Jericho - "Hisham's Palace" (which may have really been Walid II's Palace) at Khirbet al-Mafjar

Aerial View of Khirbet al-Mafjar

Aerial View of Khirbet al-MafjarClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable map

from www.govmap.gov.il

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Hisham's Palace | English | |

| Qaṣr Hishām | Arabic | قصر هشام |

| Khirbat al-Mafjar | Arabic | خربة المفجر |

Hisham's Palace, a two story Umayyad structure and an example of a Desert Castle, is the main building of the Khirbet al-Mafjar archeological site located ~3 km. north of Jericho. Originally thought to have been destroyed and abandoned after it was struck by one of the mid 8th century CE Sabbatical Year earthquakes, it is now thought to have suffered more moderate damage during that event and to have remained occupied afterwards. The final destruction and abandonment of Hisham's Palace is now thought to have occurred later.

El-Mafjar is the current name of a group of ruins lying on the north bank of Wadi en-Nu'eima in the Jordan Valley, about 2 km (1 mi.) north of Jericho, commonly referred to as "Hisham's palace" (map reference 194.143). No ancient name is known, and the site, although proven to belong to the Umayyad period, remains unidentified in ancient literature.

A deposit of lron Age pottery on the northern outskirts of Khirbet el-Mafjar has given rise to the conjecture that the biblical site of Gilgal was hereabouts. Columns carved with crosses, in secondary use, supporting arches in the courtyard of the site's Umayyad palace, suggest that there is a monastery from Byzantine Gilgal somewhere nearby, of which there is no other vestige.

- Fig. 1 - Aerial View

of "Hisham's Palace" from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General view of the excavated palace

Courtesy Pictorial Archive

Meyers et. al. (1997)

KHIRBAT AL-MAFJAR - site located near Jericho in the Jordan Valley, where excavations carried out between 1934 and 1948 brought to light the richest and the most original of all princely establishments associated with the early Islamic dynasty of the Umayyads (661-750 CE). After 1948 additional sections of the site were cleared and a process of continuing renovation was initiated to preserve the existing ruins and to make them easier for visitors to understand. The vast majority of the finds from the site and most of the records of the excavations are kept in Jerusalem, in the former Palestine Archaeological Museum, now known as the Rockefeller Museum, where several sculpted ensembles have been reconstructed.

Khirbat al-Mafjar is also known as Qasr Hisham, because a graffito found in its ruins carries the name of that particular caliph who ruled between 724 and 744. There is in fact no valid reason to associate Khirbat al-Mafjar with Hisham and, even though a reasonable and tempting hypothesis can be made about the patron of the complex (see below), it cannot be demonstrated.

The site had been identified as a significant settlement as early as 1873 by the British surveyors of Palestine. For a while it was considered to be the biblical Gilgal and the Early Christian Galgala. In fact, its excavators first believed that they had found a Christian ecclesiastical establishment. It turned out to be an Umayyad palace that was probably never completed. Its construction seems to have been abandoned rather abruptly — either because of one of the several earthquakes that affected Palestine in the middle of the eighth century or because a patron suddenly disappeared or lost interest.

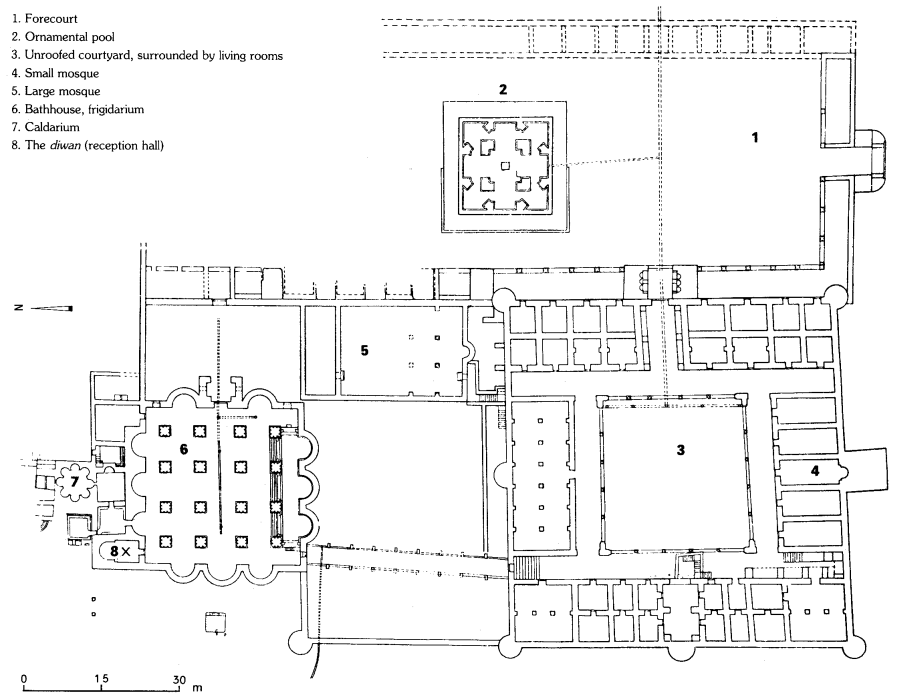

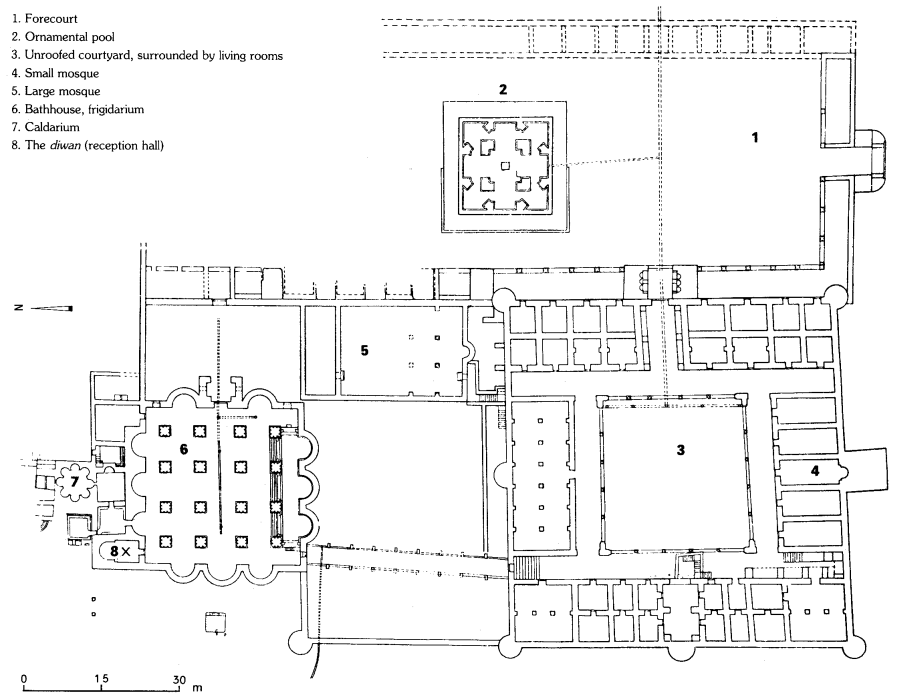

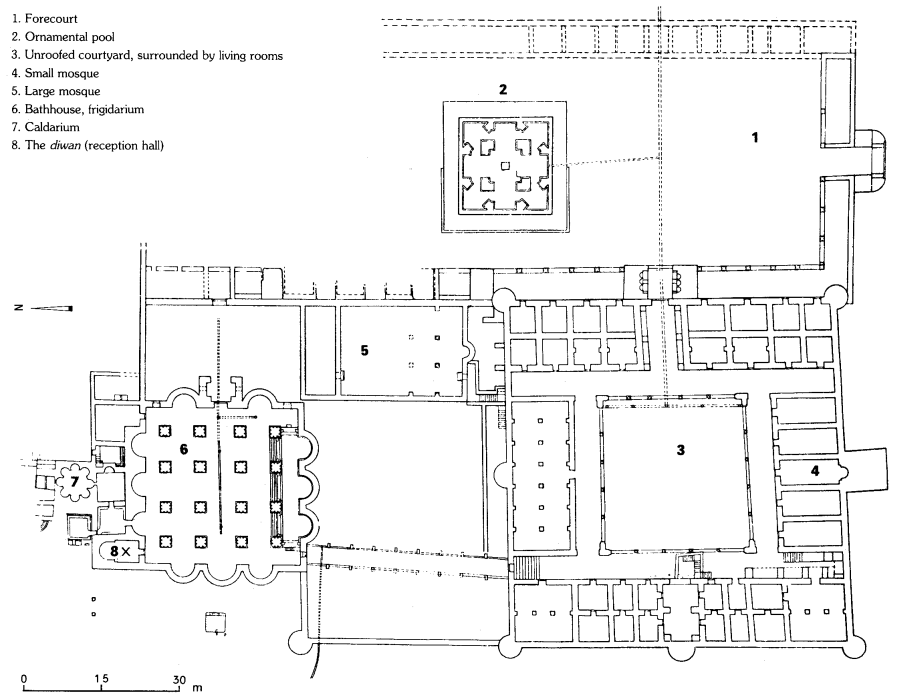

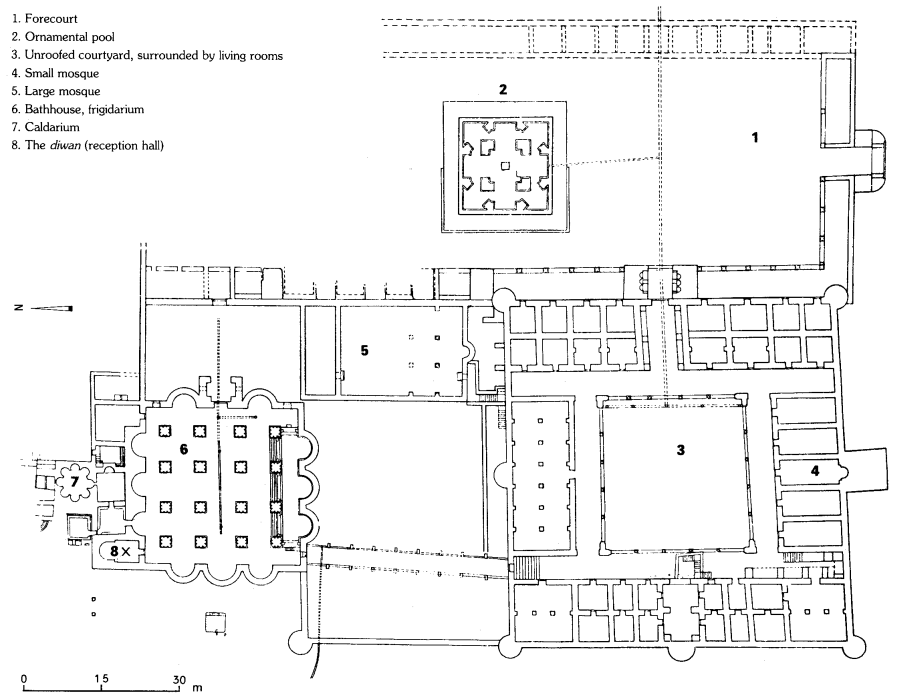

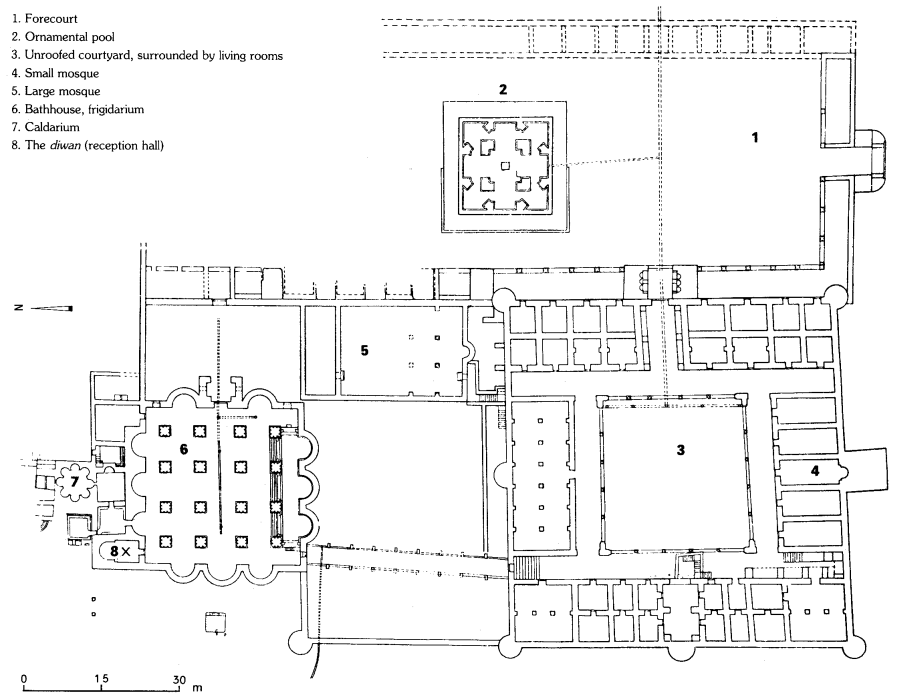

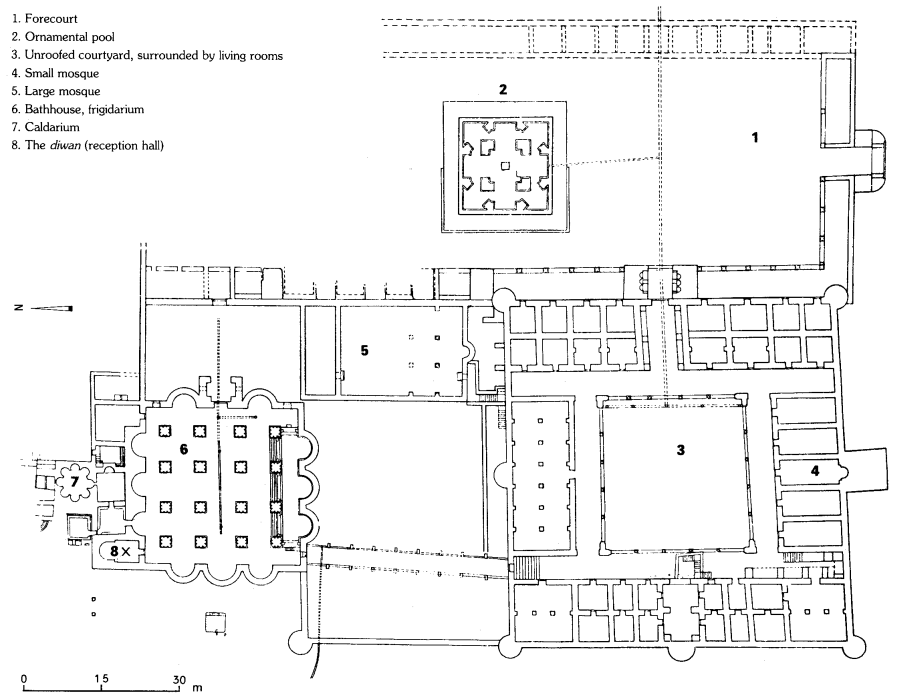

There are five parts to the establishment:

- Two-storied square castle. Roughly 70 m to the side, the complex has a porticoed courtyard with single rooms, large halls, or apartments known in Arabic as bayts, around it (see figure 1) ; although their exact functions cannot be established, these halls clearly were meant for a diverse set of activities, a relative rarity in palaces of the same type. The entrance complex is unusually large and was decorated with a striking array of stucco sculptures, ranging from traditional geometric and vegetal designs to an unusual number of representations of personages and animals, and mural paintings, some representational, on the second floor.

- Mosque. To the north of the castle, a small and architecturally sober mosque had a direct passage to the second floor of the living quarter.

- Bath. A sequence of rooms — an enormous (30 X 30 m) common room covered by an extraordinary roof of vaults and domes, a small suite of bathing rooms, a large latrine, a heavily decorated small private room, and a monumental entrance — corresponds to the usual system that issued from Roman architecture. The respective sizes of the components and especially the decoration found in them are unique in three ways: by the techniques used (mosaics, paintings, and sculptures); by the subjects depicted (princes, half-clad women, animals in all sorts of guises, a most elaborate geometry, rich vegetation), even though many of the topics have not yet been properly identified; and by the styles of depiction (its models are found in the Mediterranean world as well as in Buddhist Central Asia). A small room in the northwest corner, whose exact function is unclear, is a museum of mosaic and sculpture masterpieces.

- Forecourt. Unifying the bath, mosque, and castle as a single composition, even though they were built at different times, is a forecourt. Toward the center of the courtyard an octagonal domed pavilion stood over a small pool.

- Walled and irrigated area. A large walled and irrigated area surrounding the complex may have been used for cultivation or for hunting.

- from Taha (2011)

The excavation uncovered a significant part of the palace complex, composed of a palace, a thermal bath complex, a mosque, and a monumental fountain within a perimeter wall that was never completed38. The three first principal buildings were arranged along the west side of a common forecourt, with a fountain in its center. The area to the north was partially excavated and revealed a series of rooms that were identified probably as a caravanserai (Khan). The excavation reports were published in the QDAP by D.C. Baramki between 1936-1942 and his report on the pottery in 1942. The final report was never published due to the events of 1948. In 1959, R.W. Hamilton presented the architectural publication of the palace and other buildings including the bath.

A large scale excavation was carried out in the northern section of the palace area in early 1960. But unfortunately the result of this excavation was never published. A series of restorations were carried out in the palace during the Jordanian rule. During the Israeli occupation between 1967-1994 the palace was left abandoned. Rehabilitation work was resumed directly after the transfer of authorities to the Palestinian side in 1996 within the framework of the project for the conservation of Hisham's Palace. The work was carried out on the behalf of the Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in cooperation with the UNESCO, the Studium Biblicum Frandscanum, and it was funded by the Government of Italy39.

The previous excavation of the bath complex was carried out along five seasons, between 1944-1948, following the clearance of the palace and mosque. Hamilton reports that it was not until 1944 that excavations of the northOrn ruins begun40. Following the publications of the preliminary reports of D.C. Baramki and the monumental publication of R.W. Hamilton, Khirbet el-Mafjar was a subject of intensive archaeological research from art historic perspective. The key studies includes the works by K. Creswell, O. Grabar, D. Whitcomb41, and many others. However, the incomplete nature of Khirbet el-Mafjar publications is due to the fact that only the preliminary reports were published and the final archaeological report was never published. The other inherited problem is related to the "architectural" method of excavation and the level of the stratigraphic control. However, the last 60 years yielded a great amount of comparative stratigraphic material from a large number of sites in the area.

In 1986 D. Whitcomb reanalysed virtually the ceramic stratigraphy in the palace area, based on Baramki's measurements of the find spots. He reinterpreted Baramki's data in the palace and derived the following stratigraphic sequence, with chronological divisions between four periods. Whitcomb described the pottery assemblages associated with each period, concluding a stratigraphic sequence of the corpus of pottery published by D.C. Baramki in 1942. This method has been proved to be effective in reconstructing the occupational history of Hisham's Palace, based on the preliminary results of the new excavations.

After 60 years from the last season at the site, a small scale excavation was carried out in December 2006 by the Palestinian Department of Antiquities in the northern part of the main bath.

... Following the small scale excavation in 2006 by the Department of Antiquities, work was resumed in 2010 in the area within the framework of the Palestinian-American joint Expedition under the direction of Dr. D. Whitcomb and Dr. H. Taha48. The first season, from mid-December 2010 through mid-January 2011 succeeded in uncovering the north gate of the palace complex and began the exploration of the Umayyad town in the northern part of the site. This will lead to a more precise stratigraphic history of the site and understanding of the spatial relationship between the palace and the Umayyad town.

37 Hamilton 1959; 1993; Baramki 1936b; 1937; 1938a; 1942a; 1942b; 1947.

38 Hamilton 1959; 1993, 922; Grabar 1955, 228-235; Taha 2005; Whitcomb 2011.

39 Taha 2005.

40 Hamilton 1959, 45.

41 Creswell 1932; Grabar 1955; Whitcomb 1986.

48 Whitcomb 2011

- from Jericho - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 1 - Aerial View of "Hisham's Palace"

from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

General view of the excavated palace

Courtesy Pictorial Archive

Meyers et. al. (1997) - "Hisham's Palace" in Google Earth

- "Hisham's Palace" on govmap.gov.il

- Location Map from Stern et. al. (1993 v.2)

Map of the main sites at Jericho and its environs, Roman-Byzantine period.

Map of the main sites at Jericho and its environs, Roman-Byzantine period.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.2) - Fig. 1 - Map of the Dead Sea

fault system in the Jericho Valley from Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Geodynamic setting (inset) and schematic map of the Dead Sea fault system in the Jericho Valley. Macroseismic intensity of the 1033 A.D. earthquake occurred in the Khirbet area (data from Guidoboni and Comastri, 2005). Location of the archaeological site and of main fault traces is reported. The white square delimits the area shown in Figure 6.

Alfonsi et al (2013) - Fig. 6 - Structural sketch map

and stress-field configuration of Hisham's Palace and surroundings from Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Structural sketch map and stress-field configuration in the Hisham palace surroundings

Red line and arrows represent the coseismic rupture and slip related to the 1033 A.D. event inferred from this study

data from Hofstetter et al, 2007 and Lazar et al, 2006

Alfonsi et al (2013)

- Plan of Hisham's Palace

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Hisham's Palace

from Whitcomb (1988)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1

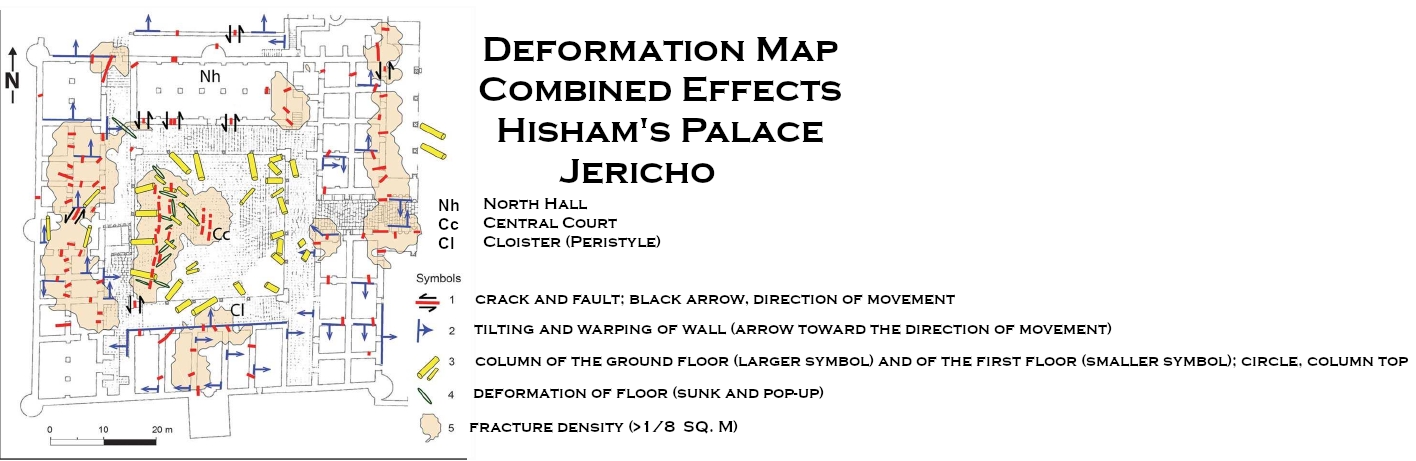

Whitcomb (1988) - Fig. 2d - Map of the surveyed

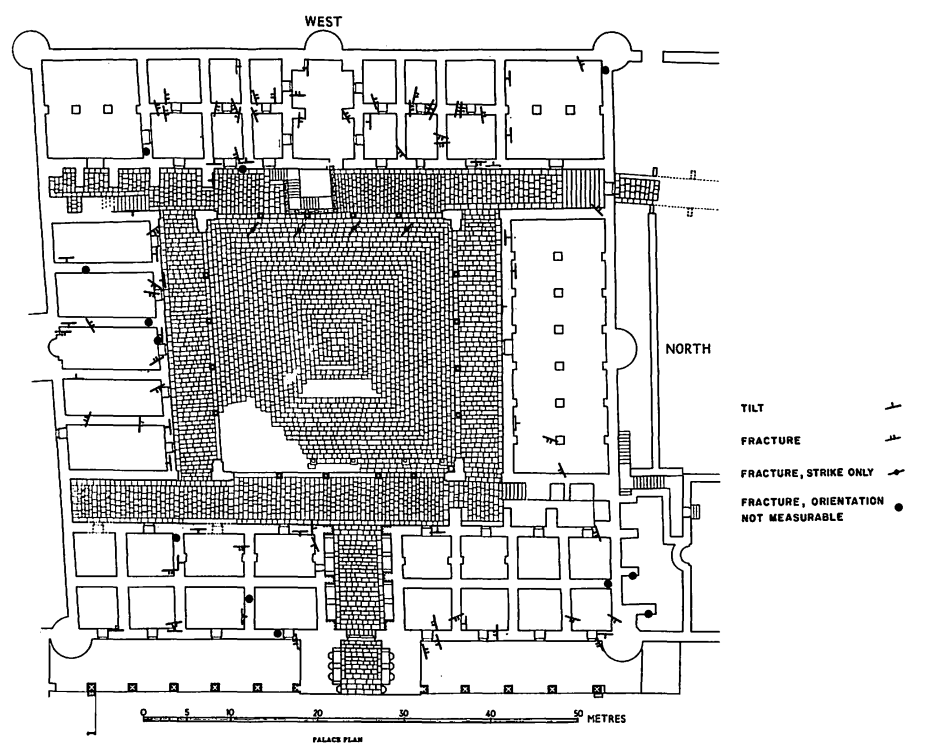

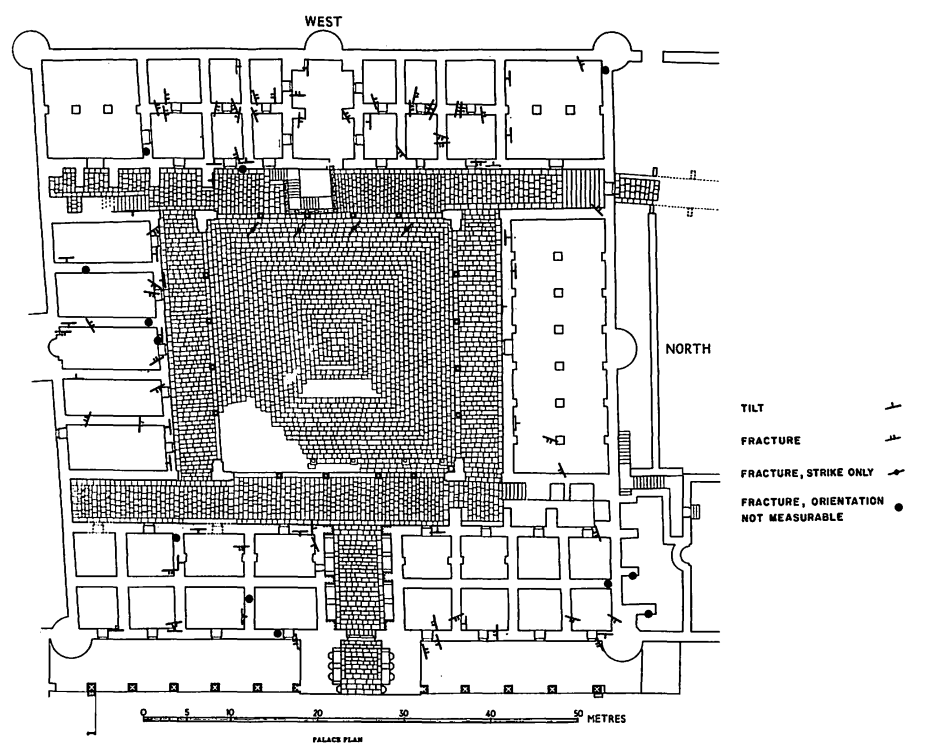

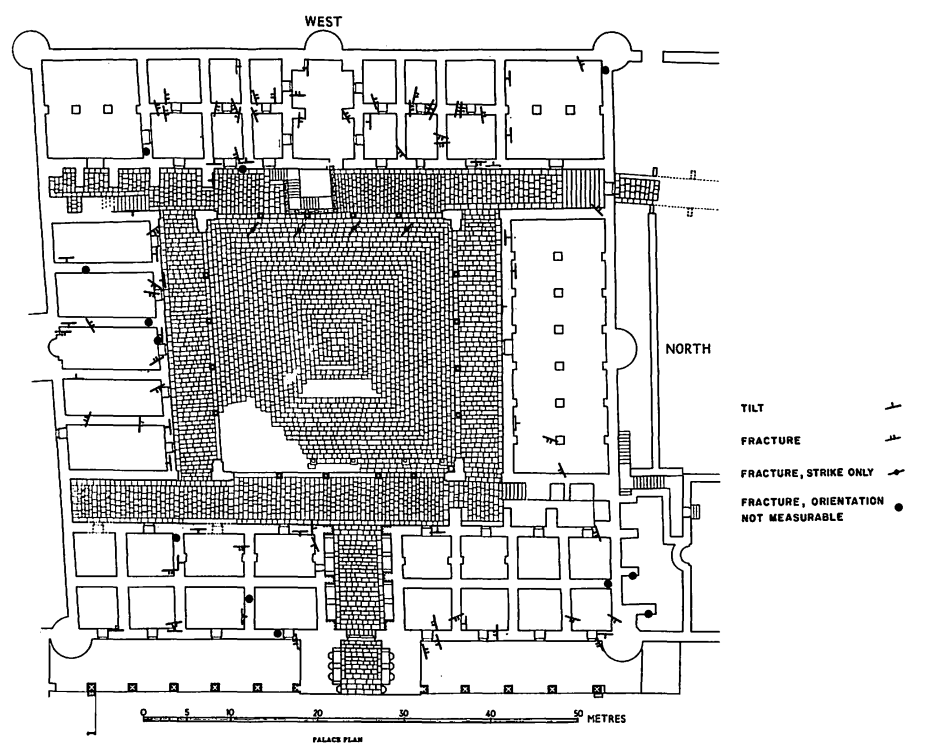

coseismic effects at Hisham's palace from Alfonsi et al (2013)

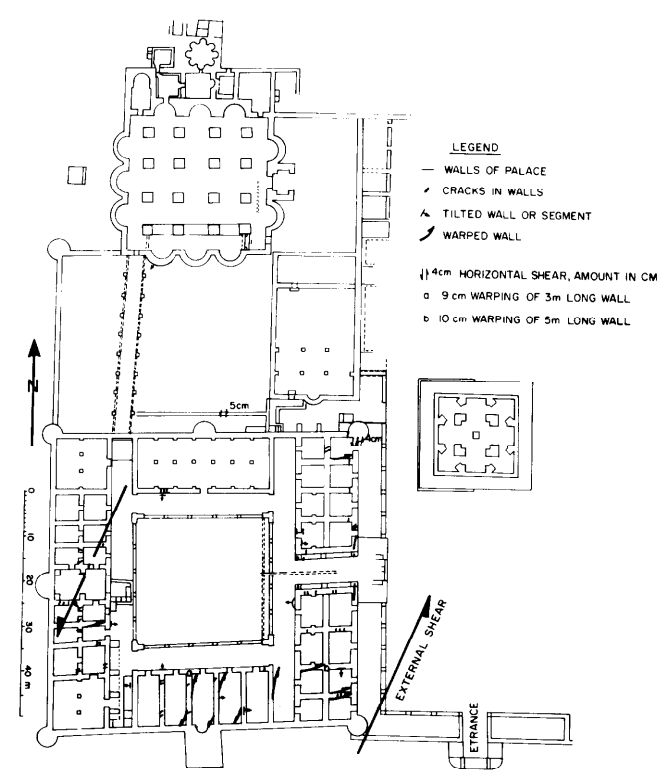

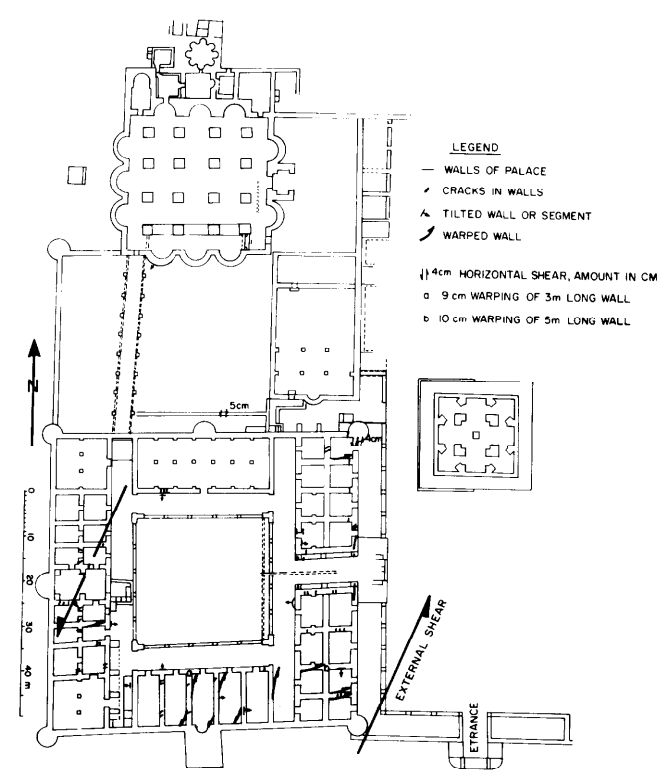

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2d

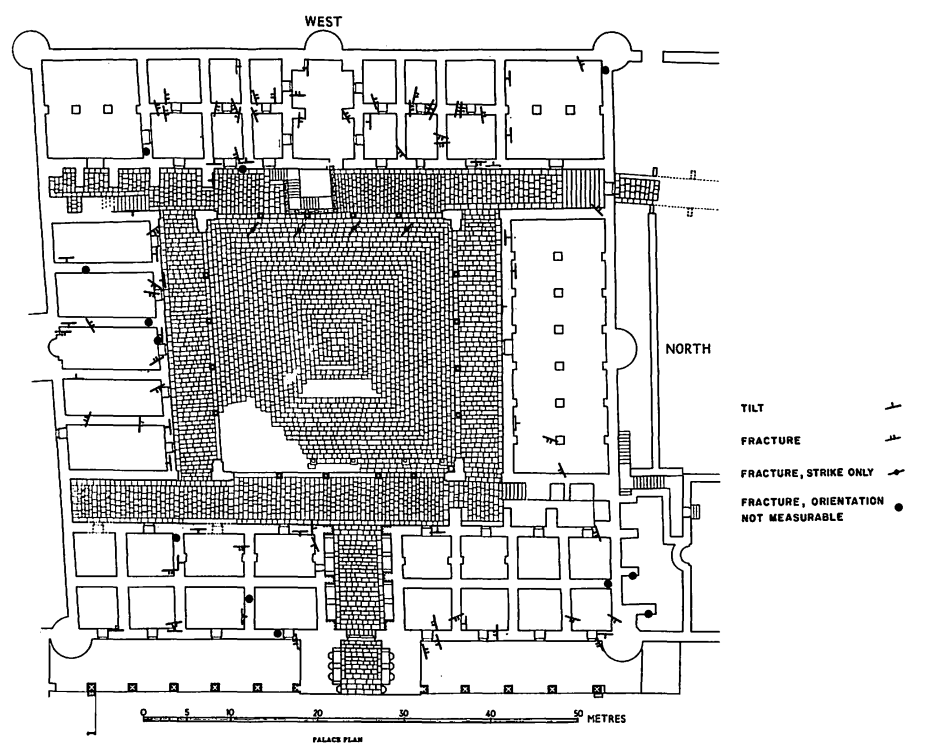

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

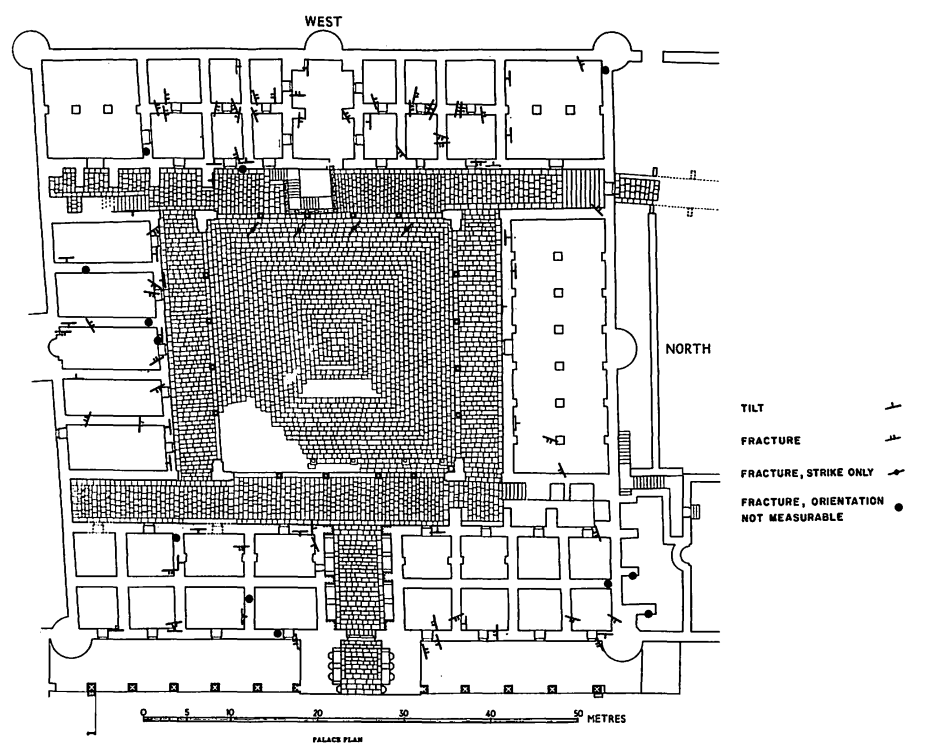

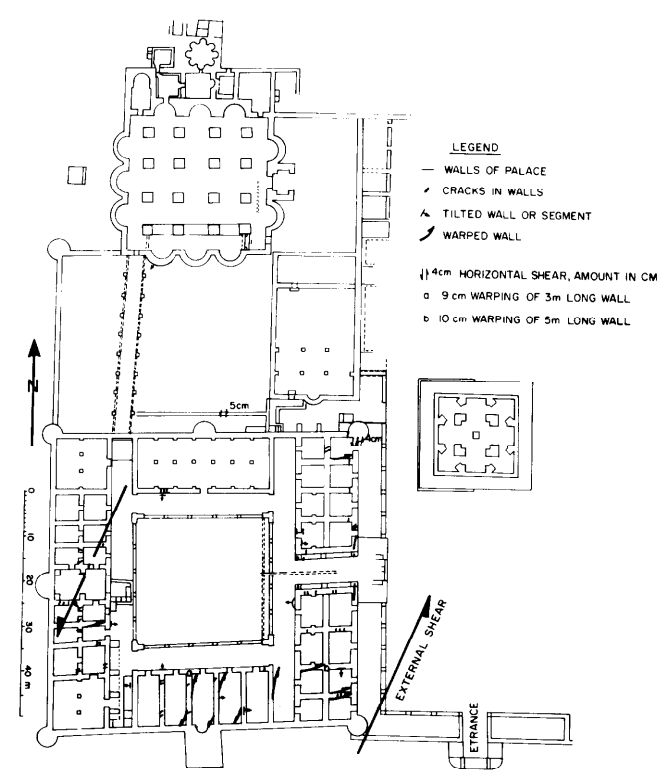

Alfonsi et al (2013) - Fig. 3 - Plan of "Hisham's Palace"

with distribution of structural damage from Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

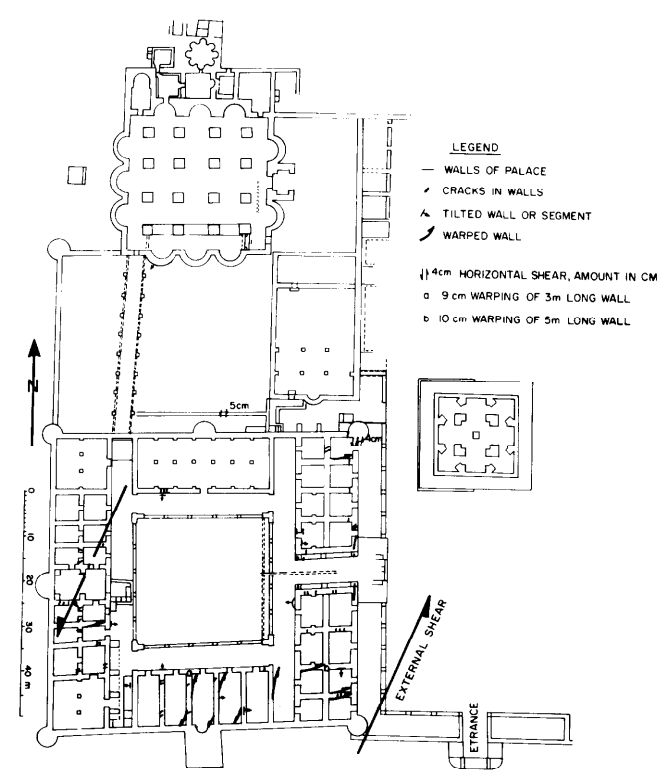

Detailed plan of the palace precinct and the distribution of structural damage

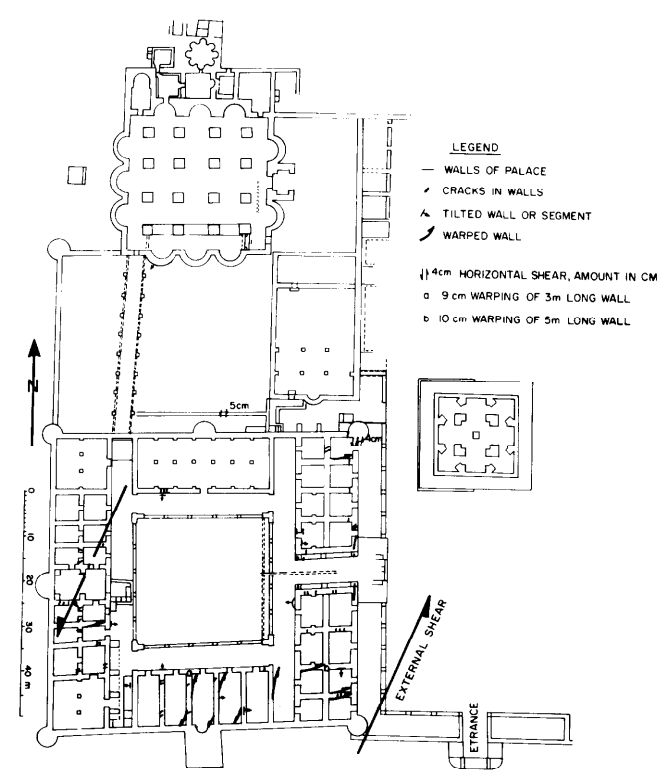

Karcz and Kafri (1981) - Fig. 12 - Plan of "Hisham's Palace"

with interpreted left-lateral shear from Reches and Hoexter (1981)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Map of the Hisham Palace close to Jericho (location 3, Fig. lc). The heavy lines indicate the main damage to the palace walls mapped in the present study. Most of the damage features are consistent with left-lateral shear parallel to the two marked solid arrows

Base map after Hamilton (1959).

Reches and Hoexter (1981)

- Plan of Hisham's Palace

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 2 - Plan of Hisham's Palace

from Whitcomb (1988)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1

Whitcomb (1988) - Fig. 2d - Map of the surveyed

coseismic effects at Hisham's palace from Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013) - Fig. 3 - Plan of "Hisham's Palace"

with distribution of structural damage from Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Detailed plan of the palace precinct and the distribution of structural damage

Karcz and Kafri (1981) - Fig. 12 - Plan of "Hisham's Palace"

with interpreted left-lateral shear from Reches and Hoexter (1981)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Map of the Hisham Palace close to Jericho (location 3, Fig. lc). The heavy lines indicate the main damage to the palace walls mapped in the present study. Most of the damage features are consistent with left-lateral shear parallel to the two marked solid arrows

Base map after Hamilton (1959).

Reches and Hoexter (1981)

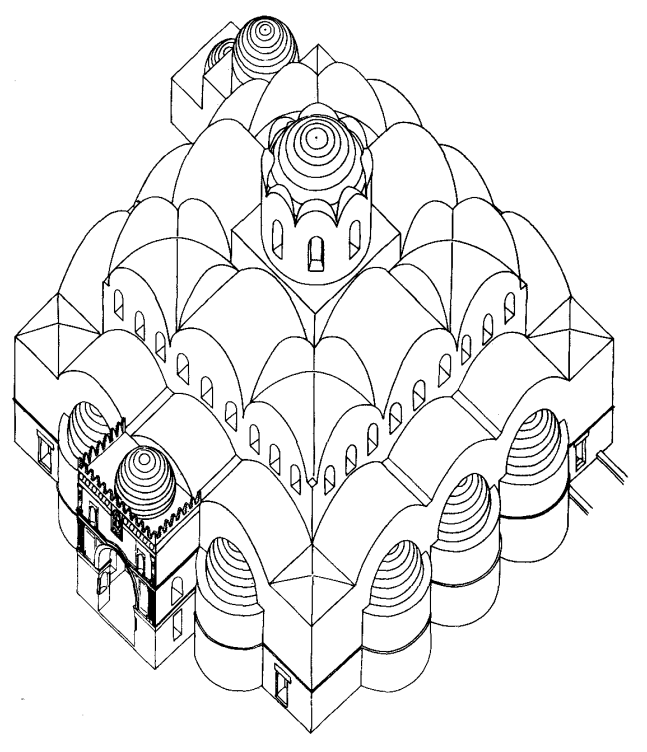

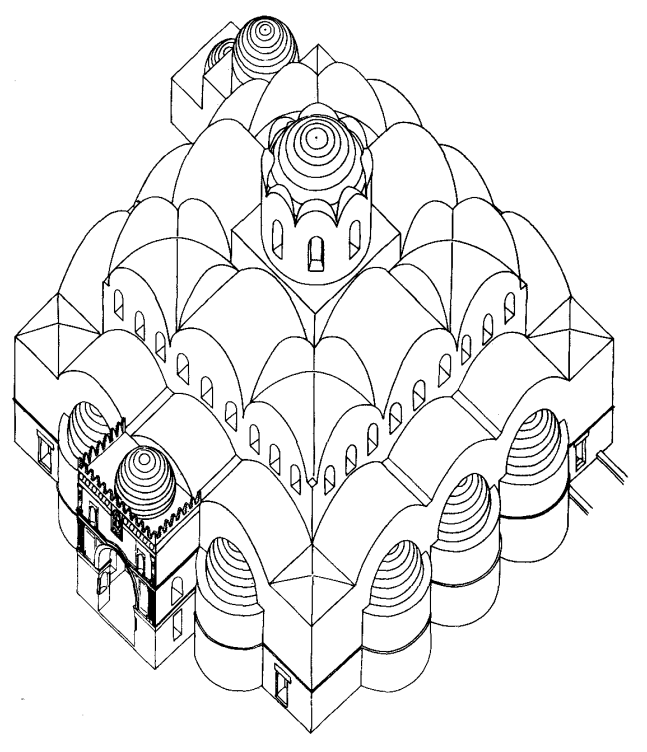

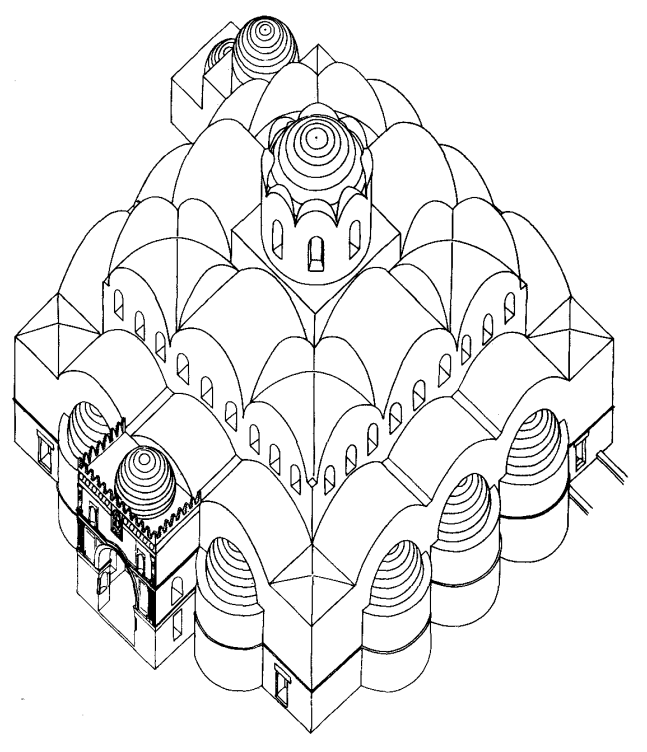

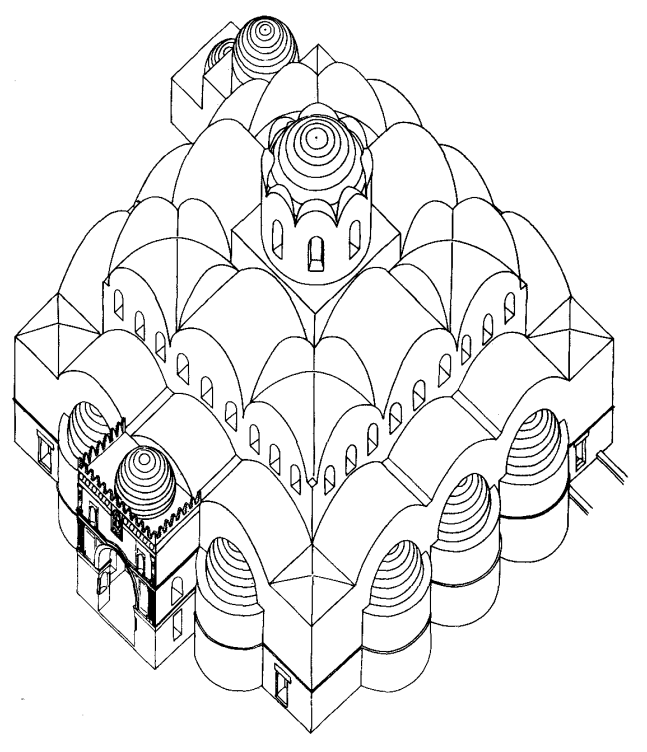

- Reconstruction of the bath

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Reconstruction of the bath.

Reconstruction of the bath.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

- from Whitcomb (1988)

| Period | Date (CE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ca. 750-800 |

Ceramics of this period occurred on or near the floor amid destruction debris, fallen columns, and stone elements and tended to occupy a stratum of about 40 cm. Also lying on the various floors were materials that Baramki took as evidence for interrupted and unfinished construction: plaster and marble screen production, stacked roof tiles, and window glass. Floors were either not laid or showed little or no wear on the limestone (see Baramki 1937: 167, for a summary of this evidence). The evidence from the drawn sherds indicates at least two-thirds of the excavated locations had substantial Period 1 artifacts on or near the floor, perhaps twice the occupation Baramki recognized (Table 1). |

| 2 | ca. 800-850 |

There is little explicit stratigraphic information on this period; taken together with deposition of Period 1, the material usually occurs within 50 cm of the floor. The distinctive forms of this period are relatively few and usually mixed with those of the preceding and following periods. Further, stratified materials of Period 2 occurred in seven locations described by Baramki as only medieval (Table 1, Period 2, in bold) and in general occurred in at least half of the excavated locations, implying a continuation of occupation rather larger than Baramki suggested (ca. 800-850). |

| 3 | ca. 900-1000 |

There are a number of locations, for example the south block, where rooms seem to have been cleared for reoccupation. The locations that produced floor level materials which Baramki called 10th to 12th century are rarer than he suggested - only four locations represented by drawings. The total evidence of Period 3 occupation (ca. 900-1000) is between two-thirds (from the drawings) and three-quarters (drawings and Baramki's description). |

| 4 | ca. 1200-1400 |

The preliminary reports described an upper layer of burnt materials, including fallen beams in the cloisters (Hamilton 1959: 28). "A large conflagration seems to have contributed to the destruction of the site during the second phase of occupation, as a layer of ash runs through the whole structure about one meter from the present surface" (Baramki 1936: 137). This can be seen in Hall I and in the entrance hall (Baramki 1937: pl. 47:1). Such a layer can hardly have been precisely regular and a photograph of the south part of the west cloister shows the burn layer at 0.5 m below surface and 1.3 m above the floor (Baramki 1936: pl. 85:2). The irregularity is noted in the courtyard (Baramki 1938: 51). The fallen arch in Room IVa appears in the burn layer at 1.8 m above the floor (Baramki 1938: 52, pl. 35:2). Baramki does not discuss the cause of this extensive burnt material, but most of the building was perhaps still carrying a wooden roof at the end of Period 3 (or possibly in the course of Period 4). The drawings confirm that only about half of the locations have materials of this last period (ca. 1200-1400). |

- from Taha (2011)

- Plan of Hisham's Palace

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Khirbet el-Majjar: plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Reconstruction of the bath

from Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Reconstruction of the bath.

Reconstruction of the bath.

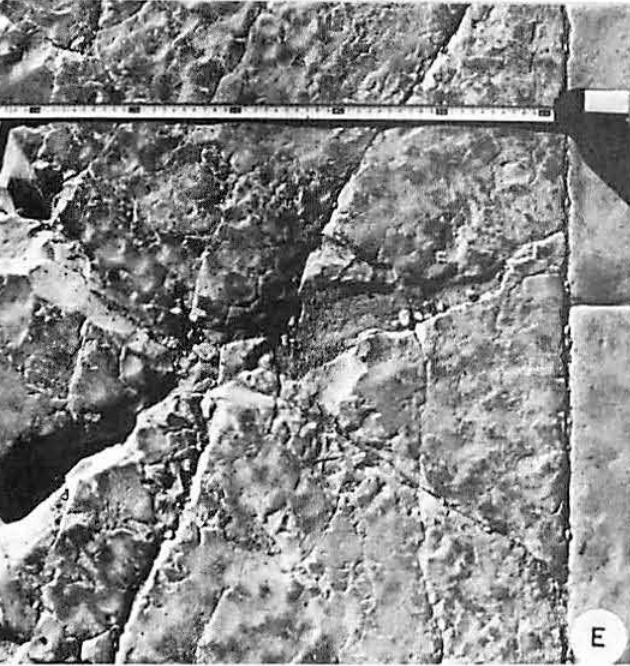

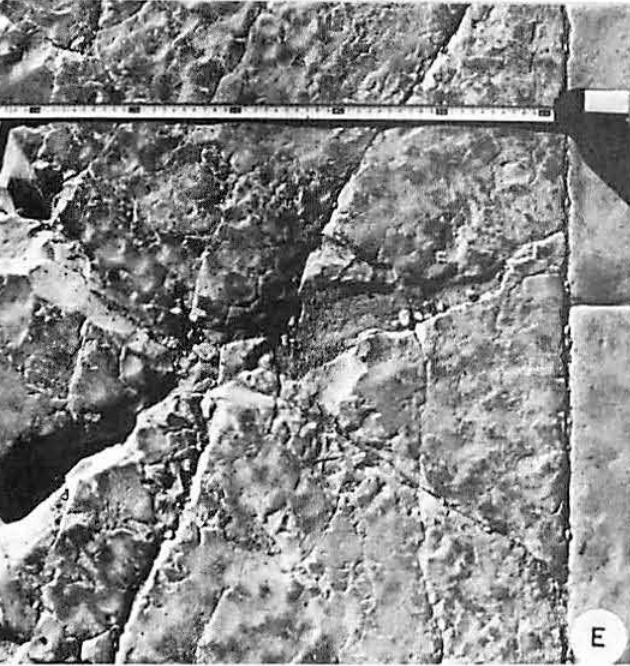

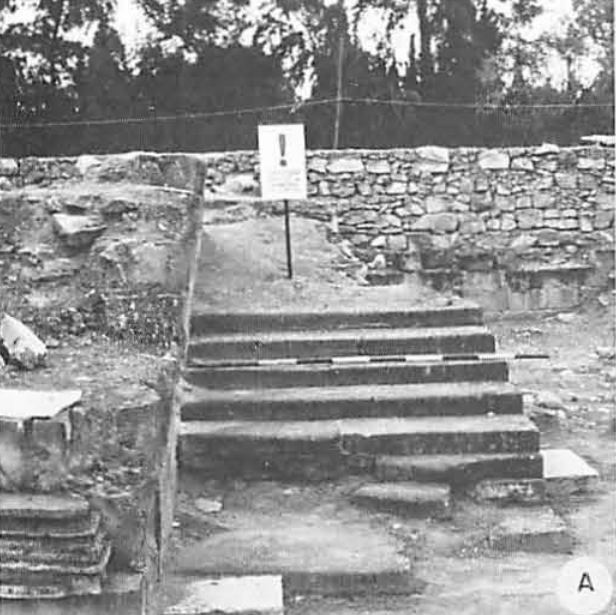

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 9 - View of Squares I and II

from Taha (2011)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Khirbet el-Mafjar: general view of squares I, II.

Taha (2011)

| Strata | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I |

topsoil layer (represented by locus 1 in square I and locus 1 in square II) covers the whole area of excavations. It is ca. I5-35 cm in thickness and consists of soft, loose soil mixed with pottery sherds. It is a layer of dark brown soil mixed with small and medium sized stones. A complete lamp was found in the south-eastern corner of square II. The debris is mixed with pottery sherds and glass fragments. Below that, there was a layer of ash mixed with stones, represented by loci 2 in squares I and II. A further stratum consists of a layer of lime, ca. 15-50 cm in thickness, and it was represented by locus 3 in squares I and II. Below the lime layer is another layer consisting of loci 8, 10 and 11 in square I, and loci 5 and 10 in square II. This stratum includes a layer of scattered stones represented by locus 9 in square I and locus 4 in square II. |

|

| II |

this stratum features the last major architectural phase in the history of the complex. It is represented by the walls W.6 and W.7 in square I and wall W.5a in square II. Wall W.5a features a secondary use of the palace stones. It was built above an earlier wall, dating most probably to the Umayyad Period. It is the same wall of the hot room and furnace. The new wall took the same north-south direction. But the construction techniques differ remarkably. Part of the wall was built on earth, projecting ca. 10 cm. The secondary nature of the wall is indicated by the use of carved stones for the earlier period, as well as using the tile fragments in filling the wall. The size of the stone ranges between 30 to 56 cm, two courses of the wall were preserved, with an average height of 26 cm, and 66-57 cm in width. The wall continues in the southern and northern directions. The wall can be associated with the room corner in square I (loci 6 and 7). Against the wall a layer of rubble and small stones, 10-16 cm in thickness (L.11) contains fragments of pottery and glass. In the same level, locus 10 consists of a stone pavement, 10 cm in thickness. The two loci 10 and 11 represent the living surfaces of this occupational period. |

|

| III |

period of abandonment represented by locus 7 in square I and loci 8 and 9 of square II. Another layer of light brownish soil above the layer of falling tile was represented by L.12 in square I. This layer of debris is mixed with large quantities of lime fragments of the plaster casting the tile roof and the surrounding wall, as well as fragment of tile and stones of different sizes. This layer covers the whole excavated area, and is about 70 cm in thickness. It contains pottery sherds, glass fragments, animal bones and an iron ring. |

|

| IV |

a layer of falling tile represented by locus 14 of square I and locus 13 in square II. It features evidence of the earthquake which struck the site. This dramatic moment in the history of the site is represented by a heavy layer of accumulation of fallen roof tile (50 cm in thickness) covering the whole area. The average size of the tile is 33 x 33 cm, and 25 x 25 cm, and 5 cm in thickness. The red coloured tile was made of rough clay mixed with straw and small stones as a temper. The tile bears different signs, indicating probably a sort of production signs, including simple incisions, wavy lines, imprints, net designs and in one case an Arabic inscription. In certain cases, foot imprints were indicated, as well as imprints of mosaic pavements. These signs could give some valuable information about production and processing of building material during the Umayyad Period. It is evident from the large bulks of tile, with a layer of mortar 2-4 cm in between, that it was used for roofing domes and building arches. An example is visible in the furnace area, with the beginning of a springing arch. However, a thick layer of plaster (5 cm) was indicated by a large fragment of white plaster found associated with this layer of destruction, 2.5 cm in thickness, mixed with soil, ash and charcoal. |

|

| V |

burnt layer below the falling tile, represented by locus 15 in square I and locus 14 in square II. A small area was excavated in the south-east corner of the square. This layer represents the period of use of the bath, connected with the activities of burning and firing wood. |

|

| VI |

this layer is represented by the earliest architectural elements in this area, represented by the eastern wall, W.5a in square I, the earthen surface, L.15 and the collapsed pilaster in the western part of square I. The fallen pilaster was built of ashlar stones, and it was a free standing column, falling to the north direction, partly over the falling tile L.14. The pilaster was built of four courses of ashlar stones; one stone bears engraved decorations. The thickness of these courses ranges between 24-40 cm, and the stone pilaster was capped with a stone, triangular in shape, indicating a beginning of a springing arch. It is on the same line of the arch on the other side of the furnace, indicating that the area was roofed. |

Whitcomb (1988:63) suggested an initial destruction affected Hisham's Palace after which occupation continued.

Ceramics of this period occurred on or near the floor amid destruction debris, fallen columns, and stone elements and tended to occupy a stratum of about 40 cm. Also lying on the various floors were materials that Baramki took as evidence for interrupted and unfinished construction: plaster and marble screen production, stacked roof tiles, and window glass. Floors were either not laid or showed little or no wear on the limestone (see Baramki 1937: 167, for a summary of this evidence). The evidence from the drawn sherds indicates at least two-thirds of the excavated locations had substantial Period 1 artifacts on or near the floor, perhaps twice the occupation Baramki recognized (Table 1).Whitcomb (1988:64) further reports that

The problem of interpretation of this ceramic evidence is one of depositional and functional implications. As mentioned above, the distribution of each type is limited to the distribution of the drawn examples, since Baramki's discussion of types incurs some distortions. More important, there is no indication of the quantity of each type and condition of preservation. Thus one can only guess whether a particular location has random sherds of refuse piles or vessels suddenly broken in their place of usage. The spread in height suggests the former depositional pattern, implying usage continuing after the cessation of building and after an initial destruction (ca. 750-800).

the deposits of Period 1 may have begun in the 740s but continued uninterrupted for the remainder of that century.

Alfonsi et al (2013) dated the causitive earthquake for the major seismic destruction at Hisham's Palace to the earthquake of 1033 CE unlike previous researchers who dated it to one of the Sabbatical Year earthquakes. Their discussion is reproduced below:

The archaeological data testify to an uninterrupted occupancy from eighth century until 1000 A.D. of the Hisham palace (Whitcomb, 1988). Therefore, if earthquakes occurred in this time period, the effects should not have implied a total destruction with consequent occupancy contraction or abandonment. Toppled walls and columns in the central court cover debris containing 750-850 A.D. old ceramic shards (Whitcomb, 1988). Recently unearthed collapses north of the court confirm a widespread destruction after the eighth century (Jericho Mafjar Project - The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago). These elements support the action of a destructive shaking event at the site later than the 749 A.D. earthquake. The two well-constrained, major historical earthquakes recognized in the southern Jordan Valley are the 749 and 1033 A.D. (Table 1; Marco et al (2003); Guidoboni and Comastri, 2005). We assign an IX—X intensity degree to the here-recorded Hisham damage, whereas a VII degree has been attributed to the 749 A.D. earthquake at the site (Marco et al, 2003). Furthermore, Whitcomb (1988) defines an increment of occupation of the palace between 900 and 1000 A.D. followed by a successive occupation in the 1200-1400 A.D. time span. On the basis of the above, and because no pottery remains are instead associated with the 1000-1200 A.D. period at Hisham palace (Whitcomb, 1988), we suggest a temporary, significant contraction or abandonment of the site as consequence of a severe destruction in the eleventh century.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Hisham's Paalace

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988) |

"Ceramics of this period occurred on or near the floor amid destruction debris, fallen columns, and stone elements and tended to occupy a stratum of about 40 cm." - Whitcomb (1988:63) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Central Court and elsewhere

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

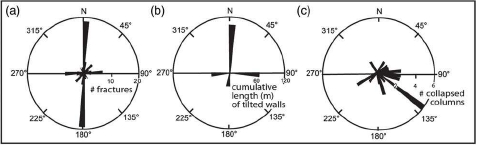

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3aView of the central court from the south: white arrows,fracture alignments along the pavement structure; black arrows,debris lying under the collapsed columns. Widespread tumbles and column failures are exposed. Alfonsi et al (2013) |

The direction of column failure is due to the traction effect of the first-floor collapse.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

east—west bearing walls

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 4b - east-west bearing wall

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bMixed Mode I—II (open-shear) fracture of an east—west-striking bearing wall (view from west). Note by JW: In Fracture Mechanics Mode I = Opening mode (a tensile stress normal to the plane of the crack) and Mode II = Sliding mode (a shear stress acting parallel to the plane of the crack and perpendicular to the crack front). Alfonsi et al (2013) 4a - east—west bearing wall of the North hall

Figure 4a

Figure 4aClosely spaced faults with 10 cm left-lateral slips crossing the east—west-oriented bearing wall of the North hall (view from southeast). Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Some structures with mixed shear (sinistral)-opening mode have also been recognized (Fig.4b).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

various locations

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3bTilted bearing wall a meter wide, the black arrow indicates the direction of inertial wall movement (view from northwest). Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7bTilted Walls Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Several walls are tilted and/or warped up to 15° (Figs. 2 and 3b).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

Room IVa - a room facing the east cloister

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Plate XXXV.2

Plate XXXV.2Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.3

Plate XXXV.3Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.4

Plate XXXV.4Skeleton under debris of fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938) |

A human skeleton found in a room facing the east cloister under debris of an arch that collapsed in 1000-1400 A.D. could be also indicative of seismic shaking (Baramki, 1938).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

Central Court and Cloisters

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 7f

Fig. 7fFractures across the western part of the central court Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 6c

Fig. 6cMisalignments in flagstone pavements, no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

The flagstones are deformed in a pop-up-like array.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

north wall of an archaeological trench 50 m north of the north hall area |

Fig. 4c

Fig. 4c

Fig. 4cPart of a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of > 50° dipping north—south-striking fractures and faults (in red) outcropping on the north wall of an archaeological trench. Blue lines allow the eye to identify the displaced flood-related deposits. View from south. Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fifty meters north of the north hall area, we observed a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of high-angle fractures and faults exposed on the northern wall of an archaeological trench (Fig. 4c) The vertical displacement across this zone is of the order of tens of centimeters. No data are available to strictly constraint the age of faulting.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

Drainage channel in the northern section of the site |

Fig. 5

Figure 5

Figure 5Drainage channel in the northern section of the site affected by fracturing closely aligned with the shear zone outcropping along the northern trench edge (view from southeast). Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Drainage channel in the northern section of the site affected by fracturing closely aligned with the shear zone outcropping along the northern trench edge- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

- There is more archaeoseismic evidence in Baramki's Excavation Reports

| Effect | Image(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Misalignments in flagstone pavements no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding |

Fig. 6a

Fig. 6aMisalignments in flagstone pavements, no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 6b

Fig. 6bMisalignments in flagstone pavements, no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 6c

Fig. 6cMisalignments in flagstone pavements, no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Gap between Walls |

Fig. 6d

Fig. 6dA joint-like gap between the outer wall and a partition wall Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Impact Fractures |

Fig. 6e

Fig. 6eFeatures of impact Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| suture between remnant and rebuilt wall |

Fig. 6f

Fig. 6fA suture between the remnant and rebuilt wall. Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Tilted Walls |

Fig. 7a

Fig. 7aTilted Walls Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7bTilted Walls Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Collapse Debris |

Fig. 7c

Fig. 7cRemnant of collapse debris Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Plate LXXV.2

Plate LXXV.2Bricks in debris at west end of Hall I Baramki (1936) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) and Baramki (1936) |

| Fractured Walls |

Fig. 7d

Fig. 7dFractures in the palace walls. Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 7e

Fig. 7eFractures in the palace walls. Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Fractured Floors |

Fig. 7f

Fig. 7fFractures across the western part of the central court Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Fractured Wall Repairs |

Fig. 7g

Fig. 7gFractures and fissures, apparently repaired in course of reconstruction Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Severely fractured Doorway |

Fig. 7h

Fig. 7hFractures near a through walk, inclined towards the sill Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Distorted and Blocked Doorway |

Fig. 7i

Fig. 7iA throughwalk , blocked during a later occupancy, with signs of deformation. Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

| Fractured Walls |

Plate LXXIV.2

Plate LXXIV.2Pier (iv) Hall I, showing effects of earthquake Baramki (1936)

Plate LXXXII.2

Plate LXXXII.2Door between Room a and hall Baramki (1936) |

Baramki (1936) |

| Fallen Arch |

Plate XXXV.2

Plate XXXV.2Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.3

Plate XXXV.3Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.4

Plate XXXV.4Skeleton under debris of fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938) |

Baramki (1938) |

| Orientation of fractures and tilted walls |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Orientation of fractures and tilted walls, palace precinct. Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)

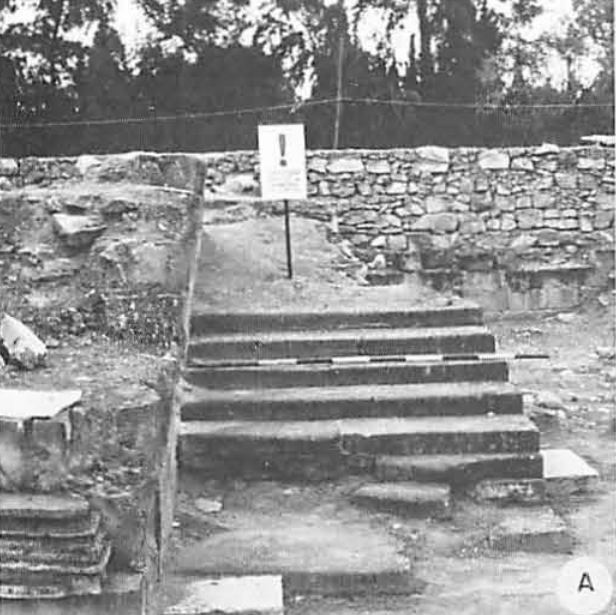

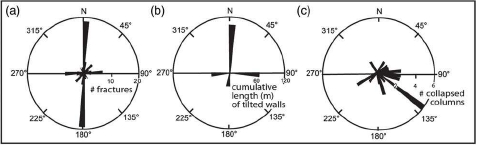

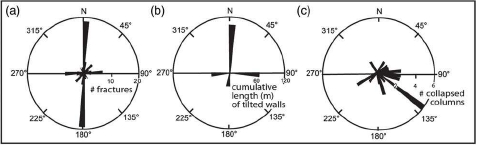

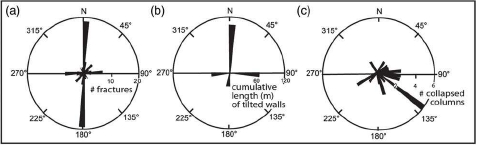

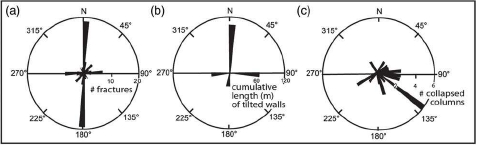

Figure 2 a-c

Figure 2 a-cRose diagrams of

(a) strike of fractures

(b) direction of tilting versus cumulative length of titled walls

(c) direction of column collapse.

Alfonsi et al (2013)

Alfonsi et al (2013) documented and measured orientations of archeoseismic damage such as tilted structures, displaced walls and pavements, and colonnade failure. By combining their their field work (70%) with previous studies (30%) by Karcz and Kafri, 1981 and Reches and Hoexter, 1981 they were able to produce an array of useful archeoseismic data. They describe the archeoseismic evidence below:

The observed damage defines a severe earthquake scenario. Most of the brittle structures affect the supporting and divisor walls ( Figs. 2, 4a

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)and 4b

Figure 4a

Closely spaced faults with 10 cm left-lateral slips crossing the east—west-oriented bearing wall of the North hall (view from southeast).

Alfonsi et al (2013)). These structures are faults and open cracks with dip generally > 50° and width up to 20 cm. The faults offset archaeological structures with left-lateral slips up to 10 cm. Some structures with mixed shear (sinistral)-opening mode have also been recognized ( Fig.4b

Fig. 4b

Mixed Mode I—II (open-shear) fracture of an east—west-striking bearing wall (view from west).

Note by JW: In Fracture Mechanics Mode I = Opening mode (a tensile stress normal to the plane of the crack) and Mode II = Sliding mode (a shear stress acting parallel to the plane of the crack and perpendicular to the crack front).

Alfonsi et al (2013)). In the western portion of the pavement of the central court, roughly north—south striking cracks and vertical deformations occur ( Fig. 3

Fig. 4b

Mixed Mode I—II (open-shear) fracture of an east—west-striking bearing wall (view from west).

Note by JW: In Fracture Mechanics Mode I = Opening mode (a tensile stress normal to the plane of the crack) and Mode II = Sliding mode (a shear stress acting parallel to the plane of the crack and perpendicular to the crack front).

Alfonsi et al (2013)). The flagstones are deformed in a pop-up-like array. These deformations have a linear continuity of about 30 m and align to the faults and shear-opening structures affecting the walls of the north and south cloister ( Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Pictures from Matson and Matson (1934-1939) showing the ruins of the palace as appeared during Baramki excavation

- View of the central court from the south: white arrows, fracture alignments along the pavement structure; black arrows, debris lying under the collapsed columns. Widespread tumbles and column failures are exposed.

- Tilted bearing wall a meter wide, the black arrow indicates the direction of inertial wall movement (view from northwest)

Alfonsi et al (2013)). The fractures at Hisham palace have a preferred north—south strike and a second-order east—west strike (Rose diagram in Fig. 2a

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)). Fracture density (shaded pale orange areas in Fig. 2d

Fig. 2a

Rose diagram of strike of fractures

Alfonsi et al (2013)) evidences two roughly north—south elongated subparallel areas located on the western side of Hisham palace, and one, also north—south elongated, on the eastern side. Fifty meters north of the north hall area, we observed a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of high-angle fractures and faults exposed on the northern wall of an archaeological trench ( Fig. 4c

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)) The vertical displacement across this zone is of the order of tens of centimeters. No data are available to strictly constraint the age of faulting. The plaster and the drainage channel close to the trench wall are affected by fracturing aligned with the deformed zone ( Fig. 5

Fig. 4c

Part of a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of >50° dipping north—south-striking fractures and faults (in red) outcropping on the north wall of an archaeological trench. Blue lines allow the eye to identify the displaced flood-related deposits. View from south.

Alfonsi et al (2013)).

Fig. 5

Drainage channel in the northern section of the site affected by fracturing closely aligned with the shear zone outcropping along the northern trench edge (view from southeast).

Alfonsi et al (2013)

Several walls are tilted and/or warped up to 15° ( Figs. 2and 3b

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)). Rose diagram in Figure 2b

Fig. 3b

Tilted bearing wall a meter wide, the black arrow indicates the direction of inertial wall movement (view from northwest).

Alfonsi et al (2013)shows the cumulative length of tilting, for which the preferred sense is north. The occurrence of this preferred sense of tilting confirms the seismic nature of the observed damage (Paz (1997)). A human skeleton found in a room facing the east cloister under debris of an arch that collapsed in 1000-1400 A.D. could be also indicative of seismic shaking (Baramki, 1938).

Fig. 2b

Rose diagram of direction of tilting versus cumulative length of titled walls

Alfonsi et al (2013)

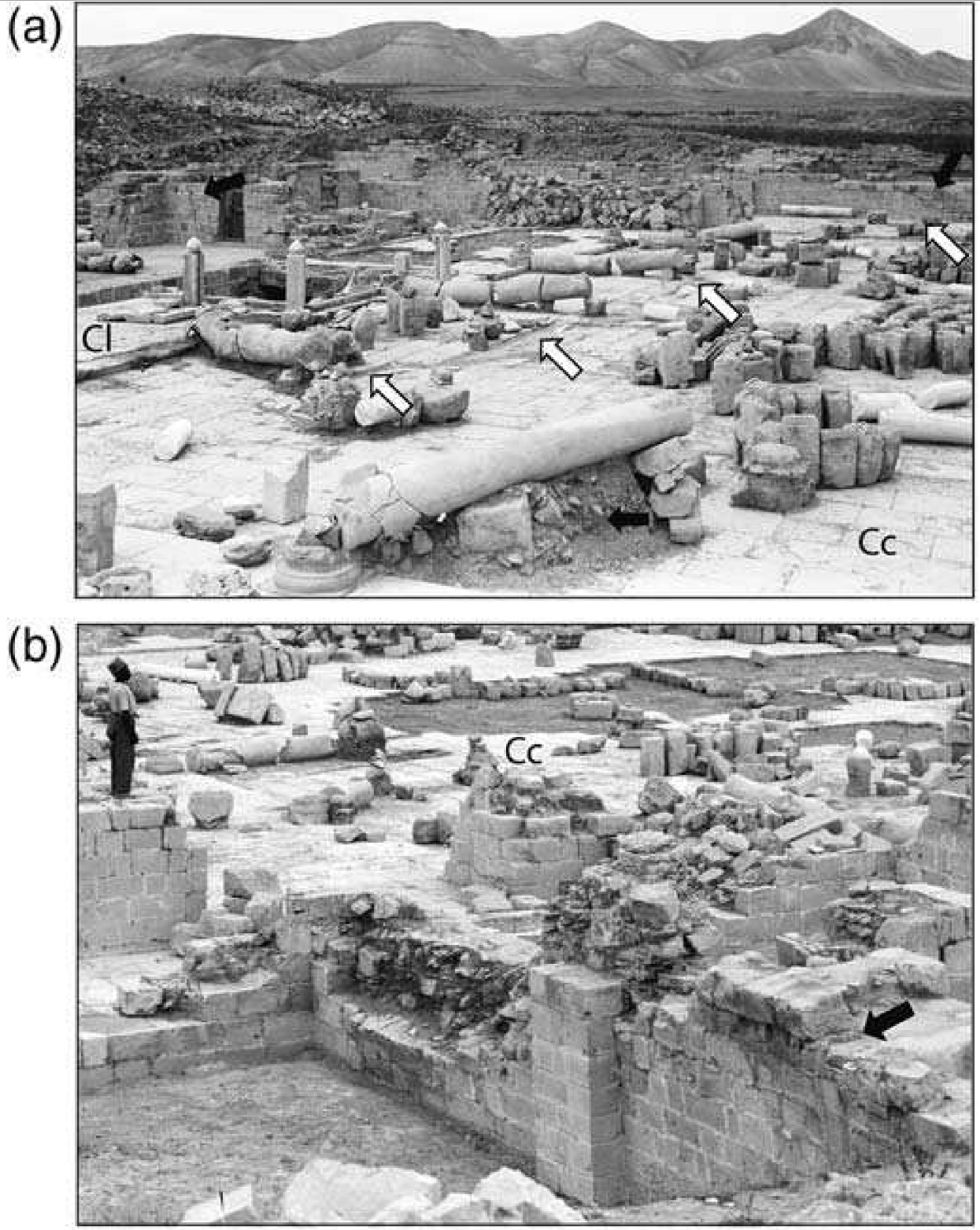

The overall position of the failed columns has been reconstructed from original reports and pictures and it is reported in Figure 2. Most colonnade collapses cluster mainly toward the southeastern quadrant (Rose diagram in Fig. 2c

Fig. 2d

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959)

Alfonsi et al (2013)). The direction of column failure is due to the traction effect of the first-floor collapse.

Fig. 2c

Rose diagram of direction of column collapse.

Alfonsi et al (2013)

- Slightly Modified by JW from from Alfonsi et al (2013)

Map of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

- Nh - North hall

- Cc - Central court

- Cl - Cloister

- crack and fault; black arrow, direction of movement

- tilting and warping of wall (arrow toward the direction of movement)

- column of the ground floor (larger symbol) and of the first floor (smaller symbol); circle, column top

- deformation of floor (sunk and pop-up)

- fracture density (>1/8 m2)

Modified by JW from Fig. 2d of Alfonsi et al. (2013)

Original plan of the palace is modified by Alfonsi from Hamilton (1959)

Click on Image to open in a new tab

Figure 2 a-c

Figure 2 a-cRose diagrams of

(a) strike of fractures

(b) direction of tilting versus cumulative length of titled walls

(c) direction of column collapse.

Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Detailed plan of the palace precinct and the distribution of structural damage

Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8Orientation of fractures and tilted walls, palace precinct.

Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12Map of the Hisham Palace close to Jericho (location 3, Fig. lc). The heavy lines indicate the main damage to the palace walls mapped in the present study. Most of the damage features are consistent with left-lateral shear parallel to the two marked solid arrows

Base map after Hamilton (1959).

Reches and Hoexter (1981)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hisham's Paalace

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988) |

"Ceramics of this period occurred on or near the floor amid destruction debris, fallen columns, and stone elements and tended to occupy a stratum of about 40 cm." - Whitcomb (1988:63) |

|

Alfonsi et al (2013) assigned a seismic intensity of VII (7) to the earlier earthquake.

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Central Court and elsewhere

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3aView of the central court from the south: white arrows,fracture alignments along the pavement structure; black arrows,debris lying under the collapsed columns. Widespread tumbles and column failures are exposed. Alfonsi et al (2013) |

The direction of column failure is due to the traction effect of the first-floor collapse.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

east—west bearing walls

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 4b - east-west bearing wall

Fig. 4b

Fig. 4bMixed Mode I—II (open-shear) fracture of an east—west-striking bearing wall (view from west). Note by JW: In Fracture Mechanics Mode I = Opening mode (a tensile stress normal to the plane of the crack) and Mode II = Sliding mode (a shear stress acting parallel to the plane of the crack and perpendicular to the crack front). Alfonsi et al (2013) 4a - east—west bearing wall of the North hall

Figure 4a

Figure 4aClosely spaced faults with 10 cm left-lateral slips crossing the east—west-oriented bearing wall of the North hall (view from southeast). Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Some structures with mixed shear (sinistral)-opening mode have also been recognized (Fig.4b).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

various locations

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3bTilted bearing wall a meter wide, the black arrow indicates the direction of inertial wall movement (view from northwest). Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7bTilted Walls Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

Several walls are tilted and/or warped up to 15° (Figs. 2 and 3b).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

Room IVa - a room facing the east cloister

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Plate XXXV.2

Plate XXXV.2Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.3

Plate XXXV.3Fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938)

Plate XXXV.4

Plate XXXV.4Skeleton under debris of fallen arch in Room IVa Baramki (1938) |

A human skeleton found in a room facing the east cloister under debris of an arch that collapsed in 1000-1400 A.D. could be also indicative of seismic shaking (Baramki, 1938).- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

Central Court and Cloisters

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of the palace of Khirbet al-Mafjar, after Barakmi 1942b, fig. 1 Whitcomb (1988)

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dMap of the surveyed coseismic effects at Hisham palace (Khirbet al-Mafjar site)

Original plan of the palace is modified from Hamilton (1959) Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fig. 7f

Fig. 7fFractures across the western part of the central court Karcz and Kafri (1981)

Fig. 6c

Fig. 6cMisalignments in flagstone pavements, no signs of distortion, crushing nor overriding Karcz and Kafri (1981) |

The flagstones are deformed in a pop-up-like array.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

north wall of an archaeological trench 50 m north of the north hall area |

Fig. 4c

Fig. 4c

Fig. 4cPart of a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of > 50° dipping north—south-striking fractures and faults (in red) outcropping on the north wall of an archaeological trench. Blue lines allow the eye to identify the displaced flood-related deposits. View from south. Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Fifty meters north of the north hall area, we observed a 6 m wide shear zone consisting of high-angle fractures and faults exposed on the northern wall of an archaeological trench (Fig. 4c) The vertical displacement across this zone is of the order of tens of centimeters. No data are available to strictly constraint the age of faulting.- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

|

Drainage channel in the northern section of the site |

Fig. 5

Figure 5

Figure 5Drainage channel in the northern section of the site affected by fracturing closely aligned with the shear zone outcropping along the northern trench edge (view from southeast). Alfonsi et al (2013) |

Drainage channel in the northern section of the site affected by fracturing closely aligned with the shear zone outcropping along the northern trench edge- Alfonsi et al (2013) |

|

Alfonsi et al (2013) assigned a seismic intensity of IX-X to the earthquake that caused the observed destruction at Hisham's Palace.

- Fig. 6 - Structural sketch map

and stress-field configuration of Hisham's Palace and surroundings from Alfonsi et al (2013)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Structural sketch map and stress-field configuration in the Hisham palace surroundings

Red line and arrows represent the coseismic rupture and slip related to the 1033 A.D. event inferred from this study

data from Hofstetter et al, 2007 and Lazar et al, 2006

Alfonsi et al (2013)

Alfonsi et al (2013) discussed the seismotectonic implications of the archeoseismic data unearthed from Hisham's Palace as follows:

The preferred sense of tilting of the Hisham walls and the colonnade-collapse direction indicate, according to structural dynamic models by Paz (1997) and Hinzen (2009) on inelastic inertial structures, a ground shaking by seismic waves coming from the northern quadrant. Although the cause of most of the earthquake-induced damage at Hisham palace is ground shaking, some of the mapped features have a clear tectonic origin. These features include the occurrence ofAll these data define a syn- and post-1033 A.D. brittle deformation zone. This zone may represent the southern prolongation of the north—south-striking, subvertical fault recognized by field and seismic data (Fig. 6). This fault accommodates the deepening of the Jericho syntectonic sedimentary basin. The prevailing left-lateral slips we recognize at Hisham palace along north—south- to north-northeast—south-southwest-striking structures are fully compatible with the strike-slip stress regime of the Jordan area of the Dead Sea fault system, which is characterized by a northwest—southeast subhorizontal σ1 (Fig. 6; Hofstetter et. al., 2007). As a result, we conclude that the 1033 A.D. earthquake originated within this stress field.

- left-lateral faults

- north—south- to north-northeast—south-southwest-striking fractures and cracks

- aligned fractures up to 30 m long crossing the whole palace formed during the 1033 A.D. earthquake

- a 6 m wide north—south- to north-northeast—south-southwest-striking shear zone affecting the ground.

Alfonsi, L., et al. (2013). The Kinematics of the 1033 A.D.

Earthquake Revealed by the Damage at Hisham Palace (Jordan

Valley, Dead Sea Transform Zone). Seismological Research

Letters, 84(6), 997-1003.

Augustinović, A. (1951). Gerico e dintorni, Jerusalem 1951

(esp. pp. 155-157).

Baer, E. (1974). A Group of North Iranian Craftsmen at

Khirbet el-Mafjar? Israel Exploration Journal, 24,

237-240.

Baer, E. (1979). Khirbet el-Mafjar. In B. Lewis et al.

(eds.), Encyclopedia of Islam, Leiden, 10-17.

Baramki, D. C. (1947). Guide to the Umayyad Palace at

Khirbet el-Mafjar, Jerusalem (repr. Amman 1956).

Bliss, F. J. (1894). Notes on the Plain of Jericho.

Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 26, 177-183 (esp.

177-181).

Cirelli, E., & Zagari, F. (2000). Gerico in epoca

bizantina e islamica. Archeologia Medievale, 27, 365-376

(esp. 368).

Clermont-Ganneau, C. (1896). Archaeological Research in

Palestine During the Years 1873-1874, Vol. II, London

(esp. 20).

Conder, C. R., & Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of

Western Palestine, Vol. III, Judaea, London (esp. 180,

211-212).

Creswell, K. A. C. (1932). Khirbet el-Mafjar. In Early

Muslim Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford, 545-577, pls. 99-110.

Crowe, Y. (1976). Survival of Classical Elements in the

Groundplan of Khirbet el-Mafjar. In Akten des VII

Kongresses für Arabistik und Islamwissenschaft,

Göttingen, 92-100.

Donceel-Voûte, P. (1999). Jéricho aux époques byzantine et

omeyyade. Dossier d’Archéologie, 240, 115-121.

Grabar, O. (1955). The Umayyad Palace at Khirbet

el-Mafjar. Archaeology, 8, 228-235.

Hamilton, R. W. (1945). Khirbet el-Mafjar. Stone

Sculpture. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in

Palestine, 11, 47-66.

Hamilton, R. W. (1946). Khirbet el-Mafjar. Stone

Sculpture. Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in

Palestine, 12, 1-19.

Hamilton, R. W. (1948). Plaster Balustrades from Khirbet

el-Mafjar. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in

Palestine, 13, 1-58.

Hamilton, R. W. (1949a). The Baths at Khirbet el-Mafjar.

Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 81, 40-51.

Hamilton, R. W. (1949b). A Mosaic Carpet of Umayyad Date

at Khirbet el-Mafjar. Quarterly of the Department of

Antiquities in Palestine, 14, 120-129.

Hamilton, R. W. (1950). The Sculpture of Living Forms at

Khirbet el-Mafjar. Quarterly of the Department of

Antiquities in Palestine, 15, 100-119.

Hamilton, R. W. (1969). Who Built Khirbet el-Mafjar?

Levant, 1, 61-67.

Hamilton, R. W. (1978). Khirbet el-Mafjar: The Bath Hall

Reconsidered. Levant, 10, 126-138.

Hinzen, K. G. (2009). Sensitivity of earthquake-toppled

columns to small changes in ground motion and geometry.

Israel Journal of Earth Sciences, 58(3-4), 309-326.

Karcz, I., & Kafri, U. (1981). Studies in Archeoseismicity

of Israel: Hisham’s Palace, Jericho. Israel Journal of

Earth Sciences, 30, 12-23.

Piccirillo, M. (1999). Le Qasr Hisham (Khirbet el-Mafjar).

Le projet de restauration. Dossier d’Archéologie, 240,

122-123.

Reches, Z., & Hoexter, D. F. (1981). Holocene seismic and

tectonic activity in the Dead Sea area. Tectonophysics,

80, 235-...

Sabelli, R. (2006). The Jericho Qasr Hisham Archaeological

Park. In Nigro & Taha (eds.), Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in

the Context of the Jordan Valley, Rome, 237-252.

Schneider, M. A. (1931). Das byzantinische Gilgal (chirbet

mefdschir). Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins,

51, 50-59.

Schwabe, M. (1946). Khirbet el-Mafjar: Greek Inscribed

Fragments. Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in

Palestine, 12, 20-30.

Taha, H. (2011). New Excavations at Khirbet el-Mafjer.

ROSAPAT 07 PADIS I, Rome – La Sapienza Expedition to

Palestine and Jordan.

Whitcomb, D. (1988). Khirbet el-Mafjar Reconsidered: the

Ceramic Evidence. Bulletin of the American Schools of

Oriental Research, 271, 51-67.

Baramki, D. C. (1936). Excavations at Khirbet el Mefjer.

Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in Palestine,

5, 132-138. – open access at Google Play

Baramki, D. C. (1937). Excavations at Khirbet el Mefjer, 2.

Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in Palestine,

6, 157-158. – open access at Google Play

Baramki, D. C. (1938). Excavations at Khirbet el Mefjer, 3.

Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in Palestine,

8, 51-53. – open access at Google Play

Baramki, D. C. (1942a). Excavations at Khirbet el Mefjer, 4.

Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in Palestine,

10, 153-159. – open access at Google Play

Baramki, D. C. (1942b). The Pottery from Khirbet el Mefjer,

4. Quarterly of the Department of Archaeology in

Palestine, 10, 65-103. – open access at Google Play

Hamilton, R. W., & Grabar, O. (1959). Khirbat al Mafjar:

an Arabian mansion in the Jordan Valley. Oxford.

R. W. Hamilton and 0. Grabar, Khirbet al-Majjar, Oxford 1959.

Conder-Kitchener, SWP 3, 211

F. J. Bliss, PEQ 26 (1894), 177

D. C. Baramki, QDAP 5

(1936), 132-138; 6 (1937), 157-168; 8 (1938), 51-53; 10 (1942), 153-159

R. W. Hamilton, Levant (1969),

61-67; 4 (1972), 155-156; 10 (1978), 126-138

K. A. C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture 1/2, Oxford

1969, 545-577; id., A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture (Revised and Supplemented by J. W.

Allan), Aldershot 1989, 178-200

0. Grabar, Archaeology 8 (1955), 236-244

R. Ettinghausen, From

Byzantium to Sassanian Iran and the Islamic World, Leiden 1972, 17-65

M. Rosen-Ayalon, IEJ23 (1973),

92-100

E. Baer, ibid. 24 (1974), 237-240

I. Karcz and U. Kafri, Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 30 (1980),

12-23

G. S. Merker, EI 19 (1987), 15*-20*

E. P. de Loos-Dietz, Bulletin Antieke Beschaving 65 (1990),

123-138

F. B. Flood, PEQ 122 (1990), 151-152

A. Lemaitre, MdB 69 (1991), 38-40.

M. Schwabe, QDAP 12 (1946), 20.

D. C. Baramki, QDAP 10 (1942), 65

D. Whitcomb, BASOR 271 (1988), 51-67.

R. W. Hamilton, QDAP 11 (1945), 47-66; 12 (1946), 1-19; 13 (1947), I; 14 (1950), 100-119.

H. Taragan, The Umayyad Sculpture of Khirbat al Mafjar, 1–2 (Ph.D. diss.), Tel Aviv

1991 (Eng. abstract)

R. Talgam, The Stylistic Origins of Umayyad Sculpture as Shown in Khirbat al-Mafjar

and Mshatta, 1–3 (Ph.D. diss.), Jerusalem 1996; id., The Stylistic Origins of Umayyad Sculpture and Architectural Decoration, 1–2, Wiesbaden 2004.

G. King, SHAJ 4 (1992), 369–376

A. Leonard, The Jordan Valley Survey, 1953: Some Unpublished

Soundings Conducted by James Mellaart (AASOR 50), Winona Lake, IN 1992, 9–23

M. Rosen-Ayalon,

Studies in the Archaeology and History of Ancient Israel, Haifa 1993, 26*; id., Art et archéologie islamiques

en Palestine (Islamiques), Paris 2002, 46–53

P. P. Soucek, Ars Orientalis 23 (1993), 109–134

T. Ulbert,

Damaszener Mitteilungen 7 (1993), 211–231

R. Ruby, Jericho: Dreams, Ruins, Phantoms, New York 1995,

297–298

D. Behrens-Abouseif, Muqarnas 14 (1997), 11–18

O. Grabar, OEANE, 3, New York 1997, 397–

399

N. Kubisch, Madrider Mitteilungen 38 (1997), 300–364

M. L. Fischer, Marble Studies, Konstanz 1998;

H. Taragan, Assaph B/3 (1998), 93–108; id., East and West, n.d., 9–29; id., The Metamorphosis of Marginal

Images: From Antiquity to Present Time (eds. N. Kenaan-Kedar & A. Ovadiah), Tel Aviv 2001, 69–78

N.

Marchetti & L. Nigro, Les Dossiers d’Archéologie 240 (1999), 115–122

G. Bisheh, The Archaeology of

Jordan and Beyond, Winona Lake, IN 2000, 59–65

P. Donceel-Voute, La mosaïque gréco-romaine 9: Actes

du 9. Colloque International pour l’Étude de la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Roma, 5–10.11.2001, Paris

2002, 151–170

F. Hilloowala, ASOR Newsletter 53/3 (2003), 8–9

H. Taha et al., Orient Express 2004/2,

40–44.

Creswell, K. A. C. A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Rev.

ed. Aldershot, 1989. See pages 179-200 for Khirbat al-Mafjar

Ettinghausen, Richard. From Byzantium to Sasanian Iran and the Islamic

World. Leiden, 1972. See chapter 3, "The Throne and Banquet Hall

of Khirbat al-Mafjar" (pp. 17-65).

Grabar, Oleg. The Formation of Islamic Art. Rev. and enl. ed. New Haven, 1987.

Hamilton, Robert William. Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in

the Jordan Valley. Oxford, 1959.

Hamilton, Robert William. Walid and His Friends: An Umayyad Tragedy. London, 1988.

Whitcomb, Donald S. "Khirbat al-Mafjar Reconsidered: The Ceramic

Evidence." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no.

271 (1988): 51-67-