Antioch

Left

LeftAerial View of Antioch from 1930s showing the city sited between the Orontes River on the lower left and the range of mountains capped by Mount Silpios. Also visible is the long modern street which follows the same lines as those of the Roman colonnaded north-south street

Click on image to open in a new tab

Kondoleon (2000)

Right

3D reconstruction of ancient Antioch

Click on image to open in a new tab

Found on es.pinterest

Attributed to OPENPICS.AEROBATIC.IO

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Antioch

English

Antioch on the Orontes

English

Antiochia ad Orontem

Greek

Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου

Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou

Greek

Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου

Antiókheia

Greek

Ἀντιόχεια

Antiochia

Latin

Antakya

Turkish

Andiok

Armenian

Անտիոք

Anṭākiya

Arabic

أنطاكية

Theoupolis

Greek

Epiphaneia

Meroe

settlement which pre-dated Antioch

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Harbiye

Turkish

Harbiyat

Arabic

حربيات

Harbiye

Arabic

دفنه

Dàphne

Greek

Δάφνη

- from Chat GPT 5, 18 September 2025

- sources: Antioch – Wikipedia

Established by Seleucus I Nicator in the early 3rd century BCE, Antioch became the capital of the Seleucid Empire and a center of Greek urban culture in the Near East. Its grid-planned streets, colonnaded avenues, and monumental architecture reflected its role as a deliberate counterpart to Alexandria. The city remained under Seleucid control until the mid-1st century BCE, when Roman influence began to dominate.

Under Rome, Antioch grew into the empire’s third city after Rome and Alexandria. It served as the capital of the province of Syria and later as a major imperial residence. The city’s prosperity supported great theatrical, bath, and civic complexes, while its cosmopolitan population included Greeks, Jews, Syrians, and later Christians. Antioch became a vital center of early Christianity, hosting one of the first Christian communities mentioned in the New Testament.

Antioch was repeatedly damaged by earthquakes, floods, and fires, which reshaped its urban fabric. The most catastrophic events included the earthquake of 115 CE, which struck during Trajan’s stay, and the disaster of 526 CE, which killed tens of thousands and was followed by fire. These calamities, alongside invasions, steadily diminished the city’s importance, though it remained a key Byzantine stronghold into the Middle Ages.

In 637 CE Antioch was taken by Arab Muslim forces, marking a major shift in the balance of power in Syria. The city returned briefly to Byzantine hands in the 10th century before falling to the Seljuk Turks. Captured by Crusaders in 1098, Antioch became the capital of the Principality of Antioch, one of the longest-lived Crusader states, until it was conquered by the Mamluks in 1268.

Later incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, Antioch never regained its earlier prominence. Yet its historical layers — Seleucid foundation, Roman metropolis, Christian center, Islamic conquest, and Crusader principality — mark it as one of the most contested and culturally rich cities of the ancient and medieval Near East.

Today, Antioch (modern Antakya) retains remnants of its ancient walls, churches, and mosaics, reminders of its former role as a crossroads of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern history. Its seismic past and political fortunes together shaped a city whose influence extended far beyond the Orontes valley.

- Antioch and surrounding

Region from Kondoleon (2000)

Antioch and surrounding Region

Antioch and surrounding Region

Kondoleon (2000) - Fig. 0.1 Archaeological

sites in the Hatay region of Turkey from De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

Fig. 0.1

Fig. 0.1

Archaeological sites in the Hatay region of Turkey

De Giorgi and Eger (2021) - Map of the Orontes

River from wikipedia

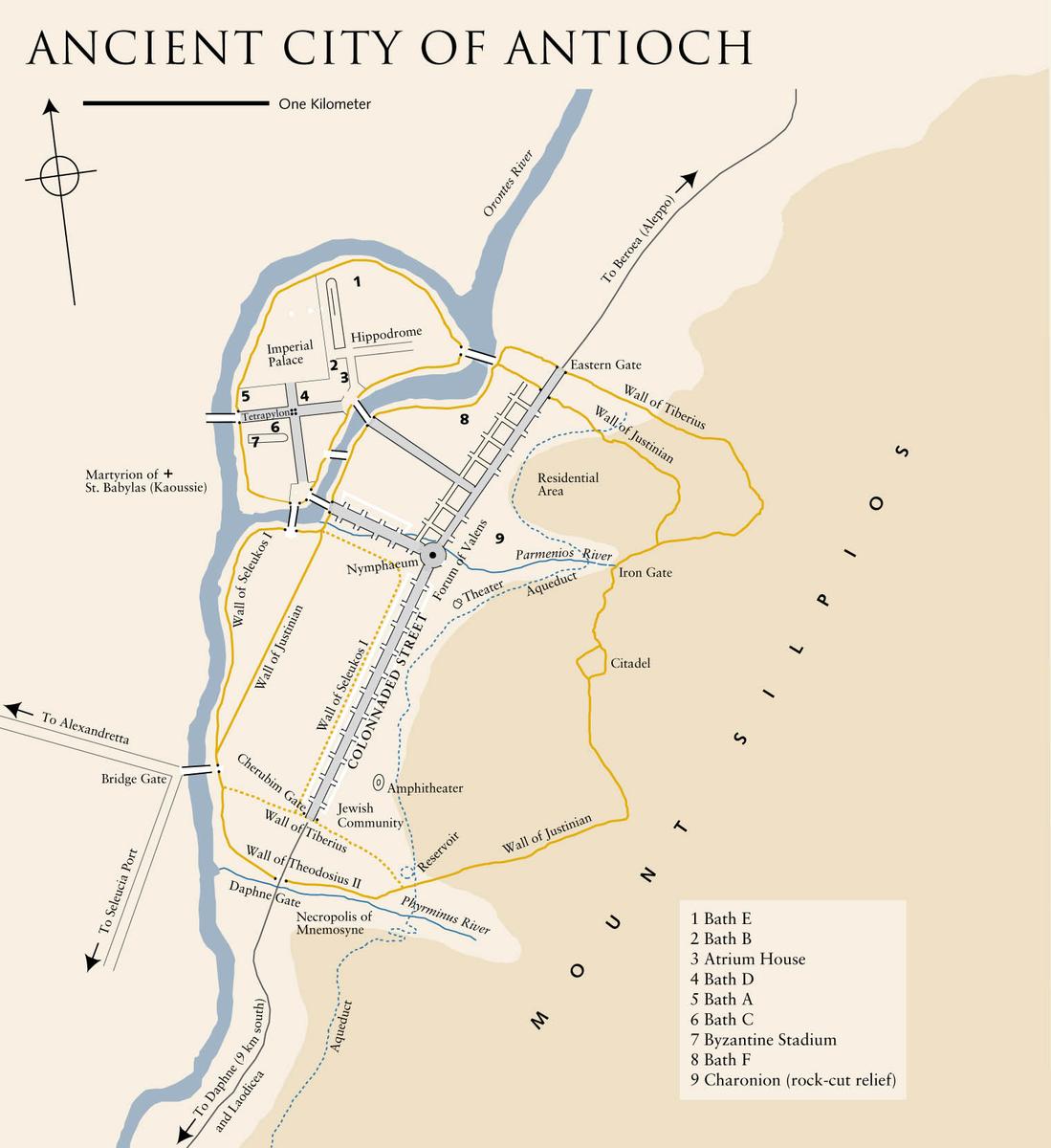

- The Ancient City of Antioch

from The Cleveland Art Museum

- Map of Antioch in Roman

and early Byzantine times from wikipedia

- Fig. 27.2 Map of earthquake

damage from the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch from De Giorgi et al. (2024)

Fig. 27.2

A map of earthquake damage from the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch (by Stephen Batiuk).

- Atrium House, new mosaics after earthquake

- Bath C, destroyed after EQ with long break in occupation

- House of Trajan's Aqueduct, damaged and abandoned after EQ

- 19-M, new colonnaded street

- Aqueduct of Trajan

- Temple Zeus Soter

- House of the Drunken Dionysus, earthquake before mosaic floors

- 16-P, Street destroyed and repaired after 115

- Hippodrome,evidence of capitals for repair after 115

- House of the Evil Eye, Lower Level, repairs due to EQ

- Villa near Bath B:mosaics / repairs after 115

- Theater, later 1st AD destroyed 341 but repaired, persists into 6th c.

- Bath E destroyed

- Bath F, evidence of capitals for repair after 458 earthquake

- 13-R Destruction Deposit

- 15-M Large Building destroyed

- 16-O vaults over Parmenius

- Bath A: abandoned after 526

- Stadium on island: this quarter destroyed 526 and thereafter outside Justinian’s city wall

- Villa 14-S on Mt Staurin destroyed

- House of the Phoenix; late ceramics and coins as TPQ for laying of mosaic here after EQ

- House of the Bird Rinceau, coin sealed between successive floors dates repairs after EQ

- House of the Buffet Supper Upper Level, below plaster floor covering mosaics were coins dating plasterfloor to post-526

- Kaoussie Church; final reconstruction after EQ

- Church at Seleucia Pieria destroyed, rebuilt anddamaged again in 528?

- 17-O Forum of Valens and Nymphaeum.

De Giorgi et al. (2024)

- Antioch and surrounding

Region from Kondoleon (2000)

Antioch and surrounding Region

Antioch and surrounding Region

Kondoleon (2000) - Fig. 0.1 Archaeological

sites in the Hatay region of Turkey from De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

Fig. 0.1

Fig. 0.1

Archaeological sites in the Hatay region of Turkey

De Giorgi and Eger (2021) - Map of the Orontes

River from wikipedia

- The Ancient City of Antioch

from The Cleveland Art Museum

- Map of Antioch in Roman

and early Byzantine times from wikipedia

- Fig. 27.2 Map of earthquake

damage from the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch from De Giorgi et al. (2024)

Fig. 27.2

A map of earthquake damage from the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch (by Stephen Batiuk).

- Atrium House, new mosaics after earthquake

- Bath C, destroyed after EQ with long break in occupation

- House of Trajan's Aqueduct, damaged and abandoned after EQ

- 19-M, new colonnaded street

- Aqueduct of Trajan

- Temple Zeus Soter

- House of the Drunken Dionysus, earthquake before mosaic floors

- 16-P, Street destroyed and repaired after 115

- Hippodrome,evidence of capitals for repair after 115

- House of the Evil Eye, Lower Level, repairs due to EQ

- Villa near Bath B:mosaics / repairs after 115

- Theater, later 1st AD destroyed 341 but repaired, persists into 6th c.

- Bath E destroyed

- Bath F, evidence of capitals for repair after 458 earthquake

- 13-R Destruction Deposit

- 15-M Large Building destroyed

- 16-O vaults over Parmenius

- Bath A: abandoned after 526

- Stadium on island: this quarter destroyed 526 and thereafter outside Justinian’s city wall

- Villa 14-S on Mt Staurin destroyed

- House of the Phoenix; late ceramics and coins as TPQ for laying of mosaic here after EQ

- House of the Bird Rinceau, coin sealed between successive floors dates repairs after EQ

- House of the Buffet Supper Upper Level, below plaster floor covering mosaics were coins dating plasterfloor to post-526

- Kaoussie Church; final reconstruction after EQ

- Church at Seleucia Pieria destroyed, rebuilt anddamaged again in 528?

- 17-O Forum of Valens and Nymphaeum.

De Giorgi et al. (2024)

Table 4.1

Table 4.1Known Church Sites in Antioch and Vicinity

De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

Fig. 0.2

Fig. 0.2Antioch Earthquakes by year, 250 BC to 1900 CE

De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

- Fig. 2.16 The House of

Trajan's aqueduct from De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

Fig. 2.16

Fig. 2.16

The House of Trajan's aqueduct

Source: Courtesy of the Antioch Expedition Archives, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University; Princeton

De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

- 1799 Engraving of the walls

of Antioch from Kondoleon (2000)

View of remains of walls and towers at the southern end of Antioch

View of remains of walls and towers at the southern end of Antioch

(Detail of engraving from Cassas 1799, no. 1, pl. 7 Harvard University Art Museums)

Kondoleon (2000) - 3D reconstruction of

ancient Antioch found on es.pinterest and attributed to OPENPICS.AEROBATIC.IO

- 1799 Engraving of the walls

of Antioch from Kondoleon (2000)

View of remains of walls and towers at the southern end of Antioch

View of remains of walls and towers at the southern end of Antioch

(Detail of engraving from Cassas 1799, no. 1, pl. 7 Harvard University Art Museums)

Kondoleon (2000) - 3D reconstruction of

ancient Antioch found on es.pinterest and attributed to OPENPICS.AEROBATIC.IO

- Fig. 2.19 The Remains of

Trajan's aqueduct from De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

Fig. 2.16

Fig. 2.16

The Remains of Trajan's aqueduct in Antakya

Source: Photograph by Andrea U. De Giorgi

De Giorgi and Eger (2021)

The earliest earthquake attested at Antioch, probably for the year 130 BCE, is described by the local Antiochene historian John Malalas (c. 490–570 CE) as θεομηνία, or “the wrath of God.

After Demetrianos, Antiochos, grandson of Grylos and son of Laodike, daughter of Ariarathes, emperor of the Cappadocians, reigned for nine years. At that time Antioch the Great suffered from the wrath of God, in the eighth year of his reign, in the time of the Macedonians, 152 years after the original laying of the foundation of the wall by Seleukos Nikator, at the tenth hour of the day, on 21st Peritios-February. It was completely rebuilt, as Domninos the chronicler has written It was 122 years after the completion of the walls and the whole city that it suffered; it was rebuilt better. (Malalas 8.25)Malalas was a late antique chronographer, a time writer. He recorded events annalistically, year-by year, with only very brief comments or literary structure to evaluate their causes or contexts, in this case some 600 years later. Malalas points to the now-lost chronicler Domninos (c. 300 CE) as his source,8 who claimed the city was “entirely rebuilt” (άνενεώθη πάσα) and “rebuilt better” (βελτίων εγένετο). There is confusion and contradiction here, for the when and who – by rulers’ genealogy, years into whoever’s reign, and date since the laying of the city walls – do not agree easily.9 Malalas seems to point to Antiochus VI by sequence (r. 148–142/1 BCE) but Antiochus VII (r. 138–129 BCE) is more likely insofar as the earthquake occurred “in the eighth year of Antiochus,” and only Antiochus VII had at least eight years in his reign! Antiochus VII is also remembered later by the epithet Euergetes or “generous,” a term typically connected to beneficence in public construction.10

Problems in chronology should be a warning to take heed of our primary sources. Whatever our author’s confusion around the year of this event, Malalas also provides a precise time and day by which the 130 BCE earthquake was later remembered to have occurred (“the tenth hour of the day, on 21st Peritios-February”). Malalas lacks any detailed description of the event or its effects, or the nature of state engagement with the reconstruction effort.

Better insight into Hellenistic earthquake recovery, at Antioch or otherwise, can come with wider context. Reports of earlier Classical earth quakes were concerned primarily with these events as portents or warnings, and unusual occurrences during wars (Thucydides I.101.2, I.128.1, III.89.2–5; Diodorus XI.63, XII.59; Plutarch Life of Cimon 16). After the age of Alexander the Great’s successors after 323 BCE, earthquakes were remembered as stimuli for international diplomatic engagement. Notably, an earthquake at Rhodes in 228 BCE causing severe damage and perhaps toppling the famous Colossus, one of the ancient world’s seven wonders, in a city renowned for its naval prowess– brought an influx of wealth into the city from all of Alexander’s competing successors, the tyrants of Sicily, and dynasts from Anatolia and the Levant. Polybius gives a lengthy account of these gifts, including not only money intended for rebuilding gymnasia and temples but also vessels for temples, catapults, statues, 170,000 pounds of wheat, the labor of master builders, and raw materials such as timber for ship buildings, pitch, iron, and lead. Such gifts were not merely magnanimous: they were intended to gain the favor of Rhodes, a critical naval power, during a period of heated warfare in the Eastern Mediterranean (Polybius 5.88–90). Polybius’s account, written several decades later with the benefit of hindsight, also takes the opportunity to shame miserly rulers of his own day (c. 140 BCE) who gave four or five talents after catastrophe, when Ptolemy III had given three hundred to Rhodes in 228 BCE. Polybius also praises the Rhodians for their ability to adroitly “convert this misfortune into an opportunity” (5.88).

Thus, earthquakes entered into the historic and diplomatic record of Mediterranean states after Rhodes in 228 BCE, with relief understood as a means for currying favor or establishing obligation between cities, states, or rulers. Seleucid kings engaged in similar efforts.11 Besides Seleucus’s gift to the Rhodians of duty free passage for their ships in his ports, he had also given substantial quantities of wheat, timber, resin, and hair (Polybius 5.89). Antiochus III had, after an earthquake of 199/8 BCE (Justin 30.4), helped to rebuild a sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos at Cos,12 repaired houses and city walls at Aegean Telos,13 a famous sanctuary at Panamara in Caria,14 and an unnamed temple near Stratonikeia.15 Such inscriptions point at a minimum toward the sustained interest of Hellenistic monarchs in financial support for the repair of temples and walls after earthquakes, besides the broader support available in extraordinary circumstances as at Rhodes after 228 BCE. Mostly lacking– though our sources would prob ably neglect such details anyway, by nature of their genres– are indicators that the Seleucids or their peers acted to rebuild rural areas, or artisanal zones in cities, or markets.

Records from a later earthquake at Antioch in 69 BCE are similarly thin on details: a later source, Justin, simply gives the improbable number of 170,000 dead (Epitome XL. 1/271), while Pompey Magnus is perhaps more plausibly attributed with reconstruction of the city’s collapsed bouleuterion after he took the city and annexed Syria for the Romans a short time later, in 64 BCE.16

8 On Domninus’s position among the sources of Malalas,

see Van Nuffelen (2017, 263).

9 Downey (1938).

10 Ambraseys (2009, 94) is also therefore incorrect in

placing the earthquake in 148 BC

11 Note, especially, Robert (1987) and Ma (1999, 88) for

Seleucid inscriptions.

12 Segre (1993, ED178, 31–32) and Habicht (1996:88). This

inscription records destruction around the sanctuary of

Aphrodite Pandamos. Note the similar text at Samos

(Habicht, 1957).

13 IGXII, 3, 30l.6–7 for Telos.

14 Holleaux (1952:209–210)for Panamara.

15 Sahin (1981, 4, l. 16–18) [... συνσεισθέ[ν]των των τεινεων ύπο του σεισμού...].

16 Malalas 8.30: κτίσας τό βουλευτήριον πεσόντα γάρ ην. For Pompey’s arrival at Antioch, see DeGiorgi and Eger (2021,71).

The earliest earthquake attested at Antioch, probably for the year 130 BCE, is described by the local Antiochene historian John Malalas (c. 490–570 CE) as θεομηνία, or “the wrath of God.

After Demetrianos, Antiochos, grandson of Grylos and son of Laodike, daughter of Ariarathes, emperor of the Cappadocians, reigned for nine years. At that time Antioch the Great suffered from the wrath of God, in the eighth year of his reign, in the time of the Macedonians, 152 years after the original laying of the foundation of the wall by Seleukos Nikator, at the tenth hour of the day, on 21st Peritios-February. It was completely rebuilt, as Domninos the chronicler has written It was 122 years after the completion of the walls and the whole city that it suffered; it was rebuilt better. (Malalas 8.25)Malalas was a late antique chronographer, a time writer. He recorded events annalistically, year-by year, with only very brief comments or literary structure to evaluate their causes or contexts, in this case some 600 years later. Malalas points to the now-lost chronicler Domninos (c. 300 CE) as his source,8 who claimed the city was “entirely rebuilt” (άνενεώθη πάσα) and “rebuilt better” (βελτίων εγένετο). There is confusion and contradiction here, for the when and who – by rulers’ genealogy, years into whoever’s reign, and date since the laying of the city walls – do not agree easily.9 Malalas seems to point to Antiochus VI by sequence (r. 148–142/1 BCE) but Antiochus VII (r. 138–129 BCE) is more likely insofar as the earthquake occurred “in the eighth year of Antiochus,” and only Antiochus VII had at least eight years in his reign! Antiochus VII is also remembered later by the epithet Euergetes or “generous,” a term typically connected to beneficence in public construction.10

Problems in chronology should be a warning to take heed of our primary sources. Whatever our author’s confusion around the year of this event, Malalas also provides a precise time and day by which the 130 BCE earthquake was later remembered to have occurred (“the tenth hour of the day, on 21st Peritios-February”). Malalas lacks any detailed description of the event or its effects, or the nature of state engagement with the reconstruction effort.

Better insight into Hellenistic earthquake recovery, at Antioch or otherwise, can come with wider context. Reports of earlier Classical earth quakes were concerned primarily with these events as portents or warnings, and unusual occurrences during wars (Thucydides I.101.2, I.128.1, III.89.2–5; Diodorus XI.63, XII.59; Plutarch Life of Cimon 16). After the age of Alexander the Great’s successors after 323 BCE, earthquakes were remembered as stimuli for international diplomatic engagement. Notably, an earthquake at Rhodes in 228 BCE causing severe damage and perhaps toppling the famous Colossus, one of the ancient world’s seven wonders, in a city renowned for its naval prowess– brought an influx of wealth into the city from all of Alexander’s competing successors, the tyrants of Sicily, and dynasts from Anatolia and the Levant. Polybius gives a lengthy account of these gifts, including not only money intended for rebuilding gymnasia and temples but also vessels for temples, catapults, statues, 170,000 pounds of wheat, the labor of master builders, and raw materials such as timber for ship buildings, pitch, iron, and lead. Such gifts were not merely magnanimous: they were intended to gain the favor of Rhodes, a critical naval power, during a period of heated warfare in the Eastern Mediterranean (Polybius 5.88–90). Polybius’s account, written several decades later with the benefit of hindsight, also takes the opportunity to shame miserly rulers of his own day (c. 140 BCE) who gave four or five talents after catastrophe, when Ptolemy III had given three hundred to Rhodes in 228 BCE. Polybius also praises the Rhodians for their ability to adroitly “convert this misfortune into an opportunity” (5.88).

Thus, earthquakes entered into the historic and diplomatic record of Mediterranean states after Rhodes in 228 BCE, with relief understood as a means for currying favor or establishing obligation between cities, states, or rulers. Seleucid kings engaged in similar efforts.11 Besides Seleucus’s gift to the Rhodians of duty free passage for their ships in his ports, he had also given substantial quantities of wheat, timber, resin, and hair (Polybius 5.89). Antiochus III had, after an earthquake of 199/8 BCE (Justin 30.4), helped to rebuild a sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos at Cos,12 repaired houses and city walls at Aegean Telos,13 a famous sanctuary at Panamara in Caria,14 and an unnamed temple near Stratonikeia.15 Such inscriptions point at a minimum toward the sustained interest of Hellenistic monarchs in financial support for the repair of temples and walls after earthquakes, besides the broader support available in extraordinary circumstances as at Rhodes after 228 BCE. Mostly lacking– though our sources would prob ably neglect such details anyway, by nature of their genres– are indicators that the Seleucids or their peers acted to rebuild rural areas, or artisanal zones in cities, or markets.

Records from a later earthquake at Antioch in 69 BCE are similarly thin on details: a later source, Justin, simply gives the improbable number of 170,000 dead (Epitome XL. 1/271), while Pompey Magnus is perhaps more plausibly attributed with reconstruction of the city’s collapsed bouleuterion after he took the city and annexed Syria for the Romans a short time later, in 64 BCE.16

8 On Domninus’s position among the sources of Malalas,

see Van Nuffelen (2017, 263).

9 Downey (1938).

10 Ambraseys (2009, 94) is also therefore incorrect in

placing the earthquake in 148 BC

11 Note, especially, Robert (1987) and Ma (1999, 88) for

Seleucid inscriptions.

12 Segre (1993, ED178, 31–32) and Habicht (1996:88). This

inscription records destruction around the sanctuary of

Aphrodite Pandamos. Note the similar text at Samos

(Habicht, 1957).

13 IGXII, 3, 30l.6–7 for Telos.

14 Holleaux (1952:209–210)for Panamara.

15 Sahin (1981, 4, l. 16–18) [... συνσεισθέ[ν]των των τεινεων ύπο του σεισμού...].

16 Malalas 8.30: κτίσας τό βουλευτήριον πεσόντα γάρ ην. For Pompey’s arrival at Antioch, see DeGiorgi and Eger (2021,71).

Roman hegemony brought with it more detailed accounts of rebuilding efforts after earthquakes throughout the Mediterranean. An earthquake in 17 CE that shook cities through out western Asia Minor is especially well documented by primary sources, who report that Augustus decreed widespread remission of taxes, direct financial support, and the visit of imperial officials to assist the affected cities (Tacitus, Annals 2.47 and 4.13.1;Strabo13.4.8).17 This package of state response set a precedent for later earthquakes (including at Antioch in 37, 41, and 115 CE), and for which local Antiochene perspectives from Malalas are supplemented by inscriptions and historians including Dio Cassius, who wrote from a senator’s perspective back at Rome. Generally, imperial Roman sources were concerned with top-down administrative details of immediate state response and issues of finance: they were less concerned with local casualties, the documentation of events from local perspectives, or even the long-term consequences of catastrophe. Two recorded earthquakes at Antioch followed in quick succession, in 37 and 41 CE.

A description of the 37 CE event during the reign of Caligula survives only in Malalas (10.18). Lacking details of destruction or casualties, the Antiochene account nevertheless preserves three key features of typical Roman earthquake response. First, money was sent directly from the emperor to the city. Second, a larger program of new urban infrastructure was set in motion or stimulated by the disaster: in this case the earthquake was quickly followed by construction of a new aqueduct, baths, and temples. Third, two senators and a prefect were sent from Rome “to protect the city and to rebuild it from the benefactions made by the emperor, and equally to make donations to the city from their private income and to live there.” Malalas adds the interesting detail that– besides a bath complex (the Varium), and a nymphaeum (the Trinymphon) decorated with statues – the senators sent from Romealso “built very many dwellings out of their private incomes.” While governmental attention to public buildings has been typical since the Hellenistic period, the focus on private housing stock seems novel. Apart from the new infrastructure that followed in the 37 CE earthquake’s wake according to Malalas– his testimony has been associated with the remains of a Roman aqueduct coming from Daphne, whose construction technique is consistent with a date in the first century CE18 – the only archaeological evidence for this event may come from Princeton’s excavations of the so-called Atrium House, where mosaics may be dated to the period after 37 CE.19

Just four years later in 41 CE, another earthquake during the reign of Claudius was accompanied by further destruction of houses, beside damage to the temples of Artemis, Ares, and Herakles (Malalas 10.23). Malalas again records here the quintessential Roman state response: the remission of local taxes paid from cities to Rome, so that cities affected by earthquakes could use these funds to directly pay for repairs themselves, instead. In the case of the 41 CE earthquake at Antioch, the “emperor Claudius relieved the guilds ... of the public service [or tax] of the kapnikon / καπνικόν, which they were providing to reconstruct the city’s roofed colonnades which had been built by Tiberius Caesar” (Malalas 10.23). Καπνικόν, from καπνός or smoke, is usually translated as a hearth tax, that is to say a tax on chimneys, which were easier to count than people; it appears here in its first instantiation, though the precise mean ing of the passage is unclear. Either the hearth tax which had been supporting the colonnade restoration (presumably after the previous earthquake of 37 CE) was lifted entirely; or the hearth tax’s funds were diverted to restoration of the colonnades (meaning that the guild members still paid, but its funds went to a new purpose).20 The hearth tax appeared rarely throughout the medieval period, before it reappeared more widely in early modern times.21 In those later forms, at least, the hearth tax was progressive in the sense that a large house or workshop would have more chimneys (and presumably money) than a smaller household.22

The first earthquake at Antioch for which we can meaningfully compare textual and archaeological evidence came in 115 CE (see Figure 27.2). It was vividly described by the Roman senatorial historian Dio Cassius (c. 155–235 CE), who was neither an eyewitness nor a contemporary. Dio Cassius recalls, however, the name of a consul who died there, and so presumably he relied on a closer source for his own account (68.24–25). Such unusual details may have been preserved because the emperor Trajan was in residence at Antioch at the time of the earthquake, to manage war with the Parthian Persians. Trajan only narrowly escaped from a collapsing building through a room’s window. He stayed outdoors in the hippodrome throughout the aftershocks. Dio Cassius reports significant destruction of houses and the loss of life – “the crash and breaking of timbers together with tiles and stones ... an inconceivable amount of dust ... The number of those who were trapped in the houses and perished was past finding out ...Great numbers were suffocated in the ruins.”

The participation of survivors in community sponsored offerings of thanksgiving, including even the construction of whole temples, may have fostered community cohesion in future earthquakes. After the 115 CE earthquake, Malalas tells us that “the surviving Antiochenes who remained then built a temple on which they inscribed ‘Those who were saved erected this to Zeus the Savior’” (11.8).

Dio Cassius says little concerning the recovery or reconstruction effort that must have followed the 115 CE earthquake, however. Malalas gives more details, indicating a major construction program sponsored by Trajan that followed the 115 CE earthquake: beginning with the sacrifice of a virgin girl named Kalliope, we are told, Trajan restored the city’s colonnades and built a new aqueduct and bath, named for himself, besides a theater (11.8–11).23

The Princeton excavators at Antioch understood the 115 CE event as a watershed in the city’s history. Literary sources became a point of reference for interpretation and dating of changes in buildings throughout the city, including damage and repair, but also abandonment or new construction: new mosaics were added in the so-called Atrium House and the House of the Drunken Dionysus,24 repairs were made at the Hippodrome, as suggested by new column capitals dated to the reign of Hadrian,25 and the city cardo was built anew26 while other streets were repaired.27 On the other hand, Bath C was destroyed in the 115 earthquake and abandoned, so too was the so-called House of Trajan’s Aqueduct.28

Leaving aside aspersions of child sacrifice from Christian chronicler Malalas, and the difficulties posed by evaluation of claims made by the Princeton excavators some 90 years later, it still stands that the initiation of significant new infra structure projects and repairs to public or private buildings followed the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch, in a pattern typical for major cities under the Roman empire. We turn now to the Byzantine.29

17 See also Ambraseys(2009).

18 Antioch II, 52; Gatier, Leblanc, and Poccardi (2004,241–242).

19 See Levi(1947, 16).

20 Downey (1961, 196,n. 145).

21 s.v. “HearthTax” and “Kapnikon” in Kazhdan (1991, 906, 1105).

22 Gurrin(2004).

23 Jeffreys (1990, 56) says “much of Malalas’ narrative on

Trajan’s activities is uncorroborated by other sources and is probably fictitious.”

24 Levi(1947, 16,40).

25 Antioch III, 150.

26 Antioch V, 30–33.

27 Antioch V,72

28 Levi(1947,289,28).

29 Mordechai and Pickett (2018)

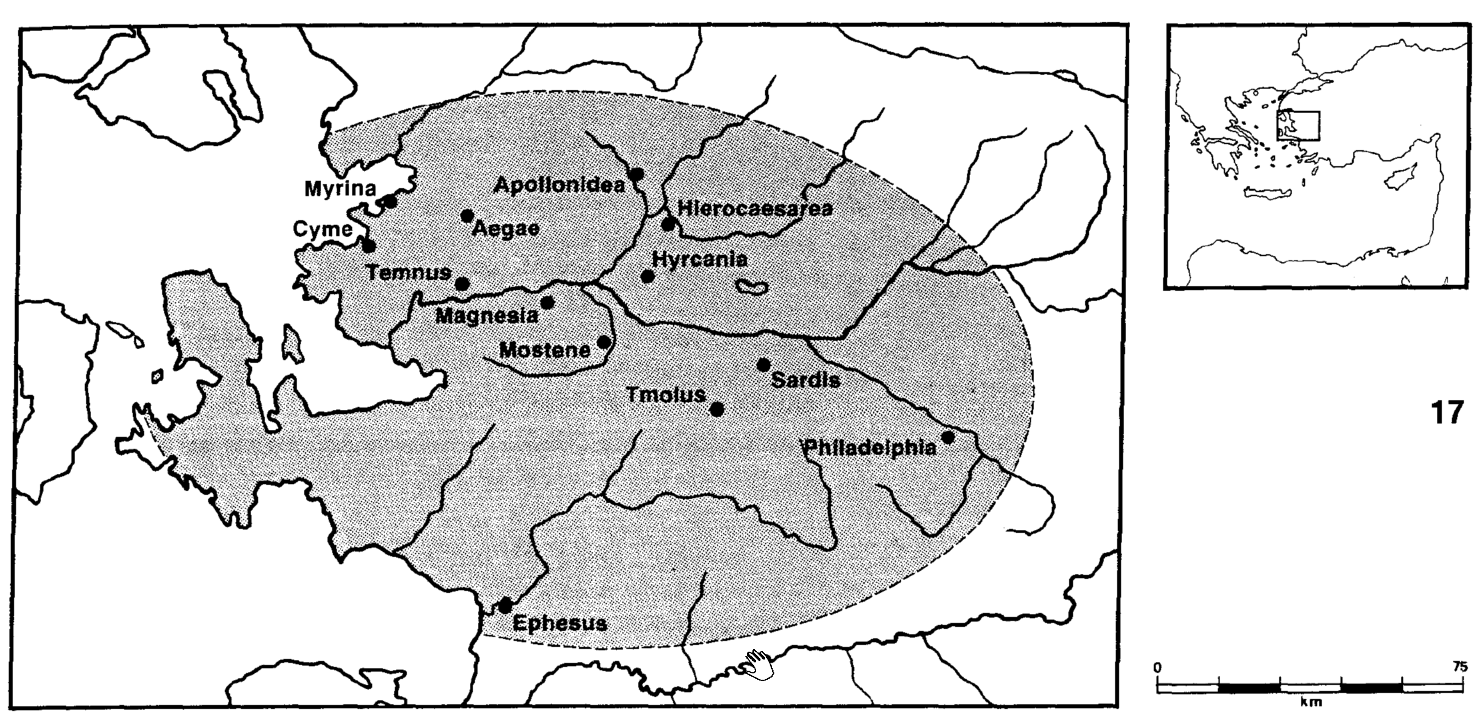

AD 17 Lydia

In AD 17 twelve towns in Asia Minor were almost totally

destroyed or heavily damaged. Details about the damage

are not given in the sources, but this was apparently a

major disaster, which fell heaviest on Sardis, then Magnesia,

and attracted the attention of the Imperial Office

in Rome.

The towns which were badly damaged were

Aegae, Apollonis, Cyme, Hierocaesarea, Hyrcania, Mosthene,

Myrina, Philadelphia, Temnus and Tmolus, all

within an area of a radius of 45 km, which extended for

a distance of 140 km along the Hermus valley.

As a result of the earthquake the ground opened

up in places and parts of the valley were uplifted and others sank; landslides added to the damage. In the cities

the disaster was worsened by the fact that the earthquake

happened at night and fires broke out immediately afterwards.

The date of the event can be deduced approximately from the records of classical authors: Strabo,

who completed his Geography about AD 20, mentions

the destruction of Magnesia ‘by the recent earthquakes’.

Eusebius gives the precise date of a.Ab. 2032/Tib.3 =

Oct. AD 16/17–Oct. AD 15/18, which fits the sequence

of events given in Tacitus. St Jerome (writing during the

fourth century) gives a year too high, Ol.199.5 = AD 18.

The earthquake happened in a region where

earthquakes were known to be frequent. Philadelphia,

for instance, had already suffered from earlier earthquakes before AD 17. It was said that ‘. . . Philadelphia is

ever subject to earthquakes; incessantly the walls of the

houses are cracked, different parts of the town being thus

affected at different times; for this reason but few people live in the town, and most of them spend their lives

as farmers in the country; yet one may be surprised at

the few, that they are so fond of the place when their

dwellings are so insecure’ (Tac. ii. 47).

Reports of the earthquake soon reached Rome,

and a senatorial commissioner, accompanied by five lectors, was charged with the relief of the area and sent to

assess the destruction and to administer aid. Sardis and

Magnesia received considerable financial assistance from

Rome, and remission of taxes was given to all the towns

damaged or destroyed by the earthquake.

The impact of this earthquake, both physical and

political, is reflected in its widespread documentation

by contemporary and near-contemporary authors, all of

whose accounts substantially agree. Individual authors

add significant details. Pliny notes that it happened during the night, which would have increased the death toll,

since everyone was indoors. Tacitus, a near contemporary, records the political response, which involved an

assessment of damage, and revealed Sardis as the worst

hit (note that Strabo says ‘not only Sardis . . .’). Sardis

and Magnesia received considerable financial assistance

from Rome as well as remission of all contributions to the

imperial exchequer for a period of five years. Ten million

sesterces were promised to Sardis by the treasury (Tac.

ii. 47), while remission of tribute to the public exchequer

for the same period was granted to the other towns that

were affected, but not necessarily destroyed by the earthquake.

Magnesia ‘ranked second in the extent of . . . losses

and indemnity’, according to Tacitus’s account; the other

cities received tax remission for the same term, and a sen-

atorial commission was sent to examine the damage in

each case and to administer relief as necessary. This sug-

gests that Sardis received its pay-out as a reaction to the

widespread and immediate sympathy, without a senatorial visitation (and also gave the emperor an opportunity

for image-enhancement, as is shown by commemorative

coins).

In gratitude they erected a colossus next to the

temple of Aphrodite in Rome, inscribed with the names

of all the cities, including Cibyra and Ephesus, which

were probably damaged in later earthquakes.

A second-century author records that ‘many dis-

tinguished cities of Asia Minor’ set up a colossus in

Rome in gratitude for Tiberius’s generous relief. This

has not been found, but an inscription on a pedestal

(see Figure 3.6) discovered in Puteoli (Pozzuoli) records

Tiberius’s restoration of the twelve Asian cities and of

Cibyra and Ephesus (see below), which from the titles

ascribed to Tiberius dates from about AD 28–30, sug-

gesting that the colossus in Rome dates from about the

same time, or shortly thereafter. This might be taken to

give some indication of the time taken for the cities to

recover, and hence of the gravity of the disaster, but it

is more likely that the twelve Asian cities, together with

Cibyra and Ephesus, took Tiberius’s reception of a new

title as an opportunity to thank him formally.

An inscription from Sardis (CIG ii. 3450/IGR iv.

1514) mentions the restoration of a temple and statue

after the earthquake, and another inscription from the

same town records the names of those who were cho-

sen as representatives to Tiberius in the aftermath of the

earthquake, and who evidently pleased him. While the

latter inscription does not mention the earthquake, it is

hard not to connect it with that disaster because repre-

sentatives of all the twelve cities are listed.

Other inscriptions refer to the restoration work in

Sardis and Thyatira (CIG 3450; Robert 1978, 404, 405), a

site not mentioned in the Puteoli inscription, which must

have perhaps suffered and been relieved earlier after the

earthquake during the period AD 6–13. The inscription

from Thyatira, about 30 miles north of Sardis, records

the restoration of a statue after an earthquake (CIG ii.

3488/IGR. iv.1237).

Also a sestertius of AD 22 mentions the restora-

tion of the cities in Asia (BMC i. Tib. 70).

Archaeological excavations on the east bank of the

Pactolus in Sardis have revealed ‘a very complicated system of substructure walls and vaults erected

by the Romans’ under the synagogue (Hanfmann and

Detweiler 1966). After the earthquake, Sardis was rebuilt

on an extensive plan. Archaeological excavations show

an unusual type of foundation construction used in the

reconstruction of part of the city on the east bank

of the river Pactolos. A grid of wooden beams under

the foundations was employed, on which the structures

were built, presumably to reduce differential settlement

(Alkim 1968, 44).

‘The greatest earthquake in human memory occurred when Tiberius Caesar was emperor, twelve Asiatic cities being overthrown in one night . . .’ (Plin. HN II. 86/LCL. i. 330).

‘In the same year, twelve important cities of Asia collapsed in an earthquake, the time being night, so that the havoc was the less foreseen and the more devastating. Even the usual resource in these catastrophes, a rush to open ground, was unavailing, as the fugitives were swallowed up in yawning chasms. Accounts are given of huge mountains sinking, of former plains seen heaved aloft, of fires flashing out amid the ruin. As the disaster fell heaviest on the Sardians, it brought them the largest measure of sympathy, the Caesar promising ten million sesterces, and remitting for five years their payments to the national and imperial exchequers. The Magnesians of Sipylus were ranked second in the extent of their losses and their indemnity. In the case of the Temnians, Philadelphenes, Aegeates, Apollonideans, the so-called Mostenians and Hyrcanaian Macedonians, and the cities of Hierocaesarea, Myrina, Cyme and Tmolus, it was decided to exempt them from tribute for the same term and to send a senatorial commission to view the state of affairs and administer relief.’ (Tac. Ann. II. 47/LCL. ii. 458–460).

‘And the story of Mt Sipylus and its ruin should not be put down as mythical, for in our own times Magnesia, which lies at the foot of it, was laid low by earthquakes, at the time when not only Sardeis, but also the most famous of the other cities, were in many places seriously damaged. But the emperor restored them by contributing money . . .’ (Str. XII. viii. 18/LCL. v. 516).

‘To the present Aelian cities we must add Aegae, and also Temnus . . . These cities are situated in the mountainous country that lies above the territory of Cyme and that of the Phocians and that of the Smyrnaeans, along which flows the Hermus. Neither is Magnesia, which is situated below Mt Sipulus, and has been adjudged a free city by the Romans, far from these cities. This city too has been damaged by the recent earthquakes.’ (Str. XIII. iii. 5/LCL. vi. 158).

‘. . . recently it [Sardis] has lost many of its buildings through earthquakes. However, the forethought of Tiberius, our present ruler, has, by his beneficence, restored not only this city but many others – I mean all the cities that shared in the same misfortune about the same time.’ (Str. XIII. iv. 8/LCL. vi. 178).

‘The cities in Asia which had been damaged by the earthquakes were assigned to an ex-praetor with five lictors; and large sums of money were remitted from their taxes and large sums were also given them by Tiberius.’ (D.C. LVII. xvii/LCL. vii. 158).

‘Apollonius the grammarian records that during the reign of Tiberius Nero an earthquake occurred and that many distinguished cities of Asia Minor were razed to the ground, which Tiberius then restored out of his own money. In gratitude the cities made him a colossus, which they erected next to the temple of Aphrodite, which is in the Roman agora, and they added to it statues of each city in order.’ (Phleg. 42/621).

‘a.Ab. 2032 Tib.3: Thirteen cities of Asia Minor collapsed in an earthquake, Ephesus, Magnesia, Sardis, Mostene, Aegae, Hierocaesarea, Philadelphia, Tmolus, Temus, Myrina, Cyme, Apollonia Dia and Hyrcania.’ (Eus. Hist. 146).

‘Ol.CXCIX.5: Thirteen cities collapsed in an earthquake, Ephesus, Magnesia, Sardis, Mostene, Aegeae, Hierocaesarea, Philadelphia, Tmolus, Tem[n]us, Myrina, Cyme, Apollonia Dia and Hyrcania.’ (Hieron. Hist. 172).

‘To the divine Tiberius Caesar, son of the divine Augustus, nephew of Julius Augustus, pontifex maximus and consul for the fourth time, imperator for the eighth time, and tribune for the 32nd time, the Augustan state restored . . . henia, Sardis, Magnesia, Philadelphia, Tmolus, Cyme, Temnus, Cibyra, Myrina, Ephesus, Apollonidea, Hyrcania, Mostene, Aegae, Hierocaesarea.’ (ILS i. 42/CIL x. 1624).

‘Socrates son of Polemaeus equipped the temple of Pardale and erected the Hera. [ . . . ] Julia Lydia his daughter restored them after the earthquake.’ (Robert 1978, 405).

‘Sabinus of Mostene has pleased [the emperor], as have Seleucus son of Nearchus of Cibyra, Claudian of Magnesia, Charmides son of Apollonius [ . . . ], Macedon son of Alexander Jocundus of Apollonidea, [ . . . ] of Hyrcania, Serapion son of Aristodemus of Myrina, and Diogenes son of Diogenes of Tem- nos.’ (CIG ii. 3450/IGR. iv. 1514).

‘Tiberius Claudius Amphimachus, greatest stephano- phoros, was honoured by the setting-up of a statue by the Areni and Nagdemi, after he judged and restituted the [borders of] the villages. And after that, when the statue and its base were damaged by an earthquake, Julia Severina of Stratonicea, his daughter, having provided a pedestal and repaired the statue, had it erected out of her own funds.’ (CIG ii. 3488/IGR. iv. 1237; Robert 1978, 404).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

(079) a night in the year 17 – Aegae, Apollonidea, Cyme,

Ephesus?, Hierocaesarea, Hyrcania, Magnesia, Mostene,

Myrina, Philadelphia, Sardis, Temnus, Tmolus

Surface Faulting

sources 1

- Strabo 12.8.18, 13.3.5, 13.4.8, 13.4.10

- Bian. apud Anthol. Pal. 9.423

- Vell. 2.126

- Sen. NQ 6.1.13; ad Luc. 14.91.9

- Plin. n.h. 2.200

- Apoll. Gramm. apud Phleg. FGrHist 257 F 36 (xiii)

- Tac. Ann. 2.47.1–4

- Suet. Tib. 48

- Dio Cass. 57.17.7

- Orac. Sibyll. 5.289

- Eus. Hieron. Chron. 172a

- Ioh. Lyd. De ost. 53

- Sol. 40.5

- Georg. Sync. 603

- Niceph. Call. 1.17

- Chron. A 84

- Chron. B 86–7

- Matt. Palm. Lib. de temp. 9

- CIL 3.7096

- CIL 10.1624 = ILS 156 add.

- SEG 28.928

- IGR 4.1514

- Foucart (1887)

- BMC K90535 D-36 D

- Weismantel (1891)

- Spinazzola (1902)

- Ambraseys (1971)

- Robert (1978)

- Mitchell (1987)

- Catalogo epigrafi (1989)

- Clementoni (1989)

- Panessa (1991)

- Manetti [1457]

- Ligorio [1574–7]

- Bonito (1691)

- von Hoff (1840)

- Mallet (1853)

- Schmidt (1881)

- Shebalin et al. (1974)

- Papazachos and Papazachos (1989)

- Guidoboni (1989)

Area affected by 17 CE Earthquake

Area affected by 17 CE EarthquakeGuidoboni et al. (1994)

On an unidentified night in 17 AD., a very violent earthquake struck the Province of Asia. Its effects were disastrous, particularly in Lydia (now part of western Turkey, opposite the Aegean Sea). The most detailed description of what happened and of the measures taken to help the victims, is to be found in the Roman historian Tacitus. He tells us that the city of Sardis suffered the worst damage, followed by Magnesia on Mt.Sipylus, the number of victims being the greater because of outbreaks of fire in the ruins, and because, since the disaster happened at night, those who tried to flee to open ground fell into fissures opened up by the earthquake. Tacitus writes:

In the same year, twelve important cities in Asia collapsed in an earthquake. It happened at night, with the result that the havoc was the less fore-seen and the more devastating. Even the usual resource in these catastrophes of rushing out into the open was unavailing, as the fugitives were swallowed up in yawning chasms. Accounts are given of huge mountains sinking, of former plains seen heaved aloft, and of fires flashing out amid the ruins. As the disaster fell heaviest on the Sardians, it brought them the largest measure of sympathy, the emperor promising ten million sesterces, and exempting them from payments to the national and imperial exchequers for five years. The Magnesians of Sipylus were ranked second as to the extent of their losses and their indemnity. In the case of the Temnians, Philadelphians, Aegeates, Apollonideans, the so-called Mostenians and Hyrcanian Macedonians, and the cities of Hierocaesarea, Myrina, Cyme, and Tmolus, it was decided to exempt them from tribute for the same period and to send a senatorial commissioner to assess the situation on the spot and administer relief. M.Ateius, a former praetor, was chosen for this purpose, because Asia was governed by a former consul, and this avoided problems arising from rivalry between equals.

Many other Greek and Latin writers record the earthquake, though their descriptions are much briefer than that of Tacitus. Nearest in time to the earthquake was Strabo, and he was also well aware of the seismicity of the region. There are three passages in his work where the earthquake is mentioned. At 12.8.18 he writes:Eodem anno duodecim celebres Asiae urbes conlapsae nocturno motu terrae, quo improvisior graviorque pestis fuit. Neque solitum in tali casu effugium subveniebat in aperta prorumpendi, quia diductis terris hauriebantur. Sedisse immensos montis, visa in arduo quae plana fuerint, effulsisse inter ruinam ignis memorant. Asperrima in Sardianos lues plurimum in eosdem misericordiae traxit: nam centies sestertium pollicitus Caesar, et quantum aerario aut fisco pendebant, in quinquennium remisit. Magnetes a Sipylo proximi damno ac remedio habiti. Temnios, Philadelphenos, Aegeatas, Apollonidenses, quique Mosteni aut Macedones Hyrcani vocantur, et Hierocaesariam, Myrinam, Cymen, Tmolum levari idem in tempus tributis mittique ex senatu placuit, qui praesentia spectaret refoveretque. Delectus est M.Ateius e praetoriis; ne consulari obtinente Asiam aemulatio inter pares et ex eo impedimentum oreretur.

for even today earthquakes have destroyed Magnesia at the foot of this mountain, when they also destroyed Sardis and the most famous cities in many other areas; but the emperor [Tiberius] had them rebuilt, after granting them tax exemptions.

(13.3.5)καί γάρ ννν τήν Μαγνησίαν τήν υπ' αυτω κατέβαλον σεισμοί, ήνίκα καί Σάρδεις καί τών άλλων τας έπιφανεστάτας κατά πολλά μέρη διελυμήναντο• έπηνώρθωσε δ' ό ήγεμών, χρήματα έπιδους.

It [Magnesia] too was reduced to ruins in the recent earthquakes.

(13.4.8)καί ταντην δ' έκάκωσαν οί νεωστί γενόμενοι σεισμοί.

The city [of Sardis...] recently lost many houses in earthquakes; but the present emperor, Tiberius, generously contributed to the restoration of this and many other cities which had shared the same fate in the same circumstances.

In the Palatine Anthology, there is an epigram by the Bithynian poet Bianor which recalls the tragic fate of Sardis:ή πόλις [...] νεωστί υπό σεισμών άπέβαλε πολλήν τής κατοικίας. ή δέ τον Τιβερίον πρόνοια, τον καθ' ημάς ήγεμόνος, καί ταντην καί τών άλλων συχνάς ανέλαβε τας ευεργεσίαις, όσαι περί τόν αυτόν καιρόν έκοινώνησαν τον αυτού πάθους.

Alas, wretched Sardis [...], you were totally overtaken by a single catastrophe when you plunged into a chasm created by an immense split in the earth. Helice and Bura were swamped by the sea; but although you were on dry land, you suffered the same fate as they did in the deep waters.

The power of the earthquake is made clear in Pliny's Naturalis historia:Σάρδιες [...] ννν δή όλαι δνστηνοι ές έν κακόν άρπασθείσαι ές βυθόν έξ αχανούς χάσματος ήρίπετε. Βονρα καθ' ή θ' `Ελίκη κεκλυσμέναι• αϊ δ' ένί χέρσω Σάρδιες έμβυθίαις είς έν 'ίκεσθε τέλος.

The greatest earthquake in human memory occurred when Tiberius Caesar was emperor, for twelve Asian cities were destroyed in a single night.

Seneca also mentions it, not only in his Naturales Quaestiones:Maximus terrae memoria mortalium exstitit motus Tiberii Caesaris principatu, xmurbi-bus Asiae una nocte prostratis.

But also, in passing, in a letter to Lucilius:Asia Minor lost twelve cities at the same time.

How many cities in Asia Minor, [...] were reduced to ruins in a single earthquake?

Suetonius mentions the help given by the emperor Tiberius. He writes:Quotiens Asίae, [...] urbes unο tremοre cecίderunt.

Tiberius was not liberal with aid even to the provinces, except in the case of Asia Minor, since the cities there had been destroyed in an earthquake.

Dio Cassius records also tax exemptions which were granted by the emperor to the damaged cities:Ne provincias quidem liberalitate ulla sublevavit, excepta Asia, disiectis terrae motu civitatibus.

A man of consular rank with five lictors was put in charge of the cities of Asia Minor which had been damaged in an earthquake, and in addition many tax exemptions were granted by Tiberius, as well as generous sums of money.

Another anecdote about the earthquake —dating to not long after it occurred — is contained in a fragment from Apollonius Grammaticus (1st century AD ) preserved in Phlegon of Tralles (2nd century AD.):Τας τε έν τή 'Ασιι πόλεσι ταίς υπο τοϋ σεισμοϋ κακωθείσαις cινήρ έστρατηγηκώς σύν πέντε ραβδοϋχοις προσετcίθη, καί χρήματα πολλά μέν έκ τών φόρων άνείθη πολλά δέ καί παρά τον Τιβερίου έδόθη.

Apollonius Grammaticus tells us that there was an earthquake during the reign of Tiberius Nero, and that many famous cities in Asia were almost totally destroyed. Later on Tiberius rebuilt them at his own expense. Consequently, they built and dedicated to him a colossal statue next to the Temple of Venus in the Roman Forum, and each of the cities subsequently put up statues.

The generosity shown by Tiberius towards the cities which had suffered in the earthquake was also commemorated in a series of sesterces bearing the image of the emperor himself.'Απολλώνιος δέ ό γραμματικός ϊστορεί έπί Τιβερίου Νέρωνος σεισμόν γεγενήσθαι καί πολλάς καί όνομαστάς πόλεις τής 'Ασίας άρδην άφανισθήναι, ας ϋστερον ό Τιβέριος οϊκεία δαπάνη πάλιν άνώρθωσεν. άνθ' ών κολοσσόν τε αυτώ κατασκευάσαντες ανέθεσαν παρά τώ τής 'Αφροδίτης ίερώ, ό έστιν έν τή 'Ρωμαίων αγορά, καί τών πόλεων έκάστης έφεξής ανδριάντας παρέστησαν.

Since the cities damaged in the earthquake were assisted by Tiberius, they erected a monument to him. It was rectangular in shape, and the base was discovered at Pozzuoli in 1693. It bears the following inscription (cm 10.1624 = Hs 156 add.), which can be dated to 30 A.D. on the basis of the titles attributed to the emperor:

To Tiberius Caesar Augustus, son of the emperor Augustus, nephew of the emperor Julius, pontifex maximus, consul for the fourth time, emperor for the eighth time, granted tribunician power for the thirty-second time, the Augustales. The city authority restored [...] Sardis [...], [Magneslia, Philadelphia, Tmolus, Cyme, Temnus, Cibyra, Myrina, Ephesus, Apollonidea, Hyrca[nia], Mostene, [Aeg]ae and [Hieroc]aesarea.

On the four sides of the base are representations of the cities which were struck by the earthquake: Sardis, Magnesia, Philadelphia, Tmolus, Cyme, Temnus, Cibyra, Myrina, Ephesus, Apollonidea, Hyrcania, Mostene, Aegae and Hierocaesarea.Ti(berio) Caesari divi / Augusti f(ilio) divi / Iu n(epoti) Augusto / pontif(ici) maximo co(n)s(uli) irrl / imp(eratori) viii trib(unicia) potestat(e) z / Augustales res publica I restituit. I [---]ihenia Sa[rdels Moron, [Magnes ]ia I Philadelphea, Tmolus, Cyme I Temnos, Cibyra, Myrina, Ephesos, Apollonidea, Hyrca[nia] I Mostene, Meg-kw, [Hieroc]aesarea.

This raises a problem, because Ephesus and Cibyra have to be added to Tacitus' list, giving not twelve but fourteen cities. The problem of Cibyra could be solved in terms of Tacitus' evidence that it was destroyed shortly before 23 AD.; and so the base from Pozzuoli could include the thanks of the cities struck by the earthquakes of 23 AD as well as 17 AD. There remains the problem of Ephesus, however, for it does not figure in Tacitus' list of twelve cities. Archaeologists do not yet seem to have found clear traces of an earthquake at Ephesus at this period; and any such evidence would inevitably be limited, because we lack a comprehensive epigraphic and archaeological study of the reconstruction of buildings in the region, such as might lead to a future regional study of the seismicity of western Asia Minor.

Given the above considerations, we can formulate at least three possible solutions to the problem:

- Ephesus as well as Cibyra may have been struck by the earthquake of 23 AD. This may seem the most reasonable solution to the problem, but certain doubts remain; for if there had indeed been an earthquake at Ephesus at that date, why did a careful source like Tacitus fail to mention such an important city? This did not escape the notice of Th.Mommsen in his edition of the inscription in cu 10.1624 (published in 1883). In his opinion, the Ephesus earthquake must have occurred shortly before the Pozzuoli inscription was made: roughly between 28 AD. and 30 AD. But the only earthquake we know of dating to about that time is one in Pontus and Bithynia; and in any case, Mommsen does not support his opinion with convincing evidence.

- Both Cibyra and Ephesus may have been only partly damaged in 17 AD., and may have been struck shortly before 23 AD. by another tremor, which reduced them to such a serious state that tax exemption became necessary.

- Both Cibyra and Ephesus may have been struck only by the earthquake of 17 AD., without the damage they suffered being so serious as to cause Tiberius to grant them tax exemption. The two cities may have made a later request to Rome for tax exemption, and this may have been granted in 23 AD.

There exists a very interesting dedicatory inscription to Tiberius (31-37 AD.), which describes him as conditor of the twelve cities destroyed in the earthquake (cll, 3.7096):

[Tiberius Caesar Augustus, son of the emperor Augustus, nephew of the emperor Julius, pontifex] maximus, granted [...] tribunician power, [c]onsul for the fifth time, founder at one and the same ti[me of the twelve] cities s[truck] by the [e]arthquake.

The inscription appears on four fragments of the architrave of a building, whose position has not been identified, in the Turkish town of Nemrud Kalesi (ancient Aegae). A very similar inscription in Greek (see Foucard 1887, pp.89-90), dating to 34-35 AD., came to light amongst the ruins of the city of Mostene, which was also damaged in the earthquake. The inscription records that Tiberius rebuilt the twelve Asian cities struck by the earthquake of 17 AD , and describes the emperor as κτίστης ένί και/ρώ δνδεκα πό/λεων (founder at one and the same time of twelve cities) — the same cities as those mentioned by Tacitus.[Ti(berius) Caesar divi Augusti f(ilius) divi Iu n(epos) Aug(ustus), p(ontifex)] m(axi-mus), tr(ibunicia) p(otestate) clo(n)s(u1) v, conditor uno tem[pore xu civitatium t]errae motu ve[xatarum].

Another inscription (sEG 28.928) records the restoration of a temple at Sardis which had been damaged in an earthquake:

"Socrates, son of Polemeus Pardalas, built the temple and dedicated it to Hera. [---] His niece Julia Lydia restored it after the earthquake".

And finally, there is an incomplete inscription (IGR 4.1514), which records that representatives of the twelve cities struck by the earthquake met at Sardis to discuss ways of expressing their gratitude to Tiberius.Σωκράτης Πολεμαίον / Παρδαλάς τόν ναόν κατε/σκενασεν καί τήν ` Ηραν άνε /Θηκεν [---] Ιουλία Λυδία ή ύωνή / αντον μετα τόν σεισμόν / έπεσκεύασεν.

Guidoboni, E., et al. (1994). Catalogue of Ancient Earthquakes in the Mediterranean Area up to the 10th Century. Rome, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica.

Roman hegemony brought with it more detailed accounts of rebuilding efforts after earthquakes throughout the Mediterranean. An earthquake in 17 CE that shook cities through out western Asia Minor is especially well documented by primary sources, who report that Augustus decreed widespread remission of taxes, direct financial support, and the visit of imperial officials to assist the affected cities (Tacitus, Annals 2.47 and 4.13.1;Strabo13.4.8).17 This package of state response set a precedent for later earthquakes (including at Antioch in 37, 41, and 115 CE), and for which local Antiochene perspectives from Malalas are supplemented by inscriptions and historians including Dio Cassius, who wrote from a senator’s perspective back at Rome. Generally, imperial Roman sources were concerned with top-down administrative details of immediate state response and issues of finance: they were less concerned with local casualties, the documentation of events from local perspectives, or even the long-term consequences of catastrophe. Two recorded earthquakes at Antioch followed in quick succession, in 37 and 41 CE.

A description of the 37 CE event during the reign of Caligula survives only in Malalas (10.18). Lacking details of destruction or casualties, the Antiochene account nevertheless preserves three key features of typical Roman earthquake response. First, money was sent directly from the emperor to the city. Second, a larger program of new urban infrastructure was set in motion or stimulated by the disaster: in this case the earthquake was quickly followed by construction of a new aqueduct, baths, and temples. Third, two senators and a prefect were sent from Rome “to protect the city and to rebuild it from the benefactions made by the emperor, and equally to make donations to the city from their private income and to live there.” Malalas adds the interesting detail that– besides a bath complex (the Varium), and a nymphaeum (the Trinymphon) decorated with statues – the senators sent from Romealso “built very many dwellings out of their private incomes.” While governmental attention to public buildings has been typical since the Hellenistic period, the focus on private housing stock seems novel. Apart from the new infrastructure that followed in the 37 CE earthquake’s wake according to Malalas– his testimony has been associated with the remains of a Roman aqueduct coming from Daphne, whose construction technique is consistent with a date in the first century CE18 – the only archaeological evidence for this event may come from Princeton’s excavations of the so-called Atrium House, where mosaics may be dated to the period after 37 CE.19

Just four years later in 41 CE, another earthquake during the reign of Claudius was accompanied by further destruction of houses, beside damage to the temples of Artemis, Ares, and Herakles (Malalas 10.23). Malalas again records here the quintessential Roman state response: the remission of local taxes paid from cities to Rome, so that cities affected by earthquakes could use these funds to directly pay for repairs themselves, instead. In the case of the 41 CE earthquake at Antioch, the “emperor Claudius relieved the guilds ... of the public service [or tax] of the kapnikon / καπνικόν, which they were providing to reconstruct the city’s roofed colonnades which had been built by Tiberius Caesar” (Malalas 10.23). Καπνικόν, from καπνός or smoke, is usually translated as a hearth tax, that is to say a tax on chimneys, which were easier to count than people; it appears here in its first instantiation, though the precise mean ing of the passage is unclear. Either the hearth tax which had been supporting the colonnade restoration (presumably after the previous earthquake of 37 CE) was lifted entirely; or the hearth tax’s funds were diverted to restoration of the colonnades (meaning that the guild members still paid, but its funds went to a new purpose).20 The hearth tax appeared rarely throughout the medieval period, before it reappeared more widely in early modern times.21 In those later forms, at least, the hearth tax was progressive in the sense that a large house or workshop would have more chimneys (and presumably money) than a smaller household.22

The first earthquake at Antioch for which we can meaningfully compare textual and archaeological evidence came in 115 CE (see Figure 27.2). It was vividly described by the Roman senatorial historian Dio Cassius (c. 155–235 CE), who was neither an eyewitness nor a contemporary. Dio Cassius recalls, however, the name of a consul who died there, and so presumably he relied on a closer source for his own account (68.24–25). Such unusual details may have been preserved because the emperor Trajan was in residence at Antioch at the time of the earthquake, to manage war with the Parthian Persians. Trajan only narrowly escaped from a collapsing building through a room’s window. He stayed outdoors in the hippodrome throughout the aftershocks. Dio Cassius reports significant destruction of houses and the loss of life – “the crash and breaking of timbers together with tiles and stones ... an inconceivable amount of dust ... The number of those who were trapped in the houses and perished was past finding out ...Great numbers were suffocated in the ruins.”

The participation of survivors in community sponsored offerings of thanksgiving, including even the construction of whole temples, may have fostered community cohesion in future earthquakes. After the 115 CE earthquake, Malalas tells us that “the surviving Antiochenes who remained then built a temple on which they inscribed ‘Those who were saved erected this to Zeus the Savior’” (11.8).

Dio Cassius says little concerning the recovery or reconstruction effort that must have followed the 115 CE earthquake, however. Malalas gives more details, indicating a major construction program sponsored by Trajan that followed the 115 CE earthquake: beginning with the sacrifice of a virgin girl named Kalliope, we are told, Trajan restored the city’s colonnades and built a new aqueduct and bath, named for himself, besides a theater (11.8–11).23

The Princeton excavators at Antioch understood the 115 CE event as a watershed in the city’s history. Literary sources became a point of reference for interpretation and dating of changes in buildings throughout the city, including damage and repair, but also abandonment or new construction: new mosaics were added in the so-called Atrium House and the House of the Drunken Dionysus,24 repairs were made at the Hippodrome, as suggested by new column capitals dated to the reign of Hadrian,25 and the city cardo was built anew26 while other streets were repaired.27 On the other hand, Bath C was destroyed in the 115 earthquake and abandoned, so too was the so-called House of Trajan’s Aqueduct.28

Leaving aside aspersions of child sacrifice from Christian chronicler Malalas, and the difficulties posed by evaluation of claims made by the Princeton excavators some 90 years later, it still stands that the initiation of significant new infra structure projects and repairs to public or private buildings followed the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch, in a pattern typical for major cities under the Roman empire. We turn now to the Byzantine.29

17 See also Ambraseys(2009).

18 Antioch II, 52; Gatier, Leblanc, and Poccardi (2004,241–242).

19 See Levi(1947, 16).

20 Downey (1961, 196,n. 145).

21 s.v. “HearthTax” and “Kapnikon” in Kazhdan (1991, 906, 1105).

22 Gurrin(2004).

23 Jeffreys (1990, 56) says “much of Malalas’ narrative on

Trajan’s activities is uncorroborated by other sources and is probably fictitious.”

24 Levi(1947, 16,40).

25 Antioch III, 150.

26 Antioch V, 30–33.

27 Antioch V,72

28 Levi(1947,289,28).

29 Mordechai and Pickett (2018)

(084) the morning of 23 March 37

- Antioch

- Daphne

- Mal. 243

- Schenk von Stauffenberg (1931)

- Sieberg (1932 a)

- Amiran (1950-51)

- Guidoboni (1989)

"During the first year of his reign [that of Caligula], Antioch the Great suffered the effects of divine wrath for the second time since the arrival of the Macedonians. It happened on 23 Dystrus, that is to say March, in the eighty-fifth year of the era of Antioch, early in the morning. The Daphne area was also damaged, and Gaius [Caligula] gave a great deal of money to the city and its surviving inhabitants".

'Εν δέ τώ πρώτω έτει τής βασιλείας αύτο έπαθεν υπό θεομηνίας 'Αντιόχεια ή μεγάλη μηνί δύστρυι τιi καί μαρτίω κγ' περί τό ανγος τό δεύτερον αυτής πάθος τούτο τό μετά τούς Μακεδόνας, έτους χρηματίζοντος πε' κατά τούς 'Αντιοχείς. έπαθε δέ καί μέρος Δάφνης· κάι πολλά χρήματα παρέσχεν ό βασιλεύς Γάίος τή αυτή πόλει καί τοίς ζήσασι πολίταις.

Guidoboni, E., et al. (1994). Catalogue of Ancient Earthquakes in the Mediterranean Area up to the 10th Century. Rome, Istituto nazionale di geofisica.

AD 37 Apr Antioch

A destructive earthquake in the region of Antioch, which

occurred at dawn, ruined the city and a part of Daphne,

one of its suburbs, with great loss of life. A landslide may

have ensued on the hill of Orontes by Antioch.

This was the second destruction of Antioch since

the arrival of the Macedonians (c. 300 BC), and the

damage was apparently so great that the emperor Gaius

responded with substantial amounts of relief and a building

programme. He had public baths built ‘near the hill of

Gaius Caesar’, bringing water to the baths by cutting an

aqueduct through the hill, and he also built temples.

The principal source for the details of this event

is Malalas, who, although writing much later in the sixth

century AD, probably drew on earlier public records

in Antioch. Although an earthquake is not mentioned

specifically in Malalas’s account, it seems reasonable to

assume that he was referring to one, since there was no

war going on at the time that might have resulted in

similar damage, and Claudius’s benefactions are typical of the

aftermath of an earthquake.

The Slavonic version of Malalas may refer to land-

slides along the River Orontes, close to Antioch: ‘there

occurred on the hill of Orontes a second fall’, although

this text is known to be corrupted. Malalas nowhere men-

tions the first disaster since the arrival of the Macedo-

nians, though it may be the earthquake, which occurred

during the occupation of Syria by Tigranes (c. 69 BC).

The date of this earthquake is given very clearly

by Malalas, as 23 Dystrus (March) in the first year of

Gaius’s reign and the 85th year of the Antiochene era,

which is 9 April AD 37. Modern scholars erroneously

give 23 March, failing to translate the date.

‘In the first year of his (Gaius’s) reign, Antioch the great suffered under divine wrath on the 23rd of the month Dystrus and March about dawn, the second time it had suffered this after the Mace- donians, in the 85th year of the Antiochene era. The district of Daphne also suffered. Gaius gave much money to the city and to the surviving citizens. And he built a public bath there, near the hill of Gaius Caesar, having sent the prefect Salianus from Rome to Antioch to build the bath there; and by cutting through the mountain he built an aqueduct from Daphne to bring water to the baths which were built beside the hill. He also built temples.’ (Mal. 243/372).

‘During the first year of his (Gaius’s) reign Antioch the Great suffered by the wrath of God; there occurred on the hill of Orontes a second fall. And having sent [money] the czar rebuilt it.’ (Mal. S. 243/53).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

Roman hegemony brought with it more detailed accounts of rebuilding efforts after earthquakes throughout the Mediterranean. An earthquake in 17 CE that shook cities through out western Asia Minor is especially well documented by primary sources, who report that Augustus decreed widespread remission of taxes, direct financial support, and the visit of imperial officials to assist the affected cities (Tacitus, Annals 2.47 and 4.13.1;Strabo13.4.8).17 This package of state response set a precedent for later earthquakes (including at Antioch in 37, 41, and 115 CE), and for which local Antiochene perspectives from Malalas are supplemented by inscriptions and historians including Dio Cassius, who wrote from a senator’s perspective back at Rome. Generally, imperial Roman sources were concerned with top-down administrative details of immediate state response and issues of finance: they were less concerned with local casualties, the documentation of events from local perspectives, or even the long-term consequences of catastrophe. Two recorded earthquakes at Antioch followed in quick succession, in 37 and 41 CE.

A description of the 37 CE event during the reign of Caligula survives only in Malalas (10.18). Lacking details of destruction or casualties, the Antiochene account nevertheless preserves three key features of typical Roman earthquake response. First, money was sent directly from the emperor to the city. Second, a larger program of new urban infrastructure was set in motion or stimulated by the disaster: in this case the earthquake was quickly followed by construction of a new aqueduct, baths, and temples. Third, two senators and a prefect were sent from Rome “to protect the city and to rebuild it from the benefactions made by the emperor, and equally to make donations to the city from their private income and to live there.” Malalas adds the interesting detail that– besides a bath complex (the Varium), and a nymphaeum (the Trinymphon) decorated with statues – the senators sent from Romealso “built very many dwellings out of their private incomes.” While governmental attention to public buildings has been typical since the Hellenistic period, the focus on private housing stock seems novel. Apart from the new infrastructure that followed in the 37 CE earthquake’s wake according to Malalas– his testimony has been associated with the remains of a Roman aqueduct coming from Daphne, whose construction technique is consistent with a date in the first century CE18 – the only archaeological evidence for this event may come from Princeton’s excavations of the so-called Atrium House, where mosaics may be dated to the period after 37 CE.19

Just four years later in 41 CE, another earthquake during the reign of Claudius was accompanied by further destruction of houses, beside damage to the temples of Artemis, Ares, and Herakles (Malalas 10.23). Malalas again records here the quintessential Roman state response: the remission of local taxes paid from cities to Rome, so that cities affected by earthquakes could use these funds to directly pay for repairs themselves, instead. In the case of the 41 CE earthquake at Antioch, the “emperor Claudius relieved the guilds ... of the public service [or tax] of the kapnikon / καπνικόν, which they were providing to reconstruct the city’s roofed colonnades which had been built by Tiberius Caesar” (Malalas 10.23). Καπνικόν, from καπνός or smoke, is usually translated as a hearth tax, that is to say a tax on chimneys, which were easier to count than people; it appears here in its first instantiation, though the precise mean ing of the passage is unclear. Either the hearth tax which had been supporting the colonnade restoration (presumably after the previous earthquake of 37 CE) was lifted entirely; or the hearth tax’s funds were diverted to restoration of the colonnades (meaning that the guild members still paid, but its funds went to a new purpose).20 The hearth tax appeared rarely throughout the medieval period, before it reappeared more widely in early modern times.21 In those later forms, at least, the hearth tax was progressive in the sense that a large house or workshop would have more chimneys (and presumably money) than a smaller household.22

The first earthquake at Antioch for which we can meaningfully compare textual and archaeological evidence came in 115 CE (see Figure 27.2). It was vividly described by the Roman senatorial historian Dio Cassius (c. 155–235 CE), who was neither an eyewitness nor a contemporary. Dio Cassius recalls, however, the name of a consul who died there, and so presumably he relied on a closer source for his own account (68.24–25). Such unusual details may have been preserved because the emperor Trajan was in residence at Antioch at the time of the earthquake, to manage war with the Parthian Persians. Trajan only narrowly escaped from a collapsing building through a room’s window. He stayed outdoors in the hippodrome throughout the aftershocks. Dio Cassius reports significant destruction of houses and the loss of life – “the crash and breaking of timbers together with tiles and stones ... an inconceivable amount of dust ... The number of those who were trapped in the houses and perished was past finding out ...Great numbers were suffocated in the ruins.”

The participation of survivors in community sponsored offerings of thanksgiving, including even the construction of whole temples, may have fostered community cohesion in future earthquakes. After the 115 CE earthquake, Malalas tells us that “the surviving Antiochenes who remained then built a temple on which they inscribed ‘Those who were saved erected this to Zeus the Savior’” (11.8).

Dio Cassius says little concerning the recovery or reconstruction effort that must have followed the 115 CE earthquake, however. Malalas gives more details, indicating a major construction program sponsored by Trajan that followed the 115 CE earthquake: beginning with the sacrifice of a virgin girl named Kalliope, we are told, Trajan restored the city’s colonnades and built a new aqueduct and bath, named for himself, besides a theater (11.8–11).23

The Princeton excavators at Antioch understood the 115 CE event as a watershed in the city’s history. Literary sources became a point of reference for interpretation and dating of changes in buildings throughout the city, including damage and repair, but also abandonment or new construction: new mosaics were added in the so-called Atrium House and the House of the Drunken Dionysus,24 repairs were made at the Hippodrome, as suggested by new column capitals dated to the reign of Hadrian,25 and the city cardo was built anew26 while other streets were repaired.27 On the other hand, Bath C was destroyed in the 115 earthquake and abandoned, so too was the so-called House of Trajan’s Aqueduct.28

Leaving aside aspersions of child sacrifice from Christian chronicler Malalas, and the difficulties posed by evaluation of claims made by the Princeton excavators some 90 years later, it still stands that the initiation of significant new infra structure projects and repairs to public or private buildings followed the 115 CE earthquake at Antioch, in a pattern typical for major cities under the Roman empire. We turn now to the Byzantine.29

17 See also Ambraseys(2009).

18 Antioch II, 52; Gatier, Leblanc, and Poccardi (2004,241–242).

19 See Levi(1947, 16).

20 Downey (1961, 196,n. 145).

21 s.v. “HearthTax” and “Kapnikon” in Kazhdan (1991, 906, 1105).

22 Gurrin(2004).

23 Jeffreys (1990, 56) says “much of Malalas’ narrative on

Trajan’s activities is uncorroborated by other sources and is probably fictitious.”

24 Levi(1947, 16,40).

25 Antioch III, 150.

26 Antioch V, 30–33.

27 Antioch V,72

28 Levi(1947,289,28).

29 Mordechai and Pickett (2018)

AD 41–54 Antioch

An earthquake caused heavy damage in Antioch. The

temples of Artemis, Ares and Hercules were ‘rent asunder’,

and many houses of important persons collapsed, as

did the city’s roofed colonnades, which had been built by

Tiberius. The emperor Claudius relieved Antioch’s guilds

of the hearth tax so that the colonnades could be rebuilt.

Malalas (Greek version) mentions this event

immediately after the Ephesus and Smyrna earthquake:

‘at that time (tote) Antioch the great was shaken . . .’

(Mal. CS 246). This could be taken to mean that Antioch

was hit by an earthquake at the same time as Smyrna and

Ephesus, but the Greek tote, ‘then’, can have two meanings,

just as ‘then’ in English can mean either ‘at the exact same

time’ or ‘next’. The latter meaning is more typical of

Malalas.

Downey’s interpretation is that the same earthquake

damaged Antioch, Smyrna, Ephesus and the other

cities, but Antioch is 900 km from these cities. This would

require an earthquake of improbable size, which would

have had to have destroyed many important cities in

Caria and Lycia as well (Downey 1961a, 196).

Note that the Slavonic version of Malalas does not

mention that Antioch was struck by ‘the wrath of God’:

it has the earthquake in Ephesus and Smyrna ‘and many

cities of Asia’ and then mentions Claudius’s tax-relief

measures for the Antiochenes ‘for the restoration of [the]

roofed colonnades’: presumably therefore Antioch is

included among the ‘other cities’ (Mal. 246/376 and

S. 246/55).

The earthquake is also mentioned by an earlier

source, which, however, does not help date the event

better than sometime between AD 48 and 54. Philostratus

writes that an earthquake occurred when there was

discord among the citizens of Antioch: from the context,

this happened during the reign of Claudius, so it was

probably this event.

‘The ruler of Syria had plunged Antioch into a feud, disseminating among the citizens suspicions such that when they met in assembly they all quarrelled with one another. But a violent earthquake happening to occur, they were all cowering, and as is usual in the case of heavenly portents, praying for one another.’ (Philostr. VA VI. 38/LCL. ii. 130).

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

(085) c. 47 Antioch

sources 1

- Philostr. V Apo 6.38

- Mal. 246