Maps

Map of Crusader States ca. 1100 CE

- from Wikimedia Commons

Map of Crusader States ca. 1100 CE

Map of Crusader States ca. 1100 CEClick on image to open a higher resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Wikimedia Commons (Helix84) from Muir's Historical Atlas (1911) - public domain

Map of The Barony of Kilikian Armenia, 1080-1199

- from Andrews (2009)

Map 1

Map 1The Barony of Kilikian Armenia, 1080-1199 (after B.H. Harut'yunyan)

©Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1937

Andrews (2009)

Armenia under Seljuk Domination, Eleventh-Twelfth Centuries

- from Andrews (2009)

Map 2

Map 2Armenia under Seljuk Domination, Eleventh-Twelfth Centuries

©Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1937

Andrews (2009)

Fortifications of the Crusader States 1100-1170 CE

- from i.pinimg.com

Map of Northern Syria and Cilicia

Greater Syria during the period of the Crusades - 1096 - 1291 CE

- from Ryan (1969)

SYRIA DURING THE PERIOD OF THE CRUSADES, 1096-1291

SYRIA DURING THE PERIOD OF THE CRUSADES, 1096-1291This map is based on one appearing in Castles and Churches of the Crusading Kingdom, by T. S. R. Boase. By permission of the Oxford University Press.

Ryan (1969)

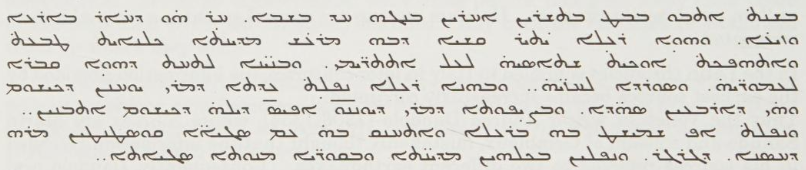

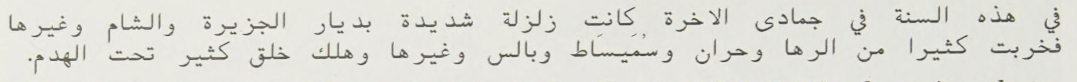

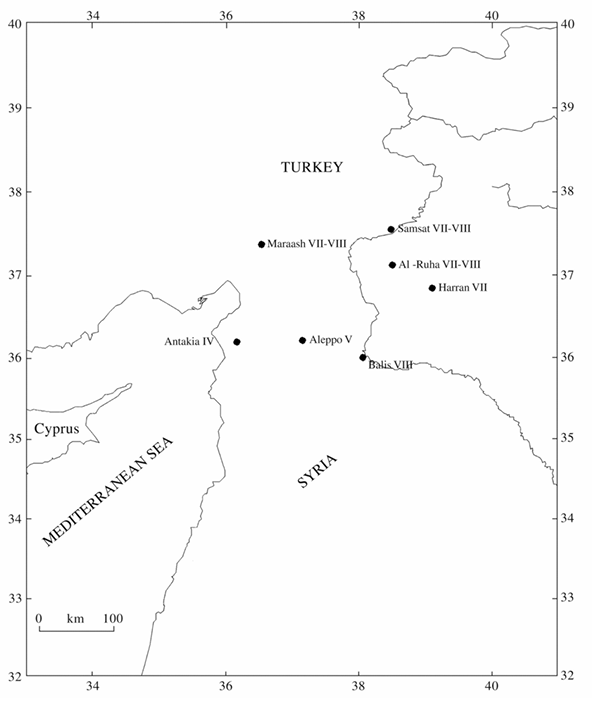

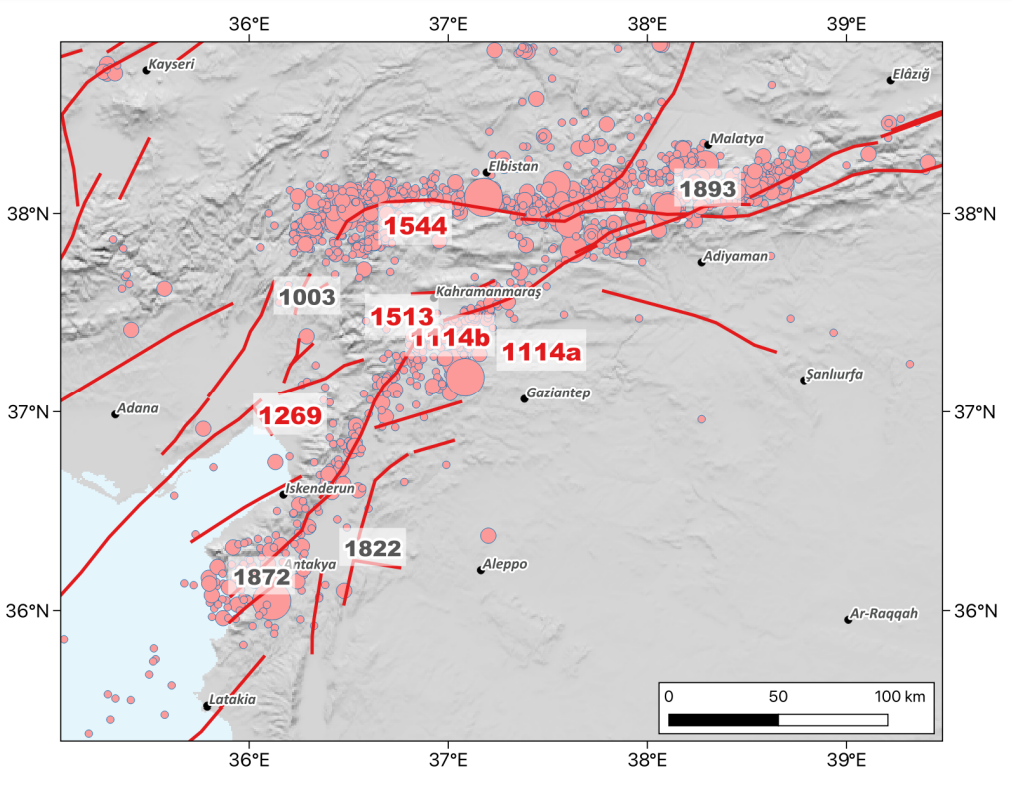

Epicenters of Major Quakes from 1114 to 1202

- from Ambraseys (2004)

Figure 1

Figure 1The dominant tectonic feature of the Levant.

- DSFS – Dead Sea fault system

- EAFS – East Anatolian fault zone

Ambraseys (2004)

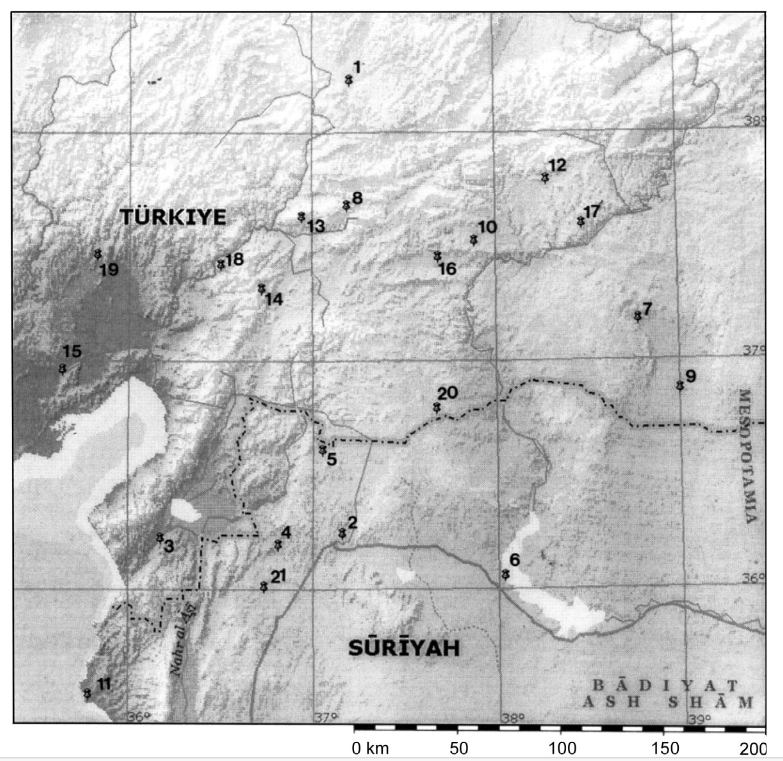

Location Map

- from Ambraseys (2004)

Location map of the earthquake of 1114.

- Ablastha

- Aleppo

- Antioch

- Atharib

- Azaz

- Balis

- Edessa

- Hiesuvank

- Harran

- Kaysun

- Latakiya

- Mansur

- Maras

- Maschegavor

- Mopsuestia

- Raban

- Samosata

- Shoughr

- Sis

- Tell Khalid

- Zaradna

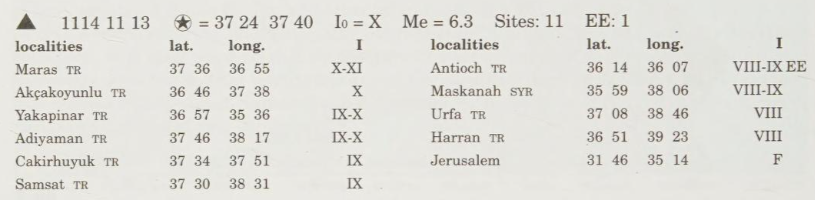

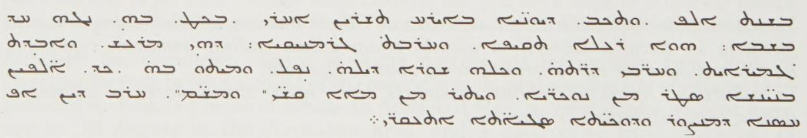

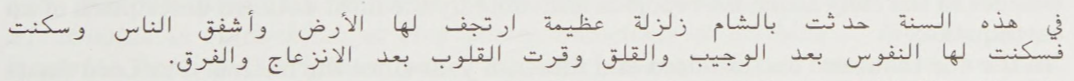

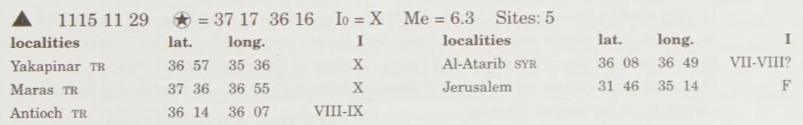

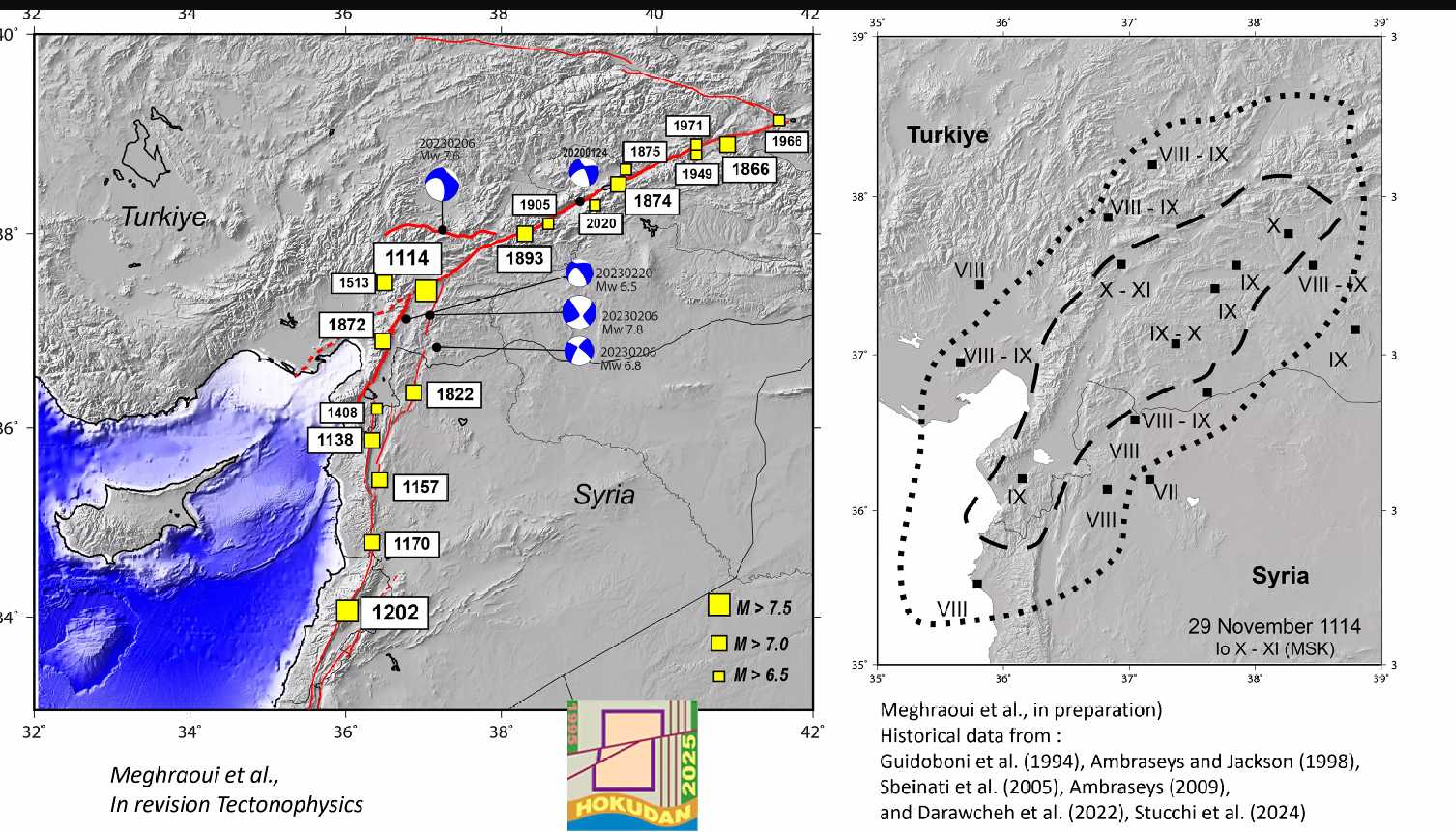

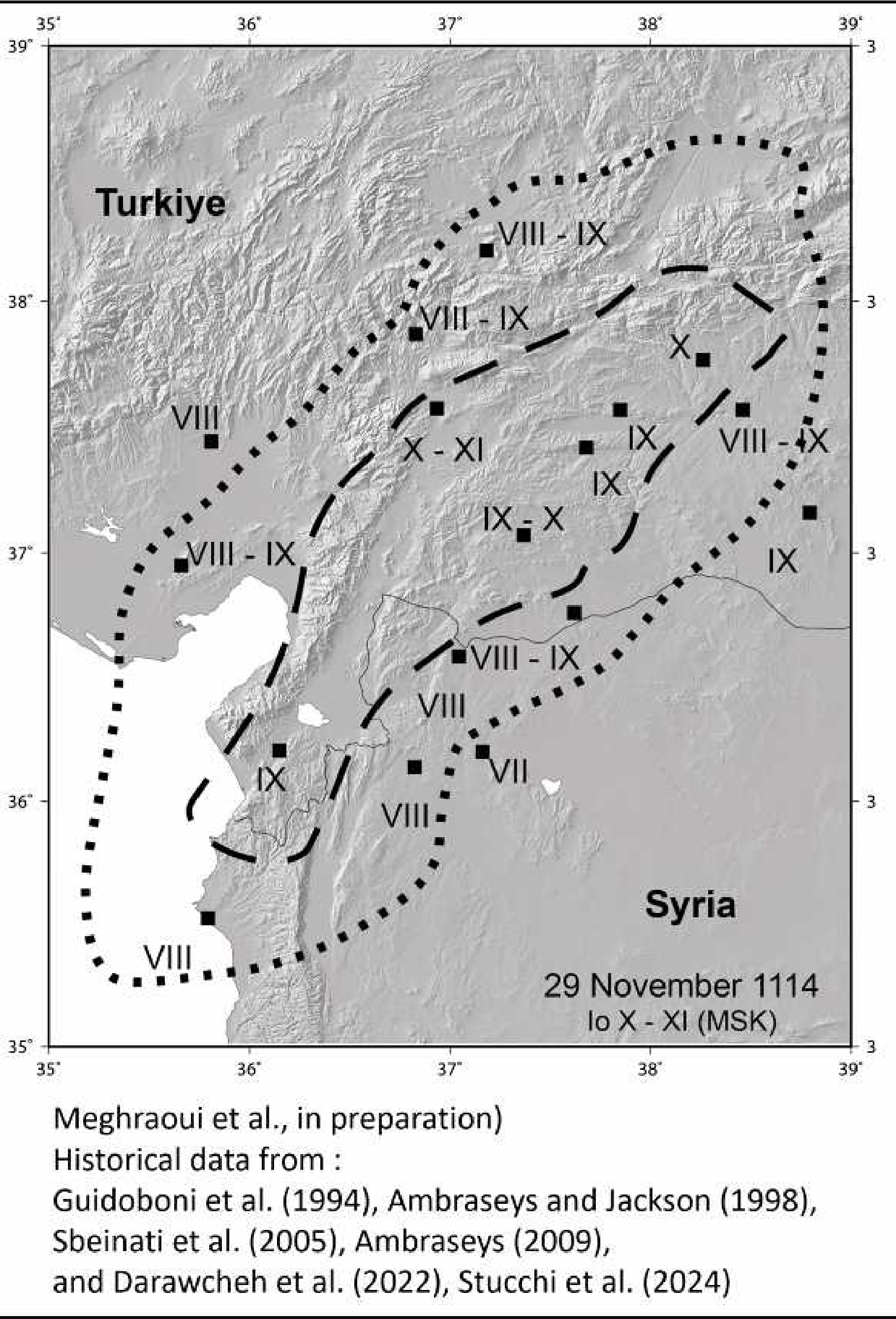

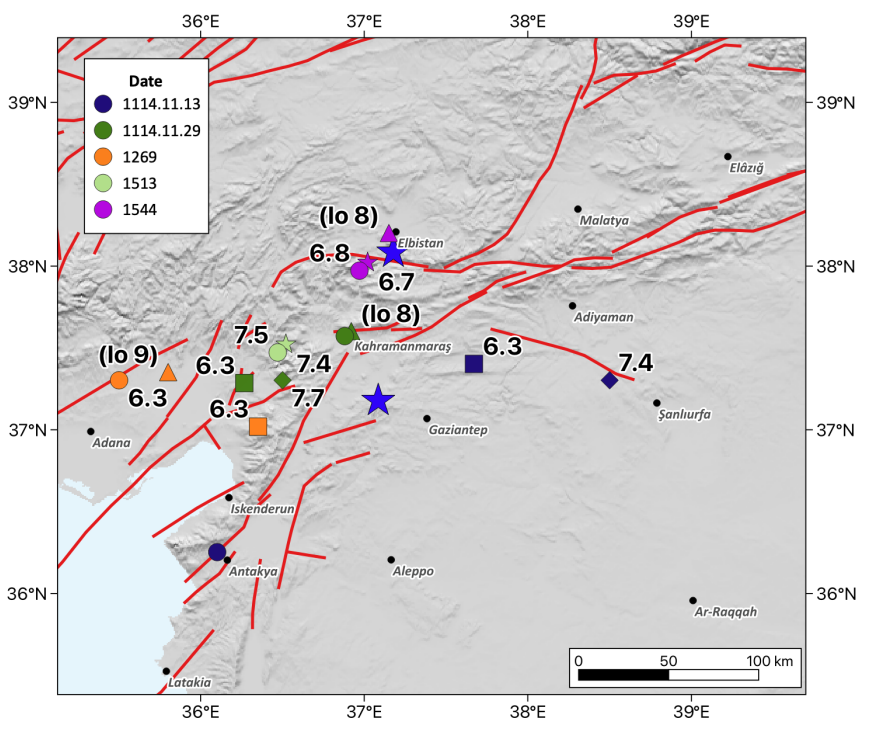

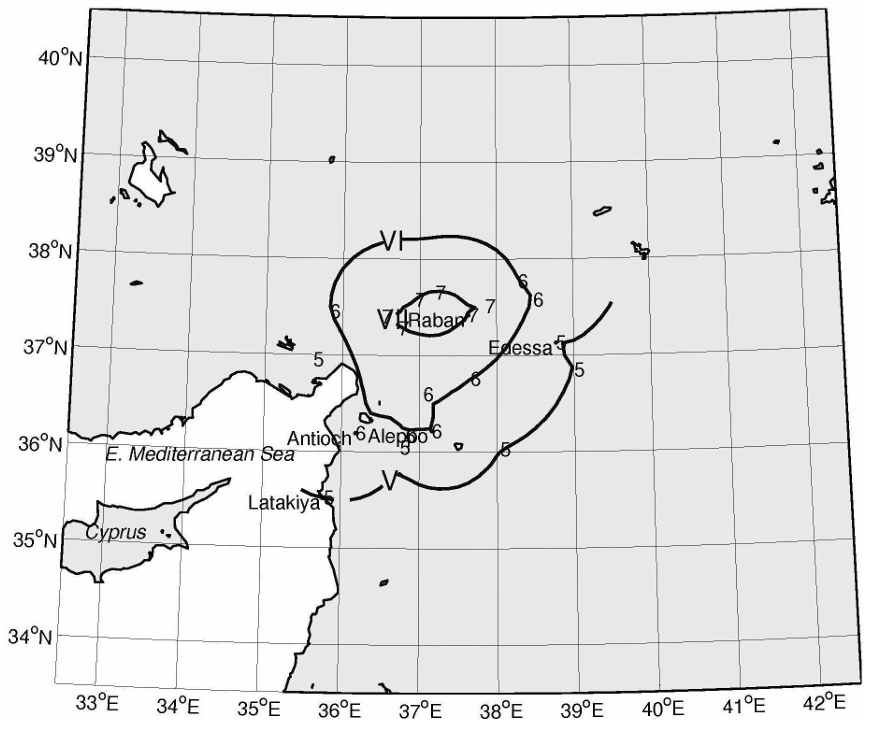

Isoseismal Map - AD 1114 Nov 29 Antioch, Maras

Ambraseys (2009)

- from Ambraseys (2009)

Figure 3.10

Figure 3.10An isoseismal map of the earthquake of 29 November 1114 produced by kriging of 21 groups of intensity points. Estimated location: 37.5◦ N, 37.2◦ E, MS = 6.9 (±0.3)

Ambraseys (2009:282)

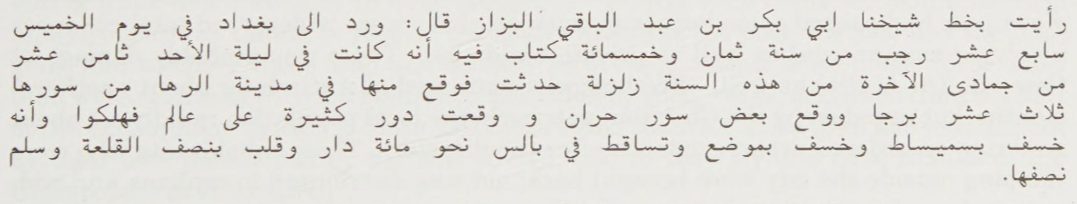

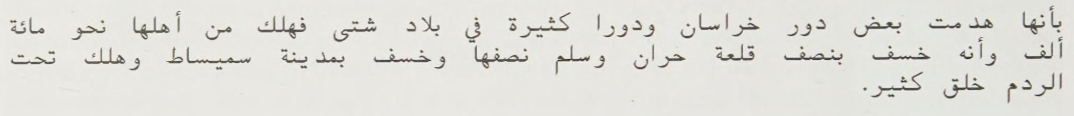

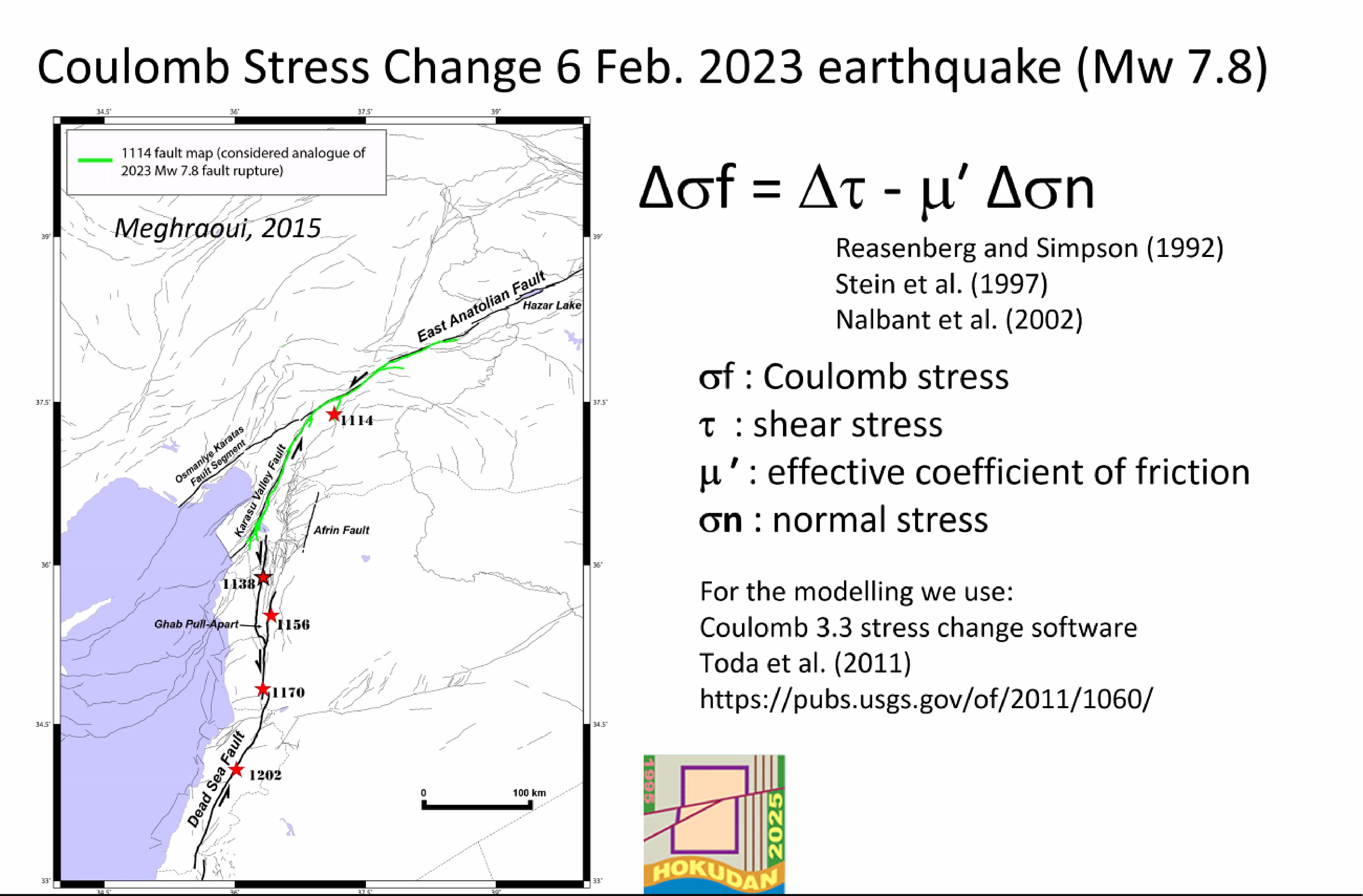

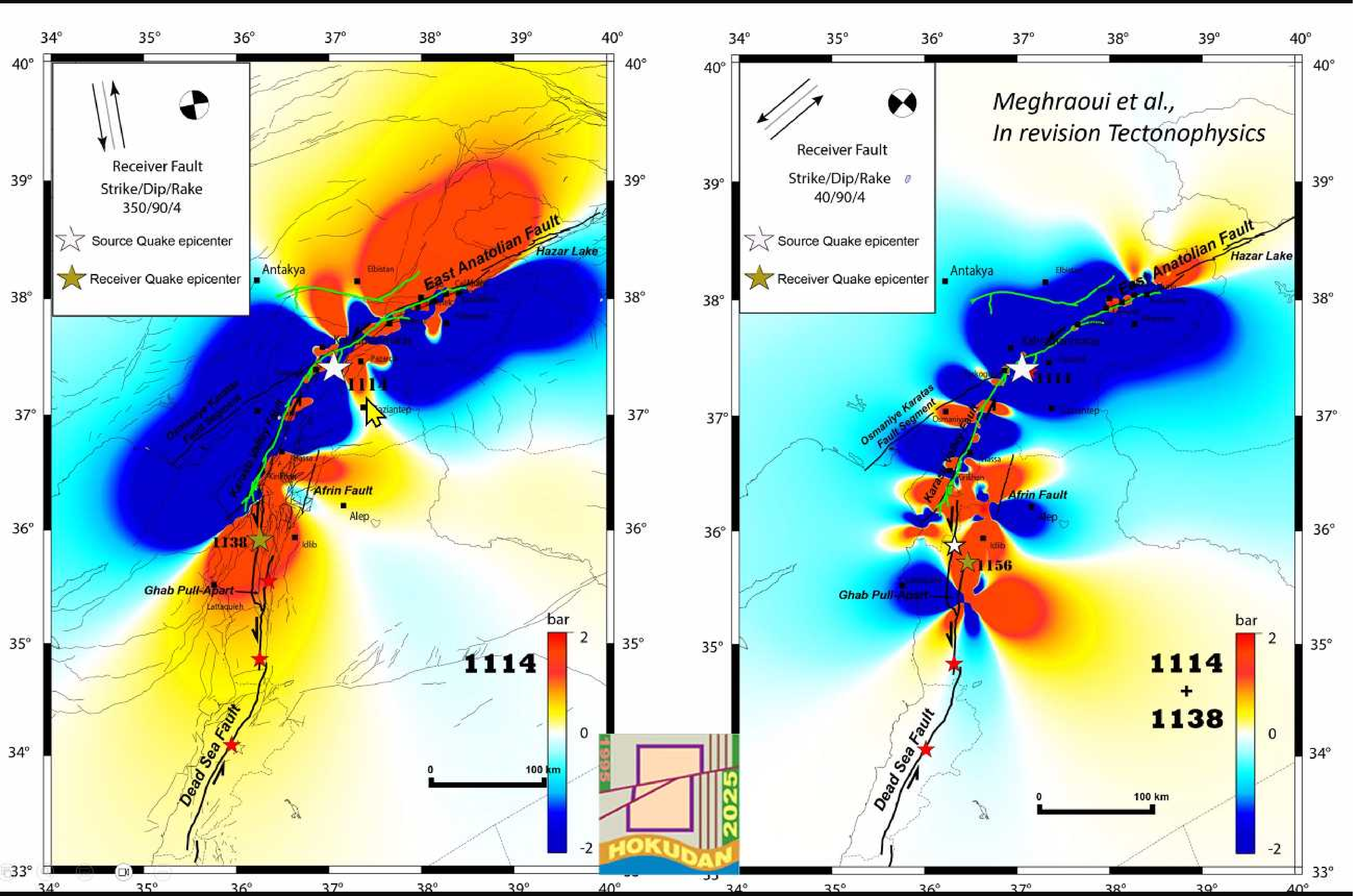

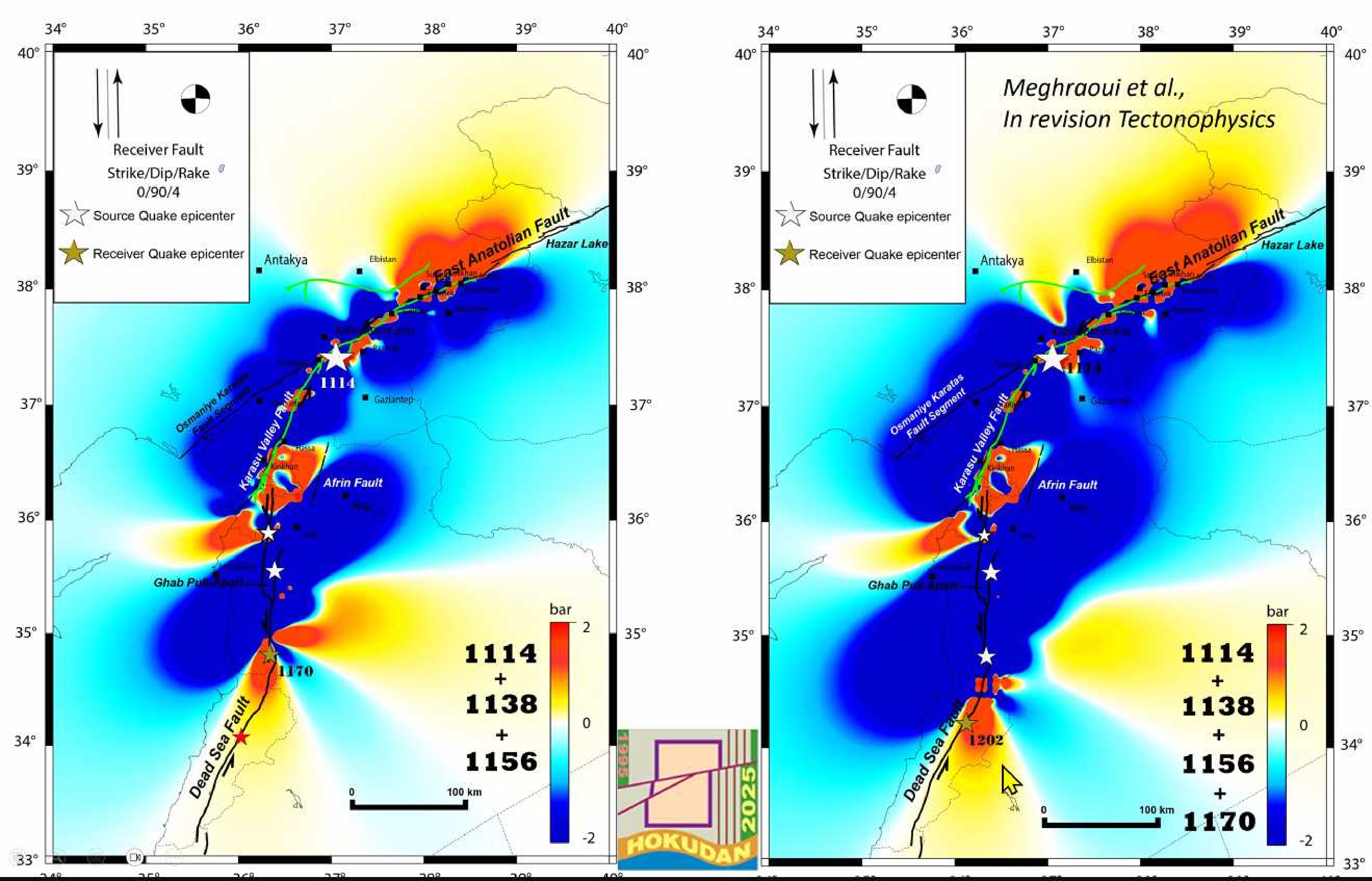

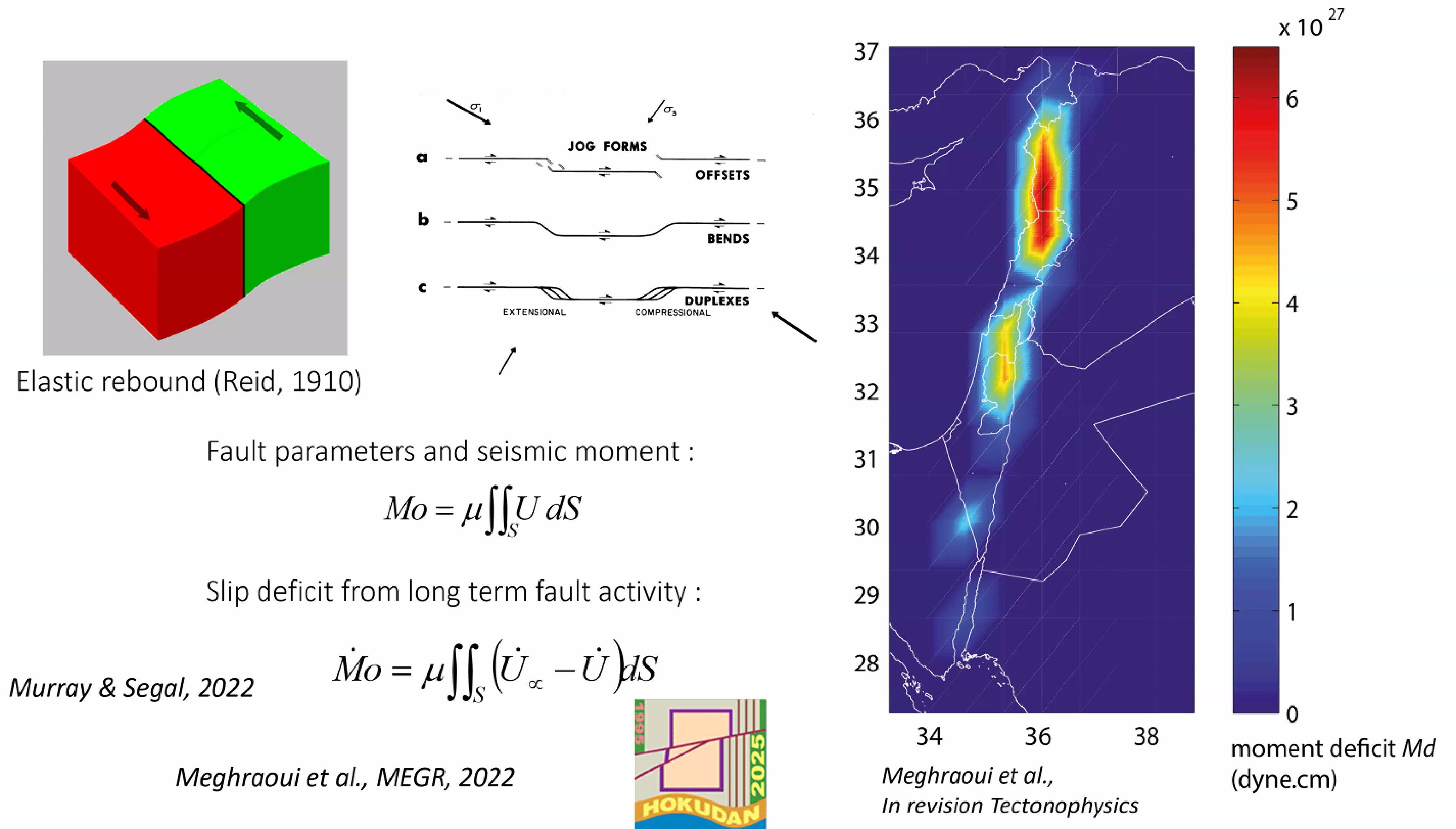

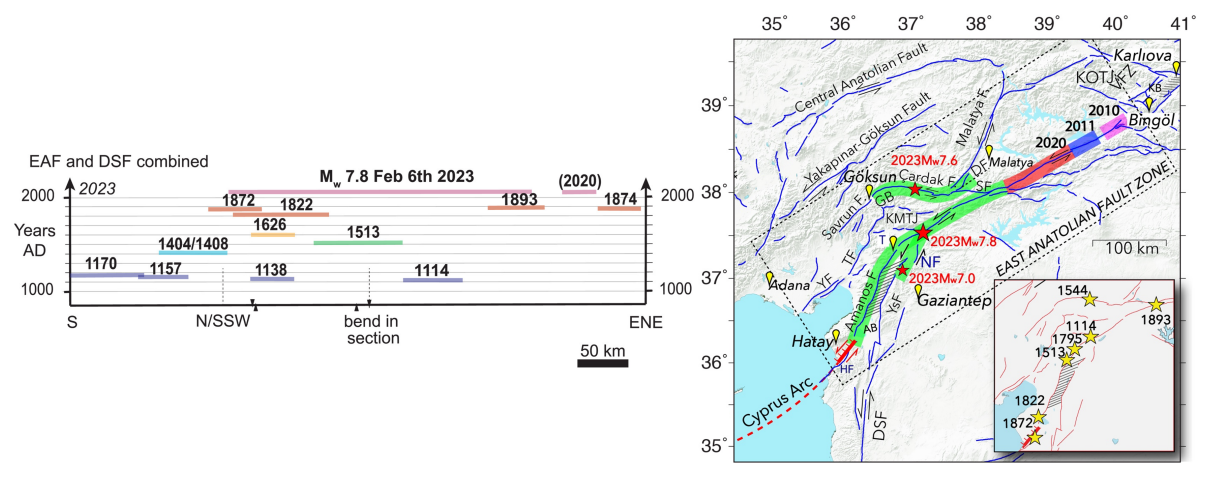

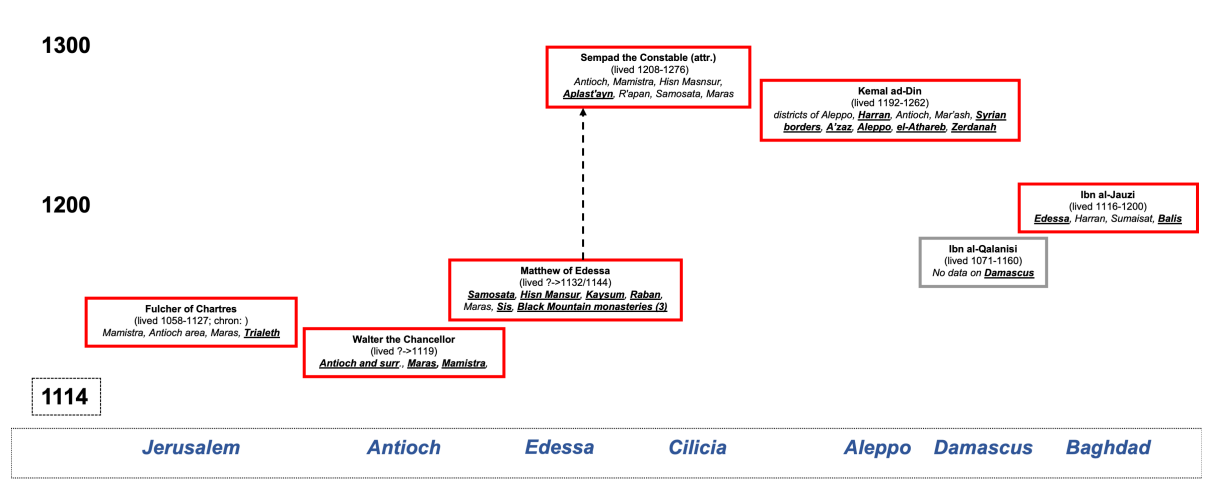

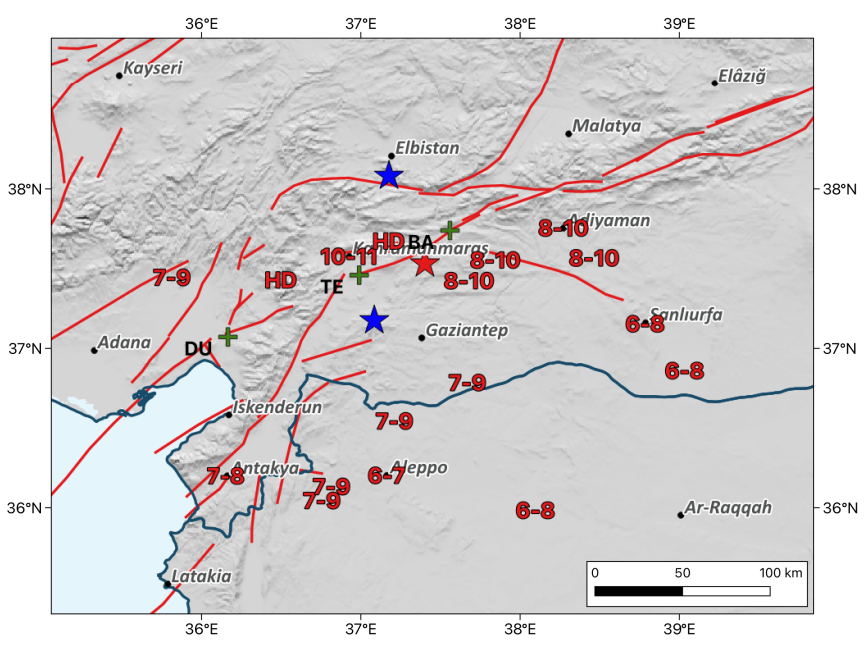

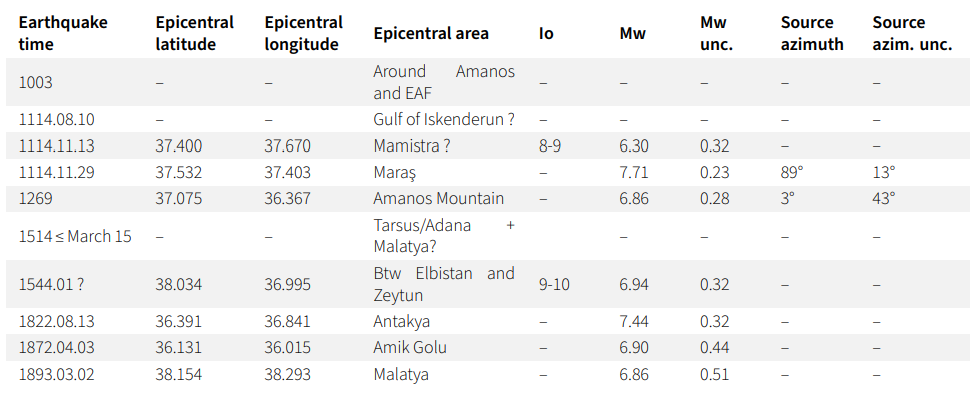

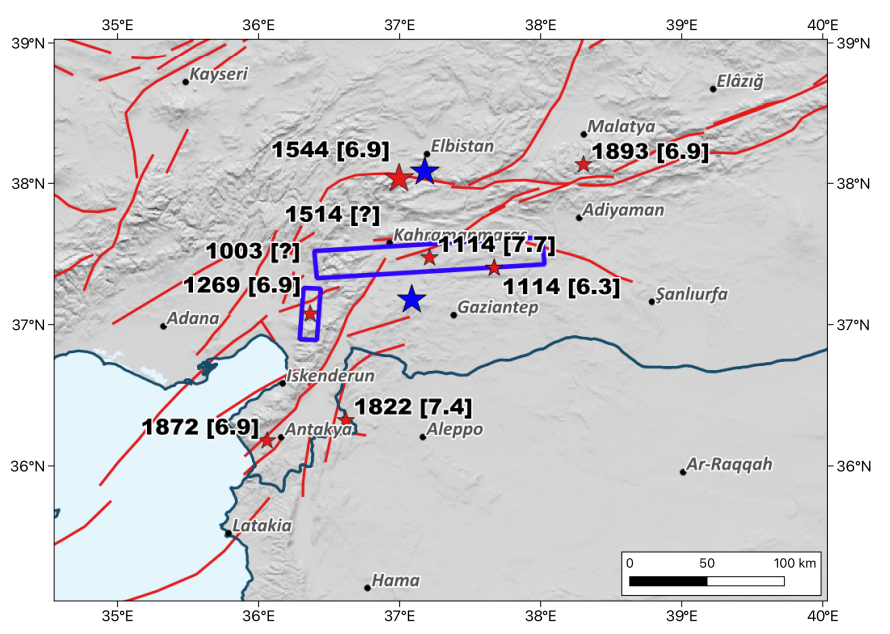

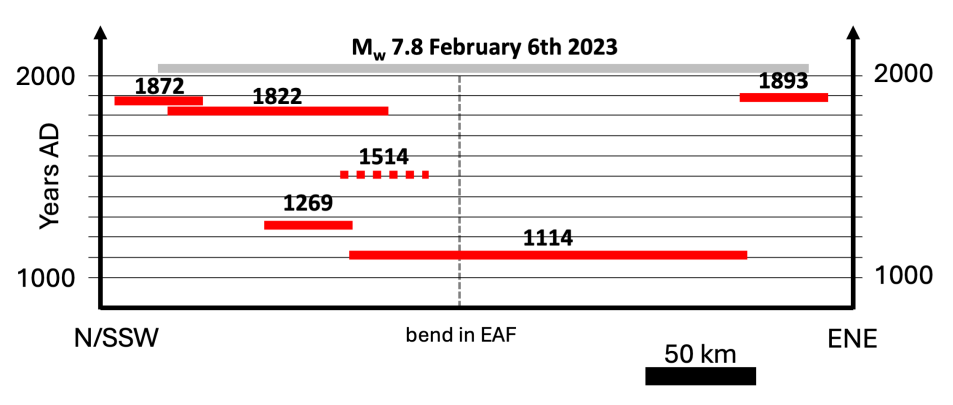

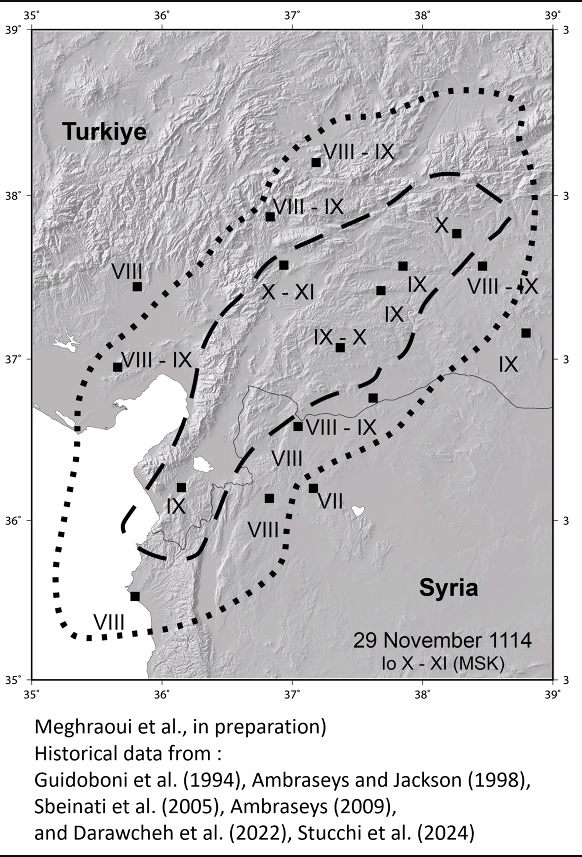

Meghraoui et al. (2025)

Intensity Data Points for the 29 November 1114 CE Earthquake.

Intensity Data Points for the 29 November 1114 CE Earthquake.Meghraoui et al. (2025)

Maps from Guidoboni and Comastri (2005)

1114 November 13 Maresia [southern Turkey]

1115 November 29 Mamistra [southern Turkey]

Broad Scale Tectonic, Fault, and Seismicity Maps

Simplified tectonic setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings

- from Tari et al. (2013)

Simplified tectonic setting of the eastern Mediterranean and surroundings, complied from Hall et al. (2005) and Reilinger et al. (2006).

- KOTJ: Karlıova Triple Junction

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş (or Türkoğlu) Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

- EAF: East Anatolian Fault

- NAF: North Anatolian Fault

- Sin: Sinai Block

- ST: Strabo Trench

- PT: Pliny Trench

- Anb: Antalya Basin

- Cb: Cilicia Basin

- Mb: Mesaoria Basin

- Lb: Latakia Basin

- Cyb: Cyprus Basin

- TR: Tartus Ridge

- HF: Hatay Fault

- MK: Misis-Kyrenia Fault Zone

- Ab: Adana Basin

- Ib: Iskenderun Basin

- KOF: Karataş-Osmaniye Fault

- PF: Paphos Fault

- white arrows and their corresponding numbers indicate the plate velocities relative to the Eurasian Plate, as derived from the GPS data

- black lines indicate major faults, and the arrows along the faults indicate offset direction

- Hatched black lines with triangles indicate subduction zones

- Hatched white rectangle shows location of inset map. B. The detailed bathymetry in the eastern Mediterranean Sea (after Hall et al., 2005)

- Black rectangle shows study area

Major Active Faults And The Morphotectonic Units

- from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2A digital elevation model for the study area and its surroundings, showing the major active faults and the morphotectonic units.

- MTJ: Kahramanmaraş or Türkoğlu Triple Junction

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

Tari et al. (2013)

GPS velocity field relative to fixed Arabian Plate

- from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19The GPS velocity field relative to fixed Arabian Plate (GPS data from Alchalbi et al., 2010; Meghraoui et al., 2011; Reilinger et al., 2006). The abbreviations indicate GPS observation campaigns by Reilinger et al. (2006) and Alchalbi et al. (2010). The fault slip rates (mm/y) were deduced from Mahmoud et al. (2012). The top numbers in each rectangle give strike-slip rates, positive being left-lateral. The other numbers in each rectangle give fault-normal slip rates, positive equalling closing.

- CAF– Cyprus-Antakya Fault

- ATJ: Amik Triple Junction

- DSF: Dead Sea Fault

Tari et al. (2013)

East Anatolian fault between Karlıova and Gulf of İskenderun

- from Duman et al. (2020)

East Anatolian fault between Karlıova and Gulf of İskenderun; Major fault zones in the vicinity plotted in black (simplified from Emre et al. 2018). Inset map shows the active tectonic framework of the Eastern Mediterranean region (from Emre et al. 2018). Dashed polygon indicates the study area. Abbreviations:

- NAFZ North Anatolian fault zone

- EAFZ East Anatolian fault zone

- NS Northern strand

- SS Southern strand

- PE Pontic Escarpment

- LC Lesser Caucasus

- GC Great Caucasus

- WAEP West Anatolian Extensional Provence

- CAP Central Anatolian Provence

- WAEP Eastern Anatolian Compressional Provence

- DSFZ Dead Sea fault zone

- HA Hellenic arc

- PFFZ Palmyra fold and fault zone

- CA Cyprian arc

- SATZ Southeast Anatolian thrust zone

- SMFS Sürgü–Misis fault system

- MKF Misis–Kyrenia fault

- MF Malatya fault

- SF Sarız fault

- EF Ecemiş fault

- DF Deliler fault

- Karlıova fault segment

- Ilıca fault segment

- Palu fault segment

- Pütürge fault segment

- Erkenek fault segment

- Pazarcık fault segment

- Amanos fault segment

- Sürgü fault segment

- Çardak fault segment

- Savrun fault segment

- Çokak fault segment

- Toprakkale fault segment

- Karataş fault segment

- Yumurtalık fault segment

- Düziçi–Osmaniye fault zone;

- Misis fault segment

- Engizek fault zone

- Maraş fault zone

Historical and Instrumental Earthquakes

- from Duman et al. (2020)

Distribution of both historical (a) and instrumental (b) earthquakes along the western segments of Sürgü–Misis fault (SMF) system around the Gulf of İskenderun (simplified from Duman and Emre, 2013). Thick red and black lines indicate the SMF system (north strand) and south strand of the East Anatolian fault zone, respectively. The locations of historical earthquakes are from Tan et al. (2008), Ambraseys (1988), Ambraseys and Jackson (1998) and Başarır Baştürk et al. (2017). The instrumental data are from Kalafat et al. (2011), Aktar et al. (2000), Ergin et al. (2004) and Kadirioğlu et al. (2018). The focal mechanisms are from Kılıç et al. (2017). The letter inside boxes refers to the source for the historical earthquakes as given by Tan et al. (2008).

- ST Shebalin and Tatevossian (1997)

- KU Kondorskaya and Ulomov (1999)

- EG Guidoboni et al. (1994)

- EG2 Guidoboni and Comastri (2005)

- AM Ambraseys (1988)

- AJ Ambraseys and Jackson (1998)

- MFS Misis fault segment

- KFS Karataş fault segment

- YFS Yumurtalık fault segment

- DİFZ Düziçi–İskenderun fault zone

- AFS Amanos fault segment

- YEFS Yesemek fault segment

- AFFS Afrin fault segment

- NFZ Narlı fault zone

- MFZ Maraş fault zone

- EFZ Engizek fault zone

- ÇOFS Çokak fault segment

- SAFS Savrun fault segment

- TFS Toprakkale fault segment

- ÇFS Çardak fault segment

- SFS, Sürgü fault segment

Duman et al. (2020)

Geologic Map of the Antakya Graben

Generalized Columnar Stratigraphic Section through the Antakya Graben

- from Tari et al. (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4A generalized columnar stratigraphic section through the Antakya Graben

Tari et al. (2013)

2023 Turkey-Syria Quakes

Gabriel et al. (2023)

Fault Map with Surface Ruptures

- Fault map with surface ruptures of the 2023 Turkey earthquake

sequence. Focal mechanisms are from the U.S. Geological Survey

(USGS; Goldberg et al., 2023). Shaded areas show the inferred extent of

historic surface ruptures labeled by year and magnitude (Duman and

Emre, 2013). Red and blue numbers correspond to fault segments

modeled in this study named following Duman and Emre (2013). The first

earthquake is modeled using six segments of the EAF:

1 and 2 Amanos segment

3 Pazarcık segment

4 Nurdağı-Pazarcık fault (NPF)

5 unnamed Erkenek splay

6 Erkenek segment. The second earthquakeruptures four segments of the SCSF

7, Çardak fault

8, Göksun bend segment

9, Malatya fault

10, unnamed Göksun splay

The Sürgü fault (segment 11) is shown in Figure 5.

Inset shows regional tectonic map modified from Barbot and Weiss (2021). Yellow circles show earthquakes of MW > 3:0 before 2021 (European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre [EMSC] catalog).- DSTF, Dead Sea Transform fault

- EAF, East Anatolian fault

- NAF, North Anatolian fault

- SCSF, Sürgü–Cardak–Savrun fault.

- Top: Geodetically inferred second invariant of principal strain rate prior to the 6 February earthquakes from Weiss et al. (2020). The black rectangle outlines the area shown in the bottom panel. (b) Bottom: zoomed view of East Anatolian fault zone principal strain rate directions in purple (first component) and pink (second component) from Weiss et al. (2020). In dark and light gray, we show the seismologically inferred maximum and minimum principal horizontal stress components from Güvercin et al. (2022), as well as in dark and light blue, the maximum and minimum principal horizontal stress orientations used in this study.

- Initial conditions for 3D dynamic rupture modeling of both large earthquakes. SHmax[°] is the orientation of the maximum horizontal compressive stress from a new stress inversion we perform (based on Güvercin et al., 2022, Fig. S5), Dc is the critical slip-weakening distance in the linear slip-weakening friction law, R0 is the maximum relative prestress ratio, and R LT R0 is the fault-local relative prestress ratio modulated by varying fault geometry and orientation. Although the assumed SHmax is the same in distinction to the dynamic rupture models in Jia et al. (2023), no additional smaller scale initial prestress or fault strength heterogeneity is prescribed.

Comparison Of Surface Displacements Predicted By Dynamic Rupture Models With Various Geodetic Observations

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Comparison of the surface displacements predicted by our dynamic rupture models with various geodetic observations. (a,b) and (e,f) Comparison of Sentinel-2 east–west displacements, Sentinel-2 north–south displacements, RADARSAT-2 azimuth offsets, and RADARSAT-2 range offsets (see Data and Resources), respectively, with the model predictions shown in the inset of each panel. (c,d) Comparison of the fault offsets measured from the east–west and north–south Sentinel-2 displacement fields across the (c) MW 7.8 and (d) MW 7.7 ruptures with the fault offsets measured from the dynamic rupture models. See also Figure S9. (g,h) Comparison of observed (orange) and dynamic rupture modeled (blue) horizontal components of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) displacements for the (g) MW 7.8 and (h) MW 7.7 earthquakes. The vector error ellipses represent a confidence interval of 95%.

Gabriel et al. (2023)

The 3D dynamic rupture scenarios of the MW 7.8 and 7.7 earthquakes

The 3D dynamic rupture scenarios of the MW 7.8 and 7.7 earthquakes.

- Snapshots of absolute slip rate of the MW 7.8 dynamic rupture scenario (see also Videos S1, S3). The earthquake activates faults 1–6 but does not coseismically trigger faults 7–10 nor 11 (Fig. 5),whichwe include in the same simulation.

- Total fault slip (first row), dip-component of fault slip (second row), peak slip rate (third row), and rupture speed (fourth row) of both dynamic rupture models.

- Snapshots of absolute slip rate of the MW 7.7 dynamic rupture scenario (see also Videos S2, S4). The model breaks faults 7–10, which are in addition to the ambient prestress (Fig. S5) affected by the stress changes of the earlier MW 7.8 dynamic rupture.

- Dynamic rupture moment release rates of the MW 7.8 (top) and the MW 7.7 (bottom) earthquakes compared to kinematic models (Goldberg et al., 2023; Melgar et al., 2023; Okuwaki et al., 2023) and more heterogeneous dynamic rupture models (Jia et al., 2023). The dynamically unfavorable fault system configuration causes a pronounced delay before the EAF ruptures in the backward direction to the southwest. Color bars are not saturated and reflect fault-local maximum values; for example, the maximum local peak slip rate is 8.8m/s during the MW 7.8 and 9.1m/s for theMw 7.7 simulation.

Gabriel et al. (2023)

Modeled And Observed Strong Ground Motions For Both The Earthquakes

(a,b) Comparison of modeled and observed strong ground motions for both the earthquakes. Synthetic (purple = MW 7.8, blue = MW 7:7, gray = more heterogeneous dynamic rupture models (Fig. S6, Jia et al., 2023) and observed (black, AFAD) ground velocity time series at near-fault strong-motion stations shown in the insets, band-pass filtered between 0.01 and 1 Hz. No amplitude scaling or time shifts are applied. The numbers on the top left of each waveform are cross-correlation coefficients with observations.

(c,d) Map of the observed peak ground velocity (PGV) measurements (AFAD, see Data and Resources) at unclipped strong-motion stations that recorded the (c) MW 7.8 and (d) Mw 7.7 earthquakes. The size of the circles indicates the PGV value, and the colors indicate the time at which the PGVoccurred. The simulated waveforms in the dynamic rupture models resolve frequencies of at least 1 Hz close to the fault system (Fig. S7). PGV is here computed as SQRT(PGVx*PGVy). For a color-coded comparison of PGV amplitudes and quantification of the differences in PGV timing and amplitudes, see Figure S8. We account for topography, viscoelastic attenuation, and off-fault plasticity but use a 1D model of subsurface structure (Table S1).

Gabriel et al. (2023)

Alternative Dynamic Rupture Scenarios For The First And Second Earthquake

(a–e) Alternative dynamic rupture scenarios for the first and (f–h) second earthquake. (a–e) Supershear rupture on the first segment (NPF) of the MW 7.8 earthquake compared to our preferred subshear model. (a,b) Strong ground motions, (c) slip-rate evolution, (d) moment rate release, fault slip, and (e) rupture speed close to the NPF–EAF intersection. (f–h) Dynamic rupture model of the MW 7.7 earthquake when the Sürgü connecting fault, or Doğanşehir segment, between the fault systems of the first and second earthquake, is added as the 11th fault. (f) Nonrupture of the Sürgü fault, which is not triggered. The resulting slip on all other faults hosting the second earthquake is the same as in our preferred 10-segment model. (g)We constrain the Sürgü fault geometry from the active fault database (Emre et al., 2018) using a dip of70° and DC = 0:5 m while keeping all other model parameters the same (Fig. 1). We explored a change in the dip of the connecting Sürgü segment to 90° (not shown), which led to equivalent dynamic rupture results. (h) The segment-local unfavorable relative prestress ratio R resulting from our regional stress model and fault geometries, preventing the second earthquake’s rupture connecting to the EAF during the MW 7.7 dynamic rupture scenario.

Gabriel et al. (2023)