Omrit

Horvat Omrit - View of the Temple Complex

Horvat Omrit - View of the Temple ComplexStern et al (2008)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Omrit | Hebrew | אומריט |

| Horbat Omrit | Hebrew | הורבט אומריט |

Omrit, located in the foothills of the Hermon range ~4 km. SW of Banias

was at the crossroads of the Tyre-Damascus and Scythopolis-Damascus routes and on the border between the

Galilee and Iturea

(J. Andrew Overman in Stern et al, 2008).

Overman in Stern et al (2008)

suggests that the Temple at Omrit may have marked the entrance to Iturea or the

related region of Banias

. Excavations have revealed Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine remains along with a brief

transient occupation in the 13th century CE

(J. Andrew Overman in Stern et al, 2008).

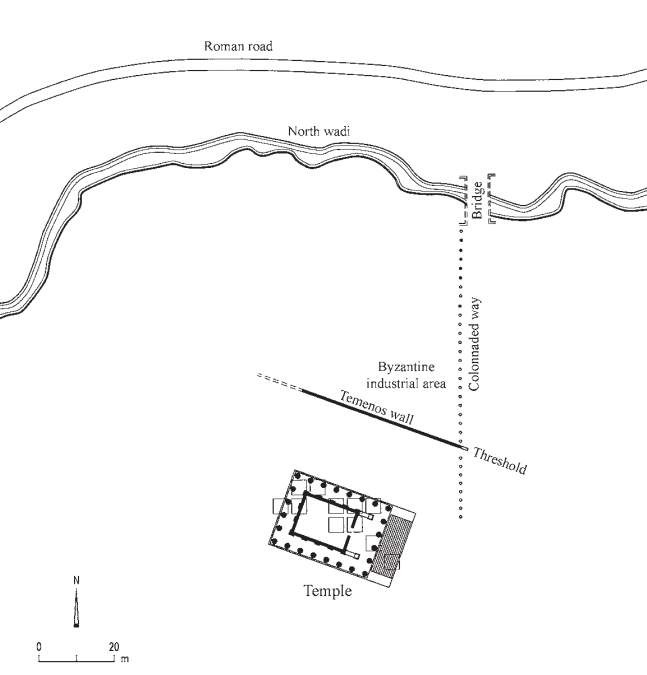

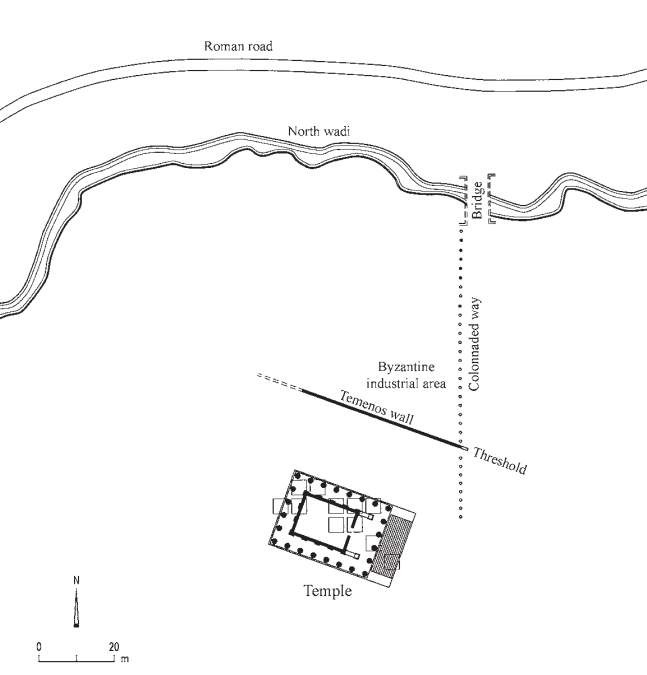

Ḥorvat Omrit is located in the foothills of the Hermon Range, 4 km southwest of Banias and east of the modern city of Qiryat Shemona. It stood near the crossroads of the ancient Tyre–Damascus and Scythopolis–Damascus routes, and on the border of Galilee and Iturea. Topographically, it is situated on the eastern side of the Ḥula Valley, where the terrain rises toward the Hermon, several kilometers southwest of the Damascus Pass. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, Omrit was part of the disputed and somewhat unruly region of Iturea (Strabo Geog. 16.2, 18). The temple at Omrit may have marked the entrance into Iturea or the related region of Banias. This rugged, mountainous area changed hands several times during the first century BCE. After the Battle of Actium, Augustus handed it over to Herod, who was charged with restoring order to it. With his characteristic brutal hand and equally audacious building program, Herod brought the region under his and Augustus’ control (Josephus, Antiq. XV, 344).

Archaeological excavations began at Ḥorvat Omrit in 1999, under the direction of J. A. Overman, with the support of Macalester College of St. Paul, Minnesota. A preliminary probe of the area had been conducted in 1974 by a team headed by G. Foerster of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Distinguishable on the site were substantial structures with numerous architectural features still standing, some in situ, as well as an extensive complex with multiple buildings, a colonnaded way, and an ornate, extremely well-preserved temple-like building. Five seasons of excavations have been completed so far, focusing primarily on the temple complex.

- Plan of Horvat Omrit Site

from Stern et al (2008)

Horvat Omrit, Plan of the Site

Horvat Omrit, Plan of the Site

Stern et al (2008)

- Reconstruction of the

Temple at Omrit from Wikipedia

Omrit (Hebrew: חורבת עומרית, romanized: Horvat Omrit) is the site of an ancient Roman temple in

the northeast corner of the Hula Valley in Israel, near the modern moshav of She'ar Yashuv. It is believed that Omrit

was built by Herod the Great in honor of Emperor Augustus around 20 BCE.

Omrit (Hebrew: חורבת עומרית, romanized: Horvat Omrit) is the site of an ancient Roman temple in

the northeast corner of the Hula Valley in Israel, near the modern moshav of She'ar Yashuv. It is believed that Omrit

was built by Herod the Great in honor of Emperor Augustus around 20 BCE.

Picture is from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem

Click on Image to see magnifiable high res version in a new tab

Tom Bahar - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 4.0 - Plan of Temple I (late 1st century BCE)

from Stern et al (2008)

Temple I - late 1st century BCE

Temple I - late 1st century BCE

Stern et al (2008) - Plan of Temple II (early 2nd century CE)

from Stern et al (2008)

Temple II - early 2nd century CE

Temple II - early 2nd century CE

Stern et al (2008) - Fig. 15 - Temple I & Temple II

site plan from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

Nelson et al (2015) - Fig. 15 - Closeup on Wall WF4

in Temple I&II site plan (Fig. 15) from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S

Nelson et al (2015)

- Fig. 15 - Temple I & Temple II

site plan from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

Nelson et al (2015) - Fig. 15 - Closeup on Wall WF4

in Temple I&II site plan (Fig. 15) from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S

Nelson et al (2015)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ES | Late Hellenistic | 125-100 BCE |

|

| ES1 | The Early Shrine | — |

|

| ES2 | The Early Shrine | 50 BCE - 50 CE |

|

| T1 | Temple One (T1) | 50 BCE - 50 CE |

|

| T2 | Temple Two (T2) | 53/54 CE - 80/81 CE |

|

| — | — | 4th to 5th Century CE |

|

| — | — | Early 7th Century |

|

| — | — | 12th to the 13th Century |

|

- Fig. 15 - Temple I & Temple II

site plan from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

Nelson et al (2015) - Fig. 15 - Closeup on Wall WF4

in Temple I&II site plan (Fig. 15) from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S

Nelson et al (2015) - Fig. 22 - Different building

phases on wall wF4 from Nelson et al (2015)

FIGURE 22

FIGURE 22

wall wF4 (from east)

Nelson et al (2015)

Nelson et al (2015:5) reports the following:

At some point during T1’s use phase, wall wF4 needed a repair (Fig. 15). It was originally built as a bonded cross-wall of P1 to support the east cella wall of T1. Later it served the same purpose for T2. However, the wall’s masonry exhibits two phases of construction, or rather, one phase of construction, followed by one phase of repair (Fig. 22

FIGURE 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S

Nelson et al (2015)). The southern half was built with P1 style masonry of dry-laid ashlars with tight fitting joints between both blocks and courses. The northern half was built with P2 style masonry of roughly-chiseled, marginally-drafted ashlars laid with a bit of mortar. In addition, there was a change in course height for the upper courses in the northern half which resulted in an awkward series of horizontal and vertical joints running down the middle of the wall.

FIGURE 22

wall wF4 (from east)

Nelson et al (2015)

Thus, wall wF4 apparently failed at some point in time but the cause of the failure must be left to speculation. An ashlar block or two within wF4 may have cracked and crushed along an unnoticed internal fissure in the stone. A fire may have caused the collapse of the roof tree or its trusses which pulled down a cella wall or two. Or, an earthquake severely jolted the building which perhaps knocked down its superstructure. Regardless, because of an internal failure or an external destructive force, wall wF4 needed a repair. The timing of this building activity is not precisely known but it may have occurred with the construction of T2 because the new blocks used in the repair were shaped and assembled in the manner of P2 masonry rather than imitating the masonry of P1. In addition, small repairs with mortar and chinking stones were made here and there on the inner faces of P1.

- Fig. 15 - Temple I & Temple II

site plan from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

Nelson et al (2015) - Fig. 15 - Closeup on Wall WF4

in Temple I&II site plan (Fig. 15) from Nelson et al (2015)

Figure 15

Figure 15

T1 and T2 state plan.

JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S

Nelson et al (2015)

Nelson et al (2015:6 footnote 19) reports that

Stoehr (2011:ch 7) discusses potential earthquake damage to T2.

Stoehr (2018:127-130) reports on damage to the third Temple which appears to be the same as T2:

The third temple was built to encase and mimic the second temple, which itself duplicated many of the features of the first temple, but on a larger scale.

... At some point near the end of the fourth century the third temple was severely damaged, likely the result of the large earthquake of 363 CE.

... The Omrit temple was not repaired, presumably because the social environment had changed, and instead a small Christian chapel was later constructed in the temenos, and much of the material from the temple quarried away. This chapel, about 25 feet long, had an apse on one end. It was built to incorporate the remains of the temple’s large altar as the foundation of its north wall. It is of uncertain date.

Another new structure, probably also a church, was under construction but likely never completed. It utilized most of the remaining temple podium. It appears to have incorporated some still-standing remnants of the original cella and colonnade, but replaced the floor which had most likely been damaged beyond repair by the earthquake of 363 CE. The floor was primarily rebuilt with items in secondary use, including spolia that probably came from the original temple such as an interior column base and pieces of marble revetment. In fact, ceramic and numismatic evidence indicates that the Byzantine builders actually excavated the fill out of some parts of the temple's substructure, before replacing it with their own fill that largely consisted of basalt boulders. This may have been because they wanted to assess the structural integrity of the foundations prior to starting new construction. A range of coins found in this later fill suggest a date of sometime around the second half of the fourth century.

... An architrave block which had evidently fallen was used to block the original temple door. The date for this modification is unclear, but perhaps a new entrance and orientation for the building was planned. Alternatively, this may have been an attempt to block access to a dangerous building, the original temple.

... Industrial facilities such as wine or olive presses, as well as other unidentified buildings, were constructed within the temenos. Some of these later facilities were built up against the side of the temple podium.

... Some temple blocks, such as corner pilaster capitals, fell onto the remains of these later buildings, after these later buildings had themselves already been largely quarried away. The find-spots for such fallen blocks are virtually the same as the original placements for the blocks in the Roman temple. They seem to have simply fallen from the higher courses of walls. Whatever the large new building on the podium might have been (or might have been intended to be) it likely incorporated recognizable temple components in their original positions, implying that a large section of the original building was intact and had been used in more-or-less its original state.202 The hybrid building was still standing, almost certainly in a partial state, into medieval times.

Quarrying over a long period of time is evident. Temple blocks, and columns from the propylaea of the temple, were found by the excavators in isolated small piles at other locations within the temenos. They give the appearance of having been loosely sorted by type, suggesting ongoing quarrying activity.203 The quarrying of materials at Omrit seems to have been a perpetual activity going into the thirteenth century. It thus seems best to characterize the final fate of the Roman temple at Omrit as "conversion to an active spoliation site."

Because the original intention seemed to be to Christianize the site, and because the work to this end (on the foundation and stylobate of the temple) began shortly after the earthquake, this also seems to be an example of a temple converted to a church. In fact, the evidence suggests that the cella was incorporated into the new building, a relatively unusual occurrence in Palestine.

Overman in Stern et al (2008)

reports that an earthquake in the middle of the eighth century CE appears to have brought about the final destruction of the site and its abandonment

.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls | Temple I - wall wF4

FIGURE 15

FIGURE 15T1 and T2 state plan. JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S Nelson et al (2015) |

FIGURE 22

FIGURE 22wall wF4 (from east) Nelson et al (2015) |

At some point during T1’s use phase, wall wF4 needed a repair (Fig. 15)- Nelson et al (2015:5) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Damage | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

|

| Damaged Floor | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

|

| Fallen columns | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

|

| Displaced Walls suggested by fallen architrave block | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 15 from Nelson et al (2015)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 15 from Nelson et al (2015)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls | Temple I - wall wF4

FIGURE 15

FIGURE 15T1 and T2 state plan. JW: Closeup on Wall WF4. WF4 is oriented N-S Nelson et al (2015) |

FIGURE 22

FIGURE 22wall wF4 (from east) Nelson et al (2015) |

At some point during T1’s use phase, wall wF4 needed a repair (Fig. 15)- Nelson et al (2015:5) |

VII+ |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fallen columns | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

V+ or VIII+ | |

| Displaced Walls suggested by fallen architrave block | Temple

Figure 15

Figure 15T1 and T2 state plan. Nelson et al (2015) |

|

VII+ |

Nelson, M. C., et al. (2015). The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: Volume 1: The Architecture, Brill.

Overman, J. A., et al. (2021). The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: Volume 2: The Stratigraphy, Ceramics, and Other Finds, BRILL.

Overman, J. A. and D. N. Schowalter (2011). The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report, Archaeopress.

Stoehr, Gregory. 2011. Chapter Seven: The Potential for Earthquake Damage to Temple Two Architecture at Roman Omrit in

Overman, J. A. and D. N. Schowalter (2011). The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report, Archaeopress.

Stoehr, Gregory. 2018 The End of Pagan Temples in Roman Palestine PhD Dissertation University of Maryland

G. Foerster, Archaeological Newsletter 4 (1978), 65–66

M. L. Fischer, Das korinthische Kapitell im Alten

Israel in der hellenistischen und römischen Periode: Studien zur Geschichte der Baudekoration im Nahen

Osten, Mainz am Rhein 1990

BAR 29/1 (2003), 57

J. A. Overman (et al.), ibid. 29/2 (2003), 40–49, 67–68;

id., When Judaism and Christianity Began (A. J. Saldarini Fest.

Suppls. to the Journal for the Study of

Judaism 85

eds. D. Harrington et al.), Leiden 2003

id., Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für

Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 10 (2004), 192–194.