Baalbek

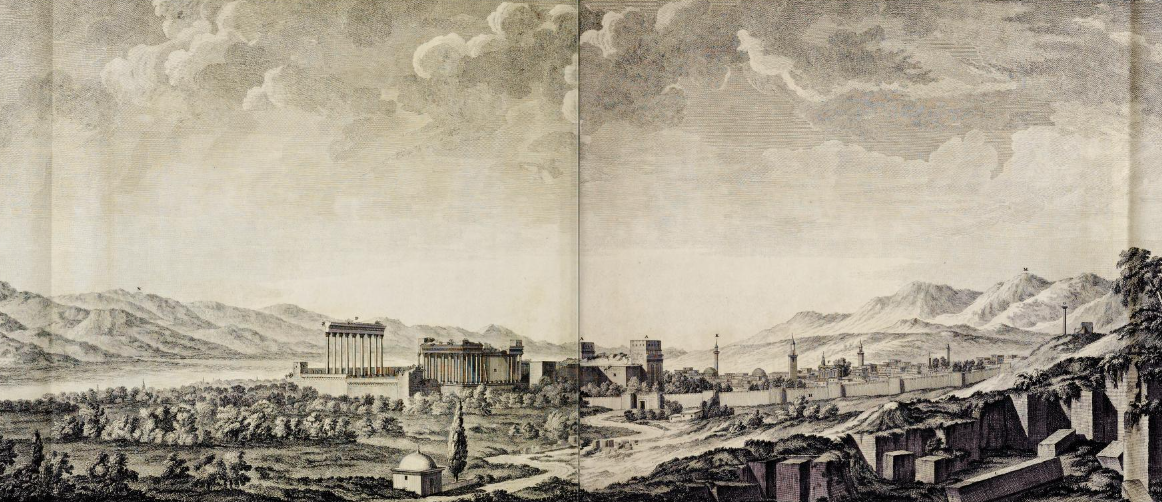

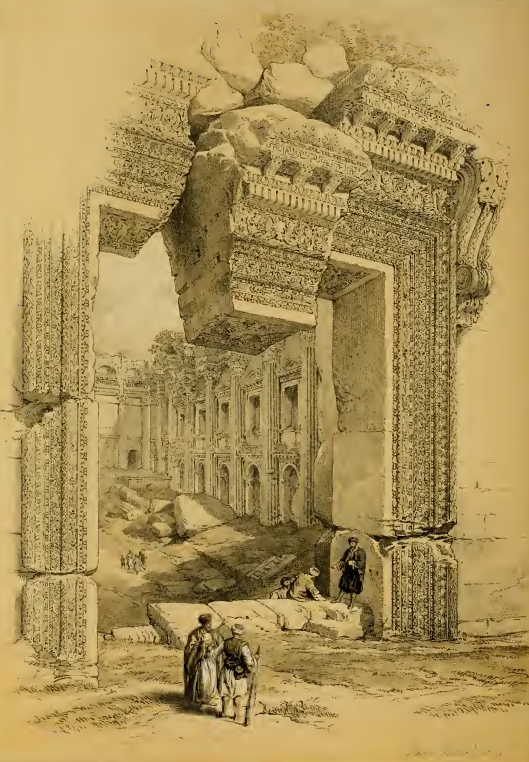

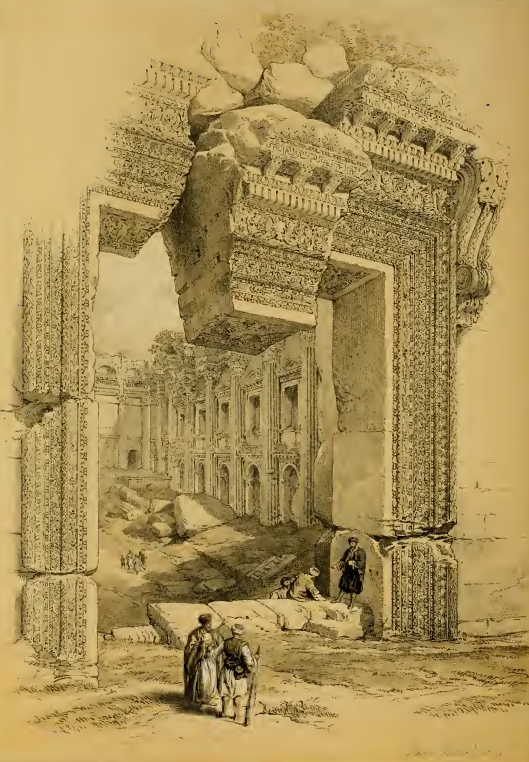

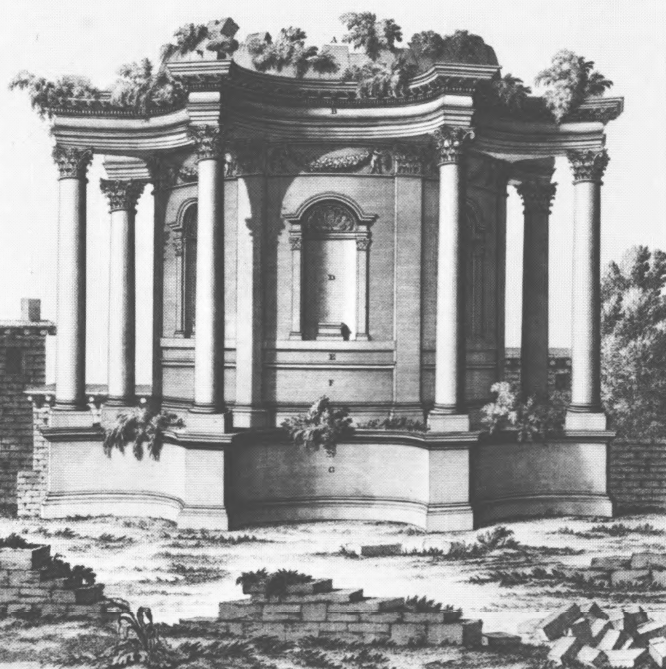

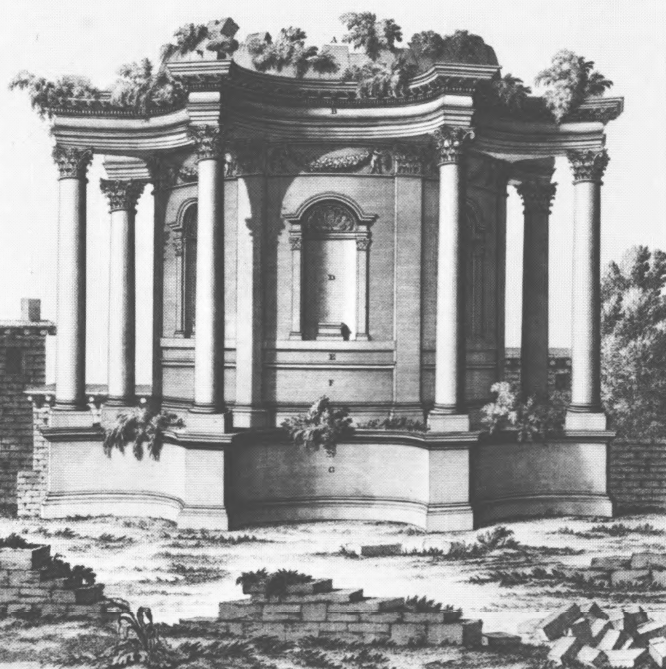

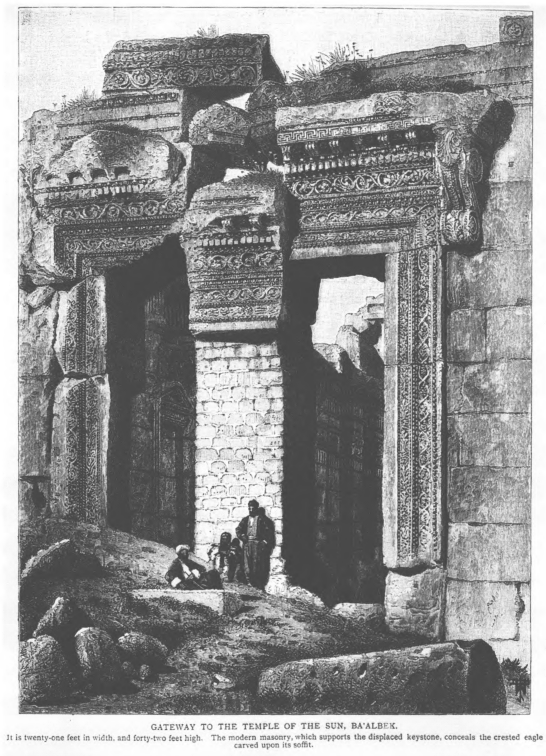

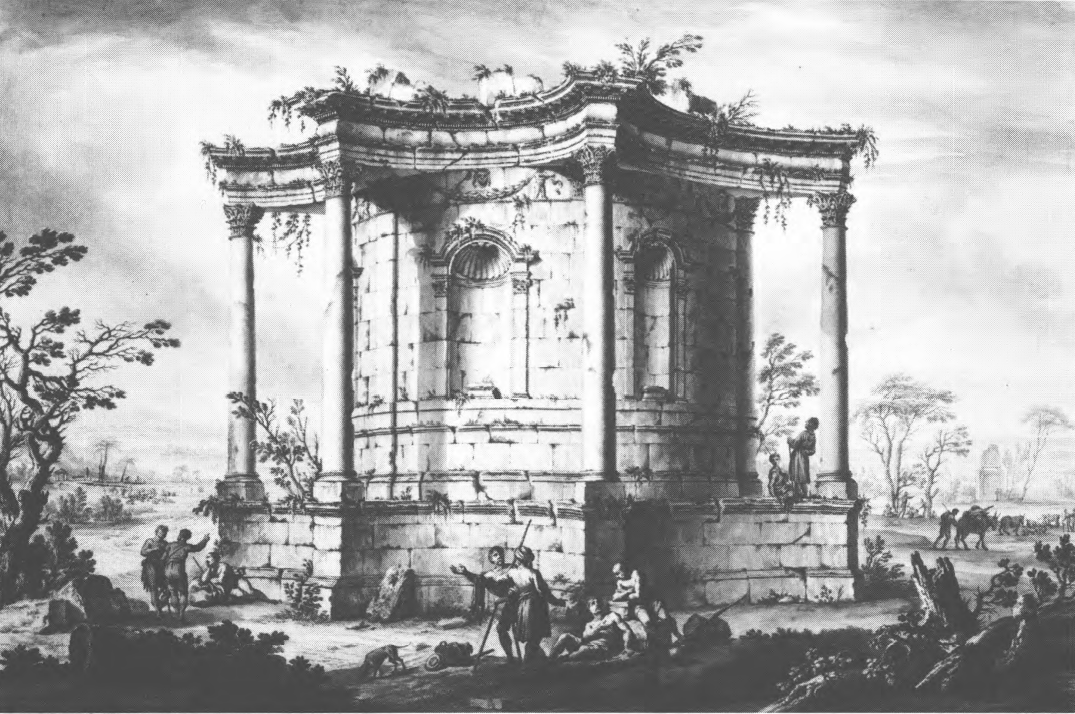

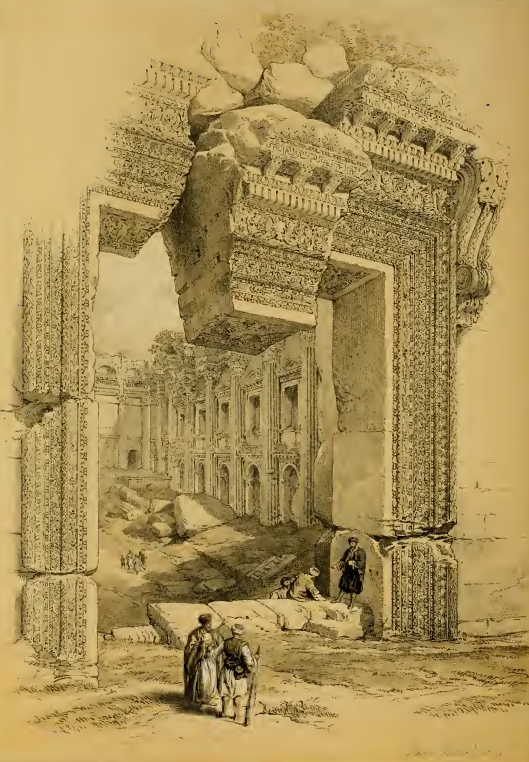

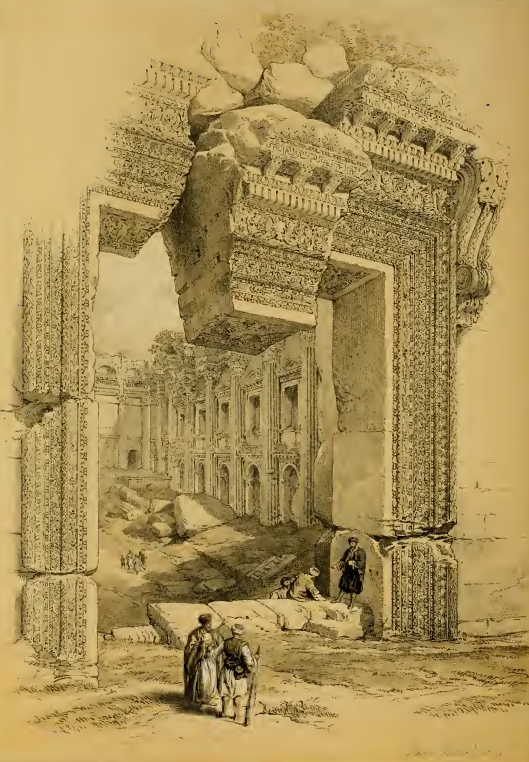

Drawing of Baalbek around 1751 CE

Drawing of Baalbek around 1751 CEWood (1757)

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Baalbek | Arabic | بعلبك |

| Baalbek | Syriac-Aramaic | ܒܥܠܒܟ |

| Belbek | Hebrew | בעלבק |

| Heliopolis | Greek | Ἡλιούπολις |

| Heliopoleos | Latin | Heliopoleos |

Baalbek is located east of the Litani River (classical Leontes) in the Beqaa Valley (وادي البقاع) ~85 km from Beirut. The Beqaa Valley, known as Coele-Syria in classical times, is bordered on the west by the Lebanon mountain range and to the east by the Anti-Lebanon range. Two springs, Ras al-'Ain and 'Ain Lejouj, a short distance away, provided caravans with water in antiquity. Baalbek is strategically placed at the highest point on a well-established trade route from Tripoli that led into the Beqaa before proceeding to Damascus or to Palmyra in Syria (Meyers et al, 1997).

Test excavations at Baalbek in 1964-1965 revealed the Bronze Age tell beneath the Great Court of the Jupiter temple. Traces of settlements dating to the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1700 BCE) were found. Other minor remains were dated to the Early Bronze Age.

In the third century BCE, when Syria became a possession of the Lagid successors of Alexander the Great who ruled from Alexandria, Baalbek was given the Greek name Heliopolis. The Macedonians must have equated the Baal of the Bekaa with the Egyptian god Re and the Greek Helios, with the purpose of establishing closer religious ties between their new dynasty in Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean world. In the second century BCE, the Seleucids, successors of Alexander who ruled from Antioch, invaded Coele Syria and drove the Lagids back to Egypt. The podium of the Jupiter temple probably dates to this period. Between 100 and 75 BCE, Baalbek was ruled by a hellenized Arab dynasty, the Itureans. In 63 BCE, the Roman emperor Pompey passed through Baalbek on his way to conquer Syria. He was succeeded by his son, who was put to death by Marc Antony. Marc Antony then gave all the Syrian territories, including Baalbek, to Cleopatra. In about 16 BCE, Augustus settled veterans of the same Roman legions in Beirut (Berytus) and Baalbek. It was then that building was begun on great Temple of Jupiter.

In the second century CE, the Great Court, with its porticoes, two altars, and two vast lustral basins, was added to the temple. At the same time construction of the Bacchus temple began. It was completed in the third century, at the same time that the Propylaea were erected and the Hexagonal Court added.

In about 330, Christianity became the official religion of the region and the Byzantine Emperor Constantine closed the temples. Emperor Theodosius destroyed them and tore down the Altar of Sacrifice and the Tower in the Great Court, replacing them with a Christian church in approximately 440. By this time the Temple of Jupiter was probably already in ruins as the result of an earthquake. Numerous architectural elements taken from the Heliopolitan Jupiter temple were reused in building the church.

In 636, after the battle of the Yarmuk River, the entire province of Syria fell to the Arabs. Mu'awiyah founded the Umayyad dynasty in 661 and took possession of the Byzantine mint at Baalbek, showing the name Baalbek inscribed in Arabic letters on the coins. Thus, the name Heliopolis, which had been in use for about a thousand years, was replaced with its original Semitic name. The temple area was transformed into a citadel and Baalbek fell successively into the hands of the 'Abbasids, the Tulunids, and the Fatimids.

During the eleventh-twelfth centuries, Baalbek suffered from floods and earthquakes and the passage of several plundering armies. The city fell to Salah ad-Din (Saladin), founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, in 1175. The Mongols arrived in Baalbek in about 1260, sacking it and destroying its mosques; they were soon overhrown by the Mamluks, however. (The Mamluks were enfranchised slaves purchased by the last Ayyubid ruler for his army. They constituted the bulk of his army in general and of his court in particular). Under the Mamluks (and until the Ottoman occupation in the sixteenth century) Baalbek enjoyed a period of calm. The fine architecture of the city's Fortress must be attributed to this period.

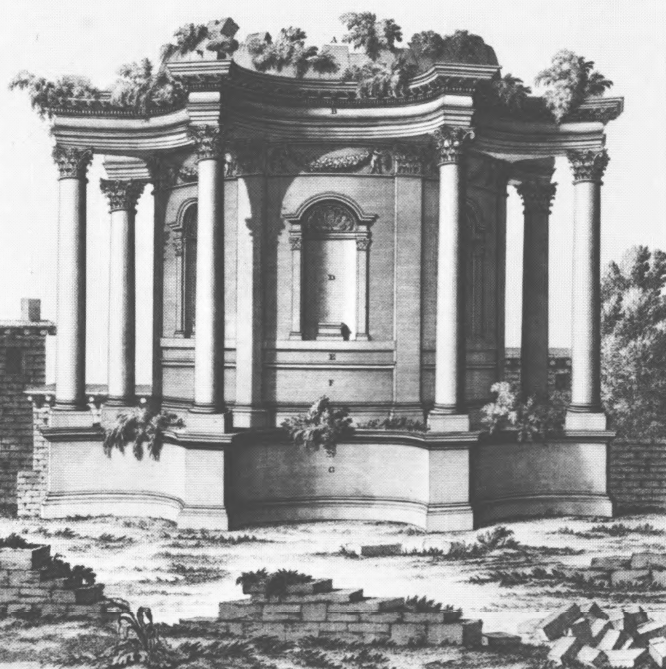

- Portico, which formed the grand front to the buildings A. B. C. D.

- Hexagonal court, to which the portico A leads

- Quadrangular court, to which the court B leads

- Great temple, to which the approach was through the foregoing portico and courts

- The most entire temple

- The circular temple

- A Doric column, whose shaft consists of several

pieces, Standing single on the elevated south-west

part of the city, where the walls include a little

of the foot of Antilibanus. We discovered nothing, either in the

size, proportions, or workmanship this column, for remarkable as a little

bason on the top of it’s capital, which communicates with a semicircular channel, cut longitudinally

down the side of the shaft, and five or fix inches

deep. We were told that water had been formerly conveyed from the bason by this

channel; but how the bason was supplied we could not

learn: as it greatly disfigures the shaft of the column, we suspect it to be a modern contrivance.

The small part of the city, which is at present inhabited, is near the circular temple, and to the south and south-west of it. We did not think the Turkish buildings worth a place in this plan; but the reader may see a view of them in the following plate. A great deal of the space within the walls is entirely neglected, while a small part is employed in gardens; a name which the Turks give to any spot near a town where there is a little shade and water. - The city walls, which, like those of most of the ancient cities of Asia, appear to be the confused patch-work of different ages. The pieces of capitals, broken entablatures,' and, in some places, reversed Greek inscriptions, which we observed in walking round them, convinced us that their last repairs were made after the decline of taste, with materials negligently collected as they lay nearest to hand, and as hastily put together for immediate defence.

- The city gates: they correspond in general with what we have said of the walls; but that which is on the north side presents the ruins of a large subassement, with pedestals and bases for four columns, in a taste of magnificence and antiquity much superiour to that of the other gates. The ground immediately about the walls is rocky, and little advantage is taken of a command of water, which might be much more usefully employed than it is at present in the gardens. Some confused heaps of rubbish, which appear to have belonged to ancient buildings, both within and without the walls, are too imperfect to deserve notice.

Plate I

Plate IPlan of the city of Balbec, (showing only the situation of the ancient buildings which remain

- Portico

- Hexagonal court

- Quadrangular court

- Great temple

- The most entire temple

- The circular temple

- A Doric column

- The city walls

- The city gates

Wood (1757)

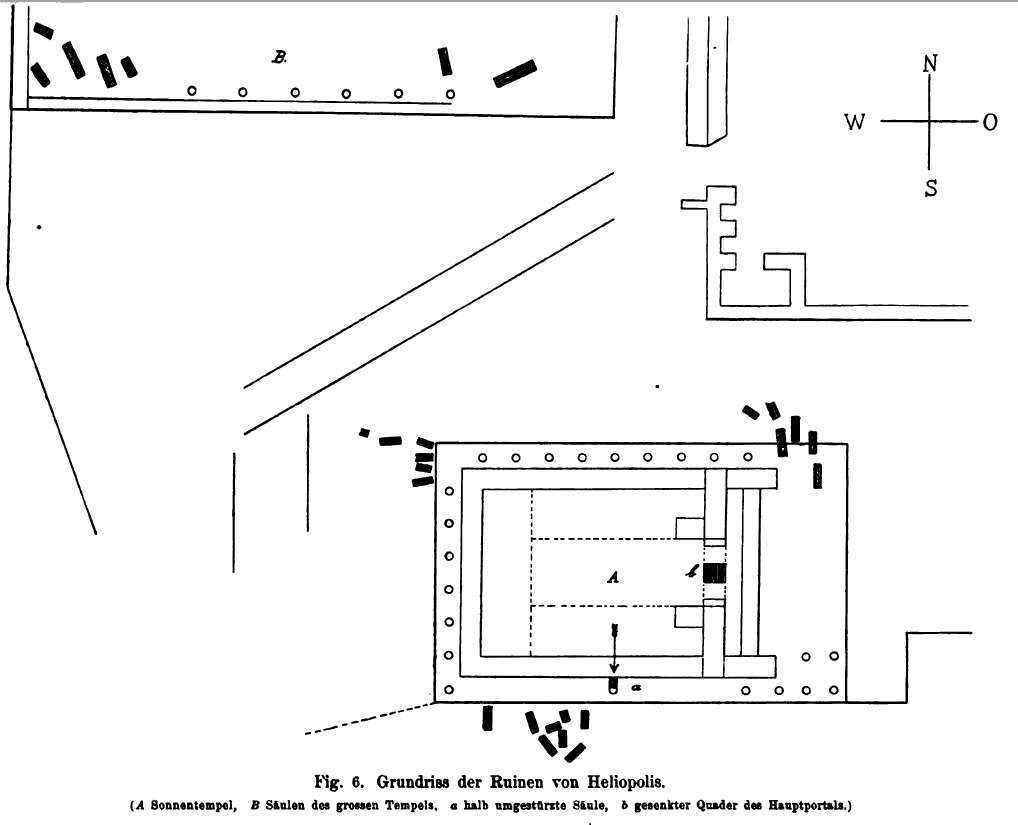

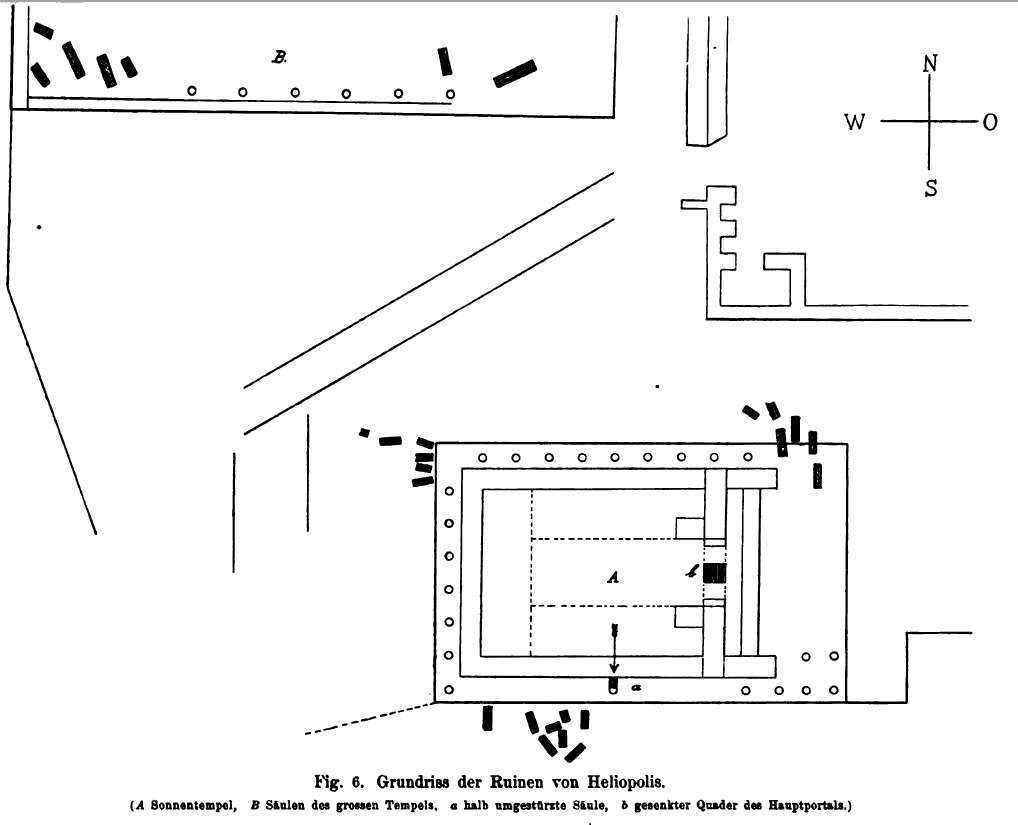

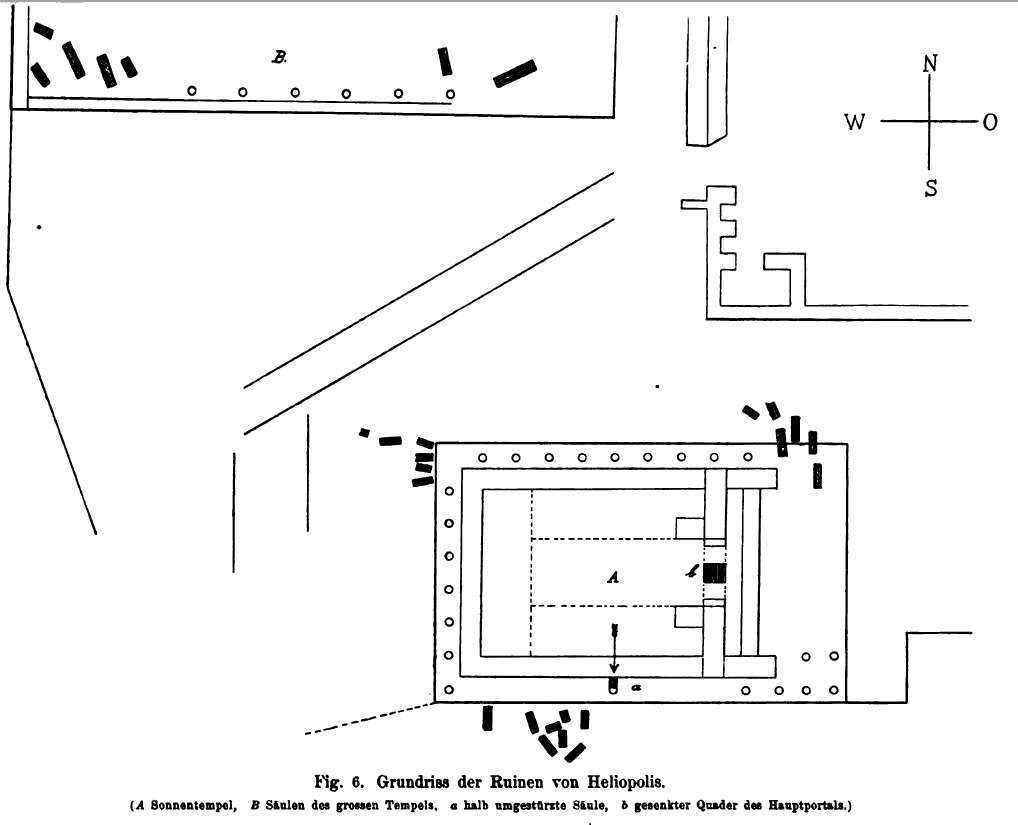

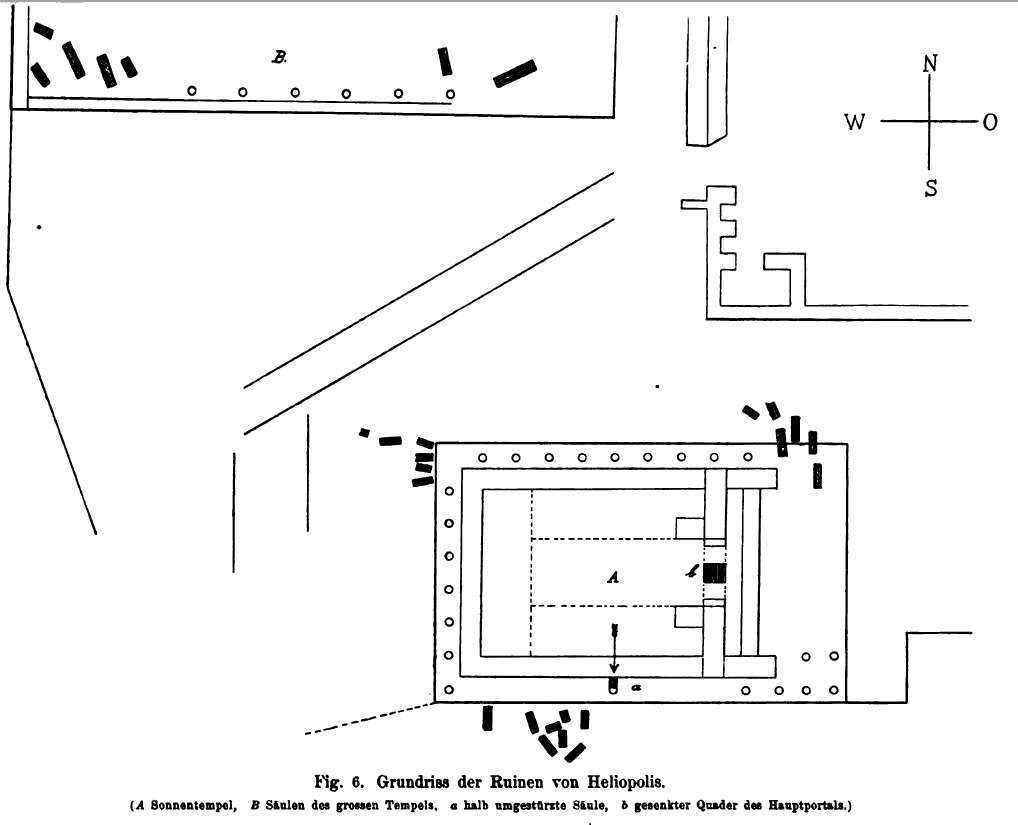

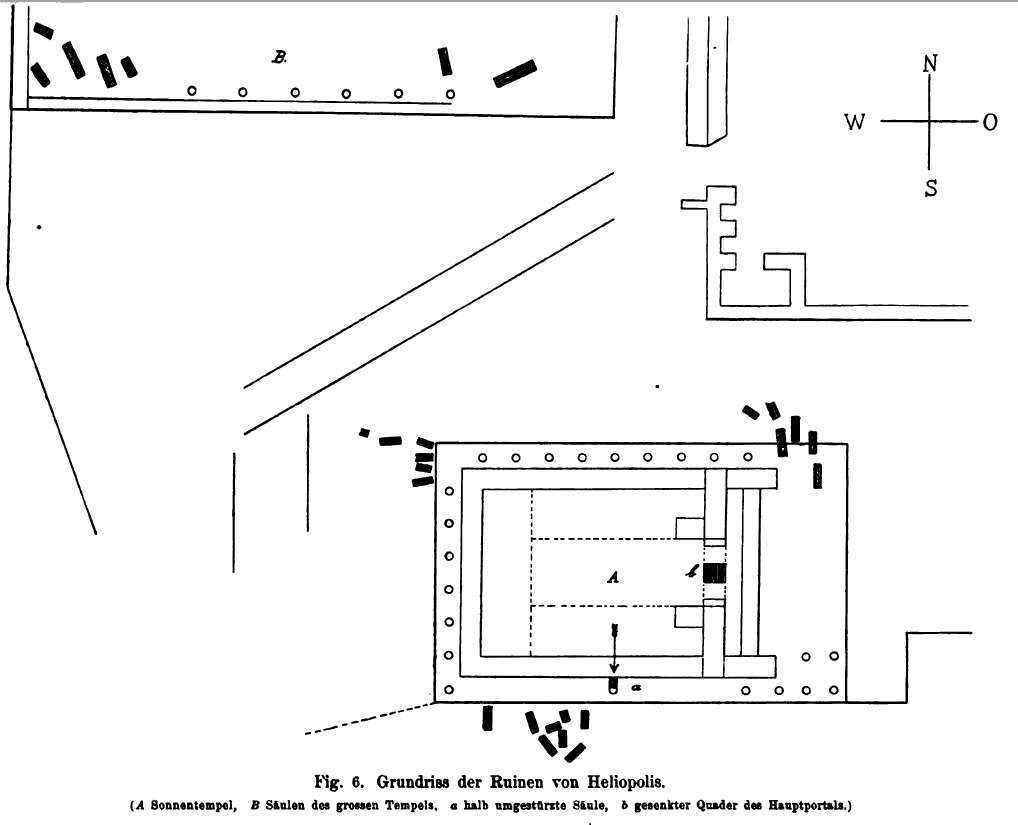

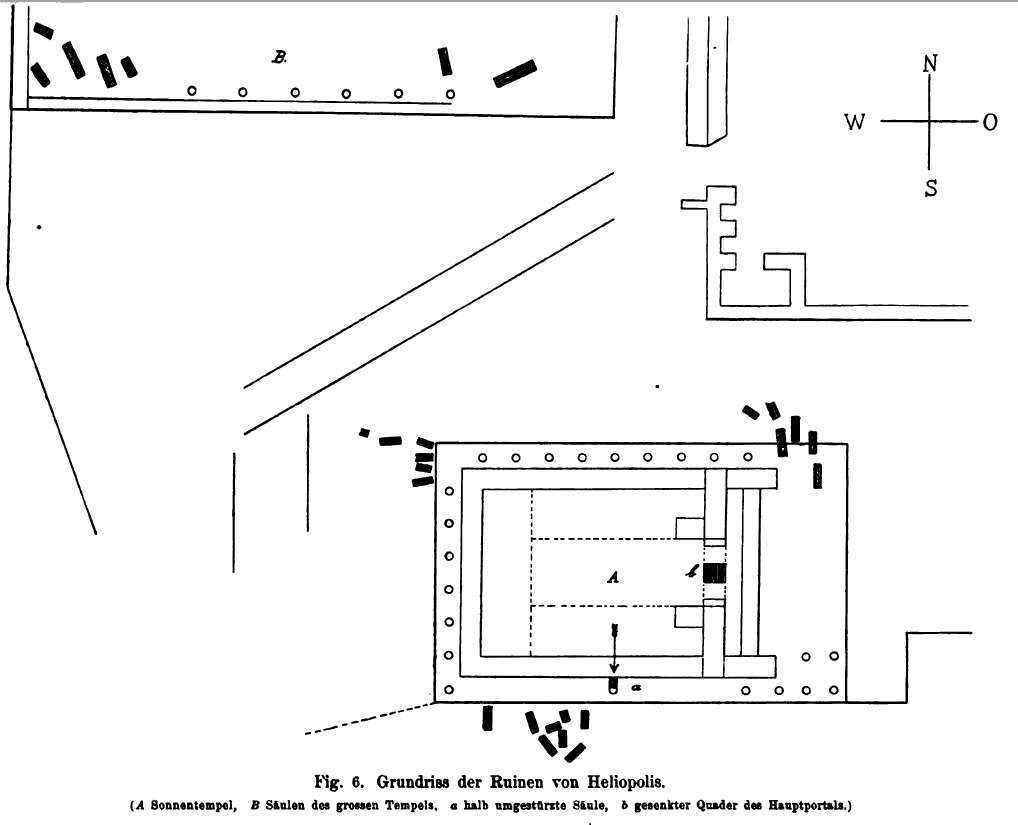

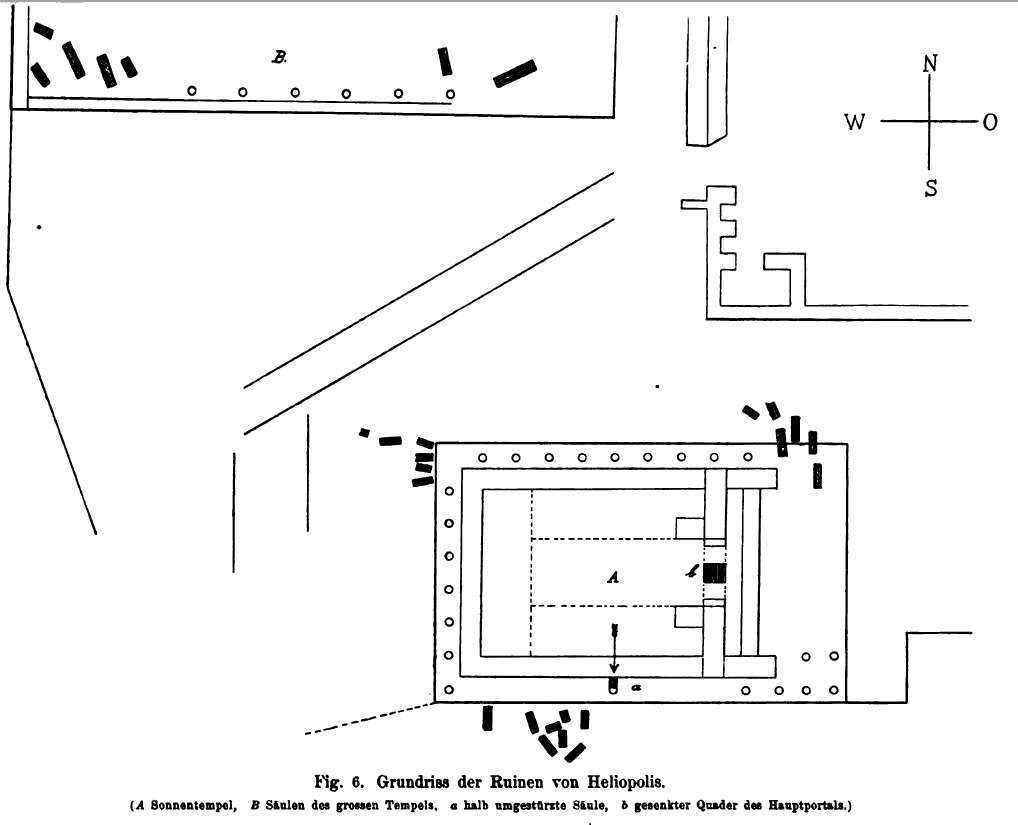

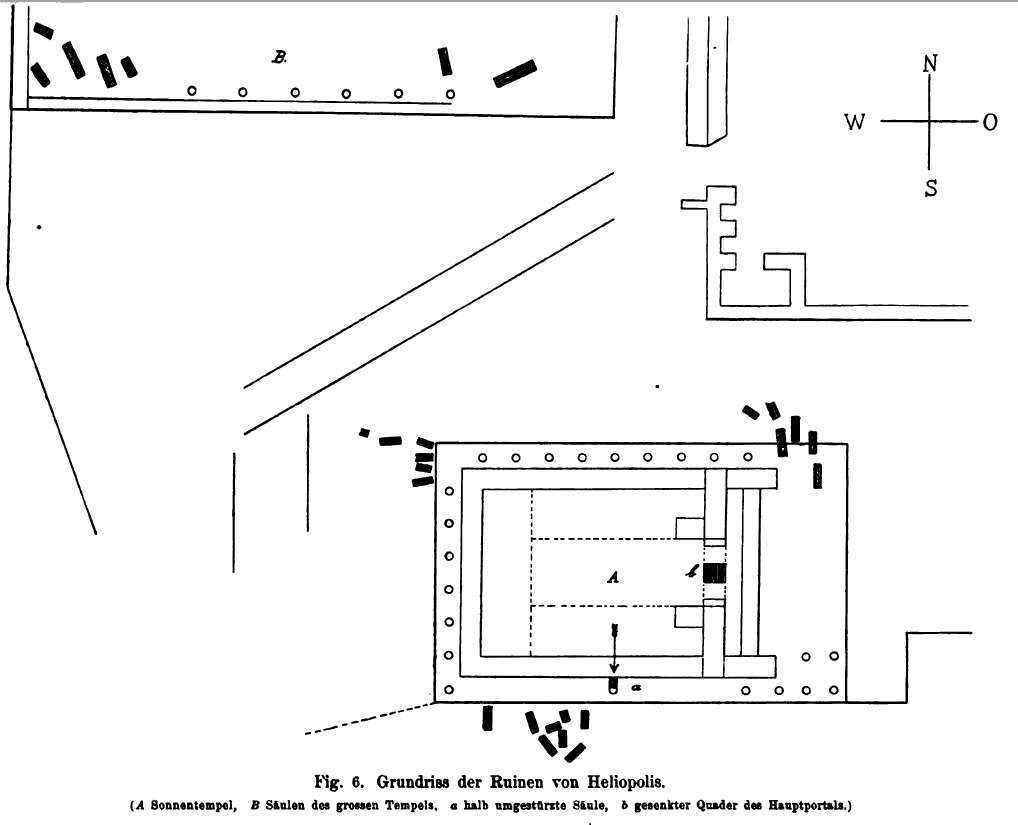

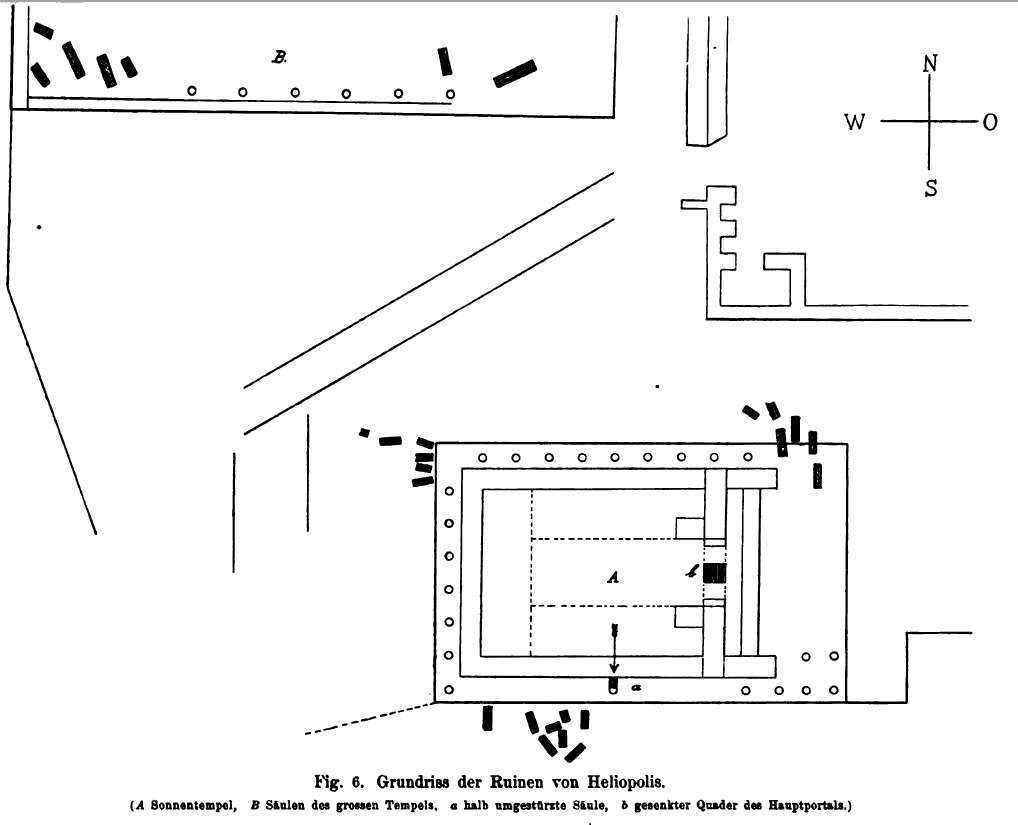

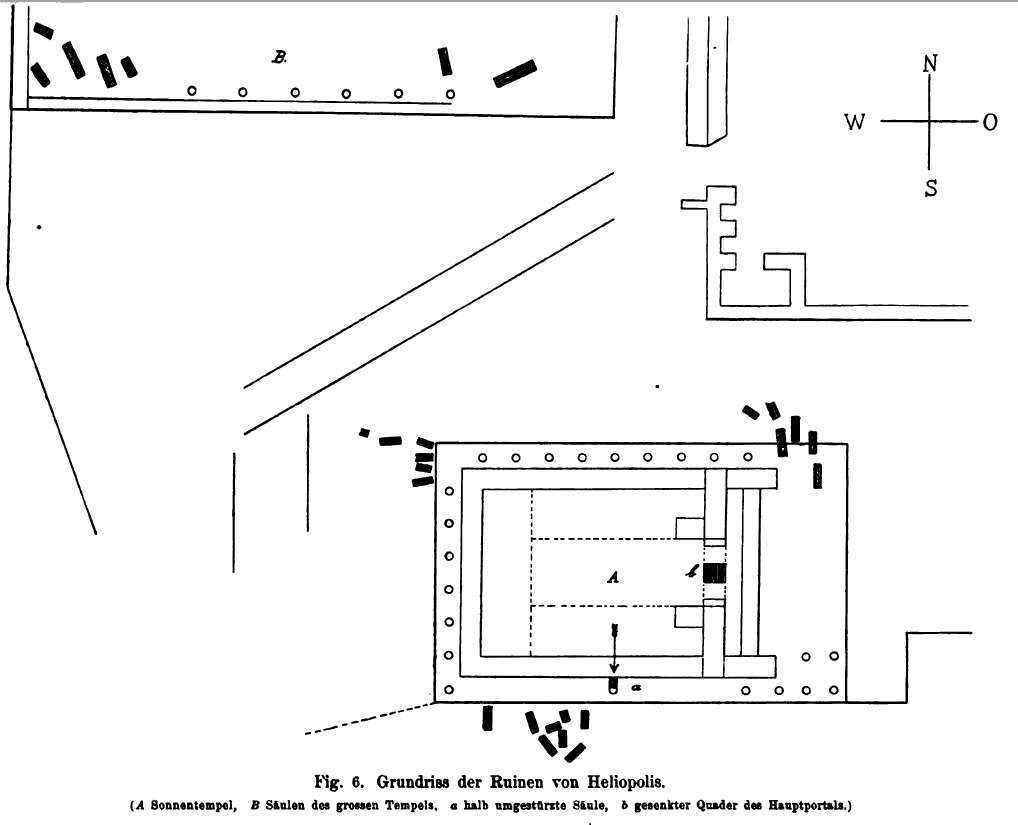

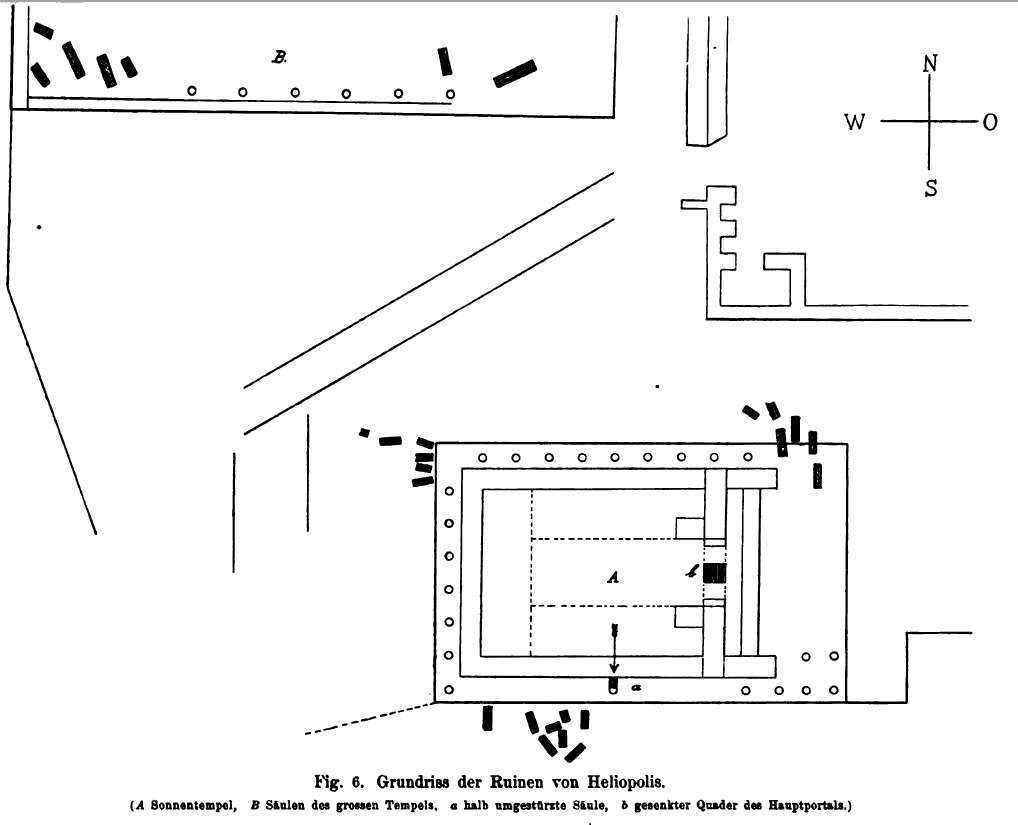

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

- Sun temple

- pillars of the great temple

- half fallen pillar

- lowered ashlar of the main portal

Dienner (1886)

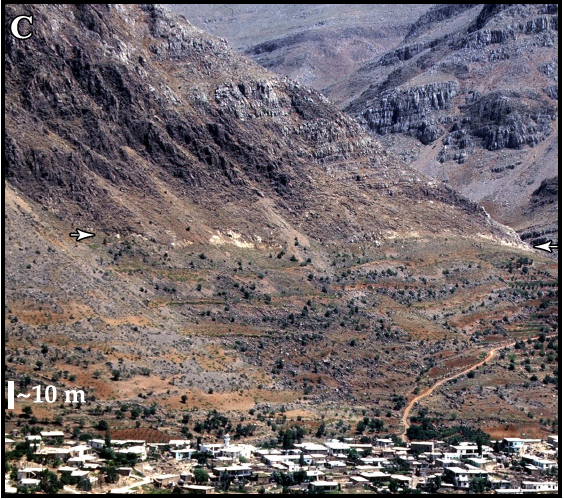

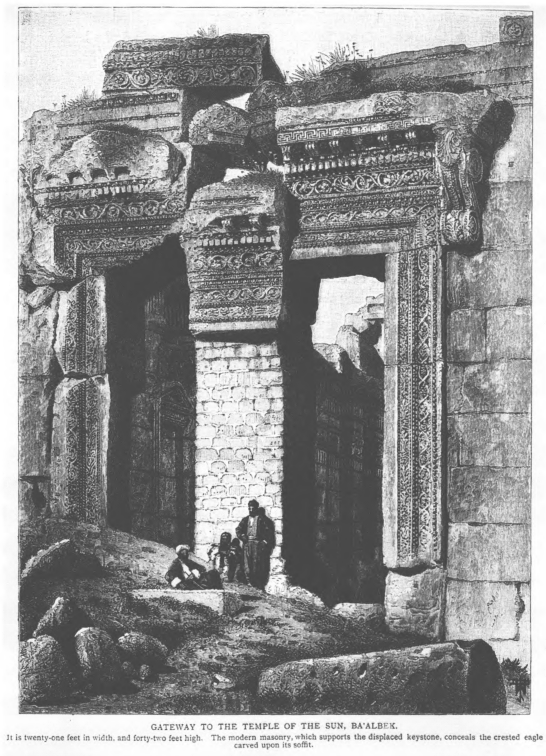

- Fig. 6.6a - Slipped keystone

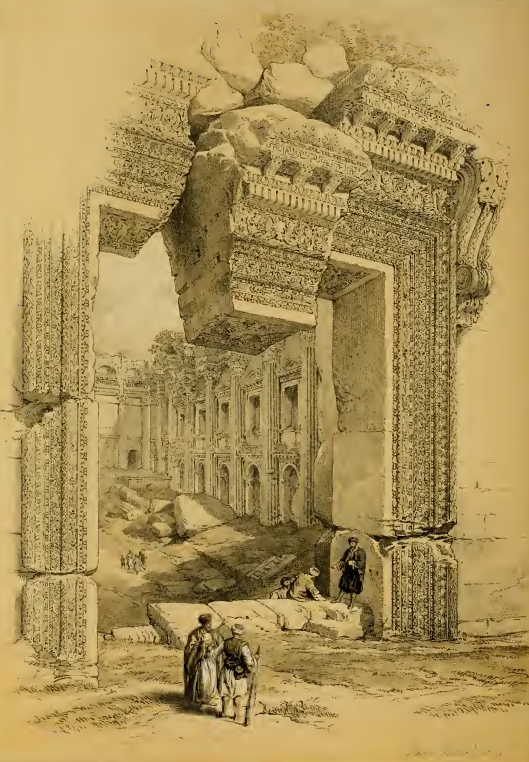

over the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.6a

Fig. 6.6a

Rich decorated flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.6b - Detailed view

of the slipped keystone over the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.6b

Fig. 6.6b

Detailed view of the flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus

Rababeh (2005) - Photo from 1843 of the

Hexagonal Court in the Temple of Jupiter at Baalbek from Metropolitan Museum of Art the

- Baalbek from Roberts (1855)

Baalbec

Baalbec

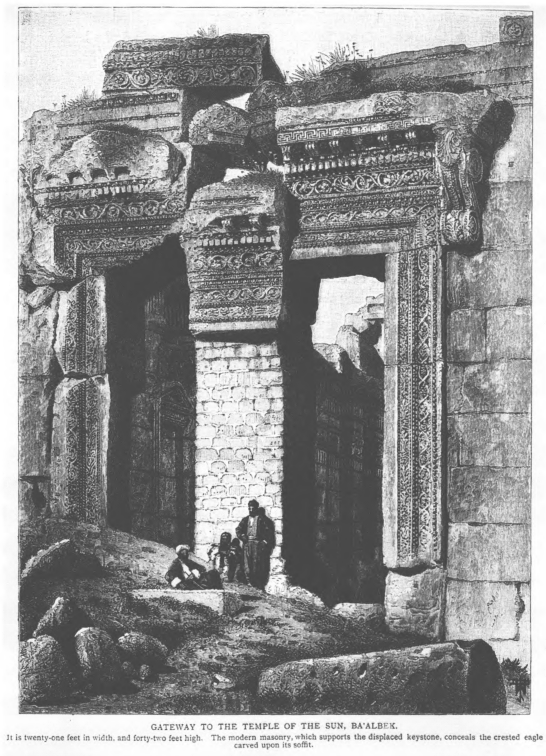

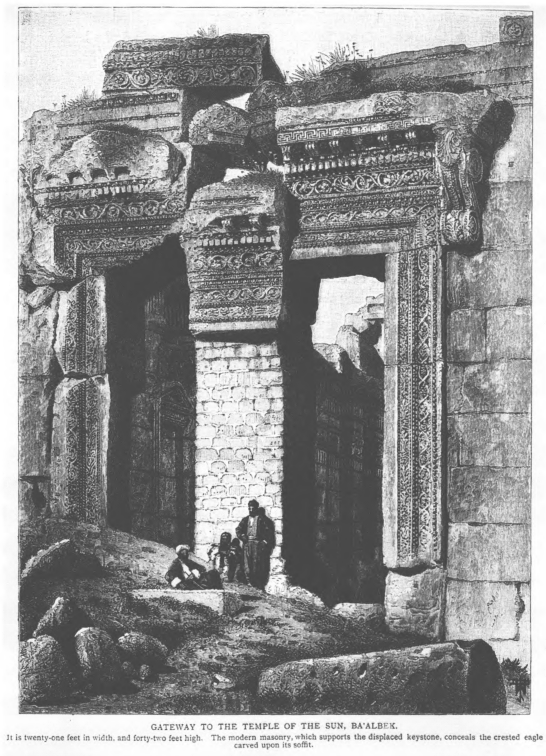

Roberts (1855) - The slipping keystone of Baalbek

from Roberts (1855)

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser Temple

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser Temple

Roberts (1855) - 'Round' Temple of Baalbek

from Roberts (1855)

Circular Temple at Baalbek

Circular Temple at Baalbek

Roberts (1855)

AD 1042 Tadmur

An earthquake caused great loss of life in Tadmur in

Syria. It is said that Baalbek was also shaken.

This information is given by a single source,

which does not comment on the effects on Baalbek,

or specify whether Baalbek was shaken by a different

earthquake. It is likely that

the Tadmur earthquake was felt only at Baalbek.

Al-Suyuti (writing in the sixteenth century)

records this event as happening in the same year as

an earthquake in Tabriz. He does not comment on the

effects on Baalbek, but, since the two cities are 250 km

apart, if Baalbek was not shaken by a different earthquake,

it is likely that the Tadmur earthquake was felt

there only.

‘. . . in the year 434 [21 August 1042 to 9 August 1043], . . . an earthquake occurred at Tadmur and at Ba’albek: most of the population of Tadmur died under the ruins.’ (al-Suyuti Kashf 56/18).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

(021) 1042 August 21 – 1043 August 9 [434 H.] Palmyra [central Syria]

sources

- al-Suyuti, Kashf p.32

- Taber (1979)

- Sieberg (1932a)

- Ben-Menahem (1979)

- Ambraseys & Melville (1982)

catalogues p.

- Poirier & Taber (1980)

- Bektur & Alpay (1988)

- al-Hakeem (1988)

The little information we have about a destructive earthquake in northern Lebanon and central Syria between 21 August 1042 and 9 August 1043 comes from a brief mention by the 15th century Arab historian al-Suyuti, who records:

“The earth shook at Palmyra [Tudmur] and Baʿalbek. Most of the inhabitants of Palmyra died in the ruins.”

Guidoboni, E. and A. Comastri (2005:80-83). Catalogue of Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Mediterranean Area from the 11th to the 15th Century, INGV.

〈068〉 1042 August 21 – 1043 August 9

Palmyra and Baalbak

Intensities

- Palmyra: >VII

- Baalbak: V

- Tabriz: III

- Egypt: III

Al-Suyuti: In the year 434 A.H. (1042 August 21–1043 August 8), an earthquake occurred in Palmyra and Baalbek. Most people in Palmyra were killed under the debris.Parametric Catalogues

- Ben-Menahem (1979): 1042 August 21, 35.1°N, 38.9°E, near Palmyra, ML=7.2, destruction of Palmyra. It was strong in Baalbak and felt in Tabriz and Egypt.

- Sieberg (1932): 1042 August 21, a strong widespread earthquake was felt in Tabriz and Egypt. The center appears to have been at Palmyra, where it killed most of its inhabitants. It was felt strongly in Baalbak. Victims were estimated at 50,000.

Sbeinati, M. R., R. Darawcheh, and M. Monty (2005). "The historical earthquakes of Syria: An analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D.", Annales Geophysicae 48(3): 347–435.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Palmyra (aka Tadmur) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

- Due to reports of continual decay, vandalism, stone-robbing, etc. to the Ruins of Baalbek during this time, it is difficult to identify all of the potential seismic damage.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Fallen Columns | Peristyle of the Great Temple (aka the Temple of Jupiter)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

Dienner (1886) |

Figure 1

Figure 1G.B. Borra 1751 'View of both temples, in their present state, from the south' Lewis (1999)

Figure 3

Figure 3J. Bruce, 1767: Baalbek, the west side of the smaller temple and the six columns of the larger temple Lewis (1999) |

|

| Dropped Keystones in Arches | Keystone of the soffit of the door of the lesser Temple

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

Dienner (1886) |

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser Temple

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser TempleRoberts (1855)

Figure 9

Figure 9F. Frith, 1857-58 : Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple Lewis (1999)

Figure 9

Figure 9Photograph, c.1880: Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple, the keystone supported by 'Burton's wall' Lewis (1999)

Fig. 6.6a

Fig. 6.6aRich decorated flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.6b

Fig. 6.6bDetailed view of the flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus Rababeh (2005) |

Lewis (1999:242) noted that the

monumental doorway of the smaller temple remained intact prior to 1759 CE.

Nor can there be any doubt that the monumental doorway of the smaller temple, with its elaborately carved lintel, remained intact in this period. The joints between the three blocks of stone of which the lintel is composed were evidently so perfect in the earlier part of the period that Monconys (1665, 348-9) and la Roque (1723, 136-7) thought that it consisted of a single piece of stone; Pococke (1745, 109) was the first to realise that there were three. None of the travellers says that there was any structural damage to the lintel, although its sculptured decorations had been damaged (Monconys 1665, 349; Nijenburg 1759, 274; Dawkins 1751, quoted below)Volney (1788:240) observed changes after the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake. The keystone of the soffit of the door of the lesser Temple descended 8 inches. Burton and Drake (1872:37) reproduced a letter from Isabel Burton written in 1870 CE which also stated that the keystone in the soffithad begun to slip about 1759and successively fell lower with every slight earthquake. |

| Collapsed Roof ? | 'Round Temple'

Plate I

Plate IPlan of the city of Balbec, (showing only the situation of the ancient buildings which remain

Wood (1757) |

Figure 2

Figure 2G.B. Borra;, 1751 'The circular temple in its present state' Lewis (1999)

Figure 6

Figure 6J. Bruce, 1767: Baalbek, the 'round temple' Lewis (1999)

Figure 2

Figure 2F. Frith, 1857-58: Baalbek, 'the round temple' Lewis (1999) |

|

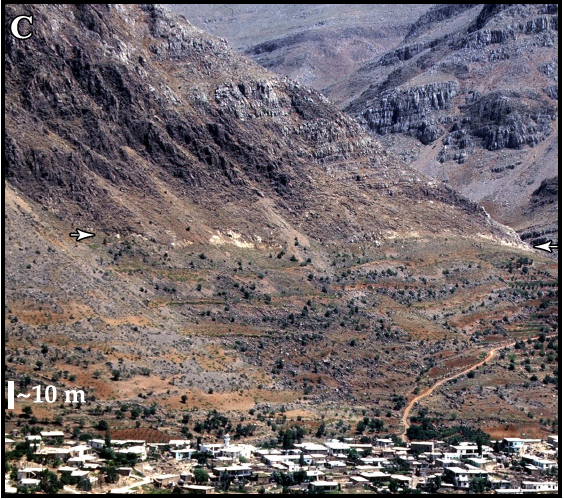

| Earth fissure |

Figure 1

Figure 1Schematic map of main active faults of Lebanese re-straining bend: bold colored lines show maximum rupture lengths of large historical earthquakes in past 1000 yr, deduced from this study and historical documents (see discussion in text). Bold ashed lines enclose areas where intensities ≥VIII were reported in A.D. 1202 (red) and November 1759 (green) according to Ambraseys and Melville (1988) and Ambraseys and Barazangi (1989).Open symbols show location of cities (squares) and sites (circles) cited in text. Black dots mark location of field photographs shown in Figure DR1 (see footnote 1). (Inset: Levant transform plate boundary.) JW: Green fault labeled SF (Serghaya fault) is Daeron et al (2005)'s postulated fault break for the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) |

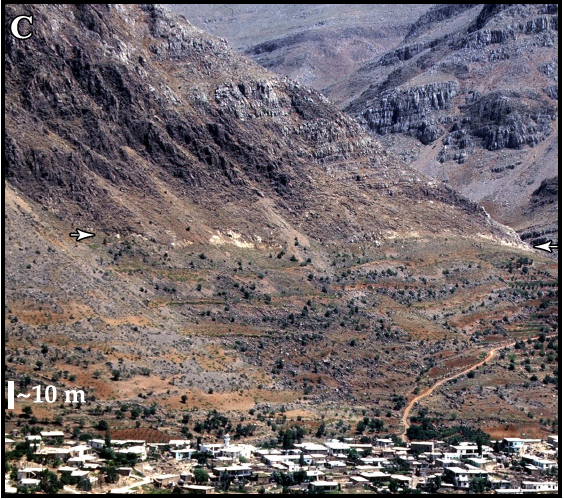

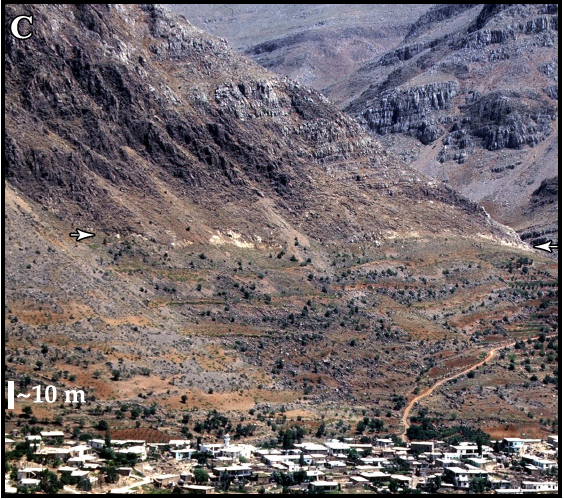

Figure DR1b

Figure DR1bfresher seismic scarplet on Serghaya fault JW: possibly due to 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) Supplemental

Figure DR1c

Figure DR1cfresher seismic scarplet on Serghaya fault JW: possibly due to 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) Supplemental |

Since October 30, a furious shock at 3:45 in the morning made us fear a fate like the one in Lisbon [JW: the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake]. We feel the continuing tremors day and night. There was another one on November 25, which was stronger and longer than the first. ... Large fissures opened up in the earth on the Baalbek side [JW: likely on 25 Nov. 1759 CE] and it is said that these cracks extend more than 20 leagues (~110 km.)- Anonymous letter, dated 29 December 1759 CE, from the French Consulate in Sidon to the Chamber of Chamber of Commerce of Marseilles (F.Ch.R., 1927:591-594) |

Side by side illustrations show that nine columns of the peristyle of the Great Temple

(aka the Temple of Jupiter) were standing in 1751 CE (left) and only six remained in 1767 CE (right).

Side by side illustrations show that nine columns of the peristyle of the Great Temple

(aka the Temple of Jupiter) were standing in 1751 CE (left) and only six remained in 1767 CE (right).Figure 1 (left)

G.B. Borra 1751 'View of both temples, in their present state,from the south'

Figure 3 (right)

J. Bruce, 1767: Baalbek, the west side of the smaller temple and the six columns of the larger temple

both Figures from Lewis (1999)

Lewis (1999:242) noted that, prior to 1759 CE, nine columns of the peristyle of the Great Temple (aka the Temple of Jupiter) remained standing.

There is no doubt that nine columns of the peristyle of the great temple remained standing throughout this period [before 1759 CE]; Belon in 1548 (1553, 4), Monconys in 1647 (1665, 348 - 9), la Roque in 1689 (1723, 127), Maundrell in 1697 (1721, 136 -7), Pococke in 1738 ( 1745, II, 110), Nijenburg or Heyman perhaps about 1720, (1759, II, 275), and Wood in 1751 (1757 passim) all mention this.After the earthquake of 25 Nov. 1759 CE, only 6 remained standing as noted by Volney (1788:239-240) who visited the Temple in 1784 CE and noticed that only six columns were still standing. This compares to the nine which had been standing as shown by Wood (1757:Tab. XXIV) based on observations made in 1751 CE.

- Volume 2

- see bottom paragraph of page 239 starting with

Several changes however have taken place

- from Volney (1788:239-240)

- from archive.org

The progressively slipping keystone at the entrance to the lesser Temple

The progressively slipping keystone at the entrance to the lesser TempleFigure 9 (left)

F. Frith, 1857-58 : Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple

Figure 10 (right)

Photograph, c.1880: Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple, the keystone supported by 'Burton's wall'

both Figures from Lewis (1999)

Lewis (1999:242) noted that the monumental doorway of the smaller temple remained intact prior to 1759 CE.

Nor can there be any doubt that the monumental doorway of the smaller temple, with its elaborately carved lintel, remained intact in this period. The joints between the three blocks of stone of which the lintel is composed were evidently so perfect in the earlier part of the period that Monconys (1665, 348-9) and la Roque (1723, 136-7) thought that it consisted of a single piece of stone; Pococke (1745, 109) was the first to realise that there were three. None of the travellers says that there was any structural damage to the lintel, although its sculptured decorations had been damaged (Monconys 1665, 349; Nijenburg 1759, 274; Dawkins 1751, quoted below)Volney (1788:240) observed changes after the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake. The keystone of the soffit of the door of the lesser Temple

descended 8 inches. Burton and Drake (1872:37) reproduced a letter from Isabel Burton written in 1870 CE which also stated that the

keystone in the soffithad begun

to slip about 1759and successively fell lower

with every slight earthquake.

- Volume 2

- see top part of page 240 starting with

It has likewise so shaken

- from Volney (1788:240)

- from archive.org

- see two-thirds down on page 37 starting with

Finally, nothing has been done to arrest the fall

- from Burton and Drake (1872:37)

- from archive.org

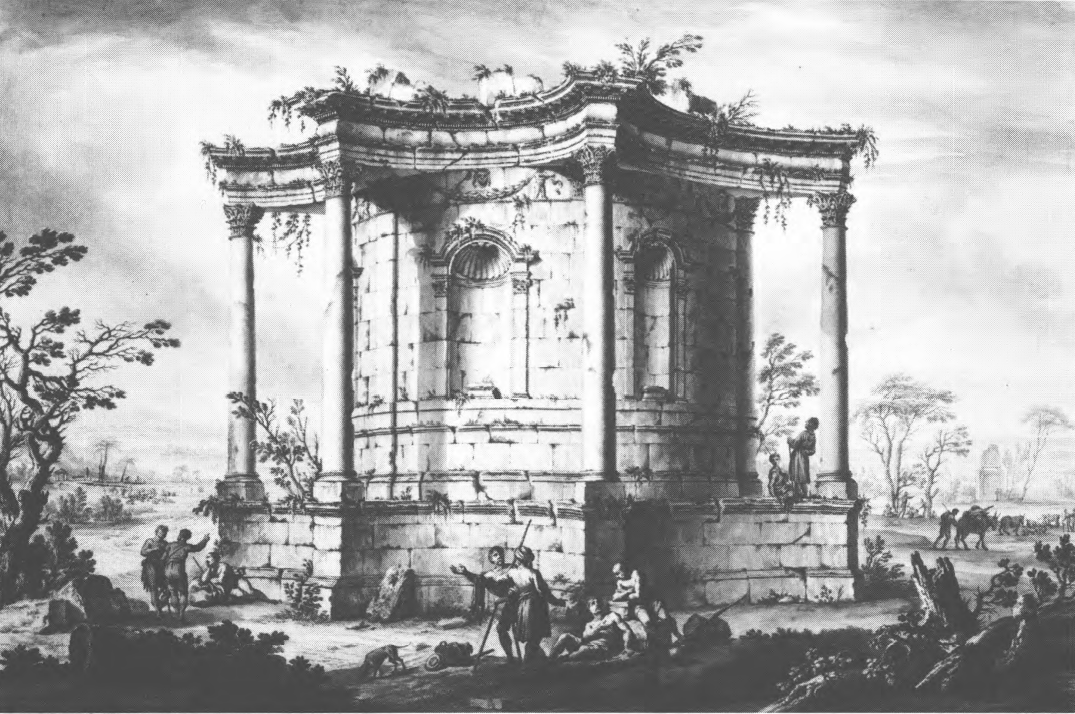

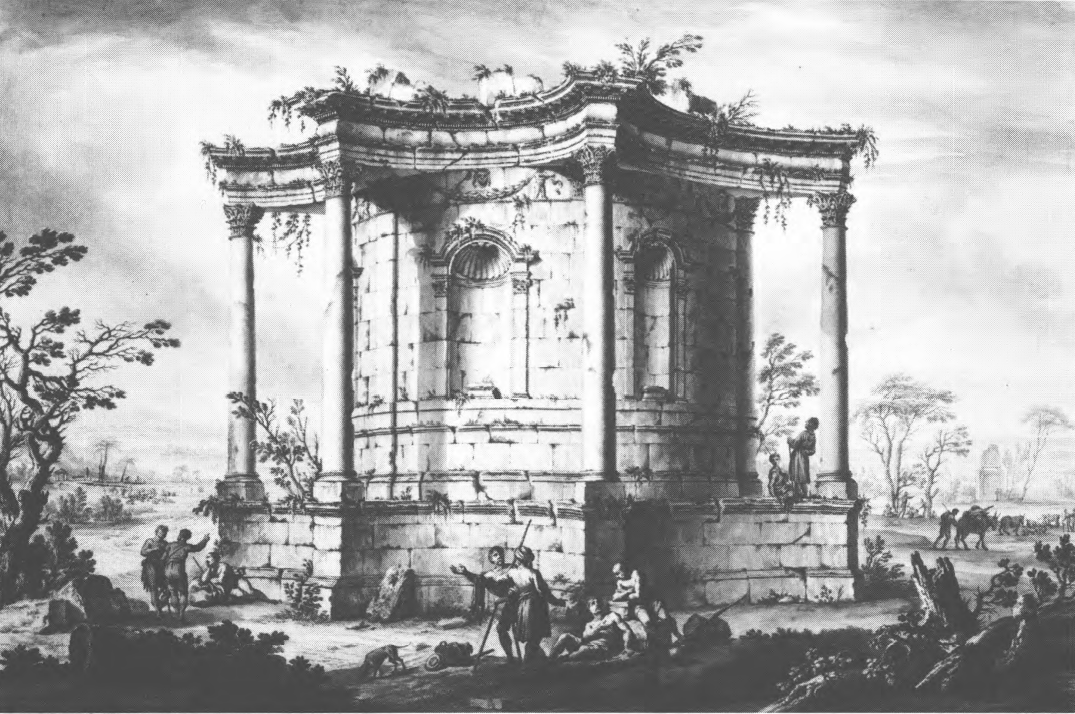

The 'Round Temple' over time

The 'Round Temple' over timeFigure 2 (left)

G.B. Borra;, 1751 'The circular temple in its present state'

Figure 6 (middle)

J. Bruce, 1767: Baalbek, the 'round temple'

Figure 8 (right)

F. Frith, 1857-58: Baalbek, 'the round temple'

both Figures from Lewis (1999)

Lewis (1999:249-252) thought it probable that the 'Round Temple' was also damaged in the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake.

Bruce's drawing of the little 'round' temple (Figure 6) gives the impression that, although the roof had fallen in, the exterior was in reasonably sound condition and Borra's two drawings (Figure 2 herein and pI. 43 in Wood) give an almost absurd impression of solidity and good order. This is at odds with Maundrell's description of the temple as being "in a very tottering state" in 1697 (1721, 135). At that time, and as late as 1751, the temple was used as a church by a Greek Orthodox congregation which later - we do not know when - abandoned it. Bruce's drawing shows only one side of the temple, the back or south side, but in 1784 Cassas produced two drawings (his pIs 56 and 57), one of the same side as Bruce's and not unlike his, and the other of the entrance or north side. The latter shows that much of the interior and of the north side had fallen away and was now completely ruined.The circular temple is also known as the round temple or temple of Venus and is located southeast of the Acropolis ( Leila Badee in Meyers et al, 1997)

The collapse must have taken place between 1751, when Wood and Borra were there and the temple was still in use, and 1784, when Cassas was there. We cannot be sure whether it took place before or after Bruce's visit, because he did not draw the northern side, but it must be thought extremely probable that the earthquakes of 1759 were responsible for this as for so much other damage in Baalbek.

- Fig. 6 - Plan of Ruins at Baalbek

from Dienner (1886)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

- Sun temple

- pillars of the great temple

- half fallen pillar

- lowered ashlar of the main portal

Dienner (1886)

Dienner (1886:252-258) made some early archaeoseismic observations at Baalbek

The following plan of the western part of the Acropolis of Ba`albek also shows in the floor plan of the two temples the position of the column fragments, the ruins of which come from the colonnades of the former. Although the position of the column shafts cannot be used to determine the direction of the tremor, since the way they fall is too much influenced by the rotation around the iron pivot at the base, a superficial overview of the distribution of their material is possible recognize that the north and south sides of the buildings were more affected by the shock of the shock than the east and west fronts.

As late as 1751, nine columns stood upright from the peristyle of the great temple. On the other hand, in 1784 Volney1 counted only six of them when he visited. The other three fell victim to the terrible earthquake of 1759. But these three fallen columns have all been thrown off to the north side, as if a southerly blow had pulled the base from under the shafts. Likewise, in the peristyle of the Temple of the Sun, nine pillars were destroyed by the earthquake of 1759, specifically on the south side of the temple. In the main portal, which is directed from north to south, the impact tore loose the middle cuboid (I) of the sketch), which bore the symbol of Helios, the winged eagle with the serpent's staff, in raised work, so that it was about a meter deep between the other two ashlars of the central bay and had to be supported by a base of masonry in 1870. A meridionally directed undulation of the ground was probably most likely to have caused the W.—O. bursting the joints between the ashlars of the porticus and thus caused the central stone to be lowered.

The most instructive point of the building for judging the nature of the earthquake is, however, at the southern peristyle of the Temple of the Sun (a of the plan sketch). While between the south-west corner of the peristyle and the colonnade of the vestibule all the columns have been thrown off the substructure of the temple, here one of them is still leaning upright against the wall of the cella. The shaft is broken off near the base, but the iron clamps which held it together withstood the force of the blow, and so the column leans due north towards the main maner, whose facade it partially damaged in its fall. Only a southward tremor could produce such an effect. The base of the stylobate was extended to the south pushed before the ceiling of the peristyle was able to yield. So the shaft of the column had to break in two and fall to the north. Any other direction of the blow would have resulted in its falling into the inner space of the peristyle or over the ramparts of the Acropolis.

Observations of this kind teach us that in the great earthquake of 1759 the seismic movement of at least one shock was north-south.Footnotes1 Volney “Journey to Syria and Egypt". Jena, 1788, II, p. 17S-186; cit. according to Socin: "Palestine et Syrie", p. 522, and Ritter, l.c. p 247.

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

- Subjective MMI Intensity Scale

- Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

- Synoptic Table of ESI 2007

Intensity Degrees from Michetti et al. (2007)

Plate I

Plate I

Synoptic Table of ESI 2007 Intensity Degrees - The accuracy of the assessment improves in the higher degrees of the scale, in particular in the range of occurrence of primary effects, typically starting from intensity VIII, and with growing resolution for intensity IX, X, XI and XII. Hence, in the yellow group of intensity degrees (XI-XII) they become the most effective tool for intensity assessment.

click on image to open a higher resolution version in a new tab

Michetti et al. (2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

|

- Simple MMI Intensity Scale

- More Subjective MMI Intensity Scale

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Palmyra (aka Tadmur) |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

- Subjective MMI Intensity Scale

- Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

- Synoptic Table of ESI 2007

Intensity Degrees from Michetti et al. (2007)

Plate I

Plate I

Synoptic Table of ESI 2007 Intensity Degrees - The accuracy of the assessment improves in the higher degrees of the scale, in particular in the range of occurrence of primary effects, typically starting from intensity VIII, and with growing resolution for intensity IX, X, XI and XII. Hence, in the yellow group of intensity degrees (XI-XII) they become the most effective tool for intensity assessment.

click on image to open a higher resolution version in a new tab

Michetti et al. (2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baalbek |

|

|

| Rupture Length (km.) | Surface Magnitude (MS) | Equation used |

|---|---|---|

| 110 | 7.5 | Generic |

| 110 | 7.5 | Equation 2 of Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) |

| 110 | 7.4 | Equation 3 of Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) |

| Rupture Length (km.) | Moment Magnitude (MW) | Equation used |

|---|---|---|

| 110 | 7.6 | Equation 11 of Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) |

| Variable | Input | Units | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| km. | Rupture Length | ||

| Variable | Output | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Surface Magnitude |

| Variable | Input | Units | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| km. | Rupture Length | ||

| Variable | Output | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Surface Magnitude |

| Variable | Input | Units | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| km. | Rupture Length | ||

| Variable | Output | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Surface Magnitude |

| Variable | Input | Units | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| km. | Rupture Length | ||

| Variable | Output | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Moment Magnitude |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Fallen Columns | Peristyle of the Great Temple (aka the Temple of Jupiter)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

Dienner (1886) |

Figure 1

Figure 1G.B. Borra 1751 'View of both temples, in their present state, from the south' Lewis (1999)

Figure 3

Figure 3J. Bruce, 1767: Baalbek, the west side of the smaller temple and the six columns of the larger temple Lewis (1999) |

|

V+ |

| Dropped Keystones in Arches | Keystone of the soffit of the door of the lesser Temple

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the ruins of Heliopolis.

Dienner (1886) |

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser Temple

The slipping keystone of the Soffit at the entrance to the Lesser TempleRoberts (1855)

Figure 9

Figure 9F. Frith, 1857-58 : Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple Lewis (1999)

Figure 9

Figure 9Photograph, c.1880: Baalbek, entrance to the smaller temple, the keystone supported by 'Burton's wall' Lewis (1999)

Fig. 6.6a

Fig. 6.6aRich decorated flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.6b

Fig. 6.6bDetailed view of the flat arch of the main doorway of the Temple of Bacchus Rababeh (2005) |

Lewis (1999:242) noted that the

monumental doorway of the smaller temple remained intact prior to 1759 CE.

Nor can there be any doubt that the monumental doorway of the smaller temple, with its elaborately carved lintel, remained intact in this period. The joints between the three blocks of stone of which the lintel is composed were evidently so perfect in the earlier part of the period that Monconys (1665, 348-9) and la Roque (1723, 136-7) thought that it consisted of a single piece of stone; Pococke (1745, 109) was the first to realise that there were three. None of the travellers says that there was any structural damage to the lintel, although its sculptured decorations had been damaged (Monconys 1665, 349; Nijenburg 1759, 274; Dawkins 1751, quoted below)Volney (1788:240) observed changes after the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake. The keystone of the soffit of the door of the lesser Temple descended 8 inches. Burton and Drake (1872:37) reproduced a letter from Isabel Burton written in 1870 CE which also stated that the keystone in the soffithad begun to slip about 1759and successively fell lower with every slight earthquake. |

VI+ |

| Earth fissure |

Figure 1

Figure 1Schematic map of main active faults of Lebanese re-straining bend: bold colored lines show maximum rupture lengths of large historical earthquakes in past 1000 yr, deduced from this study and historical documents (see discussion in text). Bold ashed lines enclose areas where intensities ≥VIII were reported in A.D. 1202 (red) and November 1759 (green) according to Ambraseys and Melville (1988) and Ambraseys and Barazangi (1989).Open symbols show location of cities (squares) and sites (circles) cited in text. Black dots mark location of field photographs shown in Figure DR1 (see footnote 1). (Inset: Levant transform plate boundary.) JW: Green fault labeled SF (Serghaya fault) is Daeron et al (2005)'s postulated fault break for the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) |

Figure DR1b

Figure DR1bfresher seismic scarplet on Serghaya fault JW: possibly due to 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) Supplemental

Figure DR1c

Figure DR1cfresher seismic scarplet on Serghaya fault JW: possibly due to 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake Daeron et al (2005) Supplemental |

Since October 30, a furious shock at 3:45 in the morning made us fear a fate like the one in Lisbon [JW: the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake]. We feel the continuing tremors day and night. There was another one on November 25, which was stronger and longer than the first. ... Large fissures opened up in the earth on the Baalbek side [JW: likely on 25 Nov. 1759 CE] and it is said that these cracks extend more than 20 leagues [~110 km.]- Anonymous letter, dated 29 December 1759 CE, from the French Consulate in Sidon to the Chamber of Chamber of Commerce of Marseilles (F.Ch.R., 1927:591-594) |

IX-X |

Burton, R., Drake, C. F. (1872), Unexplored Syria, London

Burton, R., Drake, C. F. (1872), Unexplored Syria, London

Cassas, F. (1799) Voyage Pittoresque de la Syrie~ de la

Phoenicie~ de la Palestine et de la Basse Eqypte. Paris - open access at BnF Gallica

Cook, Arthur Bernard (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. I: Zeus God of the Bright Sky, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Dienner, C. (1886), Libanon, Grudlinien der physischen

Geographie etc., Vienna: A. Holder, pp. 255–262 - open access at archive.org

Jidejian, Nina. Baalbek: Heliopolis "City of the Sun." Beirut, 1975.

Kalayan, H. (1975). "Baalbek, un ensemble recemment decouvert." Liban: Les

grands sites, Tyr, Byblos, Baalbek= Dossiers d'Archeologie [Paris: Archeologia SA] 12: 29-30.

Lewis, N. N. (1999). "Baalbek Before and After the Earthquake of 1759: the Drawings of James Bruce." Levant 31(1): 241-253.

Paturel, S. (2019). Baalbek-Heliopolis, the Bekaa, and Berytus from 100 BCE to 400 CE : a landscape transformed.

Ragette, Friedrich. Baalbek. London, 1980.

Roberts, D. (1855). The Holy Land: Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt & Nubia - open access at archive.org

Volney, C. F. (1787), Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte 1783–5,

vol. 1, p. 304

Volney (1788)

Volney, C. F. (1788), Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte 1783–5,

vol. 2, pp. 187, 212, 238–247, 269–271.

Wood, R. (1757) Ruins of Balbec otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria London - open access at Heidelberg historic literature – digitized

Wood, R. (1757) Ruins of Balbec otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria London - open access at archive.org

Jidejian, Nina. Baalbek: Heliopolis "City of the Sun." Beirut, 1975.

Kalayan, Haroutine. "Baalbek: Un ensemble recemment decouvert

(Les fouilles archeologiques en dehors de la qal'a). " Les Dossiers de

I'Archeologie 12 (September-October 1975): 2S-35.

Krencker, Daniel M. , and Willy Zschietzschmann. Rbmische Tempelin

Syrien. Vol. 1. Berlin, 1938.

Ragette, Friedrich. Baalbek. London, 1980. New panoramic guide with

a detailed, step-by-step description, complete reconstruction, a

bird's-eye-view of the city, and a comprehensive evaluation of the

antiquities.

R. Wood, The Ruins of Baalbec (1757, repr. 1971)I; T. Wiegand, Baalbek, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen und Untersuchungen 1898-1905 I-III (1921-25)MPI

D. Schlumberger, “Le temple de Mercure à Baalbek-Héliopolis,” BMBeyrouth 3 (1939)I

C. Picard, “Les frises historiées autour de la cella et devant l'adyton, dans le temple de Bacchus à Baalbek,” Melanges syriens offerts à René Dussaud (1939)I

R. Amy, “Temples à escaliers,” Syria 27 (1950)

P. Collart & P. Coupel, L'autel monumental de Baalbek (1951)PI

H. Seyrig, “Questions héliopolitaines,” Syria 31 (1954)

M. Chéhab, “Mosaïques de Liban,” BMBeyrouth 14-16 (1958-60)I

A. von Gerkan, Von antiker Architektur und Topographie, Gesammelte Aufsätze (1959)PI

J. Lauffray, “La Memoria Sancti Sepulchri du Musée de Narbonne et le Temple Rond de Baalbeck,” MélStJ 37 (1962)

R. Saïdah, “Chroniques, Fouilles de Baalbeck,” BMBeyrouth 20 (1967)

J.-P. Rey-Coquais, Inscriptions grecques et latines de la Syrie. VI. Baalbek et Beqa (1967)MI.

Wellhausen (1927:382-383) relates that in the summer of 746 CE (A.H. 128) during the 3rd Muslim Civil War, Marwan II ordered the walls of Hims, Jerusalem, Baalbek, Damascus, and other prominent Syrian cities razed to the ground. In Theophanes entry for A.M.a 6237, we can read in Mango and Scott (1997:587)'s translation (Turtledove's translation is available here):

[A.M. 6237, AD 744/5]...

- Constantine, 5th year

- Marouam, 2nd year

- Zacharias, 12th year

- Anastasios, 16th year

- Theophylaktos, 2nd year

At that time Marouam, after victoriously taking Emesa [aka Homs], killed all the relatives and freedmen of Isam. He also demolished the walls of Helioupolish [aka Baalbek] Damascus, and Jerusalem, put to death many powerful men, and maimed those remaining in the said cities.