Tiberias - Site 7354

Site 7354

Site 7354click on image to explore this site on a new tab in govmap.gov.il

- from Dalali-Amos (2016)

- from Dalali-Amos (2016)

- from Tiberias - Introduction - click link to open new tab

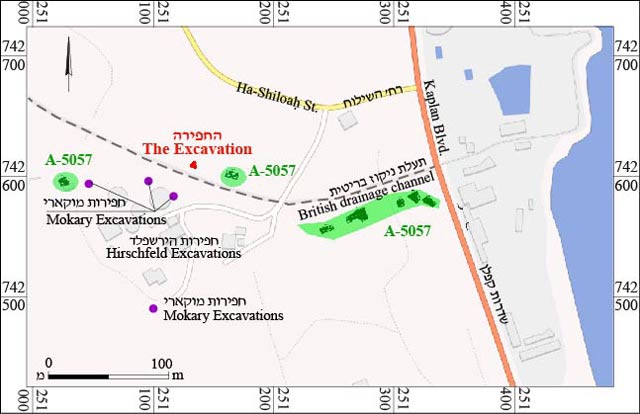

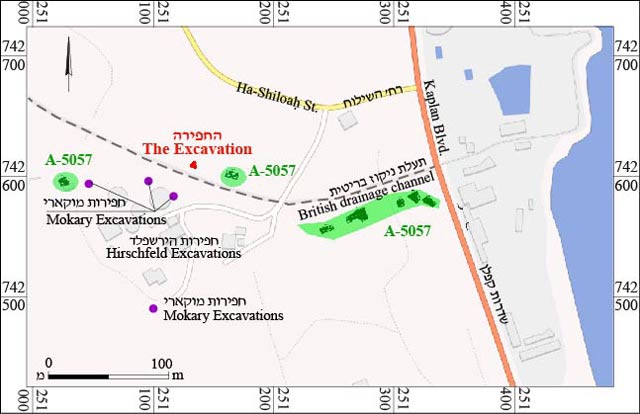

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location Map

Dalali-Amos (2016)

- Fig. 2 Plans and Sections

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plans and Sections

Dalali-Amos (2016)

- Fig. 2 Plans and Sections

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plans and Sections

Dalali-Amos (2016)

- Fig. 3 Wall 115

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The excavation area, Looking southwest

Dalali-Amos (2016) - Fig. 4 Wall 115

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

The eastern part of the square, looking west

Dalali-Amos (2016) - Fig. 5 Wall 116

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

The northwestern part of the square, looking southeast

Dalali-Amos (2016) - Fig. 7 Later strata walls

from Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Floor 110, looking south

Dalali-Amos (2016)

- from Dalali-Amos (2016)

| Stratum | Period | Date Range (CE) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Byzantine-Umayyad | ~5th-~8th centuries CE |

Description

Sections of two wide walls (W115, W116) formed a corner. The walls were built of basalt ashlars (0.25 × 0.30 × 0.35–0.53 m),

of which one, leveled course (c. 0.4 m) was preserved; the top of the course was covered with a layer of hard gray mortar.

A pavement (L122) of small and medium-sized fieldstones (5 × 15 cm) that was covered with an accumulation of soil (L118)

abutted the eastern face of W115 (length 1.5 m, width 0.9 m; Fig. 4). A hard, tamped floor (L121; thickness c. 0.1 m)

made of pebbles and hard mortar abutted W116 (exposed length 2.2 m, width 0.9 m; Fig. 5) from the north. Two sections

of a terra-cotta pipe sealed with tamped white calcareous mortar were exposed in situ beneath the floor (Fig. 6:1). |

| II | Abbasid and Fatimid | ~9th- ~11th centuries CE |

Description

The broad walls of Stratum III served as a foundation for the narrower walls of a new building. Two perpendicular walls (W106, W107; Figs. 3, 4) of the new structure were preserved: W106 (length 3.4 m, width 0.56 m) was built on top of W116, and W107 (length c. 3 m, width 0.56 m) was built on top of W115. The walls survived to a height of two courses that were constructed of roughly hewn basalt building stones (0.25 × 0.30 × 0.35–0.45 m); the second course of W107 was built of long stones (0.25 × 0.30 × 0.58 m). The top of the bottom course on both of the walls was leveled, and a layer of small stones and hard gray mortar was placed on it. Small stones were set between the stones of the second course on both walls. An opening to a room that was located north of W106 (L108, L110) was situated at the northern end of W107. In this room and in the room south of W106 (L109, L120) were thick, white plaster floors (thickness c. 5 cm; Fig. 7) set on top of a bedding of small stones that also covered the lower part of the walls. The plaster floors and their beddings were set on stone fills (L119, L124, L125) between the walls of Stratum III. This building was also abandoned, its walls were mostly dismantled and a new structure was erected on its remains. |

| I | Abbasid and Fatimid | ~9th- ~11th centuries CE |

Description

The new building was constructed with the same orientation as that of the structure in Stratum II.

Two of its walls (W101, W102) survived; they were built in part on the walls and partially on the

floors in the rooms of the previous stratum. Wall 101 (length 3.65 m, width 0.6 m) was founded on

the plaster floors of the rooms of the Stratum II building and on a section of W106 that it bisected.

two–three courses of the wall survived. It is built of large stones with small stones (0.22 × 0.30 × 0. 50 m)

in between, arranged in two rows, and a core of small fieldstones in between. The wall foundation was set on

the remains of the buildings beneath it; therefore, where the remains were high, such as Floor 108, the

foundation was two courses high, and where the remains were low, such as in Fill 119, the foundation was

three courses high. Wall 102 (length 1.9 m, width 0.6 m) was perpendicular to W101 and adjoined it from

the west; it was constructed directly on top of W106 of Stratum II (Figs. 4, 7). No floors were found

that were associated with this construction. |

| Stratum | Period | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Late Fatimid | 11th century CE | construction above the collapse caused by an earthquake (in 1033 CE?) |

| II | Early Fatimid | 9th - 10th centuries CE | continued use of the street with shops. |

| III | Abbasid | 8th - 9th centuries CE | a row of shops, the basilica building was renovated. |

| IV | Byzantine–Umayyad | 5th - 7th centuries CE | the eastern wing was added to the basilica building; the paved street; destruction was caused by the earthquake in 749 CE. |

| V | Late Roman | 4th century CE | construction of the basilica complex, as well as the city’s institutions, i. e., the bathhouse and the covered market place. |

| VI | Roman | 2nd - 3rd centuries CE | establishment of the Hadrianeum in the second century CE (temple dedicated to Hadrian that was never completed) and industrial installations; the paving of the cardo and the city’s infrastructure. |

| VII | Early Roman | 1st century CE | founding of Tiberias, construction of the palace with the marble floor on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, opus sectile, fresco. |

| VIII | Hellenistic | 1st - 2nd centuries BCE | fragments of typical pottery vessels (fish plates, Megarian bowls). |

Dalali-Amos (2016) wrote that

the Stratum III building may have been damaged in the Earthquake of 749 CE [one of the

749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes]

while noting that remains from this period were found in Stratum III in Hirschfeld’s excavation,

which he dated to the end of the fifth century until the Earthquake of 749 CE (Hirschfeld 2004:5)

. The tops of stratum III

walls (e.g. W115 and W116) were removed and leveled before construction began in overlying Stratum II. This left Stratum III walls that were just one course high and that were used as a foundation

for the Stratum II construction. Thus, although potential archaeoseismic evidence was removed in Stratum II, the missing tops of these walls may indicate that they

collapsed or were severely damaged in an earthquake.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls ? | Tops of Walls 115 and 116

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plans and Sections Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plans and Sections Dalali-Amos (2016) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The excavation area, Looking southwest Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4The eastern part of the square, looking west Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5The northwestern part of the square, looking southeast Dalali-Amos (2016) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 2 of Dalali-Amos (2016)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 2 of Dalali-Amos (2016)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed walls ? | Tops of Walls 115 and 116

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plans and Sections Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plans and Sections Dalali-Amos (2016) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3The excavation area, Looking southwest Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4The eastern part of the square, looking west Dalali-Amos (2016)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5The northwestern part of the square, looking southeast Dalali-Amos (2016) |

|

VIII + |