Beth She'an

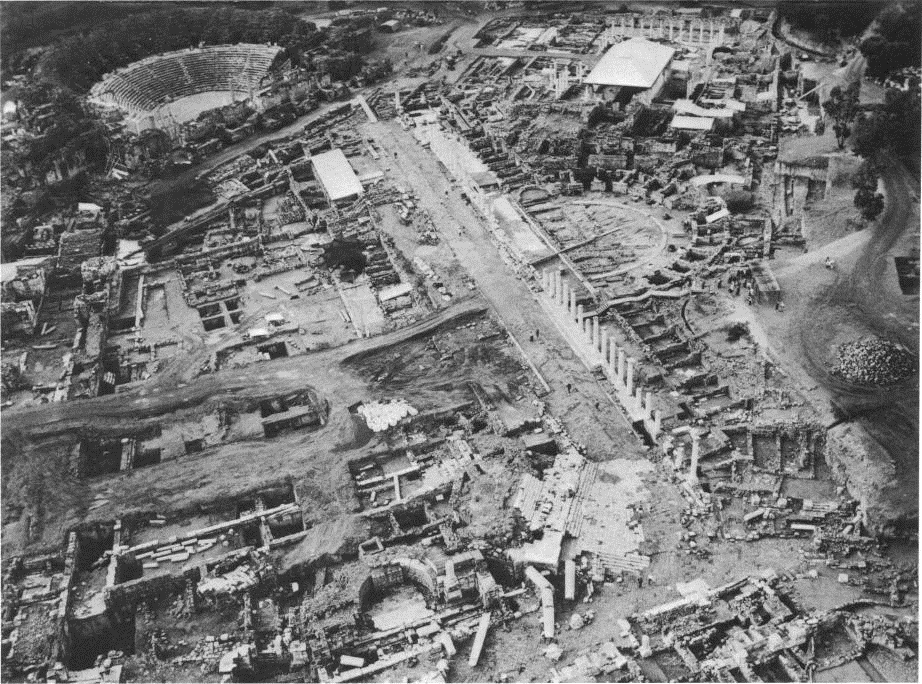

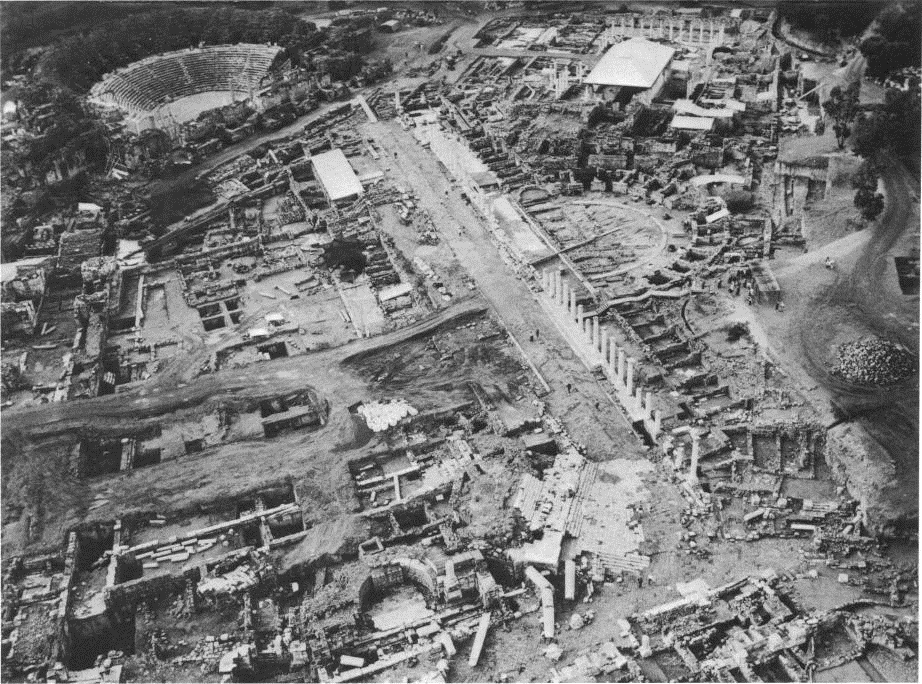

Figure 2

Figure 2Ancient Bet Shean, looking north, showing the southern plateau and the amphitheater (in the modern town) (bottom), and the tell, the valley of Nahal `Amal, and the civic center (center)

Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Beth She'an | Hebrew | בֵּית שְׁאָן |

| Beit She'an | Hebrew | בֵּית שְׁאָן |

| Beisan | Arabic | بيسان |

| Baysān | Arabic | بيسان |

| Kurat Baysān | Arabic | |

| Tell el-Husn | Arabic | تيلل يلءهوسن |

| Scythopolis | Greek | Σκυθόπολις |

| Nysa | Greek | Νῦσα |

| Nysa-Scythopolis | Greek | Νῦσα-Σκυθόπολις |

| Beshan | Semitic | |

| Beshan | Semitic | |

| Beth-sâªl | Egyptian Texts | |

| Tell Iztabba |

Beit She'an (aka Scythopolis aka Baysān) is situated at a strategic location between

the Yizreel and Jordan Valleys at the juncture of ancient roadways (Stern et al, 1993).

In Roman times, it was one of the cities of the Decapolis.

Tsafrir and Foester (1997:88-89)

note that hellenistic Scythopolis succeeded biblical Bet Shean on the tell, and in the third to second century B.C.E. expanded toward Tel Iztaba,

north of Nahal Harod

adding that the tell, which was located east of the new built-up area, became the acropolis of the larger town.

The site of Bet She'an was occupied almost continuously from Neolithic to Early Arab times

(Stern et al, 1993).

Tel Beth-Shean (Tell el-Husn in Arabic) is located at the junction of two important roads: the transversal road leading from the Jezreel and Harod valleys to Gilead, and the road running the length of the Jordan Valley. The mound is situated on a high hill that slopes toward the northwest, on the southern bank of Nahal Harod (map reference 1977.2124). Beth-Shean's location at this major junction, as well as in a fertile, water-rich valley, gave the city great strategic importance. The site was occupied almost continuously from the Late Neolithic to the Early Arab periods. Beginning in the Roman period, the city moved down into the valley to the south and west of the mound (see below), while only a temple (in the early Roman period) and a suburb (in the Byzantine and Early Arab periods) were erected on the mound itself. The mound covers approximately 10 a. Its summit is at the southeast corner; the city gate appears to have always been in the northwest, where access is easiest.

B. Mazar suggested identifying the city with 'As'annu, which appears in the Execration texts of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. However, other scholars are inclined to reject this proposal, and it appears to contradict the archaeological evidence (see below). The city is mentioned in various Egyptian sources from the New Kingdom: the list of Canaanite cities of Thutmose III [c. 1490- 1436 BCE] in the Temple of Amon at Karnak; the topographical lists of Seti I and Ramses II; and the Papyrus Anastasi I, from the time of Ramses II. In the Egyptian sources, the name always ended with "l" instead of "n." Beth-Shean is also mentioned once in the fourteenth-century BCE el-Amarna letters. In the Bible, Beth-Shean is listed as one of the cities not conquered by the Israelites (Jos. 17:11; Jg. 1:27), as well as the place where the Philistines impaled the bodies of Saul and his sons on the walls (I Sam. 31:10). Beth Shean is also mentioned in the list of administrative districts established by King Solomon (1 Kg. 4:12); it figures as an Egyptian conquest in the Shishak list at Karnak, shortly after the division of the United Monarchy. During the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods, the city was known as Nysa or Scythopolis and is mentioned in many historical sources. With the Arab conquest, the ancient Semitic name reemerged as Beisan; in fact, the Arab victory over the Byzantines in 636 CE was called the "day of Beisan."

Beth She’an is the Graeco-Roman Decapolis city of Nysa-Scythopolis11. It is situated at the junction of the northern Jordan valley and the Jezreel valley. Settlement history in Beth She’an stretches from proto-historical periods through modern times. It is enclosed by a chain of hills north of the stream Nahr Jâlûd (Naḥal Ḥarod) – the watercourse which flows through the northern fringes of the biblical settlement. To the south is Tell el-Ḥuṣn, to the east Tell Ḥammam, where one of the main cemeteries of the city is located, and to the west lies Tell Iẓṭabba. The site consists of three hills, dropping steeply on the slopes descending southwards toward Naḥal Ḥarod and more moderately on the slopes facing the plain north of the city. The two western hills of Tell Iẓṭabba are dominated by Byzantine remains, namely the Kyria Maria monastery, the monastery of the Martyr, the monastery of Andreas, and the Byzantine city wall, which extend right across the two hills. Hellenistic remains are mostly located on the eastern hill and have only been moderately disturbed by later activities, as previous excavations have shown.

While the biblical tell of Beth She’an (Tell el-Ḥuṣn) has yielded extensive settlement remains from the Early Bronze Age until late antiquity, the Roman city is mostly situated in the plain south of the tell. With the typical inventory of an Eastern Mediterranean urban center the Roman city flourished. Apart from the Late Antique remains on Tell Iẓṭabba, excavations in the area since the 1950s have shown that the mound was extensively settled during the Early Bronze Age, and in the Hellenistic period it was the site of a Seleucid foundation. This settlement was probably founded in the 160s BCE under King Antiochus IV, but in the spring of 107 BCE it was destroyed by John Hyrcanus I during the expansion of the Hasmonaean state. After this destruction, the site was not reoccupied and the communis opinio is that not until the Byzantine period, with the construction of the Christian monasteries and the city walls, parts of Tell Iẓṭabba were reoccupied; namely in the early 5th century CE when Nysa-Scythopolis became the capital of Provincia Palaestina Secunda.

11 Fuks 1983; Lichtenberger 2003, 128–170; see also Barkay 2003, 19–34.

Between 1921 and 1933, excavations were carried out at the mound under the auspices of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, directed by C. S. Fisher (1921 to 1923), A. Rowe (1925 to 1928), and G. M. FitzGerald (1930, 1933). In the first two seasons, the Early Arab and Byzantine levels were excavated over the entire mound. The 1923 to 1928 seasons focused on the Iron Age and Late Bronze Age levels on the mound's summit. In the last two seasons, the excavators reached the Middle and Early Bronze Age strata, and a probe was dug down to bedrock. Some 230 tombs dating from the Middle Bronze Age I to the Roman period were also excavated in the northern cemetery cut in the cliff face along the northern bank of the Harod valley, just opposite the mound. This was the first large-scale stratigraphic excavation in Palestine after World War I and it contributed greatly to the archaeological research of the biblical period. However, the scientific publication of the excavation results is inadequate, as only a small portion of the finds was fully published. Many years after the excavations ended, the Iron Age finds were published by F. James and the northern cemetery by E. D. Oren.

In 1983, a short season of excavations was carried out on the mound's summit by the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, directed by Y. Yadin and S. Geva. The Iron Age I strata were investigated and resulted in new conclusions about the city's development during that period. In 1989, the excavations were resumed by A. Mazar, also on behalf of the Hebrew University and of the Tourism Administration of Beth-Shean. In the renewed excavations, Middle and Late Bronze and Iron Age I strata were exposed on the mound's summit, continuing the work of the University of Pennsylvania expedition

Nine excavation seasons were conducted at Tel Beth-Shean by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem from 1989 to 1996, under the direction of A. Mazar. One major conclusion of the new excavations is that a topographic step crossing the c. 10-a. mound north of the summit, located at its southeastern corner (between the new excavation areas Q and L), was in fact the northern edge of the settlement during most of the Bronze and Iron Ages, except during the Early Bronze Age I, when settlement perhaps spread over the lower part of the mound, remains of which were found in area L. Thus, through most of the Bronze and Iron Ages the settlement at Beth Shean probably did not exceed c. 4 a. It has been suggested by B. Arubas that the mound was cut to some extent on the south and west during large scale earth moving operations during the Early Roman period, when the civil center of Nysa-Scythopolis was constructed; this might explain the lack of fortifications and the fact that buildings in all periods were found cut on the southern and western parts of the mound.

- Fig. 10 Soil Map of

the area surrounding Beth Shean from Lorenzon (2024)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Geological map of the area

drawing by Maija Holappa after Dan and Raz (1970) and Sneh et al. (1997)

Lorenzon (2024)

- Fig. 10 Soil Map of

the area surrounding Beth Shean from Lorenzon (2024)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Geological map of the area

drawing by Maija Holappa after Dan and Raz (1970) and Sneh et al. (1997)

Lorenzon (2024)

- Wide Aerial View of Beth

Shean from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

View of the ancient site (at top), the amphitheater, and the modern town (at bottom), looking north.

View of the ancient site (at top), the amphitheater, and the modern town (at bottom), looking north.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Tighter Aerial View of Beth

Shean from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Ancient Bet Shean, looking north, showing the southern plateau and the amphitheater (in the modern town) (bottom), and the tell, the valley of Nahal `Amal, and the civic center (center)

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Aerial View of Tel Beth Shean

from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Aerial View of Tel Beth Shean

Aerial View of Tel Beth Shean

Stern et. al. (2008) - Photo 1.1 Aerial View of

Tel Beth Shean from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Photo 1.1

Photo 1.1

Aerial view of Tel Beth-Shean, looking west.

- Front: Areas S

- Behind it: Areas N and Q

- Left: Areas M and R

(photo: Albatross, 1994).

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Photo 1.2 Aerial View of

Tel Beth Shean Summit with Areas Q, R, S, and N labeled from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Photo 1.2

Photo 1.2

Aerial view of the tell’s summit, looking south.

- Right: Areas Q

- Top: Area R

- Left: Area S

- Center: Area N before the start of excavations (burnt area) (1992)

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Bet Shean in Google Earth

- Bet Shean on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Google Satellite

Map of Bet She'an from BibleWalks.com

- Annotated Google Satellite

Map of Tel Bet She'an from BibleWalks.com

- Annotated Google Satellite

Map of Tell Iztabba from BibleWalks.com

- Plan of Tel Beth Shean with

city walls from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the site.

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. C General map of

Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure C

General map of Scythopolis — Bet Shean

- Civic center

- Theater

- Western bathhouse

- Palladius Street

- Valley Street

- Northeast gate and Byzantine bazaar

- Hellenistic quarter on Tel Iztaba

- Hellenistic building

- Northwest gate

- Monastery of the Lady Mary

- Church of the Martyr

- Andreas' Church

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Lidar Scan of City Model from the Archaeological Park - taken by JW

- Plan of Tel Beth Shean with

city walls from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the site.

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the site.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. C General map of

Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure C

General map of Scythopolis — Bet Shean

- Civic center

- Theater

- Western bathhouse

- Palladius Street

- Valley Street

- Northeast gate and Byzantine bazaar

- Hellenistic quarter on Tel Iztaba

- Hellenistic building

- Northwest gate

- Monastery of the Lady Mary

- Church of the Martyr

- Andreas' Church

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Lidar Scan of City Model from the Archaeological Park - taken by JW

- Map of the Mound showing

of Hebrew University expedition from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Tel Beth-Shean

Tel Beth-Shean

topographic map showing excavation areas excavation areas of Hebrew University expedition.

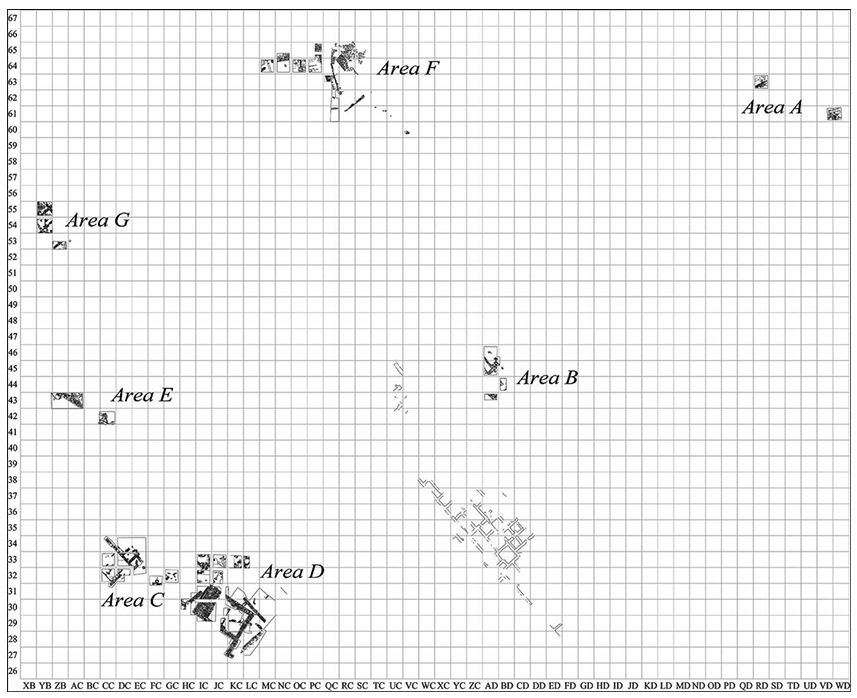

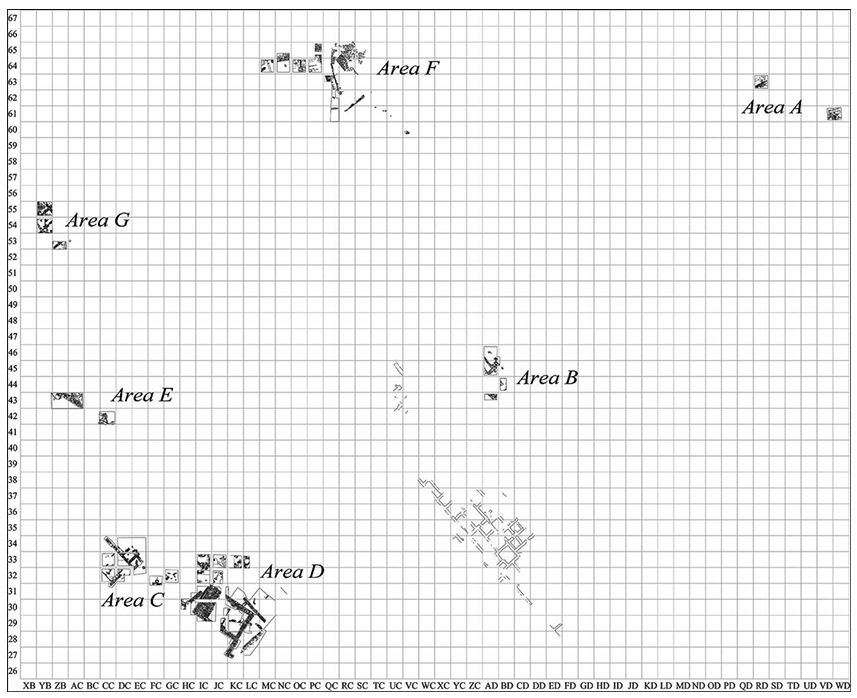

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 1.1 Tel Beth-Shean

site plan with excavation areas from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Topographic plan of Tel Beth-Shean with location of excavation areas

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Map of the Mound showing

of Hebrew University expedition from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Tel Beth-Shean

Tel Beth-Shean

topographic map showing excavation areas excavation areas of Hebrew University expedition.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. 1.1 Tel Beth-Shean

site plan with excavation areas from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Topographic plan of Tel Beth-Shean with location of excavation areas

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

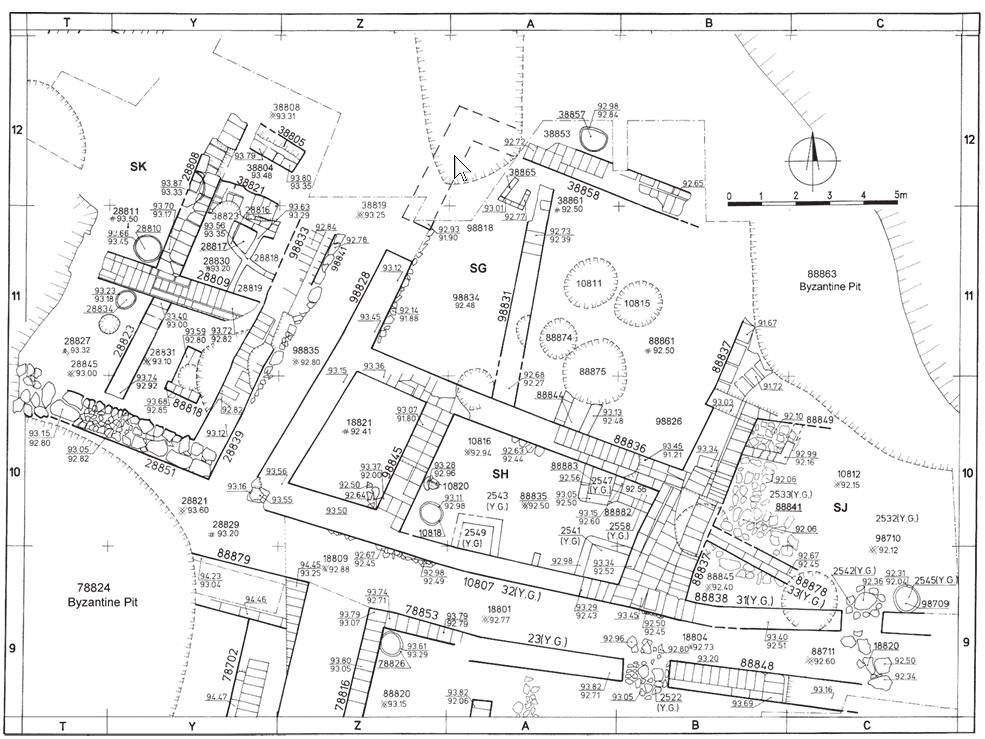

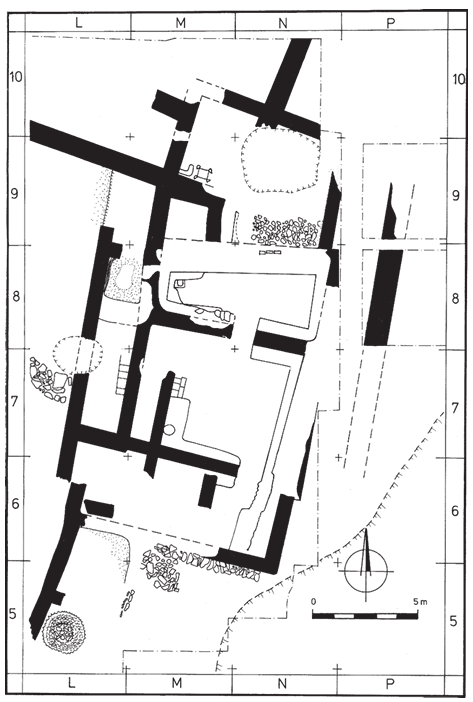

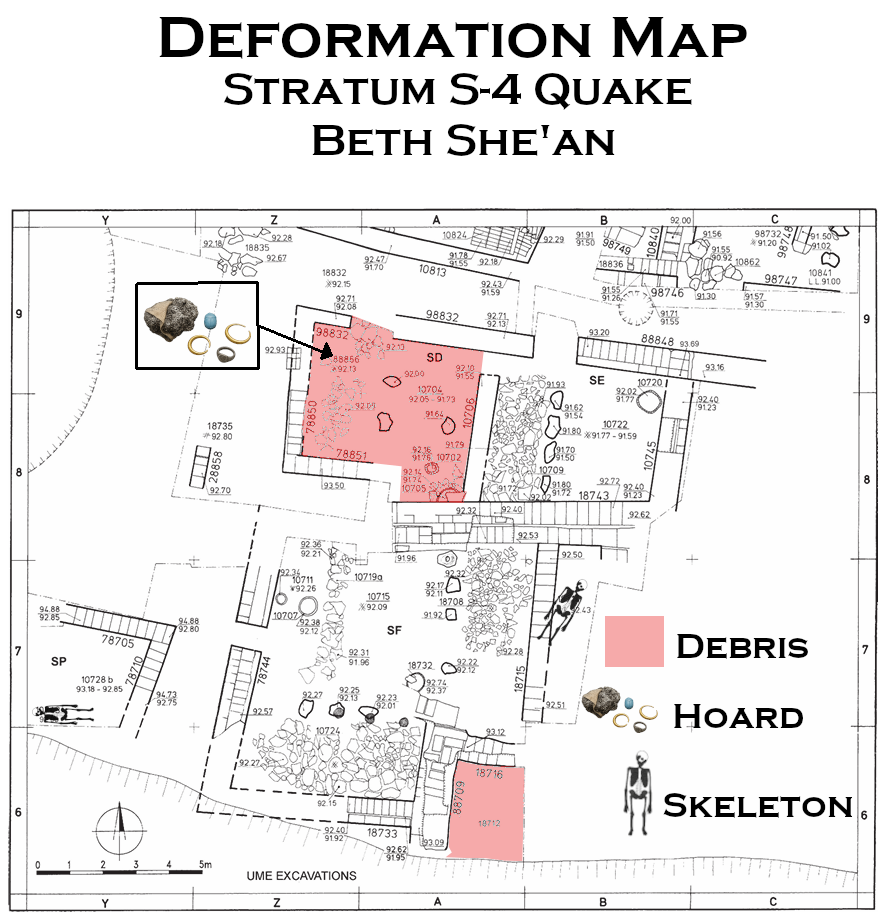

- Fig. 4.2 Schematic

plan of Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.2

Fig. 4.2

Schematic plan of Stratum S-4

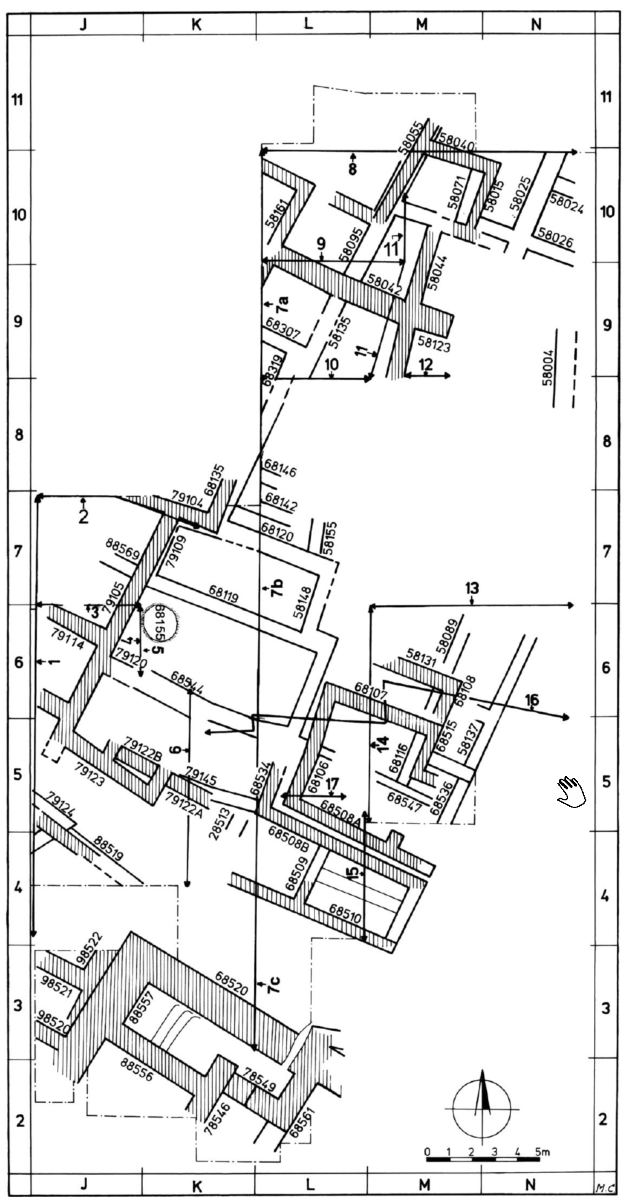

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Fig. 4.3a Schematic

plan of northern part Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.3a

Fig. 4.3a

Plan of Stratum S-4, northern part

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Fig. 4.3b Schematic

plan of southern part Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.3b

Fig. 4.3b

Plan of Stratum S-4, southern part

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Fig. 4.2 Schematic

plan of Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.2

Fig. 4.2

Schematic plan of Stratum S-4

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Fig. 4.3a Schematic

plan of northern part Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.3a

Fig. 4.3a

Plan of Stratum S-4, northern part

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Fig. 4.3b Schematic

plan of southern part Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Fig. 4.3b

Fig. 4.3b

Plan of Stratum S-4, southern part

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

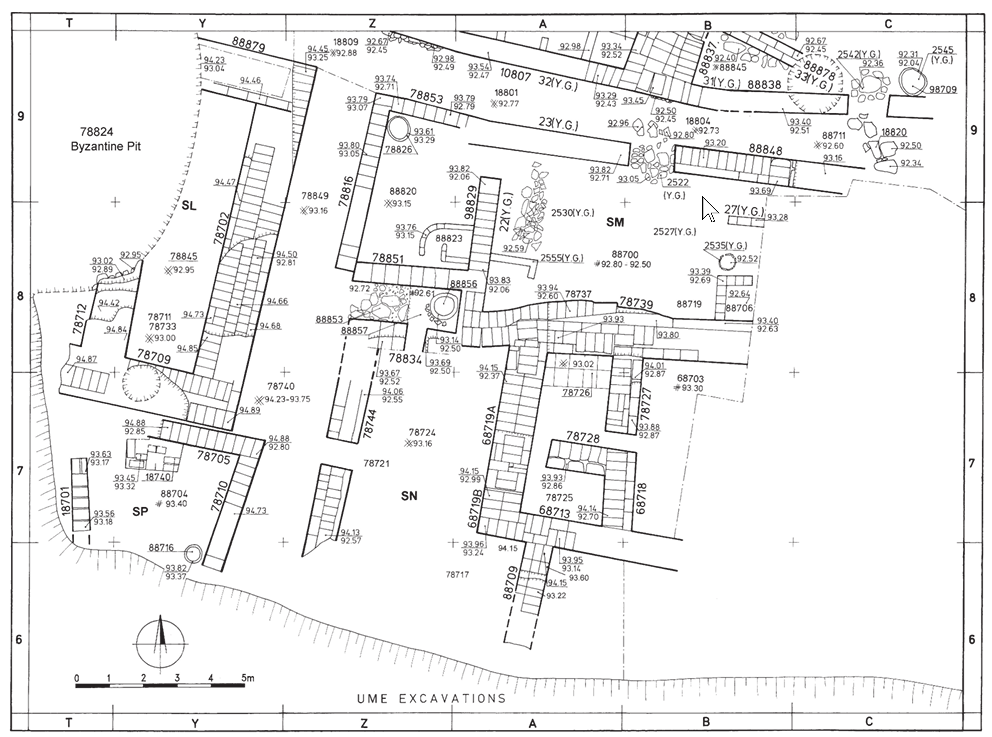

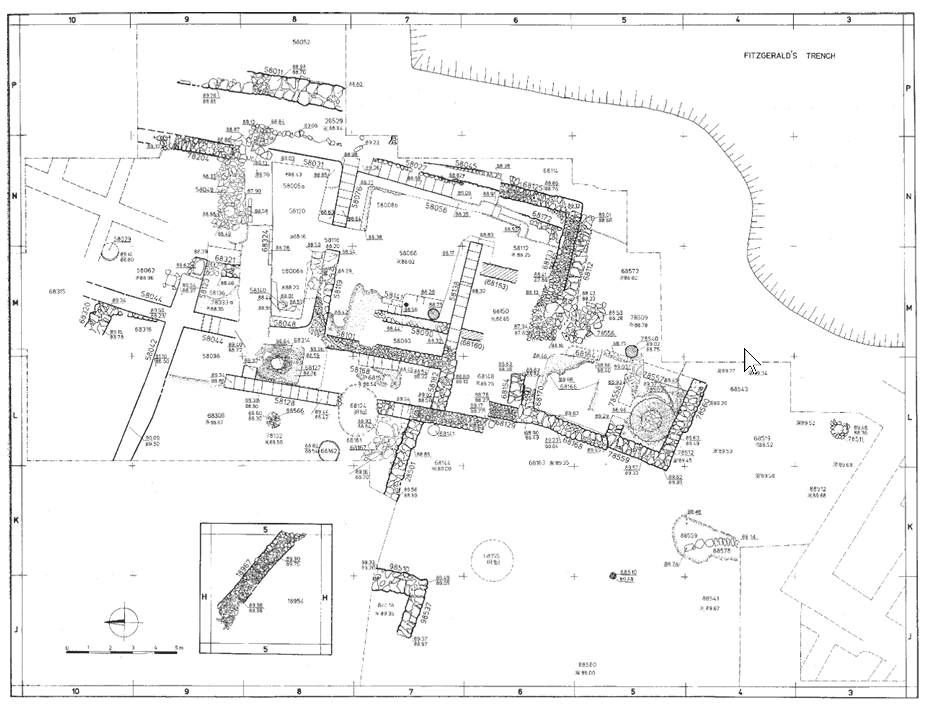

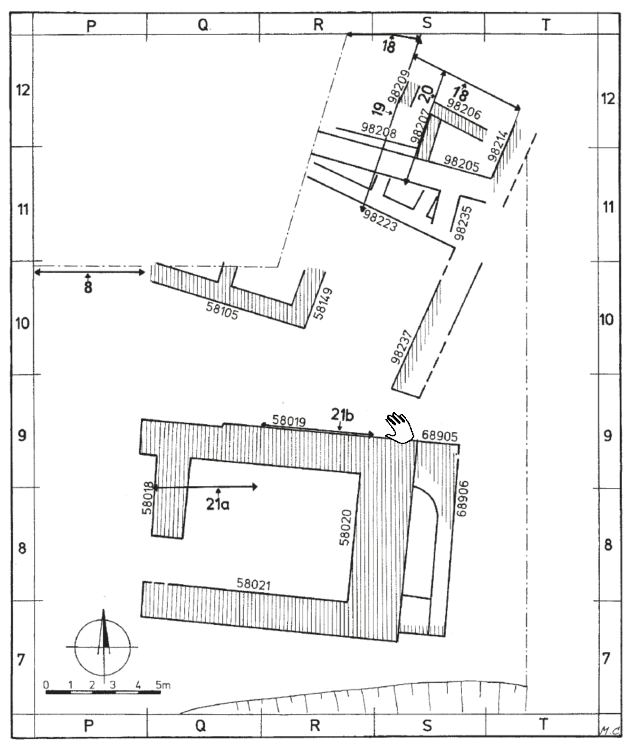

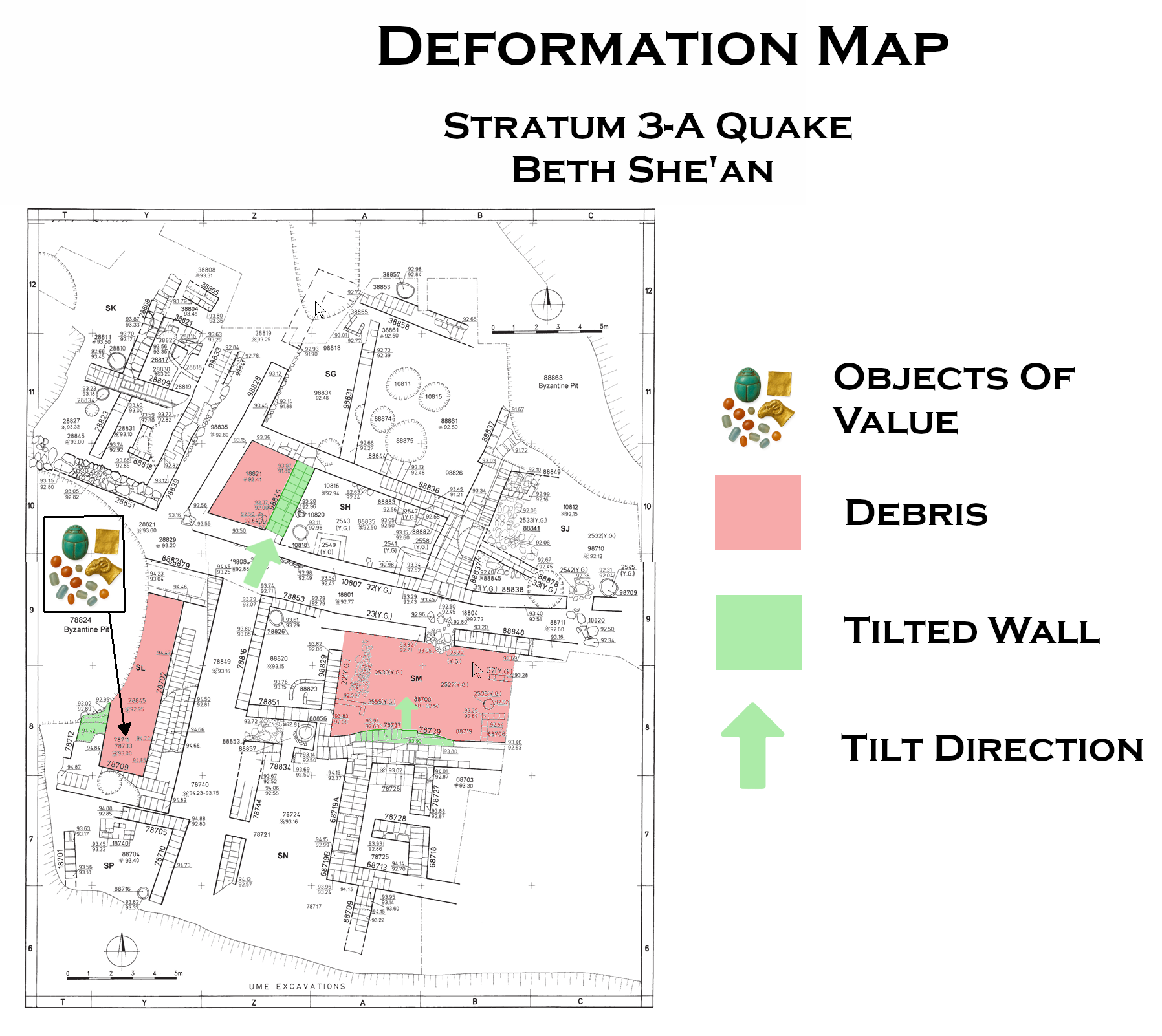

- Fig. 4.5a Plan of Stratum S-3b,

northern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.5b Plan of Stratum S-3b,

southern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.6a Plan of Stratum S-3a,

northern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.6b Plan of Stratum S-3a,

southern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.5a Plan of Stratum S-3b,

northern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.5b Plan of Stratum S-3b,

southern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.6a Plan of Stratum S-3a,

northern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

- Fig. 4.6b Plan of Stratum S-3a,

southern part from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

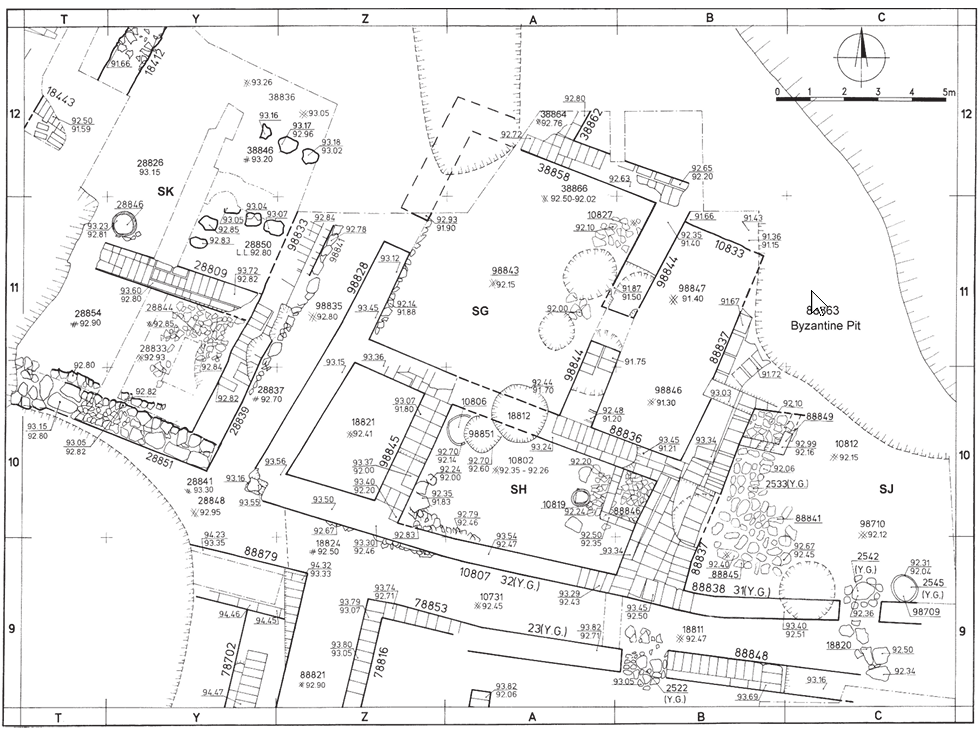

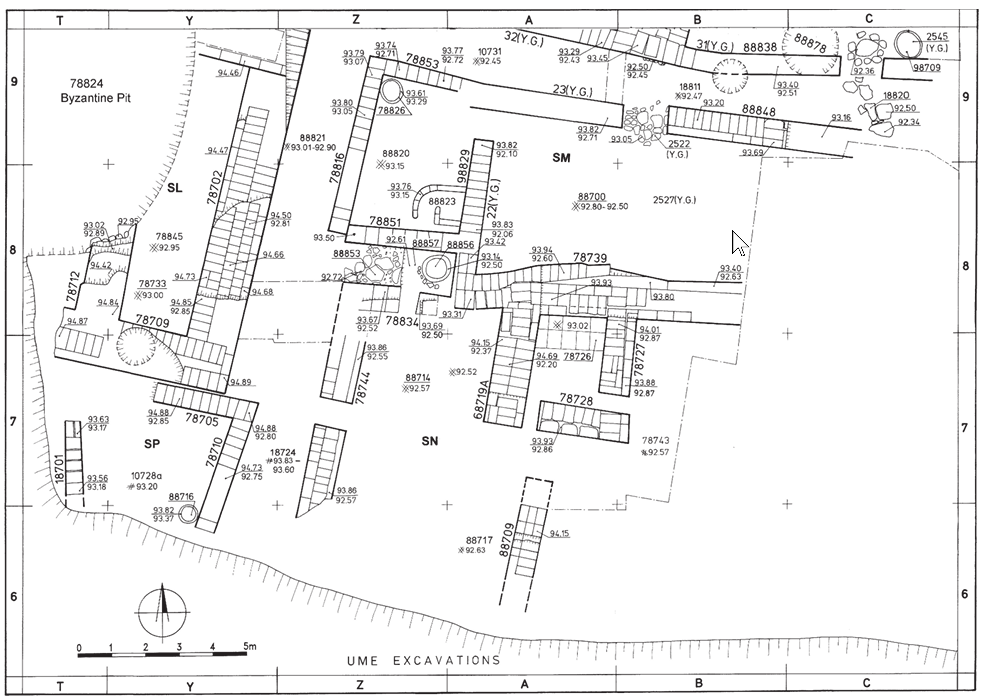

- Fig. 1.4 Plan of UME

Level VI and Late Level VI from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Fig. 1.4

Fig. 1.4

Plan of UME Level VI and Late Level VI

(James 1966: Fig. 77)

(courtesy of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania)

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Fig. 1.4 Plan of UME

Level VI and Late Level VI from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Fig. 1.4

Fig. 1.4

Plan of UME Level VI and Late Level VI

(James 1966: Fig. 77)

(courtesy of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania)

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

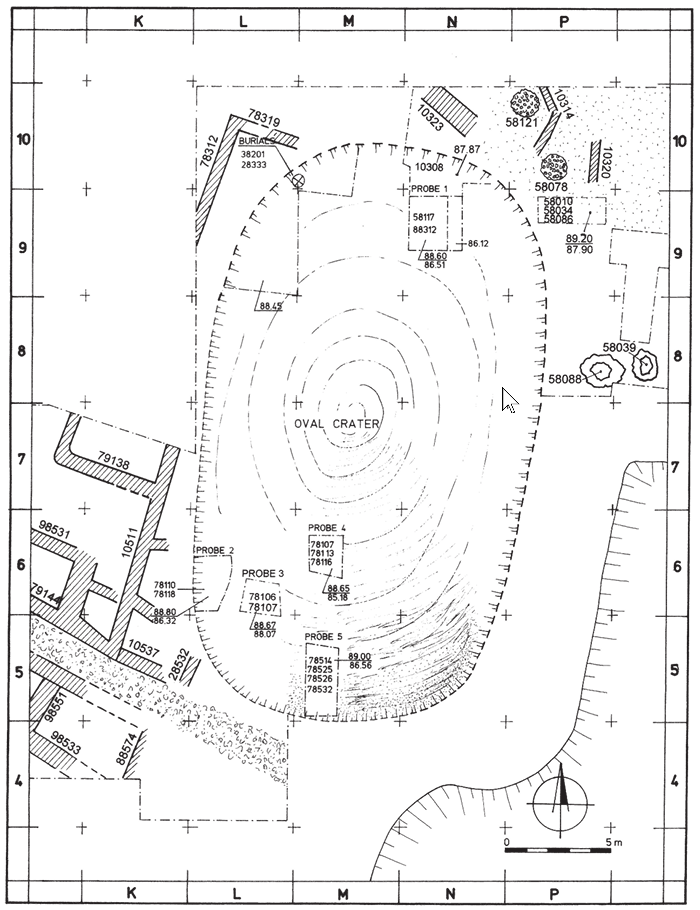

- Fig.1.6 Schematic plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.3 Plan showing

oval crater from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.17 Schematic plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.18 Reduced plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

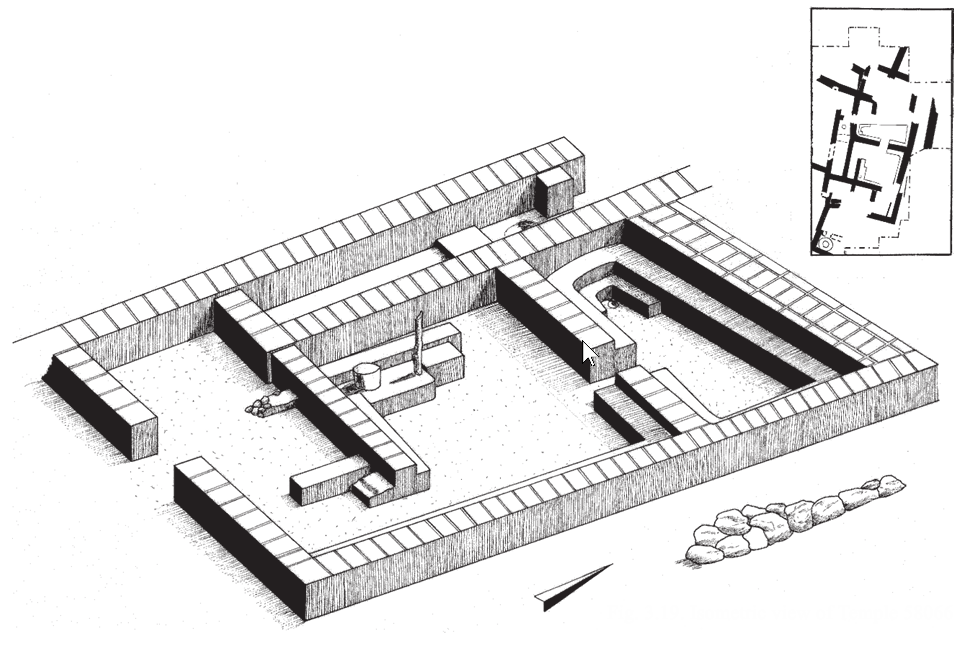

- Fig.3.19 Isometric view of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig. 1.6 Schematic plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.3 Plan showing

oval crater from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.17 Schematic plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.18 Reduced plan of Stratum R-2 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Fig.3.19 Isometric view of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Plan of city center of

Beth Shean from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the city center.

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the city center.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. D Map of the central

area of Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure D

Map of the central area of Scythopolis—Bet Shean (excavations of the Hebrew University and the Israel Antiquities Authority

- Theater

- Portico in front of the Theater

- Western bathhouse

- Propylon in Palladius Street

- Shops of the Roman Period

- Palladius Street

- Sigma

- Odeaon

- Collonnades and reconstructed Roman temenos (?)

- Dismantled Roman colonnades,with a Byzantine public building above them

- Northern Street

- Propylon and stairway to the tell

- Propylon between the temple esplanade and the tell

- Temple with the round cella

- Nymphaeum

- Monument of Antonius

- Valley Street

- Central Monument

- Roman basilica, with porticoes of the Byzantine agora above it

- Byzantine agora

- Umayyad ceramic workshop

- Roman temple

- Roman cult structures

- Public latrine

- Eastern bathhouse

- Roman portico, later Silvanus Hall

- Roman decorative pool, with Umayyad shops above it

- Silvanus Street (JW: Row of shops where coin hoard providing terminus post quem for 749 quake was found)

- Semicircular plaza

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Fig. 4.4 Map of central

Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.4

Map of central Baysān (from R. Bar-Nathan and W. Atrash, Baysān, 5, plan 1.3).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022) - Lidar Scan of City Model from the Archaeological Park - taken by JW

- Plan of city center of

Beth Shean from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the city center.

Beth-Shean (Scythopolis): plan of the city center.

Stern et. al. (2008) - Fig. D Map of the central

area of Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure D

Map of the central area of Scythopolis—Bet Shean (excavations of the Hebrew University and the Israel Antiquities Authority

- Theater

- Portico in front of the Theater

- Western bathhouse

- Propylon in Palladius Street

- Shops of the Roman Period

- Palladius Street

- Sigma

- Odeaon

- Collonnades and reconstructed Roman temenos (?)

- Dismantled Roman colonnades,with a Byzantine public building above them

- Northern Street

- Propylon and stairway to the tell

- Propylon between the temple esplanade and the tell

- Temple with the round cella

- Nymphaeum

- Monument of Antonius

- Valley Street

- Central Monument

- Roman basilica, with porticoes of the Byzantine agora above it

- Byzantine agora

- Umayyad ceramic workshop

- Roman temple

- Roman cult structures

- Public latrine

- Eastern bathhouse

- Roman portico, later Silvanus Hall

- Roman decorative pool, with Umayyad shops above it

- Silvanus Street (JW: Row of shops where coin hoard providing terminus post quem for 749 quake was found)

- Semicircular plaza

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Fig. 4.4 Map of central

Scythopolis/Bet Shean/Baysān from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.4

Map of central Baysān (from R. Bar-Nathan and W. Atrash, Baysān, 5, plan 1.3).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022) - Lidar Scan of City Model from the Archaeological Park - taken by JW

- Fig. F Southeast end of

Silvanus Street (Earthquake debris) from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure F

Segment of the remains near the southeast end of Silvanus Street, showing the collapsed shops and arcade after the earthquake of 749 C.E. (after Foerster and Tsafrir, ESI 11 [1992], fig. 45)

- Silvanus Street (only the central line of stone is marked on the plan)

- Facade and arcade of the Umayyad shops as collapsed in the earthquake of 749 C.E

- Later Umayyad building and installations

- Facade of the Umayyad shops, built on top of the Roman decorative pool

- Umayyad shops

- Stylobate and line of the Roman colonnade, later blocked by the rear wall of the Umayyad shops

- A lane crossing the Umayyad bazaar

- Opus sectile segment of the promenade around the Roman pool

- Umayyad portico built along the rear side of the shops

- A base in the line of columns and piers of the Byzantine Silvanus Hall

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) - Lidar Scan of Collapsed Storefronts on Silvanus Street by JW

- Fig. F Southeast end of

Silvanus Street (Earthquake debris) from Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

Figure F

Segment of the remains near the southeast end of Silvanus Street, showing the collapsed shops and arcade after the earthquake of 749 C.E. (after Foerster and Tsafrir, ESI 11 [1992], fig. 45)

- Silvanus Street (only the central line of stone is marked on the plan)

- Facade and arcade of the Umayyad shops as collapsed in the earthquake of 749 C.E

- Later Umayyad building and installations

- Facade of the Umayyad shops, built on top of the Roman decorative pool

- Umayyad shops

- Stylobate and line of the Roman colonnade, later blocked by the rear wall of the Umayyad shops

- A lane crossing the Umayyad bazaar

- Opus sectile segment of the promenade around the Roman pool

- Umayyad portico built along the rear side of the shops

- A base in the line of columns and piers of the Byzantine Silvanus Hall

Tsafrir and Foester (1997)

- Fig. 4.0 Post-749 earthquake

administrative complex at Baysān from Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9

Plan of the post-749 earthquake administrative complex at Baysān, c. later eighth to eleventh centuries (based on G. M. Fitzgerald, Beth-Shan Excavations 1921–23. foldout plan, modified by Alan Walmsley).

Blanke and Walmsley (2022)

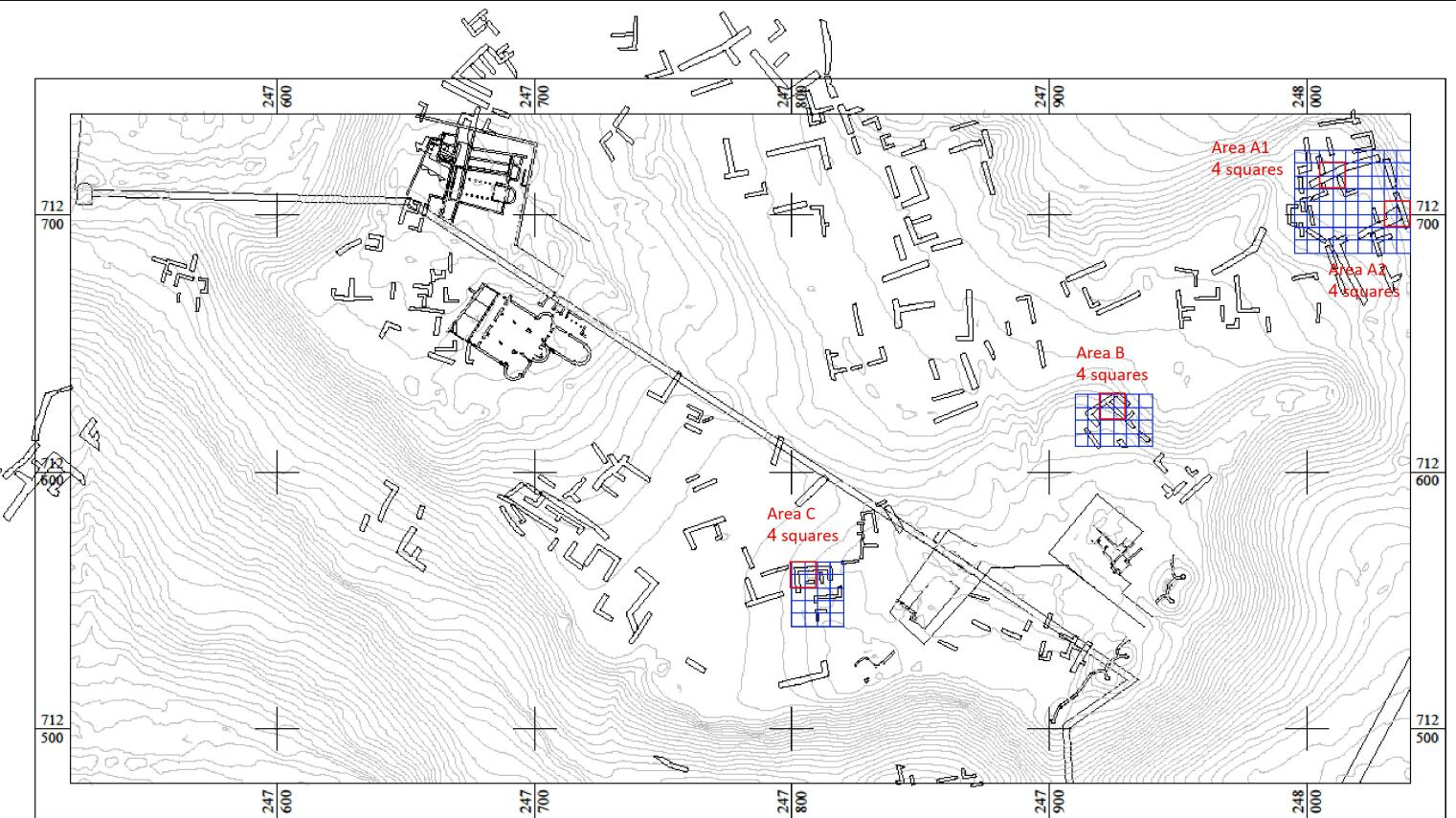

- Fig. 1 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from Edrey et al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the area of Beth Shean

Edrey et al. (2023) - Fig. 17 Site Plan of Tell

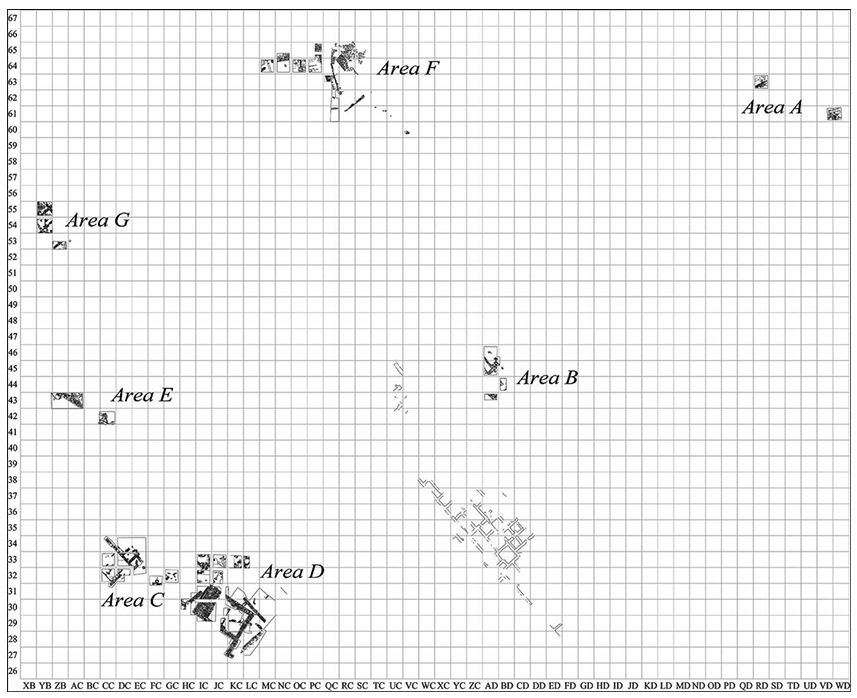

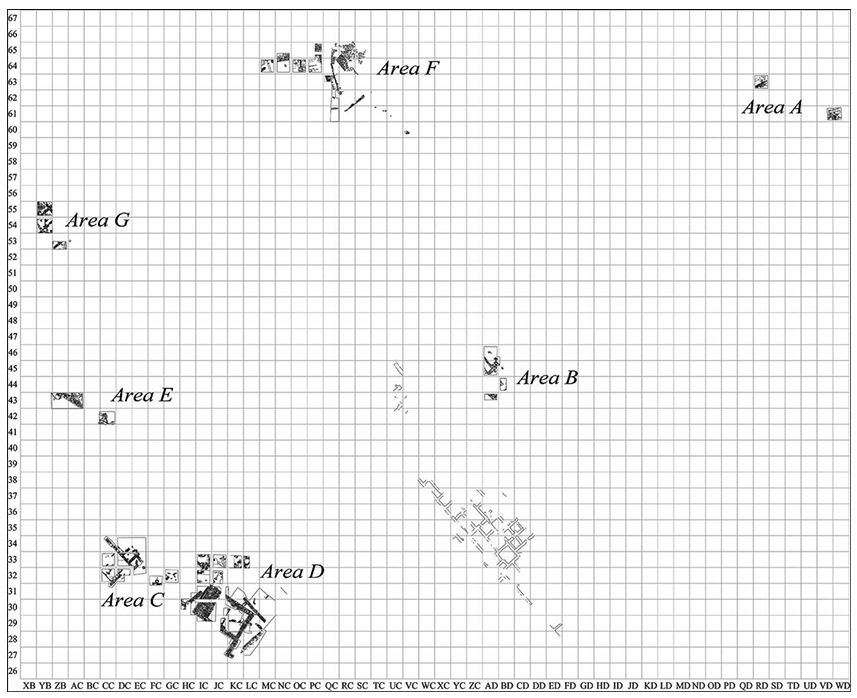

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Map of Tell Iztabba with all Areas of excavation

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 8 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Map of Tell Iztabba with Areas marked

(copyright: German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project)

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 7 Interpretation of

magnetic data from Tell Iẓṭabba from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Interpretation of magnetic data from Tell Iẓṭabba

(copyright: German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project)

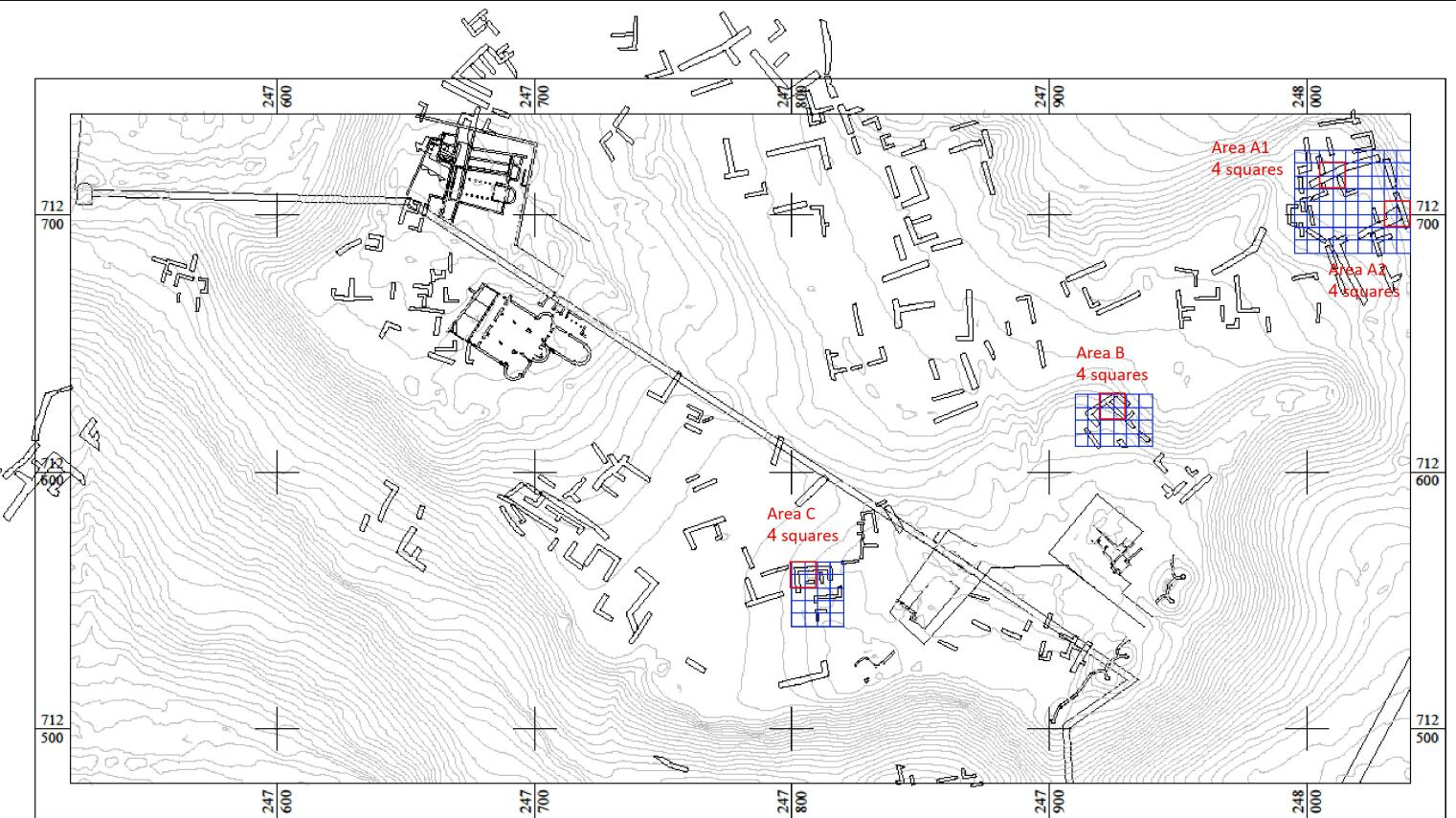

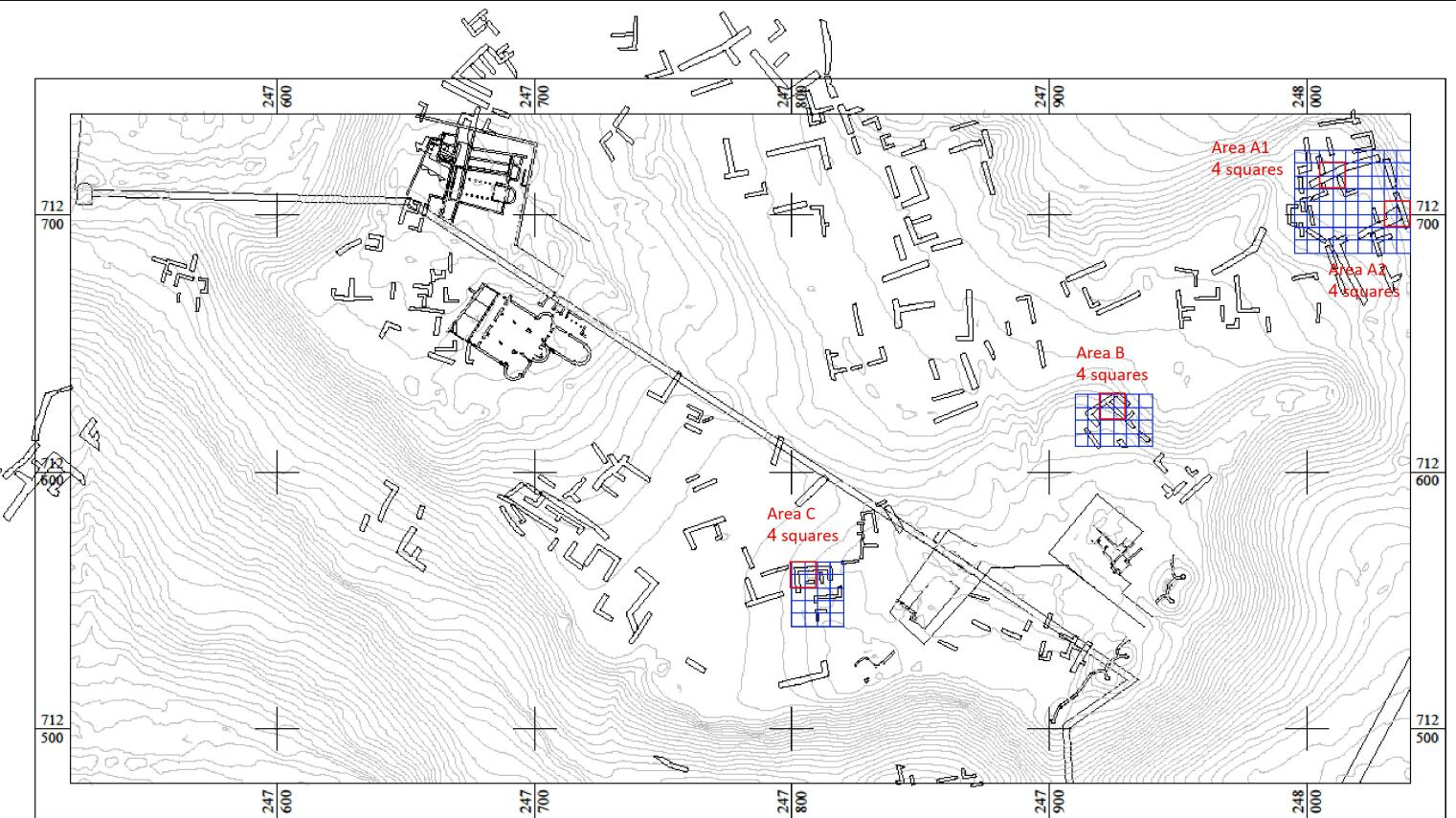

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 2 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from Edrey et al. (2023)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of Tell Iztabba (East) of the German-Israeli Tell Iztabba Excavation Project.

Edrey et al. (2023) - Fig. 1a Plan of Tel Itzabba

from Atrash et al. (2021)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Tell Iẓṭabba site plan with indication of excavated areas dug by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and by the University of Münster & el Aviv University (UM-TAU)

Atrash et al. (2021)

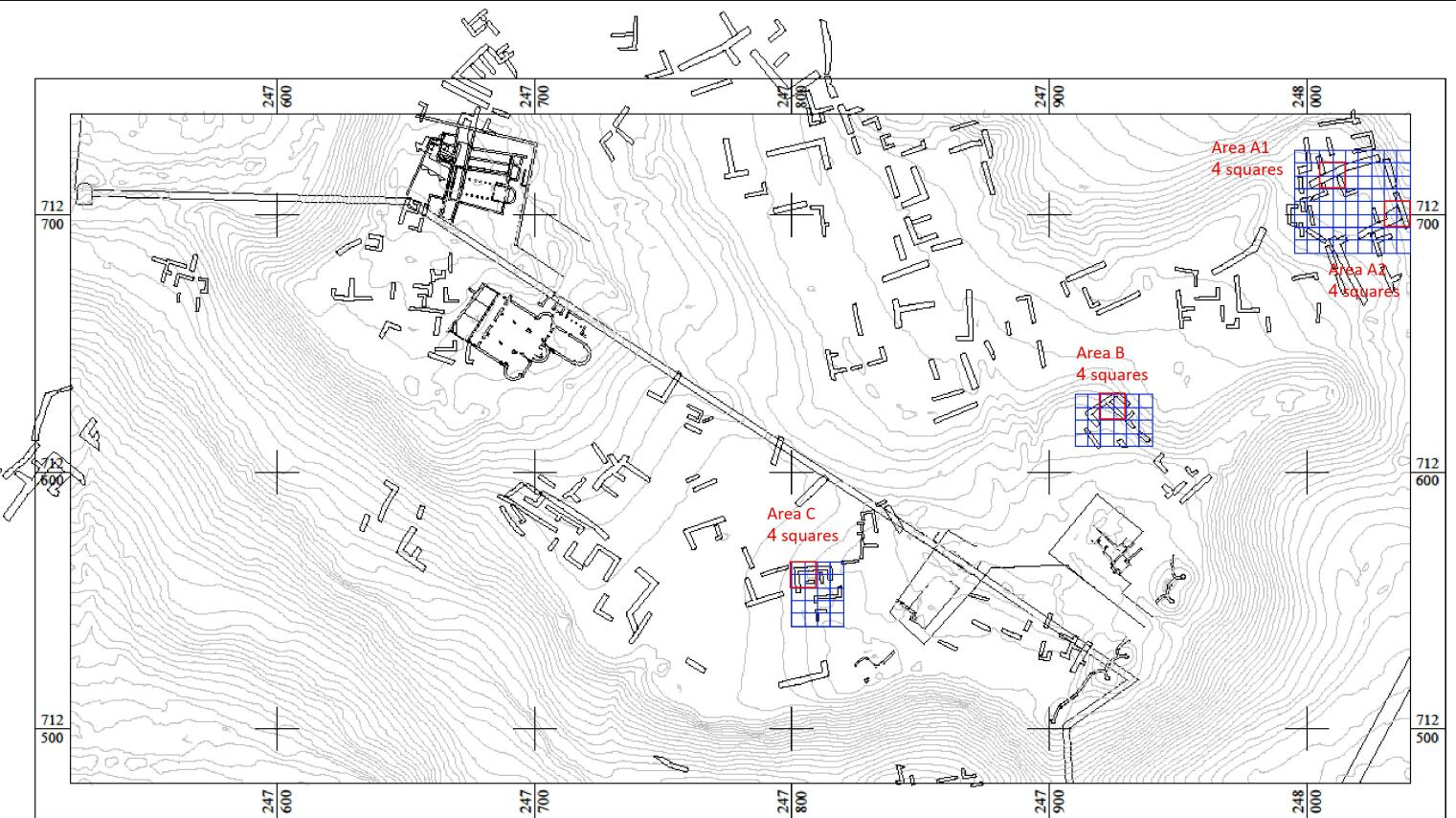

- Fig. 1 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from Edrey et al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the area of Beth Shean

Edrey et al. (2023) - Fig. 17 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Map of Tell Iztabba with all Areas of excavation

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 8 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Map of Tell Iztabba with Areas marked

(copyright: German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project)

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 7 Interpretation of

magnetic data from Tell Iẓṭabba from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Interpretation of magnetic data from Tell Iẓṭabba

(copyright: German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project)

German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 2 Site Plan of Tell

Iẓṭabba with excavation areas from Edrey et al. (2023)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of Tell Iztabba (East) of the German-Israeli Tell Iztabba Excavation Project.

Edrey et al. (2023) - Fig. 1a Plan of Tel Itzabba

from Atrash et al. (2021)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Tell Iẓṭabba site plan with indication of excavated areas dug by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and by the University of Münster & el Aviv University (UM-TAU)

Atrash et al. (2021)

- Fig. 1b Plan of Area D

from Atrash et al. (2021) and German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

Tell Iẓṭabba, Area D

(UM-TAU).

Caption from Atrash et al. (2021)

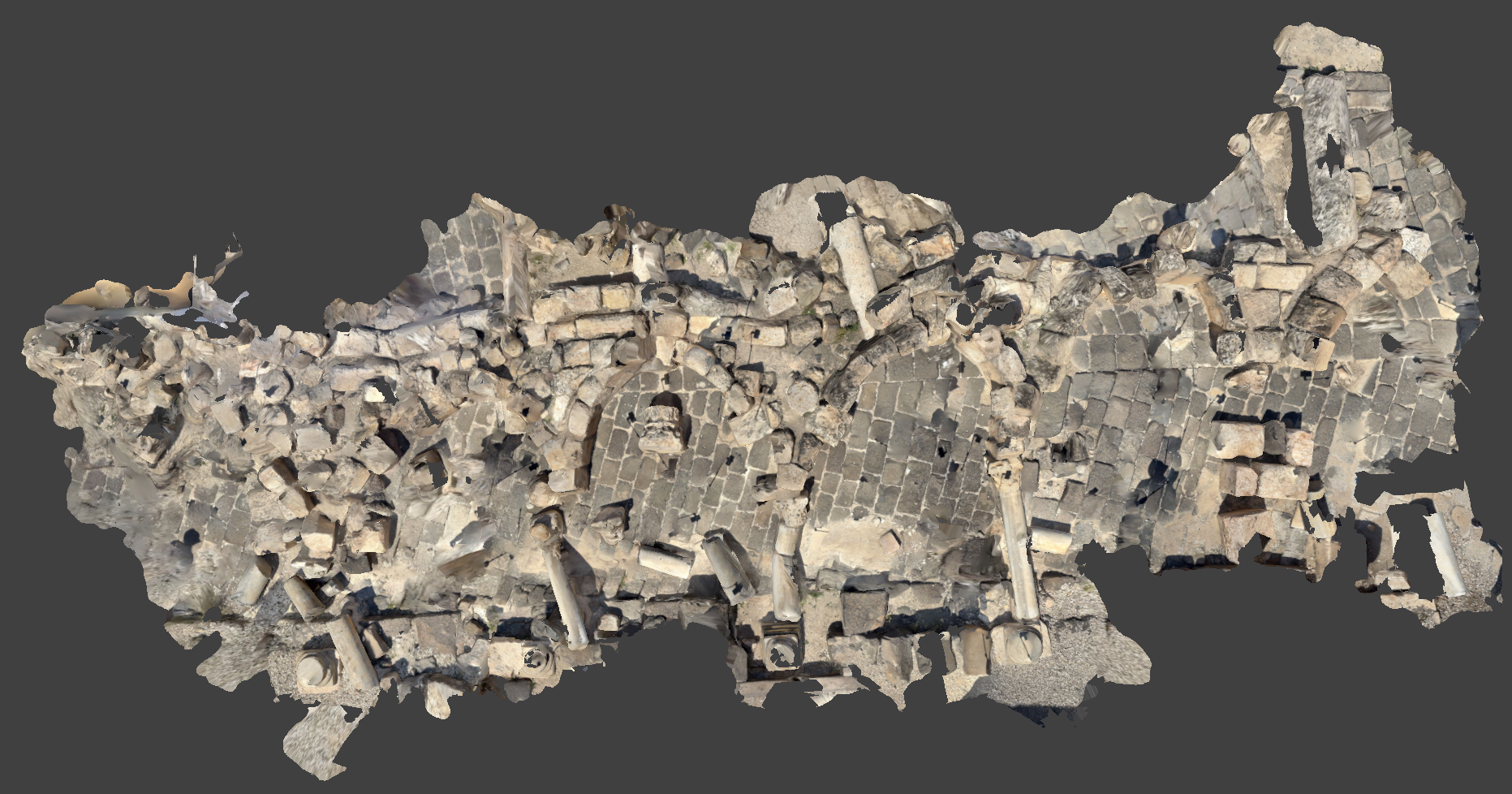

Image from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 2 Orthophoto of Area D

from Lorenzon (2024)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Ortho-photograph of Area D

(German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project 2020 Season)

Lorenzon (2024)

- Fig. 1b Plan of Area D

from Atrash et al. (2021) and German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

Tell Iẓṭabba, Area D

(UM-TAU).

Caption from Atrash et al. (2021)

Image from German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project Webpage - Fig. 2 Orthophoto of Area D

from Lorenzon (2024)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Ortho-photograph of Area D

(German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project 2020 Season)

Lorenzon (2024)

- Artists Reconstruction

of Bet She'an form the south from Atrash et al. (2022)

Cover Illustration

Cover Illustration

Artists Reconstruction of Bet She'an form the south

Atrash et al. (2022)

- the photos containing seismic destruction are largely due to one of the 749 CE Sabbatical Year Earthquakes

| Description | Photo | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plan View Drawing of Silvanus Street destruction |

Segment of the remains near the southeast end of Silvanus Street, showing the collapsed shops and arcade after the earthquake of 749 C.E. (after Foerster and Tsafrir, ESI 11 [1992], fig. 45)

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Junction of Valley Street and Silvanus Street |

Figure 4

Figure 4The junction of Valley Street (right), Silvanus Street (bottom left), and the street leading to the temple (top). The podium of the Central Monument is on the left, looking west. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Valley Street and the central monument |

Figure 5

Figure 5Valley Street and the Central Monument, looking southwest. Note the mosaic pavements of the portico on the north side of the street. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Main junction of Valley Street and Silvanus Street |

Figure 6

Figure 6The main junction of Valley Street (center), Southern Street (later Silvanus Street) (right), and the street leading to the temple (left) in front of the Central Monument (bottom), looking northeast Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| City Center |

Figure 7

Figure 7The city center of Scythopolis, looking west, showing the slopes of the tell, Palladius Street, and the western bathhouse (top,from right to left). The Roman portico is in the center, with the decorative pool and street (later Silvanus Street) on its right and the eastern bathhouse on its left. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| City Center (closer view) |

Figure 8

Figure 8The city center, looking southeast, showing Palladius Street (bottom right); Northern Street (bottom left); the temple, nymphaeum, and Central Monument (center); Valley Street (center left); the basilica and part of the Byzantine agora (center right); and the Roman portico and Silvanus Street (top) Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Slopes of the tell |

Figure 9

Figure 9Looking north toward the slopes of the tell, showing the propylon and the stairway (top), Northern Street (center), and the colonnade of the Roman temenos(?) (bottom) Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Monument of Antonius |

Figure 10

Figure 10The podium of the Monument of Antonius, looking north Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Nymphaeum - damaged in 363 but photo includes 749 collapse |

Figure 11

Figure 11The nymphaeum after the removal of the collapsed architectural members of the facade, looking southwest Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Nymphaneum - damaged in 363 but photo includes 749 collapse |

Figure 30

Figure 30Byzantine building abutting the Roman colonnade opposite the nymphaeum, looking southwest. The Byzantine foundations are lower than those of the former Roman portico. Note the early Islamic provisional walls in front of the nymphaeum. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Front of Nymphaneum - Rubble from 749 Quake |

Figure 12

Figure 12Rubble from the earthquake of 749 C.E. in front of the nymphaeum, looking west Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| fallen superstructure of nymphaeum due to 749 |

Figure 13

Figure 13Architectural members of the superstructure of the nymphaeum as they fell in the earthquake of 749 C.E., looking south Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Roman portico after reconstruction |

Figure 14

Figure 14The Roman portico after reconstruction, the decorative pool, and Silvanus Street during clearance of the rubble from the earthquake of 749 C.E., looking west. In the center are the Central Monument and the Monument of Antonius. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Palladius Street |

Figure 15

Figure 15Palladius Street (center) and the stairway of the Roman temple, with the two monolithic columns as collapsed in the earthquake of 749 C.E. (bottom left), looking southwest Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Palladius Street and sigma |

Figure 23

Figure 23Palladius Street and the sigma, looking southwest. At the top are the theater and the western bathhouse, and at the bottom are the temple and the nymphaeum. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Palladius Street and the sigma |

Figure 28

Figure 28The sigma and Palladius Street, looking east. Note the area of the Byzantine agora southeast of the street (center). Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Byzantine agora |

Figure 31

Figure 31The walls, stylobate, and oil-shale pavement of the Byzantine agora, looking north, On the right is the apse of the Roman basilica Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Roman colonnade/Silvanus Street |

Figure 32

Figure 32The Roman colonnade after reconstruction, looking southeast. Lining it on the northeast are the Roman decorative pool (partially excavated) and Silvanus Street. The rubble for the earthquake of 749 CE and the Umayyad shops are preserved in the southeast (top). Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Silvanus Street |

Figure 33

Figure 33Silvanus Street, the colonnade of the Roman portico, the decorative pool, and the partially reconstructed Umayyad shops, looking southwest Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Roman colonnade |

Figure 34

Figure 34The Roman colonnade and the northeast wing of the eastern bathhouse (bottom), looking northeast. Between them are three columns of Silvanus Hall. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Collapsed Columns on Valley Street |

Figure 48

Figure 48Columns collapsed on Valley Street in the earthquake of 749 C.E., looking southwest. Note the Umayyad walls that narrowed the street before the earthquake and the Abbasid building on top of the collapse (top right). Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Umayyad pottery kiln - folded pavement and slumped wall |

Figure 52

Figure 52Umayyad pottery kiln installed on a mosaic floor of a Byzantine shop, south of Palladius Street Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Collapsed facade of Umayyad shops on Silvanus Street |

Figure 54

Figure 54Silvanus Street during excavation and reconstruction, looking north. Note the collapse of the facade of the Umayyad shops and the arcade on the street Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Rear wall of Umayyad shops on Silvanus Street |

Figure 55

Figure 55The rear wall of the Umayyad shops, blocking the Roman colonnade along Silvanus Street, looking northwest Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Sunken pavement on Silvanus Street |

Figure 56

Figure 56Succession of layers near the southeast end of Silvanus Street, looking southeast. The lower courses of the facade of the Umayyad shops can be seen cutting the mosaic pavement of the earlier Silvanus Hall. The mosaic was laid on top of the rather loose soil and ashes with which the Roman pool had been filled, and which later sunk along with the mosaic. The steps on the edge of the pool are seen on the far end of the pool (top); their shape can also be discerned on the northeast (left) through the margins of the mosaic that remained on their original level. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Collapsed arcade of portico on Silvanus Street |

Figure 57

Figure 57Silvanus Street, the partially reconstructed facade of the Umayyad shops, and the arcade of the portico as collapsed in the earthquake of 749 C.E., looking northwest Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Umayyad coin hoard from Silvanus Street |

Figure 58

Figure 58Umayyad gold dinars found in a shop near Silvanus Street, buried under the collapse of 749 C.E. Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Silvanus Street during the removal of the rubble rom the earthquake of 749 C.E. |

Figure 59

Figure 59Silvanus Street during the removal of the rubble from the earthquake of 749 C.E., showing remains of the later line of Umayyad shops on the northwest side (left), looking southeast, and pedestals of the Roman colonnade before the anastylosis (right) Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

Tsafrir and Foester (1997) |

| Fallen Columns near Nymphaneum (?) |

Figure 10

Figure 10‘The deafening roar of devastation’: fallen columns at the crossroads of Baysan; note the impact of the column on the street paving (Walmsley). Walmsley (2007) |

Walmsley (2007) |

| Pre and Post 749 levels at Valley Street |

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10Post-749 buildings at Baysān located above the earthquake destruction level of Valley Street (Fig. 4.4 [20]); the underlying destruction level can be seen on the left (Alan Walmsley). Blanke and Walmsley (2022) |

Blanke and Walmsley (2022) |

| Earthquake destruction | Wikipedia |

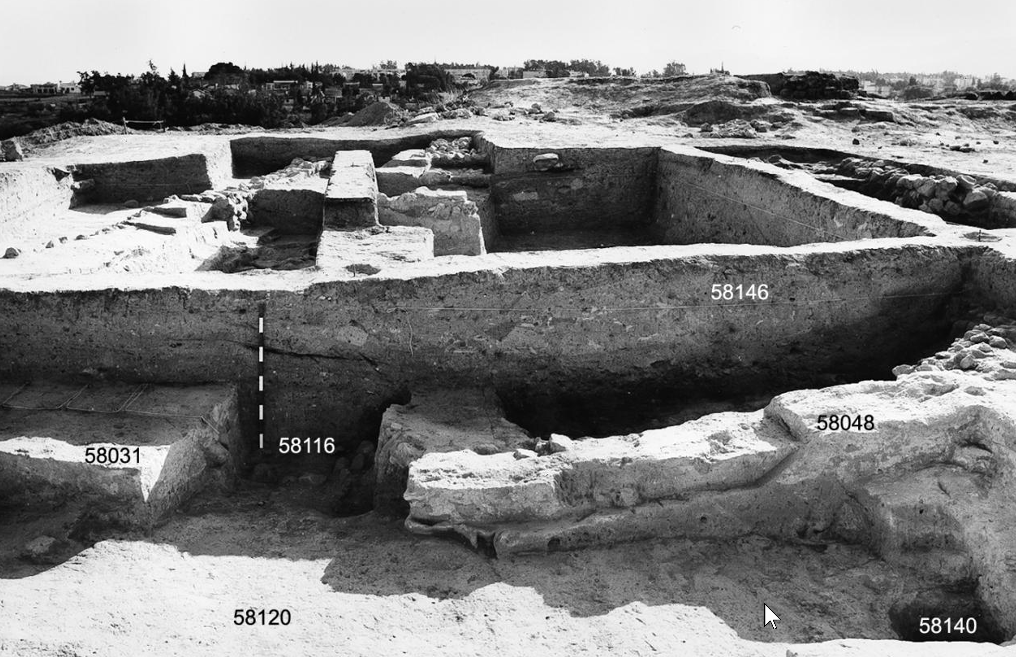

- Photo 3.59 General view

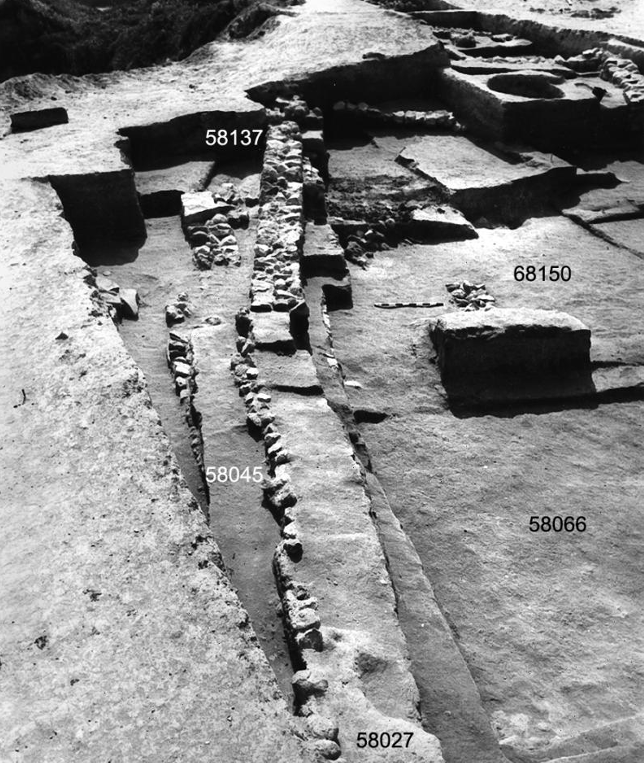

of Stratum R-2 Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.61 southeastern

corner of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.62 eastern part

of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.68 sagging and

tilting Bench 58048 of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

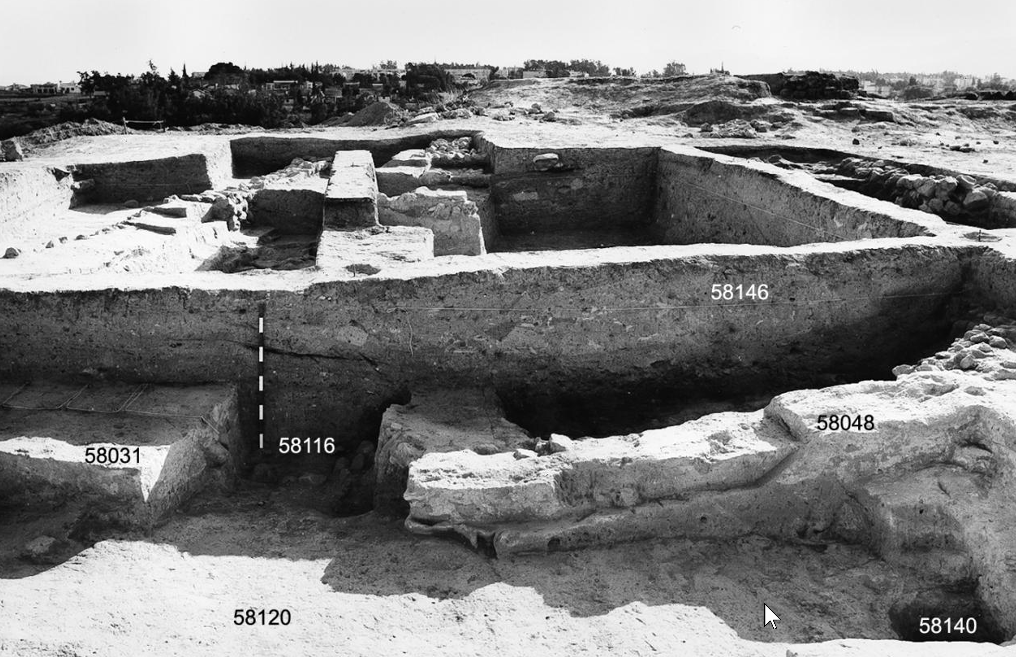

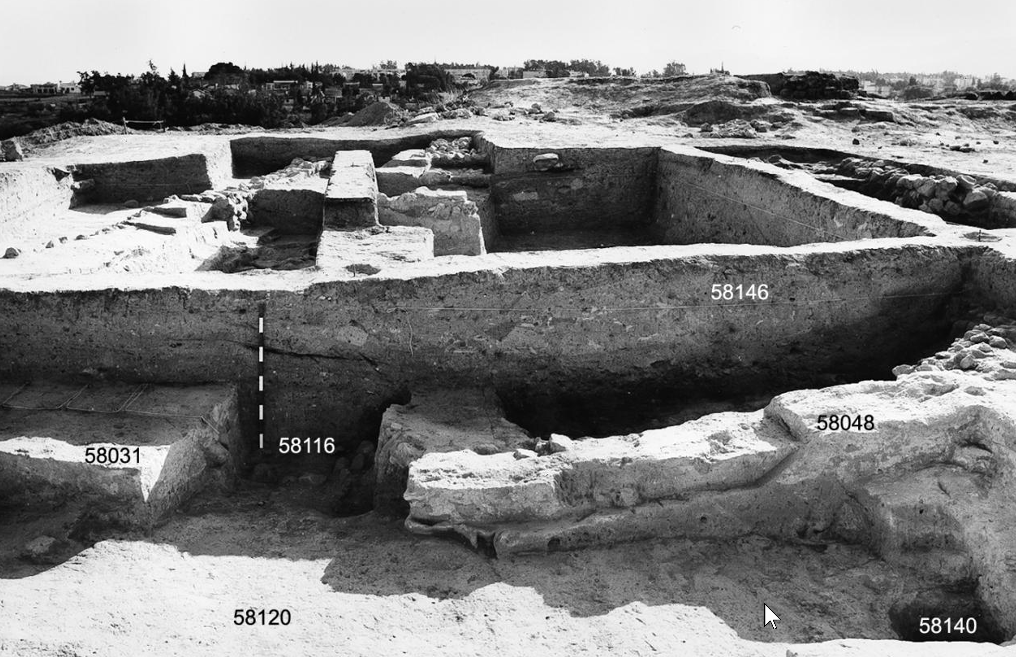

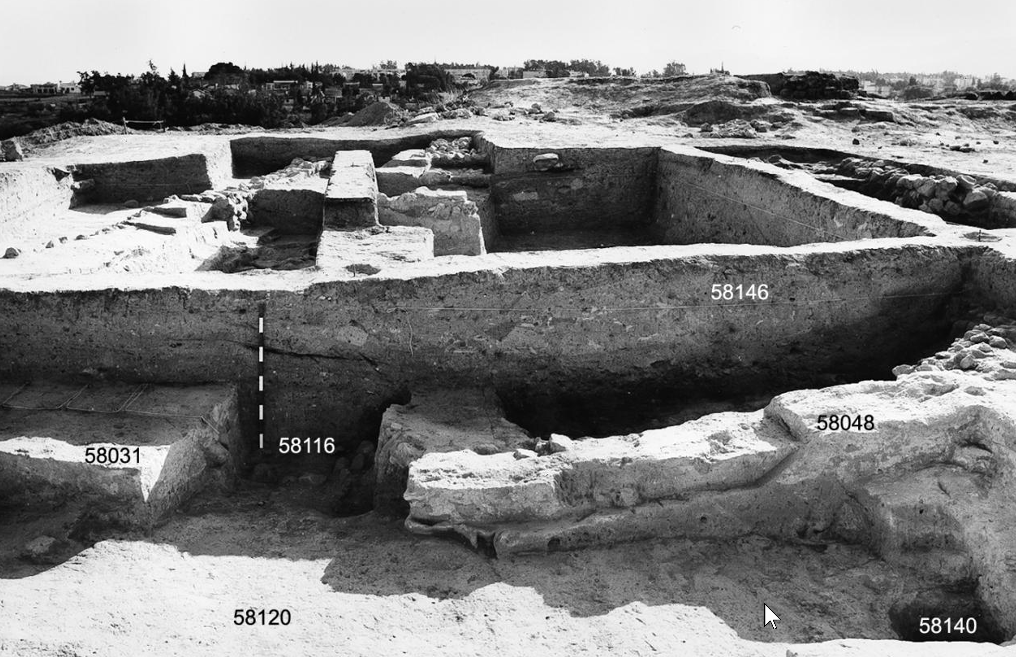

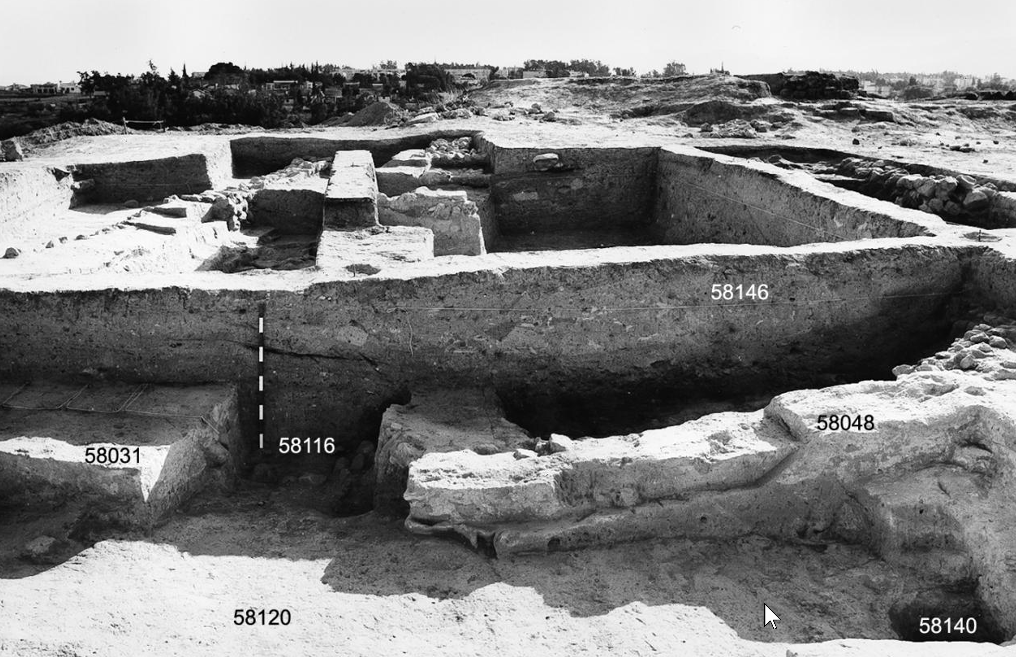

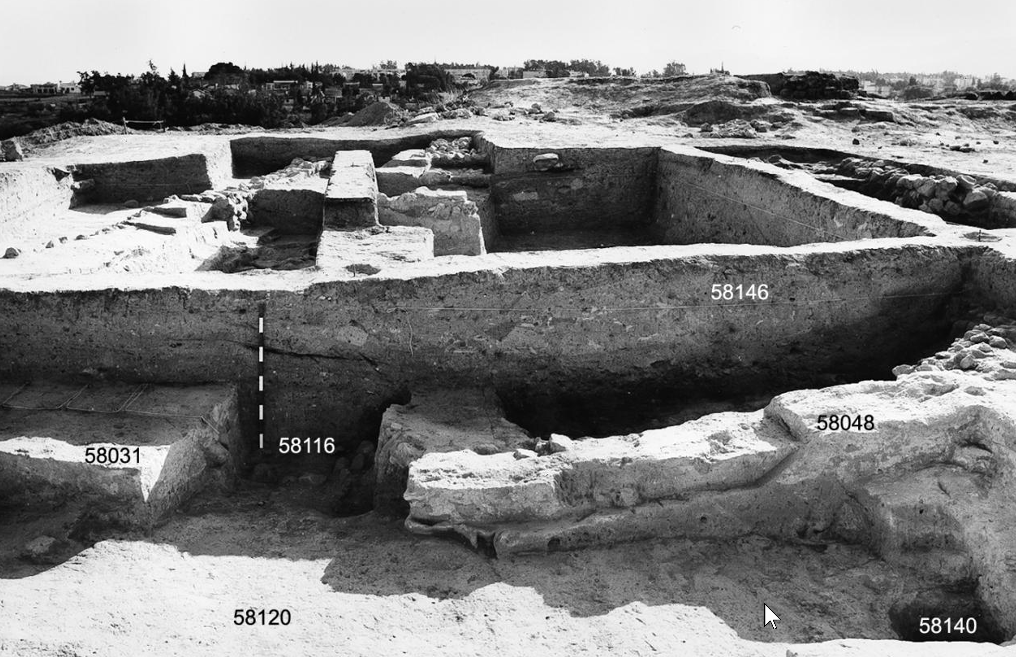

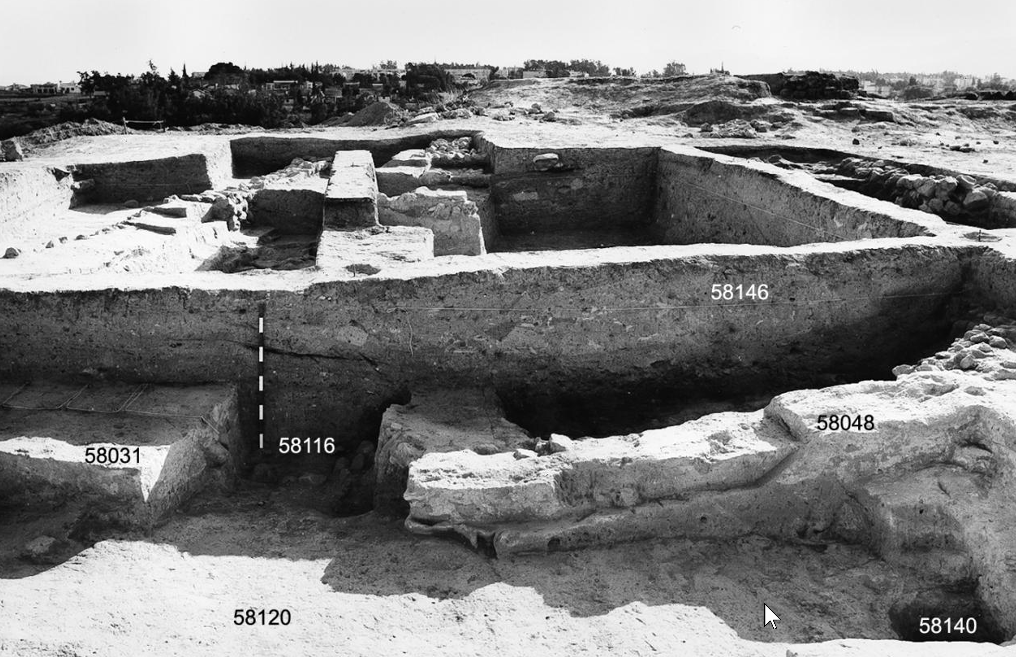

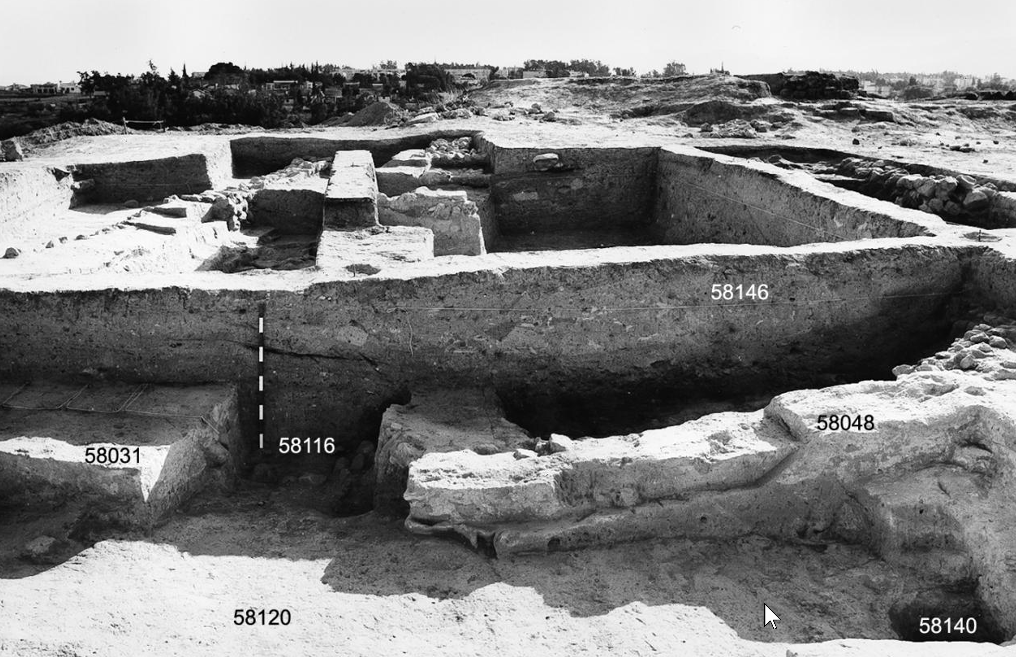

Photo 3.68

Photo 3.68

Temple 58066 during excavation, before removal of balks. Foreground: detail of the entrance area to Inner Hall 58120. Stratum R-2’ Pit 58146 is above Bench 58048. Notice the angle of Bench 58048, probably a result of seismic activity. Looking south (1989)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.59 General view

of Stratum R-2 Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.61 southeastern

corner of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.62 eastern part

of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

- Photo 3.68 sagging and

tilting Bench 58048 of Temple 58066 from Mazar and Mullins (2007)

Photo 3.68

Photo 3.68

Temple 58066 during excavation, before removal of balks. Foreground: detail of the entrance area to Inner Hall 58120. Stratum R-2’ Pit 58146 is above Bench 58048. Notice the angle of Bench 58048, probably a result of seismic activity. Looking south (1989)

Click on image to open in a new tab

Mazar and Mullins (2007)

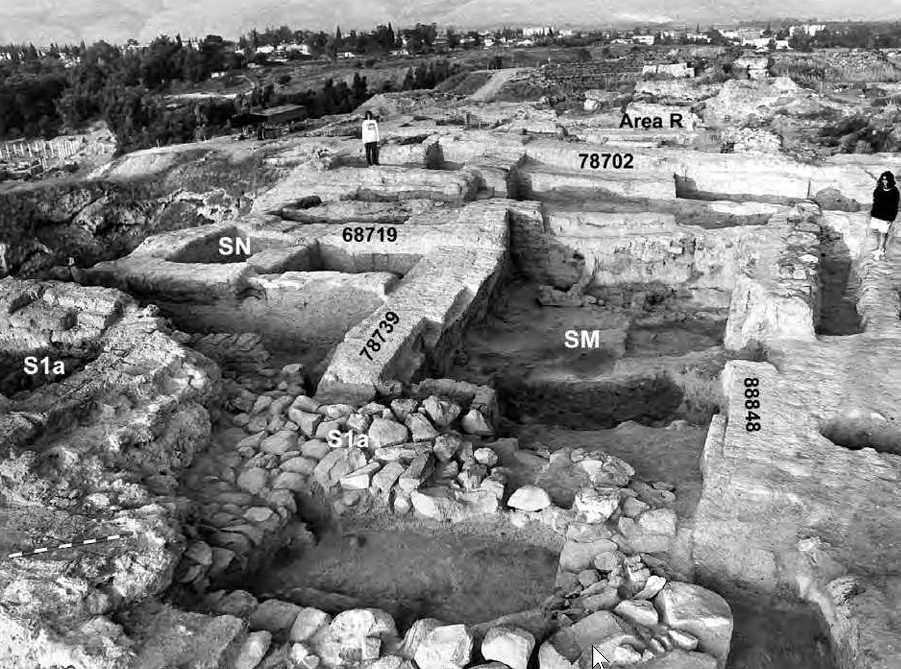

- Photo 4.1 General view

of Area S from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.1

Photo 4.1

General view of Area S, looking south.

- Right: north–south street

- Center: east–west street

- Background: Roman Byzantine remains south of the tell

(1994)

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.51 Human remains

in Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.51

Photo 4.51

Square B/7, S-4 Locus 18714. Remains of human skeleton in situ

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.52 Human remains

in Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.52

Photo 4.52

Square Y/7, S-4 Locus 10743, looking southwest. Remains of human skeleton in situ

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.34 Sloping foundation

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Photo 4.34

Photo 4.34

S-3 Building SH above S-4 Building SC, looking west. Note sloping stone foundation of Wall 98845 above large S-4 stones

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Photo 4.71 Stratum-3 Building SL

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.72 Stratum-3 Building SL

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.74 General view of

southern part of Area S from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.75 Stratum-3 Buildings

SM and SN from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.76 Stratum-3 Building

SM with Wall 78739 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.77 Stratum-3 Building

SM southwestern corner of Space 88700 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.78 Stratum-3 Building

SM from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.79 Stratum-3 Building

SM and Space 88700 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.1 General view

of Area S from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.1

Photo 4.1

General view of Area S, looking south.

- Right: north–south street

- Center: east–west street

- Background: Roman Byzantine remains south of the tell

(1994)

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.51 Human remains

in Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.51

Photo 4.51

Square B/7, S-4 Locus 18714. Remains of human skeleton in situ

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.52 Human remains

in Stratum S-4 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95)

Photo 4.52

Photo 4.52

Square Y/7, S-4 Locus 10743, looking southwest. Remains of human skeleton in situ

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009:95) - Photo 4.34 Sloping foundation

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Photo 4.34

Photo 4.34

S-3 Building SH above S-4 Building SC, looking west. Note sloping stone foundation of Wall 98845 above large S-4 stones

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009) - Photo 4.71 Stratum-3 Building SL

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.72 Stratum-3 Building SL

from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.74 General view of

southern part of Area S from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.75 Stratum-3 Buildings

SM and SN from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.76 Stratum-3 Building

SM with Wall 78739 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.77 Stratum-3 Building

SM southwestern corner of Space 88700 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.78 Stratum-3 Building

SM from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

- Photo 4.79 Stratum-3 Building

SM and Space 88700 from Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

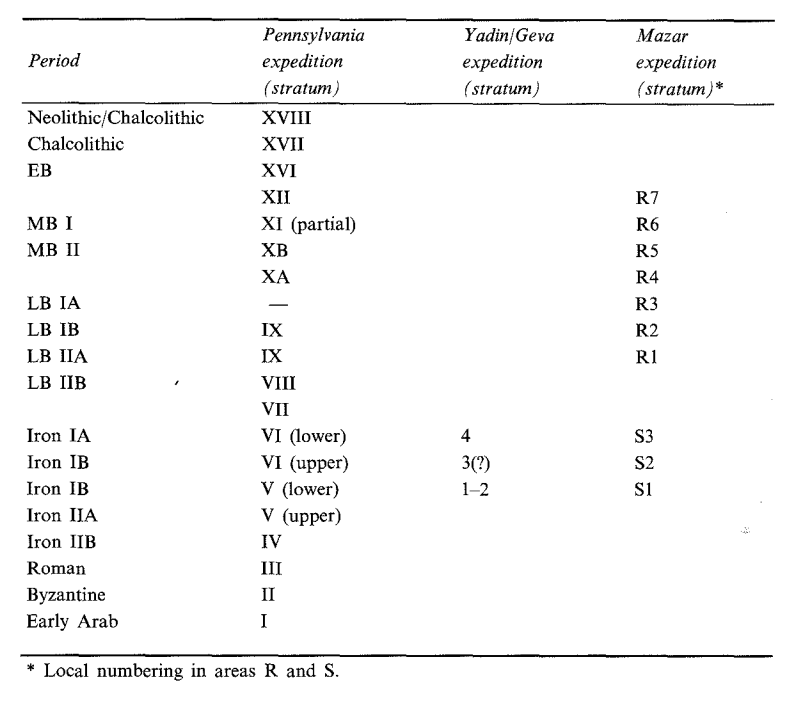

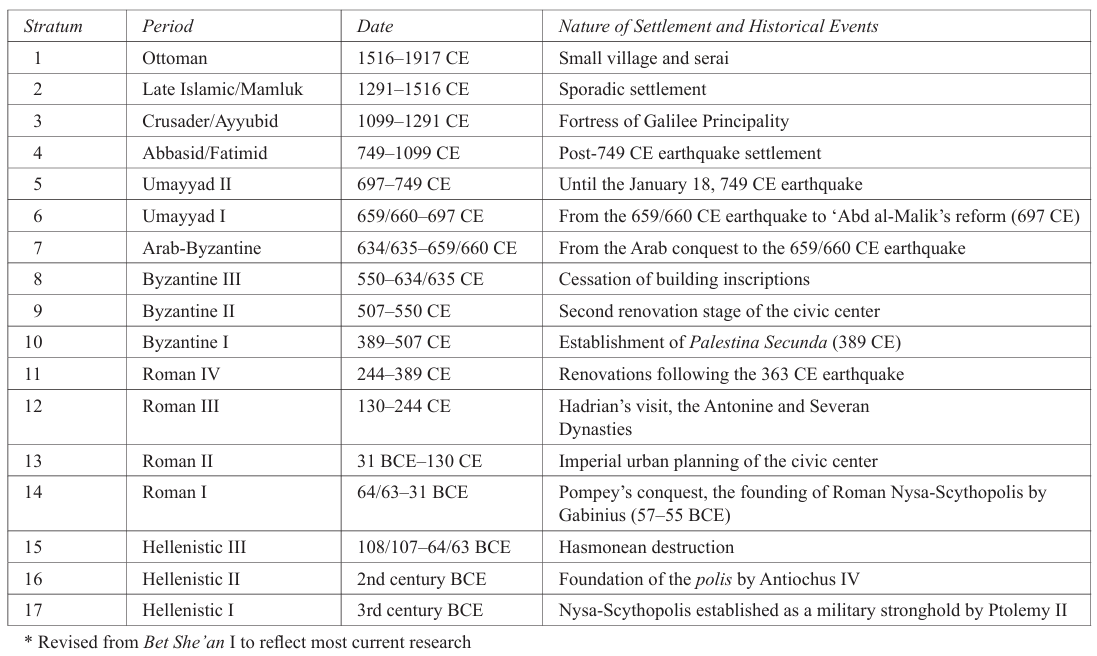

The Bet She’an Archaeological Project Chronological Chart

The Bet She’an Archaeological Project Chronological ChartBar-Nathan and Atrash (2011)

Stratigraphy of Tel Beth-Shean - This chart presents the University Museum of the University

of Pennsylvania Expedition (UME) strata and local stratigraphy in the

Hebrew University (HU) excavations at Tel Bet-Shean

Stratigraphy of Tel Beth-Shean - This chart presents the University Museum of the University

of Pennsylvania Expedition (UME) strata and local stratigraphy in the

Hebrew University (HU) excavations at Tel Bet-SheanStern et. al. (2008)

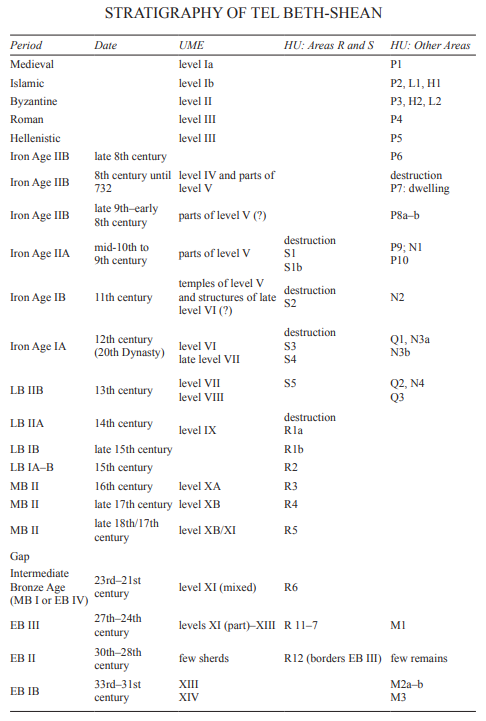

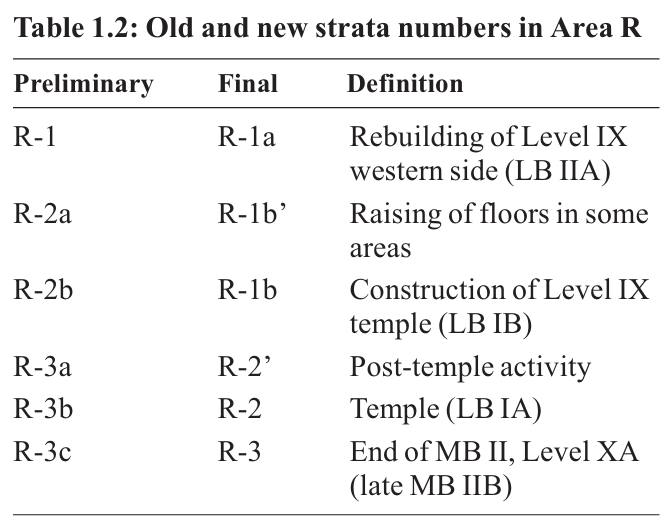

Table 1.2

Table 1.2Comparative stratigraphy of Areas N, S and Q: UME and HUexcavations

Mazar in Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

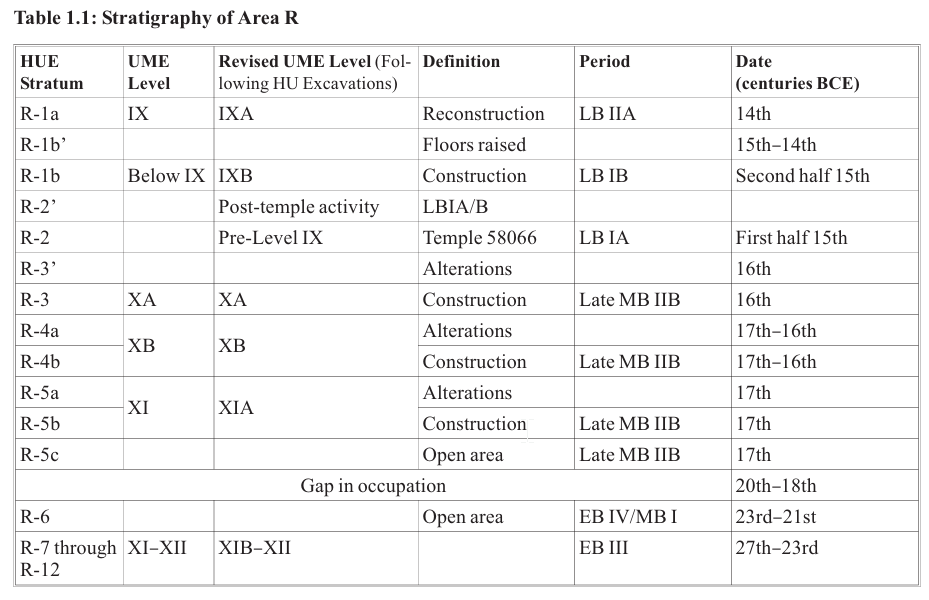

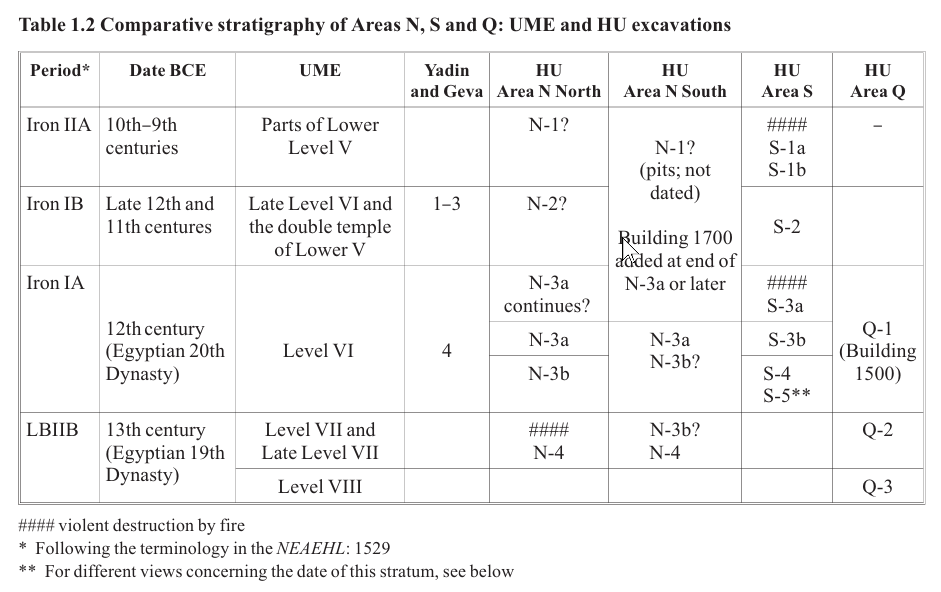

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Comparative stratigraphy of Areas N, S and Q: UME and HU excavations

Mazar in Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

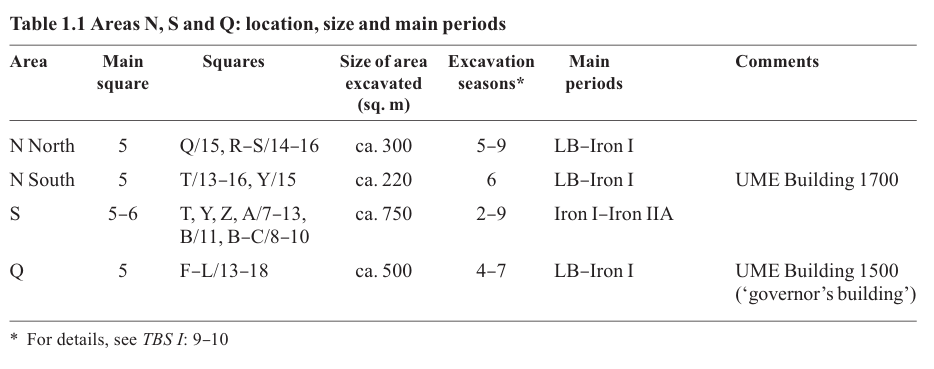

Table 4.1

Table 4.1Correlation of the stratigraphy of Area S

Panitz-Cohen and Mazar (2009)

Table 1.2

Table 1.2Old and New Strata Numbers in Area R

Mazar and Mullins (2007)

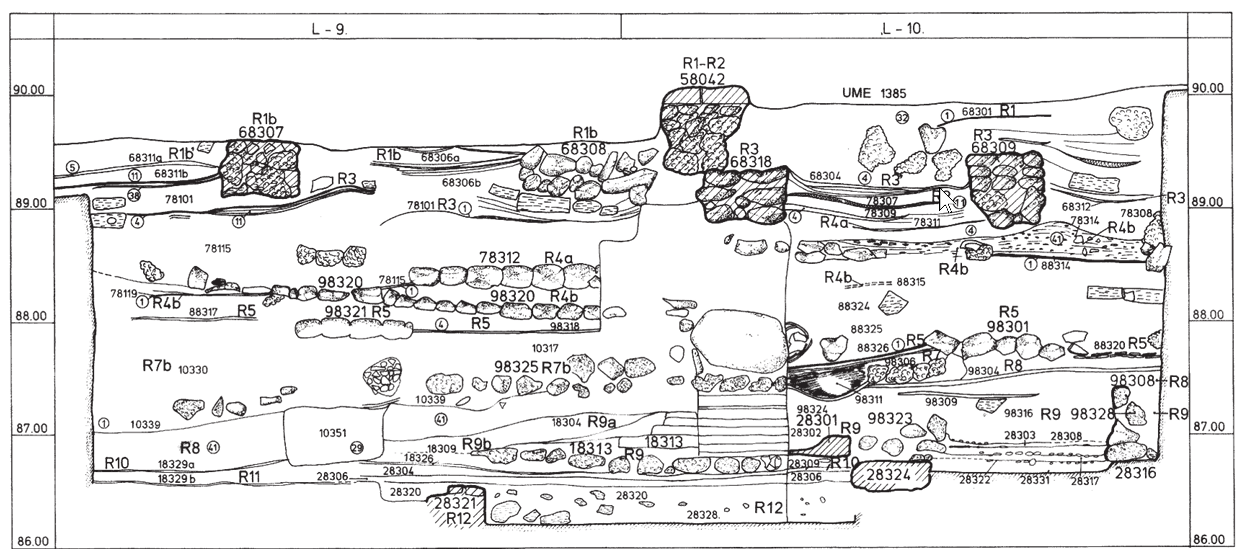

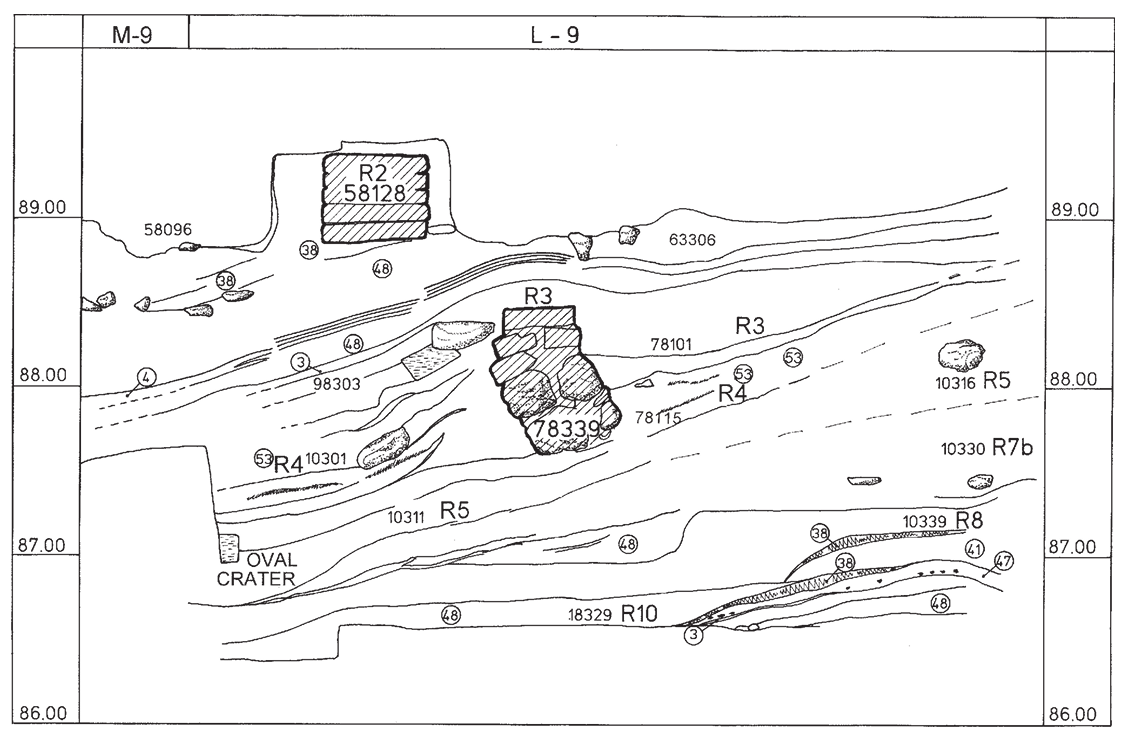

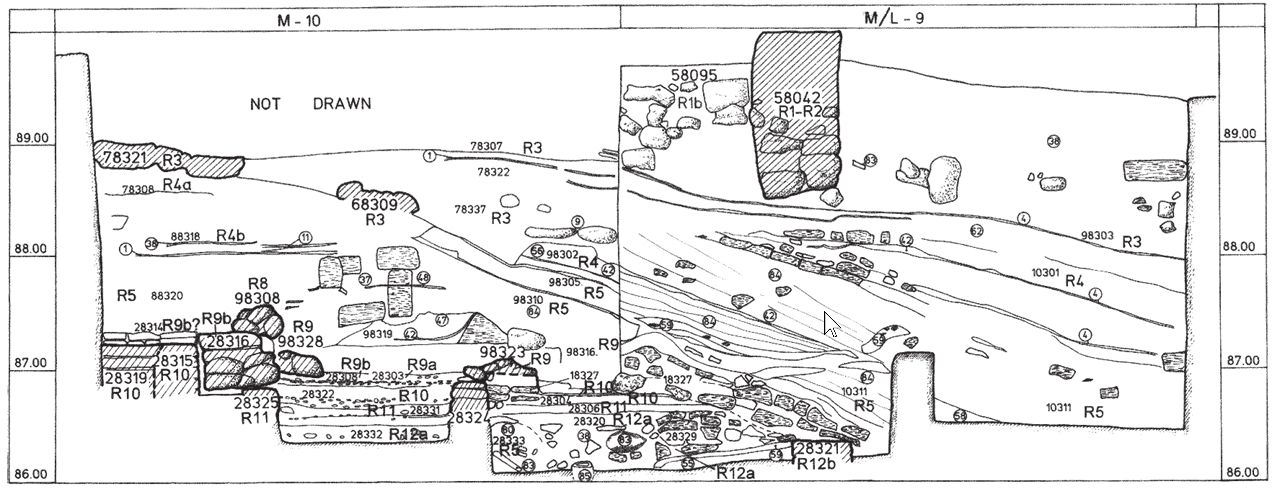

- Figs. 1.2-1.4

The UME excavations reached Middle Bronze Age remains after removing the southeastern part of the sacred enclosure of Level IX (see Fig. 2.5). FitzGerald identified three main MB occupation strata and designated them Levels XI, XB and XA. To date, no final report on this period has been published. Extensive exposure of MB remains throughout Area R enabled us to integrate our findings with the unpublished UME plans and in this way to reconstruct the plan of a large part of the MB settlement in all three strata.

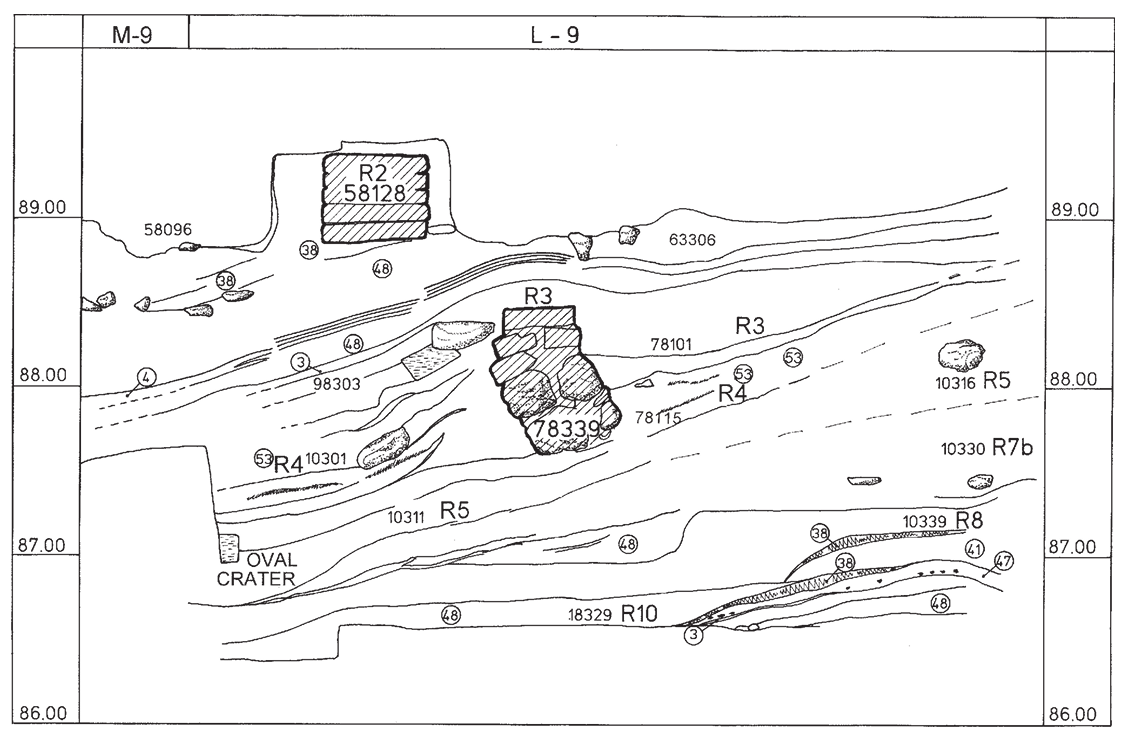

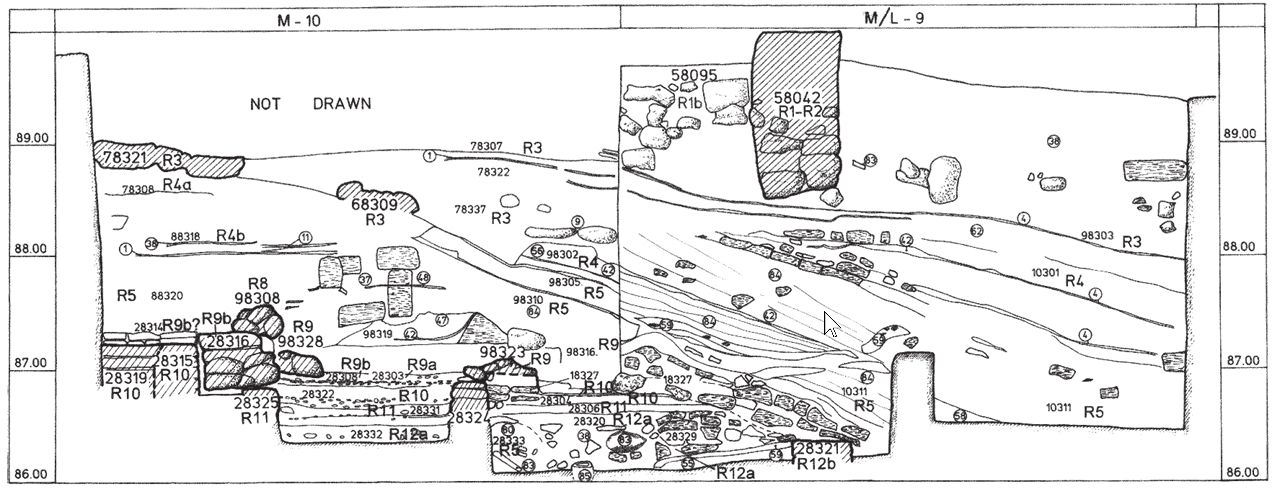

It became evident from our excavations that following scanty evidence for EB IV/MB I above the EB III settlement, an occupational gap occurred at Tel Beth-Shean until late MB IIB (for the Early Bronze Age, see Mazar, Ziv-Esudri and Cohen-Weinberger 2000; for EB IV/MB I, see Mazar 2006). No MB IIA finds were uncovered at Beth-Shean except in Tomb 92 in the Northern Cemetery (Oren 1971; 1973:61–67), which contained a few MB IIA (Oren’s MB I) bronze weapons but no pottery. This was probably the burial of a single warrior of the period and unrelated to an occupation level on the mound. The earliest MB pottery on the tell originates in Burial 38201 (Pl. 16:1–8), which may date to the earlier part of MB IIB, while the bulk of the pottery from Strata R-5 and R-4 dates from the mid to late MB IIB, and that of Stratum R-3 to the final phase of the MB IIB (end of the Middle Bronze Age). Thus, there was an occupational gap estimated at 300–500 years (depending, of course, on the date of the EB IV/MB I remains, which cannot be assigned with any precision), until sometime in the 17th century BCE when settlement at Tel Beth-Shean was revived.

A unique feature of the Middle Bronze Age occupation is a huge oval crater that occupies the entire central part of Area R (Figs. 1.2–1.3). This crater (25 × 18 m and ca. 3 m deep) originated either in the EB III or was dug into the EB III occupation during the Middle Bronze Age (see further discussion of this question below, pp. 47–48). The crater was found filled with refuse layers of ash and earth containing many pottery sherds and animal bones that had been dumped in from all sides. The pottery in this fill is homogeneous and typical to Strata R-5 and R-4 of the MB II. Since the fill layers did not include Chocolate-on-White Ware, a hallmark of the latest MB level at Tel Beth-Shean (our Stratum R-3), and since Stratum R-3 installations and floors were constructed above the area of the crater after it was filled in, the crater must have gone out of use at the end of Stratum R-4.

The original function of the crater remains unclear. If it was cut during the EB III, it may have been a local water reservoir (Arabic birke). In this case, it remained as a large depression to be reused, after a long occupational gap, by the MB II settlers as a collection pit for their trash. On the other hand, if it was cut during the MB, then its function is less clear since it was soon filled with refuse. The crater was surrounded on the west, north, and south by dwellings and on the east by a large open courtyard.

The spacious open courtyard or piazza exposed to the east of the crater continued eastward beyond the limits of the excavation. It had a white lime floor containing three circular hearths that were probably used for cooking or roasting. The function of the courtyard cannot be determined. If it was used in association with a hypothetical nearby MB temple (further to the east?), then the hearths or roasting installations could have been related to cultic activity; however, no evidence of this was found. In most of the eastern part of Area R this substantial floor was the only construction phase from the Middle Bronze Age and, as mentioned above, it was located just above the occupation debris of the EB and EB IV/MB I Ages.

West and south of the oval crater was a residential area with buildings on both sides of a street that ran parallel to the perimeter of the mound. The continuation of this street and the dwellings can be seen in the unpublished plans of Levels XIA, XB and XA kept in the archives of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. These plans, together with the evidence from the new excavations, have enabled us to reconstruct the plans of three phases of a large MB residential area (Figs. 1.2–1.4).

While no complete house plan was excavated, it appears that each structure had its own small courtyard and several rooms. Eight infant jar burials were found in the excavated area, as well as a pit burial of an 8–12-year-old child. This burial (Locus 38201), located in the northwestern corner of the large oval crater and dating to the earliest MB occupational phase, contained several pottery vessels as well as four gold earrings, two Egyptian alabaster vessels and a gold ring with an amethyst scaraboid (Fig. 1.5). Consequently, the interred child must have belonged to a wealthy family. Similar pit burials, though not as rich, were found in the UME excavations.

Although the plan of the residential quarter and the large courtyard on the eastern side of Area R reveals evidence of urban planning, Beth-Shean appears to have been a rather small, perhaps unfortified town, no more than 4–5 acres in size, occupying only the southern part of the mound. This can be deduced from our excavations in Area L (see Fig. 1.1), where Byzantine buildings were constructed directly above the EB deposits, with no evidence of any occupation from the MB through the Iron Age, apart from a few MB burials. It seems, therefore, that the northern limit of the second-millennium town was south of Area L, where there is a steep drop in the topography of the mound.

No evidence of MB fortifications was found by the UME or Hebrew University projects, even though the excavation areas reached the southern edge of the mound. This is a strange phenomenon in a period when massive fortifications were erected even at small sites throughout Palestine. One possibility is that during the Middle Bronze Age, Beth-Shean had a simple city wall that has eroded away without a trace; another possibility is that the town remained unfortified due to its high elevation and its status as a small town. If so, Beth-Shean would be one of only a few unfortified towns in the country at this time. A third possibility, suggested by B. Arubas, is that the entire southern edge of the mound had been cut away during the Roman period (see TBS I:48–56). If his suggestion is correct, then the entire southern part of the town, to an extent of approximately 20 m to the south of Area R, is missing, and there is no way to determine whether the town was fortified.

The rich and well-stratified pottery assemblage from the MB occupation strata and the burials indicates a gradual development throughout this period (see the discussion by A. Maeir, below pp. 293–298). Stratum R-5 includes a few red-slipped juglets, but these have disappeared by the time of Strata R-4 and R-3, when thin, delicate White Ware is common (primarily bowls). A few Red, White and Blue Ware vessels were found. Chocolate-on-White vessels first appear in small quantities in Stratum R-4, increasing in Stratum R-3. It should be noted at this juncture that Bichrome Wheelmade Ware is absent at Beth-Shean.

Noteworthy among the special finds are fragments of a zoomorphic rhyton painted with a gazelle and sacred tree motif—quite rare in this period, a unique hematite cylinder seal in a local style depicting a procession of three human figures and a crouching animal, and a group of Hyksos scarabs, including one bearing the name of Neferhotep I of the 13th Dynasty.

Imported pottery is rare in the Middle Bronze Age and the few Egyptian vessels are notable. A pottery bottle found in a burial from Stratum R-5, the earliest phase of MB IIB settlement on the mound, an Egyptian Tell el-Yahudiyeh black juglet from a slightly later context in Stratum R-4, and of special importance, a closed, red-slipped carinated vessel of a type known from the late Second Intermediate Period to the early 18th Dynasty in Upper Egypt. The latter was found in Stratum R-3 together with Chocolate-on-White vessels and provides an important correlation between the end of the Middle Bronze Age in Palestine and the late Second Intermediate Period–beginning of the 18th Dynasty in Egypt.

Five 14C determinations were made on samples from MB strata (see Chapter 16). A lack of short-life samples necessitated the testing of charred wood, mostly from olive trees, which has a particularly long life span. Consequently, the results are of limited value, but nevertheless interesting.

The first sample (Table 16.1) comes from Stratum R-5b and presents an earliest possible date of ca. 1660 BCE (the 1σ range), which appears somewhat too late for this phase. If accurate, it may indicate the end of this phase. The 2σ range of this sample enables an earlier date, until 1740 BCE. The second and third samples in Table 16.1 present dates some 100–200 years earlier than the time of their use in Stratum R-3. This is to be expected when sampling olive trees that can predate their time of use by hundreds of years, and could even be in secondary use. The fourth and fifth samples, also from Stratum R-3, correspond to the expected life span of Strata R-4 and R-3.

The events that brought about the end of the MB town remain unclear. There is no evidence of a total conflagration, although charred timber and ash layers were found on the floors of some Stratum R-3 rooms in the western part of the area. It appears, therefore, that the town was destroyed without being completely burned, or was abandoned under circumstances that remain unknown.

- Fig. 1.6

The temple’s broken and distorted walls and sloping floors indicate that it probably suffered earthquake damage. As it was constructed directly upon the soft fill of the MB oval crater, its walls and floors were vulnerable to sinking. Perhaps for this reason, the temple was intentionally abandoned after a period of use, its ruins backfilled and leveled in preparation for the construction of the Level IX sanctuary courtyard. As a result, we found the building empty of finds.

The temple plan is exceptional, comprising an entrance hall on the south (internal dimensions 3.4×9 m), a main hall and an inner room. The main hall (internal dimensions 5.6×7.35 m) was accessed by means of a corner entranceway from the entry hall. Plastered benches were constructed along the walls of the main hall; a bench in the western part of the hall was built at some distance from the outer wall and widened to form a small platform. A cylindrical stone standing upright on this platform may be interpreted as a sacred standing stone (baetyl), similar to one found by Rowe in the Level IX sanctuary. A small post hole at the northern end of the platform indicates the location of a wooden pillar that may have symbolized the Asherah.

The inner room was trapezoidal in shape, 1.95×3.15×8.9 m, and had plastered benches along its walls. It remains unclear whether the focal point of the cult in this temple was in the main hall or the inner room. The building had a western wing with three rooms, one of them a small chamber with a narrow, stone- lined pit surrounded by benches; its function remains obscure. A larger stone-lined pit was found in a room at the southern end of the temple that may have served as a silo or was related in some way to cult practices.

The plan of the Stratum R-2 temple, though unique, is reminiscent of the later Late Bronze and Iron Age structures defined as “temples with indirect entrances and irregular plans” (Mazar 1992: 177), and thus represents the earliest example in Israel. Sanctuary B2 at Ebla (Matthiae 1984: 31) may be a Middle Bronze Age Syrian prototype for these temples in the Levant. Later examples include the LB temples at Tel Mevorakh and the Lachish Fosse Temples. Iron Age I examples are found in Tell Qasile Strata XI–X (see references in Mazar 1992: 177).

The three main phases of MB occupation in Area R (Strata R-5, R-4 and R-3) follow the same relative sequence and appear to be equivalent to Levels XIA, XB and XA as excavated by G. M. FitzGerald (see Chapter 1). The results of a probe in Area L (TBS I: 294–295) indicate that the MB II through Iron I occupations did not extend to the northern part of the mound, and thus the towns of these periods probably did not exceed 4–5 acres in size (1.6–2 hectares / 16–20 dunams). It appears, therefore, that the MB settlement of Beth-Shean was a small unfortified town, while the dominant site was probably located at nearby Tel Reḥov (Tell eṣ-Ṣarem), ca. 6 km (3.7 miles) to the south.

In every place where earlier strata were reached, the Stratum R-5 structures rested on sparse EB IV/MB I habitation (Stratum R-6) or EB III deposits (Stratum R-7). An absence of MB IIA remains indicates a gap in occupation during this period.

A rough date for the beginning of Stratum R-5 can be determined from the pottery found in a juvenile burial in the earliest MB level (Locus 38201). Some of these vessels comprise the earliest MB pottery found in Area R of the present excavations, dating to the early 17th century BCE.

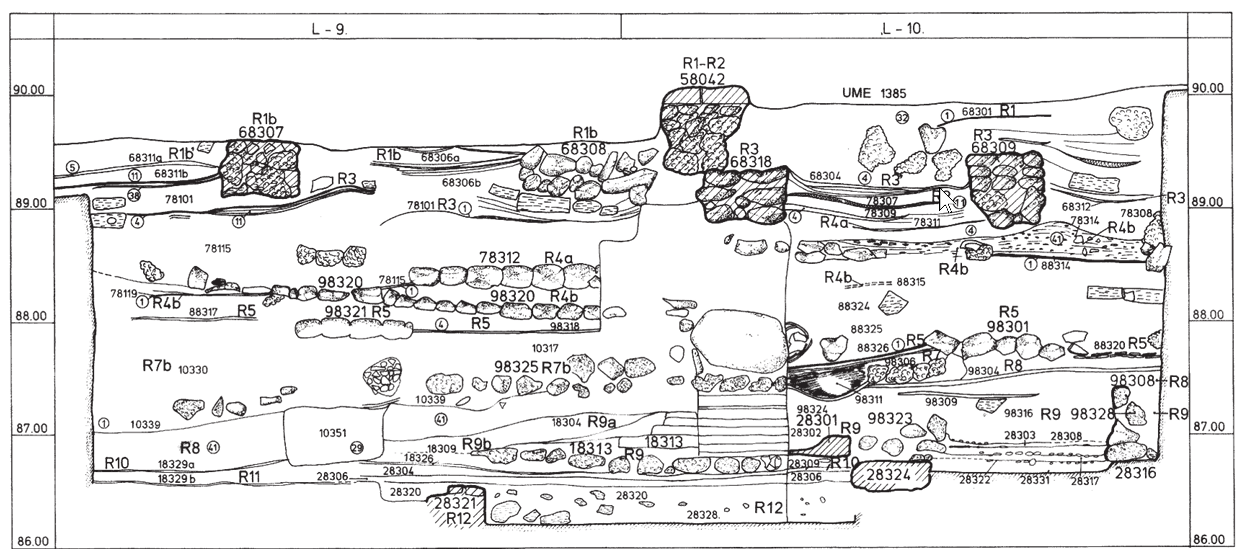

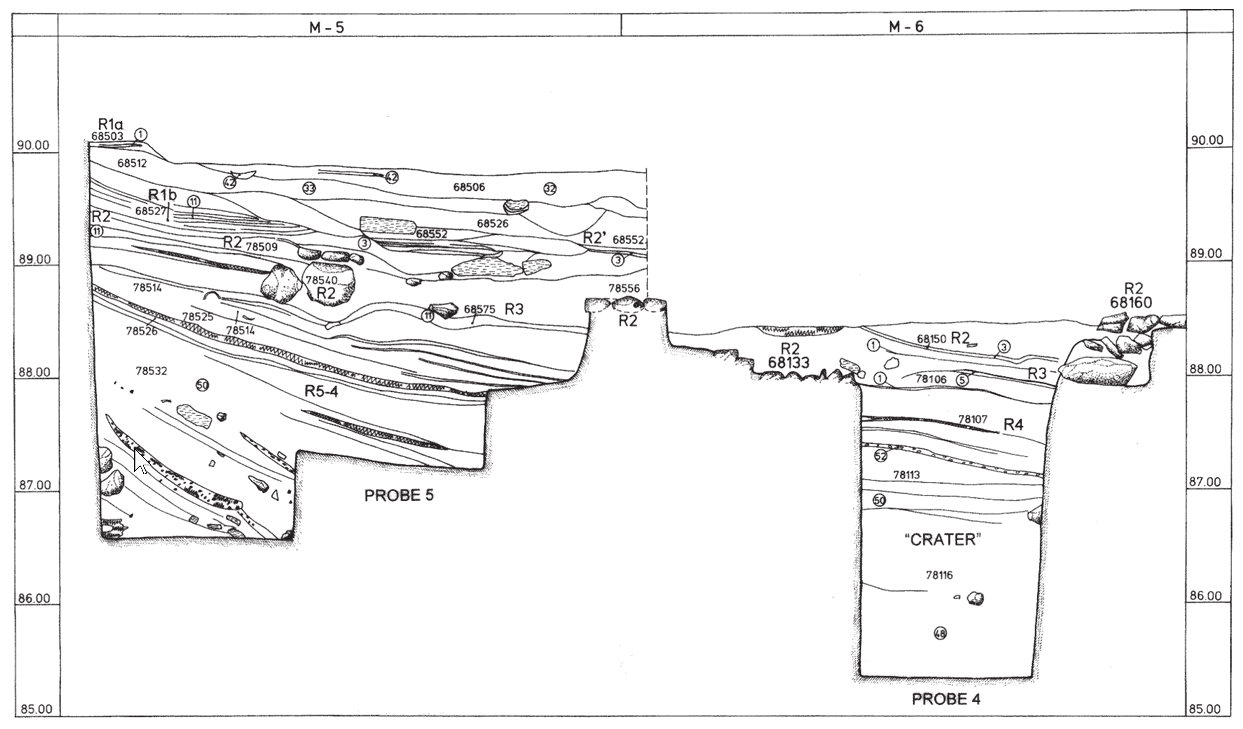

- Plans: Figs. 1.2–1.3, 3.3–3.6

- Sections: Figs. 3.38, 3.42, 3.43, 3.46, 3.48

- Pottery: Pls. 1–7

The oval crater measured approximately 18 × 25 m in size, although its boundaries could not be determined with any precision since long-term erosion caused its edges to recede considerably. However, its makeup and extent were examined by the excavation of probes at five strategic points: one in the north (Square N/9), three below Stratum R-2 Temple 58066 (Squares L-M/6) and one in the south (Square M/5). In excavations down to EB III layers in Squares L-M/9, in the northwestern part of Area Rb, approximately 100 sq m or so of EB III occupation was exposed and the section revealed the oval crater’s stratification in this area. The discussion of the EB architecture is to appear in the fourth volume of this series.

Every probe produced the same general picture—alternating layers of gray and brown fill that appear to have resulted from an accumulation of debris over a long period of time, most probably through natural erosion and continuous dumping of rubbish from all sides into the pre-existing pit. The layers all sloped towards the middle of the feature. The crater’s total depth is unknown since the center remained uninvestigated, but the results from the Square N/9 probe indicate it reached at least 3 m in depth.

Locus 79148 was a reconstruction of Stratum R-4b Room 10504; its inner dimensions were ca. 22.5 × 4.5 m. Beaten-earth Floor 79148 in the western part of the room was clearly bonded to Wall 79144 in the south and replaced the earlier stone floor. It may be that no traces of Floor 79148 were found in the eastern part of the room because the surface had been cut by Stratum R-3 Burials 98538 and 10508 (see below).

The room was bounded on the north by Wall 98531, whose western end clearly met the foundations of Wall 79134. The eastern end was less clear due to disturbance from the Stratum R-1b circular installation (68155). One apparently entered the chamber from Courtyard 98532 by way of an entrance that included a threshold made from a slab of flat basalt ca. 0.65 × 0.7 m in size and 0.4 m thick.

- Plan: Fig. 3.14

- Sections: Figs. 3.36–3.37, 3.44, 3.48

- Photo: 3.30

- Pottery: Pls. 27–30

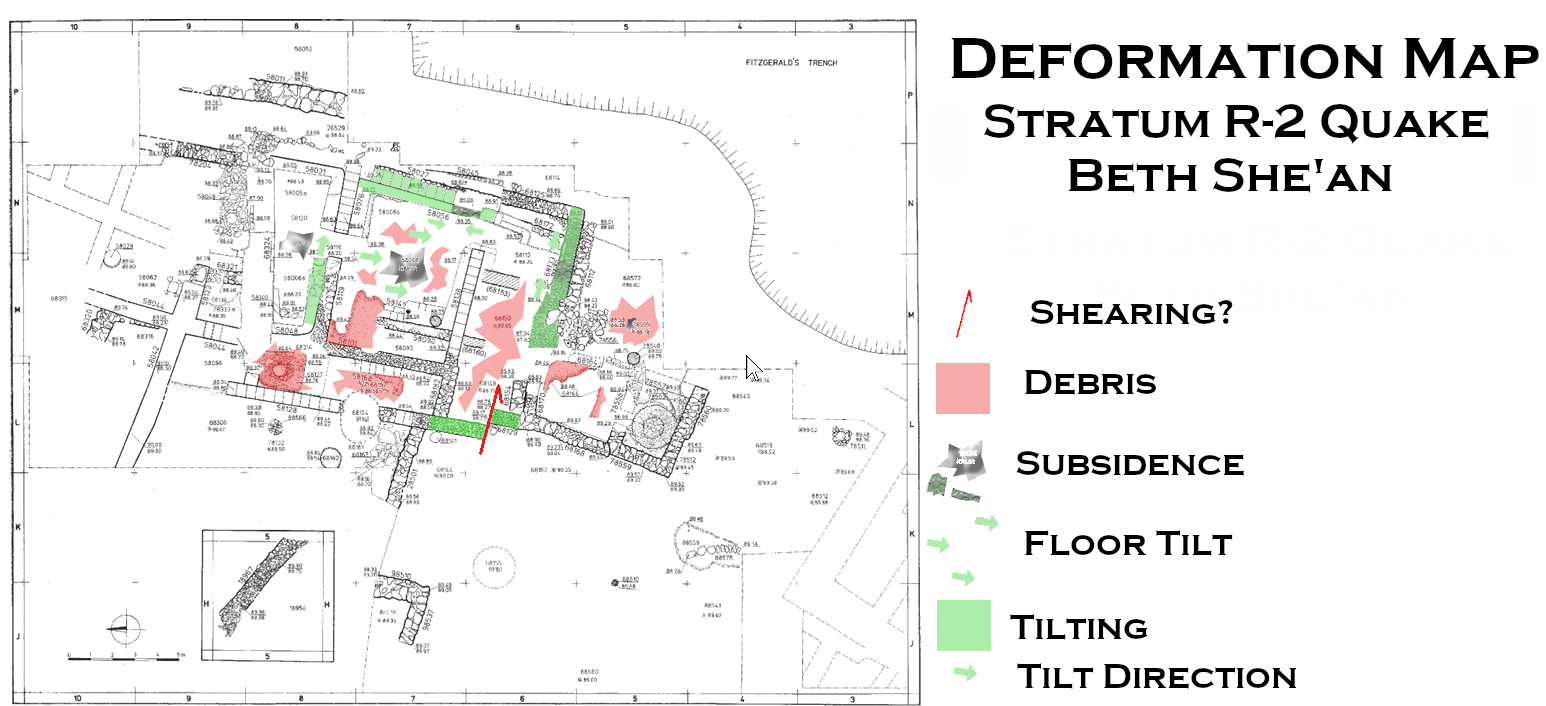

The stratigraphy here was complex since the surfaces were fragmentary and poorly preserved. The sinking of the fills in the oval crater below the piazza caused many of the surfaces to break away from their associated architecture, resulting in a series of disconnected floors that dipped, plunged and undulated in various directions. The cause of this irregular settling was probably a combination of the soft fills inside the crater and the effects of earthquakes, which are particularly strong in the Jordan Valley. For reasons that will become evident in the next chapter, we believe that one of these seismic episodes occurred towards the end of Stratum R-2.

Installation 78335 in Square M/9 was a circular stone pit, 1.6 m in diameter and 0.86 m deep, with fieldstone walls 0.35 m thick and plastered on the inside with light brown clay (Photos 3.31–3.32). The floor was made of basalt flagstones covered by fine, loose brown earth mixed with lenses of gray ash and several bones. The contents suggest that the installation was used for roasting animals, as was the case with at least one circular stone installation in Stratum R-1 (see pp. 166–168), although this installation could have had other functions as well. Additional finds included an exceptional, red-slipped Egyptian carinated vessel (Pl. 27:13) and a fragment of Chocolate-on-White Ware (Pl. 27:12). Installation 78335 went out of use in Stratum R-2 with the placement of Walls 68321 and 58123 on the stone pavement (Fig. 3.44). Its mouth was sealed by Stratum R-2 Floor 68333a of Room 58136 (Fig. 3.28).

The only surface clearly abutting the installation was Floor 78333b, which was partly sealed by R-2 Floor 78333a. The Stratum R-3 surface was covered with lightly compacted gray ash mixed with clay and plaster fragments. Two basalt stone pestles were found on it, along with large amounts of pottery and bones. On the north the surface probably connected with Floor 68322, which also produced a large number of animal bones (Photo 3.32).

Other surfaces in the vicinity probably related to Floor 78333b as well, including Pebble Floor 78327a to the east, which did not quite reach Wall 68326. In the west, a pink clay or plaster floor (98303) sloped up to abut Wall 78339. Nearby, compact striations of black and gray ash (78114) also abutted Wall 78124 and rested on a pink floor that was probably the same as Floor 98303. Differences in height of as much as 0.5 m between the various surfaces were probably the result of earthquake activity. Moreover, Installation 78335 was situated close to the center of the oval crater of Strata R-5–R-4, making it a focal point for the tilted layers on all four sides.

- Plan: Fig. 3.14

- Sections: Figs. 3.31, 3.36, 3.39, 3.47

- Section: Fig. 3.31

- Photos: 3.49–3.51

- Pottery: Pl. 31:1–11

The bricks of Wall 18949 in the northwestern corner of the building were of two sizes — large gray ones averaging 0.4 × 0.5 m and smaller yellow bricks ca. 0.27 × 0.33 m. Those of Wall 79143 (removed at the time the plan was drawn) were gray in color and averaged 0.45 × 0.55 m in size. The absence of bricks in Wall 79143 further to the east was probably the result of damage from Stratum R-1b structures here. The eastern side of the structure was marked by Wall 88539, badly ruined by an R-1b sump for a drain (see below). The wider, 1.1 m, central portion of this wall may have been a later repair and the lack of alignment suggests damage from earthquake activity.

Stratum R-2 Wall 18967 cut through Wall 18949 on the west (see insert to Fig. 3.18), but south of this disturbance the wall continued as 18938. Wall 18949 also revealed interesting constructional innovations. The basalt foundations apparently had wooden beams laid on them — a practice also seen in Stratum S-1 walls dating to the tenth–ninth centuries BCE in Area S. On top of these the mudbrick courses were placed. Such a technique may have been intended to cushion the walls from shock related to earthquakes (van Beek, forthcoming).

The southern end of Wall 18938 bonded with Wall 18917, which presumably formed the back of Building 79137. Wall 18917 from Stratum R-3 and Wall 98521 in Square J/3 from Stratum R-1b appear to be on the same line. This suggests that Stratum R-1 Southern Building 88506 may have been constructed on the earlier Stratum R-3 walls of Building 79137 to provide a firm foundation at the southern edge of the mound. Two narrow walls (18932 and 18933) were built onto Wall 18938 during a later phase of Stratum R-3 (Fig. 3.16). The reason for this thickening is unknown and may have been a repair to the wall.

There is no evidence for partition walls in this building, perhaps indicating a spacious courtyard or hall measuring 7.2 m wide from east to west. The stone paving in the northwest corner covered Stratum R-4a Wall 98551 and R-4b Bin 98552 in Squares J/4–5. In the northeast was a composite floor of flagstones and beaten earth. The earthen part in the corner was attached to Walls 79143 and 88539. All the flagstones were covered by a 3 cm layer of pink clay.

The destruction was quite heavy inside the building, similar to that found in Locus 79132 mentioned above (Square J/7). At the western end of Square J/5 a 0.2 m thick layer of black ash lay on the clay surface covering the stone pavement (Fig. 3.31). Over this lay nearly 1 m of fallen and burnt mudbrick (79133). A large beam of charred wood at least 0.1 m in diameter was noted in the section, probably part of the roofing. There were some indications of an upper floor. As can be seen in Fig. 3.31, a thick deposit of pottery (mainly storage jars) in Locus 18944 was located almost 0.5 m above the level of Flagstone Floor 79137 at 89.39 m, suggesting it may have originated on an upper floor. This same destruction debris continued into the southern part of the building, upon a beaten-earth floor with no evidence of stone paving, as Locus 18920.

After the end of Stratum R-3, a modest temple was constructed above the Stratum R-3 piazza. Apart from the temple and paved open spaces to its south and west, very few additional architectural remains from this period were found elsewhere in Area R. Thus, it seems that the temple was an isolated phenomenon, explaining why FitzGerald missed this phase in 1930 when excavating from Level IX into Level X.4 The sparse evidence for Stratum R-2 beyond the temple itself points to a time of regression and partial abandonment during the initial phase of the Late Bronze Age. After the temple ceased to exist, a short period of post-temple occupation ensued (Stratum R-2’) prior to the construction of the Stratum R-1 (Level IX) town.

4 FitzGerald (1932: 146) described how the fill immediately below the Level IX

temple produced LB pottery that we would define as typical to Stratum R-2 and

R1b, including bowls on high pedestal bases, vessels with red and black painted

decoration, and Cypriot milk-bowl fragments.

5 For example, Stratum R-2 Chamber 58136 sealed Stratum

R-3 Installation 78335 (Square M/9), while Stratum R-2 Wall 58090

passed over Stratum R-3 red-clay Installation 78123 (Square M/7).

6 Locus 58096 appears in the plans of both Strata R-2 and

R-1b, since the excavators did not properly close the locus when they

reached the bottom of the Stratum R-1b.

walls. Also un-numbered in this area is a ca. 0.1–0.2 m layer between the

bottom of Stratum R-2 Wall 58128 and the top of Stratum R-3 Wall 78339

(see section, Fig. 3.42); it rises over the hump of the Stratum R-3

mudbrick wall and then drops down into the oval crater. It could be a

leveling fill that later sank, or was affected by other causes.

7 These include Stratum R-2 Installation 78512 (Square L/5),

Stratum R-1b Basin 18939 (Square G/6), Stratum R-1b Floor 68528

(Square L/5), and Stratum R-1 Bathroom 88506 (Square K/3).

8 The group of stones shown on the plan in the

southeastern corner of Room 78502 was from a bench that was placed on

Floor 78502 in Stratum R-1b

.

8 The “well” uncovered by Rowe in the eastern part of

Level IX Room 1334 may have been a similar stone-lined installation

(Fig. 2.5).

- Sections: Figs. 3.45–3.46, 3.48, 3.55, 3.57–3.58

- Photos: 3.58–3.77

- Pottery: Pls. 38–44

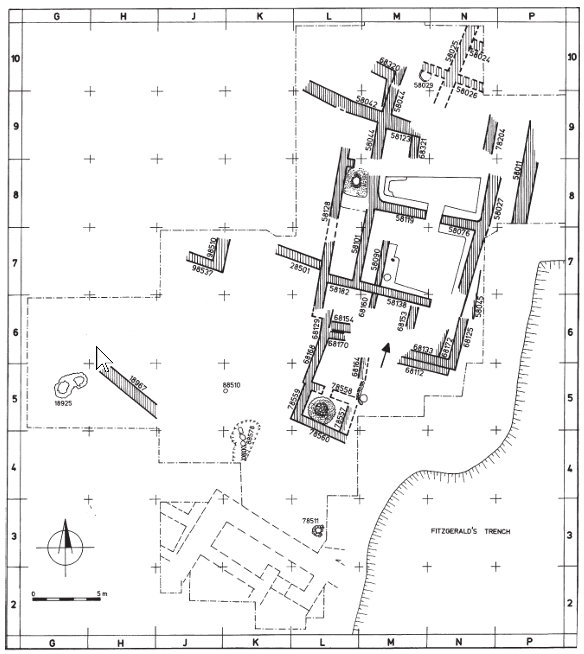

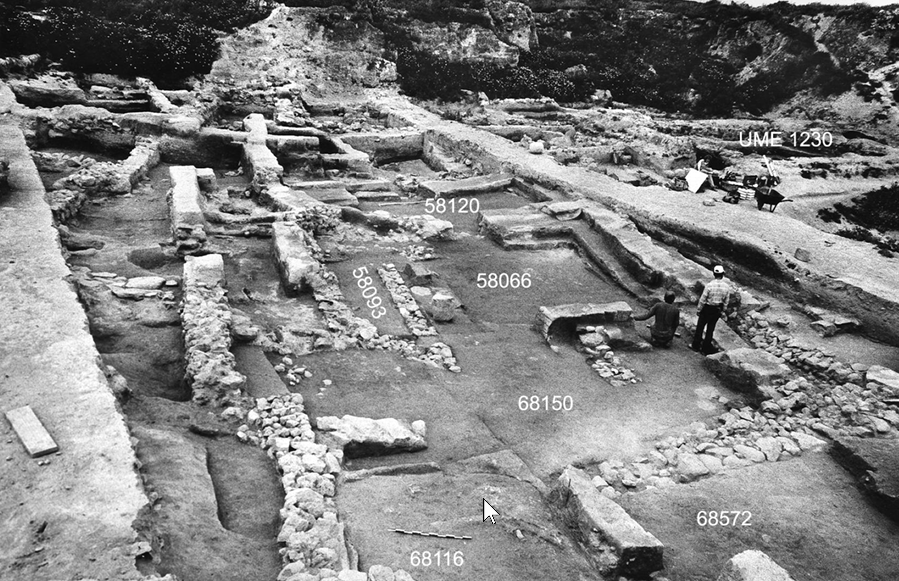

The interpretation of this structure as a temple is based on at least six interrelated factors:

- its location below subsequent temple compounds of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages (Levels IX, VII, VI and V), confirming the well-known tendency of a holy place to retain its sanctity over time (Rowe 1940)

- its isolated position surrounded by spacious courtyards

- its tripartite plan with all three rooms in a north-south line

- the arrangement of benches along the walls of the main and inner halls

- typological parallels to irregular, non-monumental temples of the second millennium BCE in the Levant (see p. 138)

- the nature of the finds that indicate a specialized function not typical to domestic assemblages or non-ritual public structures

The temple proper measured ca. 14 m (north-south) by 11.75 m (external dimensions) and was comprised of six distinct architectural units:

– Entrance Hall 68150 (Squares L–M/6)

– Main Hall 58066 (Squares M–N/7)

– Side Room 58093 (Square M/7)

– Inner Room 58120 (Squares M–N/8)

– Side Chambers 68152 and 68127 (Square L/7–8)

– Rooms 68166 and 78502 (Square L/5–6)

The temple had been seriously damaged, as testified by the broken and deformed walls. The building had also undergone several renovations, especially in the entrance hall, where evidence of repair can be seen in at least three places. For example, in the southeastern corner (Square N/7), Wall 58027 and Bench 58056 were both found tilted. Furthermore, there was an elevation difference of 0.35 m in the top levels of the plastered bench along a distance of 4.5 m. In the southwestern corner (Square L/6), Walls 68129 and 58128 appear to have been torn apart from one another. Finally, the southern wall of the temple (68133) sagged severely in the middle (Photos 3.59, 3.61–3.62, 3.68).

Such damage may be related to seismic activity. In the case of Temple 58066, the tremors not only disturbed the building itself, but caused the fills in the oval crater to settle, severely fracturing and tilting the structure.

This part of the building was particularly damaged. Most of the southern wall (68133) in Squares MN/5-6 was preserved to a single course and badly sunken in the middle, the eastern and western ends higher by about 1 m (Fig. 3.48). It was better preserved in the east where it stood three courses high at the corner with Wall 68125 (Photo 3.61). Wall 68133 measured ca. 0.7 m wide and was built of small basalt stones similar to those used in Wall 68129 (Square L/6). Wall 68170 at the western end of the entrance hall was more seriously damaged and partly missing. A short fragment of another wall (68154) behind Wall 68170 probably constituted a later reconstruction since it was built of larger stones and buttressed the feeble remains of the original.

At a later stage, Wall 68133 was widened or buttressed by the addition of Wall 68112 (Photo 3.61). This may have been an attempt to strengthen the front of the building facing Courtyard 78509. Wall 68112 was 0.65 m wide and made of larger basalt stones, one course high. The wall dropped steeply to the west where it ended at Stone Pavement 78556 (Fig. 3.48). These flat basalt stones, which formed part of the porch, lay somewhat higher than Wall 68133. One flagstone at the northwestern corner of the stone pavement contained a hollow depression that may have been a door socket.

The entrance hall was a broad room measuring ca. 3.4×9 m inside (Photo 3.60). Its earthen floor sloped from west to east. Two fragmentary walls (68153 and 68160) partitioned the room into three smaller units. Brick Wall 58138, which separated the entrance hall from the main room of the temple, was made of a single line of bricks, 0.55 m wide, preserved 0.8 m above the floor and covered on its northern face by a thick layer of white plaster.

This hall was found partially filled with a mudbrick collapse discolored by fire and mixed with charcoal from fallen beams, ash and bits of folded yellow plaster. Such destruction, noted also in Room 68166 (Squares L/5-6, see p. 125), may have resulted from seismic activity that presumably destroyed the temple.

Objects found in the debris of the entrance hall included the rim of an “Egyptian blue” bowl (Fig. 13.5:4), discovered close to the top level of the walls at the eastern end of the room. A scarab bearing a hieroglyphic sign (Fig. 8:11) and a bronze arrowhead (Fig. 9.2:3) were found on orange-clay Floor 68148 in the southwestern corner.

The main hall (58066) was approached by way of an indirect passage in the east. A basalt door socket found out of context on the edge of the adjacent bench may have belonged to a wooden door.

If Wall 58101 comprised the western side of the main hall and Wall 58027 the eastern side, its interior dimensions were 5.6 m (north-south) by 7.35 m (Photos 3.59–3.60, 3.70). Since the mound slopes from southeast to northwest, the builders apparently had to level the area, which required anchoring the lower part of Wall 58027 as a terrace with its eastern face in the ground up to 89 m (Photos 3.60–3.62). A thin line of small stones along its eastern edge may mark where the mudbrick superstructure began. A plastered bench (58056) along the western face of Wall 58027 was 0.4 m wide and ca. 0.35 m high (Photo 3.62). Wall 58045 to the east of it may have originated in Stratum R-3, since its top level of 88.38 m was 0.4 m below the bottom level of Wall 68125! Even so, Wall 58045 was included on the R-2 plan since it might originate from an earlier phase of the temple.

It is curious that Wall 58027 was not in line with the eastern wall of the entrance hall (68125), which was offset some 0.4 m to the east. However, it is clear that the two walls met (Photo 3.61). This may have been the result of various reconstructions and alterations made to the temple during its lifetime.

Considerable damage was caused to the northern end of the main hall by Stratum R-2’ Pits 58039 and 58146 (Photo 3.68). The northern wall of the main hall, east of the passage leading to the inner hall (Wall 58076), was comprised of a single line of bricks on a stone foundation. It was partially cut by Stratum R-2’ Pit 58039, but survived to a height of 0.6 m above floor level. Wall 58119 on the western side of the passage was destroyed to its foundations by Stratum R-2’ Pit 58146 (Photos 3.67–3.68).

The benches of the main hall were all made of mudbrick and coated with white plaster. Bench 58056 in the east, averaging 0.65 m wide, lined the southern face of Wall 58076 and then turned to run along Wall 58027. At the southern end of the main hall, against Wall 58138, stood a brick bench on basalt foundations. The same plaster that coated the benches also coated the floor, preserved mainly along the bottom of the benches in the northeast. The floor sloped gently from north to south. In the middle of the hall, the floor sagged severely to a low point of 88.02 m, a result of the sinking of the MB fills in the oval crater below. The debris on the floor comprised decayed mudbrick and fragments of fallen white plaster from the destroyed upper courses of the walls.

Along the western side of the main hall and attached to a narrow partition wall (58090) were two mudbrick platforms coated with plaster. The western face of Wall 58090 was also plastered, its northern tip cut by Stratum R-2’ Pit 58146. The wider, main platform on the south was preserved to a height of 0.2 m above the floor (Photo 3.64). At its southern end stood a roughly-worked, cylindrical basalt stone, 0.55 m in diameter and 0.48 m high, with a nearly flat top. It seems to have been intentionally located here and may have served a cultic function. It is strikingly similar to another stone column (78540) on the southern side of the door leading into Room 68166 from Courtyard 78509 (Square M/5).

At the northern end of the main platform a post hole, 0.2 m in diameter, was found with black ash inside (Photo 3.65). A similar feature was uncovered in the Late Bronze Age sanctuary at Tel Mevorakh where it may have supported a canopy above the platform (Stern 1984). Since the wooden post in Temple 58066 does not seem to have served a constructional purpose, it may have been cultic.

A narrower but higher platform (58141), attached to the northern end of the main platform, rose 0.56 m above the floor level of the main hall. As in the case of Wall 58090, its northern end was cut by Pit 58146. The location of these two platforms on the western side of the hall suggests that they may have been the focal point of the cult and the location of the cult image (for an alternative suggestion see below).

Behind the two brick platforms was a narrow rectangular space (58093) approached from the northern end of the main hall by means of a 2-m wide passage (Photos 3.59, 3.64, 3.66, 3.70). The lack of finds in this room precludes a proper interpretation of its function, but it may have been the repository. A rough comparison can be made with the Tell Qasile temples, where a small room behind the podium or platform was a repository for sacred implements (Qasile I: 70–71).

A 1.15-m-wide passageway (58116) linked the main hall (58066) with the inner room (Photos 3.67–3.70). This inner room (58120) was 7.9 m long (along the central east-west axis) and trapezoidal in shape—1.95 m wide at the western end and 3.15 m wide at the eastern end. Like the other rooms of the temple, the floor (58120) was made of beaten earth with traces of white plaster. Its lowest elevation, in the middle of the room where the floor sagged, was 88.16 m. White-plastered benches were located in the south and in the east. At the western end and partly along the northern wall were double benches.

A deep, square receptacle (58140) measuring ca. 0.35×0.2 m and plastered throughout, was sunken into the floor in the northwestern corner of the hall (Photo 3.67). Its purpose is unknown, though it may have been connected with Installation 98314 in the room behind it (see p. 124 and Photo 3.72 below).

The walls of the inner hall on the south, east and west were clearly defined, but the northern wall (68324) was not detected with certainty (Photo 3.67). Part of the double bench in the northwest (58048), and a poorly preserved line of bricks and plaster further to the east that met the eastern bench (58031), are the only indications for the northern wall as represented on the plan. The line of the wall as reconstructed was at a curious angle compared to the general orientation of the building, raising the possibility that the northern wall was a later addition, perhaps a repair to the original temple.

It is important to note that Wall 58044 in Square M/9 was a direct continuation of the wall behind Bench 58048 at the western end of the hall. Wall 58044 intersected with Wall 58123 eastward for 2.4 m before it abruptly ended. Perhaps in the original building phase, or in the original planning, Wall 58123 was the northern wall of the temple. If so, then the original inner hall would have had an interior width of 5.25 m. A later renovation, or a change in the plan at the time of construction, resulted in Wall 68324, which gave the room its curious trapezoidal shape.