Hammath Tiberias

Hammath Tiberias

Hammath Tiberiasclick on image to explore this site on a new tab in govmap.gov.il

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Hammath Tiberias | Hebrew | חמת טבריה |

The remains of Hammath Tiberias extend from the hot springs (el-Hammam) to the southern boundary of ancient Tiberias, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. In the Talmud, the place is identified with Hammath (Joshua 19:35), a fortified city of the tribe of Naphtali:

"Hammath-Hammatha" (J.T., Meg. 1, 70a)This identification is not certain, however, because the excavations and a survey of the Hammath area uncovered no remains earlier than the Hellenistic period. Hammath is mentioned many times in the Mishnah. Tiberias and Hammath were originally two separate cities, each surrounded by a wall of its own

"Rabbi Jeremiah said ... from Hammath to Tiberias - a mile" [J.T., Meg. 2:1-2])Subsequently, however, they were united, apparently in the first century CE:

"Now the children of Tiberias and the children of Hammath again became one city." (Tosefta, 'Eruv. 7:2)In the liturgical sources (Mishmarot 24), Tiberias was known as Ma'uziah after the priestly order that had settled in Hammath. Tiberias was forbidden to the priests because it contained a cemetery. When Tiberias became the seat of the Great Yeshiva and the Sanhedrin in the third century CE, and the spiritual center of the Jews of Palestine and the Diaspora, the suburb of Hammath shared its prominence. With the abolition of the patriarchate in about 429 CE, Hammath began to decline, but it continued to exist as a city, supporting itself with its profitable hot springs. The Jewish community remained in the city throughout the Arab period until its decline in the Middle Ages.

Two excavations have been carried out at the site. The first was undertaken in 1921 (two seasons) under the supervision of N. Slouschz. It was the first excavation by a Jewish resident of the country and the first on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Society and the Department of Antiquities. The second (two seasons in 1961-1962 and 1962-1963), under M. Dothan, assisted by I. Dunayevsky and S. Moskowitz, was on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities. The site was earlier explored by the Mandatory Department of Antiquities in 1947.

About 500 m north of the city's southern wall, Slouschz uncovered a synagogue in the form of a square basilica (12 by 12m), divided by two rows of columns into a nave and two aisles. The three entrances to the building were on the north. East of the building was a courtyard that was entered from the east, and from there a doorway led to the eastern aisle. At the southern end of the nave was a partition consisting of four small columns. The enclosed area behind it probably held the Ark of the Law. In the eastern aisle stood the "seat of Moses" (cathedra). The various levels of pavements, the mosaics, and the alterations in the structure indicate that there were several phases in the construction. However, the excavators did not succeed in tracing them. In the opinion of L. H. Vincent, there were two building phases. In the first, the entrance to the building was on the south, facing Jerusalem. Two building phases are also confirmed by the pavements, one of which is a stylized mosaic.

S1ouschz identified the synagogue with the kenishta de-Hammatha (synagogue of Hammath) mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud (Sot. 1, 16d), and assigned it to the Early Roman period. Vincent, however, disputed this identification, on the basis of a comparison with other ancient synagogues and the building's small size. In his opinion the main, late phase of construction should be attributed to the fourth to fifth centuries CE. Synagogue research since Slouschz's identification attributes this synagogue, which lacks an apse but whose entrance (according to Dothan) faces Jerusalem, to the fourth century CE. Near the synagogue the excavators uncovered part of a cemetery containing sarcophagi from the third and fourth centuries CE with the names of the deceased written in Greek - Isidorus, Symmachus son of Justus (SEG VIII, nos. 9-11) - as well as several graves dating from the Early Arab period. Among the finds are a capital decorated with a menorah, a fragment of a chancel screen with a menorah in relief, and a seven branched menorah carved in limestone. In addition to Slouschz's investigations, M. Narkiss and Z. Eshkoli published architectural details and a number of objects found in the synagogue and its vicinity.

An area of approximately 1,200 sq m was excavated near the hot springs, about 150 m west of the Sea of Galilee. The ancient buildings had been erected on an artificial terrace running parallel to the seashore from southeast to northwest, closely following the contours of the terrain. Beyond the southern limit of the main excavation area the remains of the city wall and one of its towers were uncovered. These were found to date not earlier than the Byzantine period, although they appear to rest on the remains of walls of an earlier city.

Three main construction levels were revealed, dating from the first century BCE to the eighth century CE. The numismatic evidence showed that remains from the first century BCE lay beneath level III.

The prominent features of the southern synagogue may be summarized as follows.

- At Hammath several superimposed synagogue buildings were found, beneath which was a public building whose function is not clear. The synagogues were built from the fourth to the middle of the eighth centuries.

- A unique type of synagogue was uncovered here-a broadhouse with four rooms (IIA, B). The entrance was on the side facing Jerusalem (IIB) and there was a permanent place for the Ark of the Law in a rectangular room that preceded the apse in Palestinian synagogues (IIA).

- The mosaic pavement in synagogue IIB was constructed in the spirit of the Hellenistic-Roman art of the fourth century. The zodiac depicted in the mosaic is the earliest found in the country.

- The Greek inscriptions referring to this synagogue's builders are the first to mention the patriarchs of the Sanhedrin. They contribute greatly to what is known about Judaism in the fourth century CE in Tiberias.

- The uppermost synagogue (IA) is an instructive example of Jewish architecture at the beginning of Arab rule in Palestine. It sheds light on the customs practiced in synagogues then.

- from Tiberias - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Annotated Satellite View

of Tiberias and environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Google Map of Tiberias and environs

Annotated Google Map of Tiberias and environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Satellite View

of Hammath Tiberias from biblewalks.com

Annotated Google Map of Hammath Tiberias

Annotated Google Map of Hammath Tiberias

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Hammath Tiberias in Google Earth

- Hammath Tiberias at govmap.gov.il

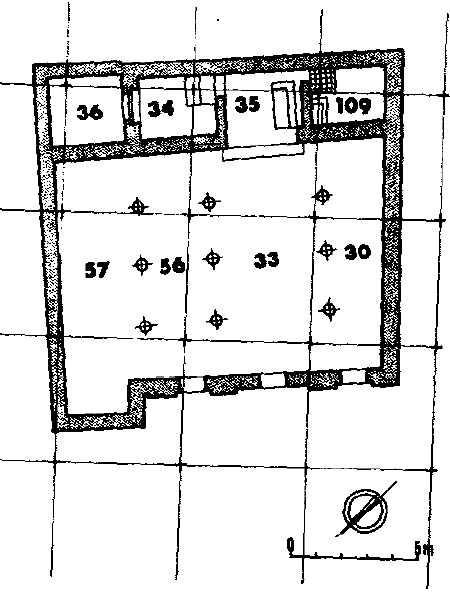

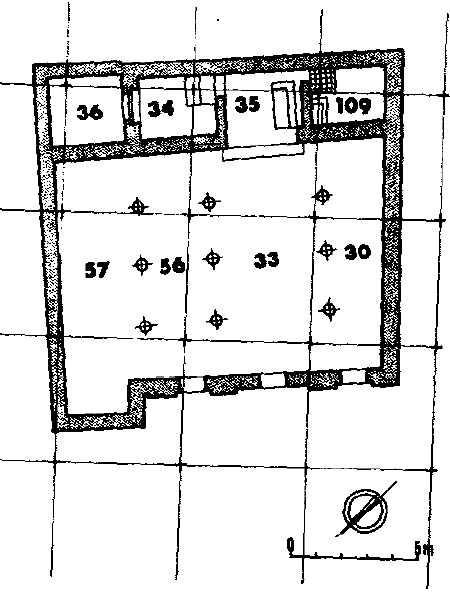

- Plan of synagogue IIA

from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Hammath-Tiberias: plan of synagogue IIA

Hammath-Tiberias: plan of synagogue IIA

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Plan of synagogue IIA

from Magness (2005:9)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plan of the Stratum IIa synagogue ("Synagogue of Severos"), Hammath Tiberias

(reproduced by permission of the Israel Exploration Society)

Magness (2005:9) - Fig. 1B Plan of synagogue IIA

by Dothan from Weiss (2009)

Fig. 1B

Fig. 1B

Hammath Tiberias. Plan of the Stratum IIa synagogue according to M. Dothan (1983, plan C and D, 22, 28)

Weiss (2009) - Fig. 5A Plan of synagogue IIA

as reconstructed by Weiss from Weiss (2009)

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5A

Author's proposed reconstruction of Hammath Tiberias, Stratum IIa

Weiss (2009) - Fig. 6 3D proposed reconstruction

of synagogue IIA by Weiss from Weiss (2009)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Three-dimensional proposed reconstruction of of the Stratum IIa synagogue (the "Severos Synagogue")

Weiss (2009)

- Plan of synagogue IIA

from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Hammath-Tiberias: plan of synagogue IIA

Hammath-Tiberias: plan of synagogue IIA

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Plan of synagogue IIA

from Magness (2005:9)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plan of the Stratum IIa synagogue ("Synagogue of Severos"), Hammath Tiberias

(reproduced by permission of the Israel Exploration Society)

Magness (2005:9)

- Fig. 1A Plan of synagogue IIB

by Dothan from Weiss (2009)

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1A

Hammath Tiberias. Plan of the Stratum IIb synagogue according to M. Dothan (1983, plan C and D, 22, 28)

Weiss (2009) - Fig. 5B Plan of synagogue IIB

as reconstructed by Weiss from Weiss (2009)

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5B

Author's proposed reconstruction of Hammath Tiberias, Stratum IIb

Weiss (2009)

- Remains of synagogues I

and II from Dothan (1968) and Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Remains of synagogues II and I, looking west

Remains of synagogues II and I, looking west

JW: photo comes from Fig. 2 of Dothan (1968) while caption comes from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

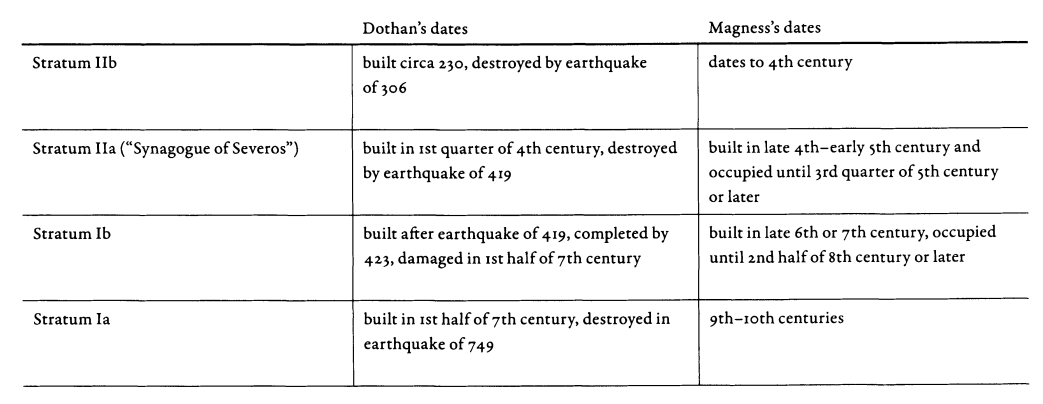

- from Magness (2005)

The chronology of the four synagogue buildings at Hammath

Tiberias (from bottom/earliest to top/latest)

The chronology of the four synagogue buildings at Hammath

Tiberias (from bottom/earliest to top/latest)Magness (2005)

| Level | Start Date | End Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beneath III | 1st century BCE ? | 1st century BCE ? |

Description

The numismatic evidence showed that remains from the first century BCE lay beneath level III |

| III | 1st or 1st half of 2nd century CE |

Description

The main building (60 by 40 m) in level III dates from the first century or first half of the second century CE. This building, only half of which was excavated, consists of a central court with halls and rooms along at least three of its sides. Two entrances to the building were found on the south side. Its plan resembles that of a public building, such as a gymnasium, and it may have already been a synagogue in that early period. All the later structures (above the building), except perhaps those of the intermediate phase III-II, were synagogues. Among the meager finds from this building is a unique glass goblet in the shape of acantharus, silvered on the inside and outside and decorated with floral reliefs below the rim. Level Ill seems to have been destroyed in the middle of the second century, and the few remains above it (intermediate phase III-II) do not appear to belong to a public building. |

|

| IIB-A | IIA - 1st half of the 4th century CE | IIA - 5th century CE |

Description

The synagogue in level II

was erected on these remains. The last

stage of the synagogue (IIA), which

was the better preserved, is based, for

the most part, on the earlier phase, IIB. It is a broadhouse (15 by 13 m),

oriented southeast to northwest, and is separated from the structures around

it. Three rows of columns, each containing three columns, divide the building

into four halls, the widest of which (the second from the west) is the nave.

Attached to the building on the south is a corridor paved with mosaics with an

entrance on the east. Although no other entrances to the building are preserved, there may have been more than one. On the north side of the building

was a room that may have contained stairs leading to the roof or to a second

story. |

| IB-A | beginning of the reign of the Umayyads | beginning of the Abbasid period |

Description

The new synagogue, IB, was oriented in the same direction as its

predecessors. Unlike them, however, it was not isolated from the other buildings, which were attached to it on the north and south, whereas streets skirted

the building on the east and west. The synagogue was built in the form of a

basilica, as was common in synagogue and church construction in the fifth

and sixth centuries CE. It was divided by two rows of columns into a nave and

two aisles. A third row of columns divided the nave transversely, thus creating

an entrance hall (pronaos). The three rows of columns supported a gallery on

the second story that ran along three sides of the building. The three main

entrances were on its north side. Three steps led from the nave to an interior

apse. East of the apse was a room with stairs ascending to the second story; to

the west was another room, where the synagogue's "treasury" was hidden in

the floor. From the western aisle, three doorways opened onto a courtyard

paved with flagstones. Its walls are well preserved. A small apse was discovered

on the southern side of the courtyard and beyond it were plastered rooms that

had served as cisterns (mikvehs ?). The mosaic in the hall was made of tiny

colored tesserae; the preserved fragments indicate that it depicted figures of

animals in addition to geometric and floral designs. Level IB was apparently

destroyed in the first half of the seventh century, perhaps when the Byzantines

reconquered the country from the Persians. The new synagogue (level IA),

probably built at the beginning of the reign of the Umayyads, is not markedly

different from its predecessor except that the small apse was no longer in use.

Part of the courtyard was covered with a roof, supported by a column, thus

creating a room in which one of the stairs of the apse was used as a bench. This

may have served as a beth midrash, or study hall. A new mosaic pavement was

laid that was decorated mainly with geometric designs, but at the entrance to

the nave there were other motifs, such as a menorah. The rich finds included

pottery of the type found at Khirbet el-Mafjar and many clay lamps, some

bearing Arabic inscriptions. A long Aramaic inscription on a jug has been

partly deciphered. It concerns a gift of oil from Sepphoris. |

Dothan, M. (1968) The Synagogues at Hammath-Tiberias,

Qadmoniot: A Journal for the Antiquities of Eretz-Israel

and Bible Lands 4 (1968): 116–123 (Hebrew) – at JSTOR

Jones, I. W. N. (2021) The southern Levantine earthquake

of 418/419 AD and the archaeology of Byzantine Petra,

Levant: 1–15

Jones, I. W. N. (2021) The southern Levantine earthquake

of 418/419 AD and the archaeology of Byzantine Petra,

Levant: 1–15 – open access

Magness, J. (1997) Synagogue typology and earthquake

chronology at Khirbet Shemaʿ, Israel, Journal of Field

Archaeology 24(2): 211–220 – at JSTOR

Magness, J. (2005) Heaven on earth: Helios and the

zodiac cycle in ancient Palestinian synagogues,

Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59: 1–52 – open access at

archive.org

Magness, J. (2007) Did Galilee decline in the fifth

century? The synagogue at Chorazin reconsidered, in

Zangenberg, J., Attridge, H. W., and Martin, D. B.

(eds.), Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient

Galilee: A Region in Transition, 259–274. Tübingen:

Mohr Siebeck

Magness, J. (2012) The pottery from the village of

Capernaum and the chronology of Galilean synagogues,

Tel Aviv 39(2): 110–122

Weiss, Z. (2009) Stratum II at Hammath Tiberias:

Reconstructing Its Access, Internal Space, and

Architecture, in A Wandering Galilean: Essays in

Honour of Sean Freyne, ed. Z. Rodgers et al.,

321–342. Leiden: Brill

Weiss, Z. (2021) Innovations in the Study of

Synagogues in Tiberias and Hammat, Qadmoniot

162 (2021): 70–77 (Hebrew) – at JSTOR

Dothan, M. (1968) The Synagogues at Hammath-Tiberias,

Qadmoniot: A Journal for the Antiquities of Eretz-Israel

and Bible Lands 4 (1968): 116–123 (Hebrew) – at JSTOR

Dothan, M. (1981) The Synagogue at Hammath-Tiberias,

in L. I. Levine (ed.), Ancient Synagogues Revealed,

Jerusalem: 63–69

Dothan, M. (1983) Hammath Tiberias: Early Synagogues,

Jerusalem

Dothan, M. (1993) Hamat Teveriya, in E. Stern (ed.),

The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in

the Holy Land, 573–577 – open access at archive.org

Dothan, M. and Johnson, B. L. (2000) Hammath Tiberias:

The Late Synagogues, Jerusalem

Milson, D. (2004) The Stratum IB Building at Hammat

Tiberias: Synagogue or Church?, Palestine Exploration

Quarterly 136(1): 45–46

Spigel, C. S. (2012) Ancient Synagogue Seating

Capacities, Tübingen: 215–227

Weiss, Z. (2009) Stratum II at Hammath Tiberias:

Reconstructing Its Access, Internal Space, and

Architecture, in A Wandering Galilean: Essays in

Honour of Sean Freyne, ed. Z. Rodgers et al.,

Leiden: Brill, 321–342

Weiss, Z. (2021) Innovations in the Study of Synagogues

in Tiberias and Hammat, Qadmoniot 162 (2021): 70–77

(Hebrew) – at JSTOR

L. H. Vincent, RB30(1921), 438-442; 31 (1922), 115-122

Goodenough, Jewish Symbols 1,

214-216

B. Lifshitz, ZDPV78 (1962), 180-184

id., Journal for the Study of Judaism 4 (1973), 43-45;

M. Dothan, IEJ\2 (1962), 153-154

id., RB 70 (1963), 588-590

id., ASR, 63-69

id., Hammath Tiberias

(Reviews), BAR 10/3 (1984), 32-44.-IEJ 34 (1984), 284-288. -JAOS 104 (1984), 577-578.- Syria 62

(1985), 362-364.- Bibliotheca Orientalis45 (1988), 401-402

Hiittenmeister-Reeg, Antiken Synagogen 1,

436-461

Archives of Ancient Jewish Art: Samples and Manual (eds. Y. Yadin and R. Jacoby), Jerusalem

1984, 1-38

D. Milson, LA 37 (1987), 303-310.

E. D. Oren, Archaeology 24 (1971), 274-277

id., IEJ 21 (1971), 234-235

id., RB 78

(1971), 435-437.

M. Dothan & B. L. Johnson, Hammath Tiberias, II: Late Synagogues, Jerusalem 2000

ibid. (Reviews) Bibliotheca Orientalis 58 (2001), 659–660. — The Roman and Byzantine Near East, 3,

Portsmouth, RI 2002, 253–260.

E. Dvorjetski, Aram 4 (1992), 425–449

13–14 (2001–2002), 485–512

id., Medicinal Hot Springs

in Eretz-Israel during the Period of the Second Temple, the Mishna and the Talmud (Ph.D. diss.), Jerusalem

1993 (Eng. abstract)

id., Latomus 56 (1997), 567–581

id., Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the

1st International Conference on Roman Baths, Bath, 30.3–4.4.1992 (JRA Suppl. Series 37

eds. J. Delaine

& D. E. Johnston), Portsmouth, RI 1999, 117–129

id. (et al.), Stories from a Heated Earth: Our Geothermal Heritage (eds. R. Cataldi et al.), San Diego, CA 1999, 34–49

G. A. Herion, ABD, 3, New York 1992,

37–38

Y. Hirschfeld, A Guide to the Antiquities Sites in Tiberias, rev. ed., Jerusalem 1992

Z. Weiss, EI 23

(1992), 156*–157*

H. Shanks, BAR 19/4 (1993), 22–31

S. Stern, Le’ela 38 (1994), 33–37

E. J. Stern,

‘Atiqot 26 (1995), 57–59

D. L. Gordon, OEANE, 2, New York 1997, 470–471

L. J. Ness, Journal of Ancient

Civilization 12 (1997), 81–92

id., Astrology and Judaism in Late Antiquity (Ph.D. diss., Miami 1990), Ann

Arbor, MI 1998

L. A. Roussin, Archaeology and the Galilee: Texts and Contexts in the Graeco-Roman and

Byzantine Periods (South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism 143

eds. D. R. Edwards & C. T. McCollough), Atlanta, GA 1997, 83–96

id., BAR 27/2 (2001), 52–56

H. Mack, Cathedra 88 (1998), 180–181

D.

Amit, From Dura to Sepphoris, Portsmouth, RI 2000, 231–234

Y. Englard, Cathedra 98 (2000), 172–173;

L. I. Levine, Jewish Culture and Society Under the Christian Roman Empire (Interdisciplinary Studies in

Ancient Culture and Religion 3), Leuven 2003, 91–131

J. Magness, Symbiosis, Symbolism and the Power

of the Past, Winona Lake, IN 2003, 363–389, 553–554

S. S. Miller, JQR 94 (2004), 27–76

D. Milson, PEQ

136 (2004), 45–56.

Jones (2021) reports that evidence for the Monaxius and Plinta Earthquake of 419 CE has been reported in Stratum IIa of the synagogue at Hammath Tiberias. Jones (2021) also reports that Magness has disputed archaeological evidence for this earthquake at the Synagogue in Hammath Tiberias and other sites in the Galilee (1997: 217-18; 2005: 8-10; 2007: 271-72; 2012: 113-14).