Petra - Petra Church (aka the Byzantine Church)

Aerial View of Virtual Reality Model of the Petra Church

Aerial View of Virtual Reality Model of the Petra ChurchClick on image to access a youtube virtual flyover video in a new tab

Zamani Project

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| The Petra Church | English | |

| The Byzantine Church at Petra | English | |

| Blessed and All-Holy Lady, the most Glorious Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary Church |

The Petra Church is a Byzantine Church in Petra

where the Petra papyri were discovered. Excavations revealed that

it was probably named for the 'Blessed and All-Holy Lady, the most Glorious Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary'

(Fiema et al, 2001). It's discovery and excavation

opened a window into Byzantine Petra of which almost nothing was known

before

(Fiema et al, 2001).

Ken Russell,

who had worked as a supervisor on excavations of the nearby Temple of the Winged Lions and Area I, can be largely credited for it's discovery and it was Ken who

initiated and spearheaded the project to excavate it. Tragically, Ken died at the age of 41 before excavations began. The final publication

of the excavations (The Petra Church by Fiema et al, 2001)

was dedicated to his memory.

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

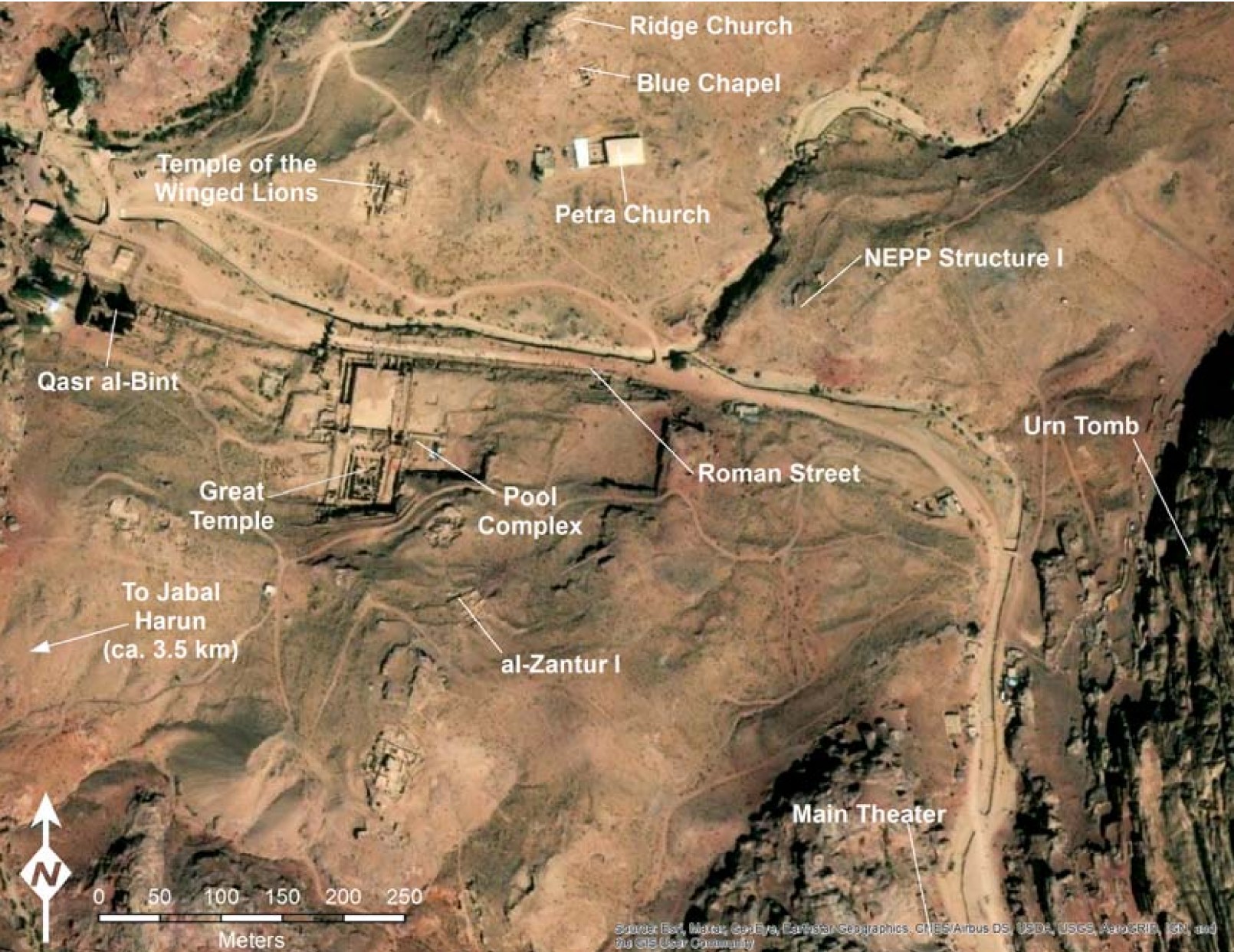

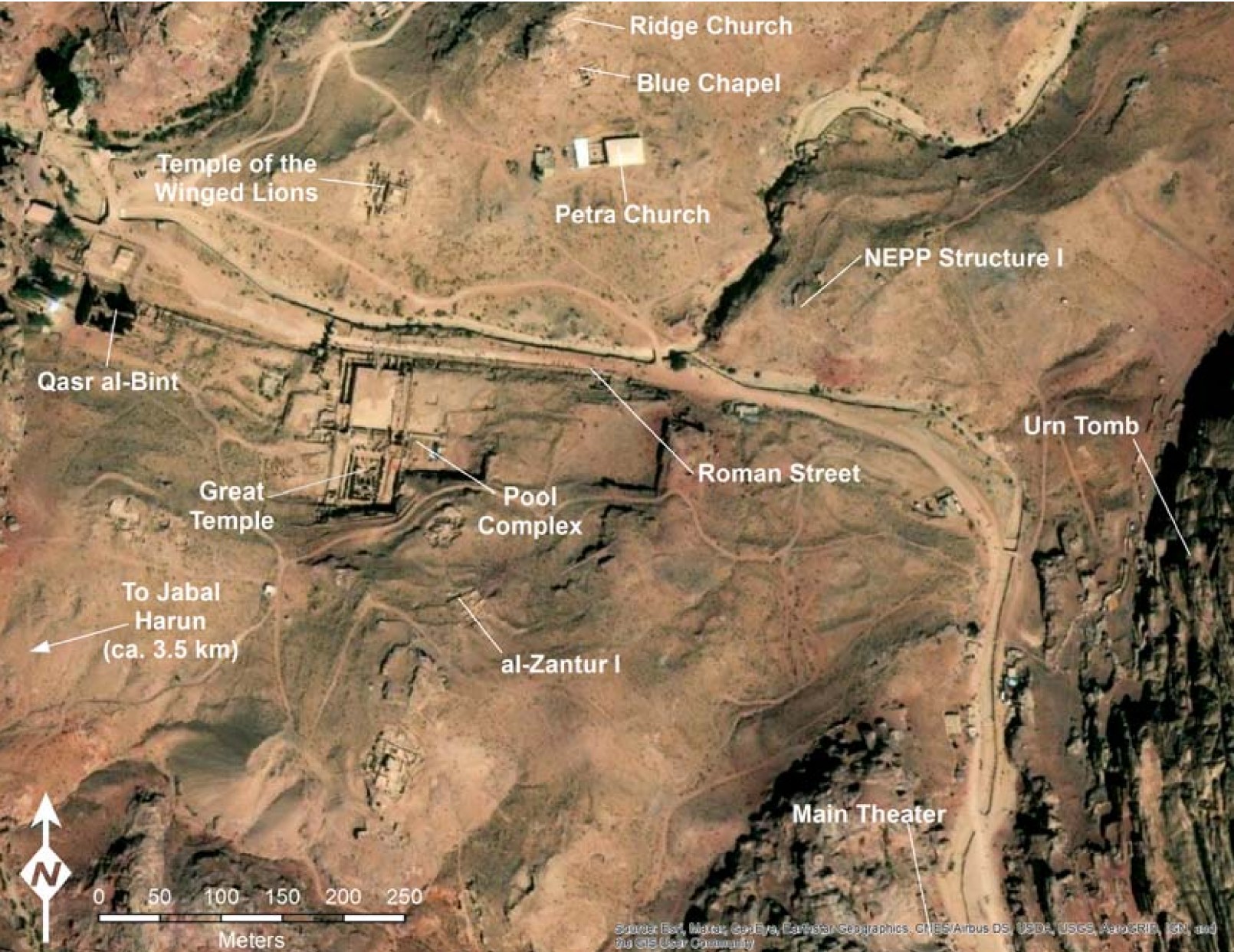

- Fig. 2 - Location Map

from Jones (2021)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of Petra with the locations of major excavations marked

Jones (2021)

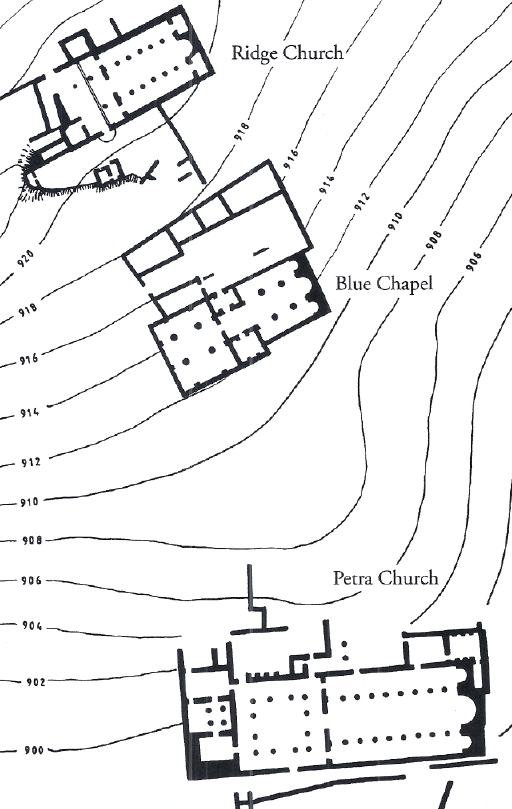

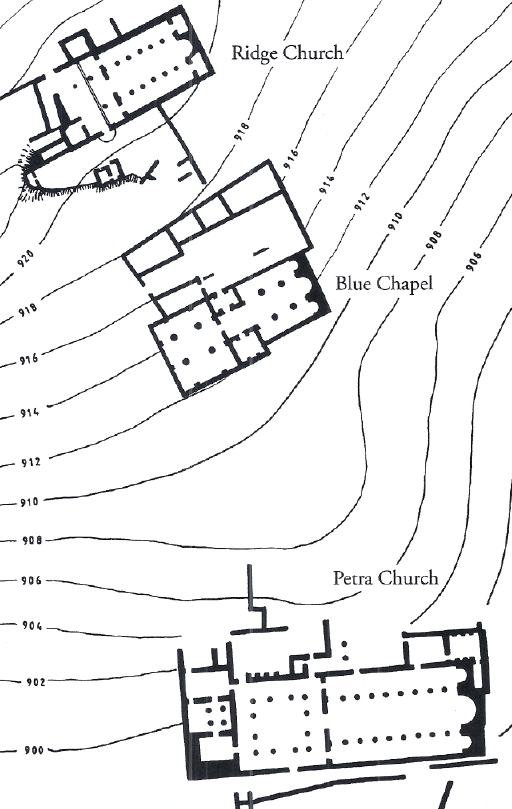

Basemap: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, USDA FSA, USGS, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, and the GIS User Community - Fig. 1.1 - Plan of the 3 churches

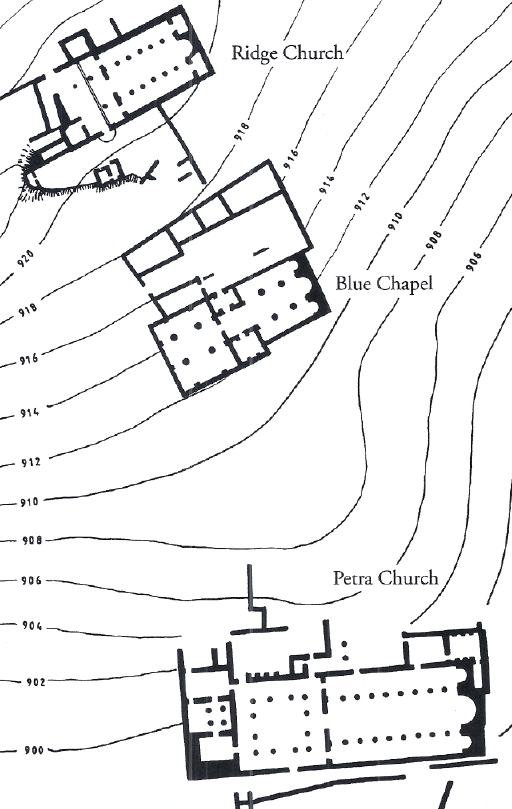

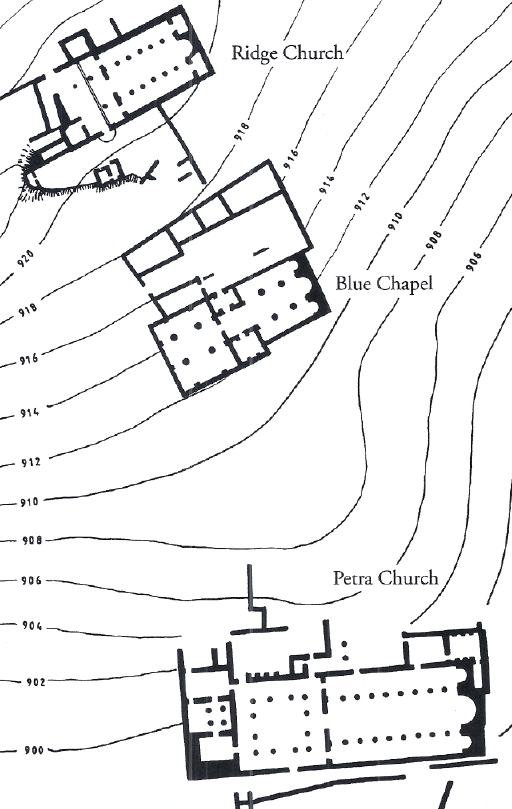

from Bikai et. al. (2020)

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1

Map of the project area courtesy of Talal Akasheh, Hashemite University, Chusanthos Kanellopoulos, and American Center of Oriental Research, Amman

Bikai et al (2020) - The 3 churches in Google Earth

- Fig. 1.1 - Plan of the 3 churches

from Bikai et. al. (2020)

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1

Map of the project area courtesy of Talal Akasheh, Hashemite University, Chusanthos Kanellopoulos, and American Center of Oriental Research, Amman

Bikai et al (2020)

- Labeled Plan modified

from Fiema et al (2001)

Plan with parts of the structure labeled in red

Plan with parts of the structure labeled in red

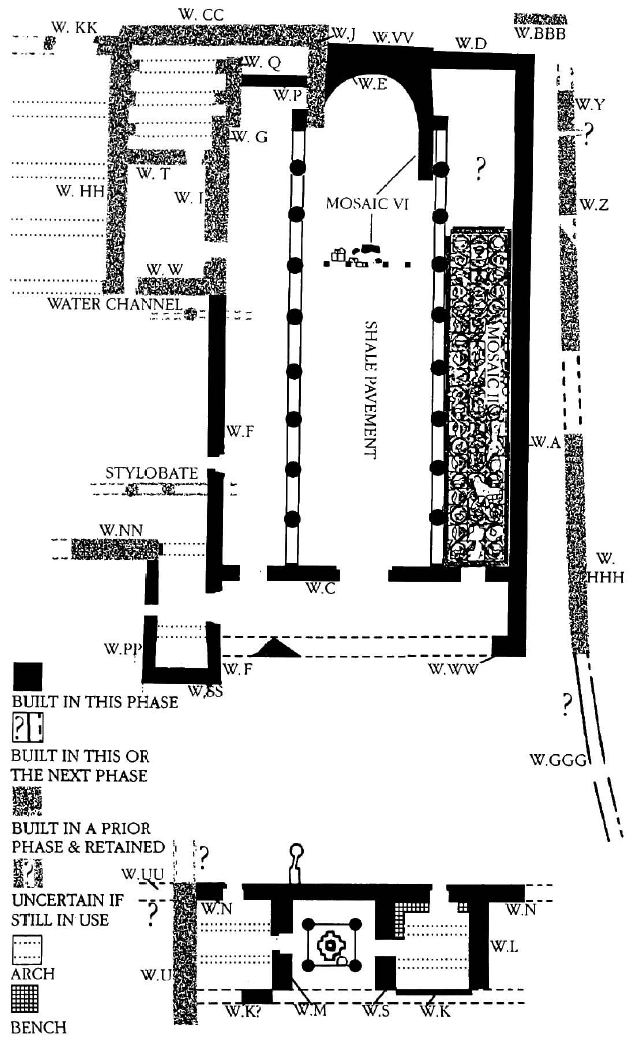

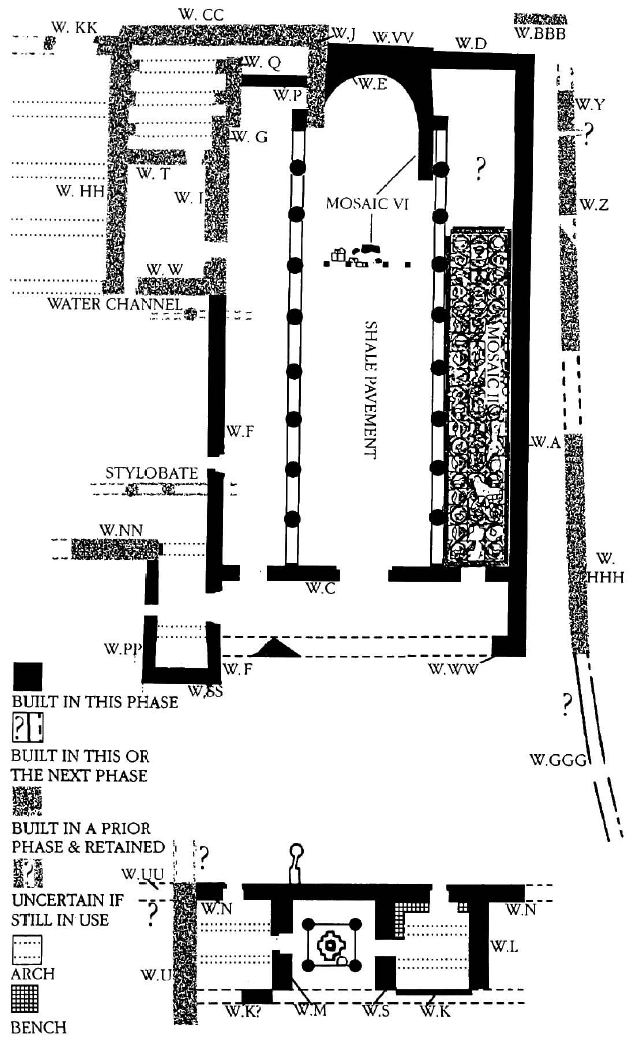

modified by JW from Fig. 4a of Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 50 - Plan of the

existing remains from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Ground Plan of the existing remains

Fiema et al (2001) - Plan of the existing remains

from Porter (2011)

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

plan by Franco Sciorilli, 2011

Porter (2011) - Plan of the existing remains

from Zamani Project

Byzantine Church - Groundplan

Byzantine Church - Groundplan

Zamani Project - Fig. 4a - General Plan

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4a

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 4b - General Plan

with excavation squares from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4b

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 1 - Plan showing

location of Rooms I, I, and XII from Fiema (2007)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Sketch-plan of the Petra church with the locations of Rooms I and II

as modified from Fiema (2001b) 10 (C. Alexander, Z. T. Fiema and S. Shraideh)

Fiema (2007)

- Fig. 50 - Plan of the

existing remains from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Ground Plan of the existing remains

Fiema et al (2001) - Plan of the existing remains

from Porter (2011)

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

plan by Franco Sciorilli, 2011

Porter (2011) - Plan of the existing remains

from Zamani Project

Byzantine Church - Groundplan

Byzantine Church - Groundplan

Zamani Project - Fig. 4a - General Plan

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4a

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 4b - General Plan

with excavation squares from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4b

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001)

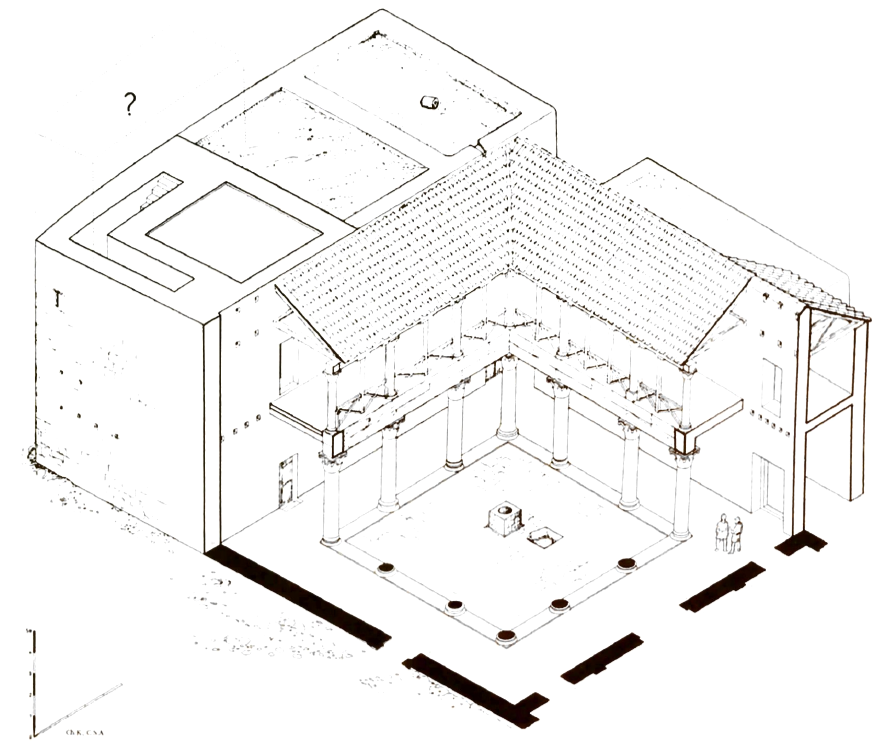

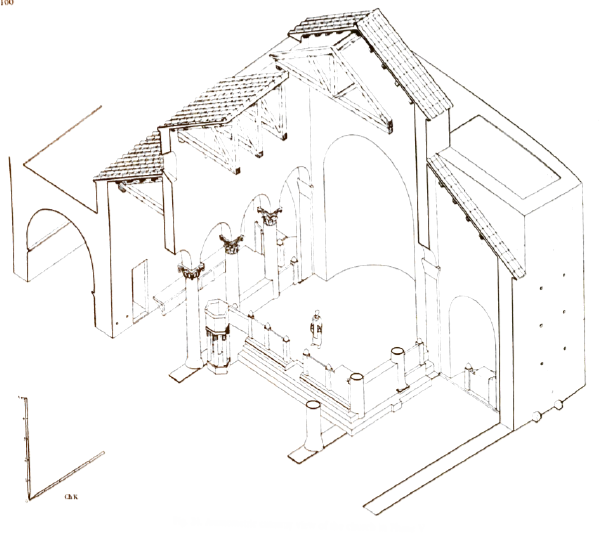

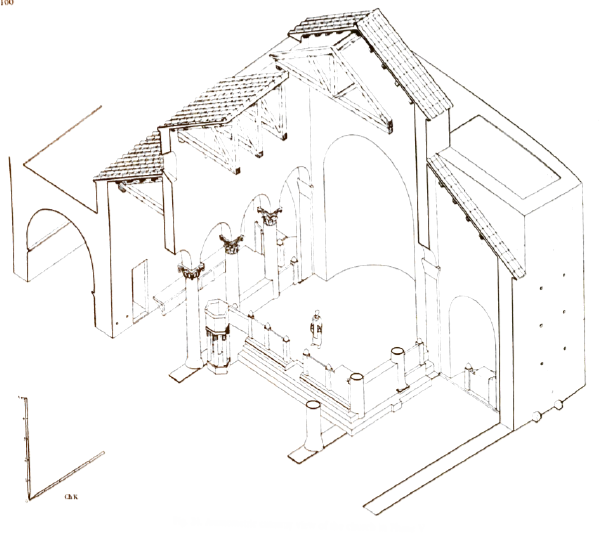

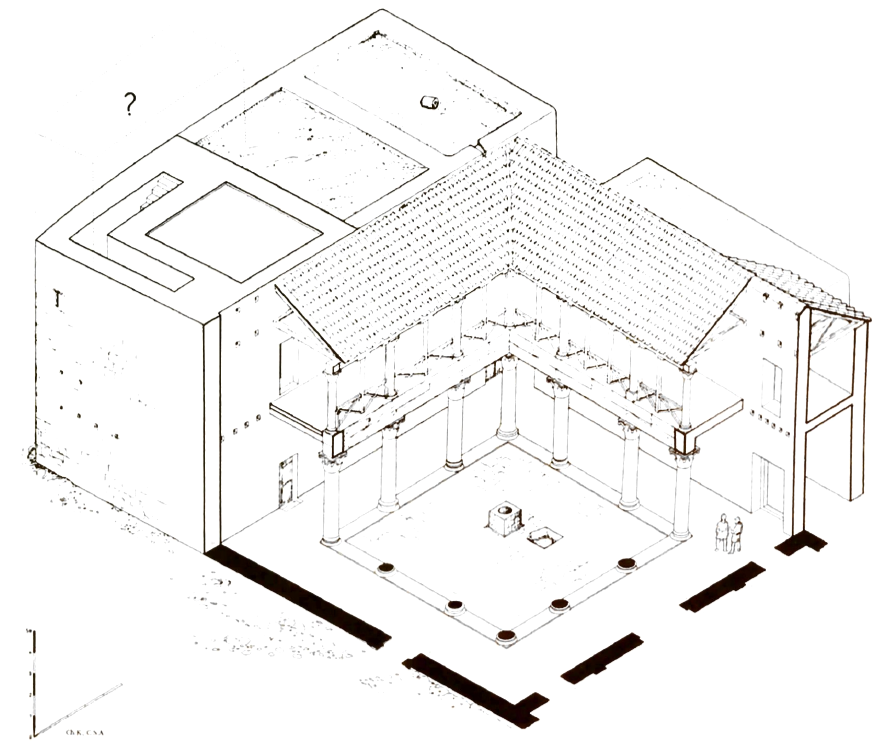

- Fig. 16 - Axonometric

view of the basilica from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Axonometric view of the basilica from the northeast

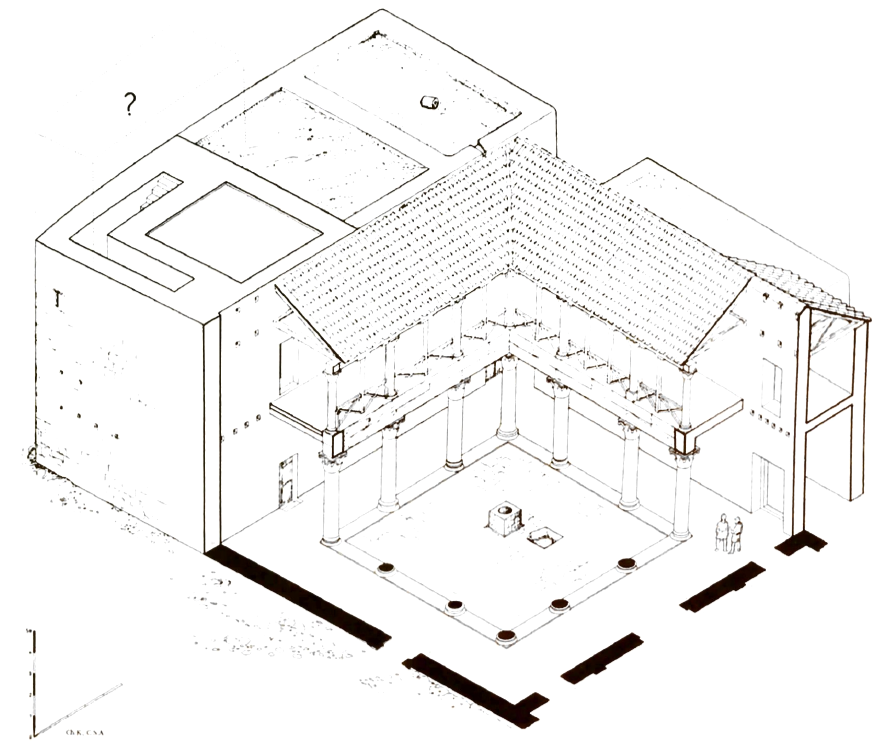

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 62 - Perspective

view of the atrium from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 62

Fig. 62

Perspective view of the atrium

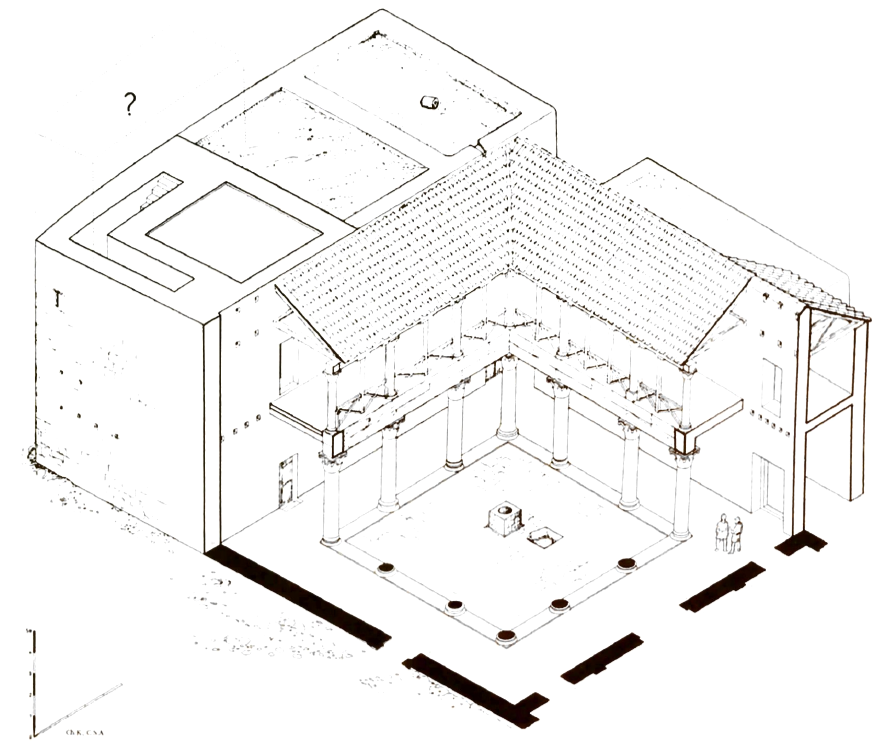

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 63 - Axonometric

reconstruction of the Phase V atrium from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 63

Fig. 63

Axonometric reconstruction of the Phase V atrium

Fiema et al (2001)

- Fig. 5 - Plan in Phase I

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Phase I

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 13 - Plan in Phase II

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

Phase II

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 21 - Plan in Phase III

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Phase III

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 26 - Drawing of interior

of Room I in Phase III from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 26

Fig. 26

Perspective view of the interior of Room I, Phase III

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 1a - Plan in Phase IV

from Sodini (2002)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Petra church, phase IV (mid-late 5th century ?)

(fig. 39 on p. 29)

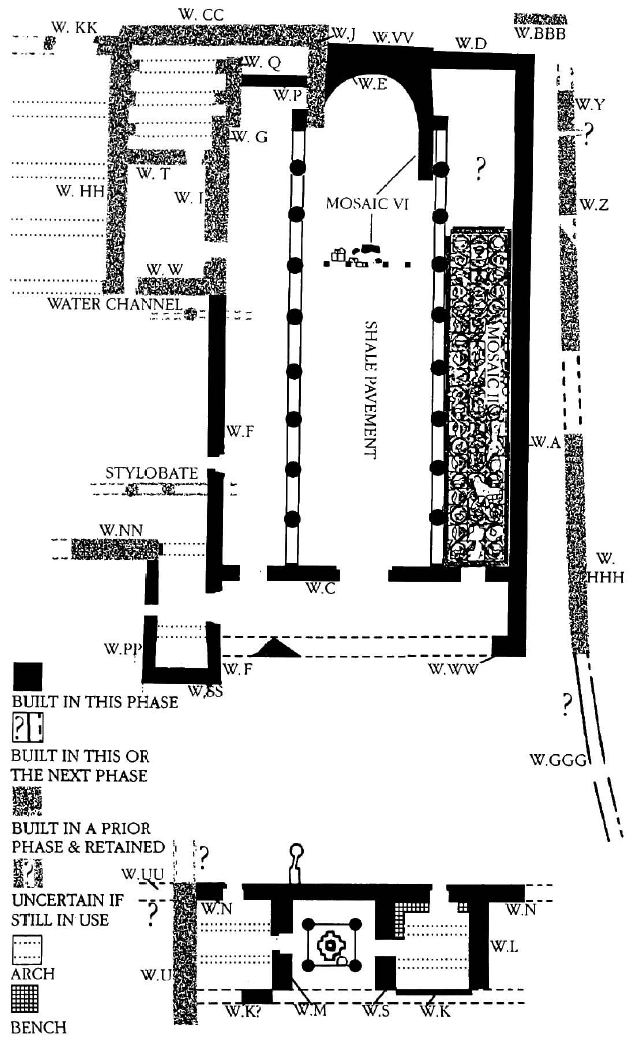

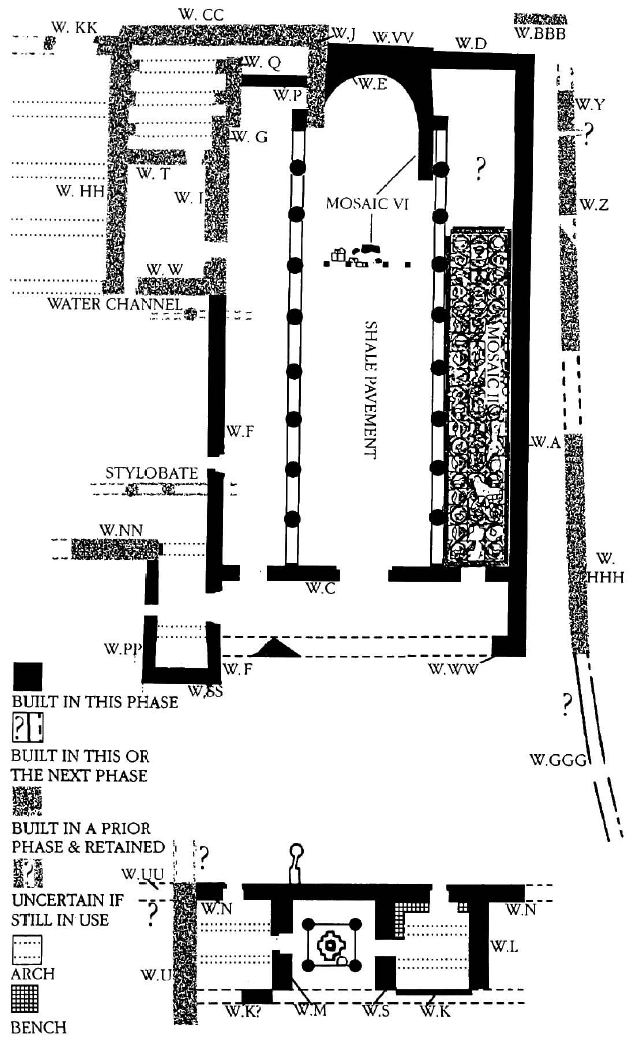

Sodini (2002) - Fig. 17 - Restored

ground plan of the complex in Phase IV from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Restored ground plan of the complex in Phase IV

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 22 - Axonometric

cutaway view of the Phase IV church with walls in front of the pastophoria from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

Axonometric cutaway view of the Phase IV church with walls in front of the pastophoria

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 59 - Section through

existing remains of Rooms IX, X, and XI from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 59

Fig. 59

Section q-q' looking through Rooms IX, X, and XI, actual state

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 60 - Restored section

through Rooms IX, X, and XI from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 60

Fig. 60

Restored section q-q' looking east through Rooms IX, X, and XI

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 61 - Axonometric cutaway

of the baptisery and flanking rooms during phase IV from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 61

Fig. 61

Axonometric cutaway of the baptisery and flanking rooms during phase IV

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 1b - Plan in Phase V

from Sodini (2002)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

Petra church, phase V (6th century ?)

(fig. 67 on p. 54)

Sodini (2002) - Fig. IV-1 - Axonometric

reconstruction of Room I and adjacent structures in phase V from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. IV-1

Fig. IV-1

Axonometric reconstruction of Room I and adjacent structures in phase V

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 24 - Axonometric

cutaway view of the church in Phase V from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Axonometric cutaway view of the church in Phase V

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 63 - Axonometric

reconstruction of the Phase V atrium from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 63

Fig. 63

Axonometric reconstruction of the Phase V atrium

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 25 - Proposed

axonometric reconstruction of the complex in Phase V from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

Proposed axonometric reconstruction of the complex in Phase V

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. IV-2 - Proposed

reconstruction of Rooms I, II, and XII from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. IV-2

Fig. IV-2

Proposed reconstruction of Rooms I, II, and XII

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 98 - Plan in Phase VI

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 98

Fig. 98

Phase VI

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 110 - Plan in Phase IX

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 110

Fig. 110

Phase IX

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 122 - Plan in Phase XI

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 122

Fig. 122

Phase XI

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 127 - Plan in Phase XIIB

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 127

Fig. 127

Phase XIIB

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 130 - Plan in Phase XIII

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 130

Fig. 130

Phase XIII

Fiema et al (2001)

- Fig. 5 - Plan in Phase I

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Phase I

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 13 - Plan in Phase II

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

Phase II

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 21 - Plan in Phase III

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Phase III

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 1a - Plan in Phase IV

from Sodini (2002)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Petra church, phase IV (mid-late 5th century ?)

(fig. 39 on p. 29)

Sodini (2002) - Fig. 1b - Plan in Phase V

from Sodini (2002)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

Petra church, phase V (6th century ?)

(fig. 67 on p. 54)

Sodini (2002) - Fig. 98 - Plan in Phase VI

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 98

Fig. 98

Phase VI

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 110 - Plan in Phase IX

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 110

Fig. 110

Phase IX

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 122 - Plan in Phase XI

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 122

Fig. 122

Phase XI

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 127 - Plan in Phase XIIB

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 127

Fig. 127

Phase XIIB

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 130 - Plan in Phase XIII

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 130

Fig. 130

Phase XIII

Fiema et al (2001)

- Fig. 2 - E/W sections

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E/W sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N/S sections

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N/S sections

Fiema et al (2001)

- Fig. 2 - E/W sections

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E/W sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N/S sections

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N/S sections

Fiema et al (2001)

- 1st tab - from Fiema et al. (2000:437)

- 2nd tab - from Fiema et al. (2009) and others

- Scroll down to bottom to access tabs

Fiema et al (2001:18) surmised that Phase II ended with an earthquake based on rebuilding evidence discussed below:

The type of construction activity in Phase III [] included massive backfilling of certain spaces with material clearly originating from a demolition. Furthermore, there was seemingly no shortage of architectural elements - including doorjambs, drums, cornices and ashlars - which were reused. This evidence all indicates that Phase II ended in disaster and was followed by a period of intense restoration and construction. This hypothesis, combined with the available absolute dating, suggests that the earthquake of A.D. 363 is the best candidate for such a disaster. That earthquake is a historically documented, major natural calamity which beset Petra during the Byzantine period. The severity of its destructive power left numerous Nabataean and Late Roman period structures in ruins, e.g., the domestic structures at ez-Zantur, the Temple of the Winged Lions and Area I, the Theater, the Colonnaded Street area, and the Southern Temple. Afterwards, some buildings were either partially abandoned or never rebuilt. Whether the Phase II structures in the excavated area were seriously affected is not apparent, but it remains a possibility. At any rate, Phase II most probably represents the 3d century A.D. and the first half of the following century, ending in A.D. 363.Dating for the end of Phase II was largely established from sounding 30 of the foundation course of Wall I, which Fiema et al (2001:18) states

... One telling indication that Phase III was initiated after a devastating earth tremor is the amount of reused stone material, presumably readily available after the disaster. In all the stone-tumble layers excavated in the interiors of the northern rooms and courts - almost 4 m deep - the number of reused doorjambs was simply astonishing. In total, 275 complete stones or recognizable fragments were retrieved from that area.

certainly dates to Phase III. Fiema et al (2001:18) reports that

two coins were found there, one unidentifiable, the other dated to A.D. 350-55.

The Phase X earthquake came after the fire of Phase VIII which is well dated and provides a terminus post quem of the end of the 6th century CE.

The terminus post quem is derived from chronological information found in the Petra papyri

which were burned in the fire. The terminus ante quem for the Phase X earthquake is provided by succeeding Phase XI which is dated to late 7th to early 8th century. However, it should be noted that

Fiema et al (2001:115) state that no easily datable

material can be associated with [Phase XI] deposits

adding that several 7th century sherds were found in strata which may have been created

during Phase XI.

Fiema et al (2001:115) concludes that Phase XI could be dated

to the 7th century A.D., probably its second half, and apparently after the first earthquake

but notes that other ceramic evidence indicates that Phase XI

could have lasted longer, i.e. until the next earthquake

.

Fiema et al (2001:111) summarized Phase X earthquake evidence as follows:

There is no evidence whatsoever to suggest that the earliest structural destruction of the church complex was caused by factors other than natural ones, and an earthquake is the most acceptable explanation. Although the density of lowermost stone deposits varied from place to place, these deposits are nevertheless evident everywhere. The earthquake damaged the already weakened structure of the church proper. Evidently, most of the columns in the basilica broke and collapsed, either in their entirety or their upper sections. That was followed by a complete failure of the arches above the capitals, and thus the clerestory walls farther up. Whatever had remained after the fire of Phase VIII i.e. elements of the roof structure, now fell. Walls A, C, and F were visibly damaged , the latter one began to lean precariously toward the south. Room II lost its vaulted ceiling and, like Rooms I and V, the upper parts of its stone superstructure. Arches broke and fell inside Room I. The atrium's porticoes collapsed, at least partially, as well as the floors in the western rooms. However, except for some shifting, at least two columns survived intact in the baptistery. The central and the side apses seemed to have escaped with little damage, but no indisputable proof can be offered for that. Also, no cracking of the ground were detected, and there was no substantial shifting of walls from their foundation courses. The latter, wherever exposed, show no particular seismic damage at all.

... Generally, the intensity of the first major tremor which affected the complex does not suggest a total catastrophe. Rather, the magnitude of destruction indicates a moderate earthquake, probably comparable to grades VII-VIII on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale (MMS).

The date of the earthquake is not easy to determine. A very general terminus post quem for this earthquake is the early 7th century A.D.

- Fig. 50 - Plan of the

existing remains from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Ground Plan of the existing remains

Fiema et al (2001) - Plan of the existing remains

from Porter (2011)

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

plan by Franco Sciorilli, 2011

Porter (2011) - Fig. 4a - General Plan

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4a

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 4b - General Plan

with excavation squares from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4b

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 1 - Plan showing

location of Rooms I, I, and XII from Fiema (2007)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Sketch-plan of the Petra church with the locations of Rooms I and II

as modified from Fiema (2001b) 10 (C. Alexander, Z. T. Fiema and S. Shraideh)

Fiema (2007)

- Fig. 50 - Plan of the

existing remains from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 50

Fig. 50

Ground Plan of the existing remains

Fiema et al (2001) - Plan of the existing remains

from Porter (2011)

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

Map of the Petra Church showing area to be lifted at the west end of the south aisle

plan by Franco Sciorilli, 2011

Porter (2011) - Fig. 4a - General Plan

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4a

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 4b - General Plan

with excavation squares from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4b

General plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections

Fiema et al (2001)

- Fig. 125 - Collapsed column of the

baptistery from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 125

Fig. 125

Room X, collapsed SE column of the baptistery

Color Image from ACOR website

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N-S section i-i'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N-S sections

Section i-i'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 2 - E-W section d-d'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E-W sections

Section d-d'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 126 - Plan showing

stone tumble in SE Aisle from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 126

Fig. 126

Stone tumble in the south aisle, probably Phase XIIA. A1.09, 10

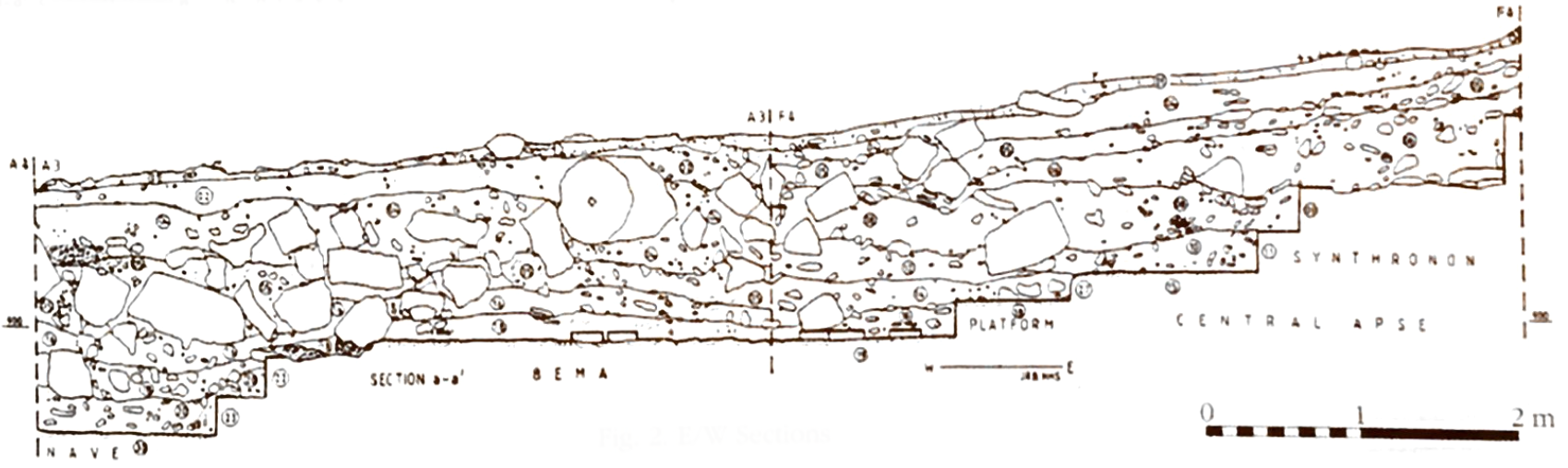

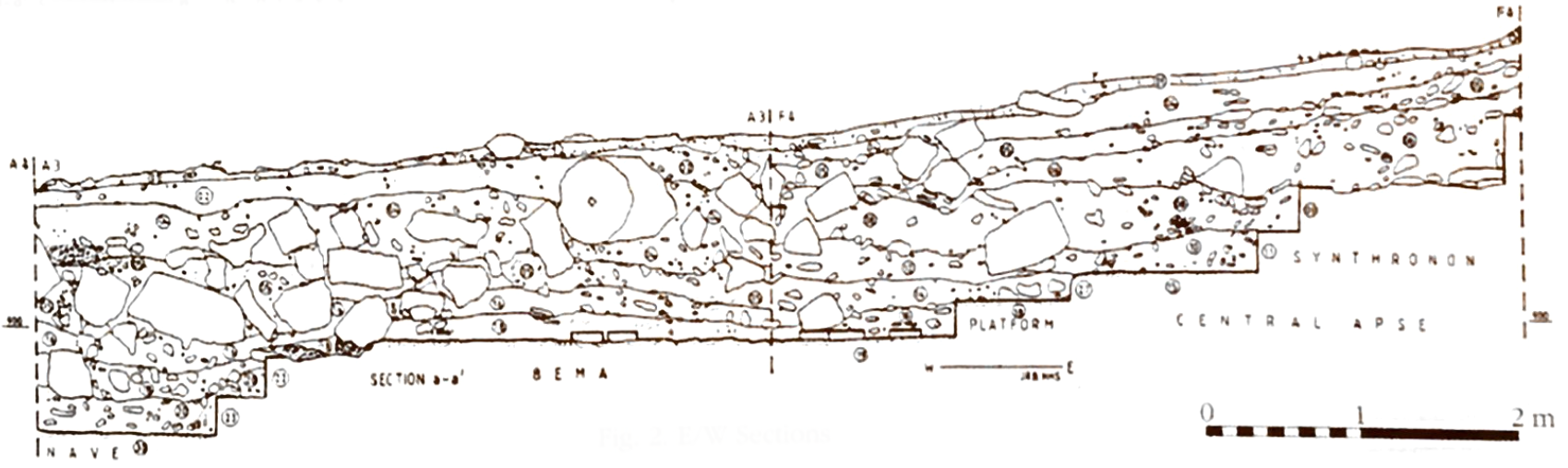

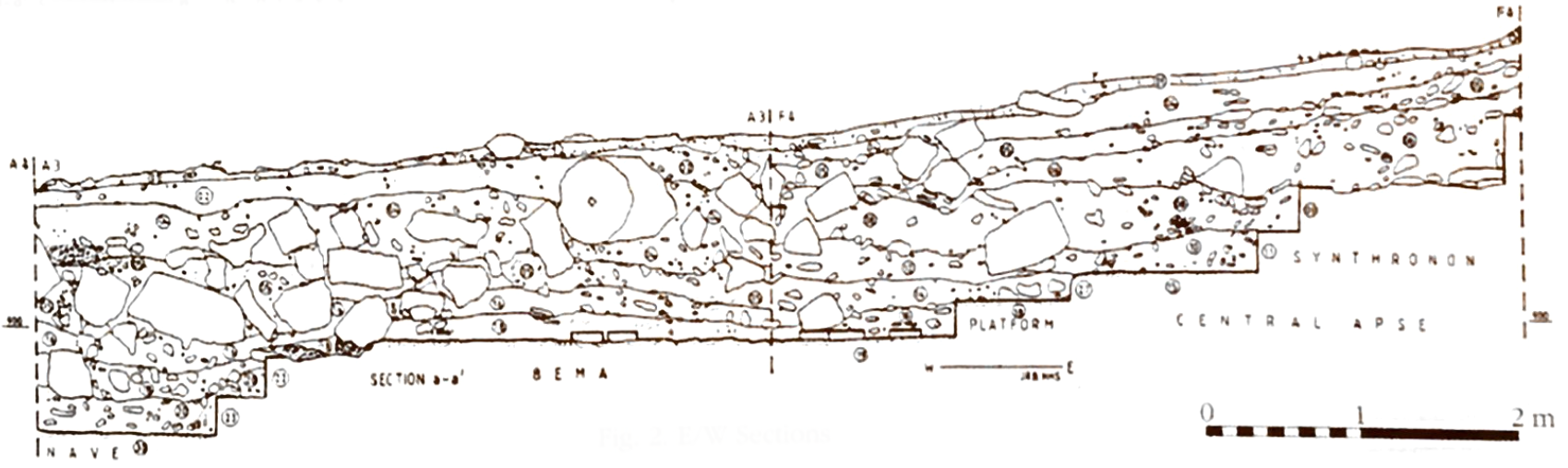

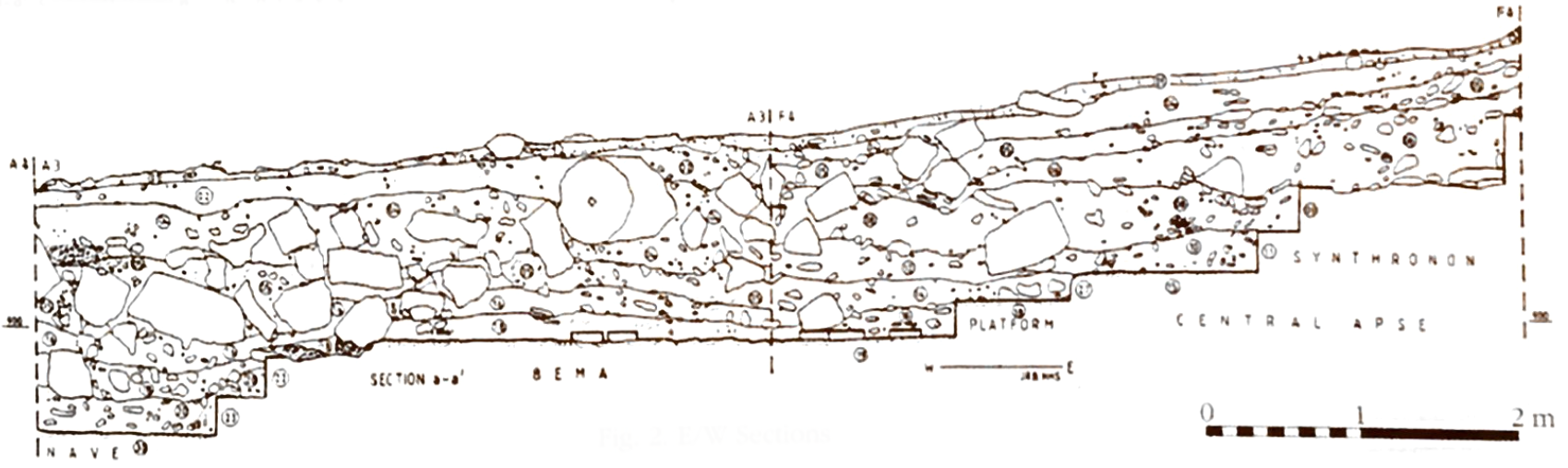

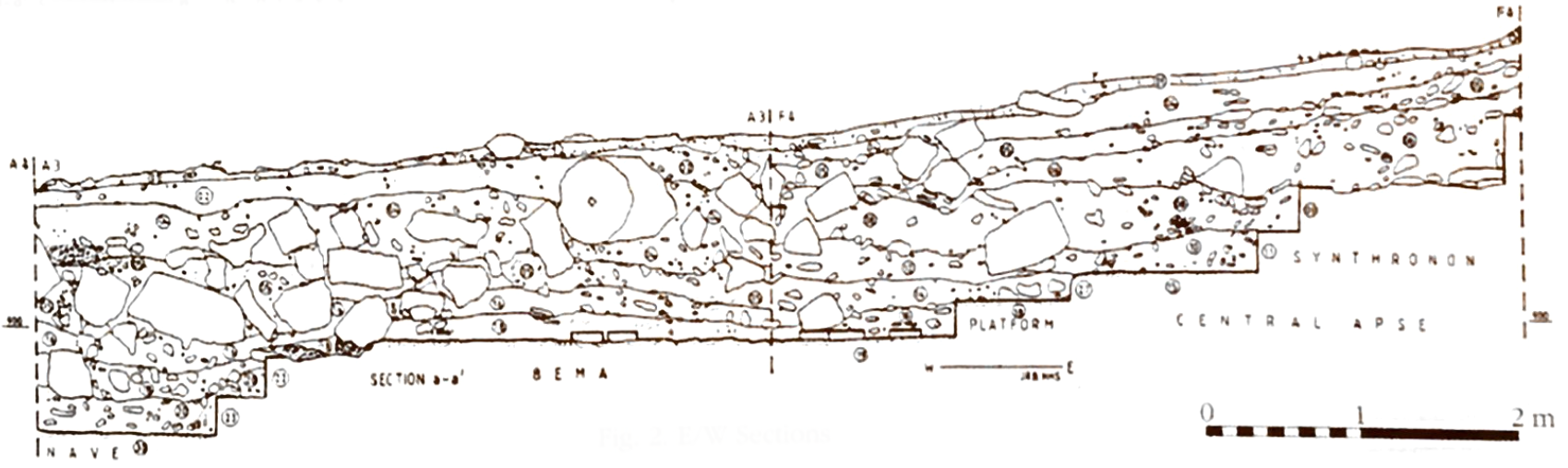

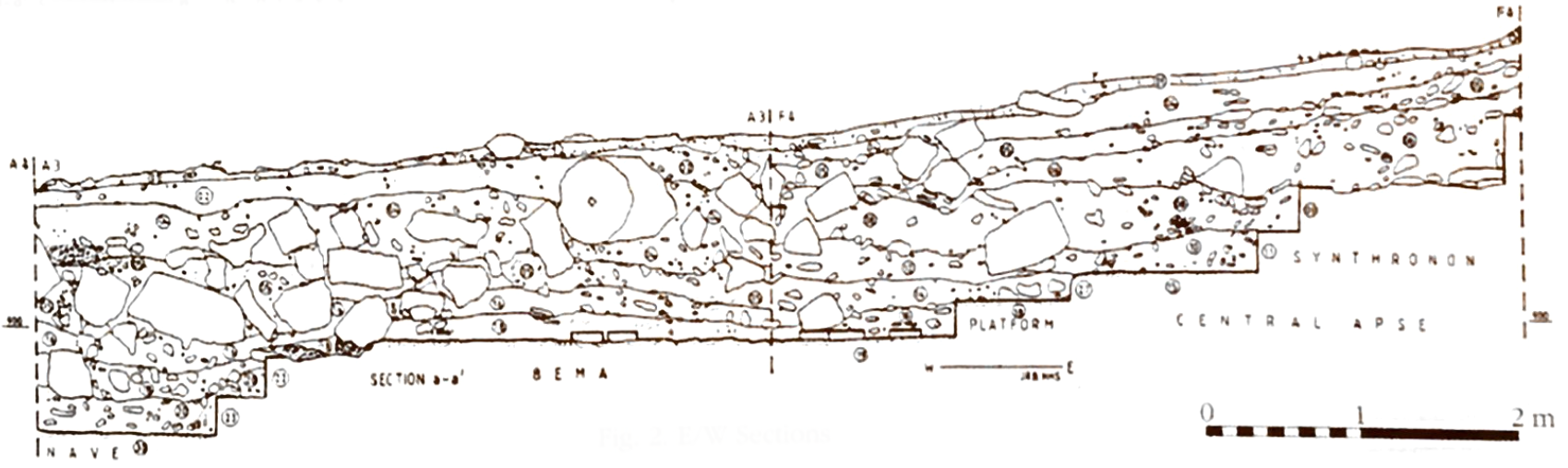

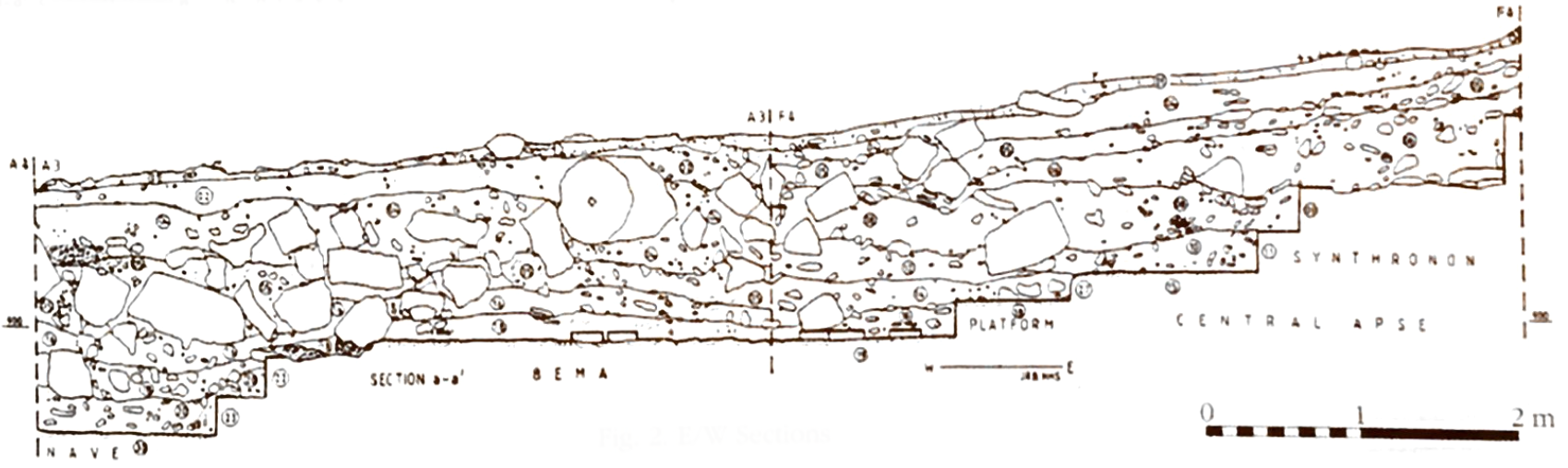

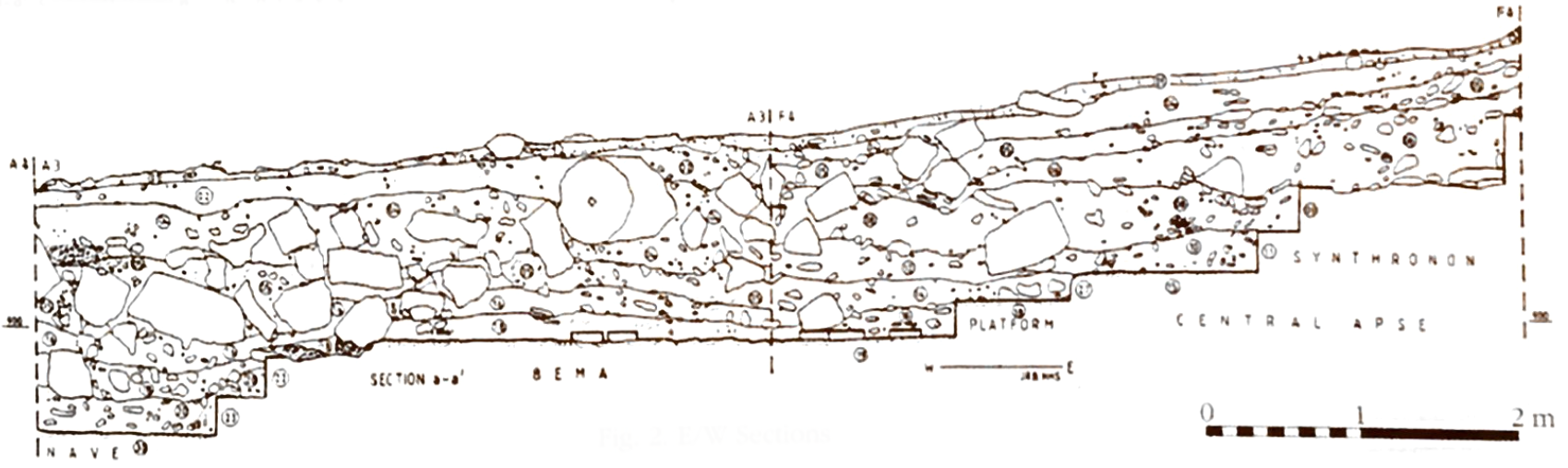

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 2 - E-W section a-a'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E-W sections

Section a-a'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N-S section b-b'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N-S sections

Section b-b'

Fiema et al (2001)

This phase is poorly understood, as is its dating. It was definitely long-lasting, thus requiring further subdivisions. Unfortunately, the stratigraphic sequences of the upper layers in the complex are too fragmentary and enigmatic to interpret. In light of these difficulties, an attempt to connect areas marked by possible human interference into meaningful spatially and temporally defined units would be pure guesswork. Therefore, the following section presents the evidence available as to activities that happened from the second earthquake until modern times. That would include the late Umayyad-Abbasid and Mamluk periods and the early Ottoman period. In the absence of well dated deposits, the association of the walls discussed below with any of these periods is impossible.

The extant remains in the complex indicate the possibility of further earth tremor(s). The indicators, upper stone tumbles, are more difficult to interpret. They may represent a single seismic event or multiple ones in a relatively short time. They also must, at least partially, account for the continuous natural deterioration and decay of the ruins. Separation of major stone collapses as separate loci was successful only in a few places. In the area of the nave, no evidence of collapse beyond that presumably associated with Phase X can be detected.

- Fig. 125 - Collapsed column of the

baptistery from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 125

Fig. 125

Room X, collapsed SE column of the baptistery

Fiema et al (2001)

This room produced the most dramatic evidence for a possible later earthquake. Two or three of the four columns which originally had supported the canopy over the baptismal font broke and collapsed on the surface of E3.30A (Fig. 125). That fall was hardly due to natural deterioration. The drums of the SE column evidently shifted and the shaft broke almost exactly at a level corresponding with the top of locus E3.30A which, by that time, had already filled up the interior. That level was ca. 899.9 m, i.e. about 1.2 m above the room's floor level. Altogether, nine drums of that column fell in a well-aligned row. Four drums of another column, the SW one, were found in the parallel row. Both rows preserved almost exact east-to-west orientation which is in striking contrast to the general north-to-south collapse observed for the first earthquake. A few drums of the third (probably NE) column and a capital fell on the same surface but not in the same orientation as the others. In addition to the column drums, collapse locus E3.29 (=D4.38) contained large quantities of ashlars and other stone material, presumably from the destruction of neighboring walls TT, S, N, and M. The presence of canopy voussoirs outside Wall TT indicates that some of them could also have fallen then, across damaged Wall TT.

- Fig. 125 - Collapsed column of the

baptistery from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 125

Fig. 125

Room X, collapsed SE column of the baptistery

Color Image from ACOR website

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N-S section i-i'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N-S sections

Section i-i'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 2 - E-W section d-d'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E-W sections

Section d-d'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 126 - Plan showing

stone tumble in SE Aisle from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 126

Fig. 126

Stone tumble in the south aisle, probably Phase XIIA. A1.09, 10

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 2 - E-W section a-a'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

E-W sections

Section a-a'

Fiema et al (2001) - Fig. 3 - N-S section b-b'

from Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

N-S sections

Section b-b'

Fiema et al (2001)

In the north apse, this event was represented by an extensive stone tumble, G4.17, which was deposited in the easternmost part of the aisle, including the interior of the apse. The tumble was about 0.5 m deep, originating at ca. 900.3 m and reaching up to 900.9. Glass and stone tesserae and even marble fragments continued in this area. It is possible that a section of that tumble could have originated from stones pushed aside during the activities of the previous phase. The second collapse was also noted in J4.05, although at a slightly higher level (900.6-901 m). That tumble contained several column drums (Fig. 3, section i-i'). Unlike G4, there were practically no finds in Square J4. Locus H4.14 also contained several column drums and larger ashlars. Its bottom was at ca. 900.5 m, and it was visibly separated from the earlier earthquake destruction (Fig. 2, section d-d'). The collapsed column in H3.11, which was found at ca. 900.2 m, might have fallen then, if not before. At any rate, the remaining columns or their broken shafts would now have finally succumbed. Notably, both Squares G4 and J4 clearly preserved what may be termed a third tumble layer.

Tumbles of high density, with many ashlars, were noted in the south apse area. beginning with F2.13 (at ca. 900.2 m) and continuing through F2.10, and 08, the latter with its top at ca. 901.1 m. Like G4, these deposits contained numerous mosaic fragments, glass, plaster flakes and loose tesserae. The confluence of the apse's wall and Wall A in this area are largely responsible for the abundance of stone material there. The destruction associated with Phase XIIA is less apparent farther west in the aisle. Perhaps loci A1.09, 08, 04, B1.04, B2.04, and C1.15, 25 may represent that event, although the density of stone deposition was not high there (Fig. 126). Locus C1.15 yielded interesting, though useless, numismatic evidence. An as of Trajan, struck in commemoration of the annexation of the Nabataean kingdom in A.D. 106 was associated in that stratum with two Late Byzantine nummi from the late 5th-6th century A.D.

The apse presumably survived the first earthquake. However, it fared much less well in the current seismic event. This time the collapse appears to have been complete. Massive tumbles H1.04, 03 = A3.04 covered the area of the bema up to 901.1 m. These are probably associated with tumble loci F4.05, 04 = G2.05, 04 in the apse, which also overlapped the eastern edge of the bema (Fig. 2, section a-a' and Fig. 3, section b-b'). While the bema tumbles still contained some wall mosaic fragments, the amount of that material in the apse loci was substantially less. The pattern of these stone deposits was not clear but it appeared to concentrate toward the west, resembling the pattern noted in the baptistery. The tremor buckled and broke the structure of the semidome resulting in its fall along with the remaining mosaics upon the central and eastern bema. The upper works of the semidome probably fell straight down on the remaining part of the synthronon and the space in Square G2.

The second earthquake apparently deposited substantial stone tumble in the area of the northern rooms.

Loci I.08, 07, 06, excluding the mosaic-rich deposits along Wall T, and II.07, 06 may be reasonably associated

with that event. The matrix of these tumbles was sandy, and the cultural material generally meager but locus

I.06 was abundant in numismatic finds. Two mid-4th century

coins, one late 4th-early 5th century piece, and one Late Byzantine coin were found there. Much more significant was

the find from locus I.08 — large fragments of a greenish-grey, ribbed storage jar, generally dated to the 7th century A.D. The

average level of the deposits in Rooms I and II extended from ca. 900 m to 901.3 m. In the courtyards, the tumble loci were even

more extensive and difficult to separate. Possibly, the collapse there is represented by IIIA.04 = IIIB.06, followed by

IIIA.03=IIIB.05, 04, the latter reaching a level of ca. 901.8 m. The presence of several possibly late 7th century sherds was noted in

IIIB.06 (=J4.15).

Stone tumble loci in the atrium may reflect the impact of the second earthquake there. Particularly, the areas marking the confluences

of walls display upper tumbles. To such belonged D2.43, C1.16, C2.02 (?), I.2.03, 02, and K3.14, 13.

Judging from the depth and density of accumulation, Walls N and YY probably suffered much damage during that

seismic episode, although human interference in the subsequent phase would have been instrumental in changing

the pattern of stone collapse. By then Wall YY was already reduced to a height of barely 1 m above the floor,

either by natural or human forces since Wall B, probably constructed in Phase XIIB, encroached on its remains.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-used ashlars (suggesting collapsed Walls) |

Petra Church | there was seemingly no shortage of architectural elements - including doorjambs, drums, cornices and ashlars - which were reused- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

|

| Re-used drums (suggesting displaced columns and drums) |

Petra Church | there was seemingly no shortage of architectural elements - including doorjambs, drums, cornices and ashlars - which were reused- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

|

| Demolition evidence | Petra Church | massive backfilling of certain spaces with material clearly originating from a demolition- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

|

| Re-used building elements | Petra Church | One telling indication that Phase III was initiated after a devastating earth tremor is the amount of reused stone material, presumably readily available after the disaster. In all the stone-tumble layers excavated in the interiors of the northern rooms and courts - almost 4 m deep - the number of reused doorjambs was simply astonishing. In total, 275 complete stones or recognizable fragments were retrieved from that area.- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Columns and Walls | Atrium,

Porticoes, Aisles, Room I, and

the center of the church

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Sketch-plan of the Petra church with the locations of Rooms I and II as modified from Fiema (2001b) 10 (C. Alexander, Z. T. Fiema and S. Shraideh) Fiema (2007) |

Description

|

|

| Collapsed clerestory walls above the colonnades and collapse of remaining portions of the burned out roof | clerestory walls were

visible from the south exterior of the church

Fig. 25

Fig. 25Proposed axonometric reconstruction of the complex in Phase V Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Collapsed columns | The Nave

notably in the western and central parts including Squares B4 and A4

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 116

Fig. 116The collapse of columns associated with Phase X Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section f-f' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 117

Fig. 117Section g-g'. J2-K1 south balk. Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Column and Wall Collapse | Area of the

nave

and North and South Aisles including squares J4, H2, H3, and G4. Some drums

could have fallen from the top of the bema in the following phase.

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section i-i' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section d-d' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 118

Fig. 118North aisle. fallen column in H3.11 and note the paving slabs in the stratum below. Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section h-h' Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Possible partial vault and wall collapse (stone tumble) and possible roof collapse (many roof tiles found in debris) | The Bema and Central Apse

including squares H1, G2, G4, and F4

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section a-a' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section b-b' Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Minor wall displacement | The south and north side apses

(aka postophorium)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Arch, column, and wall collapse | The Northern Area - Room I (western arch and perhaps other arches collapsed along with upper part of Wall G),

Room II (stone tumbles and upper floor gallery collapse above the

Portico)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 119

Fig. 119Stone tumble in the area of Courtyard IIIA and Room II with Wall F in the center Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Wall collapse | The Atrium -

upper floors of the

porticoes collapsed,

the uppermost parts of Wall XX and the Portico

landed some distance south of the wall, mostly in the area of the stylobate

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section h-h' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20Section Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 117

Fig. 117Section j-j', C1, west balk, Walls Y and Z, elevation Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 120

Fig. 120South portico of the atrium. collapse of the portico's gallery (D1.11) Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 121

Fig. 121Collapse of paving stones from the gallery of the south portico, associated with Phase X, D1.07, 11, 12, 13, 14 Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Collapsed Walls | The Western Rooms - Room XI (southern and western walls collapsed into a thick tumble - indications of 2nd story collapse from pavers),

Room X (stone tumble), large accumulation of

ashlars

observable along Wall TT

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Fractures, folds and popups on regular pavements | Damage to the Mosaic Floors in some areas of both the north and south aisles

particularly visible in the east part of the south aisle, and in the western half of the north aisle, but not restricted to these areas

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Perhaps multi-episode Stone collapse | South (east?) Exterior of the Church and in Squares F2 and A1

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section b-b' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7Walls Y and Z, conduit F2.41 Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fallen Columns | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 125

Fig. 125Room X, collapsed SE column of the baptistery Color Image from ACOR website Fiema et al (2001) |

Two or three of the four columns which originally had supported the canopy over the baptismal font broke and collapsed on the surface of E3.30A (Fig. 125).- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

| Collapsed Walls surmised from ashlar tumble | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

large quantities of ashlars and other stone material, presumably from the destruction of neighboring walls TT, S, N, and M.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

|

| Collapsed Vaults | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

The presence of canopy voussoirs outside Wall TT indicates that some of them could also have fallen then, across damaged Wall TT.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

|

| Fallen Columns | Aisles and Apses

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections Section i-i' Fiema et al (2001) |

That tumble contained several column drums (Fig. 3, section i-i'). ... At any rate, the remaining columns or their broken shafts would now have finally succumbed.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

| Collapsed Walls surmised from ashlar tumble | Aisles and Apses

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections Section d-d' Fiema et al (2001) |

Locus H4.14 also contained several column drums and larger ashlars. Its bottom was at ca. 900.5 m, and it was visibly separated from the earlier earthquake destruction (Fig. 2, section d-d'). ... Tumbles of high density, with many ashlars, were noted in the south apse area.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

| Collapsed Vaults | Apse

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

The apse presumably survived the first earthquake. However, it fared much less well in the current seismic event. This time the collapse appears to have been complete. ... The tremor buckled and broke the structure of the semidome resulting in its fall along with the remaining mosaics upon the central and eastern bema. The upper works of the semidome probably fell straight down on the remaining part of the synthronon and the space in Square G2.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | Atrium

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Walls N and YY probably suffered much damage during that seismic episode, although human interference in the subsequent phase would have been instrumental in changing the pattern of stone collapse. By then Wall YY was already reduced to a height of barely 1 m above the floor, either by natural or human forces since Wall B, probably constructed in Phase XIIB, encroached on its remains.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

- Modified by JW from Fiema et al (2001)

- Some of the specific structures which fell or were damaged (e.g. columns and walls) are guesstimated

- Fiema et al (2001) noted a preferred N-S direction of collapse in this phase

- Modified by JW from Fiema et al (2001)

- Some of the specific structures which fell (e.g. columns and walls surrounding the nave and columns over the baptistery) are guesstimated

- Fiema et al (2001) noted a preferred E-W direction of collapse in this phase

- Modified by JW from Fiema et al (2001)

- Some of the specific structures which fell or were damaged (e.g. columns and walls) are guesstimated

- Fiema et al (2001) noted a preferred N-S direction of collapse in Phase X (left)

- Fiema et al (2001) noted a preferred E-W direction of collapse in Phase XIIA (right)

Deformation Map

Deformation Mapmodified by JW from Figure 4a of Fiema et al (2001)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re-used ashlars (suggesting collapsed Walls) |

Petra Church | there was seemingly no shortage of architectural elements - including doorjambs, drums, cornices and ashlars - which were reused- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

VIII+ | |

| Re-used drums (suggesting displaced columns and drums) |

Petra Church | there was seemingly no shortage of architectural elements - including doorjambs, drums, cornices and ashlars - which were reused- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

VIII+ | |

| Demolition evidence | Petra Church | massive backfilling of certain spaces with material clearly originating from a demolition- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

? | |

| Re-used building elements | Petra Church | One telling indication that Phase III was initiated after a devastating earth tremor is the amount of reused stone material, presumably readily available after the disaster. In all the stone-tumble layers excavated in the interiors of the northern rooms and courts - almost 4 m deep - the number of reused doorjambs was simply astonishing. In total, 275 complete stones or recognizable fragments were retrieved from that area.- Fiema et al (2001:18) |

? |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Columns and Walls | Atrium,

Porticoes, Aisles, Room I, and

the center of the church

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Sketch-plan of the Petra church with the locations of Rooms I and II as modified from Fiema (2001b) 10 (C. Alexander, Z. T. Fiema and S. Shraideh) Fiema (2007) |

Description

|

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed clerestory walls above the colonnades and collapse of remaining portions of the burned out roof | clerestory walls were

visible from the south exterior of the church

Fig. 25

Fig. 25Proposed axonometric reconstruction of the complex in Phase V Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed columns | The Nave

notably in the western and central parts including Squares B4 and A4

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 116

Fig. 116The collapse of columns associated with Phase X Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section f-f' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 117

Fig. 117Section g-g'. J2-K1 south balk. Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

V+ or VIII+ |

| Column and Wall Collapse | Area of the

nave

and North and South Aisles including squares J4, H2, H3, and G4. Some drums

could have fallen from the top of the bema in the following phase.

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section i-i' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section d-d' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 118

Fig. 118North aisle. fallen column in H3.11 and note the paving slabs in the stratum below. Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section h-h' Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Possible partial vault and wall collapse (stone tumble) and possible roof collapse (many roof tiles found in debris) | The Bema and Central Apse

including squares H1, G2, G4, and F4

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section a-a' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section b-b' Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VIII+ |

| Minor wall displacement | The south and north side apses

(aka postophorium)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VII+ | |

| Arch, column, and wall collapse | The Northern Area - Room I (western arch and perhaps other arches collapsed along with upper part of Wall G),

Room II (stone tumbles and upper floor gallery collapse above the

Portico)

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 119

Fig. 119Stone tumble in the area of Courtyard IIIA and Room II with Wall F in the center Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

|

| Wall collapse | The Atrium -

upper floors of the

porticoes collapsed,

the uppermost parts of Wall XX and the Portico

landed some distance south of the wall, mostly in the area of the stylobate

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections section h-h' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20Section Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 117

Fig. 117Section j-j', C1, west balk, Walls Y and Z, elevation Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 120

Fig. 120South portico of the atrium. collapse of the portico's gallery (D1.11) Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 121

Fig. 121Collapse of paving stones from the gallery of the south portico, associated with Phase X, D1.07, 11, 12, 13, 14 Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VIII+ |

| Collapsed Walls | The Western Rooms - Room XI (southern and western walls collapsed into a thick tumble - indications of 2nd story collapse from pavers),

Room X (stone tumble), large accumulation of

ashlars

observable along Wall TT

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VIII+ | |

| Fractures, folds and popups on regular pavements | Damage to the Mosaic Floors in some areas of both the north and south aisles

particularly visible in the east part of the south aisle, and in the western half of the north aisle, but not restricted to these areas

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VI+ | |

| Perhaps multi-episode Stone collapse | South (east?) Exterior of the Church and in Squares F2 and A1

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections section b-b' Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7Walls Y and Z, conduit F2.41 Fiema et al (2001) |

Description

|

VIII+ |

Generally, the intensity of the first major tremor which affected the complex does not suggest a total catastrophe. Rather, the magnitude of destruction indicates a moderate earthquake, probably comparable to grades VII-VIII on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale (MMS).

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Atrium

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Walls N and YY probably suffered much damage during that seismic episode, although human interference in the subsequent phase would have been instrumental in changing the pattern of stone collapse. By then Wall YY was already reduced to a height of barely 1 m above the floor, either by natural or human forces since Wall B, probably constructed in Phase XIIB, encroached on its remains.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed Walls surmised from ashlar tumble | Aisles and Apses

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2E-W sections Section d-d' Fiema et al (2001) |

Locus H4.14 also contained several column drums and larger ashlars. Its bottom was at ca. 900.5 m, and it was visibly separated from the earlier earthquake destruction (Fig. 2, section d-d'). ... Tumbles of high density, with many ashlars, were noted in the south apse area.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ |

| Collapsed Walls surmised from ashlar tumble | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

large quantities of ashlars and other stone material, presumably from the destruction of neighboring walls TT, S, N, and M.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed Vaults (?) | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

The presence of canopy voussoirs outside Wall TT indicates that some of them could also have fallen then, across damaged Wall TT.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ | |

| Collapsed Vaults | Apse

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

The apse presumably survived the first earthquake. However, it fared much less well in the current seismic event. This time the collapse appears to have been complete. ... The tremor buckled and broke the structure of the semidome resulting in its fall along with the remaining mosaics upon the central and eastern bema. The upper works of the semidome probably fell straight down on the remaining part of the synthronon and the space in Square G2.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ | |

| Rotated and displaced masonry blocks in walls and drums and columns | Aisles and Apses

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3N-S sections Section i-i' Fiema et al (2001) |

That tumble contained several column drums (Fig. 3, section i-i'). ... At any rate, the remaining columns or their broken shafts would now have finally succumbed.- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ |

| Rotated and displaced masonry blocks in walls and drums and columns | Room X

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4aGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001)

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bGeneral plan of the site, showing the locations of rooms, walls, soundings, excavation squares, and sections Fiema et al (2001) |

Fig. 125

Fig. 125Room X, collapsed SE column of the baptistery Color Image from ACOR website Fiema et al (2001) |

Two or three of the four columns which originally had supported the canopy over the baptismal font broke and collapsed on the surface of E3.30A (Fig. 125).- Fiema et al (2001:115-117) |

VIII+ |

Bikai, Pierre M. 1996. “Petra Church Project, Petra Papyri.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 40: 487–489.

Bikai, P. M. (2002). The churches of Byzantine Petra, in Petra. Near Eastern Archeology, 116, 555-571

Fiema, Z. T. 2003. “The Byzantine Church in Petra.” In Petra Rediscovered:

The Lost City of the Nabataeans, edited by G. Markoe, 238–249. New York : Harry N. Abrams in association with the Cincinnati Art Museum .

Fiema, Z. T. 2007. “Storing in the Church: Artefacts in Room I of the Petra Church.” In Objects in Context,

Objects in Use. Late Antiquity Archaeology, Volume 5, edited by L. Lavan, E. Swift, and T. Putzeys, 607–623. Leiden: Brill.

Korzhenkov, A. et.al., 2016, Следы землетрясений в затерянном городе (Earthquake trails in a lost city), Nature 43

Marii, F. and M. O’Hea.2013. “A New Approach to Church Liturgy in Byzantine Arabia / Palestinia Tertia:

Chemical Analysis of Glass from the Petra Church and Dayr ‘Ayn ‘Abāṭa Monastery.” Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 11: 319–326.

Porter, B.A. (2011) The Petra Church Revisited: 1992-2011 ACOR Newsletter Vol 23.2 Winter 2011

Rucker, J. D. and T. M. Niemi (2010). "Historical earthquake catalogues and archaeological data: Achieving synthesis without

circular reasoning." Geological Society of America Special Papers 471: 97-106.

Sodini, J. (2002). La basilique de la Vierge Marie de Pétra et les églises de Jordanie in

Z. T. Fiema, C. Kanellopoulos, T. Waliszewski and R. Schick, THE PETRA CHURCH

(P. M. Bikai editor; American Center of Oriental Research, Amman 2001). Pp. xv 447, 449

dessins et photos, 30 pl. couleur, ISBN 9957-8543-0-5. - A. Michel, L

ES ÉGLISES D'ÉPOQUE BYZANTINE ET UMAYYADE DE LA JORDANIE Ve-VIIIe S.

TYPOLOGIE ARCHITECTURALE ET AMÉNAGEMENTS LITURGIQUES (Bibliothèque de

Antiquité Tardive 2; Brepols, Turnhout 2001). 471 p., 407 figs. ISBN 2-503-51172-4.

Journal of Roman Archaeology, 15, 691-699.

Sodini, J. (2003). CORRIGENDA TO JRA 15 (2002). Journal of Roman Archaeology, 16, 768-768.

Fiema, Z. T., et al. (2001). The Petra Church, American Center of Oriental Research.

Frösén, J., A. Arjava, and M. Lehtinen. (eds.). 2002. The Petra Papyri I. Amman: ACOR.

Koenen, L., J. Kaimio, M. Kaimio, M. and R. W. Danie (eds.). 2003. The Petra Papyri II. Amman: ACOR .

Arjava, A., M. Buchholz, and T. Gagos. (eds.). 2007. The Petra Papyri III. Amman: ACOR.

Arjava, A., M. Buchholz, T. Gagos, M. and Kaimio. (eds.). 2011. The Petra Papyri IV. Amman: ACOR .

Arjava, A., J. Frösén, and J. Kaimio (eds.). 2018. The Petra Papyri V. Amman: ACOR .

Photos of the Petra Church at ACOR (many photos of collapse debris uncovered during excavations)

The Petra Church at ACOR

Bibliography for the Petra Church at ACOR

Petra at Zamani Project (Includes 3D Images and Plans)

Photos of the Petra Church at Manar Al-Athar (Oxford University)

Byzantine Churches of Petra at Madain Project

Byzantine Church, Petra at Sacred Destinations

Byzantine Church Petra at Universes in Universe

| Figure | Image | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4c |

Figure 4c

Figure 4cPetra Church through-going cracks in the Great Church of Petra, piercing several stone blocks. For them to arise. A huge amount of energy needs to be released. Korzhenkov et al (2016) |

through-going cracks | Korzhenkov et al (2016) |