AD 717 Dec 24 Syria

A damaging earthquake in Syria. Although many Byzantine

and Arab writers describe this earthquake as most

destructive, they do not mention the particular localities

affected in Syria or Jazira (Mesopotamia). Aftershocks

continued for six months.

Theophanes reports a 'great earthquake' in Syria

in a.M. 6210 = September 717 to August 718. Once again

the regnal year is one too low: Leo III a.2 =18 April 716

to 17 April 717. This is reported as occurring just before

the caliph `Urnar banned wine in the cities and forced

Christians to convert to Islam'.

The Syriac sources give more details. Chron. 846

dates this event to a.S. 1029, Kanun I, 24 on Friday, at

the third hour, 'on the Feast of the Nativity' = 24 December

717, while al-Isfahani reports a recurrence of earthquakes

in Sham in a.H. 98 (25 August 716 to 13 August

717), which is probably on al-Khawarizmi's authority.

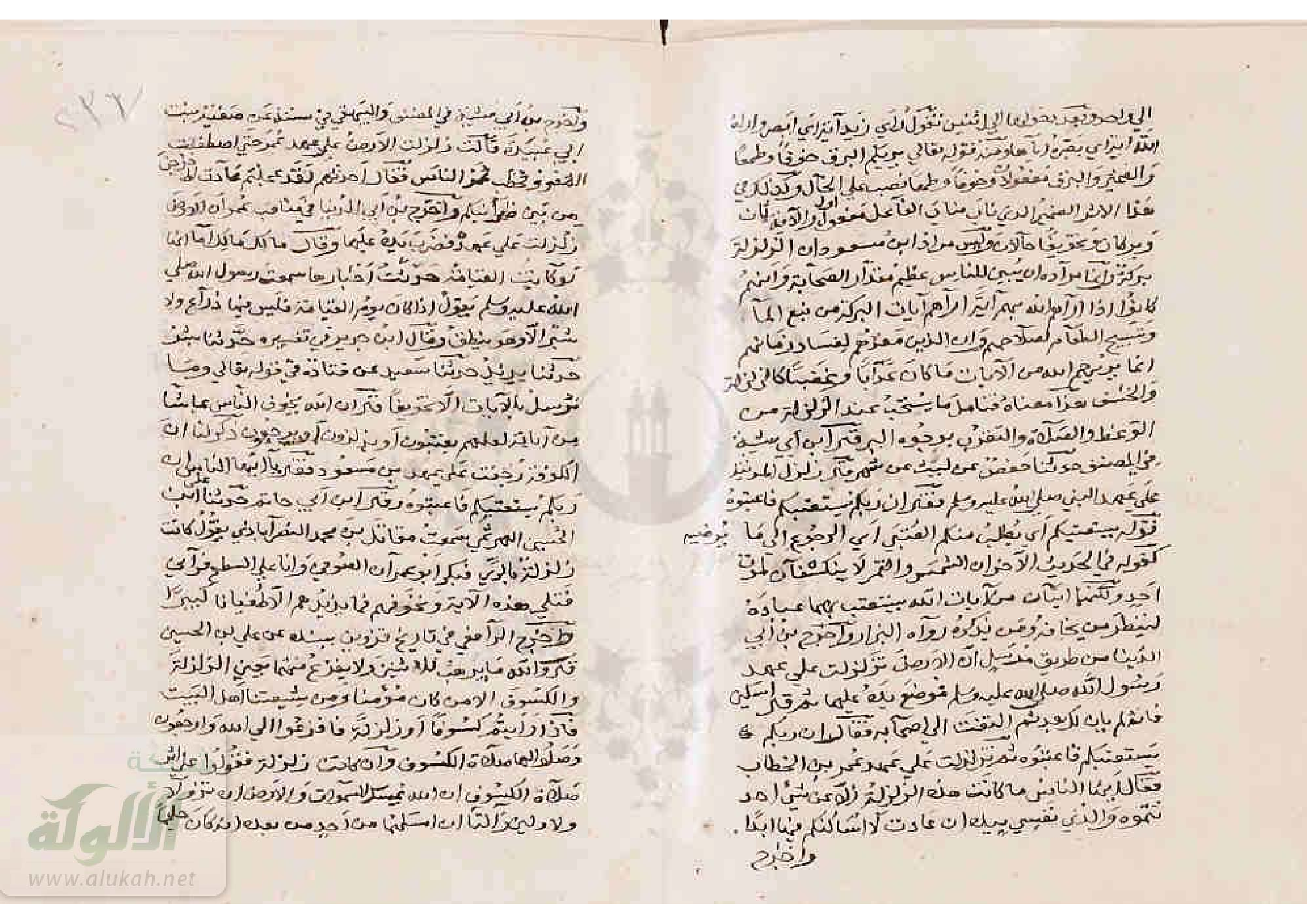

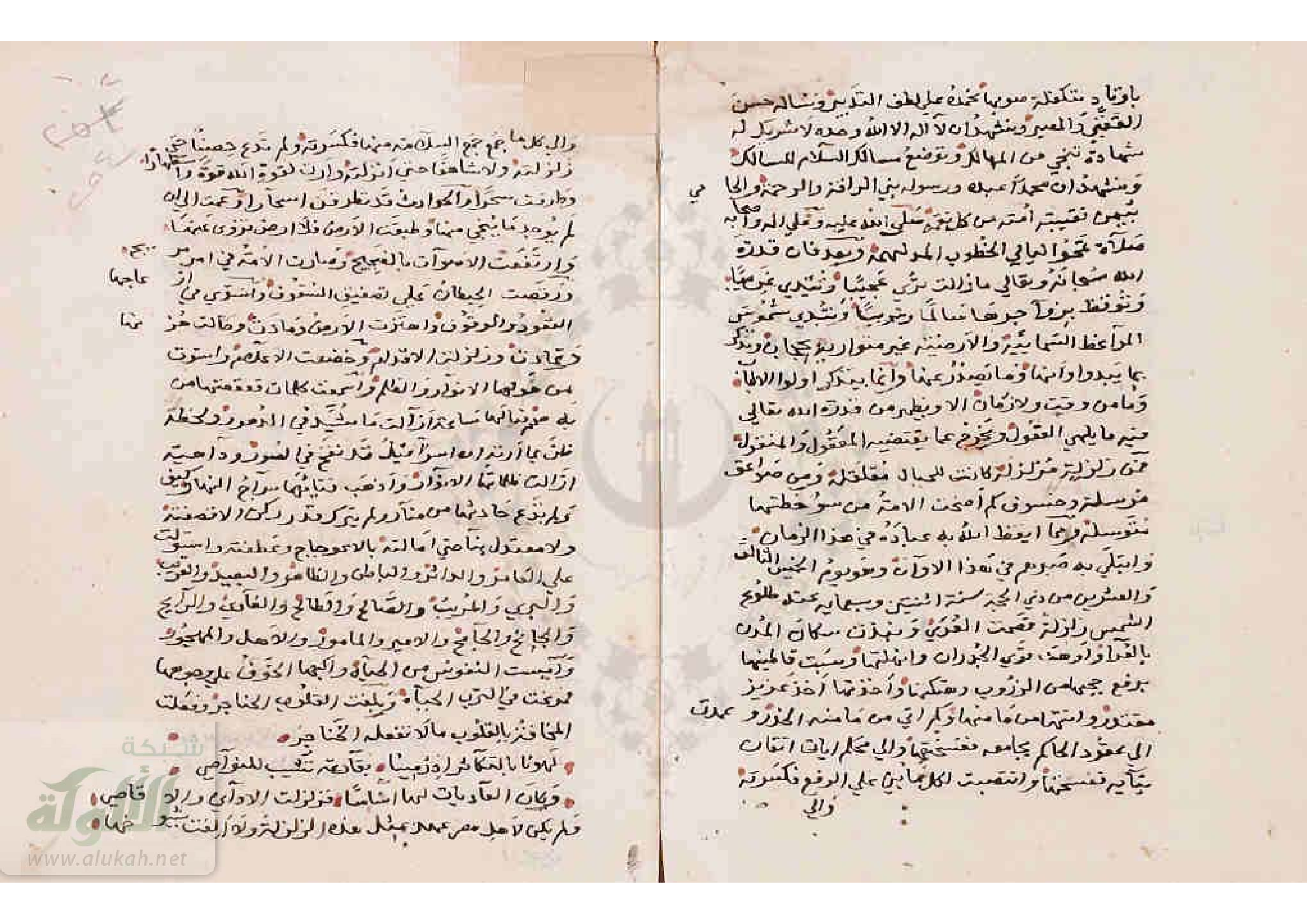

Two editions of Elias of Nisibe have important

differences: both record an earthquake in Syria and

Mesopotamia, adding that houses collapsed, which is significantly

more detail than is given by Theophanes and

the Chron. 846. Where they differ is that the Syriac edition

gives a.S. 1028 Jumada II, a year too low, if this

is the same earthquake. However, Eli. Nis. D. 33r gives

a.H. 99 Jumada II, 15, a Friday = 23 January 718. This

does not appear particularly helpful either, except that

a.H. 99 Jumada II, 15 was not a Friday but a Sunday.

Jumada I, 15th of a.H. 99 was Friday 24 December 717,

hence it is probably a copyist's error. Thus it is certain

that the entries in Elias of Nisibe refer to this rather than

to another earthquake, probably of AD 713.

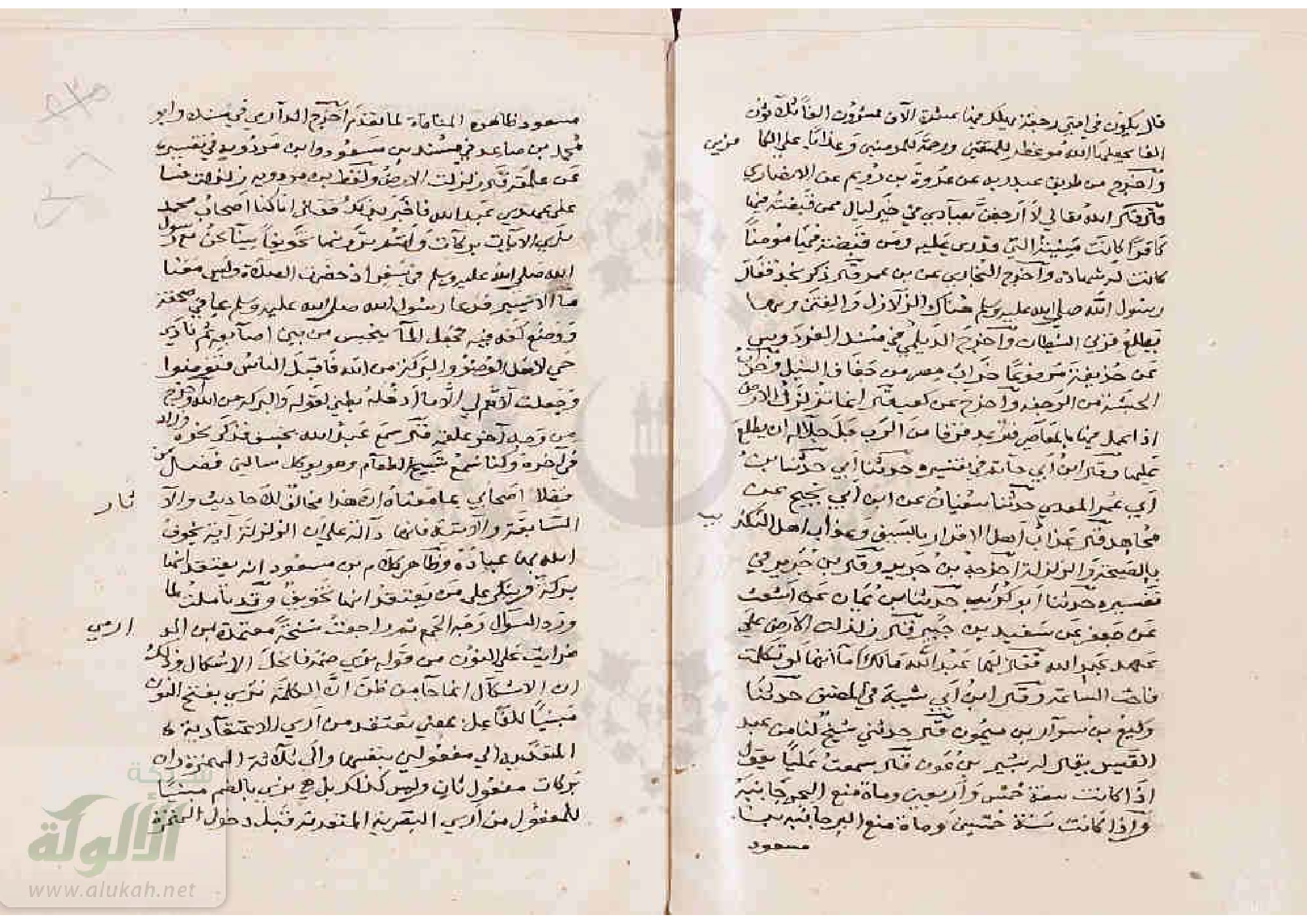

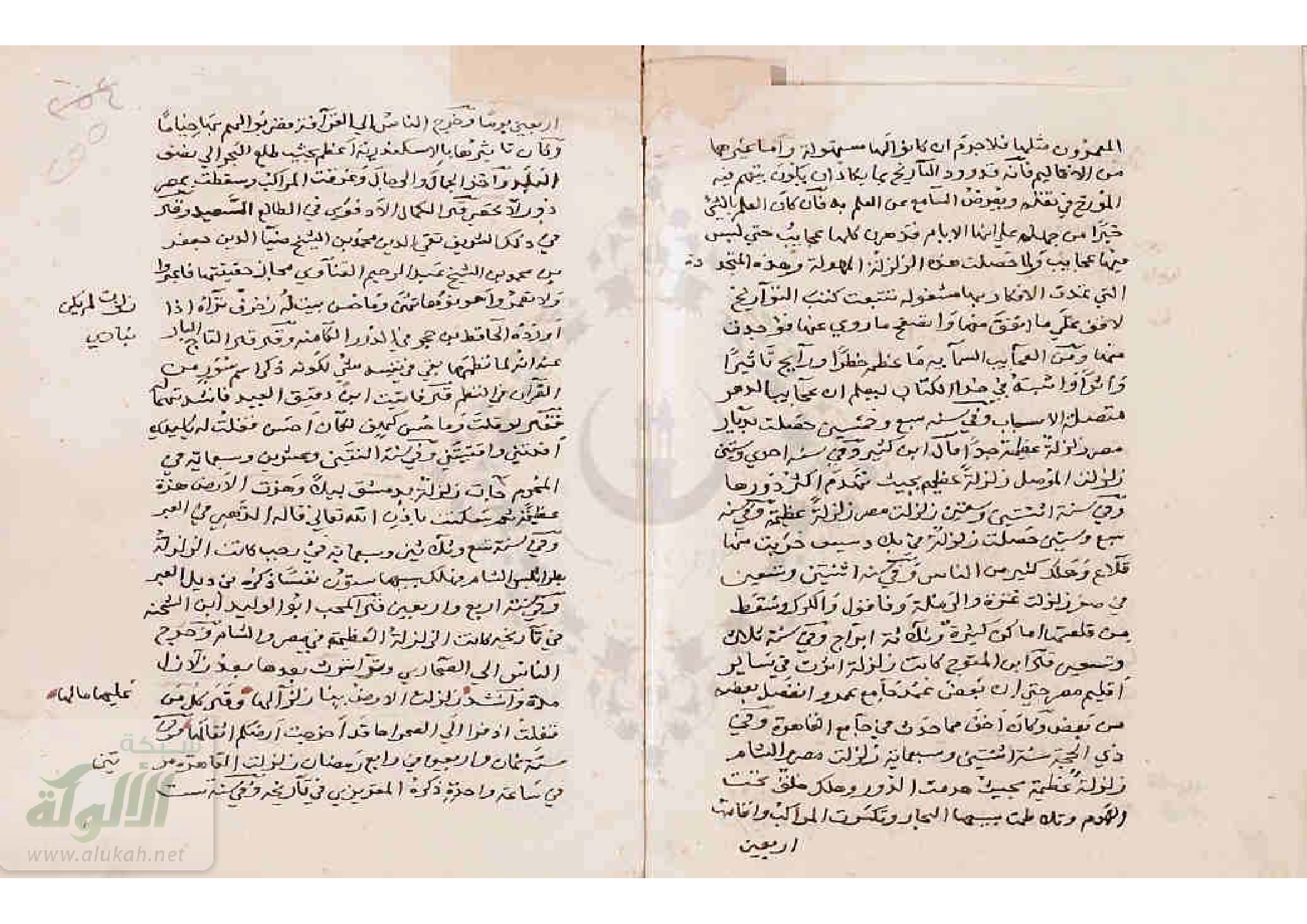

Al-Suyuti has a brief note on this earthquake

taken from the Mirat of Ibn al-Jauzi; a second entry says

that 'as we have already noted' an earthquake took place

in Syria during the caliphate of `Umar `Abd al-'Aziz. The

latter was in fact caliph from 99 Safar 10 (22 September

717) to 101 Rajab 20 (5 February 720), so this is either

an error or in fact pertains to an aftershock or to another

earthquake.

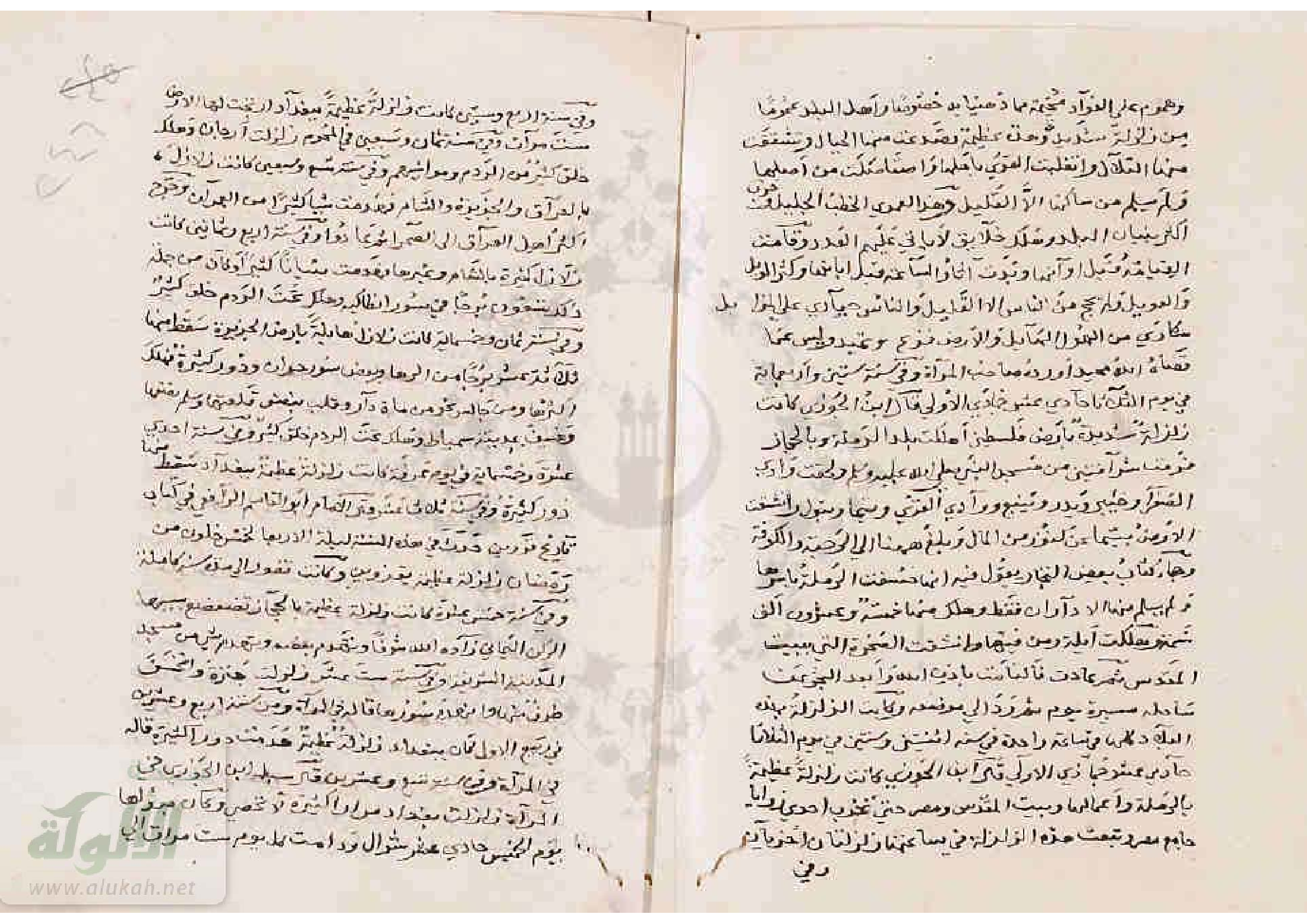

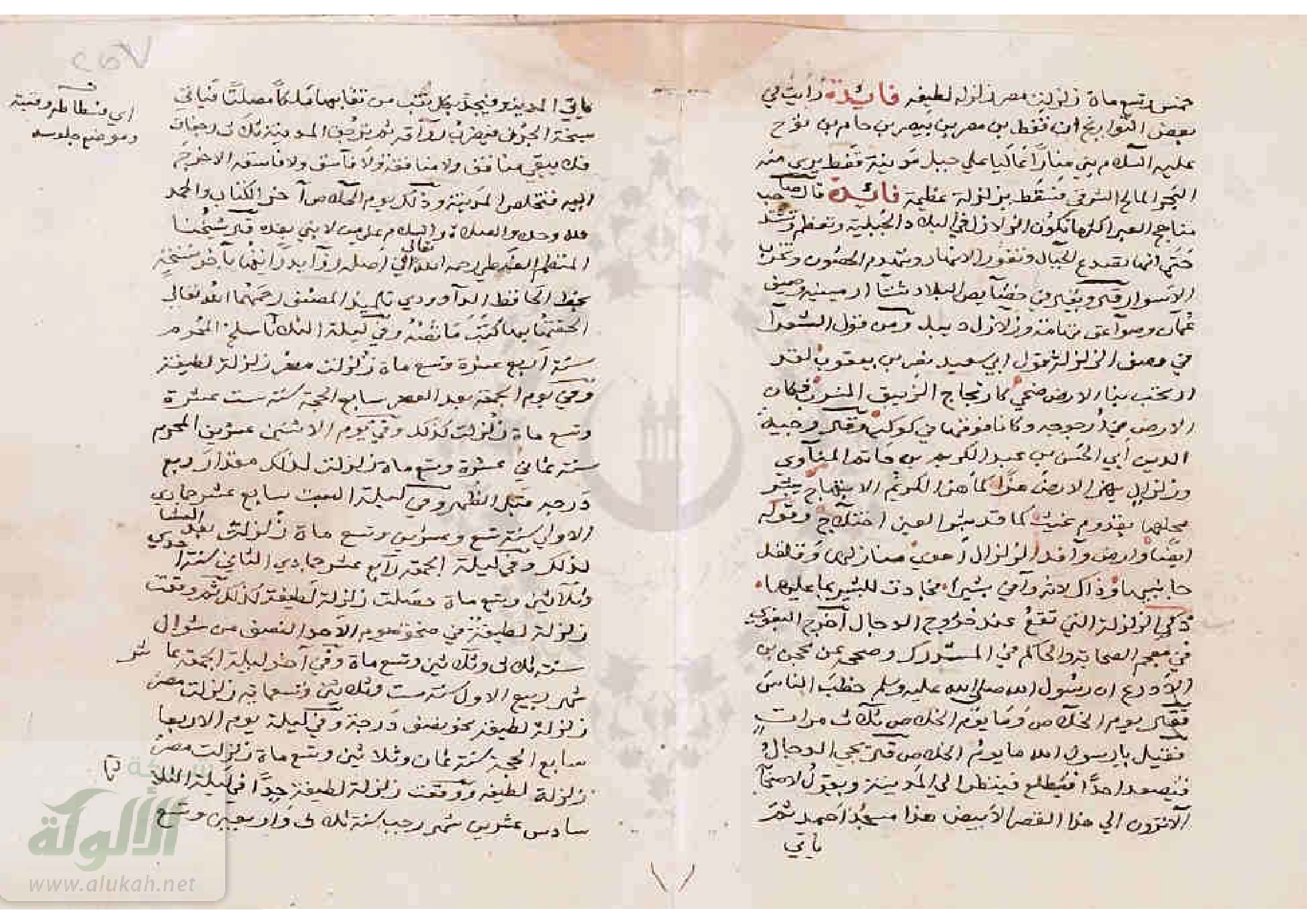

Syrian authors give 15 Jumada II 99 a.H., instead

of Jumada I, which may have led Guidoboni et al. (1994,

360-619) to include an additional earthquake in their

catalogue. Also the damage to Edessa and Batna Sarug

attributed to this earthquake by these authors is in error

since their sources refer, quite clearly, to the event in

AD 679.

Notes

(a.M. 6210) In the same year a great earthquake happened in

Syria, and `Urnar banned wine from the cities, and compelled the

Christians to convert to Islam.' (Theoph. 399).

`And in the year 1029, in the month of prior kanun, the

24th day, Friday, 3rd hour, on the feast of the Nativity, there was

a violent earthquake, and a sound like great thunder was heard.'

(Chron. 846, 234/177).

' [After the earthquake of 94 in Antiochia] in the year a.H.

98 earthquakes recurred and lasted for six months.' (al-Isfah.

187).

`Year 99 began on Saturday 14th Ab of a.S. 1028... and

at that time there was an earthquake in Mesopotamia on the day

of preparation in the middle of latter gumada, and many houses

fell. And the earthquake continued for six months.' (Eli. Nis. 161

162/177).

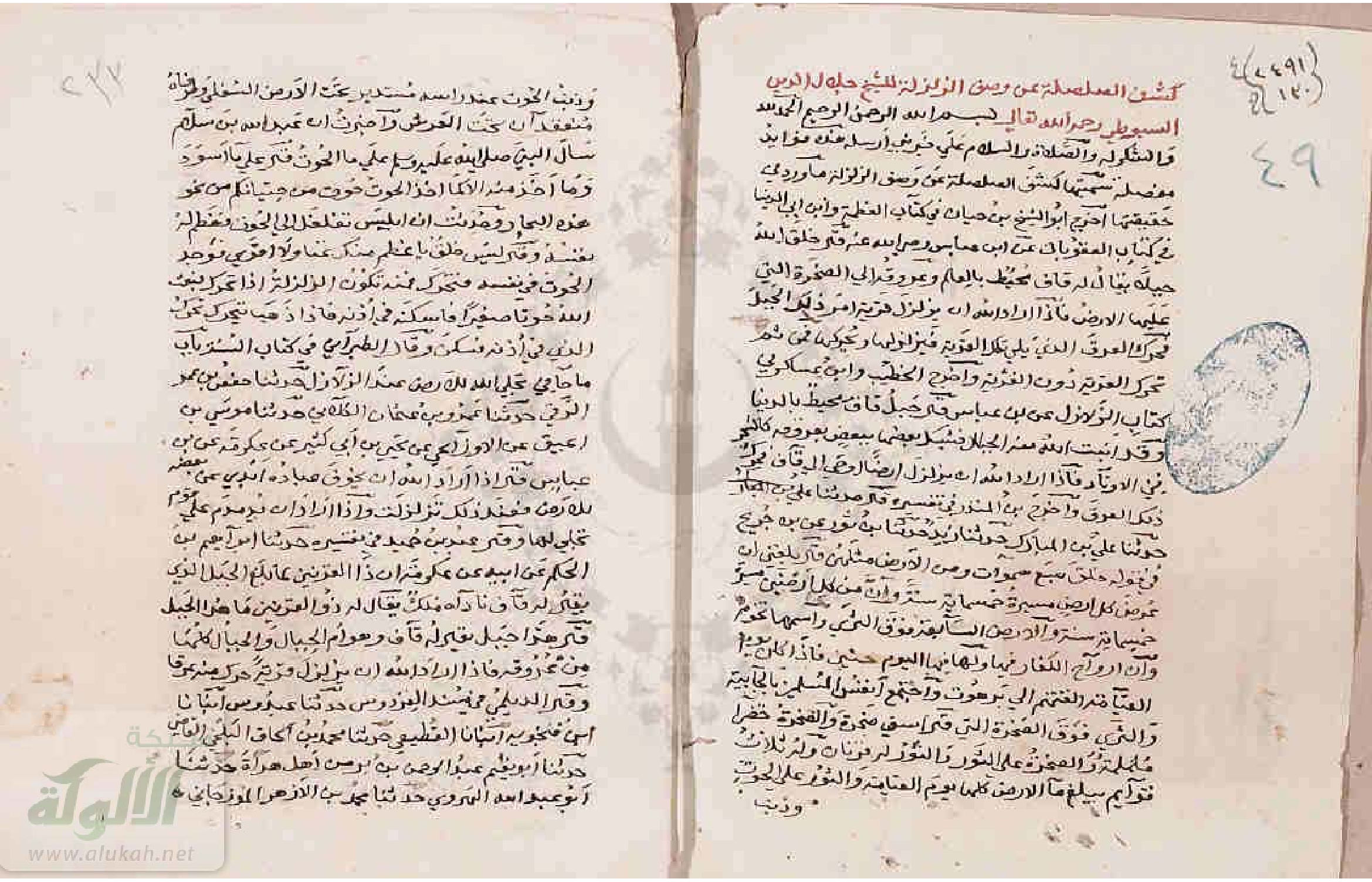

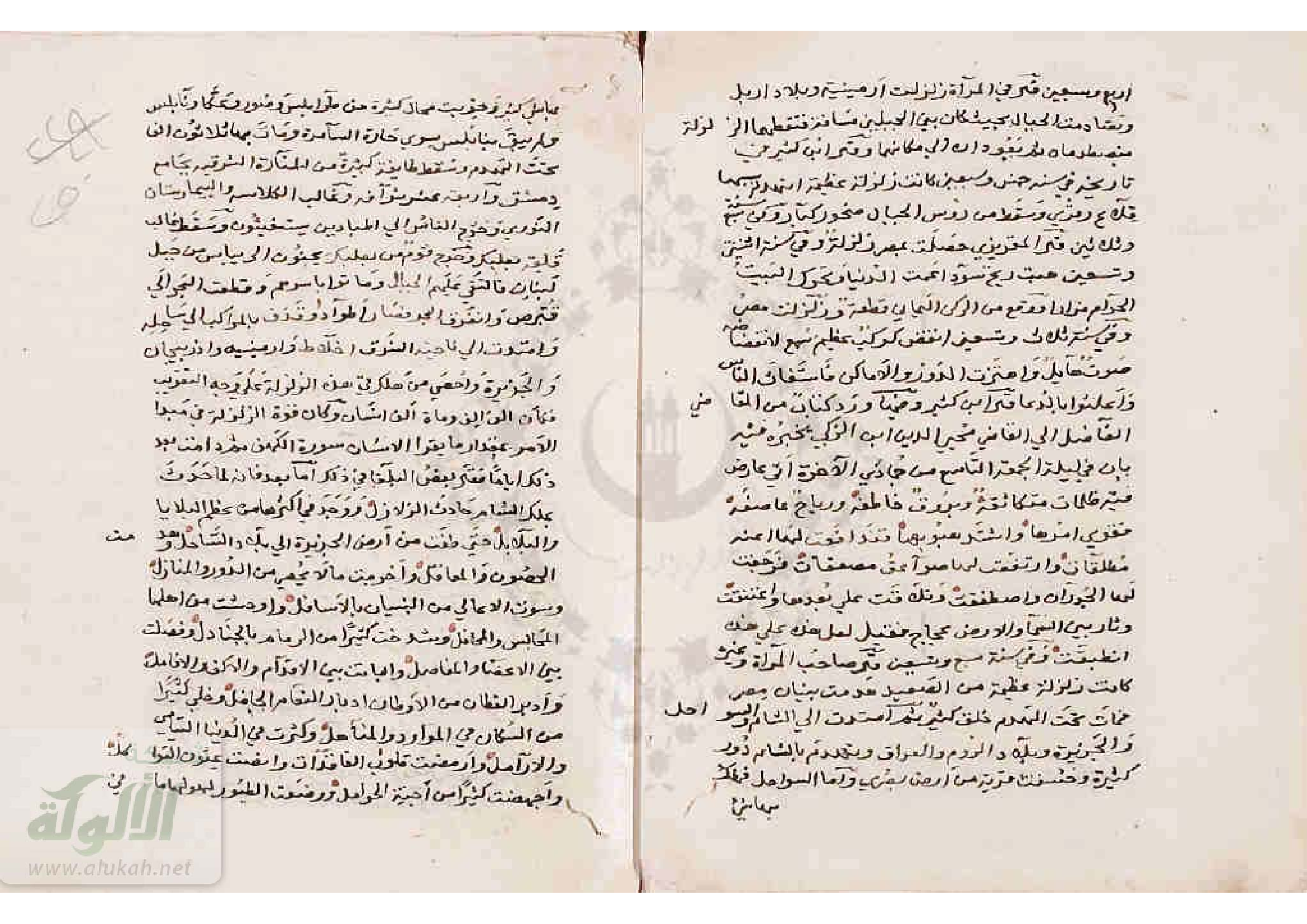

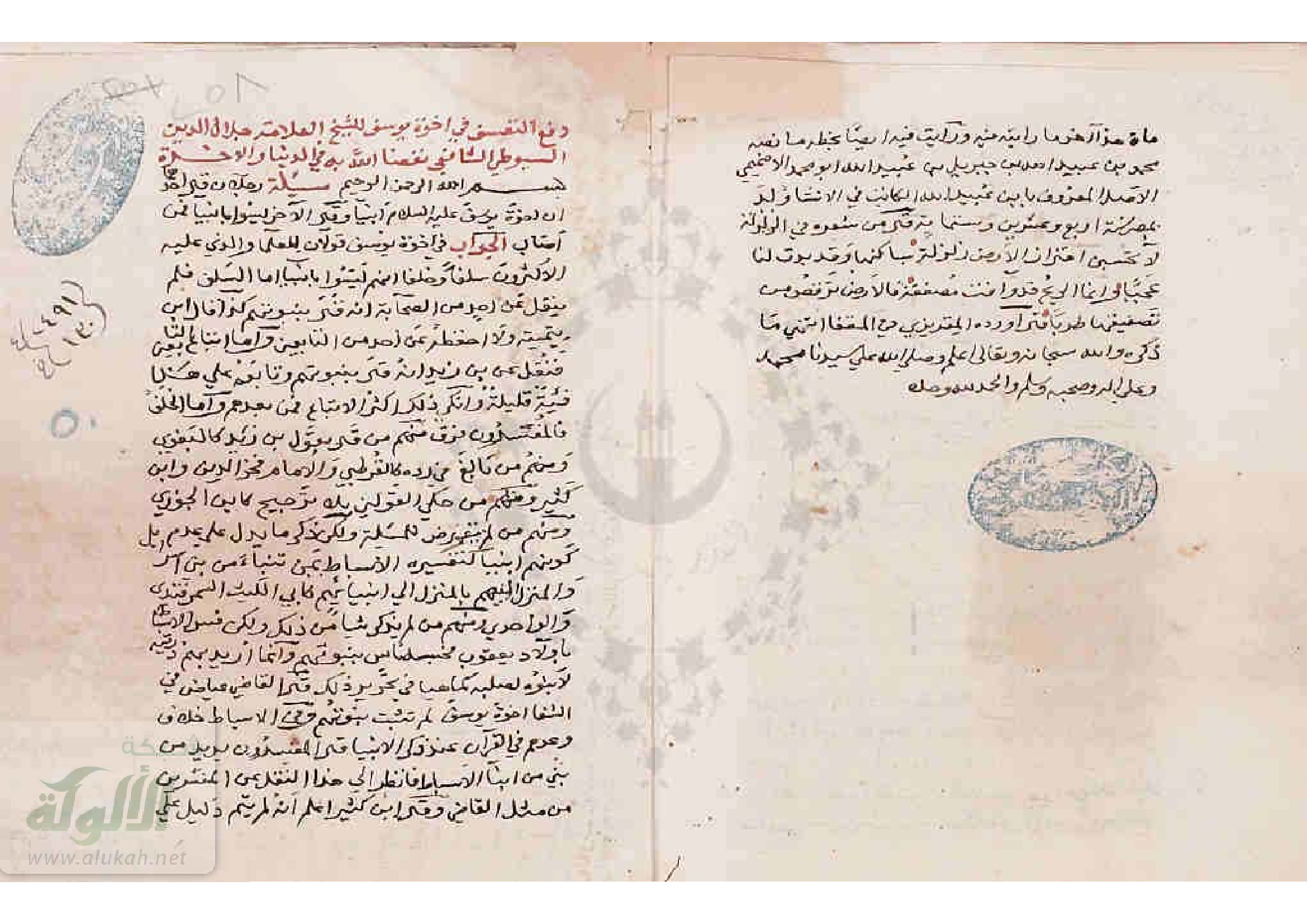

Arabic version (Eli. Nis. D. 33r)

`In the year 98 [25 August 716 to 13 August 717] earthquakes

happened again for forty days: this is what is said in al-

Mirat.' (al-Suyuti 16/9).

`In the caliphate of `Umar `Abd al-'Aziz (99 Safar 10

[22 September 717]-101 Rajab 20 [5 February 720])' (al-Suyuti

17/9).

References

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.