Beth Yerah/al-Sinnabra

Figure 8.3

Figure 8.3Parts of the palace [of al-Sinnabra] cleaned and partly re-excavated in 2009-2010. At center, the basilica apse and rooms to its south; looking west (photographed in 2015).

Da'adli (2017)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Beth Yerah | Hebrew | בית ירח |

| Khirbet al-Karak | Arabic | خربة الكرك |

| Sennabris | Hebrew | סנבראי |

| al-Sinnabra | Hebrew | צינבריי ? |

| al-Sinnabra | Arabic | |

| Sinn en-Nabra | Arabic | سينن ينءنابرا |

| Philoteria | Ancient Greek | φιλοτέρα |

| Sennabris | Ancient Greek | |

| Sinnabri | Aramaic | |

| Senbra | Early Frankish | |

| Ablm-bt-Yrh | Canaanite | |

| Ablm | Canaanite |

- sources: Greenberg et al. (2006) Bet Yerah I: The Early Bronze Age Mound, IAA Reports 30; Wikipedia: Beth Yerah; Wikipedia: al-Sinnabra; Daʿadli (2017)

Archaeological work at Beth Yerah began in the early 20th century and is closely tied to modern settlement in the Kinneret Valley. Early surveys identified the site’s importance and the distinctive Khirbet Kerak Ware . Excavations eventually revealed a fortified Early Bronze Age city with monumental architecture, including the

Circles Building, and a stratigraphy with multiple Early Bronze phases.

Adjacent to Beth Yerah is al-Sinnabra, which preserves the remains of a monumental qasr built by Muʿawiya I, the first Umayyad caliph. This complex served as an administrative and ceremonial residence in the formative decades of Islamic rule. Unfortunately, the qasr was almost completely dismantled after abandonment, leaving only foundation-level remains and erasing key archaeoseismic indicators such as collapse deposits and floor layers (R. Greenberg, pers. comm., 2021).

Early excavations in the 1940s–1950s further degraded the stratigraphic record. As Daʿadli (2017:133) observes, the removal of overburden destroyed “untold quantities of evidence” from the upper layers and led to the loss of “almost all post-Hellenistic finds.” Despite this, al-Sinnabra remains vital for understanding early Islamic political geography and the development of Umayyad monumental architecture.

Tel Beth Yerah (Khirbet el-Kerak) covers an area of approximately 50 a. along the southwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee (map reference 204.236). The mound's western boundary is the old bed of the Jordan River. Its southern boundary is the issue of the Jordan River from the Sea of Galilee. The suggestion that Khirbet el-Kerak be identified with Beth Yerah or Talmudic Ariah was made in the nineteenth century. Some authorities have identified the site with the Philoteria built by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (Polybius, V, 70, 3-4), a town in the Jewish territory under the Hasmoneans (Georgius Syncellus, I, 558-559). Others have suggested identifying it with Sennabris, mentioned by Josephus as the northernmost border point of the Jordan Valley and the camping ground of Vespasian's army (War III, 447, IV, 455). In Talmudic literature, Beth Yerah is frequently mentioned as a mixed settlement of foreigners and Jews near Sennabris (J.T., Meg. 70a, 74a).

In surveys prior to the excavations, it had become clear that the site was settled in the Early Bronze Age, and from the Hellenistic to the Arab periods. A special kind of Early Bronze Age III pottery first discovered here was named Khirbet Kerak ware by W. F. Albright. The ware's typical features are red and black burnish and incised or ribbed decoration. Since the discovery of this ware at Beth Yerah, similar pottery has been found at many other sites in Israel and in northern Syria. Its style attests that the ware originated in Anatolia.

The first excavations at Beth Yerah were carried out by the Palestine Exploration Society in 1944-1945, under the direction of B. Mazar (Maisler), M. Stekelis, and I. Dunayevsky. The expedition excavated an area on the southern part of the mound. In 1945-1946, Stekelis, M. Avi-Yonah, and Dunayevsky continued work in the south and began excavating on the northern part of the mound.

After 1949, excavations were carried out at the northern part of the site by the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, at first under the direction of P. L. O. Guy and later under P. Bar-Adon. More extensive excavations in the south and soundings in various places in the center and in the west were directed by Bar-Adon (1949-1955). In the course of the latter excavations, residential quarters were exposed, and the lines of the different city walls were examined. In 1952-1953 and 1963-1964, additional excavations and soundings were undertaken by the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, under the direction of P. Delougaz, assisted in the later seasons by H. Cantor. Their work was concentrated mainly in the northern part of the mound and, to some extent, in the center.

Under the auspices of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, excavations were carried out in 1967 on the eastern part of the mound, in strata from the Early Bronze Age, under the direction of D. Ussishkin. In 1976 salvage excavations were carried out in two areas on the northern part of the mound. The first area, near the lakeshore, was excavated under the direction of R. Amiran, Z. Yeivin, and C. Cohen. Ten strata, dating from the Early Bronze Age I to the Hellenistic period, were distinguished. Excavations directed by D. Bahat in another area to the southwest revealed three strata from the Early Bronze Age I-III, one stratum from the Hellenistic period, and one from the Byzantine period.

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

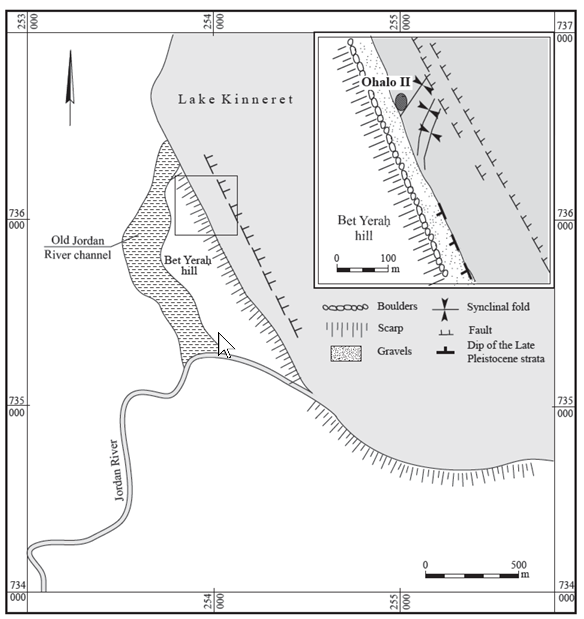

- Fig. 1.2 Fault

map of Tel Bet Yerah and vicinity from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 2.1 Early Bronze I Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

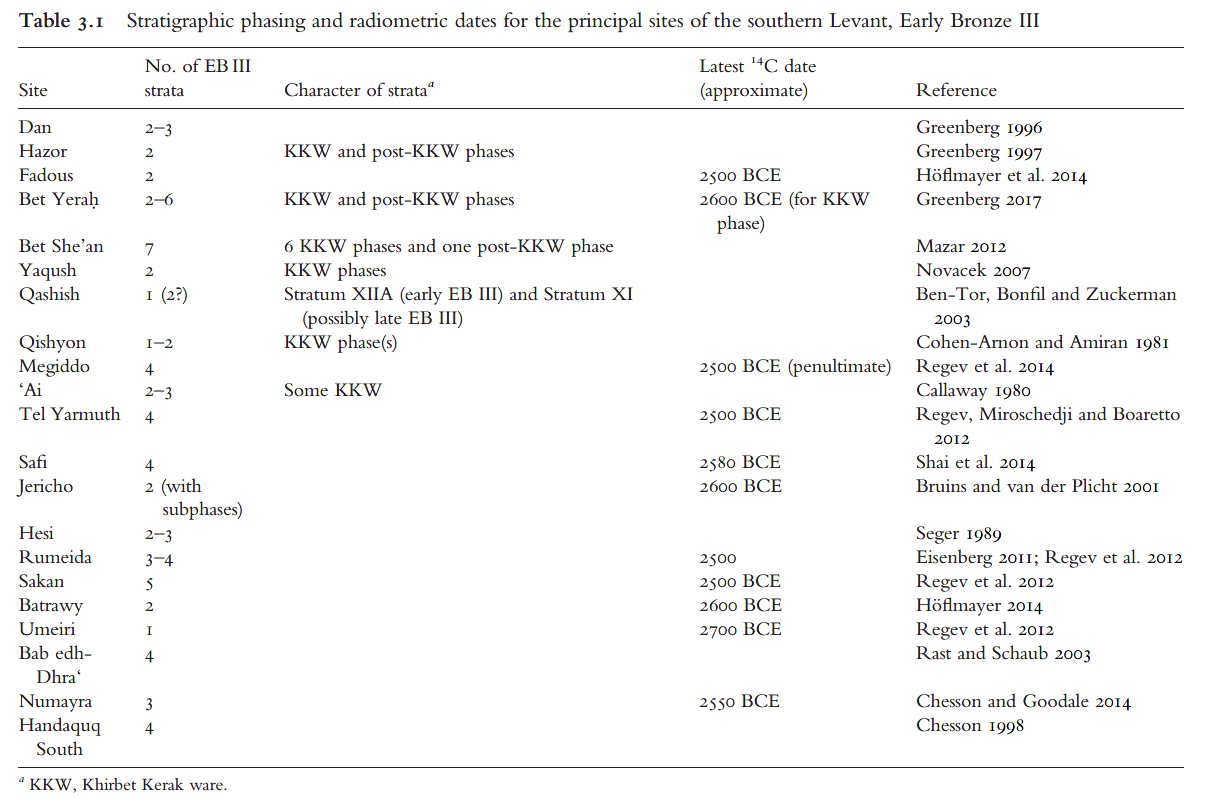

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 3.1 Early Bronze II and III Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 3.1

Fig. 3.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Intermediate Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 5.2 Middle Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 6.1 Late Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 6.1

Fig. 6.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019)

- Fig. 1.2 Fault

map of Tel Bet Yerah and vicinity from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 2.1 Early Bronze I Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 3.1 Early Bronze II and III Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 3.1

Fig. 3.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Intermediate Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 5.2 Middle Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019) - Fig. 6.1 Late Bronze Sites

from Greenberg (2019)

Fig. 6.1

Fig. 6.1

Map of sites mentioned in this chapter

Greenberg (2019)

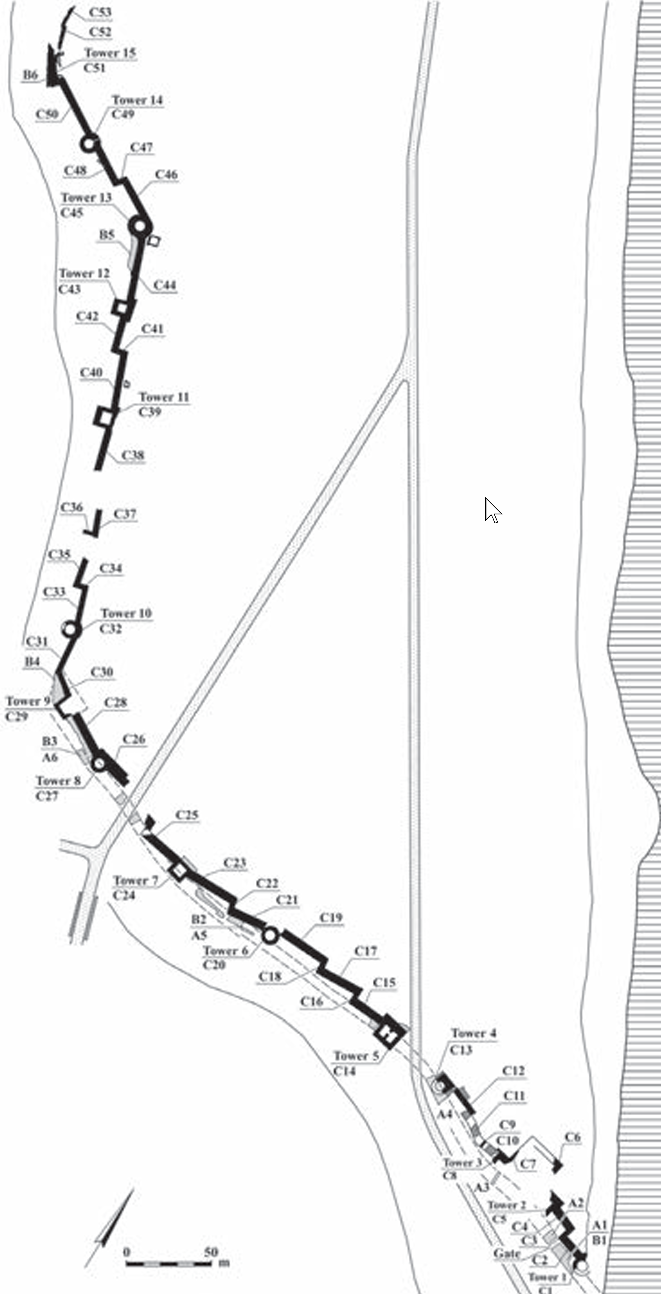

Plan 1

Plan 1Map of the principal excavation areas (see Table 1 for area codes).

Greenberg et al. (2006)

Table 1

Table 1Conspectus of Major archaeological Campaigns at Tel Bet Yerah since 1933

Greenberg et al. (2006)

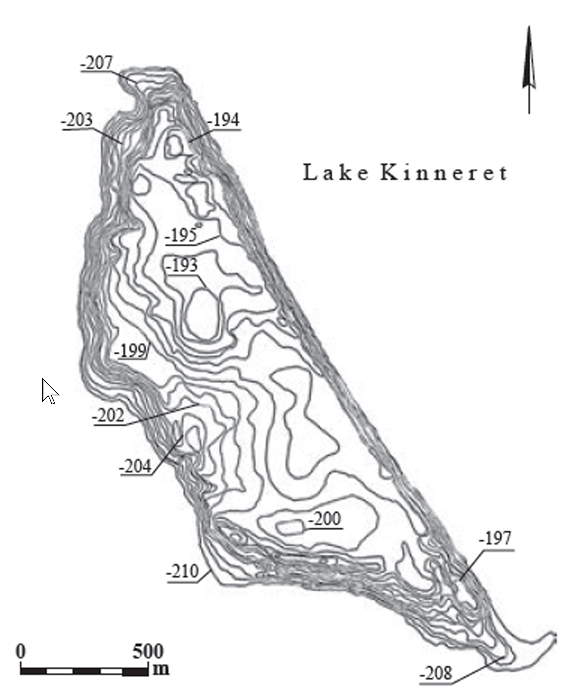

- Fig. 1.5 Modern

topography of Tel Bet Yerah from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

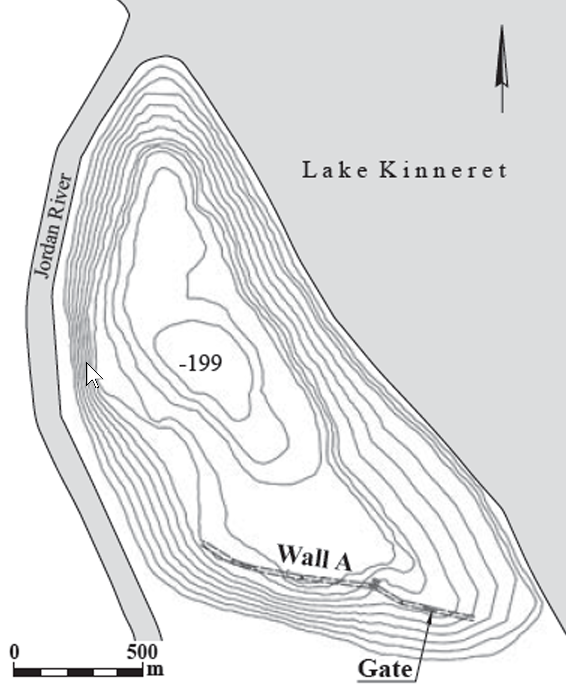

- Fig. 1.6 Reconstructed

topography of the natural mound, with line of Wall A (Period C) superimposed on it from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

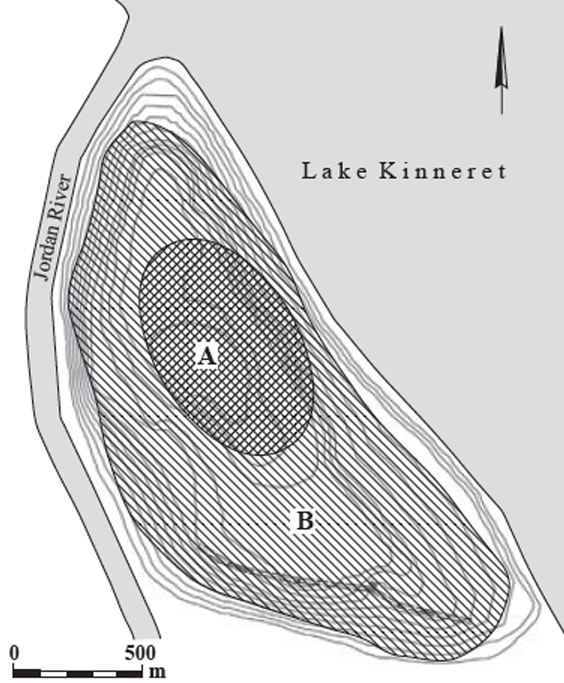

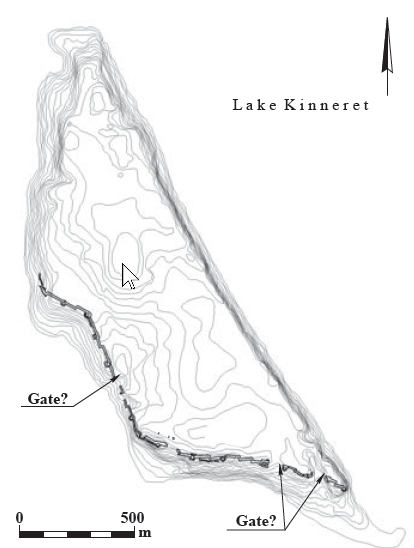

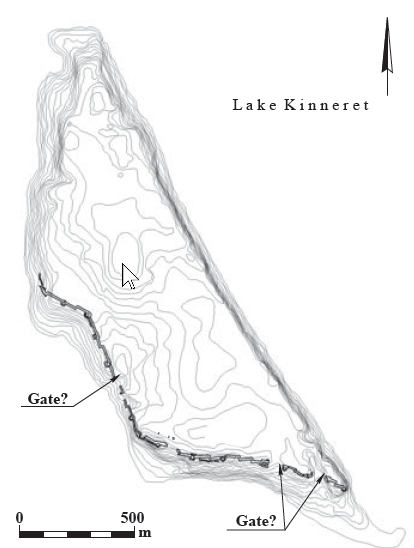

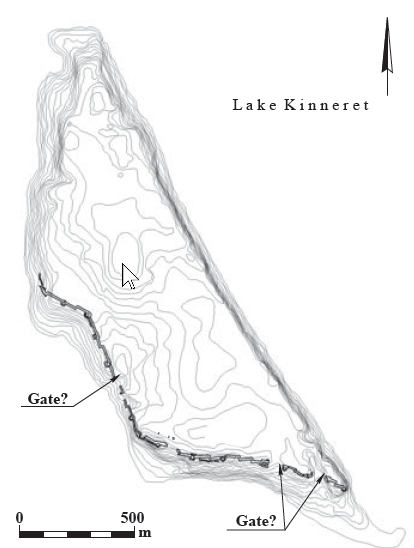

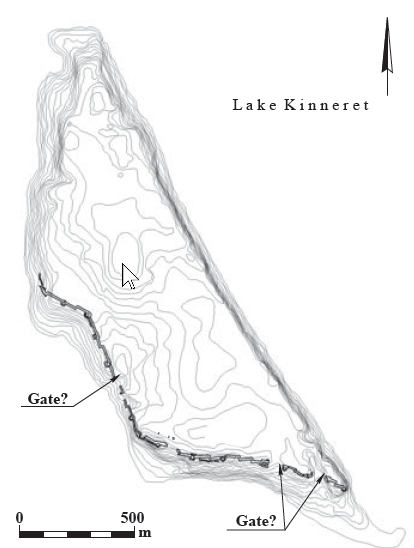

- Fig. 1.10 Contour

map of Tel Bet Yerah showing extent of Period A and B settlement from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 1.12 Modern

contour map of Tel Bet Yerah with superimposed late Period D fortification from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

Fig. 1.12

Fig. 1.12

Modern contour map of Tel Bet Yerah; with superimposed late Period D fortification, accentuating the shift of architectural mass toward the southern and western flanks of the mound, at the expense of the old acropolis.

click on image to explore this image in a new tab

Greenberg et al. (2014)

- Fig. 1.5 Modern

topography of Tel Bet Yerah from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 1.6 Reconstructed

topography of the natural mound, with line of Wall A (Period C) superimposed on it from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 1.10 Contour

map of Tel Bet Yerah showing extent of Period A and B settlement from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

- Fig. 1.12 Modern

contour map of Tel Bet Yerah with superimposed late Period D fortification from Greenberg et al. (2014:15)

Fig. 1.12

Fig. 1.12

Modern contour map of Tel Bet Yerah; with superimposed late Period D fortification, accentuating the shift of architectural mass toward the southern and western flanks of the mound, at the expense of the old acropolis.

click on image to explore this image in a new tab

Greenberg et al. (2014)

- Plan 6.1 Tel Bet Yerah

fortification walls from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.2 Segments A1,

A2 and the gate passage in Phase 1 from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.4 Wall A and

the gate passage in Phase 2 from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.5 Wall A,

Wall B, and the gate passage in Phase 3 from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.1 Tel Bet Yerah

fortification walls from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.2 Segments A1,

A2 and the gate passage in Phase 1 of Wall A from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.4 Wall A and

the gate passage in Phase 2 from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Plan 6.5 Wall A,

Wall B, and the gate passage in Phase 3 from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Fig. 6.8 Possible inner

threshold of Phase 1 gate of Wall A in sounding beneath Phase 2 pavement from Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Fig. 6.8 Possible inner

threshold of Phase 1 gate of Wall A in sounding beneath Phase 2 pavement from Greenberg et al. (2006)

Table 2

Table 2Summary Table of Local Strata and archaeological periods in principal Excavation areas

Greenberg et al. (2006)

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

The principal post-Bronze Age structure exposed on the site comprises a fort enclosing a basilical building, with a bathhouse attached to the enclosure's southern wall( Da'adli, 2017: 125 ). In addition, there are some ancillary structures outside the fort. Excavations undertaken in the 1950's

established a seventh-century CE terminus post quem for the central fortified structure and an eighth-century CE terminus post quem for the bathhouse(Da'adli, 2017 citing Greenberg and Paz, 2010). Based on historical sources, the Qasr was first constructed between 639 and 680 CE (Da'adli, 2017:126).

Chronological Evidence from Da'adli (2017) indicates occupation at the Qasr at least into the first half of the 8th century and later in ancillary structures (e.g. the Dar).

| Location | Page | Discussion |

|---|---|---|

| Basilica | 147-153 | A limited number of mosaics were found in the Basilica; some of which were defaced (Iconoclasm)

suggesting occupation which is dated to the 1st half of the 8th centurynote. |

| Southern Annex |

156-157 | Wall 162 (excavated in 2013 as W1698): A wall connecting Tower 2 and the southern addition was first excavated in 1950. As revealed in the 2009 and 2013 excavations, Channel GB 156 (excavated in 2013 as SA 1699) [part of the water system] was built into this wall, which did not have deep foundations. We may therefore assume that both the wall and the channel belong to the renovation phase of the southern annex (Fig. 8.30; Plan 8.8). A post-reform Umayyad coin (Chapter 9: Cat. No. 14) was found in the channel in 2013. The post-reform coin from Channel GB 156/SA 1699 indicates the period of use. Sanchez (2015:324) in Erdkamp, (2015) dates Umayyad post reform fals to after 696/700 CE. |

| Channel GB 159 (the water system} |

158-159 | In addition to the post-reform coin described above, from Channel GB 156/SA 1699, an oil lamp was found in one of the short drainage channels (GB 5; Fig. 8.37; see Plan 8.2); it is described as mold-decorated and the excavator proposed an "Arab" date. A complete lamp found in the IAA storerooms may be the artifact in question (see Fig. 8.60:4). This lamp type is dated to the sixth-eighth centuries CE at Jerash, while it was in use until the beginning of the ninth century CE elsewhere (Hadad 2002:68-71). Near Channel GB 5 and W4 a buff handle dated to the eighth—eleventh centuries CE was found (Fig. 8.60:3; Stacey 2004:130-132). The rim of a white-painted gray bag-shaped storage jar, dated to the fifth-eighth centuries CE, was discovered in a pit just north of the southern fortification wall (Fig. 8.60:5; Stacey 2004:126). The excavations of 2009-2010 within the enclosure yielded a mere handful of small ceramic fragments, all of either buff-ware or white-splashed jars. |

| Western Annex |

157 | Three rectangular rooms were uncovered on the western side of the basilica, numbered GB 102, GB 103 and GB 104, from north to south (see Plan 8.2). A small rectangular room abuts the western wall of Room GB 102. Channel GB 160 [the water system] splits off from Channel GB 159 [the water system] and enters the annex to Room GB 102 from the south, exiting through its western wall. The channel and the walls appear to have been built together, in a single stage (Fig. 8.32). Glazed pottery was found 0.1 m below the top of the walls in Room GB 103. Walmsley (2013:52) states that glazed wares, in Syria-Palestine [were] generally not introduced until the later eighth century at the earliest [and] always represented a small minority in the ceramic assemblage throughout the early Islamic period |

| Eastern and Northern Annex |

157 | A stylobate (W51) running parallel to the eastern side of the basilical structure supports a series of built pillar bases (0.9 x 0.6 m), placed at somewhat irregular intervals (2.55, 2.75, 2.80, 2.90 m; Fig. 8.33). This wall is built in the same method as the southern addition.12 note 12 - The excavator thought the southern rooms and stylobate to be Roman in date. Furthermore, the excavator writes that W19 was built in a different method, and that it is earlier than W51. On May 17,1950, a bronze coin was reported near W51, probably Cat. No. 21 in Chapter 9 - an Umayyad post-reform fals. Sanchez (2015:324) in Erdkamp, (2015) dates Umayyad post reform fals to after 696/700 CE. |

| Bathhouse | 169 | Finds from the bathhouse include two Umayyad coins found on the floor of the main hall (Maisler, Stekelis and Avi-Yonah 1952:222) and a chlorite vessel of eighth—tenth-century CE type (Stacey 2004:94) found near the western wall of the bathhouse (Fig. 8.60:6). During the 2009 excavation season, a portion of the northern wall of the frigidarium, which is in effect part of the curtain wall of the fortified enclosure, was sectioned. An Umayyad post-reform coin was found inside the core of the wall (Chapter 9: Cat. No. 15), apparently providing a terminus post quem for both the bath and the fortification. Sanchez (2015:324) in Erdkamp, (2015) dates Umayyad post reform fals to after 696/700 CE. |

| Kilns | 169 | Glass slag as well as a glazed ring-base was found inside Kiln GB 73. |

| Dar Unit | 171 | Isolated from the main enclosure and the bathhouse, another building or unit was exposed by Delougaz to the north of the fortified enclosure, above the remains of the tri-apsidal Byzantine church. |

| Location | Page | Discussion |

|---|---|---|

| 2-3 rooms over the bathhouse | 171 | A green glazed rim was found near W1 in Sq 02, which is on the eastern side of the wall. During the cleaning of the walls, an Islamic coin was discovered.21 note 21 - Description from December 25, 1945. A coin marked 25/2 or 2512, of Mamluk date, may be the one noted in the diary. See Chapter 9: Cat. No. 29. |

the historical record offers more details, at this point, than those provided by archaeology(Da'adli, 2017:175). However, the archaeology is in agreement with 7th and 8th century dates (Da'adli, 2017:175)).

the earliest material that can be associated with the fortified structure, ceramic, numismatic or otherwise, is consistently attributable to the seventh and eighth centuries CE. This includes the few ceramics—white-painted gray bag-shaped storage jars, buff-ware jugs with plastic knobs attached to the handle, and the molded lamp (Avissar 1996:147-149, 157; Haddad 2002:68-71), the chlorite bowl (Stacey 2004:94) and about 15 coins (see Chapter 9).The iconophobic defacing of mosaics in the Basilica was dated by Da'adli (2017:176) to the mid 8th century CE which suggests a date for the final renovation of the palace. Although historical sources indicate different phases of settlement at al-Sinnabra,

there is little surviving archeological evidencefor this (Da'adli, 2017:176). However, there may be

more facilites or sections that once were part of a palatial complexthat await excavation - e.g. between the Fort and the Dar (Da'adli, 2017:176).

One later structure was a

tower (Tower 12) and adjoining fortification walls extending east and northwhich was described by Da'adli (2017:176).

This unit could be part of some kind of citadel that may have had more towers and walls to the north and east. These might be Ayyubid in date, but hard evidence for such a date is lacking. The manner in which they overlie the earlier remains shows that the earlier, palatial structure was largely dismantled in antiquity.

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

- from Fall et al. (2023)

Table 1

Table 1Traditional and revised Early and Middle Bronze Age chronologies for the Southern Levant. (Traditional chronology based on Dever 1992; Levy 1995:fig. 3; revised chronology based on Regev et al. 2012; Fall et al. 2021; Höflmayer and Manning 2022.)

Fall et al. (2023)

This chapter deals with the fortifications excavated by P. Bar-Adon along the southern and western flanks of Tel Bet Yerah (Plan 6.1). Other excavations touched upon the fortifications at various points: the JPES excavations of 1944 (Area MS, see Chapter 2), and the Getzov excavations of 1994–1995 (Getzov 1998; 2006).

Here, however, we shall confine ourselves to the results of Bar-Adon’s work, providing as detailed a description as possible of the various elements cleared by him. An overview of the fortifications, covering all the excavations to date, has been published elsewhere (Greenberg and Paz 2005), and a summary will be provided in Volume II of this report.

The existence of Wall A had been revealed by the JPES excavations, both in Area MS and in a section cleared along the western edge of the ‘wadi’—the trough-like cut intruding upon the southeast tip of the mound (Fig. 6.1). It was also visible in the road cut formed by the Zemah–Tiberias highway. Wall A was a massive affair, eight meters thick at points, composed of several conjoined blocks of mudbrick construction. The bricks were generally rectangular, 8–10 cm thick and of various sizes: 0.55 × 0.5 m, 0.5 × 0.4 m, 0.4 × 0.3 m, 0.4 × 0.25 m, etc. Bar-Adon distinguished between two different brick fabrics: pale green, said to originate from the Lisan (marl) Formation, and darker red to brown, made of river-clay (Fig. 6.2).

Bar-Adon identified Wall A at the following points (Plan 6.1):

A1. A continuous fifteen-meter stretch excavated from the sea-scarp at the southeast tip of the mound up to the city gate (see below, Plans 6.2, 6.4).

A2. A six-meter segment partly cleared to the west of the gate (Plan 6.2).

A3. A cross section of the wall, created during landscaping operations along the side of the ‘wadi’ or gully near the southeast corner of the mound (Figs. 6.3, 6.4). Small segments of the fortification were noted on the surface just west of the gully (below, Plan 6.7).

A4. Remains of massive brick construction beneath Tower 4 in Wall C; these are probably connected to the massive mudbrick construction a couple of meters to the north and east of Tower 4, in the JPES trench of 1944 (below, Plan 6.10, and see Chapter 2).

A5. Evidence for the existence of Wall A was revealed by Bar-Adon on the surface and in a section excavated adjacent to Segment 21 in Wall C, beneath the foundations of Wall B (below, Plan 6.12).

A6. A massive segment of Wall A, preserved to a height of four meters, was exposed in a trench excavated southwest of Tower 8 in Wall C. Mudbricks lying beneath Tower 8 may well belong to Wall A as well, indicating a total preserved height of 6 m (below, Plan 6.14)!

Mention should also be made of the IAA excavations of 1994–1995 (Getzov 1998; 2006), where Wall A was sectioned at two points (Plan 6.1, between C25 and C26).

Unlike Walls B and C, which encircled the western flank of the city, remains of Wall A were reported only along the southern edge of the mound. The explanation for this could be that no defensive line was initially built on the flanks that were naturally defended by water (the Jordan River to the north and west, Lake Kinneret to the east).

Wherever sectioned, Wall A reveals complex construction in several lines of parallel, adjoined mudbrick construction. These lines are usually color-coded, being built of predominantly pale or predominantly dark bricks. Presumably, each block of construction represents the work of a different team, but we have no way of knowing whether the predominant brick-type was maintained along the entire length of each line. Bar-Adon’s sketch of the A3 section reveals at least four blocks in alternating colors (a possible fifth block is marked at the southern end of the section), totaling 7.5 m in width (see Figs. 6.3–6.5). The two middle blocks (south dark, north pale) are each 2.4–2.5 m wide and are founded on natural soil (Lisan marl or a dark layer of sterile soil formed on the marl); the two exterior blocks are eroded, 1.2–1.3 m wide, and appear also to rest on natural soil.

An archive sketch of the eastern edge of the fortifications, A1, where they are cut by the sea-scarp, shows a much more complicated picture: five blocks of construction, totaling 10 m in width, in two tiers, separated by a horizontal ash layer. The sketch is problematic, however, as photographs reveal that the section here was not perpendicular to the wall and was only perfunctorily cleaned by Bar-Adon (Fig. 6.5). In Section A4, beneath Tower 4 of Wall C, the JPES excavations revealed an apparent segment of the wall resting on earlier fills, interpreted as a possible buttress built against the inner face of Wall A (see Chapter 2). This buttress was adjoined by a pottery- bearing floor attributed to late Period C (see Figs. 2.11, 2.12). Getzov (1998; 2006:8–11) reports the existence of two adjoining lines of construction on natural soil, similar in color to the two middle blocks from Section A3, although greater in total width (the inner line being over 3 m wide). A third line was established at a higher level as an internal buttress following the partial collapse of the earlier walls.

The picture emerging from the various segments points to a core construction on the Lisan marl, consisting of two adjoined mudbrick curtain-walls with a combined width of 4.5 to 5 m. The absence of weathering on the adjoining faces within the wall—preserved at some points to a height of more than four meters—indicates that the parallel lines were constructed within a relatively short span of time. These were later enhanced by additional lines built in a similar technique; in some cases the additions were set on the natural soil; in others, on a fill composed, apparently, of collapsed debris from the wall.

Intrinsic dating evidence for the wall and gate is meager. The only deposits relating to Wall A excavated by Bar-Adon come from the gate sequence, but few diagnostic sherds remain from these deposits. The finds register is inconclusive: many of the sherds appear to be EB I in date, but several combed jar fragments are noted, as well as an admixture of much later material. Bar-Adon argued convincingly for an EB II date for the gate complex, based on the congruence between the paved gate passages and the sequence of paved streets found in Area BS, about 20 m north of the gate (for details, see Chapter 5). The evidence provided by the JPES excavations in Area MS for a late Period C (i.e., EB II) date for at least one element of the mudbrick fortification has been described in Chapter 2. Getzov, who sectioned these fortifications, suggested an EB I foundation date, based on material found in the fill adjoining the wall and in the collapsed brick superstructure (Getzov 2006:12). These, however, can only be used as a terminus post quem (as do the Period B remains found outside the wall in Area MK—see this volume, Chapter 9), so that ascription of the wall, or a part of it, to EB I must remain in doubt. The apparently non-defensive structure found by Bar-Adon beneath the gate might also argue against an EB I date for the walls, but we can only hope that future excavations will provide more solid grounds for dating.

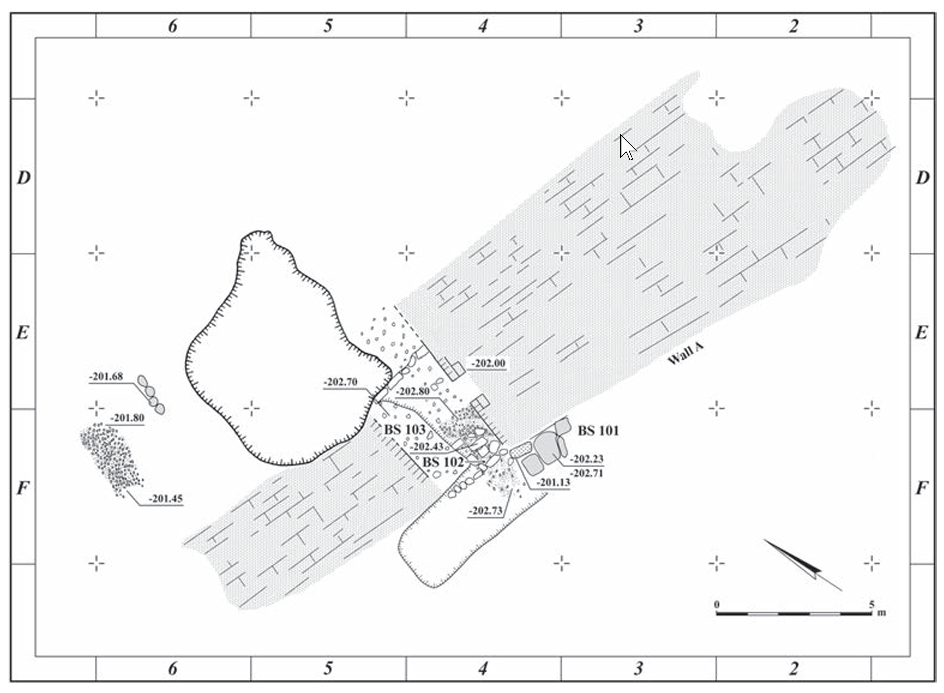

The city gate at the southeast corner of Tel Bet Yerah reveals two phases of construction that might be associated with the foundation and repair of Wall A. A third phase seems to represent the intentional blockage of the gate, perhaps in conjunction with the construction of Wall B. This is the only gate excavated at Bet Yerah, though topographical considerations, as well as the general layout of the city, point to several additional locations as possible gateways (e.g., the depression between Towers 10 and 11 on the western flank of the mound).

The early phase of the gateway was partly revealed in an L-shaped sounding (BS 102) excavated beneath the cobblestones of the later phase (Fig. 6.6). In its early phase (BS 103), the direct-entry gate passage was about 2.5 m wide. It was paved with packed beachgravel and small cobblestones at -202.65–70 m. A meter-wide construction of large stones, 0.20–0.25 m above the level of the pavement, appears to mark the outer threshold of the gate (Plan 6.3; Fig. 6.7). A similar line of stones marked by the excavator at the northern extremity of the sounding might indicate the inner threshold (Fig. 6.8). Assuming a similar width to that of the outer threshold, the entire passage would have been 5 m deep. This is the width of the core fortification lines, as seen in Section A3 (see Fig. 6.4), and we may assume, therefore, that the Phase 1 gate was built when only the two middle lines of fortification were extant. Both faces of this phase of the gate-passage were bricklined; the eastern face of the passage was interrupted by a niche about one meter wide.

Abutting the southeast side of the gate passage, leaning on the original right doorpost, was an ensemble interpreted as a gate shrine (BS 101; Fig. 6.9). It consisted of a large standing perforated basalt stone stele, 1.8 m high, 0.75 m wide, and 0.3 m thick, set into the ground about 0.4 m below the level of the threshold (approx. elev. -202.85 m). The face of the stele, which has the appearance of a large stone anchor (Bar-Adon reputedly coined the term shfifon—a biblical hapax— for objects of this type), was carefully smoothed (Fig. 6.10), while its rear was left in the rough. Three basalt blocks placed in front of the stele appear to have served as offering tables.

In an unsuccessful attempt to reach virgin soil, BarAdon deepened the sounding beneath the gate passage, revealing elements of earlier construction (Plan 6.3): a cobblestone pavement (-203.25 m) bordered by larger stones at the southern extremity (Fig. 6.11), and, at right angles to the pavement, a line of basalt slabs beneath the stele and further north, beneath the gate passage. While this construction, certainly of EB I date, could be interpreted as a yet earlier gate passage, its interpretation as a pre-fortification structure seems at least as likely. It might not even be too speculative to suggest that the large stele could have originated in this structure, which could have been an EB I temple with a pillared hall. In any case, the location of the early cobbled pavement well outside the line of the fortification argues against the gate-passage interpretation (see Chapter 9, Area MK, for additional extramural EB I construction).

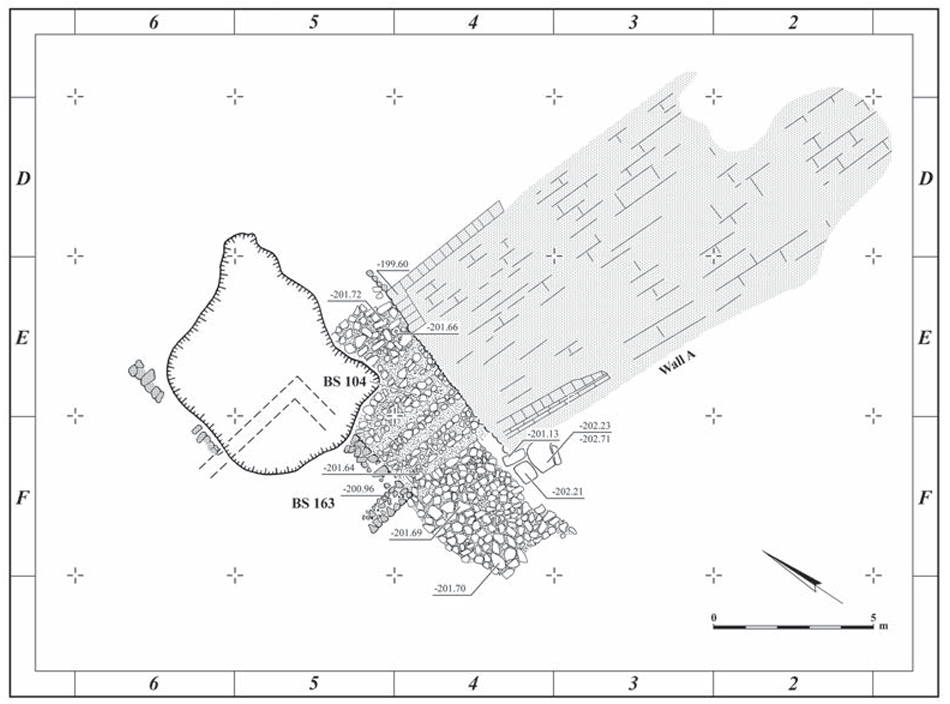

A massive fill of brick material—one meter thick in some places—resting on the Phase 1 gate passage (visible in section in Fig. 6.8) testifies to the rapid deterioration of the soft unprotected face of the passage in Wall A, possibly exacerbated by the chronic tectonic instability endemic to the Jordan Valley. Evidence for such instability can be seen in similar, massive fills of mudbrick detritus found all along Wall A. In response, the Phase 2 renovators faced the entire gate complex with stones. The gate passage (BS 104), now 3–3.5 m wide, was paved with large flat cobblestones at a level well above that of the earlier passage and gate shrine, leaving only the upper third of the pierced stele visible (Figs. 6.12, 6.13). Several parallel gaps in the pavement (Fig. 6.14) seem to indicate the presence of wooden sleepers in the central portion of the passage. This part, corresponding to the cobbled part of the Phase 1 passage, might have been roofed, with the sleepers serving perhaps as supports for roof-posts and an external wooden portal. Similar sleepers were identified as stairs at Tell el-Far‘ah North (de Vaux 1962: Pl. 21). A large door socket, its center located about 0.4 m from the eastern wall of the passage, was set into the pavement about 1.5 m short of the northern end of the gate passage (Fig. 6.13). The corresponding socket on the west side would have been in a part of the gate destroyed by modern construction. Just above the door-socket, a clear vertical seam can be seen in the Phase 2 stone facing of the gate passage. This seam might mark the addition of the third mudbrick wall-line to Wall A, in the transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2 or sometime during Phase 2. The stone facing of Wall A rounds the corner and continues along the inner face of Wall A, as was observed in a deep sounding conducted a few meters east of the gate-passage (Fig. 6.15). A wall approaching the inner eastern jamb of the gate was interpreted by the excavator as evidence for a guard tower projecting inward from the gate (Fig. 6.16). A continuation of the pavement southwards, beyond the defunct(?) shrine, may allude to the existence of an indirect entry, leading to the main gate, possibly protected by outworks or other defensive structures (not preserved).

The gate passage was protected on the west by what the excavator thought to be a stone gate tower built directly upon Wall A (BS 163). This presumed tower was badly damaged by the recent pit that intrudes upon the entire northern part of the complex. The surviving corner measures 1.5 × 2.5 m, with walls about 0.6 m wide. Its stratigraphic position is quite clear: it is set into the bricks of Wall A at elev. -202.31 m (well above the Phase 1 pavement), and the pavement of the Phase 2 gate passage fit snugly against its foundations (Fig. 6.17). There is a seeming incompatibility between the solid construction on the eastern flank of the gate passage and the rather flimsy stone structure to its west; the stone construction might be understood as a revetment rather than an independent structure. Alternatively, a rectangular tower may be reconstructed, perhaps two stories high, of which the brick superstructure did not survive. This purported tower did not project from the fortification line, as would be expected in a defensive facility—perhaps a further hint to the existence of outworks defending the gate area

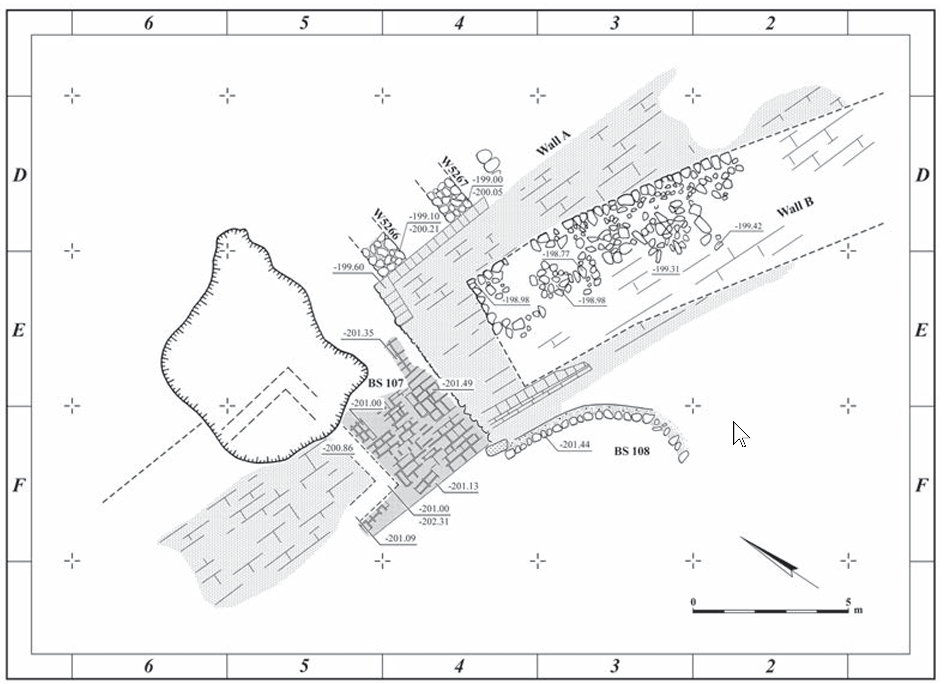

In its final phase, the entire gate passage appears to have been blocked (or raised?) with intentional mudbrick construction (BS 107). The former gate shrine, by now entirely buried but for the tip of the large stele, seems to have been replaced by a carefully laid semicircular structure (BS 108; Fig. 6.18). This phase of the gate may well be associated with the beginning of EB III and the replacement of Wall A by Wall B.

The chronic instability of the mudbrick fortification, possibly exacerbated by tectonic events and a possible late Period C earthquake indicated by widespread destruction and partial abandonment in various areas in the south of the mound, led to a considerable accumulation of detritus on both sides of Wall A. Bar-Adon correctly identified the process of deterioration when he refreshed the wadi-section cut by the JPES expedition, there noting that the ‘internal glacis’ identified by the earlier expedition was in fact the partially collapsed face of the early fortification. By early Period D (EB III) times, internal surfaces near the fortification had reached a level nearly two meters higher than the foundations (best illustrated by W5266 and W5267: Plan 6.5, Fig. 6.15), and we may assume that a similar situation developed on the outer face of the fortifications. Clearly, by the onset of EB III, Wall A could no longer function as an effective fortification and a repair was needed. Bar-Adon indeed discovered evidence for such a repair and is the first to have suggested the existence of an interim fortification between the early mudbrick and late stone town walls. He did not, however, succeed in giving much substance to this wall, and vacillated in the interpretation of its fragmentary manifestations, often preferring to consider them outworks or a glacis of the later wall. We believe that there is s ufficient evidence for an independent—if not very impressive—fortification, here termed Wall B, which may safely be attributed to the earlier part of EB III.

Wall B consists of a stone foundation, varying in height from one to four courses and averaging about four meters in breadth. It is built on top of Wall A along the southern flank of the mound and turns north to enclose the western flank as well. At one or two locations Bar-Adon found remains of the mudbrick superstructure of this wall. Fragments of Wall B were revealed at the following locations (see Plan 6.1): B1 (see Plan 6.5). A stretch of masonry built along the outer edge of Wall-Segment A1 can be identified as a foundation course of Wall B. It is preserved to a maximum height of three courses along its inner face and is 2.5 m wide at most, the outer face having disappeared due to erosion and/or stone-robbing (Fig. 6.19). Several walls ascribed to late Period D strata abut the foundation. This foundation ends abruptly a few meters short of the gate in Wall A. However, the stone facing on the eastern wall of the gate passage shows a clear addition approximately in line with Wall B (see Figs. 6.12, 6.13). Thus, the intentional mudbrick fill in the gate passage (Phase 3) may have been intended to repair, rather than block, the gate at the time of the construction of Wall B.

B2. Between Towers 6 and 7 of Wall C, in an area recorded only in a perfunctory manner by Bar-Adon, a cross section shows an abrupt shift between a three-course high stone foundation over three meters wide, clearly cut by Wall C, and a one-course foundation set upon the bricks of Wall A (below, Plan 6.12). Bar-Adon viewed these remains as part of a glacis related to Fortification C. Arguing against this interpretation are (a) the height of the stone foundation in Section 2-2 and (b) the carefully recorded foundation trench of Wall C, which clearly cuts the stone construction.

B3. Near Tower 8 of Wall C, a stretch of stone masonry topped with mudbricks was identified, sandwiched between Fortifications A and C (below, Plan 6.14). The precise configuration of Wall B is not clear in the plans left by Bar-Adon, but the character of the foundation and its abrupt termination closely resemble those of Segment B1. The bricks underlying Tower 8, attributed to Wall A, are preserved at the same elevation as the Wall B bricks, suggesting that wherever possible, the builders of Wall B left portions of Wall A intact.

B4. At the southwest corner of the mound, just outside Segment C30, Bar-Adon revealed an 8 m wide stone foundation curving northward toward the western flank of the mound (below, Plan 6.15). Originally interpreted as a glacis, the one-meter interval between Wall C and the foundation testifies that the two elements were not related. The foundation could mark the location of a tower or bastion at this strategic point in the town’s fortifications.

B5. Near the penultimate round tower (Tower 13) at the northern end of Wall C, an earlier line of fortification is clearly visible downslope from Segment C44. This segment, 3.5 m wide, merges into Tower 13 and might have incorporated a tower of its own at this point (below, Plan 6.18).

B6. Tower 15 in Wall C reveals a number of superimposed elements. A wide stone foundation emerging from beneath the salient element of the tower may well belong to Wall B (below, Plan 6.20).

Possible additional segments of the brick superstructure of Wall B seem to appear in the series of more than 20 trial sections through fortification Segments C9–C12 during the 1952–1953 seasons (see below).

In summary, Wall B seems to have been, at least in its southern flank, an opportunistic wall, set upon the mudbrick of Wall A and probably utilizing the better-preserved segments of the earlier fortification (as illustrated near Tower 8, where the Wall B stonework ends abruptly before a preserved portion of Wall A). As a rule, the new stone-based fortification was only 3.5–5 m thick (in contrast to the 6–8 m of Wall A). Wall B served as Bet Yerah’s only fortification during the greater part of EB III, including the main phases characterized by Khirbet Kerak Ware. While early Period D structures still abutted Wall A, we find later structures actually built on top of the mudbrick wall (Area BS, Local Stratum 8—see Plan 5.11) and cut by Wall C, leaving Wall B as the only candidate for fortification. In view of the massive defenses characterizing EB III towns throughout the southern Levant, Wall B might seem rather inadequate. This, however, could be a somewhat illusory perception—built as a low stone foundation with mudbrick superstructure, parts of Wall B seem to have been dismantled in order to serve the construction of the later Fortification C. Thus, Wall B has the character of a ‘ghost wall’, preserved only in short segments. Set upon the massive podium of Wall A, however, the 4–5 m wide fortification would certainly have been an imposing barrier in its original state.

The Bar-Adon excavations comprise the most extensive exposure of Early Bronze Age fortifications in Israel. However, the manner in which they were conducted leaves us with only a schematic understanding of the history of the fortification of the Early Bronze Age town at Bet Yerah. We have attempted to present both the intrinsic and circumstantial evidence for the context of construction of each system: the massive mudbrick fortification across the southern perimeter in EB II (Wall A), the opportunistic repair and reconstruction of the fortification in early EB III (Wall B) and the major overhaul in the town defenses carried out in late EB III (Wall C). While many details of the three fortification systems can be compared to contemporary fortification systems in the Levant, the Bet Yerah sequence as such is unique and must be explained in terms of the evolution of the site as a whole. Such a contextual narrative lies beyond the scope of this report and will be taken up in Volume II.

The broad extent of archaeological soundings at Tel Bet Yerah permits us to reconstruct a relatively detailed history of settlement at the site. By tracking the extent of each phase of settlement, settlement history can be reconfigured as a history of site formation. Understanding the physical appearance of the site in each phase will contribute to a better grasp of the evolution of the site as a setting for village and town life.

The physical setting of Tel Bet Yerah has been described above. In the following description, the primary contributors to the evolving morphology of the site to be kept in mind are these:

Building Materials. Basalt, and occasionally limestone, were easily obtained from the nearby slopes and the riverbed. Mudbrick of various composition was obtained by quarrying in or near the site. The quarrying of clay for mudbrick may constitute a significant factor in the morphology of the site, particularly where large quantities are concerned (as in the construction of fortifications). Source materials may be extracted from a point in or near the site. They are deposited as mudbrick on the site, and are then subject to decomposition and deflation. The matrix of the Bet Yerah mudbricks was the soft Lisan marl upon which the site was built and the valley rendzina which forms on the marl.

Building Practices. Early Bronze Age floors were often somewhat sunken in relation to external ground level, often abutting the very base of the walls. While the use of mudbrick alone is widely attested in the earliest levels, stone foundations were used in EB I and became the norm for external walls of later periods. The use of leveled-off wall stubs for foundations of later levels is common at Tel Bet Yerah, beginning in Period C, creating a very dense stratigraphic sequence and resulting in a relatively slow pace of mound build-up.

Erosion. The soft marl matrix lends itself to rapid down cutting and destabilization. This was a significant factor in the creation of the lake scarp (see above) and in gullying on the mound both during the Early Bronze Age and since that time.

Tectonic Activity. There is archaeological evidence for wall and roof collapse in Early Bronze Age Tel Bet Yerah, probably due to earthquakes or tremors. These need not have been particularly violent in order to cause damage, in view of the building materials used.

The earliest evidence for human presence on the mound comes in the form of stray finds ascribed a Neolithic date (e.g., below, Fig. 5.13). However, the first evidence for substantial occupation must be dated not before the earlier part of EB I. The most convincing evidence for this Period A occupation has been found in Areas SA and GB in the northern part of the mound, near the summit of the original mound (Figs. 1.10, 1.11; see Foreword: Table 2). In Area SA, a 0.65 m deep layer comprising at least two phases of occupation was identified. While the lowermost occupation is characterized by pits, the upper layer seems to have included mudbrick construction, although the excavators noted only decayed brick material. Period A layers were excavated in all parts of Area GB, although their depth there is not recorded.

Further evidence for Period A occupation comes from some of the soundings conducted by the Delougaz (Oriental Institute) expeditions in 1952–1953 and 1963–1964 (see Foreword: Plan 1, Table 1). As these excavations have been only partially processed (Esse 1991:42–45), only preliminary details are available: these indicate the presence of Period A pottery in Section C, north of Area GB, and in Sections J and L in the middle of the mound. Just south of these points, in Area UN, only a handful of sherds possibly predating Period B were found, and it seems that the edge of the Period A site lies between Area UN and Sections J and L. In all the remaining excavation fields—BS, MS, and EY in the southeast, GE in the southwest, and in the Delougaz soundings to the west of the acropolis—no remains of Period A are reported, nor were any observed in Area BH or AC, to the north of Sections J and L3.

Taking into account the eastern, presently eroded, slope of the mound, the Period A, or EB IA, settlement appears to have extended along an elongated oval centered on the highest part of the mound. Its maximum length might have been 600 m; its maximum width, 300 m; and its total area, perhaps 8 ha. The apparent lack of remains at various points within this oval may indicate a spread-out, straggling settlement, of the type often encountered in this period (an occupation of similar size and type has recently been posited at Tel Te'o: Eisenberg, Gopher, and Greenberg 2001:4).

The chronology of this settlement, as indicated by the pottery from the Deep Cut in Area SA, includes both the main early EB I phase, with its classic Type I Gray Burnished Ware, and a somewhat later phase that shows the beginnings of the grain-wash pottery typifying Period B. We therefore suggest a seamless transition between the two periods, with the straggling, perhaps somewhat shifting, settlement of Period A gradually evolving into the large, much more densely built up village of Period B.

3 My thanks to Gabrielle Novacek, who showed me the relevant material in the University of Chicago archives.

The late EB I settlement of Period B was long lived and possibly the most extensive of all phases of occupation at Tel Bet Yerah. Substantial remains of this phase were found in all areas of excavation, within the walled area of the mound proper and even beyond the walls. In most cases, there was evidence for more than one phase of occupation, as outlined in Table 1.1.

Omitted from Table 1.1 is Area GE, where Getzov (2006) reported on the existence of massive Period B fortifications. As shown in Bet Yerah I:236–247, the massive mudbrick fortification system, Wall A, must be dated mainly to Period C (EB II), since late Period B remains were found beneath parts of it in Areas MK and BF (beneath the earliest phase of the gate). At most, allowance may be made for the construction of a narrow mudbrick fortification at the very end of Period B. The great preponderance of Period B pottery within the in situ and collapsed mudbricks of Wall A must be ascribed to the quarrying of earlier occupation material for the preparation of the enormous quantities of mudbrick needed to build this wall. Physical evidence for this quarrying comes from a feature noted both by Mazar and by Getzov: an internal trough or “moat” bordering the northern, i.e., inner face of Wall A (see below, Fig. 2.6; Maisler, Stekelis, and Avi-Yonah 1952:172; Getzov 2006).

Apart from Area GE, all the excavation fields on Tel Bet Yerah seem to tell a similar tale: densely built up layers of occupation cover the entire mound, extending slightly beyond the confines of the later fortifications. These layers have a remarkably uniform thickness, suggesting that the spread of settlement across the mound in Period B was rapid and complete, leaving few open areas.

In all areas where virgin soil was reached, the first phase of occupation in Period B is characterized by pits. These vary in size and depth: some, narrow and deep, are obviously middens, while others may have served as floors for temporary structures (perhaps best interpreted as animal shelters). These activities may be understood to represent activity at the outer edges of the site. The pits are soon superseded by permanent architecture of remarkable variety, including rectilinear mudbrick buildings without stone foundations and round or curvilinear stone-based buildings (see below, Chapter 2, for further discussion). These structures seem, by and large, to have been abandoned in an orderly fashion. In Area BS, where the Period B remains were not disturbed by later construction, a thick layer of decayed mudbrick sealed the early remains, suggesting an extended period of abandonment at this locale. Other areas, however, revealed intrusive Period C remains quite near Period B floors (e.g., in Areas EY and SA), possibly indicating rapid rebuilding. For the most part, the Period B structures were aligned north—south/east—west.

The presence of pits underlying the earliest architecture in both Period A (Areas SA, GB) and Period B (Areas UN, MS, EY, BS) suggests that permanent settlement expanded gradually and seamlessly during Periods A and B, beginning with the highest part of the mound and advancing southward and toward the river and lake banks on either side. By the end of EB I, the entire peninsula was built up more or less evenly, preserving the fundamental topography of the mound. The thickness of deposit suggested by the Area MK section might indicate a build-up of refuse along the edges of the site that might have accentuated the edges of the large, 30 ha. village. The quality of the excavation records at this location, however, leaves much to be desired, and the alternative—a diffuse border at the edge of settlement—seems equally plausible.

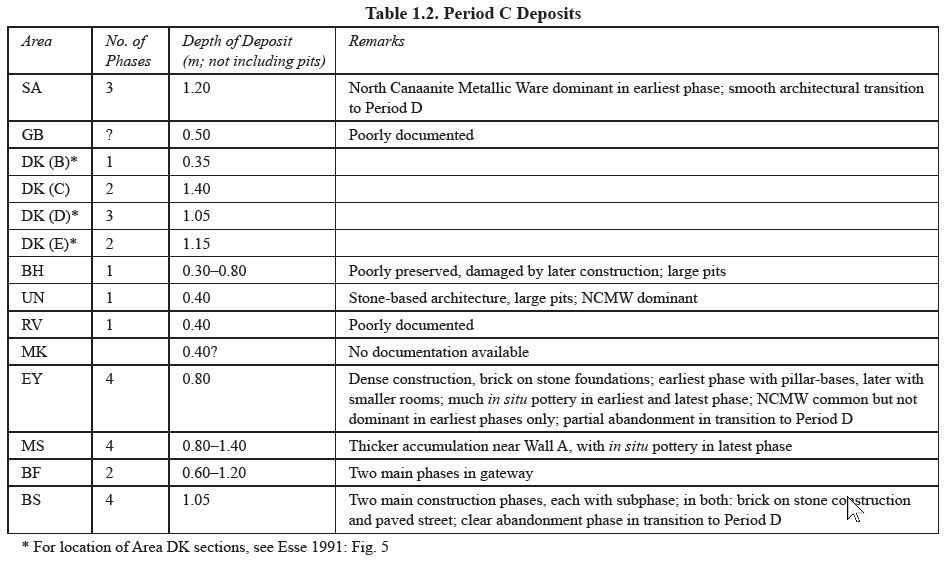

The data concerning Period C in various parts of the mound are contradictory and confused. This has to do to some extent with the quality of documentation and stratigraphic control in many of the older excavations, but perhaps, to a greater extent, with the intense sequence of construction characterizing the mound in EB II and EB III. In areas where the stratigraphy was best recorded, the average thickness of each phase was little more than 0.2 m. This means that each rebuild razed earlier remains to within a few centimeters of their floors. Table 1.2 and the description of the Period C strata present, therefore, the best approximation based on present data.

The construction of Wall A across the southern flank of the Tel Bet Yerah peninsula constitutes a turning point in the mound's physical history and in its presence in the landscape. The construction of the massive fortification, eventually attaining a breadth of 8 m and a commensurate height (perhaps 5–7 m), and of the gateway (gateways?) associated with it, created a new focus of settlement, rivaling the long-established center located on the summit of the mound. Indeed, the different sequences of accumulation evidenced at different parts of the mound seem to suggest that occupation and construction were more intense in both the north and south than in the intervening area, with a particularly swift build-up observed adjacent to Wall A, in Areas BS and MS. This build-up led eventually to the creation of a shallow depression inside the southern end of the mound, bordered on the one hand by the original slope of the mound, and on the other by the deposits built up against the wall on the south. This shallow depression eventually became more deeply incised, draining the mound through a break (gate?) in the later Early Bronze Age wall (Wall C) near the southwestern corner of the mound (below, Fig. 1.12). The erosion engendered by the depression and its extensions may be responsible for the absence of some Early Bronze Age strata in the area lying 100–200 m north of Wall A (the absence of Early Bronze strata at the northern end of their respective, parallel excavations is apparent in the sections drawn both by Makhouly [Bet Yerah I: Plan 9:2] and Getzov [2006: Fig. 1:1]). It cannot, however, have compromised Period C layers in locations further north, such as Areas UN and BH. These tend to be significantly shallower and stratigraphically poorer than the corresponding deposits in Areas SA, MS/EY, or BS, and could well indicate that the Period C settlement was not as evenly spread over the mound as that of Period B.

The presence of North Canaanite Metallic Ware as a significant component directly above Period B deposits in all areas of excavation suggests that the earliest part of Period C was that with the most intensive settlement. Indeed, the earliest phase of the gateway in Wall A indicates the existence of most elements in this wall early in Period C, and substantial stone-and-brick architecture can be found in every area excavated. As time wore on, the successive stages of reconstruction and repair appear to have affected a gradually diminishing portion of the mound, with intervening areas perhaps left in a state of abandonment or converted to intramural open spaces for use as gardens, livestock enclosures, or refuse dumps.

By the end of Period C, the houses nearest Wall A had been raised well above its foundations, forming a pronounced slope from the wall toward the interior of the town. To the observer approaching the town from the south (the only land approach possible), the tall scarp of Wall A and the cut that may well have fronted it (see Bet Yerah I: Chapter 6) would have dominated the skyline, rendering the original acropolis all but invisible. Upon entering the town through the southeastern gate, the visitor would have faced a maze of paved streets and alleys and only after pushing ahead for some minutes would he have been able to emerge into the open, gaining a view of the more widely spaced domestic compounds in the center of the mound and the important buildings that no doubt stood on its summit.

Table 1.2

Table 1.2Period C Deposits

Greenberg et al. (2014)

The crisis of late Period C asserts itself in the form of various, selective abandonments observable between Periods C and D. The first evidence of Khirbet Kerak Ware (KKW), marking the onset of Period D (EB III), falls within the pattern of the late Period C occupation. Thus, in Area BS, massive amounts of KKW are found in what seems to be a midden-tip — a surface dump forming ash- and sherd-rich layers (tips) without a pit cut; in British usage, “tip” = dump. (Local Stratum 11) covering abandoned Period C structures, and in Area EY the richest KKW deposits in Local Stratum 6 occur in open areas. The renascence of Tel Bet Yerah may well belong to a later stage, when KKW is associated with widespread new construction on the mound, as tabulated below (Table 1.3).

Beyond the fact that Period D occupation is attested in every part of the mound, only the most tentative conclusions may be drawn on the basis of the observed stratification. That is because over the greater part of the mound, the EB D I remains were exposed for at least two millennia, until the large-scale resettlement in the Hellenistic period, and, in some cases, for an additional millennium, until capped by Early Islamic settlement. The fact that the most comprehensive stratigraphic sequence occurs within the protective shadow of Wall C in the south of the mound, and in particular in Area BS—the only corner of the mound reoccupied in the Middle Bronze and Persian periods—should sound a warning against hasty conclusions regarding the relative extent or intensity of EB D I settlement.

That said, it remains clear that the focus of Tel Bet Yerah's building effort in late Period D was along the edges of the site (Fig. 1.12). The massive effort expended on the construction of Wall C appears to have come at the expense of construction in the interior of the town or on its acropolis. The Circles Building, built early in Period D, shows clear signs of decline, and no other building appears to have been erected in its place. In terms of the morphology of the mound, Period D may be said to have accentuated processes begun in Period C: The external profile of the mound was enhanced and its skyline was largely that of its massive fortifications, particularly along its vulnerable southern flank. Founded largely on top of the decayed remains of Wall A, the late fortifications would have towered some 10 m above the natural slope, forming an imposing mass for anyone approaching the site from the south or southwest. They also afforded the best protection for the inhabitants of the mound, and it was to the southeastern corner of the site that the focus of settlement shifted during the next phases of occupation.

A significant anomaly in the course of Wall C is worth noting: between Towers 3 and 4, just west of the blocked Wall A gateway, Wall C turned inward, presumably to exclude a north–south gully that had begun to form at this point. This gully might have been the intentional or unintentional result of action taken to drain the interior of the city, north of the rise formed by the city walls. Its presence is marked not only by the deviation in the line of the wall, but also by a clear dip in the elevation of the wall's foundations, as has been described in Bet Yerah I: Chapters 5, 6; and Plans 5.13, 6.6. Bar-Adon's field notes indicate that he thought there might have been a gateway at this point (although Tower 5, the Bastion, might mark the location of a gate some distance to the west). In any case, this possibility will remain forever moot, as the gully was widened, probably in Ottoman times, to serve as a road, and was further compromised in more recent times.

Another topographic anomaly in the present-day appearance of the mound—a deep depression just north of the southwestern corner—suggests the existence of another gate in Wall C. This location presently serves as the preferred ascent to the mound from the west.

The unique and fascinating Final Early Bronze phase described in Area BS (Local Stratum 6) occupied a limited area in the southeastern corner of the mound. Remarkably well-preserved remains, the original construction of which might be ascribed to late Period D (see Chapter 2), were found over the entire area excavated by Bar-Adon within the Early Bronze Age walls. In addition, a handful of sherds of unspecified provenance identified in the Area MS assemblage suggest that some of the late Period D structures excavated there might have been used in Period E as well. Taking all this into account, the extent of the Final Early Bronze Age village huddled against Wall C could hardly have exceeded 1 ha in size—a mere fraction of the original size of the Early Bronze town.

The Period E village comprised a dense huddle of contiguous houses with three- to four-course stone foundations and a mudbrick superstructure. Their contribution to the general form of the mound was the creation of a raised platform inside the line of the wall, which eventually comprised a secondary acropolis, reoccupied in Periods F and G.

The Period F (early second millennium) occupation succeeded the Period E occupation after a significant gap, lasting perhaps 300 years. By this time the Period E houses had long since collapsed, adding a layer about 0.75 m thick to this part of the mound. As far as we know, the Period F deposits (about 0.3 m in depth) are limited only to the very tip of the mound (0.1-0.2 ha in all), spilling over the fortifications to the southern slope (in Bet Yerah I:157-160 it was suggested that the houses were located on the slope, and a series of industrial installations—mainly potters' kilns—downwind and inside the wall). A further, and yet longer, gap separates Period F from the fifth- or fourth-century BCE Period G occupation (approximately 0.5 m in maximum depth), also limited to the 0.1 ha acropolis at the southeastern tip of the mound.

Evidence for extensive settlement in the Hellenistic period (Period H; third–second centuries BCE) has been found in most excavation areas on Tel Bet Yerah. Most remains may be associated with a well-planned orthogonal settlement composed of what appear to be large town-houses. Parts of such houses were found in Areas BS, MS/EY, MK/GE, SA, GB, and possibly BH as well. All were built on a virtually identical axis, parallel to the lake-scarp (the latter advanced in the years following the Hellenistic period, cutting into the Hellenistic remains). In most places, the Hellenistic construction stopped 10–30 m short of the still visible Early Bronze Age fortifications, although a number of towers in the wall were rebuilt or used for burial (see Bet Yerah I: Chapter 6). This planned settlement seems to have extended over most of the eastern half of the mound, although perhaps not contiguously, as architectural remains in Areas BH and especially UN are scant. No Hellenistic architecture at all appeared in the northern part of Area MK, and in a number of soundings in the large western plateau conducted both by Bar-Adon and the Chicago expeditions. The general impact of the Hellenistic occupation must therefore be characterized as diffuse, having little visible impact on the way the mound was experienced in the landscape.

As for the Byzantine and Islamic periods, these are represented on the mound by individual structures and cannot be said to have formed strata. The bulk of the activity in these periods was concentrated in the northern quarter of the mound. Most significant to the ultimate form of the mound was the aqueduct built to supply running water to the Umayyad baths built over the Circles Building in Area SA. The bridge that may have carried this aqueduct across the Jordan River at the northwestern corner of the mound was partially responsible for the blockage of the original river channel, which is attested from medieval times (Saarisalo 1927:76–77).

The marked lack of soil accumulation during the extended gaps in occupation, as evidenced by the Hellenistic re-use of the Early Bronze Age city walls and the construction of the late bathhouse directly on the platform of the Circles Building, indicates that the present table-like appearance of large parts of the mound does not represent its aspect in antiquity. Indeed, during most of its existence, the mound would have been perceived as a ruin with massive fortifications, fully living up to its post-abandonment Arabic name, Khirbet el-Kerak, ‘the Ruin of the Fortress’.

The evidence accumulated during seventy-five years of excavations at Tel Bet Yerah allows a systematic investigation of the evolution of the use of space on the mound, public and domestic. This chapter describes this evolution diachronically, focusing on each major period (from A to E; see Foreword: Table 2) in the mound's history, subdivided where possible according to the local stratigraphy. For each period, site-wide data culled from all available publications (including Getzov 2006 and Novacek 2007) are used to present an overview of architecture, function, and planning, in the following order: (a) domestic structures (construction, content, and presumed function); (b) shared space (courtyards, streets, refuse areas, etc.); (c) public construction (fortifications, administrative structures); (d) site-plan and organization. We conclude the presentation of each period with a discussion; we review long-term trends for the whole of the Early Bronze Age in the summary discussion (below, pp. 49–50)1.

1 A handful of Early Bronze Age sites have been

tentatively identified by Maeir (1997: Fig. 15), based

principally on Yeivin and Maisler (1944). I have not

succeeded in corroborating their existence, though it

does appear likely that there was an EB (I?) site at or

near Tell `Ubeidiya, about 3 km south of Tel Bet

Yerah. It is particularly interesting that no major

Middle Bronze Age site emerged to stake a claim to

the Kinrot Valley, and to its seemingly prime

location on the east–west and north–south routes

skirting Lake Kinneret and connecting the Jordan

Valley with the northern Levant and beyond (with the

possible exception of Tell `Ubeidiya). These

observations suggest the existence of a particular

Early Bronze Age regional configuration, not repeated

in later times, that made the site attractive for

settlement. This is an issue that needs to be tackled

in future research.

2 Abundant evidence for such utilization has been

recovered in the renewed excavations at the site.

3 My thanks to Gabrielle Novacek, who showed me the

relevant material in the University of Chicago

archives.

Despite the discovery of Period A ceramics in widely dispersed deposits on the mound (Areas SA, GB, UN, and several of the DK soundings located adjacent to these areas), little can be said of the site's organization. Mudbricks and mudbrick fragments associated with this phase testify to the presence of architecture, and the deep accumulation in Area SA (Bet Yerah I:85–89) is suggestive of intramural sub-floor burials. However, the only unambiguous and recurring features are midden-pits dug into the soft marl bedrock, identified in several areas (and confirmed in our 2007 excavations: Greenberg, Rotem, and Paz 2013). Their presence suggests spread-out habitation on the mound, with large intervening common areas—a configuration encountered at contemporary sites such as Tel Te'o and Yiftahel (Eisenberg, Gopher, and Greenberg 2001; Braun 1997). The phenomenon of pitting within or at the edges of the habitation area continues into Period B, and it is only at the end of that period that we find contiguous architecture covering large parts of the site.

The earlier part of Period B is represented mainly by pits that continue Period A patterns (see, e.g., Areas SA, Deep Cut, Local Stratum 8; EY, Local Stratum 11; BS, Local Stratum 15 [Bet Yerah I:89, 120, 343]). The most extensive exposure of this phase comes from Area EY/MS, where both pits and open spaces between them, all established on bedrock, were excavated (Bet Yerah I: Plan 8.4). Since some of the pit features appeared to be quite shallow, the early excavators of the site interpreted them as house-pits. This cannot be substantiated, as excavation techniques were not sufficiently refined to identify post-holes or other telltale signs of impermanent construction. The content of all the pits appeared to be similar, consisting mainly of domestic refuse with large quantities of ash. Identified organic material included grains of wheat, peas, and olive pits (see Appendix I: Table App. 1.1). Noteworthy finds include fishing weights (in Pit EY 646 and in open areas) and a limestone macehead. Mudbrick fragments found both in the pits and the open areas testify to architecture in the vicinity, but the only wall that might be attributed to this phase comes from Area BH, Local Phase 8 (Bet Yerah I:477).

In late Period B, we may begin to distinguish distinctive elements of domestic architecture and site organization; these are discussed in detail below.

The accumulated evidence from the mound, and especially from Areas BS and EY/MS, permits the division of Period C into an earlier and a later phase. Both phases are characterized by developed domestic architecture; the use and organization of communal space appears to undergo a very significant evolution within this time span.

Beyond the streets of the late Period C city described above, which comprise the most impressive evidence for public works, few remains of late Period C large-scale construction have been excavated. The city gate underwent significant renovation, which included not only the repaving of the entrance but the facing of the entire gate and a good part of the internal face of Wall A with stone. It appears likely that the wall itself was buttressed at various points, as suggested in Bet Yerah I:237-239). No public structures or such that can be ascribed to a. ruling elite have yet come to light.

There is a marked continuity exhibited in house construction, in nearly all areas of domestic settlement that contrasts strongly with the Period B–C transition and appears to indicate a strong sense of urban continuity throughout Period C (and indeed into Period D). Another interesting trend in the architecture in the late Period C town is the apparent co-evolution of a typical ‘Bet Yerah house’ in different parts of the mound: square structures divided into rather narrow rectangular or square living chambers and perhaps a small, partly roofed internal court (Plan 2.7). This process would indicate the gradual acceptance of the constraints and rules—stated or implied—that govern domestic construction in an urban setting, even as they affect the most intimate family settings. Thus, the relinquishing of the open spaces where communal activities took place in early Period C in favor of new houses implies a restructuring of the domestic economy toward greater reliance on the nuclear family as a basic unit of production and toward greater spatial segregation of economic activity (perhaps accompanied by increased specialization). The paving of the town’s main streets indicates a more rigid structuring of activities in the areas between the houses, which would have been given over mainly to movement of people and goods (and possibly surface runoff management). The virtual absence of storage installations or storage cellars in private homes is a corollary to the development of public space: there must have been other arrangements for the storage and distribution of staples (hence the need for public arteries). It is such unspectacular details that provide evidence—better than that offered by monumental architecture—for the emergence of a new way of life, forged by practice, within the fortification walls.

Direct unambiguous evidence that one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes (the Holy Desert Quake) caused damage to the site was not found as the site had been dismantled down to the foundations long before archaeological excavations began. Greenberg, Tal, and Da'adli (2017:217) described what they saw.

It is not clear, either from historical documents or from the evidence on the ground, what brought Umayyad al-Sinnabra to an end. Whatever the case may be, and whether its abandonment was sudden (in wake of the 749 CE earthquake?) or gradual, by the time the builders of the later structures—particularly of Tower 12 and the enceinte of which it seems to have been a part — came on the scene, the Umayyad remains had disappeared from sight, dismantled down to their foundations.However, this negative evidence appears to be the evidence that shows that al-Sinnabra was in the epicentral region when the Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year sequence struck. The complete and total collapse of the structure is what allowed it to be so easily looted. It was no longer a palace. It was a pile of dressed stones - a quarry for any building project in the area. Eventually, every stone was taken. Only the foundation cracks unearthed by Greenberg and Paz (2010) remained to tell the story of it's total destruction.

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

- Fig. 8.2 Detailed plan

of the al-Sinnabra palace from Da'adli (2017)

Plan 8.2

Plan 8.2

Detailed plan of the al-Sinnabra palace

JW: Basilica is in the center surrounded by rectangular fortified walls and guard towers at the corners. Bathhouse is bottom right attached to the southern wall of the fort

Da'adli (2017) - Fig. 1 Areas excavated

at al-Sinnabra in 2007 and 2009 from Greenberg and Paz (2010)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Aerial view of the 2007 excavation area, looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)

In excavations which took place in 2007 and 2009, Greenberg and Paz (2010) identified what be a foundation crack at the Umayyad Qasr built by Mu'awiya I in Area GB-T

Area GB-T

A new aspect of the 2009 excavations is our attempt to re-excavate and reinterpret the huge fortified complex cleared by Bar-Adon and Guy in the early 1950s but never fully published. Originally identified as a synagogue and then as a Roman or Byzantine fort, the most recent suggestion has been to identify the complex with the Early Islamic palace of al-Sinnabra. The area has been obscured for decades by the thick subtropical vegetation that characterizes the mound. Because the structure was largely dismantled in antiquity, leaving only wall and floor foundations intact, and due to the summary excavation methods used in the original excavations, our principal aim was to identify sealed or otherwise datable contexts, such as foundation trenches and subfloor deposits. Additionally, the surviving portions of the superstructure had to be revisited and recorded.

Thus far, the southwest tower of the enceinte and parts of the southern annex adjoining the large apse have been reinvestigated, two large mosaic floor segments recorded (Fig. 12), and a portion of the central floorbed removed. Some preliminary observations may be made:We are therefore confident that the Umayyad palace of al-Sinnabra has been found.

- The original wall foundations of the external fortifications, the adjoining bathhouse, and the central structure are all equally massive and deep, indicating a high level of investment, similar building concepts in all parts of the complex, and the likelihood that the superstructure was quite substantial.

- There is multiple evidence for the existence of at least two building phases in the main structure. The later phase involved wall demolition and replacement, as well as repairs in the mosaic pavements.

- We have begun to see evidence of earthquake damage; this could eventually aid in the dating of the structure.

(Fig. 13).

Figure 13

Area GB-T, foundations in the southern part of the central palace structure; foundation trenches and evidence for earthquake damage in south wall (at right), looking south.

Greenberg and Paz (2010)- A second fortified enclosure was built over part of the main enclosure. This later enclosure was never reported by the excavators.

- Although finds are sparse, the Early Islamic dating does appear to be confirmed by coins found beneath the floor of the central hall and in the foundation trench of the bathhouse.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Wall A and various areas in the south of the Mound |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huge amounts of collapsed masonry | Tower 3

Plan 8.2