Khirbat Faris

Khirbat Faris (upper left) and

Khirbat Tadun (mound to lower right) in Google Earth

Khirbat Faris (upper left) and

Khirbat Tadun (mound to lower right) in Google Earthclick on image to explore this site on a new tab in Google Earth

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Khirbat Faris

Arabic

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Khirbat Tadun

Arabic

Tadun

Arabic

- Excerpts from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Parsed and redacted from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

The story of the settlement at Khirbat Faris starts at least as early as the 13th century BC based on the finding of cylinder seals [SF 1614 and SF 1618], a limestone cosmetic palette [SF 1620], ceramics and massive stone architecture. This is a time when the Kerak Plateau, like the rest of Jordan, was under Egyptian hegemony and governed on a local level by city states, (Strange 2008: 303). Little to nothing can be said about the character of occupation apart from observing that Khirbat Faris was very clearly linked in with international trade networks. The next snapshot of the settlement is offered by the presence of 9th to 8th century BC ceramics on the Western Edge. Khirbat Faris was part of the Kingdom of Moab and neighbouring villages and towns included Dhiban and Balu'a, strongholds of King Mesha (Finkelstein and Lipschits 2011; Routledge 2000; Tushingham 1972; Worschech 1997). It is at Dhiban that the Mesha Stele was found, which chronicles the Moabite rebellion against Israel (Herr and Najjar 2008: 322).

By the 1st century AD the inhabitants of Khirbat Faris were Nabatean subjects using distinctive Nabatean wares and worshipping at the nearby temple of Al Qasr (Figures 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8) (Gysens and Marino 1997: 189-193). There seems to have been a `dynamic evolution' in Nabatean material culture at this time as evidenced by archaeological work in the larger centres of Nabataea e.g. Petra, Huwara (Humayma), Aila (Aqabah) (Schmid 2008: 377-8) as well as smaller yet obviously flourishing villages, e.g. Khirbat edh-Dharih (Villeneuve and al Muheisin 2000: 1515-63). The construction of the Khan at Khirbat Faris may well fit into this resurgence. Communication and trading routes were never far away: the north-south route commonly known as `The King's Highway' lies but 3 km to the east and this would have given ready access to the centres further south e.g. Rabbath Moab (modern Al Rabba).

The prosperity and stability of this time continued as Nabataea was annexed by the Roman Empire in AD 106. Khirbat Faris now fell within the administrative province of Arabia with its capital at Petra. The administrative change that this brought to a provincial village was probably minimal. As Freeman puts it, `communities appear to have retained their pre-Roman administrative frameworks and control of their resources, other than the taxation that they were expected to provide,' (2008: 423). However, the employment and trading opportunities brought to the population of Khirbat Faris by the upgrading of the King's Highway to the Via Nova Traiana and the construction of the Limes forts (Kennedy 2000: 134¬155) were undoubtedly substantial. The road-stations and garrisons needed not only to be built but also provisioned. As well as the major north-south route running so nearby, Khirbat Faris and Khirbat Tadun themselves lay on a minor Roman road connecting the settlement with a network of villages lying to the northwest (Worschech and Knauf 1985: 131). Al Rabba/ Areopolis, with its Roman temple (Zayadine 1971: 71), and Kerak (Charachmoba) continued to be the main commercial centres in the region: both centres were listed in Ptolemy's Geography and coins were struck at both cities in the early 3rd century.

It is the 6th—8th centuries AD that allow more extensive characterisation of the occupation at Khirbat Faris. Arguably, at this time, the whole site was known as Khirbat Tadun and was a flourishing village within the Byzantine administrative district, first of Arabia and then Palestine III with its capital at Petra, (Watson 2008: 460). Throughout Jordan the Byzantine period is seen as a peak of agricultural occupation and use of the land. Watson goes on to summarise, (2008: 447)

Numerous factors contributed to this situation, chief among them being the sense of general security that allowed settlement and food production to exist in safety. Healthy trade and economic networks encouraged an overall prosperity. An expanding religious community enjoyed the highest political support.On the Kerak Plateau, Christianity and the ecclesiastical framework had grown to have an important role within the countryside, fostering village solidarity, notwithstanding the frequent doctrinal conflicts that coloured the Christian religious life of the 4th-7th centuries. There was at least one church at Khirbat Faris, and maybe two, judging by the objects found in the trenches at both the Central Area and Highest Point as well as the analysis of the Tadun name1. The clergy would have answered to the bishop in nearby Areopolis (Al Rabba), who himself would have answered to the metropolitan bishop of Petra (Watson 2008: 473).

In subsequent centuries, the settlement at Khirbat Faris, administratively, continued to be oriented southwards. In the 10th century Ma'ab (Al Rabba) was the principle town of the region of Al Sharah only to be overtaken by Kerak in the succeeding Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods (12th-16th centuries). A comprehensive summary of the historical records of these periods is given in Walmsley (2008: 498-503). While a certain amount of this material relates to political and military events, there is also a wealth of information concerning the nature of the rural economy. As the settlement of earlier periods was strongly affected by the presence of, first the King's Highway and then the Via Nova Traiana, so too the imperatives of the Hajj played a significant role in shaping the local rural economy. Until the 16th century the Hajj caravans followed the route through Al Qasr and Ma'ab before moving further east (Petersen 1994).

... It is not until the mid-19th century that Khirbat Faris and Khirbat Tadun finally enter the written record.

1 possibly deriving from ‘St Theodoros’ via Tadur and Tadhur (Knauf 1991: 285)

- Parsed and redacted from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

In 1896, Musil records how he rode from Yarut to Imra’ through an ‘arable plain’ and passed Khirbat Tadun on his left. He describes the site as consisting of ‘a fairly well-preserved tower and the ruins of houses’ (1907–08 I:87). As part of his pioneering archaeological survey, Glueck recorded ‘two modern abandoned buildings, standing among several ruined buildings’ (1934: 62). The associated ceramics were identified as ‘Nabatean and medieval Islamic’. These ‘abandoned’ buildings were presumably Houses 1 and 2, which had been built after Musil’s travel through the area. The area was surveyed as part of the Ard Al Kerak Survey: site 55 (Worschech 1985: 43–45) and then again in Miller’s extensive survey of the Kerak Plateau (1991: 49–51. Two ruined buildings plus the traces of a third are again recorded as well as the ‘wall lines of numerous structures … (and) cisterns among the wall remains’ and the tomb. The ceramics collected during the survey ranged from Middle Bronze Age I to Late Islamic.

A recent description given by Johns describes ‘Tadun as a large mound, approximately 100 m by 30 m rising to approximately 4–5 m above the immediately surrounding area. The outlines of a substantial rectangular walled structure are visible, enclosing a large central depression and several small mounds. The Roman road identified by Worschech (1985: 131) seems to run north from Al Rabba into the south side of the mound, where there may be a gate. At the top of the mound, near its northwest corner, are exposed what may be the upper courses of a small dome, executed in fine limestone ashlar masonry. In the central depression, recent clandestine excavation has revealed a large Corinthian capital and an architrave block, both in limestone. Worschech recovered Late Roman and Byzantine sherds from the site and our own collection added a sherd of Umayyad red-on-grey painted ware to the assemblage: in 1988 further Umayyad pottery was collected from Kh. Tadun’ (Johns et al. 1989: 64–5; Worschech 1985: 41–4). Further hints as to the nature of this structure are given by the place-name itself. Knauf interprets Tadun as being Greek in origin and deriving from ‘St Theodoros’ via Tadur and Tadhur (Knauf 1991: 285). In this case Tadun may well be a church of St. Theodoros that was used at least until the 7th–8th centuries AD. As is discussed in Chapter 5, the mid-8th century earthquake(s)5 is likely to have been responsible for considerable destruction at the site and may have marked the end of occupation at Tadun.

5 See Ambraseys 2009:234–5 for detailed discussion concerning this earthquake. There were at least 3 sizeable earthquakes in the years spanning AD 746‒757 [JW: the 746 date is wrong but there were at least 3 sizeable earthquakes and perhaps as many as six in the mid 8th century CE - see 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, the 756 CE By No Means Mild Quake(s), and Jefferson Williams publication (forthcoming) on this earthquake sequence in Annals of Geophysics.] It is widely accepted that in Northern Jordan and the Jordan Valley a calamitous earthquake struck in AD 749 and caused widespread destruction. However, Ambraseys, citing the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (AD 752‒818), provides a cogent case for the date of AD 746 being preferred for this area [JW: except that he is wrong. It struck in 749. See references mentioned previously.]. Regions to the east of the Jordan Rift seemed more effected than to the west with much damage done to towns lying east of the river along the trade route that ran from Palmyra via Damascus to Ma’an and Tabuk.’

- Fig. 1.4 - Location Map from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 1.4 - Location Map from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 1.3 - Aerial View of

Khirbat Faris (left) and Khirbat Tadun (mound in lower right) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.3

Aerial view

Khirbat Faris is to the left of the road

Khirbat Tadun is to the right of the road. It is the mound in the middle right of the photo

click on image to open in a new tab

McQuitty et al. (2020)

APAAME_20070417

_DLK-0051 © David L. Kennedy, Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East. - Khirbat Faris (upper left) and Khirbat Tadun (mound to lower right) in Google Earth

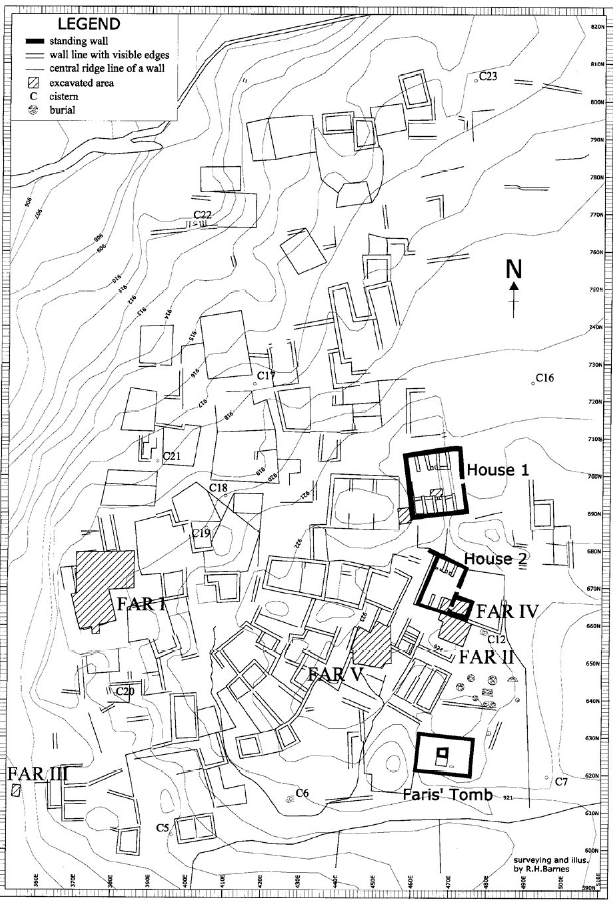

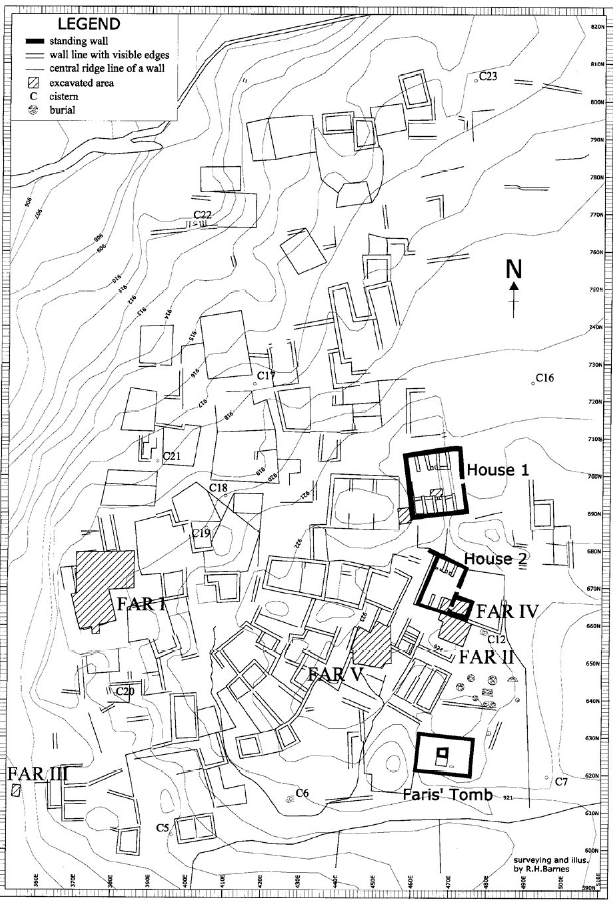

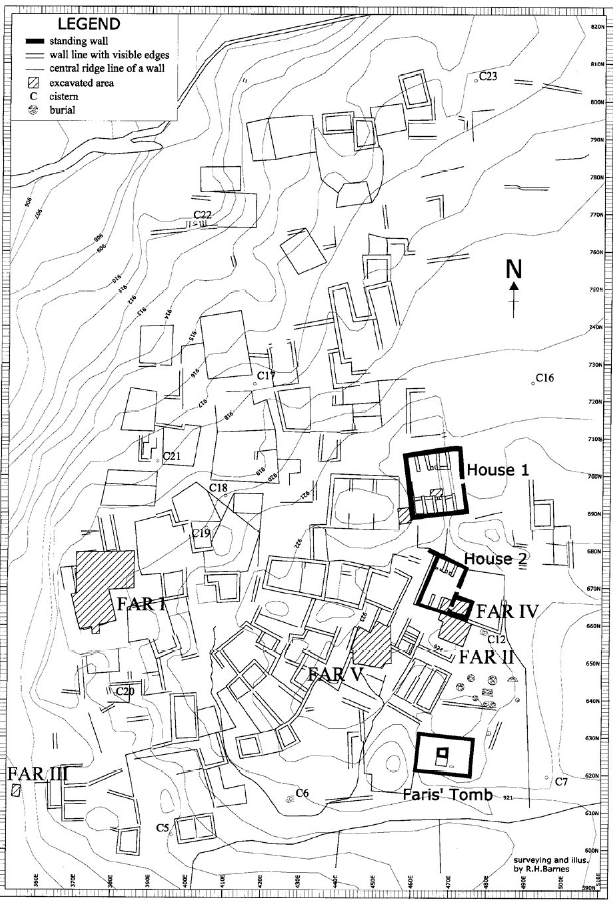

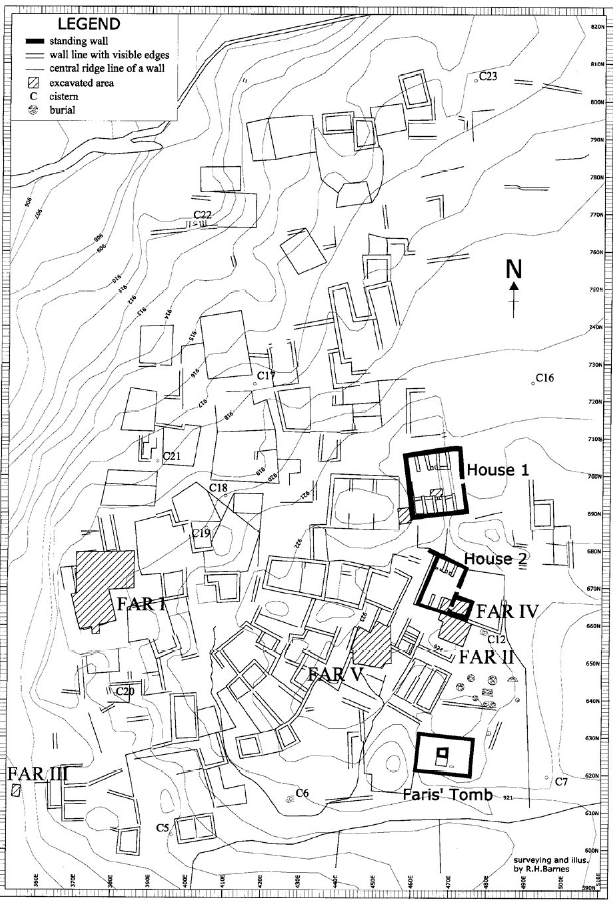

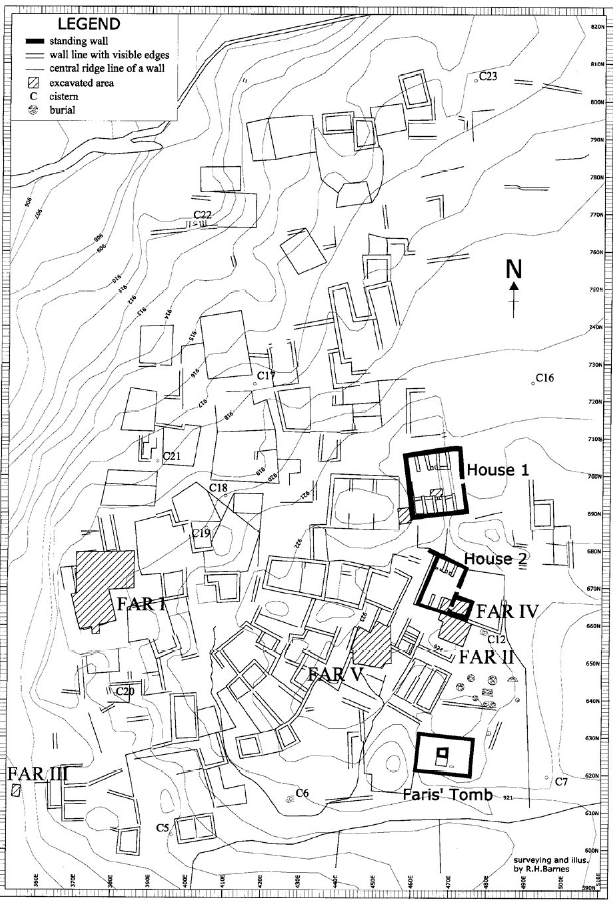

- Fig. 1.2 - Site plan

from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.1 - Site Plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 1.2 - Site plan

from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.1 - Site Plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

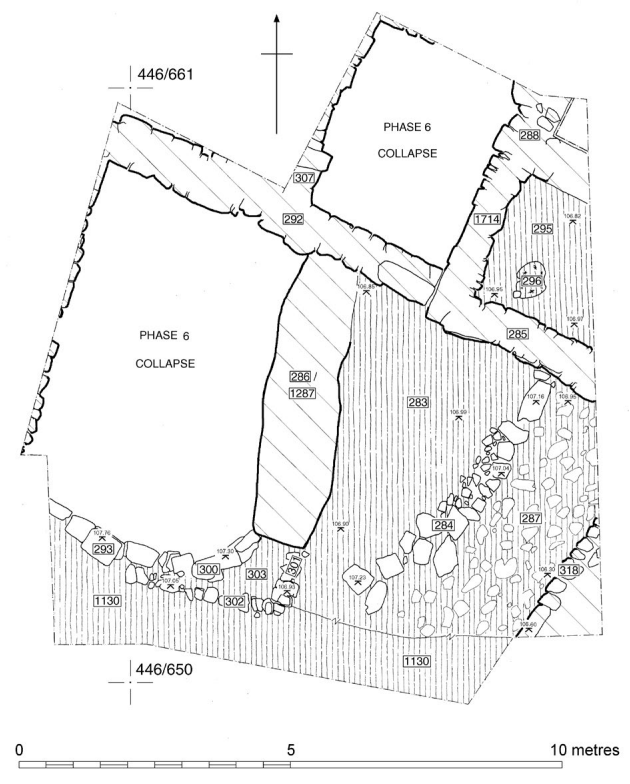

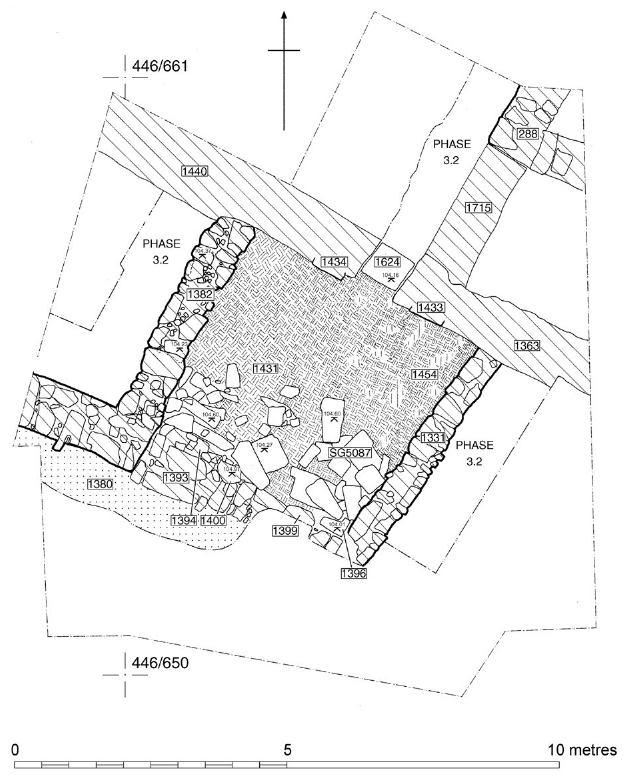

- Fig. 5.19 - Phase 3.1

plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

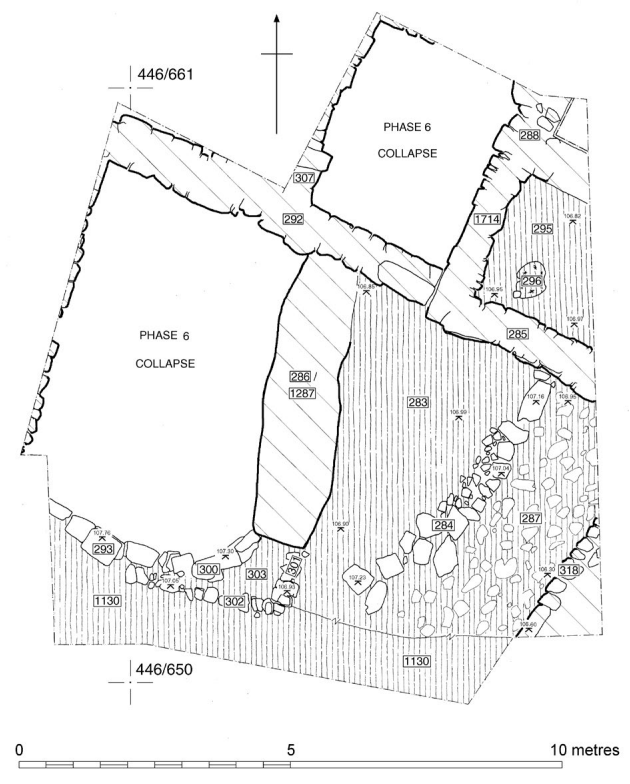

- Fig. 5.28 - Phase 7 plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.19 - Phase 3.1

plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.28 - Phase 7 plan from McQuitty et al. (2020)

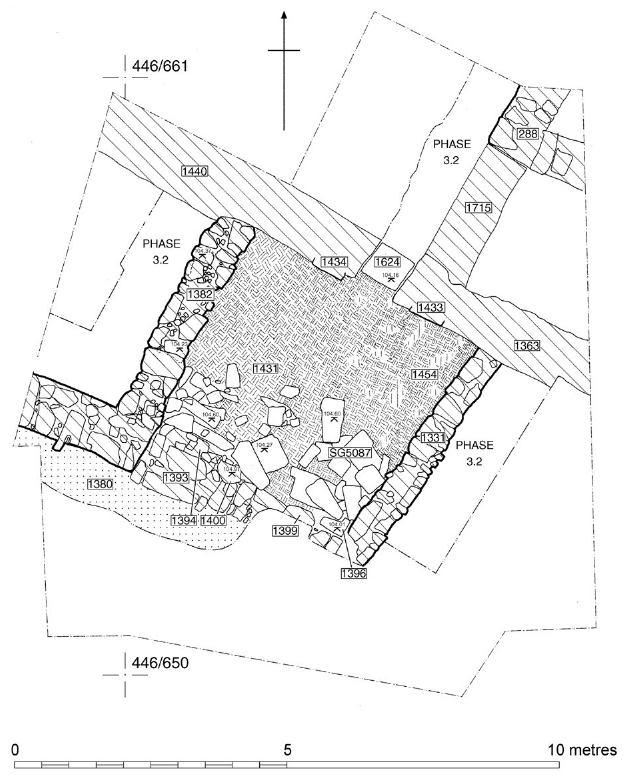

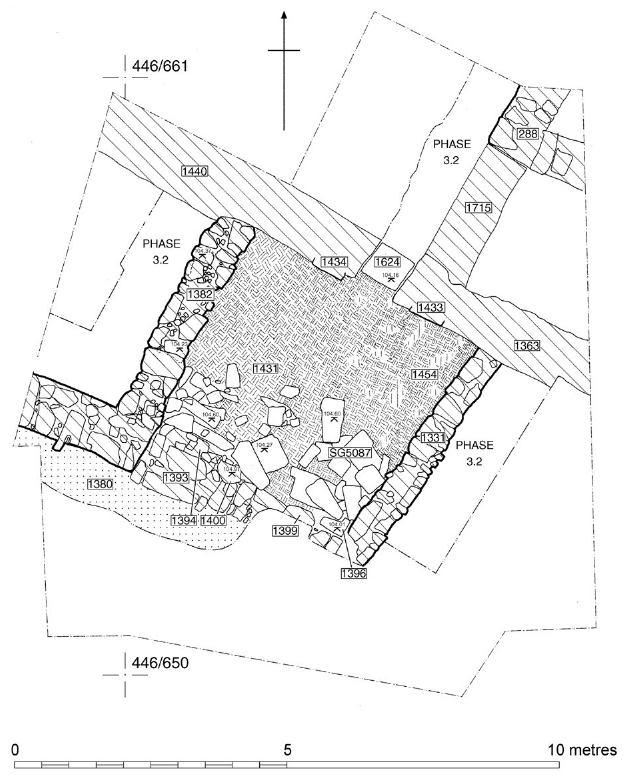

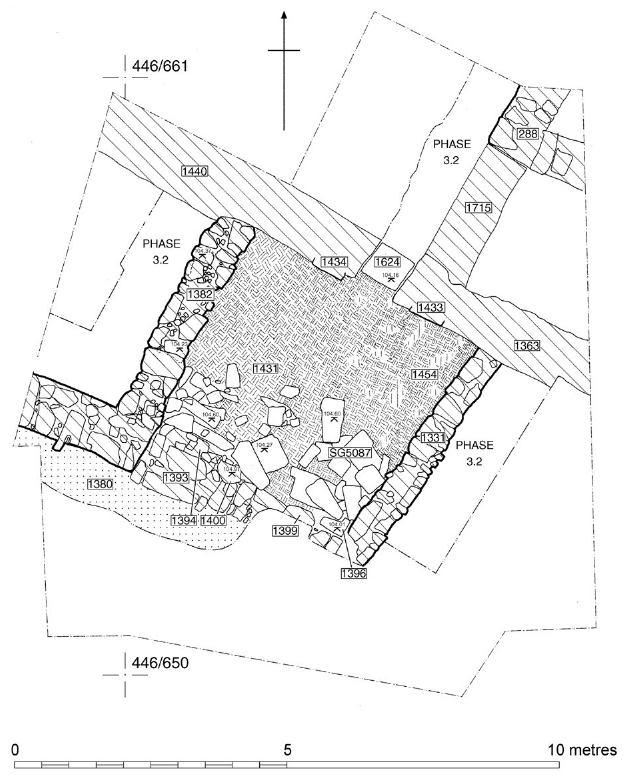

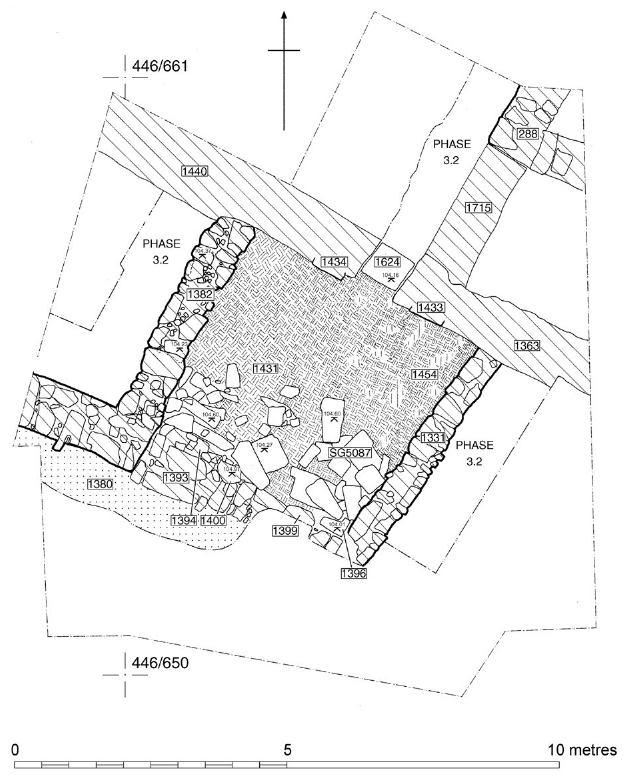

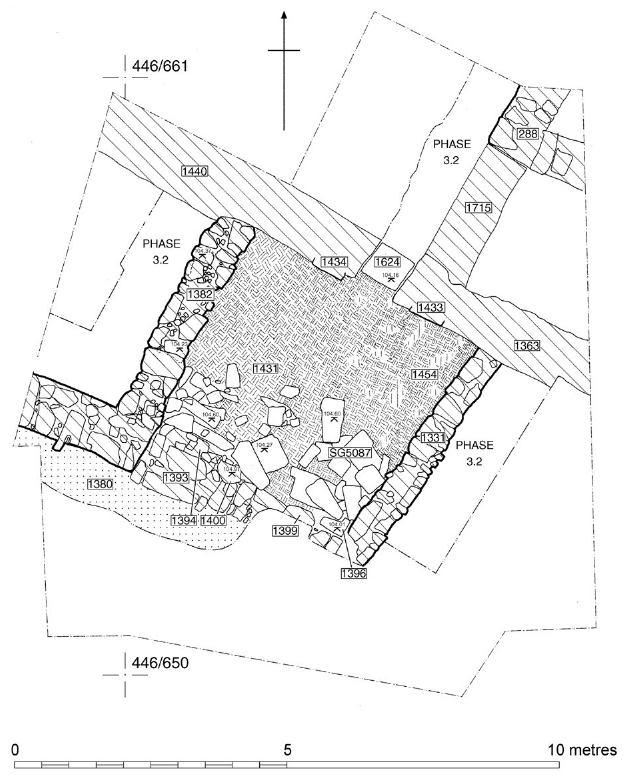

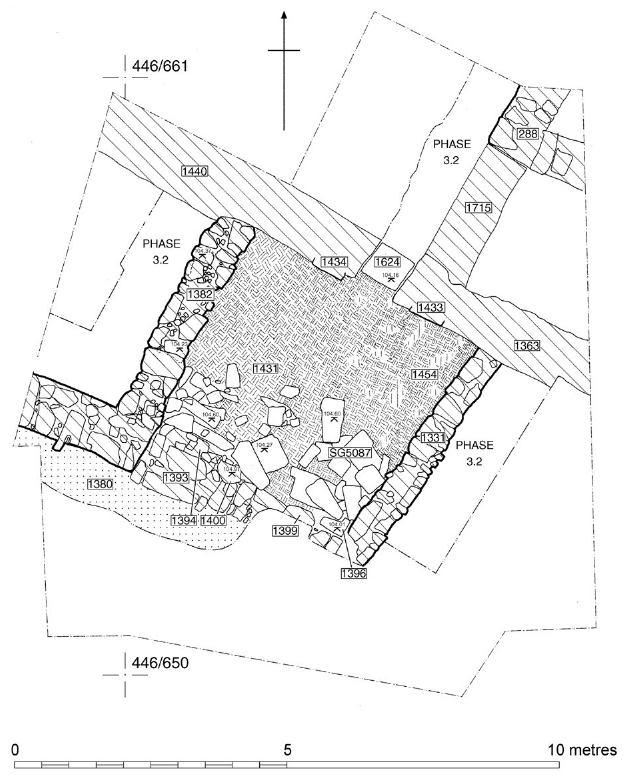

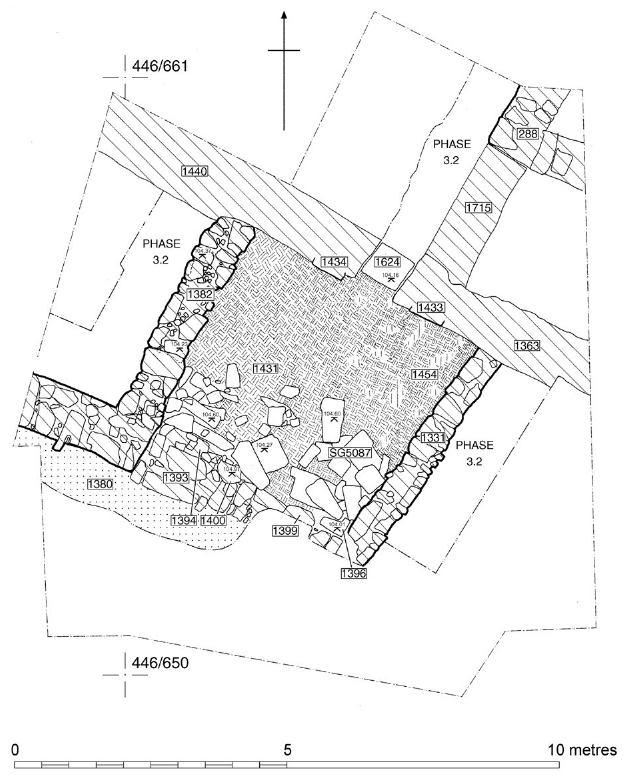

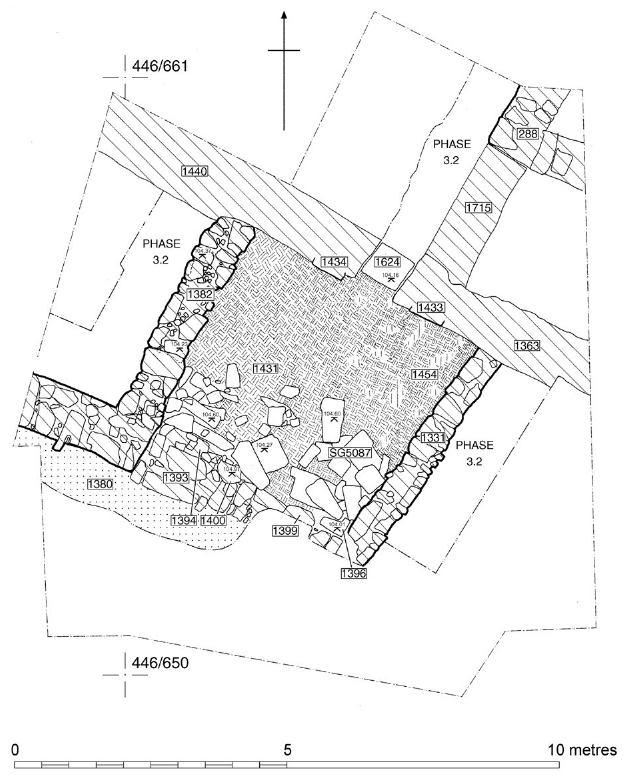

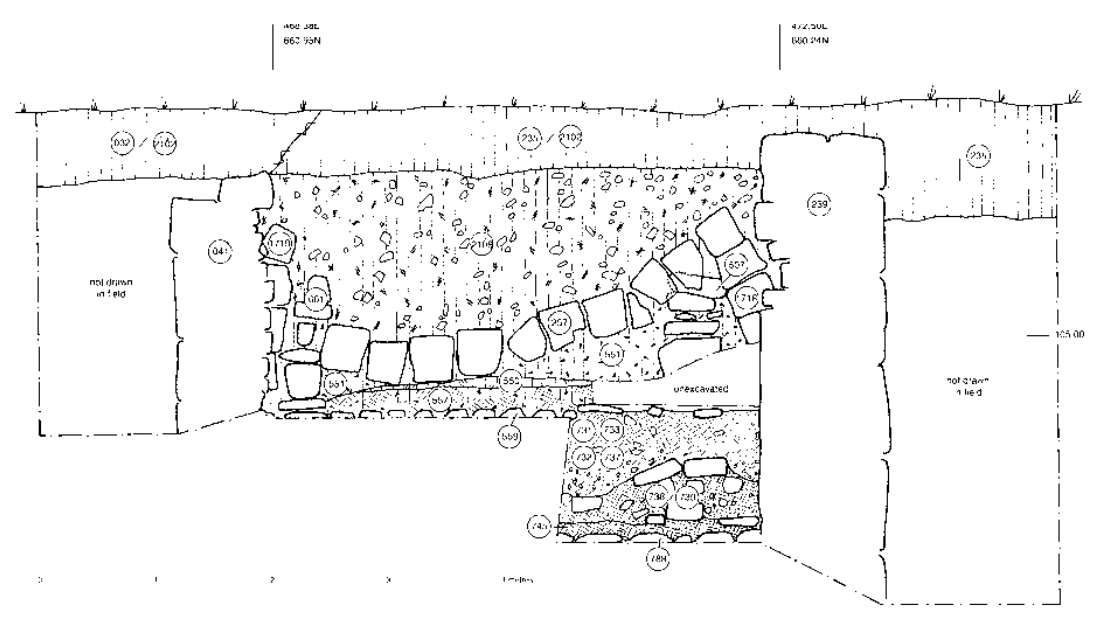

- Fig. 4.12 - Phase 3.1

plan for Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

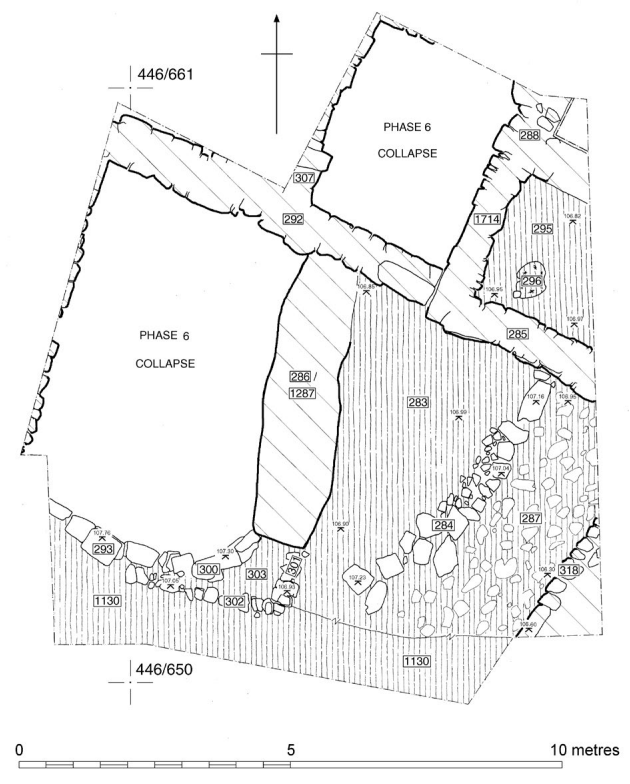

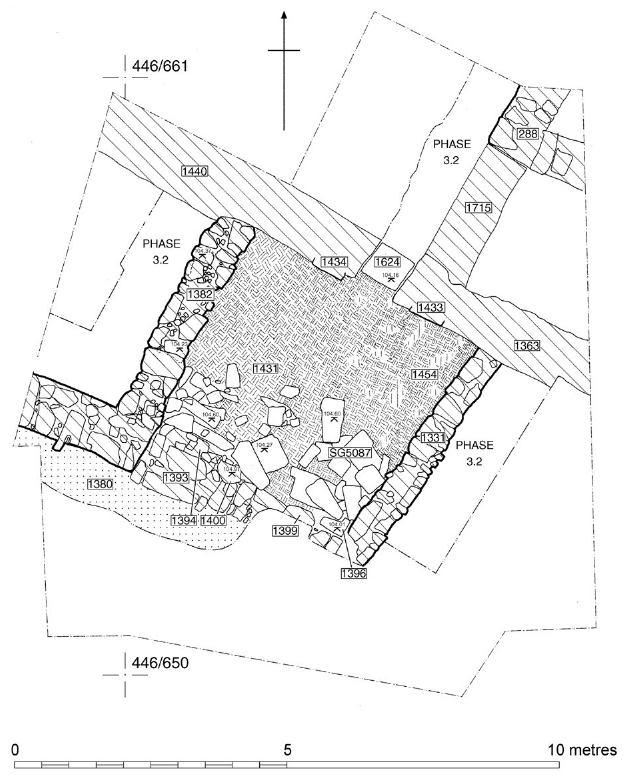

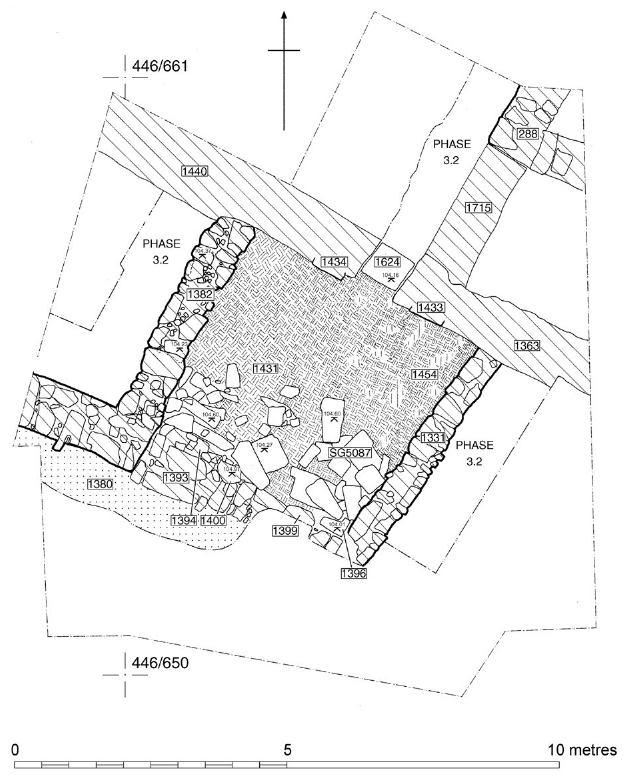

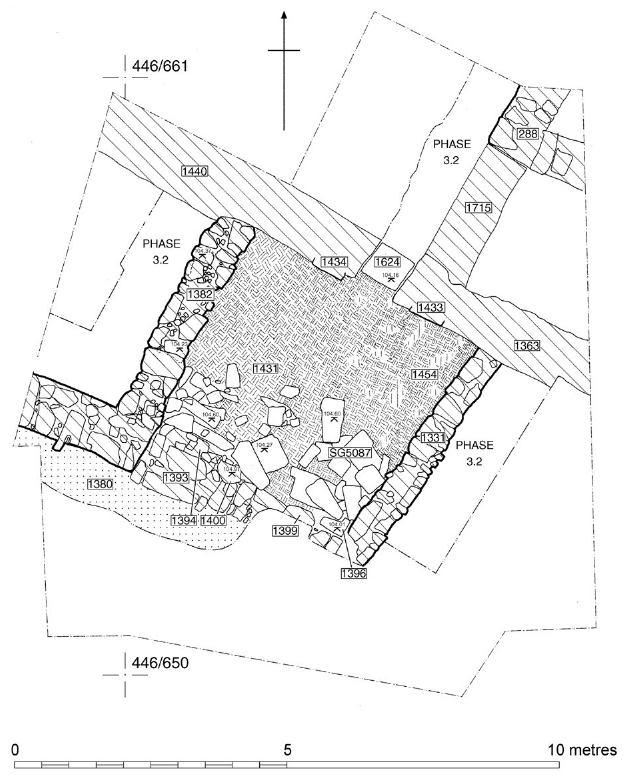

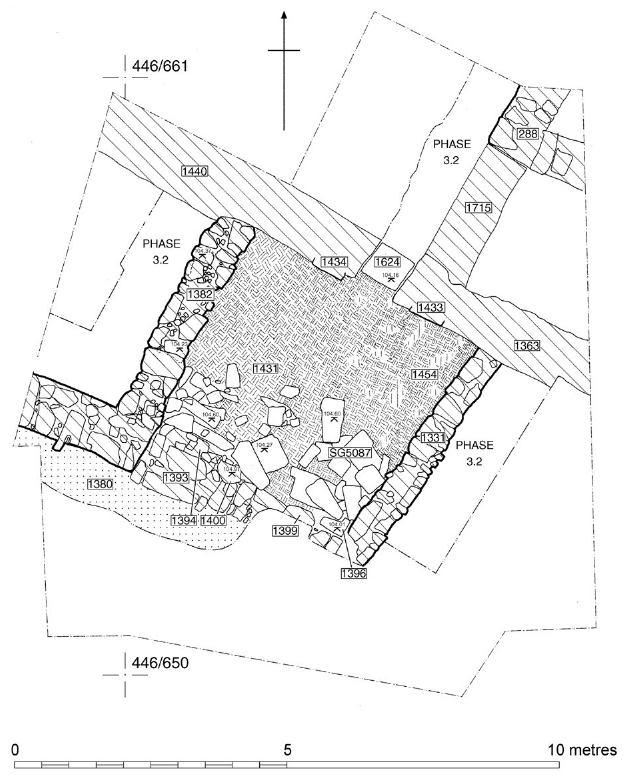

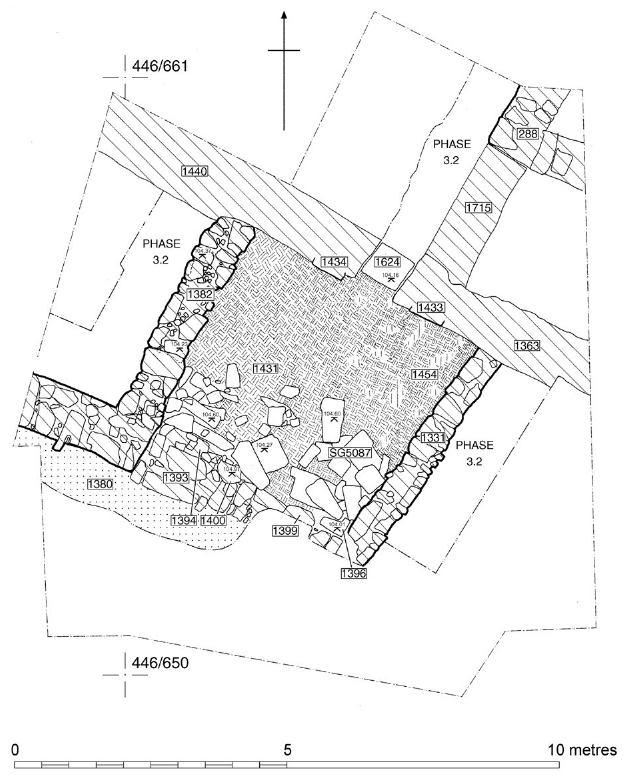

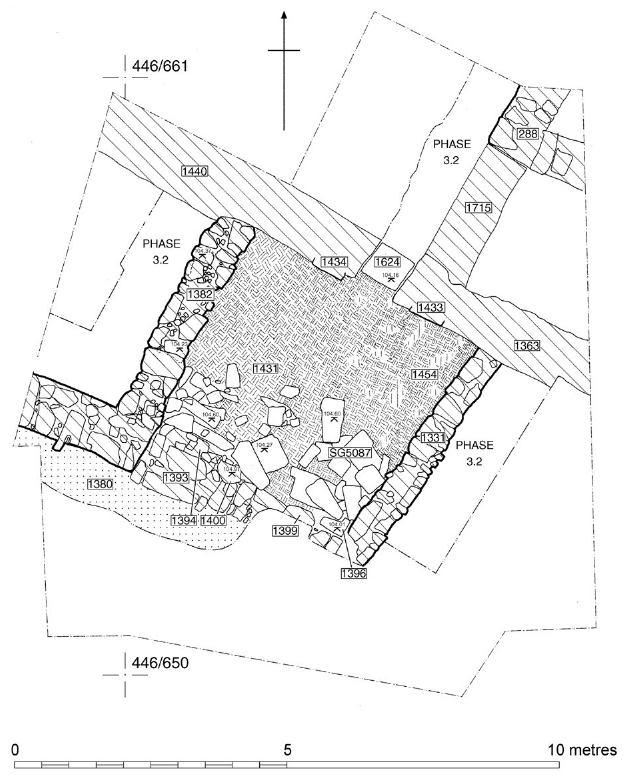

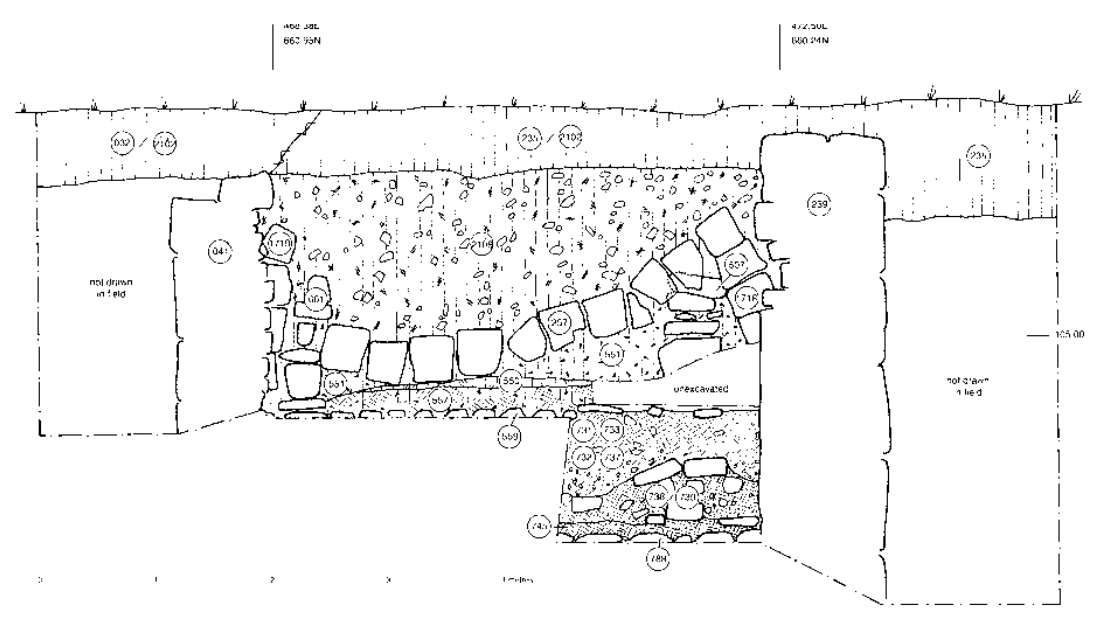

- Fig. 4.20 - Phase 3.2

plan for Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.12 - Phase 3.1

plan for Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.20 - Phase 3.2

plan for Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 6.18 - Plan of House

1 and its trenches from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 6.18 - Plan of House

1 and its trenches from McQuitty et al. (2020)

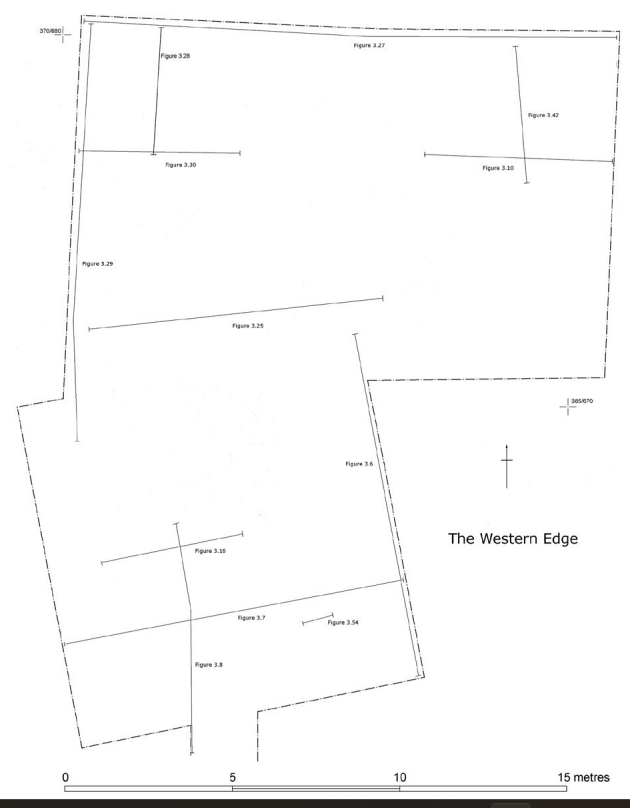

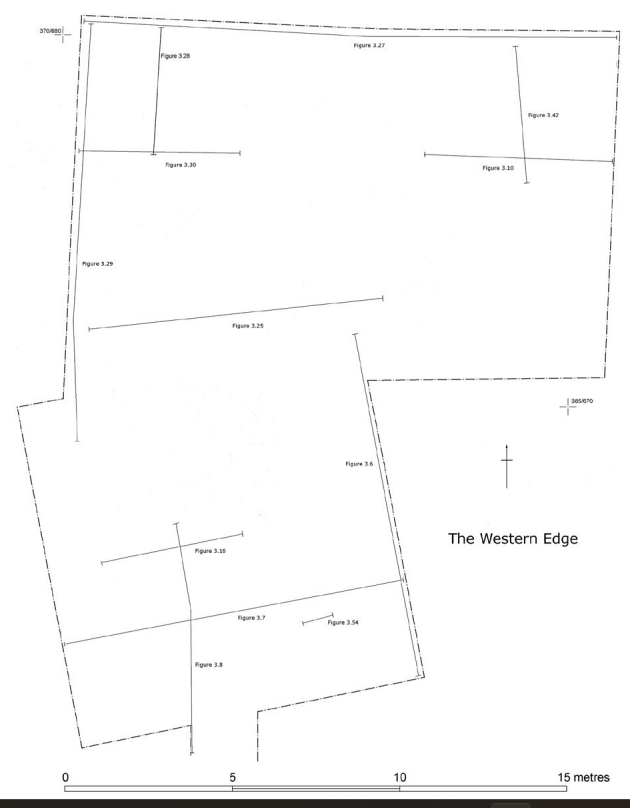

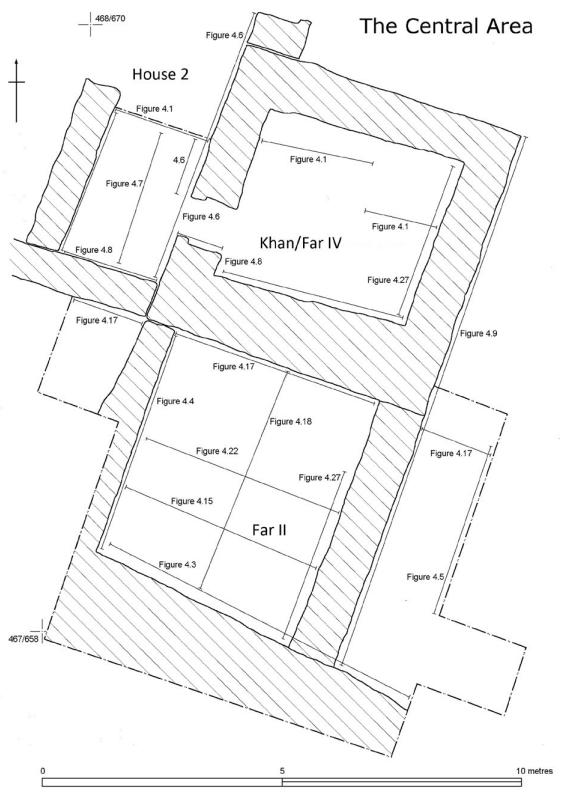

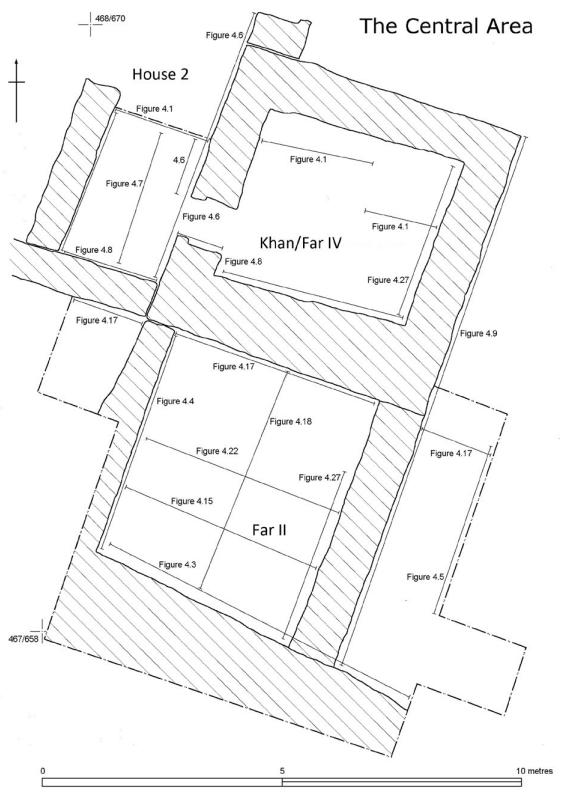

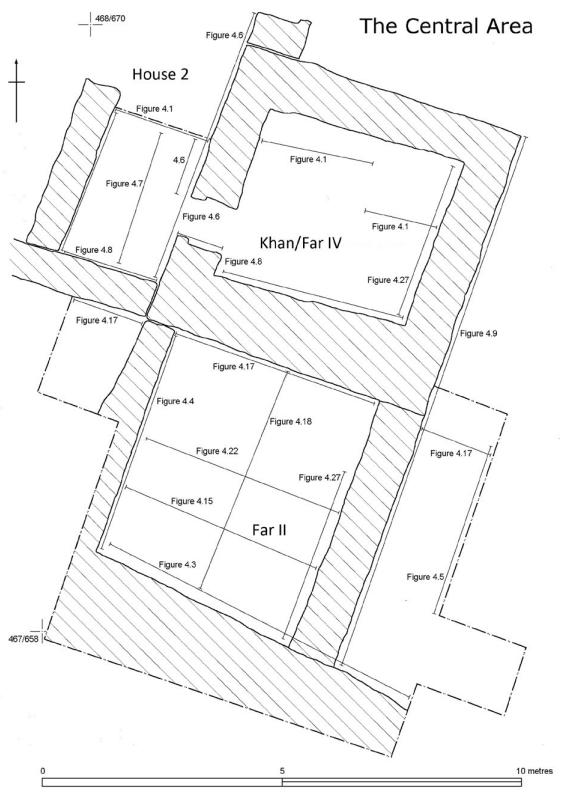

- Fig. 2.13 - The Western Edge

(Far I) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

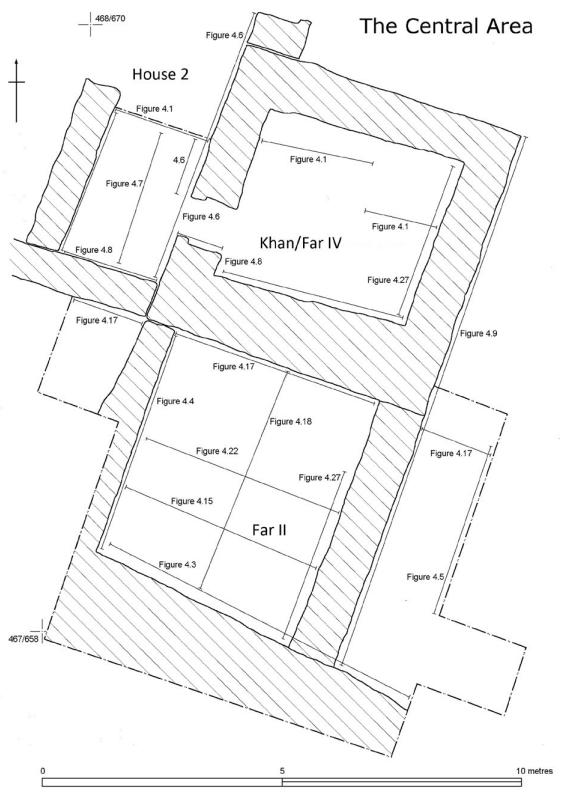

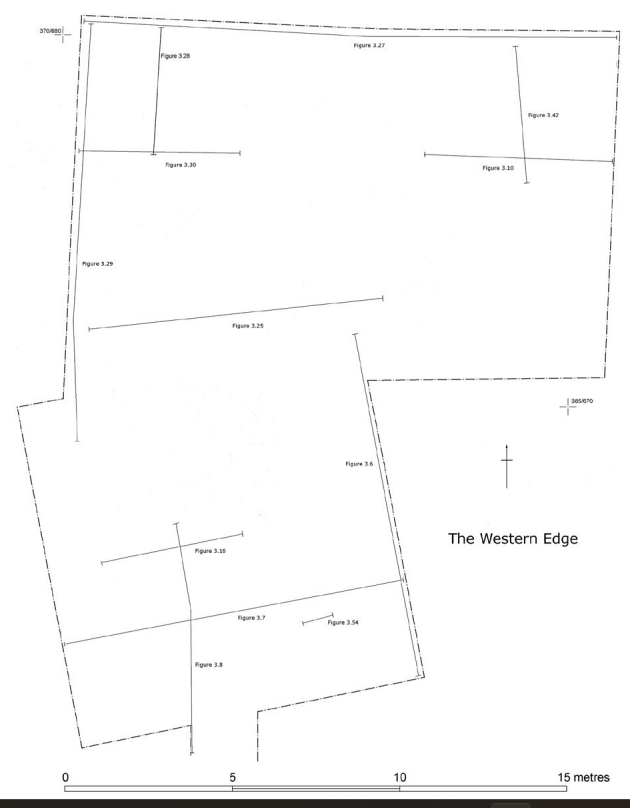

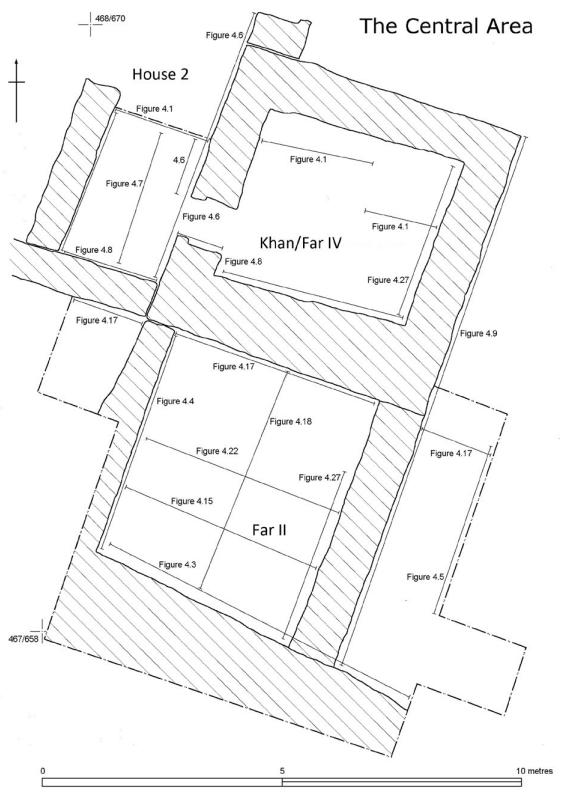

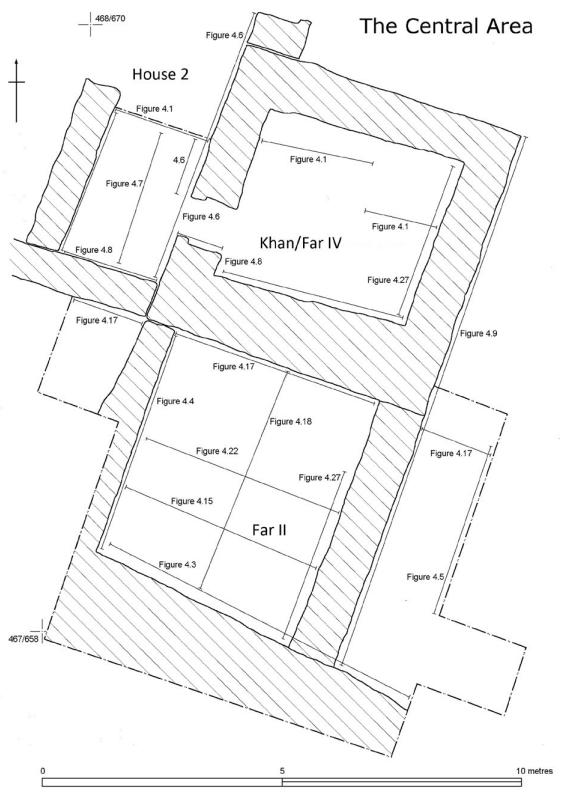

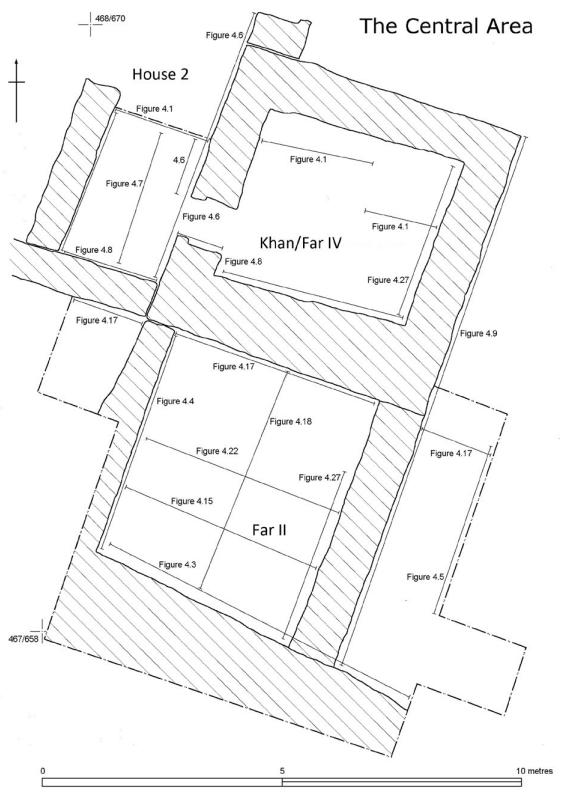

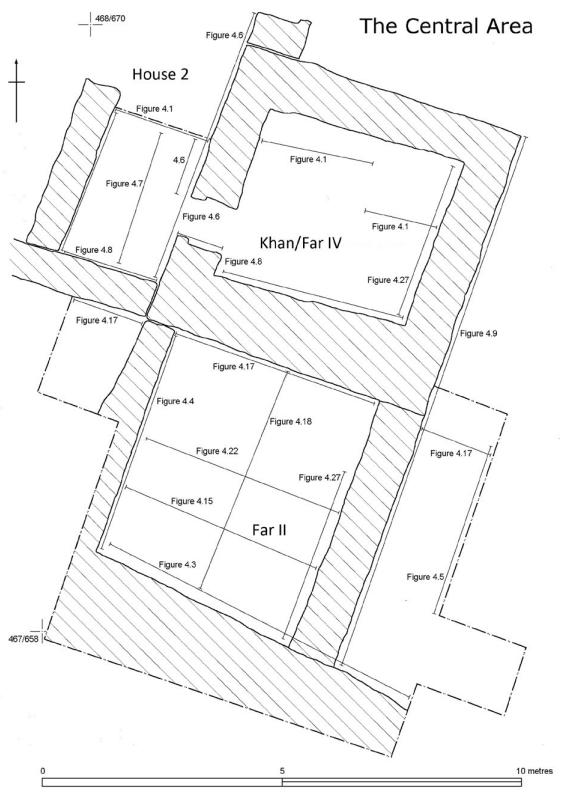

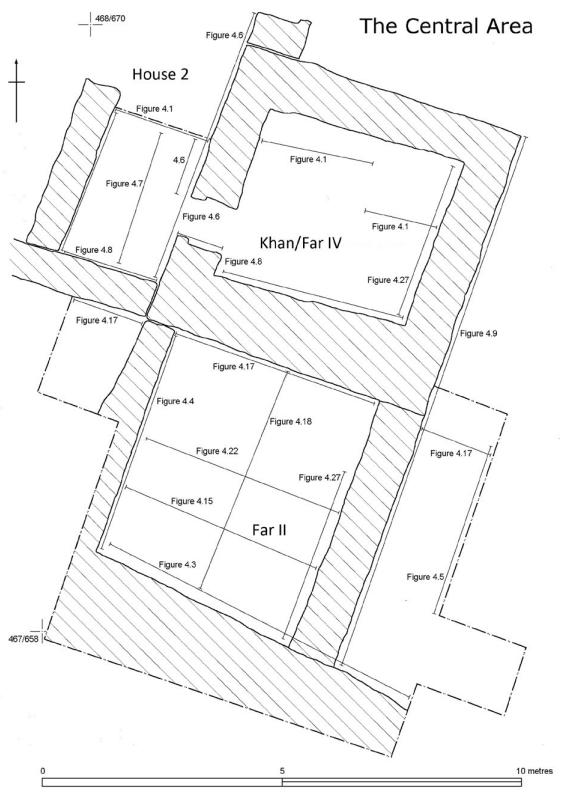

- Fig. 2.14 - The Central Area

(Far II and Far IV) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

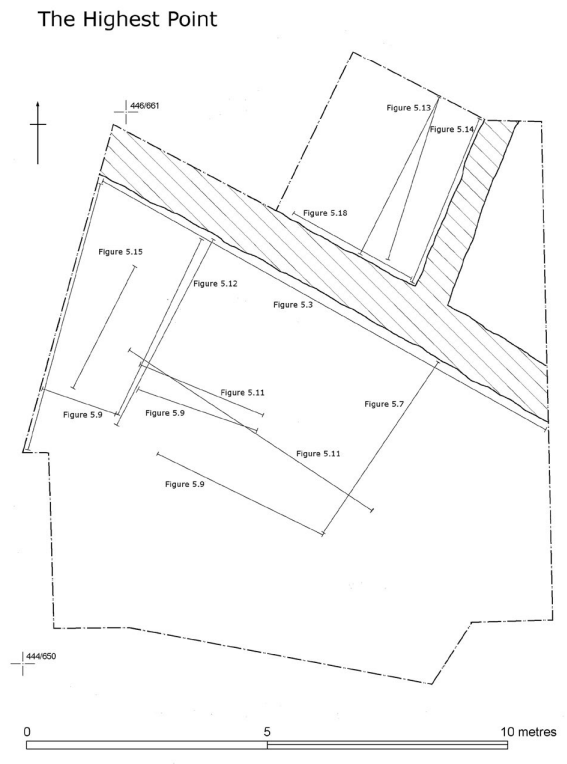

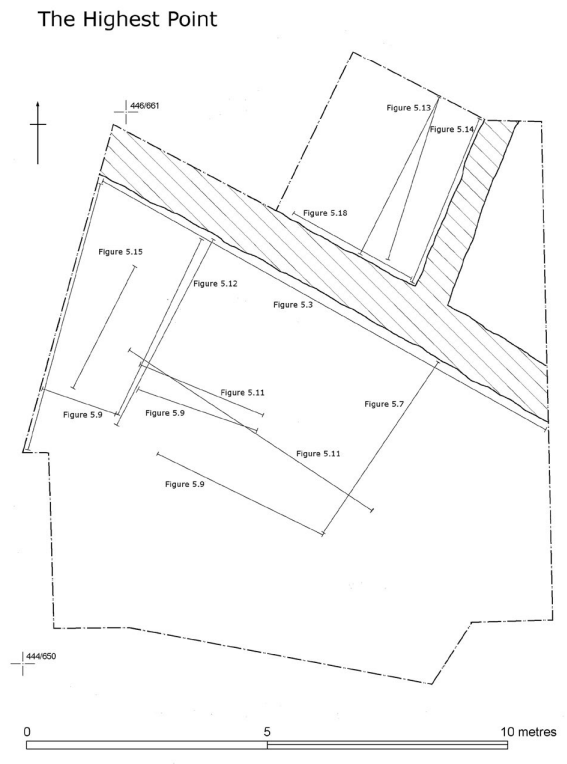

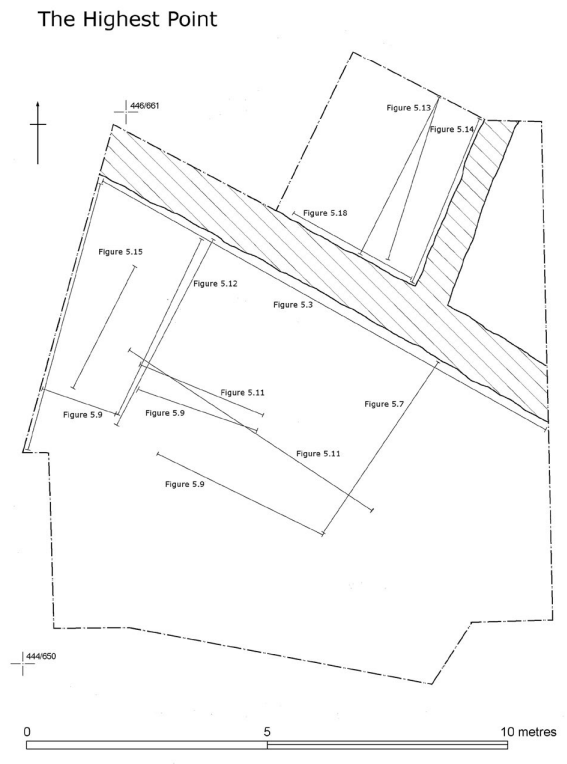

- Fig. 2.15 - The Highest

Point (Far V) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.16 - House 1

from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.13 - The Western Edge

(Far I) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.14 - The Central Area

(Far II and Far IV) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.15 - The Highest

Point (Far V) from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.16 - House 1

from McQuitty et al. (2020)

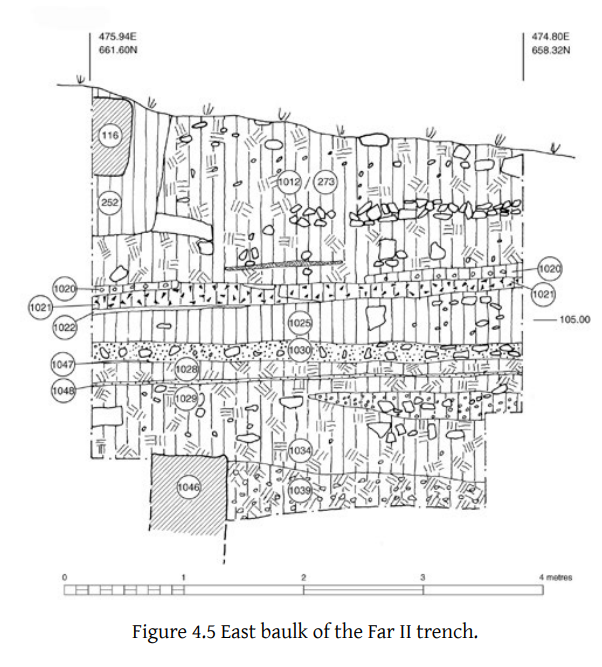

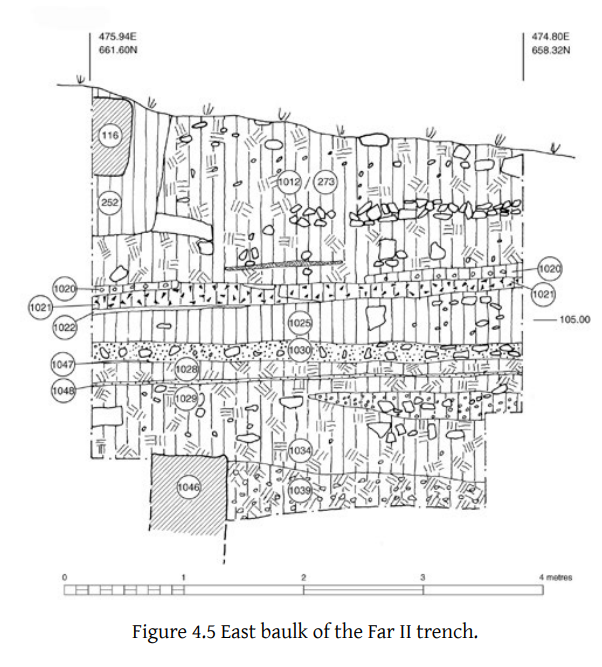

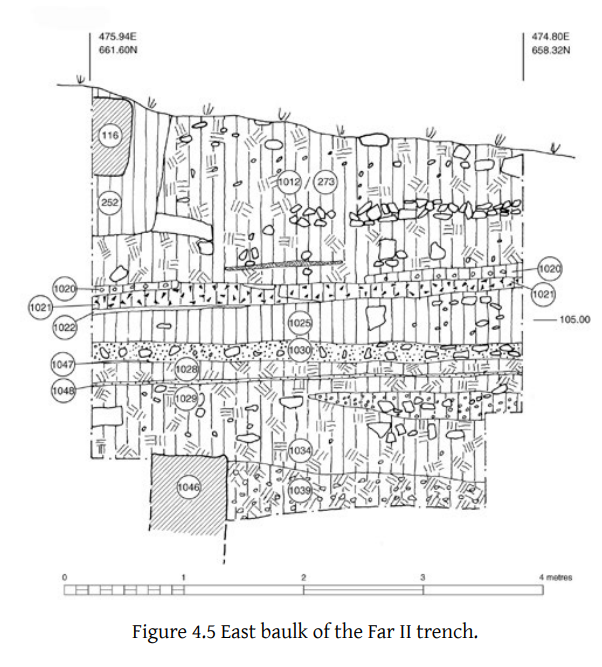

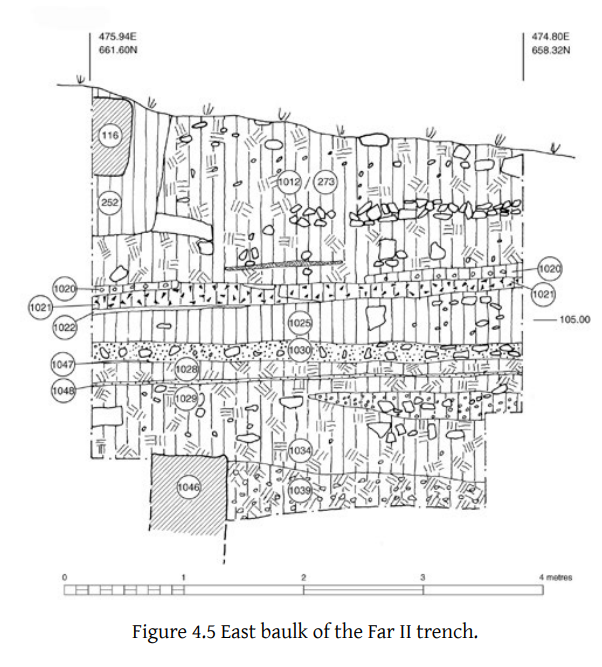

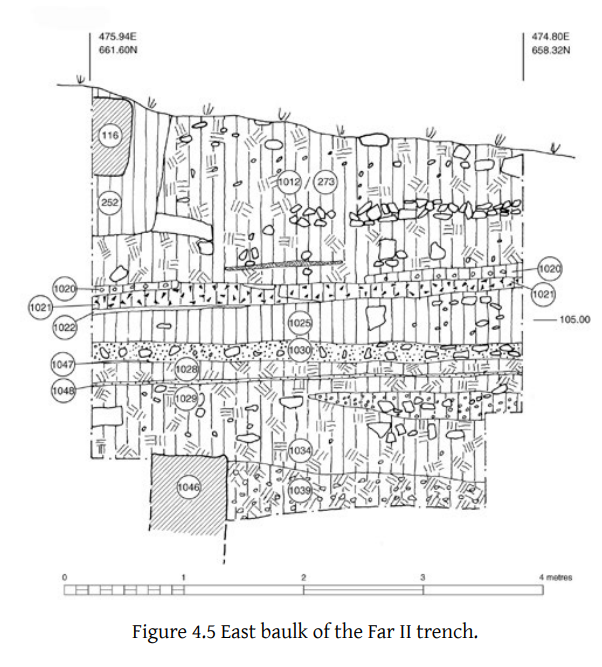

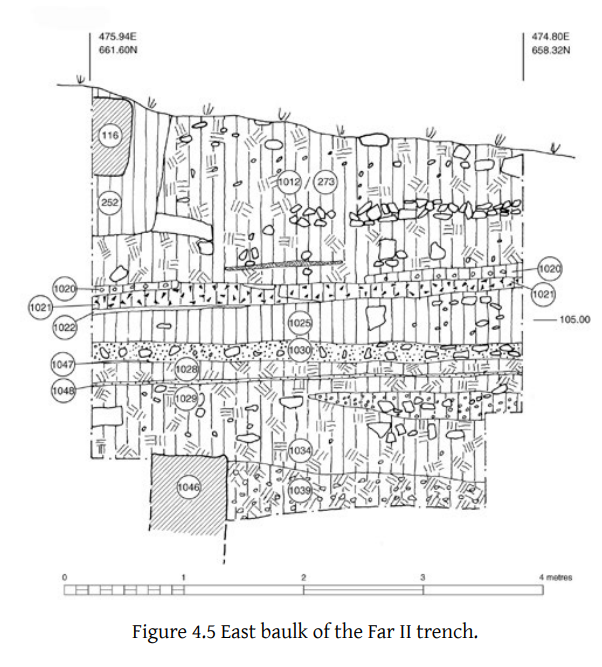

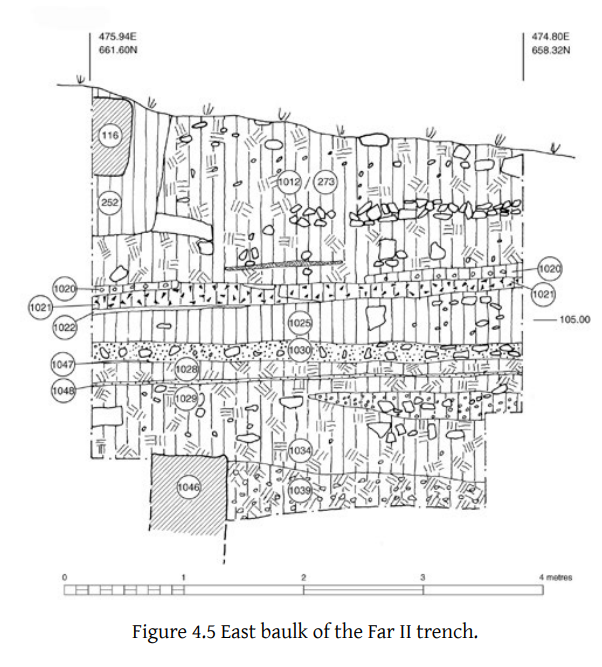

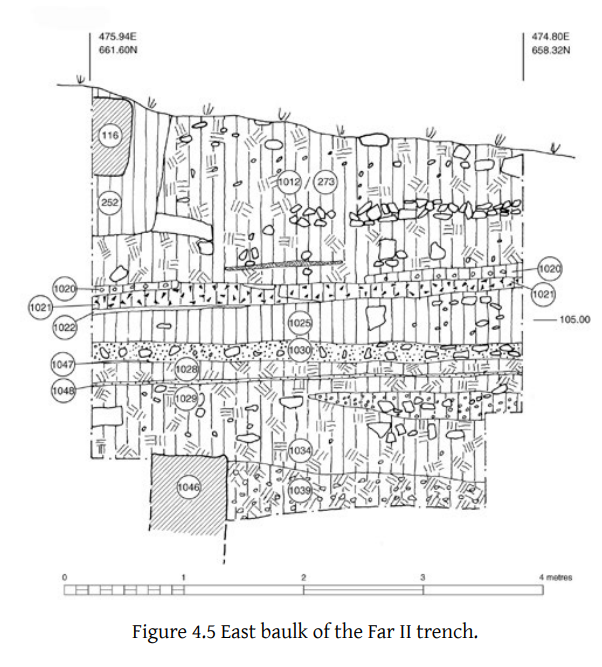

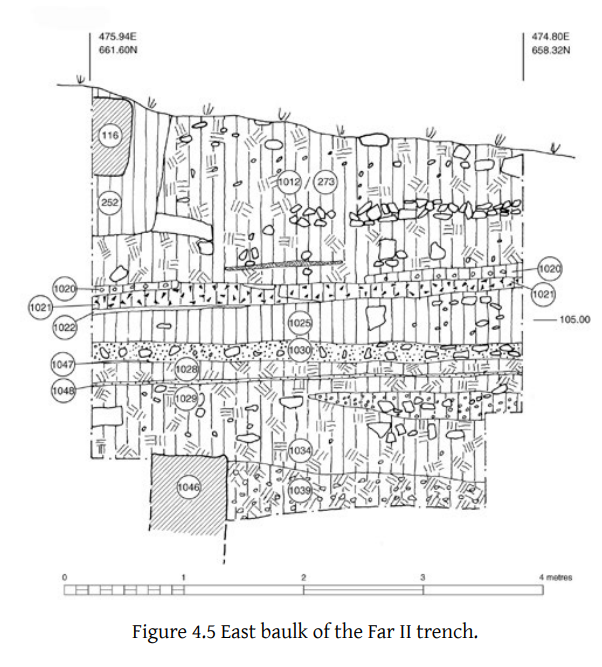

- Fig. 4.5 - East baulk

of the Far II trench from McQuitty et al. (2020)

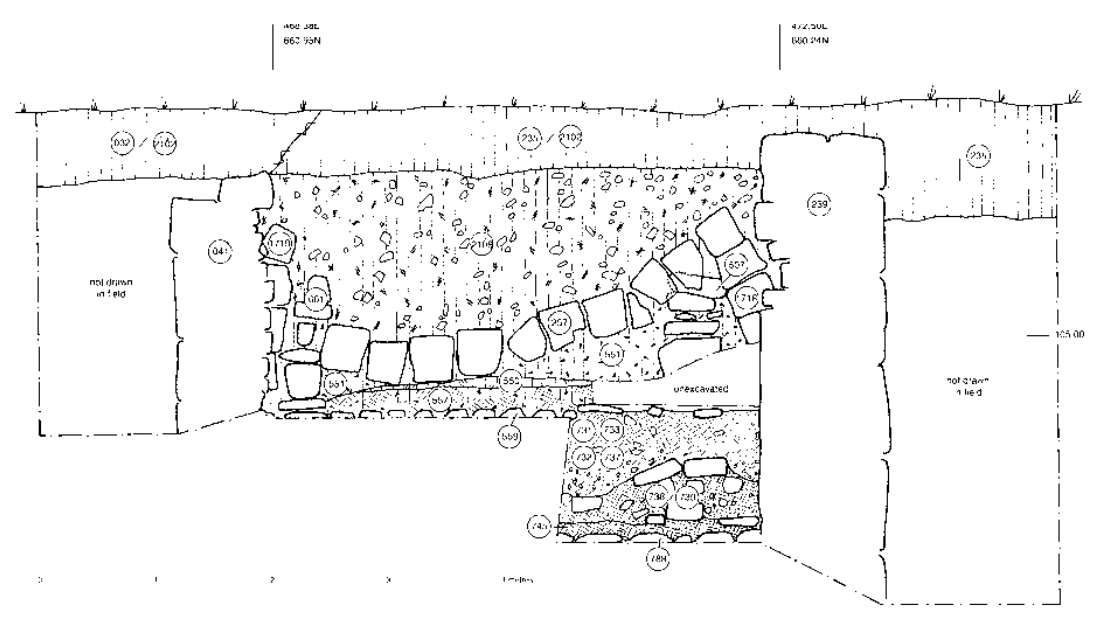

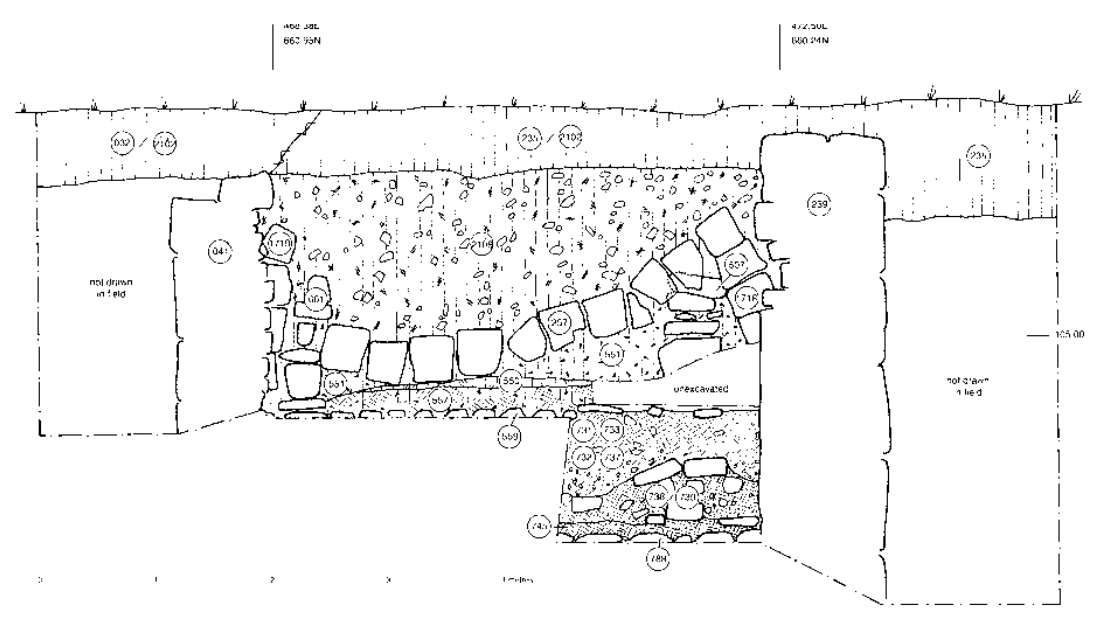

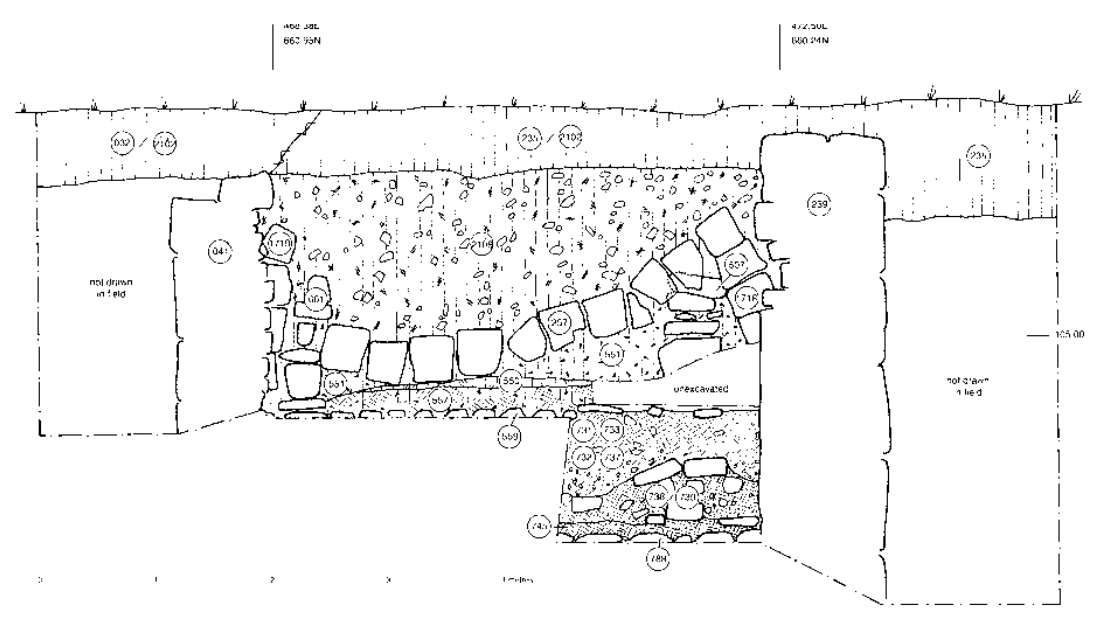

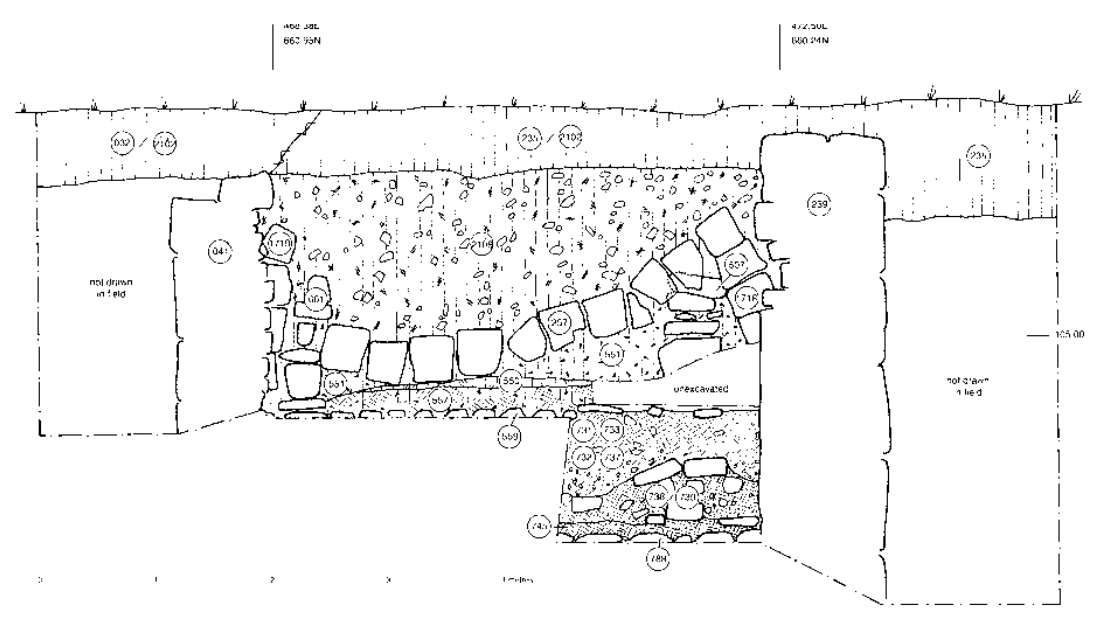

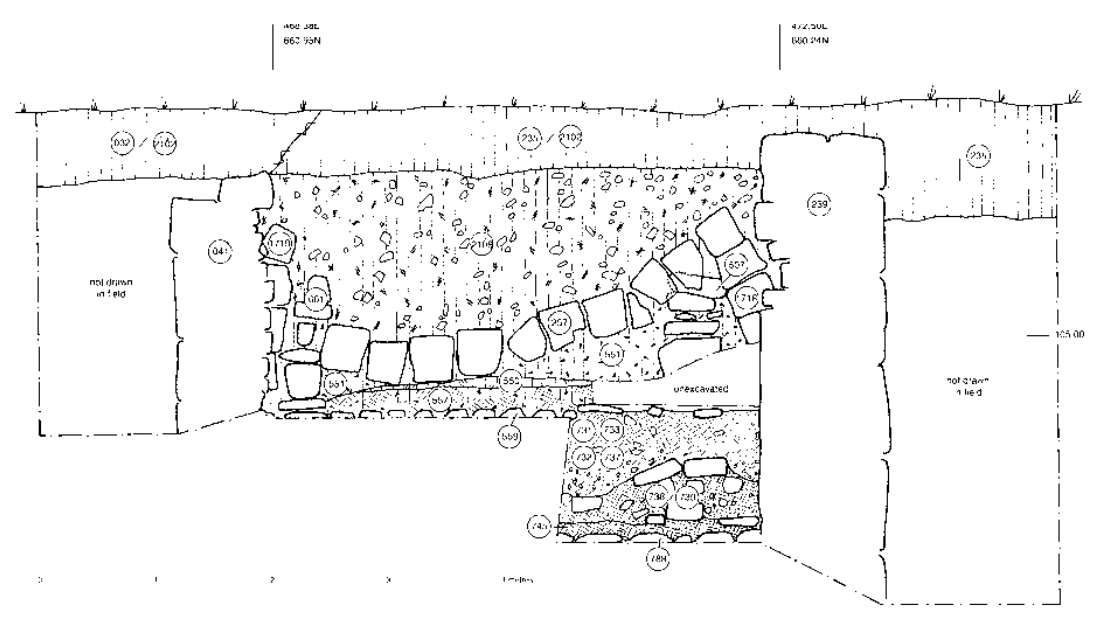

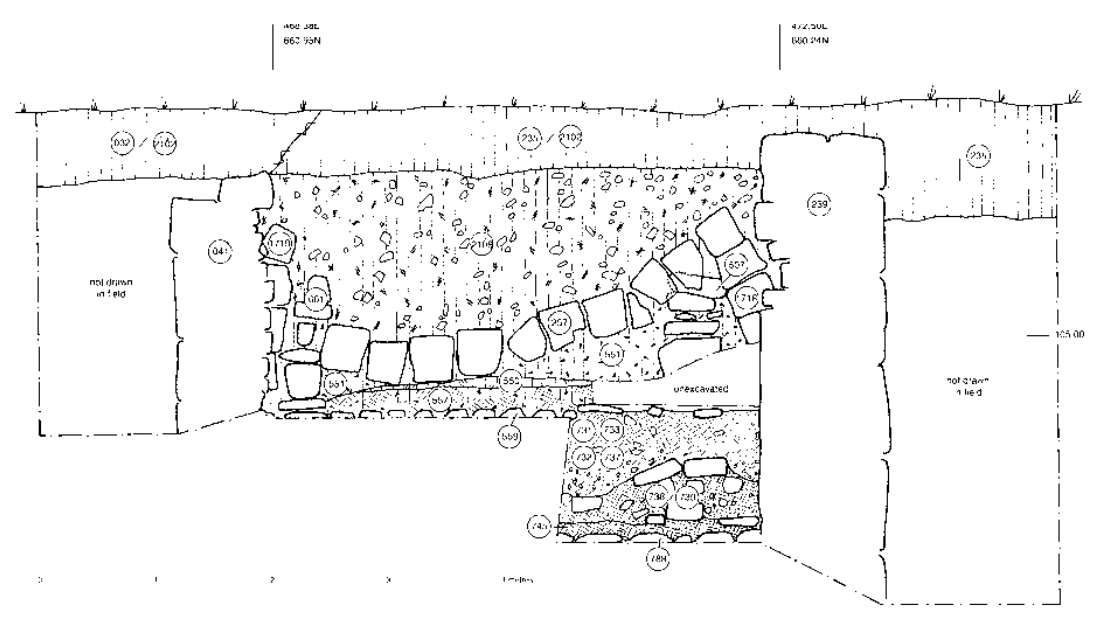

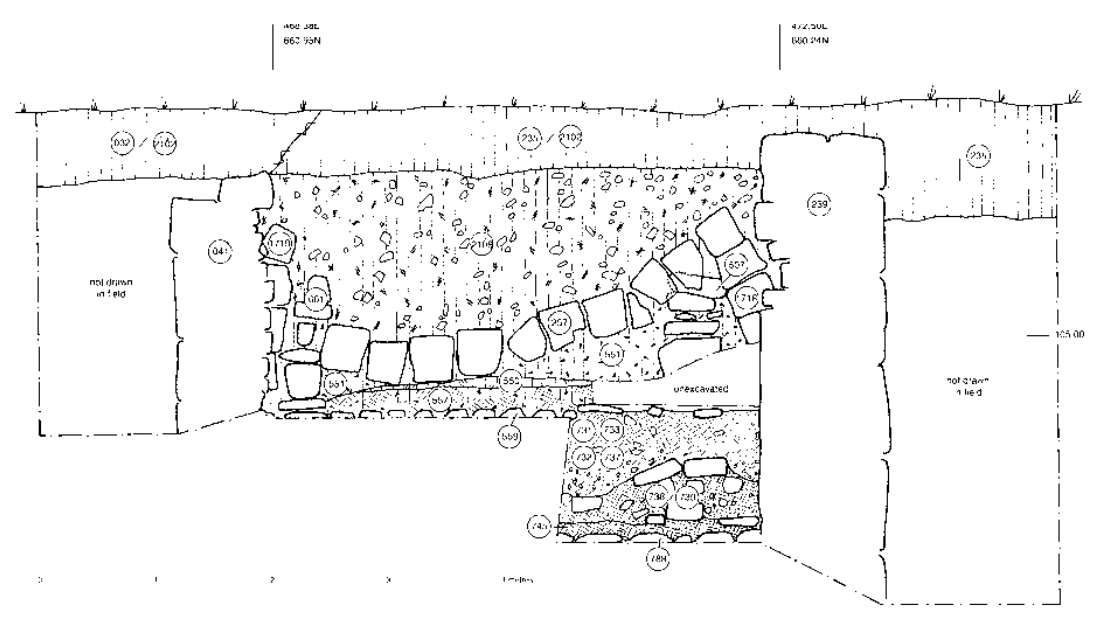

- Fig. 4.15 - East-west

section through G2003 and G2004 (Far II) showing collapsed arch from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.5 - East baulk

of the Far II trench from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.15 - East-west

section through G2003 and G2004 (Far II) showing collapsed arch from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.28 - Reconstruction

drawing of a Late Antique House based on Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.7 - Classical Vault from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.8 - Late Antique House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.9 - Transverse-Arch House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.17 - Barrel-vaulted House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.21 - Arch-and-Grain-bin

House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.28 - Reconstruction

drawing of a Late Antique House based on Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.7 - Classical Vault from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.8 - Late Antique House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.9 - Transverse-Arch House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.17 - Barrel-vaulted House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.21 - Arch-and-Grain-bin

House from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.1 - Rubble collapse

in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.6 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.20 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.23 - Phase 6 structural

rubble and roof collapse from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.24 - rubble from

McQuitty et al. (2020)

Figure 5.24

Figure 5.24

Looking east. Wall SG5094 is in the background. To the right of the scale is the range of grain-bins with pier SG5093 in the foreground. The scale rests on surface SG5072 and to the left the arch-springer SG5142 can be seen. The rubble and line of stones in the background belong to SG5079 and SG5082 respectively

click on image to open in a new tab

McQuitty et al. (2020) - Fig. 5.25 - collapsed arch

McQuitty et al. (2020)

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.25

Looking south at the collapsed arch SG5081 and standing arch SG5092 to the right. The ‘front’ of the grainbin walls SG5075 and SG5076 are in the background flanking SG5077. The collapsed roof-beams and arch-stones belong to SG5080

click on image to open in a new tab

McQuitty et al. (2020) - Fig. 6.16 - collapsed arch

in House 1from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.32 - collapsed arches

in Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.33 - collapsed arch

and roof rafter in Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.35 - tilted wall

in House 2 from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.1 - Rubble collapse

in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.6 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.20 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.23 - Phase 6 structural

rubble and roof collapse from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.24 - rubble from

McQuitty et al. (2020)

Figure 5.24

Figure 5.24

Looking east. Wall SG5094 is in the background. To the right of the scale is the range of grain-bins with pier SG5093 in the foreground. The scale rests on surface SG5072 and to the left the arch-springer SG5142 can be seen. The rubble and line of stones in the background belong to SG5079 and SG5082 respectively

click on image to open in a new tab

McQuitty et al. (2020) - Fig. 5.25 - collapsed arch

McQuitty et al. (2020)

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.25

Looking south at the collapsed arch SG5081 and standing arch SG5092 to the right. The ‘front’ of the grainbin walls SG5075 and SG5076 are in the background flanking SG5077. The collapsed roof-beams and arch-stones belong to SG5080

click on image to open in a new tab

McQuitty et al. (2020) - Fig. 6.16 - collapsed arch

in House 1from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.32 - collapsed arches

in Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.33 - collapsed arch

and roof rafter in Far II from McQuitty et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.35 - tilted wall

in House 2 from McQuitty et al. (2020)

Each context was categorised, e.g. as dump, rubble, wall, etc., and noted on the context sheets and daily excavation diaries. The categories of context were colour-coded, e.g. brown for rubble, green for pit-cut or -fill, and this was marked on the field matrices. Those representing overburden and current land surfaces were discarded for the purposes of post-excavation analysis. Using matrices compiled on site, section drawings, plans and context relationships were checked. Contexts were then grouped into sub-groups and this list can be found in Appendix 1. In the text, contexts appear as simple numbers with no prefix. A sub-group consists of a group of contexts with a high level of stratigraphic association, e.g. the cut and fill of a pit. A short description of each sub-group was written and can be found, organised by excavation area, in Appendix 2. In the text, sub-groups appear as numbers with the prefix SG. The sub-group represents the basic level of post-excavation analysis. A sub-group matrix was compiled for each area and this is the published diagram of the stratigraphy (Appendix 4).

Some of the sub-groups were collected to form groups, referred to in the text as numbers with the prefix G. A group is often a structure and consists of the walls and primary surface. Within a group, the contexts have a lower level of association and this stage is therefore open to re-interpretation. The group allows multi-phase walls to be referred to as part of the same structure. Group descriptions by area can be found in Appendix 3.

The phase represents an even lower level of direct stratigraphic association and a higher level of interpretation than the group. It is a chronological division referring to a broad stratum in which similar activities or events occurred: a grouping of sub-groups and groups. Obviously, a phase does not necessarily represent a single moment or even a single year. It is easier to compile phase plans for areas where occupation was interrupted than for areas where occupation developed gradually or was continuous, e.g. the Khan. As much distinction as possible was made between and within the phases, since one of the major aims of the project was to produce a refined chronology of the material culture. Each excavation area was phased separately and, as the final stage of the stratigraphic analysis, a concordance of phases was prepared for the whole site (Table 2.1)..

The phase is referred to in tables and other codified information as a number with the prefix P. Each sub-group (SG), group (G) and phase (P) was given a numerical prefix denoting the excavation area as follows:

- SG1.., G1.., P1... Far I - The Western Edge

- SG2.., G2.., P2... Far II, Far IV, House 2 - The Central Area

- SG3.., G3.., P3... House 1

- SG5.., G5.., P5... Far V - The Highest Point

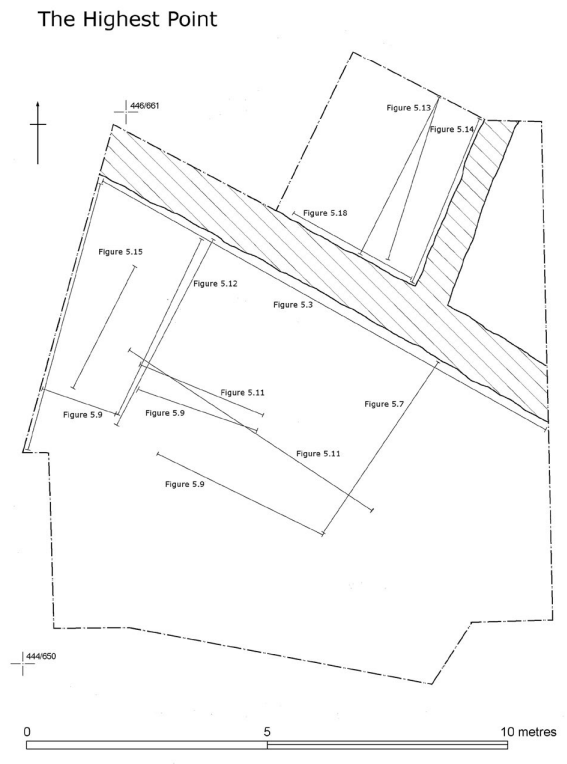

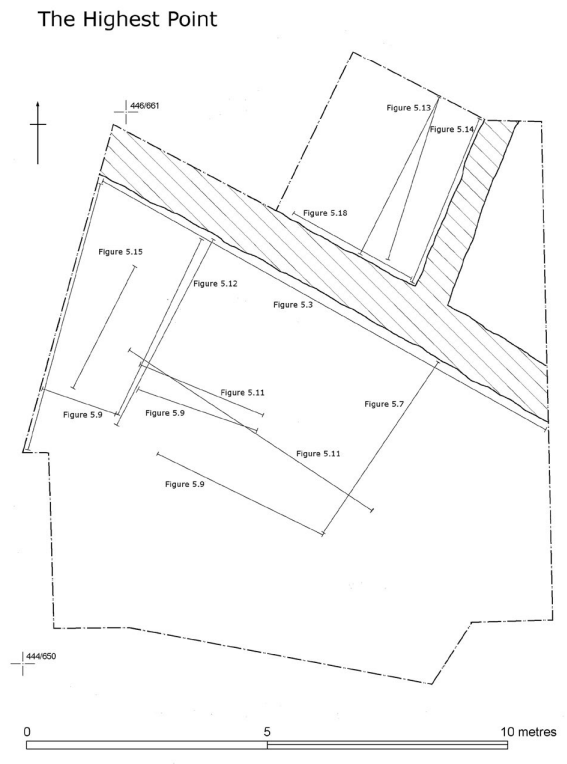

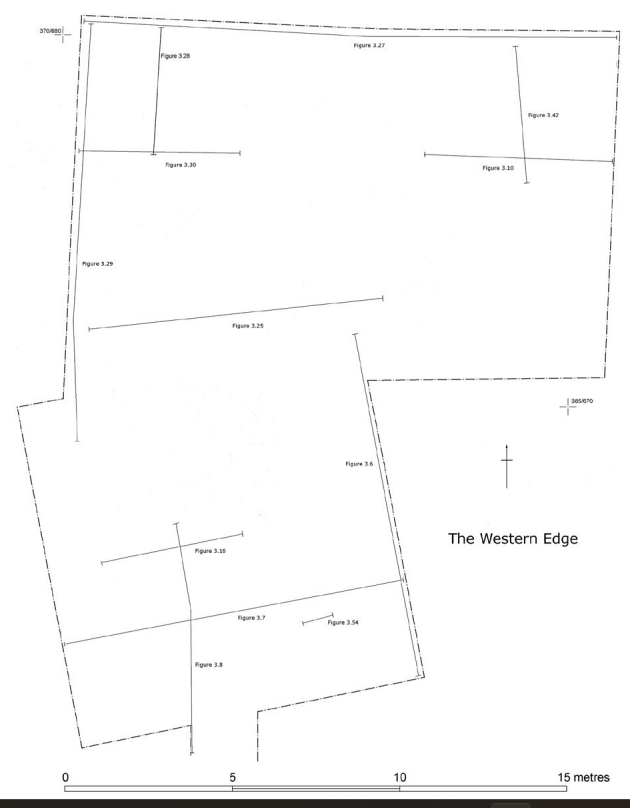

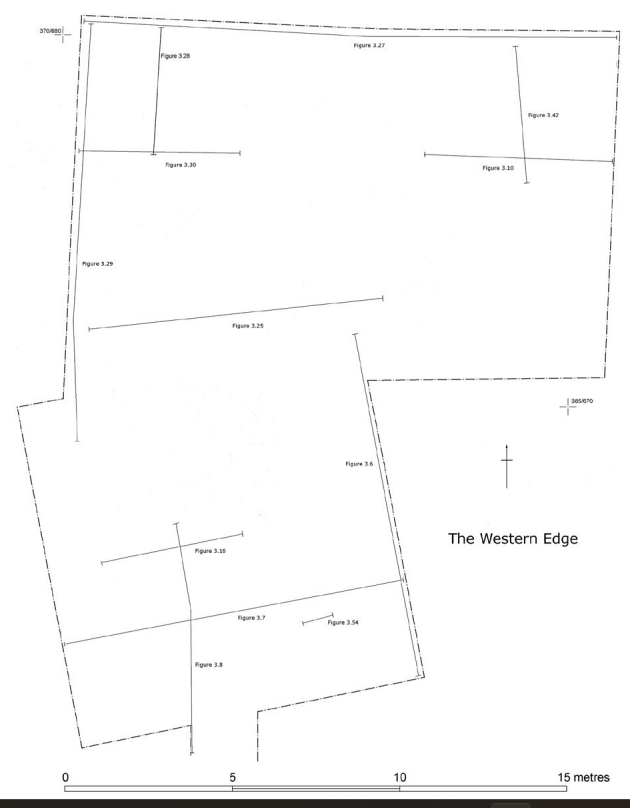

The plans in this volume are phase plans and inevitably refer to those stages of occupation in which structures were built or used. The phases of abandonment and destruction are represented in the section drawings. The locations of these section drawings are detailed on

- Figure 2.13 (Far I - The Western Edge)

- Figure 2.14 (Far II, the Khan (Far IV) and House 2 - The Central Area)

- Figure 2.15 (Far V - The Highest Point)

- Figure 2.16 (House 1).

Table 2.1

Table 2.1Concordance of stratigraphic phasing across the site.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 1.2 - Site plan

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2

Area plan around Khirbat Faris

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.1 - Site Plan

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1

Site plan of Khirbat Faris

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 1.2 - Site plan

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2

Area plan around Khirbat Faris

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.1 - Site Plan

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1

Site plan of Khirbat Faris

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

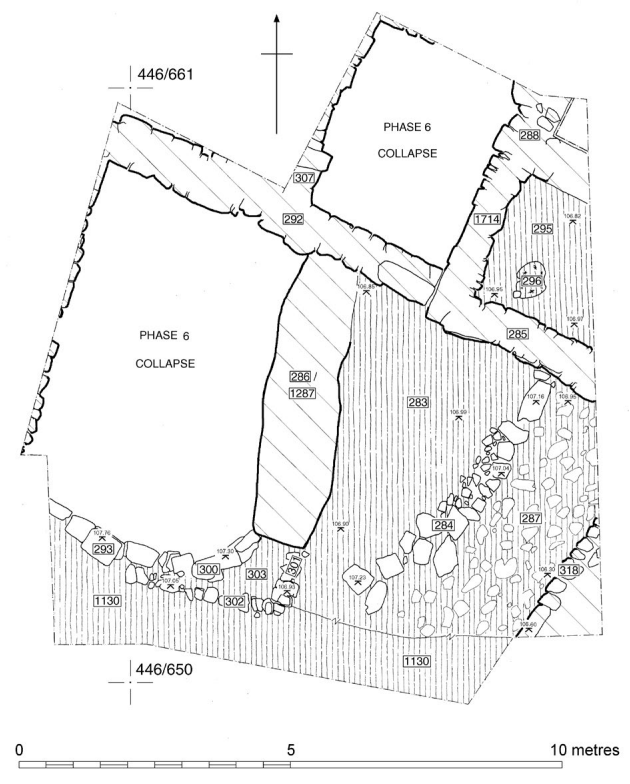

- Fig. 5.19 - Phase 3.1

plan from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.19

Figure 5.19

Phase 3.1 plan the foreground.

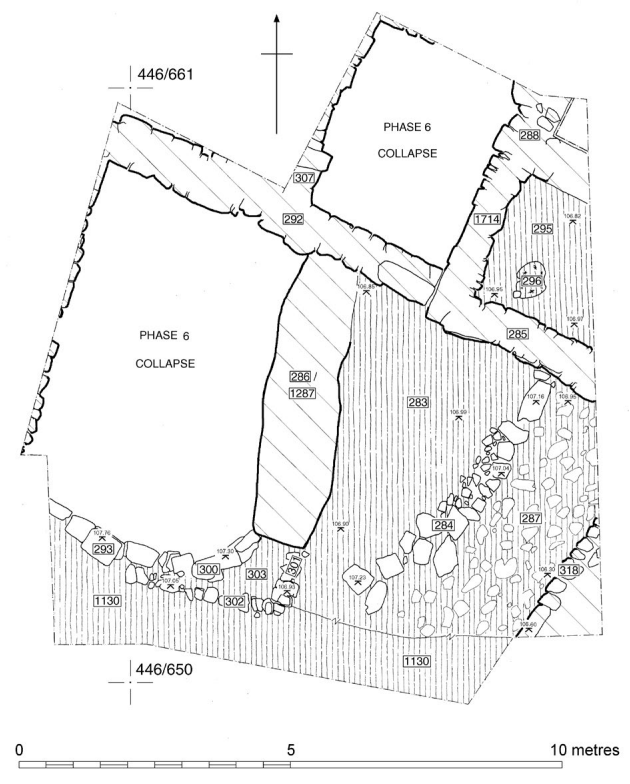

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5.28 - Phase 7

plan from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.28

Figure 5.28

Phase 7 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.19 - Phase 3.1

plan from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.19

Figure 5.19

Phase 3.1 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5.28 - Phase 7

plan from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.28

Figure 5.28

Phase 7 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.12 - Phase 3.1

plan for Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.12

Figure 4.12

Phase 3.1 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.20 - Phase 3.2

plan for Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.20

Figure 4.20

Phase 3.2 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.12 - Phase 3.1

plan for Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.12

Figure 4.12

Phase 3.1 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.20 - Phase 3.2

plan for Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.20

Figure 4.20

Phase 3.2 plan the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.13 - The Western Edge

(Far I) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.13

Figure 2.13

The Western Edge (Far I): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.14 - The Central Area

(Far II and Far IV) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.14

Figure 2.14

The Central Area (Far II and Far IV): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.15 - The Highest

Point (Far V) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.15

Figure 2.15

The Highest Point (Far V): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.16 - House 1

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.16

Figure 2.16

House 1: location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 2.13 - The Western Edge

(Far I) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.13

Figure 2.13

The Western Edge (Far I): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.14 - The Central Area

(Far II and Far IV) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.14

Figure 2.14

The Central Area (Far II and Far IV): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.15 - The Highest

Point (Far V) from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.15

Figure 2.15

The Highest Point (Far V): location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 2.16 - House 1

from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 2.16

Figure 2.16

House 1: location of sections

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.5 - East baulk

of the Far II trench from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5

East baulk of the Far II trench.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.15 - East-west

section through G2003 and G2004 (Far II) showing collapsed arch from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.15

Figure 4.15

East-west section through G2003 and G2004

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.5 - East baulk

of the Far II trench from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5

East baulk of the Far II trench.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.15 - East-west

section through G2003 and G2004 (Far II) showing collapsed arch from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.15

Figure 4.15

East-west section through G2003 and G2004

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 4.28 - Reconstruction

drawing of a Late Antique House based on Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.28

Figure 4.28

Reconstruction drawing of a Late Antique House based on Far II.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

- Fig. 5.1 - Rubble collapse

in Far V from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

View in 1989 looking northeast across the trench, showing rubble collapse and emergence of wall SG5094. Stone line SG5018 can be seen in the upper right of the picture.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5.6 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6

Looking north. An overview of G5002 in Phase 3 with the collapsed arches and roof rafters in the foreground. The excavator stands on the Phase 5 wall SG5064

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 5.20 - Arch and roof

collapse in Far V from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 5.20

Figure 5.20

View of the collapsed western arch and roof beams SG5174. The edge of a meta can be seen under a roof-beam in the foreground.

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.32 - collapsed arches

in Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.32

Figure 4.32

Far II. Looking south at collapsed arches SG2138 (upper) and SG2142 (lower).

McQuitty et. al. (2020) - Fig. 4.33 - collapsed arch

and roof rafter in Far II from McQuitty et. al. (2020)

Figure 4.33

Figure 4.33

Far II. Looking east at the collapsed southern arch, SG2138, and roof rafters.

McQuitty et. al. (2020)

... Khirbat Tadun remains unexcavated. De Saulcy visited the site in 1851 and records Tadun as ‘a small circular hillock’ that he interpreted as the ruin of a Byzantine church (1853: 341). A more recent description is given by Johns, ‘Tadun is a large mound, approximately 100 m by 30 m rising to approximately 4–5 m above the immediately surrounding area. The outlines of a substantial rectangular walled structure are visible, enclosing a large central depression and several small mounds. The Roman road identified by Worschech (1985: 131) seems to run north from Al Rabba into the south side of the mound, where there may be a gate. At the top of the mound, near its northwest corner, are exposed what may be the upper courses of a small dome, executed in fine limestone ashlar masonry. In the central depression, recent clandestine excavation has revealed a large Corinthian capital and an architrave block, both in limestone … .Worschech recovered Late Roman and Byzantine sherds from the site and our own collection added a sherd of Umayyad red-ongrey painted ware to the assemblage: in 1988 further Umayyad pottery was collected from Kh. Tadun’ (Johns et al. 1989: 64–5; Worschech 1985: 41–4). Further hints as to the nature of this structure are given by the placename itself. Knauf interprets Tadun as being Greek in origin and deriving from ‘St Theodoros’ via Tadur and Tadhur (Knauf 1991: 285). In this case Tadun may well be a church of St Theodoros that was used at least until the 7th–8th centuries AD. As is discussed in Chapter 5, the mid-8th century earthquake(s)5 is likely to have been responsible for considerable destruction at the site and may have marked the end of occupation at Tadun.

5 See Ambraseys 2009: 234–5 for detailed discussion concerning this earthquake. There were at least 3 sizeable earthquakes in the years spanning AD 746‒757. It is widely accepted that in Northern Jordan and the Jordan Valley a calamitous earthquake struck in AD 749 and caused widespread destruction. However, Ambraseys, citing the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (AD 752‒818), provides a cogent case for the date of AD 746 being preferred for this area. ‘… (an) earthquake affected the region to the east of the Jordan Rift more than it did to the west….It seems that much of the damage was done to towns lying east of the river along the trade route that ran from Palmyra via Damascus to Ma’an and Tabuk.’ JW: Ambraseys (2009) is wrong about the date of 746 CE. It should be 749 CE. See 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes.

Far I is located at the western edge of the site overlooking Wadi Zuqaiba and has a total area of 270 square metres (15 m × 18 m). The excavation of the area was continued over all six seasons (1988–1994). The surface survey suggested that occupation in this area was predominantly post-12th century (Figure 3.1 and Appendix 5).

The stratigraphic sequence of Far I may be divided into nine phases. Phase 1, which was not fully investigated, comprised a series of structures and deposits dated to the Bronze and Iron Ages. Phase 2 was a deposit of rubble around the neck of the cistern (SG1221) and may in fact be contemporary with Phase 3.

Phase 3 comprises a complex of buildings occupied during the Late Byzantine to Early Islamic period (7th–8th centuries AD). These structures were later extensively reused to provide a firm foundation for the building of Phase 5. As a result it was not possible to obtain a complete plan of the Phase 3 building complex.

Phase 4 comprises a series of deposits, cuts and structures which were found beneath the courtyard (Courtyard C) of the later Phase 5 building complex. It is possible that Phase 4 overlapped with the early stages of Phase 5.

Phase 5 is the main period of occupation and relates to the construction and use of six vaulted structures (Vaults I–VI) and their associated courtyards and alleys (Figure 3.2). It is subdivided into four sub-phases, as follows:

- P1-5.1: construction of Vault IV; reuse of the cistern (SG1221)

- P1-5.2: construction of Vaults I, II and VI, with their associated courtyards and alleys

- P1-5.3: construction of Vault V and Courtyard C

- P1-5.4: construction of Vault III.

Phase 6 represents a period of abandonment across the whole of the trench. None of the five remaining vaults collapsed, but it is assumed that they ceased to be used as dwellings. There is evidence that the area was used for ovens. Clearly, this phase must be dated after the 14th century A.D., but how long after remains undetermined.

Phase 7 represents the reuse of Vault VI as an ovenhouse and the construction of several small ovenhouses in what had been the external spaces of the Phase 5 complex. Vaults I and III seem to have remained accessible, but the entrance to Vault II was blocked, and access through the Phase 5 alleys was significantly altered. Vault V continued to be used as a dump, as in the preceding phase. There is no evidence of domestic residence in the area and it is presumed that the families who used the oven-houses in this area lived elsewhere. The ceramics from this phase were field-dated Middle to Late Islamic ‒ further study may provide a more precise date.

In Phase 8, the whole area was abandoned and the vaults of the structures collapsed. No new structures were built, but there was a human burial in the lee of the southern wall of Courtyard C and traces of a hearth or oven were found beneath the topsoil in the area of what had been Vault I.

Phase 9 represents the gradual accumulation of rubble and colluvial soil over the whole area.

A series of three interconnected trenches were excavated in the central area of the site. These trenches were laid out around two standing buildings: a wellpreserved vaulted structure, known locally as the Khan (Far IV), and one of two adjacent ruined arched houses (House 2). This complex of trenches was excavated during the 1988–1991 seasons. See Figure 2.14 for details of the location of each area and related sections.

The stratigraphic sequence of this area may be divided into eight phases. Phase 1 comprises a series of mostly unexcavated contexts, probably of different dates, none of which is later than the 1st century AD.

Phase 2 relates to the original construction of the rectangular, barrel-vaulted chamber known as the Khan (Far IV). Its east wall extended southwards, apparently to enclose one side of a paved courtyard that also included at least one other building, which was not investigated. Ceramics provide a secure terminus post quem in the 1st century AD for the construction of the Khan. The closest architectural parallels suggest that the Khan may have been built as a mausoleum, but no other evidence supports this conjecture and, if its initial use was indeed funerary, was reused later for domestic purposes.

During Phase 3, not only did the Khan continue in use, but the domestic space in this area was doubled by the transformation of the open courtyard immediately to its south into a second roofed chamber (G2004 in Far II), belonging to the architectural type of the Late Antique House. These two adjoining units — the Khan and G2004 — both faced westwards onto a paved courtyard and apparently belonged to a single domestic complex, which seems to have been constructed and first used during the Early Islamic period. The collapse of one of the two arches supporting the roof of G2004, and its consequent temporary abandonment, marks the end of Phase 3 in Far II. It is possible that damage to the Khan (repaired in Phase 4) also occurred at this time.

In Phase 4, the abandoned ruins in Far II were remodelled and reused. The reconstructed room, now called G2003, used the same walls as its predecessor and, like it, faced westward onto the paved courtyard shared with the Khan. This impression of continuity, however, is belied by the fact that G2003 is in fact a hybrid type, which incorporates elements belonging to the Transverse Arched House — a new and completely different architectural tradition. The reconstruction and original occupation of G2003 is dated to the 9th– 12th centuries AD.

In the next phase (Phase 5), dated to the 12th and 13th centuries, the Khan was used predominantly as an oven-house, while G2003 was reused for the same purpose and also adapted for grain storage. In Far II, Phase 5 was brought to an end by the collapse of the southern arch and, perhaps, by the abandonment of the area, although the ruins of G2003 remained visible, and its northern arch stood, until Phase 7.

A long interval separates the collapse of G2003 from the next construction phase, Phase 6, which is dated to the late 19th to early 20th century. During this period the Khan retained its roof and there is every reason to assume that it continued to be used, if only for periodic or seasonal occupation. Certainly, the builders of House 2 considered it to be such a useful structure that they built an Arch-and-Grain-Bin type house onto it, in such a way as to make it an annexe accessible from the southeast corner of the new house.

In Phase 7, after the collapse of the roof of House 2, the Khan continued to be used, probably as an ovenhouse. To the south, the northern arch of G2003 finally collapsed and a human grave was set into the ruins. Shortly before excavation begun, the Khan was still being used by shepherds and their sheep. Between seasons of excavation, the Khan was again used as an oven-house and House 2 became a fodder store for the sheep housed in the newly built stable on the eastern edge of the site. Thus, Phase 8 — the latest in the occupation of the area — is very much still in progress.

This phase includes the continued use of the Khan and its paved courtyard; the conversion of the courtyard to the south of the Khan into a roofed chamber (G2004) by reusing elements from its earlier external phase; and the partial collapse of G2004 and its adaptation and reuse. The main façade of these two adjoining units would have opened to the west.

(Figure 4.12)

During this sub-phase, the open paved area to the south of the Khan (described in Phase 2) was converted into an internal space (G2004) (4.50 m × 4.40 m). The south wall was created from the wall (SG2152) of an earlier building to the south of the courtyard. This wall blocked both the doorway (SG2150) and the alleyway in the southeast corner of the courtyard (SG2144) shown graphically in Figure 4.14. The north wall was formed by the Khan (SG2074) and the east wall comprised a narrow rubble stone wall (SG2145) built against the southern extension of the Khan’s east wall (SG2061). The new wall face (SG2145) incorporated a springer for one of the arches supporting the roof. The archspringer (SG2156), recorded as context 1718 in Figure 4.15, survives as three squared limestone blocks bonded into the wall (SG2145). Together with the arch-springer in the western wall (SG2158), recorded as context 1719 in Figure 4.4 and clearly visible in Figure 4.16, this formed part of the southern roof arch (SG2138), contexts 257 and 495 in Figures 4.15 and 4.18, which collapsed in Phase 5. There is no trace of the northern arch, which was probably removed in a later phase (see below Phase 2, Sub-phase 3). The total reconstructed height of the room would have been approximately 3.50 m, which is comparable to the main building of Phase 2 at The Highest Point, (G5002). It is assumed that there was an entrance in the western wall, between the two arches (SG2126) as shown in Figure 4.16. Whether this entrance originally opened into a building to the west of the excavation trench or simply led to an outside area is unknown. The presumed doorway is filled with rubble, including stone rafters resting on an in situ threshold stone (SG2118).

The floor of the room (G2004) comprised irregular stone slabs, the southern part of which (SG2127) were later robbed, and recorded as contexts 788 and 790 in Figures 4.4, 4.15, 4.17 and 4.18. Patches of ash and occupational material accumulated on the surface and these were particularly rich in artefacts (SG2128). A two-compartment stone feature (SG2124) was built against the west wall and contained large amounts of ash and fish bones. Its purpose is unclear — perhaps the compartments were originally used as stands for large water jars (ziyar, sing. zir2 ) or even as mangers, if the room was reused as a stable. There was a similar feature in the northwest corner of the room (SG2119), shown as context 805 in Figure 4.21, which was also used in Phase 4, Sub-phase 1.

To the north, the Khan continued to be used, with a rough, patchily paved and cobbled interior (SG2047, SG2051, SG2058, SG2052 and SG2049), some of which may have survived from the earlier phase. A central hearth (SG2048) was built into this cobbled floor. Outside, to the west, lay an even and substantial flagged surface (SG2090), shown in Figure 4.19 and as contexts 1091 and 1123 in Figures 4.7 and 4.8.

2 A zir is a large vessel for drinking-water.

(Figure 4.20)

Two sub-phases of Phase 2 were distinguished in the occupation of the Khan but the same two sub-phases could not be distinguished in the excavation of G2004, the room to its south. During this sub-phase, in the Khan, the rough, patchily paved and cobbled floor was replaced with another beaten earth surface (SG2041), shown as contexts 71 and 72 in Figure 4.1. A stone platform — possibly a mastaba for sitting, sleeping or storing bedding — was built along the south wall (SG2044). A substantial stone feature of unknown function (SG2045) located in the northwest corner, shown as contexts 461, 616, 619, 683, 684 and 685 in Figure 4.20, makes its first appearance in this phase and it continued to be used in later phases. Its curving walls are two courses high and as a whole, the feature is well made. The ashy lenses found within it are interpreted as ephemeral hearths. The doorway and original threshold led up and out to a paved area (P2-3.1: SG2090) which was irregular at the south end (SG2097), Figure 4.20. The paving continued southwards, beyond the southwest corner of the Khan (SG2117), which is recorded as context 103 in Figure 4.17. This corner appears to have been rebuilt during this phase.

During this period yet another beaten earth surface (SG2040), recorded as context 69 in Figure 4.1, was in use inside the Khan. It was cut by various pits and post holes (SG2038, SG2039 and SG2042). To the south, room G2004 collapsed and was no longer in use, although pit-digging and ephemeral hearth activity (SG2120 and SG2123) was evident within the ruins. The pits were dug into structural collapse which included faced and squared ashlar blocks and stone rafters (SG2118) from the assumed northern arch (SG2125). The southwest corner (SG2116) of this southern room G2004 also collapsed. Destruction debris (SG2132 and SG2133), shown as contexts 1025 and 1030 in Figure 4.5, was also found east of room G2004 in an area that is presumed to have been an open courtyard.

The ingenious conversion of the courtyard south of the Khan into an internal area, recorded as G2004, with its main façade towards the west, suggests that G2004 was conceived as part of a larger complex. The function of the complex as a whole is not clear although the excavated rooms appear to have had a domestic purpose. The artefacts found within the use, abandonment and collapse deposits were overwhelmingly Early Islamic. Large numbers of dateable lamp fragments were found and steatite vessels make their first appearance. Tile fragments and glass tesserae presumed to have come from a church in the area of The Highest Point were found in the deposits associated with the use and abandonment of the chamber G2004. While its collapse was not nearly as dramatic as building G5002 at The Highest Point — in that here the southern arch remained standing — the sequence of collapse is similar. On those grounds, it is suggested that Phase 3 of Far II, Far IV and House 2 was contemporary with Phase 3 of Far V, which lies immediately to the west.

The Far V trench was located at the highest point of the site because this was thought to be the most likely location of a public building such as a church or a mosque (Figure 5.1). The 1988 survey suggested that occupation in this area was predominantly post 12th century AD The area was excavated during four seasons (1989, 1990, 1992 and 1993). Initially Far V comprised a square area (10 m × 10 m) which was subsequently enlarged to include more of the structures uncovered in the centre of the trench.

The stratigraphic sequence of this complex may be divided into seven phases. Phase 1 represents a wall running north-south under the Phase 2 structures. It was encountered only in a sondage and was not fully investigated.

Phase 2 comprises the construction and use of two buildings and the associated external spaces (G5002 and G5004). The earliest of these structures (G5002) was a single-chamber house of the Late Antique House type built in the south of the trench with an entrance facing northwards onto a paved courtyard. The house was built and first occupied in the Late Roman and Byzantine periods (Phase 2, Sub-phase 1). Following partial abandonment and periodic reuse (Phase 2, Sub-phase 2) the house (G5002) was refurbished and extended. A new entrance was created in the southern wall and the paved courtyard to the north was transformed into a second chamber, known as G5004. The door between G5002 and G5004 was partially blocked by a stepped stile, a feature that may indicate that one of the chambers was used for animals and the other for humans. These transformations (Phase 2, Sub-phase 3) are dated to the transition between the Late Byzantine and Early Islamic periods.

Phase 3 witnessed the collapse of G5002 and the dumping of debris and rubble to the east and west of it. The destruction was sudden and catastrophic. Both the material associated with the collapse and its position in the stratigraphic sequence suggest that it occurred in the 8th century, most probably as a result of the earthquake of AD 746 (Ambraseys 2009: 235). There followed a period of years during which the debris and rubble produced by the collapse was gradually cleared away (Phase 3, Sub-phase 2). Amongst the cleared debris were fragments of marble architectural decoration and many mosaic tesserae, including small glass tesserae, which presumably came from a church, which also presumably stood close to this area. The destruction of that church or, at the very least, the dispersal of its fittings, seems to have begun before the collapse of G5002. Moreover, G5002 itself seems to have been empty or abandoned at the time of its destruction.

In Phase 4, the external space to the east of the demolished G5002 was used for various activities probably associated with an unexcavated dwelling to the north. This phase is dated to the 9th–13th centuries AD based on the material found in the excavated features.

Phase 5 comprised the construction of two TransverseArch type houses in much the same positions as the Phase 2 structures. The larger of the two (G5001) occupied the southwest part of Far V. Its principal entrance in the middle of the west wall presumably opened onto an alley or courtyard. It was single-storey building with three arches to support the flat roof. Inside there were grain-bins along the south wall and, behind these an ‘annexe’ that may have served as a store. To the northeast, a smaller, single-chamber structure (G5003) was built on the site previously occupied by (G5004). The house had a flat roof, supported by a single arch, and may have had a grain-bin behind its east wall. The main entrance opened to the west onto an alley or courtyard. The area to the east of G5001 was a courtyard, but neither house had direct access to it. Both buildings show multiple phases of use and were gradually abandoned and filled with dump and natural accumulations. This phase is dated to the Middle to Late Islamic period, that is the 13th century and later.

After the long period of gradual abandonment, the two buildings collapsed in Phase 6. A fragment of tobacco pipe found within the rubble and its matrix suggests that this collapse continued into the mid-19th century. The courtyard to the east was used for a succession of oven- or tabun-houses, perhaps associated with a dwelling to the south.

In Phase 7, natural accumulations built up against and above the ruins of G5001 and G5003. In the east of the trench, a hearth and ephemeral structures perhaps attest to the seasonal use of the area, possibly by tent dwellers, as late as the mid- to late 20th century.

G5002 was built as a single unit of the Late Antique House type that finds parallels at Khirbat Faris in G2004 of the Central Area. In its earliest configuration (Phase 2, Sub-phase 1), the building opened northwards onto a paved area. Throughout the various sub-phases, the area to its west remained paved and was very possibly always external. The building was well built and its mortar floor (SG5131) also indicates a certain quality of construction. The building probably had a flat roof as no roof tiles were found within the later roof collapse. Only a small area dating to this earliest phase of use was excavated and therefore a limited quantity of datable artefacts was recovered, but the field dating of the ceramics from this phase indicates a Late Roman date.

The building survived throughout a period of more ‘informal’ use (Phase 2, Sub-phase 2) when it seems that the interior was used more casually. The ceramics associated with these levels were identified as Byzantine and provide a sealed terminus post quem for Phase 2, Sub-phase 3. The interior of G5002 was refloored with a mortar surface (SG5132) similar to its predecessor. A hearth (SG5130) built on the mortar floor (SG5132) suggests that transient use preceded the later Phase 3 collapse of the building.

However, it seems clear that G5002 ceased to be a single unit and in Sub-phase 3 became instead part of a larger complex that extended both to the north, where a smaller Late Antique House (G5004) was constructed, and to the south. There were no built-in features to indicate a particular function of the room and there was a general paucity of domestic small-finds such as grinders, loom weights or metal cosmetic tools.

From the architectural evidence, it seems clear that this area developed but did not radically change in character over a period of some centuries. Although the eventual roof collapse of these structures in the later Phase 3 is attributed to the AD 746 earthquake, the earlier earthquake of AD 363 may have played a role in the occupational sequence of Sub-phases 1 and 2. Ambraseys (2009: 149), reproducing the words of St. Jerome, reports the devastating impact of this earthquake on the nearby Areopolis/Al Rabbah: ‘….the walls of a certain Areopolis collapsed on the same night.’ There is no excavated evidence for this event but it is almost inconceivable that Khirbat Faris would have escaped without suffering any impact.

This phase represents the collapse of architectural elements within G5002 (Phase 3, Sub-phase 1) and the dumping of debris in the areas to the north, east and west of G5002 (Phase 3, Sub-phase 2). Outside the east wall of G5002 (SG5109) there was an accumulation of rubble, silt and debris collected in even bands (SG5121, SG5124 and SG5108) that sloped up against the window (SG5125). To the west levelling layers of destruction debris and rubble (SG5065, SG5066 and SG5067) were revealed.

The remains of the arches and stone rafters that once supported the flat roof of G5002 were spectacularly and graphically preserved (SG5087, SG5100, SG5104 and SG5174), seen in Figures 5.6 and 5.20. Large amounts of loamy material, lumps of clay and small rubble were found in amongst the stones, which presumably related to the thick earthen layer that would have topped the roof; no tiles were found. Rubble of worked and unworked limestone, and chinking stones, represented the packing of the arch spandrels. The arch stones were light marly limestone, while the spandrel stones and keystone were of harder limestone. The roof rafters were of both basalt and limestone and appeared to have fallen directly downwards as opposed to sliding off the arch. A few of the limestone rafters showed signs of burning. Amongst the collapse were fragments of marble, which presumably had been used for wall cladding and paving. One basalt meta [SF 3357] shown on Figure 5.20 was preserved under the collapse. The collapse had all the appearance of being sudden rather than gradual. However, the room seems to have been empty or abandoned at the time: no concentrations of single ceramic vessels were found and the interpretation of the previous phase had suggested that the room was no longer permanently occupied and was already subject to some transient use, before it finally collapsed.

While the architectural collapse in G5002 was left, literally, where it fell, the areas to the north and west were cleared out and levelled with destruction debris moved to prepare for later construction. These deposits (SG5065, SG5066 and SG5067), shown as contexts 1128, 1420, 1445, 1446 and 1448 in Figures 5.11 and 5.15, included rubble, charcoal flecks, oven fragments, glass and burnt bone. The areas to the south of G5002, and G5004 itself, were empty of architectural debris. As always, the area to the east of G5002 presented something of an enigma: the window or door (SG5125), shown as context 1397 in Figure 5.7, seems to have been filled with debris (SG5124) and material was dumped against the wall (SG5121).

The collapse in G5002 was almost certainly the result of an earthquake and support is given to this hypothesis by the similar architectural collapse of G2004 seen in the Central Area Phase 3. The chronological parameters for the date of the collapse are set by the Late Byzantine to Early Islamic ceramics of Phase 2, Sub-phase 3, and the 9th-century and later ceramics of Phase 4. A convincing candidate would be one of the three sizeable events that took place in the period A.D. 746–757. It is most likely to have been the earthquake of 746 A.D. (Ambraseys 2009: 235). After the structural collapse, the debris was cleared, over a period of years if not decades, and this is what the deposits of Phase 3, Sub-phase 2 represent. The material associated with these deposits gives some insight into the character of the buildings in the immediate vicinity. Some glass and stone tesserae were found in the collapse, as well as fragments of marble wall cladding, coloured marble inlay ‒ possibly from an opus sectile floor ‒ a capital fragment, and part of a funerary plaque with a few words of a Greek inscription [SF 3392]. The dump heaped up against the eastern wall of G5002 (SG5121) was particularly rich including a huge number of glass and stone tesserae. A sample of the glass tesserae are pictured in Figure 7.15. In general, the other artefacts from this deposit were domestic in nature, such as grinders and steatite cooking vessels.

The trench was located here to explore the possibility of finding a public building, such as a church. While there is no specific architectural evidence to support the identification of G5002 as part of a public building, if it was not itself part of an ecclesiastical complex, the related finds indicate that it lay very near to a church.

As in the previous phase, the area to the east of G5002 continued to be an external space, although it is impossible to say whether it served the building to the north or some other structure or even a tent. As already suggested, the doorway (SG5059) that led from the courtyard northwards was probably originally covered with a lintel which was replaced with an arch during this phase. The sequence of the remodelling of this doorway is shown in Figures 5.3 and 5.18. There were comparatively few finds from the courtyard deposits which may reflect the character of occupation. Very few domestic items apart from iron spikes were found. The ceramics suggested a 9th to 11th-century date and the remaining datable material was residual.

The east-west distinction between inside and outside space survived from Phase 2 into Phase 5. There was however a major shift in orientation, so that both G5001 and G5003 faced westwards. Their simple arched doorways probably opened out onto a courtyard or alleyway. The entrances were placed in the middle of the wall parallel to the roof-supporting arches. The construction methods contrast vividly with those of the Phase 2 building, G5002. Although the arch-stones and roof rafters of earlier periods were reused, the walls were largely built of unshaped stones and boulders to produce wide and irregular walls. The massive east wall of G5001 (SG5094) was built directly on top of the rubble of its predecessor, G5002. Inside, the only builtin features indicating function were the grain-bins between the southern ends of the arches. It is suggested that the curious semi-apsidal space behind these bins, at the southern end of G5001, served as a semi-secret annexe also used for storage. A similar arrangement can be seen in the 19th-century village of ʿAyma (Biewers 1990: 112, construction no. 158; 172, construction no. 226; see also Plate 153). G5003 was on a much smaller scale but also had a flat roof of stone rafters supported by an arch. Within this small space, there were several built-in functional features, including partition walls, a tabun and a probable grain-bin accessed through the opening with a sloping lintel in the east wall (SG5168).

Both of these buildings show a similar pattern of gradual abandonment. The reason for the final abandonment of a building is usually damage to the roof. In the case of G5001, one arch was still standing while in G5003, roof rafters were still in place. This is very different from the catastrophic collapse of G5002 suggested by the sequence in Phase 3. Once they had been abandoned, these rooms filled up with dump and accumulated soil: there was no sign of pit digging within the rooms or of stone robbing. The nucleus of the settlement could have moved elsewhere on the site or the settlement as a whole could have been depopulated. Whatever the cause, the abandonment of this area seems to have been relatively well planned as no material was found obviously in situ within the rooms (but see discussion of the character of occupation, below).

There was a marked contrast in dating between the inside and outside areas. The outside area east of G5001, consisted largely of dumped material and is interpreted as clearance debris. The pits and earth surfaces included predominantly 9th- to 13th-century ceramics. Earlier material, including 7th- to 8th-century lamp fragments, a worn silver dirham dated 210 AH / AD 825–26 [SF 3091] and a metal scale pan [SF 613] pictured on Figure 8.4 has Byzantine parallels. Because there was no discernible construction cut for G5001 and more particularly for its massive east wall (SG5094), this early material was considered to be residual. The ceramics from within the buildings are Middle to Late Islamic. Inside the buildings there were very few artefacts associated with typical agricultural or domestic assemblages. This could indicate a planned abandonment since, because they were so useful, those were the very items that would not have been left behind. Alternatively, it may be that the character of occupation ‒ seasonal not permanent, storage not residential ‒ determined that such artefacts were not deposited in these buildings.

(Figure 5.27)

In essence this phase describes the abandonment of G5001 and G5003. In G5001, architectural collapse (SG5044, SG5045, SG5079, SG5080, SG5081 and SG5173), silt accumulation (SG5049 and SG5158) and dumping of material (SG5046 and SG5051) were all encountered and can be seen in Figure 5.25. The roof rafters and associated roof rubble lay jumbled amongst the G5001 arches (SG5048 and SG5071). The area to the south of this structural collapse was filled with a variety of dumps of varying compactness (SG5047 and SG5051). G5003 showed a similar pattern of structural collapse (SG5007), silt accumulation (SG5008) and dumping (SG5012).

The area east of G5001, known throughout the phases of this trench as the courtyard, did see some activity. The courtyard surface was beaten, swept earth (SG5023), including cobble dumps (SG5029). An oven- or tabunhouse, dug into the southeast corner, utilised the walls of earlier phases and also involved the construction of a new, irregular wall (SG5147). The location of the entrance to the oven-house is not clear and it is presumed to have related to a structure or tent to the south. The oven-or tabun-house (SG5043), housed at least three successive ovens or tawabin (SG5040 and SG5026) and was filled by levels of an ash dump (SG5025) and recorded as contexts 320, 663 and 1428. Its walls were flimsy, one stone wide and two courses high, and were dug down into the earlier outside area shown in Figure 5.22. A straight-sided, shallow pit (SG5021) was also dug from this level ‒ its purpose is unclear.

The deposits and features of the courtyard produced significant concentrations of 11th- to 13th-century ceramics, in addition to post-13th-century Middle Islamic ceramics. A Crusader billon denier in the name of King Amaury, datable to c. 1169–87 [SF 3069] was found within the collapse of G5001 along with a fragment of tobacco pipe [SF 385] dated to the 19th century. Abandonment clearly took place over several centuries. The tobacco pipe fragment provides both a terminus ante quem for the start of this process of collapse and ‒ at 1.80 m below the trench surface ‒ a convincing terminus post quem for the following Phase 7 and final abandonment of the whole area.

(Figure 5.28)

This phase represents the final use of the area prior to the excavation. During this last phase silts, rubble and gravel (SG5001, SG5004, SG5006, SG5019 and SG5020) accumulated amongst the ruined walls and rubble. An area in the angle of the north and east walls of G5002 was cleared and used to accommodate a hearth for a fire or saj (SG5003), shown as context 296 in Figure 5.28. In addition, the area to the east of the massive east wall of G5001 (SG5094) was cleared of rubble. An irregular line of stones, one course high, cordoned off this area (SG5018), recorded as context 284 in Figure 5.28 and pictured in Figure 5.1. The corner made by the south and east walls (SG5088 and SG5094) was squared off with a rough and ready wall (SG5039/contexts 301 and 302) to make a small enclosure. It is tempting to see these ephemeral features as evidence of seasonal use of the site by tent dwellers.

Given the nature of the deposits, it is not surprising that the dating material was mixed, but the ceramics were overwhelmingly Middle to Late Islamic. Modern material, such as nail clippers and scissors, were found together with fragments of steatite vessel fragments and early 13th-century coins [SF 503 and SF 523]. Surprisingly few domestic and household artefacts, such as grinders and querns, were found in these dumps, but a small quantity of metal and glass jewellery was present.

House 1 was the larger of the two Arch-and-GrainBin Houses standing at the site at the beginning of excavation. Its architecture was fully documented and, in 1992, two areas were excavated. The trench locations are detailed in Figure 6.18. The interior trench, (1.80 m × 2.00 m), was opened in front of the south range of grain-bins in order to reveal the full extent of the grainbin (SG3010); to expose part of the original surface of House 1; and to recover material from earlier structures. The exterior trench (5.00 m × 2.00 m) was located west of the southwest corner of House 1. The construction of this corner differed from the rest of House 1 and it was hoped that excavation would show whether it had been built over or around an earlier construction just as House 2 had been built against the earlier Khan in the Central Area. The surface survey had not indicated any predominant period of occupation, but written history and oral sources both suggested that House 1 had been built for Faris al-Majali in the late 19th or early 20th century. Excavation revealed that House 1 (G3001) and G3002 ‒ a flimsy annexe added onto its southwest corner ‒ both made use of earlier structures in their construction. House 1 appears to have remained in use for the first half of the 20th century and to have been abandoned in the 1940s or ’50s when the focus of settlement in the area shifted from Khirbat Faris to Al Qasr

(Figure 9.1, Appendix 7 Table 5.31)

The architectural stone includes: a column drum, a capital, floor tiles, wall cladding, possible inlays, a possible funerary plaque and other marble fragments possibly from church furniture. The majority, 19 out of the total 24, are pieces of worked marble. They vary in the treatment of their faces, being polished or unpolished, smooth or rough, and in thickness, with a minimum of 0.6 cm and a maximum of 3.4 cm. This is indicative that the pieces are from different objects and locations. There are also two objects of limestone [SF 949, SF 3475], one of basalt [SF 3243], one of granite [SF 955] and one of sandstone [SF 3635].

Among those the identification of which is more certain, SF 3475 (Figure 9.1A is of limestone, has one rough unworked face and an acanthus leaf carved in relief on the opposite face. This is likely to be from a column capital that could have formed part of a templon (chancel screen) (pers. com. Dr K. Politis). SF 3243 is a basalt cylinder, D20.0 cm, with one end partially intact. A column drum seems likely but for decorative rather than supportive purposes. The two pieces of marble wall cladding, [SF 2212 Figure 9.1C and SF 3247] are both fairly thin, max. 2.1 cm thick, with one smooth face and the other roughened to allow keyingin with mortar. One limestone [SF 949] and two marble [SF 3186, SF 4007] floor-tiles were identified as such because they are thicker than the wall cladding but still only have one worked face. Eleven other worked marble fragments, varying in thickness, could be from church furniture, such as a templon.

The identification of five fragments as pieces of inlay is based upon their thickness which ranges from 0.6–1.1 cm. They have flat, parallel faces. SF 1504, SF 3207 and SF 3264 are of marble, SF 3635 is sandstone, and SF 955 is probably granite. They could all have been used in an architectural context, as opus sectile flooring or facing for example. SF 1504 and SF 3207 are of green porphry marble and could be architectural or part of an object, such as a box, like the lid, SF 2210 (Figures 9.7C, 9.8) that is made of the same marble.

Lastly, SF 3392 (Figure 9.1B) of marble, may be a fragment of a funerary plaque. It preserves two lines from a carved Greek inscription with a possible reading as follows:

[☩ Κύριε ἀνάπ]αυσ-The majority of the architectural stone is Late Roman/ Byzantine in character, periods that were structurally represented across all areas of the site. It seems clear that all this stone had been reused and/or had been dumped in later periods. In contrast to other classes of finds, very little is from The Western Edge, whereas, 75% comes from The Highest Point and the majority of this is associated with the collapse probably caused by the earthquake of AD 746. Their character points to their having originally been incorporated into one or more public buildings, including a church, which may have been located near The Highest Point or further away e.g. Khirbat Tadun.

[ον τὴν ψυχὴν τοῦ δούλ]ου σου

‘Lord, put to rest the soul of your servant - -’

(pers. com. Dr C. Crowther)

(Figures 4.25, 9.15 – 18, Appendix 7 Table 5.43)

... The non-rotary querns are the earliest form and within these the saddle quern is the earliest. These have a long use history and are paralleled over a wide time and area. The one definite example, SF 4272, was unstratified. Three other possible saddle querns are SF 1273, SF 2214 and SF 3248, all from early phases of the excavated occupation levels. The circular quern, SF 2000 (Figure 9.15F), of which only a fragment is preserved, is an anomaly in form but the concave, smooth face with traces of polish leads to its inclusion in the non-rotary querns.

The rectangular quern is widespread throughout the Levant and also has a long history of use, as can be seen from the following parallels. An example from Pella (McNicoll et al. 1992: 68 RN 70120) is longer than ours at L33.00 cm and dates to the Bronze Age. From the Madaba Plains are two examples (Platt 1991: 247 1118/A 7K60.12 fig.10.1 and 777/D 6K07. 2 fig.10.3) dated to the early Persian and Late Ottoman periods respectively. From the Red Tower (Pringle 1986: 174 11) is an unillustrated example, from the final abandonment and destruction dated to the 20th century, in Area A Phase F.

The earliest example at Khirbat Faris is a fragment, SF 2305, from The Central Area in a dump associated with a complex of walls and dated to the Roman period. The only complete example, SF 3225 (Figure 9.15H), comes from accumulation and clearance levels in an outside courtyard area at The Highest Point, dating to the 7th and 8th centuries AD.

The use of the hand-operated rotary quern is believed to have become fairly widespread by the Hellenistic period. (Forbes 1965: Volume III 146). Many of the hand rotary querns found at Khirbat Faris are in contexts which suggest they were in use in earlier phases; a good example is SF 2166 (Figures 4.25, 9.16C) from The Central Area, which was reused in a paved floor in G2003, the Transverse Arch House. The floor is 9th–13th century and so, presumably, the quern dates from before this period.

The two Type 002 rotary querns, the Pompeian metae, are from G5002, the Late Antique House at The Highest Point. SF 3421 appears to have been dumped inside this room during a period of squatter-like occupation dated to the Byzantine period. SF 3357 was found beneath the roof collapse associated with the 8th-century AD earthquake. It is thought that the room had already been abandoned prior to the destruction and that the quern had been dumped inside. The date for the actual use of these querns is difficult to assess. Their upper stones, catilllae, were not found which suggests that they were not actually being used in G5002.

Within the corpus of stone finds the main categories are architectural stone fragments, agricultural and household tools and items, and objects of personal adornment, e.g. beads. The architectural stone consists mainly of tesserae, none of which were found in situ. There are also several fragments of worked marble of different architectural elements, including floor tiles, wall cladding and free standing structures. Most were found at The Highest Point within collapse and dump levels associated with the earthquake of AD 746 and are probably from a public building – a church, located within the vicinity, if not at The Highest Point itself.

Stone, brick and tile (Appendix 7 Table 5.46)

All of the structures on the site were built of stone, much of which was reused from previous periods of occupation and all of which was obtainable locally. Hard calciferous limestone was used for the roof rafters, archspringers and door lintels, and for wall construction. Fragments of decorated architectural elements found at the site were also carved from this harder limestone (Figure 10.1), which may have come from an ancient quarry located approximately 300 m north of Khirbat Faris. Softer, marly limestone was used for the archstones and in door surrounds. Basalt, from the slopes of Jabal Shihan a few kilometres north of Khirbat Faris, was employed both for roof rafters and as decoration, for example, the exterior surround of the doorway into House 1 (Figure 6.4). Apart from the finely dressed ashlar blocks used in the vault of the Khan and voussoirs of Phase 2 buildings in the Central Area and High Point trenches, the building stone in all periods was only roughly shaped or worked. The only walls constructed in foundation trenches were the arch-walls of Houses 1 and 2. Individual construction techniques are discussed below but it is generally true that, in the pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods and in the late 19th to early 20th century, house walls were double-faced with a rubble fill and regularly coursed. In the intervening periods, house walls tended to be built without a rubble core, were of varying width and used a greater amount of mud mortar for bonding their irregular courses. Most walls were butt-jointed, even when the walls joined were contemporary. It is probable that house walls were originally plastered both inside and out.

Only three examples of brick were recovered from the excavations, one of which was complete and measured 19 cm × 21.5 cm × 6.6 cm (Figure 10.2). The fabric was coarse and contained large amounts of limestone grit. The sub-group within which it was found (SG2076) is considered to be a levelling layer for internal surfaces with the Khan (see discussion of Phase 3 in Chapter 4).

Roofing tile was also extremely rare, presumably because the roofs of most structures were flat and sealed with mud plaster. Pitched, tiled roofs in this region were largely reserved for churches and other public buildings and are rare after Late Antiquity. The majority of the 19 fragments found at Khirbat Faris belong to one of two types:

- Type 1. Tegola with triangular rim. Length 31 cm, width unknown. Fabric yellow (Munsell 10YR 7/4 very pale brown) with no visible inclusions, smooth on both surfaces.

- Type 2. Tegola with inverted triangular rim. Dimensions unknown. Fabric pink (Munsell 5YR 7/4 pink) with no visible inclusions.

For ease of reference, a rigid taxonomy has been adopted to categorise the architectural types encountered at Khirbat Faris. The names given to the various types are based on their principal architectural features and their date. The types are discussed in chronological order. Much use is made of ethnographic analogy, particularly when considering the Transverse-Arch House, the Barrel-Vaulted House, the Arch-and-Grain Bin House and the Oven-House. Although such types have been noted previously, there are few detailed archaeological descriptions despite the wealth of ethnographic information regarding their construction and use in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For the Kerak Plateau, much information has been collected and summarised by the anthropologists of the Faris Project, Fidelity and William Lancaster (1999: 262–270) and the Vernacular Architecture Survey. All of the houses, in all periods, were single storey, and most seem to have been single units. Apart from the Phase 5 complex on the Western Edge, it is impossible to say from the excavation whether these units opened onto an alley or courtyard, or were part of a multi-room complex: comparison with known parallels suggests that they are more likely to have opened onto exterior spaces. At Fihl (Pella), a mid-8th-century house was built around a central courtyard (Walmsley 1988: 149); at Hisban, a suite of barrel-vaulted rooms, similar to that uncovered in Far. I, Phase 5, clustered around an open court (Walker 2003: 251); and, at Dhiban, single unit, Middle Islamic houses opened onto a courtyard (Tushingham 1972: 83–84). Further afield, Hirschfeld illustrates many examples in his comprehensive study of rural settlement in Byzantine Palestine (1997: 33–71).

(Figure 10.7)

The use of barrel-vaults is well attested in the Eastern Mediterranean from the 3rd century BC and became extremely popular in the Roman period, as the constructional demands of public monuments were met by this highly functional building technique. Barrel vaults were used primarily as a structural element ‒ for roofing subterranean cisterns, to support terraces or tiers of seating, or in series for a row of shops or as part of a larger complex, such as a bath house. Such vaults are very rarely found in isolated, free-standing, singleunit buildings. However, the Khan at Khirbat Faris is paralleled in Nabatean structures in the Negev, dated to the 1st century BC/AD At Oboda, the antechamber of a Nabatean burial cave had walls of well-dressed ashlar masonry and was roofed by a fine barrel vault built of smaller marly limestone blocks (Negev 1997: 84). In subsequent centuries, this antechamber seems to have been in almost constant use by the local Bedouin as a foul-weather shelter. Another example of the vault as mausoleum is Khirbat ‘Ain near Jerash. The Roman mausoleum was located close to a farm, a reservoir and quarries and, like Oboda but unlike the Khan at Khirbat Faris, had slots dug into the floor to hold the bodies of the dead (Kennedy and Bewley 2003: 5 and personal communication). While such parallels might suggest that the Khan was built as a funerary monument, the location of the structure might indicate a different function. Near to Khirbat Faris on the flanks of the Wadi Ibn Hammad stands Qasr Al Himma (Johns et al. 1989: 70, where it is referred to as Burj Al Majdalayn; Miller 1991: 49, Site 55). This small rectangular tower is of similar dimensions to the Khan (4.00 m × 5.00 m) and its exterior is remarkably similar. However, it is roofed not with a barrel vault but by stone rafters supported on corbels; this may, or may not, be a later alteration. As part of the preliminary survey of the area surrounding Khirbat Faris, the remains of two other possible towers, built of massive blocks, were also identified (Johns et al. 1989: 70). All these towers are situated close to the edge of the plateau and may perhaps have been part of a chain of watchtowers guarding the east-west route through the Wadi Ibn Hammad, near to its intersection with the north-south route of the King’s Highway. A similar interpretation was initially offered by Hirschfeld for a chain of structures found in a survey of the eastern edge of the Hebron hills: here, the towers were almost twice the size and surrounded by a talus (1997: 50). On the basis of subsequent research, he now classifies such structures as towered farmhouses. At least one such tower, from the west of Sa’adon in the Central Negev, is comparable in size to the Khan at Khirbat Faris (Hirschfeld 1997: Fig. 63) and, like it, has no talus. These towers are part of more extensive complexes including dwellings, sheep folds and other agricultural features (Hirschfeld 1997: 59). If the Khan belonged to a similar complex, this could explain the eastern wall (SG20161) which would have acted as a courtyard wall, enclosing the paved area, SG2148. In Palestine, such towers are interpreted as being multi-storey: there is no evidence for this in the Khan, either from incomplete stonework or in an access route to an upper floor. Given the lack of specific knowledge about rural settlement in this area during the Late Antique period and more particularly the lack of plans of sites found during the Kerak Plateau Survey, it is impossible to do more than suggest that a type of farmhouse identified in Byzantine Palestine may also occur further east. Perhaps this was the original function of the Khan at Khirbat Faris, rather than a funerary monument or military tower.

(Figure 10.8)