Palmyra

Figure 3

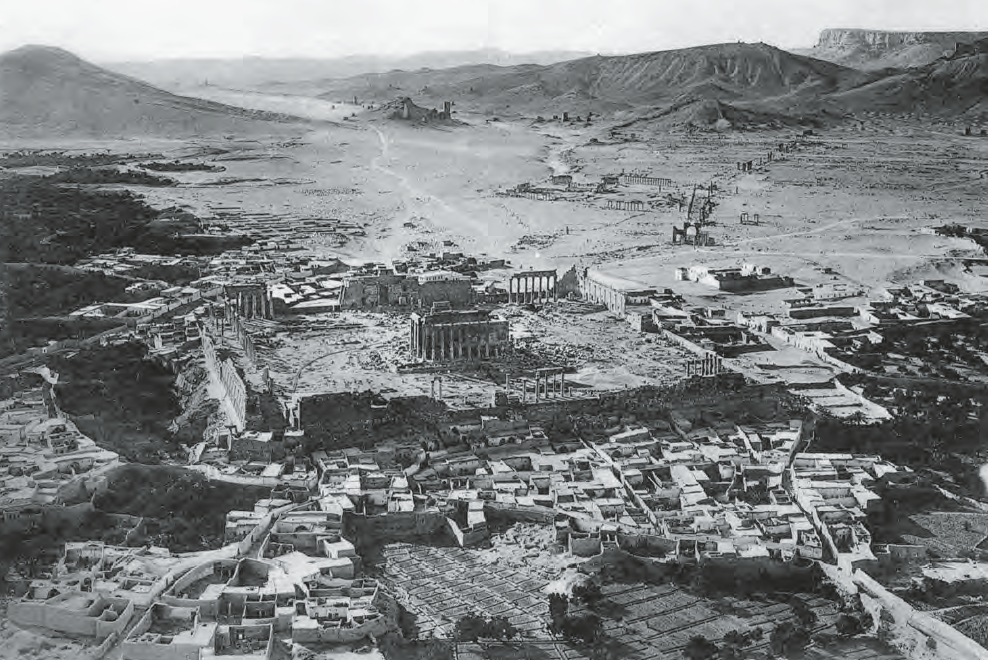

Figure 3Aerial photograph of Palmyra taken looking southwest

(Poidebard 1934, pl. 67).

Intagliata (2018)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Palmyra | Palmyrene | |

| Tadmor | Arabic | تَدْمُر |

| Tadmur | Arabic | تَدْمُر |

| dh-m-r | Western Semitic |

Palmyra has a long history of habitation dating back to the Neolithic. Located in an oasis in the center of the Syrian steppe (known as the Syrian desert - Badiat ash-Sham), it was a rest stop for caravans between Mesopotamia and Syria for at least four thousand years ( Adnan Bounni in Meyers et al, 1997). The city prospered in Hellenic and Roman times, suffered damage after the failed expansion of Queen Zenobia around 272 CE and housed a Roman Legion in the 4th century CE (Intagliata 2018:viii). Palmyra remained a major settlement until the end of the Umayyad caliphate in 750 CE (Intagliata 2018:viii).

Palmyra (Tadmor), oasis 245 km (152 mi.) east of the Mediterranean Sea and 210 km (30 mi.) west of the Euphrates River, in the center of the Syrian steppe, which is generally known as the Syrian desert (Badiat ash-Sham). Palmyra lies at the northeastern slope of Jebel al-Muntar of the Palmyrene mountain chain at an altitude of about 600 m. Palmyra is 235 km (146 mi.) from Damascus, 155 km (96 mi.) from Homs, and 210 km (130 mi.) from Deiz ez-Zor. It was always a rest stop, and for at least four thousand years a caravan station between Syria and Mesopotamia. The etymology of its ancient, and also actual, name in all Semitic languages, Tadmor, is unexplained in all known dialects. It may be derived from the West Semitic dh-m-r, which means "protect." It is called Palmyra in Greco-Latin sources, probably because of the extensive palm groves there.

The field of ruins of Palmyra and a part of the oasis are encircled by a rampart of about 6 km (4 mi.) long. A larger enclosure, known as the custom's rampart, rises up toward the mountain; its traces are still visible south of the Afqa Spring.

The city's "Grand Colonnade," a main street more than one km long, has been the city's axis since about the end of the second century CE . (Another axis belonged to the Late Hellenistic city; it was related to the Temple of Bel. The temple was later connected to the new axis through a triangular monumental arch misnamed the Arch of Triumph.)

The Temple of Bel, called the Temple of the Sun in ancient texts, is the largest and the most imposing building at Palmyra: it consists of a large, square courtyard more than 200 X 200 m in area, surrounded by four porticoes, a huge central sanctuary, a propylon, and vestiges of a large banquet hall, a basin, and an altar. The columns of the left portico and four tall columns of a nymphaeum led from the temple to a monumental arch decorated in the Severan-period style (beginning of the third century). Across from the arch, on the left portico, stand the ruins of the Temple of Nabu, which was refounded, with a beautiful propylon, in about the fourth quarter of the first century CE and completed in the second. Its monumental altar was constructed in the third century. On the right portico stands the monumental entrance added to the baths during the reign of Diocletian, at about the end of the third century. Also on tire left is an arched path leading to the semicircular colonnaded square around the theater. To the right, near the tetrapylon, is another nymphaeum and two stepped column bases that point the way to a narrow road leading to the Temple of Ba'al Shamin, which was rebuilt in 131. Another street to the left is flanked by a banquet hall and a caesareum. This street leads to the theater, senate, and agora with its annex. Beyond die tetrapylon an Umayyad market was built inside the main street. To the left there is an exedra. At the end of the street, on the hill inside the enclosure of Diocletian's camp, is the Temple of Allat. From it there is a panoramic view of the ruins, the necropolis surrounding the city, and particularly the Valley of the Tombs. The valley was the site of the tower tombs belonging to the city's richest families in the first century CE , with some dating to the first century BCE .

In the Upper Paleolithic, the area to the southeast of the site was filled with a large lake whose remains are the present salt flats. It was an excellent place for hunting, which explains the existence of the LevalloisoMousterian flint industry from about 75,000 B P in the caves and shelters in the surrounding mountains (Jarf al-'Ajla, thaniyat al-Baidah, Ad-Dawarah). Neolithic materials are encountered at different mounds in the vicinity of die oasis. Traces of scattered seventh-millennium settlements probably belong to the first sedentarization there, principally encouraged by the abundant sulfuric spring that gave birth to the oasis and subsequently to the city. Recent discoveries at el-Kowm, in the Palmyrene oasis region, confirm that the Uruk culture (end of the fourth millennium) extended to this region.

Excavation on the mound, underneath the courtyard of the Temple of Bel, uncovered primarily Early Bronze Age pottery (c. 2200-2100 BCE) especially that in the calciform Syrian tradition. The oldest written texts known relating to Palmyra (Tadmor) and the Palmyrenes (Tadmorim) were found at the Assyrian colony of Kanes (Kultepe) in Cappadocia and date to the nineteenth century BCE . The texts from Mari (Tell Hariri) also mention Palmyra and the Palmyrenes. At Emar (Meskene), texts dealing with Palmyrene citizens have been found. The eleventh-century BCE annals of Tiglath-Pileser refer to Tadmor as being in the country of Amurru.

Like Emesa/Homs, Petra, and Iturea at that time, Palmyra was independent, keeping its status as an Arab principality. It is known from Polybius (5.79) that at the battle of Raphia (217 BCE) , between the Lagid Ptolemy IV and the Seleucid Antiochus III, a certain Zabdibel with ten thousand Arabs supported the Seleucids. These were certainly Palmyrenes because the name of their chieftain is known only in Palmyrene onomastica and means "the gift of (the god) Bel."

While Syria became a Roman province in 63-64 BCE, Palmyra maintained its independence and enjoyed — according to Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. 5.88) — a privileged position between Rome and Parthia. Both, it seems, were interested in Palmyra. In 41 BCE, Marcus Antonius undertook a futile push toward the city. The Palmyrenes had, as Appian reports (5.9), gained a key trade and political position. They procured exotic goods from India, Arabia, and Persia and then traded them to the Romans. When, precisely, Palmyra was incorporated into the Roman state is a contested issue, but it may have occurred under Tiberius (14-37 CE).

In the second half of the first century CE , Palmyra was occupied by a Roman garrison. Beginning in the reign of Trajan (98-117 CE) the city's own archers, cavalry, and cameleers participated in the defense of the empire's borders on the Danube River, in England, and in Africa. In 106, following the fall of Petra, Palmyra became the most important trading center in the East. Its great prosperity was expressed in the restoration of old monumental buildings and the reconstruction of temples.

Under Hadrian (117-138) Palmyra achieved the status of a free city, as Hadriana Palmyra and, in the name of its senate and people's council, defined its own taxes and proclaimed its own decisions. Under Septimius Severus and the Syrian dynasty (first half of the third century), Palmyra was at its largest (12 km, or 7 mi., in diameter). Emperor Caracalla raised the city to the rank of a Roman colony in 212.

The foundation of the Sasanian Empire in 228 resulted in the loss of Palmyra's control over trade routes. The Palmyrenes then sought new economic opportunities under the leadership of a well-known Arabian family headed by Odainat, who held the title of governor of the Syrian province. In 262 and 267 he led two campaigns against the Sasanian capital. Odainat became dux romanorum, "chief general," of the armies of the East, corrector of the Orient, and king of the kings and imperator. The hope simultaneously of Palmyra and Rome was murdered along with his older son under mysterious circumstances.

Because his second son was too young to succeed him, his wife Zenobia took the post of regent. Highly intelligent, knowledgable, and ambitious, Zenobia knew the political situation of the Orient and the weakness of Rome. She did not hesitate to proclaim her independence and took with her son the tide of the Augusti. She soon conquered all of Syria, and her armies also occupied Egypt and Anatolia. The emperor Aurelian, forced to react quickly, defeated the Palmyrene army at Antioch and Emesa/Homs. Zenobia retreated to Palmyra, where Aurelian laid siege to her heavy defenses. Zenobia attempted to flee to the Sasanians but was caught and imprisoned in 272. In this critical situation the Palmyrenes rose up and massacred the occupying Roman garrison. Aurelian's retaliation was devastating. The ancient authors offer different versions of Zenobia's end.

In 297, the emperor Diocletian made peace with the Persians in the treaty of Nisibis, which moved the Syrian border to the Khabur River. Palmyra became a center of a network of roads where the principal road was the Strata Diocletiana linking Damascus to the Euphrates River. Inside the city a Roman camp was established and the ramparts were modified to protect the camp.

Christianity was well established in Palmyra in the fourth century. During the Byzantine period, the cellas of the temples of Bel and Ba'al Shamin and some other buildings were transformed into churches. At the end of the fifth century and at the beginning of the sixth, Palmyra was one of the residences of the Ghassanid ally of the Byzantines. According to Procopius (Deaedificiis 2.11), Justinian (527-565) fortified Palmyra's rampart and reestablished its irrigation system.

In 634 Khaled ibn al-Walid, the general of the Muslim armies, occupied Palmyra peacefully. During the Umayyad period Palmyra regained some of its importance but during the 'Abbasid period was neglected by the caliphs of Baghdad. It became important under the Burids of Damascus (twelfth century), the Ayyubids (twelfth-thirteenth centuries), and the Mamluks (thirteenth-fifteenth centuries). The Temple of Bel was transformed into a fortress, the cella becoming a mosque. The castle overlooking the city is attributed to the emir Ibn Ma'an Fakhr al-Din (1595-1634). The historian and high functionary Ibn Fadl Allah (1301-1349) refers to the splendid homes and gardens of Palmyra and to its prosperous commerce. In 1401 Timur (Tamerlane) sent a detachment against Palmyra that pillaged it. The city's decline accelerated during the Ottoman period (1516-1919). It was soon reduced to a village, at the mercy of nomadic tribes. In the last half of the twentieth century it experienced a renaissance.

The story of Palmyra and Zenobia, its beautiful and noble queen, have fascinated the Western world since the Renaissance. They have inspired literary masterpieces by D'Aubignac, Labruyere, and Moliere and paintings and tapestries. Many travelers were drawn to Palmyra: the Neapolitan Pietra della Valle (1616-1625); the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1638); English merchants from Aleppo (1678, 1691), the Frenchmen Girod and Sautet (1705); and the Swede Cornelius Loos (1710). They returned to Europe with copies of inscriptions, drawings of ruins, and sometimes incredible travel stories. The visit of two Englishmen, Robert Wood and H. Dawkins in 1751 had far-reaching effects. Their work, The Ruins of Palmyra, which appeared in English and French in 1753, signaled the beginning of systematic exploration at Palmyra. A year later, the Frenchman Jean Jacques Barthelemy and the Englishman John Swinton deciphered the Palmyrene alphabet. An ever-larger number of travelers and researchers then followed: Louis Francois Cassas (1785), C. F. Volney (c. 1785), Melchior de Vogue (1853), and J. L. Porter (1851). In 1861 William Henry Waddington copied a number of inscriptions. In 1870 the German A. D. Mordtmann edited several new texts and E. Sachau, who visited the city in 1879, devoted many articles to it.

In 1881 a Russian, S. A. Lazarew, discovered a text of the city's fiscal law, the longest economic text from the ancient world. This important document is now in the Hermitage museum. In 1889 D. Simonsen published the Palmyrene sculptures and texts of the Glyptotheque Ny Carlsberg. The collection is the result principally of the activity of M. J. Loytved, the Danish consul in Beirut.

In 1899 M. Sobernhein discovered a house tomb in the Valley of the Tombs and took the first photographs of Palmyra. Research on the entire city began in 1902 and continued in 1917 under the direction of Theodor Wiegand (1932). In 1908, 1912, and 1915 Alois Musil undertook explorations of the more distant reaches of the city. In 1914 tire French Acad6mie des Inscriptions et BellesLettres initiated a project under the direction of Antonin Jaussen and Raphael Savignac to copy all hitherto known texts, which were subsequently published by Jean-Baptiste Chabot (1922).

In 1924 and 1928 Harald Ingolt opened an excavation on Palmyra's western necropolis area, on behalf of the French Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres and the University of Copenhagen. Again in 1928, with the architect Charles Christensen, he excavated many hypogea in the same area on behalf of the Rask Orsted Foundation. Once again he dug a new hypogeum in 1937 whose excavation was completed by Obeid Taha.

In 1929 A. Gabriel achieved the first precise topographic plan of the city. New epigraphic research was undertaken by Jean Cantineau (1930-1936) that was continued by Jean Starcky in 1949, Javier Teixidor in 1965, and Adnan Bounni and Teixidor in 1975. The large Temple of Bel was cleared in 1929-1930 by Henri Seyrig, who was then director of the Antiquities Service of Syria and Lebanon, with Ja'far al-Hasani, director of the National Museum in Damascus (Seyrig, Amy, and Will, 1968-1975). Between 1934 and 1940 Seyrig and al-Hasani were the strongest proponents of carrying out archaeological research at Palmyra.

Robert Amy, Ernest Will, Michel Ecochard, Raymond Dura, and others participated in the excavations or the study of the Temple of Bel, the tomb of Yarhai (now exhibited in the National Museum of Damascus), the agora, the Villa Cassiopeia, and the Valley of the Tombs. Daniel Schlumberger (1951) investigated the environs of Palmyra and Starcky published the first comprehensive summary of Palmyrene research results.

With independence in 1946, national research at Palmyra expanded considerably. In 1952 Selim Abdul-Hak excavated the Hypogeum of Ta'i in the southeast necropolis. Beginning in 1957 Bounni initiated what is now some twenty years of research at Palmyra. Nassib Saliby, Taha, and Khaled As'ad have been his principal collaborators. This research has focused on three hypogea in the Valley of the Tombs, the main street, the Temple of Nabu, the annex of the agora, nymphea A and B, and the street of Ba'al Shamin. As'ad excavated the ramparts, the Temple of Arsu, and the Hypogeum of Amarisha, continued the excavation of the main street, and restored many buildings in collaboration with Ali Taha and Saleh Taha.

Foreign missions have been authorized by the Syrian authorities to participate in the excavations of several monuments: Paul Collart and his Swiss team worked on the temple of Ba'al Shamin in 1954-1956; since 1959 Polish excavations in the area of Diocletian's camp have been led by Kazmierz Michalowski, Anna Sadurska, and Michal Gawlikowski. In 1966-1967 Robert Du Mesnil du Buisson led excavations in the courtyard of the Bel Temple and also excavated the Temple of Belhamon, while Manot worked on the peak of Jebel al Muntar. Joint expeditions—Japanese, Swiss, and Polish—are also working with Syrian teams at Palmyra.

- Fig. 1 - Location Map from

Miranda and Raja (2022)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Palmyra and the surrounding region (courtesy of Eivind Seland, University of Bergen, Norway). Base map copyright ESRI.

Miranda and Raja (2022)

- Palmyra in Google Earth

- Fig. 3.2 - Aerial view of Palmyra

from the 1920s from Andrade and Raja (2022)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

. Aerial view of Palmyra from the 1920s.

© Rubina Raja and Palmyra Portrait Project,

courtesy of Mary Ebba Underdown.

Andrade and Raja (2022) - Fig. 3.1 - View of Palmyra

from Andrade and Raja (2022)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

View of Palmyra with the oasis in the background.

Courtesy of Jørgen Christian Meyer

Andrade and Raja (2022)

- Map 0.1 - Map of Palmyra

from Raja (2024)

Map 0.1

Map 0.1

City plan of Palmyra and its four necropoleis

Courtesy of Katarína Mokránová and Rubina Raja. Vector data were based on extended Topographia Palmyrena (Schnädelbach 2008) data, provided courtesy of Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (Orient-Abteilung, AS Damaskus).

Raja (2024) - Fig. 3.3 - Map of Palmyra and the

surrounding area from Andrade and Raja (2022)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3

Map of Palmyra and the surrounding area.

Courtesy of Klaus Schnädelbach.

Andrade and Raja (2022) - Fig. 2 - Annotated and numbered

Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Map of Palmyra from

Miranda and Raja (2022)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of Palmyra (courtesy of Klaus Schnädelbach).

Miranda and Raja (2022) - Fig. 4 - Plan of Palmyra in 1931

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The state of the ruins of Palmyra in 1931

Bureau Topographique des Troupes Françaises du Levant (detail; scale 1:10,000. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland)

Intagliata (2018)

- Map 0.1 - Map of Palmyra

from Raja (2024)

Map 0.1

Map 0.1

City plan of Palmyra and its four necropoleis

Courtesy of Katarína Mokránová and Rubina Raja. Vector data were based on extended Topographia Palmyrena (Schnädelbach 2008) data, provided courtesy of Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (Orient-Abteilung, AS Damaskus).

Raja (2024) - Fig. 3.3 - Map of Palmyra

and the surrounding area from Andrade and Raja (2022)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3

Map of Palmyra and the surrounding area.

Courtesy of Klaus Schnädelbach.

Andrade and Raja (2022) - Fig. 2 - Annotated and

numbered site plan from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Map of Palmyra

from Miranda and Raja (2022)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of Palmyra (courtesy of Klaus Schnädelbach).

Miranda and Raja (2022) - Fig. 4 - Plan of Palmyra

in 1931 from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The state of the ruins of Palmyra in 1931

Bureau Topographique des Troupes Françaises du Levant (detail; scale 1:10,000. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 4 - Map of Palmyra city

centre from Miranda and Raja (2022)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Map of the city centre of Palmyra (courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

Miranda and Raja (2022)

- Fig. 4 - Map of Palmyra

city centre from Miranda and Raja (2022)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Map of the city centre of Palmyra (courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

Miranda and Raja (2022)

- Fig. 48 - Camp of

Diocletian from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48

Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 26)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 18 - Praetorium

in Camp of Diocletian from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 28).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 52 - Plan of

the Sanctuary of Allath (Camp of Diocletian) from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52

Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 27)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 48 - Camp of

Diocletian from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48

Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 26)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 18 - Praetorium

in Camp of Diocletian from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 28).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 52 - Plan of

the Sanctuary of Allath (Camp of Diocletian) from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52

Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 27)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 23 - Plan of

House F in 2 phases from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 23

Figure 23

House F. Roman (top) and post-Roman (bottom) phases

(Gawlikowski 1996, figs 1–2)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 1 - Original

(Roman) Plan of House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The original phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a) - Fig. 2 - Final

Plan of House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The final phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a)

- Fig. 23 - Plan of

House F in 2 phases from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 23

Figure 23

House F. Roman (top) and post-Roman (bottom) phases

(Gawlikowski 1996, figs 1–2)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 1 - Original

(Roman) Plan of House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The original phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a) - Fig. 2 - Final

Plan of House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The final phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a)

- Fig. 31 - Plan and

front of Church I from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 31

Figure 31

Church I

(Gawlikowski 1990a, 41, fig. 2)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 31 - Plan and

front of Church I from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 31

Figure 31

Church I

(Gawlikowski 1990a, 41, fig. 2)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 19 - Sanctuary of

Baalshamīn from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Grande Cour and Bâtiment Nord, Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

(drawn by the author after plans at the Fonds d’Archives Paul Collart, Université de Lausanne).

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 19 - Sanctuary of

Baalshamīn from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Grande Cour and Bâtiment Nord, Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

(drawn by the author after plans at the Fonds d’Archives Paul Collart, Université de Lausanne).

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 24 - Plan of

Peristyle Building from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Peristyle Building

(Grassi and al-Asʿad 2013, 125, fig. 5)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 24 - Plan of

Peristyle Building from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Peristyle Building

(Grassi and al-Asʿad 2013, 125, fig. 5)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 7 - Al-Bakhra

Fort from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Al-Bakhrāʾ

(Genequand 2012, 75, fig. 46)

Intagliata (2018)

- Fig. 7 - Al-Bakhra

Fort from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Al-Bakhrāʾ

(Genequand 2012, 75, fig. 46)

Intagliata (2018)

- Figure 3.4 Dropped Keystone

in main arch of the colonnade from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4

Palmyra, The main arch of the colonnade. The dropped keystone indicates severe shaking parallel with the plane of the arch (in-plane deformation). ADB photo #4267. Taken on 26 September 2008 (before the arch was destroyed in 2015)

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.5 Vertical Fracture

in one of the funerary towers from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5

Palmyra, one of the funerary towers. Note the gaping vertical fracture along the centre of the wall. It is a typical damage feature caused by repeated lateral loading, which caused the swinging and ultimately the failure of the building. ADB photo #4285. Photo taken on 26 September 2008

Kázmér et al. (2024)

- Figure 3.4 Dropped Keystone

in main arch of the colonnade from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4

Palmyra, The main arch of the colonnade. The dropped keystone indicates severe shaking parallel with the plane of the arch (in-plane deformation). ADB photo #4267. Taken on 26 September 2008 (before the arch was destroyed in 2015)

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.5 Vertical Fracture

in one of the funerary towers from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5

Palmyra, one of the funerary towers. Note the gaping vertical fracture along the centre of the wall. It is a typical damage feature caused by repeated lateral loading, which caused the swinging and ultimately the failure of the building. ADB photo #4285. Photo taken on 26 September 2008

Kázmér et al. (2024)

AD 1042 Tadmur

An earthquake caused great loss of life in Tadmur in

Syria. It is said that Baalbek was also shaken.

This information is given by a single source,

which does not comment on the effects on Baalbek,

or specify whether Baalbek was shaken by a different

earthquake. It is likely that

the Tadmur earthquake was felt only at Baalbek.

Al-Suyuti (writing in the sixteenth century)

records this event as happening in the same year as

an earthquake in Tabriz. He does not comment on the

effects on Baalbek, but, since the two cities are 250 km

apart, if Baalbek was not shaken by a different earthquake,

it is likely that the Tadmur earthquake was felt

there only.

‘. . . in the year 434 [21 August 1042 to 9 August 1043], . . . an earthquake occurred at Tadmur and at Ba’albek: most of the population of Tadmur died under the ruins.’ (al-Suyuti Kashf 56/18).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

(021) 1042 August 21 – 1043 August 9 [434 H.] Palmyra [central Syria]

sources

- al-Suyuti, Kashf p.32

- Taber (1979)

- Sieberg (1932a)

- Ben-Menahem (1979)

- Ambraseys & Melville (1982)

catalogues p.

- Poirier & Taber (1980)

- Bektur & Alpay (1988)

- al-Hakeem (1988)

The little information we have about a destructive earthquake in northern Lebanon and central Syria between 21 August 1042 and 9 August 1043 comes from a brief mention by the 15th century Arab historian al-Suyuti, who records:

“The earth shook at Palmyra [Tudmur] and Baʿalbek. Most of the inhabitants of Palmyra died in the ruins.”

Guidoboni, E. and A. Comastri (2005:80-83). Catalogue of Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Mediterranean Area from the 11th to the 15th Century, INGV.

〈068〉 1042 August 21 – 1043 August 9

Palmyra and Baalbak

Intensities

- Palmyra: >VII

- Baalbak: V

- Tabriz: III

- Egypt: III

Al-Suyuti: In the year 434 A.H. (1042 August 21–1043 August 8), an earthquake occurred in Palmyra and Baalbek. Most people in Palmyra were killed under the debris.Parametric Catalogues

- Ben-Menahem (1979): 1042 August 21, 35.1°N, 38.9°E, near Palmyra, ML=7.2, destruction of Palmyra. It was strong in Baalbak and felt in Tabriz and Egypt.

- Sieberg (1932): 1042 August 21, a strong widespread earthquake was felt in Tabriz and Egypt. The center appears to have been at Palmyra, where it killed most of its inhabitants. It was felt strongly in Baalbak. Victims were estimated at 50,000.

Sbeinati, M. R., R. Darawcheh, and M. Monty (2005). "The historical earthquakes of Syria: An analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D.", Annales Geophysicae 48(3): 347–435.

Michalowski (1966:114-115) translated a fragmentary

inscription which may or may not refer to an earthquake in Palmyra in 233 CE. The inscription was written in Palmyrene and expresses gratitude to

an unknown deity for allowing two Palmyrenes to have survived what

Michalowski (1966:114-115) translated as a

shaking of (the earth). Due to the fragmentary nature of the inscription, the verb shaking is present but the object the earth is not.

Michalowski (1966:114-115) hypothesized that shaking of the earth

may have been present in the original complete inscription. 'DRGZ' is the Palmyrene word for shaking which

Ambraseys (2009:136)

lists as meaning ‘to be unsteady/restless/agitated’.

The inscription is well dated - May (Iyyar) of 233 CE (Palmyrene year 545). If the inscription describes a real earthquake,

May 233 CE is the terminus ante quem.

Ambraseys (2009:136)

found no other records for an earthquake in Palmyra for AD 233 and noted that civil unrest could also explain the inscription.

In the first half of the third century AD civil disorders were recorded after the end of the Antonine dynasty, during the rise of the Severi. Syria was subsequently divided into two, Palmyra being in the ‘Phoenician’ half. Even its garrison had to fight in the Roman campaign against the Parthians (Browning, 1979:44). Hence it is possible that the inscription might refer to the general fear of the people, ‘trembling’, on a particular occasion of disorder.

- from Michalowski (1966:114-115)

- Hard gray Limestone

- Altar of an anonymous god. Inscription on the cornice of the front of the altar in three lightly incised lines. The angle of the top molding with the former right end of the first two lines of the inscription is broken3.

- Found near the building in front of the Temple of the Signs.

1 (L BRYK) S MH L‘ (LM’) TYMRSW ER NBWZ’ W S LM LT BR NBWMR

2 .WZ PNWN MN S‘T’ DRGZ’ W ‘BD ‘MHWN GBWRT’BYR(H)

3 ’YR YWM YSgH’ SNT DXXXXV

Translation:

To him whose name is blessed forever. Taimarsô son of Nbôzâ and Salamal-lath son of Nebômar ... and freed them from the hour of the (earthquake) and showed his power with them. In the month of Iyar on the day of YSRDH of the year 545 (May of the year 233).

3 Cf. Object Catalogue, n° 31.

- from Michalowski (1966:114-115)

- Calcaire gris, dur

- Autel du dieu anonyme. Inscription sur la corniche de la face de l’autel en trois lignes légèrement incisée. L’angle de la moulure supérieure avec l’ex- trémité droite des deux premières lignes de l’inscription est brisé3.

- Trouvée près de la construction devant le Temple des Enseignes.

Texte :

1 (L BRYK) S MH L‘ (LM’) TYMRSW ER NBWZ’ W S LM LT BR NBWMR

2 .WZ PNWN MN S‘T’ DRGZ’ W ‘BD ‘MHWN GBWRT’BYR(H)

3 ’YR YWM YSgH’ SNT DXXXXV

Traduction:

A celui dont le nom est béni à jamais. Taimarsô fils de Nbôzâ et Salamal-lath fils de Nebômar ... et les a libérés de l’heure du tremblement (de terre) et a montré sa puissance avec eux. Au mois de Iyar le jour de YSRDH, de l’année 545 (mai de l’année 233).

3 Cf. Catalogue des objets, n° 31.

Palmyra (modern Tadmur, Syria), an oasis town, was a major trading hub of the Nabatean empire along the Silk Road in Antiquity. The wealth of the city is evidenced by its archaeological heritage of temples, public buildings, monuments, public spaces, and a large necropolis. Its heyday lasted from about 100 BC until Emperor Aurelian sacked it in 274 AD (Sommer 2018). A pilot archaeoseismological study included the temple of Bel, the colonnaded main street of the town, and some funeral towers. We found arches with dropped voussoirs, rotated blocks, in-plane extension gaps (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5), and axial fractures, indicating former earthquake(s) of intensity I = VII and stronger (Kázmér and Gaidzik 2021). Being very far from the plate boundary (> 180 km from the Dead Sea Fault), probably a local fault within the SW-NE Palmyra tectonic zone caused destruction.

Intagliata (2018:103) reported on seismic damage throughout Palmyra in the late 6th/early 7th century CE.

At the end of the 6th or the beginning of the following century, an earthquake wrought considerable damage to the city. Levels of destruction have been recorded in

- Praetorium in the Camp of Diocletian (Kowalski 1994, 57)

- House F in the City Centre (Gawlikowski 1992a, 74)

- Western stretch of the Great Colonnade (al-As`ad and Stuniowski 1989, 206)

- Church I (Gawlikowski 1992, 74)

- Sanctuary of Baalshamin (Intagliata 2017a)

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 48 - Camp of Diocletian

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48

Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 26)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 18 - Praetorium in Camp of Diocletian

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 28).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 52 - Plan of the Sanctuary of Allath

(Camp of Diocletian) from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52

Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 27)

Intagliata (2018)

It is surmised that the Temple of Allat was devastated in 272 CE as a consequence of the defeat of Queen Zenobia's forces by the Romans. The Temple of Allat was likely fully destroyed shortly after 380 CE when emperor Theodosius issued repeated edicts against paganism (Kowalski, 1994:48). Kowalski (1994:48) suggests that the Praetorium was built shortly after 380 CE; constructed in the southeast corner of the temenos of the Temple's ruins (Kowalski, 1994:40). Kowalski (1994:57) states that the Praetorium

must have been destroyed by an earthquake, as suggested by the way it was later rebuiltnoting that

Columns A and F must have fallen down as they were replaced by wallsand

drums were placed in the south-western corner of the peristyle and used as benches.Post earthquake rebuilding was dated to the late 6th/early 7th century as described by Kowalski (1994:57-58):

Shortly afterwards, the house was reconstructed. It might be dated by a coin found in the wall closing the rear court from the north (SU 183). The coins probably an Umayyad imitation of a Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine follis struck either in Antioch or in Antaradus. Those "Arab-Byzantine" coins are dated either to 640-670 by Cecile Morrisson (Morrłsson 1992: 312) or to the 680’s by Michael Bates (Bates 1992: 321). The coin does not mean however, that the whole building was restored at that time. No doubt, it dates the enclosure of the rear court. The house itself might have been restored a little earlier. I believe that the restored building had purely civilian character so it could be occupied only after the army had gone away. I do not think that any Roman military unit could be stationed in Palmyra while the whole of Syria was under Persian rule (A.D. 614-628). It seems, however, that the Romans returned for a short period during the reign of Heraclius, as coins of that emperor might date final abandonment of the horreum (oral communication by M. Gawlikowski). When the army had left the camp, probably squatters moved in. It was not a peaceful time, as in the neighborhood someone buried a treasure of gold coins and jewels (Michałowski 1962: 222)17.Intagliata (2018:36) also discussed seismic damage and rebuilding of the Praetorium.Footnote17 The treasure containing 27 coins and 6 other gold pieces was found west of the groma and was dated by the latest coin to the rule of Constans II (A.D. 646-651).

After a disastrous earthquake the building was reconstructed. The renovation, or part of it, is dated by a coin that is probably an imitation of a follis minted at the time of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine found in the partition wall closing the rear court of the structure. At that time, the second floor was abandoned and the inner arrangement of the building underwent significant transformations. These include the subdivisions of the courtyard into smaller units, the construction of a domed room blocking the secondary entrance, and the renovation of the main entrance. Further changes include the installation of tananTr (sing. tannar), pipes, and water basins, the reflooring of some rooms, and the blocking of passageways. Similar transformations occurred also later, before a further earthquake destroyed the house in the 11th century. Since then, the building remained abandoned until modern times, when two walls, probably garden fences, were constructed on top of its ruins (Kowalski 1994; 1995; 1999; for summary descriptions see, Sodini 1997, 486-7; Baldini Lippolis 2001, 245).Intagliata (2018:78) reports seismic damage in the Sanctuary of Allath/the Praetorium

Changes occurred in the plan of the compound at the end of the 4th—beginning of the 5th century, when a private residential building was installed in the southeast corner of the sanctuary (Kowalski 1994; 1995; 1999). The structure consists of a central peristyled courtyard and two wings of rooms to the west and south. To the south it has direct access to a 4th century barrack block (see, Chapter 3). A fragment of the cult statue of Athena was found included in the western wall of one of its rooms in the western wing. The connection with a nearby barrack block and the presence of a peristyled courtyard has inclined Kowalski to regard the building as the Praetorium, the residence of the commander of the Legio I Illyricorum (Kowalski 1994, 52-3). The building appears to have been destroyed by an earthquake at the end of the 6th or beginning of the 7th century, refurbished twice (in the 7th—8th and in the 9th centuries), and abandoned after an earthquake that occurred in the 11th century.

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 23 - Plans of House F

in different phases from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 23

Figure 23

House F. Roman (top) and post-Roman (bottom) phases

(Gawlikowski 1996, figs 1–2)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 1 - Original (Roman)

Plan of House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The original phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a) - Fig. 2 - Final Plan of

House F from Gawlikowski (1992a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The final phase of the house

Gawlikowski (1992a)

Gawlikowski (1992a) reported on excavations of what Intagliata (2018:38-39) would later label as Building F. Initial construction of the house was

safely dated to the second half of the second century ADand remained in use

until the 9th century, when it was finally abandoned along with the whole area of downtown Palmyra, as the finds from Diocletian's Camp also suggest(Gawlikowski, 1992a:68). Gawlikowski (1992a:71) reported on archaeoseismic evidence as follows:

According to the evidence collected this year, the house survived in its more or less initial stage until the late 6th century, when an earthquake seriously damaged some walls, including the partition wall between the two main areas of the house and their twin entrance. As a result, both doors were blocked, the former guest entrance through loc. 17 became dependent on the other courtyard and, as both sets of stairs in the family wing were dismantled, the upper floor seems to have disappeared from use in this part of the building.

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 31 - Plan and front

view of Church I from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 31

Figure 31

Church I

(Gawlikowski 1990a, 41, fig. 2)

Intagliata (2018)

Intagliata (2018:54) reports that Church I

seems to have been abandoned in the 7th centuryand

its walls are believed to have collapsed two centuries later (Gawlikowski 1990a, 40–3; 1991a, 89–90; 1991b, 399–410; 1992a, 73–6; 1993, 155–6; 1994, 141–2; 1998, 209–10; 2001, 123–5; Duval 1992; Westphalen 2009, 160).

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 19 - Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Grande Cour and Bâtiment Nord, Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

(drawn by the author after plans at the Fonds d’Archives Paul Collart, Université de Lausanne).

Intagliata (2018)

Intagliata (2018:35) reports on seismic damage in domestic housing built in the former Sanctuary of Baalshamin

Another house, Building B, also known as 'Quartier Arabe' in the final report of the excavations, occupies the northern portico of the Grande Cour (Fig. 20). Like the others, it consists of a large open courtyard. To the west of it was a row of rooms, communicating with the open courtyard via a `vestibule'. The habitable surface of the building would have probably occupied also the rooms of the pre-existing Batiment Nord, located immediately to the south of the Hotel Zenobia.

Building B was believed by Collart [Collart and Vicari 1969] to have been built sometime between the 4th and the 6th century, to have been obliterated by an earthquake in the 10th century, and to have been restored in the 12th century. These conclusions, however, have never received general consensus by modern scholarship. A re-examination of the original documentation of the excavations has recently advanced the hypothesis that the building underwent destruction in the 6th century and was reconstructed in Umayyad time or slightly later. Numismatic evidence, pottery, and the epigraphic record seems to confirm this development. Although very little data remains to speculate on the chronology of Buildings A and C, it is plausible that these went through the same phases of constructions, destructions, and reconstructions (Intagliata 2017a).

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 24 - Plan of Peristyle

Building from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Peristyle Building

(Grassi and al-Asʿad 2013, 125, fig. 5)

Intagliata (2018)

Intagliata (2018:42-43) discussed the archaeoseismic evidence from the same earthquake in the Peristyle Building in the Southwest Quarter.

Similar changes have been documented in the Peristyle Building in the southwest quarter (Fig. 24). Room B was paved with a red mortar floor. Rooms H and I, the largest compartments so far discovered, were subdivided in smaller units by means of partition walls.

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018)

Intagliata (2018:42-43) discussed the archaeoseismic evidence from the same earthquake in houses in the Via Praetoria of the Camp of Diocletian.

Houses in the Via Praetoria of the Camp of Diocletian shows similar features: jars installed immediately below walking levels, large mortars made with reused drums or capitals of columns, wells within the habitations, all lead to the conclusion that these small-scale changes were not exceptional occurrences in the city.

Palmyra (modern Tadmur, Syria), an oasis town, was a major trading hub of the Nabatean empire along the Silk Road in Antiquity. The wealth of the city is evidenced by its archaeological heritage of temples, public buildings, monuments, public spaces, and a large necropolis. Its heyday lasted from about 100 BC until Emperor Aurelian sacked it in 274 AD (Sommer 2018). A pilot archaeoseismological study included the temple of Bel, the colonnaded main street of the town, and some funeral towers. We found arches with dropped voussoirs, rotated blocks, in-plane extension gaps (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5), and axial fractures, indicating former earthquake(s) of intensity I = VII and stronger (Kázmér and Gaidzik 2021). Being very far from the plate boundary (> 180 km from the Dead Sea Fault), probably a local fault within the SW-NE Palmyra tectonic zone caused destruction.

Intagliata (2018:27) reports that water pipes

are believed to have been laid in Umayyad times, but were destroyed after a disastrous earthquake and

then replaced in the ʿAbbāsid era (al-Asʿad and Stępniowski 1989, 209–10;

Juchniewicz and Żuchowska 2012, 70).

Juchniewicz and Żuchowska (2012:70) report the following:

Excavation in the Camp of Diocletian, in the area of Water Gate revealed pipeline which is dated by Barański to the Abbasid Period ( Baranski, 1997, 9-10). This pipeline, as well as the earlier one dated to Omayyad Period, is clearly visible in the Great Colonnade, running along the Omayyad suq (al-Asʿad and Stępniowski 1989, 209–10). The Omayyad pipeline was replaced by the later one probably after earthquake. Some of the monumental architraves from the Great Colonnade fell down and destroyed the Omayyad conduits.Gawlikowski (1994:141) suggests that an earthquake struck the Basilica around 800 CE.

SOUNDINGS AROUND THE BASILICA

This important building, excavated in 1989 and later, has already become a tourist attraction, being the only major monument cleared between the Tetrapylon and the Funerary Temple. A church in its latest stage, it was abandoned about AD 600, before its walls finally collapsed some two centuries later, apparently toppled by an earthquake.

Palmyra (modern Tadmur, Syria), an oasis town, was a major trading hub of the Nabatean empire along the Silk Road in Antiquity. The wealth of the city is evidenced by its archaeological heritage of temples, public buildings, monuments, public spaces, and a large necropolis. Its heyday lasted from about 100 BC until Emperor Aurelian sacked it in 274 AD (Sommer 2018). A pilot archaeoseismological study included the temple of Bel, the colonnaded main street of the town, and some funeral towers. We found arches with dropped voussoirs, rotated blocks, in-plane extension gaps (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5), and axial fractures, indicating former earthquake(s) of intensity I = VII and stronger (Kázmér and Gaidzik 2021). Being very far from the plate boundary (> 180 km from the Dead Sea Fault), probably a local fault within the SW-NE Palmyra tectonic zone caused destruction.

- Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 2 - Annotated plan

of Palmyra from Intagliata (2018) (magnified)

Figure 2

Plan of Palmyra

- Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea

- Sanctuary of Bēl

- Great Colonnade

- Suburban Market

- Byzantine Cemetery

- Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade

- Church

- Baths of Diocletian

- Theatre

- Annexe of the Agora

- Agora

- Sanctuary of Arṣū

- Congregational Mosque

- Church

- Tetrapylon

- Sanctuary of Baalshamīn

- Umayyad Sūq

- Church II

- Church III

- Church IV

- House F

- Church I

- Bellerophon Hall

- Church

- Peristyle Building

- Transverse Colonnade

- Camp of Diocletian

- Sanctuary of Allāth

- Building [Q281]

- Efqa spring

- Western Acqueduct

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 48 - Camp of Diocletian

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48

Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 26)

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 18 - Praetorium in Camp of Diocletian

from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 28).

Intagliata (2018) - Fig. 52 - Plan of the Sanctuary of Allath

(Camp of Diocletian) from Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52

Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian

(Kowalski 1994, pl. 27)

Intagliata (2018)

Kowalski (1994:59) suggests that the House rebuilt from the Praetorium on top of the Temple of Allat was destroyed by an earthquake in the 11th century CE.

The house was abandoned, maybe just like most of that area in the ninth century (Gawlikowski 1992: 68). The main entrance was walled up. The house remained unoccupied until it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1042 AD (Ambraseys 1969-1971:95)20. The ruin was buried in the earth.Footnote20 This earthquake is dated to the tenth century A.D. by M.A.R. Colledge (Colledge 1976: 22). It is also mentioned by Ibn Taghri birdi in his chronicle An-Nugum az-Zahira V, p. 35 and dated to the 434th year of the Hegira, i.e. A.D. 1042.

Ambraseys (2009)'s entry for an earthquake in 1042 CE is shown below in References. Guidoboni and Comastri (2005)'s entry for this earthquake is very similar.

AD 1042 Tadmur

An earthquake caused great loss of life in Tadmur in

Syria. It is said that Baalbek was also shaken.

This information is given by a single source,

which does not comment on the effects on Baalbek,

or specify whether Baalbek was shaken by a different

earthquake. It is likely that

the Tadmur earthquake was felt only at Baalbek.

Al-Suyuti (writing in the sixteenth century)

records this event as happening in the same year as

an earthquake in Tabriz. He does not comment on the

effects on Baalbek, but, since the two cities are 250 km

apart, if Baalbek was not shaken by a different earthquake,

it is likely that the Tadmur earthquake was felt

there only.

‘. . . in the year 434 [21 August 1042 to 9 August 1043], . . . an earthquake occurred at Tadmur and at Ba’albek: most of the population of Tadmur died under the ruins.’ (al-Suyuti Kashf 56/18).

Palmyra (modern Tadmur, Syria), an oasis town, was a major trading hub of the Nabatean empire along the Silk Road in Antiquity. The wealth of the city is evidenced by its archaeological heritage of temples, public buildings, monuments, public spaces, and a large necropolis. Its heyday lasted from about 100 BC until Emperor Aurelian sacked it in 274 AD (Sommer 2018). A pilot archaeoseismological study included the temple of Bel, the colonnaded main street of the town, and some funeral towers. We found arches with dropped voussoirs, rotated blocks, in-plane extension gaps (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5), and axial fractures, indicating former earthquake(s) of intensity I = VII and stronger (Kázmér and Gaidzik 2021). Being very far from the plate boundary (> 180 km from the Dead Sea Fault), probably a local fault within the SW-NE Palmyra tectonic zone caused destruction.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Palmyra (aka Tadmur) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fallen columns | Praetorium

Figure 18

Figure 18Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation (Kowalski 1994, pl. 28). Intagliata (2018) |

Columns A and F must have fallen down as they were replaced by walls- Kowalski (1994:57) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | House F

Figure 2

Figure 2The final phase of the house Gawlikowski (1992a) |

House F is reported as having been destroyed which suggests collapsed walls |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Basilica | The walls of the Basilica (build around 600 CE) finally collapsed some two centuries later, apparently toppled by an earthquake.(Gawlikowski, 1994:141) |

|

| Broken pipes | Water Pipes destroyed (Juchniewicz and Żuchowska, 2012:70) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| House Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Domestic Structure built in the Praetorium of the Sanctuary of Allath

Plan of Palmyra

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010). Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian (Kowalski 1994, pl. 27) Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks (Kowalski 1994, pl. 26) Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation (Kowalski 1994, pl. 28). Intagliata (2018) |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Palmyra (aka Tadmur) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fallen columns | Praetorium

Figure 18

Figure 18Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation (Kowalski 1994, pl. 28). Intagliata (2018) |

Columns A and F must have fallen down as they were replaced by walls- Kowalski (1994:57) |

V+ or VIII+ | |

| Collapsed Walls | House F

Figure 2

Figure 2The final phase of the house Gawlikowski (1992a) |

House F is reported as having been destroyed which suggests collapsed walls | VIII+ |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Basilica | The walls of the Basilica (build around 600 CE) finally collapsed some two centuries later, apparently toppled by an earthquake.(Gawlikowski, 1994:141) |

VIII+ | |

| Broken pipes | Water Pipes destroyed (Juchniewicz and Żuchowska, 2012:70) | ? |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Domestic Structure built in the Praetorium of the Sanctuary of Allath

Plan of Palmyra

(redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010). Intagliata (2018)

Figure 52

Figure 52Sanctuary of Allāth, Late Antique phase, Camp of Diocletian (Kowalski 1994, pl. 27) Intagliata (2018)

Figure 48

Figure 48Camp of Diocletian. Letters indicate barrack blocks (Kowalski 1994, pl. 26) Intagliata (2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18Camp of Diocletian, Praetorium, final stage of occupation (Kowalski 1994, pl. 28). Intagliata (2018) |

|

VIII+ |

al-Asʿad, K. and Stępniowski, F. M. 1989. ‘The Umayyad Suq in

Palmyra’. Damaszener Mitteilungen 4, 205–223.

Ambraseys, N.N. (1969-1971) Documentation on historical earthquakes in the Near East, UNESCO Research Report 1969-1971, diss. (unpublished) Imperial College of Science and

Technology, Civil Engineering Dept., London

Andrade, N. and R. Raja (2022). "Alternative Urban Economies: The Case of Roman Palmyra." Journal of Urban Archaeology 6: 31-47.

Baldini Lippolis, I. 2001. Ladomus tardoantica. Forme e rappresentazioni dello spazio domestico nel citta del Mediterraneo. Imola: Bologna University Press.

Barański, M., 1997 The Western Aqueduct in Palmyra, Studia Palmyreńskie X, 7 – 17

Browning, I. (1979), Palmyra, London

Collart, P. and Vicari, J. 1969. Le Sanctuaire de Baalshamin à Palmyre: Topographie et architecture. Rome: Institut Suisse de Rome.

Colledge, M. A. R. (1976). The Art of Palmyra. Thames and Hudson.

Gawlikowski, M. (2008). Palmyra in Early Islamic Times. Rahden, M. Leidorf.

Gawlikowski, M. 1992a `Palmyra 1991'. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 3, 68-76.

Gawlikowski, M. 1992b. Palmyre 1981-1987'. Etudes et Travaux 16, 325-335.

Gawlikowski, M. (1994). PALMYRA. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean PCMA.

Genequand, D. (2008). "An Early Islamic Mosque in Palmyra." Levant 40: 3-15.

Intagliata, E. E. (2018). Palmyra after Zenobia AD 273-750:

An Archaeological and Historical Reappraisal, Oxbow Books.

Intagliata, E. E. 2017a. `The post-Roman occupation of the northern

courtyard of the Sanctuary of Baalshamin in Palmyra; A reassessment

of the evidence based on the documents in the Fonds d'Archives Paul Collart,

University de Lausanne'. Zeitschriftfiir Orientarchdologie 9,180-199.

Juchniewicz, K. and Żuchowska, M. 2012. ‘Water supply in

Palmyra, a chronological approach’. In M. Żuchowska (ed.).

The Archaeology of Water Supply. British Archaeological

Report S2414. Oxford: Archaeopress, 61–73.

Kázmér M, Gaidzik K (2021) Knowledge transfer or parallel invention—earthquake-resistant construction of the Baal temple in low-seismicity Palmyra (Syria)

. In: Costruire a fronte ai rischi ambientali nella societa antiche, Naples, 6–7 Sept 2019 (in press)

Kázmér, M., Major, B., Al-Tawalbeh, M., Gaidzik, K. (2024). Destructive Intraplate Earthquakes in Arabia—The Archaeoseismological Evidence

. In: Abd el-aal, A.ea.K., Al-Enezi, A., Karam, Q.E. (eds) Environmental Hazards in the Arabian Gulf Region. Advances in Natural

and Technological Hazards Research, vol 54. Springer, Cham..

Kowalski, S. P. 1994. `The praetorium of the camp of Diocletian in Palmyra'. Studia Palmireriskie 9, 39-70.

Kowalski, S. P. 1995. `The prefect's house in the late Roman legionary fortress in Palmyra'. Etudes et Travaux 17, 73-78.

Kowalski, S. P. 1999. `The prefect's house in the late Roman legionary fortress in Palmyra'. Etudes et Travaux 18, 161-172.

Michalowski, K. (1966), ‘Palmyra’, Fouilles Polonaises, Warsaw

Miranda, A. C. & Raja, R. (2022) 'Urban Religion in the Desert: The Case of Palmyra, An Anomalocivitas in the Roman Empire', Religion in the Roman Empire 8.2: 159-170

Rubina, Raja (2021). Pearl of the Desert: A History of Palmyra, Oxford University Press.

Rubina, Raja (ed.) (2024). The Oxford Handbook of Palmyra, Oxford University Press.

Rubina, Raja (2024) Palmyra: At the Crossroads of the Ancient World

, Journal of Archaeological Research

Sodini, J.-P. 1997. `Habitat de l'antiquite tardive (2)'. Topoi (Lyon) 7, 435-524.

Michal Gawlikowski's academia.edu page

Palmyra Exhibition at the Getty

360 degree (virtual reality) view of Palmyra at kaemena360.com

#NEWPALMYRA

Digital Collection at UC San Diego - has a digital reconstruction of the Temple of Bel

Abdul-Hak, Selim. "L'hypoge e de Ta'i a Palmyre. " Annates Archealogiques Arabes Syriennes 2 (1952): 193-251.

Bounni, Adrian, and Nassib Saliby. "Six nouveaux emplacements

fouilles a Palmyre, 1963-1964." Annates Archeohgiques Arabes Syriennes 15 (1965): 121-138.

Bounni, Adnan, et al. Le sanctuaire de Nabu a Palmyre. 1994 (catalog

only; printed text due 1997).

Bounni, Adnan, and Javier Teixidor, eds. Inventaire des inscriptions de

Palmyre. Vol. 12. Damascus, 1975.

Bounni, Adnan, and Khaled al-As'ad. Palmyra. 2d ed. Damascus, 1988.

Cantineau, Jean, ed, Inventaire des inscriptions de Palmyre. Vols. 1-9.

Beirut, 1930-1936.

Chabot, Jean-Baptiste. Choix d'inscription de Palmyre. Paris, 1922.

Collart, Paul, et al. Sanctuaire de Baalshamin a Palmyre. 6 vols. Neu -

chatel, 1969-1975.

Colledge, Malcolm A. R. The Art of Palmyra. Boulder, Colo., 1976.

Dunant, Christiane. Le sanctuaire de Baalshamin d Palmyre, vol. 3, Les

inscriptions. Rome , 1971.

Dunant, Christiane, and R. Fellman. Le sanctuaire de Baalshamin a Palmyre, vol. 6, KleinfundejObjets divers. Rome , 1975.

Fellman, R. Le sanctuaire de Baalshamin a Palmyre, vol, 5, Die Grabanlage. Rome , 1975,

Fevrier, James-Germain. Essai sur I'histoire politique et economique de

Palmyre. Paris, 1931.

Fevrier, James-Germain. La religion des, Palmyreniens. Paris, 1931.

Gawlikowski, Michal. "Di e polnischen Ausgrabungen in Palmyra,

1959-1967." Archaologischer Anzeiger (1968): 289-307.

Gawlikowski, Michal. Le temple palmyrenien: Etude d'epigraphic et de

topographic hiuoiique. Warsaw, 1973.

Gawlikowski, Michal. Recueil d'inscriptions palmyreniennes provenant de

fouilles syriennes et polonaises recentes a Palmyre. Memoires de 1'Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 16. Paris, 1974.

Ingholt, Harald. Studies over palmyresk skulptur. Copenhagen, 1928.

Ingholt, Harald. "Five Dated Tomb s from Palmyra." Berytus 2 (1935):

57-120.

Ingholt, Harald, et al. Recueil des tesseres de Palmyre. Bibliotheque Archeologique et Historique, vol. 58. Paris, 1955.

Michalowski, Kazmierz, et al. Palmyra, fouilles polonaises, 1959-1964.7

vols. Warsaw, 1960-1977.

Milik, J. T. Dedicaces faites par des dieux. Paris, 1972.

Rostovtzeff, Michael. Caravan Cities. Oxford, 1932.

Schlumberger, Daniel. La Palmyrene du nord-ouest. Paris, 1951.

Seyrig, Henri. "Ornament a palmyrena antiquiora." Syria 21 (1940):

277-328.

Seyrig, Henri, Robert Amy, and Ernest Will. Le temple de Bel it Palmyre.

2 vols. Bibliotheque Archeologique et Historique, vol. 83. Paris,

1968-1975.

Starcky, Jean, ed. Inventaire des inscriptions de Palmyre. Vol. 10. Beirut,

1949.

Starcky, Jean. Palmyre. Paris, 1952.

Starcky, Jean. "Palmyre. " In Supplement du Dictionnaire de la Bible, vol.

6, cols. 1066-1103. Paris, 1964.

Stark, Jiirgen K. Personal Names in Palmyrene Inscriptions. Oxford,

1971.

Teixidor, Javier, ed. Inventaire des inscriptions de Palmyre. Vol. ri . Beirut, 1965.

Teixidor, Javier. The Pantheon of Palmyra. Leiden, 1979.

Wiegand, Theodor. Palmyra: Ergebnisse der Expeditionen von 1902 und

1917. Berlin, 1932.

Wood, Robert. The Ruins of Palmyra, Otherwise Tedrnor, in the Desert.

London, 1753.

- from kaemena360.com - click link to open in a new tab