Beit Ras/Capitolias

Figure 3

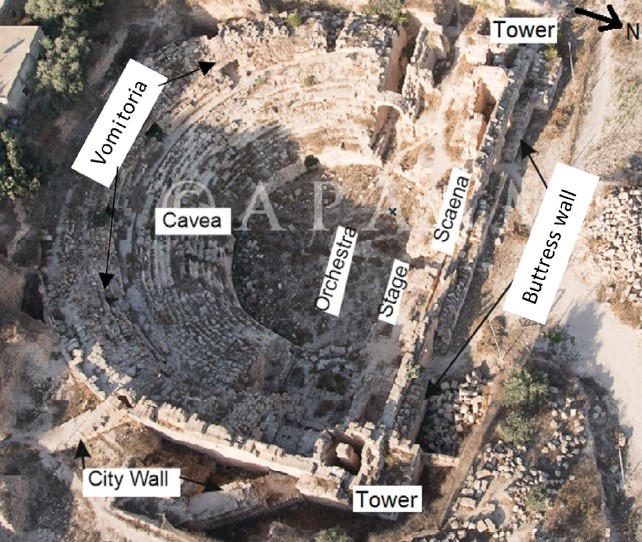

Figure 3An aerial photograph of the excavated Beit-Ras/ Capitolias theater.

Main parts of the theater are indicated. The city wall serves as a buttress in front of the scaena walls and the towers with staircases. The city wall connected with the eastern stage gate and vomitoria gate.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Photo taken on 1st October 2015 and photographed by Rebecca Elizabeth Banks (courtesy of Aerial Photographic Archive of Archaeology in the Middle East [APAAME], photo. APAAME_20151001_REB-0193. Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 3.3. East—west length 57 m).

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Beit Ras | Arabic | بييت راس |

| Capitolias | Ancient Greek | Καπιτωλιάς |

| Bet Reisha | Aramaic |

Capitolias, located by the modern town of Beit Ras in Jordan,

was one of the cities of the Decapolis. After the Muslim conquest, the town name was changed to

Beit Ras, similar to its original Aramaic name Bet Reisha.

(C. J. Lenzen in Meyers et al, 1997)

A hiatus in occupation at the site has yet been found, but a gradual decrease in size and change in use from

public space to private space seems to [have begun] as early as the tenth century CE.

(C. J. Lenzen in Meyers et al, 1997)

Beit Ras, a site located in northwestern Transjordan, 5 km (3 mi.) north of Irbid (map reference 680 X 105). Beit Ras was known as Capitolias from the first through the seventh centuries CE and was a member of the Decapolis confederation. Following Islamic hegemony over the region (c. 636 CE), the original Aramaic name, Beit Ras, was reinstituted. To date, no stratified deposits earlier than the first century CE have been excavated, although survey has provided some data earlier than the Roman period. These data, primarily pottery, were found on the ras, the highest point (about 600 m) in the immediate vicinity of the site, which may indicate the use of the ras as a lookout post prior to the formation of the city.

F. Kruse and H. L. Fleischer (1859), commenting on Ulrich J. Seetzen's travels and explorations (1806) were the first to identify Beit Ras with Capitolias. J. S. Buckingham (1816), Selah Merrill (1881), Gottlieb Schumacher (1890), Nelson Glueck (1951) and Siegfried Mittmann (1970) all visited the site and recorded certain of it's elements. G. Lankester Harding, director of antiquities for the area during the British Mandate, noted the site's importance. The Jordanian Department of Antiquities has conducted salvage excavations there, particularly in the necropolis, during the last thirty years. Systematic archaeological research was begun in 1983 with an intensive survey of the site and its immediate vicinity; excavation, begun in 1985, continues. Because the village is inhabited, research combines archaeological strategies with ethnohistorical research, oral history, and text interpretation, with the aim of elucidating all of the site's past.

In antiquity, the site was walled. The excavated portion of the wall, built in the second century CE of local limestone ashlar blocks, consists of three gates that face north. The gates were altered in the following five centuries, perhaps because of seismiturbation. In the early eighth century CE, one gate was turned into a tower. A walled acropolis has been excavated on the ras, evidencing the same constructional techniques and alterations throughout the site's occupational periods as the city wall.

Two levels of a three-tiered marketplace, known from literary sources, has been excavated north of the main decumanus, known from the city's oral history. The upper level consists of nine vaults that face north, bounded by vaults that face east and west. The region's natural bedrock was used to construct the marketplace. The rear wall of the vaults is continuous. One vault is a Roman barrel vault; the others were periodically reconstructed throughout Beit Ras's history. The vaults' interior and exterior are covered by utilitarian tesselated pavements. Marble facing found inside the vaults suggests that the upper level of the marketplace was used for selling finished products. This second story evidences the same construction. The vaults were altered considerably in the thirteenth/fourteenth century.

The city's main church has been excavated across from the first level of the vaults. Built on the remains of an earlier Roman structure, this construction dates to the mid-fifth century. It is likely that it was turned into a mosque in the early eighth century. A three-tiered water installation (ablution pool?) was built against the juncture of the church's central and southern apses. The entire area of the vaults and church remained public space until the tenth century CE, when the space was used for domestic and minor industrial activities.

An intricate water system served the city from its inception in 97/98 CE and subsequentiy. The absence of springs in the vicinity made the city dependent on rainwater and water brought from a distance. Part of a low aqueduct system was surveyed west of the city, outside the city wall. Inside the city, a well-engineered channel run-off system cut into the bedrock debouched into large cisterns. A reservoir was built on the south side of the city and periodically refurbished throughout the city's history.

The archaeological research to date indicates that Beit Ras/Capitolias was a planned Roman city, probably established for military reasons, and that it flourished in the period between the first and tenth centuries. Excavation has yielded quantities of pottery comparable to that at other Decapolis cities. No hiatus in occupation at the site has yet been found, but a gradual decrease in size and change in use from public space to private space seems to begin as early as the tenth century.

- Fig. 2 Town Plan from

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 2

Figure 2

City plan of Capitolias/Beit-Ras (modified after Al-Shami, 2005).

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4 Major parts

of a Roman Theater from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation.

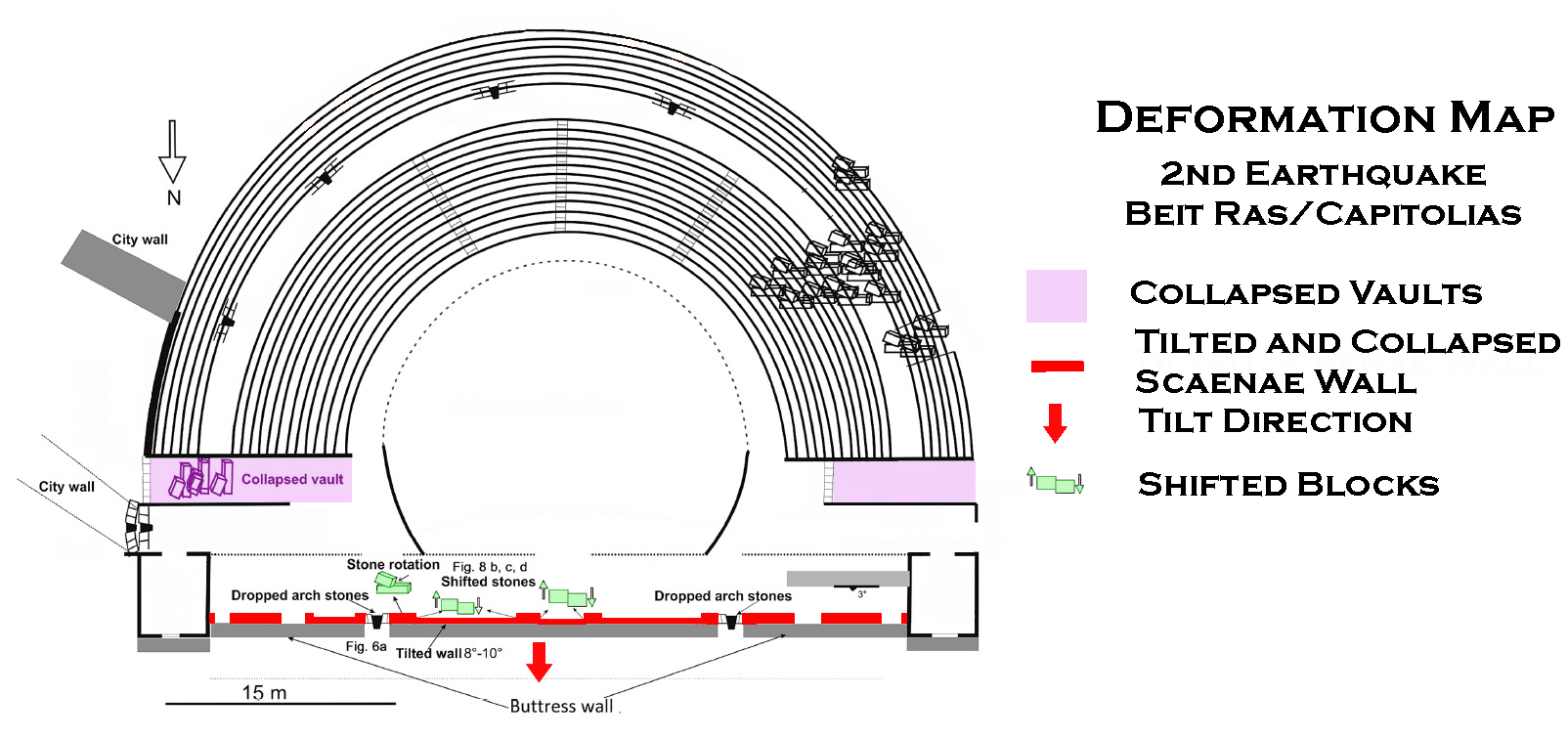

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5 Archaeoseismic Plan

of the Capitolias Theater from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4 Major parts

of a Roman Theater from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5 Archaeoseismic Plan

of the Capitolias Theater from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 1 PCMA project

Excavation area map from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Trenches excavated by the PCMA project (C) in relation to the Vaults area (A) and the Theater (B) (PCMA Beit Ras Project/R. Bieńkowski)

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 2 Map of area excavated

(sectors N, S, and SS) in 2015 and 2016 from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Sector investigated by the PCMA Project: top, results of the electrical resistivity survey (2014); bottom, extent of trenches excavated in 2015–2016 in relation to the results of the electrical resistivity survey (PCMA Beit Ras Project/interpretation of survey results J. Ordutowski; plan J. Ordutowski [2014] and M. Burdajewicz [2015–2016])

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 6 Detailed plan

of Sector S excavation from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

- light grey — floors

- hatched — mosaic floor of the winery

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016]

Mlynarczyk (2017)

- Fig. 1 PCMA project

Excavation area map from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Trenches excavated by the PCMA project (C) in relation to the Vaults area (A) and the Theater (B) (PCMA Beit Ras Project/R. Bieńkowski)

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 2 Map of area excavated

(sectors N, S, and SS) in 2015 and 2016 from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Sector investigated by the PCMA Project: top, results of the electrical resistivity survey (2014); bottom, extent of trenches excavated in 2015–2016 in relation to the results of the electrical resistivity survey (PCMA Beit Ras Project/interpretation of survey results J. Ordutowski; plan J. Ordutowski [2014] and M. Burdajewicz [2015–2016])

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 6 Detailed plan

of Sector S excavation from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

- light grey — floors

- hatched — mosaic floor of the winery

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016]

Mlynarczyk (2017)

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

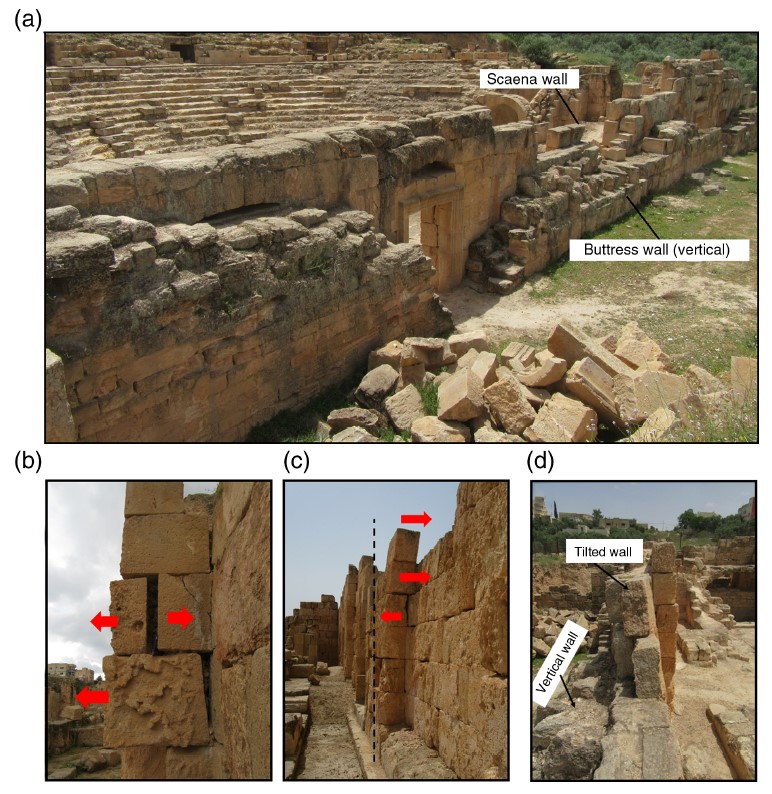

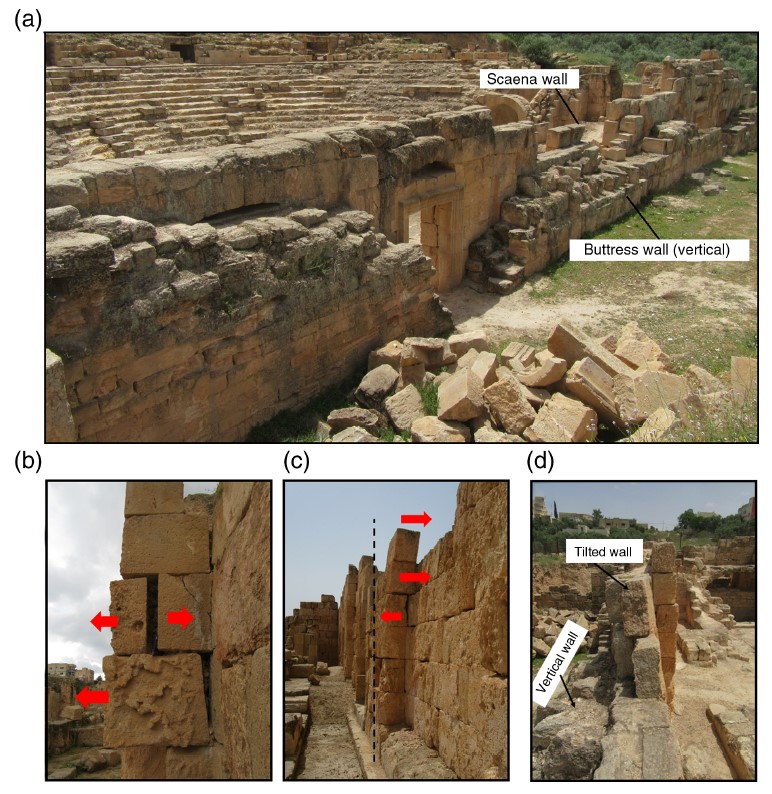

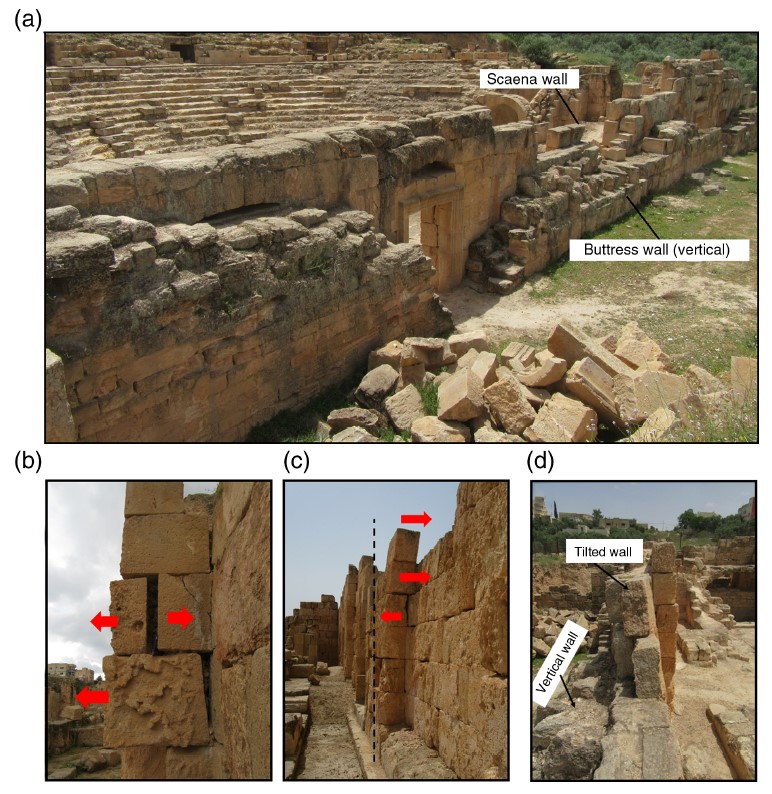

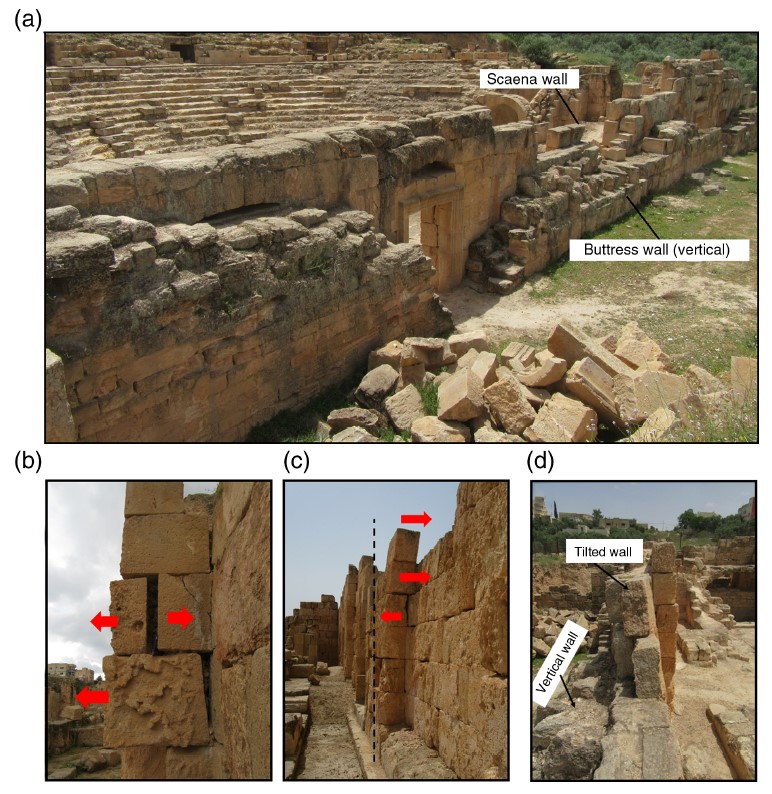

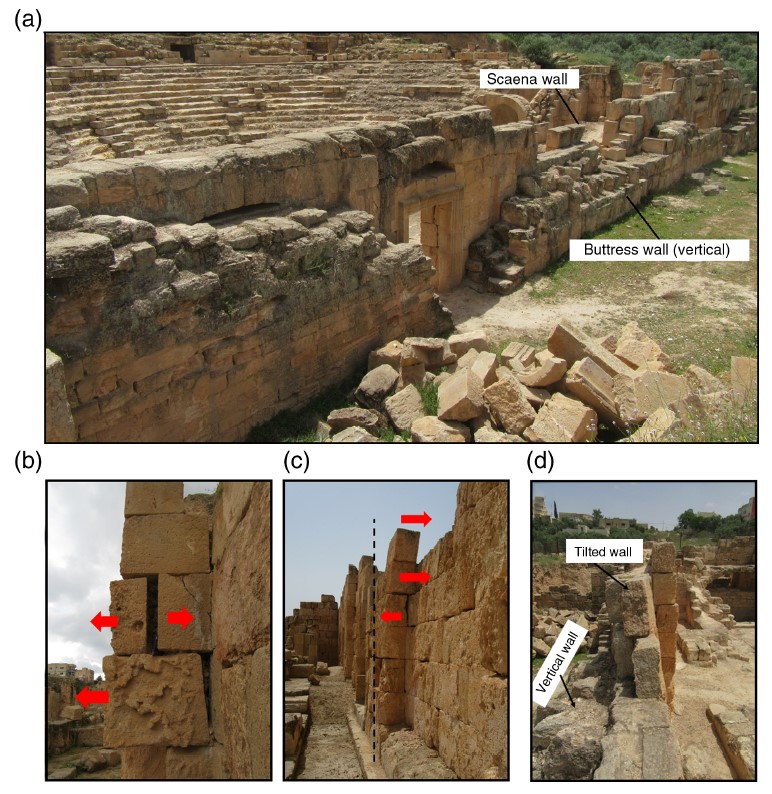

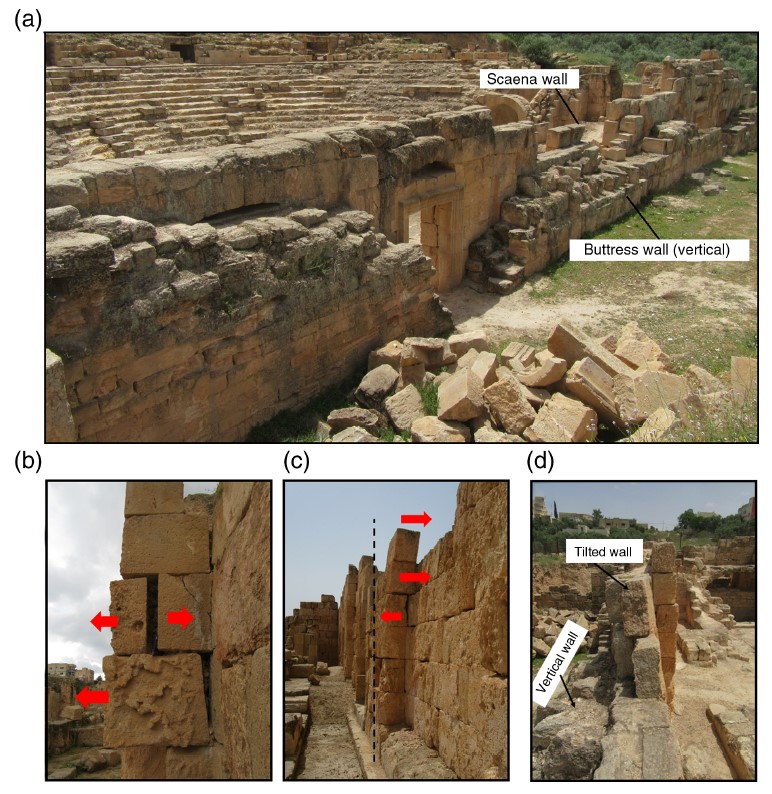

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) - Buttress Wall built

against tilting scaenae - photo by JW

Buttress Wall built against tilting scaenae

Buttress Wall built against tilting scaenae

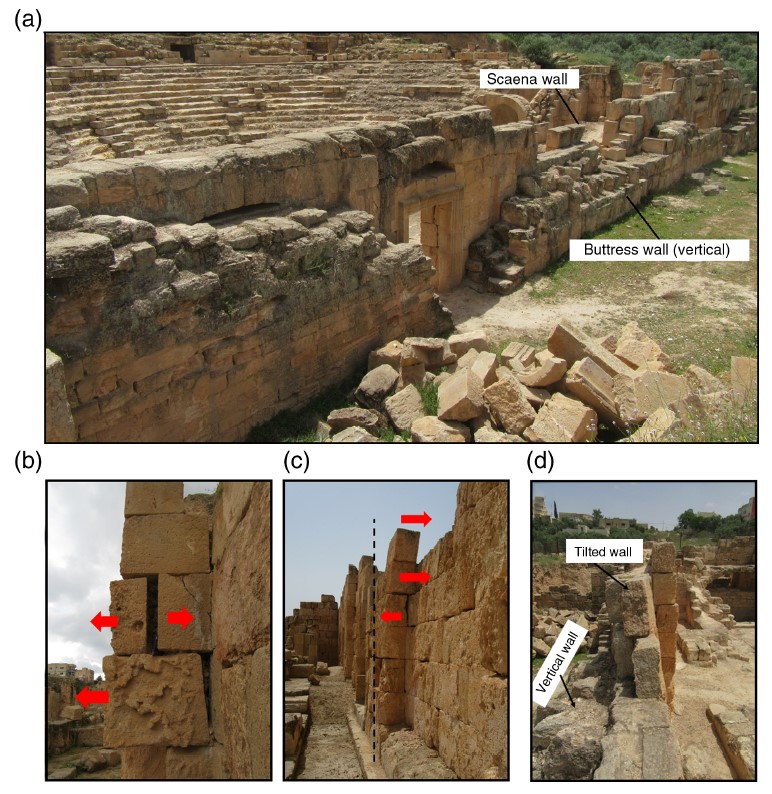

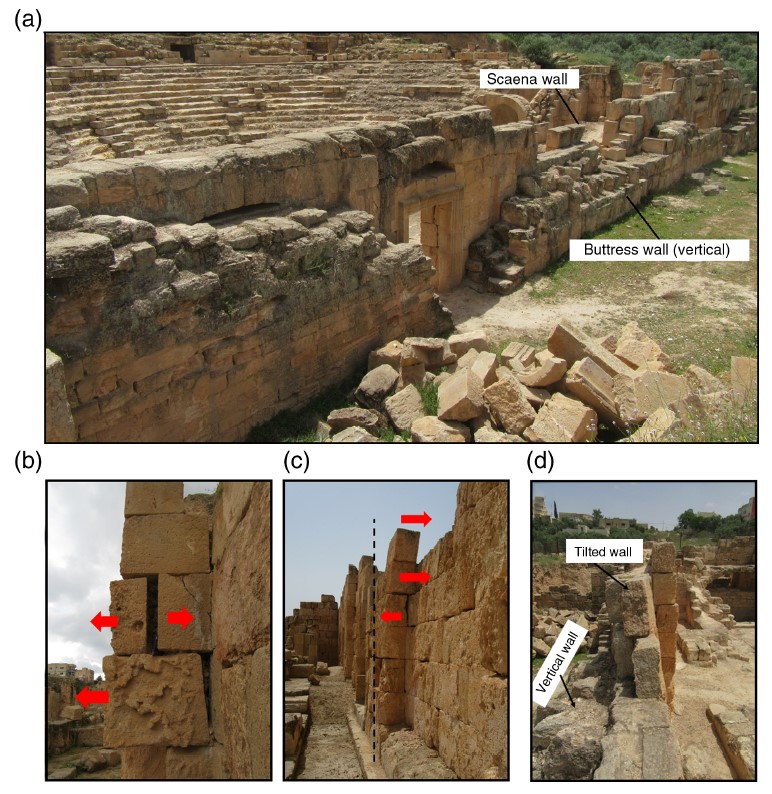

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Through-going crack

- photo by JW

Through-going crack

Through-going crack

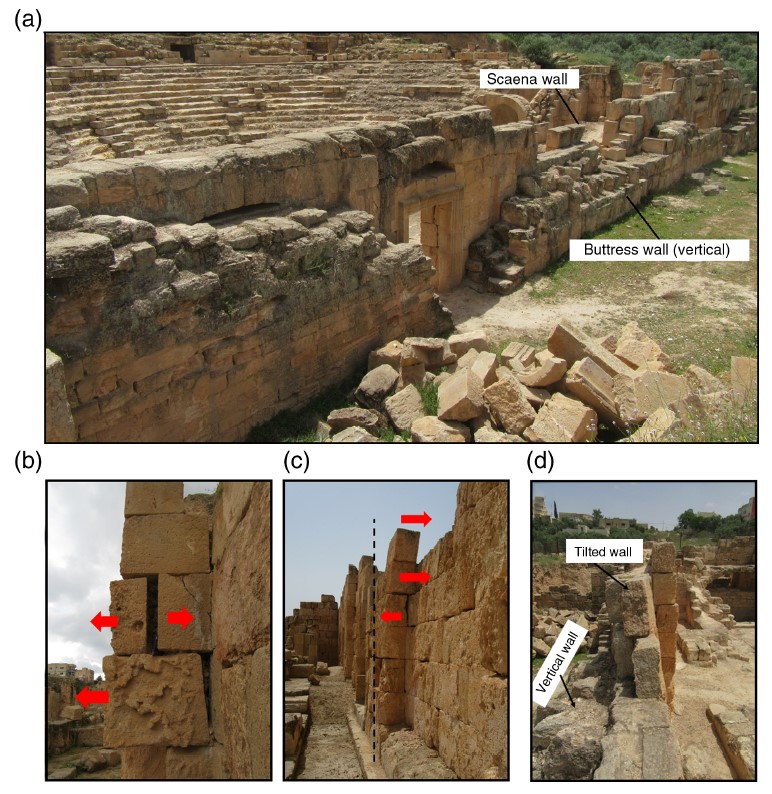

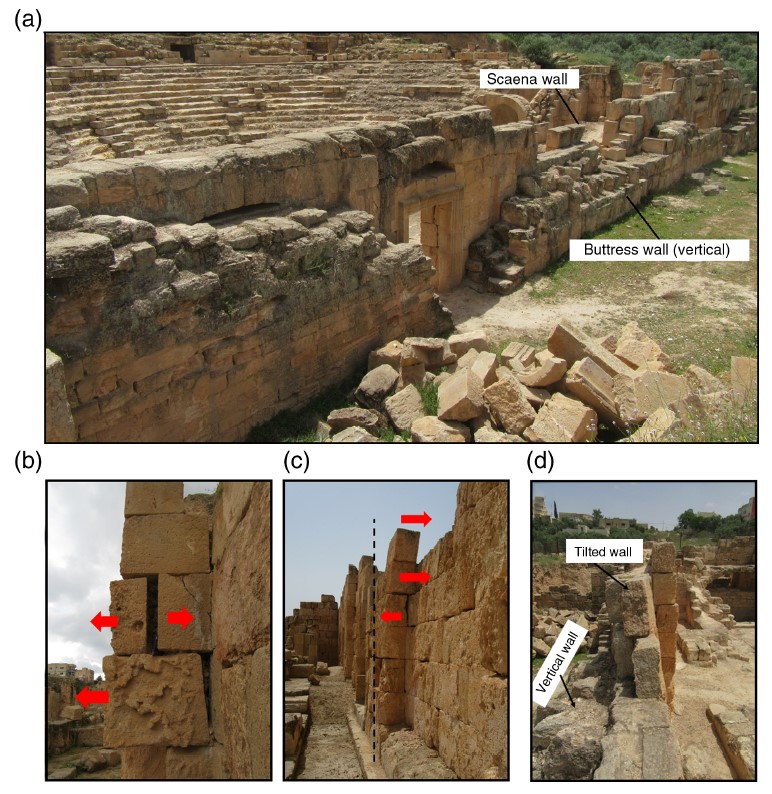

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced archstones

- photo by JW

Displaced archstones

Displaced archstones

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) - Buttress Wall built

against tilting scaenae - photo by JW

Buttress Wall built against tilting scaenae

Buttress Wall built against tilting scaenae

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Through-going crack

- photo by JW

Through-going crack

Through-going crack

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced archstones

- photo by JW

Displaced archstones

Displaced archstones

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

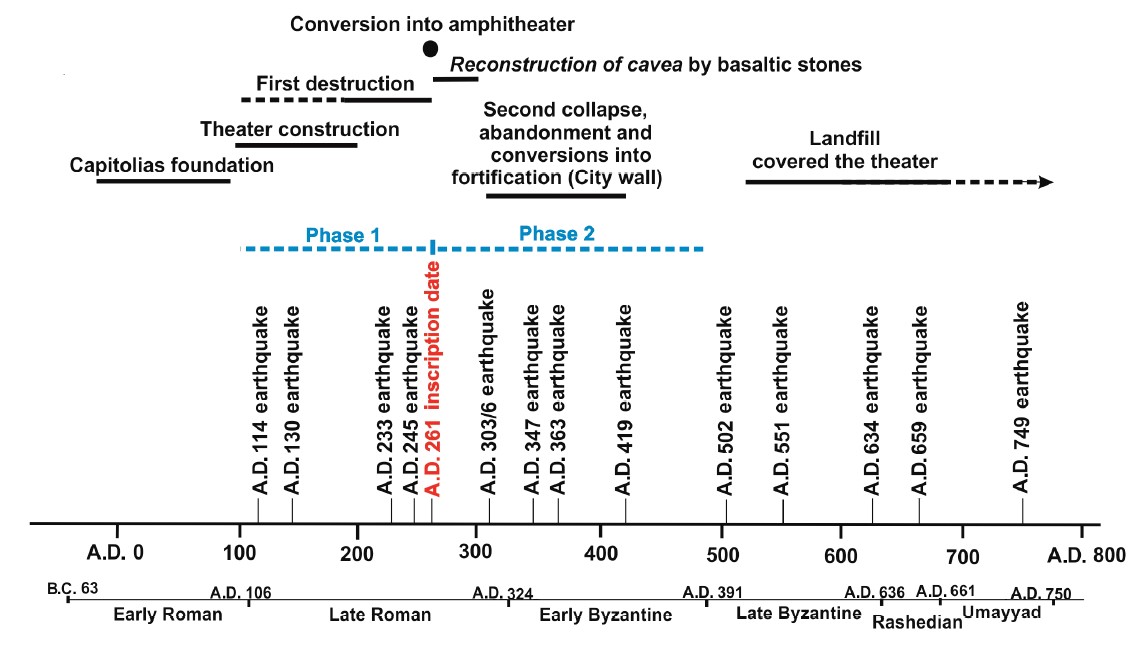

Figure 12

Figure 12Timeline of the main phases, the two main phases of major destruction, which could be earthquake events and the candidate earthquakes that affected Beit-Ras and surrounding region. Historical chronology of Jordan from Early Roman to Umayyad modified after Stager et al. (2000).

JW: 233 and 245 earthquake dates are spurious. 130 CE earthquake is questionable and may be a duplicate of the Incense Road Earthquake (listed on the timeline as 114 CE). This is why this archaeoseismic evidence represents an earthquake not reported in the historical record but discovered by archaeoseismic means.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

| Phase | Comments |

|---|---|

| The foundation of Capitolias and the construction of the theater |

|

| 1st damage and construction |

|

| Conversion of use |

|

| 2nd collapse and abandonment |

|

| 2nd restoration phase |

|

| The landfill |

|

- from Lenzen (2003)

| Phase | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| I | c. 1900 CE - present | |

| II | c. 1800-1900 CE | |

| III | c. 1500-1800 CE | |

| IV | c. 900-1500 CE | |

| V | c. 600-900 CE | |

| VI | c. 300-600 CE | |

| VII | foundation to c. 300 CE |

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) examined archeoseismic evidence in 2019 and 2020 at the theater of Capitolias. They documented archaeoseismic evidence from two earthquakes which appear to have damaged the structure - one before 260/261 CE and one after. The 260/261 CE dividing date is based on a dedicatory inscription found in a rebuilding phase where the eastern aditus maximus gate was walled up. There also appears to be archaeoseismic evidence for later earthquakes.

Earthquake Catalogs that reference earthquakes in 233 CE and 245 CE go back to

Willis (1928)

whose source was As-Soyuti. Although he later issued a correction,

Willis' (1928)

initial paper did not recognize that As-Soyuti provided Islamic AH (After Hejira) dates instead of Julian dates hence

Willis' (1928)

earthquake dates from As-Soyuti are off by ~622 years (too early). Later catalogers

copied these erroneous dates. Catalog entries going backwards illustrate this below :

Sbeinati et al (2005)

-

[019] 233 Damascus: VII.

Parametric catalogues

− Ben-Menahem (1979): 233 A.D., Ml= 6.3,damage in Damascus.

Seismological compilations

− Sieberg (1932): 233 A.D., there was an earthquake in Syria causing destruction of many houses at Damascus.

-

[020] 242-245 Antioch: VI-VII; Syria: VI-VII; Egypt: III; Iran: III.

Parametric catalogues

− Ben-Menahem (1979): 245, Ml= 7.5, near Antioch (Willis).

Seismological compilations

− Sieberg (1932): 242 or 245, a strong earthquake in Antioch and all over Syria. It was felt in Egypt and Iran.

- 233 Damage in Damask. ML = 6.3 Source: Sieberg (1932)

- 245 Near Antiochia. ML = 7.5 Source: Willis (1927)

- 233. Severe earthquake in Syria only destroys Damascus (Sehweres Erdbeben in Syrien nut Zerstiirungen in Damaskus)

- 220 Antioch; very destructive, lasted forty days Source: As-Soyuti

- 233 Damascus ; many buildings destroyed Source: As-Soyuti

- 242 Syria in general ; very violent and extended from Egypt to Persia Source: As-Soyuti

- 245 Antioch ; excessive, very widespread Source: As-Soyuti

- 220 Antiochia was destroyed by an earthquake, which lasted forty days.

- 224 An earthquake at Fergana, by which 15,000 persons perished.

- 225 An earthquake at Ahwaz for sixteen days ; it was also felt in Jebal.

- 233 At Damascus many persons were buried under their houses; the earthquake extended to Antiochia, Mesopotamia, and Mausil. It is supposed that 50,000 persons perished.

- 232 Several earthquakes, more particularly in the Maghrib and in Syria, where the walls of Damascus and Emessa were destroyed. It was felt at Antiochia and El-Awassim in Mesopotamia and Mausil.

- 233 On Thursday, the 11th of Rabi-al-Akhar, many buildings were destroyed at Damascus by an earthquake. note

- 234 At Herat, the houses were destroyed.

- 239 At Tiberias.

- 240 In the Maghrib, thirteen villages of Kairowan sunk.

- 242 In Shaban a very violent earthquake. At Tunis about 45,000 persons were buried under their houses; it extended also over Yemen, Khorasan, Fars, Syria, Bastam, Komm Kashan, Rai, el-Damaghan, Nishapur, Taberistan and Ispahan. The mountains fell down, and the earth opened so extensively that men could walk into it ; and in the village El-sud in Egypt, five stones fell from heaven. One stone fell on the tent of a Bedouin and set it on fire. The weight of these stones was ten rotles. In Yemen a hill covered with fields moved from its place and became the property of another tribe.

- 245 Earthquakes prevailed over the whole earth, and many towns and bridges were destroyed. At Antiochia a mountain fell into the sea, with 1005 houses. It had been covered with about ninety villages. The river disappeared one farsang's distance. Dreadful noises were heard at Tinnis. In Mecca all the springs disappeared. The earthquake extended over Rakka, Harran, Ras el-'Ain, Emessa, Damascus, Rokha, Tarsus, Massissa and Adina. On the shores of Syria, in Laodicea, mountains moved with their inhabitants, and when it had destroyed, El-son, it crossed the Euphrates, and was felt in Khorassan.

Note: Fourmilabs webpage converts between Islamic dates and Julian dates.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 25 June 2025

- from Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020)

The earliest identified seismic event damaged the ambulatorium, staircases, and arches, triggering reconstruction with lighter-colored chalk limestone. This phase is stratigraphically earlier than a wall that bears an inscription dated to 261 CE, indicating the repairs must have taken place before that date. The insertion of limestone ashlars to block and support the collapsed arch in the aditus maximus represents a localized stabilization strategy following this damage.

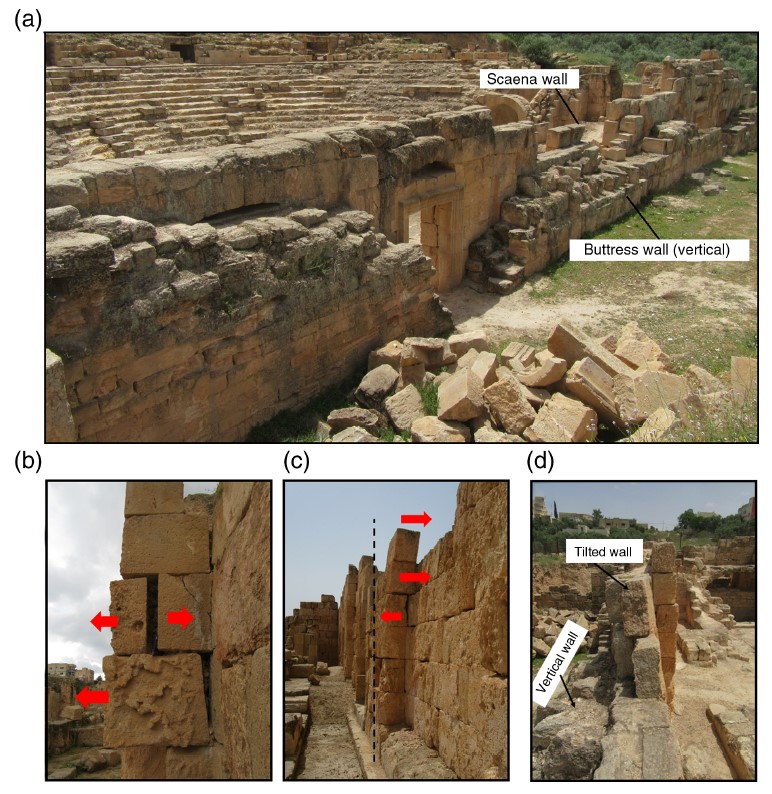

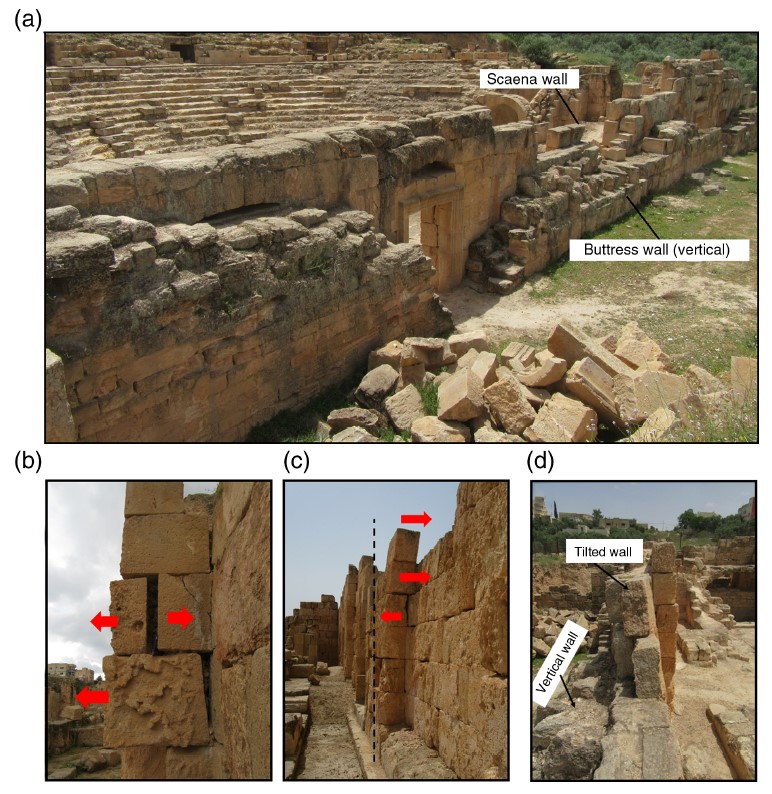

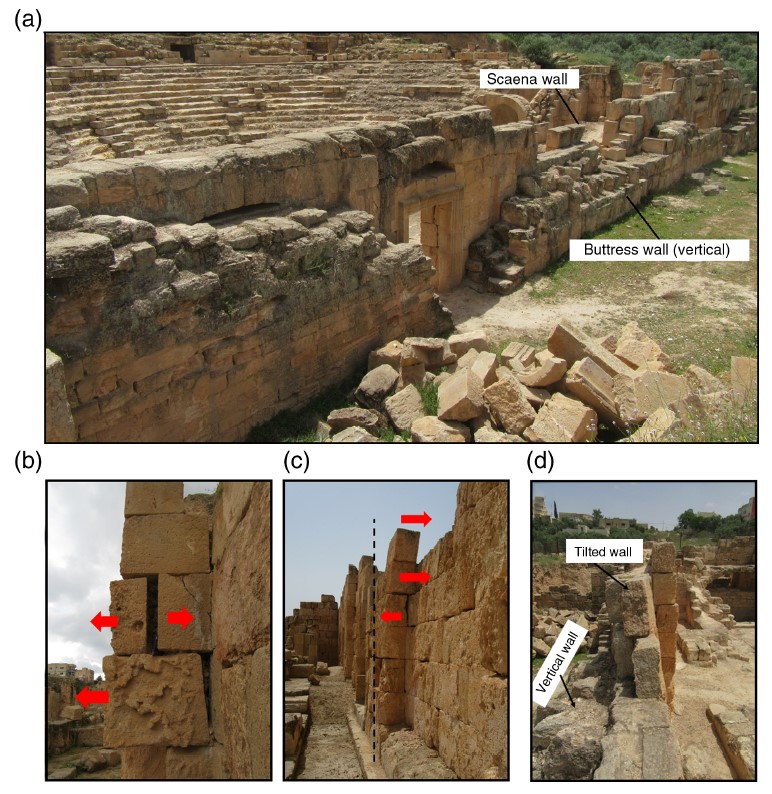

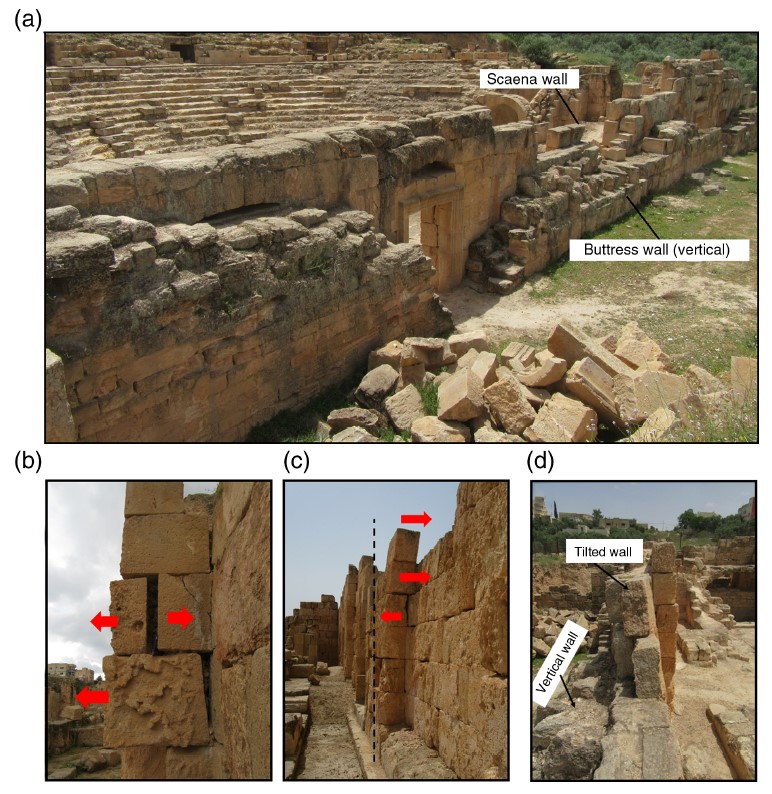

A second earthquake, likely postdating 261 CE and possibly associated with the 363 CE Cyril Quakes, caused additional structural failure. The scaenae tilted ~8° outward, and its upper two-thirds collapsed. Extensional cracks, fallen voussoirs, and dropped arches indicate widespread seismic impact. The vaulted corridor between the scaenae and the scaenae building [?] was destroyed, and several arches remained unrepaired after this event.

Later debris fills, containing tumbled blocks and arch fragments, suggest post-abandonment earthquakes during the mid to late first millennium CE. However, these are not stratigraphically associated with reconstruction layers and are instead sealed beneath later deposits.

The authors estimate shaking intensities of VIII–IX for the mid-third century event and as high as IX or more for the later collapse of the scaenae. These estimates are based on observed structural effects and comparison with the Earthquake Archaeological Effects scale.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 25 June 2025

- from Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020:12–13, fig. 9)

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

The eastern aditus maximus at the Beit-Ras/ Capitolias theatre preserves stratigraphic and structural evidence for multiple damage and repair phases likely related to earthquake activity. The original wall forming the gate passage was constructed from high-quality, dark phosphatic ashlars. This wall was later damaged, most likely by seismic shaking, prompting a reconstruction phase using lighter-colored chalk limestone blocks. An irregular joint between the dark and light stonework marks this repair boundary.

In a subsequent phase, three limestone ashlars were inserted horizontally to block and support the collapsed arch of the gate. These were positioned beneath the keystone and the springers of the former arch, effectively buttressing the weakened structure. This intervention likely postdates the initial damage and represents an effort to stabilize the gateway after structural failure, possibly caused by an earthquake.

At a later point, a basalt cube wall was constructed in the corridor behind an inscription-bearing wall. Because the inscription is dated to 261 CE, this later repair must have occurred after that date, indicating another phase of minor seismic damage and response. The differing materials, construction styles, and stratigraphic relationships reveal a sequence of damage, reconstruction, and localized stabilization associated with at least two distinct earthquakes—one prior to 261 CE and another after.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 25 June 2025

- from Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020)

The earliest identified seismic event damaged the ambulatorium, staircases, and arches, triggering reconstruction with lighter-colored chalk limestone. This phase is stratigraphically earlier than a wall that bears an inscription dated to 261 CE, indicating the repairs must have taken place before that date. The insertion of limestone ashlars to block and support the collapsed arch in the aditus maximus represents a localized stabilization strategy following this damage.

A second earthquake, likely postdating 261 CE and possibly associated with the 363 CE Cyril Quakes, caused additional structural failure. The scaenae tilted ~8° outward, and its upper two-thirds collapsed. Extensional cracks, fallen voussoirs, and dropped arches indicate widespread seismic impact. The vaulted corridor between the scaenae and the scaenae building [?] was destroyed, and several arches remained unrepaired after this event.

Later debris fills, containing tumbled blocks and arch fragments, suggest post-abandonment earthquakes during the mid to late first millennium CE. However, these are not stratigraphically associated with reconstruction layers and are instead sealed beneath later deposits.

The authors estimate shaking intensities of VIII–IX for the mid-third century event and as high as IX or more for the later collapse of the scaenae. These estimates are based on observed structural effects and comparison with the Earthquake Archaeological Effects scale.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 25 June 2025

- from Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020:12–13, fig. 9)

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 9 Multiple phase

construction at eastern orchestra gate Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

The eastern aditus maximus at the Beit-Ras/ Capitolias theatre preserves stratigraphic and structural evidence for multiple damage and repair phases likely related to earthquake activity. The original wall forming the gate passage was constructed from high-quality, dark phosphatic ashlars. This wall was later damaged, most likely by seismic shaking, prompting a reconstruction phase using lighter-colored chalk limestone blocks. An irregular joint between the dark and light stonework marks this repair boundary.

In a subsequent phase, three limestone ashlars were inserted horizontally to block and support the collapsed arch of the gate. These were positioned beneath the keystone and the springers of the former arch, effectively buttressing the weakened structure. This intervention likely postdates the initial damage and represents an effort to stabilize the gateway after structural failure, possibly caused by an earthquake.

At a later point, a basalt cube wall was constructed in the corridor behind an inscription-bearing wall. Because the inscription is dated to 261 CE, this later repair must have occurred after that date, indicating another phase of minor seismic damage and response. The differing materials, construction styles, and stratigraphic relationships reveal a sequence of damage, reconstruction, and localized stabilization associated with at least two distinct earthquakes—one prior to 261 CE and another after.

- Fig. 1 PCMA project

Excavation area map from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Trenches excavated by the PCMA project (C) in relation to the Vaults area (A) and the Theater (B) (PCMA Beit Ras Project/R. Bieńkowski)

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 2 Map of area excavated

(sectors N, S, and SS) in 2015 and 2016 from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Sector investigated by the PCMA Project: top, results of the electrical resistivity survey (2014); bottom, extent of trenches excavated in 2015–2016 in relation to the results of the electrical resistivity survey (PCMA Beit Ras Project/interpretation of survey results J. Ordutowski; plan J. Ordutowski [2014] and M. Burdajewicz [2015–2016])

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 6 Detailed plan

of Sector S excavation from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

- light grey — floors

- hatched — mosaic floor of the winery

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016]

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 10 Tumbled Blocks

from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Blocks tumbled from wall W K with part of floor F III above, view facing east (PCM/1 Belt Ras Project/photo J. Mlynarczyk)

Mlynarczyk (2017)

- Fig. 1 PCMA project

Excavation area map from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Trenches excavated by the PCMA project (C) in relation to the Vaults area (A) and the Theater (B) (PCMA Beit Ras Project/R. Bieńkowski)

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 2 Map of area excavated

(sectors N, S, and SS) in 2015 and 2016 from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Sector investigated by the PCMA Project: top, results of the electrical resistivity survey (2014); bottom, extent of trenches excavated in 2015–2016 in relation to the results of the electrical resistivity survey (PCMA Beit Ras Project/interpretation of survey results J. Ordutowski; plan J. Ordutowski [2014] and M. Burdajewicz [2015–2016])

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 6 Detailed plan

of Sector S excavation from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

- light grey — floors

- hatched — mosaic floor of the winery

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016]

Mlynarczyk (2017) - Fig. 10 Tumbled Blocks

from Mlynarczyk (2017)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Blocks tumbled from wall W K with part of floor F III above, view facing east (PCM/1 Belt Ras Project/photo J. Mlynarczyk)

Mlynarczyk (2017)

- from Chat GPT 5, 27 September 2025

- from Młynarczyk (2018)

In Area 1-S(W) Square 1(W), Floor F III was found resting directly upon quake-related debris composed of regular limestone blocks that had tumbled northward from Wall W V. These collapsed blocks lay on a compacted earthen floor (F IV) approximately 0.65 m below F III. Ceramic material sealed beneath F IV was uncontaminated and dated to the late Byzantine–Umayyad period, leading the excavator to attribute the collapse to the 749 CE earthquake.

Additional evidence of seismic damage was documented in Area 1-S, Square 9. Here, the space between Walls W II and W III was filled with ashlars that had fallen from the walls. Pottery within this destruction layer also indicated a mid-8th century date, although some intrusive Abbasid material was present. Crucially, no floor was found above the rubble, and the report notes that “the rubble was left in place without ascertaining the floor on which it rested.” This suggests that the area was abandoned following the earthquake and never reoccupied.

Further signs of earthquake damage were observed in the city’s northern defensive wall. Large concentrations of collapsed ashlars were found in the trench section, and the excavator concluded that the wall had been destroyed by the same earthquake. After this event, a north–south wall and a cobbled surface with a covered channel were constructed against the ruined fortifications, indicating some limited reorganization of the space after the city’s partial abandonment.

Post-seismic occupation appears to have been minimal. Makeshift walking levels were laid directly on top of the mid-8th century debris, and a water cistern was reused, its poorly built well-head constructed about 0.70 m above the original floor. These features, combined with intrusive pottery dating from the 10th–13th centuries, indicate sporadic activity but no significant rebuilding of the area.

Taken together, the stratigraphic evidence, debris patterns, ceramic chronology, and architectural modifications provide a strong archaeoseismic signature of the 749 CE earthquake. The destruction led to widespread abandonment of the area, leaving collapsed masonry in place and reshaping the urban landscape of Beit Ras in the early medieval period.

- Fig. 9f - Eastern

orchestra gate -

from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 9

Figure 9

External view of the eastern orchestra gate leading from the outside into the aditus maximus.

- Above the gate arch, there are two rows of ashlars of the former vault of the ambulatorium.

- Upon the collapse of the passage, the gate was walled up, allowing access to the theater via a smaller stone door below (in the lower part).

- A carved inscription from A.D. 261 dates the walling up event.

- About a meter to the right, there is a different wall, made of chalky limestone of lighter color, and has irregular contact with the original wall.

- The wall suture clearly indicates that the lighter chalk wall was attached to the darker limestone wall later, as a repair structure.

- Repair on the left by basalt cubes was carried out after the wall with the inscription was built.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020:14) discussed archaeoseismic evidence for later post-abandonment earthquakes at the Beit Ras theatre. They wrote that “filling up the cavea and orchestra of the theater happened parallel with the construction of the enclosing wall that essentially put all of the remaining building underground.”

They noted that “underground facilities are significantly less vulnerable to seismic excitation than above-ground buildings” and that because “each wall and arch are supported by embedding sediment (dump in Beit-Ras), the observed deformations of the excavated theater mostly cannot develop unless unsupported.” As a result, they concluded that “evidence of damage due to any subsequent events, such as A.D. 551, 634, 659, and 749, cannot be observed, because the possibility of collapse of buried structures is not plausible.”

They did, however, state that “potential collapse of other above-ground structures within the site of Beit-Ras cannot be ignored, such as the upper elements of the theater's structures, which were still exposed after the filling of the theater with debris.” They reported “several observations indicated that many collapsed elements of the upper parts of the theater were mixed with the debris,” citing documentation in the excavation reports of Al-Shami (2003, 2004).

They also noted that Mlynarczyk (2017) saw evidence for the 749 CE earthquake in Beit Ras where she observed a “concentration of collapsed ashlars" dated to around that time based on pottery excavated from two trenches west of the theater structure.

Regarding the eastern orchestra gate, Al-Tawalbeh et al. (2020:6) wrote: “The basalt masonry in the upper left (Fig. 9f - see above) suggests a later local collapse and repair phase, where the basalt courses are overlaying the marly-chalky limestone to the left of the walled arched eastern gate.”

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020:14) discussed archaeoseismic evidence for later post abandonment earthquakes

We believe that filling up the cavea and orchestra of the theater happened parallel with the construction of the enclosing wall that essentially put all of the remaining building underground. Underground facilities are significantly less vulnerable to seismic excitation than that above-ground buildings (Hashash et aL, 2001). Understandably, when each wall and arch are supported by embedding sediment (dump in Beit-Ras), the observed deformations of the excavated theater mostly cannot develop unless unsupported. Therefore, evidence of damage due to any subsequent events, such as A.D. 551, 634, 659, and 749, cannot be observed, because the possibility of collapse of buried structures is not plausible. However, potential collapse of other above-ground structures within the site of Beit-Ras cannot be ignored, such as the upper elements of the theater's structures, which were still exposed after the filling of the theater with debris. Several observations indicated that many collapsed elements of the upper parts of the theater were mixed with the debris, as documented in excavation reports by Al-Shami (2003, 2004). Another example suggesting the effect of the later events, such as that of A.D. 749. Mlynarczyk (2017) attributed the collapse of some sections of the city wall of Beit-Ras to this event, based on the concentration of collapsed ashlars and the age of collected pottery from two trenches excavated to the west of the theater structure.Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020:6) also noted the following about the eastern orchestra gate:

The basalt masonry in the upper left (Fig. 9f - see above) suggests a later local collapse and repair phase, where the basalt courses are overlaying the marly-chalky limestone to the left of the walled arched eastern gate.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| perimeter corridor, ambulacrum, and scaenae damaged beyond repair | perimeter corridor, ambulacrum,

and the scaenae

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| destruction of the annular passageway (ambulatorium) | ambulatorium

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| Collapsed Staircases | Staircases

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| tilting of the rebuilt scaenae wall | scaenae wall

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Fig. 8a

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

collapse of the upper two-thirdsof scaenae wall |

scaenae wall

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| vaulted corridors totally demolished | vaulted corridors

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| Shifted blocks and extensional gaps |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Fig. 8 b&c

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumble from a collapsed wall | Tumble originated from Wall WV and is located below Floor F III

Figure 5

Figure 5Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016] Mlynarczyk (2017) |

Figure 10

Figure 10Blocks tumbled from wall W K with part of floor F III above, view facing east (PCM/1 Belt Ras Project/photo J. Mlynarczyk) Mlynarczyk (2017) |

|

| Tumble from a collapsed wall | space between [Walls] W II and W III in the northeastern part of the trench

Figure 5

Figure 5Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016] Mlynarczyk (2017) |

|

|

| Wall Destruction (collapsed walls) | northern defensive wall

Figure 2

Figure 2City plan of Capitolias/Beit-Ras (modified after Al-Shami, 2005). Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020:14) distinguished seismic effects as follows:

The first major proposed earthquake may be responsible for the destruction of the annular passageway (ambulatorium), which was followed by a reconstruction that was marked by a A.D. 261 inscription. However, a definitive judgment on the time separating the first earthquake occurrence from its subsequent reconstruction, which was evidently concluded in a documentary or celebrational activity, is difficult to support.

The second earthquake activity resulted in tilting of the rebuilt scaenae wall. As a result, the upper two-thirds collapsed, and the vaulted corridors were totally demolished, which were never to be restored again.

| Damage Type | Event | Plan(s) | Figure | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Arches | ?4 |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

6a

Figure 6a

Figure 6aDamage features within displaced arches: dropped blocks of the flat arch, east door in scaena Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

The flat arches are seen as the lintel arches above the stage gates (Fig. 6a)(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:4)1 |

| Displaced Arches | ?4 |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

6b

Figure 6b

Figure 6bdropped blocks of the flat arch of the eastern stage gate (versura) Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

The eastern stage gate (versurae), trending north-south, has a flat arch and a stress-releasing segmental arch above, where two stones of the flat arch dropped down almost 3 cm (Fig. 6b)(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:4)1 |

| Displaced Arches | ?4 |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

6c

Figure 6c

Figure 6cdropped blocks of the flat arch of vomitorium, small spaces between the stones formed due to the ground shaking Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

The flat arches of most vomitoria to the cavea also are dropped down (Fig. 6c)(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:4)1 |

| Displaced Arches | ?4 |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

6d

Figure 6d

Figure 6ddropped keystone of the stress-releasing segmental arch above eastern stage gate (versura) Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

The keystone of the segmental arch above is also dropped down —4 cm. (Fig. 6d)(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:4)1 |

| Chipped corners and edges of ashlars | ?5 |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

7

Figure 7

Figure 7Chipped corners and edges of stones: (a,b) back part of the western orchestra gate (c) front part of the western orchestra gate (d) some parts of the eastern orchestra gate. The edges of blocks cracked and spalled off. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

| Tilted and Collapsed Walls | after 260/261 CE |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

8

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 8 shows a deviation of the scaenae wall from the vertical toward the north by 8°.(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5) |

| Tilted and Collapsed Walls | after 260/261 CE |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

5

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) 8

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

a vertical buttress wall (portion of the city wall) was erected behind the tilted scaenae wall (Figs. 5 and 8).(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5)3 |

| Shifted blocks and extensional gaps | after 260/261 CE |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

8 b&c

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

A number of out-of-plane extruded and shifted blocks are observed and developed across single or multiple masonry courses (Fig. 8b,c). Such features are typically associated with intervening gaps produced due to shaking directed at high angle to the wall (Kazmer, 2014), suggesting an intensity range of IX-XII (Rodríguez-Pascua et al, 2013:221-224).(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5) |

| Collapsed Staircases | before 260/261 CE and after 260/261 CE |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

5

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020:6) notes that the staircases were rebuilt after the first damaging event (before 260/261 CE); presumably with locally derived marly-chalky limestone associated with the rebuild rather than the better quality imported phosphatic limestone associated with original construction. This would indicate that the collapsed staircases presently observed collapsed a second time after another (not necessarily the 2nd) damaging event - location of the collapsed staircases is shown in the bottom left and bottom right of Figure 5. |

1 Masonry arches are common above openings in walls, spanning wall openings by diverting vertical loads from above to compressive stress

laterally (Dym and Williams, 2010). Dropped arches in a masonry building indicate an

EAE having an earthquake

intensity of VII or higher (Rodríguez-Pascua et al, 2013:221-224)

.

(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5).

2 Chipping of stone corners can occur during ground motion at any structure, especially the ones with well-cut and sharp-edged blocks.

This is because a large pressure is applied more on the corners than other parts

(Marco, 2008).

(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5)

3 The normal elevation of the scaenae

is presumed to be the same as the colonnade on top of the

cavea or even higher

(i.e., almost 13 m). Today, only the lower 5.2 m of the

scaenae is preserved. Tilted and collapsed archaeological walls

suggested an EAE seismic intensity range of IX and higher

(Rodríguez-Pascua et al, 2013:221-224).

(Al-Tawalbeh et. al., 2020:5)

4

Arches oriented ~N-S are shown in Figure 6 b&d while arches oriented ~E-W are shown in Figure 6 a&c. The two orientations would likely reflect arch

damage from two separate events since as noted by

Al-Tawalbeh et. al., (2020:10), usually an arch stone drop occurs when ground motion is parallel to the trend of the arches

(

Hinzen et al., 2016;

Martin-Gonzalez, 2018) or if it is ±45° to their strike

(

Rodriguez-Pascua et al., 2011).

Since

Al-Tawalbeh et. al., (2020:8) note that the severely damaged

vomitoria arches

were left unrepaired

after the second earthquake event, this might suggest

that these E-W trending arches were damaged in the second event and the ~N-S trending arches were damaged in the first event.

However, Al-Tawalbeh (personal communication, 2021) cautioned that it was not possible to date the arch damage noting, for example, that some arch damage could

have occurred after the building of the buttress wall and not be attributable to either the mid 3rd century CE earthquake or the 3rd-5th century CE earthquake.

Thus, while the varied orientations of the arches do indicate damage from more than one event, it is not possible to assign a date to that damage at this time.

It should also be noted that dropped keystones are also present in ~NW and ~NNW trending arches of the

vomitoria which can be observed in the Plan of the Capitolias Theater with damage locations

(Fig. 5 of

Al-Tawalbeh et al, 2020). This might suggest arch damage in more than two events.

- Plan of the Capitolias Theater with damage locations

from Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing.

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

a subsequent earthquake cracked the ashlars of the gate, causing stone spalling and breaking off.where the gate is the eastern aditus maximus where the dedicatory inscription is located. The

subsequentearthquake is not dated. It is entirely possible however that the spalling occurred during the pre 260/261 CE earthquake.

- Modified by JW from Fig. 5 of Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 5 of Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 5 of Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 5 of Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 5 of Mlynarczyk (2017)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 5 of Mlynarczyk (2017)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| perimeter corridor, ambulacrum, and scaenae damaged beyond repair - Collapsed Walls and Vaults | perimeter corridor, ambulacrum,

and the scaenae

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII + |

| destruction of the annular passageway (ambulatorium) - Collapsed Walls | ambulatorium

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII + |

| Collapsed Staircases - Collapsed Walls | Staircases

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII + |

In the abstract, Al-Tawalbeh et al, (2020) suggests a local Intensity of VIII-IX (8-9) for both the mid 3rd century CE earthquake and the 3rd-5th century CE earthquake. Al-Tawalbeh (personal communication, 2021) estimated intensity of close to IX (9) for the mid 3rd century CE earthquake based on collapse of the ambulatorium.

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tilting of the rebuilt scaenae wall | scaenae wall

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Fig. 8a

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VI+ |

collapse of the upper two-thirdsof scaenae wall |

scaenae wall

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII+ |

| Collapsed Vaults - vaulted corridors totally demolished | vaulted corridors

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII+ |

| Displaced masonry blocks - Shifted blocks and extensional gaps |

Figure 4

Figure 4Major parts of a Roman theater. It is mostly the shape of Beit-Ras/Capitolias theater at the time of construction. Modified after Fayyad and Karasneh (2004), Karasneh and Fayyad (2005), and Sears (2006), and our field observation. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

Fig. 8 b&c

Figure 8

Figure 8Deformation of scaena:

Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020)

Figure 5

Figure 5Theater plan and the position of the observed damage features. Most of the locations' damage features are marked in the drawing. Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

VIII+ |

In the abstract, Al-Tawalbeh et al, (2020) suggests a local Intensity of VIII-IX (8-9) for both the mid 3rd century CE earthquake and the 3rd-5th century CE earthquake. Al-Tawalbeh (personal communication, 2021) confirmed an estimated intensity of VIII-IX (8-9) for the 3rd-5th century CE earthquake largely based on the collapse and tilting of the scaenae.

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumble from a collapsed wall | Tumble originated from Wall WV and is located below Floor F III

Figure 5

Figure 5Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016] Mlynarczyk (2017) |

Figure 10

Figure 10Blocks tumbled from wall W K with part of floor F III above, view facing east (PCM/1 Belt Ras Project/photo J. Mlynarczyk) Mlynarczyk (2017) |

|

VIII+ |

| Tumble from a collapsed wall | space between [Walls] W II and W III in the northeastern part of the trench

Figure 5

Figure 5Trench in Areas 1-S and 1-S(W). Key

(PCMA Beit Ras Project/drawing M Drzewiecki [2015], drawing and digitizing M Burdajewicz [2015-2016] Mlynarczyk (2017) |

|

VIII+ | |

| Wall Destruction (collapsed walls) | northern defensive wall

Figure 2

Figure 2City plan of Capitolias/Beit-Ras (modified after Al-Shami, 2005). Al-Tawalbeh et. al. (2020) |

|

VIII+ |

There are no obvious indications that this location should be subject to a site effect such as a ridge effect or due to soft ground. In modeling potential causitive earthquakes from the historical record Al-Tawalbeh et al, (2020:11) used the attenuation relationship of Hough and Avni (2009) with the added site effect of Darvasi and Agnon (2019). Their VS30 values in these simulations ranged from 360-800 m/s.

Al-Shami, A. (2003). Beit Ras Irbid Archeological Project 2002, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 47, 93-104 (in Arabic).

Al-Shami, A. (2004). Bayt Ras Irbid Archaeological Project 2002, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 48, 11-22 (in Arabic).

Al-Shami, A. (2005). A new discovery at Bayt-Ras/Capitolias - Irbid, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 49, 509-519 (in Arabic).

Al-Tawalbeh, M., M. Kazmer, R Jaradat, K. Al-Bashaireh, A. Gharaibeh, B. Khrisat, and A. Al-Rawabdeh (2019).

Archaeoseismic analysis of the Roman-Early Byzantine earthquakes in Capitolias (Beit-Ras) theater of Jordan,

7th International Colloquium on Historical Earthquakes and Paleoseismology Studies, 4-6 November 2019, Barcelona, Spain, 19 pp.

Al-Tawalbeh, M., et al. (2020). "Two Inferred Antique Earthquake Phases Recorded in the Roman Theater of Beit‐Ras/Capitolias (Jordan)." Seismological Research Letters: 1-19.

Anastasio, S., P. Gilento, and R. Parenti (2016). Ancient buildings and masonry techniques in the Southern Hauran,

Jordan, J. E. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 4, no. 4, 299-320.

Bader, N., and J. B. Yon (2018). Une inscription du theater de Bayt Ras/Capitolias, Syria 95, 155-168 (in French).

Dodge, H. (2009). Amphitheaters in the Roman East, in Roman Amphitheaters and Spectacula: A 21st-Century Perspective

(Papers from an international conference held at Chester), T. Wilmott (Editor), BAR International Series, 16th-18th February, 2007, 29-46.

Dym, C. L., and H. E. Williams (2010). Stress and displacement estimates for arches, J. Struct. Eng. 137, no. 1, 49-58.

Fayyad, S., and W. Karasneh (2004). Archaeological excavation in Beit Ras theater, from 1st season to fifth season, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 48, 67-75 (in Arabic).

Frezouls, E. (1959). Recherches sur les theatres de l'Orient syrien:

Probleme schronologiques, Syria 36, nos. 3/4, 202-228 (in French).

Glueck, N. (1951). Explorations in Eastern Palestine IV, Ann. Am. Schools Orient. Res. 18, 25-28.

Hashash, Y. M. A., et al. (2001). "SEISMIC DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF UNDERGROUND STRUCTURES." Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 16: 247-293.

Hinzen, K. G., et al. (2016). "Quantifying Earthquake Effects on Ancient Arches, Example: The Kalat Nimrod Fortress, Dead Sea Fault Zone." Seismological Research Letters.

Jaradat, R, K. Al-Bashaireh, A. Al-Rawabdeh, A. Gharaibeh, and B. Khrisat (2019).

Mapping archaeoseismic damages across Jordan (MADAJ), 2nd International Congress on

Archaeological Sciences in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, The Cyprus Institute, Nicosia, Cyprus, 12-14 November 2019.

Karasneh, W., K. al-Rousan, and J. Telfah (2002). New discovery in Jordan at Beit-Ras region (ancient Capitolias), Occident Orient 7, no. 1, 9-10.

Karasneh, W., and S. Fayyad (2004). Archaeological excavations at Beit Ras theater,

working stages from the first season to the fifth season, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 48, 67-75 (in Arabic).

Karasneh, W., and S. Fayyad (2005). Beit Ras theater, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 49, 39-45 (in Arabic).

Lenzen, CJ., Gordon, R.L., and McQuitty, A.M. (1985).

Tell Irbid and Beit Ras excavations, 1985. Annual of the Department of Antiquities ofJordan, 29, 151-160

Lenzen, C.J. and Knauf, E.A. (1987). Beit Ras/Capitolias. A preliminary evaluation of the archaeological and textual evidence. Syria, 64(1), 21-46

Lenzen, C.J. (1990). Beit Ras excavations: 1988 and 1989. In Chronique archeologique. Syria, 67(2), 474-476

Lenzen, C.J. (1995). Continuity or discontinuity: urban change or demise? In S. Bourke and J.-P. Descoeudres (eds), Trade, contact,

and the movement of peoples in the eastern Mediterranean: Studies in honour of J. Basil Hennessy [Mediterranean Archaeology Supplement 3] (pp. 325-331). Sydney: Meditarch

Lenzen, C.J. (2000). Seeking contextual definitions for places: the case of north-western Jordan. Mediterranean Archaeology, 13, 11-24

Lenzen, C.J. (2002). Kapitolias — Die vergessene Stadt im Norden. In A. Hoffmann and S. Kerner (eds), Gadara - Gerasa and die

Dekapolis (pp. 36-44). Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern

Lenzen, C.J. (2003). Ethnic identity at Beit Ras/Capitolias and Umm al-Jimal. Mediterranean Archaeology, 16, 73—87

Lucke, B., et al. (2012). "Questioning Transjordan’s historic desertification: A critical review of the paradigm of ‘Empty Lands’." Levant 44(1): 101-126.

Martín-González, F. (2018). "Earthquake damage orientation to infer seismic parameters in archaeological sites and historical earthquakes." Tectonophysics.

Mlynarczyk, J. (2018). Archaeological investigations in Bayt Ras, ancient Capitolias, 2015: Preliminary report, Ann. Dept. Antiq. Jordan 59, 175-192.

Retzleff, A. (2003). New eastern theaters in Late Antiquity, Phoenix 57, nos. 1/2, 115-138.

Rodriguez-Pascua, M., et al. (2011). "A comprehensive classification of Earthquake Archaeological Effects (EAE) in

archaeoseismology: Application to ancient remains of Roman and Mesoamerican cultures." Quaternary International 242: 20-30.

Schiffer, M. B. (1986). "Radiocarbon Dating and the "Old Wood" Problem: the Case of the Hohokam Chronology." Journal of Archaeological Science 13: 13-30.

Sear, F. (2006). Roman Theaters: An Architectural Study, Oxford University Press, New York

Segal, A. (1981). Roman cities in the province of Arabia, J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 40, no. 2, 108-121.

Spijkerman, A. (1978). The Coins of the Decapolis and Provincia Arabia, M. Piccirillo (Editor), Franciscan Printing Press, Jerusalem, Israel, 322 pp.

Stager, L. E., J. Greene, and M. D. Coogan (2000). The archaeology of Jordan and beyond: Essays in honor of James A. Sauer, J. Am. Orient. Soc. 121, no. 4, 690-691.

Works by the nineteenth-century explorers and travelers mentioned

in this entry are not listed below. These works are available only in

university or other specialized libraries.

Glueck, Nelson. Explorations in Eastern Palestine, Vol. 4. Annual of the

American Schools of Oriental Research, 25/28. New Haven, 1951.

Lenzen, C. J., et al. "Excavations at Tell Irbid and Beit Ras, 1985."

Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 29 (1985): 151—159.

Lenzen, C. J. "Tall Irbid and Bait Ras. " Archivfur Orientforschung 33

(1986): 164-166.

Lenzen, C. J., and E. Axel Knauf. "Tell Irbid and Beit Ras, 1983-

1986." Liber Annuus/StudiiBibliciFranciscani 36 (1986): 361-363.

Lenzen, C. J., and E. Axel Knauf. "Beit Ras-Capitolias: A Preliminary

Evaluation of the Archaeological and Textual Evidence." Syria 64

(1987): 21-46.

Lenzen, C. J., and Alison M . McQuitty. "Th e 1984 Survey of the Irbid/

Beit Ras Region." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan

32 (1988): 265-274.

Lenzen, C.J. "Beit Ras Excavations, 1988 and 1989." Syria 67 (1990):

474-476.

Lenzen, C. J. "The Integration of the Data Bases—Archaeology and

History: A Case in Point, Bayt Ras. " In Bilad al-Sham during the

Abbasid Period; Proceedings of the Fifth Bilad al-Sham Conference, vol.

2, edited by Muhamma d Adnan al-Bakhit and Robert Schick, pp .

160-178. Amman, 1992.

Lenzen, C. J. "Irbid and Beit Ras: Interconnected Settlements between

c. A.D. 100-900." In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan,

vol. 4, edited by Ghazi Bisheh, pp. 299-307, Amman, 1992.