Minya

(left) Aerial view of Khirbet Minya looking west

(left) Aerial view of Khirbet Minya looking westClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Drone photos taken by Jefferson Williams on 11 June 2023

(right) Aerial view of Khirbet Minya looking east

Used with permission from biblewalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Minya | ||

| Horvat Minnim | Hebrew | |

| Khirbat el-Minya | Arabic | قصر المنية |

| Ayn Minyat Hisham | Arabic |

Minya, located on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee ~14 km. north of Tiberias,

contains the remains of an Umayyad palace.

(Oleg Grabar in Stern et al, 1993).

A fragmentary inscription from the reign of one of the two caliphs named Walid

(I, 705–715 CE or II, 743–744 CE) indicates that

the palace was at least partially constructed by the latter half of the Umayyad caliphate

(

Kuhnen et al, 2018).

Kuhnen et al (2018) suggest that excavations reveal that construction was probably not complete before it was

destroyed by one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes.

Kuhnen et al (2018) also reports partial rebuilding took place during Abassid or Crusader periods and a furnace on the site was in use during

Crusader and Mamluk periods.

Horvat Minnim (Khirbet el-Minya) is located on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee, about 14 km (8.5 mi.) north of Tiberias and immediately south of Tel Chinnereth (map reference 2005.2525). It is in the rich Ginnosar Valley, which has probably been occupied since ancient times, as is indicated by the caves along the cliffs to the southwest and by pottery recovered in various places in the plain and along the mountain borders to the north and west.

Attention was attracted to Horvat Minnim in the second half of the nineteenth century, when scholars and pilgrims began to cross Palestine in search of identifiable biblical sites. In the Survey of Western Palestine, conducted by the British Palestine Exploration Fund, Minnim was identified as Capernaum. This interpretation was accepted as often as it was rejected by scholars until the discovery of Capernaum farther north and the excavation of the main part of the site of Minnim.

In 1932, excavations at Horvat Minnim were begun by A. E. Mader; they continued for five seasons until 1939, under the successive direction of Mader, A. M. Schneider, and 0. Puttrich-Reignard. The excavations were sponsored by the Gorres-Gesellschaft, the Verein vom Heiligen Lande, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Islamic section of the Berlin Museum. A sounding was made in the western part of the palace by 0. Grabar and J. Perrot in 1959, on behalf of the Horace H. Rackham Fund for Research, University of Michigan. The German archaeologists revealed an almost square (73 by 67 m) building with round corner towers and a semicircular tower in the middle of each wall--except for the eastern wall, where there was a monumental domed gateway. Aside from a single narrow trench, the center of this square was not excavated, on the probably correct assumption that it merely contained a courtyard. Along the exterior walls, the excavation uncovered a mosque, a throne room, and a group of five rooms with mosaic floors with geometric designs. These were all situated on the south side. The north side contained the residential wing. The purpose of the rooms on the east and southwest could not be determined. The west side was left unexcavated for the most part. An inscription found in secondary use, which mentioned the name of the Umayyad Caliph el-Walid I (705-715), dated the palace and the mosque to the Umayyad period.

The sounding made in 1959 established the site's stratigraphy and revealed a second major occupation of Minnim in Mameluke times, when it was a major halt on the caravan route from Egypt to Syria. Later, a khan of the same name was built to the north. The palace area was then occupied by only a few insubstantial houses. The sounding also uncovered a mosaic floor in a large vaulted hall on the west side, indicating the existence of official rooms there, as well as in the southern parts of the palace. Only a few segments of the original floor have been uncovered.

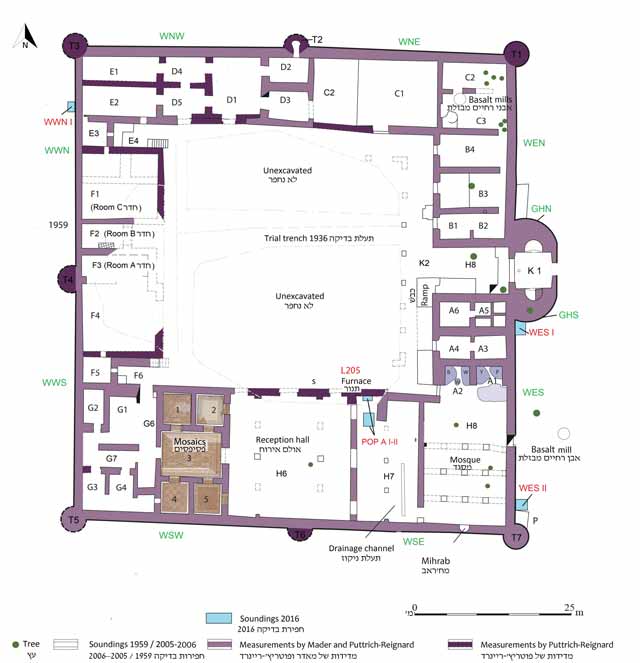

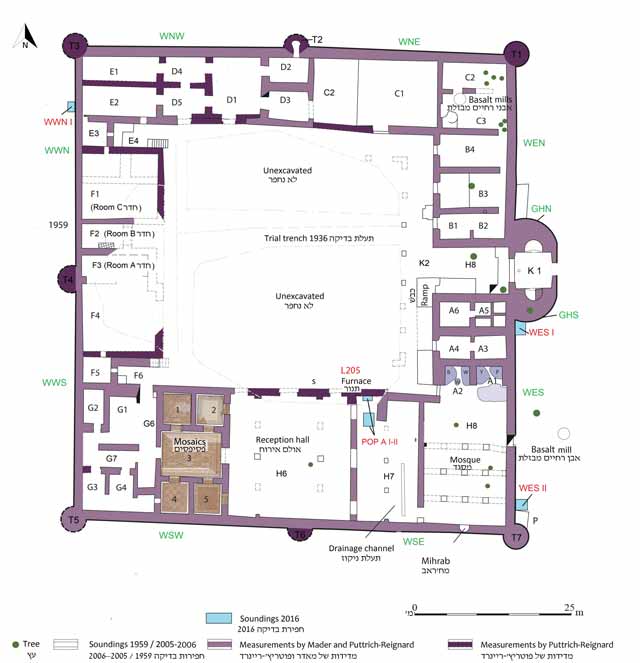

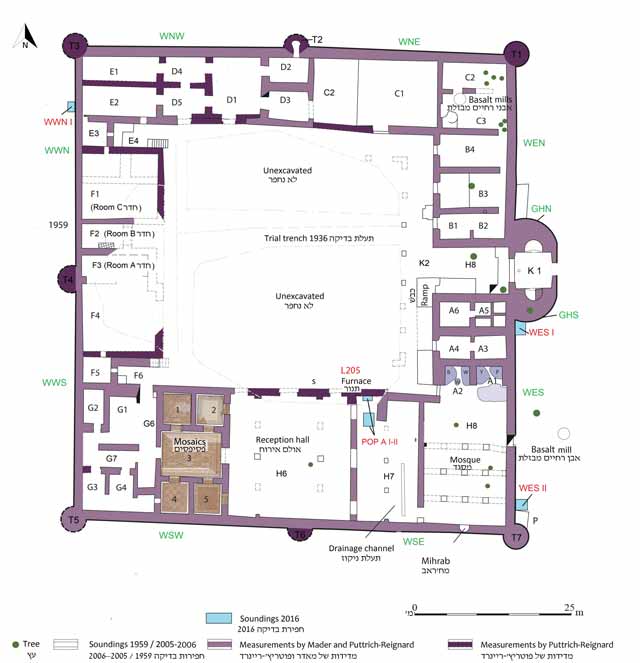

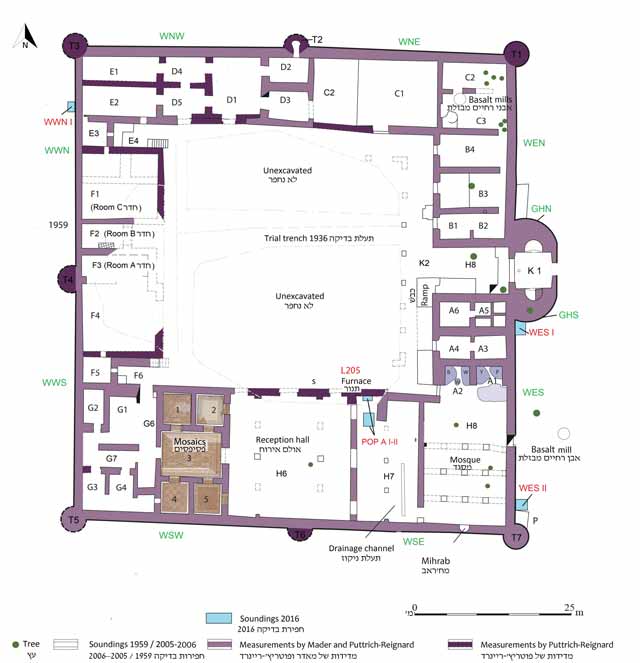

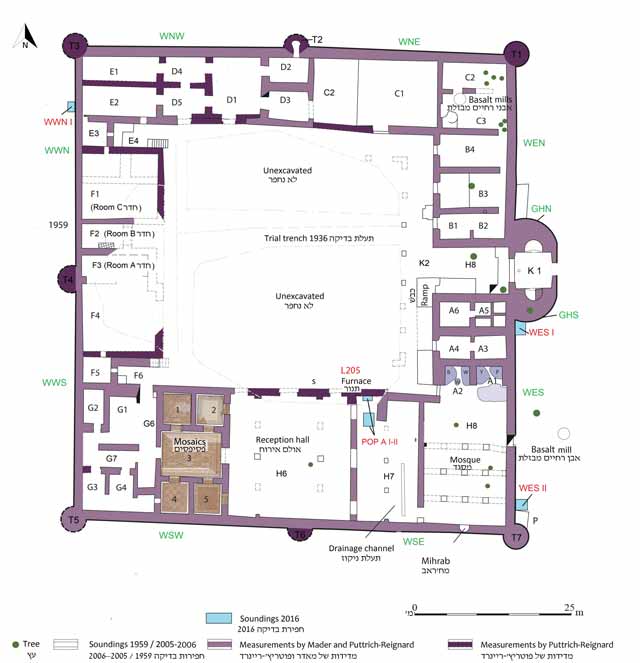

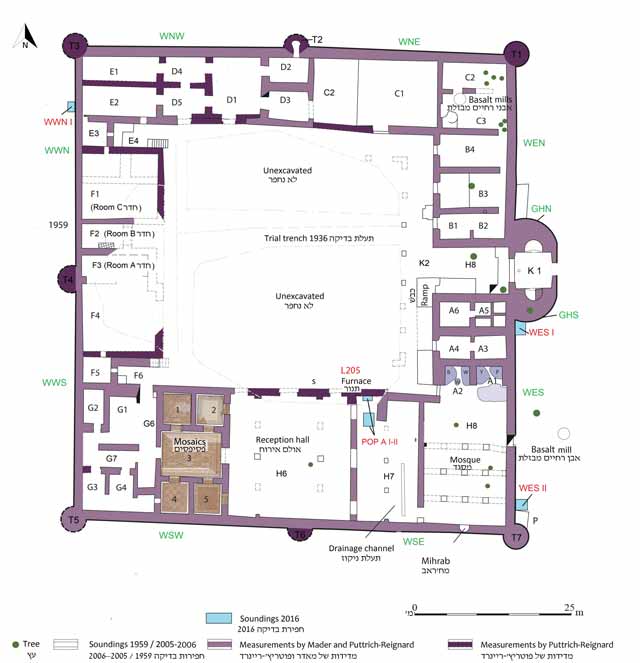

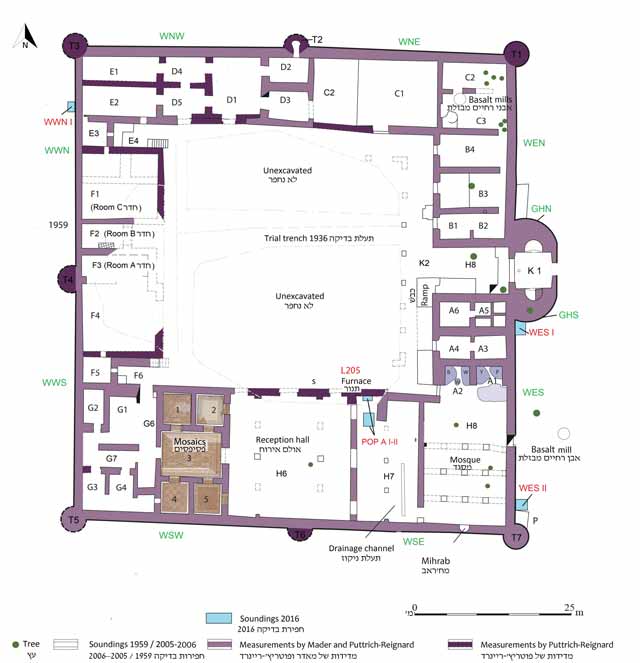

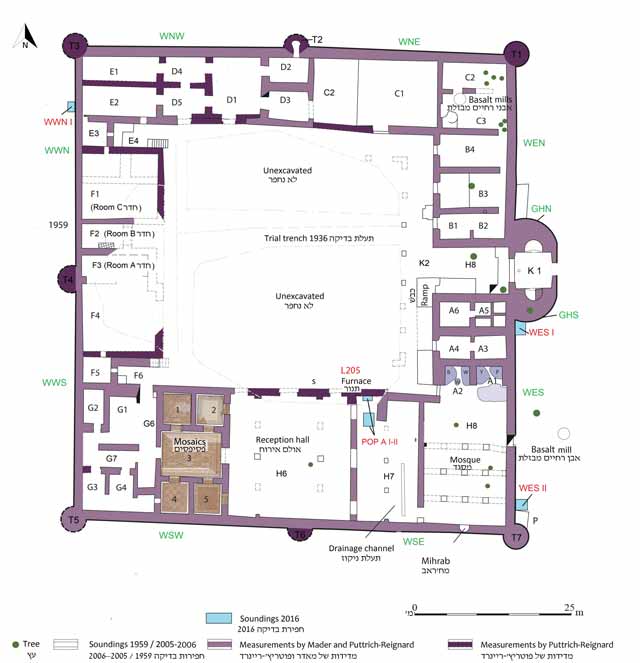

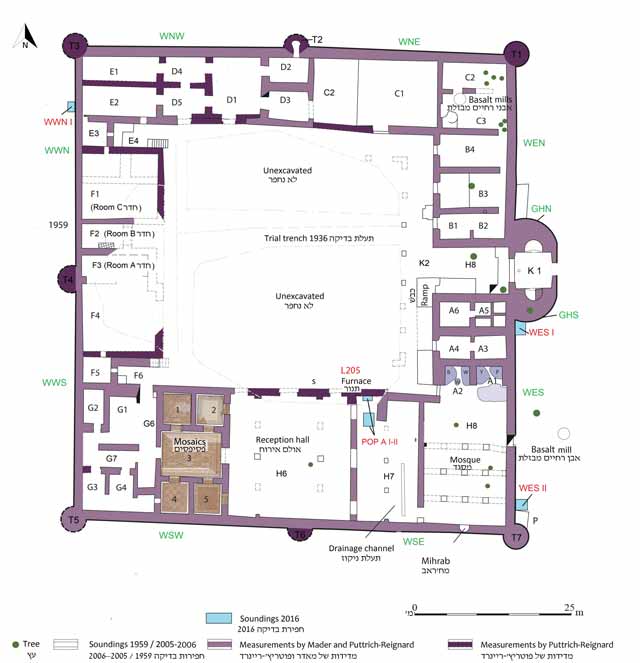

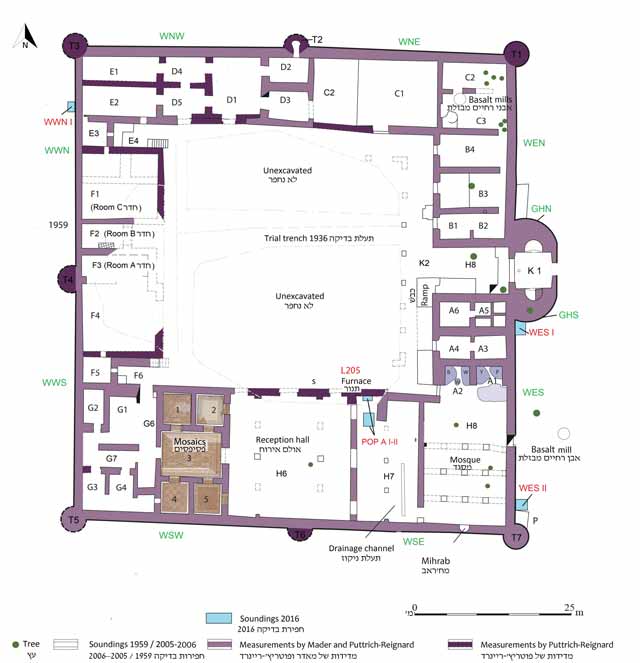

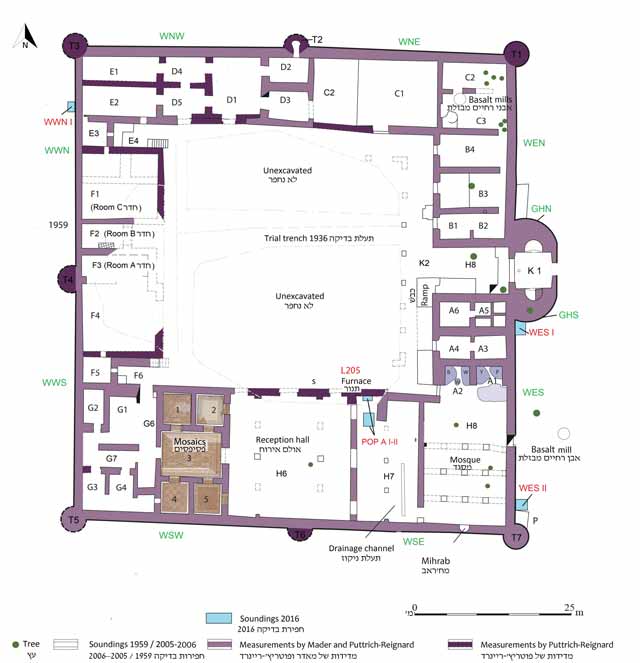

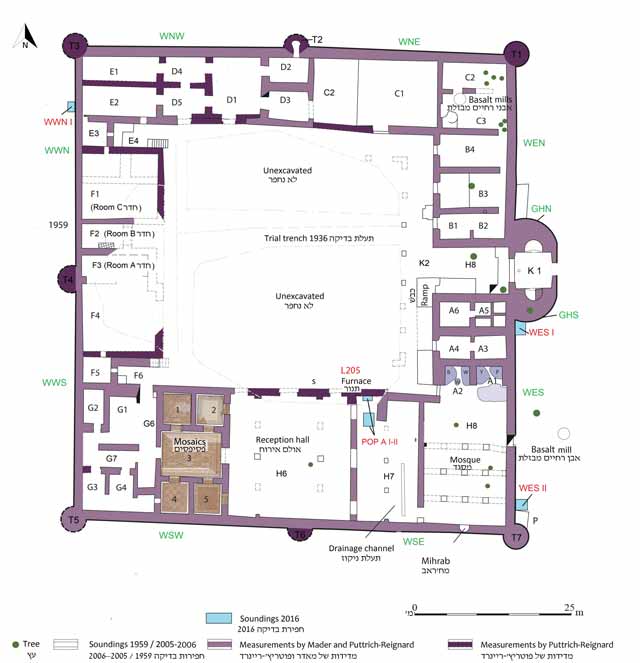

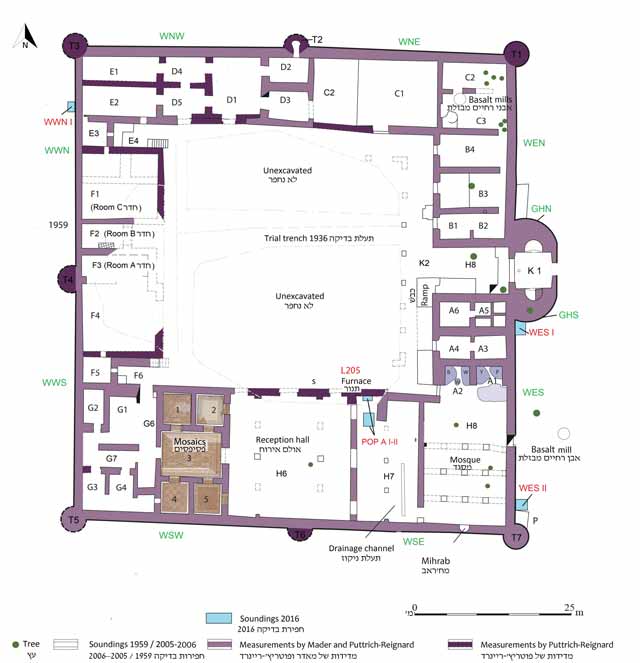

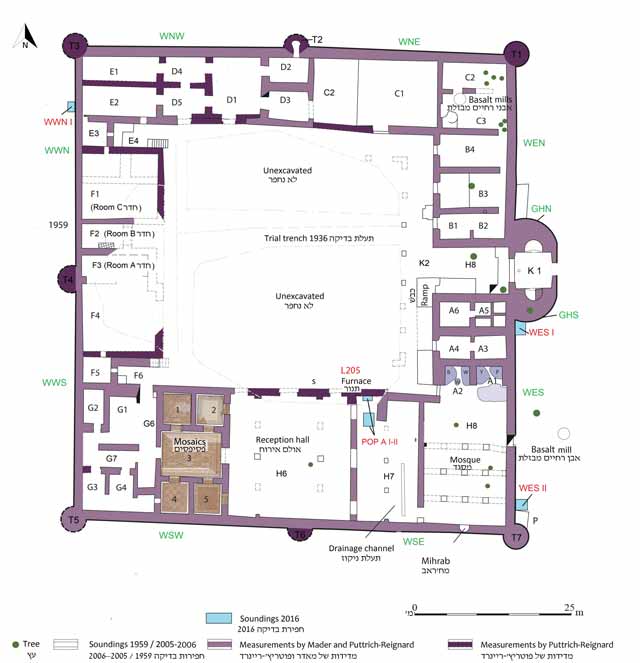

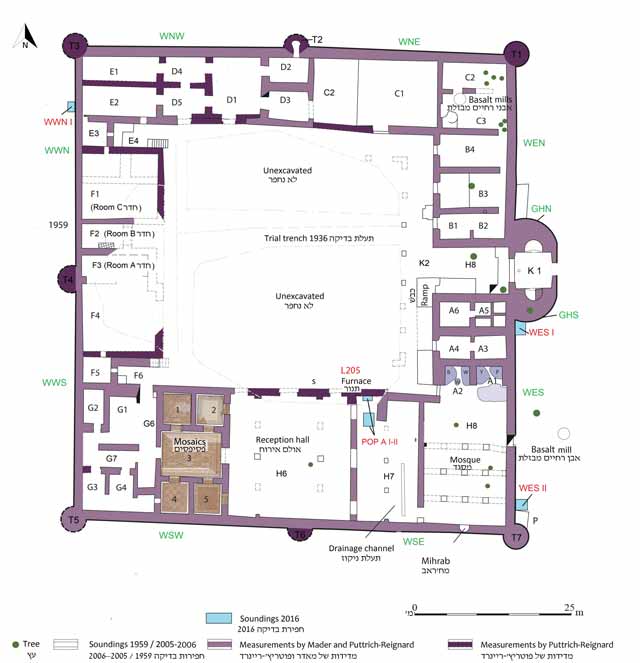

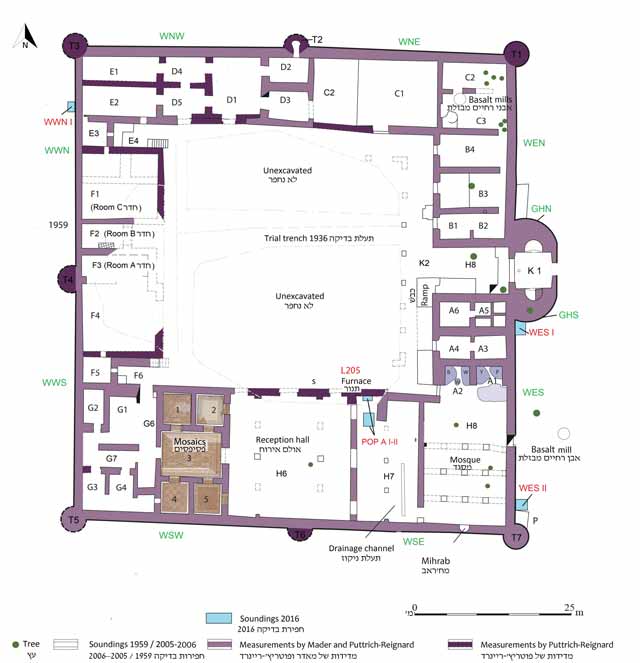

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Horvat

Minnim Site from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan

Kuhnen et al (2018)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Horvat

Minnim Site from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan

Kuhnen et al (2018)

- Figure 2 - Collapse debris

in foundation trench south of east gate (Square WES I) from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Square WES I, looking west.

Kuhnen et al (2018) - Figure 4 - Broken roof

tiles found in the fills east of WES from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Roof tiles found in the fills east of WES.

Kuhnen et al (2018)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Horvat Minnim Site

from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan

Kuhnen et al (2018) - Figure 2 - Collapse debris

in foundation trench south of east gate (Square WES I) from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Square WES I, looking west.

Kuhnen et al (2018) - Figure 4 - Broken roof

tiles found in the fills east of WES from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Roof tiles found in the fills east of WES.

Kuhnen et al (2018)

Kuhnen et al (2018) reports that excavations indicate that the palace was not completely finished before it was damaged by an earthquake which they presume to have struck in the mid 8th century CE. Square WES I, excavated at the corner between the eastern curtain wall and the southern gate tower, contained evidence of collapse.

The foundation trench was filled with debris that contained fragments of limestone ashlars mixed with basalt boulders (L123; Fig. 3). This fill yielded pottery from the Early Islamic period, with some later intrusions. The white limestone masonry of the eastern wall and the gate tower rose above a bottom course of large basalt ashlars—the method used for the construction of all the four curtain walls of the palace. It was therefore concluded that the protruding gate complex formed part of the original architectural plan. However, reused architectural elements seen in the upper courses of the gate indicate partial reconstruction in a later building phase. The fill alongside the eastern curtain wall contained numerous broken roof tiles (Figs. 2 and 4). They were made of crudely mixed clay with organic temper, and were lightly burnt. The tiles may indicate that the roof of the eastern wing, which collapsed in an earthquake apparently dated to 749 CE, was rebuilt in medieval times.

| Effect(s) | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Square WES I - foundation trench just south of east gate

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Square WES I, looking west. Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Kuhnen et al (2018) reports the presence of fragments of limestone ashlars mixed with basalt bouldersin the foundation trench in Square WES I, which was excavated at the corner between the eastern curtain wall and the southern gate tower. |

| Collapsed Roof | fill alongside the eastern curtain wall

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Square WES I, looking west. Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Roof tiles found in the fills east of WES. Kuhnen et al (2018) |

The fill alongside the eastern curtain wall contained numerous broken roof tiles (Figs. 2 and 4). They were made of crudely mixed clay with organic temper, and were lightly burnt. The tiles may indicate that the roof of the eastern wing, which collapsed in an earthquake apparently dated to 749 CE, was rebuilt in medieval times.- Kuhnen et al (2018) |

- Modified by JW from Fig. 1 of Kuhnen et al (2018)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect(s) | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Square WES I - foundation trench just south of east gate

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Square WES I, looking west. Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Roof tiles found in the fills east of WES. Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Kuhnen et al (2018) reports the presence of fragments of limestone ashlars mixed with basalt bouldersin the foundation trench in Square WES I, which was excavated at the corner between the eastern curtain wall and the southern gate tower. |

VIII+ |

| Collapsed Roof suggesting displaced walls | fill alongside the eastern curtain wall

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan Kuhnen et al (2018) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Square WES I, looking west. Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Roof tiles found in the fills east of WES. Kuhnen et al (2018) |

The fill alongside the eastern curtain wall contained numerous broken roof tiles (Figs. 2 and 4). They were made of crudely mixed clay with organic temper, and were lightly burnt. The tiles may indicate that the roof of the eastern wing, which collapsed in an earthquake apparently dated to 749 CE, was rebuilt in medieval times.- Kuhnen et al (2018) |

VII+ |

Bacharach, J. L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage." Muqarnas 13: 27-44.

Cinamon G. 2012. Huqoq Beach. HA-ESI 124.

Cytryn K. 2016. Tiberias and Khirbat al-Minya: Two Long-lived Umayyad Sites on the Western Shore of the Sea of Galilee.

In H.P. Kuhnen ed. Khirbat al-Minya: Der Umayyadenpalast am See Genezareth (Orient-Archäologie 36). Rahden. Pp. 111–130.

Hassol, E. (2015) Archaeological destruction layers and their contribution to archaeomagnetism,

Archaeoseismology and chrono-stratigraphy Dissertation in Hebrew

Kuhnen, Hans-Peter, Pines, Miriam, and Tal, Oren, 2018, Horbat Minnim Preliminary report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot Volume 130 Year 2018

Kuhnen H.P. and Bloch F. 2014. Kalifenzeit am See Genezareth: Der Palast von Khirbat al-Minya /

The age of the Caliphs at the Sea of Galilee. The Palace of Khirbat al-Minya. Mainz.

Kuhnen H.P. 2016a. Dated Evidence of Landscape Change around Khirbat al-Minya between the Hellenistic and Early Islamic Periods –

Archaeological Contributions to a Field Survey in Geoarchaeology. In H.P. Kuhnen ed. Khirbat al-Minya: Der Umayyadenpalast am See

Genezareth (Orient-Archäologie 36). Rahden. Pp. 23–55.

Kuhnen H.P. 2016b. Denkmal der Glaubensgeschichte: Der frühislamische Kalifenpalast von Khirbat al

Minya (Israel). Archäologie in Deutschland 2016 (1):14–19.

Ritter et al (2016) Umayyad foundation inscriptions and the inscription of al-Walīd from Khirbat al-Minya: text, usage, visual form in

H.P. Kuhnen ed. Khirbat al-Minya: Der Umayyadenpalast am See Genezareth (Orient-Archäologie 36). Rahden. Pp. 111–130.

A. E. Mader, QDAP 2 (1933), 188-189

0. Puttrich-Reignard, Paliistinahefte des Deutschen Vereins vom

Heiligen Lande (1939), 17-20

id., QDAP 8 (1939), 159-160

9 (1942), 209-210, 217

A.M. Schneider,

ibid. 6 (1938), 215-217

7 (1938), 49-51

id., Annates archeologiques de Syrie 2 (1952), 23-45, with

additional bibliography on theworkofGerman archaeologists

0. Grabar (et al.), IEJ 10 (1960), 226-243;

id., RB 67 (1960), 387-388

K. A. C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture i/2, Oxford, 1969, 381-389.

The Getty Conservation Institute and The Israeli Nature and National Parks Protection Authority, Khirbet

Minya/Horvat Minnim Management Planning Assessment Report, Jerusalem 2001 (unpublished)

J. Finegan, The Archaeology of the New Testament: The Life of Jesus and the Beginning of the Early Church, rev.

ed., Princeton, NJ 1992

M. Spaer, Journal of Glass Studies 34 (1992), 44–62

R. Schick, NEA 61 (1998),

74–108

H. Dudman, Galilee Revisited: with Mary Magdalene and 20 Other Immortals in Search of Jesus,

Jerusalem 2000

M. Rosen-Ayalon, Art et archéologie islamiques en Palestine (Islamiques), Paris 2002,

43–45

id. (& K. Cytryn-Silverman), IEJ 55 (2005), 216–219

J. Neguer, Conservation and Management of

Archaeological Sites 6/3–4 (2004), 247–258.

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Horvat Minnim Site

from Kuhnen et al (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan

Kuhnen et al (2018)

| Effect | Image(s) | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

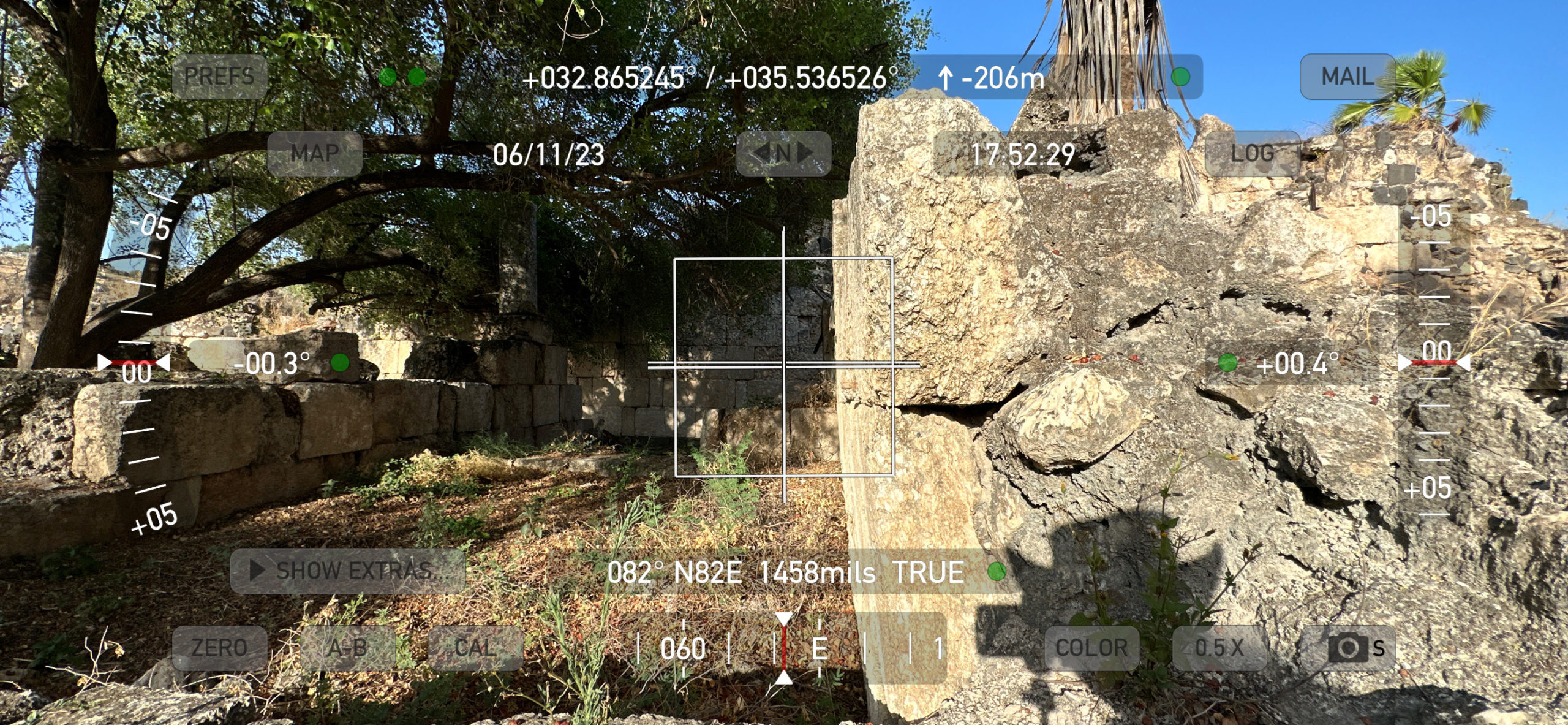

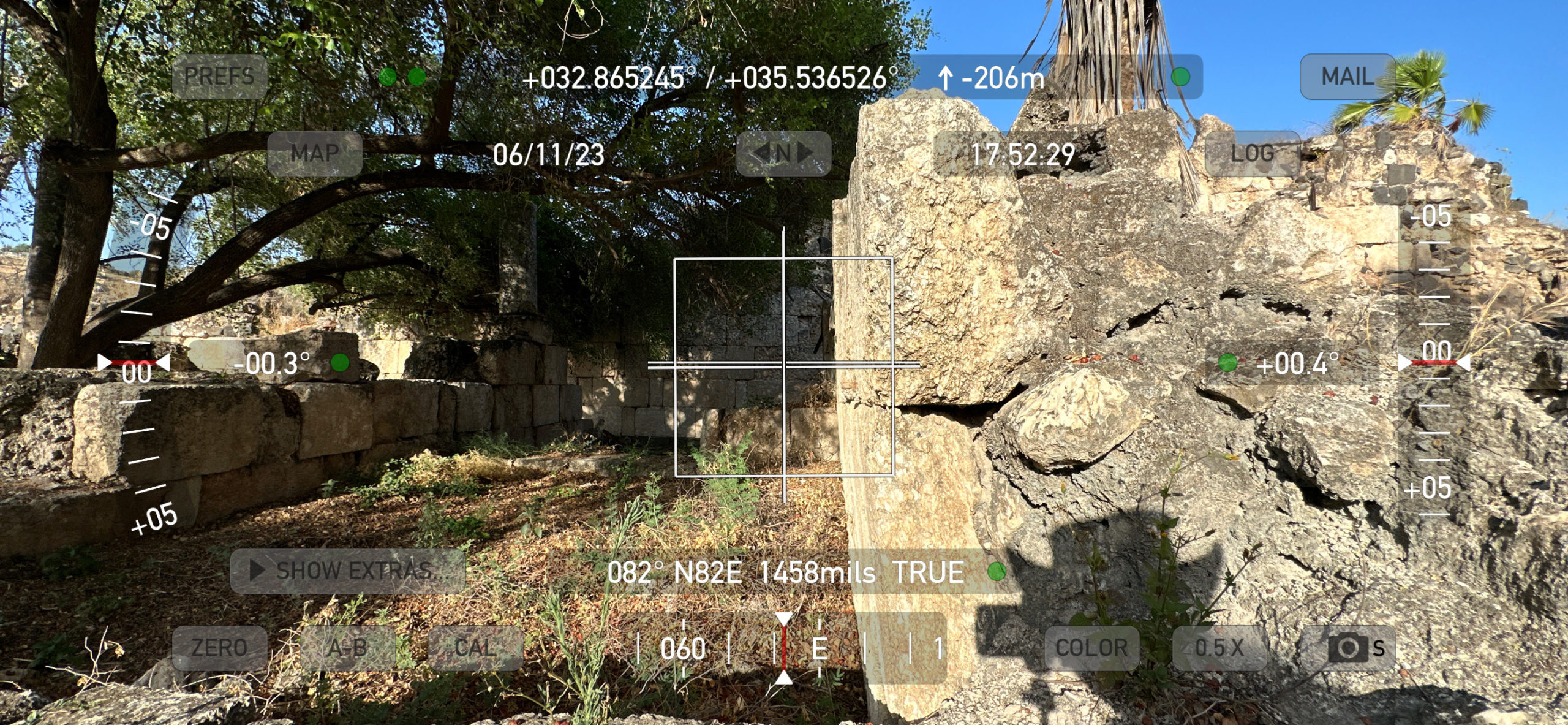

| Tilted Wall | Verticality Check

Verticality Check for tilted south wall of Area B1

Verticality Check for tilted south wall of Area B1View from the west Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 Tilt Measurement (4.1°)

Tilt Measurement (4.1°) for tilted south wall of Area B1

Tilt Measurement (4.1°) for tilted south wall of Area B1Yellow lines and box aligned with tilt View from the west Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 Azimuth Measurement (257°)

Azimuth Measurement (257°) for tilted south walls of Areas B1 and B2

Azimuth Measurement (257°) for tilted south walls of Areas B1 and B2Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

South Wall of Area B1 | JW: Parts of this wall tilt to the south. |

| Tilted Wall and Shifted Ashlars | Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars

Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars in Area B1

Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars in Area B1View from the west Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

South Wall of Area B1 | JW: Tilting is pronounced higher up in the wall where moment stresses would be higher. |

| Tilted Wall and Shifted Ashlars |

Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars

Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars in Area B2

Tilted south wall and shifted ashlars in Area B2View from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

South Wall of Area B2 | JW: This part of the south wall has a pronounced bulge (not photographed) which may have a seismic origin. Alternatively, if this wall was repurposed as a retaining wall at some time in its history, the bulge could be explained by subsurface soil pressure. |

| Tilted Wall and Shifted Ashlars |

Tilted north wall and shifted ashlars

Tilted north wall and shifted ashlars in Areas B1 and B2

Tilted north wall and shifted ashlars in Areas B1 and B2View from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

North Wall of Areas B1 and B2 | JW: Some parts of the north Wall of Areas B1 and B2 are tilted to the south while some parts of the south wall of Areas B1 and B2 are tilted to the north and to the south. Shifted Ashlars can be observed in both the north and south walls. |

| Shifted and tilted Ashlar | Shifted Ashlar

Shifted Ashlar at bottom of photo on inner South wall of fortress

Shifted Ashlar at bottom of photo on inner South wall of fortressoblique view from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 Azimuth Measurement (264°)

Azimuth Measurement (264°) for inner South wall of fortress

Azimuth Measurement (264°) for inner South wall of fortressView from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

Inner South wall of fortress | JW: Ashlar at the bottom center is shifted and tilted. The basalt stone that used to be at its base is missing and the basalt stone to the right is rotated |

| Parted Ashlars above shifted Ashlar | Parted Ashlars above shifted Ashlar

Parted Ashlars above shifted Ashlar on inner South wall of fortress

Parted Ashlars above shifted Ashlar on inner South wall of fortressView from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 Shifted Ashlar

Shifted Ashlar on inner South wall of fortress

Shifted Ashlar on inner South wall of fortressOblique view from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

Inner South wall of fortress | JW: This part of the structure appears to have bulged - parting the joints between the ashlars above the shifted and tilted ashlar. The fractures and broken corners in the lower left of the "Shifted Ashlar" photo may be related to this deformation. |

| Through-going joints | Through-going joints

Through-going joints on inner South wall of fortress

Through-going joints on inner South wall of fortressView from the east Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

Inner South wall of fortress | JW: Joints passing through 2 or more adjacent stones can indicate high levels of local intensity as the fracture has to overcome the stress shadow between the ashlars (e.g. see Korjenkov and Mazor, 1999:197-198) |

| Displaced Wall | Displaced Wall

Displaced exterior east fortress wall south of the Main gate

Displaced exterior east fortress wall south of the Main gateView from the the northeast and above Drone Photo by Jefferson Williams - 11 June 2023 |

Exterior east fortress wall south of the Main gate | JW: Displaced Wall along with some fracturing. Could be due to soil pressure if this wall acted as a retaining wall at some time in its history |

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Horbat Minya kmz file | various |