Caesarea

Aerial View of Caesarea

Aerial View of CaesareaClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from Biblewalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Caesarea | ||

| Caesarea Maritima | ||

| Keysariya | Hebrew | קֵיסָרְיָה |

| Qesarya | Hebrew | קֵיסָרְיָה |

| Qisri | Rabbinic Sources | |

| Qisrin | Rabbinic Sources | |

| Qisarya | Arabic | قيسارية |

| Qaysariyah | Early Islamic Arabic | قايساريياه |

| Caesarea near Sebastos | Greek and Latin sources | |

| Caesarea of Straton | Greek and Latin sources | |

| Caesarea of Palestine | Greek and Latin sources | |

| Caesarea | Ancient Greek | Καισάρεια |

| Straton's Tower | ||

| Strato's Tower | ||

| Stratonos pyrgos | Ancient Greek | |

| Straton's Caesarea |

King Herod built the town of Caesarea between 22 and 10/9 BCE, naming it for his patron - Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus. The neighboring port was named Sebastos - Greek for Augustus (Stern et al, 1993). Straton's Tower, a Phoenician Port city, existed earlier on the site. When the Romans annexed Judea in 6 CE, Caesarea became the headquarters for the provincial governor and his administration (Stern et al, 1993). During the first Jewish War, Roman General Vespasian wintered at Caesarea and used it as his support base (Stern et al, 1993). After he became Emperor, he refounded the city as a Roman colony. Caesarea is mentioned in the 10th chapter of the New Testament book of Acts as the location where, shortly after the crucifixion, Peter converted Roman centurion Cornelius - the first gentile convert to the faith. In Early Byzantine times, Caesarea was known for its library and as the "home-town" of the Christian Church historian and Bishop Eusebius. After the Muslim conquest of the 7th century, the city began to decline but revived again in the 10th century (Stern et al, 1993). Crusaders ruled the city for most of the years between 1101 and 1265 CE (Stern et al, 1993). After the Crusaders were ousted, the town was eventually leveled in 1291 CE and remained mostly desolate after that (Stern et al, 1993).

Herod the Great named the port city he built on the Mediterranean coast Caesarea, to honor his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus. He called the neighboring port Sebastos, Greek for" Augustus." The site is located on the Sharon coast, about midway between Haifa and Tel Aviv (map reference 1399.2115). The site's ancient name has survived into modern times in the Arabic Qaisariya. Rabbinic sources reproduced Caesarea as Qisri or Qisrin. Because it was only one of many Caesareas, Greek and Latin sources often specify Caesarea as near (the harbor) Sebastos, Caesarea of Straton, or (more commonly) Caesarea of Palestine. The emperor Vespasian granted Caesarea the rank of Roman colony, making it Colonia Prima Flavia Augusta Caesariensis, and Severus Alexander gave it the title Metropolis of the province Syria Palaestina. The name Caesarea Maritima, widely used today, was apparently unknown in antiquity. Straton's Tower (Στρατωνος Πνργος), a Phoenician port town, existed earlier on the site. The name is Greek for Migdal Shorshon, its equivalent in rabbinic texts. It is a common type of toponym meaning a fortified town, not a bastion or lookout tower, as some have thought. Whatever the meaning of Shorshon, in local legend Straton was a Greek hero, and it was he, not Herod, who founded Caesarea, which has thus also been called Straton's Caesarea.

Modern scholars suggest that the historical Straton was either a general in the Ptolemaic army in the beginning of the third century BCE or one of two Phoenicians named 'Abdashtart who ruled Sidon in the fourth century BCE. Recent ceramic finds do support limited commercial activity at the site this early, but the earliest reference to Straton's Tower is in a papyrus from the Zenon archive (P Cairo 59004) (259 BCE), which also attests an active harbor. The town flourished in the third century BCE (ceramic evidence) and especially in the later second century BCE, when the local tyrant, Zoilos, held it against the expanding Jewish kingdom (Josephus, Antiq. XIII, 324), perhaps fortifying it with the "city wall of Straton's Tower" mentioned in a rabbinic source (Tosefta Shevi'it IV, 11). The rulers of Straton's Tower apparently developed at least two protected harbors, cut into the sandstone bedrock of the coast in characteristic Hellenistic fashion - λιμην κλειστος (close haven).

The town finally passed to Alexander Jannaeus in about 100 BCE (Josephus, Antiq. XIII, 334~335). During forty years of Hasmonean rule, Straton' s Tower probably acquired a Jewish population, but the rabbis excluded the town itself (though not its territory) from the borders of Palestine (Tosefta Shevi'it IV, 11). To weaken the Hasmonean kingdom, Pompey annexed Straton's Tower and other coastal towns to Roman Syria in 63 BCE (Antiq. XIV, 76; War I, 156). The town was in a state of decay when Octavian, the future Caesar Augustus, restored it to the Jewish state in 31 BCE (Antiq. XV, 217; War I, 396).

Between 22 and 10/9 BCE, Herod built Caesarea on the site of Straton's Tower. Josephus praises the king's lavish construction, which included a theater and an amphitheater, a royal palace, the marketplace (agora), streets on a grid plan, and especially the harbor (War I, 408~414; Antiq. XV, 331~ 337; XVI, 136~141). Above the old main harborof Straton's Tower and just to the east, he created a spacious temple platform. Upon this platform he erected a temple dedicated to the goddess Roma and to the deified Emperor Augustus. Herod appears to have resettled the site with Jews as well as with Greek-speaking pagans. Nevertheless, Caesarea became a typical Greek city-state (polis) of the Hellenistic age, ruled by a city council and magistrates under a resident royal general. In the Herodian state, this city was a pagan and Greek counterweight to Jewish Jerusalem. The new harbor, Sebastos, like the city itself, emphasized Herod's links with his Roman patron, and it offered the only all-weather haven on the Mediterranean coast o his kingdom. Sebastos consisted of a renovated inner harbor, the old rock-cut main anchorage of Straton's Tower, and a much larger outer harbor basin that extended westward from the shore, encompassed within massive constructed breakwaters designed to protect moored ships from the powerful coastal surge. As vessels approached from the northwest, they passed colossal statues of the emperor's family elevated on columns that guided mariners to the harbor entrance. Visible from much farther out at sea was the harbor's lighthouse tower, named after Drusus, the emperor's current heir apparent. Josephus also mentions barrel-vaulted warehouses designed to accommodate goods passing through the harbor (War I, 413; Antiq. XV, 337). It seems that Sebastos retained its royal administrative status, unlike the municipal anchorage at the bay south of it, until it was handed over to the people of the city in about 70 CE.

When the Romans annexed Judea to the empire in 6 CE, they made Caesarea the headquarters of the provincial governor and his administration. A Latin inscription found in the theater records that one of these, Pontius Pilate, prefect of Judea, dedicated a temple at Caesarea to the emperor Tiberius (AE 1963, no. 104). The city remained the capital of Judea, later called Palaestina, until the end of classical antiquity.

In 66 CE, on the eve of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, the pagan majority massacred most of Caesarea's Jews (War II, 457). During the revolt, the Roman commander, Vespasian, wintered at Caesarea and used it as his main support base. After he became emperor, in gratitude for its loyalty, he refounded the city as a Roman colony. Caesarea became an outpost of Roman culture. Western-type duumviri headed the government and decurions (municipal senators) formed the city council. Many inscriptions from Caesarea's first three centuries are in Latin. Hostile to Caesarea, the rabbis called it "daughter of Edom," meaning "daughter of Rome," and they denied that Caesarea and Jerusalem could prosper at the same time.

In the second and third centuries, the city continued to profit from links with the Roman emperors. Hadrian, who may have paid Caesarea an imperial visit in the summer of l30, expanded its aqueduct system and may have built the city's stone circus. In response, the Caesareans dedicated a temple to Hadrian, and coins from the local mint depicted him as the colony's founder. Other imperial visitors were Septimius Severus, in 199 or 201, and perhaps Severus Alexander, in 231-232. The former founded the city's famous Pythian games, while it was Alexander who gave Caesarea the title metropolis. Christianity took at Caesarea within a few years of the Crucifixion, when Saint Peter converted the Roman centurion Cornelius (Acts 10). Indeed, this city may have harbored the first gentile Christians. Nevertheless, the virtual extinction of the Jewish community in 66 apparently implicated most Christians as well, and it is only from the later second century that there is a renewed record of a Christian church, with its own bishop. In the same period, Jews resettled in Caesarea, attracted by economic advantages. By 250, the city boasted both a celebrated rabbinic academy and the Christian school of Origen, the outstanding scholar and theologian who assembled an unparalleled library and compiled the hexapla text of the Bible. In the towns and villages of Caesarea's countryside, the population was heavily Jewish and Samaritan.

With the advent of the Christian Roman Empire (fourth-seventh centuries), Caesarea's population and economy expanded, as in the rest of Palestine. A new fortification wall enclosed far more urban space. The authorities built an additional (low-level) aqueduct system, and they continued to replace the city's street pavements following Herod's original grid plan. When Christianity became the dominant religion, a church replaced Herod's temple to Roma and Augustus on the temple platform.

In this period Caesarea remained a metropolis, or provincial capital. In 530, the Roman emperor Justinian promoted the governor stationed at Caesarea to proconsul because of the city's famous past and because it presided over a province filled with famous cities, including the one where "Jesus Christ ... had appeared on earth" (Justinian, Novella 103). The city's bishop also ranked as metropolitan of Palestine and the Caesarean see kept this prerogative even after 451, when the archbishop of Jerusalem obtained the rank of patriarch. The most famous of Caesarea's bishops was the ecclesiastical historian and apologist Eusebius (bishop c. 315-339), who recorded Christian martyrdoms in the city's amphitheater under the last pagan emperors. On the Jewish side, his contemporary was Rabbi Abbahu, who taught his daughters Greek, visited the city's baths, and maintained excellent relations with the pagan authorities. Another product of the city's learned culture was the historian Procopius of Caesarea (sixth century).

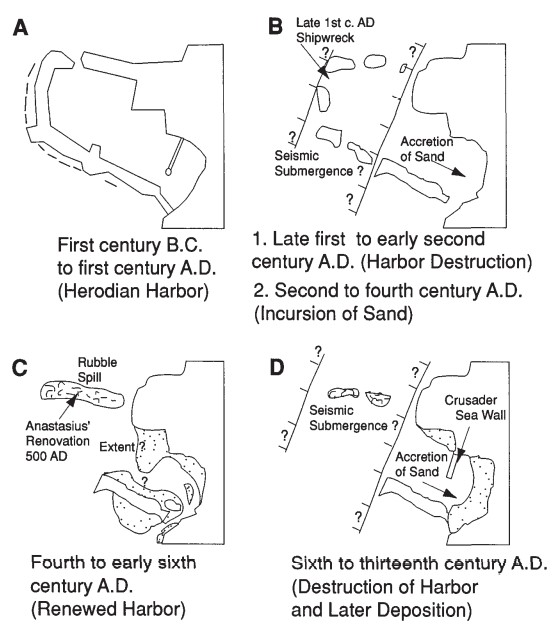

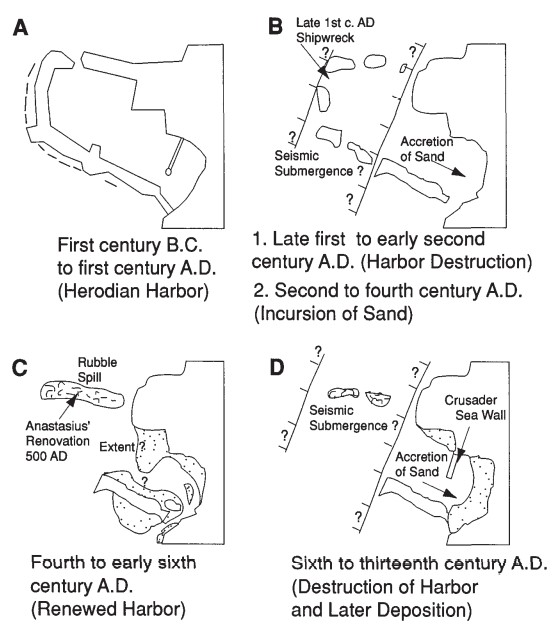

By 500, tectonic action and the coastal surge had reduced parts of the breakwaters of Herod's harbor to submerged reefs that were a hazard to navigation. The emperor Anastasius ( 492-517) undertook a major building campaign to restore Sebastos (Procopius of Gaza, Panegyricus in imperatorem Anastasium XIX, PG 87, col. 2817), and this helped Caesarea reach its pinnacle of prosperity in the sixth century. In the meantime, however, relations deteriorated between the city's Christian majority and its Samaritan and Jewish minorities. In 484, rebellious Samaritans burned Caesarea's Church of Saint Procopius. The major revolt of 529-530, when thousands of Samaritans died, fled, or were enslaved, left the territory of Caesarea denuded of her peasant farmers, a serious economic blow (Procopius of Caesarea, Arcana XI, 14-33). In 555, Samaritans - this time allied with the Jews - again burned Christian churches at Caesarea, together with the palace of the Roman governor (J. Malalas, Chron. XVIII, 487-488). These troubles presaged the invasions of the seventh century, when non-Christian minorities generally sided with the enemy. In 614, a Persian army attacked Caesarea, but the city capitulated without serious resistance. The Roman armies returned for a brief period after 628, but in 641 or 642 Caesarea fell to an Arab army after a seven-month siege.

During the next two centuries Caesarea suffered heavily from depopulation, natural building collapse, and stone robbing, and the harbors fell into disuse. By the tenth century, however, Caesarea reemerged, a prosperous town but on a much smaller scale. The geographers el-Muqaddasi and Nasiri-Khusrau mention flourishing gardens and orchards, a fortification wall, and a Great Mosque apparently situated on what had been Herod's temple platform (PPTS III, 3, 55; IV, 1, 20). In 1101, the Frankish king Baldwin I of Jerusalem and the Genoese fleet conquered Caesarea after a brief siege and established a Crusader principality. It lasted, despite periods of reconquest, until 1265. A Christian church replaced the Great Mosque on the temple platform. In 1251-1252, the French king Louis IX ("Saint Louis") labored on the fortifications with his own hands, as an act of penance. Fourteen years later, the Egyptian sultan Baybars stormed Caesarea, and in 1291 his successor leveled it and other Crusader castles along the Levantine coast to prevent their falling into enemy hands. From time to time a squatter settlement existed among the ruins after 1291, but Caesarea mostly remained desolate.

Caesarea is a large site, comprising about 235 a. within its semicircular perimeter wall. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries European travelers, such as R. Pococke and V. Guerin, published more-or-less accurate descriptions of the site. In 1873, C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener mapped and described it as part of the Survey of Western Palestine, noting, for example, the aqueducts, the semicircular (outer) perimeter wall, the medieval fortifications, and the theater. Over the next ninety years there were only chance finds. In 1945, J. Ory,forthe Mandatory Department of Antiquities, and M. Avi-Yonah, in 1956 and 1962, for the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, explored the meager remains of a synagogue revealed during winter storms along the northern seashore. In 1951, S. Yeivin excavated a marble-paved esplanade east of the Crusader city for the department, where a tractor from Kibbutz Sedot Yam had struck a colossal porphyry statue. In 1955, a large mosaic pavement on a ridge to the northeast of ancient Caesarea was also exposed accidentally.

Large-scale, systematic explorations at Caesarea date only from 1959, the first of five seasons of the Missione Archeologica ltaliana directed by A. Frova. This team studied part of the semicircular (outer) perimeter wall, demonstrating its date to be Byzantine, and exposed, for the first time, the northern segment of an inner perimeter wall, which the Missione considered Herodian. It also examined a "Christian building" to the northeast of the site and completely excavated the Herodian-Roman theater and the massive fortezza (fortress) that incorporated the ruins of the theater in the Byzantine period. During most of the same years (1960-1964) A. Negev, on behalf of the National Parks Authority, cleared the Crusader moats surrounding the present medieval city. Negev exposed numerous ancient and medieval ruins, including the facade of the temple platform and the triple-apsed Crusader basilica above it. Negev also excavated to the north of the medieval city, between it and the inner perimeter wall, where he exposed part of the Hellenistic town, and to the south of the southern Crusader moat, where he found the building he identified as the library of Origen and Eusebius. Farther north, just inland from the coast, Negev exposed and studied 300 m of the high-level aqueduct.

The Joint Expedition to Maritime Caesarea, comprising teams from twenty-one colleges and universities in the United States and Canada, began exploring the site in 1971, under the direction of R. Bull, 0. Storvick, and E. Krentz. In twelve seasons, this project excavated many sites outside the medieval city, mainly in fields A and B to the east; C, K, L, M, and N to the south; and G to the north, within the inner perimeter wall. Among the Joint Expedition's main goals was to recover the grid plan of streets laid out by Herod. In 1974, J. H. Humphrey, under Joint Expedition auspices, dug several trenches in the circus. During the same decade, in 1975-1976 and 1979, L. I. Levine and E. Netzer, representing the Hebrew University's Institute of Archaeology, explored the west-central part of the medieval city and what Netzer calls the Promontory Palace, which extends seaward to the northwest of the theater.

In more recent rescue excavations, R. Reich and M. Peleg uncovered a south gate in the ancient semicircular perimeter wall in Kibbutz Sedot Yam (1986), adjacent to the site on the south, andY. Porath studied the south gate in the medieval wall and part of the wall itself (1989-1990). Porath has also conducted extensive research on Caesarea's aqueducts. In 1990, Netzer renewed his work on the Promontory Palace. In 1989-1990, A. Raban and K. Holum organized the Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE), an international amphibious effort to explore major sectors of the ancient site. To the south of the medieval city, the Combined Caesarea Expeditions have begun work in area KK, the next insula (city block) to the south of the Joint Expedition's field C. The objective here is to explore the evolution of an urban neighborhood throughout antiquity. CCE is also excavating in area I, the inner harbor, and area TP, the temple platform, in an effort to link the harbor with what was apparently the monumental center of both the ancient and medieval city.

Caesarea is also a rare maritime site where subsurface remains of a major ancient harbor lie relatively undisturbed by postmedieval harbor construction and uncluttered by the detritus of modern commerce. In 1960, E. Link, one of the pioneers of underwater exploration, conducted a marine survey that first identified the ruins ofSebastos, Herod's great harbor. Bad weather and difficult seas limited Link's success, however, and it was not untill976 that Haifa University's Center for Maritime Studies began sustained research on Caesarea's harbors. In that year, Raban headed an intensive underwater survey. Following three additional survey and training seasons (1978-1980), R. Hohlfelder, J. Oleson, and later R. Vannjoined Raban as codirectors of the international Caesarea Ancient Harbour Excavation Project (CAHEP). During the 1980s, this team recovered the design and construction techniques Herod used for Sebastos and examined lesser harbors to the north and south of it, as well as some of the numerous shipwrecks nearby. R. Stieglitz, another project co-director, explored harbor installations on land and remains ofStraton's Tower. CCE is continuing work on Sebastos

Large-scale archaeological excavations were carried out at Caesarea from 1992 to 1998 by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA); they were directed by Y. Porath. The project included the excavation of a 100–150-m-wide strip along the coast between the theater complex to the south and the excavations of the Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE) to the north; the western part of the temple platform and the area between this platform and the eastern quay of the port of Sebastos; both sides of the southern Crusader wall (continuing the salvage excavations carried out in 1989); the bottom of the Crusader moat (cleared in the 1960s by A. Negev), from the southern gateway to the northern gateway; and the area southwest of the theater. In addition, salvage excavations were conducted within the area demarcated by the Byzantine wall; in structures outside the wall; on the necropolis; in agricultural areas to the east, north, and south of the city; and along the aqueducts that carried water to Caesarea from outside the city.

During the 1990s the face of ancient Caesarea underwent dramatic change as excavations on an unprecedented scale exposed much more of the site and resolved earlier puzzles and misconceptions. The Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE) organized in 1989 by A. Raban, of the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa, and K. G. Holum, of the University of Maryland, continued work through much of the decade and, on a more limited scale, into the new millennium. In 1993, J. Patrich joined the CCE directorate on behalf of the University of Haifa. Inside the Old City, K. Holum directed excavations on the temple platform (area TP) and in a warehouse quarter north of the inner harbor (area LL). A. Raban led excavations at the presently land-locked inner harbor and its eastern quay (area I), and at two sites along the southern edge of the temple platform (areas Z and TPS). J. Patrich excavated south of the Crusader city in areas CC, NN, and KK. In area KK, he uncovered six warehouse units, while area CC, formerly field C of the Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima (JECM), contained a government complex that accommodated the Roman provincial procurator and later the governor of Byzantine Palestine. The CCE team also devoted effort to area CV, the western side of the area CC vaults, and its maritime unit conducted underwater excavations in the harbor.

The CAHEP (Caesarea Ancient Harbour Excavation Project) consortium, led by the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa, in collaboration with the University of Colorado (led by R. L. Hohlfelder), the University of Maryland (led by R. L. Vann), and the University of Victoria, British Columbia (led by J. P. Oleson), was succeeded by the maritime unit of the CCE, a collaborative project of the University of Haifa (led by A. Raban) and McMaster University (led by E. G. Reinhardt). The ongoing project conducts an annual field season with student volunteers from both institutions as well as others from around the world. The focus of the underwater research has shifted lately toward geoarchaeology, in an attempt to comprehend the history of maritime activity at Caesarea and the demise of Sebastos in the context of environmental changes and topographical alternations on the waterfront.

- Fig. 5 The Caesarea region

from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The Caesarea region

- Western harbor basin

- Central harbor basin

- Eastern harbor basin

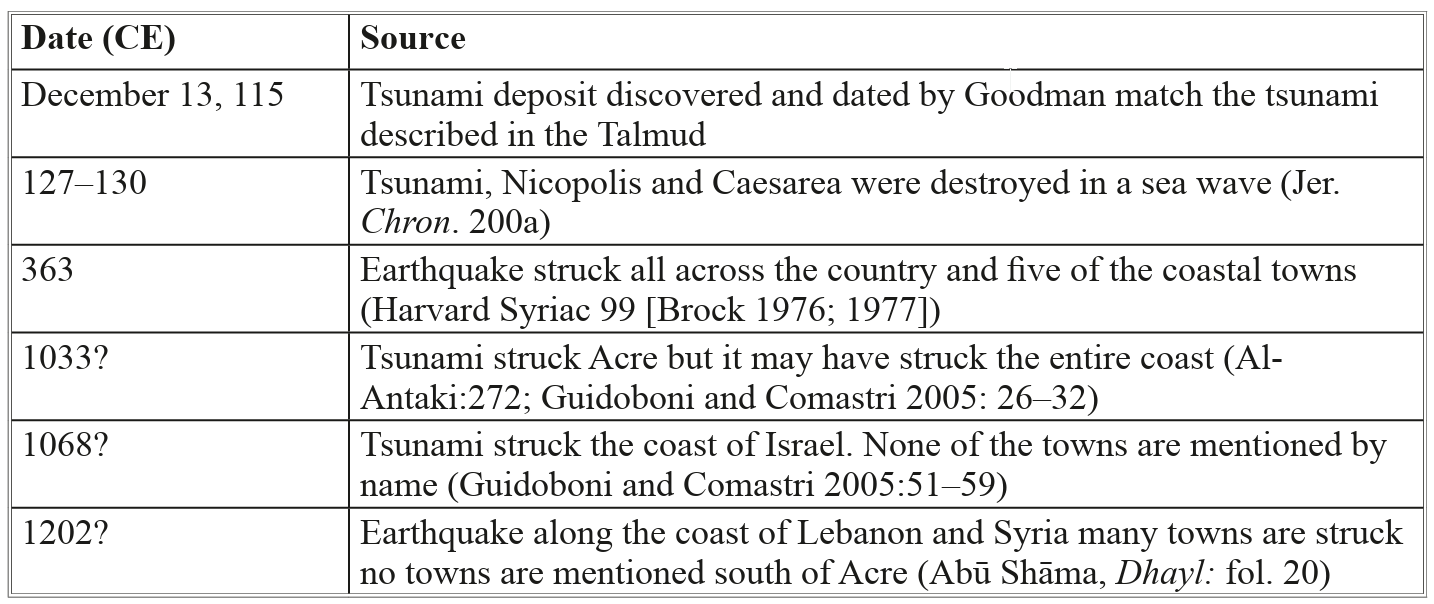

Table 1 [41,43]

Galili et al (2021)

- Fig. 5 The Caesarea region

from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The Caesarea region

- Western harbor basin

- Central harbor basin

- Eastern harbor basin

Table 1 [41,43]

Galili et al (2021)

- Aerial Photo of Caesarea

from 1918 from castellorient.fr

Aerial Photo of the city of Caesarea taken in 1918 by the German army (the North East on the left)

Aerial Photo of the city of Caesarea taken in 1918 by the German army (the North East on the left)

castellorient.fr - Fig. 5.3 Aerial photograph

of Caesarea showing projected ancient coastline from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9

Aerial photograph of Caesarea the south. Ancient coastline marked by dotted line, and solid lines mark the two basins of Straton's Tower

(Photograph: A. Blantinschter. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.71 Aerial view

of Sebastos from the south with the demarcation of the studied areas in the intermediate basin from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.71

Figure 5.71

Aerial view of Sebastos from the south with the demarcation of the studied areas in the intermediate basin

(Photograph: A. Raban)

Raban et al. (2009) - Caesarea in Google Earth

- Caesarea on govmap.gov.il

- Aerial Photo of Caesarea

from 1918 from castellorient.fr

Aerial Photo of the city of Caesarea taken in 1918 by the German army (the North East on the left)

Aerial Photo of the city of Caesarea taken in 1918 by the German army (the North East on the left)

castellorient.fr - Fig. 5.3 Aerial photograph

of Caesarea showing projected ancient coastline from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9

Aerial photograph of Caesarea the south. Ancient coastline marked by dotted line, and solid lines mark the two basins of Straton's Tower

(Photograph: A. Blantinschter. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.71 Aerial view

of Sebastos from the south with the demarcation of the studied areas in the intermediate basin from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.71

Figure 5.71

Aerial view of Sebastos from the south with the demarcation of the studied areas in the intermediate basin

(Photograph: A. Raban)

Raban et al. (2009) - Caesarea in Google Earth

- Caesarea on govmap.gov.il

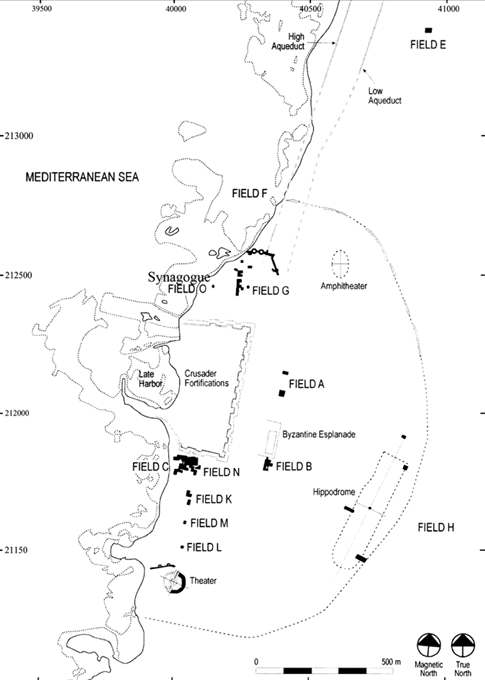

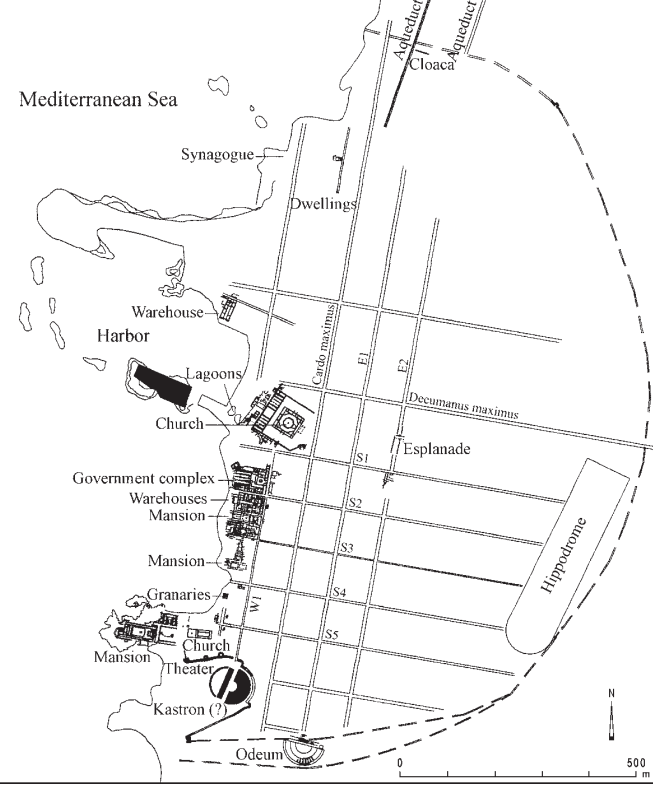

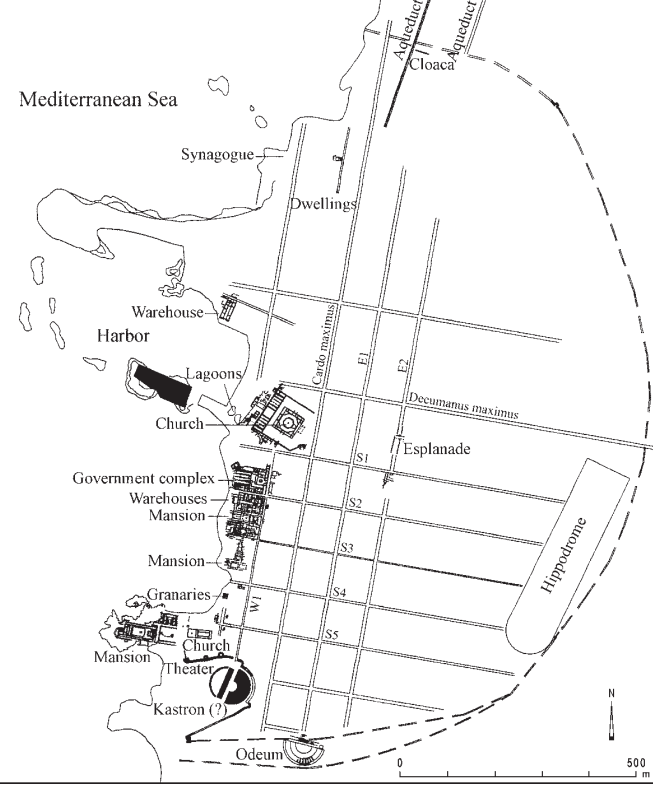

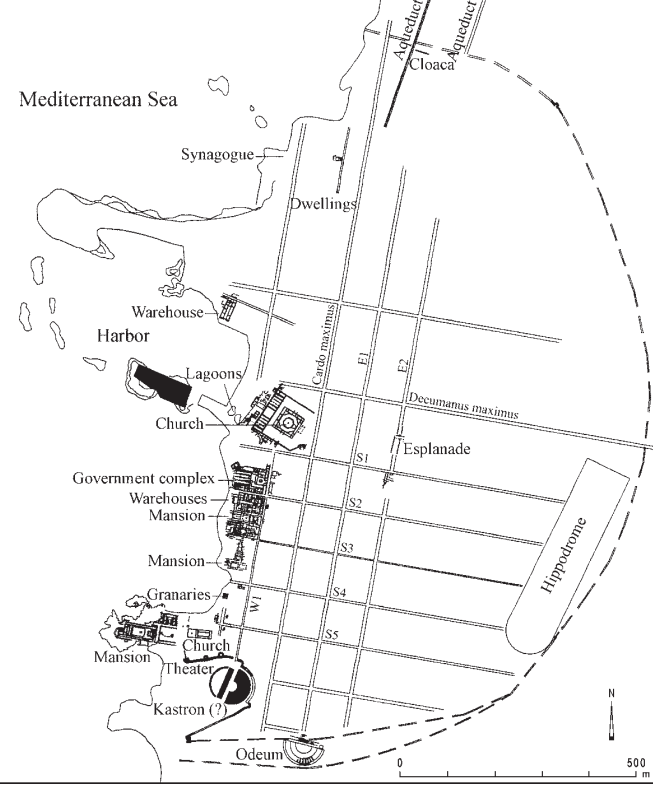

- Fig. 1 Sketch plan of Caesarea

Maritima from Toombs (1978)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima, showing the location of Fields A, B, C and H in relation to the principal visible monuments on the site.

JW: Area H, not marked on the plan, is the Hippodrome area (Toombs, 1978:229)

Toombs (1978) - Aqueducts in the vicinity of

Caesarea from Stern et. al. (2008)

Aqueducts of Caesarea

Aqueducts of Caesarea

Stern et. al. (2008) - Map of Caesarea showing

excavation areas from Stern et. al. (2008)

Caesarea: map of the site, showing excavation areas.

Caesarea: map of the site, showing excavation areas.

BAS - Herodian Caesarea from

Stern et. al. (2008)

Herodian Caesarea, up to 70 CE.

Herodian Caesarea, up to 70 CE.

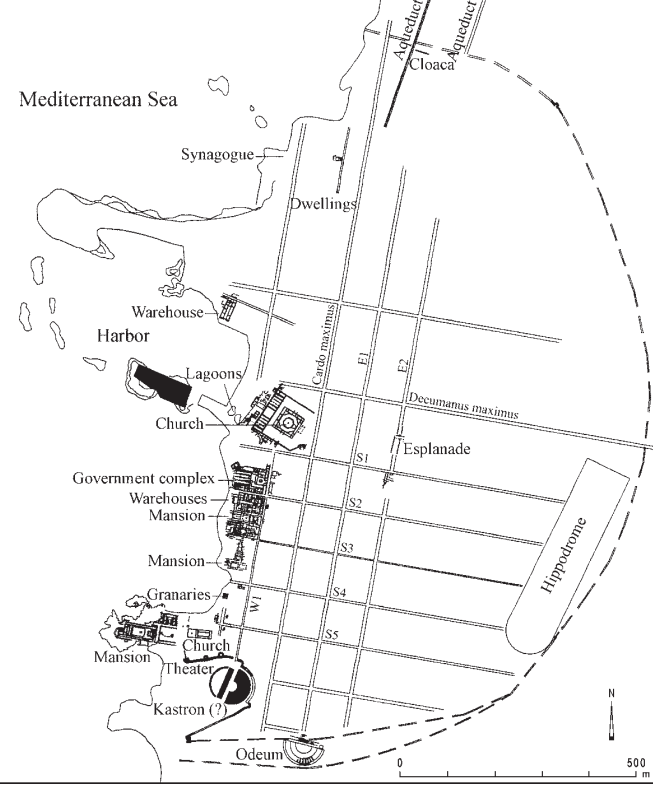

Stern et. al. (2008) - Byzantine Caesarea from

Stern et. al. (2008)

Byzantine Caesarea, sixth century CE

Byzantine Caesarea, sixth century CE

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 1 Roman and Crusader

Caesarea from Ad et al (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Roman and Crusader Caesarea, map of the excavations and the current excavation (sourced from ESI 17:38)..

JW: Excavations were in Areas D and E marked in red on the map

Ad et al (2017) - Fig. 1 Caesarea with principal

sites mentioned by Dey et al(2014)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Late antique/early Islamic Caesarea, with principal sites and excavation areas mentioned in the text.

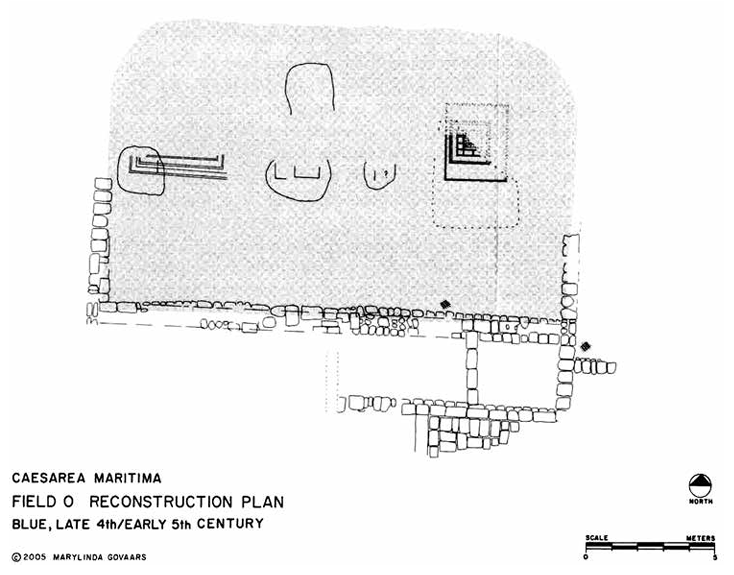

Dey et al(2014) - Fig. 1.9 Plan of early

Islamic Caesarea from Whitcomb (2016)

Figure 1.9

Figure 1.9

Plan of early Islamic Qayṣariyya

(after Whitcomb, “Qaysariya as an Early Islamic Settlement”)

Whitcomb (2016) - Fig. 3.5 Site map

of the various excavated areas from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5

Site map of the various excavated areas

(Holum, Raban, and Patrich (ed.s) P. S.)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.24 Artist's

rendering of view of the central and southern parts of Straton's Tower at the time of Zoilus from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.24

Figure 2.24

Artist's rendering of view of the central and southern parts of Straton's Tower at the time of Zoilus

(after Giannetti in Holutn, Hohlfelder. Bull, and Rohan (eds.) 1988. Fig II)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 3.9 General

plan of Herodian structures at Caesarea from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9

General plan of Herodian structures at Caesarea

(Raban Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2 Map of

the ancient city of Caesarea from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 1 Sketch plan of Caesarea

Maritima from Toombs (1978)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima, showing the location of Fields A, B, C and H in relation to the principal visible monuments on the site.

JW: Area H, not marked on the plan, is the Hippodrome area (Toombs, 1978:229)

Toombs (1978) - Aqueducts in the vicinity of

Caesarea from Stern et. al. (2008)

Aqueducts of Caesarea

Aqueducts of Caesarea

Stern et. al. (2008) - Map of Caesarea showing

excavation areas from Stern et. al. (2008)

Caesarea: map of the site, showing excavation areas.

Caesarea: map of the site, showing excavation areas.

BAS - Herodian Caesarea from

Stern et. al. (2008)

Herodian Caesarea, up to 70 CE.

Herodian Caesarea, up to 70 CE.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Byzantine Caesarea from

Stern et. al. (2008)

Byzantine Caesarea, sixth century CE

Byzantine Caesarea, sixth century CE

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 1 Roman and Crusader

Caesarea from Ad et al (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Roman and Crusader Caesarea, map of the excavations and the current excavation (sourced from ESI 17:38)..

JW: Excavations were in Areas D and E marked in red on the map

Ad et al (2017) - Fig. 1 Caesarea with principal

sites mentioned by Dey et al(2014)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Late antique/early Islamic Caesarea, with principal sites and excavation areas mentioned in the text.

Dey et al(2014) - Fig. 1.9 Plan of early

Islamic Caesarea from Whitcomb (2016)

Figure 1.9

Figure 1.9

Plan of early Islamic Qayṣariyya

(after Whitcomb, “Qaysariya as an Early Islamic Settlement”)

Whitcomb (2016) - Fig. 3.5 Site map

of the various excavated areas from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5

Site map of the various excavated areas

(Holum, Raban, and Patrich (ed.s) P. S.)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.24 Artist's

rendering of view of the central and southern parts of Straton's Tower at the time of Zoilus from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.24

Figure 2.24

Artist's rendering of view of the central and southern parts of Straton's Tower at the time of Zoilus

(after Giannetti in Holutn, Hohlfelder. Bull, and Rohan (eds.) 1988. Fig II)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 3.9 General

plan of Herodian structures at Caesarea from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9

General plan of Herodian structures at Caesarea

(Raban Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2 Map of

the ancient city of Caesarea from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 1 Roman and Crusader

Caesarea from Ad et al (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Roman and Crusader Caesarea, map of the excavations and the current excavation (sourced from ESI 17:38)..

JW: Excavations were in Areas D and E marked in red on the map

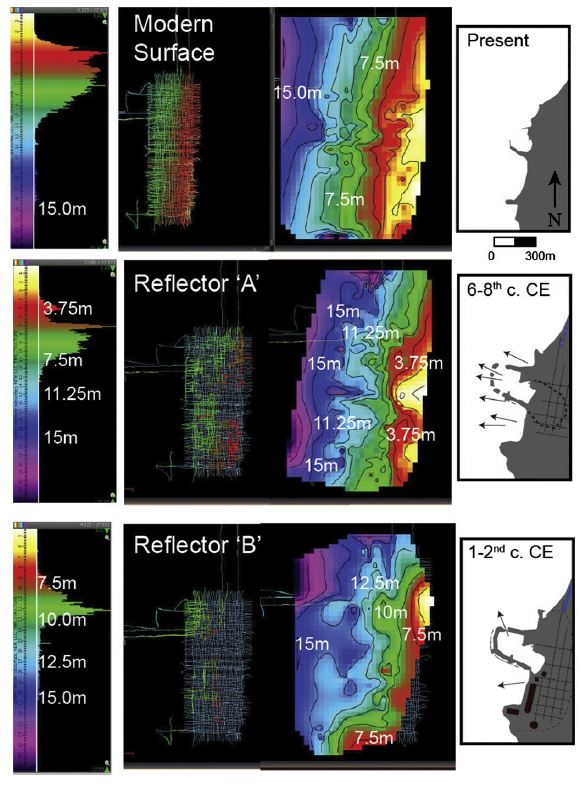

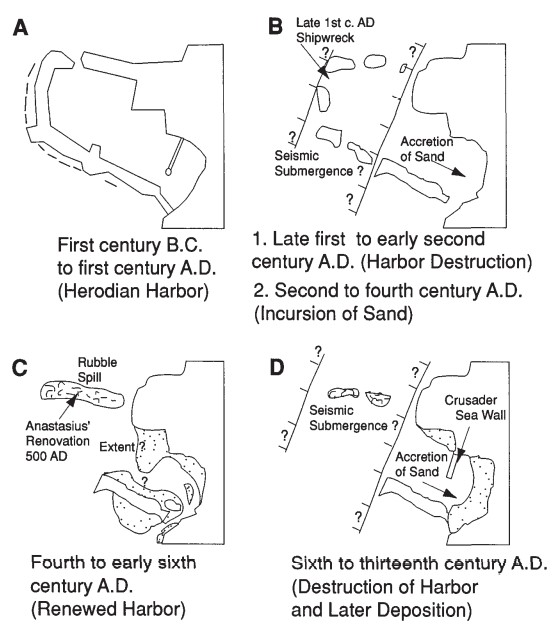

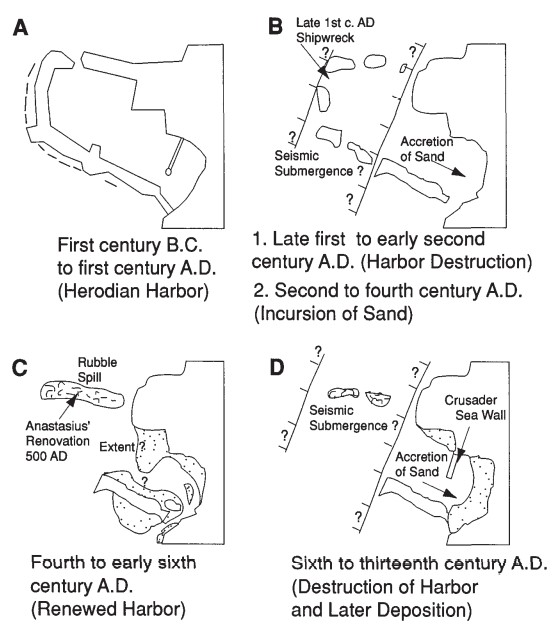

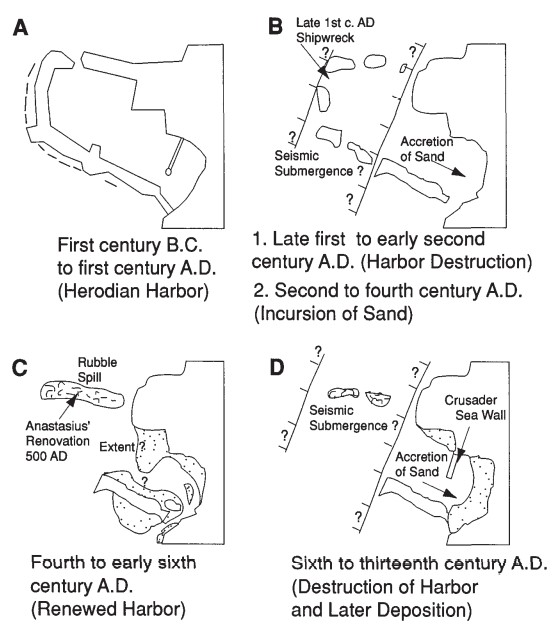

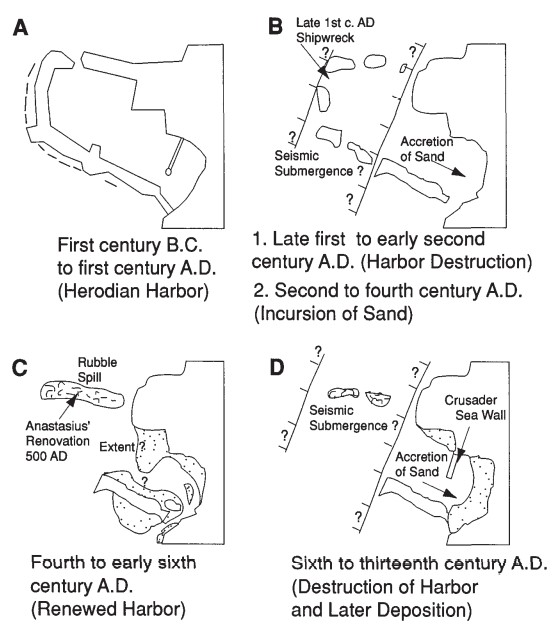

Ad et al (2017) - Fig. 1 View of ancient

harbor of Caesarea from Reinhardt and Raban (1999)

Figure 1

Figure 1

View of ancient harbor area showing rubble spill of ancient break-waters, probable configuration of Herod's harbor,

fault lines extending through harbor, and excavation areas.

Reinhardt and Raban (1998) - Fig. 4 The Roman, Herodian

harbor of Caesarea from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The Roman, Herodian harbor of Caesarea

left panel—aerial photo

right panel—artist reconstruction [43]

- Roman dock

- Roman dock

- submerged surface built of ashlars

- Crusader mole

- Beachrock deposits

Galili et al (2021) - Fig. 2.3 Excavation Areas

in NW part of Caesarea (the harbor) from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3

The excavated areas at the NW part of the site

(A. Raban, Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.22 Reconstruction

plan of the the location of the harbour basins of Straton's Tower and the line of the city walls from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.22

Figure 2.22

Plan reconstructing the location of the harbour basins of Straton's Tower and the line of the city walls

(Drawing A. Raban)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.23 Schematic

map of the inner basin c. 110 BCE from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.23

Figure 2.23

Schematic map of the inner basin c. 110 BCE

(Raban 1996b, Fig. 3)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.25 General

plan of the excavations at the north side of the intermediate harbour basin from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.25

Figure 2.25

General plan of the excavations at the north side of the intermediate harbour basin

(Raban 1996b, Fig.5)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.48 Schematic

block diagram of the main mole during phases 2, 3 from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.48

Figure 5.48

Schematic block diagram of the main mole during phases 2, 3

(A. Raban. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.69 Suggested

sketch plan of Sebastos at its final phase of construction from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.69

Figure 5.69

A suggested sketch plan of Sebastos at its final phase of construction

(A. Raban. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009)

- Fig. 1 Roman and Crusader

Caesarea from Ad et al (2017)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Roman and Crusader Caesarea, map of the excavations and the current excavation (sourced from ESI 17:38)..

JW: Excavations were in Areas D and E marked in red on the map

Ad et al (2017) - Fig. 1 View of ancient

harbor of Caesarea from Reinhardt and Raban (1999)

Figure 1

Figure 1

View of ancient harbor area showing rubble spill of ancient break-waters, probable configuration of Herod's harbor,

fault lines extending through harbor, and excavation areas.

Reinhardt and Raban (1998) - Fig. 4 The Roman, Herodian

harbor of Caesarea from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The Roman, Herodian harbor of Caesarea

left panel—aerial photo

right panel—artist reconstruction [43]

- Roman dock

- Roman dock

- submerged surface built of ashlars

- Crusader mole

- Beachrock deposits

Galili et al (2021) - Fig. 2.3 Excavation Areas

in NW part of Caesarea (the harbor) from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3

The excavated areas at the NW part of the site

(A. Raban, Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.22 Reconstruction

plan of the the location of the harbour basins of Straton's Tower and the line of the city walls from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.22

Figure 2.22

Plan reconstructing the location of the harbour basins of Straton's Tower and the line of the city walls

(Drawing A. Raban)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.23 Schematic

map of the inner basin c. 110 BCE from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.23

Figure 2.23

Schematic map of the inner basin c. 110 BCE

(Raban 1996b, Fig. 3)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 2.25 General

plan of the excavations at the north side of the intermediate harbour basin from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 2.25

Figure 2.25

General plan of the excavations at the north side of the intermediate harbour basin

(Raban 1996b, Fig.5)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.48 Schematic

block diagram of the main mole during phases 2, 3 from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.48

Figure 5.48

Schematic block diagram of the main mole during phases 2, 3

(A. Raban. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009) - Fig. 5.69 Suggested

sketch plan of Sebastos at its final phase of construction from Raban et al. (2009)

Figure 5.69

Figure 5.69

A suggested sketch plan of Sebastos at its final phase of construction

(A. Raban. Caesarea Project)

Raban et al. (2009)

- Fig. 1.10 Drawing of

the Temple Platform at Caesarea from Whitcomb (2016)

Figure 1.10

Figure 1.10

Comparative views of the Dome of the Rock (above) and the Temple Platform at Caesarea (below)

(after Whitcomb, “Jerusalem and the Beginnings of the Islamic City,” fig. 4 and Holum, “The Temple Platform,” fig. 13)

Whitcomb (2016) - Plan of Area TP containing

the Octagonal Church from Stern et. al. (2008)

Area TP: plan showing foundations of the octagonal church.

Area TP: plan showing foundations of the octagonal church.

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Fig. 1.10 Drawing of

the Temple Platform at Caesarea from Whitcomb (2016)

Figure 1.10

Figure 1.10

Comparative views of the Dome of the Rock (above) and the Temple Platform at Caesarea (below)

(after Whitcomb, “Jerusalem and the Beginnings of the Islamic City,” fig. 4 and Holum, “The Temple Platform,” fig. 13)

Whitcomb (2016) - Plan of Area TP containing

the Octagonal Church from Stern et. al. (2008)

Area TP: plan showing foundations of the octagonal church.

Area TP: plan showing foundations of the octagonal church.

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Fig. 2 Plan of the mid-7th

century irrigated garden from Taxel (2013)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Caesarea-Qaysariyya: general plan of the mid-7th century irrigated garden above the Byzantine structures in the southwestern zone (after J. Patrich, "Caesarea in transition" [supra, n. 69], fig. 12; drawing by Anna Iamim, courtesy Joseph Patrich).

Taxel (2013)

- Fig. 2 Plan of the mid-7th

century irrigated garden from Taxel (2013)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Caesarea-Qaysariyya: general plan of the mid-7th century irrigated garden above the Byzantine structures in the southwestern zone (after J. Patrich, "Caesarea in transition" [supra, n. 69], fig. 12; drawing by Anna Iamim, courtesy Joseph Patrich).

Taxel (2013)

- Fig. 130 Area CV block

plan from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 130

Figure 130

Area CV block plan

William Isenberger drawing

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 129 Aerial View of

Area CV from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 129

Figure 129

Area CV (foreground), looking east across JECM Field C. Vaults 1 and 2 lie beneath remains of U-shaped building and soil deposits in center. At upper left, JECM Areas C.7, C.8, and C.ll with exposed sub-flooring of U-shaped building. Foreground, CV/1 and CV/2 with pavement CV/1047. CV/10 lies to the right (south).

Zaraza Friedman photo.

Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

- Fig. 130 Area CV block

plan from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 130

Figure 130

Area CV block plan

William Isenberger drawing

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 129 Aerial View of

Area CV from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 129

Figure 129

Area CV (foreground), looking east across JECM Field C. Vaults 1 and 2 lie beneath remains of U-shaped building and soil deposits in center. At upper left, JECM Areas C.7, C.8, and C.ll with exposed sub-flooring of U-shaped building. Foreground, CV/1 and CV/2 with pavement CV/1047. CV/10 lies to the right (south).

Zaraza Friedman photo.

Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

- Fig. 1D Aerial view of

site LL and southern part of the Upper aqueduct from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 1D

Figure 1D

Aerial view of the archaeological site and southern part of the Upper aqueduct, where reference samples were collected. All colored dots are linked to locations where samples were taken [as references for non tsunamogenic deposits].

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 1E Aerial view of

site LL showing locations of cores, baulk, and collapsed corridor from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 1E

Figure 1E

Aerial view of Area LL, bordering the northern side of the inner harbor basin.

- Blue dots indicate cores collected within the excavation layers

- Green dots mark the southern baulk adjacent to a later crusader wall (after Ad, et. al., 2018)

- Bolded white rectangle in E highlights the Corridor area of Area LL, the primary focus of the study

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 3 Early phases Plan

of Area LL from Ad et al (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan

Ad et al (2018) - Fig. 8 Wall Collapse in

Stratum VI (Umayyad) from Ad et al (2018)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Wall Collapse looking west

Ad et al (2018) - Fig. 3 Sections of Cores

C1 and C2 and the Southern Baulk from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Cores C1 and C2 (left) and Southern Baulk section (right)

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 2B Destruction

layer(s) showing building stones suspended in anomalous sands from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 2B

Figure 2B

Anomalous layer (the top of which touched the Abbasid floor above)

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 2C Archaeological

fill directly underlying anomalous deposit along with inset of fire-burnt stones from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 2C

Figure 2C

Umayyad archaeological fill directly underlying the anomalous deposit. Inset shows fire-burnt stones in the eastern wall of the corridor, at the same level as the top of the Umayyad archaeological fill.

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Lab Analysis of

Core C1 from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 4

Core LL16 C1 results.

- Grain size distribution with depth in the core (1 cm sampling resolution) presented as a contour map as well as in conventional profiles (mean, mode, standard deviation)

- TOC [Total Organic Carbon] and IC [Inorganic Carbon] values (%) of a representative set of samples are shown as a profile for Core C1, reference samples are shown in squares (TOC) and triangles (IC) to show their comparative values to the core (yellow = aqueduct beach sand ramp; aquamarine = shallow marine (−5 m depth), see Figure 1 for specific locations).

- Total and pristine foraminiferal abundances are shown plotted by core depth, sampling resolution of 5 cm.

- B-OSL signals (photon-counts) are plotted by depth with a resolution of about 3–5 cm in units A and B, and 10 cm in Unit C.

- The far right core illustration provides the thickness of each unit to scale, and the colors of the data points correspond with visually recognizable units.

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 5 Lab Analysis of

Southern Baulk from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 5

Figure 5

'LL Southern Baulk’ Results.

- ODV [Ocean Data View] graph (far left) showing grain size distribution and grain sorting with depth in the LL Southern Baulk Section (19 samples)

- grain size statistics

- total and pristine foraminiferal abundances with depth for several samples taken from each unit

- section illustration with the thicknesses of each unit. Light green data points correspond to the upper ‘LL Southern Baulk’ section samples, while the dark green points correspond to the lower ‘LL Southern Baulk’ section samples

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 8 Projected direction

of tsunami surge from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Tsunami corridor. Based on the damage to the southern and southwestern walls and orientation of the collapsed building stones, the dominant destruction came from the southern harbor facing side of the corridor.

Everhardt et. al. (2023)

- Fig. 1D Aerial view of

site LL and southern part of the Upper aqueduct from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 1D

Figure 1D

Aerial view of the archaeological site and southern part of the Upper aqueduct, where reference samples were collected. All colored dots are linked to locations where samples were taken [as references for non tsunamogenic deposits].

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 1E Aerial view of

site LL showing locations of cores, baulk, and collapsed corridor from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 1E

Figure 1E

Aerial view of Area LL, bordering the northern side of the inner harbor basin.

- Blue dots indicate cores collected within the excavation layers

- Green dots mark the southern baulk adjacent to a later crusader wall (after Ad, et. al., 2018)

- Bolded white rectangle in E highlights the Corridor area of Area LL, the primary focus of the study

Everhardt et. al. (2023) - Fig. 3 Early phases Plan

of Area LL from Ad et al (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan

Ad et al (2018) - Fig. 8 Wall Collapse in

Stratum VI (Umayyad) from Ad et al (2018)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Wall Collapse looking west

Ad et al (2018) - Fig. 3 Sections of Cores

C1 and C2 and the Southern Baulk from Everhardt et. al. (2023)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Cores C1 and C2 (left) and Southern Baulk section (right)

Everhardt et. al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 Plan of

the Stratum IV synagogue from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 3 Plan of

the Stratum IV synagogue from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

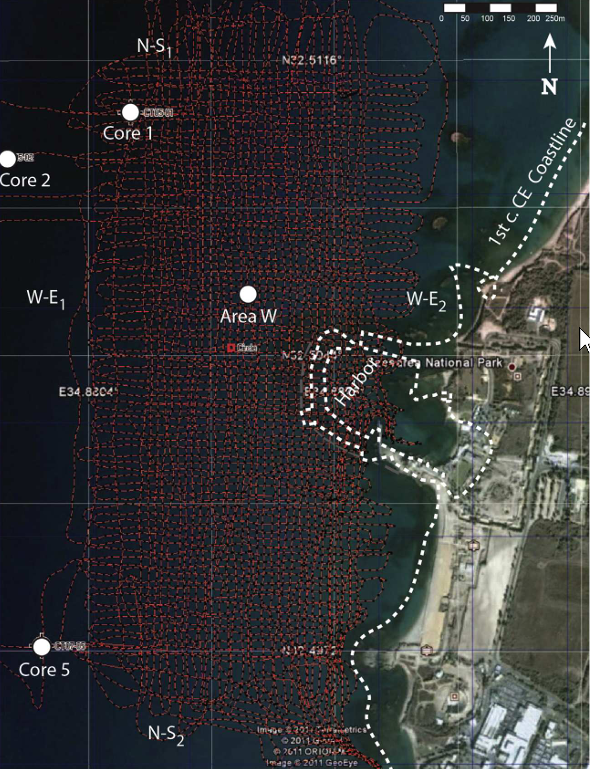

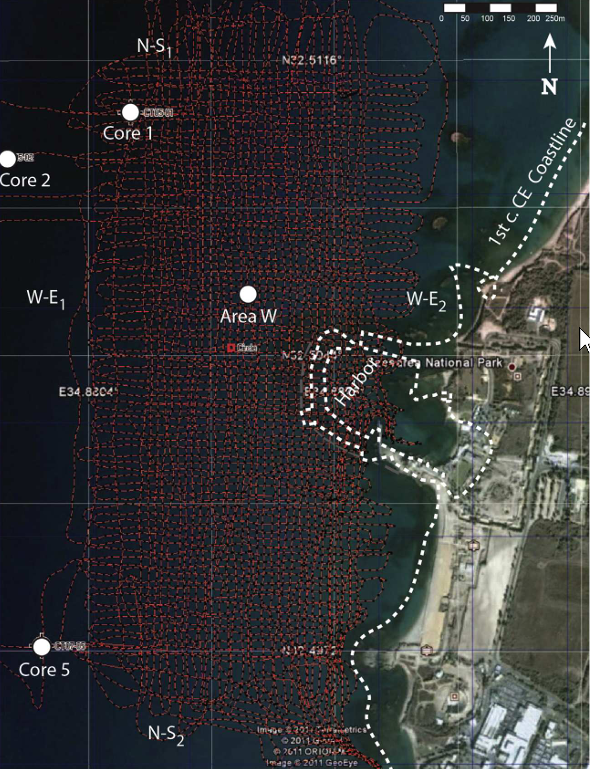

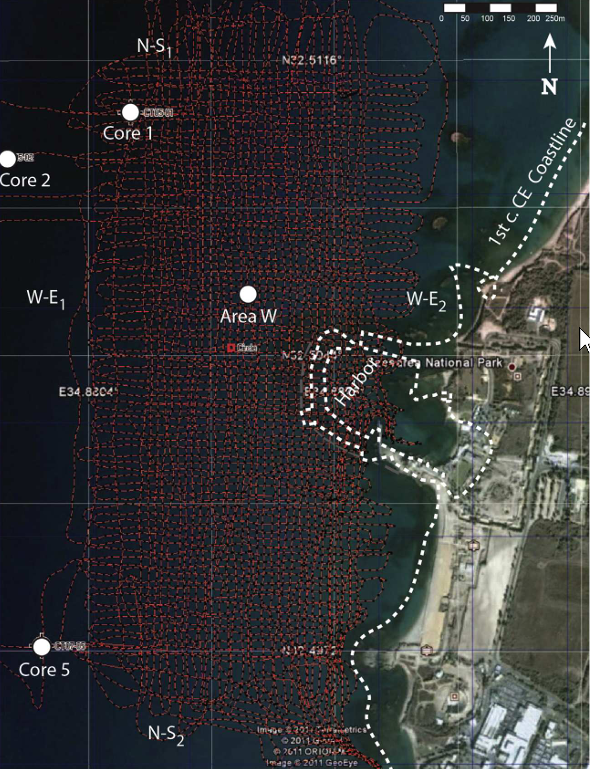

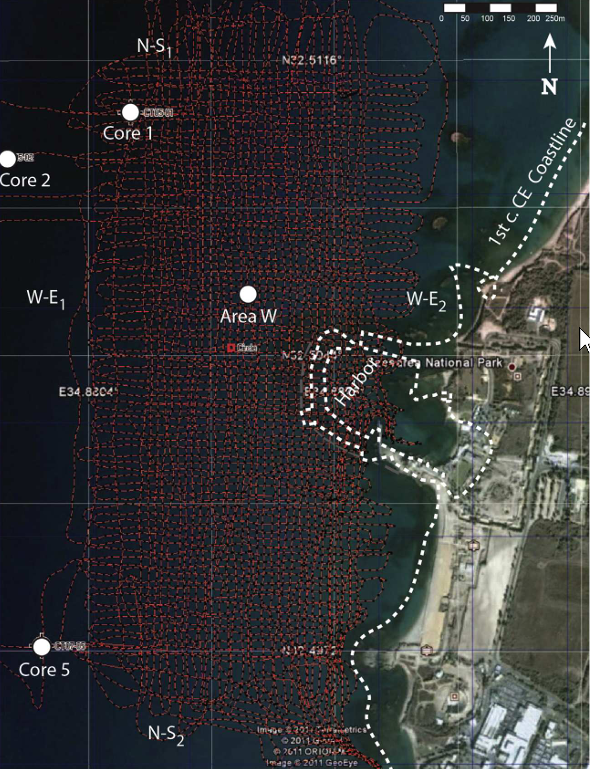

- Fig. 2 Satellite image

showing locations of Caesarea Cores 1, 2, and 5, Area W, and shot points of the 2011 CHIRP survey from Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

CHIRP profiles (red dashed lines), collected offshore of Caesarea in August 2011. Total track length was ~126 km, and profile spacing was ~5 m. Each dip profile is ~0.65 km long, while each strike profile is ~1.4 km long. Note locations of cores/seafloor excavations (red square, white dots), within which tsunamites were interpreted (Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009). Remains of the ancient Roman city lie to the east; part of the ancient harbor still exists, defined by the remains of semi-circular moles/groins visible just below “Caesarea National Park” in this satellite image. The approximate outline of the original harbor is shown (white dashed lines). White arrowheads denote the locations of the strike and dip profiles shown in Fig. 3.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

- Fig. 2 Satellite image

showing locations of Caesarea Cores 1, 2, and 5, Area W, and shot points of the 2011 CHIRP survey from Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

Figure 2

Figure 2

CHIRP profiles (red dashed lines), collected offshore of Caesarea in August 2011. Total track length was ~126 km, and profile spacing was ~5 m. Each dip profile is ~0.65 km long, while each strike profile is ~1.4 km long. Note locations of cores/seafloor excavations (red square, white dots), within which tsunamites were interpreted (Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009). Remains of the ancient Roman city lie to the east; part of the ancient harbor still exists, defined by the remains of semi-circular moles/groins visible just below “Caesarea National Park” in this satellite image. The approximate outline of the original harbor is shown (white dashed lines). White arrowheads denote the locations of the strike and dip profiles shown in Fig. 3.

Click on image to open in a new tab

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

- Fig. 132 South Balk of

Area CV/1 showing five phases from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 132

Figure 132

Area CV/1, south balk. Five phases are visible:

- pavers 1047 from ca. 575 C.E.

- structural debris above pavers from mid-7th century collapse

- light brown dune sand above collapse due to long period of abandonment (mid-7th to 10th century C.E.?)

- patch of dark soil above and left representing western end of Islamic industrial installation (10th-12th centuries C.E.) that penetrated the dune sand

- upper layers across photograph were dump from 1973/74 excavations

Lisa Helfert photo.

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 133 Structural collapse

and crushed pottery in Area CV/2 from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 133

Figure 133

Area CV/2, structural collapse from Vault 2, looking west. Ceramics crushed by falling masonry (L2017)

Lisa Helfert photo

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 1 Avi-Yonah at

the spot of discovery of the hoard from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 4 Excavation of

the Field O synagogue from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 132 South Balk of

Area CV/1 showing five phases from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 132

Figure 132

Area CV/1, south balk. Five phases are visible:

- pavers 1047 from ca. 575 C.E.

- structural debris above pavers from mid-7th century collapse

- light brown dune sand above collapse due to long period of abandonment (mid-7th to 10th century C.E.?)

- patch of dark soil above and left representing western end of Islamic industrial installation (10th-12th centuries C.E.) that penetrated the dune sand

- upper layers across photograph were dump from 1973/74 excavations

Lisa Helfert photo.

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 133 Structural collapse

and crushed pottery in Area CV/2 from Raban et al. (1993 v. II)

Figure 133

Figure 133

Area CV/2, structural collapse from Vault 2, looking west. Ceramics crushed by falling masonry (L2017)

Lisa Helfert photo

Raban et al. (1993 v. II) - Fig. 1 Avi-Yonah at

the spot of discovery of the hoard from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

- Fig. 4 Excavation of

the Field O synagogue from Raphael and Bijovsky (2014)

Stratigraphy/Chronology - Inner Harbor Areas I/1 - Z/2

Stratigraphy/Chronology - Inner Harbor Areas I/1 - Z/2Raban et al. (1989 Vol. 1)

- from excavations undertaken in the Crusader Market and Area LL ("the warehouse") by Ad et al (2017) and Ad et al (2018) respectively

| Stratum | Period |

|---|---|

| I | Modern |

| II | Late Ottoman (Bosnian) |

| IIIa | Crusader (Louis IX) |

| IIIb | Crusader (pre-Louis IX) |

| IV | Fatimid |

| V | Abbasid |

| VI | Umayyad |

| VII | Late Byzantine/Early Umayyad |

| VIII | Late Byzantine |

| IX | Early Byzantine |

| X | Late Roman |

| XI | Roman |

| XII | Early Roman |

| XIII | Herodian |

Stratigraphy of Areas CC, KK, and NN

Stratigraphy of Areas CC, KK, and NNStern et. al. (2008)

Phases of the Starting Gates of the Hippodrome

Phases of the Starting Gates of the HippodromeStern et. al. (2008)

- Toombs (1978) developed a stratigraphic framework for Caesarea after 4 seasons of excavations using the destruction layers overlying the latest Byzantine occupation as the stratigraphic key. The framework was developed primarily on balk sections from four fields - A, B, C, and H. It is considered most accurate for the Byzantine and Arab phases and least accurate for Late Arab and Roman levels.

- Dates with an asterisk (*) were derived from Note 4 in Toombs (1978:232)

- Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima from Toombs (1978)

.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima, showing the location of Fields A, B, C and H in relation to the principal visible monuments on the site.

JW: Area H, not marked on the plan, is the Hippodrome area (Toombs, 1978:229)

Toombs (1978)

| Phase | Period | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Modern | ||

| II | Crusader | 1200-1300 CE | |

| III.1 | Late Arab | 900*-1200 CE | |

| III.2 | Middle Arab Abbasid |

750-900* CE | |

| III.3 | Early Arab Umayyad |

640-750 CE | |

| IV | Byzantine/Arab | 640 CE | In A.D. 640 Caesarea fell to Arab invaders. This time the destruction was complete and irretrievable. Battered columns and the empty shells of buildings stood nakedly above heaps of tangled debris. |

| V | Final Byzantine | 614-640 CE | In A.D. 614 Persian armies captured Caesarea, but withdrew by A.D. 629. This invasion caused widespread destruction and brought the Main Byzantine Period to a close, but recovery was rapid and the city was restored |

| VI.1 | Main Byzantine | 450/550*-614 CE | |

| VI.2 | Main Byzantine | 330 - 450/550* CE | |

| VII.1 | Roman | 200*-330 CE | It seems probable that during the Late Roman Period a major catastrophe befell the city, causing a partial collapse of the vaulted warehouses along the waterfront, and the destruction of major buildings within the city. Such a city-wide disaster alone would account for the rebuilding of the warehouse vaulting and the buildings above it, as well as the virtual absence of intact Roman structures in the city proper. |

| VII.2 | Roman | 100*-200* CE | |

| VII.3 | Roman | 10 BCE - 100* CE |

- Toombs (1978) developed a stratigraphic framework for Caesarea after 4 seasons of excavations using the destruction layers overlying the latest Byzantine occupation as the stratigraphic key. The framework was developed primarily on balk sections from four fields - A, B, C, and H. It is considered most accurate for the Byzantine and Arab phases and least accurate for Late Arab and Roman levels.

- Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima from Toombs (1978)

.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Sketch plan of Caesarea Maritima, showing the location of Fields A, B, C and H in relation to the principal visible monuments on the site.

JW: Area H, not marked on the plan, is the Hippodrome area (Toombs, 1978:229)

Toombs (1978)

Figure 4

Figure 4Stratigraphic analysis of the results of the first four seasons at Caesarea, tabulated by Field.

Toombs (1978)

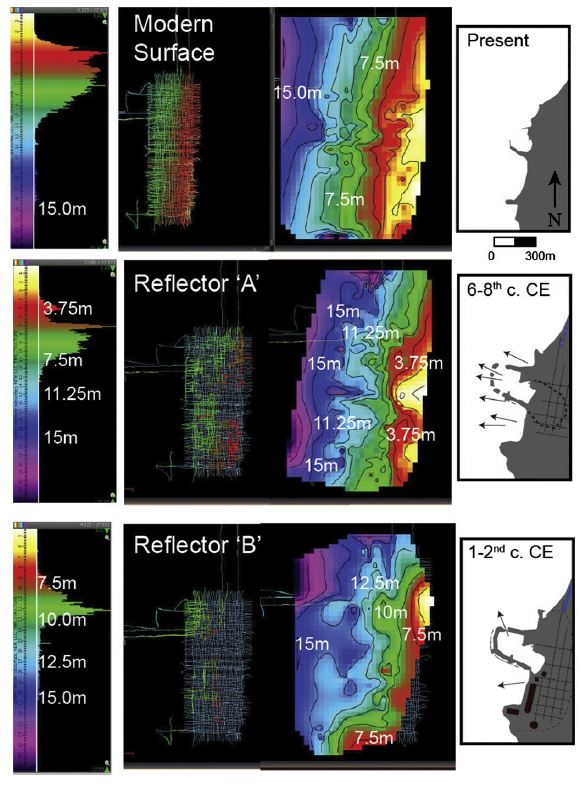

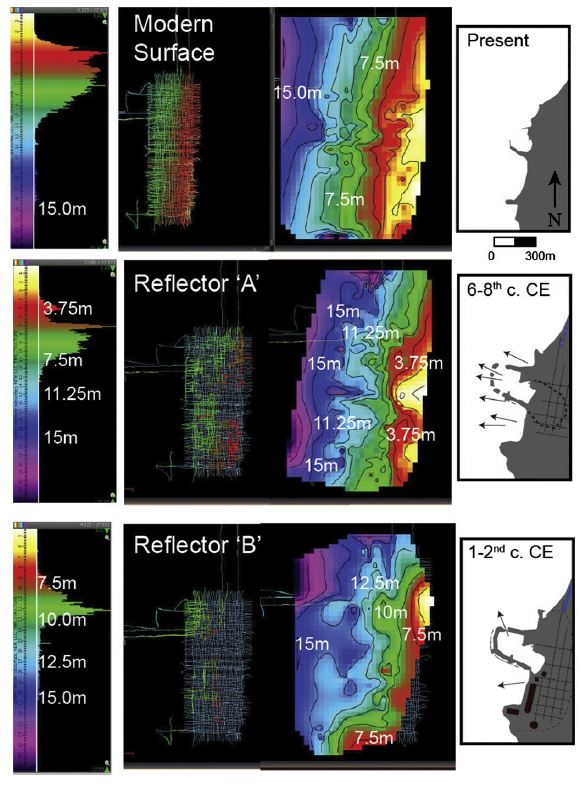

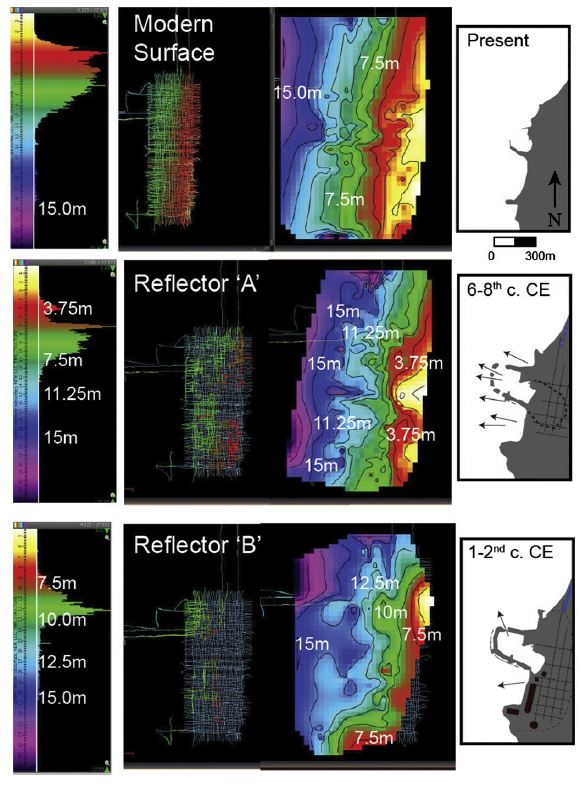

- Fig. 6 - Seismic Reflectors

and evolution of Caesarea's harbor from Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

Fig. 6

Structure maps of- the modern seafloor (top)

- reflector “A” (middle)

- reflector “B” (bottom)

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

- Fig. 6 - Seismic Reflectors

and evolution of Caesarea's harbor from Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

Fig. 6

Structure maps of- the modern seafloor (top)

- reflector “A” (middle)

- reflector “B” (bottom)

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015)

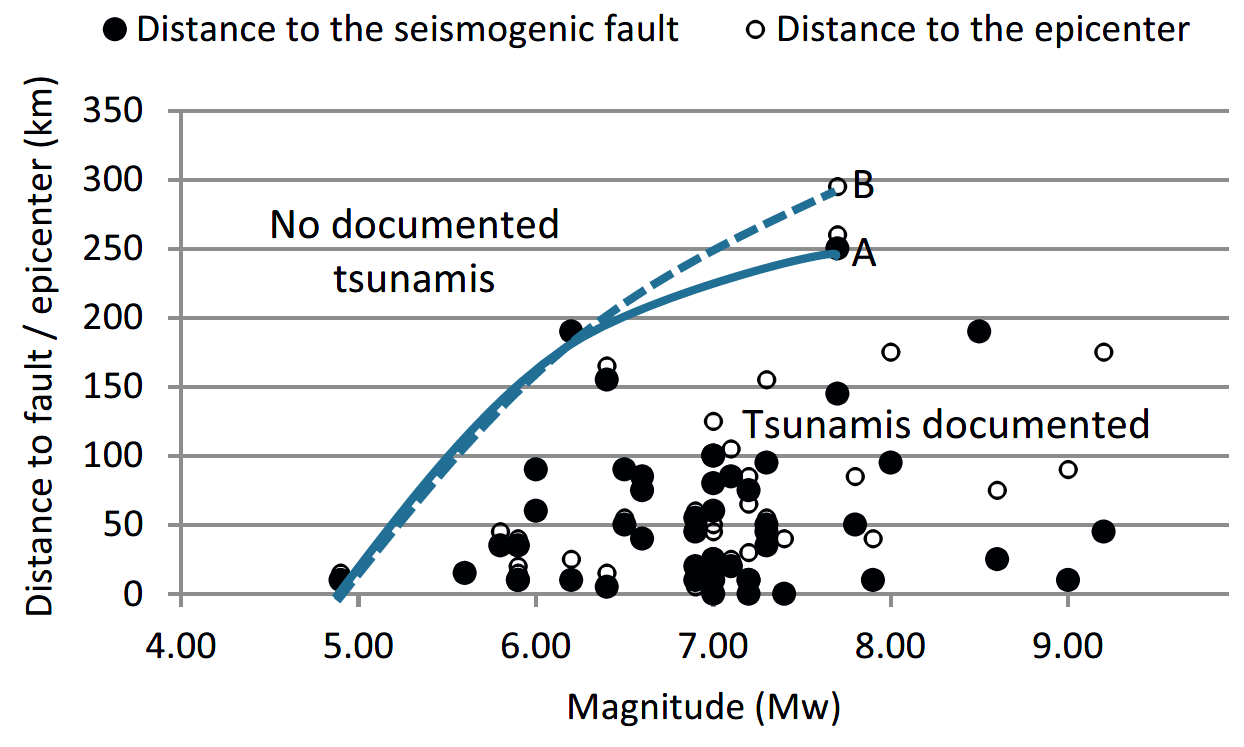

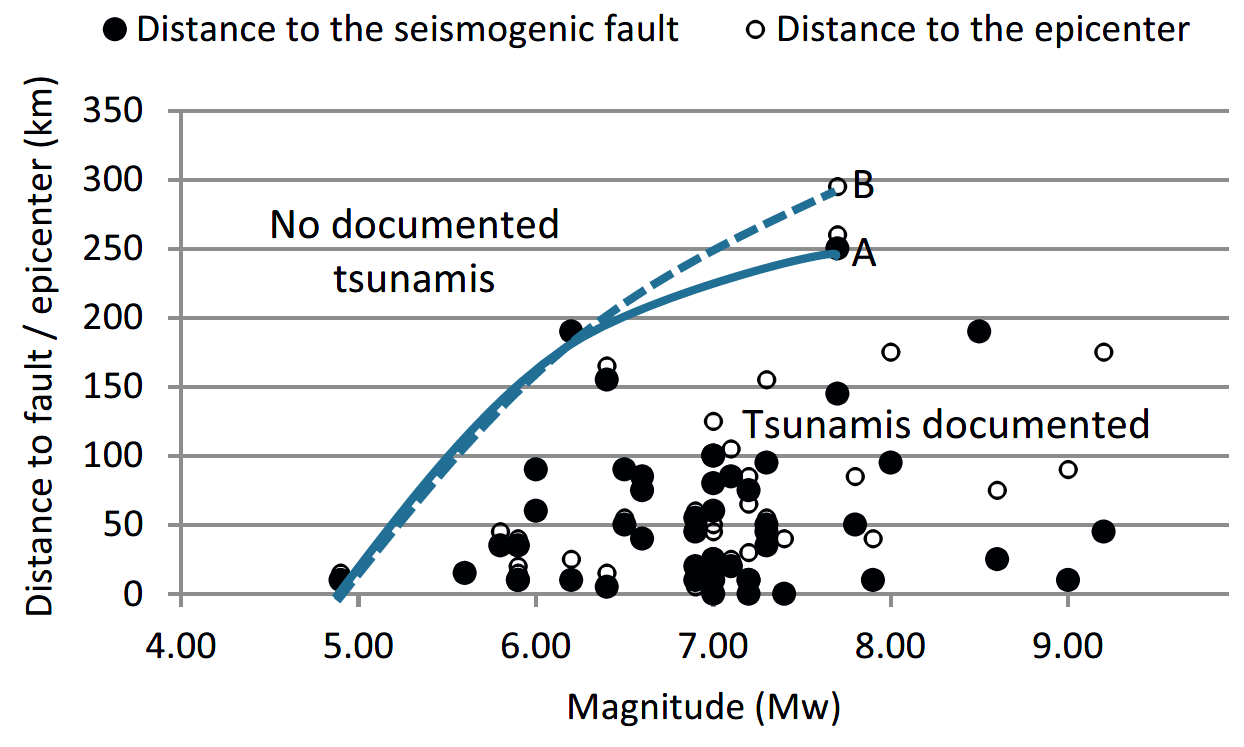

Goodman-Tchenov and Austin (2015) mapped the tsunami horizons from a high frequency seismic reflection survey (2.5-5.5 kHz. Chirp source) which produced markers ~4-5 meters below the sea floor before sea bottom multiples obscured the image. Shot spacing was ~ 5 meters. The fold of the survey is not reported. It may have been single fold. Velocity control below the seafloor is also unreported. The time-depth conversion in Figure 6 above may have been based on correlating seismic markers to core horizons. Reflector 'A' was correlated to the 5th-8th century tsunami deposit. Reflector 'B' was correlated to a 1st-2nd century CE tsunami deposit which they associate with the 115 CE Trajan Quake although I think it more likely correlates to localized shelf collapse due to the the early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake or an unknown event. Structure maps constructed from time horizons of Reflectors A and B show the apparent presence of backflow channels from both tsunami events with 3-6 channels associated with the 5th - 8th century CE horizon and 1-2 channels associated with the 1st-2nd century CE horizon. The presence of more identifiable backflow channels on Reflector A (5th - 8th century CE) than Reflector B (1st - 2nd century CE) was interpreted to be a result of harbor degradation by Byzantine-Islamic time resulting in less flow impediments from man-made structures. This appears to be supported by archeological evidence which showed more ships anchoring at sea during this time.

The construction of harbours along high energy nearshore environments, which commonly include the emplacement of hard structures both as central features (e.g., piers, jetties) as well as protective measures (e.g., wave breakers, coastal armouring), can alter coastlines in a multitude of ways. These include reconfiguring the coast’s morphology, introducing or redistributing exogenous and endogenous materials, and changing localized environmental substrate and structural conditions; and, as a result, impact the associated ecological communities. With growing coastal populations and associated coastal development, concerns over the long-term consequences of such projects are of global interest. Caesarea Maritima, a large-scale, artificially constructed ancient harbour built between 21 and 10 BCE, provides a rare opportunity to address these impacts and investigate its fingerprint on the landscape over 2000 years. To approach this, representative sediment samples were isolated and analyzed from two sediment cores (C1, C2), an excavated trench (W), and a sample of ancient harbour construction material (aeolianite sandstone and hydraulic concrete; COF). Geochemical (Itrax μXRF, magnetic susceptibility) and foraminifera analyses were conducted and results from both methods were statistically grouped into significantly similar clusters. Results demonstrated the increased presence of aeolianite-associated elemental contributions only after the construction of Caesarea as well as in particularly high concentrations following previously proposed tsunami events, during which shallower and deeper materials would have been transported and redeposited. The foraminifera data shows the appearance and eventual abundance dominance of Pararotalia calcariformata as an indicator of coastal hardening. Results suggest that they are an especially well-suited species to demonstrate changing environmental conditions existing today. In previous studies, this species was mistakenly presented as a recent Lessepsian arrival from the Red Sea, when in fact it has had a long history as an epiphyte living on hardgrounds in the Mediterranean and co-existencing with humans and their harbour-building habits. Specimens of P. calcariformata, therefore, are useful indicators for the timing of harbour construction at Caesarea and may be used as rapid and cost-effective biostratigraphic indicators on sandy nearshore coastline in future geoarchaeological studies. This has implications for future studies along the Israeli coast, including both paleoenvironmental and modern ecological assessments.

Ancient harbour sediments and stratigraphy are often studied because they contain evidence of past environmental change including climate, sea-level, and anthropogenic activity (Blackman, 1982a, 1982b; Kamoun et al., 2019, 2020, 2021; Marriner and Morhange, 2007; Reinhardt et al., 1994; Riddick et al., 2021; Riddick et al., 2022a, 2022b; Salomon et al., 2016). The analysis and interpretation of environmental proxies (e.g., microfossils, geochemistry, lithology, etc.) can be more straightforward in cases of shoreline progradation, where relative sea-level changes, siltation, and/or high input of river sediments have resulted in landlocked marine structures (i.e., within lagoons or estuaries). Sediments in these cases often record transitions from marine to more brackish/freshwater conditions associated with construction of harbour structures and/or natural barriers that are identifiable through changes in microfossil assemblages, sediment grain size and geochemistry, and other environmental indicators (Amato et al., 2020; Finkler et al., 2018; Kamoun et al., 2022; Pint et al., 2015; Stock et al., 2013, 2016).

The environmental evolution (i.e., site formation) of ancient harbour sites on high-energy, sandy coasts is more challenging to assess. Sediments from within a harbour basin can record geoarchaeological information (e.g., ancient harbour parasequences, changes in microfossil assemblages, archaeological material, etc.; Marriner and Morhange, 2006; Reinhardt et al., 1994; Riddick et al., 2021; Riddick et al., 2022a, 2022b); however, correlating stratigraphy in a harbour region can often be hindered by sediment reworking with waves and storms and by the absence of significant lithological changes in the sandy stratigraphy, with the exception of tsunamis or other large storm events (Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009). The emplacement of ancient harbours (i.e., artificial hard substrates) on naturally soft-bottomed, sandy shorelines, significantly alters the local seascape resulting in sediment erosion and accumulation as well as the formation of a hard and stable substrate (Leys and Mulligan, 2011).

Past research on ancient harbour sediments (e.g., Marriner et al., 2005; Reinhardt et al., 1994; Salomon et al., 2016) has focused on analysis of harbour muds, recognizable by their muddy-appearance (finer particle size distribution; ‘muds’; Hohlfelder, 2000), higher organic content, and increased concentrations of artifacts. In those studies, various bioindicator proxies, in particular gastropods, molluscs, ostracods, and foraminifera, were used to recognize harbour stratigraphy and related changing conditions connected to construction, destruction, and/or functionality (Kamoun et al., 2019, 2020, 2021; Marriner et al., 2005; Reinhardt and Raban, 1999). Amongst marine biomarkers, benthic foraminifera are especially popular as environmental proxies due to their known ecological preferences and tolerances, their rapid response to environmental change, and their durability in the sediment record over time (Holbourn et al., 2013; Murray, 2014). Generally, research to date on ancient harbour assemblage changes were linked to the increased presence of fine-grainedsediment preferring species (e.g., Bolivinids) as well as shifting relative abundances of the more dominant brackish Ammonia species (Goodman et al., 2009; Kamoun et al., 2022; Marriner et al., 2005; Reinhardt et al., 1994; Reinhardt and Raban, 1999). This agrees with the more general understanding that substrate is a major controlling factor in foraminifera assemblages (Langer, 1988, 1993). We hypothesize here that while the harbour muds introduce new conditions for a changing benthic foraminifera assemblage, so too can the increased presence of hard materials related to harbour construction and coastal development. These hard surfaces are especially influential on attached, epiphytic taxa. These taxa, therefore, will record a response to the introduction of artificial hard substrates in the sandy, high-energy settings seaward and beyond the protected environments of the harbour, and can act as biostratigraphic indicators of pre- and post- harbour sediments, a concept that has not previously been tested or applied.

Previously collected samples from an excavated trench area (W; Reinhardt et al., 2006), two sediment cores (C1, C2; Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009), and a piece of harbour mole material retrieved during underwater excavations in 1999 (COF; Reinhardt et al., 2001) were included in this study (Fig. 1). Seven samples (5-cm intervals) were available from W (− 11.4 to − 13.4 m below sea level (mbsl), ~0.60 km from the coast; Reinhardt et al., 2006). Nineteen samples (1-cm intervals) from the upper 126 cm were available from C1 (233 cm in length, 15.5 mbsl, ~0.82 km from the coast) and 14 samples (1-cm intervals) were available from C2 (174 cm in length, 20.3 mbsl, ~1.25 km from the coast; Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009). Radiocarbon and/or pottery dating methods were previously conducted on W, C1, and C2 samples. See Goodman-Tchernov et al. (2009) and Reinhardt et al. (2006) for further details on dating methods used. Geochemical ((μXRF, magnetic susceptibility) and foraminifera methods were applied here. The use of benthic foraminifera as biostratigraphic indicators to help correlate sediments in archaeological contexts is still a developing area of research (McGowran, 2009). The application of benthic foraminifera in this manner will be useful for future geoarchaeological studies as a rapid and cost-effective method for correlating sediments across an ancient harbour site, especially in high energy sandy shoreface settings. Results also have implications for understanding sediment transport in and around coastal structures, as well as for modern studies involving the monitoring and/or predicting of ecological changes in response to coastal anthropogenic activity.

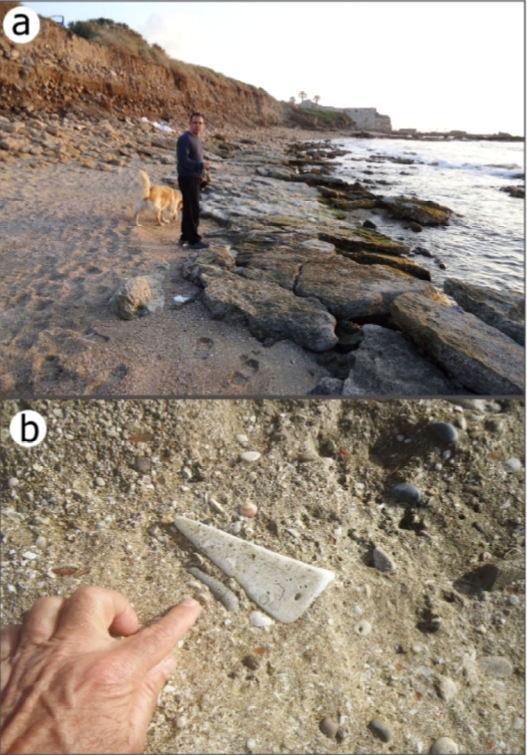

The Israeli Mediterranean coastline (Fig. 1) is mostly characterized by unconsolidated sands and Pleistocene aeolian sandstone ridges (‘kurkar’). These thick calcareous-cemented sand beds accumulated cyclically between thin layers of iron-rich paleosols (‘hamra’) and currently run parallel to the coast, both on and offshore (Almagor et al., 2000; Ronen, 2018). The southern two thirds of the coastline are characterized by sandy beaches (Emery and Neev, 1960). The tidal range is relatively small along the coast (0.4 during spring tides, 0.15 m during neap tides; Golik and Rosen, 1999). Offshore sediments are transported through two different types of nearshore currents: an inner edge of the general offshore current (which moves northwards, counterclockwise along the eastern end of the Mediterranean; Fig. 1), and a wave-induced longshore current (Emery and Neev, 1960; Goldsmith and Golik, 1980; Klein et al., 2007; Schattner et al., 2015). The largest waves in this region generally approach the coast from a WNW direction, which results in a longshore current to the northeast along the curved southern shoreline (Fig. 1). Where these waves approach parallel or at an angle opposite to that of the southern coast (e.g., some areas towards the northern coastline of Israel), a small, southward longshore current is produced (Emery and Neev, 1960; Goldsmith and Golik, 1980; Zviely et al., 2007). Located towards the northern extent of the Nile Littoral Cell, offshore sediments near Caesarea are predominantly transported from the south through this wave-induced longshore current (Emery and Neev, 1960; Goldsmith and Golik, 1980; Golik, 1993, 1997; Katz and Crouvi, 2018; Schattner et al., 2015; Zviely et al., 2007). Prior to the construction of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s, approximately 100,000 m3/yr of clastic sediments reach the coasts of Caesarea, largely sourced from Central Africa and the Ethiopian Highlands (Nir, 1984). These sediments are dominated by silica (quartz), alumina, and trivalent iron oxides (e.g., aluminosilicates) with minor amounts of heavy minerals (Goldsmith et al., 2001; Inman and Jenkins, 1984; Nir, 1984). The majority of heavy minerals include hornblende, augite, and epidotes, as well as minor amounts of resistant (e.g., zircon, tourmaline, rutile) and metamorphic minerals (e.g., sillimanite, staurolite, kyanite; Stanley, 1989). Local sources (i.e., eroded kurkar, onshore sediments, marine productivity) contribute some calcareous sediment to the nearshore environment (Goldsmith et al., 2001; Inman and Jenkins, 1984; Nir, 1984; see Supplementary Data 1 for more details on dominant minerals, compositions, and sources). Sand-sized sediment extends 3–5 km from the shore to water depths of ~25 m, while increasing amounts of silt and clay (mainly smectite, with minor kaolinite and illite) are found further offshore in slightly deeper water (30–50 m depths; Almagor et al., 2000; Emery and Neev, 1960; Nir, 1984; Sandler and Herut, 2000). The siliclastic sands, which characterize most of the nearshore, transition into more carbonate-rich sediments with higher instances of rocky substrates north of Haifa Bay (Almagor et al., 2000; Avnaim-Katav et al., 2015; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2014; Nir, 1984).

The historical site of Caesarea Maritima is located ~40 km south of Haifa, on the Israeli Mediterranean coast (34◦53.5′E 32◦30.5′N). Over six decades of research have provided details on the construction and deterioration of its harbour, also referred to as Sebastos, the largest artificial open-sea Mediterranean harbour of its time (Brandon, 2008; Hohlfelder et al., 2007). The harbour was constructed between 21 and 10 BCE using local kurkar and imported volcanic material (Vola et al., 2011; Votruba, 2007). Local kurkar is characterized by well-sorted quartz with calcite and minor amounts of feldspar, biotite, heavy minerals (e.g., hornblende, augite, zircon, rutile, tourmaline, magnetite, garnet, etc.), and allochems (Wasserman, 2021). Volcanic material has been used in concrete by the Romans since the 2nd century BCE (Oleson, 1988), often sourced from the Bay of Naples Neopolitan Yellow Tuff (NYT) deposits. Pozzolanic tuff-ash from this region was used in hydraulic concrete to form the breakwaters and foundations for harbour moles at Sebastos (Vola et al., 2011; Votruba, 2007). The mixture of lime, pozzolana, and aggregate provided a strong concrete that could set underwater. At Caesarea, the dominant coarse aggregates in the hydraulic concrete are kurkar sandstone and limestone (4 mm–20 cm in size; Vola et al., 2011). The mortar contains high proportions of pozzolanic material (yellow brown tuff ash/aggregates, lava fragments) with dominant minerals identified as sanidine, clinopyroxene, analcime, and phillipsite. The cementitious binding matrix contains similar material (calcite, tobermorite, ettringite, Calcium–Aluminum–Silic ate–Hydrate) and was likely produced by the reaction between powdered pozzolanic material, lime, and seawater. Non-pozzolanic portions include white lime clasts, kurkar sandstone aggregates, ceramics, and wood fragments, with dominant minerals identified as tobermorite, quartz, illite, anthophyllite, ettringite, halite, bassanite, and sjogrenite (Vola et al., 2011; Supplementary Data 1).

The chronology of Sebastos has been well-studied, with detailed research into the timing of deterioration and harbour use throughout antiquity (Boyce et al., 2009; Galili et al., 2021; Goodman-Tchernov and Austin, 2015; Hohlfelder, 2000; Raban, 1992, 1996; Reinhardt et al., 2006; Reinhardt and Raban, 1999). The location of Sebastos on a highenergy, mostly sandy coastline, as well as the previously established chronology of harbour construction, makes this an ideal site to assess the use of benthic foraminifera as biostratigraphic indicators of anthropogenic structure emplacement. The distribution of benthic foraminifera along the Israeli coast has been well-documented, providing a strong basis for interpreting trends within sediment samples offshore of Caesarea.

Studies of both living and dead benthic foraminifera assemblages along the Israeli coast of the Mediterranean Sea indicate that substrate type (often linked to bathymetry), food availability, and seasonality are the main factors controlling the distribution of species (Arieli et al., 2011; Avnaim-Katav et al., 2013, 2015, 2016a, 2020, 2021; HyamsKaphzan et al., 2008, 2009, 2014). Certain taxa such as Ammonia parkinsoniana and Buccella spp. are highly abundant in the shallow (3–20 m), sandy nearshore settings. Others including Ammonia inflata, Ammonia tepida, Elphidium spp., Porosononion spp., and miliolids are often observed in slightly deeper (20–40 m), silty to clayey environments further offshore on the inner Israeli shelf (Avnaim-Katav et al., 2013, 2015, 2016a, 2016b, 2017, 2020, 2021; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2008, 2009, 2014). Epiphytic taxa, which live on roots, stems, and leaves of plants (Langer, 1993; Langer et al., 1998), are highly associated with the micro- and macroalgal-covered hard substrates along the Israeli Mediterranean coast, especially the carbonate-rich rocky settings along the northern coast (Arieli et al., 2011; Avnaim-Katav et al., 2013, 2015, 2021; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2008, 2014). Coralline red algae (e.g., Galaxuara rugosa and Jania rubens) are highly abundant along the Israeli coast, along with other types of red (e.g., Centroceras sp., Ceramium sp., Bangia sp., Halopteris scoparia, Laurencia sp., Neosiphonia sp., and Polysiphonia sp.), brown (e.g., Dictyora sp., and Ectocarpus sp.), and green algae (Codium sp. and Ulva sp.; Arieli et al., 2011; Bresler and Yanko, 1995a, 1995b; Emery and Neev, 1960; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2015). Some of the most common epiphytic foraminifera taxa observed here include Amphistegina lobifera, Lachlanella spp., Heterostegina depressa, Pararotalia calcariformata, Rosalina globularis, Textularia agglutinans, and Tretomphalus bulloides, (Arieli et al., 2011; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2014). Many of these larger, symbiont bearing foraminifera are widely assumed to be more recently introduced Lessepsian species, a term used to describe Red Sea/Indian Ocean tropical species that have arrived after the construction of the Suez Canal (1869 CE). While some have been linked genetically and morphologically with their Red Sea communities, others, such as P. calcariformata (Schmidt et al., 2015; Stulpinaite et al., 2020) still have not

Specimens of P. calcariformata McCulloch, 1977 were originally identified as P. spinigera (Le Calvez, 1949) on the Israeli coast, in particular within dated, stratigraphically discreet underwater archaeological excavations and geological collections (e.g., in Reinhardt et al. (1994, 2003), Reinhardt and Raban (1999)). Schmidt et al. (2015)’s initial error occurred when they mistook the date of the first publication that reported them on this coastline for the timing of their first observation (see reference to Reinhardt et al., 1994 in introduction of Schmidt et al., 2015). In fact, the P. calcariformata in that study were firmly positioned in sediments dating to at least 1500 years ago. P. calcariformata is a well-documented epiphyte, found in highest abundances near hard substrates (up to 96% in shallow rocky habitats) of the Israeli coast (Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2014; Reinhardt et al., 2003), usually living on calcareous algae and other seaweeds (e.g., Jania rubens, Halimeda, Sargassum, Cystoseira; Arieli et al., 2011; Bresler and Yanko, 1995a, 1995b; Emery and Neev, 1960; Schmidt et al., 2015, 2018). It is observed less frequently (up to 20% relative abundances) in shallow, soft-bottomed, sandy sediments (Avnaim-Katav et al., 2017, 2020; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2008, 2009). Recent work on this species explores its microalgal symbionts (Schmidt et al., 2015, 2018) and its high heat tolerance (Schmidt et al., 2016; Titelboim et al., 2016, 2017). These studies predict that warming sea temperatures will play a role in expanding populations of P. calcariformata along the Mediterranean.

W is described in Reinhardt et al. (2006), while C1 and C2 are described in Goodman-Tchernov et al. (2009). W (~2 m of excavated sediment) contains two main shell layers: (i) a poorly sorted mix of Glycymeris spp. and pebbles from ~107–165 cm, with convex-up oriented fragments in the top portion, and (ii) a heterogeneous layer of shell fragments, ship ballast, and pottery shards from ~39–59 cm. The intervening units consist of massive, homogeneous, medium-grained sand with isolated articulated and fragmented bivalve shells and/or pebbles. The upper ~0–39 cm also contains thin layers of shells and pebbles (Fig. 2). The upper 126 cm of C1 contains two shell layers: (i) a poorly sorted mix of Glycymeris spp. and pebbles, with fragments of worn pottery from 85 to 94 cm, and (ii) poorly sorted, convex-up oriented Glycymeris spp. and pebbles from 28 to 42 cm. The intervening units are massive, tan/grey, fine-grained sand, some with isolated bivalves and/or pebbles (Fig. 2). C2 (174 cm) similarly contains two shell layers: (i) framework supported, convex-up oriented Glycymeris spp. fragments from 132 to 138 cm, and (ii) convex-up oriented Glycymeris spp. fragments from 29 to 43 cm. The intervening units are massive, tan/ Gy, fine-grained sand with some silt and isolated bivalves.

The chronology of W, C1, and C2 has been previously described (Goodman-Tchernov et al., 2009; Reinhardt et al., 2006), and units have been correlated to age ranges (radiocarbon and pottery; Table 1) and identified events (i.e., tsunami deposits; Fig. 2). W, C1, and C2 were found to capture similar event layers dating to ~1492–100 BCE (preharbour), 92 BCE–308 CE (containing the 115 CE Roman tsunami event), 238 BCE–329 CE, 400–800 CE (containing the 551/749 CE Late Byzantine/Early Islamic tsunami events), and 800 CE–present (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Elemental (μXRF) results are shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 2. Average counts of Zr increase upcore in each sampling area, with uppermost values ~2–3 times higher than those at the base (~700–1000 compared to 200–400; Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2). Ca is highly variable throughout all sampling areas, with some peaks up to 1.7× higher (~300,000) in shell layers than in sandy samples. Counts of Si remain relatively high (~17,000) throughout time, with some decreases up to 1.5–2.5× lower in shell layers. Average Ti values are variable through time (~6000) with some spikes up to 2× higher at the top and bottom of C1 and surrounding the bottom shell layer of C2. Fe follows similar trends to Ti, with values ~2× higher near the top and bottom of C1 and the darker sandy sediments of C2 (161–123 cm) compared to the intervening sandy samples (counts of ~6000–7000). Counts of Sr remain quite constant throughout all sampling areas over time (~2000), with a slight increasing trend in the upper portions of C1 and C2 (values up to ~1.3×; Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2).

Ratio results of Zr + Ti/Ca and Zr + Ti/Si are variable throughout time in W (values 0.02–0.04 and 0.20–0.34) and C2 (0.03–0.08 and 0.4–1.4), especially within tsunami event layers, though results show no clear increasing/decreasing trends over time. In C1, these ratios show a distinct increasing trend through the upper half of the core (Zr + Ti/Ca: from 0.02 up to 0.06; Zr + Ti/Si: 0.3 up to 0.7). Sr/Ca values remain relatively consistent in all coring areas (~0.10), with minor variation surrounding shell layers (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2).

Sample COF shows distinct variation in elemental composition between kurkar and hydraulic concrete (Fig. 4). On average, counts of Zr and Ti are over 10× higher in the hydraulic concrete than the kurkar. Counts of Fe are also higher in the hydraulic concrete by a factor of ~8. Ca shows the opposite trend, with counts 5× higher in the kurkar than the hydraulic concrete. Counts of Si were variable throughout both materials but were slightly higher in the hydraulic concrete. Sr peaked in the kurkar and decreased moving into the hydraulic concrete, with some variability associated with the aggregate material (Fig. 4). Ratio results for Zr + Ti/Ca are ~94× higher in the hydraulic concrete than in the kurkar, while Zr + Ti/Si values are almost 2× higher. Sr/Ca are ~4× higher in the hydraulic concrete than in the kurkar (Fig. 4).