Apamea

Left

LeftApamea in Google Earth

click on image to explore this site on a new tab in Google Earth

Right

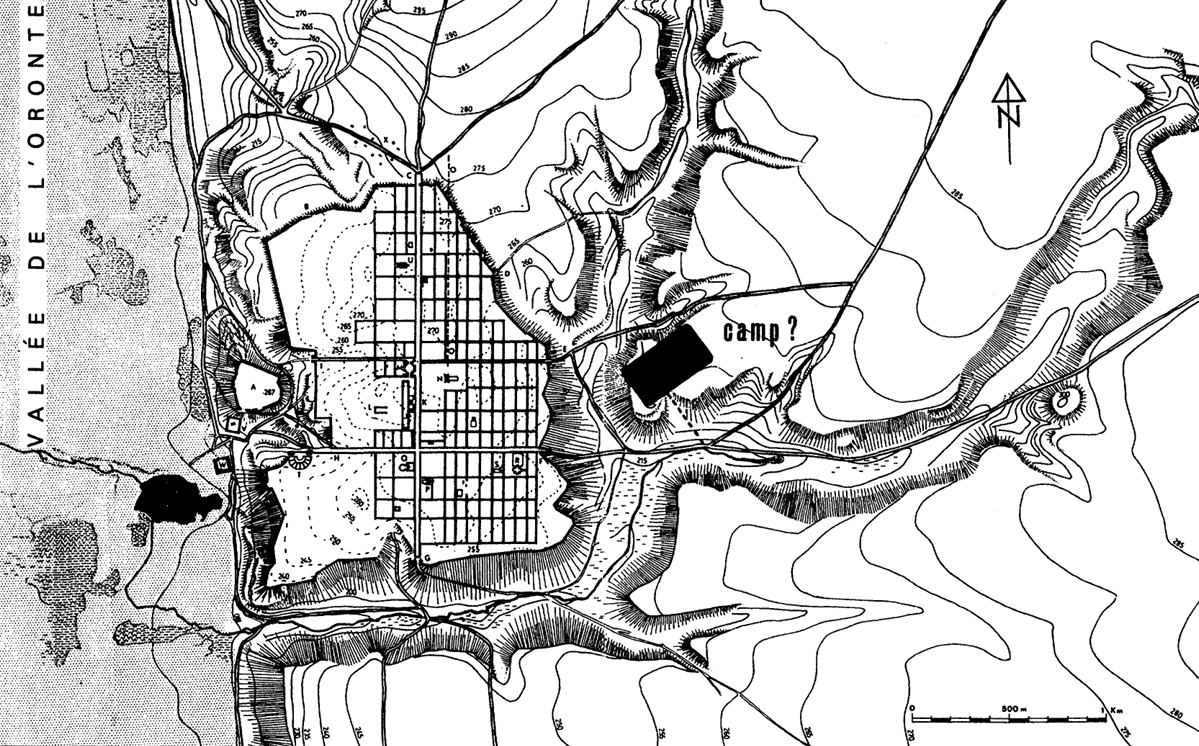

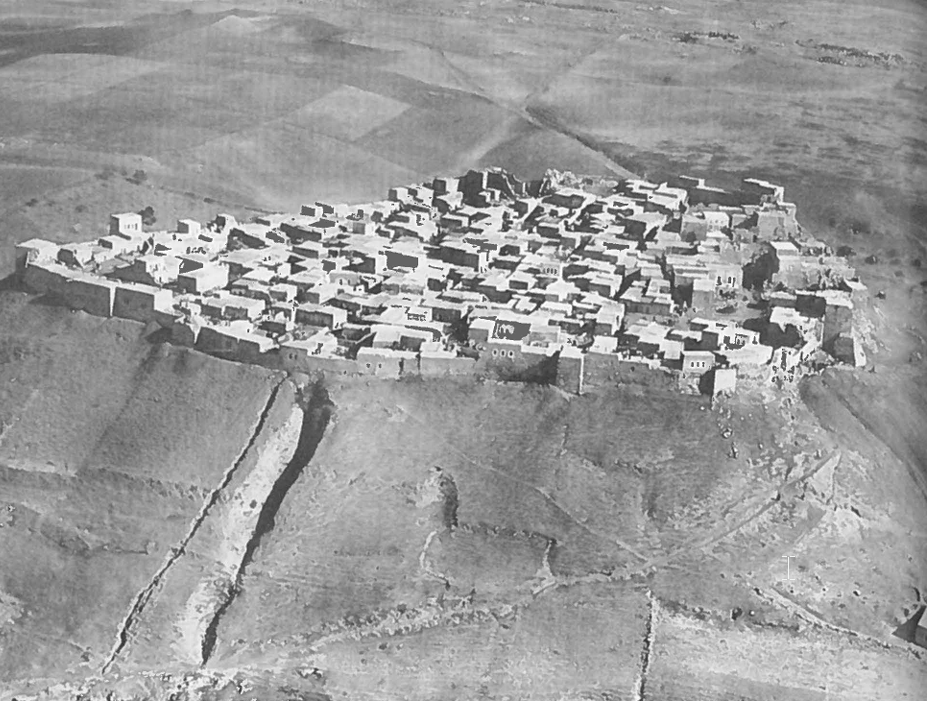

Fig. 174

The citadel and village of Qal'at el-Mudiq

(from a photograph by the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology, Beirut).

Click on image to open in a new tab

Balty (1981)

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Apamea | Latin | |

| Apameia | Greek | Ἀπάμεια |

| Afamiya | Arabic | آفاميا |

| Famiya | Arabic | |

| Femie | Old Frankish | |

| Apamea | Hebrew | אפמיאה |

| Qalaat al-Madiq, Kal'at al-Mudik, Qal'at al-Mudiq | Arabic | قلعة المضيق |

Apamea, located at Qal'at al-Mudiq in the Middle Orontes valley in Syria, "was founded in 300/299 BCE by Seleucus I Nicator with the dynastic name Apamea, related to that of the sovereign's wife, Apama" (Balty in Meyers et al., 1997). The site preserves Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic remains, along with traces of earlier periods, and was one of the four major cities of the North Syrian tetrapolis (Strabo 16.2.10). Jean Charles Balty in Meyers et al. (1997) attributes its ultimate demise to the 1157 CE Hama and Shaizar earthquake (one of the 1156–1159 CE Syrian Quakes, writing that "the severe earthquake of 1157 struck Apamea off the map."

- Fig. 1 Map of Northern Syria from Balty (1988)

- Apamea in Google Earth

- Qalaat al-Madiq in Google Earth

- Fig. 174 The citadel

and village of el-Mudiq from Balty (1981)

- Site plan of Apamea from

R Burns (flickr)

- Site plan of Apamea from

Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 Plan of Camp and

City of Apamea from Balty (1988)

- Site plan of Apamea from

R Burns (flickr)

- Site plan of Apamea from

Wikipedia

- Fig. 2 Plan of Camp and

City of Apamea from Balty (1988)

- 12th century citadel

Qal'at al-Mudiq in Apamea from Hillenbrand (2000)

Fig. 7.53

Fig. 7.53

Citadel, 12th century, Qal'at al-Mudiq (Apamea/Afamiyya), Syria

Hillenbrand (2000)

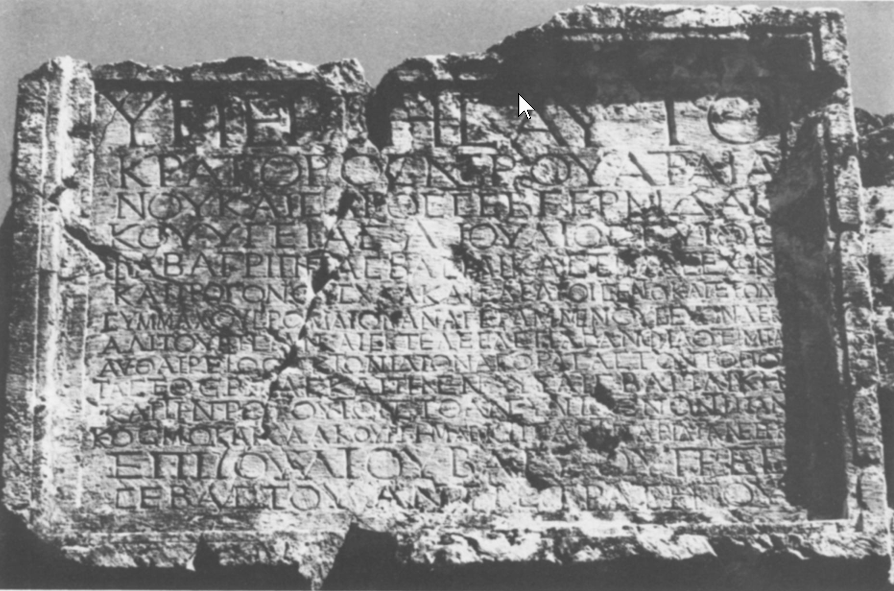

- Plate X (2) Dedicatory

Inscription of the Northern Baths from Balty (1988)

- Plate XIII (1) Southern

Face Of Tower XV, Before Dismantling Works (1986) from Balty (1988)

- Plate X (2) Dedicatory

Inscription of the Northern Baths from Balty (1988)

- Plate XIII (1) Southern

Face Of Tower XV, Before Dismantling Works (1986) from Balty (1988)

AD 115 Dec 13 Antioch

An earthquake in the Orontes valley during the morning

of 13 December AD 115 almost totally destroyed

Antioch, Daphne and four other cities, including Apamea.

This was the third time that Antioch had been destroyed

by an earthquake.

A great roar preceded the shock. People standing in the

open were thrown down and trees were uprooted and

toppled. Almost all structures in Antioch were damaged,

and three quarters of the city collapsed, killing a large

number of people, including the consul Pedo Vergilianus.

The exact number of deaths is unknown, but it must have

been exceedingly high because the emperor Trajan was

wintering there with his troops at the time, and his

presence had attracted many litigants, embassies and

sightseers; in addition to that, since the earthquake

occurred first thing in the morning, many people would

still have been indoors. Very few of those in Antioch went

unscathed, and the Emperor himself, trapped in the ruins

of his residence, made his way out through a window of

the room in which he was staying, with slight injuries.

During the remainder of the period he lived in the open,

in the hippodrome.

Antioch was covered with a thick cloud of dust thrown up

from collapsing buildings, and rescue work was hampered

by strong aftershocks, which continued for several days.

Many of the rescuers were killed by falling debris, and all

those who were left trapped in the vaulted colonnades

apparently died of hunger.

Damage extended to the suburb of Daphne; the whole town

collapsed and its reconstruction was on a par with that of

the capital of the province. The Temple of Artemis was

heavily damaged and had to be rebuilt. The destruction

extended over a large area and included Apamea on the

Orontes, 90 km south of Antioch, which suffered the same

damage as Antioch.

The other cities damaged are not named in the sources, but

it seems that the earthquake was strong further south of

Antioch, where it caused considerable concern (Krauss

1914).

In places, the names of which are not given, the ground

settled and new springs of water appeared while many

streams dried up. Landslides from the hills on the banks

of the Orontes River and rock falls from Mt Casius added

to the destruction. Aftershocks continued for many days.

It seems that after the earthquake Trajan embarked on a

massive reconstruction programme: the Median gate was

erected near the temple of Ares, and above the temple he

placed an effigy of the She-Wolf suckling Romulus and

Remus, to show that the rebuilt Antioch was a Roman

foundation. In addition he built the Nymphaeum or

Nymphagoria in honour of a virgin whom he sacrificed

for the city’s future safety: this complex was adorned

with bronzes. Trajan also re-erected two great

architraves, and built the Baths of Trajan, which were fed

from Daphne by an aqueduct. In addition there is

evidence that the theatre was damaged, and it is possible

that this earthquake damaged the Temple of Artemis in

Daphne, which had to be rebuilt.

In addition to the emperor’s own contribution towards

the restoration of Antioch, work was also carried out by

Hadrian (Mal. CS 275–278), and by a number of Roman

senators. Also in Apamea, Trajan rebuilt the colonnade,

the public bath and the water supply of the city (Balty

1988).

A major building programme about this time in Apamea,

in the Orontes valley, has been connected with this

earthquake, but there is in fact no firm evidence that it

was occasioned by seismic disturbance.

A much later writer mentions an edict issued by Trajan

after the earthquake, restricting the height of new

buildings to no more than 60 feet (Berryat 1761, 498);

but no earlier source for this detail could be found.

A rhetorical account of the earthquake is given by the

near-contemporary Dio Cassius, who, although he omits

details of reconstruction, adds the important information

that the earthquake occurred during the consulship of

Pedo Vergilianus.

Malalas (writing during the sixth century) is an important

source, both for details of Trajan’s building programme

in Antioch and for the date. Downey believes that the

building works might not all have been occasioned by the

earthquake (Downey 1961a, 215), and, since the reference

to Trajan’s foundation of the Temple of Artemis at

Daphne comes separately, after the account of a

martyrdom, it may have merely been an instance of

improvement or repairs. Also, it is unlikely that Trajan

really sacrificed ‘a beautiful Antiochene virgin called

Calliope’. Since Roman human sacrifices were unheard of

by this time, one is inclined to agree with Downey’s

interpretation that this was a Christian legend told to

discredit Trajan (Downey 1961a, 216 n. 71) (and this

would fit neatly with the martyrdom which follows the

earthquake account), Calliope the nymph being a tutelary

deity of Antioch.

Although Malalas’s chronology is notoriously confused,

in this instance the chronological elements are in fact

consistent: (a) Antiochene year 164 (October AD 115–

September AD 116); (b) two years after Trajan’s arrival

in the East (generally agreed as winter AD 113–114); (c)

December, when Pedo could be described as consul

(Lepper 1948, 71). Malalas puts the event on a Sunday at

the same time as the martyrdom of St Ignatius of

Antioch. For this reason Clinton rejects Malalas’s date

completely and dates the event to January or February AD

115, on a reconstruction of the itinerary of St Ignatius,

beginning with his arrest, which he mistakenly places in

February AD 115 (cf. Downey 1961b, 292). According to

St John Chrysostom, St Ignatius’ martyrdom took place

on 20 December 116, which was a Saturday: apparently

the martyrdom continued till 6 am on Sunday (Ioann.

Chrys. S. Ignat. 594). Hence it may well be that 13

December 115 for the earthquake is correct, in view of

the other corroborated data; Malalas has merely moved

the date of St Ignatius’s death back (Essig 1986; Lepper

1948, 54–85; Downey 1961b, 216, 218, 292).

Many other chroniclers record this event. Eusebius

(third–fourth century) dates it a.A. (year of Abraham)

2130.17 (AD 113), while the Armenian version claims

that only a third of the city was destroyed; however, St

Jerome, who dates the event Ol.CCXXIII.16 (AD 112),

says that almost the whole city was destroyed. The

earthquake is also noted by Orosius and by numerous

later Syriac chroniclers, who add no further information

(Oros. vii. 12; Ps.Dion. 123/i. 92; Chr. 724, 121/95;

Mich. Syr. vi. 4/i. 17). In addition, it is thought that

Juvenal alludes to this earthquake in his Sixth Satire (cf.

Downey 1961a, 213 n. 59).

Balty connects a major public building programme in

Apamea with this earthquake on the evidence of an

inscription found at the baths, which states that the

governor Gaius Iulius Quadratus Bassus ‘bought ground

at his own expense and founded the baths, the basilica

inside them and the portico of the street in front, with all

their decoration and bronze works of art’ (Balty 1988,

91ff.). From the fact that Hadrian superseded Bassus for

a few months as governor before his accession to the

imperium, the inscription can be dated AD 116. Since no

mention is made of an earthquake, however, there seems

little evidence to connect it with the Antioch disaster.

Indeed, given that Bassus bought the land, the bath was

clearly a new venture, not repair work, and it was very

common for governors to embark on lavish construction

programmes at their own expense in order to win

promotion.

‘While the emperor was tarrying in Antioch a terrible earthquake occurred; many cities suffered injury, but Antioch was the most unfortunate of all. Since Trajan was passing the winter there and many soldiers and many civilians had flocked thither from all sides in connection with law-suits, embassies, business or sight-seeing, there was no nation or people that went unscathed; and thus in Antioch the whole world under Roman sway suffered dis- aster. There had been many thunderstorms and portentous winds, but no one would ever have expected so many evils to result from them. First there came, on a sudden, a great bellowing roar, and this was followed by a tremendous quaking. The whole earth was upheaved, and buildings leaped into the air; some were carried aloft only to collapse and be broken in pieces, while others were tossed this way and that as if by the surge of the sea, and over- turned, and the wreckage spread out over a great extent even of the open country. The crash of grinding and breaking timbers together with tiles and stones was most frightful and an incon-ceivable amount of dust arose, so that it was impossible for one to see anything or to speak or hear a word. As for the people, many even who were outside the house were hurt, being snatched up and tossed violently about and then dashed to the earth as if falling from a cliff; some were maimed and others killed. Even trees in some cases leaped into the air, roots and all. The num-ber of those who were trapped in the houses and perished was past finding out; for multitudes were killed by the very force of the falling debris, and great numbers were suffocated in the ruins. Those who lay with a part of their body buried under the stones or timbers suffered terribly, being able neither to live any longer nor to find an immediate death.

Nevertheless, many even of these were saved, as was to be expected in such a countless multitude; yet not all such escaped unscathed. Many lost legs or arms, some had their heads bro-ken, and still others vomited blood; Pedo the consul was one of these, and he died at once. In a word, there was no kind of violent experience that those people did not undergo at that time. And as Heaven continued the earthquake for several days and nights, the people were in dire straits and helpless, some of them crushed and perishing under the weight of the buildings pressing upon them, and others dying of hunger, whenever it so chanced that they were left alive either in a clear space, the timbers being so inclined as to leave such a space, or in a vaulted colonnade. When at last the evil had subsided, someone who ventured to mount the ruins caught sight of a woman still alive. She was not alone, but had also an infant; and she had survived by feeding both herself and her child with her milk. They dug her out and resuscitated her together with her babe, and after that they searched the other heaps, but were not able to find in them anyone still living save a child sucking at the breast of its mother, who was dead. As they drew forth the corpses they could no longer feel any pleasure even at their own escape.

So great were the calamities that had overwhelmed Anti- och at this time. Trajan made his way out through a window of the room in which he was staying. Some being, of greater than human stature, had come to him and led him forth, so that he escaped with only a few slight injuries; and as the shocks extended over several days, he lived out of doors in the hippodrome. Even Mt Casius itself was so shaken that its peaks seemed to lean over and break off and to be falling upon the very city. Other hills also settled, and much water not previously in existence came to light, while many streams disappeared.’ (Dio Cass. LXVIII. xxiv– xxv/LCL. ix. 404).

‘In the reign of the same most divine Trajan Antioch the Great, situated near Daphne, suffered for the third time in the month of Apellaeus and December 13, the first day, after cock-crow, in the Antiochene year 164, and two years after the arrival of Trajan in eastern parts. The Antiochenes who remained behind and survived erected an altar in Daphne, on which they wrote, “The survivors erected this to their saviour Zeus.”

On the same night as Antioch the Great suffered, the island city of Rhodes, being a city of the Hexapolis, suffered under the wrath of God for the second time. But the most pious Trajan, having founded it once already, erected the Median Gate near the temple of Ares, where the Parmenius flows in winter, close to what is now called Macellus; and above it he inscribed an effigy of the She- Wolf who suckled Romulus and Remus, so that posterity might know that this was a Roman foundation. He sacrificed there a beautiful Antiochene virgin called Calliope as an expiatory and cleansing sacrifice for the city, in whose honour he built the Nymphagoria. And then he re-erected the two great architraves, and built many other things in Antioch, including a public bath, and an aqueduct, drawing the water from the springs of Daphne to the so-called Agriae, giving his own name to the baths and aqueduct. And the Theatre of Antioch, which was not yet finished, he completed, and placed in it, above, four columns; and in the middle of the Proscenium of the Nymphaeum he put a bronze statue of the virgin he had slaughtered, and on the upper side a bronze of the Orontes river was placed, being crowned by the kings Seleucus and Antiochus. The Emperor Trajan him-self was in the city when the earthquake happened. St Ignatius, the bishop of Antioch, was martyred in his reign.’ (Mal. 275– 276/416–417).

‘The emperor also founded the Temple of Artemis in the middle of the grove in Daphne.’ (Mal. 277/420).

‘The Emperor Hadrian, while he was still a private cit- izen and a senator, was staying with Trajan (whose nephew he was) in Antioch when the great city suffered under the wrath of God.’ (Mal. 278/421).

‘a.A. 2130.17 Antioch collapsed when Trajan was there.’ (Eus. Hist. 164, Greek).

‘There was an earthquake at Antioch, and just under a third of the city was ruined.’ (Eus. Hist. 164, Armenian).

‘Ol.CCXXIII.16: An earthquake in Antioch destroyed almost the entire city.’ (Hieron. Hist. 196).

‘... cities are tottering, the land subsides ...’ (Juv. VI. 411/LCL. 116).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

- from Balty (1988:91-94)

... There had been many thunderstorms and portentous winds, but no one would ever have expected so many evils to result from them. First there came, on a sudden, a great bellowing roar, and this was followed by a tremendous quaking. The whole earth was upheaved, and buildings leaped into the air; some were carried aloft only to collapse and be broken in pieces, while others were tossed this way and that as if by the surge of the sea, and overturned, and the wreckage spread out over a great extent even of the open country. The crash of grinding and breaking timbers together with tiles and stones was most frightful; and an unconceivable amount of dust arose, so that it was impossible for one to see anything or to speak or hear a word. As for the people, many even who were outside the houses were hurt, being snatched up and tossed violently about and then dashed to the earth as if falling from a cliff; some were maimed and others were killed. Even trees in some cases leaped into the air, roots and all. The number of those who were trapped in the houses and perished was past finding out; for multitudes were killed by the very force of the falling debris, and great numbers were suffocated in the ruins ... And as Heaven continued the earthquake for several days and nights the people were in dire straits and helpless, some of them crushed and perishing under the weight of the buildings pressing upon them, and others dying of hunger, whenever it so chanced that they were left alive either in a clear space, the timbers being so inclined as to leave such a space, or in a vaulted colonnade ... So great were the calamities that had overwhelmed Antioch at this time. Trajan made his way out through a window of the room in which he was staying ... And as the shocks extended over several days, he lived out of the doors in the hippodrome.This long, apocalyptic description of the catastrophe is to be found in the Epitome of Book LXVIII of Dio's Roman History1; the date itself is given by Malalas: it occurred at dawn on 13 December; and the Byzantine chronicler states that it was the third major earthquake in the series of disasters which had visited the city2.

Situated some 56 miles to the south, in the Orontes valley, within a zone of frequent seismic disturbances, Apamea suffered the same damage as Antioch, and its reconstruction was on a par with that of the capital of the province, where Trajan is said to have raised the two great emboloi3 and built a public bath and an aqueduct4. At Apamea too, work started with the colonnades of the main street, one of the baths and the water supply of the city.

400 m south of the northern gate, an important inscription on the main entrance of the baths—dated A.D. 116 by the mention of the governor C. Iulius Quadratus Bassus whom Hadrian superseded at the head of the province for some months before his accession—records that having bought the ground at his own expense and founded the baths, the basilica inside them and the portico of the street in front, with all their decoration and bronze works of art, a certain L. Julius Agrippa, son of Gaius, of the tribe Fabia, dedicated the whole to his native city5. A second and larger text, from the same baths, specifies that there were bronze copies of the well-known Hellenistic groups of Theseus and the Minotaur, and of Apollo, Marsyas, Olympos and the Scythian slave; it states also that the benefactor of the city built several miles of the aqueduct—a feature usually connected with the construction of such a huge building6. This L. Julius Agrippa, whose ancestors' names were inscribed at Rome on bronze tablets displayed on the Capitoline hill as friends and allies of the Roman people and whose great-grandfather Dexandros was the first high priest of the province at the time of Augustus, retained royal honours until Trajan's reign and was perhaps descended, like some tetrarchs both on his father's and on his mother's side, from the royal family of Cilicia, itself connected with the Judaean house7. However that may be, L. Julius Agrippa participated in the restoration of Apamea in proportion to his riches; the silence of our epigraphical documentation on the site, however, precludes us from knowing whether other benefactors, as in Antioch8, following the appeal of the emperor, carried out the building of houses and baths elsewhere in the city.

Work started immediately, as is clear from the dedication of the northern baths in which Trajan is Germanicus Dacicus, but not yet Parthicus, i.e. before April to August A.D. 116 and therefore just a few months after the disaster of December 115. Does this indicate that the rebuilding of the colonnade began with the northern part9, the constructions on the agora and near the middle of the city being dated in the 40s and the 60s of the century10? It is not impossible. Due to the exceptional width of the plan, restoration evidently went on for the whole century; only a catastrophe such as this earthquake could afford the opportunity for new town-planning on such a large scale. The main avenues, following the plan en croix de Lorraine which dated from the time of the city's foundation (300/299 B.C.), were enlarged to respectively c. 37 m (on the north-south axis) and 22 m (on the east-west one), instead of c. 30 and 16 m, comprising the porticoes. With a total length of nearly 2 km between the northern and the southern gates, the north-south axis represents, as the Rev. W. M. Thomson wrote after his visit to the site in 1846, 'one of the longest and most august colonnades in the world'11, and, until now, one of the best, if not the best example of those plateiai which are a characteristic feature of the urban landscape of eastern cities and especially evident since the anastylosis conducted by the Syrian General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums (Pl. X, 1). The width of the paved road at Palmyra is 11 m between porticoes 6 m wide and columns 9.50 m high12; at Antioch, it is only 9 m, between porticoes also 9 m wide13; at Apamea, however, it reaches 20.80 m between porticoes 7 m wide. The general impression is thus quite different, as this elementary comparison makes vividly clear.

In the centre of the town, reconstruction was completed only some decades later. On the agora, among the consoles of the rear wall of the porticoes, two dedications of the Council and the People to C. Julius Severus as [νπατι]κός (there is not enough space to read [σνγκλητι]κός) offer a terminus post quem of A.D. 13914; this seems to fit the more ornamented and already baroque architecture, with the alternating curvilinear and triangular frontons over the niches of the first floor and the protruding elements of the entablature; moreover, the calyx of acanthus leaves at the bottom of the columns in the North Propylea15 resembles those of the South Gate and of the Arch of Hadrian at Gerasa, dated A.D. 129/13016. C. Julius Severus' consulate was the occasion of this homage; but Severus had been legate of the Legion IV Scythica, one of the three Syrian legions during the Empire, and appointed by Hadrian governor of the province in 132 at the outbreak of the Jewish revolt, when the then governor C. Publicius Marcellus was sent to Judaea to annihilate the rebellion. No doubt it was during this period and with these functions that Severus won the esteem of the city17; as a son of another Julius Bassus, he was himself a descendant of the royal dynasty of the Attalids and perhaps a relative of L. Julius Agrippa18, whose activity during the governorship of C. Julius Quadratus Bassus might well also be explained by the importance of those family networks and C. Julius Quadratus Bassus' own relationship with Trajan, especially after the second Dacian campaign during which he had held particularly high command and earned the ornamenta triumphalia19.

Nearby, in front of the east entrance to the agora, three of the remarkable spiral fluted columns have consoles which once bore bronze statues of the emperors Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (Pl. XI, 1–2)20; the dedication was made around A.D. 166, as indicated by the epithet Parthicus Maximus given to Marcus Aurelius, and thus fifty years after the beginning of the reconstruction in the northern part of the avenue. And here too the benefactors, two brothers, Ti. Flavius Appius Heracleides and Ti. Flavius Appius Sopatros, are members of one of the greatest local families directly linked with the power structure: as convincingly argued by Jean-Paul Rey-Coquais, they seem to have received the Roman citizenship under the Flavians from Sex. Appius Severus, who was tribune of the Legion III Gallica quartered at Raphanaea, south-west of Apamea, and whose daughter Appia Severa married L. Ceionius Commodus (cos. A.D. 78 and subsequently governor of Syria), the grandfather of Lucius Verus, whence the dedication on the colonnade21. But frequent as it may have been in the local onomastic, the cognomen Sopatros suggests a connection with the famous Sopatros of the fourth century, the Apamean rhetor, father of a friend and correspondent of Libanius. An unpublished console in the rear wall of the colonnade, in front of Julius Agrippa's baths, might afford new evidence of the importance of this family at Apamea between those two termini, as it is dedicated to a Ti. Flavius Appius Sopatros, the most famous son of our Sopatros, in the year A.D. 23022. In view of the very few dedications inscribed in this place on the main street, it is no doubt a real token of local excellence, which indicates the antiquity of the family and supports the hypothesis that the Sopatroi of the fourth century might well be the Αππιοι Σώπατροι too.

To sum up so far, it is clear that the great local families—the municipal elites—participated, as they did in so many other cities in the East and in the western provinces at the same period, in this phase of embellishment of the town after the earthquake. As in many other cities too, it is not surprising to find among those benefactors, who so often performed the main liturgies and were at the very origin of the imperial cult in the province, those families which were descended from ancient local dynasts of the Hellenistic period and had kept some influence during the Empire through co-operation with the new regime. Significantly enough, the three main groups of inscriptions on the colonnade and the agora all suggest persons of this kind.

A final but fragmentary document, whose origin is unfortunately not precisely known, is also worth mentioning in this respect. It is a dedication of Agrippa, presumably L. Iulius Agrippa, to his friend the consular Iulius Quadratus, who might be either the above mentioned C. Iulius Quadratus Bassus, governor in A.D. 116, or his homonym C. Antius A. Iulius Quadratus, governor between A.D. 100/1 and 103/4 and therefore at a date before the earthquake23; particularly important is the epithet philos, which stresses the link between the local dedicator and the representative of the emperor.

As already pointed out, reconstruction continued throughout the century, judging by the style of the various sections of the north-south colonnade or by the inscriptions. By the second half of the century, together with the series of spiral fluted columns near the agora, work reached the southern part of the avenue: the decoration of a nymphaeum built near the intersection with the south decumanus, has clear, late Antonine, baroque features24; and the theatre, cut in a depression flanking the city-wall to the south of the acropolis, in a wonderful position on the edge of the Orontes valley25, has the same plan as the famous monument at Aspendos, dated by a dedicatory inscription to the reign of Marcus Aurelius26.

1 Cassius Dio LXVIII, 24–5, quoted in Loeb translation

of E. Cary .

2 Malalas 275, 3–8 (ed. Bonn) .

3 Ibid. 275, 21–2; for archaeological commentary and

1932–9 excavations, see J. Lassus, *Les portiques

d’Antioche = Antioch-on-the-Orontes V* (1972),

7, 133–4, 145–6 .

4 Malalas 276, 1–2; cf. G. Downey, *A History of

Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest*

(1961), 223 .

5 J.-P. Rey-Coquais, “Inscriptions grecques d’Apamée,”

*AAS* 23 (1973), 40–41 no. 1, pl. I, 1; cf. J. Ch. Balty,

*Guide d’Apamée* (1981), 56, fig. 50 .

6 Rey-Coquais, ibid., 41–6 no. 2, pl. I, 2; cf. *Guide

d’Apamée*, 205–6 no. 20, fig. 230 .

7 R. D. Sullivan, “The Dynasty of Judaea in the First

Century,” in *ANRW* II.8 (1977), stemma facing

p. 300 .

8 Malalas 278, 20–279, 2; cf. Downey, op. cit. (n. 4),

218 .

9 In Antioch the paving of the main colonnaded

street started at the southern end where a

commemorative inscription was placed on the

Gate of the Cherubim: Malalas 280, 20–281, 6 .

10 For console inscriptions: *IGLS* 1312–13;

W. Van Rengen, “Inscriptions grecques et latines,”

*Colloque Apamée de Syrie I* (1969), 96–7 no. 1;

id., “Nouvelles inscriptions grecques et latines,”

*Colloque Apamée de Syrie II* (1972), 104–6

nos. 4–5 .

11 W. M. Thomson, “Journey from Aleppo to Mount

Lebanon by Jeble, el-Aala, Apamia, Ribla, etc.,”

*Bibliotheca Sacra* 5 (1848), 685 .

12 A. Gabriel, “Recherches archéologiques à Palmyre,”

*Syria* 7 (1926), 81, fig. 2; A. Ostraz, “Note sur le

plan de la partie médiane de la rue principale de

Palmyre,” *AAS* 19 (1969), 109–20 .

13 Lassus, op. cit. (n. 3), 146–7 .

14 Van Rengen, “Nouvelles inscriptions,” cit. (n. 10),

106 .

15 J. Ch. Balty, *Guide d’Apamée* (1981), 72–3,

figs. 68–70 .

16 C. H. Kraeling, *Gerasa, City of the Decapolis*

(1938), 73, 401–2, pls. VIII a–b, X–XI, XXX c,

XXXI a .

17 Van Rengen, “Nouvelles inscriptions,” cit. (n. 10),

106 .

18 Contra: J.-P. Rey-Coquais, “Syrie romaine de

Pompée à Dioclétien,” *JRS* 68 (1978), 64–5 .

19 Chr. Habicht, *Die Inschriften des Asklepieions =

Altertümer von Pergamon VIII, 3* (1969), 43–53

(no. 21), pls. 8–9 .

20 *IGLS* 1312–13; W. Van Rengen, “Inscriptions

grecques et latines,” cit. (n. 10), 96–7 no. 1 .

21 Rey-Coquais, art. cit. (n. 5), 66 .

22 Unpublished console text: dedication to Ti. Flavius

Appius Sopatros, A.D. 230 .

23 List of governors of Syria: Rey-Coquais, art. cit.

(n. 18), 62–7 .

24 A. Schmidt-Colinet, “Skulpturen aus dem Nymphaeum

von Apamea/Syrien,” *AA* (1985), 119–33 .

25 J. Barlet, “Travaux au théâtre, 1969–1971,”

*Colloque Apamée de Syrie II* (1972), 150–2 .

26 K. Lanckoronski, *Städte Pamphyliens und Pisidiens*

I (1890), 179 n. 1 (no. 64 cd) .

- from Chat GPT 5, 21 September 2025

- from Krauss (1914)

Krauss suggested that Caesarea and Emmaus may have suffered earthquake damage, though the references are indirect and cannot be securely dated. The rabbinic texts emphasize darkness, ruin, and social dislocation rather than precise chronology. Still, Krauss considered these traditions possible echoes of the 115 CE catastrophe.

Thus, while archaeological or epigraphic confirmation is lacking, Krauss interpreted the rabbinic material as supporting evidence that the effects of the 115 CE earthquake extended beyond Antioch into other parts of Syria-Palestine, including Palestine proper.

JW: Damage in Palestine due to the 115 CE Trajan Quake is unlikely due to distance but such damage could have been caused by the hypothesized early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake. The ambiguous Talmudic references to an earthquake in Palestine around this time are discussed in the entry for the Incense Road Quake

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tower Collapsed | One of the Towers |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apamea and its surroundings affected | Apamea and its surroundings |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Destruction (Collapsed walls?) | Apamea |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Houses Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Houses |

|

|

| Citadel Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Citadel |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Houses Destroyed? (Collapsed Walls) | Apamea |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tower Collapsed | One of the Towers |

|

VI+? |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destruction (Collapsed walls?) | Apamea |

|

VIII+? |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Houses Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Houses |

|

VIII+ | |

| Citadel Destroyed (Collapsed Walls) | Citadel |

|

VIII+ |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Houses Destroyed? (Collapsed Walls) | Apamea |

|

VIII+ |

Balty, J. C. (1981). Guide D'apamee. Centre Belge De Recherches Archeologiques A

Apamee De Syrie Belgisch Centrum Voor Archeologische Opzoekingen Te Apamea In Syrie.

Balty, J.C. (1988). "Apamea in Syria in the Second and Third Centuries A.D."

The Journal of Roman Studies 78: 91-104.

Krauss, S. (1914). "Das Erdbeben vom Jahre 115 in Palästina." Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 58 (N. F. 22)(5/6): 290-304.

Walmsley, A. (2007b). "Economic Developments and the Nature of Settlement in the Towns and Countryside of Syria-Palestine, ca. 565-800." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61: 319-352.

Balty, Janine, et al., eds. Apamee de Syrie: Bilan des recherches archeologiques, 1065-1068. Brussels, 1969.

The results of the first four campaigns, as well as a discussion with colleagues excavating other sites

in Syria.

Balty, Janine, and Jean Ch. Balty, eds. Apamee de Syrie: Bilan des recherches archeologiques, 1969-1071. Brussels, 1972.

The results of the 1969-1971 campaigns.

Balty, Janine, and Jean Ch. Balty. "Julien et Apamee: Aspects de la

restauration de 1'hellenisme et de la politique antichretienne de

l'empereur." Dialogues d'Histoire Ancienne 1 (1974): 267-304. The

links between Apamea and Emperor Julian through an analysis of

the mosaics of the Neo-Platonic school discovered under the cathedral.

Balty, Janine, and Jean Ch. Balty. "Apame e de Syrie, archeologie et

histoire. I. Des origines a la Tetrarchie. " In Aufslieg und Niedergang

der romischen Welt, vol. II.8, edited by Hildegard Temporini, pp.

103-134 . Berlin, 1977. Ancient sources and archaeological monuments combined to present a history of Apamea.

Balty, Janine, ed. Apamee de Syrie: Bilan des recherches archeologiques, 1973-1979- Brussels, 1984.

Focuses on domestic architecture, presenting the results of the 1973-1979 campaigns in five different

houses within the context of extensive comparative material from

other sites in Syria and the Near East.

Balty, Janine, and Jean Ch. Balty. "Un programme philosophique sous

la cathedrale d'Apamee: L'ensemblc neo-platonicien de l'Empereur

Julien." In Texte et image: Actes du colloque international de Chantilly,

13 au 15 octobre 1982, pp . 167-176 . Paris, 1984. Attempts a global

analysis of the mosaics of the Neo-Platonic school.

Balty, Jean Ch., and Jacqueline Napoleone-Lemaire. L'eglise a atrium

de la Grande Colonnade. Brussels, 1969. The church through its successive architectural phases.

Balty, Jean Ch. "L'eveque Paul et le programme architectural et decoratif de la cathedrale d'Apamee." In Melanges d'histoire ancienne et

d'archeologie offerts d Paul Collart, edited by Pierre Ducrey et al„ pp .

31-46 . Cahier's d'Archeologie Romande de la Bibliotheque Historique Vaudoise, vol. 5. Lausanne, 1976. Interprets the program of

the cathedral's mosaics as influenced by the patronage of Bishop

Paul in the 630s.

Balty, Jean Ch. "Les grandes Stapes de l'urbanisme d'Apam6c-sur1'Oronte." Ktema 2 (1977): 3-16 . Sketches the evolution of town

planning through its four major phases (Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic).

Balty, Jean Ch. Guide d'Apamee. Brussels, 1981 . Intended primarily as

a guide to the monuments at Apamea, this book also provides an

extensive bibliography and numerous illustrations; the best introduction to the city.