring (45134) found with the skeleton in Locus 50 [the "Chamber of the Camels" in the north dependency of the [Area IX] Civic Complex Church; length 18 mm

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 39A Skeletons of

camel victims of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 in the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 39A

Plate 39A

View westward into Locus 50, the Chamber of the Camels [in the Area IX Civic Complex], showing several camel skeletons as excavated. The drums of the large columns in the background are in a temporary arrangement, and were subsequently re positioned properly.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 39B Skeletons of

camel victims of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 in the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 39B

Plate 39B

The intertwined skeletons of Camels B and C [in Locus 50, the "Chamber of Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex], viewed from the east.

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 40A Skeleton of

Camel victim A of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 in the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 40A

Plate 40A

Camel A skeleton in Locus 50 [the "Chamber of Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex]

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 40C Skeleton of

Camel victim F of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 40C

Plate 40C

Skeleton of Camel F [in the Area IX Civic Complex]

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 40D Skeleton of

the foetus of Camel victim B of the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake from Locus 50 in the "Chamber of the Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 40D

Plate 40D

Skeleton of foetus of Camel B in Locus 50 [the "Chamber of Camels" in the Area IX Civic Complex]

Smith et al. (1989) - Plate 40E Skeletons of

Camel victims D and E and an Ass from the Phase 5 749 CE earthquake in the Area IX Civic Complex Church from Smith et al. (1989)

Plate 40E

Plate 40E

Ass Skeleton, with legs of Camel E at upper left and the skeleton of Camel D at right [in the Area IX Civic Complex]

Smith et al. (1989)

Table I

Table IArea III: Stratigraphic Summary

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

- from Tidmarsh (2024)

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Pella: Summary of Hellenistic and Early Roman Occupation Sequence

College of Wooster and University of Sydney excavations.

Tidmarsh (2024)

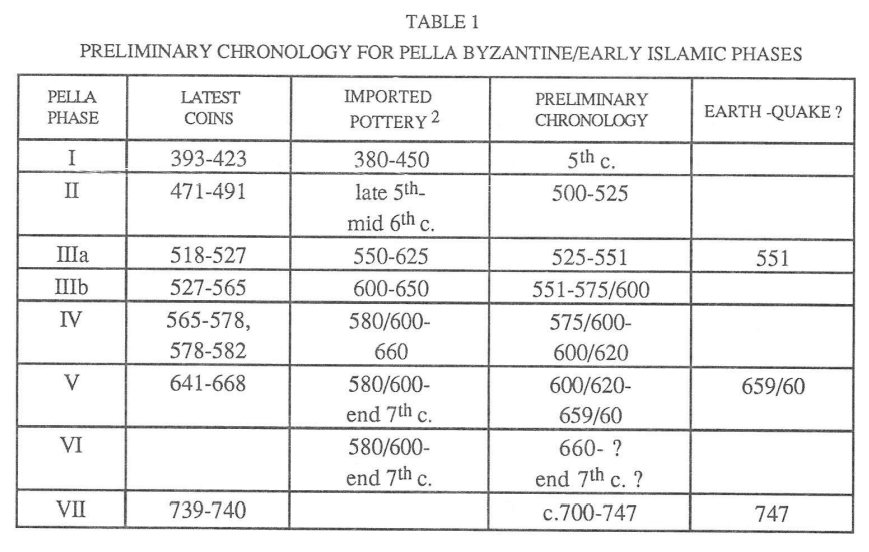

Walmsley (2007b:327) discussed redating of some of the levels at Pella

The pottery from Watson’s Phase 5 (initially dated ca. 600–640, later up to 659–60) is of primary interest here, although the preceding Phase 4 probably spanned into the early seventh century.23 Phase 5 ceramics came from particularly good deposits with little rubbish survival, making the corpus unusually clean and representative.Footnotes23 Watson, “Change,” 234, in which Phase 4 contains imports datable up to 660, and Watson proposes a possible corpus date to 620.

- from Watson (1992:234)

Table 1

Table 1Preliminary Chronology for Pella Byzantine/Early Islamic Phases

Watson (1992)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

Bourke et. al. (2009) report that EB II [Early Bronze II] occupational strata are sealed by a thick layer of destruction debris,

associated with quantities of burnt mudbrick and stone.

Immediately above these layers is an

ephemeral “squatter phase” which dates from around 2900/2800 cal BC.

Bourke et. al. (2009) characterize the EB II destruction layer as "site-wide" and "of some severity" and indicate it may

have been caused by an earthquake.

Raphael and Agnon (2018:773),

citing Bourke (2000:235) and

Bourke et. al. (2009), date this EB II destruction to around 2800 BCE and list the destruction of domestic architecture, public buildings and

defense wall.

This article reports on 10 new accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dates from early phases of the Early Bronze Age at the long-lived settlement of Pella (modern Tabaqat Fahl) in the north Jordan Valley. The new AMS dates fall between 3400 and 2800 cal BC, and support a recent suggestion that all Chalcolithic period occupation had ceased by 3800/3700 cal BC at the latest (Bourke et al. 2004b). Other recently published Early Bronze Age 14C data strongly supports this revisionist scenario, suggesting that the earliest phase of the Early Bronze Age (EBA I) occupied much of the 4th millennium cal BC (3800/3700 to 3100/3000 cal BC). As this EB I period in the Jordan Valley is generally viewed as the key precursor phase in the development of urbanism (Joffe 1993), this revisionist chronology has potentially radical significance for understanding both the nature and speed of the move from village settlement towards a complex urban lifeway.

EB II occupational strata are sealed by a thick layer of destruction debris, associated with quantities of burnt mudbrick and stone. Immediately above these layers, in shallow, much-disturbed deposits suggestive of an ephemeral short-term re-occupation (often characterized as a “squatter phase” in much regional literature), a single date (OZG878) documents occupation which could potentially date anywhere between 2900–2600 cal BC. However, given the immediate post-destruction stratigraphic context, the transitional Early Bronze Age II/Early Bronze Age III makeup of the ceramic assemblage (Bourke 2000), and the absence of even a single sherd of the Khirbet Kerak ceramic characteristic of mature Early Bronze Age III assemblages (Philip and Millard 2000), it seems probable that this ephemeral “squatter phase” dates from around 2900/2800 cal BC.

... The end of EB II occupation at Pella seems to be associated with a site-wide destruction of some severity. Cultural assemblage analysis suggests that this EB II assemblage at Pella is to be dated towards the end of the EB II period in general (Bourke 2000:252), as isolated ceramic elements that look forward to later EB III assemblages support this reconstruction. This would imply an end date for the EB II period in general somewhere between 2900/2800 cal BC. The Pella scenario is paralleled with closely similar archaeological circumstances (a site-wide destruction perhaps earthquake-related, ending all EB II occupation) and like radiometric data sets at nearby Tell Abu Kharaz (Fischer 2000:224; Philip and Millard 2000:282–3) and at Tell es-Saidiyeh (Tubb 1998:41–8; Philip and Millard 2000:283–4), further to the south in the east Jordan Valley.

Culturally, the beginning of the EB III period is generally correlated with the rise of the Egyptian Old Kingdom, and set at around 2700 BC (Stager 1992; Philip 2008). However, associating the rise of Dynasty 3 in Egypt with the beginning of the EB III period has always been tentative, with insufficient exports in either direction to knit the cultural assemblages together securely (Philip and Millard 2000:281). Placing the start date of the EB III period at around 2800 cal BC, perhaps a century earlier than traditionally posited, is consistent with EB III assays from Tell esh-Shuna (Philip and Millard 2000:284) and Tell es-Saidiyeh (Ambers and Bowman 1998:430).

EB II (3000-2700 BCE)

earthquake destruction of domestic architecture, public buildings and defense wall (the latter remained in use since the EB I), c. 2800 BCE (Bourke 2000: 235; Bourke et. al. 2009).

In Plot IIIC of Area III on Tabaqat Fahl (Pella)

Walmsley et. al. (1993:178-180) noted that mudbrick and stone debris from Walls 41 and 47 suggest

that Phase VIII was rendered uninhabitable through earthquake activity.

East-West Wall 47 was preserved to a height of 50 cm.

and most of the eastern metre of the wall had collapsed to the south in antiquity.

Wall 41,

the main city wall

, runs north-south.

Raphael and Agnon (2018:774) mentioned that the archaeologists have some reservations (S. Bourke, pers. comm.)

about whether an earthquake is responsible and report a date of ca. 1700 BCE or slightly earlier.

- Fig. 1 - Pella contour plan/area locations

from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Pella contour plan/area locations

Bourke (2004) - Fig. 7 - Plot IIIC.

Plan of Phase VIII architecture from Walmsley et. al. (1993:179)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plot IIIC. Plan of Phase VIII architecture

Walmsley et. al. (1993:179)

AREA III AND IV EXCAVATIONS

...

Middle Bronze Age IIA-IIA: Plot IIIC (East Cut Phases VIII-X)21

Phase VIII: MBIIB

At the beginning of the Tenth season, Plot IIIC was divided in half some four metres south of the north section line, and only the southern half of the trench was excavated.

Slightly over 1.25 m of deposit was removed in what was called IIIC South, exposing the very fragmentary remains of Phase VIII architecture (Fig. 7; pottery, Fig. 12:9-11).22 This architecture consisted of east-west Wall 47, and bonded into it, north-south Wall 49. Both were fairly insubstantial 40-60 cm wide walls, made up of small and medium fieldstone foundations, topped with patches of yellow and brown mudbricks. Both walls were preserved to a maximum height of 50 cm. Linking the walls together was a good rammed clay floor, 47.5. Set into this surface, in the northwest comer of the room formed by Walls 47/49, was a tabun, F.97. The probable stone paved doorway leading north from the centre of Wall 47 was disturbed by the Phase VI Pit F.75. The eastern end of Wall 47 was difficult to determine with precision, as most of the eastern metre of the wall had collapsed to the south in antiquity. However, the line itself was not in doubt, nor was the fact that it abutted the main city wall, Wall 41. In this collapse, a quantity of mudbrick debris (45.7/ 45.10) had been deposited on occupation buildup (47.2), on the floor 47.5. In colour and texture, the debris so resembled the city-wall that it seems likely that it fell from the wall's western face. The mudbrick and stone debris from Walls 41 and 47 suggest that Phase VIII was rendered uninhabitable through earthquake activity.

Intermediate Phase: MBIIB/C Burials

At some time after the abandonment of the Phase VIII architecture (Walls 47/49), and in a still obscure period before the extensive levelling associated with the construction of the Phase VII architecture (Walls 40/42/43), this area of the tell was used as a burial ground. A first intramural burial (F.98) was discovered in the northwestern margins of IIIC South, during the Tenth season (Fig. 8). This contained the body of an adult male, portions of a goat, and some sixteen ceramic vessels (ten juglets, three jugs and three bowls; for a selection see Fig. 13), a dagger and pommel, and flint (firelighter?).

Although it was the intention to leave the northern half of IIIC unexcavated for the present, erosion at the beginning of the Twelfth season revealed an elaborate multi intramural burial (F.106) several centimetres below the limit of excavation in 1986 (Fig. 9). This, too, is to be dated to the "interphase" between VIII/VII, and with more confidence, as the foundation trench for Phase VII Wall 42 cuts the northwestern margins of this second grave. It contained the articulated skeletons of at least three individuals, two adult females and an infant child. The easternmost adult is only partially preserved, as the margins of the grave were disturbed by Phase VII levelling, Phase VI Pit feature 75, and modern erosion. The grave also contained some twenty-two ceramic vessels (six jugs, three dipper juglets, six juglets, five carinated bowls, two platter bowls), two of which - a platter bowl and a globular juglet - were of the well known Tell al-Yahudiyeh Ware (Fig. 14). As the grave lay barely 20 cm below the Phase VII walls and surfaces, it seems likely that extensive levelling of the area occurred before Phase VII was constructed. The difference in time, based on ceramic evidence, does not seem to have been great, however, as the grave goods are best seen as Late MBIIB, and Phase VII ceramics placed early in MBIIC.

Probably to be associated with this "intermediate" phase is a third burial (F.107) cut through, and badly disturbed by a robber (?) pit feature 96. Feature 107 was a cist burial, lined with a single row of well formed yellow mudbricks on its north and south sides. Only the northern half of the burial, containing the articulated upper body of what is likely to be an adult female, was left relatively undisturbed. Fragments remained of a second adult burial (sex indeterminate) in the southern margins of the cist. Grave goods consisted of a jug and a juglet.

21. Plot supervisors: Sheldon Gosline and Helga

Fiedler (1988); Kate da Costa and Amanda Parrish (1990).

22. For discussion of Phase VI and Phase VII, see

T.F. Potts, S.J. Bourke et al., 'Preliminary Report on the University of Sydney's Eighth and

Ninth Seasons of Excavation at Pella in Jordan',

ADAJ 32 (1988), pp.1 30-131.

MB IIB (1750-1550 BCE)

ca. 1700 BCE or slightly earlier. The archaeologists have some reservations (S. Bourke, pers. comm.).

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006:26) described

possible seismic destruction in Phase VIC of Area III at

Tabaqat Fahl (Pella), noting that "at some stage during the

life of these structures, but after the re-laying of several

floors, a severe earthquake (?) destruction resulted in

significant damage to the entire complex." They report that

"both Wall 27 and the city wall (Wall 41) suffered major

structural damage," and that "several large pieces of the

inner face of the city wall fractured and collapsed onto

floor surfaces." They continue that "the three small cubicles

built against the inner face of the city wall suffered a

fiery destruction, with clear evidence of wall and floor

fracturing, and much broken pottery and other objects sealed

by a thick brick-filled debris layer." Wall 41 runs N–S and Wall 27 runs E–W.

- Table I Area III:

Stratigraphic Summary from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Table I

Table I

Area III: Stratigraphic Summary

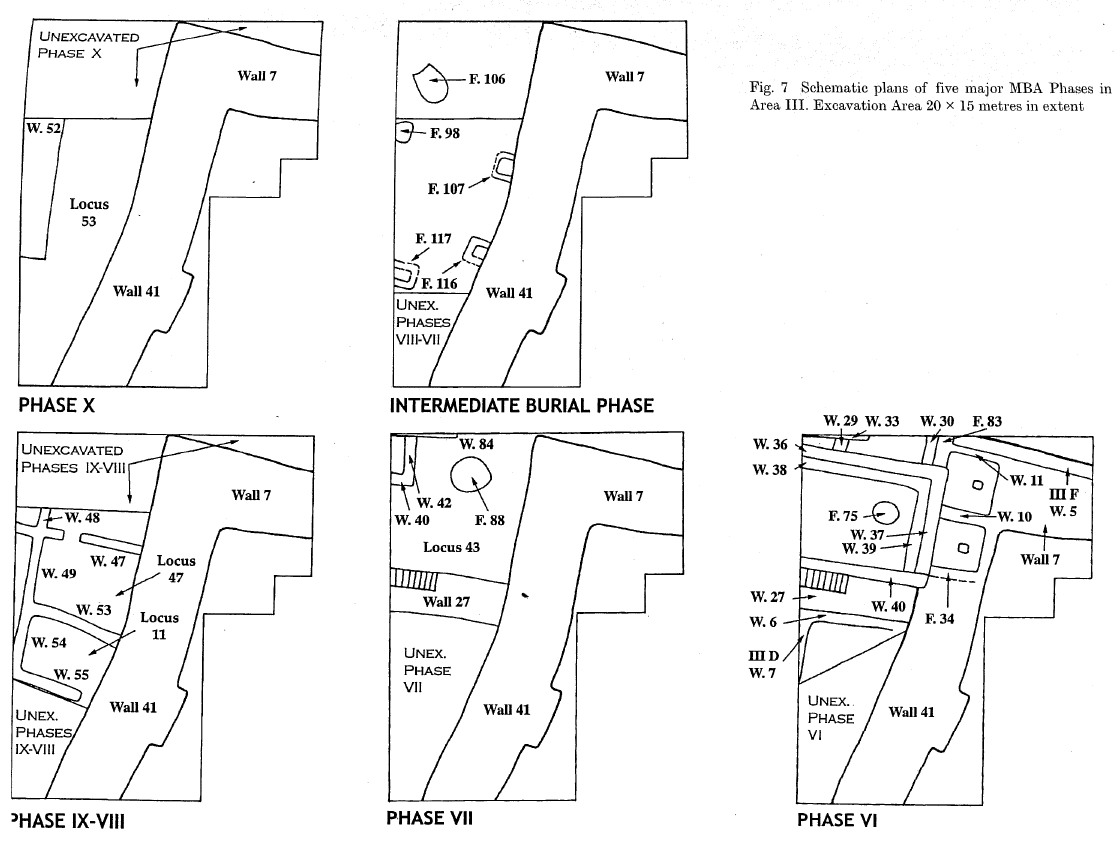

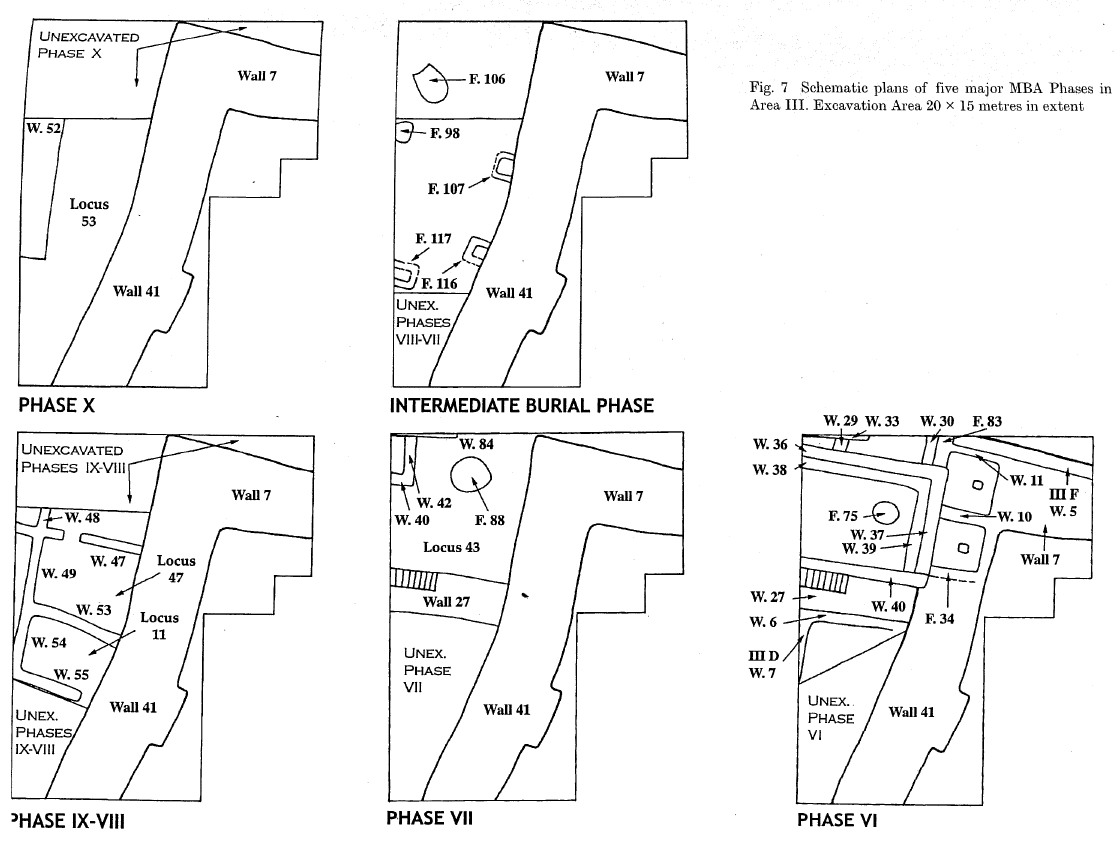

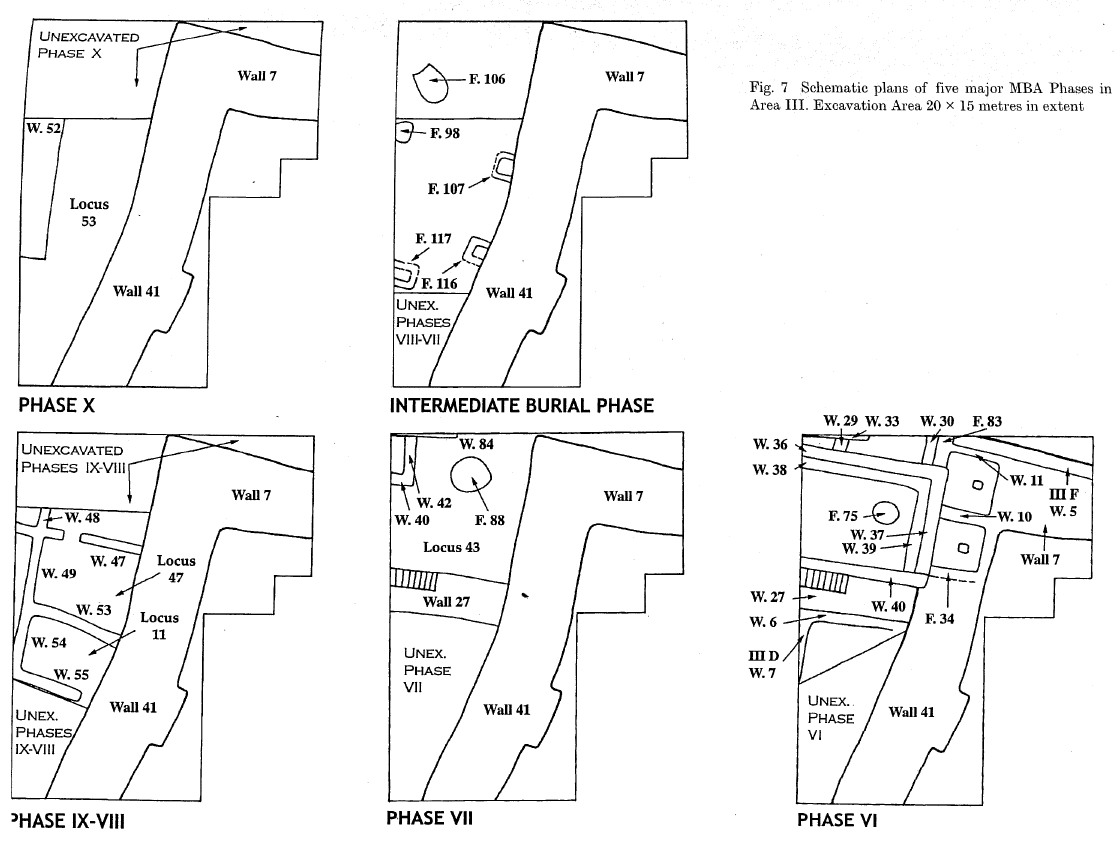

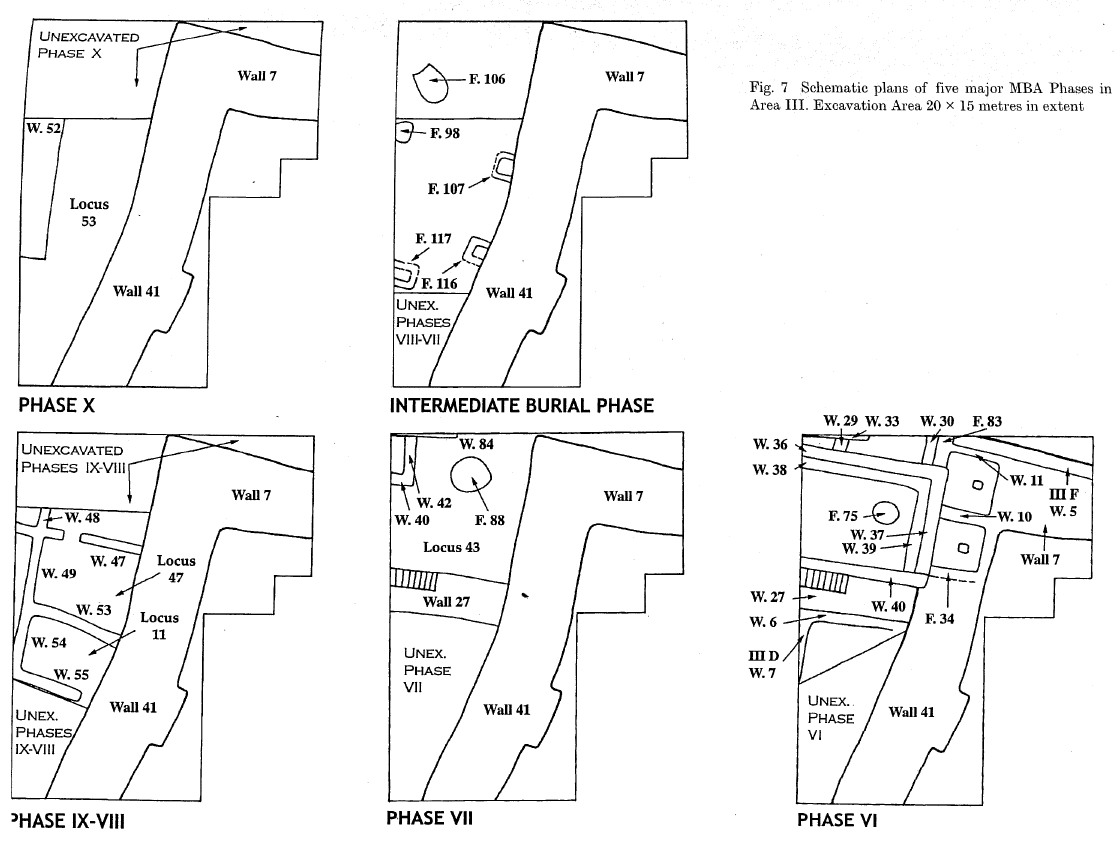

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 7 Plans of five major

Middle Bronze Age Phases in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Schematic plans of five major MBA Phases in Area III. Excavation Area 20 x 15 metres in extent

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 7 Closeup - Plan of Phase VI

in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 7 Closeup

Fig. 7 Closeup

Schematic plan of Phase VI in Area III. Excavation Area 20 x 15 metres in extent

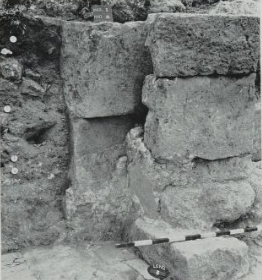

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 17 City Wall 41 Phase VII repair

in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

View of City Wall 41 Phase VII repair, built against main inner wall face in centre background, looking east

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

3. AREA III: THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE STRATIGRAPHIC SEQUENCE

... Phase VII (Figs. 17, 20, 25)

Wall 27 (Early), Walls 42-44, Oven F.88, Brick Wall F.84 and Associated Deposits

Phase VII constructions were very badly disturbed by numerous deep foundation trenches resulting from the multiple phases of substantial building activity in the succeeding Phase VI. Phase VII is made up of north-south Wall 42 and east-west Wall 44, forming part of a small room in the north-west corner of the trench. Associated with this phase is a very large circular pebble-paved oven (F.88), which takes up much of the area east of Wall 42. To the north of the oven, an east-west yellow mudbrick wall (F.84) is preserved in the north baulk, and to the south fragments of a second east-west Wall 43 make up the north and south sides of the `oven room'. A series of good plaster surfaces (43.10, 43.7, 43.2) provide a well separated occupational sequence, with 43.10 probably constructional for all features, and 43.2 the last good surface in the area. On the southern margins of the trench, a large e/w mudbrick wall, Wall 27, marks the southern limits of the Phase VII complex outlined above (Fig. 19). It seems possible that an east-west passageway ran along the outer southern face of this wall. All Phase VII deposits south of this passageway were lost to erosion.

Phase VI (Figs. 19, 21-25)

Phase VI has at least three subphases. Two represent double-wall reconstructions cut through earlier sub-phases. Several walls have substantial foundation trenches, and a number of deep pits complicate interpretation. Consequently, there are many small patches of floor surfaces associated with each of the several major and many minor alterations to the basic Phase VI groundplan. To complicate matters further, the even more massive stone foundations for the subsequent Phase V "Governor's Residence" complex fragment further an already complex stratigraphic sequence.

MAGNESS-GARDINER's (1997: 312) recent review of the Pella Phase VI stratigraphy is in error in all major points. Phase VI is not MB I in date, and is not associated with the primary construction of the city fortifications, rather with their end. Magness-Gardiner also confuses the main Phase VI architecture with later Phase V deposits. Confusion is heightened by her association of the Phase V Lion Box and cuneiform tablet deposits (Porrs 1987) with Phase VI architecture.

Phase VI C

Walls 10, 11 and F.34; Wall 27 (Late) and Associated Deposits

The monumental east-west mudbrick Wall 27, which delimited the southern complex wall in the preceding Phase VII, is thickened and its superstructure re-bricked at the beginning of Phase VI. It is possible that this re-bricking includes an east-west mudbrick staircase up to a north-south walkway, running along the inner line of the city fortification wall. A series of small cubicles (Walls 10 and 11, and F.34) were constructed in the northern margins of the walkway, probably during this phase, or just possibly in the subsequent rebuild. The foundations of the Phase V "Governor's Residence" complicates interpretation at this point.

At some stage during the life of these structures, but after the re-laying of several floors, a severe earthquake (?) destruction resulted in significant damage to the entire complex. Both Wall 27 and the city wall (Wall 41) suffered major structural damage. Several large pieces of the inner face of the city wall fractured and collapsed onto floor surfaces. The three small cubicles built against the inner face of the city wall suffered a fiery destruction, with clear evidence of wall and floor fracturing, and much broken pottery and other objects sealed by a thick brick-filled debris layer.

Phase VI B (Figs. 22-24)

III C Walls 36-40; III D Walls 6 and 7; III F Wall 5; Features 71, 83 (Fig. 18) and 85, and Associated Deposits

Following the earthquake damage, the whole complex was rebuilt. Internal structural mudbrick wall patch (F.85) and buttress (F.83) were added to the inner face of the city wall (Wall 41), and the east-west passageway along the inner face of III F Wall 7 was probably blocked. Wall 27 was cut down and rebuilt, with stone buttresses along its north (III C F.71) and south (III D Wall 6) faces shoring up the original mudbrick wall. In the central area of the trench west of the city wall and north of the rebuilt Wall 27, a substantial square double-walled room (III C Walls 36, 37 and 40 and III D Wall 7) was constructed in stone and mudbrick, faced with thick mudplaster, and provided with benches along the north (Wall 38) and east (Wall 39) interiors. No more than small scraps of a build-up of surfaces were preserved against the south face of III D Wall 6. All other deposits were lost to erosion.

The walkway and the cubicle rooms along the inner face of the north-south city wall (Wall 41) were never repaired. It seems probable that the entire region east of Wall 41 was rebuilt along different lines. A mudbrick buttress wall (III F Wall 5) was cut down against the inner northern face of III F Wall 7. Along with the III C corner buttress F.83, both constructions probably aimed at strengthening the east-west circuit wall, III F Wall 7. The north baulk intervenes at this point, so it remains unclear whether III C Buttress F.83 and III F Bench Wall 5 merely narrowed the east-west passageway, or sealed it off completely. However, subsequent deep fill layers devoid of occupational surfaces suggest infilling with Middle/Late Bronze Age tip/rubbish deposits, making it likely that the area went out of use at this point.

- Table I Area III:

Stratigraphic Summary from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Table I

Table I

Area III: Stratigraphic Summary

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 7 Plans of five major

Middle Bronze Age Phases in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Schematic plans of five major MBA Phases in Area III. Excavation Area 20 x 15 metres in extent

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 7 Closeup - Plan of Phase VI

in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 7 Closeup

Fig. 7 Closeup

Schematic plan of Phase VI in Area III. Excavation Area 20 x 15 metres in extent

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006) - Fig. 17 City Wall 41 Phase VII repair

in Area III from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

View of City Wall 41 Phase VII repair, built against main inner wall face in centre background, looking east

Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006)

At some stage during the life of these structures, but after the re-laying of several floors, a severe earthquake (?) destruction resulted in significant damage to the entire complex. Both Wall 27 and the city wall (Wall 41) suffered major structural damage. Several large pieces of the inner face of the city wall fractured and collapsed onto floor surfaces. The three small cubicles built against the inner face of the city wall suffered a fiery destruction, with clear evidence of wall and floor fracturing, and much broken pottery and other objects sealed by a thick brick-filled debris layer.Wall 41 runs N-S and Wall 27 runs E-W.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 30 June 2025

- from Bourke, Sparks, and Schroder (2006:26)

Both Wall 27 and the city wall (Wall 41) experienced significant failure. Large pieces of the inner face of the city wall fractured and collapsed onto adjacent floor surfaces. Additionally, three small cubicles built against the city wall’s inner face were destroyed by fire, exhibiting wall and floor fractures, heavy pottery breakage, and a thick debris layer composed of brick fill.

The authors cautiously interpret this widespread and sudden destruction as consistent with a seismic event, though the question mark in their phrasing indicates that this conclusion remains tentative.

The event is dated to the end of the Middle Bronze III period (ca. 1600 BCE) based on the stratigraphic position of the destruction in Phase VIC, directly below the Late Bronze Age levels, and supported by associated ceramic material.

Bourke, Sparks, and Mairs (1999:53-57) report that an entire Bronze Age complex in Area XXIV on Tell el-Husn

consisting of a single main constructional phase, and at least two phases of rebuilding

was

destroyed in a massive earthquake, probably dating towards the end of the LBIIA period

[1400-1300 BCE], based on pottery sealed in destruction layers.

A hoard of eleven leaf-shaped copper alloy arrowheads and stunning bolts all in an excellent state of preservation

were found in the destruction debris. Such arrowheads first appear during the LBA, probably in response to the contemporary

developments in scale armour.

Several burials of infants and young children were uncovered

, sealed beneath the later rebuilding phases

of the complex, which dated to the 17th century BCE (MB/LB) based on ceramics.

While discussing evidence due to the same event in Area XXII on Tabaqat Fahl (Pella),

Bourke (2004:8-9) noted that

there was a sharp warping of the underlying foundations in the north temple area [in Area XXII],

still clear today from aerial photographs.

Raphael and Agnon (2018:775), while citing

Bourke (2012), report that the same earthquake was evident due to a major change in the design of the temple

[Pella Migdol Temple ?], around 1350-1300 BCE

which was probably due to a

severe earthquake

where the western wall of the temple revealed stress-twisting and shattering.

Bourke (2004:8-9) noted that

similar earthquake-related damage is found throughout the city and in buildings on nearby Tell Husn (Bourke et al. 1999).

- from Bourke (2004)

- Fig. 1 - Pella contour plan/area locations

from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Pella contour plan/area locations

Bourke (2004) - Fig. 2 - View of Area XXXII temple precinct

from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

View of Area XXXII temple precinct.

Bourke (2004) - Fig. 3 - Schematic plans of

three main phases of temple construction from Bourke (2004)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Schematic plans of three main phases of temple construction.

Bourke (2004)

- from Bourke (2004:1)

... Investigations began in 1994 when chance discoveries in the South Field (Area XXXII) revealed the presence of a massive stone building, the largest pre-Classical structure discovered at the site (Bourke et al. 2003).

- from Bourke (2004:4)

Cult paraphernalia favours the worship of a male deity, and the simplicity of architectural design (an empty box) would favour a numinous aniconic deity. We suggest that El, father of the gods and head of the Canaanite pantheon, best fits this description of the deity worshipped in this first phase of the Pella temple. We acknowledge that there is no consensus as to the specific architectural, archaeological or iconographic paraphernalia to be associated with the worship of each male deity in the Canaanite pantheon (Dever 1983). The majority of Levantine archaeological literature on the subject of Bronze Age gods generally opts for Baal, Hadad or Dagan as the three most likely candidates to have been worshipped in Bronze Age Canaanite temples (Mazar 1992).

It is curious how little archaeological presence is accredited to El, given that he was the head of the Canaanite pantheon and ruler over all the gods. Contemporary mythological texts make clear the dominance of El in the Middle Bronze Age Canaanite pantheon (Lewis 1996; Pitard 2002), and yet few of the many Canaanite temples discovered over the last hundred years of excavation in the region has ever been specifically attributed to his worship. We believe this to be in error, and would like to suggest that the massive rectangular “empty-box” temple form, as represented by the Middle Bronze Age temples from Shechem, Megiddo, Hazor (Area A), Tel Kittan, Tell Hayyat and Pella be associated with the worship of Canaanite El. Given the geographical proximity of most of the abovementioned sites to each other, it seems probable that a specific inland central Levantine aspect of Canaanite El was being venerated (Albright 1968).

- from Bourke (2004:7-8)

The eastern facade of the temple was also remodelled, with two massive 5 x 5 metre hollow square towers built upon the projecting solid stone buttresses that flanked the original entrance to the temple. The change from the original stone and (presumably) solid brick pier superstructure to a hollow tower format may have been designed to reduce weight-stress on the abutting temple facade, or perhaps to facilitate the construction of high flanking towers.

It is no easy matter to evaluate the significance of these architectural changes for cult practice and religious belief. The changed architectural form of the early Late Bronze Age temple need not reflect any significant change in cult, but we suggest that it does. The action of dividing off a Holy of Holies for the first time is a significant departure from previous practice, and bespeaks an altered view of the relationship between man and god.

The Ugaritic religious epics (Pitard 2002) contain legends that document the triumph of Baal in a war between the gods, and is generally interpreted as recording the spread of Baal worship in early Late Bronze Age Canaan. This assumed pre-eminence seems to have led to the attribution of virtually all Late Bronze Age Canaanite temples to Baal, even though very few have any inscriptional evidence to favour such an association (Mazar 1992). Male iconography does predominate (figurines, cult statues, incense burners) so the worship of some male deity is not easily disputed. When Late Bronze Age texts do identify individual temples, they name Baal, Reshep, Hadad and Dagan as titular deities (van der Toorn et al. 1999).

As well, there is an undoubted presence (if not pre-eminence) of Baal worship in the southern Levantine Late Bronze Age, more specifically at Pella where ruling prince Mut-Balu proclaims his loyalty to Baal by his very name (Hess 1989). Thus the broad association of Baal, Hadad or Dagan worship with Late Bronze Age temples is not unreasonable. Explaining the apparent change from El to Baal worship is more of a problem, although the spread of Hurrian peoples and their distinctive religious beliefs into Canaan and southern Anatolia at this time is well documented (Na’aman 1994; Hess 1997). It may be that the spread of Baal worship into the southern Levant is broadly connected with the arrival of Hurrian immigrants and the rise of the Hurrian Mitannian empire (Klengel 1992). Indeed, it was this new presence of Hurrian Mitannians in the southern Levant that Thutmosis III claimed to have provoked his first military campaigns, which ultimately brought much of Canaan (including western Jordan) under Egyptian control for the first time (Redford 1992).

South Levantine Late Bronze Age temple architecture changes from the simple “empty-box” form of the Middle Bronze Age temples at Shechem, Megiddo and Hazor (Area A), to more architecturally complex internally subdivided structures such as those at Hazor (Area H), Lachish (Acropolis Temple) and Beth Shan (Mekal). Architectural change need not reflect change in cult practice, but when these architectural changes occur across the south Levantine landscape at the same time as new North Syrian Hurrian cultural traditions appear, there is more strength to arguments that seek to link changed architectural forms with changing religious beliefs (Hess 1989). We view the early Late Bronze Age changes to the original Middle Bronze Age temple form at Pella in this context of widespread change in cultural and religious beliefs, largely attributable to the influence of North Syrian Hurrian religious forms.

- from Bourke (2004:8-9)

The entire structure was levelled down to the stone foundations and new (much less massive) stone and mudbrick walls were built along the outer edge of the original east, south and western wall lines. However, a new north wall line was created five metres to the south of the Middle Bronze Age original, resulting in a significant narrowing of the entire structure. This was probably brought about by the sharp warping of the underlying foundations in the north temple area, still clear today from aerial photographs. At this time the original wide entrance to the Holy of Holies was narrowed and re-centred, and rebuilt using roughly dressed limestone and more carefully dressed (and drilled) basalt orthostat blocks; the latter were probably reused from earlier structures. Two small basalt column bases now flanked the re-configured entrance to the Holy of Holies. The floor of the Holy of Holies was re-laid, with new small stone foundational layers sealed by a thick, yellow, plaster floor surface. A number of distinct Egyptian-style foundation deposits were placed in shallow pits below this re-laid floor.

The new (much narrower) rectangular cella to the east of the rebuilt Holy of Holies was provided with a central colonnade at this time, indicated by the presence of three pillar bases. The western and eastern column bases had relatively small sub-structural foundations, but the central column base was provided with a massive limestone sub-structure, implying that it was designed to be the major weight-bearing support. All three column base foundations were cut into the mud brick paving of the original cella floor. Traces of burnt wooden columns were found in direct association with both of the smaller column bases. Thin, off-white plaster floors were laid across the narrowed cella area and the lower regions of the interior wall surfaces were sealed with a thick, monochrome, pale brown mud plaster.

The eastern facade of the temple was also remodelled, although subsequent Iron Age re-use in this area has made the exact form of the Late Bronze Age structure difficult to reconstruct with any confidence. However, it seems probable that the two hollow-square towers flanking the early Late Bronze Age temple entrance collapsed in the earthquake and were not rebuilt. If this interpretation is correct, then the area to the east of the reconstructed east wall would have been an open pebble-paved plaza.

These alterations to the early Late Bronze Age temple form could be interpreted as a simple structural response to severe earthquake damage, in that virtually all changes could be seen as a necessary strengthening of the original structurally unsound “hollow-box” design. However, the construction of a pillared hall, the addition of flanking columns at the entrance to the Holy of Holies, and the presence of “Egyptianising” foundation deposits may all reflect a new cultural influence at work.

While we have no reason to posit major change in local religious beliefs in the Late Bronze Age II, the architectural remodelling of the Pella temple coincides closely with the first presence of the Egyptian Nineteenth Dynasty pharaohs in the region (Redford 1992). This Late New Kingdom dynasty profoundly changed the ways in which the Canaanite empire had been administered previously, being far more inclined to interfere directly in the running of vassal states (Weinstein 1981). From this time (ca 1300 BC) an accelerated “Egyptianisation” of local elite culture can be observed, as can direct Egyptian influence on local Canaanite architectural modes (Wimmer 1990; Higginbottom 1996). With this in mind, it may be that the Egyptianising foundation deposits and the pillared hall at Pella provide evidence for an increasingly pervasive Egyptianisation of local elite culture east of the Jordan during the later New Kingdom.

The remodelled temple remained in use until the end of the Bronze Age (ca 1150 BC), when the entire site of Pella suffered a major destruction. This may also have been due to earthquake activity, although human agency remains possible, as this is the time of the enigmatic Sea People descent on Egypt, generally (if not always reliably) associated with a widespread destruction horizon throughout the region at this time (Sandars 1978).

- from Bourke (2004:9)

- from Bourke (2004:10-11)

Direct architectural parallels for the Iron Age II temple form are elusive. At Shechem (Stager 1999) and Tel Kittan (Eisenberg 1977), Iron Age II structures were reconstructed directly on top of Late Bronze Age originals, although the architectural forms are not particularly close to those at Pella. However, reasonably close parallels are found with the Iron II temples from Tel Qasile (Mazar 1980) on the Palestinian coast, and some individual design elements are paralleled in Iron Age temples at nearby Beth Shan (Rowe 1940). The contemporary material culture (and cult practice) at these two sites display an eclectic mixture of local Canaanite and “Aegean-Cypriot” influences, which many researchers equate (rather shakily) with the “Sea Peoples” (Tubb 2001), or more specifically with the better-known Biblical Philistines (Dothan 1982).

Architectural parallels are consistent with a significant change in cult practice, and offering vessels and figurines display relatively unambiguous links with the Palestinian coast for the first time during these Iron I-II horizons. Whilst it is probably unwise to equate specific politico-historical events with changing archaeological circumstances, the sharp change in cult practice at Pella does seem to indicate the presence of a major new influence in the region, with all archaeological indicators favouring a source on the Palestinian coastal plain (Singer 1994). It is difficult not to view these purely archaeological circumstances as consistent with Biblical testimony relating to the penetration of the originally coastal Philistine peoples into the eastern Jezreel Valley, which many regard as occurring at precisely this time (Raban 1991; Singer 1994).