Michael the Syrian

Michael the Syrian also known as

Michael I Rabo and Michael the Great was born in

Melitene from a clerical family in 1126 CE

(

Dorothea Weltecke in

Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, 2011). He studied at the

Monastery of Dayro d-Mor Barṣawmo where he stayed on as a Monk and

a

Prior. In 1166, he was elected

Patriarch of the

Syrian Orthodox Church, serving until

1199 when he died. This presumably would have placed him in the

Mor Hanayo Monastery

(aka the Saffron Monastery). While acting as

Partriach he

collected manuscripts of theological and historical content and restored and compiled hagiographical and liturgical works

(

Dorothea Weltecke in

Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, 2011).

Dorothea Weltecke in

Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition (2011) reports that

his canonistic work is partly conserved

in later collections, but the greater part is lost, as is his treatise on dualist heresies composed for the Lateran Council

.

Michael the Syrian is best known for his Universal Chronicle which covered "creation" until 1195 CE

(

Dorothea Weltecke in

Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, 2011).

Dorothea Weltecke in

Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition (2011) describes Michael's Chronicle and various editions as follows:

The text is not preserved in its entirety, and the layout of Michael’s chronicle was distorted through the process of copying.

Chabot’s edition is a facsimile of a documentary copy written for him in Edessa (Urfa) from 1897 to 1899. While the scribes

tried to imitate the layout, a number of mistakes were introduced. Its

Vorlage,

the only extant ms., was written in 1598 by a very competent scribe. It is kept by the community of the Edessenians in Aleppo. In view of the loss of the original, this

beautiful manuscript is the best witness for the layout of the chronicle. Fortunately it will soon be made available in print.

This ms. was probably the Vorlage

for an Arabic translation, which also sought to preserve some of the visual features,

while changing others. The Arabic translation has much the same lacunae as the Syriac text. By comparing his version with

the Arabic translation preserved in ms. London, Brit. Libr. Or. 4402 (which is one of several Arabic copies), Chabot

detected some details lost in the Syriac text. No further research has been done so far on this problem.

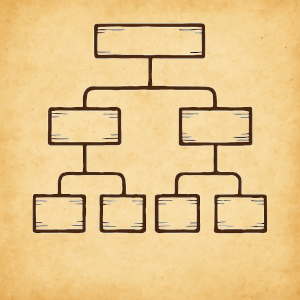

The historical material was originally organized in four columns, the first being designated as the ‘succession of the

patriarchs’, the second as ‘succession of the kings’, the chronological canon as ‘computation of the years’. No title

of the additional column, which contains mixed material, is now known. Chapters with

excursus were inserted, which

interrupted the system of columns. After an open and abrupt end, six appendices follow. The first appendix is a

monumental synopsis of all the kings and patriarchs mentioned. It was supposed to function as a directory. The

second appendix is a treatise on the historical identity of the Syrians, who are connected to the Ancient

Oriental Empires, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, and the Arameans. When the chronicle was translated into

Armenian, in two different translations, in 1246 and 1247, it was transformed according to Armenian interests.