Lake Amik (aka Lake Antioch)

Left - Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s) - Alalakh.org

Left - Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s) - Alalakh.orgRight - French postcard of The Lake of Antioch, showing its setting in Amik Plain. Early 20th century - Wikipedia - Unknown - Fair Use

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Lake Amik | English | |

| Lake Antioch | English | |

| Lake of Antioch | English | |

| Amik Golu | Turkish | |

| Buhayrat Al-Eumq | Arabic | بحيرة العمق |

| Bahr-Agoule | Arabic |

- from wikipedia

Lake Amik was located in the centre of Amik Plain (Turkish: Amik Ovası) on the northernmost part of the Dead Sea Transform and historically covered an area of some 300–350 km2 (120–140 sq mi), increasing during flood periods.[1]: 2 It was surrounded by extensive marshland.[citation needed]

Sedimentary analysis has suggested that Lake Amik was formed, in its final state, in the past 3,000 years by episodic floods and silting up of the outlet to the Orontes River.[2] This dramatic increase in the lake's area had displaced many settlements during the classical period;[3] the lake became an important source of fish and shellfish for the surrounding area and the city of Antioch.[4] The 14th century Arab geographer Abu al-Fida described the lake as having sweet water and being 20 mi (32 km) long and 7 mi (11 km) wide,[5] while an 18th-century traveller, Richard Pococke, noted that it was then locally called "Bahr-Agoule (the White Lake) by reason of the colour of its waters".[6]

By the 20th century, the lake supported around 50,000 inhabitants in 70 villages, who took part in stock raising, reed harvesting, fishing (with a particularly significant eel fishery) and agriculture, crops and fodder being grown on pastures formed during the summer as the lake waters receded.[1]: 3 They also constructed dwellings, locally known as Huğ, from reeds gathered in the lake.[citation needed]

The three rivers draining the Amik Basin form a particularly fertile environment in which continuous human occupation is attested since about 6000–7000 BC (e.g. Eger, 2011). The low-lying Amik plain was already well occupied during Chalcolithic with a settlement concentration in the central part of the plain. Starting in the Bronze Age, settlement dispersal occurred in different phases very briefly summarized here (Casana, 2007; Wilkinson, 2000). Starting around 3000 BC during the Bronze Age, sites spread to the outskirt of the plain with a concentration along an east–west corridor along the southern part of the plain, which is inferred to represent an interregional route system (Batiuk, 2005). In the Iron Age, during the first millennium BC, the tell-based settlement pattern continued its transformation to a more dispersed pattern of numerous small settlements associated with the occupation of some upland (i.e. valleys in the Jebel al-Aqra Mountain to the south of the Amik Lake; Batiuk, 2005; Casana, 2003; Casana and Wilkinson, 2005). A third phase of more intensive occupation started during the Hellenistic Period (300 BC) and ended around AD 650 during the late Roman Period. The period is characterized by the conversion of upland areas to intensive agricultural production (Wilkinson, 1997; 2000), starting probably around AD 50 by the systematic channelization of the rivers flowing into the Amik Basin and to the south into the Ghab Basin (Wilkinson and Rayne, 2010). The intensive agricultural farming and irrigation network that developed around the Amik Basin were necessary to feed the large population of the Antioch city. The city was one of the largest in the Roman Empire, with maybe up to 500,000 inhabitants including its suburbs (De Giorgi, 2007). In fact, during the late Roman Period, the Amik plain was more densely occupied than at any time in its history (Casana, 2008). The related intensive land use created the necessary preconditions for severe soil erosion to occur, but there was a long time lag between the initial settlement of upland areas starting around 300 BC and the first evidence of soil erosion occurred after AD 150 (Casana, 2008). Casana (2008) inferred that the late Roman soil erosion created widespread floodplain aggradation and rapid siltization of the man-constructed canals and transformed the fertile Amik plain to unproductive marshland. After AD 700, there was a progressive decrease in population and settlement contemporary with the decline in the Antioch city.

The history of the Amik region has been well documented. The region was home to several major archaeological excavations. During the 1930s and 1950s (Braidwood and Braidwood, 1960; Haines, 1971), the archaeological studies focused on the Amik Basin. Starting in 1995, excavations were renewed by the Oriental Institute (Chicago University) as the Amuq Valley Regional Projects (AVRP) in order to better understand the settlement pattern and the systems of land use through an interdisciplinary regional research program from the Chalcolithic to the Islamic Period (e.g. Yener, 2005, 2010; Yener et al., 2000). The defined stratigraphical sequences and the associated artifact typology found in the Amik plain are presently a standard reference for chronologies and material cultures in all the neighboring regions (Yener et al., 2000).

- Fig. 1 Simplified tectonic

setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 1

Simplified tectonic setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings, complied from Hall et al. (2005) and Reilinger et al. (2006).

- KOTJ: Karlıova Triple Junction

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş (or Türkoğlu) Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

- EAF: East Anatolian Fault

- NAF: North Anatolian Fault

- Sin: Sinai Block

- ST: Strabo Trench

- PT: Pliny Trench

- Anb: Antalya Basin

- Cb: Cilicia Basin

- Mb: Mesaoria Basin

- Lb: Latakia Basin

- Cyb: Cyprus Basin

- TR: Tartus Ridge

- HF: Hatay Fault

- MK: Misis-Kyrenia Fault Zone

- Ab: Adana Basin

- Ib: Iskenderun Basin

- KOF: Karataş-Osmaniye Fault

- PF: Paphos Fault

- white arrows and their corresponding numbers indicate the plate velocities relative to the Eurasian Plate, as derived from the GPS data

- black lines indicate major faults, and the arrows along the faults indicate offset direction

- Hatched black lines with triangles indicate subduction zones

- Hatched white rectangle shows location of inset map. B. The detailed bathymetry in the eastern Mediterranean Sea (after Hall et al., 2005)

- Black rectangle shows study area

- Fig. 2 Major active faults

and the morphotectonic units from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

A digital elevation model for the study area and its surroundings, showing the major active faults and the morphotectonic units.

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş or Türkoğlu Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 19 GPS velocity

field relative to fixed Arabian Plate from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

The GPS velocity field relative to fixed Arabian Plate (GPS data from Alchalbi et al., 2010; Meghraoui et al., 2011; Reilinger et al., 2006). The abbreviations indicate GPS observation campaigns by Reilinger et al. (2006) and Alchalbi et al. (2010). The fault slip rates (mm/y) were deduced from Mahmoud et al. (2012). The top numbers in each rectangle give strike-slip rates, positive being left-lateral. The other numbers in each rectangle give fault-normal slip rates, positive equalling closing.

- CAF– Cyprus-Antakya Fault

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 1 East Anatolian Fault

Map from Duman et al. (2020)

Fig. 1

East Anatolian fault between Karlıova and Gulf of İskenderun; Major fault zones in the vicinity plotted in black (simplified from Emre et al. 2018). Inset map shows the active tectonic framework of the Eastern Mediterranean region (from Emre et al. 2018). Dashed polygon indicates the study area. Abbreviations:

- NAFZ North Anatolian fault zone

- EAFZ East Anatolian fault zone

- NS Northern strand

- SS Southern strand

- PE Pontic Escarpment

- LC Lesser Caucasus

- GC Great Caucasus

- WAEP West Anatolian Extensional Provence

- CAP Central Anatolian Provence

- WAEP Eastern Anatolian Compressional Provence

- DSFZ Dead Sea fault zone

- HA Hellenic arc

- PFFZ Palmyra fold and fault zone

- CA Cyprian arc

- SATZ Southeast Anatolian thrust zone

- SMFS Sürgü–Misis fault system

- MKF Misis–Kyrenia fault

- MF Malatya fault

- SF Sarız fault

- EF Ecemiş fault

- DF Deliler fault

- Karlıova fault segment

- Ilıca fault segment

- Palu fault segment

- Pütürge fault segment

- Erkenek fault segment

- Pazarcık fault segment

- Amanos fault segment

- Sürgü fault segment

- Çardak fault segment

- Savrun fault segment

- Çokak fault segment

- Toprakkale fault segment

- Karataş fault segment

- Yumurtalık fault segment

- Düziçi–Osmaniye fault zone;

- Misis fault segment

- Engizek fault zone

- Maraş fault zone

- Fig. 2 Historical and

Instrumental earthquakes along the western Sürgü–Misis fault (SMF) system from Duman et al. (2020)

Fig. 2

Distribution of both historical (a) and instrumental (b) earthquakes along the western segments of Sürgü–Misis fault (SMF) system around the Gulf of İskenderun (simplified from Duman and Emre, 2013). Thick red and black lines indicate the SMF system (north strand) and south strand of the East Anatolian fault zone, respectively. The locations of historical earthquakes are from Tan et al. (2008), Ambraseys (1988), Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) and Başarır Baştürk et al. (2017). The instrumental data are from Kalafat et al. (2011), Aktar et al. (2000), Ergin et al. (2004) and Kadirioğlu et al. (2018). The focal mechanisms are from Kılıç et al. (2017). The letter inside boxes refers to the source for the historical earthquakes as given by Tan et al. (2008).

- ST Shebalin and Tatevossian (1997)

- KU Kondorskaya and Ulomov (1999)

- EG Guidoboni et al. (1994)

- EG2 Guidoboni and Comastri (2005)

- AM Ambraseys (1988)

- AJ Ambraseys and Jackson (1998)

- MFS Misis fault segment

- KFS Karataş fault segment

- YFS Yumurtalık fault segment

- DİFZ Düziçi–İskenderun fault zone

- AFS Amanos fault segment

- YEFS Yesemek fault segment

- AFFS Afrin fault segment

- NFZ Narlı fault zone

- MFZ Maraş fault zone

- EFZ Engizek fault zone

- ÇOFS Çokak fault segment

- SAFS Savrun fault segment

- TFS Toprakkale fault segment

- ÇFS Çardak fault segment

- SFS, Sürgü fault segment

Duman et al. (2020) - Fig. 3 Geologic map of

the Antakya Graben from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The geologic map of the Antakya Graben

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 4 Generalized columnar

stratigraphic section through the Antakya Graben from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

A generalized columnar stratigraphic section through the Antakya Graben

Tari et al. (2013)

- Fig. 1 Simplified tectonic

setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 1

Simplified tectonic setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings, complied from Hall et al. (2005) and Reilinger et al. (2006).

- KOTJ: Karlıova Triple Junction

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş (or Türkoğlu) Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

- EAF: East Anatolian Fault

- NAF: North Anatolian Fault

- Sin: Sinai Block

- ST: Strabo Trench

- PT: Pliny Trench

- Anb: Antalya Basin

- Cb: Cilicia Basin

- Mb: Mesaoria Basin

- Lb: Latakia Basin

- Cyb: Cyprus Basin

- TR: Tartus Ridge

- HF: Hatay Fault

- MK: Misis-Kyrenia Fault Zone

- Ab: Adana Basin

- Ib: Iskenderun Basin

- KOF: Karataş-Osmaniye Fault

- PF: Paphos Fault

- white arrows and their corresponding numbers indicate the plate velocities relative to the Eurasian Plate, as derived from the GPS data

- black lines indicate major faults, and the arrows along the faults indicate offset direction

- Hatched black lines with triangles indicate subduction zones

- Hatched white rectangle shows location of inset map. B. The detailed bathymetry in the eastern Mediterranean Sea (after Hall et al., 2005)

- Black rectangle shows study area

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 2 Major active faults

and the morphotectonic units from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

A digital elevation model for the study area and its surroundings, showing the major active faults and the morphotectonic units.

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş or Türkoğlu Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 19 GPS velocity

field relative to fixed Arabian Plate from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

The GPS velocity field relative to fixed Arabian Plate (GPS data from Alchalbi et al., 2010; Meghraoui et al., 2011; Reilinger et al., 2006). The abbreviations indicate GPS observation campaigns by Reilinger et al. (2006) and Alchalbi et al. (2010). The fault slip rates (mm/y) were deduced from Mahmoud et al. (2012). The top numbers in each rectangle give strike-slip rates, positive being left-lateral. The other numbers in each rectangle give fault-normal slip rates, positive equalling closing.

- CAF– Cyprus-Antakya Fault

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 1 East Anatolian Fault

Map from Duman et al. (2020)

Fig. 1

East Anatolian fault between Karlıova and Gulf of İskenderun; Major fault zones in the vicinity plotted in black (simplified from Emre et al. 2018). Inset map shows the active tectonic framework of the Eastern Mediterranean region (from Emre et al. 2018). Dashed polygon indicates the study area. Abbreviations:

- NAFZ North Anatolian fault zone

- EAFZ East Anatolian fault zone

- NS Northern strand

- SS Southern strand

- PE Pontic Escarpment

- LC Lesser Caucasus

- GC Great Caucasus

- WAEP West Anatolian Extensional Provence

- CAP Central Anatolian Provence

- WAEP Eastern Anatolian Compressional Provence

- DSFZ Dead Sea fault zone

- HA Hellenic arc

- PFFZ Palmyra fold and fault zone

- CA Cyprian arc

- SATZ Southeast Anatolian thrust zone

- SMFS Sürgü–Misis fault system

- MKF Misis–Kyrenia fault

- MF Malatya fault

- SF Sarız fault

- EF Ecemiş fault

- DF Deliler fault

- Karlıova fault segment

- Ilıca fault segment

- Palu fault segment

- Pütürge fault segment

- Erkenek fault segment

- Pazarcık fault segment

- Amanos fault segment

- Sürgü fault segment

- Çardak fault segment

- Savrun fault segment

- Çokak fault segment

- Toprakkale fault segment

- Karataş fault segment

- Yumurtalık fault segment

- Düziçi–Osmaniye fault zone;

- Misis fault segment

- Engizek fault zone

- Maraş fault zone

- Fig. 2 Historical and

Instrumental earthquakes along the western Sürgü–Misis fault (SMF) system from Duman et al. (2020)

Fig. 2

Distribution of both historical (a) and instrumental (b) earthquakes along the western segments of Sürgü–Misis fault (SMF) system around the Gulf of İskenderun (simplified from Duman and Emre, 2013). Thick red and black lines indicate the SMF system (north strand) and south strand of the East Anatolian fault zone, respectively. The locations of historical earthquakes are from Tan et al. (2008), Ambraseys (1988), Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) and Başarır Baştürk et al. (2017). The instrumental data are from Kalafat et al. (2011), Aktar et al. (2000), Ergin et al. (2004) and Kadirioğlu et al. (2018). The focal mechanisms are from Kılıç et al. (2017). The letter inside boxes refers to the source for the historical earthquakes as given by Tan et al. (2008).

- ST Shebalin and Tatevossian (1997)

- KU Kondorskaya and Ulomov (1999)

- EG Guidoboni et al. (1994)

- EG2 Guidoboni and Comastri (2005)

- AM Ambraseys (1988)

- AJ Ambraseys and Jackson (1998)

- MFS Misis fault segment

- KFS Karataş fault segment

- YFS Yumurtalık fault segment

- DİFZ Düziçi–İskenderun fault zone

- AFS Amanos fault segment

- YEFS Yesemek fault segment

- AFFS Afrin fault segment

- NFZ Narlı fault zone

- MFZ Maraş fault zone

- EFZ Engizek fault zone

- ÇOFS Çokak fault segment

- SAFS Savrun fault segment

- TFS Toprakkale fault segment

- ÇFS Çardak fault segment

- SFS, Sürgü fault segment

Duman et al. (2020) - Fig. 3 Geologic map of

the Antakya Graben from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The geologic map of the Antakya Graben

Tari et al. (2013) - Fig. 4 Generalized columnar

stratigraphic section through the Antakya Graben from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

A generalized columnar stratigraphic section through the Antakya Graben

Tari et al. (2013)

- Fig. 1 Active Faults and

Ancient Settlements in the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

- The Dead Sea Fault Zone between the Red Sea to the south and East Anatolian Fault to the north

- Main active faults in the Amik Basin area (from Karabacak 2007) and locations of ancient settlements (Tells) as depicted from the Antioch Museum of Archeology. The 1822 and 1872 earthquake epicentres (black stars) are from Ambraseys (1989). The ancient road between Antakya and Aleppo is indicated by dashed green line (Roat 1991).

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 2a Fault map and

Location Map of Northernmost DST from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

The northernmost section of the DSF (From Karabacak 2007) and the locations of Sıçantarla site (ST) and ancient bridge (road). Numbers with m (e.g. 100 m) indicates amount of left-lateral displacement on stream beds.

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 10a Roman roads

around the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 10a

Fig. 10a

Map of Roman roads around the Amik Basin

(redrawn from Buschmann & Högemann 1989)

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 10 b and c

Assyrian trade roads around the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 10 b and c

Fig. 10 b and c

(b) Map of Assyrian trade roads around the Amik Basin (redrawn from Roat 1991)

(c) Hittite writings on a stone near the offset ancient road (see Fig. 3b for location)

Altunel et al. (2009) - Map of the Plain of Antioch

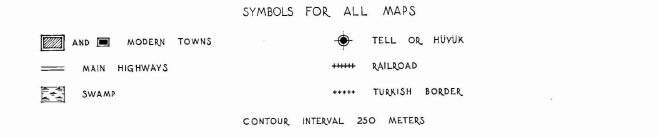

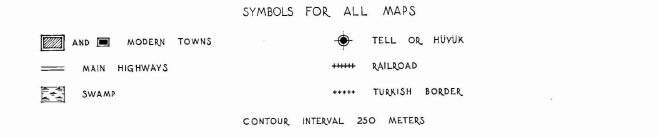

and its environs from Braidwood (1937)

The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

Key Map Scale 1:400,000

Braidwood (1937) - Map of the Plain of Antioch

and its environs (legend) from Braidwood (1937)

Legend for Map of The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

Legend for Map of The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

Key Map Scale 1:400,000

Braidwood (1937)

- Fig. 1 Active Faults and

Ancient Settlements in the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

- The Dead Sea Fault Zone between the Red Sea to the south and East Anatolian Fault to the north

- Main active faults in the Amik Basin area (from Karabacak 2007) and locations of ancient settlements (Tells) as depicted from the Antioch Museum of Archeology. The 1822 and 1872 earthquake epicentres (black stars) are from Ambraseys (1989). The ancient road between Antakya and Aleppo is indicated by dashed green line (Roat 1991).

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 2a Fault map and

Location Map of Northernmost DST from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

The northernmost section of the DSF (From Karabacak 2007) and the locations of Sıçantarla site (ST) and ancient bridge (road). Numbers with m (e.g. 100 m) indicates amount of left-lateral displacement on stream beds.

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 10a Roman roads

around the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 10a

Fig. 10a

Map of Roman roads around the Amik Basin

(redrawn from Buschmann & Högemann 1989)

Altunel et al. (2009) - Fig. 10 b and c

Assyrian trade roads around the Amik Basin from Altunel et al. (2009)

Fig. 10 b and c

Fig. 10 b and c

(b) Map of Assyrian trade roads around the Amik Basin (redrawn from Roat 1991)

(c) Hittite writings on a stone near the offset ancient road (see Fig. 3b for location)

Altunel et al. (2009) - Map of the Plain of Antioch

and its environs from Braidwood (1937)

The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

The Plain of Antioch and its Environs

Key Map Scale 1:400,000

Braidwood (1937)

Shaded relief map of southwestern part of EAF (30 m resolution SRTM data), showing the active faults in red.

- C, Çelikhan

- G, Gölbası

- K, Kahramanmaras

- O, Osmaniye

- G, Gaziantep

- A, Antakya

- T, Türkoglu

- Altunel et al. (2009), Karabacak et al. (2010)

- Karabacak (2007), Rojay et al. (2001)

- this study

- Aktug et al. (2016)

- Mahmoud et al. (2013), Aktug et al. (2016)

- Mahmoud et al. (2013), Aktug et al. (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1- Main seismotectonic framework

of the Eastern Mediterranean region with

the movement of Arabia (Ar) and Anatolia

relative to Eurasia (Eu).

- NAF, North Anatolian Fault

- EAF, East Anatolian Fault

- DSF, Dead Sea Fault

- Simplified map of the major active tectonic structures of East Anatolia, superimposed on shaded relief map derived from 30 m resolution Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data. Stars show the epicentres of the 6 February 2023 Pazarcık (MW = 7.7) and Elbistan (MW = 7.6) Kahramanmaraş earthquakes.

Yönlü and Karabacak (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Geomorphological situation of the Amik Lake, the studied pollen record sites, the nearest archaeological sites, the sedimentological study, and the paleoseismological tranches

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

- Satellite Image of

Lake Amik from the 1960s from Alalakh.org

Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s)

Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s)

Alalakh.org - Photo of Lake Amik

from the early 20th century from wikipedia

French postcard of The Lake of Antioch, showing its setting in Amik Plain. Early 20th century

French postcard of The Lake of Antioch, showing its setting in Amik Plain. Early 20th century

Wikipedia - Unknown - Fair Us - Amik Valley in Google Earth

- Satellite Image of

Lake Amik from the 1960s from Alalakh.org

Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s)

Corona satellite image with the former Lake Antioch (1960s)

Alalakh.org - Photo of Lake Amik

from the early 20th century from wikipedia

French postcard of The Lake of Antioch, showing its setting in Amik Plain. Early 20th century

French postcard of The Lake of Antioch, showing its setting in Amik Plain. Early 20th century

Wikipedia - Unknown - Fair Us - Amik Valley in Google Earth

Table 1

Table 1Calibrated 14C age results obtained from bivalves, ostracods, and micro-charcoals.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

- from El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

- Red Triangle is Coring Site

- Coring Site Location: 36°20.655′N−036°20°.948′E

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Map illustrating the location of all archaeological sites in the Amik plain (southern Turkey) with evidence of Paleolithic, Iron, Bronze, and Roman Age occupation. The largest sites are indicated by the survey number assigned by the Amuq Valley Regional Project (Casana and Wilkinson, 2005). Wilkinson (2005) studied core sediments located in the present map.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3bAge–depth diagram for Amik Lake based on calibrated 14C age results obtained from micro-charcoal remains, 210Pb and 135Cs activities, correlation with other dated sedimentary sections in the Amik Basin, and historical earthquake tie point

(data from Akyüz et al., 2006)

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3aSedimentation rate and age–depth model from radionuclides (137Cs, 228Th, and 210Pb). The combination of magnetic susceptibility and Cr2O3 is used as earthquake tie point to extrapolate the sedimentation rate.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Variations of grain-size distribution (sand, silt, and clay fractions), magnetic susceptibility (MS), and C/N ratio along the depth profile of the Amik Lake.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Evolution of major element (oxide form) and minor element (ppm) concentrations along the depth profile of the Amik Lake.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Variations of CIA, physical weathering (K2O/Ti2O), and C2O3/TiO2 and C2O3/ZrO2 ratios along the archaeological periods in the Amik plain. Gray area indicates intervals of low chemical weathering phase.

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

El Ouahabi et al. (2018)

indicate that potential seismites were also found at the following depths:

| Depth (cm.) | Label | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 330 | E3 | characterized by sand pillows in a clay matrix; the typical plastic deformation suggests that the event can be interpreted as earthquake triggered deposit. |

| 435 | unnamed | below a red clay layer, micro-sand dikes suggest another episode of plastic deformation. |

| 480 | E4 | 10-cm-thick disturbed sandy layer enriched in shells ... The top subunit is marked by a sedimentary event probably related to an earthquake. |

| 550 | E5 | a sand pillow |

| 580 | E6 | a thick sandy layer rich in plagioclase |

The Amik Basin in the Eastern Mediterranean region occupied since 6000–7000 BC has sustained a highly variable anthropic pressure culminating during the late Roman Period when the Antioch city reached its golden age. The present 6-m-long sedimentary record of the Amik Lake occupying the central part of the Basin constrains major paleoenvironmental changes over the past 4000 years using multi-proxy analyses (grain size, magnetic susceptibility, and x-ray fluorescence (XRF) geochemistry). An age model is provided by combining short-lived radionuclides with radiocarbon dating. A lake/marsh prevailed during the last 4 kyr with a level increase at the beginning of the Roman Period possibly related to optimum climatic condition and water channeling. The Bronze/Iron Ages are characterized by a strong terrigenous input linked to deforestation, exploitation of mineral resources, and the beginning of upland cultivation. The Bronze/Iron Age transition marked by the collapse of the Hittite Empire is clearly documented. Erosion continued during the Roman Period and nearly stopped during the early Islamic Period in conjunction with a decreasing population and soil depletion on the calcareous highland. The soil-stripped limestone outcrops triggered an increase in CaO in the lake water and a general decrease in ZrO2 released in the landscape that lasts until the present day. During the Islamic Period, pastoralism on the highland sustained continued soil erosion of the ophiolitic Amanus Mountains. The Modern Period is characterized by a higher pressure particularly on the Amanus Mountains linked to deforestation, road construction, ore exploitation, and drying of the lake for agriculture practices.

... The Amik Basin has a long human history, associated with dense, variable, and marked human settlements. The latter, started probably since the Neolithic time (Braidwood and Braidwood, 1960), is marked during the Bronze Age by the development of the Alalakh, the capital of a regional state (Yener and Wilkinson, 2007), and later by the rise of the antique Antioch city, the third largest city of the Roman Empire (~500,000 inhabitants; De Giorgi, 2007). In 1920, there were only about 180,000 people living in the region, and presently, Antakya (ancient Antioch) has a population of only 250,000 inhabitants (Doğruel and Leman, 2009). The Amik region had thus undergone a highly variable human occupation. It is thus a particularly interesting laboratory regarding the human impacts on the landscape in the Mediterranean region.

The history of the Amik region has been well documented. The region was home to several major archaeological excavations. During the 1930s and 1950s (Braidwood and Braidwood, 1960; Haines, 1971), the archaeological studies focused on the Amik Basin. Starting in 1995, excavations were renewed by the Oriental Institute (Chicago University) as the Amuq Valley Regional Projects (AVRP) in order to better understand the settlement pattern and the systems of land use through an interdisciplinary regional research program from the Chalcolithic to the Islamic Period (e.g. Yener, 2005, 2010; Yener et al., 2000). The defined stratigraphical sequences and the associated artifact typology found in the Amik plain are presently a standard reference for chronologies and material cultures in all the neighboring regions (Yener et al., 2000).

The present sedimentological study was undertaken in the eastern part of the Amik Lake near the junction with the Afrin River. The presently dried lake occupied the central part of the Amik Basin, a tectonic pull-apart basin. Our aim was to constrain environmental changes during the last 4000 years in relation to the different human occupation phases. The regional tectonics dominated by the Dead Sea Fault Zone (DSFZ), as well as the settlement and land-use histories since the Bronze Age, were first rapidly reviewed because they provided a necessary framework for the interpretation of the data. The analysis of an ~6-m sedimentary sequence is then presented using a multi-proxy approach (magnetic susceptibility (MS), grain size, x-ray fluorescence (XRF) geochemistry, and organic geochemistry). The age of the sequence was constrained by short-lived radioisotopes and radiocarbon dating and tie points using historical earthquakes that left a fingerprint. The results were discussed considering the different geoarchaeological data available in the area.

The 50-km-long and 50-km-wide Amik plain is a tectonic basin filled by up to 2.5-km-thick Plio-Quaternary sediments (Gülen et al., 1987) and crossed by the Dead Sea Fault (DSF). The DSF is composed of two segments, the Karasu Fault to the north bounding of the Amanus Mountain and the Hacipasa Fault to the south in the Orontes valley (Akyüz et al., 2006; Altunel et al., 2009; Karabacak and Altunel, 2013; Karabacak et al., 2010; Figure 1). The two active left-lateral strike-slip faults defined a pull apart structure and have ruptured in large destructive earthquakes during historical time (e.g. Akyüz et al., 2006).

The basin is surrounded by several mountains and plateaus. To the west stands the Amanus Mountains that culminates at 2250 m and is made of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks as well as of a large ophiolitic body (Boulton et al., 2007). To the south lies the low ranges of calcareous Jebel al-Aqra or Kuseyr Plateau. To the northeast, the Kurt Mountains culminating at 825 m are mostly composed of metamorphic rocks (Altunel et al., 2009; Eger, 2011; Karabacak and Altunel, 2013; Parlak et al., 2009; Robertson, 2002; Wilkinson, 2000).

The plain is watered by three large rivers: the Orontes, the Karasu, and the Afrin. Its central part used to be occupied by wetlands and a large shallow lake (Figures 1 and 2). The lake has a complex history with alternating extension and disappearance partly unraveled by geoarchaeological studies (Casana, 2008; Friedman et al., 1997; Wilkinson, 1997; Wilkinson, 2000). A lacustrine environment is attested around 7500 years ago until the early Bronze Age sites (Schumm, 1963; Wilkinson, 2000). Between 3000 and 1000 BC, a drying of the lake is attested by soil development and accumulation of calcium carbon at the center of the lake (Casana, 2008; Wilkinson, 1999). During the Roman Period, the environment was again more humid, and the lake surface increased to reach a maximum extent during the first millennium AD (Casana, 2007; Eger, 2011; Wilkinson, 1997). During the 19th century and the mid-20th century, the lake was the main resource for the local economy, and it was artificially drained at the beginning of the 1940s (Çalışkan, 2008); the desiccation work was completed in 1987 (Kilic et al., 2006).

... This SR [Sedimentation Rate] implies that the two layers characterized by high MS [Magnetic Susceptibility] values and Cr2O3 content in the E1 anomalous deposit would correspond to the 1872 and 1822 historical earthquakes (Akyüz et al., 2006; Figure 3a). The two segments of the DSF, the Karasu Fault and the Hacipasa Fault, have ruptured subsequently in 1822 and 1872 in M ≥7 earthquakes (Akyüz et al., 2006). The 1822 earthquake affected most specially the Afrin watershed, disturbing its water flow; Orontes River was also impacted: its course was permanently affected by a landslide (Ambraseys, 1989). The 1872 earthquake ruptured the Hacipasa Fault segment (Akyüz et al., 2006), lying a few hundred meters from the site and triggered liquefactions near the studied site (Ambraseys, 1989).

... The ages of shells are thus very unreliable and cannot be used to constrain an age–depth model. The only reliable materials are micro-charcoals.

... A composite age model was thus built combining the modern 210Pb [Sedimentation Rate], the 1872–1822 earthquake imprints, and the two youngest micro charcoal ages at 398 and 408.5 cm. .

... We identify several sedimentary layers characterized by coarse grain particles, a MS higher than the background sedimentation, reworked shells, and/or structural disturbances (plastic deformation and sand pillows).

- E1, between 20 and 60 cm, is composed of numerous reworked shells and shows two MS increases, one at 34 cm and a larger double peak between 46 and 58 cm.

- E2 (165–195 cm) is composed of two sandy layers with visible micro-sand pockets and sand dikes probably related to liquefaction. Below, two thin layers at 205 and 225 cm show minor structural disturbances associated with sands. An anomalous event with higher MS and grain size occurred at 260 cm.

- E3 lies at 330 cm and is characterized by sand pillows in a clay matrix; the typical plastic deformation suggests that the event can be interpreted as earthquake triggered deposit. At 435 cm below a red clay layer, micro-sand dikes suggest another episode of plastic deformation.

- E4 occurred at 480 cm and shows a 10-cm-thick disturbed sandy layer enriched in shells.

- E5 at 550 cm is a sand pillow.

- E6 at the core base (580 cm) is a thick sandy layer rich in plagioclase.

All identified events are reported in Figure 4.

Five different sedimentary units were identified (Figure 4) based on the core description, MS, and grain-size data.

- The top unit (unit 5) is 130 cm thick and is characterized by an average MS of 66 ± 16 SI, small variation in C/N, and significant proportion of sand size particles which reach ~80% at 48 cm depth. It is composed of three subunits based on grain size variation. The 35-cm-thick SU5-3 is characterized by low values of MS (57 ± 4 SI); sand and silt contents reach 25% and 55%, respectively. Between 20 and 35 cm, eye-visible shells absent in the top part are present and increase in number at the base of the unit. The SU5-2 subunit extends to 60 cm and is the anomalous event with no clay fraction. It shows a large downward increase in sand size particles comprising reworked shells and in MS peak reaching 120 SI. The silty sand subunit SU5-1 (60–130 cm) has more than 20% of sand fraction, a high macro-organic content, and a high C/N ratio (17 ± 6, in aver age). Its sand proportion is composed of a top rich shell layer overlying a sand-rich layer showing a large MS peak reaching 120 SI.

- The fourth unit (unit 4) extends from 130 to 196 cm and is mostly silty sand having variable MS values (70 ± 19 SI, in average) and small variation in C/N ratio. Two subunits compose this unit, namely, SU4-1 (196–160 cm) and SU4-2 (160–130 cm), based on the lithology and the grain-size distribution. The SU4-1 is rich in silt than the upper subunit (SU4-2).

- The third unit (unit 3) is located between 196 and 308 cm depth below the surface and is characterized by a slightly lower mean MS of 55 ± 25 SI, a low sand content (LT 5%), and minor changes in C/N with average values of 14.5 ± 3. Changes in MS values correspond to changes in the percentage of sand particles (0–15%). Two subunits can be distinguished, SU3-1 (308–260 cm) and SU3-2 (260–196 cm). The SU3-1 subunit shows a basal brownish layer with red nodules that contrasts with its top grayish subunit (SU3-2).

- The second unit (unit 2) is located between 308 and 450 cm below the surface and is characterized by coarser grain size (66 ± 11% of silt fraction, in average), a higher MS (132 ± 52, in average), the occurrence of reddish clay levels at the bottom, strong variations in grain size, and very large changes in C/N ratio (20 ± 20, in average) compared with unit 3 (Figure 4). This unit shows several peaks of C/N with values over 50 cor responding to terrestrial organic-rich layers. Unit 2 can roughly be divided into five subunits: SU2-1 (450–415 cm), SU2-2 (415–390), SU2-3 (390–365 cm), SU2-4 (365–330 cm), and SU2-5 (330–308 cm). The top US2-5 subunit is a sandy clay in which micro-charcoals were found and dated. The US2-4 sub unit contains several sandy layers without clay and has high MS values. The SU2-3 subunit shows wavy sandy, silty, and clay laminations and sand pillows. The SU2-2 subunit is more homogeneous and fine grained; it is topped by a red clay layer; two dated samples were extracted from this level. The SU2-1 subunit has a sand content particularly low compared with the above unit and contains a basal red clay layer.

- The basal unit (unit 1) extends from 450 cm to the bottom of the core and is characterized by high MS values (96 ± 41 SI, in average), low sand content (4 ± 6%, in average), constant C/N ratio, and the occurrence of reddish clay levels. Three subunits can be deciphered: SU1-3 (450–490 cm), SU1-2 (490–520 cm), and SU1-1 (520–580 cm). The subunit US1-3 is clayey silt and shows a low MS value compared with the sub units SU1-2 and SU1-1 which are more sandy. SU1-3 basal part has a brownish color, which contrasts the upper grayish part. The SU1-2 is underlined by a marked lithological change; MS and silt show a decrease trend, while clay shows the opposite pattern. The SU1-1 is characterized by fluctuations in grain size and MS.

We independently correlated our sedimentary cores with other dated sedimentary sections in the Amik Basin and took into account textural evidences. We focus on studied sites close to our coring site, in the eastern part of the Amik Basin, but we also consider major recorded environmental changes that would influence sedimentation at the coring location (see Figure 2). The timing of most these environmental changes was constrained within the framework of archaeological investigations (i.e. Yener et al., 2000) and is based on change in pottery styles and artifacts.

The largest environmental change, which rests on the largest body of evidences, is the large growth of a lacustrine body during the Roman/early Islamic time, which triggered an inundation of cultivated soils, the abandonment of settlements, and their shift to the outer margin of the basin (see Figures 2 and 3). The occurrence of a lake is attested in chronicles since the 4th century (Yener et al., 2000, citing Downey, 1961). The border of the lake during the Roman and late Roman Periods is attested by the sand ridge on the eastern side of the lake containing potteries from that time (Eger, 2011). A lake-level increase above this ridge is attested at sites AS 86 and AS 87 to the east and in section along the Afrin drain. The inundated cultivated lands (brown clay soils) were covered by grayish lacustrine clay. The same lake-level increase is recorded at site AS 180, which became an island during the Roman Period (Wilkinson, 2000). The lake-level increase first affected sites in the inner part of the basin and to the east and then it affected sites to the north. Sites AS 187, 32, 29, and 28 were abandoned because of flooding before the end of the 13th century (Yener et al., 2000). This large environmental change matches in our sedimentary record the change between the sandy unit 2 and the clayed unit 3 (see Figure 3b).

Three other environmental changes could have impacted the coring site. First, the Afrin canal very close to the coring site was likely completely silted by 10th century, and sites AS 86, 87, 223, and 42 along the canal occupied during the 7th century were abandoned by 10th century (Figure 2; Eger, 2011). The change in water supply would directly affect the sedimentation at the coring site and would correspond to the transition between the clayey unit 3 and the sandy clay unit 4. The second one occurred during the Ottoman/Islamic Period, again, along the Afrin River in the eastern part of the basin. Silty clay derived from the Afrin River overlies the lacustrine clay deposited since the end of the late Roman Period (Figure 3, south of site AS 89). These coarser grained deposits were related to a southward shift of the Afrin River that would have occurred after the travel of Abu-al Fida at the beginning of the 14th century in the region (Yener et al., 2000). We correlated this change with the strong increase in grain size observed between unit 4 and unit 3. The last environmental change is related to the Orontes, the largest river supplying water to the Amik Basin. The drain of the Bronze Age Tell Atchana evidenced a strong change in activity along the Orontes from a low energy aggradation to high-energy flooding (Yener et al., 2000). This environmental change would correspond to the large increase in grain size from clayed unit 1 to sandy unit 2.

As a final test regarding the age model, we compare the inferred ages of the sedimentary events with historical earth quakes in 1872, 1408, 859, and 525 that would have ruptured the Hacipasa Segment (Akyüz et al., 2006; Meghraoui et al., 2003; Yönlü et al., 2010). The main sedimentary event E2 would correspond to the 859 event, the 525 earthquake to a minor sedimentary event below, and the 1408 event would not be recorded. The events that could reflect the seismic history are compatible with the age model.

Although the 14C age model is impressive, the independent correlation of the sedimentary core with the recorded environmental changes validates it. We considered that the sediment deposited through unit 1 corresponds to the late Bronze Age (2000–1200 BC), unit 2 corresponds to the sediments deposited throughout the Iron Age (1200–300 BC) and Hellenistic Period (300–100 BC), unit 3 was deposited during the Roman and early Islamic Periods (100 BC–AD 650), unit 4 comprises the sediments from the Islamic and Ottoman Periods (AD 650–1650), and unit 1 represents the Modern Period.

Our record of the beginning of the late Bronze Age (~2500 BC) reveals continuous lacustrine or marshy environments with short or seasonal emersion. This interpretation is still compatible with previous insights based on a core and settlements in the central and southern part of the lake (Casana, 2014; Wilkinson, 2000). Tell sites AS 180 and AS181 were small farms around the late 3rd-century BC (Casana, 2014; Eger, 2008), so the lake was inferred to be very small or inexistent at that time. The fact that a lake prevailed at our coring site is due to the specific coring location near the northern extremity of the Hacipasa Fault segment, where a significant normal component is expected. Tectonic subsidence at our coring location is larger than in the central or southern part of the lake; as a consequence, a restricted water body prevailed at the studied location even though it was absent in others.

Different environments and marked changes are recorded and summarized below from the oldest to the younger one. During the Bronze Age (unit 1), the clayey fine-grained sediments with ostracod shells attest the occurrence of a low-energy lacustrine environment with little external input. Wilkinson (2005) and Yener (2005) affirmed that the fluvial environment of the early/middle Holocene in the Amik plain was relatively stable. The occurrence of brownish sediments with ostracods suggests a seasonal reduction in the water column (oxic environment) probably during summer months when the evapotranspiration is the highest. The subsequently deposited grayish clay sediments imply a renewed deepening of the water depth. These two clay types were used for the bricks of the nearby Bronze Age Karatepe Tell (AS 86; Yener, 2000). The high ZrO2, Cr2O3, and ZnO content attests the occurrence of active soil erosion in the Amanus Mountains.

A first major environmental change occurs at the transition between the late Bronze and Iron Ages. The latter is characterized by the anomalous clayey subunit SU1-3 with a high percentage of NaO and CaO and low FeO-MgO, which suggests oxic conditions with a very low water level. The upward decrease in ZrO suggests a drastic reduction in soil erosion related to aridification and/or to decreased anthropic pressure. The top subunit is marked by a sedimentary event probably related to an earthquake. During the Bronze/Iron transition, the main regional center Tell Atchana was abandoned, and Tell Ta’yinat, located 400 m more to the east, was reoccupied (Welton, 2012). The subunit is capped by a 3-mm red clay layer suggesting oxic conditions probably with temporary emersion and overlain by the sandy subunit SU2-1, in which high C/N ratio indicates terrestrial organic matter. This environmental context suggests the occurrence of a drought. An aridification during the late Bronze/early Iron Age transition was repeatedly documented in the Eastern Mediterranean and it was associated with the collapse of the Hittite civilization (end of the 13th-century BC; e.g. Kaniewski et al., 2015; Weiss, 1982). Although we document a clear major sedimentary change between the late Bronze and Iron Ages, there was no apparent societal collapse in the Amik Basin. There was a decline in settlements during the late Bronze Age, but in the Iron Age new settlements appeared and then concentrated in the southern part around the Tell Ta’yinat (Casana, 2007). The trade pattern was disrupted at the Bronze/Iron transition (Janeway, 2008), but farming increased at that time (Capper, 2012). Although a more arid environment is attested by our study, the Amik Basin was still a rich fertile land that allowed a sustainable growth of the agricultural societies in this area (Casana, 2007).

During the Iron Age, the high percentage of sand and high C/N ratio attest for the occurrence of a drier climate with a low lake level and the colonization of a terrestrial vegetation near the coring site (Figure 4). Part of this period corresponds to the arid Dark Age Period identified in Gibala-Tell (Tweini) along the Syrian coastline, at about 100 km from our site (Kaniewski et al., 2008). The variable and rapidly changing grain size of the subunits implies a high-energy environment compared with the lower unit 1. The high content in Cr2O3, ZrO2, and NiO (Figure 5) points to an ongoing soil erosion in the Amik watershed and could indicate a starting occupation of the highlands and an increased deforestation phase related to the extension of the agricultural activities such as orchards. After the Iron Period, during the Hellenistic Period, the Amik plain was densely occupied and sites in the highland started to be occupied (Gerritsen et al., 2008).

The Roman and early Islamic Periods (unit 3) were associated with the development of the Antioch city and the complete intensive occupation of the highlands. The sediments during this period are clays devoid of sands, with low MS and minimal variability implying a low-energy environment. The low C/N values indicated a low input of terrestrial organic matter. The very low terrigenous inputs during the Roman/early Islamic Periods are also attested by the low MS values during this period. Aggradation at the Judaidah and Qarqur sites (Figure 2) was an order of magnitude lower than during the Bronze/Iron Period. However, the occurrence of high colluvium thickness in the Jebel-al-Aqra low range in the late Roman Period suggests a high soil erosion episode in the Amik watershed. However, a significant portion of the sediments eroded at this time was stored locally as colluviums within the ranges by terraced terrains, in agreement with the absence of soil erosion indicators at our site, and did not reach the lake. The Roman Period (subunit SU3-1) shows some difference with the early Islamic Period (subunit SU3-2). The ZrO2 decreased sharply and would never rise again significantly suggesting a permanent fall of soil erosion at the end of the Roman Period, possibly related to a permanent removal of the mobile soil cover on sensitive areas. The transition is also characterized by an abrupt increase in CaO and a concomitant small decrease in terrigenous elements by dilution. The increase is not associated with a significant change in grain size, organic matter, and any major biological activity. This carbonate increase must be related to an increase in CaCO3 in water provided by the Afrin River associated with the canal construction and exploitation near our site (Yener, 2000). Finally, the transition and the above SU3-2 unit are marked by small sedimentary events. The period was marked by a cluster of seismicity with major earth quakes from the 6th- to the 9th-century AD (Akyüz et al., 2006). Among them, the AD 859 and 525 earthquake ruptured the Hacipasa Fault that is adjacent to our site.

During the Ottoman/Islamic Period (unit 4), the sediments deposited show an increase in the clay fraction and a fall in ZnO amount. During the Islamic Period, 50% of the settlements disappeared (Eger, 2015). The clayey sediments is attested by a very low-energy and a lacustrine environment. The small increase in grain size between units 3 and 4 may be related to changes in water inflow from the different canals of the Afrin River, in which distribution changes through time (Figure 1). Siltization of the canal near our site may have occurred (Eger, 2015), but the canal branch B more to the north passing through Aktas was built and functioning at that time (Figure 2).

The Modern Period (unit 5) starting during the 17th century is characterized by an increase in coarse particles and higher C/N ratio, suggesting an increase in terrigenous sediments with terrestrial organic matter (Figure 4). The Cr2O3, ZnO, and NiO contents increase slightly and support a renewed exploitation from the ophiolitic Amanus terrains. Enhanced erosion was caused, in particular, by the construction of the first railway line in Turkey since 1856 under the Ottoman Empire, first by a British and then by the German and French companies for both economic and strategic reasons, due to the important position of the region in the trade between Europe and Asia (Zurcher, 2004). In recent years, to increase the amount of croplands for food production, the Amik Lake was progressively dried starting as early as 1940. In 1965, about 6700 ha of the Amik Lake and 6800 ha of its surrounding wetlands were drained (International Engineering Company (IEC), 1966). Since 1965, croplands and settlements increased until a complete drying of the lake in 1970. A significant part of the former Amik Lake flooded during Spring time. The progressive drying is attested by an increase in CaO and a decrease in FeO2 (oxidation).

El Ouahabi et al. (2018:9)

claim that the 526 CE Antioch Quake

is present in their core (labeled as 525 or 529 in the article and figures) and seem to associate it

with a thin layer at 225 cm. showing minor structural disturbance.

The Amik Basin in the Eastern Mediterranean region occupied since 6000–7000 BC has sustained a highly variable anthropic pressure culminating during the late Roman Period when the Antioch city reached its golden age. The present 6-m-long sedimentary record of the Amik Lake occupying the central part of the Basin constrains major paleoenvironmental changes over the past 4000 years using multi-proxy analyses (grain size, magnetic susceptibility, and x-ray fluorescence (XRF) geochemistry). An age model is provided by combining short-lived radionuclides with radiocarbon dating. A lake/marsh prevailed during the last 4 kyr with a level increase at the beginning of the Roman Period possibly related to optimum climatic condition and water channeling. The Bronze/Iron Ages are characterized by a strong terrigenous input linked to deforestation, exploitation of mineral resources, and the beginning of upland cultivation. The Bronze/Iron Age transition marked by the collapse of the Hittite Empire is clearly documented. Erosion continued during the Roman Period and nearly stopped during the early Islamic Period in conjunction with a decreasing population and soil depletion on the calcareous highland. The soil-stripped limestone outcrops triggered an increase in CaO in the lake water and a general decrease in ZrO2 released in the landscape that lasts until the present day. During the Islamic Period, pastoralism on the highland sustained continued soil erosion of the ophiolitic Amanus Mountains. The Modern Period is characterized by a higher pressure particularly on the Amanus Mountains linked to deforestation, road construction, ore exploitation, and drying of the lake for agriculture practices.

... The Amik Basin has a long human history, associated with dense, variable, and marked human settlements. The latter, started probably since the Neolithic time (Braidwood and Braidwood, 1960), is marked during the Bronze Age by the development of the Alalakh, the capital of a regional state (Yener and Wilkinson, 2007), and later by the rise of the antique Antioch city, the third largest city of the Roman Empire (~500,000 inhabitants; De Giorgi, 2007). In 1920, there were only about 180,000 people living in the region, and presently, Antakya (ancient Antioch) has a population of only 250,000 inhabitants (Doğruel and Leman, 2009). The Amik region had thus undergone a highly variable human occupation. It is thus a particularly interesting laboratory regarding the human impacts on the landscape in the Mediterranean region.

The history of the Amik region has been well documented. The region was home to several major archaeological excavations. During the 1930s and 1950s (Braidwood and Braidwood, 1960; Haines, 1971), the archaeological studies focused on the Amik Basin. Starting in 1995, excavations were renewed by the Oriental Institute (Chicago University) as the Amuq Valley Regional Projects (AVRP) in order to better understand the settlement pattern and the systems of land use through an interdisciplinary regional research program from the Chalcolithic to the Islamic Period (e.g. Yener, 2005, 2010; Yener et al., 2000). The defined stratigraphical sequences and the associated artifact typology found in the Amik plain are presently a standard reference for chronologies and material cultures in all the neighboring regions (Yener et al., 2000).

The present sedimentological study was undertaken in the eastern part of the Amik Lake near the junction with the Afrin River. The presently dried lake occupied the central part of the Amik Basin, a tectonic pull-apart basin. Our aim was to constrain environmental changes during the last 4000 years in relation to the different human occupation phases. The regional tectonics dominated by the Dead Sea Fault Zone (DSFZ), as well as the settlement and land-use histories since the Bronze Age, were first rapidly reviewed because they provided a necessary framework for the interpretation of the data. The analysis of an ~6-m sedimentary sequence is then presented using a multi-proxy approach (magnetic susceptibility (MS), grain size, x-ray fluorescence (XRF) geochemistry, and organic geochemistry). The age of the sequence was constrained by short-lived radioisotopes and radiocarbon dating and tie points using historical earthquakes that left a fingerprint. The results were discussed considering the different geoarchaeological data available in the area.

The 50-km-long and 50-km-wide Amik plain is a tectonic basin filled by up to 2.5-km-thick Plio-Quaternary sediments (Gülen et al., 1987) and crossed by the Dead Sea Fault (DSF). The DSF is composed of two segments, the Karasu Fault to the north bounding of the Amanus Mountain and the Hacipasa Fault to the south in the Orontes valley (Akyüz et al., 2006; Altunel et al., 2009; Karabacak and Altunel, 2013; Karabacak et al., 2010; Figure 1). The two active left-lateral strike-slip faults defined a pull apart structure and have ruptured in large destructive earthquakes during historical time (e.g. Akyüz et al., 2006).

The basin is surrounded by several mountains and plateaus. To the west stands the Amanus Mountains that culminates at 2250 m and is made of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks as well as of a large ophiolitic body (Boulton et al., 2007). To the south lies the low ranges of calcareous Jebel al-Aqra or Kuseyr Plateau. To the northeast, the Kurt Mountains culminating at 825 m are mostly composed of metamorphic rocks (Altunel et al., 2009; Eger, 2011; Karabacak and Altunel, 2013; Parlak et al., 2009; Robertson, 2002; Wilkinson, 2000).

The plain is watered by three large rivers: the Orontes, the Karasu, and the Afrin. Its central part used to be occupied by wetlands and a large shallow lake (Figures 1 and 2). The lake has a complex history with alternating extension and disappearance partly unraveled by geoarchaeological studies (Casana, 2008; Friedman et al., 1997; Wilkinson, 1997; Wilkinson, 2000). A lacustrine environment is attested around 7500 years ago until the early Bronze Age sites (Schumm, 1963; Wilkinson, 2000). Between 3000 and 1000 BC, a drying of the lake is attested by soil development and accumulation of calcium carbon at the center of the lake (Casana, 2008; Wilkinson, 1999). During the Roman Period, the environment was again more humid, and the lake surface increased to reach a maximum extent during the first millennium AD (Casana, 2007; Eger, 2011; Wilkinson, 1997). During the 19th century and the mid-20th century, the lake was the main resource for the local economy, and it was artificially drained at the beginning of the 1940s (Çalışkan, 2008); the desiccation work was completed in 1987 (Kilic et al., 2006).

... This SR [Sedimentation Rate] implies that the two layers characterized by high MS [Magnetic Susceptibility] values and Cr2O3 content in the E1 anomalous deposit would correspond to the 1872 and 1822 historical earthquakes (Akyüz et al., 2006; Figure 3a). The two segments of the DSF, the Karasu Fault and the Hacipasa Fault, have ruptured subsequently in 1822 and 1872 in M ≥7 earthquakes (Akyüz et al., 2006). The 1822 earthquake affected most specially the Afrin watershed, disturbing its water flow; Orontes River was also impacted: its course was permanently affected by a landslide (Ambraseys, 1989). The 1872 earthquake ruptured the Hacipasa Fault segment (Akyüz et al., 2006), lying a few hundred meters from the site and triggered liquefactions near the studied site (Ambraseys, 1989).

... The ages of shells are thus very unreliable and cannot be used to constrain an age–depth model. The only reliable materials are micro-charcoals.

... A composite age model was thus built combining the modern 210Pb [Sedimentation Rate], the 1872–1822 earthquake imprints, and the two youngest micro charcoal ages at 398 and 408.5 cm. .

... We identify several sedimentary layers characterized by coarse grain particles, a MS higher than the background sedimentation, reworked shells, and/or structural disturbances (plastic deformation and sand pillows).

- E1, between 20 and 60 cm, is composed of numerous reworked shells and shows two MS increases, one at 34 cm and a larger double peak between 46 and 58 cm.

- E2 (165–195 cm) is composed of two sandy layers with visible micro-sand pockets and sand dikes probably related to liquefaction. Below, two thin layers at 205 and 225 cm show minor structural disturbances associated with sands. An anomalous event with higher MS and grain size occurred at 260 cm.

- E3 lies at 330 cm and is characterized by sand pillows in a clay matrix; the typical plastic deformation suggests that the event can be interpreted as earthquake triggered deposit. At 435 cm below a red clay layer, micro-sand dikes suggest another episode of plastic deformation.

- E4 occurred at 480 cm and shows a 10-cm-thick disturbed sandy layer enriched in shells.

- E5 at 550 cm is a sand pillow.

- E6 at the core base (580 cm) is a thick sandy layer rich in plagioclase.

All identified events are reported in Figure 4.

Five different sedimentary units were identified (Figure 4) based on the core description, MS, and grain-size data.

- The top unit (unit 5) is 130 cm thick and is characterized by an average MS of 66 ± 16 SI, small variation in C/N, and significant proportion of sand size particles which reach ~80% at 48 cm depth. It is composed of three subunits based on grain size variation. The 35-cm-thick SU5-3 is characterized by low values of MS (57 ± 4 SI); sand and silt contents reach 25% and 55%, respectively. Between 20 and 35 cm, eye-visible shells absent in the top part are present and increase in number at the base of the unit. The SU5-2 subunit extends to 60 cm and is the anomalous event with no clay fraction. It shows a large downward increase in sand size particles comprising reworked shells and in MS peak reaching 120 SI. The silty sand subunit SU5-1 (60–130 cm) has more than 20% of sand fraction, a high macro-organic content, and a high C/N ratio (17 ± 6, in aver age). Its sand proportion is composed of a top rich shell layer overlying a sand-rich layer showing a large MS peak reaching 120 SI.

- The fourth unit (unit 4) extends from 130 to 196 cm and is mostly silty sand having variable MS values (70 ± 19 SI, in average) and small variation in C/N ratio. Two subunits compose this unit, namely, SU4-1 (196–160 cm) and SU4-2 (160–130 cm), based on the lithology and the grain-size distribution. The SU4-1 is rich in silt than the upper subunit (SU4-2).

- The third unit (unit 3) is located between 196 and 308 cm depth below the surface and is characterized by a slightly lower mean MS of 55 ± 25 SI, a low sand content (LT 5%), and minor changes in C/N with average values of 14.5 ± 3. Changes in MS values correspond to changes in the percentage of sand particles (0–15%). Two subunits can be distinguished, SU3-1 (308–260 cm) and SU3-2 (260–196 cm). The SU3-1 subunit shows a basal brownish layer with red nodules that contrasts with its top grayish subunit (SU3-2).

- The second unit (unit 2) is located between 308 and 450 cm below the surface and is characterized by coarser grain size (66 ± 11% of silt fraction, in average), a higher MS (132 ± 52, in average), the occurrence of reddish clay levels at the bottom, strong variations in grain size, and very large changes in C/N ratio (20 ± 20, in average) compared with unit 3 (Figure 4). This unit shows several peaks of C/N with values over 50 cor responding to terrestrial organic-rich layers. Unit 2 can roughly be divided into five subunits: SU2-1 (450–415 cm), SU2-2 (415–390), SU2-3 (390–365 cm), SU2-4 (365–330 cm), and SU2-5 (330–308 cm). The top US2-5 subunit is a sandy clay in which micro-charcoals were found and dated. The US2-4 sub unit contains several sandy layers without clay and has high MS values. The SU2-3 subunit shows wavy sandy, silty, and clay laminations and sand pillows. The SU2-2 subunit is more homogeneous and fine grained; it is topped by a red clay layer; two dated samples were extracted from this level. The SU2-1 subunit has a sand content particularly low compared with the above unit and contains a basal red clay layer.

- The basal unit (unit 1) extends from 450 cm to the bottom of the core and is characterized by high MS values (96 ± 41 SI, in average), low sand content (4 ± 6%, in average), constant C/N ratio, and the occurrence of reddish clay levels. Three subunits can be deciphered: SU1-3 (450–490 cm), SU1-2 (490–520 cm), and SU1-1 (520–580 cm). The subunit US1-3 is clayey silt and shows a low MS value compared with the sub units SU1-2 and SU1-1 which are more sandy. SU1-3 basal part has a brownish color, which contrasts the upper grayish part. The SU1-2 is underlined by a marked lithological change; MS and silt show a decrease trend, while clay shows the opposite pattern. The SU1-1 is characterized by fluctuations in grain size and MS.

We independently correlated our sedimentary cores with other dated sedimentary sections in the Amik Basin and took into account textural evidences. We focus on studied sites close to our coring site, in the eastern part of the Amik Basin, but we also consider major recorded environmental changes that would influence sedimentation at the coring location (see Figure 2). The timing of most these environmental changes was constrained within the framework of archaeological investigations (i.e. Yener et al., 2000) and is based on change in pottery styles and artifacts.

The largest environmental change, which rests on the largest body of evidences, is the large growth of a lacustrine body during the Roman/early Islamic time, which triggered an inundation of cultivated soils, the abandonment of settlements, and their shift to the outer margin of the basin (see Figures 2 and 3). The occurrence of a lake is attested in chronicles since the 4th century (Yener et al., 2000, citing Downey, 1961). The border of the lake during the Roman and late Roman Periods is attested by the sand ridge on the eastern side of the lake containing potteries from that time (Eger, 2011). A lake-level increase above this ridge is attested at sites AS 86 and AS 87 to the east and in section along the Afrin drain. The inundated cultivated lands (brown clay soils) were covered by grayish lacustrine clay. The same lake-level increase is recorded at site AS 180, which became an island during the Roman Period (Wilkinson, 2000). The lake-level increase first affected sites in the inner part of the basin and to the east and then it affected sites to the north. Sites AS 187, 32, 29, and 28 were abandoned because of flooding before the end of the 13th century (Yener et al., 2000). This large environmental change matches in our sedimentary record the change between the sandy unit 2 and the clayed unit 3 (see Figure 3b).

Three other environmental changes could have impacted the coring site. First, the Afrin canal very close to the coring site was likely completely silted by 10th century, and sites AS 86, 87, 223, and 42 along the canal occupied during the 7th century were abandoned by 10th century (Figure 2; Eger, 2011). The change in water supply would directly affect the sedimentation at the coring site and would correspond to the transition between the clayey unit 3 and the sandy clay unit 4. The second one occurred during the Ottoman/Islamic Period, again, along the Afrin River in the eastern part of the basin. Silty clay derived from the Afrin River overlies the lacustrine clay deposited since the end of the late Roman Period (Figure 3, south of site AS 89). These coarser grained deposits were related to a southward shift of the Afrin River that would have occurred after the travel of Abu-al Fida at the beginning of the 14th century in the region (Yener et al., 2000). We correlated this change with the strong increase in grain size observed between unit 4 and unit 3. The last environmental change is related to the Orontes, the largest river supplying water to the Amik Basin. The drain of the Bronze Age Tell Atchana evidenced a strong change in activity along the Orontes from a low energy aggradation to high-energy flooding (Yener et al., 2000). This environmental change would correspond to the large increase in grain size from clayed unit 1 to sandy unit 2.

As a final test regarding the age model, we compare the inferred ages of the sedimentary events with historical earth quakes in 1872, 1408, 859, and 525 that would have ruptured the Hacipasa Segment (Akyüz et al., 2006; Meghraoui et al., 2003; Yönlü et al., 2010). The main sedimentary event E2 would correspond to the 859 event, the 525 earthquake to a minor sedimentary event below, and the 1408 event would not be recorded. The events that could reflect the seismic history are compatible with the age model.

Although the 14C age model is impressive, the independent correlation of the sedimentary core with the recorded environmental changes validates it. We considered that the sediment deposited through unit 1 corresponds to the late Bronze Age (2000–1200 BC), unit 2 corresponds to the sediments deposited throughout the Iron Age (1200–300 BC) and Hellenistic Period (300–100 BC), unit 3 was deposited during the Roman and early Islamic Periods (100 BC–AD 650), unit 4 comprises the sediments from the Islamic and Ottoman Periods (AD 650–1650), and unit 1 represents the Modern Period.

Our record of the beginning of the late Bronze Age (~2500 BC) reveals continuous lacustrine or marshy environments with short or seasonal emersion. This interpretation is still compatible with previous insights based on a core and settlements in the central and southern part of the lake (Casana, 2014; Wilkinson, 2000). Tell sites AS 180 and AS181 were small farms around the late 3rd-century BC (Casana, 2014; Eger, 2008), so the lake was inferred to be very small or inexistent at that time. The fact that a lake prevailed at our coring site is due to the specific coring location near the northern extremity of the Hacipasa Fault segment, where a significant normal component is expected. Tectonic subsidence at our coring location is larger than in the central or southern part of the lake; as a consequence, a restricted water body prevailed at the studied location even though it was absent in others.

Different environments and marked changes are recorded and summarized below from the oldest to the younger one. During the Bronze Age (unit 1), the clayey fine-grained sediments with ostracod shells attest the occurrence of a low-energy lacustrine environment with little external input. Wilkinson (2005) and Yener (2005) affirmed that the fluvial environment of the early/middle Holocene in the Amik plain was relatively stable. The occurrence of brownish sediments with ostracods suggests a seasonal reduction in the water column (oxic environment) probably during summer months when the evapotranspiration is the highest. The subsequently deposited grayish clay sediments imply a renewed deepening of the water depth. These two clay types were used for the bricks of the nearby Bronze Age Karatepe Tell (AS 86; Yener, 2000). The high ZrO2, Cr2O3, and ZnO content attests the occurrence of active soil erosion in the Amanus Mountains.

A first major environmental change occurs at the transition between the late Bronze and Iron Ages. The latter is characterized by the anomalous clayey subunit SU1-3 with a high percentage of NaO and CaO and low FeO-MgO, which suggests oxic conditions with a very low water level. The upward decrease in ZrO suggests a drastic reduction in soil erosion related to aridification and/or to decreased anthropic pressure. The top subunit is marked by a sedimentary event probably related to an earthquake. During the Bronze/Iron transition, the main regional center Tell Atchana was abandoned, and Tell Ta’yinat, located 400 m more to the east, was reoccupied (Welton, 2012). The subunit is capped by a 3-mm red clay layer suggesting oxic conditions probably with temporary emersion and overlain by the sandy subunit SU2-1, in which high C/N ratio indicates terrestrial organic matter. This environmental context suggests the occurrence of a drought. An aridification during the late Bronze/early Iron Age transition was repeatedly documented in the Eastern Mediterranean and it was associated with the collapse of the Hittite civilization (end of the 13th-century BC; e.g. Kaniewski et al., 2015; Weiss, 1982). Although we document a clear major sedimentary change between the late Bronze and Iron Ages, there was no apparent societal collapse in the Amik Basin. There was a decline in settlements during the late Bronze Age, but in the Iron Age new settlements appeared and then concentrated in the southern part around the Tell Ta’yinat (Casana, 2007). The trade pattern was disrupted at the Bronze/Iron transition (Janeway, 2008), but farming increased at that time (Capper, 2012). Although a more arid environment is attested by our study, the Amik Basin was still a rich fertile land that allowed a sustainable growth of the agricultural societies in this area (Casana, 2007).

During the Iron Age, the high percentage of sand and high C/N ratio attest for the occurrence of a drier climate with a low lake level and the colonization of a terrestrial vegetation near the coring site (Figure 4). Part of this period corresponds to the arid Dark Age Period identified in Gibala-Tell (Tweini) along the Syrian coastline, at about 100 km from our site (Kaniewski et al., 2008). The variable and rapidly changing grain size of the subunits implies a high-energy environment compared with the lower unit 1. The high content in Cr2O3, ZrO2, and NiO (Figure 5) points to an ongoing soil erosion in the Amik watershed and could indicate a starting occupation of the highlands and an increased deforestation phase related to the extension of the agricultural activities such as orchards. After the Iron Period, during the Hellenistic Period, the Amik plain was densely occupied and sites in the highland started to be occupied (Gerritsen et al., 2008).

The Roman and early Islamic Periods (unit 3) were associated with the development of the Antioch city and the complete intensive occupation of the highlands. The sediments during this period are clays devoid of sands, with low MS and minimal variability implying a low-energy environment. The low C/N values indicated a low input of terrestrial organic matter. The very low terrigenous inputs during the Roman/early Islamic Periods are also attested by the low MS values during this period. Aggradation at the Judaidah and Qarqur sites (Figure 2) was an order of magnitude lower than during the Bronze/Iron Period. However, the occurrence of high colluvium thickness in the Jebel-al-Aqra low range in the late Roman Period suggests a high soil erosion episode in the Amik watershed. However, a significant portion of the sediments eroded at this time was stored locally as colluviums within the ranges by terraced terrains, in agreement with the absence of soil erosion indicators at our site, and did not reach the lake. The Roman Period (subunit SU3-1) shows some difference with the early Islamic Period (subunit SU3-2). The ZrO2 decreased sharply and would never rise again significantly suggesting a permanent fall of soil erosion at the end of the Roman Period, possibly related to a permanent removal of the mobile soil cover on sensitive areas. The transition is also characterized by an abrupt increase in CaO and a concomitant small decrease in terrigenous elements by dilution. The increase is not associated with a significant change in grain size, organic matter, and any major biological activity. This carbonate increase must be related to an increase in CaCO3 in water provided by the Afrin River associated with the canal construction and exploitation near our site (Yener, 2000). Finally, the transition and the above SU3-2 unit are marked by small sedimentary events. The period was marked by a cluster of seismicity with major earth quakes from the 6th- to the 9th-century AD (Akyüz et al., 2006). Among them, the AD 859 and 525 earthquake ruptured the Hacipasa Fault that is adjacent to our site.

During the Ottoman/Islamic Period (unit 4), the sediments deposited show an increase in the clay fraction and a fall in ZnO amount. During the Islamic Period, 50% of the settlements disappeared (Eger, 2015). The clayey sediments is attested by a very low-energy and a lacustrine environment. The small increase in grain size between units 3 and 4 may be related to changes in water inflow from the different canals of the Afrin River, in which distribution changes through time (Figure 1). Siltization of the canal near our site may have occurred (Eger, 2015), but the canal branch B more to the north passing through Aktas was built and functioning at that time (Figure 2).

The Modern Period (unit 5) starting during the 17th century is characterized by an increase in coarse particles and higher C/N ratio, suggesting an increase in terrigenous sediments with terrestrial organic matter (Figure 4). The Cr2O3, ZnO, and NiO contents increase slightly and support a renewed exploitation from the ophiolitic Amanus terrains. Enhanced erosion was caused, in particular, by the construction of the first railway line in Turkey since 1856 under the Ottoman Empire, first by a British and then by the German and French companies for both economic and strategic reasons, due to the important position of the region in the trade between Europe and Asia (Zurcher, 2004). In recent years, to increase the amount of croplands for food production, the Amik Lake was progressively dried starting as early as 1940. In 1965, about 6700 ha of the Amik Lake and 6800 ha of its surrounding wetlands were drained (International Engineering Company (IEC), 1966). Since 1965, croplands and settlements increased until a complete drying of the lake in 1970. A significant part of the former Amik Lake flooded during Spring time. The progressive drying is attested by an increase in CaO and a decrease in FeO2 (oxidation).

El Ouahabi et al. (2018:9)

suggest that Event E2, composed of two sandy layers with visible micro-sand pockets and sand dikes

probably related to liquefaction

, corresponds to the

859 CE Syrian Coast Earthquake.