Jerash - Hippodrome

Restored Hippodrome at Jerash with Hadrian's Arch in the front and to the right.

Restored Hippodrome at Jerash with Hadrian's Arch in the front and to the right.APAAME

Excavations at the Hippodrome in Jerash reveal that it was first constructed in the mid to late 2nd century CE atop an earlier necropolis. It went out of use as a racetrack in the mid 3rd - mid 4th century CE due to deterioration of the structure. The site was used for various domestic and industrial activities until the 7th century after which it served as a burial ground and suffered earthquake damage in the 7th and 8th centuries (Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz, 2020).

- from Chat GPT 4o, 21 June 2025

- sources: Wikipedia: Jerash Hippodrome

Though never completed to full height, the hippodrome shows evidence of use and later modification during the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. In the modern era, the structure was partially restored and used for staged ludi and chariot shows, which ceased in the early 21st century.

Today, the hippodrome remains a prominent feature of the archaeological park at Jerash, offering insight into the urban planning and public entertainments of Roman provincial cities in the Levant.

- from Jerash - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 22 - Plan of hippodrome

(2nd and 3rd centuries CE) from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 22

Figure 22

P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing

(A.O.1995)

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) - Fig. 19 - E-W cross section of

Hippodrome showing potential foundation problems from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992)

JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement

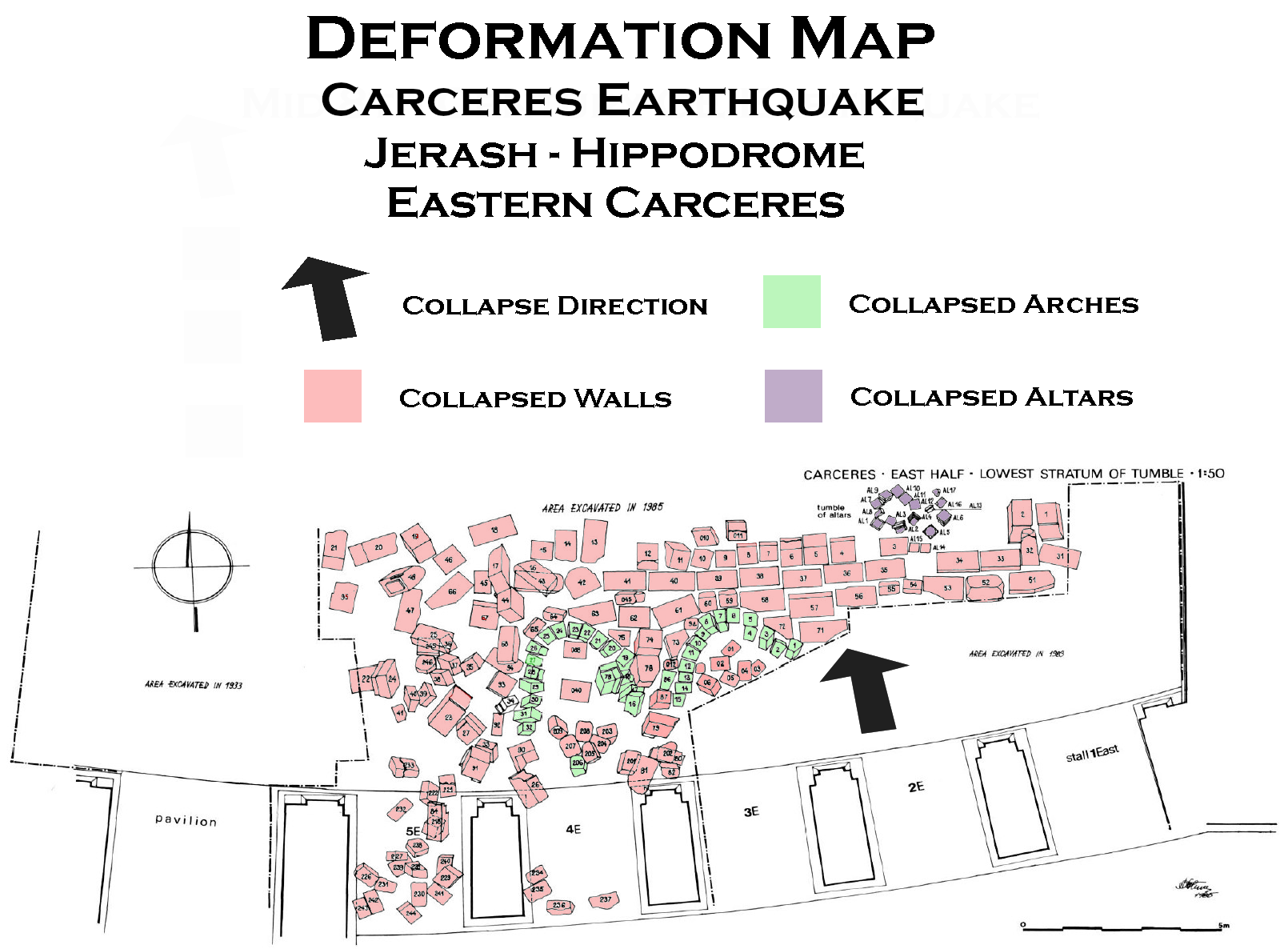

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) - Fig. 4 - Tumble layer

from mid 8th century earthquake from Ostrasz (1989)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Carceres.

East half.

Lowest stratum of tumble

JW: Note uniformity of tumble where collapsed arches appear visible

Ostrasz (1989) - Fig. 21 - Perspective

view of part of carceres from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 21

Figure 21

Perspective view of part of carceres

(A.O.1992)

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

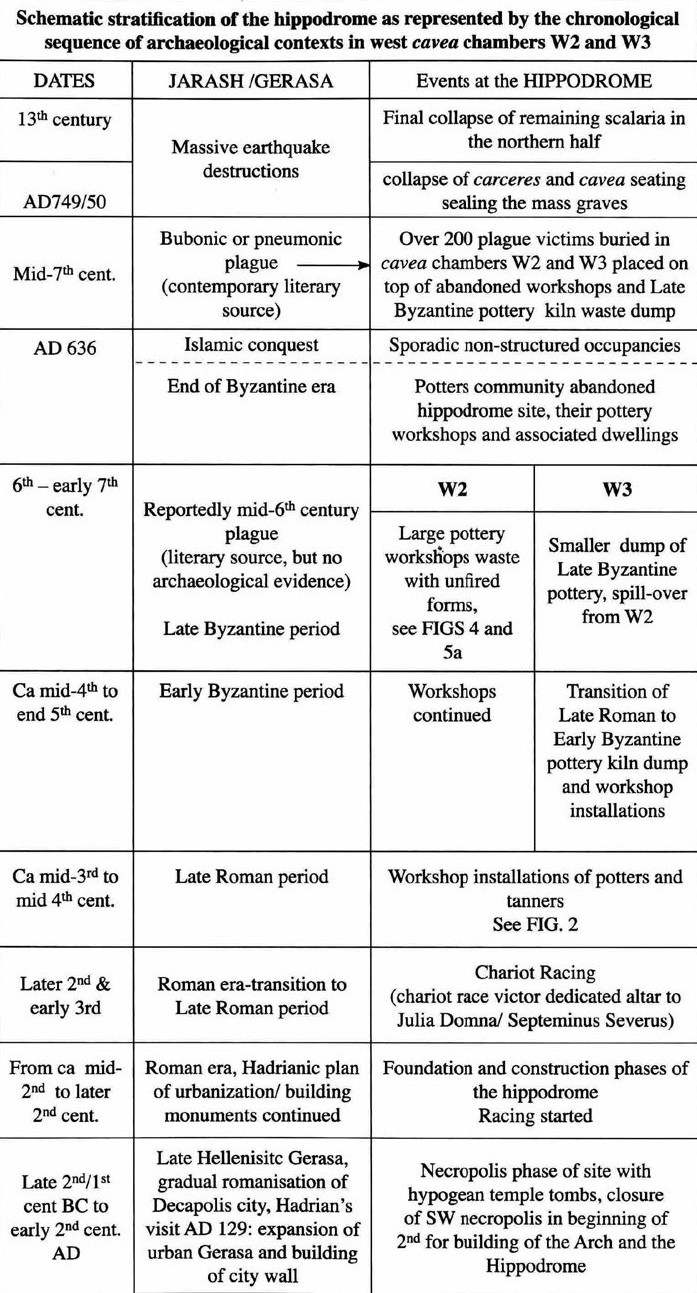

Figure 184

Figure 184Schematic Chronological chart of the Hippodrome complex showing phases of primary use and secondary occupancies

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

| Strata label | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Stm.0 | All these phases in the history of the building were witnessed by the stratigraphical composition of the fill over, inside and outside/along the architectural remains of the monument. In no place inside and along the building were found more than four superimposed distinct layers of fill. Everywhere the upper one was the sedimentary layer composed of greyish dirt, usually a score of centimetres thick. This layer is labelled Stm.0. |

|

| Stm.1 | Underneath there was the layer of the tumbled masonry. Depending on the place, and on the extent of the stone robbing activity, this layer was from 1m to 4.5m thick. It was composed mainly of the fallen dressed stones of the superstructure of the cavea but often also of a proportion of the dress stones of the outer and transverse walls, and in every case of boulders and stone chips which the builders of the hippodrome used for the construction of the walls (infra:...). All the stones were found immersed in red clayish earth which the builders used as a kind of `mortar' of the masonry (loc.cit). This layer - almost everywhere the main one in bulk - is labelled Stm.1. |

|

| Stm.2 | In some chambers of the cavea (and in all the stalls of the cavea) the layer labelled Stm.1 lay directly on the `floor' of the chambers (stalls). However, in most chambers there was an intervening layer between the bottom of Stm.1 and the `floor'. In some chambers, or in some places of one chamber, this layer was composed either of greyish soil or of this kind of soil mixed with red earth or the red earth only. This layer of the fill was always associated with intrusive structures built in the chambers or with traces of intrusive activity. This layer is labelled Stm.2. |

|

| Stm.3 | The lowest layer is the bulk of the red clayish earth of which the builders of the hippodrome formed the platform of the arena and the walking surface around the building and with which they filled in the space within the foundation walls of the chambers. The `floor' of the chambers was just the top of this red earth fill [see n.9]. This lowest layer is labelled Stm.3. In no chamber was there found evidence for any kind of true flooring ascribable to the primary structure of the hippodrome. In chambers E41-E53 the `floor' is the unlevelled surface of rock [see n.8, I.K.]. |

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 22 - Plan of hippodrome

(2nd and 3rd centuries CE) from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 22

Figure 22

P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing

(A.O.1995)

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) - Fig. 19 - E-W cross section of

Hippodrome showing potential foundation problems from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992)

JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:142)

report that the Hippodrome was already being quarried by the

end of the 4th century CE. They write that "the hippodrome

was already quarried for stone by the end of the 4th C. A

number of its seat stones was used for rebuilding (repairing)

a stretch of the city wall, which according to an inscription

mentioning the event and its date took place in 390

(ZAYADINE 1981a, p. 346)."

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:315)

also report that potters and other craftsmen took over the

structure starting at the end of the 3rd century CE.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:142)

suggest the possibility that an earthquake had damaged the

structure to such an extent that it could no longer be used

for racing. They write, "It is clear that the SW part of the

cavea had collapsed at a

certain date and that once this happened no races could be

held. This occurrence would best explain the reoccupation of

and quarrying for stone in the hippodrome. There is no direct

evidence for dating the collapse of that part of the

cavea but it is tempting to

associate it with the earthquake of 363 which affected many

sites in Palestine and NW Arabia (RUSSELL 1985, p. 39, 42).

This earthquake has not been attested at Jerash so far but the

study of the earthquakes which affected Gerasa is only in its

infancy."

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:60)

noted that upper parts of the hippodrome were the most affected

— "before an earthquake ultimately destroyed the gate, the upper

parts of the hippodrome were either dismantled or partly

destroyed by an earlier earthquake." Further discussion appears

in Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:36), where

they state: "The presence of the stones belonging to the upper

parts of the building used in the passageway of the gate in the

period of the intrusive occupancy (supra: THE MAIN GATE) and the

presence of the architrave pieces in chamber E2 used there in the

same period concurs to strengthen the possibility that before an

earthquake finally destroyed the north part of the building there

might have occurred an earlier earthquake which partly destroyed

the masonry at its upper level. Still, the human factor

(dismantling) cannot be ruled out."

The early in their report suggestion of seismic damage was revised later in the report by

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:150), where

they state that "the building ceased to serve the primary purpose

[] because of the disintegration of a large part of its masonry

and of the arena," and that "the disintegration

was caused by the extremely poor foundation of the structure."

Foundation problems, including estimates of foundation pressures,

are discussed in detail in

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:157).

An E–W cross section of a part of the Hippodrome illustrates

potential foundation problems (Fig. 19), where an uncompacted

fill of variable thickness lies underneath the majority of the

structure — something which could have easily led to differential

settlement.

Although foundation problems appear to be present, this does not

preclude the possibility that seismic damage contributed to the

demise of the Hippodrome as a racing facility. As

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) were

unaware of the mid–3rd century CE

Capitolias Theater Quake, if

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:315) have

correctly dated occupation of the structure by potters and other

craftsmen to the end of the 3rd century CE, the possibility exists

that the Hippodrome was damaged by an earthquake sometime in the

3rd century.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:142) report that the Hippodrome was used for quarrying by the late 4th century CE.

The hippodrome was already quarried for stone by the end of the 4th C. A number of its seat stones was used for rebuilding (repairing) a stretch of the city wall, which according to an inscription mentioning the event and its date took place in 390 (ZAYADINE 1981a, p. 346).Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:315) report evidence that potters and other craftsmen took over the structure starting at the end of the 3rd century CE. Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:142) suggested the possibility that an earthquake had damaged the structure to such an extent that it could no longer be used for racing.

It is clear that the SW part of the cavea had collapsed at a certain date and that once this happened no races could be held. This occurrence would best explain the reoccupation of and quarrying for stone in the hippodrome. There is no direct evidence for dating the collapse of that part of the cavea but it is tempting to associate it with the earthquake of 363 which affected many sites in Palestine and NW Arabia (RUSSELL 1985, p. 39, 42). This earthquake has not been attested at Jerash so far but the study of the earthquakes which affected Gerasa is only in its infancy.Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:60) noted that upper parts of the hippodrome were the most affected -

before an earthquake ultimately destroyed the gate, the upper parts of the hippodrome were either dismantled or partly destroyed by an earlier earthquake.Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:36) discussed this possible archaeoseismic evidence further

The presence of the stones belonging to the upper parts of the building used in the passageway of the gate in the period of the intrusive occupancy (supra: THE MAIN GATE) and the presence of the architrave pieces in chamber E2 used there in the same period concurs to strengthen the possibility that before an earthquake finally destroyed the north part of the building there might have occurred an earlier earthquake which partly destroyed the masonry at its upper level. Still, the human factor (dismantling) cannot be ruled out.The suggestion of seismic damage stemmed from earlier publications which was later revised by Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:150) where they state that

the building ceased to serve the primary purpose [] because of the disintegration of a large part of its masonry and of the arenawhere

the disintegration was caused by the extremely poor foundation of the structure.Foundation problems, including estimates of foundation pressures, are discussed in detail in Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:157). An E-W cross section of a part of the Hippodrome illustrates potential foundation problems (Fig. 19) where an uncompacted fill of variable thickness lies underneath the majority of the structure - something which could have easily led to differential settlement. Although foundation problems appear to be present, this does not preclude the possibility that seismic damage contributed to the demise of the Hippodrome as a racing facility. As Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) were unaware of the mid 3rd century CE Capitolias Theater Quake, if Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:315) have correctly dated occupation of the structure by potters and other craftsmen to the end of the 3rd century CE, the possibility exists that the Hippodrome was damaged by an earthquake sometime in the 3rd century.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 21 June 2025

- from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

According to Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:315), the Hippodrome was reoccupied at the end of the 3rd century CE by potters and other craftsmen. Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:142) suggest that the collapse of the southwest part of the cavea may have rendered the building unusable for racing, leading to its reuse and eventual stone robbing. While they note the lack of direct evidence for the date of the collapse, they state that an event “would best explain” the later reoccupation and quarrying of the site. They propose a tentative association with the 363 CE Cyril Quakes, which affected many sites in Palestine and northwestern Arabia, though they acknowledge that this earthquake has not yet been documented at Jerash and that the study of earthquakes at the site is still in its early stages.

In Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:60), the authors also note that the upper parts of the Hippodrome were either dismantled or partly destroyed by an earlier earthquake prior to a later event that finally destroyed the gate. In a later section, Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:36) state that the reuse of architectural blocks and presence of large structural fragments in secondary contexts “strengthens the possibility” that a pre-final earthquake may have damaged the upper masonry, though they allow that dismantling cannot be ruled out.

Ultimately, Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:150) shift emphasis away from seismic damage and instead attribute the loss of function to severe deterioration of the foundations. They state that the Hippodrome ceased to function as a racing venue “because of the disintegration of a large part of its masonry and of the arena,” caused by “the extremely poor foundation of the structure.” This interpretation is supported by foundation analysis in Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:157), which presents detailed pressure estimates and an E–W cross section showing a fill of variable thickness beneath the building.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 21 June 2025

- from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

In Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:60), they write that the north part of the building, including the gate structure, was destroyed by an earthquake that followed earlier partial destruction or dismantling. In Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:36), the reuse of upper masonry elements such as architraves and gate blocks in later intrusive architecture is used as indirect evidence for a final collapse event. This collapse is explicitly associated by the authors with a 7th century earthquake, which they date around the 660s CE, stating that this “destructive event... should probably be related to the earthquake of 659/660.”

While the archaeological evidence includes large-scale collapse and reuse of major architectural elements, the attribution to the 659/660 CE event is based on circumstantial timing. The authors do not cite radiocarbon or datable ceramic contexts tied directly to the collapse, but their overall phasing and interpretation suggest that the end of monumental function and the destruction of major structures aligns with the mid-7th century seismic event recorded in historical sources.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

discussed evidence for an earthquake that predated the

mid-8th century event, which left clear archaeoseismic

traces in the eastern part of the

carceres. They state that "the

final destruction of the building was caused by earthquakes,"

and that "the masonry of most of the building collapsed during

the earthquake of 659/60

[JW : Jordan Valley Quake]; only the

carceres and the south-east part

of the

cavea survived that

disaster"

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz, 2020:4).

The date of 659/660 CE appears to have been assigned through

matching with earthquake catalogs. Since the latest activity

prior to this event—presumed to be stone robbing—is dated to

the 6th century

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz, 2020:4), and

the following mid-8th century earthquake dating evidence provides a

terminus ante quem for this 6th-7th century CE event in the first half of the 8th century

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz, 2020:33), the

archaeological evidence places this earlier event somewhere

between the 6th and 7th centuries CE. The excavators also

report that the site "revealed evidence for some but only

intermittent occupation or squatting in these parts of the

building in the period between the two earthquakes"

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz, 2020:5).

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 4 - Tumble layer

from mid 8th century earthquake from Ostrasz (1989)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Carceres.

East half.

Lowest stratum of tumble

JW: Note uniformity of tumble where collapsed arches appear visible

Ostrasz (1989)

- General Plan of Jerash

from Wikipedia

- Fig. 4 - Tumble layer

from mid 8th century earthquake from Ostrasz (1989)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Carceres.

East half.

Lowest stratum of tumble

JW: Note uniformity of tumble where collapsed arches appear visible

Ostrasz (1989)

Ostrasz (1989) found archeoseismic evidence at various parts of the hippodrome which they attributed to a mid 8th century CE earthquake.

The archaeological context of the excavated sections of the cavea was found to be the same almost everywhere. On the outside of the remains of the outer and podium walls, and contiguous to them, was the stone tumble of the upper parts of the walls. The inside of the chambers was filled mainly with the tumble of the stonework of the cavea proper (seat stones and voussoirs of the stepped arches which supported the seating tiers) and with a number of stones of the outer wall. In many chambers the position of the stones displayed clearly that the stonework collapsed during an earthquake. The tumble was subsequently quarried for stone. The quarrying was very extensive; only a small proportion of the stones which made up the particular parts of the masonry was left in the tumble. The parts of the masonry which survived the disaster were also robbed of stones.Ostrasz (1989:137-138) discussed the chronology of destruction.

The stratigraphy of the fill in the chambers was very simple. In most chambers there was only one stratum (from 2 to 4 m thick) over the `floor' level: masonry tumble composed of dressed stones, boulders and rubble, all immersed in earth. 7 The tumble lay directly on the `floor' which in chambers E40-E55 is the unlevelled surface of rock and in all others the top of the fill within the foundation walls of the chambers. The fill itself is another, the lowest stratum. Is is composed of thick layers of earth and thinner and irregular layers of stone chips. In some chambers there was an intervening thin layer of earth and rubble between the top and bottom of the two strata mentioned above. The tumble outside the outer wall lay on top of a residual layer from 0.3 m to 0.8 m thick. Underneath, there is the same kind of earth with which the space within the foundation walls of the chambers (and the arena) is filled. The masonry tumble outside the podium wall lay directly on the surface of the arena 8.

The archaeological context of the carceres was very similar to that of the cavea. On both sides of the remains in situ and contiguous to them, as well as inside the staffs, there was the tumble of the upper parts of the masonry destroyed by an earthquake (fig. 4). Most of the masonry collapsed northwards, on to the arena. The bulk of the tumble was not disturbed by quarrying for stone and every stone retained its tumbled position. The tumble lay on the surface of the arena.Footnotes8 Except the middle section of the east part of the building where the tumble lies on the slope of the depression.

The excavated sections of the hippodrome displayed clearly that the building was finally destroyed by an earthquake. The best attested examples were found in the carceres, in chambers E40-E43 and E25-E28 (currently under excavation), and in the neighbouring church of Bishop Marianos. The coins and the ceramic material from the deposits sealed by the tumble provided evidence for dating the occurrence. No material dating beyond the Umayyad period was found in any of the deposits. The latest coin from the deposit under the tumble of the carceres is datable to the first half of the eighth century and the latest ceramic material found in it dates to the eighth century (Kehrberg 1989: 88). The latest coins recovered from under the tumble in chambers E40, E41, E42 and E43 were minted in 383-395, 498-518, 575/6 and between 527 and 602, respectively. The latest pottery, lamps and lamp fragments from the same deposits date to the seventh century. The only coin found under the tumble of the church of Bishop Marianos was minted in the first half of the eighth century and the objects are dated to the same period (Gawlikowski/Musa 1986: 149-153).

The finds prove that the south-east part of the cavea stood high in the seventh century and the carceres and the church still stood high in the first half of the eighth century. The lack of material dating after the middle of the eighth century shows that this part of the building was either abandoned or destroyed at, and never occupied after, this date. The archaeological context of the finds in the church clinches the matter. It shows that...the church remained in use to its end.(Gawlikowski/Musa 1986: 141), that is until the earthquake which must then have occurred about the middle of the eighth century.

Only one earthquake is securely attested in the region of ancient Palestine in the eighth century and this is the earthquake of 748 (747) (Russell 1985: 39, 47-49). It is also well attested at Jerash (Bitti 1986: 191-192; Crowfoot 1929: 19, 25; id., in Kraeling 1938: 221, 242, 244; Parapetti 1989a: passim; Parapetti 1989b: passim; Rasson/Seigne 1989: 125, 151; Seigne 1986: 247; Seigne 1989: passim). The hippodrome of Gerasa is yet another well attested example of that disaster.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27–28)

provided detailed observations of structural collapse at the

eastern

carceres (stalls 1E–5E). Stone blocks fell

in a curved, northward arc onto the

arena, with higher blocks found further

from the source, indicating a violent, forward-leaning failure.

The height of detachment—about 2 m above ground—marks a

structural "hinge" where the shock caused rotation before collapse.

The masonry construction of the

carceres—faced stone around rubble fill—

was inherently weak and heavily eroded prior to collapse.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27–28)

conclude that both the construction technique and preexisting

erosion amplified the seismic vulnerability of the structure.

Western

carceres (stalls 1W–5W) also show

a northward collapse direction, albeit with less diagnostic

evidence. This directional pattern supports a south-to-north

fall orientation which may suggest an epicenter to the north

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz 2020:31–32).

Ostrasz (1989:133–135) confirms additional

archaeoseismic signatures in the

cavea. Collapse debris contained seat

stones,

voussoirs

, and a monolith column broken into three peices along with a broken capital amongst the tumble.

Dating is provided by finds sealed beneath the tumble.

A deposit found beneath the tumble in the "area" of the

carceres included ceramics from the 1st

to 8th centuries CE, with the latest securely Umayyad. A coin

provided a terminus post quem in the first half of the

8th century

(Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz 2020:33).

Further evidence from

Ostrasz (1989:137–138) corroborates this

chronology. The absence of later material supports

destruction and abandonment after the 749 quake.

Ostrasz notes that the neighboring church of Bishop Marianos

also collapsed at this time, with sealed coins dated to the

early 8th century, and concludes that the hippodrome is a

well-attested example of the

749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes

in Jerash

(Ostrasz 1989:138).

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27-28) provided an extensive description of the fallen masonry in the eastern half of the carceres (stalls 1E-5E) noting that most of it fell northward and that local intensity was elevated. These excavations appear to have provided the clearest evidence for mid 8th century earthquake damage.

That the structure was destroyed by an earthquake is evident from the position of the fallen stones in the lowest layer of the tumble; nothing but an earthquake could make the masonry fall so. The amount of the fallen stones in the whole tumble shows that most of the masonry of the structure fell northward, onto the arena. Moreover, there is also evidence for the process itself of the fall. In this respect it has to be noted first that the standing remains of the carceres, that is to say the piers between the stalls, all stand at least two, but none more than three masonry courses high (originally the masonry of the stalls consisted of thirteen courses). Some stones in the standing masonry are slightly shifted from their original position but none was noticed to have lost its verticality. In all, the lowest parts of the masonry of the piers were little affected by the earthquake.Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:29-30) discussed the layer below the earthquake tumble.

The case of the upper parts (originally seven masonry courses high, the course of the imposts of the archivolts included is different. Only one pier (3E/4E) of the east stalls provides full evidence for how its masonry collapsed but it can be maintained (infra) that its example is representative of the situation which, during the earthquake, was found also in the case of the others. All the stones but one of the four upper masonry courses of the north face of the pier (stones 73-82) were found in the tumble. The stones of courses 4-5 (lower) fall closest, immediately against the face of the pier, the stone of course 6 (higher) slightly further from it, and the two stones of course 7 (uppermost) yet further from the pier. The pattern of the falling of the stones of this particular pier is clear. The higher the position of the stones in the masonry the further from the pier they fell. A similar pattern is noticeable in the position in the tumble of the three stones identified of pier 4E/5E (stones 84 - course 3, and 90-91 - course 7) and there is an identical pattern in the tumble of stones of the north face of pier 4W/5W (stones W113, W132, W133-135, W137, courses 4-7). This pattern indicates that the earthquake disturbed fatally not only the static balance of the structure but that it also created the force which projected the masonry (particularly its whole northern vertical layer) forward that is to say northward.

This projecting force is best evidenced by the tumble of the masonry which made up the upper part of the north façade of stalls 1E-4E (courses 8-13, from the level of the spring stones of the archivolts to the level of the crowning cornice). While in place, this part of the façade was about 23m long and 3.3m high, and its surface was about 75m2. After the fall, it covered an area of almost the same length, width (former height) and surface. In the process of falling, it described in the air a curve very close to a quarter of a circle of which the radii of the particular masonry courses were approximately concentric and of which the centre was approximately at the level and face of the top of course 3 of the piers. While the masonry of the north façade stood intact, the top of the comice course was 5.4m, the apex of the archivolts 3.6m and the spring stones of the archivolts were 2m above that level. After the fall, these elements lay at a distance of 5.5 - 6.5m, 4 - 4.4m and 2 - 2.5m, respectively, from the façade. Figuratively speaking, the whole vertical layer of the masonry making up the north façade fell from the vertical to the horizontal position just as a solid platform of a drawbridge would fall, its hinges being at the level of about 2m above ground.

Two factors contributed additionally to this pattern of collapse for which the earthquake was, of course, instrumental. One was the tectonics of the piers and especially of the upper parts of the carceres. As all other parts of the hippodrome, they were built of dressed stones on the outside while the inside was filled with boulders and stone chips set on earth. In consequence, the masonry was not cohesive in its entirety; a slightest disturbance of the static stability of the structure could (and did) immediately detach the dressed stone facing from the inner `core' of boulders, stone chips and earth. The other factor was the physical condition of most stones in the lowest courses of masonry of the piers. As in the case of the lowest courses of masonry in most parts of the hippodrome, these stones deteriorated in a much greater degree than the stones of the upper courses (for the reasons cf. infra:...). They lost most of their resistance to pressure of the masonry above; any movement of the structure combined with the pressure of that masonry could not fail to make them disintegrate instantly.

All the above considered, the process of collapse can be reliably reconstructed. The earthquake caused the structure momentarily to lean forward (northward). In that instance and in that position two things occurred simultaneously: the force of gravity made the masonry of the north façade detach itself from the inner core and the deteriorated stones making up the lower courses of the face of the piers gave way, as the support for the upper parts of the façade. In this situation the masonry could not fail to collapse. However, the gravity force alone could have made the stones of the masonry fall roughly vertically and in a rather haphazard order. They did not fall so. Instead, they described in the air a part of a circle and fell `orderly' and far from their vertical position. This shows that apart from the force of gravity there was another force, the force which catapulted the stones first horizontally before the force of gravity `pulled' them down onto the ground. This ejecting force must have been created in the moment of leaning of the whole structure forward and this shows in turn the leaning occurred instantaneously and violently.

Considering the fact that the structure fell northward it must be assumed that during the earthquake the ground under the structure moved upward at its south side and/or downward at its north side in a split second and with a great force (speed). That movement made the structure lean violently which created the force catapulting the stones forward. This force naturally increased in direct proportion to the height of the structure as is clearly witnessed by the position on the ground of the fallen masonry of the upper parts of the north façade of the carceres. To make it all happen as it happened, the earthquake must have been extremely strong.

The fallen stones show the direction of fall of the carceres. It has been observed that `During an earthquake the columns, pilasters, and walls of structures have a tendency to collapse in the opposite direction of the quake's epicenter or hypocenter.' (Russel 1985: 51-52) Accordingly, the directional pattern of collapse of the carceres indicates that the epicentre or hypocentre of the earthquake which destroyed the structure was to the south of Gerasa. The reconstruction of the process of the collapse points to a forceful earthquake. The recent studies of the earthquakes in the region of Palestine and northern Arabia from the 2nd throughout the 16th century elucidate the stronger and weaker earthquakes known in that period and region. Accordingly, both phenomena - the directional pattern of collapse and the strength of this earthquake - are, then, additional evidence (beside the deposit sealed by the tumble) for dating the occurrence (infra).

The stone tumble contained no ceramic or coin deposits. It was only the excavation of the top layer of the ground underneath the tumble that yielded the ceramic and coin material (Compendium B: Kehrberg 1989, 2004 and 2016a). The surface of the ground sealed by the tumble in front of the stalls was about 140m2 (about 7m by 20m). This surface was not level, that is to say it was not the original top surface of the arena.Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:31-32 also discussed earthquake collapse in the western half of the carceres (stalls 1W-5W) where, for a variety of reasons, archaeoseismic evidence was not as rich in details but where most of the collapse, as with the eastern stalls, fell northward. Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:33) provided a terminus post quem of the 1st half of the 8th century CE for the archaeoseismic destruction and suggested that one of the mid 8th century earthquakes was responsible.

... Ceramic deposit. (see Compendium B: Kehrberg 1989-2006, fc 2018)

Stm.2, Stm.3, and possibly Stm.1 - 1600 potsherds, 2 intact lamps and 62 lamp fragments. Most pieces are fragmentary and worn, especially the lamp fragments. A very small proportion of the material (%)20 dates from the lst throughout the 3rd century, the bulk (%) dates from the 4th throughout the 6th century, and the remainder (%) dates to the 7th and 8th centuries. In the first group, the proportion of the sherds and lamp fragments dating to the 3rd century is the least. In the second group, the proportion of the material dating to the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries was found to be roughly equal, respectively, and so was the material in the third group dating to the 7th and 8th centuries.

Finally, the excavation yielded evidence for dating the collapse of the carceres. The latest potsherds and lamps found in the area sealed by the tumble are of the Umayyad period. The latest coin underneath the tumble is datable to the first half of the 8th century. The sealed deposit contained no artefacts of a later date. Of all the material, the coin provides the relatively strictest terminus post quem for the destruction of the carceres - the first half of the 8th century. The terminus is based on the evidence ex silentio of the material of a date later than of the first half of the 8th century, but this evidence can securely be accepted as reliable considering other parts of the monument (supra....).

- from Chat GPT 4o, 21 June 2025

- from Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:27–33)

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:29–30) describe how the sealed surface beneath the tumble yielded a ceramic and coin assemblage dominated by 4th–8th century material, with no artefacts of later date. The latest coin dated to the first half of the 8th century provides a terminus post quem for destruction.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:31–32) note that collapse in the western carceres (stalls 1W–5W) was also directed northward, but less clearly exposed.

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:33) argue that the directional pattern of collapse, forceful projection of masonry, and absence of post-Umayyad material strongly support attribution to a mid-8th century earthquake, most likely the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | SW part of the cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | upper parts of the hippodrome

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | most of the hippodrome except for the carceres and the south-east part of the cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls and arches (in a northward direction) |

eastern half of the carceres (stalls 1E-5E)

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 21

Figure 21Perspective view of part of carceres (A.O.1992) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Carceres. East half. Lowest stratum of tumble JW: Note uniformity of tumble where collapsed arches appear visible Ostrasz (1989) |

Description

|

| Collapsed Walls and arches (in a northward direction) |

western half of the carceres (stalls 1W-5W)

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 21

Figure 21Perspective view of part of carceres (A.O.1992) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

|

|

cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arch damage | Beneath the cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

Plate XIVb

Plate XIVbHippodrome Two arch rings beneath the cavea.Section M. JW: Arch deformation present - possibly earthquake induced Kraeling at al (1938) |

|

| Arch damage | West cavea chambers

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

Fig. 33 P.7

Fig. 33 P.7Late Roman tannery and pottery workshops installations in west cavea chambers of the hippodrome (photos Nov. 1996) JW: Note arch damage Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 4 of Ostrasz (1989)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | SW part of the cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

VIII + | |

| Collapsed Walls | upper parts of the hippodrome

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

VIII + |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | most of the hippodrome except for the carceres and the south-east part of the cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 19

Figure 19Schematic cross-section of hippodrome (A.O.1992) JW: Note varying thickness of uncompacted fill which would likely to lead to differential settlement Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

VIII + |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224).

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls and arches (in a northward direction) |

eastern half of the carceres (stalls 1E-5E)

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 21

Figure 21Perspective view of part of carceres (A.O.1992) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Carceres. East half. Lowest stratum of tumble JW: Note uniformity of tumble where collapsed arches appear visible Ostrasz (1989) |

Description

|

VIII + |

| Collapsed Walls and arches (in a northward direction) |

western half of the carceres (stalls 1W-5W)

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020)

Figure 21

Figure 21Perspective view of part of carceres (A.O.1992) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

VIII + | |

|

cavea

Figure 22

Figure 22P.1. Ground Plan 1: 1st half of 2nd and 3rd cent., 1st phase: construction and primary use of circus – chariot racing (A.O.1995) Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020) |

|

|

Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:146-147) reporoduced an earlier article by Antoni Ostrasz in 1991 which reports on the discovery of skeletons beneath collapsed masonry which they tentatively attributed to an earthquake in Late Abbasid/Early Mamluk time. This was corrected in the 2020 report - see the final bracketed paragraph below.

An unexpected, and to say the least, dramatic discovery was made in the course of excavation in chamber W2. The upper part of the chamber was (and its lower part still is) filled with tumbled stones of the cavea (mainly the seat stones and voussoirs of the stepped arches). Human skeletal remains were found under the removed upper part of the tumble and within the tumble. This is not the case of a burial. In the north-east corner of the chamber, in an area 1.5m by 1m large and at approximately the same level, were found five skulls, all cracked, with parts missing. Directly over the skulls there were hand and arm-bons, even rib-bones and at the level of the skulls lay some vertebrae. In this area and at this level no pelvis or leg-bons were found. In the middle of the chamber there are remains (left in place) of another skeleton. In the extreme opposite part of the chamber, close to the podium wall, there were recovered from under and from within the tumble the pelvis, leg, arm and rib-bones (all at approximately the same level) of at least two individuals. No skulls were found above or beside these remains. There are, then, the skeletal remains of at least eight individuals discovered so far in the chamber. The lower part of the tumble was left in place to be excavated in the spring of 1991.

There seems to be only one plausible explanation [but see comment below, I.K-O] for the condition in which the skeletal remains were found: the individuals were killed by a sudden collapse of the cavea and such a collapse could be caused by nothing else but an earthquake. The five individuals in the north-east corner and the one in the middle of the chamber were obviously caught by the disaster inside the chamber. However, the two individuals whose remains were found in the opposite part of the chamber seem to have been surprised by the earthquake while being in the cavea and seem to have caved in the chamber together with the tumble; their skulls may be found in the lower layer of the tumble.

So far, there is no evidence for dating the occurrence. It is expected to be found when the occupation level of the chamber is reached. [see below, I.K-O] However, some tentative suggestions may be advanced already at this stage.

The earthquake occurred in the period of reoccupation of the hippodrome. This is evidenced by a well preserved intrusive doorway built within the original doorway of the chamber - a feature found in most excavated chambers of the building (Ostrasz 1989a: 55 and Fig. 2). The terminus post quem for the reoccupation is a date in the first quarter of the fourth century or, possibly, even slightly earlier (supra) and this is the terminus post quem for the disaster. However, a much later date should be considered. In 748(647) AD ab earthquake destroyed the south-east part of the hippodrome (Ostrasz 1989a: 75) but considering the situation found in chamber W2 it seems rather dubious that this earthquake was responsible for the collapse of the masonry of the chamber. The fact that the bodies of the people killed in this disaster were not recovered from the rubble for burial bespeaks a period of a great decline of the Gerasene community in every respect. What is presently known of the history of Gerasa in the last decades of the Umayyad period is not compatible with such a degree of decline43. The date of this earthquake may, therefore, be as late as a date in the Late Abbassid or even the Early Mamluk periods44.

[We completed excavation of W2 and W3 in 1993 retrieving conclusive evidence correcting the preliminary interpretation for the cause of death posited in this article; see Ostrasz 1994, and Compendium B: Kehrberg and Ostrasz 1997; 2016b, for the dating and identification of the event: the mass burial of about 200 mid-seventh century plague victims. The tumble relates indeed to the 748 earthquake, I.K.]Footnotes43 The recent students of the history of Gerasa tend to view Gerasa of the Umayyad period as an important urban centre. A tendency of overstressing the importance of Gerasa in that period is detectable but there can be no doubt that Gerasa of the Umayyad times was still a centre of some substance. For an early view on the subject cf. Kraeling 1938: 68-69. Of recent studies cf. in the first place Gawlikowski (in press and 1986: 120-121). Also: Bitti (1986: 191-192), Schaefer (1986: 411-450); Zayadine (1986: 18-20; Naghawi (1989: 219-222).

44 A sedentary community at the site of ancient Gerasa is attested to have occupied, perhaps intermittently, the North Theatre in the Late Abbassid and Mamluk periods. Cf. Bowsher, Clark in F. Zayadine (ed.), Jerash Archaeological Project 1981-1983, I. Amman: 237, 240-241, 243, 247, 315. The situation found in chamber W2 fits a picture of such an occupation rather than that in the earlier periods. [see above comment, I.K-0]