Iron Age in the Southern Levant

| Period | Time Span (BCE) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Iron I | 1200-1000 | ca. 1005-931 BCE - reigns of Kings David and Solomon |

| Iron IIA | 1000-925 | ~925 BCE - Sheshonoq I's invasion |

| Iron IIB | 925-720 | ~732 BCE - Neo-Assyrian Conquest of Israel (the Northern Kingdom) |

| Iron IIC | 720-586 | ~587 BCE - Neo-Babylonian Conquest of Jerusalem and Destruction of the First Temple |

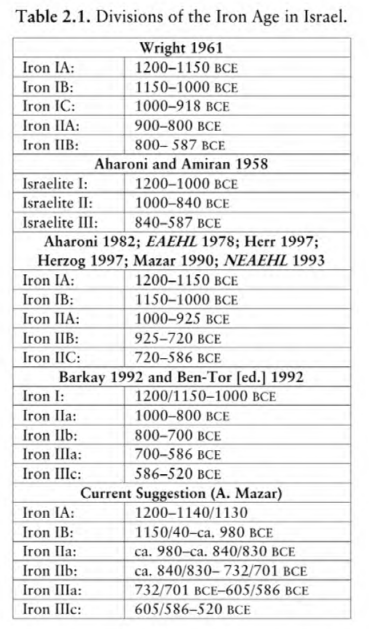

Table 2

Table 2Dates of six ceramic phases in the Iron Age in the Levant and the transition between them according to the Bayesian model (63% agreement).

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2010)

- from Mazar (2014)

| Period | Time Span (BCE) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Iron IA | 1200-1140/1130 | |

| Iron IB | 1150/1140-~980 | |

| Iron IIA | ~980-~840/830 | |

| Iron IIB | ~840/830-732/701 | ~732 BCE - Neo-Assyrian Conquest of Israel (the Northern Kingdom) |

| Iron IIIA | 732/701-605/586 | ~587 BCE - Neo-Babylonian Conquest of Jerusalem and Destruction of the First Temple |

| Iron IIIC | 605/586-520 |

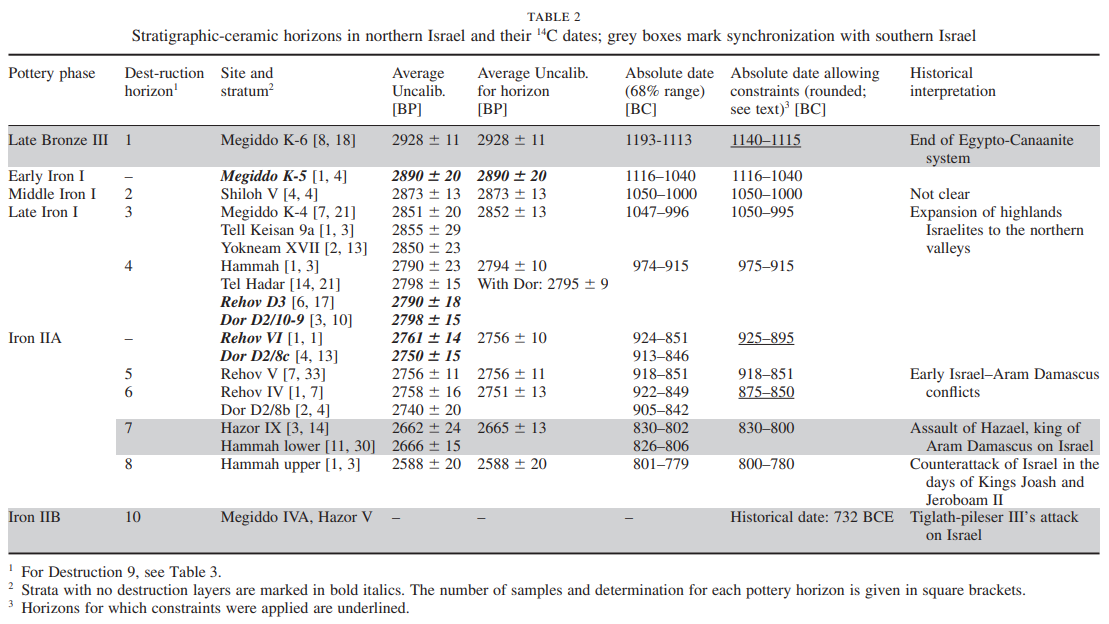

Table 2

Table 2Stratigraphic-ceramic horizons in northern Israel and their 14C dates; grey boxes mark synchronization with southern Israel

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2009)

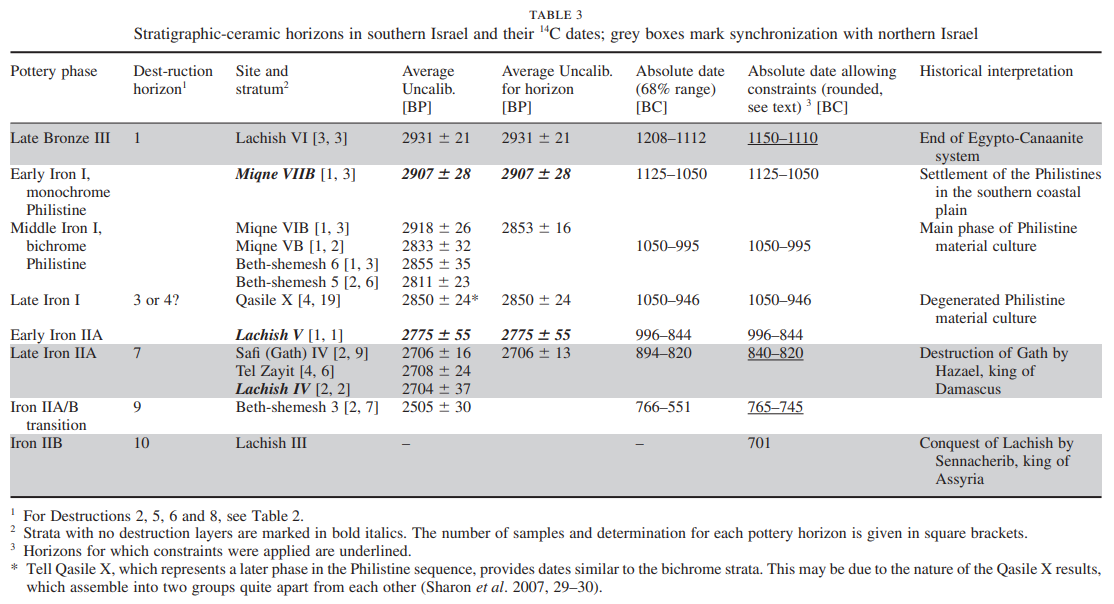

Table 3

Table 3Stratigraphic-ceramic horizons in southern Israel and their 14C dates; grey boxes mark synchronization with northern Israel

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2009)

Figure 5

Figure 5Results of the Bayesian model for six phases and six transitions in the Iron Age

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2010)

- from Mazar (2014)

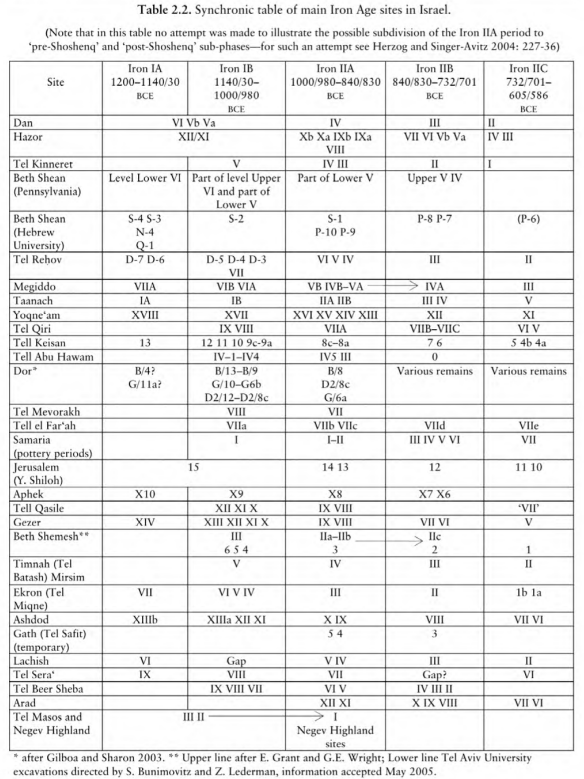

Table 2.2

Table 2.2Synchronic Table of Main Iron Age Sites in Israel

Mazar in Levy and Higham (2014)

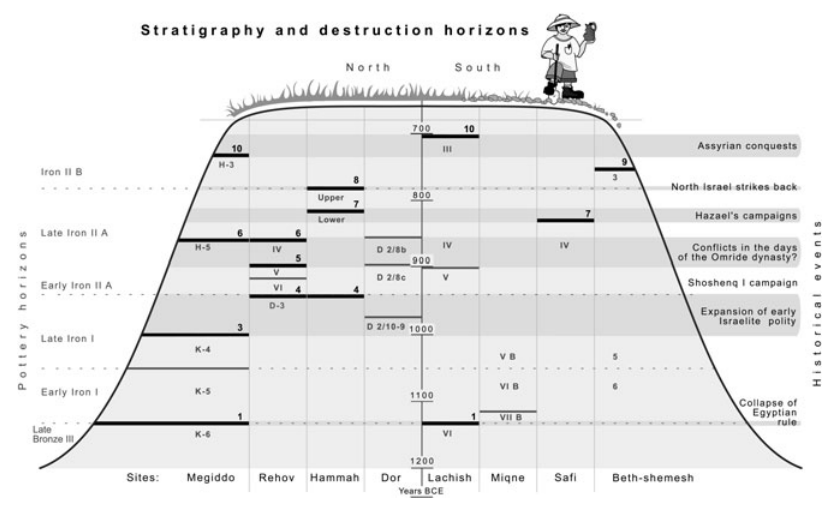

Figure 4

Figure 4Synchronization of the ten destruction horizons, pottery horizons and historical events (Destruction 2, middle Iron I, Shiloh, not marked).

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2009)

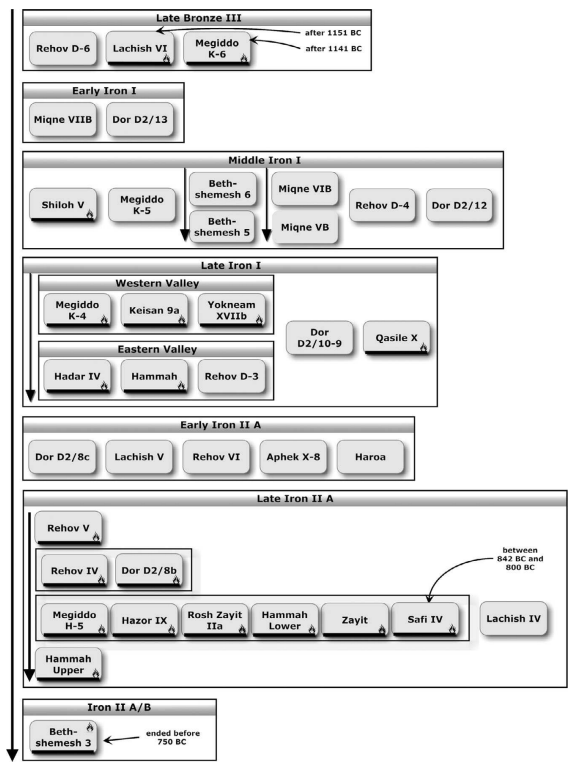

Figure 3

Figure 3The Bayesian model for six phases and six transitions in the Iron Age. Destruction layers are underlined with a thick black line; historical constraints are indicated by arrows. The late Iron IIA strata were entered in the order of the four destruction horizons that we identified elsewhere

(Finkelstein & Piasetzky 2009)

Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2010)

- from Thomas (2014:3-10)

| Period | Time Span (BCE) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Iron I | 1200-1000 | ca. 1005-931 BCE - reigns of Kings David and Solomon |

| Iron IIA | 1000-925 | ~925 BCE - Sheshonoq I's invasion |

| Iron IIB | 925-720 | ~732 BCE - Neo-Assyrian Conquest of Israel (the Northern Kingdom) |

| Iron IIC | 720-586 | ~587 BCE - Neo-Babylonian Conquest of Jerusalem and Destruction of the First Temple |

For much of the history of research into the archaeological and biblically-based historical background of the world of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, it was not thought that elements of the nature of the biblical text or the archaeological record of the southern Levant contradicted the general historicity of the United Monarchy and its description as given by the associated biblical books. In two articles published in 1958 and 1970, the noted Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin provided the high point in the search for David and Solomon ‘on the ground’. He described how three cities that had undergone major excavations in Israel, some partially under his direction, each produced a monumental casemate wall and city gate that featured three chambers on each side of the main passageway. Each was associated with pottery that was, at least at the time, commonly dated to the 10th century BC. These three cities, Hazor in the northern end of ancient Israel’s highlands, Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley adjoining the upper Mediterranean coastal plain, and Gezer on the southern coastal plain near the region inhabited by Israel’s traditional foes the Philistines, were exactly the three sites that the biblical passage 1 Kings 9:15 describes as having been ‘built’ by Solomon. Megiddo was the crown jewel, with a series of palatial buildings that appeared to be major administrative structures present in the same stratum as the casemate wall and six-chambered gate, followed by a later stratum with a four-chambered gate and what appeared to be large stables, apparently built by the Omride dynasty of the early Northern Kingdom of Israel known for their chariotry. Yadin operated with the assumption that 1 Kings 9:15 could be assumed to be historically accurate, and with the passage alongside the stratigraphy, pottery and gates, his findings appeared to provide clear indication of the sophisticated, monumental, centralised and state-directed activity that characterised Solomon’s kingdom, confirming the biblical impression of his rule1.

Later however, a movement taking place primarily within biblical studies as opposed to archaeology began to radically question the date of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament as a whole, including those books which describe the United and Divided Monarchies. This movement, primarily located in Britain and continental Europe, reached a crescendo of sorts in the 1990’s. These texts were declared to be late, dating to Persian or even Hellenistic periods, about half a millennium or more later than the events they described. Thus it was declared that the descriptions of the United and Divided Monarchies were, in common with other historical topics of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament’s authors, essentially a later ideological invention. The biblical portraits of these ancient kingdoms contained little if any historical material and even if they did, it was so bound up in the ideological, nationalistic and rhetorical goals of the authors as to be rendered indistinguishable and useless for a detailed and balanced understanding of ancient Israel. This movement came to be placed involuntarily under the label ‘Minimalism’ and its proponents ‘Minimalists’. Conversely, those who defended the historical integrity of the biblical books and the traditional picture of ancient Israel were dubbed ‘Maximalists’2. These terms have now become well known within the scholarly community, though they are designations placed upon a non-unified and non-self-designating group, and are made within an otherwise complex field that contains as many individual and nuanced views as it does scholars to have them. Thus the idea of ‘Maximalism’ versus ‘Minimalism’ does not concern this thesis. As it is, the ‘Minimalist’ paradigm as sketched out above has been rendered essentially null by the progress of historical, linguistic and archaeological research on ancient Israel and in studies that have addressed the claims and conclusions of the paradigm directly. Important studies of note include research into the diachronic position of the stage of the Hebrew language that was used to write much of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament that has revealed, primarily through comparison with relevant epigraphic materials of the Iron Age, that the Hebrew used to write much of the Deuteronomistic History, a group of books that includes the books of Samuel and Kings and to which this thesis will return, was written before the Exile of Judah to Babylonia of 586 BC3. Even more important as far as the historicity of the monarchical period are studies such as that of Baruch Halpern and William Dever that explicated and laid out in detail the amount of archaeological and textual evidence from the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, the archaeology of the southern Levant, and independent evidence and historical references from ancient Israel’s wider ancient Near Eastern world that demonstrated the general historical reliability of the material reality of ancient Israel, such as names and relative chronological setting of kings who are known from both the biblical books and from references to them in ancient Near Eastern documents4. The most definitive piece of evidence that severely undermined an outright rejection of any historicity to the United Monarchy was found in fragments in 1993 and 1994. The Aramaic stele found at Tel-Dan contains a clear reference to the Northern Kingdom of Israel and to the ‘House of David’, a common patronymic way of referring to a kingdom using the founder’s name5.

As such, this thesis does not focus on the scholarship of those often invoked as ‘Minimalist’ because, as described, their more extreme positions have been rendered essentially invalid by the progress of archaeology and by scholarship that has critically examined their claims. Observe Philip Davies’ ‘Critique of Biblical Israel’ from his In Search of ‘Ancient Israel’, in which the author constructs a situation in which the archaeological record of Iron Age civilisation in the southern Levant actually bears no connection to the civilisation and history, the ‘Israel’, described in the Bible6. Davies’ construction is in fact a bizarre form of exceptionalism, in which biblical Israel happens to be different from all other ancient cultures even though it is in fact no different, having a written history and an archaeological record that has been otherwise accepted to be the actual remains of the civilisation that is described by that written history and from which it emerged. Such thinking has now been bypassed by the debate and not a factor in considering its primary focus and the positions of its important contributors. What does concern this thesis emerged first and foremost out of archaeology. Beginning in the mid-1990s, another Israeli archaeologist named Israel Finkelstein ignited an enormous new debate over the historicity of the United Monarchy, the very debate that this thesis examines. In two articles Finkelstein set out to demonstrate what he saw as deep flaws in the structural matrix of the High Chronology. First, Finkelstein argued that one of the bases used for relative dating of sites in the Iron I and IIA, the settlement of the Philistines in southern Canaan, should be down dated from its traditional position in the 12th century BC to the 11th century BC. His argument derived from the fact that though 12th century BC Egyptian sites in southern Canaan were closely proximal to Philistine sites, these sites did not have any Philistine pottery, an apparently odd situation given their locations. Thus the Philistine settlement must not have occurred in the 12th century BC and must have been later than first thought. Finkelstein then went on to critique Yadin’s identification of the ‘Solomonic’ strata and gates described above, which he argued were inherently subjective due to the reliance on the 1 Kings passage, which seemed to him to be the central basis upon which Yadin did his dating. He took the view that the passage’s own date and relevance to the 10th century BC was not known for sure, as opposed to the possibility of it being related to a later period. He also pointed out that the stratigraphic association of the six-chambered gate at Megiddo had been challenged since Yadin’s time. In line with his arguments about the date of the Philistines’ settlement and their pottery, he concluded that the transition from the Iron I into the Iron IIA should be lowered to the end of the 10th century BC and the associated ‘Solomonic’ strata should be down-dated to the very late 10th or early 9th centuries BC. He thus concluded that construction previously attributed to Solomon was much more likely related to the Omride dynasty in the 9th century, thus stripping the Davidic-Solomonic United Monarchy of its monumental architecture as it became a kingdom, if it could still be called that, of the much poorer Iron I, which now occupied most of the 10th century BC. This new chronological system Finkelstein called the ‘Low Chronology’7. In 1997, Amihai Mazar published a critique of Finkelstein’s views, beginning a debate in which he has been one of Finkelstein’s primary sparring partners, which continues to the present8. In 2001 Mazar introduced his own revision of Iron Age Chronology in Israel, which he has come to call the ‘Modified Conventional Chronology’. This scheme is based on Mazar’s observations concerning pottery but instigated by his collaborative radiocarbon dating studies performed on samples from the excavations at Beth Shean and Tel Rehov, where Mazar has served as director. The Modified Conventional Chronology asserts that the transition from the end of Iron I to Iron IIA occurred at c. 980 BC and that the Iron IIA ended c. 830 BC. This kept alive the possibility that the aforementioned monumental building activity could be attributed to the United Monarchy, but left the situation ambiguous9.

Figure 2: Comparisons of the three chronological systems

Figure 2

Figure 2Comparisons of the three chronological systems

Thomas (2014)

It is important to note that both Finkelstein and Mazar are first and foremost archaeologists, though they have both addressed what they believe to be the historical implications of archaeological scholarship. This does not mean that those participating in the debate, including those who make important contributions to the primary models for reconstructing the United Monarchy, simply assume that archaeology must be the ‘High Court’, that is to say the final basis of judgement upon which to address the matter of the biblical picture of the United Monarchy. Finkelstein has argued that it can and should be used as such a basis, and this issue will appear when necessary in the chapters of this thesis10.

The debate therefore, as it existed in its early days and as it exists now, can broadly be said to characterise two more or less distinct positions. One, characterised but by no means exclusive to Finkelstein is generally negative about the historicity of the United Monarchy at least as it is portrayed in the biblical text even if it was a real entity of some form while the alternate position is generally positive about the historicity of the United Monarchy even though it seeks to explain its portrayal in the biblical text with critical nuance rather than a naïve total acceptance. These two positions are here simply referred to as ‘models’ as they both use various arguments and bodies of evidence in an attempt to reconstruct a picture of the historical United Monarchy and its relationship to its portrayal in the biblical text.

1 Yigael Yadin, ‘Solomon’s City Wall and Gate at Gezer’, IEJ 8:2 (1958), pp. 80-86; Yigael Yadin, ‘Megiddo of the Kings of Israel’, Biblical Archaeologist 33:3 (1970), pp. 65-96

2 Megan Bishop Moore, Brad Kelle, Biblical History and Israel’s Past (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011), pp. 33-39

3 Avi Hurvitz, ‘The Historical Quest for “Ancient Israel” and the Linguistic Evidence of the Hebrew Bible: Some Methodological Observations’, Vetus Testamentum 47 (1997), pp. 310-315

4 Baruch Halpern, The First Historians: The Hebrew Bible and History (NY: Harper and Row, 1988); Baruch Halpern, ‘Archaeology, the Bible and History: The Fall of the House of Omri-And

the Origins of the Israelite State’ in Historical Biblical Archaeology and the Future: The New Pragmatism, ed. by Thomas Levy (London: Equinox, 2010), pp.262-284; William Dever,

‘Histories and Non-Histories of Pre-Exilic Israel: The Question of the United Monarchy’ in In Search Of Pre-Exilic Israel, ed. by John Day (London: T&T Clark, 2004), pp. 65-94;

Halpern’s scholarship is of much interest in this thesis so it is necessary to explain why William Dever’s work is referred to only to a limited degree. Dever largely wrote

against so-called ‘Minimalist’ scholars prominent before Israel Finkelstein introduced his Low Chronology (for which see below in the main text). The latter

and not the former are of primary concern here, and although Dever did write in opposition to Finkelstein, he has not been Finkelstein’s main archaeological opponent

and was not involved in the discussion of complex radiocarbon dating efforts or more recent archaeological developments like Khirbet Qeiyafa, both of which have become

central to this debate. See William Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001)

5 Moore, Kelle, Biblical History and Israel’s Past, pp. 217-218

6 Philip Davies, In Search of ‘Ancient Israel’ (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), pp. 51-56; Nor does this thesis deal with the work

of any other of the other ‘Minimalists’ such as Keith Whitelam, whose most notable (or notorious) work, The Invention of Ancient Israel:

The Silencing of Palestinian History does not contribute to the archaeological and historical debate that this thesis surveys but instead

is concerned with complaining about the fact that the study of the Bible and ancient Israel has somehow obscured the true history of

‘Palestine’, see Keith W. Whitelam, The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History (Abingdon: Routledge, 1996)

7 Israel Finkelstein, ‘The Date of the Settlement in Philistine Canaan’, Tel Aviv 22 (1995), pp. 213-239; Israel Finkelstein, ‘The Archaeology of the United Monarchy: An Alternative View’, Tel Aviv 28 (1996), pp. 177-187

8 Amihai Mazar, ‘Iron Age Chronology: A Reply to Israel Finkelstein’, Levant 29 (1997), pp. 157-167

9 Amihai Mazar, Israel Carmi, ‘Radiocarbon Dates from Iron Age Strata at Tel Beth Shean and Tel Rehov’,

Radiocarbon 43 (2001), pp. 1333-42; for a more recent overview see Amihai Mazar, ‘The Debate Over the Chronology of

the Iron Age in the Southern Levant’ in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 13-28

10 Nadav Na’aman, ‘Does Archaeology Really Deserve the Status of a ‘High Court’ in Biblical Historical Research’ in Between Evidence and Ideology, ed.

by Bob Becking and Lester Grabbe (Leiden: Brill, 2010), pp. 165-183; Israel Finkelstein, ‘Archaeology as a High Court in Ancient Israelite History: A Reply to Nadav

Na’aman’, JHS 10 (2010)

- from Thomas (2014:11-13)

The first and most useful type of literature can be generally characterised as works that have sought to review the changing manner of the historical and archaeological study of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and its context. These often include review of the changing study of the United Monarchy and of the debate presently under review. This includes Moore and Kelle’s Biblical History and Israel’s Past, which surveys the history of scholarship and nature of scholarship as it is now pertaining to the entire chronological range of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament History, from the Patriarchs to the Persian period. It incorporates discussion of both textual and archaeological aspects of scholarship and individual scholars, theories, movements, and events of importance11. Historical Biblical Archaeology and the Future: The New Pragmatism edited by archaeologist Thomas Levy is a collection of papers by important scholars that review emergent and critical issues in archaeological practice and theory, text and history and the bridging of the gap between text and archaeology and the proper methodology for combining the two fields12. While these two volumes are both primarily for scholars, Israel Finkelstein’s popular book The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts, co-authored with Neil Asher Silberman has, despite its target audience, also captured the attention of scholars across Biblical Studies and stood as a general outline of his Low Chronology system and its implications for historicity, particularly of the United Monarchy. It is also where Finkelstein offered his view that an early state centred on Jerusalem never controlled the north of Israel in the 10th century BC and that the Divided Monarchy kingdoms of Israel and Judah appear to have emerged separately13. More recently Finkelstein has come together with Amihai Mazar to produce the volume The Quest for the Historical Israel, in which the two each lay out an exposition of their personal views on archaeology and its implications for biblical history as pertaining to the earliest period, the United Monarchy and then the Divided Monarchy, with a summary then provided for each period by editor Brian Schmidt14.

The second type of literature concerns a genre that has existed since well before the emergence of this debate, the ‘general history’ of ancient or biblical Israel. Histories written since Finkelstein introduced the Low Chronology in the mid-1990’s have of course needed to pay heed to the debate’s implications though they do not generally explore the mechanics of the debate as such. These include Mario Liverani’s Israel’s History and the History of Israel which actually adopts the Low Chronology and writes the resulting history, downgrading the reality of the United Monarchy to a petty state that only existed as it appears in the biblical records as the ideology and fantasy of a much later author15. Miller and Hayes’ A History of Ancient Israel and Judah represents a more moderate view in not adopting the Low Chronology whilst also adopting a fairly constrained view of the United Monarchy’s extent and the degree to which David and Solomon can be treated as kings of a large and developed stater16. A different kind of ‘general history’ is represented by Baruch Halpern’s David’s Secret Demons: Messiah, Murderer, Traitor, King. This work is both a biography and far more than a biography of David. It critically examines his life, and to a small extent that of Solomon, as portrayed in the books of Samuel and 1 Kings whilst also undertaking a thorough examination of these books on the matter of their sources, rhetoric, ideology, relationship to literature of the wider ancient Near East and their dating. Halpern also devotes much attention to the archaeology related to both David and Solomon and to how it relates to the biblical text. Its approach is firmly integrative, and it treats textual and archaeological considerations as complementary.

What these studies, excellent though they generally are, have in common is that they tend to be in some way weighted towards a specific stance upon what they discuss. They tend to represent arguments for or criticism of a particular major viewpoint in this debate. Finkelstein and Mazar’s The Quest for the Historical Israel has both, from different sides of the debate. They are also often uneven in the degree to which they delve into the minutiae of specific facets of the debate, and therefore don’t always allow the reader to access the often complex developments and arguments that are used to construct a scholar’s views. Thus, there is a gap in the literature for a work that approaches the debate without seeking to exposit the virtues of one view over another throughout, and one that allows a reader to access the intricacies of the important individual textual and archaeological facets of this debate. This thesis is intended to fill that gap.

11 Moore, Kelle, Biblical History and Israel’s Past

12 Historical Biblical Archaeology and the Future: The New Pragmatism, ed. by Thomas Levy (London: Equinox, 2010)

13 Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: Touchstone, 2001)

14 The Quest for Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel, ed. by Brian Schmidt (Brill: Leiden, 2007)

15 Mario Liverani, Israel’s History and the History of Israel, trans. by Chiara Peri and Philip R. Davies (London: Equinox, 2005)

16 J. Maxwell Miller, John H. Hayes, A History of Ancient Israel and Judah, 2nd ed. (London: SCM Press, 2006)

- Fig. 2 - Strata in

Area H in Megiddo from Finkelstein (2013:9)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The eastern and southern baulks of Area H at Megiddo, showing different layers and their relative and absolute dates

Finkelstein (2013)

2. Recent Advances in Archaeology

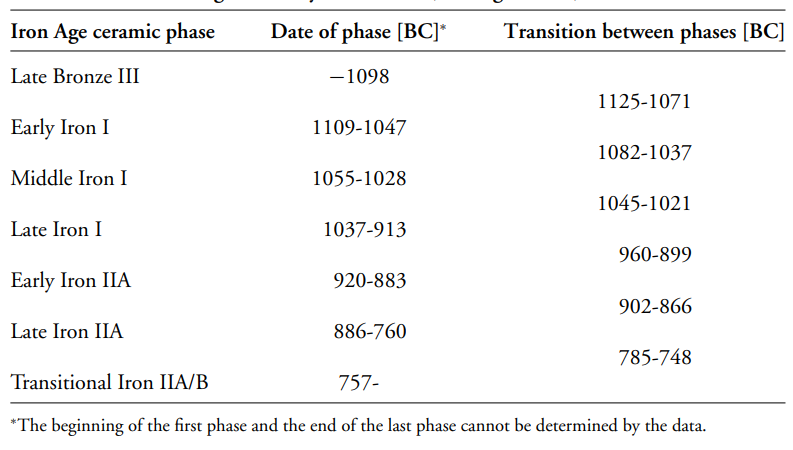

A clarification about chronology is in place here. Our knowledge of the chronology — both relative and absolute — of the Iron Age strata and monuments in the Levant has been truly revolutionized. In terms of relative chronology, intensification of the study of pottery assemblages from secure stratigraphic contexts at sites such as Megiddo and Tel Rehov in the north and Lachish in the south opened the way to establish a secure division of the Iron Age into six ceramic typology phases:

- early and late Iron I (Arie 2006; Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2006)

- early and late Iron IIA (Herzog and Singer-Avitz 2004, 2006; Zimhoni 2004a; A. Mazar et al. 2005; Arie 2013)

- Iron IIB and Iron IIC (Zimhoni 2004b)

- A statistical model based on a large number of radiocarbon determinations: 229 results from 143 samples that came from 38 strata at 18

sites located in both the north and south of Israel (Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2010, based on Sharon et al. 2007 and other studies; Table

1 here3). The radiocarbon results from Israel are the most intensive for such a short period of time and small piece of

land ever presented in the archaeology of the ancient Near East.

Table 1

Table 1

Dates of ceramic phases in the Levant and the transition between them according to recent radiocarbon results (based on a Bayesian model, 63 percent agreement between the model and the data)

Finkelstein (2013:7) - A statistical model for a single site — Megiddo: circa 100 radiocarbon determinations from about 60 samples for 10 layers at Megiddo,

which cover circa 600 years between circa 1400 and 800 B.C.E. (Tofolo et al. forthcoming; demonstration in Fig. 2). Megiddo is especially

reliable for such a model because the time span in question features four major destruction layers that produced many organic samples

from reliable contexts. This, too, is unprecedented: no other site has ever produced such a number of results for such a dense

stratigraphic sequence. The general model (table 1) represents a conservative approach for determining the dates. It creates

certain overlaps in the dates of the phases and a fairly broad range for the transition periods. When this model is adapted to

historical reasoning (e.g., the end of Egyptian rule in the Late Bronze III), one gets the following dates, which will be used

in this book (Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2011):

Phase Date Late Bronze III twelfth century until circa 1130 B.C.E. Early Iron I late 12th century and 1st half of the 11th century B.C.E. Late Iron I 2nd half of the 11th century and 1st half of the 10th century B.C.E. Early Iron IIA last decades of the 10th century and the early 9th century B.C.E. Late Iron IIA rest of the 9th century and the early 8th century B.C.E. Iron IIB rest of the 8th century and the early 7th century B.C.E.

3. The model divides the period discussed in this book slightly differently from the six ceramic phases mentioned above. It adds the Late Bronze III, divides the Iron I into three rather than two phases, and ends with the late Iron IIA. he reason for the latter is the Hallstatt Plateau in the radiocarbon calibration curve, which prevents giving accurate dates to samples that come from Iron IIB and Iron IIC contexts.

- from Mazar (2014)

Since 1996, Finkelstein (1995, 1996) went one step further by suggesting the wholesale lowering by 50 - 80 years of archaeological assemblages traditionally attributed to the 12th—10th centuries BC E. His first point was the date of the appearance of the local Mycenaean IIIC or ‘Philistine Monochrome’ pottery. Following Ussishkin (1985), he suggested lowering the appearance of this pottery by 50 years until after the end of the Egyptian presence in Canaan. This subject is beyond the scope of the present discussion, but it should be mentioned that several recent studies and discoveries, such as those at Ashkelon, negate this approach; in fact, none of the excavators of Philistia find this suggestion acceptable. It also creates unsolvable problems in correlating the archaeology of Philistia with that of Cyprus (Dothan and Zukerman 2003 ; Mazar 1985 and forthcoming; Sherratt and Master [Chapters 9 and 20, this volume;). 14C dates for this period are not of much help, due to the many wiggles and complicated shape of the calibration curve for the 11th and 12th centuries BCE . Consequently, Finkelstein suggested lowering the dates of late Iron Age I assemblages from the late 11th century to the 10th century BCE and the lowering of traditional 10th century BCE assemblages to the 9th century BCE. His view became known as the ‘Low Chronology’ for the Iron Age of Israel. This suggestion empties the 10th century BCE of its traditional contents. Sites and strata that were traditionally dated to the late 11th century BCE, such as Megiddo VIA, are dated to the 10th century BCE, until Shishak’s campaign (Finkelstein 1998a, 1998b, 1999b, 2002a, 2002b, 2004, and Chapters 3 and 17, this volume). In a separate study based on 14C dates from Tel Dor, Ayelet Gilboa and Ilan Sharon suggest an even lower chronology from that suggested by Finkelstein (see below).

- from Kletter (2004)

- from Thomas (2014:50-53)

Levy makes three primary criticisms based upon the methodology of the authors that he views as undermining their conclusions, relating to both the 2005 and 2007 publications:

- The authors present their initial data on inter-laboratory comparison as indicating no reasonable likelihood of bias between the three labs, one each in Israel, the Netherlands and the US. However, at the 95% confidence level/2σ range for the combination of samples that were used is 232 years, which he aptly states is far too wide a margin to be useful in a debate that comes down to a matter of decades105.

- Samples that are tested multiple times do not actually cluster or demonstrate the precision of the results relative to each other that might be expected, even by the Project’s investigators themselves106. Using weighted averages and weighted standard deviations for the combinations of results for a sample does not really help because, as Levy discusses with one example from the 2007 report, the individual results of a sample do not necessarily fall into the 1σ or 2σ ranges to the degree that they should107.

- The above problems are present even before coming around to actually calibrating the dates with the ‘troublesome‘, that is to say imperfect, nature of the calibration curve. The very fact that the curve produces multiple potential date ranges or a range that is very wide makes it imprecise108.

- Before getting to broad models, examination of dates from individual sites and strata for the Iron I and IIA periods taken on their own merits generally seems to either support the HC or MCC and not LC or does not have the resolution to side with any109. Additionally Mazar, being aware of dates published elsewhere and a few new dates, takes issue with the inclusion or rejection of some samples in the Project’s publications, on the basis of potentially being outliers or not secure chronologically110.

- Models run by Mazar with radiocarbon expert Christopher Bronk Ramsey in an effort to discern a rough transition from the Iron I to Iron IIA, removing results suspected to be outliers and samples that could be old wood111, seemed to place the shift in the middle of the 10th century BC112.

- Modelling for the same transition at Megiddo approximates an even earlier transition, and the assumption of the Project’s investigators that several sites’ destructions at the end of Iron I can be viewed as a single event does not hold if the relevant C14 results for those destructions are compared113.

102 Ilan Sharon, Ayelet Gilboa, A.J. Timothy Jull, Elisabetta Boaretto, ‘Report of the First Stage of the Iron Age Dating Project in Israel: Supporting a Low Chronology’ Radiocarbon 49 (2007), pp. 1-46 (pp. 3-4)

103 Ibid., p. 1

104 Ibid., p. 22; Ilan Sharon, Ayelet Gilboa, Elisabetta Boaretto, A.J. Timothy Jull, ‘The Early Iron Age Dating Project’ in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating,

ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 65-92; Elisabetta, Boaretto, A.J. Timothy Jull, Ayelet Gilboa, Ilan Sharon, ‘Dating the Iron Age I/II Transition in Israel:

First Intercomparison Results’, Radiocarbon 47 (2005), pp. 39-55

105 Thomas Levy, Daniel Frese, ‘The Four Pillars of the Iron Age Low Chronology’, in Historical Biblical Archaeology and the Future: The New Pragmatism, ed. by Thomas Levy (London: Equinox, 2010), pp. 187-202 (pp. 193-194)

106 Ibid., 194-5

107 Ibid., 195-6

108 Ibid., 197

109 Amihai Mazar and Christopher Bronk Ramsey, ‘C14 Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response’, Radiocarbon 50 (2008), pp. 159-180 (p. 172)

110 Ibid., pp. 162-171

111 The ‘Old Wood effect’ refers to a concern in dating wood and charcoal that it could come from a tree whose death long predates its

use at a site in a building or as fuel, see Robert L. Kelly, David Hurst Thomas, Archaeology 6th ed. (Belmont: Wadsworth, 2010), pp. 139-141

112 A. Mazar, Ramsey, ‘C14 Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response’, p. 175

113 Ibid., p. 176

- from Thomas (2014:53-56)

An initial major linchpin in the LC was the date of the destruction the stratum VIA at Megiddo. This was the last Iron I stratum and precedes building phases previously viewed as Solomonic. Finkelstein originally viewed it as having been destroyed by Sheshonq in the late 10th century and stated that then-current radiocarbon dating supported this115. Newer radiocarbon results have moved Finkelstein to put the destruction of stratum VIA back to the early 10th century, but he has remained firm in his conclusion of placing the beginning of Iron IIA at Megiddo in the late 10th century BC. It should be noted that Finkelstein’s own averaging of the radiocarbon dates for Megiddo stratum VA-IVB, the main Iron IIA stratum that contains large public buildings ascribed to Solomon, on their own are not so clear or precise as to be a resolution and could fit either his LC or a higher chronology116. His conclusion seems to come in the Bayesian modelling which looks for a date range of a wider geographical transition from Iron I to IIA, and thus incorporates dates from multiple sites. It also means equating Megiddo VA-IVB with strata at other sites, as Finkelstein does for other sites with later radiocarbon averaged dates, such as Hazor IX, Rehov IV and Dor D2/8b. His modelling puts the transition in the last few decades of the 9th century, and to him verifies his view of the major structures of VA-IVB most likely being built by the Omrides and not by Solomon117.

Finkelstein has connected radiocarbon dates of destruction layers at important sites in Israel to historical events which he views as having likely caused them, with specific reference to the military actions of the Aramaeans from the north in the 9th century BC and possibly later, as well as earlier events mentioned below. For the end of the Iron IIA period, Finkelstein appears to agree with Amihai Mazar’s conclusion that the end of this period can be placed at the end of the 9th century BC. He notes in particular the destruction of stratum IV at Tel es-Safi, the biblical city of Gath, which is indicated in radiocarbon dating as ending in the late 9th century BC and is connected by Finkelstein with the capture of that city in 2 Kings 12:17118.

Concerning the start of the more pivotal transition from late Iron I to early Iron IIA, Finkelstein’s more recent thinking seems to have come around to a position similar to that mentioned for Megiddo above regarding the end of late Iron I. Firstly he has come to accept the possibility that destruction layers relating to this period need not necessarily appear in connection to the invasion of Pharaoh Sheshonq in the late 10th century BC, nor do they absolutely signal the immediate end of this period. In fact Finkelstein now views the end of late Iron I as having been a gradual process starting in early 10th century and occurring in two waves in the north, for which most data are available, with some sites but not all having actual destruction layers. Finkelstein’s modelling of radiocarbon dates indicates to him that sites in the western Jezreel Valley and Acco plain including Megiddo form a group destroyed circa 1046-996 BC and sites in the eastern Jezreel Valley and Sea of Galilee including Tel Rehov were destroyed 974-915119. Finkelstein has therefore concluded that the end of the late Iron I cannot be connected to one event in entirety, specifically neither David’s nor Sheshonq’s conquests, but more likely to the expansion of the Israelite ‘polity’, remembered in some early texts such as the Song of Deborah120.

Despite this shift, Finkelstein’s thinking regarding transition from Iron I to IIA and the true beginning of Iron IIA throughout the country has remained the same since radiocarbon dating has entered the debate. Finkelstein’s Bayesian modelling places Tel Rehov stratum VI, that site’s earliest Iron IIA level, from circa 924 to 895 BC121. Stratum V, a destruction layer succeeding VI, is placed at circa 918-851 BC, likely too late to be destroyed by Sheshonq and more likely connected with the Aramaean assault on the Northern Kingdom by Ben-Hadad, with later desertions at sites such as Gath, Hazor and Tel-Hammah connected to later Aramaean conflicts122. So despite admitting to a gradual shift from Iron I to IIA, Finkelstein concludes that his current Bayesian models do not place a firm start for Iron IIA before the second half of the 10th century BC, more specifically its last few decades, and thus they are in line with the LC.

114 Israel Finkelstein, Eli Piasetzky, ‘Radiocarbon Dated Destruction Layers: A Skeleton for Iron Age Chronology in the Levant’, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 28 (2009), pp. 255-274 (pp. 255, 257-258)

115 Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: Touchstone, 2001), p. 141

116 Israel Finkelstein, Eli Piasetzky, ‘Radiocarbon, Iron IIA Destruction and the Israel – Aram Damascus Conflicts in the 9th Century BC’, Ugarit-Forschungen 39 (2007), pp. 261-276 (p. 266);

Finkelstein, Piasetzky, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing?’, p. 51

117 Israel Finkelstein, Eli Piasetzky, ‘Radiocarbon dating the Iron Age in the Levant: a Bayesian model for six ceramic phases and six transitions’, Antiquity 84 (2010), pp. 374-385 (pp. 381-382)

118 Finkelstein, Piasetzky, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing?’, p. 50-51;

Finkelstein, Piasetzky, Radiocarbon Dated Destruction Layers: A Skeleton for Iron Age Chronology in the Levant’, p. 265

119 Finkelstein, Piasetzky, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing?’, p. 51;

Finkelstein, Piasetzky, Radiocarbon Dated Destruction Layers: A Skeleton for Iron Age Chronology in the Levant’, pp. 266, 268

120 Ibid., 267

121 Finkelstein, Piasetzky, ‘Radiocarbon, Iron IIA Destruction and the Israel – Aram Damascus Conflicts in the 9th Century BC’, p. 268

122 Ibid., 270-273

- from Thomas (2014:57-60)

Mazar’s original proposal of the MCC indicates that his placement of the date of the Iron I to IIA transition was based upon contemporary radiocarbon studies, including at Rehov for which he was involved with the Bayesian modelling. This modelling takes into account dates for the final Iron I stratum, D-3, and the dates for the earliest Iron IIA stratum, VI124. The modelling then estimates a boundary phase between them. The 1σ range for this was modelled as 992-961 BC, with peak probability at 970 BC, with a 2σ range at 998-921 BC. With these dates and the fact that the lowest dates at the 2σ range were modelled at a low probability, Mazar saw this as a support for dating the transition at circa 980 BC125. Aside from Rehov, Mazar has also seen justification for this upper date in two other places. First, he notes the conclusions that both he and Finkelstein have drawn with regards to the end of Iron I at other sites including Megiddo VIA, its destruction in the early 10th century BC126. Second, he has argued in a similar manner for strata which mark the beginning of Iron IIA, including two 10th century radiocarbon dates for strata VA-IVB at Megiddo and a date of between 1000-930 BC at Bethsaida127. Mazar also sees this earlier transition confirmed in radiocarbon dates from the controversial site of Khirbet Qeiyafa, now one the most important sites outside the physical territory of the Northern Kingdom or Jordan128. The site as discussed in Chapter 1 seems to have had its main occupation around the Iron I-IIA transition, and radiocarbon dates for the site do indicate a relatively short settlement in the late 11th and early 10th enturies BC before destruction129. Additionally, Mazar has rejected a suggestion that the Iron I continued on into a later time at an eastern group of sites in the north, namely Rehov but also nearby Tel Hadar, based upon Mazar’s own modelling of Tel Hadar’s destruction to 1043-979 BC, similar to Megiddo, as well as the fact that some other sites do not feature an Iron I destruction layer and therefore cannot be used to conclude a solid end for Iron I130.

For the end of the Iron IIA period, Mazar’s conclusion of circa 840/830 BC is based upon two considerations. As with the Iron I to IIA transition, individual site dates and Bayesian modelling were involved, backing up conclusions made on pottery. Mazar accepts the conclusions of the excavators of Beth-Shemesh that stratum S-3 contains pottery indicative of a transitional phase between Iron IIA and the next period, Iron IIB and radiometric dates put this stratum in the early 8th century BC, possibly being destroyed during the North-South conflict in the time of Jehoash of Israel. Therefore, to Mazar, Iron IIA as a distinct period must have ended earlier131. Mazar was also of course influenced by his radiocarbon results from Tel Rehov, for the destruction of stratum IV, the last Iron IIA stratum. These results for samples from a burnt building occurred across a somewhat imprecise span including the late 10th century, but with the highest reasonable probability for the mid-to-later 9th century, up to 833 BC, from both the 1σ and 2σ ranges132. Other samples were less clear but at least seemed to not rule out the later 9th century for the end of this stratum133. Mazar’s final conclusion is that these dates support the MCC’s end for the Iron IIA by 830 BC134.

The other factor that has influenced Mazar in this matter is the calibration curve. The curve, frustratingly, has two plateaux in places important for discerning the beginnings and endings of Iron Age I and IIA, in the last third of the 10th century BC and between 880 and 830 BC135. This means that the curve, in the sense of its physical representation, does not have distinct enough variations for this period, so a raw radiocarbon date from this period could as a result match a wider span of dates than otherwise, making it less precise. Somewhat more accuracy can be achieved with Proportional Gas Counting, the oldest radiocarbon dating laboratory process, but this requires more of the physical sample than the newer laboratory process of Accelerator Mass Spectrometry136.

123 Amihai Mazar, ‘The Debate over the Chronology of the Iron Age in the Southern Levant’ in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 13-28 (pp. 14, 19-21)

124 The numbering of strata at Rehov begins with a letter when it refers to a strata within a particular excavation area, which is necessary as strata at a local point may not be reflected across the entirety of a

site, or may not be clearly contemporary with other local strata.

125 Hendrik J. Bruins, Johannes van der Plicht, Amihai Mazar, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Sturt W. Manning, ‘The Groningen Radiocarbon Series From Tel Rehov’,

in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 271-293 (pp. 286-288)

126 Amihai Mazar, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing? Another Viewpoint’, Near Eastern Archaeology 74:2 (2011), pp. 105-111 (p. 106)

127 A. Mazar, ‘The Debate over the Chronology of the Iron Age in the Southern Levant’, p. 25;

A. Mazar, Ramsey, ‘C14 Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response’, p. 171

128 Amihai Mazar, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, ‘A Response to Finkelstein and Piazetsky’s Criticism and ‘New Perspective’’,

Radiocarbon 52 (2010), pp. 1681-1688 (p.1686); Yosef Garfinkel, Katharina Streit, Saar Ganor, Michael G. Hasel,

‘State Formation in Judah: Biblical Tradition, Modern Historical Theories, and Radiometric Dates at Khirbet Qeiyafa’,

Radiocarbon 54 (2012), pp. 359-369 (p. 359)

129 Ibid., pp. 363-366

130 A. Mazar, Ramsey, ‘A Response to Finkelstein and Piazetsky’s Criticism and ‘New Perspective’’, p. 1685

131 A. Mazar, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing? Another Viewpoint’, p. 107

132 Amihai Mazar, Hendrik J. Bruins, Nava Panitz-Cohen, Johannes van der Plicht, ‘Ladder of Time at Tel Rehov’, in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 193-255 (pp. 243-244)

133 Ibid., pp. 246-250

134 Ibid., p. 254

135 Ibid., p. 213; A. Mazar, ‘The Debate over the Chronology of the Iron Age in the Southern Levant’, p. 20

136 A. Mazar, ‘Ladder of Time’, pp. 213-14; PGC turns the sample into a gas and county β-particles emitted, whereas

AMS simply uses a particle accelerator to break up a sample which is then analysed to determine the ration of C14 to other carbon isotopes.

- from Thomas (2014:60-62)

Area A, containing the gate, is of upmost importance. The lowest stratum above bedrock, A4a, sits below and precedes the actual construction of the gate, showing evidence of metalworking and slag waste. A radiocarbon date from this stratum was calibrated at 1130-970 BC, and its inclusion in Bayesian modelling gave the highest likelihood for this stratum as 1120 BC139. Other samples which appear to have infiltrated into the above stratum also point to metalworking in at least the 11th century BC140. The construction of the gate itself in stratum A3, after removing infiltrating samples from strata above and below, was initially indicated by one radiocarbon sample which dated 1000-985 BC in the 1σ range, but Bayesian modelling with dates from other Area A strata puts its construction apparently later, in the 10th century BC and certainly by 900 BC141. The gate’s re-use for smelting activities is seen in radiocarbon dates for the rest of the 9th century, when the gate was not in defensive use142.

Two other areas, M and S, have also produced interesting results. Area S contained a building used for metallurgical processing. Lower strata, S4 and S3, beneath the building gave radiocarbon dates of the 11th and 10th centuries BC, and it is suggested by Levy that stratum S3, which includes the beginning of large scale metal production, corresponds to A3 and the main use of the fortress gate in the 10th century143. The building itself appears to have been built in stratum S2b, and though the radiocarbon dates are wide and overlap with the 10th century BC somewhat, Levy posits its construction in the mid-9th century BC based on the results144. Area M has a similar situation, with a building constructed in stratum M2 overlaying two previous strata, M3 and M4, M3 being a large mound of slag from metalworking145. Bayesian analysis indicates to Levy that metalworking in area M most likely began circa 950 BC though the modelling leaves room for an earlier date, and that the building in area M was constructed at the end of the 10th century or during the 9th, with metalworking coming to an end in the later 9th century146. Thus the results are similar to areas S and A, and indicate to Levy a period of copper production at the site from approximately the 12th to 9th centuries BC with associated building activity as understood from the radiocarbon dating147. These results are significant for the debate from the perspective of discerning the degree of organisation in the southern Levant during the 10th century BC. These results show large scale metal extraction and production actually preceded the traditional period of the United Monarchy and continued to occur both during and after the 10th century. This was accompanied by a major construction project during the 10th century BC, the fortress and its gate, followed by further building activity in the 9th century. Therefore, KEN shows that a deliberate, managed and large scale economic activity was not foreign to the southern Levant in the 10th century BC, and indicates that the Edom area, bordering the United Monarchy, witnessed complex and organised activity around the time of the United Monarchy, adding a reasonable background to David and Solomon’s dealings with Edom.

137 Hereafter in this chapter abbreviated to KEN

138 Thomas Levy, Mohammad Najjar, Thomas Higham, ‘Ancient texts and archaeology revisited: radiocarbon and Biblical dating in the

southern Levant’, Antiquity 84 (2010), pp. 834-847 (p. 843); Thomas Levy, Thomas Higham, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Neil G. Smith,

Erez Ben-Yosef, Mark Robinson, Stefan Münger, Kyle Knabb, Jürgen P.Schulze, Mohammad Najjar, Lisa Tauxe, ‘High-precision radiocarbon

dating and historical biblical archaeology in southern Jordan’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (2008), pp. 16460-16465 (pp. 16460-16461)

139 Thomas Levy, Russel B. Adams, Mohammad Najjar, Andreas Hauptmann, James D. Anderson, Baruch Brandl, Mark A. Robinson, Thomas Higham,

‘Reassessing the Chronology of Biblical Edom: new excavations and C14 dates from Khirbat en-Nahas (Jordan)’, Antiquity 78 (2004), pp. 863-876 (p. 871)

140 Ibid., p. 871; Thomas Levy, Mohammad Najjar, Johannes van der Plicht, Niel Smith, Hendrik J. Bruins, Thomas Higham, ‘Lowland Edom and the

High and Low Chronologies’, in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 129-163 (pp. 138-139)

141 Levy et al., ‘Lowland Edom and the High and Low Chronologies’, p. 134;

Thomas, Higham, Johannes van der Plicht, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Hendrik J. Bruins, Mark Robinson, Thomas Levy, ‘Radiocarbon Dating of the Khirbat en-Nahas Site (Jordan)and Bayesian Modelling of the Results’, in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham (London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 164-178 (p. 170);

Neil Smith, Thomas Levy, ‘The Iron Age Pottery from Khirbat en-Nahas, Jordan: A Preliminary Study’, BASOR 352 (2008), pp. 1-51 (pp. 47-48)

142 Higham et al., ‘Radiocarbon Dating of the Khirbat en-Nahas Site (Jordan)and Bayesian Modelling of the Results’, pp. 170-2

143 Levy et al., ‘Reassessing the Chronology of Biblical Edom’ pp. 872-3;

Levy et al., ‘Lowland Edom and the High and Low Chronologies’, p. 149;

Higham et al., ‘Radiocarbon Dating of the Khirbat en-Nahas Site (Jordan)and Bayesian Modelling of the Results’, pp. 172-3

144 Levy et al., ‘Lowland Edom and the High and Low Chronologies’, p. 151

145 Levy et al., ‘High-precision radiocarbon dating and historical biblical archaeology in southern Jordan’, p. 16461

146 Ibid., pp. 16463-16464

147 Ibid., p. 16461; Levy et al., ‘Lowland Edom and the High and Low Chronologies’, p. 155; Thomas Levy, Mohammad Najjar,

’Some thoughts on Khirbat en-Nahas, Edom, Biblical History and Anthropology - A Response to Israel Finkelstein’, Tel Aviv 33, pp. 107-122 (p. 15)

- from Thomas (2014:63-66)

The issues mentioned above go some way to discerning why the same radiocarbon dates analysed by the same technique, Bayesian analysis, produce different models and different historical conclusions about the data as a result. Ramsey is particularly concerned about the effect of an uneven or biased distribution of radiocarbon samples across strata or sites and the problem mentioned above of a tendency towards samples from the later life of a stratum. If samples were evenly distributed as if they had come from a series of neat destruction layers of a specific period across several sites, then the picture might be clearer. But as it is, radiocarbon samples are simply not so evenly distributed as to provide precise definition for the start and end of specific periods153. Nor are the Bayesian models applied to the data, as well as the interpretation of the models and connections between events they might point to, likely to be performed and applied in the same way by different practitioners154. This can lead to the clearly different outcomes as presented in particular by Finkelstein and Mazar.

Writing on the matter of Iron Age Levantine chronology, Aegean archaeologist Susan Sherratt has come to question the degree to which radiocarbon dating can be used to construct an exact chronology and thereby write history of the Biblical era. Sherratt states that in order to do so, an exact year by year chronology as might emerge from a king list is needed. Though this may appear to be a reasonable aim with high precision calibration with a good dendrochonological record, Sherratt is doubtful that radiocarbon dating can really clarify history, even if it can appear to rule in or out a hypothesis about a historical person or event155. For example, it might indicate Sheshonq’s destruction of Rehov V, but not really anything more156. In the end, Sherratt views radiocarbon dating as simply unable to provide the fine resolution needed to draw historical inference and as such cautions against simply compiling a large group of radiocarbon dates and turning the results into a history that does not consider the relevant texts, as all that results is a pseudo-history centred on archaeological events157. Sherratt reaches the conclusion that with consideration of the results of the excavations at KEN and Rehov in combination the Iron Age Dating Project, the traditional chronology appears to only be out by the archaeologically insignificant period of about 20 years and there is little resolution within a period of about 150 years anyway, covering the time of both the United Monarchy and the Omrides158. It is worth noting that Finkelstein has made comments to the effect that radiocarbon dating of destruction layers cannot be convincingly attributed to early events as described in the Bible, but this appears to be based upon his a priori stance on the historicity of biblical events that the Bible would place before the 9th century159.

148 A. Mazar, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing? Another Viewpoint’, p. 105

149 A. Mazar, Ramsey, ‘C14 Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response’, pp. 178-179

150 A. Mazar, ‘The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing? Another Viewpoint’, p. 105

151 Steven Ortiz, personal communication, SBL Annual Meeting, 25th November 2013; Steven Ortiz, Samuel Wolff, ‘Guarding the Border to Jerusalem: The Iron Age City of Gezer’, Near Eastern Archaeology 75:1 (2012), pp. 4-19

152 A. Mazar, Ramsey, ‘C14 Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response’, p. 179

153 Christopher Bronk Ramsey, ‘Improving the resolution of radiocarbon dating by statistical analysis’, p. 61

154 Ibid., p. 60

155 Susan Sherratt, ‘High Precision Dating and Archaeological Chronologies: Revisiting an old problem’, in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. by Thomas Levy and Thomas Higham

(London: Equinox, 2005), pp. 114-125 (p. 115); Of course without clear evidence it is difficult to say how a destruction layer is to be tied to an event or ruler

otherwise attested, and no criteria for doing so other than a vague indication in the C14 dates seems to abound, which is part of the point made by Sherratt.

156 Ibid., p .120

157 Ibid., pp. 116, 119; Certainly it is a pseudo-history from the fact that a history done without some sort of text must struggle to actually be a history.

158 Ibid., p. 120

159 Finkelstein, Piasetzky, ‘Radiocarbon Dated Destruction Layers: A Skeleton for Iron Age Chronology in the Levant’, p. 267

- from Thomas (2014:66-68)

160 Levy, Frese, ‘The Four Pillar of the Iron Age Low Chronology’, p. 197

161 Michael B. Toffolo, Eran Arie, Mario A. S. Martin, Elisabetta Boaretto, Israel Finkelstein,

The Absolute Chronology of Megiddo, Israel in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages: High-Resolution

Radiocarbon Dating’ Radiocarbon (Forthcoming), pp. 18, 20-21; I greatly thank Israel Finkelstein

for providing an advance proof copy of this article for this thesis.

Iron Age in ancient Palestine is - at a rough synthesis - marked by 5 major destructive events, that basically distinguish the beginning, the end and its sub-periods, which this essay deals with8. Inside these centuries there are other minor destructions, not necessarily interpreted as outcomes of macro-events and not always related to many different sites.

The first group of destructive events roughly marks the end of the Egyptian-Canaanean system and the beginning of the Iron Age I, within an articulated and strongly differentiated panorama.

Looking at the destructions as archaeological milestones is preferable to follow not the traditional chronology, that termed the first part of 12th century BC “Iron Age IA” (contemporary to the 20th Dynasty in Egypt)9, but the revised one, that refers to it as “Late Bronze III”10. While the chronology and the nature of the initial Philistine settlement in Philistia remains partly disputed11, the continuity of Canaanite and especially Egyptian centers at certain lowland sites such as Megiddo VIIA, Lachish VI, and Beth Shean VI12, points to an attribution of this lapse of time to the preceding cultural period13. The largest and powerful Canaanite city, Hazor14, was indeed destroyed at the end of conventional Late Bronze (§ 3.3.1.), while most of other sites showed a strong continuity almost until the final part of 12th century BC. The end of the control and of the Egyptian presence in Canaan occurred during the reigns of Ramses IV-VI15, with the invasion of the Sea Peoples until ca. 1140-1130 BC. This last date can be alternatively considered the beginning of Iron Age I16 or the passage to Iron Age IB17.

The end of Iron Age I (then the beginning of Iron Age IIA) is probably the most questioned topic in recent years, since its beginning has been strongly lowered by a number of scholars, headed by I. Finkelstein. In spite of a partial disagreement about the absolute dating of the beginning and the end of the period (that seems to be slowly narrowing in these last years)18, it is remarkable that the attribution of single strata to the archaeological periodization it is often the same. Then, if there is not a definitive consensus about when (in absolute dating) and by whom and/or by what some determined settlements were destroyed, conversely there is an agreement about which strata of such sites were destroyed at the end of Iron Age IB/beginning of Iron Age IIA. I just mention a few examples Megiddo VIA (§ 3.1.1.), Tell Qasile X (§ 3.3.2.), Yokneam XVII19, Tell Keisan 9a20.

The Egyptian raid of Pharaoh Shoshenq I to Canaan ca. 925-92021 BC, an event mentioned in 1 Kings 14:25-28 (§ 2.2.2.), has been at length used as chronological peg for the end of Iron Age IIA (see the Conventional Chronology in tab. 1), with several destruction strata along the country traditionally attributed to it. Only recently it has been integrated inside the period (about at its midpoint), without any specific connotation of “epoch marker” (§ 3.2.2.)22.

The third series of destructions is associated to conflicts between Israel and Aram-Damascus throughout the 9th century BC, that, especially in the north, fix the end of Iron Age IIA. This datum, known by the sources (§§ 2.2.3.; 2.3.2.), has been deepened by radiocarbon measurements and comparative study of material culture, strengthening the idea of a long duration for the Iron Age IIA, spreading over both 10th and 9th centuries BC (§ 3.2.2.).

Table 1

Table 1Chronological span of Iron Age IIA as defined by different chronologies, with related definition and proposer.

Fiaccavento (2014)

The historical datum line for transition from Iron Age IIA to Iron Age IIB in the south (especially in Judah) is still under debate: with the lowering of the chronology it was attributed alternatively to the earthquake which occurred in the days of King Uzziah in ca. 760 BC (Jeroboam II in Israel) (§ 3.1.2.), or to the beginning of the 8th century BC, coinciding with military struggles between the reign of Israel and that of Judah, reported also in the Bible (§ 2.2.4.)

The second part of the Iron Age, Iron Age IIB and Iron Age IIC (840/800/760-732/722/70127 and 732/722/701-604/58628 BC respectively), is less disputed, as it rests on solid archaeological and historical ground29. Both the destructive campaigns of conquest carried on by the Assyrian empire in the late 8th century BC (§ 3.2.3.), than those conducted by the neo-Babylonians in late 7th - early 6th centuries BC (§ 3.2.4.) are well attested on the ground, in external historical written sources (§§ 2.3.3 - 2.3.4.) and in Bible too (§§ 2.2.4 - 2.2.5.).

8 The chronological framework constructed by I. Finkelstein and E. Piasetzky (2010b; 2011) proposes eight ceramic

phases and eight transitions which cover ca. 400 years, between the late 12th and mid-8th centuries BC. This model

provides for three sub-phases in the Iron Age I (early, middle, late), two for the Iron Age IIA (early and late),

one transitional Iron IIA/B (or terminal IA IIA) and one for Iron Age IIB and Iron Age IIC.

9 Mazar 1990, 295-230; 2008; Stern 1993, 1529.

10 According to Ussishkin’s terminology Late Bronze III spans

the period ca. 1300-1130 BC (1985; 2004, 75), the time of the Egyptian 20th Dynasty presence in Canaan.

This kind of chronological subdivision is followed also by Finkelstein and Piasetzky (2011, 52, fig. 2; 2010a),

in whose opinion Early Iron Age I is dated to ca. 1130-1050 BC (see also Nigro in this volume, 263-266).

11 The commonly accepted date of Philistine settlement in Southern Canaan is 13th - beginning of 12th centuries BC,

during the time of 20th Dynasty, probably following Ramesses III 8th-year battle against the Sea Peoples (Dothan 2000; Mazar 2008a, 90-94,

with previous references); a lower date for this event, namely at the end of 12th century BC, on the basis of the absence of

the local Monochrome Pottery at sites as Lachish, was proposed by Ussishkin (1985, 222-223; 2004, 7273; 2007) and

followed by Finkelstein (1995).

12 Beth Shean Lower VI (University of Pennsylvania), equivalent to Strata S-3, N-4, Q-1

of recent excavations (Hebrew University - Panitz-Cohen - Mazar eds. 2009).

13 A. Mazar (1992, 290-292, 296-297; 2008, 87)

underlined that the Canaanite culture continued even later, into the 11th century BC, such as in the Jezreel and Beth

Shean valleys, as well as in the Coastal Plain from Dor northwards. In spite of the acknowledgement of the disappearance

of some important LBA features, as international trade connections, and introduction of new ethnic components (initial

settlement of Philistines and other Sea Peoples along the southern coastal plain [note 11], and the growth in number

of small villages in previously marginal areas, such as the hill country region), the opted choice is to use as

distinguishing factor a “catastrophic” event for the region, the end of the Egyptian control over Canaan.

14 In this regard see the proposal moved by A. Zarzecki-Peleg and R. Bonfil (2011) who, including the city in the

Mitanni’s sphere of influence, explain the deterioration and collapse of the flourishing LBA Kingdom of Hazor as a

secondary result of the fall of the Mitannian empire. This interpretation would well explain also the contrasting

continuity displayed by the other major cities of Southern Canaan, such as Beth-Shean, Megiddo, and Lachish,

which continued to exist under the aegis of Egypt, even during the 20th Dynasty.

15 Egyptian artifacts found in terminal Late Bronze strata at Lachish (VI) and Megiddo (K6-VIIA) indicate that

they survived at least until the days of Ramses IV (1151-1145 BC) and Ramses VI (1141-1133 BC) respectively

(Ussishkin 1985 for Megiddo; Lalkin 2004 for Lachish).

16 See note 10.

17 Mazar 2005; 2011, 107, tab. 2; see Nigro in this volume, 263-266.

18 Finkelstein - Piasetzky 2011.

19 Ben-Tor - Zarzecki-Peleg- Cohen-Anidjar 2005, 10-41; Zarzecki-Peleg 2005, 22

23, 35.

20 Humbert 1980, 22-26, tab. 1; 1993, 865-866; Briend 1980, 197-203.

21 The dating of Shoshenq I’s campaign reported in the Bible (the fifth year of

Rehoboam’s reign: 925 BC; § 2.2.1.) it is well confirmed by studies based only on

internal Egyptian evidence, slightly moving the conventional date (Kitchen 2007,

166-167: 945-924 BC; Shortland 2005, 53: date of accession in the middle of the

940s BC, date of the event: 920 BC ca.), firstly suggested by K. Kitchen (1986,

187-239; 2001).

22 In the “Low Chronology” the Shoshenq’s campaign is used as chronological

point of passage between the Iron Age I and Iron Age IIA (see tab. 1).

23 Approximately the time of the “united monarchy” according to the inner-biblical

chronology.

24 More recently, as center of the actual debate, see also: Finkelstein - Piasetzky

2006; 2009; 2010a; 2010b; 2011; Finkelstein 2013, 6-10. In this proposed

chronology the dating for the early Iron Age IIA is between ca. 940/930 and

880/870 BC, with the end of the period fixed at 760 BC ca. (late Iron Age IIA =

880-760 BC).

25 The Modified Conventional Chronology is principally represented by A. Mazar

(since 1997 - Mazar 1990, 40-41; 1997, 163-164; 2008a, 98-99, where he reported

who between the archaeologist accepted the long duration for Iron Age IIA,

spreading both over 10th and 9th centuries BC), but formerly proposed by Y.

Aharoni and R. Amiran (1958).

26 Previously illustrated also in Sharon 2001; Gilboa - Sharon 2001; 2003.

27 Some chronologies prefer, as lower limit of the period, the reduction to

provinces of Damascus, Megiddo, Dor and Gilead (732 BC), some other the

conquest of Samaria by Shalmaneser V and the destruction of the Kingdom of

Israel (722/721 BC), or the conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib (701 BC).

28 This chronological peg depends on the choice of the major destructive event to

be considered the period end marker: 604 BC is the date of the conquest and the

destruction of Ashkelon in the southern coastal plain, and event marking the

definitive general conquest of Philistia, whereas 586 BC is the capture of Jerusalem

by the Babylonian army.

29 Anyway, in this case (the late 8th through the early 6th centuries BC)

radiocarbon cannot stimulate debate because of the flat section in the calibration

curve: “the Hallstatt Plateau”.

The Deuteronomistic account presents a coherent narrative spanning the conquest of the promised land to the end of the monarchy. Though it contains material from earlier periods30, it is shared opinion that it reached its present form thorough the work of two sets of editors who labored at the end of the 7th century and at the mid of the 6th century BC31. It has been suggested that it preserved historical kernels, even if redrawn a posteriori, in light of successive events.

The peculiar nature of biblical texts (and the point of view of their authors) probably pushed them to use destructions in an ideologically oriented perspective32. Anyway, texts useful to the study of some major period marker destructive events are illustrated below. These major destructions are:

- the end of the Late Bronze

- Pharaoh Shoshenq’s raid to Canaan

- Aram-Damascus war against Israel

- Uzziah earthquake

- Assyrian campaigns [Samaria takeover, Jerusalem siege and Lachish conquest]

- Babylonian conquest

30 I.e. the Song of Deborah, in the Book of Judges, is considered by many to be

one of the earliest texts in the Bible (Cross 1973, 100).

31 M. Noth believed that the Books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and

Kings were part of a single effort, done by a single author during the early Exilic

period (6th century BC). Later F.M. Cross (1973) proposed that an early version of

the history was composed in Jerusalem in Josiah’s time (late 7th century BC), then

revised and expanded during the Exilic Period; the second edition, identified by Noth.

32 Nigro in this volume, iv.

In the Deuteronomistic saga, there are two versions of the conquest and settlement of Canaan by the Israelite tribes. The conquest accounts in the Bible are contradictory, since the two versions displayed in the Book of Joshua and in that of the Judges are opposite. In the first one, the conquest of Canaan is rapid and warlike, whereas the second presents a slow and generally peaceful infiltration, in which the emergence of Israelite element in the hill country coexists with the Canaanites.

The case-study hereby illustrated is the foremost case of the fall of Canaanite capital kingdom of Hazor (Joshua 11:10-13, Judges 4:1-2, 23 24), as the conclusive episode of the conquest. This event is not mentioned in any external document, the Bible being the only source available. Biblical description, in this case, show a violent end of the city, though apparently with a different temporal development.

The campaign of the founder of the Twenty-Second Dynasty, Shoshenq, illustrated on a wall in the Temple of Amun at Karnak (§ 2.3.1.) and the biblical account in which is reported the payment that King Rehoboam gave him to save Jerusalem is the only match of the biblical text with an external source, related to 10th century BC (§ 2.2.2.).

1 Kings 14:25-26 - 25In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, Shishak king of Egypt attacked Jerusalem. 26He carried off the treasures of the temple of the Lord and the treasures of the royal palace. He took everything, including all the gold shields Solomon had made.

2 Chronicles 12:2-4 - 2Because they had been unfaithful to the Lord, Shishak king of Egypt attacked Jerusalem in the fifth year of King Rehoboam. 3With twelve hundred chariots and sixty thousand horsemen and the innumerable troops of Libyans, Sukkites and Cushites that came with him from Egypt, 4he captured the fortified cities of Judah and came as far as Jerusalem.

The conflict between Aram-Damascus and the northern reign of Israel in the 9th century BC is reported in several comparable biblical passages. The first, and isolated, hint is about the campaign of Ben-Hadad king of Damascus in the northern part of Israel, in 1 Kings 15:20. This historical event should have taken place around 885 BC33.

1 Kings 15:20 - 20Ben-Hadad listened to King Asa, and sent the commanders of his armies against the cities of Israel. He conquered Ijon, Dan, Abel-beth-maacah, and all Chinneroth, with all the land of Naphtali.

The description of the period of unrest caused by the attacks conducted by Hazael in the late 9th century BC is far more accurate and well documented. According to the Book of Kings, the king of Aram, first conquered Transjordan (2 Kings 10:32-33) and then subjugated the kingdoms of Israel and Judah (e.g. 2 Kings 9; 10:32-33; 13:3, 7, 22, 24). The biblical source describes the event of the double killing of Joram king of Israel and Ahaziah king of Judah in the course of Jehu revolt (2 Kings 9), while the Dan Stela (§ 2.3.2.) recounts that this had been done by Hazael. The alternating events described in the Bible34 seem to have their better match with the archaeological record in 2 Kings 12:17 (and hinted at by prophet Amos), where the campaign of Hazael in Philistia has been clearly linked to the destruction of Tell es-Safi/Gath (§ 3.3.3.).

2 Kings 12:17 - 17Then Hazael king of Aram went up, and fought against Gath, and took it. And Hazael set his face to go up against Jerusalem.

Amos 6:2 - 2Cross over to Calneh, and see; from there go to Hamath the great; then go down to Gath of the Philistines. Are you better than these kingdoms? Or is your territory greater than their territory?

33 Lipinski 2000, 372; contra Finkelstein (2013, 75-76, with previous references)

who retains that the description of the campaign is done on the basis of the route

of Tiglath-pileser III reported in 2 Kings 15:29, then of a later and not reliable

historical redaction.

34 See the reorganization of the order of the historical events, comparing extra

biblical texts, and the results of archaeological excavations in Finkelstein 2013,

122-124, tabs. 4-5.

A military struggle between Amaziah king of Judah and Jehoash king of Israel at the beginning of 8th century BC, with the destruction of Beth Shemesh, is reported in the book of Kings, and considered a reliable event.

2 Kings 14:11 - 11But Amaziah would not hear. Therefore Jehoash king of Israel went up; and he and Amaziah king of Judah looked one another in the face at Beth Shemesh, which belonged to Judah.

Well-known seismic event dated to ca. 762 BC, the so-called “Uzziah Earthquake”, since it happened at time of King Uzziah of Judah. This event, explicitly mentioned in e.g. Amos 1:1 and Zechariah 14:5 (but this last is a late and less reliable source), for some can be considered the end-point of Iron Age IIA.

Amos 1:1 - 1The words of Amos, who was among the herdsmen of Tekoa, which he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah king of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam the son of Joash king of Israel, two years before the earthquake.

The campaign conducted by Tiglath-pileser III in the north of the country, against the reign of Israel, is reported to in one passage in 2 Kings 15:29.

2 Kings 15:29 - 29In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria, and took Ijon, and Abelbethmaachah, and Janoah, and Kedesh, and Hazor, and Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and carried them captive to Assyria.

The fall of Samaria, capital of the northern Israelite kingdom, by the hands of Shalmaneser V (and not by Sargon II as described in the Assyrian sources; § 2.3.3.) is described twice into the Bible: 2 Kings 17:3-6 and 2 Kings 18:9-11. The texts are parallel with slight differences; we report here just one in 2 Kings 17:3-635.

2 Kings 17:3-6 - 3King Shalmaneser of Assyria came up against him; Hoshea became his vassal, and paid him tribute. 4But the king of Assyria found treachery in Hoshea; for he had sent messengers to King So of Egypt, and offered no tribute to the king of Assyria, as he had done year by year; therefore the king of Assyria confined him and imprisoned him. 5Then the king of Assyria invaded all the land and came to Samaria; for three years he besieged it. 6In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria captured Samaria; he carried the Israelites away to Assyria. He placed them in Halah, on the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes.

The campaigns of Sennacherib at the end of the 8th century BC closed the period of conquest of the Assyrian empire in the region, with the submission of the southern reign of Judah. After this event Judah was reduced to the condition of tributary vassal: Jerusalem was spared but the Shephelah was utterly destroyed and Lachish used as military camp of the Assyrian army. These struggling episodes appear in the Old Testament record in 2 Kings 18:13-1536.

2 Kings 18:13-15 - 13In the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah, King Sennacherib of Assyria came up against all the fortified cities of Judah and captured them. 14King Hezekiah of Judah sent to the king of Assyria at Lachish, saying, “I have done wrong; withdraw from me; whatever you impose on me I will bear.” The king of Assyria demanded of King Hezekiah of Judah three hundred talents of silver and thirty talents of gold. 15Hezekiah gave him all the silver that was found in the house of the Lord and in the treasuries of the king’s house.

35 The scientific tradition on this topic see 2 Kgs 17:3-4 written on the basis of the

annals of the Northern Kingdom, and that 2 Kings 17:5-6//18:9-11 were formed by

using material from the archives of Jerusalem (Becking 1992, 49, note 8).

36 The passage has its parallel in Isaiah 36-37 and 2 Chronicles 32.

The last destructive fate for the Southern Levant had the Babylonian name of Nebuchadnezzar II. The destruction of the seaport of the Philistines, Ashkelon, and the end of Philistia in general, is hinted at by the prophecy of Jeremiah: he predicted that Nebuchadnezzar would overwhelm the region.

Jer. 47:4-5 - 4For the day that is coming to destroy all the Philistines, to cut off from Tyre and Sidon every helper that remains. For the Lord is destroying the Philistines, the remnant of the coastland of Caphtor [Crete]. 5Baldness has come upon Gaza, Ashkelon is silenced. O remnant of their power! How long will you gash yourselves?

Nebuchadnezzar’s campaign of conquest and submission of the capital of Judah in 586 BC are detailed in 2 Kings 25 (parallel to 2 Chronicles 36:18 19)37. The story is sadly renown: after two years of siege to the city, the king, his family and his personal guard fled away in direction of the Arabah, but they were caught by the Chaldeans. Zedekiah saw his sons murdered and he was blinded and took captive in Babylon. Jerusalem, and the region of Judah, had a sad fate too:

2 Kings 25:8-12 - 8In the fifth month, on the seventh day of the month – which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon – Nebuzaradan, the captain of the bodyguard, a servant of the king of Babylon, came to Jerusalem. 9He burned the house of the Lord, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down. 10All the army of the Chaldeans who were with the captain of the guard broke down the walls around Jerusalem. 11Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carried into exile the rest of the people who were left in the city and the deserters who had defected to the king of Babylon – all the rest of the population. 12But the captain of the guard left some of the poorest people of the land to be vinedressers and tillers of the soil.