Mount Nebo

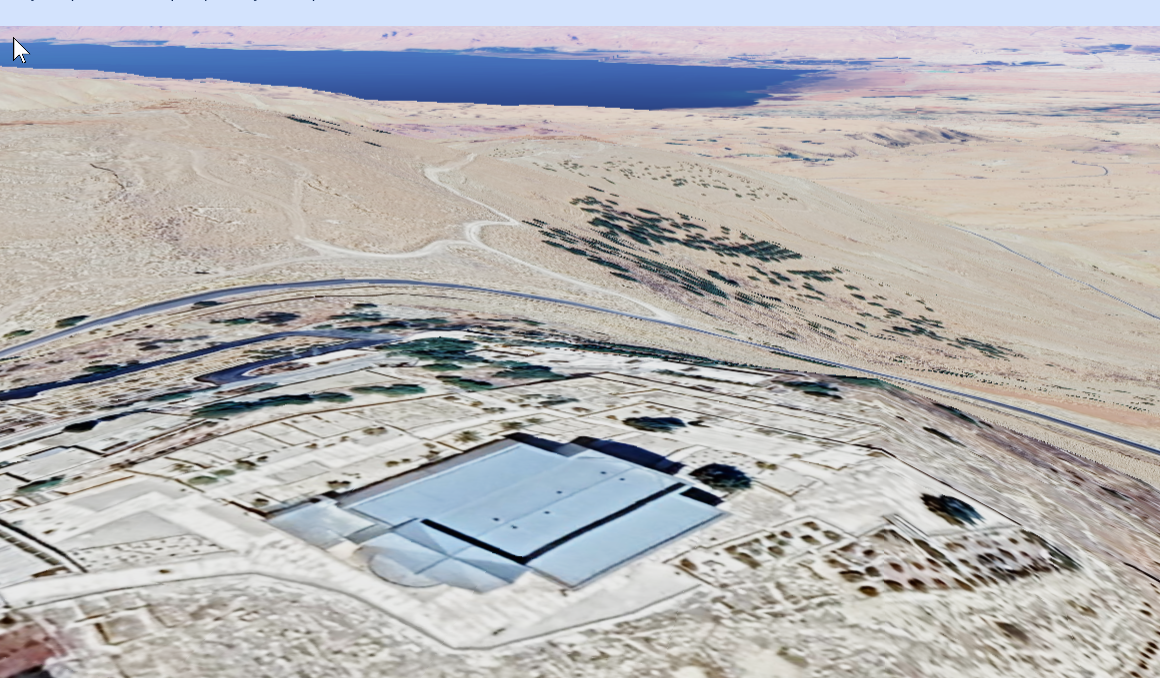

Aerial Viw of Mount Nebo

Aerial Viw of Mount Neboclick on image to open in a new tab

APAAME

Reference: APAAME_20240305_FB-0403

Photographer: Firas Bqa'in

Credit: APAAME

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Mount Nebo | English | |

| Jabal Nibu | Arabic | جَبَل نِيْبُو |

| Har Nevo | Hebrew | הַר נְבוֹ |

| Pisgah | Hebrew Bible | פִּסְגָּה |

| Fasga | Arabic | فاسعا |

| Jabal Siyāgha | Arabic | جابال سيياعها |

| Rās as-Siyāgha | Arabic | راس اسءسيياعها |

| Rujm Siyāgha | Arabic | روجم سيياعها |

| Jabal Nabo | local bedouin | جابال نابو |

| Jabal Musa | local bedouin | جابال موسا |

Mount Nebo is famous as the location where in the 34th chapter of Deuteronomy Moses climbed its peak to view the promised land before passing away. Only ~ 7km. from Madaba, it provides a commanding view of the Dead Sea, Judah, and Samaria. The ridge of Mt. Nebo has been inhabited since remote antiquity, as the dolmens, menhirs, flints, tombs, and fortresses from different epochs testify (Michelle Piccirillo in Meyers et al, 1997). Several churches and a monastery were built there in the Byzantine era.

Mount Nebo rises from the Transjordanian plateau 7 km (4 mi.) west of the town of Medeba (Madaba). It is bounded on the east by the Wadi 'Afrit (which extends into the Wadi el-Judeideh, the Wadi el-Keneiseh, and the Wadi el-Hery farther south) and on the north by the Wadi Abu en-Naml, which extends into the Wadi 'Uyun Musa to the west. Mount Nebo's highest crest reaches an altitude of 800 m above sea level. The other peaks are slightly lower. Of these, the two most historically important are the western peak of Siyagha and the southern peak of el-Mukhayyat. Nebo provides a unique natural balcony fora spectacular view of the Jordan Valley and the mountains of Judea and Samaria. The ridge of Mount Nebo was inhabited in remote antiquity, as dolmens, menhirs, flints, circles, tombs, and fortresses of different epochs testify. However, its real fame is derived from the events described in the Book of Deuteronomy 34:1-7: the final vision and death of Moses.

The Bible also associates the following events with Mount Nebo or its immediate vicinity: the passage and camp of the Israelites (Num. 21:20 ff., 33:47 ff.); the story of Balak and Balaam (Num. 23:13-26); and the concealment of the tabernacle, the ark, and the altar of incense in a cave (2 Mace. 2:4-8). From these geographical texts, it is known that Mount Nebo, part of the Abarim mountain range, was located east of the Jordan River, opposite Jericho. It was also known as Pisgah:

And Moses went up from the plains of Moab to Mount Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, which is opposite Jericho. And the Lord showed him all the land .... So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of the Lord, and he was buried in the valley in the land of Moab opposite Beth-Peor, but no man knows the place of his burial to this day (Dt. 34: 1-7)In the Bible, as in the stela of Mesha, king of Moab, Nebo is listed among the cities in the land of Moab, in the territory of Medeba (Num. 32:3, 32:38; 33:47; 1 Chr. 5:8; Is. 15:2; Jer. 48:1, 48:22; 1 Mace. 9:37). King Mesha conquered the town, killed the inhabitants, and "took from thence the vessels of Yahweh and dragged them before Chemosh" (lines 14-18). Mount Nebo, as a sanctuary dedicated to Moses, was known by scholars and visited by Byzantine pilgrims. In the fourth century CE, Eusebius, in the Onomasticon, wrote:

Nabau, which in Hebrew is called Nebo, is a mountain beyond the Jordan, in front of Jericho in the land of Moab, where Moses died. Until this day it is indicated at the sixth milestone of the city o fEsbous [which lies to the east.The Roman pilgrim Egeria (late fourth century CE) and the bishop of Maiumas in Gaza, Peter the Iberian (fifth century CE), relate in great detail their visits to the Memorial Church of Moses on Mount Nebo in Arabia. Egeria, after having crossed the Jordan on her way from Jerusalem, had stayed at Livias and then took the road to Esbous. At the sixth mile, she took a turn to the Springs of Moses and from there climbed to the summit of Mount Nebo. The bishop took the same road in search of a cure for his afflictions. After bathing in the hot Springs of Moses, with little benefit because the springs were not very hot, the party continued on its way to the hot springs of Baaru, where the waters were much hotter and more curative. The journey offered Bishop Peter and his companion the opportunity to stop at the sanctuary of Moses, where he had visited as a youth, before his conversion to Christianity (Life 82-85).

The pilgrim Theodosius (early sixth century) relates that not far from the city of Livias, east of the Jordan River, pilgrims could visit "the water made to flow from the rock, the place of Moses' death, and the hot springs of Moses where lepers come to be cured." The pilgrim of Piacenza (late sixth century) adds: "From the Jordan to the place where Moses died, it is eight miles." The survival of the name of Nebo in the region was discovered in 1838 by E. Robinson and E. Smith. It was only in 1864 that the French explorer Le Due de Luynes visited and described the important ruins covering the spur of Siyagha 9 km (5.5 mi.) west ofMedeba, overlooking the Jordan Valley. As a result of diligent research among the Bedouins in the area, it became known that the mountain was also called Jebel Nebo and Jebel Musa because of its proximity to Wadi 'Uyun Musa, on the northern slope of the mountain. The discovery in Arezzo (Italy) of Egeria's memoirs, published by F. Gamurrini of the University of Rome in 1886, and the subsequent discovery of the Syriac biography of Peter the Iberian in 1895, were decisive in the historical identification of the Memorial of Moses visited by pilgrims with the ruins on Siyagha, the western spur of the mountain. Archaeological survey and excavations have shown that an Iron Age fortress was located on the southern spur of el-Mukhayyat, and that the site was inhabited almost continuously until the Umayyad period. This justifies the historical identification proposed by scholars of the town of Nebo with the ruins of el-Mukhayyat.

H. B. Tristram, in 1872, was the first to visit the ruins of el-Mukhayyat, although the name had already been recorded in 1863 by F. de Saulcy. Members of the American Palestine Exploration Society visited Mount Nebo in 1873, led by E. Z. Steever, and in 1875, led by S. Merrill. In 1881, Mount Nebo was surveyed by the British Palestine Exploration Fund, under the direction of C. R. Conder. The flora and fauna of the mountain were studied in 1886 by G. E. Post. In 1891, G. Schumacher attempted to identify the ruined buildings on Siyagha. In 1901, A. Musil paid a number of visits to Siyagha and surveyed the ruins at el-Mukhayyat. He was the first to propose the identification of the place with the town ofNebo. The Dominican Fathers P. Janssen and R. Savignac visited the ruins of el-Mukhayyatin in 1907. There, in 1913, the mosaic floor of the Church of Saints and Martyrs Lot and Procopius was identified. It was published in 1914 by F. M. Abel. N. Glueck visited el-Mukhayyat in 1934.

The decision of S. J. Saller of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum to excavate the ruins of the Memorial of Moses prompted the superiors of the Custody of the Holy Land to purchase the spurs of Siyagha and elMukhayyat. In 1933, the Franciscan archaeologists began their exploration of the site. Three long campaigns at Siyagha-directed by Saller in 1933, 1935, and 1937-resulted in the discovery of the basilica and of a large monastery that had developed around the sanctuary in the Byzantine period. Three churches were also excavated at Khirbet el-Mukhayyat. In 1962, J. Ripamonti of the University of Caracas undertook a systematic study of the necropolis at el-Mukhayyat and excavated a small monastery (el-Keneiseh) and an Iron Age tower east ofthe ruins. Pottery found in the tombs and subsequently studied by Saller furnished excellent points of reference for developing a chronological sequence of habitation at the Mukhayyat Monastery on Siyagha hill: fragments of a Samaritan inscription. site. In 1963, the modern restoration of the Memorial of Moses was assigned to V. Corbo, who began with the mosaic floors inside the basilica. In 1976, the project was assigned to M. Piccirillo, who was later joined by E. Alliata. Work continues on the restoration of the main historic monument and one the exploration of the mountain's other antiquities.

- Mount Nebo and environs in Google Earth

- Aerial View of Mt. Nebo in Google Earth

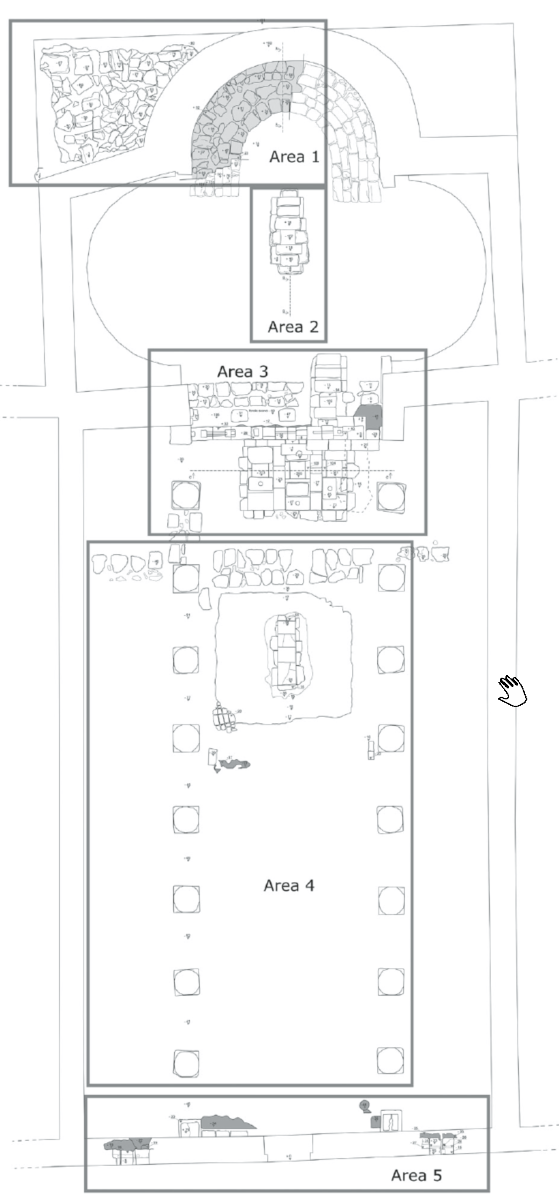

- Fig. 2 Excavation Zones

from Bianchi (2019)

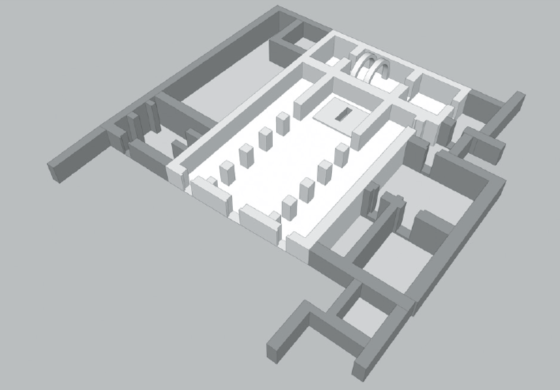

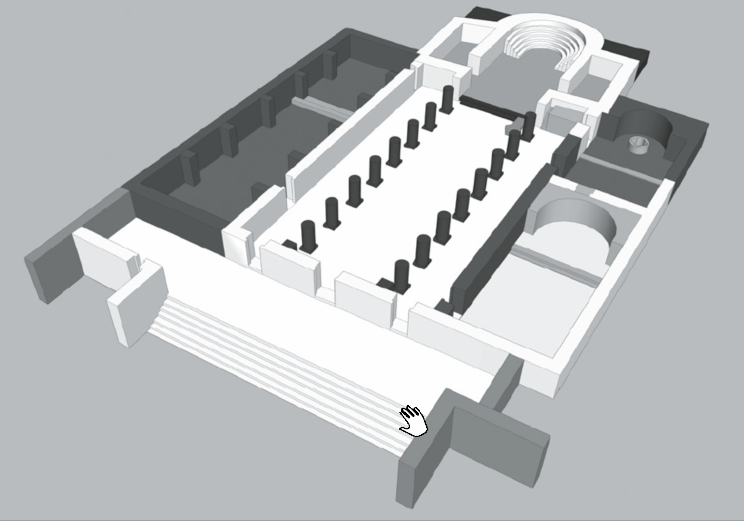

- Fig. 10 3D reconstruction

of the first architectural phase of the basilica (second half of 5th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

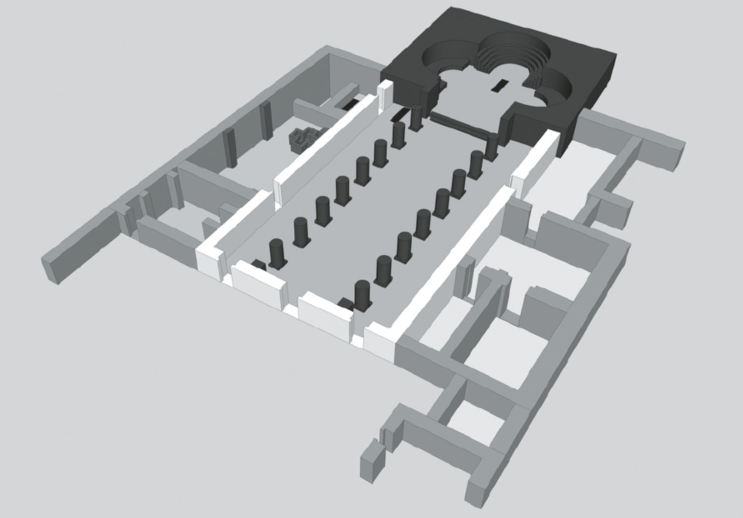

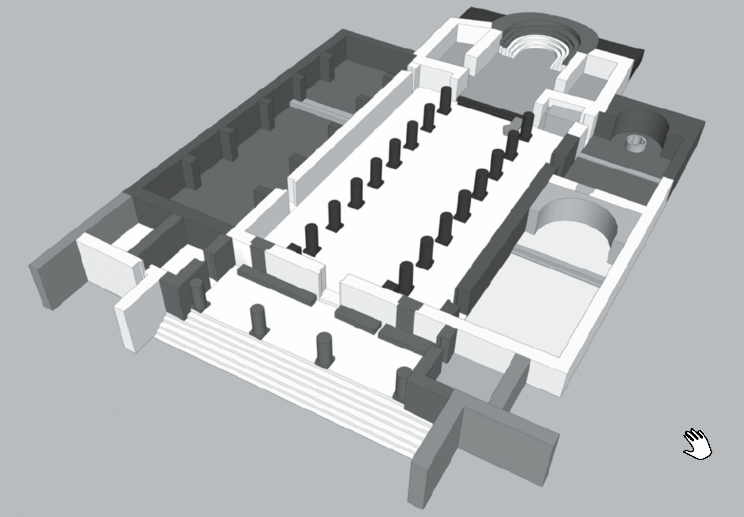

- Fig. 11 3D reconstruction

of the 2nd architectural phase of the basilica (end of 5th - beginning of 6th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 12 3D reconstruction

of the third architectural phase of the basilica (end 6th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

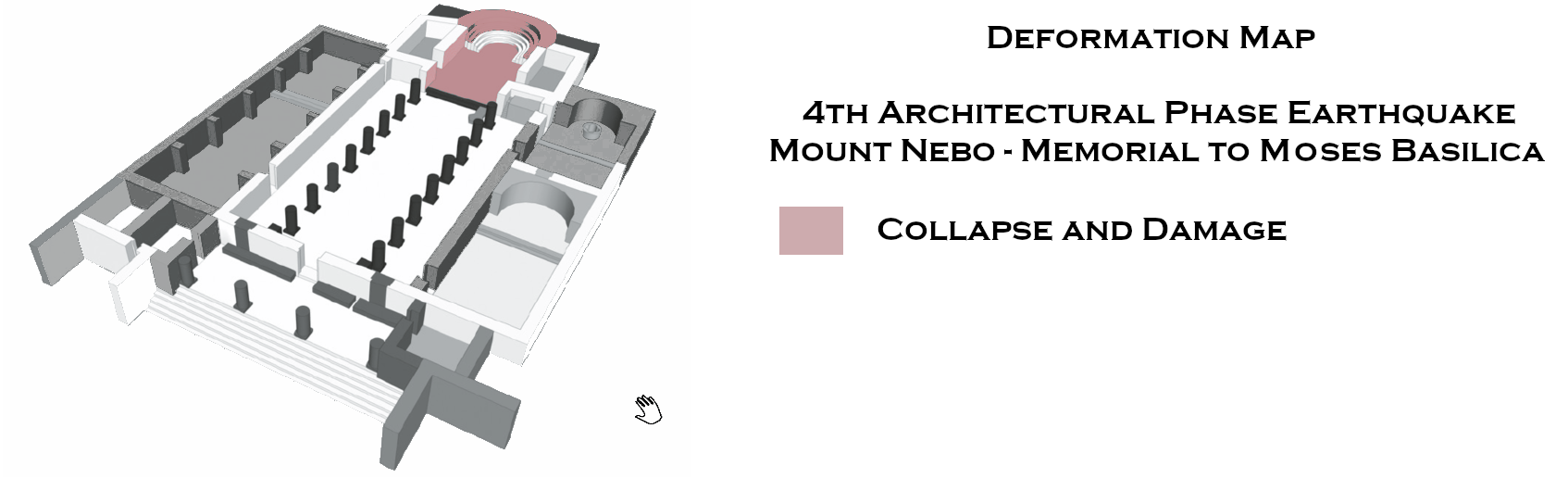

- Fig. 13 3D reconstruction

of the fourth architectural phase of the basilica (half of the eighth, after the earthquake in 749 AD) from Bianchi (2019)

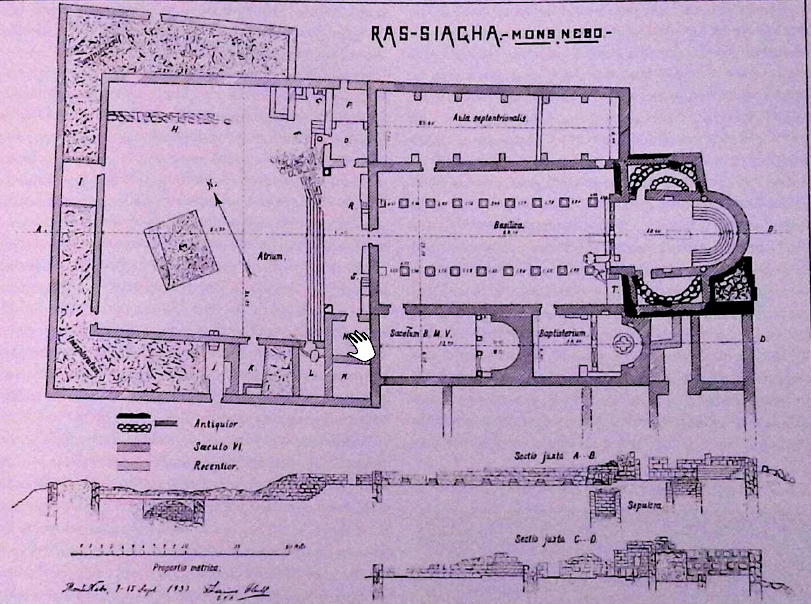

- Fig. 27 Basilica of Moses

with the west courtyard from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

- Fig. 2 Excavation Zones

from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 10 3D reconstruction

of the first architectural phase of the basilica (second half of 5th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 11 3D reconstruction

of the 2nd architectural phase of the basilica (end of 5th - beginning of 6th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 12 3D reconstruction

of the third architectural phase of the basilica (end 6th century AD) from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 13 3D reconstruction

of the fourth architectural phase of the basilica (half of the eighth, after the earthquake in 749 AD) from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 27 Basilica of Moses

with the west courtyard from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

- Fig. 4 Memorial of

Moses Plan 1 Phases I-III from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

- Fig. 4 Memorial of

Moses Plan 1 Phases I-III from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

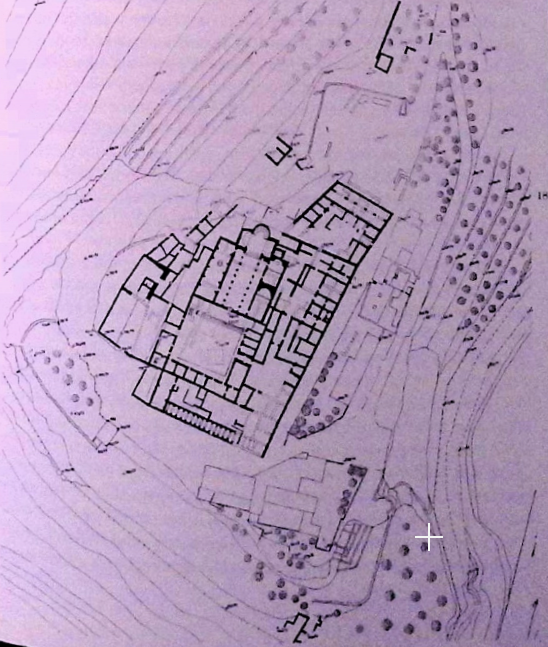

- Fig. 17 General Plan

of the monastery on the summit of Siyaga Hill from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

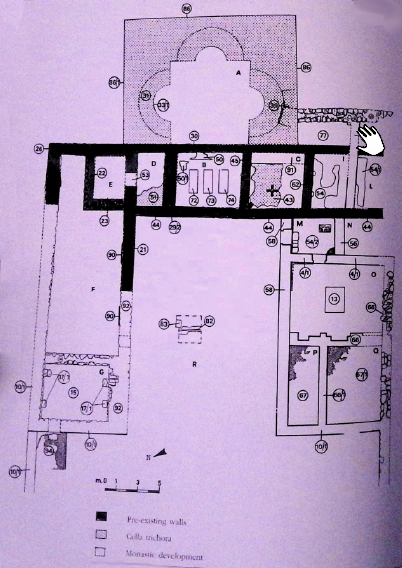

- Plan of church and monastery complex

on Siyaga Hill from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Siyagha hill: plan of the church and monastery complex.

Siyagha hill: plan of the church and monastery complex.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 1 Plan of the

monastic complex of the Memorial of Moses from Bianchi (2019)

- Fig. 17 General Plan

of the monastery on the summit of Siyaga Hill from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

- Plan of church and

monastery complex on Siyaga Hill from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Siyagha hill: plan of the church and monastery complex.

Siyagha hill: plan of the church and monastery complex.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 1 Plan of the

monastic complex of the Memorial of Moses from Bianchi (2019)

-

Theotokos Chapel dedicatory

inscription dated 762 CE - photo by JW

Dedicatory inscription from the Chapel of Theotokos, dated to 762 CE.

The date appears at the very bottom of the inscription, inside the circle just above the lower border.

“ET” is an abbreviation for “in the year,” and the year itself is given in the Anno Mundi calendar.

the Chapel of Theokotos was found at Wadi ʿAyn al-Kanīsah, downslope from the Summit church area.

Dedicatory inscription from the Chapel of Theotokos, dated to 762 CE.

The date appears at the very bottom of the inscription, inside the circle just above the lower border.

“ET” is an abbreviation for “in the year,” and the year itself is given in the Anno Mundi calendar.

the Chapel of Theokotos was found at Wadi ʿAyn al-Kanīsah, downslope from the Summit church area.

photo cleaned up slightly with A.I.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 27 Jan. 2026 - Restored Basilica at Mount Nebo - photo by JW

-

Theotokos Chapel dedicatory

inscription dated 762 CE - photo by JW

Dedicatory inscription from the Chapel of Theotokos, dated to 762 CE.

The date appears at the very bottom of the inscription, inside the circle just above the lower border.

“ET” is an abbreviation for “in the year,” and the year itself is given in the Anno Mundi calendar.

the Chapel of Theokotos was found at Wadi ʿAyn al-Kanīsah, downslope from the Summit church area.

Dedicatory inscription from the Chapel of Theotokos, dated to 762 CE.

The date appears at the very bottom of the inscription, inside the circle just above the lower border.

“ET” is an abbreviation for “in the year,” and the year itself is given in the Anno Mundi calendar.

the Chapel of Theokotos was found at Wadi ʿAyn al-Kanīsah, downslope from the Summit church area.

photo cleaned up slightly with A.I.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 27 Jan. 2026 - Restored Basilica at Mount Nebo - photo by JW

- from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998)

- generated by ChatGPT 5.2, 29 December 2025

| Phase | Period | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | The pre-existing walls | 4th cent. | Pre-existing building west of the later cella trichora, defined by ashlar-built walls (e.g., loci 30 and 21) whose orientation differs slightly from later structures. Interior partitions are hypothesized from foundation traces and mosaic limits. Sparse ceramic and numismatic material suggests an early Roman to Late Antique date. No clear evidence for seismic damage is identified in this phase. |

| II | The cella trichora | Beginning of the 5th cent. | Construction of the cella trichora, a three-apsed sanctuary aligned more precisely east–west. Walls were built partly using reused stone blocks, suggesting spoliation rather than destruction. Internal decoration included synthronon seating and rich architectural elements. Original floor levels are lost, but mosaic tesserae in underlying fills suggest early mosaic pavements. |

| III | The development of the monastery around the cella trichora | 5th cent. | Development of the monastery around the cella trichora, including elongated buildings to the west and southwest and the formation of a central courtyard. Numerous rooms paved with white mosaics were added, together with benched spaces and inscribed rooms associated with clergy. This phase reflects architectural growth rather than destruction. |

| IV | The reconstruction of the cella trichora | Mid-5th cent. | Major reconstruction of the cella trichora. Differences in wall texture and the reuse of architectural elements, often placed in anomalous positions, indicate rebuilding rather than planned modification. A new polychrome mosaic (locus 34) was laid, while dividing walls (locus 35) cut through earlier pavements. Multiple burials were inserted in adjacent areas. |

| V | The diakonikon-baptistery | 530/531 | Construction of the diakonikon–baptistery north of the courtyard. Floor levels were lowered and new basins, pilasters, and staircases installed. A mosaic inscription dates this phase to 530–531. Although extensive rebuilding occurred, it is not explicitly linked to seismic destruction. |

| VI | The basilica | Mid-6th cent. | Transformation of the complex into a three-aisled basilica. The former courtyard was roofed and incorporated into the church interior, with a pulpit, narthex mosaics, and reconfigured sanctuary access. Earlier structures were cut, repaired, and re-leveled. |

| VII | The south baptistery and the north hall | End of 6th cent. | Construction of the south baptistery and reorganization of the north hall. Floor levels were raised, sealing earlier mosaics and architectural features. A new four-lobed baptismal font was installed with a dedicatory inscription dated 597. |

| VIII | The Chapel of the Theotokos | Beginning of 7th cent. | Construction of the Chapel of the Theotokos west of the south baptistery. Doors were blocked, circulation routes altered, and mosaics cut by new walls. Rich polychrome mosaics with inscriptions were laid and floor levels adjusted. |

| IX | The final results | 8th cent. | Final reuse, repair, and gradual abandonment of the complex. Repairs employed reused architectural fragments and patchwork flooring. Umayyad-period ceramics and coins mark the last phase of occupation. |

- from Piccirillo (1982)

| Phase | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | 2nd-3rd cent. CE | On the highest spot of the mountain, towards the 2nd to 3rd century AD, a three-apsidal monument, the cella trichora (possibly a mausoleum) was built, which was used for funeral purposes, if not originally, at least at a later time, perhaps after its violent destruction. |

| II | Christian monks re-adapted the cella trichora into a church with adjoining synthronon in the central apse,

while re-using the two lateral apses as sacristies. It was in this church that the monks showed the `Memorial of Moses' to Egeria. |

|

| IIA | On the northern slope of the mountain was added later on a diaconicon-baptistry. In August 531 there took place the restoration and beautification of the diaconicon, the mosaic floor of which was laid by Soelos, Kaiomos and Elias. | |

| III | From the middle of the 6th century to the first years of the 7th, the sanctuary underwent complete reconstruction. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 29 June 2025

- from Bianchi (2019)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Byzantine | 2nd half of 5th century CE | Original construction of the basilica in a single-nave format with a baptistery at the southern end. |

| II | Byzantine | End of 5th – early 6th century CE | Reconstruction with enlargement into a three-nave church; addition of synthronon, altar area, and two side pastophoria. |

| III | Byzantine | End of 6th century CE | Architectural rearrangement: extension of the central nave, removal of older elements, inclusion of ambo, and mosaics in nave and side aisles. |

| IV | Umayyad/Abbasid | Mid-8th century CE (post-749) | Post-earthquake reorganization: western wall moved inward, new columns and capitals introduced, mosaics reused; probably reflects restoration after 749 CE earthquake. |

- from Bianchi (2019:203)

After having acquired the site thanks to the concern of the Emir Abdallah Ibn al-Husayn I, the Custody of the Holy Land began the first archaeological expeditions on July 14/ 1933 under the direction of Fr. Sylvester Saller (Saller 1941: 17). The excavations then continued with Fr. Virgilio Corbo (1963), Fr. Michele Piccirillo (1976) and Carmelo Pappalardo (2008)1 . Since 2012, the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, under the direction of Fr. Eugenio Alliata assisted by the author, have conducted some archaeological investigations in connection with the re-roofing of the ruins of the church. The geological instability of the mountain led indeed to replace the old shelter with a new one (Marino 2004: 47-64).

The aim of this article is to provide a general presentation of the excavations conducted between 2012 and 2014, with a focus on the most important discoveries and their interpretation. Due to the limited space given for this paper, the analytic study of the archaeological record will be published in a forthcoming monograph of the author (Bianchi dissertation forthcoming).

1. For the history of research, see Piccirillo and Alliata 1998: 13–52. Moreover, see the article by Franco Sciorilli in this volume.

The analysis of the last archaeological data and the review of the previous interpretations support a new hypothesis about the oldest worship building arose on Mount Nebo. The first crucial issue is related to the understanding of the space in front of the tri-conch Presbytery. According to Saller’s suggestions, this cell was the oldest shrine erected on the site and the area in front of it was an open courtyard with a mosaic floor (Saller 1941: 23–44). However, the excavation conducted by Corbo and later by Piccirillo and Alliata have determined that some walls of the church were built before the thricora cell (Alliata and Bianchi 1998: 151–154). In addition, the shape of the area in front of the cell, surrounded by regular masonry and paved with mosaics, seemed not to characterize an outdoor courtyard.

Considering all the architectural evidence, it is thus possible to assume that the first church probably showed a rectangular basilical plane divided into three naves by two series of pillars (FIG. 10). Many parallels in Transjordan support this hypothesis (Michel 2001: 18–33). The perimetral masonries related to this phase are located on the northern and western sides of the church, under the walls of the main nave which are visible today. The north wall is thus connected perpendicularly to the eastern wall and continues on the south side with the façade characterized by three doors. As aforementioned, the small portions of the mosaic floor found in the nave do not indicate epigraphically when they were laid. However, the pottery sherds and coins recovered in the preparatory layer of this mosaic provide a terminus post quem between 408 and 423 AD which suggest that the mosaic floor, and so the first church, could be dated to the second half of the fifth century AD.

The excavation of the three rooms behind the east wall of the church allowed to recover many pottery sherds of the early Byzantine period and one coin dated back between 383 and 425 AD. This data suggest that this sector was built after the second half of the fifth century AD, most probably at the time of the first architectonical phase of the basilica. The three tombs located in the central room were covered with a white mosaic floor, which is of the same type and at the level to those found by Saller and Corbo in the northern and southern rooms (Alliata – Bianchi 1998: 187, nn. 43,50,51; Saller 1941: 50; Corbo 1970: 278). It is noteworthy to mention that the quality of the mosaic of the southern room, decorated with a cross in black and white cubes, well agrees with this archaeological record (Piccirillo 1998: 268). The central room would probably be covered with an arched roof: two blocks of the arches foundations have been identified in the excavation.

Similarly, the empty tomb was probably built in this first phase because it was found sealed by the preparatory layer of the nave mosaic. In addition, looking at the topography of this burial place, it is possible to observe how the tomb is located on the higher portion of bedrock compared to the level of the nave floor. Moreover, the grave is surrounded with a shallow cut, which suggest the presence of a frontal step and two lateral walls in antiquity. According to the architectural typology of the “ sanctuaire carré” 4, it is possible to assume that square portion of the bedroom with tomb was actually under the presbytery of the oldest church provided with two lateral pastophoria.

Another key element in support of this hypothesis is given by the written sources. A reference in the *Life of Peter the Iberian*, wrote by John Rufus, recalls the presence of a special altar above the grave in the memory of the “Prophet Moses” (Peter the Iberian 2008: 177–179).

The origin of the alabaster marbles, reused in the tomb, remains an open question at this state of research. The three angular bases with fine moulding, thin slabs and three fragments of frame were probably part of the external or interior façade of a small building. If we assume a specific production related to the first memorial on Mount Nebo, the marbles might have adorned the oldest cenotaph built in the memory of Moses. In connection with this hypothesis, it is crucial to mention the description of the pulpit saw by Egeria, who visited Nebo around 384 AD.

We arrived, then, at the summit of the mountain, where there is now a church of no great size, on the very top of mount Nebo. Inside the church, in the place where the pulpit is, I saw a little raised place, containing about as much space as tombs usually contain 5.According to the textual source, the sentence a church of no great size (*ecclesia non grandis*) may properly suggest a modest building. Concerning to the location of the burial of the Prophet, the monks showed to Egeria a generic point inside the church, without providing more detailed information (*Itinerarium Egeriae*, XII, 3). Unfortunately, at this stage of the study, no stratigraphic evidence dates back to the time of Egeria. The oldest structures discovered in the site were indeed built not prior to 408/423 AD, with a gap of more than thirty years after Egeria’s visit. However, the topography of the squared area around the empty tomb might suggest that the *pulpitus* described by the pilgrim was located in this place.

It is worth to stress that no violation has occurred previously in the grave. Although the absence of human bones could suggest a later removal, the shallow type of the tomb with no traces of liquid decomposition or soil, contrast with this hypothesis. This evidence may support the identification of the tomb as a cenotaph, probably built by Christian monks. Therefore, through the creation of this memory, the Christian devotees could go on a pilgrimage to a specific site related to the worship of the prophet Moses but without any tangible remains. In addition, the detailed description of John Rufus, who mentions the oral tradition related to a vision of the prophet by a local shepherd, adds a bold rhetorical exercise to support the precise identification of the worshipped tomb (Bitton-Ashkelony and Kofsky 2006: 64–65; Satran 1995: 97–105). This evidence confirm that the cenotaph on Mount Nebo was a Christian prerogative since both the Torah and the rabbinic tradition considered unknown the burial place of Moses (Bitton-Ashkelony and Kofsky 2006: 62–81; Tromp 1993: 115–123; Manns 1998: 65–69).

In this perspective, the monastic shrine of the memorial of Moses is part of a network of Jordanian coenobia associated with the worship of the biblical figure 6 (Hamarneh 2012: 277-279).

4. The architectural typology of the sanctuaire carré was

widespread in the Christian East between the middle of

the fifth and the early seventh century AD. On this topic,

see Weber 2012: 207–254.

5. *Itinerarium Egeriae*, XII,1.

6. A deeper analysis of this issue is part of the unpublished

doctoral dissertation of the author. See Bianchi (forthcoming).

- from Bianchi (2019:209)

Furthermore, the cenotaph was completely obliterated; the three rooms behind the chancel were demolished to lengthen the three aisles at the end of which a new tri-apsidal presbytery was added. The slight divergence of the tri-conch presbytery with the masonry of the three apses, which rely upon the foundations of the nave, suggest indeed a later construction. The choice to build a tri-conch presbytery is related probably with the funerary function of this architecture, as the parallels with the Egyptian churches may suggest (Grossmann 1999: 216-236; Grossman 2007: 103-136).

The pottery and coins recovered in the excavation of the presbytery date its construction to the end of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century AD, probably at the time of abbot Elijah and the bishop Elijah of Madaba. The mosaic floor, which seals the two graves located under the presbytery and leans on the first row of the synthronon, confirms this chronological range. Moreover, according to Piccirillo the iconography of this mosaic demonstrate that it was laid before the flowering of the Justinian mosaic school of Madaba. (Piccirillo 1998: 270-272; Piccirillo 2000: 139-190).

Finally, a new diakonikon with a baptismal font was erected on the northern side of the aisle, one-meter lower than the nave (Alliata and Bianchi 1998: 168-171). The floor was covered with an exquisite mosaic, which was funded in 530 AD by three σχολαστικοί (lawyers), members of important families of the imperial administration (Piccirillo 1998: 273-287).

- from Bianchi (2019:210)

Chronologically, these architectural activities are dated back to late sixth century AD due to the mosaic Greek inscriptions and to the pottery sherds recovered under the preparation layer of the pavement (Piccirillo 1998: 296-300).

At the same time, the external wall of presbytery were rebuilt. The heterogeneity of the stone row of the apse and the archaeological records from the deep foundation cut show that a complete reconstruction occurred indeed at the end of the sixth century7.

Finally, in the first decade of the seventh century, the bishop Leontius of Madaba and abbots Martyrios and Theodoros promoted the construction of a new chapel on the southern side of the church for the worship of the Virgin Mary (Theotokos) (Alliata and Bianchi 1998: 178-179; Piccirillo 300-304).

7. For the architectonical survey of the basilica masonries and their state of conservation, see Marino 2004: 47-57.

- from Bianchi (2019:210)

The large amount of pottery and marbles with sharp fractures recovered in the excavation, as well as the disorderly arrangement of stones in the external apse buttress suggest that a brutal destruction occurred in the site. This catastrophic event is related probably to the earthquake of 749 AD. (Tsafrir 2014: 111–120) and this date might be the terminus post quem for the reconstruction of the apse.

In fact, the morphology of this structure may have been affected by the geological instability of the northern slope. The second half of the eighth century well agrees with the chronology of the pottery recovered beneath the upper rows of synthronon. Most of the sherds date indeed to the late Umayyad period, few to the Abbasid era.

At the same time the two lateral doors of the façade have been closed.

In summary, the last excavation have provided new elements related to the architectonical evolution of the basilica of the Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo.

A crucial discovery was the identification of the Christian shrine that can be probably identified with that of the ”Prophet Moses“. This evidence allows to include the coenobium of Mount Nebo within the network of the monasteries related to the worship of the biblical figures.

Moreover, the review of the old data, and the analysis of the new archaeological record suggest new hypotheses on the oldest building erected on the mountain.

The exponential growth of the pilgrimage during the Byzantine period contributed to the richness and the fame of this monastery. The donation of the devotees, the bishops and the lay people have allowed indeed the expansions and decoration of the church for almost three centuries.

The new Islamic rule does not seem to have affected the monastic privileges and the financial availability of the community. Archaeological data showed that even after a traumatic event, probably the earthquake of 749 AD, the monks were able to implement an important restoration of the basilica.

We hope that further analysis of unexcavated areas of the monastery and a deeper study of the Nebo region will allow us to get a clearer picture of the shape and functions of the sanctuary of Moses.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 29 June 2025

- from Bianchi (2019)

The attribution of these restorations to the aftermath of the 749 CE earthquake is based on stratigraphic sequencing and ceramic material. Earlier phases, particularly Phase III, which dates to the end of the 6th century CE, exhibit no evidence of seismic damage, suggesting that the structural collapse requiring Phase IV intervention occurred later.

No direct evidence of ground shaking (e.g., tilted walls or fissures) is discussed, but the contextual attribution of damage and rebuilding efforts—particularly the partial collapse of architectural elements—makes this an example of archaeoseismic reconstruction based on stratigraphic and architectural transitions dated to the mid-8th century CE.

- from Piccirillo & Alliata (1998:209-216)

- Problematic OCR - there is some paraphrasing - consult original text when in doubt

The rooms of the small monastery develop to the north and south of the chapel, which occupies the centre of the cistern wing of the complex, and extend west of the mosaic-paved courtyard, which is set in front of the chapel at a lower level and which has a cistern for gathering water. The three sectors of the complex seem to be in some way independent of one another.

There was an entrance on the north side of the courtyard in front of the church. In the final phase another door could have been used which crossed the central room of the west wing, related to the remains of a flight of steps adapted among the rocky projections of the summit upon which the monastery rises. No communication is evident in the final phase between the northern sector of the monastery and the southern sector which had an autonomous entrance in the east wall. This sector was in a state of abandonment and the identification of the rooms which develop at different levels to the east and north of the southern courtyard (D) has proved very difficult.

The western wall of the courtyard resembles more an embankment built during the restructuring of the chapel and the courtyard in front of it, set at a higher level. The north wall too is made up of large squared stones which seem to serve as a terrace to support the chapel’s south wall.

Inside the courtyard were brought to light the remains of a pilaster set against the northwest wall from which departed the first course of a horseshoe-shaped stone structure, obliterated to the north. A series of three small rooms is set against the wall that separates the courtyard from the areas within the boundary wall of the monastery. These were only partially excavated so as not to jeopardize the stability of the chapel. Area D3 still preserves part of its paved floor with a central pilaster that supported the roof. In the irregularly shaped room, between the south wall of the chapel and the boundary wall of the courtyard, was a stall oriented north–south that supported the side of the chapel. It is possible that in a previous phase there were two autonomous rooms (D5 and D6) in the area. An oil lamp, similar to others found in the monastery at Siyagha, was recovered in the yellow fill in room D5.

The western sector consists of a mosaic-paved courtyard in front of the chapel (E) and a series of habitable rooms on the west side on the mountain edge. Judging from a pilaster base inserted into the mosaic, close to the northwest corner, part of the courtyard must have been covered.

A few steps descend from the courtyard to room E4, which has a mosaic floor in white tesserae. A manhole to a cistern is set in the centre of the room, which also has a stone basin in the northeast corner. A small channel, covered with stone slabs, crosses the room in an east–west direction originating from the courtyard. This can easily be related to the underlying cistern which, when full, also fed this set of reserve water.

To the south of this room is room E1, which in the final phase could have been the point of arrival of steps partly adapted from the rock, which came up to the monastery from the spring below. In a previous phase a taboun typee oven had been built against the west wall of the room. A water canal crosses the room in an east–west direction, coming from the room at a higher level and leading to the outside. A second channel passes close to a stone basin set against the east wall. A door, which was later blocked, leads from E4 to room E5 alongside it to the south. A flight of steps leads from this isolated room to the courtyard above. The steps were added in a second instance. They abut the eastern wall which contained a plastered wall cupboard. A stone bench is laid against the south wall, possibly a door originally connected the room with the south courtyard. Beneath the west wall, a lime channel has been identified, which is cut by the south wall.

the drainage canal that closes area E4 allows one to identify this small isolated square room in courtyard E1 as a toilet. The opening of the cistern is in its vicinity. A stone bench had been added on the east wall of the courtyard to the north of the steps that lead to the chapel. On the opposite side a trap door led to the funerary crypt beneath the chapel. The space between the stairs and area E1 had been decorated with polychrome mosaic panels made of ordinary tesserae and probably containing human or animal figures. This was later replaced by stone slabs. On the other hand, the southwest corner of the courtyard reveals a stretch of a second superimposed mosaic floor, the result of a remake.

The north sector is made up of the mosaic-paved chapel and service room, as well as three rooms set in the northeast corner of the monastery at its highest point.

The single-naved chapel has a raised presbytery with an apse and a long narrow service room to the north close to the west wall. It has three doors: one on the façade, the main entrance, and two on the north wall, one leading to a room at a higher level by means of three steps close to the presbytery and the other to the service room on the façade. The stone walls of the apse have been preserved to a height of about two meters.

The stone altar, set on the chord of the apse, was constructed to replace a previous altar supported by small columns which were inserted in a second phase into the mosaic, traces of which are still clearly visible. Prior to abandonment, a tomb was excavated in the mosaic of the presbytery south of the altar. Judging from the position of the upper skeleton found in it, the tomb was reused in recent times for a Muslim burial. Beneath the collapse, in both the nave and the presbytery, directly in contact with the mosaic floor, there was a thick layer of ash which, in at least two cases, are to be related to an earthquake24. The steps leading to the presbytery showed substantial traces of plaster painted with a floral motif.

The 6th-century mosaic-paved chapel had been resumed and the mosaic redone, at least in part, in 762 (see Di Segni, inser. no. 56). This is attested by an inscription near the main door. The area of the remade mosaic floor corresponds structurally to an underlying hypogean tomb with a trap-door entrance to the right of the steps that lead to the chapel. One descended into the tomb using three steps to reach a small stone door with a cross sculptured on its lintel. The vaulted tomb has a missing ashlar at the centre replaced by a slab. Another small door in the east wall allows one to catch a glimpse of an independent wall to the inside. The workmanship of the masonry is good, with the ashlars squared and well positioned.

Inside the tomb there remained not intact burials set against the north and south walls, poorly built and covered with irregular slabs and numerous wedges. They contained the disarticulated bones of several corpses and were therefore used for secondary rather than primary burial, apart from a complete skeleton found in the north tomb placed over the other bones with its head towards the west. The remake of the mosaic can easily be related to the construction of the underlying burial place.

The door at the northwest corner of the chapel led to the main service area or diakonikon that extended along the north. The room originally had a mosaic floor decorated with a network of flowers, part of which has been preserved close to the northeast wall. The floor mosaic was restored using larger white tesserae. The east wall had traces of what could have been either a walled cupboard or a plastered window. Set against this same wall was also an oval built basin carefully plastered in white on the interior.

A flight of steps partly cut from the rock close to the presbytery leads to the north rooms. The steps were laid out as well as possible, leveling the masses of rock left in place with soil and pottery. There remained the perimeter wall of a rectangular room running parallel to the chapel as a continuation of the service area or diakonikon and which communicated with another room via an opening in its north wall. A small walled cupboard had been created on the east wall of the first room. A fourth room could possibly be reconstructed between these rooms and the north boundary wall which is missing, without it being possible to define how this area was reached and what relation it bore to the others.

Dating the complex. The style of the primitive (first) mosaic in the chapel can be dated to the 6th century (see below pp. 359ff), whereas the restoration is dated by the inscription to 762 during the time of Bishop Job of Madaba. Two probes were carried out in the courtyard E, near the north door at the monastery, both on the interior and exterior. These probes have shown that the wall on the inside cuts the floor mosaic and rests slightly deeper on the sterile, compacted clay of the mountain, whereas on the outside the wall reaches the bedrock at a greater depth. The pottery found in the interior probe, among which is a complete wash basin, is dated to the 6th century. This confirms the proposed dating for the origins of the complex, arrived at through the study of the mosaic.

24 The large missing parts of the mosaic and the re-use of the tomb by the Muslim inhabitants of the region explain the presence of polychrome mosaic tesserae scatterred on the mountain slopes, already noticed by Father Saller. Together they are a precious testimony that enables us to affirm that the collapse of the apse walls happenned in a relatively recent period.

A first day’s work was dedicated to the tower east of the spring in an attempt to identify its geometry and possibly date its construction.

A door that leads into a small room was identified in the southern wall of the tower. Few sherds found here can be dated to the Byzantine period. The building, to which no certain date can as yet be given, is distinguishable for the very large but only superficially shaped stones used in the construction of its walls. Undoubtedly it was used during the Byzantine period. One can imagine it as an outpost of the monastery that rose on higher ground, close to the spring near which passed the road that crossed the valley.

In conclusion, the structural development of the monastery at ‘Ayn al-‘Anish can be thus summarized.

- During the first phase, the monastery virtually consisted of the chapel with its diakonikon, the western courtyard, as well as the rooms of the southern sector.

- During the Umayyad period the monastery suffered iconoclastic defacement and in 762 the western sector of the chapel was redecorated with mosaic, possibly in relation to the construction of the hypogeum below the façade. Both the diakonikon and the courtyard wererelaid in mosaic, this time using larger-sized white tesserae.

Together with the north door, possibly still in use, area L4 was used as entrance with the addition of installations coming from the outside. As we have already mentioned, the two inscriptions found in the chapel floor have notably enriched the monastic vocabulary on the mountain. Together with the word monastery in minor rocky dwellings are mentioned an hegoumenos and an archimandrite of the whole holy mountain, as well as a recluse monk. These titles refer to the different forms of ascetic life which the monks led in the desert and to which we can link the small complex. The new late date (762 A.D.) recorded in the mosaic in the Theotokos Chapel at ‘Ayn al-‘Anish is a precious historical testimony to the survival of the monastic presence in the valleys and on the summit of Mount Nebo in the second half of the 8th century.

A large amount of liturgical installations from the basilica at Siyagha has been preserved, but their study nevertheless is complex. because of the long span of time during which the budding was in use as well as the multiple refurbishments that were carried out. These refurbishments can be identified easily, but it is very difficult to establish their chronology, even if a relative one. Therefore the literary sources are of some assistance. The two most quoted texts are the diary of Egeria, who saw a 'small church' towards the end of the 4th century32 and of Peter the Iberian who speaks of a 'great church' at the start of the following century.33 Egeria relates that the monks showed her what was considered at the time to be the memorial of Moses close to the pulpitum.34 Peter the Iberian mentions a 'table and altar. and under the latter stood the 'vessel of oil and grace'. Even though these witnesses are still precious, because they attest to the existence of a place of worship. they do not help us to determine the shape and set-up of the internal installations.

During the first three excavations campaigns carried out between 1933 and 1937, Father Sailer tried to match the chronology established by the excavations with what the testimonies of Egeria and Peter seemed to indicate. He thus identified a first cella trichora, dated to the 4th century, to which there would have followed a 5th century basilica corresponding to that seen by Peter the Iberian. But Father Saller admitted that he had not found any archaeological trace to prove this, because this church must have been destroyed by an earthquake and rebuilt at the end of the 6th century.35 At the time Father Sailer did not to at his disposal the new data regarding the development of the earlier phases, brought to light by the excavations carried out by Father Corbo, between 1967 and 1970,36 and Father Piccirillo in 197637 and subsequent years.38

The ruins which can be seen today correspond, for the most part, to the West stage of the development of the complex. Most of the mosaics have been removed, restored or consolidated and put hack in place, with the exception of the mosaics found an the northern annexes. Here we find the fiat baptistery dated to 530, which had been covered by another chapel during the last phase of use of the church. That situation, together with the absence of a definite general chronology, renders a synthesis of the progress in the development of the church's liturgical installations premature, and allows us only to study each installation separately

32. It. Eg. 12,1: “ubi est nunc ecclesia non grandis, in ipsa summitate montis Nabau" Maraval (1982), 172.

33. Vita Petri, Raabe (1895), 83.

34. It. Eg. 12, 1-2 Maraval (1982), 172 and 174.

35. Saller (1941), 39-46.

36. Corbo 1967, 241-258. Corbo 1970, 273-298.

37. Piccirillo (1976), 281–318; Pl. 49-80.

38. See the notes by Piccirillo (1985), 431;

Piccirillo (1986), 349; Piccirillo (1987a), 400-401;

Piccirillo (1988a), 457–459; Piccirillo

(1989), 147–175, especially 166–179; Alliata 1990. 427-466

39. Although Sailer (1941), 50 and

211–212, notices evident traces of

damage on the mosaic, due to these two walls, he thinks that they are

contemperaneous with the rest of the sanctuary, because the masonry

of these walls is similar to the one of the east apse.

The disappearance of these walls today

renders impossible the analysis of the masonry.

Bianchi (2019:210) reports that during the last

architectonical phase of the Memorial to Moses basilica

on Mount Nebo, "the two upper rows of

synthronon and the masonry of the

apse in the

presbytery were restored".

Bianchi (2019:210) suggests that "the large amount of pottery

and marbles with sharp fractures recovered in the excavation,

as well as the disorderly arrangement of stones in the external

apse buttress suggest that a brutal destruction occurred

in the site" which they indicate is "related probably to the

earthquake of 749 AD".

Conversely, Bianchi (2019:210) notes that "the morphology of this

structure may have been affected by the geological instability

of the northern slope".

In any case,

Bianchi (2019:210) states that

"the second half of the eighth century well

agrees with the chronology of the pottery recovered beneath

the upper rows of synthronon" where "most of the sherds

date indeed to the late

Umayyad period" and a "few to the

Abbasid era".

- from Chat GPT 4o, 29 June 2025

- Sources: Jordan Times report on basilica restoration, Bianchi (2019), Williams (2024) - Supplemental

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Memorial to Moses basilica |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 13 of Bianchi (2019)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 13 of Bianchi (2019)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Memorial to Moses basilica |

|

|

Alliata, Eugenio. "La ceramica dello scavo." Studium Biblicum Franciscanum (SBF)ILiber Annuus 34 (1984): 316-317.

Alliata, Eugenio. "La ceramica dello scavo della cappella del Prete Giovanni a Khirbet el-Mukhayyat." SBFi'Liber Annuus 38 (1988): 317-360.

Alliata, Eugenio. "Nuovo settore del monastero al Mont e Nebo-Siyagha." In Christian Archaeology in the Holy Land, New Discoveries:Essays in Honour of Virgilio C. Corbo, edited by Giovanni Claudio

Bianchi, D (2019) New Archaeological Discoveries in the Basilica of the Memorial of Moses, Mount Nebo,

Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 13 – at academia.edu

Bottini et al., pp. 427-466. Studium Biblicum Franciscanum (SBF),Collectio Maior, 36, Jerusalem, 1990.

Bagatti, Bellarmino. "Nuova ceramica del Monte Nebo (Siyagha)."SBFI Liber Annuus 35 (1985): 249-278.

Corbo, Virgilio. "Nuovi scavi archeologici nella cappella del battistero della basilica del Nebo (Siyagha)." SBFI Liber Annuus 17 (1967):241-258.

Corbo, Virgilio. "Scavi archeologici sotto i mosaici della basilica del Mont e Nebo (Siyagha)." SBFI Liber Annuus 20 (1970): 273-298.

Knauf, E. Axel. "Bemerkungen zur friihen Geschichte der arabischen Ortographie." Orientalia 53 (1984): 456-458.

Luynes, Du e de. Voyage d'exploration a la Mer Morte, a Petra et sur la rive gauche dujourdain, vol. I. Paris, 1874, p. 148

Milani, C. Itinerarium Antonini Placentini. Milan, 1977-

Milik, J. T. "Nouvelles inscriptions semitiques et grecques du pays de Moab. " SBFI Liber Annuus 9 (1959): 330-358.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Campagna archeologica a Khirbet el Mukhayyet (Citti dei Nebo), agosto-settembre 1973." SBF/Liber Annuus 23 (1973): 322-358.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Campagna archeologica nella basilica di Mose Profeta sul Mont e Nebo-Siyagha. " SBF/Liber Annuus 26 (1976): 281-318.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Forty Years of Archaeological Work at Mount Nebo-Siyagha in Late Roman-Byzantine Jordan."

In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, vol. 1, edited by Adnan Hadidi, pp. 291-300. Amman, 1982.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Una chiesa nell'wadi 'Ayoun Mousa ai piedi del Monte Nebo. " SBF/Liber Annuus 34 (1984): 307-318.

Piccirillo, Michele. "The Jerusalem-Esbus Road and Its Sanctuaries in Transjordan." In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, vol. 3, edited by Adnan Hadidi, pp . 165-172. Amman, 1987.

Piccirillo, Michele. "La cappella del Prete Giovanni di Khirbet el-Mukhayyat (Villaggio di Nebo). " SBF/Liber Annuus 38 (1988): 297-315.

Piccirillo, Michele, and Eugenio Alliata. "La chiesa del monastero di Kaianos alle 'Ayoun Mous a sul Mont e Nebo. "

In Quaeritur inventus colitur: Miscellanea in onore di padre Umberto Maria Fasola, vol. 40, p p . 561-586. Studi di Antichita Cristiana, 40. Th e Vatican, 1989.

Piccirillo, Michele. Chiese e mosaici di Madaba. SBF, Collectio Maior,

Piccirillo, Michele, and Eugenio Alliata. "L'eremitaggio di Procapis e

l'ambiente funerario di Robebos al Mont e Nebo-Siyagha. " In Christian Archaeology in the Holy Land, New Discoveries: Essays in Honour

of Virgilio C. Corbo, edited by Giovanni Claudio Bottini et al., pp . 391-426. SBF, Collectio Maior, 36. Jerusalem, 1990.

Piccirillo, Michele. Mount Nebo. SBF Guides, 2. 2d ed. Jerusalem, 1990.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Le due inscrizioni della cappella della Theotokos nel Wadi 'Ayn al-Kanisah-Monte Nebo. " Studium Biblicum Franciscanum)Liber Annuus 44 (1994): 521-538.

Puech, fimile. "L'inscription christo-palestinienne d"Ayoun Mous a (Mount Nebo). " SBF/Liber Annuus 34 (1984): 319-328.

Robinson, Edward, and Eli Smidi. Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai, and Arabia Petraea. Boston, 1941, vol. 2, p. 307.

Sailer, Sylvester J. The Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo. 2 vols. SBF, Collectio Maior, 1, Jerusalem, 1941.

Sailer, Sylvester J., and Bellarmino Bagatti. The Town of Nebo (Khirbet el-Mekhayyat) with a Brief Survey of Other Ancient Christian Monuments in Transjordan. SBF, Collectio Maior, 7. Jerusalem, 1949.

Sailer, Sylvester J. "Iron Age Tomb s at Nebo , Jordan. " SBF/Liber Annuus 16 (1966): 165-298.

Sailer, Sylvester J. "Hellenistic to Arabic Remains at Nebo , Jordan. "SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 5-64.

Schneider, Hilary. The Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo, vol. 3, The Pottery. SBF, Collectio Maior, 1. Jerusalem, 1950.

Stockman, Eugene. "Stone Age Culture in the Nebo Region, Jordan. " SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 122-128.

Yonick, Stephen. "The Samaritan Inscription from Siyagha: A Reconstruction and Restudy. " SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 162-221

S. Saller and H. Schneider, The Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo 1-3 (Studium

Biblicum Franciscanum Collectio Maior), Jerusalem 1941-1950

S. Saller and B. Bagatti, The Town of

Nebo ( Khirbet el-Mekhayyat) with a Brief Survey of Other Christian Monuments in Transjordan (Studium

Biblicum Franciscanum Collectio Maior 7), Jerusalem 1949

M. Piccirillo eta!., The Memorial of Moses:

The 1963-1978 Excavations in the Basilica (Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Collectio Maior 27),

Jerusalem (in prep.).

Abel, GP l, 379-384

A. Neubauer, La Geographie du Talmud, Paris 1868, 252-253;

B. Bagatti, Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 13 (1936), 4-13

23 (1957), 139-160

id., Atti del IV Congresso

di Archeologia Cristiana 2, Vatican City 1948, 89-110

id., LA 28 (1978), 145-146

35 (1985), 249-278;

S. Saller, LA 16 (1966), 165-298

17 (1967), 5-64

id., Proc., 5th World Congress of Jewish Studies 1969,

Jerusalem 1971, 54- 55

V. Corbo, LA 17 (1967), 241-258

20 (1970), 273-298

S. Yonik, ibid. 17 (1967),

162-221

S.M. Mittmann, ZDPV87 (1971), 92-94

M. Piccirillo, LA 23 (1973), 322-358

26 (1976), 281-

318

30 (1980), 494-495

33 (1983), 499-500

34 (1984), 307-318, 444

37 (1987), 400-401, 405-406

38

(1988), 297-315, 457-458

39 (1989), 265-266

40 (1990), 227-246

id., La Terra Santa (1974), 83-93;

(1977), 33-36

(1981), 21-24

id., ADAJ 21 (1976), 55- 59

32 (1988), 195-205

id., Holy Land Review 2

(1976), 112-115

id., RB84 (1977), 246-253

id., SHAJI (1982), 291-300

3 (1987), 165-172

id., MdB44

(1986), 5-19, 30-39

52 (1988), 49-51

68 (1991), 56- 59

id., La Montagna del Nebo (Studium Biblicum

Franciscan urn, Guides 2), Assisi 1986

id., Chiese e Mosaici di Madaba (Studium Biblicum Franciscanum

Collectio Maior 34), Jerusalem 1989, 147-225

id. (and E. Alliata), Christian Archaeology in the Holy

Land: New Discoveries (V. C. Corbo Fest.), Jerusalem 1990, 391-426

id., The Mosaics of Jordan (ACOR

Publications 1), Amman (in prep.)

BTS 188 (1977)

J. A. Sauer, BA 42 (1979), 9

E. Puech, LA 34 (1984),

319-328

P. Marvel, MdB44(l986), 29

E. Alliata, LA 38 (1988), 317-360

40 (1990), 247-261

id., Corbo

Fest. (op. cit.), Jerusalem 1990, 427-466

Weippert 1988 (Ortsregister)

Akkadica Supplementum 7-8

(1989), 402-403.

M. Piccirillo, Der Berg Nebo, Jerusalem 1996

id. (& E. Alliata), Mount Nebo: New

Archaeological Excavations 1967–1997, 1–2 (Mount Nebo 5

SBF Collectio Maior 27), Jerusalem 1998;

ibid. (Review) JRA 14 (2001), 693–696

Un progetto di copertura per il Memoriale di Mosé: a 70 anni

dall’inizio dell’indagine archeologica sul Monte Nebo in Giordania 1933–2003 (SBF Collectio Maior 45;

ed. M. Piccirillo), Gerusalemme 2004.

P. Mortensen, LA 42 (1992), 344–346

50 (2000), 472–474 (with I. Thuesen)

id., AJA 100 (1996),

511

M. Piccirillo, ABD, 4, New York 1992, 1056–1058

id., The Mosaics of Jordan (ACOR Publications

1), Amman 1993

id., LA 44 (1994), 521–538

53 (2003), 445–446

id., La Terra Santa 70 (1994), 21–23;

id., 5th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, Bath, England, 5–12.9.1987, Ann Arbor, MI 1995,

69–76

id., Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale 7 (1997), 437–462

id., OEANE, 4, New York

1997, 115–118

id., The Archaeology of Jordan (Levantine Archaeology 1

eds. B. MacDonald et al.), Sheffield 2001, 671–676

id., La mosaïque gréco-romaine 8: Actes du 8. Colloque International pour l’Étude

de la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Lausanne, 6–11.10.1997 (Cahiers d’archéologie romande 86

eds.

D. Paunier & C. Schmidt), 2, Lausanne 2001, 444–458

9: Actes du 9. Colloque International sur la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Paris 2002, 127–140

id., Les églises de Jordanie et leurs mosaïques: Actes de

la Journee d’Etudes..., Lyon 4.1989 (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 168

ed. N. Duval), Beirut

2003, 3–16

G. Donnan, The King’s Highway: A Journey through 10,000 Years of Civilization in the Land

of Jordan, Amman 1994

L. -A. Hunt, PEQ 126 (1994), 106–126

E. Gabrieli et al., LA 45 (1995), 499–505;

E. Alliata et al., ibid. 46 (1996), 393–399

A. Michel & M. Ciampi, ibid., 399–404

47 (1997), 463–465 (et

al.)

48 (1998), 357–416

L. Di Segni, IEJ 47 (1997), 248–254

R. G. Khouri, Jordan Antiquity Annual, 2,

Amman 1998, no. 59

F. Zayadine, NEAS Bulletin 43 (1998), 38

G. Canuti, La mosaïque gréco-romaine 7:

Actes du 7. Colloque International sur la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Paris 1999, 759–776

A. J. Graham

& T. Harrison, LA 50 (2000), 474–478

C. Sanmori & C. Pappalardo, ibid., 411–430

J. Balty, JRA 14 (2001),

693–696

D. Foran, ASOR Annual Meeting 2004

www.asor.org/AM/am.htm

LA 53 (2003), 520–521.

Alliata, Eugenio. "La ceramica dello scavo." Studium Biblicum Franciscanum (SBF)ILiber Annuus 34 (1984): 316-317.

Alliata, Eugenio. "La ceramica dello scavo della cappella del Prete Giovanni a Khirbet el-Mukhayyat." SBFi'Liber Annuus 38 (1988): 317-

360.

Alliata, Eugenio. "Nuovo settore del monastero al Mont e Nebo-Siyagha." In Christian Archaeology in the Holy Land, New Discoveries:

Essays in Honour of Virgilio C. Corbo, edited by Giovanni Claudio

Bottini et al., pp. 427-466. Studium Biblicum Franciscanum (SBF),

Collectio Maior, 36, Jerusalem, 1990.

Bagatti, Bellarmino. "Nuova ceramica del Monte Nebo (Siyagha)."

SBFI Liber Annuus 35 (1985): 249-278.

Corbo, Virgilio. "Nuovi scavi archeologici nella cappella del battistero

della basilica del Neb o (Siyagha)." SBFI Liber Annuus 17 (1967):

241-258.

Corbo, Virgilio. "Scavi archeologici sotto i mosaici della basilica del

Mont e Nebo (Siyagha)." SBFI Liber Annuus 20 (1970): 273-298.

Knauf, E. Axel. "Bemerkungen zur friihen Geschichte der arabischen

Ortographie." Orientalia 53 (1984): 456-458.

Luynes, Du e de. Voyage d'exploration a la Mer Morte, a Petra et sur la

rive gauche dujourdain, vol. I. Paris, 1874, p. 148ft'.

Milani, C. Itinerarium Antonini Placentini. Milan, 1977-

Milik, J. T. "Nouvelles inscriptions semitiques et grecques du pays de

Moab. " SBFI Liber Annuus 9 (1959): 330-358.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Campagna archeologica a Khirbet el Mukhayyet

(Citti dei Nebo), agosto-settembre 1973." SBF/Liber Annuus 23

(1973): 322-358.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Campagna archeologica nella basilica di Mos e

Profeta sul Mont e Nebo-Siyagha. " SBF/Liber Annuus 26 (1976):

281-318.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Forty Years of Archaeological Work at Moun t

Nebo-Siyagha in Lat e Roman-Byzantine Jordan." In Studies in the

History and Archaeology of Jordan, vol. 1, edited by Adnan Hadidi,

pp. 291-300. Amman, 1982.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Una chiesa nell'wadi 'Ayoun Mousa ai piedi del

Monte Nebo. " SBF/Liber Annuus 34 (1984): 307-318.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Th e Jerusalem-Esbus Road and Its Sanctuaries in

Transjordan." In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan,

vol. 3, edited by Adnan Hadidi, pp . 165-172. Amman, 1987.

Piccirillo, Michele. "La cappella del Prete Giovanni di Khirbet el-Mukhayyat (Villaggio di Nebo). " SBF/Liber Annuus 38 (1988): 297-315.

Piccirillo, Michele, and Eugenio Alliata. "La chiesa del monastero di

Kaianos alle 'Ayoun Mous a sul Mont e Nebo. " In Quaeritur inventus

colitur: Miscellanea in onore di padre Umberto Maria Fasola, vol. 40,

p p . 561-586. Studi di Antichita Cristiana, 40. Th e Vatican, 1989.

Piccirillo, Michele. Chiese e mosaici di Madaba. SBF, Collectio Maior,

34. Jerusalem, 1989. See pages 147-225.

Piccirillo, Michele, and Eugenio Alliata. "L'eremitaggio di Procapis e

l'ambiente funerario di Robebos al Mont e Nebo-Siyagha. " In Christian Archaeology in the Holy Land, New Discoveries: Essays in Honour

of Virgilio C. Corbo, edited by Giovanni Claudio Bottini et al., pp .

391-426. SBF, Collectio Maior, 36. Jerusalem, 1990.

Piccirillo, Michele. Mount Nebo. SBF Guides, 2. 2d ed. Jerusalem, 1990.

Piccirillo, Michele. "Le due inscrizioni della cappella della Theotokos

nel Wadi 'Ayn al-Kanisah-Monte Nebo. " Studium Biblicum Franciscanum)Liber Annuus 44 (1994): 521-538.

Puech, fimile. "L'inscription christo-palestinienne d"Ayoun Mous a

(Mount Nebo). " SBF/Liber Annuus 34 (1984): 319-328.

Robinson, Edward, and Eli Smidi. Biblical Researches in Palestine,

Mount Sinai, and Arabia Petraea. Boston, 1941, vol. 2, p. 307.

Sailer, Sylvester J. The Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo. 2 vols. SBF,

Collectio Maior, 1, Jerusalem, 1941.

Sailer, Sylvester J., and Bellarmino Bagatti. The Town of Nebo (Khirbet

el-Mekhayyat) with a Brief Survey of Other Ancient Christian Monuments in Transjordan. SBF, Collectio Maior, 7. Jerusalem, 1949.

Sailer, Sylvester J. "Iron Age Tomb s at Nebo , Jordan. " SBF/Liber Annuus 16 (1966): 165-298.

Sailer, Sylvester J. "Hellenistic to Arabic Remains at Nebo , Jordan. "

SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 5-64.

Schneider, Hilary. The Memorial of Moses on Mount Nebo, vol. 3, The

Pottery. SBF, Collectio Maior, 1. Jerusalem, 1950.

Stockman, Eugene. "Stone Age Culture in the Neb o Region, Jordan. "

SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 122-128.

Yonick, Stephen. "Th e Samaritan Inscription from Siyagha: A Reconstruction and Restudy. " SBF/Liber Annuus 17 (1967): 162-221.

In his entry for the 659/660 CE Jordan Valley Quake(s), Ambraseys (2009:222) notes that

Indeed, Russell remarks that it is impossible to ascertain the effects of this and the AD 632 (634) earthquake on the Mt Nebo monastery owing to the manner in which the excavations were conducted.Russell (1985:45) correlates archeoseismic destruction at Mount Nebo to the 551 CE Beirut Quake.

July 9, 551 CERussell (1985:49) correlates archeoseismic destruction at Mount Nebo to one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes.

This earthquake also appears to have been responsible for the destruction and subsequent abandonment of the Town of Nebo ( Saller and Bagatti 1949: 217, n. 2).

January 748 CERussell (1985:54) supplied the following notes.

The final destruction of the basilica at Mt. Nebo also appears to correlate with this earthquake (Schneider 1950: 2-3),

At Mt. Nebo (Sailer 1941: 45-46) and Aereopolis (Zayadine 1971) in the region of ancient Moab, recovery after the 551 earthquake apparently did not occur until the end of the century. Related to this delayed recovery is the possibility that an influx of southeastern populations from decaying urban centers like Petra subsequent to the 551 earthquake was responsible for the intensified building during the late 6th and early 7th centuries in both Moab (Sailer 1941: 248) and the Negev (Kraemer 1958: 23. 28-29; Colt 1962: 21-22).

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |