Gadara

Aerial Photograph of Gadara/Umm Qais

Aerial Photograph of Gadara/Umm QaisAPAAME CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Gadara | Greek | Γάδαρα |

| Gedaris | Greek | Γαδαρίς |

| Umm Qeis | Arabic | ومم قييس |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 23 June 2025

- sources: Wikipedia: Gadara, ummqaisheritage.com

Ancient Gadara is also associated with a well-known episode in the Synoptic Gospels—the Exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac—though the exact location of this New Testament event remains debated between Gadara, Gerasa (Jerash), and Gergesa.

The city flourished during the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods and was known for its philosophers, poets, and intellectuals, including the Cynic philosopher Menippus. Its urban layout includes a long colonnaded street, multiple theaters, a large basilica, temples, baths, and an extensive aqueduct and cistern system that demonstrate sophisticated water management in a semi-arid environment.

Archaeological work has uncovered layers of occupation and destruction spanning over a millennium. The city was partially destroyed in the mid-8th century CE, likely in the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, after which the site was largely abandoned. Today, Gadara is one of Jordan’s major archaeological parks and a key site for understanding urbanism, identity, and transition along the Hauran frontier in antiquity.

The Decapolis city of Gadara in northern Jordan is situated on a spur above the Yarmuk Valley opposite the Golan Heights. Its name derives from the Semitic word for stronghold. The town was referred to as Umm Qeis during the Middle Ages, the name deriving from the ancient Arabic mkes, meaning a border station.

Archaeological surveys indicate that Gadara was occupied as early as the seventh century BCE. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus III conquered it in 218 BCE, and in the early first century BCE its city wall was destroyed during the Maccabean invasion. But the damage was repaired and the city returned to Seleucid hands. Pompey took the city in 64 BCE and added it to the Decapolis. Rome rewarded King Herod with rule over Gadara in appreciation of Herod’s efforts to weaken Nabatean control over the region’s trade routes. The city reached its peak in the second century CE and became the home and birthplace of many writers and philosophers, prompting Meleagros to compare it with Athens. Strabo notes that visitors to the nearby hot springs of Ḥammat Gader, located on the northern bank of the Yarmuk Valley, relaxed in Gadara after bathing. Economic problems became evident in the third century CE, with the abandonment of certain building activities. In Byzantine times, the city was the seat of a bishop; a few churches were built. It declined in the sixth century, and in 636 CE, a decisive military clash between Byzantine Christians and Arab Muslims took place not far from it. Nevertheless, widespread destruction in the city was caused only later, by the earthquake of 748/749 CE.

Excavations at Gadara were mainly carried out by the German Protestant Institute in ‘Amman, under U. Wagner-Lux, T. Weber, and S. Kerner; and the German Archaeological Institute, under A. Hoffmann. During the earliest phase of settlement, the acropolis was defended by only four massive but unconnected towers of well-laid masonry. Later, in the second century BCE, the first city wall included the acropolis and a terrace to its north, where a Doric tetrastyle temple dedicated to Zeus was built. The Late Roman city wall ran much further west and north. The city had a long east–west street (decumanus maximus) crossed by shorter streets. The two circular towers of the western city gate—only their foundations preserved—flank the decumanus, while 400 m to the west are the remains of a triple arched gateway, which marked the extension of the city boundary in the latter half of the second or early third century CE, built together with the hippodrome. A nymphaeum is also located on the decumanus.

There are two theaters in Gadara, and a third located at the nearby hot springs of Ḥammat Gader. The largest is the north theater, but the best preserved is the west theater, built of black basalt stone and dating to the first and second centuries CE. Next to the west theater is a paved and colonnaded terrace, supported on the west by vaulted structures used as shops in Roman times. During the Byzantine period, an octagonal basalt church with a limestone-paved atrium was built on the terrace. The roof is supported by Corinthian capitals, taken from an earlier temple. Remains of a basilical church were exposed between the octagonal church and the west theater.

A residential area lies to the east of the west theater. Today, it is covered by the remains of an Ottoman village, built of masonry taken mostly from ancient buildings. The houses were decorated with geometric wall paintings and molded plaster.

Water was supplied to the city by two large aqueducts—primarily subterranean tunnels—conveying water from several springs to its east, among which were ‘Ein Gadara, and ‘Ein et-Trab, the latter located some 12 km away from the site. Several structures for water distribution have been found inside the city, diverting the water to the bath complex, nymphaeum, and dwellings.

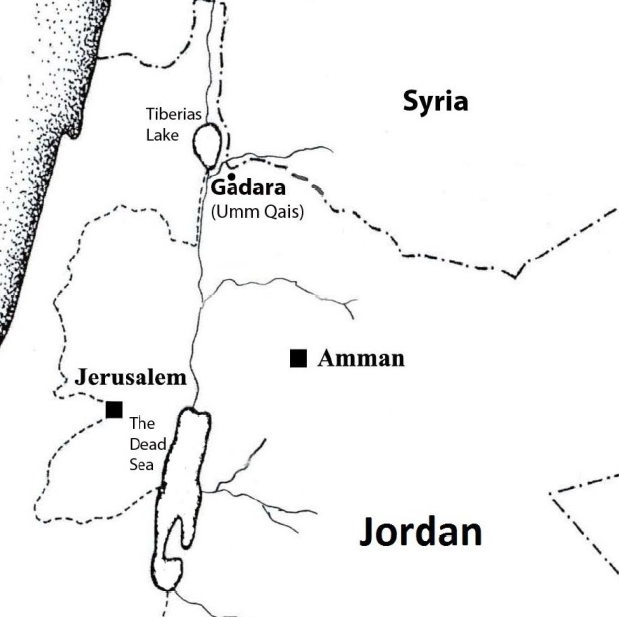

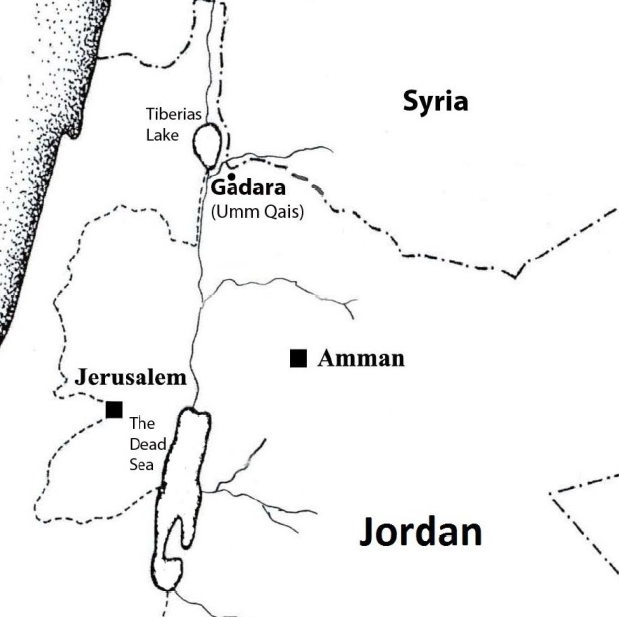

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Jordan, location of Gadara.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

- Site plan of Ancient Gadara

from www.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries)

Map of Ancient Gadara

Map of Ancient Gadara

www.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries)

- Site plan of Ancient Gadara

from www.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries)

Map of Ancient Gadara

Map of Ancient Gadara

www.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries)

- Fig. 1- Plan of Umm Qays

(ancient Gadara) Areas I and III from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plan of Umm Qays (ancient Gadara) Areas I and III.

Vriezen and Mulder (1997) - Fig. 6 - The Terrace and

its buildings in the Byzantine Period (1st half of 6th century) from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

Figure 6

Figure 6

The Terrace and its buildings in the Byzantine Period (first half of sixth century).

Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

- Fig. 1- Plan of Umm Qays

(ancient Gadara) Areas I and III from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plan of Umm Qays (ancient Gadara) Areas I and III.

Vriezen and Mulder (1997) - Fig. 6 - The Terrace and

its buildings in the Byzantine Period (1st half of 6th century) from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

Figure 6

Figure 6

The Terrace and its buildings in the Byzantine Period (first half of sixth century).

Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

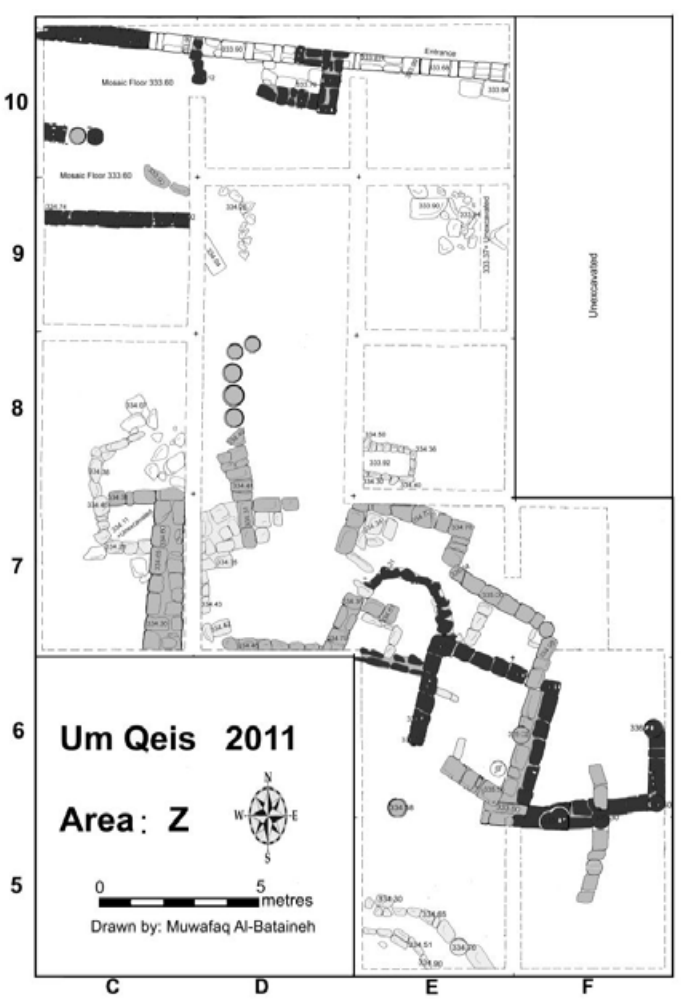

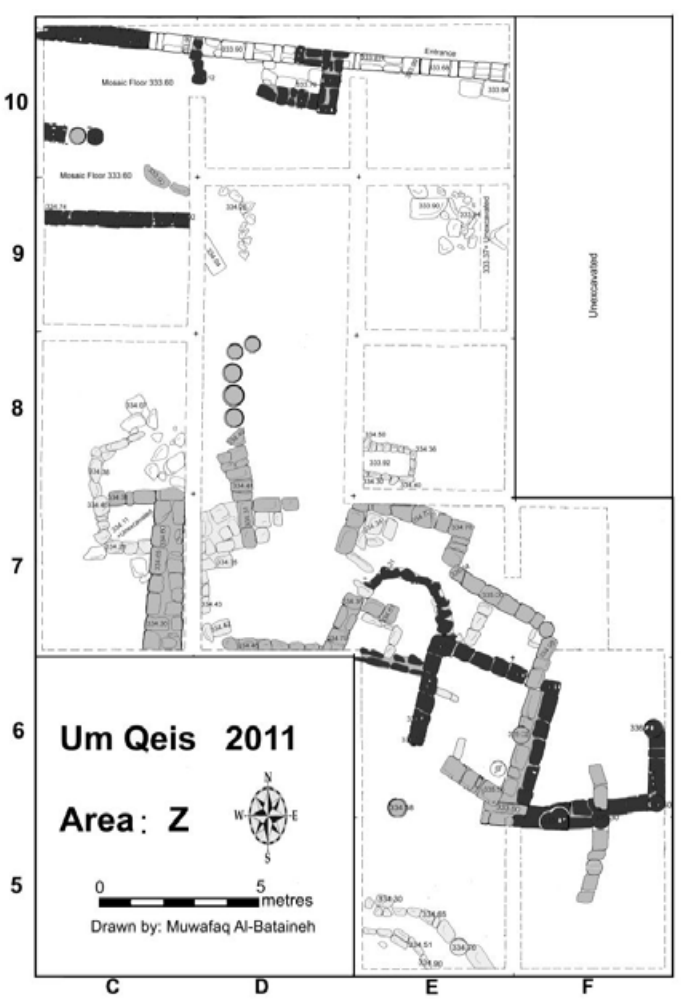

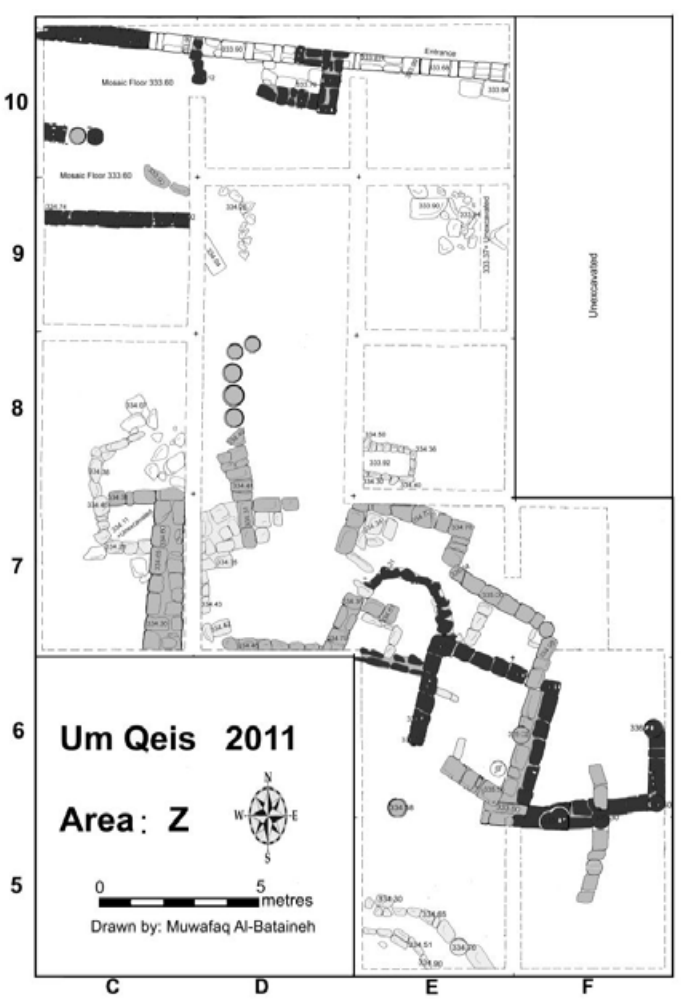

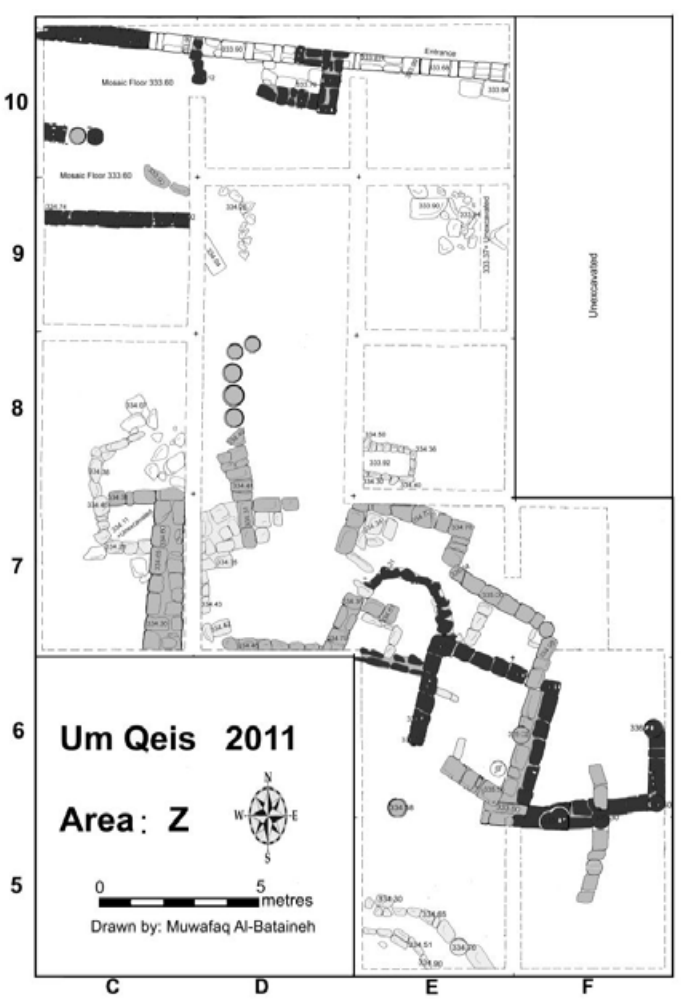

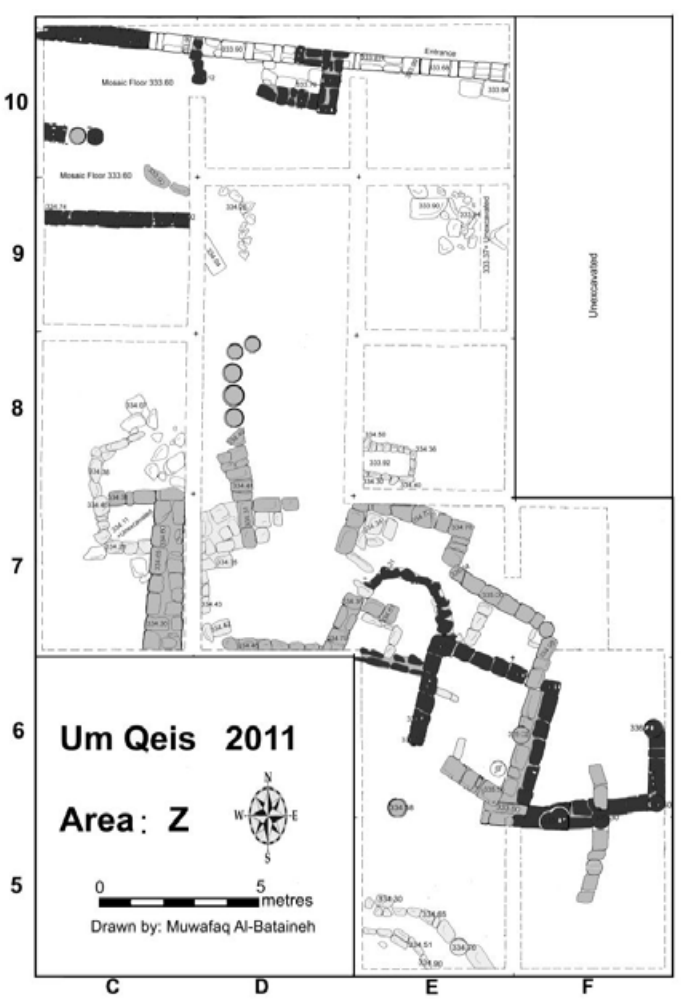

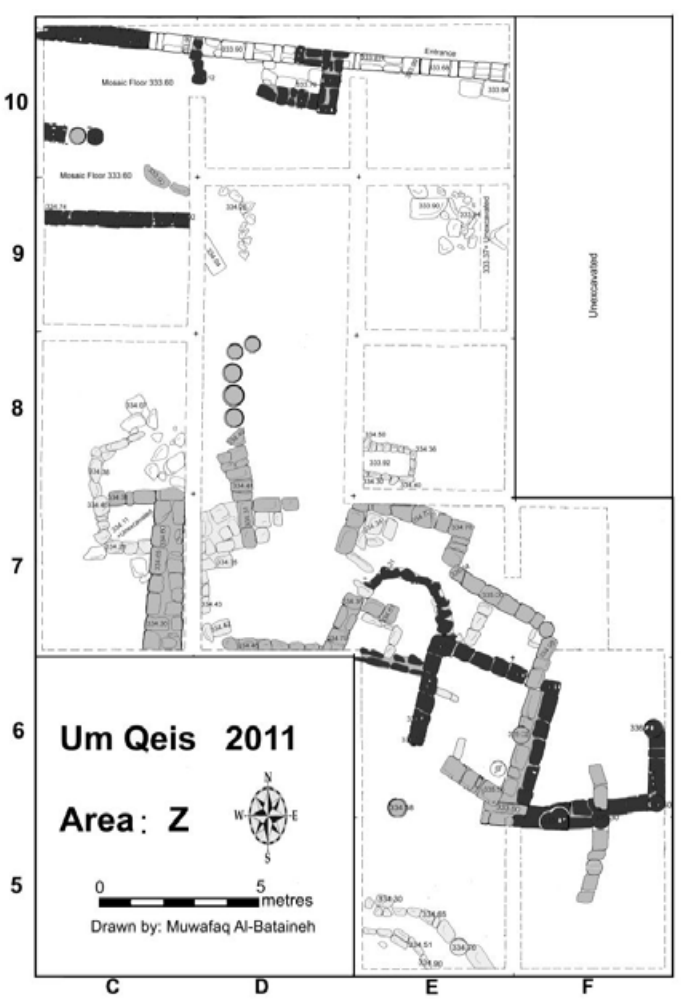

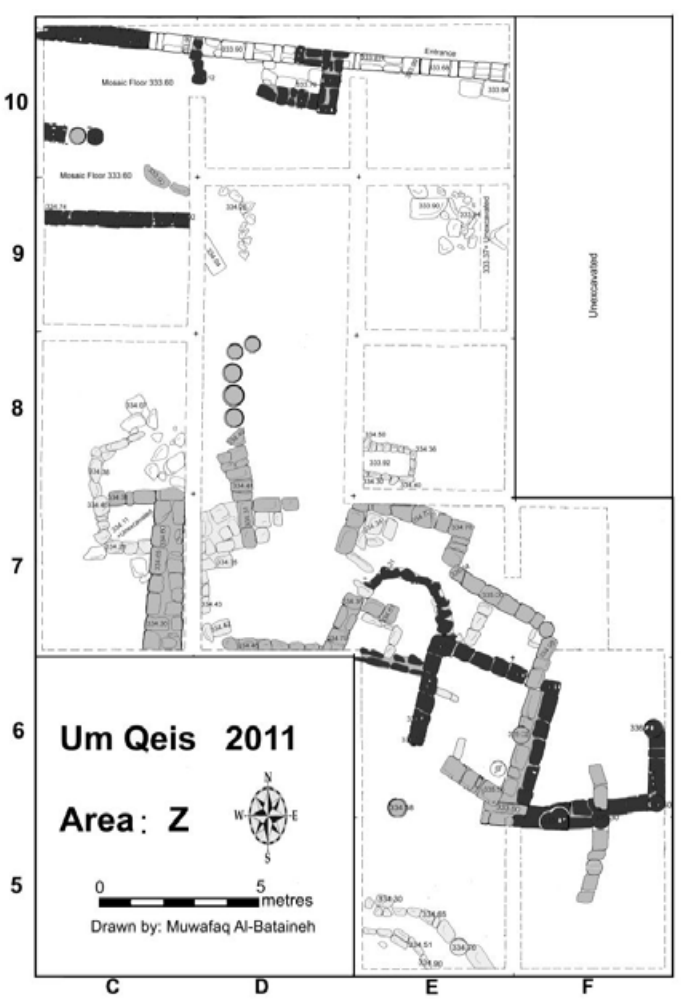

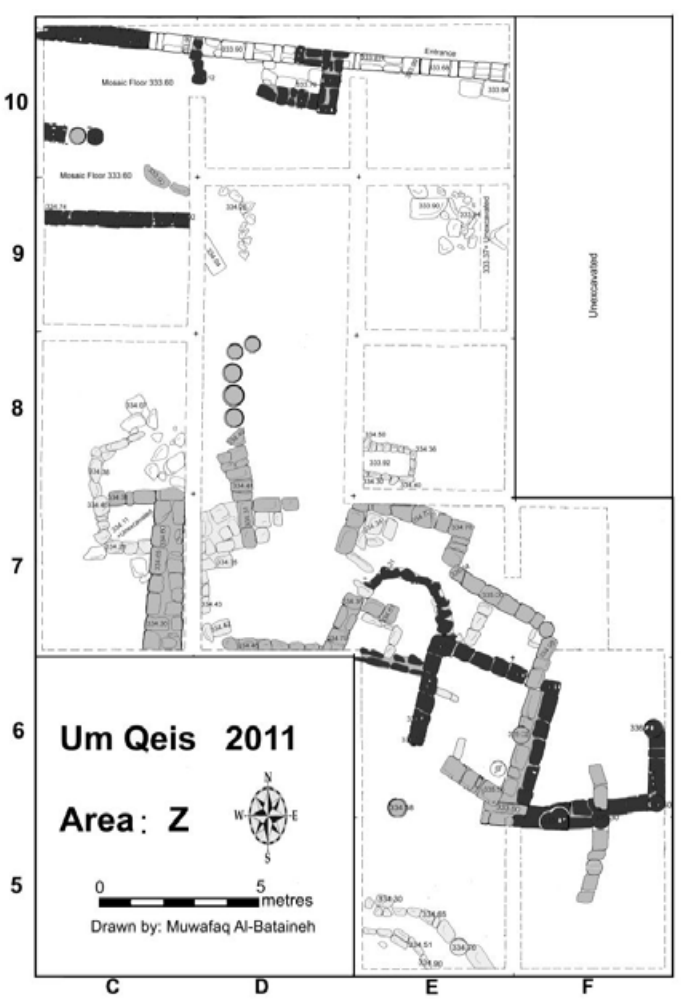

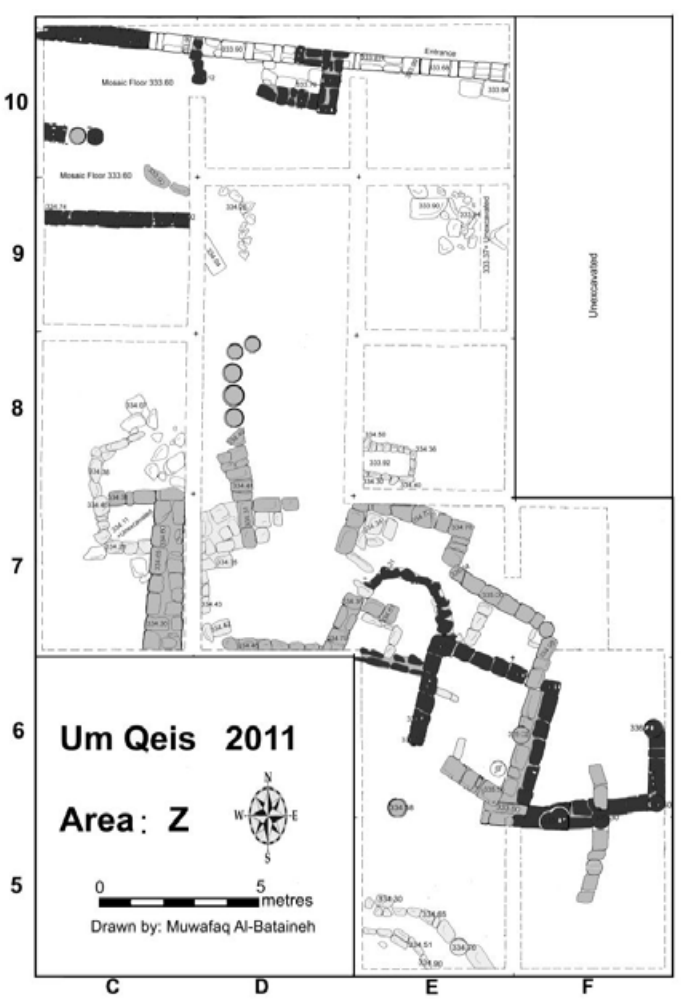

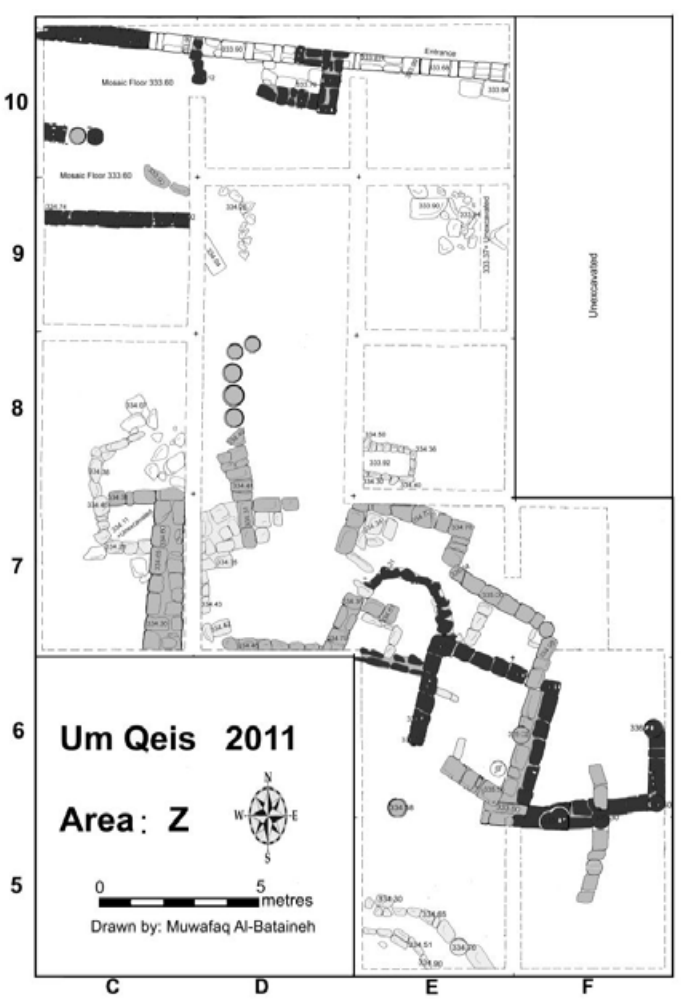

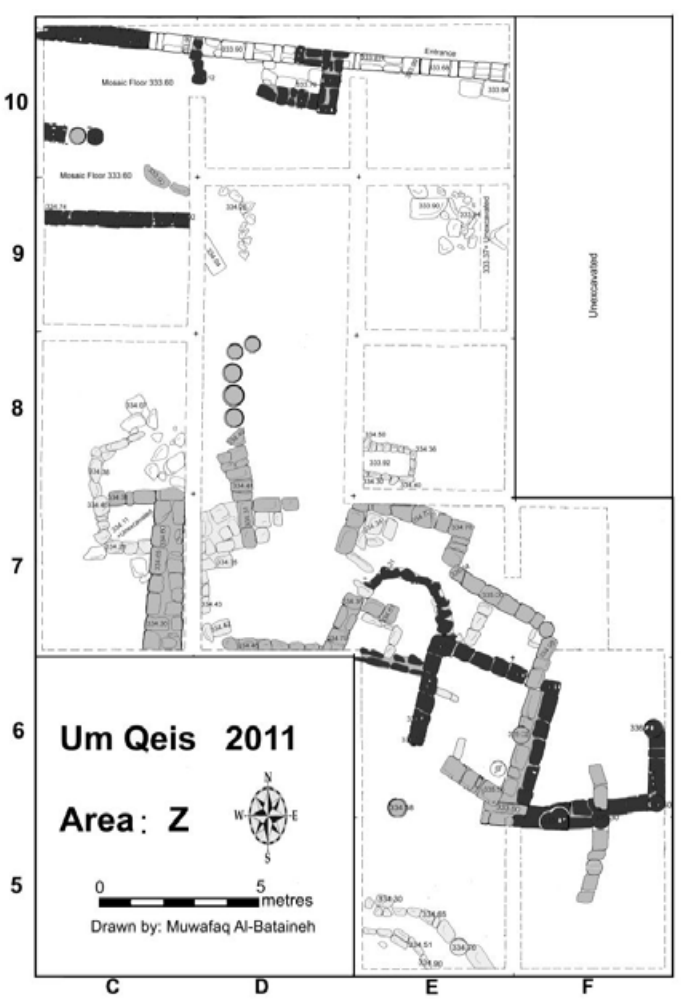

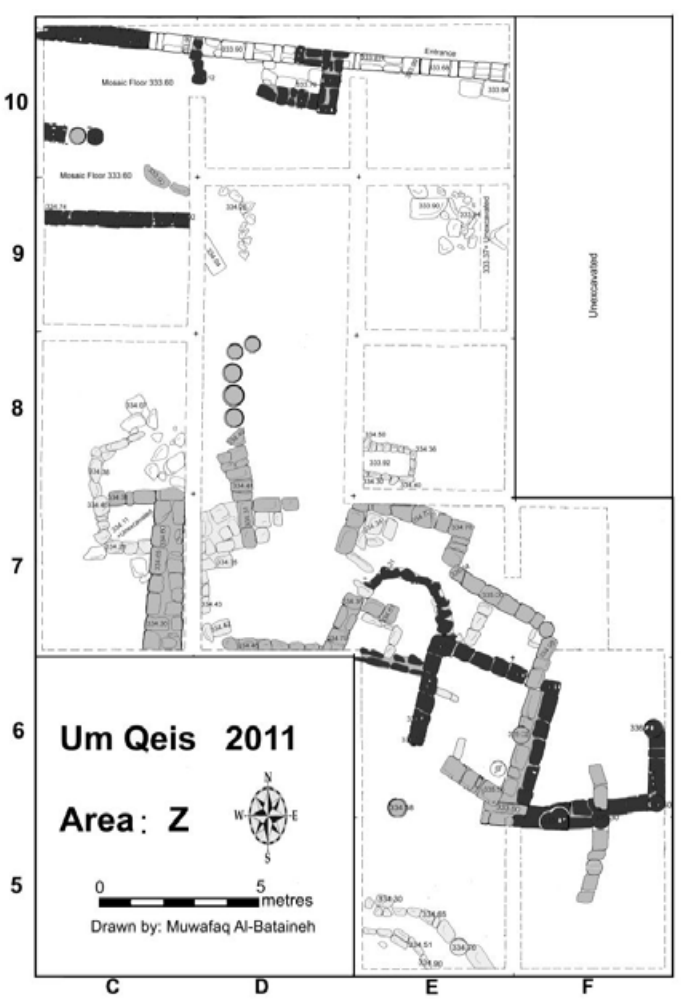

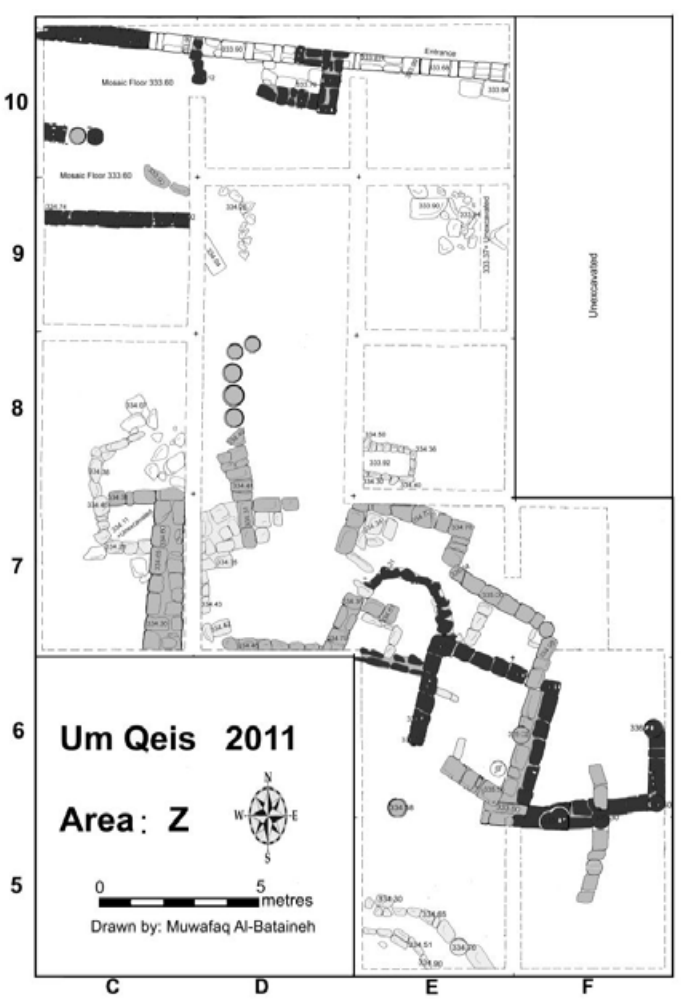

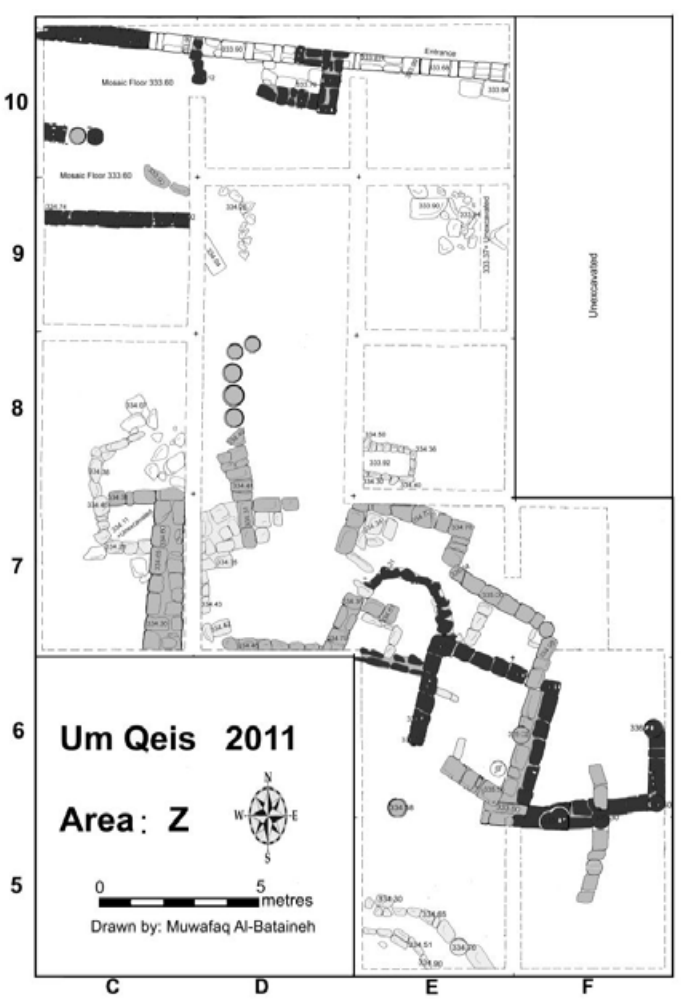

- Fig. 2 - Two phases of Abassid

occupation in Area Z from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

- Fig. 2 - Two phases of Abassid

occupation in Area Z from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

- Fig. 4 - Abassid constructions

in SE part of excavations from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Top view of the Abbasid constructions in squares E6, E7, F6 and F7, older constructions are also shown in the picture.

JW: N is to the left

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) - Fig. 3 - Mosaic Floor

in Squares C9 and C10 of Area Z from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Mosaic floor in Squares C9 and C10, Umayyad and first Abbasid Phase of occupation.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

- Fig. 4 - Abassid constructions

in SE part of excavations from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Top view of the Abbasid constructions in squares E6, E7, F6 and F7, older constructions are also shown in the picture.

JW: N is to the left

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) - Fig. 3 - Mosaic Floor

in Squares C9 and C10 of Area Z from El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Mosaic floor in Squares C9 and C10, Umayyad and first Abbasid Phase of occupation.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015)

- Fig. 3 - Fallen columns

in Gadara from Walmsley (2007)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Columns down at Jadar, A.D. 749

(Walmsley)

Walmsley (2007) - Warped Pavement of

Decumanus Maximus in Gadara - photo by JW

Warped Pavement of Decumanus Maximus in Gadara

Warped Pavement of Decumanus Maximus in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Fig. 3 - Fallen columns

in Gadara from Walmsley (2007)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Columns down at Jadar, A.D. 749

(Walmsley)

Walmsley (2007) - Warped Pavement of

Decumanus Maximus in Gadara - photo by JW

Warped Pavement of Decumanus Maximus in Gadara

Warped Pavement of Decumanus Maximus in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Tilted Upper Course in

Terrace Churches in Gadara - photo by JW

Upper Course of Basaltic Wall is Titled. Terrace Churches N of Eastern Theater in Gadara

Upper Course of Basaltic Wall is Titled. Terrace Churches N of Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Tilted Upper Course in

Terrace Churches in Gadara - photo by JW

Upper Course of Basaltic Wall is Titled. Terrace Churches N of Eastern Theater in Gadara

Upper Course of Basaltic Wall is Titled. Terrace Churches N of Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Warped Seats in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Warped Seats in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Warped Seats in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and fractured

ashlars in the Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced and fractured ashlars in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Displaced and fractured ashlars in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced vault stones

in the Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced vault stones in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Displaced vault stones in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled Corners in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled Corners in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Warped Seats in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Warped Seats in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Warped Seats in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and fractured

ashlars in the Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced and fractured ashlars in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Displaced and fractured ashlars in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced vault stones

in the Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced vault stones in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Displaced vault stones in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled Corners in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Spalled Corners in the

Eastern Theater of Gadara - photo by JW

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Spalled Corners in the Eastern Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Wide shot of Western Theater

in Gadara - photo by JW

Wide shot of Western Theater in Gadara

Wide shot of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Wide shot of Western Theater

in Gadara - photo by JW

Wide shot of Western Theater in Gadara

Wide shot of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Vault with displaced stones at bottom level towards the west - Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

- Vault with displaced stones at bottom level towards the west - Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

- Displaced and tilted

Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and tilted

Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara - digital theodolite (Az = 197) photo by JW

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 197

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Displaced and tilted

Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Displaced and tilted

Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara - digital theodolite (Az = 197) photo by JW

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Displaced Ashlars at top of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 197

Digital Theodolite Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

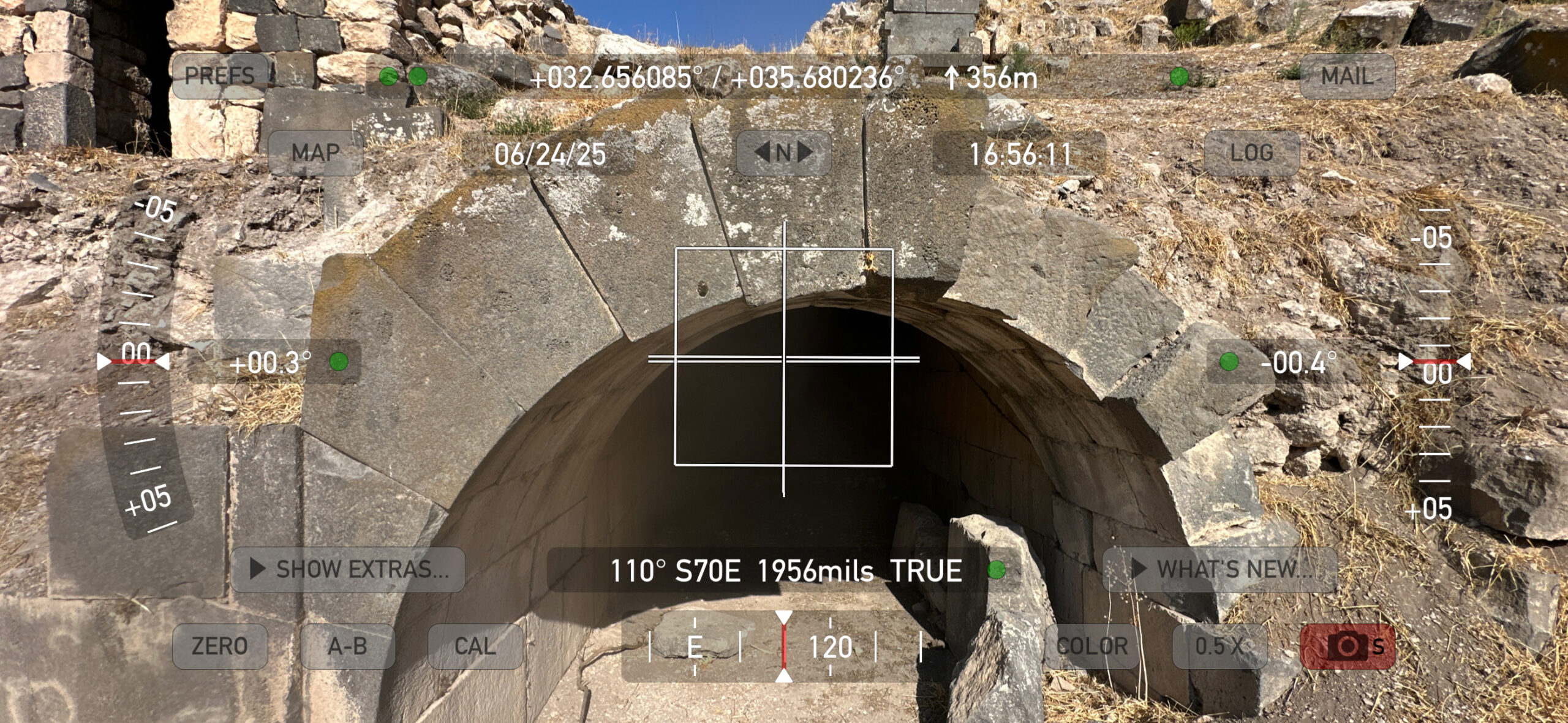

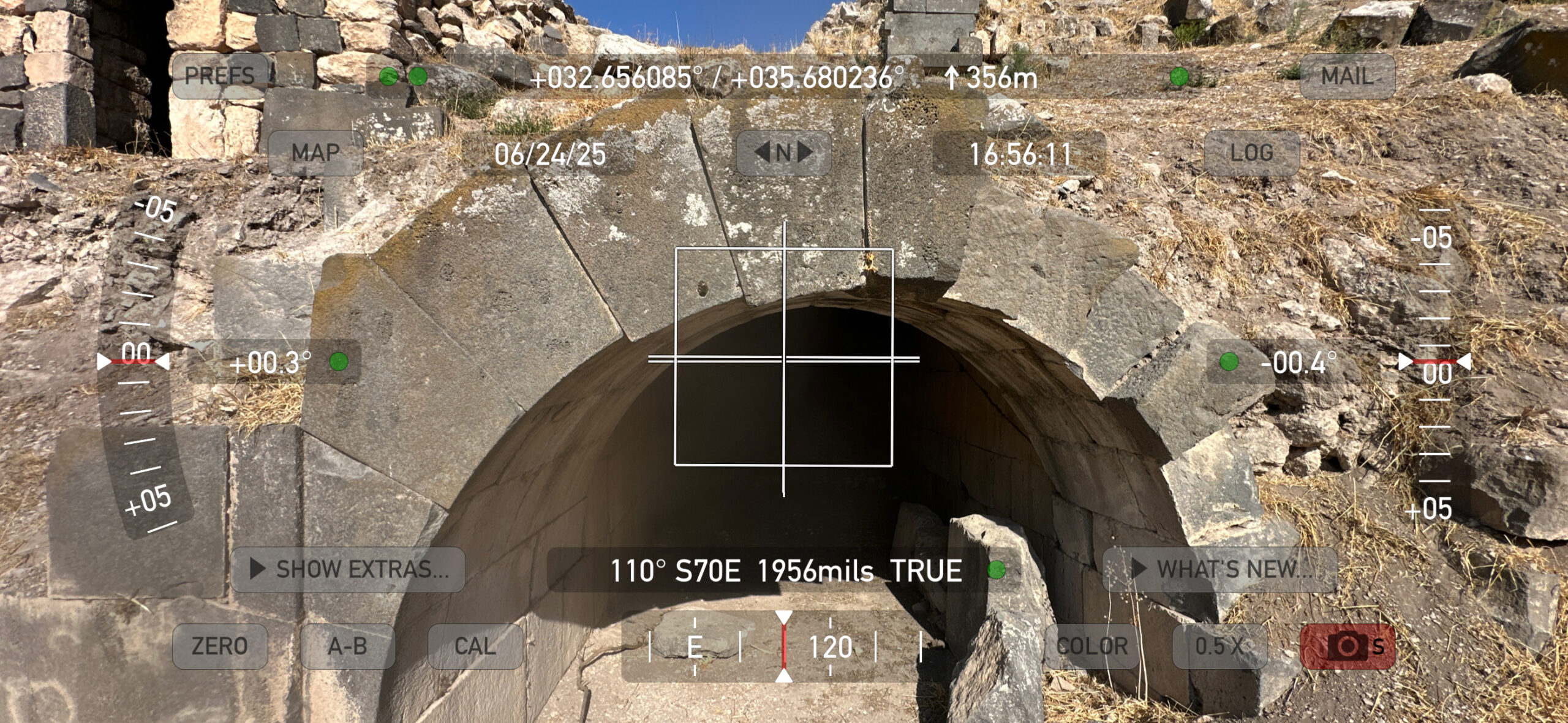

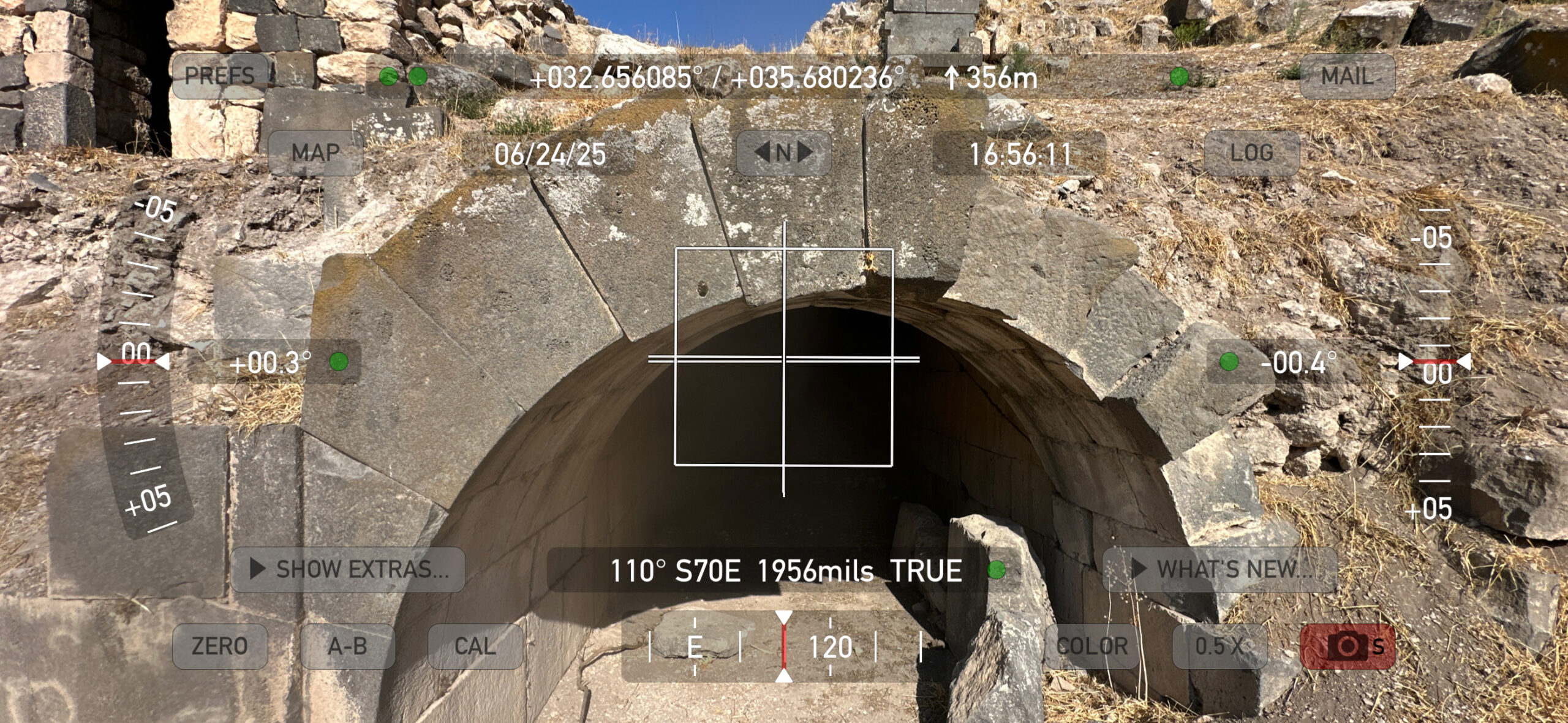

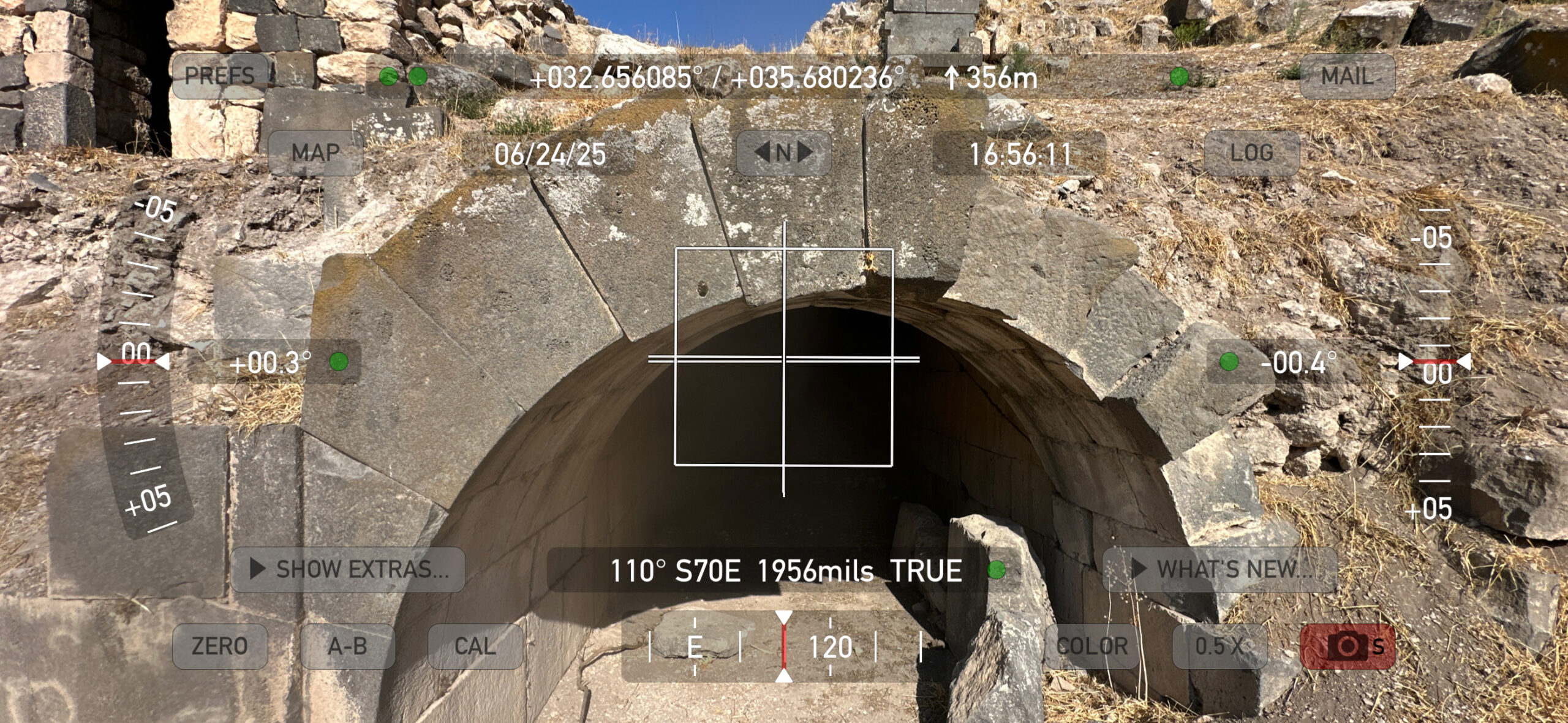

- Dropped Archstones in far

western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones in far

western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - closeup photo by JW

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at

bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - digital theodolite photo (Az = 110) by JW

Dropped Archstones at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 110

Digital theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Dropped Archstones in far

western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones in far

western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - closeup photo by JW

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones in far western arch at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at

bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara - digital theodolite photo (Az = 110) by JW

Dropped Archstones at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at bottom level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 110

Digital theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

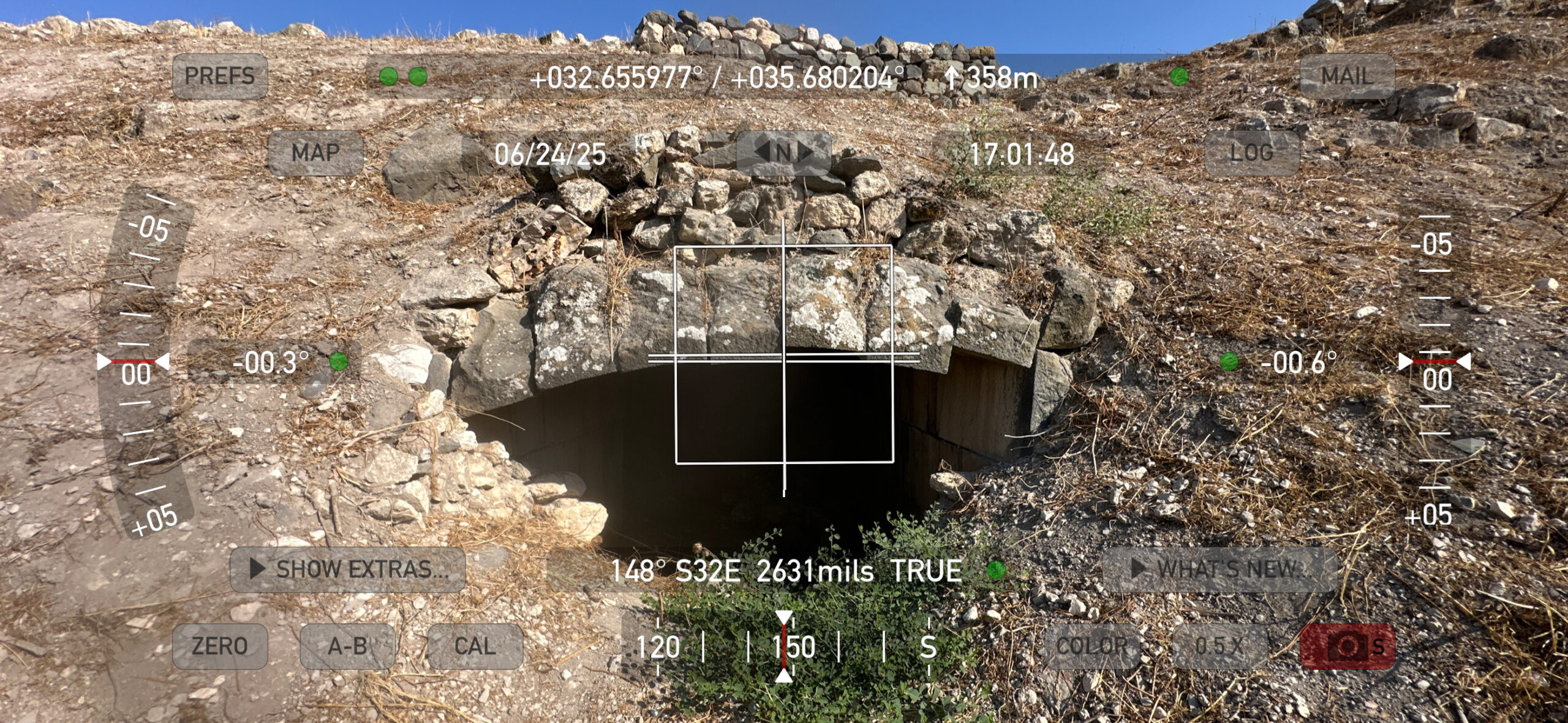

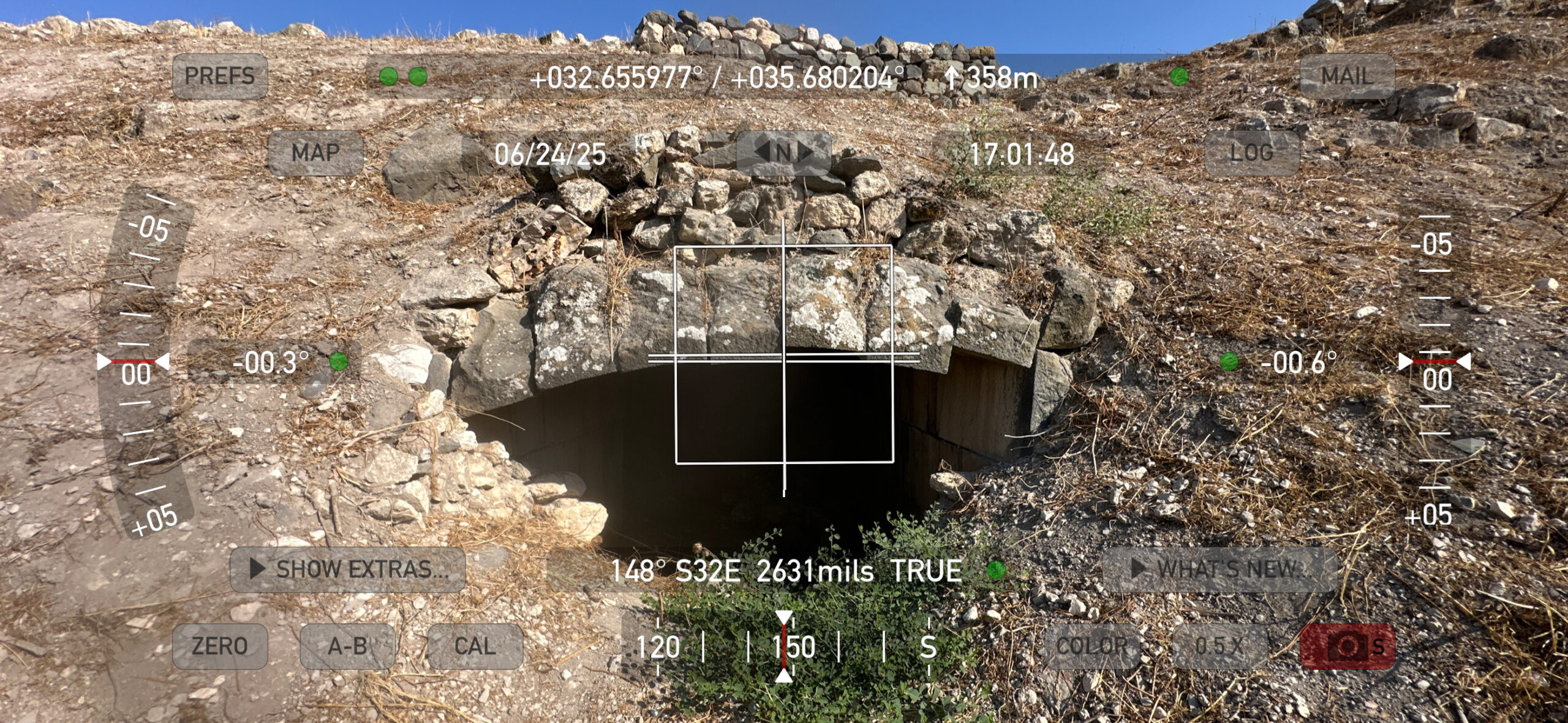

- Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

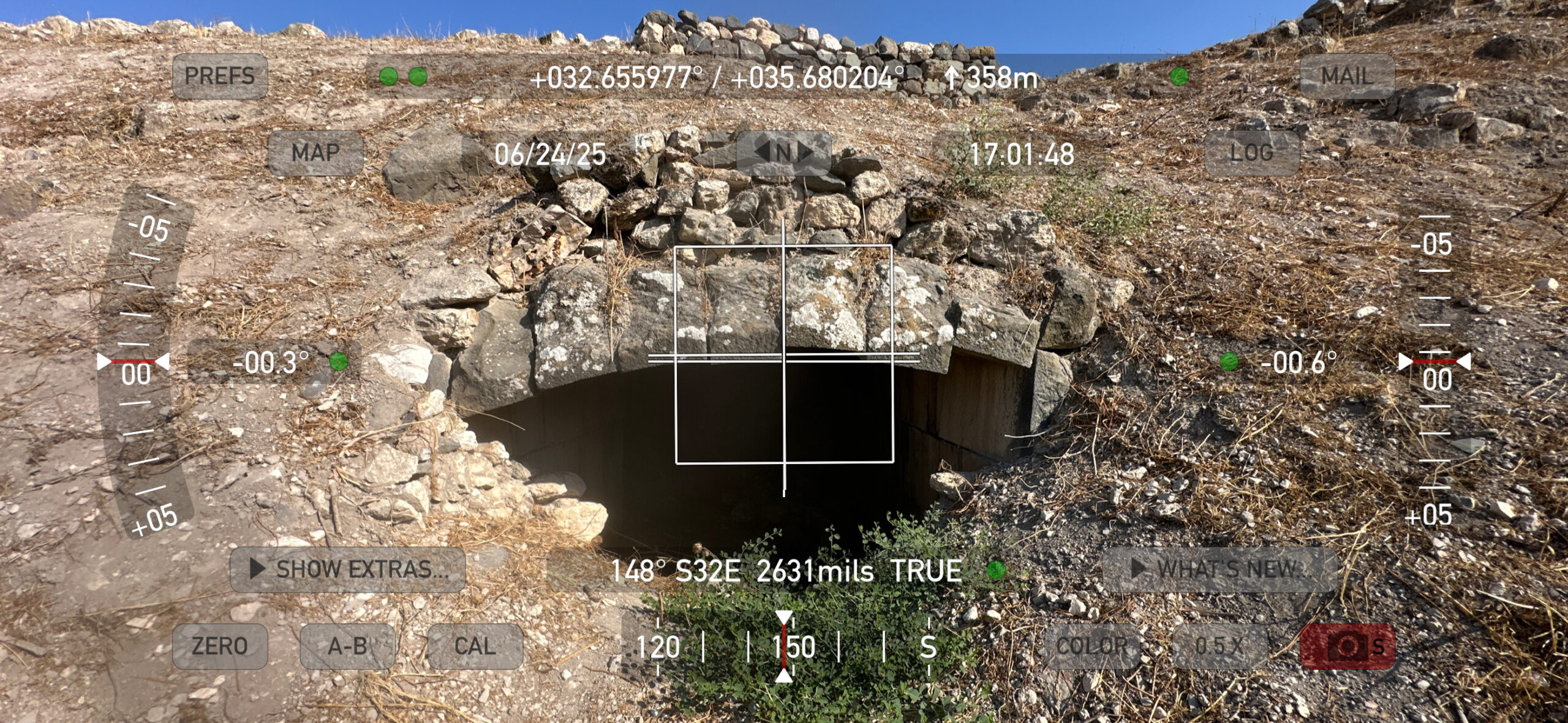

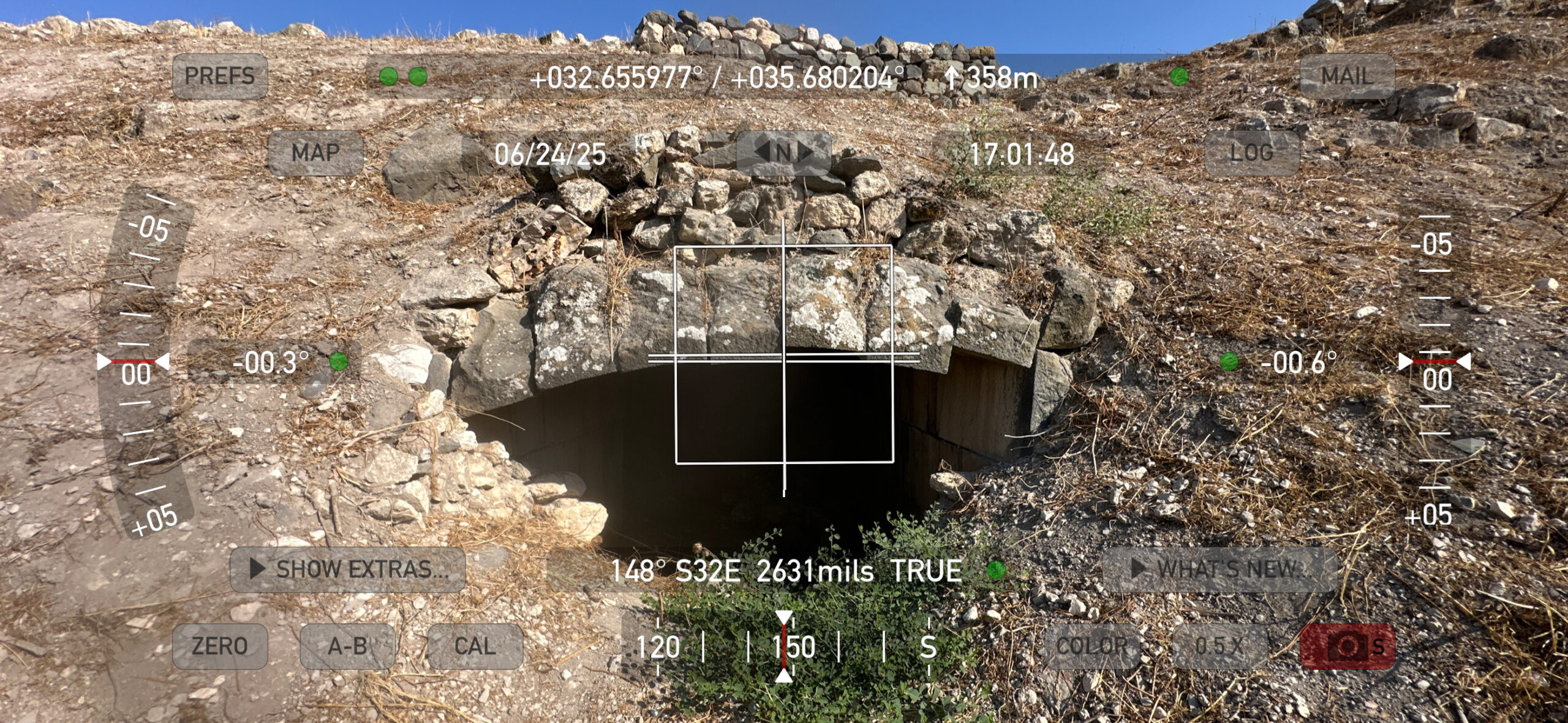

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - Digital theodolite photo (Az = 148) by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 148

Digital Theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

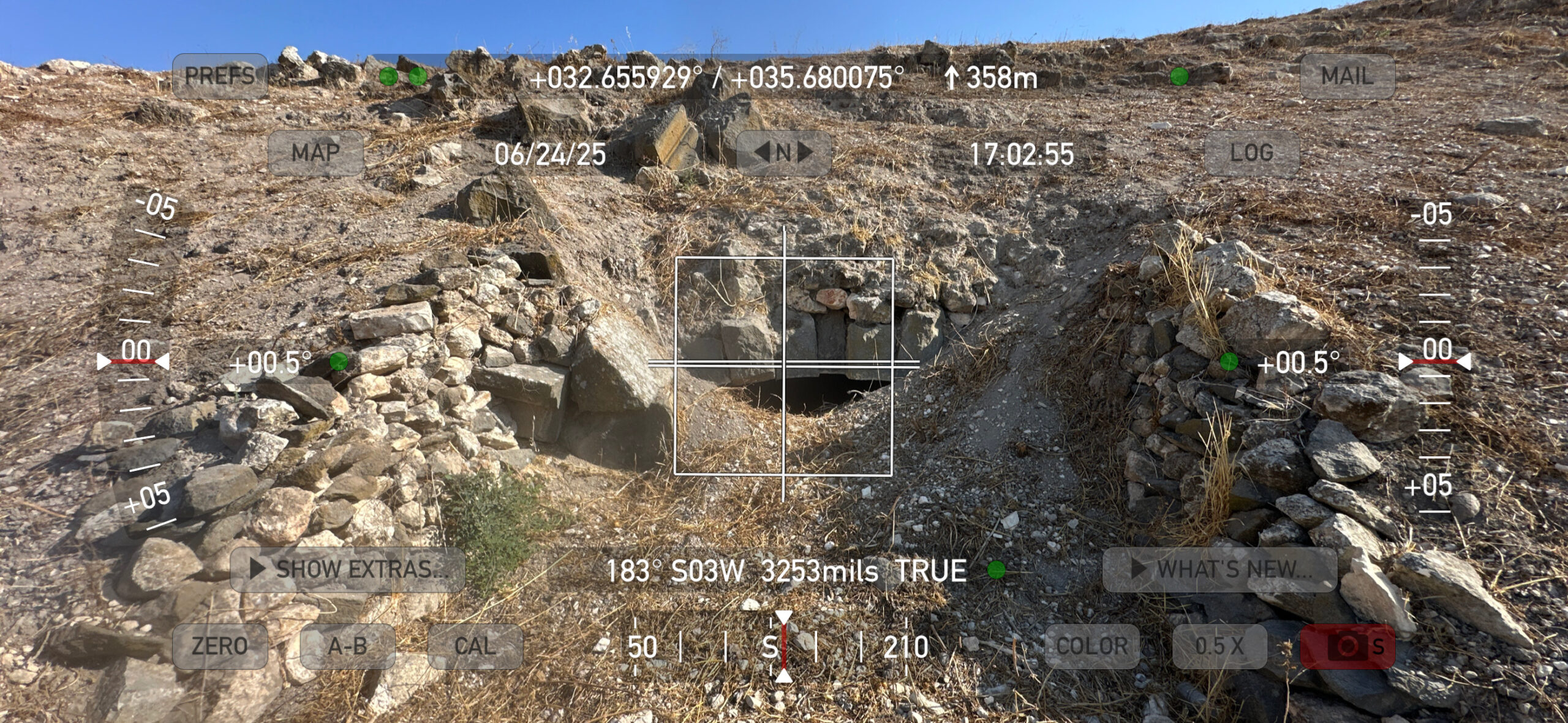

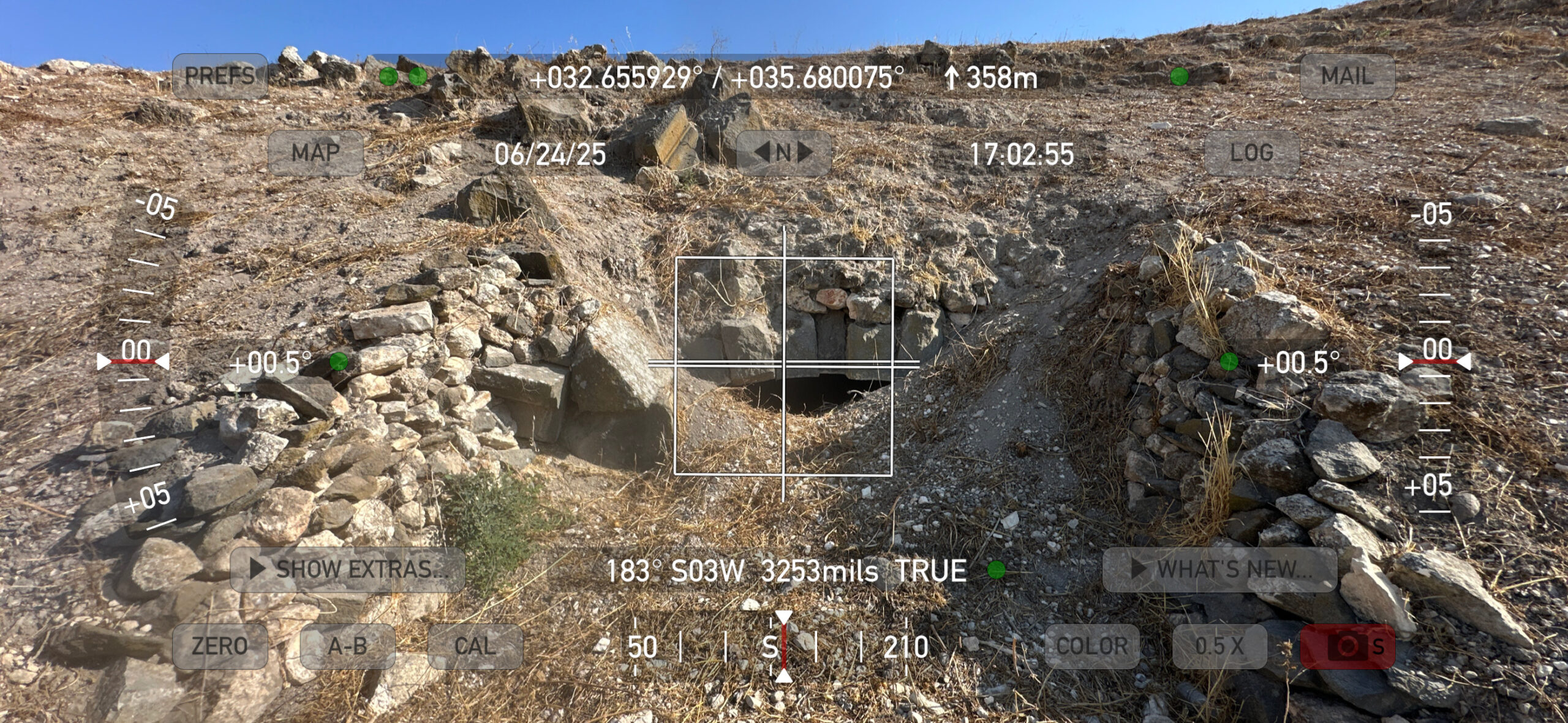

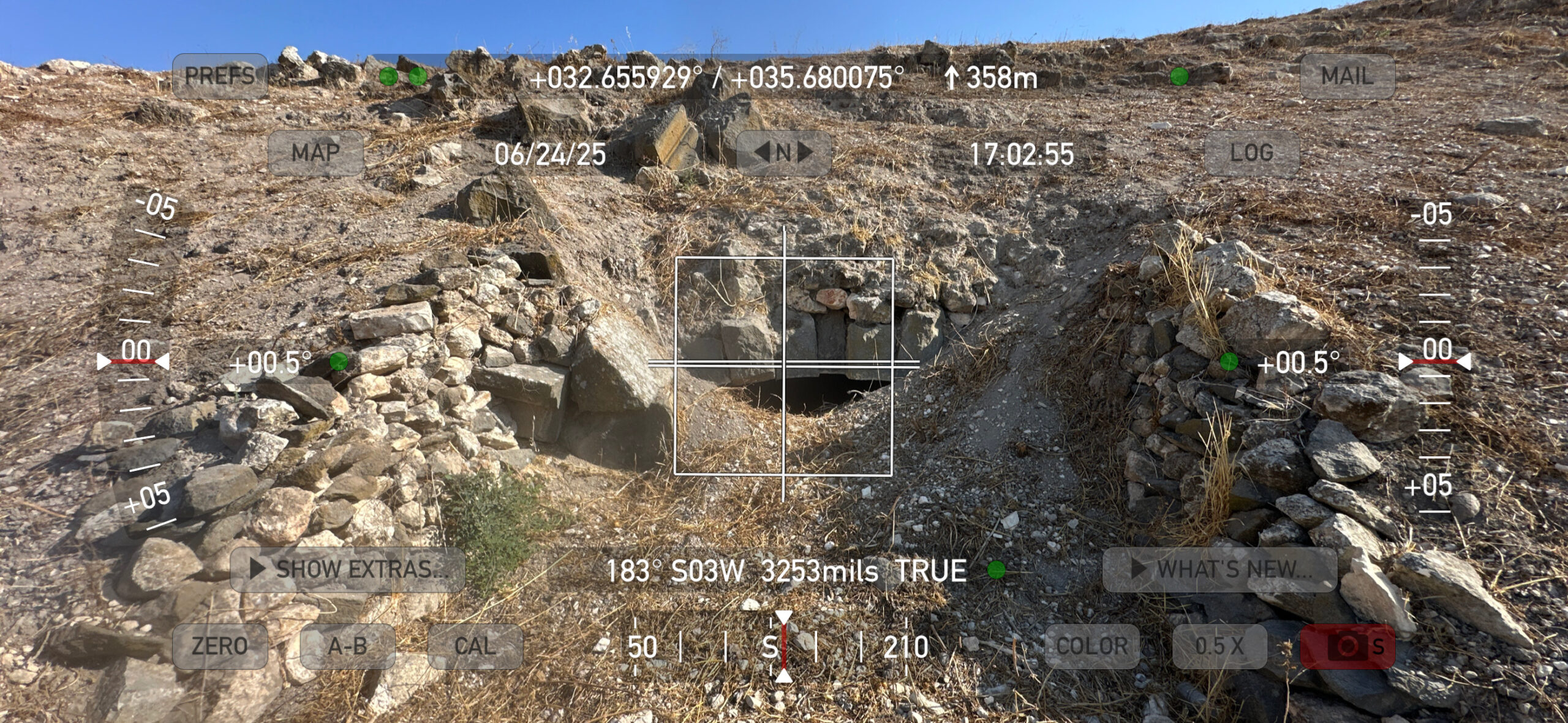

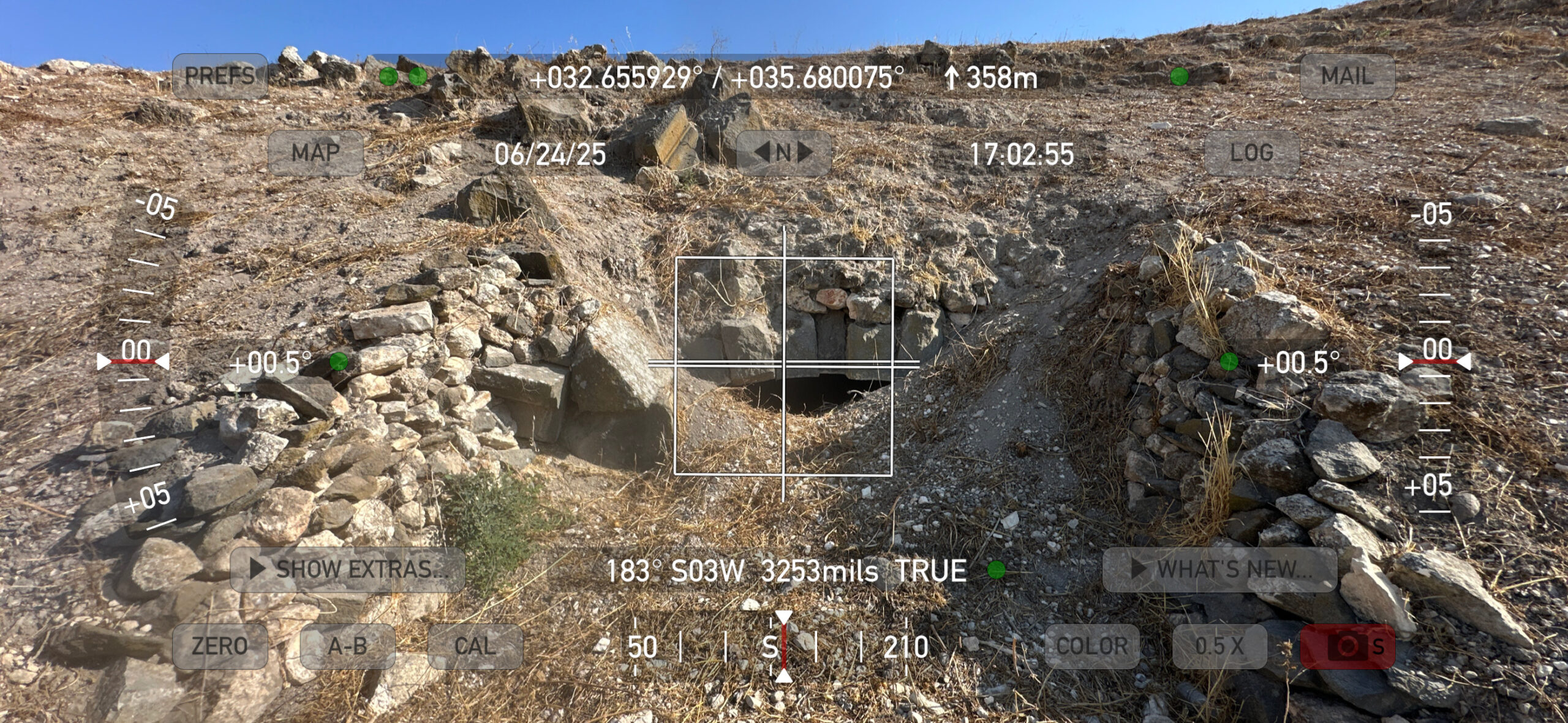

level of Western Theater in Gadara - Digital theodolite photo (Az = 183) by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 183

Digital Theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - Digital theodolite photo (Az = 148) by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 148

Digital Theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - photo by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025 - Dropped Archstones at top

level of Western Theater in Gadara - Digital theodolite photo (Az = 183) by JW

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Dropped Archstones at top level of Western Theater in Gadara

Az = 183

Digital Theodolite photo by Jefferson Williams - 24 June 2025

- Fig. 1- Plan of Umm Qays (ancient Gadara)

Areas I and III from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plan of Umm Qays (ancient Gadara) Areas I and III.

Vriezen and Mulder (1997) - Fig. 11- Fallen Columns

from Walmsley (2007)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Columns down at Jadar, A.D. 749 (Walmsley).

Walmsley (2007)

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015:14) identified two phases of Abassid occupation - the first from 750-800 CE and the second from 800 CE to 1000/1050 CE.

El-Khouri and Omoush (2015:15) noted the presence of ancient wall destruction (fallen stone layers)

in many

squares underneath the Abbasid layers, especially in Squares F5 and F6.

They

also noted the reuse of architectural elements in Abbasid constructions as well as prior destruction of a mosaic floor

(El-Khouri and Omoush, 2015:16-17).

Dating was based on pottery.

Vriezen and Mulder (1997:323)

reported that two churches in Gadara were destroyed

by an earthquake presumably the earthquake of 749

.

The ruins near Umm Qays (ancient Gadara) were surveyed in 1974 by a team from the German Protestant Institute for the Archaeology of the Holy Land headed by Ute Wagner-Lux. The ruins of the ancient buildings cover a site measuring approximately 1600 x 450 m consisting of a walled city area and an extramural area. Inside the walled city, two areas can be discerned: an Acropolis (approximately 250 x 250 m) in the east and a large Lower City in the west. The main street of the city, Decumanus Maximus, runs east-west.Walmsley (2007) reports the following archeoseismic evidence at Gadara [Jadar)

Wagner-Lux and her team made a series of excavations on the large Terrace, situated at the bottom of the western slope of the Acropolis in 1976-1979 and in 1992. This site was labelled Area I. The Terrace, measuring 95 x 32 m, is bounded on the north by the Decumanus Maximus, to the south by a Roman theatre, whereas to the west a street, a cardo, aligned with vaulted rooms built against the Terrace's retaining wall, ran south from the decumanus to the theatre. In 1977 and in 1979 the northern end of the cardo (Area III) was excavated (FIG.1).

The Terrace may be divided roughly into three parts. In the northern part (32 x 32m), a colonnaded courtyard (a so-called atrium) was found. The courtyard is entered from the Decumanus Maximus by means of three entrances. The inner space was open to the air and on three sides (perhaps on all four sides) surrounded by a colonnade and a covered passageway. A line of rooms along the eastern side of the terrace open onto the eastern passageway.

In the central part, a church complex has been excavated, which consists of two churches. The larger one is situated right in the middle of the Terrace. It is a church of the "centralised type" consisting of a square building with a narthex attached to its west side. The second church is of the "basilica type". It is built against the south wall of the centralised church. The construction of the centralised church has been tentatively dated to the first half of the sixth century. Then, there was a courtyard to the south of it, similar to the one on its northern side.

The basilica was built at a later date, that is in the middle of the seventh century. Both church buildings were destroyed by an earthquake presumably the earthquake of 749.

The centralised church and the colonnaded courtyard represent the Byzantine building phase on the Terrace. The basilica is attributed to the Late Byzantine or the Early Omayyad Period. Underneath the floors of the church buildings and the courtyard, a pavement from the Roman period has been found. To the Roman phase also belong the Terrace's retaining walls and the structures along the cardo and Decumanus Maximus. This building phase has been tentatively dated to the end of the first or the beginning of the second century AD.

at Jadar [Gadara], on a ridge overlooking Lake Tiberias, the columns of the main east-west decumanus were toppled by the earthquake (fig. 11), permanently terminating the late antique configuration of the town.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 23 June 2025

- from El‑Khouri and Omoush (2015)

Beneath the Abbasid deposits, the authors reported evidence of pre-Abbasid wall collapse, described as "ancient wall destruction (fallen stone layers)," especially concentrated in Squares F5 and F6. This damage appeared just below the Abbasid floor levels and was visible in the form of crushed stones, collapsed masonry, and fallen wall lines that had not been reconstructed before the Abbasid rebuilding (p. 15).

The reuse of architectural elements such as door frames and thresholds was noted in later Abbasid construction. This included the apparent recycling of a mosaic floor—now damaged—into the foundations of a new structure, suggesting intentional reoccupation following destruction of an earlier building (pp. 16–17).

While no specific earthquake is named, the stratigraphic position of the destruction directly beneath early Abbasid layers, coupled with the lack of post-destruction restoration before Abbasid reoccupation, provides indirect evidence for a seismic event that likely predates or coincides with the mid-8th century transition.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 23 June 2025

- from Vriezen and Mulder (1997)

The centralised church was built in the first half of the 6th century, while the basilica dates to the mid-7th century. Their joint destruction in a single seismic event strongly suggests a mid-8th century terminus ante quem for their collapse.

The seismic destruction is stratigraphically significant, as the churches were constructed atop earlier Roman-period retaining walls and pavements on the Acropolis-side Terrace. spolia from these Roman structures were reused in the Byzantine construction. No later structural rebuilding of the churches was documented, consistent with abandonment after the earthquake.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Abbasid layers, especially in Squares F5 and F6

Figure 2

Figure 2The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

|

|

| Re-used building elements | Abbasid layers

Figure 2

Figure 2The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

Figure 4

Figure 4Top view of the Abbasid constructions in squares E6, E7, F6 and F7, older constructions are also shown in the picture. JW: N is to the left El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

|

| Destruction of mosaic floor (dented from falling ashlars ?) | Squares C9 and C10 in Area Z

Figure 2

Figure 2The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

Figure 3

Figure 3The Mosaic floor in Squares C9 and C10, Umayyad and first Abbasid Phase of occupation. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

|

| Fallen Columns | main east-west decumanus

Map of Ancient Gadara

Map of Ancient Gadarawww.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries) |

Figure 11

Figure 11Columns down at Jadar, A.D. 749 (Walmsley) Walmsley (2007) |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Abbasid layers, especially in Squares F5 and F6

Figure 2

Figure 2The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

|

VIII+ | |

| Destruction of mosaic floor (dented from falling ashlars ?) | Squares C9 and C10 in Area Z

Figure 2

Figure 2The first and the second phases of occupation in the Abbasid Period, the second phase is shown in light grey, the first phase is shown in dark grey. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

Figure 3

Figure 3The Mosaic floor in Squares C9 and C10, Umayyad and first Abbasid Phase of occupation. El-Khouri and Omoush (2015) |

|

VIII+ |

| Fallen Columns | main east-west decumanus

Map of Ancient Gadara

Map of Ancient Gadarawww.BibleIsTrue.com (Lion Tracks Ministries) |

Figure 11

Figure 11Columns down at Jadar, A.D. 749 (Walmsley) Walmsley (2007) |

|

V+ |

Awad, O. (1998) Water Systems in Umm Qais. M.A Thesis (in Arabic), Yarmouk University

El- Gohary, M and Al- Shorman, A. (2010). The Impact of the Climatic Conditions on

the Decaying of Jordanian Basalt at Umm Qeis: Exfoliation as a Major Deterioration Symptom. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, vol. 10, no. 1: 143-158.

Holm-Nielsen, S.; Nielsen, I. and Andersen, F. (1986) The Excavation of Byzantine Baths in Umm Qeis. ADAJ 30: 219-232.

Haser, J. (2025) Chapter 8. The Hinterland of Gadara after the 749 Earthquake

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749, Brepolis

Khouri, L. and M. Omoush (2015). "The Abbasid occupation at Gadara (Umm Qais), 2011 excavation season." Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 15: 11-25.

Vriezen, K. J., Mulder, Nicole F. (1997). "Umm Qays: The Byzantine Buildings on the Terrace. The Building Materials of Stone and Ceramics " Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 6: 323-330.

Walmsley (2007) Households At Pella, Jordan: Domestic Destruction Deposits Of The Mid-8th C in Material Spatiality in Late Antiquity

Gadara-Umm Qes, 1: Gadara Decapolitana. Untersuchungen zur Topographie, Geschichte, Architektur und der Bildenden Kunst einer “Polis Hellenis” im Ostjordanland (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 30), by T. Weber, Wiesbaden 2002

Gadara-Umm Qes, 3: Die Byzantinischen Thermen (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 17), by I. Nielsen et al., Wiesbaden 1993

Gadara-Umm Qes, 1: Gadara Decapolitana. Untersuchungen zur Topographie,

Geschichte, Architektur und der Bildenden Kunst einer “Polis Hellenis” im Ostjordanland (Abhandlungen

des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 30), by T. Weber, Wiesbaden 2002

ibid. (Reviews) Antike Welt 35 (2004),

110. — LA 53 (2003), 449–451

Gadara-Umm Qes, 3: Die Byzantinischen Thermen (Abhandlungen des

Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 17), by I. Nielsen et al., Wiesbaden 1993

Gadara-Gerasa und die Dekapolis

(Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie

Antike Welt Sonderbände

eds. A. Hoffmann & S. Kerner), Mainz am

Rhein 2002

ibid. (Review) Parthica 4 (2002), 179–180

ABD, 2, New York 1992, 866–868

R. L. J. J. Guinee (& N. F. Mulder), Aram 4 (1992), 387–406;

id. (et al.), ADAJ 40 (1996), 207–215

id. (& N. F. Mulder), SHAJ 6 (1997), 317–322

S. Kerner, Aram 4

(1992), 407–423

id. (& A. Hoffmann), ADAJ 37 (1993), 359–384

41 (1997), 283–302

id., AJA 99 (1995),

523–524

ibid. 101 (1997), 514–515

id., Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 4 (1995), 40–46

id. (et al.), SHAJ 6 (1997), 265–270

id., Occident and Orient

4/1–2 (1999), 20–21

id., Men of Dikes and Canals: The Archaeology of Water in the Middle East. International Symposium, Petra, 15–20.6.1999. (Orient Archäologie 13

eds. H. -D. Bienert & J. Häser), Rahden

2004, 187–202

K. J. H. Vriezen, Aram 4 (1992), 371–386

id., Leiden University Department of Pottery

Technology Newsletter 13 (1995), 26–40

id., SHAJ 6 (1997), 323–330

7 (2001), 537–545

W. Karasneh

& M. Dahash, ADAJ 37 (1993), 45–60

39 (1995), 29–36

U. Wagner-Lux et al., ibid. 37 (1993), 385–395;

44 (2000), 425–431

id., ZDPV 109 (1993), 64–72

115 (1999), 51–58

id. (& K. J. H. Vriezen), Occident

and Orient 1/2 (1996), 13–14

2/2 (1997), 7–8 (et al.)

T. Batayneh, ADAJ 38 (1994), 379–384

N. Duval,

Churches Built in Ancient Times: Recent Studies in Early Christian Archaeology (ed. K. S. Painter

Society

of Antiquaries Occasional Papers 16), London 1994, 150–212

R. Gersht, Michmanim 7 (1994), 27*–36*;

R. Wenning, ZDPV 110 (1994), 1–35

N. F. Mulder, Orient Express 1995, 8–10

T. Weber, Jahrbuch für

Antike und Christentum Erganzungsband 20/2 (Atti del Congresso Internationale di Archeologia Cristiana

12, 1995), 1273–1282

id., ZDPV 112 (1996), 10–17

id., ADAJ 42 (1998), 443–456

id., Damaszener Mitteilungen 11 (1999), 433–451

id. (& J. Gutenberg), MdB 117 (1999), 61

id., Antike Welt 31 (2000), 23–35;

id., Saalburg Jahrbuch 50 (2000), 9–17

id., SHAJ 7 (2001), 531–537

A. Hoffmann, German Protestant

Institute of Archaeology in Amman 1 (1996), 2–4

id., Mitteilungen des DAI, Römische Abteilung 104 (1997),

267–300

id., Occident and Orient 2/1 (1997), 2

2/2 (1997), 5–6 (with N. Riedl)

id., Topoi. Orient-Occident

9 (1999), 795–831

id., Jahrbuch des DAI Archäologischer Anzeiger 2000, 175–233

id., SHAJ 7 (2001),

391–397

M. Nun, The Land of the Gadarenes: New Light on an Old Sea of Galilee Puzzle, Ein Gev 1996

J.

M. C. Bowsher, Levant 29 (1997), 227–246

A. -C. Janke, Occident and Orient 2/1 (1997), 5–6

R. Khouri,

Jordan Antiquity Annual, 1, Amman 1997, nos. 18, 35

2, Amman 1998, no. 66

N. Riedl, Occident and

Orient 3/2 (1997), 23–24

id., AJA 103 (1999), 485–487

id., ZDPV 115 (1999), 45–48

H. -D. Bienert (& T.

Weber), Antike Welt 29 (1998), 62–63

id. (& C. Bührig), Occident and Orient 4/1–2 (1999), 48–49

id. (et

al.), ZDPV 116 (2000), 143–145

G. M. Cohen, American Journal of Numismatics 10 (1998), 95–102

D. F.

Graf, Rome and the Arabian Frontier: From the Nabataeans to the Saracens (Variorum Collected Studies

Series CS594), Aldershot 1998, II, 785–796

F. Zayadine, NEAS Bulletin 43 (1998), 31–32

C. Bührig (& B.

De Hän), Antike Welt 30 (1999), 533–543

id., SHAJ 7 (2001), 547–552

id., AJA 109 (2005), 527–529

Jahrbuch des DAI Archäologischer Anzeiger 1999, 632–634

2000, 235–265 (by P. M. Kenrick)

2001, 683–684;

2003, 248–249

2004, 350–351

W. Thiel, Occident and Orient 4/1–2 (1999), 2–4

M. al-Daire, ibid. 5/1–2

(2000), 17–18

id., SHAJ 7 (2001), 553–560

M. Wörrle, ibid., 267–271

C. Eger, Occident and Orient 6/1–2

(2001), 2–3

S. F. Maynersen, ADAJ 45 (2001), 427–432

id., Men of Dikes and Canals: The Archaeology

of Water in the Middle East. International Symposium, Petra, 15–20.6.1999. (Orient Archäologie 13

eds.

H. -D. Bienert & J. Häser), Rahden 2004, 219–230

D. Vieweger et al., Occident and Orient 7/2 (2002),

12–14

A. Lichtenberger, INJ 14 (2003), 191–193

id., BAIAS 22 (2004), 23–34

M. Luz, Jews and Gentiles

in the Holy Land in the Days of the Second Temple, The Mishnah and the Talmud: A Collection of Articles.

Proceedings of the Conference, Haifa, 13–16.11.1995. (eds. M. Mor et al.), Jerusalem 2003, 97–107

J. Zangenberg & P. Pusch, Leben am See Gennesaret, Mainz am Rhein 2003, 117–129

J. Haser, SHAJ 8 (2004),

155–160

G. Mazor, Free Standing City Gates in the Eastern Provinces during the Roman Imperial Period

(Ph.D. diss.), Ramat Gan 2004 (Eng. abstract)

E. Villeneuve, MdB 158 (2004), 28

P. Gruson, MdB Hors

Série 2005, 36–37

F. Zens, AJA 109 (2005), 529–530

J. Dijkstra et al., Phoenix 51 (2005), 5–26.