Lod/Ramla

A rare 1698 view of Ramla by Dutch artist Cornelius de Bruijin. Depicts the city as well as the nearby caravan staging

grounds. Arab horsemen and tent camps decorate the foreground. This view was most likely rendered in secret during de Bruijin’s second world tour.

The Holy Land was then under the control of the Ottoman Empire who imposed strict limitations on pilgrims and tourist from Europe. It is highly

unlikely that de Bruijin would have been allowed to make sketches of the region openly.

A rare 1698 view of Ramla by Dutch artist Cornelius de Bruijin. Depicts the city as well as the nearby caravan staging

grounds. Arab horsemen and tent camps decorate the foreground. This view was most likely rendered in secret during de Bruijin’s second world tour.

The Holy Land was then under the control of the Ottoman Empire who imposed strict limitations on pilgrims and tourist from Europe. It is highly

unlikely that de Bruijin would have been allowed to make sketches of the region openly.

Click on image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Wikipedia and Geographicus Rare Antique Maps - Public Domain

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Lod

Hebrew

לוד

al-Lidd

Arabic

اللد

Lydda

Latin

Colonia Lucia Septimia Severa Diospolis

Latin

Lydda

Ancient Greek

Λύδδα

Diospolis

Ancient Greek

Διόσπολις

Georgiopolis

Late Byzantine and crusader sources

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

ar-Ramla

Arabic

الرملة

Ramla

Hebrew

רַמְלָה

Ramle

variant spelling

Ramlah

variant spelling

Remle

variant spelling

Rama

variant historical spelling

Arimathea

Crusader - according to wikipedia

Transliterated Name

Language

Name

Mazliah

Ramla (South)

Lod, ~15 km. southeast of Tel Aviv, has a long history of occupation. It is mentioned in the list of Canaanite towns conquered

by Thutmose III in the fifteenth century BCE

and in the Hebrew Bible,

the New Testament, and the Quran (Jacob Kaplan in Stern et al, 1993).

After the Muslim conquest in 636 CE, Lod (then named Lydda) became the capital of Jund Filistin.

In 715/716 CE, the capital was moved to the newly formed city of Ramla ~3 km. away. Historically, Ramla

has suffered frequent earthquake damage and appears to be susceptible to liquefaction. By extension, Lod should also be susceptible to liquefaction as both locations rest

on soft unconsolidated sediments in a flat coastal plain which in

times past likely had a relatively shallow water table.

The ancient mound of Lod is situated near the southern bank of Nahal Ayalon (Wadi el-Kabir) about 15 km (1 mi.) southeast of Tel-Aviv. It is completely covered by modern buildings, except on the northern side, where the edge of the mound was swept away, thus forming a section 2.5 m deep. Lod is first mentioned in the list of Canaanite towns conquered by Thutmose III in the fifteenth century BCE. It appears later only in the genealogical list of the tribe of Benjamin in connection with the wanderings of the Elpaal family and their settlement in the northern Shephelah (I Chr. 8: 12). B. Mazar accordingly considers that the town lay in ruins during most of the Late Bronze and Iron ages and was resettled only in the time of Josiah. Lod is also mentioned in the context of the return of the people from the Babylonian Exile (Ezra 2:33; Neh. 7:37, 11:35). The town is frequently mentioned in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Under the Emperor Septimius Severus, it was granted the status of a city and received the name of Diospolis. After the Arab conquest, its earlier name was restored.

From December 1951 to January 1952, J. Kaplan conducted exploratory excavations at the site on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. Three small areas were examined:

- area A - the northern edge of the mound

- area B - the two sides of a small ravine

- area C - a level area north of the above-mentioned ravine

In area B, on the two banks of the small ravine, a dump of gray earth was discovered with pottery from different periods, mainly from the Chalcolithic cultures in Israel: Wadi Rabah, stratum VIII at Jericho, and Ghassulian ware. The pottery of the first two types included sherds of low-neck jars, splay-ended loop handles, and black-burnished ware. Among the Ghassulian sherds were loop handles with triangular section, goblets, and churns.

In area C shallow cavities were found-the remains of pits dug into the white sand-that contained Neolithic pottery. Most of the pottery was characteristic of Jericho IX ware - simple and coarse ware made with a large quantity of straw, plain burnished ware, and decorated pottery with a red-painted chevron pattern, and typical Jericho IX handles, including rough loop handles, cylindrical knob handles, and triangular ledge handles.

Numerous salvage excavations were conducted on Tel Lod during the 1990s. The stratigraphy of the mound differs from area to area, but it appears that, except for a few short gaps, it was occupied from the beginning of the Pottery Neolithic period, through the Bronze and Iron Ages, and intermittently in later periods to the present. The site is located at a distance from major trade routes and was never fortified. The earliest settlement appears to have been situated at the northern part of the mound, alongside the streambed. During the Middle Bronze, Late Bronze, and Iron Ages, the settlement moved about half a kilometer to the south. In the Roman and Byzantine periods, the mound was largely abandoned and settlement concentrated to its south, in the area of today’s Old City of Lod.

Excavations at Tel Lod were conducted in 1995 on behalf of Tel Aviv University by H. Khalaily and A. Gopher, and later on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority: in 1996 by E. Yannai and R. Badich, in 1997 by E. van den Brink, and most extensively in 2000 by E. Yannai and O. Marder

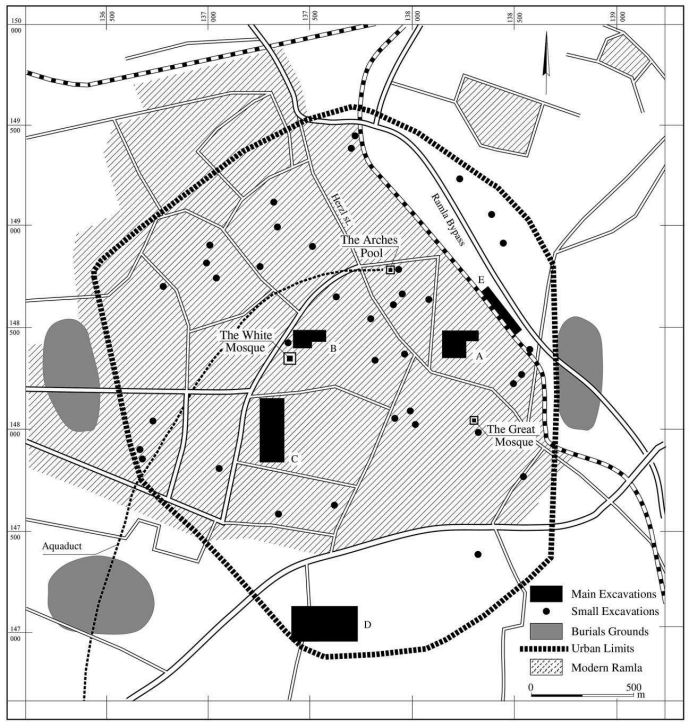

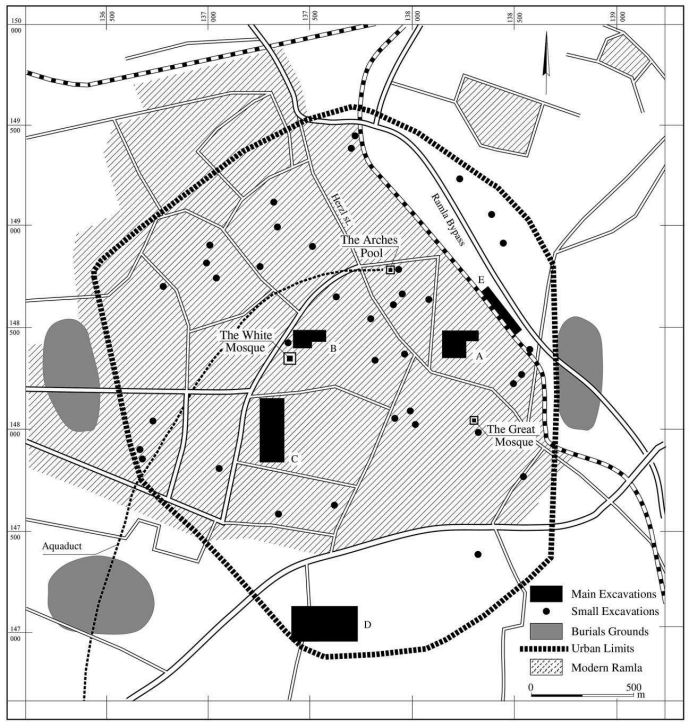

According to scholars, the name Ramla derives from the Arabic word raml, meaning "sand," probably referring to the sand dunes on which the city was built, about 4 km (2.5 mi.) south of Lod and 15 km (9 mi.) southeast of Tel Aviv (map reference 138.148). Ramla was founded in the early eighth century (712-715 CE) by the Umayyad caliph Suleiman ibn 'Abdel-Malik (brother of Walid I), the former governor of Jund Filistin (the District of Palestine). It is the only city in Palestine founded by Arabs. Ramla was first made the capital of the newly created province Filistin, which included the regions of Judea and Samaria. According to accounts by Arab geographers, Ramla was built from the ruins of nearby Lod. This destruction was not only expressed in the preferred status granted to Ramla, but also in the reuse in its construction of building materials from the ruins of Lod. To promote its growth, part of the population of Lod was also moved to Ramla.

With the city's founding, many installations and buildings, such as cisterns, a drain channel, the House of Dyers, and the mosque, were erected. Most of the Umayyad city is now covered by later construction. Only in the Umayyad mosque, called the White Mosque (which was later renovated, probably in the Ayyubid period), were several remains of that period preserved. Its minaret, which was rebuilt in the Mameluke period, is the most prominent structure of medieval Ramla.

Excavations at the White Mosque were conducted by J. Kaplan in 1949 on behalf of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. The excavations attempted to ascertain which buildings, both above ground and subterranean, belonged to the original mosque enclosure. It was revealed that the mosque enclosure was built in the form of a quadrangle (93 by 84 m), with its walls oriented to the cardinal points. It included the following structures: the mosque itself; two porticoes along the quadrangle's east and west walls; the north wall; the minaret; an unidentified building in the center of the area; and three subterranean cisterns.

Of the various excavations carried out in different areas of Ramla, the major undertaking was conducted in October 1965 by M. Rosen-Ayalon and A. Eitan, on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. This excavation was concentrated in the southwestern part of the town; however, several trial soundings on a smaller scale were dug simultaneously in an effort to broaden the general picture.

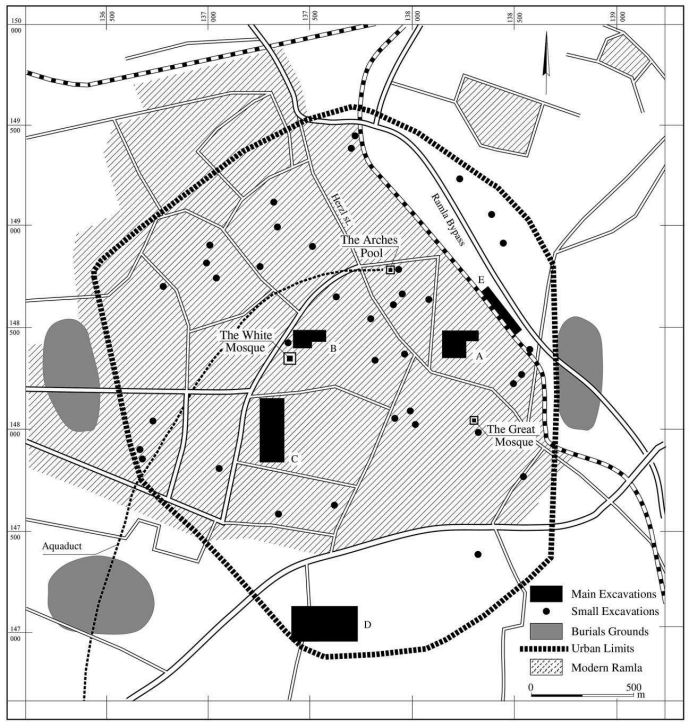

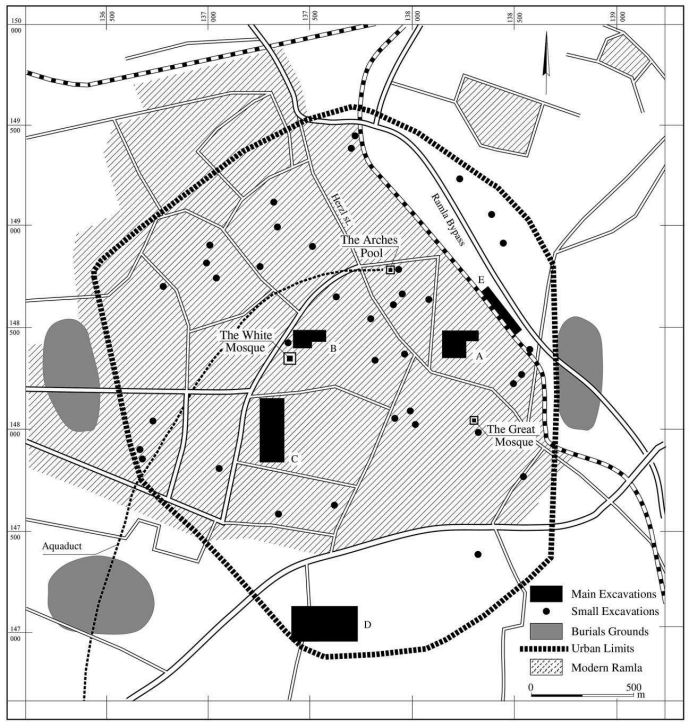

In the wake of development and construction projects, 79 salvage excavations and soundings were conducted in various parts of the city of Ramla in 1990–2003. While most of the excavations were probes at building sites or under modern streets, a number of large-scale excavations were also carried out in areas north and west of the Old City and north and south of the White Mosque. Several excavations were also conducted around the Ramla bypass road northeast of the Old City and in the western suburbs of the modern city. The aqueduct that carried water to the city from the springs at Tel Gezer was also examined in salvage excavations. Although they were conducted in non-contiguous areas, the many excavations make it possible to arrive at a tentative reconstruction of Ramla in the Early Islamic, Mameluke, and Ottoman periods. In addition to the excavations, an architectural survey of the buildings from the Middle Ages and the Ottoman period was conducted by A. D. Petersen in the center of the city.

The Umayyad aqueduct to Ramla is referred to as Qanat Bint el-Kafir (“The Heretic Daughter’s Aqueduct”) on the map of the British Survey of Palestine of 1882; the source of this name is unknown. In 1950, R. Gophna and J. Kaplan mapped a section of the aqueduct at Moshav Ptah ya. In 1998–2001, A. Gorzalczany and Y. Zelinger conducted salvage excavations along its course and exposed large sections of it.

Most of the course of the c. 10-km-long aqueduct can be reconstructed, but its water source and point of entry to Ramla have not yet been ascertained. Its source should probably be identified with the group of springs located in the vicinity of Abu Shusha, near Gezer. From there it runs northwest, entering Ramla from the south or southwest.

The aqueduct consists of a foundation of fieldstones bonded with cement and two parallel walls of dressed limestone masonry. The walls (40–50 cm wide) are plastered on their inner and outer faces and overlaid with another layer of fieldstones mixed with gray cement. The overall width of the aqueduct is about 1.5 m. Its channel is covered with flat limestone slabs averaging 30 by 80 cm and 12–15 cm thick, laid widthwise. The inside of the aqueduct was covered with an approximately 1-cm-thick layer of light red plaster composed of quartz, sherds, and shells applied to a base of sherds. Another layer of plaster was applied above this, somewhat altering the cross-section of the channel (specus), which varies along its length. In the eastern part of the aqueduct its width was distorted by the movement and inward collapse of the supporting walls and this section is at present completely blocked. Soundings made in the middle of the aqueduct revealed that it was dug into the virgin hamra soil. The aqueduct descends to a depth of c. 0.7 m and is set on a slightly wider foundation (1.50 m) made of small stones bonded in gray mortar, reaching a depth of 0.7 m below the base of the channel.

In the middle of the excavated segment of the aqueduct is a cylindrical shaped manhole, 1.30 m in diameter and preserved to a height of 0.50 m above the level of the cover stones. The superstructure is hollow and has a hexagonal internal horizontal cross-section (0.70 m in diameter). The manhole was built above a square opening set between the cover stones and is large enough for a person to enter. A similar manhole was exposed 45 m to the west, but its superstructure had collapsed. No cover stones were found in situ in the westernmost part of the exposed segment, probably having been robbed in antiquity.

Mazliah is also known as Ramla (South). Excavations revealed finds dating back to the Paleolithic however most of the site is dominated by two main stages of occupation; 7-8th centuries CE and 8th-9th centuries CE (Gorzalczany, 2008b:31).

|

Publication

|

Area

|

Permit/License

|

Institute

|

Excavator

|

|

Survey

|

A-3784

|

IAA

|

O. Shmueli and T. Kanias

|

|

|

|

A–C

|

A-4144

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

A, B

|

Y. Zelinger

|

|||

|

A

|

A-4507

B-298/2005

B-306/2006

|

Tel Aviv University

|

O. Tal and

I. Taxel

|

|

|

|

B

|

A-4454, A-4674, A-4725

|

IAA

|

A. Onn

|

|

C

|

A-4739

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

|

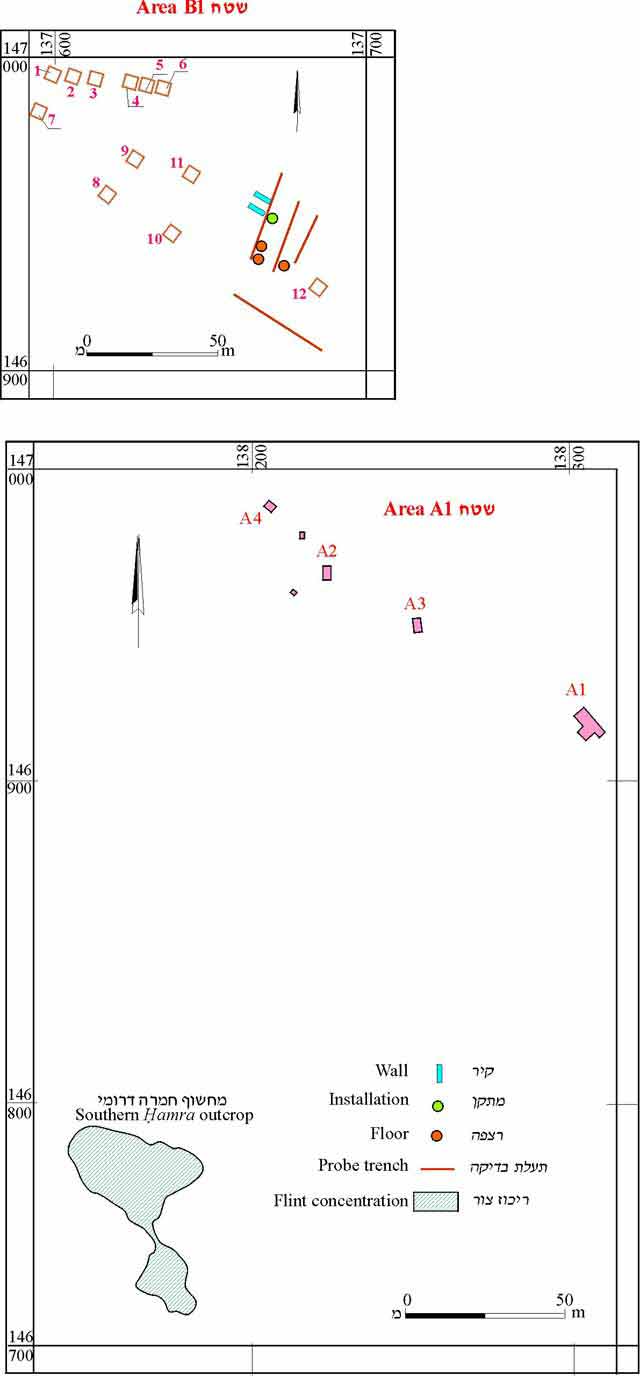

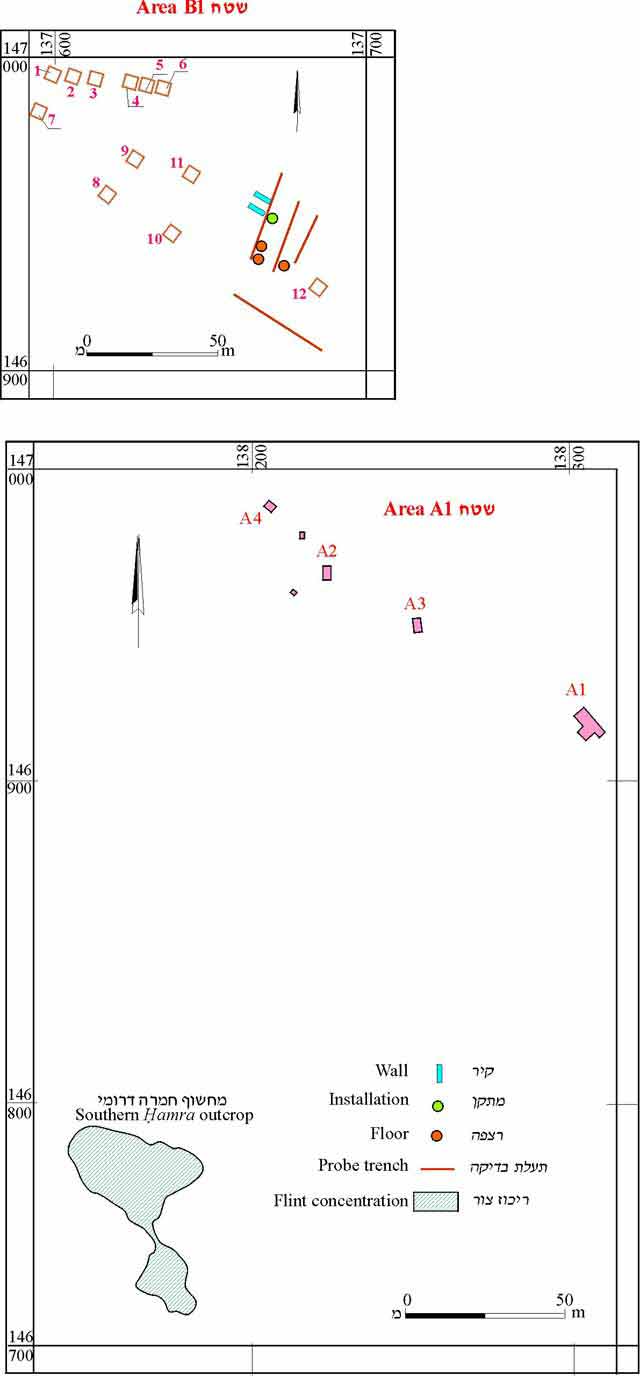

A1, B1

|

A-4910

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

|

|

C

|

B-299/2005

|

Bar Ilan University

|

R. Avisar and

J. Uziel

|

|

E

|

A-5168

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

|

F

|

Tel Aviv University

|

O. Tal and

I. Taxel

|

||

|

G, H

|

A-5311

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

|

H, I, J, K

|

A-5331

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

|

|

|

G, H1, K1, P, Q, R, S

|

|||

|

|

M, N

|

B-326/2008

|

Tel Aviv University

|

O. Tal, I. Taxel, L. Yehuda and Y. Paz

|

|

|

T

|

A-5473

|

IAA

|

A. Gorzalczany

|

- Fig. 1 - Coastal Palestine 644-800 CE

from Taxel (2013)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map

■ = urban/semi-urban/military settlement

• = rural settlement

Taxel (2013) - Fig. 1 - Location map

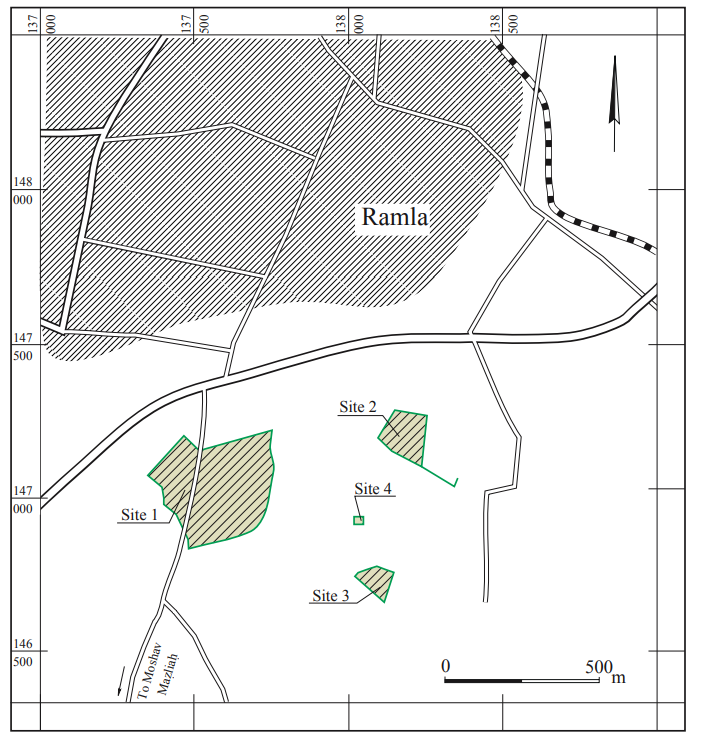

from Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map.

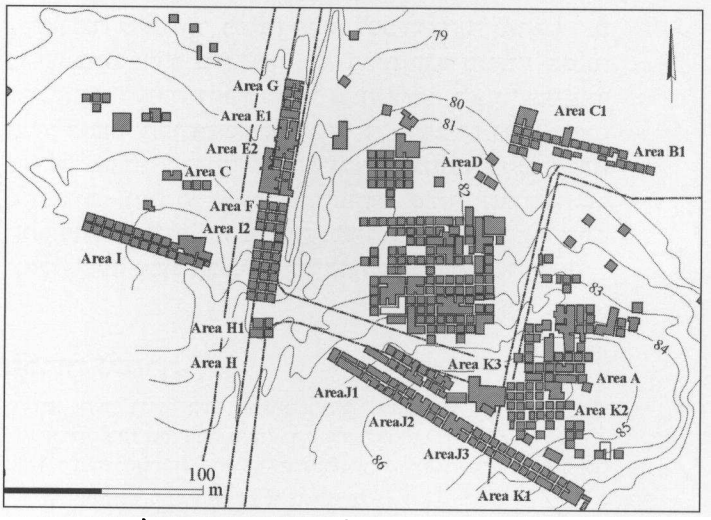

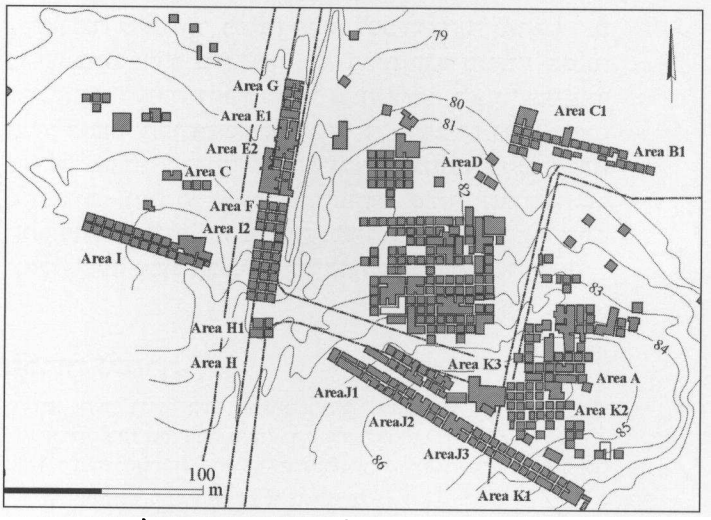

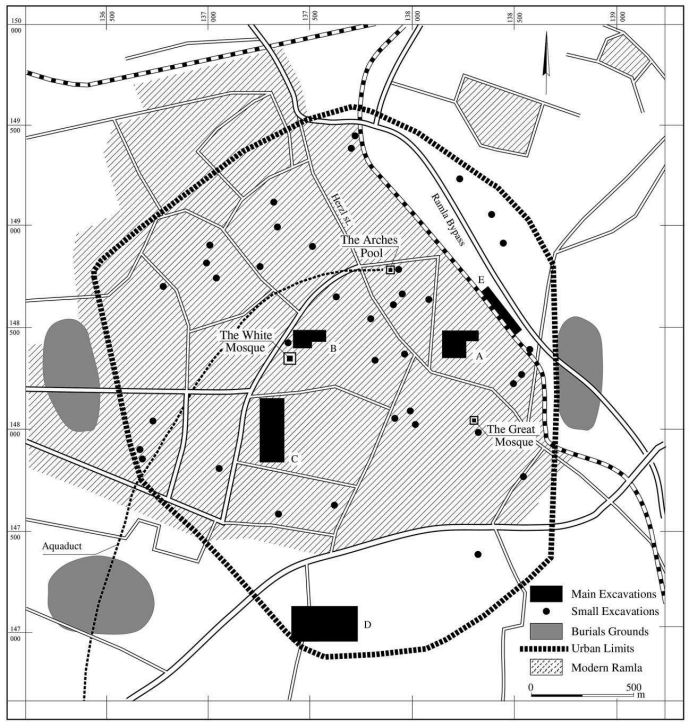

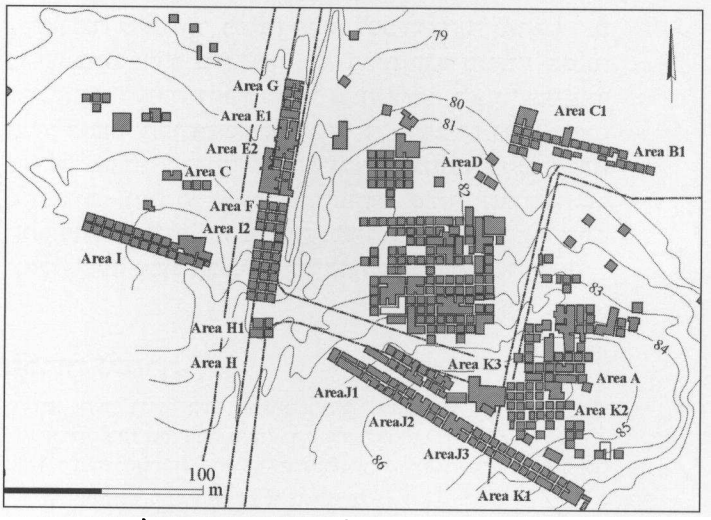

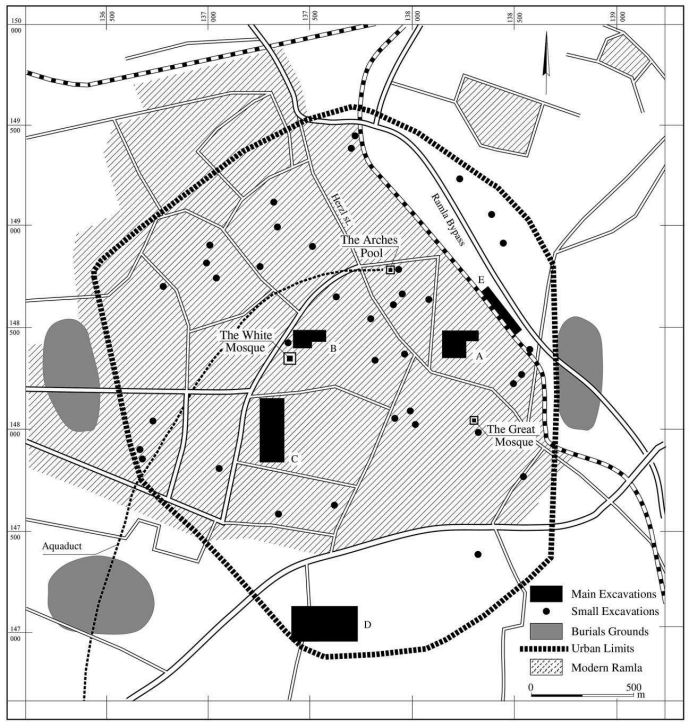

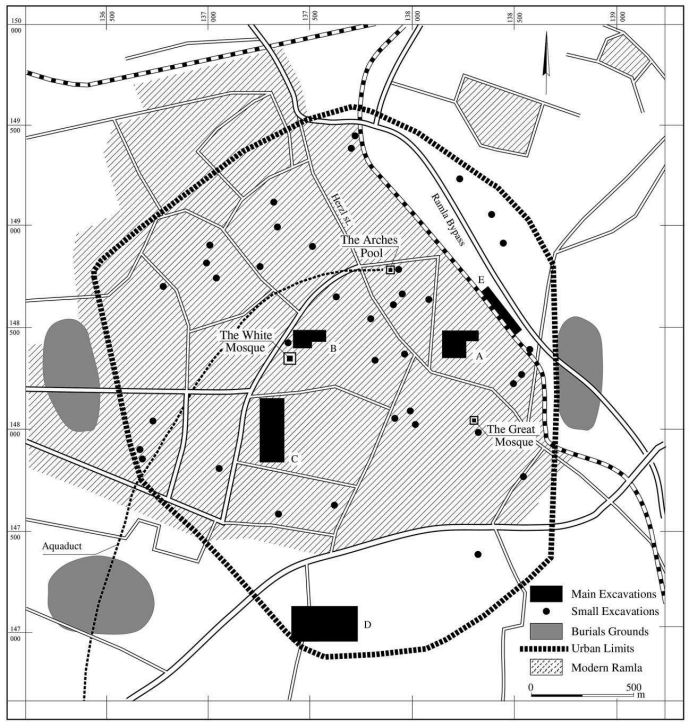

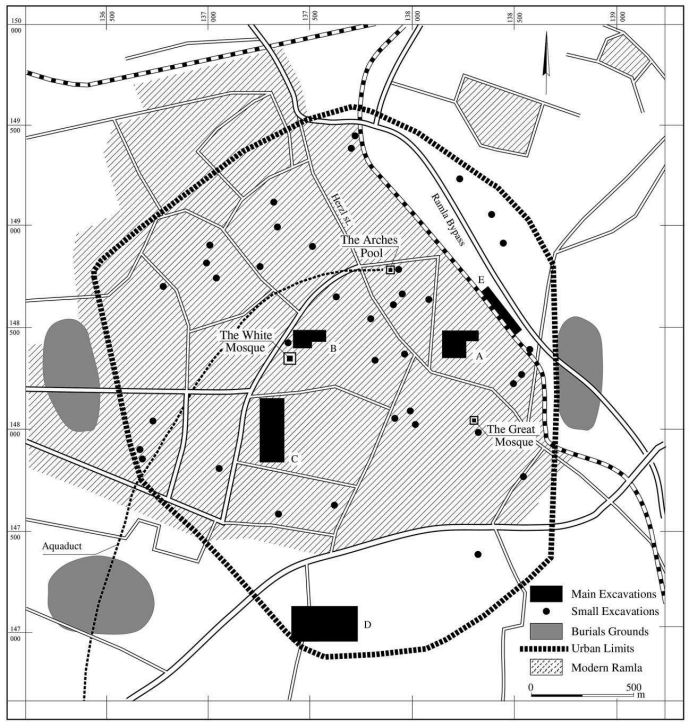

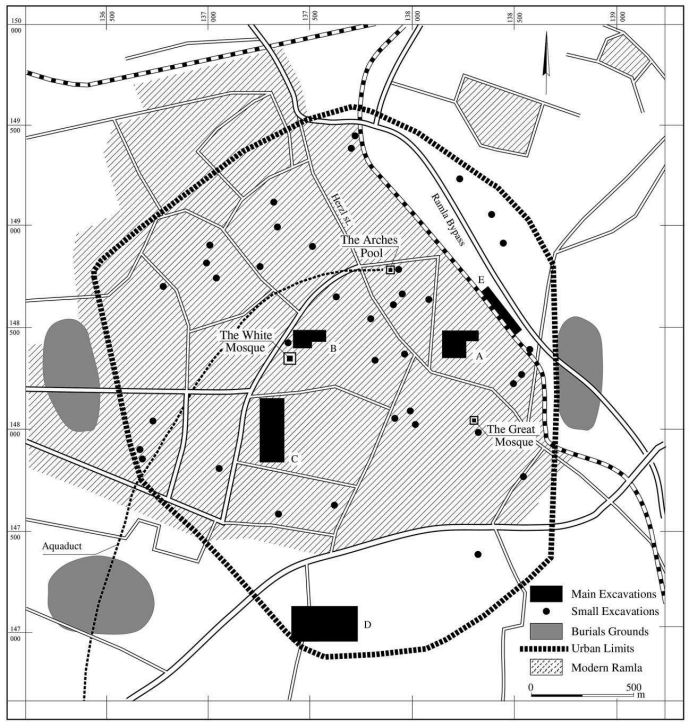

Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008) - Fig. 2 - Ramla City Limits

from Taxel (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of Ramla city limits and excavations

courtesy of G. Avni, Israel Antiquities Authority; slightly modified

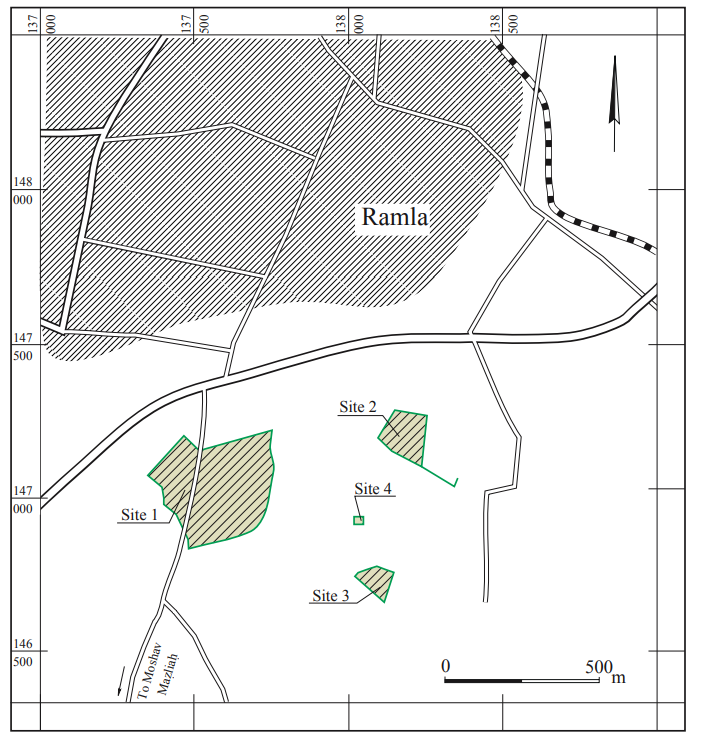

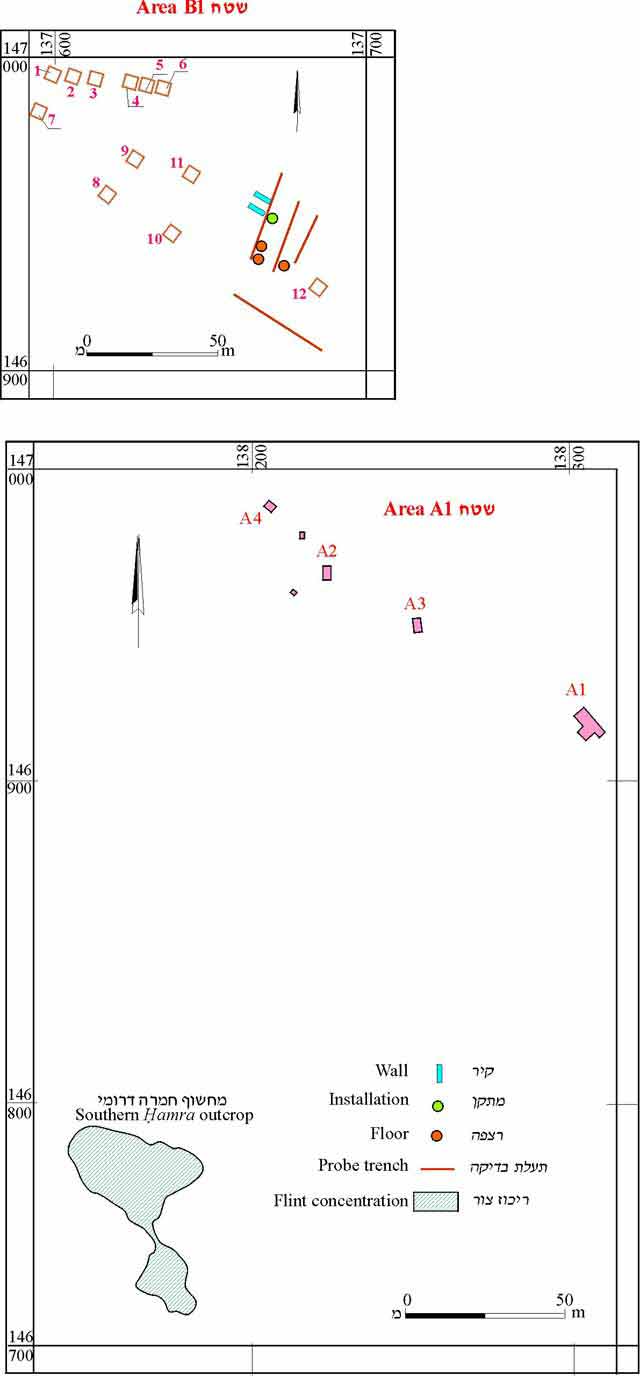

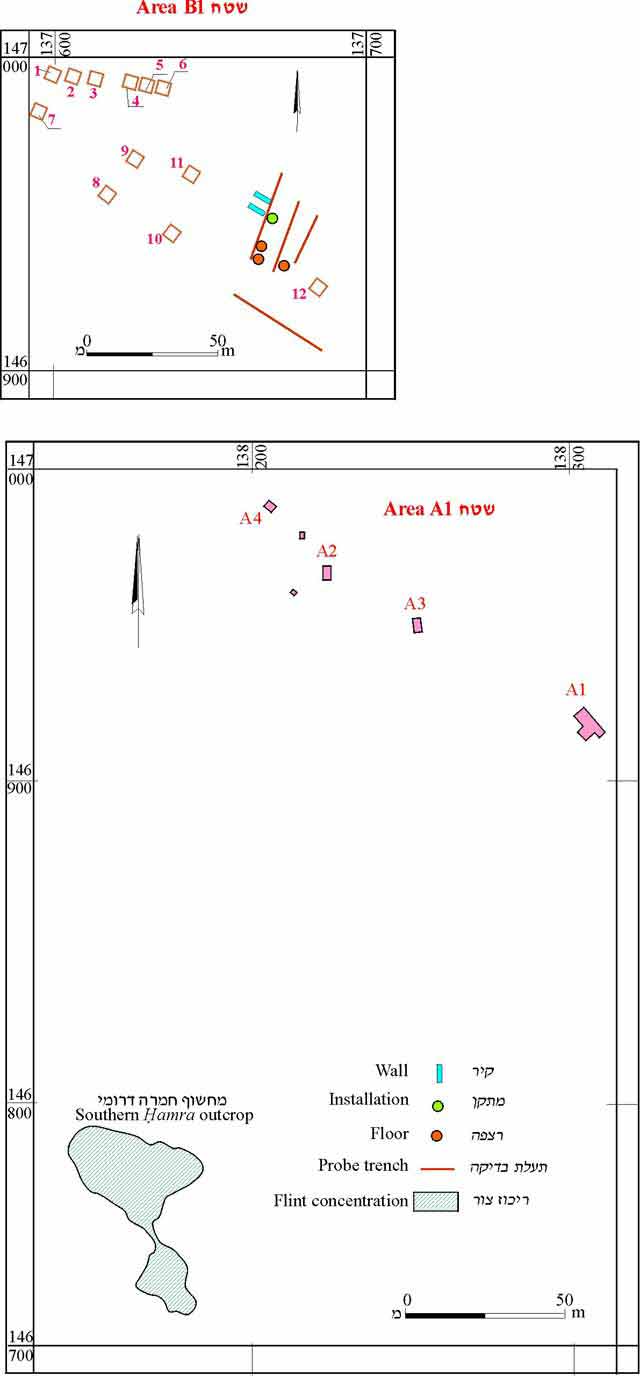

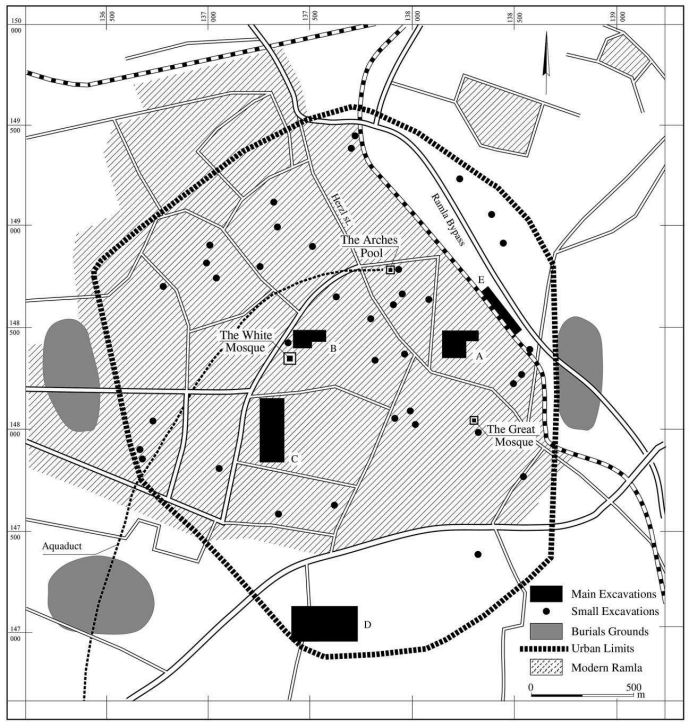

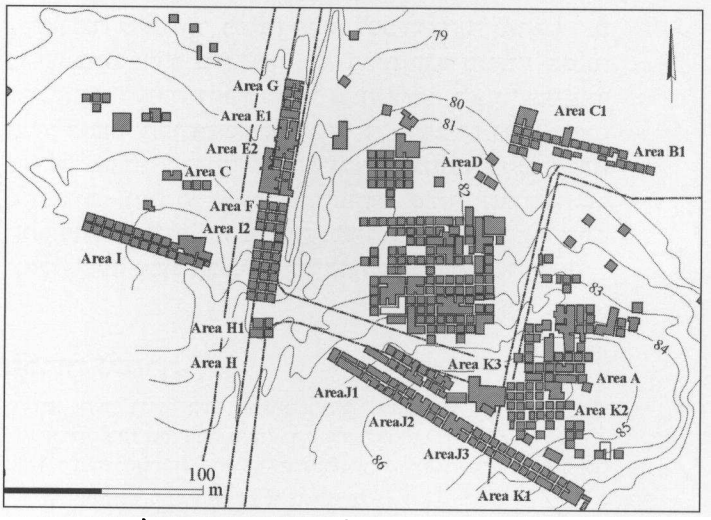

Taxel (2013) - Fig. 1.4 - Ramla (South) limits

from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.4

Fig. 1.4

Ramla (South) limits after Shmueli and Kanias 2007

Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority

Tal and Taxel (2008)

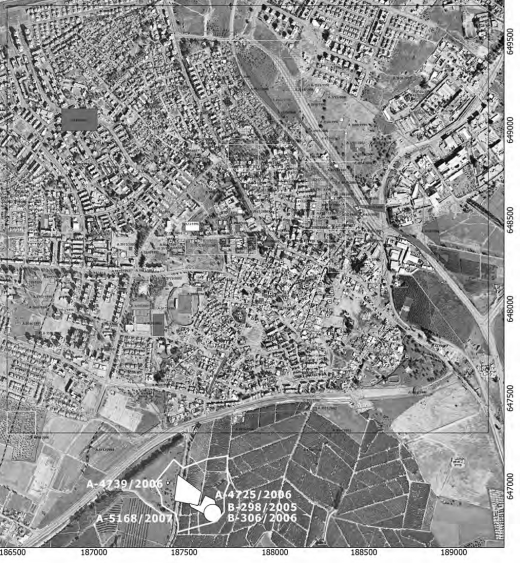

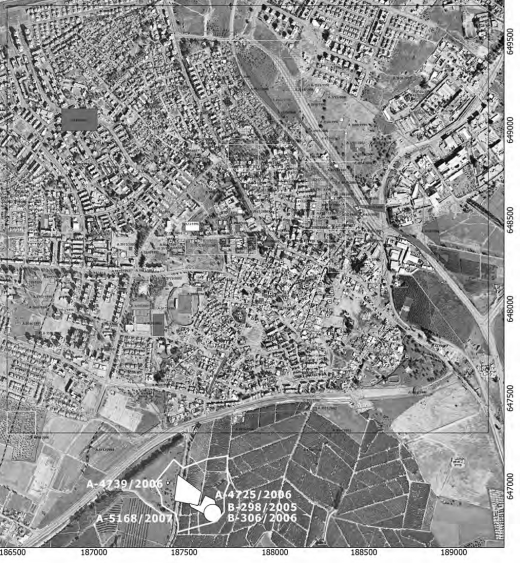

- Annotated Google Satellite View

of Lod/Ramla from BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 6.1 - Aerial view of Ramla

showing the location of the site of Ramla (South) from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.1

Fig. 6.1

Aerial view of Ramla showing the location of the site of Ramla (South)

Courtesy of G. Avni, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Lod/Ramla in Google Earth

- Lod/Ramla on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 5.3 Aerial View of White

Mosque and environs from Petersen and Pringle (2021)

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3

Ramla: the White Mosque and excavations south of it, seen from the air looking south

(© IAA)

Petersen and Pringle (2021) - General Area of Excavations at Mazliah in Google Earth

- General Area of Excavations at Mazliah on govmap.gov.il

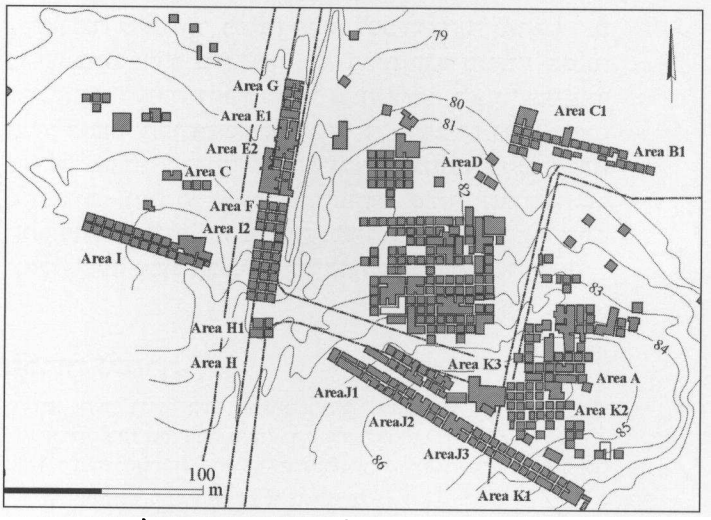

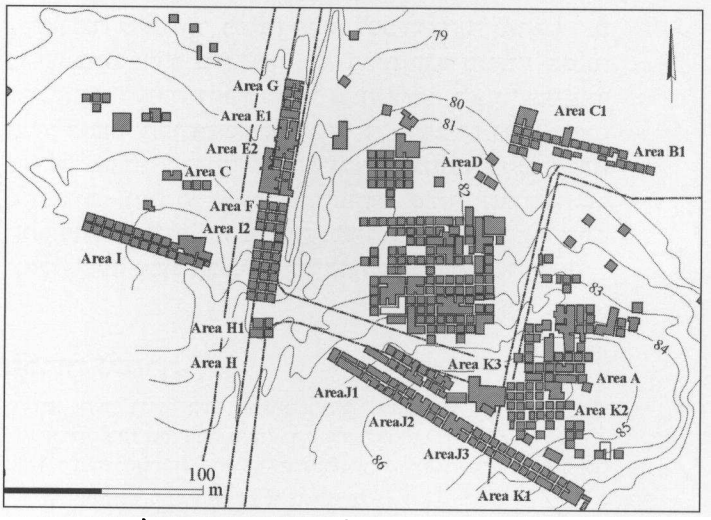

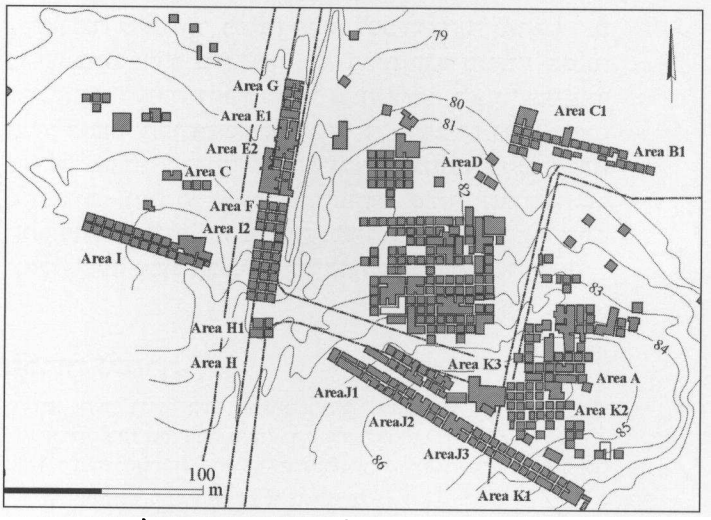

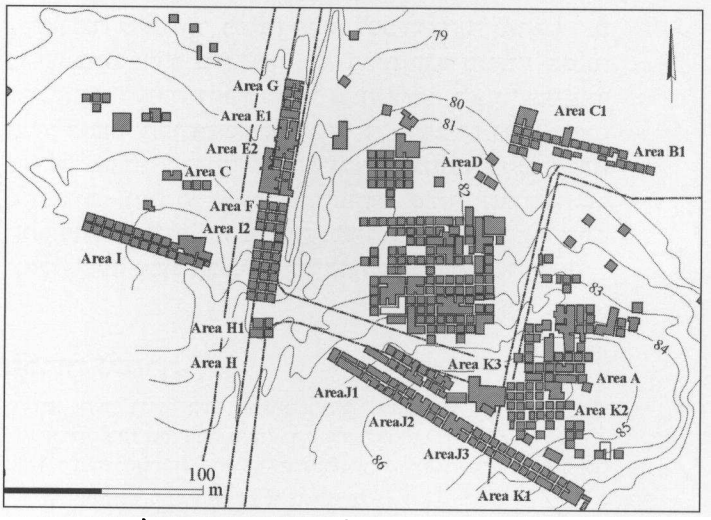

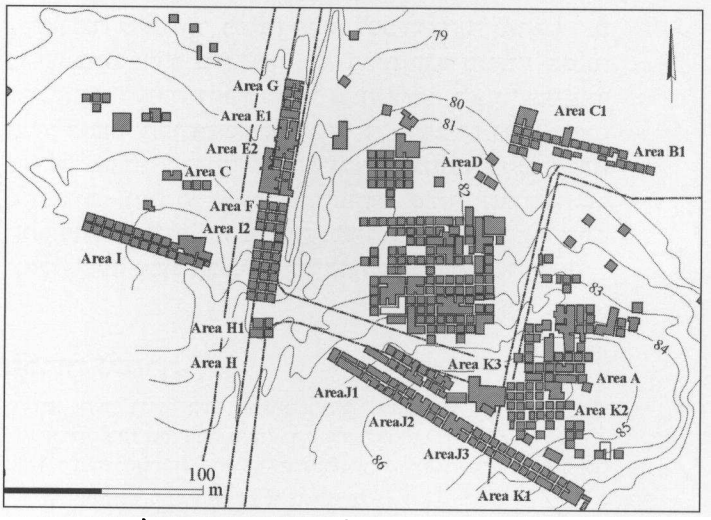

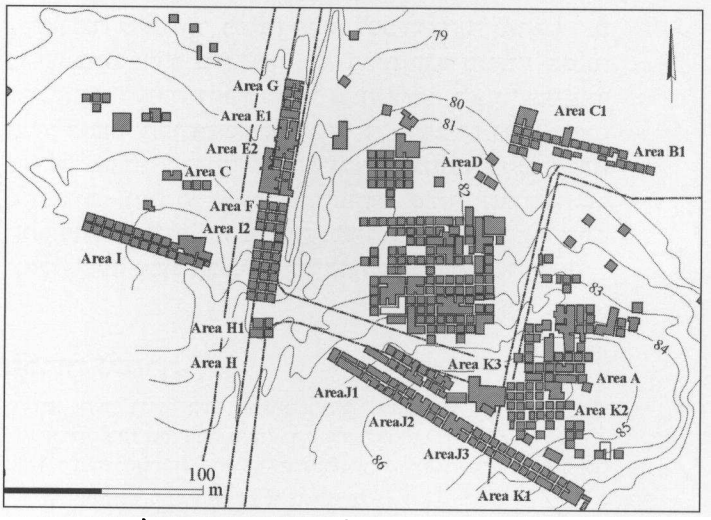

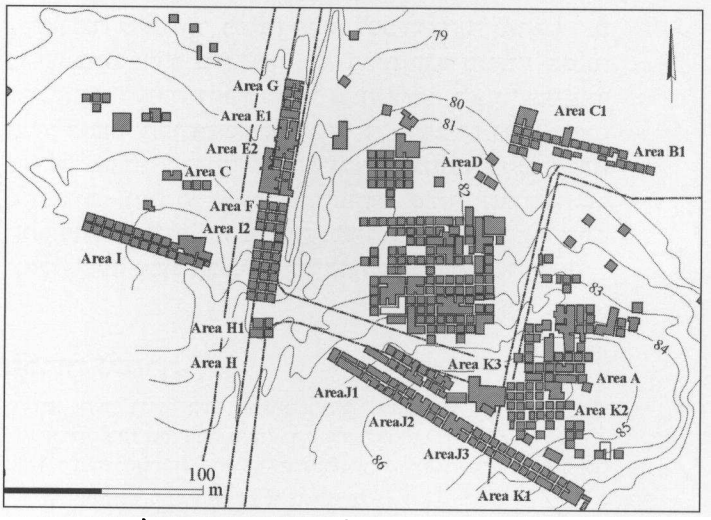

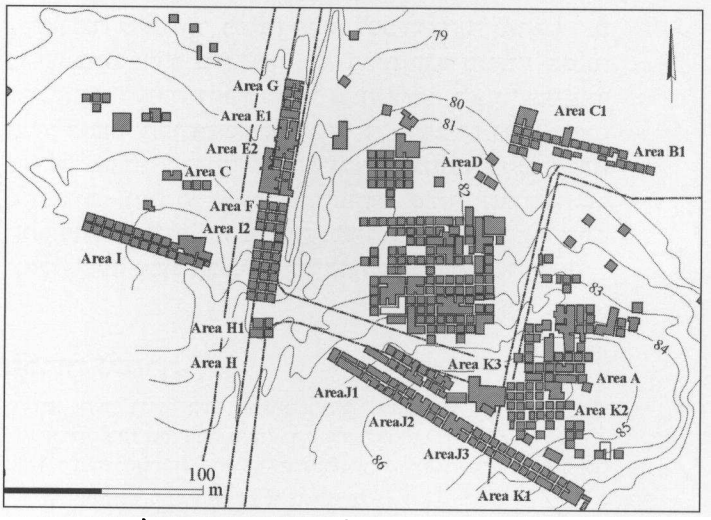

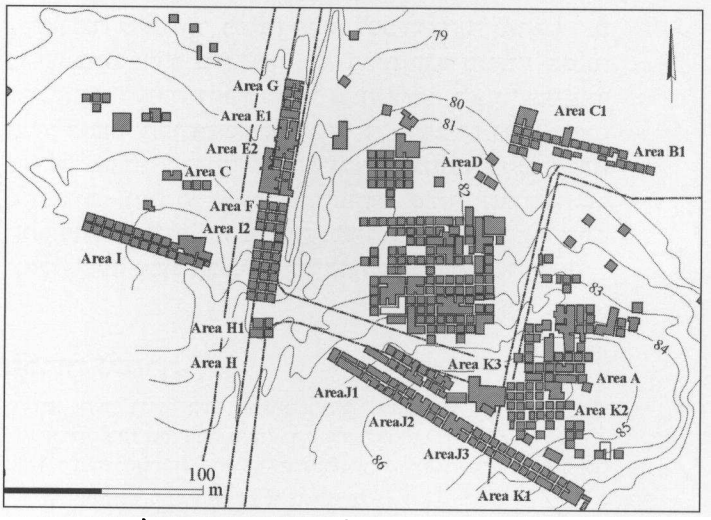

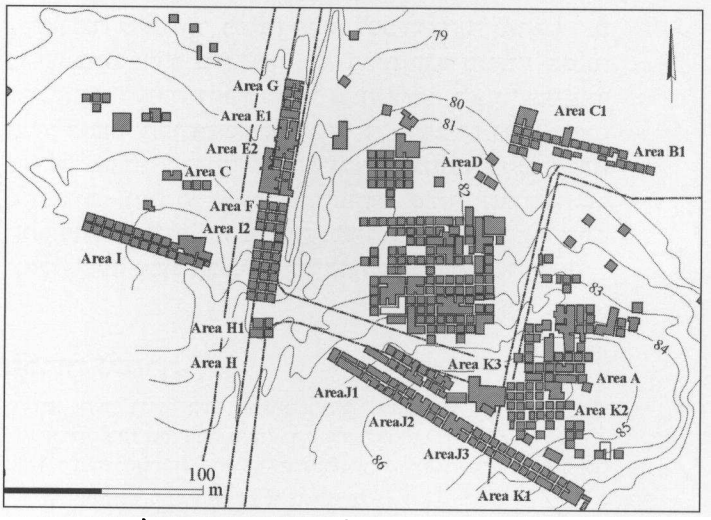

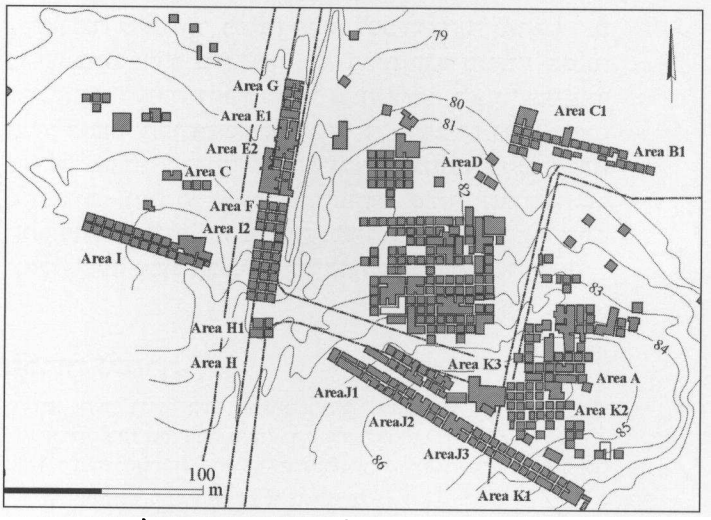

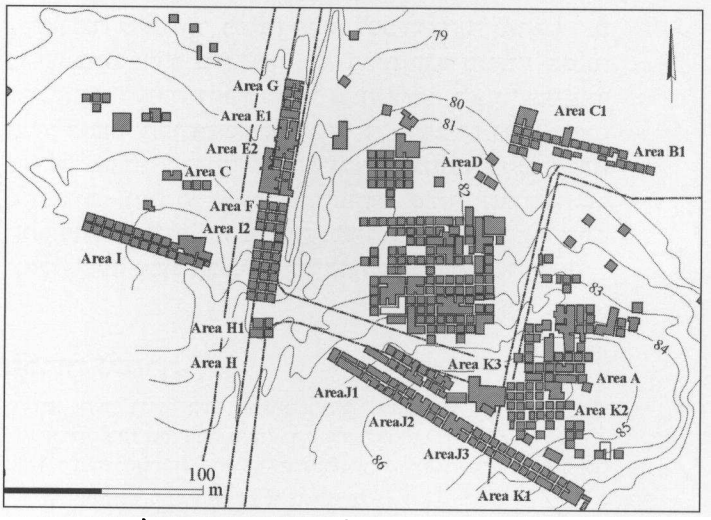

- Fig. 2 - Site Map from

Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The excavated areas

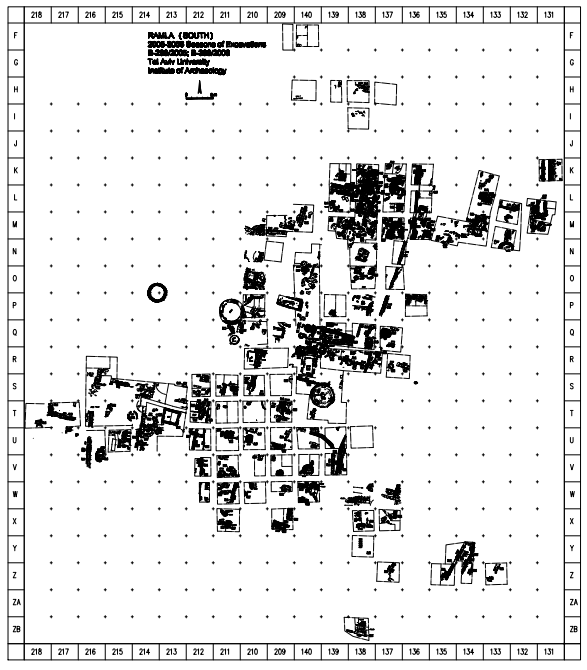

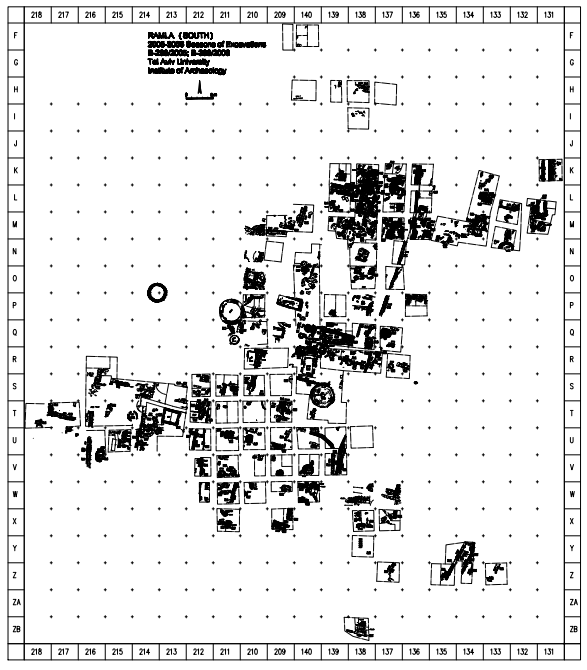

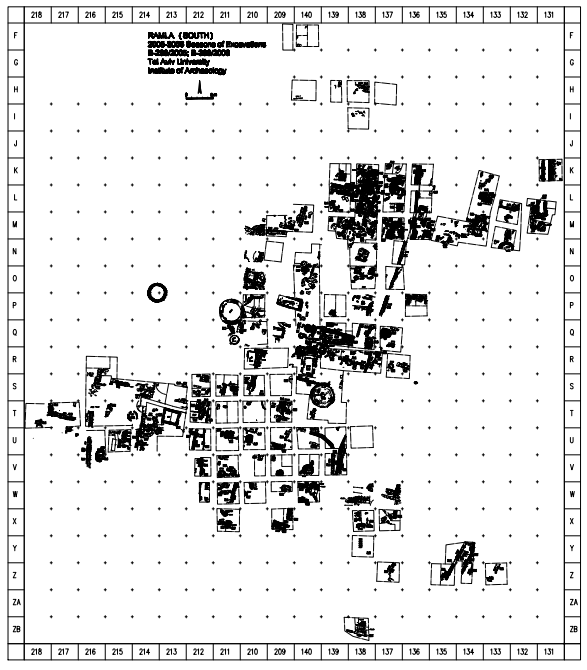

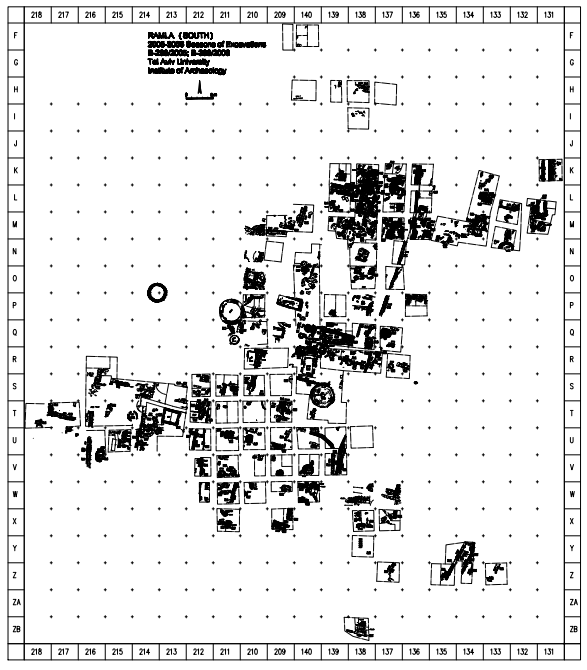

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Master Excavation Map

from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Master Excavation Map

Master Excavation Map

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 2 - Map of excavation

areas from Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Map of excavation areas.

Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008) - Fig. 2 - Plan from

Gorzalczany (2008)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

הפמ תיללכ לש יחטש הריפחה חילעמב

Gorzalczany (2008) - Fig. 1 - General Plan

from Gorzalczany and Ad (2010)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

General Plan.

Gorzalczany and Ad (2010) - Fig. 1.5 - Site map

with trial excavation areas from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.5

Fig. 1.5

Site map with indication of the trial excavation areas (A, B and C) of the Israel Antiquities Authority, on which the salvage excavation areas of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University have been outlined (modified after Gorzalczany 2006).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

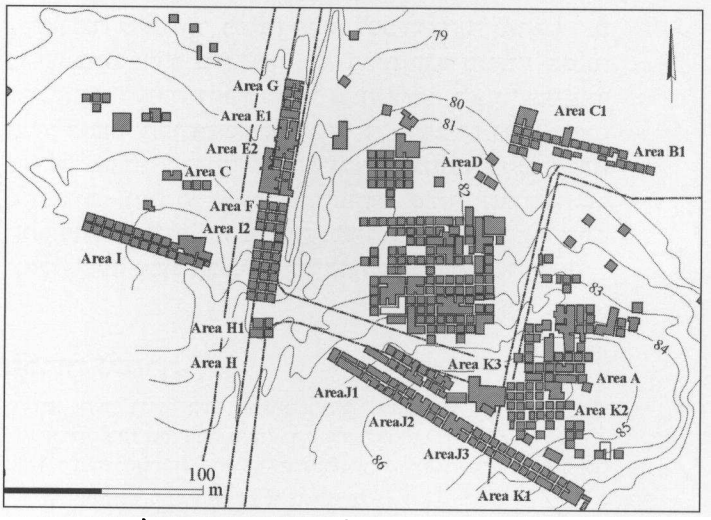

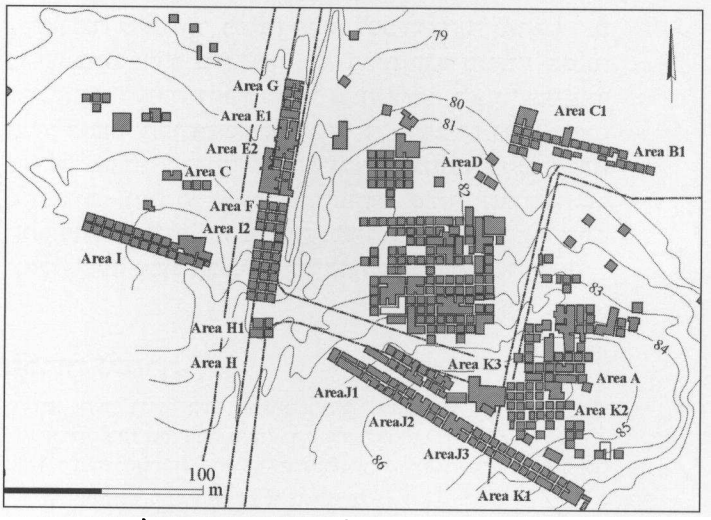

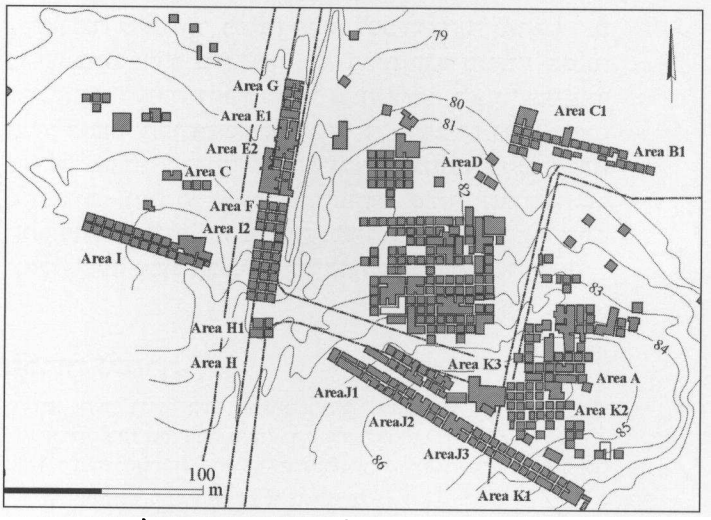

- Fig. 2 - Site Map from

Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The excavated areas

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Master Excavation Map

from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Master Excavation Map

Master Excavation Map

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 2 - Map of excavation

areas from Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Map of excavation areas.

Gorzalczany and Spivak (2008) - Fig. 2 - Plan from

Gorzalczany (2008)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

הפמ תיללכ לש יחטש הריפחה חילעמב

Gorzalczany (2008) - Fig. 1 - General Plan

from Gorzalczany and Ad (2010)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

General Plan.

Gorzalczany and Ad (2010) - Fig. 1.5 - Site map

with trial excavation areas from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.5

Fig. 1.5

Site map with indication of the trial excavation areas (A, B and C) of the Israel Antiquities Authority, on which the salvage excavation areas of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University have been outlined (modified after Gorzalczany 2006).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.4 Plan of Area B-3

and White Mosque from Petersen and Pringle (2021)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

Ramla: plan of excavated area (B3) south of the White Mosque

(© IAA)

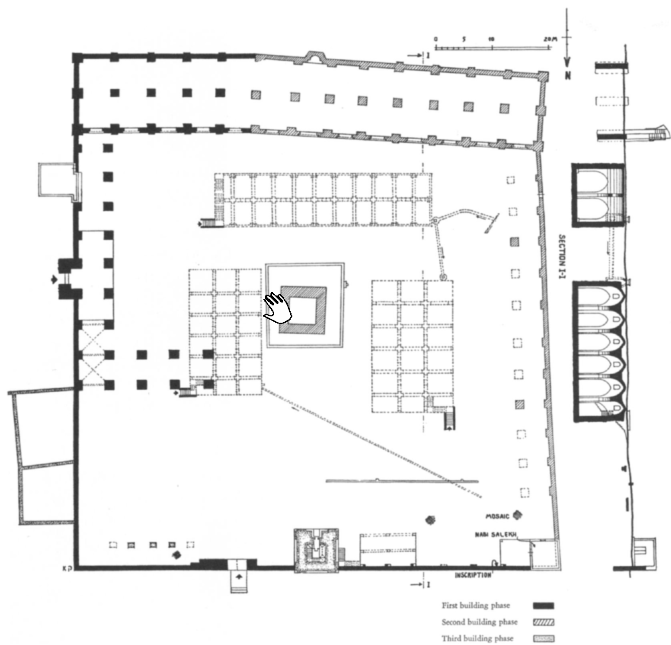

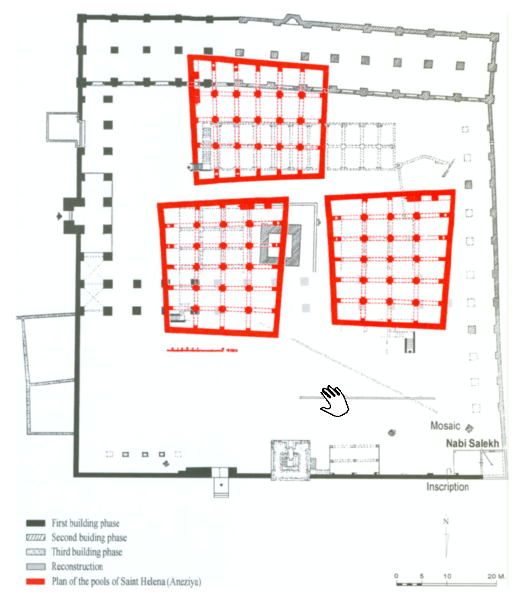

Petersen and Pringle (2021) - Fig. 1 Plan of White Mosque

of Ramla from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

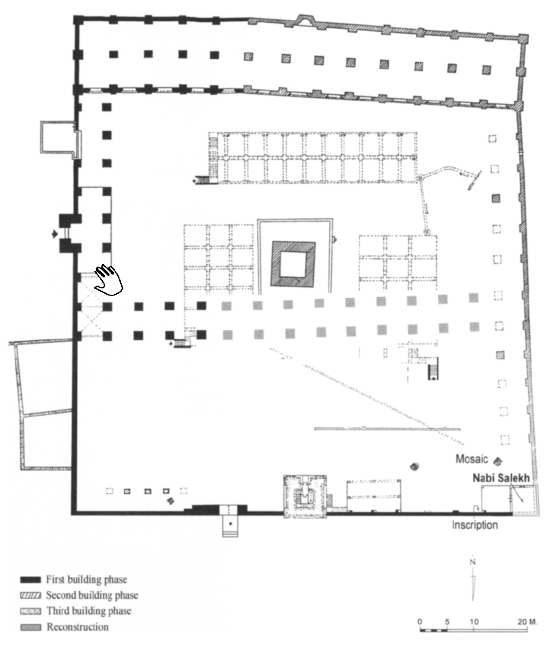

- Fig. 2 Plan of White Mosque,

showing reconstruction of northern exedra (first building phase) from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

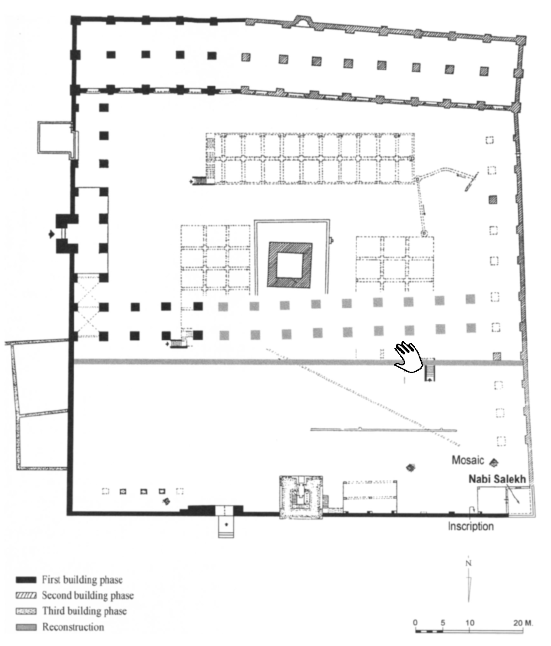

- Fig. 3 Plan of White Mosque,

showing reconstruction of northern exedra and northern boundary wall (first building phase) from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

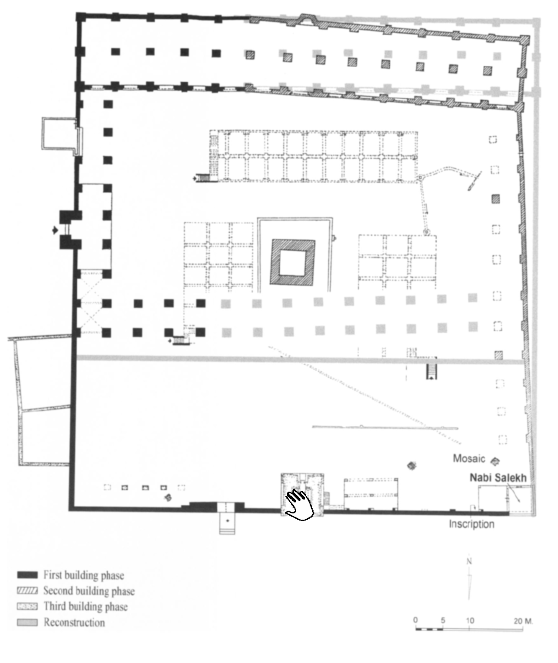

- Fig. 6 Reconstruction of

original plan of White Mosque from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 11 Abbasid cistern

superimposed over pools in White Mosque enclosure from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 5.4 Plan of Area B-3

and White Mosque from Petersen and Pringle (2021)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

Ramla: plan of excavated area (B3) south of the White Mosque

(© IAA)

Petersen and Pringle (2021) - Fig. 1 Plan of White Mosque

of Ramla from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 2 Plan of White Mosque,

showing reconstruction of northern exedra (first building phase) from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 3 Plan of White Mosque,

showing reconstruction of northern exedra and northern boundary wall (first building phase) from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 6 Reconstruction of

original plan of White Mosque from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

- Fig. 11 Abbasid cistern

superimposed over pools in White Mosque enclosure from Rosen-Ayalon (2006)

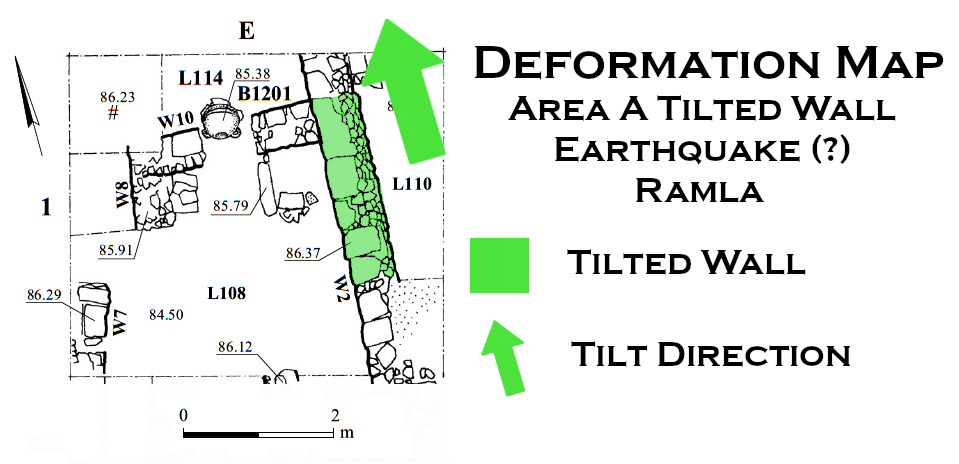

- Plan 1 - eastern squares

of Area A from Kletter (2005)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A, eastern squares

Kletter (2005)

- Plan 1 - eastern squares

of Area A from Kletter (2005)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A, eastern squares

Kletter (2005)

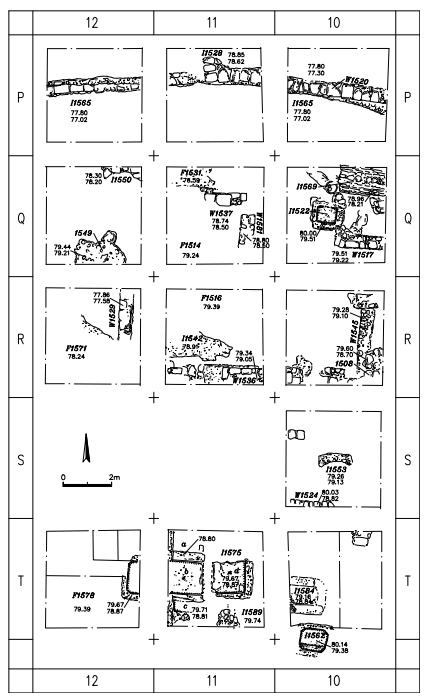

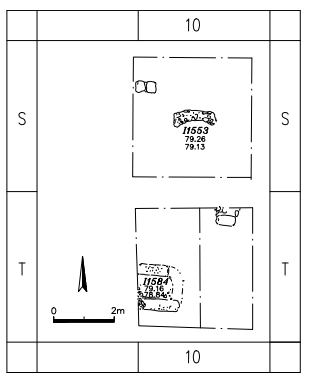

- Fig. 1.6a - General site

of the 2007 season (Squares P-T/10-12) from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.6a

Fig. 1.6a

General site plan of the 2007 season (Squares P-T/10-12).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

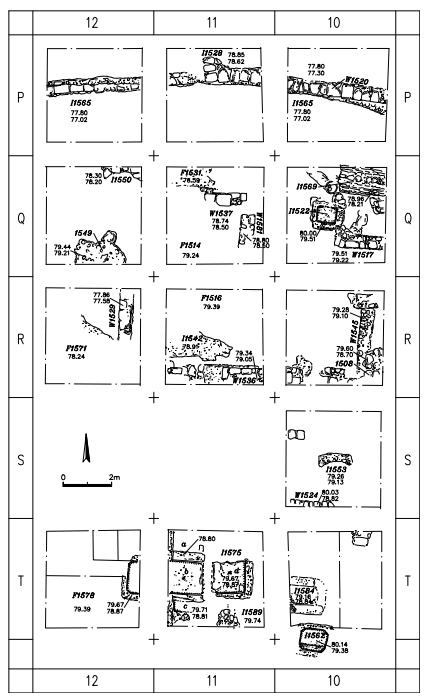

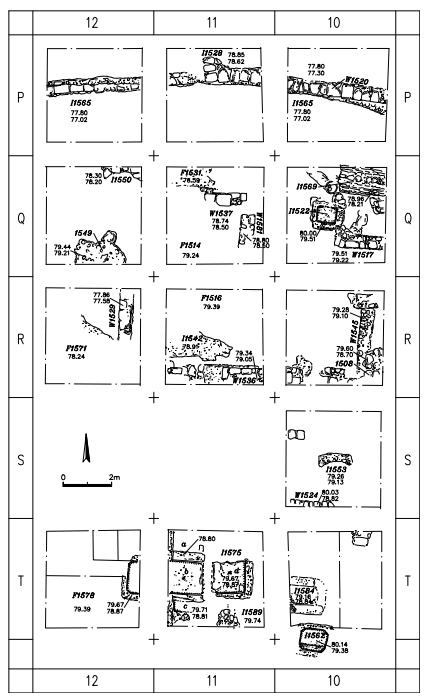

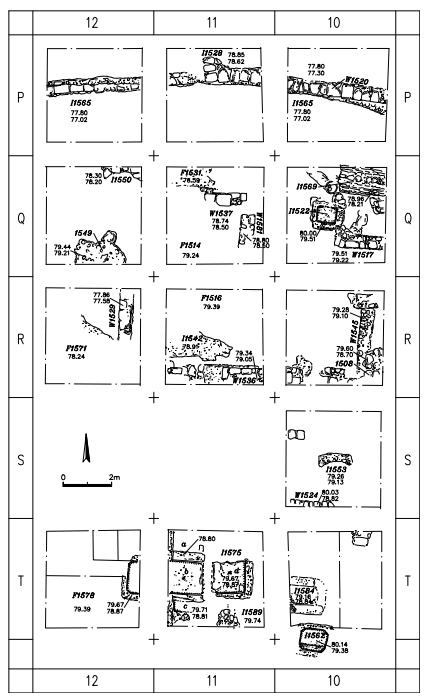

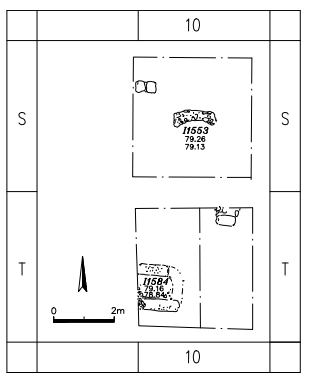

- Fig. 1.6a - General site

of the 2007 season (Squares P-T/10-12) from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.6a

Fig. 1.6a

General site plan of the 2007 season (Squares P-T/10-12).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

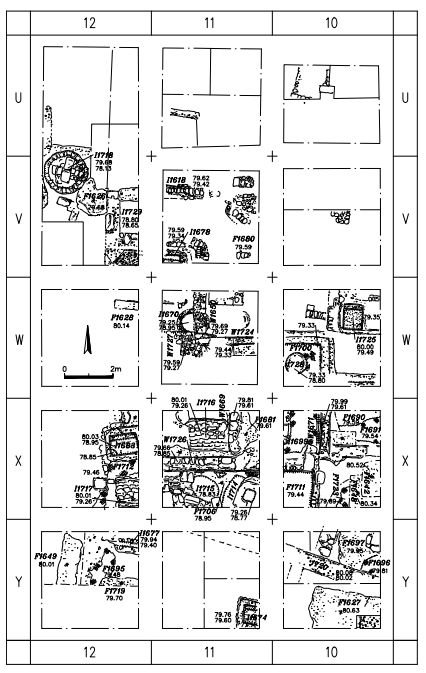

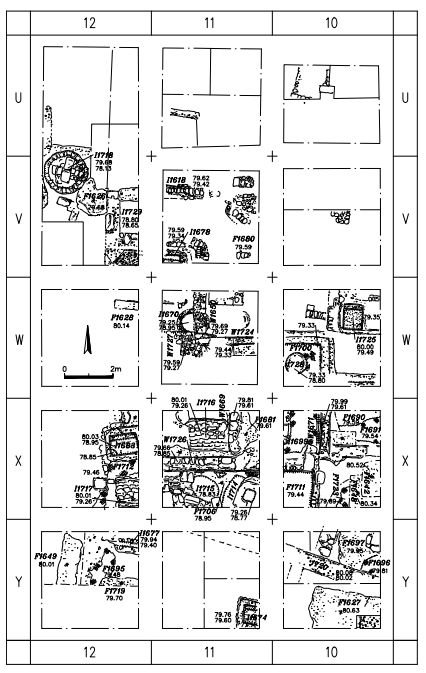

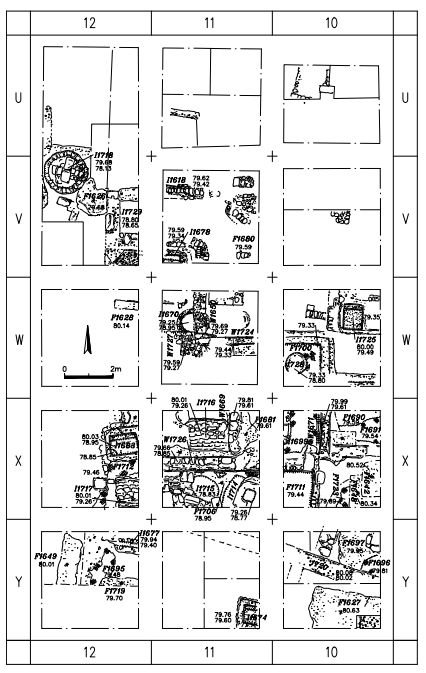

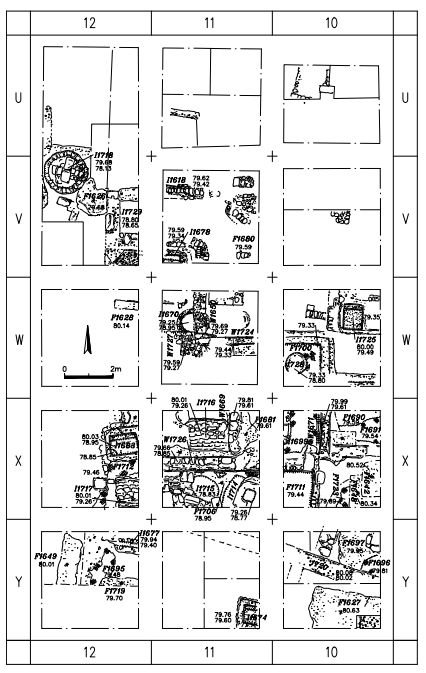

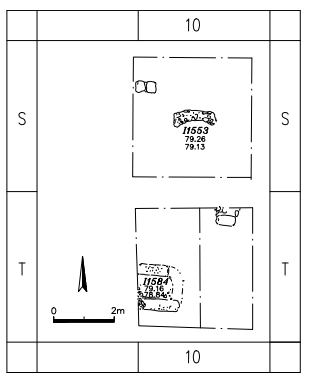

- Fig. 1.6b - General site

plan of the 2007 season (Squares U-Y/10-12) from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.6b

Fig. 1.6b

General site plan of the 2007 season (Squares U-Y/10-12).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

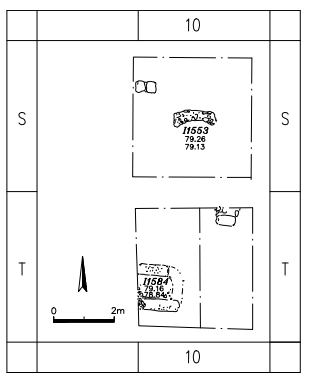

- Fig. 1.6b - General site

plan of the 2007 season (Squares U-Y/10-12) from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 1.6b

Fig. 1.6b

General site plan of the 2007 season (Squares U-Y/10-12).

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 2.1 - Plan of the

Middle Bronze Age loci from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Plan of the Middle Bronze Age loci.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 2.1 - Plan of the

Middle Bronze Age loci from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Plan of the Middle Bronze Age loci.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 4.1a - Plan of the

podium from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 4.1a

Fig. 4.1a

Plan of the podium.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 4.1a - Plan of the

podium from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 4.1a

Fig. 4.1a

Plan of the podium.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 4.3a - Plan of the

plastered pool from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 4.3a

Fig. 4.3a

Plan of the plastered pool.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 4.3a - Plan of the

plastered pool from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 4.3a

Fig. 4.3a

Plan of the plastered pool.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.1 - Plan of the

domestic complex from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Plan of the domestic complex.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.1 - Plan of the

domestic complex from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Plan of the domestic complex.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.9 - Plan of the

oil press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.9

Fig. 5.9

Plan of the oil press.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.9 - Plan of the

oil press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.9

Fig. 5.9

Plan of the oil press.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.17 - Plan of the

Northern wine press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.17

Fig. 5.17

Plan of the Northern wine press.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 5.18 - Plan of the

western wine press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.18

Fig. 5.18

Western wine press. Plan of the rectangular treading floor

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.17 - Plan of the

Northern wine press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.17

Fig. 5.17

Plan of the Northern wine press.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 5.18 - Plan of the

western wine press from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.18

Fig. 5.18

Western wine press. Plan of the rectangular treading floor

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.24 - Plan of the

pottery kilns from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.24

Fig. 5.24

Plan of the pottery kilns.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 5.24 - Plan of the

pottery kilns from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 5.24

Fig. 5.24

Plan of the pottery kilns.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.2 - Schematic site

plan of the Early Islamic remains discovered during the excavations from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Schematic site plan of the Early Islamic remains discovered during the excavations

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.2 - Schematic site

plan of the Early Islamic remains discovered during the excavations from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.2

Fig. 6.2

Schematic site plan of the Early Islamic remains discovered during the excavations

Tal and Taxel (2008)

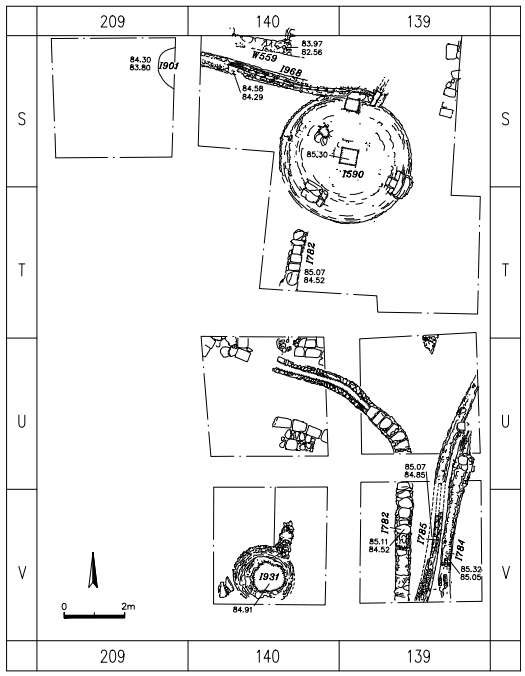

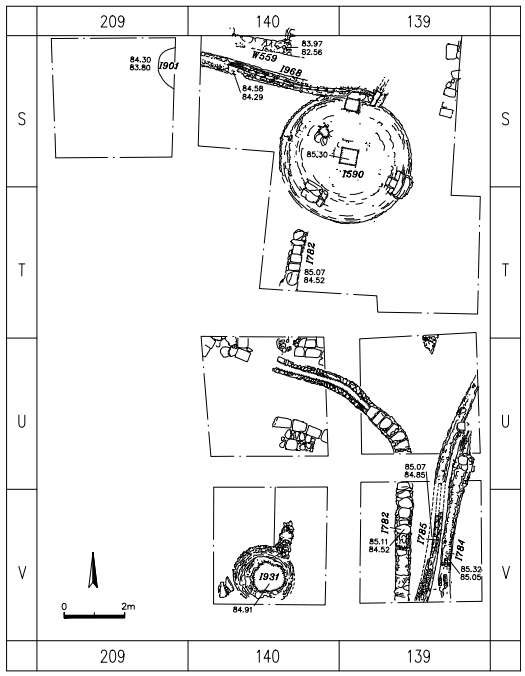

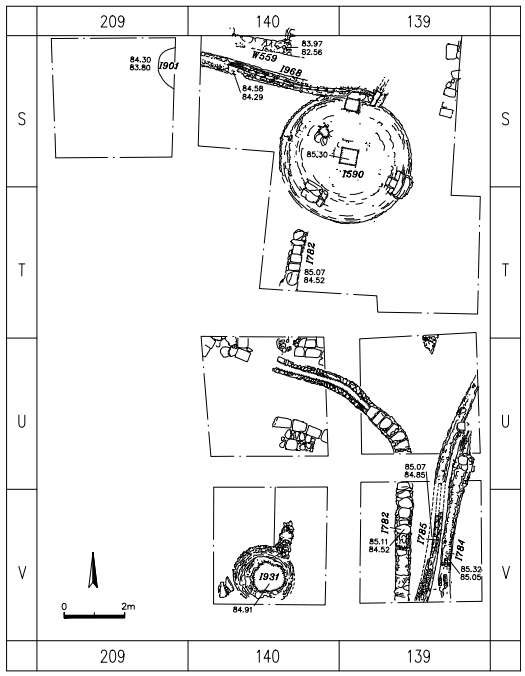

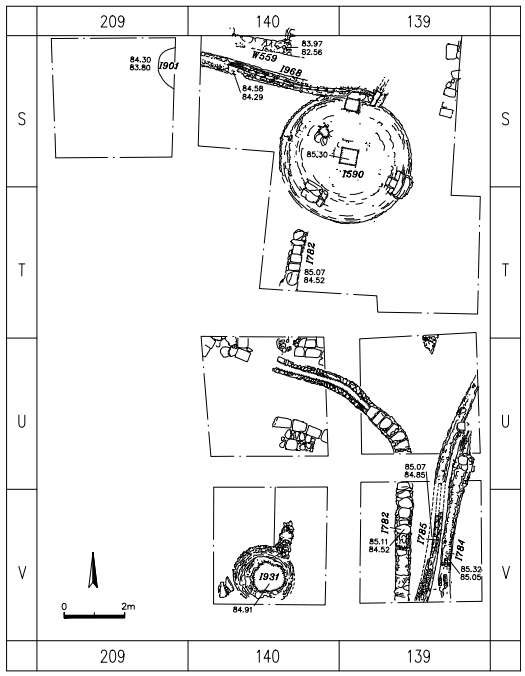

- Fig. 6.3a - Plan of Cistern

1590 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.3a

Fig. 6.3a

Plan of Cistern 1590.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.5a - Plan of Cistern

1356 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.5a

Fig. 6.5a

Plan of Cistern 1356.

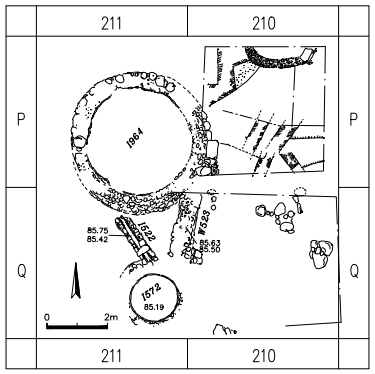

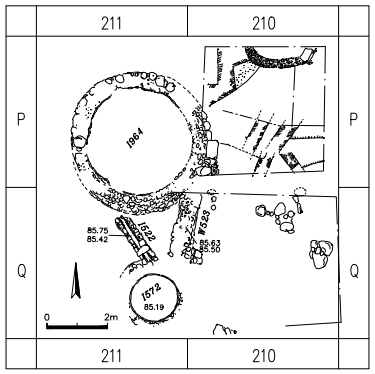

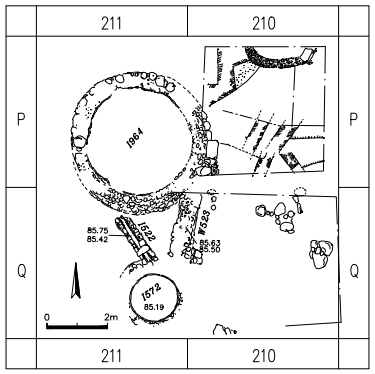

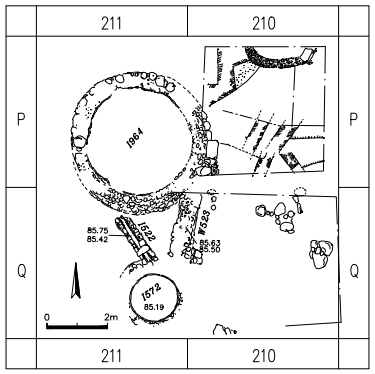

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.8a - Plan of Cisterns

1572 and 1964 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.8a

Fig. 6.8a

Plan of Cisterns 1572 and 1964

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.3a - Plan of Cistern

1590 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.3a

Fig. 6.3a

Plan of Cistern 1590.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.5a - Plan of Cistern

1356 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.5a

Fig. 6.5a

Plan of Cistern 1356.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.8a - Plan of Cisterns

1572 and 1964 from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.8a

Fig. 6.8a

Plan of Cisterns 1572 and 1964

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.15b - Plan of the

western pipe system from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.15b

Fig. 6.15b

Plan of the western pipe system.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.15b - Plan of the

western pipe system from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.15b

Fig. 6.15b

Plan of the western pipe system.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

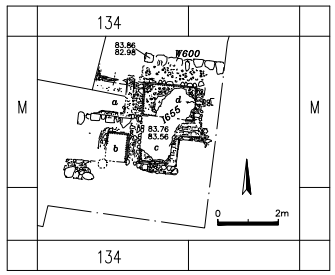

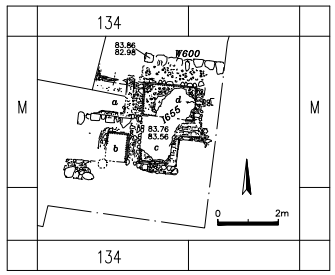

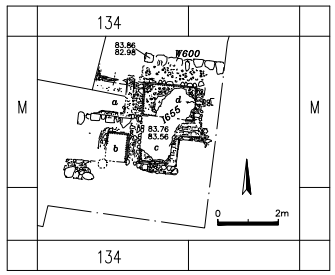

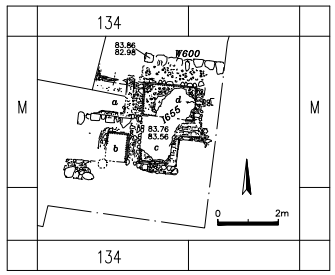

- Fig. 6.32a - Plan of Pools

1655 a-d from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.32a

Fig. 6.32a

Plan of Pools 1655 a-d.

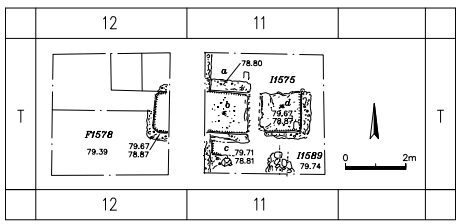

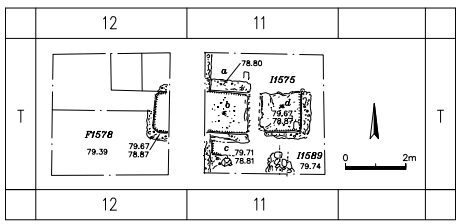

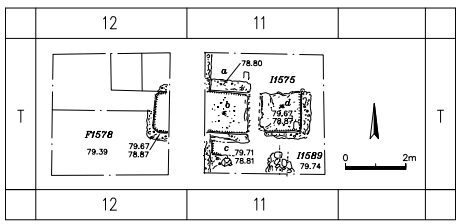

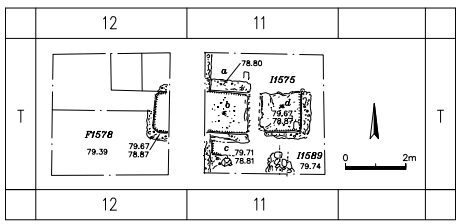

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.33a - Plan of Pools

11575 a-d from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.33a

Fig. 6.33a

Plan of Pools 11575 a-d.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Fig. 6.32a - Plan of Pools

1655 a-d from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.32a

Fig. 6.32a

Plan of Pools 1655 a-d.

Tal and Taxel (2008) - Fig. 6.33a - Plan of Pools

11575 a-d from Tal and Taxel (2008)

Fig. 6.33a

Fig. 6.33a

Plan of Pools 11575 a-d.

Tal and Taxel (2008)

- Drawing of Ramla from 1487

by Conrad Grünenberg from wikipedia and Digital Badische Landes-Bibliothek

Ramla, 1487, by Conrad Grünenberg - Double page, from Conrad Grünenberg: description of the journey from Konstanz to Jerusalem.

Lake Constance area, around 1487. Baden State Library Karlsruhe, Cod. St. Peter, pap. 32.

Ramla, 1487, by Conrad Grünenberg - Double page, from Conrad Grünenberg: description of the journey from Konstanz to Jerusalem.

Lake Constance area, around 1487. Baden State Library Karlsruhe, Cod. St. Peter, pap. 32.

Click on image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Wikipedia and Digital Badische Landes-Bibliothek - Public Domain - Painting of Ramla from 1698

by Cornelis de Bruijn from wikipedia and Geographicus Rare Antique Maps

A rare 1698 view of Ramla by Dutch artist Cornelius de Bruijin. Depicts the city as well as the nearby caravan staging

grounds. Arab horsemen and tent camps decorate the foreground. This view was most likely rendered in secret during de Bruijin’s second world tour.

The Holy Land was then under the control of the Ottoman Empire who imposed strict limitations on pilgrims and tourist from Europe. It is highly

unlikely that de Bruijin would have been allowed to make sketches of the region openly.

A rare 1698 view of Ramla by Dutch artist Cornelius de Bruijin. Depicts the city as well as the nearby caravan staging

grounds. Arab horsemen and tent camps decorate the foreground. This view was most likely rendered in secret during de Bruijin’s second world tour.

The Holy Land was then under the control of the Ottoman Empire who imposed strict limitations on pilgrims and tourist from Europe. It is highly

unlikely that de Bruijin would have been allowed to make sketches of the region openly.

Click on image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Wikipedia and Geographicus Rare Antique Maps - Public Domain - Photo of Ramla from before

1885 by Félix Bonfils from wikipedia

- Photo of Ramla from 1895

from wikipedia and the Detroit Publishing Co. Collection at the U.S. Library of Congress

- Fig. 6 - Smashed Jars

from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Warehouse in Area J1-3, with dozens of smashed jars attributed to Stratum IIIb

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 9 - Smashed Jars

from Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Shattered jars from Stratum IIIb and intact jar from Stratum IIIa; metal object in left foreground.

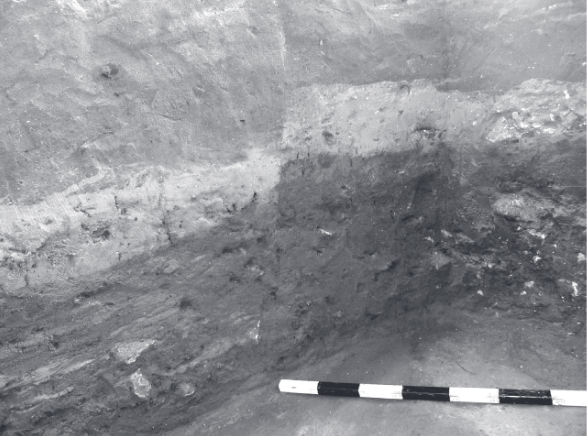

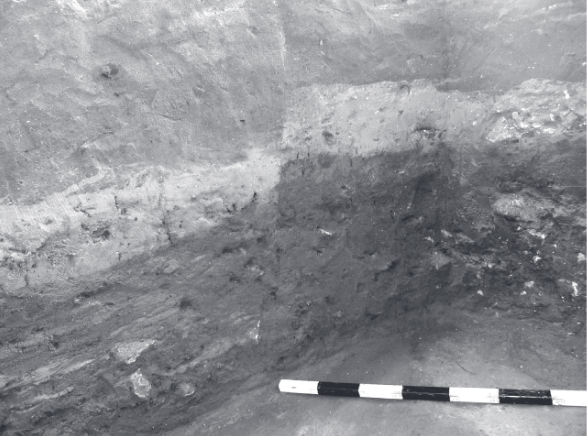

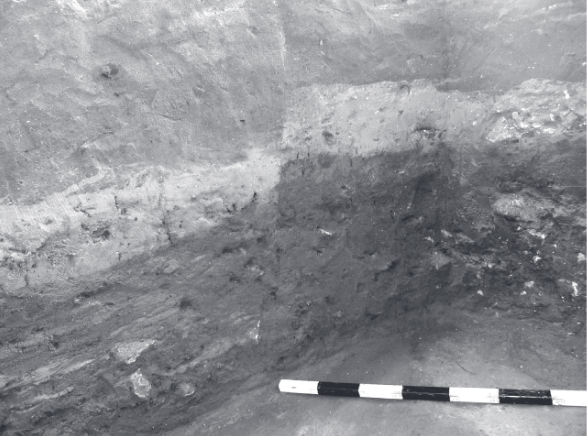

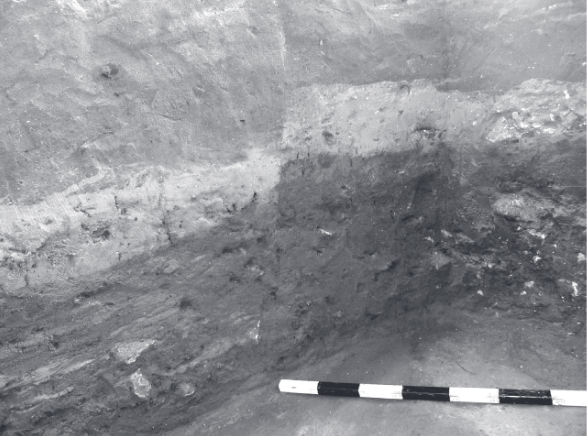

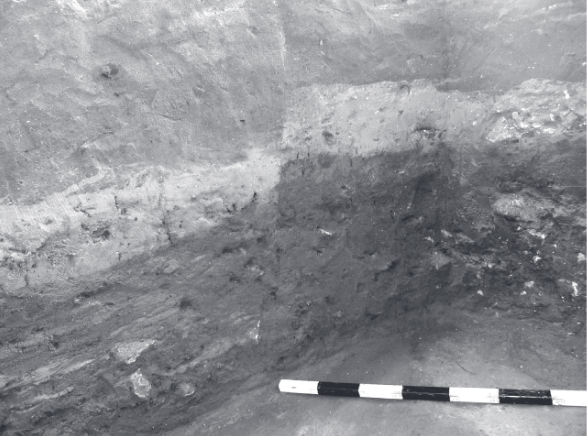

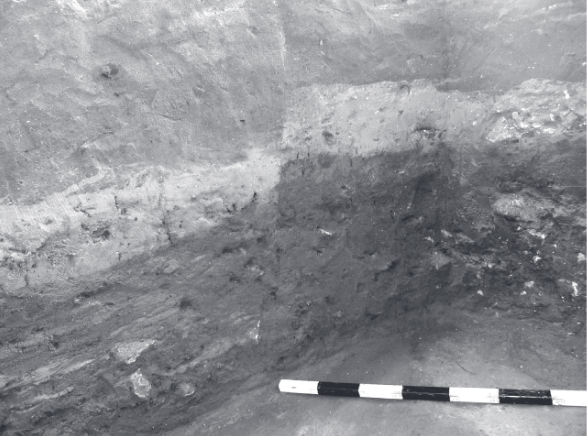

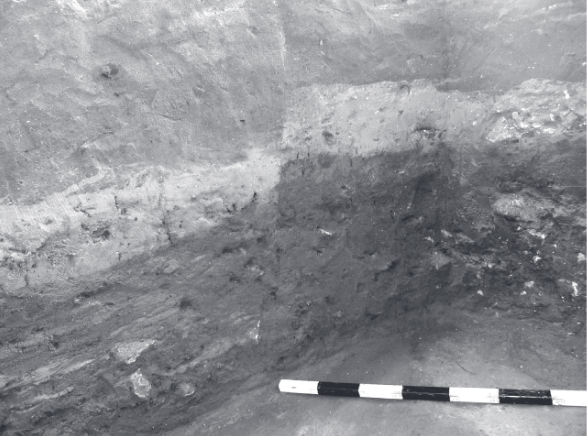

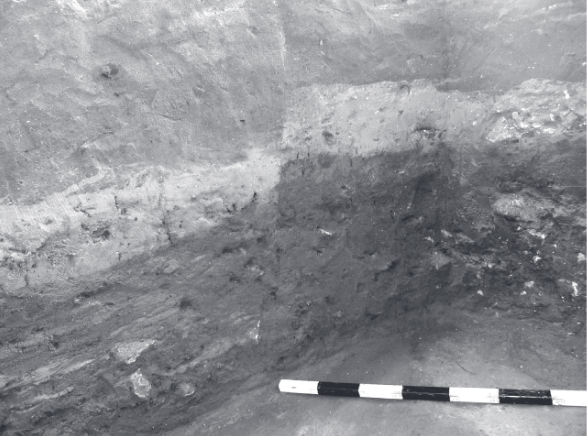

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Fig. 10 - Faulted strata

from Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 10

Figure 10

The fault in the sand and hamra strata caused by strong earthquake.

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Fig. 3 - Faulted Strata

from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Vertical section displaying superimposed layers of sand and hamra,abruptly broken by a vertical rupture

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 4 - Sunken Floor

and Column base from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Occupational layer with architectural items atop it that sank some 150 cm.

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 5 - Sunken Strata

at the antilia type water well from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Antilia well, including the pit and remains of the lifting superstructure (on the right side) that sank several meters as a whole, thus creating a configuration of layers of stepped sand and hamra. The sudden soil failure was most probably caused by the phenomenon known as liquefaction

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 2 - Collapsed Wall

with aligned courses from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Dressed stones uncovered in Area K1, which collapsed keeping the alignment in which they were originally arranged in the wall

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 6 - Tilted Wall from

Kletter (2005)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Square E1, detail of W2, looking east.

JW: Two phases are evident in this photo. The lower courses are from Phase II, the earliest phase. The single top row of crude stones are from Phase I, the later phase.

Kletter (2005)

- from Gorzalczany (2009b)

| Stratum | Period | Age | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Modern | Remains of a military installation | |

| I | 11th cent. CE | ||

| II | Fatimid | 9th-10th cent. CE | |

| IIIa | Abbasid | 8th-9th cent. CE | Industrial installations |

| IIIb | Byzantine/Umayyad | 7th-8th cent. CE | Industrial installations |

| IV | Byzantine | 4th-5th cent. CE | Pottery kilns |

| V | Roman | 1st cent. BCE - 4th cent. CE | |

| VI | Persian/Hellenistic | 4th-5th cent. BCE | Potsherds only |

| VI | Persian/Hellenistic | 4th-5th cent. BCE | Potsherds only |

| VII | Late Bronze | 15th-13th cent. BCE | Potsherds only |

| VIII | Middle Bronze | 20th-15th cent. BCE | Potsherds only |

| IX | Prehistoric | Area A |

| Phase | Features | Period | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eastern wing, including part of covered prayer hall; exedra; entrance gate; mihrab?; minaret? | Umayyad (first half of eighth century) | According to multiple textual sources, the White Mosque at Ramla was first built in the second decade of the 8th century CE (Rosen-Ayalon, 2006) |

| 2 | Extension of eastern wall; northern wall; subterranean pools | Abbasid (second half of eighth century) | |

| 3 | Renovation of prayer hall; possibly western wing | Ayyubid (twelfth century) | |

| 4 | Minaret | Mamluk (fourteenth century) |

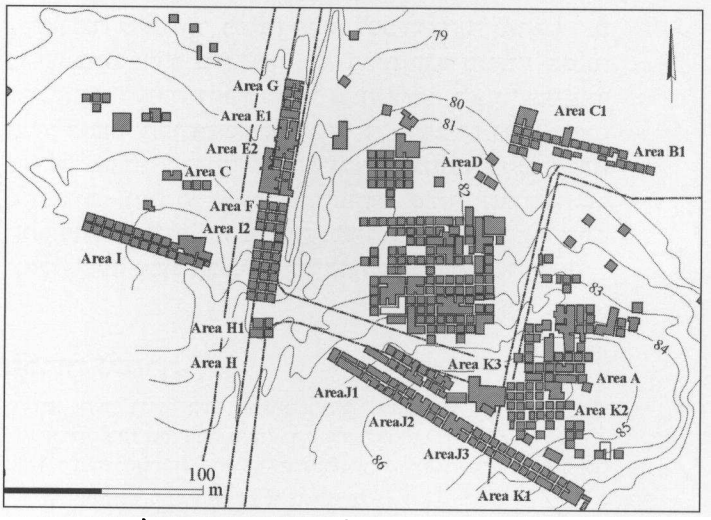

- Fig. 2 - Site Map from

Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The excavated areas

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Fig. 6 - Smashed Jars

from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Warehouse in Area J1-3, with dozens of smashed jars attributed to Stratum IIIb

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 9 - Smashed Jars

from Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Shattered jars from Stratum IIIb and intact jar from Stratum IIIa; metal object in left foreground.

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Fig. 10 - Faulted strata

from Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 10

Figure 10

The fault in the sand and hamra strata caused by strong earthquake.

Gorzalczany (2009b) - Fig. 3 - Faulted Strata

from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Vertical section displaying superimposed layers of sand and hamra,abruptly broken by a vertical rupture

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 4 - Sunken Floor

and Column base from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Occupational layer with architectural items atop it that sank some 150 cm.

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 5 - Sunken Strata

at the antilia type water well from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Antilia well, including the pit and remains of the lifting superstructure (on the right side) that sank several meters as a whole, thus creating a configuration of layers of stepped sand and hamra. The sudden soil failure was most probably caused by the phenomenon known as liquefaction

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) - Fig. 2 - Collapsed Wall

with aligned courses from Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Dressed stones uncovered in Area K1, which collapsed keeping the alignment in which they were originally arranged in the wall

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Gorzalczany (2009b) described 8th century CE earthquake evidence as follows:

Evidence of a major earthquake was discerned in Areas J2 and K1 (see Fig. 2 - site map); it included cracks along the walls of installations, large sections of collapse composed of neat ashlar stone construction that had not been robbed, floors that had dropped and walls that curved in unexpected directions. Wall collapse, which had been intentionally covered over with soil and hamra to save the building stones from being plundered, was observed. It seems that the residents of the town were concerned with the quick restoration of the settlement’s activity. Especially interesting was a series of jars, some positioned upside down, which were discovered in situ, smashed inside a room that was apparently used for storage [Fig. 6Thus, we have earthquake evidence which is precisely dated and well described. The 1.5 meter sinking of the column base (Fig. 4]. The jars dated to the first half of the eighth century CE and they seem to have been all damaged simultaneously in the same event. The room was leveled and quickly refurbished in an attempt to regain its capacity for industrial manufacture as soon as possible. The renovation of the room included the construction of new walls, with which jars dating to the second half of the eighth century CE were associated and preserved intact (Fig. 9

Fig. 6

Warehouse in Area J1-3, with dozens of smashed jars attributed to Stratum IIIb

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)). It therefore seems that we have here a small, rare chronological window, which enables us to date the earthquake.

Figure 9

Shattered jars from Stratum IIIb and intact jar from Stratum IIIa; metal object in left foreground.

Gorzalczany (2009b)

Indisputable proof of the earthquake occurrence was found in the balks of Area K1, where a fault in the layers of sand and hamra, which were split due to a fissure, stands out prominently (Fig. 10). One side of the layers in the section was lower than the other side. The fissure continued along several excavation squares and it caused a plaster floor and a column base that stood above it to sink 1.5 m [Fig. 4like this """Gorzalczany (2009b)

Figure 10

The fault in the sand and hamra strata caused by strong earthquake.

Gorzalczany (2009b)]. Such vertical movement of layers could only be caused by a powerful seismic event. An opposite fracture was discerned elsewhere on the site, where the movement was not only vertical but also horizontal, causing the layers to climb one atop the other [Fig. 5

Fig. 4

Occupational layer with architectural items atop it that sank some 150 cm.

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)]. It appears then that archaeological evidence of an earthquake, which occurred close to Ramla in the middle of the eighth century CE, can be pointed to for the first time. The dating is firmly based on the pottery and it is feasible that this is the famous earthquake of the year 749 CE.

Fig. 5

Antilia well, including the pit and remains of the lifting superstructure (on the right side) that sank several meters as a whole, thus creating a configuration of layers of stepped sand and hamra. The sudden soil failure was most probably caused by the phenomenon known as liquefaction

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Occupational layer with architectural items atop it that sank some 150 cm.

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

the entire antilia installation - the pit and the lifting superstructure device together with the layers of fill and the occupation layer abutting them - collapsed and sank several meters. Damage to surrounding areas indicates that the pit (Fig. 5) constituted the central axis of the falland

the sand layers around the antilia [that appeared] broken in a stepped formation (Fig. 5)encompassed the pit.

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018) added an observation of building stones of walls that had collapsed in a clear, `orderly' pattern found in situ (Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Dressed stones uncovered in Area K1, which collapsed keeping the alignment in which they were originally arranged in the wall

Gorzalczany and Salamon (2018)

Rosen-Ayalon (2006:72)

suggested that renovations to the White Mosque at Ramla in the second building phase was a reaction to seismic damage to the first phase from a mid 8th century CE earthquake -

noting that although not all the excavators discovered signs of destruction compatible with an earthquake, some indeed relate to this possibility.

Rosen-Ayalon (2006:72) described the physical archaeoseismic evidence as inconclusive.

The evidence is inconclusive, since a significant proportion of the finds was found in disturbed stratigraphy. In other words, even if there had been significant damage, this may not have been evident in excavation. However, even minimal disturbance — not of the magnitude caused by the eleventh-century earthquake — may have been sufficient to warrant the renovations.By comparing architectural elements (e.g. pointed arches) of the 3 subterranean cisterns of the Phase 2 mosque enclosure with architectural elements (e.g. pointed arches) of a subterranean cistern known as 'the pools of Saint Helena' or the 'Aneziya', Rosen-Ayalon (2006:74) concluded that Phase 2 mosque construction took place around 788/789 CE as construction of 'the pools of Saint Helena' is dated by inscription to A.H. 172 (788/789 CE).

Little is known of the history of the White Mosque of Ramla, the impressive remains of which dominate the environs, and its origins have not been studied systematically so far. All historical sources agree that the mosque was built at the very beginning of the foundation of Ramla, in the second decade of the eighth century CE, during the Umayyad Dynasty (660–750 CE). The city of Ramla was founded by ʿAbd al-Malik’s son, Suleiman, the ruler of Palestine, who established it as the capital of the province (EI, s.v. Ramlah). The first archaeological excavation of the site, directed by J. Kaplan, was conducted in 1949; its publication (Kaplan 1957) included a plan of the mosque (fig. 1), which still reflects our present state of knowledge, 50 years later.

The mosque contains the following components (fig. 1):

- The large quadrangular enclosure contains an open-air courtyard and a long and narrow covered area in the south; the long wall, the qibla, that faces Mecca, with the mihrab—the niche emphasising this orientation—in its centre. The minaret is situated in the north.

- Three subterranean cisterns are situated in the open courtyard.

These components are analysed below, in an effort to unravel the complex history of the site.

The excavator distinguished three building phases, shown on the plan. The first includes the eastern and part of the southern area of the enclosure, as well as the northern wall. As noted by Kaplan (1957: 98), excavation trenches dug at a number of points indicate that these walls rest on the virgin soil of Ramla (the name ‘Ramla’ is derived from the Arabic word raml, meaning ‘sand’).

According to the plan, the western part of the enclosure was constructed in the second building phase, its walls characterised by less solid foundations than those of the preceding stage (Kaplan 1957: 98). The second phase is emphasised by a 6° deviation in the orientation of the qibla and the covered prayer hall.

The construction of the minaret was attributed by Kaplan to the third building phase.

The covered prayer hall of the mosque reflects a plan characteristic of Umayyad mosques throughout Syro-Palestine and known, with minor distinctions, from various sites in the region. It consists of a long, narrow area, perhaps designed to enable a large number of congregators to assemble next to the prestigious qibla wall. The Great Mosque of Damascus (Creswell and Allan 1989: 49) and the early plan of al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem (Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1996: fig. 3), are the most prominent examples of this plan and may have served as the inspiration for the mosque of the new capital. The construction of the western part of the mosque in the second building phase evidently maintained this original plan (see below).

The eastern wall of the enclosure clearly belongs to the first building phase, as it continues the straight line of the covered prayer hall. Beyond the wall of the enclosure lies a covered exedra, an element that occurs in most mosques and was probably intended to provide protection from the elements. A row of pillar or column bases surrounding the courtyard runs parallel to the eastern wall of the mosque’s enclosure.

Two additional rows of pillar bases in this enclosure, oriented to the west (fig. 1), are attributed by Kaplan to the first phase as well. This is clearly not coincidental, since the pillars in each row and between the rows are equidistant. These two rows probably continued along the entire length of the northern line of the enclosure until its juncture with the western wall (fig. 2).1 Evidently, then, the northern exedra—which consisted of a double row of pillars—served as the boundary of the mosque enclosure in the first phase. This does not present any problem, since we are familiar with exedras with more than one row of pillars in many other mosques, such as the ancient mosque of Susa, Iran (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 135) and Raqqa, Syria (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 145), with two rows, and the later mosques of Qairawan, Tunisia (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 200) and Samarra, Iraq (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 232), with even more rows in their exedras. We may conclude, therefore, that if this is indeed the northern exedra of the mosque under discussion, the entire enclosure should be circumscribed by a northern wall. In order to determine the full size of the mosque in the first phase of construction, we postulate that the northern wall was located at the same distance from the northern pillar rows as the eastern wall from the eastern row of pillars (fig. 3). This suggests that the mosque was rectangular in shape, and not square, as in Kaplan’s plan. Confirmation for this proposal comes from other rectangular Umayyad mosques in the Syro-Palestinian region, most notably the Great Mosque of Damascus (Creswell and Allan 1989: 49) and al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem (Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1996: fig. 3). Thus, the proportions of the White Mosque, as conjectured here, appear to be similar to those of other contemporaneous mosques in the region.

Another feature, the entrance to the mosque, offers conclusive support for this proposal. Although the present-day entrance is located in the north, next to the minaret, the original main entrance—now completely covered—was uncovered by Kaplan in the original eastern wall and is indicated on his plan; it too is attributed to the first building phase. There are four pillar bases to the south of this entrance, but only three such bases to its north. If a northern wall once circumscribed the entire enclosure, the doorway would have been positioned precisely at the centre of the eastern wall, in accordance with the common architectural formula for such mosques.

It is thus likely that the original plan of the mosque conformed to this reconstruction. As implied by Kaplan, these boundaries were later blurred, although he does not elaborate on the subsequent building phases. It is proposed here that this modification resulted from one of the major earthquakes that shook the region toward the end of the Umayyad period, an event that likely destroyed both the covered hall and the northern part of the mosque.

As can be seen on the plan, both the western part of the covered hall and the western wall of the enclosure do not belong to the first phase. The entire western part, beyond the first four pillar bases, belongs to the second phase, which apparently was an attempt to reconstruct or renovate the mosque after it had been hit by the earthquake of 747 CE.2 Although not all the excavators discovered signs of destruction compatible with an earthquake, some indeed relate to this possibility. The evidence is inconclusive, since a significant proportion of the finds was found in disturbed stratigraphy. In other words, even if there had been significant damage, this may not have been evident in excavation. However, even minimal disturbance—not of the magnitude caused by the eleventh-century earthquake—may have been sufficient to warrant the renovations (see below).

To the best of our knowledge, the facade of the present-day covered hall and the nature of the construction reflect a later phase of renovation (fig. 4). This phase, which should be attributed to Salah al-Din in 1190, is mentioned in the historical sources by Mujir al-Din (1866), the well-known fifteenth-century historian. Kaplan notes that the renovation was hindered by the many burials in the environs, which made the building of the qibla—and the entire covered hall— problematic. According to Kaplan, some time probably elapsed from the time of the destruction until the reconstruction. Noteworthy is an excerpt from Ibn Batuta, from the mid-fourteenth century (1355), which relates a tradition that attributes to the area of the qibla—our southern wall—a burial of 300 saints (Ibn Batuta 1355: 128). Although a discussion of this tradition, the veracity of which is disputable, is beyond the scope of this article, it supports the architectural development proposed here, i.e. the deviation in the orientation of the qibla, due to the disturbance.

One still needs to account for the interim period between the earthquake, which occurred in the middle of the eighth century, and the renovations to which we now refer, which took place during the twelfth century. Indeed, there is evidence pointing to the important status of the mosque prior to 1190. Let us recall that not one, but two, earthquakes occurred in the interim and may both have destroyed the mosque: the first, as already discussed, took place in the eighth century, and another, devastating one occurred in 1033. This is evident from the writings of the traveller Nasir-i Khusrau, who visited Palestine one decade after the earthquake and grieved for the city of Ramla which was devastated in the early eleventh-century earthquake (1881: 21). It is highly probable that the western part of the mosque was then destroyed again. Thus, from an historical-chronological perspective, the period that elapsed should be calculated from the earthquake of 1033, in the Fatimid period, to Salah al-Din’s restoration of the mosque in 1190.

To reiterate, according to the sources, the present-day mosque reflects the Ayyubid renovations. This would include the simple mihrab which appears on the plan. However, al-Muqadassi, in his description of the mosque, elaborates on the mihrab, noting that the mosque surpasses all others in beauty, including the Damascus mosque and the al-Aqsa Mosque. To quote al-Muqadassi: “the main mosque of Ramla is called al-Abi‘ad—the White Mosque; it is more beautiful and luxurious than that of Damascus.” According to al-Muqadassi, it possesses the most luxurious mihrab, and “its minbar is second in beauty only to that of Jerusalem” (al-Muqadassi, p. 164). Al-Muqadassi, who lived in the second half of the tenth century CE in Palestine, is generally considered a reliable source.

From these descriptions we may deduce that the simple mihrab in the present-day mosque (fig. 5) is not the same one that earned al-Muqadassi’s praise and that, consequently, there must have been an earlier mihrab, belonging either to the first Umayyad phase or to the second phase of the mosque. This elaborate mihrab was presumably destroyed in the 1033 earthquake, and the present-day mihrab is probably the one renovated in Salah al-Din’s time. If this is the case, it suggests a third—hitherto unsuspected—period in the history of the mosque.

The original plan of the mosque may now be reconstructed in full (fig. 6). The 6° deviation in the orientation of the covered southern hall— presumably destroyed by the earthquakes—should be cancelled. We suggest that the renovation of the mosque included the elongation of the eastern boundary wall to its present dimensions and the construction of a northern wall, encompassing the mosque as we know it today.

The historical events led to the following developments: the city, first threatened by the Carmatians, was conquered by the Crusaders. In 1187, following the Battle of Hittin, Salah al-Din freed Ramla from the Crusaders, leading him to renovate the mosque, as mentioned above. The present-day façade of the prayer hall is a remnant of those renovations. Two further stages took place in the Mamluk period, with the construction of the minaret (see below).

The subterranean cisterns in the mosque enclosure present a real archaeological enigma. In order to describe this enigma, we will digress briefly and describe another structure, also in Ramla: the outstanding subterranean cistern known as “the pools of Saint Helena” or the Aneziya, which lies to the north of the mosque across the main road in Ramla. M. de Vogüé, one of the most prominent researchers of the late nineteenth century, studied and measured this structure, publishing it in the early twentieth century (de Vogüé 1912). In the late 1930s, Creswell published a detailed plan of the cistern (1939: 162; fig. 7). Thus, in contrast to the limited information available regarding the mosque, we possess a wealth of information and a complete plan of this cistern.

As a starting point, it should be noted that this impressive architectural compound was built in one period, with no significant changes or modifications. Moreover, an inscription, visible to this day, dates the construction to 172 AH (789 CE), the time of Harun al-Rashid (Van Berchem 1897; fig. 8). This functional architectural structure was constructed as a system of subterranean pools, a project initiated by the administration to ensure a regular water supply to the public.

It is an irregular rectangular structure, divided into squares with cross-shaped pillars, from which arches spread out (fig. 9). This is one of the few structures in the country that can be attributed with certainty to the Abbasid period, a period somewhat limited in construction initiatives in this country. In addition to the good state of preservation of the pools, they are of architectural significance: this is the first case in which the pointed arch was used systematically. Throughout the Umayyad period, preceding the Abbasid, the classical arch, with a 180° curve, was used in Muslim architecture and only sporadic use was made of the pointed arch. The Ramla cistern, constructed in the eighth century CE, exhibits the first systematic use of the pointed arch. According to de Vogüé, the Ramla cistern precedes European architecture by four centuries in the use of pointed arches, which can be seen in the hall and the galleries. This is therefore a landmark in the history of architecture in general, and in the history of Ramla in particular.

The enigma presented by the pools within the mosque enclosure is rooted in their resemblance to the cistern described above. The three pools in the mosque enclosure resemble the others in their division of the space by means of monumental cross-shaped pillars extending in arches in the four directions. In this case too, there is a systematic use of the pointed arch. Indeed, the structure is reminiscent of a cathedral (fig. 10). The walls are lined in an identical plaster to the staircases, which descend at a 90° angle to the entrance.3

As previously mentioned, the large pools are dated to 789 CE, a landmark in the history of architecture. Given the similarities between these pools and those within the mosque enclosure, the question arises as to the date of the latter. Since they are situated inside the Umayyad mosque, are they of Umayyad date too? If so, they would have been earlier than the large pools, and an earlier date than the commonly accepted date of 789 should be postulated for the architectural feature of pointed arches. Alternatively, perhaps the three pools within the mosque are Abbasid, like the large pools to which they bear an architectural resemblance. In this case they would have been built in the mosque at a later date than that of the mosque’s construction.4

In an effort to resolve this enigma, I superimposed the Abbasid cistern over the group of pools in the mosque enclosure. To my surprise, I found an exact correlation between them all (fig. 11). Evidently, both groups reflect an identical architectural plan.

Returning to the mosque, the pools in the compound indeed belong to an early period, but were presumably constructed after the eighth-century earthquake. Even if the destruction was not complete, this would have been an opportunity, with the first renovation of the mosque—that first hitherto unidentified phase. Moreover, their construction took place around the same time as the construction of the Harun al-Rashid pools. In other words, the entire first renovation of the mosque, including its subterranean cisterns, would have taken place after 747, contemporaneously with the Abbasid cistern. This resolves both the question of the date of the cisterns and the question of the pointed arches. The introduction of the three pools in the Umayyad mosque shortly after this period, under the Abbasids, would account for the new northern wall. The first one was removed for the construction of the three reservoirs. The new wall was described by Kaplan as belonging to the first stage—since he was unaware of an earlier stage and his evidence corroborated the criteria of early architecture. This is presumably the same stage at which the beautiful mihrab—whether Umayyad or Abbasid— was incorporated in the mosque. It is likely that this mihrab was the one destroyed in the 1033 earthquake, after which the simpler mihrab from the time of Salah al-Din was installed.

The last architectural element is the minaret, which, as noted by Kaplan, is built in the northern wall of the enclosure, attributed to the third phase of construction. Kaplan mentions that he did not uncover any earlier remains under the minaret in his archaeological investigations. Ben-Dov, who conducted a test pit there, also dated the minaret to the Mamluk period (1984).

An inscription at the entrance to the minaret records the date of its construction—1318, during the time of al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qala’un. Hence, the minaret is Mamluk, built on the virgin soil of Ramla. This leads to the next query: if this tower is indeed from Mamluk times and was not built atop an earlier tower, where was the ancient tower situated? After all, al-Muqadassi, in the tenth century, mentions the minaret, which he says was built by Hisham, son of ʿAbd al-Malik, the brother of Suleiman, who founded the city of Ramla. This provides conclusive evidence of the existence of a pre-Mamluk minaret. This original minaret may have been built adjacent to the first northern wall, but any conjecture regarding its location is purely speculative.

After the expansion of the area of the mosque enclosure following its destruction by the first earthquake, it is conceivable that the second minaret was situated somewhere along the northern enclosure wall, not necessarily at the same location as the Mamluk one. As for the location of the minaret in Umayyad times, excavations at various sites suggest that the minaret was not restricted to a specific location in the mosque enclosure. Suffice it to mention the mosques of Jerash and Amman in Jordan. It is hoped that future investigations will uncover the original minaret of the White Mosque.

In sum, four phases should be attributed to the White Mosque of Ramla, and not three, as was believed until now. Furthermore, we are now able to attribute to each of these phases historical information hitherto unknown and to correlate different parts of the structure with the various phases (table 1). In addition, the problem of the three cisterns has been solved.

| Phase | Features | Period | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eastern wing, including part of covered prayer hall; exedra; entrance gate; mihrab?; minaret? | Umayyad (first half of eighth century) | According to multiple textual sources, the White Mosque at Ramla was first built in the second decade of the 8th century CE (Rosen-Ayalon, 2006) |

| 2 | Extension of eastern wall; northern wall; subterranean pools | Abbasid (second half of eighth century) | |

| 3 | Renovation of prayer hall; possibly western wing | Ayyubid (twelfth century) | |

| 4 | Minaret | Mamluk (fourteenth century) |

2 For our purposes, it is irrelevant whether the

earthquake in which the mosque was damaged

occurred in 747 CE or 749 CE, as has been

proposed. For discussion of the problem of

dating the earthquake, see Tsafrir and Foerster

1997: n. 227. There may even have been two

earthquakes. There is no question, however,

that at least one earthquake occurred in the

mid-eighth century, strong enough to have

caused the damage to our mosque.

3 A Mamluk inscription at the entrance to the southern

reservoir points to its renovation, probably during

one of the Mamluk renovations of the mosque, see L.A. Mayer

4 In Rosen-Ayalon 2002, I touched upon the problematicity

of this issue. New light can now be shed on the matter.

Rosen-Ayalon (2006:72)

suggested that renovations to the White Mosque at Ramla in the third building phase occurred after the structure was damaged in the earthquake of 1033 CE.

She suggested that third phase construction was carried out in 1190 CE and should be attributed to Salah al-Din.

Rosen-Ayalon (2006:72) mentions that traveller

Nasir i-Khosero [] visited Palestine one decade after the earthquake

[of 1033 CE] and grieved for the city of Ramla which was devastated in the early eleventh-century earthquake

.

On page 64 in a passage from a French translation of Sefer Nema by

Nasir i-Khosero, we can read:

The area of the great mosque is three hundred paces by two hundred. An inscription, placed above the soffèh (bench), relates that on Moharrem 15, 425 ( December 11, 1033), a violent earthquake overthrew a large number of buildings but none of the inhabitants were injured.It should be noted that textual accounts state that Ramla suffered damage during the earthquake of 1068 CE, was the site of several battles in the 11th century CE including an attack by Turkish elements of the Fatimid Army in 1067 CE, and was the site of a series of battles between Crusaders and Islamic armies starting in 1099 CE.

Little is known of the history of the White Mosque of Ramla, the impressive remains of which dominate the environs, and its origins have not been studied systematically so far. All historical sources agree that the mosque was built at the very beginning of the foundation of Ramla, in the second decade of the eighth century CE, during the Umayyad Dynasty (660–750 CE). The city of Ramla was founded by ʿAbd al-Malik’s son, Suleiman, the ruler of Palestine, who established it as the capital of the province (EI, s.v. Ramlah). The first archaeological excavation of the site, directed by J. Kaplan, was conducted in 1949; its publication (Kaplan 1957) included a plan of the mosque (fig. 1), which still reflects our present state of knowledge, 50 years later.

The mosque contains the following components (fig. 1):

- The large quadrangular enclosure contains an open-air courtyard and a long and narrow covered area in the south; the long wall, the qibla, that faces Mecca, with the mihrab—the niche emphasising this orientation—in its centre. The minaret is situated in the north.

- Three subterranean cisterns are situated in the open courtyard.

These components are analysed below, in an effort to unravel the complex history of the site.

The excavator distinguished three building phases, shown on the plan. The first includes the eastern and part of the southern area of the enclosure, as well as the northern wall. As noted by Kaplan (1957: 98), excavation trenches dug at a number of points indicate that these walls rest on the virgin soil of Ramla (the name ‘Ramla’ is derived from the Arabic word raml, meaning ‘sand’).

According to the plan, the western part of the enclosure was constructed in the second building phase, its walls characterised by less solid foundations than those of the preceding stage (Kaplan 1957: 98). The second phase is emphasised by a 6° deviation in the orientation of the qibla and the covered prayer hall.

The construction of the minaret was attributed by Kaplan to the third building phase.

The covered prayer hall of the mosque reflects a plan characteristic of Umayyad mosques throughout Syro-Palestine and known, with minor distinctions, from various sites in the region. It consists of a long, narrow area, perhaps designed to enable a large number of congregators to assemble next to the prestigious qibla wall. The Great Mosque of Damascus (Creswell and Allan 1989: 49) and the early plan of al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem (Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1996: fig. 3), are the most prominent examples of this plan and may have served as the inspiration for the mosque of the new capital. The construction of the western part of the mosque in the second building phase evidently maintained this original plan (see below).

The eastern wall of the enclosure clearly belongs to the first building phase, as it continues the straight line of the covered prayer hall. Beyond the wall of the enclosure lies a covered exedra, an element that occurs in most mosques and was probably intended to provide protection from the elements. A row of pillar or column bases surrounding the courtyard runs parallel to the eastern wall of the mosque’s enclosure.

Two additional rows of pillar bases in this enclosure, oriented to the west (fig. 1), are attributed by Kaplan to the first phase as well. This is clearly not coincidental, since the pillars in each row and between the rows are equidistant. These two rows probably continued along the entire length of the northern line of the enclosure until its juncture with the western wall (fig. 2).1 Evidently, then, the northern exedra—which consisted of a double row of pillars—served as the boundary of the mosque enclosure in the first phase. This does not present any problem, since we are familiar with exedras with more than one row of pillars in many other mosques, such as the ancient mosque of Susa, Iran (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 135) and Raqqa, Syria (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 145), with two rows, and the later mosques of Qairawan, Tunisia (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 200) and Samarra, Iraq (Creswell and Allan 1989: fig. 232), with even more rows in their exedras. We may conclude, therefore, that if this is indeed the northern exedra of the mosque under discussion, the entire enclosure should be circumscribed by a northern wall. In order to determine the full size of the mosque in the first phase of construction, we postulate that the northern wall was located at the same distance from the northern pillar rows as the eastern wall from the eastern row of pillars (fig. 3). This suggests that the mosque was rectangular in shape, and not square, as in Kaplan’s plan. Confirmation for this proposal comes from other rectangular Umayyad mosques in the Syro-Palestinian region, most notably the Great Mosque of Damascus (Creswell and Allan 1989: 49) and al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem (Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1996: fig. 3). Thus, the proportions of the White Mosque, as conjectured here, appear to be similar to those of other contemporaneous mosques in the region.

Another feature, the entrance to the mosque, offers conclusive support for this proposal. Although the present-day entrance is located in the north, next to the minaret, the original main entrance—now completely covered—was uncovered by Kaplan in the original eastern wall and is indicated on his plan; it too is attributed to the first building phase. There are four pillar bases to the south of this entrance, but only three such bases to its north. If a northern wall once circumscribed the entire enclosure, the doorway would have been positioned precisely at the centre of the eastern wall, in accordance with the common architectural formula for such mosques.

It is thus likely that the original plan of the mosque conformed to this reconstruction. As implied by Kaplan, these boundaries were later blurred, although he does not elaborate on the subsequent building phases. It is proposed here that this modification resulted from one of the major earthquakes that shook the region toward the end of the Umayyad period, an event that likely destroyed both the covered hall and the northern part of the mosque.

As can be seen on the plan, both the western part of the covered hall and the western wall of the enclosure do not belong to the first phase. The entire western part, beyond the first four pillar bases, belongs to the second phase, which apparently was an attempt to reconstruct or renovate the mosque after it had been hit by the earthquake of 747 CE.2 Although not all the excavators discovered signs of destruction compatible with an earthquake, some indeed relate to this possibility. The evidence is inconclusive, since a significant proportion of the finds was found in disturbed stratigraphy. In other words, even if there had been significant damage, this may not have been evident in excavation. However, even minimal disturbance—not of the magnitude caused by the eleventh-century earthquake—may have been sufficient to warrant the renovations (see below).

To the best of our knowledge, the facade of the present-day covered hall and the nature of the construction reflect a later phase of renovation (fig. 4). This phase, which should be attributed to Salah al-Din in 1190, is mentioned in the historical sources by Mujir al-Din (1866), the well-known fifteenth-century historian. Kaplan notes that the renovation was hindered by the many burials in the environs, which made the building of the qibla—and the entire covered hall— problematic. According to Kaplan, some time probably elapsed from the time of the destruction until the reconstruction. Noteworthy is an excerpt from Ibn Batuta, from the mid-fourteenth century (1355), which relates a tradition that attributes to the area of the qibla—our southern wall—a burial of 300 saints (Ibn Batuta 1355: 128). Although a discussion of this tradition, the veracity of which is disputable, is beyond the scope of this article, it supports the architectural development proposed here, i.e. the deviation in the orientation of the qibla, due to the disturbance.

One still needs to account for the interim period between the earthquake, which occurred in the middle of the eighth century, and the renovations to which we now refer, which took place during the twelfth century. Indeed, there is evidence pointing to the important status of the mosque prior to 1190. Let us recall that not one, but two, earthquakes occurred in the interim and may both have destroyed the mosque: the first, as already discussed, took place in the eighth century, and another, devastating one occurred in 1033. This is evident from the writings of the traveller Nasir-i Khusrau, who visited Palestine one decade after the earthquake and grieved for the city of Ramla which was devastated in the early eleventh-century earthquake (1881: 21). It is highly probable that the western part of the mosque was then destroyed again. Thus, from an historical-chronological perspective, the period that elapsed should be calculated from the earthquake of 1033, in the Fatimid period, to Salah al-Din’s restoration of the mosque in 1190.

To reiterate, according to the sources, the present-day mosque reflects the Ayyubid renovations. This would include the simple mihrab which appears on the plan. However, al-Muqadassi, in his description of the mosque, elaborates on the mihrab, noting that the mosque surpasses all others in beauty, including the Damascus mosque and the al-Aqsa Mosque. To quote al-Muqadassi: “the main mosque of Ramla is called al-Abi‘ad—the White Mosque; it is more beautiful and luxurious than that of Damascus.” According to al-Muqadassi, it possesses the most luxurious mihrab, and “its minbar is second in beauty only to that of Jerusalem” (al-Muqadassi, p. 164). Al-Muqadassi, who lived in the second half of the tenth century CE in Palestine, is generally considered a reliable source.

From these descriptions we may deduce that the simple mihrab in the present-day mosque (fig. 5) is not the same one that earned al-Muqadassi’s praise and that, consequently, there must have been an earlier mihrab, belonging either to the first Umayyad phase or to the second phase of the mosque. This elaborate mihrab was presumably destroyed in the 1033 earthquake, and the present-day mihrab is probably the one renovated in Salah al-Din’s time. If this is the case, it suggests a third—hitherto unsuspected—period in the history of the mosque.

The original plan of the mosque may now be reconstructed in full (fig. 6). The 6° deviation in the orientation of the covered southern hall— presumably destroyed by the earthquakes—should be cancelled. We suggest that the renovation of the mosque included the elongation of the eastern boundary wall to its present dimensions and the construction of a northern wall, encompassing the mosque as we know it today.

The historical events led to the following developments: the city, first threatened by the Carmatians, was conquered by the Crusaders. In 1187, following the Battle of Hittin, Salah al-Din freed Ramla from the Crusaders, leading him to renovate the mosque, as mentioned above. The present-day façade of the prayer hall is a remnant of those renovations. Two further stages took place in the Mamluk period, with the construction of the minaret (see below).

The subterranean cisterns in the mosque enclosure present a real archaeological enigma. In order to describe this enigma, we will digress briefly and describe another structure, also in Ramla: the outstanding subterranean cistern known as “the pools of Saint Helena” or the Aneziya, which lies to the north of the mosque across the main road in Ramla. M. de Vogüé, one of the most prominent researchers of the late nineteenth century, studied and measured this structure, publishing it in the early twentieth century (de Vogüé 1912). In the late 1930s, Creswell published a detailed plan of the cistern (1939: 162; fig. 7). Thus, in contrast to the limited information available regarding the mosque, we possess a wealth of information and a complete plan of this cistern.

As a starting point, it should be noted that this impressive architectural compound was built in one period, with no significant changes or modifications. Moreover, an inscription, visible to this day, dates the construction to 172 AH (789 CE), the time of Harun al-Rashid (Van Berchem 1897; fig. 8). This functional architectural structure was constructed as a system of subterranean pools, a project initiated by the administration to ensure a regular water supply to the public.

It is an irregular rectangular structure, divided into squares with cross-shaped pillars, from which arches spread out (fig. 9). This is one of the few structures in the country that can be attributed with certainty to the Abbasid period, a period somewhat limited in construction initiatives in this country. In addition to the good state of preservation of the pools, they are of architectural significance: this is the first case in which the pointed arch was used systematically. Throughout the Umayyad period, preceding the Abbasid, the classical arch, with a 180° curve, was used in Muslim architecture and only sporadic use was made of the pointed arch. The Ramla cistern, constructed in the eighth century CE, exhibits the first systematic use of the pointed arch. According to de Vogüé, the Ramla cistern precedes European architecture by four centuries in the use of pointed arches, which can be seen in the hall and the galleries. This is therefore a landmark in the history of architecture in general, and in the history of Ramla in particular.

The enigma presented by the pools within the mosque enclosure is rooted in their resemblance to the cistern described above. The three pools in the mosque enclosure resemble the others in their division of the space by means of monumental cross-shaped pillars extending in arches in the four directions. In this case too, there is a systematic use of the pointed arch. Indeed, the structure is reminiscent of a cathedral (fig. 10). The walls are lined in an identical plaster to the staircases, which descend at a 90° angle to the entrance.3

As previously mentioned, the large pools are dated to 789 CE, a landmark in the history of architecture. Given the similarities between these pools and those within the mosque enclosure, the question arises as to the date of the latter. Since they are situated inside the Umayyad mosque, are they of Umayyad date too? If so, they would have been earlier than the large pools, and an earlier date than the commonly accepted date of 789 should be postulated for the architectural feature of pointed arches. Alternatively, perhaps the three pools within the mosque are Abbasid, like the large pools to which they bear an architectural resemblance. In this case they would have been built in the mosque at a later date than that of the mosque’s construction.4

In an effort to resolve this enigma, I superimposed the Abbasid cistern over the group of pools in the mosque enclosure. To my surprise, I found an exact correlation between them all (fig. 11). Evidently, both groups reflect an identical architectural plan.

Returning to the mosque, the pools in the compound indeed belong to an early period, but were presumably constructed after the eighth-century earthquake. Even if the destruction was not complete, this would have been an opportunity, with the first renovation of the mosque—that first hitherto unidentified phase. Moreover, their construction took place around the same time as the construction of the Harun al-Rashid pools. In other words, the entire first renovation of the mosque, including its subterranean cisterns, would have taken place after 747, contemporaneously with the Abbasid cistern. This resolves both the question of the date of the cisterns and the question of the pointed arches. The introduction of the three pools in the Umayyad mosque shortly after this period, under the Abbasids, would account for the new northern wall. The first one was removed for the construction of the three reservoirs. The new wall was described by Kaplan as belonging to the first stage—since he was unaware of an earlier stage and his evidence corroborated the criteria of early architecture. This is presumably the same stage at which the beautiful mihrab—whether Umayyad or Abbasid— was incorporated in the mosque. It is likely that this mihrab was the one destroyed in the 1033 earthquake, after which the simpler mihrab from the time of Salah al-Din was installed.

The last architectural element is the minaret, which, as noted by Kaplan, is built in the northern wall of the enclosure, attributed to the third phase of construction. Kaplan mentions that he did not uncover any earlier remains under the minaret in his archaeological investigations. Ben-Dov, who conducted a test pit there, also dated the minaret to the Mamluk period (1984).

An inscription at the entrance to the minaret records the date of its construction—1318, during the time of al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qala’un. Hence, the minaret is Mamluk, built on the virgin soil of Ramla. This leads to the next query: if this tower is indeed from Mamluk times and was not built atop an earlier tower, where was the ancient tower situated? After all, al-Muqadassi, in the tenth century, mentions the minaret, which he says was built by Hisham, son of ʿAbd al-Malik, the brother of Suleiman, who founded the city of Ramla. This provides conclusive evidence of the existence of a pre-Mamluk minaret. This original minaret may have been built adjacent to the first northern wall, but any conjecture regarding its location is purely speculative.

After the expansion of the area of the mosque enclosure following its destruction by the first earthquake, it is conceivable that the second minaret was situated somewhere along the northern enclosure wall, not necessarily at the same location as the Mamluk one. As for the location of the minaret in Umayyad times, excavations at various sites suggest that the minaret was not restricted to a specific location in the mosque enclosure. Suffice it to mention the mosques of Jerash and Amman in Jordan. It is hoped that future investigations will uncover the original minaret of the White Mosque.