Umm al-Jimal

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Umm al-Jimal | Arabic | ام الجمال |

| Umm al-Jamal | Arabic | ام الجمال |

| Umm ej Jemāl | Arabic | ام الجمال |

| Umm idj-Djimal | Arabic | ام الجمال |

| al-ʾHerrī - local name for older Roman village | Arabic | الءهيرري |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 23 June 2025

- sources: ummeljimal.org, Wikipedia

The town flourished especially between the 4th and 8th centuries CE, when it became a regional center under Roman and later Byzantine administration. A key feature of the site is its adaptive use of water management systems in an arid basaltic landscape, including cisterns, channels, and reservoirs that enabled dense urban development. At least 16 churches have been identified within the town’s limits, testifying to a vibrant Christian presence in late antiquity. The early Islamic layers, including several Umayyad-period buildings, show patterns of continuity and reuse, often incorporating earlier Roman and Byzantine structures.

Umm al-Jimal appears to have experienced significant seismic damage, which led to the partial collapse of many buildings. Archaeological excavations and surveys since the mid-20th century have helped to clarify both the chronology and the urban development of the site, and recent conservation efforts have focused on community engagement and digital preservation. The town's extensive ruins today serve as an open-air museum and a key reference point for understanding settlement patterns in the southern Hauran during the transition from classical to Islamic rule.

Bert de Vries in Meyers (1997) notes that the town is "nearly a kilometer long and a half-kilometer wide, with 150 buildings standing one to three stories high and several towers up to five and six stories."

Umm el-Jimal is an extensive rural settlement constructed of black basalt in the lava lands east of Mafraq, a seventy-minute drive northeast of Amman, Jordan (39°19' N, 36°22' E). One of the largest and most spectacular archaeological sites in Jordan, Umm el-Jimal is located on tire edge of a series of volcanically formed basalt flows that slope down from the Jebel al-Druze, a mountain 50 Ion (31 mi.) to the northeast. This sloping black bedrock provided ancient Umm el-Jimal with two basic resources: stone for constructing sturdy houses and water for drinking and agriculture. The ancient name of the site is not known. David L. Kennedy has argued convincingly that Thantia, Howard C. Butler's suggested name (see below), is better located to the west on the Via Nova (Kennedy and Riley, 1982, pp. 148- 152). Flenry I. MacAdam (1986) has put forward Surattha, from Ptolemy's Geography, as an alternative.

What survives above ground is an amazingly well-preserved Byzantine/Early Islamic town nearly a kilometer long and a half-kilometer wide, with 150 buildings standing one to three stories high and several towers up to five and six stories. The site's dramatic skyline of somber stone at first gives the impression of a bombed-out modern town. Only close up does it become apparent that this is not a modern war casualty, but an agglomerate of fifteen-hundred-year old ruins. Inside, the visitor is plunged into a scene of eerie beauty. Walls run in every direction, without apparent plan or order. Neatly stacked courses of stone protrude from a mad confusion of tumbled upper stories. The blue-gray basalt everywhere gives a somber and cool sense of shadow that belies the blaze of bright desert sun. Here and there pinnacles of wall extend their fingers of cantilevered roofing beams to create gravity-defying silhouettes against the cloudless sky. Doorways and alleys lead from room to room and building to building. Large private houses predominate, but there are also fifteen churches from the sixth and seventh centuries, a praetorium, a barrack, gates, and numerous reservoirs.

Umm el-Jimal became known to travelers in the mid nineteenth century, but the first major work there was done by the Princeton University Expedition to Southern Syria in 1905 and 1909, directed by Butler. Butler (1913) published a list of early visitors to the site who had recorded their impressions. It was first reached in 1857 by Cyril Graham, who published a brief description of the ruins the following year. In 1861-1862 William H. Waddington copied several inscriptions and, more than a decade later, Charles Doughty passed through the ruined city. At about the same time Selah Merrill, then the American consul in Jerusalem, visited it. Gottlieb Schumacher published the first architectural plans, of a church and the city gates, in 1894. In 1901 Rene Dussaud and Frederic Macler copied several inscriptions. [See the biographies of Butler, Merrill, Schumacher, and Dussaud,]

In winter 1904-1905, Butler's team made the first site map, which included public buildings: the praetorium, barracks, 15 churches, reservoirs, gates, 20 houses, and monumental tombs. He published it with an excellent text and restored plans of typical buildings (Butier, 1913). Enno Littmann cataloged numerous Greek, Latin, Nabatean, Safaitic, and Arabic inscriptions (Littmann et al, 1913). George Horsfield published early aerial photographs (Horsfield, 1937) and Nelson Glueck included Umm el-Jimal in his assessment of Nabatean influences on southern Syria (Glueck, 1951). In 1956, G. U. S. Corbett did exploratory excavations of the Julianos church, from which he determined that Butler's founding date (fourth century) was erroneously based on a reused funerary text (Corbett, 1957). [See the biographies of Horsfield and Glueck.]

The Umm el-Jimal Project (1972-1995) excavated for eight field seasons over twenty-two years, under the direction of Bert de Vries, for Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan. The first phase of the project consisted of five campaigns that ended in 1984. There is a current phase of excavation that is a series of summer field seasons. The project's overarching purpose has been to understand rural life on the Arabian desert frontier during the succession of Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic hegemonies. This began with the study of what was visible above ground—tire Late Antique town already described—but two major discoveries forced a backward expansion of historical horizons. The first was a fourth-century Roman fort (castellum) within the town's perimeter wall that was ruined and abandoned as the town grew around it. The second was a totally ruined village, about half the size of the town and 200 m to its east, dated to the heyday of Nabatean and Roman expansion in the Hauran (first-third centuries CE) .

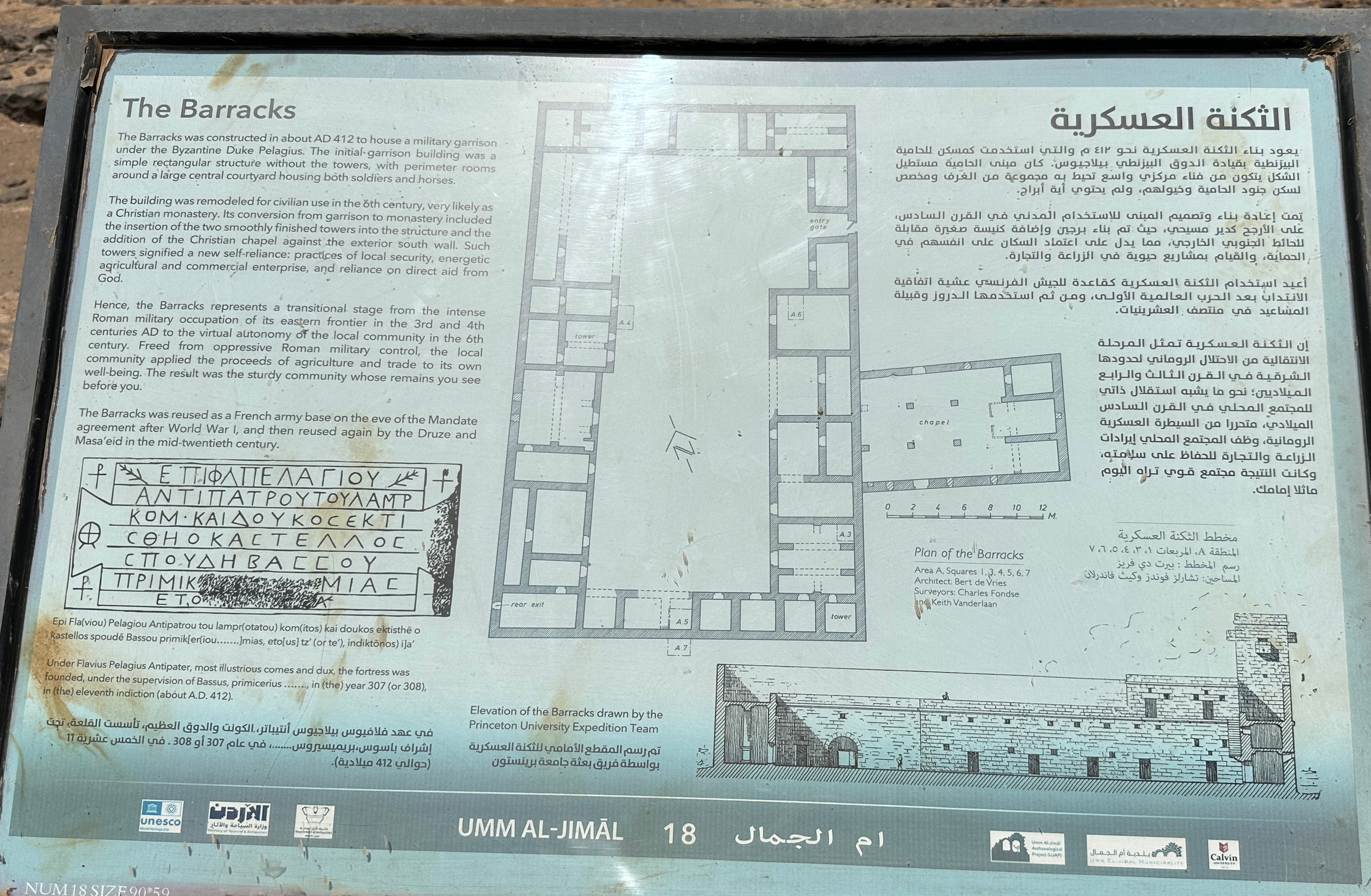

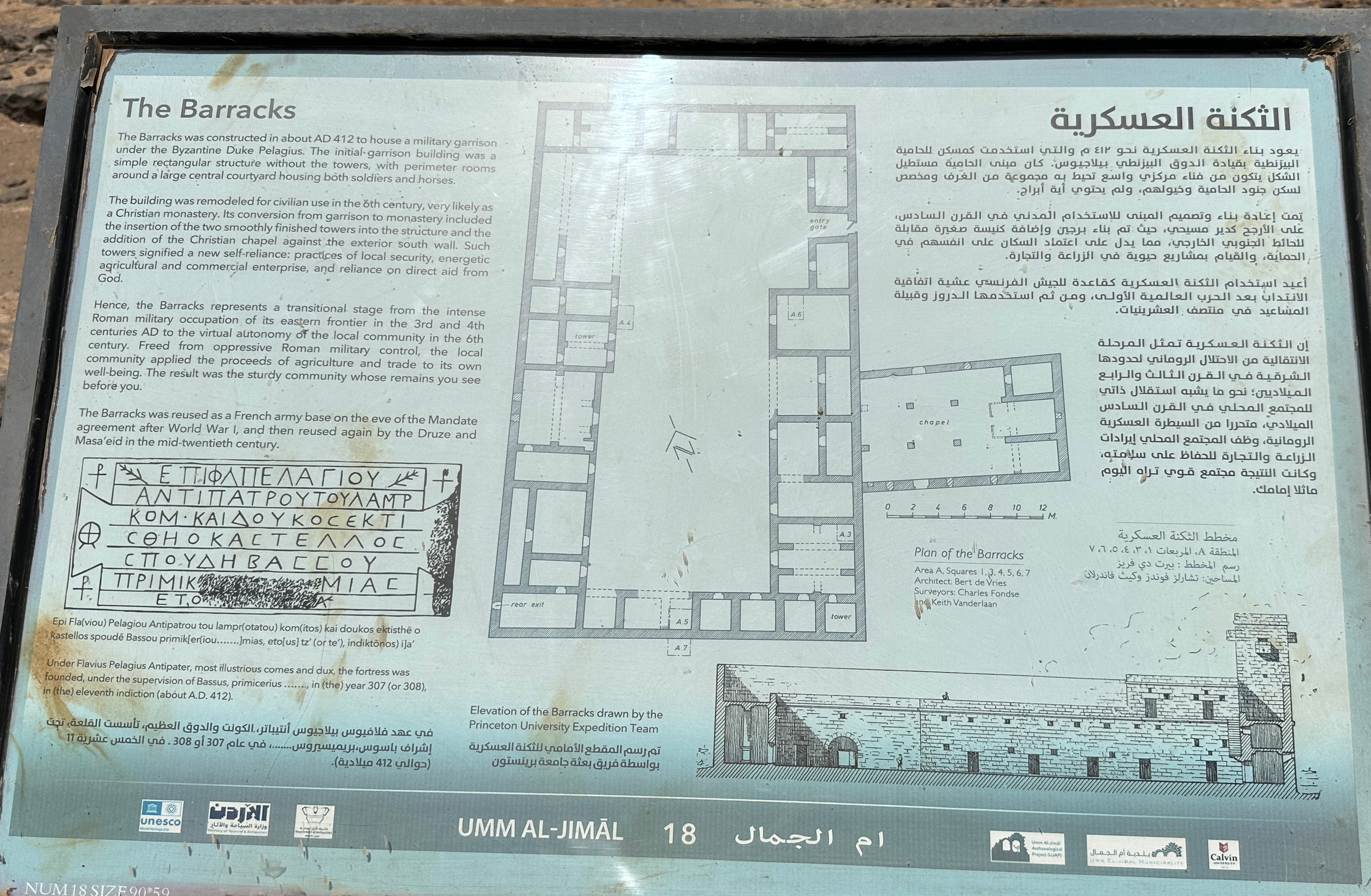

The 1972-1973 season was devoted to mapping the site, to fill in details omitted from Butler's selective architectural survey. In 1974 preliminary soundings were dug as a representative sampling, which determined that the basic stratigraphic profile ranged from Late Roman to Umayyad. In 1977 the focus was on four major sttuctures: the barrack, praetorium, house XVIII, and the perimeter wall. It was concluded that the town was continuously inhabited from the Late Roman through the Umayyad periods; no Early Nabatean Roman occupation levels were found. Fall 1977 was devoted to consolidating the barrack perimeter walls with force-pumped aerated cement.

In 1981 new work included the excavation of the northeast church, tire Numerianos church, various water channels, and the Via Nova Traiana (6 km, or 4 mi., to the west). This work confirmed that the standing buildings are mainly the product of a rural agrarian culture that flourished in the Hauran from the fourth to eighth centuries CE, A major discovery was the identification of the ruined area (100 X 100 m) between the Roman reservoir and the east church as a castellum built in about 300 and used as part of the Roman frontier defenses in the fourth century. In January 1983, the gate of house XVIII was cleared and its walls consolidated.

In 1984 further work was done on the churches and the castellum, while the focus shifted to activities outside the walls of the Byzantine-Umayyad town. These included completing a walking survey of terrain within 10 km (6 mi.) of the town and excavating cemeteries and reservoirs east of it. The major discovery in that season was the Nabatean/ Roman village (called al-Herri) buried under the rubble field adjacent to the reservoirs. The village began in the late first century CE, at the time of the last Nabatean expansion into southern Syria, flourished in the second and third centuries, and was destroyed during the turmoil of the late third century. The presence of this Nabatean/Roman site does much to explain the lack of earlier occupation layers under the Byzantine town. The numerous reused Nabatean and Greek inscribed tombstones must have been robbed from the cemeteries of this earlier village. In 1992 architectural studies of four Late Roman and Early Byzantine structures (houses 35,49,119, and the praetorium) and detailed mapping of the castellum and the Nabatean/Roman village were carried out, including low-altitude aerial photography by Wilson and Ellie Myers. These survey data have been used to develop Geographic Information System (GIS) computer images and maps of the site. The 1993 season focused on consolidation and site development, including stabilizing the high walls of the praetorium and excavating house 119 in preparation for its adaptation as a museum and visitor center. House 11 9 proved to be a completely Umayyad construction on a cleared Byzantine domestic site. Field research in the 1994 season concentrated on the systematic excavation of the Nabatean-Roman village and smdying the sixth-century burials outside the later town.

In summary, from the first to the third centuries CE, a small Arab village with both Nabatean and Roman features flourished at al-Herri. A praetorium and a few other imperial Roman sttuctures were erected 200 m to the west. In about 300, the castellum was built; it lost its military function late in the fourth century. The much smaller barrack that replaced it was constructed early in the fifth century. As the imperial military presence diminished, the Early Byzantine town (fifth-sixth centuries), consisting of 129 houses and 15 churches, prospered, a product of a self-sufficient economy and political security. This town survived in somewhat diminished form through the Umayyad period. Following plague and earthquake in the mid-eighth century, the only human presence at the site for the next century was squatters in the ruins. Then, after centuries of inactivity, the town enjoyed a brief revival when Druze resettled it between 1910 and 1935.

Umm el-Jimal is a rural town in northeastern Jordan, constructed on the edge of a basalt flow extending from Jebel el-Druze. The site is remarkably well preserved, with over 150 buildings standing, some up to their third story. A small village under Nabatean and Roman influences existed at the site from the first to third centuries CE. A castellum was built circa 300 CE, replaced late in the fourth century by barracks, much smaller in size. In the fifth and sixth centuries, the imperial military presence at the site diminished, and the town prospered, witness to the construction of 15 churches. During the last decades of the sixth century, the site suffered the twin ravages of plague and Persian invasions. The Umayyad conquest brought centralized authority to the site, and it was inhabited without interruption until its abandonment following the earthquake of 748/749 CE (see below, The Islamic Period, in this entry). It was only resettled by the Druze in 1910–1935.

The ancient name of the site is unknown. H. C. Butler suggested the name Thantia from the Peutinger Map. H. MacAdam has proposed Surattha, mentioned in Ptolemy’s Geography. Umm el-Jimal became known to travelers in the nineteenth century, but the first major work was carried out and the first site map produced by the Princeton University Expedition to Southern Syria in 1905 and 1909, directed by H. C. Butler. In 1956, G. U. S. Corbett excavated the Julianos Church. A long-term project of investigation was conducted at the site between 1972 and 1995, by B. de Vries on behalf of Calvin College, Michigan.

The small Nabatean village is located 200 m to the east of the later town. The excavations exposed three domestic structures and a roadway. The relative simplicity of the architecture and the small overall size of the settlement are indicative of a rural village.

Umm el-Jimal was a military station on the fortified frontier defensive system constructed by Diocletian and Constantine; the castellum at the site dates from this period. It is 100 by 100 m in size and surrounded by a wall with offset towers and staircase-platforms that may have served as bases for ballistae. The principia and aedes with a built base for the standards were found on the main axis. The gradual transformation from military post to civilian town was completed in the early fifth century, when the castellum was converted into a marketplace. Barracks erected inside the now constructed town walls served as a bivouac for the diminished garrison. In the sixth century, a church and extensive domestic complex were built in the southeastern part of the old castellum, while the robbed-out northern half lay in ruins.

Monumental underground tombs are located in the vicinity of the site. Their doors open into central chambers, from which multi-tiered burial vaults radiate. In addition, numerous tombstones, inscribed with the names and ages of the deceased, have been found in secondary use as corbels and stairway treads in the Byzantine town. A large number of simple cist tombs were also exposed in close proximity to the site.

In the gently sloping valley in which the site is built, numerous terrace walls, dams, and channels were surveyed, indicating intensive agricultural activity. Two huge reservoirs (c. 40 by 20 m each) were also encountered. The western one is of intriguing construction, consisting of a massive oval clay dike resting directly on the bed of the wadi. Both reservoirs, built in the Early Roman period, remained in use to the end of the late Byzantine period.

Fifteen churches were exposed at the site. The Numerianos Church has an adjoining cloister and a flagstone court to the west. A synthronon was apparently added in a remodeling of the church in the early Umayyad period. Sometime later in the Umayyad period, a wall was built separating the apse from the nave and the structure ceased to function as a church. The Double Church shows no evidence of Umayyad use or reuse. It had a series of three well-constructed plaster floors, the last of which was well preserved and painted red. The chancel screen wall contained a reused Safaitic inscription. The excavation at the Julianos Church yielded several inscriptions and a thumiasterion originating from a pagan temple and reused at the church.

The dwellings exposed at the site are mostly modest in size and consist of an open courtyard, several small rooms, and occasionally stables. In some cases, rooms are preserved to ceiling level, with the corbelled roof supported on a central arch. Some ceilings are over 5 m high.

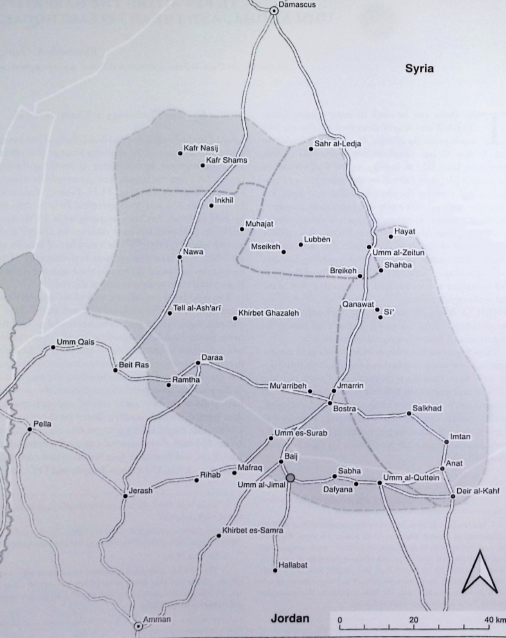

- Fig.11.1 Map of Umm al-Jimal

and surroundings from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.1 Map of Umm al-Jimal

and surroundings from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Umm al-Jimal in Google Earth

- Aerial Photo from APAAME

Umm al-Jimal

Umm al-Jimal

APAAME

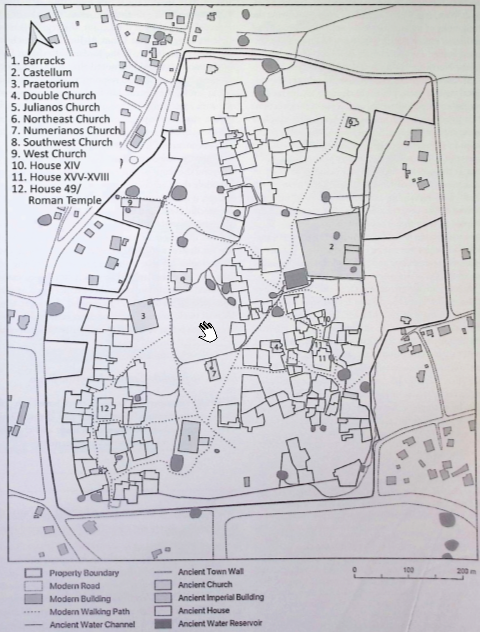

- Fig.11.2 Site Plan

from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 3 Site plan of town

and village from de Vries (1993)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of Umm el-Jimal showing town and village

Drawn by Bert de Vries and Randa Sayegh

de Vries (1993) - Fig. 2 Plan of late antique

Umm al-Jimal from de Vries (2000)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan at late antique Umm al-Jimal

(adapted from de Vries. Umm el-Jimal [1988] 94 fig. 44)

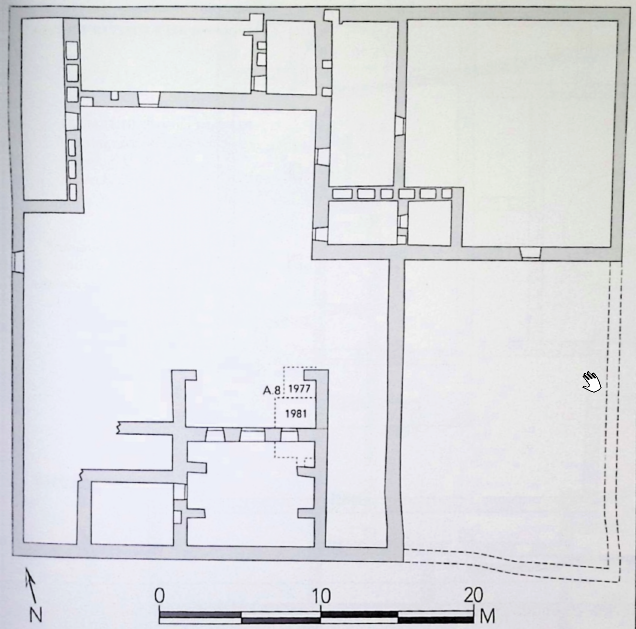

de Vries (2000) - Fig. 2 Site Plan from

de Vries, B. (1995)

2. Map of southern section of Umm al-Jimal showing the location of house 119.

2. Map of southern section of Umm al-Jimal showing the location of house 119.

Building 1 is the Barracks

2 the Praetorium

8 the temple built into house 49

13 the Numerianos church

(Drawing by B. de Vries)

de Vries (1995)

- Fig.11.2 Site Plan

from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 3 Site plan of town

and village from de Vries (1993)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Map of Umm el-Jimal showing town and village

Drawn by Bert de Vries and Randa Sayegh

de Vries (1993) - Fig. 2 Plan of late antique

Umm al-Jimal from de Vries (2000)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan at late antique Umm al-Jimal

(adapted from de Vries. Umm el-Jimal [1988] 94 fig. 44)

de Vries (2000) - Fig. 2 Site Plan from

de Vries, B. (1995)

2. Map of southern section of Umm al-Jimal showing the location of house 119.

2. Map of southern section of Umm al-Jimal showing the location of house 119.

Building 1 is the Barracks

2 the Praetorium

8 the temple built into house 49

13 the Numerianos church

(Drawing by B. de Vries)

de Vries (1995)

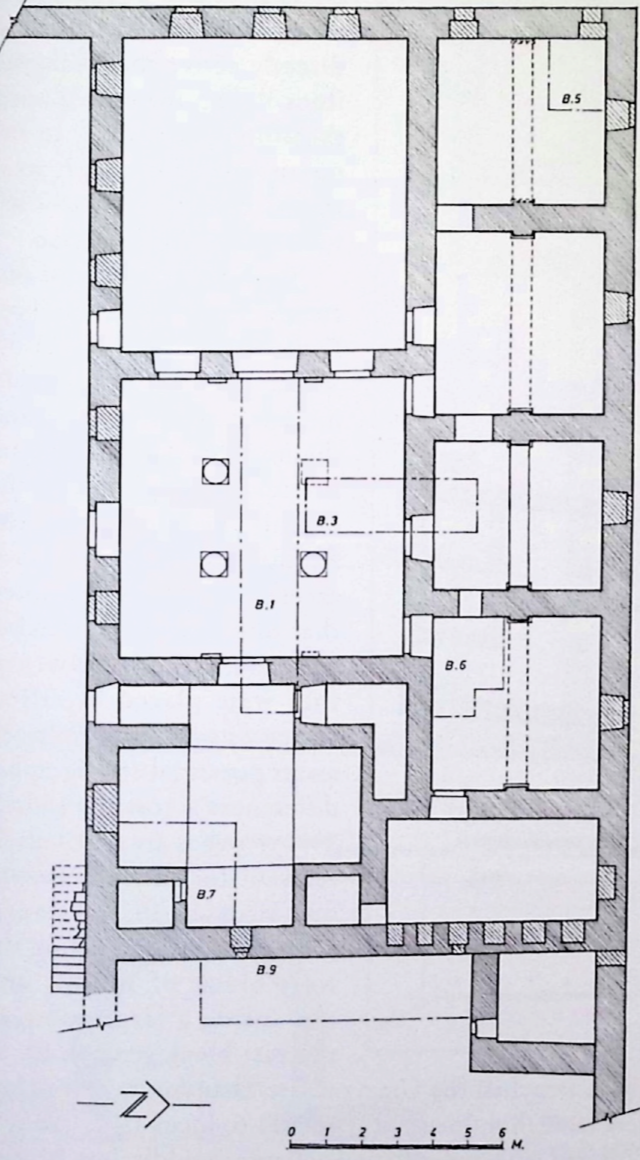

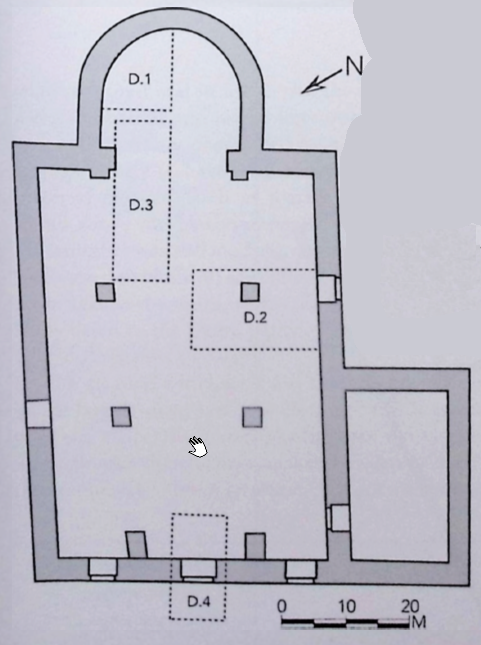

- Fig.11.3 Plan of

the Praetorium from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.3 Plan of

the Praetorium from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

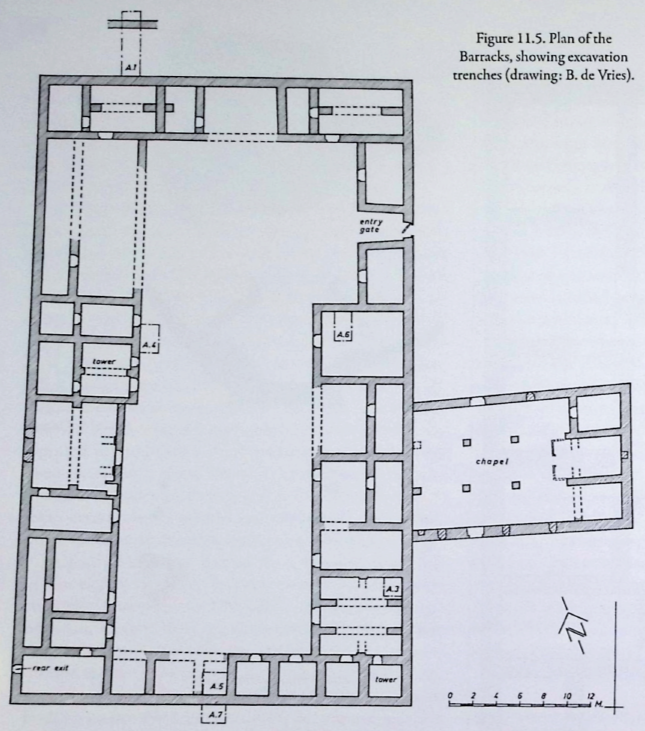

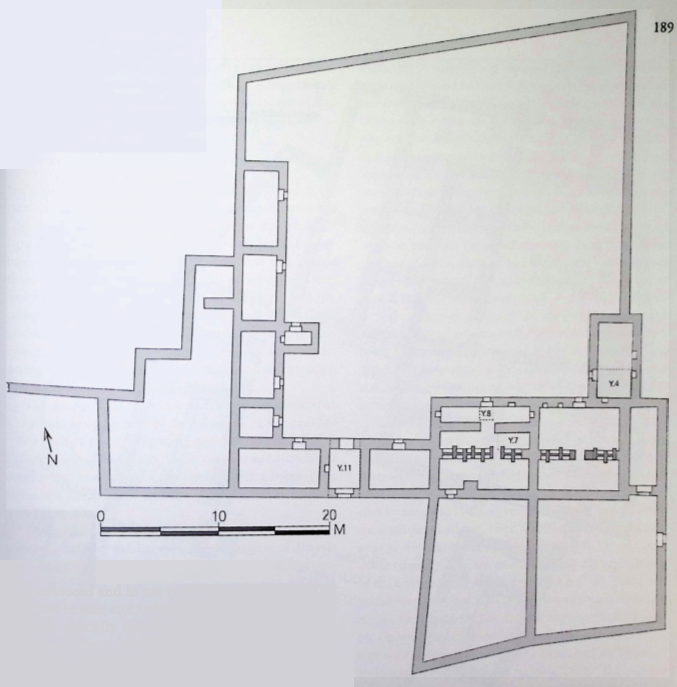

- Fig.11.5 Plan of

the Barracks from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.5 Plan of

the Barracks from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.6 Plan of

the Roman Temple from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.6 Plan of

the Roman Temple from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

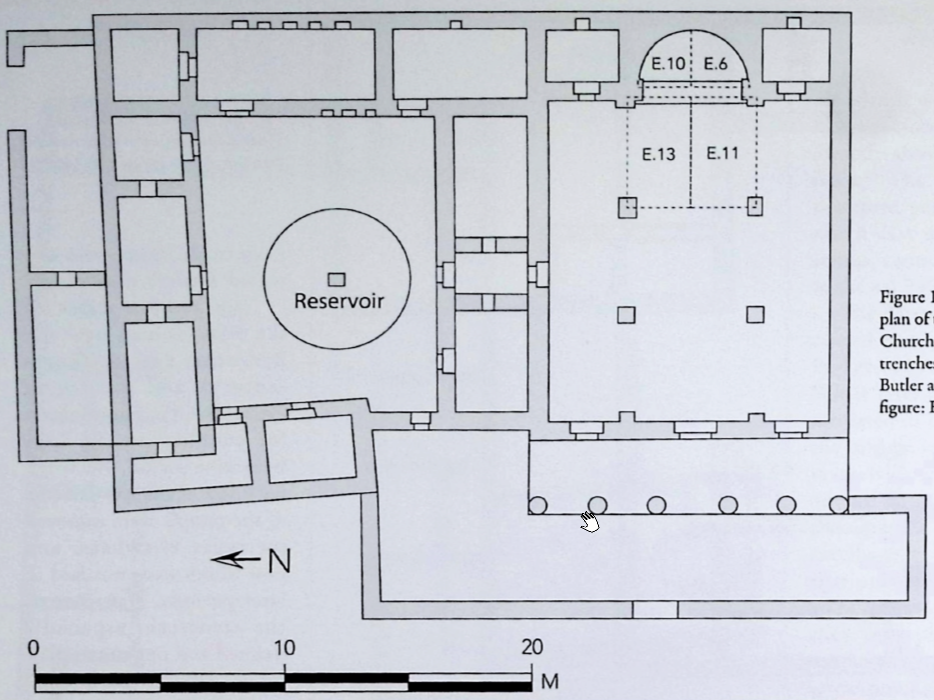

- Fig.11.7 Plan of

the Northeast Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.7 Plan of

the Northeast Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.8 Plan of

the Northeast Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.8 Plan of

the Northeast Church from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

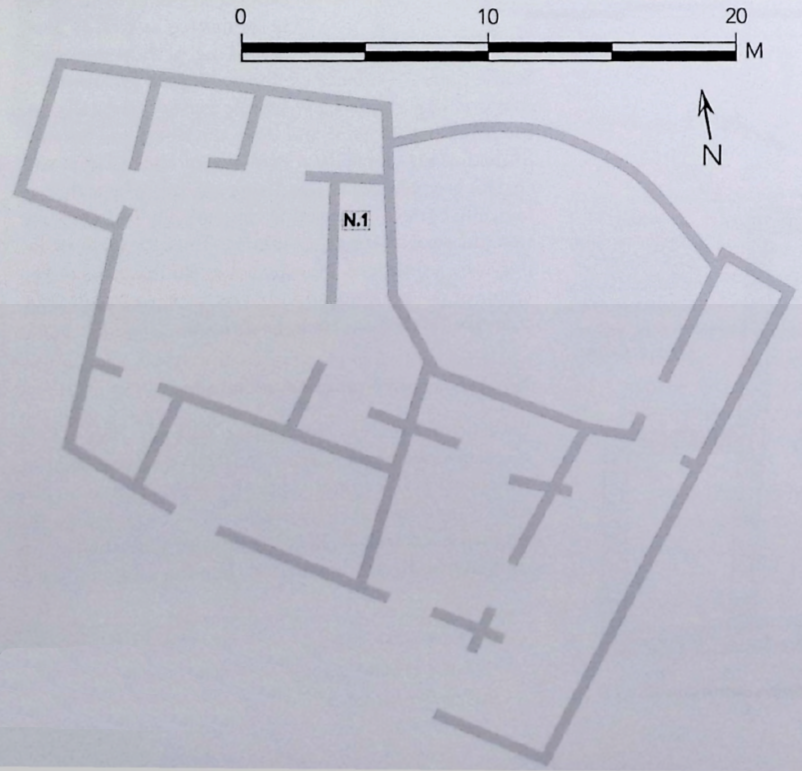

- Fig.11.9 Plan of

House XIV from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.9 Plan of

House XIV from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.10 Plan of

House 119 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.10 Plan of

House 119 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

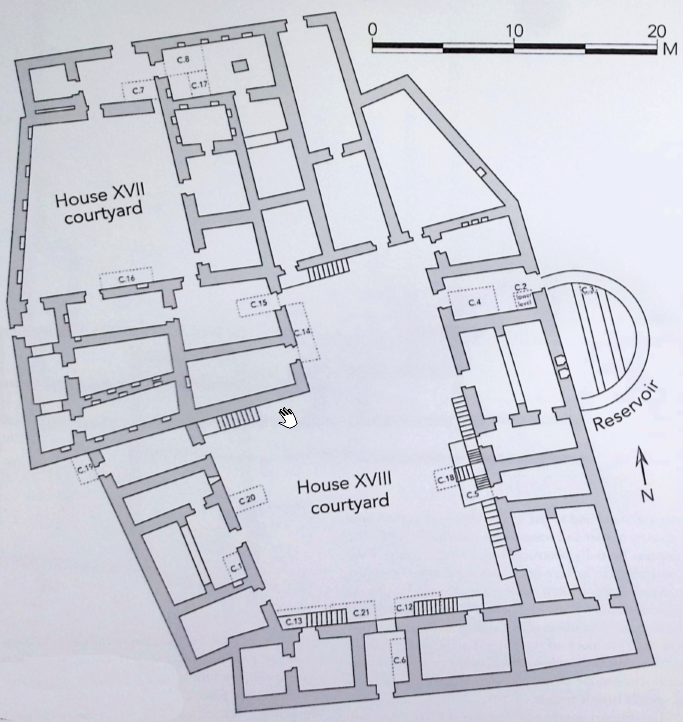

- Fig.11.11 Plan of

House XVII-XVIII from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig.11.11 Plan of

House XVII-XVIII from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 4 Plan of the castellum

from de Vries (1993)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the castellum

Drawn by Bert de Vries

de Vries (1993)

- Fig. 4 Plan of the castellum

from de Vries (1993)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of the castellum

Drawn by Bert de Vries

de Vries (1993)

- Plate 2.3 View of the Barracks

from de Vries (2000)

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3

Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks

Photo A. Walmsley

de Vries (2000) - Plate 3.1 West facade of the Barracks

from de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1

Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks

Photo A. Walmsley

de Vries (2000) - Figure 3.2 The Western

Tower of the Barracks from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls.

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.3 Western Wall

of the Barracks from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3

Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Longshot of the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Longshot of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Longshot of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

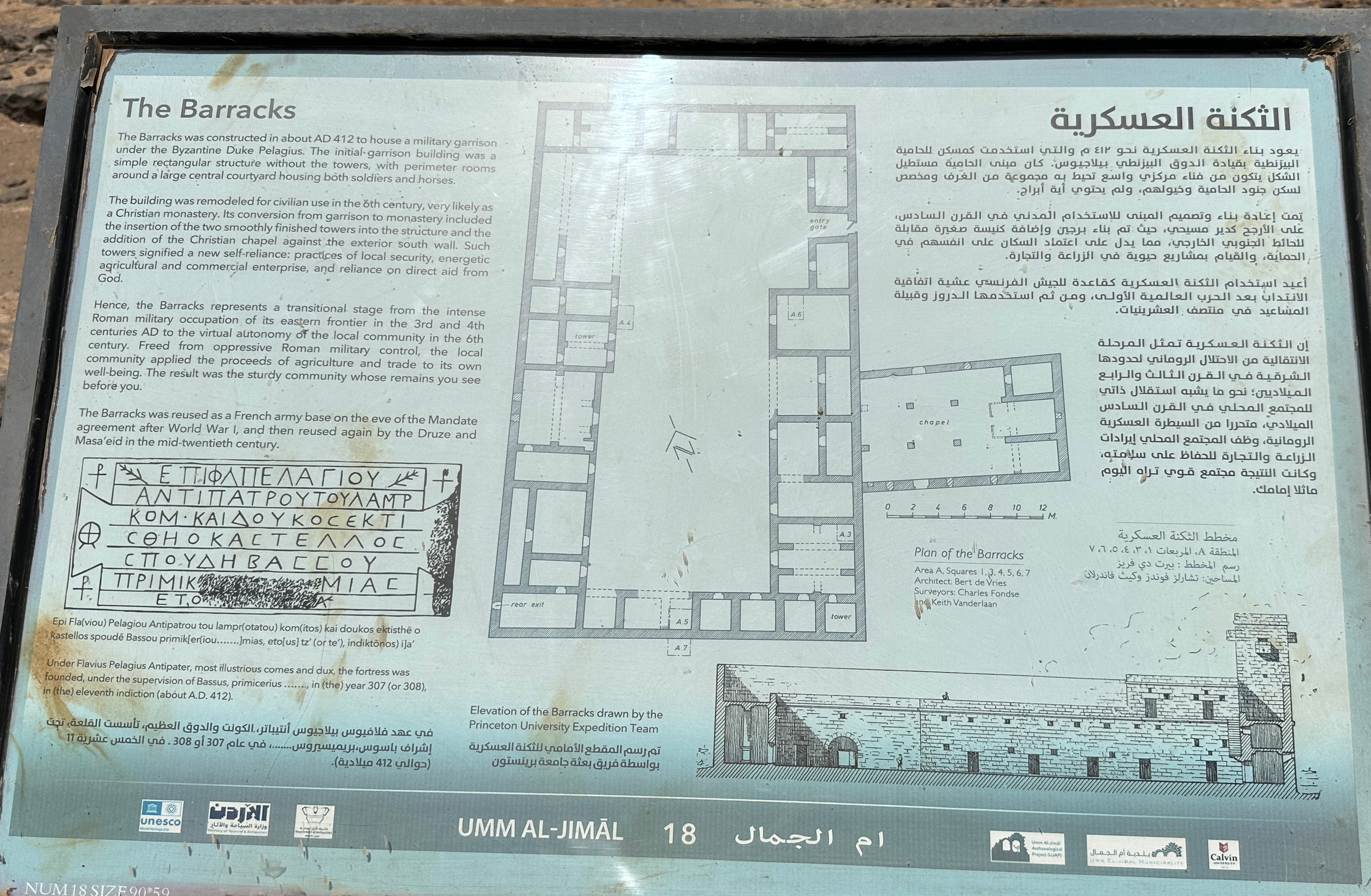

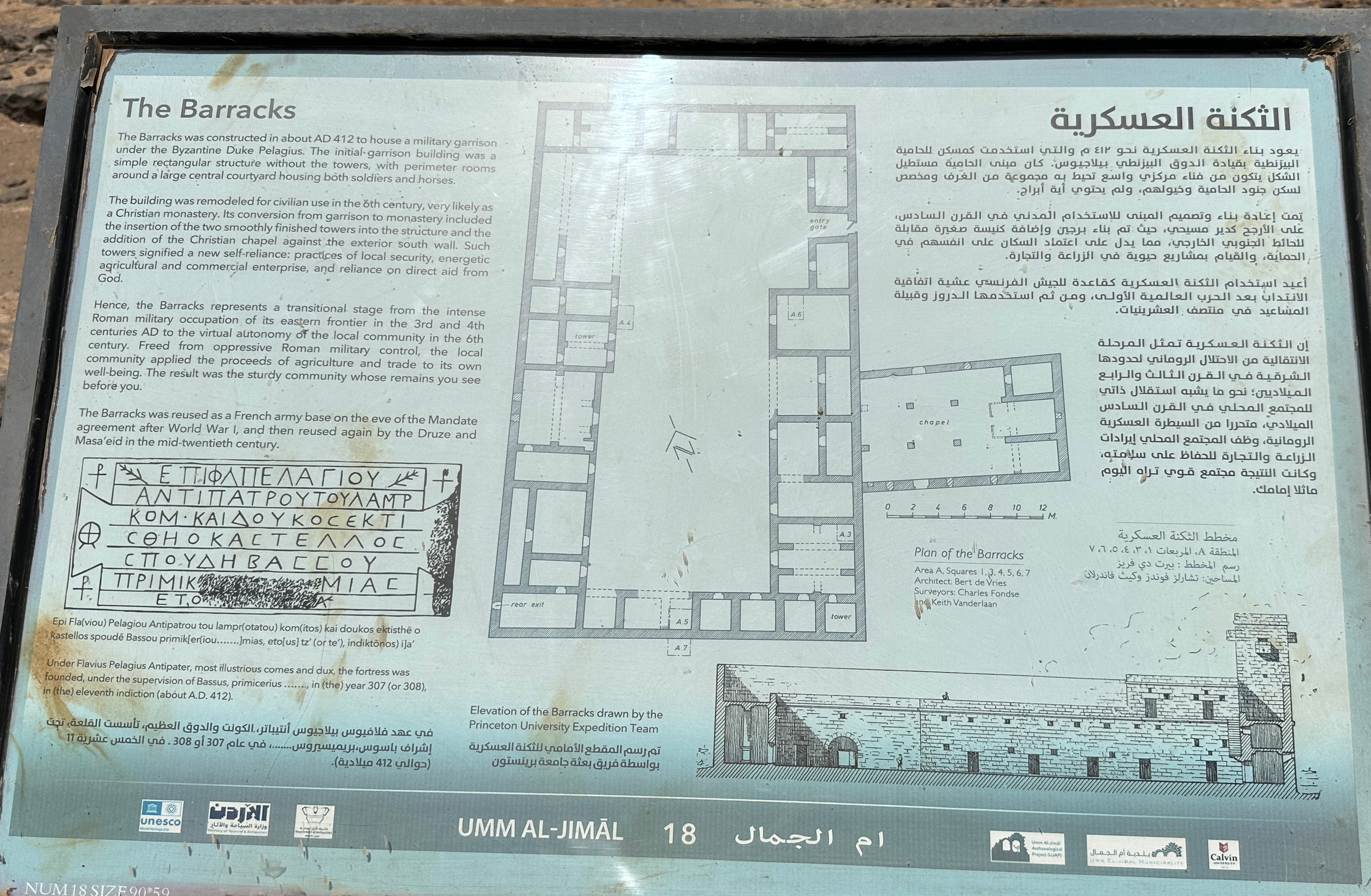

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Park signage of the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Park signage of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Park signage of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - U shaped cutout at the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Reconstructed U shaped

cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Reconstructed U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Reconstructed U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Reconstructed U shaped

cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Reconstructed U shaped cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Reconstructed U shaped cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted and Bulged Wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Tilted and Bulged Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted and Bulged Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

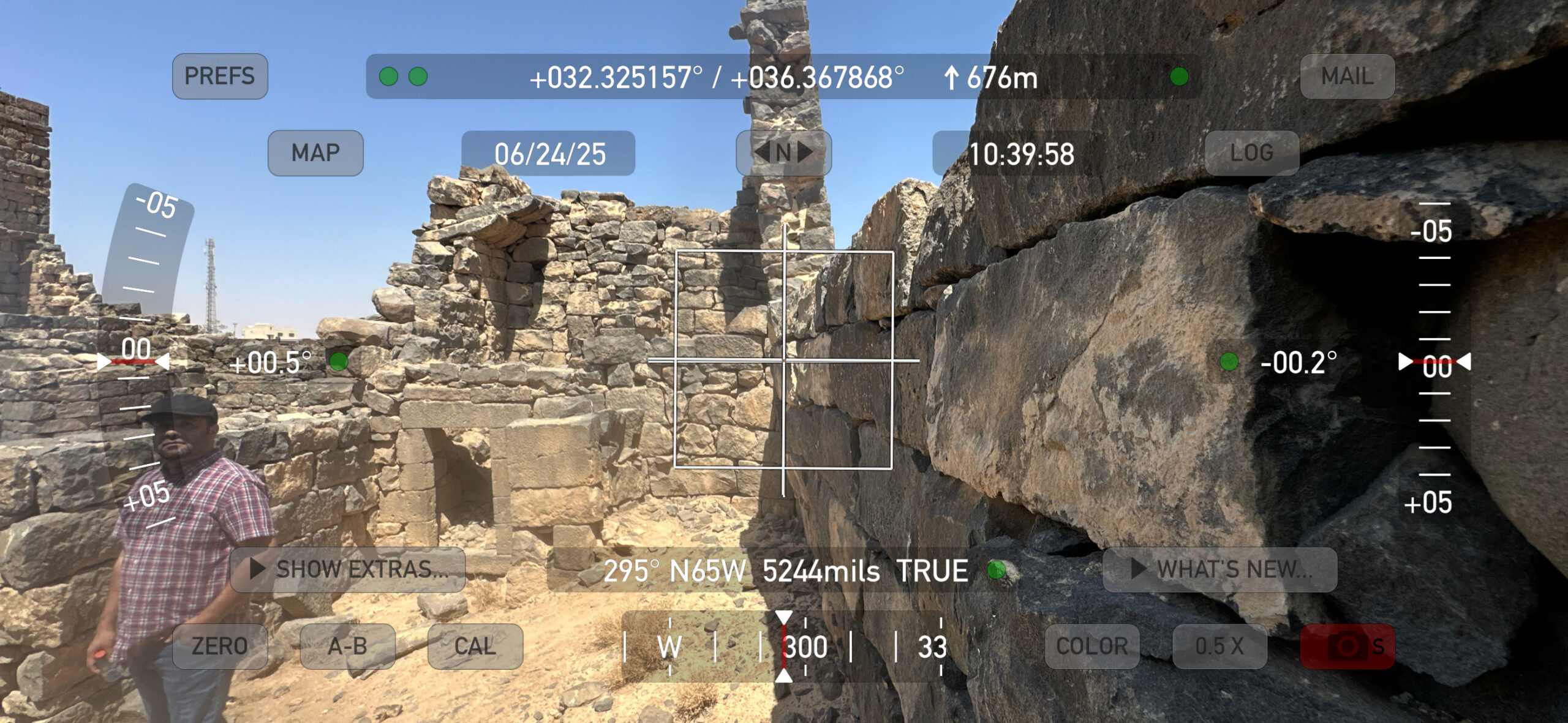

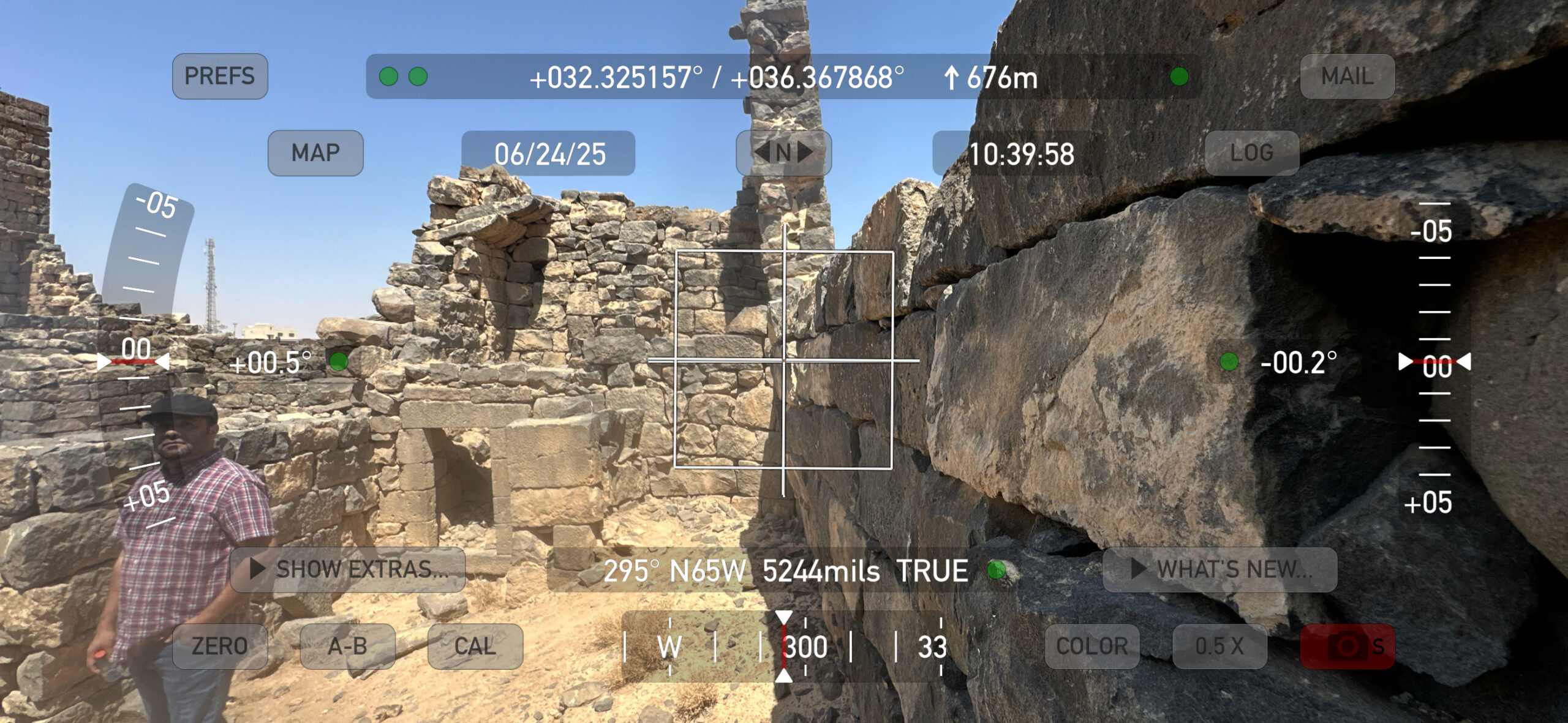

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

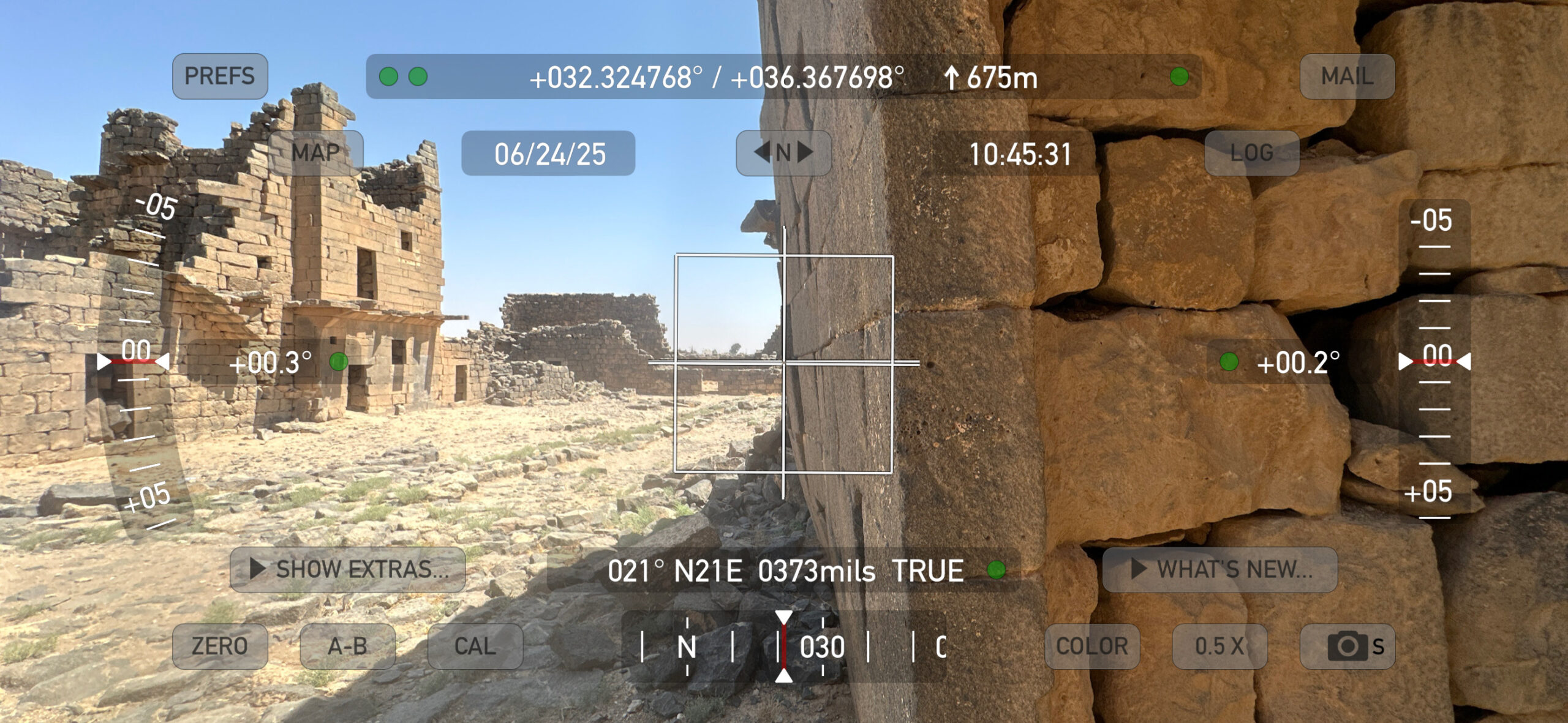

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - Az = 295 - vertical reference - digital theodolite photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Vertical Reference

Az = 295

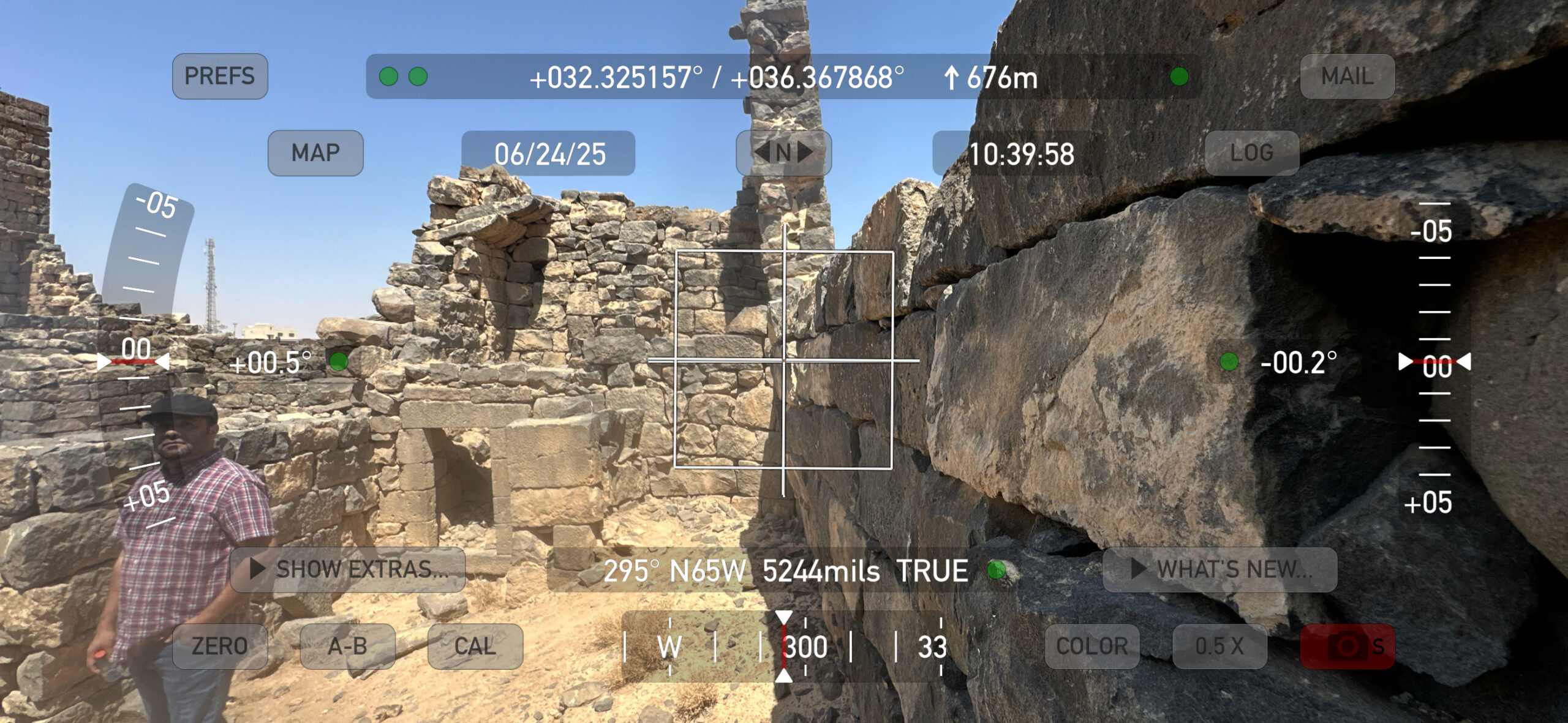

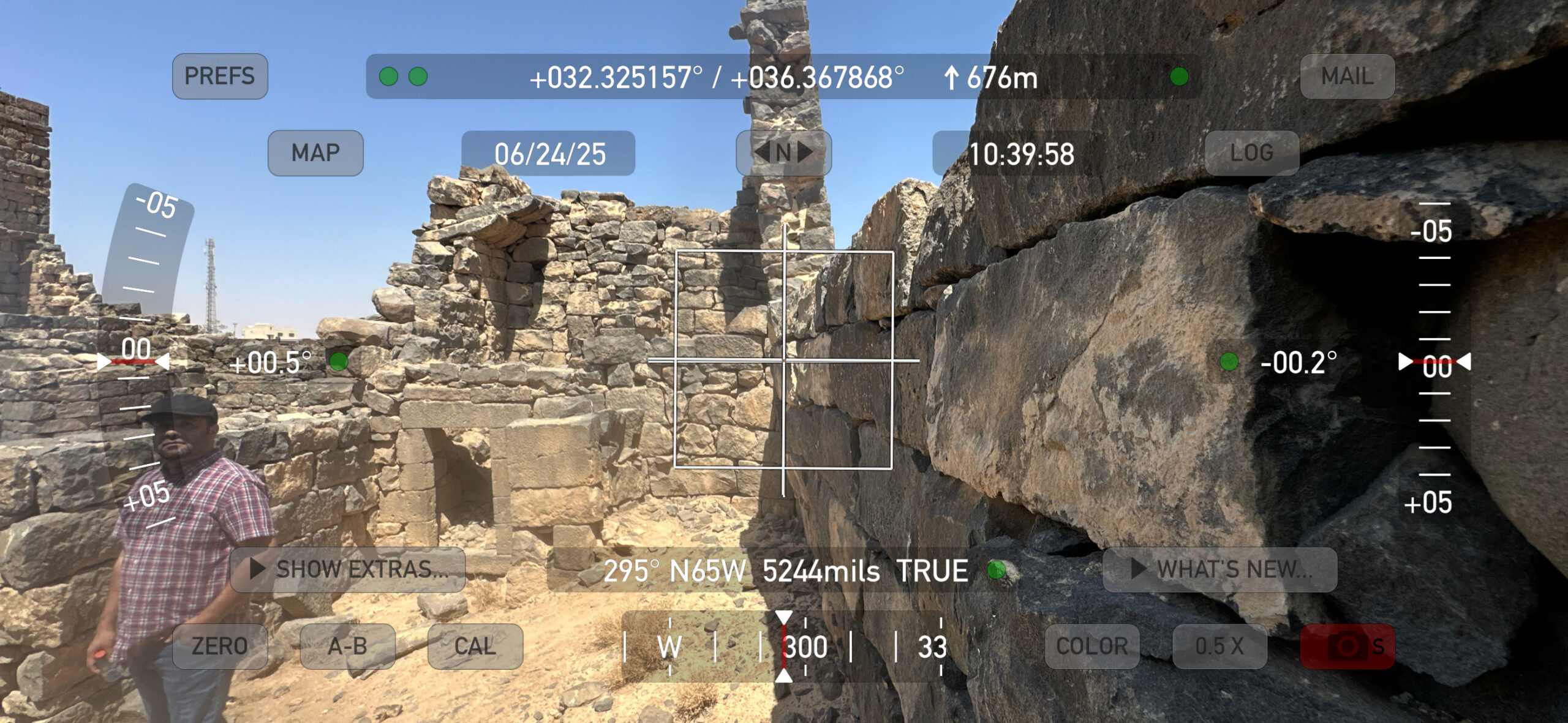

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

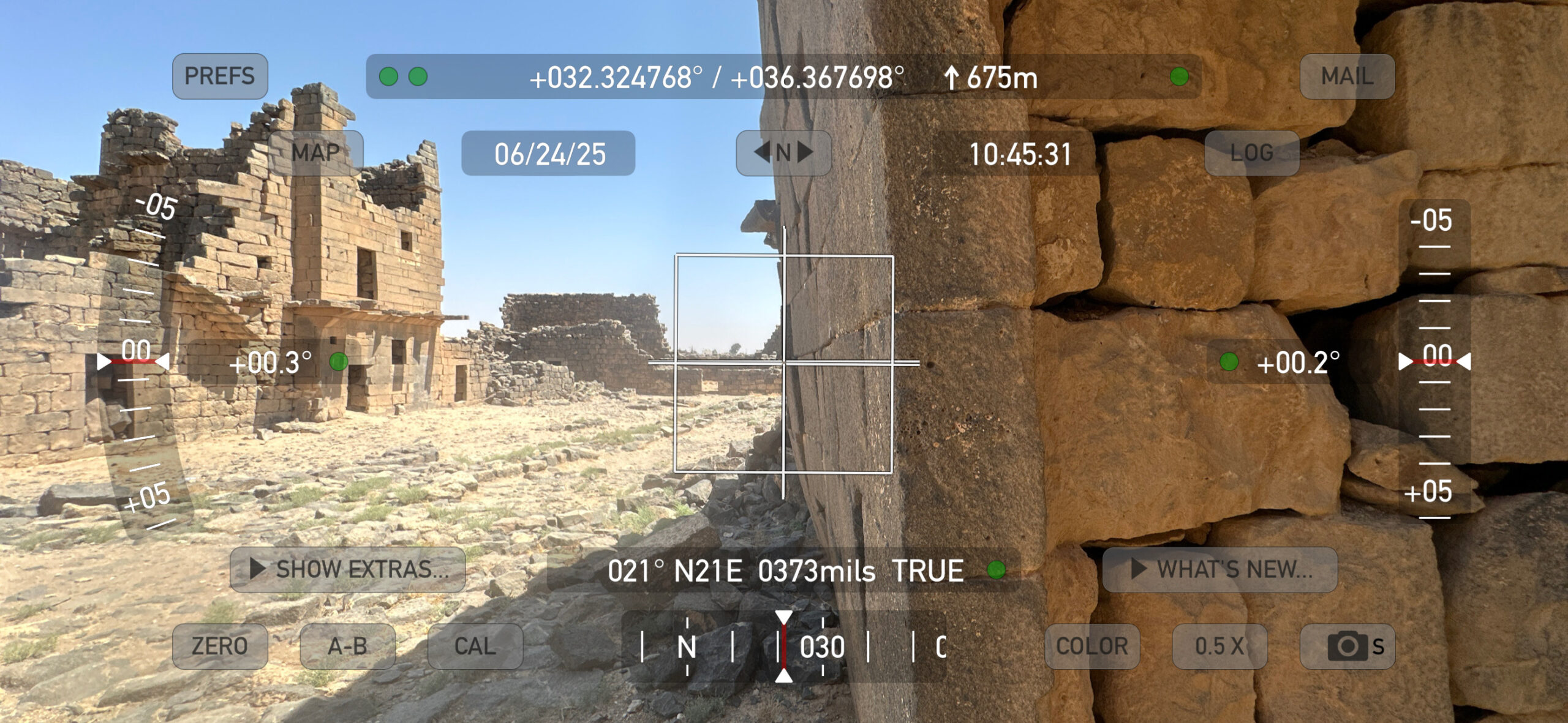

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - Az = 295 - tilt measure (6 degrees) - digital theodolite photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilt Measure (6 degrees)

Az = 295

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted Wall at the barracks

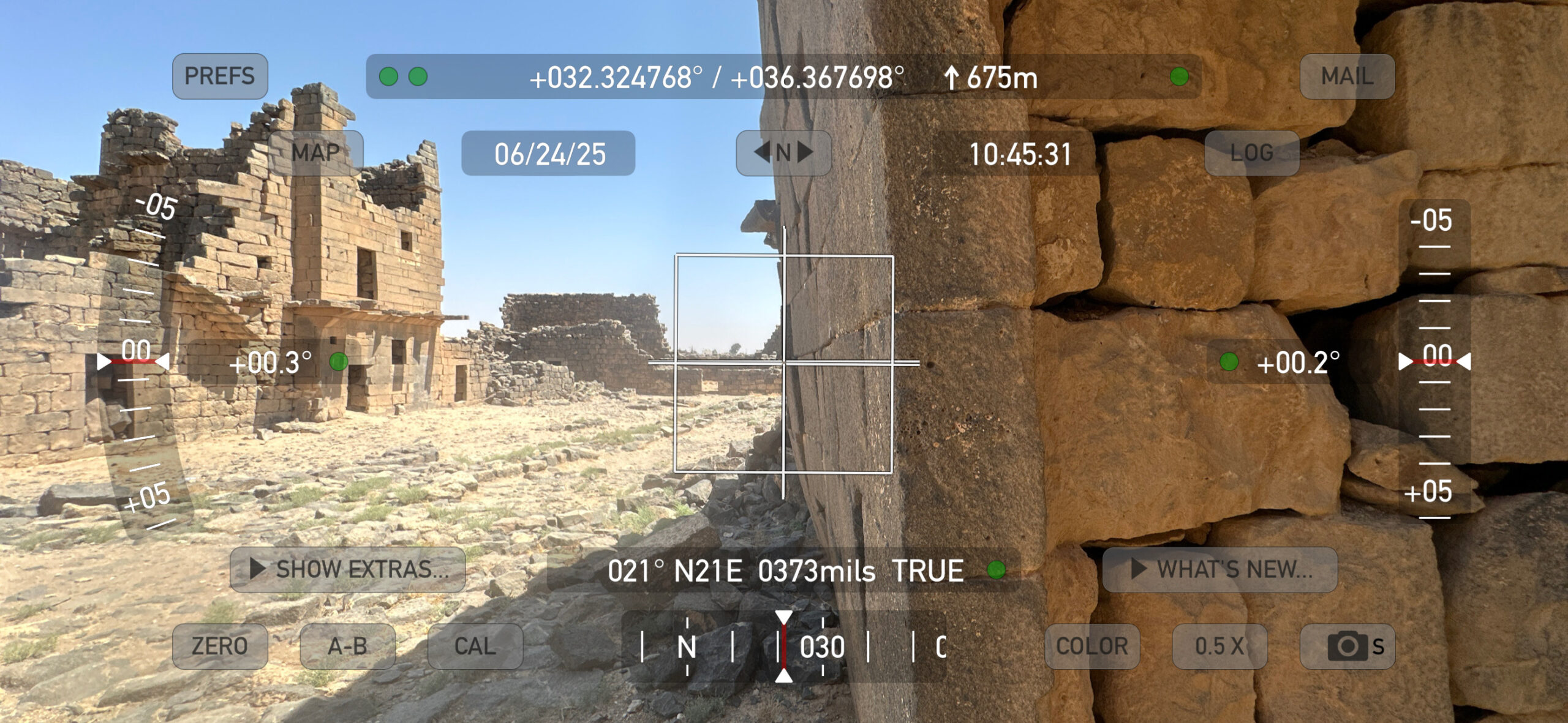

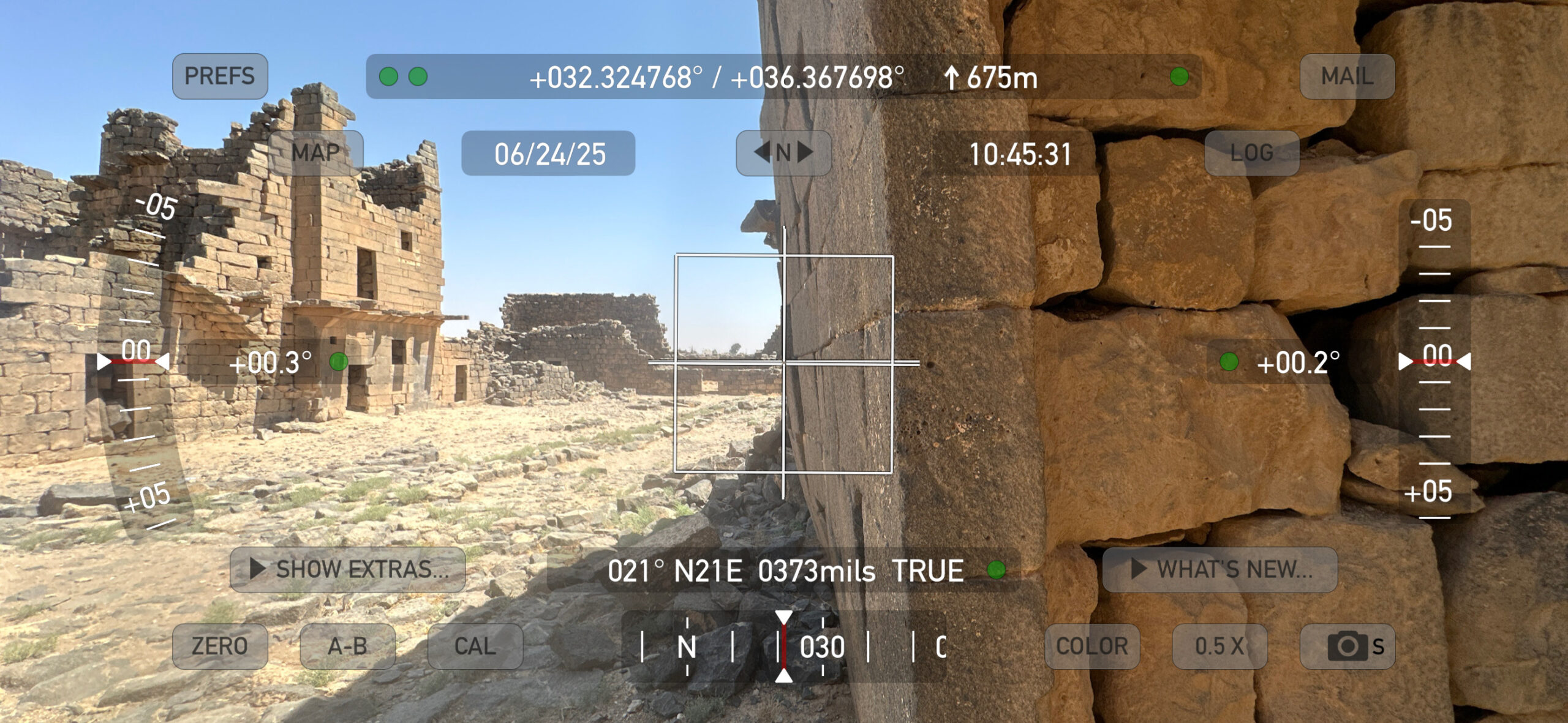

in Umm al-Jimal - Vertical Reference - Az = 21 - Digital Theodolite Photo by JW

Tilted Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Vertical Reference

Az = 21

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted Wall in the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Tilted Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Bulged Wall in the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Bulged Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Bulged Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Through-going cracks

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Through-going cracks at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Through-going cracks at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and Fractured

Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and Fractured

Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Plate 2.3 View of the Barracks

from de Vries (2000)

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3

Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks

Photo A. Walmsley

de Vries (2000) - Plate 3.1 West facade of the Barracks

from de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1

Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks

Photo A. Walmsley

de Vries (2000) - Figure 3.2 The Western

Tower of the Barracks from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls.

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Figure 3.3 Western Wall

of the Barracks from Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3

Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading

Kázmér et al. (2024) - Longshot of the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Longshot of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Longshot of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Park signage of the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Park signage of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Park signage of the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - U shaped cutout at the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Reconstructed U shaped

cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Reconstructed U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Reconstructed U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Reconstructed U shaped

cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Reconstructed U shaped cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Reconstructed U shaped cutout next to U shaped cutout at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted and Bulged Wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Tilted and Bulged Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted and Bulged Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - Az = 295 - vertical reference - digital theodolite photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Vertical Reference

Az = 295

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Strongly tilted wall

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - Az = 295 - tilt measure (6 degrees) - digital theodolite photo by JW

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Stroingly tilted wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilt Measure (6 degrees)

Az = 295

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted Wall at the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - Vertical Reference - Az = 21 - Digital Theodolite Photo by JW

Tilted Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted Wall at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Vertical Reference

Az = 21

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Tilted Wall in the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Tilted Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Tilted Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Bulged Wall in the barracks

in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Bulged Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Bulged Wall in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Through-going cracks

at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Through-going cracks at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Through-going cracks at the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and Fractured

Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and Fractured

Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Displaced and Fractured Ashlars in the barracks in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Longshot of the four

arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Longshot of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Longshot of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled corners in

the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Splalled corners in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Splalled corners in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Cracks in the West

Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Cracks in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Cracks in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Lintel Stress Damage

in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Lintel Stress Damage in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Lintel Stress Damage in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - View of subsurface

in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

View of subsurface in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

View of subsurface in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Longshot of the four

arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Longshot of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Longshot of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Arch Impost Damage

for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - closeup photo by JW

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Closeup of Arch Impost Damage for one of the four arches in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled corners in

the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Splalled corners in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Splalled corners in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Cracks in the West

Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Cracks in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Cracks in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Lintel Stress Damage

in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

Lintel Stress Damage in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Lintel Stress Damage in the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - View of subsurface

in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal - photo by JW

View of subsurface in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

View of subsurface in vicinity of the West Church in Umm al-Jimal

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- from de Vries (1992)

| Stratum | Period | Age | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| VII | Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| VI | Late Roman | 135 CE - 324 CE | |

| V | Early Byzantine | 324 CE - 491 CE | |

| IV | Late Byzantine | 491 CE - 636 CE | Earthquakes ? |

| III | Umayyad | 636 CE - 750 CE | Earthquake ? |

| Post Stratum III Gap | 750 CE - 1900 CE | ||

| II | Late Ottoman/Mandate | 1900 CE - 1946 CE | |

| I | Modern | 1946 CE - Present |

Umm al-Jimal (Jordan). The walls of the deserted Byzantine city of Umm al-Jimal in northern Jordan bear various traces of earthquake destruction. Archaeoseismological analysis comprises tilted and bulged walls, U-shaped collapse features, and rotation and extension features. These deformations indicate that at least two earthquakes struck the region (Figs. 3.2 and 3.3). The first one occurred in the late Byzantine period (between 491 and 636 AD). Restoration followed, but a second earthquake destroyed the town at the end of the Umayyad Caliphate (661 AD–750 AD). This last damage was not repaired and the site has been abandoned ever since.

Umm al-Jimal is > 70 km from the Dead Sea Fault. I = VII damage occurred in the city during the first earthquake, while a later, I = IX damage destroyed it. Many walls are still standing (Al-Bashaireh 2017; Al-Tawalbeh 2021; Al-Tawalbeh et al. 2019).

Umm al-Jimal (Jordan). The walls of the deserted Byzantine city of Umm al-Jimal in northern Jordan bear various traces of earthquake destruction. Archaeoseismological analysis comprises tilted and bulged walls, U-shaped collapse features, and rotation and extension features. These deformations indicate that at least two earthquakes struck the region (Figs. 3.2 and 3.3). The first one occurred in the late Byzantine period (between 491 and 636 AD). Restoration followed, but a second earthquake destroyed the town at the end of the Umayyad Caliphate (661 AD–750 AD). This last damage was not repaired and the site has been abandoned ever since.

Umm al-Jimal is > 70 km from the Dead Sea Fault. I = VII damage occurred in the city during the first earthquake, while a later, I = IX damage destroyed it. Many walls are still standing (Al-Bashaireh 2017; Al-Tawalbeh 2021; Al-Tawalbeh et al. 2019).

... Umm al-Jimal consists not only of the uniquely preserved town, but also a ruined adjacent early village, a complex water system with elements in and around the town, numerous fields and gardens, as well as many tombs and cemeteries in the environs — and many of these elements have been subject to survey and/or excavation. For the purposes of this essay, however, the excavations in the town are most pertinent, as they are the ones that have yielded the best architectural and stratigraphic data from the eighth century. There are thirteen excavations that might offer a glimpse into eighth-century Umm al-Jimal:

- three imperial structures (Praetorium, Castellum, and Barracks)

- four houses/house complexes (XIV, 49 / Roman Temple, and 119)

- six churches (Double, Julianos, North-East, Numerianos, South-West, and West)

After re-analyzing the stratigraphy of these excavations, only nine have yielded significant eighth-century stratigraphy and will be discussed below:

- the Praetorium

- Barracks

- all the houses

- the North-East and Numerianos Churches

Already imprecise dating faces another challenge in the eighth century: despite modern periodization changes (Umayyad to Abbasid), and despite actual political, socio-economic, and other shifts during that time, significant, traceable changes to the pottery record do not appear until around the turn of the ninth century.8 Identifying contexts from the 749 earthquake on finds alone therefore becomes difficult unless significant destruction to a structure or across a site is uncovered: at Pella, for example, collapse layers — some with bodies of those who perished during the earthquake’s destruction — were significant across numerous structures.9 While it is certain that the AD 749 earthquake heavily impacted many sites in the Levant, the region is nonetheless a large one, and Umm al-Jimal lies much farther from the epicenter in the Jordan Valley than Pella. Furthermore, it should be noted that abandonment is not the immediate, normal response to earthquake damage: at Jerash, the destruction from the earthquake was met with rebuilding,10 as seems to be a general trend.11 Sudden abandonment due only to an earthquake therefore seems unlikely, or at least must involve other underlying or concurrent issues/events.

While a detailed examination of archaeoseismology12 is beyond the scope of this essay, it is important to note that while there are methods for identifying earthquake damage, it is rarely possible to tie damage or collapse to one specific event, and one should not assume that collapse immediately followed damage.13 Archaeologists are also in danger of accepting a known earthquake date for destruction or collapse at a site and basing their chronologies off that point, when in reality the collapse may have been related to a different event, caused by human intervention, or could have occurred at some point after an earthquake.14 In general, dating at Umm al-Jimal tends toward ranges of dates rather than absolutes, which better reflects the ambiguity of much of the archaeological record.

6 Osinga 2017.

7 Osinga 2020.

8 Early Abbasid pottery shows strong continuity with late

Umayyad pottery: Alan Walmsley’s discussion and analysis of

later eighth- to mid-ninth-century pottery from Pella and from

Tell al-Husn is particularly instructive, outlining the continuity

in wares and forms, and noting the new types that appear near

the end of the eighth century — namely Islamic cream ware and

glazed wares (Walmsley and others 1993, 210-18; McNicoll and

others 1986, 193-94). Without very good stratigraphic evidence

or the presence of wares or forms known to appear in the late

eighth and ninth centuries, it is very difficult to separate late

Umayyad from early Abbasid pottery. At Umm al-Jimal, where

the average sherd weight is 5 g or less, dating these tiny sherd

fragments, mostly from pot bodies, must be done cautiously.

At Jerash, a key pottery supplier of Umm al-Jimal and many

other sites in the region, Umayyad and Abbasid ceramics are

linked by typological and ware/fabric continuation (Rattenborg

and Walmsley 2013, 101).

9 Walmsley 2007c.

10 For example, Blanke, Lorien, and Rattenborg 2010;

Walmsley and others 2008; Blanke and others 2007;

Rattenborg and Blanke 2017.

11 Ambraseys 2006, 1015.

12 Sintubin 2013.

13 Stiros 1996, 142.

14 Stiros 1996, 142-43; Sintubin 2009, 7-8.

Of the eight pertinent excavations, three have been published: the Praetorium,15 Barracks,16 and House 49 / the Roman Temple.17 The remaining houses and churches were remarked on in preliminary publications.18

15 Brown 1998.

16 Parker 1998a.

17 Parker 1998b; Parker and De Veaux 1998.

18 De Vries and others 2016; de Vries 1993; 1995..

While originally an imperial administrative building, the Praetorium became a domestic structure in the Byzantine period after it lost its military / political function. Excavated in 1977 and 1981, with preliminary results published by Brown,19 it is an unusual building at Umm al-Jimal: the cruciform room and the atrium are particularly unique features at the site and in the wider region (Fig. 11.3).

Brown’s analysis is thorough; however, she was working with preliminary pottery dating from the original excavations — dating that is now over forty years old and requires updating. A better understanding of middle and late Islamic pottery in the region, along with a careful look at older and newer stratigraphy and material ceramics at Umm al-Jimal has allowed for a reassessment of the so-called gap in occupation from c. AD 750 to the late nineteenth century.20 A scholarly preoccupation with the Druze and Mas’eid occupations at the site in the Late Ottoman / Mandate period caused earlier material culture and its analysis to be pushed to the side, but it is now clear that the Ayyubid and particularly the Mamluk period are indeed represented at Umm al-Jimal: most if not every mention of “late Ottoman” from the Umm al-Jimal publications should include or be redated to the Middle Islamic period. The Praetorium, in fact, yielded the most striking Middle Islamic find at Umm al-Jimal to date: an underglaze slip- painted wheel-thrown lamp, found on the surface (Fig. 11.4).21

There is no need to rewrite Brown’s chapter to discuss the eighth-century evidence; a shift in focus and closer attention to the eighth century and the overlying stratigraphy provides ample evidence that there were no obvious or even probable destruction / collapse contexts that could be dated to the time of the AD 749 earthquake. In trenches located in the cruciform room (trench B.1E, locus 028) and in the atrium (trench B.1W, locus 022), the eighth-century cobble floors were covered not by fallen stones, but by soil and small bits of debris; in fact, middle Islamic pottery was found directly above these floors in both instances.22 In the north-east room (trench B.6, locus 006), heavy stone collapse occurred after middle Islamic and possibly later material culture accumulated directly above the Umayyad floor.23 The major collapse, therefore, particularly in the north-east and north-west rooms, cannot be attributed to the AD 749 earthquake.

The Barracks was first discussed thoroughly by Tom Parker (1998a). While later pottery is again misdated in this chapter and the Middle Islamic finds are severely downplayed in the overall interpretation, the stratigraphic presentation is excellent. It should be noted that only six small trenches were excavated; however, they were placed in different areas of the complex to assess potential stratigraphic differences across the rooms. Two trenches are particularly relevant for this discussion: one situated in the courtyard (trench 4), abutting the west block of rooms, and one inside a large room in the east block (trench 6). In both trenches, the Umayyad use / abandonment soil layers (trench 4, locus 012; trench 6, locus 011) are not covered with architectural collapse. Middle / late Islamic pottery appears in the strata above (trench 4, locus 009, 010; trench 6, locus 007), and the heaviest collapse is not present until after this point. Given that later Islamic activity at the site appears to be seasonal or temporary, it is very unlikely that inhabitants would take the time and effort to clear collapse. Thus, as with the Praetorium, there is no evidence of eighth-century destruction in the archaeological record.

The final published excavation to be discussed in this chapter is the Roman Temple (erroneously named the “Nabataean Temple” by Howard Butler), which was later converted into a domestic structure, known as House 49. The results of the 1977 and 1981 excavations were analysed by Tom Parker and Laurette de Veaux, who corrected Butler’s misdating.24

The temple dates to the Late Roman or Early Byzantine period (fourth century), and was reused domestically, particularly for cooking, in the Late Byzantine period. The original floors and other elements of the temple were removed for reuse elsewhere, and new floors were not laid in later periods. Debris from the structure, especially painted and unpainted plaster, appears in Byzantine and early Islamic contexts, indicating a lack of or disinterest in its upkeep as well as less formal use of the structure.25 While there is evidence of some collapsed architecture that may date to the Early Islamic period, especially on the porch (e.g. loci 036 and 040), the inside and outside of the former temple bear evidence of later Islamic use (in this instance, the Druze dating appears to be archaeologically correct), indicating that any AD 749 destruction did not devastate the building. Thus, the earthquake might be a source of damage, but given the general disrepair of the building and the imprecise dating of later contexts, it is impossible to be certain.

19 Brown 1998.

20 Osinga 2017, 190-203

21 Type III.1.1.2 (Avissar and Stern 2005, 124), from the second half of the twelfth century through c. fourteenth century.

22 Brown 1998, 178. 187.

23 Brown 1998. 179, 184, 187.

24 Parker 1998b: Parker and De Veaux 1998.

25 Parker and Dc Veaux 1998, 158.

Excavations in the North-East Church revealed some of the earliest well-documented collapse, which was in fact from the Late Byzantine period — perhaps caused by the 551 earthquake, as proposed by the original excavators.26 The apse was not reused after this mid-sixth-century destruction, but the aisles and nave were refloored and in use in the Umayyad period, and a chancel barrier and screen were installed.27 While the apse was partially obstructed by a single-course wall, it was unlikely to have been converted into a mosque: material culture, such as marble chancel fragments found above the Umayyad- period floors, suggests that the structure was still used as a church and that the short wall served to block off the collapse in the apse.28 A small room against the south- west wall of the church was originally dated to the Druze period, but could alternatively be Middle Islamic in date.

The original conclusion was that the AD 749 earthquake largely destroyed the church:29 this is certainly possible, especially given that the apse was already in disrepair, but there is no conclusive evidence. Thus, the results merely show a terminus post quem of the mid-eighth century for the first major collapse. Answers to when and how the structure was reused over the next centuries require further data.

There were fifteen trenches placed throughout the Numerianos Church complex, but the most pertinent for this study are two trenches across the apse (trenches E.6 and E.10) and two trenches in the chancel (trenches E.11 and E.13) (Fig. 11.8). The pairs of trenches were separated by a secondary Umayyad-period wall that blocked the apse from the chancel area.30

In all four trenches, heavy architectural collapse is noted directly above the floors that were last used in the Umayyad period, after the blocking wall was installed. The terminus post quem for the major collapse is therefore the middle of the eighth century. In contrast to the Barracks and Praetorium, there was very little middle / late Islamic pottery in the church, and it only appeared in topsoil layers; perhaps the structure was less appealing because of the collapse or due to general instability. The Numerianos Church is very close to structures with significant ceramic evidence of middle / late Islamic activity, such as House 119 and the Barracks, and yet does not appear to have been frequented. Thus, while the evidence suggests that at least some of the tumble could indeed be a result of the AD 749 earthquake, the lack of later pottery does not mean the building collapsed immediately in the eighth century; it may have stood for decades or centuries, simply unused, before it became unstable.

26 Coughcnour n.d., 8.

27 De Vries 1993, 448

28 Coughenour n.d., 15-16.

29 Coughenour n.d., 18.

30 De Vries 1993, 448. The stratigraphy of the church will

be presented in full in a future UJAP volume; currently,

archaeological work concerning the churches in their social context is progressing.

Only one trench was excavated inside House XIV,31 located against the wall of a room or small courtyard (Fig. 11.9). Some walls of the house may date from the Late Roman or Early Byzantine period, but the structure was clearly in use in later Byzantine and Islamic times: flooring traces (flagstone and pebble/earth) were dated to the Late Byzantine period. One layer of major collapse was uncovered beneath the topsoil and above evidence of occupation which included cooking of early Islamic or later date. Few ceramic or other finds render dating difficult, and thus this collapse is best characterized as mid-eighth century or later in date.

The excavations at House 119 were more extensive; a separate volume will be required — and is planned — to discuss the stratigraphy and findings in full. For the purpose of this study, there are four key trenches: a small north-east room/stable (trench Y.4); a larger stable (trenches Y.7 and Y.8); and the house’s entrance (trench Y.11) (Fig. 11.10).

The house is the only example thus far of a domestic structure built in the Umayyad period; traces of the previous structure(s) were found during excavation, but construction of major features and the latest floors were dated to the Islamic period.32 Oddly, parts of the house seem to be unfinished: there was no floor proper in the entry room (trench Y.11), merely beaten earth, and no evidence of animal use in the mangers and stables (trenches Y.7–Y.8). The excavators concluded that the house was probably never inhabited, likely due to the AD 749 earthquake, and was instead used temporarily or sporadically in the later eighth century (e.g., cooking in trench Y.4), and then reused in the Middle or Late Islamic period. Roof beams directly over bedrock give strong evidence of eighth-century collapse in at least one area.33

That original theory is certainly possible; however, the eighth-century Abbasid occupation determined by the original ceramicist is questionable given the current difficulty of identifying changes in ceramic forms and types until nearer to the ninth century. Furthermore, the traces of cooking and the eighth-century pottery found in the same strata are not necessarily related: cooking pits are notoriously difficult to date because they disturb earlier contexts and material culture from the cooking activity itself is not always left behind. Likewise, the “accumulation in the entry gate of a thick layer of decomposed dung containing Umayyad and Abbasid pottery”34 should not conclusively date the animal use of the space to those periods; twentieth-century dung from other parts of the site, such as in House XVII’s stable, contained older pottery and no finds linked to the period of animal use. The unfortunate truth — for archaeologists — is that material culture is not always left behind with each new use of an area, especially when the activity is brief. In the case of House 119, why the structure was apparently unfinished in the eighth century and when it was in use after that period and for what purposes cannot be conclusively answered.

Excavations at the final domestic structure, House XVII–XVIII, were previously presented in detail;36 therefore, the current discussion will summarize the relevant data. Of the eighteen trenches analyzed over three seasons (1977, 2012, 2014) (Fig. 11.11), the highest concentration by area was House XVIII’s courtyard, where seven trenches were laid out. Here, significant Middle Islamic activity was uncovered: a tabun (trench C.13) and lime dump (trench C.14) are associated with the replastering of the cistern under the house (trench C.2), dated terminus post quem AD 1220.37 In the courtyard trenches, the medieval activity lies directly above a painted plaster eighth-century floor (trench C.14) and over what appears to be a minor collapse (a block and wall plaster) and eighth-century activity (trench C.13). The outside of the oven was reinforced using large, primarily eighth-century pottery pieces. In the east entrance room, trench C.4’s sixth-century floor had Middle Islamic pottery in the layer directly above it, indicating its long-term use as well as a lack of heavy collapse. Other trenches yielded similar results: Middle Islamic pottery appears directly above the sixth/eighth-century floors in most cases (for example, House XVIII’s stable, trenches C.8 and C.17), and only minor instances of collapse that might be dated to the AD 749 earthquake have been identified.

One issue to consider is whether collapse may have been cleared in Middle Islamic times; however, this activity would be unnecessary and thus unlikely. The most intensive Middle Islamic activity was in House XVIII and was based around the need for water rather than on a desire for permanent habitation: both the interior cistern and exterior reservoir were cleaned out at this time, and the sparse ceramic evidence does not suggest long-term occupation.38 The current hypothesis is that Umm al-Jimal was visited on a seasonal or temporary basis during the Middle Islamic period (and no doubt before and after as well), and that this activity was associated with semi-/nomadic society, merchant movement, or the pilgrimage route, especially in Mamluk times. Water collection and use, therefore, appears to be the primary draw of the site after its occupation proper, until its resettlement by the Druze and Mas’eid.39

The excavations at House XVII–XVIII, therefore, do not lend any credence to devastating eighth-century earthquake collapse. Given that there are many interior rooms too choked with collapse to investigate, it is certainly possible that some damage was done; however, the iconic double windows from the third storey of the house, which were only recently stabilized in 2012, are testament to the general strength of the architecture.

31 de Vries 1993.

32 de Vries 1995, 429–30.

33 de Vries 1995, 430.

34 de Vries 1995, 430.

35 de Vries 1995, 430.

36 Osinga 2017, 105–191.

37 Osinga 2017, 125–127.

38 Osinga 2017, 125–127.

39 Osinga 2017, 300.

Assessing the evidence taken from different parts of the site, it is clear that the earthquake did not “destroy” Umm al-Jimal. There may well have been damage, and it may have been a deciding factor for some in whether to leave the site; however, we have not yet uncovered evidence of serious town-wide or even single-building destruction. While an earthquake is never a boon to a site, neither is it necessarily a prelude to its populace relocating. To understand eighth-century Umm al-Jimal, we must examine the overarching social, economic, and environmental context alongside the archaeological evidence.

Alan Walmsley was the first to delve deeply into the socio-economics of north-eastern Jordan, particularly in the sixth and seventh centuries,40 and his work on the economy and society of the region in general in the Late Antique and Early Islamic periods41 remains essential. The fifth and sixth centuries saw a flurry of construction of homes and churches in the badiya, with church building particularly concentrated in the late sixth and early seventh centuries.42 Why, exactly, did these villages flourish during these centuries? The answer is probably a multitude of factors,43 including the Christianization of semi-nomadic tribes, the exploitation of arable land, the need for grain supply both locally and for export as far as southern Arabia,44 the movement of people from cities due to recurring plagues, and the loosening of imperial control.45

That Umm al-Jimal was flourishing in the early seventh century is indisputable: the sixteen churches and over a hundred houses, along with copious ceramics from the sixth and early seventh centuries found in reservoir dumps and associated construction contexts, attest to a steady supply and use of everyday goods. How, why, and when conditions began to change is impossible to pinpoint. The small number of houses excavated combined with the imprecision of pottery dating makes tracing population shifts quite difficult—and perhaps this vagueness is merely a fact we must accept. Nonetheless, examining the regional context sheds light on the general ebb and flow of pressures and changes.

The transition from Byzantium to the Islamic caliphate in the mid-seventh century left scant impact on the region: churches were still remodeled and constructed,46 and at Umm al-Jimal at least two structures were refurbished between the late seventh and early eighth centuries (the Praetorium and House XVIII), and one was constructed (House 119). The so-called Desert Castles of the arid countryside were likely an inspiration for the lavish remodeling of the Praetorium.47 Urban reorganization was also underway, particularly in industrial production, yet there is no clear impact of this economic change on the countryside.48 In general, a robust market economy based on production and exchange is evident at urban sites, where markets and public works were often part of an imperial program; furthermore, the region’s economy was strengthened by Umayyad Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik’s late-seventh-century reforms.49

No doubt a generally favourable socio-economic situation in the eighth century made the earthquake a tempting explanation for what at first appeared to be a sudden and surprising abandonment of Umm al-Jimal and nearby towns and villages; however, it is now clear that the movement of the communities in this region may have been a slow process or occurred in stages, though any precise understanding of these changes is challenging. The fact remains that few other rural settlements in the Hauran — especially those near Umm al-Jimal — have been excavated; in fact, we still do not have a firm understanding of the common ceramics at the closest sites, and whether they reveal similar economic patterns to what is happening at Umm al-Jimal.50 It is impossible to compare in a meaningful manner without data, and therefore for the present we must lean on wider-spread trends.

Three overarching factors that may have affected the population at Umm al-Jimal will be briefly introduced and assessed. First is the impact of plagues, which de Vries51 discussed as a possible culprit of population decline and a reason for the thorough clean-out and reconstruction of House 119 (see Fig. 11.10). Although often referred to as the “Justinianic Plague,” the disease lingered long past the mid-sixth century, recurring over various parts of the Levant (and elsewhere) until the mid-eighth century.52 It is certainly possible that sickness overtook Umm al-Jimal, or parts of it; perhaps studies of skeletal remains from the many cemeteries at the site will shed some light on the issue.53 If parts of the town were ravaged by plague, what evidence could we find of this, apart from mass burials? Would a population decline be identifiable or dateable? At present, the plague’s impact cannot be assessed with the available data.

A second potentially negative impact came with the mid-eighth-century shift of the caliphate’s capital from Damascus to Baghdad, thus decreasing the importance of the north–south highway so near to Umm al-Jimal (see Fig. 11.11). However, Walmsley54 cautions that the region was hardly abandoned by the Abbasids and that many governmental structures remained in place. While the political change was surely not beneficial, there is no evidence that it caused a major break in everyday life or made the north–south trade route suddenly obsolete; goods would, after all, still need to continue to flow in those directions, even if in reduced quantities. Nonetheless, the potential of decreased demand must not be dismissed offhand.

Third, the impact of climate change — its importance noted previously by de Vries55 — should be considered in light of the newest evidence (see Fig. 11.12). Analysis of combined data has shed light on general climatic fluctuations across the region: colder, drier conditions appear to have become more common in the Levant from the later seventh or eighth century.56 Less favourable agricultural conditions do not necessarily precipitate flight from a rural settlement, of course, but they can lead to changes in subsistence strategies, which can impact settled life. In a study of the environmental conditions and settlement history in the region of Abila in northern Jordan,57 the authors argue that increasingly arid conditions led not to the abandonment of the region, but rather a shift from settled farming to nomadism. Such a change is certainly possible at Umm al-Jimal: to the east, the desert has a long history of nomadic activity, though the centuries contemporary to the site have only recently been subject to more intensive study.58 Future work, particularly examining material exchange between sedentary and nomadic communities in north-east Jordan, would begin to bridge gaps in current knowledge and perhaps even create a methodology for identifying nomadic population fluctuations. For now, climate certainly remains an important factor, but we cannot know how and when its impact may have prompted social change.

40 Walmsley 2005; 2007b.

41 Walmsley 2000; 2007a; 2010; 2012.

42 Di Segni 1999.

43 Walmsley 2007b, 337; 2005, 517-518.

44 Sartre 1985, 129-132.

45 de Vries 1998c, 232.

46 Michel 2011.

47 de Vries 2000, 45.

48 Bessard 2013; Walmsley 2007b, 344-349.

49 Walmsley 2000, 270-71, 274-90.

50 This lack of comparative ceramic data from the badiyah prompted the author

to undertake the first detailed ware/fabric study of survey pottery from three sites:

Umm es-Surab, Khirbet es-Samra, and Deir al-Kahf (Osinga 2017, 245-71).

The analysis hints at both strong similarities and potential differences that require further study.

51 Dc Vries 1998c, 240.

52 Little 2007.

53 PhD candidate Jessi Spencer (Southern Illinois University) is in the process of analysing some of the skeletal remains.

Sa Walmsley 2000, 271.

55 Dc Vries 1998c, 239-40.

56 McCormick and others 2012, 201-02, 217-19.

57 Lucke and others 2012.

58 Akkermans 2020; Huigens 2019.

While the AD 749 earthquake may have caused destabilization of some structures and collapse of certain features at Umm al-Jimal (e.g. parts of the Numerianos Church), the archaeological record reveals no significant destruction that can be conclusively and solely dated to the mid-eighth century. In large part due to the inability to separate mid- and later eighth-century pottery, as well as a lack of coin-secured deposits or other chronologically significant finds, it is not possible to finely date the settled population’s abandonment of the site. Yet by drawing upon a spatially wide range of archaeological investigations across the site, patterns in the data nonetheless emerge, showing that the great earthquake is not a simple scapegoat for what was surely a complicated political, environmental, and/or socio-economic process of change.

At present, we simply cannot characterize or date the departure of the sedentary populace from Umm al-Jimal, other than to state that it almost certainly occurred prior to the ninth century. Whether this abandonment was a slow or fast process and what the underlying causes were must remain open to discussion. Although the intricacy of socio-economic and historical change is oftentimes confusing and frustrating, it should never be simplified. Tidy answers make for succinct signage and easy dissemination of information, but they rarely reflect the complex, shifting nature of archaeological interpretation and analysis. As we build a better understanding of the local and regional context, and as work at Umm al-Jimal progresses, the narrative must continue to be revisited and refined.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Barracks

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the castellum Drawn by Bert de Vries de Vries (1993) |

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls. Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

Northeast Church |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Barracks

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the castellum Drawn by Bert de Vries de Vries (1993) |

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls. Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

the Roman Temple (erroneously named the “Nabataean Temple” by Howard Butler), which was later converted into a domestic structure, known as House 49 |

|

|

|

Numerianos Church complex |

|

|

|

House XIV |

|

|

|

House 119 |

|

|

|

House XVII–XVIII |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barracks

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the castellum Drawn by Bert de Vries de Vries (1993) |

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls. Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

Northeast Church |

|

|

Kázmér et al. (2024:33) estimated a local intensity of VII (7).

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barracks

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Plan of the castellum Drawn by Bert de Vries de Vries (1993) |

Plate 2.3

Plate 2.3Umm al-Jimal: general view of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Plate 3.1

Plate 3.1Umm al·Jimal: detail of the west facade of the Barracks Photo A. Walmsley de Vries (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Umm al-Jimal. Barracks: view of the western towers from the courtyard. The U-shaped collapse scar of the third-floor wall is a typical mark of seismic shaking. Note the rotated block on the right side of the scar and the twisted wall on the left side of the photo: these are further indicators of lateral loading, twisting, and collapse of walls. Kázmér et al. (2024)

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3Umm al-Jimal. Barracks, western wall. Note the twisted walls below the U-shaped collapse feature. The wall closer to the viewer is tilted inwards, the farther one is bulging outwards. These are clear markers of repeated, strong lateral loading Kázmér et al. (2024) |

|

|

|

the Roman Temple (erroneously named the “Nabataean Temple” by Howard Butler), which was later converted into a domestic structure, known as House 49 |

|

|

|

|

Numerianos Church complex |

|

|

|

|

House XIV |

|

|

|

|

House 119 |

|

|

|

|

House XVII–XVIII |

|

|

Al-Tawalbeh et al (2019) estimated a SW-NE strong motion direction and intensities of VII-VIII (7-8) using the Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224).

Kázmér et al. (2024:33) estimated a local intensity of IX (9).

Al-Tawalbeh, M. A.., Rasheed Jaradat, Abdulla al-Rawabdeh, Khaled al-Bashaireh, Anne Gharaibeh, Bilal al-Khrisat (2019).

The Roman Barracks at Umm el-Jimal, Northern Jordan: an Archaeoseismological Analysis.

Conference: Routes, Goods, and Ties; Recent Discoveries and Problems of Southern Levantine Archaeology. Karakow, Poland.

de Vries, B. (1993) The Umm el-Jimal Project:1981-1992

de Vries, B. (1995) The 1993 and 1994 Field Seasons at Umm al-Jimal

de Vries, B. (2000). "Continuity And Change In The Urban Character Of The Southern Hauran From The 5th To The 9th Century:

The Archaeological Evidence At Umm Al-Jimal." Mediterranean Archaeology 13: 39-45.

Kázmér, M., Major, B., Al-Tawalbeh, M., Gaidzik, K. (2024). Destructive Intraplate Earthquakes in Arabia—The Archaeoseismological Evidence

. In: Abd el-aal, A.ea.K., Al-Enezi, A., Karam, Q.E. (eds) Environmental Hazards in the Arabian Gulf Region. Advances in Natural

and Technological Hazards Research, vol 54. Springer, Cham..

Littmann, E. et. al. (1913) Greek and Latin Inscriptions in Syria Section A Part 3 Umm idj-Djimal, Brill, Leiden

Osinga E.A. (2025) Chapter 11. Rewriting the Narrative: Umm al_Jimal and the AD 749 Earthquake

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis

Butler, Howard Crosby. Ancient Architecture in Syria. Publications of

the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, 1904 -

190 5 and 1909 , Division II. Leiden, 1913 . See Sectiun A (Southern

Syria), part 3 : "Umm Idj-Djimal."

Corbett, G. U. S. "Investigations at 'Julianos' Church' at Umm elJimal." Papers of the British School at Rome 2 5 (1957) : 39-65 .

de Vries, Bert. "The Umm el-Jimal Project, 1972-77. " Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan 2 6 (1982) : 97-116 . Also published

in Bulletin of the American Schoots of Oriental Research, no. 24 4 (1981) :

53-72 .

de Vries, Bert. "Umm el-Jimal in the First Three Centuries A.D." In

The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East, edited by Philip Freeman and David L. Kennedy, pp. 227-241 . British Archaeological

Reports, International Series, no. 297 . Oxford, 1986 .

de Vries, Bert. "The Umm el-Jimal Project, 1981-1992. " Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan 3 7 (1993) : 433-460 .

de Vries, Bert. "What's in a Name? The Anonymity of Ancient Umm

el-Jimal." Biblical Archaeologist 5 7 (1994) : 215-219 .

de Vries, Bert. Umm el-Jimal: A Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic

Town in Northern Jordan. Ann Arbor, 1995 .

de Vries, Bert. "The Umm el-Jimal Project, 199 3 and 199 4 Field Seasons." Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 3 9 (1995) .

Glueck, Nelson. Explorations in Eastern Palestine. Vol. 4 . Annual of the

American Schools of Oriental Research, 25 . New Haven, 1951 . See

"Eastern Syria and die Southern Hauran" (part 1 , pp. 1-34) .

Horsfield, George. "Umm el-Jamal." Antiquity 11 (1937) : 456-460 , pis.

1-4 .

Kennedy, David L., and Derrick N. Riley. Archaeological Explorations

on the Roman Frontier in North-East Jordan. British Archaeological

Reports, International Series, no. 134 . Oxford, 1982 .

Littmann, Enno, et al. "Greek and Latin Inscriptions." In Syria: Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria,

Division III, Section A, Part 3 , Umm Idj-Djimdl, pp. 131-223 . Leiden, 1913 .

Littmann, Enno. "Nabatean Inscriptions." In Syria: Publications of the

Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, Division IV,

Section A, Umm Idj-Djimdl, pp. 34-56 . Leiden, 1914 .

Littmann, Enno. "Safaitic Inscription." In Syria: Publications of the

Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, Division IV,

Section C, Part 3 , Umm Idj-Djimal, pp. 278-281 . Leiden, 1943 .

Littmann, Enno. "Arabic Inscriptions." In Syria: Publications of the

Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria, Division IV,

Section D, Umm Idj-Djimal, pp. 1-3 . Leiden, 1949 .

MacAdam, Henry I. Studies in the History of the Roman Province of

Arabia: The Northern Sector. British Arch

B. de Vries, Umm el-Jimal: A Frontier Town and its Landscape in Northern Jordan,

1: Fieldwork 1972–1981 (JRA Suppl Series 26), Portsmouth, RI 1998

ibid. (Reviews) Antiquite Tardive 7

(1999), 431–436. — BASOR 333 (2004), 91–92.