Jerash - Macellum

Jarash Macellum

Jarash Macellum

click on image to open in a new tab

Photographer: David Leslie Kennedy

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- source: Uscatescu & Marot (2000)

Its eastern entrance opened directly onto the Cardo Maximus and featured a monumental façade with 10 m-high columns, a triple-arched gateway, and a vestibule. Flanking tabernae provided commercial frontage. A fountain in the northeast corner bears a Greek inscription honoring Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus, suggesting construction around 193–211 CE.

In the Late Byzantine period, the building was repurposed for industrial functions. Archaeological evidence indicates the presence of a tinctoria (dye workshop), a lime kiln, and pottery production. These transformations reflect urban adaptation to new economic realities by the 6th and early 7th centuries CE.

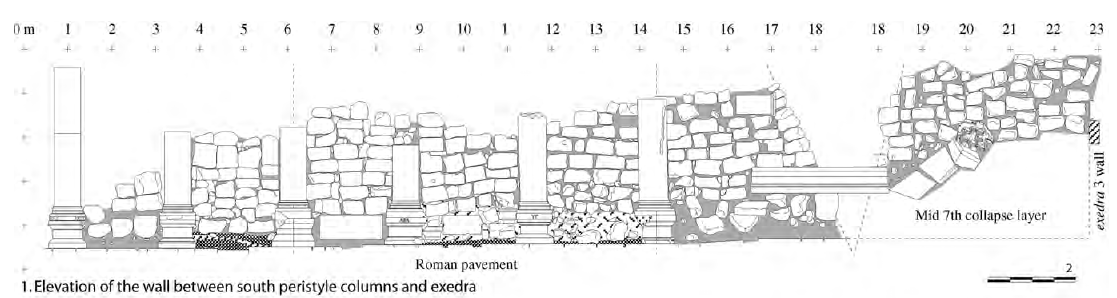

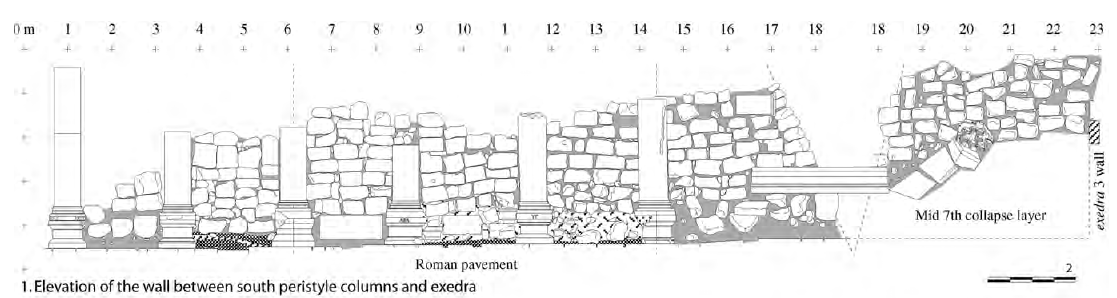

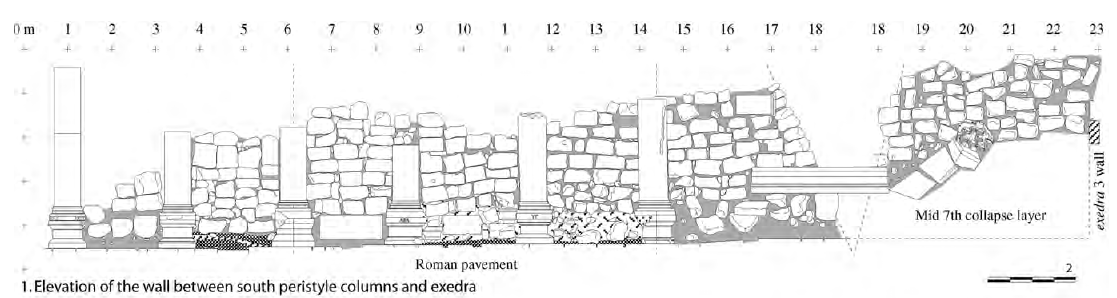

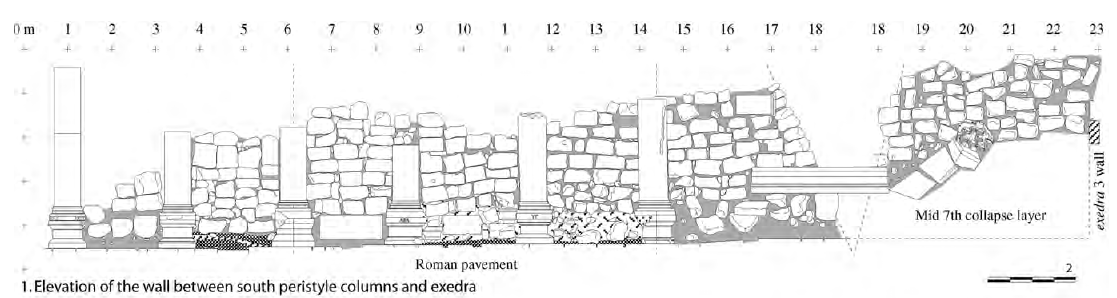

A major collapse layer was found over the southern exedra and sealed by a stone retaining wall. The authors propose that this may result from a destructive event in the early 7th century CE—possibly linked to the Sasanian invasion in 614 CE, an earthquake, or early Islamic warfare. The exact cause is undetermined.

Despite this destruction, limited reuse followed during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. Archaeological traces include grain storage pits and ceramic kilns, suggesting that portions of the macellum remained in use until the late 8th century CE, when the complex was ultimately abandoned.

- from Jerash - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Umayyad Jerash

from Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

Figure 2

Plan summarising the principal urban features of Umayyad Jarash.

- Umayyad mosque

- possible Islamic administrative centre

- market (suq)

- South Tetrakonia piazza (built over)

- Macellum, with Umayyad–Abbasid rebuilding, and south cardo, encroached by structures;

- Oval piazza domestic quarter with fountain;

- Zeus temple forecourt (kiln, monastery?)

- hippodrome and Bishop Marianos church, eighth century use

- church of SS Peter and Paul and Mortuary Church (Umayyad construction date?)

- churches of SS Cosmas and Damianus, St George and St John theBaptist, with Umayyad–Abbasid occupation and iconoclastic-effected mosaics (later eighth century)

- Christian complex of two churches (Cathedral to the east with stairs from the street, St Theodore’s to the west), mid-5th to late 6th century Bath of Placcus (north of St Theodore’s) and houses west of St Theodore’s with extensive Umayyad occupation including a kiln and oil press

- Artemis compound used for ceramic manufacture

- Synagogue church with iconoclastic-effected mosaics

- North Theatre, also industrialised with kilns

- the 1981 ‘mosque’

- central Cardo with blacksmith’s shop and offices

Map modfied from R.E. Pillen in Zayadine (1986).

Walmsley and Daamgaard (2005)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of the

Macellum

from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Macellum Plan

Uscatescu and Marot (2000) - Fig. 7.1 - Location of the

early Islamic contexts and structures from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1

Location of the early Islamic contexts and structures

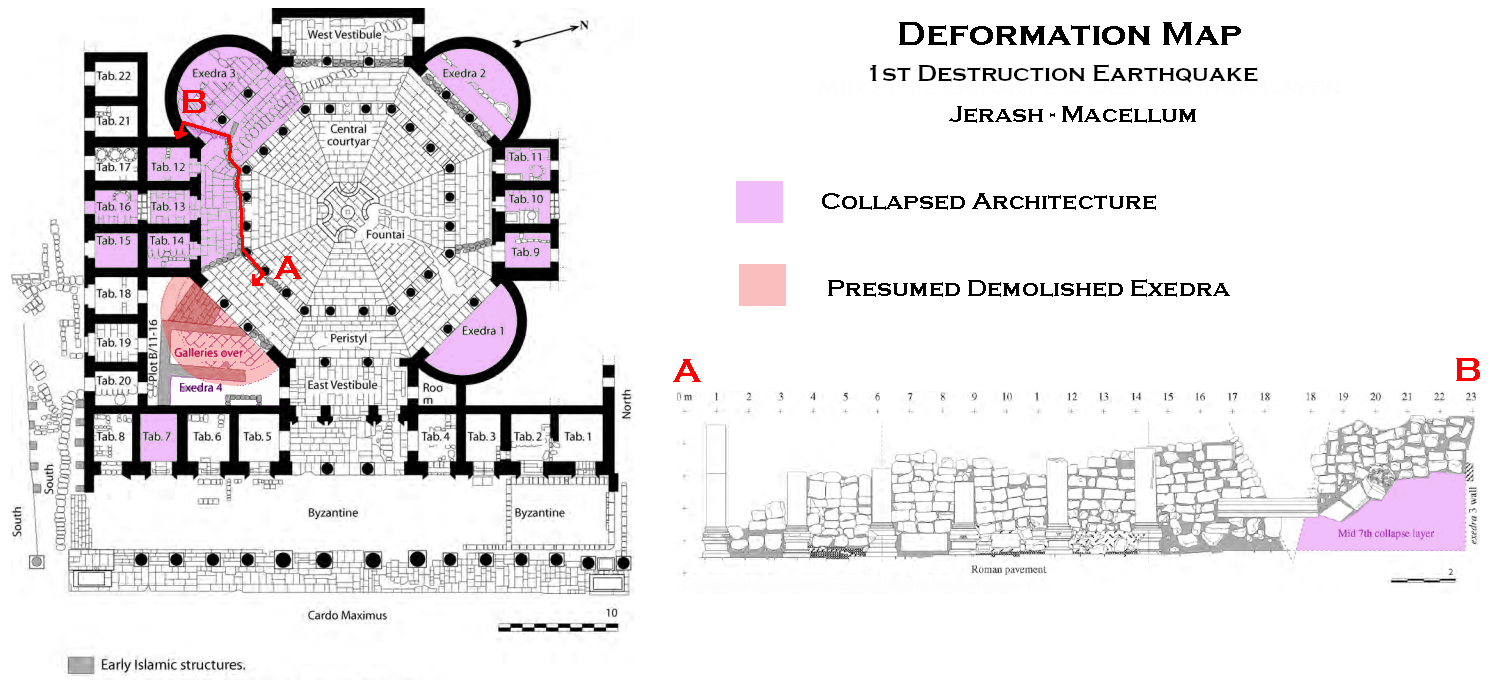

Uscatescu and Marot (2000) - Fig. 2.1 - Plan showing location

of mid 7th century CE collapse layer from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1

Location of the mid-seventh century collapse layer.

Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of the

Macellum

from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Macellum Plan

Uscatescu and Marot (2000) - Fig. 7.1 - Location of the

early Islamic contexts and structures from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1

Location of the early Islamic contexts and structures

Uscatescu and Marot (2000) - Fig. 2.1 - Plan showing location

of mid 7th century CE collapse layer from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1

Location of the mid-seventh century collapse layer.

Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

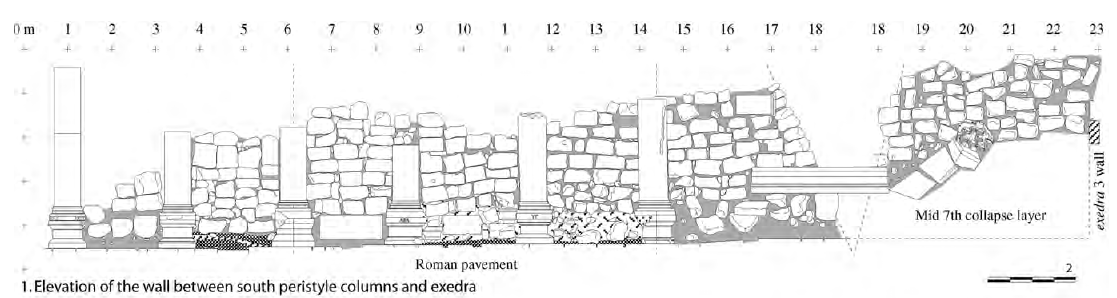

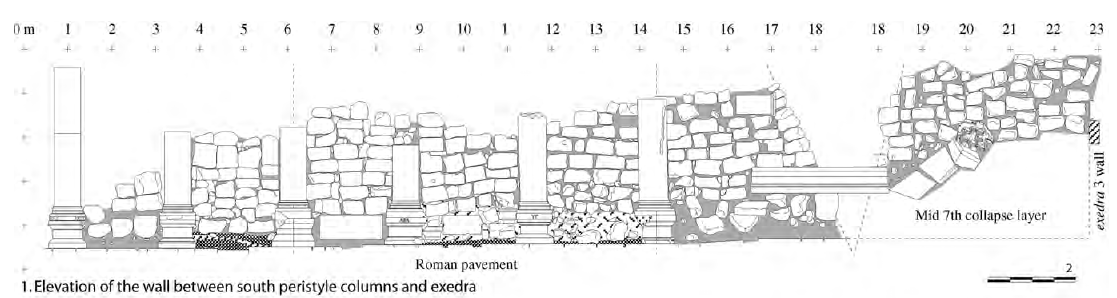

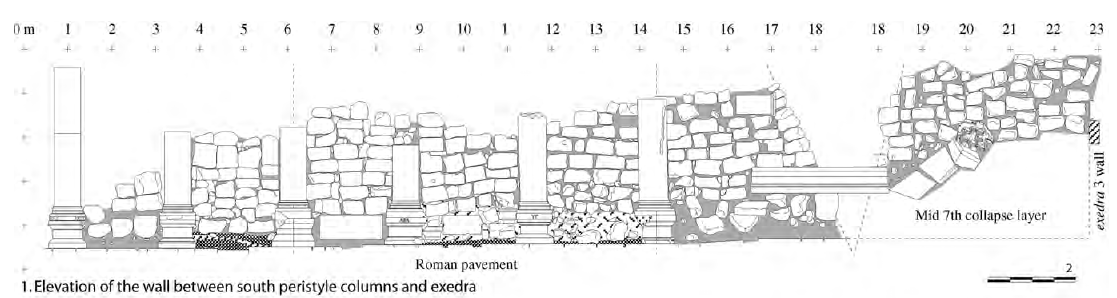

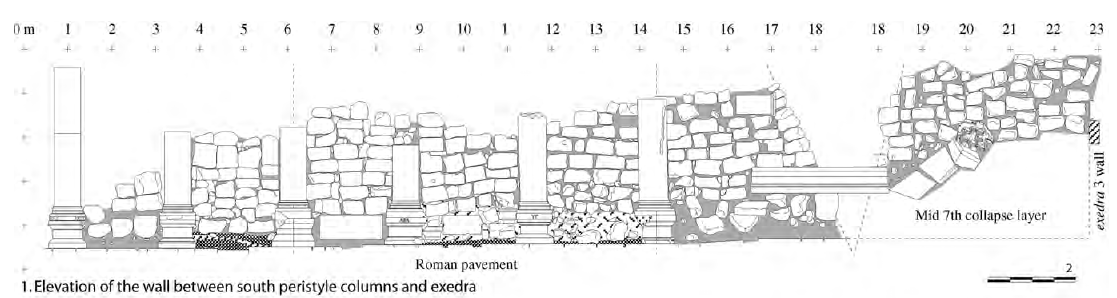

- Fig. 6.1 - Islamic wall

with mid-7th century collapse layer to the right from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1

Islamic wall between south peristyle columns and exedra 3

JW: Mid 7th century CE collapse layer to right

Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

- Fig. 6.1 - Islamic wall

with mid-7th century collapse layer to the right from Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1

Islamic wall between south peristyle columns and exedra 3

JW: Mid 7th century CE collapse layer to right

Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- source: Uscatescu & Marot (2000)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Roman | early 2nd century CE | Construction of the macellum with octagonal courtyard, peristyle, and monumental entrance onto the Cardo Maximus. Greek inscription dedicated to Julia Domna. |

| II | Late Roman–Byzantine | late 5th – early 6th century CE | Addition of southern row of tabernae, installation of lime kiln, and reuse of interior rooms for industrial purposes. Function shifts toward dye production and ceramic workshops. |

| III | Early Islamic | early to mid-7th century CE | Collapse of southern exedra and construction of retaining wall. Possible destruction linked to Sasanian invasion, an earthquake, or early Islamic conflicts. |

| IV | Umayyad–Abbasid | late 7th – late 8th century CE | Reoccupation with restricted functions—grain storage, pottery kilns, limited rebuilding. No architectural renewal. Final abandonment by end of 8th century CE. |

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:283) dated seismic destruction of the

Macellum to at the latest to the second quarter of the seventh century

based on

pottery and coins1. The seismic destruction layer was found in a sealed and undisturbed context and is well-dated.

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:281) discussed a dating revision as follows:

This destruction was previously dated to the early seventh century, but now we are compelled to withdraw this date and propose, on the basis of both pottery and coin data, a mid-seventh century chronology for this collapse, that is some 20 years later than the first proposed chronology. However, this corrected date for the Macellum destruction does not affect the established pre-Islamic phases of the building.In addition to the collapse layers found throughout the Macellum, vaulted Islamic galleries were constructed over where exedra 4 once stood. It can be presumed that exedra 4 was demolished and cleared away before construction of the galleries began.

1 Pottery and coins from the Macellum have been already published separately. Detailed information on the coins and pottery can be found in Marot (1998) and Uscatescu (1995; 1996)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- from Uscatescu & Marot (2000)

The authors interpret this collapse as marking a significant disruptive event, though they stop short of attributing it definitively to a single cause. They propose three possible explanations: (1) the Sasanian invasion in 614 CE, (2) the 631–632 CE earthquake recorded in Byzantine sources, or (3) early Islamic conflict-related destruction. The collapse layer provides a terminus post quem for these events.

No explicit faulting or directional collapse patterns were reported. However, the sudden nature of the destruction, stratigraphic sealing, and architectural displacement all suggest a rapid catastrophic event, compatible with earthquake damage. Later reuse of the building in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods confirms that the structure was never fully restored after this event.

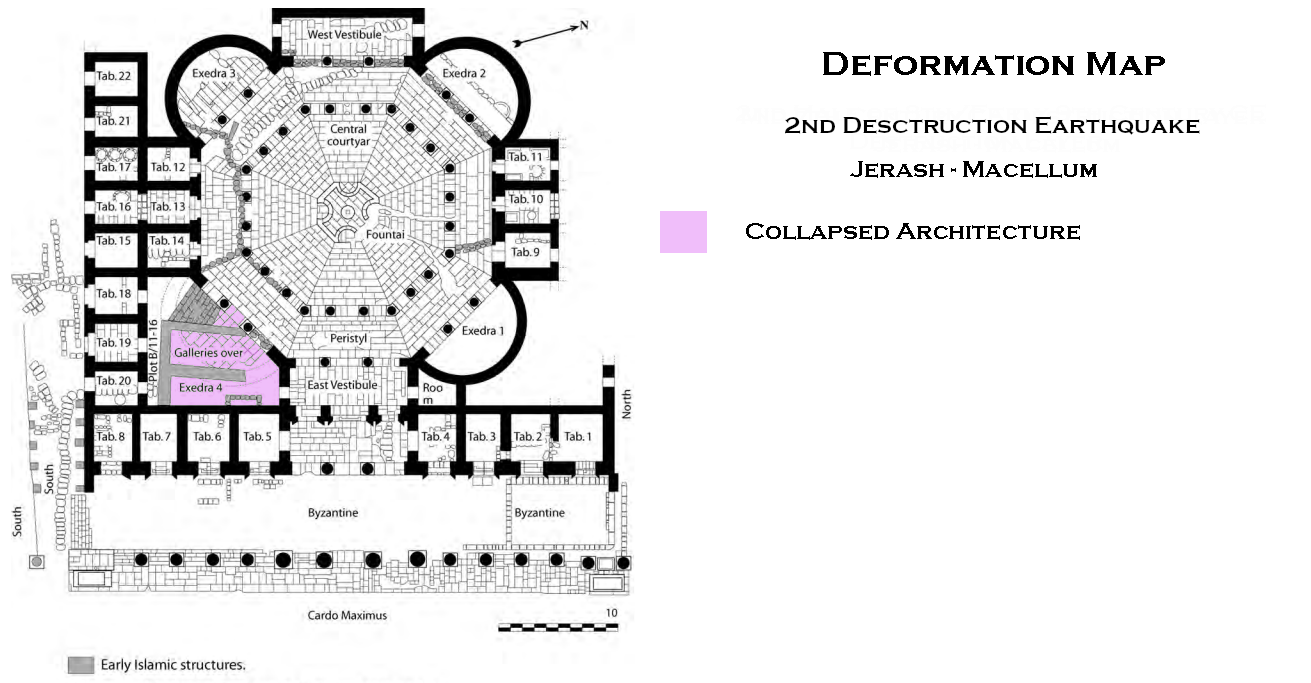

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:299) report that the building continued in use after the mid 7th century CE destruction with new structures built over parts of the ruins. A later destruction layer was present which Uscatescu and Marot (2000:298-299) discussed as follows:

The Destruction Layer of Late Umayyad/Early Abbasid Chronology over the Islamic GalleriesSome traces of an

The Islamic galleries were covered by a destruction level composed of ashlar blocks and voussoirs from the fallen walls and vaults. Archaeological analysis proves that it is also a disturbed layer, since the residual sherds account for 88.5 per cent of the total. In the case of the coins, the percentage of residuality is much higher, accounting for 92.68 percent (Table 4).

Unfortunately, only four sherds can be dated to the late Umayyad period; the rest are rubbish survival, including some transitional shapes such as imported Cypriot Late Roman D (Hayes form 9B), which has an end date of the late seventh century (Hayes 1972: 382). The Umayyad pottery is limited to a cooking-pot (Figure 9.6), a handmade grey basin (Figure 9.12) and a probably local grey amphora (Figure 9.13). The absence of any Islamic coins within this context does not help when attempting to fix a more accurate date to the collapse.

early Abbasid occupation over the destruction levelwere found at exedra 3 (Table 5b) which they discussed as follows:

This evidence points to a very short occupation, with some burnt patches identified as small fireplaces and several complete cooking-pots (Figure 9.3, 6) and some dark BGW (Figure 9.9, 11). Therefore, this level should be dated, at least, to the second half of the eighth century on stratigraphical basis. No coins were recorded.UUscatescu and Marot (2000:299) noted chronological difficulties in dating final (destruction) and abandonment.

It is difficult to ascertain the chronology of the second and final abandonment of the building. But most of the archaeological evidence recorded pointed to the second half of the eighth or early ninth centuries. Unfortunately, there is not a single undisturbed context that can be surely dated in the early Abbasid period, with the exception of sporadic occupation in exedra 3.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- from Uscatescu & Marot (2000)

Despite the high residuality, four diagnostic ceramic sherds— including a cooking pot, a handmade grey basin, and a grey amphora—support a terminus post quem in the late Umayyad period, while imported Cypriot Late Roman D (Hayes Form 9B) further constrains the terminus ante quem to the end of the 7th century CE. The destruction event itself is thus tentatively dated to the late 8th or early 9th century CE. The absence of Islamic coins from this level hinders finer chronological resolution.

A short-lived early Abbasid reoccupation was noted in exedra 3, above the destruction layer, and consisted of small hearths and intact cooking vessels. This episode, though ephemeral, supports a terminus post quem in the second half of the 8th century CE.

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:299) acknowledge the difficulty in firmly assigning a cause to this second collapse, noting that no single undisturbed context is available for dating the event with certainty. Nonetheless, the stratigraphic sequence and associated material suggest a sudden and damaging episode, possibly of seismic origin, occurring during the late Umayyad to early Abbasid transition.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

throughout Macellum

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1Location of the mid-seventh century collapse layer. Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1Islamic wall between south peristyle columns and exedra 3 JW: Mid 7th century CE collapse layer to right Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

|

exedra 4

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Islamic galleries over

exedra 4

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1Location of the early Islamic contexts and structures Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig.s 1 and 6.1.1 of Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 1 of Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

throughout Macellum

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1Location of the mid-seventh century collapse layer. Uscatescu and Marot (2000)

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1Islamic wall between south peristyle columns and exedra 3 JW: Mid 7th century CE collapse layer to right Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

|

|

exedra 4

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Islamic galleries over

exedra 4

Figure 1

Figure 1Macellum Plan Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1Location of the early Islamic contexts and structures Uscatescu and Marot (2000) |

|

|

Marot, Teresa (1998). Las monedas del Macellum de Gerasa (Yaras, Jordania): aproximación a la circulación monetaria en la provincia de Arabia.

Madrid: Museo Casa de la Moneda.

Uscatescu, Alexandra (1995). Jarash Bowls and other Related Local Wares from the Spanish Excavations at the Macellum of Gerasa (Jerash).

Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 39: 365-408.

Uscatescu, Alexandra (1996) La cerámica del Macellum de Gerasa (Yaras, Jordania).

Informes Arqueológicos/Jordania. Madrid.

Uscatescu, A. and Marot, T. (2000) The Ancient Macellum of Gerasa in the Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods: the Archaeological Evidence in

ICAAANE - Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East Volume 2 22-26 May 2000, Copenhagen ed. Ingolf Thuesen