Hammat Gader

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Hammat Gader | Hebrew | חַמַּת גָּדֵר |

| Hammata degader | Rabbinic Sources | |

| Hammat deGader | Aramaic | חחמתא דגדר |

| ema deGader | Syriac | |

| Al-Hamma | Aramaic | الحمّة |

| al-hamma al-souriya | Arabic | الحمة السورية |

| Emmatha | Ancient Greek | Ἑμμαθά |

| Amatha | Ancient Greek | Αμαθα |

| Hammeh | Arabic |

Hammat Gader is located

east of the Sea of Galilee on the

Yarmuk River in a valley below

the Decapolis city

of Gadara.

The town was famous in antiquity for its hot springs.

Five hot springs are located in the valley and the town or area is

mentioned by a number of ancient authors - e.g.

Strabo,

Origen,

Eusebius, and

Epiphanius among others

(Yitzar Hirschfeld in Stern et al, 1993).

A bath complex was first built in the 2nd century CE which reached a peak in the 5th - 7th centuries CE after which there was some sort of decline

(possibly caused by an earthquake) as indicated in an inscription found on the site detailing renovations initiated by

Mu 'awiya I, the first

Umayyad Caliph

(Hirschfeld, 1987).

Renovations were completed in 663 CE. The renovated bath complex

may have been damaged by one of the Sabbatical Year Quakes. A general decline during the

Abbasid Period finally

led to abandonment such that by the 10th century

al-Muqdisi referred to the baths in the past tense.

The site is on the Yarmuk River, 7 km (4.5 mi.) east of the Sea of Galilee (map reference 212.232), in a valley 1,450m long, 500 m wide, and 180 a. in area. The name Hammat Gader and its baths is preserved in the Arabic place name, Hammeh, and in the name of the mound on which the ancient synagogue was discovered, Tell Bani (the mound of the bath). There are five hot springs in the valley: two, 'Ein el-Jarab and 'Ein Bulos, to the north of Tell Bani (a corruption of the Greek word βαλανειον, meaning "bath"); two in the southern part, 'Ein er-Rih and 'Ein el-Maqle (Hammat Selim); and one, 'Ein Sakhneh, to the northeast of the valley of Hammat Gader. The site identified with Hammat Gader was first mentioned, although not by name, by the geographer Strabo (XVI, 2,45), who described the hot springs near the city of Gadara toward the end of the first century BCE.

The baths are mentioned by Origen (mid-third century CE) in his Commentary on John 6:41; however, the appearance of the name of the emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE) in the Eudocia inscription discovered in the excavations (see below) invites the supposition that they were built before Origen's time. They are also mentioned by Eusebius at the beginning of the fourth century (Onom. 22:25-27, 74: 11-13). At the end of the fourth century the Greek biographer Eunapius, who visited the site, wrote in his Life of Jamblichus that the baths of Hammat Gader were second in beauty only to those of Baia in the Bay of Naples. The colorful crowds of people who filled the place were described by his contemporary, Epiphanius (Haer. 30, 7). According to Talmudic sources, many sages visited Hammat Gader, from Rabbi Meir (mid-second century CE) onward: Judah ha-Nasi, Hanina, Jonathan, Hamma bar Hanina, and Ami, the latter with Judah ha-Nasi II. These scholars discussed the problems of the Sabbath boundaries between Gadara and Hammat, located below Gadara (Reeg, Ortsnamen, 258-259). The synagogue inscriptions also testify to the numbers of foreign visitors (Naveh, nos. 32-35).

In the fifth to seventh centuries, the baths building was at its most glorious. The complex was extensive and ramified. Evidence of this is found in the Hall of Fountains in which the six building inscriptions found were written in a Greek rhetorical style. In these inscriptions mention is made of Empress Eudocia (421-460), Emperor Anastasius I (491-518), and the Caliph Mu'awiya I (661-680), founder of the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus. The Eudocia inscription is a paean to the hot springs and baths of Hammat Gader. The inscription lists sixteen names of different parts of the baths building-halls, pools, and fountains-on a marble slab (71 by 181 cm) laid in the pavement beside the bathing pool in the Hall of Fountains. In the inscription, flanked by two crosses, the name of the authoress appears, Empress (Augusta) Eudocia. The name of Emperor Anastasius is mentioned in two inscriptions as having granted a money gift (λωρον) to the place. In these and in two other inscriptions, mention is made of a figure unknown from other sources, Alexander of Caesarea, the governor of Palaestina Secunda, who resided in Beth-Shean (Scythopolis), the capital of the province. According to the inscriptions, Alexander built (or restored) various portions of the structure-the bathing pools, tholos structures, and others. These building inscriptions attest to the fame of the baths at Hammat Gader and to the crowds who streamed to them for cures. The wealthy and powerful also sought to perpetuate their names in magnificent construction projects here.

In the second half of the sixth century CE, Hammat Gader was visited by the pilgrim known as Antoninus of Placentia. He testifies that the inhabitants of Hammat Gader named the medicinal baths after the prophet Elijah (Thermae Heliae). According to Antoninus, the baths were a center for the healing of lepers, who were accommodated in a hostel supported at public expense (Itinerarium Antonium, 7).

Nothing is known of the history of the baths at the end of the Byzantine period. It may be assumed, however, that they suffered damage or neglect during the troubled times in the first half of the seventh century, because they were completely renovated by Caliph Mu'awiya I shortly after he ascended the throne in Damascus. The sixth building inscription in the Hall of Fountains -which was found in situ, in the wall of the hall's central alcove, 2.1 m above the floor -- commemorates the renovation in Greek. The marble slab (50 by 80 cm) apparently was laid on the day the baths opened in 662 CE. The Umayyad restoration was carried out by the governor Abdullah Ibn Hashem and under the care of a local alderman of Gadara, Johannes.

The last phase of the baths is attested by several graffiti in Kufic script found · on the paving slabs and walls. One of the inscriptions contains the word · 'Allahuma, an early form of address to 'Allah, in use until the mid-eleventh century, at the latest. In addition, the Muslim geographer el-Muqaddasi (tenth century) speaks of the baths in the past tense. The bath complex was probably destroyed in the earthquake of 749. The fallen debris was eventually covered with earth, and the building was abandoned; however, the place continued to be visited by sick people until modern times.

The Roman baths are located in the southern portion of the recreational site of Hammat Gader, between the Roman theater and the Yarmuk River (map reference 2125.2320). The baths were built around the hot springs of 'Ein el-Maqle, whose waters reach a temperature of 51 degrees C and to which great curative powers were attributed in ancient times.

Systematic excavations in the baths began in 1979 and continued for seven seasons, until large parts of the complex were completely cleared. The excavations were conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Israel Exploration Society, and the Israel Department of Antiquities, under the direction of Y. Hirschfeld and G. Solar.

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of area around Hammat Gader

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 1 The Plain of

El-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The Plain of el-Hammeh (according to Schumacher)

Sukenik (1935) - Fig. 2 Geologic Sketch

of el-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Geologic Sketch of el-Hammeh

Sukenik (1935)

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of area around Hammat Gader

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 1 The Plain of

El-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The Plain of el-Hammeh (according to Schumacher)

Sukenik (1935) - Fig. 2 Geologic Sketch

of el-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Geologic Sketch of el-Hammeh

Sukenik (1935)

- Annotated Satellite Image

of Hammat Gader and environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hammat Gader and environs

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hammat Gader and environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Plate I View of El-Hammeh

from Sukenik (1935)

Plate I

Plate I

General view of el-Hammeh front the North. Below is seen the Yarmuk River crossed by the bridge of the Hedjaz Railway; on the left appears the hill upon which the Synagogue stood; on the top of the mountains in the centre is the site of ancient Gadara.

Sukenik (1935) - Hammat Gader in Google Earth

- Hammat Gader on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Satellite Image

of Hammat Gader and environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hammat Gader and environs

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hammat Gader and environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Plate I View of El-Hammeh

from Sukenik (1935)

Plate I

Plate I

General view of el-Hammeh front the North. Below is seen the Yarmuk River crossed by the bridge of the Hedjaz Railway; on the left appears the hill upon which the Synagogue stood; on the top of the mountains in the centre is the site of ancient Gadara.

Sukenik (1935)

- Fig. 3 Site Plan

from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of Hammat Gader and its springs.

- 'Ain el-Maqleh

- ‘Ain er-Rih

- ‘Ain el-Jarab

- ‘Ain Bulos

- ‘Ain Sa’ad el-Rar

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 7 Reconstructed

Site Plan from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Reconstructed plan of ancient Hammat Gader

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 3 Site Plan

from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of Hammat Gader and its springs.

- 'Ain el-Maqleh

- ‘Ain er-Rih

- ‘Ain el-Jarab

- ‘Ain Bulos

- ‘Ain Sa’ad el-Rar

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 7 Reconstructed Site Plan

from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Reconstructed plan of ancient Hammat Gader

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

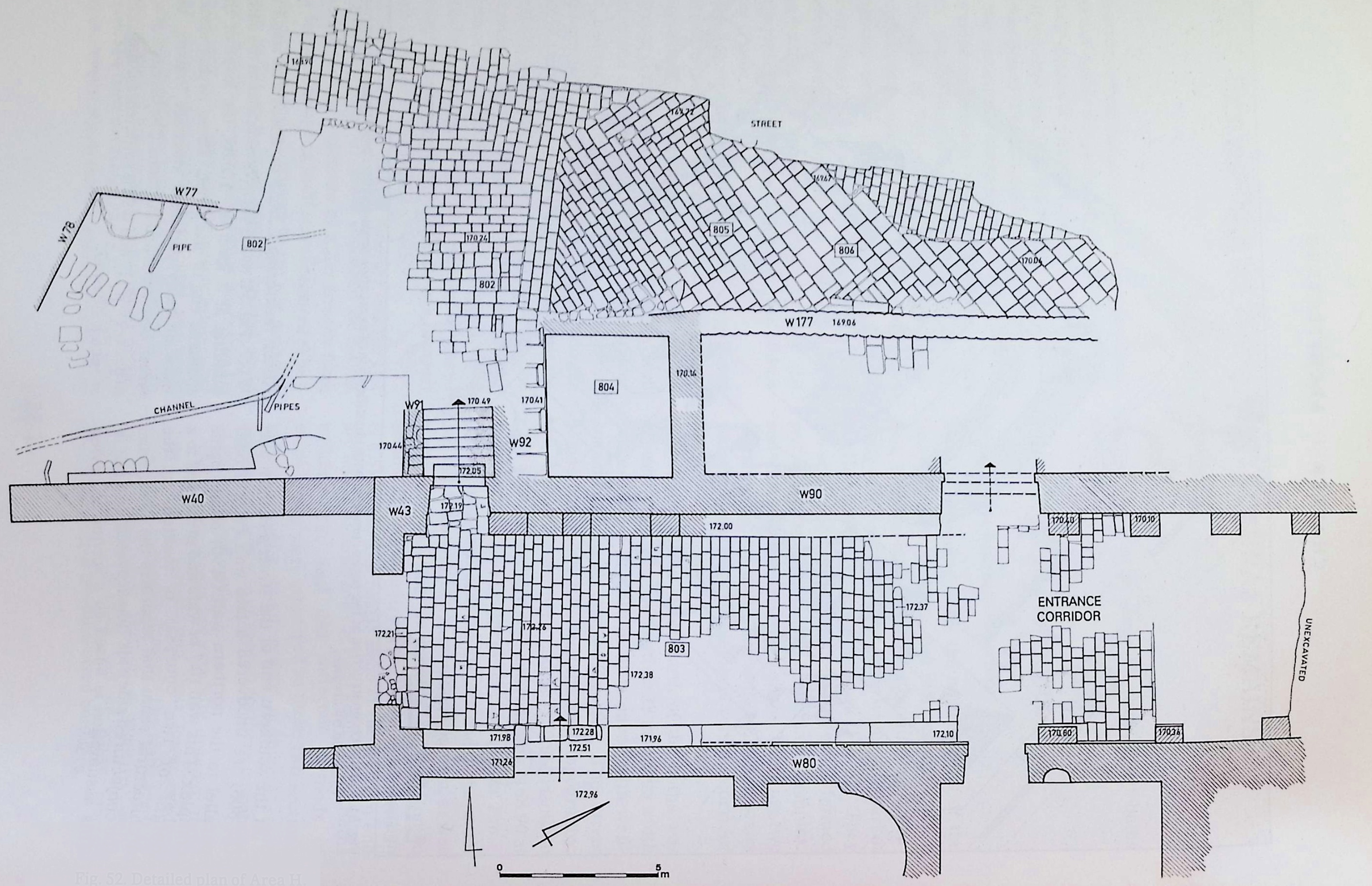

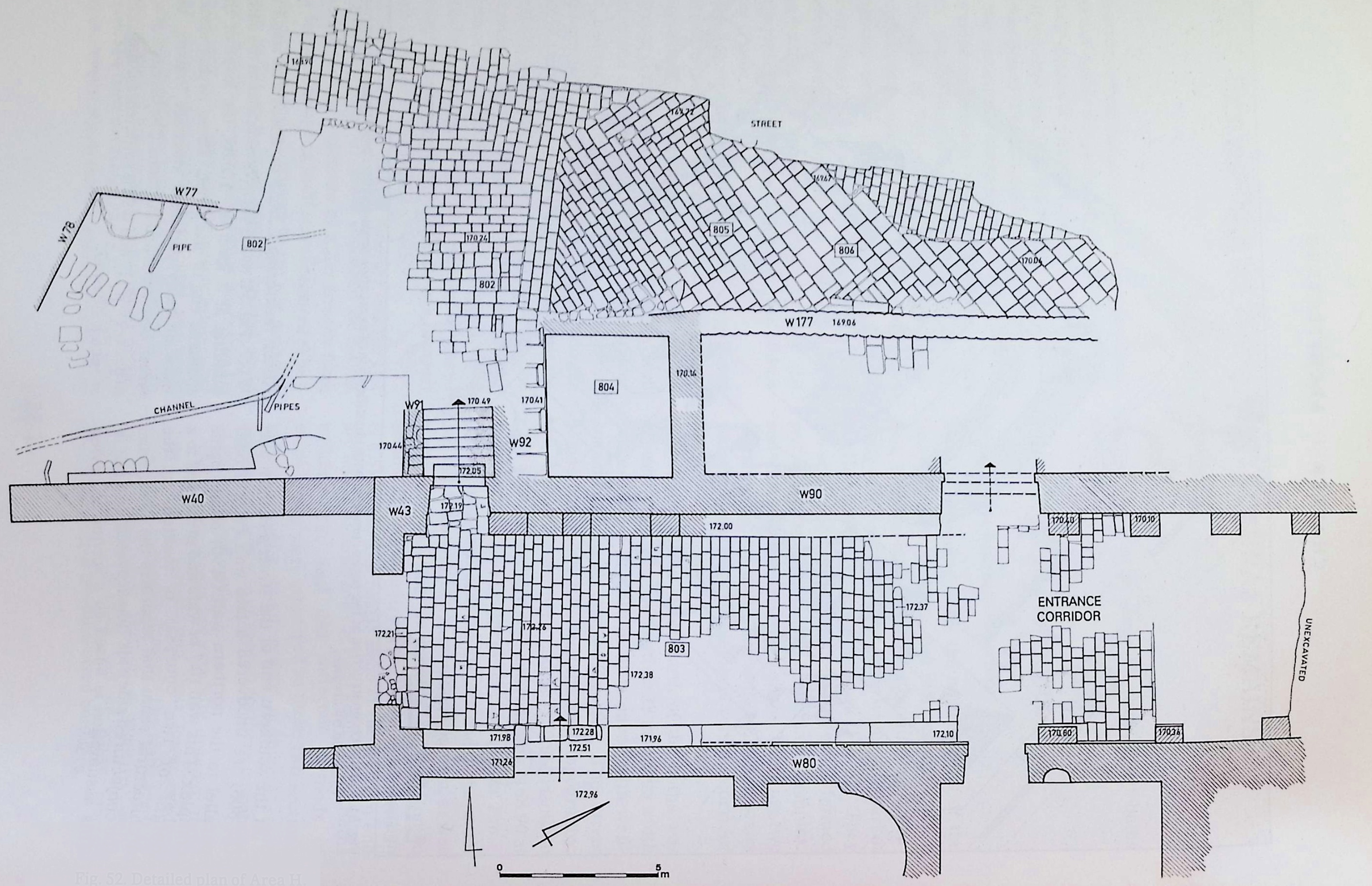

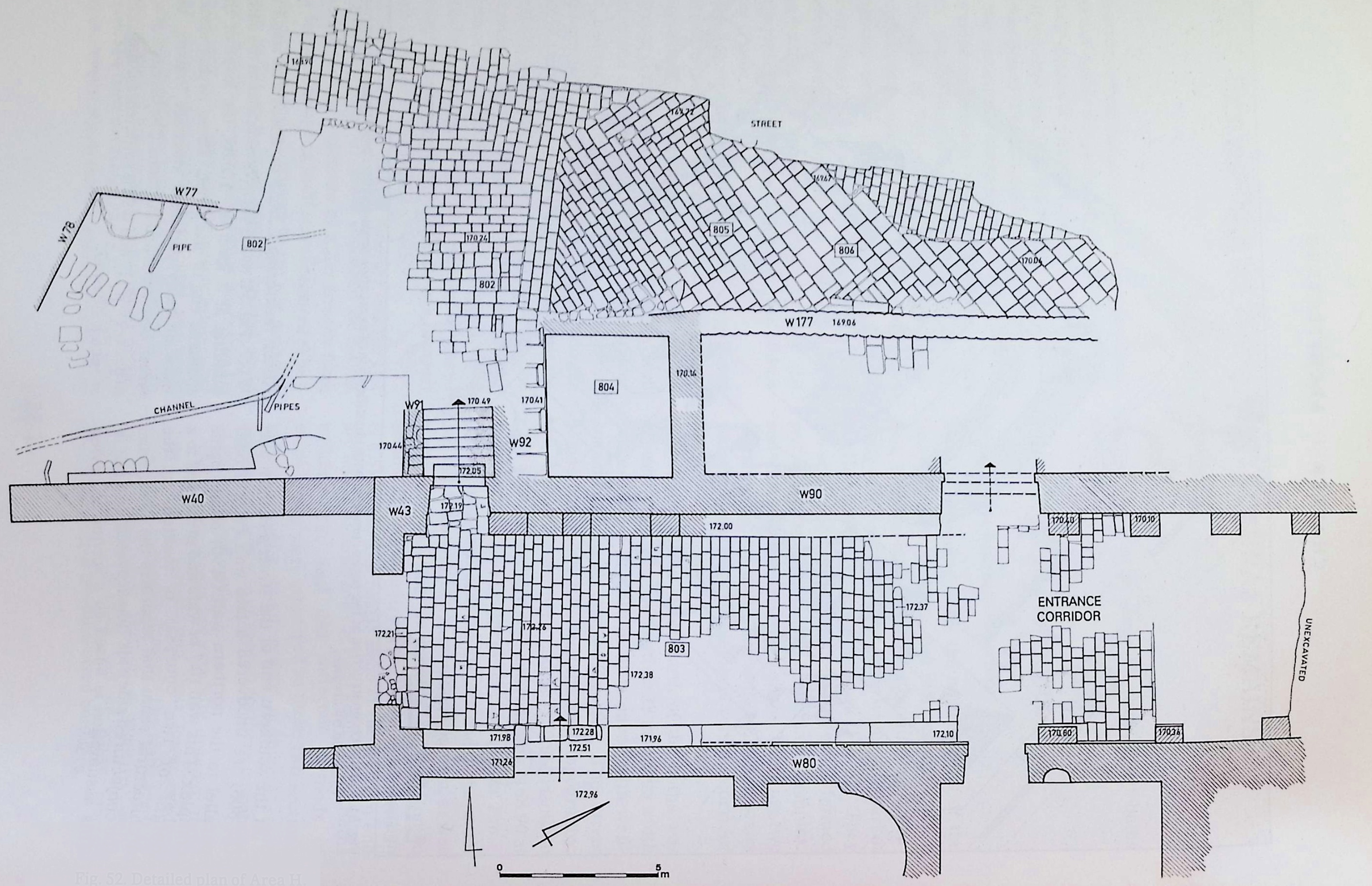

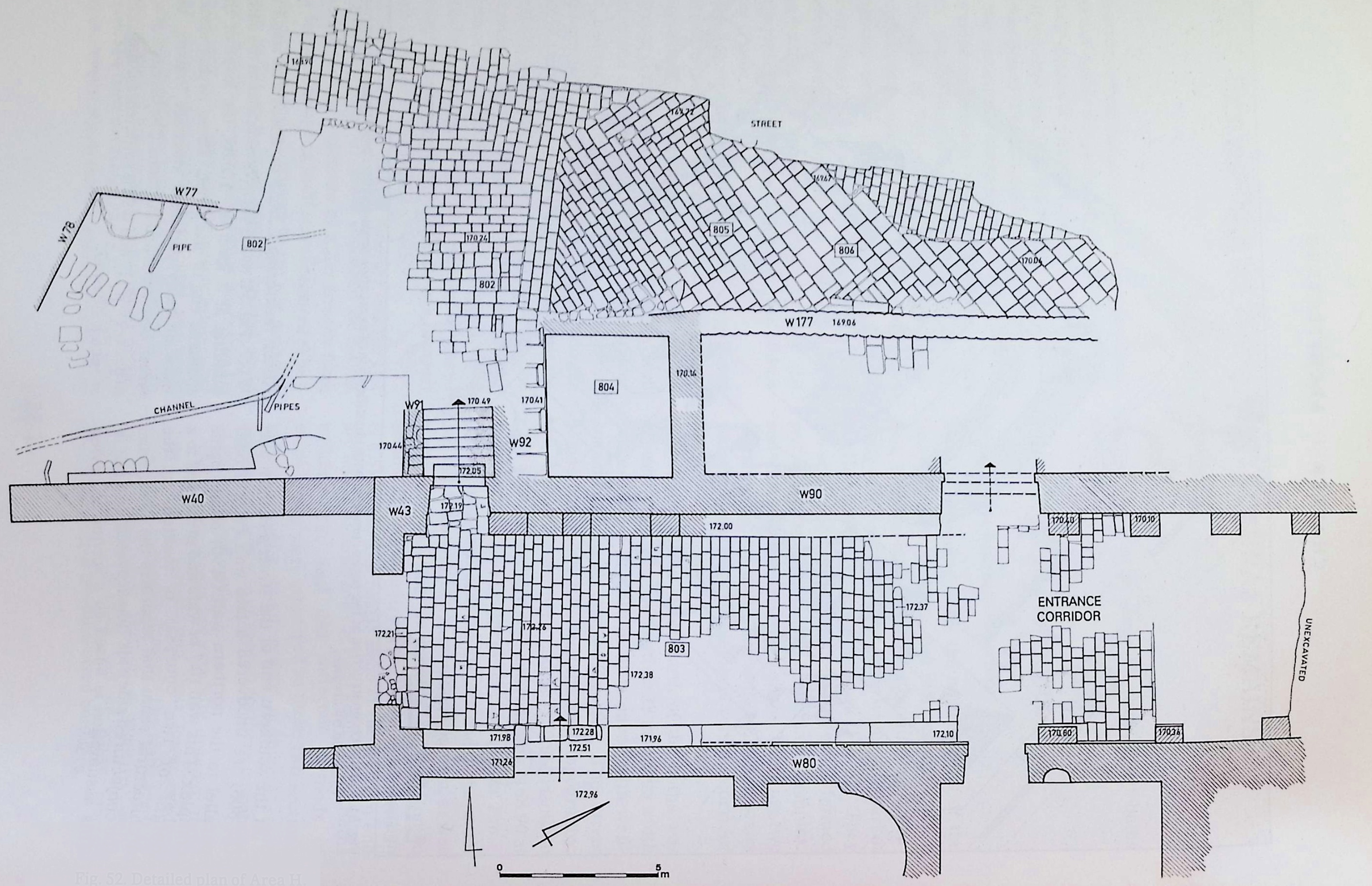

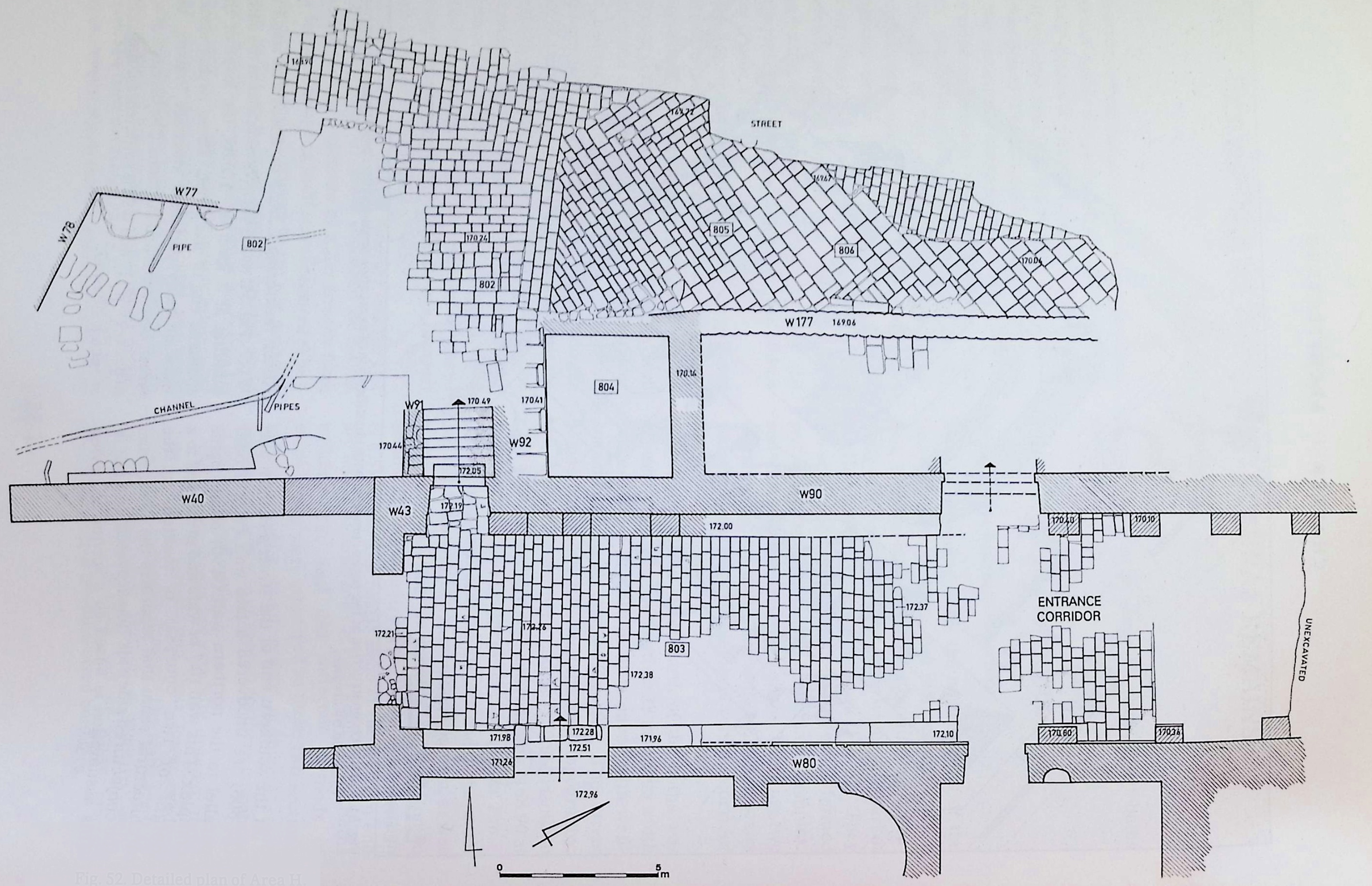

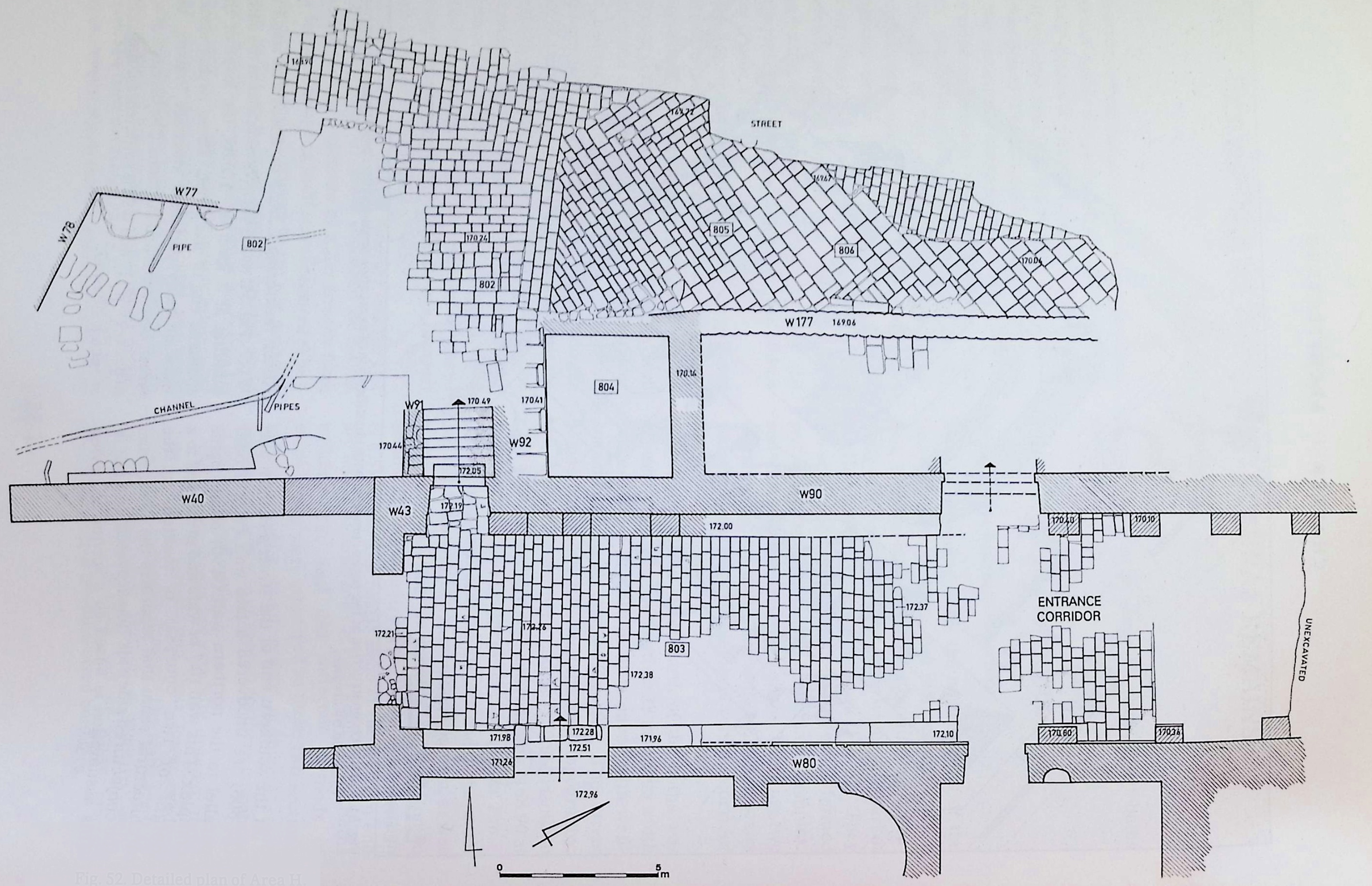

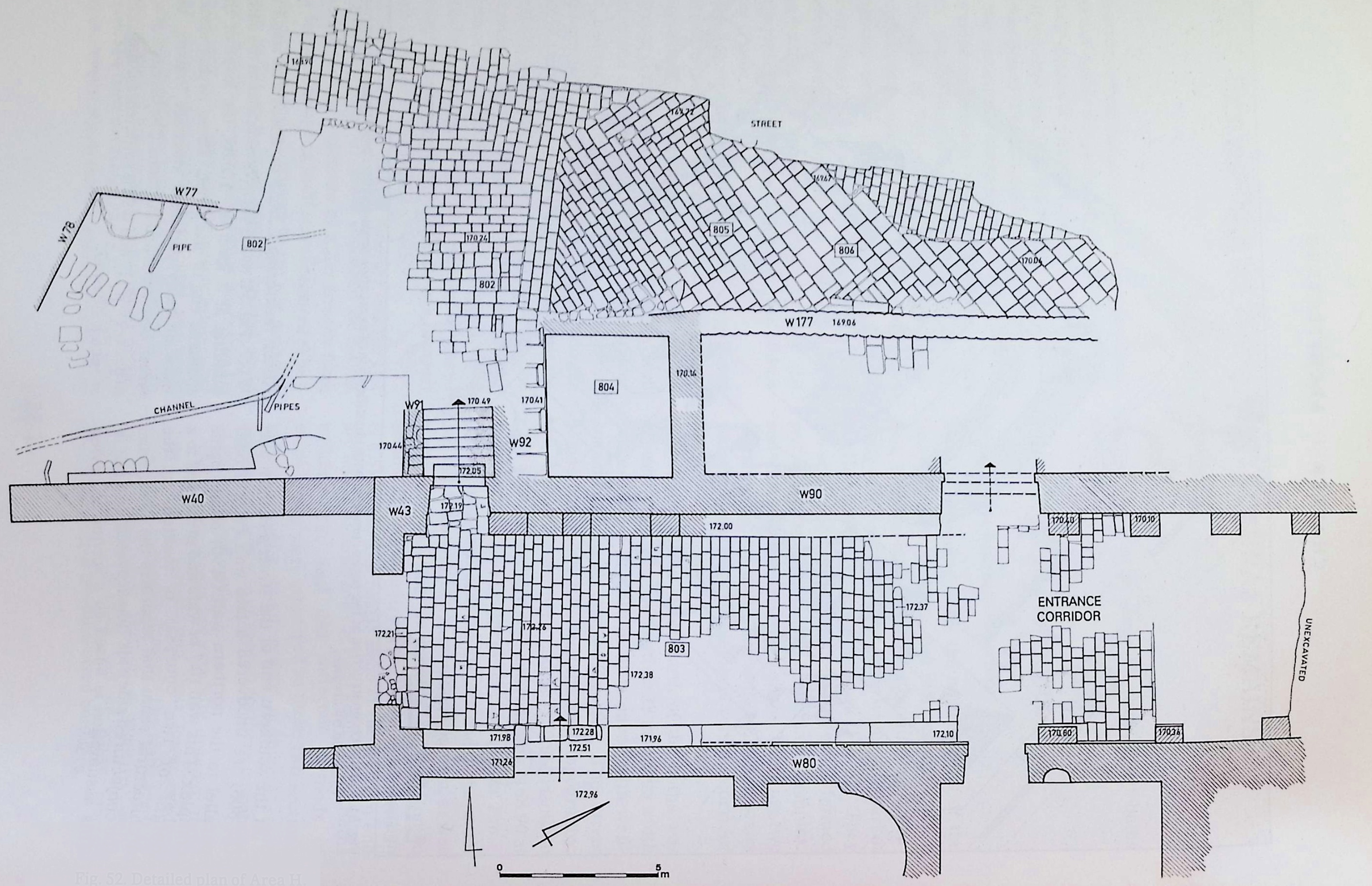

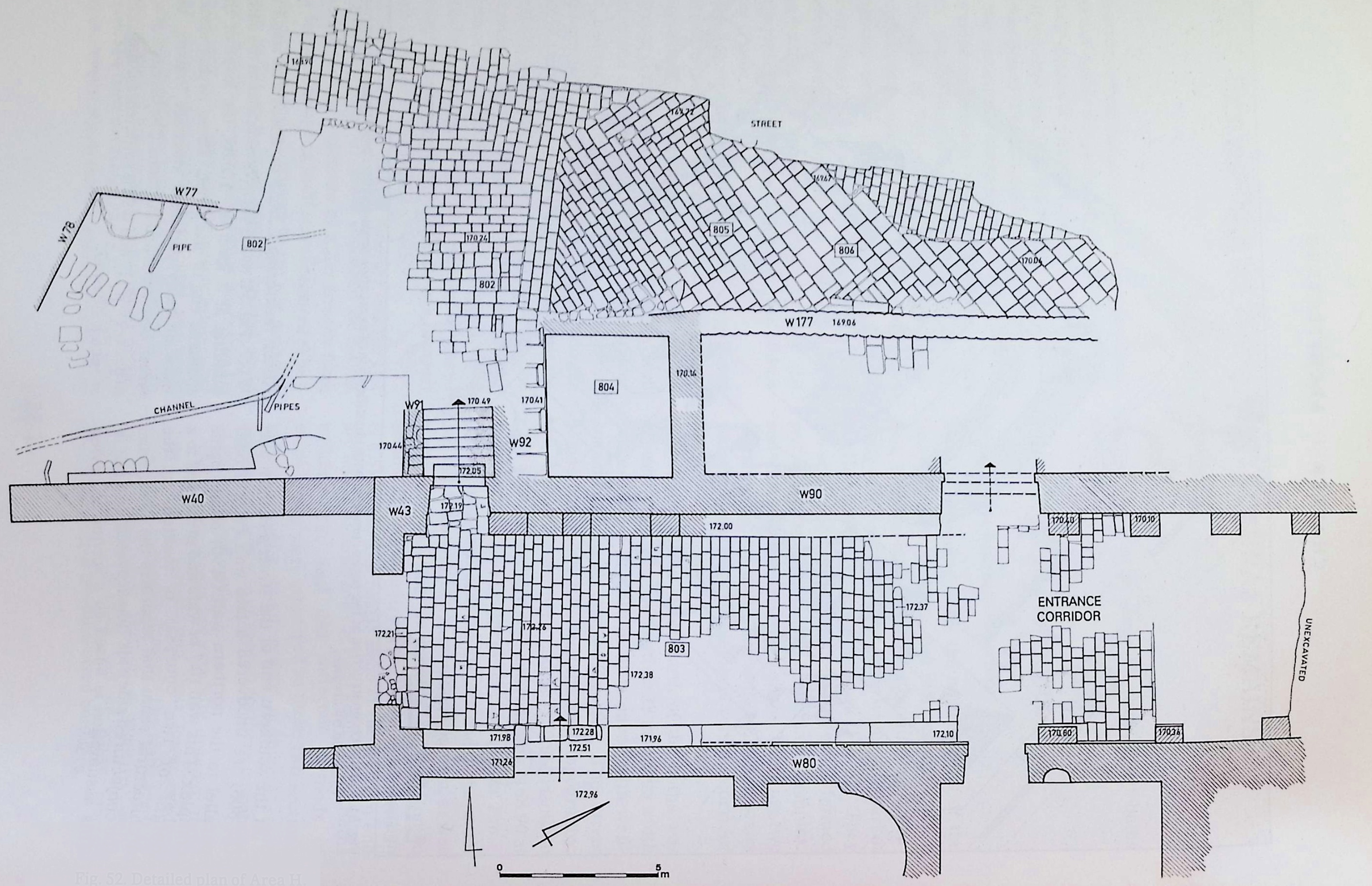

- Fig. 11 General

plan of the remains of the baths exposed in the excavations from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

General plan of the remains of the baths exposed in the excavations

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 39 Plan of

the water system of the Hammat Gader baths from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

Plan of the water system of the Hammat Gader baths.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Plan of the baths from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

Plan of the baths

Plan of the baths

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2) - Fig. 51 Partial

Reconstruction of the baths complex from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 51

Fig. 51

Partial Reconstruction of the baths complex, with identification of excavation areas and the conjectured bathing route (marked by arrows).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 252 Partial

reconstruction of the baths structure from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 252

Fig. 252

Partial reconstruction of the baths structure, looking north

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 253 Proposed

plan of the entire baths complex from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 253

Fig. 253

Proposed plan of the entire baths complex

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 254 Reconstruction

of the roofs of the baths building from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 254

Fig. 254

Reconstruction of the roofs of the baths building, looking west

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 11 General

plan of the remains of the baths exposed in the excavations from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

General plan of the remains of the baths exposed in the excavations

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 39 Plan of

the water system of the Hammat Gader baths from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

Plan of the water system of the Hammat Gader baths.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Plan of the baths from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

Plan of the baths

Plan of the baths

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2) - Fig. 51 Partial

Reconstruction of the baths complex from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 51

Fig. 51

Partial Reconstruction of the baths complex, with identification of excavation areas and the conjectured bathing route (marked by arrows).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 252 Partial

reconstruction of the baths structure from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 252

Fig. 252

Partial reconstruction of the baths structure, looking north

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 253 Proposed

plan of the entire baths complex from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 253

Fig. 253

Proposed plan of the entire baths complex

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 254 Reconstruction

of the roofs of the baths building from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 254

Fig. 254

Reconstruction of the roofs of the baths building, looking west

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 103 Detailed

Plan of Area A (Oval Hall) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 103

Fig. 103

Detailed Plan of Area A (Oval Hall).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 188 Detailed

Plan of the remains of the late periods in Area B (passage rooms) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 188

Fig. 188

Detailed plan of the remains of the late periods in Area B (passage rooms).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 65 Detailed

Plan of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 65

Fig. 65

Detailed Plan of Area C (Hall of Piers).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 178 Byzantine

tiled floor and the late remains north of the columned portal [in Area C] from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 178

Fig. 178

Plan of the Byzantine tiled floor and the late remains north of the columned portal [in Area C]

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 135 Detailed

Plan of Area D (Hall of Fountains) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 135

Fig. 135

Detailed plan of Area D (Hall of Fountains)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 85 Detailed

Plan of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 85

Fig. 85

Detailed Plan of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 52 Detailed

Plan of Area H (Entrance Corridor) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 52

Fig. 52

Detailed Plan of Area H

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 103 Detailed

Plan of Area A (Oval Hall) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 103

Fig. 103

Detailed Plan of Area A (Oval Hall).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 188 Detailed

Plan of the remains of the late periods in Area B (passage rooms) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 188

Fig. 188

Detailed plan of the remains of the late periods in Area B (passage rooms).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 65 Detailed

Plan of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 65

Fig. 65

Detailed Plan of Area C (Hall of Piers).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 178 Byzantine

tiled floor and the late remains north of the columned portal [in Area C] from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 178

Fig. 178

Plan of the Byzantine tiled floor and the late remains north of the columned portal [in Area C]

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 125 Detailed

Plan of Area D (Hall of Fountains) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 135

Fig. 135

Detailed plan of Area D (Hall of Fountains)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 85 Detailed

Plan of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 85

Fig. 85

Detailed Plan of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions).

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 52 Detailed

Plan of Area H (Entrance Corridor) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 52

Fig. 52

Detailed Plan of Area H

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan of the baths complex with location of inscriptions, arrows show orientation of each inscription.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 2 Parts of the

columned portal as found in the excavation from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Parts of the columned portal as found in the excavation, looking northwest.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Plate I The apparently

restored columned portal from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Plate I

Plate I

Columned portal in Area C. looking north

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 5 Remains of

arches and vaults in the baths building, as photographed in the early 20th century from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Remains of arches and vaults in the baths building, as photographed in the early 20th century, looking east

(Antiquities Authority Archive)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 10 Remains of

baths at the conclusion of excavations (1982) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Remains of the baths at the conclusion of excavations (1982), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 8 Collapsed

Vault from Area D from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Remains of a vault found in the debris of Area D (Hall of Fountains), looking north.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 18 Section of

the ceiling vault in Area A (Oval Hall) that fell directly on the pool floor from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Section of the ceiling vault in Area A (Oval Hall) that fell directly on the pool floor, looking east.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 84 Photograph

of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 84

Fig. 84

Photograph of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 84 Cross section

(across the width) of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 84

Fig. 84

Cross section (across the width) of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 87 The southern end

of Area A (Hall of Inscriptions), including the southern wall (W1) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 87

Fig. 87

The southern end of Area A (Hall of Inscriptions), including the southern wall (W1), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 88 Drawing of

the northern face of Wall W1 (separating Areas E and B) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 88

Fig. 88

View of the northern face of Wall W1 (Areas E and B)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 95 Debris of

vault stones on the floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 95

Fig. 95

Debris of vault stones on the floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions), looking southeast.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 159 Debris of

the vault on the floor of of the central pool of Area D (Hall of Fountains) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 159

Fig. 159

Debris of the vault on the floor of of the central pool of Area D (Hall of Fountains), looking northwest.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 160 Remains of

the vault of the southern wing found in the alluvium on the floor of the hall from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 160

Fig. 160

Remains of the vault of the southern wing found in the alluvium on the floor of the hall, looking north.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 118 Fountain

found in the alluvium above the central pool of Area A (Oval Hall) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 118

Fig. 118

Another fountain found in the alluvium above the central pool of Area A (Oval Hall). JW: Although this fountain was found atop alluvium, four fountains were reported by Hirschfeld et al. (1997:92) as being found "in debris"

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 177 Secondary Use

of architectural elements in Wall W92 in Byzantine Phase II Area H (Entrance Corridor) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 177

Fig. 177

Eastern face of W92 next to the staircase descending to the baths, looking southwest. Note the secondary use of architectural elements.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 179 Inscription No. 1

in Area C Byzantine Phase II from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 179

Fig. 179

Inscription No. 1 found in situ, looking south. Note the Byzantine floor tiles framing the inscription

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 180 Lateral cross

section showing central pool of Area C beneath Byzantine Phase II flooring from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 180

Fig. 180

Lateral cross section of the central pool of Area C (Hall of Piers) and the bathtub west of it (L.325)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 184 Dented (?) Marble

Floor in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 184

Fig. 184

Marble floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 185 Dented (?) Marble

Floor in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 185

Fig. 185

Inscriptions nos. 6 (in front) and 10 (behind) found in situ [in Area E], looking west

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 186 Floor depressed

by the collapse of the ceiling vault in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 186

Fig. 186

Engaged pilasters along W13 [JW: in Area E], looking southeast. Note the depressions made in the floor of the hall by the collapse of the ceiling's vault

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 3 Drawing from ~1820

of Remains of Roman Bath of El-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

el-Hammeh. Remains of Roman bath (from Buckingham, Travels etc.)

J. S. Buckingham, Travels in the countries of Bashan and Gilead, east of the river Jordan; including a visit to the cities of Geraza and Gainala in the Decapolis. London 1821, p. 441.

Sukenik (1935) - Fig. 191 Clay lamps from

the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B (medium shot) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 191

Fig. 191

Clay lamps from the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 191 Clay lamps from

the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B (closeup) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 191

Fig. 191

Clay lamps from the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

- Fig. 2 Parts of the

columned portal as found in the excavation from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Parts of the columned portal as found in the excavation, looking northwest.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Plate I The apparently

restored columned portal from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Plate I

Plate I

Columned portal in Area C. looking north

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 5 Remains of

arches and vaults in the baths building, as photographed in the early 20th century from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Remains of arches and vaults in the baths building, as photographed in the early 20th century, looking east

(Antiquities Authority Archive)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 8 Collapsed

Vault from Area D from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Remains of a vault found in the debris of Area D (Hall of Fountains), looking north.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 18 Section of

the ceiling vault in Area A (Oval Hall) that fell directly on the pool floor from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Section of the ceiling vault in Area A (Oval Hall) that fell directly on the pool floor, looking east.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 10 Remains of

baths at the conclusion of excavations (1982) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Remains of the baths at the conclusion of excavations (1982), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 84 Photograph

of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 84

Fig. 84

Photograph of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 84 Cross section

(across the width) of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 84

Fig. 84

Cross section (across the width) of the roof debris of Area C (Hall of Piers), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 87 The southern end

of Area A (Hall of Inscriptions), including the southern wall (W1) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 87

Fig. 87

The southern end of Area A (Hall of Inscriptions), including the southern wall (W1), looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 88 Drawing of

the northern face of Wall W1 (separating Areas E and B) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 88

Fig. 88

View of the northern face of Wall W1 (Areas E and B)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 95 Debris of

vault stones on the floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 95

Fig. 95

Debris of vault stones on the floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions), looking southeast.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 159 Debris of

the vault on the floor of of the central pool of Area D (Hall of Fountains) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 159

Fig. 159

Debris of the vault on the floor of of the central pool of Area D (Hall of Fountains), looking northwest.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 160 Remains of

the vault of the southern wing found in the alluvium on the floor of the hall from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 160

Fig. 160

Remains of the vault of the southern wing found in the alluvium on the floor of the hall, looking north.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 118 Fountain

found in the alluvium above the central pool of Area A (Oval Hall) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 118

Fig. 118

Another fountain found in the alluvium above the central pool of Area A (Oval Hall). JW: Although this fountain was found atop alluvium, four fountains were reported by Hirschfeld et al. (1997:92) as being found "in debris"

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 177 Secondary Use

of architectural elements in Wall W92 in Byzantine Phase II Area H (Entrance Corridor) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 177

Fig. 177

Eastern face of W92 next to the staircase descending to the baths, looking southwest. Note the secondary use of architectural elements.

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 179 Inscription No. 1

in Area C Byzantine Phase II from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 179

Fig. 179

Inscription No. 1 found in situ, looking south. Note the Byzantine floor tiles framing the inscription

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 180 Lateral cross

section showing central pool of Area C beneath Byzantine Phase II flooring from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 180

Fig. 180

Lateral cross section of the central pool of Area C (Hall of Piers) and the bathtub west of it (L.325)

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 184 Dented (?) Marble

Floor in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 184

Fig. 184

Marble floor of Area E (Hall of Inscriptions) looking south

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 185 Dented (?) Marble

Floor in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 185

Fig. 185

Inscriptions nos. 6 (in front) and 10 (behind) found in situ [in Area E], looking west

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 186 Floor depressed

by the collapse of the ceiling vault in Area E from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 186

Fig. 186

Engaged pilasters along W13 [JW: in Area E], looking southeast. Note the depressions made in the floor of the hall by the collapse of the ceiling's vault

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 3 Drawing from ~1820

of Remains of Roman Bath of El-Hammeh from Sukenik (1935)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

el-Hammeh. Remains of Roman bath (from Buckingham, Travels etc.)

J. S. Buckingham, Travels in the countries of Bashan and Gilead, east of the river Jordan; including a visit to the cities of Geraza and Gainala in the Decapolis. London 1821, p. 441.

Sukenik (1935) - Fig. 191 Clay lamps from

the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B (medium shot) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 191

Fig. 191

Clay lamps from the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B

Hirschfeld et al. (1997) - Fig. 191 Clay lamps from

the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B (closeup) from Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

Fig. 191

Fig. 191

Clay lamps from the fifth century in the fill of the pool in the western room of Area B

Hirschfeld et al. (1997)

It has become evident from the results of the excavation that the baths complex was built in the mid-second century and was in continuous use until its destruction in the earthquake of 749 C.E. During this period of some 600 years, there were five different phases of occupation, each of which finds architectural expression in the building. Phase I is the original structure from the second century, most probably from the time of Emperor Antoninus Pius (142-161), whose name is mentioned in one of the inscriptions found at the site. Phase II may be subdivided into two: Phase IIA dates to the mid-fourth - mid-fifth centuries, and Phase IIB from the mid-fifth century until the end of the Byzantine period (mid-seventh century). These subphases may be detected in the architectural repairs made in the baths as the result of damage probably caused by an earthquake. Inscription no. 1, which dates to the year 455 and explicitly mentions one of the earthquakes which hit the site, fixes the date of the floor in which it was embedded to Phase IIB. Phase III of the baths structure overlaps the Umayyad period, beginning with renovation activity in the time of the Caliph Mu’awiya (according to the inscription found in the excavation)and ending with the earthquake of 749. Two additional phases (IV and V) — the earlier one from the Abbasid-Fatimid period (eighth-eleventh centuries) and the later one from the Middle Ages — were discerned on top of the building’s ruins.

| Phase | Start | End | Dating Find | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ca. 150 | 363 | Eudocia inscription, other finds | Roman period |

| IIA | 363 | 450 | One of the two capitals of the columned portal, Area C | Byzantine period |

| IIB | 450 | 661 | Building activity following an earthquake mentioned in Inscription no. 1, other finds | Byzantine period |

| III | 661 | 749 | Mu’awiya inscription mentioning the cleaning of the baths, other finds | Umayyad period |

| IV | 749 | ? | Minor levels of occupation above the debris and alluvium of the “seventh quake" | Abbasid-Fatimid period (eighth-eleventh centuries) |

| V | Minor levels of occupation, undated | Middle Ages (thirteenth-fourteenth centuries) |

- from Magness (2010)

| Phase | Magness Period | Magness Date Range | Magness redating rationale | Hirschfeld period | Hirschfeld date range | Hirschfeld notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Roman | mid-2nd c. – mid-4th c. CE | Essentially retained. Early construction of the monumental baths; Magness does not challenge Hirschfeld’s basic Roman dating for the initial phase. | Roman | ca. 150 – 363 CE | Establishment of bath complex; dated mainly by general Roman material and architectural style. |

| II (H IIA+IIB) | Umayyad (renovation phase) | late 6th / 7th c. – mid-8th c. CE (Umayyad horizon) | Floors and fills (L211, 313, 321, 516) sealed with large, homogeneous groups of late 6th–7th c. coins and pottery, plus some post-reform Umayyad coins; no clear evidence for a mid-5th c. reconstruction. Inscription no. 1 cannot be securely tied to 455; Phase II renovations belong in an Umayyad context (possibly linked to the 660 or 749 earthquakes), not a mid-5th c. Byzantine event. |

IIA Byzantine IIB Byzantine |

IIA: 363 – 450 CE IIB: 450 – 661 CE |

IIA and IIB as post-363 and post-455 reconstruction phases; dated chiefly by inscriptions (incl. 455 and “earthquake” inscription no. 1) rather than the full ceramic and numismatic assemblages. |

| III | Abbasid–Fatimid (continued use phase) | ca. late 8th / 9th c. – early 11th c. CE (to earthquake of 1033) | Loci assigned by Hirschfeld to Umayyad Phase III (e.g. L302, L201, blocking walls, new installations) contain dense groups of post-reform Umayyad and later coins, 9th–10th c. lamps, and glazed wares. These show a major occupation in the 9th–10th c., with substantial investment (new pipes, working water system). Collapse and major damage are better attributed to the 1033 earthquake, not 749. | Umayyad | 661 – 749 CE | Blocking of passages and narrowing of spaces; interpreted as final Umayyad stage immediately preceding total destruction in the 749 earthquake. |

| IV | Abbasid–Fatimid / early Medieval reuse | 11th c. CE (post-1033) into Middle Ages | “Late” floors and installations with Abbasid–Fatimid and later material represent reuse after main bath operation. Magness’s re-dating of Phase III pushes the functional life of the baths later; material Hirschfeld placed in an early post-749 phase is part of the long Abbasid–Fatimid trajectory and later reuse. | Abbasid–Fatimid | post-749 – 11th c. CE | Light occupation above supposed 749 debris; interpreted as squatter levels among ruins of a complex thought destroyed “totally and instantaneously” in 749. |

| V | Late Medieval | 13th–14th c. CE | Sparse 13th-century (and later) material (e.g. handmade painted wares, glazed wares, sphero-conical vessels) marks residual, minor reuse well after baths ceased to function; broadly compatible with, but more sharply defined than, Hirschfeld’s undated “Middle Ages” phase. | Middle Ages | 13th–14th c. CE | Minor, undated occupation above earlier levels; broadly assigned to medieval period. |

| Area | Description |

|---|---|

| A | The Oval Hall, north of the Hot Spring Complex |

| B | Passage Rooms, north of Area A |

| C | The Hall of Piers, north of Area B |

| D | The Hall of Fountains (initially termed the Hall of Alcoves), in the eastern part of the building |

| E | The Hall of Inscriptions, between Areas C and D |

| F | The Service Area, west of the building |

| G | The Hot Spring Complex, in the southern part of the building |

| H | The Entrance Corridor and the street north of the building |

| J | The eastward extension of the building |

... It is not clear what fate befell the baths at the end of the Byzantine period. However, it seems that the place was struck by one of the earthquakes that occurred in the region. The resulting damage caused to the baths is attested in the “Mu’awiya inscription” (no. 54) discovered at the site. This inscription, which has been dated accurately to the year 662 C.E., notes extensive renovation activity carried out in the baths complex by the first Umayyad caliph, from Damascus.

From the results of our excavations, it appears that the Umayyad period was the baths’ last phase of utilization. In the year 749, a severe earthquake known as “the seventh quake” (Amiran, Arieh and Turcotte 1994:266-267) destroyed entire cities on both sides of the Jordan Valley, including the baths complex at Hammat Gader, thereby terminating its use as a built complex. ...

The first structural element to be described should be the foundations. In order to study this element, one must either excavate beneath or along the walls, or dismantle some of the built elements.

In the case of Hammat Gader, the structure is so complete that in very few places were we able to reach or see foundations. The only clue to their character is to be found beneath the floors of Area A, which will be described in detail in the section dealing with floors. The foundations of secondary walls were exposed in two places: Area C (W39 and W42) and Area H (W92). In the first two walls we see a course of basalt fieldstones joined together by hard bonding material. The course protrudes irregularly, up to ca. 20 cm, from the plane of the wall. Above the foundation was laid a partially worked leveling course which juts out a few centimeters from the plane of the wall.

W92 has survived only to the height of the foundations; on the one hand, it probably served as the wall of a shop and therefore is actually located outside the baths complex, and on the other, it served as the wall of a staircase descending from the street to the baths. The visible course was built of various architectural elements - column drums and bases - in secondary use. Foundations of this kind belong to a later occupation phase.

The building’s state of preservation and the fact that the walls stand vertically without cracks led us to conclude that the builders of the foundations did an excellent job, taking advantage of the best knowledge, skills, and certainly the well-known Roman cement.

The walls of the Hammat Gader baths are particularly well preserved. Their average height ranges from 4 to 5 m, and in several places exceeds 8 m! This exceptional state of preservation makes the structure one of the most important and interesting examples of Roman architecture at its best.

The walls have two main roles. The first is structural: they are load-bearing elements, i.e., they carry the load of the roofs and ceilings. The second role can be defined as architectural, since the walls, in fact, create the structure’s archi tecture. They define the spaces in which the various elements are built — doors, windows, alcoves, niches, pipes, etc. Some of the walls are ornamented.

The identification of which walls in a structure are load-bearing and which are not (we would then call them “curtain” or “partition” walls) may help us better understand the character of the roofing, ceilings, and second floors. These elements are usually missing in archaeological structures; however, at Hammat Gader we had the good fortune to find the existing evidence for some of them.

Although it should not be considered a golden rule, the division into thick and thin walls within the same structural system usually coincides with the division into load-bearing and non-load bearing walls. Nevertheless, the thickness of a wall does not always indicate its structural role, since in some cases this is the result of its height, and in many cases it is due to the presence of alcoves and niches and other infrastructural elements within the wall. In our case - in Area A - even if the remains of the vault were not found in situ, and parts of it were revealed in the ruins, we could assume, and then only from the thickness of W1 (2.7 m), that we were dealing with a wall supporting a vault. In contrast, the thickness of the long walls in Area D (3.1 m for W13 and 3.7 m for W100) is due not only to the need to support the vault, but also, as we know from the structure, to the need to include large alcoves in these walls. The alcoves are ca. 2 m deep from the plane of the wall and therefore an especially thick wall was required to contain them.

Other walls, such as those in Area H (W90, 1.2 m thick), may indicate the existence of a small and relatively light vault. Area J is possibly an exception. This area contains an especially thin wall (W107, 0.6 m thick) supporting a vault; however, this is a vault with a very small span (less than 2 m) and therefore its load is not great.

The architectural remains of the baths complex at Hammat Gader will be described below according to their phases of construction, from early to late. First we shall deal with the remains dating to the Roman period (Phase I), during which the majority of the structure’s components were built; they continued to function, albeit with modifications, until the destruction of the complex in the earthquake of 749. We shall then discuss the modifications made in the structure in the Byzantine period (Phase II) and the Umayyad period (Phase III). In concluding this architectural overview, we shall note the poor remains of what was built above the structure’s ruins after the earthquake of 749 (Phase IV) and in the Middle Ages (Phase V).

The description of the bath’s various components will follow the course which the bathers would have taken in antiquity. This route probably began in the entrance corridor (Area H) located in the northern part of the complex (Fig. 51). From this corridor the bathers entered two adjacent halls on its southern side: the Hall of Piers (Area C) and the Hall of Inscriptions (Area E). (We assume that the northern entrance to Area D was only for the operators.) As we shall see below, these halls contained large pools in which the bathing activity actually commenced. The bathers then advanced through the passage rooms (Area B) into the Oval Hall (Area A) to the south.

The climax of the bathing itinerary was the Hot Spring Hall (Area G), which contained the hottest bathing pool, as it received its water directly from the spring. The spring itself was considered to be a holy wonder, and all visitors to the site probably came to this spot. From here the bathers could proceed to the adjacent Hall of Fountains (Area D) containing the monumental swimming pool surrounded by fountains. From here one could move on to several halls and courtyards in the eastern part of the complex, only a small part of which has been excavated (Area J). Another area, the remains of which shall be described separately, is the service area (Area F) west of the baths complex.

... The floor of the entrance corridor (L. 803) is made of well-dressed basalt paving stones. The average level of the entrance corridor’s pavement is -172.37 on the east and -172.21 on the west. The slabs are rectangular, measuring ca. 0.3x0.5 m, and are laid in parallel rows at right angles to the long walls of the entrance corridor. The lower part of the stones is roughly dressed, in contrast to the surface, which is well dressed and worn as a result of foot traffic by the visitors to the baths in antiquity. Most of the slabs have remained in situ without damage. On some of them masons’ marks of various kinds could be identified. In some places it was noted that parts of the pavement had been damaged, most probably as a result of the collapse of ceilings and upper parts of walls during the earthquake of 749 C.E. ...

... We were able to glean some information regarding the ceiling of Area C from the debris found on the floor in the center of the hall (L. 306). The ceiling that had collapsed in the earthquake of 749 (according to the artifacts found there) formed a pile of debris directly overlying the hall’s floor. From a cross section through the debris, we were able to determine various details regarding the stones of the ceiling (Fig. 84). The pile of ceiling debris averages ca. 2 m in height, and on top of it a 1.4-2.0-m-thick layer of alluvium has accumulated. The fact that the stones in the debris fell one next to the other is due to the vaulted shape of the ceiling. These are regular tufa stones of the type that the builders of the baths used to construct the the ceilings (similar to those found in situ in Area B; see below). They are on the average 0.5 m long and 0.2- 0.25 m thick. Beneath them we found many pieces of glass mosaics. It appears, therefore, that the superstructures of the building, and perhaps also parts of the ceiling and the arches between the piers, were overlaid with colorful mosaics. Among the rubble we also uncovered many fragments of windowpanes; this find corroborates our assumption that windows of various shapes and sizes were installed in the walls around the hall.

... The southern wall (W1) of Area E is one of the best preserved walls in the complex (Fig. 87), attaining a height of 8.4 m above the floor of the hall and 9.5 m above that of the pool. W1 is essentially part of a longer wall shared by Areas E and B and separating them from Area A. The thickness of this wall which supports the ceilings of three halls is 2.6 m. A hot-water channel runs through its foundations, bringing water to the pool in Area E.

An examination of the northern side of the wall, in the section facing Area E, revealed that the wall at one time underwent thorough renovation (Fig. 88). This emerges from the relationship between the wall’s foundations and the plaster floor in the hall’s pool. One can clearly see that the plastered floor of the pool runs beneath the foundations of the wall, i.e., the foundations were built on top of the floor and therefore postdate it. Another instructive fact regarding renovation of this wall is that most of the masonry in this section consists of limestone, in contrast to the other parts of the wall that are built of basalt. It appears that the wall was rebuilt following an earthquake, perhaps the one mentioned explicitly in Inscription no. 1 which is dated to the mid-fifth century C.E. (Phase II; see below). This seems plausible since the wall’s foundations were hidden beneath the floor bearing the inscriptions, which covered the original pool from the mid-fifth century on. Therefore, the face of the wall in its present state, as exposed in the excavation, belongs to Phase II; however, one may also assume that the wall’s core and foundations belong to the original construction stage (Phase I).

... The water was possibly brought to the tub via a pipe, the remains of which were found in the northern wall. At the top of the western end of this wall, a section of lead pipe with the standard diameter of 9 cm was found in situ. It links up with a section of clay pipe with a similar diameter, which probably branched out to the pool, but no actual sherds of this intersection were found. The clay pipe continued northward along the western side of the pier, to an unknown destination.

Many artifacts were found in the fill of the tub, including a rich assemblage of wall mosaics. Many pieces of glass mosaics were also discovered on the floor of the main pool (L. 516) that was covered, as noted, in the Byzantine period. These mosaics most probably decorated the walls of the hall and perhaps also its vaults. In the earthquake of 749 parts of the wall mosaics fell off the walls into the tub (L. 513).

As mentioned above, not only was passage between the two central piers of W7 blocked by the rear wall of the tub, but the space between the two southern piers (L. 515) of W7 was also apparently closed off by a built parapet. One should bear in mind that this space could not have served as a passage, since all signs indicate that the main pool of Area E was built right up to the parapet. Thus, only the northern space (L. 518) in W7 offered access between Areas E and C.

In the debris covering the floor of the hall (L. 510) we found many vault voussoirs made of tufa. These stones, measuring ca. 0.2x0.6 m, were exposed in rows, as they had fallen (Fig. 95). It appears that they landed directly on the floor and penetrated it with great force. Similar tufa voussoirs were found in the northern part of the hall, forming irregular piles of debris. The large number of voussoirs is evidence of the large-scale collapse of the vault, which is attributed to the earthquake of 749 C.E.

... Around the central pool stood six marble fountains which supplied cold water. Two of them were found intact and the bases of the other four were revealed in the debris. The fountains are fairly large and similar to the one whose remains were found in Area C (Fig. 117). They are ca. 0.8 m high and their bases measure 0.54x0.64 m. In the northwestern corner a fountain was found stuck in the layer of alluvium that filled the pool (Fig. 118). This attests to the fact that the fountains were in use throughout the centuries, until the great earthquake of 749 that severely damaged the building and filled its pools with alluvium.

... Area A was roofed by a vault composed of three parts: a regular barrel vault in the center, and a semidome on either side that conforms to the oval shape of the hall. Long sections of the vault are preserved in situ. Its spring is 5.2 m above the floor. The good preservation of the vault permits reconstruction of its original shape and the estimation of its maximum height, ca. 10.6 m above the floor of the hall and 11.8 m above the pool floor.

The vault was built of tufa voussoirs. In the course of the excavation, debris containing vault stones was found here. Some of the stones fell onto the alluvium that covered the hall following the earthquake of 749 and others fell directly onto the hall’s floor. This indicates that the destruction occurred in stages. The stones of the ceiling measure 0.55 m in length, 0.3 m in height, and only 0.25 m in width.

The following review will attempt to isolate the Byzantine building stages in each of the excavation areas. For the reader’s convenience, the areas will be presented in the same order as in the previous section.

The main changes which may be attributed with certainty to the Byzantine period are the filling of the three central pools in Areas C, E, and B and the laying of new stone floors above them. At the same time, the side bathtubs in Areas C and D were also filled and covered with new paving. This activity can be dated by the inscriptions found incorporated in the floors covering these pools. The dating of the other changes attributed to the Byzantine period is based on less certain data, such as architectural seams, late floors, or the quality of construction, which is inferior to that of the Roman period but superior to that of the early Arab period.

In Area H, consisting of the entrance corridor and the street north of the baths complex, practically no changes were found that can be assigned to the Byzantine period. Thus, the street continued to be used throughout the Roman-Byzantine period. Nevertheless, in the eastern part of the exposed section of the street there is a large patch indicating a later repair which we were unable to date accurately. The patch is distinguished by the sloppy arrangement of the paving stones and by their level, which is ca. 5 cm higher than that of the rest of the street. The exposed repair is 9 m long and 2 m wide, but it is clear that its unexcavated part is even larger. The stones in the area of repair are relatively small (0.3 x 0.5 m) and their orientation differs from the diagonal arrangement of the original paving stones. No probe was conducted beneath the repair area, and its attribution to the Byzantine period is thus hypothetical.

The excavation of the room (L. 804) adjacent to W92 was not completed, and we were therefore unable to determine its stratigraphic association. Along the eastern face of W92 we found a later addition consisting of three bases and four column drums laid next to one another (Fig. 177), thus increasing the thickness of this wall by 0.8 m (from 0.7 to 1.5 m). The association of this addition with the Byzantine stage of construction is also hypothetical.

The only elements in the entrance corridor (L. 803) that can be attributed to the Byzantine period are the fillings between the pilasters along the northern wall (W90). The quality of construction of the fillings between the pilasters is fairly good, only slightly inferior to that of the original pilasters. These walls were preserved to a height of 2.1 m above the floor. Ashlars in secondary use were incorporated in the fills’ courses, the heights of which range from 0.3 to 0.4 m (owing to the lack of uniformity in the height of the stones). These fills may be part of the wall’s reinforcement added in the Byzantine period.

The columned portal separating the northern part of the hall from its lower, southern part could belong to Phase II (the Byzantine period). On the other hand, this component may be part of the original building, i.e., the Roman baths of the second century, that was damaged by an earthquake and subsequently restored. The entranceway is composed of a pair of columns found in situ between the two northern piers of the hall, and an arcuate lintel, all parts of which were found lying beneath the stone debris of the collapsed ceiling, south of the columns.

The lower parts of the columned portal that were preserved in situ are made up of column bases, bases of pilasters, and the lower half of the columns measuring 2.8 m in height. The other elements, i.e., the upper half of the columns, the capitals and parts of the arcuate lintel, were found lying on the late floor to the south of the columns, indicating that the general direction of movement during the earthquake of 749 which caused the collapse of the entire structure, including the columned portal, was from the north to the south.

The columned portal is very well constructed and richly ornamented (see below, Chapter 2); nevertheless, several factors lead us to believe that the entranceway, as we found it, was added to the hall after the earthquake of 363 C.E. Firstly, a distinct architectural seam separates the western pilaster from the pier behind it. This is a surprisingly rough and irregular seam. It appears that the builders of the columned portal did not bother to conceal it, but rather chose to emphasize it. This may have been their way of commemorating an earthquake that had destroyed parts of the building.

Secondly, close examination of the location of the columns reveals that they are not equidistant from the central long axis of the hall. This axis extends from the middle of the central niche in the southern wall (W5) to the exact center of the opus sectile carpet (L. 308) decorating the raised floor of Area C, north of the columned portal. This deviation could not be coincidental and lends support to the assumption that the columned portal was added to the hall at a later stage. However, one should also take into account that the pair of columns might have been erected in the same location during the Roman period and later underwent several changes.

On the basis of stylistic considerations (relating to one of the two Corinthian capitals), the construction of the portal is dated to the mid-fourth century C.E. On the other hand, all the other elements of the arcuate lintel and the second capital are dated to the second century (see Chapter 2). Thus, it may be assumed that the portal was erected in the first phase of construction and rebuilt in the fourth century. However, this is not certain; it is also possible that a wall or empty space existed there.

Was there a wall above the columned portal that spanned the length of the lintel, or did the lintel stand freely as a decorative element between the two piers? The upper parts of the portal’s lintel and the voussoirs of the arch were left rough and unworked, possibly indicating that they merely served to support a wall above them. On the other hand, this section of stones was at a height of 6-7 m and its poor finish was therefore not visible. Since the architraves are two straight stone beams, we may assume that they could not bear the weight of a wall above them. On the basis of this consideration. it seems that this was a freestanding portal. Moreover, the presence of such a wall would have prevented the penetration of daylight from the windows of the hall's southern part into its raised northern part.

Another element in Area C that may be attributed with certainty to Phase II is the floor covering both the central pool and the three bathtubs between the piers of the western row (W6i. The floor in the center of the hall, which is composed of three rectangular carpets, is characterized by the arrangement of its tiles in a diagonal checkerboard pattern (Fig. 178). The length of the carpets is uniform (7.8 m), but their width varies from 4.8 m (the central carpets) to 5.4 m (the northern and probably also the southern carpets). They are made up of alternating square marble and bituminous stone tiles (0.23x0.23 m); the marble tiles are white and 4 cm thick, while the bituminous stone tiles are dark colored and average 8 cm in thickness. The tiles were laid at an angle of 45° to the hall’s walls. They are framed by a pavement of bituminous stone slabs measuring 0.55 m in width and 0.3-1 m in length.

The northern carpet, on which elements of the columned portal were found, is the most complete one. In the middle of the central carpet, i.e., at the center of symmetry of the hall’s southern part, inscription no. 1 was found (Fig. 179). This inscription, measuring l x l.l m, is framed by smoothened limestone slabs (0.2 m wide). The face of the inscription shows the damage caused by the voussoirs that fell on it. On the basis of various considerations, the inscription is dated to the mid fifth century (see Chapter 3). From the contents of the inscription, we learn that it was laid after the earthquake that destroyed parts of the building. The inscription also states that this hall was converted into a recreation area. As we shall see below, the pools in adjacent Areas E and B were also filled and covered by new pavements so as to create a large surface that could conceivably have been used for sports.

The level of the floor is higher on the sides (-173.08) and drops gradually toward its center (-173.40). This difference in height of more than 0.3 m was due to the sinking of the floor, especially in its center. From a cross section of the width of the floor we were able to determine the nature of the fill beneath it (Fig. 180). The overall thickness of the fill (L. 313) ranges from 1.2 to 1.5 m; below the 0.4-m-thick floor is a 0.5-m-thick light gray layer, and beneath it, overlying the floor of the pool, is a 0.7-m-thick layer of debris containing basalt stones of various sizes (up to 0.4 m).

The rich finds beneath the Byzantine floor (L. 313) include coins from different periods, the earliest one dating from the mid-third century and the latest from the time of Justinian II (565-578). In principle, on the basis of the latter coin, we should date the floor to the second half of the sixth century, since the latest find is the determinant. However, this late date is not in accord with the dating of the floor, as noted above, to the mid-fifth century. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that although the floor was laid in the fifth century, following the earthquake mentioned in inscription no. 1, it underwent several modifications and renovations in later phases of its existence.

A final stage in the floor of Phase II is evidenced by a stone "strip” transecting the full length of the floor (Fig. 181). The “strip” is ca. 1 m wide and is made up of fieldstones with an average diameter of 0.4 m. It is located ca. 3.5 m to the east of W6 and extends from the southern wall of the pool to its northern wall. Since this strip cuts through the floor, it must postdate it. The level of the strip (-173.09) is identical to that of the floor; moreover, it is evident that an effort was made not to disturb the floor tiles on either side of it, factors indicating that the fieldstone strip is indeed later than the floor, but functioned as an integral part of it. The specific function of this strip or the purpose of its installation is not clear.

As noted, the three side bathtubs of Area C were also intentionally filled and covered with floors synchronous with that of the main hall. The best preserved floor is that above the central bathtub (L.324) of W6 (Fig. 182). It is composed of diagonally laid tiles identical in size and shape to those of the floor in the main hall, and around them is a frame of larger slabs (0.36 x 0.4 m) made of bituminous stone. The floor level (-173.08) is identical to that of the walkway.

Only the bedding beneath the floors covering the other two side bathtubs has survived. Below the bedding in the northern bathtub (L. 305), a total of 130 coins dating to the fourth-sixth centuries were found. The latest coin, as anticipated, is from the time of Justinian II - the second half of the sixth century C.E.

The finds in the southern bathtub are similar. A tightly-packed fill of fieldstones and layers of earth was found beneath the floor’s bedding (L. 321). Most of the ceramic finds there are from the fourth fifth centuries C.E., but some of the cooking pots are of a later date (sixth century C.E.).

Many modifications were made in the raised, northern part (L. 302) of Area C. However, most of them belong to the last building phase of the Umayyad period. The only finds that may be attributed to the Byzantine period are two Greek dedicatory inscriptions engraved on the pavement north of the columned portal. An Umayyad floor was laid on top of them; we may thus assume that they date from the Byzantine period.

... The bedding of the late floor in the western room (L. 211) consists of light clay and is 0.15 m thick beneath it is a brown earthen fill rich in finds, including coins, clay lamps, etc. The coins range from the time of Diocletian (end of the third century) up to the time of Justinian II (565-578). Similar numismatic finds were discovered beneath the floors of the adjacent halls (E and C); as noted above, this material could lead one to assign a late date to the laying of the floor — the end of the sixth century; however, we believe that it was laid in the mid-fifth century and later underwent repairs and renovations.

The significant finds beneath the floor include many clay lamps within the layers of fill (Fig. 191). It should be noted that most of the lamps were revealed in the lower layer immediately above the pool floor. The lamps of this type (the so-called “biconic lamps”) are dated to the fourth-fifth centuries C.E. (see Chapter 7) Their discovery on top of the pool floor substantiates our assumption that the pool was filled in the mid-fifth century C.E. The lamps probably fell to the bottom of the pool during the earthquake that demolished the building and were left in the bedding of the late floor.

It is difficult to discern distinctly Byzantine remains in Area A. Several changes that can possibly be attributed to the Byzantine period are visible in the walls. In the eastern half of W1 one can see architectural seams on both sides of the entrance connecting Areas A and E. These seams are emphasized by the transition from basalt to limestone. The limestone ashlars are large and dressed similarly to the masonry used in the northern face of the same wall section. As we have seen above, the repair of the northern face of W1 was dated, on the basis of various considerations, to the mid-fifth century, and the repair of its southern face may thus also be attributed to the same stage of construction. A similar change is noted along the southern wall (W2) of the hall: at its center is a long section of limestone construction, in contrast to the other parts that are built of basalt. This may be some sort of late repair, but, on the other hand, this part of W2 could reflect a specific construction method.

The four bathtubs in the semicircular corner alcoves were filled during Phase II. This is evident from the marble floors found above the two eastern bathtubs (L. 102, 103). In the fill beneath the floor of L. 102 we found five coins from the Byzantine period, indicating that the floor above it dates to the late Byzantine period or early Arab period. Only a small part of this floor has survive Its level is-172.99, ca. 0.3 m higher than that oi the walkway (-173.27). The floor is made of marble slabs laid parallel to the parapet of this bathtub.

The floor in the northwestern alcove (L. 107) was also found partially preserved. The level of the floor (-172.97) is ca. 0.25 m higher than that of the walkway. Here too the paving stones were meticulously laid. Beneath them voussoirs made of porous chalky (tufa) material were found. We may thus link the laying of the floor with the destruction caused by the earthquake.

... The elevating pool also underwent a significant change that may be attributed to Phase II. Apparently as a result of the earthquake, the original rectangular pool was destroyed and replaced by a much smaller round elevating pool built next to the wall (W11) delimiting the spring on the west. The remaining part of the earlier pool was filled and covered by a floor, only the bedding of which has been partly preserved (mainly as debris at the bottom of the spring). ...

The Umayyad period at Hammat Gader is characterized by a systematic blocking of passages and narrowing of architectural spaces. The Umayyad remains are relatively easily identifiable as the latest stage of construction prior to the complete destruction of the baths complex in 749. Debris of the superstructures and deposits of alluvium covered the building, making its use virtually impossible without relevelling and rebuilding. This state of affairs characterized the last phase of the building’s occupation in the period preceding the great earthquake, i.e., the Umayyad period.

The street north of the baths complex continued to be used, apparently without interruption, until the end of the Umayyad period. In contrast, new structures were added to the entrance corridor (L. 803). Along the northern wall (W90) a structure roughly built of masonry' in secondary use was erected (Fig. 211). The long wall (W120) of this structure, preserved to a height of 1.7 m, was exposed. The length of the exposed section is 13.5 m, but it is clear that the wall was originally much longer (Fig. 212). The western end of the wall is fragmentary' while its eastern is located beneath the debris in the area which has not yet been excavated. The wall is at a slight angle to W90: the distance between them is 3 m at the western end of W120, increasing to 3.6 m toward the east.

At a distance of 2.5 m from the western end of the wall is the opening of a diagonal channel (L. 810), 0.67 m wide and 1.8 m high. This channel extends to the northwest but its destination and function are not clear.

At a distance of 6.5 m east of this channel, the opening of another channel running in the opposite direction, from northeast to southwest, was discovered. A section of the latter channel, 2.7 m long, 1 m wide, and 1.3 m high, is preserved; its roofing is corbelled. It appears that these two channels led to the pool in Area D (see below).

W120 and the walls perpendicular to it (W119, W118) eliminated the use of the eastern entranceway in W90. The inferior quality of the walls of the above-mentioned structure indicates that it was erected in the last building stage of the baths complex (Phase III). In this period, the passages linking Area H with Areas C and E were blocked (see below), and only the passage in W80 leading into Area D remained open. This is an indication of the changes made in the movement of the visitors to the site during this period. The finds on the pavement of the entrance corridor (L. 803) included coins and various artifacts dating to the late Byzantine and Umayyad periods. In the southwestern corner of L. 803 the marble faces removed from the fountains in Area D (see Chapter 12) were found. It appears that they were kept on a shelf of some kind at the western end of W80. We assume that this shelf collapsed in the earthquake of 749.

... The wall (W17) opposite W28, blocking passage into Area E is preserved to a height of 2.3 m (Fig. 214). It is 1.1 m wide and built of masonry in secondary use. A window similar to the one in W28 was installed in the center of this wall. It is well built, and the recess for its shutters is preserved in the sides of the window frame. The opening of the window widens inward, toward the hall’s interior: its exterior width is 0.9 m while its interior width is 1.2 m. The windowsill is 1.1 m above the floor. This window, like the one in W28, was blocked in the final phase of occupation, before the destruction caused by the earthquake of 749. With the blocking of the passageways from Areas H and E sole access to L. 302 was from the south, i.e., from the southern part of Area C.

... All of the above-mentioned elements were found “buried" beneath the massive debris of the building. The superstructures of the hall’s walls and its ceiling collapsed directly onto the floors during the earthquake of 749.

The earthquake of 749 destroyed the building totally and instantaneously. The intensity of the earthquake is indicated by the large amounts of rubble that filled the halls. In Area D, parts of the walls and ceiling collapsed on top of one another, filling the central pool. In other areas, especially in the southern part of the baths complex, the rubble was found on top of a thick (1 m and more) layer of alluvium; in the oval pool of Area G, the alluvial fill is 1.5 m thick (Fig. 241).

The destruction appears to have been on such a large scale that the inhabitants of the site were unable to clear the rubble. Instead, they levelled the area above the ruins and made secondary use of the early masonry in order to erect temporary walls. The ceramic finds on these late levelled surfaces include 33 potsherds indicative of the Abbasid-Fatimid period (Chapter 9).

Phase IV settlement activity is evident at the southern end of Area E, as well as in Areas B and A. It appears that in these parts of the building, the vaults, or parts of them, remained standing and could be used for shelter. In the southern part of Area E (L. 500), a floor of packed earth was found on top of the ruins (Fig. 242); it was delimited on the west by a poorly-built wall (W35) running perpendicular to the southern wall (Wl). In the center of W35, a 0.6-m-wide entrance was built. It appears that this wall, together with Wl and W13, delimited a room measuring ca. 3x4 m. In the center of this room, remains were found of a cooking hearth (0.6 m in diameter) which was used by its inhabitants.

... The floor was covered by a layer of alluvium, above which, in the debris, were remains of parts of the vault. It appears that parts of the ceiling vault in Area A were still standing after the earthquake of 749. The lack of partition walls indicates that at this stage the hall served as a shelter for a relatively large group of people, and not as a domicile for individuals, as was noted in Areas E and B. The spring probably continued to attract bathers to the site and Area A may have been repaired in response to their need for living quarters.

Insignificant remains from the Middle Ages, including remnants of construction and graves, were found in various parts of the site. Such remains were revealed close to the surface and usually not in clear stratigraphic contexts. Thirty nine potsherds indicative of this period were found (see Chapter 9) scattered throughout the building itself. The small amount of potsherds and building elements from this period indicates a general state of abandonment.

Area B in the Middle Ages served as a burial site. Three graves were found close to the surface (L. 200) in its western part: two of them were built and the third was merely a human skeleton buried in the earth. The best-preserved grave is the central one, consisting of medium-sized stones, some of which were dressed and in secondary use (Fig. 246). It is rectangular, measuring 0.2x1.5 m, and has a general east-west direction. Northeast of it is a smaller grave, measuring 0.7 x 1 m.

The above-mentioned skeleton was found almost intact in the southwestern corner (Fig. 247). The corpse was laid in a prostrate position, with the head facing west and inclined slightly to the south, a position characterizing Muslim burial practice. On its left wrist was a rusty iron bracelet. Due to the lack of datable small finds, it is impossible to determine with accuracy the time of burial.

Remains of a very crudely built structure (L. 100) were exposed in the center of Area A (Fig. 248). It is made of building stones in secondary use, including parts of columns, capitals, bases, etc. It became evident that it originally consisted of two rows of basalt pillars. The rows extended in a general east-west direction. Five pillars survived in the northern row (Fig. 249), and four in the southern row; they are 1.2 m apart. The distance between the two rows — 3.5 m — is identical to that between each row and the adjacent long wall of the hall. These pillars probably served as supports for some sort of shading installation made of perishable materials.

Together with the pillar structure, a crude staircase was built opposite the entrance in W2 leading into Area G. The width of the steps is 1.8 m and their height is 0.2 m. They are located between two short walls perpendicular to W2. The level of the top step (-171.99) corresponds more or less to the bottom of the pillars, and thus we may conclude that these two elements were contemporaneous. The shading installation that was supported by the pillars was probably used by visitors who came to bathe at the site. The staircase offered direct access to Area G via the entrance in W2.

In the northeastern corner of Area E, late walls were found close to the surface. An entrance is discernible in one of the walls. Next to these walls, above the southern apsidal room (L. 517), a round lime furnace was found (Fig. 250). Its inner diameter is 2.5 m and its walls are 0.3-0.4 m thick and preserved to a height of 1.2 m. The opening to the furnace, through which wind entered, faces west. Limestone and marble masonry from the site was probably “consumed” in this furnace, including statues and architectural elements that had decorated various areas in the early periods.

In Area F west of the baths complex, remains were found of two channels close to one another and extending in a general north-south direction. They are relatively narrow, each measuring 0.2 m in width. The general direction of the channels does not relate to the baths complex, and we may therefore conclude that they were built at a stage when the building had ceased to function. At the end of the excavation part of a marble column was discovered in a cross section in the northern part of Area F (Fig. 251). The face of the column is fluted with diagonal grooves. (Such columns are termed “Apamaea columns” after the city of Apamaea in Syria where dozens of them were found.) Its height is 1.1 m and its diameter is 0.38 m. This column was probably incorporated in some part of the baths complex; its discovery in the layer of debris does not permit us to determine its date or original location.

The most outstanding and beautiful element at the Hammat Gader baths is without doubt the columned portal in Area C; its construction was intended to embellish the large space of the Hall of Piers.

The portal is composed of two engaged pilasters, between which stood two columns on square pedestals and Attic bases. The columns are crowned with Corinthian capitals. An arcuate lintel comprised of decorated architraves rests on top of the pilasters and columns.

The entire portal is of high quality and built of local basalt. The fact that the columned portal was renovated after the original phase of the hall’s construction is evident from the distinct architectural seam at its western end, between the western pilaster and the large pier west of it (Fig. 1).

Only the lower parts of the columned portal were preserved in situ, i.e., the column bases, the pilaster bases, and the lower half of the column shafts attaining a height of 2.8 m. All of the other parts, i.e., the upper half of the shafts, the capitals, and elements of the arcuate lintel, were found lying on the late floor south of the columns (Fig. 2). From this we learn that the movement caused by the earthquake that toppled the entire structure, including the columned portal, was from north to south. The only element that was not found in the excavation was the capital that rested on top of one of the engaged pilasters. It was thus possible to reconstruct the columned portal with precision.

The portal was erected at the entrance to the southern part of the Hall of Piers. Three steps were laid as a foundation for the portal. The pedestals of the columns, 0.9 m wide, rest on the upper two steps. The columns are 2.4 m apart, while the space between them and the side pilasters is 1.9 m.

The columns have Attic bases (Figs. 3, 4). The bases of the pilasters have a kind of Attic profile (Fig. 5); three courses of the western pilaster and only one of the eastern pilaster were preserved in situ. The width of the pilasters at their bases is identical to that of the column pedestals, i.e., 0.9 m. However, their length varies: the western pilaster is shorter, 0.6 m, while the eastern pilaster is 1.1 m long. At a later phase, deep, roughly hewn grooves were carved into both sides of the bases of the columns and the pilasters, apparently in order to install a partition of some sort to separate the northern part of the hall from the southern part (Fig. 6).

The full height of the columns, including the upper part of the shafts, is 5.3 m. The columns are crowned with Corinthian capitals differing from each other in style and date.1 One capital is decorated with two rows of acanthus leaves (those in the upper row are partially broken) emerging from cauliculi, a calyx in the shape of a goblet, a helix, and volutes. On one side of the abacus the flower was replaced by a heart (Fig. 7). The slight contact between the leaves and their sparse arrangement are characteristic of an earlier stage in the development of the Corinthian capital in Palestine during the second-third centuries.2 This capital is in secondary use, as indicated by carved depressions on its top, which once held a statue (Fig. 8).