Jerash - Temple of Zeus

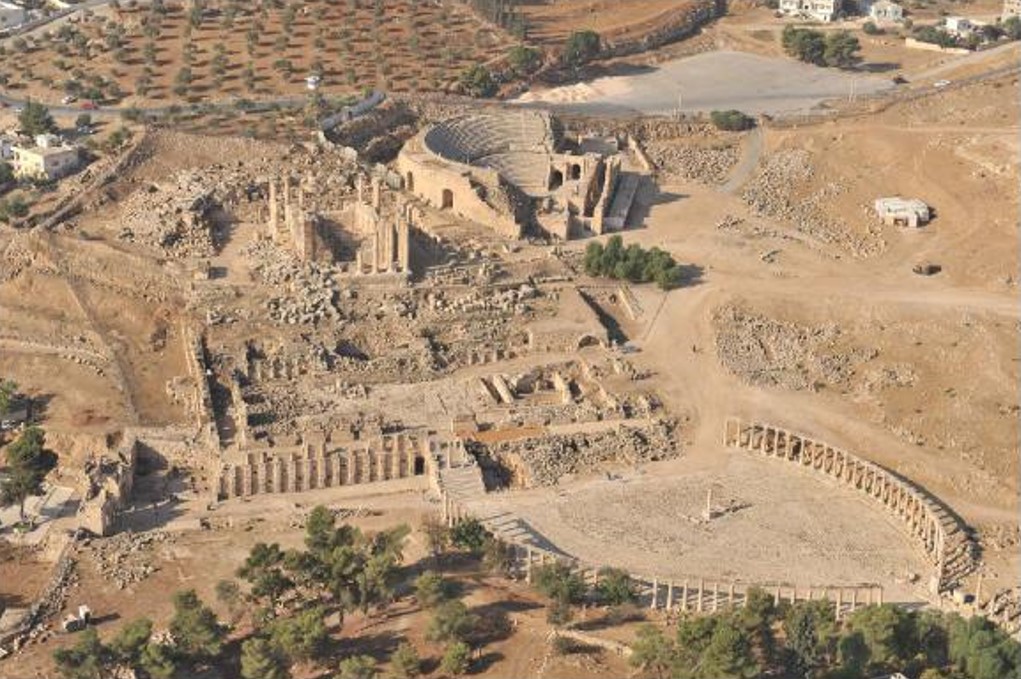

Figure 3 1.

Figure 3 1.Aerial view of Zeus Sanctuary, Oval Piazza, and South Theatre (APAAME_08.DLK-40)

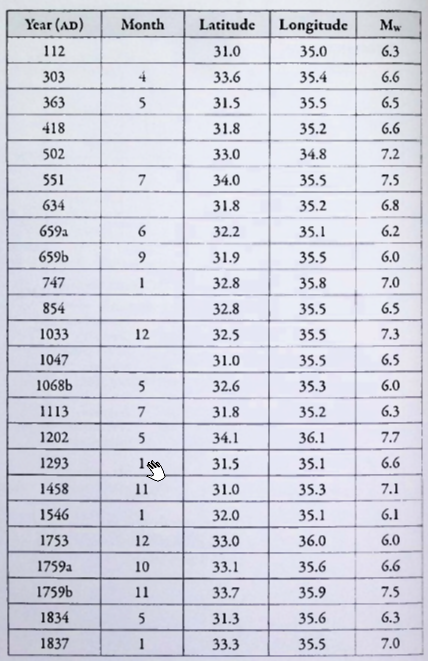

Kehrberg (2018)

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

The temple represents one of the most prominent examples of Roman religious architecture in provincial Syria. It was designed in the Corinthian order, with a peripteral colonnade of 6 × 9 columns set atop a high podium accessed by a monumental stairway.

Excavations have revealed that the sanctuary complex included not only the main temple but also an altar platform and monumental gateway. Several columns were re-erected during 20th-century restoration. Inscriptions and architectural parallels suggest the cult of Zeus remained active through the Roman and early Byzantine periods, possibly undergoing adaptation in later phases.

The temple sustained heavy damage during the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Quakes, which caused the collapse of its roof and much of its colonnade. Archaeological evidence shows extensive structural failure and later spoliation. Despite its ruin, the temple’s remains continued to shape the sacred and visual landscape of Jerash in the centuries that followed.

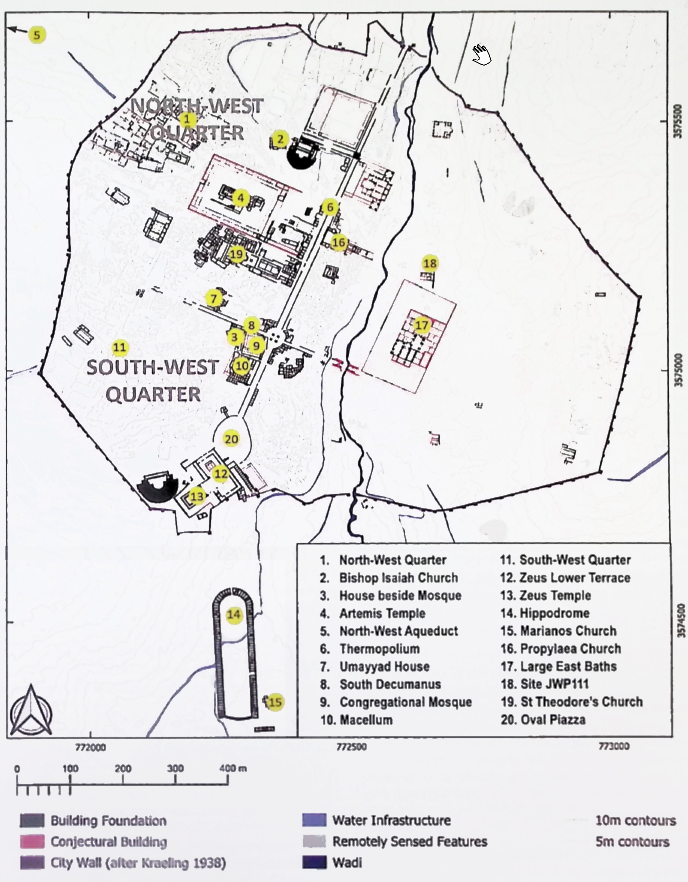

- from Jerash - Introduction - click link to open new tab

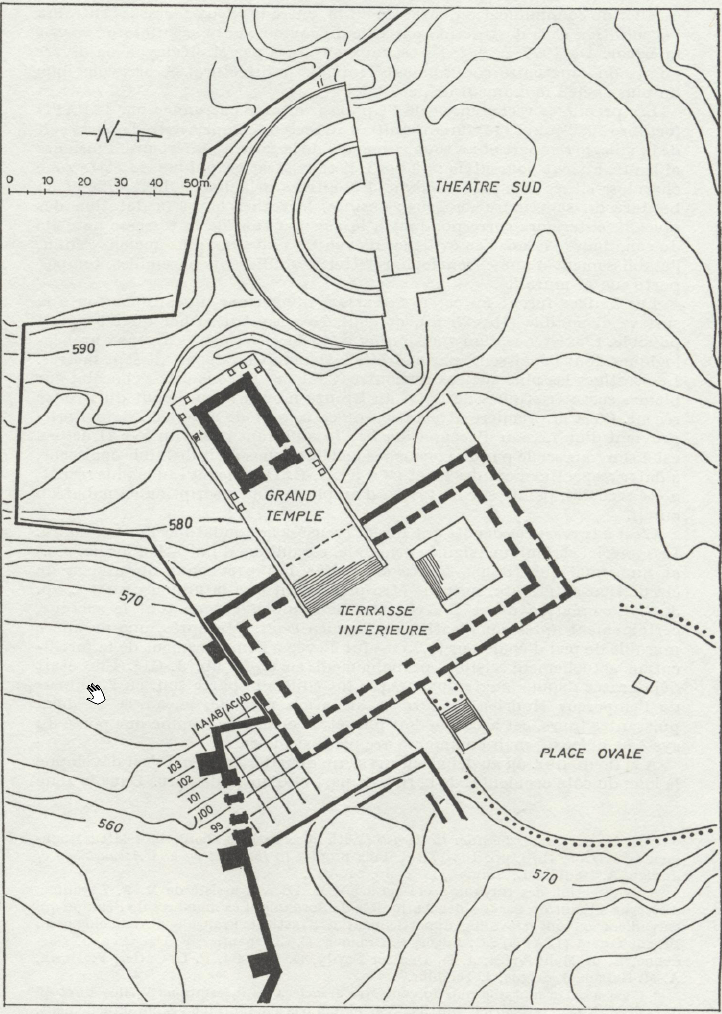

- Fig. 2 Plan of the Temple of Zeus from Seigne (1986)

- Fig. 26 Plan of the Upper

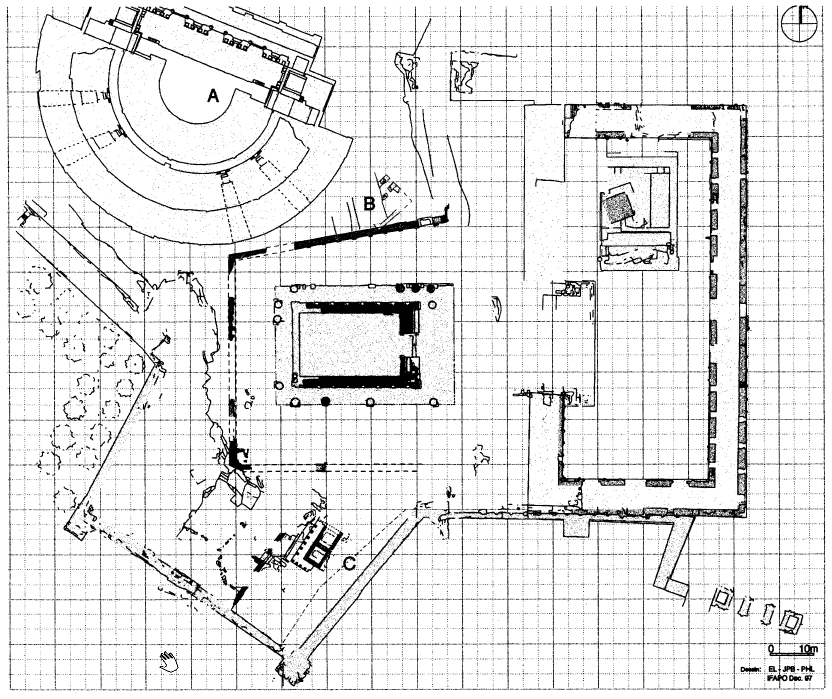

Sanctuary of Zeus from Egan and Bikai (1998)

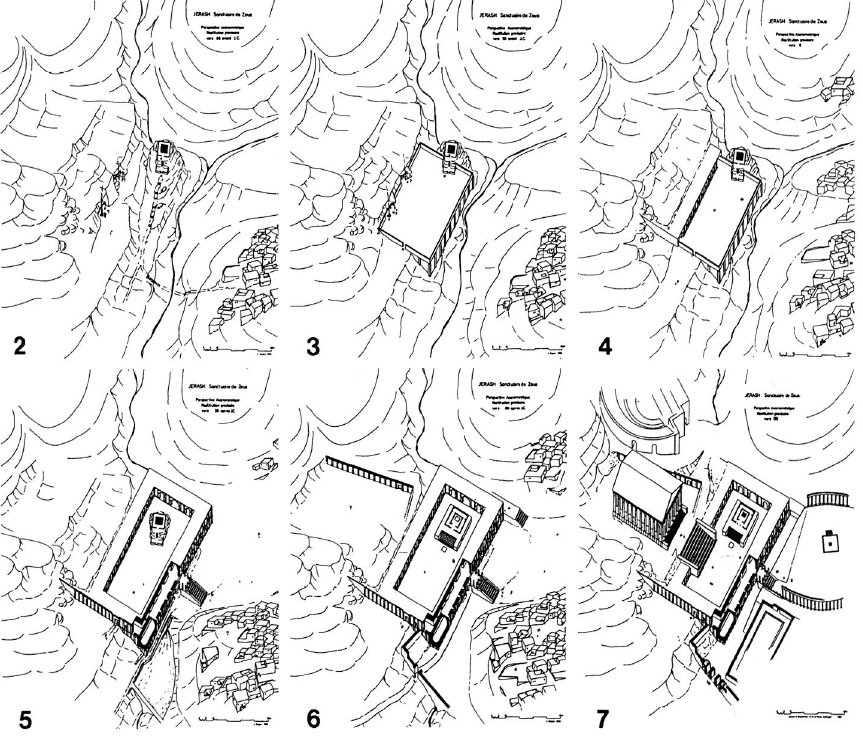

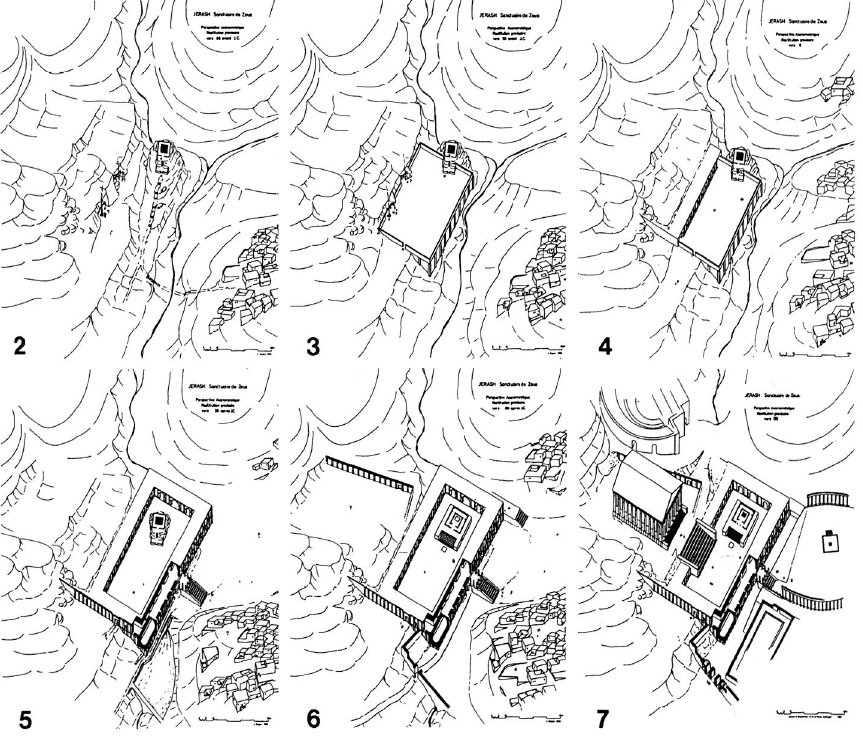

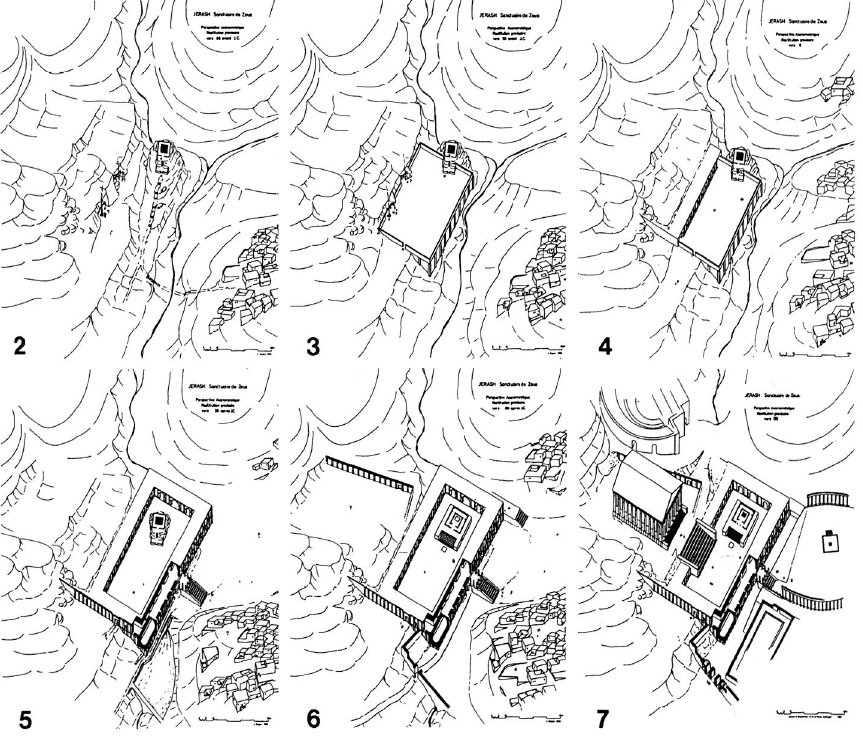

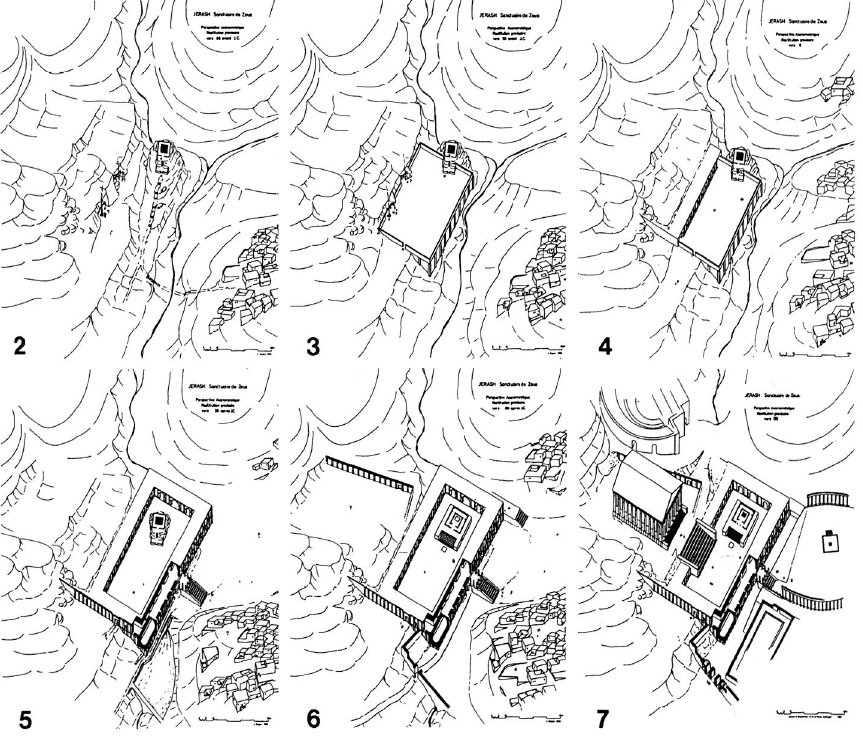

- Fig. 2 - Chronological

evolution of the sanctuary of Zeus at Jerash from Seigne (1985)

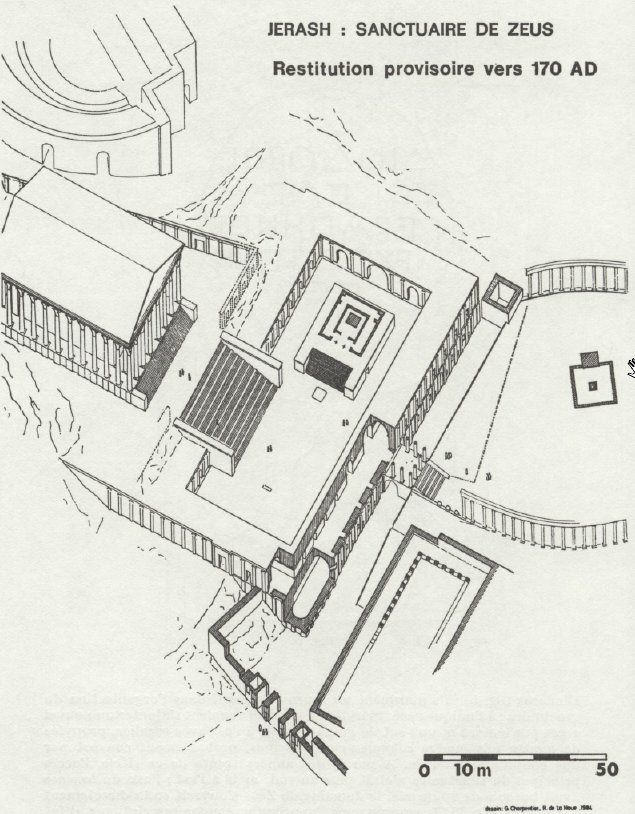

Figure 2

Figure 2

Chronological evolution of the sanctuary of Zeus in Gerasa.

- Extension of the sanctuary around 125 BC

- Extension at the turn of BC/AD

- Extension in 27-28 AD

- Addition at the beginning of the 2nd century AD

- Addition at the beginning of the 2nd century AD

(study by J. Seigne, DAO, C. Kholmayer, Th. Lepaon)

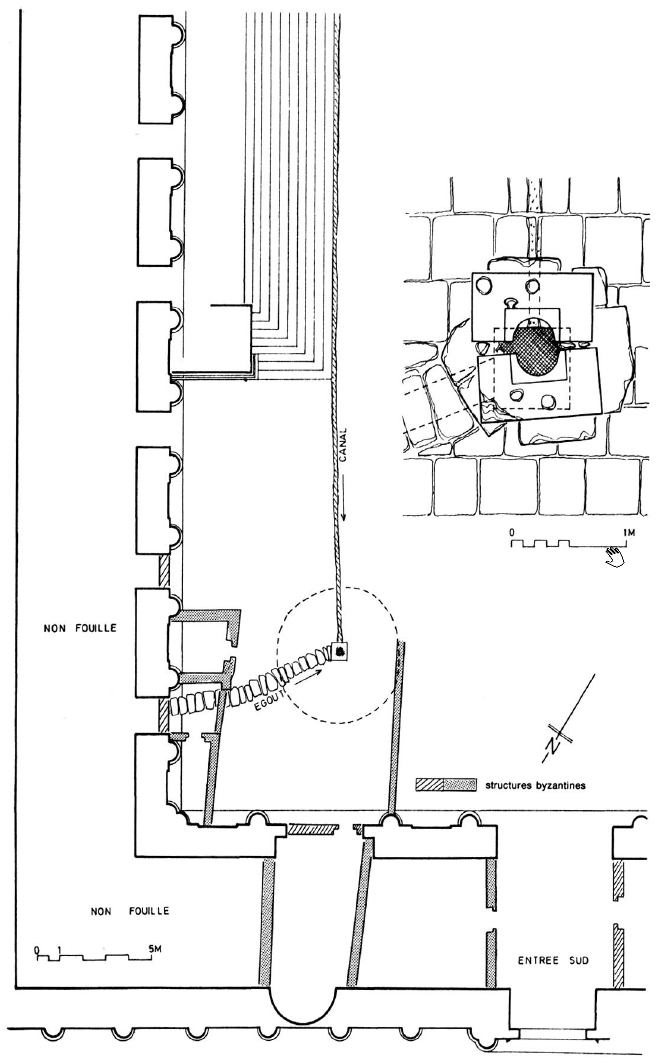

Seigne (1985) - Plate I - Lower terrace

of the sanctuary of Zeus at Jerash from Tholbecq (2000)

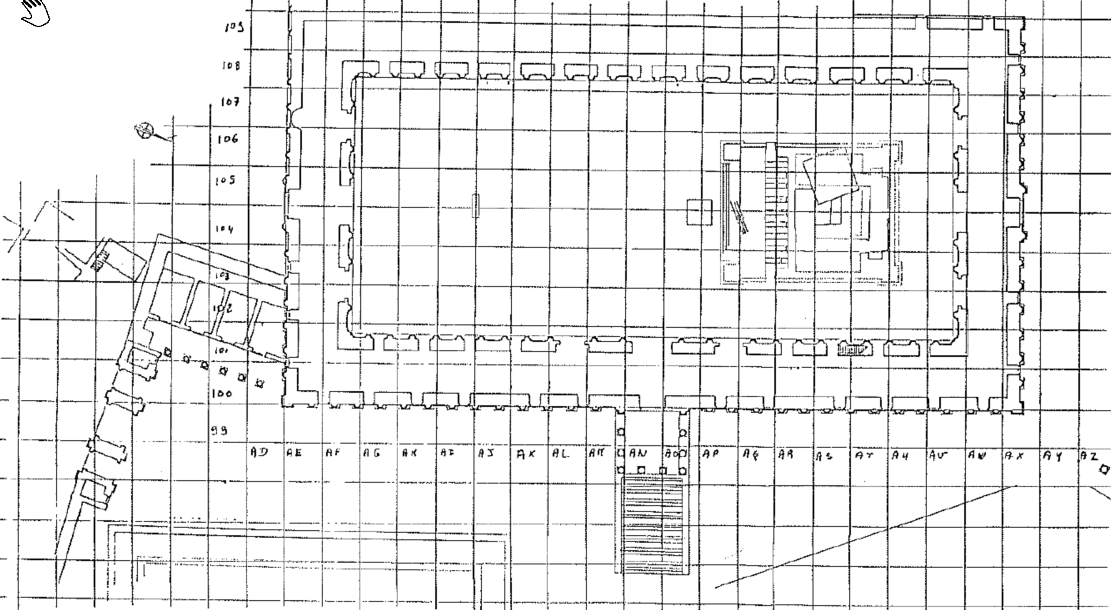

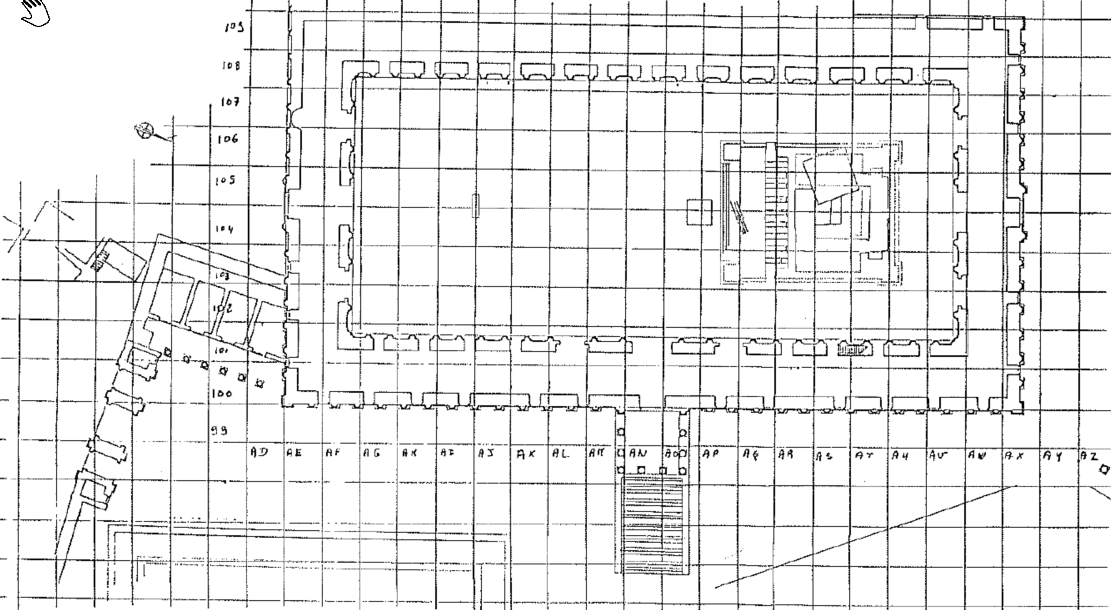

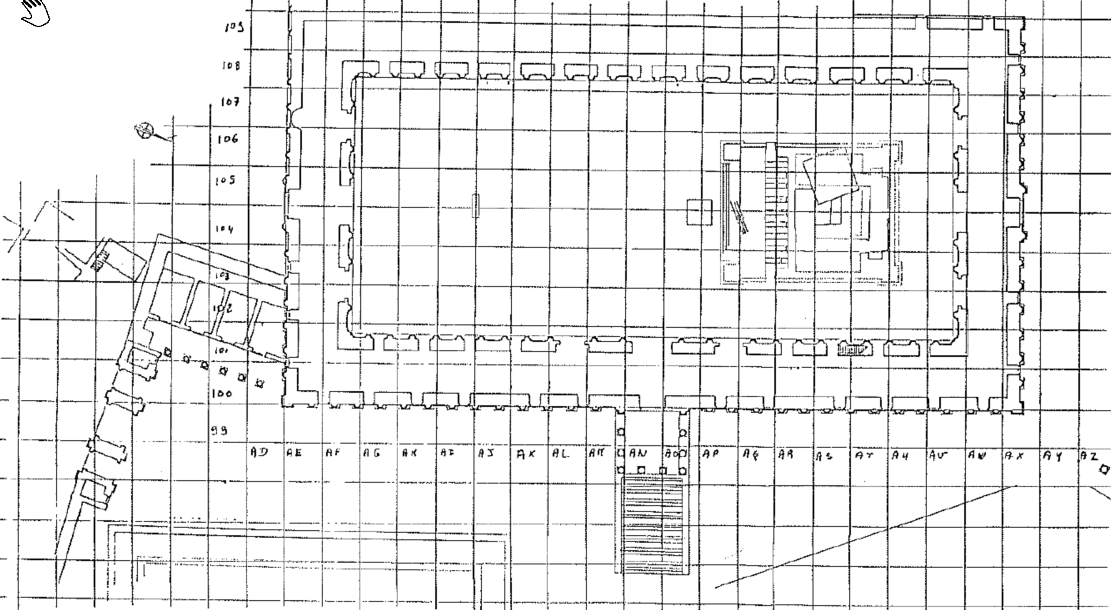

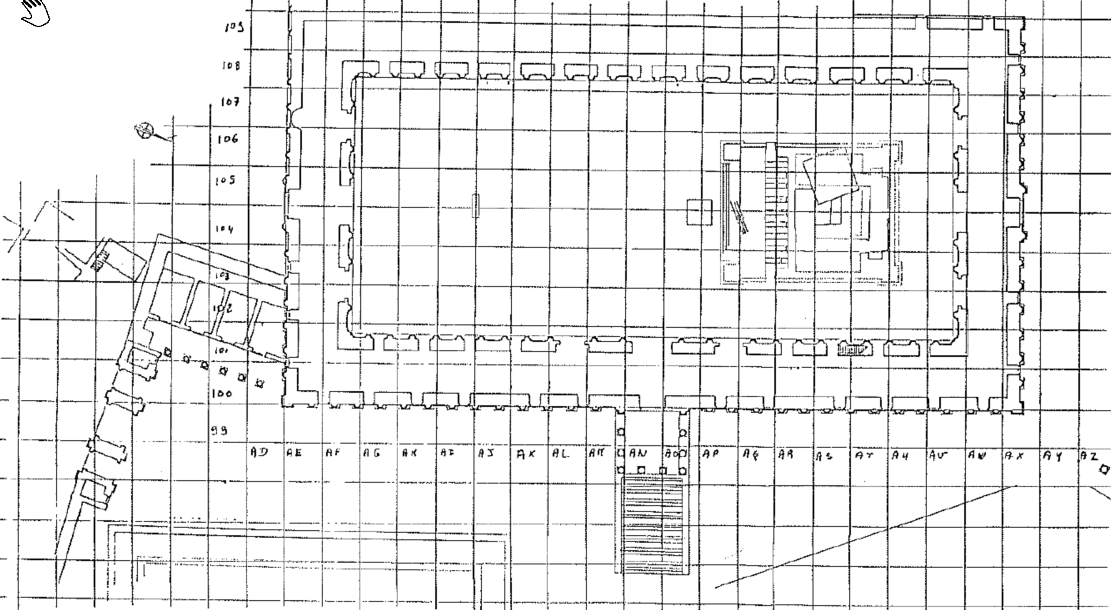

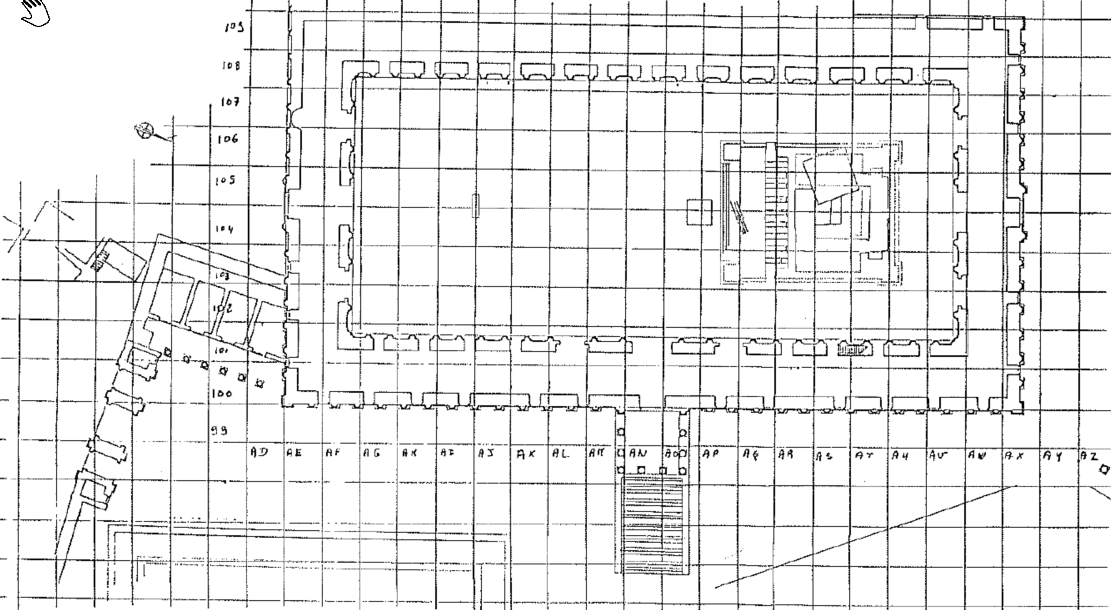

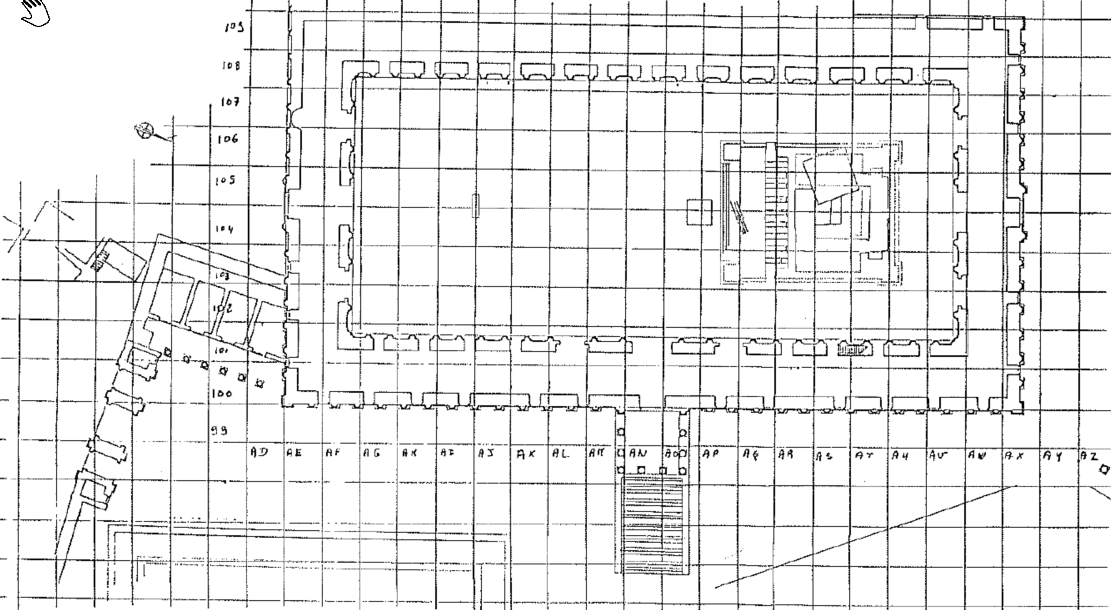

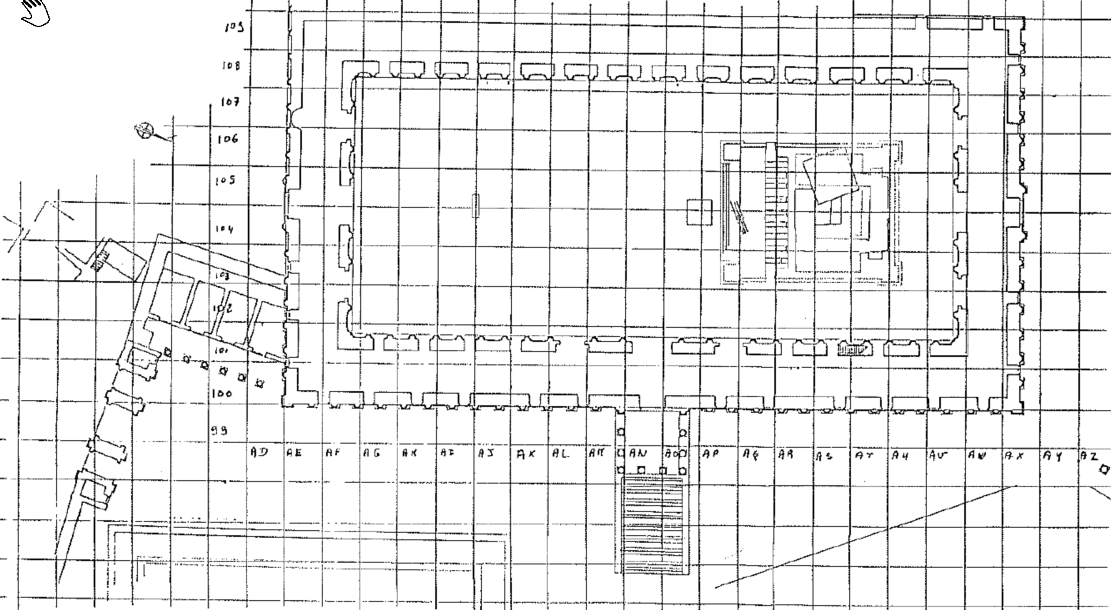

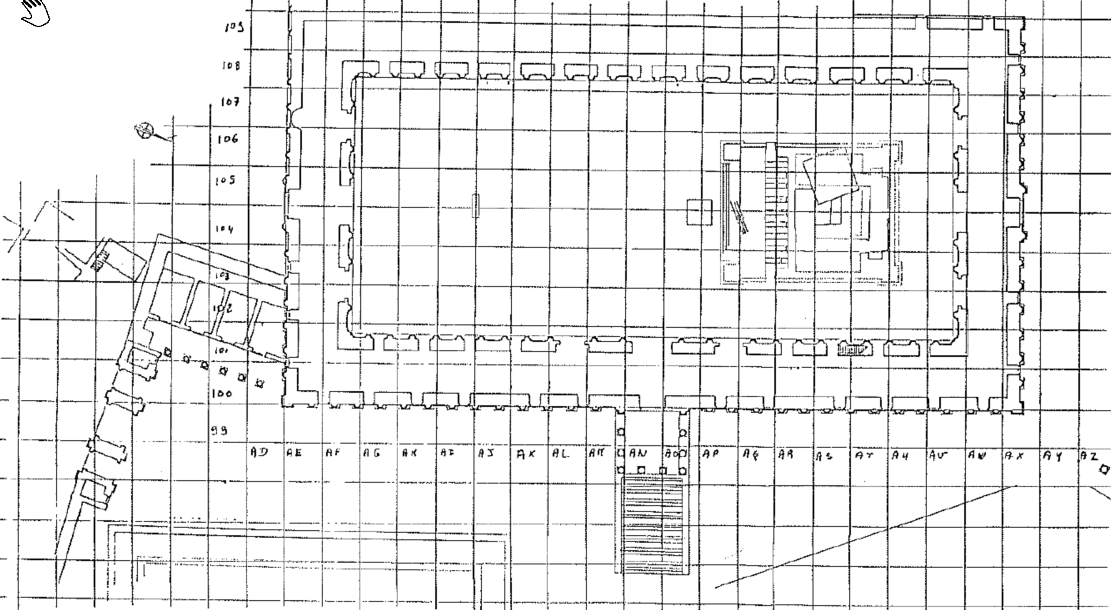

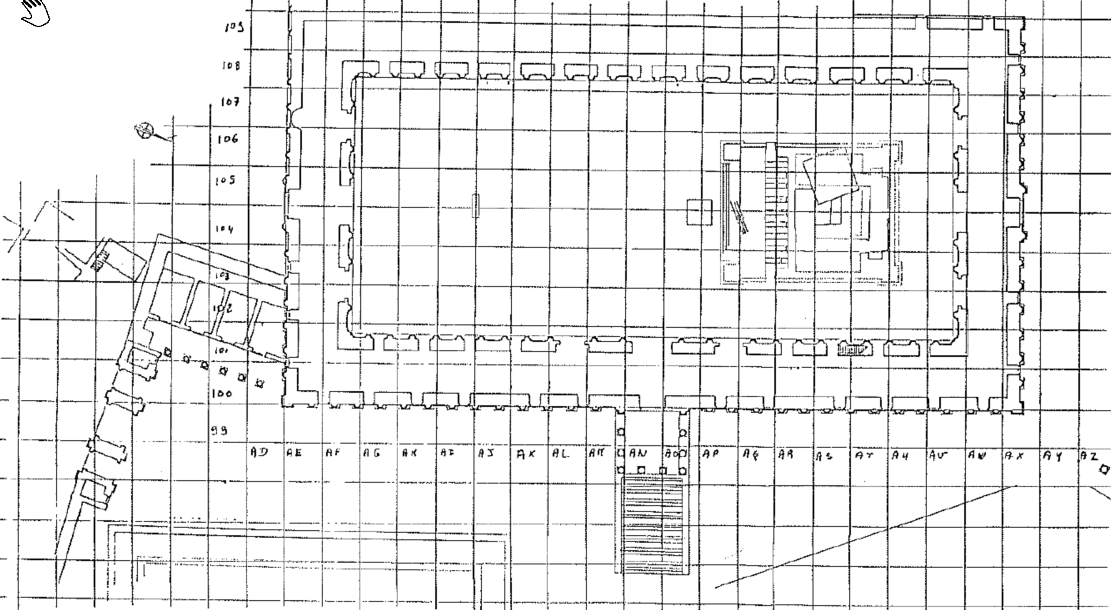

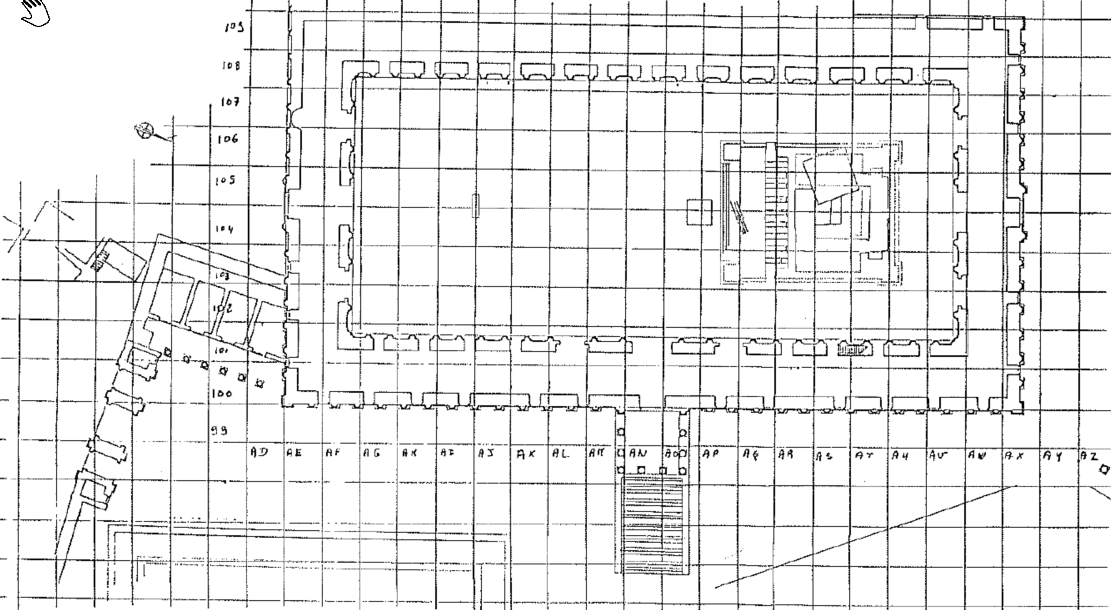

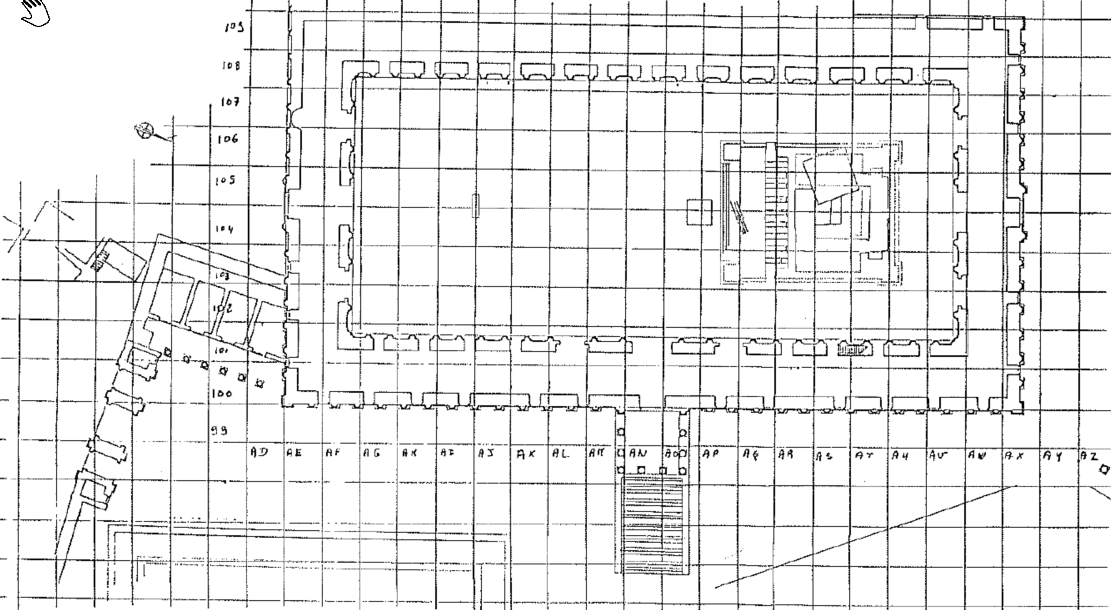

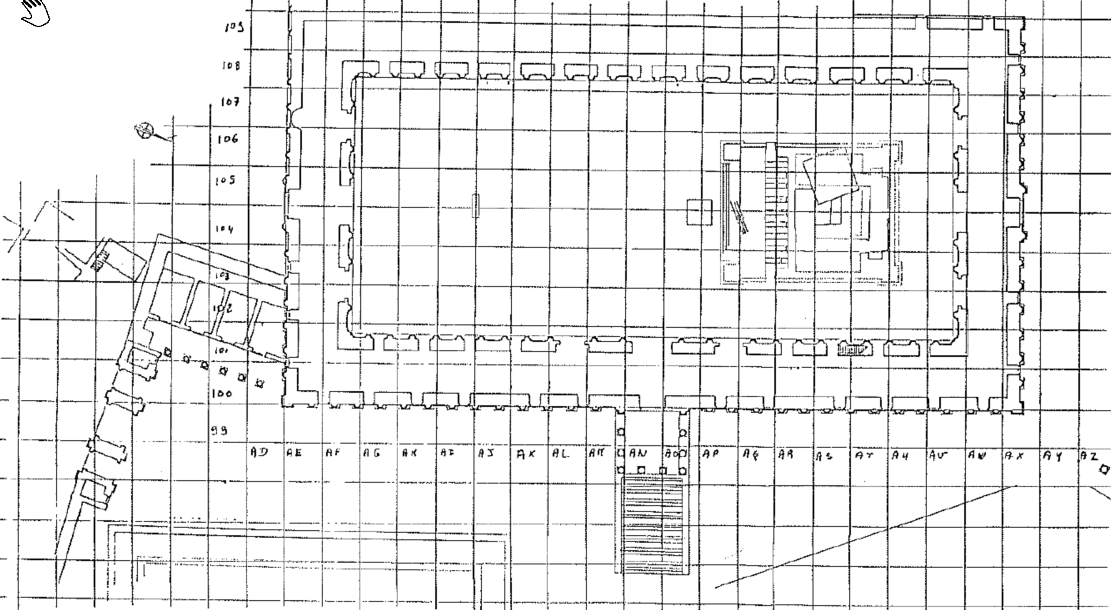

Plate I

Plate I

Lower terrace of sanctuary of Zeus (Jerash). Arrangement of grid.

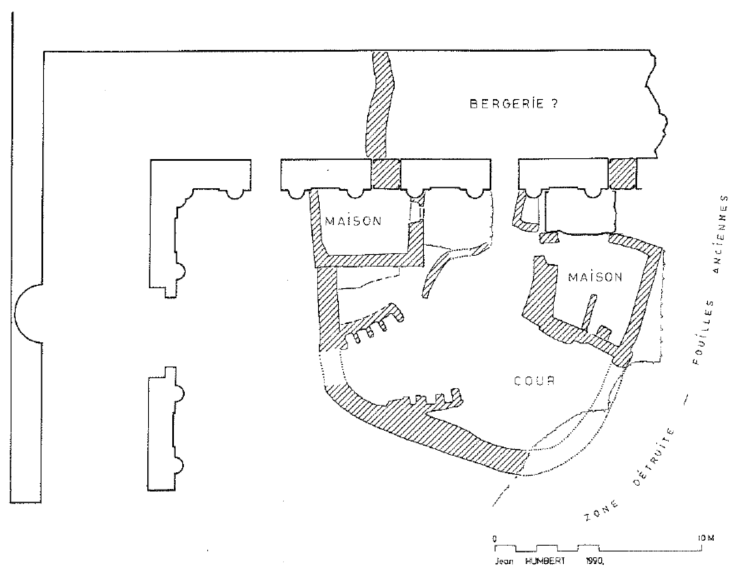

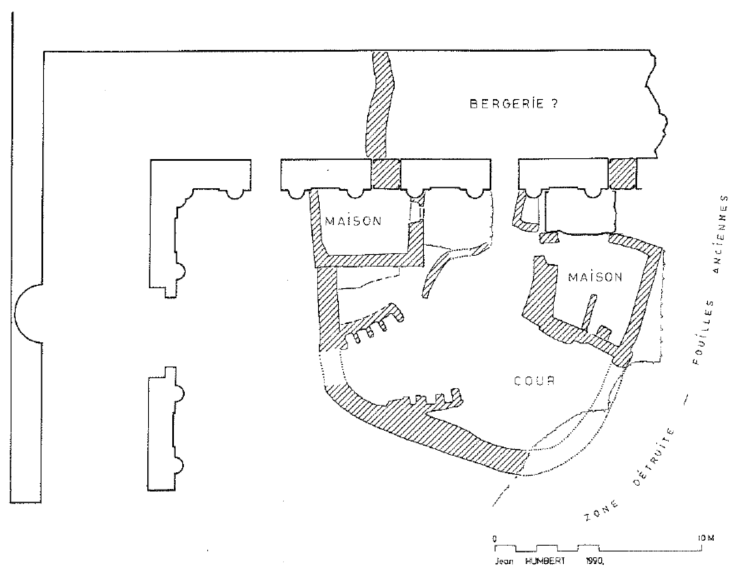

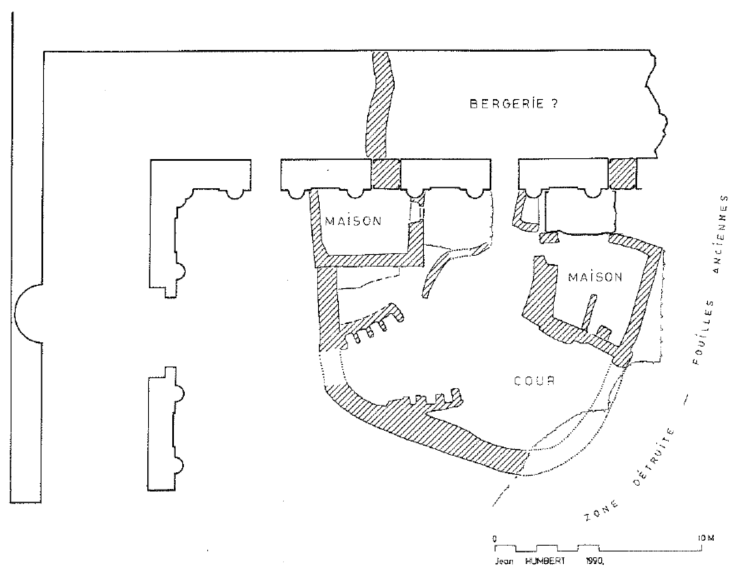

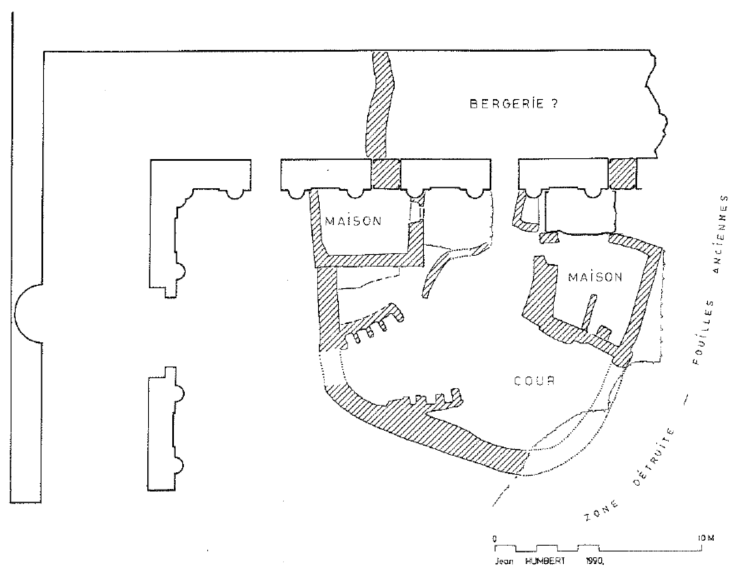

Tholbecq (2000) - Plate II - Late Islamic

structures in SW corner of the sanctuary of Zeus from Tholbecq (2000)

Plate II

Plate II

Late Islamic structures in the southwest corner of the lower terrace of the sanctuary of Zeus (Jerash).

Tholbecq (2000)

- Fig. 2 Plan of the Temple of Zeus from Seigne (1986)

- Fig. 26 Plan of the Upper

Sanctuary of Zeus from Egan and Bikai (1998)

- Fig. 2 - Chronological

evolution of the sanctuary of Zeus at Jerash from Seigne (1985)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Chronological evolution of the sanctuary of Zeus in Gerasa.

- Extension of the sanctuary around 125 BC

- Extension at the turn of BC/AD

- Extension in 27-28 AD

- Addition at the beginning of the 2nd century AD

- Addition at the beginning of the 2nd century AD

(study by J. Seigne, DAO, C. Kholmayer, Th. Lepaon)

Seigne (1985) - Plate I - Lower terrace

of the sanctuary of Zeus at Jerash from Tholbecq (2000)

Plate I

Plate I

Lower terrace of sanctuary of Zeus (Jerash). Arrangement of grid.

Tholbecq (2000) - Plate II - Late Islamic

structures in SW corner of the sanctuary of Zeus from Tholbecq (2000)

Plate II

Plate II

Late Islamic structures in the southwest corner of the lower terrace of the sanctuary of Zeus (Jerash).

Tholbecq (2000)

- Fig. 2 Site plan and

detail of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Fig. 2 Site plan and

detail of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Fig. 1 Evolutionary diagrams

of the sanctuary from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

Figure 1

Evolutionary diagrams of the sanctuary:

- The sanctuary area before any construction. Ilypothese (Drawing: J.-P. Lange).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 80/100 BC (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 60 BC (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 0 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 30 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 70 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 170 AD (Drawing: M.A.F.J.).

Click on image to open in a new tab

Rasson and Seigne (1989) - Fig. 6 Illustration of the Temple of Zeus from Seigne (1986)

- Fig. 1 Evolutionary diagrams

of the sanctuary from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

Figure 1

Evolutionary diagrams of the sanctuary:

- The sanctuary area before any construction. Ilypothese (Drawing: J.-P. Lange).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 80/100 BC (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 60 BC (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 0 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 30 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 70 AD (Drawing: J. Seigne).

- Supposed state of the sanctuary around 170 AD (Drawing: M.A.F.J.).

Click on image to open in a new tab

Rasson and Seigne (1989) - Fig. 6 Illustration of the Temple of Zeus from Seigne (1986)

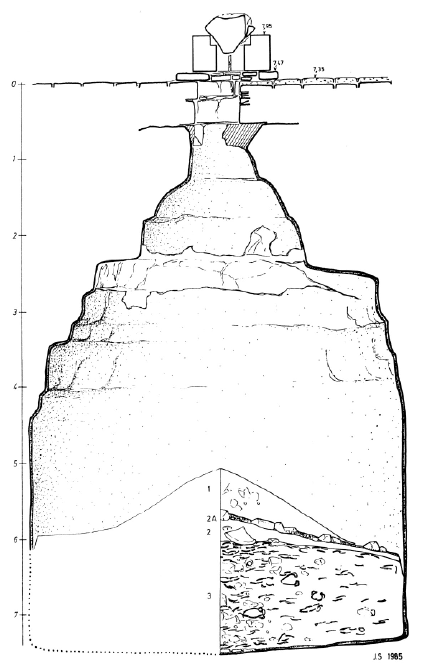

- Fig. 4 Vertical section

of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Fig. 4 Vertical section

of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Fig. 4 Vertical section

of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

- Fig. 4 Vertical section

of the cistern from Rasson and Seigne (1989)

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

- Vault in Lower Terrace - photo by JW

| Layer | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Byzantine | layer of greenish-gray clay, very compact and strongly mixed with plant materials (wood, herbs, etc.) and some bones of small animals (birds, goats, etc.). This deposit, homogeneous, laminated, and thick of about 1.50 m, is the result of an accumulation by settling in an aqueous medium of suspended organic materials. It is particularly remarkable for the extraordinary amount of ceramic material it contained. In the excavated part alone, 232 ribbed jars, 25 pots, 8 lamps, etc. were collected, intact or broken. Many objects of glass, bronze and bone were associated with them, as well as 36 coins. All these objects were evenly distributed in height in the clay mass. They were therefore abandoned gradually, for the duration of the layer 3 |

| 2 | Umayyad | level of compact red clay soil mixed with small stones. This stratum, 0.25 to 0.30 m thick, completely covered layer 3. Practically horizontal, it was set up, like the previous one in an aquatic environment. It contained little material. This stratum was itself sealed by a small level (2A) of powdered mortar and boulders from the collapse of part of the ceiling. The blocks, sometimes bulky (80, 100 kg) were only slightly sunk into the red clay layer, indicating that the tank was dried up at the time of their fall, as the clay and underlying deposits had time to harden. |

| 1 | Umayyad | unlike the previous ones, this layer did not correspond to an accumulation in an aqueous medium and had kept a conical shape, the maximum thickness (0.60 m) being normally located above the opening of the tank. It was formed of dark brown earth, very loose, mixed with stones and especially bones of various animals (sheep, goats, etc.), sometimes remained in anatomical connection (legs, fragments of spine, etc.). The remains of a human skeleton were found mixed with these animal bones. The finds included two coins, a large quantity of ceramics and glass and above all a rich set of objects in bone, ivory, soapstone, and bronze. Fragments of Ionic capitals, window railings, frieze blocks, etc., from the facades of the sanctuary were also found. |

Jean-Pierre Braun, IFAPO, reports:

In December 1996 IFAPO, with a new team under the direction of J.-P. Braun, began a project to study the Upper Temple of Zeus complex and to prepare a partial anastylosis and presentation of the site. The program entails comprehensive recording of the architectural remains and explorative excavations supervised by L. Tholbecq and L. Pontin. Two seasons of excavation and architectural studies have yielded much new information, with the following preliminary results.

Evidence that the temple was never finished is seen in the incomplete decorations on architrave blocks. In addition, bedrock outcroppings on the north and south sides of the temenos were not leveled to make a walking surface or to install a pavement. Finally, while the lower parts of the temple have been well executed, the upper parts show signs of carelessness.

Pottery and other finds from the 1997 excavations date the temenos wall to the second century A.D., the date of the temple itself, indicating that the wall was part of the original building program of the upper temple complex. The court has been defined on three sides: the north (already known), and the newly discovered sides west and south of the temple. The fact that the temenos wall was built in the second century, after the surrounding buildings, helps explain the swinging out of the temenos on the northern side of the court. The proximity of the south theater (fig. 26, A) and of the building below (fig. 26, B) limited the extent of the terrace grounds.

The 1997 fieldwork clearly established that the sanctuary complex was built on a quarry site and that the structures were designed to fit within outcroppings and quarry cuts. The use of the quarry in antiquity will be studied in detail to identify the sources of the building blocks of the temple complex.

Architectural remains discovered outside the southern temenos wall (figs. 26, C, and 27) have been identified as "banqueting halls" of the upper temple. All that remains of the second-century structures are the foundations of the biclinia, the pavement, portico, and other architectural elements. The study of their function within the temple complex (access, use, and abandonment) will add to the understanding of sacred urban centers in the Roman cities of Jordan.

The temple was not destroyed in a single but several earthquakes. The gradual collapse of the building complex was probably accelerated by the exposure of damaged parts to weathering. Excavations indicate that the earliest significant collapse took place in the later sixth century, but there is also evidence of damage in the third to early fourth centuries.

The complex functioned as a sanctuary for only a short period. In the third and fourth centuries, parts of the sacred grounds were used for industrial purposes. There are traces of Byzantine occupation, and fairly persistent if modest reoccupations occurred in confined spots during the Islamic periods: Umayyad, Mamluk, and later.

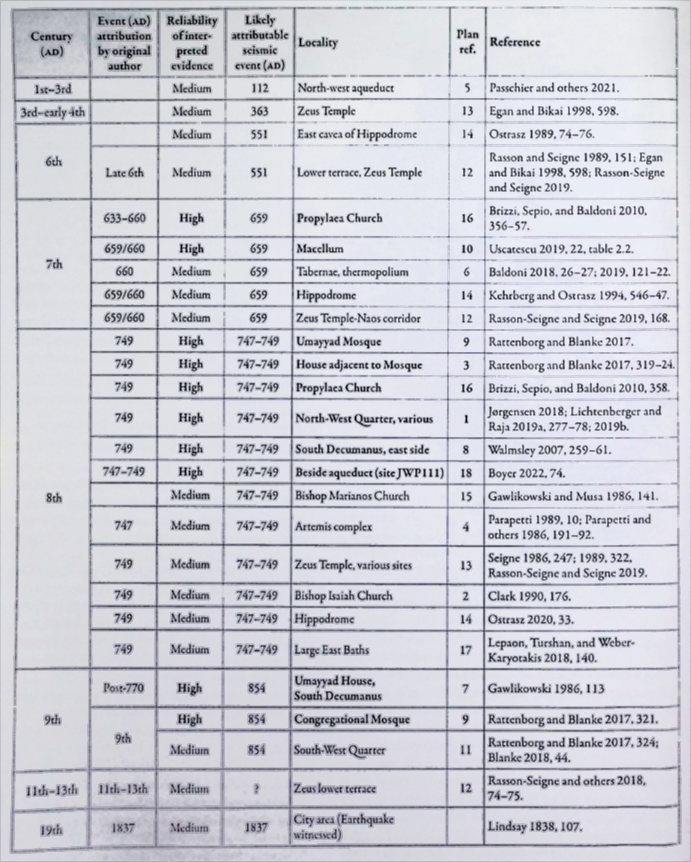

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd–early 4th | Medium | 363 | Zeus Temple | 13 | Egan and Bikai 1998, 598. | |

| 6th | Late 6th | Medium | 551 | Lower terrace, Zeus Temple | 12 | Rasson and Seigne 1989, 151; Egan and Bikai 1998, 598; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 7th | 659/660 | Medium | 659 | Zeus Temple–Naos corridor | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019, 168. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Zeus Temple, various sites | 13 | Seigne 1986, 247; 1989, 322; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 11th–13th | 11th–13th | Medium | ? | Zeus lower terrace | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and others 2018, 74–75. |

- from Seigne (1986:247)

The advent of Christianity brought about the end of the sanctuary, which suffered the same fate as the other pagan temples of the city: transformations, reoccupations, and demolitions. The great temple and its staircase served as a quarry for the construction of the churches of Saint Theodore, Saint Damian and Saint Cosmas, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint Peter and Saint Paul. The lower terrace, built of soft limestone that was not much sought after, escaped demolition but was transformed into dwellings by subdividing the vaulted corridor.

The earliest preserved levels of reoccupation date to the end of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century. Large rooms, often paved with mosaics, then occupied the vaulted corridor, while a wooden portico linking them was constructed in front of the eastern façade along its entire length. A cistern with a capacity of 130 cubic meters, dug into the southwest corner of the courtyard, supplied water to this wealthy residence.

In the middle of the sixth century, at the moment when a first earthquake destroyed the peristyle of the great temple, the sanctuary was inhabited only by farmers and craftsmen. These sheds, annexes, kitchens, and animal enclosures occupied part of the courtyard; the cistern had become only a latrine pit, and refuse accumulated in the courtyard. Although badly shaken, the vaults of the corridor of the lower terrace did not collapse during this first seismic event. Only the western corridor was partially crushed by the fall of the columns of the great temple’s peristyle.

But once again, farmers and potters settled among the ruins. More sheds, kilns, and enclosures rose in what had once been the courtyard of the sanctuary. A century later, a new earthquake (748?) caused the complete collapse of the vaults and façades of the lower terrace onto these poor Umayyad structures.

Despite the terrible destruction, the area of the sanctuary of Zeus was not abandoned. Numerous signs of reoccupation have been found across the entire extent of the former temenos. They correspond to small agricultural installations that succeeded one another from the ninth to the eighteenth centuries. The occupation was certainly not continuous but interrupted by periods—sometimes long—of abandonment. It can no longer be claimed that Jerash was totally deserted during the medieval period.

The complete architectural evolution of this major eastern sanctuary, from its origins to the imperial period, allows us to understand its growing influence on the urban organization of Jerash. It also brings to light a part of the history of the city of Chrysoroas.

Jean-Pierre Braun, IFAPO, reports:

In December 1996 IFAPO, with a new team under the direction of J.-P. Braun, began a project to study the Upper Temple of Zeus complex and to prepare a partial anastylosis and presentation of the site. The program entails comprehensive recording of the architectural remains and explorative excavations supervised by L. Tholbecq and L. Pontin. Two seasons of excavation and architectural studies have yielded much new information, with the following preliminary results.

Evidence that the temple was never finished is seen in the incomplete decorations on architrave blocks. In addition, bedrock outcroppings on the north and south sides of the temenos were not leveled to make a walking surface or to install a pavement. Finally, while the lower parts of the temple have been well executed, the upper parts show signs of carelessness.

Pottery and other finds from the 1997 excavations date the temenos wall to the second century A.D., the date of the temple itself, indicating that the wall was part of the original building program of the upper temple complex. The court has been defined on three sides: the north (already known), and the newly discovered sides west and south of the temple. The fact that the temenos wall was built in the second century, after the surrounding buildings, helps explain the swinging out of the temenos on the northern side of the court. The proximity of the south theater (fig. 26, A) and of the building below (fig. 26, B) limited the extent of the terrace grounds.

The 1997 fieldwork clearly established that the sanctuary complex was built on a quarry site and that the structures were designed to fit within outcroppings and quarry cuts. The use of the quarry in antiquity will be studied in detail to identify the sources of the building blocks of the temple complex.

Architectural remains discovered outside the southern temenos wall (figs. 26, C, and 27) have been identified as "banqueting halls" of the upper temple. All that remains of the second-century structures are the foundations of the biclinia, the pavement, portico, and other architectural elements. The study of their function within the temple complex (access, use, and abandonment) will add to the understanding of sacred urban centers in the Roman cities of Jordan.

The temple was not destroyed in a single but several earthquakes. The gradual collapse of the building complex was probably accelerated by the exposure of damaged parts to weathering. Excavations indicate that the earliest significant collapse took place in the later sixth century, but there is also evidence of damage in the third to early fourth centuries.

The complex functioned as a sanctuary for only a short period. In the third and fourth centuries, parts of the sacred grounds were used for industrial purposes. There are traces of Byzantine occupation, and fairly persistent if modest reoccupations occurred in confined spots during the Islamic periods: Umayyad, Mamluk, and later.

Around fifteen ceramic objects were found in this layer. Most of them are fragmentary. They consist mainly of common wares: cooking pots, amphorae, bowls, basins, and similar items, datable to the end of the Byzantine period or the middle of the Umayyad period.

A fragment of a painted bowl (cat. 27) is very characteristic of this period. These are bowls with a thick and nearly vertical wall and a beveled rim, made of a hard fabric of beige-pink color. The decoration, geometric or vegetal and painted in red, often covers the entire outer surface including the rim. In this example it consists of bands of red paint. These bowls are dated to the eighth century.

The fragment of a cooking plate (cat. 28) can also be dated to this period. It belongs to the tradition of Byzantine cooking plates and has many parallels at Jerash, at Pella, and elsewhere.

A fragment of grey ware also comes from this layer (cat. 29). It is the rim of a large basin with a slightly outward-flaring upper wall and a T-shaped lip with a central ridge. This fragment illustrates the evolution of these hand-built, grey-slipped basins, which occur in large numbers at Jerash beginning in the sixth century and whose initially angular profiles become more rounded over time.

Two types of cooking pots are represented in this level. The first (cat. 30) is a cooking pot with a carinated body and a vertical neck, characterized by a thick and curved wall. This type of cooking pot is known in the Umayyad period, and several examples are attested at Jerash, generally dated to the first half of the century, before 749.

The second type (cat. 31) is represented by a cooking pot with a globular body and a short flaring neck. This form is very common in the Umayyad period and has a long continuity, although it is generally completely glazed in later times. A fine ware, perhaps imported, is characterized by a very fine fabric containing few tempering particles and having a light color (beige or tan). The objects themselves are remarkable: two necks of small jugs with molded profiles (cat. 33–34), the spout of a bottle with white painted decoration (cat. 35), and the handle of a lantern with white painted decoration and a bird’s-head motif in relief with the eye details incised (cat. 36). These may be connected with the non-ceramic material from this layer, which is notable for its rarity: worked ivory objects, stone vessels, and similar items.

The dating of this ceramic assemblage poses little difficulty. A comparative study of the types represented leads us to place the material in the eighth century, probably in the first half of the century and very likely before the earthquake of 749. This dating is confirmed by the Umayyad coin found in this layer. Struck at Jerash, its minting date falls between 694 CE and 710 CE.

The pottery from the Byzantine and Umayyad periods discovered during the excavations of the French team at Jerash has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive study, although several preliminary works have outlined the main lines of its typochronology. The clearing of undisturbed structures containing archaeological material in situ makes it possible to associate ceramic productions—mostly local—with sealed occupation contexts well dated by stratigraphy from the mid-6th to the mid-8th century. Three closed assemblages were selected for the clarity of information they provide:

- a cistern discovered during the clearing of the courtyard of the lower terrace of the sanctuary of Zeus

- the southern vaulted corridor of the naos of Zeus

- the room containing the remains of the hydraulic saw, located at the eastern end of the north cryptoporticus of the sanctuary of Artemis.

The Cistern of the Lower Courtyard of the Sanctuary of Zeus The excavation of this cistern was the subject of a published article in Syria. It was dug only after 450 CE, the date of the end of the cult of Zeus and the transformation of the former sanctuary into a monastery. Throughout the first half-millennium, water had been considered an inconvenience in the sanctuary and everything was done to evacuate it rather than preserve it: paving of the courtyard, drainage channels along the walls, a wastewater channel aligned with the south entrance, etc. The transformation of the sanctuary into a monastery between 455 and 485 completely changed the situation: the water, formerly a nuisance, became indispensable for the monks.

A first attempt to dig a cistern near the south entrance failed because the subsoil was heterogeneous. The final location, in the southwest corner of the courtyard where the bedrock was solid, allowed the successful construction of a bottle-shaped cistern (diameter 5.50 m, height 7.60 m, capacity ca. 120 m³). Rainwater from the upper temple staircase was channeled into it. Its use as a water reservoir seems to have been short-lived. A century later, the monks were violently expelled, as attested by the destruction of mosaic floors and painted decoration from the upper chapel, found in the street below. The cistern was then transformed into a septic pit/dump by new squatters. Water was progressively replaced by over 1.5 m of greenish clay mixed with organic material (level 3). This deposit contained an extraordinary quantity of complete and fragmentary pottery, probably the waste of a nearby potter. A thinner layer (level 2) consisted of red clay with few inclusions, likely from the final use of the cistern as a water tank. A final upper layer (level 1), dark brown and loose, contained a human skeleton, several caprid remains, architectural fragments, and a rich assemblage of ivory, bone, steatite, bronze objects, and two coins, one being an Umayyad fils minted at Jerash after 695. The cistern was sealed after this deposit. Interpretation of the deposits:

- Level 3: progressive accumulation after the destruction of the monastery, after 550 CE

- Level 2: after the abandonment of craft installations (potter, farm, etc.), possibly following the 659/60 earthquake

- Level 1: final dumping of human and animal carcasses, probably after a natural disaster—either after the late-6th-century epidemic or the 749 earthquake.

The pottery from level 3 (catalog nos. 1–19) represents the bulk of the finds: 232 ribbed jars, 25 cooking pots, 8 lamps, 4 amphorae, fragments of fine wares, a large gray-ware basin, and many sherds. The assemblage is homogeneous and well-known: mainly locally produced tableware dated to the late 6th or early 7th century. The most characteristic feature is the overwhelming number (89%) of small ribbed jars with an oblong body, ribbed walls, an omphalos base, two small vertical handles on the shoulder, and a short vertical neck with a slightly thickened flaring rim. Many bear white-painted decoration. Numerous vessels show a small hole pierced after firing. A complete crater (cat. 9) of unusual form for the period has a bi-conical body, ring base, and large ribbon handles. The decoration consists of four white horizontal bands, with a hole added after firing. Two fragments of fine painted wares (cat. 5 and 6) feature a feline motif and a kantharos with vine branches, combining red and white paint. A pale-slipped pitcher (cat. 13) with a conical body and two large handles is also notable. Complete amphorae and many large sherds of related vessels were also recovered.

The amphorae found in this layer could not all be fully deciphered. They were likely imported from Egypt, with parallels known for example at the Kellia. They are dated from the end of the 6th century to the beginning of the 7th century. The amphora presented here shows a small drilled hole on the neck, made after firing. This seems to be the only imported pottery in this context. Eight complete lamps were found in this layer, mainly molded ‘Jerash lamps’ characterized by an oblong body decorated with radiating motifs around the filling hole (cat. 14–19). The body ends in a small raised tenon handle, sometimes remodeled into an animal-head shape. These lamps appear at Jerash at the end of the 6th century and continue into the 8th. Their stylistic variation suggests caution in establishing a firm typology. Lamp cat. 19 stands out due to its beige clay, lack of tenon, and much simpler decoration. Ceramics of Level 2 (cat. 20–26) This thin layer of red earth contained pottery dating from the end of the Byzantine / beginning of the Umayyad period: — two bowl fragments: one with thick walls and an everted lip (cat. 20), the other with thin angular walls and an inward-sloping profile (cat. 21); — several grey-ware basin fragments, one with a wave- pattern comb decoration (cat. 22); — the upper part of a ribbed cooking pot (cat. 23); — the neck of a jug/jar (cat. 24) with vertical walls and a deeply grooved lip; — a fragment of a large jug with red-painted motifs (cat. 25), typical of Umayyad-period vessels, made of beige, hard, homogeneous, well-fired clay, usually decorated with red geometric motifs.

In addition to this common ware, Level 2 also contained a completely different type of vessel: a mold-made bowl with an external face shaped as a ‘negroid head’ (cat. 26). It is well-made in homogeneous, well-fired clay. The form is that of a rounded bowl. Another such fragment was found in the sanctuary of Zeus, and L. Harding published one example already in 1949. Ceramics of Level 1 (cat. 27–36) About fifteen ceramic objects were found in this layer, mostly fragmentary, representing common ware—cooking pots, amphorae, bowls, basins—dating from the end of the Byzantine to mid-Umayyad period. A painted bowl fragment (cat. 27) is typical of this period: thick, nearly vertical walls, a beveled lip, hard beige-pink clay, with geometric or vegetal red-painted decoration covering the outside, including the rim. These bowls are dated to the 8th century. A cooking- plate fragment (cat. 28) also fits this period; it continues the Byzantine cooking-plate tradition and has many parallels at Jerash and Pella. A grey-ware basin fragment (cat. 29) represents a large hand-made vessel with a slightly everted upper wall and a T-shaped lip. It illustrates the evolution of these grey-ware basins, abundant at Jerash since the 6th century, whose profiles gradually soften over time. Two types of cooking pots appear: — cat. 30: a carinated pot with a vertical neck and thick walls, typical of the Umayyad period, with many examples in Jerash; — cat. 31: a globular pot with a short everted neck, also common into the early Islamic period.

A rarer group consists of fine beige clay vessels—possibly imports—including two juglet necks with molded rims (cat. 33–34), a bottle spout with white painted decoration (cat. 35), and a lantern handle decorated with white paint and a relief bird’s head (cat. 36). These correspond well with the rare non-ceramic objects (ivory, stone vessels, etc.) from the same layer. The dating of this assemblage is clear: comparative study places it in the 8th century, likely the first half, and before the 749 earthquake. This is confirmed by an Umayyad coin minted at Jerash between 694 and 710.

The Southern Vaulted Corridor of the Naos - Description: Located at the center of the Lower Terrace courtyard, the naos of Zeus housed cultic installations built atop a sacred high place pierced by a grotto. The oldest datable levels go back to the Late Middle Bronze Age. Over a millennium, structures were built over and around this core. After the disturbances during the First Jewish Revolt, a new naos was built around the remains of the old Hammana. Its hollow podium contained rooms accessing a small adyton where an oracle functioned. These underground structures (except the oracle chamber) were destroyed during the Second Jewish Revolt. Reconstruction aimed to restore access to the oracle, cutting new rooms into the rock under the naos stairs, and roofed with stone slabs supported by depressed arches. Curiously, this long narrow underground corridor (13.50 m by 3 m) was preserved in the Byzantine period even though the rest of the naos was dismantled in the mid-5th century.

It was reused and transformed—perhaps into a banqueting hall— with a long plastered bench added along the north wall and ‘cupboards’ cut into the walls to hold ceramic and glass vessels. Many were found crushed on the floor when the vault collapsed. The pottery from this corridor consists of the classic forms of Jerash production in the mid-7th century: red and grey common ware, ribbed cooking pots, handled craters, small ribbed jars, horizontal-handled casseroles with matching lids, gargoulettes, and lamps with animal-head tenons (‘Jerash lamps’). One imported amphora, probably Egyptian, was also found.

The Hydraulic Sawmill Description This extraordinary installation in the southern cryptoporticus of the sanctuary of Artemis was discovered accidentally. Excavated first during the 1928–1933 Anglo-American campaigns, the outflow channel had been only partially cleared. Its excavation revealed abundant, often complete pottery deposited after the abandonment of the sawmill. The machine was probably constructed under Justinian but was short-lived due to unresolved technical problems, leading to its abandonment by mid-century. The pottery consists mainly of complete or near-complete vessels: 30 ribbed cooking pots with vertical necks and folded rims; 4 jars (one with white-painted decoration); 3 gargoulettes; 5 lanterns; 1 amphora from the Kellia; bowls, cups, jugs, casseroles with horizontal handles, fine ware bowls, and multiple grey-ware basins. Two notable closed forms are: a carinated vessel with two vertical handles in light brown clay (cat. 56), and a small pouring vessel (cat. 59) decorated on the shoulder, a form absent from Byzantine levels in the sanctuary of Zeus. This ceramic assemblage dates to the mid-6th century, matching the date proposed for the sawmill's abandonment.

The material elements found in the filling correspond only to the last periods of use of the tank as a septic tank-dump (see above and below). This function was not its primitive function: the presence of a sealing coating, a draw port, the traces of wear left by the ropes on the edges of the margin alone prove that its primary function was that of water reserve. We also know that the curb was dismantled at least once before the installation of layer 3 (see above). This dismantling, made obligatory by the narrowness of the passage (0.39 m), must, in all likelihood, correspond to the last cleaning of the cistern as a water reserve. The date of construction of this tank is therefore of all materials indeterminable according to the furniture discovered in the filling. It can only be identified by the analysis of a series of external indices, in particular the water supply system.

We know that the cistern was not provided for in the original plan for the development of the terrace: the paving of the courtyard, set up at the earliest in the 70s of our era24 is sloping not towards it but towards the south door of the sanctuary, in the axis of which was found the rainwater drainage channel.

Only one water pipe led to the cistern: the simple gully dug into the pavement of the courtyard, in front of the first step of the monumental staircase leading to the great temple erected in 163 AD on the upper terrace. It must therefore be admitted that it was fitted out after the construction of the grand staircase, from which it collected runoff, and before the dismantling and reuse of the blocks of it for the construction of churches in the Byzantine era. The construction of the cistern must therefore be placed between the end of the second century AD and the beginning of the 6th century AD.

An additional clue could be provided by the blocks of the margin: the quality of the execution in the face, the presence of frames of anatyrosis on the faces of the joint are reminiscent of a work of good time rather than a Byzantine realization. Conversely, the traces of wear found on the walls, due to the friction of the ropes, are few and shallow, i.e. that the tank has been used in a low-intense way, which is in contradiction with its storage capacity (125 m3; volume actually stored according to the traces found on the walls: 95 m3), or that it was used for a short time. There is also no evidence that the curb was executed for this tank. These were blocks in reuse.

In fact, the solution lies more simply in the answer to the question: why was it suddenly necessary to store water in large quantities on the terrace of the sanctuary?

Obviously, throughout the Roman period, the problem was mainly to evacuate as completely as possible the rainwater from the entire lower terrace: paving of the courtyard, regular slope, drainage channel. Water was then a disadvantage and not a necessity.

It was quite different in the Byzantine epoch. As the excavation has shown, the sanctuary is then transformed into a vast religious complex. Chapels paved with mosaics but also housing occupy the former domain of Zeus whose vaulted corridors are then divided by transverse walls.

The installation of this Christian community (monastic?), which the study of mosaic pavements makes it possible to locate at the end of the fifth century, could not be done without a permanent supply of drinking water. A cistern became necessary. Its location was first and foremost, and naturally, chosen at the low point of gathering the waters of the courtyard, in front of the entrance to the drainage canal. Unfortunately in this sector the subsoil is very heterogeneous: natural rock very fractured and steeply sloped to the west, earth embankments to the east and north, foundations of the wall of the sanctuary to the south. The work was abandoned after a few meters as the excavations have shown. The final location, chosen because of the qualities of the subsoil, totally rocky, but completely eccentric, allowed to naturally collect only a tiny part of the rainwater. A canal, dug into the pavement and gathering all the runoff from the staircase leading to the upper temple, provided a solution to this problem.

The use of the cistern as such was short-lived, a century at most, as evidenced by the material contained in layer 3: in the second half of the 6th century it is no more than a septic pit. This transformation is to be put in direct relation with the dismantling of the staircase of access to the upper temple and the reuse of steps in the construction of churches. Deprived of its "reception basin" the tank became an empty tank.

The dismantling of the staircase seems directly linked to the abandonment of the religious installations, itself following an iconoclastic looting: all the inscriptions of the mosaic pavements were systematically destroyed and their fragments thrown out of the windows25. It is tempting to see in this destruction the mark of the violent events that occurred in Jeraseh at the time of the great monophysite crisis at the beginning of the 6th century. If this were the case, it could be said that, in all likelihood, the sanctuary then housed a Monophysite community, the whole not being reoccupied after the victory of the Chalcedonians, but on the contrary partly dismantled to build the churches of representatives of the Chalcedonian clan26.

From the middle of the 6th century the lower terrace is again occupied, but by simple farmers-breeders and some artisan potters. The old cistern, transformed into a septic tank-dump, is gradually filling up. A sewer has just hollowed out its wastewater loaded with organic materials, while jars and various containers, previously pierced, are regularly thrown there. The presence of such a mass of containers (about a thousand), largely of the same type (89% jars), remains unexplained. At most, the hypothesis can be formulated of the easy disposal of a series of scraps, which would have been done on a very regular basis for a large number of years.

One night in June 65827 a violent earthquake destroyed the small Byzantine agro-artisanal installations. The entire area was then abandoned and the paving of the courtyard, until then carefully maintained, was covered with a thick layer of red clay.

Driven by runoff, part of this material enters the tank in the process of natural drying, until the supply channels are obstructed by clay deposits.

During the terrible earthquake of 746/747 it will be used one last time as a mass grave to bury, at little cost, victims of the earthquake, human and animal, before being hermetically clogged and definitively abandoned.

Many questions remain unanswered for the moment, many conclusions, very hypothetical, will probably have to be modified, but the general history of this cistern seems very representative of the late transformations undergone by the former domain of Olympian Zeus28.

24 J. Seigne et coll. Recherches sur le sanctuaire de Zeus a Jerash dans J.A.P. I.

25 Many fragments of these pavements were found at

the foot of the eastern façade of the sanctuary,

overlooking the upstairs windows, during the

excavation of the Byzantine levels of the street leading

from Oval Square to the South Gate. The fragments of

inscription collected, too incomplete, remain for the

moment silent. The restoration work under way may

soon make these snippets of text understandable.

26 These suggestions are presented only as mere

research hypotheses.

27 See note 3.

28 We thank Jean-Baptiste I. Lambert and Jean-Michel

de Tarragon, as well as Maurice Sartre for the

assistance they have given us in the elaboration of

this article.

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd–early 4th | Medium | 363 | Zeus Temple | 13 | Egan and Bikai 1998, 598. | |

| 6th | Late 6th | Medium | 551 | Lower terrace, Zeus Temple | 12 | Rasson and Seigne 1989, 151; Egan and Bikai 1998, 598; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 7th | 659/660 | Medium | 659 | Zeus Temple–Naos corridor | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019, 168. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Zeus Temple, various sites | 13 | Seigne 1986, 247; 1989, 322; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 11th–13th | 11th–13th | Medium | ? | Zeus lower terrace | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and others 2018, 74–75. |

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- from Gawlikowski (1992)

Coins of Constans II were found in the fill and on the ground surface, while locally minted Arab-Byzantine coins were recovered below the floor of the house. These finds suggest a terminus post quem in the mid-to-late 7th century CE for the destruction episode.

The author attributes the earlier destruction to the Jordan Valley Quake(s) of 659 CE based on stratified material and historical parallels. The reoccupation layer includes subsequent architectural development, including floors, installations, and new walls built directly into the cleared area.

A second collapse marks the end of occupation at the site. A coin dated to 770 CE was found in this upper layer. While no later materials were present, the final destruction is assigned to the end of the Umayyad period, in the late 8th century CE.

Later reuse of the site includes industrial activity, such as a lime kiln and pottery production, situated on top of the destroyed house, indicating post-quake adaptive reuse. The architectural and ceramic sequence shows a clear pattern of reuse, destruction, and redevelopment consistent with earthquake damage.

The material elements found in the filling correspond only to the last periods of use of the tank as a septic tank-dump (see above and below). This function was not its primitive function: the presence of a sealing coating, a draw port, the traces of wear left by the ropes on the edges of the margin alone prove that its primary function was that of water reserve. We also know that the curb was dismantled at least once before the installation of layer 3 (see above). This dismantling, made obligatory by the narrowness of the passage (0.39 m), must, in all likelihood, correspond to the last cleaning of the cistern as a water reserve. The date of construction of this tank is therefore of all materials indeterminable according to the furniture discovered in the filling. It can only be identified by the analysis of a series of external indices, in particular the water supply system.

We know that the cistern was not provided for in the original plan for the development of the terrace: the paving of the courtyard, set up at the earliest in the 70s of our era24 is sloping not towards it but towards the south door of the sanctuary, in the axis of which was found the rainwater drainage channel.

Only one water pipe led to the cistern: the simple gully dug into the pavement of the courtyard, in front of the first step of the monumental staircase leading to the great temple erected in 163 AD on the upper terrace. It must therefore be admitted that it was fitted out after the construction of the grand staircase, from which it collected runoff, and before the dismantling and reuse of the blocks of it for the construction of churches in the Byzantine era. The construction of the cistern must therefore be placed between the end of the second century AD and the beginning of the 6th century AD.

An additional clue could be provided by the blocks of the margin: the quality of the execution in the face, the presence of frames of anatyrosis on the faces of the joint are reminiscent of a work of good time rather than a Byzantine realization. Conversely, the traces of wear found on the walls, due to the friction of the ropes, are few and shallow, i.e. that the tank has been used in a low-intense way, which is in contradiction with its storage capacity (125 m3; volume actually stored according to the traces found on the walls: 95 m3), or that it was used for a short time. There is also no evidence that the curb was executed for this tank. These were blocks in reuse.

In fact, the solution lies more simply in the answer to the question: why was it suddenly necessary to store water in large quantities on the terrace of the sanctuary?

Obviously, throughout the Roman period, the problem was mainly to evacuate as completely as possible the rainwater from the entire lower terrace: paving of the courtyard, regular slope, drainage channel. Water was then a disadvantage and not a necessity.

It was quite different in the Byzantine epoch. As the excavation has shown, the sanctuary is then transformed into a vast religious complex. Chapels paved with mosaics but also housing occupy the former domain of Zeus whose vaulted corridors are then divided by transverse walls.

The installation of this Christian community (monastic?), which the study of mosaic pavements makes it possible to locate at the end of the fifth century, could not be done without a permanent supply of drinking water. A cistern became necessary. Its location was first and foremost, and naturally, chosen at the low point of gathering the waters of the courtyard, in front of the entrance to the drainage canal. Unfortunately in this sector the subsoil is very heterogeneous: natural rock very fractured and steeply sloped to the west, earth embankments to the east and north, foundations of the wall of the sanctuary to the south. The work was abandoned after a few meters as the excavations have shown. The final location, chosen because of the qualities of the subsoil, totally rocky, but completely eccentric, allowed to naturally collect only a tiny part of the rainwater. A canal, dug into the pavement and gathering all the runoff from the staircase leading to the upper temple, provided a solution to this problem.

The use of the cistern as such was short-lived, a century at most, as evidenced by the material contained in layer 3: in the second half of the 6th century it is no more than a septic pit. This transformation is to be put in direct relation with the dismantling of the staircase of access to the upper temple and the reuse of steps in the construction of churches. Deprived of its "reception basin" the tank became an empty tank.

The dismantling of the staircase seems directly linked to the abandonment of the religious installations, itself following an iconoclastic looting: all the inscriptions of the mosaic pavements were systematically destroyed and their fragments thrown out of the windows25. It is tempting to see in this destruction the mark of the violent events that occurred in Jeraseh at the time of the great monophysite crisis at the beginning of the 6th century. If this were the case, it could be said that, in all likelihood, the sanctuary then housed a Monophysite community, the whole not being reoccupied after the victory of the Chalcedonians, but on the contrary partly dismantled to build the churches of representatives of the Chalcedonian clan26.

From the middle of the 6th century the lower terrace is again occupied, but by simple farmers-breeders and some artisan potters. The old cistern, transformed into a septic tank-dump, is gradually filling up. A sewer has just hollowed out its wastewater loaded with organic materials, while jars and various containers, previously pierced, are regularly thrown there. The presence of such a mass of containers (about a thousand), largely of the same type (89% jars), remains unexplained. At most, the hypothesis can be formulated of the easy disposal of a series of scraps, which would have been done on a very regular basis for a large number of years.

One night in June 65827 a violent earthquake destroyed the small Byzantine agro-artisanal installations. The entire area was then abandoned and the paving of the courtyard, until then carefully maintained, was covered with a thick layer of red clay.

Driven by runoff, part of this material enters the tank in the process of natural drying, until the supply channels are obstructed by clay deposits.

During the terrible earthquake of 746/747 it will be used one last time as a mass grave to bury, at little cost, victims of the earthquake, human and animal, before being hermetically clogged and definitively abandoned.

Many questions remain unanswered for the moment, many conclusions, very hypothetical, will probably have to be modified, but the general history of this cistern seems very representative of the late transformations undergone by the former domain of Olympian Zeus28.

24 J. Seigne et coll. Recherches sur le sanctuaire de Zeus a Jerash dans J.A.P. I.

25 Many fragments of these pavements were found at

the foot of the eastern façade of the sanctuary,

overlooking the upstairs windows, during the

excavation of the Byzantine levels of the street leading

from Oval Square to the South Gate. The fragments of

inscription collected, too incomplete, remain for the

moment silent. The restoration work under way may

soon make these snippets of text understandable.

26 These suggestions are presented only as mere

research hypotheses.

27 See note 3.

28 We thank Jean-Baptiste I. Lambert and Jean-Michel

de Tarragon, as well as Maurice Sartre for the

assistance they have given us in the elaboration of

this article.

Around fifteen ceramic objects were found in this layer. Most of them are fragmentary. They consist mainly of common wares: cooking pots, amphorae, bowls, basins, and similar items, datable to the end of the Byzantine period or the middle of the Umayyad period.

A fragment of a painted bowl (cat. 27) is very characteristic of this period. These are bowls with a thick and nearly vertical wall and a beveled rim, made of a hard fabric of beige-pink color. The decoration, geometric or vegetal and painted in red, often covers the entire outer surface including the rim. In this example it consists of bands of red paint. These bowls are dated to the eighth century.

The fragment of a cooking plate (cat. 28) can also be dated to this period. It belongs to the tradition of Byzantine cooking plates and has many parallels at Jerash, at Pella, and elsewhere.

A fragment of grey ware also comes from this layer (cat. 29). It is the rim of a large basin with a slightly outward-flaring upper wall and a T-shaped lip with a central ridge. This fragment illustrates the evolution of these hand-built, grey-slipped basins, which occur in large numbers at Jerash beginning in the sixth century and whose initially angular profiles become more rounded over time.

Two types of cooking pots are represented in this level. The first (cat. 30) is a cooking pot with a carinated body and a vertical neck, characterized by a thick and curved wall. This type of cooking pot is known in the Umayyad period, and several examples are attested at Jerash, generally dated to the first half of the century, before 749.

The second type (cat. 31) is represented by a cooking pot with a globular body and a short flaring neck. This form is very common in the Umayyad period and has a long continuity, although it is generally completely glazed in later times. A fine ware, perhaps imported, is characterized by a very fine fabric containing few tempering particles and having a light color (beige or tan). The objects themselves are remarkable: two necks of small jugs with molded profiles (cat. 33–34), the spout of a bottle with white painted decoration (cat. 35), and the handle of a lantern with white painted decoration and a bird’s-head motif in relief with the eye details incised (cat. 36). These may be connected with the non-ceramic material from this layer, which is notable for its rarity: worked ivory objects, stone vessels, and similar items.

The dating of this ceramic assemblage poses little difficulty. A comparative study of the types represented leads us to place the material in the eighth century, probably in the first half of the century and very likely before the earthquake of 749. This dating is confirmed by the Umayyad coin found in this layer. Struck at Jerash, its minting date falls between 694 CE and 710 CE.

The pottery from the Byzantine and Umayyad periods discovered during the excavations of the French team at Jerash has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive study, although several preliminary works have outlined the main lines of its typochronology. The clearing of undisturbed structures containing archaeological material in situ makes it possible to associate ceramic productions—mostly local—with sealed occupation contexts well dated by stratigraphy from the mid-6th to the mid-8th century. Three closed assemblages were selected for the clarity of information they provide:

- a cistern discovered during the clearing of the courtyard of the lower terrace of the sanctuary of Zeus

- the southern vaulted corridor of the naos of Zeus

- the room containing the remains of the hydraulic saw, located at the eastern end of the north cryptoporticus of the sanctuary of Artemis.

The Cistern of the Lower Courtyard of the Sanctuary of Zeus The excavation of this cistern was the subject of a published article in Syria. It was dug only after 450 CE, the date of the end of the cult of Zeus and the transformation of the former sanctuary into a monastery. Throughout the first half-millennium, water had been considered an inconvenience in the sanctuary and everything was done to evacuate it rather than preserve it: paving of the courtyard, drainage channels along the walls, a wastewater channel aligned with the south entrance, etc. The transformation of the sanctuary into a monastery between 455 and 485 completely changed the situation: the water, formerly a nuisance, became indispensable for the monks.

A first attempt to dig a cistern near the south entrance failed because the subsoil was heterogeneous. The final location, in the southwest corner of the courtyard where the bedrock was solid, allowed the successful construction of a bottle-shaped cistern (diameter 5.50 m, height 7.60 m, capacity ca. 120 m³). Rainwater from the upper temple staircase was channeled into it. Its use as a water reservoir seems to have been short-lived. A century later, the monks were violently expelled, as attested by the destruction of mosaic floors and painted decoration from the upper chapel, found in the street below. The cistern was then transformed into a septic pit/dump by new squatters. Water was progressively replaced by over 1.5 m of greenish clay mixed with organic material (level 3). This deposit contained an extraordinary quantity of complete and fragmentary pottery, probably the waste of a nearby potter. A thinner layer (level 2) consisted of red clay with few inclusions, likely from the final use of the cistern as a water tank. A final upper layer (level 1), dark brown and loose, contained a human skeleton, several caprid remains, architectural fragments, and a rich assemblage of ivory, bone, steatite, bronze objects, and two coins, one being an Umayyad fils minted at Jerash after 695. The cistern was sealed after this deposit. Interpretation of the deposits:

- Level 3: progressive accumulation after the destruction of the monastery, after 550 CE

- Level 2: after the abandonment of craft installations (potter, farm, etc.), possibly following the 659/60 earthquake

- Level 1: final dumping of human and animal carcasses, probably after a natural disaster—either after the late-6th-century epidemic or the 749 earthquake.

The pottery from level 3 (catalog nos. 1–19) represents the bulk of the finds: 232 ribbed jars, 25 cooking pots, 8 lamps, 4 amphorae, fragments of fine wares, a large gray-ware basin, and many sherds. The assemblage is homogeneous and well-known: mainly locally produced tableware dated to the late 6th or early 7th century. The most characteristic feature is the overwhelming number (89%) of small ribbed jars with an oblong body, ribbed walls, an omphalos base, two small vertical handles on the shoulder, and a short vertical neck with a slightly thickened flaring rim. Many bear white-painted decoration. Numerous vessels show a small hole pierced after firing. A complete crater (cat. 9) of unusual form for the period has a bi-conical body, ring base, and large ribbon handles. The decoration consists of four white horizontal bands, with a hole added after firing. Two fragments of fine painted wares (cat. 5 and 6) feature a feline motif and a kantharos with vine branches, combining red and white paint. A pale-slipped pitcher (cat. 13) with a conical body and two large handles is also notable. Complete amphorae and many large sherds of related vessels were also recovered.

The amphorae found in this layer could not all be fully deciphered. They were likely imported from Egypt, with parallels known for example at the Kellia. They are dated from the end of the 6th century to the beginning of the 7th century. The amphora presented here shows a small drilled hole on the neck, made after firing. This seems to be the only imported pottery in this context. Eight complete lamps were found in this layer, mainly molded ‘Jerash lamps’ characterized by an oblong body decorated with radiating motifs around the filling hole (cat. 14–19). The body ends in a small raised tenon handle, sometimes remodeled into an animal-head shape. These lamps appear at Jerash at the end of the 6th century and continue into the 8th. Their stylistic variation suggests caution in establishing a firm typology. Lamp cat. 19 stands out due to its beige clay, lack of tenon, and much simpler decoration. Ceramics of Level 2 (cat. 20–26) This thin layer of red earth contained pottery dating from the end of the Byzantine / beginning of the Umayyad period: — two bowl fragments: one with thick walls and an everted lip (cat. 20), the other with thin angular walls and an inward-sloping profile (cat. 21); — several grey-ware basin fragments, one with a wave- pattern comb decoration (cat. 22); — the upper part of a ribbed cooking pot (cat. 23); — the neck of a jug/jar (cat. 24) with vertical walls and a deeply grooved lip; — a fragment of a large jug with red-painted motifs (cat. 25), typical of Umayyad-period vessels, made of beige, hard, homogeneous, well-fired clay, usually decorated with red geometric motifs.

In addition to this common ware, Level 2 also contained a completely different type of vessel: a mold-made bowl with an external face shaped as a ‘negroid head’ (cat. 26). It is well-made in homogeneous, well-fired clay. The form is that of a rounded bowl. Another such fragment was found in the sanctuary of Zeus, and L. Harding published one example already in 1949. Ceramics of Level 1 (cat. 27–36) About fifteen ceramic objects were found in this layer, mostly fragmentary, representing common ware—cooking pots, amphorae, bowls, basins—dating from the end of the Byzantine to mid-Umayyad period. A painted bowl fragment (cat. 27) is typical of this period: thick, nearly vertical walls, a beveled lip, hard beige-pink clay, with geometric or vegetal red-painted decoration covering the outside, including the rim. These bowls are dated to the 8th century. A cooking- plate fragment (cat. 28) also fits this period; it continues the Byzantine cooking-plate tradition and has many parallels at Jerash and Pella. A grey-ware basin fragment (cat. 29) represents a large hand-made vessel with a slightly everted upper wall and a T-shaped lip. It illustrates the evolution of these grey-ware basins, abundant at Jerash since the 6th century, whose profiles gradually soften over time. Two types of cooking pots appear: — cat. 30: a carinated pot with a vertical neck and thick walls, typical of the Umayyad period, with many examples in Jerash; — cat. 31: a globular pot with a short everted neck, also common into the early Islamic period.

A rarer group consists of fine beige clay vessels—possibly imports—including two juglet necks with molded rims (cat. 33–34), a bottle spout with white painted decoration (cat. 35), and a lantern handle decorated with white paint and a relief bird’s head (cat. 36). These correspond well with the rare non-ceramic objects (ivory, stone vessels, etc.) from the same layer. The dating of this assemblage is clear: comparative study places it in the 8th century, likely the first half, and before the 749 earthquake. This is confirmed by an Umayyad coin minted at Jerash between 694 and 710.

The Southern Vaulted Corridor of the Naos - Description: Located at the center of the Lower Terrace courtyard, the naos of Zeus housed cultic installations built atop a sacred high place pierced by a grotto. The oldest datable levels go back to the Late Middle Bronze Age. Over a millennium, structures were built over and around this core. After the disturbances during the First Jewish Revolt, a new naos was built around the remains of the old Hammana. Its hollow podium contained rooms accessing a small adyton where an oracle functioned. These underground structures (except the oracle chamber) were destroyed during the Second Jewish Revolt. Reconstruction aimed to restore access to the oracle, cutting new rooms into the rock under the naos stairs, and roofed with stone slabs supported by depressed arches. Curiously, this long narrow underground corridor (13.50 m by 3 m) was preserved in the Byzantine period even though the rest of the naos was dismantled in the mid-5th century.

It was reused and transformed—perhaps into a banqueting hall— with a long plastered bench added along the north wall and ‘cupboards’ cut into the walls to hold ceramic and glass vessels. Many were found crushed on the floor when the vault collapsed. The pottery from this corridor consists of the classic forms of Jerash production in the mid-7th century: red and grey common ware, ribbed cooking pots, handled craters, small ribbed jars, horizontal-handled casseroles with matching lids, gargoulettes, and lamps with animal-head tenons (‘Jerash lamps’). One imported amphora, probably Egyptian, was also found.

The Hydraulic Sawmill Description This extraordinary installation in the southern cryptoporticus of the sanctuary of Artemis was discovered accidentally. Excavated first during the 1928–1933 Anglo-American campaigns, the outflow channel had been only partially cleared. Its excavation revealed abundant, often complete pottery deposited after the abandonment of the sawmill. The machine was probably constructed under Justinian but was short-lived due to unresolved technical problems, leading to its abandonment by mid-century. The pottery consists mainly of complete or near-complete vessels: 30 ribbed cooking pots with vertical necks and folded rims; 4 jars (one with white-painted decoration); 3 gargoulettes; 5 lanterns; 1 amphora from the Kellia; bowls, cups, jugs, casseroles with horizontal handles, fine ware bowls, and multiple grey-ware basins. Two notable closed forms are: a carinated vessel with two vertical handles in light brown clay (cat. 56), and a small pouring vessel (cat. 59) decorated on the shoulder, a form absent from Byzantine levels in the sanctuary of Zeus. This ceramic assemblage dates to the mid-6th century, matching the date proposed for the sawmill's abandonment.

| Century (AD) | Event (AD) attribution by original author |

Reliability of interpreted evidence |

Likely attributable seismic event (AD) |

Locality | Plan ref. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd–early 4th | Medium | 363 | Zeus Temple | 13 | Egan and Bikai 1998, 598. | |

| 6th | Late 6th | Medium | 551 | Lower terrace, Zeus Temple | 12 | Rasson and Seigne 1989, 151; Egan and Bikai 1998, 598; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 7th | 659/660 | Medium | 659 | Zeus Temple–Naos corridor | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019, 168. |

| 8th | 749 | Medium | 747–749 | Zeus Temple, various sites | 13 | Seigne 1986, 247; 1989, 322; Rasson-Seigne and Seigne 2019. |

| 11th–13th | 11th–13th | Medium | ? | Zeus lower terrace | 12 | Rasson-Seigne and others 2018, 74–75. |

- from Seigne (1986:247)

The advent of Christianity brought about the end of the sanctuary, which suffered the same fate as the other pagan temples of the city: transformations, reoccupations, and demolitions. The great temple and its staircase served as a quarry for the construction of the churches of Saint Theodore, Saint Damian and Saint Cosmas, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint Peter and Saint Paul. The lower terrace, built of soft limestone that was not much sought after, escaped demolition but was transformed into dwellings by subdividing the vaulted corridor.

The earliest preserved levels of reoccupation date to the end of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century. Large rooms, often paved with mosaics, then occupied the vaulted corridor, while a wooden portico linking them was constructed in front of the eastern façade along its entire length. A cistern with a capacity of 130 cubic meters, dug into the southwest corner of the courtyard, supplied water to this wealthy residence.

In the middle of the sixth century, at the moment when a first earthquake destroyed the peristyle of the great temple, the sanctuary was inhabited only by farmers and craftsmen. These sheds, annexes, kitchens, and animal enclosures occupied part of the courtyard; the cistern had become only a latrine pit, and refuse accumulated in the courtyard. Although badly shaken, the vaults of the corridor of the lower terrace did not collapse during this first seismic event. Only the western corridor was partially crushed by the fall of the columns of the great temple’s peristyle.

But once again, farmers and potters settled among the ruins. More sheds, kilns, and enclosures rose in what had once been the courtyard of the sanctuary. A century later, a new earthquake (748?) caused the complete collapse of the vaults and façades of the lower terrace onto these poor Umayyad structures.

Despite the terrible destruction, the area of the sanctuary of Zeus was not abandoned. Numerous signs of reoccupation have been found across the entire extent of the former temenos. They correspond to small agricultural installations that succeeded one another from the ninth to the eighteenth centuries. The occupation was certainly not continuous but interrupted by periods—sometimes long—of abandonment. It can no longer be claimed that Jerash was totally deserted during the medieval period.

The complete architectural evolution of this major eastern sanctuary, from its origins to the imperial period, allows us to understand its growing influence on the urban organization of Jerash. It also brings to light a part of the history of the city of Chrysoroas.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 22 June 2025

- from Gawlikowski (1992)

Coins of Constans II were found in the fill and on the ground surface, while locally minted Arab-Byzantine coins were recovered below the floor of the house. These finds suggest a terminus post quem in the mid-to-late 7th century CE for the destruction episode.

The author attributes the earlier destruction to the Jordan Valley Quake(s) of 659 CE based on stratified material and historical parallels. The reoccupation layer includes subsequent architectural development, including floors, installations, and new walls built directly into the cleared area.

A second collapse marks the end of occupation at the site. A coin dated to 770 CE was found in this upper layer. While no later materials were present, the final destruction is assigned to the end of the Umayyad period, in the late 8th century CE.

Later reuse of the site includes industrial activity, such as a lime kiln and pottery production, situated on top of the destroyed house, indicating post-quake adaptive reuse. The architectural and ceramic sequence shows a clear pattern of reuse, destruction, and redevelopment consistent with earthquake damage.

The material elements found in the filling correspond only to the last periods of use of the tank as a septic tank-dump (see above and below). This function was not its primitive function: the presence of a sealing coating, a draw port, the traces of wear left by the ropes on the edges of the margin alone prove that its primary function was that of water reserve. We also know that the curb was dismantled at least once before the installation of layer 3 (see above). This dismantling, made obligatory by the narrowness of the passage (0.39 m), must, in all likelihood, correspond to the last cleaning of the cistern as a water reserve. The date of construction of this tank is therefore of all materials indeterminable according to the furniture discovered in the filling. It can only be identified by the analysis of a series of external indices, in particular the water supply system.

We know that the cistern was not provided for in the original plan for the development of the terrace: the paving of the courtyard, set up at the earliest in the 70s of our era24 is sloping not towards it but towards the south door of the sanctuary, in the axis of which was found the rainwater drainage channel.

Only one water pipe led to the cistern: the simple gully dug into the pavement of the courtyard, in front of the first step of the monumental staircase leading to the great temple erected in 163 AD on the upper terrace. It must therefore be admitted that it was fitted out after the construction of the grand staircase, from which it collected runoff, and before the dismantling and reuse of the blocks of it for the construction of churches in the Byzantine era. The construction of the cistern must therefore be placed between the end of the second century AD and the beginning of the 6th century AD.

An additional clue could be provided by the blocks of the margin: the quality of the execution in the face, the presence of frames of anatyrosis on the faces of the joint are reminiscent of a work of good time rather than a Byzantine realization. Conversely, the traces of wear found on the walls, due to the friction of the ropes, are few and shallow, i.e. that the tank has been used in a low-intense way, which is in contradiction with its storage capacity (125 m3; volume actually stored according to the traces found on the walls: 95 m3), or that it was used for a short time. There is also no evidence that the curb was executed for this tank. These were blocks in reuse.

In fact, the solution lies more simply in the answer to the question: why was it suddenly necessary to store water in large quantities on the terrace of the sanctuary?

Obviously, throughout the Roman period, the problem was mainly to evacuate as completely as possible the rainwater from the entire lower terrace: paving of the courtyard, regular slope, drainage channel. Water was then a disadvantage and not a necessity.

It was quite different in the Byzantine epoch. As the excavation has shown, the sanctuary is then transformed into a vast religious complex. Chapels paved with mosaics but also housing occupy the former domain of Zeus whose vaulted corridors are then divided by transverse walls.

The installation of this Christian community (monastic?), which the study of mosaic pavements makes it possible to locate at the end of the fifth century, could not be done without a permanent supply of drinking water. A cistern became necessary. Its location was first and foremost, and naturally, chosen at the low point of gathering the waters of the courtyard, in front of the entrance to the drainage canal. Unfortunately in this sector the subsoil is very heterogeneous: natural rock very fractured and steeply sloped to the west, earth embankments to the east and north, foundations of the wall of the sanctuary to the south. The work was abandoned after a few meters as the excavations have shown. The final location, chosen because of the qualities of the subsoil, totally rocky, but completely eccentric, allowed to naturally collect only a tiny part of the rainwater. A canal, dug into the pavement and gathering all the runoff from the staircase leading to the upper temple, provided a solution to this problem.

The use of the cistern as such was short-lived, a century at most, as evidenced by the material contained in layer 3: in the second half of the 6th century it is no more than a septic pit. This transformation is to be put in direct relation with the dismantling of the staircase of access to the upper temple and the reuse of steps in the construction of churches. Deprived of its "reception basin" the tank became an empty tank.

The dismantling of the staircase seems directly linked to the abandonment of the religious installations, itself following an iconoclastic looting: all the inscriptions of the mosaic pavements were systematically destroyed and their fragments thrown out of the windows25. It is tempting to see in this destruction the mark of the violent events that occurred in Jeraseh at the time of the great monophysite crisis at the beginning of the 6th century. If this were the case, it could be said that, in all likelihood, the sanctuary then housed a Monophysite community, the whole not being reoccupied after the victory of the Chalcedonians, but on the contrary partly dismantled to build the churches of representatives of the Chalcedonian clan26.

From the middle of the 6th century the lower terrace is again occupied, but by simple farmers-breeders and some artisan potters. The old cistern, transformed into a septic tank-dump, is gradually filling up. A sewer has just hollowed out its wastewater loaded with organic materials, while jars and various containers, previously pierced, are regularly thrown there. The presence of such a mass of containers (about a thousand), largely of the same type (89% jars), remains unexplained. At most, the hypothesis can be formulated of the easy disposal of a series of scraps, which would have been done on a very regular basis for a large number of years.

One night in June 65827 a violent earthquake destroyed the small Byzantine agro-artisanal installations. The entire area was then abandoned and the paving of the courtyard, until then carefully maintained, was covered with a thick layer of red clay.

Driven by runoff, part of this material enters the tank in the process of natural drying, until the supply channels are obstructed by clay deposits.

During the terrible earthquake of 746/747 it will be used one last time as a mass grave to bury, at little cost, victims of the earthquake, human and animal, before being hermetically clogged and definitively abandoned.

Many questions remain unanswered for the moment, many conclusions, very hypothetical, will probably have to be modified, but the general history of this cistern seems very representative of the late transformations undergone by the former domain of Olympian Zeus28.

24 J. Seigne et coll. Recherches sur le sanctuaire de Zeus a Jerash dans J.A.P. I.

25 Many fragments of these pavements were found at

the foot of the eastern façade of the sanctuary,

overlooking the upstairs windows, during the

excavation of the Byzantine levels of the street leading

from Oval Square to the South Gate. The fragments of

inscription collected, too incomplete, remain for the

moment silent. The restoration work under way may

soon make these snippets of text understandable.

26 These suggestions are presented only as mere

research hypotheses.

27 See note 3.

28 We thank Jean-Baptiste I. Lambert and Jean-Michel

de Tarragon, as well as Maurice Sartre for the

assistance they have given us in the elaboration of

this article.

Around fifteen ceramic objects were found in this layer. Most of them are fragmentary. They consist mainly of common wares: cooking pots, amphorae, bowls, basins, and similar items, datable to the end of the Byzantine period or the middle of the Umayyad period.

A fragment of a painted bowl (cat. 27) is very characteristic of this period. These are bowls with a thick and nearly vertical wall and a beveled rim, made of a hard fabric of beige-pink color. The decoration, geometric or vegetal and painted in red, often covers the entire outer surface including the rim. In this example it consists of bands of red paint. These bowls are dated to the eighth century.

The fragment of a cooking plate (cat. 28) can also be dated to this period. It belongs to the tradition of Byzantine cooking plates and has many parallels at Jerash, at Pella, and elsewhere.

A fragment of grey ware also comes from this layer (cat. 29). It is the rim of a large basin with a slightly outward-flaring upper wall and a T-shaped lip with a central ridge. This fragment illustrates the evolution of these hand-built, grey-slipped basins, which occur in large numbers at Jerash beginning in the sixth century and whose initially angular profiles become more rounded over time.

Two types of cooking pots are represented in this level. The first (cat. 30) is a cooking pot with a carinated body and a vertical neck, characterized by a thick and curved wall. This type of cooking pot is known in the Umayyad period, and several examples are attested at Jerash, generally dated to the first half of the century, before 749.

The second type (cat. 31) is represented by a cooking pot with a globular body and a short flaring neck. This form is very common in the Umayyad period and has a long continuity, although it is generally completely glazed in later times. A fine ware, perhaps imported, is characterized by a very fine fabric containing few tempering particles and having a light color (beige or tan). The objects themselves are remarkable: two necks of small jugs with molded profiles (cat. 33–34), the spout of a bottle with white painted decoration (cat. 35), and the handle of a lantern with white painted decoration and a bird’s-head motif in relief with the eye details incised (cat. 36). These may be connected with the non-ceramic material from this layer, which is notable for its rarity: worked ivory objects, stone vessels, and similar items.

The dating of this ceramic assemblage poses little difficulty. A comparative study of the types represented leads us to place the material in the eighth century, probably in the first half of the century and very likely before the earthquake of 749. This dating is confirmed by the Umayyad coin found in this layer. Struck at Jerash, its minting date falls between 694 CE and 710 CE.

The pottery from the Byzantine and Umayyad periods discovered during the excavations of the French team at Jerash has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive study, although several preliminary works have outlined the main lines of its typochronology. The clearing of undisturbed structures containing archaeological material in situ makes it possible to associate ceramic productions—mostly local—with sealed occupation contexts well dated by stratigraphy from the mid-6th to the mid-8th century. Three closed assemblages were selected for the clarity of information they provide:

- a cistern discovered during the clearing of the courtyard of the lower terrace of the sanctuary of Zeus

- the southern vaulted corridor of the naos of Zeus

- the room containing the remains of the hydraulic saw, located at the eastern end of the north cryptoporticus of the sanctuary of Artemis.