[1] Amos says that the prophet received visions ‘. . . during

the reigns of Uzziah king of Judah and Jeroboam son of

Jehoash king of Israel, two years before the earthquake . . .’

(Amos, I. 1).

[2] ‘. . . they shall go into the holes of the cracks and into

the caves of the earth when He arises to shake (terrify) the

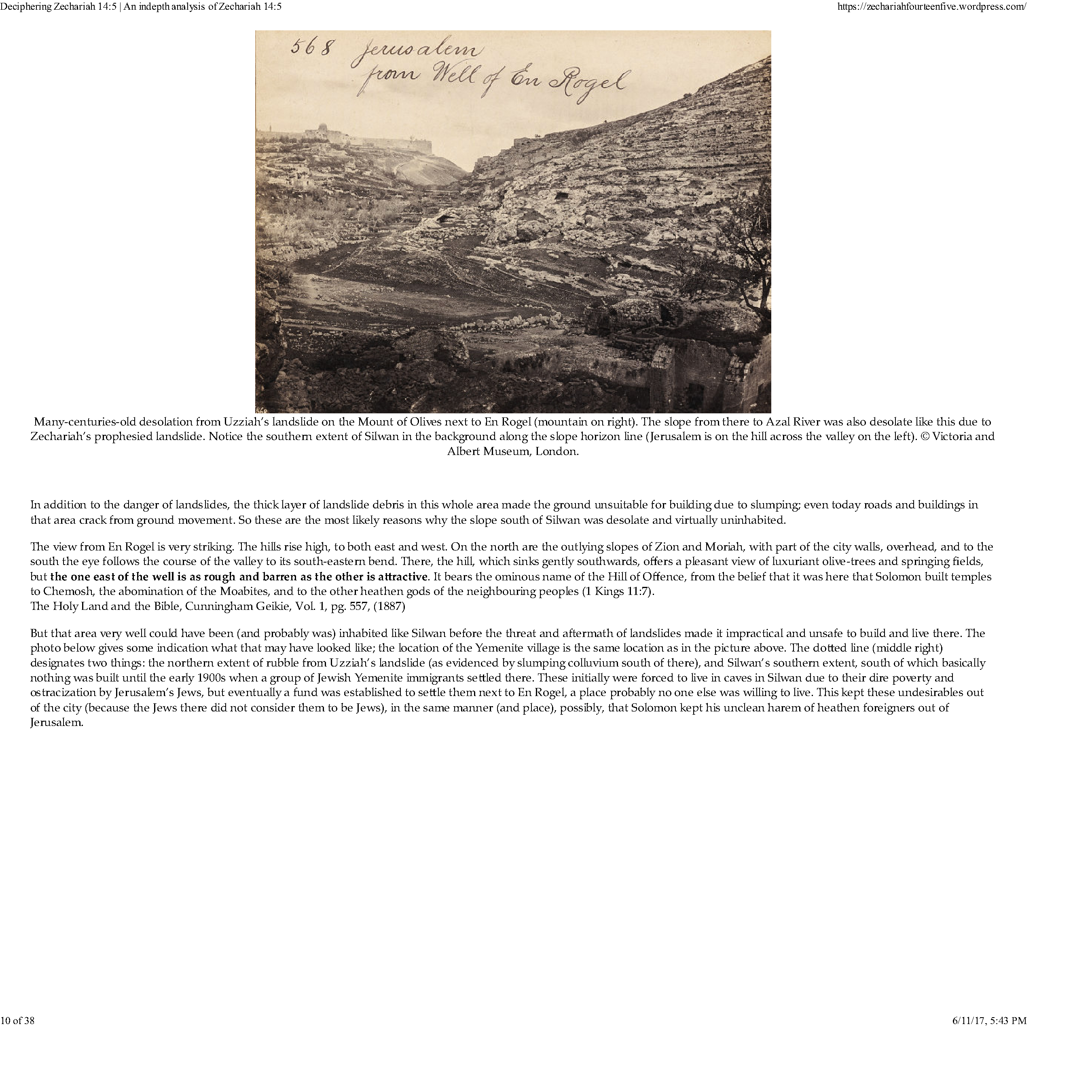

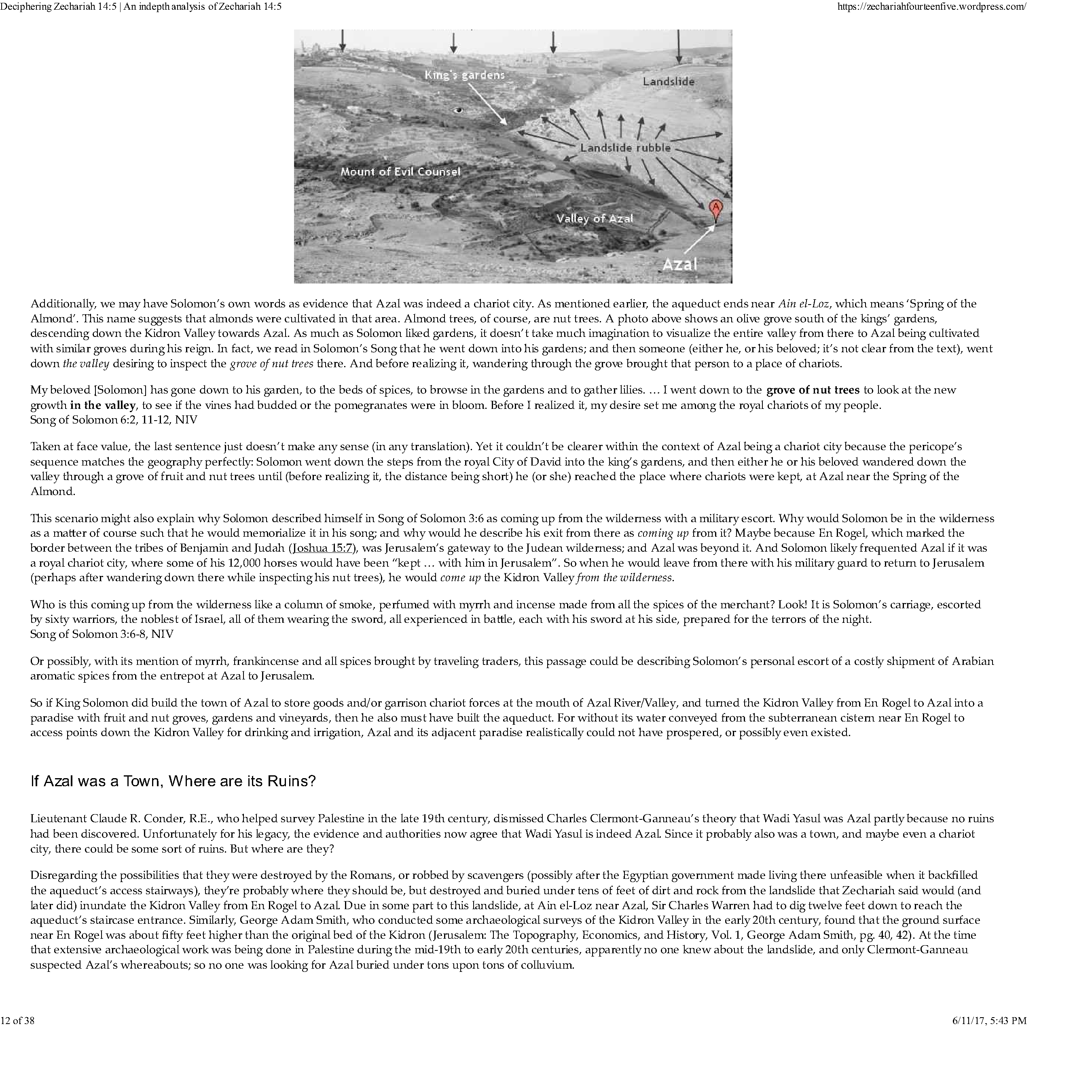

earth . . .’ (Isa. II. 19, 21).

[3.1] ‘. . . the Lord will go out fully armed for war, to fight against

those nations. That day his feet will stand upon the Mount

of Olives, to the east of Jerusalem, and the Mount of Olives

will split apart, making a very wide valley running from east

to west, for half the mountain will move towards the north

and half toward the south. You will escape through that valley,

for it will reach across to Azel. You will escape as your

people did long centuries ago from the earthquake in the

days of Uzziah, king of Juda . . . [c. 767–753 BC]’ (Zech.

xiv. 4–5).

[3.2] ‘And the mountain will split in half, forming

a wide valley that runs from east to west . . . Then you people will

escape from the Lord’s mountain, through this valley,

which reaches to Azal. You will run in all directions, just

as everyone did when the earthquake struck in the time of

King Uzziah of Judah.’ (Contemporary English Version).

[3.3] ‘And the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east

to west by a very wide valley; so that one half of the

Mount shall withdraw northward, and the other half southward . . . And the valley of my mountains shall be stopped

up, for the valley of the mountains shall touch the side of

it; and you shall flee as you fled from the earthquake in the

days of Uzzi’ah king of Judah.’ (Revised Standard Version).

[3.4] ‘And the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east

to west by a very great valley; and half of the mountain

shall remove toward the north and half of it toward the

south . . . And you shall flee by the valley of my mountains;

for the valley of the mountains shall reach to Azel; and you

shall flee, as you fled from before the earthquake in the days

of Uzziah king of Judah.’ (Amplified Bible).

[3.5] ‘And the Mount of Olives shall be split in the midst thereof

toward the east and toward the west, and there shall be a

very great valley; and half of the mountain shall remove

toward the north, and half of it toward the south . . . And you

shall flee by the valley of my mountains; for the valley of the

mountains shall reach unto Azel. And you shall flee, like as

you fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah.’

(American Standard Version).

[3.6] ‘And the Mount of Olives shall cleave in the midst thereof

toward the east and toward the west, and there shall be a

very great valley; and half of the mountain shall remove

toward the north and half of it toward the south . . . And you

shall flee by the valley of my mountains; for the valley of the

mountains shall reach unto Azal; you shall even flee, like as

you fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah

king of Judah.’ (Darby English Version).

[3.7] ‘And the Mount of Olives shall cleave in the midst thereof

toward the east and toward the west, and there shall be a

very great valley; and half of the mountain shall remove

toward the north, and half of it toward the south . . . And you

shall flee to the valley of the mountains; for the valley shall

reach unto Azal; you shall flee, like as you fled from before

the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah.’ (King

James Version).

[4] ‘And ye shall flee to the valley of the mountains;

for the valley of the mountains shall reach unto Azal . . .’ (Masoretic

text).

[5] ‘And the valley of my mountains shall be stopped up; for

the valley of the mountains shall touch the side of it . . .’

(Revised text).

[6] ‘. . . a great earthquake shook the ground and a rent was

made in the temple, and the bright rays of the sun shone

through it, and fell upon Uzziah’s face, insomuch that the

leprosy seized upon him immediately. And before the city,

at a place called Eroge, half the mountain broke off from

the rest on the west, and rolled itself four furlongs and stood

still at the east mountain, till the roads, as well as the king’s

gardens, were spoiled by the obstruction . . .’ (Joseph.AN:

IX. x. 4).

[6a] ‘. . . when leprosy appeared on Uzziah’s brow, at the same

moment the temple split open and the fissure extended for

twelve miles in each direction . . .’ (Nathan ha-Bavli. ix).

[7] ‘. . . the posts of the temple moved when the Lord spoke . . .’

(2 Chron., XXVI. 16–17; 2 Kings XV.1–7).

[8] Timna (Tel Batash)

(Rotherberg and Lupu 1967, 59; Rothenberg 1972, 128,

149–150; Mazar 1993 = in fact 1160–1156).

[9] Tel Beersheba (Tel Sheva)

Estimated period of occurrence: 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘. . . and Beersheva depends largely upon the opinion of Aharoni,

thus far unsupported by an adequate publication, see Y. Aharoni et al., Beer-Sheba I. Excavations at

Tell Beer-Sheba, 1969–1971 Seasons (Tel Aviv 1973) 107.’

(Dever 1992, 35* n. 10).

‘At Tel Beersheba, Strata V and IV cover the period

equivalent to that of Stratum XI at Tel Arad. The plan of

Stratum III at Tel Beersheba is, again, drastically

different from that of Stratum IV. The former solid city wall

and city gate were completely razed, and a new fortification

system was constructed. We subscribe to the “low chronology”,

these changes may not be attributed to Shishak’s

raid or to the division of the alleged United Monarchy. If

so, what generated such a cultural shift? Since typological

modification runs parallel to drastic changes in the design

of settlements, as observed at Tel Beersheba and Lachish,

they should be related to significant events. Tentatively this

development might be associated with a severe earthquake

dated to c. 760 BCE, based on biblical references (Dever

1992). A strong earthquake in the southern part of the

Judean Kingdom might explain the total destruction of the

upper parts of the fortification systems at Tel Arad XI and

Beersheba IV and the need to rebuild them in Strata X and

III, respectively’ (Herzog 2002, 97–98).

[10] Tel Arad

Estimated period of occurrence: c. 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘At Arad, a new fortress was erected that only partially used the previous casemate wall.

A solid wall surrounded by a glacis protected the fortress of Stratum X.

A new imposing gate and an elaborate water system were

constructed in this phase. As shown above, the temple, too,

was first erected in this stratum. At Tel Beersheba, Strata V

and IV cover the period equivalent to that of Stratum XI at

Tel Arad . . . Tentatively this development might be associated

with a severe earthquake dated to c. 760 BCE, based

on biblical references (Dever 1992). A strong earthquake

in the southern part of the Judean Kingdom might explain

the total destruction of the upper parts of the fortification

systems at Tel Arad XI and Beersheba IV and the need to

rebuild them in Strata X and III, respectively.

The pottery assemblage of Stratum X at Tel Arad is remarkably

different from that of Stratum XI and exhibits new

forms that display similarity to the assemblages known from

the destruction layers of the end of the 8th century (Aharoni

and Aharoni 1976).

The time span of the three strata was apparently

fairly short. Attributing the destruction of the fortress of

Stratum XI to the earthquake of ca. 760 BCE, the

construction of the Stratum X fortress may be dated to 750 BCE. The

circumstances of the destruction of the Stratum X fortress

and its reconstruction in Stratum IX are unclear’ (Herzog

2002, 97–98).

‘As stated above, the material culture of Stratum

XI resembles that of Lachish Level IV. The excavators

attribute the destruction of Level IV at Lachish to an

earthquake during the reign of Uzziah in 760 or 750 BCE, so

that this date may mark the end of Stratum XI at Arad and

the establishment of Stratum X. If we accept this view, then

Stratum XI existed for a lengthy period, approximately 150

years’ (Singer-Avitz 2002, 162).

[11] Lachish (Hesy)

Estimated period of occurrence: 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘Level IV apparently came to a sudden end, but it

seems clear that this was not caused by fire. On the other

hand, the lower house of Level III and the rebuilt enclosure

wall followed the lines of the Level IV structures, while the

Level IV city wall and gate continued to function in Level

III; these facts point towards the continuation of life

without a break. Considering that the fortifications remained

intact, we can hardly identify this level with the city which

was stormed and completely destroyed in the fierce

Assyrian attack. Here we may mention M. Kochavi’s suggestion

(made during a visit to the excavations in 1976 and quoted

here with his kind permission) that the end of the Level IV

structures may have been caused by an earthquake.

A natural catastrophe of this sort would, perhaps, be compatible

with the above findings. Of interest in this connection is the

earthquake mentioned in Amos 1:1 and Zech. 14:5, which

occurred around 760 BCE during the reign of Uzziah, king

of Judah’ (Ussishkin 1977, 52).

‘The case of Lachish IV is perhaps the strongest’

(Dever 1992, 35* n. 10).

‘Since typological modification runs parallel to

drastic changes in the design of settlements, as observed

at Tel Beersheba and Lachish, they should be related to

significant events. Tentatively this development might be

associated with a severe earthquake dated to c. 760 BCE,

based on biblical references (Dever 1992)’ (Herzog 2002,

97).

[12] Iraq al Amir

(Butler 1907, 13 = 760?)

[13] Tel Gezer

Estimated period of occurrence: 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘According to Macalister, a number of ashlar towers had been inserted into the Late Bronze Age Outer Wall

by Solomonic engineers. In order to test this claim it was

decided to locate his “Tower VII” (situated immediately

north of the “Egyptian Governor’s Residency”, according

to Macalister’s plan) and open two soundings – one against

each of the inner and outer faces of the “tower” – in order

to determine if indeed the “towers” were constructed in the

manner and at the time Macalister claimed (see Plates 4,

6, and 19). After clearing off the top of the Outer Wall,

however, it was discovered that Macalister’s “Tower VII”

was not a tower at all, but rather an offset that was similar to what he found further west in his trenches 22–29,

a stretch of wall which he described as “rebuilt”. Macalister had apparently found the same corner as our team

and had simply drawn in the other three corners on his

plan.

Excavation against the inner face of the “tower”

reached bedrock in just over a meter (Plate 14).

A foundation trench, which showed up clearly in the eastern balk,

indicated that the offset was initially constructed in the 8th

century B.C. Later, during the Hellenistic period, a second

trench had been dug into the earlier one, suggesting that at

least part of the wall was rebuilt during this period. Indeed,

the ashlars in the upper two or three courses of the wall

were poorly laid. They were uneven and not in the header–

stretcher fashion. Thus they were probably reused from the

earlier Iron Age construction.

The fact that the earliest architectural phase of the

offset dated no earlier than the 8th century B.C. would seem

to raise doubts about the claims of those who have argued

for an earlier dating of the Outer Wall. However,

excavation along the outer face of “Tower VII” revealed at

least nine courses (ca. 5 m.) of excellent header–stretcher

masonry. Although bedrock could not be reached in this

sounding, the pottery from the lowest level of fills against

the outer face consisted of red-slipped 10th century B.C.

wares.

Above these 10th century fills (which were more

than 2 m. thick) were at least two plastered surfaces which

ran up against the wall face. The debris on these surfaces

included fallen ashlar blocks in a bricky fill containing 8th

century B.C. sherds. The debris layers may be evidence of

both an earlier 8th century earthquake (see below) and a

later 8th century B.C. Assyrian destruction (Plate 15). The

latter was followed much later by a hasty repair and rebuild,

probably during the Maccabean period (2nd century B.C.).

Thus, based on the results of the excavation along

the outer face of “Tower VII”, it appears that the Outer

Wall was originally constructed at least by the 10th century

B.C., and probably earlier. The discoveries in Square 22 to

the east (see below) even suggest the possibility of an

initial construction in the LB II. Engineers of the Iron 11 and

Hellenistic periods apparently found it necessary to repair

isolated sections of the inner face (which rested on the top

of an escarpment), thus leading to the discrepancy between

the dates for the construction of the inner and outer faces of

the Outer Wall.

Macalister’s Tower VI

In the hope of finding a genuine Solomonic tower

inserted into a Late Bronze Age wall, it was decided to move

east and attempt to locate Macalister’s “Tower VI”.

According to Macalister’s top plan, Tower VI was located between

25 m. and 30 m. east of Tower VII (Plate 19).

Using the bulldozer to clear away Macalister dump and post-Macalister

debris accumulation (which included some 1947 Jordanian

army trenches), it was not long before an ashlar block of

what appeared to be the southwest corner of Macalister’s

Outer Wall Tower VI was uncovered.

Unfortunately, excavations indicated that this

“tower” was also only an offset (Plate 16). However, the

pottery from the foundation trench indicated that the

earliest phase of this stretch of the Outer Wall was

founded probably during the 10th century B.C. Two additional pieces of

evidence also support a 10th century B.C. dating. First, a

stone of the lowest course of the inner face of the Outer Wall

is roughly bossed in a fashion typical of foundation

ashlars of the 10th century. Second, this lowest course is clearly

cut by the later “tower” or offset, indicating that this stretch

of the wall preceded the construction of the “tower”. Since

the “inserted tower” dated to the 9th/8th century B.C. (see

below), the wall must be dated earlier. While this second

line of evidence is not sufficient by itself to provide a 10th

century date, the bossed ashlar and the 10th century trench

combine to make a 10th century B.C. date for this section of

the wall most probable.

Sometime during the 9th/8th century B.C. the upper

courses of the Outer Wall were remodelled with large

ashlars to create an offset. The ashlar offset was “inserted”

more than a meter into the 10th century B.C. wall line.

The 9th/8th century ashlar inserts and wall appear

to have been destroyed sometime during the 8th century

B.C. Several lines of evidence suggest that the agent of

destruction was an earthquake. For one thing, several

sections of the Outer Wall had been clearly displaced from

their foundations by as much as 10 to 40 cm. Furthermore,

these wall sections were all severely tilted outward toward

the north. That this tilting was not due to slow subsidence

over a long period of time was evident from the fact that

intact sections of upper courses of the inner face of the wall

had fallen backwards into the city. Only a very rapid

outward tilting of the wall, such as that caused by an

earthquake, could cause these upper stones to roll off backwards,

away from the tilt. If the wall’s outward tilt had occurred

slowly, the stones on the top of the wall should have

fallen off toward the downward-sloping outer face of the

wall.

The southwest corner of the ashlar insert had

been similarly displaced from its foundational cornerstone,

although to a lesser degree because of the greater stability

of the ashlar construction. However, even the cornerstone

had been split longitudinally because of the great pressure

created by the lateral movement of the upper courses. This

same tremendous pressure also created fissures in the

ashlar stones that penetrated through several courses.

The reason the foundation stones were not themselves dislodged to

any significant degree is probably due to the fact that they

were set into levelled out depressions cut directly into the

bedrock.

Evidence for an 8th century B.C. earthquake has

been discovered at several other sites, such as Hazor. It

is not impossible that the wall was destroyed by

the well-known earthquake of Amos 1 and Zech 14:5 (ca. 760 B.C.)’

(Younker 1991).

‘Here, too, the “tower” we expected to find (Macalister’s “tower VI”)

turned out to be simply an offset portion

of ashlar masonry (Fig. 1). This later wall, dated by eighth-century

B.C.E. sherds in the secondary back-filled trench,

was probably destroyed by the well-known earthquake of

Amos 1 and Zech. 14:5, c. 760 B.C.E. Not only was the

ashlar “tower” cracked from top to bottom and the adjoining

boulders violently thrown off their foundations, but a long

stretch of the wall to the east was tilted sharply outward

in one piece (Fig. 2). Preliminary research indicated that

the Gezer–Ramla region has been subject to repeated

earthquake damage in historical times; an earthquake

hypothesis, therefore, seems plausible’ (Dever and Younker 1991,

286).

‘While the two Iron Age phases in the “Outer Wall”

were so crystal clear in the sections that they constituted a

“textbook” example of stratigraphy, of more interest was

the evidence they preserved of an earthquake destruction of

the second, 9th/8th century BCE phase. The evidence was

twofold. (1) First, all three courses of the large rectangular

blocks just at the “tower” offset were cracked clear through,

from top to bottom, the heavy stones still approximately

in place but with a large open gap running from top to

bottom (Ill. 3). (2) Second, immediately to the west of the

“tower” offset, the foundation course (here of marginally

drafted ashlars) was still in situ; but the upper two courses

of rougher boulders were found radically displaced upward

and outward, but still lying in a row – as though they had

violently “jumped” off their foundations (Ill. 4).

Now it seems evident that such severe damage cannot have

resulted simply from the usual siege tactics carried out

at ancient walled Palestinian towns. There was none

of the typical evidence of burning: no calcinated stones; no

trace of undermining and collapse; no evidence of battering

or forcing of the wall inward. On the contrary, the wall had

fallen suddenly outward, “split apart” violently.

For some time I resisted the suggestions of various staff

members that perhaps an earthquake was the best

explanation. And certainly I – not identifying with

traditional “biblical archaeology” – did not have the earthquake

of Amos or Zachariah in mind, despite the 9th/8th century

BCE date for the wall that we had posited on quite

independent archaeological grounds. Nor at the moment did I recall

Yadin’s earthquake hypothesis at Hazor. Yet, in the end, the

evidence seemed overwhelming. Several of our group from

California, including Associate Director Randy Younker,

had personally seen just such earthquake damage, even to

the fact that random areas of the wall had been affected,

and this seemed to provide the confirmation that we

needed.

A final probe still farther east, in Area 20, yielded

further evidence. Here we cleared a stretch of the same wall

for some 15 m. At first, our efforts to trace the wall eastward

failed. Because we were following the projected line from

the “tower” offset on a straight course and had found no

stones, we supposed that the top course was robbed out. To

our surprise, we later discovered what was clearly the line

of the top course curving radically, a long section bowed

outward yet still intact. Furthermore, the tops of the whole

line of stones were tilted outward at an angle of ca. 10–15

degrees (Ill. 4).

One could, I suppose, argue that here we are dealing

simply with subsidence, perhaps because the bedrock

dipped downward at this point (as indeed it did). A more

reasonable explanation, however, would seem to be an

earthquake that displaced the whole section bodily,

especially as the foundations were already weak. Certainly a

battering ram, or the work of sappers, could not have produced

such a peculiar phenomenon as this whole stretch of wall

tipped outward. It does indeed resemble rather closely one

of Schaeffer’s toppled walls at Ugarit’ (Dever 1992, 30).

[14] Tel Michal

(Mazar 1993, 298 = ?).

[15] Tell Qasile

Estimated period of occurrence: Stratum XI of Tel Qasile

belongs to the phase Iron Age IB (= first half of the

eleventh century BC).

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘Stratum XI was completely cleared in the southern

part of the mound, where a large building, built mostly of

kurkar stones, was found. The structure’s plan was not fully

traced. East of it was a large square, and nearby were two

clay crucibles containing remains of smelted copper. In the

northern sector of the mound, the buildings in this stratum

were destroyed down to their foundations when the stratum

X buildings were erected. The nature of the ruins indicates

that the settlement was destroyed by an earthquake.

The fortifications in Area B include a massive brick

wall (c. 5 m thick) in stratum XI. No architectural

continuity was noted between strata XII and XI. The latter was laid

out on a different plan and a new wall was added.

It was possible to distinguish clearly between the

different Iron Age I strata (XII–X) at Tell Qasile; thus,

separate and well-defined pottery assemblages could be

established. Changes and developments can be traced in the

ordinary local pottery, in which the Canaanite pottery tradition

continues, as well as in the Philistine ware. The stratum XII

Philistine pottery includes bowls, kraters, jugs with strainer

spouts, and stirrup jars. The pottery contains several

distinctive features that date it to the early phase of its

appearance in Israel: thick white slip and bichrome decoration on

some of the vessels with narrow, close-set lines, similar to

the Mycenaean “close style”; the bird motif is limited to

stratum XII (only one example was found in stratum XI).

The ceramic assemblage of stratum XI is similar to that

of stratum XII. However, a change is discernible in the

Philistine pottery: there is a deterioration in ornamentation, and monochrome decorations become more frequent.

Other finds in this stratum include bronze arrowheads, a

bone graver, spindle whorls, flint sickle blades, numerous

loom weights, and various stone objects, such as grindstones

and mortars. Iron objects were not found in Area A in strata

XII and XI’ (Dothan and Dunayevsky 1993).

[16] Samaria (Shechem)

Estimated period of occurrence: 784–750 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘In the Shechem essay it was argued that the end

of Shechem 9b correlates to the end of Samaria Building Period 2.

Excavations at Shechem 9b yielded evidence

that it had been destroyed by an earthquake, and this was

interpreted as the level destroyed by the earthquake of

Uzziah’s day. Since the end of Samaria 2 correlates to the

end of Shechem 9b, this means the destruction of Samaria 2

could well have resulted from the same earthquake. Wright

describes the destruction of Samaria 2 (which required a

rebuilding under Samaria 3):

“In Period III a wholesale rebuilding of the

structure adjacent to the northern enclosure walls, and also of

the royal palace to the west, suggests that a catastrophe had

brought Period II to a close . . . The stones employed for this

purpose were re-used from earlier buildings; some still had

plaster adhering to them. The date for this period is given as

ca. 840–800 B.C. [sic].” (BASOR, 155, pp. 18–19.)

The 2nd ceramic phase in use at the time of the

earthquake (as we are interpreting it) was used as fill for

Jeroboam’s rebuilding operations – i.e., Building Period 3.

From this point on until the destruction of Samaria, the 3rd

Ceramic Phase developed. This is enough time to allow for

Wright’s view that the difference between Pottery Periods

3 & 4 was of a “similar interval” to the difference between

Pottery Periods 2 & 3. The time would be from 783 BC to

721 BC – 62 years, the date of Sargon’s capture of the city.

The date of Uzziah’s earthquake

According to Wright, the Ostraca House of

Samaria correlates with Building Period 3 . . . In his article,

“The Samaria Ostraca: An Early Witness to Hebrew Writing,” Ivan T. Kaufman points out that the ostraca were not

found on the floor of the Ostraca House but were found

in the fill underlying it. This was affirmed also by Anson

F. Rainey . . . From this, we can infer that the ostraca were

found in the fill of Building Period 3, and hence would correlate to our 2nd ceramic phase. If the 2nd ceramic phase

was brought to an end by Uzziah’s earthquake, as we have

argued, then it may be possible to link the ostraca to the

earthquake. This is of considerable importance, because

one thing we know about these ostraca is that they can be

dated. Some of the ostraca are dated to the 15th year of an

unnamed king, and some are dated to the 9th or 10th years of

an unnamed king. The lack of any intervening years, among

other things, led Kaufman and Rainey to regard these years

as belonging to a single date of two co-regent kings, rather

than to different dates of one king (cf., Kaufman, p. 235.).

We cannot go into great detail about it, but the conclusion of

Anson Rainey’s discussion of these finds is that they should

be dated to 784/783 BC, during the time of Jeroboam 2.

Thus, the ostraca are something like a stopped watch during

an accident or explosion. Just as the watch gives the actual

time of the accident or explosion, so the ostraca provide, on

our theory, the actual year of the earthquake, c. 783 BC.

Courville himself dated the earthquake of Uzziah’s

day to 751–750 B.C, based on a Jewish legend reported

by Josephus. (Exodus Problem, 2:122–23.) The prophet

Zechariah is quoted as a source indicating the severity of

the earthquake . . . Josephus claimed that the earthquake was

God’s judgment on Uzziah for his attempt to burn incense

to the Lord, a rite reserved to the priests alone (2 Chr.

26:17–18). Josephus speaks of a rent made in the temple,

and bright sunlight falling on the king’s face, as he was

seized with leprosy. The king’s son, Jotham, perforce had to

become the acting king, c. 750 B.C., while Uzziah remained

in a quarantined house for the rest of his reign. Courville

concludes from this that the earthquake must have happened in the year 751–750 B.C.’ (Crisler 2004).

[17] Tell Deir Alla

Estimated period of occurrence: 800–750 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘I have already mentioned that the site was shaken

by earthquake round 1200 B.C. The destruction of the

buildings of Phase M, the phase to which the Aramaic

text belongs, was also caused by an earthquake. Deir Alla

has suffered more earthquakes, not only during the time

of habitation but also afterwards. These earthquakes and

tremors caused vertical cracks which in the excavated area

run mostly in east–west direction. When tracing the frequency of these cracks along a north–south line we find

at least one every twenty cms. The tell is thus cut into vertical slices and these slices may have sunken for instance

from a few cms. to several cms. and sometimes shifted sideways, whereas most of them apparently under the pressure

from higher parts of the tell are inclined to lean out to the

north. Expressed in geological terms we have found, be it in

miniature size normal faults and even pivot faults. Cracks

reaching the present surface must have been caused after the

tell had reached that height and cannot therefore be dated

to the stratigraphy . . .Moreover, unless all the cracks that

run through the deposits overlying Phase M and their exact

position had been recorded, we would not be able to say

whether any cracks seen in Phase L stop at the floor levels

of Phase M. However we had several other indications. We

have recorded cracks and shifts of material that run through

the ruined buildings but stop at the point where erosion

began to level off the debris. These were caused by a second shock which followed the first one after the buildings

collapsed and the fire caused by the earthquake had burned

itself out. I shall have to refer to the second shock in relation

to the position of the text.

However, the first shock was also recorded. There

is a long crack about 10 cms. wide running through the

deposits of a little lane which formed during Phase M and

is almost 60 cms. high. This crack is closed further to the

east but here a horizontal shift could be seen because the

crack runs lengthwise through the low stump of a mud brick

wall. The clay mortar between the bricks on both sides of

the crack does not fit together any longer. The horizontal

shift was about 10 cms. Such cracks have not only been

recorded on paper but also on “pull offs”, a method used

in agriculture to take a thin slice of earth to the laboratory

(Franken 1965b), in order to keep an authentic record of

the accumulation of deposits. The slice is thick enough to

make samples from it for microscopic analysis. Incidentally

horizontal shifts of more than 30 cms. were recorded. It was

the second shock which brought the preserved fragments of

the Aramaic text down from their support’ (Franken 1976,

7–8).

‘We have seen that Phase M consists of traces of a

situation that must have existed one day in the past when

an earthquake hit the site and traces of the impact of the

first and the second earthquake shock. We must now

consider the value of the interpretation of Phase M as a

sanctuary. The earthquake has nothing to do with this

interpretation, but had it not been for the earthquake the text

might not have been preserved. Also thanks to the earthquake many objects were found which otherwise might have

disappeared for ever. The plan of the buildings has to be

partly hypothetically reconstructed since some walls were

dislocated at floor level leaving barely any traces of where

they stood before the destruction. Also a number of objects

like the text were knocked about when the shocks hit the

site. In contrast to two earlier earthquake phases we did

not find human victims in the ruins. This may indicate that

the disaster took place during daylight but it seems more

likely that the destruction happened at night when there was

nobody in these rooms. Somewhere there was a fire burning in a breadoven or otherwise, because the first shock was

followed by a conflagration, wooden objects burned away

like the looms, of which we found the clay weights in several rooms, and charred beams which may also partly have

belonged to other wooden furniture. But what was left, the

less perishable objects, was found and reconstructed as far

as possible’ (Franken 1976, 12).

‘Pl. 16a shows the plan of four rooms. On this

plan the entrance to room GG205 from the south is located

between walls BB 320 and BB 427. When found this

entrance was blocked by a wall fragment. The blockage may

have been caused by the earthquake. In the corner formed

by wall BB 320 and the blocked doorway eighteen burned

clay loom weights were found lying on the floor. Eighty

cms. north of the corner and lying against wall BB 320

inside room GG 205 three remarkable objects were found

in the debris on the floor: the inscribed stone, a goblet on a

high foot with a spout (R. no. 1990) and an outsize loom

weight (R. no. 2006). A large piece of charred wood lay

beside these objects in front of the passage between rooms

GG 205 and GG 102. The goblet (pl. 16b) was only slightly

damaged near the rim; the stone and loom weight were complete . . .’ (Franken 1976, 15).

‘This phase IX is the same as phase M in previous

countings. Much of it had been excavated in 1967 in an area

of c. 25 × 25 m NW of the trenches dug during the last three

seasons. Much of the architecture had been revealed, and

some of it has been published preliminarily in J. Hoftijzer,

G. van der Kooij, Aramaic Texts from Deir Alla, Leiden,

1976, (Pls. 16–19) and in A.D.A.J. op. cit. 1978, p. 64, fig. 6

(square B/C5). During this season excavations of phase M

were done in one square only, namely in B/C6, to the E of

B/C5, labeled EE 400 and EE 300 respectively in 1967. In

1967 it became clear that all the phase M architecture excavated had been destroyed by earthshock and fire. The room

found in B/C6 was destroyed by fire too.

The walls are partly still standing up to 1.25 m high,

and the room is found filled with burnt roof and wall debris.

For a plan of the walls combined with those of B/C5 see

plan drawing (fig. 5). The height of the debris (deposits 61

and 63) is shown on (Pl. XX, 2) where the floor is visible as well as the E most part of the burnt debris. Note

also the lower course of mudbricks 57 going N–S at the top

of the photograph. To the left is a doorway with a quern

at the threshold. See also (Pl. XXI, 1) for a photograph of

one stage in the removal of the debris inside the room. In

the NW corner the floor of the room is visible. An especially interesting feature is the antler found as fallen almost

directly on the floor of the room (Pl. XXI, 2). Some of the

artifacts found may be mentioned here. Plates (XXVIII, 2–

XXIX, 2) show some of the pottery found. A sealed jar

handle (see Pl. XXX, 1). A shard with graffiti writing and

drawing (Pl. XXX, 2). Phase IX probably has to be dated

in the 8th century B.C. (Pl. XXXI)’ (Ibrahim and Kooij

1979, 48–50).

‘The empirical evidence at Deir Alla, dated to

the mid-8th century BE, perhaps by the famous “Balaam

Inscription”, is stronger’ (Dever 1992, 35 n. 10).

‘The details of their language [of the texts], restoration,

script, reading, and interpretation are still under discussion;

however, following a preliminary palaeographic

dating to the Persian period, and then in the editio princeps to about 700 BCE (Hoftijzer and Kooij, 1976), most

commentators now agree that the palaeography fits the dating of the archaeological context: about 800 BCE (Hoftijzer

and Kooij, 1991) or the first half of the eighth century BCE.

Indeed, the earthquake that destroyed level M/IX at Deir

Alla could well be the one mentioned in Amos 1:1 (cf. Also

4:11, 6:8–11, 8:8, and 9:1; and Zec. 14:5), dated to about 760

BCE’ (Lemaire 1997, 139).

[18] Tell al Hama

(Mazar 1993, 208 = ?).

[19] Tell al Saiidiyeh

(Mazar 1993, 208 = ?).

[20] Khirbet al Asiq (En Gev)

(Dever 1992, 34 n. 10 = n.d.).

[21] Tel Mevorakh

(Mazar 1993, 298 = ?).

[22] Megiddo

Estimated period of occurrence: c. 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘What did we excavate in the season of 2000 in

Area H? At the lowest level, we reached an elaborate

semi-monumental building added to a pre-existing, small-scale

domestic occupation (Phase H6b). The monumental building was never finished; it may have housed some squatters in

the period of its abandonment (Phase H6a). Squatter occupation continued in the ruins (Phase H5d), followed by the

construction of city Wall 325 (Phase H5c). It is obvious

from the inclination of the Area H surfaces that Wall 325

represents the first city wall of Iron Age Megiddo. Throughout the different phases of occupation of Level H5, Area H

is devoid of architecture; it contains a sequence of more than

20 floor levels with abundant traces of open-air domestic

activity. There was domestic architecture immediately to the

south of Area H (unexcavated), for the occupation of Phase

H5a was terminated by an earthquake, which cracked the

city wall and strewed parts of walls of these southern buildings all over Area H. Our Phases H6b–a should be assigned

to the University of Chicago’s Stratum V, while our Phases

H5d–a (plus Levels H4 and H3 excavated in past seasons)

cover the time-span of the University of Chicago’s Stratum

IVA.

How to decipher all this historically? The commencement of elaborate construction in Level H6b testifies

to the prosperity at the end of the Omride dynasty as its

abandonment may reflect the consequences of Jehu’s revolt.

The destruction of Phase H6a and the subsequent squatter-occupation (H5d) illustrate the fate of

Israel under Aramaean domination (II Kgs 10:32–33; 13:3, 22).

The construction of the city wall in Level H5c indicates the

beginning of Israel’s recovery under Joash and Jeroboam II (II

Kgs 13:24f; 14:25–28). City Wall 325 was the wall of the city

conquered by Tiglat-pileser III in 733 BCE. The destruction

of Phase H5a should probably be attributed to the earthquake in the time of Jeroboam II, mentioned in Amos 1:1

and archaeologically also attested at Hazor and Tell Deir

’Alla in the Jordan Valley, where it toppled and buried the

stele with the famous Balaam-text.

Synchronizing the stratigraphy of Area H with the

biblical record is perfectly possible within the framework

of the “Low Chronology”. According to the traditional

chronology, Phase H6b (= University of Chicago’s VA)

should reflect the time of Solomon. The subsequent decline

would then be due to the demise of the “United Monarchy”

and the civil wars in Israel between Jeroboam I and Omri.

It would have been Omri or Ahab who built city Wall 325

But then, the earthquake of Jeroboam II’s time would not

have left any trace in the occupational deposits, whereas the

earthquake in our Phase H5a escaped the attention of the

ancient texts’ (Knauf 2002).

‘In the summer of 2000 we carried out fieldwork

at Megiddo, with the aim of tracing evidence of ancient

earthquakes. We were looking for structural damage such

as tilted walls, cracks and fractures in stones etc. We located

about a dozen spots with possible evidence for tectonic

activity. Following are three examples.

Extension cracks occur in the six-chambered, Iron

II gate complex. Rows of ashlars in the middle of the walls

(enclosed between other rows) are fractured. Horizontal

sliding of the fragments occurred everywhere in the same

direction, nearly parallel to the face of the wall. The damage was probably caused by earthquake-related horizontal

shaking. The 8th century Stratum III gate built on top of the

six-chambered gate is not damaged. Therefore, this event

may be linked to the biblical reference to a major earthquake in the time of Jeroboam II, ca. 760 BCE.

In Area L, the stone and plaster floors of the Stratum IVA “stables” are level, while the walls and fills of

Stratum VA–IVB Palace 6000 are tilted. This indicates a

deformation after the construction of the palace, but before

the building of the “stables”, a deformation which may be

linked to the 8th century event mentioned above’ (Shmulik

and Amotz 2002).

[23] Tell Abu Hawam

Estimated period of occurrence: 1126–1050 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘Stratum IVA (dates) from c. 1125 to c. 1050 B.C.

This city was violently destroyed, possibly by earthquake’

(Warren and Hankey 1989, 161).

[24] Tel Hazor

Estimated period of occurrence: 760 BC.

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘Stratum VI was found to have been destroyed by

a violent earthquake which could be associated with the one

mentioned in Zechariah (14:5) and Amos (1:4) in the days

of King Uzziah, c. 760 B.C.’ (Yadin 1972, 11).

‘Stratum VI, Area A, Building 2a.

The house was severely damaged by an earthquake; all the walls and pillars were tilted southwards. In

all the rooms, as well as in the western part of the court,

huge blocks of ceiling plaster were found sealed off by the

floors of Stratum V, which were built 1.5 m. above the floors

of Stratum VI. The reason for this is that, although the walls

of Stratum VI were still standing after the earthquake, they

were so tilted that only their tops could be used, and even

those only as a base for the new foundations. The earthquake which destroyed Stratum VI seems to be the one

referred to in the Bible, which occurred during the reign of

King Uzziah (c. 760 B.C.)’ (Yadin 1972, 181)

‘Area A, Stratum VI, Building 2a.

Due to the excellent construction of building 2a, we

can trace in it the effects of the earthquake which destroyed

Stratum VI better than anywhere else in the excavation area.

Its strongly-built walls remained standing to a considerable

height, but the earthquake is evidenced by their tilt southwards, particularly that of the three pillars (Pl. XXV, 2). In

all the rooms and in the northern part of the courtyard, we

came upon great quantities of debris comprising lumps of

plaster from the collapsed ceilings (Pl. XXVII, 1, 4), resembling those that we found in storeroom 148 in 1956 (Hazor

I, p. 23)’ (Bent-Tor 1989, 41–44).

‘A later, more modest effort to utilize seismic

chronology was that of the late Yigael Yadin, who saw the

destruction of Hazor VI (Area A) as dramatic evidence of

the earthquake of ca. 760 BCE, citing the biblical texts mentioned above. Despite the clear evidence of several displaced

walls and cracked surfaces at Hazor, Yadin’s earthquake

hypothesis does not seem to have attracted much attention. This was possibly because of the author’s well known

predilection towards using biblical texts to explain or corroborate archaeological phenomena – a style of “biblical

archaeology” that Yadin popularized with enviable success,

but one that left some of his professional colleagues skeptical.

Nevertheless, when the Hazor excavations were

resumed in 1990 under the direction of Amnon Ben-Tor,

further evidence of a Stratum VI earthquake came to light,

especially in a street and drain in Area A that seemed simply to have split down the centre – difficult to explain by

any other hypothesis. And since Stratum VI dates to the

early 8th century BCE on independent grounds (as one may

maintain, with Yadin), the well known earthquake of ca.

760 BCE seems a likely candidate’ (Dever 1992, 28).

‘The destruction of Phase H5a [in Megiddo]

should probably be attributed to the earthquake in the time

of Jeroboam II, mentioned in Amos 1:1 and archaeologically also attested at Hazor and Tell Deir Alla . . .’ (Knauf

2002).

[25] Jerusalem

Estimated period of occurrence: 760–750 BC. (Guidoboni

1989, 632 n. 17).

Extract of pertinent statement by author relating to earthquake damage:

‘Going further back in time, the Bible records

Zechariah’s prophecy, based upon the description of a large

earthquake which occurred during the reign of King Uzziah

around 760 BC: “ . . . and the Mount of Olives shall cleave

in the midst thereof toward the E and toward the W, and

there shall be a very great valley; and half of the mountain

shall remove toward the N, and half of it toward the S. And

ye shall flee . . . like as ye fled from before the earthquake in

the days of Uzziah King of Judah” (Zechariah, Chapter 14,

Verse 4–5).

This earthquake happened probably somewhere E

of Jerusalem, most likely along the Jericho fault. Apparently, the offset of the rocks across it was great enough to

reveal the northward slip of the eastern side relative to the

southward slip of the western side. This motion is remarkably similar to the motion observed in the 1927 Jericho

earthquake, and is, of course, consistent with the N–S movement of the plates in this area’ (Nur and Ron 1996, 81).

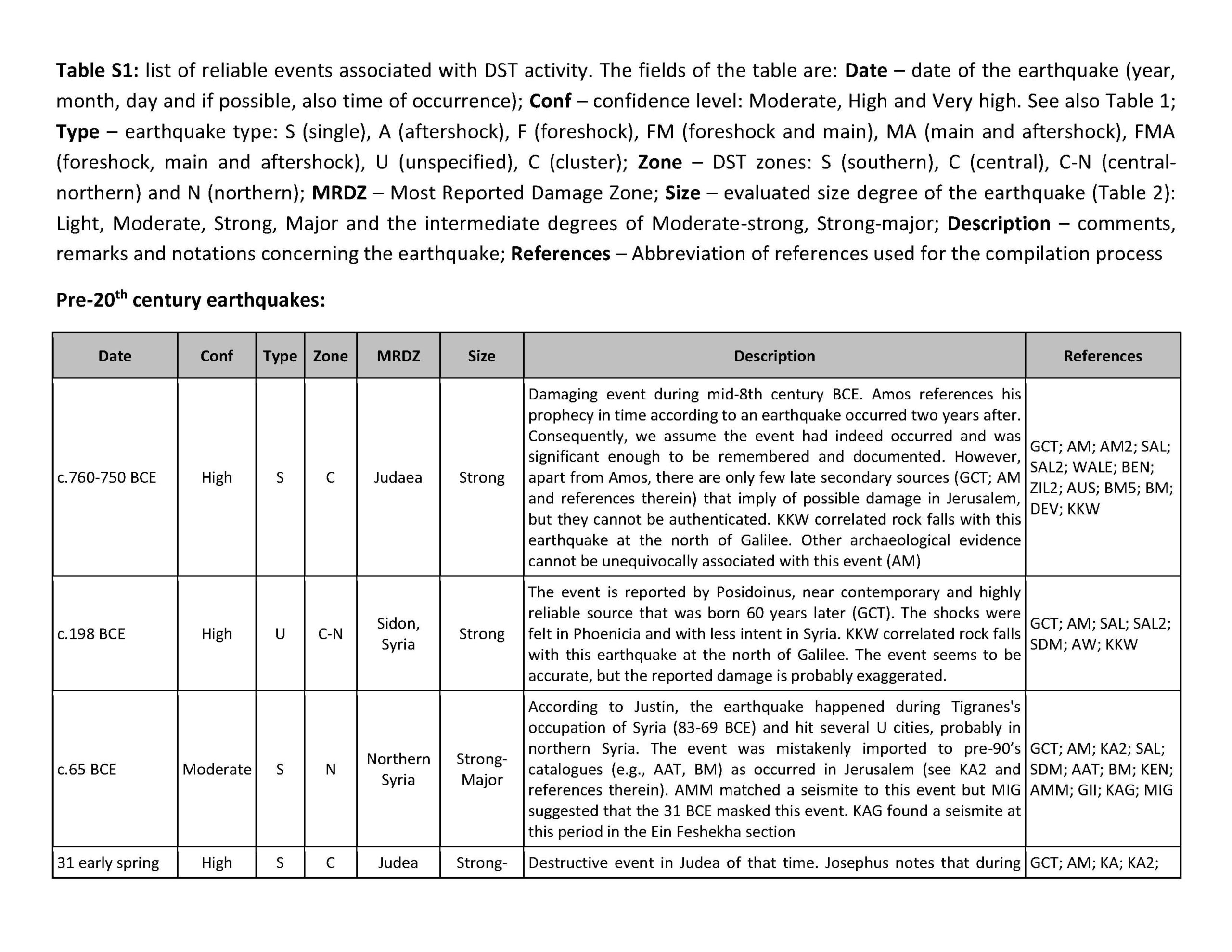

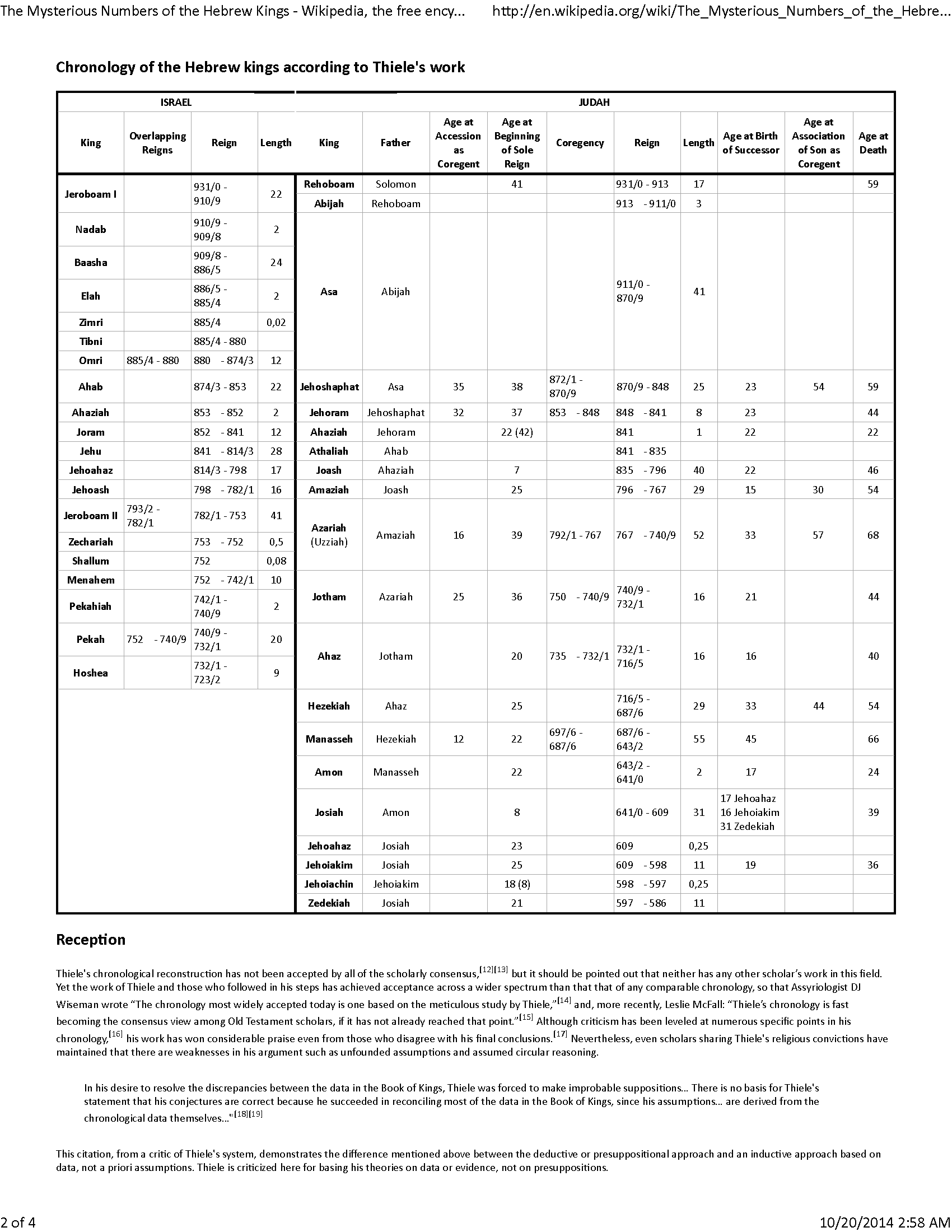

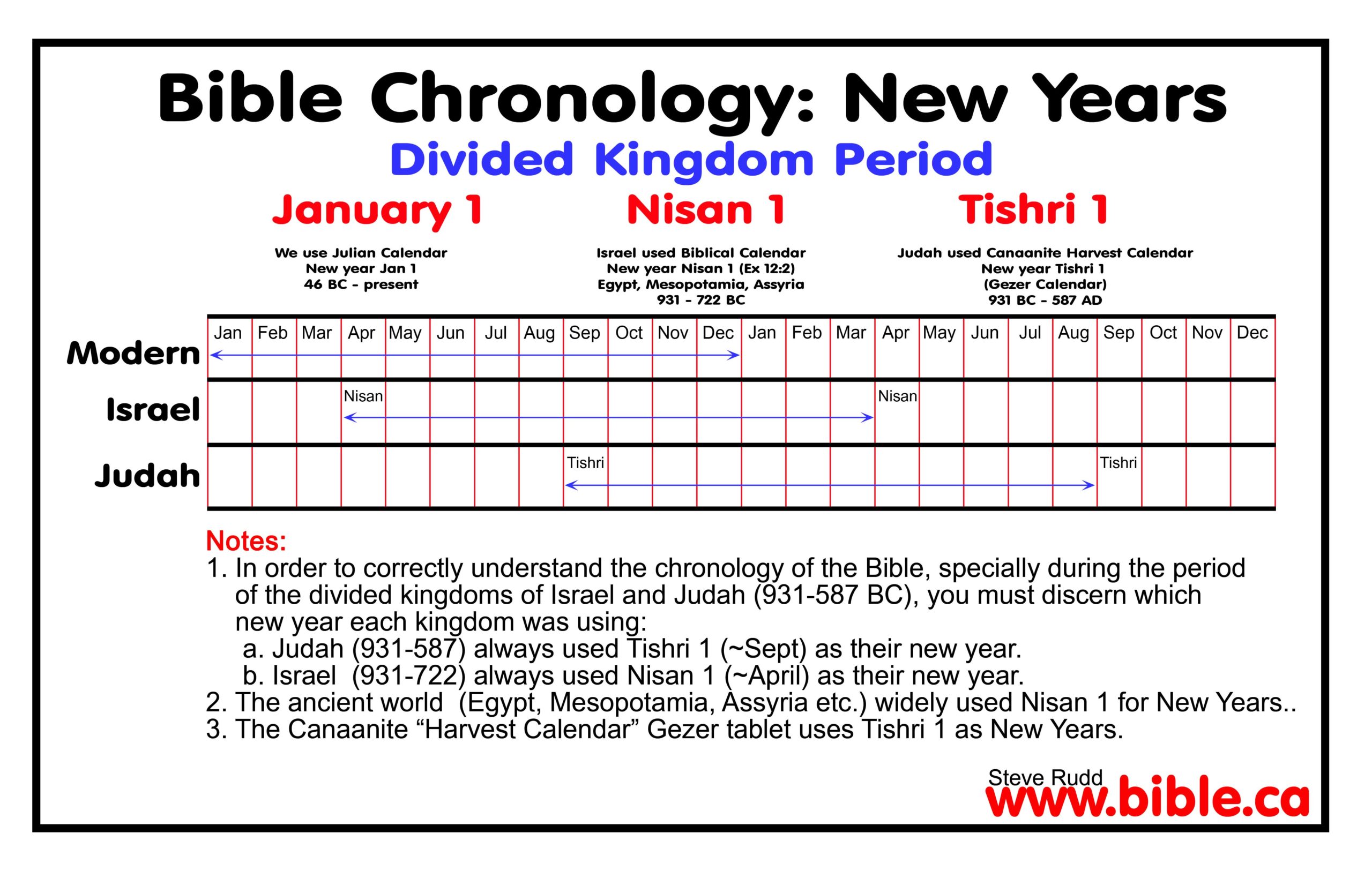

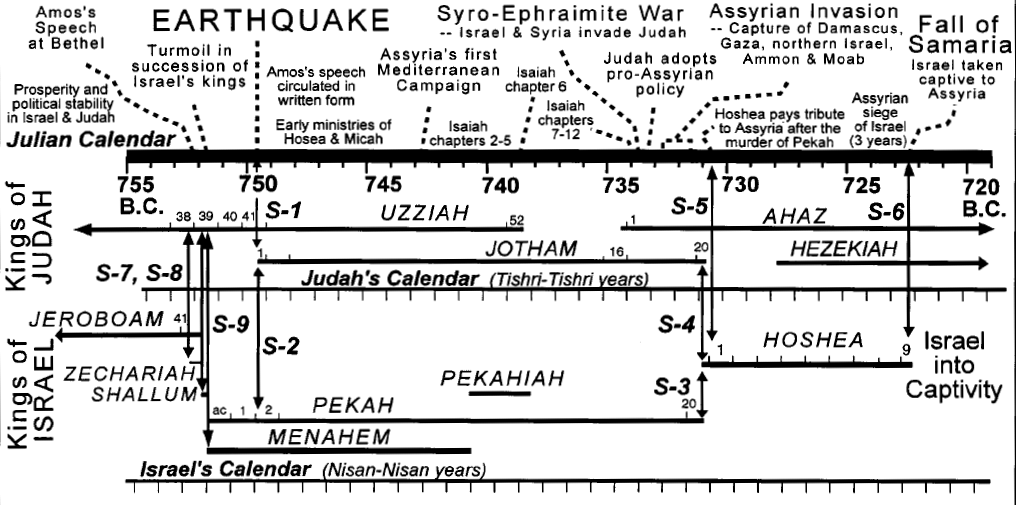

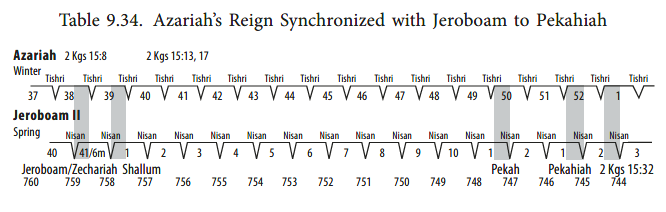

Fig. 6 - Time line showing the historical context and dating of Amos's earthquake.

Synchronisms, which are shown as vertical arrows under the time line, allow Amos's earthquake to be dated to 750 B.C.

The chronology of Hebrew kings follows Thiele (1983) with slight revisions by Finegan (1998).

Fig. 6 - Time line showing the historical context and dating of Amos's earthquake.

Synchronisms, which are shown as vertical arrows under the time line, allow Amos's earthquake to be dated to 750 B.C.

The chronology of Hebrew kings follows Thiele (1983) with slight revisions by Finegan (1998). from Onstott (2015)

from Onstott (2015)