Jerusalem - City Walls

Ottoman Walls surrounding the Old City in Jerusalem

Ottoman Walls surrounding the Old City in JerusalemEitan F. on Wikipedia - Public Domain

Jerusalem has been surrounded by a series of different walls since ancient times. The walls that are currently visible surrounding the Old City were constructed in Ottoman times in the 16th century CE.

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

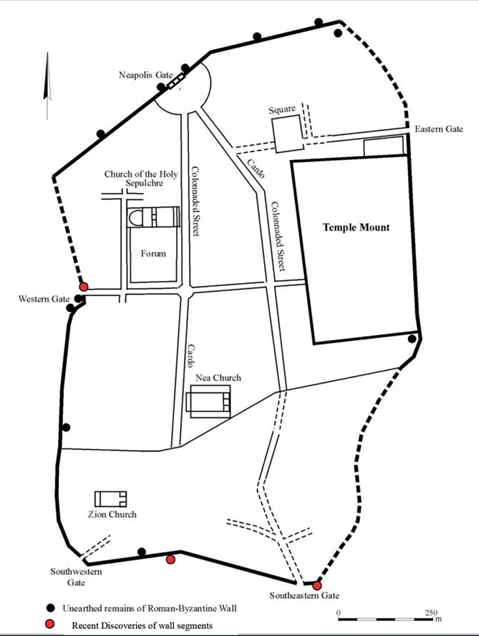

- Fig. 2 - Roman-Byzantine city walls

and exposures from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421)

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed.

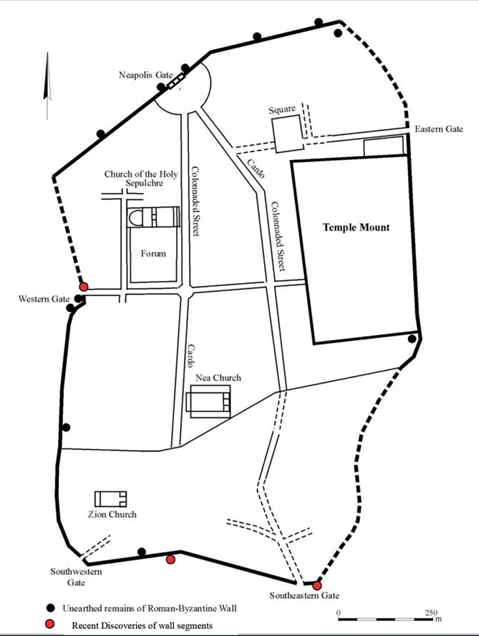

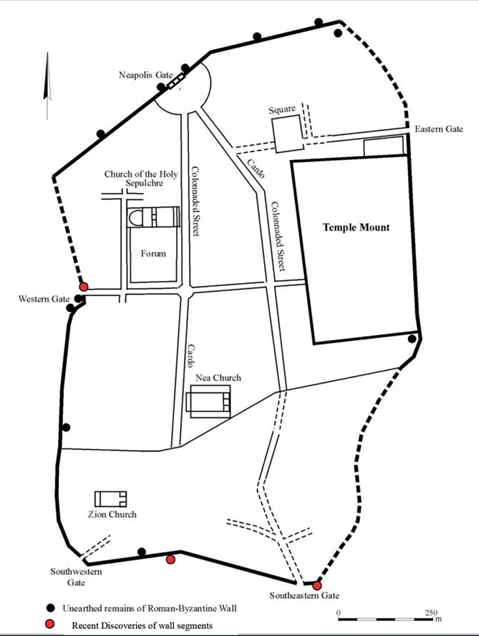

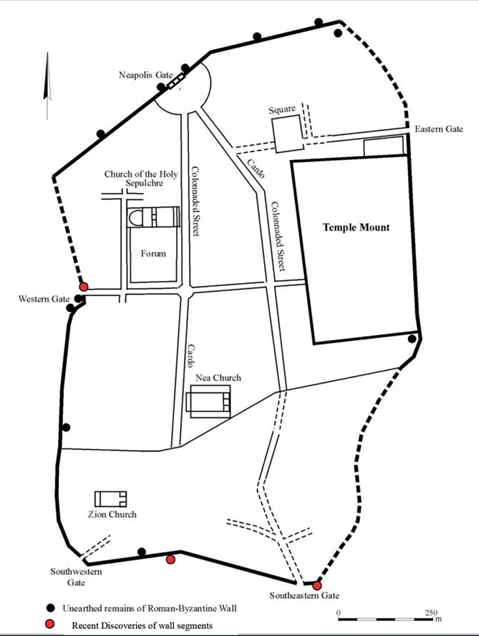

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 15 The Early

Byzantine city wall where dots mark exposed segments and recent finds from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

The Early Byzantine city wall. Dots mark places where segments of the wall were exposed, red dots are recent excavation finds. After Tsafrir 2000, drawing by Natalya Zak, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Click on image to open a magnifiable image in a new tab

Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022) - Fig. 5 - Jerusalem’s city walls

from the Early Islamic period to the Ottoman period from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Jerusalem’s city walls from the Early Islamic period to the Ottoman period (after Seligman 2001 and Weksler-Bdolah 2011).

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 21 - Jerusalem’s city walls

the Roman–Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Jerusalem’s city walls in the Roman–Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

- Fig. 2 - Roman-Byzantine

city walls and exposures from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421)

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed.

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 15 The Early

Byzantine city wall where dots mark exposed segments and recent finds from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

The Early Byzantine city wall. Dots mark places where segments of the wall were exposed, red dots are recent excavation finds. After Tsafrir 2000, drawing by Natalya Zak, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Click on image to open a magnifiable image in a new tab

Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022) - Fig. 5 - Jerusalem’s city walls

from the Early Islamic period to the Ottoman period from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Jerusalem’s city walls from the Early Islamic period to the Ottoman period (after Seligman 2001 and Weksler-Bdolah 2011).

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 21 - Jerusalem’s city walls

the Roman–Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Jerusalem’s city walls in the Roman–Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of north wall

of the Old City of Jerusalem from Hamilton (1944)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence.

Figure caption from Magness (1991)

Hamilton (1944)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of north wall

of the Old City of Jerusalem from Hamilton (1944)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence.

Figure caption from Magness (1991)

Hamilton (1944)

- Herod’s Gate area: Map

showing excavation areas from Stern et al (2008)

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Stern et al (2008)

- Herod’s Gate area: Map

showing excavation areas from Stern et al (2008)

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 16 The Early

Byzantine wall near Damascus Gate from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

- Fig. 17 Late Roman

wall cut by the corner of the SE tower of the Byzantine Wall from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

- Fig. 18 Corner of SE

tower of the Byzantine Wall, looking north from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

- Fig. 19 The Early

Byzantine wall in the Ophel excavations from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

The Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina was founded in the second century over the remains of the Second Temple period Jewish city of Jerusalem.61 The Roman city mostly ignored the remains of the Jewish city and made no use of the ruined fortifications, known as the First Wall, the Second Wall, and the Third Wall of the Second Temple Period.62 The only exception was a segment of the western wall of the First Wall, where the Roman Tenth Legion was stationed.63. It is widely accepted that the newly-founded colony of Aelia Capitolina was unwalled and its limits were marked by monumental, free-standing city gates64.

The accepted view associates the construction of Jerusalem’s Late Roman fortifications with the departure of the legio X Fretensis during the reign of Diocletian, and suggests that around the year AD 300, a city wall following more or less the course of the present-day Ottoman city wall was built around the Roman colony64. The wall was expanded to incorporate Zion in the mid-fifth century, probably by the empress Eudocia who then resided in Jerusalem. Another opinion proposes that Aelia Capitolina remained unwalled throughout its existence and that only at a later date was Jerusalem surrounded with a wide circuit wall, which enclosed the present-day old city of Jerusalem, Mount Zion, the City of David, and the Ophel66. According to this proposal, the construction of the wall was probably related to the Christianization of the city and took place at some time during the fourth or fifth centuries (late-antique times)67.

The earliest cartographic representation of Jerusalem appears on the Madaba Map, where it is depicted as an oval-shaped city surrounded with walls (Fig. 14)68. These walls included the present-day Old City, Mount Zion, the City of David, and the Ophel hill. Seventeen square towers were integrated into the course of the walls, and another five or six towers may be reconstructed in the ruined part of the mosaic69.

Three main arched city gates were incorporated into the walls in the north, east, and west. The Madaba representation of the mid-sixth century sets a terminus ante quem for the construction of the walls. They were exposed below the courses of the present-day Ottoman walls in the north and the west, around Mount Zion in the south and along the City of David and the Ophel hill in the east. Remains were exposed under the Ottoman walls on both sides of Damascus Gate (Fig. 16)70, under the courses of the western Ottoman walls near David’s Tower in the citadel,71 further north, under the road which enters Jaffa Gate today,72 and under the building of the Imperial Hotel, documented in the late nineteenth century.73

South of Jaffa Gate, the walls were documented in the Armenian Garden74 as well as on the slopes of Mount Zion75. A southeastern corner of a gate-tower in the southeast corner of the walls, which was documented in the late nineteenth century by Frederick Bliss and Archibald Dickie76 and re-excavated by Kathleen Kenyon77, was recently re-discovered in our excavations on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (Figs. 17 and 18)78. On the Ophel hill, segments of the walls have been investigated in the past (Fig. 19).79

61 For summaries on the archaeological remains of

Aelia Capitolina and the city’s layout, cf. Vincent/Abel 1914,

1–88, Geva 1993a, Tsafrir 1999a, Weksler-Bdolah 2020. Many

scholars have suggested reconstructions for the city plan of

Aelia Capitolina, e.g. Germer-Durand 1892, Bar 1993, Magness

2000, Eliav 2003, Avni 2005, Ehrlich/Bar 2004 inter alia.

62 Ios. Bell. Iud. 5, 136 and 142–149.

63 Ios. Bell. Iud. 7, 1–4.

64 Avi-Yonah 1976b, Geva 1993, Tsafrir 1999, 136,

Bahat 1990 and Mazor 2004, 109–119.

65 Hamilton 1952, Avi-Yonah 1954, 147, Tsafrir 1975,

17–19, Tsafrir 1999a, 140–141, and Bahat 1990.

66 Geva 1993b, 761–762, Wilkinson 1990, 90, Wilkinson

2002, 51–53 and 314 with map 11, as well as Weksler-Bdolah

2006–2007, Weksler-Bdolah 2007, Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 418–420,

and Weksler-Bdolah 2020, 138–140.

67 Geva 1993, 771–772. The chronology of the Roman and

Byzantine periods used below reflects common scholarly modes of

periodization. In Israeli research, especially on the history

and archaeology of the Levant and the city of Jerusalem, a

different periodization is common: 63 BC–70/135 AD (Early

Roman), 70/135–324 AD (Roman/Late Roman), 324–636 AD

(Byzantine).

68 Avi-Yonah 1954.

69 Tsafrir 1999b, 345.

70 Hamilton 1944, fig. 3, Turler/De Groot/Solar 1979

and Avni/Baruch/Weksler-Bdolah 2001.

71 Johns 1950 and Geva 1983.

72 Sion/Puni 2011.

73 Merrill 1886, 20, Schick 1887 and Vincent/Steve

1954.

74 Tushingham 1985.

75 Bliss/Dickie 1894, Chen/Margalit/Pixner 1994 and

the recent excavation of Zelinger 2010.

76 Bliss/Dickie 1898, 94–96 with plate XI.

77 Kenyon 1974, 269 with plate 6.

78 Weksler-Bdolah/Lavi 2013.

79 Warren/Conder 1884, Mazar 1995 and Mazar 2007,

181–200.

The walls’ mode of construction is similar around their entire circuit. The wall is built of ashlar, limestone blocks, arranged in levelled courses. Some of the blocks were originally prepared for the wall, as indicated by their smooth faces and medium size (height ca. 0.50–0.70 m, length ca. 0.7–1.40 m). Others were re-used Hasmonean blocks or re-cut Herodian blocks. The Hasmonean blocks were slightly smaller, and they were characterized by faces with margins along four sides and a central protruding boss. The re-cut Herodian blocks were the largest (height ca. 1 m and length ca. 1.7–2 m). Their faces had margins along two or three sides, and the central boss was flattened. Based upon their monumental size and shape, these blocks presumably originated from the ruins of King Herod’s monumental buildings and were cut and reduced to fit their new setting, therefore having margins only along two or three instead of all four sides. In rare cases double-bossed blocks were used as well. The lower courses of the walls were laid in a stepped manner so that every course was set back in relation to the course which it overlaid, whereas the upper courses of the walls were laid vertically one above the other.

The similarity and the contemporary dating of all wall segments supports their interpretation as parts of a single wide circuit wall which was constructed some time before the mid-fifth century – a date supported by results of the recent excavations. Inside Jaffa Gate, the excavators suggested a late-fourth century date for the construction of the wall.80 On Mount Zion, the excavator dated a segment of a plaster floor that possibly abutted the inner face of the wall, but was damaged when the upper courses of the wall were robbed, as “not prior to 409 AD,”81 and concluded the wall was built by the empress Eudocia in the mid-fifth century. However, an earlier possible date for the wall’s construction in the late-fourth or early-fifth century should be considered, since the wall already existed once the floor was laid.82 In another excavation,83 the foundation trench of the wall’s southeastern tower cut a late Roman wall (second to fourth centuries), clearly postdating it. The fact that no remains of the late-antique walls are known below the southern line of the Ottoman walls (which has been suggested in the past as the southern line of Aelia Capitolina’s walls built in ca. AD 300), makes it less viable that Jerusalem’s late-antique walls were built in two phases.

The perimeter of the walls enclosed the areas of the present-day Old City of Jerusalem, Mount Zion, the City of David, and the Ophel hill. The course was probably dictated by the size of the settled area of the city at this time, and by the natural topography. During their construction, remains of the Second Temple Period fortifications were integrated into the course of the walls, and also partly dictated its route. In the north, between Damascus Gate and Herod’s Gate, the late-antique walls overlapped the route suggested as the line of the Second Wall.84 In the west (north of David’s Tower) the walls followed a segment of a wall documented at the end of the nineteenth century which has been suggested as the route of the Second or Third Wall.85 South of David’s Tower and around Mount Zion, the City of David, and the Ophel, the walls overlapped the route of the First Wall. Some of the old fortifications were incorporated into the late-antique walls, such as David’s Tower and the eastern wall of the Temple Mount. The integration and usage of older fortifications within new lines of fortifications is a well-known fact. In Jerusalem, for example, the Hasmonean First Wall from the Second Temple period followed the course of Hezekiah’s Wall of the First Temple period, integrating parts of older fortifications within its route.86 Many sections along the Ottoman City walls of Jerusalem were built directly above or somewhat to the side of the remains of wall segments and towers from various periods, ranging in date from the Second Temple Period, to late-antique and medieval times.87 A similar phenomenon has been documented in Italy, where fortifications in many towns were reconstructed in the third century incorporating gates and segments of previous walls.88

The walls’ circuit was influenced by the size of the city at the time of its construction. The wide perimeter united the area of Aelia Capitolina with two hills which were part of the core of Biblical Jerusalem, but which were outside the city’s boundaries in Roman times: the southeastern hill (the area of the Ophel and the City of David) and the south-western hill, which later became known as Christian Zion, which corresponds with areas of the modern Jewish and the Armenian Quarters within the Ottoman wall, as well as Mount Zion outside the wall. Since it appears that the south-western hill was the campsite of the *legio X Fretensis*, it was not considered part of the city’s boundaries in Roman times. Moreover, following the departure of the legion which was transferred to Aila in the late third century AD, the site of the camp remained uninhabited for some decades, perhaps due to its military ownership. It was finally released to civic use not before the second half of the fourth century.89 In all likelihood, the construction of the city walls post-dated the expansion of the city into the empty areas of the southern hills, a process which now can be more accurately dated thanks to new archaeological material: the building of private residences on the southeastern hill started in the first half of the fourth century,90 while the southwestern hill was released to civic use and predominantly became the home to several Christian monasteries, hermitages, and churches from the second half of the fourth century onwards. A recent excavation dated the external wall of the so-called King David’s Tomb building to the late fourth century.91 This building is traditionally identified as part of the late-antique Church of Zion. The construction of the city walls unified the area of the Roman city, the abandoned campsite of the legio X Fretensis, and the southeastern hill into one big entity:the holy city of Jerusalem as depicted in the Madaba mosaic.

80 Bliss/Dickie 1894, 163; Chen/Margalit/Pixner 1994, 80–81.

81 Sion/Puni 2011, 62–63.

82 Zelinger 2010, 48.

83 Weksler-Bdolah/Lavi 2013, 181.

84 Hamilton 1944, fig. 3; Tüfler/De Groot/Solar 1979; Avni/Baruch/Weksler-Bdolah 2001.

85 Johns 1950; Geva 1983.

86 Vincent/Steve 1954, 121–122; Tsafrir 1999a, 136.

87 Geva 1993b, 761–762; Wilkinson 1990, 90; Wilkinson 2002, 51–53, 314 map 11; Weksler-Bdolah 2006–2007;

Weksler-Bdolah 2007; Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 418–420; Weksler-Bdolah 2020, 138–140.

88 Ward-Perkins 1984, 203–228.

89 Tsafrir 1999a, 140–141.

90 Avni 2005, 142–143.

The Jerusalemite builders made extensive use of Hasmonean and Herodian ashlars in secondary use which were placed in the facing parts of the walls, so that a late-antique visitor to the city would necessarily see them. In addition to this, some re-used architectural fragments of distinctly classical carving were discovered in the core of the wall on Mount Zion.92 The walls’ construction was precisely executed all around its circuit with great care. The stone courses were leveled and arranged according to the size and texture of the stones, thus creating a unified homogenous appearance. It is obvious that the wall was built of carefully selected stones, medium-sized ashlars that were purposely hewn for this matter, Hasmonean stones, and Herodian blocks were used for the facing of the wall, whereas other carved masonry was used for the core. Just as in Constantinople, where all parts of the late-antique walls were newly built, the facing side of the Jerusalemite walls was designed in a manner that must have impressed the visitors to the city. The monumental appearance of the wall was created not only by its beauty, but also by the fact that the space immediately around the wall, both inside and out, was left vacant of buildings. Nowhere along the wall have remains of abutting structures been discovered, thus verifying the legal status of city walls and gates as res sanctae – holy things, which could not become the object of private ownership.93

The extensive use of spolia characterized the late-antique walls of Jerusalem, like buildings in many other cities of the Empire. The re-use of classical building materials as a symbol of the victory of Christianity over its predecessors while maintaining the connection to the classical heritage has been noted by many scholars.94 In Jerusalem, Christianity rivaled the memory of Judaism more than it competed with paganism. The construction of the late-antique walls, which largely depended on the usage of stones from the ruined Temple Mount, or from other Second Temple Period Jewish buildings, can therefore be interpreted as a representation in stone of the victory of Christianity over Judaism.95 Moreover, the integration of monumental Herodian stones in the walls attest to the lesser importance of the Herodian monuments at the time of the walls’ construction, and probably also to an explicit imperial permission to re-use them, as otherwise this would have been prohibited by law.96 However, the walls were built about 300 years after the destruction of the Jewish city, and it might be argued that the builders of the wall used the abundant stones without recognizing them as Jewish. Yet, the selective choice of spolia only of Jewish origin does suggest that this was done on purpose, reflecting the builders’ involvement and struggle with the Jewish history of Jerusalem.

However, the use of spolia in late-antique buildings and in particular in city walls can also be explained as a practical solution, making it possible to quickly remove ruined buildings, for example after an earthquake. This might be true for Jerusalem as well, which suffered a severe earthquake in AD 363, which was described in several historical documents, including a letter attributed to the city’s bishop, Cyril of Jerusalem.97 The damage caused by the earthquake is also attested in the archaeological evidence elsewhere in the city. Recently, a peristyle house of the fourth century whose destruction can be dated to the year AD 363, has been excavated south of the Temple Mount.98 The lack of any archaeological evidence relating to the earthquake in any segment of the late-antique city walls does suggest that they were built later than AD 363. However, the meticulous construction of the late-antique walls as well as their overall shape shows that they were not built in haste or in war times, but were rather planned in advance and aimed at reflecting the prosperity, the high status, and wealth of the city at the time of construction. In addition to defending the holy city, they also demonstrated aesthetic beauty, which impressed the observers and mirrored the important status of Jerusalem.99

92 Chen/Margalit/Pixner 1994, 80.

93 Johnson 1983, 62–63.

94 Tsafrir 1998; Ward-Perkins 1984, 203–228; Wharton 1995;

Saradi-Mendelovici 1990.

95 Euseb. d.e. 3, 140–141 describes Roman public buildings,

which used the Jewish Temple’s stones; cf. Tsafrir 1975,

95–96. It is possible that the builders of the late-antique

walls would have been able to also find Herodian stones in

the ruins of more recent, pagan buildings.

96 Cassiod. Var. 3, 49 (ed. Fridh/Halpron–Lund 1973, CCSL 96)

mentions an example from Catania, where the emperor’s

permission was requested in order to use the ruined

amphitheatre’s building materials for the reconstruction of

the city walls. This indicated that the use of spolia was

not spontaneous in late antiquity. Ruins had a legal status

and a specific imperial decree was required in order to use

them. Permission was granted or denied according to their

state of preservation, their location, their symbolic

significance or their aesthetic value; cf. Ward-Perkins

1984, 206–218.

97 Brock 1976, 103, and Brock 1977.

98 Ben-Ami/Tchekhanovets 2013.

99 Gregory 1982, 56–57.

The walls’ construction can be seen as part of a period abounding in building activity in Jerusalem in the fourth and fifth centuries, which was affiliated with the city’s rise in status and the advancement of Christianity. The reason for Jerusalem’s importance in late antiquity was primarily religious and derived from its uniqueness as the physical center of Christianity and its status as a holy city. Even though no imperial building inscriptions from late-antique Jerusalem are (yet) known, the involvement of imperial and provincial authorities in the construction of the walls has often been suggested, prompted by the involvement of a late-antique empress alleged by the sources. This leads to the question of who funded the resources for the walls and what implications such a case of imperial involvement would have for Jerusalem. Around the year AD 400, city walls were constructed in several important cities of Palestine, such as the provincial capitals of Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda – Caesarea Maritima and Scythopolis – as well as in the important city of Aila at the Red Sea in Palaestina Tertia.100 Perhaps, Jerusalem, which began to flourish and underwent urban development due to the impact of Christianity, followed suit. This may be connected with the administrative reorganization of the area around this time, but perhaps also with security problems and the fear of barbarian invasions that shook the west of the Empire.

The evidence from the written sources confirms the dating of the walls’ construction between the late fourth and the mid-fifth century.101 In his account of the life of Peter the Iberian, the Vita Petri Hiberi,102 John Rufus states that Jerusalem was unwalled at the time of Constantine: “When it was rebuilt by the Christian Emperor Constantine, the Holy City, Jerusalem, at first was still sparsely populated and had no [city] wall, since the first [city] wall had been destroyed by the Romans. There were few houses and [few] inhabitants.”103 Many pilgrims, for example the Pilgrim of Bordeaux, Egeria, as well as Paula and Jerome, visited Jerusalem during the course of the fourth century.104 Their reports reflect the emergence of Jerusalem’s sacred topography, the construction of churches in holy places, and the development of a specific local liturgy.105 The pilgrims’ acquaintance with the limits of the city is obvious. The pilgrim of Bordeaux left Jerusalem to climb Zion,106 Paula “entered Jerusalem”, and “passing on, she climbed Zion.”107 According to Egeria, Jerusalem was entered and exited through a city gate.108 It appears that the city domain was well defined and marked by city gates, or some other boundary markers. A circuit wall was not mentioned in any of these accounts, most likely, it seems, because no such wall existed at that time. Indeed, it is possible to argue that the circuit wall was not important, and therefore not described by the pilgrims, but such a claim ignores the considerable significance of city walls in late antiquity. Furthermore, the reference of the writers to segments of older walls and ruined gates encountered in Zion and near the pool of Siloam109 indicates that they in fact paid attention to fortifications, considered them important, and wrote about them even when they lay in ruins. It is reasonable to assume that if a circuit wall had existed when they visited Jerusalem in the fourth century, they would not have failed to mention it. Moreover, the description and reference to the city walls in the fifth-century accounts (once the walls were already built), supports the assumption that the late-antique city walls were not ignored.

The walls of Jerusalem are first mentioned by Eucherius, in his letter to Faustinus, written in the first half of the fifth century: “The site of the city is almost forced into a circular shape, and is enclosed by a lengthy wall, which now embraces Mount Zion, though this was once just outside.”110 The description fits with Jerusalem as portrayed in the Madaba Map and provides a terminus ante quem for the construction of the circuit wall before Eucherius’ death. Yet, the arrival of Peter the Iberian in Jerusalem, ca. AD 437–438, may set an earlier terminus ante quem for the construction of the circuit wall, relying on the narrative provided by John Rufus:

When they had reached the outskirts of the holy city of Jerusalem which they loved, they saw from a high place five stades away the lofty roof of the holy church of the Resurrection, shining like the morning sun, and cried aloud, ‘See, that is Sion the city of our deliverance!’ They fell down upon their faces, and from there onwards they crept upon their knees, frequently kissing the soil with their lips and eyes, until they were within the holy walls (Syriac: ’shure qaddishe’) and had embraced the site of the sacred cross on Golgotha.111As the sense of "Syriac word" (’shura’) in Syriac is usually ‘city walls,’ the description seems to attest to the existence of fortifications in Jerusalem when Peter entered the city in AD 437–438,112 while it cannot be ruled out that reference is being made to ruined fortifications such as the ‘Zion wall’ which was mentioned by the Pilgrim of Bordeaux in the west, or the Temple Mount’s wall in the east.113

A number of accounts from the sixth century (Malalas, Cassiodorus, the Piacenza Pilgrim, and the Chronicon Paschale)114 attest to the involvement of the empress Eudocia in rebuilding of the walls in Jerusalem, influenced by Psalm 51:18: “Let it be thy pleasure (εὐδοκία) to do good to Sion, to build anew the walls of Jerusalem.”115 The accounts vary, stating that Eudocia enlarged the city and surrounded its circumference with better walls, improved their condition, or renewed the whole circuit of the Jerusalem walls. Modern scholars suggest interpreting these statements as reflecting Eudocia’s renewal of the ancient wall around Zion (the Second Temple Period’s ‘First Wall’), therefore naming it ‘Eudocia’s wall,’116 whereas the ancient accounts clearly attribute the enclosing of the whole city and the renewal of the whole circuit of walls to Eudocia. Attributing the whole line of fortifications to Eudocia suggests its probable dating between AD 437/438, the time of her first pilgrimage to Jerusalem,117 or to between AD 444, when she returned to Jerusalem for good, and Eucherius’s death sometime between AD 449–455.118 This, however, contradicts John Rufus’s testimony, if with his references to ‘holy walls’ he is describing the city walls of Jerusalem. The archaeological record, too, seems to favor an earlier date for the construction of the walls in the late fourth century or early fifth century at the latest.119

If we accept such a dating (i.e. late fourth/early fifth centuries AD), the attribution of the wall to Eudocia in the historical sources may be explained either in the sense that she restored an existing wall, or simply by a confusion in the tradition. As the first account which associated Eudocia with the wall’s reconstruction was written about a century after her death, there may have been some uncertainty and confusion with regard to her life and deeds. The existence of three successive Byzantine empresses with almost similar names in the course of the fifth century – Eudoxia, Arcadius’s wife, Eudocia, Theodosius II’s wife, and Eudoxia, Theodosius II’s daughter – undoubtedly caused confusion, as seen in coins121 and legends.122 Oddly, Cassiodorus and the Piacenza Pilgrim, in telling the story, give the name of the empress as Eudoxia, although they identify her as Theodosius II’s wife. Might the wall have been initiated by Eudoxia, and falsely attributed to Eudocia?123

100 On Caesarea Maritima, cf. Lehmann 1994, on Scythopolis,

cf. Tsafrir/Foerster 1997, 102, and Mazor 2004, 28, and on

Aila, cf. Parker 2003, 332.

101 Sh. Weksler-Bdolah would like express her gratitude to

Dr Leah di Segni for her help in translating and discussing

the various sources mentioned below.

102 The account was written in the late fifth century

probably by John Rufus and is preserved in a Syriac and a

Georgian translation. The Syriac version was edited and

translated into German by Raabe 1895 and translated into

English by Horn/Phenix 2008. The Georgian version was

translated into English by Lang 1976, 57–80. Some passages

of the text exist in Hebrew translations by A. Horvitz, cf.

Tsafrir 1975, 37–38, Tsafrir 1999, 303, and Bitton-Ashkelony

1989, 108.

103 Ioh. Ruf. Vit. Petr. Hib. 64 (ed. Horn/Phenix = Raabe

1895, 44), cf. Tsafrir 1975, 37–38 as well as Tsafrir 1999b,

274–275 and 303. Yoram Tsafrir doubted the credibility of

John Rufus’ testimony, however, given that the information

provided in this passage is in accordance with other fourth-

and fifth-century accounts, it seems that one should accept

it. Moreover, the emphasis on the fact that the city was

unwalled in the times of Constantine, whereas Peter the

Iberian, who arrived in 437/438 entered through ‘holy walls’

(see below), adds to the historicity of the description. The

Georgian version gives the following passage: “At this time,

the holy city of Jerusalem was still lacking in inhabitants,

as well as being deprived of walls, since the former walls

had been destroyed by the Romans,” cf. Lang 1976, 65–66,

which implies that Jerusalem was deprived of walls when

Peter the Iberian visited the city.

104 On the Itinerarium Burdigalense, cf. the commentaries by

Tsafrir 1975, 32–34 and 91–94, Wilkinson 1981, 123–147, and

Limor 1998, 30–34. On the Itinerarium Egeriae, cf. Wilkinson

1981, 122–147, and Limor 1998, 88–114, and on Paula and

Jerome, cf. Hier. ep. 108 with the commentaries and

discussions in Tsafrir 1975, 113, Limor 1998, 142–143, and

Wilkinson 2002, 79–92.

105 For detailed studies, cf. Wilkinson 1981, Wilkinson 2002,

Limor 1998, Limor 1999, Hunt 1982, Tsafrir 1975, Tsafrir 1999

as well as the references given below.

106 Itin. Burdig. 592: Item exeuntibus Hierusalem, ut ascendas

Sion (“Moreover, as you leave Jerusalem to climb Zion”).

107 Hier. Ep. 108,9: ingressa est Hierosolymam. Paula passed

on her left the tomb of Queen Helena of Adiabene and then

entered Jerusalem.

108 Itin. Eg. 36,3 and 43,7.

109 For the wall near the pool of Siloam, cf. Itin. Burdig.

592,1: in ualle iuxta murum est piscine (“in the valley

beside the wall is the pool”), for the wall of Zion, cf. Itin.

Burdig. 592,5: intus autem intra murum Sion (“inside the wall

of Sion”). Ruined gates are mentioned in Hier. ep. 108,9: non

eas portas, quas hodie cernimus in fauillam et cinerem

dissolutas (“not meaning the gates we see now, which have

been reduced to dust and ashes”).

110 Eucherius 6,25,3 (Freypont 1965, 237–243). The account

was translated and interpreted by Tsafrir 1975, 132–134

(Hebrew); Limor 1999, 159–160 (Hebrew) and Wilkinson 2002,

94–98 (English). It is widely accepted to relate the account

to bishop Eucherius of Lyons, who died between 449–455 AD.

However, the formula ut fertur in the title of Freypont’s

edition, implies that at least in the editor’s eyes, the

account may not be authentic.

111 John Rufus Vita Petri Hiberi 38 (= Raabe 26–27), trans.

Lang 1976, 54. The Georgian version is slightly shorter, but

very close to the Syriac version, cf. Bitton-Ashkeloni 1999,

107–108. Coming from Constantinople by foot, Peter and his

companions could have reached Jerusalem from the west, north

or east, depending on the route they used. Their first sight

of Jerusalem, while standing on a high place, may allow to

specify on this this: The view of the Church of the Holy

Sepulcher, opposite of it the Church of Ascension on the top

of the Mount of Olives, as provided in the Syriac version of

the Vita. This description suggests that their viewpoint was

a high place northwest of the present day Old City of

Jerusalem (maybe near the so-called Russian Compound), and

their entrance took place, accordingly, through one of the

western or northern gates.

112 Cf. Payne Smith, s.v. “ ” p. 568, given ‘city walls’ and

‘bulwark’ as the most common translation. However, we cannot

exclude the possibility that John Rufus, by using this

expression, meant the precinct walls of the Church of the

Holy Sepulcher or the Second Temple Period walls of the

Temple Mount visible to travelers who were coming to

Jerusalem from the Jericho road – or even the remains of the

Second Temple Period ‘Zion wall’ mentioned by the Pilgrim of

Bordeaux (see above). Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah would like to

express her gratitude to Sebastian Brock and Brouria Bitton-

Ashkeloni for discussion on the Syriac terminology.

113 Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah would like to thank Leah Di Segni

for her helpful remarks relating this account.

114 Ioh. Mal. Chron. (357–358, Dind.), Cassiod. Exp. in Ps. 50

(CC 97, 468), Itin. Plac. 1c (confusing her name), and Chron.

Pasch. ad ann. 585.

115 Cf. also Hunt 1982, 221–248.

116 Conrad Schick was the first who identified the Zion wall,

which were unearthed by Frederick Bliss and Archibald Dickie,

with the wall built ca. 440 by the empress Eudocia (Bliss

1894, 254). His suggestion was commonly accepted, cf. Dalton

1895, 28, Avi-Yonah 1976b, 621–622, Tsafrir 1975, 21 and

132–135, as well as Tsafrir 1999, 287–295. Bliss suggested two

phases in the development of the late-antique walls on Mount

Zion: First, around the beginning of the fifth century (a

wall which was built to protect the Church of Zion and which

did not include the Pool of Siloam within its precinct). Then,

around 450, Eudocia rebuilt the wall (named by Bliss ‘upper

wall’) around Zion and the pool, cf. Bliss/Dickie 1898,

307–309 and 321–323.

117 The suggestion of attributing Eudocia’s initiative to her

first pilgrimage (around 438), was made by Leah Di Segni, who

suggested comparing it with the enlargement of Antioch’s

walls due to Eudocia’s endeavors (Ioh. Mal. 14 (346–357,

Dind.), Evagr. HE 1,20, cf. also Holum 1982, 117–118).

118 Dalton 1895, 28 dated the rebuilding of the walls by

Eudocia to between 438–454.

119 The pottery assemblage characterizing the surface of the

wall builders, consisted mostly of local ware, dated from the

late third to the fifth century, thus enabling to relate the

wall with Eudocia. Yet, the lack of imported ware, that is

usually more abundant in assemblages from the fifth century

AD, suggested the wall was build prior to the fifth century,

when imported ware had become more abundant. Shlomit Weksler-

Bdolah would like to thank Jodi Magness for this comment.

120 John Malalas, for example, not always distinguished

between authentic history and popular memories (such as folk

tales) of events, cf. Holum 1982, 114.

121 Boyce 1954.

122 Drake 1980, 148–155.

123 Aelia Eudoxia married Arcadius at 395 AD, she was

proclaimed Augusta at 400 AD and died in 404 AD. Eudoxia was

involved in the Holy Land, and was portrayed as a devoted

supporter of Christianity in the Imperial Court (Holum 1982).

An inscription incised on the pedestal of a statue which was

unearthed in the city of Scythopolis reads: ‘Artemidorus set

up a golden (statue of) Eudoxia, the queen of all earth,

visible from every place in the country’ (Tsafrir 1998, 217),

indicating her appreciation in the capital of Palaestina

Secunda.

The walls of Constantinople and Jerusalem were not constructed simultaneously, but close together in time. The frequent references in the ancient sources to imperial involvement in the holy city supports the assumption that not only in Constantinople did the city walls constitute a highly visible imperial monument, but that the imperial family was involved in building the walls of Jerusalem as well: Aelia Eudoxia, wife of Arcadius and mother of Theodosius II, or Eudocia, wife of Theodosius II, may have played a decisive role. But even if both the walls of Constantinople and the walls of Jerusalem were in one sense or another imperial building projects, they significantly differed in their design, function, and symbolism.

The Theodosian walls of Constantinople, constructed between 404/405 and 413 AD, were the largest urban defense work of late antiquity. They were completed in the reign of Theodosius II, who, however, was only four years old when construction works started and thirteen when the walls were finished. The original planning and initiative should thus be attributed to his father, Arcadius, and to the praefectus praetorio per Orientem Anthemius. In Jerusalem, the overall similarity of the excavated wall segments suggests that the whole circuit of the walls was built in one single phase within a rather short period of time. Jerusalem’s late-antique wall unified within its course the Roman colonia Aelia Capitolina, the Christian hill of Zion (in the area of the abandoned campsite of the legio X Fretensis) as well as the southeastern hill (with the area of the Ophel and the city of David). The archaeological evidence suggests a time frame for the construction between the late fourth and the mid-fifth century.

The walls of Constantinople were the first monumental structure built in layered masonry. The parts which were later changed and added differ from the Theodosian workmanship; the parts which were constructed in late Byzantine times are noticeably different. Hardly any spolia were used in the initial construction: the Constantinopolitan walls were a prestigious and completely new building project for which the re-use of older building materials was not considered appropriate. As in Constantinople with its ostentatiously new walls, the Jerusalem walls were likewise built in a manner that must have impressed visitors to the city. However, the conscious selection and integration of spolia of Jewish origin suggests a distinct symbolic message, reflecting the builders’ involvement and struggle with the Jewish history of Jerusalem.

In both cities, the walls considerably expanded the cities’ limits, reflecting a period of expansion and growth in the early fifth century. While in Constantinople the wall enlarged the walled territory towards the west, in Jerusalem the perimeter of the walls united the area of the Roman city, the abandoned campsite of the Roman legion, and the hill which once formed the core of the Biblical city into one entity: the holy city of Jerusalem. The Theodosian walls of Constantinople were a highly visible display of imperial power, and they were obviously also meant to fortify the capital of the Roman Empire: the construction of the walls answered the need for monarchic representation and security for the inhabitants of the City of Caesar. The walls of Jerusalem, the City of God, on the other hand, were built as a vigorous symbol of Christian victory over Judaism. They reflect the desire of the builders to preserve the urban heritage, and more precisely – to preserve Jewish “symbols” of the Second Temple period – such as the Herodian stones, which were traditionally associated with the Herodian Temple Mount, and at the same time change their meaning.

- from Chat GPT 5, 15 September 2025

- from Asutay-Effenberger and Weksler-Bdolah (2022)

The walls themselves, however, show **no traces of earthquake damage**, suggesting that the circuit walls of Jerusalem were **built after the 363 CE event**. The careful planning and fine masonry of the walls further indicate that they were not hurried repairs to seismic destruction but rather deliberate construction reflecting prosperity and the elevated status of Jerusalem in the late fourth or fifth centuries.

Thus, archaeoseismic evidence is present indirectly: the 363 earthquake provides a **terminus post quem** for the construction of Jerusalem’s late-antique fortifications, and the reuse of building stones likely originated in part from demolition of earthquake-damaged structures.

- Fig. 2 - Roman-Byzantine city walls

and exposures from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421)

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed.

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 1 - Plan of north wall

of the Old City of Jerusalem from Hamilton (1944)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence.

Figure caption from Magness (1991)

Hamilton (1944)

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421) summarized exposures of the Roman-Byzantine wall:

the Roman-Byzantine wall was used continuously from the time of its construction until the mid-8th century, after which it was partially damaged, probably by an earthquake (Weksler-Bdolah, 2007:97). Evidence of renovations discovered in several places along its route indicate that the wall continued to be used after the mid-8th century.

Magness (1991) examined ceramics and numismatics from

Hamilton (1944)'s excavations of Jerusalem's city walls near the Damascus Gate

and established a terminus post quem of the first half of the 8th century CE for wall repairs.

Magness (1991) characterized the level used to establish

the terminus post quem as one of the most securely dated assemblages of published Byzantine and Umayyad pottery from an excavation

in Jerusalem.

Magness (1991) examined ceramics from Tushingham (1985)'s excavations of the southwest corner of the city walls in the Armenian Garden. Magness (1991) redated rebuilding from the 7th century CE to the 8th century CE.

It seems likely that when Jerusalem's buildings suffered several destructions during the earthquake, that its city wall was also damaged.66 Indeed, several excavations around the city walls show signs of repair works during the period in question.

Precisely when the wall circuit used during the Byzantine period — the so-called 'Eudocia Wall' — was built and how long it remained functional is debated amongst scholars.67 However, one can be quite certain that during the eighth century AD, under discussion here, the same city wall was still in use.

J. Magness reassessed some of these repair phases in the Byzantine–Early Islamic city wall circuit based on a re-evaluation of the pottery — especially the precise distinction of Byzantine and Umayyad ceramic material — to clarify the chronology of the wall repairs. She concluded that, for instance, excavations by R. Hamilton along the northern part of the city wall during the 1930s revealed “clear evidence for a reconstruction of the city wall in the vicinity of the Damascus Gate no earlier than the first half of the eighth century C.E.”68

In the city's south-west, an additional stretch of the city wall with “clear evidence for a major rebuild” from the same time period was found in the Armenian Garden by A. D. Tushingham.69 This part of the wall was also reassessed based on the pottery evidence by J. Magness. She re-attributes some of the excavated pottery forms found in the city wall’s foundation trenches to the (Late) Umayyad period70. Consequently, J. Magness suggests an Early Islamic, Umayyad date for the repair of the city wall rather than the sixth century, as stated by A. D. Tushingham.71

Therefore, it can be said that Jerusalem’s city walls were reconstructed or renovated in the middle of the eighth century AD based on the two re-evaluated archaeological examples, which show that renovation works were carried out in this time period.72 However, it cannot be stated with certainty that these repair phases of the city wall are a result of the AD 749 earthquake rather than later measures to reconstruct buildings. It is also possible that these rebuilding measures were part of other construction projects in the eighth century AD — for instance, the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s city walls ordered by Caliph Hisham between AD 728 and 744 — because the walls were previously torn down by his predecessor Caliph Marwan II, as described by Theophanes.73

The archaeological material does provide a terminus post quem —the first half of the eighth century AD—for the partial reconstruction of the city walls, but due to the proximity of both events in question, an exact attribution to one of them, at least in the case of the city walls, cannot be given.

66 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421.

67 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421-24; Zimni 2023, 286-90.

68 Magness 1991, 212.

69 Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

70 Magness 1991, 212-13.

71 Magness 1991, 215; Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

72 Excavations in the area of the citadel suggest further

alterations of the early Islamic city wall (Magness 1991,

214; Wightmann 1993, 233).

73 Theophanes, Chronicle 422, p.114; Wightmann 1993, 235;

Magness 1991, 215.

- Fig. 2 - Roman-Byzantine city walls and exposures

from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421)

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed.

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 5 - Jerusalem’s city walls from the Early Islamic period

to the Ottoman period from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Jerusalem’s city walls from the Early Islamic period to the Ottoman period (after Seligman 2001 and Weksler-Bdolah 2011).

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 21 - Jerusalem’s city walls the Roman–Byzantine,

Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods from Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Jerusalem’s city walls in the Roman–Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusader/Ayyubid, and Ottoman periods

Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) - Fig. 1 - Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem

from Hamilton (1944)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence.

Figure caption from Magness (1991)

Hamilton (1944) - Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

from Stern et al (2008)

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Herod’s Gate area: map showing excavation areas

Stern et al (2008)

Historical evidence and limited archaeological evidence indicates that Jerusalem's city walls were reconstructed in the late 10th - early 11th century CE - possibly partly in response to seismic damage. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011:421-423) discussed this.

The Abandonment of the Roman–Byzantine Wall and the Construction of a New Line of Fortifications in the Late Early Islamic Period (Late 10th–Early 11th Century)Baruch, Avni, and Parnos in Stern et al (2008) encountered what they interpreted as the Early Islamic Wall in areas A and C near Herod's Gate (location 14 in Fig. 5 of Maps and Plans). They found a stone collapse which they dated using ceramics

The precise date of the abandonment of the Roman–Byzantine wall is difficult to determine. Archaeological finds and historical sources indicate a date around the late 10th or early 11th century C.E. Ceramic finds and coins in earthen layers that abut the wall indicate that the Roman–Byzantine wall was used continuously from the time of its construction until the mid-8th century, after which it was partially damaged, probably by an earthquake (Weksler-Bdolah 2007: 97). Evidence of renovations discovered in several places along its route indicate that the wall continued to be used after the mid-8th century. In 870 C.E., the monk Bernard (Bernardus Monachus) described the Zion Church and the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu on Mount Zion as being located within the city (Tobler 1874), thus indicating that at this time the Roman–Byzantine wall was still being used. The archaeological remains of some Early Islamic buildings of the 8th and 9th centuries on the Ophel–– outside the present line of the city walls (Ben Ami and Tchehanovetz 2008) support the assumption that this area was included within the city’s domain at that time, thus indicating that the Roman–Byzantine wall was still being used. Finally, Muqaddasi’s description from 985 C.E. (quoted in le Strange 1890: 212–13) enumerates eight gates within the walls of the city and has been interpreted in the past as referring to the new, shorter line of the city wall that was built on the route of the Ottoman wall (Tsafrir 1977). However, it is possible that Muqaddasi described the Roman–Byzantine city wall that was still in use at the time of his writing (Ben-Dov 1993; Bahat 1986; 2003).

In June 1099, the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem after a long siege. The description of the blockade in the Crusader chronicles indicates that the wall they faced followed a route similar to the present Ottoman walls. It appears, therefore, that during the late 10th or early 11th century, at some time before the Crusaders’ conquest of Jerusalem, the Roman–Byzantine wall was abandoned, and a new, Early Islamic line of walls was erected around Jerusalem. The late Early Islamic (either Abbasid or Fatimid) wall enlarged the city’s area in its northwestern and northeastern corners, whereas in the south, the size of the city was significantly reduced, with the City of David, the Ophel, and Mount Zion left outside the walls.5

... Tsafrir (1977: 154) suggested dating the construction of the new Early Islamic wall to the Abbasid period in the late 10th century. A different suggestion has been made by Prawer (1985; 1991) and by Bahat (2003: 63 n. 7), who related the construction of the wall to the Fatimid rulers following the probable destruction of the Roman–Byzantine wall in the earthquake of 1033. Prawer and Bahat relied on historical sources, which attest to the construction and repair of a wall in Jerusalem between 1033 and 1063 (Prawer 1991: 5). Yahya Ibn Saʿid of Antioch, for example, described the renovation of Jerusalem’s walls during the reign of the Early Islamic Sultan al-Zahir. He specifically mentioned that “the oficers in charge intended to destroy the church of Mount Zion, as well as other churches, so as to bring their stones to the wall.” 6 It is therefore apparent that the new perimeter left the churches on Mount Zion outside the new line of the walls (Prawer 1985: 2; 1991: 5). Furthermore, the testimony by Nasir-i-Khusraw, from the year 1047, 7 describes Tsafrir (1977: 154) suggested dating the construction of the new Early Islamic wall to the Abbasid period in the late 10th century. A different suggestion has been made by Prawer (1985; 1991) and by Bahat (2003: 63 n. 7), who related the construction of the wall to the Fatimid rulers following the probable destruction of the Roman–Byzantine wall in the earthquake of 1033. Prawer and Bahat relied on historical sources, which attest to the construction and repair of a wall in Jerusalem between 1033 and 1063 (Prawer 1991: 5). Yahya Ibn Saʿid of Antioch, for example, described the renovation of Jerusalem’s walls during the reign of the Early Islamic Sultan al-Zahir. He specifically mentioned that “the officers in charge intended to destroy the church of Mount Zion, as well as other churches, so as to bring their stones to the wall.”6 It is therefore apparent that the new perimeter left the churches on Mount Zion outside the new line of the walls (Prawer 1985: 2; 1991: 5). Furthermore, the testimony by Nasir-i-Khusraw, from the year 1047,7 describes Jerusalem as a city surrounded by formidable walls and mentions the Siloam Pool as located some distance outside the city wall.Footnotes5. See Wightman 1993: 246–48. For a detailed study of the Crusaders siege and conquest of Jerusalem and reference to the sources, see Prawer 1991: Maps 1–3, 8, 10, 16. Earlier studies include Röhricht 1901: 183–214; Peyré 1859).

6. Annals Yahia ibn Said Antiochensis (CSCO; Scriptores Arabici, Textus, Series 3, vii; Paris, 1909) 272.

7. Nasir-I-khusraw, Relation de Voyage, trans. C. Scheffer (Paris, 1881).

to the end of the Early Islamic period (tenth–eleventh centuries CE). They suggested that the wall they uncovered was

probably the fortification penetrated by the Crusaders in 1099which, if correct, would indicate that the collapse was caused by human agency

AN EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD FORTIFICATION AND QUARTER

The principal Early Islamic period remains were exposed in area A, where a massive wall was revealed directly beneath and along the course of the Old City wall. It is built of roughly shaped stones and is of entirely different construction than the Roman–Byzantine wall found in area B. Additional segments of the wall were exposed in area C. Also exposed in area C were carefully carved, profiled masonry stones—perhaps part of a gate that once stood in this area—among a stone collapse. The pottery found within this collapse, like that of the earth fill associated with segments of the wall found in area A, is dated to the end of the Early Islamic period (tenth–eleventh centuries CE). The wall uncovered is probably the fortification penetrated by the Crusaders in 1099.

... CRUSADER AND AYYUBID PERIOD FORTIFICATIONS

Based upon detailed historical descriptions of the Crusader conquest, it was in this area of the city that the Crusaders broke through the walls of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099. Actual evidence for the line of the city wall of Jerusalem during the Middle Ages was found in the excavation next to the Old City wall in areas A and C. The above mentioned Early Islamic period wall was buttressed by a fortification preserved as a row of piers. Another wall was found to extend 25 m from the remains of the massive piers southward. Earth fills containing numerous iron arrowheads were associated with the remains of the wall with piers.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Jerusalem

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the text

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the textStern et al (2008) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

near the Mosque of Omar and near an unnamed Mosque

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the text

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the textStern et al (2008) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) city walls near the Damascus Gate

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence. Figure caption from Magness (1991) Hamilton (1944) southwest corner of the city walls in the Armenian Garden

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jerusalem

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the text

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the textStern et al (2008) |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

near the Mosque of Omar and near an unnamed Mosque

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the text

Map of the Old City and its environs; numbers refer to excavation sites discussed in the textStern et al (2008) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) city walls near the Damascus Gate

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Plan of north wall of the Old City of Jerusalem, showing the location of the areas excavated by Hamilton. In 1937-38, Hamilton conducted excavations in five areas along the north wall. Sounding A, located against the western face of the western tower at the Damascus Gate, provided the most substantial and valuable sequence. Figure caption from Magness (1991) Hamilton (1944) southwest corner of the city walls in the Armenian Garden

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Roman-Byzantine city wall (after Tsafrir 2000, Weksler-Bdolah 2006-7). Dots mark places where segments of the Roman-Byzantine wall were exposed. Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (2011) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Various locations |

|

|

Asutay-Effenberger, Neslihan and Weksler-Bdolah, Shlomit (2022) Delineating the Sacred and the Profane: The Late-Antique Walls of Jerusalem and Constantinople

, in Klein, Konstantin M. and Wienand, Johannes (ed.s)

City of Caesar, City of God: Constantinople and Jerusalem in Late Antiquity, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2022.

Baruch, Y., Avni, G., and Parnos, G. Jerusalem: The Herods Gate Area. Pp. 1819–21 in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological

Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 5 (supplementary volume), ed. Ephraim Stern

et al. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Baruch, Y., and Reich, R. 1999 Renewed Excavations at the Umayyad Building III. Pp. 128-40 in New Studies on

Jerusalem: Proceedings of the Fifth Conference, Dec. 23,1999, ed. A. Faust and E. Ba-

ruch. Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press.

Ben-Dov, M. 1971 The Omayyad Structures near the Temple Mount. Pp. 37-44 in The Excavations in

the Old City of Jerusalem near the Temple Mount: Second Preliminary Report 1969-70

Seasons, ed. B. Mazar. Jerusalem.

Ben-Dov, M. 1976 The Area South of the Temple Mount in the Early Islamic Period. Pp. 97-101 in Je-

rusalem Revealed: Archaeology in the Holy City 1968-1974, ed. Y. Yadin. New Haven:

Yale University Press.

Ben-Dov, M. Broshi, M., and Tsafrir, Y.1977 Excavations at the Zion Gate

Ben-Dov, M. 1983 Jerusalem's Fortifications: The City Walls, Gates and the Temple Mount. Tel-Aviv: Zemorah- Bitan. [Hebrew]

BEN Dov, M. (1985): In the shadow of the Temple, Keter, Jerusalem.

Ben-Dov, M. 1993 Jerusalem Fortifications and Citadel: Eighth to 11th Centuries. Pp. 793-95 in The

New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 2, ed. E. Stern,Ben-Dov, M.

BEN Dov, M. (2002): Historical atlas of Jerusalem, Continuum, London.

- site specific archeoseismic evidence is not presented.

Broshi, M., and Gibson, S.1994 Excavations Along the Western and Southern Walls of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Pp. 147-55 in Ancient Jerusalem Revealed, ed. H. Geva. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Galor, K. and G. Avni (2011). Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 years of archaeological research in the Holy City, Penn State Press.

Gevaʿ, H. (2019). Ancient Jerusalem revealed: archaeological discoveries, 1998-2018, Israel Exploration Society.

Hamilton, R. W.1944 Excavations Against the North Wall of Jerusalem, 1937—8. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities of Palestine 10: 1-54.

Lewinson-Gilboa, A. and Aviram, J. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

1994 Excavations and Architectural Survey of the Archaeological Remains along the

Southern Wall of the Jerusalem Old City. Pp. 311-20 in Ancient Jerusalem Revealed,

ed. H. Geva. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Magness, J. (1991). "The Walls of Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period." The Biblical Archaeologist 54(4): 208-217.

B. Mazar, The excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem (Jerusalem, 1969), 20

B. Mazar: The Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem, EI 9 (1969), pp. 161-174, ref.p. 173 (Hebrew).

Mazar, B. and M. Ben-Dov (1971). The excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem near the Temple Mount :

preliminary report of the second and third seasons, 1969-1970.

Mazar and B. Mazar (1971).

"The Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem Near the Temple Mount — Second Preliminary Report, 1969—70 Seasons

/ החפירות הארכיאולוגיות ליד הר-הבית: סקירה שנייה, עונות תשכ"ט—תש"ל."

Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה י: 1-34. (in Hebrew)

Mazar 1975, The Mountain of the Lord. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. p. 269

Mazar, E. and B. Mazar (1989). "EXCAVATIONS IN THE SOUTH OF THE TEMPLE MOUNT: The Ophel of Biblical Jerusalem." Qedem 29: III-187.

Reich, Ronny and Shukron, Eli (2006) Excavations in the Mamillah Area, Jerusalem:

The Medieval Fortifications, in: ‘Atiqot 54 (2006),

pp. 125-152 (Ayyubid wall)

Tsafrir, Y. 2000 Procopius and the Nea Church in Jerusalem. An Tard 8: 149-64.

Tushingham, A. D. (1985) Excavations in Jerusalem 1961-1967, I (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum). - can be borrowed with a free account from archive.org

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2001 Jerusalem, The Old City Walls. Hadashot Arkheologiot / Excavations and Surveys in Israel 113: 79*-80*.

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2003 The Fortifications of Jerusalem During Late Roman, Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods

(3rd/4th to 8th cent.). M.A. thesis. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [Hebrew]

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2005 Jerusalem, the New Gate. Excavations and Surveys in Israel: 117

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2006 The Old City Walls of Jerusalem:

The Northwestern Corner. Atiqot 54: 95-119 [Hebrew]; 163-64 [English summary].

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2006-7 The Fortifications of Jerusalem in the Byzantine Period. Aram 18-19: 85-112.

Weksler-Bdolah, S., 2007 Reconsidering the Byzantine Period City Wall of Jerusalem. Eretz-Israel 28: 88-101. [Hebrew]

Weksler-Bdolah, S. 2011 The Fortification System in the Northwestern Part of Jerusalem from the Early

Islamic to the Ottoman Periods. Atiqot 65: 105-30 [Hebrew]; 73*-75* [English

summary].

Weksler-Bdolah, S. forthcoming Jerusalem, Kikar Zahal's tunnel. Hadashot Arkheologiot.

Wellhausen, J. (1973): The arab kingdom and its fall, Curzon Press, London, pp. 592.

Wightman, G.J. (1993): Walls of Jerusalem, Mediterranean Archaeology Studies Suppl. 4 (Med. Arch Univ. Sydney), p. 331.

Zimni, J. (2023) 'Urbanism in Jerusalem from the Iron Age to the Medieval Period at the Example of the DEI Excavations on Mount Zion'

(unpublished doctoral thesis, Bergische Universitic Wuppertal)

Zimni-Gitler, J. (2025) Chapter 10. Traces of the AD 749 Earthquake in Jerusalem: New Archaeological Evidence from Mount Zion

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis

Tushingham. A. D. Hayes, J. W. (1985). Excavations in Jerusalem 1961-1967. Vol. 1 Vol. 1. Toronto, Royal Ontario Museum.

Mazar, E. 2007 The Ophel Wall in Jerusalem in the Byzantine Period. Pp. 181-200 in The Temple

Mount Excavations in Jerusalem 1968-1978 Directed by Benjamin Mazar, Final Reports,

vol. 3: The Byzantine Period. Qedem 46. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University.

Wellhausen (1927:382-383) relates that in the summer of 746 CE (A.H. 128) during the 3rd Muslim Civil War, Marwan II ordered the walls of Hims, Jerusalem, Baalbek, Damascus, and other prominent Syrian cities razed to the ground. In Theophanes entry for A.M.a 6237, we can read in Mango and Scott (1997:587)'s translation (Turtledove's translation is available here):

[A.M. 6237, AD 744/5]...

- Constantine, 5th year

- Marouam, 2nd year

- Zacharias, 12th year

- Anastasios, 16th year

- Theophylaktos, 2nd year

At that time Marouam, after victoriously taking Emesa [aka Homs], killed all the relatives and freedmen of Isam. He also demolished the walls of Helioupolish [aka Baalbek] Damascus, and Jerusalem, put to death many powerful men, and maimed those remaining in the said cities.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Jerusalem kmz file | various |