Capernaum

Left - Aerial Photo of excavation areas of Capernaum around the Greek Orthodox Church

Left - Aerial Photo of excavation areas of Capernaum around the Greek Orthodox ChurchRight - Aerial Photo of excavation areas of Capernaum around the Franciscan Church

click on either image to open a high res magnifiable version of that image in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Capernaum | New Testament and Josephus | καπερναούμ |

| Kefr Nahum* | Talmudic Literature | כפר נחום |

| Kefar Tanhum* | Medieval Jewish Sources | כפר תנחום |

| Tanhum* | Medieval Jewish Sources | תנום |

| Talhum* | Arabic | تالهوم |

| Tell Hum* | Arabic | تيلل هوم |

Capernaum lies on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. The town was founded by the Hasmoneans and is featured prominently in all four canonical gospels of the New Testament. It may have served as a base for Jesus' ministry as it is the reputed hometown of the disciple Matthew and close to Betsaida which was the hometown of Simon Peter, Andrew, John, and James. To the northeast are the remains of a synagogue and surrounding a Roman-Byzantine village lie the remains of an early Islamic village (Magness, 1997).

The site of Capernaum consists of the remains of a village, a synagogue, and an octagonal church. It is located on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, about 5 km (3 mi.) from 'En Sheva' (Heptapegon), 5 km (3 mi.) from the upper Jordan River, and near the second Roman milestone from Chorazin (map reference 204.254). It is identified with the Capernaum mentioned in the New Testament and in Josephus, and with the Kefar Nahum of Talmudic literature and later sources. According to the traveler Arculf (seventh century CE), this was an unfortified village that extended along the shore of the Sea of Galilee and ended in the north at the foot of the surrounding hills (Adamnanus, De Locis Sanctis II, XXV; CCSL 175, 218). The written sources that mention Capernaum speak of two buildings of particular interest: the house of Simon Cephas (Saint Peter), which was converted into a church; and a synagogue built of dressed stones, to which many steps ascended (Peter the Deacon, De Locis Sanctis; CCSL 175, 98- 99).

Capernaum is not mentioned in the Old Testament. It was, however, of great importance in the New Testament, for it was the center of Jesus' Galilean ministry. Matthew (9:1) calls it Jesus' "own city," for it was here that Jesus preached and performed many miracles, and where five of the twelve Apostles-Peter, Andrew, James, John, and Matthew-were chosen (Mt. 4:13-22,8:5-22, 9:1-34; Mk. 1:21-34,2:1-17; Lk. 7:1-10). According to the Gospels, Jesus stayed many times in the house of Peter and taught in the synagogue built by a Roman centurion (cf. Lk. 7:5).

Josephus relates that he was brought here after being wounded in battle near the Jordan River (Life, 403). He also refers to the springs of Heptapegon as the springs of Capharnaum (War III, 520).

According to Epiphanius (Haer. 30, 11), until the fourth century Capernaum was inhabited only by Jews, who would not have gentiles, Samaritans, or Christians in their midst. But the local Jewish population included Minim (the followers of Jesus). The Midrash implies that a Judeo-Christian community existed in Capernaum in the beginning of the second century. Rav Issi of Caesarea, who lived toward the end of the third century CE, cursed the inhabitants of Capernaum, thus inferring that the Judeo-Christian community may still have flourished then (Kohelet Rab. 1, 8). On the other hand, observant Jews still lived in Capernaum after Christianity became the state religion in the time of Constantine. This is known from a sixth-century Aramaic inscription in the mosaic floor of the synagogue at Hammat Gader, which mentions a donor named Yosse bar Dosti ofCapernaum (CIJ, no. 857; Naveh, no. 33).

From the eighth century onward, there is a paucity of sources mentioning Capernaum, but the place was not completely abandoned. Burchardus writes in 1283 that Capernaum, which had previously been a flourishing settlement, was a poor village containing seven fishermen's houses in a state of near collapse (Baldi, no. 449). Jacobus de Verona (1335) relates that wicked Saracens resided there (Baldi, no. 452).

The name Capernaum has been preserved for generations. In medieval Jewish sources the site was called Kefar Tanhum, or simply Tanhum, and to this day it is called Talhum (from Tanhum) in Arabic or, less correctly, Tell Hum.

The American explorer E. Robinson related in 1838 that the ruins of this "desolate and mournful" place contained an impressive building he correctly identified as a synagogue. The partial soundings conducted by C. Wilson and R. E. Anderson in 1856, and by H. H. Kitchener in 1881, led to further damage to the synagogue building by the inhabitants of the area. When the Franciscan Order purchased the site in 1894, it was forced to cover the remains of the synagogue with earth. In 1905, the excavations of the synagogue were renewed by H. Kohl and C. Watzinger. The two were succeeded by the architect W. von Menden, who continued to excavate until the beginning of World War I. From 1921 to 1926, G. Orfali partly unearthed an octagonal building south of the synagogue, and reconstructed parts of the synagogue itself. Systematic excavations of the village were resumed from 1968 onward by V. Corbo and S. Loffreda of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum in Jerusalem. They examined the foundations and strata beneath the floors of the synagogue and the octagonal building. In 1978, V. Tzaferis also began to uncover remains of the dwellings in the area belonging to the Greek Orthodox church

Artifacts and some isolated walls of the second millennium BCE (Middle Bronze and Late Bronze ages) and some Early Bronze Age sherds were excavated in some areas. After a gap during the Israelite period, the site was resettled in the Persian period and grew considerably in the Roman and Byzantine periods. In the seventh century CE, several quarters of the village were abandoned, while some Byzantine houses were used well into the Arab period. Under the Umayyad rulers of Damascus the site was fully reoccupied, but the synagogue and the octagonal church were abandoned. The rise of the Abbasid dynasty of Baghdad marked the decline of Capernaum.

Capernaum was unfortified throughout all the phases of its existence. Based on the remains found on the surface and in the excavations of the site, it may be determined that the village extended for about 300m along the shore of the Sea of Galilee in an east-west direction, and that the monumental synagogue was erected in the center of this axis. Between the shore and the hills, about 200m north of the synagogue, a mausoleum is situated outside the northern boundary of the village. Our knowledge of the Hellenistic and Roman strata comes predominantly from the areas under and around both the synagogue and the octagonal church. The period of maximal expansion of the village began in the fourth century CE. Capernaum was a relatively small village (c. 10-12 a. in area); its inhabitants earned their livelihood from fishing, agriculture, and commerce. It was crossed by the imperial road that followed the Jordan River and the western side of the Sea of Galilee. Of special interest is the discovery here of a Roman milestone from the time of the emperor Hadrian, bearing the following inscription:

IMP(erator)Its translation is

C[A]E[S]AR DIVI

[TRAIA]NI PAR(thici)

F(ilius) [DIVI NERVAE] [N]EP(os) TRAI

[ANUS] [HA]DRIANUS AUG(ustus)

lmperator Caesar, son of the divine Trajan, the conqueror of the Parthians, grandson of the divine Nerva, Trajan Hadrian AugustusDuring the reign of Herod Antipas and Philip, Capernaum was a border village with a customs office (Jesus' disciple Matthew was a customs official here; cf. Mt. 9:9.) The private houses in the village were built of basalt, wheras the public buildings, such as the synagogue and the octagonal church, were built of white limestone. The houses are characterized by large courts surrounded by small dwelling chambers. The life of an extended family centered around a communal court. In the courts were ovens, staircases for access to the roofs, and only one exit to the street. The excavations seem to indicate that the planning of the village was organic and orderly. The main street extended from the synagogue to the octagonal church in a north-south direction. Several lanes oriented east-west led to the main street and divided the village into quarters and small neighborhoods.

The antiquities area of Capernaum has been owned by two churches, the Franciscan and the Greek Orthodox, since the end of the nineteenth century. The area belonging to the Franciscan Order has received a great deal of attention, whereas that of the Greek Orthodox church was a "no man's-land" until 1967.

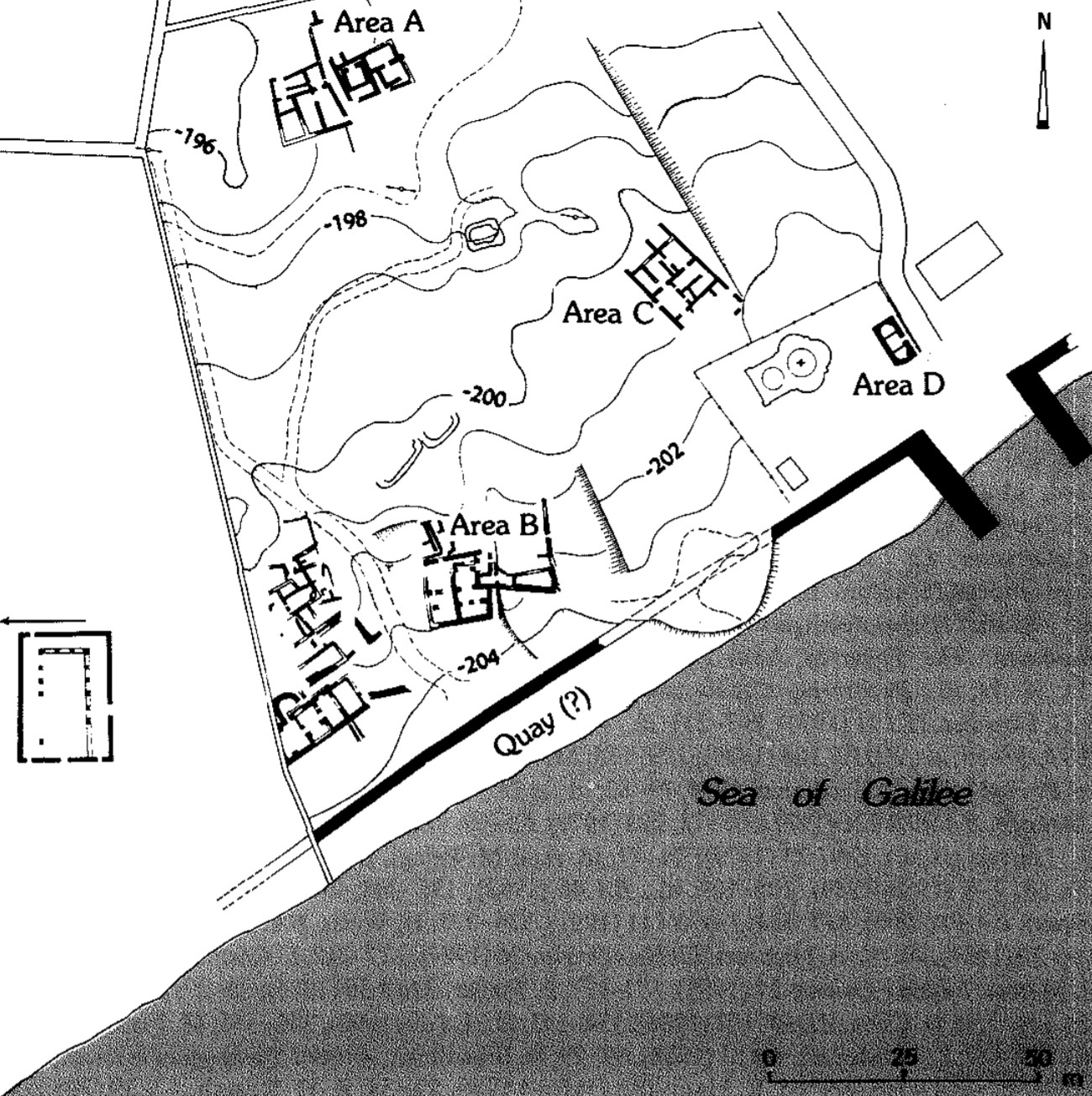

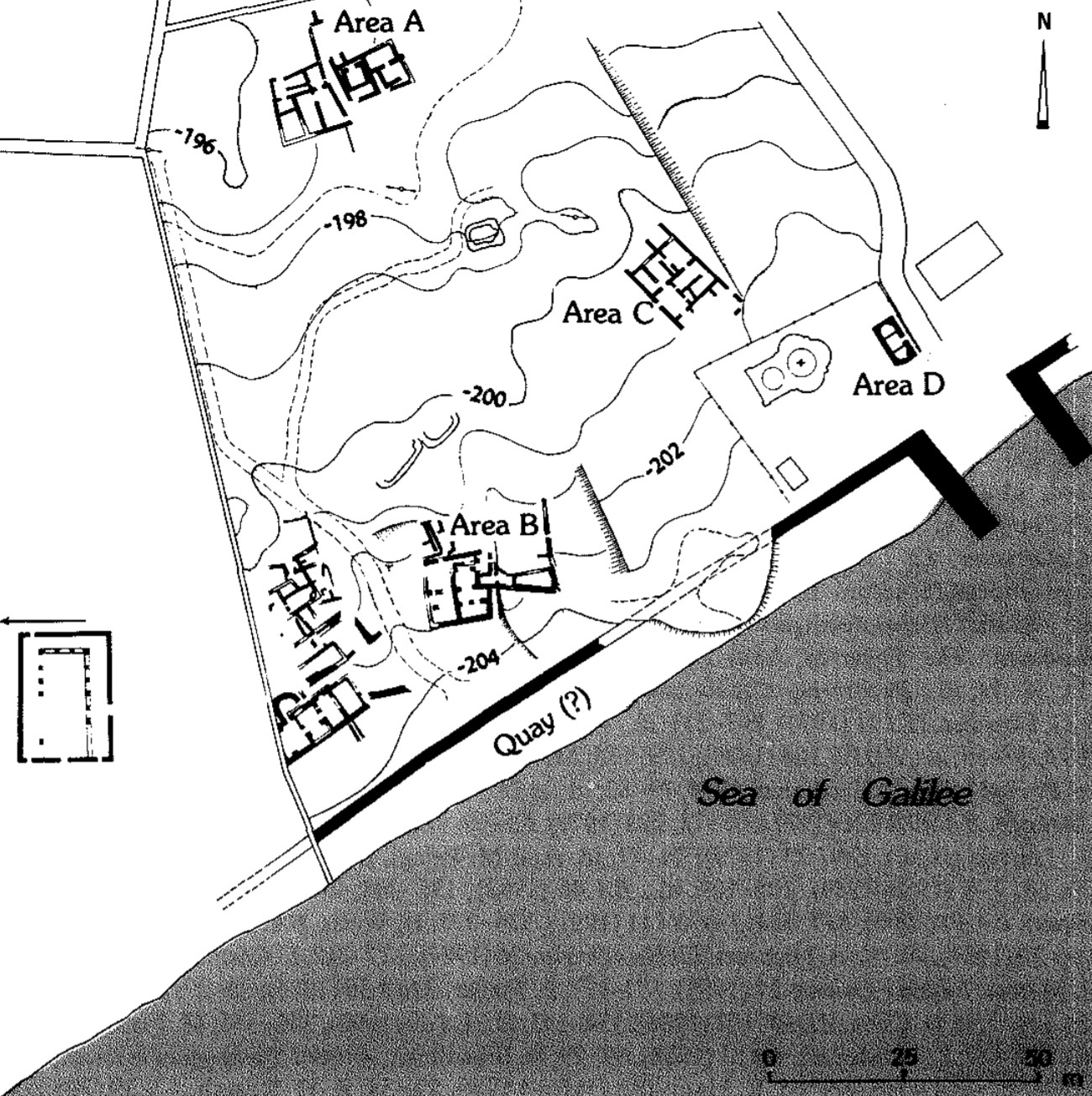

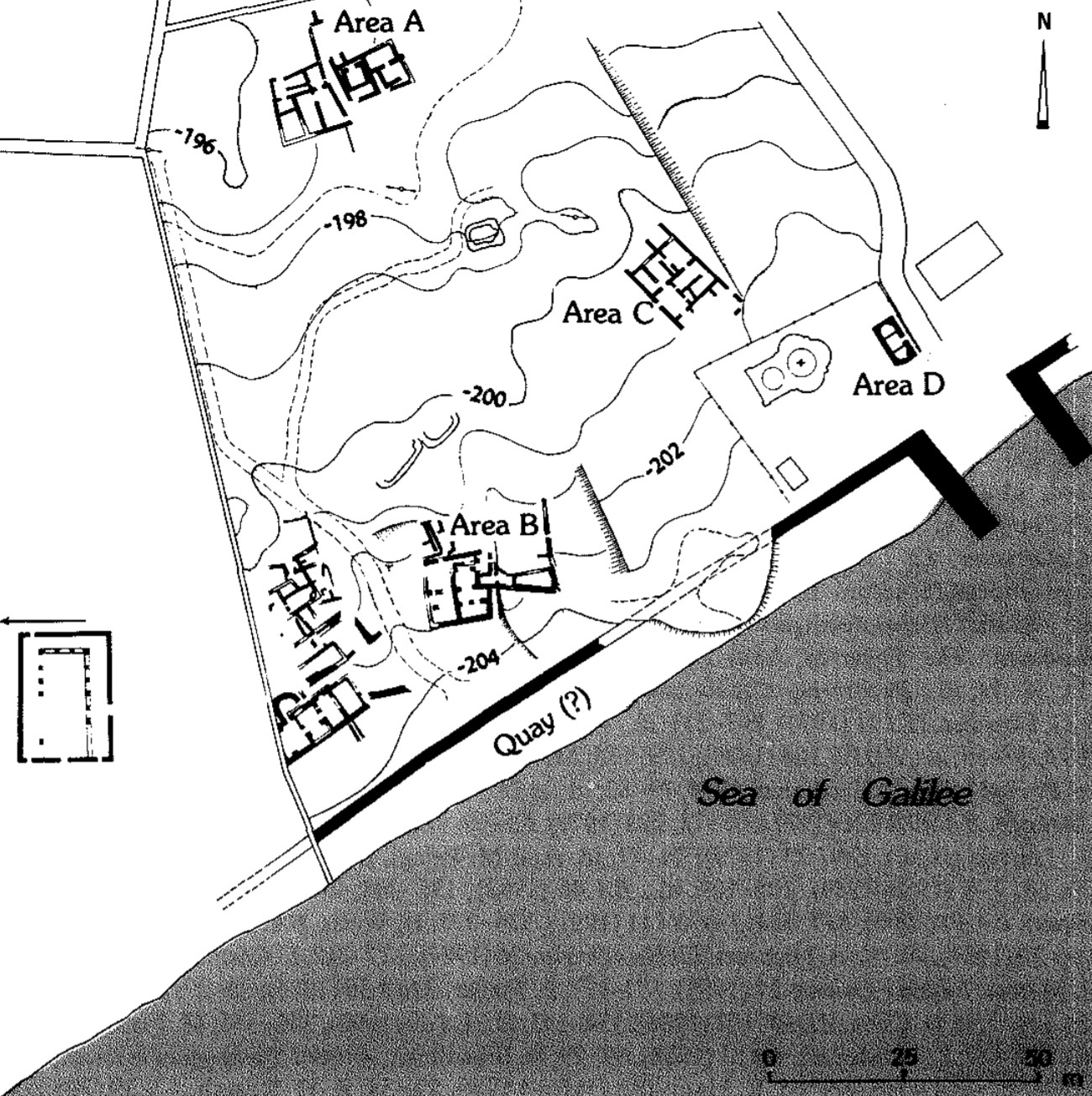

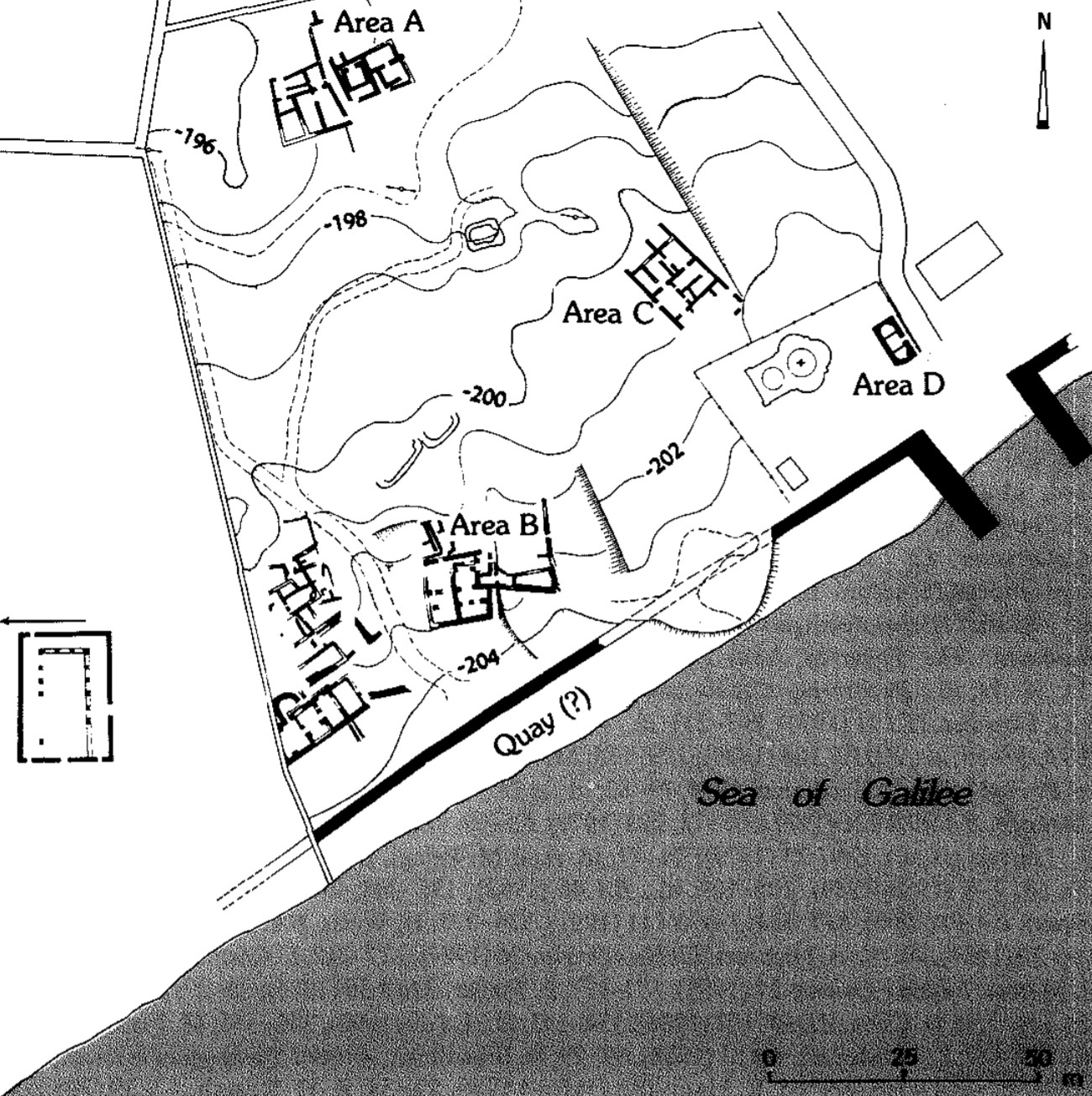

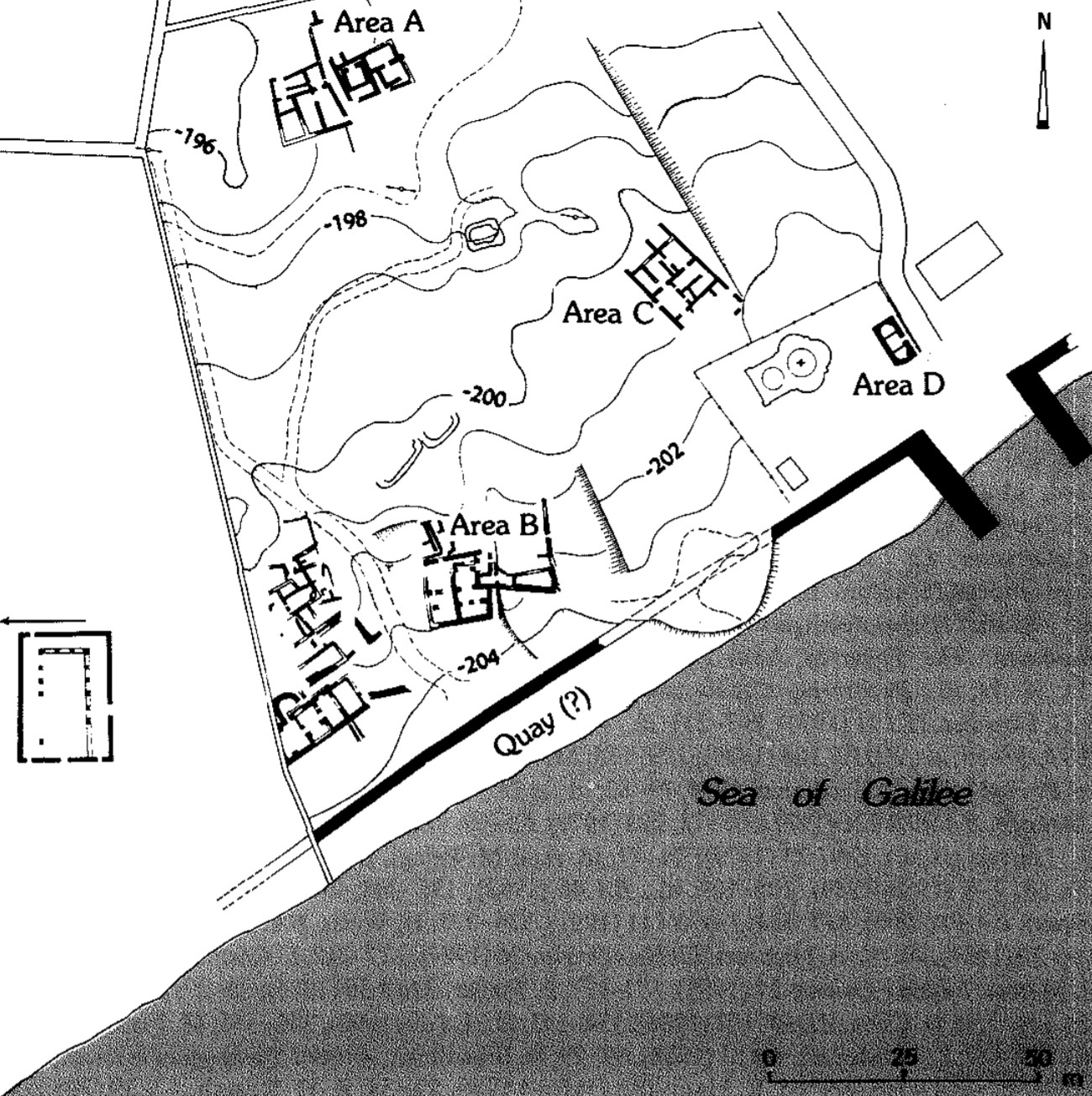

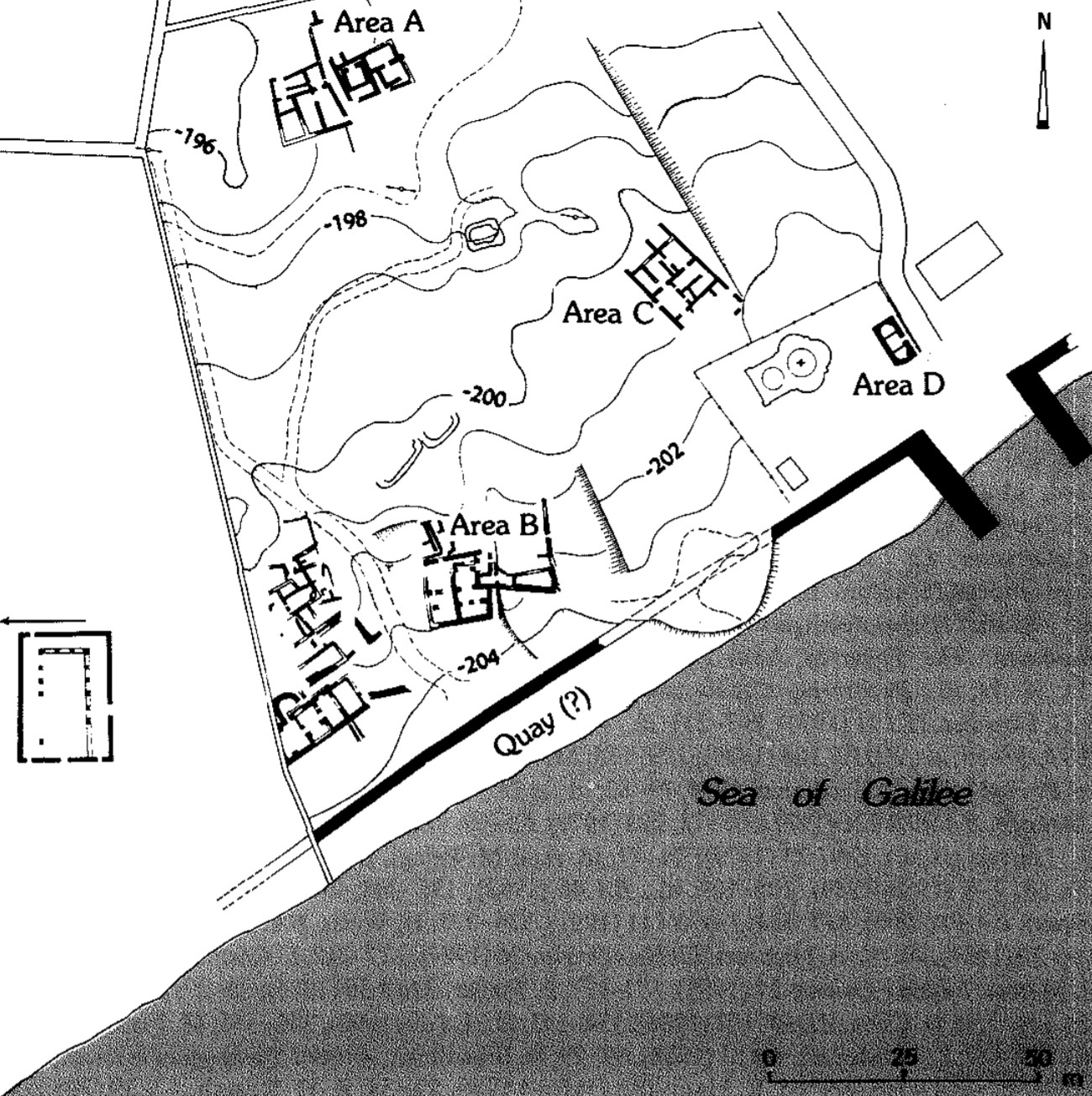

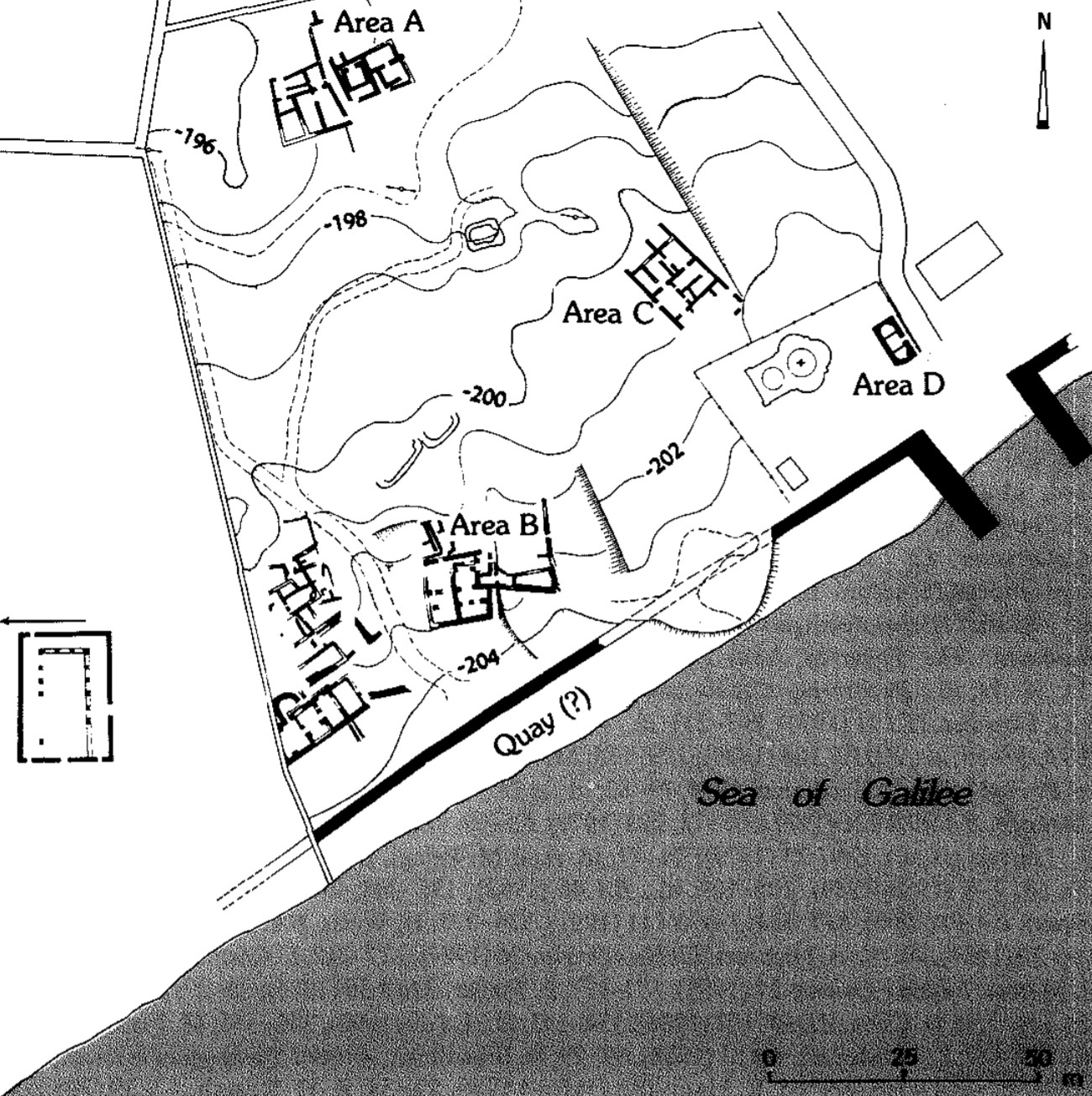

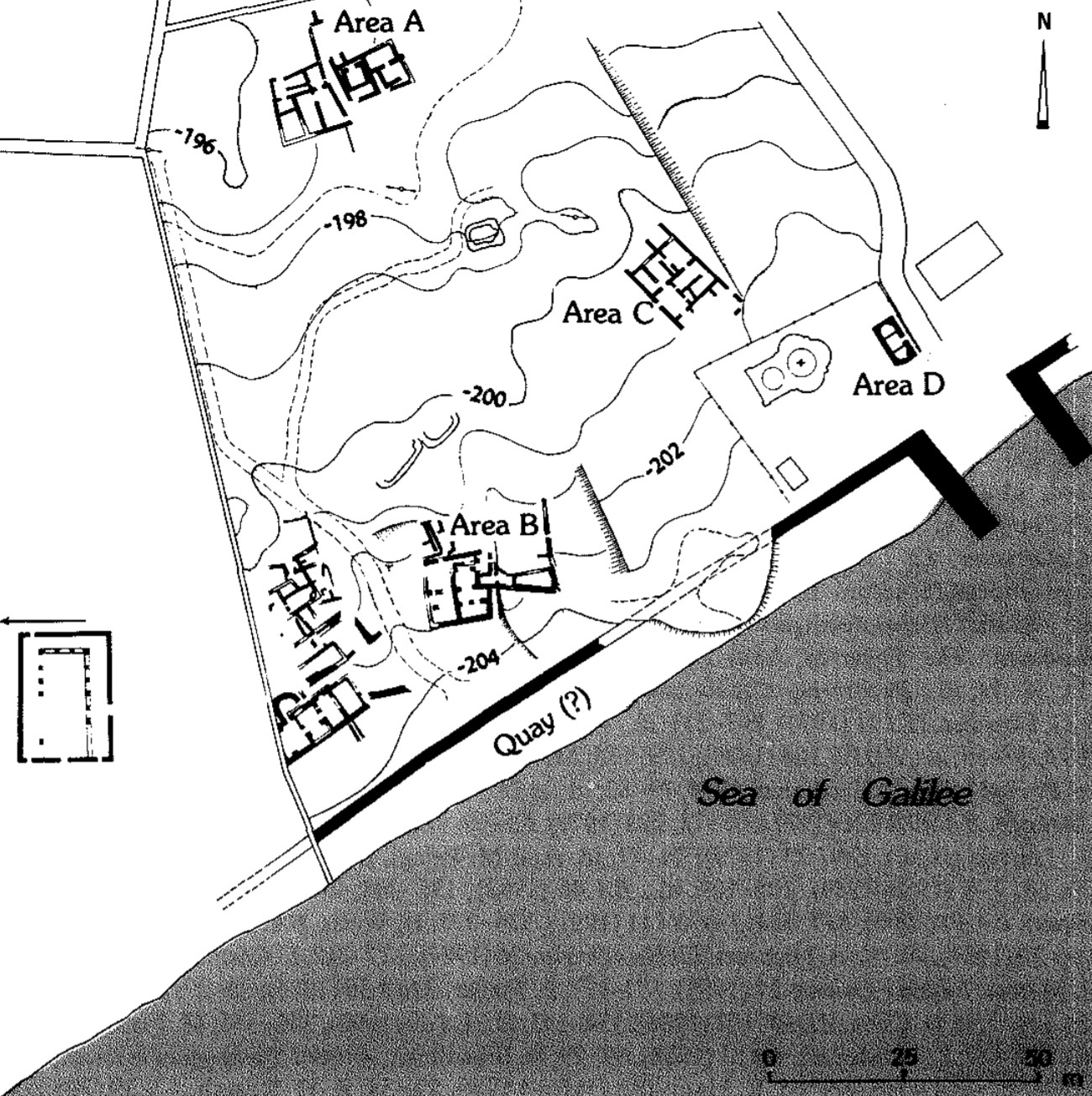

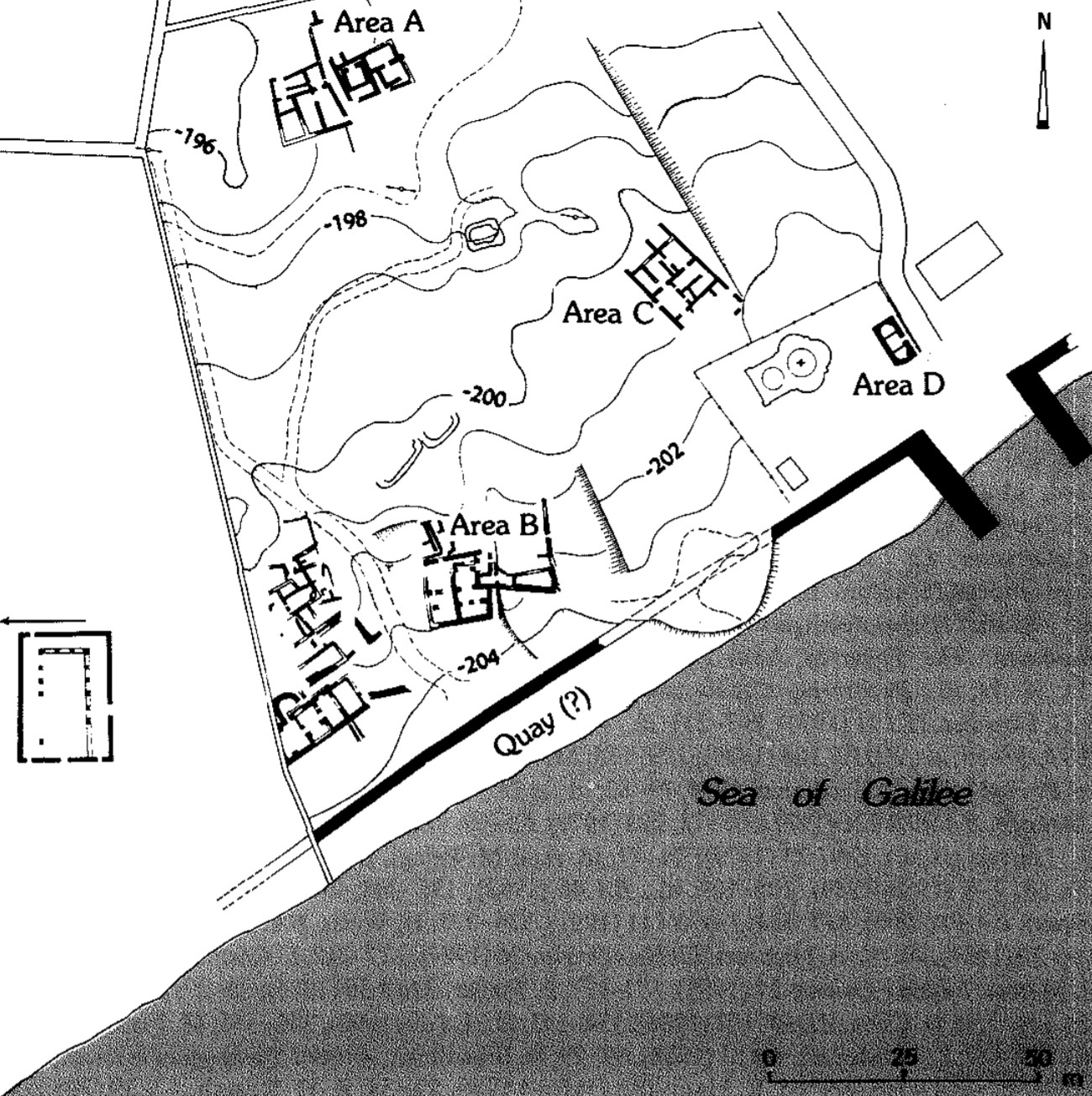

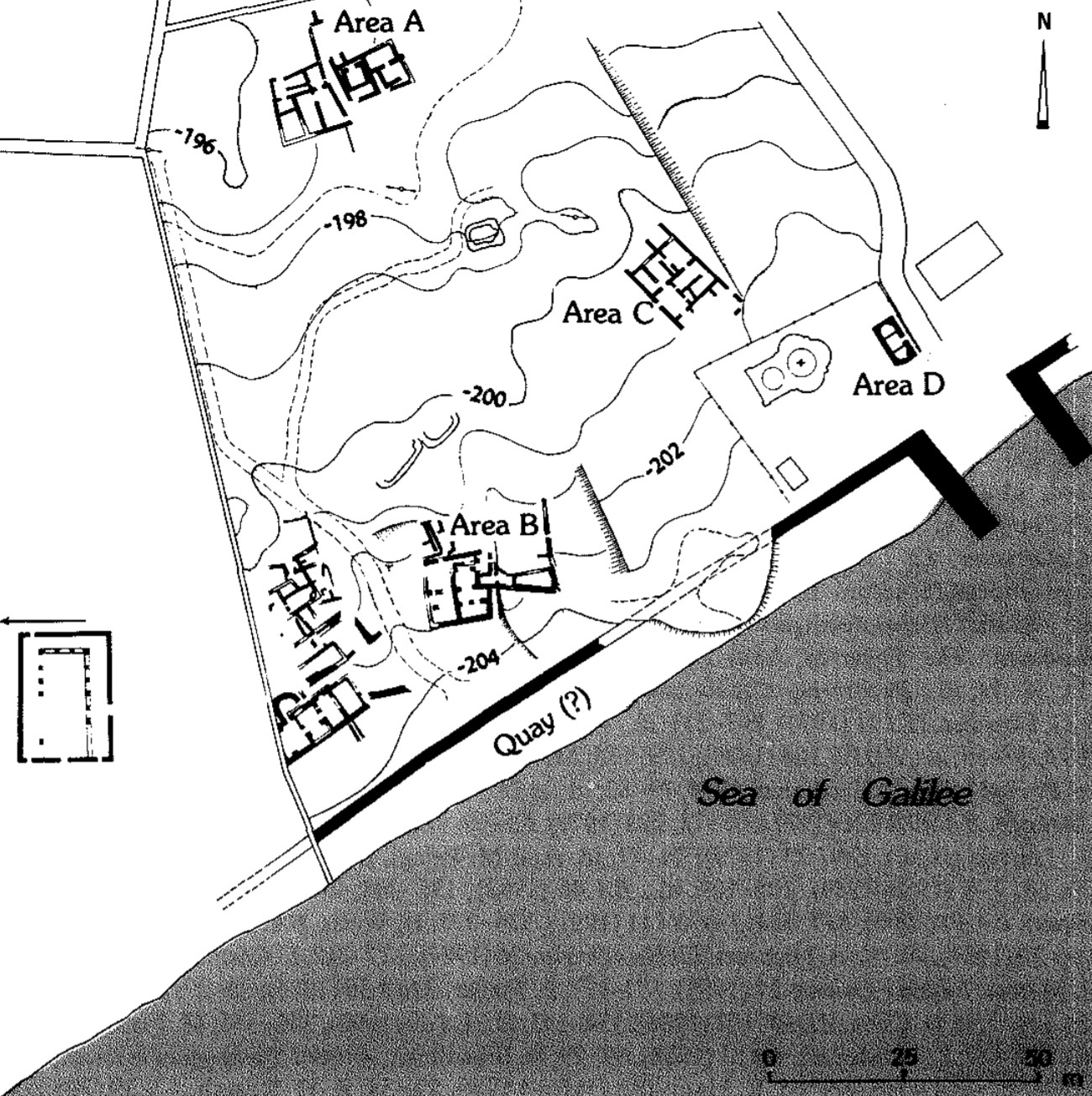

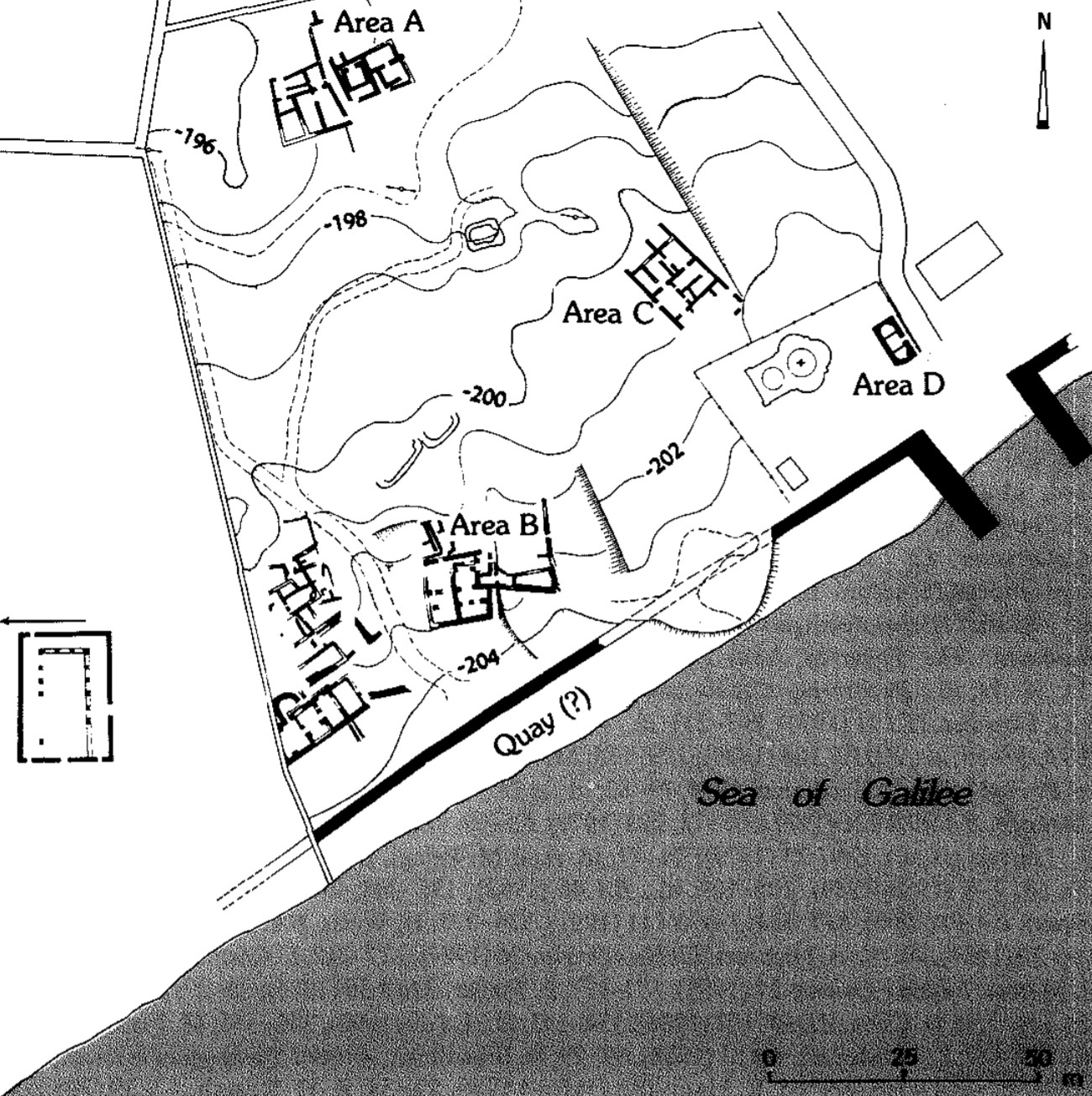

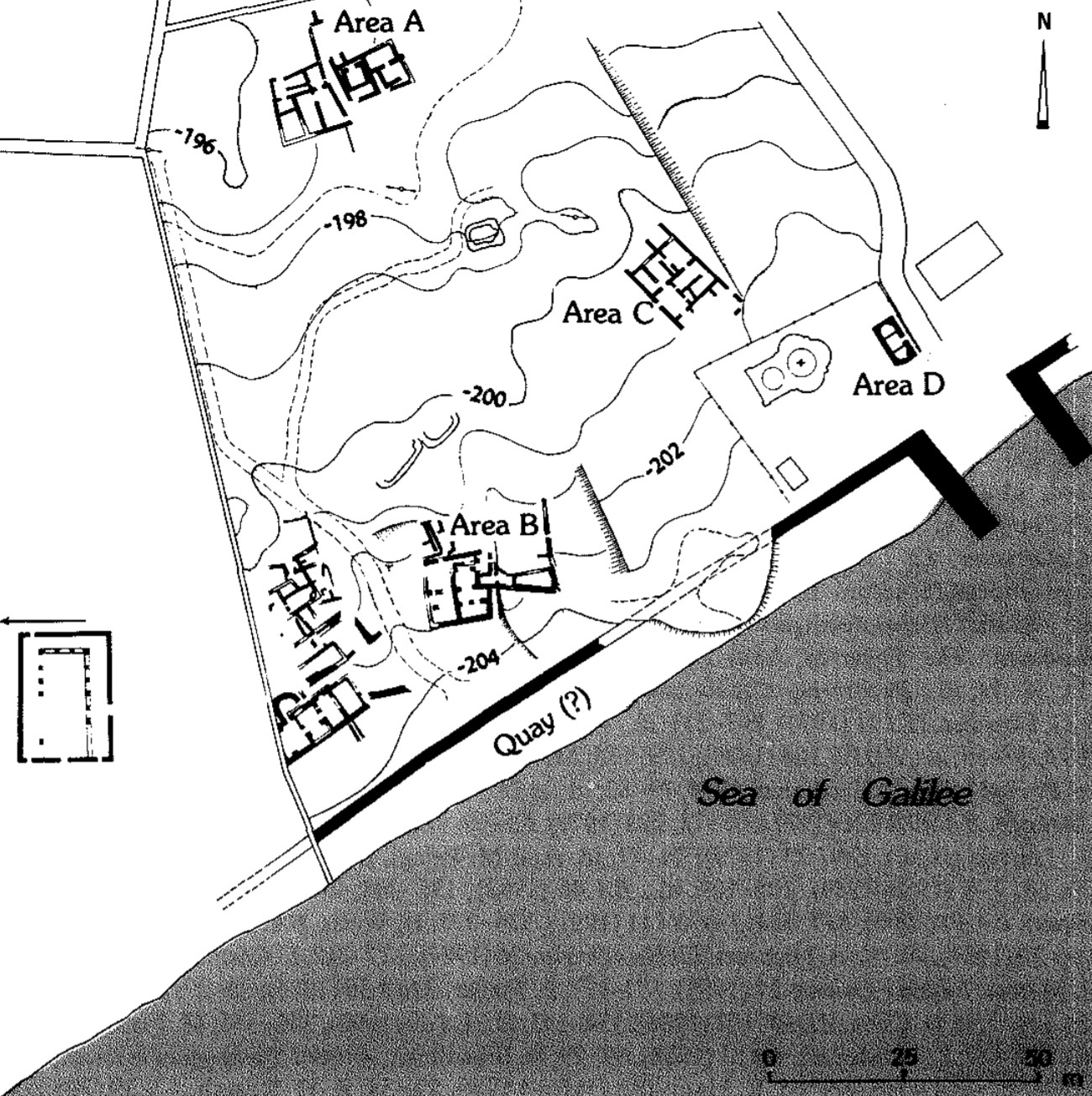

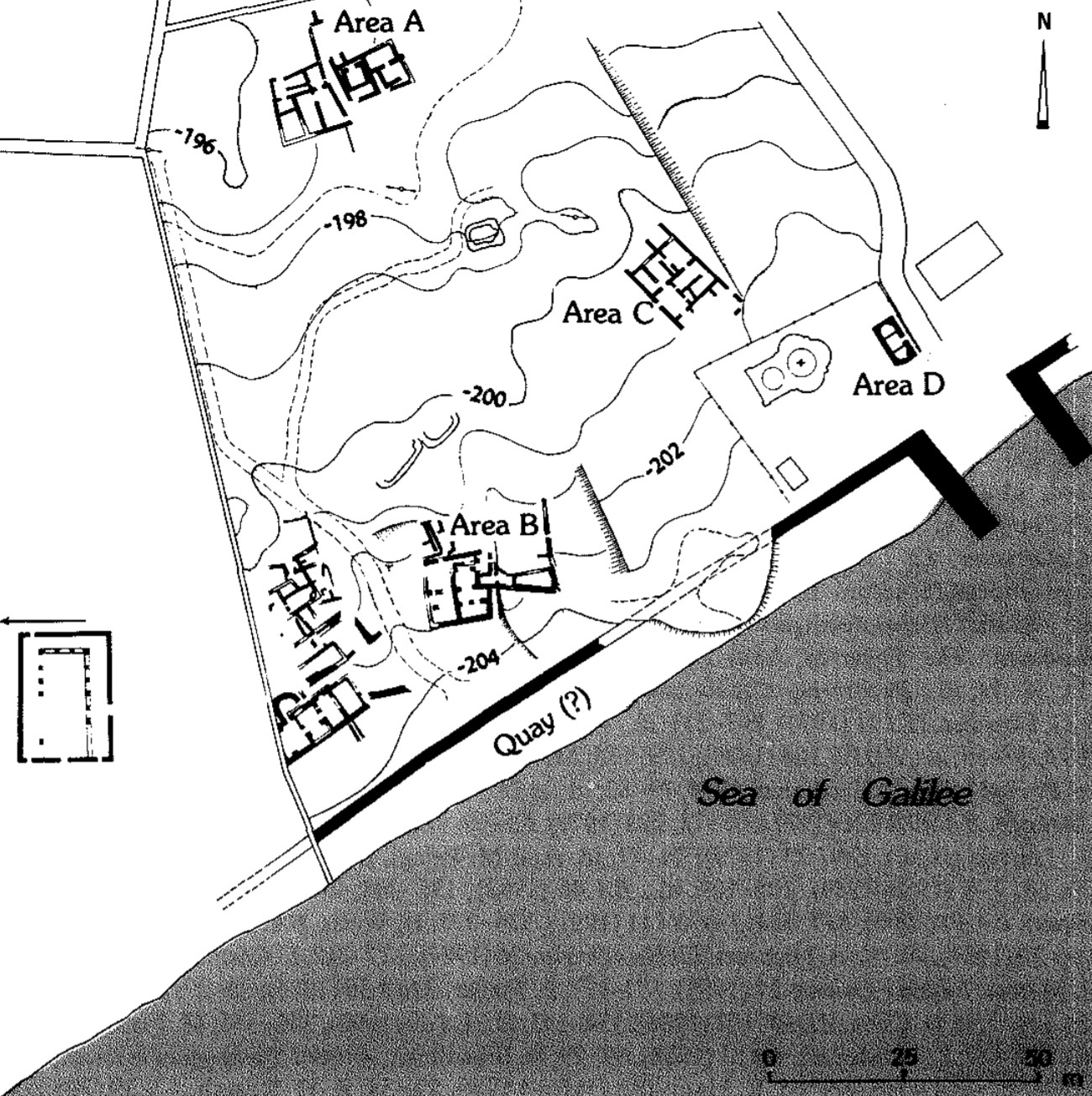

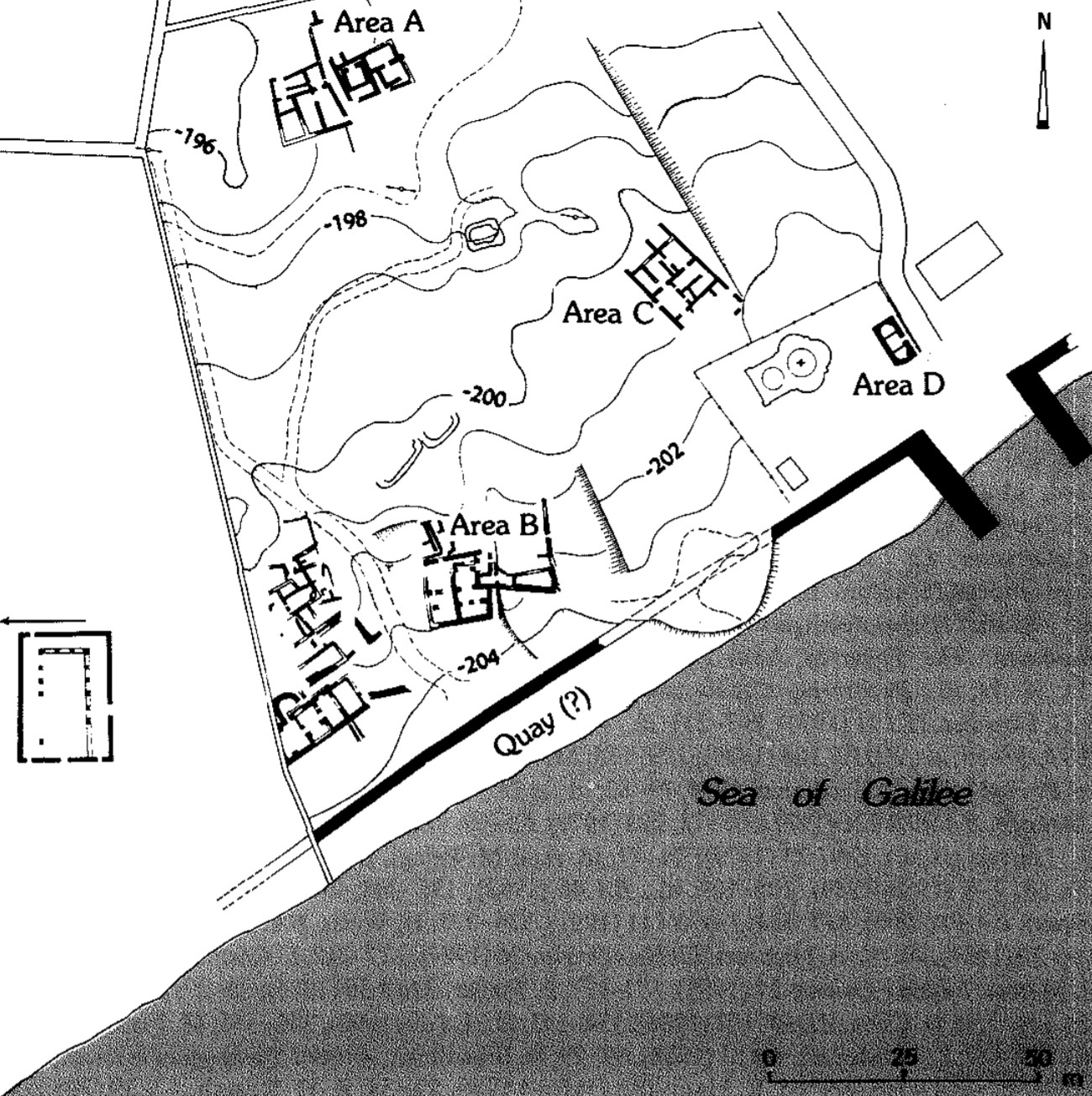

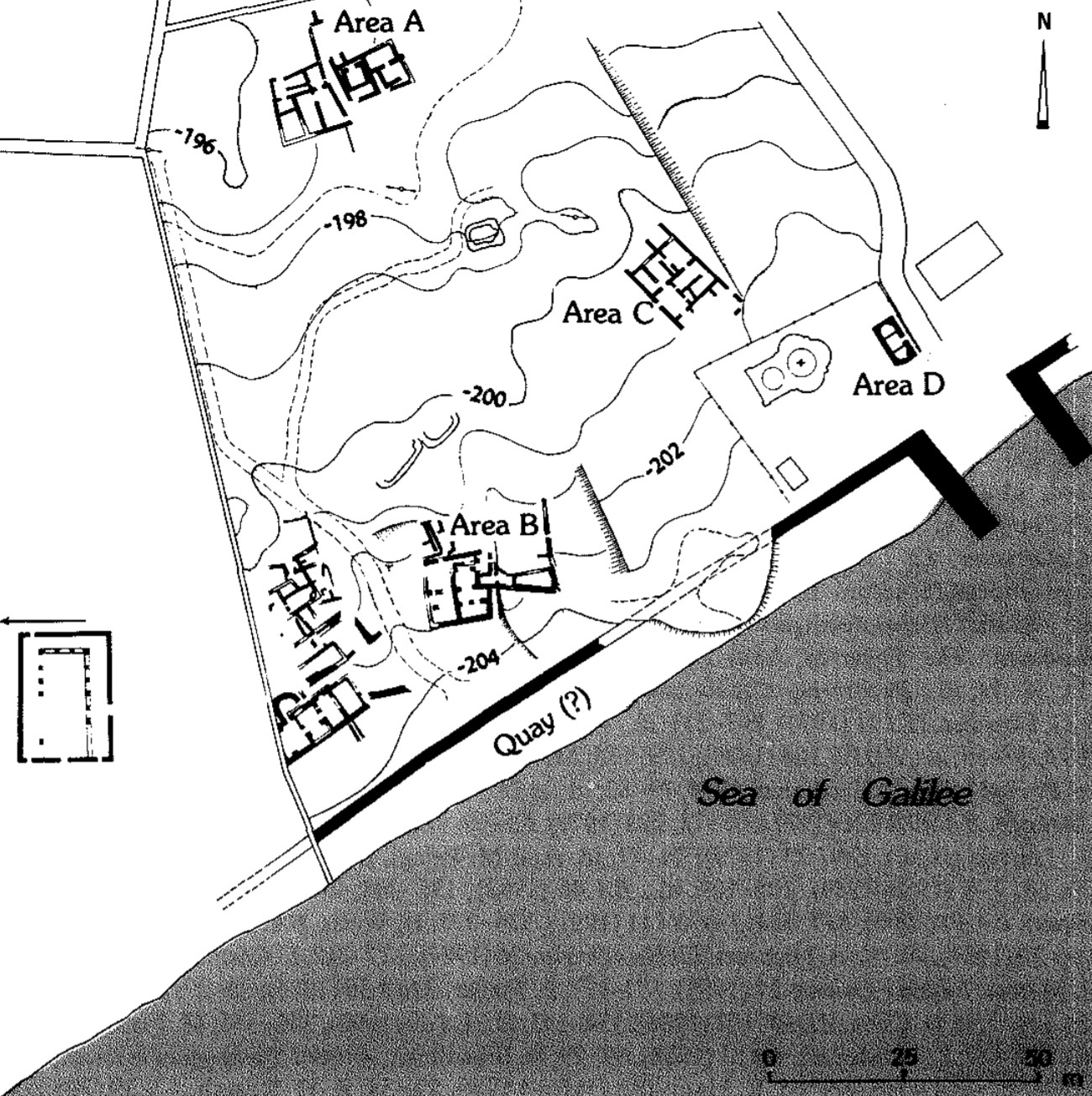

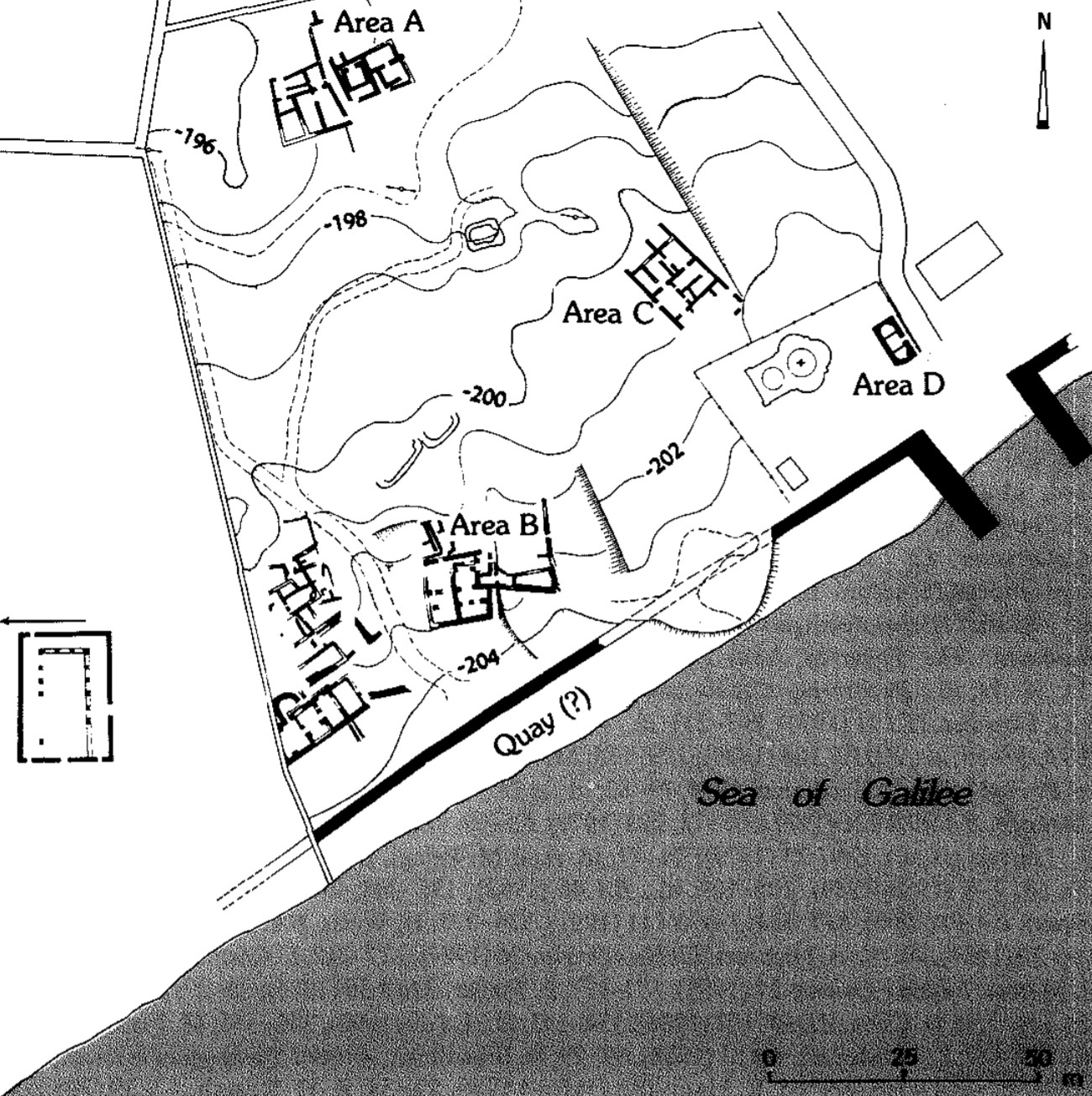

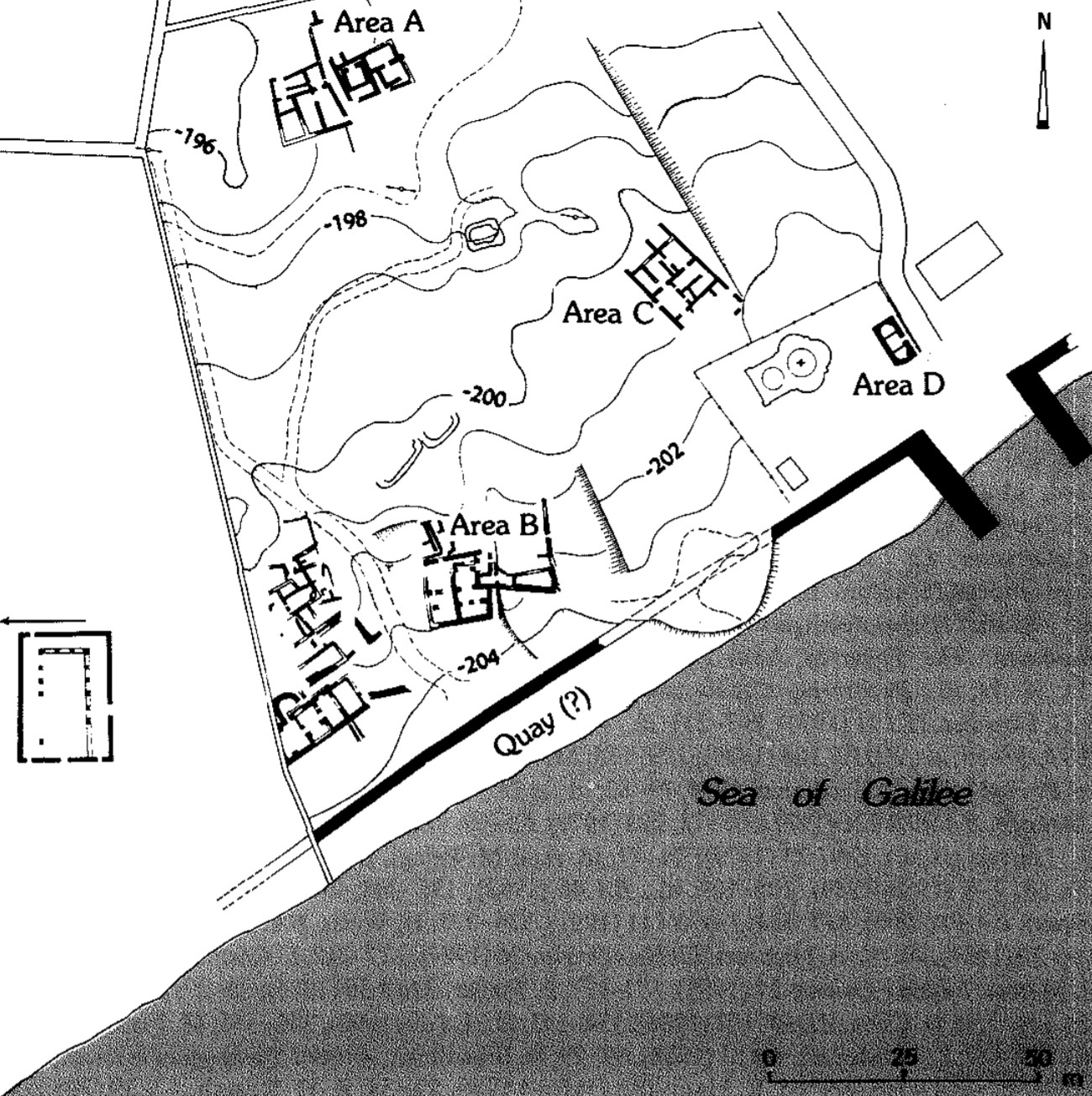

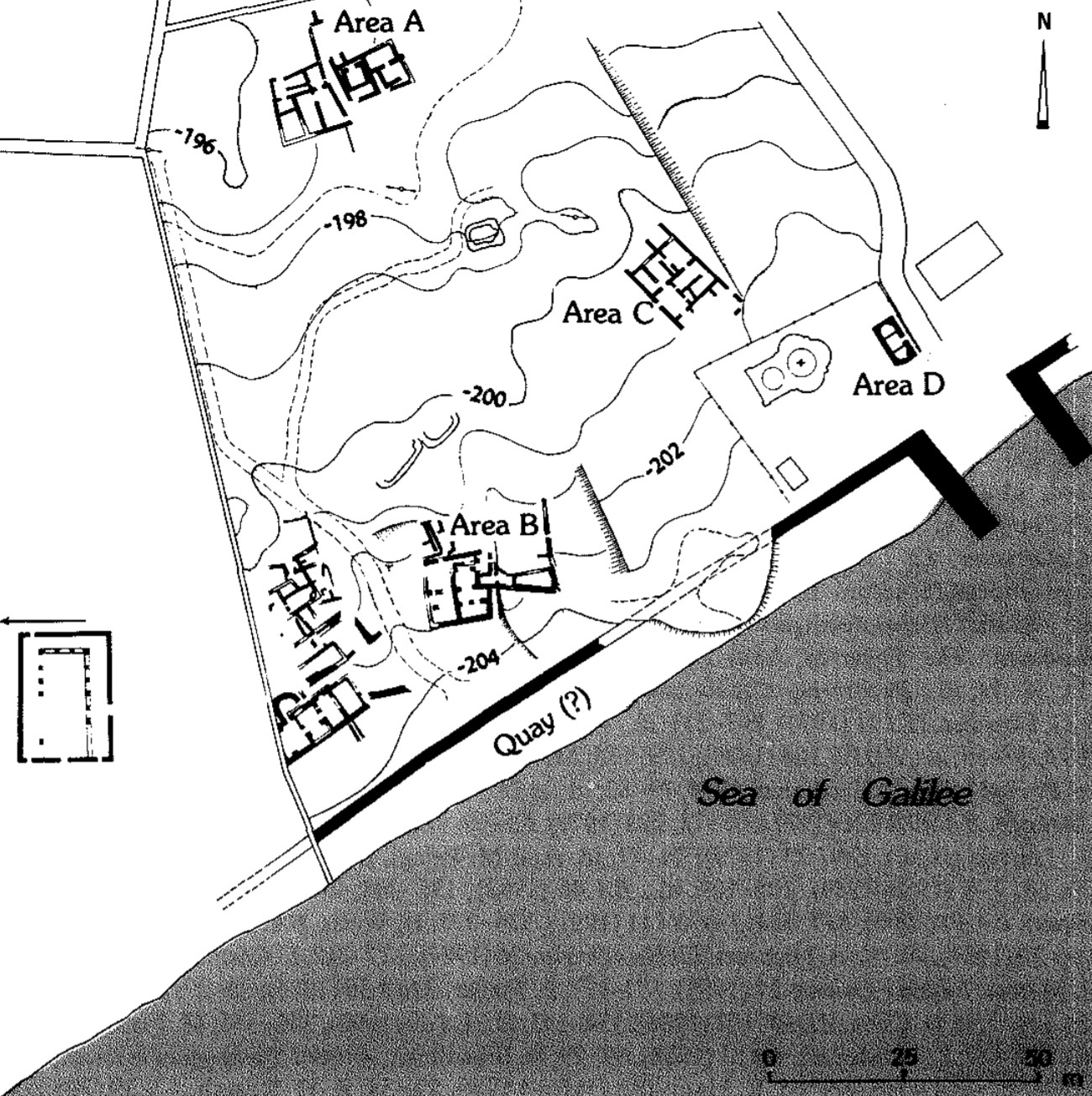

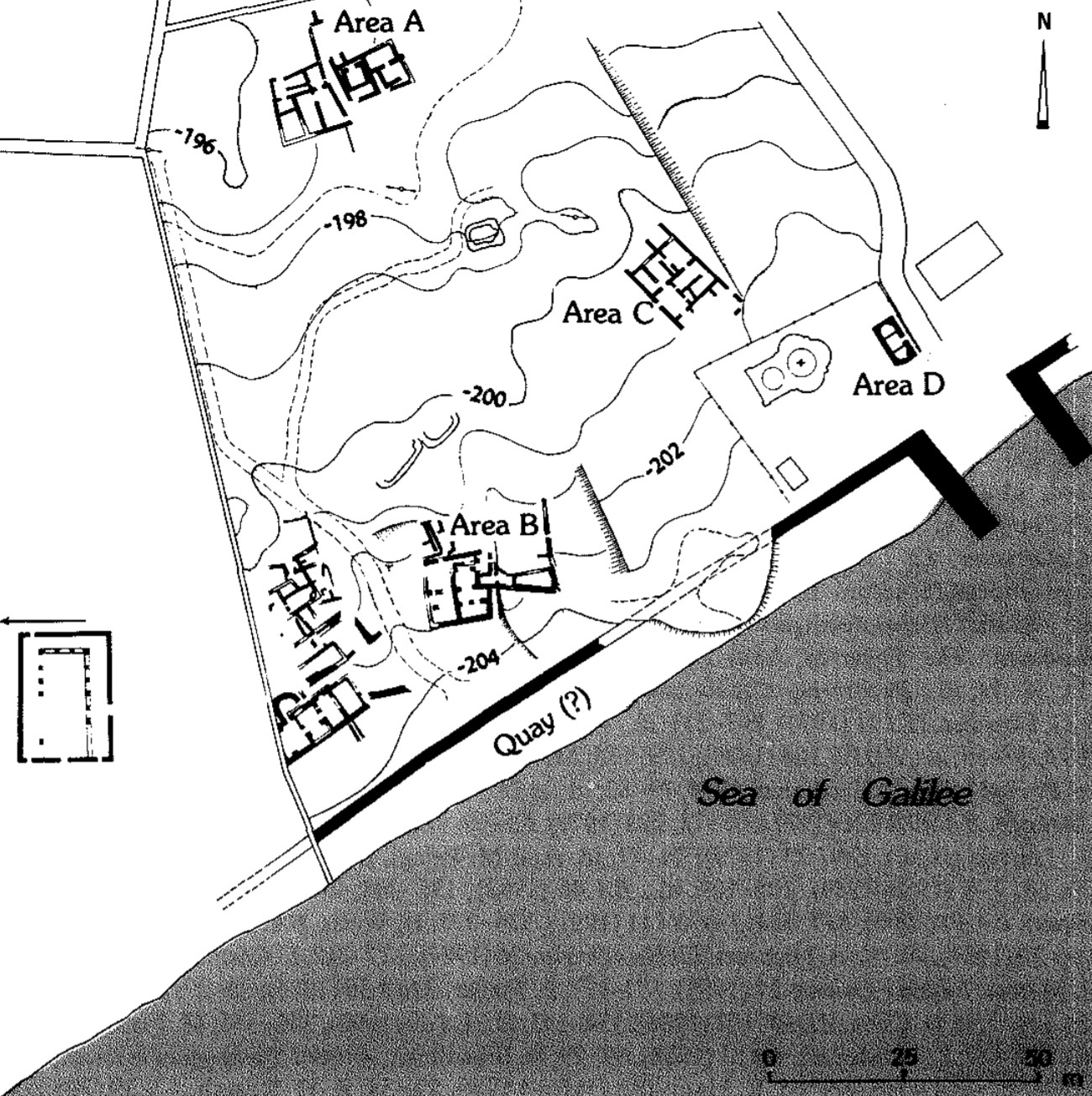

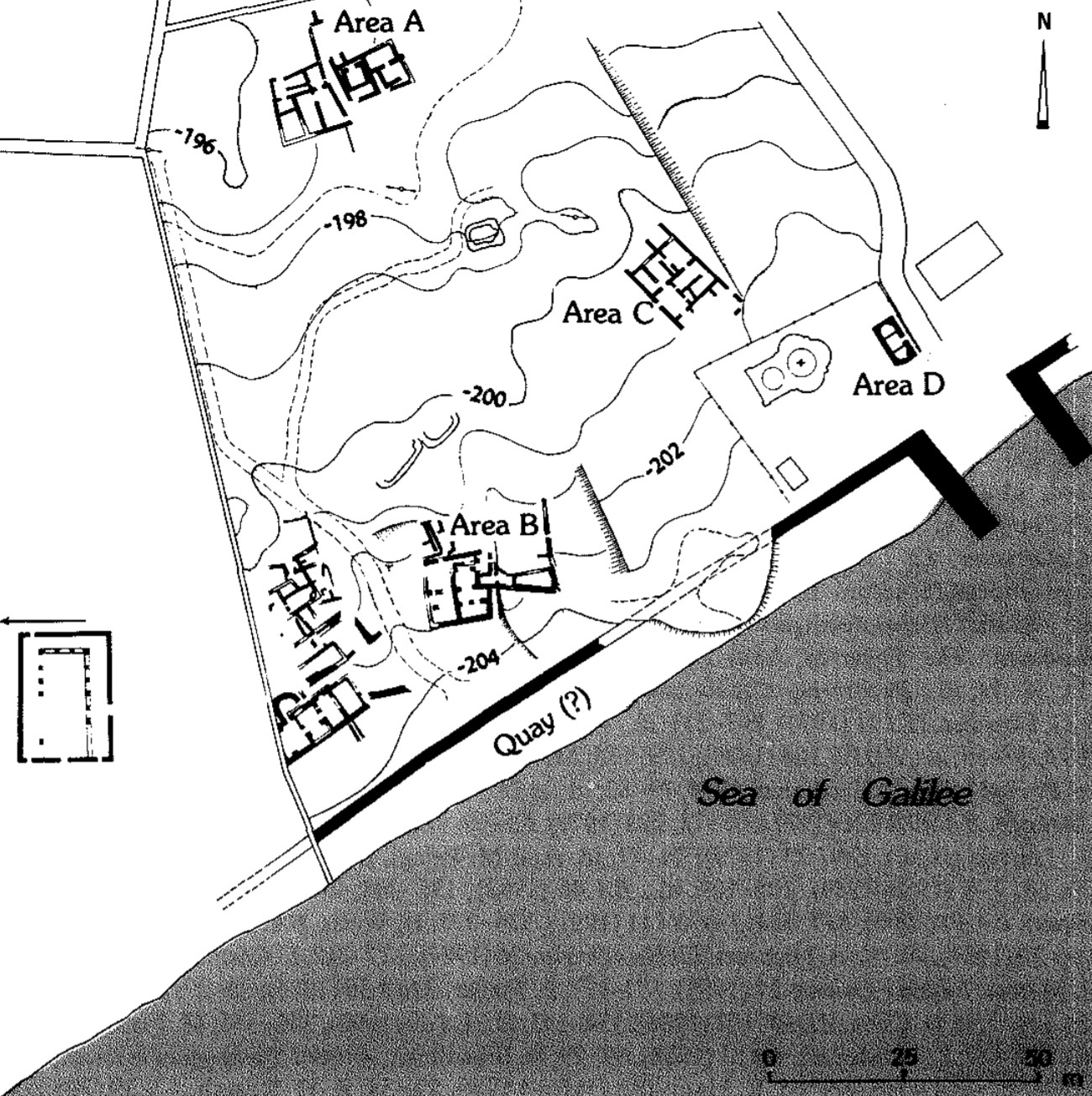

From 1978 to 1982, five excavation seasons were carried out in this area (east of Capernaum's well-known excavations) under the direction of V. Tzaferis, on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. These excavations shed new light on the history of the Jewish settlement and provide increased knowledge of the site's stratigraphical sequence. Four areas (A, B, C, D), covering a total of about 5 a., were cleared in the course of five seasons of excavations.

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- Fig. 6 Plan of the synagogue

from Magness (2001)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Plan of the synagogue at Capernaum

Reproduced with permssion from Corbo 1975: PI. 11

Magness (2001) - Fig. 7 North-south section in

trench 1 from Magness (2001)

Figure 7

Figure 7

North-south section in trench 1 in the synagogue at Capernaum, looking west.

Reproduced with permission from Corbo 1975: Fig. II.

Magness (2001) - Fig. 8 East-west section in

trench 2 from Magness (2001)

Figure 8

Figure 8

East-west section in trench 2 in the synagogue at Capernaum, looking south.

Reproduced with permission from Corbo 1975: Fig. 12.

Magness (2001)

- Fig. 6 Plan of the synagogue

from Magness (2001)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Plan of the synagogue at Capernaum

Reproduced with permssion from Corbo 1975: PI. 11

Magness (2001) - Fig. 7 North-south section in

trench 1 from Magness (2001)

Figure 7

Figure 7

North-south section in trench 1 in the synagogue at Capernaum, looking west.

Reproduced with permission from Corbo 1975: Fig. II.

Magness (2001) - Fig. 8 East-west section in

trench 2 from Magness (2001)

Figure 8

Figure 8

East-west section in trench 2 in the synagogue at Capernaum, looking south.

Reproduced with permission from Corbo 1975: Fig. 12.

Magness (2001)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- Fig. 32 stone debris from

Stratum IV earthquake (?) in Building D of Area A from Tzaferis et al. (1989)

Fig. 32

Fig. 32

Area A Stratum IV Building D stone debris from earthquake (?) on floor looking east

Tzaferis et al. (1989

- Fig. 32 stone debris from

Stratum IV earthquake (?) in Building D of Area A from Tzaferis et al. (1989)

Fig. 32

Fig. 32

Area A Stratum IV Building D stone debris from earthquake (?) on floor looking east

Tzaferis et al. (1989

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

Tzaferis (1989) excavated areas around the Greek Orthodox Church in Capernaum from 1978-1982 and divided up the strata, according to Magness (1997), via pottery, coins, and oil lamps. He also presented the following stratigraphy, again according to Magness (1997):

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| I | mid-10th century to 1033 |

| II | mid-9th to mid-10th century |

| III | 750 to mid-9th century |

| IV | 650 - 750 |

| V | early 7th century to 650 |

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| I | late 10th to early 11th century |

| II | late 9th century to early 10th century |

| III | late 8th century to early 9th century |

| IV | ends in 746 CE |

| V | first half of 7th century to first half of the 8th century |

was apparently destroyed in the earthquake that struck the region in 746 CE [as] evidenced by the great quantity of huge stones in the piles of debris and by the ash covering the stratum throughout the area.Stratum IV, according to Magness (1997) was apparently primarily dated based on a coin hoard found buried beneath a paving stone in a room in Area A (Tzaferis 1989: 17; Wilson 1989: 145). The hoard

consists of 282 gold dinars of of the Umayyad "post-reform" type, dating from 696-97 to 743-44(Magness, 1997). The latest coin dated to A.H. 126 (25 October 743 - 12 October 744 CE). Wilson (1989:163-64) made the following comments about the hoard1:

The latest dinar in the Capernaum hoard is dated A.H. 126, which means that the hoard could not have been buried before A.D. 744. It may be possible, in this case, to pinpoint the date even more precisely. According to ancient historians, a disastrous earthquake shook the Jordan Valley in A.D. 746, severely damaging the Temple Mount, destroying Khirbet Mefjer, damaging Jerash, and, significantly, smashing Tiberias, some 19 km. from Capernaum. Evidently both history and nature conspired against Capernaum during the years A.D. 744-746. First, the civil chaos following the death of Hisham reached out into Palestine, particularly involving such aristocratic estates as Khirbet Minyeh, whose master could not have avoided being on the wrong side of the conflict at some point. Under the dangerous circumstances, the owner of the hoard deposited his treasure. In the very midst of this conflict, the earthquake played havoc up and down the entire Jordan Valley. If the hoard's owner was not killed in the succession conflict, or destroyed along with his town in the earthquake, he may have fallen, or at least been prevented from returning to his fortune. . . . (Wilson 1989: 163-64)Magness (1997) observed that while

the hoard could not have been buried before 744, when the latest coins it contained were minted, it could have been deposited at any time after that date.Magness (1997) further noted that ceramic evidence (particularly when compared to ceramic evidence at Pella) was in conflict with the dating of Stratum IV and suggested that the coins were deposited during the Abassid period - a time when there was a noted shortage of Abassid coinage as the Abassids had moved their capital from Damascus to Baghdad and apparently fewer coins were minted in Syria. This could then explain why no coins were found minted after A.H. 126 (25 October 743 - 12 October 744 CE). Magness (1997) went on to question whether there was an earthquake destruction level at the top of stratum IV:

Elsewhere in the publication the destruction of stratum IV is attributed to the earthquake of 746-47.5 However, The evidence from stratum IV at Capernaum is inconsistent with earthquake destruction. No human or animal victims have been discovered, there is no evidence for the extensive collapse of buildings, and no assemblages of whole or restorable vessels were found lying smashed on the floors. In fact, almost no whole or restored vessels are published from Capernaum. The coins at Pella were found scattered on the floors of the buildings, buried beneath the earthquake collapse. In contrast, at Capernaum the hoard was carefully buried beneath the pavement of a room. It could have been deposited due to an impending (and presumably, human) threat. However, since it does not fit the profile of an emergency hoard, I believe that it represents the carefully hidden personal savings of an individual or individuals. Finally, the fact that the ceramic assemblage from stratum IV at Capernaum differs significantly from that associated with the 746-47 earthquake at Pella indicates that they are not contemporary.Magness (1997) redated Stratum IV as well as the oldest layer, Stratum V, based on ceramic evidence. While she noted thatFootnotes5

The structures of Stratum IV were probably all destroyed by an earthquake, as is suggested by a huge rock resting upon and blocking Street 1, and by the fallen debris, especially in Building D(Tzaferis 1989: 16, 20).

the few whole or restorable vessels illustrated from stratified stratum V contexts at Capernaum have parallels from the 746-47 earthquake destruction level at Pella, the absence of clearly later types, such as Mefjer ware, suggests a terminus ante quem of ca. 750 for stratum V.Magness (1997) noted that Stratum V was a thin occupational level which means there is limited ceramic evidence. She suggested that there appeared to be no break in the occupational sequence from V to IV. Magness (1997) proposed redating Stratum IV and V as follows:

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| IV | ca. 750 to the second half of the ninth century |

| V | ca. 700-750 |

1 The quote comes from Magness (1997) with a note to See also Tzaferis 1989: 17

- from Magness (1997:481)

- from Magness (1997:481)

One problem central to this discussion concerns the dating of glazed pottery and "Mefjer ware," a type of fine, buff ware characteristic of the early Islamic period in Palestine. According to Tzaferis, the Capernaum excavations provide evidence for the appearance of glazed pottery and Mefjer ware in Palestine by the mid-seventh century C.E. (Tzaferis 1989: xix, 30). Before examining the basis for the dating of these ceramic types, it is necessary to review the occupational sequence at Capernaum.

Tzaferis' excavations were concentrated in four main areas, designated A, B, C, and D. Within these areas, five main occupational phases were distinguished (V-I), on the basis of separate floor levels and architectural modifications within the buildings (Tzaferis 1989: 1-9). The published dates are as follows:

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| V | early 7th century to 650 (all dates C.E.) |

| IV | 650 - 750 |

| III | 750 to mid-9th century |

| II | mid-9th to mid-10th century |

| I | mid-10th century to 1033 |

The five main floor levels found enable five occupational phases to be distinguished, allowing for controlled, sealed loci from which most of the pottery exemplars were chosen. Dated coins and oil lamps accompanying these established phases also aid in dating. (Peleg 1989: 31)In other words, the primary basis for dating was the pottery, together with numismatic evidence and oil lamps, when available. Here the first indications of circular argumentation appear. Since Peleg and Berman assumed that glazed pottery and Mefjer ware dated to the Umayyad period, the first level in which these types appear is attributed to the Umayyad period. This was then used as a basis for assigning these types to the Umayyad period ! In her discussion of Mefjer ware, Peleg noted that "at Ramla, this ware appears in stratified contexts from the first period on the site — from the beginning of the 8th century A.D." (Peleg 1989: 103).1 Thus, based on the evidence from Ramla, Peleg and Berman were predisposed to date glazed pottery and Mefjer ware to the Umayyad period. As I have noted elsewhere, the incorrect assignment of these types to the Umayyad period because of the Ramla excavations is common in Israel (Magness 1994: 204-5, n. 3; also see Walmsley 1994). At Capernaum, however, the association of glazed pottery and Mefjer ware with a coin hoard would seem to support the assignment of these types to the Umayyad period. As Berman stated, "the use of glazing at Capernaum during the Umayyad period is borne out by evidence directly associated with the gold coin hoard. Sherds with yellow and green monochrome lead glaze were found among the debris surrounding the hoard. Thus, one can decidedly conclude that glazing was prac-ticed during the early decades of the 8th century A.D. and probably earlier" (Berman 1989: 124). In fact, the chronology of the two earliest strata, V and IV, was established on the basis of this coin hoard. The numismatic evidence is thus crucial for understanding the chronology of Capernaum.

1 Also see Berman's statement that "preliminary reports of the excavations at Ramla indicate that glazing, while not over-whelmingly popular, was practiced [in the Umayyad period]" (1989: 124).

- from Magness (1997:483-484)

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

The latest dinar in the Capernaum hoard is dated A.H. 126, which means that the hoard could not have been buried before A.D. 744. It may be possible, in this case, to pinpoint the date even more precisely. According to ancient historians, a disastrous earthquake shook the Jordan Valley in A.D. 746, severely damaging the Temple Mount, destroying Khirbet Mefjer, damaging Jerash, and, significantly, smashing Tiberias, some 19 km. from Capernaum. Evidently both history and nature conspired against Capernaum during the years A.D. 744-746. First, the civil chaos following the death of Hisham reached out into Palestine, particularly involving such aristocratic estates as Khirbet Minyeh, whose master could not have avoided being on the wrong side of the conflict at some point. Under the dangerous circumstances, the owner of the hoard deposited his treasure. In the very midst of this conflict, the earthquake played havoc up and down the entire Jordan Valley. If the hoard's owner was not killed in the succession conflict, or destroyed along with his town in the earthquake, he may have fallen, or at least been prevented from returning to his fortune. . . . (Wilson 1989: 163-64)In other words, the dramatic historical events and natural disasters which occurred at the end of the Umayyad period are presented as the context for the burial of the hoard. Though this conclusion is possible in light of the date of the latest coins in the hoard, it is not borne out by the ceramic evidence.

The hoard could not have been buried before 744, when the latest coins it contained were minted. However, it could have been deposited at any time after that date. Wilson noted that whereas emergency hoards usually contain a high percentage of specimens from the years immediately prior to burial, the Capernaum hoard reverses this pattern; over two-thirds of the coins are dated between A.H. 77 and 101, and there is a decided decline in the number of specimens per year after that. In addition, the older specimens were no more worn than the later ones (Wilson 1989: 159). Another important point emerges in connection with the bronze and silver coins recovered in the Capernaum excavations: "The site yielded a high percentage of coins from the 4th century A.D. and from the Umayyad period. Noticeably absent are coins from the Byzantine period (except for one example) and the Abbasid period" (Wilson 1989: 139). In other words, though by the publication team's own account there is evidence for continuous occupation at Capernaum through the Abbasid period, not a single Abbasid coin was recovered. I have noted elsewhere that the paucity of fifth-century coins has made it difficult to distinguish fifth-century occupation levels in Jerusalem, and has led to the misdating of fifth-century ceramic types to the fourth century (Magness 1993: 165; also see Magness, in press). The same phenomenon appears to be true of the Abbasid period. Abbasid coins are rare or unattested at many sites with Abbasid occupation in Palestine. In fact, Meyers, Kraabel, and Strange have remarked upon this phenomenon in relation to Khirbet Shema', pointing out that from the ninth to eleventh centuries, few copper and silver coins were struck in Syria (1976: 163).2 The site of Capernaum, with its evidence for flourishing Abbasid occupation but without a single Abbasid coin, provides clear evidence for this phenomenon. Because they are often found in association with the more common Umayyad coins, Abbasid ceramic types have often been misdated to the Umayyad period.

2 Also see Whitcomb 1991: 78-79: "The rarity of Abbasid issues in excavations parallels known production of mints in Palestine. . . .

Except for a few issues in the early 9th century, there is no mint activity until the Tulunids [890 A.D.] and then only at Filistin [Ramla?]."

- from Magness (1997:484)

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

Again, the best evidence comes from Pella, where Mefjer ware, glazed pottery, and "cut-ware" are not at¬tested in the earthquake destruction level of 746-47. Instead, these types have been found at Pella in securely-dated Abbasid levels. In fact, all three types appear there in contexts dating to the second half of the ninth century C .E.:

Glazed pottery appears in limited quantity for the first time, although plain fabrics are still in the majority. Also new are the increasingly common Samarra-style, thin-walled, pale cream jars and strainer jugs with often deep finger rilling marks inside the body and a knife trimmed lower body. These vessels are either plain or decorated with incisions; incised bowls and water flasks in the same fabric are also present. Straight sided, hand-made bowls make an appearance. These are highly decorated with incised, cut and painted geometric designs on the out¬side, and with painted lines inside. Three new types of moulded ceramic lamps occur. . . . The remainder of the pottery in Group 2 represents a continuation of earlier wares. . . . Group 2 can be very tentatively placed in the later third century A.H. (second half of the ninth century A.D.). (Walmsley 1991: 8)These same types are described in association with stratum IV at Capernaum:

The "chip-carved" bowls ("cut-ware") appear now at Capernaum for the first time, and seem to remain in vogue for a very short period. . . . Side-by-side with the "chip-carved" bowls we see, also for the first time, the "Mefjer" group of bowls and jars, made in a light, soft-firing ware. . . . (Peleg 1989: 112)Thus, parallels with Pella suggest that the stratum IV occupation at Capernaum came to an end some time in the second half of the ninth century, instead of in the mid-eighth century. This date is over one-hundred years later than that suggested by the publication team, and it affects the chronology of the other strata at Capernaum.

Glazed bowls were relatively uncommon in Stratum IV, although the technique was employed. . . . Sherds with yellow and green monochrome lead glaze were found among the debris surrounding the [gold coin] hoard. (Berman 1989: 124)

6 Peleg 1989: figs. 42: 3, 4, 6, 16, 21, 24, 32, 35, 39, 45, 46, 48; 44: 1; these survival pieces do not provide evidence for the continued production and use of these types in stratum IV, as claimed by Peleg 1989: 112.

Stratum V at Capernaum, which was assigned to the first half of the seventh century, represents the earliest occupation level uncovered in Tzaferis' excavations. In area A, at the top of the mound, the stratum V remains rested upon a thin layer of soil with early Roman pottery but no architecture. This suggests that the settlement in this area was newly established in the early Islamic period; the Roman pottery should be associated with the Roman settlement to the south and southeast of area A, and in the Franciscan part of the property (Tzaferis 1989:10).7 According to Peleg, "The earliest stratum at Capernaum—Stratum V—represents the transition from the final Byzantine phase to the Early Arab period, during which several distinguished pottery forms appear. These forms, however, are very few in number and very limited in repertoire, possibly because Stratum V is represented by a very thin occupational layer" (Peleg 1989: 32). The assignment of this stratum to the first half of the seventh century seems to have been dictated by the assignment of the next stratum (IV) to ca. 650-750. The redating of stratum IV proposed here affects the dating of stratum V, since there appears to be no break in the occupational sequence.

Again, due to the inclusion of material from above, below, and within the floors, the pottery illustrated from stratified contexts in stratum V includes a mixture of types of various dates. Among the earliest are Late Roman mortaria (Peleg 1989: fig. 43: 7-9; see Magness 1992: 130) and Galilean bowls (Peleg 1989: figs. 43: 20; 44: 2-5, 7; see Adan-Bayewitz 1993), which range in date from the second to fifth centuries. There are also numerous fragments of Late Roman Red Ware bowls, the latest of which date to the seventh century.8 The Roman and Byzantine pottery undoubtedly derives from earlier occupational levels which were not uncovered in the excavations, or from the adjacent Roman and Byzantine settlement. Some of it may have been brought in with fills to level the area when the early Islamic settlement was established. However, the latest ceramic types illustrated from stratified contexts point to a date in the first half of the eighth century for stratum V. Prominent among these are examples of red-painted ware (Peleg 1989: figs. 45: 9; 51: 1), which appeared only at the end of the Umayyad period, toward the middle of the eighth century (see Magness 1994: 203; McNicoll et al. 1986: 193). In addition, the few whole or restorable vessels illustrated from stratified stratum V contexts at Capernaum have parallels from the 746-47 earthquake destruction level at Pella (compare Peleg 1989: figs. 52: 1 and 57: 1 with Walmsley 1982: pl. 145; and Peleg 1989: fig. 55: 5 with Walmsley 1982: pl. 143: 3). On the other hand, the absence of clearly later types, such as Mefjer ware, suggests a terminus ante quem of ca. 750 for stratum V. Thus, a review of the ceramic evidence indicates a date in the first half of the eighth century for stratum V at Capernaum. It is difficult to ascertain what brought this stratum to an end, though the publication does not provide explicit evidence for earthquake destruction.

7 In area C, architectural remains of the early Roman period, designated stratum VI, were revealed in a small probe beneath stratum V; see Tzaferis 1989: 4.

8 Peleg 1989: 32-42; fig. 42: 2, 7, 8, 12, 13, 18, 20, 22, 25¬27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 40.

The latest piece illustrated from a stratified stratum V context appears to be fig. 42: 40,

which should be identified as Cypriot Red Slip Ware, form 9, type B, dated ca. 580/600

to the end of the seventh century; see Hayes 1972: 379—82.

- from Magness (1997:485)

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| V | ca. 700-750 |

| IV | ca. 750 to the second half of the ninth century |

- from Vasilios Tzaferis in Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

The antiquities area of Capernaum has been owned by two churches, the

Franciscan and the Greek Orthodox, since the end of the nineteenth century.

The area belonging to the Franciscan Order has received a great deal of

attention, whereas that of the Greek Orthodox church was a "no man's-land" until 1967.

From 1978 to 1982, five excavation seasons were carried out in this area

(east of Capernaum's well-known excavations) under the direction of

V. Tzaferis, on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums.

These excavations shed new light on the history of the Jewish settlement and

provide increased knowledge of the site's stratigraphical sequence. Four

areas (A, B, C, D), covering a total of about 5 a., were cleared in the course

of five seasons of excavations.

In area D, in the northeast of the excavated area, remains of a massive building close to the shore of the Sea of Galilee were found. This building consists of two concave, semicircular pools flanking a raised platform built of thick, plastered walls. It is difficult to determine the nature ofthe pools because of later construction on the site. The pools were apparently used to store fish that were subsequently moved to the raised platform between them. The water in the pools drained into the Sea of Galilee through clay pipes.

In area C, located in the southeastern part of the excavated area, is a large square building (c. 13 by 13m) in which five occupational strata can be discerned, dating from the Byzantine period-the beginning of the seventh century CE-to the end of the tenth century. The building's plan, nature, and finds indicate that initially it was a public building; in later phases it was private

In area B, located in the central part of the site, near the Sea of

Galilee, is a building in which five building phases can be distinguished,

dating from the seventh century CE to the Middle Ages. In the first phase

of the structure (stratum V, dating to the beginning of the seventh century),

the building was a single unit that measured 12.7 by 12.5 m. About two-thirds

of its area is preserved. The northern part of the building has, to date, not

been excavated. Its walls and floors were coated with a thick layer of plaster,

which prevented water from entering. In stratum IV (seventh and eighth

centuries), internal changes were made in several parts of the structure, and it

was divided into three unequal units by columns and pilasters that supported

its roof and perhaps even its second story. In stratum III (eighth and ninth

centuries), the previous character of the building was preserved, except for

the addition of several walls and a court integrated into its plan. The floor of

this court was built of flat basalt stones, distinguishing it from the structure's

other, plastered floors. In stratum II (the Late Abbasid period), the plan of

the building is obscure.

From the tenth century, represented by stratum I, several one- or two

room huts are preserved. The quality of the their construction is poor.

The excavations in the last three seasons were concentrated in area

A, located at the summit of the mound in the southwestern part of the

excavated area. Five strata can be discerned, dating from the beginning

of the seventh to the tenth centuries CE. In its first phase (stratum V, the

first half of the seventh to the first half of the eighth centuries), the buildings of

the settlement in this area constituted independent units consisting of small

and large rooms integrated with courts and streets. The entrances in the units

permitted passage from room to room, and the courts and streets facilitated

access from one unit to another. A central street with an east~west orientation curving northward runs between the eastern and western complexes. At

the northern end of the street, a plastered drainage channel covered with flat

stones turns eastward, following the line of the street. Flanking the center of

the street are two parallel drainage channels.

The walls of the buildings are of local flat basalt stones. Between the

courses is a fill of smaller stones. The construction is "dry," except for

some places in which plaster is visible. The walls are generally 60 to 70

em thick. Some of the buildings (and all the courts and streets) are paved

with beaten earth, and others with basalt. The basalt pavement was apparently laid in rooms whose especially elaborate entrance was of high building

quality; the pavement not only enabled passage between the rooms themselves, but also exiting from the building. These rooms were apparently of

special significance in the life of the community. The height of their floors

differs from room to room, as does the height of the thresholds and lintels.

The width of the entrances ranges from 0.6 to 1.9 m; their position, orientation, and size are not uniform. The plan of the settlement in this area and its

rich finds---cooking vessels, baking ovens (tabuns ), and millstones-indicate

that the structures were for private use.

Beneath the Byzantine plastered pavement is Early Roman pottery, and

below that, bedrock. This sequence also appears in area C of the settlement.

There is evidence in one of the rooms of an Early Bronze Age occupation.

Settlement was renewed here after an extended gap in the Byzantine period in

stratum V. Below the stone pavement of one of the rooms a treasure of282

gold dinars from the Umayyad period was found.

Stratum IV was apparently destroyed in the earthquake that struck the

region in 746 CE [JW: should be 749 CE]. This is evidenced by the great quantity of huge stones in the

piles of debris and by the ash covering the stratum throughout the area.

After the earthquake, the plan of the settlement underwent fundamental

change. In strata III (late eighth and early ninth centuries) and II (late ninth

and early tenth centuries), the settlement here was of a different nature.

The building complexes differed in

their internal division: the number

of rooms was increased and their size

was reduced. The street was blocked

by walls that formed additional dwelling rooms integrated into the residential system of one of the complexes.

The quality of construction declined. There are only a few architectural remains in stratum I (late tenth

and early eleventh centuries).

No evidence of walls or fortifications has yet been found in the excavated area, except for a wall about 1.5

m thick that extends from the area of

Capernaum owned by the Franciscans and continues along the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. However, this wall probably did not serve

as a defense but as a quay; its main

purpose was to prevent water from

entering the settlement, especially

to protect it from changes in the level

of the Sea of Galilee. The inhabitants of ancient Capernaum anchored their

fishing boats alongside it (in stormy weather they probably used smaller and

more secure anchorages, such as the one seen opposite the fish pond).

The pottery finds attest to continuous settlement from the

seventh to tenth centuries: many cooking utensils and everyday vessels

(such as bowls, storage vessels, and kraters), Mafjar ware, and glazed vessels. Small deposits of Early and Late Roman pottery were also found.

Many metal tools were also uncovered in the excavations, mainly agricultural tools, such as hoes, a sickle, and plowshares, as well as fishing

accessories, including lead weights. A fairly large number of glass vessels

and some cosmetic vessels were also found.

The first inhabitants of the settlement were Jews, except for a small group

Minim (Judea-Christians) who apparently settled in the area beginning in the

first century, in the wake of the Galilean ministry of Jesus and his Apostles.

The site's lack of literary and archaeological evidence in the period following

the Arab conquest led to the conclusion still held by some scholars, that the

settlement was destroyed or abandoned with the end of Byzantine rule in

Palestine. The new evidence revealed in the excavations in the area owned by

the Greek Orthodox church, however, shows that not only was the settlement

not destroyed following the Arab conquest, but that it continued to exist and

flourish. It is possible that in the period following the Arab conquest the

composition of the local population began to change. It was Jewish until the

fifth and sixth centuries and showed an increase in its Christian element after

the conquest. The settlement was apparently abandoned only upon the

arrival of the Crusaders. Indeed, when the Russian abbot Daniel visited

Palestine in the beginning of the twelfth century, he described Capernaum

as an abandoned and destroyed city.

Table of Stratigraphy at Capernaum (Areas A and C)

Table of Stratigraphy at Capernaum (Areas A and C)Tzaferis et al. (1989)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

The original excavator Loffreda (1973:37) used primarily numismatic evidence to date construction of a synagogue near the Franciscan Church in Capernaum

to the last decade of the fourth to the middle of the fifth century A.D.

.

The synagogue was built on an artificial platform which was built on top of the remains of an earlier village (stratum A). Chronology was established (but debated - see below) after construction

of the synagogue but not before leaving the timing and cause for destruction and/or abandonment of the underlying village in question.

Russell (1980)

speculated that the village was damaged or destroyed by the northern Cyril Quake of 363 CE

citing numismatic evidence to bolster his case.

After publications by

Loffreda (1972) and

Loffreda (1973),

there was opposition to the dating of the construction of the synagogue at Capernaum to the

late 4th or early 5th century AD. Opposing scholars dated these synagogues later with Magness (2001)

suggesting a terminus post quem of the 3rd quarter of the 5th century CE and an estimated 6th century CE date for it's construction.

The synagogue complex consists of three units:

- a prayer hall (20.4 m by 18.65 m)

- a court to the east (11.25 m wide at the front)

- a porch along the facade of the building, which faced south toward Jerusalem

"Insula no. 2" of the village prevented the builders of the synagogue from constructing a magnificent access way to the southern facade of the building. They were forced to build two sets of stairs flanking the southern porch, one at the eastern end and the other at the western end. Another set of stairs was uncovered near the northeastern corner of the court. Along the facade were five entrances, three leading to the prayer hall and two to the court in the east. The court had three other entrances on its northern side. The three openings in the eastern wall of the court were not doorways but large windows, judging from the street level, which was lower on this side by about 2 m. The prayer hall and the court were connected by an entrance in between.

The plan of the synagogue is that of a basilica: the broad rectangular area of the prayer hall is divided into a wide nave and three aisles-in the east, west, and north-by a stylobate, supporting sixteen columns. Double benches ran along the east and west walls. The court to the east has an irregular trapezoidal plan. The area of this court was also divided into a large open central area by a stylobate. It was surrounded on three sides-from the north, east, and south-by roofed porticoes. The focal point of the synagogue was in the south. Flanking the central entrance the foundations of two aediculae were uncovered. They did not block the passageway, as Watzinger thought. The prayer hall, the court to the east, and the porch to the south were paved with thick stone slabs laid on a layer of mortar.

The synagogue was built of limestone brought from afar and stood in sharp contrast to the modest basalt houses. The synagogue is distinguished by its size and the richness of its inner and outer ornamentation. Its interior was covered with multicolored plaster and decorated with reliefs. The richly ornamented architectural details are unique among the synagogues of Palestine. In the renewed excavations, additional ornamented fragments were found in secondary use in village houses dating to the Middle Ages.

Despite the great wealth of architectural remains left from the synagogue, its structure still cannot be reconstructed precisely. Only after a precise cataloging of all the parts found will it be possible to resolve those problems the reconstruction entails. Thus, for example, Watzinger maintained that there was a women's gallery above the aisles; the entrance to it, according to him, was through an external entrance above the small appended room at the northwestern corner. Corbo, after examining all the problems connected with the northern stylobate, proposed to reconstruct the synagogue without a women's gallery, as a basilica with a high hall surrounded by low aisles, in classical basilican style.

The figurative and decorative motifs of the synagogue in Capernaum are variegated and rich. Only one human figure has been discovered to date: the face of a Medusa carved in the western benches, close to the entrance. Depictions of animals are more common. Noteworthy among the well-preserved parts not damaged by iconoclasts are a cornice decorated with a sea horse and two eagles flanking a garland. The lintel of the central entrance to the prayer hall is decorated with the Roman imperial eagle. Two eagles facing each other are engraved on the keystone of the arch, below the gable in the center of the facade. Two freestanding (and headless) carved lions apparently served as acroteria. Another lion is carved on the lintel of the entrance to the western aisle. Also present are typical Jewish motifs carved on a Corinthian capital, such as a seven-branched menorah flanked on one side by a shofar and on the other by an incense shovel; especially noteworthy is an engraving of a temple resembling a wheeled chariot, which may be interpreted as a Torah ark. There is a wide range of floral and geometric motifs, such as date palms, grape clusters, pomegranates, acanthus leaves, rosettes, pentagrams, and hexagrams. Cantharus and shell motifs also are common.

On a column in the nave a Greek inscription is preserved that reads "Herod, son of Mo[ni]mos, and Justus his son, together with (his) children, erected this column." On the shaft of another column, which apparently stood in the court of the synagogue, is an Aramaic inscription: [Hebrew Lettering] (Halfu, the son of Zebidah, the son of Yohanan, made this column. May he be blessed) (CIJ, nos. 982-983).

The exploration of the

strata beneath the synagogue that began in 1969 continued for many years

and yielded important results. In the excavator's opinion, it was established

that the synagogue was built at the end of the fourth century CE, wheras the

construction of the court in the east was completed only in the fifth century.

This conclusion is based on a large number (more than 25,000) of Late

Roman coins and on the pottery finds; the construction of the synagogue

in accordance with the Byzantine foot reinforces it. However, according to

other scholars, only the last phases of the synagogue belong to the fourth and

fifth centuries and its initial construction is to be dated to the third century. In

addition, a portion of the Hellenistic-Roman village was uncovered under

the extensive area on which the monumental synagogue stood. Upon removal of the artificial fill for the synagogue's podium, houses with basalt

walls and floors were found. They had entrances, courts, ovens, and sets of

stairs. In one place (trench 21 ), a massive wall and a floor of beaten earth from

the Late Bronze Age were uncovered under the Hellenistic-Roman stratum.

In the area below the central nave, unlike in the other areas, only a floor of

basalt stones from the beginning of the first century CE was uncovered. The

area of this floor is too large for it to have served a domestic dwelling; it

probably belonged to a public building. In light of the common practice in the

East of erecting synagogues (and churches) on the identical sites of earlier

synagogues and churches, this lower floor most likely belonged to a synagogue as well. The New Testament (Lk. 7:5) states that the synagogue visited

by Jesus in Capernaum was built by a Roman centurion. In a text written by

Peter the Deacon in 1137 (but probably based on a much earlier composition,

the fourth-century Itinerarium of Egeria), the synagogue mentioned in the

New Testament was located at the site of the monumental synagogue. Corbo

correlates the large first-century floor, mentioned above, with a massive

basalt wall that was encountered only in the area of the prayer hall. In

his opinion, this wall was not built as a foundation for the synagogue which is white limestone and is dated to the Late Roman period-but belongs to the first-century synagogue built by the Roman centurion, on which

the later synagogue partially rests. Loffreda suggests that the basalt wall

belongs to an intermediate stage, between the pavement of the first century and the synagogue of the Late Roman period.

- from Magness (2001:21-26)

Unfortunately, the excavators have published only a fraction of the potsherds and the approximately 25,000 coins they have found beneath the pavement of the synagogue.41 Since the exact provenience of the pottery (and of many of the coins) is not provided, it is difficult to evaluate the building’s chronology. However, a review of the numismatic and ceramic evidence suggests it was constructed in the sixth century, instead of by the third quarter of the fifth century as the excavators have proposed. Most of the coins found beneath the pavement of the synagogue date to the fourth and fifth centuries, with a few earlier specimens present. The pre-fourth century coins noted by Tsafrir in the lower layers of Stratum B are apparently associated with the Hellenistic and early Roman houses beneath the synagogue, which, according to the excavators, were occupied at least until the fourth century.42 Fourth to early fifth century coins were the most numerous in the fills beneath the synagogue’s floor, with the latest specimens reported until recently dating to the reign of Leo I, ca. 474.43 Though the excavators have interpreted this evidence as meaning that the synagogue’s construction was completed by the third quarter of the fifth century, it actually means that it was constructed no earlier than the third quarter of the fifth century. In other words, the coins found under the floor of the synagogue provide a terminus post quem, not a terminus ante quem, for its construction.

Other published numismatic evidence points to a construction. date in the sixth century. This includes Loffreda’s reference to a “very few Byzantine coins” from the hoard of 2,920 coins found on the south side of the western aisle of the prayer hall.44 Unfortunately, because they have not been published, the number, identification, and date of these “Byzantine” coins are unknown. Most of the rest of the coins from this hoard date to the late fourth and early fifth centuries. The excavators seem to have disregarded the Byzantine coins because they did not accord with their proposed terminus ante quem in the third quarter of the fifth century.45 Another hoard discovered in Trench XII in the synagogue’s courtyard contained 20,323 fractional bronze coins, coin fragments, and counterfeits embedded in the mortar layer underlying the stone pavement. Specimens dating to Zeno’s second reign (476-491) are among the latest of the fifteen percent of the coins from this hoard that have been analyzed and published so far.46 Instead of indicating that the synagogue was completed shortly after 476, as E.A. Arslan concluded, these coins provide a terminus post quem of 491 for its construction.47 The hoard also includes a number of imitation Axumite coins, which according to Arslan were in circulation from the third quarter of the fifth century to the third quarter of the sixth century. The lower end of this range seems to be based largely on the assumption that the synagogue’s construction was completed no later than the beginning of Zeno’s second reign (476): “Se a Cafarnao l’accumulo... sembra chiudersi poco dopo l’inizio del secondo regno di Zeno.”48 However, Arlan noted that Axumite coins have been found elsewhere in contexts dating to the sixth century: “...in altri luoghi la presenza della moneta axumita appare prolungarsi notevolmente. A Baalbek viene riconosciuta in un contesto chiuso con Giustino II (565-578)."49 According to Bijovsky, “these [imitation Axumite] coins circulated in the area during the sixth century, as part of the repertory of Byzantine nummi.”50 The coins thus indicate a sixth century date for the construction of the synagogue at Capernaum.

The pottery found beneath the synagogue is consistent with the coin evidence. The most closely dated pieces belong to imported Late Roman Red Ware bowls. Though the illustrated sherds are not accompanied by descriptions of the fabric or identifications according to J.W . Hayes’ typology, most can be identified on the basis of the line-drawings.51The following types are represented beneath the pavement:

- African Red Slip Ware Form 59, dated ca. 320-420.52

- Late Roman “C” (Phocean Red Slip) Ware Form 1, dated from the late fourth century to third quarter of the fifth century.53

- Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 1, dated from the late fourth century to about the third quarter of the fifth century.54

- Late Roman “C ” (Phocean Red Slip) Ware Form 5, dated around 460 through the first half of the sixth century.55

- Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 2, dated mainly to the late fifth and early sixth century.56

- Late Roman “C ” (Phocean Red Slip) Ware Form 3, dated mainly to the second half of the fifth and first half of the sixth centuries.57

Other considerations support the assignment of the synagogue’s construction to the first half of the sixth century or later. As Loffreda himself acknowledged, the variants of Late Roman “C ” (Phocean Red Slip) Ware Form 3 bowls represented under the synagogue date to the first half of the sixth century: “I do agree with Dr. Hayes in recognizing this new feature as quite common in the first half of the sixth century A.D. However, on the evidence of coins, its appearance in Caphamaum must be set in the third quarter of the fifth century, during the reign of Leo I.”58" Second, since there appears to be a fairly large number of sherds representing this form and Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 2 (as well as smaller amounts of Late Roman “C ” Form 5) under the synagogue, time must be allowed for these types to have appeared, been in use, been broken and discarded, and then imported with the fills deposited beneath the synagogue. A date in the first half of the sixth century or later is also supported by the evidence of local ceramic types. Pieces of metallic storage jars with white painted decoration on a dark background were found in the fill of the courtyard and porch and were embedded in the stucco fragments that decorated the synagogue’s interior.59 Evidence from Jerusalem suggests that the white-painted decoration first appeared on these northern Palestinian bag-shaped jars during the sixth century.60 Other types described (but not illustrated) as embedded in the stucco fragments include a casserole with bevelled rim and large horizontal handles and an oil lamp decorated with a cross in relief.61

It is apparent from the excavators’ publication of the synagogue excavations that they have progressively raised the construction date of the synagogue from the late fourth and early fifth century to the mid-fifth century and finally to the third quarter of the fifth century, as later and later coins were discovered beneath the floor. This has also led them to stretch the duration of construction over the course of about seventy-five years or more, beginning in the late fourth or early fifth century.62 When Loffreda first prepared the publication of the pottery from the excavations at Capernaum in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he and Corbo proposed a late fourth to early fifth century date for the synagogue (which was, of course, much later than die previously accepted date).63 Loffreda based much of his chronology and typology of the local pottery on its association with coins of the third to fifth centuries.64 However, the numismatic evidence can be misleading and provides only a very rough terminus post quem. In addition, Loffreda’s earliest publications of the pottery from the synagogue appeared in print before Hayes’ typology of imported Late Roman Red Wares.65 By the time Hayes’ volume was published, indicating a range from the second half of the fifth through first half of the sixth century for some of the types represented beneath the synagogue, a terminus ante quem in the third quarter of the fifth century had already been established by the excavators. It is now necessary to examine the nature of the numismatic evidence, which is crucial to the dating of the “Galilean” type synagogues.

38 Loffreda, “The Synagogue of Caphamaum,” p. 26

39 Ibid., pp. 26-27; Corbo, Cafarnao, p. 168; LofTreda, “Late Chronology,” p. 52.

In his most recent article, “Coins from the Synagogue at Caphamaum,” Loffreda

proposed a slighly later date for the beginning of construction: “it seems that the

initial date of the entire synagogue building (prayer hall, eastern courtyard and

balcony) was not before the beginning of the 5th century, while the final date of the

project is still kept at the last quarter of the fifth century” (p. 233).

40 Sukenik, op. cit., p. 72; Loffreda, “Late Chronology,” p. 52.

41 S. Loffreda, “Potsherds from a Sealed Level of the Synagogue of the Synagogue

at Caphamaum,” in Liber Annum 29, 1979, p. 218; Loffreda, “Late Chronology;” A.

Spijkerman. “Monete della sinagoga di Cafarnao,” in La Sinagoga di Cafarnao (Jerusalem, 1970),

pp. 125-139; E.A. Arslan, “Monete axumite di imitazione nel deposito

del cortile della Sinagoga di Cafarnao,” in Liber Annuus 46, 1996, pp. 307-316; Loffreda,

“Coins from the Synagogue at Caphamaum;” E.A. Arslan, “II deposito monetale della Trincea XII nel cortile della sinagoga di Cafarnao,” in Liber Annuus 47,

1997, pp. 245-328. LofTreda (“Coins from the Synagogue at Caphamaum,” p. 230),

lists a total of 24,575 coins found in all of the trenches and strata (A-C) beneath

the floor of the synagogue, with a chart of their numbers according to trench and

stratum.

42 Tsafrir, op. cit., p. 156; also see Loffreda, “Coins from the Synagogue at Caphamaum,” pp. 230, 240-241; Loffreda, “Late Chronology,” pp. 54-55; Loffreda,

“The Synagogue of Caphamaum,” p. 14, for third and fourth century coins from

Stratum A.

43 Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p. 218; see below for coins dadng to the reign of Zeno.

44 Loffreda, “The Synagogue of Caphamaum,” p. 15.

45 Though in many other places the original stone pavement was no longer in

place, only here did the excavators use this as a reason for disregarding the numismatic evidence: “Since the stone pavement had been removed in ancient times, the

presence of very few Byzantine coins can be disregarded for our purpose,” Loffreda,

“The Synagogue of Caphamaum,” p. 15.

46 Arslan, “II deposito monetale della Trincea XII;” for the coins of Zeno see p.

322, nos. 1911-1913.

47 Ibid., p. 247, “II complesso venne quindi sigillato non molto tempo dopo 476 d.C.”

48 Arslan, “Monete axumite,” p. 313.

49 Ibid., pp. 313-314.

50 M Bijovsky, op. cit., p. 83.

51 Hayes, op. cit. The pottery from the synagogue is not published in Loffreda,

Cafarnao II. La Ceramua (Jerusalem, 1974), though it is possible to correlate some of

the pottery types published elsewhere from the synagogue with those illustrated in

that volume.

52 Hayes, ibid., pp. 96-100; for illustrated examples, see S. LofTreda, “La Ceramica della sinagoga di Cafarnao,” in La Sinagoga di Cafarnao (Jerusalem, 1970), p. 78,

Fig. 3:13; S. Loffreda, “Ceramica ellenisdco-romana nel sottosuolo della sinagoga di

Cafarnao,” in Botdni, G.C., ed., Studia Hierosolymitana III, jVtU’Ottaio Centmario Francescano (Jerusalem, 1982), p. 21, no. 10.

53 M Hayes, ibid., pp. 325-327; for illustrated examples, see Loffreda, “La Ceramica,” p. 78, Fig. 3:1.

54 M Hayes, ibid., pp. 372-374; for illustrated examples see Loffreda, ibid., p. 78, Fig. 3:2-3.

55 Hayes, ibid., pp. 339-340; for illustrated examples, see Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p.

19, no. 21; Loffreda, “Ceramica ellenisdco-romana,” p. 21, no. 41.

56 Hayes, ibid., pp. 374-376; for illustrated examples, see Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p.

19, nos. 15-20; Loffreda, “Ceramica ellenisdco-romana,” p. 21, no. 15.

57 Hayes, ibid., pp. 329-338; for illustrated examples see Loffreda, “La Ceramica,”

p. 78, Fig. 3:5, 8; Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p. 19, nos. 1-14; Loffreda, “Ceramica

ellenisdco-romana,” p. 21, nos. 21-34. The following later types appear to be represented as well:

- Late Roman “C ” (Phocean Red Slip) Ware Form 10, dated from the late sixth to mid-seventh centuries (Hayes, pp. 343-346; for an illustrated example see Loffreda, “La Ceramica,” p. 78, Fig. 3:11).

- Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 7, dated mainly to the second half of the sixth to early seventh centuries (Hayes, pp. 377-379; for illustrated examples see Loffreda, “La Ceramica,” p. 78, Fig. 3:9, 12).

- Possibly Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 9, dated from ca. 550 to the end of the seventh century {Hayes, pp. 378-382; for what may be illustrated examples of this type see Loffreda, “La Ceramica,” p. 78, fig. 3:7; Loffreda, “Ceramica ellenisdcoromana,” p. 21, nos. 12-13).

58 Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p. 218.

39 Corbo, Cafarnao, pp. 149, 165.

60 Magness, Jerusalem Ceramic Chronology, p. 32.

61 Corbo, Cafarnao, p. 149.

62 Compare the dates in the following: Loffreda, “The Synagogue of Capharnaum,” p. 26: “In conclusion the Synagogue of Caphamaum was built not earlier than the second half of the fourth century A.D. and completed at the beginning of the fifth century.” Corbo, Cafarnao, p. 168: “In base alle numerosissime monete ed all'abbondante ceramica, proveniend da contesti stradgrafici diversi e nondimeno in constante armonia fra di loro, siamo pienamente convinti che gli edifici della sinagoga furono iniziad, come minimo, verso seconda meta del quarto secolo dopo Christo e che il lavoro fu portato a termine, con la posa dei pavimenti, verso git uiizt della seconda nuta del quinto secolo dopo Christo" (my emphasis). Loffreda, “Potsherds,” p. 220: “The latest pieces...suggest that the pavement of the courtyard of the synagogue cannot be earlier than the mid-fifth century A.D., while the latest coins of Leo I bring us to a date around 474 A .D .” Arlsan, “Monete axumite,” p. 308: “L’ipotesi piu probabile...appare quella del deposito vodvo di offerte...formatosi progressivamente a pardre da una data Torse da collocare in eta teodosiana (dopo la demonetizzazione dell maiorina) e condusasi con la costruzione della pavimentazione della Sinagoga in un anno di non molto successivo alVmizio del seconda regno di Zenone (476 d.C.)" (my emphasis). In his most recent article, Loffreda has suggested that construction began in the early fifth century; see “Coins from the Synagogue of Capharnaum,” pp. 332-333: “After the recent identification of many other coins, it seems that the initial date of the entire synagogue building (prayer room, eastern courtyard and balcony) was not before the beginning of the 5th century, while the final date of the project is still kept at the last quarter of the 5th century.”

63 V.C. Corbo, “Nuovi scavi nella sinagoga di Cafarnao," in La Swagoga di Cafarnao, dopo gli sewn del 1969 Jerusalem, 1970), p. 60; Loflreda, “La Ceramica.”

64 LofTreda, Cafarnao II.

65 Hayes, op. cit.; see LofTreda, “La Ceramica,” and “The Synagogue of Caphamaum.”

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

- General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Greek Orthodox church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Greek Orthodox church. Area A is top left.

Stern et al (1993 v. 1) - General plan of the excavations

in the area of the Franciscan church from Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

General plan of the excavations in the area of the Franciscan church

Stern et al (1993 v. 1)

In the excavations around the Greek Orthodox Church, Vasilios Tzaferis in Stern et al (1993)

states that Stratum IV in Area A was apparently destroyed in the earthquake that struck the region in 746 CE [as] evidenced by the great quantity of

huge stones in the piles of debris and by the ash covering the stratum throughout the area [Area A].

Magness (1997), however, redated Stratum IV, placing its

end date in 2nd half of the 9th century CE rather than the middle of the 8th century. This redating appears

to have been largely based on comparison with ceramic assemblages at Pella. In Magness (1997)'s

redated stratigraphy, Stratum V ended around 750 CE. She noted that it is difficult to ascertain what brought this stratum [V]

to an end, though the publication [excavation report of Tzaferis] does not provide explicit evidence for earthquake destruction

.

- from Magness (1997:481)

- from Magness (1997:481)

One problem central to this discussion concerns the dating of glazed pottery and "Mefjer ware," a type of fine, buff ware characteristic of the early Islamic period in Palestine. According to Tzaferis, the Capernaum excavations provide evidence for the appearance of glazed pottery and Mefjer ware in Palestine by the mid-seventh century C.E. (Tzaferis 1989: xix, 30). Before examining the basis for the dating of these ceramic types, it is necessary to review the occupational sequence at Capernaum.

Tzaferis' excavations were concentrated in four main areas, designated A, B, C, and D. Within these areas, five main occupational phases were distinguished (V-I), on the basis of separate floor levels and architectural modifications within the buildings (Tzaferis 1989: 1-9). The published dates are as follows:

| Stratum | Age (CE) |

|---|---|

| V | early 7th century to 650 (all dates C.E.) |

| IV | 650 - 750 |

| III | 750 to mid-9th century |

| II | mid-9th to mid-10th century |

| I | mid-10th century to 1033 |

The five main floor levels found enable five occupational phases to be distinguished, allowing for controlled, sealed loci from which most of the pottery exemplars were chosen. Dated coins and oil lamps accompanying these established phases also aid in dating. (Peleg 1989: 31)In other words, the primary basis for dating was the pottery, together with numismatic evidence and oil lamps, when available. Here the first indications of circular argumentation appear. Since Peleg and Berman assumed that glazed pottery and Mefjer ware dated to the Umayyad period, the first level in which these types appear is attributed to the Umayyad period. This was then used as a basis for assigning these types to the Umayyad period ! In her discussion of Mefjer ware, Peleg noted that "at Ramla, this ware appears in stratified contexts from the first period on the site — from the beginning of the 8th century A.D." (Peleg 1989: 103).1 Thus, based on the evidence from Ramla, Peleg and Berman were predisposed to date glazed pottery and Mefjer ware to the Umayyad period. As I have noted elsewhere, the incorrect assignment of these types to the Umayyad period because of the Ramla excavations is common in Israel (Magness 1994: 204-5, n. 3; also see Walmsley 1994). At Capernaum, however, the association of glazed pottery and Mefjer ware with a coin hoard would seem to support the assignment of these types to the Umayyad period. As Berman stated, "the use of glazing at Capernaum during the Umayyad period is borne out by evidence directly associated with the gold coin hoard. Sherds with yellow and green monochrome lead glaze were found among the debris surrounding the hoard. Thus, one can decidedly conclude that glazing was prac-ticed during the early decades of the 8th century A.D. and probably earlier" (Berman 1989: 124). In fact, the chronology of the two earliest strata, V and IV, was established on the basis of this coin hoard. The numismatic evidence is thus crucial for understanding the chronology of Capernaum.

1 Also see Berman's statement that "preliminary reports of the excavations at Ramla indicate that glazing, while not over-whelmingly popular, was practiced [in the Umayyad period]" (1989: 124).

- from Magness (1997:483-484)

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

The latest dinar in the Capernaum hoard is dated A.H. 126, which means that the hoard could not have been buried before A.D. 744. It may be possible, in this case, to pinpoint the date even more precisely. According to ancient historians, a disastrous earthquake shook the Jordan Valley in A.D. 746, severely damaging the Temple Mount, destroying Khirbet Mefjer, damaging Jerash, and, significantly, smashing Tiberias, some 19 km. from Capernaum. Evidently both history and nature conspired against Capernaum during the years A.D. 744-746. First, the civil chaos following the death of Hisham reached out into Palestine, particularly involving such aristocratic estates as Khirbet Minyeh, whose master could not have avoided being on the wrong side of the conflict at some point. Under the dangerous circumstances, the owner of the hoard deposited his treasure. In the very midst of this conflict, the earthquake played havoc up and down the entire Jordan Valley. If the hoard's owner was not killed in the succession conflict, or destroyed along with his town in the earthquake, he may have fallen, or at least been prevented from returning to his fortune. . . . (Wilson 1989: 163-64)In other words, the dramatic historical events and natural disasters which occurred at the end of the Umayyad period are presented as the context for the burial of the hoard. Though this conclusion is possible in light of the date of the latest coins in the hoard, it is not borne out by the ceramic evidence.

The hoard could not have been buried before 744, when the latest coins it contained were minted. However, it could have been deposited at any time after that date. Wilson noted that whereas emergency hoards usually contain a high percentage of specimens from the years immediately prior to burial, the Capernaum hoard reverses this pattern; over two-thirds of the coins are dated between A.H. 77 and 101, and there is a decided decline in the number of specimens per year after that. In addition, the older specimens were no more worn than the later ones (Wilson 1989: 159). Another important point emerges in connection with the bronze and silver coins recovered in the Capernaum excavations: "The site yielded a high percentage of coins from the 4th century A.D. and from the Umayyad period. Noticeably absent are coins from the Byzantine period (except for one example) and the Abbasid period" (Wilson 1989: 139). In other words, though by the publication team's own account there is evidence for continuous occupation at Capernaum through the Abbasid period, not a single Abbasid coin was recovered. I have noted elsewhere that the paucity of fifth-century coins has made it difficult to distinguish fifth-century occupation levels in Jerusalem, and has led to the misdating of fifth-century ceramic types to the fourth century (Magness 1993: 165; also see Magness, in press). The same phenomenon appears to be true of the Abbasid period. Abbasid coins are rare or unattested at many sites with Abbasid occupation in Palestine. In fact, Meyers, Kraabel, and Strange have remarked upon this phenomenon in relation to Khirbet Shema', pointing out that from the ninth to eleventh centuries, few copper and silver coins were struck in Syria (1976: 163).2 The site of Capernaum, with its evidence for flourishing Abbasid occupation but without a single Abbasid coin, provides clear evidence for this phenomenon. Because they are often found in association with the more common Umayyad coins, Abbasid ceramic types have often been misdated to the Umayyad period.

2 Also see Whitcomb 1991: 78-79: "The rarity of Abbasid issues in excavations parallels known production of mints in Palestine. . . .

Except for a few issues in the early 9th century, there is no mint activity until the Tulunids [890 A.D.] and then only at Filistin [Ramla?]."

- from Magness (1997:484)

- Mentions of an earthquake in 746 and/or 747 are misdated but do refer to the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, specifically the Holy Desert Quake of this seismic sequence

Again, the best evidence comes from Pella, where Mefjer ware, glazed pottery, and "cut-ware" are not at¬tested in the earthquake destruction level of 746-47. Instead, these types have been found at Pella in securely-dated Abbasid levels. In fact, all three types appear there in contexts dating to the second half of the ninth century C .E.:

Glazed pottery appears in limited quantity for the first time, although plain fabrics are still in the majority. Also new are the increasingly common Samarra-style, thin-walled, pale cream jars and strainer jugs with often deep finger rilling marks inside the body and a knife trimmed lower body. These vessels are either plain or decorated with incisions; incised bowls and water flasks in the same fabric are also present. Straight sided, hand-made bowls make an appearance. These are highly decorated with incised, cut and painted geometric designs on the out¬side, and with painted lines inside. Three new types of moulded ceramic lamps occur. . . . The remainder of the pottery in Group 2 represents a continuation of earlier wares. . . . Group 2 can be very tentatively placed in the later third century A.H. (second half of the ninth century A.D.). (Walmsley 1991: 8)These same types are described in association with stratum IV at Capernaum:

The "chip-carved" bowls ("cut-ware") appear now at Capernaum for the first time, and seem to remain in vogue for a very short period. . . . Side-by-side with the "chip-carved" bowls we see, also for the first time, the "Mefjer" group of bowls and jars, made in a light, soft-firing ware. . . . (Peleg 1989: 112)Thus, parallels with Pella suggest that the stratum IV occupation at Capernaum came to an end some time in the second half of the ninth century, instead of in the mid-eighth century. This date is over one-hundred years later than that suggested by the publication team, and it affects the chronology of the other strata at Capernaum.