There were many battles between the Franks and Turkic- Syrian armies. We

are extremely fortunate that detailed accounts of two of the most important

encounters have survived, written by someone who was not only a participant but who had taken an active role in the planning of each battle. His

accounts show just how dangerous Turkic bands could be. These were armies

of extraordinary violence, elemental and ferocious even by the standards of

the time, but by no means easy to wield as an instrument of policy: armies

with huge tactical strengths if used well, but with equally profound strategic

limitations.

27

In 1115 the sultan of Baghdad was trying to create a unified Muslim

front against the Franks. He was faced with the usual problems. The major

Muslim states in the region, such as Aleppo and Damascus, tended (entirely

correctly) to see Baghdad as just as much of a threat to their independence

as the Franks. In February 1115, Bursuq, the lord of Hamadhan, was chosen

to lead Baghdad’s expeditionary force into the region, with a thankless

brief: to try to kick the local Muslims into line and lead them in a war to

destroy the Christian states.

28

The local Muslims, and particularly the Damascenes under their Turkic

overlord, Tughtigin, had other ideas, and did not greet this call to arms with

enthusiasm. On the contrary, when Bursuq led his army into the region, the

Damascenes formed an alliance with Prince Roger of Antioch to work

against the sultan’s general. The armies of the other Frankish states also

mustered together in the north to form an uneasy alliance with Damascus

against the invaders.

29

Bursuq withdrew in the face of this formidable force and waited long

enough for the allied troops to disperse. Then, when it was difficult for them

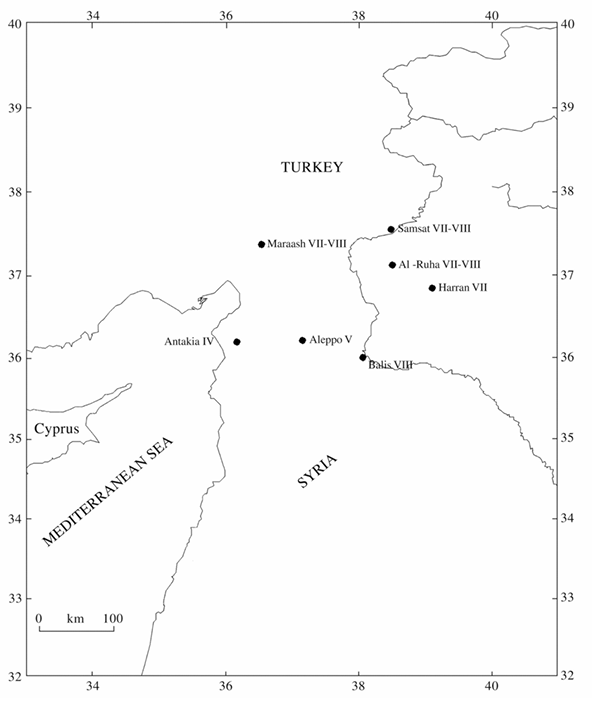

to reassemble quickly, he invaded the Principality of Antioch in strength. This

presented Prince Roger with the traditional problem facing Frankish

commanders: whether to act or to wait. A large Muslim force was loose within

his lands, capable of inflicting massive damage on towns and castles that had

already been devastated by earthquakes the previous year. Ma’arrat- an- Nu’man

was captured. The important Christian castle of Kafartab was put under siege

and eventually fell on 5 September 1115. Roger could ask for help from his

allies again, and await their arrival, with Bursuq destroying large swathes of

the frontier. Or he could move on his own to try to stem the invasion.

He chose the latter course. Strategy and caution suggested the prudence

of waiting for reinforcements, but the emotional cost of doing so, and the

loss of prestige it entailed, was immense. Roger and his nobles preferred to

meet Bursuq on the field of battle, rather than suffer the humiliation of

seeing their lands ravaged and their people killed.

We know the size of the Christian forces with some degree of certainty.

They consisted of the field army of Antioch, together with the smaller allied

army of the County of Edessa, commanded by Baldwin of Bourcq. Walter

the Chancellor, who was present at the muster, wrote that the Antiochene

and Edessan component of the allied forces that had gathered at Apamea

earlier in the summer to face Bursuq’s initial invasion were good- quality

troops, but had numbered no more than 2,000 men.

30

Other sources, both Muslim and Christian, suggest that greater efforts

had been taken to boost the numbers of the second muster in September,

and that it eventually consisted of some 500–700 cavalry and 2,000 infantry

‘of all kinds, Franks and Armenians alike’. Much of the cavalry seem to have

been Turcopoles, so the local Christians would have formed a very large

part of the army as a whole.

31

Descriptions of the Muslim army are vaguer. Bursuq had sufficient

subsidies from Baghdad to make him a popular employer and, as well as

the mercenaries that this allowed him to employ, he had brought large

contingents from the Jazira and Mosul. A significant Turkic contingent

from Sinjar was present, under their Emir Tamirek, whom Bursuq seems to

have placed in charge of most of the Muslim cavalry on the day of the battle.

Under duress, the city state of Mardin had also provided a company of

soldiers, led by their emir’s son, acting in the uncomfortable dual capacity

of sub- commander and hostage.

32 Shaizar was another more or less willing

ally. They certainly provided troops for the expedition, with separate

detachments from Shaizar being present at both the siege of Kafartab

and at the battle of Tell Danith.

33 But even they were wary. Although

Bursuq was allowed to camp nearby, he and his men were not allowed into

Shaizar itself.

Altogether, Ibn al- Athir suggests that Bursuq had an army of some

15,000 men available for his invasion, although we know that the separation of various detachments, for instance to Kafartab and Buza’a, had

reduced their numbers by the time the battle took place.

34 One Christian

source suggested that Bursuq had a total of 8,000 men with him at Tell

Danith, perhaps excluding the usual ‘volunteers’ and non- combatants: this

sounds plausible, given the casualties that the army took on the day, and is

not necessarily at odds with Ibn al- Athir’s assessment.

35

The Christians had mustered at Rugia, just east of the Orontes river.

Panic- stricken reports were coming in from the local communities that

Turkic troops were back in the region. On 13 September the army of

Antioch and Edessa set off in column of march along the road to Hab,

where Bursuq and his army were thought to be. There was inevitably some

nervousness in the ranks. The expectation was that they would encounter

the Turkic army later that day. They had not waited for reinforcements

from Tripoli or Jerusalem, and they knew that they would be heavily

outnumbered. The column moved quickly, to try to keep the initiative.

Light cavalry detachments were flung out in front of the army and on the

flanks, to ensure that maximum warning was received of the enemy’s

presence.

36

It was an anticlimax. The reports of the immediate whereabouts of the

Muslim army had proved false. Perhaps it was Turkic raiding or foraging

parties that had caused the local villagers to panic. Either way, the march to

battle proved fruitless, and once the army reached Hab, they camped for an

uncomfortable night’s sleep outside the small Frankish fortified settlement

there.

37

The army rose early on the morning of 14 September. The scouts had

been on patrol throughout the night. We know that most of the light cavalry,

certainly among the rank and file, were local Christians, Syrians or

Armenians, but there were probably also some Turkic mercenaries, as translators were needed to verify their intelligence reports. A few months earlier,

for instance, Antiochene scouts had returned from Muslim territory to

report on Bursuq’s plans and preparations for war. Roger wanted to inter

view them in person, but could only do so with the aid of an interpreter.

38

The reconnaissance detachments that had headed north were

commanded by a Frank, however, Theoderic of Barneville, a Norman

knight whose family had settled in Sicily and had joined in the First

Crusade.

39 When Theoderic returned he could barely contain his excite

ment. He and his men had scouted up into the Sarmin valley, a fertile area

with good water supplies and well known to the Franks, to ensure that it

was a safe position for the army to make camp later in the day. When they

got there, however, the Antiochene scouts found that the Muslims were

already starting to camp around the springs. Crucially, Bursuq’s army were

not only unaware of the proximity of the Franks, but they had not yet fully

mustered in the valley: part of the army was there, but other detachments

were arriving piecemeal. Some tents were already pitched, but others were

yet to be set up. Roger was elated but knew that he needed to act quickly. He

jumped on his horse and rode to each of the army’s sub-commanders for

discussions, urging the men to get their weapons ready and prepare for

battle as soon as possible.

40

The army, like all armies of this period, was deeply religious. Spiritual

preparations were just as important as the sharpening of swords or the

adjustment of battle lines. The troops had received mass earlier in the

morning, with William, bishop of Jabala, conducting the service and delivering what seems to have been an appropriately militaristic sermon. ‘In that

very place’, we are told, ‘the renowned bishop, bearing in a spirit of humility

the Cross of holy wood in his reverend hands, circled the whole army; and

while he showed it to all of them he affirmed that they would claim victory

in the coming battle through its virtue, if they charged the enemy with resolute heart and fought trusting Lord Jesus.’

41<

With the religious inspiration completed, it was time for more secular

morale boosting. It was always going to be difficult to compete with the

True Cross, or even a fragment of it, but Roger made a good, soldierly

attempt. His speech in the approach to the battle of Tell Danith was recorded

in some detail. The army was small and the speech could have been heard

by most of the men. It was not flowery or particularly clever, but its

simplicity makes it all the more credible. This was a young leader talking to

a group of hardened veterans, each potentially looking death in the face.

He started by reminding them how important it was that their actions as

men should be remembered with honour. He then followed up with the

comfort that any who died in the battle ahead would have been fighting for

a just cause and would be well received by the Lord. More practically, and

probably in much more comfortable territory, he ended up by telling them

to charge in with the lance but then to get stuck into hand- to- hand combat

with swords. He could give them no certainties, but he could talk of honour,

consolation and, most importantly, instructions for battle.

42<

Before the army set off, there were still things to do. Stronger detach

ments of light cavalry were sent out along the road to the Sarmin valley, to

ensure that the situation had not changed and that the Franks would not be

entering a trap. Once they had been sent off, the order of march was

decided. This was more than just a formality, because the order of march

would determine the order of deployment on the field. The army of Edessa,

commanded by Count Baldwin of Bourcq, was given the honour of the

vanguard. Although smaller than the Antiochene forces, the Edessans were

veterans of numerous campaigns against Turkic raiders, and were trusted

to launch the initial attack.

43

Finally, Roger personally rode up and down the army to emphasise the

need for discipline with regard to plunder. If anyone paused to start collecting

booty in the middle of the battle, he promised that the punishments would be

severe. The customary sentence for disobedience in the Antiochene army at

this time seems to have been blinding, something picked up from their

frequent interactions with the Byzantine army to the north of the principality.

44 As if that was not enough, Bishop William also went to each unit to

reinforce Roger’s edict: he emphasised the threats of physical punishment

which would accompany disobedience by plundering, but culprits would

also be condemned, ‘he assured them, to suffer eternal damnation’.

45<

This was not as excessive as it might seem. Plunder was an essential part

of any medieval campaign, and a great motivator for the men. In this

instance, however, the scouts were reporting that much of the enemy camp

was at the end of the valley closest to the Franks, and that Bursuq’s troops

were gradually filtering into the valley from the other end. Plundering

normally took place towards the end of a battle, as a routing enemy fled to

the rear through their baggage train and camp. In this case, with the Muslim

camp in front of their main army, the Franks were going to be offered plenty

of plundering opportunities before the battle had been decided. If discipline broke down at that point, disaster would be inevitable. The Franks

would hopefully have surprise on their side, but were also heavily outnumbered: once battle began, Bursuq’s troops could be given no opportunity to

regroup and rally.

As the Franks entered the valley, the Muslim forces were entirely unpre

pared. Foraging parties were still out. The camp was only half set up, with

further troops and supplies gradually filtering through. And a significant

body of Turkic troops had left the army to occupy Buza’a.

46 To make matters

worse, Bursuq misinterpreted what he saw taking place in front of the

camp, and instead of pulling his troops back to form a defensive line, began

to send men forward to capture what he thought were Frankish scouts. It

was only when the Antiochene banners came into sight that Bursuq real

ised that he was facing the field army of the northern Franks. Perhaps

convinced that Prince Roger would wait for reinforcements before trying to

intercept him, as he had done before, Bursuq had split his forces, marched

his troops without proper discipline, and, above all, had failed to grasp even

an approximate sense of the location of the Frankish army.

47

He withdrew his main line back through the camp, trying to use his

heavier troops to form an impromptu defensive position on the hill of Tell

Danith. The main body of Turkic horse archers, who would need mobility

if they were to be used to best effect, were pulled back behind the hill under

the command of the Emir Tamirek of Sinjar, with orders to outflank and

surround the Franks once they were fully committed to their front.

48

The Franks deployed across the valley floor, facing the Muslim camp,

with Tell Danith behind it. The Edessan army was the vanguard division,

holding the left of the Frankish line, and split into three main units. The

Turcopole light cavalry archers were deployed on the far left. A unit of

knights and other troops, including a Cilician contingent led by Guy Le

Chevreuil, one of Antioch’s leading noblemen, was posted on the left with

orders to move up to attack Tell Danith from its flank. The core of the

Edessan army, led by Count Baldwin himself, were positioned to charge

frontally to the left of the hill.

49

The main Antiochene army was split into two divisions, in the centre

and right of the line, each echeloned behind the other, and with the central

division commanded by Prince Roger himself. Having the divisions drawn

back had the advantage of providing a reserve and rearguard if needed

(always important when facing large numbers of nomadic horse archers)

while at the same time positioning them to launch a direct attack on

Bursuq’s troops on Tell Danith when the moment was right.

The first Frankish attacks were launched in a staggered way, across the

Muslim front and progressing from left to right. The Turcopoles moved

forward on the far left, to try to prevent the Christian army being outflanked.

The Cilicians and Baldwin of Bourcq’s Edessans moved through the

wreckage of the hastily abandoned camp and tore on up into the left of Tell

Danith. The initial charge inflicted some damage on Bursuq’s defence lines

on the hill, but once the first shock of impact was over, lances were shattered or discarded, and the fighting settled down to the close combat of

sword and shield. The Franks began to carve their way through the Muslim

lines: ‘recovering their strength . . . they put the enemy to flight, hacked

them to pieces and killed them’.

50

Once the Frankish heavy cavalry were fully committed on the left, the

Turkic cavalry to the rear of Tell Danith launched their attack. This was well

timed. With the Frankish troops on the left already occupied, they attacked

the Frankish light cavalry and ‘at a swifter pace they caused the Turcopoles,

who were shooting arrows at them, to be swallowed up among our men’.

51

The Turcopoles fled before Tamirek’s men could connect with them,

retreating back towards the army’s centre and the relative safety of the

Christian infantry. In fact, there was little else they could do. Heavily

outnumbered, and probably outclassed as well, their position on the left

could only hope at best to slow down the Turkic advance, and buy additional time for the Frankish heavy troops in the centre to do their work.

Tamirek’s troops then began to sweep round behind the Christian main

lines, bypassing the Cilician and Edessan units. The Christian chronicles

were correct in suggesting that the Turkic cavalry had diverted around the

Frankish divisions on the left for sound military reasons, as ‘they did not

dare to attack it, and they could not use a constant bombardment of arrows

to disrupt the charge’.

52 Charging unbroken Frankish knights at close quarters was never going to play to their strengths.

Indeed, probably as was always intended, they continued to move

towards the rear of the Christian centre, attempting to disrupt their all

important heavy cavalry charge in other parts of the line. They were gradually engaged by men from the Antiochene divisions. The first troops they

faced were those of Robert fitz- Fulk, probably in Prince Roger’s central

division, who turned to face them with his men. The Turkic cavalry met

them as the Frankish troops were ‘advancing from the right, head on’.

53

Robert, known to his more literally minded friends as ‘Robert the Leper’,

led a powerful contingent from his frontier lands in Zardana, the major

castle of Saone and the nearby town of Balatanos.

54 The fighting in the

centre was fierce. One of the casualties was Robert Sourdeval, from a Sicilian

Norman family, who had had a distinguished career working with Prince

Roger. He and his men charged into the oncoming Turkic troops and were

surrounded. The reins of his horse were cut during the fighting and he was

brought down by Turkic archers. His men were completely routed.

55

Robert fitz- Fulk survived, helped by the swift arrival of reinforcements

from the Frankish right. The tough frontier contingent from al- Atharib, led

by their lord Alan, and troops from Harim, commanded by Guy Fresnel,

rushed to contain the Muslim light cavalry and succeeded in neutralising

the threat they posed to the rear of the Christian army.

56

Tamirek’s men had done the best they could under the circumstances.

But as long as the Franks held their nerve they could do little more than

distract. Prince Roger committed his reserves to cope with the light cavalry

to his rear and remained focused on the tactical priority: the destruction of

the core of Bursuq’s army on Tell Danith in front of his battle line. He gave

the order to charge, and the central division crashed into the Muslim troops

on the hill in front of them. The Frankish division on the right flank

followed almost immediately. The charge was particularly aimed at Bursuq

and his retainers, as Roger’s men ‘assailed the enemy in wondrous manner

wherever they saw the mass was densest’. Desperate attempts were made to

try to stop the Frankish cavalry charge with archery, but with no success.

The knights carried on through the hail of arrows and hurled themselves

onto the centre of Bursuq’s forces. The Muslim army, already reeling from

Baldwin of Bourcq’s assault on the left, collapsed almost immediately. The

rout began and Bursuq’s troops ‘at first resisted for a little while, then

suddenly fled’.

57

As the Muslim forces broke and ran, the detritus of their baggage train

slowed down their pursuers for a short while. As Walter the Chancellor

later wrote, the ground was ‘partly covered by dead bodies, partly crammed

by a mass of camels and other animals laden with riches, which were a

hindrance to killing for our men, and a help to escape for those fleeing’. The

Turcopoles, having been humiliated by the Turkic cavalry earlier in the day,

were now unleashed to maximise the damage to the retreating army. The

initial pursuit continued beyond the town of Sarmin, with the Christian

cavalry ‘running them through, wounding them and killing them’.

58

Some of the fleeing Muslim troops spread out across the countryside,

and tried to hide in nearby villages, only to find themselves attacked by the

local farmers. The villagers, who had been terrorised by the Turkic raiders

over the previous days, took their revenge in full. An additional operation

by the Frankish cavalry and light troops was put in place over the next

couple of days to round up the Muslim stragglers dispersed in the area.

59

Muslim casualties were high, reflecting the scale of the defeat in their

centre and the punishing nature of the pursuit. One Frankish chronicle

estimated that ‘three thousand Turks were killed, and many captured.

Those who escaped death saved themselves by flight. They lost their tents

in which were found much money and property. The value of the money

was estimated at 300,000 bezants. The Turks abandoned there our people

whom they had captured, Franks as well as Syrians, and their own wives

and maid- servants.’

60

Roger remained on the field of victory for two or three days after the

battle, so the army could regroup and tend to its wounded. Discipline about

the distribution of booty was vitally important at this stage, in order to

ensure the continued motivation of the cavalry detachments which were

still in pursuit of enemy stragglers. Pursuit after defeat was the most important opportunity to inflict casualties on an enemy army. If the pursuing

troops, and particularly the cavalry, thought that their share of the plunder

would be gone before they returned, this chance would be lost. He delayed

the division of spoils for three days to ensure a fair distribution of the

plunder and as suitable encouragement for the mopping- up operation, and

he ‘personally directed the wealth which was brought to him to be kept for

him . . . the rest was to be shared out, as his sovereignty and the custom of

that same court demanded’.

61

Usama was part of the Muslim garrison at the recently captured castle of

Kafartab when the battle took place, but left an account of the personal loss

his family had sustained on the field. His father, who had been with Bursuq

at Tell Danith, came back having ‘had all his tents, camels, mules, baggage

and furniture taken from him’.

62 Hearing of Bursuq’s defeat, Usama and his

comrades killed the Christian prisoners they had taken ten days earlier and

set off back to Shaizar.

63

The leaders of the Muslim army seem to have left the battlefield with

embarrassing speed, leaving their men behind. Despite the large number of

casualties, ‘the army lost no commander nor even any well- known

personage’.

64 Bursuq’s personal performance on the day was so poor that

elaborate excuses were made for him. Ibn al- Athir suggested, implausibly,

that he wanted to take part in the fighting but was prevented by the ‘camp-

followers and pages’ who surrounded him. Bursuq died the following year

‘full of remorse for this defeat’.

65 He had commanded a polyglot force, some

of whom were there more or less unwillingly. But he had also split his forces

in the face of the enemy and, despite the large numbers of light cavalry at

his disposal, had remained ignorant of his enemy’s intentions or location.

The element of surprise was reflected in the casualties his men suffered,

and in the large number of prisoners taken.

The young Prince Roger had much to be pleased with. His men had

been heavily outnumbered but the cohesiveness of the army in attack

and the heavy weight of a Frankish charge had won the day and inflicted

massive damage on the Muslim force. There were lessons to be learned,

however, and lessons are taught more compellingly by defeat than by

victory.

Too much had been asked of the Turcopoles. They were extremely useful

light cavalry, important for a wide range of tasks. They made a major

contribution to the Frankish success through their role as scouts in the

run- up to the battle and in the pursuit that took place afterwards. But

although they were horse archers, it was too risky to expect them to face

large numbers of Turkic troops on their own. The nomads were the experts,

living the role in a way that more regular troops could never achieve. And

there were always more of them. Outnumbered and outclassed, the

Turcopoles could not be expected to hold a flank on their own.

The other lesson was far more important but also more counterintui

tive. Roger and his nobles could logically deduce from their victory that a

well- led Franco- Armenian army, even when outnumbered, could face an

enemy invasion on its own: it did not need to wait for reinforcements.

Instead of holding back, and watching its people being slaughtered and its

towns destroyed, such an army could see off an invading force on its own.

The beguiling quality of this ‘lesson’ was, of course, that it was partially

true. On a good day, in good circumstances, and with the enemy commanded

by someone who was more of a diplomat than a battlefield general, this

could all be true.

The risks, however, were far less apparent. And the risks of open combat

under less than ideal conditions were always greater for the Franks than the

potential benefits. At best, victory would inflict some casualties on the

enemy and bring an invasion to a halt. But the casualties never amounted

to very much. Muslim commanders were rarely killed or captured: they had

good horses and tended not to fight in the front line. There was an almost

limitless number of Turkic tribesmen, waiting to be tempted off the steppes

by the lure of the plunder. A major victory might gain respite for a year,

possibly two, but little more than that.

The consequences of defeat in battle against nomadic armies, on the

other hand, were huge. The Christians were always outnumbered, and their

ability to replace highly skilled and heavily armoured warriors was

extremely limited. Frankish commanders often needed to fight in the front

line, in order to maximise their chances of success. In the event of defeat,

casualties among the infantry, harried remorselessly by Muslim light

cavalry, could be catastrophic. Vital garrisons would already have been

stripped back to create the field army and give it a chance of victory: if the

field army was lost, then town after town, castle after castle, would fall.

Where a Muslim defeat might be a temporary setback, a similar defeat for

the Franks, if fully exploited, could lead to virtual annihilation.

Victory felt good, but for Roger and his men, the battle of Tell Danith

was the medieval equivalent of a schoolboy placing winning bets on his

first day at the races: satisfying but dangerously deceptive

27. We are also lucky in having a wonderful translation and commentary on this work by Susan

Edgington and Tom Asbridge, which brings it so vividly to life: Walter the Chancellor, The

Antiochene Wars, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999.

28. Barber 2012, pp. 102–4. This is either Barber, M. and K. Bate tr. (2002) The Templars, Manchester Medieval Sources, Manchester.

or Barber, M. and K. Bate tr. (2010) Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th–13th

Centuries, Crusade Texts in Translation 18, Farnham.

29. Barber 2012, p. 104. This is either Barber, M. and K. Bate tr. (2002) The Templars, Manchester Medieval Sources, Manchester.

or Barber, M. and K. Bate tr. (2010) Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th–13th

Centuries, Crusade Texts in Translation 18, Farnham.

30. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 89–90.

31. Albert of Aachen, Historia Ierosolimitana, ed. and tr. S.B. Edgington, Oxford, 2007., pp. 854–5; IA I, p. 173; ME, p. 219.

32. Ibn al- Athir, The Chronicle of Ibn al- Athīr for the Crusading Period from al- Kāmil fī’l- Ta’rīkh, parts 1 and 2, tr. D.S. Richards, Crusade Texts in Translation 13 and 15, Aldershot, 2006, 2007. I, p. 166.

33. Usama ibn Munqidh, The Book of Contemplation, tr. P.M. Cobb, London, 2008., p. 88.

34. Ibn al- Athir, The Chronicle of Ibn al- Athīr for the Crusading Period from al- Kāmil fī’l- Ta’rīkh, parts 1 and 2, tr. D.S. Richards, Crusade Texts in Translation 13 and 15, Aldershot, 2006, 2007. I, p. 166; KD RHCr Or. III, p. 609.

35. Albert of Aachen, Historia Ierosolimitana, ed. and tr. S.B. Edgington, Oxford, 2007., pp. 856–7.

36. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 98.

37. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 98.

38. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 87.

39. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 99 n. 136.

40. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 99.

41. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 98–9 and n. 132.

42. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 99–101.

43. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 99–100.

44. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 92.

45. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 101.

46. Kamal al- Din. Extraits de la Chronique d’Alep par Kemal ed- Din, in RHCr Or., vol. 3, Paris, 1872, pp. 571–690. III, pp. 609–10.

47. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 101.

48. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 101–2.v

49. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 102.

50. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., pp. 103–4.

51. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 103.

52. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 103.

53. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 103.

54. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 103 n. 166.

55. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 104.

56. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 105.

57. Fulcher of Chartres, A History of the Expedition to Jerusalem, 1095–1127, tr. F. Ryan, ed. H. Fink, Knoxville, 1969., pp. 213–14.

58. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 106.

59. William of Tyre, A History of Deeds done beyond the Sea, tr. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey, 2 vols, Records of Civilization, Sources and Studies 35, New York, 1943. I, p. 505;

Kamal al- Din. Extraits de la Chronique d’Alep par Kemal ed- Din, in RHCr Or., vol. 3, Paris, 1872, pp. 571–690. III, pp. 609–10.

60. Fulcher of Chartres, A History of the Expedition to Jerusalem, 1095–1127, tr. F. Ryan, ed. H. Fink, Knoxville, 1969., p. 214.

61. Walter the Chancellor, The Antiochene Wars, tr. T.S. Asbridge and S.B. Edgington, Crusade Texts in Translation 4, Aldershot, 1999., p. 106; William of Tyre, A History of Deeds done beyond the Sea, tr. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey, 2 vols, Records of Civilization, Sources and Studies 35, New York, 1943. I, p. 505.

62. Usama ibn Munqidh, The Book of Contemplation, tr. P.M. Cobb, London, 2008., p. 88.

63. Ibn al- Athir, The Chronicle of Ibn al- Athīr for the Crusading Period from al- Kāmil fī’l- Ta’rīkh, parts 1 and 2, tr. D.S. Richards, Crusade Texts in Translation 13 and 15, Aldershot, 2006, 2007. I, p. 173.

64. Kamal al- Din. Extraits de la Chronique d’Alep par Kemal ed- Din, in RHCr Or., vol. 3, Paris, 1872, pp. 571–690. III, p. 610.

65. Ibn al- Athir, The Chronicle of Ibn al- Athīr for the Crusading Period from al- Kāmil fī’l- Ta’rīkh, parts 1 and 2, tr. D.S. Richards, Crusade Texts in Translation 13 and 15, Aldershot, 2006, 2007. I, p. 173.

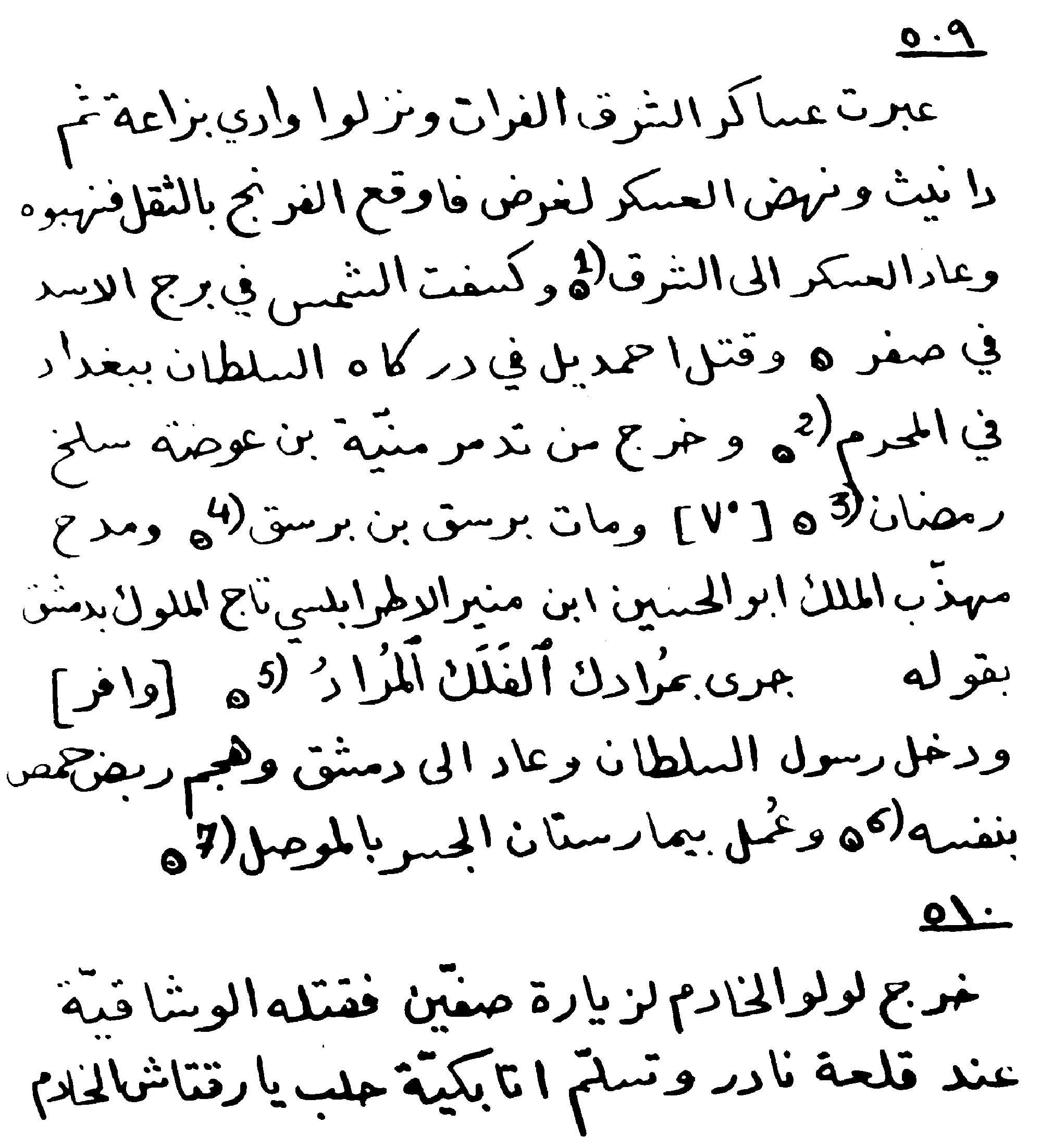

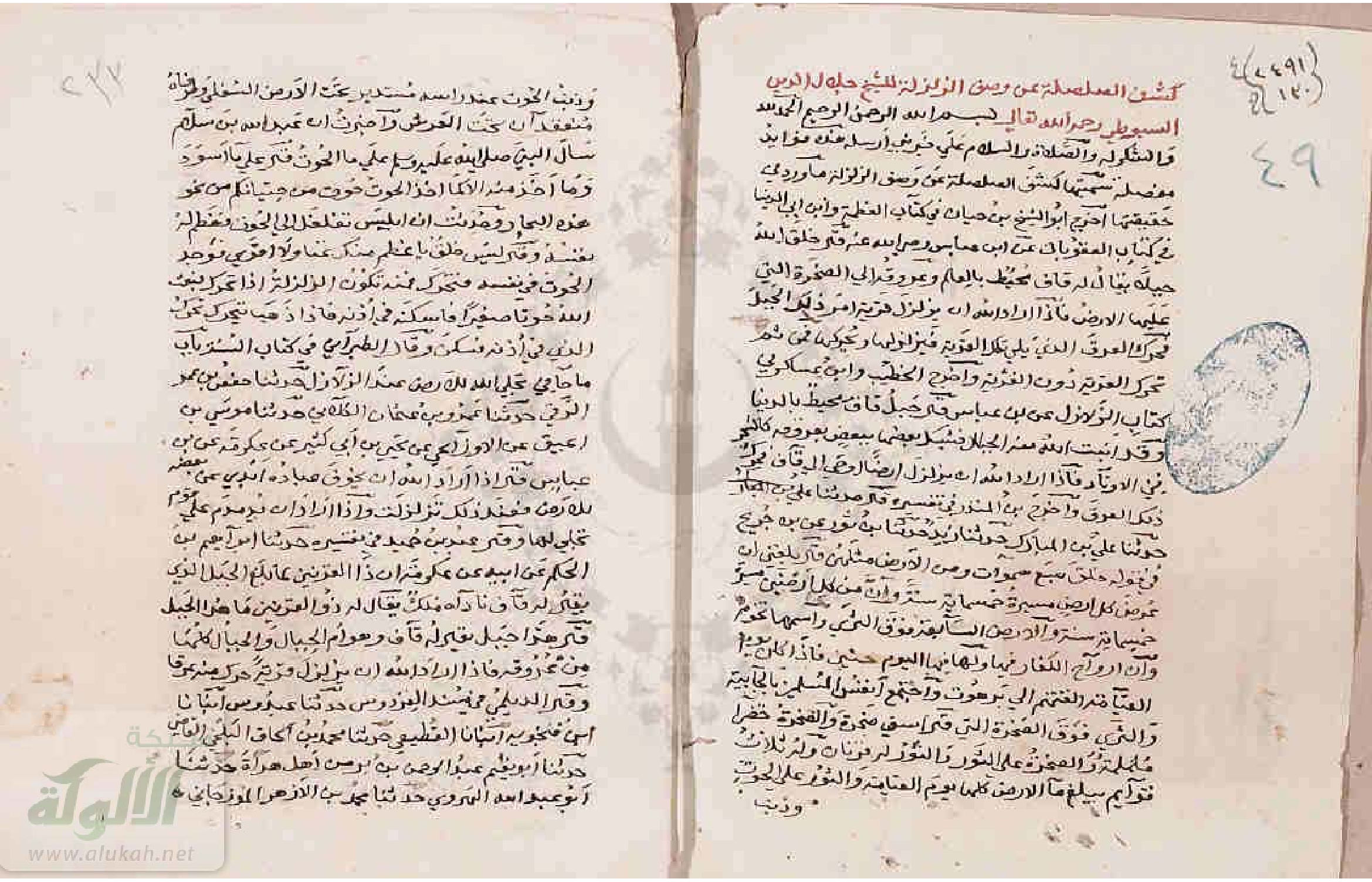

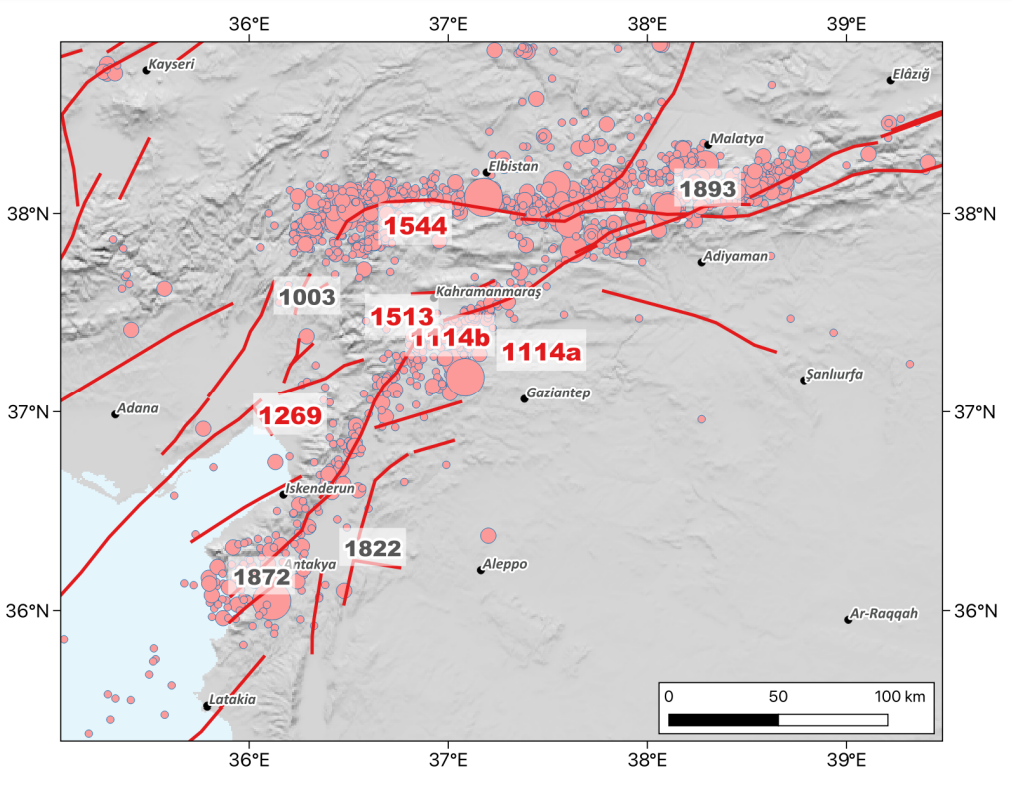

Map of Crusader States ca. 1100 CE

Map of Crusader States ca. 1100 CE Map 1

Map 1 Map 2

Map 2 SYRIA DURING THE PERIOD OF THE CRUSADES, 1096-1291

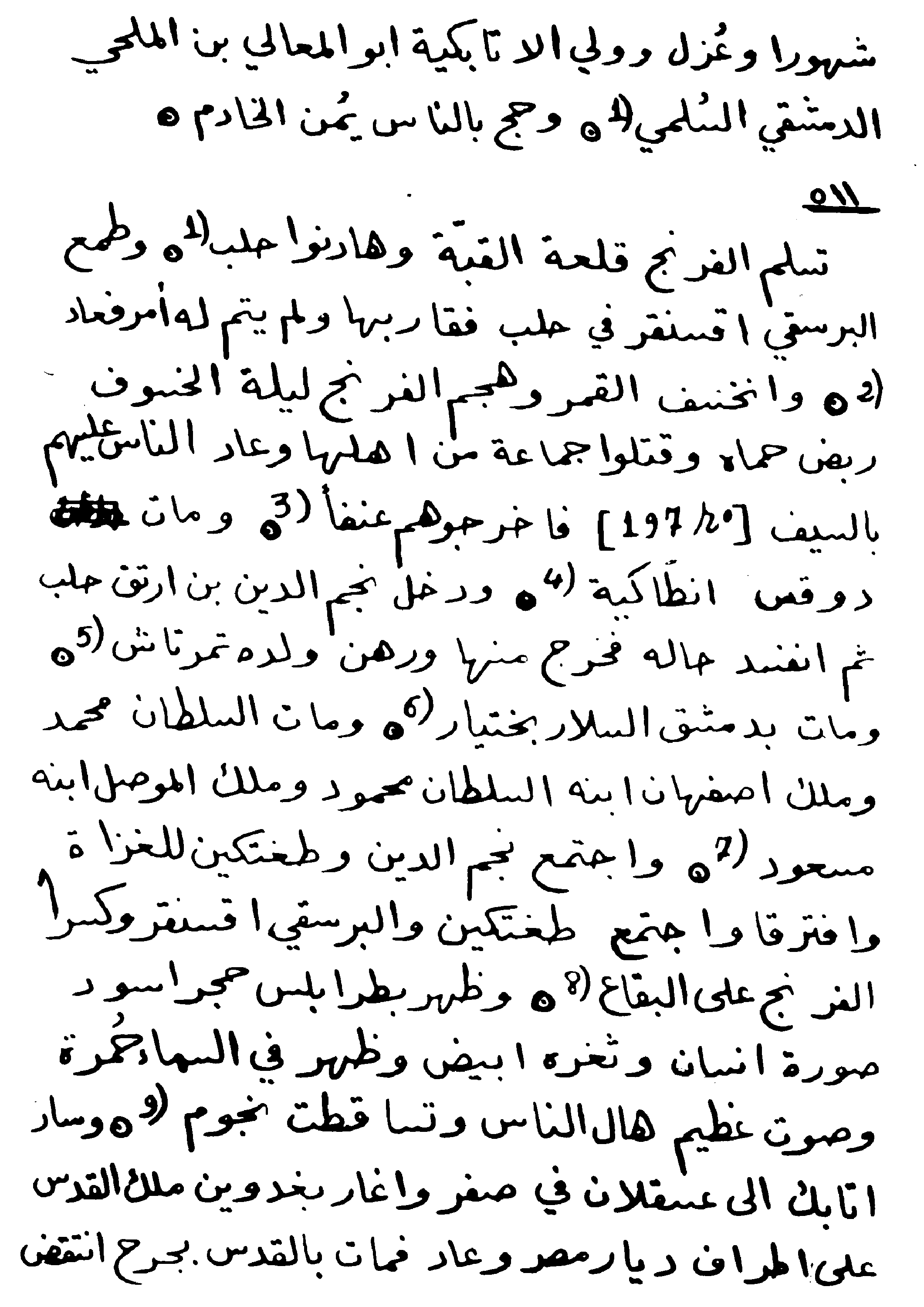

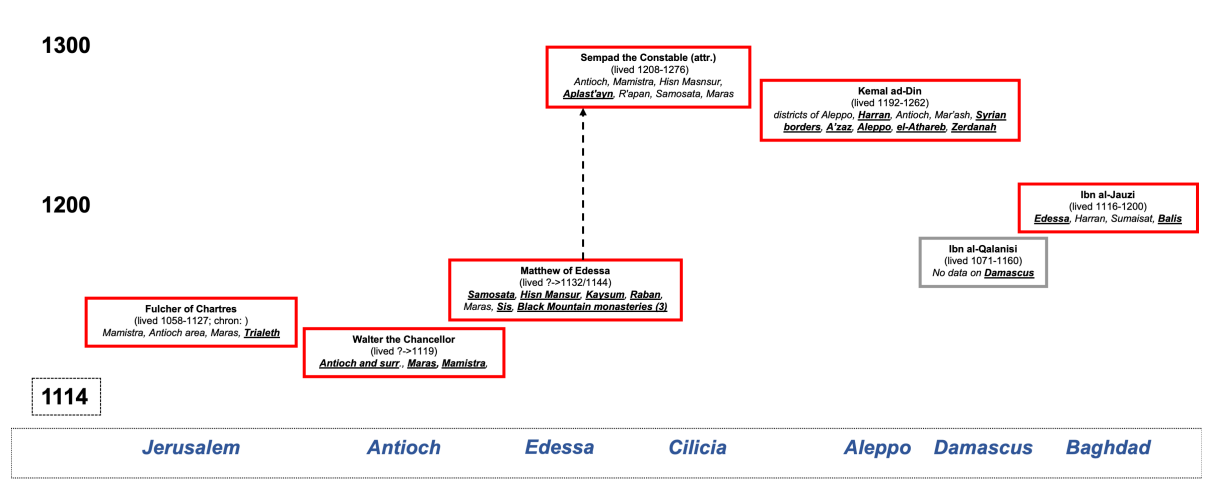

SYRIA DURING THE PERIOD OF THE CRUSADES, 1096-1291 Figure 1

Figure 1

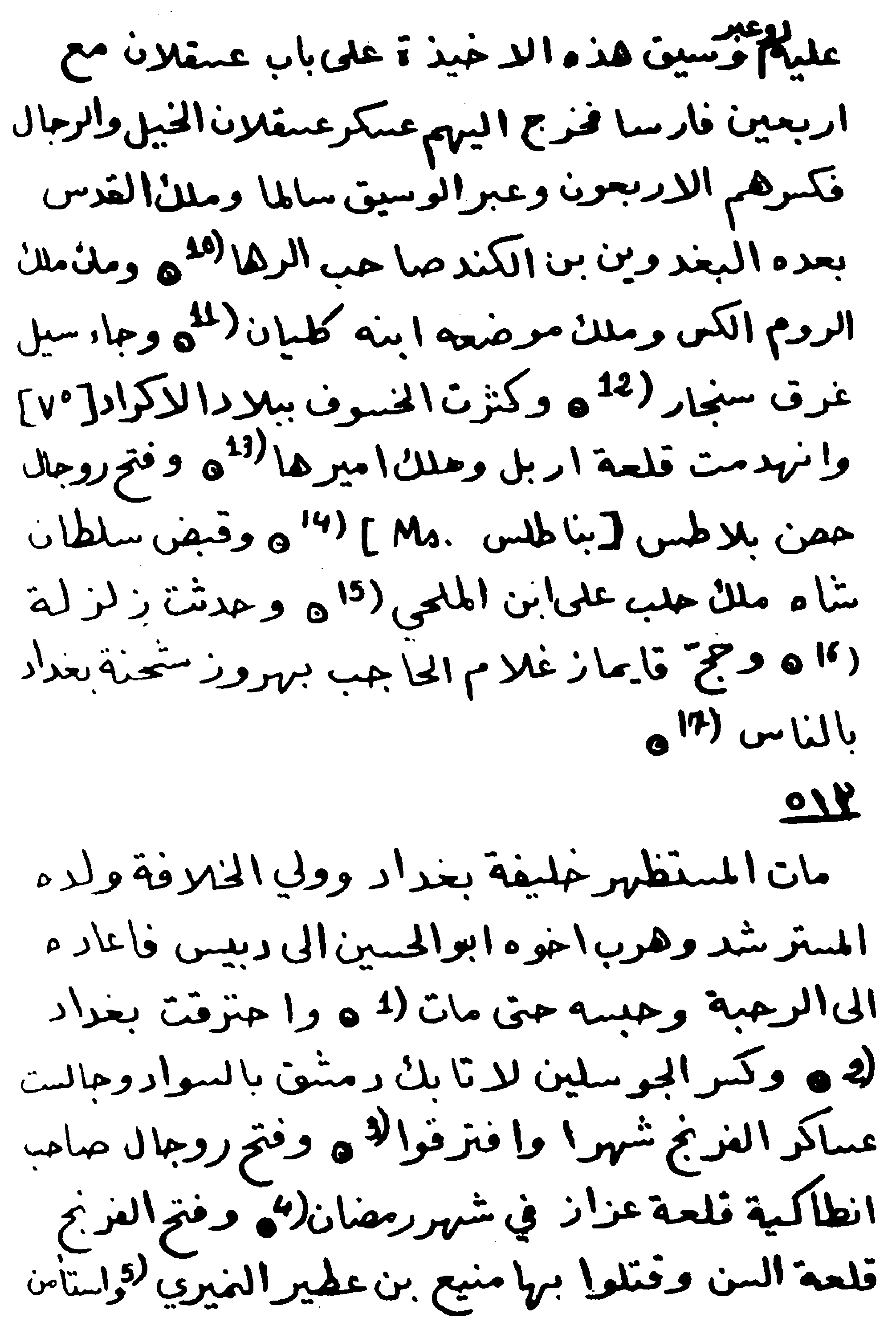

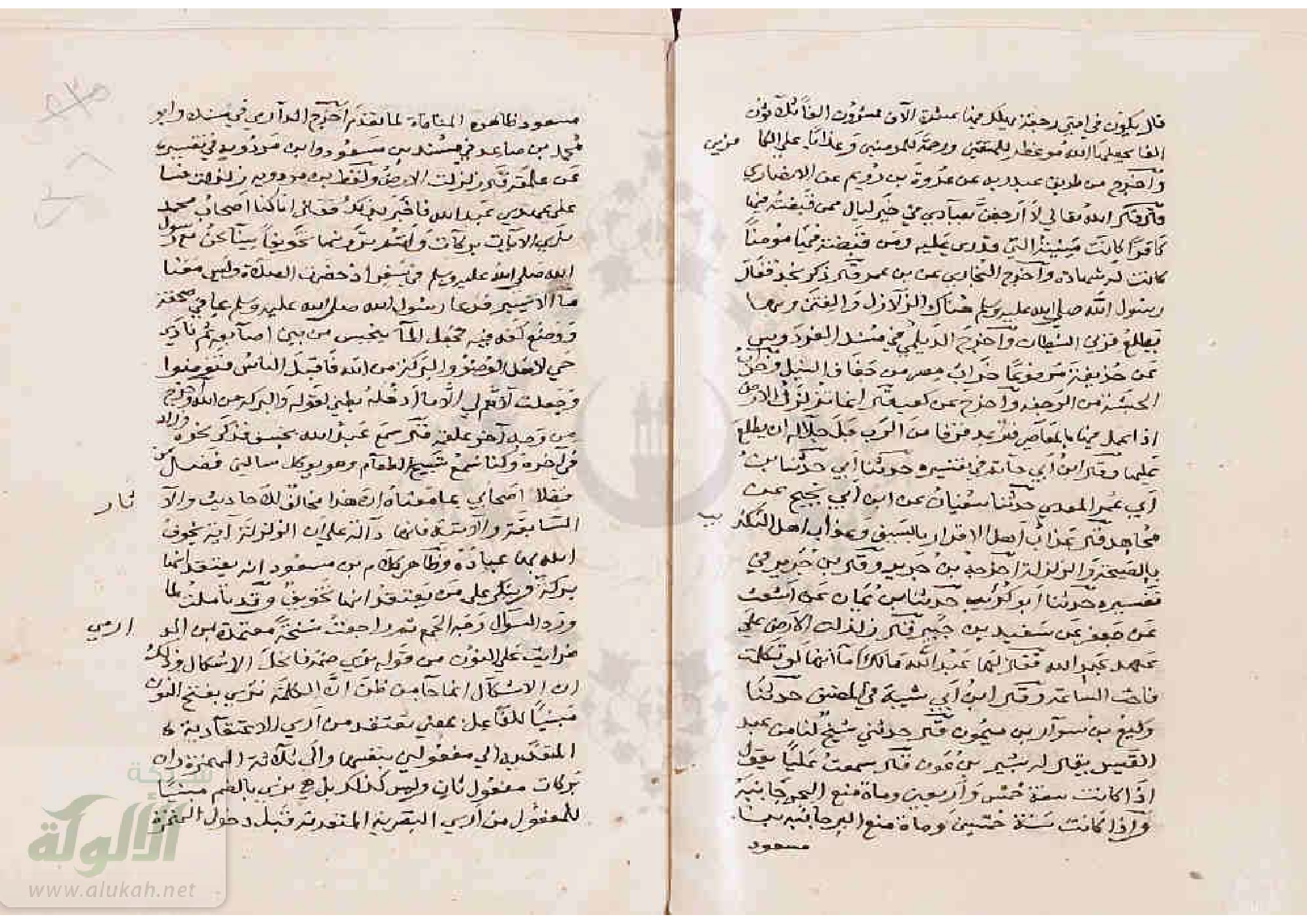

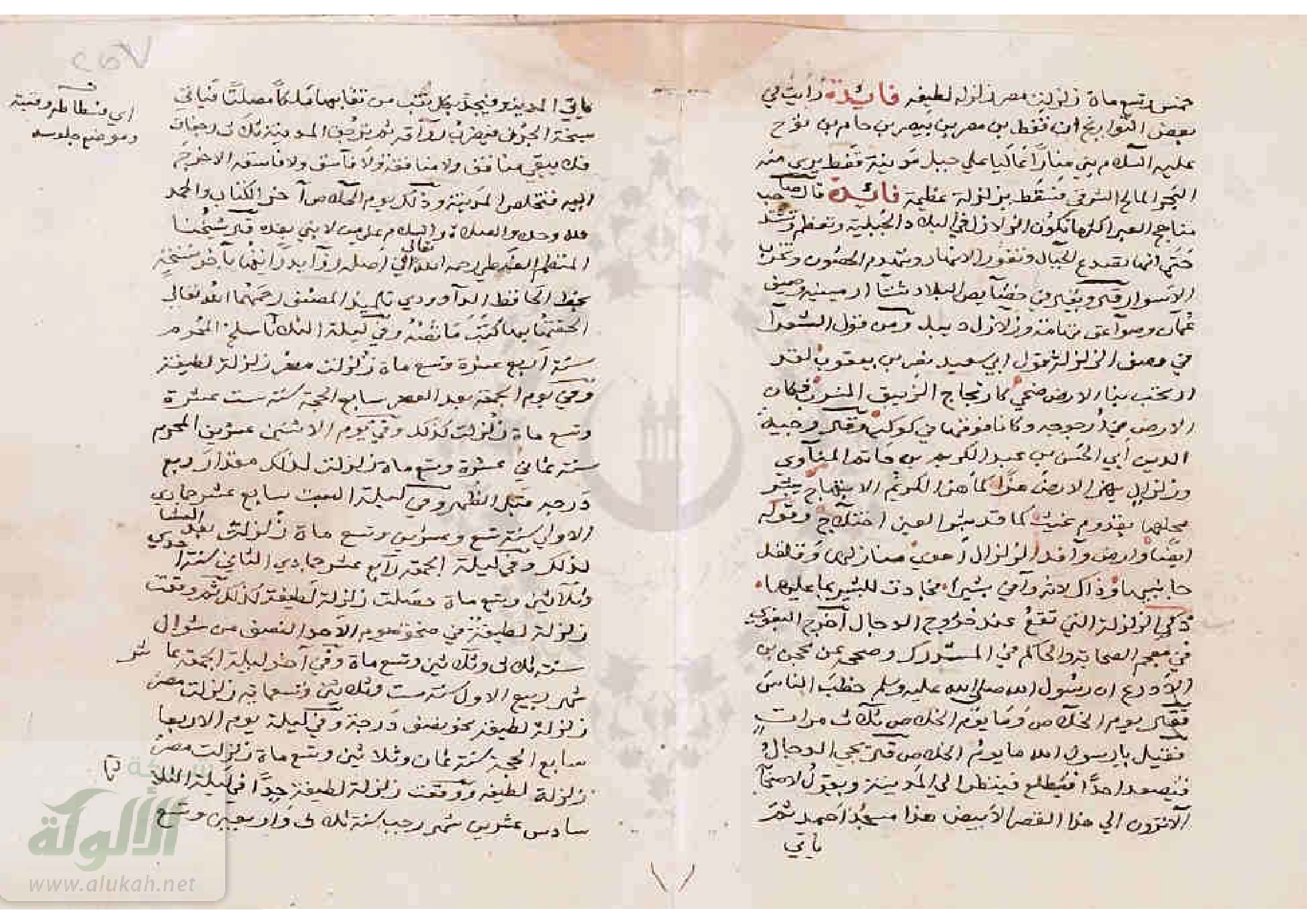

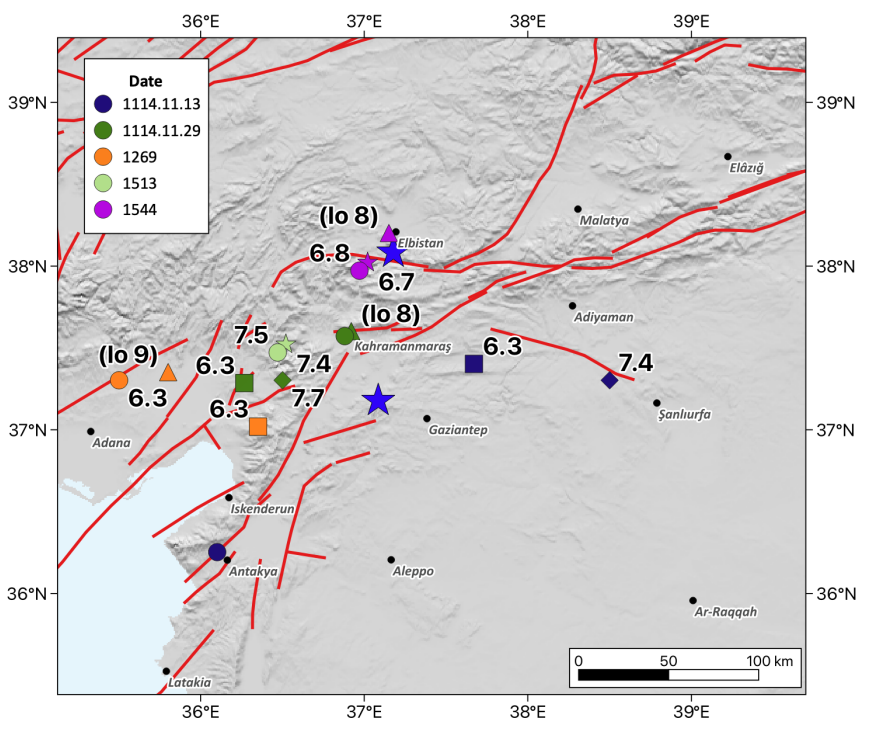

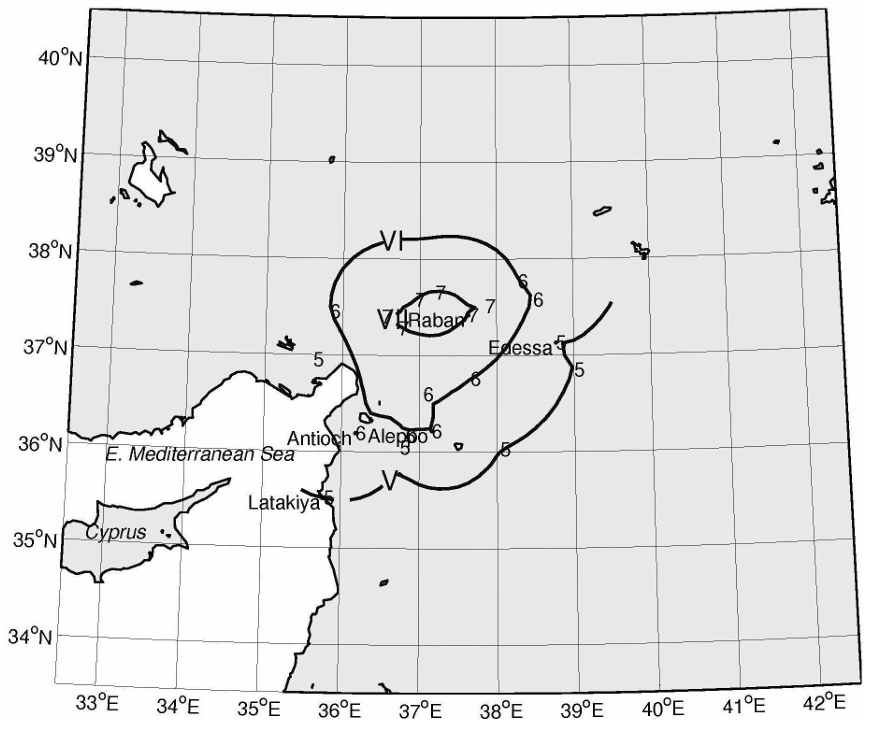

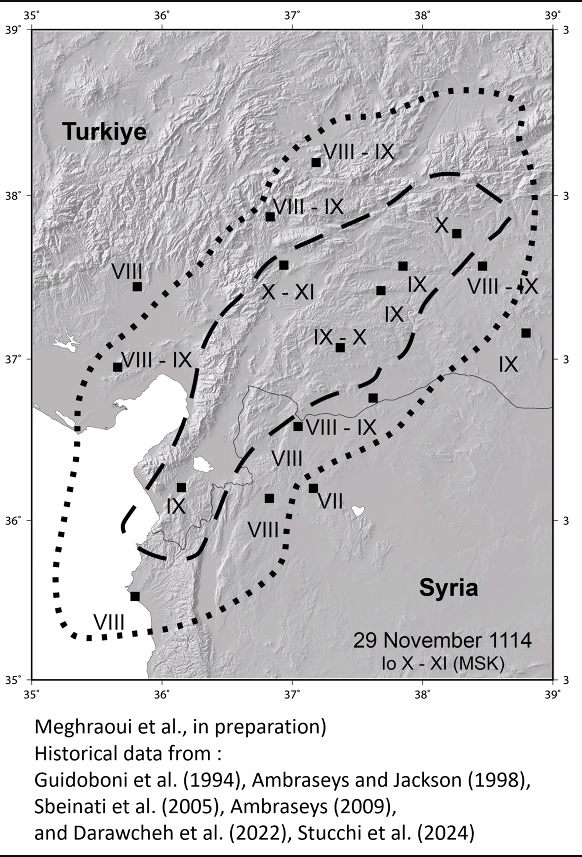

Figure 3.10

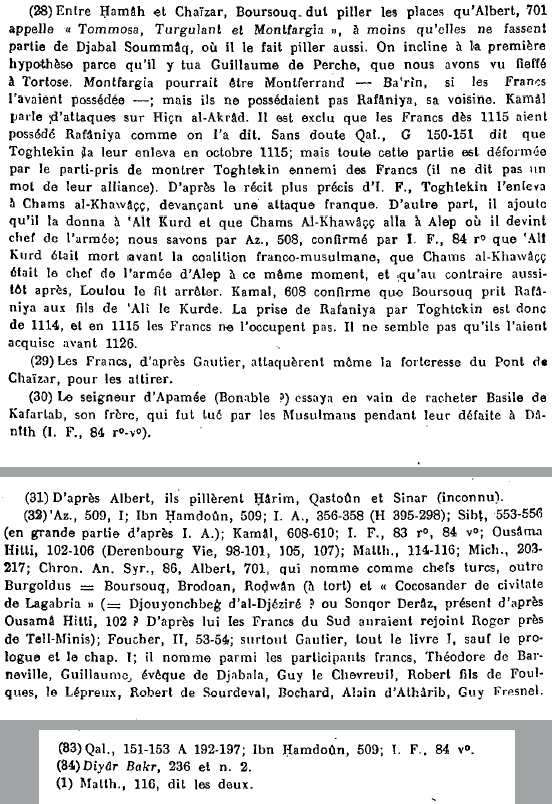

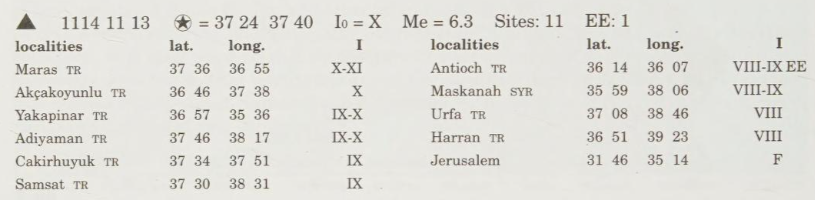

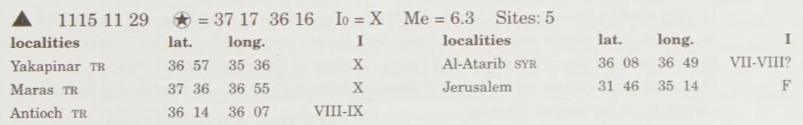

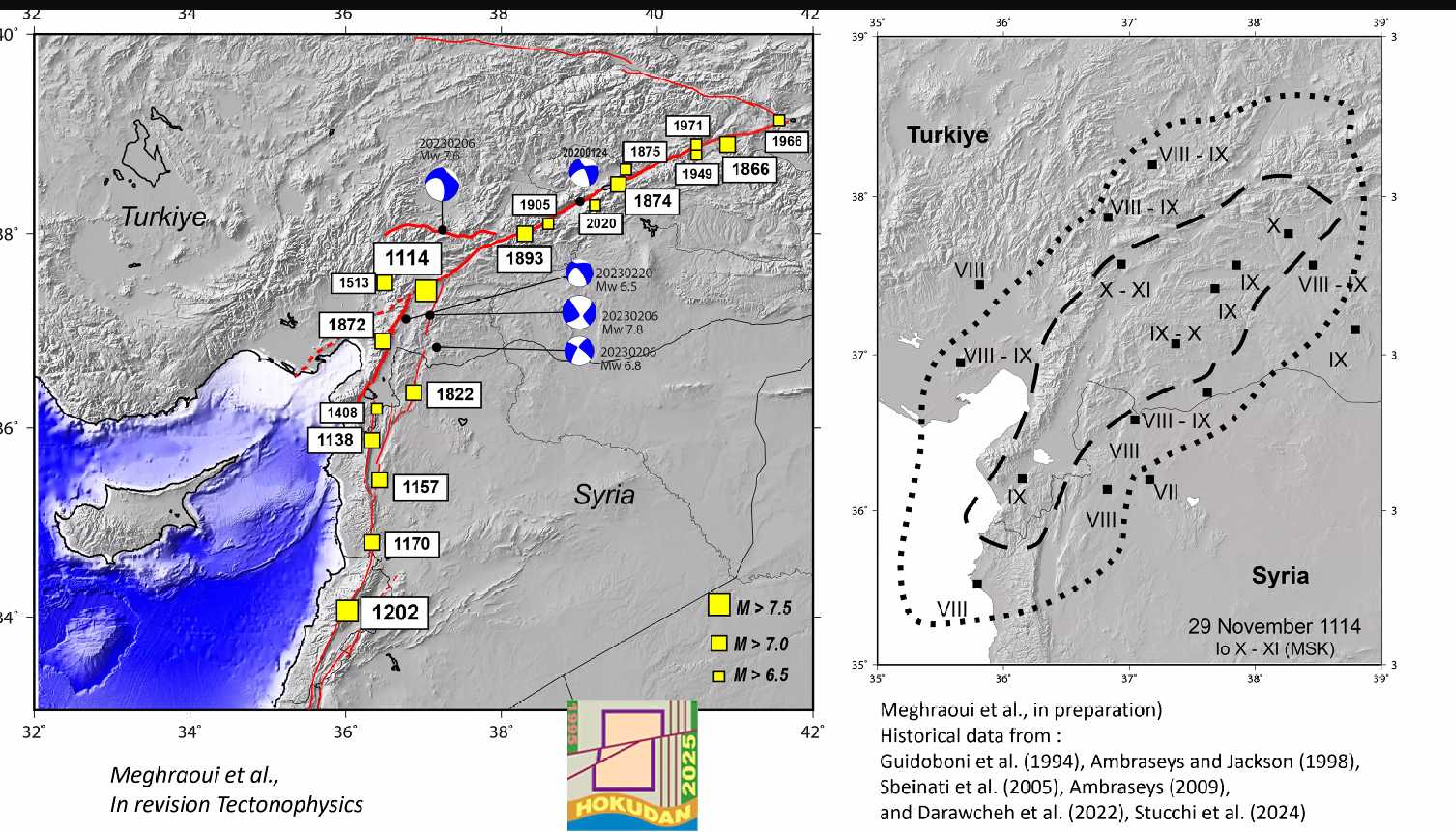

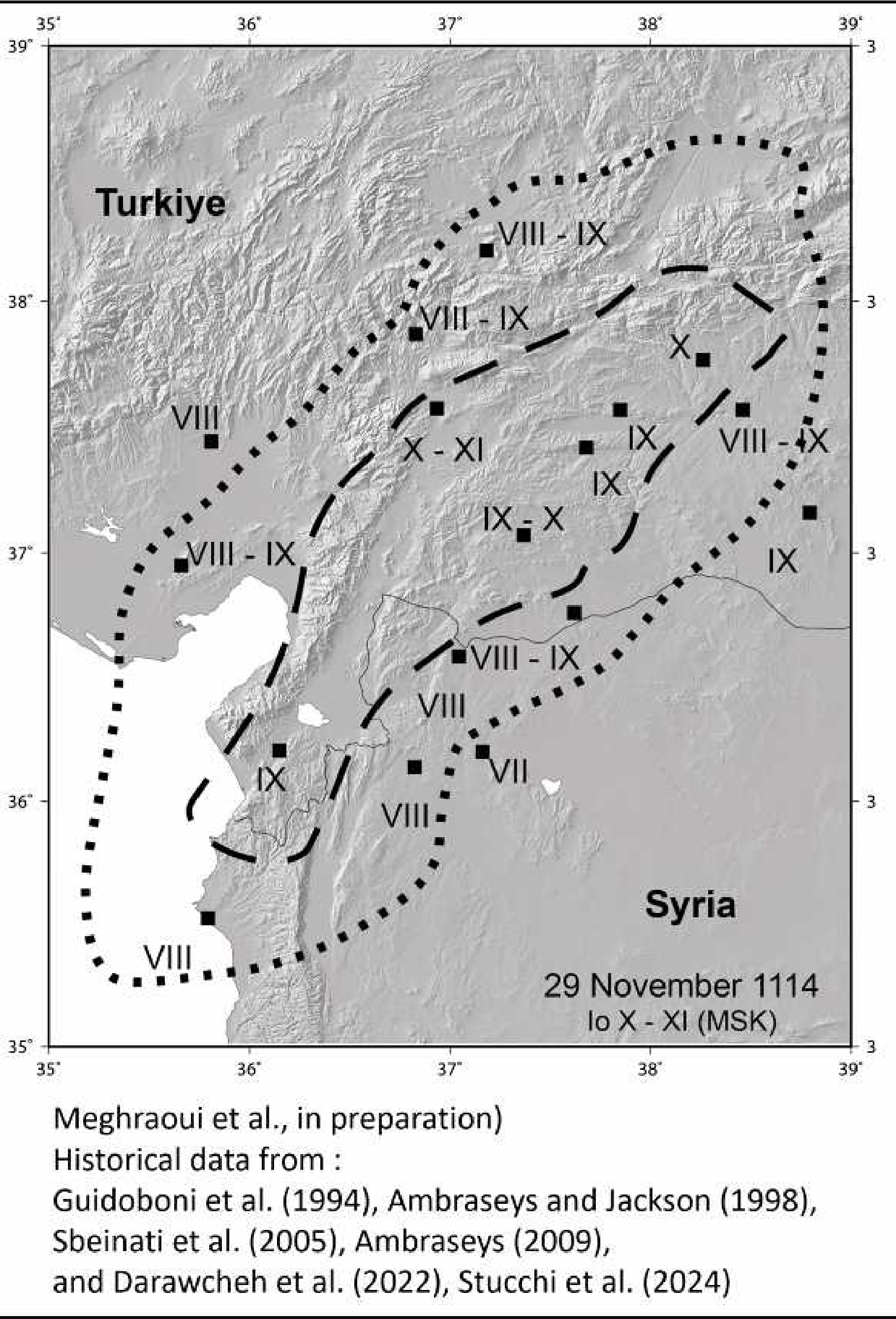

Figure 3.10 Intensity Data Points for the 29 November 1114 CE Earthquake.

Intensity Data Points for the 29 November 1114 CE Earthquake.

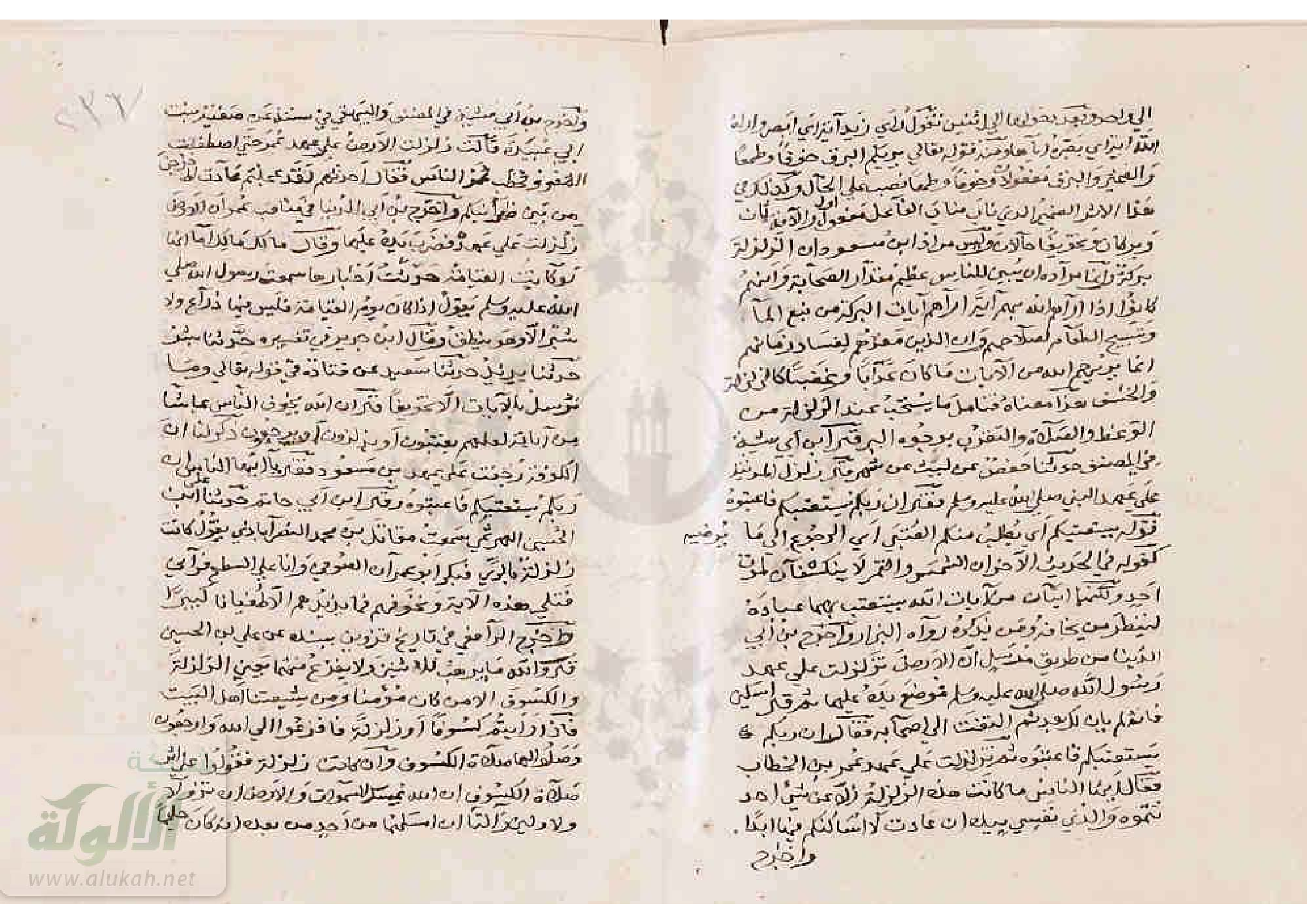

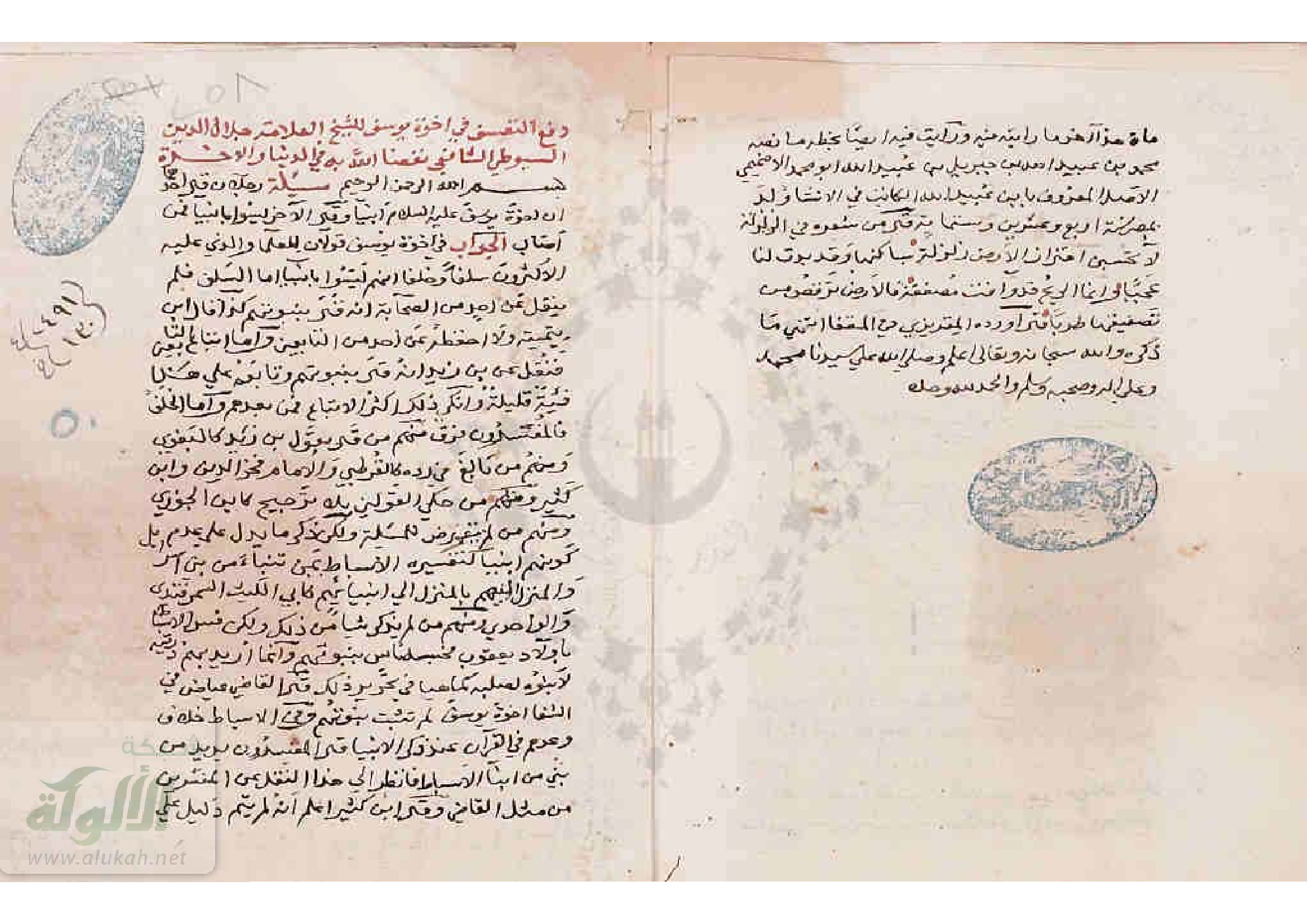

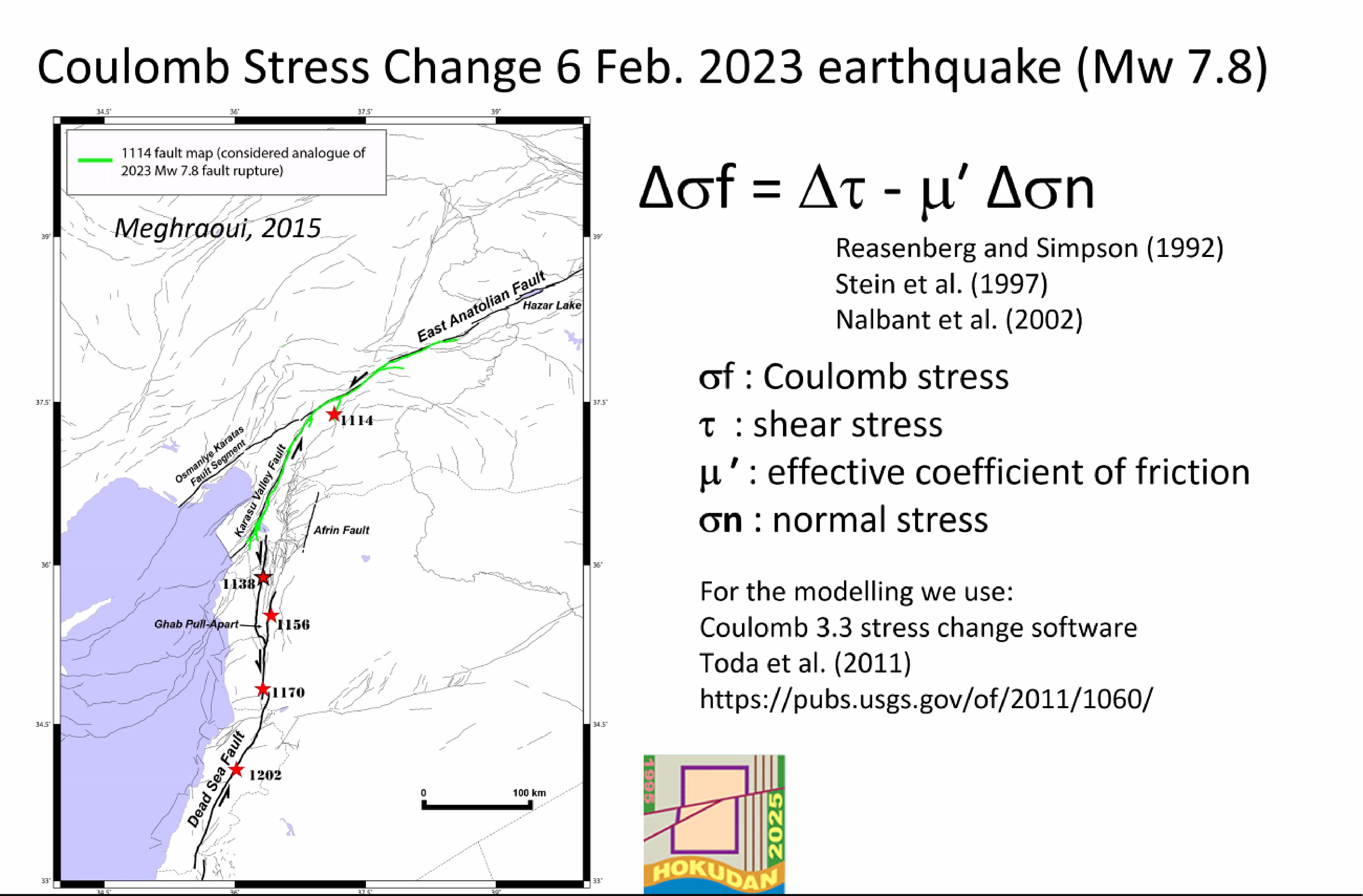

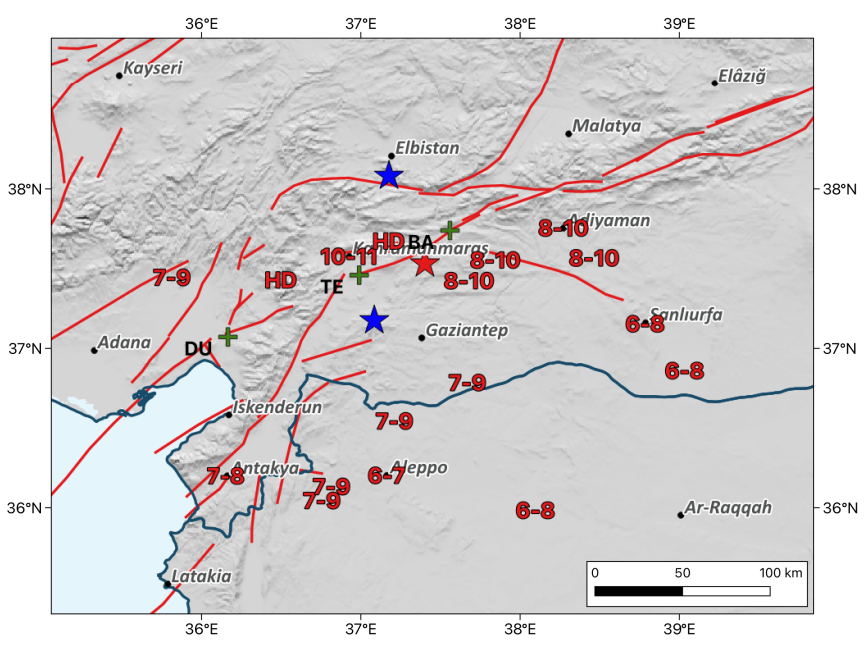

Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 19

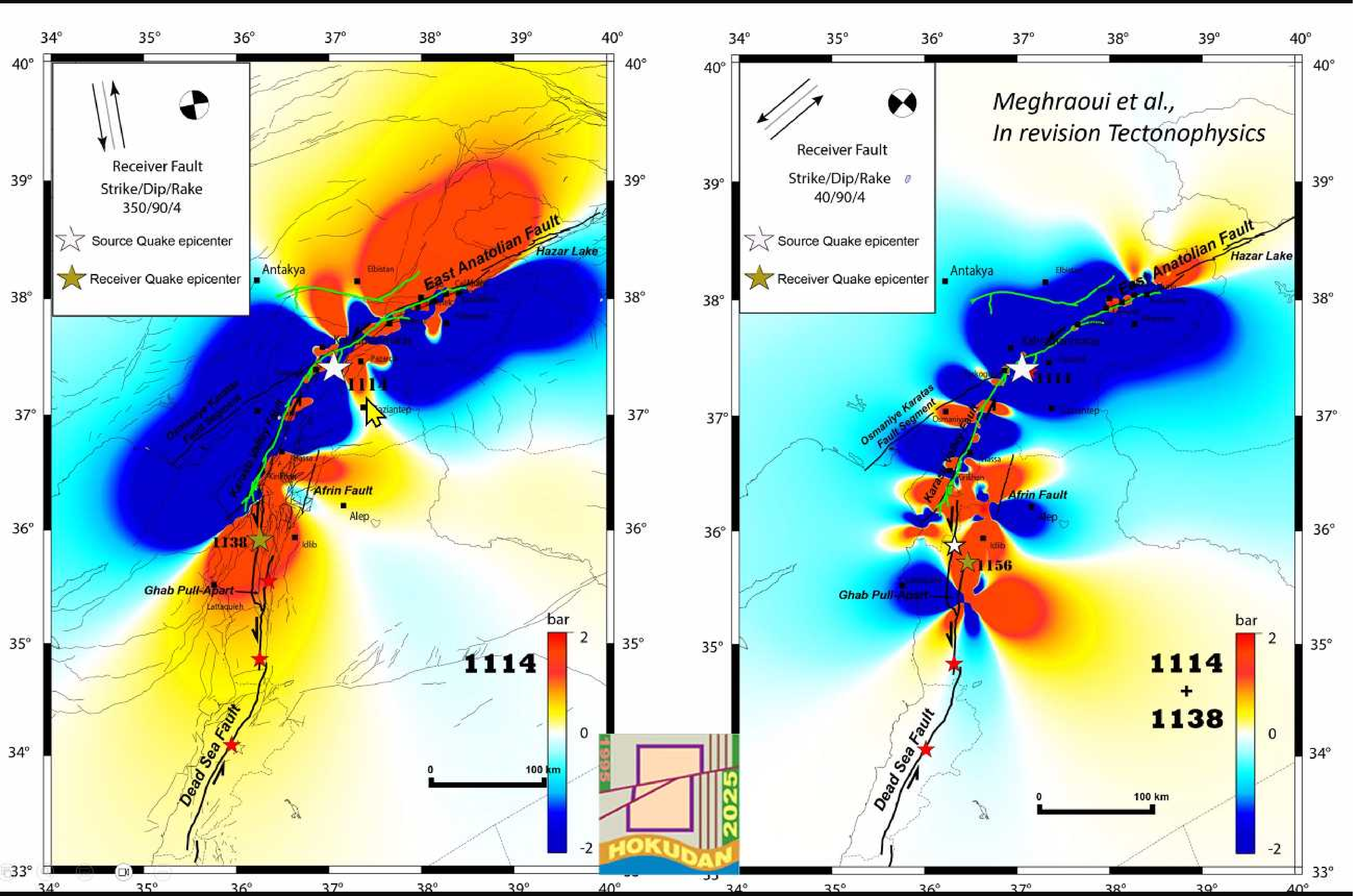

Fig. 19

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Fig. 2

Fig. 2