Sepphoris

Aerial View of Sepphoris

Aerial View of Sepphorisclick on image to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

AVRANGR - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 4.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Sepphoris | Ancient Greek | Σεπφωρίς |

| Tzipori | Hebrew | צִפּוֹרִי |

| Kitron | Hebrew | |

| Rakkath | Hebrew | |

| Saffuriya | Arabic | صفورية |

| Eirenopolis | Greek | |

| Autocratoris | Greek | Αὐτοκρατορίδα |

| Diocaesarea | Greek | διοκαισαρεία |

| Le Saphorie | Crusader |

Ancient Sepphoris is clearly identified with the ruined village of Safuriyye, the present-day Moshav Zippori. The site overlooks the Beth Netofa Valley in the central Lower Galilee, about 5 km (3 mi.) northwest of Nazareth (map reference 176.239). Sepphoris is first mentioned by Josephus in connection with the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (Antiq. XIII, 338), but a few remains from the Iron Age II found here attest to an earlier settlement. In the Hasmonean period, Sepphoris was probably the administrative center of the whole of Galilee. In around 57-55 BCE, the Roman proconsul Gabinius made Sepphoris the capital of the district of Galilee (Antiq. XIV, 91; War I, 170). Sepphoris submitted to Herod, who attacked the city during a snowstorm in 3 7 BCE (Antiq. XIV, 414; War I, 304 ). After Herod's death, the Romans conquered thecityin the "warofVarus" and sold its inhabitants into slavery (Antiq. XVII, 289; War II, 68). With the partition of Herod's king dom, Sepphoris was granted to his son Antipas, who resided here until he founded Tiberias and made it the new capital of Galilee. Antipas fortified Sepphoris and changed its name to Autocratoris, according to Josephus (Antiq. XVIII, 27). During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, the inhabitants of Sepphoris sided with Vespasian, surrendered their city to him (War III, 30-34), and struck coins in his honor as the "peace maker" (ειρηνοποιος). After the destruction of the Temple, the priestly family of Jedaiah settled in Sepphoris. During Trajan's reign, coins were minted here by the Jewish local government; the words "Emperor Trajan gave" were stamped on them. During the reign of Hadrian, the "old government" of Sepphoris - the Jewish local city government (Mishnah, Qid. 4:5) - was abolished, a gentile administration was appointed, and probably, at the same time, the name of the city was changed to Diocaesarea (Διοκαισαρεια, the city of Zeus and of the emperor). Yet, after Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi and the Sanhedrin established their seat here for seventeen years before the rabbi's death, at the end of the second century (J.T., Kil. 9:4, 32b), the local government of the city was once more turned over to a Jewish town council. Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi redacted the Mishnah in Sepphoris. At the beginning of the third century, the minting of coins by the Jews was renewed here; the coins were stamped "Covenant of friendship and mutual aid between the holy council and the senate of the Roman people."

Sepphoris is mentioned many times in Talmudic literature and was known throughout its existence as a Jewish city. In the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods many scholars lived here; the best known are rabbis Halafta, Ele'azar ben 'Azariah, and Jose ben Halafta. The seat of the Sanhedrin was also in Sepphoris until it was moved by Rabbi Yohanan to Tiberias in the time of Rabbi Judah Nesiah, the grandson of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi. During the reign of Emperor Constantine, a certain Josephus the Apostate tried in vain to erect a church here (Epiph., Haer. 30, 4~12). In the reign of Constantius II, the Jewish revolt against Gallus Caesar, led by Patricius, began in Sepphoris (351 CE). The Roman troops garrisoned in the city were disarmed, and the rebels gained control. The Roman commander Ursicinus succeeded in crushing the revolt, but, in spite of the reports of the Christian sources (Jerome, Chron., Olymp. 282; Socrates, HE II, 33; Sozomenos, HE IV, 7), he failed to level the city. In a letter sent by Cyril, bishop of Jerusalem, mention is made of an earthquake that struck Palestine in 363, making special note of the total destruction of Sepphoris. The town was later partly restored and continued to be a Jewish city until the fifth century; in the sixth century, however, it had a Christian community, headed by a bishop. Bishops ofSepphoris participated in the synods of Jerusalem in 518 and 536. In Crusader times, Sepphoris (Le Sephorie) was a city and fortress in the province of Galilee. Remains of a Crusader church and fortress still stand at the site. In the eighteenth century, the governor of Galilee, Dhahir el-'Amr, refortified it.

The rich historical legacy of Sepphoris is linked with its central geographical location and the diversity of its inhabitants. Substantial quantities of Iron Age II potsherds uncovered at the site indicate that Sepphoris was settled by the seventh or sixth century B.C.E.. On the basis of the many black Attic-ware sherds discovered there, as well as a beautiful animal-shaped rhyton and a drinking goblet of the Persian period, it can be assumed that, by the mid-fifth century or slightly later, there was a small settlement at Sepphoris, , perhaps the residency of a military garrison which was stationed there. In this respect it is noteworthy to mention that a small tell, just east of the spring of Sepphoris, is listed (following preliminary surveys) as belonging to the Persian period.

Josephus, the well-known first century Jewish historian, provides the earliest literary attestation of Sepphoris (Antiquities 13.2.5). He first mentions the site in reference to Ptolemy Lathyrus's unsuccessful attempt (ca. 100 B.C.E.) to capture the city during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus, one of the most important Hasmonean kings (103-76 B.C.E.). Numerous Hasmonean coins found during excavation, including coins of Jannaeus, together with other late Hellenistic artifacts and traces of architecture, lend credibility to Josephus's statement that Sepphoris was already a major Galilean stronghold in the first century. He calls it "the strongest city of Galilee" (War 2.5.10f.).

The Jewish population of Sepphoris goes back at least to Hellenistic times, and perhaps to as early as the Persian period. Sepphoris was apparently the home town of many priests, some of whom even served as high priests in the Jerusalem Temple.

Sepphoris became a city of prominence in Roman times when in 57 B.C.E. Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, divided the Jewish territory into five administrative districts or councils, called synedria. At that time he made Sepphoris the Galilean center of one of the councils (War 1.170 and Antiquities 14.91).

Interesting circumstances surround Sepphoris's occupation by Herod, in 40 B.C.E. (Antiquities 17.271). Both Antigonus, the last Hasmonean king (Antiquities 14.413), and Herod the Great used Sepphoris as a secure staging platform from which to launch their Galilean careers. For all intents and purposes, Sepphoris had already become the capital of the Galilee by that time.

During the riots that broke out after Herod's death in 4 B.C.E., a Galilean rebel named Judas attacked Sepphoris in an attempt to get arms; the city was so well fortified that the attempt failed. Varus, the legate of Syria, is said to have destroyed the city in retaliation and to have sold its inhabitants into slavery (Antiquities 17.271 and War 2.56)..

Sepphoris was presumably enlarged and/or rebuilt by Herod Antipas who, in the early first century C.E. according to Josephus, made the city the "ornament of all Galilee" (Antiquities 18.2.1). Antipas called the city "Autokratis," which possibly indicates its role as a capital city with self-autonomy.

Although it lost some of its prestige when Antipas shifted his northern base to Tiberias in 54 C.E., Sepphoris again became the capital of Galilee and a prestigious city under the procurator Felix, when he transferred it to the territory of Agrippa II (on the eve of the First Revolt against Rome). On that occasion, Felix renewed the jurisdictional authority of Sepphoris and moved the royal bank and the archives of important documents from Tiberias to that city (Life 38).

The unique stance taken by the inhabitants of Sepphoris during the First War against Rome (66-70 C.E.) may shed additional light on the nature of its population in the first century. The city is reported by Josephus to have taken a pacifistic position, with its citizens unwilling to oppose Rome. Josephus contends that he led two separate attacks against the recalcitrant Sepphoreans. The coins minted at Sepphoris in the year 67/68 C.E. bear the legend Eirenopolis, "City of Peace." Josephus (War 3.30-32) reports the following:

From Antioch Vespasian pushed on to Ptolemais [Acco]. At this city he was met by the inhabitants of Sepphoris in the Galilee, the only people of the province who displayed pacific sentiments. For, with an eye to their own security and a sense of the power of Rome, they had already, before the coming of Vespasian, given pledges to Caesennius Gallus, received his assurance of protection, and admitted a Roman garrison; now they offered a cordial welcome to the commander-in-chief, and promised their active support against their countrymen.The fact that the name Vespasian appears on the Sepphoris coins only one year before he became emperor tends to corroborate Josephus's claims of the pro-Roman stance assumed by the local population. The inhabitants of Sepphoris apparently added the future emperor's name to the coin legend on their own initiative and not on the orders of any high official. A similar action was undertaken by the officials of Caesarea Maritima, who also put Vespasian's name on their coin mints in anticipation of his ascent to the throne.

The Sepphoreans' desire to cooperate with Rome is mentioned numerous times by Josephus, who himself adopted a similar position after giving up his Galilean military command in nearby Jotapata in 68 C.E. The refusal of the Sepphoreans to become directly involved in the rebellion that was brewing perhaps reflects the aristocratic bent of the city, which included landowners and priests. Other Galileans strongly disapproved of the accommodations made by Sepphoris, and also by Josephus, to Roman rule. None of this, however, undermined the strong loyalties to Judaism that all of the concerned parties shared.

The population of the Galilee in general was undoubtedly undergoing change after the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., and more than that, following the Second War against Rome (132-135 C.E.) — the Bar Kochba War - when refugees from the south moved north, some of them to Sepphoris. Unfortunately, the role played by the once pacifistic Sepphoreans in the Bar Kochba War is obscure, since the part taken by any Galileans in this war is far from being clear.

The priestly clan of Jedaiah is believed to have relocated in Sepphoris (after the latter war), although the influence of such a group on the local leadership is not evident in the immediate, post-destruction period.

Nevertheless, the large priestly community at Sepphoris, associated with one particular priestly course (mishmar), lent a further degree of authority to the Jewish community here.

The form of the pagan Roman presence at Sepphoris can be fairly well understood. It is probable that, until the reign of Hadrian (117-139 C.E.), the Galilee was predominantly Jewish in character. In Hadrian's time, however, either as a result of the Bar Kochba War or for other reasons, the ancient government of Sepphoris - in all likelihood the local Jewish governmental body — was abolished and a gentile administration installed. At this time the city became known as "Diocaesarea," i.e., city of Zeus (Dio) and the emperor. Hadrian adopted the title Zeus Olympus and a Capitoline temple was apparently built at the site. That these changes occurred during Hadrian's reign is indicated by the discovery of a milestone from Sepphoris bearing the legend "Diocaesarea" and dating to 130 C.E. The milestone was located on the road from Acco to Tiberias. At this time, however, Roman soldiers of the Sixth Legion were stationed in the Galilee at nearby Legio (modem Lejjun), the northern border of which corresponded to the southern border of Sepphoris-Diocaesarea.

Nevertheless, the fact that Sepphoris's name is replaced by a pagan one — "Diocaesarea" - at this time reflects the growing pagan influence in the region in general and at Sepphoris in particular. After two exhausting wars with the Jews, the Romans were determined to tighten their grip on the population of the Galilee and succeeded in doing so through a policy of urbanization. Changing the city name to "Diocaesarea" thus appears to correspond with the broader political aims of the Roman Empire, which attempted to attain greater control of the local community by constructing buildings, installing local Roman administrators, and by generally adopting a more visible presence.

Judeo-Roman coins continued to be minted at Sepphoris for most of the period between the two wars, but coins bearing the title "Diocaesarea" first appeared under Antoninus Pius (138-161 C.E.). Although there is a fifteen-year cessation of coinage right before the Second Revolt, such a gap is not necessarily related to the existence of rebellious factions in Sepphoris.

Sepphoris became the focal point and center of Jewish life and learning during the seventeen years that the Patriarch Rabbi Yehuda ha-Nasi (Judah the Prince) resided in the city (ca. 200-217 C.E.). During this time the Sanhedrin, or judicial seat of authority, was moved there. It was probably at Sepphoris that Rabbi Judah completed his work on the codification and redaction of the Mishnah, the centerpiece of the Talmud and basis of all Jewish learning to come.

In addition to his leadership role in the field of scholarship, Rabbi Judah was a central figure in contemporary Palestinian politics. His position in the Roman Empire was such that rabbinic literature depicts him as a friend of the Roman emperor — perhaps Antoninus Pius, but more probably Caracalla (also known as Antoninus), who reigned from 198 to 217 C.E. At this time a coin of Sepphoris, already known as Diocaesarea, provides astonishing testimony to a treaty of friendship between the Roman Senate and the Sepphoris Council or boule, the official governing bodies representing the two peoples. The inscription on the coins of Caracalla are a variation on the following: "Diocaesarea the Holy City, City of Shelter, Autonomous, Loyal, (a treaty of) friendship and alliance between the Holy Council and the Senate of the Roman people."

The interpretation of the coins of Caracalla minted in Sepphoris tends to support the historicity of the talmudic accounts that idealized a relationship between Rabbi Judah and the Roman emperor. The combination of literary, archaeological, and numismatic evidence, while not unique in ancient history, lends great credence to the talmudic view that several members, and possibly a majority, of the Council of Sepphoris were Jewish in the time of Rabbi Judah. This may be the only instance of such Jewish political involvement in ancient Eretz Israel in that period. All of this underscores the important economic and political role of Sepphoris in the third century C.E.

Given the likelihood that Rabbi Judah could actually have been an acquaintance of the Roman emperor and that Jews served on the Council of the municipality in his time, possibly even constituting a majority, the prominence of Sepphoris in Jewish history in the Middle-Late Roman period is not surprising. The rabbinic legends surely preserve idealized and exaggerated statements about the Patriarch and Caracalla. In fact, they depict Rabbi Judah as being wise as Solomon and as one before whom the emperor humbled himself. Yet all the talmudic accounts, while perhaps lacking in historical accuracy, certainly attest to Rabbi Judah's skills and political acumen in a time of growing Jewish influence in Palestine.

Rabbi Judah's presence and activity in Sepphoris attracted many sages from nearby regions and also from Babylon. Noted among them are Rabbi Natan Halevi, Rabbi Yosi Bar-Yehuda, Rabbi Shimeon Ben Elazar and Rabbi Shimeon Ben Mansi. Following the completion of the Mishna and the death of Rabbi Judah, it is recounted that a rabbi returned to Babylon, bringing Rabbi Judah's Mishna to the Babylonians. Sepphoris's reputation as a center of Jewish learning did not cease with the death of Rabbi Judah and the subsequent removal of the Sanhedrin to Tiberias. Indeed, both cities retained their reputations as seats of noted rabbinic authorities throughout the rabbinic period. Indeed, with the exception of Jerusalem, no cities in ancient Palestine are mentioned more often in rabbinic literature than Sepphoris and Tiberias.

Among the sages who remained in Sepphoris, despite the Sanhedrin's move to Tiberias, were Rabbi Chiyeh Bar-Abba and Rabbi Elazar Ben-Pedat. Other famous talmudic scholars, such as Rabbi Yochanan Nafcha and Rabbi Shimeon Ben-Lakish, now settled in Sepphoris.

The fact that so many sages lived in Sepphoris caused an increase in the number of synagogues and "batei-midrash" (study houses) in this city. The Jerusalem Talmud tells of the day of Rabbi Judah's death as follows;

"Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi was dying at Zippori... It was the eve of the Sabbath and the inhabitants of all the cities assembled for the mourning over Rabbi. They set his body down in eighteen synagogues and then conveyed him to Beit Shearim" (Tal. Yer. Kil. 89.32).Several of these synagogues are even familiar to us by names such as the "Synagogue of the Gofneans" (the synagogue apparently founded by refugees from the city of Gofna in northern Judea) or the "Synagogue of the Babylonian Jews at Sepphoris." In reference to the latter synagogue, we learn that Rabbi Judah used to sit and study the Torah at its front. Further evidence of the synagogues comes from a Greek inscription, found at Sepphoris, which mentions "the well known head of the synagogue of the people of Tyre."

In addition to the synagogues at Sepphoris, there were also "batei-midrash" (study-houses) in which the sages studied Torah and expounded it before the public. It is told, for example, that Rabbi Chanina built a Beit Midrash at Sepphoris with his own money, and it is further told that Rabbi Yochanan and Rabbi Shimeon Ben-Lakish met to discuss a certain problem at the Beit Midrash of Rabbi Minaya.

Sepphoris may also have been home to a group of minim or Judeo-Christians (who later apparently merged with the Christian community). A few second century Jewish sources mention a certain person, named Jacob (who is unknown in later Christian sources), coming from the nearby village of Sichnin; Jacob is said to have discussed Jesus, in Sepphoris, with Rabbi Eliezar (a notable sage of the second century), and to have healed the sick in Jesus' name. The ’ Church Father Eusebius, however, by the third century, does not mention any "Christians" at Sepphoris.

Thus far, neither clear relevant archaeological evidence nor sufficient historical references throw much light on the existence of a Christian community at Sepphoris during the fourth century C.E. One reference, dated to early in the fourth century, mentions a Jewish convert (to Christianity) from Tiberias named Justus (earlier identified by the name Josephus), who gained permission to build a church at Sepphoris. This source seems to be reliable; but without other external literary or archaeological evidence for any fourth century church, it is difficult to verify. There is no doubt, though, that the Christian population of Galilee in general was growing rapidly in the periods before and after the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire in 313 C.E. by Constantine and its subsequent adoption as the state religion by Theodosius the Great. Sepphoris, however, seems to have maintained its dominant Jewish character through all this period.

By the mid-fourth century, during the reign of Constantius II (337-361 C.E.), Sepphoris is reported to be the center of anti-Roman feelings in its opposition to the local rule of Gallus Caesar. The precise details of the so-called Gallus Revolt (351-352) are difficult to reconstruct. Sepphoris was devastated at about this time; but the cause was more likely a natural catastrophe, namely the great earthquake of 363 C.E., which put an end to the glories of the Roman occupation of the city. Indeed, the splendid villa with its mosaics and perhaps even the adjacent theater, were buried in the collapse and went out of use at this time.

Sepphoris was soon rebuilt and probably continued to exist as a flourishing center also during the Byzantine period. Both archaeological as well as historical data provide evidence for this period. In the fifth and sixth centuries the city was the seat of a bishopric, whose bishops participated in at least two ecumenical councils. One of the historical sources mentions the fact that a bishop of Sepphoris attended the Council of Chalcedon in 451 C.E. To this period, perhaps, belongs the origin of the tradition that Joachim and Anna (the parents of Mary, mother of Jesus) were residents of Sepphoris. This belief, which has support in the patristic literature, is still upheld in the Roman Catholic Church. (In 1985 the sisters of the Catholic orphanage located today at Sepphoris organized a celebration to commemorate the 2000th anniversary of the birth of Mary.) Archaeological data also attest to the continuation of urban life at Sepphoris even in the Early Arabic period.

Although the history of medieval Christianity at Sepphoris remains unclear, the well-preserved Crusader Church of Saint Anne, which still stands in its early Gothic splendor, provides eloquent testimony to the importance of Sepphoris in Christian history.

In sum, the literary sources richly document the existence of varied communities living at Sepphoris, side by side with the prominent Jewish community, during the Roman and Byzantine periods. Archaeology, however has illuminated only the Jewish and pagan (Roman) presence until the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth centuries C.E., when archaeology and literary sources combine to present a picture of Christians existing alongside a dominant Jewish population and a strong Roman presence. The literary sources point to Sepphoris's continued leadership in the political, economic, and religious affairs of its region. Archaeological evidence has now confirmed that picture and has provided important new discoveries, which shed light on this period of great change and cultural development. That literary, spiritual, and religious creativity could have occurred in a flourishing oriental city is not surprising. That it occurred in the Jewish community at the very pinnacle of achievement alongside a lively paganism replete with a theater and a large villa with a splendid mosaic and grand banquet hall is testimony to the urban setting as a catalyst for a constructive symbiosis in late antiquity.

Excavations were first carried out at Sepphoris in the early 1930s under the direction of L. Waterman of the University of Michigan. Two sections were cut to the east and west of the fortress (see below). About fifty years later, work was resumed by two separate expeditions. The first, begun in 1983 under the direction of J.P. Strange of the University of Tampa, Florida, conducted a survey of the buildings, cisterns, and burial systems across the site. The second expedition, begun in 1985, is a joint project of Duke University, North Carolina, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, under the direction of E. M. Meyers, E. Netzer, and C. Meyers, and from 1990, under the direction of Netzer and Z. Weiss from the Hebrew University at Jerusalem. This expedition concentrated on the summit of the site and the area surrounding it. In 1975-1985 a survey of the site's aqueducts was conducted by Z. Zuck; the results were published in a separate report. Since then, a few burial systems have either been excavated or surveyed, along with isolated remains, shedding light on the city's history.

- Location Map from

Strange et al. (2006)

Location Map

Location Map

Strange et al. (2006) - Gallus Revolt Location

Map from Nathanson (1986)

Gallus Revolt Location Map

Gallus Revolt Location Map

Nathanson (1986)

- Aerial View of Sepphoris

from wikipedia

- Annotated Satellite View

of Sepphoris and surroundings from BibleWalks.com

- Aerial Photo of Tzipori

Acropolis from pixabay

- Sepphoris in Google Earth

- Sepphoris on govmap.gov.il

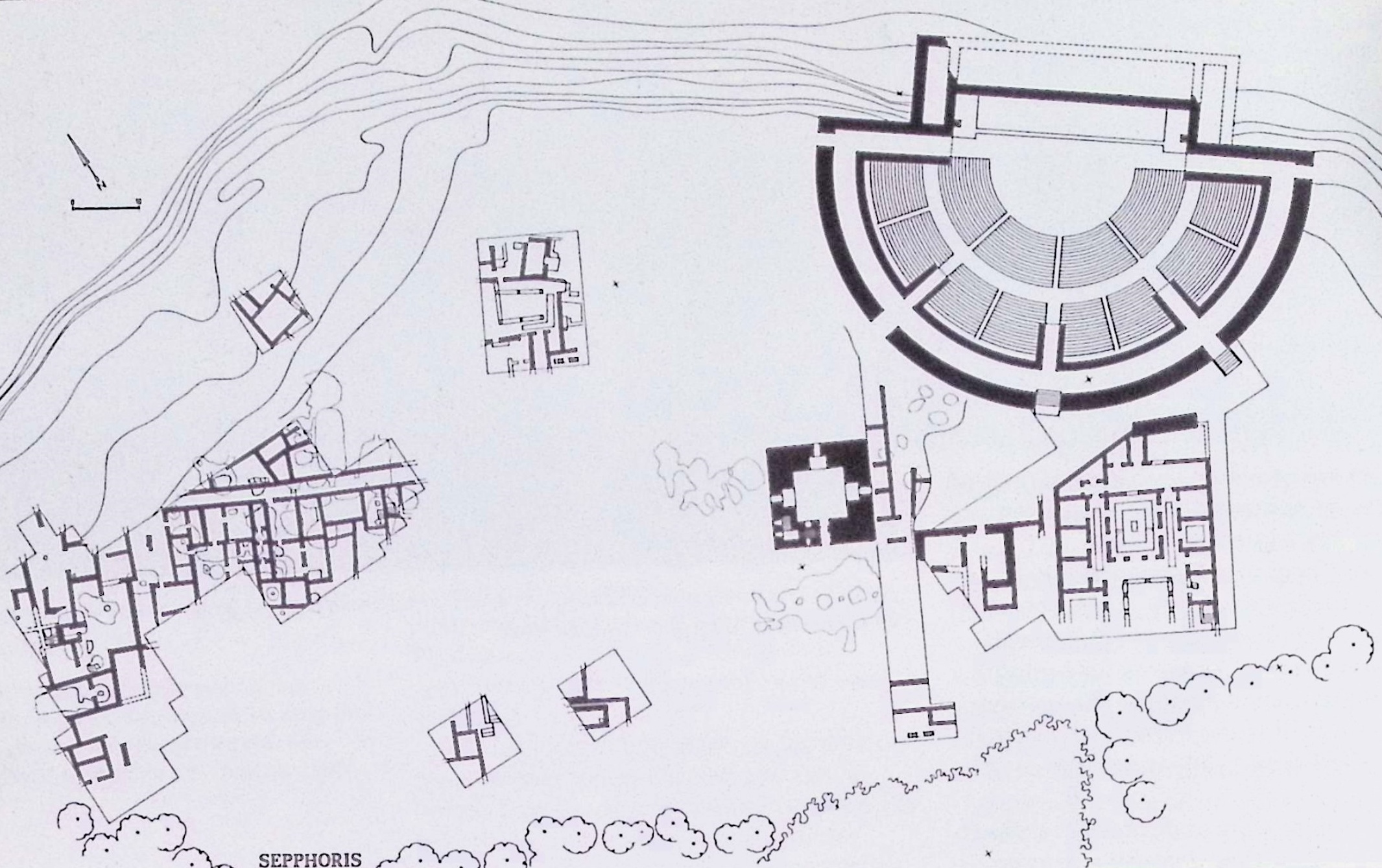

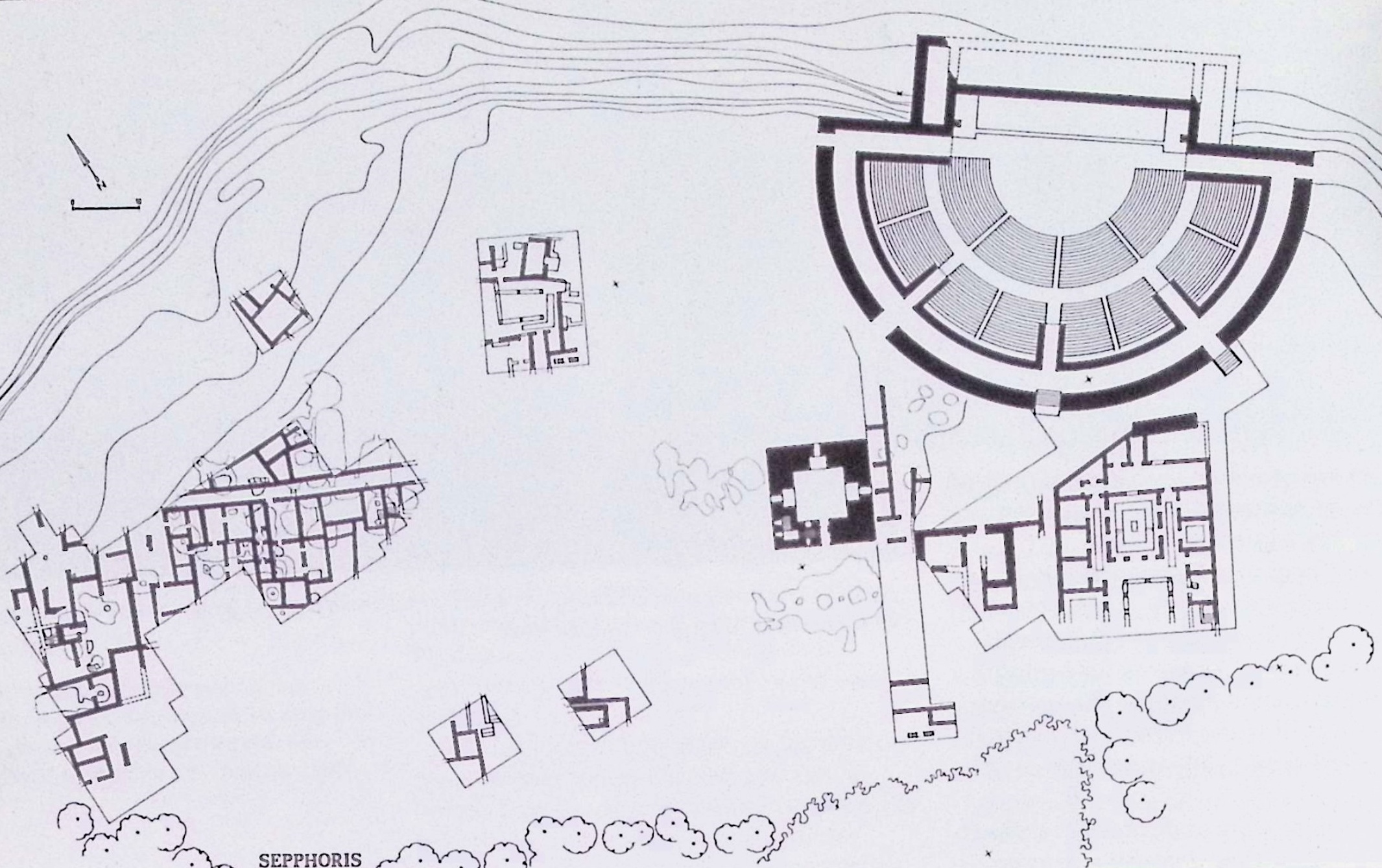

- Site Plan from

Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of the site showing location of excavated areas and of major features (theater, citadel, villa with mosaic)

Plan of the site showing location of excavated areas and of major features (theater, citadel, villa with mosaic)

Meyers et al. (1992) - Site Plan from

Stern et al. (1993 v.4)

Sepphoris: general plan of the excavations.

Sepphoris: general plan of the excavations.

Stern et al. (1993 v.4) - Site Plan from

National Park of Israel

Site Plan of Tzipori.

Site Plan of Tzipori.

National Park of Israel

- Site Plan from

Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of the site showing location of excavated areas and of major features (theater, citadel, villa with mosaic)

Plan of the site showing location of excavated areas and of major features (theater, citadel, villa with mosaic)

Meyers et al. (1992) - Site Plan from

Stern et al. (1993 v.4)

Sepphoris: general plan of the excavations.

Sepphoris: general plan of the excavations.

Stern et al. (1993 v.4) - Site Plan from

National Park of Israel

Site Plan of Tzipori.

Site Plan of Tzipori.

National Park of Israel

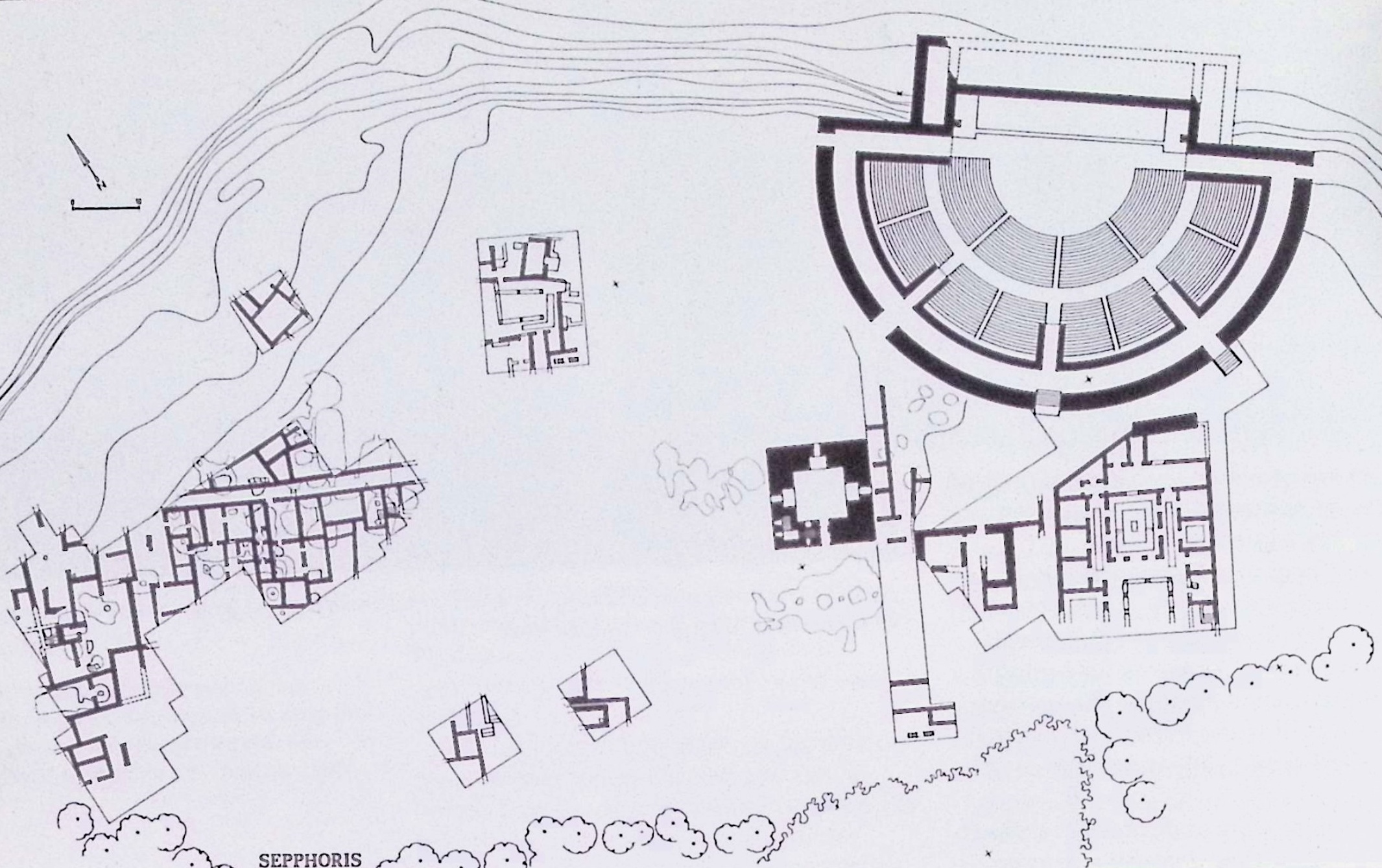

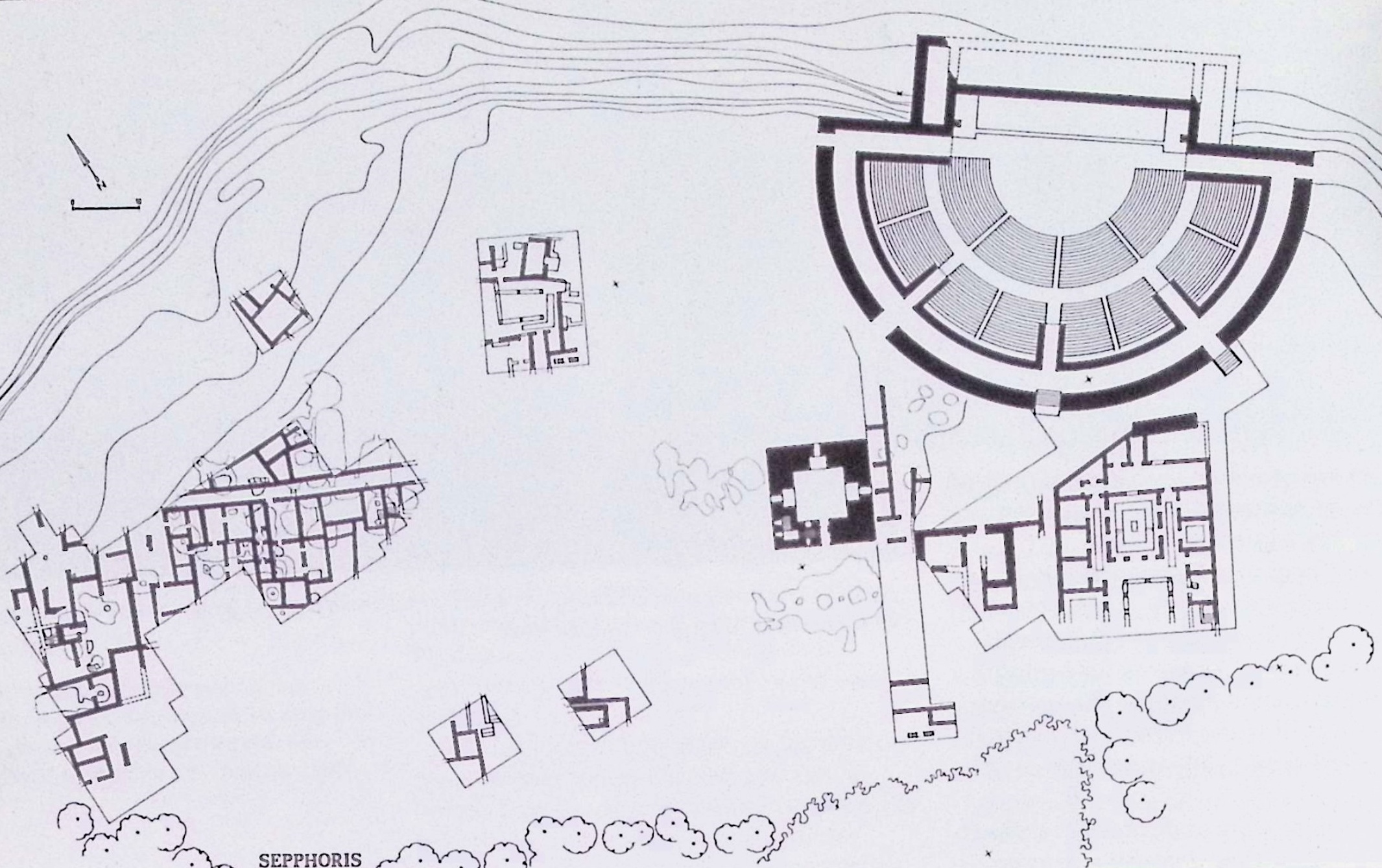

- Fig. 10 Plan of the

eastern side of the acropolis from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Plan of the eastern side of the acropolis showing:

- The Citadel

- The Theater

- The Dionysos Mosaic Building

- The Storehouse

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Fig. 10 Plan of the

eastern side of the acropolis from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Plan of the eastern side of the acropolis showing:

- The Citadel

- The Theater

- The Dionysos Mosaic Building

- The Storehouse

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Plan of residential

area on western side of the acropolis from Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of residential area on western side of the acropolis. A major east-west

road runs across the northern edge of this domestic area, which was inhabited

continually from Hellenistic times (ca. 100 B.C.E.) to the Byzantine era (seventh century C.E.).

Plan of residential area on western side of the acropolis. A major east-west

road runs across the northern edge of this domestic area, which was inhabited

continually from Hellenistic times (ca. 100 B.C.E.) to the Byzantine era (seventh century C.E.).

Meyers et al. (1992)

- Plan of residential

area on western side of the acropolis from Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of residential area on western side of the acropolis. A major east-west

road runs across the northern edge of this domestic area, which was inhabited

continually from Hellenistic times (ca. 100 B.C.E.) to the Byzantine era (seventh century C.E.).

Plan of residential area on western side of the acropolis. A major east-west

road runs across the northern edge of this domestic area, which was inhabited

continually from Hellenistic times (ca. 100 B.C.E.) to the Byzantine era (seventh century C.E.).

Meyers et al. (1992)

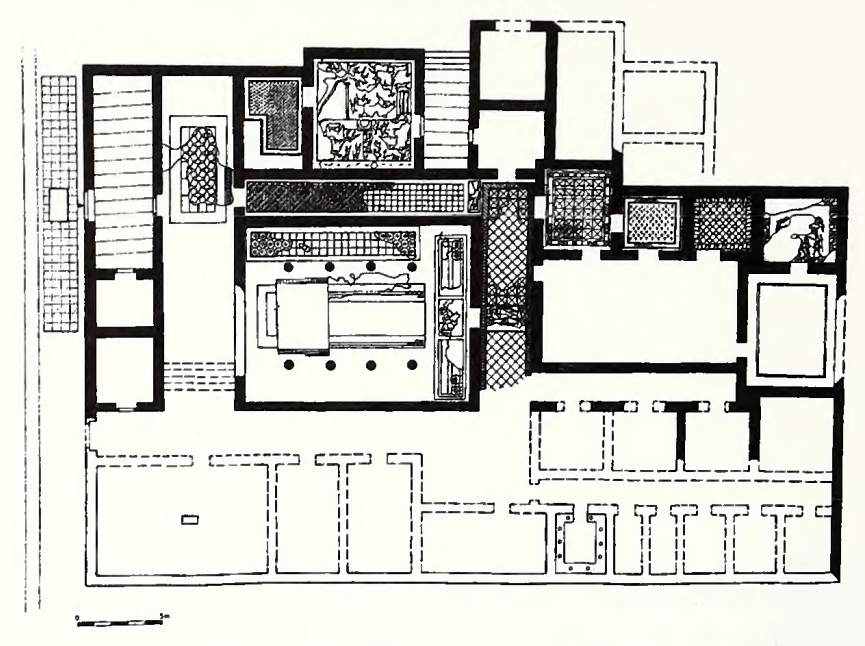

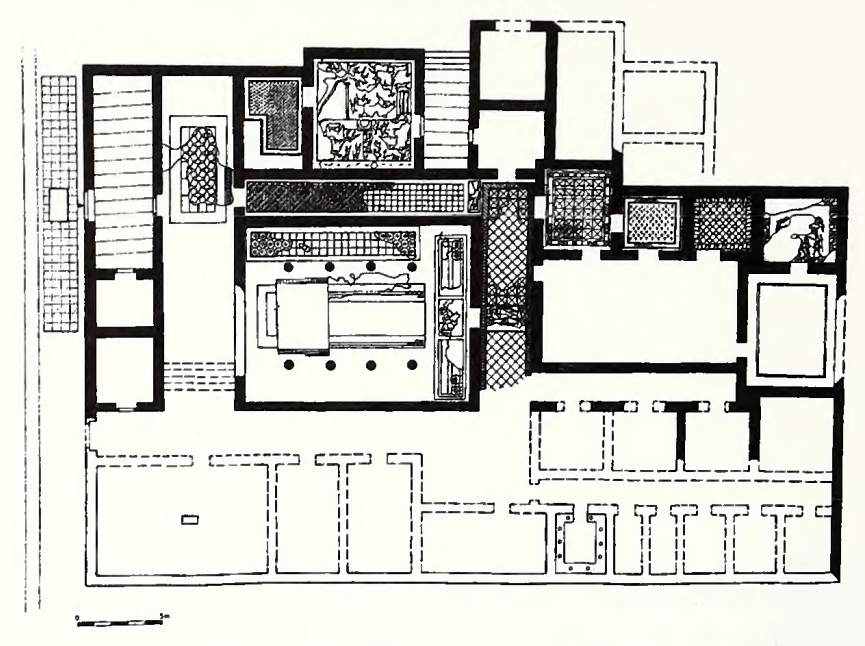

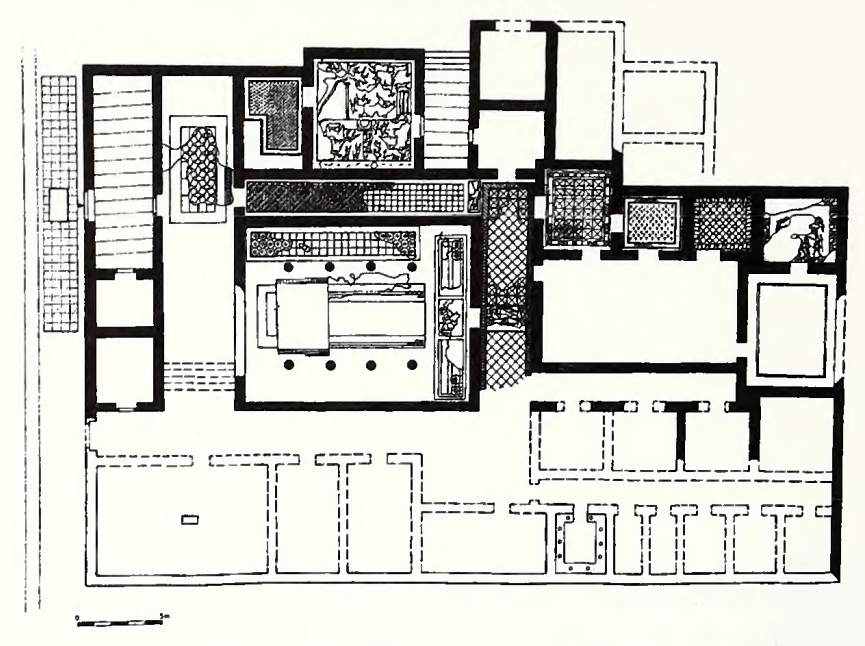

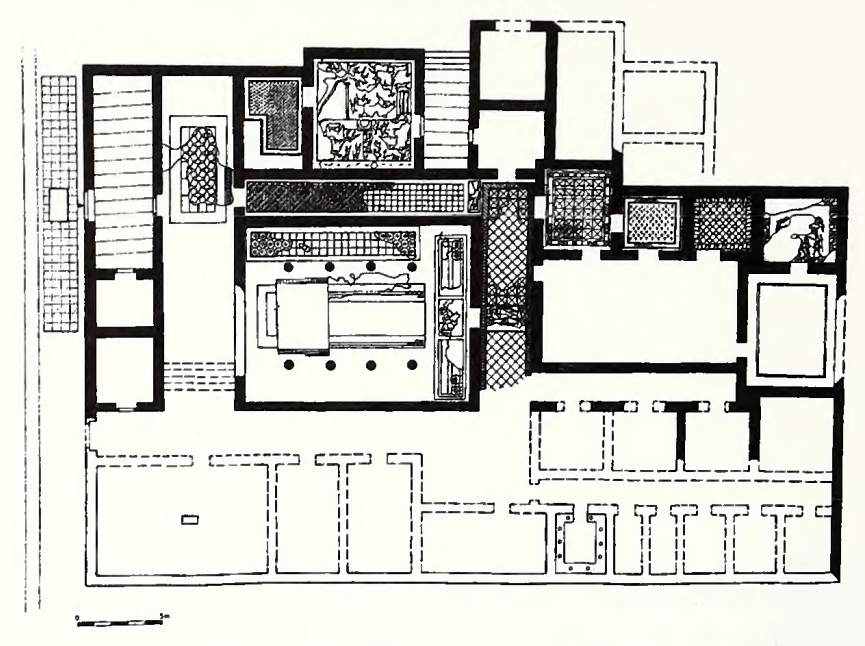

- Fig. 46 Plan of the

Dionysos mosaic building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Plan of the Dionysos mosaic building showing the location of the triclinium (reception hall) mosaic, near the top center of the plan.

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996) - Plan of villa with

mosaic floor from Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of villa with mosaic

floor. A peristyle

courtyard, with

reflecting pool, is

situated to the south of

the triclinium (banquet

hall). Various rooms,

some with plain or

geometric mosaic floors,

surround the central

banquet room.

Plan of villa with mosaic

floor. A peristyle

courtyard, with

reflecting pool, is

situated to the south of

the triclinium (banquet

hall). Various rooms,

some with plain or

geometric mosaic floors,

surround the central

banquet room.

Meyers et al. (1992)

- Fig. 46 Plan of the

Dionysos mosaic building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Plan of the Dionysos mosaic building showing the location of the triclinium (reception hall) mosaic, near the top center of the plan.

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996) - Plan of villa with

mosaic floor from Meyers et al. (1992)

Plan of villa with mosaic

floor. A peristyle

courtyard, with

reflecting pool, is

situated to the south of

the triclinium (banquet

hall). Various rooms,

some with plain or

geometric mosaic floors,

surround the central

banquet room.

Plan of villa with mosaic

floor. A peristyle

courtyard, with

reflecting pool, is

situated to the south of

the triclinium (banquet

hall). Various rooms,

some with plain or

geometric mosaic floors,

surround the central

banquet room.

Meyers et al. (1992)

- Fig. 32 Plan of the

fifth-century C.E. Nile festival building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 32

Fig. 32

Plan of the fifth-century C.E. Nile festival building.

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Fig. 32 Plan of the

fifth-century C.E. Nile festival building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 32

Fig. 32

Plan of the fifth-century C.E. Nile festival building.

Courtesy: The Hebrew University Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Fig. 1.01 Field I

Squares from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 1.01

Fig. 1.01

Field I Squares with Dates excavated

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.03 USF Excavation

Squares superimposed on Waterman's excavations from the 1930s from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.03

Fig. 6.03

Waterman's finds with USF Squares

Strange et al. (2006)

- Fig. 1.01 Field I

Squares from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 1.01

Fig. 1.01

Field I Squares with Dates excavated

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.03 USF Excavation

Squares superimposed on Waterman's excavations from the 1930s from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.03

Fig. 6.03

Waterman's finds with USF Squares

Strange et al. (2006)

- Fig. 4.01 Location of

Squares 1-3 and Tower from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 4.01

Fig. 4.01

Location of Squares 1-3 and Tower

Strange et al. (2006)

- Fig. 4.01 Location of

Squares 1-3 and Tower from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 4.01

Fig. 4.01

Location of Squares 1-3 and Tower

Strange et al. (2006)

- Fig. 2 The Basilica

from Waterman et al. (1937)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The Basilica

Waterman et al. (1937)

- Fig. 2 The Basilica

from Waterman et al. (1937)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The Basilica

Waterman et al. (1937)

- The Theater (restored)

from Waterman et al. (1937)

The Theater (restored)

The Theater (restored)

Waterman et al. (1937)

- The Theater (restored)

from Waterman et al. (1937)

The Theater (restored)

The Theater (restored)

Waterman et al. (1937)

- Illustration of public

area fo the city from Meyers et al. (1992)

Drawing of public area of the city, showing citadel, theater, and villa with mosaic floor (on right).

Drawing of public area of the city, showing citadel, theater, and villa with mosaic floor (on right).

Meyers et al. (1992) - Fig. 52 Reconstruction

of the eastern basilical building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 52

Fig. 52

Reconstruction of the eastern basilical building, showing the main entrance and its four porches opening onto the cardo (main north-south street).

Courtesy: University of South Florida Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Illustration of public

area fo the city from Meyers et al. (1992)

Drawing of public area of the city, showing citadel, theater, and villa with mosaic floor (on right).

Drawing of public area of the city, showing citadel, theater, and villa with mosaic floor (on right).

Meyers et al. (1992) - Fig. 52 Reconstruction

of the eastern basilical building from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 52

Fig. 52

Reconstruction of the eastern basilical building, showing the main entrance and its four porches opening onto the cardo (main north-south street).

Courtesy: University of South Florida Expedition

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Fig. 4.03 Square I.1,

Southeast Balk showing 1024 and 1025 destruction layers from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 4.03

Fig. 4.03

Square I.12, Southeast Balk

JW: Layers 1024 and 1025 are mid 4th century CE destruction layers

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.08 Square I.12,

North Balk from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.08

Fig. 6.08

Square I.12, North Balk

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.09 Square I.12,

East Balk from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.09

Fig. 6.09

Square I.12, East Balk

Strange et al. (2006)

- Fig. 4.03 Square I.1,

Southeast Balk showing 1024 and 1025 destruction layers from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 4.03

Fig. 4.03

Square I.12, Southeast Balk

JW: Layers 1024 and 1025 are mid 4th century CE destruction layers

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.08 Square I.12,

North Balk from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.08

Fig. 6.08

Square I.12, North Balk

Strange et al. (2006) - Fig. 6.09 Square I.12,

East Balk from Strange et al. (2006)

Fig. 6.09

Fig. 6.09

Square I.12, East Balk

Strange et al. (2006)

- Photo of citadel from

Meyers et al. (1992)

The citadel, or fort, of Sepphoris is the most prominent structure on the site today and can be seen from as

far away as Nazareth, several miles to the east. Its foundations may date to the Byzantine period, but it has

been rebuilt many times. Most of the present cornerstones are rubble filed Roman sarcophagi that were

probably incorporated into the building in Byzantine or Crusader times. The most recent rebuilding took

place in the late nineteenth century, when Abdul Hamid (1816-1909) had the structure rebuilt for use

as a schoolhouse. It was used as such by the local Arab villagers until the 1948 war.

The citadel, or fort, of Sepphoris is the most prominent structure on the site today and can be seen from as

far away as Nazareth, several miles to the east. Its foundations may date to the Byzantine period, but it has

been rebuilt many times. Most of the present cornerstones are rubble filed Roman sarcophagi that were

probably incorporated into the building in Byzantine or Crusader times. The most recent rebuilding took

place in the late nineteenth century, when Abdul Hamid (1816-1909) had the structure rebuilt for use

as a schoolhouse. It was used as such by the local Arab villagers until the 1948 war.

Meyers et al. (1992) - Fig. 9 Photo of citadel

and theater from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

The Roman theater against the backdrop of the Crusader/ Ottoman citadel on the summit of the Sepphoris acropolis. Constructed at the end of the first century C.E. or later, the theater could seat around 4,500 spectators.

Photo: Ehud Netzer

Nagy et al. (1996)

- Photo of citadel from

Meyers et al. (1992)

The citadel, or fort, of Sepphoris is the most prominent structure on the site today and can be seen from as

far away as Nazareth, several miles to the east. Its foundations may date to the Byzantine period, but it has

been rebuilt many times. Most of the present cornerstones are rubble filed Roman sarcophagi that were

probably incorporated into the building in Byzantine or Crusader times. The most recent rebuilding took

place in the late nineteenth century, when Abdul Hamid (1816-1909) had the structure rebuilt for use

as a schoolhouse. It was used as such by the local Arab villagers until the 1948 war.

The citadel, or fort, of Sepphoris is the most prominent structure on the site today and can be seen from as

far away as Nazareth, several miles to the east. Its foundations may date to the Byzantine period, but it has

been rebuilt many times. Most of the present cornerstones are rubble filed Roman sarcophagi that were

probably incorporated into the building in Byzantine or Crusader times. The most recent rebuilding took

place in the late nineteenth century, when Abdul Hamid (1816-1909) had the structure rebuilt for use

as a schoolhouse. It was used as such by the local Arab villagers until the 1948 war.

Meyers et al. (1992) - Fig. 9 Photo of citadel

and theater from Nagy et al. (1996)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

The Roman theater against the backdrop of the Crusader/ Ottoman citadel on the summit of the Sepphoris acropolis. Constructed at the end of the first century C.E. or later, the theater could seat around 4,500 spectators.

Photo: Ehud Netzer

Nagy et al. (1996)

Two destructions were visited upon Sepphoris in the middle of the 4th century CE.

In 351-352 CE, Sepphoris was at the epicenter of the

Gallus Revolt.

According to several ancient authors including Jerome, Socrates Scholasticus, and Sozomen, the city was

burned, razed to the foundations, or destroyed

(

Strange et al., 2006:22-23). A little over a decade later, the city was destroyed or damaged by an earthquake.

In a letter attributed to Cyril of Jerusalem, we can read that

the whole of Sepphoris (SWPRYN) and its territory (χωρα)

was overthrown

by the northern

363 CE Cyril Quake.

Meyers et al. (1992:17) suggested that mid-4th century CE rebuilding evidence

in Sepphoris was largely due to the

363 CE Cyril Quake while adding that the splendid villa with its mosaics and perhaps even the adjacent theater,

were buried in the collapse and went out of use at this time.

Strange et al. (2006:63), however, suggested that destruction debris in the cavea of the theater was deliberately

placed there during the cleanup which followed the city's destruction/damage stemming from the

Gallus Revolt.

Strange et al. (2006:122) opined that while it is theoretically possible that the earthquake of 363 C.E.

destroyed the Villa, it is not likely, for the simple reason that no one repaired the Villa or rebuilt it, nor did

excavation reveal smashed stones or walls that were thrown down

.

Strange et al. (2006:122) added that all of the rooms that we probed were filled with

erosion and deliberate fill

.

Strange et al. (2006:47) also proposed that the Tower (aka the Citadel) was constructed in the mid-4th century CE

after domestic structures on the summit were destroyed due to the

Gallus Revolt.

In the excavation report of

Strange et al. (2006), several mid 4th century CE destruction layers were encountered. For example:

- In Square I.12 of Field I,

Strange et al. (2006:80) identified L12016,

a thick [50-78 cm.] layer of soil with charcoal and ash

which markedthe destruction of the Villa [JW:Another Villa?]

. Strange et al. (2006) used coin evidence to produce a terminus post quem of 355-361 CE for L12016. -

Strange et al. (2006:98) found

traces of destruction

in theeast balk of Square I.10

. -

Strange et al. (2006:122) assigned abandonment and/or damage and/or destruction of the villa to Phase 4 and dated this phase

to

between 351 and 361 C.E., judging from the stratigraphy and the coins.

- In Square I.1 adjacent to the Tower

(aka the Citadel),

Strange et al. (2006:47) found what may be two destruction layers - Locus 1025 which contained ash and charcoal

evidently from a 4th century fire

and Locus 1024 on top of Locus 1025. Locus 1024 wasa 30 cm. thick destruction layer, dark with ash, and containing potsherds from the Early Roman through the Late Roman periods

.

-

Waterman et al. (1937:30 n. 52) reports that

that

large architectural fragments belonging to the masonry of the theater

were foundat various depths

nearer the top

of Cistern No. 8. Waterman et al. (1937:30) surmised that these fragments were caused by a mid 4th century CE destruction due to an abundance of Byzantine sherds and a lack of post Byzantine sherds in Cistern No. 8. -

Waterman et al. (1937:30-31) found evidence of burning, a disturbed and overturned floor, uncharred

human remains, and an uncharred pickaxe in Room 10. The 8-10 cm. thick burned layer was also found

a good distance to the north of this room (Room 10), near the theater, [and] in the debris immediately south of it.

JW: The Villa of Meyers et al. (1992) and the Villa(s) of Strange et al. (2006) may not be the same Villa.

Sepphoris may also have been home to a group of minim or Judeo-Christians (who later apparently merged with the Christian community). A few second century Jewish sources mention a certain person, named Jacob (who is unknown in later Christian sources), coming from the nearby village of Sichnin; Jacob is said to have discussed Jesus, in Sepphoris, with Rabbi Eliezar (a notable sage of the second century), and to have healed the sick in Jesus' name. The ’ Church Father Eusebius, however, by the third century, does not mention any "Christians" at Sepphoris.

Thus far, neither clear relevant archaeological evidence nor sufficient historical references throw much light on the existence of a Christian community at Sepphoris during the fourth century C.E. One reference, dated to early in the fourth century, mentions a Jewish convert (to Christianity) from Tiberias named Justus (earlier identified by the name Josephus), who gained permission to build a church at Sepphoris. This source seems to be reliable; but without other external literary or archaeological evidence for any fourth century church, it is difficult to verify. There is no doubt, though, that the Christian population of Galilee in general was growing rapidly in the periods before and after the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire in 313 C.E. by Constantine and its subsequent adoption as the state religion by Theodosius the Great. Sepphoris, however, seems to have maintained its dominant Jewish character through all this period.

By the mid-fourth century, during the reign of Constantius II (337-361 C.E.), Sepphoris is reported to be the center of anti-Roman feelings in its opposition to the local rule of Gallus Caesar. The precise details of the so-called Gallus Revolt (351-352) are difficult to reconstruct. Sepphoris was devastated at about this time; but the cause was more likely a natural catastrophe, namely the great earthquake of 363 C.E., which put an end to the glories of the Roman occupation of the city. Indeed, the splendid villa with its mosaics and perhaps even the adjacent theater, were buried in the collapse and went out of use at this time.

Sepphoris was soon rebuilt and probably continued to exist as a flourishing center also during the Byzantine period. Both archaeological as well as historical data provide evidence for this period. In the fifth and sixth centuries the city was the seat of a bishopric, whose bishops participated in at least two ecumenical councils. One of the historical sources mentions the fact that a bishop of Sepphoris attended the Council of Chalcedon in 451 C.E. To this period, perhaps, belongs the origin of the tradition that Joachim and Anna (the parents of Mary, mother of Jesus) were residents of Sepphoris. This belief, which has support in the patristic literature, is still upheld in the Roman Catholic Church. (In 1985 the sisters of the Catholic orphanage located today at Sepphoris organized a celebration to commemorate the 2000th anniversary of the birth of Mary.) Archaeological data also attest to the continuation of urban life at Sepphoris even in the Early Arabic period.

Although the history of medieval Christianity at Sepphoris remains unclear, the well-preserved Crusader Church of Saint Anne, which still stands in its early Gothic splendor, provides eloquent testimony to the importance of Sepphoris in Christian history.

In sum, the literary sources richly document the existence of varied communities living at Sepphoris, side by side with the prominent Jewish community, during the Roman and Byzantine periods. Archaeology, however has illuminated only the Jewish and pagan (Roman) presence until the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth centuries C.E., when archaeology and literary sources combine to present a picture of Christians existing alongside a dominant Jewish population and a strong Roman presence. The literary sources point to Sepphoris's continued leadership in the political, economic, and religious affairs of its region. Archaeological evidence has now confirmed that picture and has provided important new discoveries, which shed light on this period of great change and cultural development. That literary, spiritual, and religious creativity could have occurred in a flourishing oriental city is not surprising. That it occurred in the Jewish community at the very pinnacle of achievement alongside a lively paganism replete with a theater and a large villa with a splendid mosaic and grand banquet hall is testimony to the urban setting as a catalyst for a constructive symbiosis in late antiquity.

Ancient Sepphoris is clearly identified with the ruined village of Safuriyye, the present-day Moshav Zippori. The site overlooks the Beth Netofa Valley in the central Lower Galilee, about 5 km (3 mi.) northwest of Nazareth (map reference 176.239). Sepphoris is first mentioned by Josephus in connection with the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (Antiq. XIII, 338), but a few remains from the Iron Age II found here attest to an earlier settlement. In the Hasmonean period, Sepphoris was probably the administrative center of the whole of Galilee. In around 57-55 BCE, the Roman proconsul Gabinius made Sepphoris the capital of the district of Galilee (Antiq. XIV, 91; War I, 170). Sepphoris submitted to Herod, who attacked the city during a snowstorm in 3 7 BCE (Antiq. XIV, 414; War I, 304 ). After Herod's death, the Romans conquered thecityin the "warofVarus" and sold its inhabitants into slavery (Antiq. XVII, 289; War II, 68). With the partition of Herod's king dom, Sepphoris was granted to his son Antipas, who resided here until he founded Tiberias and made it the new capital of Galilee. Antipas fortified Sepphoris and changed its name to Autocratoris, according to Josephus (Antiq. XVIII, 27). During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, the inhabitants of Sepphoris sided with Vespasian, surrendered their city to him (War III, 30-34), and struck coins in his honor as the "peace maker" (ειρηνοποιος). After the destruction of the Temple, the priestly family of Jedaiah settled in Sepphoris. During Trajan's reign, coins were minted here by the Jewish local government; the words "Emperor Trajan gave" were stamped on them. During the reign of Hadrian, the "old government" of Sepphoris - the Jewish local city government (Mishnah, Qid. 4:5) - was abolished, a gentile administration was appointed, and probably, at the same time, the name of the city was changed to Diocaesarea (Διοκαισαρεια, the city of Zeus and of the emperor). Yet, after Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi and the Sanhedrin established their seat here for seventeen years before the rabbi's death, at the end of the second century (J.T., Kil. 9:4, 32b), the local government of the city was once more turned over to a Jewish town council. Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi redacted the Mishnah in Sepphoris. At the beginning of the third century, the minting of coins by the Jews was renewed here; the coins were stamped "Covenant of friendship and mutual aid between the holy council and the senate of the Roman people."

Sepphoris is mentioned many times in Talmudic literature and was known throughout its existence as a Jewish city. In the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods many scholars lived here; the best known are rabbis Halafta, Ele'azar ben 'Azariah, and Jose ben Halafta. The seat of the Sanhedrin was also in Sepphoris until it was moved by Rabbi Yohanan to Tiberias in the time of Rabbi Judah Nesiah, the grandson of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi. During the reign of Emperor Constantine, a certain Josephus the Apostate tried in vain to erect a church here (Epiph., Haer. 30, 4~12). In the reign of Constantius II, the Jewish revolt against Gallus Caesar, led by Patricius, began in Sepphoris (351 CE). The Roman troops garrisoned in the city were disarmed, and the rebels gained control. The Roman commander Ursicinus succeeded in crushing the revolt, but, in spite of the reports of the Christian sources (Jerome, Chron., Olymp. 282; Socrates, HE II, 33; Sozomenos, HE IV, 7), he failed to level the city. In a letter sent by Cyril, bishop of Jerusalem, mention is made of an earthquake that struck Palestine in 363, making special note of the total destruction of Sepphoris. The town was later partly restored and continued to be a Jewish city until the fifth century; in the sixth century, however, it had a Christian community, headed by a bishop. Bishops ofSepphoris participated in the synods of Jerusalem in 518 and 536. In Crusader times, Sepphoris (Le Sephorie) was a city and fortress in the province of Galilee. Remains of a Crusader church and fortress still stand at the site. In the eighteenth century, the governor of Galilee, Dhahir el-'Amr, refortified it.

- from Brock (1977)

On how many miracles took place when the Jews received the order to rebuild the Temple, and the signs which occurred in the region of Asia.15

116 The letter, which was sent from the holy Cyril, bishop of Jerusalem, concerning the Jews, when they wanted to rebuild the Temple, and (on how) the land was shaken, and mighty prodigies took place, and fire consumed great numbers of them, and many Christians (too) perished.

2 To17 my beloved brethren, bishops, priests, and deacons of the Church of Christ18 in revery district : greetings, my brethren.19 'The punishment of our Lord20 is sure, and His sentence (ὰποφασις) that He gave concerning the city of the crucifiers is faithful, and with our own eyes we have received a fearful sight21 for22 truly did the Apostle say that 'there is nothing greater than the love of God'.23 Now, while the earth was shaking24 and the entire people suffering25, I have not neglected to write to you about everything that has taken place here.26

3 At the digging of the foundations of Jerusalem, 'which had been ruined because of the killing of its Lord, the land shook considerably27, and there were great28 tremors in the towns29 round about.

4 Now even though the person bringing the letter is slow, nevertheless I shall still write and inform you that we are all well, by the grace of God and the aid of30 prayer. Now I think that you are concerned for us, (and) our minds were tearing us—not only our own, but all our brethren's as well, who are with us, that I should tell you too about what happened amongst us.31

5 We have not written to you at length, beyond the earthquake that took place at God's (behest). For many Christians too living in these regions, as well as the majority of the32 Jews, perished at that scourge — and not just in the earthquake, but also as a result of fire and in the heavy33 rain they had.

6 At the outset, when they wanted to lay the foundations of the Temple on the Sunday previous to the earthquake, there were 'strong winds and storms34, with the result that they were unable to lay the Temple's foundations that day35. It was on that very night that the great earthquake occurred, and we were all36 in the church of the Confessors, engaged in prayer. After this we left to go to the Mount of Olives, which is situated to the east of Jerusalem, where37 our Lord was raised to His glorious38 Father. We went out into the middle of the city, reciting a psalm,39 and we passed40 the graves of the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah, and we besought the Lord of the prophets that, through the prayers of His prophets and apostles, His truth might be seen by His worshippers in the face of the audacity of the Jews41 who had crucified Him

7 Now they42 (sc. the Jews), wanting to imitate43 us, were running to the place where their synagogue usually gathered, and they found the synagogue doors closed. They were greatly amazed at what had happened and stood around in silence and fear when suddenly the synagogue doors opened of their own accord, and out of the building there came forth fire, which licked up the majority of them, and most of them collapsed and perished in front of the building. The doors then closed of their own accord, while the whole city looked on at what was happening, and the entire populace, Jew and Christian alike, cried out with one voice, saying 'There is but one God, one Christ, who is victorious' ; and the entire people rushed off and tore down the idols and (pagan) altars that were in the city, glorifying and praising Christ, and confessing that He is the Son of the Living God. And they drove out the demons of the city, and the Jews, and the whole city received the sign of baptism, Jews as well as many pagans, all together, so that we thought that there was not a single person left in the city who had not received the sign (σημειον) or mark (τνπος) of the living Cross in heaven. And it instilled great fear in all.

8 And the entire people thought that, after these signs which our Saviour gave us in His Gospel, the fearful (second) coming of the day of resurrection had arrived. With trembling of great joy we received something of the sign (ημιεὶον) of Christ's crucifixion, and whosoever did not believe in his mind found his clothes openly reprove him, having the mark of the cross stained on them.

9 As for the statue (ἀνδριάς) of Herod which stood in Jerusalem, which the Jews had thrown down in (an act of) supplication (?) (δέησις), the city ran and set it up where it had been standing.

10 Thus we felt compelled to write to you the truth of these matters, that everything that is written about Jerusalem should be established in truth, that 'no stone shall be left in it that will not be upturned'.

11 Now we should like to write down for you the names of the towns which were overthrown : Beit Gubrin—more than half of it ; part of Baishan, the whole of Sebastia and its territory (χωρα), the whole of Nikopolis and its territory (χωρα) ; more than half Lydda and its territory (χωρα) ; about half of Ashqelon, the whole of Antipatris and its territory (χωρα) ; part of Caesarea, more than half Samaria ; part of NSL', a third of Paneas", half of Azotus, part of Gophna, more than half Petra (RQM) ; Hada, a suburb of the city (Jerusalem)—more than half ; Jerusalem more than half. And fire came forth and consumed the teachers of the Jews. Part of Tiberias too, and its territory (χωρα), more than half 'RDQLY' (Areopolis or Archelaisa), the whole of Sepphoris (SWPRYN) and its territory (χωρα), 'Aina d-Gader; Haifa (? ; TAP) flowed with blood for three days ; the whole of Japho (YWPY) perished, (and) part of 'D'NWS.

12 This event took place on Monday at the third hour, and partly at the ninth hour of the night. There was great loss of life here. (It was) on 19 Iyyar of the year 674 of the kingdom of Alexander the Greek. This year the pagan Julian died, and it was he who especially incited the Jews to rebuild the Temple, since he favoured them because they had crucified Christ. Justice overtook this rebel at his death in enemy territory, and in this the sign of the power of the cross was revealed, because he had denied Him who had been hung upon it for the salvation and life of all.

All this that has been briefly written to you took place in actual fact in this way.

14 I translate B ; the main variants of A are given in the footnotes.

15 Letter of Cyril bishop of Jerusalem.

16 A omits § 1.

17 pr. Cyril bishop of Jerusalem.

18 our Lord.

19 in all regions.

20 With (in) our Lord punishment.

21 in our own sight it specifically received it ; greetings !

22 Just as, my brothers.

23 om. of God.

29 shook.

25 world suffered.

26 om. here.

27 the land suffered specifically.

28 om. great.

25 + and cities.

30 + your.

31 seeing that we too, because we (were) there, struggled for ourselves.

32 Not only were we not harmed by the earthquake that took place at God's (behest), but no Christian who was here (was harmed), but many.

33 om. heavy.

34 winds and strong storms.

35 the foundations as they had wanted ; for it was in their mind to lay the Temple's foundations the following day.

36 fled and took refuge in.

37 whence.

38 om. glorious.

39 psalms.

40 + between.

41 those (who).

42 the Jews.

43 The folio of A containing the rest of the letter is lost.

a Guidoboni et. al. (1994)

state that there are "palaeographic reasons to suggest that the

debated 'RDQLY in Cyril's letter may be a reference to Areopolis rather than Archelais".

... One of the formative events of the fourth century C.E. is the Revolt against Gallus Caesar in the middle of the century. The best Hellenic historian of the fourth century’, Ammianus Marcellinus, does not mention the revolt, though he is quite familiar with the reign of Gallus and with Ursicinus (a figure whom the Jewish sources also connect with the revolt).70

Therefore, the main source for the Gallus Revolt is the fourth century’ Hellenic writer Aureoles Victor, who is almost contemporary with the events mentioned, writing between 359 and 361. His account mentions that an

. . . insurrection of the Jews who had raised up Patricius impiously in the form of a kingdom was suppressed.(Liber de Caesaribus 42).71 It names an unknown pretender, connects the revolt to no particular city, and goes on to tell us the emperor ordered Gallus’ death because of Gallus’ “murderous nature.” The event should date to 352 or 353 C.E.

It is the fifth century Christian writer, Jerome (386-419), who adds the specification that three Palestinian cities, including Sepphoris, participated:

Gallus crushed the Jews, who murdered the soldiers in the night, seizing arms for the purpose of rebellion, even many thousands of men, even innocent children and their cities of Diocaesarca, Tiberias, and Diospolis and many villages he consigned to flames. (Chron. 238).It is two outstanding Christian historians of the early fifth century C.E., Socrates Scholasticus (ca. 380-post 439) and Sozomen (his Η. E. written 439-450) who clearly located the center of the revolt at Sepphoris.72

Socrates says:

About the same time there arose another intestine commotion in the East, for the Jews who inhabited Diocacsarea in Palestine took up arms against the Romans, and began to ravage the adjacent places. But Gallus, who was called Constantius, whom the emperor, after creating Caesar, had sent into the East, dispatched an army against them, and completely vanquished them; after which he ordered that their city Diocacsarea should be razed to the foundations. (Hist. Ecc. 2.33)Sozomen adds details on the end of Gallus.

The Jews of Diocacsarea also overran Palestine and the neighboring territories; they took up arms with the design of shaking off the Roman yoke. On hearing of their insurrection, Gallus Caesar, who was then at Antioch, sent troops against them, defeated them, and destroyed Diocacsarea. Gallus, intoxicated with success, could not bear his prosperity, but aspired to the supreme power, and he slew Magnus, the quaestor, and Domitian, the prefect of the East, because they apprised the emperor of his innovations. The anger of Constantius was excited; and he summoned him to his presence. Gallus did not dare to refuse obedience, and set out on his journey. When, however, he reached the island Elavona he was killed by the emperor’s order; this event occurred in the third year of his consulate, and the seventh of Constantius. (Hist. Ecc. 4.7)Was there a Jewish revolt under Gallus? Four of the five earliest sources indicate that there was. The three Christian sources (Jerome, Socrates, and Sozomen) indicate that Diocacsarea was one of three cities involved (Jerome) or was itself the center of the revolt (Socrates and Sozomen). Two of the three Christian writers were located in Palestine (Jerome) or familiar with it (Sozomen wrote in Constantinople but was originally from Bethelia near Gaza).73 The notices of the revolt seem genuine enough, and the writers most familiar with Palestine take it as genuine and indicate that Sepphoris was a key “player” and a key “sufferer” in the event. The small number of cities involved, and its unknown cause made it an obscure event to writers not so thoroughly familiar with Palestine. The destruction materials that are found in mid-fourth century loci across our excavation’s fields support such a conclusion.

Although Jerome lived in Bethlehem, he only traveled around the country one brief time upon his arrival in the Holy Land.74 Nonetheless he is our source to the effect that Sepphoris (“Seppforine”) received its name Diocacsarea from Antoninus Pius (Liber Locorum 17.14). Yet when he reports that Jonah was buried at Sepphoris (Preface to the Book of Jonas 25.1119), he has likely con fused Jonah and some famous rabbi (perhaps Judah himself).

Palladius (419 C.E.), The Lausiac History, ch. 46, relates the story of Melanie “the Thrice Blessed”, who cared for Orthodox Christians from Egypt whom the Arian emperor Valens (364-378) exiled to some place near Diocacsarea in the late fourth century C.E. This company included six monks and twelve bishops and priests. If the story is indeed historical, then it is arresting to think that being sent to the city territory of Sepphoris was to be in exile during the latter half of the fourth century C.E. We may infer that Sepphoris, a Jewish city, may in fact have been punished as a result of Gallus’ Revolt.75 The action of Valens tends to confirm the story in Epiphanius about Count Joseph building churches under Orthodox patronage at Diocacsarea (see above), that is, Valens would have seen Diocacsarea as Orthodox territory, even though Jewish, perhaps also damaged in Gallus’ Revolt.

The leading proponent of an interpretation of these texts which denies that the revolt ever occurred is J. Schaefer.76

...

70 Menachem Mor, “Tlte Events of 351-352 in Palestine

The Last Revolt Against Rome?” In 'The Eastern Frontier of

the Roman Empire. Proceedings of a Colloquium Held at Ancyra in

September 1988, edited by D. H. French and C. S. Lightfoot,

Part II, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph

No. 11, BAR International Series 553 (ii), 1989: 335-353.

71 Mor 1989: 337.

72 Johannes Quasten, Patrology, Vol. 3 (Utrecht/Antwerp:

Spectrum, 1963): 533 and 535.

73 Quasten, Patrology, 534.

74 J. Wilkenson, “L’Apport de Saint Jerome a la Topographie,” RB 8l (1974): 245 57, esp. 256-57.

75 Palladius: The Lausiac History, translated by Robert T.

Meyer. Ancient Christian Writers, 34. London: Longmans,

Green and Co. and Westminster: The Newman Press, 1965: 123-25.

76 J. Schaefer, “Der Aufstand gegen Gallus Caesar.” In

Tradition and Interpretation in Jewish and Christian Literature: Essays

in Honor of Jurgen C. H. Lebram, Studia Post-Biblica 36.

ed. J. W. van Henten et al., Leiden: Brill. 1986: 184-201.

Schaefer's arguments seem to us to have been effectively met

in Barbara Nathanson. 'Jews, Christians, and the Gallus

Revolt in Fourth-century Palestine,” BA 49 (1986): 26-36.

Square 1.1 1983: Probe on north side of the Tower, supervised by Robert Ingraham

Square 1.2 1983: Probe at the northwest corner of the Tower, supervised by John McRay

Square 1.3 1983: Probe 1 m west of 1.2 into occupation levels to bedrock and to four rock cut chambers, supervised by Alice Ingraham

Square 1.3 1985: Excavation inside the four chambers, supervised by C. Thomas McCollough and Robert Ingraham

Square 1.6 1985: Probe to reveal the opening of chamber C205, supervised by C. Thomas McCollough

In his 1931 excavations, Leroy Waterman apparently dug at the northwest corner of the 'Lower but did not leave a clear record of his work in the area. The lone sentence in his Preliminary Report that refers to this activity could not be understood until modern materials were encountered during the excavation of Square I.2 (sec below). The report provides no dimensions for the extent of Waterman’s probe. Yeivin simply says, “This fragment [of an inscribed mortuary urn] was recovered from a deep shaft sunk at the northwest corner of the Crusaders’ Citadel on the summit of the hill.”1

Waterman engaged in substantial excavations on the east side of the Tower. In his Preliminary Report, Plate V, Fig. 2, one secs a view to the north of that part of his trench S-I, just east of the Tower. In that photograph one can see a wall parallel to the cast wall of the Tower with three cross walls running to the west underneath the Tower.1 2 This single course of stones appears to be of typical Herodian preparation. The stones have drafted margins and trimmed bosses on their east side, suggesting that one is looking at the outside of a building. As much as 50 Roman feet of it appears to be concealed beneath the Tower to the west.3

Yeivin suggested that the stones in the “Citadel” were from a Hasmonean palace, and that this palace was the “old castra” mentioned by the rabbis (M Arakhin 9.6). But the “old castra” was not to be identified with the building found on the east side of the Tower. He described the fragment of that building as seen in Plate V, Fig. 2, as “one outer wall and four thinner partition walls, dividing the inner space into five rooms.” Based on the discovery of a first century lamp inside “room 2” of the building, and of painted stucco fragments “with designs of red pomegranates and green leaves,” Yeivin concluded that the building dated from the first century C.E. and indeed was likely built by Herod Antipas.4

1 Yeivin, op. cit., 27.

2 A fourth cross wall may be visible as two Herodian

stones in Plate VI, Figs. 1 and 2.

3 The plan of this building was never published by Waterman. It appears in Makhouly’s plan of trench S-H on file

in the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem.

4 Yeivin, “History and Archaeology" in Waterman, Preliminary Report, 28.

The first square was a 5 x 5 m. plot located directly against the north wall of the Tower. It was not centered on the north wall, but was laid out one meter cast of the cast side of Square 2. Therefore the center of Square 1 lay six meters cast of the northwest corner of the Tower. The entire 5x5 m. square was excavated rather than leaving 1 m. balks on the north and cast sides, the method adopted elsewhere. This provided fully 25 square meters of exposure in this first square. The plan above, together with the final top plan and balk drawing of 1.1 should help the reader follow the narrative description of excavation in this square.

As we have noted, our stratigraphic objective was to expose the full range of deposition against the north side of the Tower and, if possible, to determine the founding date for the building. We also wanted to investigate any other architecture that might remain in this area. Since Waterman showed a large structure emerging from beneath the east wall of the Tower in his trench S-I, it seemed possible that there might be similar structures to be found on the north side as well.

The stratigraphic situation encountered (see Fig. 4.03. Square 1.1, Southeast Balk) was consider ably more complicated than Waterman's notes suggested. Loci 1000 and 1002 appear to be a loosely compacted, modern surface, undoubtedly a schoolyard, since, according to local informants. the building had been used as a school until 1948. The yellowish layer Locus 1007 was likely also part of this schoolyard debris. The contents of these loci included modern materials, among them a Palestinian penny of 1932 found in Locus 1002. These first three loci extended to a depth of about 90 cm. or to an elevation of 289.40 m.

Locus 1008 was the first layer that did not contain any modern materials. The latest potters’ was from the Arab I period although this debris may well represent an occupation layer that should be associated with a later, perhaps medieval, use of the ’lower. The soil contained a great deal of while plaster debris which appeared to be the remains of an unpainted, plastered wall destroyed in antiquity. The debris had apparently been transported over some distance, however, since none of it was in pieces larger than 3 cm. in diameter. This was the first soil layer to be relatively rich in small finds, yielding a Roman provincial coin of the 2nd century, perhaps minted at Neapolis,7 nine registered glass fragments, six ceramic stoppers, two lamp fragments, live ceramic water pipe fragments, two iron spikes, and one iron nail.8 Fragments of ceramic water pipe, with a diameter of approximately 10 cm. were also found. Like the plaster mentioned above, these apparently have their origin elsewhere.

At an elevation of 288.382 m. a marked change in the contents of the soil was noted. The new layer contained a great deal of ash. The layer was loosely compacted and appeared to be a natural deposition by wind and water. Locus 1018, toward the eastern end of the square contained one badly worn and, therefore, unidentifiable bronze coin,9 three ceramic water pipe fragments, three lamp fragments, fragments of two iron spikes and one nail. The soil with less ash, toward the western end of the square, was designated Locus 1014 Five coins were found in this locus, a coin of Probus (276 282 C.E.),10 a coin of Valentinian II (383 C.E.),11 a coin of Constantinius II (351-361 C.E.),12 and two unidentifiable coins.13 The locus also produced a rich array of small finds, including nine registered glass sherds, a lamp fragment, a ceramic stopper, two fragments of bone pins, a bronze pin, a bronze blade, an iron blade and two iron spikes. The latest pottery from these two loci is Early Byzantine, which is consistent with the evidence from the identifiable coins.

At an elevation of 288.385 several stones appeared. Removal of the last few centimeters of Loci 1014 and 1018 revealed a line of stones which were designated Wall Locus 1013. The layers of soil on either side of this wall were designated Locus 1021 and Locus 1016. This material was more firmly compacted.

The first surface that was hard enough to support walking was Locus 1022, directly upon which accumulated Locus 1021. The surface, Locus 1022, lay at an average elevation of about 287.85 in. A low wall one row of stones wide, Wall Locus 1013, parallel to the face of the Tower and about 1.33 m. from the Tower wall, separated Locus 1021 from its counterpart next to the Tower, or Locus 1010. The latest materials found in these loci were from the Early Byzantine period. The finds in Locus 1021, the accumulation upon Locus 1022, were six glass fragments, two ceramic stoppers, two intact Byzantine lamps, three fragmentary lamps, and one iron nail. Those registered from Locus 1010 included two glass fragments, one lamp top, and two bone pins. The large number of lamps and the bone pins imply that the debris was from settled occupation.

Locus 1022 contained one bronze coin of Constantinus, two ceramic lamp handles, one lamp base with red burnished slip, a ceramic stopper, and a fragment of a water pipe. The pottery was Early Byzantine in date. Locus 1022 appears to have been a second surface upon a lower surface, namely Locus 1011, a substantial layer of plaster that ran throughout the excavated portion of the square at an elevation of 287.550.

Beneath the wall, Wall Locus 1013, and the two accumulations on either side was Locus 1011, a hard floor formed of clay and lime. This layer, at approximately the level of the lowest course of stone of the Tower,14 was apparently laid as a working surface for the construction of the building. It was so hard when first encountered that die excavation team thought it was ancient cement. This layer was almost devoid of finds, as one might expect of a lime and clay layer. The contents were two lamp fragments, one ceramic stopper, and one iron nail. Beneath Locus 1011 and next to the Tower the lower layer made up for the application of clay and lime layer Locus 1011, designated Locus 1015, was a hard soil, perhaps water-washed, which contained Persian to Early Roman ceramics. This layer contained hardly any artifactual material at all although there was a coin of Gallienus (259 C.E.),15 one black-slipped Hellenistic lamp top, and one iron spike. We posit that this layer, Locus 1015, was material excavated by the builders of the Roman Tower to form the make-up for clay and lime surface, Locus 1011. Locus 1011 extended the full five meters from the Tower wall.

Two other layers were found beneath Locus 1011 north of Wall Locus 1019. The first was Locus 1024, a 30 cm. thick destruction layer, dark with ash, and containing potsherds from the Early Roman through the Late Roman periods, but few other artifacts, namely one ceramic stopper and two ceramic lamp fragments, one with red slip. Locus 1024 in turn rested upon Locus 1025, a layer black with ash and charcoal from a major conflagration. The ash was evidently from a 4th century fire. This layer contained a coin of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 B.C.E.),16 two Middle Roman lamp nozzles, two ceramic stoppers, one bone needle, and one fragment of a basalt grinder. Beneath the destruction layer and north of Wall Locus 1019 the team found a heavy layer of stones about 40 cm. thick, designated Locus 1027. To the south, next to the Tower wall, smaller stones on top (Locus 1017) were distinguishable from relatively larger stones beneath (Locus 1023). This seemed to be a result of disturbances by the workmen, since Locus 1017 and Locus 1020 contained Late Roman potsherds, whereas the rocky layer, Locus 1027 contained nothing later than Early Roman potsherds. Furthermore, directly beneath Locus 1020, next to the Tower wall 1012, was a hard, cement-like lens of clay and lime material which contained Early Byzantine potsherds.

The founding of the Tower took place between 286.26 and 286.51 m. in elevation in this square. The foundation layer was tightly compacted soil and rocks, designated Locus 1026. almost devoid of finds, and containing sherds from the Early Roman occupation. The slightness of the foundation was a surprise, as the team anticipated that foundations would be cut into bedrock. No such procedure had been carried out, however. Such a foundation suggests that the builders did not intend that their tower would stand for long.

The second surprise in Square I.1 was the construction of what we originally called the “Citadel wall", or W1012. We had expected the building stones on this side to resemble the huge Herodian stones in the southwest comer of the Tower. The soil layers in Square I.1 concealed about 4.2 m. of this wall, which was constructed of stones with drafted margins and trimmed bosses. The stones in each course range in length from 60 to 100 cm. But the courses averaged only 38 cm. high, ranging in height from a low of 27 cm. to a high of 55 cm. There is a tendency for the stones to be higher toward the foundation. The masons cut these stones with a margin of about 5 cm. on each stone.

In the center of the northeast face of the Tower, then, the wall does not resemble a Herodian Tower, or does so only superficially. The stones surely were taken from houses which once stood in the vicinity. The sarcophagi which were used at the corners probably came from the necropolis to the south. They' were likely not moved very' far. Another find to be accounted for are several fragments of ceramic water pipes. A glance at the list of artifact list shows eight registered fragments of ceramic water pipe in Square 1.1. In like fashion four such fragments were found in Square I.2. Since no water installation was found in either square, it raised the question whether a bath lay in the vicinity.

Therefore the sequence of events that can be isolated in Square 1.1 is as follows:

- Slight remains of ER to LR domestic occupation upon bedrock.

- Thorough LR destruction and burning at this level, including the stripping of all building stone from the area.

- The founding of the lower upon closely packed stones and soil from the ER/MR layers. This founding necessitated the cleaning of the LR burn layers away from the immediate area of the foundations.

- The laying of a lime and clay layer all around the Tower at the level of the lowest course of stones. The addition of this feature occurred at the same time as the founding of the Tower, practically speaking. The coins are of mid-fourth century and give the latest date for the founding and for construction of the lime and clay layer.17

- The building of the Tower from stones taken from pre-existing structures in the area and using Roman sarcophagi at the corners.

- The occupation and use of the Tower continuously from mid-fourth century C.E. until the modern period, when it was last used as a school by the citizens of Saffuriyeh.

5 Registry number 830212.

8 The word 'spike” is reserved for nails in excess of 18 cm.

in length with a shaft diameter of 1.0 1.4 cm

9 Registry number 893977.

10 Registry number 830231.

11 Registry' number 830233.

12 Registry' number 830234.

13 Registry numbers 030232 & 830235.