Archaeomagnetic Dating

- excerpts from ars technica

So, once the iron is heated past 770°C, it loses it's magnetism. Once it cools back down below 770°, it then regains it's magnetism and what will happen is that the magnetic domains in the iron will tend to line up in the direction of any external magnetic field - which would be the Earth's field.

Now, while they do not know which way the pots were facing in the kiln, nor do they know what direction the kiln was facing, the orientation and arrangement of the magnetic domains can show the strength of the magnetic field and, knowing that the handles in the pots were generally horizontal, they can also show the azimuth of the field - the direction it's pointing up or down.

... During the 1st millennium BCE, the kingdom of Judah was a bustling urban civilization, full of markets, bureaucrats, and scholars. They used an ancient lunar calendar system, and chroniclers noted the years of each new political regime as well as other significant social changes. At Tel Socoh, in Judah, there was a small industry devoted to the production of storage jars, and the artisans there carefully stamped the ruling monarch's symbols into each jar's handle. When archaeologists compare historical records with these symbols, it's relatively straightforward to get an exact date for a jar's manufacture. Luckily for geoscientists in the 21st century, jar handles tend to survive longer than other bits of pottery.

The basic assumption underlying the paleointensity method (Thellier and Thellier 1959) is that TRM (magnetization acquired on cooling) is quasi-linearly proportional to the intensity of the field (B) in which it was acquired:

TRM=αβ Equation 1

The laboratory procedure in the Coe variant of the Thellier method (Coe et al. 1967) is illustrated in Fig. 43.1. The procedure involves a series of double heating steps at progressively elevated temperatures through which the ancient TRM (TRManc) is gradually replaced by a laboratory TRM (TRMlab) acquired in a controlled field (Blab). The measurements through this procedure are plotted on a so-called “Arai plot” (Nagata et al. 1963) displaying the ancient TRM (gradually erased) on the y-axis and the laboratory partial TRM (pTRM) (gradually acquired) on the x-axis (Fig. 43.1). First, the natural remnant magnetization (NRM) of the specimen (assumed to be thermal in origin) is measured and plotted on the intercept of the y-axis of the Arai plot (Fig. 43.1a). Then, the specimen is heated to temperature T1 under a null magnetic field (“zerofield”). This procedure demagnetizes part of the ancient TRM (Fig. 43.1b). The specimen is then heated again to T1, but cooled in the presence of controlled field Blab (“infield”) leading to an acquisition of laboratory pTRM. Using vector arithmetic, the portions of TRManc “remaining” and pTRMlab “acquired” are calculated and the point T1 (pTRM remaining versus pTRM acquired) is plotted on the Arai plot (Fig. 43.1b–c). These double heating steps continue at increasingly elevated temperatures, where at every second step we run an “alteration check” (Coe et al. 1978), by which we repeat an “infield” step at a lower temperature (triangles in Fig. 43.1d). This step tests whether alteration of the ferromagnetic minerals had occurred by heating the sample. Finally, after completing all the steps (usually 10–15 different temperatures are required), the nature of the Arai plot can determine whether a paleointensity can be calculated. If the plot conforms an ideal straight line, as shown in Fig. 43.1e, then from the slope of the line (equal to TRMancient/TRMlaboratory), the paleointensity is calculated by:

Bancient=slope*Blaboratory Equation 2

Fig. 43.1

Fig. 43.1Schematic illustration of the Coe variant of the Thellier method (see text for details)

Shaar et al. (2022)

In this study we follow the IZZI variant of the Thellier method (Tauxe and Staudigel 2004), by which the order of the “infield” and the “zerofield” alternate in each succeeding step. Also, we carry out two additional experiments for calculating a correction for TRM anisotropy (e.g., Selkin et al. 2000) and for the effect of cooling rate (e.g., Genevey and Gallet 2002). The anisotropy correction compensates for the dependency of TRM on the magnetic fabric (as the direction of Blab is different than Banc). The cooling rate correction compensates for the dependency of TRM on cooling rate (the ancient cooling time was many hours, while in the lab cooling took only 20–40 minutes).

A complete paleointensity procedure is a process that requires 1–2 hours for each of 30 to 50 heating steps for a batch of 54–72 specimens. This amount of time, combined with the time required to measure the specimens, makes the Thellier and Thellier method laborious and time consuming. The time and the effort built into the laboratory protocol is perhaps the main weakness of the method.

One of the most difficult paleointensity methodological problems to deal with concerns data analysis. Here, in addition to the Arai plot, we use “Zijderveld” plots (Zijderveld 1967) of Cartesian components (x,y,z) of the zero field steps, plotted as x versus y and x versus z as in the insets to Fig. 43.2. The root of the data analysis problem is that often specimens do not yield ideal straight lines in both the Arai and the Zijderveld plots as in Fig. 43.2a. Instead, there may be a linear or quasi-linear segment that could be interpreted differently by different researchers. The problem of ambiguity in the interpretation inserts considerable noise to the published paleointensity database. To address this problem Shaar and Tauxe (2013) developed a computer program for automatic interpretation. This program is capable of analyzing many thousands of specimens (the long term target of the project) in a consistent, objective and reproducible fashion, while calculating robust error estimations of the results (for more details, see Shaar and Tauxe 2013; Shaar et al. 2015). To make the automatic interpretation meaningful, the user has to choose specific criteria for screening out only the most “reliable” results (e.g., Fig. 43.2a or similar). This is done by a set of statistics defined in Shaar and Tauxe (2013) and Paterson et al. (2014). Fig. 43.2b–d shows some examples of specimens failing the criteria used in this study. Figure 43.2b shows an Arai plot with only partial linear segment; Fig. 43.2c shows a zigzagged, non-linear pattern; Fig. 43.3d shows non-linear Zijderveld plots in the inset (see Paterson et al. 2014 for definitions).

A discussion of the various paleointensity statistics and the acceptance criteria are beyond the scope of this article. Yet, for the sake of completeness we list in Table 43.1 the criteria used in this study (for more details, see Paterson et al. 2014; Shaar et al. 2016).

Table 43.1

Table 43.1Acceptance Criteria

Shaar et al. (2022)

The Hebrew Bible and other ancient Near Eastern texts describe Egyptian, Aramean, Assyrian, and Babylonian military campaigns to the Southern Levant during the 10th to sixth centuries BCE. Indeed, many destruction layers dated to this period have been unearthed in archaeological excavations. Several of these layers are securely linked to specific campaigns and are widely accepted as chronological anchors. However, the dating of many other destruction layers is often debated, challenging the ability to accurately reconstruct the different military campaigns and raising questions regarding the historic ity of the biblical narrative. Here, we present a synchronization of the historically dated chronological anchors and other destruction layers and artifacts using the direction and/or intensity of the ancient geomagnetic field recorded in mud bricks from 20 burnt destruction layers and in two ceramic assemblages. During the period in question, the geomagnetic field in this region was extremely anomalous with rapid changes and high intensity values, including spikes of more than twice the intensity of today’s field. The data are useful in the effort to pinpoint these short-term variations on the timescale, and they resolve chronological debates regarding the campaigns against the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the relationship between the two kingdoms, and their administrations.

We reconstructed the direction and/or intensity of Earth’s magnetic field recorded in 20 burnt destruction layers exposed at 17 archaeological sites and in two ceramic assemblages (SI Appendix,Tables S1–S6). From the destruction layers we sampled sun-dried mud bricks (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), which had acquired thermoremanent magnetization (TRM) when the sites were destroyed by fire. In one case we sampled a kiln that had gone out of use when the site had been destroyed. The data, obtained from the analysis of 1,186 specimens from 144 samples, are shown in Fig. 1 along with our recent compilations of published data from the Levant and Western Mesopotamia (3–5).Fig.1A also displays an archaeointensity curve (LAC.v.1.0) (5), constructed using a transdimensional Bayesian method (6) based on all these data (see SI Appendix, Detailed Methods and Fig. S2). Detailed results are presented in SI Appendix,Figs.S3–S9 and Tables S7, S8, S10, S12–S15. All the archaeomagnetic data, as well as the interpretations presented here, are available in the MagIC database.

According to historical sources, Hazael, King of Aram Damascus, led at least one military campaign to the Southern Levant and according to the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 12:18) he destroyed Gath of the Philistines. This event left an extensive destruction layer and, based on historical and archaeological data including radiocarbon, there is a wide consensus that it should be dated to ca. 830 BCE (20), although the possibility that it occurred in 798 BCE was suggested in the past (21). Both the archaeomagnetic direction and intensity from Gath show outstanding agreement with three other destruction layers dated to the ninth century BCE (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10):

- Tel Rehov Stratum IV (22)

- Horvat Tevet Level V (23)

- Tel Zayit Level XIII (only intensity results were obtained) (24)

Our study of a destruction layer in Tel Beth-Shean, a major city located only 5 km from Tel Rehov, demonstrates the application of archaeomagnetism to resolve a chronological debate. The excavator of the site suggested that Beth-Shean had been destroyed by either Pharaoh Shoshenq I (biblical Shishak) in ca. 920 BCE or by Hazael in the late ninth century BCE (25) and recently favored the later date (22). However, according to ceramic typology it could have been concurrent either with Stratum IV or with the earlier Stratum V at Tel Rehov, which included the destruction by fire of unique mud beehives and was dated by radiocarbon to ca. 900 BCE (22). Archaeomagnetic dating of Beth-Shean (Fig. 3A) shows that at a 95% confidence level the destruction occurred before ca. 880 BCE and at a 68% confidence level it occurred before ca. 900 BCE. The magnetic inclination of Beth-Shean is in agreement with this dating constraint, showing a difference of ~4° from the reference inclination of Gath, Rehov IV, and Tevet V and no overlap in their α95 confidence cones (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Thus, we conclude that there must be a time gap between the destruction of Beth-Shean and that of Gath, Rehov IV, Tevet V, and Tel Zayit XIII.

The archaeointensity data (Fig. 1A) and the archaeomagnetic dating of Beth-Shean and Horvat Tevet Level VII (23) (Fig. 3 A and B) support the possibility that both sites were destroyed concurrently with the unique apiary in Stratum V at Tel Rehov, which was destroyed by fire in the late 10th to early ninth century BCE according to radiocarbon dating (22, 26). Historically, these three early destructions could be the result of the well discussed and debated Egyptian campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I (26). Shoshenq’s campaign is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 14:25–26) and in his Triumphal Relief at Karnak (Egypt), where Rehov and Beth-Shean are depicted side by side as prisoners of war, each representing a conquered city. A similar example of archaeomagnetic dating that sheds light on the historical interpretation of a destruction is the Judean city at Tel Beth-Shemesh. According to ceramic typology and radiocarbon dating, this destruction occurred after the times of Hazael’s campaigns. Due to the plateau in the radiocarbon calibration curve (27), radiocarbon alone does not allow for high resolution dating of this destruction. The excavators dated it to ca. 790 BCE and, based on the description in 2 Kings 14:11–13, attributed this destruction to Jehoash, King of Israel (28). According to our archaeointensity-derived age (Fig. 3D), the excavators’ suggestion seems more probable than other suggestions that date the destruction to the middle of the eighth century BCE (1).

In 733 to 732 BCE, Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria, conquered the northern parts of the Kingdom of Israel, as described in biblical and Assyrian sources. The attribution of the destructions at Bethsaida (29) and Tel Kinnerot (30) to this period is widely accepted. The agreement between our archaeointensity results from these two sites reinforces their concurrent destruction (Figs. 1A and 2). During another Assyrian campaign, led by King Sennacherib in 701 BCE, Tel Lachish Stratum III was destroyed. Unequivocal evidence of the siege, battle, and destruction by fire has been exposed at the site (2, 31). The attack on Lachish is mentioned in 2 Kings 18–19; Isaiah 36–37; 2 Chronicles 32 and narrated in Assyrian reliefs. According to biblical and Assyrian sources, many other Judean sites were destroyed during the 701 BCE campaign but none are securely identified. Our archaeomagnetic data from Tel Beersheba (32), Tel Zayit Level XI (24), and Tell Beit Mirsim (33) argue for their destruction during the 701 BCE campaign (Fig. 2). Despite the marginal overlap of inclination results from Tel Eton and Lachish III, the destruction of Tel Eton also presumably occurred during an Assyrian campaign of the late eighth century BCE (34).

After the Assyrian withdrawal from the Levant, the Babylonians conquered the region in several campaigns led by Nebuchadnezzar II. The exact date of destruction of the Philistine city of Ekron is debated, but it surely occurred during one of the Babylonian campaigns between 604 and 598 BCE (35, 36). The 586 BCE Babylonian campaign led to the destruction of Tel Lachish Stratum II (2, 37) and to the destruction of Jerusalem (3, 36) and its temple (2 Kings 24:18; Jeremiah 1:3; 39:2; 52:5–6), bringing the Kingdom of Judah to its end. Our direction results from Lachish II, based on an intact mud–brick wall, represent the geomagnetic direction in 586 BCE more accurately and precisely than a previous estimation that was based on collapsed material from Jerusalem (3). There is a difference of ~3° in inclination between the destruction of Batash and that of Lachish II, and the α95 confidence cones of these two sites do not overlap (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, our intensity results from Tel Batash overlap with those from neighboring Ekron but not with those from the 586 BCE destruction of Jerusalem (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the archaeomagnetic intensity results, with some possible support from the direction results, suggest that Batash, like Ekron, was destroyed by the Babylonians in ca. 600 BCE (Figs. 2 and 3F), perhaps in 604 BCE as the excavator assumed (38) and not during the 586 BCE campaign as has recently been suggested (39). The direction results from Ashdod-Yam (40) may suggest that it too was destroyed in ca. 600 BCE.

The intensity results from Tel Malhata (41) are slightly lower than those recorded in Lachish II. This supports the hypothesis (39) that in 586 BCE the Babylonian army was focused on Jerusalem and had no interest in going far south to the area of Malhata. It seems that after 586 BCE, when the Kingdom of Judah ceased to exist, the eastern and southern periphery of the kingdom collapsed, probably in a gradual process, and sites were destroyed, perhaps by the Edomites or other nomadic elements (Fig. 2). The Edomite threat to the collapsing Judean kingdom is reflected in the Hebrew Bible and in a few ostraca discovered in Arad and Horvat Uza (36).

Our large, well-dated dataset enabled revisiting the debated dating of two sets of stamped storage jar handles that were part of the administrative system of the Kingdom of Judah (39): an early subset of LMLK handles (meaning in Hebrew “belonging to the king”) and the “private” stamped handles bearing names, probably of officials. Since these two sets were found in destruction layers dated to 701 BCE and not in later contexts, it is accepted that they were in use until 701 BCE (39). However, the introduction date of these sets is debated. It has recently been suggested that their introduction was after the 733 to 732 BCE Assyrian campaigns, a suggestion based mainly on historical assumption and on the fact that no handles of these types were found in destruction layers from the Kingdom of Israel that are attributed to these campaigns (39). However, comparing our results from the destruction layers to previous archaeointensity measurements from handles of both types (42) and to measurements from four LMLK handles reported here (SI Appendix, Tables S1, S6, S8, and S15) supports an even earlier introduction. Due to the similar intensity results from all six destruction layers dated to 733 to 701 BCE, it seems unlikely that the field intensity changed considerably during this short period. The intensity results of all measured “private” handles and some of the early LMLK handles are lower than the field recorded during the 733 to 701 BCE campaigns and are in agreement with published data from the first half of the eighth century BCE. Following these results, as demonstrated in the archaeomagnetic dating of the “private” stamped handles (Fig. 3E), we suggest that both sets could have already been in use during the first half of the eighth century BCE. This suggestion is relevant to the debate regarding the appearance of a complex polity in Judah. The absence of these Judean handles from the 733 to 732 BCE destruction layers in the Kingdom of Israel should not be regarded as a chronological constraint. It can be understood in the context of the rivalry between the two kingdoms, as reflected in biblical narratives regarding the destruction of Beth-Shemesh mentioned above and the unsuccessful Israelite attack on Judah in the attempt to force the kingdom to join the anti-Assyrian coalition (2 Kings 16:5–8) (21).

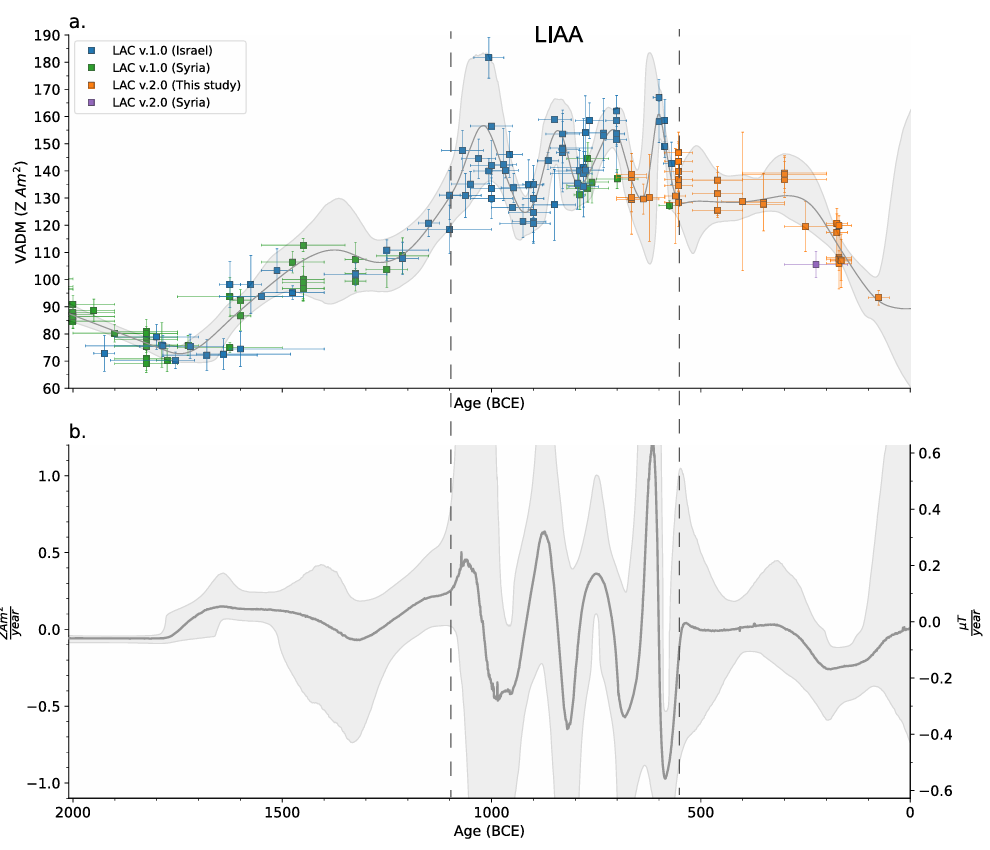

During the investigated period, the geomagnetic field in the Levant was anomalous compared to the past several millennia, with high field intensity values reaching twice the intensity of today’s field, angular deviations from the averaged direction, and a fast secular variation rate (4, 5, 42–45). The precisely dated data reported here constrain the evolution of the Levantine geomagnetic anomaly and are an essential part of the new LAC.v.1.0 reported in Shaar et al. 2022 (5). In particular, our results point to the existence of a hitherto unrecognized spike in ca. 600 BCE (Fig. 1). This spike came after a relatively weak field during the seventh century BCE, as represented in the late LMLK stamped handle group, and was followed by a rapid decrease, reinforced by new data from Tel Malhata and Ramat Rahel (46) (SI Appendix, Table S8).

This research demonstrates how an archaeointensity curve constructed from a dense archaeomagnetic dataset in which the chronology rests on radiocarbon (for periods before the eighth century BCE) and firm historical ages (from the eighth century BCE and on) can be used as a powerful chronological tool. This is especially useful during the Hallstatt Plateau (ca. 800–400 BCE) (27), a period in which the resolution of radiocarbon dating is limited. This research also demonstrates the direct applicability of archaeomagnetism to solving questions related to the synchronization of archaeological contexts, especially its potential to negate concurrency. The Aramean, Assyrian, and Babylonian campaigns turned out to have occurred at times of very high geomagnetic field intensity and are separated by well-defined minima. This should also be very useful for future dating efforts, distinguishing these major campaigns from other periods in the history of the Levant.

- from Vaknin et al. (2022)

Archaeomagnetic results.

- Field intensity results shown with LAC.v.1.0 (5) displayed as the virtual axial dipole moment (VADM)

- The angle between the horizontal component and the geographic north (Declination)

- The angle from the horizontal plane (Inclination)

All directions are relocated to Jerusalem. Results from destruction layers are represented by colored circles (for color key, see Fig. 3). Note that some destruction layers have only intensity (A) or direction (B–C) results. Intensity results from pottery discussed in the text are represented by black squares. Intensity data included in LAC.v.1.0 (5) from Israel (squares) and Syria (diamonds) are marked in gray. Previously published directions (3, 4) from the Levant are marked in gray dots. Chronological anchors are highlighted in bold. Note that the locations of the symbols on the time axis within the horizontal error bars were assigned arbitrarily, according to the different chronological considerations including the archaeomagnetic results. These assigned ages (SI Appendix, Tables S2–S6 and S9) are not considered as part of the prior data for the AH-RJMCMC model.

Vaknin et al. (2022)

Fig. 1

Archaeomagnetic results.

- Field intensity results shown with LAC.v.1.0 (5) displayed as the virtual axial dipole moment (VADM)

- The angle between the horizontal component and the geographic north (Declination)

- The angle from the horizontal plane (Inclination)

All directions are relocated to Jerusalem. Results from destruction layers are represented by colored circles (for color key, see Fig. 3). Note that some destruction layers have only intensity (A) or direction (B–C) results. Intensity results from pottery discussed in the text are represented by black squares. Intensity data included in LAC.v.1.0 (5) from Israel (squares) and Syria (diamonds) are marked in gray. Previously published directions (3, 4) from the Levant are marked in gray dots. Chronological anchors are highlighted in bold. Note that the locations of the symbols on the time axis within the horizontal error bars were assigned arbitrarily, according to the different chronological considerations including the archaeomagnetic results. These assigned ages (SI Appendix, Tables S2–S6 and S9) are not considered as part of the prior data for the AH-RJMCMC model.

Vaknin et al. (2022)

- from Vaknin et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Map of the studied destruction layers and the different military campaigns. A schematic illustration of possible routes is presented following Rainey and Notley (21). Chronological anchors are highlighted in bold

Vaknin et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Map of the studied destruction layers and the different military campaigns. A schematic illustration of possible routes is presented following Rainey

and Notley (21). Chronological anchors are highlighted in bold

Vaknin et al. (2022)

- from Vaknin et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Archaeomagnetic dating using archaeointensity marginalized dating (6).

- Tel Beth-Shean

- Horvat Tevet Level VII

- Tel Zayit Level XIII

- Tel Beth-Shemesh

- "Private” stamped handles (42)

- Tel Batash The prior age range used by the AH-RJMCMC algorithm (6) is based on historical and archaeological considerations, including radiocarbon when available, and is represented as a uniform probability density function (gray background). The posterior age probability distribution is shown in blue.

Vaknin et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Archaeomagnetic dating using archaeointensity marginalized dating (6).

- Tel Beth-Shean

- Horvat Tevet Level VII

- Tel Zayit Level XIII

- Tel Beth-Shemesh

- "Private” stamped handles (42)

- Tel Batash The prior age range used by the AH-RJMCMC algorithm (6) is based on historical and archaeological considerations, including radiocarbon when available, and is represented as a uniform probability density function (gray background). The posterior age probability distribution is shown in blue.

Vaknin et al. (2022)

Two parameters used to describe the magnetic field direction at a point on the surface of the earth.

D refers to the declination angle and I to the inclination angle

Two parameters used to describe the magnetic field direction at a point on the surface of the earth.

D refers to the declination angle and I to the inclination angleAgnes Pointu at Paleomagnetism For Rookies at joidesresolution.org

Two parameters used to describe the magnetic field direction at a point on the surface of the earth.

D refers to the declination angle and I to the inclination angle

Agnes Pointu at Paleomagnetism For Rookies at joidesresolution.org

- from Hassul et al. (2024)

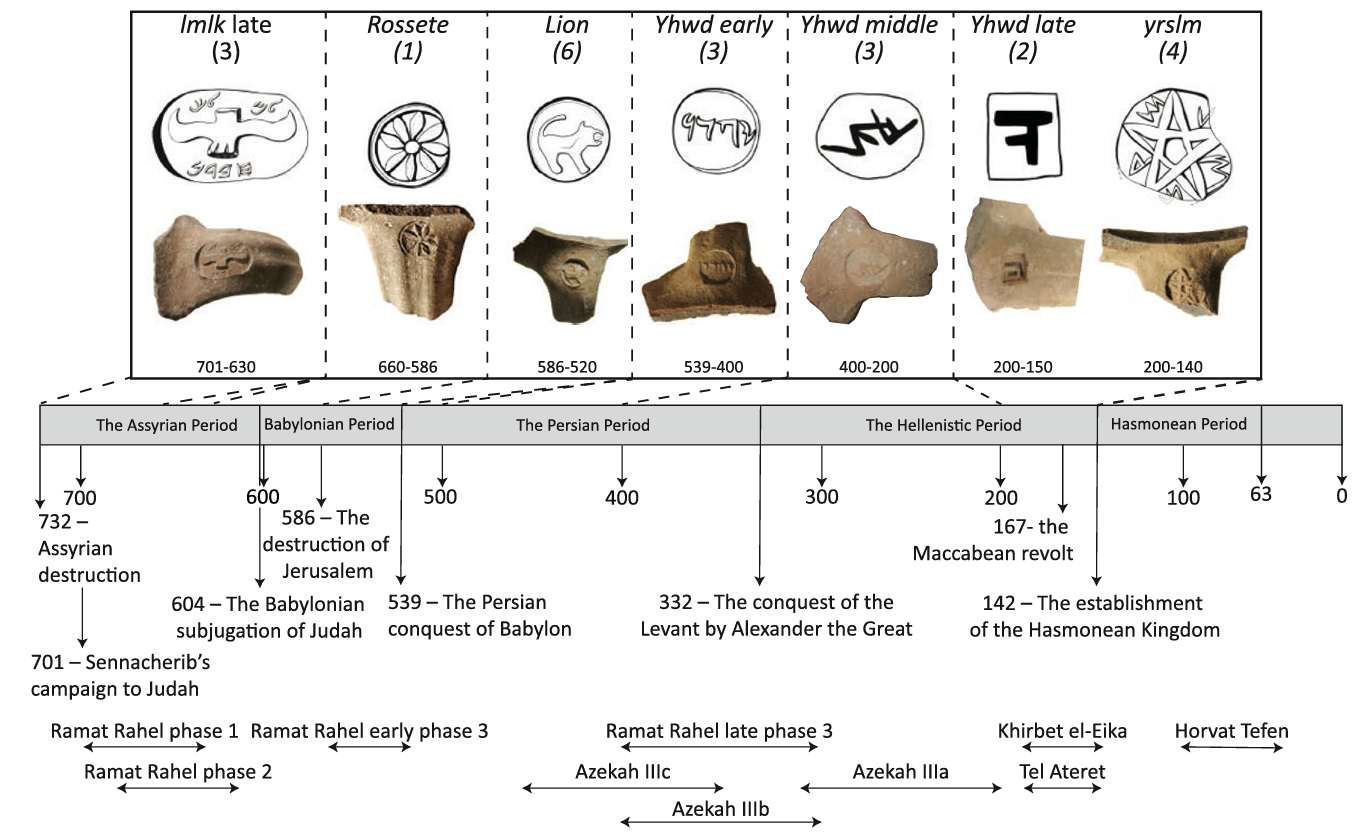

Figure 1

Figure 1Judean stamp impressions and chronological framework. Each panel in the top row shows a schematic illustration, a representative picture of a stamp category, and its estimated age of use. The number of types (archaeomagnetic groups) analyzed in this study is indicated in brackets under the impression name. The time scale indicates the main historically dated events mentioned in the text. The lower row shows the age of the other archaeological contexts; all ages provided are BCE.

Redrawn following Lipschits (2021).

Hassul et al. (2024)

- from Hassul et al. (2024)

Figure 8

Figure 8LAC.v.2.0 and comparison with predictions of geomagnetic models. The black curve and gray area show the mean values and the 95% credible interval. Models were calculated for the location of Jerusalem (31.78°N, 35.20°E).

Hassul et al. (2024)

- from Hassul et al. (2024)

Figure 9

Figure 9Duration of the Levantine Iron Age Anomaly.

- LAC.v.2.0: data and curve during the first two millennia BCE

- Rate of change in field intensity and VADM [virtual axial dipole moment]

Hassul et al. (2024)

The practice of stamping storage jars with royal seals as part of a taxation administrative system was widespread in Judah between the 8th and the 2nd centuries BCE (Lipschits, 2021). During the manufacturing of large oval four‐handled storage jars, some specific jars were pre-labeled by stamping an impression onto the wet clay just before firing. These stamped jars were used for delivering goods, such as wine or oil as tax. Over time, due to political and economic changes, the seal impression systems evolved; some systems went out of use and other systems replaced them. As a result, the different families of seals, each distinguished by a unique symbolic motif, formed a continuous typological framework that can be linked to an absolute historical chronology.

The Judahite stamped jar system has been thoroughly studied (Bocher & Lipschits, 2013; Koch & Lip schits, 2013; Lipschits, 2021; Lipschits & Vanderhooft, 2011, 2014; Lipschits et al., 2010; Ornan & Lip schits, 2020; Vanderhooft & Lipschits, 2007) and was recently summarized by Lipschits (2021), who provided a comprehensive classification of the seals according to their iconographic motifs and time of use. Figure 1 displays the seven main impression categories discussed in this study and their age spans. Each impression category has a series of variants, hereafter referred to as “types,” and even “sub-types.” Archaeologically, it is difficult to distinguish between the time of use of the various types within a specific impression category. Hence, we group the archaeomagnetic samples according to type and assign them similar age spans in an effort to investigate possible temporal relationships. The collection we use was excavated from several sites, mostly from Ramat Rahel and Tel Azekah, but also from Socoh and several excavations in Jerusalem (Figure 2, Table S1). Only the type is used as a consideration for arranging samples into groups, while the location in which the jar was found is a parameter that is not taken into account when defining groups. Our work continues the study of Ben-Yosef et al. (2017), who carried out an archaeointensity analysis of stamped jars and reported data from 27 samples: 23 of which belong to the main impression categories shown in Figure 1,three of which are private stamps that are not shown in the figure and one is an incision impression (concentric circle). These data are included in our revised analysis as detailed below.

The lmlk impression system was the first to be used. It consists of three main components: the Hebrew word lmlk, meaning “(belonging) to the king” in the upper part of the stamp impression, a royal emblem in the center, and a name of a place in the lower part. The combinations of two different royal emblems, four names of places and several patterns for the positioning of the letters around the symbol define nineteen different seal types. The lmlk impression system is divided into two categories: lmlk early and lmlk late. The former was in use before the destruction of Judah by Sennacherib in 701 BCE, and the latter was in use under the first era of the Assyrian administration in the 7th century BCE. The three “lmlk late” types studied here- MIIb, ZIIb and XII (Figure S1 in Supporting Information S1) are dated to 701–630 BCE, following the maximum age range of the lmlk im pressions suggested by Ben-Yosef et al. (2017).

The Rosette impressions are small and rounded and bear a single rosette motif with no inscription. The stamp types differ in the number and shape of the petals, the existence or non-existence of a frame, and an inner core. The Rosette stamp impressions went out of use during the final destruction of Judah by the Babylonians in 586 BCE.The date of their introduction is less clear, so we set the earliest possible date to 660 BCE, following Vaknin et al. (2020).

The Lion impressions are small and mostly rounded in shape. They include the image of a lion depicted in profile in various positions, with no inscription. Six types are studied here: lion type 3,4,5,6,7, and 8 (Figure S2 in Supporting Information S1). The Lion impression system was in use under Babylonian rule, that is, after the 586 BCEdestruction of Judah. When the Persians took over Judah in ca. 539 BCE, this system was gradually replaced by the yhwd stamp impression system. Thus, the use of Lion impressions is estimated between 586 BCE and ca. 520 BCE.

The yhwd impressions represent a transition from the use of symbols to script only. This complex system consists of 17 types with more than 50 variations. It was used for about 400 years from the late 6th century BCE until the second half of the 2nd century BCE. The yhwd impressions are chronologically divided into three categories: early, middle, and late (Figure S3 in Supporting Information S1) on the basis of the following criteria: their paleographic properties, a linguistic study of the transition from Aramaic to the Hebrew language, comparison of the impressions with the yhwd coins minted in the same periods of time, and on the basis of the historical context of the development of Judah under the rule of the Persian, Ptolemaic and the Seleucid empires (Lipschits & Vanderhooft, 2011).

The yrslm impressions represent a new era with the reappearance of iconographic elements alongside writing. The impressions include a pentagram with a script in ancient Hebrew reading yrslm (“Jerusalem”) between its vertices. Here, we focus on five types: a, b, c, d, and f (Figure S4 in Supporting Information S1), where we unite type c and type d into a single type labeled c/d because of the difficulty in distinguishing between them. The yrslm impression is associated with the weakening of the imperial hold on the region, the Maccabean revolt (ca. 167 160 BCE), and regaining full independence under Simon Maccabaeus (142 BCE). Therefore, we estimate the age span of yrslm impressions to ca. 200–140 BCE (Bocher & Lipschits, 2013)

Hassul, E., et al. (2024). "Geomagnetic Field Intensity During the First Millennium BCE From Royal Judean Storage Jars: Constraining the Duration of the Levantine Iron Age Anomaly."

Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 25(5): e2023GC011263. - open access

Paterson, G.A., Tauxe, L., Biggin, A.J., Shaar, R. and Jonestrask, L.C. 2014. On Improving the Selection of Thellier-Type Paleointensity Data

. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 15: 1180–1192.

Shaar et al. (2022) The Tel Megiddo Paleointensity Project: Toward a Higher Resolution Reference Curve for Archaeomagnetic Dating

. In: Finkelstein, I., and Martin, M.A.S. Megiddo VI. The 2010 – 2014 Seasons. Volume III. Tel Aviv.

Vaknin et al. (2022) Reconstructing biblical military campaigns using geomagnetic field data

, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119 (44) e2209117119